i

iProject Gutenberg's In Wildest Africa Vol 2 (of 2), by Carl Georg Schillings This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: In Wildest Africa Vol 2 (of 2) Author: Carl Georg Schillings Release Date: June 16, 2017 [EBook #54923] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IN WILDEST AFRICA VOL 2 (OF 2) *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Kim, Wayne Hammond and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

i

i

ii

iii

v

| CHAP | PAGE | |

| VIII. | IN A PRIMEVAL FOREST | 319 |

| IX. | AFTER ELEPHANTS WITH WANDOROBO | 370 |

| X. | RHINOCEROS-HUNTING | 431 |

| XI. | THE CAPTURING OF A LION | 470 |

| XII. | A DYING RACE OF GIANTS | 511 |

| XIII. | A VANISHING FEATURE OF THE VELT | 550 |

| XIV. | CAMPING OUT ON THE VELT | 578 |

| XV. | NIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY UNDER DIFFICULTIES | 637 |

| XVI. | PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAY AND BY NIGHT | 657 |

vi

vii

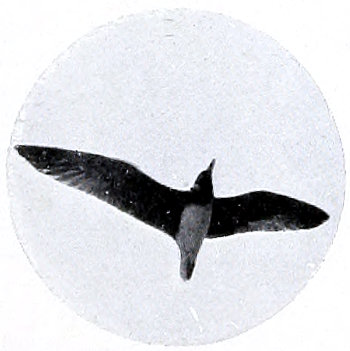

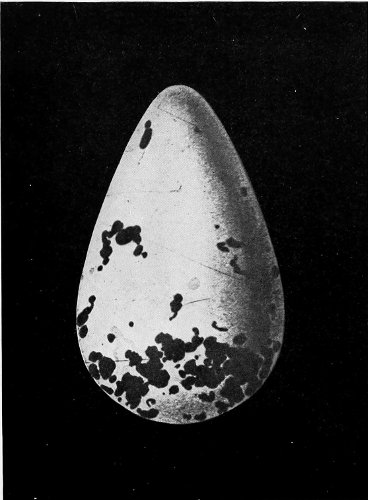

CORMORANTS.

List of Illustrations in Vol. II

CORMORANTS.

List of Illustrations in Vol. II319

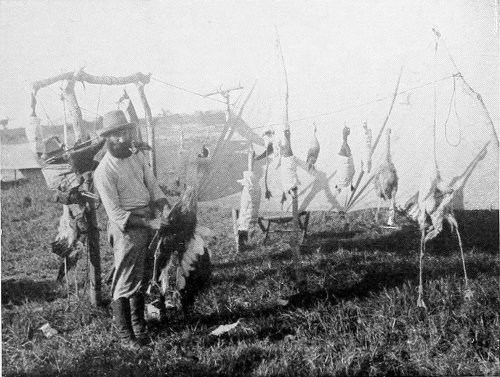

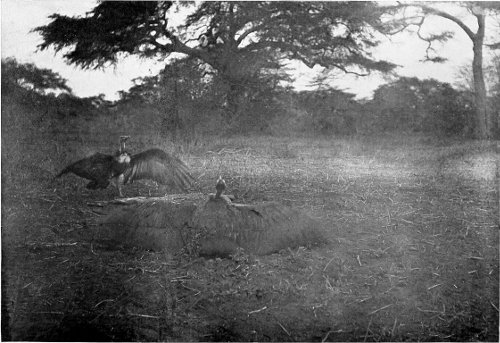

SPURRED GEESE (PLECTROPTERUS GAMBENSIS).

VIII

SPURRED GEESE (PLECTROPTERUS GAMBENSIS).

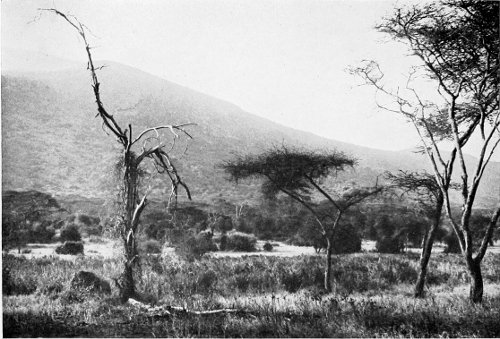

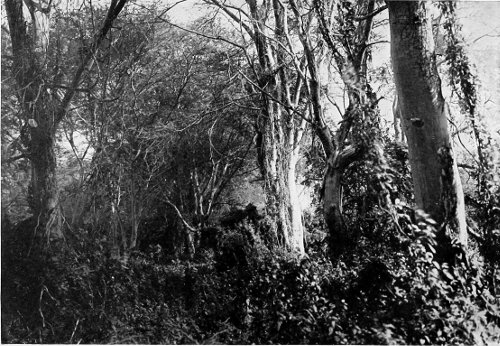

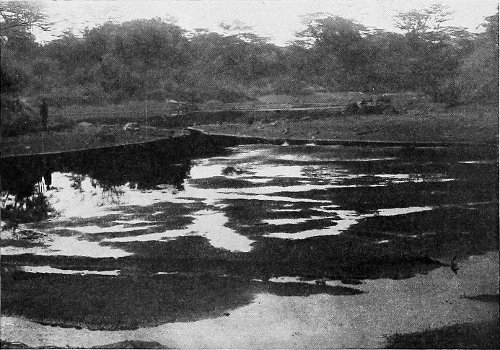

VIIIScenes of marvellous beauty open out before the wanderer who follows the windings of some great river through the unknown regions of Equatorial East Africa.

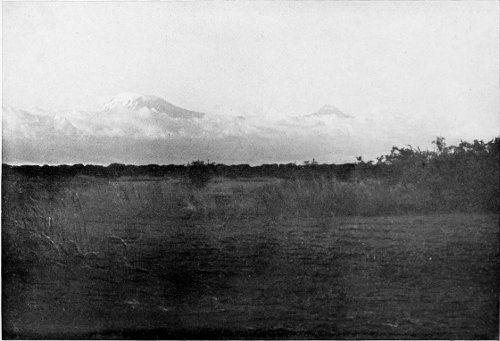

The dark, turbid stream is to find its way, after a thousand twists and turns, into the Indian Ocean. Filterings from the distant glaciers of Kilimanjaro come down into the arid velt, there to form pools and rivulets that traverse in part the basin of the Djipe Lake and at last are merged in the Rufu River. As is so often the case with African rivers, the banks of the Rufu are densely wooded throughout its long course, the monotony of which is broken by a number of rapids and one big waterfall. Save in those rare spots where the formation of the soil is favourable to their growth, the woods do not extend into the velt. Trees and shrubs alike become parched 320 a few steps away from the sustaining river. The abundance of fish in the river is tremendous in its wilder reaches—inexhaustible, it would seem, despite the thousands of animal enemies. The river continually overflows its banks, and the resulting swamps give such endless opportunities for spawning that at times every channel is alive with fry and inconceivable multitudes of small fishes.

It is only here and there and for short stretches that the river is lost in impenetrable thickets. Marvellous are those serried ranks of trees! marvellous, too, the sylvan galleries through which more usually it shapes its way! They take the eye captive and seem to withhold some unsuspected secret, some strange riddle, behind their solid mass of succulent foliage. It is strange that these primeval trees should still survive in all their strength with all the parasitic plants and creepers that cling to them, strangling them in their embrace. You would almost say that they lived on but as a prop to support the plants and creepers in their fight for life. Convolvuli, white and violet, stoop forward over the water, and the golden yellow acacia blossoms brighten the picture.

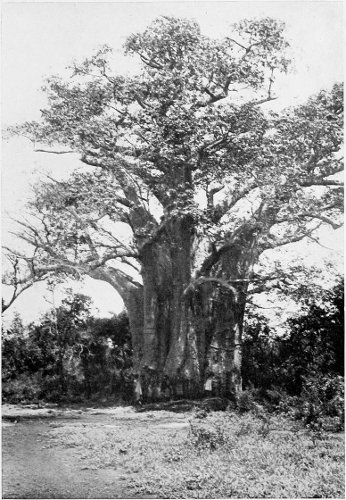

In the more open reaches dragonflies and butterflies glisten all around us in the moist atmosphere. A grass-green tree-snake glides swiftly through the branches of a shrub close by. A Waran (Waranus niloticus) runs to the water with a strange sudden rustle through the parched foliage. Everywhere are myriads of insects. Wherever you look, the woods teem with life. These woods screen the river from the neighbouring velt, the uniformity of which is but seldom broken in upon by 321 322 323 324 325 patches of vegetation. The character of the flora has something northern about it to the unlearned eye, as is the case so often in East Africa. It is only when you come suddenly upon the Dutch palms (Borassus æthiopicus, Mart., or the beautiful Hyphæne thebaica, Mart.) that you feel once again that you are in the tropics.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

VIEW OF MAWENZI, THE HIGHEST PEAK BUT ONE OF KILIMANJARO, TAKEN WITH A TELEPHOTO-LENS.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

VIEW OF KILIMANJARO, TAKEN AT SUNSET.

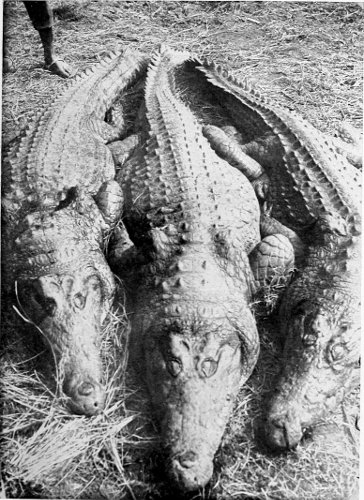

The river now makes a great curve round to the right. A different kind of scene opens out to the gaze—a great stretch of open country. In the foreground the mud-banks of the stream are astir with huge crocodiles gliding into the water and moving about this way and that, like tree-trunks come suddenly to life. Now they vanish from sight, but only to take up their position in ambush, ready to snap at any breathing thing that comes unexpectedly within their reach. Doubtless they find it the more easy to sink beneath the surface of the river by reason of the great number of sometimes quite heavy stones they have swallowed, and have inside them. I have sometimes found as much as seven pounds of stones and pebbles in the stomach of a crocodile.

The deep reaches of the river are their special domain. Multitudes of birds frequent the shallows, knowing from experience that they are safe from their enemy. One of the most interesting things that have come under my observation is the way these birds keep aloof from the deep waters which the crocodiles infest. I have mentioned it elsewhere, but am tempted to allude to it once again.

Our attention is caught by the wonderful wealth of bird-life now spread out before us in every direction. Here comes a flock of the curious clatter-bills (Anastomus 326 lamelligerus, Tem.) in their simple but attractive plumage. They have come in quest of food. Hundreds of other marsh-birds of all kinds have settled on the outspread branches of the trees, and enable us to distinguish between their widely differing notes.

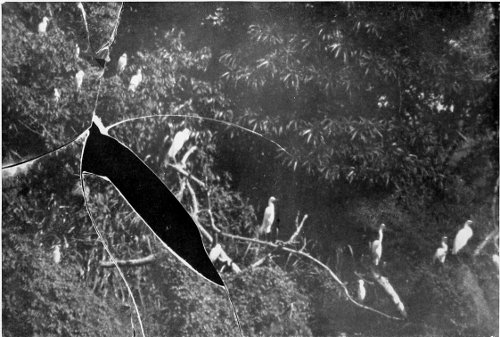

Among these old trees that overhang the river, covered with creepers and laden with fruit of quaint shape, are Kigelia, tamarinds, and acacias. In amongst the dense branches a family of Angolan guereza apes (Colobus palliatus, Ptrs.) and a number of long-tailed monkeys are moving to and fro. Now a flock of snowy-feathered herons (Herodias garzetta, L., and Bubulcus ibis, L.) flash past, dazzlingly white—two hundred of them, at least—alighting for a moment on the brittle branches and pausing in their search for food. Gravely moving their heads about from side to side, they impart a peculiar charm to the trees. Now another flock of herons (Herodias alba, L.), also dazzlingly white, but birds of a larger growth, speed past, flying for their lives. Why is it that even here, in this remote sanctuary of animal life, within which I am the first European trespasser, these beautiful birds are so timorous? Who can answer that question with any certainty? All we know is, that it has come to be their nature to scour about from place to place in perpetual flight. Perhaps in other lands they have made acquaintance with man’s destructiveness. Perhaps they are endowed with keener senses than their smaller snow-white kinsfolk, which suffer us to approach so near, and which, like the curious clatter-bill (which have never yet been seen in captivity), evince no sign of shyness—nothing 327 328 329 but a certain mild surprise—at the sight of man.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

KIBO IN THE FOREGROUND, WITH THE SADDLE-SHAPED RANGE CONNECTING IT WITH MAWENZI IN THE DISTANCE. THE AVERAGE HEIGHT OF THIS “SADDLE” IS MORE THAN 16,OOO FEET.

Now, with a noisy clattering of wings, those less comely creatures, the Hagedasch ibises, rise in front of us, filling the air with their extraordinary cry: “Heiha! Ha heiha!”

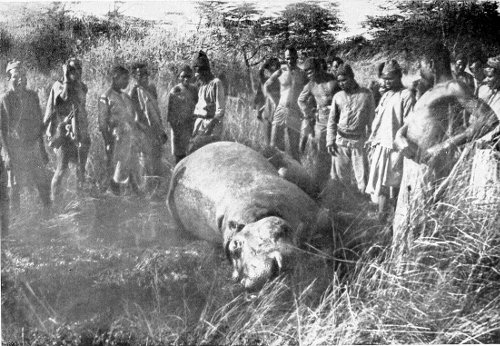

Now we have a strange spectacle before our eyes—a number of wild geese, perched upon the trees. The great, heavy birds make several false starts before they make up their minds to escape to safety. They present a beautiful sight as they make off on their powerful wings. They are rightly styled “spurred geese,” by reason of the sharp spurs they have on their wings. Hammerheads (Scopus umbretta, Gm.) move about in all directions. A colony of darters now comes into sight, and monopolises my attention. A few of their flat-shaped nests are visible among the pendent branches of some huge acacias, rising from an island in mid-stream. While several of the long-necked fishing-birds seek safety in flight, others—clearly the females—remain seated awhile on the eggs in their nests, but at last, with a sudden dart, take also to their wings and disappear. Beneath the nesting-places of these birds I found great hidden shaded cavities, the resorts for ages past of hippopotami, which find a safe and comfortable haven in these small islands.

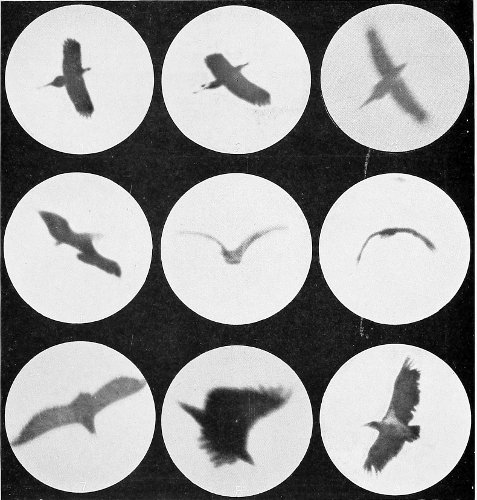

The dark forms of these fishing-birds present a strange appearance in full flight. They speed past you swiftly, looking more like survivals from some earlier age than like birds of our own day. There is a suggestion of flying lizards about them. Here they come, describing a great 330 curve along the river’s course, at a fair height. They are returning to their nests, and as they draw near I get a better chance of observing the varying phases of their flight.

But look where I may, I see all around me a wealth of tropical bird-life. Snow-white herons balance themselves on the topmost branches of the acacias. Barely visible against the deep-blue sky, a brood-colony of wood ibis pelicans (Tantalus ibis, L.) fly hither and thither, seeking food for their young. Other species of herons, notably the black-headed heron, so like our own common heron (Ardea melanocephala, Vig., Childr.), and further away a great flock of cow-herons (Bubulcus ibis, L.), brooding on the acacias upon the island, attract my attention. Egyptian Kingfishers (Ceryle rudis, L.) dart down to the water’s edge, and return holding tiny fishes in their beaks to their perch above.

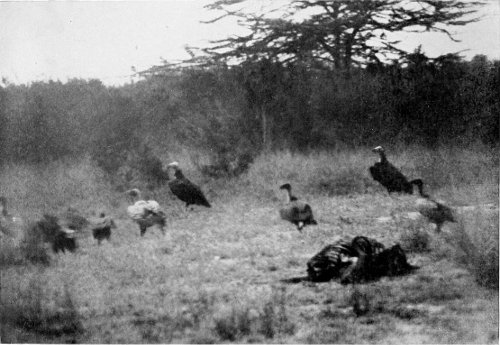

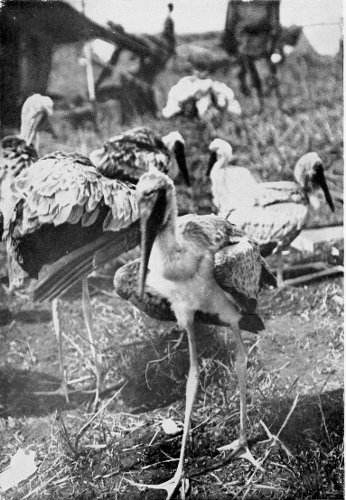

The numbers and varieties of birds are in truth almost bewildering to the spectator. Here is a marabou which has had its midday drink and is keeping company for the moment with a pair of fine-looking saddled storks (Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis, Shaw); there great regiments of crested cranes; single specimens of giant heron (Ardea goliath, Cretzschm.) keep on the look-out for fish in a quiet creek; on the sandbanks, and in among the thickets alongside, a tern (Œdicnemus vermiculatus, Cab.) is enjoying a sense of security. Near it are gobbling Egyptian geese and small plovers. A great number of cormorants now fly past, some of them settling on the branches of a tree which has fallen into the water. They are followed by Tree-geese (Dendrocygna viduata, L.), 331 332 333 some plovers and night-herons, numerous sea-swallows as well as seagulls; snipe (Gallinago media, Frisch.), and the strange painted snipe (Rostratula bengalensis, L.), the Actophylus africanus, and marsh-fowl (Ortygometra pusilla obscura, Neum.), spurred lapwing (Hoplopterus speciosus, Lcht.), and many other species. Now there rings out, distinguishable from all the others, the clear cry—to me already so familiar and so dear—of the screeching sea-eagle, that most typical frequenter of these riverside regions of Africa and so well meriting its name. A chorus of voices, a very Babel of sound, breaks continually upon the ear, for the varieties of small birds are also well represented in this region. The most beautiful of all are the cries of the organ-shrike and of the sea-eagle. The veritable concerts of song, however, that you hear from time to time are beyond the powers of description, and can only be cherished in the memory.

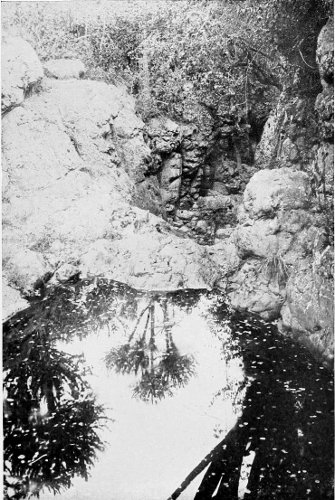

C. G. Schillings, phot.

RIVER-BED VEGETATION ON THE VELT.

There is a glamour about the whole life of the African wonderland that recalls the forgotten fairy tales of childhood’s days, a sense of stillness and loveliness. Every curve of the stream tells of secrets to be unearthed and reveals unsuspected beauties, in the forms and shapes of the Phœnix palms and all the varieties of vegetation; in the indescribable tangle of the creepers; in the ever-changing effects of light and shade; finally in the sudden glimpses into the life of the animals that here make their home. You see the deep, hollowed-out passages down to the river that tell of the coming and going of the hippopotamus and rhinoceros, made use of also by the crocodiles. It is with a shock of surprise that you see a specimen of our 334 own great red deer come hither at midday to quench his thirst—a splendid figure, considerably bigger and stronger than he is to be seen elsewhere. A herd of wallowing wart-hogs or river-swine will sometimes startle you into hasty retreat before you realise what they are. The tree-tops rock under the weight and motion of apes unceasingly scurrying from branch to branch. Every now and again the eye is caught by the sight of groups of crocodiles, now basking contentedly in the sun, now betaking themselves again to the water in that stealthy, sinister, gliding way of theirs.

Not so long ago the African traveller found such scenes as these along the banks of every river. Nowadays, too many have been shorn of all these marvels. Take, for instance, the old descriptions of the Orange River and of the animal life met with along its course. No trace of it now remains.

I should like to give a picture of the animal life still extant along the banks of the Pangani. The time is inevitably approaching when that, too, will be a thing of the past, for it is not to be supposed that advancing civilisation will prove less destructive here.

So recently as the year 1896 the course of the river was for the most part unknown. When I followed it for the second time in 1897, and when in subsequent years I explored both its banks for great distances, people were still so much in the dark about it that several expeditions were sent out to discover whether it was navigable.

That it was not navigable I myself had long known. Its numerous rapids are impracticable for boats even in the 335 336 337 rainy season. In the dry season they present insuperable obstacles to navigation of any kind.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

A FISHERMAN’S BAG! THREE CROCODILES SECURED BY THE AUTHOR IN THE WAY DESCRIBED IN “WITH FLASHLIGHT AND RIFLE.”

The basin of the Djipe Lake in the upper reaches of the Pangani, and the Pangani swamps below its lower reaches, formed a kind of natural preserve for every variety of the marvellous fauna of East Africa. It was a veritable El Dorado for the European sportsman, but one attended by all kinds of perils and difficulties. The explorer found manifold compensation, however, for everything in the unexampled opportunities afforded him for the study of wild life in the midst of these stifling marshes and lagoons. The experience of listening night after night to the myriad voices of the wilderness is beyond description.

Hippopotami were extraordinarily numerous at one time in the comparatively small basin of the Djipe Lake. In all my long sojourn by the banks of the Pangani I only killed two, and I never again went after any. There were such numbers, however, round Djipe Lake ten years ago that you often saw dozens of them together at one time. I fear that by now they have been nearly exterminated.

Here, as everywhere else, the natives have levied but a small tribute upon the numbers of the wild animals, a tribute in keeping with the nature of their primitive weapons. Elephants used regularly to make their way down to the water-side from the Kilimanjaro woods. My old friend Nguruman, the Ndorobo chieftain, used to lie in wait for them, with his followers, concealed in the dense woods along the river. But the time came when the elephants ceased to make their appearance. The old hunter, whose body bore signs of many an encounter 338 with lions as well as elephants, and who used often to hold forth to me beside camp fires on the subject of these adventures, could not make out why his eagerly coveted quarry had become so scarce. Every other species of “big game” was well represented, however, and according to the time of the year I enjoyed ever fresh opportunities for observation. Generally speaking, it would be a case of watching one aspect of wild life one day and another all the next, but now and again my eyes and ears would be surfeited and bewildered by its manifestations. The sketch-plans on which I used to record my day’s doings and seeings serve now to recall to me all the multiform experiences that fell to my lot. What a pity it is that the old explorers of South Africa have left no such memoranda behind them for our benefit! They would enable us to form a better idea of things than we can derive from any kind of pictures or descriptions.

I shall try now to give some notion of all the different sights I would sometimes come upon in a single day. It would often happen that, as I was making my way down the Pangani in my light folding craft, or else was setting out for the velt which generally lay beyond its girdle of brushwood, showers of rain would have drawn herds of elephants down from the mountains.1 Even when I did not actually come within sight of them, it was always an intense enjoyment 339 340 341 342 343 to me to trace the immense footsteps of these nocturnal visitors. Perhaps the cunning animals would have already put several miles between my camp and their momentary stopping place. But their tracks afforded me always most interesting clues to their habits, all the more valuable by reason of the rare chances one has of observing them in daylight, when they almost always hide away in impenetrable thickets. What excitement there is in the stifled cry “Tembo!” In a moment your own eye perceives the unmistakable traces of the giant’s progress. The next thing to do is to examine into the tracks and ascertain as far as possible the number, age and sex of the animals. Then you follow them up, though generally, as I have said, in vain.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

CLATTER-BILLS SETTLING UPON THE BARE BRANCHES OF RIVERSIDE TREES.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

CLATTER-BILLS (ANASTOMUS LAMELLIGERUS, Tem.).

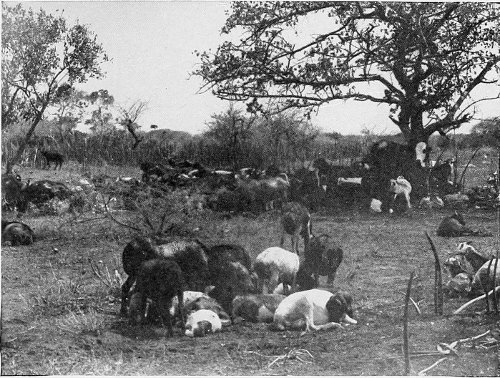

The hunter, however, who without real hope of overtaking the elephants themselves yet persists in following up their tracks just because they have so much to tell him, will be all the readier to turn aside presently, enticed in another direction by the scarcely less notable traces of a herd of buffaloes. Follow these now and you will soon discover that they too have found safety, having made their way into an impenetrable morass. To make sure of this you must perhaps clamber up a thorny old mimosa tree, all alive with ants—not a very comfortable method of getting a bird’s-eye view. Numbers of snow-white ox-peckers flying about over one particular point in the great wilderness of reeds and rushes betray the spot in which the buffaloes have taken refuge.

The great green expanse stretches out before you monotonously, and even in the bright sunlight you can see 344 no other sign of the animal life of various kinds concealed beneath the sea of rushes waving gently in the breeze. Myriads of insects, especially mosquitoes and ixodides, attack the invaders; the animals are few that do not fight shy of these morasses. They are the province of the elephants, which here enjoy complete security; of the hippopotami, whose mighty voice often resounds over them by day as by night; of the buffaloes, which wallow in the mud and pools of water to escape from their enemies the gadflies; and finally of the waterbuck, which are also able to make their way through even the deeper regions of the swamp. Wart-hogs also—the African equivalent of our own wild boars—contrive to penetrate into these regions, so inhospitable to mankind. We shall find no other representatives, however, of the big game of Africa. It is only in Central Africa and in the west that certain species of antelope frequent the swamps. In the daytime the elephant and the buffalo are seldom actually to be seen in them, nor does one often catch sight of the hippopotami, though they are so numerous and their voices are to be heard. As we grope through the borders of the swamp, curlew (Glarcola fusca, L.) flying hither and thither all around us, we are startled ever and anon by a sudden rush of bush and reed buck plunging out from their resting-places and speeding away from us for their life. Even when quite small antelopes are thus started up by the sound of our advance, so violent is their flight that for the moment we imagine that we have to deal with some huge and perhaps dangerous beast.

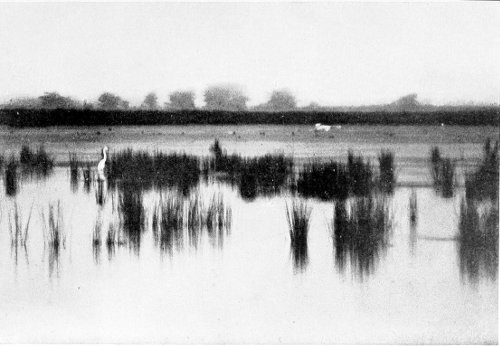

In those spots where large pools, adorned with wonderful 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352 353 354 355 water-lilies, give a kind of symmetry to the wilderness, we come upon such a wealth of bird-life as enables us to form some notion of what this may have been in Europe long ago under similar conditions. The splendid great white heron (Herodias alba, L., and garzetta, L.) and great flocks of the active little cow-herons (Bubulcus ibis, L.) make their appearance in company with sacred ibises and form a splendid picture in the landscape. Some species of those birds with their snow-white feathers stand out picturesquely against the rich green vegetation of the swamp. When, startled by our approach, these birds take to flight, and the whole air is filled by them and by the curlews (Glareola fusca, L.) that have hovered over us, keeping up continually their soft call, when in every direction we see all the swarms of other birds—sea-swallows (Gelochelidon nilotica, Hasselg.), lapwings, plovers (Charadriidæ), Egyptian geese, herons, pelicans, crested cranes and storks—the effect upon our eyes and ears is almost overpowering.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

A MARSHLAND VIEW. AN OSPREY IN AMONG THE REEDS—THE BIRD FOR WHOSE PROTECTION QUEEN ALEXANDRA OF ENGLAND HAS LATELY PLEADED.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

SNOW-WHITE HERONS MADE THEIR NESTS IN THE ACACIAS NEAR MY CAMP AND SHOWED NO MARKED TIMIDITY.

A SINGLE PAIR OF CRESTED CRANES WERE OFTEN TO BE SEEN NEAR MY CAMP.

A SNAKE-VULTURE. I SUCCEEDED TWICE ONLY IN SECURING A PHOTOGRAPH OF THIS BIRD.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

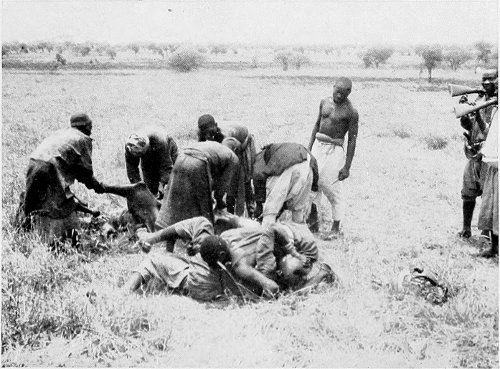

PREPARING TO SKIN A HIPPOPOTAMUS. THE PRESERVATION OF THE HIDE OF THIS SPECIMEN PROVED UNSUCCESSFUL. IT IS ALMOST IMPOSSIBLE TO PRESERVE HIPPOPOTAMUS-HIDES WITHOUT HUGE QUANTITIES OF ALUM AND SALT, BOTH VERY HARD TO GET IN THE INTERIOR OF AFRICA. THE SKIN OF THE HEAD IS THINNER AND MORE MANAGEABLE THAN THAT OF THE REST OF THE BODY.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

HIPPOPOTAMI, POPPING THEIR HEADS OR EARS AND SNOUTS UP ABOVE THE SURFACE OF THE WATER.

How mortal lives are intertwined and interwoven! The ox-peckers swarm round the buffaloes and protect them from their pests, the ticks and other parasites. The small species of marsh-fowl rely upon the warning cry of the Egyptian geese or on the sharpness of the herons, ever on the alert and signalling always the lightning-like approach of their enemy the falcons (Falco biarmicus, Tem., and F. minor, Bp.). All alike have sense enough to steer clear of the crocodiles, which have to look to fish chiefly for their nourishment, like almost all the frequenters of these marshy regions. 356

The quantities of fish I have found in every pool in these swamps defy description—I am anxious to insist upon this point—and this although almost all the countless birds depend on them chiefly for their food. Busy beaks and bills ravage every pool and the whole surface of the lagoon-like swamp for young fish and fry. The herons and darters (Assingha rufa, Lacèp. Daud.) manage even to do some successful fishing in the deeper waters of the river. And yet, in spite of all these fish-eaters, the river harbours almost a superabundance of fish.2

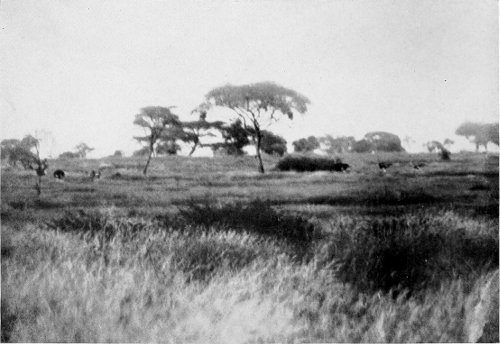

Wandering along by the river, we take in all these impressions. For experiences of quite another kind, we have only to make for the neighbouring velt, now arid again and barren, and thence to ascend the steep ridges leading up to the tableland of Nyíka.

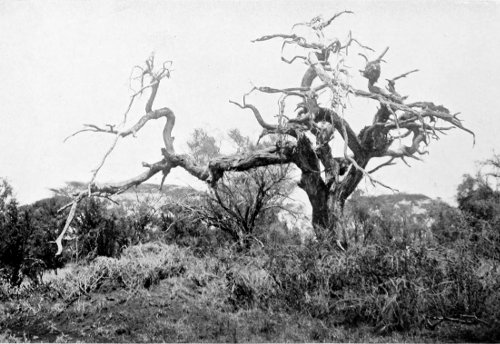

Behind us we leave the marshy region of the river and the morass of reeds. Before us rises Nyíka, crudely yellow, and the laterite earth of the velt glowing red under the blazing sun. The contrast is strong between the watery wilderness from which we have emerged and these higher ranges of the velt with their strange vegetation. Here we shall find many species of animals that we should look for in vain down there below, animals that live differently and on scanty food up here, even in the dry season. The buffaloes also know where to go for fresh young grass even when they are in the marshes, and they reject the ripened green grass. The dwellers on the velt are only to be found amidst the lush vegetation of the 357 358 359 360 361 valley at night time, when they make their way down to the river-side to drink.3 It is hard to realise, but they find all the food they need on the high velt. When you examine the stomachs of wild animals that you have killed, you note with wonder the amount of fresh grass and nourishing shrubs they have found to eat in what seem the barrenest districts. The natives of these parts show the same kind of resourcefulness. The Masai, for instance, succeeds most wonderfully in providing for the needs of his herds in regions which the European would call a desert. I doubt whether the European could ever acquire this gift. Out here on the velt we shall catch sight of small herds of waterbuck, never to be seen in the marshes. We shall see at midday, under the bare-looking trees, herds of Grant’s gazelles too, and the oryx antelope. Herds of gnus, going through with the strangest antics as they make off in flight, are another feature in the picture, while the fresh tracks of giraffes, eland, and ostriches tell of the presence of all these. Wart-hogs, a herd of zebras in the distance—like a splash of black—two ostrich hens, and a multitude of small game and birds of all descriptions add to the variety. But what delights the ornithologist’s eye more than anything is the charming sight of a golden yellow bird, now mating. Up it flies into the sky from the tree-top, soon to come down again with wings and tail outstretched, recalling our own singing birds. You would almost fancy it was a canary. 362 Only in this one region of the velt have I come upon this exquisite bird (Tmetothylacus tenellus, Cal.), nowhere else.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

HEAD OF A HIPPOPOTAMUS (HIPPOPOTAMUS AFR. ARYSSINICUS, Less.) WHICH I ENCOUNTERED ON DRY LAND AND WHICH NEARLY “DID” FOR ME.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

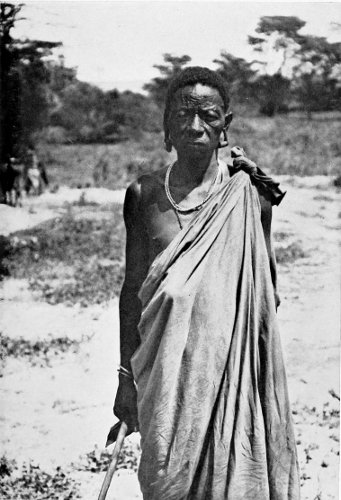

MY OLD FRIEND “NGURUMAN,” A WANDOROBO CHIEF. HIS BODY IS SEARED BY MANY SCARS THAT TELL OF ENCOUNTERS WITH ELEPHANTS AND LIONS.

Thus would I spend day after day, getting to know almost all the wild denizens of East Africa, either by seeing them in the flesh or by studying their tracks and traces, cherishing more and more the wish to be able to achieve some record of all these beautiful phases of wild life. I repeat: as a rule you will carry away with you but one or another memory from your too brief day’s wandering, but there come days when a succession of marvellous pictures seem to be unrolled before your gaze, as in an endless panorama. It is the experience of one such day that I have tried here to place on record. Professor Moebius is right in what he says: “Æsthetic views of animals are based not upon knowledge of the physiological causes of their forms, colouring, and methods of motion, but upon the impression made upon the observer by their various features and outward characteristics as parts of a harmonious whole. The more the parts combine to effect this unity and harmony, the more beautiful the animal seems to us.” Similarly, a landscape seems to me most impressive and harmonious when it retains all its original elements. No section of its flora or fauna can be removed without disturbing the harmony of the whole.

Within a few years, if this be not actually the case already, all that I have here described so fully will no longer be in existence along the banks of the Pangani. When I myself first saw these things, often my thoughts went back to those distant ages when in the lands now known as Germany the same description of wild life was 363 364 365 366 367 368 369 extant in the river valleys, when hippopotami made their home in the Rhine and Main, and elephants and rhinoceroses still flourished.... What I saw there before me in the flesh I learnt to see with my mind’s eye in the long-forgotten past. It is the duty of any one whose good fortune it has been to witness such scenes of charm and loveliness to endeavour to leave some record of them as best he may, and by whatever means he has at his command.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

EGYPTIAN GEESE.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

A WOUNDED BUFFALO.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

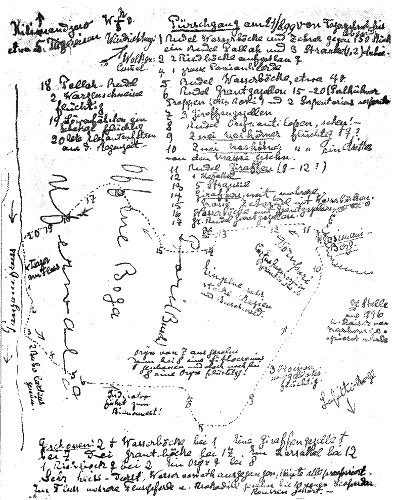

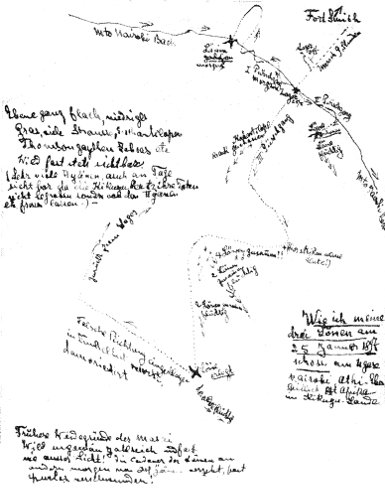

FACSIMILE REPRODUCTION OF ONE OF MY HUNTING RECORD-CARDS, ENUMERATING ALL THE DIFFERENT ANIMALS I SIGHTED ONE DAY (AUGUST 21, 1898) IN THE COURSE OF AN EXPEDITION IN THE VICINITY OF THE MASIMANI HILLS, HALF-WAY UP THE PANGANI RIVER. THE DOTTED LINE SHOWS MY ROUTE AND THE NUMBERS INDICATE THE SPOTS AT WHICH I CAME UPON THE VARIOUS SPECIES OF GAME. AT ANOTHER TIME OF THE YEAR THIS DISTRICT WOULD BE ENTIRELY DESTITUTE OF WILD LIFE.

A SEA-GULL. 370

A MASAI THROWING HIS SPEAR.

IX

A MASAI THROWING HIS SPEAR.

IX“Big game hunting is a fine education!” With this opinion of Mr. H. A. Bryden I am in entire agreement, but I cannot assent to the dictum so often cited of some of the most experienced African hunters, to the effect that Equatorial East Africa offers the sportsman no adequate compensation for all the difficulties and dangers there to be faced.

I cannot subscribe to this view, because to my mind these very difficulties and dangers impart to the sport of this region a fascination scarcely to be equalled in any other part of the world. It is only in tropical Africa that you will find the last splendid specimens of an order of wild creation surviving from other eras of the earth’s history. It is not to be denied that you must pay a high price for the joy of hunting them. That goes without 371 saying in a country where your every requisite, great and small, has to be carried on men’s shoulders—no other form of transport being available—from the moment you set foot within the wilderness. I am not now talking of quite short expeditions, but of the bigger enterprises which take the traveller into the interior for a period of months. I hold that this breaking away from all the resources of civilised life should be one of the sportsman’s chief incentives, and one of his chief enjoyments. I can, of course, quite understand experienced hunters taking another view. Many have had such serious encounters with the big game they have shot, and above all such unfortunate experiences of African climates, that they may well have had enough of such drawbacks.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

A POWERFUL OLD HIPPOPOTAMUS ON HIS WAY TO HIS HAUNT IN THE SWAMP AT DAYBREAK. ONE OF MY BEST PHOTOGRAPHS.

Their assertions, in any case, tend to make it clear that sport in this East African wilderness is no child’s play. In reality, all depends upon the character and equipment of the man who goes in for it. The apparently difficult game of tennis presents no difficulties to the expert tennis-player. With an inferior player it is otherwise. So it is in regard to hunting in the tropics. It is obvious that experience in sport here at home is of the greatest possible use out there—is, in fact, absolutely essential to one’s success. Only those should attempt it who are prepared to do everything and cope with all obstacles for themselves, who do not need to rely on others, and whose nerves are proof against the extraordinary excitements and strains which out there are your daily experience.

I myself am conscious of a steadily increasing distaste for face-to-face encounters with rhinoceroses, and with 372 elephants still more. There are indeed other denizens of the East African jungle whose defensive and offensive capabilities it would be no less a mistake to under estimate. The most experienced and most authoritative Anglo-Saxon sportsmen are, in fact, agreed that, whether it be a question of going-after lions or leopards or African buffaloes, sooner or later the luck goes against the hunter. Of recent years a large number of good shots have lost their lives in Africa. If one of these animals once gets at you, you are as good as dead. To be chased by an African elephant is as exciting a sensation as a man could wish for. The fierceness of his on-rush passes description. He makes for you suddenly, unexpectedly. The overpowering proportions of the enraged beast—the grotesque aspect of his immense flapping ears, which make his huge head look more formidable than ever—the incredible pace at which he thunders along—all combine with his shrill trumpeting to produce an effect upon the mind of the hunter, now turned quarry, which he will never shake himself rid of as long as life lasts. When—as happened once to me—it is a case not of one single elephant, but of an entire herd giving chase in the open plain (as described in With Flashlight and Rifle), the reader will have no difficulty in understanding that even now I sometimes live the whole situation over again in my dreams and that I have more than once awoke from them in a frenzy of terror.

Of course, a man becomes hardened in regard to hunting accidents in course of time, especially if all his adventures have had fortunate issues. When, however, a man has repeatedly escaped destruction by a hairs-breadth only, and 373 374 375 376 377 when incidents of this kind have been heaped up one on another within a brief space of time, the effects upon the nervous system become so great that even with the utmost self-mastery a man ceases to be able to bear them. As I have already said, the total number of casualties in the ranks of African sportsmen is not inconsiderable.

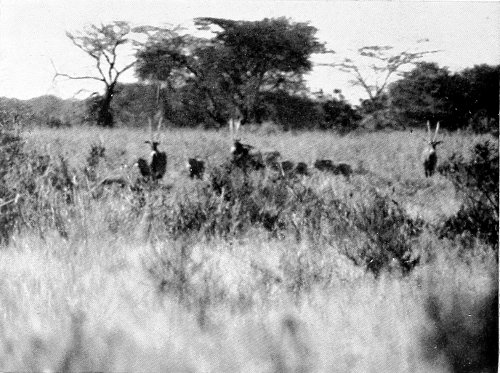

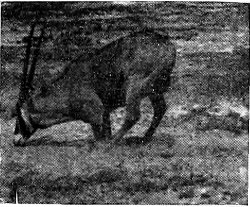

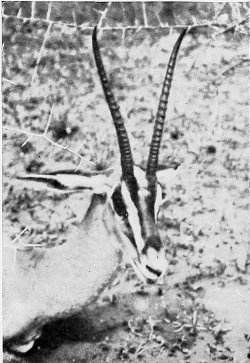

ORYX ANTELOPE BULL, NOT YET AWARE OF MY APPROACH.

A HERD OF ORYX ANTELOPES (ORIX CALLOTIS, Thos.), CALLED BY THE COAST-FOLK “CHIROA.”

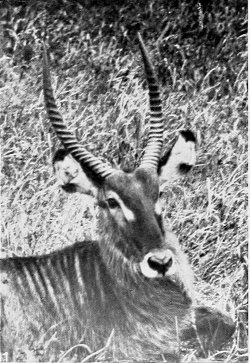

WATERBUCK. THEY SOMETIMES LOOK QUITE BLACK, AS THIS PHOTOGRAPH SUGGESTS. IT DEPENDS UPON THE LIGHT.

HEAD OF A BULL WATERBUCK (COBUS ELLIPSIPRYMNUS, Ogilb.).

In Germany, of course, we have time-honoured sports of a dangerous nature too, but these are exceptions—for instance, killing the wild boar with a spear, and mountain-climbing and stalking.

In order to understand fully the mental condition of the sportsman in dangerous circumstances such as I have described, it is necessary to realise the way in which he is affected by his loneliness, his complete severance from the rest of mankind. There is all the difference in the world between the situation of a number of men taking up a post of danger side by side, and that of the man who stands by himself, either at the call of duty or impelled by a sense of daring. He has to struggle with thoughts and fears against which the others are sustained by mutual example and encouragement.

But, as I have said, the great fascination of sport in the tropics lies precisely in the dangers attached. Therein, too, lies the source of that pluck and vigour which the sport-hardened Boers displayed in their struggles with the English. The perils they had faced in their pursuit of big game had made brave men of them.

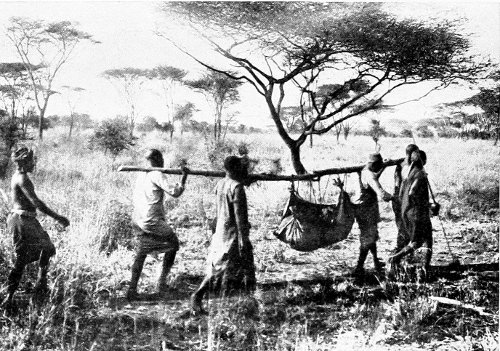

Now let us set out in company with the most expert hunters of the velt on an expedition of a rather special 378 kind—the most dangerous you can go in for in this part of the world—an elephant-hunt. In prehistoric days the mammoth was hunted with bow and arrow in almost the same fashion as the elephant is to-day by certain tribes of natives. Taking part in one of their expeditions, one feels it easy to go back in imagination to the early eras of mankind. This feeling imparts a peculiar fascination to the experience.

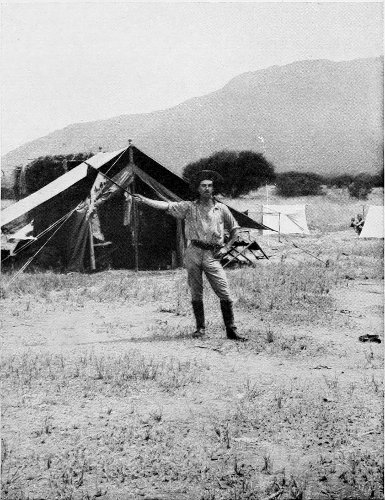

After a good deal of trouble I had got into friendly relations with some of these nomadic hunters. It was a difficult matter, because they fight shy of Europeans and of the natives from the coast, such as my bearers and followers generally. I knew, moreover, that our friendship might be of short duration, for these distrustful children of the velt might disappear at any moment, leaving not a trace behind them. However, I had at least succeeded, by promises of rich rewards in the shape of iron and brass wire, in winning their goodwill. After many days of negotiation they told me that elephants might very likely be met with shortly in a certain distant part of the velt. The region in question was impracticable for a large caravan. Water is very scarce there, rock pools affording only enough for a few men, and only for a short time. At this period of the year the animals had either to make incredibly long journeys to their drinking-places, or else content themselves with the fresh succulent grass sprouting up after the rains, and with the moisture in the young leaves of the trees and bushes.

I set out one day in the early morning for this locality with a few of my men in company with the Wandorobo. 379 380 381 382 383 After a long and fatiguing march in the heat of the sun, we encamp in the evening at one of the watering-places. To-day, to my surprise, there is quite a large supply of water, owing to rain last night. The elephants, with their unfailing instinct, have discovered the precious liquid. They have not merely drunk in the pool, but have also enjoyed a bath; their tracks and the colour and condition of the water show that clearly. Therefore we do not pitch our camp near the pool, but out in the velt at some distance away, so as not to interfere with the elephants in case they should be moved to return to the water.

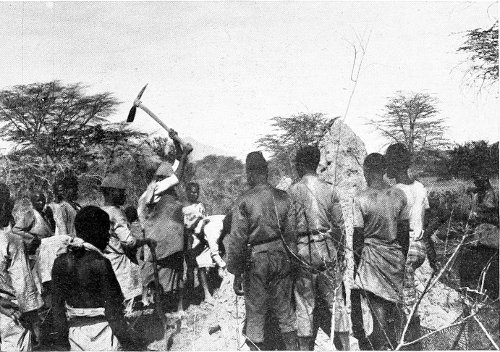

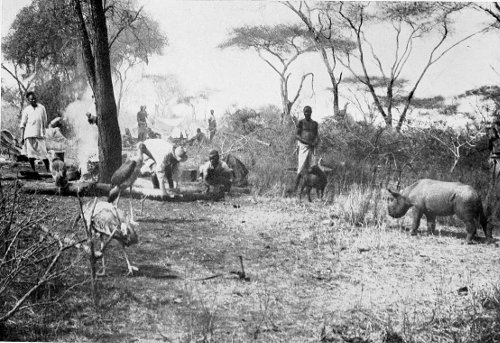

C. G. Schillings, phot.

MY WANDOROBO GUIDES ON THE MARCH, WITH ALL THEIR “HOUSEHOLD FURNITURE” ON THEIR BACKS!

C. G. Schillings, phot.

A PARTY OF WANDOROBO HUNTERS COMING TO MY CAMP. I GOT SEVERAL OF THEM TO ACT FOR ME AS GUIDES.

But the wily beasts do not come a second time, and we are obliged to await morning to follow their tracks in the hope of luck. The Wandorobo on ahead, I and two of my men following, make up the small caravan, while some of my other followers remain behind at the watering-place in a rough camp. I have provided myself with all essentials for two or three days, including a supply of water contained in double-lined water-tight sacks. For hour after hour we follow the tracks clearly defined upon the still damp surface of the velt. Presently they lead us through endless stretches of shrubs and acacia bushes and bow-string hemp, then through the dried-up beds of rain-pools now sprouting here and there with luxuriant vegetation. Then again we come to stretches of scorched grass, featureless save for the footsteps of the elephants. As we advance I am enabled to note how the animals feed themselves in this desert-like region, from which they never wander any great distance. Here, stamping with their mighty feet, they have smashed some young tree-trunks 384 and shorn them of their twigs and branches; and there, with their trunks and tusks, they have torn the bark off larger trees in long strips or wider slices and consumed them. I observe, too, that they have torn the long sword-shaped hemp-stalks out of the ground, and after chewing them have dropped the fibres gleaming white where they lie in the sun. The sap in this plant is clearly food as well as drink to them. I see, too, that at certain points the elephants have gathered together for a while under an acacia tree, and have broken and devoured all its lower branches and twigs. At other places it is clear that they have made a longer halt, from the way in which the vegetation all around has been reduced to nothing. We go on and on, the mighty footsteps keeping us absorbed and excited. We know that the chances are all against our overtaking the elephants, but the pleasures of the chase are enough to keep up our zest. At any moment, perhaps, we may come up with our gigantic fugitives. Perhaps!

How different is the elephant’s case in Africa from what it is in India and Ceylon! In India it is almost a sacred animal; in Ceylon it is carefully guarded, and there is no uncertainty as to the way in which it will be killed. Here in Africa, however, its lot is to be the most sought-after big game on the face of the earth; but the hunter has to remember that he may be “hoist with his own petard,” for the elephant is ready for the fray and knows what awaits him. With these thoughts in my mind and the way clearer at every step, the Wandorobo move on and on unceasingly in front.

It is astonishing what a small supply of arms and 385 386 387 388 389 utensils these sons of the velt take with them when starting out for journeys over Nyíka that may take weeks or months. Round their shoulders they carry a soft dressed skin, and, hung obliquely, a strap to which a 390 few implements are attached, as well as a leathern pouch containing odds and ends. Their bow they hold in one hand, while their quivers, filled with poisoned arrows, are also fastened to their shoulders by a strap. In addition they carry a sword in a primitive kind of scabbard. Thus equipped they are ready to cope with all the dangers and discomforts of the velt, and succeed somehow in coming out of them victorious.

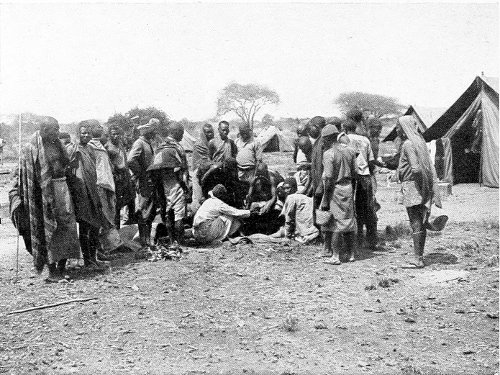

C. G. Schillings, phot.

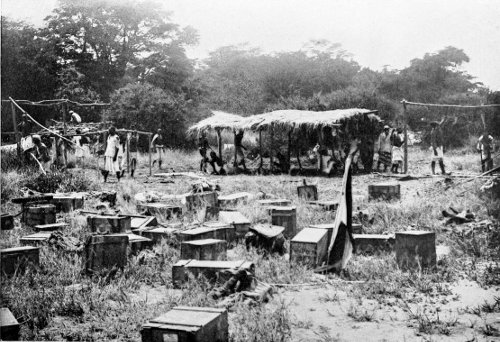

A FEAST OF HONEY. A HONEY-FINDER HAD LED US TO A HIVE, AND HERE MY MEN MAY BE SEEN REJOICING IN THE RESULTS.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

ACACIA TREE DENUDED BY ELEPHANTS.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

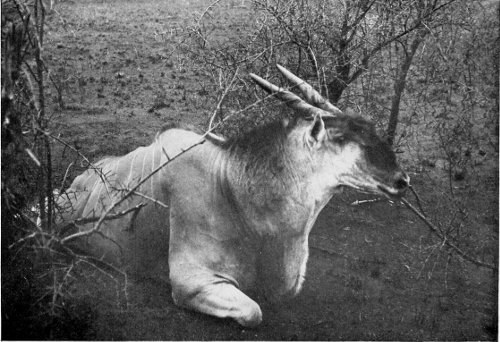

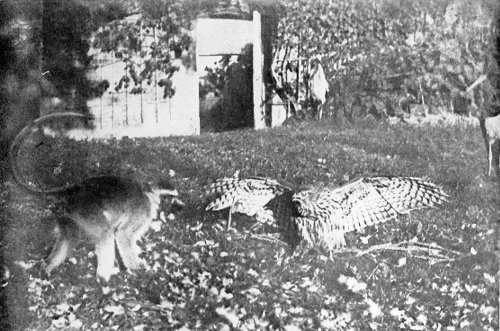

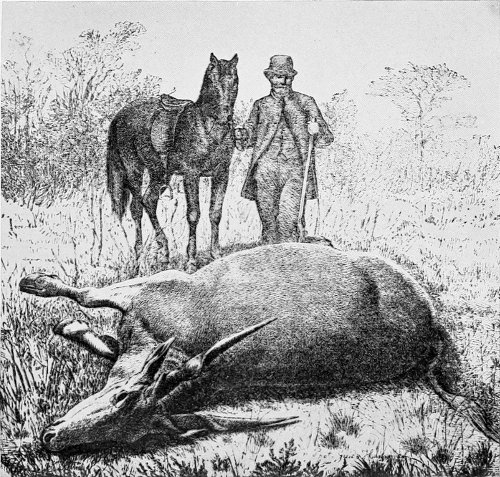

AN ORYX ANTELOPE’S METHODS OF DEFENCE.

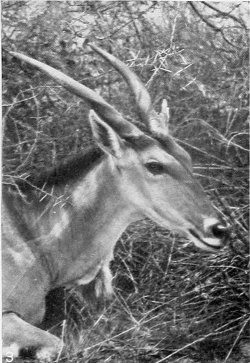

A DWARF KUDU (STREPSICEROS IMBERBIS, Blyth). I HAVE NEVER YET SUCCEEDED IN PHOTOGRAPHING THIS ANIMAL ALIVE AND IN FREEDOM. SO FAR I HAVE BEEN ABLE TO PHOTOGRAPH ONLY SPECIMENS WHICH I HAVE SHOT.

How thoroughly the velt is known to them—every corner of it! To live on the velt for any time you must be adapted by nature to its conditions. We Europeans should find it as hard to become acclimatised to it as the 391 392 393 394 395 Wandorobo would to the conditions of civilised life in Europe. The one thing they are like us in being unable to forego is water—and even that they can do without for longer than we can. The most important factor in their life as hunters is their knowledge where to get water at the different periods of the year. Their intimate acquaintance with the book of the velt is something beyond our faculty for reading print. Our experiences in our recent campaigns in South-West Africa have served to bring home the wonderful way in which the natives decipher and interpret the minutest indications to be found in the ground of the velt and know how to shape their course in accordance with them.

ZEBRAS.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

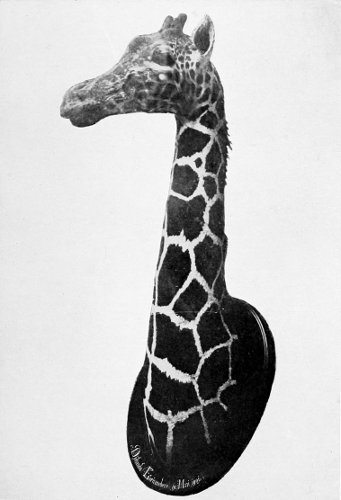

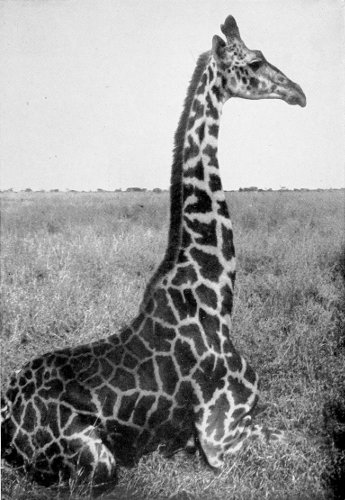

GIRAFFE STUDIES (GIRAFFA SCHILLINGSI, Mtsch.) SECURED BY TELEPHOTO-LENS.

ZEBRAS (EQUUS BOHMI) OUT ON THE OPEN VELT.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

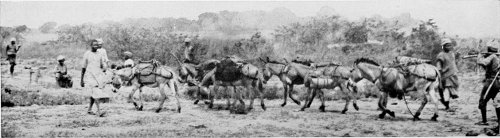

MY MASAI DONKEYS ARRIVING IN CAMP, ESCORTED BY ARMED MEN. BEARERS ADVANCING TO MEET THEM AND TO UNBURDEN THEM OF THEIR LOADS.

This had already been brought home to me in the regions through which I had travelled. You must have had the experience yourself to realise the degree to which civilised man has unlearnt the use of his eyes and ears. Whether it be a question of finding one’s bearings or deciding in which direction to go, or of sizing up the elephant-herds from their tracks, or of distinguishing the tracks of one kind of antelope from those of another, or of detecting some faint trace of blood telling us that some animal we are after has been wounded, or of knowing where and when we shall come to some water, or of discovering a bee’s nest with honey in it—in all such matters the native is as clever as we are stupid. We may make some progress in this kind of knowledge and capability, but we shall always be a bad second to the native-born hunter of the velt.

With such men to act as your guides you get to feel 396 that traversing Nyíka is as safe as mountain-climbing under the guidance of skilled mountaineers. You get to feel that you cannot lose your way or get into difficulties about water. One reflection, however, should never be quite absent from your mind—that at any moment these guides of yours may abandon you. That misfortune has never happened to me, and it is not likely to happen when the natives are properly handled. Moreover, your friendship with them can sometimes be strengthened by the establishment of bonds of brotherhood. A time-honoured practice of this kind, held sacred by the natives, can be of the greatest benefit. I am strongly in favour of the observance of these praiseworthy native customs, and have always been most ready to go through with the ceremonies involved.

I endeavour to win the goodwill of my guides by keeping to the pace they set—an easy matter for me. In every other way also I take pains to fall in with the ways and habits of the Wandorobo, so as to attenuate that feeling of antagonism which my uncivilised friends necessarily harbour towards the European. I owe it to this, perhaps, that they did their utmost to find the elephant-tracks for me.

For hour after hour we continue our march, in and out, over velt and brushwood, coming every few hours to a watering-place, and meeting in the hollow of one valley an exceptionally large herd of oryx antelopes. Under cover of the brushwood, and favoured by the wind, I succeed in getting quite near this herd and thus in studying their movements close at hand. 397

C. G. Schillings, phot.

PEARL-HENS ON AN ACACIA TREE. 398

C. G. Schillings, phot.

A PAIR OF GRANT’S GAZELLES TAKING TO FLIGHT. 399

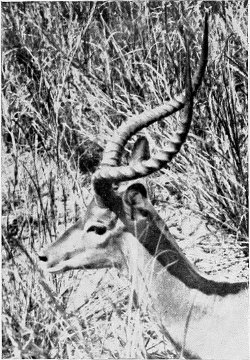

In the bush, not far from these oryx antelopes, I come unexpectedly on a small herd of beautiful dwarf kudus. They take to flight, but reappear for a moment in a glade. This kind of sudden glimpse of these timid, pretty creatures is a real delight to one. Their great anxious eyes gaze inquiringly at the intruder, while their large ears stand forward in a way that gives a most curious aspect to their shapely heads. The colouring of their bodies accords in a most remarkable degree with their environment, and this accentuates the individuality of their heads, seen thus by the hunter. Off they scamper again now, in a series of extraordinarily long and high jumps, gathering speed as they go, and unexpectedly darting now in one direction, now in another. It is very exciting work tracking the fugitive kudu, and when it is a question of a single specimen you may very well mark it down in the end; but according to my own experience it is next to impossible to follow up a herd, for one animal after another breaks away from it, seeking safety on its own account.

Now we come again to an open grassy stretch of velt. With a sudden clatter of hoofs a herd of some thirty zebras some hundred paces off take to flight and escape unhurt by us into the security of a distant thicket. The older animals and the leaders of the herd keep looking backwards anxiously with outstretched necks. Even in the thicket their bright colouring makes them discernible at this hour of the day. But our attention is distracted now elsewhere. Far away on the horizon appear the unique outlines of a herd of giraffes. The 400 timorous animals have noted our approach and are already making away—stopping at moments to glance at us—into a dense thorn-thicket. The wind favours us, so I quickly decide to make a detour to the right and cut them off. After a breathless run through the brushwood I succeed in getting within a few paces of one of the old members of the herd. This way of circumventing a herd of giraffes—my followers helping me by moving about all over the place, so as to put them off the scent—has not often proved successful with me, because it can only be managed when both wind and the formation of the country are in one’s favour.

To-day I have no mind to kill the beautiful long-limbed beast, but it is delightful to get into such close touch with him. Now he is off, stepping out again, swinging his long tail, his immense neck dipping and rising like the mast of a sea-tossed ship, and the rest of the herd with him.

Now, just because I have no thought of hunting, every kind of wild animal crosses my path! Their number and variety are beyond belief. We come upon more zebras, oryx antelopes, hartebeests, Grant’s gazelles, impalla antelopes; upon ostriches, guinea-fowl (Numida reichenowi and Acryllium vulturinum, Hardw.), and francolins. The recent rains seem to have conjured them all into existence here as though by magic.

But everything else has to give precedence to the elephant-tracks, which now are all mixed up, though leading clearly to the next watering-place, towards which we are directing our steps down a way trodden quite 401 402 403 404 405 hard by animals, evidently during the last few days. Large numbers of rhinoceroses have trampled down this way to the water, but neither they nor the elephants are to be seen in the neighbourhood while the sun is up. They are too well acquainted with the habits of their enemy man, and they keep at a safe distance out on the velt. To-day, therefore, I am to catch no glimpse of either elephant or rhinoceros. Wherever I turn my eyes, however, I see other animals of all sorts—among others, some more big giraffes. I am not to be put off, however, and I decide to follow up the tracks of a number of the elephants, evidently males, giving myself up anew to the unfailing interest I find in the study of their ways, and confirming the observations I had already made as to their finding their chief nourishment on the velt in tree-bark and small branches.

GRANT’S GAZELLES.

A GOOD INSTANCE OF PROTECTIVE COLOURING. A HERD OF GRANT’S GAZELLES ALMOST INDISTINGUISHABLE FROM THEIR BACKGROUND OF THORN-BUSH.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

A GRANT’S GAZELLE BUCK STANDING OUT CONSPICUOUSLY ON THE DRIED-UP BED OF A LAKE NOW SO INCRUSTATED WITH SALT AS TO LOOK AS THOUGH SNOW-COVERED.

FOUR GRANT’S GAZELLES.

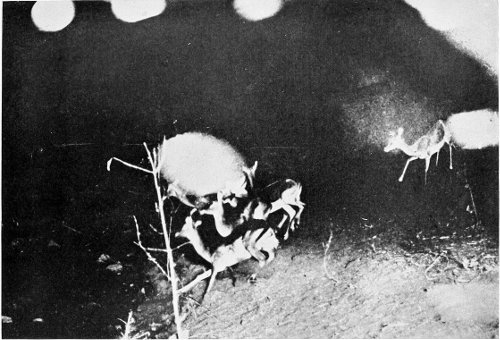

Night set in more quickly than we expected while we were pitching camp before sunset in a cutting in a thorn-thicket. Spots on which fires had recently been lit showed us that native hunters had been there a few days before, and my guides said they must have been the Wakamba people, keen elephant-hunters, with whom they live at enmity, and of whose very deadly poisoned arrows they stand in great dread. Therefore we drew close round a very small camp-fire, carefully kept down. The glow of a big fire might have brought the Wakamba people down on us if they were anywhere in the neighbourhood. It seems that natives who are at war often attack each other in the dark. It may easily be imagined, then, that the first hours of our “night’s repose” were 406 not as blissful as they should have been! After a time, however, our need of sleep prevailed, sheer physical fatigue overcame all our anxieties, and my Wandorobo slumbered in peace. They had contrived a “charm,” and had set up a row of chewed twigs all round to keep off misfortune. Unfortunately it is not so easy for a European to believe in the efficacy of these precautions! It was interesting to observe that the Wandorobo evinced much greater fear of the poisoned arrows of the Wakamba than of wild animals. In view of my subsequent experience, I myself in such a situation would view the possibility of being attacked by elephants with much greater alarm.

As it happened, however, this night passed like many another—if not without danger, at least without mishap.

Day dawned. No bird-voices greeted it, for, strange to relate, we found nothing but big game in this wooded wilderness, save for guinea-fowl (Numida reichenowi and Acryllium vulturinum, Hardw.) and francolins. The small birds seem to have known that the water would soon be exhausted, and that until the advent of the next rainy season this was no place for them.

In the grey of early morning we made our way out again into the velt. We had to visit the neighbouring watering-places and then to follow up some fresh set of elephant-tracks. It turned out that some ten big bull-elephants had visited one of the pools, and had left what remained of the water a thick yellowish mud. They had rubbed and scoured themselves afterwards against a 407 408 409 410 411 clump of acacia trees. Judging from the marks upon these trees some of the elephants in this herd must have been more than eleven feet in height. With renewed zest we followed up the fresh, distinct tracks through the bush, through all their twistings and turnings. Again we came upon all kinds of other animals—among others, a herd of giraffes right in our path. But these were opportunities for the naturalist only, not for the sportsman who was keeping himself for the elephants and would not fire a shot at anything else unless in extreme danger. Later, at a moment when we believed ourselves to have got quite close to the elephants, I started an extraordinarily large land-tortoise—the biggest I have ever seen. I 412 could not get hold of it, however—I was too much taken up with the hope of reaching the elephants; but after several more hours of marching I had to call a halt in order to gather new strength. In the end we did not overtake them. They had evidently been seriously disquieted either by us or earlier by the Wakamba people. While we were pitching our camp in the evening, nearly a day’s journey from our camp of the night before, we sighted one after another three herds of elands and four rhinoceroses on their way out into the velt to graze. During these two days I had come within shot of about ten rhinoceroses while on the march, and had caught glimpses of many more in the distance.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

THE HERDS OF GRANT’S GAZELLES ARE SOMETIMES MADE UP ENTIRELY OF MALES, SOMETIMES ENTIRELY OF FEMALES. IN THIS PICTURE WE SEE A NUMBER OF YOUNG DOES IN SEARCH OF THE SCANTY FRESH GRASS ON A PORTION OF THE VELT WHICH NOT LONG BEFORE HAD BEEN BURNT UP.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

A SMALL HERD OF GRANT’S GAZELLES. THE KILIMANJARO RANGE IN THE BACKGROUND.

YOUNG MASAI HARTEBEEST. I DID NOT SUCCEED IN MY EFFORTS TO BRING BACK A SPECIMEN OF THIS SPECIES.

The third day’s pursuit of the elephants also proved entirely fruitless. We did not even come within sight of a female specimen.

My guides were now of opinion that the animals must be so thoroughly alarmed that any further pursuit would be almost certainly in vain, so we made our way back as best we could in a zigzag course to my main camp, and reached it on the morning of the fourth day.

Most elephant-hunts in Equatorial Africa run on just such lines as these and with the same result, yet they are among the finest and most interesting experiences that any sportsman or naturalist can hope to have. The wealth of natural life that had been given to my eyes during those three days was simply overpowering. But if you have once succeeded in getting within range of an African elephant, all other kinds of wild animals seem small fry to you. You have the same kind of feeling that the German 413 414 415 416 417 sportsman has when after a Brunft stag—he cares for no other kind of game; he has no mind for anything but the stag. But the elephant fever attacks you out in Africa even more virulently than the stag fever here at home.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

A HERD OF HARTEBEESTS (BUBALIS COKEI, Gthr.).

HARTEBEESTS WITH YOUNG.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

WATERBUCK.

Yet it is fine to remember one’s ordinary shooting expeditions in the tropics. You need some luck, of course—the velt is illimitable and the game scattered all over it. But if the rains have just ceased, if you have secured good guides, if you yourself are equal to facing all the hardships, then indeed it is a wonderful experience. There is no doubt about it—you have to be ready for a combination of every kind of strain and exertion. You can stand it for a day perhaps, or two or three, but you must then take a rest. The man who has gone through with this may venture on the experiment of pursuing elephants for several days together. He will, I think, bear me out in saying that until you have done that also you do not know the limits of endurance and fatigue.

The most glorious hour in the African sportsman’s life is that in which he bags a bull-elephant. When he succeeds in bringing the animal down at close range in a thicket such as I have so often described, his heart beats with delight—it is just a chance in such cases what your fate may be. Wide as are the differences in the views taken by experienced travellers and by other writers in regard to African sport in general, they are all agreed that elephant-hunting is the most dangerous task a man can set himself. The hunting of Indian or Ceylon elephants—save in the case of a “rogue”—is not to be 418 compared with the African sport as I understand it. I do not mean the easy-going, pleasure-excursion kind of hunt ordinarily gone in for in the African bush, but a one-man expedition, in which the sportsman sets himself deliberately to bag his game single-handed. That, indeed, is my idea of how one should go after big game in such countries as Africa in all circumstances whatever.

Barely as many as a dozen elephants have fallen to my rifle. Some of these I killed in order to try and get hold of a young specimen which I might bring to Europe in good condition—a desire which I have long cherished, but which has not yet been fulfilled. Others I killed so that I might present them to our museums.

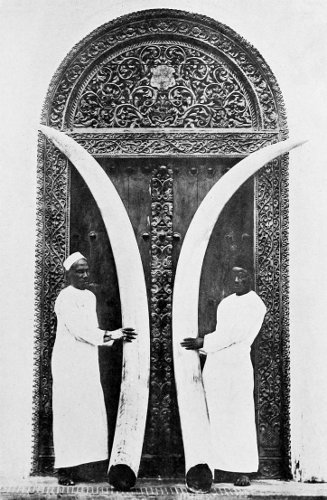

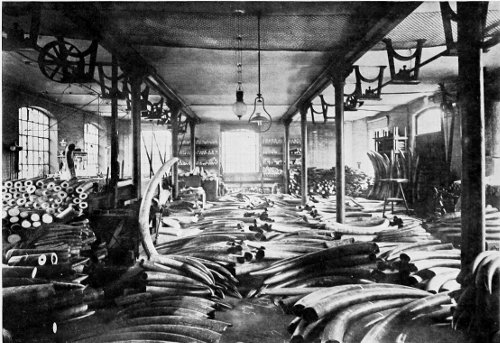

There were immense numbers of other bull-elephants that I might have shot, and that are probably now roaming the velt, but that I had to spare because I was more intent upon photographing them. My photographs are, however, ample compensation to me. While, too, it is pleasant to me to reflect that I have left untouched so many elephants that came within easy range, I hope, none the less, some day to bring down a specimen adorned with a really splendid pair of tusks. This is an aspiration not often realised by African sportsmen, even when they have been hunting for half a lifetime. Elephants with tusks weighing nearly five hundred pounds, like those in our illustration, are extremely rare—even in earlier times they were met with perhaps once in a hundred years.

The hunting of an African elephant, I repeat in conclusion, is a source of the greatest delight to the 419 420 421 422 423 sportsman, for even if he does not bag his game he is well rewarded for his pains by all the interest and excitement of the chase. But no one who has not himself gone through with it can estimate what it involves. Even with the most perfected equipment in regard to arms, it is often a matter of luck whether you kill the animal outright and on the spot.

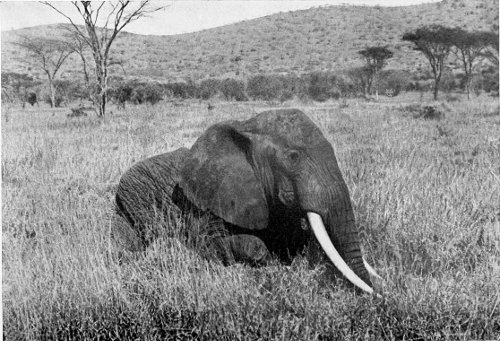

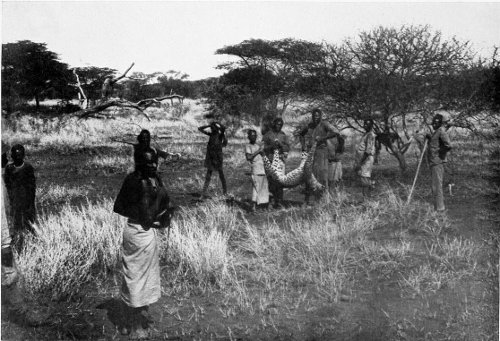

C. G. Schillings, phot.

THE SKINNING OF AN ELEPHANT. THIS SPECIMEN IS NOW IN THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM, BERLIN.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

PREPARING TO SKIN AN ELEPHANT.

An experience I had in the Berlin Zoological Gardens illustrates this. I was called in to dispatch a huge bull-elephant which had to be killed, and which had rejected all the forms of poison that had been administered to it. In order to give it a quick and painless end I selected a newly invented elephant-rifle, calibre 10·75, loaded with 4 gr. of smokeless powder and a steel-capped bullet. On reflection the steel cap seemed to me too dangerous in the circumstances, so I had it filed off. I shall allow Professor Schmalz to describe what now happened: “The first shot entered the skin between the second and third ribs, and then simply went into splinters. It did no serious damage to the interior organs, and a stag thus wounded would merely take madly to flight. A piece of the cap reached the lung, but only a single splinter had penetrated, causing a slight flow of blood. The second shot was excellently placed, namely just below the root of the lung. It lacerated both the lung arteries and both the bronchial, and thus caused instant death.”

The fact that, with such a charge, a bullet fired at a distance of less than four yards should have gone into splinters in this way says more than one could in a long 424 disquisition, and serves to explain the secret of many a mishap in the African wilderness.4

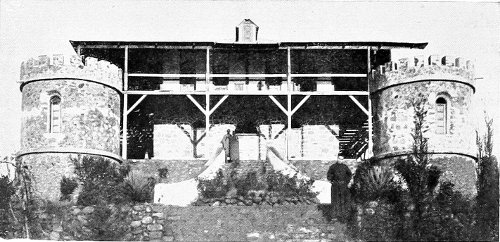

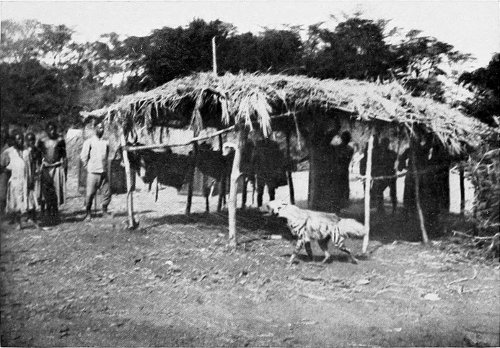

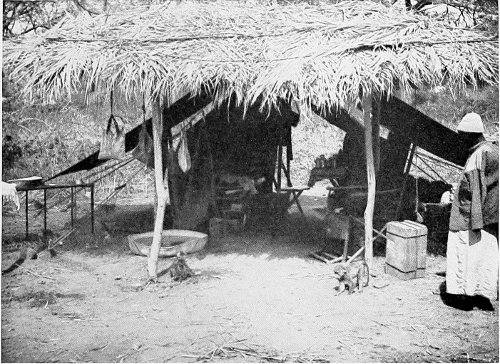

A MISSIONARY’S DWELLING NEAR KILIMANJARO IN WHICH I STAYED SEVERAL TIMES AS GUEST. 425 426

C. G. Schillings, phot.

HEAD OF A BULL-ELEPHANT KILLED BY THE AUTHOR. NOW IN THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM, BERLIN.] 427

C. G. Schillings, phot.

A FINE SPECIMEN OF A BULL-ELEPHANT KILLED BY THE AUTHOR. 428 429

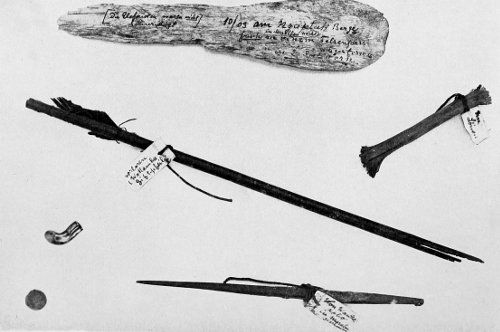

C. G. Schillings, phot.

SOME AFRICAN TROPHIES. 1. SPLINTER FROM AN ELEPHANT-TUSK BROKEN OFF IN A ROCKY REGION. 2. PORTION OF A TREE BRANCH WHICH I FOUND STUCK IN THE JAW OF A CAPTURED LION. 3. PORTION OF A POISONED ARROW WHICH HAD BEEN STICKING IN AN ELEPHANT THAT I WAS TRACKING; ARROW OF THE KIND USED BY THE WAKAMBA HUNTERS. 4. NICKEL BULLET, PUT OUT OF SHAPE, WITH WHICH I BROUGHT DOWN AN ELEPHANT. 5. IRON BULLET USED BY A NATIVE. 6. POISONED DART FOUND STICKING IN THE WING OF A MARABOU. 430

431

BLACK-HEADED HERONS (ARDEA MELANOCEPHALA. VIG. Childr.).

X

BLACK-HEADED HERONS (ARDEA MELANOCEPHALA. VIG. Childr.).

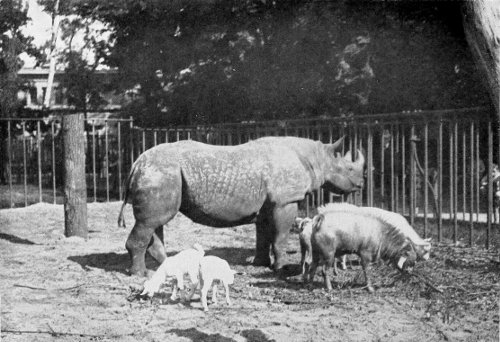

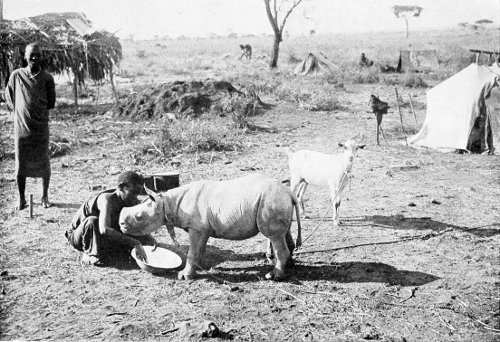

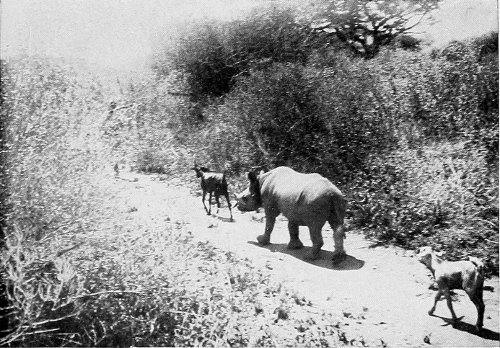

XMany sportsmen of to-day have no idea what numbers of rhinoceroses there used to be in Germany in those distant epochs when the cave-dweller waged war with his primitive weapons against all the mighty animals of old—a war that came in the course of the centuries to take the shape of our modern sport.

The visitor to the zoological gardens, who knows nothing of “big game,” finds it hard perhaps to think of the great unwieldy “rhino” in this capacity. Yet I am continually being asked to tell about other experiences of my rhinoceros-hunting. I have given some already in With Flashlight and Rifle. Let me, then, devote this chapter to an account of some expeditions after the two-horned African rhinoceros—one of the most interesting, powerful, and dangerous beasts still living. 432

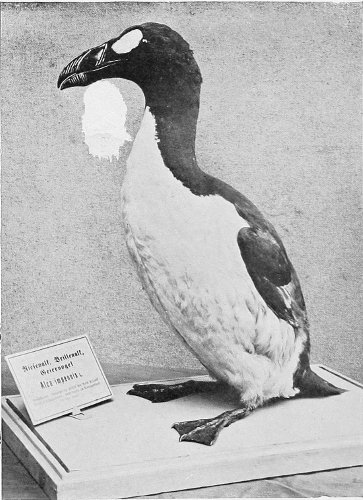

Rhinoceroses used to be set to fight with elephants in the arena in Rome in the time of the Emperors. It is interesting to note that, according to what I have often heard from natives, the two species have a marked antipathy to each other. It is recorded that both Indian and African rhinoceroses used to be brought to Europe alive. In our own days they are the greatest rarities in the animal market, and must be almost worth their weight in gold. Specimens of the three Indian varieties are now scarcely to be found, while the huge white rhinoceros of South Africa is almost extinct. The two-horned rhinoceros of East Africa is the only variety still to be met with in large numbers, and this also is on its way swiftly to extermination.

The kind of hunt I am going to tell of belongs to quite a primeval type, such as but few modern sportsmen have taken part in. But it will be a hunt with modern arms. It must have been a still finer thing to go after the great beast, as of old, spear in hand. That is a feeling I have always had. There is too little romance, too much mechanism, about our equipment. In this respect there is a great change from the kind of hunting known to antiquity.

It was strength pitted against strength then. Strength and skill and swiftness were what won men the day. Later came a time when mankind learnt a lesson from the serpent and improved on it, discharging poisoned darts from tightened bow-strings. The slightest wound from them brought death. Then there was another step in advance, and the hunter brought down his game at 433 434 435 436 437 even greater ranges with bullets of lead and steel. A glance through the telescopic sight affixed to the perfected rifle of to-day, a gentle pressure with the finger, and the rhinoceros, all unconscious of its enemy in the distance, meets its end.

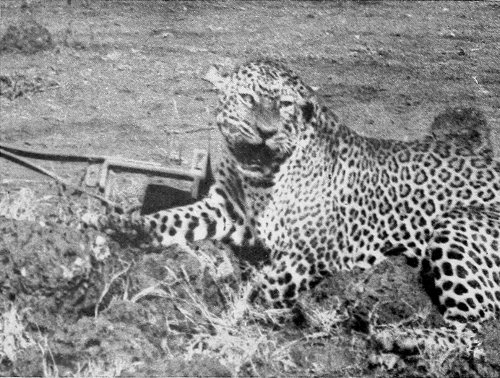

C. G. Schillings, phot.

RHINOCEROS HEADS.

C. G. Schillings, phot.

RHINOCEROS HEADS.

But there is at least more danger and more romance for the modern hunter in this unequal strife when it takes place in a wilderness where bush and brushwood enforce a fight at close quarters. Then, if he doesn’t kill his beast outright on the spot, or if he has to deal with several at a time, the bravest man’s heart will have good reason to beat fast.

Now for our start.

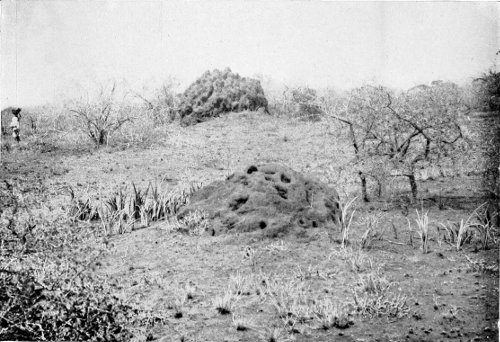

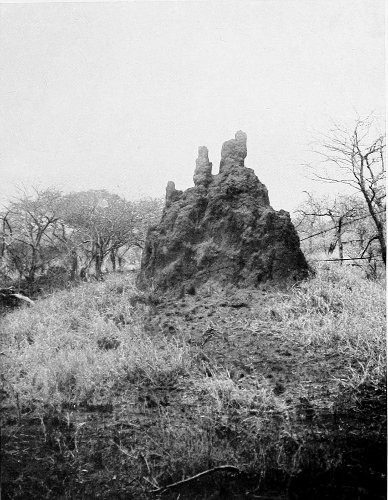

We make our way up the side of a hill with the first rays of the tropical sun striking hot already on the earth. The country is wild, the ascent is difficult, and we have to dodge now this way, now that, to extricate ourselves from the rocky valley into which we have got. The vegetation all around us is rank and strange; strong grass up to our knees, and dense creepers and thorn-bushes retard our progress. Here are the mouldering trunks of giant trees uprooted by the wind, there living trees standing strong and unshaken. But as we advance we come gradually to a more arid stretch, and green vegetation gives place to a rocky region, broken into crevices and chasms. Here we find the rock-badger in hundreds. But the leaders have given their warning sort of whistle, and they are all off like lightning. It may be quite a long time before they reappear from the nooks and crannies to which they have fled. Lizards share these 438 localities with them, and seem to exchange warnings of coming danger. A francolin flies up in front of us with a clatter of wings, reminding one very much of our own beautiful heath-cock. The “cliff-springer” that miniature African chamois, one of the loveliest of all the denizens of the wilderness, sometimes puts in an appearance too. It is a mystery how it manages to dart about from ridge to ridge as lightly as an india-rubber ball. If you examine through your field-glasses, you discover to your astonishment that they do not rest on their dainty hoofs like others of their kind, nor can they move about on them in the same fashion. They can only stand on the extreme points of them. It looks almost as though nature were trying to free a mammal from its bonds to mother earth, when you see the “cliff-springer” fly through the air from rock to rock. It would not astonish you to find that it had wings. Now here, now there, you hear its note of alarm, and then catch sight of it. It would be difficult to descry these animals at all, only that there are generally several of them together.... Deep-trodden paths of elephants and rhinoceroses cut through the wooded wilderness; paths used also by the heavy elands, which are fitted for existence alike in the deep valleys and high up on the highest mountain. I myself found their tracks at a height of over 6,000 feet, and so have all African mountain-climbers worthy of the name, from Hans Meyer, the first man to ascend Kilimanjaro, down to Uhlig, who, on the occasion of his latest expedition up to the Kibo, noted the presence of this giant among antelopes at a height of 15,000 feet.

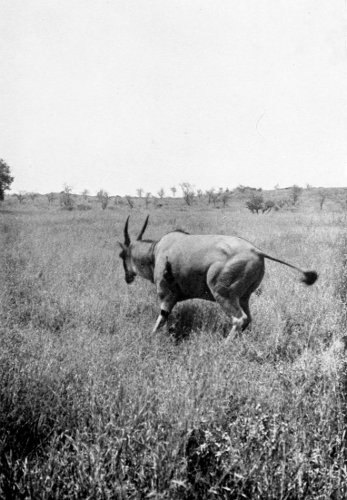

C. G. Schillings, phot.

AN ELAND BULL (OREAS LIVINGSTONI, Sclat.). I MANAGED TO PREPARE THIS ANIMAL’S SKIN SUCCESSFULLY, AND IT MAY NOW BE SEEN IN FLAWLESS CONDITION IN THE BERLIN NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM. 439

It is strange to contrast the general disappearance of big game in all other parts of the earth with their endless profusion in those regions which the European has not yet opened out. I feel that it sounds almost incredible when I talk of having sighted hundreds of rhinoceroses with my own eyes: incredible to the average man, I mean, not to the student of such matters. Not until the mighty animal has been exterminated will the facts of its existence—in what numbers it throve, how it lived and how it came to die—become known to the public through its biographer. We have no time to trouble about the living nowadays.

For weeks I had not hunted a rhinoceros—I had had enough of them. I had need of none but very powerful specimens for my collection, and these were no more to be met with every day than a really fine roebuck in Germany. It is no mean achievement for the German sportsman to bag a really valuable roebuck. There are too many sportsmen competing for the prize—there must be more than half a million of us in all!

It is the same with really fine specimens of the two-horned bull-rhinoceros. It is curious, by the way, to note that, as with so many other kinds of wild animals, the cow-rhinoceros is furnished with longer and more striking-looking horns than the bull, though the latter’s are thicker and stronger, and in this respect more imposing. The length of the horns of a full-grown cow-rhinoceros in East Africa is sometimes enormous—surpassed only by those of the white rhinoceroses of the South, now almost extinct. The British Museum contains specimens 440 measuring as much as 53½ inches. I remember well the doubts I entertained about a 54-inch horn which I saw on sale in Zanzibar ten years ago, and was tempted to buy. Such a growth seemed to me then incredible, and several old residents who ought to have known something about it fortified me in my belief that the Indian dealer had “faked” it somehow, and increased its length artificially. It might still be lying in his dimly lit shop instead of forming part of my collection, only that on my first expedition into the interior I saw for myself other rhinoceroses with horns almost as long, and on returning to Zanzibar at once effected its purchase. A second horn of equal length, but already half decayed when it was found on the velt, came into my possession through the kindness of a friend. I myself killed one cow-rhinoceros with very remarkable horns, but not so long as these.

There is something peculiarly formidable and menacing about these weapons of the rhinoceros. Not that they really make him a more dangerous customer for the sportsman to tackle, but they certainly give that impression. The thought of being impaled, run through, by that ferocious dagger is by no means pleasant.

In something of the same way, a stag with splendid antlers, a great maned lion, or a tremendous bull-elephant sends up the sportsman’s zest to fever-pitch.

It is astonishing how the colossal beast manages to plunge its way through the densest thicket despite the hindrance of its great horns. It does so by keeping its head well raised, so that the horn almost presses against 441 442 443 the back of its massive neck, very much after the style of our European stag. But it is a riddle, in both cases, how they seem to be impeded so little.

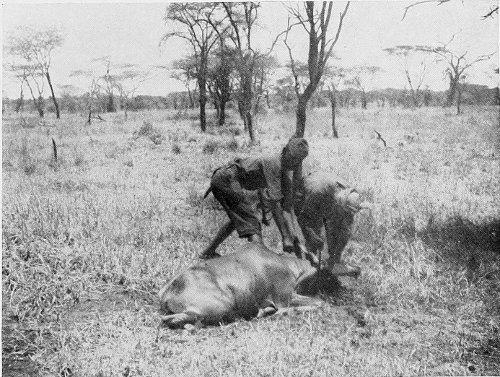

C. G. Schillings, phot.

AN ELAND, JUST BEFORE I GAVE IT A FINISHING SHOT.

I felt nearly sure that I could count on finding some gamesome old rhinoceroses up among the mountains, and my Wandorobo guides kept declaring that I should see some extraordinary horns. They were not wrong.

I strongly advise any one who contemplates betaking himself to the velt after big game to set about the enterprise in the true sporting spirit, making of it a really genuine contest between man and beast—a genuine duel—not an onslaught of the many upon the one. Many English writers support me in this, and they understand the claims of sport in this field as well as we Germans do at home. The English have instituted clearly defined rules which no sportsman may transgress. In truth, it is a lamentable thing to see the Sonntagsjäger importing himself with his unaccustomed rifle amid the wild life of Africa!

I shall always look back with satisfaction to the great Schöller expedition which I accompanied for some time in 1896. Not one of the natives, not one of the soldiers, ventured to shoot a single head of game throughout that expedition, even in those regions which until then had never been explored by Europeans. The most rigid control was exercised over them from start to finish. I have good grounds for saying that this spirit has prevailed far too little as a general thing in Africa.

I have invariably maintained discipline among my own followers, and they have always submitted to it. How 444 difficult it is to deal with them, however, may be gathered from the following incident which I find recorded in my diary.

On the occasion of my last journey, a black soldier, an Askari, had been told off to attach himself for a time to my caravan. Presently I had to send him back to the military station at Kilimanjaro with a message. A number of my followers accompanied him, partly to fetch goods, etc., from my main camp, partly on various other missions that had to be attended to before we advanced farther into the velt. The Askari was provided, as usual, with a certain number of cartridges. When my men returned, a considerable time afterwards, I discovered quite accidentally that one of them bore marks on his body of having been brutally lashed with a whip. His back was covered with scars and open wounds. After the long-suffering manner of his kind, he had said nothing to me about it until his condition was revealed to me by chance—for, as he was only one of the hundred and fifty attached to my expedition, I might never have noticed it. It transpired that not long after he had set out the Askari, against orders, had shot big game and, among other animals, had bagged a giraffe, whose head—a valuable trophy—he had forced my bearers to carry for him to the fort. The particular bearer in question had quite rightly refused, whereupon the Askari had thrashed him most barbarously with a hippopotamus-hide whip—a sjambok. I need hardly say that he was suitably punished for this when I lodged a formal complaint against him. Had it not been for his ill-treatment of my bearer, however, I 445 should never have heard of the Askari’s shooting the giraffe, for he had succeeded in terrorising all the men into silence.

AN ELAND BULL, THE LEADER OF A HERD WHICH AT THE MOMENT OF THIS PHOTOGRAPH WAS IN CONCEALMENT BEHIND THE THORN-BUSHES.

Now we move onwards, following the rhinoceros-tracks up the hill-slopes, where they are clearly marked, and in among the steep ridges, until they elude us for a while in the wilderness. Presently we perceive not merely a hollowed-out path wrought in the soft stone by the tramplings of centuries, but also fresh traces of rhinoceroses that must have been left this very day. We are in for a first-rate hunt.

We have reached the higher ranges of the hills and are 446 looking down upon the extensive, scantily-wooded slopes. Are we going to bag our game to-day?

I could produce an African day-book made up of high hopes and disappointments. Not, indeed, that returning empty-handed meant ill-humour and disappointment, or that I expected invariable good luck. But a day out in the tropics counts for at least a week in Europe, and I like to make the most of it. Then, too, I had to reserve my hunting for those hours when I could give myself up to it body and soul. How often while I have been on the march at the head of heavily laden caravans have the most tempting opportunities presented themselves to me, only to be resisted—fine chances for the record-breaker and irresponsible shot, but merely tantalising to me!

On we go through the wilderness, still upwards. I am the first European in these regions, which have much of novelty for my eyes. The great lichen-hung trees, the dense jungle, the wide plains, all charm me. The heat becomes more and more oppressive, and I and my followers are beginning to feel its effects. We are wearying for a halt, but we must lose no time, for we have still a long way before us, whether we return to our main camp or press onwards to that wooded hollow yonder, four hours’ march away, there to spend the night.

A vast panorama has been opening out in front of us. We have reached the summit of this first range of hills, and are looking down on another deep and extensive valley. My field-glasses enable me to descry in the far distance a herd of eland making their way down the hill, and two bush-buck grazing hard by a thicket. But these have 447 no interest for us to-day: we are in pursuit of bigger game. Suddenly, an hour later, my men become excited. “Pharu, bwana!” they whisper to me from behind, pointing down towards a group of acacia trees on a plateau a few hundred paces away. True enough, there are two rhinoceroses. I perceive first one, then the other lumbering along, looking, doubtless, for a suitable resting-place. My field-glasses tell me that they are a pair, male and female, both furnished with big horns. Now for my plan of campaign. I have to make a wide circuit which will take me twenty-five minutes, moving over difficult ground.

Arrived at the point in question, I rejoice to see that the animals have not got far away from where I first spied them. The wind is favourable to me here, and there is little danger at this hour of its suddenly veering round. I examine my rifle carefully. It seems all right. My men crouch down by my order, and I advance stealthily alone.

I am under a spell now. The rest of the world has vanished from my consciousness. I look neither to right nor left. I have no thought for anything but my quarry and my gun. What will the beasts do? Will this be my last appearance as a hunter of big game? Is the rhinoceros family at last to have its revenge?

I have another look at them through my field-glasses. The bull has really fine horns; the cow good enough, but nothing special. I decide therefore to secure him alone if possible, for his flesh will provide food in plenty for my men. On I move, as noiselessly as possible, the wind still in my favour. Up on these heights the rhinoceroses miss their watchful friends the ox-peckers, 448 so faithful to them elsewhere, to put them on their guard.

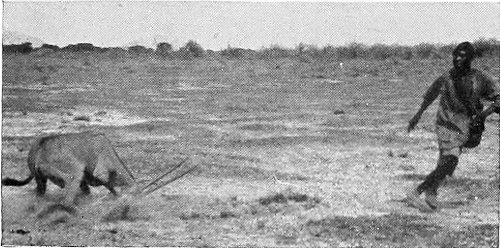

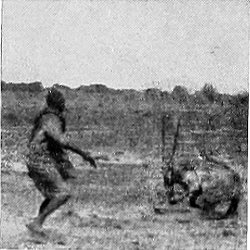

Often have my followers warned me of the presence of a “Ndege baya”—a bird of evil omen. Many of the African tribes seem to share the old superstitions of the Romans in regard to birds. Certainly one cannot help being impressed by the way in which the ox-peckers suddenly whizz through the air whenever one gets within range of buffalo or hippopotami.