This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Campaign of Sedan

The Downfall of the Second Empire, August-September 1870

Author: George Hooper

Release Date: June 1, 2017 [eBook #54823]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CAMPAIGN OF SEDAN***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/campaignofsedand00hoop |

Transcriber’s Note

BOHN’S STANDARD LIBRARY

THE CAMPAIGN OF SEDAN

“The policy of your Government will bring you to Jena,” said M. de Moustier to Herr von Bismarck during the Crimean War. “Why not to Waterloo?” was the prompt and prophetic reply.

Wo Kraft und Muth in deutscher Seele flammen.

AUTHOR OF “WATERLOO: THE DOWNFALL OF THE FIRST NAPOLEON: A

HISTORY OF THE CAMPAIGN OF 1815,” ETC.

WITH MAP AND PLANS

LONDON

GEORGE BELL AND SONS

1909

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

When it was decided to publish a new and cheaper edition of Mr. George Hooper’s “Sedan,” the question arose whether anything should be added to it. My father had intended, should a new edition be called for, to revise and correct the work, and to furnish it with an index. After due consideration it has been decided to make no additions to the book, except the index, which has been carefully compiled. A few errors that had crept into the text of the original edition have been corrected; but in other respects the volume remains as it was left by its author.

WYNNARD HOOPER.

SOUTH KENSINGTON,

October, 1897.

The War of 1870–71 was opened by a campaign of thirty days, complete in itself, and the author must plead the dramatic unity of the great event as a reason for treating it in a separate form. Although the foundation of those ulterior successes which enabled the Germans to proclaim the King of Prussia Emperor in Germany, and to do so in the palace of Louis XIV., yet, from an historical point of view, the astonishing series of battles and marches which ended in the Investment of Metz, and the Capitulation of Sedan may be regarded as standing apart, because they carried with them the Downfall of the Second Empire. The Campaign of Sedan, in this respect, is the supplement of the Campaign of Waterloo; but, of course, there is no resemblance between Napoleon III. and Napoleon I., nor in the political and military conditions and results of the two catastrophes.

The materials at the disposal of any author who ventures to narrate the campaign are abundant and yet incomplete. The History of the War prepared by the German Staff is minute even to weariness, but it must always stand as the authentic foundation of every narrative. Unreadable to the general public, it is invaluable to the soldier-student, and to all who wish to know what the German Army is like, and how it wages war. It need scarcely be said that the Staff narrative is the basis of this book, which is an endeavour to present its essence in a succinct and readable form. Unhappily, the French accounts are wanting in precision, so that it is difficult to comprehend how they fought their battles, and impossible to ascertain accurately what was their numerical strength at any moment. The deficiency is serious, because it mars the completeness of the story, and frustrates every attempt to do them full justice. For, if the Army, as an Army, was wasted by incapable commanders, the soldiers fought well and did nothing to derogate from their old renown. They had to encounter better commanders, more numerous and better soldiers, and they were beaten, but they were not disgraced. The whole lesson of the war is lost, if the fact is ignored that the German Army, from top to bottom, was superior in every way to that of Napoleon III., as well as more numerous; and that what made it superior was the spirit of Duty, using the word in its highest sense, which animated the host, from the King, who was its shining exemplar, to the private who was proud to rival his King.

The contrast, which this war exhibited, between the French and German methods of making and using an Army is so violent, that it becomes painful, and imparts an air of one-sidedness to the narrative. But the facts must be stated, although the bare statement suggests partiality in the narrator. I have, nevertheless, tried to be impartial, and in doing my best, I have found it impossible to read the abounding evidence of Imperial neglect, rashness and indecision, without feeling pity for the soldiers and the nation which had to bear the penalties. The French Army has been remodelled and increased enormously; the secular quarrel between Germany and France is still open; and some day it may be seen whether the Republicans, out of the same materials, have been able to create an Army such as the Imperialists failed to produce. Whether they have succeeded or not, it may be fervently hoped that the deep impression which the examples of thoroughness, revealed by the wars of 1866 and 1870, made on our own country will never be effaced; and that the public will insist that our small Army, in every part, shall be as good as that which crossed the French frontier in 1870, and triumphed in the Campaign of Sedan.

KENSINGTON, April 6th, 1887.

THE CAUSES OF THE WAR.

French Demands for the Rhine—Luxemburg—An Interlude of Peace—The Salzburg Interview—The Emperor seeks Allies—The Hohenzollern Candidature—The French Government and the Chamber

THE GATHERING OF THE HOSTS.

German Mobilization—French Mobilization—War Methods Contrasted

STAGE THUNDER.

The Combat at Saarbrück—Preparing to go Forward—Positions on August 4—The Moral and Political Forces

INVASION IN EARNEST.

The Combat on the Lauter—French Position on the Saar—German Position on the Saar

TWO STAGGERING BLOWS.

1. Woerth—The Battle Begins—Attack on Woerth—Attack on the French Right—Attack on Elsasshausen—MacMahon Orders a Retreat—The Close of the Battle. 2. Spicheren—The Battle-field—The Germans Begin the Fight—The Red Hill Stormed—Progress of the Action—Frossard Retires

VACILLATION IN METZ.

The Emperor Resigns his Command—The German Advance—The German Cavalry at Work—The Germans March on the Moselle

VON MOLTKE KEEPS THE WHIP HAND.

The French Propose to Move—The Battle of Colombey-Nouilly—Von Golz Dashes In—The End of the Battle—The French Retreat—The Germans Cross the Moselle—The Cavalry Beyond the Moselle—Orders for the Flank March—The Emperor Quits the Army

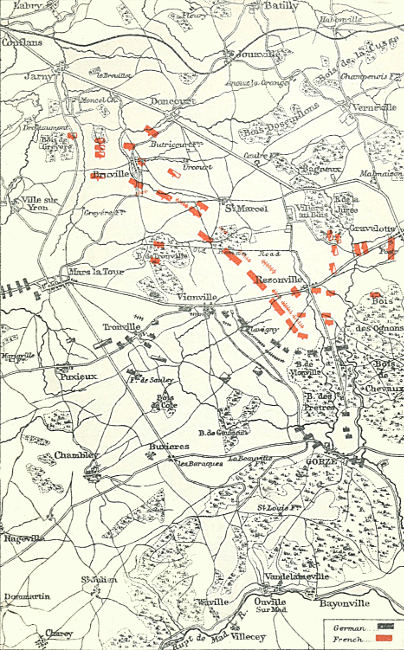

THE FRENCH RETREAT THWARTED.

Vionville-Mars la Tour—The Vionville Battlefield—The French are Surprised—The Third Corps Strikes In—Arrival of Bazaine—Bredow’s Brilliant Charge—The Fight becomes Stationary—Arrival of the Tenth Corps—The Great Cavalry Combat—End of the Battle

PRESSED BACK ON METZ.

Marshal Bazaine—The Battlefield of Gravelotte—The German Plans—The Battle of Gravelotte—Prince Frederick Charles at the Front—Steinmetz Attacks the French Left—Operations by the German Left Wing—General Frossard Repels a Fresh Attack—The Last Fights near St. Hubert—The Prussian Guard on the Centre and Left—The Capture of St. Privat

THE STATE OF THE GAME, AND THE NEW MOVES.

The King Marches Westward—The Cavalry Operations—The Emperor at Chalons and Reims—MacMahon retires to Reims—The Chalons Army Directed on the Meuse

THE GRAND RIGHT WHEEL.

The Cavalry Discover the Enemy—Movements of the French—The Marshal Resolves, Hesitates, and Yields—Movements of the Germans—Effects of MacMahon’s Counter-orders—German and French Operations on the 29th—The Combat at Nouart—The State of Affairs at Sundown—The Battle of Beaumont—The Surprise of the Fifth Corps—The Flight to Mouzon

METZ AND STRASBURG.

The Battle of Noisseville

SEDAN.

German Decision—Confusion in the French Camp—The Movements of the Germans—The Battlefield of Sedan—The Battle of Sedan—MacMahon’s Wound and its Consequences—Progress of the Battle on the Givonne—The March on St. Menges—The Eleventh and Fifth Corps Engage—The Condition of the French Army—The French Cavalry Charge—General de Wimpffen’s Counter stroke—The Emperor and his Generals—King William and his Warriors—How the Generals Rated Each Other—The Generals Meet at Donchery—Napoleon III. Surrenders—The French Generals Submit—The End

I. The German Field Armies—II. The French Army—III. The Protocol of Capitulation—IV. A List of the Principal Works Consulted for the Campaign of Sedan

MAP AND PLANS.

THE CAMPAIGN OF SEDAN.

INTRODUCTION.

In July, 1870, fifty-five years after the Allied Armies, who had marched from the decisive field of Waterloo, entered Paris, a young diplomatist, Baron Wimpfen, started from the French capital, for Berlin. He was the bearer of a Declaration of War, from the Emperor Napoleon III., to William I., King of Prussia; and the fatal message was delivered to the French Chargé d’Affaires, M. le Sourd, and by him to the Prussian Government on the 19th of July. Thus, once again, a Napoleon, at the head of a French Empire, was destined to try his strength against the principal German Power beyond the Rhine.

Yet, under what different conditions! The Emperor was not now the Napoleon who surrounded the Austrians at Ulm, broke down the combined forces of Austria and Russia at Austerlitz, and extorted a peace which set him free to overthrow, at Jena and Auerstadt, the fine army left by Frederick the Great, and allowed to crystallize by his weak successors. Nor did the late Emperor find in his front a divided Germany, and the mere survival of a great military organization. He found a united people, and an army surpassing in completeness, as it did in armaments—the [p 2] victors of Prague, Rosbach, and Leuthen. The Germany known to the Congress of Vienna had disappeared—the deformed had been transformed. The little seed of unity, sown early in the century, had grown into a forest tree. The spirit of Arndt had run through the whole Teutonic nation, which, after the turmoil of 1848 had subsided, and the heavy hand of Russia had been taken off by the Crimean War, found a leader in the strongly-organized kingdom of Prussia. When the weak and hesitating will of Frederick William IV. ceased, first, by the operation of a painful disease, and then by extinction, to disturb the course of his country’s fortune, Prussia, in a few years, became practically a new Power. King William I., who crowned himself with his own hands at Königsberg, began his task, as a ruler, in a grave and earnest spirit, holding that kingship was not only a business, but a trust, and taking as his watchwords, Work and Duty. No monarch in any age, no private man, ever laboured more assiduously and conscientiously at his métier, to use the word of Joseph II., than the King of Prussia. He became Regent in 1858, when Napoleon III. was engaged in preparing for his Italian campaign against the House of Austria. French policy, with varying watchwords, had run that road for centuries; and, during the summer of 1859, it was the good fortune of the Emperor to win a series of victories which brought his army to the Mincio, and before the once famous Quadrilateral. The German Bund had taken no part in the fray, but the rapid successes of the French aroused some apprehensions in Berlin, and there went forth an order to mobilize a part of the army, which means to put each corps on a war-footing, and to assemble a force in Rhenish Prussia. Whatever share that demonstration may have had in producing the sudden arrangement between the rival Emperors, who [p 3] made peace over their cigarettes and coffee at Villafranca, the experiment tried by the Berlin War Office had one important result—it brought to light serious defects in the system then practised, and revealed the relative weakness of the Prussian army. From that moment, the Regent, who soon became King by the death of his brother, began the work of reforming the military system. For this step, at least from a Prussian standpoint, there was good reason; since the kingdom, although it was based on a strong and compact nucleus, was, as a whole, made up of scattered fragments lying between great military Powers, and therefore could not hope to subsist without a formidable army. The relative weakness of Prussia had, indeed, been burnt into the souls of Prussian statesmen; and King William, on his accession, determined that as far as in him lay, that grave defect should be cured. A keen observer, a good judge of character and capacity, his experience of men and things, which was large, enabled him at once to select fit instruments. He picked out three persons, two soldiers and a statesman, and severe ordeals in after years justified his choice. He appointed General von Roon, Minister of War, and no man in modern times has shown greater qualities in the organization of an army. He placed General von Moltke at the head of the General Staff, which that able man soon converted into the best equipped and the most effective body of its kind known to history. It rapidly became, what it now is, the brain of the army, alike in quarters and in the field. Finally, after some meditation, he called Herr Otto von Bismarck from the diplomatic service, which had revealed his rare and peculiar qualities, and made this Pomeranian squire his chief political adviser, and the manager of his delicate and weighty State affairs.

Thenceforth, the long-gathering strength of Prussia, the [p 4] foundations of which were bedded deep in the history of its people, began to assume a form and a direction which great events revealed to astonished and incredulous Europe. The experiment undertaken by the King and his chief councillors was rendered less difficult by that effect of the Crimean War which so materially lessened the influence of Russia in Germany. The intimate and friendly relations subsisting between the two Courts remained unbroken, and to its preservation in fair weather and foul, Prussia owed, to a large extent, the favourable conditions surrounding the application and development of her policy. It seemed as necessary to Prussian, as it now does to German interests, that the Russian Government should be, at least, benevolently neutral; and probably the art of keeping it so was profoundly studied by Herr von Bismarck when he filled the post of Ambassador to the Court of St. Petersburg. The large military reforms designed by the King and his advisers aroused an uncompromising opposition in the native Parliament, which was only overcome by the firmness with which King William supported his outspoken and audacious Minister. The victory was secured by methods which were called, and were, unconstitutional. The control of the Chamber over the Budget was placed in abeyance, by a clever interpretation of the fundamental law. It was held that if the Deputies could not agree with the Government respecting the estimates of the current year, the law which they had sanctioned in the preceding year still remained valid. Thus the taxes were collected, appropriated and expended, just the same as if the Chamber had not virtually “stopped the supplies” in order to defeat the measures which were intended to give the army stability, numbers, efficiency and cohesion. The whole transaction ran counter to English maxims and customs; but it should be remembered that Parliamentary Government, and [p 5] especially government by party, were never, and are not even now established in Berlin. The net result of the contest was the renovation and the strengthening of the National Army to an extent which, while it did not exceed, perhaps, the expectations of those who laboriously wrought it out, left some Powers of Europe ignorant, and others incredulous respecting its value.

Not that the military institutions of Prussia, dating back from the “new model,” devised during the stress of the Napoleonic Wars, had been fundamentally altered. Nothing was done except to increase the numbers, close up and oil the machinery, render its working prompt and easy by prudent decentralization, give it a powerful brain in the General Staff, and impart to the whole system a living energy. The art of war, if the phrase may be allowed, was, in accordance with venerable traditions rooted in the Hohenzollern House, taken up as a serious business; and that deep sense of its importance which prevailed at the fountain head, was made to permeate the entire frame. That is the real distinguishing characteristic of the Prussian, now the German army, as contrasted with the spirit in which similar labours were undertaken by some other Powers. The task was a heavy one, but the three men who set about it were equal to the task. King William, with a large intelligence, a severe yet kindly temper, and a thorough knowledge of his work, threw himself heart and soul into the business, and brought to bear upon its conduct that essential condition of success, the “master’s eye.” General von Roon framed or sanctioned the administrative measures which were needed to create an almost self-acting and cohesive organism, which could be set in motion by a telegram, as an engineer starts a complicated piece of machinery by touching a lever. Von Moltke, as chief of the General Staff, supplied the directing [p 6] intellect, and established a complete apparatus for the collection and classification of knowledge, bearing upon military affairs, which might be applied wherever needed. These men, working with “unhasting, unresting” diligence, founded a school of war, not based on “the law of the Medes and Persians which altereth not,” but upon the vital principle that a good army should possess in itself such a power of adaptation, as will make it always abreast with the latest genuine discoveries in tactics, arms, material appliances, and discipline. Also the army was treated as a great school in which officers and men alike were teaching and learning from dawn to sunset, throughout the allotted period of service. The principal trio had other and able helpers, but they were the main springs moving and guiding the marvellous product of constant labour applied by rare capacity.

The ultimate, although not the immediate, effect of the French successes at Magenta and Solferino, was the creation of an Italian kingdom, which included within its boundaries, Naples, Sicily, the States of the Church, except Rome, and of course the Duchies on the right bank of the Po. The price of compliance, exacted by the Emperor Napoleon, whose plans had been thwarted, was the cession to him of Nice and Savoy. Venice and the territory beyond the Mincio remained Austrian for several years. While the map of Italy was in course of reconstruction, the political conflict in Berlin raged on with unintermitted violence. Simultaneously the Austrian Emperor was induced to assert his claims to predominance in Germany, but the plans laid, in 1863, were blighted by the prompt refusal of William I. to take any share in them. It was the first symptom of reviving hostility between the two Powers, although a little later, on the death of the King of Denmark, they were found, side by side in arms, to assert [p 7] the claims of the German Bund upon Holstein, Schleswig and Lauenburg, and avert the occupation of those countries by the troops of Saxony and other minor States alone. The campaign which ensued brought the new model of the” Prussian army to the test of actual experiment. But the brave adversaries they had to encounter, if stout in heart, were weak in numbers; and Europe did not set much store by the victories then achieved by Prussia. The public and the Governments were intently occupied with the Secession War in the United States of America, and the astounding expedition to Mexico, which was designed to place an Austrian Archduke on “the throne of the Montezumas,” under illustrious French patronage. Thus the quality of the troops, the great influence of the famous “needle-gun,” the character of the staff, and the excellent administrative services escaped the notice of all, save the observant few. The political aspects of the dispute were keenly discussed. Lord Palmerston and Lord Russell were, at one moment, disposed to fight for the Treaty of 1851; but the Danish King committed grave blunders; Russia stood aloof, the Emperor Napoleon III. distinctly refused to enter the lists, and the House of Commons was decidedly averse to war. Here it should be noted that the French Emperor, meditating on the value to him of the rival Powers in Germany, had determined to stand well with both. He hoped to please Austria by making the brother of Francis Joseph Emperor of Mexico, and to keep open the possibilities of an alliance with Prussia, by throwing no obstacles in her way on the Eider.

Then began the great strife between the two Governments which had wrested the Elbe Duchies from the Dane. When the short war ended, certain divisions from each army were posted in the conquered country, and the rivalry which animated the two Courts was carried on by diplomats and [p 8] statesmen. Prussian policy, since the days of Frederick II., had leaned always towards, if not an alliance with Russia, yet the maintenance of a solid understanding with that growing Power. Herr von Bismarck, who was a deep student in the history of his own country, and who had always nourished large ideas, kept steadily on the well-trodden path, but imparted to his methods a boldness, an inventiveness, and an energy most unusual in Prussian statescraft. The Polish insurrection of 1864 gave him an opportunity which he did not neglect, and while the poor patriots were assisted from the side of Galicia, on the Posen frontier they were ruthlessly repressed, the Russian and Prussian troops making common cause, and crossing the frontier whenever that step seemed needful. The ill-fated Poles, of course, were defeated; Prussia had recorded a fresh claim upon the benevolent neutrality of Russia, while Austrian “ingratitude,” never forgiven in St. Petersburg, took a deeper tinge in the eyes of the Czar. The Prussian Government had not long to wait for their reward. During the summer of 1865, the abiding quarrel between Vienna and Berlin, respecting the future status of the conquered or restored Duchies, nearly came to an open rupture. Neither side, however, was ready for a blow, and the “Convention of Gastein,” which Bismarck, in a letter to his wife, defined as a mode of “pasting together the cracks in the building,” was devised to gain time. The Prussian army, still incomplete from the royal and the military point of view, had been augmented after the Danish war, and the new levies of horse and artillery had not acquired the requisite instruction. So the summer and autumn of 1865 wore away, revealing the spectacle of King William and Herr von Bismarck battling fiercely with the Parliament, and not so clearly displaying Von Moltke and Von Roon labouring hourly to bring the [p 9] machine intrusted to their charge up to the highest attainable efficiency. There were other reasons for delay. As it was more than probable that the South Germans, and possible that the King of Hanover would not rank themselves with Prussia, but go with Austria and the Bund, an ally was wanted who would divide the forces of the largest Power. That ally was found in the newly united kingdom of Italy.

But before the Italian envoy astonished the diplomatic world by his apparition at Berlin, in March, the controversy between Austria and Prussia had gone on rapidly, step by step, nearer towards a rupture. Count Mensdorff, on behalf of the Emperor Francis Joseph, set up a claim to full liberty of action in the Duchy of Holstein, and began openly to favour the pretentions of the Duke Frederick of Augustenburg to the Ducal Chair. That position was vigorously contested by Herr von Bismarck, who put an opposite construction on the Treaty, which created what was called the “condominium.” The consequence was a frequent and animated exchange of despatches, containing such “arguments” as seemed proper to the occasion. Into the merits of this dispute it is needless to enter now, since the whole drift of the verbal struggle shows that while Prussia was intent on providing a solid ground on which to fight out a long-standing quarrel—“inevitable,” said Von Moltke, “sooner or later,”—Austria was by no means inclined to shrink from a test directly applied to her position in Germany. Whatever line she had taken her rival would have discovered, or tried to discover, an opposing course; but, it so happened, that, whether by chance or miscalculation, Count Mensdorff, the Austrian Foreign Minister, managed his case so as to give advantages to his abler antagonist. In the last days of February a great council was held in Berlin. Not only the King and his [p 10] chief Minister, but General von Moltke and General von Manteuffel, from Schleswig, took part in its deliberations. It was the turning point in the grave debate, so far as Prussian action was concerned; for the decision then adopted unanimously, was, that Prussia could not honourably recede, but must go forward, even at the risk of war. No order was given to prepare for that result, because the organization of the army was complete, and moreover, because “the King was very adverse to an offensive war.” Nevertheless, from that moment such an issue of the dispute became certain to occur at an early day. Yet neither party wished to fight over the Duchies; each felt that the cause was too paltry. The Austrians, therefore, extended the field, by appealing to the Bund, a move which gave Herr von Bismarck the advantage he so eagerly sought. He answered it by resolving to push, in his own sense, the cause of federal reform. Learning this determination early in March, M. Benedetti observed to Herr von Bismarck that it would insure peace. “Yes,” answered the Minister President,—“for three months,” a very accurate forecast by a prophet who could fulfil his own prediction, and who desired to fight the adversary promptly, lest a reconciliation should be effected between Vienna and Pesth, and Hungary, from a source of weakness, should thus become a tower of strength.

A few days later, March 14th, General Govone, from Florence, arrived in Berlin. His advent had been preceded by attempts, on the part of Bismarck, to discover how the French would look on a Prusso-Italian alliance. The subject was delicate, and even after the General’s arrival, it was officially stated that he had come, exclusively, to study the progress in small arms and artillery! The pretence was soon abandoned, and the negotiations were avowed; but the conclusion of a treaty was delayed for some days, [p 11] because no specific date could be fixed on for the outbreak of war, Prussia having determined, at least to make it appear, that she was not the aggressor. At length a form of words was devised, which satisfied both Powers, stipulating that Italy was to share in the war, providing it began within “three months,” and the Convention was signed on the 8th of April. Not, however, before it had been well ascertained that France had really helped on the Prussian alliance and desired to see war ensue, although, avowedly, she did not interfere, giving out that she stood neuter, and that the understanding which might be ultimately come to between France and Prussia would be determined by the march of events, the extension of the war, and the questions to which it might give rise. This language foreshadowed the policy which the Emperor, if not M. Drouyn de Lhuys desired to follow; and as Russia, recently obliged in the Polish troubles, was friendly, if not allied, Herr von Bismarck was convinced that no foreign power would array itself on the side of Austria, unless the campaign were prolonged.

Henceforth, the aim of each disputant was to secure a vantage-ground in Germany. Austria had partially collected troops in Bohemia and Moravia, and had secretly stipulated with several States to call out four Federal corps d’armée; while Prussia, who could wait, being always ready, had only carried her preparations forward to a certain extent. M. von Beust, the Saxon Minister, then intervened with a proposal that the Diet should name arbiters, whose decision should be final; a suggestion instantly rejected by the principals in the quarrel. The Emperor Napoleon III., towards the end of May, when Prussian mobilization had practicably been completed in eight corps, produced his specific—the characteristic proposal that a Conference should be held in Paris to study the means of maintaining the peace. Prussia accepted the [p 12] offer, but Austria put an end to the hopes of Napoleon, by stipulating that no arrangement should be discussed which would augment the territory or power of any party of the Conference, and in addition that the Pope should be invited to share in any deliberations on “the Italian Question.” These pretensions, by excluding, what everyone wanted, the cession of Venetia to Italy, decided the fate of the Conference. “They desire war at Vienna,” said Von Bismarck to Count Benedetti. “These conditions have been conjured up solely for the purpose of giving the States in South Germany time to complete their military preparations.” And when the news came officially from Paris that the Austrian answer had killed the project, the Minister President shouted in the French Ambassador’s presence “Vive le Roi!” The solution was war. The Prussian army, for once, had been mobilized by slow degrees. More than a month elapsed between the first precautionary and the final steps, but by the 12th of May the entire active army had been summoned to arms. The Conference project was a last attempt, made, indeed, after all hope of arresting the conflict had vanished, alike in Vienna and Berlin; and it was followed by events in Holstein, which put an end to the period of suspense, and formed a prelude to the war. Practically, but without actual fighting, General von Manteuffel compelled the Austrian brigade, under Field-Marshal von Glablenz, to retreat swiftly over the Elbe. The pretext for this strong measure was the fact that Austria, by her sole will, had summoned the Estates to meet at Itzehöe, and had thus infringed the rights of King William! Thereupon Austria requested the Diet at Frankfort to call out all the Federal Corps; and her demand was complied with, on the 14th of June, by a majority of nine to six. The Prussian delegate protested, and withdrew, leaving Austria, Bavaria, Saxony, Wurtemburg, the two Hesses, [p 13] and several minor States, in open combination against Prussia. But the same stroke which isolated the latter, also destroyed the German Bund, invented by the kings and statesmen of 1815, to preserve internal tranquillity, and safeguard the Fatherland against France. The arrangement implied the co-operation of two Powers; one purely German, yet subordinate; the other parcel German, and mainly consisting of divers peoples outside Germany; and it fell to pieces at a blow, because the time had arrived when one of the two must attain supremacy. Side by side with the secular dynastic conflict arose in the nation that longing for unity which could only be accomplished by a thoroughly German Power.

That Power was Prussia, trained for the task by the steadfast labours of two hundred years. The army she had formed did its work swiftly. Pouring through Saxony and over the Silesian Mountains, the King and his son, July 3rd, crushed the Austrians, on the memorable field of Sadowa, near Königgrätz. The Hanoverian troops, after winning the fight at Langensalza, had been obliged to surrender, and in South Germany the army employed to overcome the Confederates was equally victorious. On the 22nd of July, so swiftly had the main body moved, the Prussians were in front of Vienna and Presburg on the Danube. Four days afterwards, the Emperor Napoleon having struck in with an offer of mediation, which was accepted, the preliminaries of a peace were signed at Nikolsburg, on the 26th of July, and the final treaty was settled and ratified at Prague, on the 23rd of August, long after King William and his formidable Minister were once more in Berlin. By this instrument, Austria was excluded from Germany; a Northern Confederation, reaching to the Main, was founded; Hanover, the Elbe Duchies, Hesse-Cassel, and other territories, were annexed to Prussia; and [p 14] a formal statement was inserted, declaring that Napoleon III., to whom Austria had ceded Venetia, had acquired it in order to hand over the city and Terra Firma, as far as the Isonzo, to Victor Emmanuel, when the peace should be re-established. Prussia thus became the acknowledged head of Germany, at least as far as the Main; and the national longing for complete unity was about to be gratified in a much shorter time than seemed probable in 1866.

Naturally, the astonishing successes won by Prussian arms against the Federal Corps, as well as the Austrians, compelled the South German States to sue for peace, and accept public treaties, which, while leaving them independent, brought them all, more or less, within the limits of a common German federation. But something more important was accomplished at Nikolsburg. Herr von der Pfordten, the Bavarian Prime Minister, repaired thither towards the end of July, and Bismarck was in possession of information, including a certain French document, which enabled him to state the German case in a manner so convincing and terrifying, that the Bavarian agreed to sign a secret treaty, bringing the army within the Prussian system, and stipulating that, in case of war, it should pass at once under the command of King William. That which Von der Pfordten conceded the Ministers of Wurtemburg and Hesse Darmstadt could not refuse, and thus provision was made, on the morrow of Sadowa, for that concentration of armed Germany which overwhelmed France in 1870–71. So that, although nothing formally constituting a United Germany had been done, Prussia, by securing the control of all her forces, and knowing that a strong and deeply-rooted public sentiment would support her, was satisfied that, providing time could be gained in which to arm, instruct and discipline upon the Prussian model the South Germans and the troops raised from the annexed provinces, she would be [p 15] more than a match for France. South Germany, indeed, had long known her relative helplessness against the French. Perhaps it would be more correct to say that the real peril was more perceptible to the soldiers and statesmen than to the people, many of whom were strongly imbued with democratic ideas of the French type. Yet, although they hungered for what they understood as liberty and independence, they were still German, and did not fail to see that their cherished desires could not be gratified either under French patronage or French prefects. The soldiers and statesmen had early perceived the full secret of South German dependence. The Archduke Charles, who had great knowledge and harsh experience to guide him, pointed out that the French posts on the Rhine had placed the country south of the Main at the mercy of France. “As long as the Rhine frontier from Huningen to Lauterbourg remains in her hands,” wrote a Prussian staff-officer at a later period, “Germany is open on the Rhine frontier to an invasion directed upon the Southern States.” No stronger testimony to the sense, if not to the reality of insecurity could be adduced, than the remarkable fact that, even so far back as the Crimean War, the then King of Wurtemberg, in conversation with Herr von Bismarck, set forth, significantly, the feelings, the hopes and the dread of South Germany. “Give us Strassburg,” he said, “and we will unite to encounter any eventuality … for until that city shall become German, it will always stand in the way of Southern Germany, devoting herself unreservedly to German unity and to a German national policy.” Hence it will be seen that, beyond the Main, there were traditional, yet very real fears of French invasion; and that these apprehensions had no small share in facilitating the acceptance of the secret military treaties, and in shaping the course of subsequent events.

Thus much it seems needful to state, in order that some portion of the earlier transactions which had a great influence in bringing on the war of 1870, may be recalled to the reader’s mind. The short, sharp and decisive duel fought between Austria and Prussia for leadership in Germany, created a profound impression throughout Europe. Austria was irritated as well as humbled; Russia, although the Czar remained more than friendly, was not without apprehensions; but the French ruler and his ministers were astounded, indignant and bewildered. The telegram, which reported the Battle of Sadowa, wrenched a “cry of agony” from the Court of the Tuileries, whose policy had been based on the conjecture or belief that Prussia would be defeated, and would call for help. The calculation was, that Napoleon III. would step in as arbiter, and that while he moderated the demands of Austria, he would be able to extort territorial concessions from Prussia as the reward of his patronage. M. Drouyn de Lhuys would have had his master strike in, at once, and cross the Rhine, or occupy the Palatinate; but the Emperor was not then in the mood for heroic enterprises; he feared that his army was not “ready,” and, besides, he still thought that by arrangement he could obtain some sort of “compensation” from Prussia, at the expense of Germany. But all he did was to pose as mediator at Nikolsburg; and Herr von Bismarck, who had done his utmost to keep him in a dubious frame of mind, regarded it as “fortunate” that he did not boldly thrust himself into the quarrel. The “golden opportunity” slid by; M. Drouyn de Lhuys resigned; and Imperial France acquiesced, publicly, in the political and territorial arrangements which, for the first time, during the lapse of centuries, laid broad and deep the foundations of German Unity, and, as a consequence, rendered inevitable a France-German War.

THE CAUSES OF THE WAR.

The Treaty of Prague, the secret military conventions signed at Nikolsburg, the ascendancy secured by Von Bismarck, now elevated to the dignity of a Count, together with the complete removal of alien Powers from Italy, wrought a radical change in the political relations of the European States. Excluded from Germany, although including powerful German elements, the dominions of Austria still extended to the verge of Venetia and the Lombard plains; but as the Prussian statesman had already hinted, her future lay Eastward, and her centre of gravity had been removed to Buda-Pesth. In the South German Courts, no doubt, there was a bias towards Vienna, and a dislike of Prussia; yet both the leaning and the repugnance were counterbalanced by a deeper dread of France rooted in the people by the vivid memories of repeated and cruel invasions. Russia, somewhat alarmed by the rapid success of King William, had been soothed by diplomatic reassurances, the tenour of which is not positively known, although a series of subsequent events more than justified the inference made at that time, that promises, bearing on the Czar’s Eastern designs, were tendered and accepted as a valuable consideration for the coveted boon of benevolent neutrality, if not something more substantial. Like Russia, [p 18] France had lost nothing by the campaign of 1866; her territories were intact; her ruler had mediated between Austria and Prussia; and he had the honour of protecting the Pope, who, as a spiritual and temporal Prince, was still in possession of Rome and restricted territorial domains. But the Napoleonic Court, and many who looked upon its head as a usurper, experienced, on the morrow of Sadowa, and in a greater degree after the preface to a peace had been signed at Nikolsburg, a sensation of diminished magnitude, a consciousness of lessened prestige, and a painful impression that their political, perhaps even their military place in Europe, as the heirs of Richelieu, Louis XIV., and Napoleon, had been suddenly occupied by a Power which they had taught themselves to contemn as an inferior. Until the summer of 1866 the Emperor Napoleon fancied that he was strong enough to play with the Prussian Minister a game of diplomatic finesse; indeed, he seems to have thought that the Pomeranian gentleman would be an easy prey; but having thus put it to the proof, he did not concur in the maxim that it is as pleasant to be cheated as to cheat, especially when the result is chiefly due to complaisant self-deception. On the other hand, Herr von Bismarck had no longer any delusions concerning Louis Napoleon. If, at an early period, when the English Radicals were considering whether the new Emperor was “stupid,” a proposition they had taken for granted theretofore, he had over-estimated the capacity of the self-styled “parvenu,” later experience had reduced the estimate to just proportions, and had produced a correct judgment upon the character of one who, down to the last, was always taken for more than he was worth. If any one knew him well, it was probably his cousin, the Duc de Morny, and M. St. Marc Girardin has preserved a sentence which is an illuminative commentary upon so many curious [p 19] transactions during the Second Empire. “The greatest difficulty with the Emperor,” said De Morny, “is to remove from his mind a fixed idea, and to give him a steadfast will.” His fixed ideas were not always compatible one with another. He professed great devotion to the “principle of nationalities;” yet he desired to carry the French frontiers as far as the Rhine, adding further German populations and Flemish towns whose inhabitants are not French to those acquired by Louis XIV. He wished for peace, no doubt, when he said that the Empire was synonymous with that word, but he also hungered for the fruits of war; and, knowing that his internal position and his external projects required, to uphold the one and realize the other, a strong and complete army, he had neither the wit to construct a trustworthy instrument, nor the ceaseless industry needed to make the most of an inferior product, nor that absolute independence of the party whose audacity gave him his crown, which would have enabled him to select, in all cases, the best officers for the higher and highest commands. Before, and during the war of 1866, he wavered between two lines of policy, hoping to combine the advantages of both; and when it was over he demanded compensation for his “services” as an alarmed spectator, although he had made no bargain for payment, but had stood inactive because he conjectured that it would be the more profitable course.

In making that calculation he erred profoundly. M. Benedetti, the French Ambassador to the Court of Berlin, was instructed as early as the first week in August, 1866, to claim the left bank of the Rhine as far as, and including the important fortress of Mainz. “Knowing the temper [p 20] of the Minister-President,” and knowing also, as he had repeatedly told his Government, that all Germany would resist any proposal to cede the least portion of territory, he first sent in a copy of M. Drouyn de Lhuys’ despatch, and afterwards called on the Minister. Prince von Bismarck, in 1871, published in the official newspapers his account of the famous interview, which shows that Benedetti, as he had pledged himself to do, resolutely pressed the large demand. He was told that it meant war, and that he had “better go to Paris to prevent a rupture.” Unmoved, he replied that he would return home, “but only to maintain a proposition the abandonment of which would imperil the dynasty.” “The parting words” of the Prussian statesman to Count Benedetti, as nearly as they could be remembered by the man who spoke them, were calculated to suggest grave reflections. “Please to call His Majesty’s attention to this,” said Herr von Bismarck. “Should a war arise out of this complication, it might be a war attended by a revolutionary crisis. In such a case the German dynasties are likely to prove more solid than that of the Emperor Napoleon.” It was a menace and a prophetic warning, which touched a sensitive fibre in the heart of the French ruler, who, after a conversation with Count Benedetti, wrote, on the 12th of August, a remarkable letter to M. de Lavalette, who became the ad interim successor of M. Drouyn de Lhuys. Expressing his fears lest “the journals” should taunt him with the refusal of his demand for the Rhine provinces, he directed that the report should be contradicted, flatly; and he added, “the true interest of France is not to obtain an insignificant increase of territory, but to aid Germany in constituting herself after a fashion which will be most favourable to our interests and those of Europe.” Neither Dodona nor Delphos could have been more oracular. Alarmed as he was, he did not altogether [p 21] recede from his position, but occupied it in a different way. On the 16th of August a fresh set of proposals was forwarded to Count Benedetti, comprising a regular scale of concessions—the frontiers of 1814 and the annexation of Belgium, or Luxemburg and Belgium, or the Duchy with Belgium, without Antwerp, which was to be “declared a free city.” The last-named device was designed “to obviate the intervention of England” when the projected act of violence was committed. “The minimum we require,” wrote the French Government to M. Benedetti, “is an ostensible treaty which gives us Luxemburg, and a secret treaty which, stipulating for an offensive and defensive alliance, leaves us the chance of annexing Belgium at the right moment, Prussia engaging to assist us, by force of arms, if necessary, in carrying out this purpose.” If Herr von Bismarck asked what he should gain by such a treaty, the answer was to be that he would secure a powerful ally, and that “he was only desired to consent to the cession of what does not belong to him.” The official papers on which these statements are founded were discovered and acquired by the Germans in Cerçay, M. Rouher’s château, during the war of 1870; neither their authenticity nor the construction put on them have ever been contested; and they show, plainly, what was the kind of projects nourished by the French Court in 1866–67. The precise manner in which Count von Bismarck actually dealt with them has not been revealed, but he kept a rough copy of the project drawn up by Benedetti, which was handed to him by the French Ambassador in 1867, and the boxes of papers found at Cerçay gave him the draft treaty itself annotated by the Emperor. Practically, the secret negotiation dropped, was not renewed for several months, and was only “resumed, subsequently, at various times,” without producing any other result than that of letting Bismarck know the plans [p 22] which were conceived in Paris, and inducing him to keep the Napoleonic Government in play. There can be no doubt on one point. The Prussian statesman did, at various periods, probably at Biarritz in 1865, when he captivated Prosper Merimée, and afterwards, while refusing point-blank to cede an inch of German soil, ask his interested auditors why they could not indemnify themselves by seizing Belgium. But a grim smile of irony must have lighted up his face when he pointed to a prey which would not have to be ceded, but caught and overpowered by main strength. He was tempting, probing, playing with the Frenchman, employing what he called the “dilatory” method, because he wanted time to equip the new and still imperfect Germany; and, considering their own dark schemes, can it be said that they deserved better treatment?

Having direct knowledge of the steps taken by France in August, 1866, the earliest recorded formal attempt to procure secret treaties on the basis of territorial concessions, with what searching comment must Bismarck have read the astonishing diplomatic circular, signed by M. de Lavalette, and sent out on the 2nd of September, at the very time when the dark proceedings just briefly sketched were in full swing! It was a despatch framed for public consumption, and intended to present the Imperial policy in a broad, generous, and philosophic light, having no relation to the course which, either then or afterwards, the French ruler followed. Louis Napoleon told the whole world that France could not pursue “an ambiguous policy,” at the moment when he was meditating the forcible acquisition of Belgium. The Emperor painted himself as one who rejoiced in the change effected by the war, perhaps because it shattered the treaties of 1815. Prussia, he said, had insured the independence of Germany; and France need not see in that fact any shadow cast over herself. [p 23] “Proud of her admirable unity, and indestructible nationality, she cannot oppose or condemn the work of fusion going on in Germany.” By imitating, she took a step nearer to, not farther from, France; and the Imperial philosopher professed not to see why public opinion “should recognize adversaries, instead of allies, in those nations which—enfranchised from a past inimical to us—are summoned to new life.” But there was consolation for those alarmed patriots who could read between the lines. Petty states, they were assured, tended to disappear and give place to large agglomerations; the Imperial Government had always understood that annexations should only bring together kindred populations; and France, especially, could desire only such additions as would not affect her internal cohesiveness—sentences which, like finger-posts, pointed to the acquisition of Belgium. The war of 1866, it was admitted, showed the necessity of perfecting the organization of the army; yet smooth things were predicted by the Imperial soothsayer, for, on the whole, the horizon, in September, as scanned from Paris, seemed to be clear of menacing possibilities, and a lasting peace was secure! The despatch was, in fact, prepared and administered as a powerful anodyne. By keeping the French moderately quiet, it suited the purposes of Bismarck, who, well aware of the uneasiness which it covered, felt quite equal to the task of coping with each fresh attempt to obtain “compensation” as it might arise. Perhaps Louis Napoleon was sincere when he dictated this interesting State paper, for it is not devoid of some “fixed ideas” which he cherished; yet probably it may take rank as a curious example of the subtle tactics which he often applied to deceive himself, as well as to cajole his people and his neighbours. At all events, his will, if he willed peace, did not endure for he soon sanctioned and set in motion renewed [p 24] projects, for he intended to push forward the boundary posts of France.

As he found Prussia polite yet intractable, and prompt to use plain language, if concessions were demanded, the Emperor Napoleon formed, or was advised to form, an ingenious plan whereby he hoped to secure Luxemburg. He entered into secret negotiations with Holland for the purchase of the Duchy. The Queen of Holland, a Princess of the House of Würtemburg, was a keen partizan of France. She it was, who, in July, 1866, uttered a cry of warning which reached the Tuileries. “It is the dynasty,” she wrote, “which is menaced by a powerful Germany and a powerful Italy, and the dynasty will have to suffer the consequences. When Venetia was ceded, you should have succoured Austria, marched on the Rhine, and imposed your own conditions. To permit the destruction of Austria is more than a crime, it is a blunder.” Perhaps the notion that Luxemburg could be acquired by purchase came from this zealous, clear-sighted, and outspoken lady. Wherever it may have originated, the scheme was hotly pursued, negotiations were opened at the Hague, the usual Napoleonic operations were actually begun to obtain a plébiscite from the Duchy. Count von Bismarck was discreetly sounded by M. Benedetti, with the usual indefinite result, and the consent of the King of Holland was obtained without much difficulty. At the same time there was a strong current of opposition in the Dutch Government, and Prince Henry, the Governor of Luxemburg, made no secret of his hostility. The King himself was subject to recurring tremors caused by his reflections on the possible action of the Prussian Court; and his alarms were only mitigated or allayed from [p 25] time to time by assurances based, in reality, on M. Benedetti’s “impressions” that the Chancellor was not unfavourable to the plan of cession. The truth is that M. Benedetti did not accurately perceive the position which Bismarck had taken up from the outset. It might be thus expressed: “Luxemburg belongs to the King of Holland. It is his to keep or give away. If you want the Duchy, why don’t you take it, and with it the consequences, which it is for you to forecast.” The French Court and its Ministers still laboured under the belief that they could manage the Berlin Government, and they put their own interpretation on the vague, perhaps tempting language of the Chancellor. At a certain moment, the fear, always lurking in the King of Holland’s breast, gained the mastery, and he caused the secret to be disclosed to the public. “He would do nothing without the consent of the King of Prussia;” and by revealing the negotiations he forced on a decision. The incident which terrified the King of Holland was, no doubt, startling. M. Thiers had made a strong anti-German speech in the Chamber, and M. Rouher had developed his theory of the “trois tronçons,” or triple division of Germany. The Chancellor, who had acquired full knowledge of French pretensions from French Ministers, answered both statesmen by printing, in the foreground of the “Official Gazette,” the treaty which gave King William the control of the Bavarian army, in case of war. That fact also produced a decisive effect upon the Dutch monarch, who saw in this characteristic indirect retort to the French parliamentary display a menace specially directed against himself. Hence the revelation sufficed to thwart the bargain, then so far finished that signatures were alone wanting to render it binding. The German people fired up at the bare mention of such a proposal as the cession of a German province. M. de Moustier, vexed and taken aback, called [p 26] on Bismarck to restrain the passions of his countrymen, and vainly urged the Dutch monarch to sign the treaties. On the morning of the day when he was to be questioned in the Reichstag, Bismarck asked Benedetti whether he would authorize the Minister to state in the Chamber that the treaties had been signed at the Hague. The Ambassador could not give the required authority, seeing that although the King, under conditions, had pledged his word to the Emperor, the formal act had not been done, because Prussia had not answered the appeal for consent from the Hague. On April 1, 1867, while Napoleon was opening the Exhibition in Paris, Herr von Bennigsen put his famous question respecting the current rumours about a treaty of cession. If the French were not prepared for the fierce outburst of Teutonic fervour, still less could they relish the question put by Herr von Bennigsen and the answer which it drew from the Chancellor. The former described the Duchy as an “ancient province of the collective Fatherland,” and the latter, while “taking into account the French nation’s susceptibilities,” and giving a brief history of the position in which Luxemburg stood towards Germany, made his meaning clear to the French Court. “The confederate Governments,” he said, “are of opinion that no foreign power will interfere with the indisputable rights of German States and German populations. They hope to be able to vindicate and protect those rights by peaceful negotiations, without prejudicing the friendly relations which Germany has hitherto entertained with her neighbours.” Napoleon and his advisers were not likely to misconstrue language which, although it lacked the directness of Von Bennigsen’s sentences, obviously meant that the French scheme could not be worked out. Indeed, a few days earlier, the Chancellor had used a significant phrase. Answering a question in the Chamber, he said:—“If the [p 27] previous speaker can manage to induce the Grand Duke (of Luxemburg) to come into the North German Federation, he will be able to say that he has called an European question into existence; what more, Time alone can show.” The phrase could hardly have escaped the notice of M. de Moustier, and coupled with the second reply, already quoted, gave rise to indignation not unmixed with alarm. At first the Emperor seemed determined not to recede, and he took counsel with his generals, who could not give him encouragement, because they knew that the Government was absolutely without the means of making even a respectable defence against an invasion. The period of suspense at the Tuileries did not endure long. Shortly after the scene in the Reichstag, the Prussian Minister at the Hague brought the matter to a crisis by a message which he delivered to the Dutch Government. The King of the Netherlands, he is reported to have said, can act as he pleases, but he is responsible for what he may do. If he had believed that the meditated cession was a guarantee of peace, it was the Minister’s duty to destroy the illusion. “My Government,” he added, “advises him in the most formal manner, not to give up Luxemburg to France.” The blow was fatal; the King of course, took the advice to heart, and such a stroke was all the more deeply felt in Paris because there the Emperor, who had considered the end gained, now knew from Marshal Niel that it would be madness to provoke a war. Yet, unless a loophole of escape could be found, war was imminent. M. de Moustier discovered a safe and dignified line of retreat. The Chancellor had referred to the treaty of 1839 which governed the status of Luxemburg; M. de Moustier took him at his word, and virtually brought the dispute within the purview of Europe, by formally demanding that the Prussian garrison should be withdrawn. He held that [p 28] since the German forces were practically centred in the hands of Prussia, Luxemburg, no longer a mere defensive post, had become a menace to France. In this contention there was much truth, seeing that the new Confederation of the North, and its allies in the South, constituted a political and military entity far more formidable and mobile than the old Bund. When the Chancellor refused a demand, which his adversaries assert he was at one time prepared to grant, the French Government, declaring that they had no wish for other than friendly relations with Berlin, appealed to Europe. The dispute ended in a compromise arranged as usual beforehand, and settled at a conference held in London. The garrison was withdrawn, the fortifications were to be razed, and the Duchy, like Belgium, was thenceforth to be neutral ground, covered by a collective guarantee of the Powers; but it still remained within the German Zollverein.

There were at work several influences which largely operated to determine a peaceful issue. The French possessed no real army, and the Emperor had only just begun to think about the needful military organization on a new model; he had, besides, on hand an international Exhibition, by which he set great store; and in addition a summons to withdraw a garrison did not provide a casus belli certain to secure the support of public opinion. Nor did the Prussian Government consider the moment opportune, or the question raised a suitable ground on which to determine the inveterate cause of quarrel between France and Germany. Upon this subject Dr. Busch has recorded some characteristic observations made by the Chancellor, at Versailles, in 1870. “I remember,” he said, “when I was at the Paris Exhibition of 1867, I thought to myself ‘how would it have been by now, if we had fought out the Luxemburg quarrel? Should I be in Paris, or the French in [p 29] Berlin?’ We were not nearly as strong then as we are now. The Hanoverians and Hessians of that day could not have supplied us with so many good soldiers as to-day. As for the Schleswig-Holsteiners, who have lately been fighting like lions, they had no army at all. The Saxon army was broken up, and had to be entirely reconstructed. And there was but little to be expected from the South Germans. What splendid fellows the Würtembergers are now, quite magnificent! but in 1866 no soldier could help laughing at them, as they marched into Frankfort like a civic guard. Nor was all well with the Baden forces; the Grand Duke has done a great deal for them since then. Doubtless public opinion throughout Germany was with us, if we had chosen to make war about Luxemburg. But that would not have made up for all those shortcomings.” It is plain, from this retrospective comment, which comes in aid of other evidence, that the great conflict, deferred to 1870, was nearly brought about in 1867, and that France was saved from utter rout, at that early period, by the operation of a set of influences over which neither of the principal actors had full control. The Franco-Dutch negotiation was the last attempt which the Emperor Napoleon made to obtain territory by direct or furtive diplomatic processes. In the early stages of the risky business he had full confidence in his own ascendancy, not to say “preponderance” in European councils. He was rudely undeceived. Herr von Bismarck had tempted him with all kinds of suggestions, but the Emperor himself, his Ministers and Ambassadors had been content to take the “impressions,” which they derived from confidential conversations, for definite, binding promises. One French agent correctly described the fact when he said that “Herr von Bismarck is ready, not to offer us compensations, but to allow us to take them;” he might have added, “if we can [p 30] and at our own risk.” There is no published evidence that the Prussian statesman ever offered to cede Luxemburg, or sanction the annexation of Belgium, or preclude himself from adopting, at any conjuncture, the line which appeared most accordant with German interests. On the contrary, long after the interviews at Biarritz and in Paris, and the battle of Sadowa, Napoleon III., to use his own terms, wanted, at least, “une certitude relative” that the Prussian Government would not interpose any obstacle in the way of French “aggrandizement” in the North. He asked, not for words, but an act which he could never obtain; and the Luxemburg incident proved to him conclusively that nothing could be gained by making demands on the Court of Prussia. In 1867 and afterwards in November, 1870, according to Dr. Busch, Bismarck described with his usual frankness the hesitation of the Emperor. He had not understood his advantages, in 1866, when he might have done a good business, although not on German soil, was the earlier commentary. The later was more illuminative. “In the summer of 1866,” said Bismarck, “Napoleon had not the pluck to do what was the right thing from his point of view. He ought—well, he ought to have taken possession of the subject of Benedetti’s proposal [Belgium], when we were marching against the Austrians, and have held it in pawn for whatever might happen. At that time we could not stop him and it was not likely that England would attack him—at least he might have waited to see.” On this it may be observed that the influence of Lord Cowley and Lord Clarendon would probably have sufficed to turn him from such a plan had it entered into the Emperor’s mind; and had he delivered the blow, in defiance of their protests, or without consulting them, England, at that time, would have been enraged at the treachery, and would have certainly occupied Antwerp. The Emperor was a man who caressed [p 31] audacious projects which he had not always the nerve and courage to carry out. What is more astonishing, he did not or could not provide the means essential to the accomplishment of his desires. Thus the precedent afforded by his conduct in 1866 was followed in 1867, and in each case the result was the same—vexatious failure.

The war-clouds sank below the horizon, the Paris Exhibition was duly opened, sovereigns and princes, statesmen and generals, journeyed to the French capital, and the Court of the Tuileries gave itself up to amusement, gaiety, and dissipation, neglecting nothing which could give pleasure to its illustrious guests. It was the last hour of splendour, the sunset of the Empire. Yet the brilliant scenes, which followed each other day by day, were even then flecked with dark shades. If politics were evaded or ignored in the palace, they were not absent from the highways. Polish hatred found vent in the attempt of Berezowski to slay the unfortunate Emperor Alexander II., and M. Floquet shouted in his ear as he passed through the Courts of Justice, “Vive la Pologne!” The crime and the insult augured ill for the future of that Franco-Russian alliance which Charles X. endeavoured to establish and certain French statesmen have always sighed for. M. Hansen records a sharp observation made by Prince Gortchakoff during the Polish insurrection which the Western Powers regarded with friendly eyes. The Vice-Chancellor held that France and Russia were natural allies, because their interests were the same. “If the Emperor Napoleon will not admit it,” he roughly said, “so much the worse for him. Governments vanish, nations remain.” Still, in 1867, he did not find the nation more favourable than the Government had been in 1864. Twenty years later, although Russia had [p 32] become less unpopular, at least with the politicians, and a yearning for a Russian alliance had gathered strength, the ultras proved how little they understood some conditions essential to its gratification by clamoring for the pardon and liberation of Berezowski! The Prussian King and Queen were not exposed to any outrage, and the Parisians gazed with curiosity upon Bismarck and Moltke, whom they admired, and had not yet learned to detest; but the sparkling and joyful assemblies, although the actors, on both sides, were doubtless sincere at the time, nevertheless suggests a famous incident in the French Revolution which figures on historical pages as “le baiser de l’amourette.” And underneath the shining surface were concealed gnawing anxieties and fears. The Emperor Napoleon had dreamed that he could found a Mexican empire, and he had induced the Austrian Archduke Maximilian to accept at his hands an Imperial crown. The enterprise, which was pushed on by French troops, not only failed, but irritated England, who had been deceived, and offended the United States, whose Government, victors in a civil war, would not tolerate the establishment of the “Latin race” in the centre of the huge continent. Not only had it become necessary to recall the troops, but to bear a still deeper misfortune—if the word may be applied to the consequences of a reckless and unscrupulous adventure. It was while opening the Exhibition that the earliest hints reached the Emperor of an event which dealt him a heavy blow; and, on the eve of the day fixed for the distribution of prizes to the competitors he had assembled, came the confirmation of the dreaded intelligence, whispered weeks before. The gallant Archduke and Emperor Maximilian, who had fallen into the hands of the triumphant and implacable Mexicans, had been tried and shot, a deed which his French patron was powerless to avenge.

The tragedy of Quaretaro reacted upon European politics, and incidentally emphasized afresh the perennial antagonism between France and Germany. Still smarting from the wounds of 1866, Austria hungered for an ally, and the Saxon Count von Beust, whom the Emperor Francis Joseph had made his Chancellor, was eager to try one more fall with Count von Bismarck. Swayed by political reasons, the Austrian Emperor not only did not resent the death of his brother, but was even willing to welcome as his guest Louis Napoleon, who had so successfully seduced the Archduke by dangling before him the bait of an Imperial crown. The French Emperor and his Empress, therefore, travelled in state through South Germany to Salzburg, where they met their Austrian hosts. The occasion was, nominally, one of condolence and mourning, and the vain regrets on both sides were doubtless genuine. Yet it so chanced that the days spent in the lovely scenery of Salzburg were given up to gay mirth and feasting—not to sorrow and gloom; and that the irrepressible spirit of politics intruded on the brilliant company gathered round an open grave. Both emperors felt aggrieved; one by the loss of his high estate in Germany and his Italian provinces, the other because his demand for the Rhenish territory had been rejected, and he had not been allowed to take Belgium or buy Luxemburg. The common enemy was Prussia, who had worsted Austria in battle, and France in diplomacy and at Salzburg, perhaps earlier, the ground plans were sketched for an edifice which the architects trusted might be built up sufficiently large and strong to contain, at least, two allies. The sketch was vague, yet it was definite enough at least to reveal the designs of the draughtsmen; and the Emperors returned home still in jubilation.

Perhaps the Emperor Napoleon suffered some pangs of disappointment. “Austria was his last card,” says M. Rothan, who, from the French standpoint, has so keenly studied the period preceding the war of 1870. He wanted an offensive and defensive alliance, which Austria would not accord, Count von Beust fearing that so grave a fact would never escape the lynx-eyes of Bismarck, who, when it came to his knowledge, would not fail to provoke a war before either ally had fully, or even partially, completed his military preparations, then so much in arrear. Not only were they backward in 1867, but Austria, at all events, was still unprovided in 1870. The Archduke Albrecht, who visited Paris during the month of February of that year, impressed the fact on the Emperor Napoleon. “The story runs,” says M. Rothan, “that, after having quitted the study of his Majesty, the Archduke returned, and; through the half-opened door, exclaimed, ’sire, above all things do not forget, whatever may happen, that we shall not be in a fit state to fall into line before a year.’” Hence, it may well be that the Austrian Chancellor was even then determined, in case of a conflict, to shape his policy in accordance with the first victories; and that the meditations of the Emperor Napoleon, as he re-crossed the Rhine, were tinged with bitter reflections on his political isolation. A little later, when he knew that Bismarck had discovered the drift of the conversation at Salzburg, his anxieties must have become more poignant. That Chancellor, who had secured afresh the goodwill of Russia, and beheld with satisfaction the effect of the Imperial display on Germany, enlarged, in a circular despatch, on the proof thus once more afforded that German national feeling could not endure “the mere notion” of “foreign tutelage” where the interests of the Fatherland were concerned. Germany had a right to mould her own fortunes and frame her own [p 35] constitution. So that, as Von Buest had foreseen, the dreaded Chancellor had promptly turned to account even the colloquies of Salzburg. “France, with one hand,” he said, “presents us with soothing notes, and with the other permits us to see the point of her sword.” There was no open quarrel between the two antagonists, but each suspected and closely watched the other. M. Rothan, himself a vigilant and zealous official, furnishes an amusing example. In November, 1866, he learned from “a Foreign minister accredited to a South German Court,” what was to him the appalling fact that the Imperial work of mediation at Nikolsburg had been counteracted, “even before it had been sanctioned by the Treaty of Prague.” He referred to the now famous military treaties. M. de X―, his informant, he says, obtained his knowledge of the secret by a sort of inquisitorial method, “a la façon d’un juge d’instruction,” that is, he affirmed the existence of the documents, and thus extorted confessions, express or implied. “The Bavarian Foreign Minister,” he said, blushed; “the Minister of Würtemberg was confused; the Minister of Baden did not deny it, and the Minister of Hesse avowed everything.” Further, M. de X― asserted that, when it was no longer necessary to keep France in good humour, Prussia would enforce the clauses which gave her supreme command, and would bring the Southern armies into harmony with her own organization. Apparently, this authentic information did not obtain a ready belief in the autumn of 1866; but it alarmed and disturbed the French Court, and the public confirmation of the unwelcome report, less than a year afterwards, visible to all men in the actual re-organization of the Southern armies, together with the failure to purchase Luxemburg, still further increased the suspicion, deepened the alarm, and aroused the indignation of the Emperor at the slights [p 36] inflicted on France, who, as the “predominant” Continental power and the “vanguard of civilization,” always considered that she ought to have her own way.

In the beginning of 1868 the principal parties were engaged in preparing for a conflict which each considered to be inevitable; and the other Powers, great and small, more or less concerned, were agitated by hopes and fears. Russia desired to recover her freedom of movement in the East, and especially to throw off what Prince Gortchakoff called his “robe de Nessus,” the clause in the treaty of Paris which declared the Euxine to be a neutral sea. Austria aimed at the restoration of her authority in Germany, and was not yet convinced that her path lay eastward. Italy had many longings, but her pressing necessity was to seat herself in the capital of the Cæsars and the Popes, once again occupied by the French, who had re-entered the Papal States to expel the Garibaldians. It was in the skirmish at Mentana that the new breech-loading rifle, the Chassepot, “wrought miracles,” according to General de Failly, and established its superiority over the “needle gun.” Holland, Belgium, and even Switzerland were troubled by the uncertain prospect which the Imperial theory of “large agglomerations” had laid bare; Spain was in the throes of a revolutionary convulsion; and England—she had just mended her constitution, and had begun to look on Continental politics with relative indifference, except in so far as they affected the fortunes of “parties,” and might be used strategically as a means of gaining or holding fast the possession of power. Yet so strained were the relations of France and Prussia that General von Moltke actually framed, in the spring of 1868, [p 37] the plan of campaign which he literally carried out in 1870—a fact implying that even then he considered that his Government was sufficiently prepared to encounter the new and imperfectly developed scheme of army organization and armament originally devised by the Emperor and Marshal Niel, and modified to satisfy the objections and suspicions raised in a deferential Senate and an obliging Chamber of Deputies. For while the Opposition distrusted the Emperor, the whole body shrank from the sacrifices which Cæsar and his Minister of War considered necessary to the safety of the State from a defensive, and absolutely indispensable from an offensive point of view. The prime actors in the drama expressed a love of peace, perhaps with equal sincerity: but as Germany thirsted for unity, all the more because France, true to her traditional policy, forbad it, the love so loudly avowed could not be gratified unless Germany submitted, or France ceased to dictate. “I did not share the opinion of those politicians,” said Bismarck in July, 1870, “who advised me not to do all I could to avoid war with France because it was inevitable. Nobody,” he added, “can exactly foresee the purposes of Divine Providence in the future; and I regard even a victorious war as an evil from which statesmanship should strive to preserve nations. I could not exclude from my calculations the possibility that chances might accrue in France’s constitution and policy which might avert the necessity of war from two great neighbour races—a hope in connection with which every postponement of a rupture was so much to the good.” The language is a little obscure, but the meaning will be grasped when it is remembered that his remark on the “chances” referred to the probable grant of increased freedom to the French Parliament, which he thought would fetter the Court and thwart the politicians. That forecast was not justified by the event, since it was [p 38] the partially-liberated Chamber and the Liberal Ministry which so hastily sanctioned the declaration of war. The truth is, however, that each rival nationality inherited the liabilities contracted in the past. The French had been accustomed for more than two hundred years to meddle directly in Germany and find there allies, either against Austria, Prussia, or England; and the habit of centuries had been more than confirmed by the colossal raids, victories, and annexations of Napoleon I. A Germany which should escape from French control and reverse, by its own energetic action the policy of Henri IV., Richelieu, Louis XIV., his degenerate grandson, Louis XV, and of the great Napoleon himself, was an affront to French pride, and could not be patiently endured. The opposing forces which had grown up were so strong that the wit of man was unable to keep them asunder; and all the control over the issue left to kings and statesmen was restricted to the fabrication of means wherewith to deliver or sustain the shock, and the choice of the hour, if such choice were allowed.