9 History of the United States.

CHAPTER I.

HOW THIS LAND WAS FOUND.

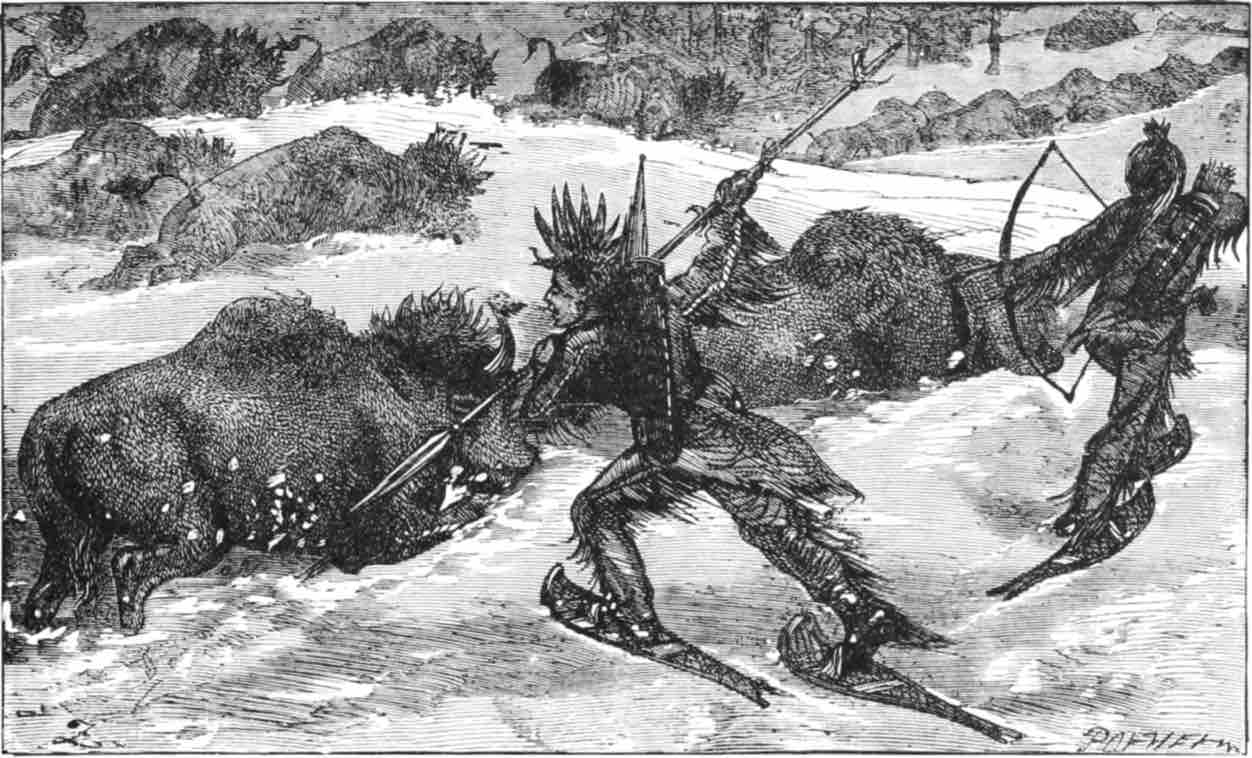

IN-DI-ANS HUNTING IN THE SNOW.

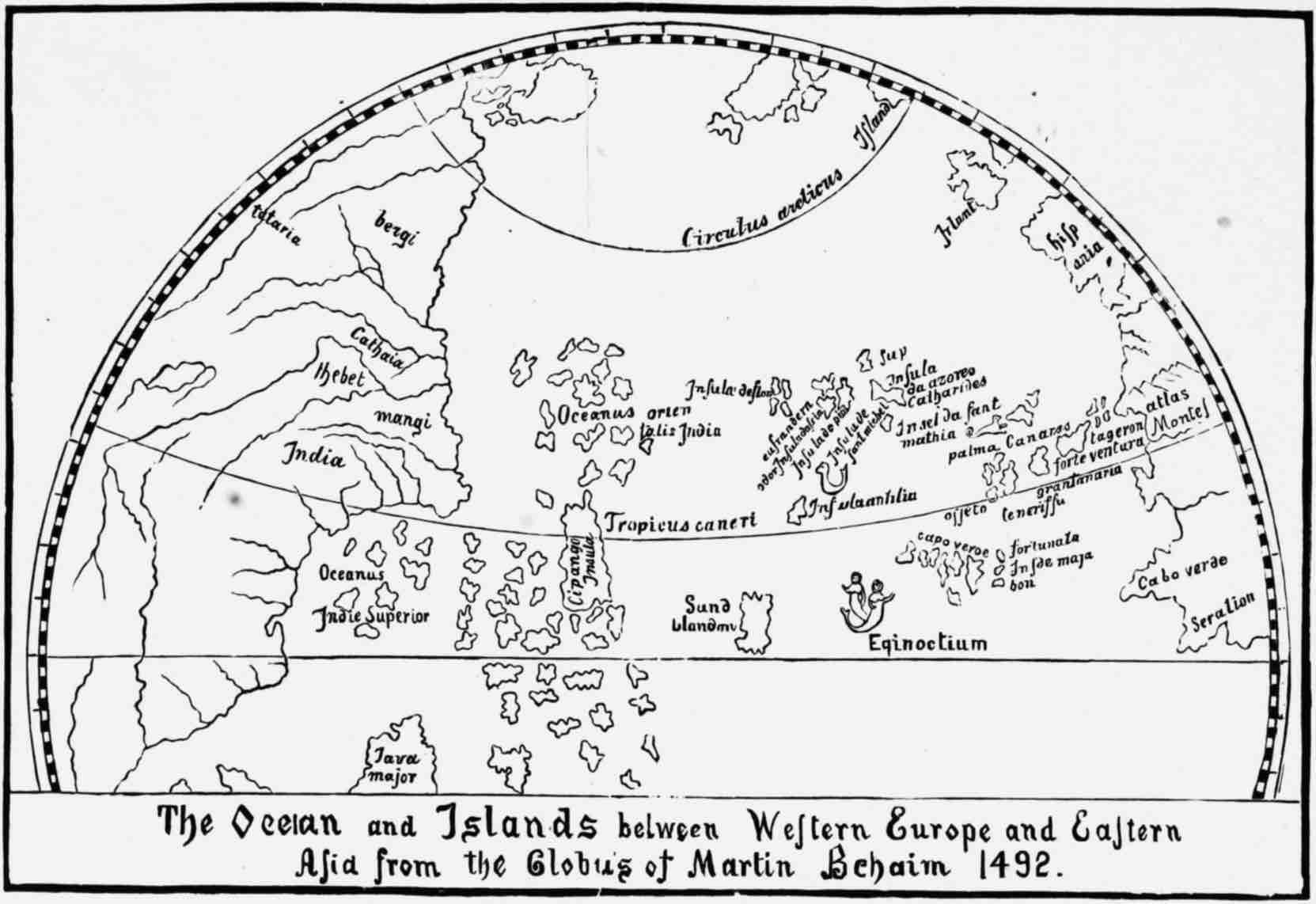

For a long time, in past years, it was not known that the world was round. If the men in those days had been told that a ship could start from a port and sail straight on for months and come round to 10 the same place, it would have made them laugh as at a good joke. They did not know the real shape of the earth, but thought it was a flat plane.

In those days our land was the home of the In-di-ans, or red men, as we call them, from their dark skins. The red man does not live in a house, but in a sort of tent or hut. The tribes of red men had all this land for their own when Co-lum-bus was born. The great woods, the green plains, the bright streams, were all theirs. They made their wars in a strange and fierce style, and wore at their belts locks of hair, cut from the heads of those slain by their hands. These locks, cut from the head with part of the skin, they call a scalp. It was the pride of an In-di-an to have scalps hung at his belt. No one had taught him that this was wrong, and he did not have the Word of God to show him the right way.

When Co-lum-bus was a mere boy he was fond of the sea and ships. He would go and watch the waves, and think about how ships were made, and the best way to sail them. He was born in Gen-oa, which is by the blue sea; so when he was a small boy he could watch the white sails come in. Such queer ships they had there, with strange high prows! As time went on, and he grew of age, he made trips in these ships, and was in sea-fights, and once or twice he was in a wreck. So you see he had a 11 chance to grow strong and brave for the work he had to do.

What he read in books taught him that the world was round, and not flat, as was thought in those times. So he knew that if he could sail west he would come to a new land. He thought of this a long time, and at last he grew more sure of it, but he could get no one else to think as he did. He spent ten years in this way. He was full of plans; but he could get no help and no gold. He was too poor to do all with no aid from his friends. At last he went to Spain.

There were a King and Queen there who were kind to Co-lum-bus; but at first they would not give their gold to help him. They thought this was a wild dream. At last, with a sad heart, he made up his mind to turn his back on the court of Spain.

While on his way, a man came to him from Queen Is-a-bel-la. She had sent him word that she would help him; "that she would pledge her own gems to give him aid." But she did not have to do this, as means were found when Co-lum-bus went back to the court. His heart was made glad; for they gave him a small fleet of three ships, and on the 3d of August, 1492, the sun rose on the fleet as it went forth on its way to the new land. All was strange to the new crew, and they had all 13 sorts of queer thoughts and fears of the sea. They had not been out of sight of land in all their lives; and when they saw the deep, dark sea on all sides, they were full of fear that they would not see their homes again. The trade-wind which took them west so fast, would keep them, they thought, from their land when they had the wish to go back. At last they grew so full of fear, they swore they would not go on, and Co-lum-bus had hard work to make them. But soon there were signs of land, and some land birds flew by the ship; and one of the crew found a branch of a tree on the waves, which had some fresh red fruit on it.

Oh, how glad they were! Co-lum-bus felt so sure that he was near land, he gave word for the ships to lie by that night. No man thought of sleep. They all kept watch on deck to see this strange new coast for which they had borne so much.

In the night a cry of joy was heard. Co-lum-bus had seen a light far off, and a shout of "Land! land!" soon came from all sides.

When the sun rose they all saw a green strip of shore some five miles long. The men fell at the feet of Co-lum-bus and shed tears of joy. Then they sang a hymn of praise to God, who had kept them and brought them safe and sound to this new place. They got out the small boats and put men 14 and arms in them, with flags, and a band to play a march of joy, and the crews made their way to the shore. Co-lum-bus, in a rich dress with his drawn sword in his hand, sprang on the beach, and then the crew came next. They set up a cross, and all knelt at its foot and gave thanks for their safe trip. Then Co-lum-bus set up the flag of Cas-tile and Le-on, and took the new land for the crown of Spain.

While they stood there with shouts of joy and songs, some strange dark shapes stole up with soft steps to their side. The crew thought these men must have come from a new world, as they saw their dark skins and the gay paint and plumes they wore. Co-lum-bus gave them the name of In-di-ans, for he thought the new coast was part of In-dia. He did not know that he had found a new land. These men with red skins were glad to kiss the feet of the Span-iards, and change their gold chains and rude rings for the beads and pins the crew gave to them.

Co-lum-bus spent some time in the new land he had found, and then he set sail for home to take his friends and the Queen the great news. A wild storm came on the way home, and Co-lum-bus thought that all was lost, so he wrote his tale on a cake of wax and put the cake in a cask and threw it in the sea; so that if he had gone down in the 15 storm, all that he had found would not be lost to the world.

But God took care of Co-lum-bus and his crew. They got back to their homes once more and had a grand time. The King and Queen gave them a new and fine fleet; and in time they came back and saw new points of land on which to build homes, and they found, too, South A-mer-i-ca.

There were some in Spain who did not like Co-lum-bus, for he had won gold and fame, while they had none. So they told false tales of him; and when his friend, Queen Is-a-bel-la, died, he was once brought back from the land he had found in chains. How sad that was!—was it not? At last he had to die old and poor, and this land did not have his name. It had no name for some time; but at last an I-tal-ian, who made a few trips there, and wrote of what he saw, gave his name to the new world. His name was A-mer-i-cus Ves-pu-ci-us. That is a hard name for you to say, but you can all say A-mer-i-ca, and that is the name of our land.

16 CHAPTER II.

THE NEW WORLD.

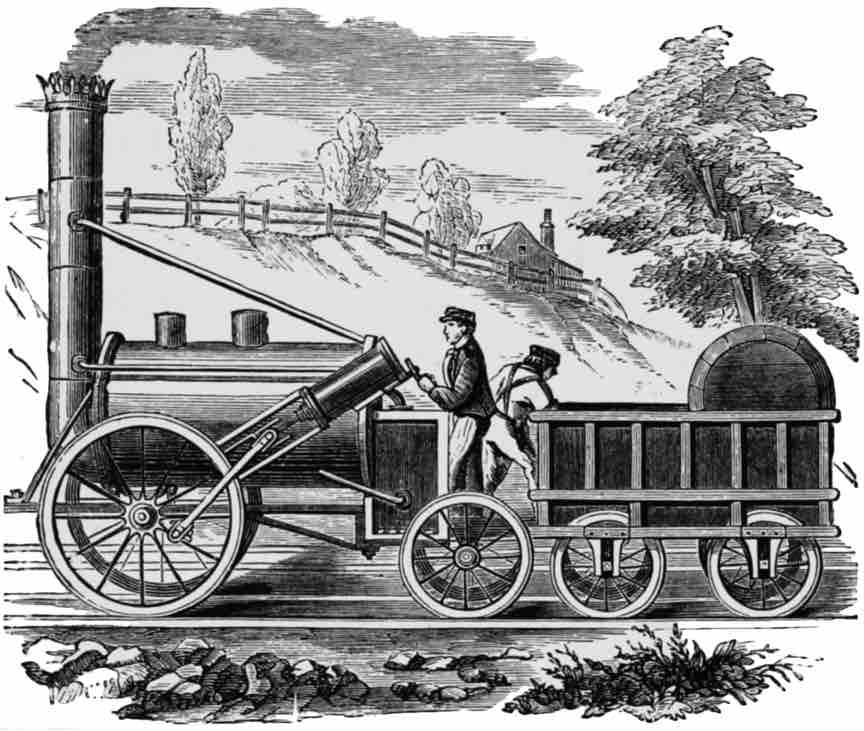

When the news of this land of gold spread over the world, Eng-land and France and Spain all sent ships to see what they could find. They each thought they would like to have a slice. The Eng-lish thought they had some rights, as one of their men, named Ca-bot, had, in truth, been the first to touch this new shore. The next time he came, he made his way down the coast to what we call Vir-gin-ia, and set up a claim for Eng-land.

Then the King of France sent a man to plant his flag here, and he gave the name of New France to part of our coast. But though Eng-land and France both set claim to the land, they did not send men here to live for a long time.

At last Queen E-liz-a-beth gave one of the great men at court, called Sir Wal-ter Ral-eigh, a claim to a large tract of land in A-mer-i-ca. He came with two ships, and found the red skins kind. They brought him gifts, and he went back to tell of all the strange things he had seen, and some came to live on the new shores. But the red skins were 17 hard to live with, and the small group of white men could get no food, and were near death, when a brave man, named Sir Fran-cis Drake, came with a ship and took them off to their homes. The next band that came met a sad fate, for they all fell by the hand of the red men.

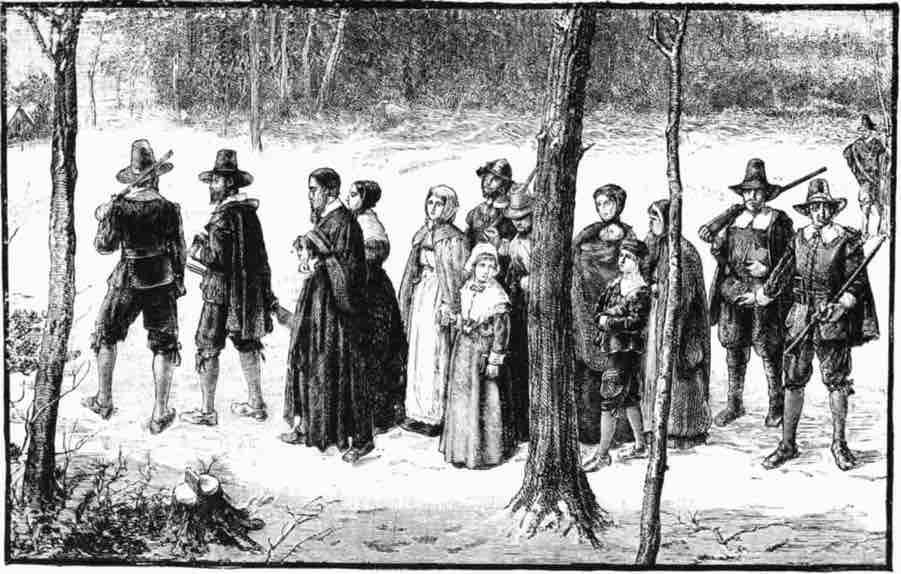

There were some in Eng-land who had a great wish to see this new world. They thought they would like to live in a land with no King, and have a church where they could pray to God in their own way. They were called "Pil-grims," for they went from place to place and would sing psalms and pray, and they were full of joy at the thought of their new home.

Do you know the name of the ship they came in? It is a sweet name, and you must keep it in your mind—The May-flow-er. They did not have a smooth trip, and a storm blew them on to the coast of Mass-a-chu-setts. It was bare and cold, but it was nice to see land at all. There were all sorts of fowl there, and they saw a whale; but when they went to shoot it the gun burst. They made their way to a vale where there was a spring, and there they took their first drink in the new land.

IN-DI-AN FLINT-HEADED ARROW.

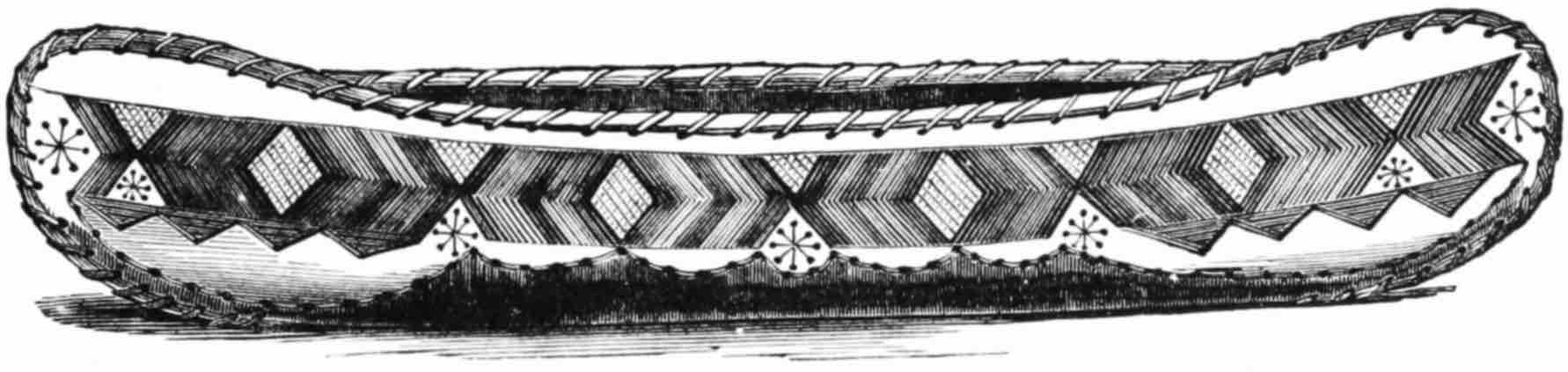

There was a rock called Plym-outh Rock, and here they made their homes and built the first house. It was in 1620, in a cold time of the year, that the 18 May-flow-er brought her crew to Plym-outh Rock. There was not much food, and they had from the first a foe whom they could not trust or make a friend. These were a new race of men. They had brown skins; were tall and straight, with long, coarse black hair. They had no books, and got their food in the hunt, or caught fish in the streams. They made boats of birch bark—queer, long things, with a point at each end. They could make bows, and would pound their corn with two stones for their bread. They took the skins of beasts for their clothes, for they knew how to dress them. Each tribe had its head man, called a chief, and their great joy was in war. When their foes took them, they would not pray for their lives. They were brave in their own way, and would show no fear at the sight of the fire that was to burn their flesh.

Their wives, the squaws, would dress the food and do all the hard work at home. They were the ones who dug each small patch of ground and put in the beans and corn. The men had a 19 scorn for work. They were made to fight, they thought. They would say, "The Great Chief gave the white man a plow and the red man a bow, and sent them in the world to gain food, each in his own way."

In this new land there was not a horse, cow, sheep, cat, dog, or hen to be found. You would not like such a place, would you? What did the young people do for pets in those days? No chicks to feed, no puss with her soft, warm fur, for small hands to stroke.

But the new homes were not left in peace. The red men saw that their doom was near. They felt that they would have to move on and on, to give place to these men who knew so much; who read books and had schools, and taught their young ones to pray. So they took the guns that they had bought from the white men and went to war with them. When they took them they would tie them fast to stakes, burn them to death, and all the time the flames were at work, these fierce red men would 20 dance a war dance of joy. They bought rum from the white men, and it made them like brutes.

They knew that the white men had come to take their land, and that was cause for their hate. And so the white men, in their turn, felt no love for the red skin, and thought they did well to push him back more and more, and take all they could from him. The white men were to blame, for they first gave the vile rum to the red men, and that made them wild. They would burn down the white man's house at night, and kill his wife and babes. Think how sad it must be to wake up in the night and find the hot blaze of a fire in your face, and the wild war-whoop of an In-di-an in your ears. But you can lie down in your bed in peace, for there is no one to harm you—you live in good times.

But those who were brave enough to come and live in this new land, had a hard life at first. There were no snug farms as now, with fields of green corn and wheat. At times the poor men could not get much to eat, and one wrote home: "The crumbs that fall from your meals would be sweet to me. When I can get a cup of meal and boil It with a pinch of salt, I give thanks as for a great feast. The In-di-ans at times bring corn and trade it for clothes or knives. One day they gave 21 me a peck of corn for a small dog. It would be a strange thing to see a piece of roast beef or veal here."

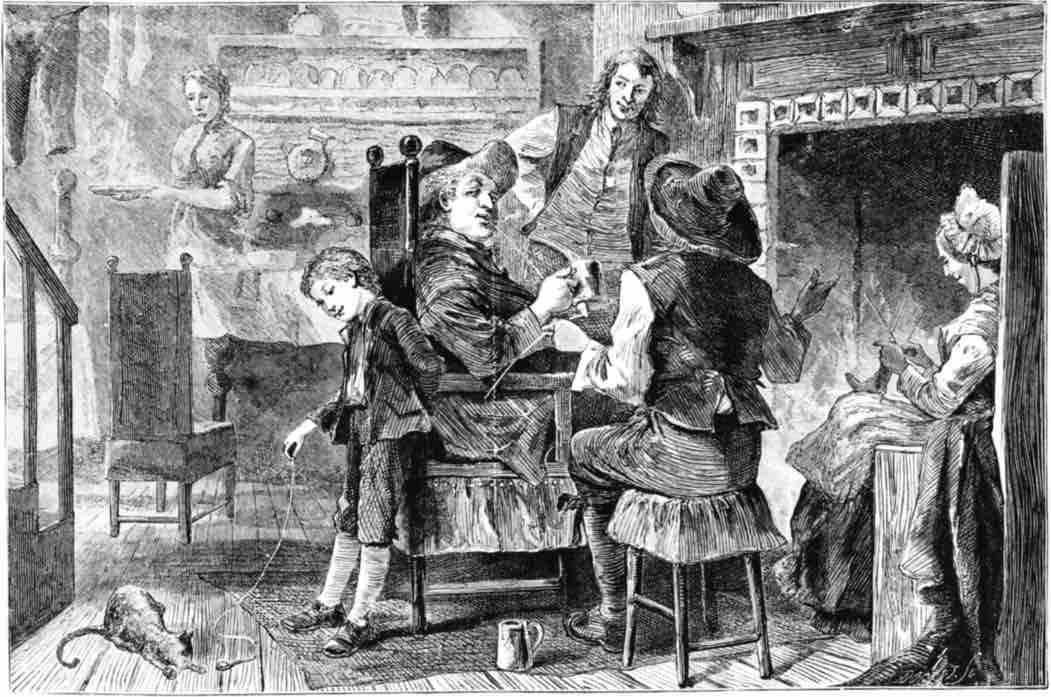

PIL-GRIMS ON THEIR WAY TO CHURCH.

It will not seem strange, then, that, in such hard times, death came to these small bands and took some away. But those who were left kept up brave hearts, and would not go back to their old homes; and though all were so poor, there was not a case of theft in four years. They grew to like the land, and one said, "A sup of New Eng-land air is worth more than a draught of Old Eng-land ale."

For one of the first bands of men who came here, made their homes in a place to which they gave the name of New Eng-land, after their old home. As time went on each place grew to be a town, and soon had a church and a school of its own. If we had gone in one of those towns on the Lord's day, we would have seen some strange sights. As the clocks struck nine, there would come out a man who would beat a drum or blow a conch shell, or ring a bell to call all the folks to church. As we drew near to this church, we would have seen that it was built of logs, with a small flag to wave on it. There would be a fence of stakes round it, and a man with a gun on guard near it. Those who went in left all their guns in his care.

23 If you look at this church you will see that it has no glass panes like ours, but small and dull and thick ones set in lead. It is the style now to like that old thick glass, and to use it once more. You might see on the front of this church, near the door, the heads of wolves that had been slain in the hunt in the past year.

In this church the old men sat on one side, and the young men were not with them. They had their own place. So, too, the boys did not sit by the girls. Most of the boys sat on the stairs, and there was a man there as a sort of guard to see that they did not talk. He had a long rod or wand in his hand, with a hare's foot on one end, and a hare's tail on the other. He would let no one go to sleep. If he saw a girl nod, he would touch her on the face with the soft brush of the hare's tail; but if it were a boy who was caught in a nap, he got a sharp rap from the hare's foot. So you see in those times one could not make such a snug nest in the pew and take a long sleep as one does now; and they had to stay three or four hours in church. It must have been hard for small folks not to nod at times.

When they sung, it was out of a book by the name of "The Bay Psalm Book," and they did not know more than ten tunes. In those days no one 24 could stay from church but for a good cause, or else they had to pay a fine. And if a man staid from church a month, he was put in the stocks, or in a cage of wood, where all could see him and laugh and jeer at him.

You do not know what stocks are in these times, but if you had stood in a New Eng-land town then, you would have seen a strange thing made of wood, by the road near the church. This queer frame of wood would hold a man fast so that he could not move, and you may think a day in the stocks would be hard to bear, and would make one's bones ache.

A house in such a town, in those days, was all built on the ground floor; so there were no stairs. It was made of earth or logs, and had a steep roof of thatch. The place for the fire was built of rough stones. It was large enough to burn logs four feet long, and had so much room in it that a man and his wife and boys and girls could sit in it and look up at the sky.

The dress in those days was not the same as it is now. The men wore small clothes, which came to the knee like a small boy's in these times, and they had stiff ruffs round their necks and caps of rich stuff on their heads. The young men wore fine belts, and great high boots which were made with a roll at the top. The girls wore silk hoods in the 25 streets, and stiff rich gowns, with long waists, and lace caps on feast-days. But folks could not wear gay clothes if the law did not think they had means to spend for such fine things.

They had some queer laws in those days. Those who had done wrong had to stand in the stocks, which held them by the feet and neck, so they could not get away, or they had to mount stools in church. If a man had a wife who had the name of a bad scold, a cleft stick was put on her tongue, or she was made to take a cold dip in a stream. I dare say you think those were hard laws, and you are glad to live in these days. But that was a race who had the fear of God in their hearts; their aim was to do just right and to rule the land in the best way.

26 CHAPTER III.

THE RED MEN AND THEIR WARS.

At first, before they had time to plant the fields, the men could but hunt and fish for food; but as years went by, they had farms, and made glass and things for trade; they wove cloth of wool, and some from a plant that grows in the south, of which you may know the name. It is white and soft.

They had not much coin, and so they had to do the best they could with skins and corn, or what they could get for trade. The first mint to make coin was set up in Mass-a-chu-setts in 1652. This coin had a pine tree on one side, and the name of the State. One side had a date and N. E. for New Eng-land. All this coin was known as "pine-tree coin." In time the land at Plym-outh Bay and those near took one name, "Mass-a-chu-setts."

In the meanwhile the small band who had made homes in Vir-gin-ia had come to grief. They had been men of good birth in their own land, and did not know much of hard work. They had come in search of wealth. Great tales had been told of the gold here. It had been said one could pick up 27 great lumps of gold, as large as a hen's egg, in the streams. They found that all this was not true, and that a man had to work hard to live. They grew sick, and death came in their midst to make things more sad; so that they lost more than half of their small band.

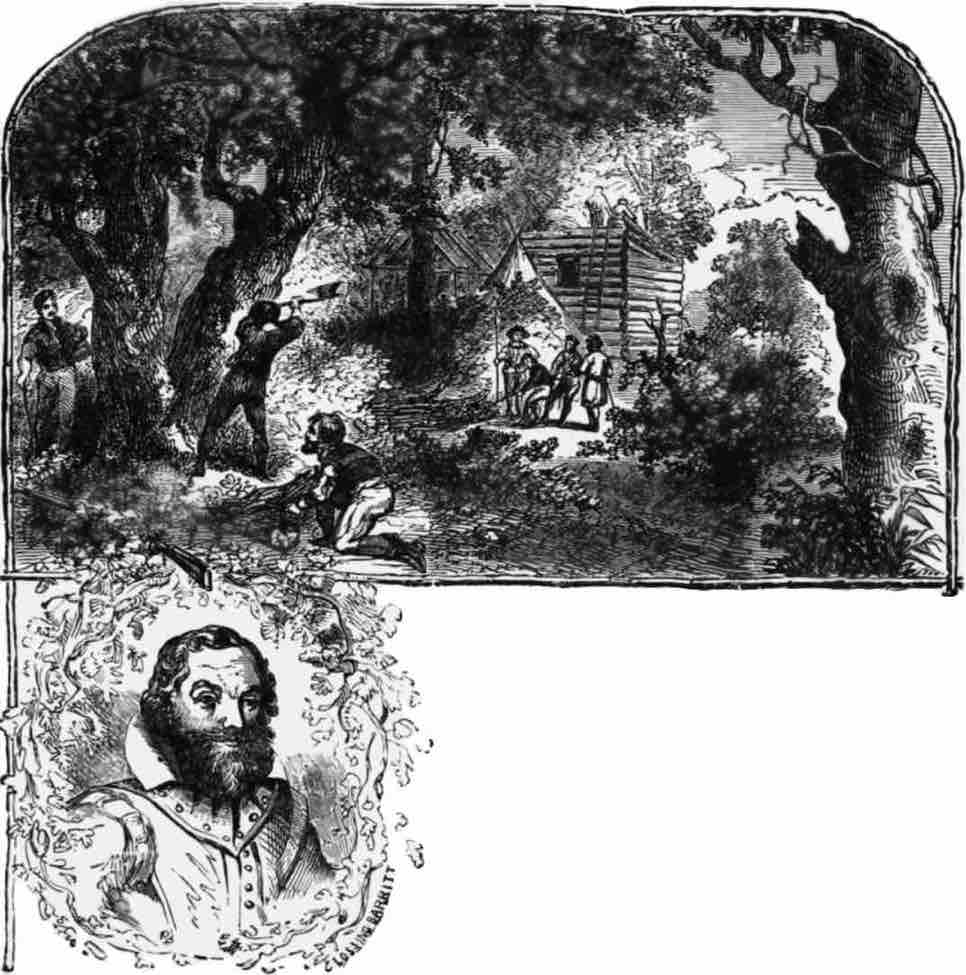

BUILD-ING IN VIR-GIN-IA.

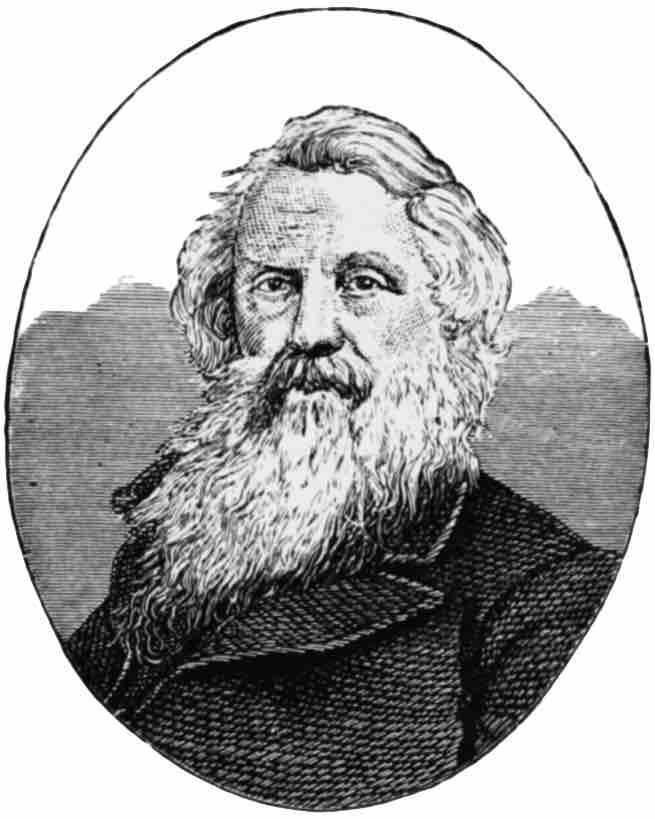

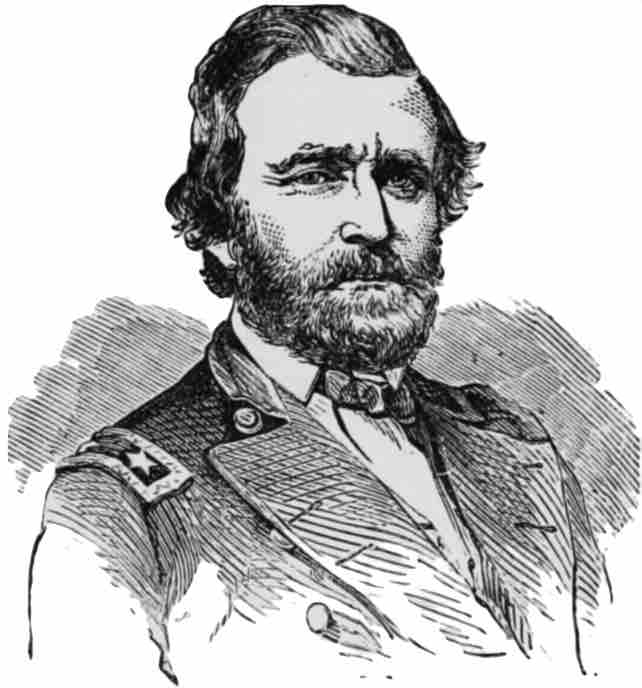

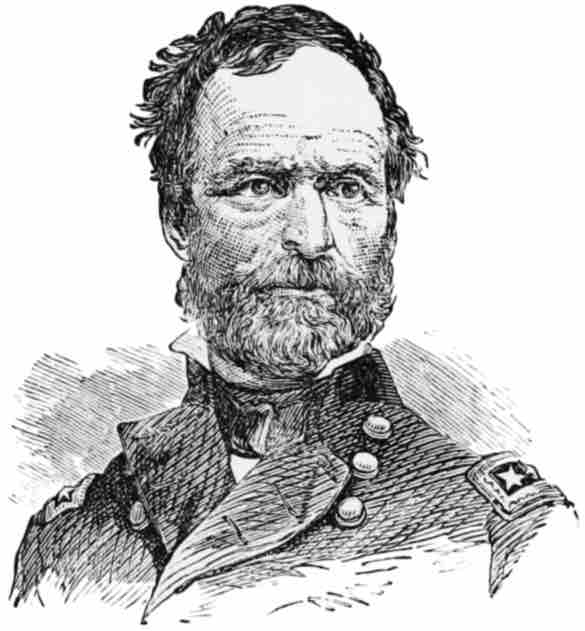

JOHN SMITH.

One man, John Smith by name, did great things for them. He had been brave from his birth. He had been in wars oft, and once he built him 28 a lodge of boughs in a forest and took his books with him, that he might learn the art of war. Once he went to fight the Turks. He is said to have been sold as a slave. It may be all these tales are not true; but it is true he taught his own friends in Vir-gin-ia how to live. He got them to build a fort and log huts for the cold times. He made friends as far as he could of the In-di-ans, so that he could get boat loads of food from them. He said that "he who would not work might not eat;" so no man could be a drone in the hive. Each one must learn to swing the axe in the woods or to hunt and to fish.

Once the In-di-ans took him and they told him that he must die. Their great chief Pow-ha-tan had said the word; so his head was laid upon a stone, and a huge war club raised to strike the blow. But a young girl was seen to spring to his side, throw her arms round his neck, and pray that he might be set free. She was the pet of the tribe, for she was the child of their chief; and so Cap-tain Smith was set free. You may be sure he was full of thanks to his kind young friend, and it is said she might have been seen on her way to James-town more than once, as time went on, with small stores of corn for the white men. And when she grew up a white man made her his wife.

TO-BAC-CO PLANT.

29 But at last a bad wound made Cap-tain Smith go back to Eng-land, and things grew worse and worse in Vir-gin-ia. Food was more and more scarce, and a sad time came, which was long known as "Starving Time." It was in 1609. At last they all made up their minds to go back to their old home. None shed a tear as the sun rose on that day; they had known bad times in the new land, and did not grieve to go. But as their ship made its way down the bay, they met Lord Del-a-ware, with a great stock of food, and new men to swell the ranks. So they were glad to turn back and try the place once more; and in the course of time they throve and built and spread, and that part of the land made a new State, which we know as Vir-gin-ia. In that State was first grown a weed which you have seen men smoke and chew.

The folks in Mass-a-chu-setts went by the name of "Pu-ri-tans." They had left their old home that they might pray to God in their own way, and they thought that their own way was the right one. When men came in their midst who did not think 30 as they did, they were sent out of the place. There was a class called Quak-ers, or Friends, who were mild, and did all they could for peace; but they thought they had their rights as well as the rest, and might serve God in their own way. They did not believe in wars, and would not bear arms. They would not hire a man to preach for them; but when they met, each one spoke as he felt the thought come in his heart. They kept the laws, and did to all men as they wished them to do to them. They said "thee and thou" for "you," and "yea and nay" for "yes and no;" but this could hurt no one, and it seems strange to us that they were not let stay in the place. They had to fly for their lives, and four were put to death. In these days all men are free to serve God in their own way.

And in that time there was one man to raise his voice for the poor Quak-ers, and all who were like them. This man was Rog-er Will-iams. He held that the State had no right to say what men should think and feel. You may be sure those who were high in place did not like to hear that; so he had to fly from his home one cold day, and for a time he hid in the woods. But the In-di-ans gave him a home, and one chief made him a gift of a piece of land, which he called "Prov-i-dence," as it was to him like a gift from God. And so the State of 31 Rhode Isl-and, where this town was built, was known as a place where thought was free. The Quak-ers were glad to find a home in that State, where they could dwell in peace.

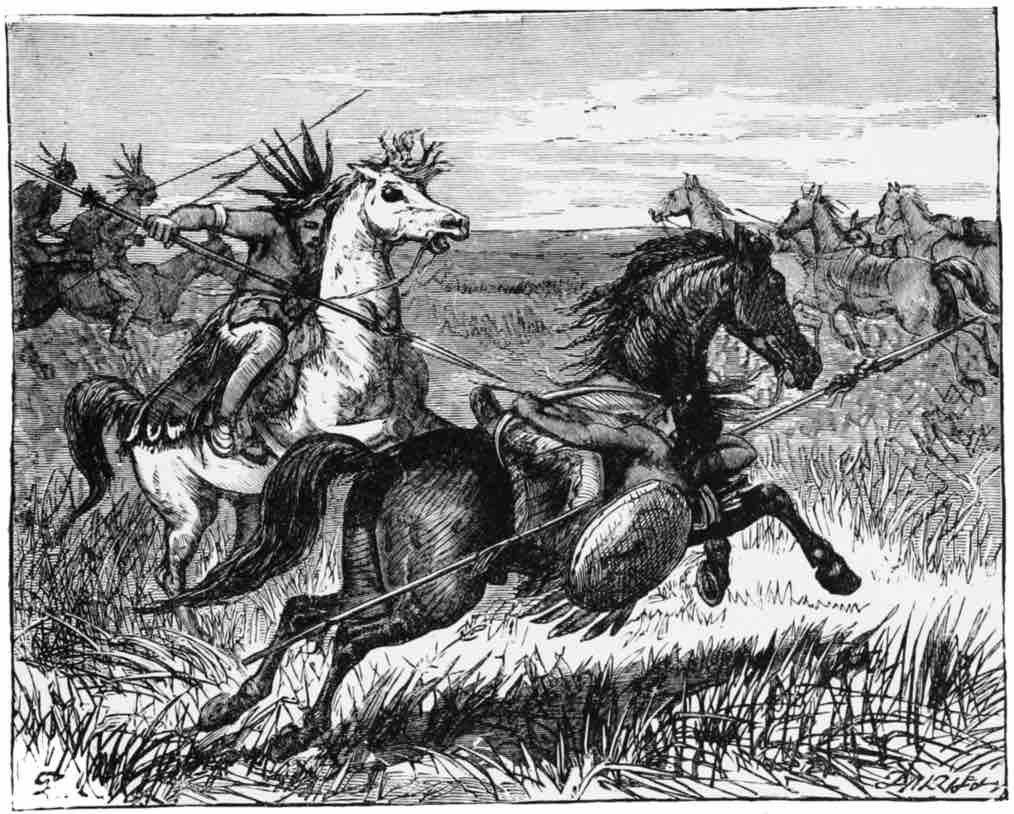

IN-DI-ANS RID-ING.

In 1675, a war, known as King Phil-ip's war, broke out in Mass-a-chu-setts. King Phil-ip was an In-di-an chief who saw that the white man would soon own all the land, and he knew that 32 meant death to his race. He made a plan to kill all the white men. The first blow fell on the Lord's day, as the folks were on their way home from church. The men flew to arms, and did not dare to lay them down when they were in the field at work, or at their homes. When they went to church they would stack them at the door.

King Phil-ip and his men made their camp in a great swamp, where it was hard for the white men to reach them. Here they laid up a store of food, and had great tribes of red men. They would not fight in the wide fields, but would skulk in nooks, and rush out and hold all the land in fear, for the foe would seem to be on all sides. At last they were made to leave their strong hold, and could find no place to hide. There was a fight, and the In-di-ans fell thick and fast. Phil-ip ran, but one of his own tribe, who had a grudge, shot him dead. He had done all he could for his own folk, but fell by the hand of one of them at last.

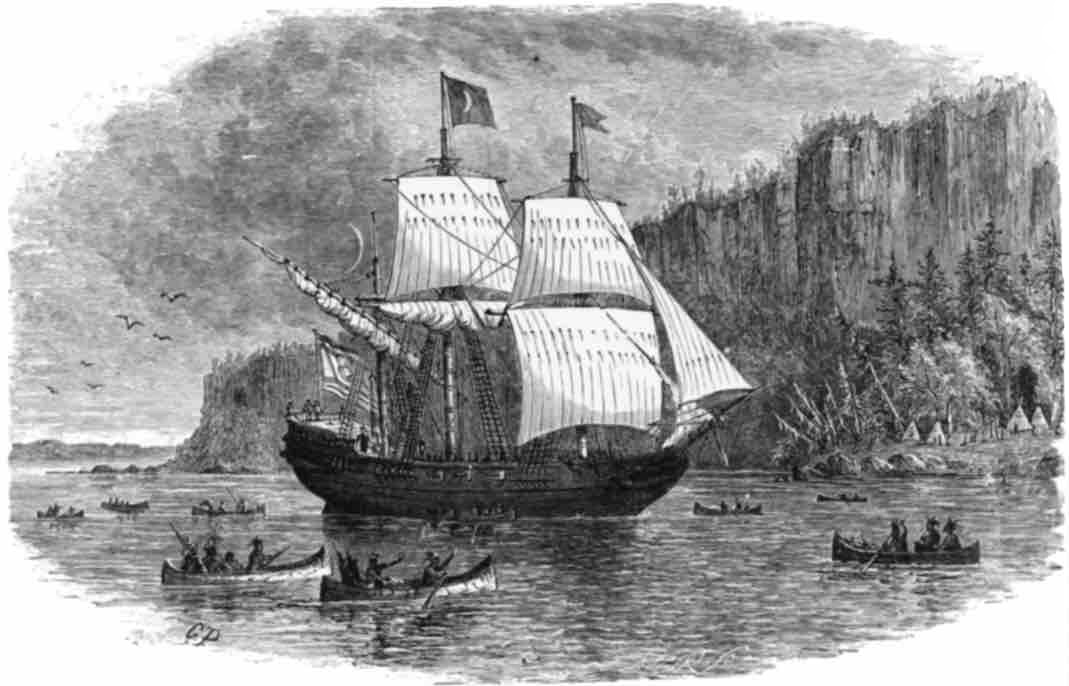

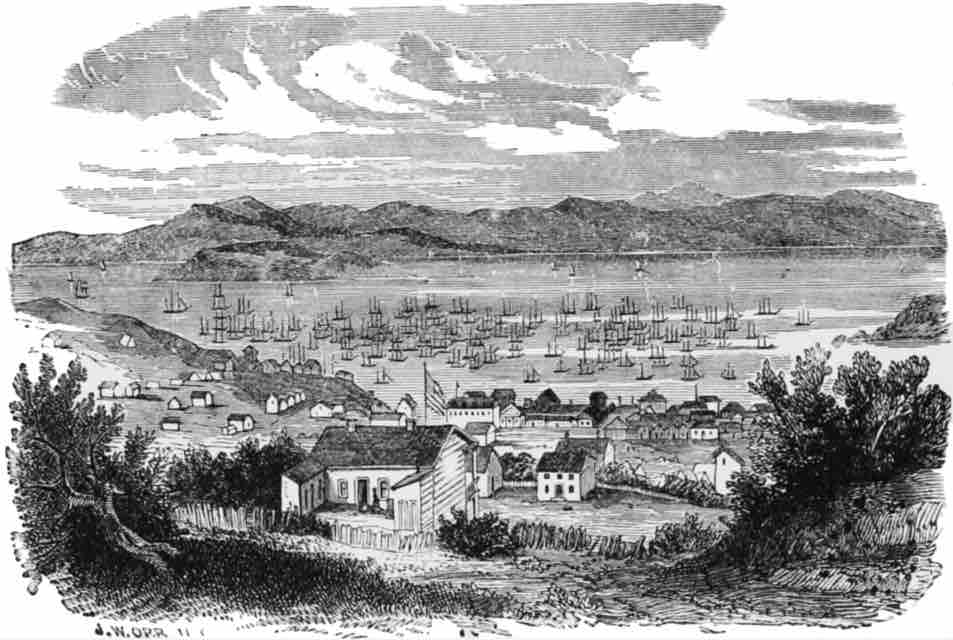

All this time the King of Eng-land was at the head of this land as well, and the men he sent were wont to rule things with a high hand. They would not grant what our men thought to be their rights. Dutch ships had come in to trade for furs with the In-di-ans. Some of the crews stayed here and made their homes in a place they called New Am-ster-dam. 33 It is now known by the name of New York. These first Dutch men bought the land from the In-di-ans, and it was to go to their heirs through all time.

THE DUTCH AT NEW AM-STER-DAM.

A band of Swedes made their home in Del-a-ware. A Quak-er by the name of Will-iam Penn bought a grant of land from the King. He thought to make a home for all his sect, who had as hard a time in Eng-land as they did here. He sent a band of these men here, and the next year he came too. He met the In-di-ans by a great elm tree. He was a kind and good man, and would not take 35 their land from them. He bought it and made them his friends. "We will live in love with Will-iam Penn and his heirs," said they, "as long as the sun and moon shall shine." And it is said that to this day a red man is loathe to shed Quak-er blood.

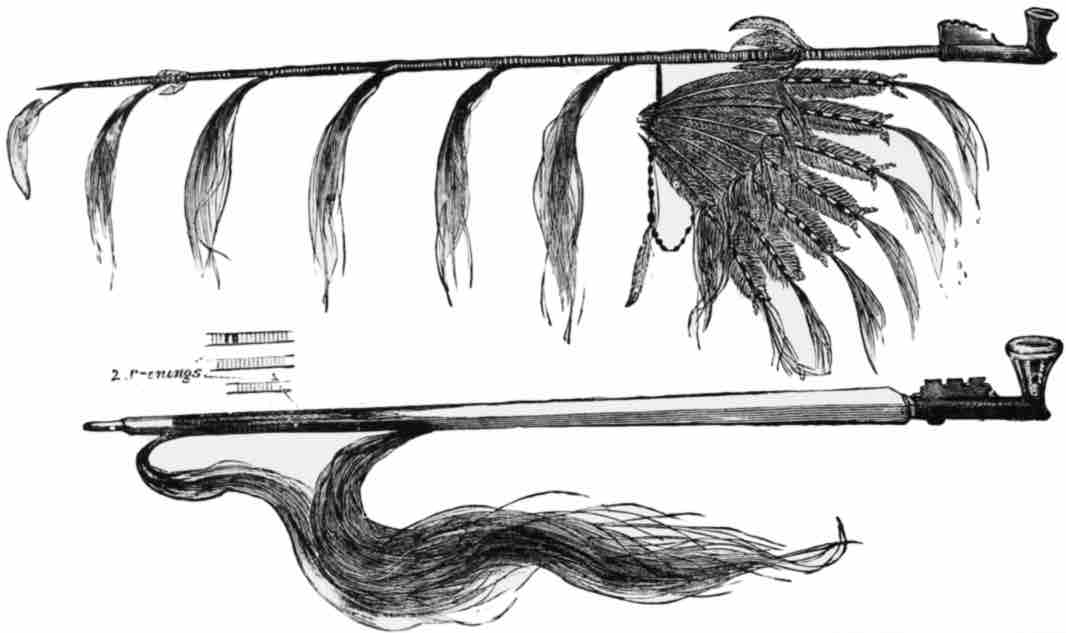

IN-DI-AN PIPES.

In 1683, Penn bought land from the Swedes and laid out a town, to which he gave the name of Phil-a-del-phia. It stood in the midst of a wood, and the wild deer ran by the men who came to take a look at their new home. When Penn came, he sent out a call for all the men to meet in one place, and there he met with them, and they laid out the code or kind of laws they were to have. This code was known as "The Great Law." No one could vote that did not believe in Christ; and all might pray to God in their own way. So you see the Quak-ers did not wish to force men to believe as they did. They felt that was not right or just.

36 Penn did all he could for his sect, and was mild and good to the red men. He said to them, "We meet on the broad path of good faith and good will. I will deal with you in love. We are one flesh and blood."

So our land grew, and State by State was laid out, and towns were built, and all this time the King of Eng-land was at the head of the whole. There were more In-di-an wars; for the red men gave the new folk no peace. They would come down from the depths of the woods of Can-a-da on their snow shoes, and drag men and their wives from their beds and scalp them and set their homes on fire. Many a child, too, had to fly with the rest in the cold night, with bare feet and few clothes on, to seek a place to hide from this fierce foe.

IN-DI-AN SNOW SHOE.

In 1754, a war broke out which we call the "French and In-di-an War." The Eng-lish had at this time a great strip of land on our coast which they held as their own. It was like a string to the 37 great bow of French land, which went from Que-bec to New Or-leans. Both French and Eng-lish laid claim to part of the land; and those who had the wish to live in peace could not but look on in fear.

The French built three forts, and that made all feel that they meant to hold the land. A young man by the name of George Wash-ing-ton, was sent to ask that they should pull down these forts. You have heard of George Wash-ing-ton, I know. You have been told that he was "first in peace, first in war, and first in the hearts of all." You have, I am sure, heard the tale of the fruit tree that he cut, and how he could not tell a lie to save him. He was a boy then, and some one had made his heart glad with the gift of a small axe. What should a boy do with such a thing, if he could not cut with it? So George went round to try the sharp edge of his axe, and, as bad luck would have it, he came on a young fruit tree. It may be that the fruit was of a rare kind, and so when it was found that the bark of the tree had been cut in such a way that one could hope for no more fruit, the cry rang out on all sides, "Who has done this deed?"

Our small boy was not at peace in his own mind. He did not know in what shape the wrath might fall on him; but he came forth in a brave 38 way and said, "I did it, Father, I can not tell a lie. I cut it." We are glad there has been one boy who could not tell a lie, and we hope there are some in our own times.

So this George Wash-ing-ton, then a young man, was sent to the French man who was at the head of the forts, to say that he must take them down at once. He had a hard time to get there, for it was cold, and the streams were big with the rains. The snow fell and froze as it fell. His horse gave out, and he had to go on foot. He had one man with him, and they struck out in to the woods. They had to cross a stream on a rude raft, and they were caught in the ice. It bore them on with great speed, and when Wash-ing-ton threw out his pole to check the speed, he fell in the stream. But he knew how to swim, and so he got to land. When day came, it grew still more cold, and the stream froze in such a way that he could walk on it to the place where he would be.

The men at the French forts would not say that they would give them up. In fact, they made boasts that they could hold them in spite of all, and so the war went on. The French would dart out and seize Eng-lish ships, and then the Eng-lish would march on the French, and do them all the harm they could. Wash-ing-ton fought on the side of the 39 Eng-lish in this war. Once the In-di-ans laid in wait for them in the wood, and as the men were on the march with their flags and beat of drum, they heard the fierce war whoop on all sides. The Brit-ish troops did not know how to deal with such a foe; but our men sprang down and fought them in their own way.

One chief made a vow that he would kill Wash-ing-ton. Four balls were sent through his clothes. Twice his horse was shot. Gen-er-al Brad-dock, who was at the head of the Eng-lish troops, was shot and borne from the field to die. There was a great fright, and the men fled on all sides. Wash-ing-ton did what he could to save them from the foe, like a brave man. But the French went on and built more forts, and our men were at their wits' end to hold their own with foes on all sides.

There were six tribes of the red men who were their friends, and I would tell you their names if they were not too long and hard.

But you will find in the State of New York lakes and streams which bear the same names. We ought to bear them in mind, as they were of great use in those times. So it was thought best for all our men to meet in a town by the name of Al-ba-ny, to fix on a way to keep these six tribes our friends, and to join with them to fight the 40 French. Al-ba-ny was then a small town with few in it; but it had a stone fort. Here our men met the chiefs and had a talk with them. The chiefs told our clan they were not so wise and brave as the French, or they would build forts like them.

But there was one wise man in our midst, Ben-ja-min Frank-lin. He had been a poor boy, so poor that when he went in to the great town of Phil-a-del-phia, he had but a few cents. But he knew how to print; and more than that he was fond of books, and so could learn all sorts of things. He brought with him a small print on which was shown a snake cut in parts. Each part had on it the name of one of the States. He said they must be made one or die, and that to be one was the way to be great. But our men did not see their way clear to do this yet. We know they made the States one in time.

The death of Gen-er-al Brad-dock was a great blow to their hopes. They saw that all the red-coats, as we call the Eng-lish, were not brave; but could run as fast as the rest. Still they took some forts, with long names, from the French in this war. They made a move on them at Que-bec, with Gen-er-al Wolfe at the head of our troops.

A DUTCH HOUSEHOLD IN NEW AM-STER-DAM, NOW NEW YORK.

Quebec was one of the strong forts of the world. At first Gen-er-al Wolfe lost at all points. But he 42 found at last a way to go in boats. With no noise they made their way to land, and up a steep hill, and at dawn the French woke to see red-coats on all sides. Their Gen-er-al Mont-calm led them out of the fort to fight. If he had not, he might have won the day, for the fort was strong. But he chose to fight in the wide field, and so we won.

At the time of the fight, Gen-er-al Wolfe, who had been struck by a death shot, heard shouts of joy, "They fly—they fly!" "Who fly!" came from his white lips. "The French." "Then praise God, I die at peace," he said, with his last breath.

Gen-er-al Mont-calm, too, on the French side, had a wound, and was told he could not live. "I am glad of it," he said, "for then I shall not live to see my town yield to the foe." So you see they were two brave men who fell that day. In five days a peace was made with France; for she gave up most of the land to which she had laid claim.

But there were some of the red men who did not want this peace with the Eng-lish. They had seen the red-coats run away from them, and they thought they might now strike a blow for their own homes and land. The French made them think they would help them. "The King of France has but slept for a time," they said, "but he will soon wake up, and then he will drive the foe from the homes 43 of the red men, and give them back their land."

IN-DI-AN CHIEF.

There was one brave chief, Pon-ti-ac, who heard all this with a glad heart. "I will live and die a French man," he said, and he sent men to each 44 town to bear a belt with red or black beads on it, and a knife with a red stain on it; these meant war. The knife was of the kind with which they were wont to scalp the foe, and the red stain told that deeds of blood were at hand. When this belt and knife were kept, Pon-ti-ac knew that the chiefs there would join the war. Their first move was on a fort at De-troit.

IRON TOM-A-HAWK.

STONE TOM-A-HAWK.

This was Pon-ti-ac's plan. He would go some day to the fort with some men and ask leave to come in and show them a war dance. 45 While some were in the dance, a few would stroll through the fort and see all that could be seen. Then they would go once more as if for a call, with arms hid in their clothes, and strike down the white men when they did not look for it. The first part of this plan went on all right; but one of the squaws, who was a friend to the head man of the fort, told him what the red men meant to do. So when Pon-ti-ac and his men went in the fort, each with his gun hid in his clothes, they found ranks of men with arms to meet them, and they were glad to get out with their lives.

But Pon-ti-ac would not give up, for he made more friends, and laid siege to De-troit in 1763. It was a long siege for the red man, but it held out, though food was scarce, and the men in it felt that they must soon starve. Pon-ti-ac at last had to make peace, and met his own death at the hands of a red man, who was mad with drink; and so the French and In-di-an war came to an end.

46 CHAPTER IV.

THE WAR THAT MADE US FREE.

For a time all were at peace; but at last a war broke out that took more time, and cost more men, than all the wars of the past. You have heard of it, it may be, by the name of the Rev-o-lu-tion.

There are some old men who fought in that war, who are alive this day. You see the cause of this war came out of what our men thought to be their wrongs. They thought the rule of Eng-land too hard, and that they should have their own men to rule them. They would have gone on as they were, if they had thought that Eng-land was just to them; but she put a tax on the things they had to use. She had a large debt to pay, and so she thought it fair our men should help to pay it; and our men held that they ought to have a voice as to what the tax should be, and fix what they knew to be right.

Do you know what a tax means? It meant, in this case, that when our men bought a thing, they had to pay a few cents more than its real price, and these few cents were to go to Eng-land. Of course these few cents from all sides grew to be a good 47 sum, and was quite a help. Eng-land, at this time, made a law which we know by the name of the "Stamp Act." This law, which gave to Eng-land a tax on all deeds, was one great cause of the wrath of our men. One man made a speech on it that was put in print, and the boys in the schools spoke it. In all the States men took the same view; so that the Stamp Act may be said to have lit the fire which in time made such a blaze.

In all the States men stood up for what they thought their rights, and they made up their mind that they would not pay this tax on Eng-lish things, but would learn to make them of their own. Men and their wives took a vow that the fine clothes from their old home should not tempt them, but they would spin and weave, and wear what they made, though it might be poor and coarse. One brave dame wrote to her friends, "I hope there are none of us but would wrap up in the skins of sheep and goats to keep us warm, if we must else pay a tax which is not just on the goods of Eng-land."

The wrath at the Stamp Act grew more fierce each day, and the men who were sent to put it in force did not dare to do so. One was caught and made to say that he would give the thing up. He was made to fling up his hat and cry as they told him, three times, in words which meant that they 48 were right and the King was wrong. No one was found so bold as to put the Stamp Act in force; and the news went to the King and set him in a great rage. Some of their own great men were on our side, and were glad we did not yield.

At last the King gave up the Stamp Act, but said he had a right to tax us as he chose. There was great joy here at the news that the Stamp Act was to be heard from no more. The bells were rung, and flags were flung out on the breeze, and all who were held for debt were made free. For a year there was no more heard of a tax; but then a new act came. This tax was made on tea and glass, and such things, which were in use all the time. This woke new wrath, and troops had to come out to keep the peace, which our men said they would not bear. The boys from the schools felt the wrong, and would call the "red-coats" in scorn by that name; and the young men made a vow that they would drive them from the town.

There were street fights each day; and the men were more and more set to have their rights. The folk wore the rough clothes which they spun and wove, and would not buy a yard of Eng-lish cloth. Then they sought to find some plant that they might use for tea, so that they would not have to buy tea and pay the tax on it. They must have 49 had some queer drinks at that time. When the King found they were so set in their way, he gave up all but the tax on tea. Then he sent three large ship loads of it here, in the hope that our folk would want it so much when they saw it, that they would be glad to pay the tax.

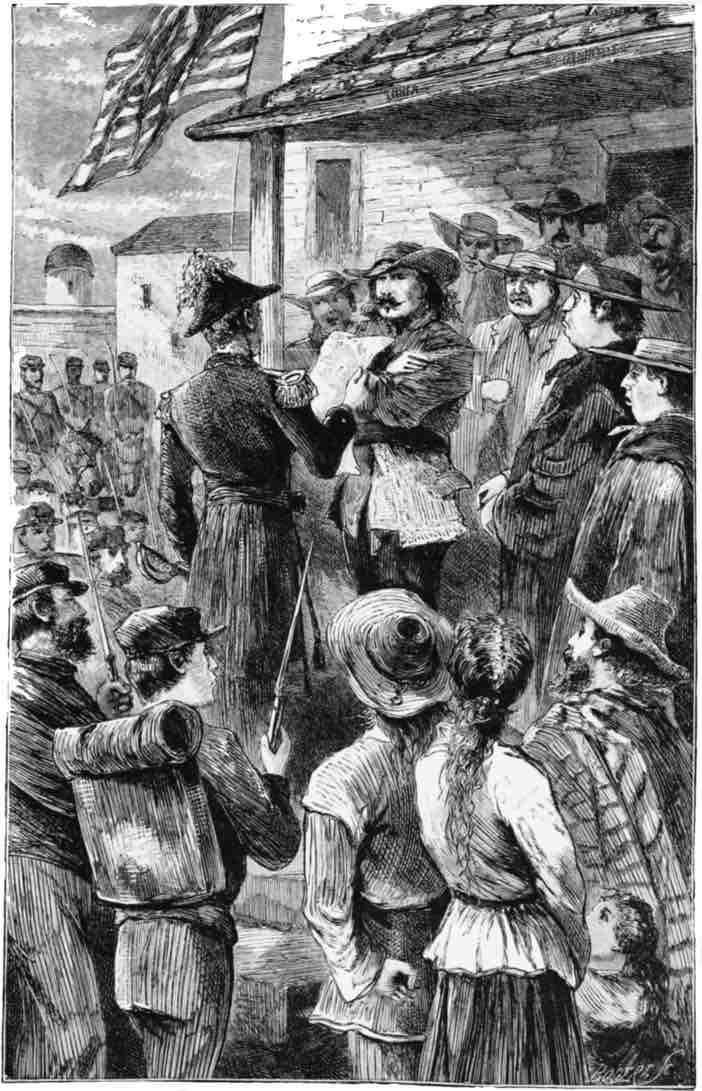

But our men had made up their minds that this tea should not land. So when the tea ships came in, a guard was set on them by our men as they lay at the wharf, so that the tea should not be brought to shore. A large crowd of men met in a Hall in Bos-ton, to say what should be done with the tea; and at last they gave out, that if the tea were sent back where it came from, all would be well. But the head man, who was sent here to rule us by the King, would not do this, and said so. When this was told to the crowd, a war-whoop was heard at the porch, and some men in the dress of In-di-ans made a rush down to the wharf, and went on board of the three tea ships, and cast all the chests of tea in the bay. Then they went home in peace and did no one harm. This was the "Bos-ton Tea Par-ty," and is so known at this day.

At New York and Bos-ton they did not try to land the tea when they heard of this, but took it back. At one time the tea was set on fire. All this made our men more and more set on their own 50 way; and the King grew in a rage with them. He made some strong laws, sent troops to Bos-ton, and put in force a bill called a Port Bill, which would not let a boat go in or out the port, save that it brought food or wood. One of their own men stood up and said this was a "bill to make us slaves." And the wood and food had to be brought in a new route, and not straight in the bay. Not a stick of wood or a pound of flour could be brought in a row boat, or straight in from a near point; it must all go round to the place where the Eng-lish saw fit, where they could stop it and see just what was there.

Of course this was hard for the good folk of Bos-ton, and they did not bear their wrongs in peace. They had gifts sent them by land—of grain and salt fish and sheep. From the South came flour and rice, and some times gold for the poor. So that the Port Bill made all feel to them like friends, for all towns took up the cause of Bos-ton as their own.

This was just what the wise men at the court of King George had said would be the case. They knew it would make our folk more strong to drive them with hard laws to fight. And so it came to pass, as the two great men, Burke and Fox, had said, King George was set in his way, and would 51 not change, but did his best to push the laws through. The Bos-ton Port Bill was one of the things that made the States one. For they had but one mind on these harsh laws, and stood as one man for the right. The day when this Port Bill was first put in force, the Town Hall in one of the towns was hung with black, as for a death; the Bill was on it, and the toll of bells was heard all day.

If we could have stood in Bos-ton in those days, we would have seen that there was not much work, and no ships at the wharves but those of Eng-land. There were guns in view, and men with red-coats in the streets. There were tents on the green, and clubs that met each night, to talk of this strange turn in things, and what was best to do. They did not want war, but saw no way to get out of it. Great men spoke of it here and there, and each speech was read at the clubs.

"We must fight," grew to be the cry. But there were some, of course, who felt sad at all this, who thought it wrong not to do the will of the King in all things. They said this land would come to grief, for we were the ones who had the most to lose by war. These men had the name of "To-ries," and the rest did not look on them as friends, but held them as foes. Some of these men went back 52 to their old homes, and came here in the troops of the King to fight their old friends. Some stayed and came round to new views, and took part in the wars that came to pass in time. All knew that the ranks of the King would be made of men who had fought in wars, and were known to be brave; while on our side they would be raw men, who did not know the art of war. But still our men were brave, and they said, with strong hearts, "The strife may be long, but the end is sure. We will fight for our homes, for our lands, for the right. We will be free!"

53 CHAPTER V.

THREE GREAT FIGHTS.

In each town, at this time, men thought but of war, and how to train for it; so that in case of need each one could spring to arms at once. Guns were put in a safe place, and stores of food were bought. The Brit-ish in their turn kept watch on all, and more troops were brought in.

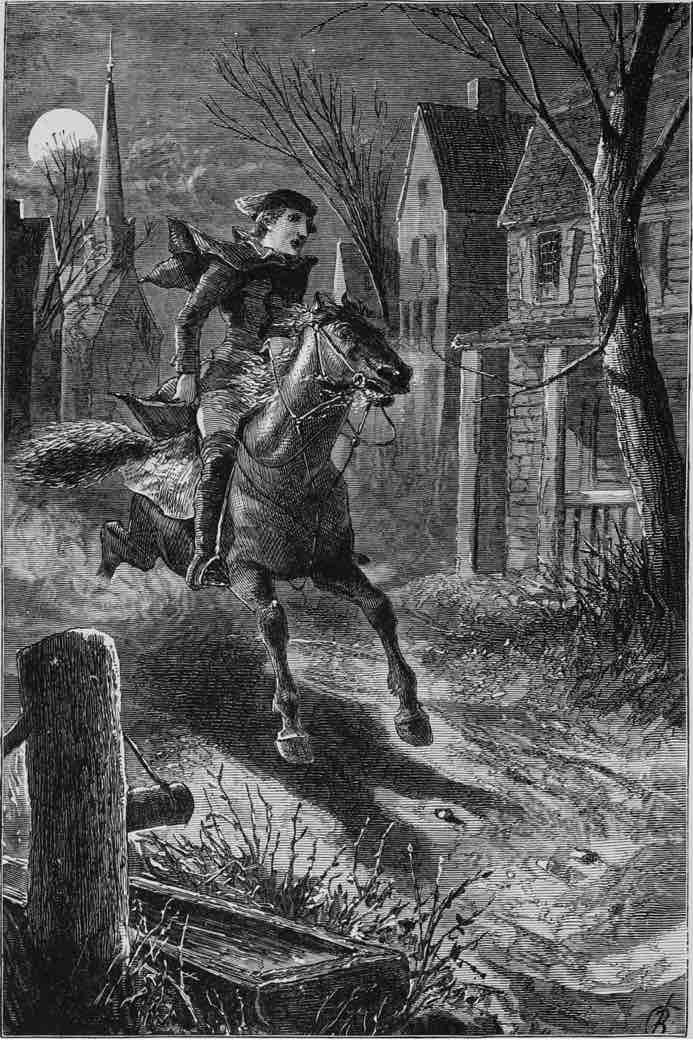

Our men made a plan, that when it should be known that a large force of the Brit-ish were to move out of Bos-ton at night, a light should be hung out of the North Church by way of a sign. One night the watch by the Charles saw the light gleam high on the church, and they knew some move was on hand. At once all was stir and noise. Men rode here and there to find out what it meant. One went in a boat, and then took a fleet horse to seek out two of the wise and great men, and see what was best to do. The man who took this ride, and went from house to house with a call to those who slept, was Paul Re-vere. There is a song this day on that ride.

You may be sure there was no more sleep in a 54 house that night. When he rode by—"Do not make so much noise," said one on guard.

"Noise," said Paul Re-vere, "there will be noise ere long; the foe is on us!"

All this time the Eng-lish troops had made a swift, still march. They thought no one had seen or known their move; but all at once the bells in each church rang out a wild peal. In each town the church bell sent a call to each home. So it was plain that all was known. Paul Re-vere and the scouts had done the work well. The Brit-ish sent back for more troops. They came, and they were told to hold the bridge at Con-cord. But when Ma-jor Pit-cairn, who was at the head of the Brit-ish, came to Lex-ing-ton at dawn, he found a great crowd of men with arms.

"What do ye here?" he said, in wrath, "go to your homes! Why don't ye lay down your arms?" But as they made no move to go, his troops sent forth a fire on them, which they gave back with a will. Eight of our men got their death wounds that day, and this was the first blood shed in the war.

The Brit-ish then gave three cheers and set out on a march to Con-cord. The people of that town made haste to move their stores of food and arms to a safe place in the woods. Their scouts took the North bridge, and could see that the Brit-ish were 55 in the streets of the town; that they had set the court house on fire, and cut down the pole, and laid waste the stores they found. So the men on the bridge made up their minds they would try to drive this foe out. There were but few of them, but they had strong hearts.

One of their head men said, "I have not a man who fears to go." He was the first who was shot, and fell dead. Still they went on and made a brave fire, so that the Brit-ish set out to run. But they could not go back as they came; for by this time our men for miles round, came in on all sides. Some were in their shirt sleeves, they had come in such haste; but each one had a gun in his hand, and took his place back of a tree or stone wall, where he could get good aim. One of the Brit-ish wrote home that the men came so fast, they would seem to drop from the sky.

At each step the Brit-ish troops took, a shot would come from some side, and a man would fall dead. At last such a fear came on our foe, that they broke into a run. They did not know what to do. They had no more shot, and could not give back the fire. One of them wrote, "They had to lie down for rest on the ground, and their tongues hung out of their mouths like dogs spent by the chase." All the way to Bos-ton they felt the 56 fire of our men, and they were glad to get back to their great ships, the men of war, and rest where they could be safe. They had lost three times more men than the A-mer-i-cans.

There was a great stir in the court of the King when the news was brought that their troops had run from a hand full of raw men, who had no skill in the art of war. Poor Lord Per-cy, who had been at the head of the Eng-lish, came in for hard names, though he was a brave man. They were mad, and had to give vent to their wrath on some one. In A-mer-i-ca it was felt that this was the first blow struck; and Sam-u-el Ad-ams, when he heard the news at Lex-ing-ton, said, "Oh, what a grand day this is!" for he knew this strife would not end till all the States were free.

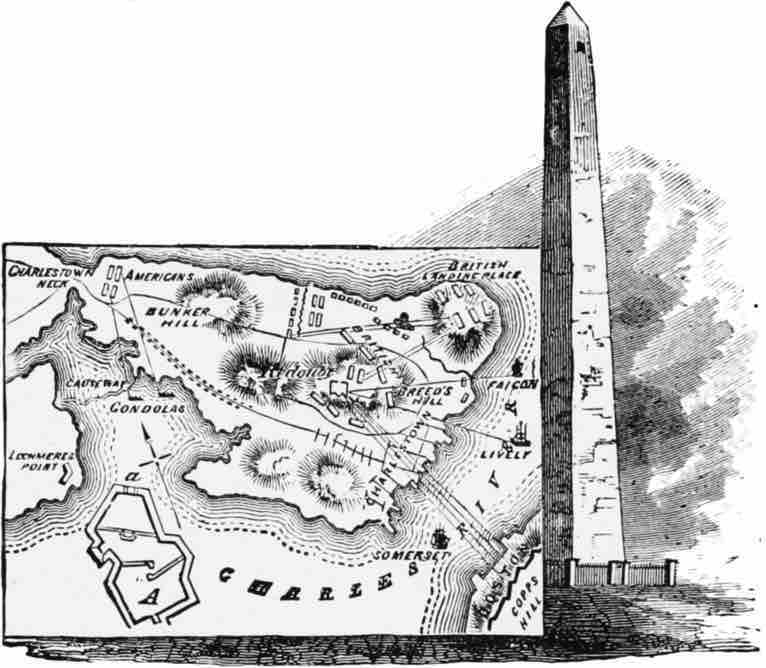

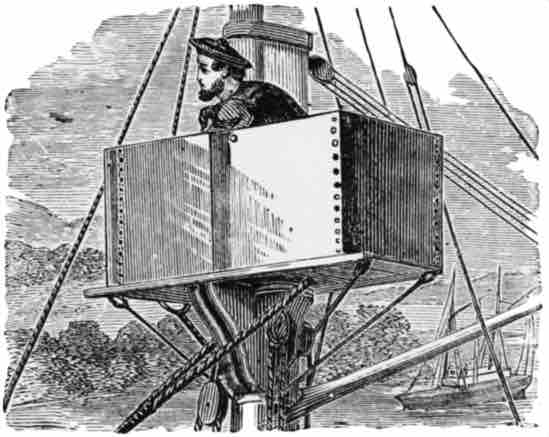

There were some hills near Bos-ton, and our men knew that there was a plan to gain them, and make a place for Eng-lish troops on them. You see, if the foe had such high ground, they could have a grand chance to fire down on those in the town. So our men stole out by night and threw up earth works, and took all the troops they could get from all parts, and put them in charge there. In the mean while they sent their wives and young ones out of the town, so that none but Brit-ish troop were left there. They made no noise in their 57 march that night; no one heard them, and the bells in the church struck twelve ere they dug a sod. But they were soon at work, and could hear the guard on the man-of-war cry out each hour, "All's well."

When the day came, and the sun rose, the earth works were seen from the ships, and at once they sent out a fire on them. So in Bos-ton the troops woke to see the true state of things, and were not slow to do their best. But our men went on with their work, spite of the shots. One of the foe had a glass through which he could see each move of our men round the works. "Will they fight?" said he. "To the last drop of their blood," said one who stood near.

So they made up their minds to lose no time, but to make a raid on the works that day. It was a hot day in June. Part of our men stood by a rail fence, on the edge of a hill, by the name of Bun-ker Hill; part were back of the mounds which were but half made. Then the rail fence was made to screen the men back of it, by a lot of new mown hay, put in to fill up the gaps.

JO-SEPH WAR-REN.

The Brit-ish troops went in boats, and took their stand on the bank of the Charles. They had two men to our one, and were full of skill in the use of arms. Our men had come in from the farm or the 58 shop. They did not know what a drill meant; but their place was more safe back of the earth works, while the troops of the foe were out in full sight in the field. It is a grand sight; the long lines, the red coats and white pants of the Brit-ish; the white cross belts, the beat of drums, the play of fifes. The sky is clear and hot. Great white clouds sail on the blue. The folks crowd on the roof of each house in the town.

So our men laid in wait, as the troops took up a slow march on them. The Eng-lish found the day hot, and they had their arms and food to weigh them down. But they had no doubts, and their march was sure. They would fire now and then, and few shots fell on them. On they came, 59 till they got ten rods from the earth works. Then the word rang out on our side, "Fire!" When the smoke was gone it was seen that the dead lay on the ground here and there; and those who were left had set off to run.

PLAN OF BUNK-ER HILL. MON-U-MENT.

A great shout went up from the forts; a cheer came back from those at the rail fence. They, too, had held back their fire to the last, and then three fourths of those who had set out to chase them fell in the ranks, and the rest ran. Gen-er-al Put-nam was one of our great men in this fight. When the foe came on, he had said to his men, "Aim low; wait till you can see the whites of their eyes," and their aim was sure. When they saw the Brit-ish troops in flight, they thought they would give them chase; but they had no more shot, and so could not make good what they had won. They fell back with sad hearts, one by one, and lost more as they did so than they had done in the fight.

60 This was the fight of Bunk-er Hill, and though the A-mer-i-cans did not win the day, they made plain to all men that they had stout hearts, and could deal a blow for their rights. In this fight Gener-al War-ren lost his life.

61 CHAPTER VI.

FIRST IN WAR—FIRST IN PEACE.

The first thing George Wash-ing-ton was heard to ask when news came of this fight was, "Did our men stand fire?" And when he was told that they did, he said, "Then the rights of our land are safe." From this day our men took heart and were of good cheer. The Brit-ish lost one in four of their men in that fight; and on our side we did not lose half as much. In Eng-land men did not know what to make of so great a loss to their troops from so small a force as ours.

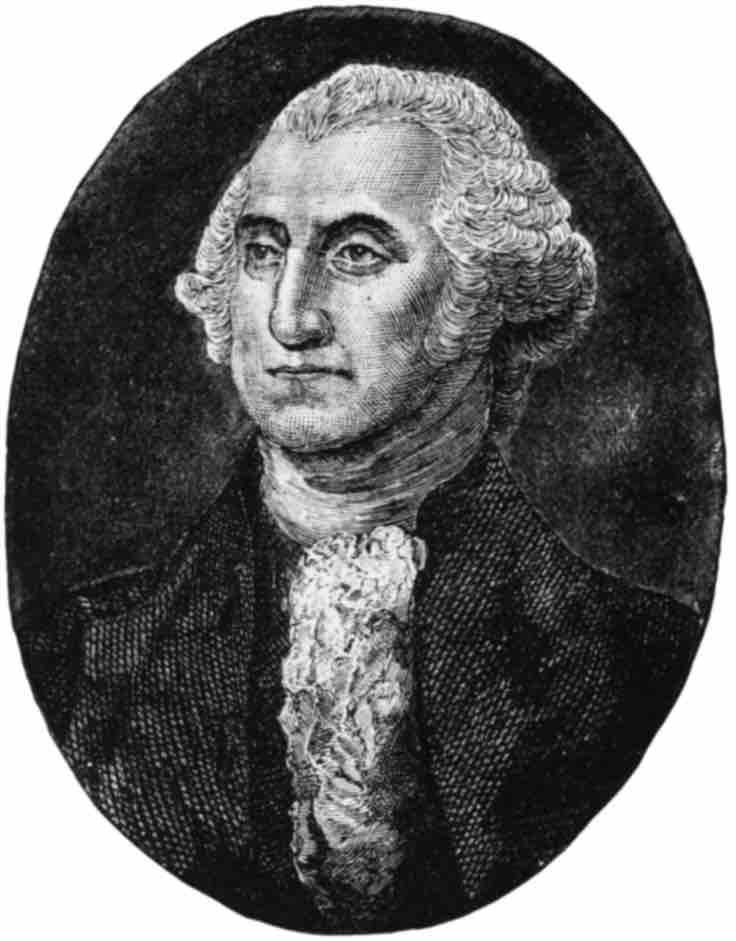

In this land there was a call for more troops, and George Wash-ing-ton was put at their head. He had shown that he was a brave and true man. He came from Vir-gin-ia, his home, and met the rest 'neath a great elm tree in Cam-bridge. This tree is known as the "Wash-ing-ton Elm" to this day. All felt a wish to see this brave man, who had no small fame; they came from all sides to greet him, and saw a man more than six feet tall, with a broad chest, large hands and feet, a fine face, a clear eye, and the air of one born to rule. He 62 wore a blue coat, with buff small clothes, and a black plume in his hat.

Wash-ing-ton saw, in his turn, a crowd of men of all sorts and kinds, rude and rough in their looks, and with odd kinds of arms, no two of which were alike, in their hands. Some were in old coats, some in their shirt sleeves. No state suits or gold bands or fine plumes were there. And when Gen-er-al Wash-ing-ton went round to the camp, he found things were in a bad state. Some had straight lines of tents, neat and nice, but most were in small huts made of boards or stones or turf. The food was rough and scarce, and the men had not the first means for war; not as much as would load their guns more than a few times.

It would not have been strange if Wash-ing-ton had felt his heart sink at such a sight. But he went to work in a brave way to do the best he could. Some store ships of food fell, by good luck, in the hands of our men, who had been sent out to get what they could; so that food was not so scarce. But still they had no food for their guns, and could not march on the foe.

The Brit-ish troops still held Bos-ton; but could not get food and wood for fires. The small-pox, too, broke out in their midst. They had to pull down an old house now and then and burn it to 63 keep warm; and they sent crowds out of the town to be fed. They put troops in each church, and made a play house of the Town Hall. At times they would send out play bills to Wash-ing-ton and his men. They did not want them to know that things were so hard with them.

Once in this hall they had a play on the times. It was meant to show how they were shut in by the foe, and of course to make fun at the same time. In one part, a man in a dress like Wash-ing-ton, with a great wig, and a long sword all rust, came on the stage. By his side was a green lad, with an old gun. This was done to cast a slur on our men. But just then there was a cry, "The Yan-kees are on Bunk-er Hill." At first this was thought to be a part of the play; but when Gen-er-al Howe said, in a loud voice, "Men, to your posts!" there was great fright. Men ran, their wives fell in a faint, and all felt there was no fun in such a scare. In a short time the Eng-lish left Bos-ton; for they could not be safe from the fire that came down on them from all the hills round.

But they did not give up the fight. When the King and his court heard of Bunk-er Hill, they made up their minds they would rule this land, let it cost what it would. So they cut off our trade as far as they could, and they brought in all the men 64 they could find from all lands which would give them help. So you may be sure they had a great crowd to come on us and try to bend us to their will. But our folk kept up a stout heart in the face of all. They felt they had gone too far to go back.

There were some wise men who were known as the "Con-gress," who had met in Phil-a-del-phia. They gave it as their mind that "These States are and of right ought to be free;" and they stuck to this text. The troops had to fight, and it was the part of Con-gress to raise the men, the pay, and the arms. It would seem that they had the worst part to do. To be sure, when they thought of the past, they might take heart. In the face of such a foe, it must be said, our men had done well. Doc-tor Frank-lin felt that way; but there were some rich men who thought it would be death to the States to make war. 65

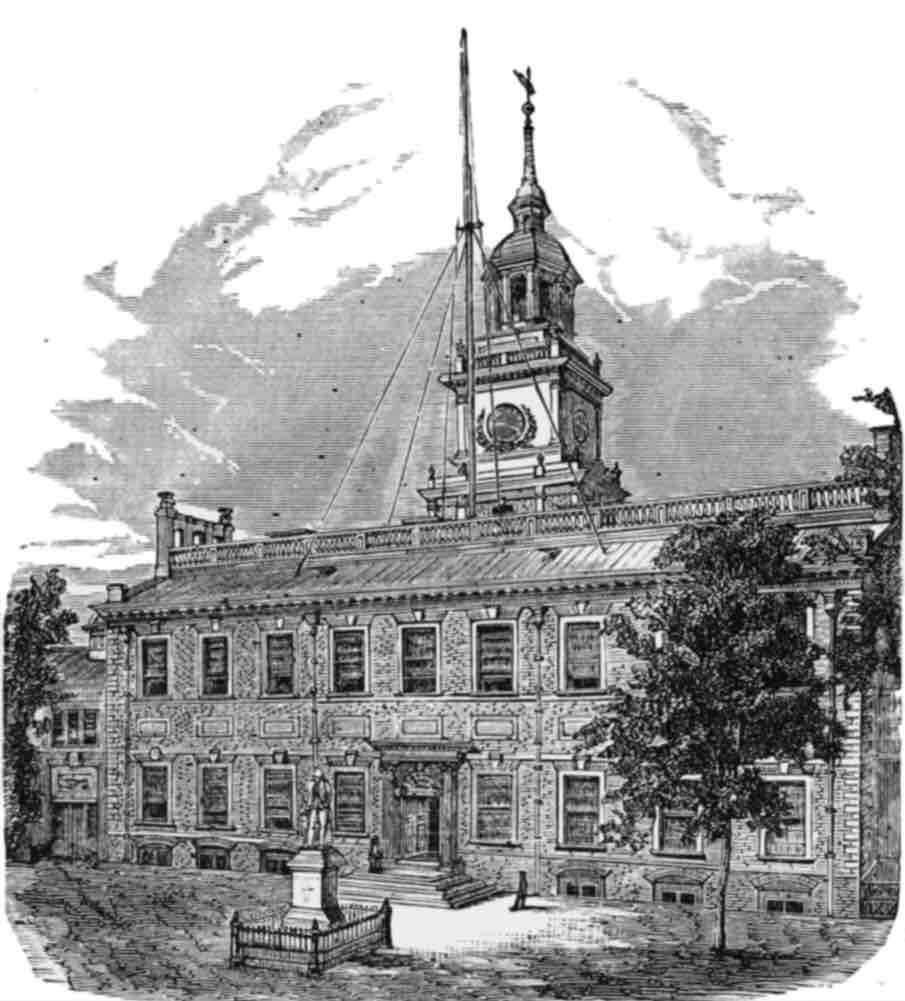

So Con-gress met to see if it were best that they should strike the blow at once that would make them free. They had more than one talk on this, and at first the time did not seem ripe. They were to break all ties with Eng-land, to pay no more tax, and to try to find help if they could, in their fight to be free. Some great men wrote out the plan, and you can still see it in the Hall in Phil-a-del-phia. This sheet is called the "Dec-la-ra-tion of In-de-pend-ence." It meant that they were bound to be free, and so they wrote it down. It was made Ju-ly 4th, 1776, and that is why you hear the noise of fire works and see signs of joy on each Fourth of Ju-ly since that day.66

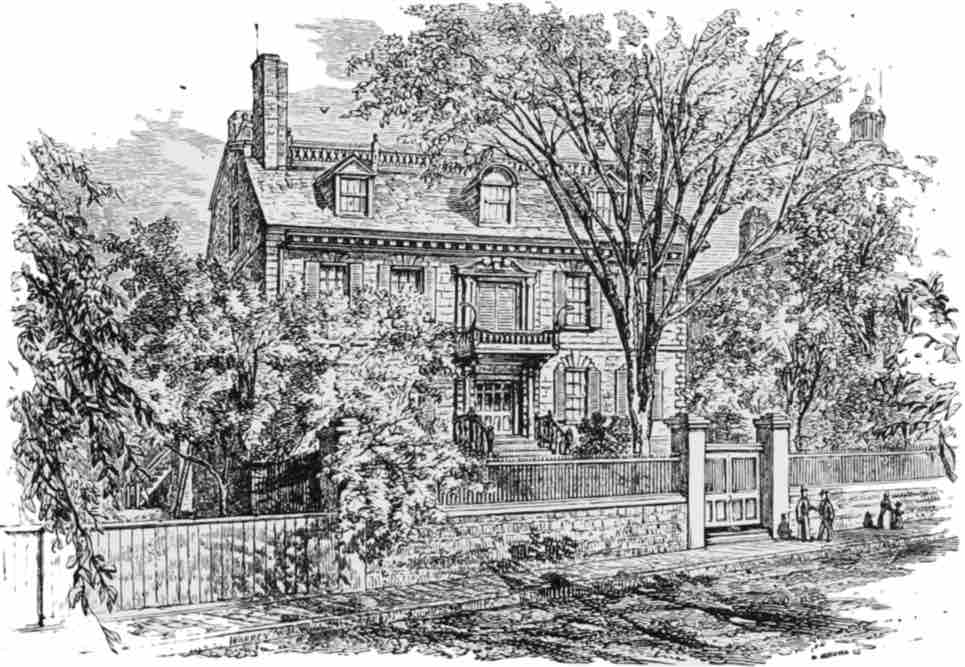

JOHN HAN-COCK'S RES-I-DENCE, BOS-TON.

When the men came to sign this Dec-la-ra-tion, the one who wrote his name first, said, "We must be one; we must all pull the same way; we must hang side by side." "Or we shall hang with none at our side," said Frank-lin. But no doubt there were sad hearts that day, though these words did raise a laugh.

IN-DE-PEND-ENCE HALL.

They did not change this dec-la-ra-tion much from the way they wrote it first. There was one clause on the slave trade which the men from the South did not like; so it was struck out. There were twelve States—though they did not call them States in those days—that gave their vote for it. New York would not vote at all. The bell of the State House was to ring if the "Dec-la-ra-tion" should pass. This bell had 67 been put up years since, and one might read on it, though these are not just the words, "Let all the land be free." So the old man who was wont to ring this bell, put his boy at the door of the hall where the men met.

When at last the Dec-la-ra-tion should pass, the man who kept the door was to make a sign to the boy. You may think how all hearts beat when this boy ran out with a cry of "Ring, ring;" and what a peal of joy rang out from the bell! Then the Dec-la-ra-tion was read to each of the troops, and there were loud cheers on cheers from all sides. That night the form of George the Third, on horse-back, which had been wrought in stone, and stood in one of the squares, was laid low in the dust by the crowd.

Yet for all this brave show, the men were sad at heart. They knew how poor they were, and how few, and the true state of the troops, and all that could be brought to put them down. They set out to make a flag of their own; for they had all sorts of flags at this time. One had a pine tree on a white ground, and was known as the "pine tree flag." On this flag were words which meant, "Call to God for help."

When Wash-ing-ton came to take the head of the troops, he had a new flag made with stripes of 68 red and white, as now; but on one end was a red and white cross, like that which marks the Brit-ish flag. This flag went with our troops in Bos-ton, when the Brit-ish took up their march out of that place. But, by vote of Con-gress, a change was made, and it was said that our flag must have red and white stripes, and white stars on a blue ground—a star and a stripe for each State. Now when they make a new State, they put a new star on our flag. Count them and see how strong we are.

The first man to hoist the new flag was Cap-tain Paul Jones. He was at the head of a man-of-war, and from that ship it was first flung out on the breeze. This is the flag that now waves in town and camp, and on our ships to all the ports of the land. We have more stars now, but the stripes stay the same.

69 CHAPTER VII.

THE REST OF THE WAR.

Up to this time, most of the fights had been round Bos-ton. But Wash-ing-ton now saw that there would be a move made on New York; so he sent Gen-er-al Lee to help keep the town, and he soon went there too. Some men came to their aid from the South, and Lord Howe, with a great mass of Eng-lish troops, were there to meet them. Lord Howe had word from King George first to speak of peace, but he did not know to whom he should speak. He wrote a note to "George Wash-ing-ton;" but our chief would not read it, as he said his true name, as head of the troops, should be on it. So Lord Howe wrote no more. He saw that the hour to fight had come.

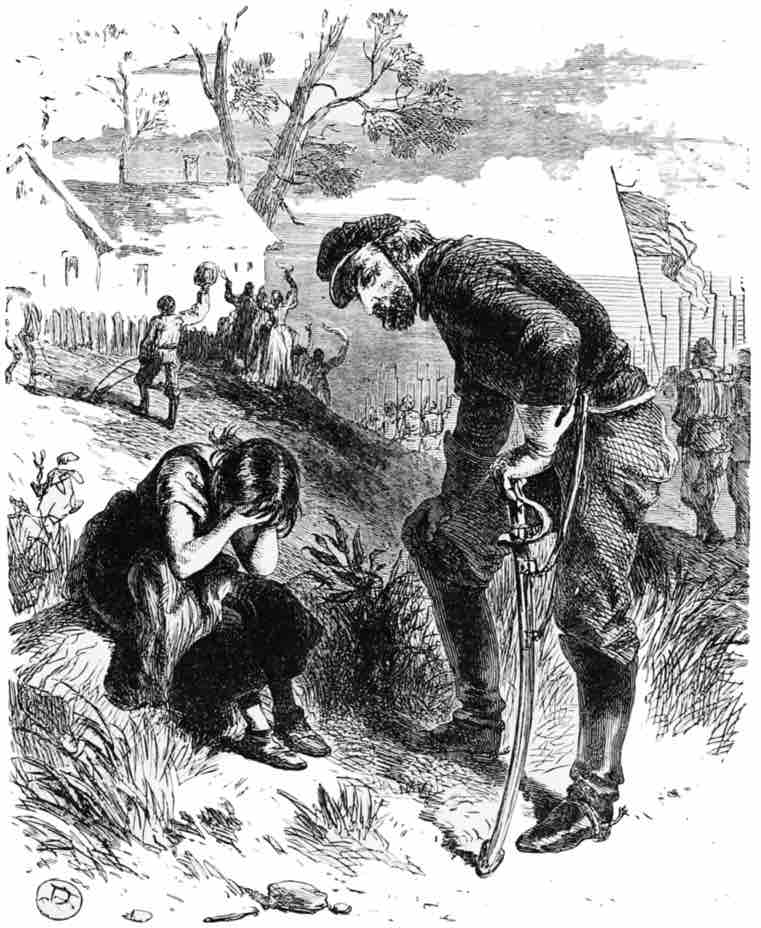

At first the A-mer-i-can troops came to grief, and Wash-ing-ton and his men had to make their way back for a time. The Brit-ish took heart from this, and our men were sad. They were poor, and had few clothes, and some had no shoes for that long, hard march; so that one could track their steps by the blood on the ground.

70 Wash-ing-ton saw there was no time to lose, and he must strike a swift blow. He knew there were troops of Ger-mans at Tren-ton, and that they still held to the ways of their land. Do you know the name of that day when you have a tree with nice gifts and lights hung on it? It is the day when Christ was born, and which we keep to this time for His sake. Well, Wash-ing-ton knew these folk would cling to the ways of their old homes. That they would keep the feast and be off their guard. So on the eve of that day he set out to march on them with his men. A storm of sleet came up in the night, but they went on, and when the dawn rose, these brave men, who had come through the snow and ice, stood in ranks for the fight. Some one wrote a note, and a man ran all the way to Tren-ton to warn the Ger-mans. But they were at cards. The Gen-er-al had his cards in his hands, and it was his turn to play. He must look at his cards first.

Yes, his life is at stake, but he does not know it. In the dim gray of the dawn our men march in on them. There is the sound of wheels and a shout. Co-lon-el Kall hears the drums beat, and the cards drop from his hands—too late! He got his death in that fight, and all his men were held and bound. These things put our troops in heart once more, and it was the wish of all to go on; but they had a 71 hard, sad time through the days of storm and cold at Val-ley Forge.

If we could see that camp at Val-ley Forge, in our mind's eye, we would know how much those poor men had to bear in this war to make us free. They had lost some by death, and more were ill. They had so few clothes to put on when they slept, that some sat up all night by the fires to keep warm. At one time there were few who had shoes, and the sick had to lie on the bare ground, for want of straw. The head men had to wear old quilts or bed spreads round in the camp, to keep them warm, for want of the right kind of clothes.

The troops were not paid; or the sort of pay they got would not buy them food. Food was so scarce that, at last, the pass word was, "No food—no man." There were men in this camp who had been at the court of kings; who had fed on rich food, and had wine to drink, and now they were like to starve.

All this time Wash-ing-ton did his best to keep up the heart of his troops. He did not tell Con-gress how few and worn they were; and there were those who gave him blame that he did not do great things with these few worn out men. All this time the Brit-ish troops in Phil-a-del-phia had what they chose of good fare, and led a gay life. Some of 72 them, with Gen-er-al Bur-goyne at their head, in the mean time, had two or three fights with our men, but found they did not gain much. At last they were glad to go back. Just as they made a move to do so, our men had the luck to hem them in on all sides in one place and won the day. This was at Sar-a-to-ga. This was good news to those in Val-ley Forge. It brought cheer to them, and they felt brave to go on.

In Eng-land men did not know what to make of our luck. It made a stir in France, where we had friends; and some of their young men came here to join our troops. We had some great French men with us at that time. One whose name is still held in love by all—the great La-fa-yette.

At this time France made a vow to us that she would stand our friend, and give us aid. When this was known in Eng-land, fears rose on all sides; for they knew how much help France could give, and how strong it would make us. They sent men over to talk to us of peace, but it was too late. The A-mer-i-cans had no thought but to be free, and they would take no less than that. But these men still came, and thought they would see what bribes could do. A large sum of gold was held out to Gen-er-al Reed, if he would aid their cause. He said, "I am not worth so much; but such as I am, 74 the King of Eng-land has not so much gold as would buy me!"

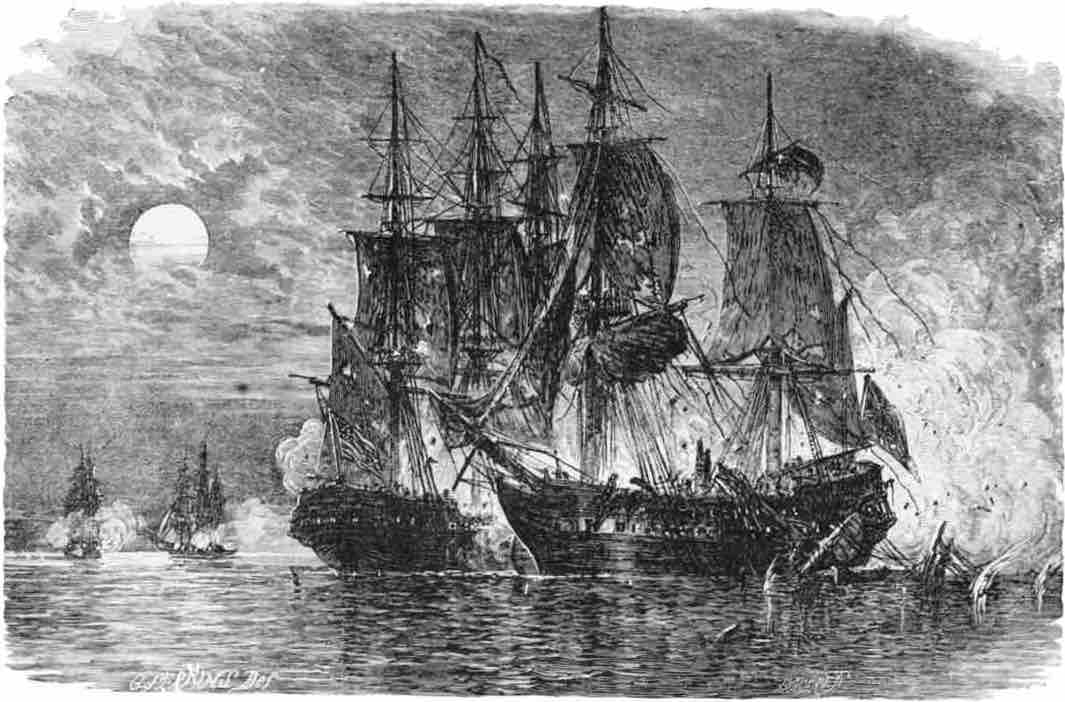

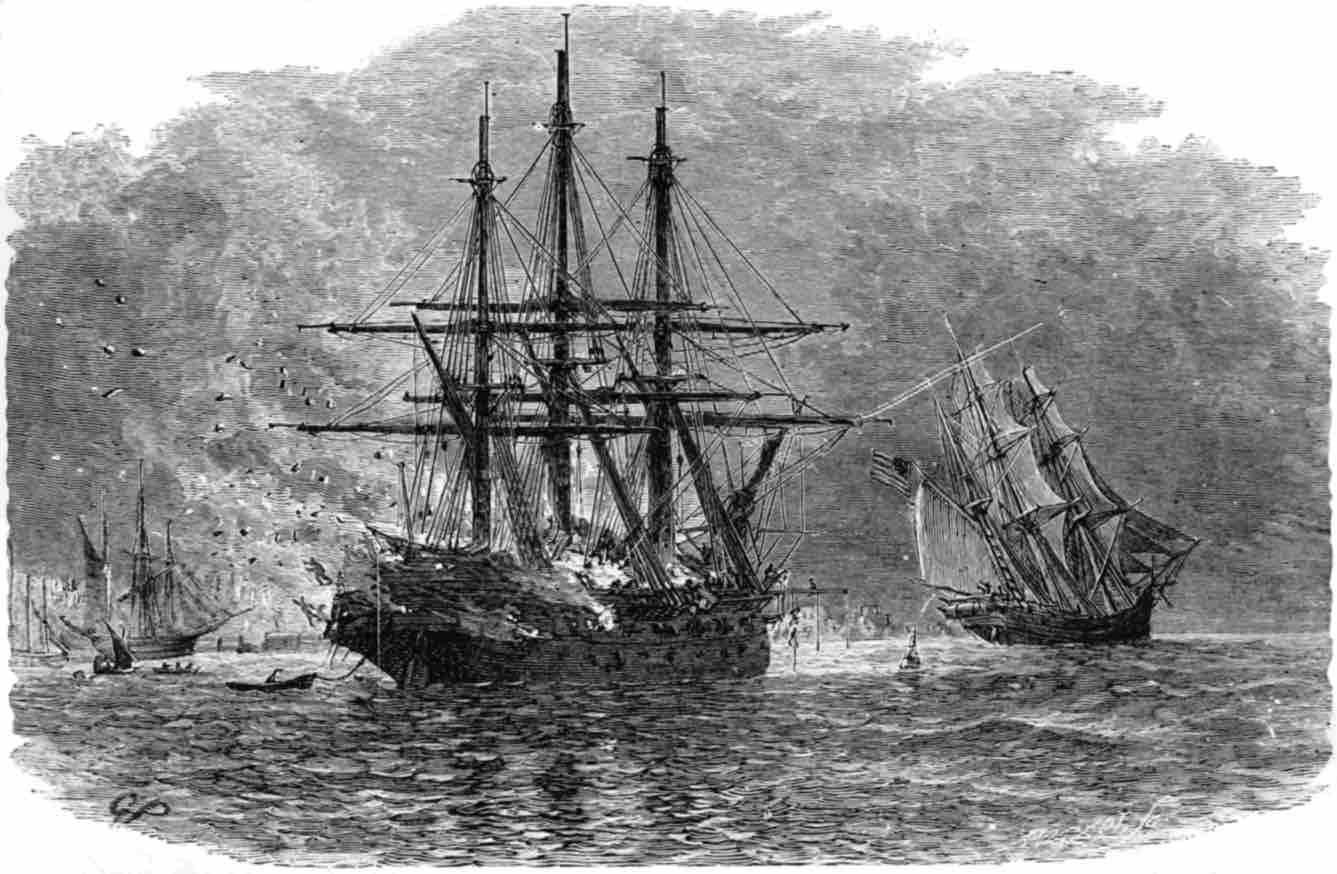

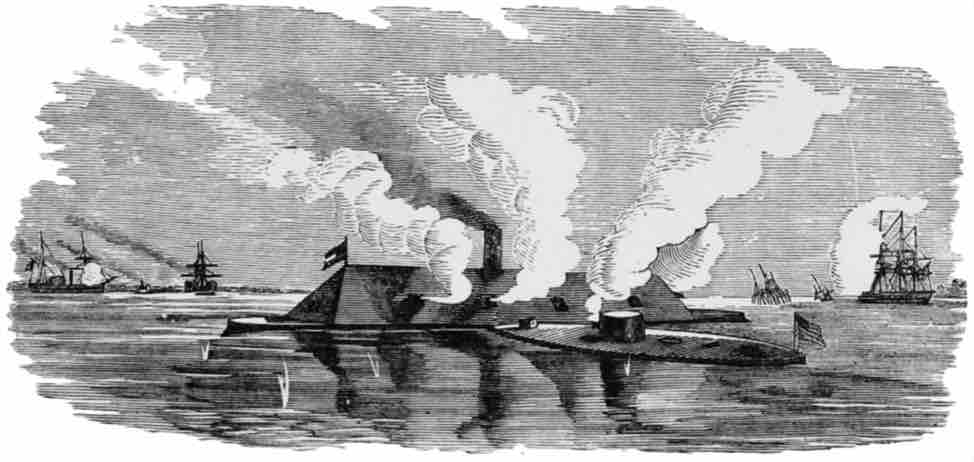

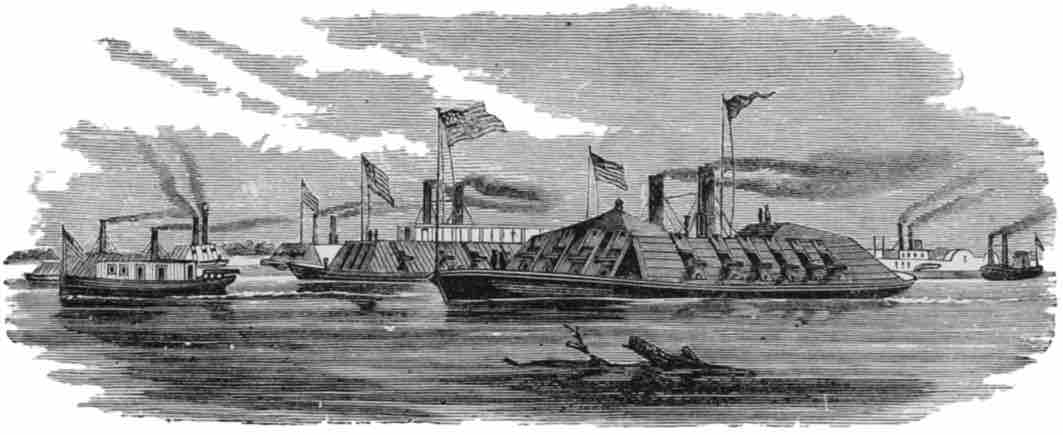

PAUL JONES'S SEA FIGHT.

But the aid from France was less than they thought it would be. Fleets were sent, but they gave small help to the cause. And so the war went on for three years more. At times our men would make a good fight, and then there would be dark days when the foe had things all his own way. The Eng-lish had paid some tribes of In-di-ans to fight on their side; and once there was a sad scene, where men and their wives and babes were put to death by these fierce wild men. This was not war, of course. We give it a much worse name.

Then there were sea-fights. In one of these, the men on the ships fought three hours, and the ships took fire more than once; but at last the Brit-ish gave up. In that ship the man who took the lead on our side was Paul Jones.

There is a tale told of what the brave wife of one of those men, to whom we give the name of Friends, did for our cause at this time. Gen-er-al Howe made his home in her house, a long low brick one, at Tren-ton. He said to her one day, "I want to have some friends here to night, and I would like to have the spare back room to meet them in."

"It shall be as thee says," said Friend Ruth.

75 "See that all the folks in the house are in bed at a good hour," said Gen-er-al Howe.

"I will move that they go," said Friend Ruth.

So when the men came to see Gen-er-al Howe that night, it was all still in the house. Friend Ruth let them in.

"You may go to bed and stay till I call," said Gen-er-al Howe.

Ruth went to her room and lay down awhile; but did not take off her clothes. She must know what these men meant to do. At last she took off her shoes and went to the door of the room, and put her ear to the key hole. This is what she heard. Some one reads, "Our troops will make a move by stealth on the foe, and we will take them ere they know we are on them!"

There was no more sleep for Friend Ruth that night. She lay in her bed till dawn; but all her aim was to think of a plan to help our troops, and not to let them fall in the snare. At last she hit on a plan to get out of the lines. She was in need of some flour; and to get flour, she must go to a grist mill, for they did not sell it at stores in those days. Gen-er-al Howe could not say he would not let her get flour, as he ate at her house; so he gave her a pass. While they ground the grist for her at the mill, she rode on as fast as she could, till she came 76 to one of our guards. She said some words to him in a low voice, and rode back, got her flour, and was home in no time.

When Gen-er-al Howe came on our troops the next day, he found them all drawn up in rank and file in good trim to meet him. He thought it best not to have a fight at all; and it was a strange thing to him how they could have known of his move.

Down in the South there were brave men at the head of our troops. One was Ma-ri-on, who led his men through the woods by paths that were known to few. They gave him the name of the "Swamp Fox," and the Brit-ish cast slurs on him, and said he would not come out for a fight in a bold way, but took their posts at night, and when they were off guard. But he gave them a proof of what he could do, when he and Greene fought them and won the day in a fair field. Greene made such a name in this fight that he took rank next to Wash-ing-ton from that time.

We have to tell a sad tale now of one of our own men—a man, too, who had won fame in the war. He had shown that he was brave; but men did not like him much, for he thought more of his own gain than of his land, and he had the wish for a high place, which he did not get. His name was Ben-e-dict Ar-nold, and his bad act was, that he 77 made a plan to sell his own land to the Eng-lish. He wrote to the foe all he could of the moves our troops were to make, and their state, but he did not sign his own name. Once he had his camp at the head of some men at West Point, and he made up his mind to give this place, which was strong with forts, to the Brit-ish. This he would have done, and the whole land would have come to grief, but for a chance that brought the vile plan to light.

One day a young man rides down the path by the stream. There is a wood of oak near. On the ground, by the trees, there are three young men. They have a game of cards. They have been out all night, and have sat down to rest.

They hear the sound of hoofs.

"Some one on his way to New York for trade," says one.

His friend peers out. "No; his clothes are too good for that," he says.

All three spring to their feet, and cry, "Halt!"

The man on the horse stops, and says, "I hope you are on our side."

"Which side is that?" cry the men.

"The side of the King."

"All right," they say; for they wish to find out more.

"Thank God, I am once more with friends!" he 78 says, as he takes out his gold watch. "I must get on. I am in great haste."

"We can not let you go," say the men.

"But I have a pass."

"Whose?"

"Gen-er-al Ar-nold's."

"You must get off your horse."

"But, I tell you, you will get in a scrape if you stop me. Read this pass."

MA-JOR AN DRÉ.

"No good. You said you were Brit-ish; we must search you."

"I have naught."

"We will see. Take off your coat."

The coat is laid off, and the boots. Ah, what is this? The hand of Ar-nold in this; and "West Point" the date. A shout went up, "He is a spy!"

He was a young Eng-lish man by the name of An-dré. He took his watch and purse, and said he would give them all, if they would let him go free. They would not, but took him to the near A-mer-i-can Post to try him. Of course, what Ar-nold had done all came out. He had known this would be the case, for as soon as the news was brought that An-dré was in the hands of our men, he took leave of his wife, gave a kiss to his boy, and sped on his 79 way to an Eng-lish ship. He got to Eng-land, and was paid a large sum of gold; and they gave him a fine place at the head of some troops; but no man would make a friend of him. The Eng-lish had been glad to use him, but they would not take him by the hand.

You may think what a life he had. His own land had cast him out, but he came back to fight her at the head of the foe. But the new land where he had made his home had no real place for him. Once in the great house in Eng-land, where the wise men meet to talk of their laws, one rose to make a speech. But when he saw Ar-nold in a seat near him, he said, "I will not speak while that man is in the house." Long years after, when one of the great men of France had it in his mind to come to this land, he went to Ar-nold for some notes to his friends. Ar-nold said, "I was born in A-mer-i-ca. I spent my youth there; but Ah! I can call no man in A-mer-i-ca my friend."

In the mean time An-dré, the young Eng-lish man, who had met Ar-nold, and got the plans which were to give us up in to the hands of the foe, was shown to be a spy. There was but one doom for a spy. He must be hung. All felt for his fate. He was young, and had a fine face, and the air of good birth; but his hour had come. Tears were 80 shed at his death; though he was our foe. All knew he was a brave man, who had not been slow to risk his life in the cause of his land. He thought he was right, and took all means to serve his own ends. For Ar-nold, who would have sold his own, there was but hate, and they gave him a name which would serve to show what his crime had been to all time—Ar-nold the Trai-tor!

All this while the French had been our friends; but they had not met with a chance to show what they could do, till a great fight came which made an end of this war. This was at a place by the name of York-town, in Vir-gin-ia. Wash-ing-ton was there with his troops, and the French Gen-er-al, who had a hard name, which you may learn one of these days, was with him at the head of his men. They took the best works of the Brit-ish, and made such a brave stand, that Lord Corn-wal-lis thought it would be wise to leave by night, with all his troops. But a storm came, and they could not get off, so they all had to give up to Wash-ing-ton.

There was a grand scene that day, in the fall of 1781, when Wash-ing-ton and his French friends stood in two ranks, and their old foes took up a slow march by them, and laid down their arms as they went. Great was the joy in all the land when 81 the news was known. Those who woke that night in Phil-a-del-phia, heard the watch cry, "Past two o'clock and Corn-wal-lis is ours!" When the news came to Con-gress, they sent out word for a day to be set, in all the States, to give thanks to God, and all who were held for debt, or for crime, or what cause it might be, were set free, that they might share the great joy.

Well might they all be glad, for this meant the end of the war. It had cost them dear in gold as well as lives; but it had been worse for Eng-land than for them. The sums she had spent were vast, and one could not count the lives she had lost. Add to this the fact that she had lost this great land, which had once been all her own, and now was made free. Our land now took a new name. You can read it, I know, though it is not in short words, "The U-nit-ed States of A-mer-i-ca."

82 CHAPTER VIII.

IN TIMES OF PEACE.

When peace came, the men who had been in camp went to their own homes. They were all poor, and did not know what to do. There was no gold in the land, but a kind of cash which was so bad that it took more than you could count to buy a pair of shoes. Gen-er-al Wash-ing-ton found his task more hard to keep all in good cheer, now there were no fights on hand, than when they were at war. There had to be a tax on some things to keep all right, and they did not want to pay the tax, or their debts at this time. Wash-ing-ton felt that things were at loose ends, and he must make them more strong.

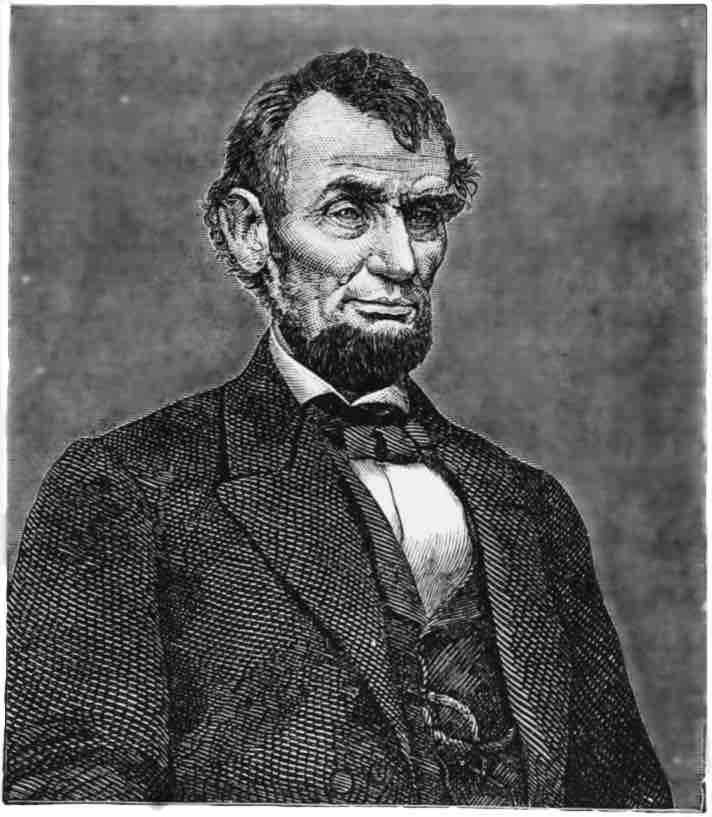

GEORGE WASH-ING-TON.

83 Each State had a wish to be first; and it would seem that, with no foe to fight, they were on the point of war with their own selves. There was need of a strong hand to rule the whole land. So men were sent out of each State to meet in Phil-a-del-phia and talk of the best plan. They had a long talk, and at last wrote what we call the "Con-sti-tu-tion." Ten of the States gave it their vote at once; but three held back for a while.

There were grand times in our land when it was known that the Con-sti-tu-tion was to be our guide; that we were to be in truth, "The U-nit-ed States of A-mer-i-ca," with one will, one aim, one soul as it were, while time should last.

A great crowd came out in Phil-a-del-phia to show their joy. Each trade had its men there, with the tools of the trade in their hands. There was a grand car, made in the shape of that bird which we chose as the sign of our land. It was drawn by six steeds, and in it sat those who were to judge the folk in our great courts. They held a staff, and on it was our "Con-sti-tu-tion," in a frame, and on the top of the staff a cap, which we might call the cap of the free—a kind they were fond of in France at that time. There were ten ships on the river, gay with flags and gilt, to show forth the ten States that had cast their vote in the right way.

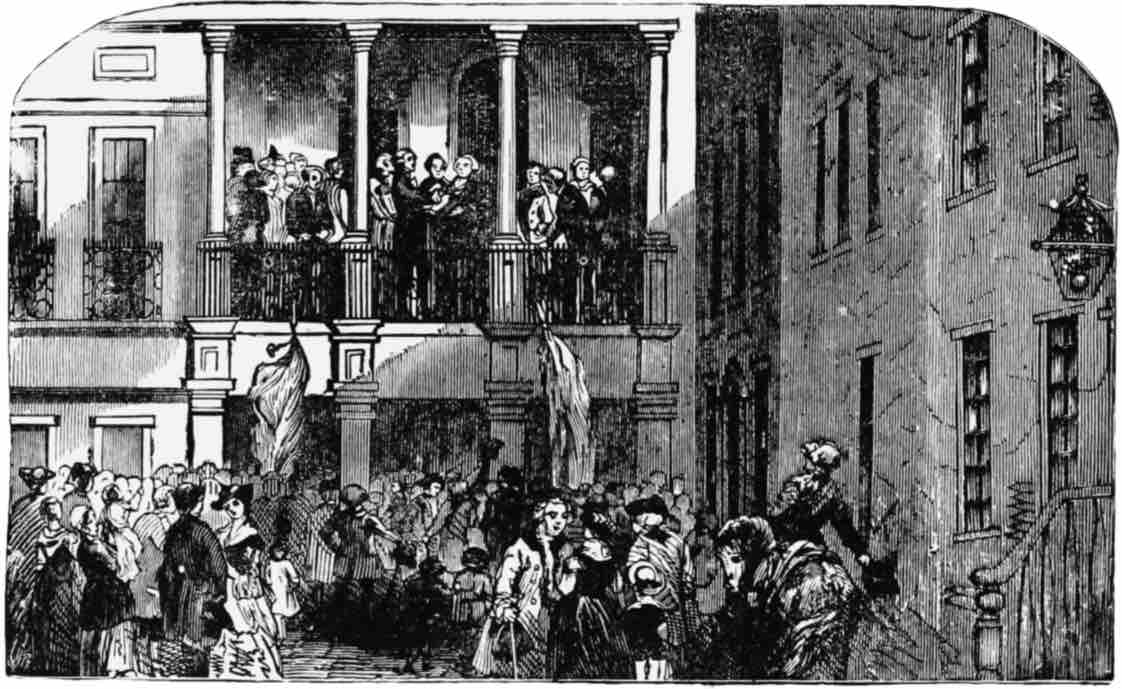

84 George Wash-ing-ton was made the first Pres-i-dent, and as he took his way to New York, which was then the seat of rule, he met joy and kind words on all the route.

At Tren-ton, where he had fought, there was an arch thrown out on a bridge, where he must pass. This was hung with wreaths, and young girls stood with hands full of sweet buds and bloom, which they flung in his path, as they sung a song to greet him, and thank him for all he had done.

WASH-ING-TON MADE PRES-I-DENT.

As he drew near New York, a barge came out to meet him. It had a crew all in white, and was meant to show the States—a man for each State. Then more boats came to join them, with our flag 85 on each. Wash-ing-ton was led in great state to his new home. When the time came for him first to meet with the folk and take the oath to be true to the Con-sti-tu-tion, there was such a rush to the place that some one said, "One might walk on the heads of the crowd." When Wash-ing-ton came out where all could see him, and the oath was read to him, and he took it, a great cheer rent the air, and a cry rang out, "Long live George Wash-ing-ton, Pres-i-dent of the U-nit-ed States." There was a flag flung out from that Hall, a peal of bells rang, and a blast was sent out from the guns, to show the joy and the love with which they took him for their chief. This was on April 30, 1789.

War is bad for all folks; for it is hard, when it is past, for men to learn the arts of peace. Wash-ing-ton found the whole land in debt. They did not want a tax, and the red men were still their foes. But in a few years he made a great change. The In-di-ans were put down, and France and Spain and Eng-land were brought to deal with us as friends. It was a man by the name of John Jay, who wrote out the terms with Eng-land, and so we had peace for a time.

Just then there was a great fight in France, not with a foe, but in their own midst. The men there had seen how our land had won the day, and they 86 had a mind to be free and have no King. They did not go at it in the same way that we did; but shed much blood of their own folk, and cut off the heads of their King and Queen, and did things which made good men sad. But they said they did it all to be free. There was a reign of fright for a time. But at last, the mob could rule no more, and they were glad to take a King.

Wash-ing-ton kept up great state, for those times, in his own home, and when he drove out he had a state coach, cream white in hue, and drawn by six steeds on state days. He took but one horse on the Lord's day, when he rode to church. This coach was of the shape of a half sphere, and had wreaths, and the forms of small fat boys with wings, drawn on it in gay tints. He set days for all to come and see him in his home. Those who came would see Wash-ing-ton in front of the fire place, and near him the band of great men who gave him help with their wise words. He would be, seen in a coat of black, with a vest of white or pearl, and buff gloves. His hair was made white with a kind of dust they had in use in those days; and it was put in a sort of silk bag at the back of his head. That was a queue.

He would have his hat in his hand, and he wore a long sword. He did not shake hands with 87 his guests, but made them a bow, and had some word for each. His wife, too, had times for her friends to come; and all must be in full dress—the dames in low necks and short sleeves. On the birth day of Wash-ing-ton, men would meet to dine in all the large towns; and those who made rhymes would write odes to the great man. There were some who did not like all this state and form and show. They thought it was too much like the style of kings in the old land, and they would have been glad to have a new mode here. They did not wish to see a Judge in a robe of red, or the man who was to preach in the church in a wig, with gown and bands. They were for plain dress and plain ways.

You may see now bits of the stiff, rich silks of those days, or it may be a quaint old gown, rich in lace, which has been kept from that time. You may see in your mind the dame who wore it, as she waves her fan, sent from France, with the head of Wash-ing-ton on it. The hair of this dame would be drawn high on her head, and made white with the dust of which I spoke, and put in great puffs. The men whose trade it was to dress hair in those days had such a crowd of folks to fix, that they had to get up at four to do the work. I have heard of great dames who sat up all night to 88 keep their hair in good style for some ball, or the play. The men, too, thought quite as much of dress as their wives, and in those days they did not wear plain cloth suits as now. Then a man put on a wig, and a white stiff stock, that held up his chin; a vest of white silk, it may be with rose-buds on it, and all the rest of his clothes were rich.