Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The cover image has been created for this version, and is placed in the public domain.

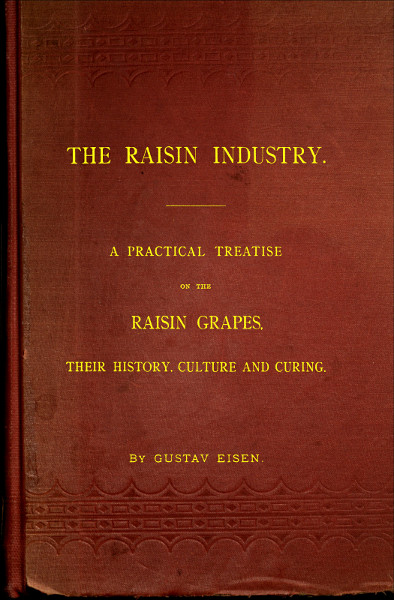

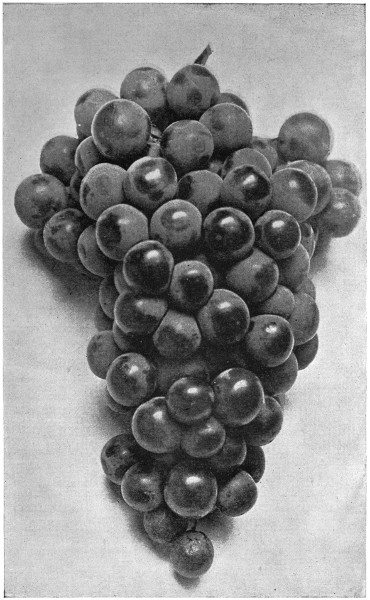

Muscat of Alexandria Raisin Grape, First Crop. One-half Natural Size.

A PRACTICAL TREATISE

ON THE

RAISIN GRAPES,

THEIR HISTORY, CULTURE AND CURING.

By GUSTAV EISEN.

SAN FRANCISCO:

H. S. CROCKER & COMPANY, STATIONERS AND PRINTERS,

1890.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1890, by

GUSTAV EISEN,

in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

f late years the raisin industry has been prominently before the horticulturists of California. Many people now make their living and acquire wealth by the cultivation of the raisin grapes, and many are now studying the methods of cultivation, pruning, curing and packing while waiting for their vines to bear. The literature of the raisin industry is a very scant one, and, with the exception of a few notices in works of travel, or in treatises on general fruit culture, we find not a single book in which this important and interesting industry is made the special subject of study and discussion. A book on the raisin industry may, therefore, be considered timely. I have endeavored to so write it that it would contain something of interest to all those connected with the growing and curing of the raisin grapes, to those who have already succeeded in building up fame and fortune, as well as to those who have just begun the cultivation of the vine, and who have as yet only realized the pleasures, but not the profits, of the industry. The historical part of the book will principally interest the former; for the latter the practical part on cultivation, pruning, curing and packing is intended.

As our climate and other conditions differ from those of any other country in the world, so must our methods of cultivation and curing differ from those practiced elsewhere. Foreign methods, while interesting and, in some respects, of great importance to us, had to be greatly modified and improved upon before our growers succeeded in producing raisins equaling the best from the raisin districts of the Old World. It has cost years of experimenting and study to attain success, as well as much money and disappointment to many who had nothing to guide them when they commenced.

These processes by which success was achieved can now become the property of all, and a safe guide to even the most inexperienced beginners. The methods advocated here are the result of practical experience of the author, as well as of the most successful raisin-growers of this State.

For the benefit of those of our readers who now study the raisin industry at a distance, but whose steps may in the future be directed to this Coast, a descriptive tour through the raisin districts of our State has been added in order that they may see what our country is like,—the country of the raisin and the fig; the country of almonds, olives, oranges and prunes; the country where health, profit and enjoyment are more than anywhere else derived from horticultural pursuits. It is for these prospective readers, that the short biographical sketches of our principal raisin-men are intended,—short records of the pioneers of the raisin industry,—men who have broken the way which is now easy to travel, and through whose experience and perseverance others are now being benefited.

GUSTAV EISEN.

San Francisco, Cal., October, 1890.

[i]

| PAGE. | |

|---|---|

| HISTORICAL | 5 |

| Raisins | 5 |

| The Currant | 6 |

| Muscatels | 7 |

| Dehesa Raisins | 7 |

| Lexias or Lye-dipped Raisins | 9 |

| Various Kinds of Raisins | 10 |

| —Muscatels; Currants; Belvideres; Black Smyrnas; California Malagas; California Sun-dried Sultanas; Seedless Muscatels; Thompson Seedless; Dried Grapes; Lexias; California Dipped; Smyrnas; Faros; Huascos. | |

| RAISIN DISTRICTS | 10 |

| Foreign Districts | 10 |

| Raisins in Ancient Times | 10 |

| Modern Raisin Districts | 11 |

| The Malaga District | 12 |

| —Extent and Age; Climate; Soil; location of the Vineyard; Varieties of Grapes; Characteristics of the Raisins; Yield of Grapes; Distances of the Vines; Pruning; Manuring and Fertilizing; Drying Floors or Sequeros; Drying and Curing; Packing; Labor. | |

| Valencia and Denia | 15 |

| —Extent of the District; Soils and Appearance of the District; Climate; Irrigation; Quality of the Raisins; Planting and Care; Dipping and Scalding; Drying and Curing; Packing and Disposing of the Crop; Export and Production. | |

| Corinth and Currants | 22 |

| —Historical and Geographical Notes; Characteristics and Quality; Soil and Irrigation; Preparation of the Land; Distances of the Currant Vines; Care of Cuttings; Planting and Grafting; Pruning the Vines; Care of the Vineyard; Ringing the Branches; Drying and Curing; Cost of Currant Vineyards in Greece; Consumption and Production. | |

| Smyrna Raisins | 30 |

| —Districts in Smyrna; Climate; Care of the Vines; Dipping, Drying and Curing; Production and Export; Cost of Vineyards in Smyrna; Other Varieties of Raisins. | |

| Italy and Italian Raisins | 36 |

| —Lipari and Belvidere; Pantellaria; Calabria. | |

| Chile and Huasco Raisins | 36 |

| —Characteristics; Location; Varieties; Soils; Climate; Irrigation; The Vineyard; Drying and Curing. | |

| California Raisin Districts | 38 |

| A General Review | 38 |

| —Early History; Later Planting; Acreage and Crops. | |

| Yolo and Solano | 40 |

| —Soil and Climate; The Vineyard; The Crop. | |

| Northern California | 43 |

| —General Remarks; Placer County; Yuba County; Sutter County; Colusa County; Butte County; Tehama County; Shasta County. | |

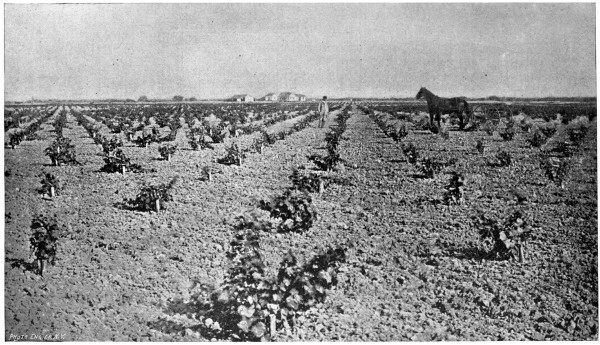

| Fresno, Merced, Tulare and Kern | 44 |

| —Extent and Location; Soils and Climate; Irrigation; The Vineyard; Pruning and Other Operations; The Crop. | |

| San Bernardino County[ii] | 48 |

| —Location and Acreage; Climate; Irrigation; Soils; The Vineyard; The Crop; The Profits and Other Items. | |

| Orange County and Santa Ana | 52 |

| —General Remarks; Location; Climate; Soils and Ripening; The Vineyard; The Crop and its Curing; Yield and Profits. | |

| San Diego and El Cajon | 55 |

| —Location and Acreage; Climate and Rainfall; Soils; The Vines and the Vineyard; The Crop. | |

| Other Raisin Districts | 59 |

| CLIMATIC CONDITIONS, SOILS, LOCATION AND IRRIGATION | 60 |

| Climatic Conditions Favorable and Unfavorable to the Raisin Industry | 60 |

| —Limits of the Raisin Districts; Dry Seasons, Spring and Fall Rains; Winter Rains; Frost in Spring and Winter; Summer Temperature; Winds, Injurious and Beneficial; Fogs and Moisture in the Air; Ideal Conditions of Climate. | |

| Soils | 67 |

| —General Remarks; Malaga; Valencia and Denia; Smyrna; Zante; Chile; Fresno; Other Soils in San Joaquin Valley; Orange County; Redlands and Riverside; El Cajon; Subsoils; Hardpan Soils; Comparative Value of Soils; Alkali Soils; Fertilizing. | |

| Irrigation | 77 |

| —Introductory Notes; the Necessity of Irrigating the Raisin Vines; Health and Longevity of Irrigated Vines; The Bearing Quality of Irrigated Vines; Quality of Irrigated Grapes; Various Methods of Irrigation; Irrigation by Flooding; Irrigation by Furrowing; Subirrigation; Seepage; Drainage; The Influence of Irrigation on the Soil. | |

| THE RAISIN GRAPES | 87 |

| —Introductory Notes; Muscatel or Gordo Blanco; Muscat of Alexandria; Huasco Muscat; Other Varieties of Muscat; Seedless Sultana; Black Currant; Other Varieties of Currants; Thompson Seedless; Other Seedless Grapes; Malaga; Feher Szagos; Other Raisin Grapes. | |

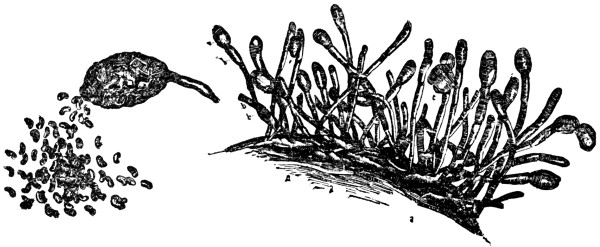

| DISEASES AND INSECT PESTS | 93 |

| Powdery Mildew or Uncinula | 93 |

| —General Notes; Characteristics; History and Distribution; Remedies. | |

| Downy Mildew or Peronospora | 95 |

| —General Notes. | |

| The Vine Plague | 96 |

| —Characteristics; Nature and Cause; Damages; Remedies. | |

| Leaf-hopper | 98 |

| —Characteristics; Damages; Distribution; Remedies. | |

| Red Spider | 100 |

| —Characteristics; Remedies. | |

| Caterpillars | 100 |

| —Characteristics; Damages; Remedies. | |

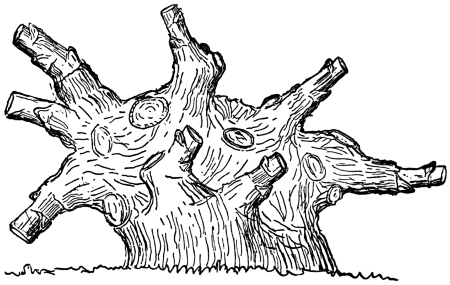

| Black-knot | 102 |

| —Characteristics; Remedies. | |

| Grasshoppers | 102 |

| —General Notes; Remedies. | |

| THE RAISIN VINEYARD | 104 |

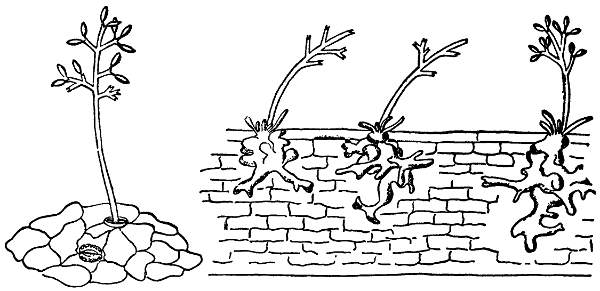

| Planting | 104 |

| —Distances for Muscat Vines; the Marking Out of a Vineyard; Relative Value of Cuttings and Rooted Vines; The Making of Cuttings; The Care of Cuttings; Planting Cuttings; Care of Young Cuttings; Transporting Cuttings to Distant Parts; Rooting Cuttings; Care of Rooted Cuttings; Planting Rooted Vines; Proper Time for Planting; Cost of Cuttings and Rooted Vines; Winter Plowing; Plowing Devices; Cultivation; Back-furrowing; Cross-plowing; Weed-cutters; Cutter-sled; Hoeing; Time for Cultivation. | |

| Grafting the Muscat on Other Stocks[iii] | 117 |

| —Time for Grafting Raisin-vines; Points to be Observed in Grafting; Various Methods of Grafting; Stocks and their Influence. | |

| Various Summer Work | 121 |

| —Sulphuring; Tying Over; Covering the Vines; Thinning the Crop; Ringing the Vines; The Vineyard Labors of the Year. | |

| Pruning | 124 |

| —Winter Pruning or Pruning Hard Wood; Bleeding of the Vines; Summer Pruning or Pruning Green Wood; Root-pruning; Suckering. | |

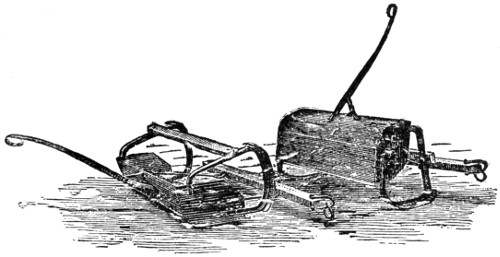

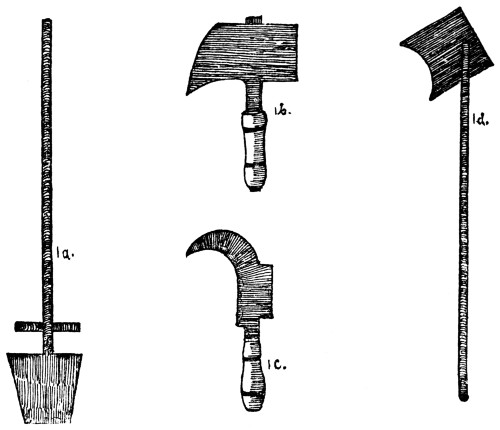

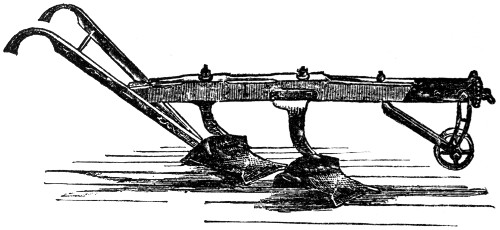

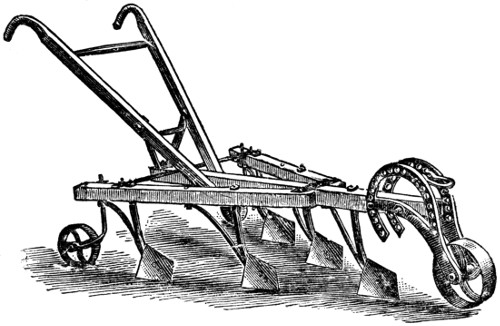

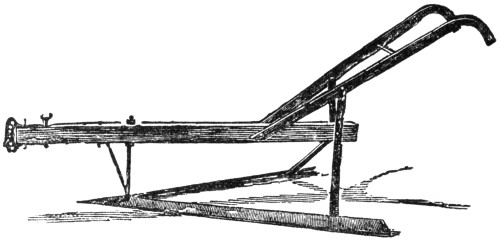

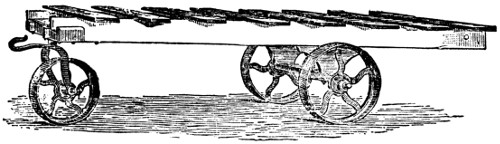

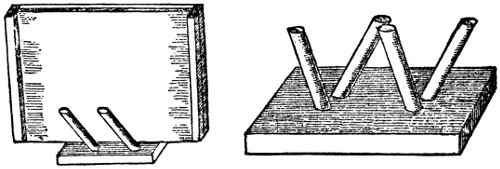

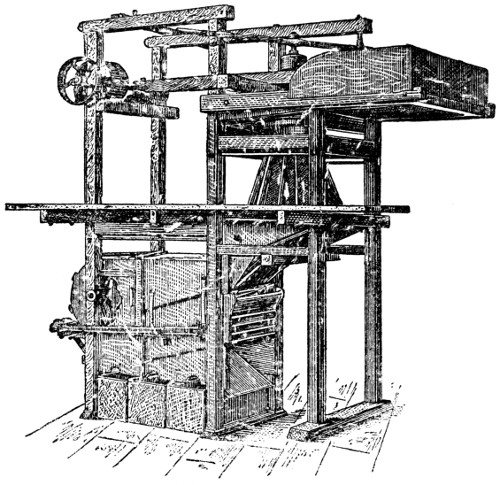

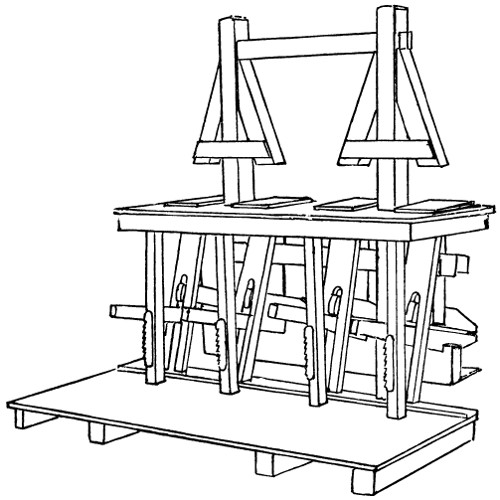

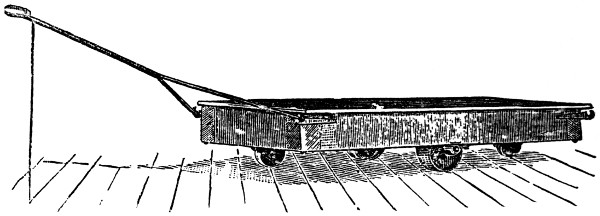

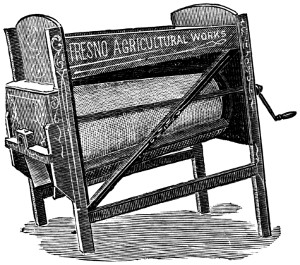

| Various Vineyard Tools | 130 |

| —General Notes; The Sheep’s-foot; The Planting-bar; The Dibble; Planting Chains; Spades; Hoes; Plows; Cultivators; Randel Disc Cultivators; The Ash-trough; Sulphuring Cans and Bellows; The Cutter-sled; Vineyard Trucks; Shears. | |

| DRYING AND CURING | 133 |

| California Sun-dried Raisins | 133 |

| —Notes; Time of Ripening; Signs of Maturity; Picking; Cleaning; Drying on Trays; Turning; Reversing; Slanting the Trays; Elevating the Trays; Stacking Against Rain and Dew; Taking Up; Covering; Drying-floors; Dryers; Sweatboxes; Trays for Drying. | |

| California Lye-dipped Raisins | 149 |

| —General Notes; Dipping Process; Drying and Curing; Stemming, Grading and Packing. | |

| THE PACKING-HOUSE | 153 |

| Buildings and Mechanical Appliances | 153 |

| —The Packing-house; The Stemmer and Grader; The Sweating-house; The Presses; Boxes and Cartoons; Packing Frames and Packing Trays; Facing-plate; Scales; Labeling Press; Tables; Bags and Bagholders; Trucks; Trays for Weighing; Followers; Paper; Tin Boxes. | |

| Loose Raisins | 158 |

| —Stemming and Assorting; Packing and Cleaning; Sacking; Facing, Top-up Method; Facing, Top-down Method; Comparative Value of the Two Methods. | |

| Layer Raisins | 162 |

| —Sweating and Equalizing; Packing Layers, Top-up Method; Packing Layers, Top-down Method; Filling; Nailing and Trimming; Labels. | |

| STATISTICS OF IMPORTATION, PRODUCTION AND PRICES | 169 |

| —Production of Raisins in California from 1873 to 1889; Number of Acres in Raisin Grapes in California in 1890; California and Malaga Prices, Importation, etc., from 1871 to 1889; Exports of Malaga Raisins from 1864 to 1889; Exports of Valencia Raisins from 1850 to 1889; First Cost of Crop of Valencia Raisins; Production and Distribution of Smyrna Raisins from 1844 to 1884; World’s Raisin Production in 1890; Importation of Raisins, Currants and Figs into the United States from 1873 to 1878; Importation of Raisins, Currants and Figs into the United States from 1879 to 1888; Consumption of Currants and Raisins per Head of Total Population in 1884; Prices Ruling in the California Raisin Districts. | |

| THROUGH THE CALIFORNIA RAISIN DISTRICTS | 181 |

| Through San Joaquin Valley to Fresno | 181 |

| From Los Angeles to Santa Ana | 189 |

| From Santa Ana to San Diego | 192 |

| El Cajon | 195 |

| Riverside | 199 |

| Redlands | 202 |

| An Hour in a Packing-house | 205 |

| RAISIN-GROWERS AND THEIR VINEYARDS | 208 |

| —G. G. Briggs; R. B. Blowers; Robert McPherson; T. C. White; Miss M. F. Austin; Joseph T. Goodman; A. B. Butler; William Forsyth; A. D. Barling; San Joaquin Valley Raisin Packers of 1889. | |

| LITERATURE | 215 |

| —Introductory; List of Books of Reference. | |

| GENERAL INDEX | 219 |

THE RAISIN INDUSTRY.

A PRACTICAL TREATISE ON THE RAISIN GRAPES,

THEIR HISTORY, CULTURE AND CURING, WITH

SPECIAL REFERENCE TO CALIFORNIA,

BY GUSTAV EISEN.

Copyrighted.

The word “raisin” as spelled and pronounced to-day, is not of very ancient origin, but rather a corruption and evolution of older words, both spelled and pronounced differently. Thus Falstaff replies to Prince Hal: “If reasons were as plentiful as blackberries, I would give no man a reason upon compulsion” (Henry IV, Act II, scene 4). Also, Cooper, in his dictionary of 1685, indicates that “raisin” and “reason” are of identical sounds. The derivation of the word has, again, been very variously suggested either from “red” or “rose” color, connecting it with the German and Danish word “rosine;” and it has even been suggested that the word was derived from the fact that the raisins were cured in the “rays” of the sun. The true derivation, however, is from the Latin word “racemus,” meaning a bunch or cluster. Richardson, who first points out this derivation, quotes: “Whether a reisyn (E. V. graap, racemus) of Effraym is not better than the vindages of Abiezer” (Wicliffe Judges VIIJ, 2). “And there shall be left in it as a rasyn” (E. V., braunches of a cluster). Marginal note, “A rasyn is a lytil bow with a lytil fruit” (Idem. Is., XVIJ., 6). But we have much older testimony of this derivation being the correct one. An old document states that, in 1265 A. D., the Countess of Leicester paid in London twelve shillings for fourteen pounds, or, as the statement reads in Latin, “Pro uno fraello racemorum;” which, translated, would be, “for one frail of bunches.” The evolution of the Latin word racemus was thus seen to have been accomplished rapidly enough; but, on account of the illiteracy of the olden times, it was spelled and pronounced promiscuously. Thus we meet with such spellings as “reysyns,” in 1266; “reysons,” in 1447 (“Russell’s Book of Nurture”). In 1554 the Stationers’ Company in London paid twopence for one pound of “greate reasons;” while Andrew Borde, in his “Dietary” of 1542, says that “great raysens be nutrytyve, specyally yf the stones be pulled out.” In 1578 Dodoens speaks of dried raysens. In 1685 the word “raisin” is used and spelled as in our days, and[6] from that time on the different spellings were used, if not promiscuously, still without any great uniformity. The term of “greate raysens” was introduced to distinguish them from the smaller raisins, or currants. In our own days, the latter is seldom classed or alluded to as a “raisin” proper, although it, strictly speaking, should be considered as such. The tendency at present in California is to make the distinction between “raisins” and “dried grapes,” meaning by the former certain varieties of grapes which have been skillfully dried and cured, and which are superior in taste, flavor, thinness of skin and saccharine matter. “Dried grapes,” again, are simply any kind of grape, especially wine-grapes, which have only been dried, and which have not undergone that skillful treatment which the grape-grower is so proud of, and justly enough designates as “curing.” They are an outgrowth from the late efforts of the French wine merchants to make genuine French wine out of anything that is sweet, and as they are immensely preferable to beets, potatoes and glucose, they will always be in demand.

With the above definition of the “raisin” accepted, we can proceed to consider their different varieties, their names and derivations. The old designations of the different varieties were derived from the places where they were produced, without special reference to the grapes from which the raisins were made. Thus we had Malagas, Currants, Valencias, Denias, Turkish and Italian raisins. But since it has been found that the same kinds of raisins have been produced in very different localities, and that some localities can produce all the different kinds, a new division has been found necessary. Thus, disregarding the many various brands with which this and other markets are flooded, the following different varieties of raisins will be found the principal ones: Currants, Muscatels, Dipped and Sultana.

The currant is one of the very oldest raisins known. As early as 75 A. D. Pliny speaks of the fine grapes grown in Greece, the berry being thin-skinned, juicy and sweet, and the bunch being exceedingly small. This, then, must be the currant of later times. After this first mention of this grape, the same drops out of history for ten centuries, and the name currant is first to be identified with raisins de Corauntz, or rather, “reysyns de Corauntzs” as late as 1334. As early as the eleventh century, a lively traffic in this kind of raisins had taken place between the Greek producers, the Venetians and other of the Mediterranean merchant nations. In 1334 we find them called “corauntz;” in 1435, “corent;” and old MS. of the Grocers’ Company in London, speaks of “x butts and vi roundelletts of resins of Corent.” Thus spelled, the name was used for years. In 1463 “reysonys of Corawnce” were three pence per pound, and in 1512 the Duke of Northumberland paid two pence per pound for rasyns of Corens. In 1554 the name had changed to currans, and the Stationers’ Company provided for a banquet “5 punde of currans at one shilling and eight pence.” In 1558 the same company provided for “6 punde of currance for 2 shillings.” In 1578 we find in[7] Lytes’ translation of Dodoens’s “Herbal,” in the description of different varieties of vines, that “Small raysens, commonly called Corantes, but more rightly raysens of Corinthe. The fruit is called in the shoppes of the countrie,[1] passulae de Corinthe; in French, raisins de Corinthe; in base Almaigne (Dutch) Corinthea; in English, Currantes, and small raysens of Corynthe.” Here, then, is indicated for the first time that the true and correct name should be “raisins of Corinth.” But we need not follow this evolution any longer; there can be no possible doubt that the name currant, the one now accepted for this class of raisins, is derived from the town of Corinth, on the mainland of Greece,—the Morea of our days, the Peloponnesus of the ancients. Until the time when the Turks conquered Greece, the port of Corinth was the principal point of export for this class of raisins, and while, after the subjection of Greece this commerce entirely ceased, still this fruit always continued to bear the name by which it first became known to commerce.

[1] Holland, Dodoens was a learned Dutch botanist.

The principal and most valued class of raisins are the Muscatels or Muscats. They all derive their name from the Muscatel or Muscat grape, from which these raisins are made. As to the origin of the name Muscat, opinions differ. The most popular one is that the grape got its name from the supposed musky flavor peculiar to this variety of grape. It is, however, far more likely that the name is a very ancient one, and derived from the Latin word Musca, meaning a fly,—these fine grapes when drying being especially attractive to flies. The Romans called this grape, “Uva Apiaria,” meaning bee grapes, or grapes beloved by bees, from the fact that the bees are especially attracted to these grapes when they are being dried. The Muscat or Muscatel would then not originally designate a certain variety of grapes, but grapes used for drying generally. In the course of time the name was transferred to or especially given to the best grape for drying purposes,—the Muscatel of our own times.

The finest or at least the most expensive brand of raisins made is the Dehesa raisin of Malaga. They are produced from the Muscatel variety and the name they bear has an interesting origin, giving us at the same time an insight in the development of the agricultural and horticultural resources of Spain. The word “Dehesa” is found by reference to a good Spanish dictionary to mean pasture ground. The “Dehesa” raisins then are pasture-ground raisins, or raisins grown on former pasture ground. The way the raisins came to be given such a name is as follows. Between the years 800 and the end of the fifteenth century, the fairest part of Spain as well as Portugal was occupied by the Moors. Contrary to their nature in other countries, they proved here extremely industrious, and excelled both as merchants, artisans and agriculturists. The waters of the streams were conducted to the land in[8] aqueducts, dams were thrown across the rivers, reservoirs were formed, and the whole of Southern Spain became most highly cultivated, rich and prosperous. In fact, if the historians are to be believed, and the yet remaining views of former grandeur can be trusted, no country either in ancient or modern times has ever in prosperity rivaled the ancient Moorish kingdoms of Granada and Andalusia. In the thirteenth century the Christian knights and kings of Central and Northern Spain succeeded in conquering the Moors, who again were unmercifully expelled, massacred or enslaved, their cities burned and razed, and the fertile and cultivated districts utterly ruined. Vast tracts were depopulated and abandoned, and, nature taking its course, wild grass, shrubbery and trees soon covered the former highly cultivated plains. In the course of time these uncultivated lands attracted the attention of the highland shepherds, who drove their herds to them during the winters, again returning to the mountains at the advent of the dry season.

By degrees the self-taken rights of the sheepmen became more widely recognized, and, while the less valuable lands were taken possession of by the poorer peasantry, these pasture lands were set apart for the exclusive use of the sheep-owners. The pasture lands thus being free, it was no wonder that the sheep industry flourished, and that the flocks increased. The wool industry soon became one of the most important in Spain. The flocks were principally owned by nobles and monks, and the poor peasants, who constituted the only agricultural population, had very little if any chance to oppose the ever greater encroachments of the wandering flocks or their insolent owners. The Merinos, or moving sheep, were wintered in the warm valleys of Andalusia, Murcia and Estremadura, only to be again removed to the cooler mountains of Leon and Castille at the advent of spring. What curse this would entail on the agricultural population is easy to be seen. The sheep were moving in bands of 10,000 each, and 700 to 800 such flocks were moved annually twice through a country devoid of fences or inclosures of any kind. Numerous disputes and constant bloody fights arose between farmers and the shepherd, to settle which the “Council of the Mesta” was instituted. In tyranny, this dreaded institution was only equaled by the famous Inquisition, with which in birth and death it was almost contemporaneous. In the year 1556 a code of laws was promulgated, and a compromise was entered upon. But the tyranny of the shepherds, upheld through their “Mesta,” was in no way diminished. The latter continually extended its power, encroached upon new territory, appropriating gradually the finest pastures of Spain, and finally obtained a monopoly of the wool trade. Its tyranny became at last intolerable. The shepherds of the Mesta were more dreaded than robbers and highwaymen in every place through which they passed. Agriculture became almost impossible. At last the “Mesta” was abolished by the Cortez in Cadiz in 1812, and a few years afterwards the pastures or Dehesas were sold. One of the finest Dehesas near Velez, Malaga, was planted to Muscatel grapes, and through the combined fertility of the soil, and the abundance of moisture, the vineyard proved a great success. So fine[9] were the grapes grown there that they attracted great attention; no such fine grapes had ever been seen in Andalusia before. The merchants to whom the first raisins were sold were much astonished, and wonderingly asked whence they came. The reply, “from the Dehesa,” was from that time on applied to the finest Muscatel grapes.

The third class of raisins are the dipped raisins, so called from being dipped in boiling lye before being dried and cured. The Spanish name for these raisins is Lexias. The name Lexia is, again, derived from a more ancient word, the Latin lixivium, or lixia, meaning lye. To-day the continental name for this class of raisin is Lexias, when the more specific names of Denias and Valencias are not used. Here, in America, we generally use these names, and whenever we speak of Valencias and Denias we mean the dipped raisins of these districts. To the above three classes of raisins we might appropriately add Sultanas and Malagas. The Sultanas are made from the Sultana grape, a seedless grape from Asia Minor, now grown in many Mediterranean countries, as well as here in California. The Malagas, again, were originally the Muscatels grown around Malaga, in Spain; but of late this name is being, with considerable confusion, applied to a coarser raisin made in California from a grape here called, for want of a better name, the Malaga grape.

Among names which were formerly much used, but which have gone out of use, was the Solis, or sun-dried raisins, especially the sun-dried Muscatels of Malaga. As early as 1295 A. D., the Muscatels were generally called thus: Raisins of the sun; Solis, or sun-dried, so as to distinguish them from the inferior dipped, or Lexias. In our own time, this name was nearly being revived, when a couple of years ago our California sun-dried raisins were spoken of in opposition to our machine-dried raisins, and when both classes had their earnest and enthusiastic champions.

We cannot leave this chapter on names without referring to classes of raisins receiving their names from certain localities. Of course, the number of such names may be almost endless. It is, however, only of interest to refer to the principal ones, such as have been known to commerce in former days or are yet known. Thus, we designate as Malagas any of the raisins grown and shipped from Malaga. The Smyrnas (formerly Smirna) are those from Smyrna, in Asia Minor, both sun-dried and dipped raisins; the Alicantes, dipped raisins, from Alicante, in Spain; the Denias, dipped raisins from Denia, in Spain; the Valencias, dipped raisins from Valencia (include Denias); the Lipari, raisins from the Island of Lipari, near Sicily; the Belvideres, from the same island and from the Island of Pantellaria; the Calabrian raisins, from Calabria, in Italy; the Faro raisins, from the port of Faro, in Algarve, Portugal. We have above already referred to the currants, from the town of Corinth and the Grecian Islands, and the Malagas, from Malaga. The latter were also known as “great raisins,” on account of their superior quality. Among the[10] latter we should, of course, count the California raisins; but, unfortunately, our raisin-growers have not until quite recently recognized the necessity of adopting names which should at once show the locality where the raisins are produced. But we will return to this further on.

a. Sun-dried raisins.

1. Muscatels, or Muscats, from Malaga or California. The former, also known at various periods as “Solis,” or sun-dried, or “great raisins,” on account of their very superior qualities.

2. Currants, raisins made of the small currant grape, originally from Corinth.

3. Belvideres, raisins from Calabria, in Italy, and from the Islands of Lipari and Pantellaria, near Sicily.

4. Black Smyrna, properly only a dried grape, not exported to this country.

5. California Malagas, made from the Malaga grape.

6. California sun-dried Sultanas, made from the Sultana grapes in this State. And, lastly,—

7. Seedless Muscatels, made in California, and being the smallest Muscats separated from the larger seed-bearing berries.

8. Thompson Seedless, a new, very promising raisin now being produced in this country from vines imported originally from Constantinople, producing seedless grapes, slightly larger than the Sultanas.

9. Dried grapes of any description, especially wine grapes, exported from this and Mediterranean countries for wine-making to France, England and the Eastern States.

b. Dipped raisins.

10. Lexias, or Dipped Muscatels, from Denia, Valencia, Alicante, in Spain.

11. California Dipped, especially second-crop Muscatels. Proper name not yet established.

12. Smyrnas, which again may be either Sultanas, Chesmes or Elemês. The first from the Sultana grape, the two latter, the “red” grapes, from Dipped Muscatels.

13. Faros, from Algarve, in Portugal, not known in this country.

c. Dried in the shade.

14. Huasco raisin, from Chile. To this list might be added many more varieties of less importance.

Previous to the production of raisins in California within the last twenty years, the raisin industry of the world was entirely confined to the Mediterranean district of Europe and Asia. At that period, however,[11] raisin grapes became more disseminated, and raisins were produced to begin with in small quantities in widely distant countries, such as Chile, Australia and California. By virtue of their climatic conditions, the Mediterranean countries were the only parts of Europe where raisin culture could be successfully carried on, though it is almost certain that the original home of the raisin grapes must be looked for elsewhere. In searching for the original habitat for the ancient varieties of raisin grapes, we must look further east to ancient Persia, or to the tablelands of Western Asia generally. In remotest antiquity, grape culture was carried on there, and in the ancient records of travelers in those countries we find mentioned dried and seedless grapes. We can trace the origin of two varieties of raisin grapes to the beginning of our era, which must then already have attained perfection. As has been mentioned before, Pliny spoke of a small, sweet and remarkable grape grown by the Greeks, evidently the “currant;” he also mentions Uva Zibebae and Uva Alexandria.

The Latins generally spoke of Uvae Apiariae or Uvae Muscae, our present Muscatels or dried grapes generally. This carries us back fully nineteen centuries. But we may well believe, even in want of records, that the drying of grapes was practiced centuries before.

Leaving remote antiquity, it was only in the Mediterranean basin, and in comparatively modern times, that the drying of grapes developed to an important industry, and in more recent times yet that grapes were exported to Northern Europe. While thus the industry is old, it was not until the eleventh century, at the time of the Crusades, that it became important. The returning knights brought with them taste for and acquaintance with the products of the East. Northern Europe became the consumers of raisins, regarding them as the greatest luxuries, only to be afforded by the rich. It has been reserved for our time to make the raisin a necessity even in humbler homes. The perfection to which the raisin industry has attained is of modern origin not yet half a century old.

The raisin districts of the world are not large, and while for centuries every effort was made to extend the planting of raisin grapes and their curing into raisins, few of these efforts have been crowned with success. While raisin grapes may grow and be turned into raisins in almost every part of the Mediterranean basin, experience has demonstrated that it has only proved a paying business in comparatively few localities. The reasons of this are not fully apparent; but they are evidently dependent both upon climatic conditions and upon the capability of the natives to learn and profit by the experiences of others, and upon their enterprise in venturing upon a new industry. On the other hand, it is not likely that, even with extensive experiments and with the aid of large capital, the growing and curing of the raisin grapes could be very extensively extended. The question there as well as here is not one alone of agricultural consideration, but a financial problem dependent upon the labor supply, the facilities for shipping, climatic conditions during the curing[12] season, etc. Such being the case, all the more interest is attached to those localities and districts where the raisin industry flourishes, and where there is every probability that it will remain a success.

—Malaga has been known to export raisins since 1295 A. D., but must have been a raisin-producing district centuries before. The raisin cult, then, is no doubt of Phœnician origin, and has been practiced in the same locality for two thousand years or more. Under the Romans the raisin industry was continued, but appears to have deteriorated and later on to have been abandoned altogether, as the local tradition credits the Moors with having re-introduced the raisin grape into Velez Malaga. The raisin district of Malaga extends along the southern coast of Spain for a distance of sixty or seventy miles. The district is subdivided into several other districts. Thus, the subdistrict of Malaga proper occupies a plain eighteen miles long by nine miles wide, in the northeast corner of which is situated the town of Malaga.

The best part of the whole district is, however, found at Velez Malaga, situated northeast of Malaga proper. It was here the raisin grape was first planted by the Romans or Phœnicians, and it was here also the devastating phylloxera first made its appearance. The raisin vineyards extend here not over a vega or plain, but occupy the fertile country along the coast or the litoral towards Malaga proper.

Beyond Velez Malaga to Algaroba, the Muscatel grape is of inferior quality, and is greatly superseded by the red Muscats, principally exported to France.

Another district is Marbella, on the coast, and in the interior we find Ronda and Albuñol. Of the principal towns in these districts, the population of Malaga is 120,000, that of Velez Malaga 24,000, of Marbella 7,700, and of Ronda 19,000.

—The climate of Malaga is the very mildest. Frost is almost unknown, and is never heavy. The average temperature of Malaga during the winter months of November to January is 56 degrees Fahrenheit, while that of Pau in France is 41, and that of Nice 47. Malaga is well sheltered on the north and east by mountains, but is open to the south. It is the most equitable climate of Europe, although the winds are sometimes trying. The summer is very tempered. The air is, however, moist, and fog, while rare, is not entirely absent. Rain sometimes falls during the growing season of the grapes, and quite frequently during the drying season. But the fog is warm and not specially injurious to the grapes, the latter often growing within reach of the spray on the seashore.

—The soil of the Malaga vineyards varies considerably, the best being a reddish clayey loam with much sand and gravel. But we have also other varieties of soil, such as the white ash, gray alluvial soils, and the very sandy loam on the hills.

—In former years, the vineyards were principally located on the hillsides, only occasionally extending to the level plains. Of late, however, the hillside vineyards have[13] suffered from the phylloxera and various other diseases, and many of them have been dug up. The lowland vineyards are now the best, although even they are, by far, not free from disease. Few of the vineyards are located on entirely level ground, there being but little such in the district. The nature of the country is rolling, with small valleys or flats. The raisin grapes grow apparently well both inland and on the coast. According to Consul Marston, about eighty per cent of the vineyards are situated on rolling land, ten per cent on lowland and ten per cent on the very coast. The vineyards on the coast are actually within reach of the spray.

The vineyards are generally small, none being over eighty acres in extent. Most contain, perhaps, from three to four acres each; while from twenty to forty acres is considered a good-sized vineyard.

—The principal variety used is the Gordo Blanco or Muscatel. It is identical with the grape known by us under that name, and which was imported to us from Malaga. But several types are found, although none superior to the Gordo Blanco.

—The Malaga raisins were, until lately, the finest raisins in the world, and for the present have only the California raisins to compete with. They are characterized by great sweetness, deep bluish color, great size and by good keeping qualities. The best raisins are those called Dehesas, being produced on the valley lands of the districts.

—The yield of Malaga vineyards varies of course. The best yield eight or nine tons of grapes to the acre,—just like those of California. But there is a great difference between new and old vineyards. In many vineyards where formerly the yield was nine tons, the soil has been so exhausted by continuous croppings that to-day, even with manuring, two or three tons of grapes must be considered a high yield.

—The older vineyards had their vines set seven feet by seven feet, but of late the vines are planted generally eight feet by four feet, thus much closer than by us in California.

—The pruning of the vineyard is performed very much as in California. Formerly the soil had to be removed from the vines before they could be pruned; now this is not necessary except while the vines are very young. The various branches are pruned back to a few inches, with two eyes each, while the heads are elevated only a few inches above the ground.

—The Malaga vineyardist fully understands the value of manuring his vineyards, and uses for this purpose not only all fertilizers available at home, but also imports directly from distant countries. The most valued fertilizers are the Mexican and Chilean guanos or phosphates. The Mexican phosphate costs in Malaga sixty-five dollars per ton; still it is used by all the principal vineyardists, who know the value of fertilizers. In fact, concentrated fertilizers are a necessity to the Malaga vineyards; without them they could not be cropped. Even the most virgin soil is exhausted in ten years’ time by constant croppings of raisin grapes; no paying crops could be expected if fertilizers were not used yearly. This fertilizing[14] of the soil is, however, of recent origin, and fifty years ago was almost unknown.

When home manures are used, it is placed in holes dug round the roots of the vines, which, after exposure to the air for several months, are again filled up at the advent of spring, generally in March, before the vines start to bud.

—The raisins, when picked, are dried on so-called sequeros, or drying-floors, characteristic of the Malaga district. These floors are of different sizes and lengths in different vineyards, but everywhere constructed on the same general principles. Where an incline or a hill is found, the floor may simply be built on the slope, with no artificial elevation; but, where the ground is level, the structure of the sequero is different. The floor must always face the south, and the back is raised to give the floor the proper slope. The sequero thus consists of four walls, the front one of which is only a foot high, and the back wall from six to eight feet high. The side walls slope between these, generally with an angle of forty-five degrees. In length, these floors vary from forty to fifty feet, according to the different ideas of the vineyardists. The whole interior is filled with black gravel, and is tamped hard. These sequeros are divided in beds, fourteen feet or so wide, by tiles that are sunk, thus forming walks of several feet in width, and which also serve for leading off the rainwater. Around every little bed of this kind are small upright tiles to prevent the rainwater entering from the walks. Finally, in the center of the bed, is a long row of upright tiles, high enough to support either boards, mats, or more generally canvas, in order that they may shed the rain into the tile walks. The value of such floors is evident. Being covered with canvas, etc., every night, the heat is preserved, and every morning, when the sun rises, the grapes are yet warm. The drying on such beds has never, in fact, been interrupted. The drying-floors are also useful in case of too hot weather, when the grapes can be properly sheltered with canvas and prevented from being cooked; when finally dried, the covering, again, will serve to keep the moisture from too quickly evaporating.

—When the grapes are picked, the best vineyardists separate the bunches immediately in three different grades. Each grade is placed by itself on the gravelly drying-ground, and remains there to dry. When half dried, they are taken bunch by bunch by a workman, who picks out bad or overdried berries and rubbish, and in putting the bunch back turns it over. In ten days the grapes are generally dried, provided the weather has been favorable. Every night the canvas covering is slid down over the sequero, and the grapes protected from dew and cold, or rain. The drying is sometimes greatly hastened by the Terral or hot winds blowing from the plains of La Mancha, a wind very similar in its effect to the desert wind of Riverside and Santa Ana, in California.

—The raisins in Malaga are packed by the large growers themselves, and every such grower packs almost to a man. The generally accepted idea that a few packers living in Malaga pack all the raisins[15] is erroneous. This is not the case.[2] Nearly all packers there are also growers owning their own vineyards. The raisins are all packed in 22-pound boxes or in quarters, etc., according to the demands of the trade.

[2] According to A. B. Butler.

The various raisin brands packed in Malaga are different according to the different markets that are to be supplied. Thus for England we have: Finest Dehesa, three crown; finest Dehesa, two crown; finest Dehesa, one crown; Dehesa; Choice layers; London layers, three crown; London layers, two crown; London layers, one crown.

For France again we have: 1 Imperiaux; 1 Royaux; Couches; Surchoix; Choix; Ordinaire; Surcouches, etc.

The loose raisins or Brena and the seedless or Escombro generally go to the continent or even to the United States. The old terms Garoon or Sun are now never used.

For American markets we have: Imperial Dehesa; Royal finest Dehesa; finest Dehesa; fine Dehesa; Dehesa; London layers, three crown; London layers, two crown; London loose, one, two and three crown.

Boxes are generally made from fir imported from Portugal, at fifteen cents each. Of late years, however, they are also received from Canada, and cost only seven cents each.

—The labor in Malaga is the most expensive in Spain, the best laborer being paid forty cents per day, while in Denia the labor is obtained for fifteen cents only; but it must be remembered that the packing of the Malaga raisins is a much more particular work than the packing of the dipped Denias.

The price paid for Malaga raisins at the packing-house is at an average of seven cents per pound for the best, or from one to two cents more than what is paid in California. The lower grades bring from two and a half cents upwards.

—The Valencia raisins, or, as they are called, the Lexias or Spanish dipped raisins, are produced in the province of Valencia, situated on the east coast of Spain. The district contains three sub-districts, the southern one, the Alicante district, extending from Villa Joyosa in the north to Elche in the south. The raisins of the Alicante district are inferior to those produced in the other districts, both as regards quality and quantity. The most northerly district is the Valencia district proper, extending from Cullera in the south to Castellon in the north. North of the latter place the Muscat grape does not come to perfection, and even within this district comparatively few raisins are now produced as compared with a few years ago. But the bulk of all the raisins produced in the province are exported from Valencia city, and hence these raisins are known as Valencias, while in reality they come principally from Denia.

The bulk of the Valencia raisins come from the central district, or the Denia sub-district, comprising the land between Villa Joyosa in the south and Cullera in the north, or about thirty miles on each side of the town of Denia. Towards the interior the raisin district extends[16] at the most nine miles, but the average is less, so that the whole district over which the Denia vineyards are spread includes only an area of 350 square miles, equal to ten townships of land, or about 224,000 acres. A large part of this land is not cultivated, and consists of mountains and waste places only suitable as watersheds. The town of Denia is the principal town of the sub-district, and has now a population of about 2,600 people. It is situated about half way between Valencia in the north and Alicante in the south, on the shore of the Mediterranean, in about the latitude of Sacramento in California, or thirty-eight degrees, fifty minutes north. Being one of the oldest towns in Spain, Denia was first founded by the Phœnicians, who here established the worship of Diana, from which word the name Denia is a corruption. The Phœnicians also introduced the grapes, and possibly also the drying of raisins; but the local tradition gives the honor of the latter industry to the Moors, who are said to have brought with them the variety of grape known as the Muscat of Alexandria. During a part of the year, Denia is the export harbor for the raisins of the district. This is only possible in the early part of the raisin season, as then only are the winds favorable,—the so-called harbor being nothing but a roadstead. Later in the season, when storms and rains set in, all the raisins are shipped to Valencia by railroad, and from there exported by steamers and sailing vessels.

Among other industries of the Denia district are the cultivation of onions, the manufacture of cotton goods, its sardine fisheries, etc., all giving work to the vineyard workers during a time of the year when there is nothing or but little to do in the vineyards and packing-houses.

The raisins of Denia are not all of the same quality, but vary according to the locality where grown. The whole district is dotted with small villages, all producing raisins. The principal ones of these are, besides Denia proper, Jabea, Jaraco, Jerrea, Oliva, Pedreguer, Jalon, Gandia, Ondara, Vergel, etc. Of these, Denia proper produced in 1876 over 2,500 tons of raisins, Jabea 1,700 tons, Oliva 1,600 tons, Pedreguer 1,000 tons, Retoria 900 tons, Jalon 850 tons, Ondara and Benisa 800 tons each. But, besides these, there are some twenty odd more villages or smaller raisin centers, which produce from 200 to 700 tons each, or an aggregate of 20,000 tons of raisins.

—The soils of the province of Valencia, where the vineyards are situated, are of various kinds, such as cretaceous and calcareous soils, containing admixtures of clay, sand and gravel. The color is often red, changing to gray where irrigation has been practiced, but much of the soil is of an ashy white color, similar to that of bottom lands generally. In many of the lower situated plains, the soils are blackish or dark gray, especially so where stable or other manures have been used for years.

Many vineyards are situated on the hillsides or on the rolling lands, where the gravelly soils produce raisins of smaller size and in less quantity, but sweeter and finer flavored. But the largest bulk of the vineyards are on comparatively level land, which can be and which is irrigated. The raisins produced on these low grounds in the moist and[17] cool valleys are larger, but not of equal flavor and sweetness. In wet seasons, the hillsides are preferred, the valley lands then being too wet and cold. Accordingly, as the seasons are wet and cold, or dry and warm, the various localities produce raisins of different qualities, which again are valued and paid for differently. The extent of the valley or plain lands decides the extent of the raisin districts, and of late years the rolling vineyards have decreased in quantity, while those on the plains have increased, until at the present time almost all the plain lands are occupied with raisin vineyards, especially in the Denia sub-district.

—The climate of Denia and its surroundings is rather cold and windy; damaging spring frosts, as well as early fall rains, frequently interfere with the setting of the grapes and with the harvesting of the crop; it has even happened several times that the entire crop has been seriously injured by one of these, or by both causes combined. Farther north, or in the Valencia district proper, the climate is milder, and frost is rare. Oranges are here at home, while the culture of raisin grapes becomes less every year. North of Castellon the climatic conditions are such that no raisin culture is possible.

As compared with the climate of Malaga, that of Denia is much less favorable to the raisin grape. The production of sun-dried and undipped raisins in Denia is not possible, and, although it has been attempted several times, it has seldom succeeded. The rainfall of Denia averages twelve inches per year. The rainiest months are those of November, February and April, but the heaviest rainfall at one time occurs quite frequently in the first week of September, while light showers are not uncommon in August, at that time doing much damage to the grapes or the just exposed raisins.

—Not only is irrigation necessary to grow the vines successfully and to produce an abundance of grapes, but the irrigation in the province of Valencia is necessary to the health and longevity of the vines. Nowhere else in Spain is the water so abundant, and no saving of the water is necessary in the majority of the districts. Through an abundance of water, the soil on the lowlands has now filled up to such an extent, that in the best vineyards the surface water is only from five to eight feet from the surface of the ground. Those vines which could not be irrigated have gradually become diseased, and the hillside vineyards are being rapidly abandoned and devoted to something else. Upon the abundance and constancy of the water depends the prosperity of the whole province, and there is hardly a more prosperous country in Spain. To show the close connection between irrigation and raisin production in Spain, it will no doubt interest many to know something of the irrigation system and the irrigation districts of the province of Valencia, than which no more important ones are found in Spain.

The district of Alicante is supplied with water from the river Monegre, and the Elche district from the river Minalapo. In the northern part of the province is the Murviado irrigation district, taking its water from the river Palencia. The Jucar irrigation district, situated immediately south of the huerta of Valencia, takes its water from the[18] Jucar river, distributing 850 cubic feet of water per second upon some 50,000 acres of land.

The Valencia irrigation district consists of 26,350 acres of land close to the town of Valencia, and is watered by the river Guadalaviar, or, as it is generally called, the Turia. The water is distributed through eight canals, each carrying from 35 to 120 cubic feet of water per second, the combined low-water discharge of all the canals being from 250 to 350 cubic feet of water per second. Of the importance of irrigation in this district, we can judge when we learn that the above 26,350 acres contain 72,000 inhabitants and sixty-two villages, or an average of 1,774 people per square mile, not including the city of Valencia itself, with a population of 120,000 people. It is also remarkable that this enormous population on a territory not as large as the arable land surrounding any one of our principal inland towns in California, is not alone due to the irrigation and care of the land, but to the minute subdivision of the land, which makes this culture and irrigation possible. It is a practical illustration of the value of the colony system as inaugurated in California, showing what we can expect of our inland plains when they become fully irrigated and the land properly subdivided.

—It has already been stated that the grapes grown in Denia are the Muscat of Alexandria, which were introduced there by the Moors. Farther south, in the Alicante district, other varieties are more common, but play no important part in the raisin production of the district. The Valencia raisins are inferior to those of Malaga, the want of heat requiring them to be dipped in lye before drying. This, again, gives these raisins a peculiar reddish, semi-transparent color, which unfits them for table raisins. The Valencia raisins are principally used for cooking; even the best grades of Valencias are inferior to the inferior grades of Malaga raisins. During the last season (1889) large quantities of Denia grapes were cured on the Malaga style, and with great success. Large quantities of such sun-dried Denias were sent in bulk to Malaga, and there repacked for export to the United States, the Malaga crop having so diminished that the usual demand could not be supplied. Years in which such sun-drying is possible in Denia are rare.

—The Muscat cuttings are planted generally in February. The best cuttings are considered to be those taken from vines at least six years old. The cuttings are set at various distances according to the richness of the soil. The richer the soil the less room is given the vines. Thus the vines are set either five by eleven feet or five by twelve feet, or, in other words, they are set in rows eleven or twelve feet apart, with the vines five feet apart in the row. The depth of the cutting is regulated by the moisture of the surface soil, but averages eighteen inches. The vines begin to bud in the middle of March, and are from the start subject to great care and constant cultivation. The first operation after the cutting is planted is to cut off the top bud as soon as the vine starts to grow, leaving the two shoots only from the two lower buds. No more shoots are allowed to grow the first year. Next winter the smaller of these two branches[19] is cut off completely and the remaining branch is pruned back to two eyes. In the second year the young shoots from the vine are allowed to grow to ten inches or so long, when all are cut away except two of the strongest. Next winter again these are pruned so to leave only two eyes on each, or four buds on the whole vine. In the succeeding years the branches are gradually increased in number, but always pruned back to two eyes. After the vine is five years old, it is seldom increased as to branches; it is then always pruned back to the same number of spurs. It can be said that the Denia growers pay less attention to the quality of the raisins, and prune more to attain quantity. They leave more spurs on their vines than do those in Malaga, and in this respect resemble many of our own California growers, who frequently leave from twelve to fifteen spurs on a vine. The vines in Denia are also raised higher above the ground than in Malaga, very much as we have been in the habit of pruning our own vines. At the age of three years the vines come into bearing; but no fine raisins are made until the vines are five or six years old.

—The dipping process is one of the greatest importance, and gives the peculiar characteristics to the Valencia or Denia raisins. As a similar process will sometime or other be more generally used in California, a more detailed description may prove interesting to California growers. We can probably not do better than to imitate them, although in mechanical appliances we will readily improve upon their methods. The dipping is always done at the drying ground or secadero. The larger part of the dipping apparatus, or the kettles, are placed under the ground so as to save heat and fuel. A trench eight or nine feet in length is dug to the depth of three or four feet. At one end is built a chimney protruding three or four feet above the level of the ground. In the other end of the trench is built a brick wall with an opening for feeding the fire. Some trenches are lined inside with bricks, making them more permanent and solid. On the top of this flue, and on a level with the ground, are built the kettles or boilers, containing not less than twenty gallons each. The boiler nearest the fire entrance is destined to contain a solution of lye or ashes, the one next to the chimney being for boiling water only.

The lye is made from the ashes of burnt vine cuttings, together with lime and sometimes some salt, by men who have acquired the art from years of experience, and who know by the appearance of the scalded grapes whether the solution is too strong or too weak. If too weak, the skins of the grapes will be insufficiently cut, which will delay the drying of the grapes, and cause them to rot if the weather is damp and foggy. If, again, the lye solution is too strong, the skin will be destroyed and the berries seriously injured.

The grapes to be dipped should be perfectly ripe. If dipped before, they will become inferior both as to color and taste. The perfect ripeness is a most important point. The grapes are picked in baskets of about ten pounds each, and carried to the scalder. The man nearest him on the right fills a perforated ladle with about twenty pounds of the grapes. The ladle is made either of wire netting or of[20] tin or zinc, with large perforated holes about three-eighths of an inch wide. There is a scalder at each boiler. The first scalder dips the grapes in the scalding water for a second, and immediately hands them to the second scalder, who dips the same ladle in the boiling lye solution for not over two seconds. The grapes are then carefully turned out on trays to dry.

The dipping first in scalding water is of the greatest importance, both in washing off the dust of the grapes and in preparing them to receive the alkali wash with more effect. Since the hot-water process was introduced, the Valencia raisins have materially improved in quality. The grapes are never rinsed in cold water after being dipped, and it is more than likely that the lye prevents molding, as, according to A. B. Butler, dipped raisins are sometimes exposed to the rain for three weeks without being totally ruined. In California, our dipped and washed raisins spoil quickly if exposed to rain. The object of dipping is, of course, to slightly crack the skins so as to allow the water to readily evaporate. Dipped raisins dry sometimes in five days, while undipped raisins would require as many weeks. Efforts to produce sun-dried raisins without dipping them have repeatedly been made in Denia; but they are invariably spoiled by the rain, and lately two firms were ruined in their attempts to dispense with the dipping process.

—After the grapes have been properly dipped, the drying proceeds very quickly. The grapes are immediately spread on cane trays or cañezos, about six feet long by three or four feet wide. These cane trays are made of the common Italian reed or Arundo donax, which grows everywhere, even in California, and is here incorrectly known as bamboo. The trays are made either of split or of entire canes tied strongly together. These trays are placed flat on the ground, only leaving enough space around each one to allow the workmen free access to the tray on all sides. After having been exposed to the sun for three days, the grapes are turned, in order to dry evenly on both sides. On the fifth day, the raisins are turned again, and, if the weather has been favorable, many of the raisins are then ready to pack. A day or two after this, all the raisins are ready, and are collected and housed. If, again, the weather has been unfavorable, the drying is very much delayed. At the approach of rain, the mats or trays are taken up and piled on the top of each other, under sheds previously made. Every drying ground has stationary appliances for this purpose. These simply consist of poles stuck in the ground, and extending five or six feet above the same. Other cross-rafters or scantlings are nailed between the poles, thus forming rows of roofless sheds eight or nine feet wide, of greater or shorter length. Painted canvas, or simply mats or empty reed trays, are used as covers, under which the raisin trays are piled. Under and between each tray are placed five little cubes of wood, for the purpose of lifting the tray and preventing it from pressing too heavily on the grapes underneath.

—When at last the raisins are dried, they are either stored by the producer, or, as is more generally the case, are taken to the merchant or packer who has supplied the grower’s wants during the year in anticipation of the coming crop. There are thus a number of special packers in Denia, who own large and splendid packing-houses in which the crop is yearly handled. The grower never packs himself, the enhanced value of the raisins not being sufficient to warrant the trouble. One of the best and by far the largest packing-houses in Denia is owned by J. D. Arquimbau. A more perfectly equipped establishment is not found anywhere else.

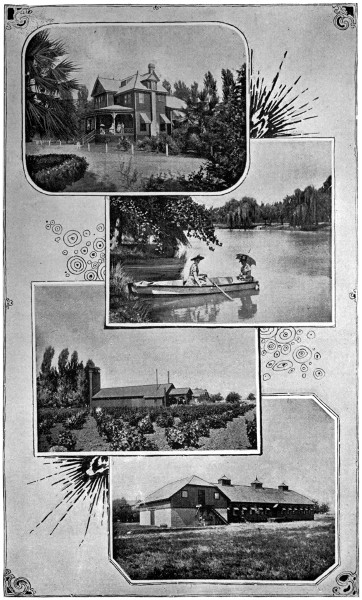

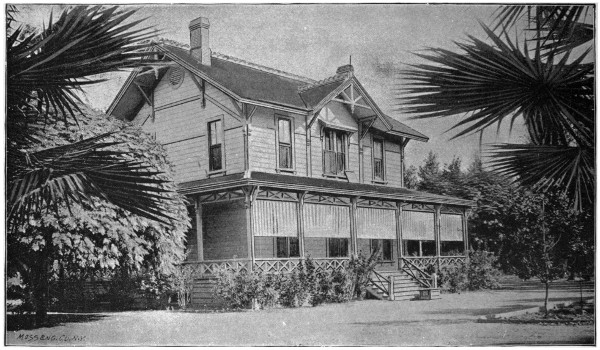

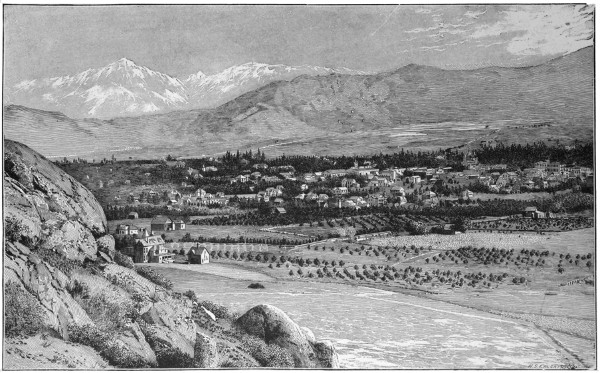

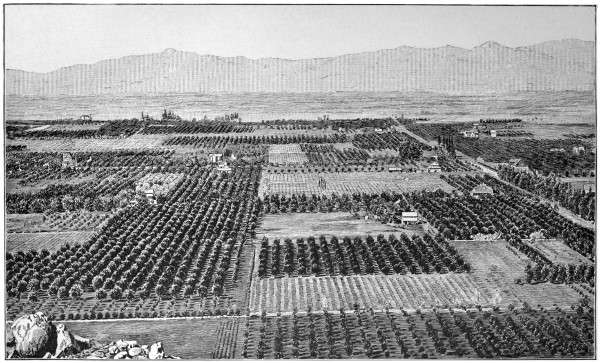

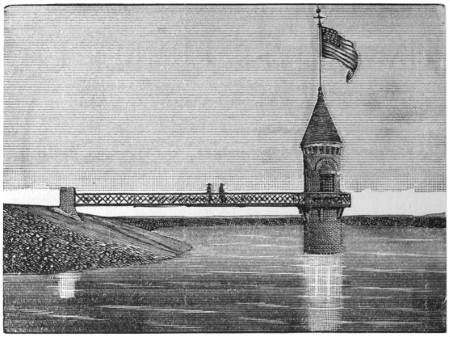

Views from Col. Wm. Forsyth’s Raisin Vineyard, Near Fresno: Residence, Lake, Raisin Dryer, Packing House.

[21]

All of the packing is done by women, while the men do the carting of the raisins from the vineyards to the packing-houses. During the balance of the year, when there is no more work in the packing-houses, these very men occupy themselves with the sardine fishery, while their wives then dress the sardines and pack them in oil. They have thus work all the year round,—an absolute necessity in a country where the wages are so small, and where the poor man has no chance to save up a capital. The wages paid for packing in Denia is only fifteen cents per day; while in Malaga the same work commands from forty to sixty cents per day. In some of the warehouses in Denia, from two to three hundred women are employed, as well as a number of men. The boxes now used are halves of twenty-eight pounds, or quarters of fourteen pounds each. The large or whole boxes of fifty-six pounds each are no longer in use. The raisins are all packed “off-stalk,” or, as we say, “loose.” Bunch or stem raisins, or “on-stalk” raisins, are seldom seen. This great improvement in packing is of recent origin, and is due entirely to the influence of English merchants. Some thirty years ago, the raisin industry of Valencia had so deteriorated, that it threatened to entirely cease. The cause of the deterioration was principally the habit of the buyers to pay for crops, not according to the quality of the raisins, but according to the quantity. The small farmer with a few hundred pounds of raisins carefully cured was paid less, or at least not any more, than the man who had hundreds of tons carelessly cured. As a consequence, it was to no one’s interest to take any particular pains in curing. The raisins deteriorated; no care was paid to packing; anything, almost, stalks, dirt and bruised berries were dumped in boxes together; brands, trade-marks and labels were unknown. The whole business was apparently going to ruin. The orders from England became less and less every year. Those from America almost ceased. The “equality price” or “average price,” which has been so much in vogue in California, actually ruined the Valencia raisin industry. We ought to take a lesson from them, and change this system in time, or we will be in the same bad fix as they were.

The improvement in Valencia raisins was entirely due to the energetic efforts of English gentlemen. Mr. George Graham, agent for an English firm, established himself in Valencia, investigated the raisin business, and, seeing the true cause of the ruin, set himself to work to remedy the same. He introduced better methods in growing, curing and packing; and through his efforts a better price was paid for a better grade of raisins, and it was not long before the raisin business was on an entirely different footing.[22] The object of the grower was from that on, not only to increase the quantity, but to increase the quality as well. To begin with, the raisins were shipped off-stalk or loose; but the boxes were not faced. Now the raisin boxes are all faced, and the raisins are carefully selected and assorted. As a consequence, the Denia trade has of late years increased enormously, until at present all the land available has been planted to raisins. There is at present but little or no first-class raisin land left in Denia, and it looks as if the raisin production there could not be further expanded.

—Although the raisin industry had long existed in the province of Valencia, it was only in late years that it assumed an importance. They were already known as Duracinae by the Romans. Re-introduced or improved by the Arabs or Moors, it soon became a prominent industry, and the export of raisins to England was already of some consequence in the time of William and Mary. In the year 1638, Lewis Roberts, in his merchant map of commerce, informs us that Denia raisins cost eighteen rials or three shillings per hundred weight. In 1664, Gandia raisins were quite famous, and were known as Pasas. At the end of the last century, the raisins from Denia and Liria reached forty thousand quintals, or two thousand tons, distributed as follows: Spain, six thousand; France, six thousand; England, twenty-eight thousand,—equal to one million, four hundred and thirty thousand boxes, forty thousand quintals, or two thousand tons. In 1862, the raisin export from Valencia had dwindled down to seven thousand tons. In 1876, it had again risen to nineteen thousand tons, and in 1883 to forty thousand tons. Of these, nine hundred and seventy-nine thousand boxes were exported to the United States, one million, three hundred and eighty-five thousand were sent to England, and four hundred and thirty-six thousand found their way to other parts of Europe and Spain. In 1888, the yield was two million, three hundred and sixteen thousand boxes of twenty-eight pounds each, equal to thirty-two thousand, four hundred and twenty-four tons. If packed in twenty-pound boxes, this crop would have equaled three million, two hundred and forty thousand, four hundred boxes, or four times as much as California produced at the same time. The crop of 1889 is calculated to have reached two million, eight hundred thousand boxes of twenty-eight pounds each.

When we remember that this class of raisins is as yet hardly produced in California, and that the nine hundred and seventy-nine thousand boxes or more imported could and should be supplied by us, it would seem that our fears of overproduction will not immediately be realized. The tendency of the raisin market is now to supplant these Valencia dipped raisins with California undipped or sun-dried raisins, the California Sultanas being considered superior for the same purpose that Valencias were formerly used.

—The principal and only raisins of any great commercial importance which are produced by Greece are the currants. We have already spoken of their name, and its[23] supposed origin from the town of Corinth, and of their having been mentioned by Pliny in the year 75 A. D. The currants must thus very early have been of considerable importance as a commercial product, although the great increase in their production is of more recent date. The crusades which brought the nations of the North in contact with the Orient and the South also spread the knowledge of the Grecian currants to the distant parts of Europe. After the Latin conquest, currants became a commercial article, and we have every reason to suppose that, as early as the beginning of the thirteenth century, currants had reached the English shores, and that in the middle of the fourteenth century the English trade was fully established. Raysins of Corauntz were quoted in 1374 at two pence and three farthings per pound, equivalent to one dollar and twenty-five cents in our money at its present value. In 1513, the first English consul was appointed at Chios, and from that time on a direct traffic was maintained between the Grecian Islands and the North of Europe. In 1582, Hakluyt writes that efforts had been made to introduce the coren plant or vine into England, but that the same failed to fruit. The first introduction of the Zante vine into England is supposed by Anderson to have taken place in 1533. In the end of the sixteenth century, the currant traders were in full intercourse with the Venetians on the Island of Zante, and the Turks on the mainland or Morea. In 1581, the Levant Company received a monopoly in the trade of the small fruits called currants, being the raysins of Corinth. According to Wheler, who traveled in the Ionian Islands in 1675, Zante produced enough currants to charge five or six vessels, Cephalonia three or four, and Nathaligo, Missolonghi and Patros one each. Some few were also brought down from the Gulf of Lepanto.

As to the native home of the currants, opinions have considerably differed. Some have supposed Zante or Naxos to have been the original home of this grape; while others, with better reasons, have held that their original home was Corinth. Beaujour, who was French consul in Greece in 1790, says: “The fruit is not indigenous to Morea. No writer before the sixteenth century mentions it, and the result of my inquiries is that the currant came from Naxos into the Morea about 1580. It is true no such plant now exists in Naxos, but it has similarly disappeared from the territory of Corinth, though it is very certain it was cultivated there in former days, when the Venetians held the country.” This account does not agree with the statements of Comte Grasset St. Sauveur, consul to the Ionian Islands from France in 1781. He states, in his History of the Ionian Islands, that “the first plants were imported from Corinth to Zante about two centuries ago” (or about 1580). There are no exact records of the time or of the introducer; but the date is fixed by the regulations of the Senate of Venice relating to custom duties. It is likely this introduction took place not much before 1553, and was caused by the hostility of the Turks, who then held Morea, to the merchant vessels of the other nations of Europe, who in fact forbade them any entrance to the Gulf of Corinth, the principal export place for the currants. Thus John Locke, who in 1553 describes Zante, speaks of other products of the island, but not of currants.

[24]

Hakluyt states that, in 1586, the chief commodities of the island were “oyle and currants.” The latter, then, must have been introduced some time in the middle of the sixteenth century. Lithgow, a Scotch traveler who in 1609 visited the islands and published an account of the same in 1633, informs us that, besides oyle and wine, Zante produced one hundred and sixty thousand chickens of currants, each chicken of gold being equal to nine shillings of English money. And he adds that the custom duties on those currants amounted to twenty-two thousand piasters (one piaster is equivalent to six shillings), a sum of money which those Islanders could not have afforded (they having been, not above sixty years ago, but a base, beggarly people, and in an obscure place) if it were not that in England there are some who cannot digest bread, etc., without these currants. This seems to imply that, since the introduction of the currant culture in the Island of Zante about the year 1550, the Zanteans had suddenly become comparatively wealthy. So suddenly had this important industry spread, that in 1610, according to Sandys, the chief export of both Zante and Cephalonia was currants. In 1612, Coryat says that “Zante is famous for its wine, oile and currants.” Fynes Moryson, in his “Itinerary” published in 1617, states that “the English merchant vessels exported currants from Zante and Cephalonia, and from Petrasso in the Gulfe of Corinth.” Tavernier says, in 1678, that, “Corinth exports great quantities of currants. Patras does the same, which is all the trade from those two places.” In 1682, Wheler states that “the ports of Patros, Nathaligo and Missolonghi, all three together having enough to lade only one good ship every year.” Randolph, in 1689, mentions that currants were first planted on the plains of Corinth, and that the plain about Vostizza produced corn, currants and wine. Of Zante, he says that it produced two thousand tons of currants. Thus it will seem as if, through the fostering care of the Venetians, the currant trade was transplanted from the mainland of Morea to the Islands of Zante and Cephalonia, there to become of almost national importance. Until the Turks were expelled from Morea, the latter never made any serious efforts to recover the lost trade. First in later times the culture of currants has again spread on the mainland, especially on the northern shore of the Gulf of Corinth, and to-day the combined production of the Morean vineyards is largely in excess of that of the Ionian Islands.

In our times the currants are exported either from the mainland of Greece, the Morea, the ancient Peloponnesus, or from the Grecian Islands,—Cephalonia and Zante. In Morea, the principal ports for the exportation of the currants are Patras and Vostizza, although other ports export a few. Even the Islands of Ithaca and Santa Maura contribute a few. Efforts have been made to extend the culture of the currant vine, and introduce it to other islands, but not with any great degree of success. This is entirely attributed to climatic conditions.

—The currants are small, seedless raisins produced from the currant grape, which again is characterized by small clusters, which, when perfect, are very compact like the heads of Indian corn or maize. The skin of the berries is thin, the pulp very[25] sweet, with a strong flavor and aroma. The raisins are similarly aromatic and very sweet, sometimes semi-transparent, but generally dark violet. The flavor of the raisins is entirely distinct from the Muscatel, and is very superior to that of the also seedless Sultana raisins.

—The soil best suited to the currant grape is a calcareous marl, which must be of good depth, loose, and easily worked. Such marls are also prized for their great power of retaining moisture. But vineyards are planted in Cephalonia, Zante and Ithaca in the most different soils and situations. They are found in gray marls, in red clay, on the plains and among the hills, in fact, in the most widely different situations. The soil of Zante contains a small percentage of sulphate of lime or gypsum, which is by many considered indispensable for the successful and profitable culture of the currant vine. The currant vine thrives especially in low and rich land which can be irrigated, and irrigation is quite essential to the perfect development of the grapes. Many vineyards, however, are not irrigated, the irrigation, of course, only being practicable on the plains. This irrigation is practiced from October to the end of December, often while the natural rainfall supplies the artificial watering. The lands are generally small freeholdings, owned by the peasants. The most valuable currant vineyards are situated on the rich and level valley lands.

—The preparation of the land for a currant vineyard is expensive, as the land is hardly ever level enough to admit of the vines being immediately planted. The surface is therefore first leveled and divided up in smaller cheeks or flats, each one surrounded by a bank. The whole is covered with a network of ditches, which are necessary for the perfect irrigation of the soil. Where there is water enough, the vineyards are irrigated in November and December, and are then flooded as often as practicable, the water sometimes standing on the ground for weeks in succession. In perfectly arranged vineyards, the irrigation is so managed that the water flows from one check to another, and is first shut off at the advent of the New Year, when the pruning and cultivation begins. By this plentiful irrigation, the ground becomes thoroughly soaked, and remains saturated until the next season, when rain again sets in and fills the irrigation canals. No summer irrigation is used in old vineyards, and in young vineyards only in case of great necessity.

—The vines are set at various distances, in some places four feet each way, in others again six by ten, giving a various number of from 740 to 2,622 to the acre. In some places, the old practice of planting the vines in groups of four still exists. Each group consists of four vines one and a half feet apart, and each group distant six feet from each other either way. Of late, however, the vines are planted farther apart, probably because the soil is becoming exhausted, a favorite way being to have the vines closer one way than the other.

—Great importance is attached to procuring cuttings from a distance, or in getting new strains. Cuttings from the nearest vineyard are never used, as they[26] are considered to produce inferior vines, and not do as well. To procure cuttings or vines, the old vines are sometimes cut a few inches below the surface of the soil, causing the parent plant to throw off numerous suckers or shoots, which the following winter are separated and used as we do rooted vines here in California. Three or four years will elapse before they come into regular bearing. Some vineyards are produced by grafting the black currant on the wine grape, and many wine vineyards that do not pay are thus transformed into paying raisin vineyards. The grafted vines come into bearing much sooner than those grown from cuttings. The grafting is performed in Zante as follows: The soil is dug away from the main trunk of the old vine to the depth of from twelve to eighteen inches, and the trunk cut off square at the bottom of the pit. Two or three scions are then inserted in the trunk, and made to slightly project above the ground, in no case with more than two or three eyes. Clay is then applied to the joint of the graft, and the trunk slightly covered with leaves, and the hole then filled up with soil. The grafting is done in the spring, and the cuttings must be kept dormant in dark and cool cellars.