Emblem of the League of Walkers

Emblem of the League of Walkers

GOING AFOOT

A Book on Walking

BAYARD H. CHRISTY

Published for

the League of Walkers

BY

ASSOCIATION PRESS

New York: 347 Madison Avenue

1920

Special acknowledgment is gladly made to the respective publishers for permission to use the following copyrighted material:

Quotations from the Journals of Henry D. Thoreau, copyright by Houghton, Mifflin & Company; “Trees,” by Joyce Kilmer, copyright by George H. Doran Company; “Uphill,” from “Poems,” by Christina Rossetti, copyright by Little, Brown & Company, Publishers, Boston; “Overflow,” by John Banister Tabb, copyright by Small, Maynard & Company; “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” by William Butler Yeats, copyright by The Macmillan Company.

None of the above material should be reprinted without securing permission.

Copyright, 1920, by

The International Committee of

Young Men’s Christian Associations

To

GEORGE J. FISHER

at Whose Instance, and With Whose

Kindly Aid, These Pages Were Written

| I. | How to Walk | 1 |

| Posture—Wearing Apparel—Equipment—Care of Body and Equipment—Companions. | ||

| II. | When to Walk | 39 |

| At What Season—The Hours of the Day—Speed and Distance—Stunt Walking—Championship Walking—Competitive Walking. | ||

| III. | Where to Walk | 63 |

| Choice of Surroundings—Nature of Country—The Goal and the Road—Maps—Walking by Compass. | ||

| IV. | Walking Clubs in America | 79 |

| The Appalachian Mountain Club—The Green Mountain Club—Wanderlust of Philadelphia—Walking Clubs of New York—Some Western Clubs—Association of Mountaineering Clubs. | ||

| V. | Organization and Conduct of Walking Clubs | 103 |

| The Activities of a Walking Club—Rules for Hiking—A Club Constitution—Juvenile Clubs—League of Walkers. | ||

| Bibliography | 141 |

I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks,—who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering, which word is beautifully derived “from idle people who roved about the country, in the Middle Ages, and asked charity, under pretense of going à la Sainte Terre,” to the Holy Land, till the children exclaimed, “There goes a Sainte-Terrer,” a Saunterer, a Holy-Lander. They who never go to the Holy Land in their walks, as they pretend, are indeed mere idlers and vagabonds; but they who do go there are saunterers in the good sense, such as I mean. Some, however, would derive the word from sans terre, without land or a home, which, therefore, in the good sense, will mean, having no particular home, but equally at home everywhere. For this is the secret of successful sauntering. He who sits still in a house all the time may be the greatest vagrant of all; but the saunterer, in the good sense, is no more vagrant than the meandering river, which is all the while sedulously seeking the shortest course to the sea. But I prefer the first, which, indeed, is the most probable derivation. For every walk is a sort of crusade, preached by some Peter the Hermit in us, to go forth and reconquer this Holy Land from the hands of the Infidels.

—Henry D. Thoreau, “Walking.”

Observe the vigorous man as he walks: the stride is long and free; the feet come surely and firmly to the ground, without twist or jar, toes pointed straight ahead; the pelvis, swaying easily, carries an erect body; the arms swing in alternate rhythm with the legs; the head is borne free over all; breathing is deep and long; the blood courses strongly. Every member shares in the activity.

It must be the pedestrian’s ideal, when he comes to consider the matters of clothing and burden, in the least possible degree to interfere with these full natural bodily motions: Clothing, while serving its purposes of protection, must not bind nor rub; it may help to maintain, but it may not disturb normal circulation. Burdens must be so imposed as to be sustained with least effort, and to leave the limbs unincumbered.

Footgear is of first importance. If one is to walk comfortably, pleasurably, effectively, the muscles of the feet must have free play; there may be no cramping, straining, nor rubbing; no unnatural position. In Japan the elegant people toddle along in rainy weather upon blocks of wood which raise their dainty slippers above the mud; but your rickshaw runner splashes through the street on soles as pliant as gloves. Shoes and stockings serve but one purpose—that of protection. If roads were smooth and clean,[4] people who live in temperate climates would go barefoot.

When one walks long and hard, the blood-vessels are distended and the feet increase appreciably in size. More than that, in the act of walking, the forward part of the foot is constantly changing in shape: the toes alternately spread and contract, bend and straighten. The whole supple member is full of muscular activity.

The pedestrian accordingly will not advisedly clothe his feet in cotton stockings and close-fitting shoes, however well made. The consequences of so doing would be rubbing and blisters, impaired circulation and lameness. Nor will he put on canvas shoes, nor heelless shoes, nor rubber-soled shoes, nor shoes with cleats across their soles, such as football players wear.

The best material for stockings is wool, and for shoes, leather. The preference for woolen stockings is not primarily because of warmth—even in hottest weather they are preferable. It is because the material is elastic and agreeable to the skin. In winter, warmth is an added advantage; and, when one’s footgear is soaked through with water, there is far less danger of taking cold in woolen stockings than in cotton.

Stockings should be bulky and shoes roomy. The layer of knit wool between foot and shoe leather is elastic; it gives the exercising foot free play, cushions the weight of the body, and, by filling all the space, prevents rubbing. The rough bulky stockings known as lumbermen’s socks are excellent. If their coarseness is harsh to the skin, finer socks (of cotton, if preferred) may be worn beneath. If the woolen stockings available are light, wear two pairs together. Never wear[5] a stocking so small or so badly shrunken as to draw or constrain the toes.

Shoes should be roomy. They should when put on over heavy stockings make snug fit about the heel and beneath the arch of the foot, but the forward part should be soft and wide, to give the toes full play. The “sporting” shoes of shops are to be let alone. The army shoes are excellent, both of the Munson and of the Hermann lasts; they have been carefully designed for just such service as the pedestrian requires, and they are most successful. It has just been said that shoes should be large; they should be considerably larger than the wearer’s ordinary city shoes, both in length and in width. It is not sufficient to find a shoe which is comfortable in the shop; the shoe may be wide enough, but unless there be some allowance in length, one’s toes will, after ten miles of hard walking, be squeezed till they are tender and blistered. A man who ordinarily wears a 9 B, for example, should buy a 9½ D. There should be as much allowance as that, at the least. A roomy shoe, its looseness well filled (though not packed tight) with bulky, springy, coarse wool, coarsely knit, is the very best foot covering. An additional advantage should be mentioned: a tight shoe, retarding circulation, may in extreme wintry weather increase unduly the danger of frosted feet. Heavy stockings and roomy shoes are free of that defect.

There are no water-tight shoes, except in shop windows; and, if there were, they would at the end of a long walk, have become very uncomfortable.

A pair of army shoes should, with proper care, last, without resoling, for 200 to 300 miles of[6] walking—depending on the roughness of the way, and whether one is “hard on his shoes.” If one is planning a longer tour than this, he should provide two pairs of shoes, and wear them on alternate days—a plan which, but for the added weight, would in any case be preferable.

Some men prefer to walk in knickerbockers, others in long trousers (see below). Most of those who prefer long trousers wear shoes with high tops, reaching to the middle of the calves, and covering and confining the ends of the trouser legs. Again, bad conditions of footing—such as deep snow, for instance, or bog land, or low dense growth—may render high shoetops advantageous. Low shoes are not advisable under any conditions. For the open road, shoes of ordinary height are best. They should be laced, not buttoned.

For certain kinds of service, shoes should be specially adapted. Rubber heels are excellent on macadam roads, but it should be borne in mind that on hard wet surfaces rubber slips. The value of rubber heels is greatest when walking through level, well-settled regions. When they are worn, it is well to carry an extra pair.

Hobnails are to be used only when necessary. Any attachment to, and particularly any excrescence from, the sole of the shoe, is disadvantageous. Iron hobs add appreciably to the weight; and they tend to localize a pressure which should be evenly distributed over the whole sole. For walking in level or in moderately hilly regions, for such simpler mountaineering as consists in traversing highways and mounting wooded slopes, one does not require hobnails; the soles of his shoes should be of plain leather. One should let alone the rubber hobs and inlays, the small scattered spikes, such as he sees attractively[7] displayed as part of the golfer’s outfit. To the pedestrian these things are not worth the fancy prices asked; indeed, they are worth nothing to him. Hobnails, then, must justify themselves in advantages which outweigh their disadvantages; this they do in difficult mountaineering. Worse than useless on the level, they become in the high mountains practically a necessity. For climbing steep slopes, the rock faces and the dense short turf of mountain tops, for scaling precipices of “rotten” rock, for traversing snowfields and icy ledges, one needs to be “rough shod.” In the Alps the soles of the mountaineers’ shoes are studded all about their rims with flügelnägel—great square-headed hobs of iron, with “wings” overlying the edges of the soles. Soft iron proves to be the very best material to give purchase on rock surfaces, whether wet or dry, and on ice and snow, too, it is best. These flügelnägel, known as “edging nails,” and round hobs for the middle of the sole, called “Swedish hobnails,” may be had in this country from dealers in sportsmen’s goods.

For mounting icy slopes, steel spikes in leather carriers, called crampons, are secured to the feet over one’s shoes. These, it is believed, are not now procurable in this country.

For snowshoeing a soft-soled shoe is preferable. Deerskin moccasins are not serviceable for, unless protected by some outer covering, they soon become water-soaked, and then they are worse than useless. Shoepacks are good, and “Barker” shoes better. Barker shoes are made with vamp of rubber and upper of leather. On this subject, see “The Snowshoe Manual,” compiled by the Snowshoe Section of the Appalachian Mountain Club.

Special footwear is provided for other particular pursuits: The duck hunter on the tide-water procures hip-boots of rubber; the ski-runner wears shoes of special design, and so does the skater. But here we are in realms of sports other than walking.

Footgear, then, must be comfortable, durable, adequate.

Sufferers from weak or falling arches will wisely modify these suggestions, according to the advice of a reliable orthopedist. Indeed it is well for any one who goes seriously about walking to have his feet examined by a competent adviser, that he may guard against latent defects and prevent difficulty.

Clothing should afford necessary protection; should be light in weight, should be loose, and should be so planned that, as one grows warm in walking, the superfluous may be taken off. It is best that the temperature of the body be kept as nearly even as possible, and there is danger of chill, if one stands in cold wind—as on a mountain top, for instance—while his underclothing is saturated with perspiration. Ordinarily one’s clothing will (besides shoes and stockings) include underwear, shirt, trousers, coat, and hat.

In summer, underwear has no value for warmth; it should be of cotton, sleeveless, and cut short at the knees. If, however, one is walking in the mountains, or at a cooler season, he will do well to carry with him a flannel undershirt, to wear at the end of the day, when resting. In cool weather light woolen underwear covering both arms and legs is best—and when the thermometer falls low or one is to endure unusual exposure, the underwear should be heavier. Some pedestrians will leave cotton underwear[9] out of account altogether, wearing, by preference, light wool, and, on a very hot day, none.

The shirt should be of flannel, light or heavy, according to season. In milder weather, cotton shirts, such as the khaki-colored ones worn in the army and procurable at army supply stores, are good. On a summer walking tour it is well to provide one’s self with one cotton shirt and one of flannel. The collarband should be large; collar and cuffs should be of one piece with the shirt.

In the matter of trousers, one man will prefer long ones; another, short.

Knickerbockers, for summer wear, should be of khaki (or of one of the various close-woven cotton fabrics which pass under that name; a material called “cold stream duck” is good), or of jean; for winter, they may be of corduroy or of woolen goods. The army breeches, narrowed at the knee, and laced close to the calf of the leg, are riding breeches, really; and, while fairly good, they are not of best design for walking, since they restrain somewhat free movement of the knee. Knickerbockers should be full at the knee, and should end in a band to buckle about the leg immediately below the knee joint. Such walking breeches may be had of dealers in sportsmen’s goods.

Leggings. If knickerbockers are worn, the calf of the leg should be properly covered. In spite of such disadvantages as those incident to travel on dusty roads and over burr-grown land, long stockings secured at the knee are best for summer wear, without more. Spiral puttees are good in cool weather; in summer they are uncomfortably hot, and even when carefully put on, are somewhat confining. They have one notable[10] advantage: when used in deep snow they prevent, as no other leggings can, melting snow from running down the legs and into the shoes. For ordinary service the canvas puttees worn in the army are better than the spirals—indeed these canvas puttees are on the whole more satisfactory to the pedestrian than any other covering applied over shoes and stockings. Leather puttees are unnecessarily heavy, and their imperviousness is an actual disadvantage. It is only when traveling through dense undergrowth and briars that leather puttees are really serviceable—and that sort of wear is very hard on the puttees. High shoetops, too, become under such conditions useful, as has already been noted.

In wearing breeches laced about the calf, and in wearing spiral puttees, care should be taken that they do not bind. Many of our soldiers in the recent war suffered from varicose veins, and this was attributed in part to the emergency, that many men unused to physical labor had to carry heavy knapsacks. But it was attributed in part, too, to binding too tightly the muscles of the legs.

For one special service heavy leg covering is desired: To the hunter traversing the swamps and palmetto-grown plains of Florida, there is some danger of snake bites. Ordinarily, apprehensions about snakes are to be laughed at. The feet, ankles, and legs to a point two or three inches above the knees, should be protected. This protection may be effective either by being impenetrable, or by being bulky and thick, or by virtue of both these characteristics. One expedient, now on the market, consists of leggings having an interlining of wire gauze. Another may be improvised: a bulky wrapping of quilted material, incased in tough leggings of leather or[11] canvas. Care must be taken to protect the ankles below the reach of an ordinary pair of puttees. Any covering such as here suggested must in the nature of the case be heavy and uncomfortable, and will not be worn unnecessarily. One can only say for it, that it is better than a snake bite.

Long trousers should be of smooth close-woven material, not easily torn by thorns, and, for winter wear particularly, resistant to penetration by wind. The legs of the trousers should be confined within shoetops or leggings. Long stockings are not required, only socks. In long trousers, the knee movement is quite free. This rig is particularly good for rough work.

Some men prefer to wear a belt; others, suspenders. The drag of long trousers is greater than of knickerbockers, and, generally speaking, the man who wears knickerbockers will prefer a belt; and the man who wears long trousers, suspenders. The belt, when worn, should not be drawn very tight. The best belt is the army belt, of webbing; it should not be unnecessarily long.

In summer a coat is needed only when resting, or as protection from rain. On one summer tour, the writer found himself comfortable without a coat, but in its place a sweater and a short rubber shirt, fitting close at neck and wrists and with wide skirts, to cover man and knapsack together. Such a rubber shirt, called in the supply houses a “fishing shirt,” may be had of willow green color, or white or black. A sweater is so convenient to carry, and so comfortable, as to be all but indispensable; but, as protection from rain, the rather expensive, and for all other purposes useless, fishing shirt is by no means a necessity; a canvas coat or the coat of an old[12] business suit will answer well. One does not walk far in a downpour, and the slight wetting of a passing summer shower will do no harm. In the Tyrol where, before the War, walking as recreation was developed as nowhere else, many pedestrians carried neither coat nor sweater, but a long full cape of heavy, close-woven, woolen material; when not needed, the cape is carried hanging over the knapsack. Such a cape serves, in some degree, the purposes of a blanket.

A convenient mode of carrying a coat is described by Mr. William Morris Davis, in “Excursions around Aix-les-Bains” (see Bibliography). Mr. Davis says:

“Clothing should be easy fitting, so that discomfort shall not be added to fatigue. Even in warm weather, a coat will often be wanted on a ridge crest, or mountain top: it can be best carried as follows:—Sew the middle of a 30- or 35-inch piece of strong tape inside of the back of the collar; sew the ends of the tape to the bottom of the arm holes: pass the arms through the loops of the tape, and let the coat hang loosely on the back; it will thus be held so that nothing will fall from the pockets and the arms and hands will be free.”

For winter wear, one will dispense with any such garment as a fishing shirt, but will require both coat and sweater. The sweater should be a warm one, and the coat should be, not heavy nor bulky, but windproof rather.

A valuable garment for cold weather is the Alaska “parka,” a shirt-like frock, light, windproof, and it may be made storm-proof. Made of heavy denim or of khaki cloth and worn over a sweater, the parka is very satisfactory. Description[13] in detail will be found in Appalachia, Vol. XI, No. 3, page 287.

The hat should shield a man’s head from a driving rain, and, if it be a bald head, from the sun. If the man wears spectacles, the brim of the hat should shield the glass from rain and from the direct rays of the sun. The hat should be small enough and soft enough to be rolled up and tucked away when not needed. An old soft felt hat will do; the crown should be provided with ventilation holes of generous size; a leather sweatband is uncomfortable, particularly in hot weather, and may sometimes cause bothersome infection of a sunburned and abraded brow. The writer has found a white duck hat, its brim faced with green underneath, very serviceable in summer. In tropical countries the familiar pith helmet is an almost necessary protection.

One who wears eyeglasses should be careful to provide himself with spectacles, preferably metal-rimmed, and on a long tour will advisedly carry a second pair, and even the prescription. See further regarding spectacles, under the caption, “Colored glasses,” page 22.

The choice of clothing for cold weather may be governed by these few simple rules: (1) The objective is maximum warmth with minimum weight. (2) The trunk of the body—the spine, particularly—the upper arms, and the thighs should be most warmly protected. (3) Let the clothing be soft and bulky within (of wool chiefly), and externally let it be substantially windproof. The hoods worn by the Eskimos are made of the skins of water-fowl, worn feathered side in. (4) Have no crowding of clothing under the arms. (5) Do not wear long coat-skirts; let the coat be belted at the waist. (6) Protect the[14] ears, when necessary, with a knitted “helmet,” or with a cap having an ear-flap which, when not needed, folds across the crown. (7) Woolen gloves or, better still, mittens should be worn, and, outside of these, if it be very cold, loosely fitting leather mittens. (8) Except in extremely cold weather, do not wear leather garments, nor fur. Even a fur cap is intolerable when one becomes warm in walking.

The color of clothing is not unimportant. Whether as naturalist or sportsman one desires to be inconspicuously clad, or as a mere wayfarer on dusty roads he wishes to conceal, so far as may be, the stains of travel, he will choose khaki color, or the olive drab made familiar nowadays in the uniforms of the navy aviators. Gray flannel trousers, a white sweater, a bright-colored necktie, for wear in the evenings, are good as part of the equipment. But to that subject the next chapter will be devoted.

In planning an extended hike one will ordinarily have to reckon on some railway traveling. City clothes may be sent by express to the point where walking ends. Then the return journey may be made comfortably and inconspicuously.

The foregoing notes for men will be found sufficient to indicate what is a suitable costume for women pedestrians. With a woman’s needs particularly in mind, it should be said that skirts should be short, hanging at least six inches clear of the ground; shoetops may be accordingly higher; and all garments should be loose. When walking in remote regions, many women will prefer to wear knickerbockers rather than skirts, and in mountaineering knickerbockers are requisite. Even bloomers are objectionable. In[15] such case a woman’s costume more nearly approaches that of men.

A girl, writing of a tour upon the Long Trail in Vermont (see page 84), says: “Khaki riding breeches are best, as they are of light weight and briars do not catch on them. I can’t picture any one taking the Trail in a skirt.”

The Appalachian Mountain Club prescribes a climbing outfit for women in the New England mountains, as follows: High laced boots with Hungarian nails; woolen stockings and underwear, light weight; woolen or khaki waist, skirt, and bloomers; felt hat; leather belt.

And the Alpine Club of Canada publishes this among other notes upon women’s costume: “It is the dropping of the waist line down to the hips that is the secret of a woman’s wearing her knickerbockers gracefully. The top of the knickerbockers should hang on the point of the hips, with the belt as loose as possible. This makes discarding corsets, which of course is absolutely necessary, most comfortable.”

These notes on costume are intended to cover the subject, and to serve as reminder and advice to those contemplating walking tours of all sorts. But the practice of walking as an art and recreation does not by any means require such elaborate preparations. Otherwise, the devotees would be few. For an extended tour, or even for a holiday excursion, one may well give consideration to these many matters; but for a Saturday afternoon walk, it will suffice to put on proper footgear, leave one’s overcoat at home, carry a sweater if need be, use forethought about details, and be ready to betake one’s self from office to highway, with assurance of comfort and enjoyment. And beyond this, there[16] still remains to be spoken of the daily round of walking from home to work and back again, from office to restaurant at noon. This daily regimen of walking requires no special costume—admits of none, indeed. It may be that as one is thoughtful to take more steps on the routine path of life, he will give more careful attention to the shoes he buys and to clothes. But let no one close his mind to the subject with the too hasty conclusion that walking requires an impossible amount of special clothing. Any one who cares to, can make any needed modification of his ordinary business costume, without making himself conspicuous, and probably with gain in comfort and consequent well-being.

On a one-day excursion, a man will walk unburdened; and, on exceptional longer trips, pack-horses may carry the baggage from one camping ground to another; but, ordinarily, on a tour continuing day after day, one will carry on his own back all that he requires. Should his route lie through settled country, where shelter and bed are to be found in farmhouse or wayside inn, the man will travel with lighter load, and with greater freedom and enjoyment; if he must carry his blanket, too, walking becomes harder work. It may be that one will spend his vacation in the woods, and journey partly afoot, partly by canoe. In that case, a good part of his walking will be the arduous toting of impedimenta (canoe included) across portages, from one lake or stream to another. Proportionately as his burden is heavier, the sojourner in the wilderness will be disposed so to plan his trip that he may stop for[17] successive nights at favorite camping places. From these he will make shorter trips, and, unencumbered, climb mountains, perhaps, or explore other parts of the country about.

The bulk of what is carried should be borne on the back. Drinking cup may be hung to the belt; knife, watch, money, and various other small articles will be carried in pockets; map-case, field glasses, or fishing rod may be slung by straps from the shoulders or carried swinging in one’s hand, ready for use; but, for the rest, everything should be carried in the knapsack.

In case the pedestrian is traveling in settled country and is not obliged to carry a blanket (and such is by far the freest, pleasantest way to go afoot), the best knapsack to be found is of a kind in general use in the Tyrol. It goes under its native German name, rucksack. It is a large, square-cornered pocket, 20-24 inches wide and 16-18 deep, made of a light, strong, closely woven, specially treated fabric, of a greenish-gray color, and all but water-proof. The pocket is open at the top, slit a few inches down the outer face, is closed by a drawing string, and a flap buckles down over the gathered mouth. Two straps of adjustable length are secured, each at one end to the upper rim of the sack at the middle point, and at the other end to one of the lower corners. When the filled knapsack is in place, the supporting straps encircle the shoulders of the wearer, the closed mouth lies between the shoulder blades, the bottom corners extend just above the hips, while the weight of the burden, hanging from the shoulders, rests in the curve of the back. Genuine Tyrolean knapsacks are, since the War, no longer procurable in this country; good copies of them are, however, to be[18] had in our sporting-goods shops. The army knapsack is fairly good.

In case the pedestrian makes his tour in some remote region, where lodging places are not certainly to be found, he will be obliged to carry his blanket, and probably some supply of food. In such case, he will choose a larger knapsack. The sack known as the “Nessmuk” is a good one; and another, somewhat larger, is the “Gardiner.” These sacks are neither of them large enough to contain both blanket and the other necessary articles of camping equipment; the blanket should then be rolled and the roll arched upon and secured to the knapsack after the latter has been packed. Grommets sewed to the knapsack afford convenient means for securing the blanket roll in place. A still larger (and heavier) knapsack, large enough to contain one’s camp equipment, blanket and all, is called the “Merriam Back Pack.” It is recommended by an experienced camper, Mr. Vernon Bailey, chief field naturalist of the U. S. Biological Survey.

In hot weather the knapsack becomes uncomfortably wet with perspiration. Wicker frames, sometimes used to hold the sack away from the back to allow circulation of air beneath, are bothersome and uncomfortable.

For carrying heavier burdens short distances, as when making portage on a camping trip, a pack harness is used. Its name sufficiently explains its nature. An additional device, called a tump line, may, if desired, be bought and used with the pack harness. The tump line is a band which, encircling the load on one’s back, passes over the forehead. With its use the muscles of the neck are brought into play, aiding the shoulders[19] and back in carrying. It is astonishing, what an enormous burden a Canadian Indian can manage with the aid of harness and tump line. These articles may be bought at sportsmen’s stores, and at the posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company, in Canada.

The equipment for a summer walking tour, on which one is not obliged to carry a blanket, should weigh from ten to twenty pounds, according as one carries fewer or more of the unessentials. It is impossible to draw up lists of what is essential and what merely convenient, and have unanimity; one man will discard an article which to another is indispensable; the varying conditions under which journeys are taken will cause the same man to carry different articles at different times. The ensuing lists are intended to be suggestive and reasonably inclusive; for any given walk each individual will reject what he finds dispensable.

Requisites carried in one’s pockets: Watch; knife; money; compass; matches; handkerchief.

Requisites carried in the knapsack: Change of underclothes, stockings, and handkerchiefs; toilet articles; mending kit; grease for shoes.

Articles which, though not necessary, are altogether to be desired: Second outer shirt; second pair of walking shoes, particularly if the tour be a long one; sweater; pair of flannel trousers, light socks and shoes (gymnasium slippers are good), and necktie for evening wear; medicaments; notebook and pencil; postcards or stamped envelopes; a book to read.

Articles which may be requisite or desired, according to season or circumstance, to be carried in pocket or knapsack or, some of them, slung from the shoulders ready for use: Colored[20] glasses; pajamas; head net, as protection against mosquitoes; woolen underclothing; gloves or mittens; knitted helmet; naphtha soap, for washing woolens; map case; canteen; culinary articles; whistle; clothes brush; flashlight.

An indefinitely long list might be made of articles which a man will choose, according to taste and inclination. A bird-lover will carry a pair of binoculars; a collector, his cases; the fisherman, rod and fly-book. Some member of almost every walking party will carry a camera.

Notes upon some of the articles thus far enumerated will be useful:

The pocketknife should be large and strong, with one or two blades; leave in the showcase the knife bristling with tools of various kinds; see that the blades are sharp.

Let the watch be an inexpensive one; leave the fine watch at home; do not wear a wrist watch, particularly not in warm weather. At the wrists perspiration accumulates and the circulating blood is cooled. Any surface covering at that point, and particularly a close-fitting band, is in hot weather intolerable. But, regardless of season, a wrist watch is in the way, and is sure soon or late to be damaged. For the pedestrian its disadvantages greatly outweigh the small convenience it affords.

The best moneybag is a rubber tobacco pouch; a leather bill-folder and its contents will soon be saturated with perspiration.

A compass is a requisite in the wilderness, but not elsewhere. Regarding compasses, see further pages 75 and 116.

Matches should be carried in a water-tight case.

Toilet articles will include, at a minimum, soap,[21] comb, toothbrush and powder. A sponge or wash-rag is desirable. A man who shaves will, unless journeying in the wilderness, carry his razor. The soap may be contained in a box of aluminum or celluloid; the sponge in a sponge bag; the whole may be packed in a handy bag or rolled in a square of cloth and secured with strap or string.

Towel and pajamas are not indispensable; because of weight, they should be classed as pedestrian luxuries.

The mending kit will include thread, needles, and buttons, and here should be set down safety pins, too, an extra pair of shoestrings, and—if one wears them—an extra pair of rubber heels. A small carborundum whetstone may be well worth the carrying.

The best dressing for leather is mutton tallow. Various boot greases of which tallow is the base are on the market; one, called “Touradef,” is good. There are lighter animal oils, more easily applied; a good one is called “B-ver” oil. Mineral oils are not so good; “Viscol,” the most widely used of these, is sold in cans of convenient size and shape.

Medicaments should be few; a disinfectant (permanganate of potassium in crystalline form, or tablets of Darkin’s solution), a cathartic (cascara is best—it may be had in tabloid form, called “Cascaral Compound”), iodine, a box of zinc ointment, a roll of adhesive tape, and a small quantity of absorbent cotton will suffice for casual ailments. If one is going into the wilderness, he may well take a first-aid kit—with knowledge, how to use it—and medicine to deal with more violent sickness; ipecac and calomel. In malaria-infested regions, one should carry[22] quinine, with directions for administering. Talcum powder and cocoa butter are, in proper time, soothing. Citronella is a defense against mosquitoes; another repellent is a mixture of sweet oil or castor oil, oil of pennyroyal, and tar oil; spirits of ammonia is an antidote to their poison.

As to reading matter, each will choose for himself. The book carried may be the Bible, it may be “The Golden Treasury,” it may be “The Three Musketeers.” Again, it may be a handbook of popular science or a map of the stars.

Regarding map and map case, see page 75.

Colored glasses. On snowfields, on the seashore, where light is intense, the eyes should be screened. The best material, carefully worked out for this purpose, is Crooks glass. Its virtue lies in this: that it cuts out both the ultra-violet rays and the heat rays at the opposite end of the spectrum. Crooks glass may be had in two grades: Shade A and Shade B. Shade A, having the properties just described, is itself almost colorless; Shade B is colored, and cuts out, in addition, part of the rays of the normal spectrum. Goggles may be had of plain sheets of Crooks glass, and these will serve merely as a screen; but, if one wears glasses anyway, since two pairs worn at once are difficult to manage, it is well to have one’s prescription filled in Shade A, and (if one is going to climb snow peaks or walk the seabeach) then a second pair in Shade B. Ordinary colored glasses will serve a passing need; amethyst tint is best.

A canteen is requisite in arid regions and when climbing lofty mountains; elsewhere it is sometimes a justified convenience.

The writer well recalls the amazement of two Alpine guides some years ago when, on the top[23] of a snow peak, hot coffee was produced from a thermos bottle. He hastens to add that the thermos bottle was not his; he regards such an article as a sure mark of the tenderfoot.

Even though one be traveling light, the pleasures of a summer holiday may be widened by providing one meal a day and eating it out of doors. In order to accomplish this, one needs to carry a few culinary articles: A drinking cup, of course—that is carried in any case, conveniently hung to the belt. Then one should have plate, knife, fork, spoon, a small pail, perhaps a small frying pan, canisters of salt and pepper, a box of tea, a bag of sugar, a receptacle for butter. Most of these articles, and some toilet articles as well, may be had made of aluminum. Do not carry glassware, it is heavy and breakable. Don’t carry anything easily broken or easily put out of order. But even here make exceptions. For example, a butter jar is better than a butter box. The writer, for one, despises an aluminum drinking cup; when filled with hot coffee it is unapproachable, when cool enough not to burn the lips the coffee is too cold to be palatable; he, therefore, in spite of its weight, chooses to carry an earthenware cup.

A whistle will have value chiefly for signaling between members of a party.

A party of two, three, or four will carry more conveniences than a man journeying alone. For illustration, in the party, one camera is enough, one map case, one pail, one butter jar; and these may be distributed, so that, while carrying only part, each member of the party may enjoy all. With a camera in the party, a supply of films will be stowed away in a knapsack; a light, collapsible tripod may be worth the taking, if one[24] cares to secure pictures under poor conditions of light.

Two usual items of an amateur equipment, better left at home, are a hatchet and a pedometer. A hatchet is of no value, except in the wilderness, and not always is it worth carrying even there. Ordinarily a stout, sharp knife will answer every purpose. When one is on a camping trip on which he makes long stops, he will care for something better than a hatchet—a light axe. Regarding the uses of a pedometer see page 116.

If the contemplated tour lies through the wilderness, and accommodations for the night are not to be had under roofs along the way, one must carry his blanket. The blanket should be selected with lightness and warmth in view. The army blankets are fair, but softer, lighter, warmer ones may be had. Blankets should be of generous dimensions. A large double blanket should not exceed eight pounds in weight, and single blankets should weigh half as much. The Hudson’s Bay blankets are justly famous.

A blanket enveloped in a windproof blanket cloth is very much warmer than if not so shielded. Herein lies the virtue of a sleeping bag. Similarly, a tent—particularly a small one, for one or two men—keeps out wind and retains warm air. With the use of a tent, the weight of blankets may be less. The blanket cloth serves both to keep the wind from penetrating the blanket and also to keep the blanket dry. It prevents penetration of moisture from the ground; and, if one is not otherwise protected, it shields one from dew and from light rain. The blanket cloth, too, must be of the least weight consistent with service. Because of weight, rubber blankets[25] and oiled ponchos are out of the question. Better light oilcloth, or, better still, the material called “balloon silk” (really finely woven, long-fiber cotton) filled with water-proofing substance. “Tanalite” is the trade name for a water-proof material of this sort of a dark brown color. A tarpaulin seven feet square made of tanalite is, all things considered, the most serviceable blanket cloth. With blanket and tarpaulin, one’s pack should not exceed 25-30 pounds in weight. A mode of rolling blanket and tarpaulin and of securing the roll to the knapsack is suggested on page 18.

Blanket pins are worth carrying. By using them one may keep himself snug, nearly as well as in a sleeping bag.

A small cotton bag, useful in a pack, may be stuffed with clothing and serve as a pillow.

A satisfactory sleeping bag will hardly be found in the shops; those that are serviceable are too heavy for the pedestrian. And yet the idea embodied in the sleeping bag, the idea of attaining maximum warmth from the materials used, jumps precisely with the pedestrian’s needs.

The difficulty with the sleeping bags on the market is that they are made for gentlemen campers, and not for those who take up their beds and walk. For one thing, the gentleman camper has abundance of clothing, with changes of all kinds. But the pedestrian sleeps in his clothes. Of course he does. It would be folly for him to carry in his pack the equivalent of what he wears on his back. His day clothes should be serviceable as night clothes, too. All he need carry is the additional protection required when he is resting on the ground in the colder night hours. And, in addition, he will have a change[26] of the garments which lie next his skin; but no more. If when sleeping a man is not wearing all that he carries, then he is carrying more than is necessary. He may, indeed, have stuffed in his pack woolen underclothes, for night wear only. For another thing, in making choice between one material and another, the weight of the material is important in far greater degree to the walker than to the gentleman camper. With these considerations in mind, the pedestrian contrives his sleeping bag of the lightest material available to serve the ends in view.

Essentially, a sleeping bag is a closed covering of two layers: an inner layer of heat-insulating material, and an outer layer of water-tight, wind-tight material. Even the gentleman camper, scornfully referred to above, chooses the lightest, warmest blankets he can find; the pedestrian can do no better. However, he does not take so many. But, respecting the outer covering, the pedestrian refuses the heavy water-proofed duck of the ordinary sleeping bag, and selects instead water-proofed balloon silk.

The simplest sleeping bag may be made by folding a six by six wool blanket within a cover of water-proofed balloon silk and sewing together the bottom edges, and the side edges, too, from the bottom upward, to within a foot or so of the top. The bag measures approximately three feet by six, and should not weigh more than five and one half pounds.

Instead of the blanket, other material may be used. Men differ in the amount of covering they require; and then there are the inequalities of climate and season to be reckoned with. A suitable material, lighter than wool and affording less warmth, is sateen; a somewhat warmer, somewhat[27] heavier, substitute for the wool blanket is a down quilt. When still greater warmth is needed the blanket may be double, or blanket and down quilt may be combined.

A rectangular bag, such as that just described, may be criticized in two particulars: for one thing, it is not long enough for a man of good stature, and, for another thing, there is waste material in it. It would be just as warm and just as serviceable if, instead of being three feet wide at the bottom, it were at that point only two feet wide.

The specifications of an excellent sleeping bag for pedestrian use are given in a pamphlet published by the Appalachian Mountain Club, “Equipment for Mountain Climbing and Camping,” by Allen H. Bent, Ralph Lawson, and Percival Sayward, and with the courteous assent of the designers, are here incorporated.

A bag made on the dimensions given is suitable for a man five feet eleven inches tall.

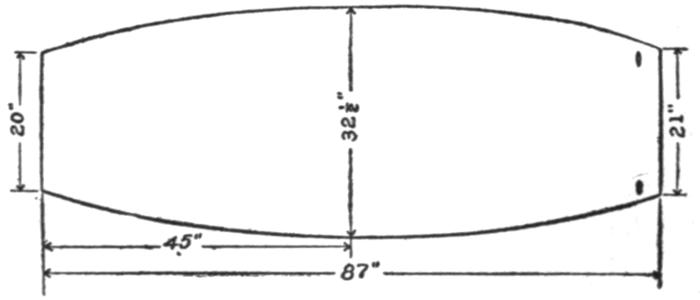

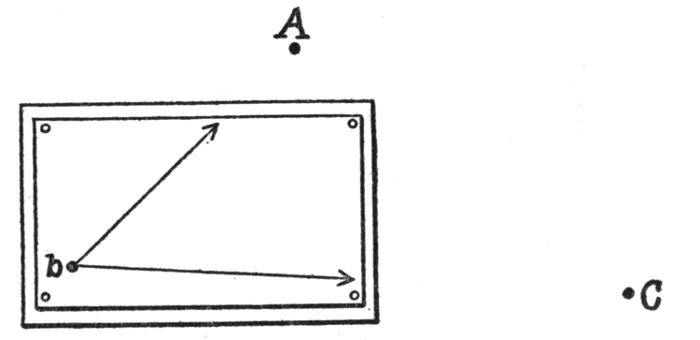

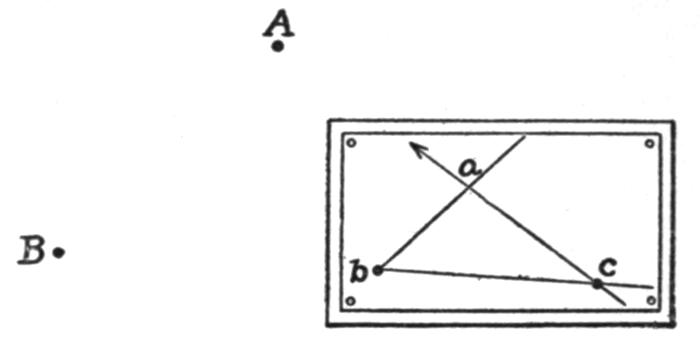

A strip of the material for the inner layer is cut to the pattern indicated below. It is 87 inches long, and at its widest point 32½ inches across. The widest point is 45 inches from the foot. At the foot the strip is 20 inches wide, and at the head, 21 inches. The sides are outwardly curved. This is the under strip.

A second upper strip is, in over-all dimensions, a duplicate of the first, but for the fact that it is 9 inches shorter. From the foot up and for a length of 78 inches it is identical with the first strip, but at that point it is cut short. A face opening is cut in the upper edge of the second strip, 10 inches across and 11 inches deep.

These two strips are superposed and their overlying edges are sewed together. All edges are properly hemmed or bound.

As the user lies in the bag, his feet just reaching the bottom, his face is encircled in the face opening. The excess length of the under strip then becomes a flap, to fold over his head. Buttons and buttonholes may be provided, as indicated in the drawings, to secure the flap in such position.

The material for the outer layer is cut to the same pattern, with sufficient enlargement of dimensions to allow the outer bag to contain the inner bag and cover it smoothly.

The outer material will preferably be water-proofed balloon silk (“tanalite”); the inner material may be sateen, or blanketing, or down quilt. The designers suggest still another material: Australian wool wadding, encased in sateen.[29] They say, “a brown sateen material is the best covering, as a very finely woven goods is necessary to keep the wool from working through. The bag does not need to be quilted, but should be ‘tied through’ about every six inches.”

The balloon silk outer bag should weigh about one and one-quarter pounds; the bag of sateen should weigh about two and one-quarter pounds. C. F. Hovey Co., 33 Summer St., Boston, and the Abercrombie & Fitch Co., Madison Ave. and Forty-fifth St., New York, have made bags to these specifications.

It remains only to add a word respecting the outer cover of balloon silk. Balloon silk, which in reality is a fine-woven cotton, is, relatively speaking, a delicate material, and furthermore it is not perfectly water-tight. The great advantage of lightness justifies its use. But the bag must be carefully handled, and after hard service the cover must be renewed.

Dr. Charles W. Townsend, of Boston, an experienced camper, writes:

“The sleeping bag is a home-made affair, that takes up only a small part of the room in a rucksack, and weighs four pounds. It is made of lamb’s wool wadding, lined with sateen, and covered with flannel. It is about six and one-half feet long and tapers, so as to be wider at the mouth than at the foot. With ordinary clothing, I have slept warm in it with a temperature of forty degrees. I have also a balloon-silk cover, which can be arranged to guy-ropes, to make a lean-to tent over my head, and gauze curtains for insects. I think that weighs two and one-half pounds.”

A tent will be carried when the route lies through unsettled country. In a sparsely settled[30] region, one will run the risk of heavy rain for a night or two, rather than bother with a tent; but in the wilderness, a tent is a necessity, for even such a tarpaulin as has been described as a suitable blanket cover, is not perfectly water-tight. One cannot sleep out in a driving rain storm. At a pinch, of course, one can make shift, and perhaps under rock ledge or shelter of boughs keep fairly dry; but after a wet night in the open, one needs assured protection the second night. The lightest tents are made of balloon silk; they weigh four pounds and upwards. Two men traveling together will have a tent in common and will distribute and equalize their burdens. As has been said, a tent affords warmth (particularly when carefully pitched, with a view to making it wind-tight) and, accordingly, blankets need not be so heavy. Though water-proofed balloon silk is not perfectly water-tight, one may keep perfectly dry in a balloon silk tarpaulin or sleeping bag, within a balloon silk tent.

A note on sleeping out is proper. In summer, when there is no rain, one should sleep under the open sky; he should choose as his sleeping place an exposed ridge, high and dry. In such a situation he will suffer least annoyance from mosquitoes, and, if the night be cool, he will be warmer than in the valley. Seldom in temperate climates is the night too warm for sleeping out of doors; but even on such a night the air on the hilltop is fresher. If it be windy, a wind-break may be made of boughs or of cornstalks (on a cool night in autumn a corn-shock may be made into a fairly comfortable shelter.) In case the evening threatens rain, one may well seek a barn for protection; if one is in the wilderness, he will search out an overhanging rock, or build[31] a lean-to of bark or boughs. Newspaper is a good heat insulator, and newspapers spread on the ground where one is to lie make the bed a warmer, drier one. Newspaper will protect one’s blanket from dew. Be careful when lying down to see that shoes and clothing are under cover. If the night proves to be colder than one has anticipated and one’s blanket is insufficient (or if, on another tour, the days are so hot that walking ceases to be a pleasure—though they have to be very hot for that), it may be expedient, at a pinch, to walk by night and rest by day.

Such food as must be carried will be selected to save weight, so far as is consistent with nutriment. Rolled oats are excellent; so also is soup powder (put up in “sausage” form, imitating the famous German erbswurst), and dried fruits and vegetables, powdered eggs, and powdered milk. The value of pemmican is known. All these articles may be obtained at groceries and at sportsmen’s stores. Seldom, however, will one wander so far as to be for many days beyond the possibility of buying food of more familiar form. Shelled nuts, raisins, dried fruit, malted milk tablets, and lime juice tablets are good to carry on an all-day excursion. Food bags of “paraffined” cotton fabric will prove useful. It is well to bear in mind that food may be distributed along the way, sent in advance by mail, to await at post offices one’s coming.

The special equipment of the mountaineer—alpenstock, ice axe, rope, crampons, scarpetti, etc.—need only be mentioned. They are not needed in climbing the mountains of eastern America, but only on giddy peaks, snowfields, and glaciers. Those interested will consult the works on mountaineering mentioned in the Bibliography.

From the pages of a pamphlet of the Appalachian Mountain Club this note is taken:

“Equipment does not end with the purchase of proper food, clothing, climbing and camping outfit. The prospective climber should give some thought to his physical and mental equipment. A strong heart, good lungs, and a reasonable amount of physical development and endurance are among the requisites and so, too, are courage, caution, patience and good nature. If in addition he is interested in topography, geology, photography, animal or plant life, by so much the more is his equipment, and consequently his enjoyment, increased.”

As to speed of walking and distance, see below, page 51; as to preliminary walking, in preparation for a tour, see page 53.

One hardly needs the admonitions, eat plain food, sleep long, and keep body and clothing clean. The matter of food becomes complicated when one has to carry the supply of a day or two or of several days with him. Be careful to get, so far as possible, a large proportion of vegetable food—fresh vegetables and fruit.

When walking, the system requires large amounts of water, and, generally speaking, one should drink freely. If one stops by a roadside spring on a hot day, he should rest a few minutes before drinking, and, if the water be very cold, he should drink sparingly. It is refreshing before drinking, and sometimes instead of drinking, to rinse mouth and throat with spring water. In the Alps the guides caution one not to drink snow water. In settled regions, drink boiled water only, unless assured of the purity of the[33] source. Beware of wells. It is a matter of safety, when traveling, to be inoculated against typhoid fever. Practice restraint in the use of ice cream, soda water, sweets, coffee, and tea.

The pedestrian should be careful to get as much sleep as normally he requires at home, and somewhat more. He may not be so regular in hours, for he will find himself inclined to sleep an hour at midday, and at times to walk under the starlight, to be abroad in the dawn. And a walking tour would be a humdrum affair, if he did not yield to such inclination.

A bath at the end of the day—a sponge bath, if no better offers—is an indispensable comfort. While on the march one will come upon inviting places to bathe. Bathe before eating, not immediately after. If the water is very cold, it is well to splash and rub one’s body before plunging in. If much bathing tends to produce lassitude, one should limit himself to what is necessary.

Don’t overdo; on the march, when tired out, stop at the first opportunity—don’t keep going merely to make a record. Don’t invite fatigue. If, in hot weather, free perspiration should fail, stop immediately and take available measures to restore normal circulation.

Lameness in muscles is due to the accumulation of waste matter in the tissues; elimination may be aided and lameness speedily relieved by drinking hot water freely and by soaking one’s body in a warm bath: the internal processes are accelerated, in freer blood circulation, while much is dissolved out through the pores of the skin. At the end of a long hard walk, the most refreshing thing is a drink—not of ice water, not of soda water, but a pint or so of hot water. Rubbing oil as a remedy for lame muscles is hardly worth[34] carrying; alcohol is a mistake. Bruised muscles should be painted lightly with iodine.

Care of feet. Always wash the feet thoroughly at the end of a tramp, and dry carefully, particularly between the toes. If the skin cracks and splits between the toes, wash at night with boric acid and soften with vaseline. It is better to allow toenails to grow rather long, and in trimming cut them straight across.

When resting at noon take off shoes and stockings, and, before putting them on again, turn the stockings inside out. If the weather be mild, let the feet remain bare until about to set out again; if there be water available, bathe the feet immediately on stopping. If, on the march, the arch of the foot should grow tired, consciously “toe in.”

If there is rubbing, binding, squeezing, with consequent tenderness at any point, stop at once, take off shoe and stocking, and consider what is to be done. It may suffice to protect the tender spot, applying a shred of absorbent cotton secured with a strip of adhesive tape; perhaps the thickness of the stocking may be changed, or the lacing of the shoe be eased or tightened. By tighter lacing sometimes the play of the foot within the shoe may be diminished and undesirable rubbing or squeezing overcome. Talcum powder sprinkled on the foot will help to relieve rubbing, and soap rubbed on the stocking outside, above the tender place, is efficacious.

Sometimes, in spite of forethought, one may find one’s self walking in ill-fitting shoes; for example, the shoes though broad enough may be too short, and one’s toes in consequence may be cramped and squeezed in the toe of the shoe—particularly on down grades—until they become tender and even blistered. If then other expedients[35] fail, one has to examine his shoe carefully, determine precisely where the line of binding strain lies, and then—remembering that the shoe as it is, is worthless to him—slit leather and lining through, in a line transverse to the line of strain.

Should a blister, in spite of care, develop, let it alone, if possible. Don’t interfere with nature’s remedial processes. But, if one must go on walking with the expectation that the blister unless attended to will tear open, then one should drain it—not by pricking it through, however. Take a bright needle, sterilize it in the flame of a match, and run it under the skin from a point to one side, and so tap the blister. Then cover the area with adhesive tape. If there is abrasion, paint the spot with iodine, or apply a few crystals of permanganate of potassium and a drop or two of water, then cover with absorbent cotton and adhesive tape.

Be careful, on setting out in the morning, that any soreness or lameness of the preceding day has been met by the measures described.

Corns are caused by wearing tight or ill-fitting shoes. If one has a corn, he should get rid of it before attempting distance walking, and should thereafter wear shoes such as to assure him immunity.

For sunburn, use talcum powder or cocoa butter. Do not expose large areas of the body to sunburn.

A cramp in the side may easily be relieved by drawing and retaining a deep breath, and bending over.

The bowels should be kept open, and will be, if one orders his food aright. Constipation is to be carefully guarded against. One may, in spite of[36] himself, after hard walking in hot weather, find difficulty. A harmless emergency relief is an enema of a few ounces of the colorless inert oil now sold under such names as “Russian” oil and “Nujol” (the Standard Oil Company’s preparation).

Medicines are to be used only in emergency: cascara for constipation, or, in case of a sudden violent onset of illness, calomel; capsicum plaster for internal inflammation. But hot water within and without will generally relieve distress, and is the best remedy. But do not experiment; if a physician is available, call him.

Ammonia is an antidote for insect stings.

Snake-bites are, newspaper reports to the contrary, very, very rare. The bite of a poisonous serpent (rattlesnake or copperhead) requires heroic treatment. Suck the wound, cut it out immediately with a sharp knife, fill the incision with permanganate of potassium crystals and drop water upon the permanganate.

Care of clothing. Underclothes and stockings worn today may be washed tomorrow at the noon hour. Shirt, trousers—and underclothing too—should go to the tub every few days, as opportunity offers.

Shoes should be cleaned each day, washed in cold water and greased. If wet they should be carefully dried in gentle heat. Leather is easily ruined by scorching; never dry a shoe in heat unendurable to the hand. Shoes packed in newspaper overnight will be measurably dried by absorption. Keep the leather pliant with grease or oil, but not saturated. If one is going to walk through bogs, or in shallow water, then his shoes should be copiously oiled, but ordinarily one should oil his shoes with sparing hand.

Dr. Finley, President of the University of the State of New York, and Commissioner of Education, finely says:[1] “It is figurative language, of course, to speak of God’s ‘walking’ with man. But I do not know where to find a better expression for the companionship which one enjoys when walking alone on the earth. I should not speak of this if I thought it was an experience for the patriarchs alone or for the few. A man does not know one of the greatest satisfactions of life if he has not had such walks.”

The prophets of the cult—Hazlitt and Stevenson—are quite eloquent on the point, that the first joys of walking are reserved for those who walk alone; even Emerson cynically observes that a dog may on occasion be better company than a man. But the solitary Thoreau admits that he sometimes has a companion, while sociable Lawrence Sterne prettily says, “Let me have a companion of my way, were it but to remark how the shadows lengthen as the sun declines.”

Ordinarily, we prefer—most of us—to walk in company; if the tour is an extended one, continuing through many days, we certainly do. And nothing is more important than the choice of companions. A mistake here may be a kill-joy. Daily, hourly intercourse rubs individuality upon individuality, till every oddity, every sensitive point, is worn to the quick. Be forewarned, then, and be sure of one’s companions. Conversely, let a man be sure of himself, resolutely refusing to find offense, or to lose kindliness, good humor, and good will. “’Tis the best of humanity,” says Emerson, “that goes out to walk.”

A common interest in things seen, stimulated perhaps by reading matter carried along, may be the selective process in making up a party; but friendship underlies all.

A proved company of two, three, or four is best. With greater numbers, the party loses intimacy and coherence; furthermore, if dependent on hospitality by the way, difficulties arise. A housewife who willingly provides for two, may hesitate to entertain six.

If there be one in the party who has an aptitude for it, let him keep a journal (in the form of letters home, perhaps). Such a record, illustrated by photographs, is a souvenir to afford long-continued delight.

When walking in out-of-the-way places it is the part of prudence always to have a companion; for, otherwise, in case of mishap, a man might be in sorry plight, or even in actual danger.

Any day—every day, if that were possible. Says Thoreau, “I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day at least [in the open]”; and, again, he says of himself that he cannot stay in his chamber for a single day “without acquiring some rust.”

Recall Thoreau’s Journals. Their perennial charm lies largely in this, that he is abroad winter and summer, at seedtime and at harvest, in sun and rain, making his shrewd observations, finding that upon which his poetic fancy may play, finding the point of departure for his Excursions in Philosophy.

“The first care of a man settling in the country should be to open the face of the earth to himself by a little knowledge of Nature, or a great deal, if he can; of birds, plants, rocks, astronomy; in short, the art of taking a walk. This will draw the sting out of frost, dreariness out of November and March, and the drowsiness out of August.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Resources.”

The Daily Walk. Walking is to be commended, not as a holiday pastime, merely, but as part of the routine of life, in season and out. Particularly to city-dwellers, to men whose occupations are sedentary, is walking to be commended as recreation. Will a man assert himself too busy?—his neighbor plays a game of golf a week; he himself, perhaps, if he will admit it,[42] is giving half a day a week to some pastime—may be a less wholesome one.

It is worth a man’s while to reckon on his walking every day in the week. It may well be to his advantage, in health and happiness, to extend his daily routine afoot—perhaps by dispensing with the services of a “jitney” from the suburban station to his residence, perhaps by leaving the train or street car a station farther from home, perhaps by walking down town to his office each morning.

The Weekly Walk. The environs of one’s home can scarcely be too forbidding. A range of ten miles out from Concord village satisfied Thoreau throughout life. Grant the surroundings of Concord exceptional—Thoreau’s demands were exceptional. Those who will turn these pages will be for the most part city folk; the resident of any of our cities may, with the aid of trolley, railway, and steamboat, discover for himself a dozen ten-mile walks in its environs—many of them converging to his home, some macadam paved and so available even in the muddy season, and any one of them possible on a Saturday or a Sunday afternoon.

What could a pedestrian ask more? A three-hour walk of a Saturday afternoon—exploring, perhaps, some region of humble historic interest, studying outcroppings of coal or limestone, making new acquaintance with birds, bees, and flowers, and enjoying always the wide sky, the sweep of the river, the blue horizon. No other recreation is comparable to this.

It is pleasurable to walk in fair, mild weather; but there is pleasure on gray, cold, rainy days, too. To exert the body, to pit one’s strength against the wind’s, to cause the sluggish blood to[43] stream warm against a nipping cold, to feel the sting of sleet on one’s face—to bring all one’s being to hearty, healthful activity—by such means one comes to the end, bringing to his refreshment gusto, to his repose contentment.

The consistent pedestrian will score to his credit, every week throughout the year, ten miles of vigorous, sustained tramping. Five hundred miles a year makes an impressive showing, and is efficacious: it goes far to “slam the door in the doctor’s nose.”

The Walking Tour. Apart from, or, better, in addition to the perennial weekly walking about one’s home, there is the occasional walking tour: a two or three-day hike, over Labor Day, perhaps, or Washington’s Birthday; and then there is the longer vacation tour of two or three weeks’ duration.

With important exceptions, we, in our northern latitudes, arrange our walking tours in summer time. And, so far as concerns the exceptions, it will here suffice to remind ourselves of mountain climbing on snowshoes in winter, of ski-running and skating, and of the winter carnivals of sport held in the Adirondacks, in the Alps, and in the Rocky Mountains. In our southern states, however, no disadvantage attaches to winter; to the contrary, over a great part of that region, winter is the pleasanter season for the pedestrian. But summer is the season of vacations, and is, generally speaking, the time of good roads, fair skies, and gentle air. Then one can walk with greatest ease and freedom.

The choice of the particular fortnight for the “big hike” may be governed by all sorts of considerations; if the expedition be ornithological, and there is free choice, it will be taken in May[44] or June, or perhaps in September; if to climb Mt. Ktaadn, it will preferably be in August. Again, one’s employer may, for his own reasons, fix the time. It is well, therefore, to formulate general statements, helpful in making choice of place, when once the season has been fixed.

In early summer, from the time the snow melts till mid July, the north woods are infested with buzzing, stinging, torturing mosquitoes; to induce one to brave these pests, large countervailing inducements must needs appear. Mountaineering in temperate latitudes is less advisable in the early summer than later; there is more rain then, and nights are cold, and, in the high mountains, soft snow is often an impedance. Throughout much of our country, June is a rainy month. In May and June, accordingly, and early July, one should by preference plan his walk in open settled country, in the foothills of mountain ranges, or across such pleasant regions as central New York or Wisconsin.

Late July, August and September are, for the most part, hot and dusty. At that season, accordingly, the great river basins and wide plains should be avoided; one should choose rather the north woods, the mountains, or the New England coast.

For the pedestrian September in the mountains and October everywhere are the crown of the year; the fires of summer are then burning low, storms are infrequent, the nip in the air stirs one to eagerness for the wide sky and the open road.

“The world has nothing to offer more rich and entertaining than the days which October always brings us, when after the first frosts, a steady shower of gold falls in the strong south wind[45] from the chestnuts, maples and hickories: all the trees are wind-harps, filling the air with music; and all men become poets, and walk to the measure of rhymes they make or remember.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Country Life.”

If one is so fortunate as to have his holiday abroad, he will find the Italian hills or the Riviera delightful either in early spring or in late autumn; he will find the Alps at their best in midsummer; and, at intermediate seasons, there remain the Black Forest and the regions of the Seine, the Rhine, and the Elbe. As for Scotland and Ireland, no one has ventured to say when the rains are fewest.

“Can you hear what the morning says to you, and believe that? Can you bring home the summits of Wachusett, Greylock, and the New Hampshire hills?”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Country Life.”

It is well, and altogether pleasantest, on the hike, to be under way early in the morning; and sometimes—particularly if the day’s march be short—to finish all, without prolonged stop. Ordinarily, it is preferable to walk till eleven or twelve o’clock, then to rest, wash clothing, have lunch, read, sleep, and, setting out again in the middle of the afternoon, to complete the day’s stage by five or six o’clock. Afterward come bath, clean clothes, the evening meal, rest, and an early bed.

But one’s schedule should not be inflexible; one should have acquaintance with the dawn, he should know the voices of the night. One forgets how many stars there are, till he finds himself[46] abroad at night in clear mountain air. An all-night walk is a wonderful experience, particularly under a full moon; and, in intensely hot weather, a plan to walk by night may be a very grateful arrangement.

Dr. John H. Finley, of the University of the State of New York, writes in the Outlook[3] reminiscently of walking by night:

“But the walks which I most enjoy, in retrospect at any rate, are those taken at night. Then one makes one’s own landscape with only the help of the moon or stars or the distant lights of a city, or with one’s unaided imagination if the sky is filled with cloud.

“The next better thing to the democracy of a road by day is the monarchy of a road by night, when one has one’s own terrestrial way under guidance of a Providence that is nearer. It was in the ‘cool of the day’ that the Almighty is pictured as walking in the garden, but I have most often met him on the road by night.

“Several times I have walked down Staten Island and across New Jersey to Princeton ‘after dark,’ the destination being a particularly attractive feature of this walk. But I enjoy also the journeys that are made in strange places where one knows neither the way nor the destination, except from a map or the advice of signboard or kilometer posts (which one reads by the flame of a match, or, where that is wanting, sometimes by following the letters and figures on a post with one’s fingers), or the information, usually inaccurate, of some other wayfarer. Most of these journeys have been made of a necessity that has prevented my making them by day, but I have in every case been grateful afterward for the necessity. In this country they have been usually among the mountains—the Green Mountains[47] or the White Mountains or the Catskills. But of all my night faring, a night on the moors of Scotland is the most impressive and memorable, though without incident. No mountain landscape is to me more awesome than the moorlands by night, or more alluring than the moorlands by day when the heather is in bloom. Perhaps this is only the ancestors speaking again.

“But something besides ancestry must account for the others. Indeed, in spite of it, I was drawn one night to Assisi, where St. Francis had lived. Late in the evening I started on to Foligno in order to take a train in to Rome for Easter morning. I followed a white road that wound around the hills, through silent clusters of cottages tightly shut up with only a slit of light visible now and then, meeting not a human being along the way save three somber figures accompanying an ox cart, a man at the head of the oxen and a man and a woman at the tail of the cart—a theme for Millet. (I asked in broken Italian how far it was to Foligno, and the answer was, ‘Una hora’—distance in time and not in miles.) Off in the night I could see the lights of Perugia, and some time after midnight I began to see the lights of Foligno—of Perugia and Foligno, where Raphael had wandered and painted. The adventure of it all was that when I reached Foligno I found that it was a walled town, that the gate was shut, and that I had neither passport nor intelligible speech. There is an interesting walking sequel to this journey. I carried that night a wooden water-bottle, such as the Italian soldiers used to carry, filling it from the fountain at the gate of Assisi before starting. Just a month later, under the same full moon, I was walking between midnight and morning in New Hampshire. I had the same water-bottle and stopped at a spring to fill it. When I turned the bottle upside down, a few drops of water from the fountain of Assisi fell[48] into the New England spring, which for me, at any rate, has been forever sweetened by this association.

“All my long night walks seem to me now as but preparation for one which I was obliged to make at the outbreak of the war in Europe. I had crossed the Channel from England to France, on the day that war was declared by England, to get a boy of ten years out of the war zone. I got as far by rail as a town between Arras and Amiens, where I expected to take a train on a branch road toward Dieppe; but late in the afternoon I was informed that the scheduled train had been canceled and that there might not be another for twenty-four hours, if then. Automobiles were not to be had even if I had been able to pay for one. So I set out at dusk on foot toward Dieppe, which was forty miles or more distant. The experiences of that night would in themselves make one willing to practice walking for years in order to be able to walk through such a night in whose dawn all Europe waked to war. There was the quiet, serious gathering of the soldiers at the place of rendezvous; there were the all-night preparations of the peasants along the way to meet the new conditions; there was the pelting storm from which I sought shelter in the niches for statues in the walls of an abandoned château; there was the clatter of the hurrying feet of soldiers or gendarmes who properly arrested the wanderer, searched him, took him to a guard-house, and detained him until certain that he was an American citizen and a friend of France, when he was let go on his way with a ‘Bon voyage’; there was the never-to-be-forgotten dawn upon the harvest fields in which only old men, women, and children were at work; there was the gathering of the peasants with commandeered horses and carts in the beautiful park on the water-front at Dieppe; and there was much besides; but they were experiences for the[49] most part which only one on foot could have had.”

In answer to a request for a contribution to this handbook, Dr. Finley replies generously, and to the point:

“I have never till now, so far as I can recall, tried to set down in order my reasons for walking by night. Nor am I aware of having given specific reasons even to myself. It has been sufficient that I have enjoyed this sort of vagrancy. But since it has been asked, I will try to analyze the enjoyment.

“1. The roads are generally freer for pedestrians by night. One is not so often pushed off into the ditch or into the weeds at the roadside. There is not so much of dust thrown into one’s face or of smells into one’s nostrils. More than this (a psychological and not a physical reason) one is not made conscious by night of the contempt or disdain of the automobilist, which really contributes much to the discomfort of a sensitive traveler on foot by day. I have ridden enough in an automobile to know what the general automobile attitude toward a pedestrian is.

“2. Many landscapes are more beautiful and alluring by moonlight or by starlight than by sunlight. The old Crusader’s song intimates this: ‘Fair is the sunlight; fairer still the moonlight and all the twinkling starry host.’ And nowhere in the world have I appreciated this more fully than out in Asia Minor, Syria, and Palestine, where the Crusaders and Pilgrims walked by night as well as by day. But I have particularly agreeable memories, too, of the night landscapes in the Green Mountains.

“3. By night one is free to have for companions of the way whom one will out of any age or clime, while by day one is usually compelled, even when one walks alone, to choose only from the living and the visible. In Palestine, for example,[50] I was free to walk with prophet, priest, and king by night, while by day the roads were filled with Anzacs and Gurkhas and Sikhs, and the like. Spirits walk by day, but it takes more effort of the imagination to find them and detach them. One of my most delightful night memories is of a journey on foot over a road from Assisi that St. Francis must have often trod.

“4. There is always the possibility of adventure by night. Nothing can be long or definitely expected, and so the unexpected is always happening. I have been ‘apprehended’—I do not like to say ‘arrested’—several times when walking alone at night. Once, in France, I was seized in the street of a village through which I was passing with no ill intent, taken to a guard-house and searched. But that was the night of the day that war was declared. Once, and this was before the war, I was held up in Rahway, toward midnight, when I was walking to Princeton. I was under suspicion simply because I was walking, and walking soberly, in the middle of the road.

“5. By day one must be conscious of the physical earth about one, even if there is no living humanity. By night, particularly if one is walking in strange places, one may take a universe view of things. Especially is this true if the stars are ahead of one and over one.

“6. Then it is worth while occasionally to see the whole circle of a twenty-four hour day, and especially to walk into a dawn and see ‘the eye-lids of the day.’ I had the rare fortune to be on the road in France when the dawn came that woke all Europe to war. And I was again on the road one dawn when the war was coming to its end out in the East.

“7. There are as many good reasons for walking by night as by day. But no better reason[51] than that one who loves to walk by night can never fear the shadow of death.

“You will ask if I have any directions to give. I regret to say that I have not. I seldom walk with else than a stick, a canteen of water, and a little dried fruit in my pocket—and a box of matches, for sometimes it is convenient to be able to read signboards and kilometer posts even by night.”

Stevenson speaks contemptuously of “the championship walker in purple stockings,” and indeed it is well to heed moderate counsel, lest, in enthusiasm for walking, one misses after all the supreme joys of a walk. At the same time, there is danger of too little as well as of too much. To loiter and dilly-dally (to borrow again Stevenson’s phrase) changes a walk into something else—something more like a picnic.

Really to walk one should travel with swinging stride and at a good round pace. Ten or twenty miles covered vigorously are not half so wearying to body nor to mind as when dawdled through. One need not be “a champion walker in purple stockings” covering five miles an hour and fifty miles a day.