| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/rudestonemonumen00ferg |

When, in the year 1854, I was arranging the scheme for the 'Handbook of Architecture,' one chapter of about fifty pages was allotted to the Rude Stone Monuments then known. When, however, I came seriously to consult the authorities I had marked out, and to arrange my ideas preparatory to writing it, I found the whole subject in such a state of confusion and uncertainty as to be wholly unsuited for introduction into a work, the main object of which was to give a clear but succinct account of what was known and admitted with regard to the architectural styles of the world. Again, ten years afterwards, while engaged in re-writing this 'Handbook' as a 'History of Architecture,' the same difficulties presented themselves. It is true that in the interval the Druids, with their Dracontia, had lost much of the hold they possessed on the mind of the public; but, to a great extent, they had been replaced by prehistoric myths, which, though free from their absurdity, were hardly less perplexing. The consequence was that then, as in the first instance, it would have been necessary to argue every point and defend every position. Nothing could be taken for granted, and no narrative was possible. The matter was, therefore, a second time allowed quietly to drop without being noticed. I never, however, lost sight of the subject, and I hoped some time or other to be able to treat of it with the fulness its interest deserves; and in order to forward this project, in July, 1860, I wrote an article in the 'Quarterly Review,' entitled 'Stonehenge,' in which I stated the views I had then formed on the subject; and again, ten years afterwards, in April of last year, another article, entitled 'Non-Historic Times' in the same journal, in which I added such new facts and arguments as I [Pg vi] had gathered in the interval. The principal object it was sought to attain in writing these articles, was to raise a discussion on the moot points which I hoped would have tended towards settling them. If any competent archæologist had come forward, and could have pointed out the weak point in the argument, he would have rendered a service to the cause; or if any leading authority had endorsed the views advocated in these articles, the public might have felt some confidence in their correctness. This expectation has not been fulfilled, but they have probably not been without their use in preparing the minds of others for the views advanced in them, while, as no refutation has appeared, and no valid objection has been urged against them, either in public or in private, I may fairly consider myself justified in feeling considerable confidence in their general correctness.

Till antiquaries are agreed whether the circles are temples or tombs or observatories, whether the dolmens are monuments of the dead or altars for sacrificing living men, and whether the mounds are tombs or law courts, it seems impossible, without arguing every point, to write anything that will be generally accepted. Still more, till it is decided whether they are really prehistoric or were erected at the periods where tradition and history place them, it seems in vain to attempt to explain in a simple narrative form either their age or uses. As a necessary consequence of all this confusion, it is scarcely practicable at present to compile a work which shall be merely a Historical and Statistical account of the Rude Stone Monuments in all parts of the world; but till something is settled and agreed upon, we must be content with one which to a certain extent, at least, takes the form of an argument. Many of its pages which would have been better employed in describing and classifying, are occupied with arguments against some untenable theory or date, or in trying to substitute for those usually accepted, some more reasonable proposition. Notwithstanding this, however, it is hoped [Pg vii] that this work will be found to contain a greater number of new facts regarding Rude Stone Monuments, and of carefully selected illustrations extending over a larger area, than have yet been put together in a volume of the same extent.

It may fairly be asked, and no doubt will, how I dare to set up my opinions with regard to these monuments in opposition to those of the best informed antiquaries, not only in this country but on the Continent? The answer I would venture to suggest is, that no other antiquary, so far as I am aware, has gone so carefully and fully into the whole subject, or has faced all the difficulties with which the questions are everywhere perplexed. The books that have hitherto been written are either the work of speculative dreamers, like Stukeley, Higgins, or Vallancey, who having evolved a baseless theory out of their own inner consciousness, seek everywhere for materials to prop it up, and are by no means particular as to the inferences they draw from very obscure or slender hints: or they are, on the other hand, the works of local antiquaries, whose opinions are influenced mainly by what they find in their own researches. The works of such men are invaluable as contributions to the general stock of knowledge, but their theories must be received with caution, as based on too narrow a foundation either of facts or inferences; for it need hardly be insisted upon that no amount of local experience can qualify any one to write on such a subject as this. It does not even seem sufficient that an author should be familiar with all the varieties of megalithic remains. Unless he has also mastered the other forms of architectural art, and knows in what manner and from what motives the styles of one people are adopted from or influenced by that of another race, he will hardly be able to unravel the various tangled problems that meet him at every step in such an investigation. When looked at, however, from the same point of view, and judged by the same laws as other styles, that of the dolmen builders does not appear either [Pg viii] mythical or mysterious. They seem to be the works of a race of men actuated by the same motives and feelings as ourselves, and the phenomena of their arts do not seem difficult of explanation.

It is because I have spent the greater part of my life in studying the architecture of all nations, and through all ages, that I believe myself entitled to express an opinion on the perplexed questions connected with megalithic remains, though it differs widely from that generally received, and that I dare to face the objection which is sure to be raised that my work is based on too narrow an induction, and that I have overlooked the evidences of primæval man which exist everywhere. It is not, however, that I have neglected either the evidence from the drift, or from the caves, but that I have rejected them as irrelevant, and because I can hardly trace any connexion between them and the megalithic remains, to the investigation of which this work is specially devoted. I have also purposely put on one side all reference to hut circles, Picts' houses, brochs, and other buildings composed of smaller stones, which are generally mixed up with the big stone monuments. I have done this, not because I doubt that many of these may be coeval, but because their age being doubtful also, it would only confuse and complicate the argument to introduce them, and because, whenever the age of the great stones is determined these minor monuments will easily fit into their proper places. At present, neither their age or use throws any light either for or against that of the great stones.

It need hardly be remarked, to anyone who knows anything about the subject, that the difficulties in the way of writing such a book as this are enormous, and I do not believe any one could, in a first edition at all events, avoid all the pitfalls that surround his path. The necessary information has to be picked up in fragments from some hundreds of volumes of travels, or the Transactions and Journals of learned Societies, none of which are specially devoted to the subject, and very [Pg ix] few of which are indexed, or have any general résumé of their contents. Add to this that the older works are all untrustworthy, either from the theories they are twisted to support, or from bad drawing or imperfect knowledge; and too many of the modern examples are carelessly sketched and still more carelessly engraved. Another source of difficulty is, that it is rare with readers of papers and writers in journals to quote references, and sometimes when these are given they are wrong. I have thus been forced to limit the field from which my information is taken very considerably. I have tried hard to introduce no illustration I could not thoroughly depend upon, and I have not intentionally quoted a single reference I had not verified from the original authorities.

In one respect I cannot but feel that I may have laid myself open to hostile criticism. On many minor points I have offered suggestions which I do not feel sure that I could prove if challenged, and which, consequently, a more prudent man would have left alone. I have done this because it often happens that such suggestions turn the attention of others to points which would otherwise be overlooked, and may lead to discoveries of great importance; while if disproved, they are only so much rubbish swept out of the path of truth, and their detection can do no harm to any one but their author. Whatever my shortcomings, I am too much in earnest to look forward with any feelings of dismay to such a contingency.

Besides the usual motives which prompt the publication of such a work as this, there are two which seem to render its appearance at this time particularly desirable. The first is to promote enquiry by exciting interest in the subject; the second is to give precision to future researches. So long as everything is vague and mythical, explorers do not know what to observe or record: this work, however, presents a distinct and positive view of the age or use of the megalithic remains, and every new fact must tend either to upset or confirm the theory it seeks to establish. With this view, I need hardly add that I shall be extremely grateful for any new facts or additional sources of [Pg x] information which may be communicated to me, either through the public press or privately. Numerous persons having local experience must know many things which may have escaped me. It is very probable that these may induce me to modify some of the details of this work; but so much is now known, and the field from which my inductions are gathered is so wide, that I have no fear that they will touch the main arguments on which the theory of this work is founded.[1]

However this may be, I trust that this work may lay claim to being, in one respect at least, a contribution to the cause of truth regarding the much-disputed age and use of these Rude Stone Monuments. It states distinctly and without reserve one view of the mooted question, and so openly that any one who knows better can at once pull away the prop from my house of cards and level it with the ground. If one thing comes out more clearly than another in the course of this investigation, it is that the style of architecture to which these monuments belong is a style, like Gothic, Grecian, Egyptian, Buddhist, or any other. It has a beginning, a middle, and an end; and though we cannot yet make out the sequence in all its details, this at least seems clear—that there is no great hiatus; nor is it that one part is prehistoric, while the other belongs to historic times. All belong to the one epoch or to the other. Either it is that Stonehenge and Avebury and all such are the temples of a race so ancient as to be beyond the ken of mortal man, or they are the sepulchral monuments of a people who lived so nearly within the limits of the [Pg xi] true historic times that their story can easily be recovered. If this latter view is adopted, the whole, it appears to me, hangs so perfectly together, and presents so complete and so rational an account of all the local or historical facts which are at present known concerning these remains, that I feel great confidence that it must eventually be adopted as the true explanation of the phenomena. If it is it will have this further advantage, that when any serious attempt is made to investigate either the history or the manners and customs of these ancient peoples, it is probable that these megalithic remains will be found to be the best and surest guide.

From the circumstances above detailed, this work would have been a much more meagre production than it is hoped it will be found, had it not been for the kindness of many friends who have assisted me in my undertaking. My chapter on Ireland, for instance, would have been much less full had not Sir W. Wilde, Mr. Eugene Conwell, and Mr. Moore assisted me with illustrations and information; and for my knowledge of Scotch antiquities I owe much to my friend John Stuart, of Edinburgh, while Sir Henry Dryden's invaluable collections have been of the utmost service to me both as regards Scotland and Brittany. Professor Säve and Mr. Hildebrand have materially aided me in Sweden, and M. Riaño in Spain; but the post apparently suppresses any correspondence on archæological subjects with France and Denmark. Without the kindness of Sir Bartle Frere and his elder brother in lending me drawings, or Colonel Collinson in procuring information, my account of the Maltese antiquities would have been very much less satisfactory than it is; and I also owe my best thanks to Mr. Walhouse, of the Madras Civil Service, and Mr. Burgess, of Bombay, for their assistance in respect to Indian antiquities. I have tried in the text to acknowledge my obligations to these and all other parties who have assisted me. If I have omitted any, I trust they will believe it has not been intentionally, but through inadvertence.

For myself, I hope I may be allowed to plead that I have spared no pains in investigating the materials placed at my disposal, and no haste in forming my conclusions; and I may also add, they are by no means those of predilection or that I wished to arrive at. When I first took up the subject, I hoped that the rude stone monuments would prove to be old,—so old, indeed, as to form the "incunabula" of other styles, and that we might thus, by a simple process, arrive at the genesis of styles. Bit by bit that theory has crumbled to pieces as my knowledge increased, and most reluctantly have I been forced to adopt the more prosaic conclusions of the present volume. If, however, this represents the truth, that must be allowed to be an ample compensation for the loss of any poetry which has hitherto hung round the mystery of the Rude Stone Monuments.

Langham Place, Dec. 1, 1871.

Footnotes

[1] What is really wanted now is, a "Megalithic Monument Publication Society." After the meeting of the Prehistoric Congress at Norwich, a committee for this purpose was formed in conjunction with the Ethnological Society. After several meetings everything was arranged and settled, but, alas! there were no funds to meet the necessary expenses, or, at least, risk of publication, and the whole thing fell through. To do what is wanted on a really efficient scale a payment or a guarantee of 1000l. would be necessary, and that is far beyond what is attainable in this poor country. If it could be obtained, the materials are abundant. Sir Henry Dryden alone could fill a volume with the materials he already possesses; and Lieut. Oliver, Mr. Conwell, and others, have drawings sufficient to keep the society at work for a long time.

| PAGE | |

| Introductory | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Preliminary Observations. Tumuli—Dolmens— | |

| Circles—Avenues—Menhirs | 29 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| England. Avebury and Stonehenge | 61 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Minor English Antiquities. Aylesford—Ashdown— | |

| Rollright—Penrith—Derbyshire— | |

| Stanton Drew—Smaller Circles—Dolmens | 116 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Ireland. Moytura—Cemeteries—Boyne— | |

| Lough Crew—Clover Hill—Dolmens | 175 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Scotland. Orkney Stone Circles—Orkney Barrows— | |

| Maes-Howe Dragon and Serpent-Knot— | |

| Holed Stone of Stennis—Callernish—Aberdeenshire Circles— | |

| Fiddes Hill—Clava Mounds—Stone at Aberlemmo— | |

| Sculptured Stones—Crosses in Isle of Man | 239 |

| CHAPTER VII.[Pg xiv] | |

| Scandinavia and North Germany. Introductory—Battle-fields— | |

| Harald Hildetand's Tomb—Long Barrows—Tumuli— | |

| Dolmens—Drenthe: Hunebeds | 275 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| France. Introductory—Distribution of Dolmens—Age of Dolmens— | |

| Grottes des Fées—Demi-Dolmens—Rocking Stones—Carnac— | |

| Locmariaker—Alignments at Crozon—Age of the Monuments— | |

| What are these Monuments?—They must be Trophies— | |

| Time of the Fight—M. Bertrand's List of Dolmens in Thirty-one | |

| Departments of France | 325 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Spain, Portugal, and Italy. Introductory—Dolmens— | |

| Portugal—Italy | 377 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Algeria and Tripoli. Introductory—Bazinas and Chouchas— | |

| Free-Standing Dolmens—Age of Dolmens—Circle near Bona— | |

| The Nasamones—Origin of African Dolmen-builders—Tripoli: | |

| Trilithons—Buddhist Monument at Bangkok | 395 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Mediterranean Islands. Malta—Sardinia—Balearic Islands | 415 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Western Asia. Palestine—Sinai—Arabia—Asia Minor—Circassia— | |

| The Steppes—Cabul | 438 |

| CHAPTER XIII.[Pg xv] | |

| India. Introductory—Eastern India—Khassia—Western India— | |

| Geographical Distribution—Age of the Stone Monuments— | |

| Comparison of Dolmens—Buddhism in the West | 455 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| America. North America—Central America—Peru | 510 |

| Appendix A.—Glens Columbkille and Malin | 520 |

| "B.—Oden's Howe, &c., Upsala | 526 |

| "C.—Antiquities of Caithness | 527 |

| Index | 533 |

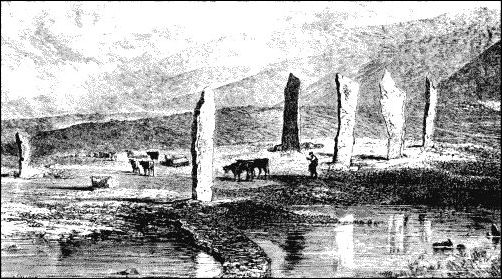

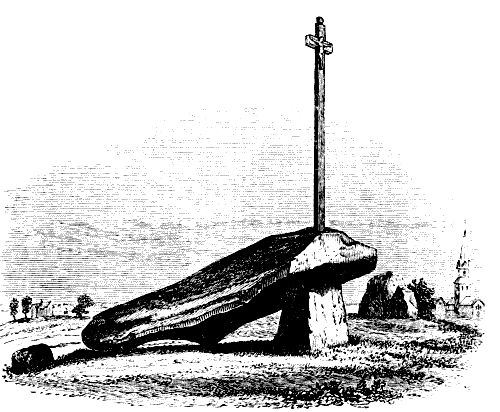

Frontispiece.—Standing Stones of Stennis. Vignette.—Demi-Dolmen at Kerland.

| NO. | PAGE | ||

| 1. | Section of Tomb of Alyattes | 31 | |

| 2. | Elevation of Tumulus at Tantalais | 32 | |

| 3. | Plan and Section of Chamber in Tumulus at Tantalais | 32 | |

| 4. | Section and Plan of Tomb of Atreus at Mycenæ | 33 | |

| 5. | View of Cocumella, Vulci | 33 | |

| 6. | View of principal Chamber in Regulini Galeassi Tomb | 34 | |

| 7. | Dolmen in Castle Wellan, Ireland | 46 | |

| 8. | Dolmen de Bousquet | 46 | |

| 9. | Tee cut in the Rock on a Dagoba at Ajunta | 47 | |

| 10. | Nine Ladies, Stanton Moor | 49 | |

| 11. | Chambered Tumulus, Jersey | 51 | |

| 12. | Avenues, Circles, and Cromlech, near Merivale Bridge, Dartmoor | 55 | |

| 13. | Lochcrist Menhir | 60 | |

| 14. | View of Avebury restored | 62 | |

| 15. | Plan of Avebury Circle and Kennet Avenue | 63 | |

| 16. | Circle on Hakpen Hill | 76 | |

| 17. | Section of Silbury Hill | 78 | |

| 18. | Iron Bit of Bridle, Silbury Hill | 81 | |

| 19. | Plan of Avebury | 81 | |

| 20. | Elevation of the Bartlow Hills | 83 | |

| 21. | Marden Circle | 85 | |

| 22. | General Plan of Stonehenge | 90 | |

| 23. | Stonehenge as at present existing | 92 | |

| 24. | Plan of Stonehenge restored | 93 | |

| 25. | Tomb of Isidorus, at Khatoura | 100 | |

| 26. | Country around Stonehenge | 102 | |

| 27. | Countless Stones, Aylesford | 116 | |

| 28. | The Sarsen Stones at Ashdown | 122 | |

| 29. | Sketch Plan of King Arthur's Round Table, with the side, | ||

| obliterated by the road, restored | 128 | ||

| 30. | Arbor Low | 140 | |

| 31. | Vases and Bronze Pin found in Arbor Low | 141 | |

| 32. | Section of Gib Hill | 141 | |

| 33. | Summit of Minning Low, as it appeared in 1786 | 142 | |

| 34. | Plan of Chambers in Minning Low | 142 | |

| 35. | Fragment of Drinking Cup from Benty Grange | 145 | |

| 36. | Fragment of Helmet from Benty Grange | 145 | |

| 37. | Circles at Stanton Drew | 149 | |

| 38. | View of the Circles at Stanton Drew | 150 | |

| 39. | Rose Hill Tumulus | 154 | |

| 40. | Snaffle-Bit found at Aspatria | 156 | |

| 41. | Side Stone, Aspatria Cist | 157 | |

| 42. | Mule Hill, Isle of Man, View of Cists | 157 | |

| 43. | Circle of Cists at Mule Hill | 157 | |

| 44. | Circles on Burn Moor, in Cumberland | 160 | |

| 45. | Boscawen Circles | 161 | |

| 46. | Park Cwn Tumulus | 163 | |

| 47. | Tumulus, Plas Newydd | 166 | |

| 48. | Entrance to Dolmen, in Tumulus, Plas Newydd | 166 | |

| 49. | Dolmen at Pentre Ifan | 168 | |

| 50. | Dolmen at Plas Newydd | 169 | |

| 51. | Arthur's Quoit, Gower | 170 | |

| 52. | Plan of Arthur's Quoit | 171 | |

| 53. | Hob Hurst's House, on Baslow Moor, Derbyshire | 172 | |

| 54. | Circle on Battle-field of Southern Moytura | 177 | |

| 55. | Cairn on Battle-field of Southern Moytura | 177 | |

| 56. | The Cairn of the "One Man," Moytura | 179 | |

| 57. | Urn in the Cairn of the "One Man," Moytura | 179 | |

| 58. | Battle-field of Northern Moytura | 181 | |

| 59. | Sketch Plan of Circle 27, Northern Moytura | 182 | |

| 60. | View of Circle 27, Northern Moytura | 183 | |

| 61. | Dolmen, with Circle, No. 7, Northern Moytura | 183 | |

| 62. | Rath na Riog, or, Cathair of Cormac, at Tara | 194 | |

| 63. | View of Mound at New Grange | 201 | |

| 64. | New Grange, near Drogheda | 203 | |

| 65, 66. | Ornaments at New Grange | 205 | |

| 67. | Branch at New Grange | 207 | |

| 68. | Sculptured mark at New Grange, of undecided character | 207 | |

| 69. | Chambers in Mound at Dowth | 208 | [Pg xviii] |

| 70, 71. | Ornaments in Dowth | 210 | |

| 72. | Cairn T, at Lough Crew | 214 | |

| 73. | The Hag's Chair, Lough Crew | 215 | |

| 74. | Two Stones in Cairn T, Lough Crew | 216 | |

| 75. | Cell in Cairn L, at Lough Crew | 217 | |

| 76. | Stone in Cairn T, Lough Crew | 222 | |

| 77. | Stones in Sculptured Graves, Clover Hill | 223 | |

| 78. | Dolmen at Knockeen | 229 | |

| 79. | Plan of Dolmen at Knockeen | 230 | |

| 80. | Calliagh Birra's House, north end of Parish of Monasterboice | 230 | |

| 81. | Plan and Section of Chamber in Greenmount Tumulus | 232 | |

| 82. | Dolmen of the Four Maols, Ballina | 233 | |

| 83. | Sketch-Plan of Monument in the Deer Park, Sligo | 234 | |

| 84. | Circle at Stennis | 242 | |

| 85. | Dragon in Maes-Howe | 245 | |

| 86. | Wurm-Knot, Maes-Howe | 245 | |

| 87. | Plan and Section of Maes-Howe | 246 | |

| 88. | View of Chamber in Maes-Howe | 247 | |

| 89. | Monument at Callernish | 259 | |

| 90. | Circle at Fiddes Hill | 264 | |

| 91. | Plan of Clava Mounds | 266 | |

| 92. | View of Clava Mounds | 266 | |

| 93. | Stone at Coilsfield | 267 | |

| 94. | Front of Stone at Aberlemmo, with Cross | 269 | |

| 95. | Back of Stone at Aberlemmo | 269 | |

| 96. | Cat Stone, Kirkliston | 271 | |

| 97, 98. | Crosses in Isle of Man, bearing Runic Inscriptions | 273 | |

| 99. | View of Battle-field at Kongsbacka | 279 | |

| 100. | Part of the Battle-field of Braavalla Heath | 281 | |

| 101. | Harald Hildetand's Tomb at Lethra | 282 | |

| 102. | Long Barrow, Kennet, restored by Dr. Thurnam | 284 | |

| 103. | Long Barrow at Wiskehärad, in Halland | 288 | |

| 104. | Battle-field at Freyrsö | 292 | |

| 105. | Dragon on King Gorm's Stone, Jellinge | 296 | |

| 106. | Dolmen at Herrestrup | 303 | |

| 107. | Dolmen at Halskov | 304 | |

| 108. | Dolmen at Oroust | 306 | |

| 109. | Diagram from Sjöborg | 307 | |

| 110. | Dolmen near Lüneburg | 308 | |

| 111. | Double Dolmen at Valdbygaards | 309 | |

| 112. | Plan of Double Dolmen at Valdbygaards | 309 | |

| 113. | Triple Dolmen, Höbisch | 309 | |

| 114. | View of Interior of Chamber at Uby | 311 | |

| 115. | Plan of Chamber at Uby | 311 | |

| 116. | Dolmen at Axevalla | 313 | |

| 117. | Head-stone of Kivik Grave | 314 | |

| 118. | Graves at Hjortehammer | 316 | |

| 119. | Circles at Aschenrade | 317 | |

| 120. | Plan of Hunebed near Emmen | 320 | |

| 121. | Dolmen at Ballo | 321 | |

| 122. | Dolmen at Sauclières | 334 | |

| 123. | Dolmen at Confolens | 337 | |

| 124. | Plan of Dolmen at Confolens | 337 | |

| 125. | Dolmen near Mettray | 342 | |

| 126. | Dolmen at Krukenho | 342 | |

| 127. | Holed Dolmen, at Trie | 344 | |

| 128. | Dolmen of Grandmont | 344 | |

| 129. | Demi-dolmen, Morbihan | 344 | |

| 130. | Demi-dolmen, near Poitiers | 347 | |

| 131. | Demi-dolmen at Kerland | 347 | |

| 132. | Pierre Martine | 347 | |

| 133. | Pierre Martine, end view | 348 | |

| 134. | Pierre Branlante, near Huelgoat, in Brittany | 348 | |

| 135. | Map of Celtic Antiquities, near Carnac | 352 | |

| 136. | Carnac Antiquities, on enlarged Scale | 353 | |

| 137. | Head of Column at St.-Barbe | 355 | |

| 138. | Long Barrow at Kerlescant | 356 | |

| 139. | Hole between Two Stones at Kerlescant | 357 | |

| 140. | Entrance to Cell, Rodmarton | 357 | |

| 141. | Vases found at Kerlescant | 357 | |

| 142. | Plan of Moustoir-Carnac | 358 | |

| 143. | Section of Moustoir-Carnac | 358 | |

| 144. | Section of Chamber of Moustoir-Carnac | 359 | |

| 145. 146. | Sculptures at Mané Lud | 361 | |

| 147. | View of Dol ar Marchant | 361 | |

| 148. | End Stone, Dol ar Marchant | 362 | |

| 149. | Hatchet in Roof of Dol ar Marchant | 362 | |

| 150. | Stone found inside Chamber at Mané er H'roëk | 364 | |

| 151. | Plan of Gavr Innis | 364 | |

| 152. | Sculptures at Gavr Innis | 364 | |

| 153. | Holed Stone, Gavr Innis | 364 | |

| 154. | Alignments at Crozon | 367 | |

| 155. | View of the Interior of Dolmen at Antequera | 383 | |

| 156. | Plan of Dolmen called Cueva de Menga, near Antequera | 384 | |

| 157. | Dolmen del Tio Cogolleros | 385 | |

| 158. | Sepultura Grande | 386 | |

| 159. | Plan of Dolmen at Eguilar | 387 | |

| 160. | Plan of Dolmen at Cangas de Onis | 387 | |

| 161. | Dolmen of San Miguel, at Arrichinaga | 387 | |

| 162. | Dolmen at Arroyolos | 389 | |

| 163. | Dolmen at Saturnia | 392 | |

| 164. | Bazina | 397 | |

| 165. | Choucha | 398 | |

| 166. | Dolmen on Steps | 398 | |

| 167. | Tumuli, with Intermediate Lines of Stones | 399 | |

| 168. | Group of Sepulchral Monuments, Algeria | 399 | |

| 169. | Plan and Elevation of African Tumulus | 400 | |

| 170. | Dolmen with Two Circles of Stones | 401 | |

| 171. | Dolmens on the Road from Bona to Constantine | 402 | |

| 172. | Four Cairns enclosed in Squares | 402 | |

| 173. | Tombs near Djidjeli | 404 | |

| 174. | Circle near Bona | 405 | |

| 175. | Trilithon at Ksaea | 411 | |

| 176. | Trilithon at Elkeb | 412 | |

| 177. | Buddhist Monument at Bangkok | 413 | |

| 178. | Giants' Tower at Gozo | 417 | |

| 179. | Plan of Monument of Mnaidra | 419 | |

| 180. | Section through Lower Pair of Chambers, Mnaidra | 419 | |

| 181. | Entrance to Chamber B, Mnaidra, showing Table inside | 420 | |

| 182. | North End of Left-hand Outer Chamber at Mnaidra | 421 | |

| 183. | Plan of Hagiar Khem, partially restored | 423 | |

| 184. | View of Madracen | 424 | |

| 185. | Nurhag | 428 | |

| 186. | Nurhag of Santa Barbara | 428 | |

| 187. | Section and Ground-plan of Nurhag of Santa Barbara | 429 | |

| 188. | Map of La Giara | 430 | |

| 189. | Talyot at Trepucò, Minorca | 435 | |

| 190. | Talyot at Alajor, Minorca | 435 | |

| 191. | Dolmens at Kafr er Wâl | 441 | |

| 192. | Holed Dolmen | 447 | |

| 193. | Holed Dolmen, Circassia | 447 | |

| 194. | Baba | 448 | |

| 195. | Four-cornered Grave | 448 | |

| 196. | Tumulus at Alexandropol | 450 | [Pg xix] |

| 197. | Uncovered Base of a Tumulus at Nikolajew | 451 | |

| 198. | Circle near Peshawur | 452 | |

| 199. | Circle at Deh Ayeh, near Darabgerd | 453 | |

| 200. | View in Khassia Hills | 462 | |

| 201. | Khassia Funereal Seats | 463 | |

| 202. | Menhirs and Tables | 464 | |

| 203. | Turban Stone, with Stone Table | 464 | |

| 204. | Trilithon | 464 | |

| 205. | Dolmen at Rajunkoloor | 468 | |

| 206. | Plan of Open Dolmen at Rajunkoloor | 468 | |

| 207. | Closed Dolmen at Rajunkoloor | 468 | |

| 208. | View of Closed Dolmen at Rajunkoloor | 468 | |

| 209. | Arrangement of Dolmens at Rajunkoloor | 470 | |

| 210. | Cairns at Jewurgi | 472 | |

| 211, 212. | Sections of Cairn at Jewurgi | 472 | |

| 213. | Double Dolmen, Coorg | 473 | |

| 214. | Tomb, Nilgiri Hills | 473 | |

| 215. | Sepulchral Circles at Amravati | 474 | |

| 216. | Iron Pillar at the Kutub, Delhi | 481 | |

| 217. | Sculpture on under side of cap-stone of Nilgiri Dolmen | 483 | |

| 218. | Dolmen at Iwullee | 484 | |

| 219. | Plan of Stone Monuments at Shahpoor | 485 | |

| 220. | Cross at Katapur | 486 | |

| 221. | Dolmen at Katapur | 487 | |

| 222. | Dolmen with Cross in Nirmul Jungle | 487 | |

| 223. | Lanka Ramayana Dagoba | 490 | |

| 224. | Dolmen at Pullicondah | 491 | |

| 225. | Rail at Sanchi, near Bhilsa | 492 | |

| 226. | View of the Senbya Pagoda, Burmah | 497 | |

| 227. | Enclosure in Newark Works, North America | 511 | |

| 228. | Plan of Uprights, Cromlech D I., Columbkille | 521 | |

| 229. | Position of Stones of D III. | 522 | |

| 230. | Plan of D VI. | 522 | |

| 231. | Plan of Cromlechs of Group E. | 523 | |

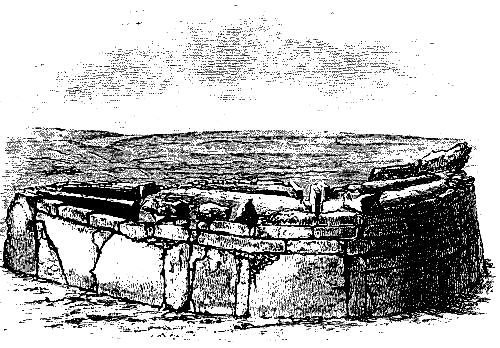

| 232. | Horned Cairn, Caithness | 528 | |

| 233. | Dolmen near Bona, Algeria | 532 |

DIRECTION TO BINDER.

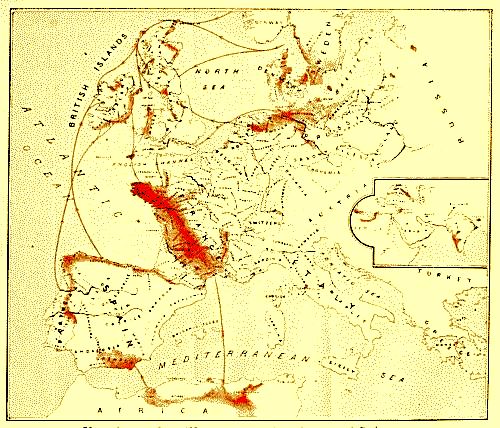

The Map illustrating the distribution of Dolmens to be placed at the end of the Volume.

So great and so successful has been the industry recently applied to subjects of archæological research that few of the many problems in that science which fifty years ago seemed hopelessly mysterious now remain unsolved. Little more than forty years have elapsed since Champollion's discoveries enabled us to classify and understand the wonderful monuments of the Nile Valley. The deciphering of the cuneiform characters has in like manner enabled us to arrange and affix dates to the temples and palaces of Babylon and Nineveh. Everything that was built by the Greeks and the Romans has been surveyed and illustrated; and all the mediæval styles that arose out of them have been reduced to intelligible sequences. The rock-cut temples of India, and her still more mysterious dagobas, have been brought within the domain of history, and, like those of Burmah, Cambodia, or China, shown to be of comparatively modern date. The monuments of Mexico and Peru may be said still to defy those who are endeavouring to wrest their secrets from them; but even for these a fairly approximate date has been obtained. But amidst all these triumphs of well-directed research there still remains a great group of monuments at our own doors, regarding whose uses or dates opinions are nearly as much divided as they were in the days of rampant empiricism in the last century. It is true that men of science do not now pretend to see Druids sacrificing their bleeding victims on the altar at Stonehenge, nor to be able to trace the folds of the divine serpent through miles of upright stones at Carnac or at Avebury; but all they have yet achieved is simple unbelief in the popular fallacies, nor have they hitherto ventured to supply anything better to take [Pg 2] their places. They still call the circles temples, but without being able to suggest to what god they were dedicated, or for what rites they were appropriate, and, when asked as to the age in which they were erected, can only reply in the words of the song, that it was "long long ago."

This state of affairs is eminently unsatisfactory, but at the same time to a great extent excusable. Indeed it is not at first sight easy to see how it is to be remedied. The builders of the megalithic remains were utterly illiterate, and have left no written records of their erection; nor are there any legible inscriptions on the more important monuments which would afford any hints to the enquirer. What is even more disheartening is that in almost every instance they are composed of rough unhewn stones, not only without any chisel marks, but even without any architectural mouldings capable of being compared with those of other monuments, or, by their state of preservation, of giving a hint as to their relative age.

"They stand, but stand in silent and uncommunicative majesty."

So silent, indeed, that it is hardly to be wondered at that fanciful antiquaries have supplied them with voices most discordantly and absurdly various, or, on the other hand, that the better class of enquirers have shrunk from the long patient investigations and thoughtful ponderings which are necessary to elicit even a modicum of truth from their stolid reticence.

If the investigation into the age and uses of the megalithic remains were a new subject which had for the first time been taken up some thirty or forty years ago, it is probable that a solution might have been obtained before now, or at all events would not be far off. When, however, an investigation gets into a thoroughly vicious groove, as this one has done, it is very difficult to rescue it from its false position. The careless are willing to accept any empirical solutions that are offered, however absurd they may be, and the thoughtful are deterred from meddling with an enquiry which has hitherto led only to such irrational conclusions.

The first of those who, in this country at least, led off the wild dance was the celebrated Inigo Jones, the architect of Whitehall. It [Pg 3] seems that when King James I. was on a visit to the Earl of Pembroke at Wilton, he was taken to see Stonehenge, and was so struck with its majesty and mystery that he ordered his architect to find out by whom it was built, and for what purpose. Whether the treatise containing the result of his enquiries was ever submitted to the King is not clear. It certainly was not published till after its author's death, and though it shows a very creditable amount of learning and research, the results he arrived at were very startling. After a detailed statement of the premises, his conclusions—as condensed in the Life prefixed to his treatise—were "That it was a Roman temple, inscribed to Cœlus, the senior of the heathen gods, and built after the Tuscan order."

This theory was attacked by Dr. Charleton, one of the physicians of Charles II. He had corresponded for some time with Olaus Wormius, the celebrated Danish antiquary, and struck with the similarity in form and of construction that existed between the monuments in Denmark and those of this country, he came to the conclusion that Stonehenge and other similar monuments were erected by the Danes, and consequently after the departure of the Romans. This attack on the theory of Inigo Jones raised the wrath of a Mr. Webb, by marriage a relative, who replied in a very angry treatise, in which he reiterates all Jones's arguments, and then, adding a considerable number of his own, he concludes by triumphantly—as he supposes—restoring Stonehenge to the Romans. [2]

So far no great harm was done; but Dr. Stukeley, who next appeared in the controversy, was one of the most imaginative of men and one of the wildest of theorists. His studies had made him familiar with the Druids, whom classical authorities describe as the all-powerful priests of the Celtic race, but who had no temples; on the other hand, his travels made him acquainted with Stonehenge and Avebury, to the latter of which attention had just been called by the researches of his friend Aubrey. Here, then, were temples without priests. What could be so natural as to join [Pg 4] these two, though in most unholy matrimony. Our stone circles must be temples of the Druids! But there was still one difficulty. What divinities did they worship therein? Cæsar tells us that the Celts or Celtic Druids principally worshipped Mercury and some other Roman gods whom he named; [3] but no images of these gods are found in these temples, nor anything that would indicate a dedication to their worship. Unfortunately, however, Pliny [4] tells a very silly tale, how in Gaul the snakes meet together on a certain day and manufacture from their spittle an egg (Anguinum), which, when complete, they throw aloft, and if any one wants it, he must catch it in a blanket before it falls to the ground, and ride off with it on a fleet horse, for if the snakes catch him before he crosses a running stream, a worse fate than Tam o' Shanter's may befall him! He then goes on to add that this egg was considered as a charm by the Druids. From this last hint Dr. Stukeley concluded that the Druids were serpent-worshippers, and consequently that Stonehenge, Avebury, &c., were serpent temples—Dracontia, as he calls them, daringly assuming that a word, which in the singular was only the name of a plant, was actually applied by the ancients to serpent temples, of the form of which, however, they were as ignorant as the Doctor himself. Having advanced so far, it only remained to adapt the English circles to this newly discovered form of worship, and Avebury was chosen as the principal illustration. There was a small circle on Hakpen Hill, which had a stone avenue formed by six or eight stones running east and west; between West Kennet and Avebury there was another avenue leading to the circles, but trending north and south. By introducing a curved piece between these fragments, Hakpen became the head of the snake, the avenue its body; Avebury a convoluted part of it, and then a tail was added, a mile long, on the authority of two stones in the village, and a dolmen, called Long Stone Cove, about halfway between Avebury and the end of the tail! Stanton Drew and other circles were treated in the same way; curved avenues, for which there is not a shadow of authority, except in the Doctor's imagination, were added wherever required, and serpents manufactured wherever wanted. It never [Pg 5] seems even to have occurred to the Doctor or his contemporaries to ask whether, in any time or place, any temple was ever built in the form of the gods to be worshipped therein or thereat, or how any human being could discover the form of the serpent in rows of stones stretching over hills and valleys, crossing streams, and hid occasionally by mounds and earthworks. On a map, with the missing parts supplied, this is easy enough; but there were no maps in those days, and in the open country it would puzzle even the most experienced surveyors to detect the serpent's form.

Had so silly a fabrication been put forward in the present day, it probably would have met with the contempt it deserves; but the strangest part of the whole is that it was then accepted as a revelation. Even so steady and so well informed an antiquary as Sir Richard Colt Hoare adopts Dr. Stukeley's views without enquiry. His magnificent works on 'Ancient and Modern Wiltshire,' which are not only the most splendid, but the most valuable works of their class which this country owes to the liberality and industry of any individual, are throughout disfigured by this one great blemish. He sees Druids and their Dragons everywhere, and never thinks of enquiring on what authority their existence rests.

It is not of course for one moment meant to contend that there were not Druids in Europe in ancient days. Cæsar's testimony on this point is too distinct, and his knowledge was too accurate to admit of any doubt on this point. It is true, however, that the description of them given by Diodorus,[5] and Strabo,[6] who mix them up with the bards and soothsayers, detracts somewhat from the pre-eminence he assigns to them: but this is of minor importance. The Druids were certainly the priests of the Celts, and had their principal seat in the country of the Carnutes, near Chartres, where, however, megalithic remains are few and far between. Neither Cæsar, however, nor any one else, ever pretended to have seen a Druid in England. Suetonius met 'Druidæ' in the Island of Anglesea (Mona),[7] but none were ever heard of in Wiltshire, or Derbyshire, or Cumberland, where the principal monuments are [Pg 6] situated; nor in the Western Islands, or in Scandinavia. Still less are they known in Algeria or India, where these megalithic remains abound. According to the Welsh bards and Irish annalists, there were Druids in Wales and Ireland before the introduction of Christianity. But, even admitting this, it does not help us much; as even there they are nowhere connected with the class of monuments of which we are now treating. Indeed, it has been contended lately, and with a considerable show of reason, that the Celts themselves, even in France, had nothing to do with these monuments, and that they belong to an entirely different race of people.[8] It is not, in short, at all necessary to deny either the existence of the Druids or their power. The real difficulty is to connect them in any way, directly or indirectly, with the stone monuments: and it seems still more difficult to prove that the Celts ever worshipped the serpent in any shape or form. [9]

Notwithstanding all this, in the present century, an educated gentleman and a clergyman of the Church of England, the Rev. Bathurst Deane, adopts unhesitatingly all that Stukeley and his school had put forward. He took the trouble of going to Brittany, accompanied by a competent surveyor, and made a careful plan of the alignments of Carnac. [10] Like the avenues at Avebury, they certainly bore no resemblance to serpent forms, to eyes profane, but looked rather like two straight lines running nearly parallel to one another at a distance of about two miles apart. But may not an intermediate curvilinear piece some three miles long have existed in the gap and so joined the head to the tail? It is in vain to urge that no trace of it now exists, or to ask how any human being could trace the forms of serpents seven or eight miles long in an undulating country, and how or in what manner, or to what part of this strange deity or monster, he was to address his prayers.

It would be incorrect, however, to represent all antiquaries as [Pg 7] adopting the Ophite heresy. Another group have argued stoutly that Stonehenge was an observatory of the British Druids. This theory was apparently suggested by views published by Daniell and others of the observatories erected by Jey Sing of Jeypore at Delhi, Ougein, Benares, and elsewhere in India. All these, it is true, possess great circles, but each of all these circles contains a gnomon, which is as essential a part of such an astronomical instrument as it is of a sun-dial, and no trace of such a feature, it need hardly be said, occurs in any British circle. One antiquary, who ought to be better informed,[11] concluded that Stonehenge was an observatory, because, sitting on a stone called the Altar on a Midsummer morning, he saw the sun rise behind a stone called the Friar's Heel. This is the only recorded observation ever made there, so far as I know; and if this is all, it is evident that any two stones would have answered the purpose equally well, and as the Altar stone is sixteen feet long, it allows a latitude of observation that augurs ill for the Druidical knowledge of the exact sciences. Neither Mr. Ellis, however, nor Dr. Smith, nor the Rev. Mr. Duke,[12] nor indeed any of those who have taken up the astronomical theory, have yet pointed out one single observation that could be made by these circles that could not be made as well or better without them. Or, if they were orreries, as is sometimes pretended, no one has explained what they record or represent in any manner that would be intelligible to any one else. Till some practical astronomer will come forward and tell us in intelligible language what observations could be performed with the aid of the circles of Stonehenge, we may be at least allowed to pause. Even, however, in that case, unless his theory will apply to Avebury, Stanton Drew, and other circles so irregular as to be almost unmeasurable, it will add little to our knowledge.

It might be an amusing, though it certainly must be a profitless, task to enlarge on these and all the other guesses which have from time to time been made with regard to these mysterious remains. It is not, however, probable that theories so utterly groundless will [Pg 8] be put forward again, or, if promulgated, that they will be listened to in future. The one excuse for them hitherto has been that their authors have been deprived of all their usual sources of information in this matter. It is not too much to assert that there is not one single passage in any classical author which can be construed as alluding directly or indirectly to the megalithic remains on these isles or on the continent. With all their learning and industry, the antiquaries of the last century could only find one passage which, with all their misapplied ingenuity, they could pervert to their purposes. It was this—in his second book, Diodorus, quoting from Hecatæus, mentions that in an island, not less in size than Sicily, and opposite to Celtica, there existed among the Hyperboreans a circular temple magnificently adorned.[13] Stukeley and his followers immediately jumped to the conclusion that the island not less than Sicily and opposite Gaul must be England, and the circular temple Stonehenge, which was consequently dedicated to Apollo and the serpent Python, and our forefathers were the Hyperboreans, and our intercourse with Greece clear and frequent. It is marvellous what a superstructure was raised on such a basis. But against it may be urged that the whole of the second book of Diodorus is dedicated solely to a description of Asia. In the preceding chapter he describes the Amazons, who, if they ever existed, certainly lived in that quarter of the globe. In the following chapters he describes Arabia, and even in this one (xlvii.) he speaks of the Hyperboreans as inhabiting the northern parts of Asia. By the utmost latitude of interpretation we might assume this island to have been in the Baltic—Œsel probably, Gothland possibly, but certainly not further west. It is impossible Diodorus could be mistaken in the matter, for in his fifth book he describes the British Isles in their proper place, and with a very considerable degree of accuracy.[14] But, after all, what does it amount to? In this island there was a circular temple. We are not told whether it was of wood or of stone, whether hypæthral, or roofed, or vaulted, and certainly there is not a shadow of a hint that it was composed of a circle of rude stones like those in this country with which the antiquaries of the last century tried to [Pg 9] assimilate it.

It is little to be wondered at if all this rashness of speculation and carelessness in quotation should have produced a belief that the solution of the problem was impossible from any literary or historical data, or if consequently our modern antiquaries should have grasped with avidity at a scheme, first proposed by the Danes, which seemed at all events to place the question on a scientific basis. No country could well be more favourably situated for an enquiry of this sort than Denmark. It is rich in megalithic remains of all sorts. Its tumuli and tombs seem generally to have been undisturbed; and it was exceptionally fortunate in having a government with sufficient common sense to enact a law of treasure-trove, so just and, at the same time, so liberal as to prevent all metal articles from finding their way to the melting pot, and governors so intelligent as fully to appreciate the scientific value of these early remains. In consequence of all this, the museums at Copenhagen were soon filled with one of the richest collections of antiquities of this sort that was ever collected, and when brought together it was not difficult to perceive the leading features that connected them in one continuous sequence.

First it appeared that there was an age extending into far prehistoric times, when men used only implements of stone and bone, and were ignorant of the use of any of the metals; then that an age had succeeded to this when the use of bronze was known, and also probably that of gold; and, lastly, that there was a third age, when iron had been introduced and had superseded the use of all other metals for weapons of war and utilitarian purposes.

The Danish antiquaries were somewhat divided in opinion as to the exact period when bronze was first introduced, some carrying it back as far as 2000 B.C., others doubting whether it was known in Denmark more than 1000 or 1200 years B.C., but all agreed that iron was introduced about the Christian era. Having satisfied themselves on these points, the Danish antiquaries proceeded at once to apply this system to the monuments of their country. Any tomb or tumulus which was devoid of any trace of metal was dated at once at least 1000, probably [Pg 10] 2000, years before Christ, and might be 10,000, or 20,000 years old, or even still older. Any tomb containing bronze was at once set down as dating between the war of Troy and the Christian era; and if a trace of iron was detected, it was treated as subsequent to the last-named epoch, but still as anterior to the introduction of Christianity, which in Denmark dates about the year 1000 A.D.

This system seemed so reasonable and philosophical, compared with the wild theories of the British antiquaries of the last century, that it was instantly adopted both in the country of its birth and in England and France; and the succession of the three ages—stone, bronze, and iron—was generally looked upon as firmly established as any fact in chronology. Gradually, however, it has been perceived that the hard and fast line at first drawn between them cannot be maintained. At the last meeting of the International Archæological Congress, held at Copenhagen in the autumn of 1869, it was admitted on all hands that there was a considerable overlap between each of the three ages. Men did not immediately cease to use stone implements when bronze was introduced; and bronze continued to be employed for many purposes after the use of iron was well known.[15] Antiquaries have not yet made up their minds to what extent the overlap took place; but on its determination depends the whole value of the scheme as a chronometric scale.

If the Danes, instead of breaking up their "finds" and distributing them in cases according to a pre-conceived system, had kept and published a careful record of the places where the contents of their museums were found, and in what juxtaposition, we should not probably be in our present difficulty. Under the circumstances, it is perhaps fortunate that we had no central museum, but that our antiquaries have published careful narratives of their proceedings. Sir Richard Colt Hoare's great works are models of their class, but are scarcely to be depended upon[Pg 11] in the present instance, as the importance of flint and flint implements was not appreciated in his time to the extent it now is.[16] The explorations of the Messrs. Bateman in Derbyshire are more completely up to the mark of the science of the present day. A few extracts from one of their works will show how various and how mixed the contents of even a single group of tombs are, and will prove consequently how little dependence can be placed on any one class of objects to fix the age of these monuments.

In his 'Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire,' published in 1848 by Thomas Bateman, we find the following among other interesting facts, taking them as they are found arranged in his volume, without any attempt at classification:—

On Winster Moor (p. 20), a gold Greek cross—undoubtedly Christian, with a fibula of the same metal richly ornamented, and a quantity of glass and metal ornaments.

Pegges Barrow (p. 24). Several Anglo-Saxon ornaments, most probably of the seventh or eighth century.

In a barrow at Long Roods (p. 28) were found two urns, with calcined bones and a brass coin of Constantine, of the type "Gloria exercitus."

In Haddon Field Barrow (p. 30) were found 82 brass coins: among them Constantine 9, Constans 17, Constantius II. 9, family of Constantine 3, Urbs Roma 1, Constantinopolis 2, Valentinian 5, Valens 12, Gratian 3. The remainder illegible.

At Gib Hill, near Arbor Low (p. 31), of which more hereafter, there were found a flint arrow-head 2½ inches long, and a fragment of a basaltic celt; also a small iron fibula, and another piece of iron of indeterminable form.

On Cross Flatts (p. 35) the weapons found with the skeleton were an iron knife, the blade 5 inches long; a piece of roughly chipped flint, probably a spear-head; and a natural piece of stone of remarkable form. A similar iron knife and a stone celt were afterwards found within a [Pg 12] few yards of the barrow, probably thrown out and overlooked when first opened.

In Galley Lowe (p. 37), a very beautiful gold necklace set with garnets, and a coin of Honorius; but towards the outer edge of the Lowe, and consequently, as far as position goes, probably later, another interment, accompanied with rude pottery, a small arrow-head of grey flint, and a piece of ironstone.

In the great barrow at Minning Lowe (p. 39) were found coins of Claudius Gothicus, Constantine the Great, Constantine Junior, and Valentinian.

In a smaller barrow close by were found fragments of a coarse, dark-coloured urn, a flint arrow-head, a small piece of iron, part of a bridle-bit, and several horses' teeth; lower down, a cist with an iron knife, with an iron sheath; and on the outer edge another interment, accompanied by a highly ornamented drinking-cup, a small brass or copper pin, and a rude spear or arrow-head of dark grey flint.

In Borther Lowe (p. 48) were found a flint arrow-head much burnt and a diminutive bronze celt.

In Rolley Lowe (p. 55) were found a brass coin of Constantine, and a brass pin 2¾ inches long; and lower down a rude but highly ornamented urn, and with it two very neat arrow-heads of flint of uncommon forms; and in another part of the barrow a spear-head of coarse flint, with the fragments of an ornamented drinking-cup.

In a barrow on Ashford Moor (p. 57) were found, scattered in different parts, a small iron arrow-head and five instruments of flint.

In Carder Lowe (p. 63) were found several instruments of flint, amongst the latter a neatly formed barbed arrow-head; and lower down, with the primary interment, a splendid brass or bronze dagger; a few inches lower down a beautiful axe hammer-head of basalt. In another part of the barrow another interment was discovered, accompanied by an iron knife and three hones of sandstone.

A barrow was opened at New Inns (p. 66), where, along with the principal interment, was found a beautiful brass dagger, with smaller rivets than usual; and in another part a skeleton, with two instruments of flint, and some animal teeth.

In Net Lowe (p. 68), close to the right arm of the principal interment, a large dagger of brass, with the decorations of its handle, consisting of thirty brass rivets; two studs of Kimmeridge coal. With the above-mentioned articles were numerous fragments of calcined flint, and amongst the soil of the barrow two rude instruments of flint.

At Castern (p. 73), in one part of the mound, an instrument was found, with a fine spear-head of flint, and a small arrow-head of the same. In other parts, but in apparently undisturbed earth, a circular instrument, and various chippings of flint, and the handle of a knife of stag's horn, riveted in the usual way on to the steel. A similar one is figured in Douglas's 'Nenia Britannica,' plate 19, fig. 4, as found with an interment in one of the barrows on Chartham Downs, Kent.

In Stand Lowe (p. 74), on digging towards the centre, numerous flint chippings and six rude instruments were found, and above the same place a broken whetstone. The centre being gained, an iron knife was found of the kind generally attributed to the Saxons. This was immediately followed by a bronze box and a number of buckles, fibulæ, and articles of iron, silver, and glass, all showing the principal interment to have been of very late date. Mr. Bateman adds—"the finding of instruments of flint with an interment of this comparatively modern description is rather remarkable, but by no means unprecedented."

In a barrow midway between Wetton and Ilam (p. 79) with the interment were found three implements of flint of no great interest, some fragments of an ornamented urn, and an iron pin, similar to the awl used by saddlers at the present day. Mr. Bateman adds—"one precisely similar was found in a barrow on Middleton Moor in 1824."

In a second barrow near the same place were found the remains of a coarse and rudely ornamented urn with its deposit of burnt bones. A third brass coin of Constantine the Great was also found on the summit, just under the surface.

In Come Lowe (p. 95), with an interment of a very late period, were found gold and iron ornaments and glass beads, as well as the usual chippings of flint and rats' bones.

In Dowe Lowe (p. 96) the most remote interment consisted of two much [Pg 14] decayed skeletons lying on the floor of the barrow about two yards from its centre; one was accompanied by a fluted brass dagger placed near the upper bone of the arm, and an amulet of iron ore with a large flint implement, which had seen good service, lying near the pelvis.

The other tumuli examined by this indefatigable explorer either contained objects generally of the same class or nothing that was of interest as marking their age. If his other works, or those of others, were abstracted in the same way, numerous examples of the same sort might be adduced. The above, however, are probably sufficient to show how little reliance can be placed on the hard and fast distinction between the flint, bronze, and iron ages which have hitherto been supposed to govern every determination of age in this science. If in a hundred short pages of one man's work so many instances of overlapping, and, indeed, of reversal of the usual order of things, can be found, it is easy to understand how many might be added if other works were also examined. All, however, that is wanted here is to show that the Danish system is neither perfect nor final, and that we must look for some other means of ascertaining the age of these monuments if we are to come to a satisfactory conclusion regarding them.

The fact is that, though a tomb containing only stone and bone implements may be 10,000 or 20,000 years old, unless it can also be shown that stone and bone were no longer used after the Christian era, it may also be as modern, or more so, than that epoch. Unless, also, it can be proved that stone implements were never used after iron was introduced, or that bronze was never employed down to a late period, this system is of no avail; and after the examples just quoted from the Bateman diggings, it seems the merest empiricism to assume that the use of each class of implements ceased on the introduction of another; and till it can be shown at what date their use did really cease, any argument based on their presence is of very little value. This, however, is a task to which no antiquary has yet applied himself; all have been content to fix the age of the monuments from the assumed age of their contents, empirically determined. It is a far more difficult task, however, to ascertain the age of the contents from that of the monument in which they are found; it is a task that requires an [Pg 15] investigation into the history and circumstances of each particular example. With the scant materials that exist, this is by no means easy; but as it seems the only mode by which truth can be arrived at, it is the task to which we propose to devote the following pages; should it prove impossible, we may indeed despair.

It is curious to observe how different would have been the fate of this science, had the Scandinavians followed up the line of investigation commenced by their writers in the sixteenth century. Olaus Magnus, for instance, Archbishop of Upsala, writing in 1555, describes the megalithic remains of Sweden with the sobriety and precision with which a man in the present day might give an account of the cemeteries of Kensal-green or of Scutari. Some, he tells us, marked battle-fields, some family sepulchres, others the graves of greatly distinguished men.[17] In like manner, Olaus Wormius, in 1643, describes the tombs of the kings of Denmark as a writer in the present day might the Plantagenet sepulchres in Westminster Abbey.[18] Neither have any doubt or hesitation about the matter, and though Dr. Charleton was hasty in following this author too implicitly in applying his data to this country, still, so far as I can form an opinion, if that line of research had been steadily followed out, there would now have been as little doubt about the age of Stonehenge, as there is about that of Salisbury Cathedral. Stukeley, however, cut the vessel adrift from the moorings of common sense, and she has since been a derelict tossed about by the winds and waves of every passing fancy, till recently, when an attempt has been made to tow the wreck into the misty haven of prehistoric antiquity. If ever she reaches that nebulous region, she [Pg 16] may as well be broken up in despair, as she can be of no further use for human purposes.

Whether this will or will not be her fate must depend on the result of the new impulse which has within the last ten or twelve years been given to the enquiry. Hitherto it seems certainly to be in a direction which, it is to be feared, is not likely to lead to any greater degree of precision in the enquiry. While the Danish "savans" were arranging their collections in the museums at Copenhagen, M. Boucher de Perthes was quietly forming a collection of flint implements from the drift gravels of the valley of the Somme, which far exceeded all hitherto found in antiquity. For many years his discoveries were ridiculed and laughed at, till in 1858 the late Hugh Falconer visited his museum at Abbeville, and being then fresh from his investigations at Kent's Hole and the Gower Caves,[19] he at once saw their value and proclaimed it to the world. Since then it has not been disputed that the flint implements found in the valley of the Somme are the works of man, and that from the position in which they are found their fabricators must have lived at a period on the edge of the glacial epoch, and when the configuration of the continent differed from what it now is, and when probably the British isles were still joined to France. Similar implements have before and since been found in Suffolk,[20] and other parts of England in analogous circumstances, and all allied with a fauna which was extinct in these parts before historic times.[21] If you ask a geologist how long ago the circumstances of the globe were such as these conditions represent, he will answer at once not less than a million of years! But they deal in large figures, and it is not necessary to investigate them now. It was a very long time ago.

Even more interesting than these for our present purposes was the [Pg 17] discovery a few years later of human remains in the valleys of the Dordogne and other rivers of the south of France. Here geology does not help us, but climatology does. At that time the climate of the south of France was so cold that the inhabitants of these caves had all the habits of people now dwelling in the Arctic regions. Their principal domestic animal was the reindeer, but they were familiar with the woolly-haired mammoth, the cave bear, and the aurochs. The climate was so cold that they could throw on one side the débris of their feasts, and floor their dwelling with marrow bones and offal without dreading pestilence or even suffering inconvenience. They were, in fact, in every respect, so far as we have the means of judging, identical with the Esquimaux of the present day, and must have inhabited a climate nearly similar to that of Arctic North America. How long ago was this? We know from the pictures in the tombs near the pyramids that the climate of Egypt was the same 5000 or 6000 years ago as it is now, and we have no reason to suppose that, while that of the southern shores of the Mediterranean remained unchanged, the northern would vary in any very different ratio. Clearing of forests may have done something, but never could have accounted for such a change as this. If we take 50,000 or 60,000 years instead of 5000 or 6000, it will not suffice for such a revolution, though geologists will be wroth if we assume only 100,000; as a convenient number this will answer our present purposes.

Having at least this space of time at their disposal, the tendency of modern antiquaries has been to sweep everything into this great gulf. Why, they ask, may not Stonehenge and Avebury be 10,000, 20,000, or 50,000 years old? Man then existed, and why may he not have erected such monuments as these? Of course he might, but there is no proof that he did, and as no single tangible reason has yet been adduced for supposing them so old, the mere presumption that they might be so cannot count for much.

To my mind the force of argument seems to tend the other way. If a race of men lived on the face of the globe for 100,000 years so utterly unprogressive as these cave men, incapable of discovering the use of metals for themselves during that long period, or even of adopting them from Egypt and the East, where bronze certainly, and most probably iron, were known at least 6000 or 7000 years ago; if this people [Pg 18] used flint and bone during all this period, is it likely that they would adopt new-fangled implements and new customs the first time they were presented to them? The Esquimaux have been familiar with the Danish settlers in Greenland for some centuries, and could easily have procured improved implements and many of the advantages of civilization had they been so inclined. They have not been changed a hair's-breadth by the influence of the stranger. The red man of North America has been in contact with the white man for centuries now. Has he changed, or can he change? In Alaska, and to the northward of Vancouver's Island, there is a race of savages, called Hydahs, with all the artistic tastes and faculties of the men of the Dordogne caves, and with about the same degree of civilization.[22] All these are dying out, and may soon disappear, but they present at this day exactly the same phenomenon as we see in the south of France, say 10,000 years ago. They have been exterminated in all the civilized parts of Europe by the progressive Aryan races who have usurped their places; and it seems only too certain that, like them, their American kindred must perish before the growing influence of the white man, but they cannot change. In so far as we can judge from such facts as are before us, if any family of this old people still lurked among our hills or on any rocky island, their habits, or customs, and their implements, would be as like those of the cave men as those of the Esquimaux or Alaska savages are at the present day. It appears most unphilosophical to apply to those people the principles of progress that are found among the higher races of mankind, and to represent them as eagerly seizing on any improvement offered them, and abandoning their old faith and their old habits at the bidding of any wandering navigator that visited their shores.

This is not the place to enter on such an enquiry, but so far as can at present be seen, it seems that mankind has progressed not so much by advance within the limits of certain races as by the superposition of more highly organized races over those of an inferior class. Thus we have those stone men of the caves who possessed the world for 100,000 or a million of years, and made no more progress in that period than [Pg 19] the animals they were associated with. Even the progress from a chipped to a polished stone implement seems to have been taught them by a foreign bronze-using people. We have then such races as the Egyptian, the Chinese, or the Mexican, who can progress to a certain point, but stop and cannot go beyond; and, lastly, we have the Aryans, the last to appear in the field, but the most energetic, and the only truly progressive race. Our great error in reasoning with regard to the older races seems to be that we insist on applying to them the reasoning and principles which guide us, but which are wholly inapplicable to the less progressive races of mankind.

All this will be plainer in the sequel; but in the meanwhile it may safely be asserted that, up to this time, no royal road has been discovered that leads to an explanation of our megalithic antiquities. No one has yet been able so to classify the contents of cognate monuments as to construct a chronometric scale which is applicable for the elucidation of their dates; and no à priori reasoning has been hit upon that is of the smallest use in explaining either their age or their peculiarities. The one path that seems open to us is a careful examination of each individual monument, accompanied by a judicial sifting of all or any traditions that may attach to it, and aided by a comparison with similar monuments in other countries. By this means we have a chance of arriving at a fair proximate degree of certainty; for, though no one monument will tell its own tale directly, a multitude of whispers from a great number may swell into a voice that is clear and distinct and be audible to every one; while no system yet invented, and no à priori reasoning, can lead to anything but deepening the ignorance that now prevails on the subject. This is especially true with regard to the great megalithic circles in this country. With the rarest possible exceptions, no flint and no bronze or iron implements have been found within their precincts. They cannot be older than the invention of flint implements, and iron has been in continuous use since the art of smelting its ores was first discovered. If, therefore, they have no written or traditional history which can be relied upon, their age must for ever remain a mystery. The conviction, however, under which this book is written is that such a history does exist; that, when all the traditions attached to the monuments are sifted [Pg 20] and weighed, they amount to such a mass of circumstantial evidence as suffices to prove the case and to establish the main facts of their history and use, wholly independently of any system or of any external testimony.

Direct literary evidence, in the sense in which the term is usually understood, cannot be said to exist. As before mentioned, no classical author alludes, either directly or indirectly, to these megalithic structures; yet they could not have been ignorant of them if they existed. When Cæsar and his army witnessed the fight between his galleys and the fleet of the Veneti in the Morbihan, he must have stood—if he occupied the best place—on Mont St. Michel, if it then existed, and among the stone avenues of Carnac. Is it likely that such an artist would have omitted the chance of heightening his picture by an allusion to the "standing stones" of Dariorigum? The Romans occupied Old Sarum probably during the whole time they remained in this island, and the Via Badonica passed so immediately under Silbury Hill that they could not have been ignorant of either Stonehenge or Avebury. Nor in France could they possibly have missed seeing the numerous dolmens with which the country is covered. Notwithstanding all this, the silence is absolute. The circular temple of the Hyperboreans is the only thing any one has ever pretended to quote against this; and that, for reasons given above being inadmissible, any argument based on it falls to the ground.

Neither Cæsar nor Tacitus, though describing the religious observances of our forefathers, make any mention of temples; nor, indeed, does any other classical author. Tacitus[23] tells us that the Germans worshipped only in groves; and though this is hardly to the point, his relations with Agricola were so intimate that had the Gauls and Britons had temples of stone, he could hardly have avoided alluding to them. The inference from Cæsar and all the other authors is the same, but there is no direct evidence either way.

There is no passage in any classical authors which connects the Druids, either directly or indirectly, with any stone temples or stones of any sort. Dracontia are wholly the creation of Dr. Stukeley's very fertile imagination.

So far, therefore, as negative evidence goes, it is complete in showing that our megalithic circles did not exist in the time of the Romans, and that they were not temples. Unfortunately, however, no amount of negative evidence is sufficient to prove an affirmative, though it may suffice to establish a strong presumption in favour of a particular view, and, at all events, clears the way for the production of any direct evidence which we may have. The direct written evidence that has been adduced is, however, of the most shadowy character. It amounts to little more than this:—that every allusion to these monuments in mediæval authors, every local tradition, every scrap of intelligence we have regarding them, points to a post-Roman origin. No writer, of any age or country, suggested their being prehistoric or even pre-Roman before the age of Stukeley,—say 1700.

There is, so far as I know, only one paragraph in any classical author which mentions a French or British temple; but it belonged to so exceptional a community that it would hardly be safe to base an argument upon it. A "hieron," Strabo tells us, existed at the mouth of the Loire, inhabited by a colony of women who lived apart from their husbands, but the roof or thatch of the roof of whose temple was renewed annually:[24] a fact that shows, in the first place, that it had a roof, and in the second, that it was not a very dignified or permanent structure.

It would add very much to the clearness of our conception on this subject if the early Christian writers had left us some descriptions of the temples of the Britons when the missionaries first came among them. Though not quite so silent on the subject as the classical authors, their direct evidence is far from being so complete as might be wished. One of the passages most distinctly bearing on this question is found in a letter which Pope Gregory the Great addressed to the Abbot Millitus, then on a mission to England. In this letter he instructs him by no means to destroy the temples of the idols belonging to the English, but only the idols which are found in them; and adds, "Let holy water be made, and sprinkled over them. Let altars be [Pg 22] constructed, and relics placed on them; insomuch as if these temples are well constructed, it is necessary that they should be converted from the worship of dæmons to the service of the true God. So that the people, seeing their temples are not destroyed, may put away errors from their hearts, and, acknowledging the true God and adoring Him, may the more willingly assemble in the places where they were accustomed to meet."[25] A little further on he adds, in order that no apparent change may be made, "that on great festivals the people may erect huts of boughs around those churches which have been converted (commutatæ) from temples."

The fair inference from this paragraph seems to be that there was so little difference between the temples of the Pagans and the churches of the Christians that a little holy water and a few relics—as much esteemed in the West as in the East in those days—were all that was required to convert the one into the other.

We gather the same impression from another transaction which took place at Canterbury about the same time. After taking possession of the Cathedral, built of old by the Romans,[26] St. Augustine obtained from the recently converted King Ethelbert the cession of the temple in which he had been accustomed to worship his idols, and without more ado dedicated it to St. Pancras, and appropriated it as a burying place for himself and his successors from the circumstance of its being outside the walls.[27] We further learn from Gervaise[28] that it was so used till Cuthbert, the second archbishop, got permission to allow burials within the walls, and then erected the baptistry of St. John for this purpose, where apparently Becket's crown now stands. Afterwards the [Pg 23] monastery of SS. Peter and Paul, now St. Augustine's, was erected "in fundo Templi"—whatever that may mean—but at that time St. Augustine seems to have accepted the Pagan temples as perfectly appropriate to Christian rites.

In like manner when King Redwald, after his conversion to Christianity was persuaded by his wife not rashly to forsake the faith of his forefathers, he set up two altars side by side in his temple (in fano), and dedicated the one to Christ, the other to the "victims of the dæmons."[29] The temple, apparently, was equally appropriate to either.

A still more instructive example is the description of the destruction of the church at Godmundingham by Coifi—the heathen priest—on his conversion to Christianity. He first desecrated it by throwing a spear into it—whether by the door or window we are not told—and then ordered his people to burn it to the ground with all its enclosures. These, therefore, must all have been in wood or some equally combustible material.[30]