| Number 21. | SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 1840. | Volume I. |

The little rocky island of Dalkey forms the south-eastern extremity of the Bay of Dublin, as the bold and nearly insulated promontory of Howth forms its north-eastern termination. It is separated from the mainland of the parish from which it takes, or to which, perhaps, it gives its name, by a channel called Dalkey Sound, which is about nine hundred yards long, three hundred and eight yards wide at its south entrance, and two hundred and nine yards wide at its north entrance; the soundings in mid-channel varying from ten to five fathoms. This channel was anciently considered a tolerably safe and convenient harbour, and was the principal anchorage for ships frequenting the little castellated seaport town of Dalkey, from which merchandise was transferred to Dublin, as well by boats as by cars. Hence also the harbour of Dalkey was frequently used in former times on state occasions for the embarkation or landing of the Irish viceroys and other state officers. The Lord Deputy Philip de Courtney landed here in 1386, and Sir John Stanley, the deputy of the Marquis of Dublin, in the following year. In 1414, Sir John Talbot, then Lord Furnival, and afterwards the renowned Earl of Shrewsbury, landed here as Viceroy of Ireland; and in 1488, Sir Richard Edgecombe embarked at this harbour for England, after having taken the homage and oaths of fidelity of the nobility who had espoused the cause of Lambert Simnel. Here also landed Sir Edward Bellingham, Lord-Lieutenant in 1548, and Sir Anthony St Leger in 1553; and it was from this harbour that the Earl of Sussex, in 1558, embarked a large body of forces to oppose the Scottish invaders at the isle of Rathlin; and lastly, again, it was here that the unfortunate Sir John Perrot landed as viceroy in 1584. The conversion of this sound into an asylum harbour was at one time contemplated by government, and a plan for the purpose was proposed by the Committee of Inland Navigation; but from certain objections which were made to it, the project was abandoned. The situation would certainly have been a more imposing and magnificent one than that ultimately chosen.

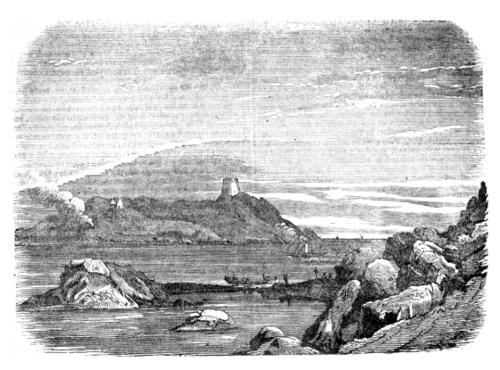

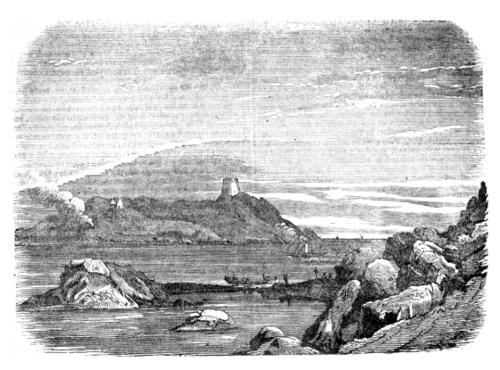

The island of Dalkey is of a nearly oval form, having a very irregular surface, in part rocky, and in part consisting of a fertile salt marsh, very valuable for the cure of sick cattle, who by feeding on it quickly recover and fatten. It is five hundred and twenty-eight yards long from north to south, and three hundred and eight yards wide from east to west, and comprises about twenty-nine acres of pasture. Its shore is rocky, and in some parts precipitous, and it commands the most beautiful views of the bays of Dublin and Killiney. Among several springs of fresh water on it, one on its south-west side has long been considered to possess sanative properties, and was formerly much resorted to for the cure of scurvy and other diseases. On the same side there are the roofless walls of an ancient church dedicated to St Benet or Benedict, the patron of the parish; and at its south-eastern extremity there is a battery, and a Martello tower which differs[Pg 162] from all the other structures of this class erected on the Irish coast, in having its entrance not at the side but on its top. It is traditionally stated that during the remarkable plague which visited Dublin in 1575, many of the citizens fled to this island for safety.

Dalkey island has several smaller ones contiguous to it, one of which, denominated Lamb Island, is covered with grass, while the others present a surface of bare granite. Of the latter islets one is called Clare Rock, and another the Maiden Rock, an appellation derived from a tradition said to be of twelve hundred years’ antiquity, that twelve young maidens from Bullock and Dalkey having gone over to this rock to gather duilisk, they were overtaken by a sudden storm so violent as to prohibit assistance from the larger island, and all miserably perished. To the north of these islands is situated the group of rocks called the Muglins, extending one hundred and thirty-two yards in length, and seventy-one in width. On those rocks, in 1765, the pirates Mac Kinley and Gidley were hanged in chains for the murder of Captain Glass.

Most of the features we have thus noticed, together with a portion of the adjacent shore of the bay, are exhibited in our prefixed illustration; and to the older citizens of our metropolis, as well as to many others of our countrymen, they must, we think, awaken many stirring recollections of the striking changes in the appearance of the scenery in many districts adjacent to the city, as well as in the character of the citizens themselves, which have taken place within the present century. It does not, indeed, require a very great age for any of us Dublinians to remember when the country along the southern shore of our beautiful bay, from Dunleary to the land’s-end on Dalkey common, presented a nearly uniform character of wildness and solitude—heathy grounds, broken only by masses of granite rocks, and tufts of blossomy furse, without culture, and, except in the little walled villages of Bullock and Dalkey, almost uninhabited. The district known as the Commons of Dalkey, which extended from the village to the eastern extremity of the bay, “the Sound,” or channel lying on its north-east, and the rocky hill of Dalkey on its south—this in particular was a locality of singularly romantic beauty, a creation of nature in her most sportive mood, and wholly untouched, as it would appear, by the hand of man. Giant masses of granite rocks, sometimes forming detached groups, and at others arranged into semicircular and even circular ledges, gave the greatest variety and inequalities of surface, and formed numerous dells of the greenest sward, so singularly wild and secluded that the elves themselves might justly claim them as their own. To these natural features should be added those of the rocky iron-bound coast, with its little coves, commanding from its cliffs the most delightful views of Killiney Bay, the Sound, the Island of Dalkey, and the Bay of Dublin. These latter features still remain, and can never change; but of all the others which we have noticed, what is there left? Scarcely a vestige that would remind the spectator of what the locality had been. The rocks have been nearly all removed, or converted into building materials for an assemblage of houses of all kinds of fantastic construction, surrounded for the most part by high and unsightly stone walls; and, except in the views obtained from some spots in it, the picturesque beauty of Dalkey common is gone for ever.

The common of Dalkey is now a place of life—a suburb, as we might say, of the city; but at the period to which we have alluded, it was ordinarily a scene of the most desert solitude. A few cottages stretching from the village along its southern boundary, and a solitary cabin originally built by miners, and which still remains, were the only habitations to be seen. But though thus uninhabited, it was not at all times a scene of loneliness. On Sundays and other holidays its rocks and dells were peopled with numerous pic-nic or sod parties of the middle class of the citizens. The song went round, and the echoes were startled by the merry notes of the fiddle or the flute, to which the several groups of happy dancers footed the Irish jig and country dance. Nor were such pic-nics confined exclusively to the citizens of the middle class—the sporters of jaunting cars and jingles. Parties of the higher ranks occasionally assembled here on week days, and had their rural fetes on a larger and more magnificent scale. It was our own good fortune to be an invited guest to one of these, of which we may be permitted to give some account, as an example of a state of manners and usages of society in Ireland now no longer to be found in persons of the class to which we refer. It was a pic-nic party given by the Alexanders, the Armits, and the present popular and deservedly honoured veteran the Commander of the Forces in Ireland—then lieutenant-colonel of the 18th or Royal Irish Fusileers, which were at the time quartered in Dublin. On the morning of as beautiful a day in June as ever came, the inhabitants of the leading thoroughfares of the city, and those along the road side from Dublin to Dunleary, were surprised by the unusual crowds of open carriages of all kinds conveying the youth and beauty of the aristocracy of the metropolis to the chosen scene; and when the fine band of the Fusileers, in their magnificent full-dress uniforms of blue and gold, were seen to pass along on the same route, innumerable parties of the inferior ranks of the inhabitants of the city and south-eastern suburbs were hastily formed to follow in their wake. At noon, or a little after, not only the majority of the original party were assembled in a beautiful and extensive green amphitheatre, surrounded by rocky cliffs, but those cliffs were themselves covered by a crowd of smaller parties—tributary stars around the more splendid galaxy that occupied the centre of the brilliant scene.

Two splendid marquees were erected at an early hour in the morning—one for the accommodation of the ladies, the other for the dinner party; and two beautiful pleasure-yachts which conveyed a portion of the invited to the scene, rested at anchor in the Sound, and with their white sails and coloured streamers contributed their share of life and beauty to the landscape. Let the reader then imagine what a spectacle was presented when the groups of quadrille-dancers—the beauty and gallantry of the metropolis and its vicinity—commenced dancing on the greensward to the music of one of the finest of military bands—what a delight to the happy multitude of spectators who looked on at the graceful and tempered gaiety of high life! The mind of the accomplished painter Watteau, in his finest pictures of the fetes champetres of the French, never conceived any thing so exquisitely beautiful and romantic.

This party did not disperse till after sunset. After an early dinner, dancing was again resumed; and it is worthy of remark that throughout the day there was not a single instance of rudeness or indecorum on the part of the uninvited spectators—no attempt even to approach beyond the natural rocky boundary which they had chosen for themselves—and that the festivities were concluded with mutual pleasure to all the parties who had participated in them. Alas! of the gay party then assembled—the gentle maidens in all the bloom of youthful beauty, the frank young soldiers, the men of fortune, the delighted parents—of all these how many now lie low! More, reader, than you could possibly imagine! Nor can we avoid exclaiming again, alas that such scenes of rational pleasure, in which the higher and the humbler classes came together in healthful and innocent enjoyment, are not now to be seen in our country as they were heretofore!

But while our memory with changeful feelings of pleasure and of pain fondly lingers on the brilliant scene we have attempted to sketch, we must not forget that our subject requires of us a notice of festivities of a very different character of which Dalkey was in former times the scene—when Dublin and its suburbs poured forth their crowds to enjoy the fun and drolleries of the crowning of Dalkey’s insular king!—when Dalkey, its Common, its Sound, and its Island, on a June day annually for several years, presented a spectacle of life, gaiety, good-humour, and enjoyment, such perhaps as was rarely ever exhibited elsewhere. What a glorious day was this for the Dunleary, Bullock, and Dalkey boatmen! Generous fellows! they would take over his majesty’s lieges to his empire for almost nothing—frequently for nothing; but, being determined enemies to absenteeism, they would not allow them to depart on the same terms, but would mulct those with taxes ad libitum who desired to abandon their country. And again, what a glorious day was this for the jingle-drivers of the Blackrock, the noddy-drivers, and the drivers of all other sorts of hired carriages in Dublin! Has it never occurred to the Railroad people to revive these forgotten frolics? What a harvest they might reap! But what do we say? The thing is impossible. The mirthful temperament, the thoughtless gaiety, the wit and humour that characterised the citizens in those days, are gone for ever. The Dublinians have become a grave, thoughtful, and serious people—we had almost said, a dull one. Their faces no longer wear a cheerful and happy look; the very youths of our metropolis seem to be ignorant of what merriment is, or at best to suppose that it consists in puffing tobacco smoke!

Ah! very different were the notions of their predecessors,[Pg 163] the nobility and gentry of his Majesty the King of Dalkey! Smoking would not at all have suited their mercurial temperament: it would have been the last thing that they would have thought of to have had their tongues tied and their mouths contorted into ugliness in the ridiculously serious effort to hold a cigar between the lips, and look absurdly important! These fellows thought that mouths were given for a very different purpose—to sing the manly song, to throw forth, not clouds of tobacco smoke, but flashes of wit and humour; and we are inclined to think they were right.

We are not about to describe the annual ceremony of the coronation of the Dalkey king, though we should gladly do so if we had the power, for the memory of it, as an interesting illustration of the character of Irish society in days not very remote, should not be allowed to die. We have indeed been an eye-witness of some of these brilliant follies, but we were young at the time, and our memory only retains a general impression of them. We can recollect that the green island figured in our woodcut, as well as the common, presented one mass of living beings, gaily dressed and arranged into groups of happy parties, each with its own musicians. We can recollect also that the dress of the ladies was almost invariably white, with green silk bonnets—a costume that gave a singularly brilliant effect to the scene. A large marquee was erected about the centre of the island for the use of his Majesty and attendant nobles, and a cordon was drawn around it, within which none others were permitted to enter. There was a military band in attendance upon the royal party; and while the noblemen and ladies of the court danced upon the sod within the bounds, to the music of the state minstrels, the subjects of the monarch danced outside.

But these were only the evening festivities. The day was devoted to graver purposes—the landing of his Majesty and nobles from the royal barge under a salute of twenty-one guns, the band playing “God save the King,” and the assembled multitude rending the air with their acclamations! Then the ceremony of his coronation, and afterwards his journey through his dominions, attended by his nobles! At an early hour the monarch with his court proceeded in ludicrously solemn procession from the palace to the church—the roofless ruin figured in our cut—in which the ceremony was performed with a mock gravity which was, however thoughtlessly profane, still irresistibly humorous. The nobles, with painted faces and a profuse display of stars and ribbons, had their titles and appropriate badges of office. There was the grand chamberlain, with his bunch of old rusty keys—the archbishop with his paper mitre and his natural beard of a month’s growth! The very titles of these great personages were conferred in a spirit of drollery, and made characteristic of the peculiarities of the individuals who bore them. Thus there was a Lord of Ireland’s-eye—a grave-looking gentleman who had lost one of his visual organs; a Lord Posey—a gentleman who was remarkable for his habit of carrying a bunch of flowers at his breast; and so on. All the nobility were wits, orators, and generally first-rate vocalists, and the royal visitors were similarly gifted. Charles Incledon, the prince of ballad-singers of his time, here sang his “Black-eyed Susan” and other charming ditties, and John Philpot Curran, the greatest wit of the world, set the table in a roar with his meteor flashes. But the prime spirits of the court were his Majesty himself, Stephen Armitage, his Lord High Admiral Luke Cassidy, and his archbishop —— Gillespy. The long coronation sermon of the latter was one of the richest treats of the day, and produced effects such as sermon never produced before.

During this august and imposing ceremony, the church was not only crowded to excess, and its ruined walls covered with human beings, but it was also surrounded with a dense mass of anxious listeners. As to his Majesty himself, he was at times the gravest and at times the merriest of monarchs, much of his humour consisting in the whimsical uncertainty of his movements, for there never was a crowned head more capricious or changeable in disposition than the King of Dalkey. He would set out attended by his court on a journey to some distant region of his dominions, change his mind in a minute and alter his route elsewhere, and again change it within a few minutes; and all these mutations of purpose were most loyally approved of and sympathised in by his majesty’s nobles and subjects. Another trait in King Stephen’s character was his love for song; and when the word ran through his empire that at the royal banquet his majesty had commenced or was about to commence his favourite “Love is my passion and glory,” there was scarcely one of his subjects, male or female, who did not make a rush to get within earshot of him. Peace be with thee, Stephen! thou wert a king “of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy;” and though thy reign was short and thy dominions small, thou madest more of thy subjects truly happy than many monarchs whose reigns were as much longer as their possessions were more extensive!

Imperfect as these recollections of the Dalkey festivities are, they will perhaps convey to many who have not hitherto heard of them some slight idea of their character; and they will, we trust, excite some surviving actor in them to preserve their memory in a fuller and more graphic record. They were, it will be seen, a sort of extemporaneous acted drama of the Tom Thumb kind, admirably preserving the unities of time and place—the time being one day, and the place—his majesty’s empire! As to the theatre on which it was acted, it was most admirably adapted for the spectacle, and had the most abundant accommodation for the audience. The scenery too was real scenery—not painted canvass, that required distance to give it the effect of reality: the greensward, the blue sky and bluer sea, the rocky islands, the distant hills and mountains, were painted by the hand of the greatest of all Artists; and the theatre, instead of miserable foot-lights, had its illumination from the glorious sun, the greatest of all His visible works!

It may be supposed that these annual festivities must have been productive of scenes of drunkenness and quarrelling, and we cannot state of our own knowledge whether they were so or not: but we have been informed that they did not lead to such results; and the statement would seem true, from the fact that no accident ever occurred to any of those engaged in them—a singular circumstance, if we consider the dangers to which so many persons were exposed in consequence of having to cross the sound in crowded boats at a late hour in the evening.

P.

It was not till after the preceding article had been in type that we were informed that a notice of the Dalkey festivities had recently appeared in the preface to the first volume of the beautiful edition of the poems of our own national poet, Moore, just published; and as it adds some interesting facts to those furnished by our own recollections, we gladly present them to our readers, in the perfect confidence that they will be read with that intense pleasure which his writings have rarely failed to afford.

“It was in the year 1794, or about the beginning of the next, that I remember having for the first time tried my hand at political satire. In their very worst times of slavery and suffering the happy disposition of my countrymen had kept their cheerfulness still unbroken and buoyant; and at the period of which I am speaking the hope of a brighter day dawning upon Ireland had given to the society of the middle class in Dublin a more than usual flow of hilarity and life. Among other gay results of this festive spirit, a club or society was instituted by some of our most convivial citizens, one of whose objects was to burlesque, good-humouredly, the forms and pomps of royalty. With this view they established a sort of mock kingdom, of which Dalkey, a small island near Dublin, was made the seat; and an eminent pawnbroker named Stephen Armitage, much renowned for his agreeable singing, was the chosen and popular monarch.

Before public affairs had become too serious for such pastimes, it was usual to celebrate yearly at Dalkey the day of this sovereign’s accession; and among the gay scenes that still live in my memory, there are few it recalls with more freshness than this celebration on a fine Sunday in summer of one of these anniversaries of King Stephen’s coronation. The picturesque sea views of that spot, the gay crowds along the shores, the innumerable boats full of life floating about, and above all, the true spirit of mirth which the Irish temperament never fails to lend to such meetings, rendered the whole a scene not easily forgotten. The state ceremonies of the day were performed with all due gravity within the ruins of an ancient church that stands on the island, where his mock majesty bestowed the order of knighthood upon certain favoured personages, and among others I recollect upon Incledon the celebrated singer, who rose from under the touch of the royal sword with the appropriate title of Sir Charles Melody. There was also selected for the favours of the crown on that day a lady of no ordinary poetic talent, Mrs Battier, who had gained much fame by some spirited satires in the manner of Churchill, and whose kind encouragement of my early attempts in versification were to me a source of much pride. This lady, as was[Pg 164] officially announced in the course of the day, had been appointed his Majesty’s Poetess Laureate, under the style and title of Henrietta Countess of Laurel.

There could hardly be devised a more apt vehicle for lively political satire than this gay travestie of monarchical power and its showy appurtenances so temptingly supplied. The very day indeed after this commemoration there appeared in the usual record of Dalkey state intelligence, an amusing proclamation from the king, offering a large reward in cronebanes (Irish halfpence) to the finder or finders of his Majesty’s crown, which, owing to his ‘having measured both sides of the road’ in his pedestrian progress from Dalkey on the preceding night, had unluckily fallen from the royal brow.”

We have met and conversed with every possible representative of the various classes that compose general society, from the sweep to the peer, and we feel ourselves bound to say that in no instance have we ever met any individual, no matter what his class or rank in life, who was really indifferent to the subject of dreams, fairies, and apparitions. They are topics that interest the imagination in all; and the hoary head of age is inclined with as much interest to a ghost-story, as the young and eager ear of youth, wrought up by all the nimble and apprehensive powers of early fancy. It is true the belief in ghosts is fast disappearing, and that of fairies is already almost gone; but with what new wonders they shall be replaced, it is difficult to say. The physical and natural we suppose will give us enough of the marvellous, without having recourse to the spiritual and supernatural. Steam and gas, if Science advance for another half century at the same rate as she has done in the last, will give sufficient exercise to all our faculties for wondering. We know a man who travelled eighty miles to see whether or not it was a fact that light could be conveyed for miles in a pipe under ground; and this man to our own knowledge possessed the organ of marvellousness to a surprising degree. It is singular, too, that his fear of ghosts was in proportion to this capacious propensity to wonder, as was his disposition when snug in a chimney corner to talk incessantly of such topics as were calculated to excite it.

In our opinion, ghosts and fairies will be seen wherever they are much talked of, and a belief in their existence cultivated and nourished. So long as the powers of the imagination are kept warm and active by exercise, they will create for themselves such images as they are in the habit of conceiving or dwelling upon; and these, when the individual happens to be in the appropriate position, will even by the mere force of association engender the particular Eidolon which is predominant in the mind. As an illustration of this I shall mention two cases of apparition which occurred in my native parish, one of which was that of a ghost, and the other of the fairies. To those who have read my “Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry,” the first which I shall narrate may possess some interest, as being that upon which I founded the tale of the “Midnight Mass.” The circumstances are simply these:—

There lived a man named M’Kenna at the hip of one of the mountainous hills which divide the county of Tyrone from that of Monaghan. This M’Kenna had two sons, one of whom was in the habit of tracing hares of a Sunday, whenever there happened to be a fall of snow. His father it seems had frequently remonstrated with him upon what he considered to be a violation of the Lord’s day, as well as for his general neglect of mass. The young man, however, though otherwise harmless and inoffensive, was in this matter quite insensible to paternal reproof, and continued to trace whenever the avocations of labour would allow him. It so happened that upon a Christmas morning, I think in the year 1814, there was a deep fall of snow, and young M’Kenna, instead of going to mass, got down his cock-stick—which is a staff much heavier at one end than at the other—and prepared to set out on his favourite amusement. His father seeing this, reproved him seriously, and insisted that he should attend prayers. His enthusiasm for the sport, however, was stronger than his love of religion, for he refused to be guided by his father’s advice. The old man during the altercation got warm; and on finding that the son obstinately scorned his authority, he knelt down and prayed that if the boy persisted in following his own will, he might never return from the mountains unless as a corpse. The imprecation, which was certainly as harsh as it was impious and senseless, might have startled many a mind from a purpose which was, to say the least of it, at variance with religion and the respect due to a father. It had no effect, however, upon the son, who is said to have replied, that whether he ever returned or not, he was determined on going; and go accordingly he did. He was not, however, alone, for it appears that three or four of the neighbouring young men accompanied him. Whether their sport was good or otherwise, is not to the purpose, neither am I able to say; but the story goes that towards the latter part of the day they started a larger and darker hare than any they had ever seen, and that she kept dodging on before them bit by bit, leading them to suppose that every succeeding cast of the cock-stick would bring her down. It was observed afterwards that she also led them into the recesses of the mountains, and that although they tried to turn her course homewards, they could not succeed in doing so. As evening advanced, the companions of M’Kenna began to feel the folly of pursuing her farther, and to perceive the danger of losing their way in the mountains should night or a snow-storm come upon them. They therefore proposed to give over the chase and return home; but M’Kenna would not hear of it. “If you wish to go home, you may,” said he; “as for me, I’ll never leave the hills till I have her with me.” They begged and entreated him to desist and return, but all to no purpose: he appeared to be what the Scotch call fey—that is, to act as if he were moved by some impulse that leads to death, and from the influence of which a man cannot withdraw himself. At length, on finding him invincibly obstinate, they left him pursuing the hare directly into the heart of the mountains, and returned to their respective homes.

In the mean time, one of the most terrible snow-storms ever remembered in that part of the country came on, and the consequence was, that the self-willed young man, who had equally trampled on the sanctions of religion and parental authority, was given over for lost. As soon as the tempest became still, the neighbours assembled in a body and proceeded to look for him. The snow, however, had fallen so heavily that not a single mark of a footstep could be seen. Nothing but one wide waste of white undulating hills met the eye wherever it turned, and of M’Kenna no trace whatever was visible or could be found. His father now remembering the unnatural character of his imprecation, was nearly distracted; for although the body had not yet been found, still by every one who witnessed the sudden rage of the storm and who knew the mountains, escape or survival was felt to be impossible. Every day for about a week large parties were out among the hill-ranges seeking him, but to no purpose. At length there came a thaw, and his body was found on a snow-wreath, lying in a supine posture within a circle which he had drawn around him with his cock-stick. His prayer-book lay opened upon his mouth, and his hat was pulled down so as to cover it and his face. It is unnecessary to say that the rumour of his death, and of the circumstances under which he left home, created a most extraordinary sensation in the country—a sensation that was the greater in proportion to the uncertainty occasioned by his not having been found either alive or dead. Some affirmed that he had crossed the mountains, and was seen in Monaghan; others, that he had been seen in Clones, in Emyvale, in Fivemiletown; but despite of all these agreeable reports, the melancholy truth was at length made clear by the appearance of the body as just stated.

Now, it so happened that the house nearest the spot where he lay was inhabited by a man named Daly, I think—but of the name I am not certain—who was a herd or care-taker to Dr Porter, then Bishop of Clogher. The situation of this house was the most lonely and desolate-looking that could be imagined. It was at least two miles distant from any human habitation, being surrounded by one wide and dreary waste of dark moor. By this house lay the route of those who had found the corpse, and I believe the door was borrowed for the purpose of conveying it home. Be this as it may, the family witnessed the melancholy procession as it passed slowly through the mountains, and when the place and circumstances are all considered, we may admit that to ignorant and superstitious people, whose minds even under ordinary occasions were strongly affected by such matters, it was a sight calculated to leave behind it a deep, if not a terrible impression. Time soon proved that it did so.

An incident is said to have occurred at the funeral which I have alluded to in the “Midnight Mass,” and which is certainly[Pg 165] in fine keeping with the wild spirit of the whole melancholy event. When the procession had advanced to a place called Mullaghtinny, a large dark-coloured hare, which was instantly recognised, by those who had been out with him on the hills, as the identical one that led him to his fate, is said to have crossed the road about twenty yards or so before the coffin. The story goes, that a man struck it on the side with a stone, and that the blow, which would have killed any ordinary hare, not only did it no injury, but occasioned a sound to proceed from the body resembling the hollow one emitted by an empty barrel when struck.

In the meantime the interment took place, and the sensation began like every other to die away in the natural progress of time, when, behold, a report ran about like wildfire that, to use the language of the people, “Frank M’Kenna was appearing!” Seldom indeed was the rumour of an apparition composed of materials so strongly calculated to win popular assent or to baffle rational investigation. As every man is not a Hibbert or a Nicolai, so will many, until such circumstances are made properly intelligible, continue to yield credence to testimony which would convince the judgment on any other subject. The case in question furnished as fine a specimen of a true ghost-story, freed from any suspicion of imposture or design, as could be submitted to a philosopher; and yet, notwithstanding the array of apparent facts connected with it, nothing in the world is simpler or of easier solution.

One night, about a fortnight after his funeral, the daughter of Daly, the herd, a girl about fourteen, while lying in bed saw what appeared to be the likeness of M’Kenna, who had been lost. She screamed out, and covering her head with the bed-clothes, told her father and mother that Frank M’Kenna was in the house. This alarming intelligence naturally produced great terror; still, Daly, who notwithstanding his belief in such matters possessed a good deal of moral courage, was cool enough to rise and examine the house, which consisted of only one apartment. This gave the daughter some courage, who, on finding that her father could not see him, ventured to look out, and she then could see nothing of him herself. She very soon fell asleep, and her father attributed what she saw to fear, or some accidental combination of shadows proceeding from the furniture, for it was a clear moonlight night. The light of the following day dispelled a great deal of their apprehensions, and comparatively little was thought of it until evening again advanced, when the fears of the daughter began to return. They appeared to be prophetic, for she said when night came that she knew he would appear again; and accordingly at the same hour he did so. This was repeated for several successive nights, until the girl, from the very hardihood of terror, began to become so far familiarised to the spectre as to venture to address it.

“In the name of God,” she asked, “what is troubling you, or why do you appear to me instead of to some of your own family or relations?”

The ghost’s answer alone might settle the question involved in the authenticity of its appearance, being, as it was, an account of one of the most ludicrous missions that ever a spirit was dispatched upon.

“I’m not allowed,” said he, “to spake to any of my friends, for I parted wid them in anger; but I’m come to tell you that they are quarrellin’ about my breeches—a new pair that I got made for Christmas day; an’ as I was comin’ up to thrace in the mountains, I thought the ould ones ’ud do betther, an’ of coorse I didn’t put the new pair an me. My raison for appearin’,” he added, “is, that you may tell my friends that none of them is to wear them—they must be given in charity.”

This serious and solemn intimation from the ghost was duly communicated to the family, and it was found that the circumstances were exactly as it had represented them. This of course was considered as sufficient proof of the truth of its mission. Their conversations now became not only frequent, but quite friendly and familiar. The girl became a favourite with the spectre, and the spectre on the other hand soon lost all his terrors in her eyes. He told her that whilst his friends were bearing home his body, the handspikes or poles on which they carried him had cut his back, and occasioned him great pain! The cutting of the back also was found to be true, and strengthened of course the truth and authenticity of their dialogues. The whole neighbourhood was now in a commotion with this story of the apparition, and persons incited by curiosity began to visit the girl in order to satisfy themselves of the truth of what they had heard. Every thing, however, was corroborated, and the child herself, without any symptoms of anxiety or terror, artlessly related her conversations with the spirit. Hitherto their interviews had been all nocturnal, but now that the ghost found his footing made good, he put a hardy face on, and ventured to appear by daylight. The girl also fell into states of syncope, and while the fits lasted, long conversations with him upon the subject of God, the blessed Virgin, and Heaven, took place between them. He was certainly an excellent moralist, and gave the best advice. Swearing, drunkenness, theft, and every evil propensity of our nature, were declaimed against with a degree of spectral eloquence quite surprising. Common fame had now a topic dear to her heart, and, never was a ghost made more of by his best friends, than she made of him. The whole country was in a tumult, and I well remember the crowds which flocked to the lonely little cabin in the mountains, now the scene of matters so interesting and important. Not a single day passed in which I should think from ten to twenty, thirty, or fifty persons, were not present at these singular interviews. Nothing else was talked of, thought of, and, as I can well testify, dreamt of. I would myself have gone to Daly’s were it not for a confounded misgiving I had, that perhaps the ghost might take such a fancy of appearing to me, as he had taken to cultivate an intimacy with the girl; and it so happens, that when I see the face of an individual nailed down in the coffin—chilling and gloomy operation!—I experience no particular wish ever to look upon it again.

Many persons might imagine that the herd’s daughter was acting the part of an impostor, by first originating and then sustaining such a delusion. If any one, however, was an impostor, it was the ghost, and not the girl, as her ill health and wasted cheek might well testify. The appearance of M’Kenna continued to haunt her for months. The reader is aware that he was lost on Christmas day, or rather on the night of it, and I remember seeing her in the early part of the following summer, during which time she was still the victim of a diseased imagination. Every thing in fact that could be done for her was done. They brought her to a priest named Donnelly, who lived down at Ballynasaggart, for the purpose of getting her cured, as he had the reputation of performing cures of that kind. They brought her also to the doctors, who also did what they could for her; but all to no purpose. Her fits were longer and of more frequent occurrence; her appetite left her; and ere four months had elapsed, she herself looked as like a spectre as the ghost himself could do for the life of him.

Now, this was a pure case of spectral illusion, and precisely similar to that detailed so philosophically by Nicolai the German bookseller, and to others mentioned by Hibbert. The image of M’Kenna not only appeared to her in daylight at her own house, but subsequently followed her wherever she went; and what proved this to have been the result of diseased organization, produced at first by a heated and excited imagination, was, that, as the story went, she could see him with her eyes shut. Whilst this state of mental and physical feeling lasted, she was the subject of the most intense curiosity. No matter where she went, whether to chapel, to fair, or to market, she was followed by crowds, every one feeling eager to get a glimpse of the girl who had actually seen, and what was more, spoken to a ghost—a live ghost.

Now, here was a young girl of an excitable temperament and large imagination, leading an almost solitary life amidst scenery of a lonely and desolate character, who, happening to be strongly impressed with an image of horror—for surely such was the body of a dead man seen in association with such peculiarly frightful circumstances as filial disobedience and a father’s curse were calculated to give it—cannot shake it off, but on the contrary becomes a victim to the disease which it generates. There is not an image which we see in a fever, or a face whether of angel or devil, or an uncouth shape of any kind, that is not occasioned by cerebral excitement, or derangement of the nervous system, analogous to that under which Daly’s daughter laboured. I saw her several times, and remember clearly that her pale face, dark eye, and very intellectual forehead, gave indications of such a temperament as under her circumstances would be apt to receive strong and fearful impressions from images calculated to excite terror, especially of the supernatural. It only now remains for me to mention the simple method of her cure, which was effected without either priest or doctor. It depended upon a word or two of advice given to her father by a very sensible man, who was in the habit of thinking on these[Pg 166] matters somewhat above the superstitious absurdities of the people.

“If you wish your daughter to be cured,” said he to her father, “leave the house you are now living in. Take her to some part of the country where she can have companions of her own class and state of life to mingle with; bring her away from the place altogether; for you may rest assured that so long as there are objects before her eyes to remind her of what happened, she will not mend on your hands.”

The father, although he sat rent free, took this excellent advice, even at a sacrifice of some comfort: for nothing short of the temptation of easy circumstances could have induced any man to reside in so wild and remote a solitude. In the course of a few days he removed from it with his family, and came to reside amidst the cheerful aspect and enlivening intercourse of human life. The consequences were precisely as the man had told him. In the course of a few weeks the little girl began to find that the visits of the spectre were like those of angels, few and far between. She was sent to school, and what with the confidence derived from human society, and the substitution of new objects and images, she soon perfectly recovered, and ere long was thoroughly set free from the fearful creation of her own brain.

Now, there is scarcely one of the people in my native parish who does not believe that the spirit of this man came back to the world, and actually appeared to this little girl. The time, however, is fast coming when these empty bugbears will altogether disappear, and we shall entertain more reverend and becoming notions of God than to suppose such senseless pranks could be played by the soul of a departed being under his permission. We might as well assert that the imaginary beings which surround the couch of the madman or hypochondriac have a real existence, as those that are conjured up by terror, weak nerves, or impure blood.

The spot where the body of M’Kenna was found is now marked by a little heap of stones, which has been collected since the melancholy event of his death. Every person who passes it throws a stone upon the heap; but why this old custom is practised, or what it means, I do not know, unless it be simply to mark the spot as a visible means of preserving the memory of the occurrence.

Daly’s house, the scene of the supposed apparition, is now a shapeless ruin, which could scarcely be seen were it not for the green spot that was once a garden, and which now shines at a distance like an emerald, but with no agreeable or pleasing associations. It is a spot which no solitary schoolboy will ever visit, nor indeed would the unflinching believer in the popular nonsense of ghosts wish to pass it without a companion. It is under any circumstances a gloomy and barren place, but when looked upon in connection with what we have just recited, it is lonely, desolate, and awful.

Some twenty years ago it was not unusual in the south of Ireland to see boys assembled about a fire of straw, loudly exulting over a flame-surrounded victim, whose attempts to escape, rendered nugatory by a timid retraction as it were into himself, served but to call forth louder shouts of triumph from his persecutors, who thought they justified their savage deed by proclaiming its hapless object as a witch, a robber of orchards, and a sucker of cows. Leaving to our antiquarian friends to discover whether the cruel act in question was not a holocaust originating in the mystic rites of Pagan times, it is for us to vindicate the wronged, and show the absurdity of the charges by which wrong has been maintained, and at the same time to indicate such matter as may serve to direct kindness to that innocent victim of ignorance, the inoffensive Hedgehog. That it is not a witch according to the old law, may be proved in a court of justice spite of the popular opinion and in defiance of the authority of Shakspeare, whose witches in Macbeth are warned that the proper time had come to commence their infernal incantations by “thrice and once the hedge-pig whined.” We have no witness that a hedgehog ever rode a broomstick or vomited knives, skewers, coals of fire, or any such like legal proofs of witchcraft; neither, perhaps you exclaim, is the writer of so much nonsense a witch. True it is that the creature so named has its place nowhere in the classification of a zoologist, yet still an undefined idea of its existence floats in the imagination of the most ignorant, and it is not extraordinary that an opinion once universal should still linger in unenlightened minds. In no way do we consider superstitious prejudices can better be extinguished than by inducing accuracy of observation of natural phenomena, which shows that nothing supernatural exists. The second charge, that the hedgehog is a robber of orchards, is a very old one. Pliny, as translated by Holland, states—“Hedgehogs make their provision beforehand of meat for winter in this wise: they wallow and roll themselves upon apples and such fruit lying under foot, and so catch them up with their prickles, and one more besides they take in their mouth, and so carry them into hollow trees.”

Now, this has no foundation in fact. True it is that the hedgehog is very often found in the neighbourhood of orchards; but then this may be accounted for by the fact that the fences of such places are usually of exactly the thick and unfrequented kind the animal best likes to inhabit. Our repeated experience has never enabled us to discover that a hedgehog will eat apples; on the contrary, in early youth, when imbued with the general belief that this fruit was their diet, we have in more than one or two instances (most cruelly as we now believe) starved to death unfortunate specimens, which we shut up in a box with an ample supply of apples, not one of which they ever ate. That a magpie will steal and hide silver spoons, or a raven silk stockings, we know, and may use it as an argument that animals steal what they do not want; but that a hedgehog steals apples in the way stated, experiment will at once prove to be untrue, for, from the varied position of the points of the spines when fixed, it is impossible to fasten an apple upon them; and when they are not fixed, they yield at once to the pressure made in the attempt. Though domesticated hedgehogs can easily be brought to feed on bread and milk or dressed vegetables, yet all our observation goes to prove that in a state of nature, or when permitted to stray in a garden, they never eat any but animal food. This is at variance with the generally received opinion, which is supported by the authority of White, who, in his admirable History of Selborne, complains that hedgehogs injured his garden by boring with their long snouts under the plantain that grew in his grass walks, eating off the root upwards, leaving the tufts of leaves untouched, and defacing his grounds by making unsightly holes. He then immediately goes on to prove that these identical animals used beetles as no inconsiderable portion of their food. Now, it strikes us that his previous observation was not made with his usual accuracy, and that the hedgehogs did not eat the roots of plantain, but dug up where they had been to catch the larvæ of beetles that had just devoured them. Thus rooks have been charged with wantonly plucking up grass, while the truth is, that they only pull up plants attacked at the root by the larvæ of the cockchaffer or some other of the Phytophagous coleoptera (as vegetable-eating beetles are called), catch in the fact the destructive insect, and so stop its ravages; thus rendering important services to those who, for lack of accurate observation, falsely accuse and mischievously shoot them. Trusting we have satisfied you that the hedgehog does not steal apples, we come to the next charge, that he sucks cows. To refute this we have the best possible evidence in the animal’s mouth, the structure of which is completely unsuited to the accomplishment of such an object. That he will drink milk with avidity when domesticated, is certain, but this is only a taste he acquires in common with hundreds of other animals: there is scarcely one that may not be induced to relish such diet. Having thus cleared our hero (a name he fully deserves, as he wins battles by passive resistance) from the charges brought against him, we proceed to give some anecdotes of our personal knowledge, and shall finish with a few interesting facts in his history, for the information of those who take pleasure in accurate acquaintance with nature’s works.

We have before mentioned our starving of hedgehogs by endeavouring to make them eat apples. In one of these cases we suffered no small retribution. We were at school in these days, and a practice existed amongst us called “slating.” It was an innocent imitation of the murderous attacks made in Dublin by short-sighted combinators on such of their fellow tradesmen as refused obedience to their mischievous laws. With us it consisted in waylaying each other in the dark passages, and striking with the open palms the hats or caps of the surprised over the eyes. Having been thus treated many times, we bethought ourselves of turning our starved hedgehog to account, and proceeded to skin him with the intent of making a cap; so that when again “slated,” the attacking party would find reason to call out in the words of Chaucer,

Accordingly, having hanged the animal up against a tree, we were essaying, by pulling, to effect a solution of continuity, as a surgeon would call it, between his body and skin, when the nail gave way, and he came down with considerable force on our forehead, accupuncturating us most awfully. The pain at the time was very great, and considerable soreness continued for several days, so much so that we were induced to suspect that some poisonous virus existed. We introduce this story for the purpose of calling attention to the effects of the spines when brought into action. Though experience induces us to believe that their punctures are more painful than those of pins and needles, we have not been able to ascertain why they should be so. Disabled in our attempt, we abandoned the skin, and it became common property. It was for some time used as one of the instruments for initiating the Johnny Newcomes into the mysteries of school life. Not a few will recollect how, when chilled by a previous salting or seasoning, as we called it, of snow crammed into the mouth, eyes, nose, and down the back, their sense of vitality was aroused, when escaping to bed they threw themselves on its thorny pre-occupant. Many, doubtless, then heartily wished themselves again within the zone of mamma’s apron-string; but the affair usually ended by storing up vengeance for, and the implement for executing it on, the next comer. A few years afterwards we procured another hedgehog, and provided him with earthworms, which he munged with great gusto. We mixed a few of them with bread and milk, and thus initiated him into this new diet. We tried him with frogs, mice, sparrows, and various other animal matters, of all of which he partook freely, and he soon became quite domesticated. We provided him a bed made in an old footstool in the kitchen; in this he remained during daylight rolled up in a ball of hay, from which it was quite a troublesome matter to extricate him; he could not be disentangled from it at all, without picking it carefully from his spines. Yet when he pleased himself to move, he came forth quite free, and did not drag a single filament out with him. He soon acquired a habit of making his appearance when tea was being served; the hissing of the water in the urn seemed to be his signal that his only meal was ready, for he regularly followed the servant who bore it into the tea-room, where he was indulged with a saucer of bread and milk on the rug before the fire. Having eaten as much as he desired, he commenced trotting about the room, taking precisely the same course round the legs of chairs and tables each time; and so he continued without a moment’s cessation to the latest hour the household remained up. Like the Guinea-pig, he seemed to have the greatest dislike to running across the room. In the morning he was always found snug in his bed. At length he disappeared, but previously did good service by devouring the cockroaches and beetles which infested the house. The desire of the hedgehog to pursue a beaten track was further evidenced by one we kept in a garden, which continued for months the course he first took, though a portion of it consisted in climbing with difficulty over some tiles, which a few inches on either side would have avoided. We often put things in his path, and watched his proceedings: he shrunk at first on finding the obstruction, and then tumbled over it in the best way he could.

Again we got another, and having heard that he may be at once tamed by indulging him in whisky, we mixed some in a saucer with sugar, and dipping his nose into it, he licked his chops, then ventured to make a lap at the enticing material, and, “startled at the sound himself had made,” he shrunk in, but came out again presently and lapped away most eagerly. The spirit soon showed its power, and like other beasts that indulge in it, he was any thing but himself; and his lacklustre leaden eye was rendered still less pleasing by its inane drunken expression. He staggered towards us in a ridiculously get-out-of-my-way sort of manner; however, he had not gone far before his potation produced all its effects; he tottered, then fell on his side; he was drunk in the full sense of the word; he could not even hold by the ground. We could then pull him about by the feet, open his mouth, twitch his whiskers, &c.: he was unresisting. There was a strange expression in his face of that self-confidence which we see in cowards when inspired by drinking. We put him away, and some twelve hours afterwards found him running about, and, as was predicted, quite tame, his spines lying so smoothly and regularly that he could be stroked down the back, and handled freely. We turned him into the kitchen to kill the cockroaches, and know nothing further of him.

Having given you so much of his manners, let us turn to his structural peculiarities. He is a small animal, not much larger than a rat when stripped of his spines and the muscular apparatus connected with them. It is this that enables him to roll himself up so as to present a chevaux-de-frize-like defence, impregnable to all ordinary enemies; and as there is much singularity in it, we will endeavour to describe it. On the back of the animal, between the skin and ribs, there is a large oval muscle with thickened edges, partially attached to the skin and spines. From this spring certain muscular bands, which are fixed firmly at the other ends to the head, tail, breast, and other parts of the body. The whole may be likened to a sort of elastic mantle, kept on the back by straps. When the owner wishes to roll up, he bends his body, then tightening the straps, he pulls the edge of the elastic mantle over, which contracting, draws it in as if it were a running string in a bag; at the same time the spines are fixed rigidly for defence by the straining of the muscles. There are many other interesting points in his anatomy. He possesses, as we do, well developed clavicles or collar-bones, which only exist in a rudimentary form in many quadrupeds. The peculiarities of his structure have exposed him to much, we will not say wanton cruelty, as its object was the increase of knowledge; it therefore should not be heavily censured, while so many unmeaning barbarities exist under the name of sports. It is stated as a proof of his endurance, that he has died without a groan under the slow process of zootomy inflicted upon him while nailed to a table. Such practices are seldom if ever engaged in at the present time.

The hedgehog is certainly a very apathetic creature, and at a low temperature becomes torpid; when in this condition he is doubtless devoid of feeling. Torpidity in many animals seems to stand in the place of migration in others, as a necessary condition when provision of food depends on season: in this case the fact seems to argue in favour of our position—that the hedgehog is in a state of nature strictly insectivorous; were it not so, torpidity would not seem necessary, as roots of vegetables could be had with facility as well at one season as the other. The hedgehog while torpid loses weight rather rapidly, so that the power of its remaining in this state is limited perhaps to a very few months.

The French academicians maintained long since that there were two species of hedgehog in their country. In reference to this, Ray, with his usual sagacity, after describing the common species, expresses a disbelief of there being another in Europe; a doubt since fully confirmed: for the dog and hog urchin, as the supposed species were called, have no more existence than the dog and hog badgers of our sportsmen have as distinct animals. Old authors notice several species under the name of hedgehog; but it appears by more accurate observation that but two of the animals mentioned by them are entitled to this name, viz. the one in question and the long-eared urchin of Siberia.

Since 1832, at least three other species have been enrolled in the records of science. It is said that when hedgehogs are born, their ears as well as their eyes are closed, and the former circumstance is noticed as a unique fact; however, another instance of imperforate ears occurred to us, in the case of a black bear cubbed at the gardens of the Royal Zoological Society of Ireland: it lived but a few hours. The ear of the hedgehog, in the structure of its bony parts, presents some peculiarities strikingly different from most other quadrupeds.

The hedgehog is said to feed occasionally on cantharides; a single beetle of which would occasion death or serious injury to most animals. If this be true, it is only another example of what often occurs in nature, illustrating the old proverb “what is one’s meat is another’s poison.” In addition to the use of the hedgehog as the destroyer of cockroaches, his skin was an important monopoly in the time of the Romans, being used both as a clothes-brush and an instrument for hackling hemp. His calcined eyes formed part of an ointment which the ancients tell us had such a wonderful efficacy as to enable persons using it to see in the dark. His gall was used to take off hair, his fat to put it on, &c.

He is still eaten in the south of Europe; but, judging from his food and appearance, we would not recommend the practice here. The hedgehog, or urchin, as he is sometimes called, belongs to the order of Insectivora, and possesses much of the character and habits of shrews. His scientific name is Erinaceus Europæus; but we have headed this article with his Irish appellation, which is perhaps the only one not inserted in our popular authors.

B.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE IRISH PENNY JOURNAL.

Sir—I would feel happy should the few remarks I will at present offer be found worthy of insertion in your columns—it is on the subject of waterproofing cloth, or other fabrics, cotton, silk, leather, &c.

When the matter first came before the public, being determined if possible to ascertain the secret, after many unsuccessful experiments I found all the requisite properties to consist in a concentrated solution of acetate of alumina, which can be procured at a cheap and a moderate rate, by mixing equal quantities of sulphate of alum (common alum) and acetate of lead (sugar of lead), and dissolving them in water: one pound of each may be purchased for one shilling, which may be dissolved in one gallon and a half of boiling water, and well mixed; when cold, the supernatant liquid should be removed from the sediment, which consists of sulphates of lead, potash, &c. Any article of dress, no matter how slight the fabric, if well saturated in it, and allowed to dry slowly, will bear the action of boiling water, and not permit it to pass through: it is a remarkable fact, and there are many others connected with the same solution well worthy of investigation. I should be glad if some of your learned correspondents would favour us with the reason why the boiling water will not pass through, and the steam of the water will. Thinking it a subject not totally unworthy of examination, I remain, Sir, your most obedient servant,

Thomas Irwin,

Apothecary and Chemist, 48 Cuffe St.

True Charity.—The lowest order of charity is that which is satisfied with relieving the immediate pressure of distress in individual cases. A higher is, that which makes provision on a large scale for the relief of such distress; as when a nation passes on from common almsgiving to a general provision for the destitute. A higher still is, when such provision is made in the way of anticipation, or for distant objects; as when the civilization of savages, the freeing of slaves, the treatment of the insane, or the education of the blind and deaf and mutes, is undertaken. The highest charity of all is, that which aims at the prevention rather than the alleviation of evil. It is a nobler charity to prevent destitution, crime, and ignorance, than to relieve individuals who never ought to have been made destitute, criminal, and ignorant.

Employment for the Unhappy.—The unhappy are indisposed to employment: all active occupations are wearisome and disgusting in prospect, at a time when every thing, life itself, is full of weariness and disgust. Yet the unhappy must be employed, or they will go mad. Comparatively blessed are they, if they are set in families, where claims and duties abound, and cannot be escaped. In the pressure of business there is present safety and ultimate relief. Harder is the lot of those who have few necessary occupations, enforced by other claims than their own harmlessness and profitableness. Reading often fails. Now and then it may beguile; but much oftener the attention is languid, the thoughts wander, and associations with the subject of grief are awakened. Women who find that reading will not do, will obtain no relief from sewing. Sewing is pleasant enough in moderation to those whose minds are at ease the while; but it is an employment which is trying to the nerves when long continued, at the best; and nothing can be worse for the harassed, and for those who want to escape from themselves. Writing is bad. The pen hangs idly suspended over the paper, or the sad thoughts that are alive within write themselves down. The safest and best of all occupations for such sufferers as are fit for it, is intercourse with young children. An infant might have beguiled Satan and his peers the day after they were couched on the lake of fire, if the love of children had chanced to linger amidst the ruins of their angelic nature. Next to this comes honest, genuine acquaintanceship among the poor; not mere charity-visiting, grounded on soup-tickets and blankets, but intercourse of mind, with real mutual interest between the parties. Gardening is excellent, because it unites bodily exertion with a sufficient engagement of the faculties, while sweet, compassionate nature is ministering cure in every sprouting leaf and scented blossom, and beckoning sleep to draw nigh, and be ready to follow up her benignant work. Walking is good, not stepping from shop to shop, or from neighbour to neighbour, but stretching out far into the country, to the freshest fields, and the highest ridges, and the quietest lanes. However sullen the imagination may have been among its griefs at home, here it cheers up and smiles. However listless the limbs may have been when sustaining a too heavy heart, here they are braced, and the lagging gait becomes buoyant again. However perverse the memory may have been in presenting all that was agonizing, and insisting only on what cannot be retrieved, here it is first disregarded, and then it sleeps; and the sleep of the memory is the day in Paradise to the unhappy. The mere breathing of the cool wind on the face in the commonest highway is rest and comfort which must be felt at such times to be believed. It is disbelieved in the shortest intervals between the seasons of enjoyment; and every time the sufferer has resolution to go forth to meet it, it penetrates to the very heart in glad surprise. The fields are better still: for there is the lark to fill up the hours with mirthful music; or, at worst, the robin and the flocks of fieldfares, to show that the hardest day has its life and hilarity. But the calmest region is the upland, where human life is spread out beneath the bodily eye, where the mind roves from the peasant’s nest to the spiry town, from the schoolhouse to the churchyard, from the diminished team in the patch of fallow, or the fisherman’s boat in the cove, to the viaduct that spans the valley, or the fleet that glides ghostlike on the horizon. This is the perch where the spirit plumes its ruffled and drooping wings, and makes ready to let itself down any wind that heaven may send.—From Deerbrook, a Tale, by Harriet Martineau.

Childhood.—Childhood is like a mirror, catching and reflecting images from all around it. Remember that an impious or profane thought, uttered by a parent’s lips, may operate on the young heart like a careless spray of water thrown upon polished steel, staining it with rust which no after scouring can efface.

Printed and published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; J. Drake, Birmingham; Slocombe & Simms, Leeds; Frazer and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.