The Project Gutenberg EBook of Nelson The Newsboy, by

Horatio Alger Jr. and Arthur M. Winfield and Edward Stratemeyer

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Nelson The Newsboy

Or, Afloat in New York

Author: Horatio Alger Jr.

Arthur M. Winfield

Edward Stratemeyer

Release Date: March 19, 2017 [EBook #54389]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NELSON THE NEWSBOY ***

Produced by David Edwards, Martin Pettit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

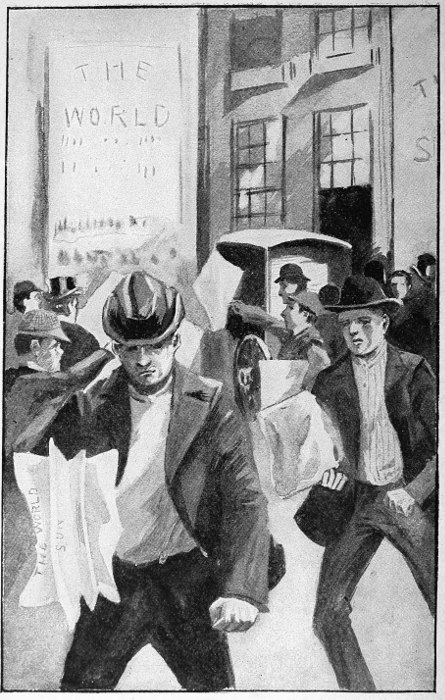

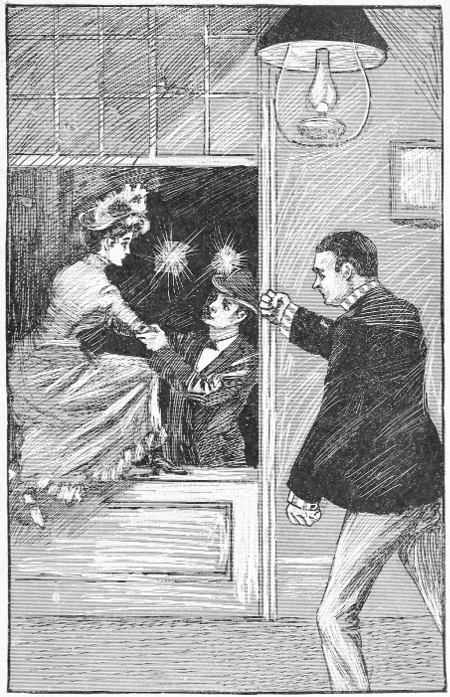

"HE CAUGHT SIGHT OF THE BULLY NEWSBOY WHO HAD ROBBED

HIM."—Frontispiece.

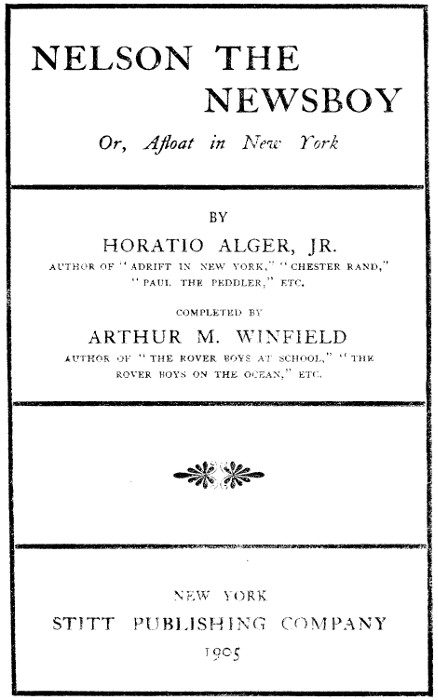

Nelson the Newsboy.

Or, Afloat in New York

BY

HORATIO ALGER, JR.

AUTHOR OF "ADRIFT IN NEW YORK," "CHESTER RAND,"

"PAUL THE PEDDLER," ETC.

COMPLETED BY

ARTHUR M. WINFIELD

AUTHOR OF "THE ROVER BOYS AT SCHOOL," "THE

ROVER BOYS ON THE OCEAN," ETC.

NEW YORK

STITT PUBLISHING COMPANY

1905

THE YOUNG BOOK AGENT;

Or, Frank Hardy's Road to Success.FROM FARM TO FORTUNE;

Or, Nat Nason's Strange Experience.LOST AT SEA;

Or, Robert Roscoe's Strange Cruise.JERRY, THE BACKWOODS BOY;

Or, The Parkhurst Treasure.NELSON, THE NEWSBOY;

Or, Afloat in New York.YOUNG CAPTAIN JACK;

Or, The Son of a Soldier.OUT FOR BUSINESS;

Or, Robert Frost's Strange Career.FALLING IN WITH FORTUNE;

Or, The Experiences of a Young Secretary.

12mo, finely illustrated and bound. Price, per volume, 60 cents.

NEW YORK

STITT PUBLISHING COMPANY

1905

Copyright, 1901, by

THE MERSHON COMPANY

All rights reserved

"Nelson the Newsboy" relates the adventures of a wide-awake lad in the great metropolis. The youth is of unknown parentage and is thrown out upon his own resources at a tender age. He becomes at first a newsboy, and from that gradually works up to something better. He is often tempted to do wrong—the temptation becoming particularly hard on account of his extreme poverty—but there is that in his make-up which keeps him in the right path, and in the end he becomes a victor in more ways than one.

So much for the seamy side of life in New York, which, alas! is by far the greater side. On the other hand, there are those who are well-to-do and aristocratic who are interested in learning what has become of the boy, and these furnish a view of life in the upper society of the metropolis. How the youthful hero fares in the end is told in the pages which follow.

In its original form Mr. Alger intended this story of New York life for a semi-juvenile[Pg iv] drama. But it was not used in that shape, and when the gifted author of so many interesting stories for young people had laid aside his pen forever, this manuscript, with others, was placed in the hands of the present writer, to be made over into such a volume as might have met with the noted author's approval. The other books having proved successful, my one wish is that this may follow in their footsteps.

Arthur M. Winfield.

June 15, 1901.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Introducing the Hero, | 1 |

| II. | A Quarrel over a Dollar, | 9 |

| III. | Sam Pepper's Resort, | 17 |

| IV. | Down at the Ferry, | 25 |

| V. | Nelson Speaks His Mind, | 35 |

| VI. | A Book Agent's Trials, | 43 |

| VII. | A Harsh Alternative, | 55 |

| VIII. | The Combination of the Safe, | 63 |

| IX. | A Pair Well Matched, | 69 |

| X. | Gertrude Leaves Her Home, | 77 |

| XI. | Afloat in New York, | 85 |

| XII. | Nelson Recovers Some Money, | 94 |

| XIII. | A Question of Business, | 102 |

| XIV. | Bulson Receives a Setback, | 111 |

| XV. | Buying Out a News Stand, | 119 |

| XVI. | Nelson and Pepper Part, | 127 |

| XVII. | A Bold Move, | 134 |

| XVIII. | In the Hands of the Enemy, | 140 |

| XIX. | Nelson to the Rescue, | 147 |

| XX. | The Home in the Tenement, | 155 |

| XXI. | Nelson Makes a Present, | 162 |

| XXII. | A Disappointment, | 170 |

| XXIII. | An Unsuccessful Quest, | 176 |

| [Pg vi]XXIV. | A Decoy Letter, | 183 |

| XXV. | Mark Horton Relents, | 190 |

| XXVI. | Nelson on Shipboard, | 198 |

| XXVII. | Down the Jersey Coast, | 206 |

| XXVIII. | Gertrude Has an Adventure, | 215 |

| XXIX. | A Surprise on the Road, | 224 |

| XXX. | Comparing Notes, | 233 |

| XXXI. | Bulson Grows Desperate, | 240 |

| XXXII. | Somebody Waits in Vain, | 248 |

| XXXIII. | Questions of Importance, | 257 |

| XXXIV. | Father and Son—Conclusion, | 266 |

NELSON THE NEWSBOY.

"Herald, Times, Tribune! All the news of the day! Have a paper, sir? All about the terrible fire in Harlem! Two lives lost!"

High and clear above the din made by the cabs, trucks, and street cars a boyish voice could be heard. The speaker was but fifteen years of age, tall and thin, with a face that betokened a refinement unusual to such a station in life. But if the lad's look was above the average, his clothes were not, for they were in tatters, while the hat and shoes he wore had seen far better days.

"A fire in Harlem, eh?" queried a stout gentleman, as he stopped short in front of the newsboy.

"Yes, sir; a big one, too, sir. Which paper will you have?"

"Which has the most in about the fire?"

"All about the same, sir. Better take 'em all, sir. Then you'll be sure to have all the news," added the newsboy shrewdly.

At this the stout gentleman laughed.

"I don't know but what you are right," he said. "Give me one of each."

The words were scarcely uttered when the newsboy had the papers ready for him. Taking the several sheets, the stout man passed over a dime and started to cross the crowded thoroughfare.

"Change, sir!" cried the boy, and dove into his pocket for a handful of cents.

"Never mind the change, lad."

"Thank you, sir!" The newsboy wheeled quickly. "Herald, Times, Tribune! Who'll have a paper? All the latest news! Extra!"

The stout man stepped from the curb into the gutter, and there halted to let a truck go by. As he waited he began to scan one of the newspapers he had purchased. Suddenly he gave a violent start.

"Fire in the Starmore apartment house!" he muttered. "The building I purchased only last month! What bad luck is this?"

Still staring at the newspaper, he passed onward behind the heavy truck. Another truck[Pg 3] and a street car were coming from the opposite direction, and both traveling at a good rate of speed.

"Hi! look out!" yelled the truck-driver, and the street-car bell clanged violently. But the stout man was too absorbed in the newspaper to heed the warnings.

The cry of the truck-driver reached the ears of the quick-witted newsboy, and in a flash he saw the danger.

"Oh, the gentleman will be run over!" he muttered, and throwing his papers on the pavement, he made a leap into the street and grabbed the man by the arm. Just as he drew the stout individual back the truck horse plunged forward, grazing the man's side. Had it not been for the newsboy, the stout gentleman would have collapsed in the gutter. But as it was each, in a moment more, gained the pavement in safety.

"Phew! that was a narrow escape," puffed the stout gentleman, as soon as he could get back some of the wind he had lost in his consternation.

"So it was," answered the newsboy, as he stepped about to pick up his scattering stock in trade.

The stout gentleman brought out a large[Pg 4] handkerchief and began to mop his face, for the excitement had put him into a perspiration.

"My lad, you've done me a great service," he went on, after the boy had collected his papers.

"That's all right, sir," was the ready reply. "Sorry you lost your papers. The truck cut 'em up, and they are all muddy, besides."

"Never mind the papers—you can sell me another set. But I want to thank you for what you did for me."

"You're welcome, sir. Here's the other set of papers."

"If it hadn't been for you, I might have fallen under that horse and truck!" The stout man shuddered. "Here is pay for the papers and for your services to me."

As he finished he held out a two-dollar bill.

"Why, it's two dollars!" cried the newsboy in astonishment. Then he added quickly, "I can't change it."

"I don't want you to change it. I want you to keep it."

"What for?"

"For what you did for me."

"What I did aint worth two dollars."

"Let me be the judge of that, my lad. What is your name?"

"I'm Nelson, sir."

"What is your full name?"

At this question the boy's face fell, and his mouth trembled a little as he gave his answer.

"I don't know, sir."

"What, you don't know what your name is?" cried the stout gentleman in astonishment.

"No, sir."

"But—but—you must have some name. Where do you live?"

"I live over on the East Side with an old sailor named Samuel Pepper. He keeps a lunch room."

"Is he a relative?"

"He calls himself my father—not my real father, you know; only he says he adopted me when I was a little kid. Everybody around there calls me Nelson, or Sam Pepper's boy."

"I see. And he sends you out to sell papers?"

"No, sir; I go out on my own hook."

"But you ought to go to school."

"I go to night school sometimes, when Sam lets me."

"Didn't he ever send you to day school?"

At this Nelson, for so we will call him for the present, shook his head.

"Sam don't like the schools. He says if I go I'll get too smart for him. He says I am almost too smart already."

"Too bad!" The stout gentleman was going[Pg 6] to say something more, but suddenly remembered about the fire in Harlem. "Perhaps I'll see you again, Nelson. I can't stop now. Do you know why I forgot myself in the street? It was because that fire proved to be in an apartment house that I purchased only a month ago."

"Your house! That's a big loss, sir."

"The place was insured, so I shall not expect to lose much. I must get up there at once and see see how it was those lives were lost."

In a moment more the stout gentleman was crossing the street again, but this time taking very good care that he should not be taken unawares.

Nelson started to sell more papers, when another boy, who had been selling papers further down the block, came hurrying toward him.

"Wot did de old gent give yer, Nelse?" he asked.

"Gave me two dollars."

"Two dollars! Jest fer hauling him back out of de gutter?"

"I kept him from being run over by a truck."

"Den he oughter give yer ten or twenty."

"Two was more than enough, Billy."

At this Billy Darnley drew down his mouth.

"I would have struck him fer a twenty, sure," he went on.

"You always were greedy, Billy," answered Nelson.

"Do you mean dat fer an insult, Nelse?"

"I mean it for the truth."

"You're gittin' too high-toned fer dis business, Nelse."

"I don't think I am."

"Lend me a dollar of dat money, will yer? I'll pay yer back ter-morrow."

At this Nelson shook his head.

"I'm sorry, Billy, but I'd rather keep my money."

"Are you afraid to trust me?"

"I don't see why I should trust you. You earn as much money as I do."

"You didn't earn dat two dollars."

"The gentleman thought I did."

"He was a soft one."

"He was a very nice man," retorted Nelson promptly.

"O' course you'd stick up fer him. Let me have de dollar."

"What do you want to do with it?"

Now in truth Billy thought of nothing but to have a good time with the money, but he did not deem it prudent to tell Nelson so.

"I—I want to buy myself a new pair of pants," he stammered.

"Your pants are better than mine."

"No, da aint—d'are full o' holes."

"Why don't you sew them up, as I do?"

"I aint no woman, to use a needle. Come, hand over de dollar!" And Billy held out his dirty fingers.

"I shan't let you have it, and that ends it," said Nelson firmly.

He started to move on, but in a moment more Billy Darnley was beside him and had him clutched firmly by the arm.

As Nelson had said, he was of unknown parentage and practically alone in the world. As far back as he could remember he had lived with Sam Pepper, a shiftless, unprincipled man, who in the last ten years had followed the sea and a dozen other callings, and who was at present the proprietor of a lunch-room on the East Side—a place frequented by many persons of shady reputation.

Where he had come from, and what his real name was, were complete mysteries to Nelson, and it must be confessed that in the past he had paid scant attention to them; this being largely due to his immature years. Now, however, he was growing older, and he often found himself wondering how it was that he was living with Sam Pepper.

Once he had asked the man, but the only answer he received was a growl and a demand that he stop asking foolish questions. "You're only a kid yet," said Pepper. "Wait till you're old enough; maybe then you'll learn a thing or two."[Pg 10] And so Nelson waited, but did not cease to wonder.

Many of Sam Pepper's intimates were hard customers, and Nelson was of the opinion that Pepper himself was no better, although he was not in a position to prove it. The boy was driven out to earn his own living, and the only time that Pepper was liberal with him was when the man was in liquor.

More than once Nelson had thought to run away from the man and his evil associates, but found himself unable to do so. The main reason for his remaining was that he felt Pepper held the mystery of his past, and if he went away that mystery would remain forever unsolved.

As Nelson had said, he had gained a scanty education by attending night school. To this education he had added some useful reading, so he was advanced as far as most boys in much better circumstances. Learning appeared to come easy to him, showing that his mind was of the superior sort.

Nelson had started out that morning with a determination to sell all the papers possible, and keep on with his efforts until he had eight or ten dollars to his credit. With this amount he intended to invest in a suit which he had seen advertised for six dollars, a cap, and a cheap pair of[Pg 11] shoes. He did not know but what Pepper might find fault with him for "cutting such a swell," but he was willing to risk it.

Before meeting the stout gentleman Nelson's assets amounted to three dollars and forty cents. With the ten cents for papers and the two dollars extra, he now found himself with five dollars and half to his credit. This was not a fortune, but as Nelson had never before possessed more than three dollars at one time, it was, to his way of thinking, considerable.

The suggestion that he lend Billy Darnley a dollar did not appeal to him. In the first place he knew Billy to be both a bully and a spendthrift, who was more than likely to squander the money on pie, ice cream, cigarettes, and a ticket to some cheap burlesque show, and in the second place he was more than satisfied that Billy would never refund the loan, not having returned a quarter loaned him months before.

"Let go my arm, Billy!" he cried, as the big newsboy brought him to a halt.

"Why can't yer let me have de dollar?" questioned Billy. "I'll make it right wid yer, Nelse; take me word on it."

"How is it you haven't paid back that quarter I let you have?"

"I did pay it back."

"No, you didn't."

"Yes, I did. I—I give it to Sam one day to give to yer."

By the look on his face Nelson knew that the bully was falsifying.

"Sam never told me, and I guess he would if it was so. Now let me go."

"I want dat dollar first."

"You shan't have it."

Nelson had scarcely spoken when Billy Darnley made a sudden clutch for the pocket of his vest.

Much dilapidated, the pocket gave way easily; and in a twinkle the bully was running up the street with five dollars in bills and a bit of cloth clutched tightly in his dirty fist.

"Hi! stop!" cried Nelson, but instead of heeding the demand, the bully only ran the faster. Soon he passed around a corner and down a side street leading to the East River.

Nelson was an excellent runner, and, papers under his arm, he lost no time in making after the thief. Thus block after block was passed, until pursued and pursuer were but a short distance from one of the ferry entrances.

A boat was on the point of leaving, and without waiting to obtain a ferry ticket, Billy Darnley slipped in among the trucks going aboard. A gate-keeper tried in vain to catch him, and then[Pg 13] came back and shut the gate, just as Nelson reached it.

"Open the gate!" cried Nelson, so out of breath he could scarcely utter the words. "Open the gate, quick!"

"Go around to the other entrance," replied the gate-keeper, and then added, "Are you after that other newsboy?"

"I am. He stole five dollars from me."

"Five dollars! That's a good one. You never had five dollars in your life. You can't get a free ride on any such fairy tale as that. You go around and buy a ticket, or I'll call a policeman."

In despair Nelson looked through the high, slatted gate and saw that the gates on the ferryboat were already down. A bell jangled, and the big paddle wheels began to revolve. In another moment the boat had left the slip and was on its way to Brooklyn.

"He's gone—and the five dollars is gone, too!" groaned Nelson, and his heart sank. He knew that it would be useless to attempt to follow the bully. Billy would keep out of sight so long as the money lasted. When it was spent he would re-appear in New York and deny everything, and to prove that he was a thief would be next to impossible, for, so far as Nelson knew, nobody had seen the money taken.

He had now but fifty cents left, and a stock of papers worth half a dollar more, if sold. With a heavy heart he walked away from the ferryhouse in the direction from whence he had come.

Nelson had scarcely taken his stand at the corner again when a young lady, very stylishly dressed, came out of a neighboring store, looked at him, and smiled.

"Did you catch him?" she asked sweetly.

"Who, miss; the big boy who stole my money?" questioned Nelson quickly.

"Yes."

"No, ma'am; he got away, on a Brooklyn ferryboat."

"And how much did he steal from you?"

"Five dollars."

"Why, I didn't think—that is, five dollars is a nice sum for a newsboy, isn't it?"

"Yes, ma'am; but I was saving up for a new suit of clothes."

"And he got away from you? Too bad! I wish I could help you, but unfortunately I have spent all of my money but this." She held out a quarter. "Will you accept it?"

Nelson looked at her, and something compelled him to draw back.

"Excuse me—but I'd rather not," he stammered. "Much obliged, just the same."

"You had better take the money," went on the young lady, whose name was Gertrude Horton. But Nelson would not listen to it, and so she had to place the piece in her purse again. Then she entered the coach standing near and was driven rapidly away. The newsboy gazed after the coach curiously.

"What a lot of money it must take to keep up such style!" he thought. "Those folks spend more in a week, I guess, than some folks on the East Side spend in a year. I don't wonder Sam is always growling about not being rich—after he's been out among the wealthy people he knows. I must say I'd like to be rich myself, just for once, to see how it feels."

Long before noon Nelson's stock of newspapers was exhausted. Without going to Sam Pepper's restaurant for lunch he stopped at a small stand on a side street, where he obtained several crullers and a cup of coffee for five cents. His scanty meal over he purchased a supply of evening papers and set to work to sell these, with the result, by nightfall, that all were gone, and he was thirty-five cents richer.

Sam Pepper's place on the East Side was half a dozen steps below the pavement, in a semi-basement, which was narrow and low and suffering greatly for a thorough cleaning. In the front[Pg 16] was a small show window, filled with pies and vegetables, and behind this eight or ten tables for diners. To one side was a lunch counter for those who were in a hurry, and at the back was a small bar. The cooking was done in a shed in the rear, and beside this shed were two rooms which Nelson and Sam Pepper called their home.

The whole place was so uninviting it is a wonder that Sam Pepper had any trade at all. But his prices were low, and this was a large attraction to those whose purses were slim. Besides this Sam never interfered with those who came to patronize him, and it may as well be stated here that many a crime was concocted at those tables, without the police of the metropolis being the wiser. To Sam it made no difference if his customer was the worst criminal on the East Side so long as he paid his way.

"We've all got to live," he would say. "The world owes every man a living, and if he can't git it one way he must git it in another."

The secret of Sam Pepper's looseness of morals was the fact that he had seen better days, and his coming down in the world had caused him to become more and more reckless. At the present time money was tight with him, and he was fast approaching that point when, as we shall soon see, he would be fit for any desperate deed.

"Well, how have you done to-day?" asked Sam Pepper, when Nelson entered the lunch-room and came to the rear, where Pepper stood mixing some liquors.

"Oh, I sold quite a few papers," answered Nelson.

"How many?"

"Over a hundred."

"Then I guess you made over a dollar?"

"I did."

"That's more than I've made to-day," growled Pepper. "Business is growing worse and worse."

Nelson knew that he must have made more than a dollar, but he did not say anything on the point. He saw that Sam Pepper was in an ugly mood.

"It seems to me you ought to begin paying something for your keep," went on the lunch-room keeper, after he had returned from serving the drinks he had been mixing.

"All right, I'm willing," said Nelson readily. "But I don't get much from here now, remember."

"It's not my fault if you are not here at dinner time. Plenty of eating going to waste."

"I am not going to eat other folks' left-overs," said the newsboy, remembering the offer made to him several days before.

"Those left-overs are good enough for the likes of you, Nelson. Don't git high-toned before you can afford it."

"What do you want me to pay?"

"You ought to pay me at least five dollars a week," growled Sam Pepper, after a crafty look into the boy's face.

"Five dollars a week!" ejaculated Nelson in surprise. "Why, I don't make it, excepting when business is good."

"Well, it's got to be five dollars a week after this."

"I can get board at other places for three."

"You won't go to no other place. You'll stay here, and if you make a dollar or more a day you'll pay me the five dollars."

"But who will buy me any clothes?"

"Aint that suit good enough?"

"No, it's not. I was saving up to buy another suit, but Billy Darnley stole five dollars of the[Pg 19] savings from me this morning," went on Nelson bitterly.

"Stole five dollars from you? I don't believe you."

"It's true."

"Then you ought to lose the money, seeing that you didn't pass it over to me," grumbled Sam Pepper. "After this, you let me save your money for you."

At this point some customers came in, and Sam had to wait on them. Seeing this, the newsboy passed around the bar and into the two rooms which he and Pepper called home. They were gloomy and foul-smelling, but the newsboy did not mind this, for he was used to the surroundings. Yet his heart was heavy, as he threw himself into a dilapidated chair and gave himself up to his thoughts.

The new suit of clothes seemed further off than ever, for, if he must pay Sam Pepper five dollars a week for his board, it would be utterly impossible for him to save a cent. The extra money would be needed to buy fresh papers each day.

"It isn't fair!" he muttered. "It isn't fair, and I won't stand it! I'll run away first; that's what I'll do!"

Running away was no new idea, but, as before, he thought of the past and of what Sam Pepper[Pg 20] might have locked up in his breast. No, it would not do to go away. He must unlock the mystery of the past first.

"I'll question Sam to-night, and I'll make him tell something," he said.

The resolve had hardly crossed his mind when Pepper opened the door with a bang, as it flew back against the wall.

"Come out here and help me," he snarled. "There is plenty of work to do. The kitchen woman has left me in the lurch. Throw off your coat and git into that dishpan, and be lively about it."

Without a word, Nelson did as bidden. He had washed dishes before, and though the pile beside him was by no means small, he soon made away with them. Then Pepper set him to polishing up the knives, forks, and spoons, and this task took until it was time to close for the night.

After the lunch-room had been locked up, and most of the lights put out, Sam Pepper went to the bar and mixed himself an extra-large glass of liquor. This was his "nightcap," as he called it, and usually, after drinking it, he would retire.

To-night, however, after consuming the liquor, he went into one of the back rooms and got out his best coat and his hat.

"I'm going out an hour or so," he said. "You keep good watch while I'm away."

"All right," answered Nelson. He was disappointed at not being able to question Pepper, but saw there was no help for it. Soon the man was gone, and Nelson was left alone. Pepper had locked the street door and taken the key with him.

The day's work had made Nelson tired, but he was in no humor for sleeping, and tumbled and tossed for a long while after lying down upon his hard couch. He thought of the stout gentleman, of the big newsboy who had robbed him, and of the kind young lady who had offered him assistance. For some reason he could not get the young lady out of his mind, and he half wished he might see her again.

Then his thoughts came back to himself. Who was he, and how had he come into Sam Pepper's care? Surely the man must know all about the past. What could Pepper be hiding from him?

At last he fell asleep, and did not rouse up until early morning. Sam Pepper was just returning, and a glance showed that the man was more than half under the influence of liquor.

"It's a good game," muttered Pepper to himself, as he stumbled around, preparing to retire,[Pg 22] "A good game, and it will make me rich. And Nelson shall help me, too."

"Help you at what?" asked the newsboy sleepily.

"Never mind now, you go to sleep," answered Pepper sharply.

He pitched himself on his bed and was soon snoring lustily, and seeing this Nelson did not attempt to disturb him. He slept soundly for the rest of the night, and by six o'clock was outdoors and on his way to get his supply of morning papers.

Pepper had warned him to come back by eleven o'clock, to go at the dishes again, for the kitchen woman was not coming back. This made him cautious about investing in newspapers. However, trade proved brisk, and by ten o'clock he had sold out, and cleared sixty cents.

"I won't buy any more papers until after dinner," he said to himself. "I'll walk down to the ferry and see if I can find out anything about Billy Darnley."

At the ferry there was the usual rush of passengers, the noise of the heavy trucks coming and going, and the shrill cries of the newsboys. Nelson stopped near the ferryhouse to view the scene.

Hardly had he paused when his attention was[Pg 23] attracted to a quarrel between a large newsboy and a small one. The larger lad was shaking his fist in the face of the smaller.

"You keep away from dis corner, Paul Randall!" said the big newsboy. "If yer don't I'll fix yer, remember dat!"

"I have as much right here as you, Len Snocks!" replied the little fellow.

"Yer aint got no right here at all!" blustered Len Snocks. "Dis is my spot, see?"

"You didn't pay for it."

"Don't yer talk back ter me!" howled Len Snocks, and catching the little lad's stock of papers he threw them down in the mud of the street. "Now clear out, or I'll t'row you down de same way," he went on.

The scene made Nelson's blood boil. He recognized both boys, and knew that Paul Randall helped support a mother who was half blind. Len Snocks was a bully belonging to the crowd with whom Billy Darnley associated.

Rushing across the roadway, Nelson caught Len Snocks by the arm and held him tightly.

"You big brute!" he cried. "Why don't you tackle a fellow your own size?"

"Oh, Nelson, he has spoiled my papers!" sobbed Paul, running to save what was left of the stock.

"Lemme go!" snarled Len Snocks. "Lemme go, do yer hear?"

"You must give Paul clean papers for the dirty ones," returned Nelson firmly.

"I won't do it!"

"I'll make you do it."

"Make me?" roared Len. "I'd like to see you try it."

In a twinkle Nelson placed one foot behind the bully. Then he gave the big newsboy a shove which landed him flat on his back. On the instant he was down on top of Len.

"How many papers are dirty, Paul?" he asked.

"Two Suns, a World, and a Journal," was the quick answer.

"Take 'em out of Len's pile."

"Lemme up, or I'll kill you!" howled the bully, and struggled to arise. But Nelson was master of the situation. He continued to hold Len down, and did not let go until Paul had the papers he wished. Then he leaped up, squared off on the defensive, and awaited the outcome of the encounter. Paul lost no time in placing himself behind his newly found champion.

Len Snocks' eyes flashed dangerously when he confronted Nelson. For a long time he had had matters all his own way around the ferryhouse, and the only boys who were allowed to sell papers there besides himself were such as would toady to him and help him sell his over-supply when trade was dull with him. Often he made the lads pay him five or ten cents for selling papers there, when trade was extra lively.

Paul Randall had no father, and his mother being half blind and quite feeble, the lad felt that every cent he earned must be brought home. Consequently he refused to give Len anything, and this made the big newsboy come to the conclusion that Paul must be driven to seek sales elsewhere. In matters of business newsboys are often as scheming and unfair as are certain men in higher walks of life. Money is everything to them, and they will do almost anything to obtain it.

"Wot do yer mean by t'rowin' me down?"[Pg 26] cried Len, as he doubled up his grimy fists, which had not seen soap or water for many a day.

"You know what I mean, Len Snocks," retorted Nelson. "Paul has as much right to sell papers here as you have."

"No, he haint!"

"I say he has, and he'll sell papers here, too, and you shan't stop him."

"Won't I?"

"If you try it, you'll run against me again, remember that."

"I've a good mind to give you a lickin' fer t'rowin' me down," blustered Len, but he made no effort to begin the chastisement.

"If you want to fight, I'm here now," answered Nelson calmly. He understood fully that Len was as much of a coward as he was of a bully.

Len looked around, to see if there was anybody at hand to give him assistance. But all the boys were small, and he felt they could not do much against Nelson, who was known to be strong.

"Yer want to make me lose me trade," he muttered. "I'll fight yer when de rush is over." And he moved toward the ferry entrance.

"All right, I'll be ready for you any time," called Nelson after him. "And, remember, leave Paul alone after this."

"Oh, Nelson, how good you are!" cried Paul[Pg 27] impulsively. "I don't know what he wouldn't have done to me if you hadn't come up."

"If he tackles you again let me know, Paul."

"I will."

"How is your mother?"

"She isn't much better. She can just get around our rooms, and that's all."

"Can she see?"

"Not much. The landlord said she ought to go to the hospital and have her eyes operated on, but she doesn't want to go and leave me."

"But maybe it would be best for her, Paul."

"Well, I'm willing, Nelson. But how is it you aint selling papers to-day?" went on Paul curiously.

"I've sold out. What have you got left?" Our hero surveyed the stock. "Phew! Eighteen! That's a lot."

"Len kept chasing me, so I couldn't sell much," answered the little boy, with a look of concern on his pale face.

"Give me ten of them," said Nelson, and took that number. "Now you go over there and I'll stay around here. We ought to get rid of 'em between us."

"Good for you, Nelson!" cried Paul, and his face brightened.

Soon both were at it, crying their wares with[Pg 28] the other boys. Len Snocks saw the move, and scowled more than ever, but did not dare to interfere. In half an hour the papers were all sold, and our hero turned the money over to Paul.

"You ought to have something for selling the ten," said the little fellow.

"Never mind; you keep the money, Paul. You'll need it, I know."

"Thank you."

"By the way, have you seen anything of Billy Darnley since yesterday noon?"

"I saw him about two hours ago."

"Here?"

"Yes, he came off the boat from Brooklyn."

"I'm sorry I missed him. Do you know where he went?"

"Went to get some papers, I think. He stopped to talk to Len Snocks for a few minutes."

"Humph! Did he give Len anything?"

"I think he gave him a quarter."

"I'm sorry I missed him. He stole five dollars from me yesterday—nearly all I had saved up."

"Oh, Nelson! He ought to be arrested."

"It wouldn't do any good. The police wouldn't believe me, and I haven't any witnesses, excepting a young lady I don't know."

Len Snocks was leaving the vicinity, and now[Pg 29] Nelson hastened after him. Soon he ranged up beside the big newsboy.

"Len, I want to ask you a question."

"Wot do you want now?" growled Len.

"Where did Billy Darnley go after he came off the ferry?"

At this question a crafty look came into Len Snocks' eyes.

"Find out fer yerself—I haint answerin' questions," he growled.

"Billy stole some of my money yesterday."

"Dat aint none o' my affair, is it?"

"I suppose not. But he gave some of it to you?"

"Didn't give me a cent."

"He was seen to give you money."

"Ha! has dat Paul Randall been a-blabbin'?" cried Len savagely. "I'll fix him, if he has!"

"You let Paul alone, or it will be the worse for you. Then you won't tell me where Billy went?"

"I don't know. He didn't tell me nuthin'."

Len Snocks would say no more, and satisfied that it would be time lost to question him further. Nelson hurried on and made his way back to the lunch-room.

He was somewhat late, and as soon as he entered Sam Pepper began to storm at him. The[Pg 30] man was in a worse humor than ever, and lashed our hero with his tongue every time he entered the kitchen.

"Here I am a-breaking my back to make a living, and everything going wrong!" he muttered. "You ought to have been here an hour ago. I wanted some more meat from the butcher shop and two dozen more of pies. I think I'll shut up the place at the end of the week. An honest man can't git along, no matter how hard he tries. Now look out, or you'll smash those plates and glasses, and that'll be more money out of my pocket. Hang the lunch business, anyway!"

But his troubles were not yet at an end. In his ill humor he served a customer with a steak that was both tough and half burnt. The customer refused to pay for the meat, and a quarrel ensued which ended in a fight. Two tables were overturned and the crockery smashed before the troublesome customer was ejected, and, in the meantime, several other customers slipped out without paying.

"It's no use, Nelson; I'm going to give it up," growled Sam Pepper, when it was after two o'clock, and the run of midday trade had come to an end. "There are easier ways to make a living than by running a lunch-room."

"Last night you spoke about a good game to[Pg 31] make you rich," answered Nelson curiously, "What did you mean by that?"

"When did I say that?"

"When you came in and went to bed."

"I don't remember it."

"Well, you said it, and you said something about getting me to help you."

"Did I say anything else?" asked Pepper in some alarm.

"No."

The man drew a breath of relief.

"I must have been a bit off in my head, Nelson. You see I met some old friends, and they treated to champagne—and I'm not used to that any more. They make an easy living, they do."

"Perhaps they can help you to something better."

"They won't have to help me—if I've a mind to work as they work."

"What do they do?"

"Oh, they work on the principle that the world owes them a living, and they are bound to have it."

"Of course they don't beg?"

At this Sam Pepper burst into a loud laugh.

"You're not so green as all that, Nelson."

"Well, what do they do then?" persisted the boy.

"Oh, a number of things! One runs a mail-order business. He is advertising two things just now. One is a steel engraving of Washington, indorsed by the government as a true picture of the first President, mounted on cardboard, all ready for framing, for fifty cents, and the other is a complete sewing machine for one dollar."

"How can he sell a sewing machine for a dollar?"

"When some fool sends on a dollar for the machine he sends him a needle, and when another fool sends fifty cents for the steel engraving he sends him a postage stamp picture of Washington stuck on a bit of cardboard."

"Oh!"

"He's smart, and the law can't get hold of him," went on Sam Pepper. "Another of the men is selling tips on the races. If his customer wins he gets a percentage. He gets one fool to bet one way and another fool to bet the other way, and no matter which wins he gets his share of the prize."

"I should think he would have a job, looking for fools," said the newsboy. "Folks ought to know better."

"The world is full of people who want to get something for nothing, and these men know it.[Pg 33] But they don't make much of a pile. That's got to be made in another way."

"What way?"

"There are lots of ways, Nelson; some good and some bad. Ever been down in Wall Street?"

"Yes, but I don't know anything of the business there."

"Folks down there gamble in stocks and bonds, and such like. Sometimes they squeeze a poor man out of everything he's got, but they do it so as the law can't touch 'em—and there's where they have the advantage over an East Side gambler, who runs the risk of being arrested if his victim squeals. But Wall Street aint any better than the East Side, for all that."

"Some nice gentlemen in Wall Street, though," said Nelson reflectively.

"A high hat don't make an honest man, Nelson; you ought to know that by this time. They are all thieves and swindlers, and an honest man has no show against 'em. If you want to be rich, you've got to be like 'em!" went on Sam Pepper, bringing his fist down on the table at which he sat. "You can't make anything bein' honest."

To this the newsboy remained silent. He had heard such talk before, so he was not as much shocked as he might otherwise have been.

"I guess I'll go out and sell some evening[Pg 34] papers," he said, after a pause, during which Sam Pepper seemed to sink into deep thought.

"No, I don't want you to go out; I want to have a talk with you," answered Pepper. "There won't be no business for an hour or two, and I'll lock the door, so nobody can interrupt us. It's got to come sooner or later, and it might as well come now."

Locking the front door to the lunch-room, Pepper came to the rear of the place, poured himself a glass of liquor and tossed it off, and then sank in a chair by the last table.

"Sit down, Nelson," he said.

The boy sat down and gazed curiously at the man before him. Instinctively he realized that a crisis in his life was approaching. He felt that the old life was speedily to become a thing of the past.

"Nelson, aint you often wondered who you was?" went on Pepper.

"To be sure I have!" cried the boy. "But you will never tell me anything," he added bitterly.

"Well, I kept the secret for your own good, my boy."

"How?"

"When I came to New York and settled on the East Side I made up my mind to lead an honest[Pg 36] life and bring you up honestly. I did it, too; didn't I?"

"So far as I know, yes."

"I did it, but it was hard scratching, and you know it. Many were the times I didn't know how to turn myself, and if it hadn't been for some friends helping me, I would have gone under. Those friends were the only ones I ever knew. They weren't honest, but—well, we'll let that pass. They helped me, and I aint going back on 'em."

"But what about me?"

"I'm coming to that, Nelson. As I said before, I wanted to bring you up honestly; for your mother was honest, even if your father wasn't."

"My father!" ejaculated the newsboy. "What was he?"

"He was a good-hearted man, Nelson—a fine-hearted man, who did lots of good."

"But you said he wasn't honest."

"No, he wasn't, if you must know. He was a burglar, and made his living by taking from the rich what they didn't deserve to have. He was my friend, and he was one of the men who helped me when I lost all I had at the yacht races."

"But—but I don't understand," faltered Nelson. "What was his name?"

"I can't tell you that."

"Is he dead?"

"Yes; he died when you was a little kid not more than three years old. We both lived in another city then—I won't tell you where. Your father was shot while entering a house to rob a man who had once robbed him when he was in business. Your father died in a hospital, and I was with him. Your mother was dead, and he didn't know what to do with you. I said I'd take you, and he made me promise to go to sea first and then to another city and bring you up the best I could. He didn't want you to know your name, and so I got to calling you Nelson after the English admiral, and you can sign yourself Nelson Pepper after this, if you want to."

"Then you won't tell me where I came from?"

"No; excepting that it was a good many miles from here. It wouldn't do any good to rake up old scores. If your father hadn't died of the shot, he would have been sent to prison for ten or fifteen years."

"What was the name of the man who shot him?"

"It won't do you any good to know that, either—he's dead and gone, too."

There was a pause, and the newsboy gave something like an inward groan. The revelation that Pepper had made was truly a shocking one, and the boy was so dazed and bewildered he could[Pg 38] scarcely think. His father a burglar, and shot down while in the act of committing a robbery! What a degradation!

"I've told you all this for a purpose," went on the man. "Now I've got some more to tell you, if you'll promise to keep your mouth shut."

"What else is there?"

"Will you keep silent if I tell you?"

"Yes."

"And do you promise not to say a word of what I have just told you?"

"Why should I—it wouldn't be anything to my credit," answered Nelson.

"But I want you to promise."

"All right; I promise."

"That's good. I know if you give your word you'll keep it. Now, I've got a plan in my head to square accounts, so to speak, and git rich at the same time."

"What plan?"

"Well, you see, it's like this: There's a rich gent lives up near Central Park. I won't give you his name, but I don't mind telling you that he's a distant relative of the fellow who shot your father, and he used to help that other man in his dealings against your father. I don't know as he remembers your father now, but he's a man you ought to get square on, anyway."

"How?"

"I'm coming to that, my boy. This man is old and feeble and has something of an office in his library at home. There is a safe in the library, but it's old-fashioned and can easily be opened. In that safe the old man keeps thousands of dollars all the time, for it's too much for him to go back and forth to the bank, and he aint the one to trust anybody else."

Sam Pepper paused suggestively and looked Nelson full in the eyes. Then he began to whistle softly to himself.

"Do you mean that you think I ought to rob that safe?" questioned our hero.

"You won't have to do the job alone, lad; I'll be on hand to help you."

"But I—I never stole anything in my life."

"It won't be stealing, exactly. That man owes you something. If it hadn't been for him and his relative your father might have been rich and never got into any burglary. I have looked the ground over, and the job will be dead easy. There is a back alley and an iron fence that both of us can climb over without half trying. Then I can git a diamond cutter for the window glass, and the rest will be just as easy as wink."

"And if you are caught, what then?"

"We won't git caught, Nelson. The old man[Pg 40] has only a niece living with him, a girl of seventeen or eighteen, and an old housekeeper who is half deaf. The rest of the help comes in the morning and leaves after supper."

There was another pause. Nelson sank beside the table, with his face in his hands. Suddenly he looked at Sam Pepper again.

"Did you say that man had robbed my father—I mean the man who shot him?"

"Sure he did, Nelson."

"Then perhaps my father wasn't a burglar, after all. Perhaps he was entering the house to get evidence against the man."

"No, he went in to—er—well, to steal, if you must have it straight."

"Sam Pepper, I don't believe you!"

"Nelson!"

"I don't believe you, so there! You won't tell me my name, or where I came from, or anything, and you are only trying to make out my father was a thief so as to get me to turn thief, too."

"I've told you the truth, lad."

"And I repeat I don't believe you. What is more, I won't help you in your plans of robbery. I've been honest so far, and I mean to remain honest. You ought to be ashamed of yourself for trying to make me a thief."

The newsboy had risen to his feet and, as he[Pg 41] spoke, his face glowed with earnestness. Now Sam Pepper sprang up, his features full of baffled passion.

"How dare you talk to me, you miserable pup?" he roared. "I've a good mind to thrash you well for this! Haven't I clothed and fed you for years? And this is what I git for it! I've told you the truth about yourself, only I didn't paint your father as black as I might, not wishing to hurt your feelings. He was a burglar, and before he was shot he served two sentences in prison."

"I don't believe it—and I never will," retorted Nelson, but with quivering lips. "Where was this? Tell me, and I'll soon find out if it is true."

"I won't tell you a thing more—unless you promise to help me as you should."

"I won't help you—and that's the end of it."

"You owe me something for keeping you all these years."

"I don't believe you would have kept me if you weren't paid for it."

"I never received a cent—not a penny. You've got to pay me back somehow."

"Well, I am not going to do it by stealing," answered Nelson doggedly.

"Then how are you going to do it?"

"I don't know yet."

"I'm going to give this place up soon, and of course the living rooms will go, too."

"I can find another place to live."

"You want to git out of paying me that five dollars a week, don't you?" sneered Pepper.

"I can't pay five dollars. But I'll pay what I can. How much do you think I owe you?"

"A good deal—seeing that I've kept you ten years or longer."

"Didn't my father leave anything?"

"About forty dollars—not enough to keep you three months."

"He hadn't any property?"

"Nothing."

"Well, as I said before, I'll do what I can—when I am able."

"And you won't help me to——" Pepper paused.

"I won't steal—I'll starve first," returned Nelson, and taking up his hat, he unlocked the door, and walked away from the lunch-room.

When Nelson left the lunch-room he scarcely knew what he was doing. The conversation which had occurred had been an important one, but his head was in such a whirl that just now he could make little or nothing out of it.

He had no desire to sell papers,—indeed, he had no desire to do anything,—and all he did was to walk up the street and keep on walking until he was well uptown. Then he began to cross the city in the direction of Broadway.

At last he began to "cool off" a bit, and then he went over all that had been said with care. As he did this he became more and more convinced that Sam Pepper had not told him the truth concerning his parent.

"He is holding something back," he told himself. "And he has some object in doing it. He shall never make me a thief, and some day I'll force him to tell his secret."

"Hullo, Nelson! what brings you up here?"

The question was asked by a young man who[Pg 44] carried a flat bag in his hand. The man was an agent for books, and the boy had met him many times before.

"Oh, I just came up for a walk," answered our hero. "How is business, Van Pelt?"

"Poor," answered George Van Pelt, as he set down his bag, which was heavy. "Haven't made but half a dollar so far to-day."

"That's no better than selling newspapers."

"I don't suppose it is, and you don't have to carry around such a bag as this, either. But I would have made more to-day if a customer hadn't tripped me up."

"How was that?"

"There was a young gent living near Central Park named Homer Bulson, wanted me to get certain French books for him. I got the books, but when I went to deliver them he refused to take them, saying they were not what he had ordered."

"Were they?"

"They were. I could make him take them, according to law, but to sue a man is expensive. But now I've got the books on my hands, and they cost me over three dollars."

"Can't you sell them to somebody else?"

"I hardly think so. You see, they are books on poisons, and there isn't much call for that sort of thing."

"Poisons! What did he want to do with them?"

"He said when he ordered them, that he was studying to be a doctor, and was going to make poisons a specialty."

"It's a shame you can't make him take the books."

"So it is. I suppose I could make him take them, if I wanted to create a row. But I can't do that. I haven't the cheek."

"I'd make him take them, if I was in your place. Anyway, I'd tell him I was going to sue him if he didn't pay up. Perhaps that might scare him."

"I was thinking something of doing so. Do you really think it might make him come down?"

"I know some folks hate to think they are going to be sued. And if he lives in a fine house he must be pretty high-toned."

"Oh, he is! He's a young bachelor, and lives in fine style, directly opposite the home of his rich uncle."

"Then I'd try him again, before I'd give up."

"I will. Do you want to come along?" went on George Van Pelt, who hated a quarrel.

"I might as well. I'm not doing much just now," answered Nelson.

"Of course you haven't given up selling[Pg 46] papers?" went on George Van Pelt, as the two walked along.

"No. But I wish I could get something better to do."

"That's hard these times, Nelson. How much a day can you make at it?"

"From seventy-five cents to a dollar and a quarter. Sometimes I make a dollar and a half, but that's not often."

"The books used to bring me in from three to five dollars a day. But the department stores cut the prices now, and soon the whole book-agent business will be ruined."

"What will you go into then?"

"I don't know. If I had the money I'd start a newsstand—for papers and books, too."

"That would pay, if you could get hold of the right corner," said our hero, with interest.

"I know of a good corner on Third Avenue. The man who keeps it now is old and wants to sell out."

"What does he want for the stand?"

"A hundred dollars. Of course the stock isn't worth it, but the business is."

"That depends on what he takes in a day."

"He averages seventy-five dollars a week. But it would be more, if he was able to get around and attend to it."

"A hundred dollars a week would mean about thirty dollars profit," said Nelson, who was quick at figures. "How much is the rent?"

"Five dollars a week."

"That would leave twenty-five dollars for the stand-keeper. Does he have a boy?"

"Yes, and pays him three dollars a week."

"Maybe we could buy the stand together, Van Pelt. You know all about books, and I know about the newspapers. We ought to make a go of it."

"That's so, but——" The book agent looked rather dubiously at our hero's clothes. "How about the cash?"

"We might save it somehow. I'm saving up for a suit now."

"You need the suit."

"I expected to get it in a few days. But Billy Darnley robbed me of five dollars, so I've got to wait a bit."

"Well, if we could raise that money we might buy out the stand and try our luck," continued George Van Pelt, after a thoughtful pause. "I think we'd get along. How much have you."

"Only a dollar or two now."

"I've got fifteen dollars, and about ten dollars' worth of books."

"Couldn't we get the man to trust us for the stand?"

"He said he might trust me for half the amount he asks, but fifty dollars would have to be a cash payment."

"We'll raise it somehow!" cried Nelson enthusiastically. The idea of owning a half interest in a regular stand appealed to him strongly. In his eyes the proprietor of such a stand was a regular man of business.

The pair hurried on, and at length reached the vicinity of Central Park, and Van Pelt pointed out the house in which the rich young man who had refused to take the books lived.

"Perhaps he won't let me in," he said.

"Wait—somebody is coming out of the house," returned our hero.

"It's Mr. Bulson himself," said George Van Pelt.

He hurried forward, followed by Nelson, and the pair met the young man on the steps of his bachelor abode.

Homer Bulson was a tall, slim young fellow, with light hair and blue eyes. His face was somewhat weak, but in his eyes was a look full of scheming cunning. He was faultlessly dressed in the latest fashion, wore a silk hat, and carried a gold-headed cane.

"Mr. Bulson, I must see you about these books," said George Van Pelt, coming to a halt on the steps of the stone porch.

"I told you before that I did not wish to be bothered," answered the young man coldly.

"But you ordered the books, sir."

"I will not discuss the matter with you. Go away, and if you bother me again I shall call a policeman."

"My friend hasn't done anything wrong," put in Nelson boldly. "You ordered some books from him, and you ought to pay for 'em."

"What have you to do with this matter?" demanded the rich young man, staring harshly at our hero.

"This man is my friend, and I don't want to see him swindled," said our hero.

"Swindled!"

"That's it. You ordered some books on poisons from him, and now you don't want to pay for 'em. It's a swindle and an outrage. He's a poor man, and you haven't any right to treat him so."

"Boy, if you speak like that to me, I'll have you put under arrest," stormed Homer Bulson in a rage.

"You must take the books," put in George Van Pelt, growing braver through what Nelson was[Pg 50] saying. "If you won't take them, I'll sue you for the amount."

"Sue me?"

"Yes, sue you."

"And I'll put the reporters on the game," added the newsboy. "They like to get hold of society notes." And he grinned suggestively.

At this Homer Bulson's face became filled with horror. For more reasons than one he did not wish this affair to become public property.

"To sue me will do no good," he said lamely.

"Yes, it will," said the book agent. "You have money and will have to pay up."

"Or else your rich uncle will pay for you," said Nelson, never dreaming of how the shot would tell. Bulson grew very pale.

"I—I will take the books and pay for them," he stammered. "Not because I think I ought to take them, mind you," he added, "but because I wish no trouble in public. Where are the books?"

"Here." And George Van Pelt brought two volumes from his satchel.

"How much?"

"Just what I told you before, Mr. Bulson—five dollars."

"It's a very high price for such small books."

"They are imported from France, remember, and besides, books on poisons——"

"Give them to me."

The books were passed over, and Homer Bulson drew from his vest pocket a small roll of bills. He handed over a five to George Van Pelt.

"Now begone with you," he said sourly. "And don't ever come near me again for another order."

"Don't worry, I won't come," answered the book agent. "You are too hard a customer to suit."

He pocketed the money and rejoined Nelson on the sidewalk. Then both started to walk away.

As they did so our hero glanced across the way and saw, in a window of the house opposite, the young lady who had offered her assistance after Billy Darnley had robbed him.

She recognized him and smiled, and he promptly touched his hat respectfully.

Homer Bulson saw the act and so did George Van Pelt, and both stared at Nelson.

"Whom did you see?" asked Van Pelt, as they walked down the street.

"A lady who once offered to help me," said Nelson. "She was in that house. She has left the window now."

"Why, that is where that man's rich uncle lives!" exclaimed the book agent.

"Is it?" cried our hero. "Then perhaps the lady is a relative to him."

"Perhaps."

"What is the uncle's name?"

"Mark Horton. I understood that he was once a rich merchant of Philadelphia. But he's a sickly old man now. I wanted to sell him some books, but they wouldn't let me see him."

"I hope that young lady isn't a relative to that Homer Bulson," mused Nelson. "If he is, he can't be very nice company for her."

"That's true, Nelson."

"You said you tried to sell books there but they wouldn't let you in."

"No, the gentleman was too sick to see me—at least that is what they said. But perhaps it was only a dodge to keep me out."

"I suppose they play all sorts of tricks on you—to keep you out of folks' houses," went on the newsboy thoughtfully.

"Sometimes they do. Some folks won't be bothered with a book agent."

"And yet you've got to live," laughed Nelson.

"Yes, all of us have got to live. But lots of folks, especially those with money, won't reason that way. They'll set a dog on you, or do worse,[Pg 53] just to get rid of you. Why, once I had a man in Paterson accuse me of stealing."

"How was that?"

"It was the first week I went out selling books. I was down on my luck and didn't have any clothes worth mentioning."

"Like myself, for instance," interrupted the newsboy, with a laugh.

"If anything my clothes were worse. Well, I was traveling around Paterson when I struck a clothing shop on a side street. I went in and found the proprietor busy with a customer, and while I waited for him I picked up a cheap suit of clothes to examine it. All of a sudden the proprietor's clerk came rushing out of a back room and caught me by the arm.

"'You vos goin' to steal dot coat!' he roared.

"'No, I wasn't,' I said. 'I was just looking at it.'

"'I know petter,' he went on, and then he called the proprietor and both of them held me."

"I reckon you were scared."

"I was, for I didn't know a soul in the town. I said I wasn't a thief, and had come in to sell books, and I showed them my samples. At first they wouldn't believe a word, and they talked a whole lot of German that I couldn't understand. Then one went out for a policeman."

"And what did you do then?"

"I didn't know what to do, and was studying the situation when the other man suddenly said I could go—that he didn't want any bother with going to court, and all that. Then I dusted away, and I never stopped until I was safe on the train and on my way back to New York."

"Did you ever go to Paterson after that?"

"No, I never wanted to see that town again," concluded George Van Pelt.

Homer Bulson was a fashionable man of the world. He had traveled a good deal and seen far more of a certain kind of "high life" than was good for him, either mentally or morally. He was fond of liquor and of gambling, and had almost run through the money which an indulgent parent had left him.

He was alone in the world, so far as immediate members of his family were concerned, but he had an uncle, Mark Horton, just mentioned, and also a cousin, Gertrude Horton, who was the ward of the retired merchant. This Gertrude Horton was the young lady who had offered to assist Nelson, and who had just recognized our hero from her seat at the window opposite.

In the fashionable world Homer Bulson cut a "wide swath," as it is commonly called, but he managed to keep his doings pretty well hidden from his uncle, who supposed him to be a model young man.

The young man's reason for this was, his uncle[Pg 56] was rich and at his death would leave a large property, and he wished to become heir to a large portion of what Mark Horton left behind him. He knew his uncle was a strict man, and would not countenance his high mode of living, should he hear of it.

Homer Bulson watched Nelson curiously, and then looked across the street to see if he could catch his cousin Gertrude's eye. But the young lady was now out of sight.

"How is it that she knows that street boy?" Bulson asked himself, as he walked into the house to stow away the books he had purchased. "I don't like it at all—seeing that he was with the man who sold me these books. I hope he doesn't ever tell her I've been buying books on poisons."

Entering one of his rooms—he occupied several—he locked the door and threw himself into an easy-chair. Soon he was looking over the books, and reading slowly, for his knowledge of French was decidedly limited.

"Oh, pshaw! I can't make anything out of this," he exclaimed at last. "That English book on poisons I picked up at the second-hand book store is good enough for me. I might as well put these in a fire." But instead he hid them away at the bottom of a trunk.

With the books on poisons out of his sight,[Pg 57] Homer Bulson turned to his wardrobe and made a new selection of a suit of light brown which his tailor had just brought to him.

He was putting on the suit when there came a knock on the door.

"Who's there?" asked the young man.

"Mr. Grodell, sir," was the answer.

Mr. Grodell was the agent of the apartment house, and had come for his rent.

Homer Bulson was behind four months in payments, and the agent was growing anxious for his money.

"Very sorry, Mr. Grodell, but I am just changing my clothes," said the spendthrift.

"Then I'll wait," was the answer.

"Better not, it will take some time."

"I am in no hurry, Mr. Bulson," said the agent.

"Oh, pshaw! why does he bother me!" muttered Homer Bulson. "I haven't got any money for him."

He did not know what to do, and scratched his head in perplexity.

"Come around Saturday and I will pay you in full," he called out.

"You told me you would pay me last Saturday, Mr. Bulson."

"I know I did, but I was disappointed about a[Pg 58] remittance. I will surely have your money this coming Saturday."

"Without fail?"

"Without fail."

"All right, Mr. Bulson. But I must have it then, or else take possession of the rooms." And with this parting shot the agent departed.

"The impudent fellow!" muttered Homer Bulson. "To talk to me in that fashion! He shall wait until I get good and ready to pay him!"

Nevertheless, the young man's pocketbook was very nearly empty, and this worried him not a little.

Several times he had thought of applying to his uncle for a loan, but each time had hesitated, being afraid that Mark Horton would suspect his extravagant mode of living.

"But I must get money somehow," he told himself.

At last he was dressed, and then he peered out into the hallway.

The agent had really gone, and satisfied on this point Homer Bulson left the residence for a stroll on Fifth Avenue.

This occupied over an hour, and then he walked over to one of the clubs to which he was attached, where he dined in the best of style.

After dinner came a game or two of billiards,[Pg 59] and then he took a cab to his uncle's mansion near the Park.

He found Mark Horton seated in an invalid's chair in the library, and nearby was Gertrude trying her best to make the elderly man comfortable.

Evidently the elderly man was in a bad humor, for his eyes flashed angrily as the nephew entered.

The trouble was Mark Horton and his niece Gertrude had had something of a quarrel. The invalid wished Gertrude to marry her cousin Homer, and the girl did not desire the match, for she realized what a spendthrift and generally worthless fellow Bulson was.

Both knew that their uncle had made a will leaving his property divided equally between them, and Gertrude was almost certain that Bulson wished to marry her simply in order to gain control of everything.

The girl hated very much to displease her uncle, for she realized what troubles he had had in the past. A fearful railroad accident had deprived the man of his beloved wife years before, and shortly after this happening other trials had come to him, which had broken him down completely. What these trials were will be revealed as our story progresses.

"Well, Uncle Mark, how goes it to-day?" asked Homer Bulson, on walking in.

"Not very well, Homer," was the feeble answer.

"Uncle Mark had quite a bad attack about two hours ago," put in Gertrude Horton. "I had to send for the doctor."

"Wasn't he here this morning?"

"Yes, but I thought best to have him again," answered the girl.

"That's right."

"The doctor seems to do me small good," put in the invalid, in a feeble voice. "He doesn't seem to understand my case at all."

"He is one of the best physicians in New York," answered Homer Bulson.

"So you said before, Homer. Well, I doubt if I ever get any better."

"Oh, Uncle Mark!" cried Gertrude, much shocked.

"I seem to be completely broken down," went on the invalid. "At times the strangest of sinking spells come over me. I feel very, very old."

There was a painful silence, and Gertrude rearranged the pillow behind the invalid's head.

"Did you see about those stocks to-day, Homer?" went on Mark Horton. "I had forgotten about them."

"I did, sir."

"And what did the broker say?"

"He urged me to hold on awhile longer."

"And you have them still?"

"Yes, uncle."

"Very well; do as he advises. Some day, when I am stronger, I must attend to many other business matters."

"Oh, Uncle Mark, don't worry about business," pleaded Gertrude, passing her arm around his neck.

There was another pause and Mark Horton gazed sharply at Gertrude. Then he turned to Homer Bulson.

"She won't marry you, Homer—I don't know why," he said.

The face of the young man fell, and he bit his lip.

"Well, I suppose she will do as she pleases," he remarked, somewhat sarcastically.

"I think I should be allowed to make my own choice," said Gertrude. She had already refused Bulson several times.

"I can't understand it," said the invalid. "To my mind you are just suited to each other."

"I do not think so," answered Gertrude.

"And why not?"

"I would rather not say, Uncle Mark."

"You can't have anything against me personally," put in Bulson, with a scowl.

"But I have!" cried the girl. "You go to the race-track, and drink, and gamble, and I do not like it."

A stormy scene followed, in which all three in the room took part. Strange to say, Mark Horton sided with his nephew, for he did not realize the blackness of Bulson's character.

"You are prejudiced and foolish," cried the invalid at last, turning to his niece. "You do not wish to please me in anything." And so speaking, he arose and tottered from the room. Homer Bulson made as if to follow him, then reconsidered the matter and sank back into a chair. Poor Gertrude burst into a flood of tears.

"Gertrude, you are making a great mistake," said Homer Bulson, after a pause broken only by the sobbing of the girl.

"Please don't speak to me, Homer," she answered. "I have heard enough for one day."

"You have no right to blacken my character," he said with assumed dignity.

"Uncle Mark forced me to speak the truth."

"It was not the truth. But let that pass. Why didn't you tell him you would marry me?"

"Because I don't want to marry you."

"But you might let him think that you——"

"I am above practicing a deception upon him, Homer."

"Oh, you aren't a saint!" he sneered. "I know why you are so loving to him—you thought to get all of his money. Now you are trying to blacken my character, so that you may get all of it, anyway. But the game won't work."

"I told him what I did simply to let him know why I didn't care to marry you, Cousin Homer."

"And why are you so opposed to me?"

"I do not like your ways. Isn't that enough? As for Uncle Mark's money, I trust he will live a long time to enjoy it himself."

"Uncle Mark can live but a short while longer. Anybody can see that. He is exceedingly feeble."

"You seem to wish his death," replied Gertrude sharply.

"I? No, indeed; I hope he does live. Haven't I done what I could for him—giving him wines and the like? And he has the best of doctors—on my recommendation."

"I don't think the wine you gave him is doing any good. He seems to become weaker after it, instead of stronger."

"Bosh! If he hadn't the wine, he would collapse utterly."

At this the girl merely shrugged her shoulders.

This was not the first time that Homer Bulson and herself had quarreled over the care their uncle should have. To the girl the retired merchant seemed to grow unexpectedly weak in spite of all she could do. The doctor, too, was baffled, and said he had never come across such a strange case before.

"If you won't marry me, you shall not turn Uncle Mark against me," went on Bulson sternly.[Pg 65] "If you try it, you will repent it as long as you live."

So speaking, he strode from the room and made after Mark Horton, who had gone to his private apartment on the second floor.

He found the retired merchant resting in an easy-chair by the window, his head bowed low.

"Cheer up, uncle," he said, placing his hand on the other's shoulder. "Let me pour you a glass of wine."

And he walked to a medicine closet in a corner and got out a bottle he had brought a few days before.

"Thank you, Homer; I will have a little wine," replied the retired merchant.

The wine was poured out and Mark Horton gulped it down. Homer Bulson watched him closely, and then turned away his face to hide a sinister smile.

"I cannot understand Gertrude," said Mark Horton. "I always thought she preferred you."

"I think she has another person in view," answered Bulson, struck with a certain idea.

"Another? Who is it?"

"I would rather not say, uncle."

"But I demand to know."

"I cannot tell you his name. But he is a [Pg 66]common sort of person. He went past the house a while ago and she nodded and smiled to him."

"And how long has this been going on?"

"Oh, several months, I dare say. They meet in the evening on the sly. But please don't tell Gertrude that I spoke of this."

"What does the man do?"

"I am not sure, but I think he is in the theatrical business, when he has an engagement—something on the variety stage."

"What! My Gertrude the wife of a variety actor? Never, Homer, never!" groaned Mark Horton. "This is too much! I will speak to her at once!"

"Uncle, you just promised not to let her know——"

"You'll be safe, Homer, never fear. But I won't have this—I'll cast her out first."

"I suppose she wanted to keep this a secret until after you—that is——"

"Until after I am dead, so that she can use up my money on her actor husband," finished Mark Horton bitterly. He suddenly sprang to his feet. "But she shall marry you, Homer, and nobody else. That is final."

"Pray do not excite yourself too much, uncle. Let the matter rest for a few days."

"And if I should die in the meantime, what[Pg 67] then? No, Homer; delays are dangerous. I—I—feel as if I cannot last much longer. Who knows but what this night may prove my last?"

And Mark Horton sank back again in his chair and covered his face with his hands.

"Uncle, in case anything should happen to you, may I ask what you have done with your will?" asked Bulson, after a long pause. "Or, perhaps Gertrude knows about this?"

"Yes, she knows, but you must know, too. Both the old will and the new one are in the safe in the library, in the upper compartment on the right side. On the left side are two gold pieces which I brought home with me when I visited the mint in California."

"Is that all the money there is in the safe?"

"No, there is more gold than that—in a secret compartment at the bottom. There is a spring to open this compartment on the left side, a small gilded knob. It is right I should tell you of this, otherwise you might never find the secret compartment."

"And the combination of the safe?" went on Bulson, more anxiously than ever.

"The combination is 0, 4, 25, 12, 32, and once around to the left to 0 again. You had better put it down. I have it written on a slip in my pocketbook."

"Then it won't be necessary for me to put it down," answered the nephew, but he took good care to remember the combination, nevertheless.

It was now time for Mark Horton to retire, and, the wine having made him drowsy, he soon forgot his anger against Gertrude and went to sleep.

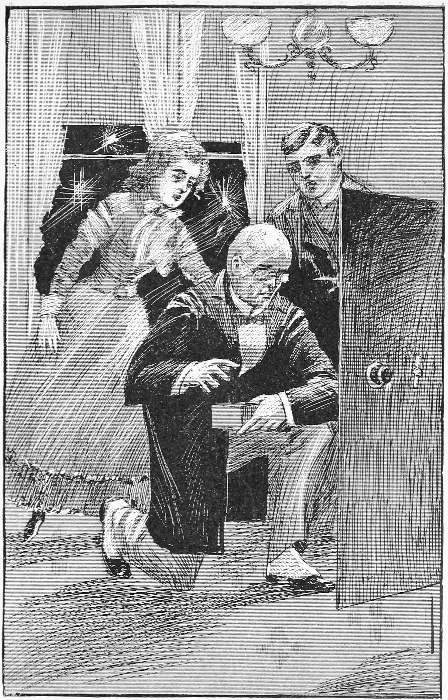

When Homer Bulson went below he paused in the hallway and glanced through the doorway into the library.

He saw that Gertrude had left the apartment and that it was empty.

None of the servants were about, and the housekeeper, an elderly lady, was also nowhere to be seen.

"I wonder if I dare do it so soon?" he muttered to himself. Then he shut his teeth hard. "I must do something! I have used up my last dollar, and I can't go around empty-handed. Uncle Mark will never grow strong enough to know."

Going to the front door he opened it, then slammed it violently and made a noise as if he was descending the steps. Then he closed the door with care and stole back into the gloom of the library. It was now after midnight, a fitting time for the desperate deed this misguided young man had undertaken.

After leaving George Van Pelt Nelson felt more like working, and buying a large supply of evening papers he was soon hard at it, crying his wares as loudly as possible.

Business proved brisk, and by seven o'clock he had sold out. Then he went back to the lunch-room.

Sam Pepper met him with a scowl.

"Concluded to come back after all, eh?" he said. "Work piling up on me and nobody to help. Pitch in, quick, or I'll thrash you good; do you hear?"

The rest of the evening passed in almost utter silence between them. By ten o'clock the most of the lunch trade came to an end. At eleven Sam Pepper began to lock up.

"I'm going out," he said. "An old friend is sick. Maybe I won't be back till morning. Watch things good while I'm gone."

"Who is sick?" asked our hero.

"None of your business. You mind what I[Pg 70] told you, and keep your mouth closed," growled the lunch-room keeper.

Nelson had noticed a heavy handbag lying in the corner of the back room, and now he saw Sam Pepper pick the bag up. As the man moved it, something inside struck together with a hard, metallic sound, as if the bag might contain tools.

When Sam Pepper went out he wore a big slouch hat and a coat which he had not donned for years. He usually wore a derby hat, and his general appearance surprised the newsboy not a little.

"He acts as if he wanted to be disguised," thought the boy. "Something is up, sure."

Then of a sudden he remembered the talk he had had with Pepper about robbing an old man—the man who had in some way been connected with his father's downfall, if Pepper's story was true. Was it possible Pepper was going to undertake the job that very night, and alone?

"I believe he is!" thought Nelson. "And if that's so, I'll follow him!"

With the boy, to think was to act, and in a few minutes he was prepared to follow Sam Pepper. The man had locked the front door and taken the key with him. Nelson slipped out of a rear window and fastened the window from the outside by means of a nail shoved into a hole in a corner—a trick he had learned some time before.

When the boy came out on the street he ran up the thoroughfare for a couple of blocks, and was just in time to see Sam Pepper making his way up the stairs of the elevated railroad station. When the train came along Pepper entered the front car, and our hero took the car behind it. Nelson buttoned up his coat and pulled his hat far down over his eyes to escape recognition, but Sam Pepper never once looked around to see if he was being followed.