THE HARVEST OF A QUIET EYE.

LEISURE THOUGHTS

FOR

BUSY LIVES.

By the Author of “My Study Chair,” “Musings,” etc.

LONDON:

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY,

56, Paternoster Row; 65, St. Paul’s Churchyard;

And 164, Piccadilly.

Project Gutenberg's The Harvest of a Quiet Eye, by John Richard Vernon

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Harvest of a Quiet Eye

Leisure Thoughts for Busy Lives

Author: John Richard Vernon

Release Date: February 28, 2017 [EBook #54261]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HARVEST OF A QUIET EYE ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Charlie Howard, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

With Numerous Illustrations by

Noel Humphreys, Harrison Weir, Wimperis Pritchett, Miss Edwards,

and other eminent Artists.

THE HARVEST OF A QUIET EYE.

LEISURE THOUGHTS

FOR

BUSY LIVES.

By the Author of “My Study Chair,” “Musings,” etc.

LONDON:

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY,

56, Paternoster Row; 65, St. Paul’s Churchyard;

And 164, Piccadilly.

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

| The Old Year and the New | 1 |

| Musings on the Threshold | 23 |

| Spring Days | 41 |

| Musings in a Wood | 63 |

| The May-days of the Soul | 85 |

| Summer Days | 101 |

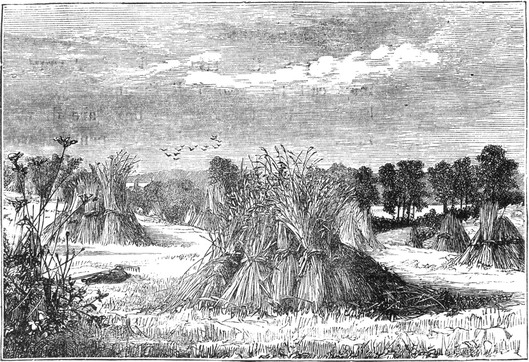

| Musings in the Hay | 123 |

| The Beauty of Rain | 145 |

| Autumn Days | 161 |

| Musings on the Sea-shore | 183 |

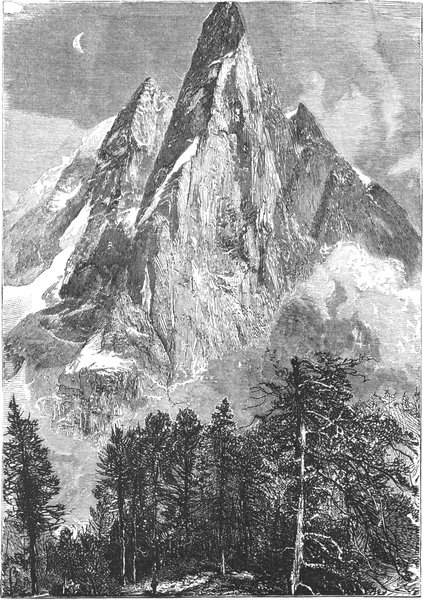

| Musings on the Mountains | 199 |

| Musings in the Twilight | 221 |

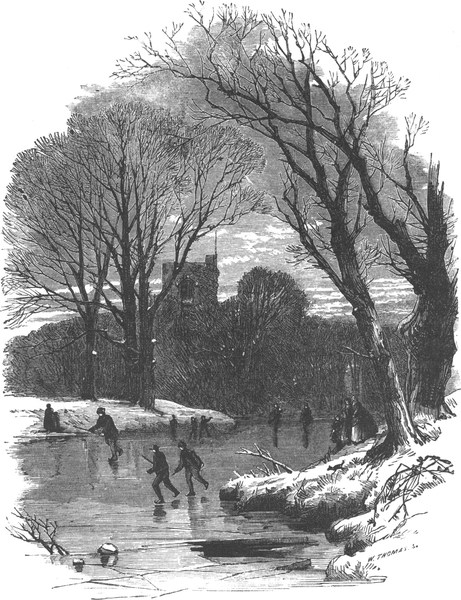

| Winter Days | 241 |

| The End of the Seasons | 265 |

| Under Bare Boughs | 283 |

These papers, written in the intervals of parish work, have appeared in the pages of the Leisure Hour and the Sunday at Home. Their publication in a collected form having been decided upon by others, it only remained for me, by careful revision and excision, to render them as little unworthy as might be of starting for themselves in the wide world.

I shall not say that I am sorry that they are thus sent forth on their humble mission. Indeed, I am glad. “Brief life is here our portion”:—and surely the wish is one natural to all earnest hearts, that our work for our Master in this sad and sinful world should not have its term together with thex quick ending of our short day’s labour here:—and a book has the possibility of a longer life than that of a man. The Night cometh, when none can work; how sweet, if it might be, that when the day is ended, when the warfare, for us, is over, we may have left some strong watchwords, or some comfortable and cheering utterances, still ringing in the ears of those who stepped into our place in the unbroken ranks.

Yes, the evening soon falls on the field; the day is brief, nor fully employed; inanimate things seem to have an advantage over us; streams flow on, and mountains stand;

And I may be permitted to hope that possibly these meditations may have such power and perform such, service in their modest way. They have but the ambition of a flower that looks up to cheer, or a bird’s note that tranquilly, amid storms, continues a simple melody from the heart of its tree. They will, like these, be easily passed by, but, like these, may have a message for hearts that will look and listen.

There is certainly, in the present age, a want of writing that shall rest and brace the mind; of meditative writing of a tendency merely holy and practical, rather shunning than plungingxi into controversy:—not the cry of the angry or startled bird, but its evening and morning orisons rather. A contemplative strain; one linked with things of earth, and hallowing them—one heard beside “the common path that common men pursue”:—one rising from the common work-a-day experiences, joys, and pains—rising from these and carrying them up with it heavenward, until even earth’s exhalations catch the light of an unearthly glory. We want more of this spiritual rest; more of this standing apart from the perturbations of the day; more of retirement and retired thought—thought that shall leave the throng, with its absorbed purpose and pushing and jostling, always eager, often angry; and having secured a lonely standing-point apart from it all, become better able to judge of the real truth and importance, also of the just relation of things.

I cannot claim to have done more than make a slight attempt towards the supply of this want. Nay, I would rather lay claim not to have attempted. This is the age of effort and strain; it were well that thought were sometimes permitted to be natural, spontaneous, and simply expressive of that which the heart’s meditations have laid by in store. A stream thus welling up will want the precision and the single aim of the artificial jet, but it will have its modest use and value to cheer and to refresh lowly grasses, and perhaps to water the roots of loftier growths in its vagaries and meanderings.

In these times men will be held nothing if not controversial;xii and rival parties will skim the book for shibboleths before they read or throw it by. Assuredly fixed principles and definite teaching are (if ever at one time more than another) of special importance in the present day; and I am not one who think it well to blow both hot and cold at pleasure. Only I would ask, is there absolute need that we be always blowing either? may we not sometimes be permitted simply to breathe? There are occasions on which I find myself compelled to blow one or the other, but I grudge the good breath spent in the exertion, and prefer to return to the normal state of even respiration. A story, told of Archbishop Leighton’s youth, is to the point:—“In a synod he was publicly reprimanded for not ‘preaching up the times.’ ‘Who,’ he asked, ‘does preach up the times?’ It was answered that all the brethren did it. ‘Then,’ he rejoined, ‘if all of you preach up the times, you may surely allow one poor brother to preach up Christ Jesus and eternity.’”

No doubt, we must be militant here on earth, militant against every form of error—old error undisguised, and old error in a new dress; but the more need that we should secure breathing times when we may sheathe the biting sword and lay the heavy armour by. Perhaps many with whom we war, or from whom we stand aloof in suspicion, would be found, when the vizors were raised, to be brothers, and henceforth warriors by our side.

xiii One word as to the title of this book. “The Harvest of a Quiet Eye.” This has always been a favourite line with me, and now I take it to describe my unpretentious volume, though this be rather a handful gleaned than a harvest got in. With some people this gleaning by the way would be contemned, in their single-eyed advance upon some goal; with some it is a thing continual and habitual, this instinctive gathering and half-unconscious storing of hints and touches of wayside beauty—a process so well described in Wordsworth’s verses. To have an eye for the wide pictures and slight studies of Nature; to gather them up, in solitary walks which thus are not lonely; to lay them by, together with the heart’s deeper thoughts, its associations, meditations, and reminiscences;—this is to fashion common things into a beauty which, to the fashioner at least, may be a joy for ever.

—this has been with me the secondary occupation of many a walk, solitary or in company. A rosy sunbeam slanting down a bank, and catching the stems of the ferns and the tops of the grasses; a coral twist of briony berries; a daisy inxiv December;—the eye would be caught, and the train of grave or anxious musing intermitted without being broken off, by the ever-allowed claim of Nature’s silent poetry. And often the deeper meaning of such poetry would run parallel with the mind’s thought—sometimes suggest for it a new path.

“Few ears of scattered grain.” Though this be all my harvest, yet if that be grain at all which has been collected, it may have its use. He who with a very little fed a great multitude, has a ministry for even our humble handfuls. At His feet be this laid: may He accept and bless it, and deign to refresh and hearten by its means some few at least of those who, faint and weary, are following Him in the wilderness of this world!

A HAPPY NEW YEAR!

Words repeated by how many myriads, in how many zones—tropic, temperate, frigid, wherever the English tongue is spoken! Words said commonly with more of meaning and sincerity than fall to the lot of many almost-of-course salutations. Words in which there is a shade of melancholy, and a gleam of gladness; a lingering of regret, with the very new birth of anticipation. “A Happy New Year.”

Ah, but it is not unlike parting with an old friend, the saying good-bye to the Old Year. And it seems unkind to turn from him who has so long dwelt with us, and to take up too jauntily with a new friend.

4 He had his faults: but, at any rate, we know them; and those of the new-comer have yet to be discovered. And his virtues seem to stand out in bolder relief, now that we feel that we shall never see him again. Such experiences, too, we have had together! we have been sad and merry in company, and the days of our past society come with a warm rush to our heart:—

And so we keep hold still of his hand, loth, very loth indeed to part—as we sit in silence by the flickering fire, and listen to the sudden bursts and sinking of the bells.

It is our habit—(I speak in the name of myself, and of many of my readers)—it is an immemorial custom with us, to assemble, all that can do so, in the old home, from which we have at different times taken wing—to gather together there again, on the last night of the Old Year. I have heard the plan objected to, but I never heard any objections that to my mind seemed weighty ones. True, the gaps that must come from time to time, are perhaps most of all brought prominently, sadly before us, at such a gathering as this. We miss the husband, the brother, the sweet girl-daughter, the little one’s pattering feet—ah, sorely, sorely then! Last year the familiar face was here, and now, now, far away, under the white sheet of snow. This is sad, but it is not a mere unstarlit night of gloom. Nay, I maintain that, to those who look at it rightly, more and brighter stars of comfort shine out then than at other times to compensate for the deepening dark. There is5 the comfort of sympathy, and of seeing in all surrounding faces how the lost one was loved. But, especially, it seems as though, when all are met again, he may not be far away from the circle that was so unbroken upon earth:—

And most of all, there is the old-fashioned, but ever new comfort—balm, indeed, of Gilead, for every bereaved heart.

“I would not have you to be ignorant, brethren, concerning them which are asleep, that ye sorrow not, even as others which have no hope.

“For if we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so them also which sleep in Jesus will God bring with him.”

And these home gatherings, yearly growing more incomplete, and yearly increasing, lead the heart to glad thought of that reunion hereafter, in that House of our Father in which the mansions are many, the Home, one.

Well, you are gathered, my friend and reader, you and your dear ones, about your father’s fireside on this last night of the Old Year. The hours have stolen on: at ten o’clock the servants came in, and the last family prayers have been offered up, and the last thanksgiving of the assembled household for this year; and the chamber candlesticks have been set out, and the father has drawn his chair near the fire, and another log cast upon it crackles and flashes; and each and all announce the intention of seeing the Old Year out and the New Year in.

Cheery talk, reminiscent talk, pensive talk, thankful talk; a little silence. The wind flaps against the window, and throws6 against it a handful of the Old Year’s cast-off leaves. The clock on the mantelpiece gives eleven sharp, clear tings. The year has but an hour to live. And now the wind brings up a clear ring of bells; and then sinks, that the Old Year may die in peace, and his requiem be well heard over the waking land.

But an hour to live! And the burden of depression that ever comes with the exceeding sweetness of bells, loads, grain after grain, the descending scale of your spirits. It is a solemn time, a time for quiet: a time in which it is well to leave even the dear faces, and to get you apart alone with God.

So you steal away from the fireside blaze; and ascend the creaking stairs, and enter your own room; and close the door, even as a dear Friend long ago advised; and offer the last worship of the year—confessions, supplications, intercessions, praises. You go over the dear names, sweet beads of the heart’s rosary, telling them one by one to God, with their several wants and needs. You mention once more the special blessings to them and to yourself of the past year. You put, once more, all the future for them and for you into that kind, wise Father’s hand; and you feel rested then, and at peace. A few words read, for the last time this year, in the Book of books; and now there is yet a little space for quiet thought about the dying year, before his successor enters at the door.

And it is then, as you sit pensively before the dancing fire, alone in your silent room—while the bell music now comes in bursts, and now dies in whispers—that a sort of abstract of many thoughts that have hovered about you all day is7 summoned up before your mind. It is the hour of soft regret, helped, I say, by those merry, melancholy bells, which

You have had your sad times in the year that is so nearly dead; you have shed your bitter tears; you have had your lonely hours, your weariness of this unsatisfying, disappointing world. Unkindness, estrangement, bereavement, intense solitariness of the spirit, when it is conscious that not another being than the Creator can ever understand, far less supply, its want, or heal its woe—these experiences, these wearing, shaping, refining operations of the kind Father are part of your memories of the dying year. While their bitterness was present with you, you would have said that it was impossible that you could ever regret to part with the year that brought them. “Ring out,” you would have said, “ring out, wild bells, this unkind and bitter year; this year that hath brought a blight over my life; this year that hath dispelled the dreams of youth, and changed into a wilderness that which did blossom as the rose. Ring out, and let this hard year die. Fleet, hours and days and weeks and months, and set a distance between me and what I long to call the past. Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky; gladly would I say now, even now, while I listened to you—

But those hours of bitterness are now, even now, of the past. That sharp pain, or that weary ache, is dulled, perhaps removed. Perhaps you have learned God’s lesson in it, and can thank8 Him, though the ache still dwells in the heart’s heart; at any rate, the Old Year is passing away; the sad Old Year, the glad Old Year; on the whole—yes, on the whole, the dear Old Year. He is with you but for a few minutes more; he has come to say good-bye.

Who does not unbend at such a time? In all the friendships, in all the ties of life, there comes up surely all the warmth, all the kindly feeling of the heart, when the time comes which is to end that connection for ever. There may have been some old grudges, discontents, heart-burnings, jealousies, disappointments. But they are forgotten now, and the eyes have a kindly light, and the lips a tender word, and the hand a hearty shake, when it has indeed come to saying good-bye.

And so with the Old Year, whatever he has been to us, whatever little disagreements we may have had, whatever heart-burnings, they are not much remembered now.

It is a friend that is leaving you, you are not glad to part with him; good-bye, Old Year, good-bye.

Another regretful thought, as the twilight flickers and dances on the blind, and those bells still dance hand-in-hand, row after row, close up to the window, and still pass away hardly perceived into the distant fields. The dying Year brought some happiness, some love; this is now warm and safe in the nest of the heart; the coming time may fledge it, and it may, some summer day, take sudden wing and fly.

Youth is especially the time, perhaps, for a sort of tender9 prophetic hint of the evanescence and passing away of hopes, loves, dreams. It is indeed but a rose-leaf weight on the heart, but a gossamer passing across the sun; yet there it frequently is. The iron hand of real crushing bereavement, of actual anguish, has never yet had the heart in its gripe, to crush out all that more tender sentiment. Yet some soft, faint shadows of darker hours do, unaccountably, fall early across the daisy fields of youth. And thus in youth a certain foreshadowing, in mature years a stern experience, brings into the heart at this time a thoughtful dread of losing what we already have; an undefinable apprehension of the future. This time next year, when the New Year has become the Old, and its time has come round to say good-bye, what changes may have come to us, to our circle, to our home! Will all be then as it is now? Will love, perhaps newly-acquired, still nestle in our heart, or will it have even taken wings like a dove, and have left it—

Oh, who shall tell? Answer, quiet heart, that hast learned to trust in God; and rest, rest peacefully, brightly, hopefully, on the answer that God hath taught thee!

But a quarter of an hour left now of the Old Year’s life! and the wind brings the bells in a sudden burst like rain against the window. Before you join the group downstairs there is yet another, the saddest subject for regretful thought. The past hours of the past days of the year nearly past might have been better spent, oh, how much so, than they have been!

“Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might.” Has that been the rule of the past year? Ah, if it had been,10 how different a year to look back upon! How many opportunities neglected altogether! How many but weakly and slackly employed! Opportunities that can never come again, that, employed or neglected, are past now. The word that might have done infinite good, but that was not spoken—cowardice, weak complaisance, in a word, worldliness, God’s enemy, fettered the tongue: excuses were ready, though the heart did not believe them, and God’s soldier failed, and the devil had the better of that field. Again, actions, that sloth or love of worldly ease caused to die out into smoke when they should have been eager leaping fire. An opportunity came, once and again, of doing something for God. The duty was a laborious one, a painful one; nevertheless, however painful, it must be done; you had resolved that it should be done; you had even sought help upon your knees for the work. But mark the carnal coward spirit creeping over the spiritual manly resolve: a friend came in, a persuasion turned you; your heart, alas! hardly really in earnest, did not set itself as a flint to its purpose; too willing to be turned aside, it basely accepted the tempting excuse, and laboured thereupon to believe itself really acquitted from the duty. Those opportunities passed away, the noble action was not done, the faithful word was never spoken, the heart’s reproaches became dull, and the duty ceased its ceaseless gnawing at the conscience. But amid the fitful sinking and falling of the firelight and the bells as you sit on the rug, hand-shading your eyes—the neglected opportunity comes back, with all its reproach, even newer and keener than at the first; back again to accuse your faint-heartedness, to upbraid your lukewarm11 love; to tell you of One who died for you, and yet for whom you shirk the least distasteful labour, the least taking up the cross, and denying yourself to follow Him.

And, besides all this, when you think of the whole past year, even of its hours (how few, and how grudged!) when you have tried to do the work which the Master put into your power to perform for Him, how conscious you are of the want of heart in even your best endeavours; you cannot but feel how hard the world’s votaries have been working for their master, and how slackly you have been labouring for your Master and only Saviour—how they have been running, with eyes fixed on the goal; and how you have been hobbling and limping, looking behind, and on this side and on that, not with single purpose, pressing towards the mark—ah, no!

And you think, then, what this life might have been—might be. A life that looked straight forward, that turned not to the right hand nor to the left, that paused for no alluring of pleasure, for no constraining of business—

“This way and that dividing the swift mind,”

and wasting its energy and powers. A life that set God first, utterly first; that shouldered aside the world’s jostling, distracting importunities; that left the little concerns, the little loves, the little jealousies of this brief life, staring after its eager, swift, stedfast advance, whenever they would have interposed to hinder it. A life that really and in good earnest, not half-heartedly and in pretence, should leave all to follow Christ. Something of the unflinching, unswerving, unpausing persistency of those old Jesuits; only in the service of Christ,12 and not in that of the Pope and the Inquisition. You think of a St. Paul, and his onward, onward still, “in weariness and painfulness, in watchings often, in hunger and thirst, in fastings often, in cold and nakedness,” and you think of your lagging, loitering——!

Ah, well, that is best: on your knees once more, for pardon and for grace—grace to love Him more and serve Him better in the year so near at hand! God shall wipe away all those tears that love for Him made to flow, and the blessed Saviour’s perfect righteousness shall hide all our vile and miserable rags; yet even the saved, we can almost fancy, will wish with a feeling akin to regret, to have loved the blessed Lord more; and he who has gained but five pounds will surely wish that it had been ten. For our opportunities, it often seems to me, are such as angels might long to have. Where all are serving God, and we have no longer a sinful nature dragging us back, nor a glittering world around us, nor a subtle tempter at our ear—it will seem little, methinks, to serve God then and there. But now, and here, in a world lying in wickedness, where the more part are not on Christ’s side, but rather leagued with or deserters to the devil, the world, and the flesh—oh, what an Abdiel opportunity to stand up, a speaking, living protest in life’s least and greatest thought, word, and act; a burning and a shining light, reflecting the beams of the Sun of Righteousness in a dark and naughty world!

Ah, may this quiet hour of thought, of regretful meditation, by God’s grace, be the point on which you have collected your powers and energies for a forward spring, that shall not grow slack through eternity!

15 Five minutes to twelve now. The hour of Regret is near its close. The hour of Anticipation is close at hand. The Old Year’s bells are running down, and the Old Year’s life is passing with them. Five minutes more. First you bow your head, and adore the Almighty and the All-loving—God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost—for the Past, for the Present, and for the Future. Then you go downstairs, according to old custom, to join the rest of the dear circle at the open window, and to listen for the ceasing of the bells.

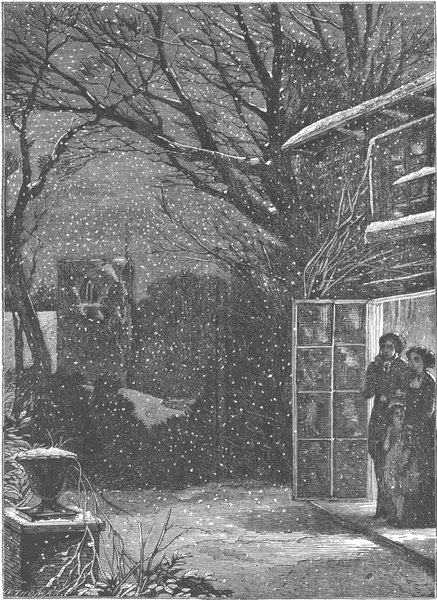

They are gathered at the window, standing quietly and thoughtfully; those that are nearest and dearest linked with loving arms; they are silent, or speak in a subdued tone. You might almost think that they were indeed standing by some bedside, watching the last breathing of a friend; for a solemn thing it is, the passing from one to another of these stepping-stones in the brook of life, and seeing the other shore seem to gather a more distinct shape through the mist of the future.

You join the group. A cold, moist air, full of films of snow, comes out of the dark night into the warm, bright room. The bells are running away; you might almost fancy them the sands, the last few grains of the Old Year’s life. Suddenly they stop, and in the breathing silence a deep clang falls from the church tower,—another,—ten more yet,—and the Old Year is dead.

“A happy New Year!—a happy New Year!” Warm kisses, and hearty shakes of the hand, and, like the crash of a great breaker that has seemed to pause for a moment in the air, down bursts the glad, the melancholy ring of bells again,16 and floods the bare shore of silence,—still lingering, seething, receding, gathering into new bursts again, and yet again.

A happy New Year! The Past is past, the Old Year is dead, the hour of Regret is gone by, the time of Anticipation is here; not good-bye now, but welcome; not lingering retrospect, but earnest advance. Life is too short for long mourning; not much time can be spared to meditate by the fresh grave of the past. Forward, towards the unknown future: grasp its opportunities, its sorrows, its joys, to be woven into some fabric for the Master’s use! On, towards the untried future, bravely, trustfully, hopefully, cheerfully; but remember you can never overtake it. It changes into the present even as you come up with it; and it is now, or never, that you must be serving God.

But good night to all, or good morning—which?—and then upstairs, and tired, to bed. When you wake, things will go on much as usual, though the Old Year be dead, and sentry January have relieved sentry December. Only for a time you will find yourself dating still 18—, and, if untidy, you will have to smear, if tidy, to erase, the last figure, and substitute the number of your new friend.

Anticipation. This is especially the dower of the young, if Regret be often the possession of the old. What a strange, glorious thing a New Year is to the child! Little of the feelings that I have been describing find place in the breast17 of the boy and girl, that were fast asleep and warm in their beds, while you and the bells were at conference: little of such musings trouble them, as they bound out of bed in the morning, and scuttle off in their night-gowns, patter patter, in a race, to be the first to wish father and mother a happy New Year. They are growing out of childhood: that is the joy for them: another of those vast periods has passed. Happy Spring, that does but long to shed and cast away her myriad white blossoms; and to rush on towards the full-grown Summer:—unknowing in the least, of the sober, misty, tear-strung, if fruitful, Autumn boughs! A happy New Year, little ones! Far be it from me to strip Spring boughs in order to imitate the Autumn which they cannot know! God keep you, my children; God teach you, and God bless you!

A little farther on. Anticipation is glowing warmly in the heart of the young man and the young woman. The time of childhood is left behind. The time of independence, the time of manhood, is drawing near: that time which shall transform into realities the great things,—the noble, world-stirring deeds, that have hitherto been only schemes. That time when the loves that are budding in the heart shall burst into exquisite blossoms, and never a frost nip them, and never a rude wind carry at unawares a loose petal away.

A happy New Year. The heart accepts this wish, fearlessly, without doubt, before the strife; before the rough work of a field or two in the scarce-tried warfare of life has smirched the glittering armour, and shorn the gay plumes, and changed the18 song before the battle into hard labouring sobs, in the stern hand-to-hand tussle with sin and with sorrow, with disappointment and dismay. Before many a scheme overturned, many a brave effort fallen dead as bullets against a stone wall, many a seeming hopeful struggle forced back by the sheer dead weight of evil, has made the heart sick and the knees to tremble, and brought an early weariness and hint of despair over the amazed Recruit; a touch of that felt by the Sage of old: “It is enough: evil is too strong for me: I can do no more than others have done before: my schemes have come to nothing, my bubbles have burst: now let me die.” But the Recruit becomes the Veteran, and is content to wait, where he was once ready to despair. He does not hope so much, and therefore is not so much dismayed; he relies now not so much on earthquake efforts, as on the still small voice uttered to the world by the life which is given to God. He is content to labour,—and to leave it to the Master to give the increase.

Yes, the young heart, even when lit with heavenly love, and full of great designs for God, must submit to the overthrow of the bright visions that anticipation set before it. How much more, when its fire was lit from earth; and earth’s loves, or fame, or pleasure, or power, were the prizes for which life’s battle was to be fought. Vanity and vexation of spirit, disappointment, dismay, despair; these are the ruins that shall be won for Moscows, if that battle be fought to the end!

A happy New Year. That glad wish of youth may come to sound, to the man, nothing but bitter irony. But much of the19 early hope, and more than the early peace, comes back to the veteran worker for God.

A happy New Year, young man and young woman! God grant it you, in the one true sense of the word. It need not be a freedom from sorrow: this is an ennobling, useful discipline, that I may not wish you to avoid. But, to be happy, it must be free from sloth and wilful sin.

Look out from your window again, at the snow sheet which has silently, deeply, fallen upon the earth. Let it be very20 early in the morning, while the world is asleep and the broad moon and the glittering stars watch alone over the smooth, sparkling, white face of the land. Not a footstep, so far as you see, has impressed the smooth, pure snow; not a dark cart-track has yet left a long stain on the spotless road. No thawing penitential drippings have made dark wells in it here and there; no rude sweeping has piled the snow in stained heaps hither and thither by the path. All is yet pure, untouched, undefiled.

This is the New Year upon which we have entered, as we look at it from the casement of the Old Year, before yet one step has been placed on its first moment. All as yet unstained, and white, and calm.

For how short a time to remain so! Can we set our first step upon it without somewhat marring its virgin beauty? And then the traffic, the hurrying of many feet, the crushing of many wheels; thought, word, and deed, too often unwatched and unsanctified by prayer; oh, what a change soon, and how short a time that purity and calm has lasted!

New Year; clean New Year; how dark, how defiled, how changed will you be, when you also are now waxing old, and ready to vanish away! The white virgin opportunity all passed by, leaving dark, dreary, sodden fields, and roads churned up into yellow mud. The clinging spotless moments—flakes that, in innumerable combination, made up the great stainless carpet of the untrodden New Year; for them there will be many a trickling rivulet of penitential tears; and the steam and mist of heavy sighs that go up to God because of life’s work too faintly, slackly done. Well then, that is well.21 Better, of course, if this could have been, that the pure year had remained unstained.

But well, if we are indeed humbly striving, and if hearty repentance, and a true, lively, cleansing faith follow upon our many, many sad failings, faults, and shortcomings. For, sweet words!—

“If any man sin, we have an Advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous: and He is the propitiation for our sins.”

And, glorious thought! if we are indeed loving and seeking after purity and holiness, striving because of the hope within us, to purify ourselves, even as He is pure—then know this, we shall not love, and seek, and strive in vain.

Think of that! So that, when our last hour comes, and the bellringers are ready for us, to ring out the Old Year of this life, and to ring in the New Year of the next; and we are looking (our near and dear ones still by us) out of the casement of the Old Year of TIME, what may we then see? There shall be stretched out before us the immeasurable unstained tract of the New Year of ETERNITY, unsullied, spotless, pure and white; and we need not then be afraid to enter upon that. The blood of Jesus, which cleanseth from all sin, will have so cleansed us, that even our footprints will not stain nor mar it. The spots and the defilements, the tears and the sighs, they will lie all behind us then, in the Old Year which is dead. Ring out,22 oh, ringers, then—toll not, but ring out the year of sadness and of sin, of weak strivings, cold hearts, and dull love! Ring out the year of partings and estrangements, of death and tears! And ring in—oh, that it might be so for every reader of this chapter!—ring with none but joy-notes, ring in that everlastingly happy New Year!

I call February the Threshold of the Year. In January we were indoors, beside the fire, and there seemed little of new and various to tempt us out. But February comes, and with it the first dream of change, the first scarce-heard whisper of the Spring. The faint possibility of a snowdrop, hinting its yet undrooping white through a peaked green film; the distant hope of a primrose bud, peeping—with yellow point, for all the world just like that of a coloured crayon—out of the young, crisp, green leaves that are crowning the limp, ragged ones of last year; the wild dream of a find of those sweet buds—little geologists’ hammers, with white or violet noses—among their round seeds and drilled leaves, in some warmer corner;26 such, summonings as these woo the steps to the threshold on a strayed mild day late in February. The black, soaked trees have, we find, taken a warm hue of life; the dull willow bushes have the gleam of golden hair; the first soft air of the year comes to our hearts with a gush of promises; flowers and leaves seem possible to the heart waking from its winter stagnation; trees and men alike feel a new life, a fresh impulse. Even though we have become hard wood and wrinkled rind, our sap is, nevertheless, stirred:

And, perhaps, we are content to pause on the threshold, and lean against the lintel, and survey the smile close at hand, and the gleam far away; and, while the robin draws near in a cheerful, not to say jovial, sympathy with our humour, and the faint branchy shadows move tenderly on the glistening lawn, to muse on the year’s threshold, concerning the programme that the wind is whispering among the bushes, and the promises that the warm air is wafting into the heart.

Musings on the Threshold. Such musings might take many an obvious high road, or quaint turn, we must feel, as we stand on the threshold of our house, and of the year, looking out upon the herald-gleam, and fanned by what seems a Spring air; an air that summons sweet thoughts of March, April, May—scarce June yet; certainly not October or November. On the threshold of the Spring; this we would rather say, and forget27 that it is really the threshold of the year,—that thing composed of smiles and tears, of gleams and showers, of full green boughs and bare sticks, of promises and disappointments, of growth and life, and decay and death. For instance, with regard to these threshold musings, how often, ere we shall have passed on so far in life’s journey, that we stand on the threshold of the next state,—how often do we pause for awhile upon some threshold, and lean back against the door and muse. On the threshold of joy, or on the threshold of misery; on the threshold of hope, or on the threshold of despair; on the threshold of school, or of the holidays; on the threshold of wearing tail-coats; of being flogged or expelled; of gaining the three head prizes of the school,—these gave musings to some in early days. Later, on the threshold of a pluck, or of a double first-class; on the threshold of first love; and—oh, the dim, delicious look-out, and long, ecstatic musings!—on the threshold of being married; of parting with some beloved one,—and ah, how a stern hand seems to drag you forth from your contemplation here, when your musings were scarce begun! On the threshold of the first fall from purity or honour,—and, alas, the dismal journey that shall follow upon the threshold left, and the first step taken! On the threshold of repentance; and angel-eyes watch eagerly, and angel-hands poise above their golden harps; and at the first step forward a ringing rapture peals up into the trembling roof of Heaven. “Musings on the Threshold”:—are there not then, highways and by-paths which such musings might well take? But it is time for us to choose our present road; and, to do so, we will even go back to the beginning of a certain well-trodden way,28 upon which every one of us is found, some far back, some near the middle, some tottering on close to the goal.

On the threshold of Life. Yes, once upon a time we stood there: and the Spring air was rife with half-shaped songs and indistinct delicious whispers; and we knew that the hedges and copses were full of all sweet promise-buds; and there were songs in the distance, and an interminable thronging of inexhaustible flowers; and life seemed too sweet, when the first blossom that was our own was grasped in our hand, and the stir of life growing conscious and intelligent first made the heart glow and kindle, as we paused musing upon the Threshold, and looked out upon the sweet, strange opening year of Life.

Ah well, the step soon has to be taken, that marks the beginning of separation from those lovely, unreal dreams. There is Solomon’s way of leaving them—much labour, and little profit, and a bitter heart at the end. And there is that other way of leaving them—the hearing once and again, and gradually heeding, an oft-repeated solemn call, “Follow Me.” Out of the sunshine into the shadow; away from dreamy threshold musings, into the rough and stony highway; drop the flowers and clasp the cross: for how run the instructions given long ago, and given to all; given by precept, and given by example? “Whosoever will come after Me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow Me.”

How true of those who—at last, and after long hesitation—take the first step, and leave the threshold of this world’s young dreams, and begin to follow Him; how true that29 “little did they know to what they pledged themselves, when, in that first season of awe, they arose and followed His voice. But now they cannot go back, for they are too nigh to the unseen One, and His words have sunk deeply within them. Day by day they are giving up their old waking dreams; things they have pictured out and acted over in their imaginations and their hopes, one by one they let them go, with saddened but willing hearts. They feel as if they had fallen under some irresistible attraction, which is hurrying them into the world unseen; and so in truth it is. He is fulfilling to them His promise: ‘And I, if I be lifted up from the earth, will draw all men unto Me.’ Their turn is come at last, that is all. Before, they had only heard of the mystery; now, they feel it. He has fastened on them His look of love, even as on Peter and on Mary; and they cannot choose but follow, and in following Him, altogether forget both themselves and all their visions of life.”

How strange it is, verily, after we have for many years now, followed that Voice,—followed it, no doubt, with many a declension, many a wavering, many a wayward swerving, and almost turning back; yet, on the whole, followed it, and that with less of timidity, and more of implicitness, as experience justified hope;—how strange, about midway in the journey, to look back at life’s threshold! The January of infancy had past; the February of awakening, conscious life had come, and we came out from our dormant state, and paused upon the threshold, and looked forth upon the world. And now we look back, and with a strange, wondering interest, contemplate that single lonely figure that was ourself, leaning30 in wrapt musing; the small home behind it; and before, the siren murmurs, and warm, flattering airs of the fairy, enticing Future. The magic dreams, the mirage-reveries, the profuse promises, the unshaped hopes, the just-caught notes of some divine, distant melody: all the flowers to blossom; and all the birds to come. Ah, what sweet, wild musings were those! Far away we seemed to catch a gleam of that

And even tears had their sparkle, and melancholy its charm, and death its unreal beauty.

Thus, we remember, once stood that figure, solitary in its own individuality, upon the threshold, and looking out upon life. And, contemplating our present self, we feel that it is “the same, yet not the same.” How changed all has become! It is not only nor chiefly that flowers are less valued than fruit-germs, or sparkling glass than rough, hereafter-to-be-cut diamonds; it is not only, nor so much, that the world’s promises and life’s young dreams have failed us, as that we have turned away from them. That our taste has altered; that the things that then were all, are now nearly nothing; that what once rose before us a golden mirage, seems now as but bare sand; that what seemed gain, would be now held33 as loss; that what seemed too rare, and delicious, and high, and exquisite, and sublime, for more than trembling hope, has now become as refuse in our thought.

Time was, when other thoughts and purposes than these which now possess us, held sway in our hearts. Time was, when we stood on the threshold, dazzled, and wondering, in a delicious dream, which of all the sublime or lovely paths that opened before us we should pursue. Time was, when at last we began to heed a kind, but still small Voice, that had from the first been speaking to us; when a grave Eye that had from the first watched us, at last fixed our attention. Time was, when we were compelled as it were, at first with hesitating, reluctant step, to follow that Voice and that Look—away from those bright gay paths, or grand aspiring ways, down a lowly, narrow way, strewn with thorns and stones, and sloping into a mist-hid valley. Time was—if we followed still—that the disturbing, distracting sounds and sights above being left behind and hushed,—the mist lifted, and, lo! the valley was a pleasant valley, an abode of “peace that the world cannot give”: and if the way were still rough sometimes, there were undying flowers of unearthly beauty here and there; and if the lark was away, the nightingale was singing; and it was answered to us, yea, our heart returned answer to itself, that, albeit narrow and strait at first, the name of that way was, in very truth, the Way of Pleasantness and the Path of Peace.

Ah, yes, if once we, with purpose of heart, set ourselves to follow His guiding, how God draws us on! We clutch at this, and would rest at that; and surely this is the Chief good, and34 the Ideal beauty? But no; the early flowers depart, and the late, and we leave the threshold and wander on; and February goes, and March goes, and even June, and August; and sorrowfully and wonderingly we look up at God, following Him on through life, even into the grave September, and the hushed October, and the tearful November; and so into the winter of alienation from the world, which death’s snow comes to seal.

But ere this we have found out His meaning in life, and the flowers of earth are no more regretted; and there is no point at which we would choose to have rested, now that we look back upon the past experiences and events of the journey; and both our hands are laid in His, and we look up with unutterable trust and ineffable love. It was not so once:

And then He has led you, little by little, with gentle steps, hiding the full length of the way that you must tread, lest you should start aside in fear, and faint for weariness. And as it has been, so it must be; onward you must go; He will not leave you here; there is yet in store for you more contrition, more devotion, more delight in Him. A few years hence, and you will see how true these words are. If by that time you have not forsaken Him, you will be nigher still, walking in strange, it may be solitary paths, in ways that are “called desert”; but knowing Him, as now you know Him not, with a fulness of knowledge, and a bowing of heart, and a holy self-renouncement, and a joy that you are altogether His. What35 now seems too much, shall then seem all too little; what too nigh, not nigh enough to His awful cross. Oh, how our thoughts change! A few years ago, and you would have thought your present state excessive and severe; you would have shrunk from it then, as at this time you shrink from the hereafter. But now you look back, and know that all was well. In all your past life you would not have one grief the less, or one joy the more. It is all well.

And so it is, then, that we are led on from our February threshold, on through the maturing, decaying months, until the silent Winter comes. And what then? Is it to be the same over again—the same promises and disappointments, the same dreams and awakenings, the same unreal glory at the threshold, and the same gradual weaning from it on the journey?

Not so. To us the years are not repeated, nor is the “second life, only the first renewed.”

But I love to wander, nevertheless, in my musings far beyond the journey to the Land whither the journey is tending. Beyond this state of probation to that of fruition; beyond striving, to attainment; beyond discipline, to perfection; beyond warfare, to victory; beyond labour, to rest; beyond constant slips and shortcomings, and half-heartedness at best, to stedfast holiness; beyond the cross, to the crown. We are yet within doors: oh, what will open before us on the threshold of that next year!—when the first wonder of its January36 has passed, and the amazed and almost dizzied soul has straightened and uncrumpled its wings, and collected its powers, and can calmly begin to understand its change, and to muse on its future, and to grasp the idea of the possession upon which it has come: to anticipate the endless succession of amaranthine flowers, ever increasing in glory throughout the months of Eternity, and the songs that shall ever throng more and more abundant and ecstatic, and never migrate nor pass away!

On the Threshold. Those in Paradise are now musing on the threshold, waiting for their full consummation and bliss both in body and soul, waiting for that coming of the Lord with regard to which they are still crying out, “How long?” and are bid to “rest yet for a little season.” And so then they rest, and wait upon the threshold, and contemplate the mighty and magnificent panorama outspread before them as their Future. The Voice is still there, and the Look; and they wait its summons, to leave the threshold, and to follow once again. But how different that following then! How far other than of old that summons! Not to paths of humiliation and discipline, and hills of difficulty, and valleys of shadow, but to realms of brightness and beauty unspeakable, and to heights to which earth’s ambitions never soared. From the threshold of blessedness into the domain of glory; from Abraham’s bosom to the throne of the Lamb; from a star to the Sun in His strength.

And so may we think of our dead that fell asleep in Jesus, as waiting upon that blessed threshold, contemplating that ravishing prospect, which is theirs, and may be ours. Nor37 do we enough thus think of and realise the state of the departed. The poisonous fungi of error have made us shy of the mushroom of truth. “The superstition of ages past has recoiled into the sadduceeism of to-day.” And so we, the dying, compassionate those who have begun to live, and who stand upon the threshold of the yet higher and more perfect life of the resurrection. Let us think of them more nobly, more worthily, more truly. Let us not heap their burial with gloom; let not our souls dwell with their bodies under the sodden clay. They are changed, but they are not lost; they are “still the same, and yet are not what they were; they have passed from the humiliation of the body to the majesty of the spirit. The weakness, and the littleness,38 and the abasement of life are gone; they are now excellent in strength, full of heavenly light, ardent with love, above fallen humanity, akin to angels.” “Blessed and happy dead!—great and mighty dead! In them the work of the new creation is well-nigh accomplished; what feebly stirs in us, in them is well-nigh full. They have passed within the vail, and there remaineth only one more change for them,—a change full of a foreseen, foretasted bliss. How calm, how pure, how sainted are they now! A few short years ago, and they were almost as weak and poor as we; burdened with the dying body we now bear about; harassed by temptations, often overcome, weeping in bitterness of soul, struggling with faithful, though fearful hearts, towards that dark shadow from which they shrank, as we shrink now.”

We on our threshold and they on theirs; then let us think of them and of ourselves so. We have left the threshold of life, and are nearing the threshold of Death, or rather of the beginning of Life indeed. They behold the prospect at which we guess, and which we burn to see. But because it may be ours one day, we are already sharers with them, and our higher union is rather cemented than interrupted. “The unity of the saints on earth with the Church unseen is the straitest bond of all. Hell has no power over it, sin cannot blight it, schism cannot rend it, death itself can but knit it more strongly. Nothing is changed but the relations of sight: like as when the head of a far-stretching procession, winding through a broken, hollow land, hides itself in some bending vale, it is still all one; all advancing together; they that are farthest onward in the way are39 conscious of their lengthened following; they that linger with the last are drawn forward as it were by the attraction of the advancing multitude.” Or, in another figure, beautifully has it been said, that when the Sun of Righteousness passed out of sight, the splendour of His hidden shining is reflected by His saints, “till the night starts out full of silver stars.” “In stedfast and silent course” they pass on, some disappearing below the horizon, some resplendent in mid-heaven, some just emerging from the other boundaries. And when the last has arisen, and some are yet sparkling in the blue vault, the Sun shall arise with sudden glory, and they all shall render to Him their light. But until that time, which no man knoweth, neither the angels of heaven, it is awaiting upon the threshold, in mighty musing upon the glory yet to be revealed; and, “until all is fulfilled,” the desire of the Church unseen is stayed with the “white robes” and the sound of the “Bridegroom’s voice.” Let us comfort one another with these words and these thoughts.

And now thus have we mused upon the Threshold, beginning first with the threshold of the life that is expecting death, and then soaring boldly to the threshold of the life that is expecting the Resurrection. We need reminding in this age that there are two sides to this expectation. There is “a certain fearful looking for of judgment and of fiery indignation,” as well as an ardent, and eager, and rapturous anticipation and longing for His coming who cometh quickly, though He seem to tarry. And it is well to ask, when death ends our journey here, upon which threshold shall we prefer to wait, and which musing shall be our choice: the dreadful40 looking-for of judgment, or the ecstatic longing to hear that Voice which once said, “Follow Me,” speak again to us, even to us, the incredible words—“Well done, thou good and faithful servant: enter thou into the joy of thy Lord.” Choose we, my friends, carefully, prayerfully, deliberately, finally, and at once; for “Behold, now is the accepted time; behold, now is the day of salvation.”

What a delicious thing is the first real Spring day! A burst into a buttercup-field! What a thing of mad enjoyment for the legs, and eyes, and hands, and mind of the young human animal! What a sweet time to think of, in our sentimental moods, now that we are growing old! And yet, in that time of fresh animal life, there was not reflection enough to allow of deliberate and actual enjoyment of its hilarity and lightness of heart. It welled up bubbling and singing with the gladness of a spring, that yet is glad only because it is glad, and not because it is pure and bright. For it knows not yet of aught that is muddy and foul,44 shallow and stagnant. It knows not of drought, and deadness, and impurity, and dulness, and death. How knows it, therefore, why it ought to be glad? Sing on, sweet stream, but you must be left to learn, as you roll seawards, into a sober old river, why you used to sing as a bright untroubled stream.

So, I suppose, except for the impetus and rush of early life, in its Spring days, before it has been checked here, and wasted there, and hemmed in, and spread out, and turned away, and thwarted, until its rush, and song, and glee have settled into a quiet, useful soberness, or into a foul stagnant pool that cannot often bear to call to mind those old pure, careless days—except for that first impetus and rush, I suppose it is more an absence of something than a presence of aught, that makes the child’s heart so glad. Anxious thought for soul and body of self and others; disappointment, regret, estrangements, remorse, satiety, failing powers; none of these check the young limbs, and the young lungs, and the young heart, as a sight of the brimming Spring meadow bursts upon the enchanted young eyes, and there is a shout, and a scamper, and a bound; and lo! the little naked legs are deep in green grass, and yellow bobbing buttercups, and starry radiant daisies.

I can’t feel towards the buttercups and daisies exactly as I did in those very early days. It is indeed a very primitive state of things, when these are as gold and silver coins to the young eager grasping hand, that would yet hold more when already by twos, and ones, and threes, the white discs and yellow cups struggle out of the little space that the finger and thumb cannot quite close in. You very soon get to slight these humble flowers; and, losing your easy content, aim45 higher, even at cowslips, primroses, and here and there an early purple orchis. That is, perhaps, the most simple-hearted and easily-contented time of life, which asks no more for its riches than both hands full of buttercups and daisies, guineas and shillings bright and fresh coined from the mint of Spring.

I remember well a wide meadow shut in with tall hedges, in which, for a Spring or two, while we were young enough to enjoy them, there was, for my two sisters and myself, a very scramble of such coins. Out on some mild April day, when the sun shone brightly, and the air was a growing air, and the paths dry. Out with our governess, we three, for a walk. A fortnight of soft April showers, or warm damp days, keeping us within the garden while the field was being dressed, had46 prepared for us a surprise. We ran our hoops along the dry paths, until the winner of the race caught sight of that fair meadow. Through the white wicket-gate then, the hoop thrown aside into the yielding grass, and the three pairs of little hands were busy enough soon. At first, the aim was merely to pick what came to hand, and quantity, not quality, was in demand. But, so soon do we begin to undervalue that which is abundant for that which is less easily attained, in a little while we were busy after rarities; mere white daisies were passed over, and those with a “crimson head” were sought; also, I remember, those with a scarlet jewel in the centre of the boss of gold. Cowslips were rare in the fields about us; were anyhow rare at that early time of year. Fancy then our exultation, if we should come upon a pale bent head, the delicate trembling spotted yellow, curving upwards towards the sheath of faint green. The bound towards it; the excitement of feeling the juicy crisp stalk break, and then rushing away with the treasure! I remember such a find now, though I be far on in life beyond that early stage marked by that slight drooping flower.

But of course the daisies and buttercups, even before “whole summer fields were theirs by right,” soon lost their fascination, even in those early simplest days, before the advance of other rarer flowers. We could pass the meadow soon, without bounding into it, on our way round the park wall on a violet expedition. We could scent these out, and would eagerly part the crowding leaves and the binding ivy-nets that hid them. Not much fear lest we should gather enough of them to risk dropping any from an over-filled hand.47 Still, we mostly went home well content, with a close-clipped neat dark-blue bunch in one hand, with here and there a pure white prize, or a large one merely purple tinged, gleaming out of the dark. These white- and purple-tinged violets, you must know, had become our prizes, being rare, found seldom indeed by the park wall, but oftener on some mighty sandhills, that towered above the road a little way beyond our daisy-field, and seemed to bury the deep-lying road, with its winding carriages and pigmy passengers.

Out for a long walk now, even to that deep chalk-pit, where not one cowslip hung, rare, unique, precious, but hundreds, nay thousands, bent their pale yellow heads, and scented the air with their sweet faint breath. So juicily they snapped, without that drawback which I deplore in primroses—the long sinew that a hasty picking leaves behind, to the marring of the flower. Baskets we had, trowels in them, to collect some roots for the misused pieces of ground known as our gardens: and woe betide an early orchis, if we came across it. Nearly always, after a long and patient digging, when the final pull came, a long blanched stalk, with no root at the end, would meet our disappointed eyes.

But of course the great thing was to collect unlimited flowers. And really, if you turned me loose into the Bank of England, into that room in which those aggravating fellows shovel about the gold in coal-scuttle scoops, and bade me gather my fill, I am sure the delight would be neither so fresh, so sweet, nor so wholesome, as that entering unchecked upon the rich cowslip-wealth, trembling all over the short turf of the sloping side of the chalk-pit which ended our expedition.48 Two principal objects had we in collecting these flowers—for as the year goes on, even children seek use as well as beauty in their gettings; first to make cowslip balls, many and large, when we got home; next, to make cowslip tea. There is, or was, a keen delight in the former of these pursuits. The excitement and delight of the first cowslip ball made is feverish and unsettling. The long, tight string upon which are hung the poor flowers with their tails pinched off; the filling that string, the tying it, with here and there a cowslip tumbling out; and then the playing with the sweet-scented soft toy, till the room is littered with its scattered wealth, these are things to remember even now. But, no doubt, the great thing was the cowslip tea—allowed to us that night instead of milk-and-water; and to be drunk in real teacups instead of mugs. The solemn shredding the yellow crown out of its green calyx; seated, all three, at our little low table with the deep rim; the growing heap of prepared flowers; then the piling them into the teapot, the excitement of seeing the boiling water poured upon them; the grave momentous pause while the tea was brewing; and the hearty, but really at last abortive, endeavour to persuade ourselves and each other that we liked the filthy concoction, and found it really a treat. Ah, life has many a cup of cowslip tea in it; delightful in the preparation, exciting in the anticipation, but most disappointing when it comes to the actual partaking!

We must not stop now to run down that green path into the wood—our one wood, nor to see which shall first enter it with a bound; we must not stop, although we know that a little later in the year there were some rare choice treasures49 there. A firmament of starry wood anemones; and here and there a bent spike of wild hyacinth, not yet ripened into its deep full blue; and here and there a pale green orchis, coming out of its two ribbed leaves, valued because rarer than its purple brother, that but rarely yet towered with its tall rich spike above the clustering milky flowers. And on one bank that we knew, just two or three roots of primroses, the only roots that grew wild for miles about that part, each tendering to us its crowded offering of sweet faint flowers, and deeper yellow buds imbedded in the crisp, crumpled leaves. And then the lords and ladies: lord, handsomest—lady, rarest: I could pick and unroll them now. They call to mind a glad, bright little address of a child to the flowers, with which I will conclude these reminiscent wanderings among the old wildflower fields of youth:—

Why have I recalled these child remembrances of early Spring days? Why, but to add that those keen delights, those exquisite, though unintellectual and reasonless, appreciations are gone—in this life for ever! Wherefore I say in this life, I mean presently to show: suffice it now to say that the Summer and Autumn of human life, dry and dusty, or sorrowful and decaying, have done quite, except for some50 tender sweet reminiscent hints, with the freshness, and the glee, and the gladness of the old Spring days.

These lines of Wordsworth express, very exquisitely, the thought at which I have just been catching. Something goes, as we grow old—a gladness, a suddenness of appreciation of enjoyment is lost; and the dark Summer foliage is not the same with the fresh light green of the young Spring leaves. And when a gush of the old keen relish comes back for a moment, there is regret as well as sweetness in the tears that suddenly dim the eyes.

Spring days, sweet Spring days, my quiet heart and rested eye tell me that there is no fear but that I enjoy you still!

This exquisite poetry has its voice of delight for me, and as I shut my eyes, it brings a change over the bare boughs and the Winter land. I dream of the chill black hedges and trees, flushing first into redness, and then “a million emeralds burst51 from the ruby buds.” I dream of the birds coming back, one after one, until the poetry of the flowers is all set to music. And I go out into the land to behold, not only to dream of and image, these things. I watch for the delicious green, tasselling the earliest larch (there is one every year a fortnight in advance of the others) in the clump of those trees beside the road on my way home. I look, in a warm patch that I know, for the first primroses, and when I find them mildly and quietly gazing up at me from the moss, and ivy, and broken sticks, and dead leaves, a surprise, although I was expecting them, and a dim reflection of that old child-joy, bring with a rush to my heart again those “Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.” And in the garden I wander through the bare shrubberies, varied with bright green box, and gather in my harvest there. The little Queen Elizabeth aconites, gold-crowned in their wide-frilled green collars; these are no more scant, and just breaking with bent head through cracking frosty ground. They have carpeted the brown beds, and are even waxing old and past now. The snowdrops have but left a straggler here and there; and the miniature golden volcano of the crocus has spent its columns of fire. The hazels are draped with slender, drooping catkins; the sweetbriar is letting the soft sweet-breathed leaves here and there out of the clenched hand of the bud. The cherry-tree is preparing to dress itself almost in angels’ clothing, white and glistening, and delicious with all soft recesses of clear grey shadow, seen against the mild blue sky. The long branches of the horse-chestnut trees, laid low upon the lawn, are lighting up all over with the ravishing crumpled emerald that bursts52 like light out of the brown sticky bud—-as sometimes holy heavenly thoughts may come from one whose first look we disliked; or as God’s dear lessons unfold out of the dark sheath of trouble. The fairy almond-tree—of so tender a hue that you might fantastically imagine it a cherry-tree blushing—casts a light scarf over a dark corner of the shrubbery. The laburnum is preparing for the Summer, and is all hung with tiny green festoons. Against the blue sky, on a bare sycamore branch, that stretches out straight from the trunk, a glad-voiced thrush seems thanking God that the Spring days are come. Wedged tight into three branching boughs, near the stem of a box-tree, I find a warm secure nest, filled with five little blue-green eggs. It is still a delight to me to find a nest; a delight, if not now a rapture, an intoxication.

All these I see on one Spring day or another, as I walk into my garden, or out into the changing lanes. All these I see, and all these I love. But I see them, and I love them tenderly and quietly, not with the wonder and the glee of life’s early Spring days. I am sad, partly because I know that a great deal of that old wondering ecstatic thrill has gone.

It must be so, naturally, if only from the mere fact that53 things must lose their newness, and so their wonder, to the eye and the heart. Do what you will, you must become accustomed to things. And the scent of a hyacinth or of the may, will cease when familiar to be the wonderful enchanting thing that childhood held it to be. And the thirtieth time that we see, to notice, the first snowdrop bursting through the pale green sheath above the brown bed, is a different thing from the third time. We appreciate delights keenly when we are young, seek the same in later years, but never find them; and then all our life remember the search more or less regretfully. So Wordsworth, the old man, addresses the cuckoo that brought back his young days and his young thoughts by its magic voice:—

Ah well, I must get on to my moral. I must not wail like an Autumn wind among the young flowers, and the bright leaves, and the blithe songs of the sweet Spring days, else I54 shall lay myself open to the reproach of the poet describing one who—

It is not true really, that we are leaving behind our best, when we have passed into the Summer, or even into the Autumn days. But there is a degree, a portion of truth in it. There is a sense, no doubt, in which even the Summer does lose a beauty which is the peculiar possession of life’s Spring days.

First then (to divide sermon-wise), what is that we lose, when we lose Spring days? I have hinted at this loss in nearly all that has been written above. We lose the gladness of inexperience, the gladness and enjoyment that is not thoughtful, nor such as can give a reason for itself, but that is merely natural, and welling up irresistibly like a spring. We lose the newness of things—aye, more, far more than this, we lose the newness of ourselves, the freshness of our own heart. This is (with some in a greater, with some in a less degree) what we discover that we have left behind, when we look back on life’s Spring days. Some of us, with a tender half-regretful watering, keep a hint, a reminiscence, of that old freshness. But many heedlessly suffer the world’s dust to coat it over, and the world’s drought to shrivel it up.

But now, what may we have gained, if there be something lost in our leaving Spring days behind? If we lose a little, let us not fear but that our gain is far larger than our loss. We55 gain gladness and we gain sadness (I use the word gain advisedly)—the gladness and the sadness of experience. A gladness that is part of the depth of a grave river now; profound, if not light-hearted like the little spring. A gladness that, when it comes, is more rational than merely animal; that has a reason to give for itself, and does not exist merely because it exists. A joy that is far more rare, also less ecstatic, but that is higher and deeper, having its birth in the intellect, and not simply in the life of the human creature.

To exemplify my meaning. In art, compare the mere admiration without knowledge, with the intelligent appreciation. Turned loose without knowledge into a picture-gallery, how many things you admire, almost everything; and how fresh and uncritical is your admiration! But gain knowledge of art, gain experience; and you straightway lose in quantity what you yet gain in quality. You admire fewer pictures, but your admiration of the few is a different thing from that old admiration of the many. It is a higher thing, more intelligent, more subtle, more refined. It is an appreciation now, not merely an ignorant admiration. You are harder to please; in one sense you have lost; but manifestly, on the whole you have gained.

And so with the gladness of manhood. It is a deeper, graver, more fastidious, yet a more reasonable and higher feeling than the gladness of the child. The sparkle, and bubble, and glitter, and singing have gone; but in their stead is a strength, an earnestness, an undercurrent not easily stayed or stemmed or turned aside. The gladness which is intelligent is better than the gladness which is instinctive.

56 And the sadness of experience (for we cannot live long in this world without discovering that life is exquisitely sad)—the sadness which comes with experience—is this also a gain? No doubt it is—no doubt it is. A wise man once told us that sorrow is better than laughter; that the house of mourning is better than the house of feasting. And a Greater than Solomon endorsed with His lips and with His life the declaration, “Blessed are they that mourn.”

And who that regards life in its true aspect, but must bow a grave assent to this verdict? He who watches the effect on himself of God’s teaching, and of the lessons which He sets to be learnt, will understand what the Master means by His saying. He who regards his own life as something more than a bee’s life, or a butterfly’s life; he who sees that the life of man has its schooling, meant to raise it above our natural meannesses, and petulances, and impulses, and weaknesses, and selfishnesses, and ungenerousness—into something high and noble and stedfast, exalted, sublime, angelic, godlike; he who thus thinks of life, and watches life with this idea ever in view,—will find it not hard in time to thank God for having made him sad, even while the sadness is fresh and new and keen in his subdued and wounded heart. Disappointed in many things, and with many people, he will accept the disappointment with a quiet, anguished, thankful heart, feeling that God, who tore from him his prop, is raising the trailing vine from the ground, and instructing its tendrils to twine around Himself, the only support that can never fail them. And this is well, he knows, who is a watcher of life, and a learner of its lessons.

57 And when sadness has produced this, its right and intended effect of sweetening, and not souring the soul, a fresh advantage and gain steals, starlike, into the darkened sky. The heart that has been made lonely, except for God’s then most nearly felt presence, in a sorrow, is that which is the most braced and disentangled for the great and noble deeds of life. With a sad and a disappointed, if yet still a loving, tender heart, we can go out on God’s work, go out to face evil, or to do good, more easily and thoroughly oftentimes, than when this great grave, the world, shows to us “its sunny side.” Sadness, to him who humbly and prayerfully is seeking to learn God’s lesson in life, has not a weakening, but a tonic power. God, who sends the sadness, sends also the health and the strength; yea, the strength arises from the sadness. Something of what I mean is grandly expressed in the following extract:—

“There are moments when we seem to tread above this earth, superior to its allurements, able to do without its kindness, firmly bracing ourselves to do our work as He did His. Those moments are not the sunshine of life. They did not come when the world would have said that all around you was glad; but it was when outward trials had shaken the soul to its very centre, then there came from Him ... grace to help in time of need.”

Sadness, then, which braces and strengthens the character, which raises it into something nobler than it would otherwise have been; which sets a man free and stirs him up for great and noble acts, for a resolute devoted doing of Christ’s work on earth—such an experience is certainly a gain; and if this be our own, even when the Autumn woods are growing58 bare, we are not to wish to have back the old sweet Spring days.

Now one more loss and gain has occurred to my mind, contemplating those Spring days that seem, but are not, so far behind me in life. How often we pine after the innocence of childhood! how the poetry of our hearts, and of our writers, loves mournfully to recur to this!

But here again a little thought will show us that we need not have left our best behind, when the Spring days are with us no more. Deliberate and intelligent goodness and holiness is a better thing than mere innocence of childhood, which, again, is rather the absence of something than the presence of aught. There has been merely neither time nor opportunity yet for much evil doing: there was no intelligent choice of good because of its goodness. And thus, if the man (although he have sinned far more than the child can have done) has yet, at last, and through much sharp experience, learnt life’s great lesson, and has become (however it be but incipiently) holy and good, that deliberate and positive, though imperfect goodness, is far better than the mere negative innocence of the child. Angelic innocence is, and the innocence of Adam would have been, no doubt, intelligent innocence. But now that we have fallen, that innocence (which, after all, is but comparative) of childhood is little else but the lack of time and knowledge and opportunity for sin. Such innocence is59 merely a negative thing, while holiness is positive. And he who is ripening into holiness in life’s Summer, need not regret the mere innocence of its Spring days. In life’s filled, and alas, blotted pages, if, amid many smears and stains, the golden letters of GOODNESS at last begin to gleam forth in a clear predominance, he who considers wisely will not regret much the newness of the book, whose pages are only white and pure, because scarce yet written in at all.

“The world passeth away, and the lust thereof.” All is evanescent, passing away; not only the objects that we desire, but even our desire and appreciation of them too. Nor does this only apply to that which is worldly, in an evil sense, but to some objects sad to lose, but which to have still, but no longer to be able to appreciate, is yet a sadder but an inevitable loss. When we look back upon life’s Spring days, something really sweet, and beautiful, and desirable, seems left behind and gone. Not life’s best; not the grape, but the bloom on it; not the deep blue day, but the strange glory of the morning sky. Something seems lost. I am fond of maintaining that it will yet hereafter be found. In Heaven, I think, there will be not only beauty, fairer than our fairest Spring days; but an appreciative power, undying, ever existing; and hearts that shall not know what it is to be growing old. This life is one, I again toll, of incessant passing away. Friends and joys leave us, and even if they did not, the power of enjoying often goes, and hands that were once little close-locked hands, deteriorate into flabby, cold fishes’ fins.

60 Here, you must lose, if you would gain; you must spend if you would buy. Hereafter it may be different. A hint of this seems given in an old prophecy of choice things to be had without money, and without price. ’Tis all clear profit there, I conclude; you add, without subtracting.

Yes, in that Land (to illustrate by a fancy) the Winter flowers will come, one after one, breaking through the frost-bound beds, and when the time comes at which we shall expect them to go, they will surprise us by staying with us still. The sweet, faint, mild Spring primroses will brim the copses, and spill over, trickling down the banks; the daffodils (not Lent-lilies there) will dance over the meadows in a golden sheet, and will wonder to find that they are additions, not substitutes. The trembling cowslips, the starry anemones, the wood-fulls of hyacinths, the rose campions, the purple orchis spires, these will supplement, not supplant, the fair growth that used to fade at the first footfall of their advent. And so the sweetbriar roses, red and burning, and their paler sisters with unscented leaves, and the clematis snow, and the honeysuckle clusters, and the meadow-sweet; these will come not to fill an empty cup, but a full one, and one that yet, though full, is ever capable of containing more. And so snowdrops need not die for violets to come, nor violets vanish to make room for the rose. And Autumn will not supersede Summer, nor come, except to add its quota of beauty. “How then?” ask you, “shall we not soon arrive at the end of the delights of the year, and weary with their sameness?” No, I reply, for I think we shall not stop at Summer in Heaven, but ever go on into new and lovelier seasons;61 appreciating old pleasures with unweary hearts, but ever adding to them new.

“Old things are passed away.” That is, perhaps, this old fading state of things, of objects, and capacity of enjoying them: and our hearts that once were young, but that still (except for the youth and freshness that religion can preserve in them) will be ever growing so old—so old.

“Behold I make all things new.” All things—our hearts then, too: they will be again fresh, and that old forgotten or sorrowfully remembered child wonder, and appreciation, and love may come back; and the “forgets” of our later years be called to mind again:—