The Project Gutenberg EBook of American War Ballads and Lyrics, Vol. 2 (of

2), by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: American War Ballads and Lyrics, Vol. 2 (of 2)

A Collection of the Songs and Ballads of the Colonial Wars,

the Revolutions, the War of 1812-15, the War with Mexico

and the Civil War

Author: Various

Editor: George Cary Eggleston

Release Date: February 19, 2017 [EBook #54211]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMERICAN WAR BALLADS, LYRICS, VOL 2 ***

Produced by David Edwards, Paul Marshall and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Knickerbocker Nuggets

Nugget—“A diminutive mass of precious metal.”

26 VOLS. NOW READY

For full list see end of this volume

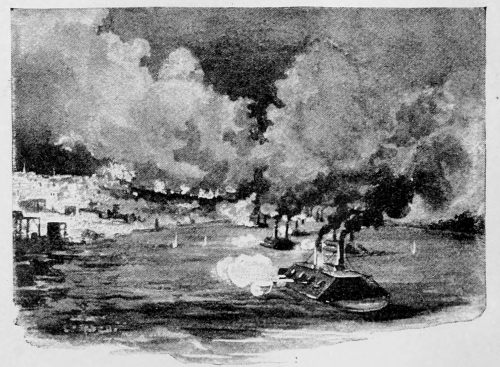

RUNNING THE BATTERIES.

AMERICAN WAR BALLADS

AND LYRICS

A COLLECTION OF THE SONGS AND BALLADS OF THE

COLONIAL WARS, THE REVOLUTION, THE WAR

OF 1812-15, THE WAR WITH MEXICO

AND THE CIVIL WAR

EDITED BY

GEORGE CARY EGGLESTON

VOLUME II.

NEW YORK AND LONDON

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

The Knickerbocker Press

Copyright

G. P. Putnam’s Sons

1889

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

Electrotyped and Printed by

G. P. Putnam’s Sons

[iii]

CONTENTS.

| |

PAGE. |

| The Civil War—Continued |

1 |

| Lyon |

3 |

| My Maryland |

6 |

| Battle Hymn of the Republic |

10 |

| The Picket Guard |

12 |

| The Countersign |

14 |

| Jonathan to John |

19 |

| There’s Life in the Old Land Yet |

26 |

| Never or Now |

28 |

| Boy Brittan |

30 |

| The “Cumberland” |

35 |

| On Board the “Cumberland” |

38 |

| The Sword-Bearer |

45 |

| The Old Sergeant |

48 |

| The “Varuna” |

56 |

| The River Fight |

58 |

| Sheridan’s Ride |

72 |

| Kearney at Seven Pines |

75 |

| Stonewall Jackson’s Way |

77 |

| Marching Along |

80 |

| The Burial of Latané |

82[iv] |

| Tardy George |

85 |

| Wanted—A Man |

88 |

| Overtures from Richmond |

91 |

| Barbara Frietchie |

95 |

| Music in Camp |

99 |

| Fredericksburg |

103 |

| Treason’s Last Device |

106 |

| In Louisiana |

109 |

| John Pelham |

113 |

| The Battle of Charleston Harbor |

116 |

| Running the Batteries |

120 |

| Keenan’s Charge |

124 |

| Death of Stonewall Jackson |

127 |

| Under the Shade of the Trees |

129 |

| Stonewall Jackson |

131 |

| The Black Regiment |

132 |

| Little Giffen of Tennessee |

136 |

| Gettysburg |

138 |

| At Gettysburg |

147 |

| John Burns of Gettysburg |

150 |

| Woman’s War Mission |

156 |

| Three Hundred Thousand More |

160 |

| Lee to the Rear |

162 |

| “Kearsarge” and “Alabama” |

167 |

| The Bay Fight |

170 |

| The Loyal Fisher |

193 |

| Sherman’s March to the Sea |

195 |

| Sherman’s March |

198[v] |

| The Year of Jubilee |

200 |

| The Conquered Banner |

203 |

| Somebody’s Darling |

207 |

| Left on the Battle-Field |

209 |

| Driving Home the Cows |

211 |

| After All |

214 |

| “He’ll See It when He Wakes” |

216 |

| The Réveille |

218 |

| Réveille |

220 |

| The White Rose |

222 |

| The Blue and the Gray |

230 |

| Ready |

233 |

| A Georgia Volunteer |

235 |

| “How are You, Sanitary?” |

239 |

| The Men |

243 |

| The Guerillas |

245 |

| When This Cruel War is Over |

249 |

| Cavalry Song (Stedman) |

252 |

| Cavalry Song (Raymond) |

254 |

| The Cavalry Charge (Taylor) |

256 |

| The Cavalry Charge (Durivage) |

258 |

| Roll-Call |

261 |

| Reading the List |

263 |

| A Woman of the War |

265 |

| Glory Hallelujah! or, John Brown’s Body |

270 |

| Marching through Georgia |

273 |

| The Battle-Cry of Freedom |

275 |

| Tramp, Tramp, Tramp |

277[vi] |

[vii]

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| |

PAGE. |

| Running the Batteries |

Frontispiece |

| The Civil War |

1 |

| The Countersign |

15 |

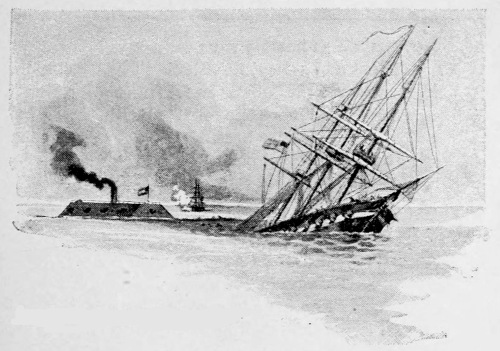

| The “Cumberland” |

35 |

| Sheridan’s Ride |

72 |

| Barbara Frietchie |

95 |

| Fredericksburg |

103 |

| In Louisiana |

109 |

| John Pelham |

113 |

| Running the Batteries |

120 |

| Keenan’s Charge |

124 |

| The Black Regiment |

132 |

| Gettysburg |

138 |

| John Burns of Gettysburg |

150 |

| Three Hundred Thousand More |

160[viii] |

| “Kearsarge” and “Alabama” |

167 |

| The Bay Fight |

170 |

| The Conquered Banner |

204 |

| Driving Home the Cows |

211 |

| After All |

214 |

| Cavalry Song |

252 |

Typogravures by W. Kurtz.

[1]

PART II.

THE CIVIL WAR

[2]

[3]

LYON.

By HENRY PETERSON.

Sing, bird, on green Missouri’s plain,

Thy saddest song of sorrow;

Drop tears, O clouds, in gentlest rain

Ye from the winds can borrow;

Breathe out, ye winds, your softest sigh,

Weep, flowers, in dewy splendor,

For him who knew well how to die,

But never to surrender!

Up rose serene the August sun

Upon that day of glory;

Up curled from musket and from gun

The war-cloud gray and hoary.

It gathered like a funeral pall

Now broken and now blended,

Where rang the bugle’s angry call,

And rank with rank contended.

[4]

Four thousand men, as brave and true

As e’er went forth in daring,

Upon the foe that morning threw

The strength of their despairing.

They feared not death—men bless the field

That patriot soldiers die on—

Fair Freedom’s cause was sword and shield,

And at their head was Lyon!

The leader’s troubled soul looked forth

From eyes of troubled brightness;

Sad soul! the burden of the North

Had pressed out all its lightness.

He gazed upon the unequal fight,

His ranks all rent and gory,

And felt the shadows close like night

Round his career of glory.

“General, come lead us!” loud the cry

From a brave band was ringing—

“Lead us, and we will stop, or die,

That battery’s awful singing.”

He spurred to where his heroes stood,

Twice wounded—no wound knowing—

The fire of battle in his blood

And on his forehead glowing.

[5]

Oh, cursed for aye that traitor’s hand,

And cursed that aim so deadly,

Which smote the bravest of the land,

And dyed his bosom redly!

Serene he lay, while past him prest

The battle’s furious billow,

As calmly as a babe may rest

Upon its mother’s pillow.

So Lyon died! and well may flowers

His place of burial cover,

For never had this land of ours

A more devoted lover.

Living, his country was his pride,

His life he gave her dying;

Life, fortune, love—he naught denied

To her and to her sighing.

Rest, patriot, in thy hill-side grave,

Beside her form who bore thee!

Long may the land thou diedst to save

Her bannered stars wave o’er thee!

Upon her history’s brightest page,

And on Fame’s glowing portal,

She’ll write thy grand, heroic rage

And grave thy name immortal.

[6]

MY MARYLAND.

By JAMES R. RANDALL.

The despot’s heel is on thy shore,

Maryland!

His torch is at thy temple door,

Maryland!

Avenge the patriotic gore

That flecked the streets of Baltimore,

And be the battle queen of yore,

Maryland, my Maryland!

Hark to an exiled son’s appeal,

Maryland!

My Mother State, to thee I kneel,

Maryland!

For life or death, for woe or weal,

Thy peerless chivalry reveal,

And gird thy beauteous limbs with steel,

Maryland, my Maryland!

[7]

Thou wilt not cower in the dust,

Maryland!

Thy beaming sword shall never rust,

Maryland!

Remember Carroll’s sacred trust,

Remember Howard’s warlike thrust,

And all thy slumberers with the just,

Maryland, my Maryland!

Come! ’tis the red dawn of the day,

Maryland!

Come with thy panoplied array.

Maryland!

With Ringgold’s spirit for the fray,

With Watson’s blood at Monterey,

With fearless Lowe and dashing May,

Maryland, my Maryland!

Dear Mother, burst the tyrant’s chain,

Maryland!

Virginia should not call in vain,

Maryland!

She meets her sisters on the plain,

“Sic semper!” ’tis the proud refrain

That baffles minions back amain,

Maryland!

Arise in majesty again,

Maryland, my Maryland!

[8]

Come! for thy shield is bright and strong,

Maryland!

Come! for thy dalliance does thee wrong,

Maryland!

Come to thine own heroic throng

Stalking with liberty along,

And chant thy dauntless slogan-song,

Maryland, my Maryland!

I see the blush upon thy cheek,

Maryland!

But thou wast ever bravely meek,

Maryland!

But lo! there surges forth a shriek,

From hill to hill, from creek to creek,

Potomac calls to Chesapeake,

Maryland, my Maryland!

Thou wilt not yield the Vandal toll,

Maryland!

Thou wilt not crook to his control,

Maryland!

Better the fire upon thee roll,

Better the shot, the blade, the bowl,

Than crucifixion of the soul,

Maryland, my Maryland!

[9]

I hear the distant thunder-hum

Maryland!

The “Old Line’s” bugle, fife, and drum,

Maryland!

She is not dead, nor deaf, nor dumb;

Huzza! she spurns the Northern scum—

She breathes! She burns! She’ll come! She’ll come!

Maryland, my Maryland!

[Southern.]

[10]

BATTLE-HYMN OF THE REPUBLIC

By JULIA WARD HOWE.

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord;

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps;

They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps;

I can read His righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps;

His day is marching on.

[11]

I have read a fiery gospel writ in burnish’d rows of steel;

“As ye deal with my contemners, so with you my grace shall deal”;

Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with his heel,

Since God is marching on.

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat;

He is sifting out the hearts of men before His judgment-seat;

Oh, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! be jubilant, my feet!

Our God is marching on.

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me:

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on.

November, 1861.

[12]

THE PICKET GUARD.

By ETHEL LYNN BEERS.

“All quiet along the Potomac,” they say,

“Except now and then a stray picket

Is shot, as he walks on his beat, to and fro,

By a rifleman hid in the thicket.

’Tis nothing—a private or two, now and then,

Will not count in the news of the battle;

Not an officer lost—only one of the men,

Moaning out, all alone, the death-rattle.”

All quiet along the Potomac to-night,

Where the soldiers lie peacefully dreaming;

Their tents, in the rays of the clear autumn moon,

Or the light of the watch-fires, are gleaming.

A tremulous sigh, as the gentle night wind

Through the forest leaves softly is creeping;

While stars up above, with their glittering eyes,

Keep guard—for the army is sleeping.

There’s only the sound of the lone sentry’s tread,

As he tramps from the rock to the fountain,

[13]

And thinks of the two in the low trundle bed

Far away in the cot on the mountain.

His musket falls slack—his face, dark and grim,

Grows gentle with memories tender,

As he mutters a prayer for the children asleep—

For their mother—may Heaven defend her!

The moon seems to shine just as brightly as then,

That night, when the love yet unspoken—

Leaped up to his lips—when low-murmured vows

Were pledged to be ever unbroken.

Then drawing his sleeve roughly over his eyes,

He dashes off tears that are welling,

And gathers his gun closer up to its place

As if to keep down the heart-swelling.

He passes the fountain, the blasted pine tree—

The footstep is lagging and weary;

Yet onward he goes, through the broad belt of light,

Towards the shades of the forest so dreary.

Hark! was it the night wind that rustled the leaves?

Was it moonlight so wondrously flashing?

It looks like a rifle—ah! “Mary, good-bye!”

And the life-blood is ebbing and plashing.

All quiet along the Potomac to-night,

No sound save the rush of the river;

While soft falls the dew on the face of the dead—

The picket’s off duty forever.

[14]

THE COUNTERSIGN.

[In his admirably edited collection of poems of the civil war, entitled

“Bugle Echoes,” Mr. Francis F. Browne introduces this poem with the

following note:

“There has been no little dispute as to the authorship

of this poem. The Philadelphia Press, in 1861, said it

was ‘written by a private in Company G, Stuart’s engineer

regiment, at Camp Lesley, near Washington.’ But it may now

be stated positively that it was written by a Confederate

soldier, still living. The poem is usually printed in a

very imperfect form, with the fourth, fifth, and sixth

stanzas omitted. The third line of the fifth stanza affords

internal evidence of Southern origin.”—Editor.]

[15]

THE COUNTERSIGN.

Alas! the weary hours pass slow,

The night is very dark and still;

And in the marshes far below

I hear the bearded whippoorwill;

[16]

I scarce can see a yard ahead,

My ears are strained to catch each sound;

I hear the leaves about me shed,

And the spring’s bubbling through the ground.

Along the beaten path I pace,

Where white rays mark my sentry’s track;

In formless shrubs I seem to trace

The foeman’s form with bending back,

I think I see him crouching low;

I stop and list—I stoop and peer,

Until the neighboring hillocks grow

To groups of soldiers far and near.

With ready piece I wait and watch,

Until my eyes, familiar grown,

Detect each harmless earthen notch,

And turn guerrillas into stone;

And then, amid the lonely gloom,

Beneath the tall old chestnut trees,

My silent marches I resume,

And think of other times than these.

Sweet visions through the silent night!

The deep bay windows fringed with vine,

The room within, in softened light,

The tender, milk-white hand in mine;

[17]

The timid pressure, and the pause

That often overcame our speech—

The time when by mysterious laws

We each felt all in all to each.

And then that bitter, bitter day,

When came the final hour to part;

When, clad in soldier’s honest gray,

I pressed her weeping to my heart;

Too proud of me to bid me stay,

Too fond of me to let me go,

I had to tear myself away,

And left her, stolid in my woe.

So rose the dream, so passed the night—

When, distant in the darksome glen,

Approaching up the sombre height

I heard the solid march of men;

Till over stubble, over sward,

And fields where lay the golden sheaf,

I saw the lantern of the guard

Advancing with the night relief.

“Halt! Who goes there?” my challenge cry,

It rings along the watchful line;

“Relief!” I hear a voice reply;

“Advance, and give the countersign!”

[18]

With bayonet at the charge I wait—

The corporal gives the mystic spell;

With arms aport I charge my mate,

Then onward pass, and all is well.

But in the tent that night awake,

I ask, if in the fray I fall,

Can I the mystic answer make

When the angelic sentries call?

And pray that Heaven may so ordain,

Whene’er I go, what fate be mine,

Whether in pleasure or in pain,

I still may have the countersign.

[Southern.]

[19]

JONATHAN TO JOHN.

By JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL.

[This poem is a part of the second series of “The

Bigelow Papers,” a work wholly unmatched in the literature

of humor, that has an earnest purpose and well matured

thought for its sources of inspiration. The poem was called

forth by what is known as “the Trent affair.” Captain

Wilkes, commanding the United States man-of-war, San

Jacinto, boarded the British mail steamer Trent on the

8th of November, 1861, and took from her the Confederate

commissioners Mason and Slidell. Great Britain resented

the act, and for a time there was serious apprehension of

war between that country and the United States; but as the

seizure of the commissioners on board a neutral vessel was

deemed to be an act in violation of international law, the

Government at Washington, after inquiry into the facts,

surrendered the prisoners. The version of the poem here

given is a correct one, taken from the collected edition

of Mr. Lowell’s poems. An abridged and otherwise imperfect

version is given in many collections.—Editor.]

[20]

[21]

JONATHAN TO JOHN.

It don’t seem hardly right, John,

When both my hands was full,

To stump me to a fight, John,—

Your cousin, tu, John Bull!

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

We know it now,” sez he,

“The Lion’s paw is all the law,

Accordin’ to J. B.,

Thet’s fit for you an’ me!”

You wonder why we’re hot, John?

Your mark wuz on the guns,

The neutral guns, thet shot, John,

Our brothers an’ our sons:

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

There’s human blood,” sez he,

“By fits an’ starts, in Yankee hearts,

Though ’t may surprise J. B.

More ’n it would you an’ me.”

[22]

Ef I turned mad dogs loose, John,

On your front parlor stairs,

Would it just meet your views, John,

To wait an’ sue their heirs?

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess,

I on’y guess,” sez he,

“Thet ef Vattel on his toes fell,

’Twould kind o’ rile J. B.,

Ez wal ez you an’ me!”

Who made the law thet hurts, John,

Heads I win—ditto tails?

“J. B.” was on his shirts, John,

Onless my memory fails.

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

(I’m good at thet),” sez he,

“Thet sauce for goose ain’t jest the juice

For ganders with J. B.,

No more’n with you or me!”

When your rights was our wrongs, John,

You didn’t stop for fuss,—

Brittany’s trident prongs, John,

Was good ’nough law for us.

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess,

Though physic’s good,” sez he,

“It doesn’t foller thet he can swaller

Prescriptions signed ‘J. B.’

Put up by you an’ me.”

[23]

We own the ocean, tu, John,

You mus’ n’ take it hard,

Ef we can’t think with you, John,

It’s just your own back yard,

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

Ef thet’s his claim,” sez he,

“The fencin’ stuff’ll cost enough

To bust up friend J. B.

Ez wal ez you an’ me!”

Why talk so dreffle big, John,

Of honor when it meant

You didn’t care a fig, John,

But jest for ten per cent?

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

He’s like the rest,” sez he;

“When all is done, it’s number one

Thet’s nearest to J. B.,

Ez wal ez t’ you an’ me!”

We give the critters back, John,

Cos Abram thought ’twas right;

It warn’t your bullyin’ clack, John,

Provokin’ us to fight.

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

We’ve a hard row,” sez he,

“To hoe just now; but thet, somehow,

May happen to J. B.,

Ez wal ez you an’ me!”

[24]

We ain’t so weak an’ poor, John,

With twenty million people,

An’ close to every door, John,

A school house an’ a steeple.

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

It is a fact,” sez he,

“The surest plan to make a Man

Is, think him so, J. B.,

Ez much ez you or me!”

Our folks believe in Law, John;

An’ it’s fer her sake, now,

They’ve left the axe an’ saw, John,

The anvil an’ the plow.

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess,

Ef ’t warn’t fer law,” sez he,

“There ’d be one shindy from here to Indy;

An’ thet don’t suit J. B.

(When ’t ain’t ’twixt you an’ me!)”

We know we ’ve got a cause, John,

Thet ’s honest, just, an’ true;

We thought ’t would win applause, John,

Ef nowhere else, from you,

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

His love of right,” sez he,

“Hangs by a rotten fibre o’ cotton;

There ’s natur’ in J. B.,

Ez wal ez you an’ me!”

[25]

The South says, “Poor folks down!” John,

An’ “All men up!” say we,—

White, yaller, black, an’ brown, John;

Now which is your idee?

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

John preaches wal,” sez he;

“But, sermon thru, an’ come to du,

Why there’s the old J. B.

A-crowdin’ you an’ me!”

Shall it be love or hate, John?

It’s you thet ’s to decide;

Ain’t your bonds held by Fate, John,

Like all the world’s beside?

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

Wise men fergive,” sez he,

“But not ferget; an’ some time yet

Thet truth may strike J. B.,

Ez wal ez you an’ me!”

God means to make this land, John,

Clear thru, from sea to sea,

Believe an’ understand, John,

The wuth o’ bein’ free.

Ole Uncle S., sez he, “I guess

God’s price is high,” sez he;

“But nothin’ else than wut he sells

Wears long, an’ thet J. B.

May larn, like you an’ me!”

[26]

THERE’S LIFE IN THE OLD LAND YET.

By JAMES R. RANDALL.

[First printed in the Richmond Examiner.

Written while the author was in prison.]

By the blue Patapsco’s billowy dash

The tyrant’s war-shout comes,

Along with cymbal’s fitful clash,

And the growl of his sullen drums.

We hear it, we heed it with vengeful thrills,

And we shall not forgive or forget;

There’s faith in the streams, there’s hope in the hills,

There’s life in the old land yet!

Minions! we sleep but we are not dead;

We are crushed, we are scourged, we are scarred;

We crouch—’t is to welcome the triumph tread

Of the peerless Beauregard.

Then woe to your vile, polluting horde,

When the Southern braves are met;

There’s faith in the victor’s stainless sword,

There’s life in the old land yet!

[27]

Bigots! ye quell not the valiant mind

With the clank of an iron chain;

The spirit of freedom sings in the wind,

O’er Merriman, Thomas, and Kane;

And we, though we smile not, are not thralls,—

Are piling a gory debt;

While down by McHenry’s dungeon walls

There’s life in the old land yet!

Our women have hung their harps away,

And they scowl on your brutal bands,

While the nimble poniard dares the day,

In their dear, defiant hands.

They will strip their tresses to string our bows,

Ere the Northern sun is set;

There’s faith in their unrelenting woes,

There’s life in the old land yet!

There’s life, though it throbbeth in silent veins,—

’T is vocal without noise;

It gushed o’er Manassas’ solemn plains,

From the blood of the Maryland Boys!

That blood shall cry aloud, and rise

With an everlasting threat;

By the death of the brave, by the God in the skies,

There’s life in the old land yet!

NEVER OR NOW.

By OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES.

Listen, young heroes! your country is calling!

Time strikes the hour for the brave and the true!

Now, while the foremost are fighting and falling,

Fill up the ranks that have opened for you!

You whom the fathers made free and defended,

Stain not the scroll that emblazons their fame!

You whose fair heritage spotless descended,

Leave not your children a birthright of shame!

Stay not for questions while Freedom stands gasping!

Wait not till Honor lies wrapped in his pall!

Brief the lips’ meeting be, swift the hands clasping:

“Off for the wars!” is enough for them all.

Break from the arms that would fondly caress you!

Hark! ’t is the bugle-blast, sabres are drawn!

Mothers shall pray for you, fathers shall bless you,

Maidens shall weep for you when you are gone!

[29]

Never or now! cries the blood of a nation,

Poured on the turf where the red rose should bloom;

Now is the day and the hour of salvation,—

Never or now! peals the trumpet of doom!

Never or now! roars the hoarse-throated cannon

Through the black canopy blotting the skies;

Never or now! flaps the shell-blasted pennon

O’er the deep ooze where the Cumberland lies!

From the foul dens where our brothers are dying,

Aliens and foes in the land of their birth,—

From the rank swamps where our martyrs are lying,

Pleading in vain for a handful of earth,—

From the hot plains where they perish outnumbered,

Furrowed and ridged by the battle-field’s plough,

Comes the loud summons; too long you have slumbered,

Hear the last Angel-trump—Never or Now!

1862.

[30]

BOY BRITTAN.

(Battle of Fort Henry, Tenn., Feb. 6, 1862.)

By FORCEYTHE WILLSON.

I.

Boy Brittan—only a lad—a fair-haired boy—sixteen,

In his uniform,

Into the storm—into the roaring jaws of grim Fort Henry—

Boldly bears the Federal flotilla—

Into the battle storm!

II.

Boy Brittan is master’s mate aboard of the Essex—

There he stands, buoyant and eager-eyed,

By the brave captain’s side;

Ready to do and dare. Aye, aye, sir! always ready—

In his country’s uniform.

Boom! Boom! and now the flag-boat sweeps, and now the Essex,

Into the battle storm!

[31]

III.

Boom! Boom! till river and fort and field are over-clouded

By battle’s breath; then from the fort a gleam

And a crashing gun, and the Essex is wrapt and shrouded

In a scalding cloud of steam?

IV.

But victory! victory!

Unto God all praise be ever rendered,

Unto God all praise and glory be!

See, Boy Brittan! see, boy, see!

They strike! Hurrah! the fort has just surrendered!

Shout! Shout! my boy, my warrior boy!

And wave your cap and clap your hands for joy!

Cheer answer cheer and bear the cheer about—

Hurrah! Hurrah! for the fiery fort is ours;

And “Victory!” “Victory!” “Victory!”

Is the shout.

Shout—for the fiery fort, and the field, and the day are ours—

The day is ours—thanks to the brave endeavor

Of heroes, boy, like thee!

The day is ours—the day is ours!

Glory and deathless love to all who shared with thee,

And bravely endured and dared with thee—

The day is ours—the day is ours—

Forever!

[32]

Glory and Love for one and all; but—but—for thee—

Home! Home! a happy “Welcome—welcome home” for thee!

And kisses of love for thee—

And a mother’s happy, happy tears, and a virgin’s bridal

wreath of flowers—

For thee!

V.

Victory! Victory!...

But suddenly wrecked and wrapt in seething steam, the Essex

Slowly drifted out of the battle’s storm;

Slowly, slowly down—laden with the dead and dying;

And there at the captain’s feet, among the dead and the dying,

The shot-marred form of a beautiful boy is lying—

There in his uniform!

VI.

Laurels and tears for thee, boy,

Laurels and tears for thee!

Laurels of light, moist with the precious dew

Of the inmost heart of the nation’s loving heart,

And blest by the balmy breath of the beautiful and the true;

[33]

Moist—moist with the luminous breath of the singing spheres

And the nation’s starry tears!

And tremble-touched by the pulse-like gush and start

Of the universal music of the heart,

And all deep sympathy.

Laurels and tears for thee, boy,

Laurels and tears for thee—

Laurels of light and tears of love forevermore—

For thee!

VII.

And laurels of light, and tears of truth,

And the mantle of immortality;

And the flowers of love and immortal youth,

And the tender heart-tokens of all true ruth—

And the everlasting victory!

And the breath and bliss of Liberty;

And the loving kiss of Liberty;

And the welcoming light of heavenly eyes,

And the over-calm of God’s canopy;

And the infinite love-span of the skies

That cover the valleys of Paradise—

For all of the brave who rest with thee;

And for one and all who died with thee,

And now sleep side by side with thee;

And for every one who lives and dies,

On the solid land or the heaving sea,

Dear warrior-boy—like thee.

[34]

VIII.

O the victory—the victory

Belongs to thee!

God ever keeps the brightest crown for such as thou—

He gives it now to thee!

O young and brave, and early and thrice blest—

Thrice, thrice, thrice blest!

Thy country turns once more to kiss thy youthful brow,

And takes thee—gently—gently to her breast;

And whispers lovingly, “God bless thee—bless thee now—

My darling, thou shalt rest!”

[35]

THE “CUMBERLAND.”

By H. W. LONGFELLOW.

At anchor in Hampton Roads we lay,

On board the Cumberland sloop of war,

And at times from the fortress across the bay

The alarm of drums swept past,

Or a bugle blast

From the camp on shore.

Then far away to the south uprose

A little feather of snow-white smoke,

And we knew that the iron ship of our foes

Was steadily steering its course

To try the force

Of our ribs of oak.

[36]

Down upon us heavily runs,

Silent and sullen, the floating fort,

Then comes a puff of smoke from her guns,

And leaps the terrible death,

With fiery breath,

From each open port.

We are not idle but send her straight

Defiance back in a full broadside!

As hail rebounds from a roof of slate

Rebounds our heavier hail

From each iron scale

Of the monster’s hide.

“Strike your flag!” the rebel cries,

In his arrogant old plantation strain.

“Never!” our gallant Morris replies;

“It is better to sink than to yield!”

And the whole air pealed

With the cheers of our men.

Then like a kraken, huge and black

She crushed our ribs in her iron grasp!

Down went the Cumberland all awrack,

With a sudden shudder of death,

And the cannon’s breath

For her dying gasp.

[37]

Next morn, as the sun rose over the bay,

Still floated our flag at the mainmast head.

Lord, how beautiful was Thy day!

Every waft of the air

Was a whisper of prayer,

Or a dirge for the dead.

Ho! brave hearts that went down in the seas,

Ye are at peace in the troubled stream.

Ho! brave land! with hearts like these,

Thy flag, that is rent in twain,

Shall be one again,

And without a seam!

[38]

ON BOARD THE “CUMBERLAND.”

(March 8, 1862.)

By GEORGE H. BOKER.

“Stand to your guns, men!” Morris cried.

Small need to pass the word;

Our men at quarters ranged themselves,

Before the drum was heard.

And then began the sailors’ jests:

“What thing is that, I say?”

“A ’long-shore meeting-house adrift

Is standing down the bay!”

A frown came over Morris’ face;

The strange, dark craft he knew;

“That is the iron Merrimac,

Manned by a rebel crew.

“So shot your guns, and point them straight;

Before this day goes by,

We’ll try of what her metal ’s made.”

A cheer was our reply.

[39]

“Remember boys, this flag of ours

Has seldom left its place;

And where it falls, the deck it strikes

Is covered with disgrace.

“I ask but this: or sink or swim,

Or live or nobly die,

My last sight upon earth may be

To see that ensign fly!”

Meanwhile the shapeless iron mass

Came moving o’er the wave,

As gloomy as a passing hearse,

As silent as the grave.

Her ports were closed, from stem to stem

No sign of life appeared.

We wondered, questioned, strained our eyes,

Joked,—every thing but feared.

She reached our range. Our broadside rang,

Our heavy pivots roared;

And shot and shell, a fire of hell,

Against her sides we poured.

God’s mercy! from her sloping roof

The iron tempest glanced,

As hail bounds from a cottage-thatch,

And round her leaped and danced;

[40]

Or, when against her dusky hull

We struck a fair, full blow,

The mighty, solid iron globes

Were crumbled up like snow.

On, on, with fast increasing speed,

The silent monster came;

Though all our starboard battery

Was one long line of flame.

She heeded not, nor gun she fired,

Straight on our bow she bore;

Through riving plank and crashing frame

Her furious way she tore.

Alas! our beautiful, keen bow,

That in the fiercest blast

So gently folded back the seas,

They hardly felt we passed!

Alas! Alas! My Cumberland,

That ne’er knew grief before,

To be so gored, to feel so deep

The tusk of that sea-boar!

Once more she backward drew a space,

Once more our side she rent;

Then, in the wantonness of hate,

Her broadside through us sent.

[41]

The dead and dying round us lay,

But our foeman lay abeam;

Her open portholes maddened us;

We fired with shout and scream.

We felt our vessel settling fast,

We knew our time was brief;

“The pumps, the pumps!” But they who pumped

And fought not, wept with grief.

“Oh, keep us but an hour afloat!

Oh, give us only time

To be the instruments of heaven

Against the traitors’ crime!”

From captain down to powder-boy,

No hand was idle then;

Two soldiers, but by chance aboard,

Fought on like sailor-men.

And when a gun’s crew lost a hand,

Some bold marine stepped out,

And jerked his braided jacket off,

And hauled the gun about.

Our forward magazine was drowned;

And up from the sick-bay

Crawled out the wounded, red with blood,

And round us gasping lay.

[42]

Yes, cheering, calling us by name,

Struggling with failing breath,

To keep their shipmates at the port,

While glory strove with death.

With decks afloat, and powder gone,

The last broadside we gave

From the guns’ heated iron lips

Burst out beneath the wave.

So sponges, rammers, and handspikes—

As men-of-war’s men should—

We placed within their proper racks,

And at our quarters stood.

“Up to the spar-deck! Save yourselves!”

Cried Selfridge. “Up, my men!

God grant that some of us may live

To fight yon ship again!”

We turned—we did not like to go;

Yet staying seemed but vain,

Knee-deep in water; so we left;

Some swore, some groaned with pain.

We reached the deck. Here Randall stood:

“Another turn, men—so!”

Calmly he aimed his pivot-gun:

“Now, Tenney, let her go!”

[43]

It did our sore hearts good to hear

The song our pivot sang,

As rushing on, from wave to wave,

The whirring bomb-shell sprang.

Brave Randall leaped upon the gun,

And waved his cap in sport;

“Well done! well aimed! I saw that shell

Go through an open port.”

It was our last, our deadliest shot;

The deck was over-flown:

The poor ship staggered, lurched to port,

And gave a living groan.

Down, down, as headlong through the waves

Our gallant vessel rushed,

A thousand gurgling, watery sounds

Around my senses gushed.

Then I remember little more;

One look to heaven I gave,

Where, like an angel’s wing, I saw

Our spotless ensign wave.

I tried to cheer, I cannot say

Whether I swam or sank;

A blue mist closed around my eyes,

And every thing was blank.

[44]

When I awoke, a soldier-lad,

All dripping from the sea,

With two great tears upon his cheeks,

Was bending over me.

I tried to speak. He understood

The wish I could not speak.

He turned me. There, thank God! the flag

Still fluttered at the peak!

And there, while thread shall hang to thread,

O let that ensign fly!

The noblest constellation set

Against our northern sky.

A sign that we who live may claim

The peerage of the brave;

A monument, that needs no scroll,

For those beneath the wave!

[45]

THE SWORD-BEARER.

By GEORGE H. BOKER.

Brave Morris saw the day was lost;

For nothing now remained

On the wrecked and sinking Cumberland

But to save the flag unstained.

So he swore an oath in the sight of heaven

(If he kept it, the world can tell):

“Before I strike to a rebel flag,

I’ll sink to the gates of hell!

“Here, take my sword; ’tis in my way;

I shall trip o’er the useless steel:

For I’ll meet the lot that falls to all,

With my shoulder at the wheel.”

So the little negro took the sword,

And oh! with what reverent care!

Following his master step by step,

He bore it here and there.

[46]

A thought had crept through his sluggish brain,

And shone in his dusky face,

That somehow—he could not tell just how—

’Twas the sword of his trampled race.

And as Morris, great with his lion heart,

Rushed onward from gun to gun,

The little negro slid after him,

Like a shadow in the sun.

But something of pomp and of curious pride

The sable creature wore,

Which at any time but a time like that

Would have made the ship’s crew roar.

Over the wounded, dying, and dead,

Like an usher of the rod,

The black page, full of his mighty trust,

With dainty caution trod.

No heed he gave to the flying ball,

No heed to the bursting shell;

His duty was something more than life,

And he strove to do it well.

Down, with our starry flag apeak,

In the whirling sea we sank;

And captain and crew and the sword-bearer

Were washed from the bloody plank.

[47]

They picked us up from the hungry waves—

Alas! not all. And where,

Where is the faithful negro lad?

“Back oars! avast! look there!”

We looked, and as heaven may save my soul,

I pledge you a sailor’s word,

There, fathoms deep in the sea he lay,

Still grasping his master’s sword.

We drew him out; and many an hour

We wrought with his rigid form,

Ere the almost smothered spark of life

By slow degrees grew warm.

The first dull glance that his eyeballs rolled

Was down toward his shrunken hand;

And he smiled, and closed his eyes again,

As they fell on the rescued brand.

And no one touched the sacred sword,

Till at length, when Morris came,

The little negro stretched it out,

With his eager eyes aflame.

And if Morris wrung the poor boy’s hand,

And his words seemed hard to speak,

And tears ran down his manly cheeks,

What tongue shall call him weak?

[48]

THE OLD SERGEANT.

By FORCEYTHE WILLSON.

“Come a little nearer, Doctor,—thank you!—let me take the cup:

Draw your chair up,—draw it closer,—just another little sup!

Maybe you may think I’m better; but I’m pretty well used up,—

Doctor, you’ve done all you could do, but I’m just a going up!

“Feel my pulse, sir, if you want to, but it ain’t much use to try—”

“Never say that,” said the surgeon, as he smothered down a sigh;

“It will never do, old comrade, for a soldier to say die!”

“What you say will make no difference, Doctor, when you come to die.

“Doctor, what has been the matter?”—“You were very faint, they say;

You must try to get to sleep now.”—“Doctor, have I been away?”

[49]

“Not that anybody knows of!”—“Doctor—Doctor, please to stay!

There is something I must tell you, and you won’t have long to stay!

“I have got my marching orders, and I’m ready now to go;

Doctor, did you say I fainted!—But it couldn’t ha’ been so,—

For as sure as I’m a Sergeant, and was wounded at Shiloh,

I’ve this very night been back there, on the old field of Shiloh!

“This is all that I remember: The last time the lighter came,

And the lights had all been lowered, and the noises much the same,

He had not been gone five minutes before something called my name:

’Orderly Sergeant—Robert Burton!’—just that way it called my name.

“And I wondered who could call me so distinctly and so slow,

Knew it couldn’t be the lighter,—he could not have spoken so;

[50]

And I tried to answer, ‘Here, sir!’ but I couldn’t make it go!

For I couldn’t move a muscle, and I couldn’t make it go!

“Then I thought: It’s all a nightmare, all a humbug and a bore:

Just another foolish grapevine[1]—and it won’t come any more;

But it came, sir, notwithstanding, just the same way as before:

‘Orderly Sergeant—Robert Burton!’ even plainer than before.

“That is all that I remember, till a sudden burst of light,

And I stood beside the river, where we stood that Sunday night,

Waiting to be ferried over to the dark bluffs opposite,

When the river was perdition and all hell was opposite!

“And the same old palpitation came again in all its power,

And I heard a bugle sounding, as from some celestial tower;

[51]

And the same mysterious voice said: ‘It is the eleventh hour!

Orderly Sergeant—Robert Burton—It is the eleventh hour!’

“Doctor Austin!—what day is this?”—“It is Wednesday night, you know.”

“Yes,—to-morrow will be New Year’s, and a right good time below!

What time is it, Doctor Austin?”—“Nearly twelve.” “Then don’t you go!”

Can it be that all this happened—all this—not an hour ago!

“There was where the gun-boats opened on the dark, rebellious host,

And where Webster semi-circled his last guns upon the coast;

There were still the two log-houses, just the same, or else their ghost,—

And the same old transport came and took me over—or its ghost!

“And the old field lay before me all deserted far and wide;

There was where they fell on Prentice,—there McClernand met the tide;

[52]

There was where stern Sherman rallied, and where Hurlbut’s heroes died,—

Lower down, where Wallace charged them, and kept charging till he died.

“There was where Lew Wallace showed them he was of the canny kin,

There was where old Nelson thundered, and where Rousseau waded in;

Then McCook sent ’em to breakfast and we all began to win—

There was where the grape-shot took me, just as we began to win.

“Now, a shroud of snow and silence over every thing was spread;

And but for this old blue mantle and the old hat on my head,

I should not have even doubted, to this moment I was dead,—

For my footsteps were as silent as the snow upon the dead!

“Death and silence!—Death and silence! all around me as I sped!

And behold a mighty Tower, as if builded to the dead,—

To the Heaven of the heavens, lifted up its mighty head,

Till the Stars and Stripes of Heaven all seemed waving from its head!

[53]

“Round and mighty-based it towered—up into the infinite—

And I knew no mortal mason could have built a shaft so bright;

For it shone like solid sunshine; and a winding stair of light,

Wound around it and around it till it wound clear out of sight!

“And, behold, as I approached it—with a rapt and dazzled stare,—

Thinking that I saw old comrades just ascending the great stair—

Suddenly the solemn challenge broke of,—‘Halt! and who goes there?’

‘I’m a friend,’ I said, ‘if you are.’—‘Then advance, sir, to the stair!’

“I advanced!—that sentry, Doctor, was Elijah Ballantyne!—

First of all to fall on Monday, after we had formed the line:

‘Welcome, my old Sergeant, welcome! welcome by that countersign!’

And he pointed to the scar there, under this old cloak of mine!

[54]

“As he grasped my hand, I shuddered, thinking only of the grave;

But he smiled and pointed upward, with a bright and bloodless glaive;

‘That’s the way, sir, to head-quarters.’—‘What head-quarters?’—‘Of the brave.’

‘But the great tower?’—‘That was builded of the great deeds of the brave.’

“Then a sudden shame came o’er me at his uniform of light;

At my own so old and tattered, and at his so new and bright;

‘Ah!’ said he, ‘you have forgotten the new uniform to-night,—

Hurry back, for you must be here at just twelve o’clock to-night!’

“And the next thing I remember, you were sitting there, and I—

Doctor—did you hear a footstep? Hark!—God bless you all! Good-bye!

Doctor, please to give my musket and my knapsack when I die,

To my son—my son that’s coming,—he won’t get here till I die!

[55]

“Tell him his old father blessed him as he never did before,—

And to carry that old musket”—Hark! a knock is at the door!—

“Till the Union”—See! it opens!—“Father! Father! Speak once more!”

“Bless you!”—gasped the old gray Sergeant, and he lay and said no more.

[56]

THE “VARUNA.”

(Sunk April 24, 1862.)

By GEORGE H. BOKER.

Who has not heard of the dauntless Varuna?

Who has not heard of the deeds she has done?

Who shall not hear, while the brown Mississippi

Rushes along from the snow to the sun?

Crippled and leaking she entered the battle,

Sinking and burning she fought through the fray;

Crushed were her sides and the waves ran across her,

Ere, like a death wounded lion at bay,

Sternly she closed in the last fatal grapple,

Then in her triumph moved grandly away.

Five of the rebels, like satellites round her,

Burned in her orbit of splendor and fear;

One, like the pleiad of mystical story,

Shot, terror-stricken, beyond her dread sphere.

[57]

We who are waiting with crowns for the victors,

Though we should offer the wealth of our store,

Load the Varuna from deck down to kelson,

Still would be niggard, such tribute to pour

On courage so boundless. It beggars possession,—

It knocks for just payment at heaven’s bright door!

Cherish the heroes who fought the Varuna;

Treat them as kings if they honor your way;

Succor and comfort the sick and the wounded;

Oh! for the dead let us all kneel to pray!

[58]

THE RIVER FIGHT.

By HENRY HOWARD BROWNELL.

[Admiral Farragut was so impressed with this

irregular but spirited description of the river battle below New

Orleans that he sought out the author and their acquaintance ended

in a warm friendship. Brownell having expressed a desire to witness

a naval conflict, Farragut took him on board the Flagship Hartford

at the time of the storming of the Mobile forts, and the poet repaid

the courtesy with the poem which appears elsewhere in this collection,

called “The Bay Fight.”—Editor.]

Do you know of the dreary land,

If land such region may seem,

Where ’tis neither sea nor strand,

Ocean, nor good, dry land,

But the nightmare marsh of a dream?

Where the Mighty River his death-road takes,

’Mid pools and windings that coil like snakes,

A hundred leagues of bayous and lakes,

To die in the great Gulf Stream?

[59]

No coast-line clear and true,

Granite and deep-sea blue,

On that dismal shore you pass,

Surf-worn boulder or sandy beach,—

But ooze-flats as far as the eye can reach,

With shallows of water-grass;

Reedy Savannahs, vast and dun,

Lying dead in the dim March sun;

Huge, rotting trunks and roots that lie

Like the blackened bones of shapes gone by,

And miles of sunken morass.

No lovely, delicate thing

Of life o’er the waste is seen

But the cayman couched by his weedy spring,

And the pelican, bird unclean,

Or the buzzard, flapping with heavy wing,

Like an evil ghost o’er the desolate scene.

Ah! many a weary day

With our Leader there we lay.

In the sultry haze and smoke,

Tugging our ships o’er the bar,

Till the spring was wasted far,

Till his brave heart almost broke.

For the sullen river seemed

As if our intent he dreamed,—

All his sallow mouths did spew and choke.

[60]

But ere April fully passed

All ground over at last

And we knew the die was cast,—

Knew the day drew nigh

To dare to the end one stormy deed,

Might save the land at her sorest need,

Or on the old deck to die!

Anchored we lay,—and a morn the more,

To his captains and all his men

Thus wrote our old commodore—

(He wasn’t Admiral then):—

“General Orders:

Send your to’gallant masts down,

Rig in each flying jib-boom!

Clear all ahead for the loom

Of traitor fortress and town,

Or traitor fleet bearing down

“In with your canvas high;

We shall want no sail to fly!

Top sail, foresail, spanker, and jib,

(With the heart of oak in the oaken rib,)

Shall serve us to win or die!

“Trim every sail by the head,

(So shall you spare the lead,)

Lest if she ground, your ship swing round,

Bows in shore, for a wreck.

[61]

See your grapnels all clear with pains,

And a solid kedge in your port main-chains,

With a whip to the main yard:

Drop it heavy and hard

When you grappel a traitor deck!

“On forecastle and on poop

Mount guns, as best you may deem.

If possible, rouse them up

(For still you must bow the stream).

Also hoist and secure with stops

Howitzers firmly in your tops,

To fire on the foe abeam.

“Look well to your pumps and hose;

Have water tubs fore and aft,

For quenching flame in your craft,

And the gun crew’s fiery thirst.

See planks with felt fitted close,

To plug every shot-hole tight.

Stand ready to meet the worst!

For, if I have reckoned aright,

They will serve us shot,

Both cold and hot,

Freely enough to-night.

“Mark well each signal I make,—

(Our life-long service at stake,

[62]

And honor that must not lag!)

What e’er the peril and awe,

In the battle’s fieriest flaw,

Let never one ship withdraw

Till the orders come from the flag!”

Would you hear of the river fight?

It was two of a soft spring night;

God’s stars looked down on all;

And all was clear and bright

But the low fog’s clinging breath;

Up the River of Death

Sailed the great Admiral.

On our high poop-deck he stood,

And round him ranged the men

Who have made their birthright good

Of manhood once and again,—

Lords of helm and of sail,

Tried in tempest and gale,

Bronzed in battle and wreck.

Bell and Bailey grandly led

Each his line of the Blue and Red;

Wainwright stood by our starboard rail;

Thornton fought the deck.

[63]

And I mind me of more than they,

Of the youthful, steadfast ones,

That have shown them worthy sons

Of the seamen passed away.

Tyson conned our helm that day;

Watson stood by his guns.

What thought our Admiral then,

Looking down on his men?

Since the terrible day,—

(Day of renown and tears!)

When at anchor the Essex lay,—

Holding her foes at bay,—

When a boy by Porter’s side he stood,

Till deck and plank-shear were dyed with blood;

’Tis half a hundred years,—

Half a hundred years to a day!

Who could fail with him?

Who reckon of life or limb?

Not a pulse but beat the higher!

There had you seen, by the starlight dim,

Five hundred faces strong and grim:

The Flag is going under fire!

Right up by the fort,

With her helm hard aport,

The Hartford is going under fire!

[64]

The way to our work was plain.

Caldwell had broken the chain

(Two hulks swung down amain

Soon as ’twas sundered).

Under the night’s dark blue,

Steering steady and true,

Ship after ship went through,

Till, as we hove in view,

“Jackson” out-thundered!

Back echoed “Philip!” ah! then

Could you have seen our men.

How they sprung in the dim night haze,

To their work of toil and of clamor!

How the boarders, with sponge and rammer,

And their captains, with cord and hammer,

Kept every muzzle ablaze.

How the guns, as with cheer and shout—

Our tackle-men hurled them out—

Brought up on the water-ways!

First, as we fired at their flash,

’Twas lightning and black eclipse,

With a bellowing roll and crash.

But soon, upon either bow,

What with forts and fire-rafts and ships,

(The whole fleet was hard at it now,)

All pounding away!—and Porter

[65]

Still thundering with shell and mortar,—

’Twas the mighty sound and form!

(Such you see in the far South,

After long heat and drought,

As day draws nigh to even,

Arching from north to south,

Blinding the tropic sun,

The great black bow comes on,

Till the thunder-veil is riven,—

When all is crash and levin,

And the cannonade of heaven

Rolls down the Amazon!)

But, as we worked along higher,

Just where the river enlarges,

Down came a pyramid of fire,—

It was one of your long coal barges.

(We had often had the like before.)

’Twas coming down on us to larboard,

Well in with the eastern shore;

And our pilot, to let it pass round,

(You may guess we never stopped to sound)

Giving us a rank sheer to starboard,

Ran the Flag hard and fast aground!

’Twas nigh abreast of the Upper Fort,

And straightway a rascal ram

[66]

(She was shaped like the Devil’s dam)

Puffed away for us, with a snort,

And shoved it, with spiteful strength,

Right alongside of us to port.

It was all of our ship’s length,—

A huge, crackling Cradle of the Pit!

Pitch-pine knots to the brim,

Belching flame red and grim,

What a roar came up from it!

Well, for a little it looked bad:

But these things are, somehow, shorter,

In the acting than in the telling;

There was no singing out or yelling,

Or any fussing and fretting,

No stampede, in short;

But there we were, my lad,

All afire on our port quarter,

Hammocks ablaze in the netting,

Flames spouting in at every port,

Our fourth cutter burning at the davit

(No chance to lower away and save it).

In a twinkling, the flames had risen

Half way to main-top and mizzen,

Darting up the shrouds like snakes!

Ah, how we clanked at the brakes,

And the deep, steaming pumps throbbed under,

Sending a ceaseless flow.

[67]

Our topmen, a dauntless crowd,

Swarmed in rigging and shroud:

There, (’twas a wonder!)

The burning ratlines and strands

They quenched with their bare, hard hands;

But the great guns below

Never silenced their thunder.

At last, by backing and sounding,

When we were clear of grounding,

And under headway once more,

The whole rebel fleet came rounding

The point. If we had it hot before,

’Twas now from shore to shore,

One long, loud, thundering roar,—

Such crashing, splintering, and pounding,

And smashing as you never heard before!

But that we fought foul wrong to wreck,

And to save the land we loved so well,

You might have deemed our long gun-deck

Two hundred feet of hell!

For above all was battle,

Broadside, and blaze, and rattle,

Smoke and thunder alone;

(But, down in the sick-bay,

Where our wounded and dying lay,

There was scarce a sob or a moan).

[68]

And at last, when the dim day broke,

And the sullen sun awoke,

Drearily blinking

O’er the haze and the cannon smoke,

That ever such morning dulls,—

There were thirteen traitor hulls

On fire and sinking!

Now, up the river!—through mad Chalmette

Sputters a vain resistance yet,

Small helm we gave her our course to steer,—

’Twas nicer work then you well would dream,

With cant and sheer to keep her clear

Of the burning wrecks that cumbered the stream,

The Louisiana, hurled on high,

Mounts in thunder to meet the sky!

Then down to the depths of the turbid flood,—

Fifty fathom of rebel mud!

The Mississippi comes floating down,

A mighty bonfire from off the town;

And along the river, on stocks and ways,

A half-hatched devil’s brood is ablaze,—

The great Anglo-Norman is all in flames,

(Hark to the roar of her trembling frames!)

And the smaller fry that Treason would spawn

Are lighting Algiers like an angry dawn!

[69]

From stem to stern, how the pirates burn,

Fired by the furious hands that built!

So to ashes forever turn

The suicide wrecks of wrong and guilt!

But as we neared the city,

By field and vast plantation,

(Ah! millstone of our nation!)

With wonder and with pity,

What crowds we there espied

Of dark and wistful faces,

Mute in their toiling places,

Strangely and sadly eyed,

Haply ’mid doubt and fear,

Deeming deliverance near,

(One gave the ghost of a cheer!)

And on that dolorous strand,

To greet the victor brave,

One flag did welcome wave—

Raised, ah me! by a wretched hand,

All outworn on our cruel land,—

The withered hand of a slave!

But all along the levee,

In a dark and drenching rain,

(By this ’twas pouring heavy,)

Stood a fierce and sullen train,

A strange and frenzied time!

[70]

There were scowling rage and pain,

Curses, howls, and hisses,

Out of Hate’s black abysses,—

Their courage and their crime

All in vain—all in vain!

For from the hour that the Rebel Stream

With the Crescent City lying abeam,

Shuddered under our keel,

Smit to the heart with self-struck sting,

Slavery died in her scorpion-ring

And Murder fell on his steel.

’Tis well to do and dare;

But ever may grateful prayer

Follow, as aye it ought,

When the good fight is fought,

When the true deed is done.

Aloft in heaven’s pure light,

(Deep azure crossed on white,)

Our fair Church pennant waves

O’er a thousand thankful braves,

Bareheaded in God’s bright sun.

Lord of mercy and frown,

Ruling o’er sea and shore,

Send us such scene once more!

All in line of battle

[71]

When the black ships bear down

On tyrant fort and town,

’Mid cannon cloud and rattle;

And the great guns once more

Thunder back the roar

Of the traitor walls ashore,

And the traitor flags come down.

[72]

SHERIDAN’S RIDE.

By THOMAS BUCHANAN READ.

Up from the south, at break of day,

Bringing to Winchester fresh dismay,

The affrighted air with a shudder bore,

Like a herald in haste to the chieftain’s door,

The terrible grumble, and rumble, and roar,

Telling the battle was on once more,

And Sheridan twenty miles away.

And wider still those billows of war

Thunder’d along the horizon’s bar;

And louder yet into Winchester roll’d

[73]

The roar of that red sea uncontroll’d,

Making the blood of the listener cold,

As he thought of the stake in that fiery fray,

With Sheridan twenty miles away.

But there is a road from Winchester town,

A good broad highway leading down:

And there, through the flush of the morning light,

A steed as black as the steeds of night

Was seen to pass, as with eagle flight,

As if he knew the terrible need

He stretch’d away with his utmost speed;

Hills rose and fell; but his heart was gay,

With Sheridan fifteen miles away.

Still sprang from those swift hoofs, thundering south,

The dust like smoke from the cannon’s mouth,

Or the trail of a comet, sweeping faster and faster,

Foreboding to traitors the doom of disaster.

The heart of the steed and the heart of the master

Were beating like prisoners assaulting their walls,

Impatient to be where the battle-field calls;

Every nerve of the charger was strained to full play,

With Sheridan only ten miles away.

Under his spurning feet, the road,

Like an arrowy Alpine river flow’d

And the landscape sped away behind

Like an ocean flying before the wind;

[74]

And the steed, like a bark fed with furnace ire,

Swept on, with his wild eye full of fire.

But, lo! he is nearing his heart’s desire;

He is snuffing the smoke of the roaring fray,

With Sheridan only five miles away.

The first that the general saw were the groups

Of stragglers, and then the retreating troops;

What was done? what to do? a glance told him both.

Then striking his spurs with a terrible oath,

He dash’d down the line, ’mid a storm of huzzas,

And the wave of retreat checked its course there, because

The sight of the master compell’d it to pause.

With foam and with dust the black charger was gray;

By the flash of his eye, and the red nostril’s play,

He seem’d to the whole great army to say:

“I have brought you Sheridan all the way

From Winchester down to save the day.”

Hurrah! hurrah for Sheridan!

Hurrah! hurrah for horse and man!

And when their statues are placed on high,

Under the dome of the Union sky,

The American soldier’s Temple of Fame,

There with the glorious general’s name

Be it said, in letters both bold and bright:

“Here is the steed that saved the day

By carrying Sheridan into the fight,

From Winchester,—twenty miles away!”

[75]

KEARNEY AT SEVEN PINES.

By EDMUND CLARENCE STEDMAN.

So that soldierly legend is still on its journey—

That story of Kearney who knew not to yield!

’Twas the day when with Jameson, fierce Berry, and Birney,

Against twenty thousand he rallied the field.

Where the red volleys poured, where the clamor rose highest,

Where the dead lay in clumps through the dwarf oak and pine,

Where the aim from the thicket was surest and nighest,

No charge like Phil Kearney’s along the whole line.

When the battle went ill, and the bravest were solemn,

Near the dark Seven Pines, where we still held our ground,

He rode down the length of the withering column,

And his heart at our war-cry leapt up with a bound.

He snuffed, like his charger, the wind of the powder,—

His sword waved us on, and we answered the sign;

[76]

Loud our cheer as we rushed, but his laugh rang the louder:

“There’s the devil’s own fun, boys, along the whole line!”

How he strode his brown steed! How we saw his blade brighten

In the one hand still left—and the reins in his teeth!

He laughed like a boy when the holidays heighten,

But a soldier’s glance shot from his visor beneath.

Up came the reserves to the mellay infernal,

Asking where to go in—through the clearing or pine?

“Oh, anywhere! Forward! ’Tis all the same, Colonel:

You’ll find lovely fighting along the whole line!”

Oh, evil the black shroud of night at Chantilly,

That hid him from sight of his brave men and tried!

Foul, foul sped the bullet that clipped the white lily,

The flower of our knighthood, the whole army’s pride!

Yet we dream that he still—in that shadowy region

Where the dead form their ranks at the wan drummer’s sign—

Rides on, as of old, down the length of his legion,

And the word still is Forward! along the whole line.

[77]

STONEWALL JACKSON’S WAY.

By J. W. PALMER.

[Mr. William Gilmore Simms tells us that this

poem, stained with blood, was found on the person of a dead soldier of

the Stonewall brigade after one of Jackson’s battles in the Shenandoah

Valley. Its authorship, long unknown, has been discovered by

Mr. Francis F. Browne.—Editor.]

Come, stack arms, men! Pile on the rails,

Stir up the camp-fire bright;

No growling if the canteen fails,

We’ll make a roaring night,

Here Shenandoah brawls along,

There burly Blue Ridge echoes strong,

To swell the brigade’s rousing song

Of “Stonewall Jackson’s way.”

We see him now—the queer slouched hat

Cocked o’er his eye askew;

The shrewd, dry smile; the speech so pat,

So calm, so blunt, so true.

[78]

The “Blue-light Elder” knows ’em well;

Says he, “That’s Bank’s—he’s fond of shell;

Lord save his soul! we’ll give him—” well!

That’s “Stonewall Jackson’s way.”

Silence! ground arms! kneel all! caps off!

Old Blue Light’s goin’ to pray.

Strangle the fool that dares to scoff!

Attention! it’s his way.

Appealing from his native sod,

In forma pauperïs to God:

“Lay bare Thine arm; stretch forth Thy rod!

Amen!” That’s “Stonewall’s way.”

He’s in the saddle now. Fall in!

Steady! the whole brigade!

Hill’s at the ford, cut off; we’ll win

His way out, ball and blade!

What matter if our shoes are worn?

What matter if our feet are torn?

“Quick step! we’re with him before morn!”

That’s “Stonewall Jackson’s way.”

The sun’s bright lances rout the mists

Of morning, and, by George!

Here’s Longstreet, struggling in the lists,

Hemmed in an ugly gorge.

[79]

Pope and his Dutchmen, whipped before;

“Bay’nets and grape!” hear Stonewall roar;

“Charge, Stuart! Pay off Ashby’s score!”

In “Stonewall Jackson’s way.”

Ah! Maiden, wait and watch and yearn

For news of Stonewall’s band!

Ah! Widow, read, with eyes that burn,

That ring upon thy hand.

Ah! Wife, sew on, pray on, hope on;

Thy life shall not be all forlorn;

The foe had better ne’er been born

That gets in “Stonewall’s way.”

[Southern.]

[80]

MARCHING ALONG.

By WILLIAM B. BRADBURY.

[During the Civil War this song was frequently

sung upon the march by the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac.

Except “When this Cruel War is Over” and the doggerel about “John

Brown’s Body,” there was scarcely any song so often heard. The name

of the leader was changed, from time to time, to accord with the

facts.—Editor.]

The army is gathering from near and from far;

The trumpet is sounding the call for the war;

McClellan’s our leader, he’s gallant and strong;

We’ll gird on our armor and be marching along.

Chorus.—Marching along, we are marching along,

Gird on the armor and be marching along;

McClellan’s our leader, he’s gallant and strong;

For God and our country we are marching along.

[81]

The foe is before us in battle array,

But let us not waver, or turn from the way;

The Lord is our strength, and the Union’s our song;

With courage and faith we are marching along.

Chorus.—Marching along, etc.

Our wives and our children we leave in your care;

We feel you will help them with sorrow to bear:

’Tis hard thus to part, but we hope ’twon’t be long:

We’ll keep up our heart as we’re marching along.

Chorus.—Marching along, etc.

We sigh for our country, we mourn for our dead;

For them now our last drop of blood we will shed;

Our cause is the right one—our foe’s in the wrong;

Then gladly we’ll sing as we’re marching along.

Chorus.—Marching along, etc.

The flag of our country is floating on high;

We’ll stand by that flag till we conquer or die;

McClellan’s our leader, he’s gallant and strong;

We’ll gird on our armor and be marching along.

Chorus.—Marching along, etc.

[82]

THE BURIAL OF LATANÉ.

By JOHN R. THOMPSON.

[Captain Latané, of Stuart’s Confederate

cavalry was killed during the Pamunkey expedition in 1862. He was

buried by a company of women, one of whom read the service for the

dead, while a little girl strewed flowers on the grave.—Editor.]

The combat raged not long, but ours the day;

And, through the hosts that compassed us around,

Our little band rode proudly on its way,

Leaving one gallant comrade, glory-crowned,

Unburied on the field he died to gain—

Single of all his men, amid the hostile slain.

One moment on the battle’s edge he stood—

Hope’s halo, like a helmet, round his hair;

The next beheld him, dabbled in his blood,

Prostrate in death—and yet, in death how fair!

Even thus he passed through the red gates of strife,

From earthly crowns and palms, to an immortal life.

[83]

A brother bore his body from the field,

And gave it unto strangers’ hands, that closed

The calm blue eyes, on earth forever sealed,

And tenderly the slender limbs composed:

Strangers, yet sisters, who, with Mary’s love,

Sat by the open tomb, and, weeping, looked above.

A little child strewed roses on his bier—

Pale roses, not more stainless than his soul,

Nor yet more fragrant than his life sincere,

That blossomed with good actions—brief, but whole;

The aged matron and the faithful slave

Approached with reverent feet the hero’s lowly grave.

No man of God might say the burial rite

Above the “rebel”—thus declared the foe

That blanched before him in the deadly fight;

But woman’s voice, with accents soft and low,

Trembling with pity—touched with pathos—read

Over his hallowed dust the ritual for the dead.

“’Tis sown in weakness, it is raised in power!”

Softly the promise floated on the air,

While the low breathings of the sunset hour

Came back responsive to the mourner’s prayer.

Gently they laid him underneath the sod,

And left him with his fame, his country, and his God!

[84]

Let us not weep for him, whose deeds endure!

So young, so brave, so beautiful! He died

As he had wished to die; the past is sure;

Whatever yet of sorrow may betide

Those who still linger by the stormy shore,

Change cannot harm him now, nor fortune touch him more.

[Southern.]

[85]

TARDY GEORGE.

[This poem was written at a time when the

impatience of the Northern people with the delay of McClellan to make

use of the means so lavishly provided for him, was scarcely to be

restrained. For many months McClellan had been in command of a vast

army, perfectly equipped and thoroughly disciplined, yet month after

month went by with nothing done and nothing attempted. The discontent

of the people found much angrier expression than was given to it in

these stanzas, but this is one of the best metrical protests that

appeared.—Editor.]

What are you waiting for, George, I pray?

To scour your cross-belts with fresh pipe-clay?

To burnish your buttons, to brighten your guns;

Or wait you for May-day and warm-spring suns?

Are you blowing your fingers because they are cold,

Or catching your breath ere you take a hold?

Is the mud knee-deep in valley and gorge?

What are you waiting for, tardy George?

[86]

Want you a thousand more cannon made,

To add to the thousand now arrayed?

Want you more men, more money to pay?

Are not two millions enough per day?

Wait you for gold and credit to go,

Before we shall see your martial show;

Till Treasury Notes will not pay to forge?

What are you waiting for, tardy George?

Are you waiting for your hair to turn,

Your heart to soften, your bowels to yearn

A little more toward “our Southern friends,”

As at home and abroad they work their ends?

“Our Southern friends!” whom you hold so dear

That you do no harm and give no fear,

As you tenderly take them by the gorge—

What are you waiting for, tardy George?

Now that you’ve marshalled your whole command,

Planned what you would, and changed what you planned,

Practised with shot and practised with shell,

Know to a hair where every one fell,

Made signs by day and signals by night;

Was it all done to keep out of a fight?

Is the whole matter too heavy a charge?

What are you waiting for, tardy George?

Shall we have more speeches, more reviews?

Or are you waiting to hear the news;

[87]

To hold up your hands in mute surprise,

When France and England shall “recognize”?

Are you too grand to fight traitors small?

Must you have a nation to cope withal?

Well, hammer the anvil and blow the forge—

You’ll soon have a dozen, tardy George.

Suppose for a moment, George, my friend—

Just for a moment—you condescend

To use the means that are in your hands,

The eager muskets and guns and brands;

Take one bold step on the Southern sod,

And leave the issue to watchful God!

For now the nation raises its gorge,

Waiting and watching you, tardy George.

I should not much wonder, George, my boy,

If Stanton get in his head a toy,

And some fine morning, ere you are out,

He send you all “to the right about”—

You and Jomini, and all the crew

Who think that war is nothing to do

But to drill and cipher, and hammer and forge—

What are you waiting for, tardy George?

January, 1862.

[88]

WANTED—A MAN.

By Edmund Clarence Stedman.

[This virile cry for a fit leader for the Army

of the Potomac was inspired by an editorial article of Henry J. Raymond

in the New York Times. It was written in 1862, when the popular

feeling of chagrin and humiliation over McClellan’s failure and Pope’s

disaster at Manassas was most intense. Mr. Lincoln was so strongly

impressed by the poem that he read it to his Cabinet.—Editor.]

Back from the trebly crimsoned field

Terrible words are thunder-tost;

Full of the wrath that will not yield,

Full of revenge for battles lost!

Hark to their echo, as it crost

The Capital, making faces wan:

“End this murderous holocaust;

Abraham Lincoln, give us a MAN!

[89]

“Give us a man of God’s own mould,

Born to marshal his fellow-men;

One whose fame is not bought and sold

At the stroke of a politician’s pen;