This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

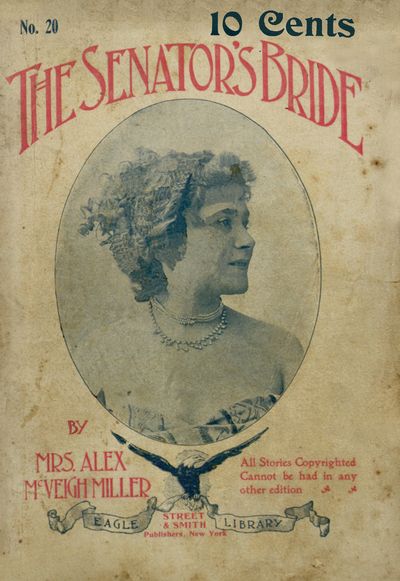

Title: The Senator's Bride

Author: Mrs. Alex. McVeigh Miller

Release Date: February 8, 2017 [eBook #54134]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SENATOR'S BRIDE***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Villanova University Digital Library. See https://digital.library.villanova.edu/Item/vudl:440123# |

Images may be clicked to view larger versions.

10 Cents

No. 20

|

MRS. ALEX |

All Stories Copyrighted |

EAGLE LIBRARY

STREET

& SMITH

Publishers, New York

| EAGLE LIBRARY |

A weekly publication devoted to good literature. By subscription. $5 per year. July 12, 1897 Entered as second-class matter at N. Y. post-office. |

NO. 20 |

An Explosion in Prices!

The Sensation of the Year!

STREET & SMITH'S

EAGLE LIBRARY

OF

12mo. Copyrighted Books.

RETAIL PRICE, 10 CENTS.

No. 1 of this series contains 256 pages full size, 12mo. Succeeding issues are of similar bulk. Paper and printing equal to any 25 cent book on the market. Handsome and Attractive Cover of different design for each issue.

16—The Fatal Card. By Haddon Chambers and B. C. Stephenson.

15—Doctor Jack. By St. George Rathborne.

14—Violet Lisle. By Bertha M. Clay.

13—The Little Widow. By Julia Edwards.

12—Edrie's Legacy. By Mrs. Georgie Sheldon.

11—The Gypsy's Daughter. By Bertha M. Clay.

10—Little Sunshine. By Francis S. Smith.

9—The Virginia Heiress. By May Agnes Flemming.

8—Beautiful but Poor. By Julia Edwards.

7—Two Keys. By Mrs. Georgie Sheldon.

6—The Midnight Marriage. By A. M. Douglas.

5—The Senator's Favorite. Mrs. Alex. McVeigh Miller.

4—For a Woman's Honor. By Bertha M. Clay.

3—He Loves Me, He Loves Me Not. By Julia Edwards.

2—Ruby's Reward. By Mrs. Georgie Sheldon.

1—Queen Bess. By Mrs. Georgie Sheldon.

THESE BOOKS CAN BE HAD IN NO OTHER SERIES

BY

Mrs. ALEX. McVEIGH MILLER.

NEW YORK:

STREET & SMITH, Publishers,

31 Rose Street.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1887,

By Street & Smith,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C.

CHAPTER I. THE FALL OF A METEOR.

CHAPTER II. TOO LATE.

CHAPTER III. "SWEETHEART, GOOD-BY."

CHAPTER IV. RENUNCIATION

CHAPTER V. WHAT THE WINNER'S HAND THREW BY.

CHAPTER VI. LULU.

CHAPTER VII. "I HATE IT—I HATE HER!"

CHAPTER VIII. "BUT AS FOR HER, SHE STAID AT HOME."

CHAPTER IX. "WHEN A WOMAN WILL, SHE WILL."

CHAPTER X. AT THE CAPITOL.

CHAPTER XI. "IT MAY BE FOR YEARS, AND IT MAY BE FOREVER."

CHAPTER XII. "FATE HAS DONE ITS WORST."

CHAPTER XIII. ON THE OCEAN.

CHAPTER XIV. "IN HIS HEART CONSENTING TO A PRAYER GONE BY."

CHAPTER XV. "HOPE SPRINGS ETERNAL IN THE HUMAN BREAST."

CHAPTER XVI. "SMILING AT GRIEF."

CHAPTER XVII. "TO BE, OR NOT TO BE."

CHAPTER XVIII. "OTHER REFUGE HAVE I NONE."

CHAPTER XIX. A NEW YEAR'S GIFT.

CHAPTER XX. WEDDING CARDS.

CHAPTER XXI. "RUE."

CHAPTER XXII. ON TIPTOE FOR A FLIGHT.

CHAPTER XXIII. IN MEMPHIS.

CHAPTER XXIV. LULU TO HER MOTHER.

CHAPTER XXV. THE PATHOS OF A QUIET LIFE.

CHAPTER XXVI. LULU TO HER MOTHER.

CHAPTER XXVII. "NEARER MY GOD TO THEE."

CHAPTER XXVIII. LULU TO HER MOTHER.

CHAPTER XXIX. LAST WORDS.

CHAPTER XXX. "BABY FINGERS, WAXEN TOUCHES."

CHAPTER XXXI. AT HER FEET.

THE FALL OF A METEOR.

—Jean Ingelow.

It was 1866, on the evening of a lovely spring day, and my heroine was gathering flowers in one of the loveliest of the lovely gardens of that sea-port city, Norfolk, Virginia.

A lovely garden indeed, with its spacious area, its graveled walks and fountains, its graceful pavilions, its beautiful flowers, and the tasteful villa that rose in the midst of this terrestrial paradise looked very attractive outlined whitely against the dark green of the lofty grove of trees stretching far into its rear. Built on the suburbs of the city, in the portion of it known as Ocean View, you could scarcely have imagined a fairer prospect than that which met the eyes of the two gentlemen who idly smoked and talked on the wide piazza fronting the sea.

The sun was setting in a blue May sky, sinking slowly and sadly beneath the level of the sea, while far away, just faintly outlined by its fading beams, glimmered the white sails and[Pg 4] tapering spars of an outward-bound ship. How lonely it looked on that vast ocean in the fading light,

To a poetic mind, the sight suggested many exquisite similitudes, and Bruce Conway took the cigar from between his lips and mused sadly as befitted the occasion, till the voice of his companion jarred suddenly on his dreamy mood.

"Bruce, my boy, will you favor me with the earthly name of the white-robed divinity whom I have observed for the last half-hour flitting about this paradisiacal garden? Since my advent here at noon to-day, I have not had the pleasure of meeting my amiable hostess, yet I am persuaded that this youthful creature cannot be your aunt."

"Smitten at sight—eh, Clendenon?" answered Mr. Conway, with an attempt at archness. "That, my dear fellow, is my aunt's companion, Miss Grey. She is coming this way, and I'll introduce you."

He puffed away indolently at his fragrant cigar, while the young girl of whom he had spoken came up the broad avenue that led to the piazza steps, bearing on her arm a dainty basket heaped high with flowers and trailing vines that overflowed the edges of her basket and clung lovingly about her white robe. She was, perhaps, seventeen years of age, and endowed with a rare and peerless loveliness. A Mary of Scots, a Cleopatra might have walked with that stately, uplifted grace, that rare, unstudied poetry of motion. Slender, and tall, and lithe, with her pale gold ringlets and marvelous fairness was combined so much innocent sweetness that it brought the guest to his feet in involuntary homage and admiration, while Mr. Conway himself tossed away his cigar, and, hastening to meet her, took the flowery burden from her arm, and assisted her up the steps.

"Miss Grey, allow me to present to you my friend, Captain Clendenon," he said, in his graceful, off-hand way.

"Perfectly beautiful, faultily faultless!" murmured the captain to himself, as he bowed over the delicate hand she shyly offered.

With quiet grace she accepted the chair he placed for her,[Pg 5] and, taking up a great lapful of flowers, answered a question Mr. Conway asked:

"Yes, your aunt's headache is better, and she will be down this evening. These flowers are for the drawing-room. You know how she loves to see a profusion of flowers about the house through the whole season."

It was like Bruce Conway's graceful impudence to quote those lines, smiling up into the Hebe-like face of the girl. He was the spoiled darling of fortune, the handsome idol of the fair sex, as perfect in his dark, manly beauty as she in her opposite angelic type. Yet she hesitated, trifling saucily with her flowers, and half denying the rose he craved.

"I am chary of giving away roses obtained at the price of so many thorns," said she, holding up a taper finger with a dark-red scratch marking a zigzag course over its whiteness. "Gather your roses yourself, sir."

"If I might gather those that blossom on your cheeks, I might take the risk of the thorns," he answered, daringly.

The roses referred to deepened to vivid crimson, the golden lights in the pansy-colored eyes sent a fiery gleam along the black-fringed lashes, as she answered, indignantly:

"You forget yourself, and presume, sir."

"I did, indeed, but you know my idle habit of jesting. Pardon me."

"Willingly, so that the offense is not repeated," she answered, more gently, as she continued at her task, grouping the flowers into tasteful bouquets, and ending by a fragrant gift to each gentleman of a tiny posy for his button-hole, that restored sociability and brought back the ease that had marked the first of the interview.

"And to-morrow, Bruce," said the captain, presently, "I shall see the last of you for years, if not forever. What possesses you to go wandering off to Europe in this mad fashion?"

A smothered cry of astonishment caused him to look at Grace[Pg 6] Grey. She was looking straight at Bruce Conway, the rose-bloom dying away from her cheeks, and the beautiful eyes, eager, questioning, startled, with a woman's love looking out of them, and a woman's love revealed, alas! too plainly, in that mute gaze.

Conway's dark eyes met hers for a moment with answering love in their dark depths. Only a moment, though, and then they wavered and fell, and he indifferently answered her mute question:

"You look surprised, ma petite. Well, it is true that I leave here to-morrow for an extended tour over Europe. I have long thought of it, and the time has come at last."

No answer. She could not have spoken if life or death had hung on a single sentence from those sweet lips, from whence the rose-tint had faded, leaving them cold and white, and drawn as if in pain. She gathered up her fragrant burdens and carried them into the house, leaving a momentary shocked silence behind her.

Presently the captain spoke, in the calm, assured tone in which we chide a dear and intimate friend:

"Bruce, have you been flirting with that pretty, innocent child?"

Conway fidgeted a little, but he answered nonchalantly enough:

"Why do you ask? Have you fallen in love with her?"

"I was not speaking of myself; we will keep to the subject, if you please. She loves you." His voice grew tender, reverential.

"Well?"

That simple monosyllable might have expressed many things. In Bruce Conway's non-committal tone it meant nothing.

"You will marry her?"

"Why, no."

The words came out with a jerk, as if they must be said, and the sooner the better. The purple twilight hid his face and expression, yet the captain persevered:

"Yet you love her?"

"Taking your assertion for granted," said Conway, coolly, "is that any reason why I should marry Miss Grey?"

"It seems one to me."

"Very probably; but, mon ami, your view on this, as on many other things, are old-fashioned and absurd, or, at least, behind the times we live in. Do you happen to know, old fellow, that I have completely run through my handsome fortune, and that my 'great expectations' as my aunt's solo heir and favorite are all I have to depend on?"

"I know it. What then?"

"'What then?'" boyishly mimicking the sober tone of the older man. "If I must tell you, Clen, my aunt has positively interdicted me from making love to her fair companion. I might be courteously polite, soberly kind—nothing more, on pain of disinheritance and eternal banishment from my relative's imperious presence."

"You have disobeyed her."

"Not I. I have debarred myself from that exquisite pleasure, and kept strictly to the letter of my aunt's command. I have never told her I loved her, never addressed her a single word of love, save in the ideal, poetical quotations to which she can attach no real meaning. I am not to blame," talking a little savagely; "and I suffer, too. I must go away. It is madness for me to stay here longer, and cruel to her. My heart aches for her—she is so fair, so pure, so trusting. I dare not stay here another day, or I should break through Aunt Conway's prohibition and tell her all that is in my heart. But once away from the sight of her maddening beauty, I can forget her, and returning home some time, take possession of my handsome inheritance, and thank my lucky stars for the decision I made to-day."

"Think a moment, dear friend. Is it not just as possible that a day may come when you shall bitterly regret that decision? When for the sake of the loving, trusting, friendless child you desert to-day, you would peril not only your hopes of present fortune and earthly prosperity, but your aspirations for a brighter world?"

"Why pursue a useless subject? I have let you have your say out, and heard you in patience. Now hear me. I do love[Pg 8] Grace Grey so passionately that, having had everything I wanted heretofore in life, it is a hard struggle to be compelled to resign her. But though I feel that I am acting almost a villainous part, I cannot incur my aunt's penalty. Love of ease and luxury is inherent in my nature, and I would not resign the power of gratifying these propensities for the sake of any woman's love. Even if I risked all to do the love-in-cottage romance, what have I left to offer Miss Grey along with my name and love?"

"Your broad breast to shield her; your clear brain and strong arms to toil for her."

"Mere visionary fancies! I am too indolent to work with head or hands. My vocation is that of an idler. I shall go to Europe, see all that is to be seen, shiver foggy London, plunge head and soul into the gay and giddy circles of dear delightful Paris, return, inherit Aunt Conway's fortune, marry some heiress of her choosing, and live happy ever after."

"I doubt it. Good-night."

"Come back—you are not going? I shall drive you into town after tea—my aunt expects to see you—Clendenon, I say!"

He hurried down the walk after the tall, proud form stalking coldly away, and stopped him with a hand upon his shoulder.

"Clen, are you angry with me? Don't think of it! You know there are some subjects on which we never agree. I am sorry I did not hear your expostulations with more patience. That is saying more than I would say to any other man living, but I don't forgot that it is for me you wear that empty sleeve across your breast—that you gave freely to save my worthless life the strong arm that was worth more than a dozen such men as I. And are we to separate at last for a woman's sake?"

It was true. They had shared the same camp-fire, slept under the same scanty blanket, battled side by side in the far-famed gray uniform, and when death threatened the one the strong arm of the other had been raised to shield him. Had it been necessary he would have given his life as freely as he gave his strong left arm.

He could not forget in a moment the friendship of years, but[Pg 9] he yielded half-reluctantly to the detaining hand that drew him back to the house.

"I confess that I go back with you unwillingly," he said, in his grave, frank way. "You have shown me a new phase of your character, Bruce, and I do not in the least admire it. I trust yet to hear you repudiate your decision as unworthy of yourself as well as unjust to the girl whose sacred love you have trifled with."

"Perhaps I may yet," was the hurried reply. "I am so divided between conflicting emotions that I scarcely know my own mind yet. I may yet decide as you wish me to do."

Part of this was said to conciliate his friend, and part of it was true, for Bruce Conway did not err when he said that he scarcely know his own mind. The most of his failings and follies, as of a great many other people, arose from this amiable trait in his character.

He had not decided when the pleasant social ceremony of the nine o'clock tea was over, and leaving Captain Clendenon deep in converse with his stately hostess, he beguiled the younger lady into a walk down to the sea-shore. There standing, arm in arm, on the pebbly beach, he almost made up his mind. For she was so beautiful, and he loved beauty. A love of beauty was inherent in his luxurious nature, and Grace Grey was the fairest creature he had ever beheld as she lifted her shy glance to his in the brilliant moonlight, while as yet neither had spoken a word.

Why need they have spoken? It needed but that his hand should seek and hold hers in that lingering clasp that tells the all and all of love. But the soft breeze went sighing past like a spirit, the eternal sea surged strangely on, the stars burned, and the moon went under a transient cloud, while far away in the southern heavens a great red meteor flamed out and shone brilliantly among the silver stars. Both saw it at once, and both uttered an affected cry of surprise—affected, I say, because I do not think anything would have surprised them then, they were so absorbed in each other, so happy and yet so unhappy, as they stood together there, their young hearts throbbing "so near and yet so far."

She did not dream as she watched that fiery orb of light that[Pg 10] her future hung on its transient beaming. She knew, with a woman's keen intuition, that he had brought her there to learn her fate. What it was to be she could not guess. Certainly she did not think that the man beside her had staked their two futures on the hazard of a meteor, and that when it paled and faded from the stormy sky he whispered to himself: "As was my love for her! Burning and comet-like as was that meteor, it shall fade as soon and leave me free."

Was it? Did the future prove so? Tenderly—more tenderly than he had ever done—he lifted the thin white drapery, half falling from her shoulders, and folded it closely about her.

"How heavily the dew falls," he said, kindly. "We had better return to the house."

Mrs. Conway looked curiously up as the pair came slowly into the drawing-room, and was content with what her keen glance read in the faces that wore the light mask of indifferent smiles.

"Gracie, child," in her most affable way, "don't let our guest leave us without the rare treat of hearing you sing. Captain Clendenon, will you turn the music for her?"

"The attraction of Grace's music, its greatest charm, lies in its wonderful pathos and expressiveness," condescended the haughty hostess, as the guest's firm lip softened while listening to the spirit-like melodies that sobbed and wailed along the piano keys, answering to the touch of the skillful fingers and the sweet voice.

At length she selected an old song, and with a single glance at Conway, sang the first stanza through:

The wounded young heart could sustain itself no longer. She rose and passed hastily from the room. It was her farewell to[Pg 11] her unworthy lover. When he left home in the early dawn, amid the tearful lamentations of his adoring aunt, Miss Grey had not arisen from her feverish slumbers.

TOO LATE.

Mrs. Conway was not wearing the willow for her wandering nephew. On the contrary, her elegant rooms constantly witnessed merry gatherings, where mirth and music reigned supreme. She was still a handsome woman, still a brilliant woman, and the world of society, fashion, and folly held her as one of its leaders. The delicate state of her health had improved, she had dispensed with her fair companion, and on a sweet spring night, just four years from the date of the beginning of this story, she was giving a splendid ball in honor of the wife of the distinguished and handsome Senator Winans, of Virginia.

The elite of Norfolk was gathered there, the house was garnished with wreaths and garlands of flowers, till the long drawing-rooms opening into each other looked like fast succeeding vistas of intoxicating bloom. Music rose voluptuously overall, and the proud hostess moved among her guests looking handsome as a picture, and young for her fifty-four years, in the sea-green silk and misty laces that accorded so well with her dark eyes and hair, and sweetly smiling mouth.

But under all her brightness and gayety Mrs. Conway carried an uneasy pang in her proud heart. It was the neglect of her[Pg 12] idolized nephew. She had never had any children of her own, and at the death of her husband the orphan boy of her only brother crept into her heart, and held the only place in it that was worth having; for the heart of a fashionable fine lady, I take it, has little room to spare from the vanities of dress and fashion; but whatever vacant room there remained in Mrs. Conway's, it all belonged to her self-exiled nephew, and for many months no news had come of the traveler. He had roved from one end of Europe to the other, and wearied of it all, but still talked not of coming home, and his aunt missed him sadly. He had been unfeignedly fond of her. He was her nearest living relative, her chosen heir, and she wanted him home for the few remaining years of her life. But with the underlying strength of her proud heart she kept those feelings to herself, and none were the wiser for them.

And in the midst of the music and dancing a stranger crept to the door of the anteroom, and looked anxiously in—Bruce Conway. A little thinner, a little bronzed by travel, a little more grave looking, but every bit as handsome as the dashing young follow who had gambled with a meteor for his chance of happiness and—lost.

Was he looking for his aunt? Twice she passed near enough to have touched him with her hand, but he smiled and let her pass on, not dreaming of his near presence.

At last his eyes encountered what they sought, and, half unconsciously, he drew nearer, and scanned the peerless vision framed in the door-way of the conservatory, in the soft but brilliant light of the wax-lights half-hidden in flowers.

Was she a creature of this lower earth? He had thought, that spring four years ago, with Grace Grey at seventeen, leaning on his arm, looking into his face in the moonlight, that she was more a creature of heaven than earth. He thought so again to-night, as he looked at her leaning there under the arch of flowers that framed the conservatory door. He thought of all the living loveliness, the sculptured perfection, the radiant beauty that seemed to breathe on the canvas—all he had seen in his wanderings from shore to shore—and nothing he could recall was half so glorious as Grace Grey at twenty-one, in her calm repose, standing quietly looking on at the scene, seeming herself, to the[Pg 13] fascinated eyes that beheld her, like a young angel strayed away from paradise.

Mr. Conway slipped around and entered the room by a side door in the rear of where she stood. At sound of his footstep she turned slowly and looked at him carelessly, then looking again, threw up one hand. Was she going to faint? Not she! Her face whitened, her pansy-violet eyes grew black with intense emotion, but without a tremor she offered the little cold hand he had dashed away from him so long before. It was as cold now as it had been then—had it never been warm since, he wondered.

"Welcome home!" he heard in the remembered music of her voice.

"Oh, Grace, my darling, my wronged little love!" He knew his own mind at last, and was down on his knees before she could prevent him, passionately entreating, "My darling, will you forgive me, and give yourself to me? I have come home to make reparation for the past. I never knew how dear you were, how entirely I loved you, till the ocean rolled between us."

For a moment the silence of unspeakable emotion fell between them; she struggled for speech, waving her hand for him to pause, while over her pure, pale face a flood of indignant crimson warmly drifted.

"Rise, sir," she answered, at last, in low, proud tones, "such words are an insult to me!"

"And why? Oh! Grace, can you not forgive me, can you not love me? You loved me once, I know. Don't send me away. Promise that I may still love you, that you will be my worshiped wife!"

She did not laugh at him, as you or I might have done, my reader. It was not in the nature of the girl Bruce Conway had scorned for her low estate to be anything but sweet and merciful. She looked at him, still faintly flushed and excited, but answered with unconsciously straightening figure, and a firm but gentle dignity peculiar to her always:

"Possibly you are not aware, Mr. Conway, that your words of love are addressed to one who is already a wife—and mother."

Mr. Conway had never fainted in his life, but with a feeling that sense and strength were giving way, he rose, and, dropping[Pg 14] into a chair, white as death, looked at the young creature whose quiet assertion of matronly dignity had fallen on his ears like a death-warrant. And as he looked, with that strange power we have of discriminating details even in the most eventful hours, he noticed many things that went far to prove the truth of her words. He had left her poor and almost friendless, her richest dress a simple white muslin, and scarcely another piece of jewelry than the simple trinket of gold and pearls that clasped the frill of lace at her white throat. To-night she wore a sweeping robe of costly white silk, with flouncings of real lace, that was worth a small fortune in itself. There were diamonds on the wavering swell of her white bosom, depending from the pearly ears, scintillating fire from her restless taper wrists, clasping her statuesque throat like sunshine glowing on snow. She was wealthy, prosperous, beloved now, he read in the restful peace that crowned her innocent brow; and bitterest thought of all to the man who had loved and deserted her—another man called her his wife—another man's child called her mother.

While she stood with that flush of offended wifely dignity burning hotly on her pure cheek, while he looked at her with a soul's despair written on his handsome features, a gentleman entered the room carrying an ice. He was tall and splendidly handsome, his countenance frank, and pleasant, but a slight frown contracted his brow as he took in the scene, and it did not clear away as the lady said, distantly:

"Mr. Conway, allow me the pleasure of presenting to you my husband, Senator Winans."

Both gentlemen bowed ceremoniously, but neither offered the hand. Mr. Conway hated Winans already, and the gentleman thus honored felt intuitively that he should hate Conway. So their greeting was of the briefest. The discomfited traveler turned and walked over to the Hon. Mrs. Winans.

"I beg your pardon," he said, in low, earnest tones; "I did not know—had not heard the least hint of your marriage."

He was gone the next moment. Senator Winans looked inquiringly at his beautiful young wife. She did not speak; he fancied she shrank a little as he looked at her, but as he set down the ice on a small flower-stand near by, she took up the little golden spoon and let a tiny bit of the frozen cream melt[Pg 15] on her ruby lip, while a faint smile dimpled the corners of her mouth.

"My love," he said, lifting the small, white hand, and toying with its jeweled fingers, "are you ill? Your hand is cold as ice."

"I never felt better in my life," smiling up into his questioning eyes, and nestling the small hand still closer in his. "The cold cream chilled me after dancing so much, or," her natural truthfulness asserting itself, "I may be a little nervous, and that makes my hands cold."

"And what has made you nervous to-night?" his tone unconsciously stern and his thoughts full of the dark, despairing face that had looked up from the depths of the arm-chair at his queenly looking wife.

"Nothing," she answered, dreamily, while a swift flush burned on her cheek, and she turned away a little petulantly and began to trifle with the ice again.

"I beg your pardon, but it was something, and that something was the man who has just left us. Who and what is he?"

"Mr. Bruce Conway, nephew and heir of our hostess. He has been abroad four years, I think, and but just returned."

"An old acquaintance of yours, then?"

"Well, yes."

She turned toward him with marvelous sweetness and self-command.

"During my stay with Mrs. Conway I was naturally brought frequently in contact with her nephew. I found him a pleasant acquaintance."

"Nothing more—was he not a lover?"

His beautiful dark eyes seemed to burn into her soul, so full were they of jealous pain and sudden doubt.

She came up to him, crossing her round white arms over one of his, looking up at him with an arch, merry smile.

"I really cannot say, since he never confessed to a tender passion for me. The difference in our stations precluded anything of the sort. You must remember that there are few men like you, my loyal love, who stooped to lift a beggar-maid to share your throne."

Her eyes were misty and full of unshed tears, partly out of[Pg 16] gratitude and love for him, and partly—she could not help it—because she was conscious of a sharp, agonized remembrance of a night four years before, the very thought of which made her turn white and cold as death as she leaned upon her husband's arm.

One hand beneath her dimpled chin lifted her face to meet his gaze. She met it sweetly and frankly, but he knew her well enough to know that the intense blackness of her dilated eyes denoted deep emotion.

"Tell me the truth, Gracie," he entreated. "That man looked at you as no mere acquaintance ever looked at a woman—looked at you as he had no right to look at the wife of another man! What mystery is this you are trying to withhold from me? If you refuse to answer what I have a right to know you force me to seek satisfaction from him."

He was terribly in earnest. The baleful fire of doubt and jealousy burned in his eagle gaze, and startled the young creature who read its language with a vague doubt creeping into her soul. She did not want to deceive her husband—still less did she want to tell him the truth for which he asked.

"Spare me!" she entreated. "There is nothing to tell, my love—nothing of any consequence, I mean. It would but annoy you to hear it, mortify me to tell it," and once more the warm blush of insulted matronly pride tinged the girlish cheek with crimson.

"For all that I insist upon having an explanation of the scene I witnessed here after leaving you scarcely a minute before!"

Unconsciously to himself he shook off the small hands that clasped his arm in his eager interest and excitement. She did not replace them, but, folding both her arms across her breast, lifted her pale, earnest face to his.

Her answer came low and sweet, though perhaps a trifle impatient, as though the subject seemed to her scarcely worth this "wordy war."

"Well, then, Mr. Bruce Conway startled me very much by entering here quite suddenly and making me an offer of his hand, declaring that he had learned to love me while abroad. I checked him by telling him that I was a wife and mother. You[Pg 17] heard his apology to me—he did not know of my marriage. That is all there is to tell."

He looked at her and half smiled at thought of Conway's discomfiture; but the passing merriment was displaced in a moment by the sharp pain tugging at his heart-strings. He had the jealous Southern nature to perfection. He could not endure even the thought that another had ever enshrined in his heart the image of Grace, his lovely girl-bride. So sharp a pang tore his heart that he could not move nor speak.

"Paul, my husband"—she looked up at him as wondrously fair in his eyes as she had been in Bruce Conway's, and with a timid grace that was infinitely becoming to her—"surely you do not blame me. I could not help it. I am sorry it has happened. I cannot say more."

It was not in human nature to withstand the mute pleading of her manner, or the soft gaze that met his own. He stooped and touched his lips to her pure brow.

"Let us go, love," he said. "I confess that I shall feel better away from here and in our pleasant home."

"But this reception was given for us. Our hostess will feel offended at so early a departure."

"I will tell her we were called away—that is, unless you wish to remain."

"No, indeed; I would rather be at home with my precious baby; and your wishes are always mine, Paul."

How exquisitely she tempered wifely submission and obedience with gentleness and love! If there was a cross in her life, she wreathed it over with flowers. Her soothing voice fell like the oil of peace on the troubled waters of his soul.

Long after their adieus to their hostess had been spoken, and his arm had lovingly lifted her into her carriage, Bruce Conway's eyes watched vacantly the spot where she had vanished from his sight, while that haggard wanness of despair never left his face. Never until the hour in which he knew her irrevocably lost to him did he realize how deeply rooted in his soul his love had been. Amid all the glories of the old world he had felt that life was a desert without her, and in the Arabian deserts the knowledge had dawned slowly upon him, that even here her mere presence would have created a paradise of bliss.[Pg 18] Far away from her, unconsciously to her, he had mentally renounced his anticipated inheritance, and come home with the fixed intention of winning her, and toiling, if need be, cheerfully for her.

Not a thought of disappointment, not a possibility of her marriage had crossed his mind. It was left to this hour, when he stood there listening to the slow crunch of her carriage wheels that seemed grinding over his heart as they rolled away, to know his own heart truly, and to feel how much better than he knew himself his friend had known him when he said, on almost the same spot where he now stood alone:

"Is it not just as possible that the day may come when for the sake of the loving, trusting, friendless child you desert to-day, you would peril not only your hopes of present fortune and future prosperity, but your aspirations for a brighter world?"

It had come. Passionate heart, undisciplined temper, unsatisfied yearnings clamored fiercely for the woman who had loved him as he would never be loved again. He would have given then, in his wild abandonment to his love and despair, all his hopes of fortune, his dreams of fame, his chances of futurity, to have stood for one hour in the place of the man who, even then in his beautiful home, clasped wife and child in one embrace to his noble heart, while he thanked God for the treasure of a pure woman's love.

A touch on his shoulder, a voice in his ear jarred suddenly on his wild, semi-savage mood.

"Be a man, Bruce, old fellow, be a man. It is too late for unavailing regrets. Call all your manhood to your aid."

"Clendenon, is it you?" He turned and wrung his friend's hand with a grip that must have pained him. "Have you come to exult over my misery with the stereotyped 'I told you so?'"

"Can you think it of me? Bruce, I have watched you for the last five minutes, and I understand your feelings. From my soul I pity you!"

"Don't! Sympathy I cannot bear—even from you, old boy. Clen, how long has it been—when was she,"—a great gulp—"married?"

"More than eighteen months ago Senator Winans saw her[Pg 19] first at one of your aunt's receptions, where she was brought forward to perform a difficult sonata for a musical party. He saw and loved (what man could see her and not love her?) There was a brief courtship, a brilliant marriage, under the rejoicing auspices of your aunt, and the beautiful Hon. Mrs. Winans was the belle of last season in Washington, as her husband was one of the most notable members of the Senate. She has been 'the fashion' ever since."

"So she was like all other women, after all," sneered Conway, in jealous rage. "Sold herself. So much beauty, intellect, and frivolity—for a brilliant establishment, a proud name, and high position."

"I think not. They live very happily, I am told. He is worthy any woman's love, and has won hers, no doubt. And, Bruce, I don't think anything could make her worldly or calculating. As much of the angel is about her as is possible for mortal to possess."

Conway looked suddenly up into the handsome, inscrutable face of the speaker.

"Clen, mon ami, if it had to be any one else than me, I wish it had been you that had married her. You are deserving of any blessing that can come into a good man's life."

"Thanks," his friend answered, simply, and moved aside to make way for Mrs. Conway, who swept out on the piazza and up to the side of her nephew. Somehow the news of his return had been noised about the rooms, and she had come to seek him, vexed and mortified that he had not come to her, but still very happy to know that he was there at all.

"My dear boy," she said, as she clasped his hand and took the gallant kiss he offered, "this is, indeed, a joyful surprise. Will you come up into my boudoir, where we can have a quiet chat to ourselves, before your many friends claim your attention?"

Silent and moody he followed her. Once within the quiet seclusion of her own special apartment, and she turned upon him with a sudden storm of reproaches.

"Bruce, what is all this I hear? That gossiping old maid, Miss Lavinia Story, has spread from one guest to the other a sensational report of your meeting Mrs. Winans in the conservatory[Pg 20] just now, and proposing to her under the impression that she was still Miss Grey, my late companion. It can't be true of you; don't say it is, and make me ashamed of you in the very hour of your return. You could not have been guilty of such rashness and stupidity. Give me authority to deny it to our friends."

"I can't do it." He was always rather laconic in his way of speaking, and he answered her now in a moody, don't-care, scarcely respectful sort of style, without even looking at her. "It's all true, every word of it, and more besides."

"Bruce, Bruce, what madness!"

"Was it? Well, I suppose you did not expect as much manliness as that even from one who had been so ready to sell himself for your gold. But I could not do it, Aunt Conway. You know well enough that I loved her. That was why you were so willing I should go away. But I did not forget her so easily as I thought I would. My love only strengthened with time until I resolved to resign my claims to your fortune, come home, win her, and work for her like a man. I came, saw her, forgot all about the proprieties, and spoke at once. I didn't stop to think why she wore silk instead of muslin, diamonds instead of flowers. I saw only her heavenly, sweet face, and blundered straight into—making a laughing-stock of myself for all your acquaintance!"

"Exactly!" groaned Mrs. Conway. "Miss Story eavesdropped—she pretends to have heard it purely accidentally. The old—"

"News-carrier!" grimly suggested her nephew, finding her at a loss for a word.

"You may well say that! She will have it all over Norfolk to-morrow. Oh! how it mortifies my pride to have anything occur to disgrace me so! Bruce, I could almost find it in my heart to curse you!"

"And I you! You are to blame for it all. But for you and your foolish pride of wealth and position, I might have wooed and won her; but while I wavered in my shameful vacillation and selfishness, a better and nobler man has stepped in between us! You are proud to welcome him, proud to do him honor; proud to welcome her in her beauty and grace, now that you have put her forever out of my reach. But you are well repaid[Pg 21] to-night. Look at my blasted hopes and ruined life, and curse yourself, your gold, everything that has come between two loving hearts and sundered them forever!"

He threw the words at her like a curse, stepped outside the door, and slammed it heavily after him.

She saw him no more that night.

"SWEETHEART, GOOD-BY."

"You may go, Norah," said Grace Winans, looking up from the child on her breast at the sleepy-eyed nurse. "If I need you again I can ring the bell;" and, smiling, Norah bowed and withdrew.

It was almost twelve o'clock, and Grace had exchanged her ball-dress for a white neglige, and sat in the nursery, holding her babe in her arms, and smiling thoughtfully down at the tiny, winsome face. Mother and child made a wondrously fair picture in the soft shade of the wax-lights, that burned with subdued brightness in the dainty, airy, white-hung room. The girlish mother leaned a little forward as she sat in the low rocking-chair, her bright curls falling over the loosely flowing white dress like a golden glory. Her pure, innocent eyes looked down at the babe that nestled in her arms, and a low murmur of tenderness escaped her lips.

"My Birdie! my baby!"

"Still sitting up, Grace?"

It was the voice of her husband entering to pay his nightly visit to the little bright-eyed babe—sole heir of his proud name and wealth.

"I am not tired," she answered, in her fresh young voice, "and our little darling is so sweet I cannot bear to lay him down. Only look at him, Paul!"

Paul Winans bent down and clasped mother and child in one fond embrace.

"My two babes!" he whispered.

A sunny smile broke over the young wife's face. The pet name pleased her, for she was still scarcely more than a child in her quick appreciation of affection, and, like a child, she could scarcely have understood an affection that did not express itself in tender epithets and warm caresses. She nestled her bright head against his arm, sighing softly in the fullness of her content.

Tender and trustful as a little child, always ready to sacrifice her own wishes to those of others, only asking to love and be loved, our pretty Grace made a charming wife and mother. Prosperity had not spoiled her warm heart nor her clear judgment, and the greatest aim of her loving life was to please her noble husband in all things—her highest ambition to be to him always, as she was then, the guiding star of his life.

Over this exquisite picture of domestic peace and love broke the storm-cloud and the tempest. It was but a moment after Paul Winans kissed his happy wife before the stillness of the midnight hour was broken by a sound that rose from the street below, and was directly beneath the window.

First, a mournful guitar prelude; then a man's voice singing in the very accents of despair, and he finished the song of which Grace had sung the first stanza for him four years before:

Husband and wife listened in unbroken silence to the strain. The senator's arm tightened about his wife and child, and she[Pg 23] sat mute and still, every line of her face as moveless as if carved from marble. But as the lingering notes died away, her hand sought and touched the tiny blue-and-silver tassel that depended from the bell-cord, and sent its low tinkle through the house.

Norah, who always answered the nursery-bell, came in after the lapse of a moment. To her Mrs. Winans said, in a voice that sounded stern and cold for her silver-sweet tones:

"Norah, go to the front door and tell that madman that he had better move on—that the family do not wish to be disturbed by such nonsense at this hour of the night."

The woman withdrew obediently.

Paul Winans turned, and walked restlessly up and down the room.

"So he dares come and serenade my wife directly under my window!"

His dark eyes blazed, his cheeks flamed, and his hand involuntarily clenched itself.

Grace looked up at him, still immovably calm and silent; but a slight nervous movement of her arm showed that she heard and understood. She looked up questioningly as Norah appeared in the door-way.

"He was gone, ma'am, before I got down to the door."

"Very well; you may go, then."

And, as before, Norah went out, with her small courtesy, and left the pair alone.

"Grace!"

"Well, dear?"

Her voice had the same sweet cadence as usual, and her smile was as gentle as ever when she looked up at the princely form before her. His voice, his look, showed his insulted pride and outraged heart. Her only trace of emotion showed in marble pallor and darkening eyes.

"I do not understand this!" his voice slow and intense. "I thought I had found a pearl so pure and isolated that no other man's eyes had ever looked on it to covet its beauty for himself. That was my highest glory. Fame, fortune, pleasure were nothing to me in comparison with my pride in my wife, and that pride was the greater because a passionately jealous[Pg 24] nature like mine is only satisfied in holding the first place in the beloved heart. And this I thought I held in yours. To-night I learn for the first time that long before I ever met you another man looked on you to love you; perhaps you loved him."

His voice died away in a throb of passionate pain. He leaned against the rosewood, lace-draped crib, and looked down at her with their child in her arms, hoping she would deny it. She did not. Dead silence fell between them, and her soft eyes never wavered in their frank, upward look at him. They met his calmly, expectantly, their starry, inscrutable depths telling no secrets.

"Grace!"

"What is it, Paul?"

"Say something—you are so cold—anything to allay the fire that burns in my veins. I think I am mad to-night."

"My dearest, what can I say more than I have already told you? Mr. Conway proposed to me under a most mortifying mistake. I am not answerable for a man's infatuation with a fair face. I do not know what has induced him to make such a demonstration here to-night. Possibly he is under the influence of wine, and hardly knows the folly he is perpetrating; possibly we may never see or hear of him after this. Let us dismiss him from our thoughts."

Spoken so sweetly, so calmly, so indifferently. Her seeming calmness subdued and quelled momentarily his stormy feelings, as a strong, well-balanced mind always curbs a fitful, unquiet one.

"Then you do not care for him, Grace?"

She was threading her slim fingers meditatively through the dark curls that clustered on the brow of her child. She glanced up, her snow-white cheek flushing a fitful scarlet, her voice and look full of proud reproach.

"Paul, you are speaking to the mother of your child."

That quiet dignity recalled him to a sense of what was due to his wife. His brow cleared, his voice softened, as he answered:

"I beg your pardon, Gracie, dearest. I ought to have known your pure heart better than to insult it by a doubt. Your heart, I know, is mine now, or you would never have been my wife.[Pg 25] I know your pure honor and truth too well to think otherwise. But oh, my love, my sweet wife, if I knew—if I knew that your warm, true heart had ever throbbed with one sigh of love for another, I should, even though it had happened before I ever saw you, never again know one happy moment. You may think it is jealous madness—it may be—but it is inherent in my nature, and I cannot help it. I repeat that I could never, never be happy again."

No answer. Grace Winans' white arms wreathed themselves around her baby, pressing it closer, as if to still the sharp pang that struck home to her very heart. A faint shiver thrilled her, and rising, she laid the little sleeper in its downy nest, smiling a little sadly as she looked, but smiling still, for this tiny rosebud was the sweetest and most wonderful thing that had ever come into her lonely life. Deeply as she had loved the first object of her young affections, purely and truly as she loved her gifted husband, the strongest, deepest, most intense passion of her life was her maternal love. Some one has written half jestingly that "the depths of a woman's love can never be sounded till a baby is dropped into her heart," but it is true of the majority of women. It was especially true of Grace Winans. That little, rosy, lace-robed slumberer, small as it was, enshrining a human soul, was the idol of the young mother's life. Perhaps she was excusable. It was the only thing that had ever loved her purely and unselfishly. She could scarcely recollect her parents, she could not recall any one who had ever lavished on her such love as this child gave her, so devoted, so unreasoning, so absorbing; and deeply, unselfishly as she loved her husband, she loved his child better, though no word nor sign ever betrayed the fact to his jealous eyes. She reached up to him now, and drew him to her side, holding his arm about her waist with both dimpled white hands.

"My darling," she whispered, "don't be so unreasonable. You have no cause to be jealous, none at all. My whole heart is yours—yours and the baby's. You must have faith in me, Paul—have faith in me, and trust me as you do your own heart."

Drawing his moody face down to hers she kissed him with child-like simplicity. At the persuasive touch of those tender lips his brow cleared, his listless clasp tightened around her,[Pg 26] and both arms held her strained closely to his breast, his lips raining kisses on her brow, her cheeks, her lips, even her fair golden hair.

"Now you are like yourself," the musical voice whispered gladly. "You will not be jealous and unhappy again. I am yours alone, dear one—heart, and soul, and body—your own loving, happy little wife."

The sunshine on her face was tenderly reflected on his. She was so sweet and winsome, so womanly, yet withal so child-like and oh, so beautiful! His strange, unusual mood was not proof against the witchery of her loveliness, her flowing hair, the subtle perfume breathing from her garments, the tenderness of her words and looks.

"I don't think another man in the world has such a precious wife!" he said.

And though she knew that every man's private opinion regarding his own wife was the same, she took heart at his words of praise, and laughed archly. They two were that novel sight "under the sun," a pair of married lovers. Why need he have gone back to the forbidden subject? Ah! why have we always "done that which we ought not to have done?" Because he wanted to make himself miserable, I suppose. There is no other reason I can assign for his persistence; and, as for that, there is no reason whatever in a jealous man. "He is simply jealous for he is jealous," and where Shakespeare could not find a reason for a thing, how can I?

"Gracie, may I ask you one question?"

"You may—certainly."

"And will you answer it truthfully?

"If I answer it at all," she gravely made answer, "it must needs be truthfully, for I could not reply to you otherwise. But why ask a question at all? I do not care to question you of your past; why should you question me of mine? Let past and future alone, Paul. The present only is ours—let us enjoy it."

And heedless of the warning shadow that fell across her pathetic face, he persevered:

"Only tell me this, my precious wife. This Bruce Conway, who went away to Europe to learn that he loved you, and came[Pg 27] back to tell you so. Gracie, in that past time when you knew him—before you ever knew me—did you—tell me truly, mind—did you ever love him?"

The question she had dreaded and shrunk from all the time! She knew it would come, and now that it had, what could she say?

How easy it would have been to confess the truth to a less passionate and jealous mind. It was no sin, not even a fault in her, and she was not afraid to tell him save with the moral cowardice that makes one dread the necessary utterance of words that must inflict pain. What harm was there in that dreamy passion that had cast its glamour over a few months of her girlhood? It was unkind in him to probe her heart so deeply. She dared not own the truth to him if its telling were to make him unhappy! And along with this feeling there was another—the natural shrinking of a proud woman from laying bare the hidden secrets of her soul, pure though they be, to mortal sight. A woman does not want to tell her husband, the man who loves her, and believes her irresistible to all, that another man has been proof against her charms, that the first pure waters of love's perennial fountain had gushed at the touch of another, who let the tide flow on unheeding and uncaring, and a man has no business to ask it. But where does the line of man's "little brief authority" cross its boundaries? We have never found out yet. It is left, perhaps, for some of the fair and curious ones of our sex who are "strong-minded" in their "day and generation" to solve that interesting problem.

So, Gracie, debarred by confession by so many and grave considerations, in desperation, parried the question.

"Paul, do you know that I am sleepy and tired, while you are keeping me up with such idle nonsense? If we must begin at this late day to worry over our past loves and dreams, suppose you begin first by telling me how many separate ladies you loved before you ever met me! Come, begin with the first on the list."

"It begins and ends with—yourself," he said, gravely and firmly.

"Like the story of Mrs. Osgood's Evelyn," she rejoined, smiling, and beginning to hum lightly:

Then breaking off, she says more seriously and softly:

"Then try to think that is the same with me. Don't worry over such idle speculations. I am tired and half sick, dear."

"Gracie, you drive me to desperation. I asked you a simple question—why do you try to evade it?"

"Because it is unfair to me. I haven't asked you any such ridiculous questions. I won't submit to be catechised so, positively, I won't! Don't be angry, dear. I am sure the slightest reflection on your part will convince you that I am right. I have partly forgotten the past; have ignored it anyhow, not caring to look back any further in my life than the two years in which I have known and loved you. All the happiness I ever really knew has been showered on me by your lavish hand. Be content in knowing that and spare me, Paul."

"I thank you, Grace, for your sweet tribute to me, but I asked you a question and I am—waiting for your answer."

"I thought I had answered you plainly enough, Paul. Why will you persist in making us both unhappy?"

"Gracie, will you answer or not?"

"Oh, darling! you have worried me into a nervous chill. I am cold as ice," and to prove the truth of her words she pressed two icy little hands upon his cheek, and for the first time in his life he pushed his fairy away from him.

"You must not trifle with me, Grace."

"You still insist on it, Paul?"

"I still insist on it."

"At the risk of your own unhappiness?"

"Yes."

She looked at him sadly as she leaned across the crib near him, but not touching him.

"Paul," she ventured, suddenly, "even supposing that I had loved another before I ever met you, what difference can that make to you? I love you truly now."

"So much difference, my wife, that I think I could never[Pg 29] again be happy if I knew you had ever loved another than myself; but I cannot bear this suspense. I ask you nothing about other men. I only ask you, did you ever love Bruce Conway?"

She could not utter a falsehood; she could not escape his keen, persistent questioning; she must be frank with him and hope for the best. That was the only way the poor little heart reasoned then; so with down-dropped eyes, and a sound in her ears that recalled the whisper of the ocean in her ears one parting night, she drew a little farther away from him, and answered, in a hushed, low voice, much like a chidden child's:

"I did."

A silence fell between them so hushed that she could hear her own heart beat. He had put up his hand to his face, and she could not see his features nor guess what effect her words had on him.

"Paul," she ventured, almost frightened at the sound of her own voice in the stillness, "don't think of it any more. I was nothing but a simple, dreaming child, and it is just as natural for a young girl to fancy herself in love with the first handsome young man who flatters her as it is for our baby there in his crib to cut his teeth and have the measles when he grows older. It seems absurd to make yourself miserable over so trifling a thing. I didn't like him so very much, indeed I didn't. I soon learned how unworthy he was of any woman's love. He is a fickle, wavering, unprincipled man, who never knows his own mind, unworthy a second thought of yours, my noble husband."

Unflattering verdict! but a true one. She understood the man who had trifled with her young heart almost better than he did himself. In that time when he had wavered so fatally between his pride and his happiness she had fathomed his very soul with her suddenly awakened perceptions, and she understood him well. She could look back now and thank Heaven for what had seemed then a calamity scarcely to be borne. What it had cost her only Heaven knew, for in her way she was a proud woman, and never "wore her heart on her sleeve;" but nobody stops to question how hard a struggle has been so that victory crowns it at last. To the world it matters little[Pg 30] who of its toiling, striving atoms have been patient pilgrims to

so that they return with palms of victory in their hands and the cross of honor upon their breasts. And Gracie, too, had fought a battle in her life and conquered; if it left ineffaceable scars they were hidden in her heart and left no token upon her fair, inscrutable face.

He made no reply to her wistful defense.

She went up to him and touched his hand with hers, still intent on making peace with this proud, impatient spirit. He only put her very gently but firmly away from him, and in a moment after turned suddenly and left the room. She heard him go down to his study, close his door, and fall heavily into a chair.

Then her repressed impatience and anger broke out, as she paced back and forth, like a spirit, in her flowing hair and long white robe.

"The idiot! the madman! to come back here after all this time, and throw the shadow of that unhappy love all over my future life! Did he think that I had no pride? that I would bear coldness, carelessness, neglect, and be glad to meet him after four years had passed, and say yes to the question that in all honor he should have asked before he went? I think I could spurn him with my foot if he knelt before me again as he did to-night!"

How she scorned him! How superb she was in her just anger and resentment! Her changeful eyes darkened and flashed with pride, her lip curled, her cheek glowed, her light step seemed to spurn the floor.

"Mamma, mamma!" The soft, frightened voice of her child, waking suddenly from his rosy sleep, recalled her to herself. In an instant she was by his side, bending over him, kissing his brow, his lips, his hands, his hair, in a passion of grieving tenderness.

"My darling, my comfort, my pretty boy! I am so glad that you are a boy! You will never know the pains, the penalties, the trials and crosses of a woman's life. If you were a little[Pg 31] girl, and I knew that if you lived you must bear all that I have borne and must still endure, I could bear to see you dead rather than live to say, as I have done: 'Mother, why didn't you let me die when I was a little child?'"

The little clock on the marble mantel chimed out the hour of three in soft musical notes. She lifted the child in her arms, and, passing into her sleeping apartment, laid him down on her own bed, for she never slept without her treasure in her arms. Then, kneeling by his side, she whispered a brief, agonized petition to Heaven before laying her tired form down in the snowy nest of linen and lace.

When the soft summer dawn began to break faintly over the earth, Paul Winans rose up from his tiresome vigils and stole up stairs with a noiseless footstep that did not waken her from her exhausted sleep. Her child nestled close to her heart, and her lips, even in her fitful slumber, were pressed upon his brow just as she had fallen asleep. The long curls of her golden hair flowed over both, and wrapped them in a mantle of sunshine. Her face wore a look of remembered pain and grief that went to his heart, as kissing both so softly that they did not stir, he laid a note upon the pillow, and went down the stairs and out into the street.

RENUNCIATION

—Tennyson.

A misty, overcast morning dawned gloomily after the night of Mrs. Conway's ball. In spite of it the lady rose early. She had not slept at all, and, nervous and depressed, she roamed over the disordered house, from which the servants were busily removing the debris of the evening's entertainment. Every moment she expected to see her nephew enter, and as the day wore on and he failed to present himself, her impatience brooked control no longer, and she sent a messenger into Norfolk to the[Pg 32] National Hotel, his usual stopping-place in the city, to inquire after him.

The boy's swift horse carried him into the city and back in two hours. He came into the lady's presence bowing and grinning, the very picture of a sleek, good-natured, well-fed darkey.

"Did you see him, John?"

"Yaas'm, I see him," grinned John, his hands in his pockets complacently jingling the nickels his young master had just bestowed on him.

"You gave him my message? What did he say?"

"Yaas'm; he say as how"—here John stopped jingling his nickels long enough to make a low dip of his woolly head, as befitting the proper deliverance of the message he had—"he will do heself de hon'r ob takin' tea wid you dis even."

"Was that all he said?"

"All he says to you, ma'am—he ast me how come I stay 'long wid ole mis' all dis time, and not go off like do rest of de little nigs? I tell him——"

Here John stopped to chuckle softly at the remembrance.

"Well, you told him what?"

"As how old mis' couldn't git 'long 'thout me nohow," and here John turned and made a hasty exit in obedience to a "Go along, you impudent little monkey!" from the said "ole mis'."

He was at the gate that evening, ready to take his master's horse when he cantered up in the gloom of the overcast sunset.

"Glad to see you, Marse Bruce. Hopes you've come to stay. De ole place nuvver seemed like home without you," said the young darkey, who as a boy had blacked Bruce Conway's boots, run his errands, served as an escape-valve for all his ill humors, and withal adored him, now welcoming him home with the hearty affection that was so deeply rooted in his simple nature.

Freedom had not spoiled John in the least—possibly because so far as kind treatment and almost unlimited indulgence went, he had been free all his life.

But the young man merely threw him the reins, and with a careless "Take good care of him, John," walked off in the direction of the house.

"Humph!" commented the merry little darkey, as he led the horse off to the stable. "Sulky! I dersay he's come to give[Pg 33] the madam fits for lettin' of his sweetheart git married afore he come back. Serves him right, though. Why didn't he marry her fust, and take her 'long wid him to that furrin parts? Poor, pretty little dear! she did look just like an angel las' night, and they do say Marse Bruce took on some when he seen her."

For the servants had all been woefully disappointed when Bruce hurried off to Europe without the grand wedding that the cook had prophesied would take place between himself and Miss Grey; and the story of the last night's contretemps having been duly rumored from parlor to kitchen, was the all-absorbing subject of comment between cook, chambermaid, and boy-of-all-work—their sympathies and indignation being in such a fluctuating state just now that they could hardly decide who was the most deserving of their sympathy—the young man who, as they phrased it, had gone off and apparently jilted his sweetheart, or the young lady whom he had returned to find had really jilted him.

And the young man who was furnishing food for so much feminine gossip and conjecture that day, quite heedless of it all, walked on up the steps and into the stately presence of his expectant aunt.

She came forward very cordially, concealing any possible annoyance she felt under an appearance of affection. She began to see that reproaches and anger were not the way to bring this vacillating, reckless young fellow to his senses.

"I trust you are feeling well after your fatigue of last evening," he pleasantly observed, as they shook hands.

"No, I cannot say that I am. I have had no sleep, and felt worried and anxious about you, my dear boy."

"I am sorry to have caused you any such annoyance," he answered, repentantly, throwing himself wearily among the cushions of a luxurious sofa—"very sorry, indeed, Aunt Conway. I am not worth being a source of anxiety to any one."

The inflection of sadness and weariness in his tone touched her heart, and swept away all lingering resentments. She looked at him as he lay among the bright embroidered cushions, looking so handsome, yet so worn and hopeless, and her womanly pity found vent in the simple words:

"My poor boy!"

"Don't pity me!" he answered, impatiently. "I am not deserving of pity, and I don't want it. A man must sink very low, indeed, to become the object of a woman's pity."

What a strange mood he was in! Accustomed to him as she was, she could not fathom him this evening. She folded her hands in her lap and looked at him wistfully. He grew restless under her gaze, shifting his position so that the light should not strike on his features.

"You sent for me to give me a scolding, I suppose," he said, with a short, dry laugh. "I am here to receive it."

"I did not," she answered. "I sent for you because this is your home, and I want you to stay with me if you will. It is very lonely here with no one of my kindred, Bruce, and I am getting to be quite an old woman now. Why cannot you give me the solace of your company and affection for my few remaining years?"

"My affection!"

No words can do justice to the reckless cynicism of his look and tone.

"Aunt Conway, I have very little affection to give any one. My heart seems dead in my bosom. I came home, so full of noble resolves, so full of hope, that my downfall has almost banished reason from its throne. And as for my company, I fear I cannot even give you that. I owe it to myself, to you, more than all to the wife of Senator Winans, to take myself away from here, where no sight of me can recall my injustice to her, and my crowning folly of last night."

"Bruce!"

"Well?"

"You shall not talk so—shall not leave me again. Let Mrs. Winans alone. You have been in banishment three—nay, four years for her already. You shall not go again. Norfolk is surely large enough for you two to live in without crossing the path of each other. As for what happened last night, it is rather mortifying, but it will soon be forgotten. Stay with me, Bruce; there are plenty of beauties in Norfolk who will soon teach you to forget Mrs. Winans."

"Forget her! Is it likely, when the prevailing topic of Norfolk is the lovely Mrs. Winans, the brilliant Mrs. Winans, the[Pg 35] accomplished Mrs. Winans, with her accomplishments of fashion and folly? It seems quite the fashion to talk about her now. No, Aunt Conway, you cannot dissuade me from my purpose. I shall go away from here until I can learn to be a man. Here I renounce my ill-fated love for her, and pledge myself to forget her as an honorable man should do."

His aunt looked at him, her regret and pain mingled with admiration. He looked so noble, so proud, so manly as he spoke, that for a moment she felt a pang at the thought of the wrong she had done; for that she had done wrong she knew full well. She had known of her nephew's passionate love for Grace Grey and knew that with her he would have found all the happiness that is vouchsafed to mortals. But for a scruple of worldly pride and position she had separated them, punishing herself thereby; for in the long years of his banishment she had felt too truly that she had, in tearing apart those two loving hearts, bitterly wounded her own. The repressed longing for her boy, the pain of knowing herself unloved and uncared for, had been a daily thorn in her heart, a wound

For a moment, as she looked at him in his manly beauty and brave renunciation, a better impulse stirred her heart, and thinking of the fair young creature who had made such sunlight in this dreary, splendid home, a vague wish came into her soul that she had let them have their way, and not so rudely sundered what God had joined together.

Too late! When we take it upon ourselves to shape the life-destinies of others we must not expect to undo our work when we find it completed and unsatisfactory to us. When we see the hearts that our intermeddling has bruised and torn go from us hungry and empty we must not expect them to turn to us for the happiness we denied them.

Oh, fathers and mothers, maneuvering sisters, aunts, and relatives, when the young birds are mating and building, why cannot you let them alone? Why cannot you understand that your special experience and wisdom were given you by God for your guidance alone, and that every one cannot walk the same[Pg 36] chalked-out path, that every thinking, living mind must choose for itself whether or not it be wisely or well?

"As we make our beds we lie" has passed into a truth, but is it likely that any other will make it better for us than we try to do for ourselves? To be plain, no one has a right to dictate to us the way we are to walk in life; or, if they have, why has God given to every one of us thinking, reasoning, yearning minds, capable of knowing what we want and what we need better than any one can know for us?

"Bruce," she said, gently, "I have wronged you, you know. It was wrong of me to tempt you with my gold to desert the girl you loved, and who loved you. I never felt until this hour how basely I had acted. If I could undo my work I would. But I trust you may yet find happiness, and that the memory of all this suffering may pass from your soul as rain-drops from a rose, leaving it brighter and lovelier after the storm."

"Nay," he said, smiling faintly and sadly, "since you have descended to simile, let me remind you that there are two sides thereto. How often have I seen in this lovely garden of yours the crushed rose-leaves covering the ground, rain-beaten, pallid, and torn, as the storm had passed and left them. So it is most likely to be with me."

"I trust not. At any rate, Bruce, I ask your forgiveness. It is asking much, I know, when I reflect that but for me you would have wedded the girl you loved, and who, through my fault, is irrevocably lost to you. But you are all I have to love—all I have to love! Don't deny me."

"I do not," he answered, slowly. "Don't blame yourself entirely Aunt Conway. Blame my weak, wavering, vacillating will, that made me hesitate between Grace Grey and the noble inheritance you offered me. We are about equal, I think. I sold myself—you bought me!"

Oh, Grace, you are avenged! Deeply as you scorned him your contempt was not deeper than that which in this hour he felt for himself.

"I thank you, Bruce, dear boy, that you do not accord me all the blame, though I feel I fully deserve it. Let us change the subject to one more pleasant."

"In one moment, but first I have a confession to make. You may hear it from others, so I would like you to hear it first from me. You know that I am truthful, though unstable, and you can believe just what I say—not all the varnished reports you may hear."

"Go on," she said anxiously, as he paused.

"Well, then, I left you last night in a bad state of mind. I was mad, I think—simply mad—and in Norfolk I took more wine than was good for me. I swore to myself that I would not give up Grace. I hated her husband for having won her—I hated the child that calls her mother and him father—I hated you for separating us, and I swore that as she had loved me once she should love me again. Under the influence of this madness I took a guitar and sung under the window of the grand Winans' mansion a love-song—yes, aunt," laughing a little as she recoiled in dismay, "I dared to sing a love-song—I dared to serenade the married belle of society and queen of beauty with a love-song she had sung for me on the eve of our parting four years ago."

"Oh, Bruce! what have you done?"

"Gotten myself into a difficulty, perhaps. The question is, did they hear me, or were they all asleep? If they heard and know me, I have undoubtedly provoked the wrath of that haughty Senator who calls her his own. I propose to extricate myself from this dilemma by leaving the place as quietly as I returned; not through cowardice, Aunt Conway, I won't have you think that," his eye flashed proudly, "but because I have caused her trouble enough already. I'll not stay here to bring further trouble and comment upon her. I won't have her pure name dragged through the scandal of an affair of honor. The only thing is to go away—that is the only reparation I can make, to go away and forget her, and be myself forgotten."

There was much that was noble in him yet; much that was high-toned, chivalric, high-spirited, and tender—all of it, alas, marred by that vacillating will, that wavering, doubting nature that was so long in making its mind up, and when made up soon changed it again.

The tea-bell suspended further converse on the subject. He gave her his arm in courtly fashion, and they descended to the[Pg 38] dining-room, both too preoccupied to observe the curious kindly black faces that peeped at them from obscure stations, eager to see the handsome young master they remembered so well, and to see how he looked "since he'd come back and found his sweetheart married and gone," as if people wore their hearts in their faces. Ah, if they did what a gruesome looking crowd would meet us whithersoever we went.

Dainty and elegant as was the evening meal, I think Bruce Conway and his handsome old aunt scarcely did justice to it. Her callous, worldly heart was stirred as it had not been for years. For Bruce, I think he might as well have eaten chips for all he enjoyed the spring chicken, the pickled oysters, the rosy ham, and warmly-browned biscuit, the golden honey and preserves, the luscious fruits, the fragrant tea and chocolate. Across the glimmer of flowers, and silver, and dainty cut-glass, and edibles, a shadowy form sat in the vacant chair at the opposite side of the table, which had been the wonted place of the rosy reality. A girl's fair face looked across at him, her white hands trifled with the silver knife and fork, reached the preserve across to him, poured the cream into his tea, showed him a dozen kindly attentions, and once he said, absently, "No, I thank you, Grace," and looked up into the shiny black face of John, who was changing his plates for him, and who nearly exploded with repressed laughter, but said, with mock earnestness, and a pretense of misapprehension:

"Ole mis' nuvver say Grace afore meals, Marse Bruce, cepen' 'tis when de minister stays to tea, sir."

"Leave the room, you young scamp," said Mr. Conway, irascibly, and John went, nothing loth to indulge himself in a fit of laughter at the expense of his beloved young "Marse Bruce." But the little incident served to make Bruce more wide-awake, and rousing himself to realities the pansy-eyed phantom fled away from Mrs. Conway's well-appointed table.

"That boy is a perfect clown," complained the lady; "he's not fit to wait on the table at all. I shall have to secure a good dining-room servant."

Mrs. Conway had said this so often that there was small danger of its being put into execution. She was attached in a great degree to the servants around her, all of whom had belonged to[Pg 39] her in the days of slavery, and who when "set free," during the war, had, unlike the majority of the freedmen who sought new homes, promptly taken service at extravagant wages from their whilom mistress and owner. John had grown up to his seventeenth year in the service of his indulgent "ole miss," and he was fully persuaded of the interesting fact that she "couldn't do 'thout him, nohow."

After tea the two repaired to the brightly lighted drawing-room. The dull damp day rendered the closed shutters rather agreeable than otherwise, and shut out thus, from the sight of much that would have pained him, the young man made an effort to entertain his aunt, narrating many of his adventures abroad, and interesting an unthought-of listener, who was lazily curled up outside the door listening to the sprightly converse of the returned traveler.

"Wonder if all dat kin be true," pondered John, dubiously; "but course 'tis, if Marse Bruce says so. John Andrew Jackson Johnson, you ain't fitten to be a Conway nigger if you can't believe what your young gentleman tells," and thus apostrophizing himself, John relapsed into silence. Nevertheless, his mouth and eyes during the next hour were often extended to their utmost capacity, and I fear that if any other than Bruce Conway had presumed to relate such remarkable things, John would have been tempted to doubt his veracity.

A sharp peal of the door-bell compelled him to forego his pleasant occupation to answer it. He came back with a card on a silver salver.

"Gentl'man to see Marse Bruce; showed him into libr'y, sir; he wished to see you 'lone, sir," announced John, with much dignity.

Mr. Conway took the card, and Mrs. Conway looked over his shoulder.

"Captain Frank Fontenay, U. S. A.," he read aloud, and Mrs. Conway said:

"A military gentleman—who is he, Bruce? I don't know him."

"Nor I," said her nephew, grimly.

He was white as marble, but his dark eyes never wavered in their firm, cold glitter. Whatever else he was, Bruce Conway[Pg 40] was not a coward. He gently released himself from his aunt's detaining hand.

"I will go and see this gentleman," he said.

"Oh, Bruce!"—she clung to him in a nervous, hysterical tremor—"I feel as if something dreadful were going to happen. Don't see him at all."

He smiled at her womanly fears.

"My dear aunt, don't be hysterical. John, call Mrs. Conway's maid to attend her. Aunt Conway, there is nothing to alarm you—nothing at all;" and, putting her back on her sofa, he went out to meet his unbidden guest.

The captain was a fine-looking man, of perhaps forty years, blue-eyed, blonde-haired, and much be-whiskered. He stood very courteously in the middle of the floor, hat in hand, as Bruce entered the library.

"Mr. Conway?" he interrogated, smoothly.

"At your service, sir," said Bruce.

"Mr. Conway," said the gentleman, with a glittering smile that showed all his lovely white teeth, "I am the bearer to you of a message from Senator Winans. My friend, sir, considers himself insulted by you, and demands such satisfaction as all gentlemen accord each other."

He placed an open note in Mr. Conway's hand, who silently perused it.

It was a challenge to fight a duel.