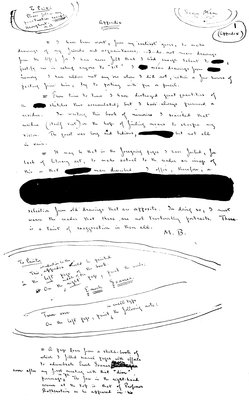

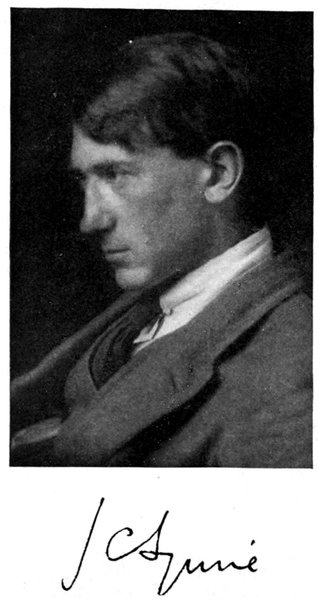

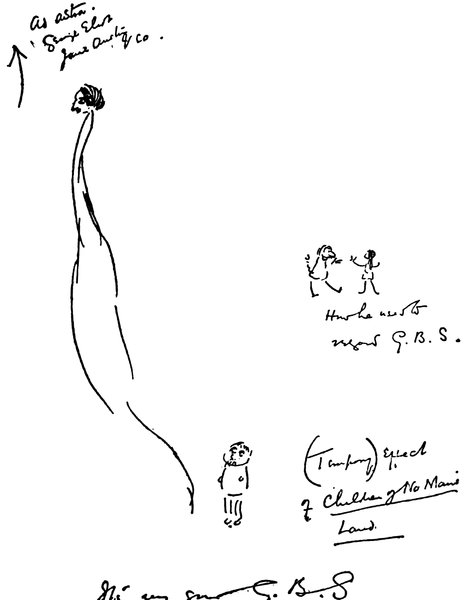

A PAGE FROM THE MANUSCRIPT OF MAX BEERBOHM’S “SEVEN MEN”

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Borzoi 1920, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Borzoi 1920

Being a sort of record of five years' publishing

Author: Various

Release Date: January 17, 2017 [EBook #53979]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BORZOI 1920 ***

Produced by Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Many readers have doubtless long been familiar with the catalogs issued now and again by European publishers—no bare lists of authors and titles, but such wholly charming productions as, for example, the annual almanacks of the Insel-Verlag of Leipzig. As I approached the conclusion of my first five years’ publishing it seemed to me—in view of the uncommon friendliness of so many readers—that they, at any rate, would perhaps receive with favor a more permanent record of the early activities of the Borzoi than it would be possible to present in the usual sort of American publisher’s announcement. Authors—may I say my authors?—greeted the idea with such enthusiasm (how generous their coöperation the following pages abundantly testify) that it soon took fairly definite shape. The original papers are of course the real excuse for The Borzoi 1920, while the balance of the book is intended simply to be useful—to the individual reader, the bookseller, and the librarian. I have tried to make the bibliography complete, but the Who’s Who is confined to writers who are, I hope, more or less definitely associated with my list (and from whom I could get the necessary information).

My best thanks are due many for whatever success Borzoi Books may have achieved. Those, first, who wrote them, and especially the generous contributors to this volume; the booksellers, who have been both friendly and intelligent in their coöperation; the critics who have been for the most part both understanding and encouraging; the loyal co-workers in my own office; and last, but not least, the readers who have made the whole venture possible.

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Maxim Gorky | ix |

| PART ONE | ||

| WRITTEN ESPECIALLY FOR THE BORZOI 1920 | 1 | |

| The Movies | Claude Bragdon | 3 |

| Maxwell Bodenheim | Witter Bynner | 6 |

| On the Art of Fiction | Willa Cather | 7 |

| Astonishing Psychic Experience | Clarence Day, Jr. | 9 |

| Max Beerbohm | Floyd Dell | 12 |

| Joseph Hergesheimer | Wilson Follett | 15 |

| On Drawing | A. P. Herbert | 20 |

| A Note on the Chinese Poems translated by Arthur Waley | Joseph Hergesheimer | 24 |

| Willa Cather | H. L. Mencken | 28 |

| Van Vechten | Philip Moeller | 32 |

| On H. L. Mencken | George Jean Nathan | 34 |

| A Sketch | Sidney L. Nyburg | 37 |

| Chant of the Nurses | Eunice Tietjens | 41 |

| A Memory of Ypres | H. M. Tomlinson | 42 |

| On the Advantages of Being Born on the Seventeenth of June | Carl Van Vechten | 48 |

| The Master of the Five Willows | Arthur Waley | 52 |

| PART TWO | ||

| A BRIEF WHO’S WHO OF WRITERS PARTICULARLY IDENTIFIED WITH THE BORZOI | 53 | |

| PART THREE | ||

| SELECTED PASSAGES FROM BORZOI BOOKS | 63 | |

| How He Died | Conrad Aiken | 65 |

| From “Youth and Egolatry” | Pío Baroja | 68 |

| From “The Romantic Woman” | Mary Borden | 71 |

| October | Robert Bridges | 74 |

| “Letters of a Javanese Princess” | Louis Couperas | 75 |

| April Charms | William H. Davies | 79 |

| A page from “The Three Mulla Mulgars” | Walter de la Mare | 80 |

| Burbank with a Baedeker; Bleistein with a Cigar | T. S. Eliot | 81 |

| From “Where Angels Fear to Tread” | E. M. Forster | 83 |

| Dorothy Easton’s “The Golden Bird” | John Galsworthy | 86 |

| War and the Small Nations | Kahlil Gibran | 88 |

| A First Review | Robert Graves | 89 |

| Joe Ward | E. W. Howe | 90 |

| Doc Robinson | E. W. Howe | 92 |

| John Davis | E. W. Howe | 92 |

| Concerning “A Little Boy Lost” | W. H. Hudson | 93 |

| Ancient Music | Ezra Pound | 96 |

| Fire and the Heart of Man | J. C. Squire | 97 |

| Preface to “Deliverance” | E. L. Grant Watson | 101 |

| PART FOUR | ||

| A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ALL BORZOI BOOKS FROM 25 SEPTEMBER 1915 TO 25 SEPTEMBER 1920 | 103 | |

| Postscript | 133 | |

| A Page from the Manuscript of Max Beerbohm’s “Seven Men” | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Witter Bynner | 6 |

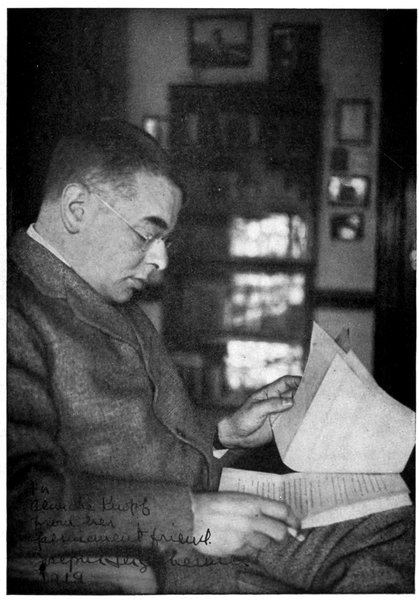

| Floyd Dell | 12 |

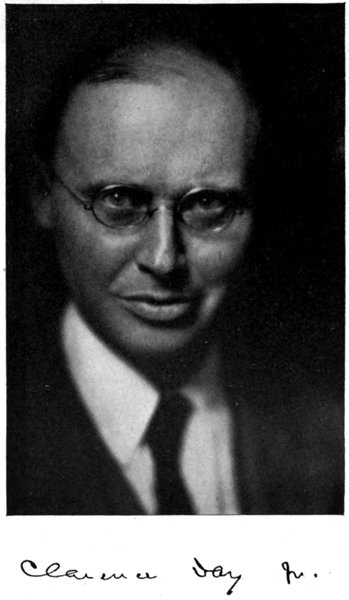

| Clarence Day, Jr. | 12 |

| Joseph Hergesheimer | 15 |

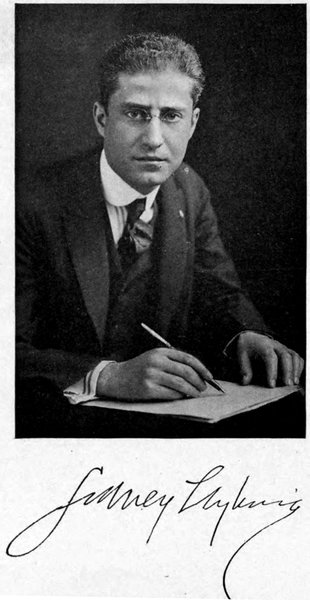

| Sidney L. Nyburg | 28 |

| Willa Cather | 28 |

| Carl Van Vechten | 32 |

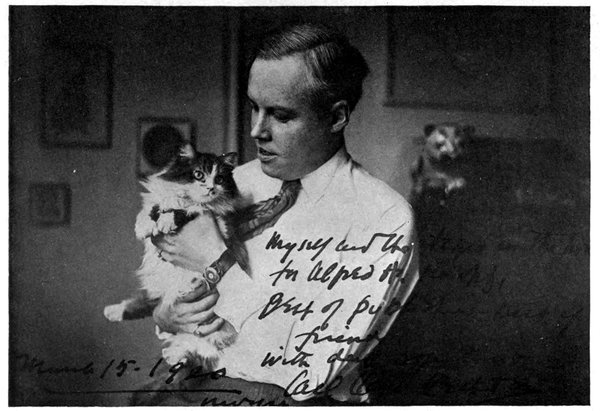

| H. L. Mencken | 34 |

| George Jean Nathan | 34 |

| Eunice Tietjens | 41 |

| Pío Baroja | 41 |

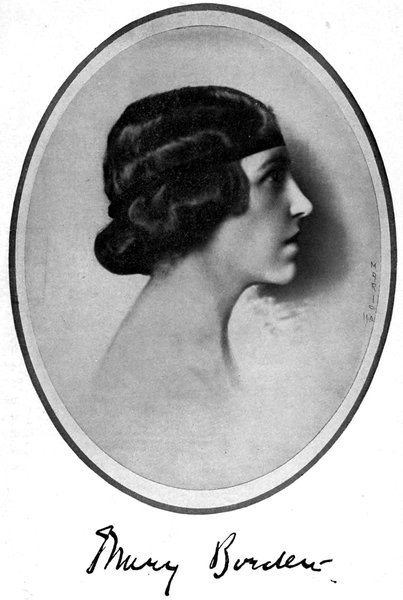

| Mary Borden | 72 |

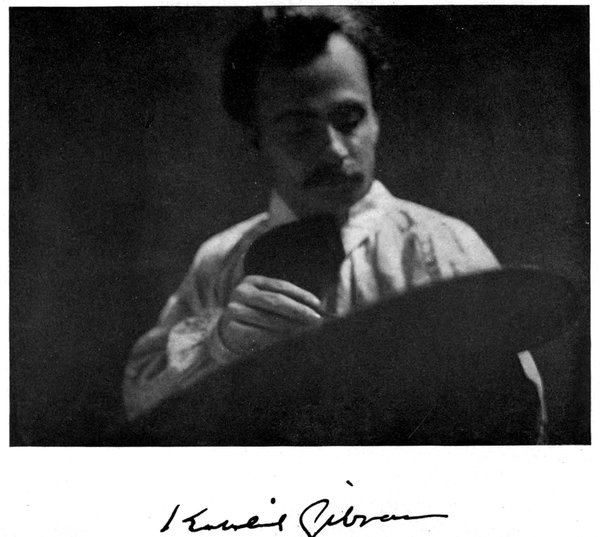

| Kahlil Gibran | 89 |

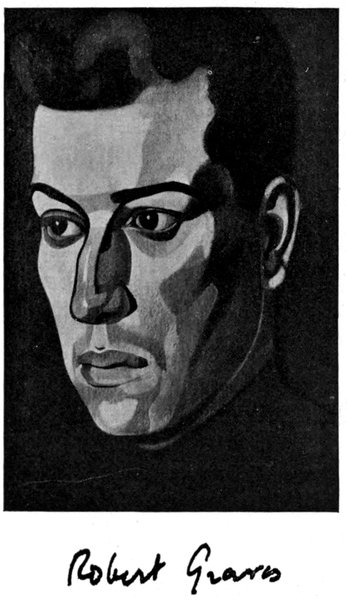

| Robert Graves | 90 |

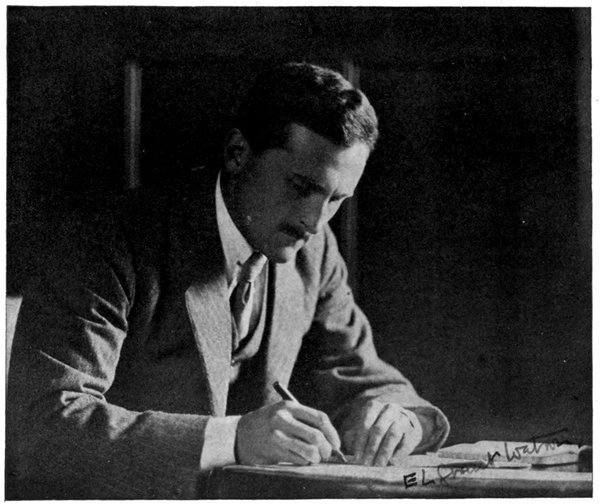

| J. C. Squire | 90 |

| E. L. Grant Watson | 102 |

[The following—reprinted from the Athenæum (London) of June 11th, 1920, and translated by S. Kotliansky is part of Gorky’s preface to the first catalogue of “World Literature,” the publishing house founded by him under the auspices of the Bolshevik government. It is reprinted here as a plea, as noble as it is typical of Gorky, for good books.

Is it necessary to speak of the necessity of a serious study of literature, or at least of a wide acquaintance with it? Literature is the heart of the world, winged with all its joys and sorrows, with all the dreams and hopes of men, with their despair and wrath, with their reverence before the beauty of nature, their fears in face of her mysteries. This heart throbs violently and eternally with the thirst of self-knowledge, as though in it all those substances and forces of nature that have created the human personality as the highest expression of their complexity and wisdom aspired to clarify the meaning and aim of life.

Literature may also be called the all-seeing eye of the world, whose glance penetrates into the deepest recesses of the human spirit. A book—so simple a thing and so familiar—is, essentially, one of the great and mysterious wonders of the world. Some one unknown to us, sometimes speaking an incomprehensible language, hundreds of miles away, has drawn on paper various combinations of a score or so of signs, which we call letters, and when we look at them, we strangers, remote from the creator of the book, mysteriously perceive the meaning of all the words, the ideas, the feelings, the images; we admire the description of the scenes of nature, take delight in the beautiful rhythm of speech, the music of the words. Moved to tears, angry, dreaming, sometimes laughing over xthe motley printed sheets, we grasp the life of the spirit, akin or foreign to ourselves. The book is, perhaps, the most complicated and mightiest of all the miracles created by man on his path to the happiness and power of the future.

There is no one universal literature, for there is yet no language common to all, but all literary creation, in prose and poetry, is saturated with the unity of feelings, thoughts, ideals shared by all men, with the unity of man’s sacred aspiration towards the joy of the freedom of the spirit, with the unity of man’s disgust at the miseries of life, the unity of his hopes of the possibility of higher forms of life, and with the universal thirst for something indefinable in word or thought, hardly to be grasped by feeling, that mysterious something to which we give the pale name of beauty, and which comes to an ever brighter and more joyous flower in the world, in our own hearts.

Whatever may be the inward differences of nations, races, individualities, however distinct may be the external forms of states, religious conceptions and customs, however irreconcilable the conflict of classes—over all these differences, created by ourselves through centuries, hovers the dark and menacing spectre of the universal consciousness of the tragic quality of life and the poignant sense of the loneliness of man in the world.

Rising from the mystery of birth, we plunge into the mystery of death. Together with our planet we have been thrown into incomprehensible space. We call it the Universe, but we have no precise conception of it, and our loneliness in it has such an ironical perfection that we have nothing with which to compare it.

The loneliness of man in the Universe and on the earth, which is to many “a desert, alas! not unpeopled”—on earth amid the most tormenting contradiction of desires and possibilities—is realized only by few. But the faint feeling of it xiis implanted in the instinct of nearly every man like a noxious weed, and it often poisons the lives of men who appear to be perfectly immune from that murderous nostalgia which is the same for all ages and peoples, which tormented equally Byron the Englishman, Leopardi the Italian, the writer of “Ecclesiastes,” and Lao-Tse, the great sage of Asia.

This anguish that arises from the dim sense of the precariousness and tragedy of life is common to great and small, to every one who has the courage to look at life with open eyes. And if a time is to come when men will have overcome this anguish and stifled in themselves the consciousness of tragedy and loneliness, they will achieve that victory only by the way of spiritual creation, only by the combined efforts of literature and science.

Besides its envelope of air and light all our earth is surrounded with a sphere of spiritual creativeness, with the multifarious rainbow emanation of our energy, out of which is woven, forged or moulded all that is immortally beautiful; out of which are created the mightiest ideas and the enchanting complexity of our machines, the amazing temples and tunnels that pierce the rock of great mountains, books, pictures, poems, millions of tons of iron flung as bridges across wide rivers, suspended with such miraculous lightness in the air—all the stern and lovely, all the mighty and tender poetry of our life.

By the victory of the mind and will over the elements of nature and the animal in man, striking out ever brighter sparks of hope from the iron wall of the unknown, we men can speak with legitimate joy of the planetary significance of the great efforts of our spirit, most resplendently and powerfully expressed in literary and scientific creation.

The great virtue of literature is that by deepening our consciousness, by widening our perception of life, by giving shape to our feelings, it speaks to us as with a voice saying: All ideals and acts, all the world of the spirit is created out of xiithe blood and nerves of men. It tells us that Hen-Toy, the Chinaman, is as agonizingly unsatisfied with the love of woman as Don Juan, the Spaniard; that the Abyssinian sings the same songs of the sorrows and joys of love as the Frenchman; that there is an equal pathos in the love of a Japanese Geisha and Manon Lescaut; that man’s longing to find in woman the other half of his soul has burned and burns with an equal flame men of all lands, all times.

A murderer in Asia is as loathsome as in Europe; the Russian miser Plushkin is as pitiable as the French Grandet; the Tartufes of all countries are alike, Misanthropes are equally miserable everywhere, and everywhere every one is equally charmed by the touching image of Don Quixote, the Knight of the Spirit. And after all, all men, in all languages, always speak of the same things, of themselves and their fate. Men of brute instincts are everywhere alike, the world of the intellect alone is infinitely varied.

With a clearness irresistibly convincing, fine literature gives us all these innumerable likenesses and infinite varieties—literature, the pulsing mirror of life, reflecting with quiet sadness or with anger, with the kindly laugh of a Dickens or the frightful grimace of Dostoevsky, all the complications of our spiritual life, the whole world of our desires, the bottomless stagnant pools of banality and folly, our heroism and cowardice in the face of destiny, the courage of love and the strength of hatred, all the nastiness of our hypocrisy and the shameful abundance of lies, the disgusting stagnation of our minds and our endless agonies, our thrilling hopes and sacred dreams—all by which the world lives, all that quivers in the hearts of men. Watching man with the eyes of a sensitive friend, or with the stern glance of a judge, sympathizing with him, laughing at him, admiring his courage, cursing his nullity—literature rises above life, and, together with science, lights up for men the paths to the achievement of their goals, to the development of what is good in them.

xiiiAt times enchanted with the beautiful aloofness of science, literature may become infatuated with a dogma, and then we see Emile Zola viewing man only as a “belly,” constructed “with charming coarseness,” and we also see how the cold despair of Du Bois Reymond infects so great an artist as Gustave Flaubert.

It is obvious that literature cannot be completely free from what Turgeniev called “the pressure of time”; it is natural, for “sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.” And it may be that the evil of the day poisons more often than it should the sacred spirit of beauty, and our search for its “inspirations and prayers”; these inspirations and prayers are poisoned by the venomous dust of the day. But “the beautiful is the rare,” as Edmond Goncourt justly said, and we most certainly often consider lacking in beauty and insignificant habitual things—those habitual things which, as they recede into the past, acquire for our descendants all the marks and qualities of true, unfading beauty. Does not the austere life of ancient Greece appear to us beautiful? Does not the bloody, stormy and creative epoch of the Renaissance with all its “habitual” cruelty enrapture us? It is more than probable that the great days of the social catastrophe we are going through now will arouse the ecstasy, awe and creativeness of the generations that will come after us.

Nor let us forget that though Balzac’s “Poor Relations,” Gogol’s “Dead Souls,” “The Pickwick Papers,” are essentially books that describe conditions of actual life, there is hidden in them a great and imperishable lesson which the best university cannot provide, and which an average man will not have learnt so exactly or so clearly after fifty years of hard-working life.

The habitual is not always banal, for it is habitual for man to be consumed in the hell fire of his vocation, and this self-consumption is always beautiful and necessary, as it is instructive for those who timidly smoulder all their life long, without xivblazing up in the bright flame that destroys the man and illuminates the mysteries of his spirit.

Human errors are not so characteristic of the art of the word and image; more characteristic is its longing to raise man above the external conditions of existence, to free him from the fetters of the degrading actuality, to show him to himself not as the slave, but as the lord of circumstance, the free creator of life, and in this sense literature is ever revolutionary.

By the mighty effort of genius rising about all circumstances of actuality, saturated with the spirit of humanity, kindling its hatred from the excess of passionate love, fine literature, prose and poetry, is our great vindication, and not our condemnation. It knows that there are no guilty—although everything is in man, everything is from man. The cruel contradictions of life that arouse the enmity and hatred of nations, classes, individuals, are to literature only an inveterate error, and she believes that the ennobled will of men can and must destroy all errors, all that which, arresting the free development of the spirit, delivers man into the power of animal instincts.

When you look closely into the mighty stream of creative energy embodied in the word and image, you feel and believe that the great purpose of this stream is to wash away for ever all the differences between races, nations, classes, and, by freeing men from the hard burden of the struggle with each other, to direct all their forces to the struggle with the mysterious forces of nature. And it seems that then the art of the word and image is and will be the religion of all mankind—a religion that absorbs everything that is written in the sacred writings of ancient India, in the Zend-Avesta, in the Gospels and Koran.

I must protest against the movies, though I be stoned to death for it in the middle of Longacre Square.

My sight is either jaundiced or clairvoyant: which, I leave the reader to decide.

Strip life of its color, mystery, infinitude; make it stale, make it grey, make it flat; rob the human being of his aura, deny him speech, quicken his movements into galvanic action; people a glaring parallelogram with these gigantic simulacra of men and women moved by sub-human motives; drug the tormented nerves with music, so that the audience shall not go mad—this is the movie as it is to me.

The other day I read a panegyric on the most beautiful of all moving pictures. I forced myself to sit through it though I could scarcely forbear shrieking aloud. It was an amusement seemingly devised for devils in hell.

Only degradation of the soul and a vast despondency result from this seeking joy in the pictured suffering wickedness, weakness of others; in this orgy of sex-sentimentality, silliness, meaningless violence. Such amusement either depraves the mind or arrests its action, and makes of the heart a mechanical toy which must be shaken violently before it will act.

Why do people go to the movies? Because their caged souls seek forgetfulness and joy as insistently as blind eyes yearn for light. But joy is such a stranger to them that they ignorantly mistake this owl-eyed Monster of Darkness for the Blue Bird of Happiness. I have asked many why they go to 4the movies, and have heard many reasons—most of them bad—but one answer recurs like a refrain: “There isn’t any thing else to do.” It reminds me of John Russel’s reason why Eliza (of Uncle Tom’s Cabin) crossed the river on the ice. “The poor girl had no other place to go—all the saloons were closed.”

Today all the saloons are closed, and professional philanthropy prides itself on the fact that more men go now to the movies. The saloon was an evil institution, but the prostitution of the mind is worse than any poisoning of the nerves.

The priests of the temple of the Movie Momus do not know that they are offering a form of amusement which stifles the mind and hardens the heart. Doubtless they believe the contrary, but it is a case of the blind led by the blind: Neither know where they are going, and each depends upon the other to lead the way. Producers, impresarios, scenario-writers have always their ears to the ground to catch the first faint rumble of condemnation or approval. Their business is frankly to assimilate the popular taste in order to reproduce it. But this taste is fickle, being that of a child with a digestion impaired by too much of the wrong kind of food. The movie public is like the Athenian populace always eager for “some new thing,” and like the Roman mob it shows an insatiable greed for danger (to others) cruelty and destruction. Of daring it demands more daring; of beauty more nudity; of wickedness a deeper depth of wickedness; scenery must be ever more sumptuous, orgies more orgiastic, violence more violent. Lacking anything to turn its imagination away from these things, into some new channel, the public can only build high and higher this particular house of cards.

There is a great deal talked and written about the “educational value” of the movies, and this acts as a deterrent to many persons who are minded, as I am, to denounce this evil in the market place. But such deceive themselves with the 5word “education,” forgetting that mankind is one. In order that some may learn easily a few merely physical facts, such people countenance and support an institution that eats at the very heart of the spirit of man.

I hear in anticipation the crushing argument against my point of view: The Movies constitute the fourth largest industry in the world; they command the respect of governments, the service of the press, the participation of captains of industry, cabinet members, international bankers. But all this is quite beside the point, and reminds me of the answer once given to my criticism of an absurd soldiers’ monument: “It cost fifty thousand dollars and was carved out of a single piece of granite that weighed ten tons.”

The Movies too are carved out of a single piece of granite: the granite of ignorance of the obscure spiritual forces now active in the secret hearts of men.

On a vast scale, in infinite variety of detail, the Movies show

May not the unforeseen, amazing, ultimate result be to recoil in horror from the image there presented? The Movies represent the quest of joy aborted. Perhaps their true purpose is to bring bitter, but salutary knowledge.

While poets have been placed by the critics in this or that category and have lent themselves more or less to the indignity, Maxwell Bodenheim has continued as he began, a poet of disturbing originality. Whether you like him or not, you cannot evade him. Let him once touch you and a perfume is upon you, pungent and yet faint, offensive and yet delicate, of the street and yet exotic. It is as if Pierian springs bubbled crystalline from the nearest sewer, forcing from you a puzzled and troubled enjoyment. It is as if a diamond leered or a rose exhaled sulphur or a humming-bird lanced your self-respect. It is a drunken thief’s hand, still deft, in the poetic treasury; nuances pouring Niagaran; sensibilities crowding in masquerade; madness mocking sanity; ideas dancing nude through confetti; a falsetto growl; a whispered song; a rainbow in the loose:—and yet, all the while a human eye watching the incredible kaleidoscope, an eye that sees and makes you see likewise, good and evil, beauty and pain, opposing and commingling their designs. Historically Bodenheim’s work is likely to share with Donald Evans’ very different “Sonnets from the Patagonian” the distinction of having initiated in American poetry for better or worse the season and influence of fantastic impressionism. Evans has now become almost orthodox, his green orchid is put away; but Bodenheim still wears in his lapel the coloured ghost of a butterfly-wing whose veinings mock at human progress.

One is sometimes asked about the “obstacles” that confront young writers who are trying to do good work. I should say the greatest obstacles that writers today have to get over, are the dazzling journalistic successes of twenty years ago, stories that surprised and delighted by their sharp photographic detail and that were really nothing more than lively pieces of reporting. The whole aim of that school of writing was novelty—never a very important thing in art. They gave us, altogether, poor standards—taught us to multiply our ideas instead of to condense them. They tried to make a story out of every theme that occurred to them and to get returns on every situation that suggested itself. They got returns, of a kind. But their work, when one looks back on it, now that the novelty upon which they counted so much is gone, is journalistic and thin. The especial merit of a good reportorial story is that it shall be intensely interesting and pertinent today and shall have lost its point by tomorrow.

Art, it seems to me, should simplify. That, indeed, is very nearly the whole of the higher artistic process; finding what conventions of form and what detail one can do without and yet preserve the spirit of the whole—so that all that one has suppressed and cut away is there to the reader’s consciousness as much as if it were in type on the page. Millet had done hundreds of sketches of peasants sowing grain, some of them very complicated and interesting, but when he came to 8paint the spirit of them all into one picture, “The Sower,” the composition is so simple that it seems inevitable. All the discarded sketches that went before made the picture what it finally became, and the process was all the time one of simplifying, of sacrificing many conceptions good in themselves for one that was better and more universal.

Any first rate novel or story must have in it the strength of a dozen fairly good stories that have been sacrificed to it. A good workman can’t be a cheap workman; he can’t be stingy about wasting material, and he cannot compromise. Writing ought either to be the manufacture of stories for which there is a market demand—a business as safe and commendable as making soap or breakfast foods—or it should be an art, which is always a search for something for which there is no market demand, something new and untried, where the values are intrinsic and have nothing to do with standardized values. The courage to go on without compromise does not come to a writer all at once—nor, for that matter, does the ability. Both are phases of natural development. In the beginning, the artist, like his public, is wedded to old forms, old ideals, and his vision is blurred by the memory of old delights he would like to recapture.

I have a friend who, when she hears a strange voice on the telephone, can visualize the person—that is to say, she sometimes can, if it interests her. She half-closes her eyes, tilts her head back, stares away off into space; and then she slowly describes the appearance of whoever is telephoning, almost as well as though he or she were standing before her. It is one of those supernatural gifts that seem to our times so startling.

The reason I mention this is, that though I hadn’t supposed I was that sort of person, I had one of these mysterious psychic visions myself, years ago. It came to me while I was reading Mr. Knopf’s first announcements of books. I had never seen the man, never heard a word of what he was like, yet his image suddenly arose clear as a photograph before my inner eye. There he stood, tall and thin, an elder statesman, with a bushy white beard; round, glowing eyes, ivory skin; an animated savant.

He spoke in his circulars as a man of great taste and authority. I pictured him as a French Academician of American birth.

Year by year as I read his new catalogs this image grew stronger. People would ask me, “Have you met this man Knopf?” and I would say: “No, I haven’t, but I can tell you what he’s like just the same. I’m a bit of a 10psychic.” And then I would describe my strange vision. This sometimes annoyed them: they would even ask, “But how do you know?” I would then describe the sense of quiet certitude that comes with such an experience.

Then one evening I met Mr. Knopf—in the flesh, as we phrase it. I found he had changed. He was more human, and in a way more impressive, but less picturesque. Instead of being tall and thin he was of medium-size, strong, and well-formed. And he wasn’t exactly what you’d call old: in fact he was in his twenties; and instead of a bushy white beard, he had only a small black moustache.

It is not for me to explain this astonishing and almost incredible discrepancy. I must leave that to the Psychical Research Society, to which I wish all success. The only way I can account for it is to suppose that Mr. Knopf has more than one personality. I admit I did not see in my vision the side he physically presents to the world. But it may be I am such a powerful psychic that I saw something deeper. I saw the more appropriate vehicle of his innermost soul.

We sat down for a talk. I tried out of courtesy not to use this power of mine any further. Even when I gave him my manuscript to publish, and we began to talk terms, I endeavoured not to peer into his heart. He gave me good terms however. He explained that his idea of a publishing house was a sort of a companionable enterprise, and that authors and publishers ought to be friends. They at least ought to try.

I carefully looked over his list to see who his author-friends were, and picked out one or two pretty rum ones and asked him about them. He admitted with composure that of course every man made mistakes. I said anxiously that I hoped I had made none in choosing him as my publisher. He said probably not; but it was harder for him to pick out the right 11authors. He added however that he had done very well—up to now.

We stared thoughtfully at each other....

I glanced at his list again. It did consist chiefly of quality belles lettres, after all. He really seemed to care about books. But then I wondered suspiciously if the very fact of his being so cultivated had made him a poor man of business. His appearance was certainly forceful and energetic, but nevertheless—

I decided to have one more vision. I half-closed my eyes, the way that friend of mine does, and tilted my head back. Mr. Knopf seemed surprised. I paid no attention to this, but coolly gazed right into his mind. It was a tall, roomy mind, with long rows of thoughts, like onions on rafters—thoughts of bindings and dogs and Archimedes and authors and what-not. In the middle was a huge pile of packing cases (mostly unopened) containing his plans and ambitions in the publishing world. I am sorry now I didn’t unpack a few to see what they were, but they looked pretty solid; and I was distracted by seeing, way over in a corner, his thoughts of myself. As these were at that time rather mixed, I prefer not to describe them. My catching sight of them at all was merely one of those unhappy annoyances that must often upset a seer’s life. It’s one of the risks of the business.

As I gazed on, indignantly, something drew across his mind like a truck, only even more massive. I presently discerned that it was a large strong intention to go. Simultaneously—for the man is well coordinated—he said good-bye and went out.

I was left there alone in my rooms, with my weird psychic gift. I may add that after a brief contemplation of it, I rang for the janitor, and in spite of his bitter objections, transferred it to him.

The very name of Max Beerbohm carries the mind back to the time when he first emerged as a literary figure—the time of the Yellow Book—the time of Whistler’s letters and Swinburne’s newest poem, of velvet jackets and plush knee-breeches, and foot-in-the-grave young poets who caroused mournfully at the sign of the Bodley Head. But it was above all the period of the Enoch Soameses who are celebrated by Max Beerbohm in his latest volume, “Seven Men”—an age of strange young Satanists who would be content with nothing less than founding a new English literature upon the cornerstone of their own thin sheaves of unintelligible poems. They are dead, now—they got tired of waiting for their immortality to begin—and forgotten, except for the wreaths of tender and ironic phrases which Max Beerbohm lays from time to time on their graves. He survives them, the Last of the Esthetes. And yet Enoch Soames would say bitterly that it was just like Fate that the Last of the Esthetes should be a man who never was an Esthete at all!

And there is something to the Enoch Soames point of view. Max Beerbohm’s title to Estheticism is rather precarious. His words may be the words of Dorian Grey, but the laughter behind them is surely the laughter of Huck Finn! Yes, under the jewelled stylistic cloak of Max Beerbohm, what do you find but the simple-hearted amusement of a healthy child? From the story of the Young Prince in “The Complete Works of Max Beerbohm,” to the celebrated Bathtub passage in “Zuleika Dobson,” the whole effect consists in the sudden substitution of the obvious for the recherché. You thought you were going to have to pretend to enjoy pickled nightingale’s tongues, and you find—greatly to your relief—that it is just ice-cream-and-cake!

13And yet his style cannot be said to be mere masquerade. Max Beerbohm, it is hardly to be doubted, loves the magic of word and phrase and rhythm as devoutly as any pure soul who ever took opium in an attic for art’s sake.

I like to think of Max Beerbohm as a boy who ran away to sea and was captured and brought up by a band of pirates. The pirates, you understand, are that romantic crew who embarked under the Yellow flag upon a career of ruthless literary destruction in the ‘Nineties, at a time when it seemed that the deeps of literature were given over to a peaceful and profitable traffic in morals and ethics, pieties and proprieties and puerilities. What havoc they did create! The royal Victorian navy, for all its literary big guns, was helpless against them. It was not, in fact, until Captains Gilbert and Sullivan sailed out against them in the good ship Patience that they received any serious setback! And if we go to the log-books of Gilbert and Sullivan for further information about this particular adventure, we shall find it, I think, in “The Pirates of Penzance”—where the tender and confident relations of the virtuous young hero and his piratical captors may serve as an illuminating picture of young Max Beerbohm in piratical captivity among the Esthetes.

He learned his manners from them; and a more graceful band of literary desperadoes never existed. Nothing could exceed the savoir faire with which they scuttled the traditions and made the familiar virtues walk the fatal plank. And so it is that when we read Max Beerbohm today, the superb gallantry of his style suggests that he is going to commit a felonious assault upon our most treasured ideals. But he never does. 14You are stopped by a gun-shot across your bow, and you prepare for the worst. But the worst is merely a jolly invitation in a boyish voice to a game of marbles.

The combination is irresistible.... I am reminded of an authentic tale of the South seas. A band of wicked mutineers set their captain and officers afloat in an open boat, and sailed to Pitcairn Island, where they proceeded to live in the most Nietzschean fashion imaginable, enslaving the natives, taking their wives away from them, and living in fabulous luxury. They were a fractious lot, however, and they quarrelled among themselves, and shot each other up, and went insane and committed suicide, until the natives got tired of it, and revolted and killed them all—all except one gentle person who had got mixed up with the mutineers by mistake. He was not a Nietzschean; he believed at heart in all the old-fashioned virtues. And where the Nietzscheans had failed, he succeeded—so notably that when the island was rediscovered half a century later, he was ruling there in a little peaceful paradise, the Last of the Mutineers. There is something about gentleness, it would seem, that makes for survival. And I like to think that Max Beerbohm remains with us to tell the story of quaint, devil-worshipping literary mutineers like Enoch Soames, precisely because he cannot bear ever to press home the shining blade of his wit to its most deadly extent—because he does not really want to hurt anybody after all, not even Enoch Soames.

Photograph by Robert H. Davis

When Mr. Knopf asked me to pay my brief respects to Joseph Hergesheimer, he must have been aware that I had not the material for an intimate portrait. He and my other readers must forgive me, then, if what I shall have to say tallies rather better with the exigencies of formal public criticism than with the more delightful convenances of this altogether jolly family party. After all, there is a certain advantage—especially for a person of amiably weak will—in knowing an author’s public aspects better than his private and personal. I cannot profess to be of those austere souls who can criticize the book of a friend as if he were not a friend, or, knowing and liking a man, can read or appraise his books uninfluenced by a charm which would still exist even if the books did not. Because of this distrusted weakness of my own temper, I insist on being glad that I never met or even saw Joseph Hergesheimer until “The Three Black Pennys” had become a solid part of my awareness of things—the things that do most richly signify. I never had any reason to think well—or ill—of this author until the Pennys and “Gold and Iron” had exerted their swift effortless compulsion. Even now, I can lay claim to no more than what the biographic essayist calls, in his standard idiom, a “literary friendship”—meaning thereby the occasional exchange of abysmally polite letters on purely impersonal subjects or personal subjects impersonally dealt with.

Yet even I have my one sufficiently quaint, sufficiently spicy reminiscence. And meet it is I set it down—partly because it seems too precious to die, even more because otherwise, as time shuffles the cards of our mortal anecdotage, it will be sure to turn up, with only the substitution of one name for another, as part of the mythos surrounding the late Jack London, or Richard Harding Davis, or some still flourishing nominee for an epitaph and an official biography.

It was three o’clock of a rainy summer morning in 1918. Hergesheimer and your present scribe were sleeping—or rather we were not—in the twin beds of a guest-room at San-Souci, in Hartsdale. A Nox Ambrosiana had been put behind us, and, we fatuously supposed, a few hours of ambrosial sleep lay ahead. It had been a great night, dedicated to much fine talk of Art, and as free from “the posings and pretensions of art” as Conrad’s Preface to “The Nigger.” But that is not the story.

Somewhere in the blackness under our opened windows, vocal in his forlornness, was Bistri, the flesh-and-blood original of the borzoi whose mere inadequate outline appears on a really amazing proportion of the most distinguished books now being published in These United States—or, if your literary capital be Arnold Bennett’s, Those United States. This Bistri, a perfectly incredible yet perfectly actual milk-white creature of enormous size, decorative as a dryad, but possessed of something less than half a gill of brains within his extremely dolichocephalic head, was frank to assert—and reiterate—his disapproval of the pelting rain and his cynical disillusionment in respect to the kindly graces of humankind. The sound was like the ululating whimper of a punished child, only it hinted no promise of subsiding, ever.

Genius, supine in the dark across the room, grew first restive, 17then indignant, then furious, and thence, passing round the circle of exhausted emotions, came back by the way of despair to a disgusted silence. Not so Bistri: silence was the last thing to fall within the orbit of his intentions, so long as the Master and Maker of dogs vouchsafed him breath and being. Gradually the silence of genius, there across the room, acquired a subtly grim texture. When next the voice of genius spoke, it was tensely, with suppressed ferocity, as through clenched teeth. What it said was this: “I’ll bet Scribner has got no such damned dog.”

The rest, after Gargantuan laughter, was silence.... Ah, but was it, quite? Or did the speaker of these words, also deeming them too precious to die, retail them at late breakfast to the mistress of the borzoi, even as their sole hearer presently reported them at earlier breakfast to the borzoi’s master? It would be interesting to know—and not very surprising either way.

So far the record of a personal and temperamental susceptibility, of some incidental interest, perhaps, to the curious. What remains to speak of is the deeper susceptibility of which Mr. Hergesheimer’s books are the record, and which runs through all his public work, a determining law and a binding continuum; that enormous and delicate susceptibility to sights, sounds, forms, colours, movements, aspects, which is at once his purpose and his effect, his unconscious excuse for being and his conscious claim to self-justification. He might say, in the words of a document already referred to, and important in the history of fictional art: “My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel—it is, before all, to make you see. That—and no more, and it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there according to your deserts: encouragement, 18consolation, fear, charm—all you demand and, perhaps, also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask.”

We can all see now, with the glib wisdom of after the event, that Mr. Hergesheimer’s career before its one sharp early break is—comparatively—all promise, and after that break—comparatively—all performance. In “The Lay Anthony” and “Mountain Blood” one finds a slight uneasiness or unevenness of recital, the result, I think, of a subconscious attempt to make the manner dignify and sanction two performances not, in matter, quite good enough to receive that ultimate sanction, style. With and after “The Three Black Pennys,” and very specially in “Java Head” and “Wild Oranges,” which remain thus far the masterpieces of perfect formal integrity, this discrepancy is lost from the reckoning. The artist has an exigent discrimination of that which is good enough for him to touch, and his touch upon it is exquisite.

But in one respect, the betrayal of a born artist’s susceptibility, the works of promise are at one with the works of performance. The man who could not help going out of his way, in “The Lay Anthony,” to allude to “Heart of Darkness” as “the most beautiful story of our time,” was simply predestined to write a book of which susceptibility to beauty should actually be the theme—as he did in “Linda Condon.” And the man who, in “Java Head,” achieved so supreme a saturation with the aromas and essences of loveliness, had prefigured his own future when, in “Mountain Blood,” he wrote: “The barrier against which he still fished was mauve, the water black; the moon appeared buoyantly, like a rosy bubble blown upon a curtain of old blue velvet.”

Just here, in the crystallization of his own sensitivity into the objective forms of beauty, lies the peculiar distinction of Hergesheimer. It is an aristocratic distinction. It is, if you go by the counting of tastes, a distinctly un-American trait. This fact it is, rather than any less fundamental consideration, 19which explains—even if it does not justify—those critics who even before they discover how to divide his name properly into syllables, discover that there is something slightly exotic about him. Exotic or autochthonous—what does it matter? The point is, Mr Hergesheimer’s power “to make you hear, to make you feel ... before all, to make you see” is the condition of his success as a coiner of beauty. It is also his way, whatever way another artist may take, to reveal to us those glimpses of deep truth for which we may, indeed, have forgotten to ask, but for which, once they are opened to our sight, we can never forget to be grateful.

It is commonly said that everybody can sing in the bathroom; and this is true. Singing is very easy. Drawing, though, is much more difficult. I have devoted a good deal of time to Drawing, one way and another; I have to attend a great many committees and public meetings, and at such functions I find that Drawing is almost the only Art one can satisfactorily pursue during the speeches. One really cannot sing during the speeches; so as a rule I draw. I do not say that I am an expert yet, but after a few more meetings I calculate that I shall know Drawing as well as it can be known.

The first thing, of course, is to get on to a really good committee; and by a good committee I mean a committee that provides decent materials. An ordinary departmental committee is no use: generally they only give you a couple of pages of lined foolscap and no white blotting-paper, and very often the pencils are quite soft. White blotting-paper is essential. I know of no material the spoiling of which gives so much artistic pleasure—except perhaps snow. Indeed, if I was asked to choose between making pencil-marks on a sheet of white blotting-paper and making foot-marks on a sheet of white snow I should be in a thingummy.

Much the best committees from the point of view of material are committees about business which meet at business premises—shipping offices, for choice. One of the Pacific Lines 21has the best white blotting-paper I know; and the pencils there are a dream. I am sure the directors of that firm are Drawers; for they always give you two pencils, one hard for doing noses, and one soft for doing hair.

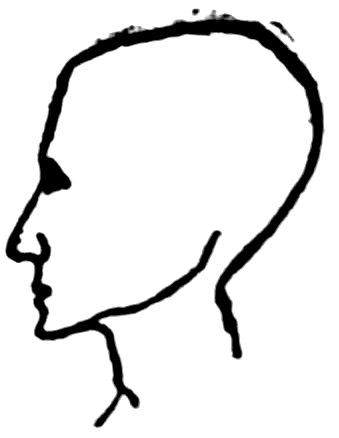

Fig. 1

When you have selected your committee and the speeches are well away, the Drawing begins. Much the best thing to draw is a man. Not the chairman, or Lord Pommery Quint, or any member of the committee, but just A Man. Many novices make the mistake of selecting a subject for their Art before they begin; usually they select the chairman. And when they find it is more like Mr. Gladstone they are discouraged. If they had waited a little it could have been Mr. Gladstone officially.

Fig. 2

As a rule I begin with the forehead and work down to the chin (Fig. 1).

When I have done the outline I put in the eye. This is one of the most difficult parts of Drawing; one is never quite sure where the eye goes. If, however, it is not a good eye, a useful tip is to give the man spectacles; this generally makes him a clergyman, but it helps the eye (Fig. 2).

Now you have to outline the rest of the head, and this is rather a gamble. Personally, I go in for strong heads (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

I am afraid it is not a strong neck; I expect he is an author, and is not well fed. But that is the worst of strong heads; they make it so difficult to join up the chin and the back of the neck.

The next thing to do is to put in the ear; and once you have done this the rest is easy. Ears are much more difficult than eyes (Fig. 4).

I hope that is right. It seems to me to be a little too far to the southward. But it is done now. And once you have put in the ear you can’t go back; not unless you are on a very 22good committee which provides india-rubber as well as pencils.

Fig. 4

Now I do the hair. Hair may either be very fuzzy and black, or lightish and thin. It depends chiefly on what sort of pencils are provided. For myself I prefer black hair, because then the parting shows up better (Fig. 5).

Until one draws hair one never realizes what large heads people have. Doing the hair takes the whole of a speech, usually, even one of the chairman’s speeches.

Fig. 5

This is not one of my best men; I am sure the ear is in the wrong place. And I am inclined to think he ought to have spectacles. Only then he would be a clergyman, and I have decided that he is Mr. Philip Gibbs at the age of twenty. So he must carry on with his eye as it is.

I find that all my best men face to the west; it is a curious thing. Sometimes I draw two men facing each other, but the one facing east is always a dud.

There, you see (Fig. 6)? The one on the right is a Bolshevik; he has a low forehead and beetling brows—a most unpleasant man. Yet he has a powerful face. The one on the left was meant to be another Bolshevik, arguing with him. But he has turned out to be a lady, so I have had to give her a “bun.” She is a lady solicitor; but I don’t know how she came to be talking to the Bolshevik.

Fig. 6

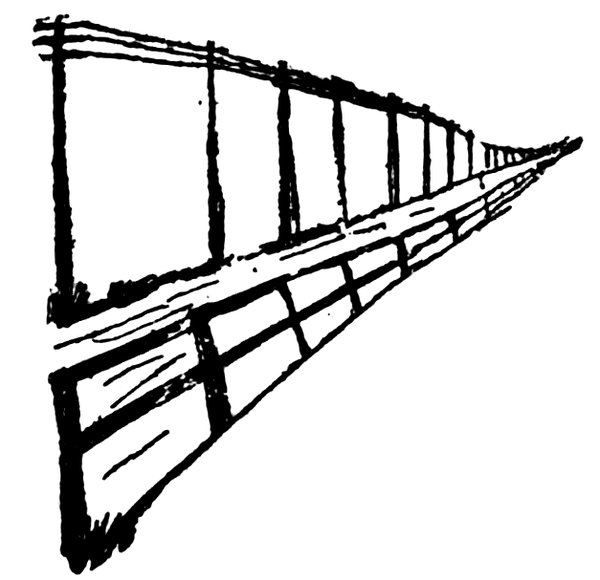

23When you have learned how to do Men, the only other things in Drawing are Perspective and Landscape.

Fig. 7

PERSPECTIVE is great fun: the best thing to do is a long French road with telegraph poles (Fig. 7).

I have put in a fence as well.

LANDSCAPE is chiefly composed of hills and trees. Trees are the most amusing, especially fluffy trees.

Here is a Landscape (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8

Somehow or other a man has got into this landscape; and, as luck would have it, it is Napoleon. Apart from this it is not a bad landscape.

But it takes a very long speech to get an ambitious piece of work like this through.

There is one other thing I ought to have said. Never attempt to draw a man front-face. It can’t be done.

It is the special province of poetry, as of charming women, to delight rather than afford the more material benefits. Nothing could be vainer than putting either of them to the rude uses of life; they are the essence of aristocracy; and the indifference, the contempt really, with which the mass of people regard poetic measures, and conversely, the disdain of charm for the whole common body of opinion, show clearly the wide separation between prosaic fact and fancy. The former has the allegiance of the mob, as it should, since, without imaginative sensibility, the mechanical process of existence is a stupid multiplication of similar instincts; while fancy, poetry, beauty, the properties of delicate minds and aspirations, are, by the very qualities necessary to their being, limited to a select few.

There were ages, long submerged now by the obliterating tide of progress, when poetry was, generally, a force in men’s lives; and then, as well, women’s beauty was held above their mere animality; but the levelling democracy of Christian religions, lending a new power to the resentment and suspicions of congregations of the inferior, ended perhaps for ever reigns of distinction. Yet, ironically, while sects vanished over night and fanatics were denied even the final distinction of martyrdom, while great empires sank leaving no ripple on the surface of memory, stray lines of wanton poetry, the record of lovely bodies, remained imperishable.

25They were deathless—such frivolities as the Trojan Helen and the words Sappho strung from her loneliness—because they were the inalienable property of the heart ... the clamorous dogmas were nothing more than the pretentions of anthropomorphic vanity. But that, with its tinsel promises and brimstone threats, a sentimental melodrama, gathered the audiences, the credulity, of humanity, and left unattended the heroic performance of naked beauty. This, at its best, was a sheer cool cutting of marble; but there was another beauty, hardly inferior, where embroidered garments and carmine and jade, both hid and revealed less simple but scarcely less significant emotions.

For this reason, while Ionic Greece is no longer a part of modern consciousness, the poem written by the sixth emperor of the Han dynasty, perhaps two thousand years ago, is identical with the present complex troubled mind: an autumn wind rises and white clouds fly, the grass and trees wither, geese go south—sadly he remembers his love and the pagoda-boat on the Fēn River. That, particularly, is the singular validity of the Chinese poems translated by Mr. Waley; page after page they are the mirror of the splintered colours, the tragic apprehensions and sharp longing, of a later unhappiness. Already, then, China was old and civilized, its philosophers had analysed hope into maxims of stoical and serene conduct; and its poetry was written in an unsurpassable dignity of repression.

The latest imagery, nothing in the world if not visual in perceptions of utmost fragile truth, is not so acute in observation and artifice as the song, in the second century, of Sung Tzu-hou. (She sees the fruit trees in blossom and, forgetting about her silkworms, begins to pluck the branches.) And no contemporary, it may be no Western, poet has approached the reflective cadences, the refrain of memory steeped in longing, that gives the lines of Po Chü-i their magic semblance to the 26wistful and fleet realities of mind. He has, but in greater degree, Verlaine’s power to invest lovely frivolities with permanence; an ability Arthur Symons occasionally brushed. His Old Harp, of cassia-wood and jade stops and rose-red strings, neglected for the Ch’iang flute and the Ch’in flageolet, vibrates with a tenderness of ancient forgotten melodies beyond any evocation of the Fêtes Galantes.

The poetry of those dynasties and men, however, aside from everything else, is made timeless, for us, by the celebration of its women, the wives, the concubines, the dancers of Hantan. They were, objectively, inconceivably different from the woman of today; yet the passions, the fidelity, they inspired, a little attenuated by the dust of centuries, are precisely the same which the heart retains. The Chinese women have always served an ideal of personal beauty, of correct formality, transcending any other: in May their satins are worked with the blossoms of spring and in October with chrysanthemums. Socially they occupied the women’s gardens—a position now regarded with contempt—but they were not, because of that, inferior. They dominated the masculine imagination and provided, together with music, the recompense of existence checkered by the dark squares of fate.

There are, too, as many wives praised as dancers summoned, as much constancy as there is incontinent pleasure. An emperor sends to all parts of China for wizards, hoping that they may bring back the spirit of his mistress. The General Su An, absent on service, begs the woman with whom his hair was plaited not to forget the time of their love and pride. Indeed, on the other side, in the poetry there is a marked restraint: the dancers are a stiff frieze in peacock blues and orange and gold behind the fragrant vapours of incense.

All is tranquillized, even the battle pieces are softened as though in distance, and the satire, often pungent and universal, is subdued by the realization of its uselessness. There is 27wine, in cups and jars, and drunkenness: Po Chü-i returns home, leaning heavily on a friend, at yellow dusk; but there are no raised voices or disturbance; and, soothed by the swallows about the beams, a candle flame in the window, the moon crowning the tide, he hears only the music of flutes and strings. There are roc and phoenix and red jungle fowl, ibis and cranes and wild swan along the river; women with bright lips sway to the silver tapping of their bells, ladies, long of limb, enter with side glances under moth eye-brows, and after them others with faces painted white, their deep sleeves reeking with scent. But they are only momentary; they are left, plucking vainly at the coats of those who will not stay, and the pure dawn holds a mango-bird singing among flowers.

They are poems that dwell on the green of mulberry trees and fields of hemp, on the oxen in the village streets, the burnished pools of carp, the lotus banks and rice furrows and glittering fret of snow. And there, equally, they are completely in the mood, or, rather, perfections of the attempted mood, of the present. In English lyrical poetry alone, and that, except for John Masefield, the beauty of yesterday and not today, have the settings of life been so beautifully refashioned. An ability of long habited lands; for its power is not in described nature, but the love of a particular soil—feathery bamboo at the door, a hollow of daffodils, are symbols not so much of recurrent seasons as of a deep-rooted passionate attachment for the city of Lo-yang or for the Devon sod. Without sincerity of human emotion words are no better than broken coloured glass.

If the United States ever becomes civilized and develops a literature, no doubt the Middle West will be the scene of the prodigy. The two coasts are washed by too many paralysing and distracting waves. Boston, after three hundred years, remains a mere suburb of London, timorous, respectable and preposterous—a sort of ninth-rate compound of Putney and Maida Vale. New York is simply a bawdy free port, without nationality or personality. As for San Francisco, New Orleans, Philadelphia and Baltimore, once so saliently individual, they scarcely exist any longer, save for banking, political and census purposes. But in the Middle West the authentic Americano is still a recognizable mammal, and shows all his congenital spots, particularly upon the psyche. More, he has become introspective and a bit conscience-stricken, and so begins to analyse and anatomize himself. The fruits are “The Spoon River Anthology,” the novels of Norris and Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson’s terrific tales, the Little Theatre business, Lindsay and his uneasy college yells, George Ade and his murderous satire, Willa Cather and her poignant evocation of the drama of the prairie. Count out Hergesheimer and Cabell and you will scarcely find an imaginative writer doing genuinely sound work—that is, an imaginative writer of the generation still squarely on its legs—who is not from beyond the Alleghenies. Chicago is the centre of the new writing fever, as it is the centre of nearly all other native fevers.

29Four or five years ago, though she already had a couple of good books behind her, Willa Cather was scarcely heard of. When she was mentioned at all, it was as a talented but rather inconsequential imitator of Mrs. Wharton. But today even campus-pump critics are more or less aware of her, and one hears no more gabble about imitations. The plain fact is that she is now discovered to be a novelist of original methods and quite extraordinary capacities—penetrating and accurate in observation, delicate in feeling, brilliant and charming in manner, and full of a high sense of the dignity and importance of her work. Bit by bit, patiently and laboriously, she has mastered the trade of the novelist; in each succeeding book she has shown an unmistakable advance. Now, at last, she has arrived at such a command of all the complex devices and expedients of her art that the use she makes of them is quite concealed. Her style has lost self-consciousness; her grasp of form has become instinctive; her drama is firmly rooted in a sound psychology; her people relate themselves logically to the great race masses that they are parts of. In brief, she knows her business thoroughly, and so one gets out of reading her, not only the facile joy that goes with every good story, but also the vastly higher pleasure that is called forth by first-rate craftsmanship.

I know of no novel that makes the remote folk of the western farmlands more real than “My Antonía” makes them, and I know of none that makes them seem better worth knowing. Beneath the tawdry surface of Middle Western barbarism—so suggestive, in more than one way, of the vast, impenetrable barbarism of Russia—she discovers human beings bravely embattled against fate and the gods, and into her picture of their dull, endless struggle she gets a spirit that is genuinely heroic, and a pathos that is genuinely moving. It is not as they see themselves that she depicts them, but as they actually are. And to representation she adds something more—something 30that is quite beyond the reach, and even beyond the comprehension of the average novelist. Her poor peasants are not simply anonymous and negligible hinds, flung by fortune into lonely, inhospitable wilds. They become symbolical, as, say, Robinson Crusoe is symbolical, or Faust, or Lord Jim. They are actors in a play that is far larger than the scene swept by their own pitiful suffering and aspiration. They are actors in the grand farce that is the tragedy of man.

Setting aside certain early experiments in both prose and verse, Miss Cather began with “Alexander’s Bridge” in 1912. The book strongly suggested the method and materials of Mrs. Wharton, and so it was inevitably, perhaps, that the author should be plastered with the Wharton label. I myself, ass-like, helped to slap it on—though with prudent reservations, now comforting to contemplate. The defect of the story was one of locale and people: somehow one got the feeling that the author was dealing with both at second-hand, that she knew her characters a bit less intimately than she should have known them. This defect, I venture to guess, did not escape her own eye. At all events, she abandoned New England in her next novel for the Middle West, and particularly for the Middle West of the great immigrations—a region nearer at hand, and infinitely better comprehended. The result was “O Pioneers” (1913), a book of very fine achievement and of even finer promise. Then came “The Song of the Lark” (1915)—still more competent, more searching and of even finer promise. Then came “The Song of the Lark” (1915)—still more competent, more searching and convincing, better in every way. And then, after three years, came “My Antonía,” and a sudden leap forward. Here, at last, an absolutely sound technique began to show itself. Here was a novel planned with the utmost skill, and executed in truly admirable fashion. Here, unless I err gravely, was the best piece of fiction ever done by a woman in America.

31I once protested to Miss Cather that her novels came too far apart—that the reading public, constantly under a pressure of new work, had too much chance to forget her. She was greatly astonished. “How could I do any more?” she asked. “I work all the time. It takes three years to write a novel.” The saying somehow clings to me. There is a profound criticism of criticism in it. It throws a bright light upon the difference between such a work as “My Antonía” and such a work as—.... But I have wars enough.

Carl Van Vechten’s mental gesture is more or less unique in American literature. His work has about as much relation to what might be considered the “serious classical output” of writing today as irresistible footnotes have to filling an all too fulsome history. Whereas the bulk of the intellectual page of contemporary American writing is for the most part of transitional importance Mr. Van Vechten’s essays are replete with the delightful essence of what is importantly transitory.

As a critic of the fine arts and other things, his range is not so immense as it is extraordinary. How can one keep on the hat of appreciation before the work of a writer who improvises as adroitly about cats as about prima donne, who in one book tells the only authoritative story of the music of Spain, in another makes or breaks the fame of some famous player and in still another goes far afield to bring into the glow of his praise some hidden personage from some remote and delicious byway of life and letters? If he mounts into his garret to unopen ancient chests and write of olden things, he doesn’t neglect at the same time to look from his high window at what is going on about him. In the midst of the gorgeous hurry of New York he hears the quieter melody of far off places. He is a cosmopolitan critic and at the same time a critic of cosmopolis.

33Music is never very far from his pages. He is acknowledged as one of the most important of the musical critics in America because he has had the wise wisdom of not writing about music at all. He is one of the few musically informed who has sensibly refrained from any vacant analysis of tonal mysteries, one of the very few indeed who realizes the futility of filling soundless books with sounding but empty treatises on sound. He has had the rare and modest grace of letting music sing or play or “symphonize” for itself. His chief concern has been with interpretations and interpreters. Taking the one or the other as his theme he has written critical variations and the result has been critical creation.

His work has the quality of rare, spontaneous and intriguing talk. There is about his writing an air of delicate and urbane gossip, a knowledge and thought that does not take itself in any sense or at any moment as too profound to admit of a digression into gaiety. It is not so much what he knows as the very particular and personal way in which he knows it. His one cliché is a desperate detestation of all critical clichés. The woof of his thought is a charming destroyal of all accepted standards, the web of his thinking is a delicate but constructive anarchy. When he builds up we are grateful, when he tears down we are equally grateful because he always leaves behind him the intricate, infernally informed and fascinating machinery of his annihilation.

In the monthly department, “Répétition Générale,” which we jointly conduct in The Smart Set Magazine, there was some months ago incorporated the following paragraph:

“When one of us, in the course of his critical writings, indulges himself in polite words about the other, it is a common antic of the newspaper literary supplement professors to observe that this encomium is merely by way of mutual log-rolling, that it is based upon no sounder critical ground than our friendship for each other and our commercial alliance, and that it is perhaps not honestly believed in by either the one or the other. This, of course, is idiotic. We are friends and partners, not because we admire each other’s beauty, or each other’s conversation, or each other’s waistcoats or wives, but because we respect each other professionally, because each to the other seems to know his work in the world, and how to do it, and how to do it—it may be—just a little bit better than the next nearest man. This, obviously, is the soundest of all bases for friendship. It is not friendship that makes men approve one another; it is mutual approval that makes them friends.”

35Let me add a word about Mencken in particular. I respect him, and am his friend, because he is one of the very few Americans I know who is entirely free of cheapness, toadyism and hypocrisy. In close association with him for more than twelve years, I have yet to catch him in a lie against himself, or in a compromise with his established faiths. There have been times when we have quarrelled and times, I dare say, when we have hated each other: but when we have met again it has been always on a ground of approval and friendship made doubly secure and doubly substantial by the honesty of his point of view (however wrong I have held it), by the wholesomeness of his hatred, and by his frank and ever self-doubting conduct at our several Appomattoxes.

Perhaps no man has ever been more accurately mirrored by his writings than this man. He has never, so far as I know, written a single line that he hasn’t believed. He has never sold a single adjective—and there have been times when opulent temptations have dangled before him. And on certain of these occasions he could have used the money. There may be times when he is wrong and when his opinions are biased—I believed that there are not a few such times—yet if he is wrong, he is wrong honestly, and if he is biased, he neither knows it in his own mind nor feels it in his own heart. He is the best fighter I have ever met. And he is the fairest, the cleanest, and the most relentless.

But does he accept himself with forefinger to temple, with professorial wrinkles, as an Uplifting Force, a Tonic Influence? Not on your ball-room socks! No critic has ever snickered at him as loudly and effectively as he snickers at himself. “What do you think of your new book?” I usually ask him when he has finished one. And his reply generally is, “It’s got some good stuff in it—and a lot of cheese. What the hell’s the use of writing such a book, anyway? My next one....”

Life to him is a sort of Luna Park, and he gets the same sort of innocent, idiotic fun out of it. He would rather drink a glass of good beer than write; he would rather talk to a 36pretty girl than read; he would rather wallop the keys of a piano than think; he would rather eat a well-cooked dinner than philosophize. His work, which so clearly reflects him spiritually, represents him equally clearly in helpless revolt against his corporeal self.

This; a snapshot of Henry Mencken, for ever applying the slapstick to his own competence, constantly sceptical of his own talents, and ever trying vainly to run away from the pleasure that his temperament rebelliously mocks. I am happy to know him, for knowing him has made the world a gayer place and work a more diverting pastime. I am glad to be his partner, his collaborator, his co-editor, his drinking companion, and his friend. For after all these many years of our friendship and professional alliance, there is only one thing that I can hold against him. For ten years he has worn the damndest looking overcoat that I’ve ever seen.

Many years ago it was my privilege to know a sturdy, forthright Judge who had, in his own youth, faced a jury upon a charge of murder. He had attempted no shifty, technical defence, but admitted frankly that he had killed a man, and had the best of reasons for having done so. The jury agreed with him and set him free, to sentence many another less fortunate creature, during his long and honoured career on the bench. I remember how often I used to wonder as I watched him meting out punishments whether he ever meditated upon his own narrow escape. If he did, it never seemed to temper his severity. He was there to deal out what he felt sure was justice, and the closed pages of his own personal history had nothing at all to do with his appraisement of the degrees of guilt or innocence of the culprits who stood before him.

Every one who, like myself, has committed the crime of authorship and afterwards presumes to sit in judgment upon the art of fiction is in a position somewhat analogous to that of my old friend, the Judge. It is true my own sins of this character have been few and obscure. Nevertheless, they must have been marked by the Recording Angel, and underscored with a sinister emphasis, since the Recording Angel has also for many generations coquetted with the business of professional book-making.

And my plea must be precisely that of this same militant Judge. After all, it’s not a bad excuse. Today’s criminal is 38no less red-handed because of the indelible stain we succeed in hiding so neatly under our own well-fitting glove.

One can afford carelessly to ignore the cheap jibes of those who insist on the obvious and meaningless taunt: “Why don’t you write as you say you would have other American fictionists write?” with the equally obvious retort that, if any author really succeeded in writing the book of which he dreamed, it would mean no more than that his dream was a tawdry, worthless thing.

It is enough for me, at least, to know what I wish to embody in my own writings, no matter how far short of success I may fall in the endeavour, or how certainly my adherence to my own beliefs may cost me the interest of a public in whose commendation I would find a healthy, human enjoyment, provided always, I could have it without compromise.

I believe, then, that fiction is something vastly more than a medium of amusement. I believe it has been, in all countries and ages, that art best fitted to interpret life to the human beings who share that life. I think it can be and should be made a revelation of man’s emotion, impulse and character. To me, it seems that any and every phase of human life, any and every choice of scene and dramatis personae is worthy of the fictionist’s study, and his only inflexible obligation is to paint life as he sees it instead of sophisticating his tints and outlines to portray what he would prefer seeing, or to depict what he thinks his readers would like to see, or, worst of all, to prove some pet thesis. I hold it as fundamental that, if one can give an understanding picture of any phase of life, no matter how trivial it may be intrinsically, he has contributed something to the comprehension of the most important of all things—Men and Women.

By his very choice of fiction as his mode of expression, the author is committed to some sense of form. He has acknowledged 39also the duty of telling some kind of a story which shall not prove unbearably dull to the sensitive and alert reader. If he has no story at all, he is an essayist in an ill-fitting disguise. If he cannot or will not endeavour to interest some portion of the public, he might as well keep a diary and secure it under lock and key; but the writer holds himself and his art too cheaply who makes no demands whatever upon his reader. A fictionist’s public has no right to a predigested diet, or to a menu skilfully arranged to give it only what it happens to enjoy.

Unless the author has something actually craving utterance, there is no excuse for his intrusion into a world already well provided with printed matter, and if he feels this impulse for expression he cannot satisfy it if he expresses the conception of his critics, his publishers, or that inarticulate abstraction called the public. If speaking his own thought, the public will not buy his wares, then it must go without them, and he must earn his bread in another fashion. But if this public chooses to traffic with him at all, it must do so upon his terms and at the price of some little effort upon its own part. If the reader will expend no such energy to gain a new idea or a new point of view regarding those ideas, then the thing he attempts to assimilate so easily will, after all, profit him nothing. The author is not the servant of his public. He is a man with something to say. If passers-by choose to listen—good. If they prefer to ignore him, he may not therefore seek some more alluring jingle of words to catch their fancy. If he descends to such devices he is a mere brother of the mountebank. He must paint truth as he sees it even if he realizes that other and better men cannot accept his pictures as truth. It is not his function to reproduce other men’s images, whether better or worse than his own. He must be austere to deny himself the luxury of preaching. If his work is what it ought 40to be, the reader may be stimulated to fashion out his own deductions, but the hedonist who sets out to point a moral, usually ends most immorally by distorting a character.

Last of all—for here lies the vital differences between the work of a mere honest craftsman and a true artist,—I should like to hope that in my pages, I might now and then capture some gleam of beauty—beauty of form, or of thought, or of comprehending insight. For without this, fiction is a thing of effort, dead and mechanical, however well intentioned. But beauty is the gift of the capricious gods, and no one by taking thought, or by the exercise of weary toil can feel sure of counting it among his treasures.

Sleep, my child! For if you sleep you shall have three cities, three villages and three monasteries. In the cities you shall command, in the villages you shall walk at leisure, in the monasteries you shall pray.

Sleep, my child! For if you do not wish to command, nor to walk at leisure, nor to pray, sleep shall carry you away to the vineyards of the Sultan. The Sultan shall give you grapes, the Moons of the Harem shall give you roses and the odalisques shall make you cakes of sesame.

Sleep, my child, sleep!

As for the city itself you probably know all about it, and wish you had never heard of it. As for me I had been in it so often that my mouth didn’t get so dry on wet days, when walking up that Sinister Street from Suicide Corner to what was once the Cloth Hall. There I was, one summer day, in a silence like deafness, amid ruins which might have been in Central Asia, and I, the last man on earth, contemplating them. There was something bumping somewhere, but it wasn’t in Ypres, and no notice is ever taken in Flanders of what doesn’t bump near you. So I sat on the disrupted pedestal of a forgotten building and smoked, and wondered why I was in the city of Ypres, and why there was a war, and why I was a fool.

It was a lovely day, and looking up at the sky over what used to be a school dedicated to the gentle Jesus, which is just by the place where one of the seventeen-inchers has blown a forty-foot hole, I saw a little round cloud suddenly appear in the blue, and then another, and then lots in a bunch, the sort of soft little cloudlets on which Renaissance cherubs rest their chubby hands, and with fat faces on one side consider mortals from cemetery monuments. Then came down dull concussions from the blue, and right over head I made out two Boche ‘planes. A shell case banged the pavé near me and went on to make a white scar on a wall. Some invisible things were whizzing about. One’s own shrapnel is often tactless. 43There was a cellar and I got into it, and while the intruders were overhead I smoked and gazed at the contents of the cellar—the wreckage of a bicycle, a child’s chemise, one old boot, a jam pot, and a dead cat. Owing to an unsatisfactory smell of many things I got out soon and sat on the pedestal again.

A figure in khaki came straight at me across the square, his boots sounding like the deliberate approach of Fate in solitude. It stopped, saluted, and said, “I shoodden stay ‘ere, sir. They’ve been gitten sights, and they gen’ally begin about now. Sure to drop some ‘ere.”

At that moment a mournful cry went over us, followed by a crash in Sinister Street. My way home! Some masonry fell in sympathy from the Cloth Hall.

“Better come with me till it blows over, sir. I’ve got a dug-out near.”

We turned off sharp, and not really before it was time to move, into a part of the city unknown to me. There were some unsettling noises, worse no doubt because of the echoes, behind us; but it is not dignified to hurry when you look like an officer. You ought to fill your pipe. I did so, and stopped to light it. Once I paused in drawing it, checked by the splitting open of the earth in the first turning to the right and the second to the left, or thereabouts.

“That’s a big ‘un, sir,” said my soldier, who then took half a cigarette from his ear, and a light from my match: we then resumed our little promenade. By an old motor bus, whose windows were boards, whose colour was War-Office neuter, but who, for memory’s sake, still bore on its forehead the legend “Liverpool Street,” my soldier hurried slightly, and was then swallowed up. I was alone. While looking about for possible openings, I heard his voice under the road, and then saw a dark mouth, low in a broken wall, and crawled in. Finding my way by touching the dark with my forehead and my shins, I found a lower smell of graves hollowed by a candle and a 44bottle. And there was my soldier, who provided me with an empty case, and himself another, and we had the candle between us. On the table was a tin of condensed milk suffering from shock, and some documents under a shell-nose. Pictures of partly clad ladies began to dimmer from the walls through the gloom. Now and then the cellar trembled.

“Where’s that old ‘bus come from?” I asked.