Whilst now with rapture burning,

Thy smiles and sighs returning,

Say wilt thou love be mine?

See—the songsters’ wings are spreading,

Each grove and arbour threading,

To seek their Valentine.

Then while all hearts are striving,

And at Love’s Arts conniving,

Send offerings to his shrine.

May we, our pledge renewing,

Our patrons favor wooing,

Prove their true Valentine.

Vol. XXXIV. FEBRUARY, 1849. No. 2.

Table of Contents

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXIV. PHILADELPHIA, FEBRUARY, 1849. No. 2.

———

BY JOHN TODD.

———

In one of those long, low, one-story, unpainted houses which succeeded the log-houses in Vermont as the second generation of human habitations, lay a sick woman. She knew, and all her friends knew, that her days were numbered, and that when she left that room it would be in her winding-sheet for the grave. Yet her face and her spirit were calm, and the tones of her voice, like those of the dying swan, were sweeter than those of life. She had taken an affectionate leave of all her children, in faith and hope, save one—her eldest son—a mother’s boy and a mother’s pride. By great economy and unwearied industry this son had been sent to college. He was a mild, inoffensive, pale-faced one; but the bright eye did not belie the spirit that dwelt in a casket so frail. He had been sent for, but did not reach home till the day before his mother’s death. As soon as she knew of his coming, she immediately had him called to her room, and left alone with her. Long and tearful was their conversation. Sweet and tender was this last interview between a mother and son who had never lacked any degree of confidence on either side.

“You know, my son, that it has always been my most earnest wish and prayer that you should be a preacher of the gospel, and thus a benefactor to the souls of men. In choosing the law, you are aware, you have greatly disappointed these hopes.”

“I know it, dear mother; and I have done it, not because I like the law so much, but because I dare not undertake a work so sacred as the ministry, conscious as I am that I am not qualified in mind, or body, or spirit, for the work. If I dared do it, for your sake, if for no other reason, I would do it.”

“In God’s time, my dear son, in God’s time, I trust you will. I neither urge it, nor blame you. But promise me now, that you will never undertake any cause which you think is unjust, and that you will never aid in screening wrong from coming to light and punishment.”

The son said something about every man’s having the right to have his case presented in the best light he could.

“I know what you mean,” said she; “but I know that if a man has violated the laws of God and man, he has no moral right to be shielded from punishment. If he has confessions and explanations to offer, it is well. But for you to take his side, and for money, to shield him from the laws, seems to me no better than if, for money, you concealed him from the officers of justice, under the plea that every man had a right to get clear of the law if he could. But I am weak and cannot talk, my son; and yet if you will give me the solemn promise, it seems as if I should die easier. But you must do as you think best.”

The young man bent over his dying mother, and with much emotion, gave her the solemn promise which she desired. Tender was the last kiss she gave him, warm the thanks which she expressed, and sweet the smile which she wore, and which was left on her countenance after her spirit had gone up to meet the smiles of the Redeemer.

Some months after the death of his mother, the young man left the shadows of the Green Mountains, and toward a more sunny region, in a large and thrifty village, he opened his office; the sign gave his name, and under it, the words, “Attorney at Law.” There he was found early and late, his office clean and neat, and his few books studied over and over again, but no business. The first fee which he took was for writing a short letter for his black wood-sawyer, and for that he conscientiously charged only a single sixpence! People spoke well of him, and admired the young man, but still no business came. After waiting till “hope deferred made the heart sick,” one bright morning a coarse-looking, knock-down sort of a young man was seen making toward the office. How the heart of the young lawyer bounded at the sight of his first client! What success, and cases, and fees danced in the vision in a moment!

“Are you the lawyer?” said the man, hastily taking off his hat.

“Yes, sir, that’s my business. What can I do for you?”

“Why, something of a job, I reckon. The fact is I have got into a little trouble, and want a bit of help.” And he took out a five dollar bill, and laid it on the table. The young lawyer made no motion toward taking it.

“Why don’t you take it?” said he. “I don’t call it pay, but to begin with—a kind of wedge—what do you call it?”

“Retention-fee, I presume you mean.”

“Just so, and by your taking it, you are my lawyer. So take it.”

“Not quite so fast, if you please. State your case, and then I will tell you whether or not I take the retention-fee.”

The coarse fellow stared.

“Why, mister, the case is simply this. Last spring I was doing a little business by way of selling meat. So I bought a yoke of oxen of old Maj. Farnsworth. I was to have them for one hundred dollars.”

“Very well—what became of the oxen?”

“Butchered and sold out, to be sure.”

“By you?”

“Yes.”

“Well, where’s the trouble?”

“Why, they say, that as I only gave my note for them, I need not pay it, and I want you to help me to get clear of it.”

“How do you expect me to do it?”

“Plain as day, man; just say, gentlemen of the jury, this young man was not of age when he gave Maj. Farnsworth the note, and therefore, in law, the note is good for nothing—that’s all!”

“And was it really so?”

“Exactly.”

“How came Maj. Farnsworth to let you have the oxen?”

“Oh, the godly old man never suspected that I was under age.”

“What did you get for the oxen in selling them out?”

“Why, somewhere between one hundred and thirty and one hundred and forty dollars—they were noble fellows!”

“And so you want me to help you cheat that honest old man out of those oxen, simply because the law, this human imperfection, gives you the opportunity to do it! No, sir; put up your retention-fee. I promised my dying mother never to do such a thing, and I will starve first. And as for you—if I wanted to help you to go to the state’s prison, I could take no course so sure as to do what you offer to pay me for doing. And, depend upon it, the lawyer who does help you, will be your worst enemy. Plead minority! No; go, sir, and pay for your oxen honestly and live and act on the principle, that let what will come, you will be an honest man.”

The coarse young man snatched up his bill, and muttering something about seeing Squire Snapall, left the office.

So he lost his first fee and his first case. He felt poor and discouraged, when left alone in the office; but he felt that he had done right. His mother’s voice seemed to whisper, “Right, my son, right.” The next day he was in old Maj. Farnsworth’s, and saw a pile of bills lying upon the table. The good old man said he had just received them for a debt which he expected to lose, but a kind Providence had interposed in his behalf. The young lawyer said nothing, but his mother’s voice seemed to come again, “Right, my son, right.”

Some days after this a man called in the evening, and asked the young man to defend him in a trial just coming on.

“What is your case?”

“They accuse me of stealing a bee-hive.”

“A bee-hive!—surely that could not be worth much!”

“No, but the bees and the honey were in it.”

“Then you really did steal it?”

“Squire are you alone here—nobody to hear?”

“I am all alone.”

“Are you bound by oath to keep the secrets of your clients?”

“Certainly I am.”

“Well, then, ’twixt you and me, I did have a dab at that honey. There was more than seventy pounds! But you can clear me.”

“How can I?”

“Why, Ned Hazen has agreed to swear that I was with him fishing at Squanicook Pond that night.”

“So, by perjury, you hope to escape punishment. What can you afford to pay a lawyer who will do his best?”

The man took out twenty dollars. It was a great temptation. The young lawyer staggered for a moment—but only for a moment.

“No, sir, I will not undertake your case. I will not try to shield a man whom I know to be a villain from the punishment which he deserves. I will starve first.”

The man with an oath bolted out of the office, and made his way to Snapall’s office. The poor lawyer sat down alone, and could have cried. But a few dollars were left to him in the world, and what to do when they were gone, he knew not. In a few moments the flush and burning of the face was gone, as if he had been fanned by the wings of angels, and again he heard his own mother’s voice, “Right, my son, right.”

Days and even weeks passed away, and no new client made his appearance. The story of his having refused to take fees and defend his clients got abroad, and many were the gibes concerning his folly. Lawyer Snapall declared that such weakness would ruin any man. The multitude went against the young advocate. But a few noted and remembered it in his favor.

On entering his office one afternoon, the young man found a note lying on his table. It read thus,

“Mrs. Henshaw’s compliments to Mr. Loudon, and requests, if it be not too much trouble, that he would call on her at his earliest convenience, as she wishes to consult him professionally, and with as much privacy as may be.

“Rose Cottage, June 25th.”

How his hand trembled while he read the note. It might lead to business—it might be the first fruits of an honorable life. But who is Mrs. Henshaw? He only knew that a friend by that name, a widow lady, had lately arrived on a visit to the family who resided in that cottage. “At his earliest convenience.” If he should go at once, would it not look as if he were at perfect leisure? If he delayed, would it not be a dishonesty which he had vowed never to practice? He whistled a moment, took up his hat, and went toward “Rose Cottage.” On reaching the house, he was received by a young lady of modest, yet easy manner. He inquired for Mrs. Henshaw, and the young lady said,

“My mother is not well, but I will call her. Shall I carry your name, sir?”

“Loudon, if you please.”

The young lady cast a searching, surprised look at him, and left the room. In a few moments the mother, a graceful, well-bred lady of about forty, entered the room. She had a mild; sweet face, and a look that brought his own mother so vividly to mind, that the tears almost started in his eyes. For some reason, Mrs. Henshaw appeared embarrassed.

“It is Mr. Loudon, the lawyer, I suppose,” said she.

“At your service, madam.”

“Is there any other gentleman at the Bar of your name, sir?”

“None that I know of. In what way can you command my services, madam?”

The lady colored. “I am afraid, sir, there is some mistake. I need a lawyer to look at a difficult case, a man of principle, whom I can trust. You were mentioned to me—but—I expected to see an older man.”

“If you will admit me,” said Loudon, who began to grow nervous in his turn, “so far into your confidence as to state the case, I think I can promise not to do any hurt, even if I do no good. And if on the whole, you think it best to commit it to older and abler hands, I will charge you nothing and engage not to be offended.”

The mother looked at the daughter, and saw on her face the look of confidence and hope.

The whole afternoon was spent in going over the case, examining papers, and the like. As they went along, Loudon took notes and memoranda with his pencil.

“He will never do,” thought Mrs. Henshaw. “He takes every thing for granted and unquestioned; and though I don’t design to mislead him, yet it seems to me, as if he would take the moon to be green cheese, were I to tell him so. He will never do;” and she felt that she had wasted her time and strength. How great then was her surprise when Loudon pushed aside the bundles of papers, and looking at his notes, again went over the whole ground, sifting and scanning every point, weighing every circumstance, pointing out the weak places, tearing and throwing off the rubbish, discarding what was irrelevant, and placing the whole affair in a light more luminous and clear than even she had ever seen it before. Her color came and went as her hopes rose and fell. After he had laid it open to her, he added, with unconscious dignity,

“Mrs. Henshaw, I think yours is a cause of right and justice. Even if there should be a failure to convince a jury so that law would decide in your favor, there are so many circumstantial proofs, that I have no doubt that justice will be with you. If you please to entrust it to me, I will do the best I can, and am quite sure I shall work harder than if I were on the opposite side.”

“What do you say, Mary?” said the mother to the daughter. “You are as much interested as I. Shall we commit it to Mr. Loudon?”

“You are the best judge, but it seems to me that he understands the case better than any one you have ever talked with.”

Loudon thanked Mary with his eyes, but for some reason or other, hers were cast down upon the figures of the carpet, and she did not see him.

“Well, Mr. Loudon, we will commit the whole affair to you. If you succeed we shall be able to reward you; and if you do not, we shall be no poorer than we have been.”

For weeks and months Loudon studied his case. He was often at Rose Cottage to ask questions on some point not quite so clear. He found they were very agreeable—the mother and the daughter—aside from the law-suit, and I am not sure that he did not find occasion to ask questions oftener than he would have done, had it been otherwise.

The case, briefly was this. Mr. Henshaw had been an active, intelligent and high-minded man of business. He had dealt in iron, had large furnaces at different places, and did business on an average with three hundred different people a day. Among others, he had dealings with a man by the name of Brown—a plausible, keen, and as many thought, an unprincipled man. But Henshaw, without guile himself, put all confidence in him. In a reverse of times—such as occur once in about ten years, let who will be President—their affairs became embarrassed and terribly perplexed. In order to extricate his business, it was necessary for Henshaw to go to a distant part of the land, in company with Brown. There he died—leaving a young widow, and an only child, Mary, then about ten years old, and his business in a condition as bad as need be. By the kindness of the creditors their beautiful home called Elm Glen, was left to Mrs. Henshaw and her little girl, while the rest of the property went to pay the debts. The widow and her orphan kept the place of their joys and hopes in perfect order, and everybody said “it didn’t look like a widow’s house.” But within four years of the death of Mr. Henshaw, Brown returned. He had been detained by broken limbs and business, he said. What was the amazement of the widow to have him set up a claim for Elm Glen, as his property! He had loaned Mr. Henshaw money, he said—he had been with him in sickness and in death; and the high-minded Henshaw had made his will on his death-bed, and bequeathed Elm Glen to Brown, as a payment for debts. The will was duly drawn, signed with Mr. Henshaw’s own signature, and also by two competent witnesses. Every one was astonished at the claim—at the will—at every thing pertaining to it. It was contested in court, but the evidence was clear, and the will was set up and established. Poor Mrs. Henshaw was stripped of everything. With a sad heart she packed up her simple wardrobe, and taking her child, left the village and went to a distant State to teach school. For six years she had been absent, and for six years had Brown enjoyed Elm Glen. No, not enjoyed it, for he enjoyed nothing. He lived in it; but the haggard look—the frequent appeal to the bottle—the jealous feelings which were ever uppermost—and his coarse, profane conversation, showed that he was wretched. People talked, too, of his lonely hours, his starting up in his sleep, his clenching his fist in his dreams, and defying “all hell” to prove it, and the like.

Suddenly and privately, Mrs. Henshaw returned to her once loved village. She had obtained some information by which she hoped to bring truth to light, for she had never believed that her husband ever made such a will in favor of Brown. To prove that this will was a forgery was what Loudon was now to attempt. An action was commenced, and Brown soon had notice of the warfare now to be carried on against him. He raved and swore, but he also laid aside his cups, and went to work to meet the storm like a man in the full consciousness of the justice of his cause. There was writing and riding, posting and sending writs—for both sides had much at stake. It was the last hope for the widow. It was the first case for young Loudon. It was victory or state’s prison for Brown. The community, one and all took sides with Mrs. Henshaw. If a bias could reach a jury, it must have been in her favor. Mr. Snapall was engaged for Brown, and was delighted to find that he had only that “white-faced boy” to contend with; and the good public felt sorry that the widow had not selected a man of some age and experience; but then they said, “women will have their own way.”

The day of trial came on. Great was the excitement to hear the great “will case,” and every horse in the region was hitched somewhere near the courthouse.

In rising to open the case, young Loudon was embarrassed; but modesty always meets with encouragement. The court gave him patient attention, and soon felt that it was deserved. In a clear, concise, and masterly manner, he laid open the case just as it stood in his own mind, and proceeded with the evidence to prove the will to be a forgery. It was easy to show the character of Brown to be one of great iniquity, and that for him to do this was only in keeping with that general character. He attempted to prove that the will could not be genuine, because one of its witnesses on his death-bed had confessed that it was a forgery, and that he and his friend had been hired by Brown to testify and swear to its being genuine. Here he adduced the affidavit of a deceased witness, taken in full before James Johnson, Esq. Justice of the Peace, and acknowledged by him. So far all was clear, and when the testimony closed it seemed clear that the case was won. But when it came Mr. Snapall’s turn, he demolished all these hopes by proving that though James Johnson, Esq. had signed himself Justice of the Peace, yet he was no magistrate, inasmuch as his commission had expired the very day before he signed the paper, and although he had been re-appointed, yet he had not been legally qualified to act as a magistrate—that he might or might not have supposed himself to be qualified to take an affidavit; and that the law, for very wise reasons, demanded that an affidavit should be taken only by a sworn magistrate. He was most happy, he said, to acknowledge the cool assurance of his young brother in the law; and the only difficulty was that he had proved nothing, except that his tender conscience permitted him to offer as an affidavit a paper that was in law not worth a straw, if any better than a forgery itself.

There was much sympathy felt for poor Loudon, but he took it very coolly and seemed no way cast down. Mr. Snapall then brought forward his other surviving witness—a gallows-looking fellow, but his testimony was clear, decided and consistent. If he was committing perjury, it was plain that he had been well-drilled by Snapall. Loudon kept his eye upon him with the keenness of the lynx. And while Snapall was commenting upon the case with great power, and while Mrs. Henshaw and Mary gave up all for lost, it was plain that Loudon, as he turned over the will, and looked at it again and again, was thinking of something else besides what Snapall was saying. He acted something as a dog does when he feels sure he is near the right track of the game, though he dare not yet bark.

When Snapall was through, Loudon requested that the witness might again be called to the stand. But he was so mild, and kind, and timid, that it seemed as if he was the one about to commit perjury.

“You take your oath that this instrument, purporting to be the will of Henry Henshaw, was signed by him in your presence?”

“I do.”

“And you signed it with your own hand as witness at the time?”

“I did.”

“What is the date of the will?”

“June 18, 1830.”

“When did Henshaw die?”

“June 22, 1830.”

“Were you living in the village where he died at the time?”

“I was.”

“How long had you lived there?”

“About four years, I believe, or somewhere thereabouts.”

Here Loudon handed the judge a paper, which the judge unfolded and laid before him on the bench.

“Was that village a large or a small one?”

“Not very large—perhaps fifty houses.”

“You knew all these houses well, I presume?”

“I did.”

“Was the house in which Mr. Henshaw died, one story or two?”

“Two, I believe.”

“But you know, don’t you? Was he in the lower story or in the chamber when you went to witness the deed?”

Here the witness tried to catch the eye of Snapall, but Loudon very civilly held him to the point. At length he said, “In the chamber.”

“Will you inform the court what was the color of the house?”

“I think, feel sure, it wasn’t painted, but didn’t take particular notice.”

“But you saw it every day for four years, and don’t you know?”

“It was not painted.”

“Which side of the street did it stand?”

“I can’t remember.”

“Can you remember which way the street ran?”

“It ran east and west.”

“The street ran east and west—the house two story, and unpainted, and Mr. Henshaw was in the chamber when you witnessed the will. Well, I have but two things more which I will request you to do. The first is to take that pen and write your name on that piece of paper on the table.”

The witness demurred, and so did Snapall. But Loudon insisted upon it.

“I can’t, my hand trembles so,” said the witness.

“Indeed! but you wrote a bold, powerful hand when you signed that will. Come, you must try, just to oblige us.”

After much haggling and some bravado, it came out that he couldn’t write, and never learned, and that he had requested Mr. Brown to sign the paper for him!

“Oh, ho!” said Loudon. “I thought you swore that you signed it yourself. Now one thing more, and I have done with you. Just let me take the pocket-book in your pocket. I will open it here before the court, and neither steal nor lose a paper.”

Again the witness refused, and appealed to Snapall; but that worthy man was grinding his teeth and muttering something about the witness going to the devil!

The pocket-book came out, and in it was a regular discharge of the bearer, John Ordin, from four years imprisonment in the Pennsylvania Penitentiary, and dated June 15, 1831, and signed by Mr. Wood, the worthy warden.

The young advocate now took the paper which he had handed to the judge, and showed the jury, that the house in which Mr. Henshaw died was situated in a street running north and south—that it was a one-story house—that it was red, the only red house in the village, and moreover, that he died in a front room of the lower story.

There was a moment’s silence, and then a stifled murmur of joy all over the room. Brown’s eyes looked blood-shot; the witness looked sullen and dogged, and Mr. Snapall tried to look very indifferent. He made no defence. The work was done. A very brief, decided charge was given by the judge, and, without leaving their seats, the jury convicted Brown of forgery!

“That young dog is keen, any how!” said Snapall.

“When his conscience tells him he is on the side of justice,” said Loudon, overhearing the remark.

It was rather late in the evening before Loudon called on his clients to congratulate them on the termination of their suit, and the recovery of Elm Glen. He was met by Mary, who frankly gave him her hand, and with tears thanked and praised him, and felt sure they could never sufficiently reward him. Loudon colored, and seemed more troubled than when in the court. At length he said abruptly, “Miss Henshaw, you and your mother can now aid me. There is a friend of yours—a young lady, whose hand I wish to obtain. I am alone in the world, poor, and unknown. This is my first law-case, and when I may have another is more than I know.”

Mary turned pale, and faintly promised that she and her mother would aid him to the extent of their power. Then there was a pause, and she felt as if she, the only one who was supposed to be unagitated and cool, must speak.

“Who is the fortunate friend of mine?”

“Don’t you suspect?”

“Indeed, I do not.”

“Well, here is her portrait,” handing her a miniature case. She touched a spring and it flew open, and in a little mirror, she saw her own face! Now the crimson came over her beautiful face, and the tears came thick and fast, and she trembled; but I believe she survived the shock; for the last time I was that way, I saw the conscientious young lawyer and his charming wife living at Elm Glen; and I heard them speak of his first law-suit!

———

BY R. H. STODDARD.

———

What wiser is the world in this bright age—

What better than in the darkened days of old?

Survey the Past, its blotted scroll unfold;

Compare it with the Present’s golden page—

It is no worse; the world was cruel then,

And hearts were trampled on, and spirits bled,

And tears and blood like summer rain were shed,

And men were what they always will be—Men!

Experience teaches naught, man will not heed

And profit by the lessons. Fools can read;

The task is said by rote; we do not learn,

But live in ancient ignorance and crime.

There is no hope—the Future will but turn

The old sands in the failing glass of Time!

———

BY E. CURTISS HINE, U. S. N.

———

Bright dreams were mine in life’s young day,

Too bright, too fair to last,

Fresh flow’rets sprung beside my way,

And fragrance round it cast;

And hopes as radiant as the dyes

That angel-artists spread,

Upon the western sunset skies,

To my young heart were wed.

Bright days, sweet days, forever gone!

Ye can return no more,

I’m doomed to tread the sands alone

That skirt life’s desert shore!

Afar, upon the ocean wide,

My bark of hope went down,

I saw the angel leave my side,

And all things on me frown.

But there are paintings hanging yet

In memory’s ghostly halls,

And bright young faces looking down

Upon me from the walls.

The gentle smile that thrilled my soul,

In life’s young break-of-day,

The small white hands once clasped in mine,

Are pictured there for aye.

There is a form, I see it now,

More radiant far than all,

The full, dark eye, the snowy brow

That held my heart in thrall.

But, O, that voice, so low and sweet!

I ne’er shall hear it more;

The fond, warm heart hath ceased to beat—

My dream of bliss is o’er.

And still another picture there—

A being young and bright;

The captive sunbeams in her hair,

A form of love and light;

The deep blue tints that stain the sky,

When summer bids it gleam,

Are mirrored in her laughing eye,

Like violets in the stream.

I deemed those forms forever fled

From time’s bleak desert shore,

And that the light upon me shed,

Could visit me no more.

But late I saw a vision bright,

And fair as those of old,

That taught to me this lesson trite—

The heart can ne’er grow cold!

O, charming, charming young Christine

Long years may pass away,

But cannot seize the love I ween,

Of young life’s joyous day!

O, would some gem like thee were mine

Upon my breast to wear,

Through Sorrow’s dreary hour to shine,

And light the night of Care;

My glance upon mankind should fall

Contented, happy, free,

And I should richer feel than all,

My only treasure thee!

But, O, my lot is wild and drear,

And sad the night-winds moan;

Upon life’s tree the leaves are sere,

And I am all alone.

———

BY MRS. S. A. LEWIS.

———

It hath been said, “for all who die,

There is a tear;

Some pining, bleeding heart to sigh,

O’er every bier;”

But in that hour of pain and dread,

Who will draw near,

Around my humble couch, and shed

One farewell tear?

Who watch life’s last dim parting ray,

In deep despair,

And soothe my spirit on its way,

With holy prayer?

What mourner round my bier will come,

In weeds of wo,

And follow me to my long home,

Solemn and slow?

When lying on my clayey bed,

In icy sleep,

Who there, by pure affection led,

Will come and weep?

And by the moon implant the rose

Upon my breast,

And bid it cheer my dark repose,

My lowly rest?

Could I but know when I am sleeping

Low in the ground,

One faithful heart would there be keeping

Watch all night round,

As if some gem lay shrined beneath

That sod’s cold gloom,

’Twould mitigate the pangs of death,

And light the tomb.

Yes! in that hour, if I could feel,

From halls of glee

And Beauty’s presence, one would steal

In secresy,

And come and sit and weep by me

In night’s deep noon;

Oh! I would ask of memory

No other boon.

But, ah! a lonelier fate is mine—

A deeper wo;

From all I love in youth’s sweet time

I soon must go,

Drawn round me my pale robes of white

In a dark spot,

To sleep through death’s long, dreamless night,

Lone and forgot.

A TRUE STORY.

(DEDICATED TO MY FRIEND MARTHA W. B——.)

———

BY CAROLINE C——.

———

Away with weary cares and themes!

Luring wide the moonlit gate of dreams!

Leave free once more the land which teems

With wonders and romances!

I know that thou wilt judge aright

Of all that makes the heart more light,

Or lends one star-gleam to the night

Of clouded Melancholy!

—J. G. Whittier.

I fancy, my good reader, that you are about as familiar with the physical appearance of this exalted personage, the far-famed Man in the Moon, as is your most obedient. That you have gazed upon him with love-kindled eyes many and many a witching summer night, I have not the shadow of a doubt—that you have often lamented the provoking imperfectness of your vision, which presents such insurmountable difficulties and obstructions in the way to your beholding clearly what manner of man he truly is, I cannot have much hesitation in believing; reasoning as I do, from my extensive knowledge of what passes in the minds of other people, and from the thoughts and feelings I have had myself in regard to the peculiar personalities of this mysterious gentleman.

Until recently I never indulged in the hope of being counted among the benefactors of my race, but, my fair countrywomen, I hope I do not presume too much, when I say that I shall hereafter merit this honor at your hands, for am I not going to speak to you of events which, wonderful as they are, have hitherto never come to the knowledge of our present generation? I cannot conscientiously make known to you the mysterious means by which I became cognizant of the following events, yet do I hold myself clear of any breach of confidence when I lay before you these wondrous facts, upon the truth of which you may rely, on my veracity as a story-teller!

Long, long ago there lived in a far country, among the mountains, which towered to heaven much in the manner of mountains now, a young maiden, who must certainly have been one of the progenitors of “The Sinless Child;” for in personal beauty, and in excellence and purity of mind, this girl was unsurpassed, perhaps unequaled in her day. A “rare and radiant maiden” was she, albeit unaccomplished and unlearned.

Kind, generous and affectionate was Rose May, having withal such a reasonable amount of spirited independence in her nature, as a child born and bred among the mountain wilds would be like to have.

It was a glorious dwelling-place, that of my heroine! Grant May, her father, was a shepherd, a rugged man of middle age, whose furrowed face bore testimony to the fact, that he had encountered and weathered many a hard storm in the course of his life. A true son of the mountains was he; for three or four generations back his fathers had lived, shepherds, in these same wild heights, and I doubt much if this son of his father could ever have breathed the warmer and gentler air of a less elevated home. Occasionally, but at long intervals, he had wandered away to the world below him, but, like the eagle, his eyry and his affections were fixed amid the towering heights, the rugged scenes and bracing air of the mountains—there was the home for which Nature and a forty years’ residence had fitted him.

The shepherd’s house was built in what, to an eye unaccustomed to such scenes, would seem a most dangerous situation. But it was just to the contrary. Erected on the side of a deep ravine at the bend of the stream, it was sheltered on three sides from the rough, wild winds of winter; and in summer it seemed half buried in the vegetation, which was nowhere on the mountains so abundant as about this place. Above, beneath, and around the cottage there were hardy bushes and flowering shrubs, and towering high above them the pine-trees and the strong-limbed offspring of that rugged clime; and higher still above the flowers, and bushes, and pines, spread the bright deep blue sky, which seemed to rest its mighty arches on the peaks and crags of those great heights.

Yes, it was a glorious home, a noble dwelling-place, that of young Rose May! The voice of the southern wind, when it crept so softly up the mountain, and through the branches of the pines, to kiss her brow, and tell her of the wild beauty of the land from which it wandered, that voice was sweet and welcome music to her ear; but no less loved and welcome was the trumpet-blast of the storm, when it came rushing like a fiend’s voice past her home, or like the challenge of a giant fresh from the strong fortress where the soldiery of Winter were garrisoned. Rose loved the flowers, the gay bright blossoms which in midsummer bloomed about her home, but more keen was her delight in the grandeur which made her heart to thrill, and her blood to leap wildly through its veins, when on awakening some dreary mornings of winter, she saw the pine-trees loaded with the wealth of glittering icicles, which glowed and blazed with a splendor greater than if the treasuries of all the kings and princes of earth had been melted and poured over those same stately scions of the soil.

Nature in all her phases was beautiful, and welcome to Rose May; but there was something in the heart of the girl which made her sympathize with, and rejoice more keenly in the grand and terrible shapes the great Queen chose during more than eight months of the year to appear in. Therefore Rose May was most truly a daughter, a bright, strong-hearted, noble daughter of the mountains.

They had aptly named this maiden after the queen of the flowers. For though there were many sons in Grant May’s household, Rose was the only daughter, and she was like a rose indeed, the fairest as well as tenderest bud opening beneath the family roof-tree. The bloom of health was on the maiden’s cheek—the glow of health was in her veins and in the calm beating of her heart, which told so steadily “all’s well.”

While Grant May and his sons were absent from their home all day, tending to their many flocks, Rose remained with her mother at home, assisting her with willing hand in the domestic toils; and a steady and invaluable helpmate was she, spinning yarn from the sheep her father called her own, and then knitting the proceeds into stout socks and mittens for them who labored out of doors; and ingeniously contriving numerous garments, whereby to keep the ears, necks and feet of her wild, light-hearted brothers warm in the dreadful winter weather. Rose was, in fact, quite a pattern maid; never complaining, or caring to rest herself even when she was aweary, while there was any work left for her mother to do—and the last thing she ever would have thought to boast of was ignorance of any part of the book of domestic economy—which volume, if you, my dear reader, have had any occasion to thumb, you know very well is not printed with the most readable or understandable type.

Rose May had not many companions. There were, it is true, other families, and numbers of them, scattered among the mountains, but these lived at long distances from each other, and were so circumstanced as to preclude the possibility of frequent visitings. But when these far-off neighbors did meet, it was with the warm and earnest good feeling which people so situated would be likely to entertain for each other. Perhaps their mutual interest was even more sincere and honest, their friendship more generous and truthful, than if they had been able to hold more frequent and familiar communication with each other, partaking, as necessarily they did, each and all, of the mundane nature, for they had scarcely time to discover one another’s particular failings and short-comings.

There were two families, however, whose members maintained a more familiar intimacy with the household of Grant May than the other mountaineers. And for this reason. In both these families there was a son—each, only sons, too, who regarded Rose May with fonder eyes than mere friendly interest would warrant; they both loved her with all the devotion their wild, earnest spirits were capable of—both acknowledged her the queen of the mountain flowers, and the object of their supreme regard.

One of these youths was named Joseph Rancy; his father was the wealthiest of the shepherds—the son would be the old man’s sole heir. This fact alone was one calculated to greatly enhance the merits of the young man—to make him a favored guest—a much sought for friend—and an acceptable suitor, especially in the eyes of parents who had a double eye to their daughter’s happiness and good fortune.

Joseph was a tall, robust, free-spoken youth, with a heart whose honesty forbade his lips ever speaking a word which could not safely be echoed in its recesses. But his very bluntness, though it arose from his honesty of purpose, was not perhaps calculated to make him a great favorite with that class of people said to be lovers of soft words and honied speeches. Joseph was a great favorite with Grant May and with the young brethren of Rose. They liked him for his generosity and daring, and for many noble traits of character he evinced, which I will not now stop to enumerate. The young man knew he stood well in their eyes—but about her whose favor he cared for more than all the rest, he was as yet in a state of doubt and perplexity.

The other youth who visited so frequently Grant May’s cottage was Rob Horn. To say Rob was handsome as a picture would be rather a doubtful compliment; but handsome he was, tall and straight as an Indian, with a bright, smiling face—which (but for a treacherous expression sometimes seen lurking about the mouth) seemed to hail every man a brother and friend; then his hair was black as a raven’s wing, eyes ditto—a becoming bloom on his brown cheeks, graceful, light-hearted, cheerful and companionable—there, you have Rob Horn—is he one you would suppose Rose May might love?

Rob also was an only son—but the great difference between him and Joseph Rancy was, that his father was far from wealthy, having only managed to keep partially “above board,” during all the long years of his earthly pilgrimage.

More than once Rob had roved away from his mountain home to the low-land villages, for his was a restless spirit, and his were roving eyes, that grew weary at times of looking always on the same grand scenes; but still he seemed to retain an unextinguishable affection for his native home, for after a short absence he always returned to his father’s humble cot, with his head full of the scenes he had looked upon in the busy world, but with his curiosity satisfied, and his heart all right toward home. The reason, however, of his invariable return was, that up in the old eagle’s eyry (that is in Grant May’s cottage) there was the little bird whose wild, free-gushing songs was the attractive power which always called him back.

And among the fairer faced damsels who lived in cities, were there none whom Rob thought comparable with the unfettered-by-fashion Rose May? Was there none whose smile made his heart thrill with rapture? Was there not one whose voice was sweeter than an angel’s to his ear, whose words were dearly remembered, and treasured long after they were uttered? Let us see.

Sitting by the blazing fire in Grant May’s kitchen during the long, pleasant winter evenings, and telling to the gathered family the strange fashions and habits of the people with whom he had occasionally mingled—describing to the wondering children modes of life which they in their simplicity had never dreamed of, and to the father the changes which had occurred in public affairs, and to the mother, of the women, whose acquaintance he had made, and of the friends she had known in her girlhood whom he had chanced to meet, it is not to be supposed that he neglected all this while, and thought not at all of the fair young listener, to please whom he would have talked on forever, had that been necessary—no, indeed, she was not forgotten, for during many years Rob had been incessantly at work, forming a telegraph route between his heart and her own; he was even then, during those winter evenings, busy in that great work of his life, and ere long he was determined to prove if the work was perfect—but he delayed sending the first real dispatch—he feared lest it should be uncomprehended and unanswered.

To Rose, Rob had always seemed kind, and noble, and honest—in short, all that man ought to be—all that Joseph Rancy was. And a keener insight than she possessed, or many mortals on earth possess, would have been requisite in this case to detect the true gold from the glittering dross. Even when the maiden’s father discovered how all the inclination and affection of his child chose Rob instead of Joseph, he did not see any insurmountable objection lying in the way to the child’s union with the former—and it was only with a sigh for the fortune which might have been his daughter’s, that he gave up all idea of her ever wedding Joseph Rancy.

These two boys had always been the most intimate and best of friends. In earlier days the visits which they planned together to make to their young friend, Rose, were unmarred by jealous thoughts, they were marked as the best of their weekly holydays. No matter how deep the snow might lie on their path toward Grant May’s cot, these appointments, which they made between themselves, were ever regularly kept; for the thought of the bright faces which always gave them such a hearty welcome, and made for them a place by the warm fire with such ready zeal, was a sufficient inducement for them to brave the coldest weather, and the stormiest day.

But as the two grew older, and learned to distinguish between friendliness and love, they did, sorry am I to tell, grow jealous of one another, and at last, before they had concluded it were better to make these visits to Rose alone, each by himself, when Rose had unwittingly spoken in a tone more kindly to one of them, and evinced in any way an innocent and thoughtless preference, the other walked homeward with closed lips and aching heart, and in most unsocial mood.

Joseph Rancy had never dared to speak openly to Rose May of love. It was strange that one so stout-hearted as he, with all the advantages of wealth, beside possessing much personal beauty, should falter as he tried to tell a simple mountain maid he loved her! But so it was. The words refused to obey his bidding when he tried to utter them. He had not lived even in those busy places where men and women congregate, yet he did know that “faint heart never won fair lady,” and the very knowledge of that truth but increased his fears. Poor fellow! he doubted his own powers to please, and he knew that Rob Horn was a powerful and much to be feared rival. But Joseph was one who could not easily give up a thought he had cherished for so long. It was a hope it would have been hard for him to relinquish; he could never forget that he had loved Rose May, even though she turned a relentlessly deaf ear to his suit; his heart would never be satisfied with the affection of another woman. And I say but the truth, when I tell you he was worthy of her love—more worthy, if a less dashing lover than Rob Horn. There was less glitter in him, far more real worth, less of admiration, and passion, than deep and earnest love in his thoughts of Rose.

He had placed his hopes upon her returning affection; and it is not agreeable with the natural order of things, to suppose that he would for ever continue irresolute in a case momentous as this; and so, once again, with the express desire to hear his fate decided by her lips, he set out on a summer morning, determined that his resolution should hold out till he had heard his doom from her own voice.

The day was favorable; oh! if the event might only prove so, too! The time also seemed propitious, for before Joseph had half way reached her father’s house, he met Rose May. She was gathering wild-flowers, and when she saw him coming toward her, she gayly bade him assist her in the pleasant work. I know not if those simple people ever studied the “language of flowers;” perhaps, however, the science is a natural one, but this I know, that there was a great preponderance of mountain-roses, buds, and half-opened blossoms, in the flowers Joseph gathered for the little lady. Ah, what a lucky wight! the beautiful summer morning—the silent wood—the naturalness of the offer of his heart with the flowers he gave her! Surely Fate, for once, was propitious! But notwithstanding the chances were with him, and the hour was one of a thousand, Joseph still hesitated and delayed; and it was not till all the flowers were gathered, and Rose had actually set out on her homeward path, that Joseph nerved himself to the pitch requisite.

And, indeed, it was quite a point in his destiny he had reached; the next step you plainly see was an important, an all important one to him. It had been the hope of years that he might win, and one day wed, Rose May; he had lived in that hope; its working out had been one of the most blessed of his thoughts; and now, in five short minutes (perhaps less) he would know if this dear dream were to have fruition, or was it to pass away like the morning dew, leaving him no possibility of ever indulging in it again, that is, with reason—and Joseph was a reasonable youth.

As I have stated, he was an uneducated youth, that is, uneducated in the schools, and ignorant and innocent of polite learning, therefore he knew but one way of discovering a fact, and that was by asking a question point-blank. When Rose was about emerging from the wood, from whence a little path led down the ravine to her father’s house, he paused in the walk, and said quite distinctly,

“Wait a moment, Rose May. I came to ask you a question I have thought to ask you this long time—will you love me—will you be my wife?”

“Yours, Joseph,” replied Rose, as honestly and unreservedly as the question had been put; “Yours—how can you think of such a thing?”

“I have thought of it for years, Rose. You have so many brothers and friends, like enough you have considered me as one of them; but I, I have no sister, Rose, no friend I hold half so dear as you. It does not strike me as such a very strange thing to ask you; if you will only think of it, I do not ask you to answer me to-day. Perhaps when you think it all over, the matter will not seem so strange; and I would not have you answer me in haste, dear Rose.”

“Never, Joseph Rancy,” answered Rose, speaking rapidly, but kindly, though so firm. “I have always thought of you as a dear friend, that is true, but I can never be any more than that.”

“Will you not say any thing more, Rose? Think again; you call me your dear friend, oh, be my wife, my best and dearest friend. Your home is so happy, think of mine, lonely and dreary as it is now; what a paradise it might be were you there! Rose, dear Rose May, I pray you only to think again.”

“I have thought, Joseph; do not speak to me so any more, it pains me; there are many others who might make your home as happy, far happier than I; forget that you have had such thoughts about me, my friend.”

“How can I forget,” said Joseph, sadly, while for a moment longer he retained her to hear his words, for she was hastening away. “Tell me, Rose,” he said, falteringly, “is there any other—do you love any body better than me?”

“Yes, my father and mother.”

“Not them—I don’t mean them; the love I ask is not the kind you give to them—but is there another—”

“It is not right in you to ask me such questions, you know it is not. Don’t make me think the less of you as a friend by going too far now.”

“Forgive me dear, dear Rose—I’m going. Don’t let what I’ve said trouble you; I’d let my tongue be burned with hot iron before speaking what I have to you to-day, if I thought ’twould make you less happy.”

“Good-by, Joseph, now you are what you always have been, generous and good; and if I don’t love you as you could wish, I honor you from my heart—good-by.”

There was a lingering sadness in the maiden’s voice as she spoke, that convinced Joseph she was honest in her words, and that she did sincerely grieve to have been the cause of disappointment to him; yet that knowledge did not soothe nor allay the heart-wound she had given him; and he went back to his home, feeling, as I suppose many a poor mortal has felt before, disconsolate and unhappy. Still Joseph was a young man of sound mind, and he loved Rose May even better than ever he had before; her very firmness made him respect her for it, though that firmness was all directed against his suit.

Often as he thought over the unmeasurable distance there must forever be, even in thought, between them, so often came the soothing remembrance that it was not lack of worth on his part that made her reject him. Had she not said she honored him? And was not such respect and kindly feeling, indeed, the highest and the purest kind of love? Might he not some day convince her that it was also the best love, and the one most conducive to happiness in wedded life? But, alas! close upon this thought came the death-blow to all hope, for Joseph was convinced that she would wed another.

Yes, and there was one she had promised to wed—one for whom she had more than respect—one whom she more than honored—and he none other than Rob Horn! He was the fortunate youth whose telegraph-dispatch was successful in receiving a speedy and satisfactory reply. Fortune favored him; does she favor only the good, and the deserving, and true?

The home of one of the most powerful of the spirits was in these mountains—a spirit loving justice and equity, who watched the scales wherein the good and evil were weighed with jealous eye. This being of power took much interest in the affairs of the shepherds; sometimes she had even deigned to speak with them in her quiet, unostentatious way; and when she taught them, it was generally on some subject of domestic good or household economy. Almost all her instructions had been of this nature, for they were a quiet, religious people among whom she lived, giving away very rarely to the temptations of vice; but once or twice the spirit had spoken in rather strong and understandable language, to an offender who rarely in his sinful life had any “compunctious visitings.” No one had ever seen her bodily, and yet there was but one person who dared to disbelieve in the spirit’s existence, but one who would not recognize her power; and who should this reckless one be but the wild youth, Rob Horn? He dared to say, and say openly, too, that there was never any such being in existence, and that from the very nature of things there never could be. Some people will never believe in any thing out of the ordinary range of facts, more especially if they be in a state of partial ignorance—and of this very class of persons was Rob; the spirit had never manifested herself in any shape to him, and he, poor mortal! fancied she never could.

It was the only point in her lover’s nature that Rose May feared—this skepticism; for Rose was a firm believer in all spiritual existences; and often, but unavailingly, she had besought Rob to at least speak in a manner more respectful of the powerful agent, who would, she knew, work him wo if he continued obdurate in his unbelief. But there was nothing in the natural world the young man feared, there was no danger he dared not brave—why then tremble at the unseen, unknown, unheard? Why give heed to the superstitious fears of old women and maidens? Instead of being able in this case to convince her lover, Rose, after all, was herself almost persuaded by his jests and ridicule to doubt the existence of the power, which she also had never seen or heard. She began to give place in her mind to Rob’s words, that it was the idlest thing in the world to believe in such romantic impossible existences. But as yet Rose had kept her growing infidelity to herself; she would not have dared to breathe to her mother even, who was firm in the faith, her strengthening doubts; perhaps it was well for her she did not dare.

It was night—the night previous to his bridal day—and at a late hour Rob left the home of Rose, and bent his steps through the rough path that led to his own dwelling-place. The happy fellow, if we may judge from facts, was in a most delightful state of mind, well-pleased with himself and his bride-to-be, and with all the world beside. “To-morrow” was his wedding-day, and ever thereafter Rose May, the brightest flower of the mountains, was his own! And well might he rejoice.

Grant May had yielded to the youth’s solicitations with a good grace when he found his child’s hope and love were directed toward Rob; and it was no difficult thing to win the consent of the mother, for he had always been in high favor with her, since he brought her from his wanderings in the valley, the inestimable gift of a few bright pieces of useful furniture, which occupied the most honorable places and positions in her household.

In a few days after the festivities following the great occasion were over, Rob, with his bride, were to make the journey to the nearest large town, which plan was of itself half enough to make young Rose wild with joy, for the greatest multitude she had ever seen gathered, was on the Sabbath days, when twenty or thirty of the mountain people met in the little church to worship.

It was a bright moonlit night, the soft light streamed over the path he was to tread, as Rob returned home. The parting kiss of Rose was warm on his forehead; he fancied she was beside him, walking in the same path, and nearly all the way he talked soft words of love as though she were by to hear. When the young man had nearly reached his home, he encountered Joseph Rancy. These two had been far from cordial in their greetings of late, and with good reason, for Rob’s manner to Joseph had been that of triumph, and Joseph’s that of a man heart-sore and jealous of the success of his rival.

This night, however, Joseph Rancy had come out with the express purpose of meeting his friend of other days, and to speak with him in the manner of by-gone time, as kindly and as generously. When he had come up directly in front of Rob, he was still unobserved; he paused then, and holding out his hand, said,

“I came out on purpose to meet you, Rob.”

Horn took the proffered hand in his own, and said,

“I am glad to see you, truly, Rancy; we have not met of late.”

“No; we haven’t been the friends we once were, Rob. I have shunned you because—because you seemed to triumph over me, my old friend. You who have been so successful where I failed so bitterly.”

“Was it my fault that I succeeded in winning Rose May, tell me that,” replied Horn, sharply. “Where’s the blame, then, if I did rejoice?”

“No blame, none, none,” said Joseph, mildly, “you have been fortunate indeed, I wish you and yours much joy Rob, now and ever.”

“Hold,” cried Rob as Joseph turned away, “you will come to the church to-morrow, will you not. You will wish to see Rose married?”

“Rob!” exclaimed Joseph, in a tone of deep reproach, “no—I can bear to know you are going to marry her—I can hope for you, and pray for you both—but to see her married to another! You will not need me there.”

When he finished speaking Joseph went off quickly on his way, and Rob Horn pursued his path home; the only answer he returned to Joseph’s grief was a smothered laugh, which stifled as it was in the stillness of the night, the disappointed seeker of peace heard distinctly.

All that night Joseph Rancy sat on the opposite bank of the ravine where he might look on the dwelling-place of Rose May, and all that night he prayed for her happiness, and strove hard to banish all unfriendly thoughts toward Rob Horn from his mind. But when the morning came, long before the sun rose he wandered away among the mountains, that he might be far off from the place where she would be given to another.

Rob went on to his home—the cot was still as sleep, for his father and mother had hours before retired to their rest. He went to his chamber, and soon upon the easy couch he slept. And then Rob dreamed; of course there was but one he could dream of all that night, his young and beautiful bride, the girl he would be so proud to hear the old priest pronounce his wife. But though he could only dream of her, it does not follow that his night visions were pleasant—far enough from pleasant was the truth in this case.

He fancied that the spirit of the mountain, (the same in whose existence he had doubted for so long,) came to him with an angry frown on her spirit countenance. He trembled, yes he, the strong iron-willed youth trembled when he looked on her; he had never feared or quailed before. When she had come quite close to his bedside, and rested her hand upon his shoulder, where it lay like lead, and gazed so sternly upon him, Rob said to her:

“Why dost thou come here to disturb me, and trouble my dreams, thou terrible shape?”

And the spirit answered:

“Tell me instead, what is it thou art about to do?”

“That is quickly told,” said Horn, “to-morrow I shall marry Rose May, the loveliest maid the sun ever shone upon.”

“Ah, Rob Horn, Rob Horn,” said the spirit sternly, interrupting him, “bethink thee what it is thou wilt do! bethink thee what has become of thy betrothed in the distant village? does she wear thy ring? does she remember thy kiss, and thy love vows? what of her Rob Horn?”

When the spirit spoke thus Rob was amazed, and he could not hide his amazement; his face became suddenly very red—was it the confusion of guilt? and for a moment he was completely abashed. But soon he rallied again, and said,

“I cannot marry two wives. I have loved Rose May all my life—I must marry her; the maiden in the village can find another bridegroom.”

“Thou art not worthy to wed one like Rose May, but there is one worthy of her whom thou hast triumphed over many a time, and even this very night, because thou hast been more successful than he—beware, thou may’st go too far.”

“Too far! She will be mine to-morrow—what power in heaven or earth can separate us? She is mine—mine—mine!”

“Thou mayest deceive thyself. I ask thee, wilt thou not give up Rose May and betake thee to the pale and sorrowing maid who has awaited thy coming so long?”

“Give her up? My Rose! never! Thou fool to ask it of me!”

“And yet I do ask thee again, wilt thou not be just? Do that which thine honor and truth require of thee—the girl thou hast deserted will die.”

“Be death her bridegroom then! Who art thou to take my Rose from me? She is mine, I will wed no other!”

“Why so sure? Did ever such wickedness as is in thee prosper? Thou hast a bad heart Rob Horn, and a thousand things may come between thee and her, even after the priest proclaims her thine. There is nothing sure or stable for one like thee! give her up now, or beware—a fate more terrible than thou canst think may be in store for thee.”

“Begone thou prating fool! rather will I give my life up than my Rose, my bride, my beautiful!”

So firmly was this third repetition of his determination spoken that Rob awoke, and as might be supposed he found himself alone, and the sunlight streaming brightly through his little window. Heartily congratulating himself that it was all a dream, the young man arose, and ere long had tastefully adorned himself with the new raiment prepared for the momentous occasion.

The morning was verging toward noon, when in the simple church the wedding party gathered before the altar.

There was beautiful Rose May and her handsome bridegroom, and after the manner of things, of necessity, the twain never in their lives looked so charmingly as then. And there were the parents of the bridegroom and the bride, happy as parents might be, who believed they were about to witness the consummation of their children’s joy. And there also were all the young brothers of Rose, bright and smiling, as such little folks on such occasions invariably are. These were all gathered about the altar; the body of the church was nearly filled with the young friends of the to-be-married ones, and the sturdy old mountaineers with their wives.

It would not be strictly cleaving to truth to say that Rob Horn was wholly at ease that morning—far otherwise, for that strange dream of his tormented him. It was foremost in his mind, claiming even in that holy hour more of his thought than the gentle, excited girl who leaned in trusting fondness on his arm. Why should a merely ugly dream annoy him so? Was the young skeptic’s disbelief in spirits shaken? Had he in reality a promised bride awaiting him in the far-off village? Have patience with me, by the dénoument you will know it all.

They were kneeling before the altar. The consecrated hands of the old priest were raised in blessing above them, he was about pronouncing the uniting words, and Rob, the bridegroom, was thinking even then if there were in reality spirits he had overpowered his visitant, at least, by his boldness and firmness, when suddenly there came a shape of light floating through the open door of the church. It moved on noiselessly through the holy edifice above the heads of the astonished and alarmed congregation, until it came to the altar, and there it paused. And then a voice soft and thrilling as the voice of the summer breeze, yet distinctly audible to every soul gathered there, said—

“Rise, Robert Horn, thou shalt not speak the marriage vows!”

And pale as death, Rob, unable to resist these words, lifted up himself.

Then distinctly as before, the voice said—

“Did I not tell thee to beware? Did I not forbid thee to wed this maid, thou, who hast another plighted to thee, one who waits and watches for thee, wondering at thy long delay? Did I not bid beware—didst thou not laugh at my words? Answer me, Robert Horn?”

The bridegroom lifted up his eyes to the shape before him and said, but with a voice that trembled—

“Thou didst bid me beware, but I am here notwithstanding—here to take this woman for my wife, and Rose is here, she is mine, and thou, whatsoever thou art, canst not and shalt not part us.”

“Thou hast sealed thy fate,” answered the Spirit of the Mountain, “for thy wickedness, thy falseness, and thy unbelief, thou shalt be banished away from the earth for ever! And it shall be a part of the misery of thy banishment, that once in every month from thy prison-house thou shalt look down upon this lower world. Thou shalt see, and know, and feel, all the pangs, and the bliss, and the glory of love, and yet hereafter never share it with any mortal! The water-brooks, the oceans, and the seas, shall reflect thy image, and thou shalt know the bitterness of seeing even these unconscious soulless things unknowing thee, uncaring for thee. Thou shalt live on for years till they are counted by centuries, long after she thou hast so shamefully deserted sleeps the quiet, blessed sleep of death; thou shalt live to mourn and to lament over a fate thou canst not change. Thy doom is more dreadful than thou canst yet conceive of! Come, wait not even for her last embrace, come—come—come!”

Swiftly away they passed, the spirit and the wifeless bridegroom, without one parting look, or kiss, or word with the trembling girl forever separated from the forever exiled youth. In an instant the little church was vacant, and without its walls might be seen gathered a group of terrified people, and foremost among them the widowed Rose, gazing on the far upper flight of poor Rob Horn.

The new moon that night came up in all her glorious beauty, and sailed on calmly as she was wont to do over the broad blue upper sea; and night after night she glided over the vast expanse, unfurling gradually wider and wider her sails, till in full and perfect splendor she at last appeared. And then, yes then Rose May beheld her lover once more; but oh that shadowy glimpse she caught of him was worse to her than had she looked on utter vacancy. She knew that he was gazing on her home, that he looked in despair on her, but, alas! she saw no more the tender light that filled once his beautiful, dark eyes; she heard no words from his silenced lips, and it was like a torturing dream to her to look upon him thus, and fancy all the horrors of his banishment.

And what of Rob? He dwells in moon-land yet! among the elevated “mountains of the moon,” instead of those dear, wild heights his dwelling place on earth. Who ever could have dreamed that the wretched Wandering Jew had an unknown companion in yon bright sphere, whose lot was yet more miserable than his own? Who ever thought a “breach of promise” might be visited on unfaithful man, in quite another and more effectual way, than by laying strong hold on his most precious purse-strings?

Oh, ye soft-hearted maidens, I pray you henceforth bear in mind who is the captive knight to whom so oft your fond eyes are directed, “oft in the stilly night,” when he doth stand on the brink of the “moon mountains” and gazeth down so sadly on the world, remember ye this story I have told, and turn away and leave him quite alone. Sing not in pensive strains the praise he loves to hear, laud not the beauty of the exile’s home, for oh his strained ear is strong to catch your words, his eye is quick to note your admiration. Let him not gladden in one word from thee.

And ye, gay-hearted knights, so strong to promise, and so slow to do; ye who do count it pastime to win woman’s love, and then fling it away as ye would cast aside the flower of lost fragrance, but be ye warned in time, for spirits are, and moon-land yet may find room in its borders for thy feet!

And now what more remains for me to tell. You have guessed, I know, how the warm-hearted spirit taught Rose May that Joseph Rancy possessed all the good and attractive qualities of the lost lover, with none of his sins and follies! You have guessed that one gay morning the old church doors were opened for another bridal party—that young Rose stood again in marriage garments before the altar, and Joseph by her side. You have guessed how the Spirit once more glided through the “place of prayer,” to add her blessing to that which the priest pronounced over the bridegroom and the bride.

Why speak of the happy home where Joseph Rancy dwelt with his beautiful lady-love? Why tell of all that wedded bliss which people for the most part in our world have heard of already, or else desire in an especial manner to hear of, and to know. And why say that all the teachings and advice which the Spirit deigned to administer to these two blest mortals, was ever received and heeded by them with the utmost care and gratitude?

Do you believe in dreams? No! Why not? Have you, indeed, yet to learn, that through them the good spirits whisper to us advice, and peace, and warning, and consolation! Are you so cold and dull as to believe there are no ministering spirits, no guiding guardian angels? Do you, can you scornfully repel the idea that the forests and mountains, the oceans and the plains, have their myriad viewless intellectual inhabitants? Ah, foolishly unwise, may these powerful agents have mercy on you, and charitably bear with your shameful, willful blindness!

What then—must I set you down as more ignorant and unlearned than even simple Joseph Rancy? Fling all your book-learning aside and be a very child in all knowledge, I beseech you, if that will give you faith in these surrounding millions, to believe in them, and a keen mental eyesight to behold them. And do not, above all things, dare to brave the possible malignance of Rob Horn, that is, if you regard the preservation of your worldly wealth. Gather not in your harvests, and your winter stores, while he is gazing full upon you, rather follow honest Joseph’s example, shear all shearable sheep, reap in the wealth of your apple-trees, and massacre your swine while Rob is sleeping in the shade of the mountains, just before he awakens from his slumber to gaze openly upon your doings. And if you manifest your faith in my story in no other way than in doing this, I shall be satisfied, and feel, whether you admit it or not, that I have for once “well done.”

THE MIRROR OF LIFE.

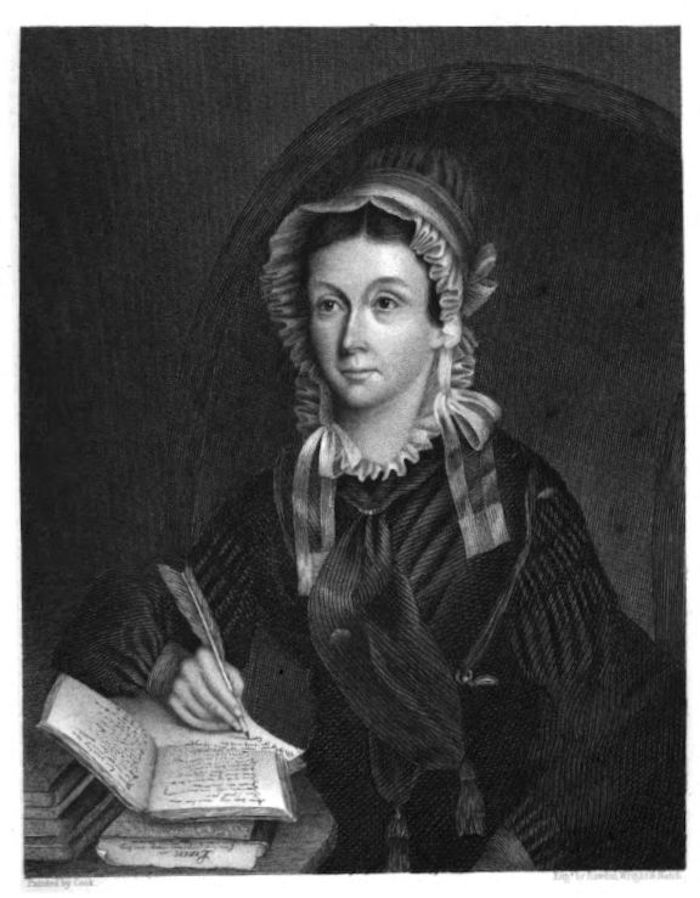

Engraved expressly for Graham’s Magazine

BY W. A. WILMER FROM A PICTURE BY W. A. CONORROE

[SEE ENGRAVING.]

Sweet child, whose gentle eyes upon

The mirror’s polished surface rest,

Thy heart no grief has ever known,

No anxious care disturbs thy breast.

O, may the coming time, to thee

Calm as the present ever prove;

And she who guards thy infancy

Live years of rapture in thy love.

—Anna.

———

BY MRS. LYDIA H. SIGOURNEY.

———

Hail, Father Thames! ’Tis joy to me

Once more thy face and haunts to see;

For lingering verdure, soft and rare,

Makes thine autumnal carpet fair;

And ’mid thy bordering heights is seen

The strong and patient evergreen,

While checkering sunbeams gild thy way,

And lightly with thy ripples play.

Spare not to give me smile of cheer,

And kindly bid me welcome here;

For some, who erst my hand would take,

And love me for affection’s sake,

Sleep the cold sleep that may not break;

And though to fill their vacant place

Are blooming brows and forms of grace,

Who still a favoring glance extend,

And greet their parent’s cherished friend,

Yet mingling with that welcome dear,

Are voices that they may not hear;

For visioned forms around me glide,

And tender memories throng my side,

Till tears, like pearl-drops, all apart,

Swell in the silence of the heart.

———

Methinks thou speak’st of change. ’Tis true;

What hand may hold the morning dew

All unexhaled through lengthened day,

To sparkle ’neath the westering ray?

Who dreams his flowing curls to keep,

While years roll on, in eddies deep?

The elastic feet, that sprung untired,

Where cliffs o’er towering cliffs aspired;

The heart, untaught a pang to bear,

The cheek that ne’er had paled with care,

The eye, undimmed by sorrow’s rain—

How could I bring these back again?

Change hath a part in every loan

And gift that youth doth call its own,

Nor grants old Earth a bond or claim,

Without the endorsement of his name;

So, that’s the tenure, father dear,

By which we hold possession here,

And be not strict to mark with shame,

Unless thyself wert free from blame,

For, in thy presence be it told,

That even thou art changed and old.

Methinks, with wild resentment’s flash,

I hear thy rising currents dash—

But still my charge I’ll deftly prove;

Where are the healthful flowers that wove

Fresh garlands here, in copse and grove?

The golden-rod, of sunny hue,

Heart’s-ease and violets deeply blue,

The lustrous laurel, richly drest,

That through the sober alders prest;

These blossomed when I saw thee last,

Yet now, dismantled branches cast

Keen challenge to the mocking blast,

And fallen leaves, in eddies dank,

Reproachful strew thy mottled bank.

Thy shrouded dells, where lovers stole,

Or poets mused with raptured soul—

Where are they now? I ask in vain;

Strange iron steeds that scorn the rein,

With shriek, and tramp, and nostrils bright,

The herds amid thy pastures fright;

And clashing wheel, and spindle’s force,

Oft drain thy faithful allies’ source,

Shetucket, with his roughened breast,

And Yantic, that I love the best;

While granite walls, and roofs of grace,

Usurp the moping owlet’s place.

Yes, thou art changed, the world hath made

High inroad on thy hermit shade.

But, say’st thou, that with spirit true

Thou keep’st a glorious goal in view;

Heaven speed thee on, with feet of glee,

And bless thy bridal with the sea;

Dear River! that doth lingering stay,

Laving the sandals, on thy way;

Of the fair city of my birth,

Perchance, the loveliest spot on earth.

Be thou our guide. Thy steadfast eye

Might teach us our own goal to spy;

For to that goal, through smile and tear,

Each winged moment brings us near;

Oh! may it be that blissful shore,

Where chance and change are known no more.

———

BY C. L. WHELER.

———

Let the poet-lord bepraise the sword

That gleams on Conquest’s track;

Be’t mine to prolong a humbler song—

The song of the woodman’s axe!

’Tis meet to sing of th’ lowliest thing

That graces the reign of Peace,

And add our praise, in hearty lays,

Or prayers for bright increase.

In the ruddy flood of battle’s blood

Its splendor ne’er was dimmed,

For a gentler fame awaits its name

Than e’er the soldier hymned.

Like a pioneer, with voice of cheer,

It breaks the forest’s gloom,

And maketh the earth give joyous birth,

And like a garden bloom!

And the palace dome, or peasant’s home,

It rears with brave command;

For no towering oak its lusty stroke

Could ever yet withstand.

Ho! the axe is king of the wildwood ring,

And of the lordly trees,

For before his blow they bow them low

That laugh at the mountain breeze.

And his trophies bright are truth and light,

And Plenty’s golden store;

For no drop of teen e’er dims the sheen

That flashed in days of yore!

Then praise to the king of the wildwood ring,

The woodman’s shining axe;

For a gentler fame awaits its name

Than the sword or Conquest’s tracks.

A TALE OF THE FEUDAL AGES.

———

BY W. GILMORE SIMMS, AUTHOR OF “GUY RIVERS,” “THE YEMASSEE,” “RICHARD HURDIS,” &c.

———

The analysis of the dreaming faculty has never yet been made. The nearest approach to it is in our own time, and by the doctors of Phrenology. The suggestion of a plurality of mental attributes, and of their independence, one of the other, affords a key to some of the difficulties of the subject, without altogether enabling us to penetrate the sanctuary. Many difficulties remain to be overcome, if we rely upon the ordinary modes of thinking. My own notion is, simply, that the condition of sleep is one which by no means affects the mental nature. I think it probable that the mind, accustomed to exercise, thinks on, however deep may be the sleep of the physical man; that the highest exercise of the thinking faculty—that which involves the imagination—is, perhaps, never more acutely free to work out its problems, than when unembarrassed by the cares and anxieties of the temperament and form; and that dreaming is neither more nor less than habitual thought, apart from the ordinary restraints of humanity, of which the memory, at waking, retains a more or less distinct consciousness. This thought may or may not have been engendered by the topics which have impressed or interested us during the day; but this is not necessary, nor is it inevitable. We dream precisely as we think, with suggestions arising to the mind in sleep, spontaneously, as they do continually when awake, without any special provocation; and our dreams, in all probability, did not our memory fail us at awaking, would possess that coherence, proportion and mutual relation of parts, which the ordinary use of the ratiocinative faculties requires. I have no sort of doubt that the sleep of the physical man may be perfect, even while the mind is at work, in a high state of activity, and even excitement in its mighty store-house. The eye may be shut, the ear closed, the tongue sealed, the taste inappreciative, and the nerves of touch locked up in the fast embrace of unconsciousness, while thought, fancy, imagination, comparison and causality, are all busy in the most keen inquiries, and in the most wonderful creations. But my purpose is not now to insist upon these phenomena, and my speculations are only meant properly to introduce a vision of my own; one of those wild, strange, foreign fancies which sometimes so unexpectedly people and employ our slumbers—coherent, seemingly, in all its parts, yet as utterly remote as can well be imagined from the topics of daily experience and customary reflection.