The cover image was restored by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/kittyboyschristm00blan |

The cover image was restored by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

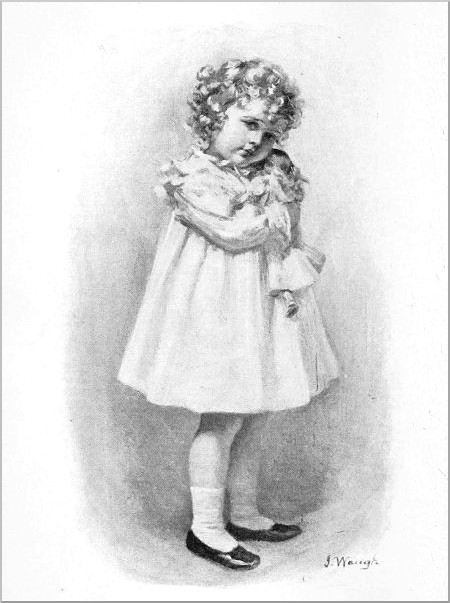

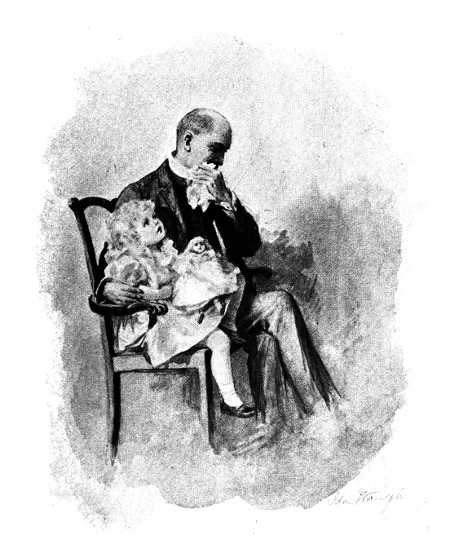

A solemn-faced little midget, about six years old, clasping to her breast

a battered doll, stood before them—Page 31]

Copyright by

GEORGE W. JACOBS & CO.

1898

Kittyboy was lost. It was an evident fact. He stood on the corner of the alley which led into a wide street to which he had been chased by an aggressive dog, and with every hair bristling, looked around for a friendly door, but they were all shut closely; and the snow was beginning to fall, in an uncertain way, just a flake here and there, displaying exquisitely perfect crystals on the stone steps and the brick pavement, then melting away very slowly.

Kittyboy tucked his four small paws neatly under him, and crouched in a corner,[8] once in a while giving a plaintive little "meow," which no one noticed, if any one heard. Yet, after all, Kittyboy's losing of himself was not such a dreadful thing, for he was always being kicked aside as a troublesome beast, even before his little mistress, Annie Brady, was sent away to a Home, being considered by her uncle's family in the light of a nuisance, quite as great as Kittyboy himself. Nevertheless, in spite of his rather unpleasant experiences in the world, Kittyboy was full of a happy confidence in humanity scarcely to be expected. So, presently seeing a figure coming up the street, he rose from his compact attitude and ran along by the railing of an area, rubbing his sides against the narrow bars, and finally followed the figure up the broad steps; then, as the latch-key was turned in the door, he saw his opportunity, and slipped in.

It was rather late; eleven o'clock or more, and getting colder every minute. The house was very quiet, no one astir anywhere; a light, however, was burning in one room, where a warm fire blazed in the open grate, the sight of which so delighted Kittyboy that he began to purr contentedly. The light, now turned up, showed more distinctly what manner of person it was whom Kittyboy had followed: an elderly man, with keen, sharp eyes; he was somewhat portly, was well dressed, and brisk in his movements. Kittyboy's little black form, snuggled in one corner, where he sat blinking at the fire, was not noticed by this other occupant of the room, who, lighting a cigar, sat down by a table, stretched out his legs comfortably, and unfolded the evening paper.

Presently, the sharp sound of a coal[10] dropping on the polished hearth disturbed Kittyboy's nap, and he jumped up, with visions of whips cracking over his head, and gave a leap away from the fire. The sharp noise also attracted the attention of the reader, who looked over the top of his newspaper to see four little furry feet daintily stepping across the rug.

"What are you doing here! Get out, cat!" came an exclamation in so much milder language than that to which Kittyboy was accustomed, that he considered it in the light of an overture, and springing up on the arm of the chair, in which this new acquaintance was sitting, he proceeded to play with the newspaper, patting the two sides, with ears very much forward, and an alert look on the wise little face, as if in momentary expectation of seeing a mouse jump out from the folds of the sheet.

The very audacity of the performance tickled the man's fancy. "You impudent little beast," he said; "how did you get in here, anyhow? Aha! I know. I believe I saw you as I came up the steps. You must have slipped in behind me. But this will never do; you will have to get out again. No cats allowed in my house."

For answer, Kittyboy began to rub his head against the arm nearest him, purring softly.

The man regarded him less severely. "If I'm going to turn you out, I may as well give you something to eat. You are none too well fed, I see," he remarked; and, rising, he took his way to another room, where, after hunting around, he found in the larder a pitcher of cream, set away by the housekeeper for her master's morning coffee. All unconscious of bringing dismay to the worthy woman, Dr.[12] Brewster emptied the contents of the pitcher in a saucer and set it down, watching Kittyboy eagerly lap up this unexpected treat.

"Now you must go," said the doctor; and Kittyboy followed confidently at his heels. But the draught of icy wind which greeted him as the front door was opened, caused the little fellow to scamper back to the library, where, before the open fire, he again sat down and began complacently to wash his face.

Back into the room came Dr. Brewster, laughing in spite of himself. "You are a sly little rascal," he said; "come, come," and he picked up the unresisting little creature, which cuddled down comfortably in his arms, as if it were beyond the bounds of possibility that a second attempt should be made to put him out, and the good doctor actually began to[13] have compunctions. "I always vowed I'd never have a cat in the house," he said, under his breath; "am I to give in at this late day? Well! you audacious little wretch, I'll let you stay till morning. It's too cold a night to turn any creature out of doors," and Kittyboy's triumph was complete when he was put down on the hearth-rug and allowed to continue his ablutions, while the doctor resumed his paper.

But it was strange that the presence of a little black cat could turn a sober man's interest from foreign news and the quotations of the stock market, and that he should have found himself dwelling on the memory of two little eager faces which he had seen that day gazing into a window decked out with Christmas toys, and, furthermore, that twice he should have read over an item which went as follows:

"Every year, about Christmas time, a[14] number of letters find their way to the Post Office; they are variously addressed to Santa Claus, Kris Kringle, or St. Nicholas, and are the outcome of childish faith. One is forced to wonder how often they must be followed by disappointment, since there can appear no claimant for them."

The doctor, we have said, read the paragraph twice over, and then, lowering his paper, sat looking thoughtfully into the fire. After a while a smile broke over his face, and he returned to his sheet. But the smile did not leave his lips till he extinguished the light and went to his room, leaving the sleeping Kittyboy curled up on the hearth-rug in a condition of delicious warmth and comfort.

When, the next morning, at the sight of buckets and brooms brought in by the housemaid, Kittyboy scampered out, it was to find refuge in the dining-room, just[15] as the doctor opened the door to go to his breakfast. This time Kittyboy was not driven out, for the cheery waitress said, "It brings good luck, doctor, sorr, to have a cat come to the house, especially a black cat." And by the time the doctor had finished, indulgently feeding Kittyboy with bits from his own plate, and Kittyboy had responded by such antics as kept the doctor laughing, it was an understood thing that the little cat was fairly adopted into the family.

The invasion of a common little street cat into the bachelor's household quite scandalized the good housekeeper, who could not get it out of her head that Kittyboy had in some way purloined the cream, but, said the cheerful Maggie, "It's far too quiet here to suit me, and the doctor actually ate his breakfast this morning without the paper at his elbow. I certainly am[16] glad to see some sort of a young creature about the house." The housekeeper gave a sniff, but even she smiled furtively a moment later at sight of Kittyboy wildly chasing his tail.

Buttoning himself up well in his overcoat, the doctor, after breakfast, took his way down town, and went straight to the city Post Office. He did not stop as he passed through the long corridor till he reached the private office of the Postmaster himself.

"Hello, Brewster, what brings you here so early?" questioned that worthy, looking up from his desk. "Haven't any complaints to make about Uncle Sam's mail, have you? Don't be too hard on us if things aren't just on time. There is a great rush from now till after the holidays, and you old bachelors are so methodical that, if a letter is a minute[17] and a quarter late, you think the entire Post Office system is tottering. Sit down."

"No," replied the doctor. "I didn't come to complain, Hardy, I came to see if I could collect the mail for Santa Claus."

Mr. Hardy put down his pen, and stared at his visitor. "What are you driving at, anyhow?" he asked. "Oh, I see; some charity Christmas tree, or something. How much will let me off, doc?"

The doctor smiled. "I'm not on that errand at all. I simply want to know if it is possible to have any letters, now lying in this office, addressed to Santa Claus, delivered to me?"

Mr. Hardy looked thoughtful for a moment. "Are there any such letters?" he then asked.

The doctor felt in his pocket for the last evening's paper, which he had taken[18] the precaution to carry with him, and silently pointed out the paragraph he had read the night before.

Mr. Hardy nodded understandingly. "I don't see why you shouldn't have them," he replied finally; "I'll get them for you, doc, if it's possible," and, leaving the office, he presently returned with about half a dozen letters, which he handed to his friend. "There you are," he said. "No need to ask what you're going to do with them. It's just like the things you used to do when we were lads. It takes me back to the old days when Christmas comes around. Come up and see us, doc; the latch string is always out," and he turned to his desk, as the doctor with his budget left the room.

The latter went directly to his club, and opened the funny, smudgy little notes. Some of them printed; some sprawled[19] across a wide page, some very zig-zag and uncertain.

"Don't, good Santa Claus, forget our corner," read one, "20uth and Purl street, if you can't git down the chimney cause they are reggyters come in the window, we'll leave it a little bit open so you can hist it easy.

"Bob."

"That youngster's all right," nodded the doctor. "I know the locality, and there's not a doubt but that his stocking will be well-filled."

The next was printed.

"I am a good girl bring me the doll. Fill wants a bow narrow,"

—but there was no address, and this, too, was laid aside.

Then came a queer little, half-printed, half-written epistle:

"Dear Santa: I want a new papa and a new kitten. Conny says kittens are easy enuff to get, but papas are much harder and very spensive. but I dont want just any kitten please, cause my dear Jollity was black and all the kittens this year are grey. if you have any black ones to spare please bring me one and a papa with a red ribbon around its neck. dont go to grandpas at Fort wurth where we were last year cause we aint there now we are at 610 west 12 street.

"Elinor Temple."

As the doctor read the signature a red flush mounted to his forehead, and he cast a confused look around him; then he slipped the letter into his pocket, took two or three turns up and down the room, and returned to his examination of the rest of the mail.

The last two letters were pitiful appeals from homes of want and misery; timid little requests, full of childish faith, which made the doctor shake his head and blink his eyes, frowning the while. These letters he also put aside, and then paced the floor in deep thought.

It was high noon when he turned toward home. He had forgotten all about Kittyboy, but when the confident little beastie came rubbing up against him, purring softly, the doctor smiled, as if a sudden thought had struck him, and stooping down, he rubbed Kittyboy's head; after which performance the artful little creature rolled over on his back, and turned his gold-colored eyes upon the doctor, inviting a frolic; then up and away he scudded, with arched back and curved tail, the very embodiment of a witch's familiar.

"You little imp of darkness!" cried[23] the doctor. "Such capers in the house of a sober bachelor! You'll be occupying my bedroom next and calling it your own." A prediction which speedily came true, for that very night Kittyboy slyly crept up behind the doctor, and, hiding himself, craftily bided his time, and in the dead of night stole forth and curled himself up on the foot of the bed, waking the doctor in the morning by licking his hand with a red, rough, little tongue. And then followed wild, frantic gambols, dancing and prancing over everything; coquettings with the tassels of a dressing gown; tussles with a slipper; mock fears of a very innocent reflection in the glass; delicate tip-toeings about the dressing table, with attempts to pry into every box and drawer; then one leap into the air and a waltzing after a little black tail whose existence Kittyboy seemed only that[24] moment to have discovered. All this so entertained the doctor, that he lay in bed shaking with laughter at the absurd antics, and went down to breakfast with Kittyboy on his shoulder.

After this it was evident that Kittyboy considered the second-story front bedroom as his own. To be sure he generously allowed Dr. Brewster to share it, to occupy the bed, if he were not in the middle of it; or the doctor might sit in any comfortable chair for which Kittyboy had no immediate use; but the lordly little creature took possession so absolutely that the doctor's sense of humor was greatly tickled by this overweening complacency and confidence, and he meekly took another chair when Kittyboy occupied the better one, or, indeed, moved over to the right side of the bed if Kittyboy preferred the left.

It was the evening of the day which had seen the doctor at the Post Office. It seemed to him that it had been many more than twenty-four hours since the sly little cat had followed him indoors, and had ingratiated himself into the good man's favor. Already the doctor was making a confidant of this same little waif.

"What would you do about it, you little limb of Satan?" he asked, as he opened the letter he had so carefully put aside that morning. "Come, you shall decide. Let us see what sort of oracle you can make. You started this, anyhow, as I remember. Now get me out of it, if you can."

Kittyboy winked soberly, as the doctor thus addressed him, but looked very wise, as if he knew much more than he proposed to tell.

The doctor softly stroked the black[26] fur, which was less rough than it had been the day before. "Shall I go or not?" he asked. "You can advise, and then, like others in the same position, I'll do as I choose. Here is the letter." He shook it at the little creature, who grabbed it in both paws, rolled over with it once or twice, then taking it in his mouth he jumped down from the table and walked off with his prize to the chair where a soft felt hat of the doctor's was lying. Into this jumped Kittyboy, letter and all, and, curling himself up, looked with a knowing wink at the man who was watching him.

"Into this jumped Kittyboy"—Page 26]

"Nothing could be plainer," laughed the doctor. "Go is the word. Pick up your hat and its contents, you say. Here we are, take us and go. Such wisdom! For real out and out witchcraft, commend me to a black cat. Ah, Kittyboy, it is well you did not live in the time of those old[27] fellows, my ancestors, Wrastling Brewster and Preserved Fish, and the rest, or we'd both be strung up for practicing the black arts, although such names as they had were enough to choke them without hanging.

"Well, my small wizard, go it is, since your suggestion suits my inclination; who knows? who knows?" He sat absently stroking the little cat, who had returned to the table, and it was evident that something had given him food for deep, and not altogether unpleasant, reflection, for the evening paper lay untouched, and the open fire seemed to hold the man's fixed attention. Was it Kittyboy's sorceries that caused past events to rise as flames from ashes, to add a new warmth to a half-chilled memory?

The next morning it was that Dr. Brewster turned his steps toward a quiet[28] street in a modest quarter of the city. An open square gave a pleasant, airy appearance to the neighborhood. The sun was shining brightly, but the air was frosty, and the doctor stepped along briskly. His footsteps did not falter until he reached the house, 610 West Twelfth Street, and then for a moment he paused, taking off his hat and wiping his brow as if it were a warm day. Immediately after, however, he mounted the steps with a firm step and gave the bell a vigorous pull. It was answered by a neat maid, who paused expectantly for the card, which the doctor did not produce. "Tell Mrs. Temple a friend wishes to see her," was his message.

He was ushered into a small room, which was warm and cosy. A fire glowed in a Baltimore heater. There were pretty, tasteful articles scattered about, which gave the room a cheerful, homelike look.[29] The doctor picked up a book from the table, put it down again, nervously took two or three turns up and down the floor, and finally stationed himself, with his hands behind him, at one of the windows, fixing his eyes upon the street.

Presently some one entered, and a soft voice said, "You wished to see me?"

The doctor turned abruptly, and held out his hand to the tall, fair woman who stood before him. "Elinor," he said,—the color mounted to the lady's cheek,—"Dr. Brewster," she faltered. "How—where did you learn of me?"

"At the club," replied the doctor, gravely and truthfully.

"It is truly good to see an old friend," continued Mrs. Temple. "You know—you have heard."

"I know nothing but that you are here," answered the doctor.

"My husband died two years ago," went on Mrs. Temple. "He was very good to me, and he idolized our little daughter." Her eyes dropped before the doctor's earnest gaze, but they had already told that which the doctor had for so many years longed to know, whether in marrying big, wealthy, dissipated Captain Temple, Elinor Arsquith had pleased merely herself, or whether to spare her father's good name she had sacrificed her girlhood.

He drew in his breath quickly, and for a moment no word was spoken between them.

"And your little girl?" asked the doctor, breaking the silence.

"She is with me here. I lost two little ones in Texas, and Elinor is all I have left. I felt that for her sake I must seek a different climate, and that is why I am here."

At that moment the curtains before the[31] door parted, and a small figure appeared. A solemn-faced little midget, about six years old, clasping to her breast a battered doll, stood before them.

"Come in, dear, and speak to the doctor," Mrs. Temple said, glad of an interruption to a conversation which was becoming embarrassing.

The little one advanced slowly, till she stood by the doctor's side. "Must I put out my tongue?" she asked.

The doctor smiled. "No, I think I wouldn't. It's pretty cold for even a tongue to be out to-day."

The child laughed merrily. "I wanted to go and buy mamma a little bunch of vi'lets, but she said I would freeze my nose off, and I wouldn't be pretty without any nose, would I?" Then, glancing down at her dilapidated, noseless doll, she looked a little abashed. "Excuse me, Lily," she[32] said gravely; "I didn't mean to hurt your feelings. I love you just as much as if you had as big a nose as the doctor's. I didn't have any money in my bank, anyhow," she continued, "and mamma could not spare any five centses. You know we aren't rich any more. I 'spect the flowers are frozen up, anyway."

"I'll get the violets for you," said the doctor, without looking at Mrs. Temple. "I know a nice, warm place where they live, and if you'll trust me I think I can find some fresh, sweet ones."

Elinor clasped her hands. "You're very nice," she assured him. "And if you won't give me any nasty medicine, I'll love you very much."

"I promise no nasty medicine," agreed the doctor, and their friendship was sealed. So well did it proceed that when the doctor took his leave, an hour later, Elinor[33] hugged him frantically, saying, "Doctor, come to-morrow. I get so lonely, and so does mamma. I wish you'd come every day," and the doctor's smile answered the suggestion.

"Mamma," said the child, after the doctor had left them, "is that a very nice man?"

"Why, darling; yes—of course—yes—he is very nice."

"I fought so," she returned confidently. "Is he very 'spensive?"

"Oh, you mean—wealthy. I think so, enough so, at all events. What funny questions. Why do you want to know?"

"Just 'cause I like to ask funny questions. Mamma, do you like bread?"

"Why, you midget, you are just asking questions to tease your mudder. You know I like bread."

Elinor laughed gleefully, and looked down at her doll. "Lily told me a secret to-day," she said, "and she won't let me tell till Christmas. It's a very nice one, but I can't tell you, mamma."

"Very well. I will wait till Christmas."

"Don't you want to know it?" the child asked, anxiously.

"Not if you don't want to tell it."

"But I do, only Lily won't let me. Mamma, this morning I was a kitten."

"You were? I didn't discover it."

"I was. I had a red ribbon round my neck, and I was black, and Lily was Elinor Temple, and she played with me. See where I scratched her. Do you want me to be a kitten for you, mamma?"

"Not if you scratch, nor if you have to turn black."

That amused Elinor greatly.

"I doesn't have to. I've just make-believe claws. Mamma, are you going to take me to church on Christmas?"

"Why, of course. Don't you want to go?"

"I didn't last Sunday; it was so long. The man in the white gown said so much. I fink he was a chatterbox."

"Why, Elinor! what a thing to say about the good rector."

"Well, mamma, it is what you say about me when I talk a long time, and you love me."

Mrs. Temple smiled. "Then you don't want to go to church on Christmas?"

"Oh, but I do; I like to hear the little boys sing, and I like to see the green things, but——"

"You get tired sitting so long?"

"Oh, no, mamma; I couldn't get tired; I get too much rested."

"I see. Well, dearie, we will go to the early service, which is not so long."

"And then come home and have the Santa Claus part of it for dessert; that will be nice. I wish the doctor would come soon; I want to ask him somefing."

The doctor did come soon. Indeed, there was scarcely a day after this which did not see his stalwart form turning into the quiet street, and the affection between the grave man and the pretty child grew apace, so that many confidences passed between them.

One afternoon the two were cosily occupying one big chair, in the absence of Mrs. Temple, who was glad to leave her treasure so well satisfied to stay at home, while she attended to some Christmas shopping.

"Let's talk about Christmas," said Elinor, cuddling down by the side of the doctor, after watching her mother out of sight.

"Isn't there a Santa Claus?" she asked.

"So I have always been told."

"There, I said so; Bill says there isn't."

"And who is Bill?"

"Oh, a friend of mine," returned Elinor, jauntily.

"I should like to know something about him."

"Oh, he's just a boy with——" she clapped her hands over her mouth, and looked, with eyes full of laughter, at the doctor.

"What?"

"Oh, doctor, it isn't nice to make remarks about the dress of your friends," returned the little monkey, drawing down her mouth demurely, and looking up mischievously from under her long lashes.

"Then suppose we don't mention his dress. Tell me something else about him."

"He has a very dirty face," said Elinor, with a little chuckle.

"He has? That is unfortunate. Why doesn't he wash it?"

"I reckon 'cause he hasn't any soap or towels."

"But he can get water easily."

"Yes; but, doctor, don't you know how horrid it is to have your face washed, and to stand with it all dripping, 'specially in cold weather? and if you had no towel, you know, you wouldn't want to wash your face, either."

"Perhaps not. Well, Bill is a boy with a dirty face. Is that all? Has he nothing else to boast of?"

"Yes; he has a sister named Gerty. I s'pose she has a dirty face, too. I never saw her, 'cause she's got the rickets, and her grandfather has had yaller janders; but they is about gone. I think they must be rather pretty, don't you?"

"What?"

"Why, the yaller janders. It sounds like some sort of a flower, I always fink of—what are the yellow fings that come in the spring—the early ones?"

"Daffodils?"

Elinor shook her head. "Not zactly; mamma said they were about the same."

"Oh, jonquils."

"Yes, that's it; are they anything alike?"

"Like what? Daffodils?"

"No; like yaller janders. Are yaller jonquils anything like them?"

"No. I can't say that they are."

"Have you any at your house?"

The doctor laughed—"Fortunately, no, I know of none nearer than a hospital."

"Oh, do they grow in hospitals?"

"Sometimes."

"Will you take me there and show them to me?"

"I don't believe you would be particularly pleased to see anyone with what Bill calls 'yaller janders.'"

"Why not?"

"Because it is not a very pleasant disease to gaze upon."

"Is it a sickness? Oh, I'm so disypointed. I fought they were flowers, and I was so glad the old grandfather had them. That's a dreffel disypointment," she added, after a moment's silence.

"But you have not told me about Bill," the doctor reminded her. "Where did you meet him—at a party?"

"No-o," contemptuously. "I met him in the square. He sells vi'lets. I reckon that's why I fought his grandfather had flowers—yaller jander flowers.—Is bronicles flowers?"

"I never heard of them."

"Oh, dear, I s'pect that's another disease.[42] You see it fooled me to see Bill selling vi'lets. I kind of fought he had a big garden full, or his grandfather had. He said his grandfather used to go out selling flowers till sumfing got the matter with his bronicles, and they couldn't stand the east wind."

The doctor laughed so heartily that Elinor looked quite aggrieved.

"I'll not tell you any more," she said, "if you make fun of me, and I was going to tell you lots."

"Oh, please pardon my laughter. I'll try not to be so silly again. You see, I sometimes laugh at nothing at all. It is a habit I have formed from living alone."

Elinor looked at him very soberly. She wasn't quite sure whether this was earnest or not, but his being alone seemed a sufficient excuse, and, moreover, appealed to her sympathies, so she took hold of one[43] of her friend's big fingers, and held it confidingly.

"Tell me truly," she said, "do you believe in Santa Claus?"

"Most certainly. I think he is the greatest invention of any age."

"Oh, good! That sounds so certain sure. That's what Connie says. I didn't make it up. I did make up sumfing once."

"You did? What was it?"

"A——I don't know what to call it. I'll tell you, and then you'll know." She nestled her golden head against the doctor's shoulder, and looked up in his face. "I was jumping in the cellar one day with Ida Miller, and I made a tree-men-jus jump, and I said, 'Oh, Ida, I made a jump right smite the javelin.' Don't you fink that's fine? I have said it over lots of times, 'cause I like the way it sounds, somefing like the Bible, you know."

"I think it is one of the most grandiloquent phrases I ever heard. You do not know how I admire it."

"Do you, really?"

"Yes, really."

"Then, I'm glad I told you. Now, I'll tell you somefing else. It's a secret, but Lily said I might tell you. She won't let me tell mamma. It's about Bill. Do you want to hear it?"

"Very much."

"And you won't tell?"

"No."

"Cross your heart?"

"Yes; cross my heart."

"Then, it is this: Bill said he didn't believe there wa'n't no Santa Claus. He said it just that way." She stopped and looked searchingly at the doctor, but he was listening attentively.

She gave her little mirthful chuckle[45] and went on. "Then I said, 'if you write to him, and he brings you what you ask, I reckon you'll believe in him,' and he said he'd be a blamed fool to do such a fing. He said blamed fool——"

"All right, he said blamed fool."

Elinor buried her head in the doctor's sleeve and laughed silently. Then she looked up with eyes still full of mirth. "That was so funny," she said.

"What was?"

"To hear you say blamed fool. Did you ever say it before?"

"Perhaps."

"Don't you like to say it? I do. I go off in the corner and say it to Lily sometimes, just 'cause I like to hear myself. Do you do that?"

"Go off by myself and say it to Lily? I haven't any Lily."

"No, of course, but you might say it[46] just the same to a chair—or—or anyfing. Mamma says it's not nice for a lady to say it, and that's why I'm doing it all I can now, 'cause I'll be a lady some day, and then I can't. There are lots of fings that way. Anyhow, Bill said it, and I told him he was an aggynorstic. That sounds like a dreadful word, but it isn't, for I heard mamma call somebody that, and I asked her what it meant, and she said it meant a person that doesn't believe. I fought it would scare Bill, for I fink it has a scary sound, like the day of wrath."

The doctor turned away his head, and, taking out his handkerchief, buried his face in it, a violent fit of coughing seeming to overtake him.

Elinor looked quite alarmed, but the doctor assured her it was only a small matter, and though very red in the face,[47] he resumed a grave demeanor and asked Elinor to continue her tale.

"The Doctor turned away his head,

and taking out his handkerchief,

buried his face in it"—Page 46]

"Well," she went on, "'then Bill,' I said, 'you're an aggynorstic,' and he stared at me so hard. 'I don't like aggynorstics,' I said, and he said 'what'll I do about it?' And I said, 'you write to Santa Claus just like'——Oh, my! I was just going to tell such a precious secret. I won't, though——Anyhow, I made him promise he'd write to Santa Claus if I'd buy vi'lets whenever I had any money in my bank. And he did write, and now I reckon he'll find out. He's real e'cited over it."

"And where does he live?"

"Oh, back in a little street that runs skwy-eyed, Connie says, across this. It's a horrid little street, and mamma won't let me go there, but I know where it is."

"And where does Bill sell his violets?"

"In the square, by the fountain. He has beautiful red hair and the loveliest freckles you ever saw. I wish I had freckles and red hair; don't you?"

"I can't say that I do desire them greatly, and I'm sure I like you much better as you are."

"Do you? Well, maybe you do, but I don't. Do you fink Santa Claus got Bill's letter? I hope he did, for it seems dreadful for anyone to have no Santa Claus and no Christmas; it makes me feel sorry inside, as if I had eaten too many cakes. Do you fink he got it?"

"That depends upon where he mailed it."

"Why, in the post-office box, of course. The one on the corner, by the square, that says U. S. mail on it. What makes them turn it hind part before? Why don't they say mail us? It means the letters you put[49] in, of course. It's so the man with the funny little wagon will know."

The doctor frowned; then he laughed. It was such a funny translation of the U. S. mail. But just such fantastic ideas he knew took possession of the child. "That's all right," he said. "Uncle Sam does put things wrong-end-foremost sometimes. You tell Bill that if he put his letter in the box there's not the slightest doubt but that it will be answered."

"I saw him put it in. He showed it to me, and I went with him to mail it. He can write pretty well, for he went to school before that time; about—about the bronicles, you know."

The doctor nodded understandingly.

"Do you believe Santa Claus will have enough turkeys to go around? Mamma says, if he hasn't, I may send Bill and Gerty some of mine. I'm going to try to[50] eat a very little piece, but I like turkey, and I hope Bill and Gerty will have a whole one to themselves, and I hope Gerty will get a doll, and if she doesn't, I'll have to send her the one Santa Claus brings me."

"Why would you have to?"

"Why, 'cause I wouldn't be such a piggy-wiggy as to keep two, and she not have any. It wouldn't be nice of me, when I have Lily. Could you have lots of fings when you knew somebody else didn't have any?"

This was a home thrust, made so truthfully and innocently that the doctor wondered why all these years' Christmastide had not brought home to him such a reproach. He had eaten, drunken, been comfortable and care free, while just such opportunities had been waiting for him as this year offered.

"Well," he said, as he took his departure,[51] "it's all right about Santa Claus, you tell Bill."

"And you won't tell anyone," whispered Elinor.

He assured her that the secret was safe, and went off with a very warm feeling inside. There seemed to be an expansiveness of light in the setting sun; a brightness about existence in general, which even cases of "yaller janders" and weak "bronicles" could not overshadow.

"I must look after that family," mused the doctor. "Bless the young things! a frolicsome kitten and a little earnest child, full of faith and love of human kind, can be wonderful factors in the matter of happiness. Strange how I have gone along missing both and not knowing what I missed. Let me see. I'll send Hooper to look after grandfather's 'bronicles;' he smiled broadly at the remembrance of the garbled word. I'd rather not have the little one know that I've a hand in it, and 'twill be good for Hooper to try his hand at that sort of thing. Let me see if that[53] youngster's letter reached its proper destination." He stopped and pulled out the packet he carried.

Yes, there it was, signed "Bill." The doctor stood and read the poor smudgy, mis-spelled little missive over, put it back in his pocket, and walked thoughtfully on, not knowing that at that very moment he was passing the writer, who, with his meagre supply of wan-looking violets, was offering them for sale.

Bill as little knew that the letter over which he had spent much thought and hard labor was resting in the doctor's pocket, for he imagined it to be in the hands of a red-nosed, white-haired individual, with a jolly countenance and a twinkling eye—such a one as could be seen, more or less realistically represented in shop windows. A very different looking person, indeed, from this portly, prosperous-appearing[54] man with the keen eyes, who wore "swagger clothes, and didn't care nothin' fer poor cusses, or he'd 'a bought somethin' from a feller." Bill's ire was roused by this kind of person, so indifferent and absent-minded, as never even to glance at the violets, nor give a regretful negative, as some nice ladies did.

"Talk about old Santa Claus," muttered Bill, "if he is anybody at all, he ain't friends to nobody but rich folks; that's what I say. I ain't never heard from him, an' I guess I ain't never goin' to, what's more."

But, as if to chide his lack of faith, Elinor herself appeared like a reproving angel at his side. "Bill," she said, standing on tip-toe that she might see the box-cover in which the violets lay, "Bill, have you sold lots to-day?"

"No, I ain't," he answered, rather crossly.

"Oh, then, I can spend all these five centses. The doctor picked them all out of his pocket for me, and told me to buy vi'lets for mamma. So, I have to. Ten five centses, see. I told mamma I would come right back. She is watching out of the window for me."

Bill's face took on a little sunshine. Ten bunches! Why, it would nearly clean out his stock. What luck!

"Say," he said, in a low voice, "'bout that Santa Claus, you know. Time's gittin' clost."

"Yes," said Elinor, eagerly holding out her hands to receive the violets.

"I don't believe he comes to poor folks," continued Bill; "mind, I don't say there ain't no Santa Claus; but I say he ain't no friend o' folks what lives in Hitchen's court."

"Oh, but he is. Dr. Brewster says so,[56] and he knows everyfing—he does truly—and he told me to tell you that there was a Santa Claus, really, really." Bill stared at the ground. "And he said if you put your letter in the box, Santa Claus will surely get it there, and you will get an answer. So, now," and she walked off with a little switch of her skirts, and a decided sort of air, as she would say there was no further doubt possible.

Bill looked after her. Ten bunches of violets meant a corresponding amount of faith, and an hour later an empty box lid went home with him. But the very fact of the emptiness of the box cover meant a fullness of belief. And Gerty; poor little, rickety Gerty, also received a prop to her faltering hopes in Bill's words. "They are a Sandy Claus, Gert, sure as shootin'! A big bug what I knows about says so. Ain't you glad?"

"Are you goin' to believe in him?" asked Gerty, in an excited whisper.

"Yes, I am," sturdily returned Bill.

"So'm I, then," answered Gerty. "I'm goin' to believe he'll bring me a doll, and a—a orange, and a—a new frock, and a—a picture book and candy, and—" her whisper rose shrilly as she became more ambitious, "and a—a turkey!" The climax was reached.

"Sho!" said Bill, doubtfully, "I don't believe he'll do all that."

"What's the use of believing at all if you don't believe he can do every bit?" returned Gerty, who did not regard half measures with favor. "I'm goin' to believe I'll git it all—and more," she added, with an extra touch of defiance of fate.

Bill looked at her half-admiringly. Such temerity was beyond his mental stature, although, given a proper field for physical[58] valor, and he'd show no white feather, as various urchins in the neighborhood could testify.

"How long is it before Christmas?" asked Gerty. "Three days, ain't it?"

"'Bout that. Say, Gert, we ain't ast fur nothin' fur grandpop in that letter."

"Why, yes, we did. We ast fur a doctor to cure his bronicles. Don't you know?"

"So we did. How is he?"

"I don't know, he's kinder yaller yit, an' he can't eat much."

A sharp rap at the door interrupted them, and a smiling young man entered to to their "Come in."

"Is this—Bill?" he asked.

The boy nodded.

"Your grandfather, he's ill?"

"Hm-hm," returned Bill, looking suspiciously at the visitor's careful attire.

"Ah, yes." The young man put up an[59] eye-glass and peered around the dingy rooms, Bill meantime eying him, as much as to say, what business is it of yours how we look?

"Could I see him?" queried the young man.

"I dunno. See here. What d'yer want? I'll pay yer rent. Yer needn't go badgerin' gran'pop about it."

The young man stared. "Bless me, my son. I don't want any rent. I'm," he smiled, and whimsically took out his card case. "Pardon me for not properly introducing myself. I am Dr. Hooper, and I have been asked to call professionally on your grandfather by a friend of his."

"Whew!" Bill gave voice to a low whistle, and glanced at Gerty, who had taken the card with a funny little air of polite acceptance, and, at a word from her brother, led the way into a hole of a room,[60] hardly more than a closet, where an old man lay.

The doctor remained about fifteen or twenty minutes, and when he again came into the presence of the boy and his sister, he said:

"I think your grandfather will be better under my immediate care, and I will see that he is removed—if—if you don't object—to a pleasant room in a pleasant place."

"An 'orspital?" queried Gerty.

The young man nodded.

"Say, look here, he ain't goin' to no 'orspital," objected Bill.

"He is, too," retorted Gerty; then turning to the doctor, "You can take him." She gave the permission grandly. "I know all about it and Bill don't. I've seen one."

"My son," said the doctor, addressing Bill, "your sister is a person of unusual[61] acumen. She—she knows a good thing when she sees it. I give you my word that the friend of whom I spoke thoroughly approves of your grandfather's removal."

"And can't we see him?" asked Bill, looking very dubious.

"Bless you, yes, every day, if you want to."

"And will you bring him back for Christmas?" asked Bill again.

The doctor considered. "If it is possible. At least, I can promise you shall eat your Christmas dinner together."

The two children exchanged glances. The answer implied that there was to be a Christmas dinner.

"I will come to-morrow morning in my carriage for him," added the doctor. "That is, if I may."

"Yer hear that, Gert? A kerridge. Ain't we swagger?" and Bill laughed.

He followed the young doctor to the door, and shut it after him as he went outside. Plucking him by the sleeve, he asked in a low tone, "Mister doctor, that there friend what sent you. Say, honest now, tell a fellow square. Was it old Sandy Claus?"

The doctor hesitated, looked down at the earnest, ugly little face, lighted up by a strong hope, its dirt and unhealthy color but dimly descried in the flaring light of the dingy court, and he felt a new concern for this "gutter-snipe" with whom he had suddenly come in contact. He laughed softly and said, "Yes; you're about right. Call him Santa Claus."

Bill went in and shut the door very solemnly. Things were happening mysteriously, and he felt somewhat awed at what his experiences implied.

Dr. Brewster received a call from his young assistant that same evening. He entered with a bored, blase air into the doctor's study, and stood staring, and, slapping his gloves together as if he had not one single idea in his noddle. Then he spoke.

"The old fellow—in Hitchen's Court, you know—beastly dirty hole, by the way—he needs looking after, wants a sunny room and good nourishment, and all that sort of thing. He'll get worse if he stays there. I'm going to take him to our hospital, if you don't mind."

"Take him?" the doctor chuckled.

The young man flushed, "Yes. Bah Jove! I can't see an old fellow like that, don't you know, dying for want of a little attention. Now, doctor, I'm no charity fiend, but—I say, what are you chuckling about?"

"At your past record in the matter of pet charities, and your open expressions regarding those who have them. Go on, Sig, my dear fellow. You said you'd take him."

The young man flung off his overcoat, displaying his evening dress and the flower in his button-hole. "Yes, I said take him—in my carriage to-morrow morning." He looked up, as if expecting protest.

"Bless you, man, I don't object if you don't," returned the older man. "He's an old fraud, doubtless, has no 'bronicles' to speak of, and wouldn't know 'yaller janders'[65] from scarlet fever. Where do you purpose placing him?"

"In the pay ward," said the young doctor, defiantly.

Dr. Brewster threw back his head and laughed.

"But, I say, doctor," continued the other, "you ought to see him, such a pitiful-looking, white-haired, old chap, with those kids on his hands for years. I say, he's been handicapped, you know. And—Bah Jove! doctor, what did you send me there for?"

"To see how you liked Hitchen's Court."

The young man passed over the reply. "I say it's a beastly shame," he went on. "That old chap is a better fellow than I am any day, I say, there's something wrong."

"Desperately so, I grant you—with us."

The young man looked up quickly. "It's beastly," he repeated.

"Sig, you're a huge joke," laughed the doctor. "Go 'long with you and your paupers. By the way, what about the children?"

The young man smiled broadly. "They are a pair. I believe that poor little wretch of a red-headed snipe supports the family. Ah, doctor, I say we're nowhere with my Lord William. Such airs; bluffed me off at first."

He sat on the arm of the chair, swinging one foot thoughtfully. Dr. Brewster looked at him. Young, good-looking, rich; what the public called "a howling swell;" a dilettante in his profession, yet possessing ability, if but the proper motive stirred his impulses. He had been wont to maintain that half the world's poor were whining impostors, and the other half incorrigible reprobates.

The elder man watched him with a half smile. "You'll take the old man, then, and I'll see to the young ones," he remarked after a time.

Sigourney Hooper slipped on his overcoat again. "By the way," he said, "they think Santa Claus sent me," and he gave a grin of amusement.

Dr. Brewster looked grave. "Who is Santa Claus, anyhow?" he returned. "The embodiment of goodness, charity and kindly feeling."

"They were right, then," replied Sigourney, holding out his hand. "We'll have to give them a Christmas, doctor, for I promised not to keep grandfather from the bosom of his family on that festal day. Holy Moses! Festivities in that hole! Ugh!"

Dr. Brewster sat smiling to himself long after his visitor had departed. A[68] wheel within a wheel, the ripples caused by the dropping of the smallest of pebbles; the movings toward a broad humanity set astir by the prattle of a child; by the instinctive appeal for warmth and protection made by a little hunted animal; the breath of the spirit on the face of the waters! He pondered over these mysterious forces, while Kittyboy purred contentedly at his elbow.

Kittyboy fared well these days. He never failed to station himself by the doctor's chair at meal time, and was so indulged in the matter of tid-bits that his coat grew as sleek as satin; and if he had not been of such a very volatile temperament, it is quite likely that he would have become fat and lazy.

The housekeeper confided to Maggie that something had made the doctor grow ten years younger, and the housemaid[69] immediately attributed the fact to the presence of Kittyboy. Certain it is that the doctor busied himself with many things to which he had heretofore seemed indifferent, and his sober establishment underwent all sorts of changes. "All on account of the cat," said Maggie.

A well-to-do physician who has retained just enough practice to keep him contented is rather an enviable individual, and Dr. Brewster looked the picture of genial content as he stepped into his carriage on Christmas Eve. Just where he went was best known to his coachman, who had long ago learned the value of keeping his own counsel. But the faith in Santa Claus which that evening justified was felt in more than one wretched dwelling. Especially did two anxious little souls, who had staked their last hope on the letter they had sent, feel that their mustard seed of[70] belief had indeed grown to gigantic size when hampers and bundles from Santa Claus were displayed to their glad and astonished eyes.

"Oh, Bill, I said I believed he'd bring all I wanted, and more," cried Gerty, laughing and crying at the same time. "And he did, he did. And grandpop's gone to stay in that grand room and get well, and I'm goin' to get well, and we've a whole turkey and fixins, Bill, fixins. I never said nothin' about them. And gran'pop 'll be here an' help us eat it. An', oh, Bill. They are a Sandy Claus, they are, ain't they?"

"Well, I should smile," replied Bill, surveying the bountiful supplies before him.

"An' you'll tell that little gal first thing, won't you?" said Gerty.

"Won't I!" returned Bill, too happy for more speech.

The doctor paced the floor a long time that night. He thought of many things; of the dreary dwellings he had that day seen; of the sorrowing poor; of the little it had taken to make a few hearts glad, and most of all he thought of little Elinor Temple and her mother. He remembered a Christmas Eve which had promised him a great joy, but which had brought him a great sorrow—the sorrow which he had kept locked in his heart for fifteen long years. Not once had he faltered in his faith in the girl who had turned from the young physician, just starting on his career, and had married rollicking Captain Temple. Dr. Brewster smiled sadly as he remembered how Mrs. Temple had said but the day before: "We sometimes make errors of judgment, but if we err from a mistaken motive of unselfishness, we suffer just the same." And that had told the[72] whole story. It was the only justification she had ever attempted, the only reference to what he knew she must have endured; but he had inadvertently heard many things during these past weeks. He had re-read, with fresh delight, an old chapter in his life. He had opened his heart to the love of an innocent child, and the door being open, what else fair and beautiful might not find admittance.

There was a rare exultation in the doctor's smile, as the bells rang in the midnight hour, and declared the promise of peace and good will.

On Christmas morning around Kittyboy's neck was fastened, by the doctor's own hand, a bright red ribbon. Then he was placed in a basket and deposited upon the cushions of the doctor's carriage.

With the basket in his hand, Dr. Brewster entered Mrs. Temple's cozy[73] sitting-room, where a hearty welcome awaited him.

"Elinor has such a host of pretty things," said the child's mother, "and yet she seems a little disappointed. She tells me there are two gifts she specially wanted, which Santa Claus did not bring her, but she will not tell me what they are."

"I think I know," returned the doctor, smiling. "Come here, Dot, Santa Claus asked me to bring your gifts to you, because he could not trust any one else, and he knew I'd take better care of them than some others."

Elinor looked at him gravely from under her long lashes, and watched eagerly while he uncovered the basket, from out of which jumped a sleek black little kitten, which stretched himself comfortably, looking up with friendly eyes at the doctor.

"Oh, mine own Jollity!" cried Elinor.[74] "Oh, mamma, see! Oh, isn't Santa Claus good?" and she clasped Kittyboy rapturously in her arms. "And the other present," she said, laughing, "you couldn't bring that in a basket."

"It is here, if mamma will let you keep it," and the doctor took the child on his knee, hiding his face in her curly locks. "Tell mamma what it is," he whispered.

"Oh, mamma," cried the child, "I wrote to Santa Claus and asked him for a new kitty and a new papa. That was the secret Lily and I had." For a moment she looked puzzled, and then a light broke over her face, while she let the kitten go, and clasped the doctor's neck closer, closer. "And, oh mamma," she continued, "when Santa Claus has sent me such a beautiful, 'spensive papa, you will let me keep him, won't you?" And the mother, amid laughter and blushes, could not say her nay.

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE:

Obvious printer errors have been corrected. Otherwise, the author's original spelling, punctuation and hyphenation have been left intact.