The Project Gutenberg EBook of Merry's Book of Puzzles, by J. N. Stearns This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Merry's Book of Puzzles Author: J. N. Stearns Editor: Robert Merry Release Date: December 31, 2016 [EBook #53847] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MERRY'S BOOK OF PUZZLES *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Lesley Halamek, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

This book is actually three volumes in one, each complete in itself. The page numbering starts at the beginning for each new volume.

The rest of the Transcriber's Note is at the end of the book.

EDITED BY ROBERT MERRY.

NEW YORK:

THOMAS O’KANE, PUBLISHER,

130 NASSAU STREET.

The innumerable readers of Merry’s Museum will here meet with many familiar faces, lighted up by pleasant smiles, and hear the same old jovial laughter that greeted them in the olden time.

Our motto is that of our noble State—“Excelsior!” Our readers will see that we have not buried the talents of our contributors in napkins—but seek to bring them out into the bright day: For Genius—like the lamp of Aladdin—needs constant polishing to bring out its lustre and full effect.

Our object has been to instruct by smiles—not frowns; to cheer the dear hearts of the young girlhood and boyhood; to strew flowers among the necessary thorns of existence. In a word, we try in these pages to make the sad happy—the happy still happier.

Hence, pure fun will be found as beautiful in these pages, as honey amid the flowers of Hybla.

Robert Merry to his friends

A kindly greeting sends,

With a general assortment of questions,

Conundrums, Charades,

Puzzles, Riddles of all shades,

And Rebuses, as aids

To intellectual and social digestion.

If the young Merry host

Acquaintance should boast,

Or kindred, or authorship pat,

With some of our jokes,

We confess—(’tis no hoax)—

To amuse other folks,

We have riddled the Museum “Chat.”

Now we beg you will show,

If you happen to know,

Why the Editor, painstaking soul?

Is like the cold storm

Which, in climates bright and warm,

Where gallinippers swarm,

Come shivering down from the pole?

3. Who prolongs his work to as great a length as possible, and still completes it in time?

4. Why are young ladies like arrows?

5. Why is a philanthropist like an old horse?

6. How can five persons divide five eggs, so that each man shall receive one, and still one remain in the dish?

7. How many soft-boiled eggs could the giant Goliah eat upon an empty stomach?

8. What fishes have their eyes nearest together?

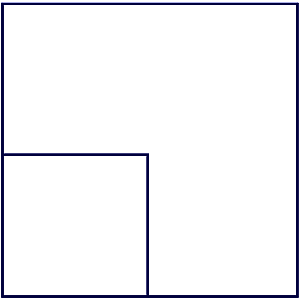

9. Two fathers have each a square of land. One father divides his so as to reserve to himself one-fourth in the form of a square; thus—

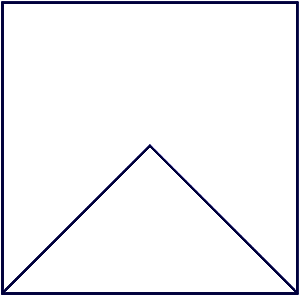

The other father divides his so as to reserve to himself one-fourth in the form of a triangle; thus—

They each have four sons, and each divides the remainder among his sons in such a way that each son will share equally with his brother, and in similar shape. How were the two farms divided?

12. What is that which is often brought to table, often cut, but never eaten?

13.

My first is four-sixths of a step that is long,

My second is a person of state;

My whole is a thing that is known to be wrong,

And is a strong symptom of hate.

14. Why are your nose and chin always at variance?

15.

Without my first you can not stand,

My second beauteous fair command;

Together I attend your will,

And am your humble servant still.

16. Why ought a fisherman to be very wealthy?

17. Why is a man in debt like a misty morning?

18. Who was the first that bore arms?

19. There is a word of seven letters; the first two refers to man, the first three refers to woman, the first four signifies a great man, the seven a great woman.

20. I am a word of five letters. Take away my first and I am the name of what adorns the estate of many of the nobility of England. Take away my first and second, and I am the name of a place where all the world was once congregated. Take away my last, and I am the name of a beautiful mineral. Take away my two last, and I am the name of a fashionable place of resort. I am small in stature, but capable of doing a great deal of mischief, as I once did in London in the year 1666.

21. Spell eye-water four letters.

22. Why is swearing like an old coat?

23. Why is a thump like a hat?

24. Why is an inn like a burial-ground?

27. If a fender cost six dollars, what will a ton of coal come to?

28. What word is that to which if you add a syllable, it will make it shorter?

29.

My first is a very uncomfortable state,

In cold weather it mostly abounds.

My second’s an instrument formed of hard steel,

That will cause the stout foe to stagger and reel,

And when used, is a symptom of hate.

My whole is an author of greatest renown,

Whose fame to the last day of time will go down.

30. What is the longest and yet the shortest thing in the world; the swiftest and yet the slowest; the most divisible and the most extended; the least valued and the most regretted; without which nothing can be done; which devours every thing, however small, and yet gives life and spirits to every object, however great?

31.

My first is found in every house,

From wintry winds it guards.

My second is the highest found—

In every pack of cards.

My whole, a Scottish chief, is praised

By ballad, bard, and story,

Who for his country gave his life,

And, dying, fell with glory.

32. Why are handsome women like bread?

33. Why is an avaricious man like one with a short memory?

34. What river in Bavaria answers the question, Who is there?

35. Why is a man with wooden legs like one who has an even bargain?

38. Why is a parish bell like a good story?

39. What belongs to yourself, yet is used by others more than yourself?

40.

In camps about the centre I appear;

In smiling meadows seen throughout the year;

The silent angler views me in the streams,

And all must trace me in their morning dreams,

First in the mob conspicuous I stand,

Proud of the lead, and ever in command.

41. The head of a whale is six feet long; his tail is as long as his head and half his body, and his body is half of his whole length. How long is the whale?

42. A hundred stones are placed, in a straight line, a yard distant from each other. How many yards must a person walk, who undertakes to pick them up, and place them in a basket stationed one yard from the first stone?

43.

My first is a part of the day,

My last a conductor of light,

My whole to take measure of time,

Is useful by day and by night.

44. I am a word of three syllables, each of which is a word; my first is an article in common use; my second, an animal of uncommon intelligence; my third, though not an animal, is used in carrying burdens. My whole is a useful art.

45.

There was a man who was not born,

His father was not born before him,

He, did not live, he did not die,

And his epitaph is not o’er him.

46. Why is a nail, fast in the wall, like an old man?

47. Why does a miller wear a white hat?

50.

My first is a letter commanding to wed,

Or to lift your sole till it reaches your head;

Nothing worth as a whole, it is plain to all men

That divided in halves, it is equal to ten;

My second, though nothing, compared to the other,

Is worth more as a partner than its double-faced brother;

It moans and it sighs, and when joined to my first,

Pronounces the doom of the sinner accursed.

My third, you will find his whole value depends

On the worth and position of neighbors and friends,

And, when both the other two following fair,

Changes doom to desire, and a curse to a prayer.

My fourth, though it formeth no part of a hundred,

Shows where it can justly and evenly be sundered;

’Tis found in the elements everywhere present,

’Tis found in all seasons, unpleasant or pleasant,

’Tis the chief of all lands, and yet can not wait

On continent, hemisphere, empire, or state.

Though ne’er in Great Britain suspected to lower,

’Tis the heart of each quarter of that mighty power;

It always belonged to the animal race,

In the mineral kingdom they gave it a place,

And, being impartial, they could not deny,

The vegetable order its virtue to try;

And yet, since creation, it never was known

In beast, bird, or fish, root, branch, stem, or stone.

My whole you’ll find growing in pasture and barns,

Or grown in coats, carpets, warm blankets, and yarns,

In England, in Saxony, France, and old Wales,

And in sundry more places it always prevails.

Of quadrupedal origin—still it is known

In bipedal families oft to be shown;

But the strangest of all its strange forms, and conditions

Is seen in the covering of sage politicians.

53. What is that which is invisible, but never out of sight?

54. When is a boat like a knife?

55. What part of London is in France?

56. How many black beans will make five white ones?

57. Why is a dandy like a haunch of venison?

58. What kin is that child to its father who is not its father’s own son?

59. Why is a rose-bud like a promissory note?

60. What biblical name is there which expresses a father calling his son by name, and his son replying?

61. Why is an orange not like a church bell?

62. Why is the largest city in Ireland likely to be the largest city in the world?

63.

Three-fourths of a cross, and a circle complete,

An upright where two semicircles meet,

A rectangle triangle standing on feet,

Two semicircles, and a circle complete.

64. What smells most in a drug shop?

65. Why should doctors attend to window-sashes?

| 66. G. a. | p |

| A. |

67. What is that which every one can divide, but no one can see where it has been divided?

68. Spell hard water with three letters.

69. What letters of the alphabet come too late for supper?

72.

Pronounced as one letter, and written with three,

Two letters there are, and two only in me;

I’m double, I’m single, I’m black, blue, and gray,

I am read from both ends, and the same either way,

I am restless and wandering, steady and fixed,

And you know not one hour what I may be the next.

I melt, and I kindle—beseech, and defy,

I am watery and moist, I am fiery and dry.

I am scornful and scowling, compassionate, meek;

I am light, I am dark, I am strong, I am weak.

I’m piercing and clean, I am heavy and dull;

Expressive and languid, contracted and full.

I’m a globe and a mirror, a window, a door,

An index, an organ, and fifty things more.

I belong to all animals under the sun,

And to those who were long understood to have none.

My language is plain, though it can not be heard,

And I speak without even pronouncing a word.

Some call me a diamond—some say I am jet;

Others talk of my water, or how I am set.

I’m a borough in England, in Scotland a stream,

And an isle of the sea in the Irishman’s dream.

The earth without me would no loveliness wear,

And sun, moon, and stars at my wish disappear.

Yet so frail is my tenure, so brittle my joy,

That a speck gives me pain, and a drop can destroy.

73. What vessel is that which is always asking leave to move?

74. Translate the following into Latin—

42, 8 rocks, e e e e e e e e e e, 46. 2. 14. 8. 0.

75. How is it that you can work with an awl, but not with a forceps; while I can work with a forceps, and not with an awl?

77.

Add, was the word the master gave to Dick,

Dick scratched his head, and looking rather thick,

Replied, “Hereafter it would make it stick.”

“Dick,” cried the master, “rudeness is a sin;

Behold the stocks, I’ll surely put you in.”

“That,” answered Dick, “won’t alter it a feather,

Hereafter it would make it hold together.”

“Dick,” said the man, “if you insult me so,

Your shoulders and my rod I’ll put in Co.”

“ ’Tis all the same,” said Dick, “my worthy master,

Hereafter it would make it stick the faster.”

78. Why is France like a skeleton?

79. Why is a woodman like a stage actor?

80. Why is the hour of noon on the dial-plate like a pair of spectacles?

81. Why is the best baker most in want of bread?

82.

Whether old Homer tippled wine or beer,

Julep or cider, history is not clear;

But plain it is—the bard, though wont to roam,

But for one liquid, never had left home.

83. Why is a coward like a mouse-trap?

84. Why is green grass like a mouse?

85. What two reasons why whispering in company is not proper?

86.

My first is found on the ocean wave,

In the spring, the pit, and the mine;

My second below earth’s surface you have,

Where seldom the sun can shine.

My whole your dinner-table must grace,

And seldom fails to obtain a place.

87. Why is a gooseberry pie like counterfeit money?

89. Why does a fisherman blow his horn?

90. Why is there no danger of starving in a desert?

91.

Take half of the needle

By which sailors steer

Their ship through the water,

Be it cloudy or clear;

Do not really break it—

This of all things were worst—

But in your mind take it,

And this makes my first.

At thanksgiving or Christmas,

My second you see;

With care well compounded,

From grain, shrub, and tree.

My whole like some people

Who make great pretense,

Of words have a plenty,

But no great stock of sense.

92. How is it that Methuselah was the oldest man, when he died before his father?

93.

My first is a negative greatly in use,

By which people begin when they mean to refuse;

My second is Fashion, or so called in France,

But, like other whims, is the servant of chance.

An article always in use is my whole,

With texture and form under fashion’s control;

But, alas! not a thing can it see which goes by,

Although many have four sights, and all have one eye.

94. What is that which, supposing its greatest breadth to be four inches, length nine inches, and depth three inches, contains a solid foot?

96.

My tongue is long, my breath is strong,

And yet I breed no strife;

My voice you hear both far and near,

And yet I have no life.

97. A waterman rows a given distance, a, and back again in b hours, and finds that he can row c miles with the current, for d miles against it. Required, the time of rowing down, the time of rowing up, the rate of current, and the rate of rowing.

98.

As I was beating on the far east grounds,

Up starts a hare before my two greyhounds;

The dogs, being light of foot, did fairly run,

To her fifteen rods, just twenty-one;

And the distance that she started up before,

Was six-and-ninety rods, just and no more;

Now, I would have you Merry boys declare

How far they ran, before they caught the hare.

99. Is it possible to put twelve pieces of money in six rows, and have four in a row?

100. A gentleman sent a servant with a present of nine ducks, with this direction—

“To Alderman Gobble, with ix. ducks.”

The servant took out three, and contrived it so that the direction corresponded with the number of the ducks. He neither erased nor altered a letter. How did he do it?

101.

Four letters form me quite complete,

As all who breathe do show;

Reversed, you’ll find I am the seat

Of infamy and woe.

Transposed, you’ll see I’m base and mean,

Again of Jewish race;

Transposed once more, I oft am seen

To hide a lovely face.

103.

My first is the name to an article given

For ladies and dandies to put on their linen;

It comes from the forest, I’ve heard people say,

And is made from the skin of an animal gay.

My second is a fruit that comes from the South,

The juice of it is sour, and ’twill pucker your mouth;

’Tis found in candy shops all over the town,

And, stranger to say, it is almost round.

My whole is an article that is often seen

In the gardens and fields almost covered with green;

It is very sweet, and also pleasant to eat,

And in hot summer days affords a rich treat.

104. My first is half of what implies good-humor; my second makes sense of my first; my third sounds like the cry of a kitten; my fourth is a consonant and vowel combined; my fifth, with the addition of the initial of my third, would imply silence; and my whole is what many boys and girls prize highly.

105.

I am composed of twelve letters.

My 2, 8, 9, is a substance dug out of the earth.

“ 6, 11, 12, 8, is a numeral.

“ 4, 2, 3, is an ancient instrument of war.

“ 12, 8, 1, is a vessel used in former times.

“ 5, is a vowel.

“ 4, 7, 1, 9, is a hard substance.

“ 10, 9, is a pronoun.

My whole is now before you.

106. My first is appropriate, my second ’tis nine to one if you guess it. My whole elevates the sole above the earth.

107. Why is a conundrum like a monkey?

108. What do we all do when we first get into bed?

111. There is one word in the English language which is universally considered a preventive of harm; change a certain letter in it, and you make it an act of cruelty.

112.

My first may be fashioned of iron or wood,

And at window or door for safety is placed;

In village or town it does more harm than good,

Leading people their health, time, and money to waste.

My second’s a lady, bewitching and fair,

And for love of her people will labor and strive;

Will rise before dawn, and be wearied with care,

And pursue her with ardor as long as they live.

My whole is what ladies admire and approve,

The shopkeeper’s boast—the purchaser’s prize;

’Tis a ninepenny chintz—’tis a one-shilling glove—

It is something which makes people open their eyes.

113. At what distance must a body have fallen to acquire the velocity of 1,600 feet per second?

114. Of what trade is the sun in May?

115. Why is a small horse like a young musk-melon?

116.

My first must grace a legal deed,

With its companion, firm and red;

Its help in marriage, too, they need,

Before the blessing can be said.

My second half a hundred is,

If in the shortest way you spell;

You soon must guess me after this,

I may as well the secret tell.

My whole, by his celestial strains

Bears the rapt soul to worlds above;

The Great Creator’s power proclaims,

And tells of the Redeemer’s love.

119. My first is a boy’s nickname; my second is meant for defense; my third is a preposition; my fourth is one of the articles; my fifth is one of the United States. My whole is a large city in Europe.

120.

My first is stationed near your heart,

And serves to brace the mortal frame;

Of young and old it forms a part,

And to fair woman gives a name.

Who builds a ship must it employ,

To give it strength to stem the flood,

And Adam felt no real joy

Till in new form by him it stood.

My second may be long or short,

Or tight or loose, or wet or dry,

Of cotton, silk, or woolen wrought,

Of any texture, strength, or dye—

Be made of iron, gold, or steel,

Of love or hate, of good or ill,

May gently bind, or heavy feel,

May give support, or rudely kill.

My whole is formed by fashion, skill, and care,

And what few ladies from their dress can spare.

121. How long would a ball be falling, from the top of a tower that was 400 feet high, to the earth?

122. Why are chairs like men?

123. The foot of a ladder 60 feet long remaining in the same place, the top will just reach a window 40 feet high on one side of the street, and another 30 feet high on the other side. How wide is the street?

124. There is a pile of cannon-balls, the ground tier of which contains 289 balls, and the top tier one ball. Require the whole number of balls in a pile.

127.

What skillful housewife does not know

When, where to place my first?

When nicely done, it will not show;

Conspicuous, it is worst.

My second all the world must do,

Either with head or hand,

In different ways the same pursue,

On water, or on land.

My whole a picture is of life,

Varied with good or ill,

With bright or dull, with light or dark,

Arranged with art and skill.

128. What is that which will make you catch cold—cure the cold—and pay the doctor’s bill?

129. Why is a joke like a cocoa-nut?

130. When did Esau, the hairy man, lose his whiskers?

131. Why do postmasters deserve the execration of all true Americans?

132.

Just equal are my head and tail,

My middle slender as can be,

Whether I stand on head or heel,

’Tis all the same to you or me.

But if my head should be cut off,

The matter’s true, although ’tis strange,

My head and body, severed thus,

Immediately to nothing change.

133. If a loafer, smoking a cigar, sets fire to the brush on his upper lip, is it a case of spontaneous combustion?

134.

liv sin transgre procur damn

A ing er s ssion ed ation.

dy Redeem pa purchas salv

138.

Go wide o’er the world,

And everywhere seek me—

In earth, sea, or air,

Thou never shalt meet me!

Go wide o’er the world—

I always am there—

Wherever thou roamest,

In earth, sea, or air!

Go speak to the woodland,

And question of me—

Oh ne’er shall thou find me,

With forest or tree!

Go, speak to the woodland,

I ever am there,

And live in its whispers,

Though lighter than air!

Go, winnow the wave,

And seek for my breath—

Ah, ocean and river,

Reveal but my death!

Go, winnow the wave,

Tho’ with winter it shiver—

There—there shalt thou find me,

’Mid ocean and river!

In whirlwinds I revel,

Yet in zephyrs expire—

I flourish in warmth,

And I perish in fire!

The winter I cherish,

Yet each season I shun;

Half living in harvest,

In summer, undone!

I come with the warlock—

I go with the ghoul—

I shriek with the wizard—

I hoot with the owl!

I ride on the hazel

Which witches have rent—

I fly on the wing

Which the eagle hath bent.

I come and I go—

Oft unseen and unsought;

I live but in words—

I perish in thought.

So to all and to each,

I bid you adieu;

Yet to all and to each,

I stay double with you!

139. Why is the boy that disturbs a hive like a true Christian?

140. What is that which has eyes and sees not, ears and hears not, nose and smells not, yet is often regarded as the beau-ideal of a human being?

141. Why is the elephant his own servant?

142. Which of the forest trees bears gain?

143. Who was the heaviest of mechanics?

144.

I’m a heavy drag—few things more slow.

Cut off my head, and give me a bow,

And swiftly through the air I go.

145. Why are two heads better than one?

146. Why is a cart-horse always in the wrong place?

147.

I follow the plough, and yet I never walk,

Have plenty of teeth, yet neither eat nor talk,

Am strongly barred, and yet I never close,

I scratch and break, but never deal in blows.

148. What is that which has many leaves, but no stem?

149. Why is the letter F like an incendiary?

150. Arithmetical Puzzle.—This consists of six slips of paper or card, on which are written numbers as expressed in the following columns—

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | |||||

| 3 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 17 | 33 | |||||

| 5 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 18 | 34 | |||||

| 7 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 19 | 35 | |||||

| 9 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 20 | 36 | |||||

| 11 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 21 | 37 | |||||

| 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 22 | 38 | |||||

| 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 23 | 39 | |||||

| 17 | 18 | 20 | 24 | 24 | 40 | |||||

| 19 | 19 | 21 | 25 | 25 | 41 | |||||

| 21 | 22 | 22 | 26 | 26 | 42 | |||||

| 23 | 23 | 23 | 27 | 27 | 43 | |||||

| 25 | 26 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 44 | |||||

| 27 | 27 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 45 | |||||

| 29 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 46 | |||||

| 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 47 | |||||

| 33 | 34 | 36 | 40 | 48 | 48 | |||||

| 35 | 35 | 37 | 41 | 49 | 49 | |||||

| 37 | 38 | 38 | 42 | 50 | 50 | |||||

| 39 | 39 | 39 | 43 | 51 | 51 | |||||

| 41 | 42 | 44 | 44 | 52 | 52 | |||||

| 43 | 43 | 45 | 45 | 53 | 53 | |||||

| 45 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 54 | 54 | |||||

| 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 55 | 55 | |||||

| 49 | 50 | 52 | 56 | 56 | 56 | |||||

| 51 | 51 | 53 | 57 | 57 | 57 | |||||

| 53 | 54 | 54 | 58 | 58 | 58 | |||||

| 55 | 55 | 55 | 59 | 59 | 59 | |||||

| 57 | 58 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | |||||

| 59 | 59 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 61 | |||||

| 61 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | |||||

| 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 |

The slips being thus prepared, a person is to think of any one of the numbers which they contain, and to give [pg 37] to the expounder of the question those slips in which the number thought of occurs. To discover this number, the expounder has nothing to do but to add together the numbers at the top of the columns put into his hand. Their sum will express the number thought of.

Example.—Thus, suppose we think of the number 14. We find that this number is in three of the slips, viz., those marked B, C, and D, which are therefore given to the expounder, who, on adding together 2, 4, and 8, obtains 14, the number thought of.

The trick may be varied in the following manner: Instead of giving to the expounder the slips containing the number thought of, these may be kept back, and those in which the number does not occur be given. In this case, the expounder must add together, as before, the numbers at the top of the columns, and subtract their sum from 63. The remainder will be the number thought of.

The slips containing the columns of numbers are usually marked with letters on the back, and not above the columns, as we have expressed them. This renders the deception more complete, as the expounder, knowing beforehand the number at the top of each column, has only to examine the letters at the back of the slips given him, when he performs the problem without looking at the numbers, and thus renders the trick more extraordinary.

151.

A pair of little quadrupeds,

Transpose them, and you’ll find

The lords of ocean, or the aids

For disciplining mind;

Or that which cheers the midnight hour,

Or gilds the flagstaff high;

Now test your transposition power,

And for the answer try.

152. When is a chair like a rich lady’s dress?

153. One p, one i, four a’s, two r’s, two s’s, two l’s—what do they make, and who has made a fortune by them?

154. What odd number will give, on being divided, a half clear of a fraction?

155.

I’m in the book, but not on any leaf;

I’m in the mouth, but not in lip or teeth;

I’m in the atmosphere, but never in the air;

I wait on every one, but never on a pair;

I am with you wherever you may go;

And every thing you do I’m sure to know;

Though when you did it I should not be there,

Yet when ’twas done, you’d find me in the chair.

156. What is the difference between Joan of Arc and Noah’s ark?

157.

I am composed of seventeen letters.

My 4, 6, 10, is what we all do.

“ 5, 8, 14, 11, is a great part of the body.

“ 1, 13, 9, 15, is the name of a fish.

“ 7, 16, 2, 10, is a part of speech.

“ 13, 8, 3, is the name of a fowl.

“ 6, 15, 14, is a girl’s name.

“ 17, 6, 10, 15, is very useful to vessels.

“ 13, 6, 12, is a personal pronoun.

My whole is what we may all expect if we live.

158. My first is an instrument, which, though small, has more power than any monarch on earth. It is the lover’s friend and the poet’s pride; yet has overthrown kingdoms, ruined reputations, set folks together by the ears, and caused more destruction than plagues, pestilence, or famine. My second, though not quite so mischievous, is very destructive when in improper hands, and my whole, though employed against my first, is deemed its friend and improver.

159. This is a most excellent pastime. It should be played in a spacious place, out of doors, if possible, and the more there are engaged in it, provided they be of the same height and agility, the better is the sport. We will suppose a dozen at play:—Let eleven of them stand in a row, about six yards apart, with all their faces in one direction, arms folded, or their hands resting on their thighs, their elbows in, and their heads bent forward, so that the chin of each rests on his breast, the right foot advanced, the back a little bent, the shoulders rounded, and the body firm. The last begins the sport by taking a short run, placing his hands on the shoulders of the nearest player, and leaping with their assistance—of course, springing with his feet at the same time—over his head, as represented in the cut. Having cleared the first, he goes on to the second, third, fourth, fifth, etc., in succession, and as speedily as possible. When he has gone over the last, he goes to the proper distance, and places himself in position for all the players to leap over him in their turn. The first over whom he passed, follows him over the second, third, fourth, etc.; and when he has gone over, the one who begun the game places himself in like manner for the others to jump over him. The third follows the second, and so on until the parties are tired.

160.

His heart was sad, and his foot was sore,

When a stranger knocked at the cottager’s door;

With travel faint, as the night fell down,

He had missed his way to the nearest town,

And he prayed for water to quench his thirst,

And he showed his purse as he asked for my first.

The cotter was moved by the stranger’s tale,

He spread the board, and he poured the ale:

“The river,” he said, “flows darkly down

Betwixt your path and the lighted town,

And far from hence its stream is crossed

By the bridge on the road that you have lost;

Gold may not buy, till your weary feet

Have traversed the river and reached the street,

The thing you ask; but the wandering moon

Will be out in the sky with her lantern soon;

Then cross o’er the meadow, and look to the right,

And you’ll find my second by her light.”

My second shone like a silver floor,

When the traveler passed from the cotter’s door;

He saw the town on its distant ridge,

Yet he sighed no more for the far-off bridge;

And his wish of the night soon gained its goal,

For he found my first when he reached my whole.

161. What two letters of the alphabet make a prophet?

| 162. I 8 0 | M |

| day. |

163. Plant an orchard of twenty-one trees, so that there shall be nine straight rows, with five trees in each row, the outline a regular geometrical figure, and the trees all at unequal distances from each other.

| 164. B 0 yy | nor | for U c what a fool u b. |

| nice |

166. Why is a horse like the prophet Elijah?

167. Why is a new married man like a horse?

168. Why is it profitable to keep fowl?

169. My first is a collection of water; my second is used when speaking of myself; my third is a fruit; my whole is a town in Hindostan.

170. “Thomas,” said Charles, “you are good at figures, please give me a figurative answer to this question:—What ought one to do who arrives at a friend’s house too late for dinner?”

Thomas, after thinking a little, wrote the following—1028,40. What was his meaning?

171. A teacher, having fifteen young ladies under her care, wished them to take a walk each day of the week. They were to walk in five divisions of three ladies each but no two ladies were to be allowed to walk together twice during the week. How could they be arranged to suit the above conditions?

172.

My first is a letter, an insect, a word,

That means to exist; it moves like a bird.

My next is a letter, a small part of man,

’Tis found in all climes; search where you can.

My third is a something seen in all brawls.

My next you will find in elegant halls.

My last is the first of the last part of day,

Is ever in earnest, yet never in play.

My whole gives a light, by some men abhorred,

The blessings from which no pen can record.

173. What number is that, which, added separately to 100 and 164, shall make them perfect squares?

174. Why is the letter F like death?

175. Why are mortgages like burglars?

176.

I’m composed of letters four,

A turkey, cock, or hen;

Behead me, and I upward soar.

Put on my head again,

Transpose me, then a beast I am,

Both bloodthirsty and wild,

That preys on many a helpless lamb,

And oft devours a child.

177. I am a word of three letters, signifying to spoil or injure. Transposed, I am an animal. Transposed again, I am a part of the human frame.

179.

I have wings, yet never fly—

I have sails, yet never go—

I can’t keep still, if I try,

Yet forever stand just so.

180. Why is a grist-mill like an orange-tree?

181. What Scripture character was a stupid sheep?

182. What animal that always has a cold chin is used to keep the ladies’ chins warm?

183. What two reasons why a young lady going to the altar is certainly going wrong?

184. Why is it dangerous for a teetotaler to have more than two reasons for the faith that is in him?

185. What is the most cheerful part of an arsenal?

186. When does the tongue assume the functions of the teeth?

187. My first is company, my second is without company, and my third calls company.

188.

An emblem of stupidity,

My first in forests found;

Up in air oft rises high,

Though fastened to the ground,

But by sharp means it is removed,

And managed various ways;

By art or skill may be improved,

Or, perhaps, it makes a blaze.

My second is of every kind,

Is good, or bad, or gay;

Is dull or bright, to suit all minds,

By night as well as day.

The patient seaman keeps with care my whole,

And well it knows his secrets night and day;

And though it has no tongue, nor heart, nor soul,

It tells the story of the ship’s long way.

189. There is a word of six letters. Take off three letters at either end, and add another letter, and it will make one of the most useful members of the body.

190.

Tell me why is it, if you lend

But forty dollars to a friend,

It does your kindness more commend

Than if five hundred you should send?

191. What is that which is less tired the longer it runs?

192. Why is a tailor finishing your pants like a polite host serving his guests with water-fowl?

193. What was a month old at Cain’s birth, that is not five weeks old now?

194. What looks worse on a lady’s foot than a darned stocking?

195. Which of the girls can answer questions best?

196. What is the shape of a kiss?

197.

My first is a busy industrious thing,

Without which no bundle your porter can bring;

My second is nothing to speak of, yet stands

For thousands and millions, in money or lands;

My third is a question we meet every day,

Relating to things we do, think, or say;

My whole is the questioner—once it was you,

If not, ’twas your brother, or cousin, or—whew!

It was somebody else whom your grandmother knew.

198. I am composed of four letters. We do not 4 2 3, 1 4 2 3, 2 3, 3 4 2.

199.

My first is a preposition.

“ second implies more than one.

“ third is a pronoun.

“ fourth some people do not pay.

“ whole is not consistent.

200.

I am a word of four letters often used in prayer.

Transposed, I become what every one professes.

Transposed again, I become an adjective, the qualities of which every one despises.

Transposed again, I am part of a horse.

201.

My first is poison, slow yet sure,

That preys on many frames;

Compounded oft of things impure,

And called by many names.

My first and second form my whole,

That’s one of Satan’s dens;

Many a man has lost his soul,

Through meeting there with friends.

202.

I am a word of four letters—the name of a Cape.

Transposed, I am a portion of the earth’s surface.

Transposed again, I am a kind of meat.

Transposed again, I become a verb signifying to wash.

203.

I prove 2 = 1, thus:—

x = a; then x2 = ax

x2 - a2 = ax - a2

(x + a)(x - a) = a(x - a)

x + a = a

2a = a

2 = 1

Who will detect the fallacy?

204. In what ship, and in what capacity, do young ladies like to engage?

205.

Ethereal thing, on unseen wing,

Through space my first is wandering;

It nothing sees, it nothing knows,

Yet all that’s known and seen it shows.

Brick, iron, mud, stone, reed, or wood,

My second in all climes has stood—

A lodge, a nest, where love may rest,

Or a prison, gloomy, dark, unblest.

Away on the bleak and desolate peak

Where the rude tempests howl and shriek,

Like a friendly eye, looking out from the sky.

My whole to the wanderer gleams on high.

206. What kind of a ship did Solomon object to?

207. There are two numbers whose product added to the sum of their squares is 109, and the difference of whose squares is 24.

208.

In every hedge my second is,

As well as every tree,

And when poor school-boys act amiss,

It often is their fee.

My first likewise is always wicked,

Yet ne’er committed sin,

My total for my first is fitted,

Composed of brass or tin.

209. My first is a pronoun; my second is not high; my third we must all do; my fourth is a pronoun of multitude; my whole is musical.

210. What is the difference between a grandmother and her infant grandchild?

211. Add one to nine and make it twenty.

212. What is that which the dead and living do at the same time?

213.

When winter months have passed away,

And summer suns shine bright,

You ope the coffer where I lay,

And bring my first to light.

My second is a valiant knight,

Who wears his crest and spur,

And when he’s challenged to a fight,

He does not long demur.

My whole, as ancient fables say,

Was once a friend of Juno,

In dress he makes a great display—

His name by this time you know.

214. Why is a bullet like a tender glance?

215.

When innocence first had its dwelling on earth,

In my first’s lovely form it alighted;

And still to this time, from the hour of its birth,

In my first it has greatly delighted.

My second’s a part of a smart lady’s dress,

Yet on age it may also be found;

Again, ’tis a garb when the heart feels distress—

And my whole does with pleasure abound.

216. Why are children at play like a bird in her nest?

217.

My first is male or female, young or old,

’Tis very sad if you are forced to doubt one;

Much must we pity the false heart or cold,

Who is so selfish as to live without one.

My second is a noble work of art,

Which brings together distant shores and lands;

Though neither feet it has, nor head, nor heart,

’Tis often furnished with a hundred hands.

My whole in youth or age, sickness or health,

In joy or sorrow, charms to life can give;

Without it, all in vain are hoards of wealth,

By it unblest in solitude we live.

218. What spice are the Hindoos fond of?

219. Why is a dog like a tanner?

220. Why are A B’s successors seedy?

221. What is nothing good for?

222. I am composed of four letters—the initials of four of the principal personages in Europe—the name of a river in Russia; transposed, I am a part of the Crystal Palace; transposed again, I am not proud, although elevated above the heads of most people.

223.

My first is when the summer wind

Sweeps rustlingly through the trees,

When the jasmine spray and the eglantine

Are swayed by the whispering breeze;

My second, a weapon of bloody strife,

Of steel, so cruel and cold,

Which ruthlessly takes the soldier’s life,

The cowardly, and the bold;

My whole is a Poet, by every one known,

So wide is his renown.

224. Why is the letter y like a young spendthrift?

226.

My first in the garden luxuriantly grows,

Delicious and sweet, as every one knows;

My second a noisy, vain, garrulous thing,

The lord of a harem, as proud as a king;

My whole is still prouder, and seems to rejoice

As much in his tail as he does in his voice.

227. One man said to another, “Give me one of your sheep, and I shall have twice as many as you.” The other replied, “No, give me one of yours, and I shall have as many as you.” How many had each?

228. Where were potatoes first found?

229. Where did cherries come from?

230. Why is a ship under full sail like Niagara?

231.

O’er a mighty pasture go

Sheep in thousands, silver white;

As to-day we see them, so

In the oldest grandsire’s sight.

They drink—never waning old—

Life from an unfailing brook;

There’s a shepherd to their fold,

With a silver-horned crook.

From a gate of gold let out,

Night by night he counts them over;

Wide the field they rove about,

Never hath he lost a rover:

True the dog that helps to lead them,

One gay ram in front we see;

What the flock, and who doth lead them,

Sheep and shepherd, tell to me?

232. I am a word of four letters. Take off my hat, and you have something which you do every day. Take off my head, and you have a preposition. Leave off my head and put on my hat, and you have something used before a door. Entire, and taken backward, with my two middle letters transposed, I am a very convenient thing. I, myself, am often eaten.

233. What part of a ship was Cain?

234. What animal resembles the sea, and why?

235. What animal is the most windy, and why?

236. What animal is like an apothecary?

237. What animal is like a stone-breaker?

238. A man had a bar of lead that weighed 40 lbs., and he divided it into four pieces in such a way as to allow him to weigh any number of pounds from one to forty. How did he manage the matter?

239. What is the best key to a good dinner?

240. Why is a farm-yard like a hotel?

241. If a woman stands behind a tree, how does the tree stand?

242. Wherein does a turkey-cock differ from a lady?

243. Three men buy a grindstone, 40 inches in diameter, on equal shares. Each one is to use it until he has worn away his share. How many inches in diameter must each one use?

244. What two letters of the alphabet do children like best?

245. Why are Cashmere shawls like deaf persons?

246.

Ye mortals—wonder! I’m an elf,

A strange, mysterious thing;

More powerful than all the sprites

Within a magic ring.

I speak—although I have no tongue—

I speak, and thrill the soul;

I sing—and many a song I’ve sung

Resounds, while ages roll.

I am a weapon, strong and keen,

All made of glittering steel;

But human souls—not senseless flesh—

My sharp two-edges feel.

The greatest writer e’er was born—

But, ah!—a thievish elf;

For what I write is not, alas!

Original with myself.

I often take a cooling bath;

But, like the Ethiop’s skin,

When I have bathed, I’m blacker still

Than when I did begin!

Most kind am I; I glad the heart

Of many a wretched wight,

And many a sufferer is by me

Transported with delight.

Most cruel I; I’ve pierced the soul

With cutting, burning darts;

I’ve dashed the fondest hopes to earth,

I’ve crushed the lightest hearts.

Yet wise and powerful as I am,

A very slave am I;

I’m forced the mandates to obey

Of both the low and high.

Now, witty brains, tell who this is,

Who blesses and who curses;

Who has no hands, yet still who is

The writer of these verses.

248. Why is an Indian like a scholar?

249. How much silk is required to make a spherical balloon, 16 inches in diameter, without allowing for seams?

250. All children love to go to sea, and why?

251.

That gentle picture dost thou know,

Itself, its hues, and splendor gaining?

Some change each moment can bestow,

Itself as perfect still remaining;

It lies within the smallest space,

The smallest framework forms its girth,

And yet that picture can embrace

The mightiest objects known on earth:

Canst thou to me that crystal name

(No gem can with its worth compare)

Which gives all light, and knows no flame?

Absorbed is all creation there!

That ring can in itself inclose

The loveliest hues that light the heaven,

Yet from its light more lovely goes

Than all which to it can be given!

252.

From 6 take nine, from 9 take 10;

From 40 take 50, and 6 remain.

253. Why is marriage like truth?

254. Required to divide 45 in four parts, so that the first part with two added, the second with two subtracted, the third divided by two, the fourth multiplied by two, shall equal each other.

255. Where was Major Andre going when he was captured?

256.

There is a mansion, vast and fair,

That doth on unseen pillars rest;

No wanderer leaves the portals there,

Yet each how brief a guest!

The craft by which that mansion rose,

No thought can picture to the soul;

’Tis lighted by a lamp which throws

Its stately shimmer through the whole.

As crystal clear, it rears aloof

The single gem which forms its roof,

And never hath the eye surveyed

The master who that mansion made.

257. Why is a sculptor like a man who “splits his sides with laughter?”

258. Why were the Scribes and Pharisees like a great conflagration?

259. My first is a collection of water, my second is used when speaking of myself, my third is a fruit, my whole is a town in Hindostan.

260.

X U R, X U B,

X, 2 X U R 2 me.

261. Why was Daniel like Nebuchadnezzar’s image?

262. Several things are necessary to make this sport safe and pleasant. First, a strong bar on which to balance your board or plank. Secondly, a strong, straight-grained board or plank, which will not crack nor twist. Thirdly, an equal weight at each end, or nearly so. Fourthly, a clear head, and a steady hand, or foot, to keep up an even motion. With these all right, you will go up and down as easily and smoothly as men of business do, or political parties;—but, hallo there, boys, John has tumbled off, and you will have a smash at the other end, which will leave John’s partner in doubt whether he is up or down.

263. What island in the Pacific is always at this sport?

264. What is there at the same time philosophical and ungrammatical in this sport?

265. Why is an elephant like a lady’s veil?

266.

I was before the world begun,

Before the earth, before the sun;

Before the moon was made, to light

With brighter beams the starry night;

I’m at the bottom of the sea,

And I am in immensity;

The daily motion of the earth

Dispels me, and to me gives birth;

You can not see me if you try,

Although I’m oft before your eye;

Such is my whole. But, for one part,

You’ll find in taste I’m rather tart;

Now I become the abode of men—

And now, for groveling beasts, a pen;

I am a man who lives by drinking;

Anon I keep a weight from sinking;

To take me, folks go far and near;

I am what children like to hear;

I am a shining star on high;

And now, its pathway through the sky;

My strength o’erpowers both iron and steel;

Yet oft I’m left behind the wheel;

I’m made to represent a head;

Am found in every loaf of bread;

Such are the many forms I take,

You can not count all I can make;

Yet, after all, so strange am I,

Soon as you know me, then I die.

267. Henry is four feet high and William is five. The sum of their heights multiplied by five is equal to their father’s age, plus fifteen. How old was their father?

268. My first is the name of a river, my second is a pleasant beverage, my third is what we are too apt to do, and my whole is the name of an ancient city.

269. The deaf and dumb converse with each other, and with their teachers, by signs made with their hands. There are two ways of making the letters with the fingers; in one, both hands are used; in the other, only one. Above, you see how the letters are made with one hand.

270. When are the letters like the keys of a piano?

271.

Up and down two buckets ply

A single well within;

While the one comes full on high,

One the deeps must win.

Full or empty, never ending,

Rising now, and now descending,

Always while you quaff from this,

That one lost in the abyss,

From that well the waters living

Never both together giving.

272.

Come from my first—ay, come! the battle dawn is nigh,

And the screaming trump and thundering drum are calling thee to die!

Fight as thy father fought, fall as thy father fell;

Thy task is taught, thy shroud is wrought, so forward, and farewell!

Toll ye, my second, toll! Fill high the flambeau’s light,

And sing the hymn of a parted soul beneath the silent night,

The wreath upon his head, the cross upon his breast,

Let the prayer be said, and the tear be shed—so take him to his rest.

Call ye my whole—ay, call the lord of lute and lay,

And let him greet the sable pall with a noble song to-day;

Go, call him by his name! no fitter hand may crave

To light the flame of a soldier’s fame on the turf of a soldier’s grave.

273. Once in a minute, twice in a moment, once in a man’s life?

274. A man said “I lie.” Did he lie, or did he tell the truth?

276. Why should a hound never be admitted into the house?

277. Why is your favorite puppy like a doll?

278. How can a person live eighty years, and see only twenty birthdays?

279. What is the difference between twenty four quart bottles, and four and twenty quart bottles?

280. How will you arrange four 9’s so as to make one hundred?

281.

Amid the serpent race is one

That earth did never bear;

In speed and fury there be none

That can with it compare.

With fearful hiss—its prey to grasp—

It darts its dazzling course,

And locks in one destroying clasp

The horseman and the horse.

It loves the loftiest heights to haunt—

No bolt its prey secures;

In vain its mail may valor vaunt,

For steel its fury lures!

As slightest straw whirled by the wind,

It snaps the starkest tree;

It can the might of metal grind,

How hard soe’er it be!

Yet ne’er but once the monster tries

The prey it threats to gain:

In its own wrath consumed it dies,

And while it slays is slain.

282. A went to a shoemaker, B, and ordered a pair of boots. At the time appointed for their completion, A called for his boots. The price was $5. A gave B a 20 dollar note, which, not being able to change, he went to C, who gave him four $5 notes. B gave A three of the notes, and kept one. The next day C came to B and told him his $20 note was a counterfeit. B gave C four $5 notes, three of which he borrowed from D. How much did B lose by the operation?

284. When he is caught stealing, what does he catch?

285. How many feet ought a thief to have?

286. Why is Tom Tumbledown like Adam when he saw the apple?

287. A friend asserted to me a day or two since, that forty horses only had eighty-four legs. How did it come?

288.

Moce ye inugeison nose hist dilerd suesg

Ti si ton cufidlift ouy liwl socfens,

Thaw si hatt burmen—hiwhc fi ouy ivdedi,

Ouy hent liwl hington veale no theire dies?

289. Our family is large, but not much more than one third as large as that of Jacob when he went to live in Egypt. But, like the family of that ancient patriarch, we often migrate to other countries. We do not keep together, whether at home or abroad; we are scattered about in every direction,—at once masters, servants, and slaves to forty-four millions of people. Not a book is printed without our aid; and, what is stranger still, we are all found at the same time in every book in every library and country where the English language is spoken; and on almost every page. Sometimes, though rarely, two of us stand side by side. It is still more rare for us all to appear together arranged in the same order. Nothing is more common with people than to place us in rows or platoons; but whether in militia, army, or navy—for some of us are employed in all these—we are seldom arranged twice alike. Sometimes one of us stands first; sometimes another. Sometimes a row or platoon consists of only two or three of us; at others of many more; and occasionally of twelve, fifteen, or twenty; and, strangest to relate of all, we can be so placed as to make out about 50,000 rows, no two of which will be exactly alike. Must we not, then, be a useful family? And what, think you, is our family name?

290. | | | | | | . Add five more marks to these six, so as to make nine.

291. What tree is that, which has twelve branches, thirty leaves on each branch, and each leaf white on one side, and black on the other?

292.

293. Which of the planets would the tortoise like best to live in?

294. Why is a picture surrounded by books like a happy man?

295. Mother sent Mary for an evergreen. The gardener brought a holly. Mary pointed to the sky, and the gardener brought what she wanted. What did Mary mean?

296. When the day breaks, what becomes of the fragments?

297. Novus vir bonus vir ivit ad caudam vel habere suam vestem homines mortuos.

298. EE Marriage ee.

299. What bird is that which has no wings?

300. Add something to 9 to make it less.

301. Why is Satan on a shed like a bankrupt?

302. How is it that trees put on their summer dresses, without opening their trunks?

303. Of three words make one, by the insertion of a single letter.

304. Of a word of one syllable, make a word of three syllables, by the addition of a single letter.

305.

Ages ago, when Greece was young,

And Homer, blind and wandering, sung;

Where’er he roamed, through street or field,

My first the noble bard upheld;

Look to the new moon for my next,

You’ll see it there, but if perplexed,

Go ask the huntsman, he can show

My name—he gives it many a blow;

My whole, as you will quickly see,

Is a large town in Tuscany,

Which ladies soon will recognize—

A favorite head-dress it supplies.

306. Why is an elephant like a chair?

307. Mr. —wood being at the . of king of terrors, 10

mills for his quakers, and who, which and what. They

odor for Dr. Juvenile Humanity, who ![]() to Dr. Hay

preservers, and little devil behold scarlet his assistance;

but, B 4 he arrived, the not legally good

to Dr. Hay

preservers, and little devil behold scarlet his assistance;

but, B 4 he arrived, the not legally good

| changed color, and | taker | was ct for. |

| the |

308. Given the street and the hour, to find at once the number of children in the street.

309. Given the section of the city, to find at once the number of loafers and vagabonds that infest it.

310. This is a very curious and interesting kind of a tree. It is found, loaded with every variety of strange fruit, on tables, bare floors, or carpets. It has no roots, but is most wonderful for its yielding powers, though it bears only once a year, and that always on Christmas Eve. The last one that I saw was at Uncle Hiram Hatchet’s. Cousin Hannah thus describes it:

“At last, when none of us expected it, he (Uncle H.) threw open the folding doors, and let us into the little parlor. There was displayed the Christmas tree, in all its glory. Every little twig bore some present; dolls [pg 70] and doll furniture, pins, ear-rings, bracelets, slippers, watch-guards and purses, ships, windmills, and beautiful books, besides all sorts of fruits and bon-bons, and all blazing with light from the numberless candles that seemed to grow out of the branches.”

A tree that, without life or root,

Without a blossom, bud, or flower,

Bears various and most precious fruit,

That comes and goes in one short hour.

311.

My first is an adjective, short and dry,

Which an absence of moisture seems to imply,

Or, in reference to mind, that kind of wit,

Which is slack on the rein, and sharp on the bit

My second is a sort of hole, or den,

Unfit for the resort of timid men,

Whence once the righteous came safely out,

While the wicked were wholly put to rout.

My whole is an author of classic fame,

If you know the man, please tell me his name.

312. What poet do miners value most?

313. What poet is least distinguished for brevity?

314. Which of the English poets would be most likely to make a lion feel at home?

315. Why were the Amalekites never allowed to speak?

316. Which of the reptiles is a mathematician?

317. What Scripture character would have made a suitable husband for a tall laundress?

318. What two syllables of the marriage ceremony are most interesting to the priest?

319. What part of a house measures about two quarts?

320. When is a door not a door?

321. Why are ladies sitting on the stoop, like an unfinished house?

322. What stone opens and shuts at your convenience?

323.

Read see how me

Down will I love

And you love you

Up and you if

324. Why is a thing purchased like a shoe?

325. Why is a man who makes a wager of a cent, like a person recovering from illness?

326. Why is an unpaid bill like the moisture in the morning?

327. Why is a sanguinary epistle like a surgeon?

328.

Ere from the east arose the lamp of day,

Or Cynthia gilt the night with paler ray—

Ere earth was form’d, or ocean knew its place,

Long, long anterior to the human race

I did exist. In chaos I was found,

When awful darkness shed its gloom around.

In heaven I dwell, in those bright realms above,

And in the radiant ranks of angels move.

But when th’ Almighty, by his powerful call,

Made out of nothing this stupendous ball,

I did appear, and still upon this earth

Am daily seen, and every day have birth.

With Adam I in Paradise was seen,

When the vile serpent tempted Eve to sin;

And, since the fall, I with the human race

Partake their shame and manifest disgrace.

In the dark caverns of old ocean drear

I ever was, and ever shall appear.

In every battle firmly I have stood,

When plains seem lav’d, whole oceans dy’d with blood.

But, hold—no more! It now remains with you

To find me out and bring me forth to view.

329. Why is a lost child like you?

330. Why is Fremont equal to eight honest politicians?

331. How did Jonah feel when the whale swallowed him?

332. Why were the Hebrews called sheep?

333. Why is it dangerous to flirt in a hay-field?

334. Under what tree is it most proper to make love?

335. Under what shade can you dance best?

336. Why is a dashing young buck a favorite with the ladies?

337. 1. I am constantly in the midst of money. 2. I am continually putting people in possession of property. 3. I increase the number of most things that come in my way. 4. I am no friend to the distressed needlewomen, for I render needles unnecessary. 5. Yet whenever I undertake a dress, I infallibly make it sit. 6. I am quarrelsome, [pg 74] for a word and a blow is my maxim. 7. In fact, with me a word becomes a weapon. 8. And merriment becomes slaughter. 9. It is commonly remarked that drink converts men into swine, but I transform wine itself into the same animals. 10. Deprived of me, certain railway speculations come out in their true character. 11. A team can draw a wagon well without me, still, when I am in front, the speed is wonderfully increased. 12. Marvelous products may be obtained from peat, but when I am extracted from earth, pure oil alone remains. 13. Let me go before, and a story is sure to be stale. 14. And if I am left out, it will be political. 15. I am strongly attached to pluralities. 16. With respect to free trade, I turn corn itself into contempt. 17. I am in the midst of Russia and Prussia, and abundant among the Swiss. 18. Were I withdrawn from that unhappy country, Spain, nothing would be left but grief. 19. After sport, when I take my departure, the evening is often finished with what remains. 20. At a soiree I am always in good time. 21. In person I am much bent, though I was formerly more upright. 22. As to my education, I was always head of the school. 23. Though invariably at the bottom of my class. 24. With me age looks wise. 25. But a gentleman is better without me, as accompanied by me he appears feminine. 26. On the contrary, a lady ought not to part with me, for if she loses me she seems masculine. 27. I am an unwelcome visitor, for with me sorrow begins and happiness ends. 28. Sadness commences, and, 29. Bliss terminates. 30. Yet it is in my power to transform cares into what is delightful.

338. Nebuchadnezzar’s lions were very undevout when Daniel was with them, and very poetical with his enemies. Please explain.

339. Why is a hunter like an omnibus pickpocket?

340.

Figures, they say, won’t lie; but here

Is something either false or queer.

I find that, in my family,

One taken from two still leaves me three,

And two from two, by the same score,

Leaves a remainder of just four.

341.

My first is a measure much used in the East,

Or a close-covered vehicle drawn by one beast;

My second is a prefix—a small preposition—

Two thirds of a tavern—a paid politician;

My whole, though part of a vessel, has stood

Alone on the prairie, or ’neath the great wood,

And often is found, poor, wretched, and mean,

The city’s proud palaces squatting between.

342. Take two numbers, such that the square of the first, plus the square of the second, shall equal 8; while the first, plus the product of the first and second, shall equal 6.

N. B.—If any choose to work this out algebraically, it will be found to be no trifling puzzle. See Merry’s Museum for 1856.

343.

What’s that the poor’s most precious friend,

Nor less by kings respected—

Contrived to pierce, contrived to rend,

And to the sword connected.

It draws no blood, and yet doth wound;

Makes rich, but ne’er with spoil;

It prints, as earth it wanders round,

A blessing on the soil.

The eldest cities it hath built,

Bade mightiest kingdom rise; it

Ne’er fired to war, nor roused to guilt:

Weal to the states that prize it!

344. When is a political candidate like Samson’s guests?

345. What is the most suitable dance to wind off a frolic?

346.

Revolving round a disk I go

One restless journey o’er and over;

The smallest field my wanderings know,

Thy hand the space could cover:

Yet many a thousand miles are passed

In circling round that field so narrow:

My speed outstrips the swiftest blast,

The strongest bowman’s arrow.

347. Why are buckwheat cakes like the caterpillar?

349. Why do girls blow bubbles better than boys?

350. What is the difference between a boy and his shadow?

351. Why is a soap-bubble like Adam?

352.

I have no life, yet, as I fly,

A thing of beauty to the eye,

I bear, my glittering shape beneath,

A part of my Creator’s breath;

With ever-changing shade and hue

I rise and vanish from the view,

And, though a phantom deemed, I share,

In portions, water, earth, and air.

353.

I go, but never stir,

I count, but never write,

I measure and divide, and, sir,

You’ll find my measures right.

I run, but never walk,

I strike, but never wound,

I tell you much, but never talk,

In my diurnal round.

354. When a boy falls into the water, what is the first thing he does?

355. How would the proposed removal of the Pope to Jerusalem be a false move for the Papacy, and a true one for the Papal States?

356. Why is a coachman a generous man?

357. Why is a dog like a clock-maker’s safe?

358. Why is the cook more noisy than a gong?

359. Describe a partisan, and answer a question in the same words.

360.

A word of one syllable call to your mind,

The letters of which will, if rightly combined,

Provide you with two kinds of fuel—ay, more,

A warm piece of clothing—and fasten your door.

361.

Let two Roman fives at extremities meet.

At the right hand of these, add two circles complete;

Then five times one hundred place at the right hand,

And a nice winter’s comfort they make as they stand.

362. What number is that which can be divided by 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, leaving, in each case, a remainder of 1, and by 7, without a remainder?

363. How long ago were trunks first used?

364.

I’m black or white, I’m brown or gray,

I’m tall or flat, I’m grave or gay,

As soft as wool, or stiff as tin,

A nest for wits to nestle in.

I hold great intellects, yet oft

Am bothered with the weak and soft,

And sometimes crusty, hard, and thick

They fill me with well burned brick.

Fashion controls me, yet I wear

Some aspects to make fashion stare.

Though always for one place designed,

I change as often as the wind.

[pg 80]I’m dumb, and yet, in spite of that,

Make more than half of every “Chat,”

I’m mild—yet none can hate—(don’t doubt me)

Nor raise a fighting-cock without me.

365.

In every home I stand confessed,

A friend of quiet, peace, and rest;

Take off my head, and on your head

My streamers rise, black, brown, or red;

Cut now again, and take my neck off,

You leave my substance not a speck of,

But, with ethereal lightness gay,

I pass in idle breath away.

366. What relation is the door-mat to the scraper?

367. In what do grave and gay people differ at church?

368. What sea would make the best sleeping-room?

369.

’Tis said of lawyers Grab and Clinch,

They take an ell when you offer an inch;

But I can do a smarter thing—

Give me an ell, I will make it ring;

If for advice you come to me

When you are ill, I call for the fee;

If any road you chance to wend,

You think you’ve reached the very end,

I come and give it such a turn,

You find there’s something yet to learn;

If to the inn you seek for rest,

I chuck you in a box or chest;

The beggar’s rags I make so proud,

He of his garments boasts aloud;

The aged and infirm with me

Lose caution and timidity;

For, young or old, to every one

I furnish, if not muscle, bone.

371. In what does a dog differ from a groom in his treatment of a horse?

372.

One of a gallant vagrant band,

My name is known in every land;

In all earth’s changes I am there;

Without me none may war declare,

Or treat of peace, or try their parts

On manufacture, tillage, arts;

By me a patient saint of old

Was changed into a warrior bold;

I made old Abner’s father near;

His wife was deaf, I made her hear;

His house I put upon his back;

His jaw an iron bond I make;

Bad spirit by my presence claims

To be the end of human aims;

And a young bear is seen to be

A coveted jewel of the sea.

373. Problem.—To make a restless child quiet and contented.

374. Problem.—To teach a child to be honest, industrious, and useful.

375. Why is Merry’s Museum like a note falling due?

376.

I consist of eleven letters.

My 9th, 7th, and 1st, is where infants often repose;

“ 3d, 10th, and 7th, is a foreign plant much used by us;

“ 1st, 7th, 5th, 9th, 4th, and 11th, is to treat by word of mouth;

“ 6th, 4th, 7th, and 8th, is a delicious fruit;

“ 2d, 7th, and 3d, to do which affords great satisfaction;

“ 4th, 7th, and 5th, is an essential part of the head;

“ 3d, 10, 7th, and 8th, is often used for joy or sorrow;

“ whole is the name of a distinguished writer for Merry’s Museum.

377. Why is Merry’s Museum like a good wife?

378. I am composed of twelve letters.

W. 2, all 6, 2, 10, with 10, 5, 2, 9, which a 12, 8, 1, 7, 5, i, 6, 6, 11, 4, 10, not to have, and which a 3, 8, 1, 12, 5, 9, 11, 4, 2, l. 5, 12, i. 6, 11, 9, 2, 6.

379. Why is Merry’s Museum like a good mother?

380.

What was the difference—can you show—

Between the Prodigal in his woe,

And Lazarus, in his low estate,

Feeding on crumbs at Dives’ gate?

381. What fish does a bride wear on her finger?

382. Why is Merry’s Museum like a printing-office?

1.

The rose shall cease to blow,

The eagle turn a dove,

The stream shall cease to flow,

Ere I will cease to love.

The sun shall cease to shine,

The world shall cease to move,

The stars their light resign,

Ere I will cease to love.

2. Short shoes and long corns to the enemies of freedom.

3. The rope-maker.

4. Because they can not be got off without a bow (beau).

5. Because he stops at the sound of wo.

6. One takes the dish with the egg.

7. One, after which his stomach is not empty.

8. The smallest.

9. The first geometrical puzzle is solved in this way—

The second puzzle is solved in this way—

The different colors represent the several sons’ portions.

10.

The tiger couches in the wood,

And waits to shed the traveler’s blood;—

So couch we.

We spring upon him to supply

What men unto our wants deny;

And so springs he.

11.

Work, work, work!

My labor never flags;

And what are its wages? A bed of straw,

A crust of bread—and rags,

That shattered roof—this naked floor,

A table—a broken chair,

And a wall so blank, my shadow I thank

For sometimes falling there!

With fingers weary and worn,

With eyelids heavy and red,

A woman sat in unwomanly rags,

Plying her needle and thread.

[pg 86]Stitch! stitch! stitch!

In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

And still with a voice of dolorous pitch.

She sang the “Song of the Shirt.”

12. A pack of cards.

13. Striking.

14. Because words are passing between them.

15. Footman.

16. Because his is all net profit.

17. Because he is surrounded with dues (dews).

18. Adam.

19. Heroine.

20. Spark.

21. Tear.

22. Because it is a bad habit.

23. Because it is felt.

24. Because it is a resting-place for the traveler.

25.

There’s a grim hearse horse,

In a jolly round trot,

To the churchyard a poor man is going, I wot.

The road it is rough,

And the hearse has no springs,

And hark to the dirge the sad driver sings—

“Rattle his bones over the stones,

He’s only a pauper, whom nobody owns.”

26.

Of all the birds that e’er I did see,

The owl is the strangest in every degree,

For all the long day she sits in a tree,

And when the night comes, away flies she,

To whit-to-whoo.

To whom drinkest thou? Sir Noodles, to you.

This song is well sung, I make you a vow,

And he is a knave that aileth now.

Nose, nose, and who gave thee that jolly red nose?

Cinnamon and ginger, nutmeg and cloves,

And they gave me my jolly red nose.

27. To ashes.

28. Short.

29. Shakespeare.

30. Time.

31. Wallace.

32. Because they are often toasted.

33. Because he is always for getting.

34. I, ser.

35. Because he has nothing to boot.

36.

Full five hundred years I’ve hung,

In my old grey turret high,

And many a different theme I’ve sung,

As the hours went winging by.

I’ve pealed the chimes of a wedding morn;

Ere night I’ve sadly tolled to say

That the maid was coming love lorn,

And here I end my lay.

37.

The joyful can sing on spirit wings

Each morn his lofty height,

In rapt’rous notes he sweetly sings,

And hails th’ approaching light;

But I from grief no solace know,

No portal from the night,

All joys to me insipid grow,

Afford me no delight.

38. Because it is often tolled (told).

39. Your name.

40. The letter M.

41. Forty-eight feet.

42. In solving this question it is clear that to pick up the first stone and put it into the basket, the person must walk two yards, one in going for the stone and another in returning with it; that for the second stone he must walk four yards, and so on increasing by two as far as the hundredth, when he must walk two hundred yards, so that the sum total will be the product of 202 multiplied by 50, or 10,100 yards. If any one does not see why we multiply 202 by 50 in getting the answer, we refer him to his arithmetic.

43. Hour-glass.

44. Pen-man-ship.

45.

There was a man who was Nott born,

His father was Nott born before him;

He did Nott live, he did Nott die,

And his epitaph is Nott o’er him.

46. Because it is in firm (infirm).

47. To keep his head warm.

48.

Hark! the muffled drum sounds the last march of the brave,

The soldier retreats to his quarters, the grave,

Under Death, whom he owns his Commander-in-chief,

No more he’ll turn out with the ready relief;

But in spite of Death’s terrors or cannon’s alarms,

When he hears the last trump he’ll stand to his arms!

Farewell! brother soldiers, in peace may you rest,

And light lie the turf on each veteran breast,

Until that review when the souls of the brave

Shall behold the chief ensign, fair mercy’s flag, wave;

Then, freed from Death’s terrors and hostile alarms,

When we hear the last trump, we’ll stand to our arms.

49. Doctor Long expects Dr. Short to explain the misunderstanding between them.

50.

To you who live single, if this at all trouble you,

My first comes in kindness, commanding to double you.

And again, it will double you, if, like a clown,

You lift high your sole, and bend your head down;

Or, cut it in twain, two V’s will appear,

And V counting five, both make ten it is clear.

My second, alas! comes shrouded in gloom,

It is O, which makes wo, the sinner’s sad doom.

Now see what a change comes over the scene,

If my third, which is O, be added again.

Now ’tis woo—and what bachelor’s heart does not beat,

To woo a sweet damsel, to keep warm his feet;

To cheer by her smiles his lone hours—and thus

Escape, by good fortune, the bachelor’s curse!

My fourth and my last, as I’ll go on to tell,

Is nought more or less than a capital L.

Now L being fifty, will even divide

One Hundred, or teachers and books have all lied.

Now examine with care, and plain you will see

That to unlock a secret, an L is the key;

For woo, with L added, is changed into wool,

Whether worn on a sheep, or an African’s skull.

[pg 88]Whether made into clothing, for bed or for body,

For “sage politician” or some other noddy.

It is used, the world over, in commerce and trade;