Transcriber's Notes: This edition of Jessie Trim was published

by

Tinsley Brothers (London) in two installments exerpted from the following issues

of Tinsleys' Magazine:

Vol. XIV. From January to June 1874. Chapters I.-XXV.

https://books.google.com/books?id=Dj8xAQAAMAAJ

(Mercantile Library, New York; New York Public Library)

Vol. XV. From July to December 1874. Chapters XXVI.-LI.

https://books.google.com/books?id=1-kRAAAAYAAJ

(Mercantile Library, New York; New York Public Library)

Chap.

II. I am frightened of my Shadow.

III. My Grandmother's Long Stocking.

V. I play the Part of Chief Mourner.

VI. In which a great Change in my Circumstances takes place.

VII. In which a Fairy in a Cotton-Print Dress is introduced.

IX. Uncle Bryan introduces himself.

XI. In which I take part in some lawless Expeditions.

XII. A singular Episode in our quiet Life.

XIV. The World becomes bright again.

XV. Jessie's Rosewater Philosophy.

XVI. The Stone Monkey Figure gives up its Treasures.

XVII. The true Story of Anthony Bullpit.

XVIII. Uncle Bryan commences the Story of his Life.

XIX. Strange Revelations in Uncle Bryan's Life.

XX. Uncle Bryan concludes his Story.

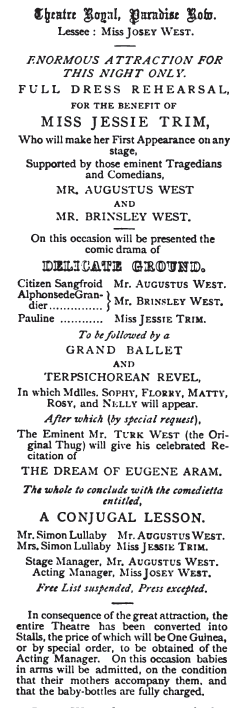

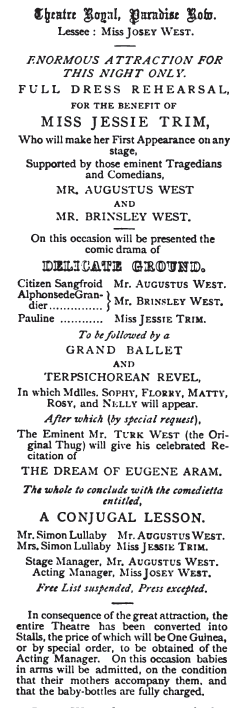

XXII. I am introduced to a Theatrical Family.

XXIII. The Sunday-night Suppers at the Wests'.

XXIV. Turk, the First Villain.

XXV. Holding the Word of Promise to the Ear.

XXVI. We enjoy a deceitful Calm.

XXIX. Preparations for an important Event

XXXI. My Mother expresses her Fears concerning Jessie.

XXXII. Jessie makes an Explanation.

XXXIV. Turk West's Appearance at the West-end Theatre, and its Results.

XXXVI. I speak plainly to uncle Bryan.

XXXVII. Turk makes a Confession.

XXXVIII. Mr. Glover declines to satisfy me.

XLI. Josey West declares that she has got into her proper Groove.

XLII. From Frances to her Husband, Bryan Carey.

XLV. Old Mac expresses his Opinion of Mr. Glover.

XLVIII. Josey West laments her crooked Legs.

As my earliest remembrances are associated with my grandmother's wedding, it takes natural precedence here of all other matter. I was not there, of course, but I seem to see it through a mist, and I have a distinct impression of certain actors in the scene. These are: a smoke-dried monkey of a man in stone, my grandmother, my grandfather (whom I never saw in the flesh), and a man with a knob on the top of his head, making a meal off his finger-nails.

Naturally, this man's head is bald. Naturally, this man's nails are eaten down to the quick. I am unable to state how I come to the knowledge of these details, but I know them, and am prepared to stand by them. Sitting, as I see myself, in a very low armchair--in which I am such an exact fit that when I rise it rises with me, much to my discomfort--I hear my grandmother say:

'He had a knob on the top of his head, and he was always eating his nails.'

Then a solemn pause ensues, broken by my grandmother adding, in a dismal tone:

'And the last time I set eyes on him was on my wedding-day.'

The words are addressed not so much to me as to the smoke-dried monkey of a man in stone, which had occupied the place of honour on the mantelpiece in my grandmother's house, and which she had brought with her as a precious relic--(Jane Painter, I remember, always called it a relict)--when she came to live with us. The head of this stone figure is loose, and wags upon the slightest provocation. When something falls in the room, when the door is slammed, when a person walks sharply towards it, when it is merely looked at I sometimes fancy. I am not prepossessed in its favour, and I regard it with uneasy feelings, as probably possessing a power for evil, like a malevolently-inclined idol. But my grandmother, for some mysterious reason, values it as a very precious possession, and sits staring dumbly at it for hours. I watch her and it until, in my imagination, its monkey-face begins to twitch and its monkey-lips to move. At a certain point of my watch, I fancy that its eyes roll and glare at me, and I cover mine with my hands to shut out the disturbing sight. But I have not sufficient courage to remain blind for more than a very few moments, and I am soon fascinated into peeping at the figure through the lattice of my fingers. My grandmother observes me, and says:

'I see you, child! Take your fingers away.'

I obey her timidly, and with many a doubtful glance at the monkey-man, I ask:

'Does it see me, grandmother?'

My grandmother regards it with a gloomy air; evidently she has doubts. She does not commit herself, however, but says:

'It will belong to you, child, when I am gone. It must be kept always in the family.'

The tone in which she utters these words denotes that evil will fall upon the family when this heirloom is lost sight of. I am not grateful for the prospective gift. It has already become a frightful incubus; it weighs me down, and is a future as well as a present torment. I think it has lived long enough--too long--and that when my grandmother goes, she ought to take it with her. Happening to catch the eye of the figure while this thought is in my mind, I am convinced that it shows in its ugly face a consciousness of my bad feeling towards it; its eyes and lips threaten me. It would have terrified, but it would not have surprised me to find it suddenly gifted with the power of speech, and to hear it utter dreadful words. But happily for my peace of mind no such miracle happens. I look at my grandmother, and I begin to fancy that she, from long staring at it, bears in her face a resemblance to the face of the monkey-man. For how much longer will my grandmother sit and stare at it? For how many more days and weeks and years? She has frequently told me that naughty boys were invariably 'fetched away' to a dismal place by Some One wearing horns and a tail. She made no mention of naughty girls; and sometimes when she has been delighting me with these wholesome lessons, a sort of rebellion has possessed me that I was not born a girl. Now, if Some One were to come and 'fetch' my grandmother away, it would not grieve me; I should rejoice. But I dare not for my life give utterance to my thought. Says my grandmother, with a nod at the stone figure, which, suddenly animated by a mysterious influence, returns the nod:

'I had it in my pocket on my wedding-day.'

The circumstance of its being a guest at my grandmother's wedding invests it with an additional claim to my protection when she is gone. How happy I should be if it would fall into the fireplace, and break into a thousand pieces!

'Grandmother!'

'Well, child.'

Was the man with the knob on the top of his head----'

My grandmother interrupts me.

'You mean the gentleman, child.'

'Yes, I mean the gentleman--and who was always eating his nails,--was he like that?' Pointing to the stone monkey-figure.

'Like that, child! How can such an idea have entered your head? No; he was a very handsome man.'

A pure fiction, I am convinced, if nothing worse. How could a man with a knob on his head, and who was always eating his nails, be handsome?

'Your grandfather used to be very jealous of him; he was one of my sweethearts. I had several, and nine proposals of marriage before I was twenty years of age. Some girls that I knew were ready to scratch their eyes out with vexation. He proposed, and wished to run away with me, but my family stepped in between us, and prevented him. You can never be sufficiently grateful to me, child; for what would have become of you if I had run away and married him, goodness only knows!'

The reflection which is thus forced upon me involves such wild entanglements of possibilities that I am lost in the contemplation of them. What would have become of me? Supposing it had occurred--should I ever have been?

'He told me,' continues my grandmother, revelling in these honey-sweet reminiscences, 'after I had accepted your grandfather, that life was valueless without me, and that as he had lost me, he would be sure to go to the Devil. I don't know the end of him, for I only saw him once after that; but he was a man of his word. He told me so in Lovers' Walk, where I happened to be strolling one evening--quite by accident, child, I assure you, for I burnt the letter I received from him in the morning, for fear your grandfather should see it. Your grandfather had a frightfully jealous disposition--as if I could help the men looking at me! When we were first married he used to smash a deal of crockery, with his quick temper. I hope he is forgiven for it in the place he has gone to. He was an auctioneer and valuer; he had an immense reputation as a valuer. It was not undeserved; he fell in love with me. Oh, he was clever, child, in his way!'

Although I am positive that I never saw my grandfather, I have, in some strange way, a perfect remembrance of him as a little man, very dapper, and very precisely dressed in a snuff-coloured coat and black breeches and stockings. Now, my grandmother was a very large woman; side by side they are, to my mind, a ridiculous match. I have grown quite curious concerning my grandmother's lover, and I venture to recall her from a moody contemplation of the monkey-figure into which she is falling.

'But about the man with the knob, grandmother?' I commence.

'Child, you are disrespectful! The man with the knob, indeed!'

'The gentleman, I mean, who wanted to marry you. What was his name?'

'Bullpit. He was connected with the law, and might have become Lord Chancellor if I hadn't blighted him.'

'Did he behave himself at your wedding, grandmother?'

'Save the child!' she exclaims. 'You don't suppose that Mr. Bullpit was at my wedding, do you? Why, there would have been murder done! Your grandfather and he would have torn each other to pieces!' These latter words are spoken in a tone of positive satisfaction, as adding immensely to my grandmother's reputation.

'But I thought you said that the last time you saw him was on your wedding-day?'

'So I did, child; but I didn't say he was at the wedding. We were coming out of church---- Deary, deary me! I can see it as if it was only yesterday that it took place! The church was scarcely three minutes' walk from mother's house, and the expense would not have been great, but your grandfather, who was a very mean man, did not provide carriages, and we had to go on foot. It was the talk of the whole neighbourhood for months afterwards. I never forgave him for it, and I can't forget it, although he is in his grave now, where all things ought to be forgotten and forgiven. Remember that, child, and if you have anything to forget and forgive, forget and forgive it. Animosity is a bad thing.'

My grandmother gives me time to remember if I have anything to forget and forgive. I feel somewhat remorseful because of the hard thoughts I have borne towards her, and I mentally resolve that when she is in her grave I will endeavour to forget and forgive.

'We walked,' she continues, from mother's house to the church, and from the church back again. It was like a procession. There were five bridesmaids, and mother and father, and your grandfather's mother and father,'--(I am a little confused here with so many mothers and fathers, and, notwithstanding my efforts to prevent it, they all get jumbled up with one another)--'whom we could very well have done without, and the Best Man, who did not know how to behave himself, making the bridesmaids giggle as he did, as if my wedding was a thing to be laughed at! and a great number of guests with white favours in their coats--all but one, who ought to have known better, and who was properly punished afterwards by being jilted by Mary Morgan. Everybody in the town came to see us walk to church, and when the fatal knot was tied, the crowd round the church door was so large that we could scarcely make our way through it. The Best Man misbehaved himself shamefully. He pretended to be overcome by grief, and he sobbed in such a violent manner as to make the mob laugh at him, and the bridesmaids giggle more than ever. I knew what they did it for, the hussies! They thought he was a catch; a nice husband he turned out to be afterwards! When we were half way between the church and mother's house, our procession met another procession, and for a minute or two there was a stoppage and great confusion, and several vulgar boys hurrayed. What do you think that other procession was, child?'

I ponder deeply, but am unable to guess.

That other procession, child, was made up of policemen and riff-raff. And in the middle of it, with handcuffs on, was Anthony Bullpit. He had been arrested on a warrant for forgery. What with the confusion and the struggling, the processions got mixed up together, and as I raised my eyes I saw the eyes of Anthony Bullpit fixed upon me. Such a shock as that look of his gave me I shall never forget--never! I knew the meaning of it too well. It meant that all this had occurred through me; that life without me was a mockery; that he had arranged everything so that we should meet immediately the fatal knot was tied; and that he was on his road to ---- where he said he would go.'

'He must have been a very wicked man, grandmother.'

'A wicked man, child! How dare you! He was as innocent as I was, and he did it all to punish me. I fainted dead away in the middle of the street, and had to be carried home, and have hartshorn given to me, and brown paper burnt under my nose. When I came to, I looked more like a blackamoor than a bride, and my wedding dress was completely spoilt. And nothing of all this would have occurred, child, if it had not been for the meanness of your grandfather. If he had provided carriages we should never have met. When poor Mr. Bullpit was put upon his trial he would not make any defence. Your grandfather said the case was so clear that it would only have aggravated it to defend it. But I knew better. When he pleaded guilty, I knew that he did it to spite me, and to prove that he was a man of his word. I wanted to go to the trial, but your grandfather objected; and when I said I would go, he locked all the doors in the house, and took the keys away with him. Your grandfather has much to answer for. Mr. Bullpit was transported for twenty-one years. Some wicked people said it was a mercy he wasn't hanged. If he had been, I should never have survived it. Poor Anthony!'

I was too young to exercise a proper judgment upon this incident in my grandmother's life, but it is imprinted indelibly upon my memory. I knew very well that I did not like my grandmother, and that I did not feel happy in her society. Often when I wished to go out into the sunshine to play, she would say,

'Bring the boy in here, and let him keep me company. It will do him more good than running about in the dirt.'

And her word being law in the house, I used to be taken into the room where she sat in her armchair, staring at the monkey-man on the mantelshelf, and used to be squeezed into my own little armchair, and placed in the corner to keep her company. For a certain sufficient reason I deemed it advisable to be companionable; for once I had sulked, and was sullen and ill-tempered. Then my grandmother had said:

'The child is unwell! He must have some physic.'

She herself prescribed the medicine--jalap, which was my disgust and abhorrence--and the dose, which was not a small one. Out of that companionship sprang my knowledge of the man with the knob on the top of his head, and who was always eating his nails. By some process of ratiocination I associate him with the smoke-dried monkey of a man in stone, and I hate them both honestly. As for Anthony Bullpit being innocent of the crime for which he was transported, I smile scornfully at the idea. He is my model for all that is disagreeable and bad, and I never see a man whose nails are bitten down to the quick without associating him--often unjustly, I am sure--with meanness and trickery.

There was a reason for my being doomed to the companionship of my grandmother, and for my being made her victim as it were. Our family circle comprised five individuals: my grandmother, my father and mother, myself, and a baby-brother. My parents had, through no fault of their own, drifted into that struggling-genteel class of persons whose means never quite come up to their efforts to make an appearance. We had been a little better off once upon a time, but unfortunately my father's health had failed him, and at the period of which I am writing he was confined to his bed, unable to work. My mother, what with her anxiety and her ignorance of the world, was to a certain extent helpless. Therefore, when my grandmother proposed to come and live with us, and bring her servant, and pay so much a week for board and lodging, her offer was gladly accepted. It was a current belief that my grandmother had a 'long stocking' somewhere, with plenty of money in it, and to this long stocking may be attributed much of my unhappiness at that time. For it had come to be recognised that I was to be my grandmother's heir, and that her long stocking would descend to me. It was, perhaps, regarded as a fair arrangement that, as my grandmother's property was to be mine when she was dead, I was to be my grandmother's property while she was alive; and I have no doubt that care was taken that her whims with respect to me should be carefully attended to, so that my inheritance might not be jeopardised. My mother did not know that I was unhappy; I was as a child somewhat secretive by nature, and I kept my thoughts and feelings much to myself. Besides, I had an intuitive perception of the state of affairs at home, and I felt that if I offended my grandmother my parents might suffer.

I have already mentioned the name of the servant whom my grandmother brought with her to our house; it was Jane Painter. She had been with my grandmother for many years, from girlhood I believe, and she was now about thirty years of age. In appearance she was a thin, sharp-featured, pale-faced woman; in manners she was a viciously-minded creature, fond of pinching children on the sly in tender places, assuming the while, to deceive observers, an expression of amiability, which intensified the malignity of her conduct. From the moment she entered our house she became the enemy of every person in it, and waged open and secret war upon all of us. Her service with my grandmother had been a very easy one, but things were different when her mistress changed her residence. She had to do double the work she had been accustomed to, and as we were the direct cause of this, she was not slow in showing resentment. My mother, patient as she always was, made light of the woman's infirmities of temper, believing that she was necessary to my grandmother; Jane Painter, however, declined to accept the olive-branch which my mother held out to her, and would certainly not have remained in the house but for one inducement. This was made clear to us a very few days after the change. My mother had occasion to remonstrate with her for some piece of impertinence, and Jane Painter ran into my grandmother's room in a fury, and demanded to know if she was to be treated like a galley-slave. My mother stood quietly by, listening to the servant's complainings. Said my grandmother,

'You must do what my daughter desires you to do, Jane. I told her you would help her in the house.'

'I won't be ordered about as if I was a bit of dirt!' exclaimed Jane Painter, gasping.

'O Jane!' remonstrated my mother.

'Don't O Jane me!' and then followed the unreasoning argument. 'I'm flesh and blood the same as you are!'

'Jane,' said my grandmother, 'I mustn't be worried; my nerves won't stand it. I sha'n't be here long, and you know what I have promised you.'

'Whose servant am I--yours or hers?'

'Mine, Jane, and a very good servant you've been. I hope for your own sake you are not going to be different now.'

'Haven't I served you faithfully?' asked Jane Painter, sobbing herself into a quieter emotional stage.

'Yes, Jane, yes; and you shall be remembered for it.'

'Haven't I waited on you hand and foot?'

'Yes, Jane, yes; and you shall be remembered.'

'When you was took bad with the spasms,' blubbered Jane, didn't I stop up with you all night till I was fit to drop?'

'Yes, Jane; and I haven't forgotten you for it. You shall be remembered, I tell you.'

By being remembered, my grandmother meant that Jane Painter was set down in her will for a certain portion of the contents of her long stocking; and but for this inducement it was pretty clear that Jane Painter would have taken her departure. The war she waged against us from this time was passive, but bitter. I, as the recognised heir to the long stocking, and as being likely, therefore, to diminish her portion, came in for the largest share of her ill-temper and animosity, and she showed much ingenuity in devising means to torment me. Parting my hair on the wrong side, brushing it into my eyes, rubbing the soap in my mouth and only half-wiping my face after I was washed, buttoning my clothes awry, running pins into me, holding me suspended by one arm as we went down stairs; these were the smallest of my sufferings. An incident, laughable in itself, but exceedingly painful in its effect upon me, comes vividly to my remembrance here; and it afforded Jane Painter an opportunity of inventing a new torture, and of inflicting upon me the sharpest and most terrible distress I ever experienced. It occurred in this way:

Whether it was that the dull companionship of a peevish old woman was having its due effect upon me, or whether it sprang from my natural constitution, I was growing to be very nervous. I was frightened of being alone in the dark; a sudden noise startled me painfully; any unusual exhibition of tenderness brought tears to my eyes. One bright summer afternoon I was sitting with my grandmother. Everything about me was very quiet; my grandmother had not spoken for a long time, and I listened to the regular sound of her breathing which told me she was asleep. I tried all kinds of devices to while away the time. I looked at the wall and traced the pattern of the paper; I tried to stare the monkey-man on the mantelshelf out of countenance; I closed my eyes and placed the tips of my forefingers on them, and then opened them to assure myself that the world had not come to an end; I counted the rise and fall of my grandmother's capacious bosom till I grew so confused that the billows before me seemed to swell and fill the room. There was no pleasure to be gained from any of these tasks, and I felt weary and dispirited. The sunshine streaming in at the parlour-window seemed to say, 'Why are you stopping in that dull room? Come out and play.' I gazed wistfully at the light, and thought how nice it would be outside. I felt that I should like to go. But I knew from rueful experience how cross my grandmother would be if I made a noise and awoke her; and I was so tightly fixed in my little armchair that I could not extricate myself without a struggle. I dared not attempt to wrench myself free from its embrace in the room; it might fall to the ground. There was nothing for it but to try and escape from the room with the chair fixed to me. The sunshine grew brighter and brighter, and more and more tempting. My grandmother really seemed to be fast asleep. I stretched out my hand and touched her dress: she always dressed in silk, and sat in state. Her steady breathing continued. I coughed, and whispered, 'Grandmother!' but she did not hear. I spoke more loudly. 'Grandmother!' There was no response, and then I thought I would venture. I rose, with my chair attached to me--the firmest and closest of friends--and crept slowly and softly out of the room into the passage. There I released myself, and then ran out into the sunshine. In aglow of delight I flitted about like a butterfly escaped from prison. I was in the full height of my enjoyment, when turning my head over my shoulder, I saw my long ungainly shadow following me, and in sudden unreasoning fright I ran away from it. I screamed in terror as I saw it racing fast at my heels, as if trying to leap upon me and seize me, and my mother happening at that moment to come to the street-door, I flew towards her in a paroxysm of terror, and, clutching tight hold of her, hid my face in her gown. In that position my mother, with soothing words, drew me into the house, and I was only pacified by being assured that the 'black man' who had frightened me had disappeared; and certainly, when I was persuaded to look around I saw no trace of him. My grandmother, awakened by my screams, did not fail to give me a solemn lecture for my bad behaviour in stealing from the room, and she improved the occasion by making me tremble with new fears by her dreadful prophecies as to what the 'black man' would do to me if I dared to be naughty again. The incident had a serious effect upon me, and I was ill for a week afterwards. The doctor who was attending my father said that I was of a peculiarly sensitive temperament, and that great care must be taken of me.

'The nervousness,' he said, which has been the cause of his fright may, if not counteracted, produce bad results by-and-by. The lad's nature is essentially womanly and delicate. None the worse for that--none the worse for that!'

He laid his hand upon my head in a very kind manner, and tears rushed to my eyes. Seeing these, he immediately removed his hand, and gave my cheek a merry pinch.

'He will grow out of it?' questioned my mother, anxiously.

'Oh, yes,' was the reply, cheerfully uttered, 'he will grow out of it; but you must be careful with him. Don't let him mope; give him plenty of exercise and fresh air.'

'I should like a pony,' I said. My mother's troubled eyes sought the floor. If she could only have seen a magic pumpkin there!

'Then,' continued the doctor, until he is older and stronger I would fill his mind with cheerful fancies. Tell him as many stories as you please of fairies, and princesses, and flowers, and such-like; but none about ghosts. You would like to hear about beautiful fairies rising out of flower-bells, and sailing in the clouds, and floating on the water in lilies, would you not, my lad?'

I nodded gaily; his bright manner was better than all the medicine.

'Do they really do all these things, sir?'

'Surely; for such as you, my boy.' I clapped my hands. 'You see!' he said to my mother.

Many a time after this did my mother ransack her mental store, and bring forth bright-coloured fancies to make me glad. She told Jane Painter what the doctor said, and asked her to tell me the prettiest stories she knew. Jane Painter replied with one of her sweetest smiles. It was part of her duties to put me to bed every night, and one night, soon after I was well, she came into my room in the dark, as I was lying half awake and half asleep. She crept up the stairs and into the room so stealthily that I had no consciousness of her presence until a sepulchral voice stole upon my ears saying,

'Ho! Mister Friar, Don't be so bold, For fear you should make My 'eart's blood run cold!'

My heart's blood did run cold at these dreadful words, and I uttered a cry of fright. Then Jane Painter spoke in her natural tone.

'I knew a boy once, and his name was Namby-Pamby. He was the greatest coward that ever breathed, and he was always telling tales. I know what happened to him at last. You're like him. Perhaps it'll happen to you. A fine boy you are! You ought to have been born a rabbit. I suppose you'll tell your mother. All cowards do.' Here she must have put her head up the chimney, for her voice sounded very hollow as she repeated, 'Ho! Mister Friar, Don't be so bold, For fear you should make My 'eart's blood run cold!'

I cannot describe my terror. I wrapped the counterpane tightly round my head, and lay all of a tremble until Jane Painter thought fit to take her departure. From that night she inflicted the most dreadful tortures upon me. The first thing she did after putting me to bed was to blow out the candle; then she would calmly sit down and tell me frightful stories of murders and ghosts. Blood was her favourite theme; she absolutely revelled in it, and to this day I cannot look upon it without a shudder. She would prowl about the room, muttering:

'I smell blood! I smell blood!'

And then:

'Let him be alive, Or let him be dead, I'll have his blood to make my wine, I'll grind his bones to make my bread.'

After that she would grind her teeth, and make sounds as though she were drinking.

'Serve him right, too, the little coward! Grind his bones on two large stones. His blood and brine I'll drink for wine.'

I suffered this martyrdom in silence. I would not tell my mother, as all cowards did. What the effect on me would have been if circumstances had allowed Jane Painter to continue her persecution I am afraid to think; but fortunately for me the event occurred which she was waiting for. My grandmother died very suddenly. The last words she was heard to utter were, Poor Anthony!' I was not sorry when she died. I tried to look sad, as everybody else looked, but I knew that I was a dreadful hypocrite.

There was a friend of the family of whose name I have no remembrance, and whom, from a certain personal peculiarity, I must denominate Snaggletooth. He was a large man--very tall, and round in proportion--with a glistening bald head, a smooth full-fleshed face, and clear gray eyes. In repose, and when he was not speaking, he was by no means an unpleasant-looking man; his face was benignant, and his clear gray eyes beamed kindly upon you. But directly he smiled he became transformed, and his features were made to assume an almost fiendish expression by reason of a hideous snaggle-tooth which thrust itself forward immediately he opened his mouth. It stuck out like a horn, and the change it effected in his appearance was something marvellous.

As the friend of the family, Snaggletooth came forward and offered his assistance. My father being confined to his bed by sickness, there was no man in the house to look after the funeral of my grandmother, and Snaggletooth's services were gladly accepted. I fancy that he was fond of funerals, from the zealous manner in which he attended to the details of this and a sadder one which followed not long afterwards. Setting this fancy aside, he proved himself a genuine and disinterested friend. We had no near relatives; my mother was an only daughter, and my father had but one brother, older than he, whom I had never seen, and who had disappeared from the place many years ago. He was supposed to be dead; and from certain chance words which I must have heard, I had gained a vague impression that he was not a credit to the family.

It was a strange experience for me to sit in my grandmother's room after her death, gazing at her empty armchair. I could not keep away from the room; I crept into it at all hours of the day, and sat there trembling. I mentally asked the stone monkey-figure what it thought of my grandmother's death, and I put my fingers in my ears lest I should hear an answer. Jane Painter found me there in the evening when she came to put me to bed, and stated that my grandmother's spirit was present, and that she was in communication with it. She held imaginary conversations with my grandmother's ghost in the dusk, speaking very softly and waiting for the answers. The effect was ghastly and terrifying. These conversations related to nothing but poor me, and the exquisite pain Jane Painter inflicted upon me by these means may be easily imagined.

The first thing Snaggletooth did after my grandmother's funeral was to search for her long stocking and the treasures it was supposed to contain. Taking the words in their literal sense, I really thought that the long stocking would be found hidden somewhere--under the bed perhaps, or among the feathers, or up the chimney--stuffed with money, in shape resembling my grandmother's leg, which I knew from actual observation to be a substantial one.

'Perhaps she made a will,' observed Snaggletooth to my mother. Jane Painter was present, hovering about us with hungry jealous eyes, lest she should be cheated.

'She did make a will,' said Jane Painter, 'and I'm down in it.'

'Then we will find it,' said Snaggletooth cheerfully.

My grandmother's desk was opened, and every piece of paper in it was examined. No will was there, nor a word relating to it. Her trunk was searched with a like result.

'Never mind,' said Snaggletooth, with a genial smile, 'we shall be sure to find the old lady's long stocking.'

And he set to work. But although a rigid search was made, no long stocking could be found. Snaggletooth became immensely excited. Very hot, very dusty and dirty, and with his shirt-sleeves tucked up to his shoulders, he gazed at vacancy, and paused to take breath. Disappointed as he was up to this point, his faith in my grandmother's long stocking was not shaken; he had it not, and yet he saw it in form as palpable as the lisle-thread stockings of my grandmother, which were scattered about the room. A closer and more systematic search was commenced. The hunt became more and more exciting, and still not a glimpse of the fox's tail could be seen. Under Snaggletooth's instructions the bedstead was taken down, the pillows and mattresses were ripped open (Snaggletooth being determined not to leave a feather unturned), the posts were sounded to discover if they were hollow, and the strictest examination was made of every vestige of my grandmother's clothing without a satisfactory result. Dirtier and hotter than ever, and covered with fluff and feathers, Snaggletooth looked about him with an air of 'What next?' His eye fell upon my grandmother's armchair. Out came the stuffing that it contained, and nothing more. My grandmother's footstool: a like result. Her portly pincushion: nothing but bran. Up came the carpet, and almost blinded us with dust. And then Snaggletooth sat down in the midst of the wreck and said disconsolately:

'I am afraid we must give it up.'

So it was given up, and the mystery of my grandmother's long stocking took honourable place in the family records as an important legend for ever afterwards.

Jane Painter passed through many stages of emotion, and ended by being furious. She vowed--no, she swore; it is more appropriate--that she had been robbed, and openly declared that my mother had secreted my grandmother's long stocking, and had destroyed the will. Nay, more; she screamed that she had seen the treasure, which consisted of new Bank of England notes and a heap of gold, and that in the will my grandmother had left her three hundred pounds.

'Woman!' exclaimed Snaggletooth, rising from the ruins, 'be quiet!'

'Woman yourself!' screamed Jane Painter. 'You're in the plot to rob a poor girl, and I'll have the law of you; I'll have the law, I'll have the law!'

'Take it and welcome,' replied Snaggletooth. 'I hate it.'

But he was no match for Jane Painter, and he retired from the contest discomfited; did not even stop to wash his face.

My mother was sad and puzzled. I did not entirely realise at the time the cause of her sadness, because I did not know how poor she really was, but I learnt it afterwards. She gathered sufficient courage to tell Jane Painter that of course she could not stop in the house after what she had said.

'If every hair in your head was a diamond,' gasped Jane Painter, 'I wouldn't stop. No, not if you went down on your bended knees! I'll go to-morrow.'

Then she pounced upon two silk dresses and some other articles of clothing, and said that my grandmother had given them to her. My mother submitted without a word, and Jane Painter marched to her room and locked them in her box. She did as much mischief as she could on her last evening in our house; broke things purposely and revenged herself grandly on poor little me. After undressing and putting me to bed as usual, and after smelling about the room, and under the bed, and up the chimney for blood, she imparted to me the cheerful intelligence that my grandmother's ghost would come and take me away exactly at twelve o'clock that night. Near to our house was a church, and many a night had I lain awake waiting for the tolling of the hour; but I never listened with such intensity of purpose as I listened on this night. As midnight drew near, I clenched my fists, I bit my lips, I drew my knees almost up to my nose. I trembled and shook in the darkness. I would not look, I thought; and when the hour tolled, every note seemed charged with terrible meaning, and I shut my eyes tighter and held my breath under the clothes. But when the bell had done tolling, my state of horrible curiosity and fear compelled me to peep out, and there in the middle of the room stood a tall figure in white. So loud and shrill were my hysterical cries that my mother ran into the room, there to find Jane Painter in her nightdress. I think the woman herself; fearful lest she had gone too far, was glad to quit the house the following day without being called to account for her misdeeds. She did not leave without a few parting words. She called us all a parcel of thieves, and said that a judgment would fall upon us one day for robbing a poor servant of the money her dead mistress had left her.

Misfortunes never come singly, and they did not come singly to us. It was not for us to give the lie to a proverb. Often in a family, death is in a hurry when it commences, and takes one after another quickly; then pauses for a long breath.

In very truth, sorrow in its deepest phase had entered our house, and my mother's form seemed to shrink and grow less from the day she put on mourning for my grandmother. But if my mother had her troubles, I am sure I had mine; and one was of such a strange and terrible nature that, even at this distance of time, and with a better comprehension of things, a curiously-reluctant feeling comes upon me as I prepare to narrate it. It is summarised in a very few words. I murdered my baby-brother.

At least, such was my impression at the time. For a long while I was afflicted by secret remorse and by fear of discovery, and never till now have I made confession. There was only one witness of my crime: our cat. I remember well that my father was said to be sinking at the time, and my mother, having her hands full, and her heart, too, poor dear! placed me and my baby-brother in the room in which I used to sit with my grandmother. My task was to take care of the little fellow, and to amuse him. He was so young that he could scarcely toddle, and we had great fun with two oranges which my mother had given us to play with. It required great strength of mind not to eat them instead of playing with them; but the purpose for which they were given to us had been plainly set down by my mother. All that I could hope for, therefore, was that they might burst their skins after being knocked about a little, when of course they would become lawful food. We played ball with them; my baby-brother rolling them towards me, not being strong enough to throw them, and I (secretly animated by the wish that they would burst their skins) throwing them up to him, with a little more force than was actually necessary, and trying to make him catch them. I cannot tell for how long we played, for at this precise moment of my history a mist steals upon such of my early reminiscences as are related in this and the preceding chapters--a mist which divides, as by a curtain, one part of my life from another. My actual life will soon commence, the life that is tangible to me, as it were, that stands out in stronger colour and is distinct from the brief prologue which was acted in dreamland, and which lies nestled deep among the days of my childhood. Cloud-memories these; most of us have such. Some are wholly bright and sweet, some wholly sad and bitter, some parti-coloured. When the dreamland in which these cloud-memories have birth has faded, and we are in the summer or the winter of our days, fighting the Battle, or, having fought it, are waiting for the trumpet-sound which proclaims the Grand Retreat, we can all remember where we received such and such a wound, where such and such a refreshing draught was given to us, at what part of the fight such and such a scar was gained, and at what part a spiritual vision dawned upon our souls, captivating and entrancing us with hopes too bright and beautiful ever to be realised; and though our blood be thin and poor, and the glory of life seems to have waned with the waning of our strength, our pulses thrill and our hearts beat with something of the old glow as the remembrance of these pains and pleasures comes upon us!

To return to my baby-brother. The dusk steals upon us, and we are still playing with the oranges. The cat is watching us, and when an orange rolls in her direction she, half timidly, half sportively, stretches out her paw towards it, and on one occasion lies full-length on her stomach, with an orange between the tips of her paws, and her nose in a straight line with it. I hear my baby-brother laugh gleefully as I scramble on all-fours after the orange. The dusk has deepened, and my baby-brother's face grows indistinct. I throw the orange towards him. It hits him in the face, and his gleeful laughter changes to a scream. I absolutely never see my baby-brother again, and never again hear his voice. All that afterwards refers to him seems to be imparted to me when it is dark, and so strong is my impression of this detail that in my memory I never see his face with a light upon it. My baby-brother is taken suddenly ill, I am told. I go about the house, always in the dark, stepping very gently, and wondering whether my secret will become known, and if it does, what will be done to me. Still in the dark I hear that my baby-brother is worse; that he is dangerously ill. Then, without an interval as it seems, comes the news that my baby-brother is dead, and I learn in some undiscoverable way that he has died of the croup. I know better. I know that I gave him his death-blow with the orange, and I tremble for the consequences. But no human being appears to suspect me, and for my own sake I must preserve silence. Even to assume an air of grief at my baby-brother's death might be dangerous; it might look as if I were too deeply interested in the event; so I put on my most indifferent air. There are, however, two things in the house that I am frightened of. One is our old Dutch clock, the significant ticking and the very ropes and iron weights of which appear to me to be pregnant with knowledge of my crime. Five minutes before every hour the clock gives vent to a whirring sound, and at that sound, hitherto without significance, I tremble. There is a warning in it, and with nervous apprehension I count the seconds that intervene between it and the striking of the hour, believing that then the bell will proclaim my guilt. It does proclaim it; but no person understands it, no one heeds it. I lean against the passage wall, listening to the denunciation. Snaggletooth comes in and stands by my side while the clock is striking. I look up into his face with imploring eyes and a sinking heart. He taps my cheek kindly, and passes on. I breathe more freely; he does not know the language of the bells. The other thing of which I am frightened is our cat. I know that she knows, and I am fearful lest, by some mysterious means, she will denounce me. If I meet her in the dark, her green eyes glare at me. I try to win her over to my side in a covert manner by stroking her coat; but as I smooth her fur skilfully and cunningly, I am convinced that she arches her back in a manner more significant than usual, and that by that action she declines to be a passive accessory to the fact. Her very tail, as it curls beneath my fingers, accuses me. But time goes on, and I am not arrested and led away to be hanged. When my baby-brother is in his coffin I am taken to see him. The cat follows at my heels; I strive to push her away stealthily with my foot, but she rubs her ear against my leg, and will not leave me. I do not see my baby-brother, because I shut my eyes, and I sob and tremble so that they are compelled to take me out of the room; but I have a vague remembrance of flowers about his coffin. I am a little relieved when I hear that he is buried, but the night that follows is a night of torture to me. The Dutch clock ticks, 'I know! I know!' and the cat purrs, 'I know! I know!' and when I am in bed the shade of Jane Painter steals into the room, and after smelling about for blood, whispers in a ghastly undertone that she knows, and is going to tell. Of the doctor, also, I begin to be frightened, for after his visit to my father's sick-room, my mother brings him to see me--being anxious about me, I hear her say. He stops and speaks to me, and when his fingers are on my wrist, I fancy that the beating of my pulse is revealing my crime to him.

But more weighty cares even than mine are stirring in our house, and making themselves felt. My father's last moments are approaching, and I hear that he cannot last the day out. He lasts the day out, but he does not last the night out. As the friend of the family, Snaggletooth remains in the house to see the end of his old comrade. He and my father were schoolboys together, he tells me. 'He was the cleverest boy in the school,' Snaggletooth says; 'the cleverest boy in the school! He used to do my sums for me. We went out birds'-nesting together; and many and many's the time we've stood up against the whole school, snowballing. A snowball, with a stone in it, hit him in the face once, and knocked him flat down; but he was up in a minute, all bloody, and rushed into the middle of our enemies, like a young lion--like a young lion! He was the first and the cleverest of all of us--I was a long way behind him. And now, think of him lying there almost at his last breath, and look at me!' Snaggletooth straightens himself as he walks upstairs, murmuring, 'The cleverest boy in the school! And now think of him, and look at me!'

Snaggletooth's wife is in the house, and helps my mother in her trouble. In the night this good creature and I sit together in the kitchen--waiting. My mother comes in softly two or three times; once she draws me out of the kitchen on to the dark landing, and kneels down, and with her arms around my neck, sobs quietly upon my shoulder. She kisses me many times, and whispers a prayer to me, which I repeat after her.

'Be a good child always, Chris,' she says.

'I will, mother.' And the promise, given at such a time, sinks into my heart with the force of a sacred obligation.

Then my mother takes me into the kitchen, and gives me into the charge of Snaggletooth's wife, and steals away. Snaggletooth's wife begins to prattle to amuse me, and in a few minutes I ascertain that she in some way resembles Jane Painter; for--probably influenced by the appropriateness of the occasion for such narrations--she tells me stories in a low tone about the Ghost of the Red Barn, and the Cock-lane Ghost, and Old Mother Shipton. The old witch is a favourite theme with Snaggletooth's wife, and I hear many strange things. She says:

'One night Mother Shipton was in a terrible rage, and she told the grasshopper on the top of the Royal Exchange to jump over to the ball on St. Paul's Church steeple. And so it did. Soon after that, London was burnt to the ground.'

I muse upon this, and presently inquire: 'Was it an accident?'

'The fire? No; it was done on purpose.'

'Was it because the grasshopper jumped on to the steeple that London was set on fire?'

'Of course,' is the reply. 'That was Mother Shipton's spite.'

Snaggletooth's wife tells so many stories of ghosts and witches that the air smells of fire and brimstone, and I see the cat's tail stiffen and its eyes glow fearfully. Then I hear a cry from upstairs, and Snaggletooth's wife rises hurriedly, and looks about her with restless hands, and the whole house is in a strange confusion. Snaggletooth himself comes into the room, and as he whispers some consoling words to me--only the import of which I understand--his great tooth sticks out like a horn. He looks like a fiend.

Notwithstanding her limited means, my mother had always managed to keep up a respectable appearance. Popular report had settled it that my grandmother was a woman of property and that my father had money; and the fact that my grandmother's long stocking had proved to be a myth was most completely discredited. We are supposed, therefore, to be well to do, and the scandal would have been great if my father had not received a respectable funeral. Public opinion called for it. My mother makes a great effort, and quite out of love, I am sure, and not at all in deference to public opinion, buries my father in a manner so respectable as to receive the entire approval of our neighbours. Public opinion called for mutes, and two mutes--one with a very long face and one with a very square face--are at our door, the objects of deep and attentive contemplation on the part of the sundry and several. Public opinion called for four black horses, and there they stand, champing their bits, with their mouths well soaped. Public opinion called for plumes, and there they wave, and bow, and bend, proud and graceful attendants at the shrine of death. Public opinion called for mock mourners, and they are ready to parody grief, with very large feet, ill-fitting black gloves, and red-rimmed eyes, which suggest the idea that their eyelids have been wept away by a long course of salaried affliction. Never all his life had my father been so surrounded by pomps and vanities; but public opinion has decided that on such solemn occasions grief is not grief unless it is lacquered, and that common decency would be outraged by following the dead to the grave with simple humility.

The interior of our house has an appearance generally suggestive of graves and coffins. The company is assembled in the little parlour facing the street--my grandmother's room--and in her expiring attempt at respectability my mother has provided sherry and biscuits. The blinds are down although it is broad day; a parody of a sunbeam flows through a chink, but the motes within it are anything but lively, and float up and down the slanting pillar in a sluggish and funereal manner, in perfect sympathy with the occasion. The cat peeps into the room, debating whether she shall enter; after a cautious scrutiny she decides in the negative, and retires stealthily, to muse over the uncertainty of life in a more retired spot. The company is not numerous. Snaggletooth is present, and the doctor, and two neighbours who approve of the sherry. These latter invite Snaggletooth's attention to the wine, and he pours out a glass and disposes of it with a sadly resigned air; saying before he drinks it, with a tender reference to my father as he holds it up to the light, Ah! If he could!' Conversation is carried on in a deadly-lively style. I think of my baby-brother, and a wild temptation urges me to fall upon my knees and make confession of the murder; but I resist it, and am guiltily dumb. Snaggletooth, observing signs of agitation in my face, pats me on the shoulder, and says, 'Poor little fellow!' The two neighbours follow suit, and poor-little-fellow me in sympathising tones. After this, they approach the decanter of sherry with one intention. There is but half a glass left, which the first to reach the decanter pours out and drinks, while the second regards him reproachfully, with a look which asks, On such an occasion should not self be sacrificed? Before the lid of the coffin is fastened down, I am taken into the room by Snaggletooth to look for the last time upon my father's face. I see nothing but a figure in white which inspires me with fear. I cling close to Snaggletooth. He is immensely affected, and mutters, 'Good-bye, old schoolfellow! Ah, time! time!' As I look up at him, his bald head glistens as would a ball of wax, and something glistens in his eyes.

When the coffin is taken out of the house, there is great excitement among the throng of persons in the street. They peep over each other's shoulders to catch a glimpse of the coffin and of me. I cannot help feeling that I am in an exalted position. A thrill of pride stirs my heart. Am I not chief mourner?

I stand by the side of a narrow grave, dug in a corner of the churchyard, and shaded from the sun's glare by a triangular wall, the top of which is covered with pieces of broken bottles, arranged with cruel nicety and precision, so that their sharp and jagged ends are uppermost. Standing also within the shadow of the triangular wall are a number of tombstones, some fair and white, others yellow and crumbling from age, which I regard with the air of one who has acquired a vested interest in the property. I do not understand the words the clergyman utters, for he has an impediment in his speech. But as the coffin is lowered, I am impelled gently towards the grave, from which I shrink, however, apprehensive lest I shall be thrust into it, and buried beneath the earth which is scattered on the coffin with a leaden miserable sound. When the service is ended, I hear Snaggletooth mutter, 'Think of him lying there, and look at me! And we were schoolfellows, and played snowball together!' Snaggletooth shows me my grandmother's grave, and the grave of my baby-brother. I dare not look upon the latter, knowing what I know. Then Snaggletooth, still with head uncovered, stands before a little gave over which is a small marble tombstone, with the inscription, 'Here Lieth our Beloved Daughter.' Seeing that his tears are falling on the grave, I creep closer to him, and he presses me gently to his side. I read the inscription slowly, spelling the words, 'Here Lieth our Beloved Daughter,' and I look at him inquiringly.

'My daughter,' he says; 'the sweetest angel that ever breathed. She was three years and one day old when she died, nearly five years ago. Poor darling! Five years ago! Ah, time! time!'

As we pass out of the churchyard I notice again the broken glass on the top of the wall, and I say,

'Isn't that cruel?'

'Why cruel?' asks Snaggletooth. 'No one can get in without hurting himself.'

Snaggletooth regards me with an eye of curiosity.

'And who do you think wants to get into such a place, my little fellow?'

I do not answer, and Snaggletooth adds,

'The angels, perhaps. Good--good. But they come in another way.'

'No one can get out without hurting himself,' I suggest.

'That is a better thought; but if they lived good lives----'

'Yes, sir.'

'Walls covered with broken glass won't hurt them.'

Snaggletooth looks upwards contemplatively. I look up also, and a sudden dizziness comes upon me and overpowers me. Snaggletooth catches me as I am falling.

'You are not well, my little fellow.'

'No, sir; I feel very weak, but the doctor says I shall get over it.'

Snaggletooth lifts me in his arms, and I fall asleep on his shoulder as he carries me tenderly home.

Here we are, my mother and I, sitting in the little parlour. My mother has been crying over me, and perhaps over the sad future that lies before us. Not a sound now is to be heard. My condition is a strange one. Everything about me is very unreal, and I wonderingly consider if I shall ever wake up. All my young experiences come to me again. I see my grandmother and myself sitting together. There upon the mantelshelf is the figure of the smoke-dried monkey of a man in stone, wagging his head at me; there is the man with the knob on the top of his head--what is his name? Anthony--yes, Anthony Bullpit--making a meal off his finger nails. In marches my grandmother's long stocking, bulged out with money to the shape of a very substantial leg, just as I had fancied it--that makes me laugh; but my flesh creeps as I hear Jane Painter's voice in the dark, telling of blood and murder. The last word, as she dwells upon it, brings up my baby-brother, and I hear the Dutch clock tick: 'I know! I know!' But it ticks all these fancies into oblivion, and ticks in the picture of the churchyard. I see the graves and the tombstones, and I read the inscription: 'Here Lieth our Beloved Daughter.' How it must grieve her parents to know that their beloved daughter is lying shut up in the cold earth! I raise a portrait of the child, with fair hair and laughing eyes, and I wonder how she would look now if she were dug up, and whether her parents would know her again. Night surprises me confined within the triangular wall of the churchyard. The gates are closed, and I cannot pass out. The moon shines down icily. The cold air makes my fevered blood hotter. I must get out! I cannot stop confined here for ever! I dig my fingers into the wall; desperately I cling to it, and strive to climb. Inch by inch I mount. With an exquisite sense of relief I reach the top, but as I place my hands upon it they are cut to the bone by the broken glass, and with a wild shudder I sink into darkness and oblivion!

When I recovered from the fever of which the experiences just recorded were the prelude, I found that we had removed from the house in which I was born, and that we were occupying apartments. We had removed also from the neighbourhood; the streets were strange, the people were strange; I saw no familiar faces. Hitherto we had been living in Hertford, and many a time had I watched the barges going lazily to and fro on the River Lea. The place we were in now was nothing but a village; my mother told me it was called Chipping Barnet. I cannot tell exactly what it was that restrained me from asking why the change had been made; it must have been from an intuitive consciousness that the subject was painful to my mother. But when, after the lapse of a year or so, we moved away from Chipping Barnet, and began to live in very humble fashion in two small rooms, I asked the reason.

'My dear,' said my mother, 'we cannot afford better.'

I looked into her face; it was pale and cheerful. But I saw, although no signs of repining were there, that care had made its mark. She smiled at me.

'We are very poor, dear child,' she said; and added quickly, with a light in her eyes, 'but that is no reason why we should not be happy.'

She did her best to make me so, and poor as our home was, it contained many sweet pleasures. By this time I had completely lost sight of Snaggletooth and all our former friends and acquaintances. I did not miss them; I had my mother with me, and I wished for no one else. Already, my former life and my former friends were becoming to me things of long ago. My mother often spoke of London, and of her wish to go there.

'I think it would be better for us, Chris,' she said.

'Is London a very large place?' I asked. 'As large as this?' stretching out my arms to gain an idea of its extent.

My mother told me what she knew of London, which was not much, for she had only been there once, for a couple of days, and I said I was sure I should not like it; there were too many people in it. My idea of perfect happiness was to live with my mother in some pretty country place, where there were fields and shady walks and turnstiles and narrow lanes, and perhaps a river. I described the very place, and artistically dotted it with lazy cattle listening for mysterious signs in earth or air, or looking with steady solemn gaze far into the horizon, as if they were observing signs hidden from human gaze. I also put some lazy barges on the river, 'Creeping, creeping, creeping,' I said, 'as if they were so tired!'

'And we would go and live in that very place, my dear,' said my mother, 'if we had money enough.'

'When you get money enough, mother, we will go.'

'Yes, my dear.'

Other changes were made, but not in the direction I desired. Like a whirlpool, London was drawing us nearer and nearer to its depths, and by the time I was twelve years of age we were nearly at the bottom of the hill down which we had been steadily going. My clothes were very much patched and mended now; all our furniture was sold, and we were living in one room, which was rented to us ready furnished. The knowledge of the struggle in which my mother was engaged loomed gradually upon me, and distressed me in a vague manner. We were really now in London, although not in the heart of the City; and my mother, whose needle brought us bread and very little butter, often walked four miles to the workshop, and four miles back, on a fruitless errand. Things were getting worse and worse with us. My mother grew thinner and paler, but she never looked at me without a smile on her lips--a smile that was often sad, but always tender. At night, while she worked, she taught me to read and write; there was no free school near us, and she could not afford to pay for my learning. But no schoolmaster could have taught me as well as she did. She had a thin, sweet voice, and often when I was in bed I fell asleep with her singing by my side. I used to love to lie thus peacefully with closed eyes, and float into dreamland upon the wings of her sweet melodies. I woke up sometimes late in the night, and saw her dear face bending over her work. It was always meek and cheerful; I never saw anger or bad passion in it.

'Mother,' I said one night, after I had lain and watched her for a long time.

She gave a start. 'Dear child; I thought you were asleep.'

'So I have been; but I woke up, and I've been watching you for a long, long time. Mother, when I am a man I shall work for you.'

'That's right, dear. You give me pleasure and delight. I know my good boy will try to be a good man.'

'I will try to; as good as you are. I want to be like you. Could I not work now, mother?'

'No, dear child; you are not strong enough yet.'

'I wish I could grow into a strong man in a night,' I thought.

My mother came to the bedside and rested her fingers upon my neck. What tenderness dwells in a loving mother's touch! I imprisoned her fingers in mine. She leant towards me caressingly and kissed me. Sleep stole upon me in that kiss of love.

I saw a picture in a shop window of a girl whose bright fresh face brought my mother's face before me. But the girl's face was full of gladness, and her cheeks were glowing; my mother's cheeks were sunken and wan. Still the likeness was unmistakably there, and I thought how much I should love to see my mother as bright as this bright girl. I spoke to her about it, and she went to see the picture, which was in the next street to ours. She came back smiling.

'It is like me, Chris,' she said; 'as I was once.'

'Then you must have been very, very pretty,' I said, stroking her cheek.

My mother laughed melodiously.

'When I was young, my dear,' she said with innocent vanity, blushing like a girl, 'I was thought not to be ugly.'

'Ugly, indeed!' I exclaimed, looking around defiantly. 'My mother couldn't be ugly!'

'What do you call me now, Chris?'

'You are beautiful--beautiful!' with another defiant look. My mother shook her hand in mild remonstrance. 'You are--you are! But you're pale and thin, and you've got lines here--and here.' I smoothed them with my hand. 'And, mother, you're not old!'

'I'm forty, Chris.'

'That is not old. Tell me--why did you alter so?'

'Time and trouble alter us, dear. We can't be always bright.'

I thought that I might be the trouble she referred to, and I asked the question anxiously.

'You, my darling!' she said, drawing me to her side and petting me. 'You are my joy, my comfort! I live only for you, Chris--only for you!'

I noticed something here, and, with a touch of that logical argumentativeness for which I was afterwards not undistinguished, I said:

'If I am your joy and comfort, you ought to be glad.'

'And am I not glad? What does my little boy mean by his roundabouts?'

'You cried when you said I was your joy and comfort.'

'They were tears of pleasure, my dear--tears that sprang from my love for my boy. Then perhaps they sprang from the thought--for we will be truthful always, Chris--that I should like to buy my boy a new pair of boots and some new clothes, and that I couldn't because I hadn't money enough.'

'You would buy them for me if you had money?'

'Ah! what would I not buy for my darling if I had money!'

How delicious it was to nestle in her arms as she poured out the love of her heart for me! How I worshipped her, and kissed her, and patted her cheek, and smoothed her hair.

'You are like a lover, my dear,' she said.

'I am your lover,' I replied, and murmured softly to myself, 'Wait till I am a man! wait till I am a man!'

That night I coaxed my mother to talk to me of the time when she was young, and she did, with many a smile and many a blush; and in our one little room there was much delight. She picked out the daisies of her life, and laid them before me to gladden my heart. Simple and beautiful were they as Nature's own sweet flower. She showed me a picture of herself as a girl, and I saw its likeness to the picture I had admired in the shop window. She sang me to sleep with her dear old songs, full of sweetness and simplicity. How different are our modern songs from those sweet old airs! The charm of simplicity is wanting--but, indeed, it is wanting in other modern things as well. The spirit of simplicity dwells not in crowded places.

Then commenced my first conscious worship of woman. I held her in my heart as a devotee holds a saint. How good was this world which contained such goodness! How sweet this life which contained such sweetness! She was the flower of both. Modesty, simplicity, and truth, were with her invariably. To me she became the incarnation of purity.

Time went on, and low as we were we were still going down hill steadily and surely. It is a long hill, and there are many depths in it. Work grew slack, and in the struggle to make both ends meet, my mother was frequently worsted; there was often a great gap between. I do not wonder that hearts sometimes crack in that endeavour. Yet my mother ('by hook and by crook,' as I have heard her say merrily) generally managed in the course of the week to scrape together some few coins which, jealously watched and jealously spent, sufficed in a poor way to keep body and soul together. How it was managed is a mystery to me. The winter came on: a hard winter. Bread went up in price; every additional halfpenny on a four-pound loaf was a dagger in my mother's breast. We rubbed through this hard time somehow, and Christmas glided by and the new year came upon us. A cold spring set in, and work, which had been getting slacker and slacker, could not now be obtained. Still my mother did not lie down and yield. She tried other shops, and received a little work--very little--at odd times. There came a very hard week, and my mother was much distressed. On the Friday night I heard her murmuring to herself in her sleep as I thought, and I fancied I heard her sob. I called to her, but she did not answer me. Her breath rose and fell in regular rhythm. Yes, she was asleep, and the sob I thought I heard was born of my fancy. I was thankful for that!

The next day was Saturday, and my mother went out early in the morning, and returned at two o'clock with the saddest of faces.

'No work, mother?' I asked.

'No, my dear,' she replied; 'but come, my child, you must be hungry.'

There was little enough to eat, but my boy's appetite, and the cunning way my mother had of placing our humble fare before me, made the plain food as sweet as the best.

I noticed that she ate nothing, and I tried to persuade her to eat.

'I have no appetite, my dear,' she said, and added in reply to my sorrowful look, 'My little boy doesn't know what I've had while I was out this morning.'

Deeper thought than usual seemed to occupy her mind during the afternoon, and she suddenly started up, and hurriedly threw on her bonnet and shawl.

'Are you going to try again, mother?'

'Yes, my darling; I must try again.'

She did not return until late, but she returned radiant, and said, as she took my face between her two hands, and kissed me:

'Child, dear child! God bless those who help the poor!'

She did not bid me repeat the words; but some deep meaning in her voice impelled me to do so, and I said in a solemn tone, what the words seemed to demand,

'God bless those who help the poor!'

She nodded pensively as she knelt before me, and as I looked at her somewhat earnestly, her face flushed, and she rose, and bustled about the room, putting things in order. I think she tried to hide her face from me, and that her bustling about was a pretence.

'And now, Chris,' she said presently, drawing her breath quickly, as though she had been running, 'let us go out and get something nice for supper, and for dinner to-morrow. Put on your cap, dear; you must be hungry.'

I was; and I was glad, indeed, to hear the good news, and to accompany her on such an errand. She consulted me as to what she should buy, and made me very proud and happy with her 'What do you say to this, dear?' and 'Would you like this, my darling?' We returned home loaded with meat, potatoes, and one or two little delicacies. I was in a state of great satisfaction, and we made quite merry over the trifling incident of a few potatoes rolling out of my mother's apron down the stairs in the dark. Bump, bump, bumping,' I said, as I scrambled down after them, 'as if they knew their way in the dark, and could see without a candle.'

'Potatoes have eyes, my dear,' said my mother; and we laughed blithely over it.

My mother's mood changed after supper. We always said a very simple grace after meals. It was, 'Thank God for a good breakfast!' 'Thank God for a good dinner!' or whatever meal it was of which we had partaken. Our 'Thank God for a good supper!' being said, most earnestly by my mother, she cleared away the things, and said,

'Now we will see how rich we are.'

We sat down at the table, side by side, and my mother took out of her pocket what money it contained. I thought that our all had been expended in our frugal purchases, but I was agreeably mistaken. There were still left two sixpences and a few coppers. My mother selected a battered halfpenny, and regarded it tenderly--so tenderly, and with so much feeling, that her tears fell on it. I wondered. A battered halfpenny, dented, dirty, bruised! I wondered more as she kissed it, and held it to me to kiss.

'Why, mother?' I asked, as I kissed.

In reply, she told me a story.

'My dear, there lived in a great forest a poor woman who had no friend in the world but one--a bird that she loved with all her heart and soul, and who, not being big enough or strong enough to get food for himself, depended, because he couldn't help it, upon what this poor woman could provide for him. There were other birds that in some way resembled the bird that belonged to this poor woman, and that she loved so dearly, and many of these were also compelled to wander about the great forest in search of food; but they found it so difficult to obtain sufficient to eat, and they met with so many sad adventures in their search, that their wings lost their strength, and their hearts the brightness that was their proper heritage--for they were young birds, whose time for battling with the world had not arrived. The poor woman did not wish her dear bird to meet with such sad experiences until he was strong and able to cope with them. I can't tell you, my dear, how much she loved her bird, and how thoroughly her whole heart was wrapped up in her treasure. Once she had friends who were good to her; but it was the will of God that she should lose them, and she and her bird were left alone in the world. She had many difficulties to contend with, being a weak and foolish woman----'

I shook my head, and said, 'I am sure she wasn't; I am sure she wasn't!' My mother pressed me closer to her side, and continued, her fingers caressing my neck:

----'And the days were sometimes very dark for her, or would have been but for the joy she found in her only treasure. A time came when her heart almost fainted within her--for her bird was at home hungry, and there was no food in the nest, and she did not know which way to turn to get it. She wandered about the forest with rebellious thoughts in her mind--yes, my dear, she did!--and out of her blindness and wickedness--hush, my dearest!--out of her blindness and wickedness, she began almost to doubt the goodness of God. She thought, foolish woman that she was! that there was no love in the forest but the love which filled her breast; that pity, compassion, charity, had died out of the world, and that she and her bird were to be left to perish. But she received such a lesson, my dear, as she will never forget till her dying day. While these despairing thoughts were in her mind, and while her rebellious heart was crying against the sweetest attributes with which God has endowed His children, a fairy in a cotton-print dress came to her side----'

Mother!'

'It is true, my dear. A fairy in a cotton-print dress came to her side, and with a sweet word and a sweeter look put into her hand a talisman--call it a stone, my dear, if you will--a common, almost valueless piece of stone; and the touch of the pretty little fairy fingers to the poor woman's hand was like the touch of Moses's rod to the rock, when the waters came forth for the famished people. And she prayed God to forgive her for doubting His goodness, and the goodness of those whom He made in the image of Himself. Then, as she looked at the common piece of stone which the fairy had given to her, she saw in it the face of an angel, and she kissed it again and again, as I do this.'

After a little while my mother wrapped the halfpenny in a piece of paper, and put it by, saying she hoped she would never be compelled to spend it.

During the whole of the following week my mother was unsuccessful in obtaining work. It was not from want of perseverance that she did not succeed, for she came home every day weary and footsore.

'The sewing-machines are keeping many poor women out of work,' she said.

'Then they are bad things,' I exclaimed; 'I wish they were all burnt!'

'No, my dear; they are good things; they are blessings to many poor creatures. Why, Chris, if I had one, we should be quite rich!'

But she did not have one, and her needles were at a discount, so far as earning bread for us was concerned. On the Saturday she went out again early, and did not come home until late at night. Good fortune had again attended her, and she brought home a little money.

'Have you seen the fairy in the cotton-print dress?' I asked gaily. My mother nodded sorrowfully. Saturday's a lucky day, mother,' I said, rubbing my hands.

'Yes, my child,' she answered, with a heavy sigh.

She added another halfpenny to the one she had kissed and put by last week, and we went out again to make our purchases. Another week followed, and another, with similar results and similar incidents. Then my mother fell sick, and could not, although she tried, keep the knowledge of her weakness from me; a sorrow of which I was not a sharer was preying on her heart. I did not know of it; but I saw that my mother was growing even paler and thinner, and often, when she did not think I was observing her, I saw the tears roll down her cheek, and her lips quiver piteously. Friday night found us with a cupboard nearly empty, and with but one halfpenny in our treasury--the first battered and bruised halfpenny, which my mother hoped she would never be compelled to spend. Those she had added to it had gone during the week. She looked at it wistfully:

'Must we spend it, Chris?'

'Is the angel's face there?' I asked.

'Yes, I see it.' And she kissed the battered coin again.

'Then we must keep it,' I said stoutly.

When I awoke the next morning, my mother was kneeling by my bedside, and when she saw my eyes resting on her face, she clasped me in her arms, and so we lay for fully half an hour, without a word being spoken. There was a little milk left for breakfast, and this my mother made into very weak milk-and-water. The bread she cut into four slices. One she ate, two she gave to me, and one she put into the cupboard. She laid the battered halfpenny on the mantelshelf.

'Now, Chris,' she said, as she put on her poor worn bonnet, 'when you are hungry you can eat the slice of bread that's in the cupboard; and if I am not at home before you are hungry again, you can buy some bread with that halfpenny. Kiss me, dear child.'

'But, mother,' I remonstrated, you are too ill to go out. You ought to stay at home to-day.'

I dare not, child. I must go out. Why, doesn't my Chris want his supper to-night, and his dinner to-morrow? And don't I want my supper and dinner, too?'

'Are you going to the workshop, mother?'

'I am going that way, child.'