GEORGE PHILIP & SON LTD.

Longmans. Green & Co., London, New York, Bombay & Calcutta.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Ireland under the Stuarts and during the Interregnum, Vol. I (of 3), 1603-1642, by Richard Bagwell This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Ireland under the Stuarts and during the Interregnum, Vol. I (of 3), 1603-1642 Author: Richard Bagwell Release Date: November 7, 2016 [EBook #53473] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IRELAND UNDER THE STUARTS, VOL 1 *** Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Vol. I.

By the same Author

IRELAND UNDER THE TUDORS

Vols. I. and II.—From the First Invasion of the Northmen to the year 1578.

8vo. 32s.

Vol. III.—1578-1603. 8vo. 18s.

LONGMANS, GREEN, & CO.

London, New York, Bombay, and Calcutta

IRELAND

UNDER THE STUARTS

AND

DURING THE INTERREGNUM

BY

RICHARD BAGWELL, M.A.

AUTHOR OF ‘IRELAND UNDER THE TUDORS’

Vol. I. 1603-1642

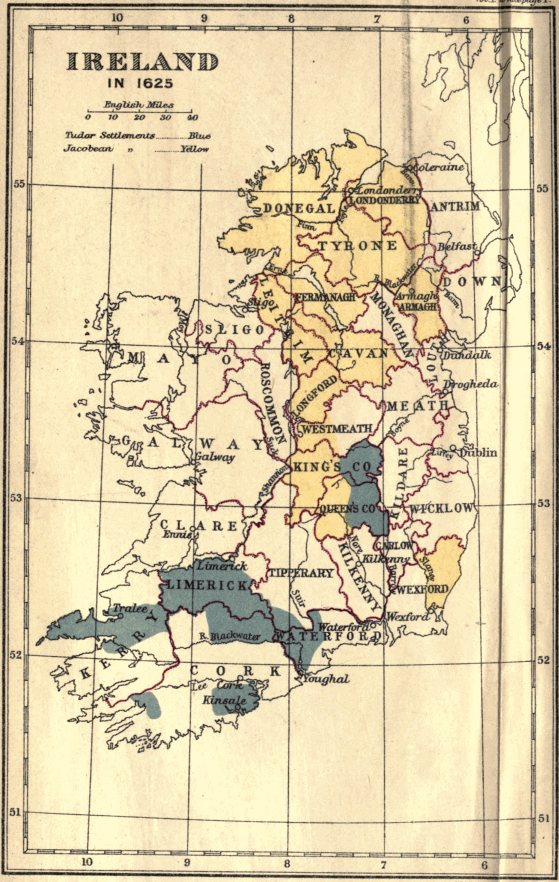

WITH MAP

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK, BOMBAY, AND CALCUTTA

1909

All rights reserved

These volumes have been written at such times and seasons as could be made available during an active life in Ireland, and this may induce critics to take a merciful view of their many shortcomings. I have been diligent, but there is still much extant manuscript material which I have been unable to use. Ireland is the land of violent and persistent party feeling, and no party will be pleased with the present work, for I hold with an ancient critic that the true function of history is to bring out the facts and not to maintain a thesis. If I am spared to finish the third volume, it will bring the narrative down to the Revolution, and will contain chapters on the Church or Churches and on the social state of Ireland.

The dates of all documents relied on have been given, and unless it is otherwise stated they are among the Irish State Papers calendared from 1603 to 1660. Many papers, chiefly, but not exclusively, from the Carte manuscripts, were printed by Sir J. T. Gilbert in the ‘Contemporary History of Affairs in Ireland,’ or in the ‘History of the Confederation and War in Ireland.’ As these collections are more generally accessible than the Bodleian Library, I have referred to them as far as they go. The ‘Aphorismical Discovery,’ which forms the nucleus of the first, is cited under that title, and the narrative of Bellings in the second under his name. The original Carte papers at Oxford have been often consulted, as well as the transcripts in the Public Record Office, while the manuscripts in the British Museum and in[Pg vi] Trinity College, Dublin, have not been neglected. In the case of old tracts and newsletters, of which I have read a great many, dates and titles are given.

The late Lord Fitzwilliam did not consider it consistent with his duty to let Dr. Gardiner see the Strafford correspondence preserved at Wentworth Woodhouse, and my application to his successor has also been refused. No restriction seems to have been imposed on the editors of Laud’s works, of which the last instalment was published as late as 1860. All the Archbishop’s letters are printed, Strafford’s being omitted only because they would have taken too much room. In 1739 Dr. William Knowler, working under Lord Malton’s directions, published the well-known Strafford Letters, and Mr. Firth has thrown fresh light upon them by printing some of the editor’s correspondence in the ninth volume of the ‘Camden Miscellany.’ ‘There is,’ Knowler wrote, ‘four or five times the number of letters uncopied for one transcribed, and yet I believe those that shall glean them over again won’t find many things material omitted.’ Yet Laud’s editors thought it worth while to publish a good deal of what had been left out, and probably there is still something to be done.

I have made some examination of the famous depositions in Trinity College, Dublin, concerning the rebellion of 1641, but it is unnecessary to repeat Miss Hickson’s arguments, which appear to me conclusive. The documents may be pronounced genuine in the sense that they really are what they profess to be, but they are all more or less ex parte statements, and the witnesses were not cross-examined. Deductions may be made on these grounds, especially in the case of numerical estimates, but there is a vast mass of other evidence as to the main facts. The matter is discussed pretty fully in Chapter XX.

It is unnecessary to describe here the various contemporary histories and memoirs referred to in the text and[Pg vii] notes. Sir Richard Cox’s ‘Hibernia Anglicana’ should be used with caution. Cox was a strong partisan, but he was not a liar, and he wrote at a time when there were still living witnesses.

The maps at the beginning of each volume are intended as helps to the reader, and make no pretension to completeness. Fuller details as to the various colonies or plantations may be found in Mr. Dunlop’s map, No. 31 in the Oxford Historical Atlas. As to the short-lived Cromwellian settlement much may be learned from the map in Gardiner’s ‘Commonwealth and Protectorate,’ iii. 312, and from that in Lord Fitzmaurice’s ‘Life of Petty.’ The more lasting arrangements made after 1660 will be the subject of full discussion in my third volume. The innumerable sieges, battles and skirmishes from 1641 to 1653 may be traced in any large map of Ireland, and cannot be shown in a small one. The state of affairs at the critical moment of the first truce in 1643 is illustrated by the map in Gardiner’s ‘Great Civil War,’ i. 264.

My best thanks are due to Mrs. Shirley for lending me fourteen volumes of tracts concerning the rebellion from the library at Lough Fea. They have been very useful.

I received some valuable hints from my friend, the late C. Litton Falkiner, whose untimely death is a loss to Ireland.

Marlfield, Clonmel:

December 26, 1908.

OF

THE FIRST VOLUME

| CHAPTER I | |

| MOUNTJOY AND CAREY, 1603-1605 | |

| PAGE | |

| Accession of James I. | 1 |

| Agitation in Irish towns | 2 |

| Insurrection at Cork | 8 |

| Reform of the currency | 14 |

| Chichester made Lord Deputy | 15 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| CHICHESTER AND THE TOLERATION QUESTION, 1605-1607 | |

| The laws against Recusancy | 17 |

| Proclamation against toleration | 19 |

| Cases of Everard and Lalor | 21 |

| Attempt to enforce uniformity—the Mandates | 23 |

| Bacon on toleration—Sir P. Barnewall | 27 |

| The Mandates given up | 29 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE FLIGHT OF THE EARLS, 1607 | |

| Tyrone at Court | 30 |

| O’Cahan’s case | 31 |

| Death of Devonshire | 33 |

| Earldom of Tyrconnel created | 34 |

| Departure of Tyrone, Tyrconnel, and Maguire | 37 |

| The fugitives excluded from France and Spain | 39 |

| Reasons for Tyrone’s flight—Lord Howth | 41 |

| Uncertainty as to the facts | 42 |

| [Pg x]Lord Delvin’s adventures | 44 |

| Royal manifesto against the Earls | 47 |

| Tyrone leaves the Netherlands | 48 |

| He reaches Rome | 49 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| REBELLION OF O’DOGHERTY, 1608 | |

| The settlement at Derry | 51 |

| O’Dogherty and Paulet | 53 |

| Derry surprised and sacked | 54 |

| Flight and death of O’Dogherty | 56 |

| A ‘thick and short’ war | 58 |

| A Donegal jury | 60 |

| Forfeitures | 61 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE SETTLEMENT OF ULSTER | |

| The tribal system | 63 |

| Chichester’s plan of colonisation | 66 |

| Bacon on the settlement | 67 |

| The Scots in Ulster—Bishop Montgomery | 68 |

| Church and Crown | 70 |

| Chichester and Davies | 71 |

| British settlers invited | 72 |

| The natives neglected | 74 |

| The survey | 75 |

| Londonderry and Coleraine | 76 |

| Sir Thomas Phillips | 77 |

| Slow progress | 78 |

| English and Scots compared | 79 |

| Carew’s prophecy | 81 |

| Settlers and natives | 82 |

| Bodley’s and Pynnar’s surveys | 85 |

| The Londoners’ settlement | 87 |

| English, Scotch, and Irish | 88 |

| Optimism at Court | 90 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| CHICHESTER’S GOVERNMENT TO 1613 | |

| Sir John Davies on circuit | 91 |

| Uniformity in Ulster—Bishop Knox | 97 |

| Irish swordsmen deported to Sweden | 99 |

| [Pg xi]Piracy on the Irish coast | 101 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| THE PARLIAMENT OF 1613-1615 | |

| No Parliament for 27 years | 108 |

| A Protestant majority | 109 |

| Roman Catholic opposition | 110 |

| Violent contest for the Speakership | 112 |

| Sir John Davies on the constitution | 114 |

| Patience of Chichester | 116 |

| Royal commission on grievances | 117 |

| Election petitions—new boroughs | 118 |

| Opposition delegates in London | 120 |

| Doctrines of Suarez: Talbot, Barnewall, and Luttrell | 122 |

| Rival churches—neglect of religion | 122 |

| Ploughing by the tail | 124 |

| Chichester found upright by the Commissioners | 126 |

| The King verbally promises toleration | 127 |

| But tries to explain away his language | 128 |

| Bacon as philosopher and Attorney-General | 129 |

| The King’s speech on parliamentary law | 130 |

| Legislation | 132 |

| The Protestant majority insufficient | 134 |

| Taxes not easily collected | 135 |

| Legislation against the Recusants abandoned | 136 |

| James falls back upon prerogative | 137 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| LAST YEARS OF CHICHESTER’S GOVERNMENT, 1613-1615 | |

| The Ormonde heritage | 139 |

| The MacDonnells in Antrim | 141 |

| Irish expedition to the Isles | 142 |

| Plot to surprise the Ulster settlements | 145 |

| Chichester recalled; his position and character | 147 |

| Death of Tyrone and Tyrconnel | 149 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| ST. JOHN AND FALKLAND, 1616-1625 | |

| St. John tries to enforce uniformity | 150 |

| Charter of Waterford forfeited | 152 |

| Plantation of Wexford | 153 |

| General dissatisfaction | 156 |

| Bishop Rothe’s strictures | 160 |

| Plantation in Longford and King’s County | 162 |

| The new plantations not successful | 164 |

| Plantation of Leitrim | 166 |

| [Pg xii]Irish swordsmen in Poland | 167 |

| Unpopularity of St. John | 168 |

| Lord Deputy Falkland | 169 |

| Ussher and the civil power | 170 |

| Effect of the Spanish match in Ireland | 171 |

| Falkland’s grievances | 173 |

| Death and character of James I. | 174 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| EARLY YEARS OF CHARLES I., 1625-1632 | |

| Accession of Charles I. | 175 |

| Quarrel between Falkland and Loftus | 175 |

| The case of the O’Byrnes | 176 |

| Alleged plot of Lord Thurles | 180 |

| The ‘graces’ | 180 |

| The bishops declare toleration sinful | 181 |

| Irish soldiers in England | 182 |

| Poynings’s law | 183 |

| Falkland recalled | 184 |

| Wentworth as a judge | 185 |

| The religious orders attacked | 186 |

| St. Patrick’s Purgatory | 188 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| GOVERNMENT OF WENTWORTH, 1632-1634 | |

| Wentworth’s antecedents | 190 |

| His alliance with Laud—‘thorough’ | 192 |

| His other friends | 193 |

| Conditions of Wentworth’s appointment | 195 |

| His journey delayed by pirates | 198 |

| His arrival in Ireland | 199 |

| His opinion of the officials | 201 |

| First appearance of Ormonde | 203 |

| Reforms in the army | 203 |

| Church and State—Bishop Bramhall | 205 |

| Wentworth, Laud, and the Earl of Cork | 206 |

| Algerine pirates—sack of Baltimore | 207 |

| Wentworth suppresses piracy | 209 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| THE PARLIAMENT OF 1634 | |

| Wentworth’s parliamentary policy | 211 |

| Wentworth and the Irish nobility | 213 |

| [Pg xiii]How to secure a majority | 214 |

| Parliamentary forms and ceremonies | 215 |

| Wentworth’s speech | 216 |

| Supply voted | 219 |

| Wentworth refused an earldom | 220 |

| The ‘graces’ not confirmed | 221 |

| Parliamentary opposition overcome | 222 |

| Judicial functions of Parliament—Gookin’s case | 223 |

| Taxation | 226 |

| Parliament dissolved | 227 |

| Convocation | 227 |

| The Thirty-nine Articles adopted | 228 |

| Wentworth successful in all directions | 229 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| STRAFFORD AND THE ULSTER SCOT | |

| Rise of Presbyterianism in Ulster | 231 |

| Wentworth, Laud, and Bramhall | 232 |

| Bishop Adair’s case | 233 |

| The Covenant | 236 |

| The Black Oath | 238 |

| Repression of the Presbyterians | 239 |

| A ‘desperate doctrine’ | 242 |

| Wentworth wishes to drive out the Scots | 243 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| WENTWORTH’S PLANS OF FORFEITURE AND SETTLEMENT | |

| Defective titles | 245 |

| Large colonisation schemes | 246 |

| Roscommon, Sligo, and Mayo submit | 247 |

| Resistance of Galway | 249 |

| Treatment of the Galway people—Clanricarde | 250 |

| Injustice of Wentworth’s policy | 251 |

| Attack on the Londoners’ plantation | 252 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| CASES OF MOUNTNORRIS, LOFTUS, AND OTHERS | |

| Lord Wilmot’s case | 255 |

| The Mountnorris case | 256 |

| Martial law in time of peace | 257 |

| Hard treatment of Mountnorris | 261 |

| Case of Lord Chancellor Loftus | 264 |

| Judgment of Royalist contemporaries | 267 |

| Wentworth and Lord Cork | 268 |

| [Pg xiv]Vindictive action of Wentworth | 270 |

| Sir Piers Crosbie’s case | 271 |

| Wentworth and Trinity College | 273 |

| Provost Chappell | 274 |

| The Irish lecture abandoned | 275 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| STRAFFORD’S GOVERNMENT, 1638-1640 | |

| Wentworth’s account of his services | 276 |

| His power practically unchecked | 278 |

| Country life and game laws | 279 |

| Wentworth chief minister | 281 |

| Made Lord Lieutenant and Earl of Strafford | 282 |

| Meeting of an Irish Parliament | 283 |

| Supply voted | 283 |

| Declaration in praise of Strafford | 284 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| STRAFFORD’S ARMY | |

| Lord Antrim’s plot against Scotland | 285 |

| Wentworth garrisons Carlisle | 287 |

| The new Irish army | 288 |

| Muster and disbanding | 291 |

| Danger from disbanded soldiers | 292 |

| Recruits for France and Spain | 293 |

| Owen Roe O’Neill and Preston | 295 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| TRIAL AND DEATH OF STRAFFORD | |

| Wandesford as Strafford’s Deputy | 297 |

| The Irish Parliament refractory | 298 |

| Strafford commander-in-chief | 299 |

| Strafford at York | 300 |

| His arrest | 301 |

| The Irish Parliament repudiate Strafford | 302 |

| Death of Wandesford | 303 |

| Trial of Strafford | 304 |

| Death and character of Strafford | 308 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| THE REBELLION OF 1641 | |

| Parsons and Borlase Lords Justices | 312 |

| [Pg xv]Roman Catholic majority in Parliament | 313 |

| Apprehensions of a rising | 315 |

| Rory O’More, Lord Maguire, and others | 317 |

| The plot to seize Dublin is frustrated | 319 |

| Outbreak in Ulster | 320 |

| The government weak | 321 |

| Ulster fugitives in Dublin | 323 |

| State of the Pale | 326 |

| Ormonde made general—Sir H. Tichborne | 327 |

| The Irish Parliament after the outbreak | 329 |

| The news reaches the English Parliament | 330 |

| And the King | 330 |

| Relief comes slowly | 331 |

| Monck, Grenville, Harcourt, and Coote | 332 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| PROGRESS OF THE REBELLION | |

| Savage character of the contest | 333 |

| Conjectural estimates | 334 |

| The rising in Tyrone | 335 |

| In Armagh and Down | 336 |

| In Fermanagh | 337 |

| In Cavan—the O’Reillys | 338 |

| In Monaghan | 342 |

| The Portadown massacre | 342 |

| Imprisonment and death of Bedell | 344 |

| Irish victory at Julianstown | 347 |

| Belfast and Carrickfergus | 348 |

| The Pale joins the Ulster rebels | 349 |

| Meeting at Tara | 350 |

| Defence of Drogheda | 351 |

| Fire and sword in the Pale | 357 |

| Ireland in 1625, to illustrate colonization projects | to face p. 1 |

IRELAND UNDER THE STUARTS

The change from Elizabeth to James I. marks the transition from an heroic age to one very much the reverse. The new court was scandalous, and after the younger Cecil’s death public affairs were administered by a smaller race of men, not one of whom gained the love or admiration of his countrymen. Raleigh, the typical Elizabethan, spent thirteen years in the Tower, and died on the scaffold. But outside the sphere of politics the first Stuart reign must be regarded with interest, for it saw the production of Shakespeare’s finest plays and of Bacon’s chief works. Meanwhile England had peace, and silently prepared for the great struggle. Eliot and Pym, Wentworth and Cromwell, were all young men, and Milton was born some three years before Prospero drowned his book. The great Queen died at Richmond very early on March 24. By nine o’clock Sir Robert Carey was spurring northwards with the news, and King James was proclaimed in London the same morning. It was not until the next day that Cecil found time to send Sir Henry Danvers to Ireland, but the news had preceded the official messenger by a full week, so that Mountjoy was quite prepared. Danvers landed at Dublin on April 5, and within an hour after the delivery of his letters King James was duly proclaimed. Oddly enough, Tyrone, who had reached Dublin the day before, was the only peer of Ireland present, and he signed the proclamation which was circulated in the country. Three[Pg 2] days later he made submission on his knees to the new sovereign, ‘solemnly swearing upon a book to perform every part thereof, as much as lay in his power; and if he could not perform any part thereof he vowed to put his body into the King’s hands, to be disposed at his pleasure.’ The earl’s submission was ample in substance, and humble enough in form; but Sir William Godolphin, who had brought him to Dublin, warned the English Government that he would not remain a good subject unless he were treated reasonably.[1]

Neither his relations with his own mother nor with Queen Elizabeth had given any reason to suppose that the new king was attached to the religion of Rome. Tyrone had offered his services to James years before, and was told that he would be reminded of this when it should please God ‘to call our sister the Queen of England to death.’ After his raid in Munster Tyrone wrote in rather a triumphant strain, but still obsequiously, to the King of Scots. This did not prevent James from offering his help to Elizabeth when the Spaniards took Kinsale, for which she thanked him. A rumour that his Majesty was a Catholic was nevertheless widely circulated in Ireland, and caused a strange ferment in the corporate towns. Much stress was also laid upon his descent from ancient Irish kings. During the Queen’s later years mass had been freely celebrated in private houses, and a strong effort was now generally made to celebrate it publicly in the churches. Jesuits, seminaries, and friars, says the chronicler Farmer, ‘now came abroad in open show, bringing forth old rotten stocks and stones of images, &c.’ The agitation was strong in Kilkenny, Thomastown, Waterford, Limerick, Cork, and in the smaller Munster towns; and even Drogheda, ‘which since the conquest was never spotted[Pg 3] with the least jot of disloyalty,’ did not altogether escape the contagion. In the latter town a chapel had long been connived at, but the municipal officers firmly repressed the agitation and even committed a man who had ventured to express a hope of open toleration. Mountjoy declared himself satisfied, but a note in his hand shows that he was still suspicious. Probably he thought it wiser not to have north and south upon his hands at the same time.[2]

On the evening of March 26, Carey reached Holyrood with the news of Queen Elizabeth’s death, and on the 28th Mountjoy was appointed Lord Deputy by Privy Seal. Before this was known in Ireland the Council there had elected him Lord Justice according to ancient precedent; so that practically there was no interregnum. Ulster was now almost quiet, and the Viceroy could draw enough troops from thence to make any resistance by the corporate towns quite hopeless. On April 27 he marched southwards with about 1,200 foot, of whom one-third were Irish, and 200 horse. At Leighlin he was joined by Ormonde, who had been opposed by the Kilkenny people acting under the advice of Dr. James White of Waterford, a Jesuit, and of a Dominican friar named Edmund Barry, who was said to be James Fitzmaurice’s son. Ormonde was accompanied by Sir Richard Shee, the sovereign, who was an adherent of his, and Mountjoy was easily induced to pardon the townsmen upon their making humble submission. Dr. White was vicar-apostolic in Waterford, and his authority seems to have been recognised in Ossory also, there being at this time no papal bishop in either diocese. He forbade the people to hear mass privately, and enjoined them to celebrate it openly in the churches, some of which he[Pg 4] reconsecrated. Barry went so far as to head a mob in attacking the suppressed convent of his order, which was used as a sessions-house. The benches and fittings were broken up, and the conqueror said mass in the desecrated church. This friar came to Mountjoy, said that he had believed himself to be acting in a way agreeable to the King, and promised to offend no further now that his Majesty’s pleasure to the contrary was known. The Lord Deputy did not enter Kilkenny, but went straight to Thomastown, which had behaved in the same way. The town being small and penitent, it was thought punishment enough that the army should halt there for the night. Wexford had already fully submitted by letter, and Mountjoy marched from Thomastown to within four miles of Waterford, and there he encamped on the fourth day after leaving Dublin.[3]

The Suir at Waterford was unbridged until 1794, and the citizens doubtless thought that Mountjoy would be long delayed upon the left bank. But Ormonde, who had proclaimed King James at Carrick some weeks before, now brought enough boats from that place to carry over the whole army. Mountjoy encamped at Gracedieu, about a mile and a half above the city. There could now be no question of resistance, but some of the citizens came out and pleaded that by King John’s charter they were not obliged to admit either English rebel or Irish enemy, though they would receive the Deputy and his suite. As against a viceroy this argument was in truth ridiculous, and the Lord Deputy had only to say that his was the army which had suppressed both rebels and enemies. If resistance were offered he would cut King John’s charter with King James’s sword. It was then urged that the mayor had no force to restrain the mob unless the popular leaders could be gained over. Mountjoy consented to see Dr. White—who had just preached a sermon at St. Patrick’s, in which he called Queen Elizabeth Jezebel—and a Dominican friar who had acted with him. Sir Nicholas[Pg 5] Walsh the recorder had been pulled down from the market cross when he attempted to proclaim King James, and Sir Richard Aylward, who was a Protestant, had escaped with difficulty, some citizens expressing regret that they had not both lost their heads. Walsh thought he owed his preservation more to having relations among the crowd than to any dregs of loyal compunction. The Jesuit and the Dominican now came to the camp in full canonicals and with a cross borne before them, which Mountjoy at once ordered to be lowered. White fell on his knees, protesting his loyalty and acknowledging the King’s right. A discussion arose as to the lawfulness of resistance to the royal authority, and the book learning which Essex had made a reproach to Mountjoy now stood him in good stead. According to one not very probable account, the Lord Deputy had a copy of St. Augustine in his tent, and convicted White of misquoting that great authority. ‘My master,’ he said, ‘is by right of descent an absolute King, subject to no prince or power upon the earth; and if it be lawful for his subjects upon any cause to raise arms against him, and deprive him of his regal authority, he is not then an absolute King, but hath only precarium imperium. This is our opinion of the Church of England, and in this point many of your own great doctors agree with us.’ James was of course no absolute king in our sense of the word, for he had no power to impose taxes; but the long reign of Elizabeth, the wisdom which had on the whole distinguished her, and the terrible dangers from which she saved England, had taught men to look upon the sceptre as the only protection against anarchy or foreign rule. Experience of Stuart kingcraft was destined to modify public opinion.[4]

White was allowed to return to Waterford, being plainly told that he would be proclaimed a traitor unless he pronounced it unlawful for subjects to resist their sovereign. The prospect of being hanged by martial law quickened his theological perceptions, and he came back after nightfall with the required declaration. Lord Power also came to make peace for the townsmen, and Mountjoy promised to intercede[Pg 6] for them with the King. Next morning the gates were occupied, at one of which the acting mayor surrendered the keys and the civic sword. The latter was restored to the corporation, but the keys were handed to the provost-martial. Sir Richard Aylward was brought back in triumph, bearing the King’s sword before the Viceroy, who grimly remarked that he would leave a garrison of 150 men in one of the gate-towers so that the mob might not again prove too strong for the mayor. An oath of allegiance was generally taken even by the priests, but White and two other Jesuits seem to have avoided putting their names to it. Mountjoy notes with just pride that his soldiers, drawn out of the hungry north and excited by the hope of plunder, did not do one pennyworth of mischief in the city, though provisions were exorbitantly dear. The place was at their mercy all day, but the whole force, except the 150 men, evacuated it in perfect order before nightfall.[5]

The Irish Catholics were at this time more or less persecuted, and toleration is so excellent a thing that the historical conscience is likely to be in favour of those who claimed it. But in the then state of Ireland it is doubtful whether the public exercise of both religions was possible. The sovereign of Wexford said his fellow townsmen would have been satisfied with the use of one church without any meddling with tithes or other property of the Establishment. But the ultramontane priests, though they might have provisionally accepted this in some large towns, aimed at complete supremacy, and they were the real popular guides. Mr. Pillsworth, the parson of Naas, when he saw the people flocking to high mass, fled to Dublin and thence to England. He may have been a timid man, but his terror was not altogether unfounded. At Navan, another clergyman named Sotherne, accompanied by several gentlemen, saw two friars in the dress of their order and began to question them in the King’s name. ‘James, King of Scotland,’ said the elder of the two in Latin, ‘is a heretic; may he perish with thee and with all who have authority under him.’ Sotherne charged him with high[Pg 7] treason, but the constable was foiled by the mob who gathered round him. ‘Thy companions,’ said the friar, ‘are no Christians since they suffer thee among them,’ and he repeated this several times in Irish for the benefit of the bystanders. A Mr. Wafer, who said he had known the friar for twenty years, and that he was an honest man, rebuked Sotherne as a ‘busy companion,’ and pointedly observed that he would get no witnesses to support his charge of treason. As some of the crowd seemed bent on violence, Sotherne bade the constable do nothing for this time, and so returned to his lodging. He remonstrated afterwards with Wafer, who said that he ‘thought no less, but I would grow a promoter, and that was cousin-german to a knave; wishing his curse upon all those that would assist in apprehending either friar or priest.’ And popular opinion was entirely on Mr. Wafer’s side.[6]

But perhaps the best testimony is that of two Irish Jesuits, writing to their own general, and not intending that profane eyes should ever see what they had written:—‘From our country we learn for certain that the Queen of England’s death being known in Waterford, Cork, and Clonmel, principal towns of the kingdom, the ministers’ books were burned and the ministers themselves hunted away, and that thereupon masses and processions were celebrated as frequently and upon as grand a scale as in Rome herself. The Viceroy did not like this, and sent soldiers to garrison those towns, as he supposed, but the beauty of it is that those very soldiers vied with each other in attending masses and Catholic sermons. In the metropolitan city of Cashel, to which we belong, there was one solitary English heretic, and, on the news of the Queen’s death being received, they threatened him with fire and every other torment if he would not be converted. Fearing to be well scorched he made himself a Catholic, whereupon the townsmen burned his house, so that even a heretic’s house should not remain in their city. But when the Viceroy came near enough to threaten Cashel, and the[Pg 8] Englishmen came forward to accuse the townsmen, he merely ordered them to rebuild the house at their own expense.... I only beg your Paternity to show this letter to the most illustrious and most reverend Primate of Armagh (Peter Lombard), and to excuse me for not having written to him specially because I am unwilling to multiply letters in these dangerous times.’[7]

The mere approach of Mountjoy was enough to overawe Cashel, Clonmel, and the other inland towns. Limerick was bridled by the castle, and the disorders there did not come to much. But at Cork things took a much more serious turn. When leaving Ireland Carew had left his presidential authority in the hands of Commissioners, of whom Sir Charles Wilmot was the chief. The corporation of Cork now declared that the Commissioners’ authority ceased on the demise of the Crown, and that they were sovereign within their own liberties. Captain Robert Morgan arrived at Cork on April 11 with a copy of the proclamation and orders for the Commissioners from Mountjoy. Wilmot was in Kerry stamping out the embers of Lord Fitzmaurice’s insurrection, and Sir George Thornton, who was next in rank, called upon the civic authorities to proclaim King James. Thomas Sarsfield was mayor, and he might have obeyed but for the advice of William Meade, the recorder, who defied Thornton to exercise any authority within the city, reminding him that too great alacrity in proclaiming Perkin Warbeck had brought great evils upon the kingdom. Being rebuked by Boyle for breaking out into violent language, he replied that there were thousands ready to break out. Power was claimed under the charter to delay for some days, and Meade sent a messenger to Waterford for information as though the Lord Deputy’s letters were unworthy of credit. Captain Morgan vainly urged that he had himself been present when Ormonde, the most cautious of men, had proclaimed the King at Carrick-on-Suir. Thornton and the other Commissioners, including Chief Justice Walsh[Pg 9] and Saxey the provincial Chief Justice, were kept walking about in the streets while the corporation wasted time, and at last they were told that no answer could be given until next day. The mayor and recorder protested their loyalty, but pretended among other things that time was necessary to enable them to make due preparation. In vain did Thornton and his legal advisers insist on the danger of delay, and upon the absurdity of Cork refusing to do what London and Dublin had done instantly. Meade would listen to nothing; and one clear day having elapsed since Morgan’s arrival, Thornton went with his colleagues and about 800 persons to the top of a hill outside the town, where he solemnly proclaimed King James. Lord Roche was present, and the country folk seemed quite satisfied. The mayor soon followed suit at the market cross. The ceremonial of which the corporation had made so much was only the drinking of a hogshead of wine by the people, and no doubt that was a function which the citizens were always ready to perform at the shortest notice.[8]

Mass was now openly celebrated, the churches reconsecrated in the recorder’s presence, and the Ten Commandments in the cathedral scraped out so as to make some old pictures visible. The town was full of priests and friars, one of whom claimed legatine authority, and ‘they had the cross carried like a standard before them throughout the streets,’ every one being forced to reverence it. It was openly preached that James was no perfect king until he had been confirmed by the Pope, and that the Infanta’s title was in any case better. Gradually these tumultuary proceedings ripened into open insurrection, and 200 young men in two companies were ordered to be armed and maintained by the citizens. It was indeed proposed to arm the whole population from twelve to twenty-four years, but there was not time for this. Lieutenant Christopher[Pg 10] Murrough, who had served the League in France, was active during the whole disturbance. The mayor, who vacillated between expressions of loyalty and acts of disrespect to the new sovereign, had evidently the idea of a free city in his head, and said he was ‘like the slavish Duke of Venice and could not rule the multitude.’[9]

‘I myself,’ says an eye-witness, ‘saw in Cork on Good Friday a procession wherein priests and friars came out of Christ’s Church with the mayor and aldermen, and best of citizens going along the streets from gate to gate all singing, and about forty young men counterfeiting to whip themselves. I must needs say counterfeiting because I saw them (although bare-footed and bare-legged), yet their breeches and doublets were upon them, and over that again fair white sheets, everyone having a counterfeit whip in his hand—I say a counterfeit whip because they are made of little white sticks, everyone having four or five strings of soft white leather neither twisted nor knotted—and always as their chief priest ended some verses which he sung in Latin these counterfeits would answer miserere mei, and therewith lay about their shoulders, sides, and backs with those counterfeit whips; but I never saw one drop of blood drawn, therefore their superstition is far worse than the Spaniards’, who do use such whipping upon their bare skin, that the blood doth follow in abundance, which they do in a blind zeal, and yet it is far better than those counterfeits did.’[10]

Cork was then a walled town, but being commanded by high ground can never have been strong. Outside the south gate and bridge and not far from where the Passage railway station now stands Carew had begun to build a fort with the double object of overawing the town and of[Pg 11] intercepting a foreign enemy. After the battle of Kinsale the work had been discontinued, and no guns were mounted. The north gate was commanded by Shandon Castle, which was in safe hands. The east and west sides of the city were bounded by the river, which ran among marshy islands. The approach from the open sea was partly protected by a fort on Haulbowline Island, at the point where the Lee begins finally to widen out into the great harbour, and the seditious citizens had visions of destroying this stronghold, which the recorder pronounced useless and hurtful to the corporation. Inside the town and near the north gate was an old tower known as Skiddy’s Castle, used as a magazine for ammunition and provisions. The citizens refused to allow stores to be carried out to the soldiers and at the same time obliged them to remain outside. One alleged grievance was that two guns belonging to the corporation were detained at Haulbowline, and Thornton against Boyle’s advice exchanged them for two in the town which belonged to the King. Lieutenant Murrough was placed in charge of Skiddy’s Castle, every Englishman’s house was searched for powder, ‘a priest being forward in each of these several searches,’ and the inmates expected a general massacre. Sir George Thornton left the town, Lady Carew took refuge in Shandon, and Lord Thomond’s company was sent for. Wilmot arrived with his men when the disturbances had lasted for more than a week, but the townsmen would not listen to reason, and began to demolish Carew’s unfinished fort. The recorder admitted that he had instigated this act of violence. Wilmot took forcible possession of the work, but forbade firing into the town on pain of death. The inhabitants then broke out into open war, sent round shot through the Bishop’s palace where the Commissioners lodged, and killed a clergyman who was walking past. They severely cannonaded Shandon, but, as Lady Carew reported, ‘never did any harm to wall or creature in it,’ and did not frighten her in the least.

On May 5 Thornton brought up a piece of Spanish artillery from Haulbowline, and when three or four shots had[Pg 12] pierced houses inside the walls, a truce was made. Five days later Mountjoy arrived.[11]

The question of a legal toleration for the Roman Catholics and of municipal freedom for the town had been carefully mixed up together, and the possession of all Government stores by the citizens made the rising troublesome for the moment if not actually formidable. The chief commissary, Mr. Allen Apsley, was the mayor’s prisoner from April 28 to May 10, and his evidence fortunately exists. First there was an attempt to get the troops out of the neighbourhood by refusing provisions which were undoubtedly the King’s property. At last it was agreed that the stores should be removed by water to Kinsale, but the opportunity was taken to extort an extravagant freight, and when the vessel was laden she was not allowed to leave the quay. After Wilmot’s arrival on April 20 or 21, it was pretended that he wished to get possession of the town by treachery, and the mayor said he was ‘as good a man and as good a gentleman as Sir Charles Wilmot, if the King would but knight him, and give him 200 men in pay, and the like idle comparisons.’ Four days later this valiant doge had guns mounted on the gates, and the provisions and powder were disembarked again. The mayor first tried to make Apsley swear to answer all his questions, and on his refusal confined him to his own house. Two days later the recorder put him into the common gaol, and bail was refused. There seems to have been an attempt to make out that Apsley had committed treason by helping Wilmot to get possession of the stores, but of this even there was no proof.[12]

Meade and his party strongly urged that Mountjoy should be forcibly resisted, but more prudent counsels prevailed, and the town had to receive a garrison of 1,000 men. The chief points having been occupied by his soldiers, the Lord Deputy entered by the north gate, and saw ploughs ranged on both sides of the street as if to show that the extortion of the soldiers had made the land lie idle. The[Pg 13] old leaguer Murrough, a schoolmaster named Owen MacRedmond, who had openly maintained the Infanta’s title, and William Bowler, a brogue-maker, were hanged by martial law. The recorder, who had land, was reserved for trial, and was ultimately acquitted by a jury at Youghal, though he was undoubtedly guilty of treason by levying war. The foreman was fined 200l. and the rest 100l. apiece, but it became evident that no verdict could be expected in any case where matters of religion might be supposed in question. Meade went abroad and remained in the Spanish dominions for many years. He is heard of at Naples, too poor to buy clothes for a servant, but in 1607 he was at Barcelona and receiving a pension of 11l. per month. In 1611 he wrote a letter of advice to the Catholics of Munster, grounded on the Act 2 Eliz., chap. 2, in which he showed that they were not bound to go to church, but the attempt to enforce attendance had then been practically abandoned.[13]

Mountjoy left Ireland on June 2, 1604, after being sworn in as Lord Lieutenant, and he never returned. He was created Earl of Devonshire, and continued till his death to have a decisive voice in the affairs of the country which he had reduced. Vice-Treasurer Sir George Carey was made Deputy, and was at once engaged with the currency question, for the state of the coinage had furnished a pretext to the Munster malcontents, and may really have had something to do with their late proceedings. He soon had the help of Sir John Davies, a native of Wiltshire, whose name is inseparably connected with Irish history, but who had been hitherto better known as a poet than as a statesman. It was perhaps the striking example of Hatton’s promotion that made the young barrister sing of dancing, but it was a poem on the immortality of the soul which attracted the King’s attention. Devonshire wished him to be made Solicitor-General for Ireland, and James readily complied. He arrived in[Pg 14] November, and found the country richer than he supposed after all the wars, but suffering from the uncertainty caused by a base coinage.

The money issued in 1601 contained only 25 per cent. of silver, but it was easily counterfeited with a much greater alloy, and interested people gave out that it contained no silver at all. Soon after his accession James consented to revert to the old practice of Ireland, and to establish a currency containing 75 per cent. of silver; but this was ordered by proclamation to be received as sterling. The name sterling had hitherto been applied to the much purer coinage of England, and a new element of confusion was thus introduced. The base coin of 1601 was cried down at the same time, so that a shilling should be received for fourpence of the new money. When Davies arrived he found that people would not take the dross even at the reduced rate, and they were even more unwilling to do so when another proclamation cried down the new and comparatively pure shillings also from twelvepence to ninepence. The King had granted 20,000 pardons in a few months, but Davies was of opinion that he would gain more popularity by giving twopence for every bad shilling and then recalling the whole issue than by all his clemency. The Solicitor-General could speak feelingly, his fees on all the pardons being paid in copper, while the royal revenue was in the same way reduced almost to nothing. Soldiers and officials were the greatest losers, for they had to take what the proclamations allowed, while traders could not be forced to do so. A few were sent to prison for refusing, but this only caused discontent without securing obedience, and there was a riot at Galway. The matter was brought to a crisis by a case decided in the summer of 1604.[14]

The bad money was proclaimed current in May 1601, and in April, while the pure coin of England was still current in Ireland, one Brett of Drogheda, merchant, having bought wares from one Gilbert, in London, became bound to Gilbert[Pg 15] for 200l. on condition to pay the said Gilbert, his executors or assigns 100l. sterling current and lawful money of England at the tomb of Earl Strongbow in Christchurch, Dublin, on a certain future day, which day happened after the said proclamation of mixed monies. On that day Brett tendered 100l. in mixed money of the new standard. The question was whether this tender was good. Sir George Carey, being Deputy and Vice-Treasurer, ordered the case to be stated for the judges who were of the Privy Council, and they decided after an immense display of learning that Brett had rightly tendered in the only lawful money of Ireland, that Gilbert was worthy of punishment for refusing to receive it, and that the Irish judges could take cognisance of no money except what was established by proclamation. The several courts of record in Dublin accepted this as law, and all the cases pending were so decided. In other words, Ireland repudiated the greater part of her debts. The situation created was intolerable, for credit was destroyed; but it was not till the beginning of 1605 that the English Government made up its mind that the various kinds of coin in Ireland might be lawfully current for their true value. In 1607 English money was made legal tender in Ireland at the rate of sixteen pence Irish to the shilling. All who knew the country best wished to have one coinage for England and Ireland, but official hindrances were constantly interposed, and the difficulty was not got over until after the unification of the two Exchequers in 1820. Some establishment charges are still paid with deductions for the difference between old Irish and sterling money.[15]

Carey retained the Vice-Treasurership along with the acting Viceroyalty, the power of the sword and of the purse being thus held in a single hand. Under these circumstances it is not surprising that charges of extortion should have been brought against him, and that he should be accused of having become very rich by unlawful means. He had only[Pg 16] one-third of the viceregal salary, two-thirds being reserved for Devonshire as Lord-Lieutenant. There is no evidence that Salisbury or Davies gave much credit to the charges against Carey, who was himself anxious to be relieved, and who suggested that Sir Arthur Chichester should fill his place. Chichester, who had gained his experience as Governor of Carrickfergus, at first refused on the ground that he could not live on one-third of the regular salary, and he was given an extra 1,000l. per annum with 500l. for immediate expenses. He remained at the head of the Irish Government until 1616.[16]

[1] Lord Deputy and Council to the Privy Council, April 6; Tyrone to Cecil, April 7; submission of Tyrone, April 8; Godolphin to Carew, April 19. Farmer’s chronicle of this reign begins at p. 40 of MS. Harl. 3544 with a panegyric on ‘Elizabeth the virgin Queen and flower of Christendom that hath been feared for love and honoured for virtue, beloved of her subjects and feared of her enemies, magnified among princes and famozed through the world for justice and equity.’ Since these chapters were written Farmer’s book has been printed by Mr. Litton Falkiner in vol. xxii. of the English Historical Review.

[2] In Cambrensis Eversus, published in 1662, John Lynch says ‘the Irish no longer wished to resist James (especially as they believed that he would embrace the Catholic religion), and submitted not unwillingly to his rule, as to one whom they knew to be of Irish royal blood,’ iii. 53. Lynch was a priest in 1622. Stephen Duff, Mayor of Drogheda, to the Lord Deputy and Council, April 13; Mountjoy to Cecil, April 19, 25 and 26; Francis Bryan, sovereign of Wexford, to Mountjoy, April 23. James VI. to Tyrone, December 22, 1597, in Lansdowne MSS. lxxxiv. Tyrone to James VI., April 1600 in the Elizabethan S.P. Scotland. Letters of Elizabeth and James, Camden Society, p. 141. Farmer’s Chronicle.

[3] Muster of the army, April 27; Lord Deputy and Council to the Privy Council, Mountjoy to Cecil, and Sir G. Carey to Cecil, May 4; Humphrey May to Cecil, May 5.

[4] Authorities last quoted; also Smith’s Waterford.

[5] Authorities last quoted; also Hogan’s Hibernia Ignatiana, p. 121.

[6] Hogan’s Hibernia Ignatiana, p. 118; Declaration of Edward Sotherne, June 16.

[7] Barnabas Kearney and David Wale to Aquaviva (Italian), July 7, 1603, from London, in Hibernia Ignatiana, p. 117. The burning of the service-book is mentioned in the official correspondence.

[8] Brief Declaration in Carew, 1603, No. 5; account written by Richard Boyle in Lismore Papers, 2nd series, i. 43. As clerk of the Munster Council Boyle was an eye-witness of all these proceedings. Moryson’s Itinerary, part ii. book iii. chap. 2.

[9] Brief Relation in Carew, 1603, No. 5; Irish State Papers calendared from April 20 to May 14; Lismore Papers, 2nd series, i. 43-73; Mountjoy to the Mayor of Cork, May 4, in Cox, p. 7. The full account in Smith’s Cork is mainly founded on the Lismore collection. Lady Carew’s letter of May 5, 1603, among the State Papers and Lady Boyle’s of March 18, 1609, in the Lismore Papers are both printed verbatim, and are interesting to compare as specimens of ladies’ composition.

[10] Farmer’s Chronicle in MS. Harl. 3544. Farmer was a surgeon.

[11] Authorities last quoted.

[12] Apsley’s account in Lismore Papers, 2nd series, i. 66.

[13] Notices of Meade in the Calendars of State Papers, Ireland, especially No. 355 of 1611, where his tract is entered as among the Cotton MSS. There is another copy in the Bodleian, Laudian MSS. Misc. 612, f. 143. The proceedings at Meade’s trial are calendared under 1603, No. 184.

[14] Davies to Cecil, December 1, 1603; proclamations calendared at October 11 and December 3.

[15] Le Case de Mixt Moneys, Trin. 2 Jacobi in Davies’ Reports, 1628; State of the Irish coin, calendared at June 12, 1606; Lord Deputy Chichester and Council to the Privy Council, calendared at March 2, 1607.

[16] Chichester was sworn in February 3, 1604-5.

The question of religious toleration was one of the first which Chichester had to consider, for the movement in the Munster towns was felt all over Ireland. Priests and Jesuits swarmed everywhere, and John Skelton on being elected Mayor of Dublin refused after much fencing to take the oath of supremacy. Sir John Davies, who had yet much to learn in Ireland, thought that the people would quickly conform if only the priests were banished by proclamation. Saxey, chief justice in Munster, was much of the same opinion, but both these lawyers admitted the insufficiency of the Established Church. The bishops, among whom there were scarcely three good preachers, seemed to them more anxious about their revenues than about the saving of souls.

The experience of James’s only Irish Parliament was to show it was scarcely possible to legislate against the Roman Catholics even when many new boroughs had been created for the express purpose of making a Protestant majority. The Act of Uniformity passed at the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign remained in force, but little was done under it as long as she lived. It only provided a fine of one shilling for not attending church on Sundays and holidays, and could have little effect except upon the poor, though it might give great annoyance. Another Act prescribed an oath acknowledging the Queen’s supremacy, both civil and ecclesiastical, and denying that any ‘foreign prince, person, prelate, State, or potentate hath or ought to have any jurisdiction,’ &c. This oath might be administered to all ecclesiastical persons, to judges, justices, and mayors, and to all others in the pay of the Crown on pain of losing their offices. The open maintenance and advocacy of foreign authority was more severely[Pg 18] visited, the penalties being the forfeiture of all goods and chattels, real and personal, with a year’s imprisonment in addition, for those not worth 20l. The second offence was a præmunire, and the third high treason. And so the law remained during the whole reign of James. The English oath of allegiance prescribed after the Gunpowder Plot involved a repudiation of the Pope’s deposing power; but this was not extended to Ireland.[17]

The repressive power in the hands of the Irish Government was weak as against the population in general, but so far as law went it was ample against the priests, who, of course, could not take the oath of supremacy; and against officials who were of the same way of thinking. Mountjoy was successful against the recalcitrant towns, but his back was no sooner turned than Sir George Carey reported that the country swarmed with ‘priests, Jesuits, seminaries, friars, and Romish bishops; if there be not speedy means to free this kingdom of this wicked rabble, much mischief will burst forth in a very short time. There are here so many of this wicked crew, as are able to disquiet four of the greatest kingdoms in Christendom. It is high time they were banished, and none to receive or aid them. Let the judges and officers be sworn to the supremacy; let the lawyers go to the church and show conformity, or not plead at the bar, and then the rest by degrees will shortly follow.’ Protestant bishops naturally agreed, though Sir John Davies thought their own neglect had a good deal to say to the matter; but he admitted that the Jesuits came ‘not only to plant their religion, but to withdraw the subject from his allegiance, and so serve the turn of Tyrone and the King of Spain.’ Now that Ireland was at peace, he thought it probable that they would gladly go away, and cites the case of Fitzsimon, a Jesuit who had petitioned to be banished. Fitzsimon, however, had been five years a prisoner in the Castle, during one month of which he had converted seven Protestants, including the head[Pg 19] warder. The King released him mainly on the ground that he did not meddle in secular matters, and he was on the Continent till 1630, when he returned to Ireland and lived there till long after the great outbreak of 1641. About the time of Fitzsimon’s release the Protestant Bishop of Ossory was able to give the names of thirty priests who haunted his diocese, including the famous Jesuit James Archer, who was said to have legatine authority. Archer was closely connected with Tyrone, and had been his frequent companion in London, disguised as a courtier or as a farmer, and busy with Irish prisoners in the Tower. Davies advised that priests and Jesuits should be captured when possible and sent to England, where the penal laws could take hold of them; and if this were done, he thought all Ireland would go comfortably to church. Chief Justice Saxey gave much the same advice in a more truculent form. The opinions of all Englishmen officially concerned with Ireland are reflected in the King’s famous proclamation of July 4, 1605, which Chichester, who had then succeeded to the government, found awaiting him in Dublin on his return from the north.[18]

James begins by repudiating the idea prevailing in Ireland since the Queen’s death that he intended ‘to give liberty of conscience or toleration of religion to his subjects in that kingdom contrary to the express laws and statutes therein enacted.’ He insisted everywhere on uniformity, resenting all rumours to the contrary as an imputation on himself, and even, as was reported, declaring that he would fight to his knees in blood rather than grant toleration. Owing to false rumours, the Jesuits and other priests of foreign ordination had left their lurking-places and presumptuously exercised their functions without concealment. The King therefore announced that he would never do any act to ‘confirm the hopes of any creature that they should ever have from him any toleration to exercise any other religion than that which[Pg 20] is agreeable to God’s Word and is established by the laws of the realm.’ All subjects were therefore charged to attend church or to suffer the penalties provided. As to the Jesuits and others who sought to alienate their hearts from their sovereign, ‘taking upon themselves the ordering and deciding of causes, both before and after they have received judgments in the King’s courts of record ... all priests whatsoever made and ordained by any authority derived or pretended to be derived from the See of Rome shall, before the 10th day of December, depart out of the kingdom of Ireland.’ All officers were to apprehend them and no one to harbour them, on pain of the punishments provided by law. If, however, any such Jesuit or priest would come to the Lord Lieutenant or Council, conform, and repair to church, he was to have the same liberties and privileges as the rest of his Majesty’s subjects.

Devonshire, however, who was still Lord Lieutenant, was opposed to making any curious search for priests who did not ostentatiously obstruct the Government, and his views prevailed with the English Council. Chichester willingly acquiesced, and reported some weeks after the appointed day that no priests, seminaries, or Jesuits of any importance had left the country and that searches, even if desirable, would be useless, ‘for every town, hamlet, or house is to them a sanctuary.’ Just about Carrickfergus, where he was personally known, some secular priests had conformed, and Davies, who thought Government could do everything, believed the multitude would naturally follow. ‘So it happened,’ he said, ‘in King Edward the Sixth’s days, when more than half the kingdom of England were Papists; and again in the time of Queen Mary, when more than half the kingdom were Protestants; and again in Queen Elizabeth’s time, when they were turned Papists again.’ He did not see that the national sentiment of England was permanently hostile to Roman aggression, while the authority of the Crown was accepted as the only refuge against anarchy. The state of feeling which existed in Ireland was just the opposite.[19]

Sir John Everard, second justice of the King’s Bench, was ordered to conform or resign, though admitted to be a very honest and learned man. It was so difficult to find a successor for this able judge that he was continued in office for eighteen months after the King’s order, when he resigned rather than take the oath of supremacy. Of his loyalty in civil matters there was no question, and he received a pension of a hundred marks, which Chichester wished to make a hundred pounds. In 1608, when the Irish refugees in Spain contemplated a descent upon Ireland, Everard refused to take part in the plot, and he lived to contest the Speakership with Sir John Davies in the Parliament of 1613.[20]

December passed, and yet none of the priests had left the country. The Gunpowder Plot was discovered in the meantime, but there was no evidence of ramifications in Ireland, and the English Government half drew back from the policy of the late royal proclamation. It was decided, and apparently at Chichester’s suggestion, that no curious search should be made for clergymen of foreign ordination. The immediate result of the severe measures taken in England was to drive the Jesuits and other priests over to Ireland, where the law was weaker and less perfectly enforced, and where they were sure of a good reception.

Robert Lalor, who had for twelve years acted as Vicar-General in Dublin, Kildare, and Ferns, was, however, arrested. He had powerful connections in the Pale, and it was thought that his prosecution might strike terror into others, more especially as he was a party to many settlements of land. Lalor was convicted under the Irish Act of 1560 as an upholder of foreign jurisdiction in matters ecclesiastical, and remained in prison for some months. He then petitioned the Deputy for his liberty, and was induced to[Pg 22] confess in writing that he was not a lawful Vicar-General, that the King was supreme governor, without appeal, ‘in all causes as well ecclesiastical and civil,’ and that he was ready to obey him ‘either concerning his function of priesthood, or any other duty belonging to a good subject.’ After this his imprisonment was greatly relaxed, and he was allowed to see visitors freely, to whom he boasted that he had not allowed the King any power in spiritual causes. It was then resolved to indict him under the Statute of Præmunire (16 Richard II.), which was of undoubted force in Ireland, for receiving a papal commission, for assuming the office so conferred, and for exercising every kind of episcopal jurisdiction under it, especially ‘by instituting divers persons to benefices with cure of souls, by granting dispensations in causes matrimonial, and by pronouncing sentences of divorce between divers married persons.’ The case was tried by a Dublin city jury, and all the principal gentlemen in town were present as spectators. Lalor tried to draw a distinction between ecclesiastical and spiritual, but this was quickly overruled, and his former confession was read out in open court. Davies went into the legal argument at great length, and in the end Lalor was fain to renounce the office of Vicar-General and to crave the King’s pardon. The jury then found the prisoner guilty, and in the absence of Chief Justice Ley, Sir Dominick Sarsfield gave judgment accordingly. Part of the penalty was the forfeiture of goods, and this was important, because the Earl of Kildare and other great proprietors had used the late Vicar-General’s services as a trustee, and the Crown lawyers had thus a powerful engine placed in their hands. Lalor was probably banished according to law, as his name disappears from the State correspondence. He had ceased to be of any importance, for his confession destroyed his influence with the recusants.[21]

The Irish Statute of 1560 was the only one available for coercing the laity, and its fine of one shilling, even when[Pg 23] swelled by costs, was altogether insufficient to impress the gentry or wealthier traders, and it was resolved to eke it out by recourse to the prerogative pure and simple. All men’s eyes naturally turned to the seat of government, and the first example was made there. Mandates under the Great Seal were directed to sixteen aldermen and merchants, of whom Skelton, the late mayor, was one, ordering them to go to church every Sunday and holiday, ‘and there to abide soberly and orderly during the time of common prayer, preaching, or other service of God.’ They refused upon grounds of conscience, and the case was tried in the Castle Chamber. During the proceedings and while the court was crowded, Salisbury’s dispatch arrived with the news of the Gunpowder Plot, and Chichester ordered it to be read out by Bishop Jones, who had just been made Lord Chancellor, and who took the opportunity to make a loyal speech. This dramatic incident may or may not have influenced the decision which imposed a fine of 100l. upon six aldermen and of 50l. each upon three others, one of whom, being an Englishman, was ordered to return to his own country. Five days later similar sentences were passed upon three more, while three were reserved to try the effect of a conference with Protestant theologians. One of the sixteen escaped altogether by conforming to the established religion, and he was the only one who did conform. This could not be thought a brilliant success, and the mandates were soon subjected to a direct attack.[22]

In the province of Munster, where Sir Henry Brouncker succeeded Carew in the summer of 1604, a more energetic course was followed. Brouncker had for many years farmed the customs of wine imported into Ireland, and had probably in that way learned much of the underground communications with Spain. He found Cork swarming with priests and seminaries who said mass almost publicly in the best houses and strenuously maintained that it was ‘his Majesty’s pleasure to tolerate their idolatry.’ For a time he was interrupted by[Pg 24] the plague, but soon resumed his efforts to fill the churches and to apprehend the priests of Rome. His idea was to clear the towns while leaving the country districts alone, but he had little success, for the proscribed clergy were everywhere favoured and harboured in gentlemen’s houses under the name of surgeons and physicians. Brouncker maintained that he was of a mild disposition, but that he was driven by the obstinacy of the people to take sharp courses. In one circuit of his province he deposed the chief magistrates in every town except Waterford, ‘where the mayor was conformable,’ and he threatened them all with the loss of their charters. He thought it possible to collect enough fines to make the black sheep support the white.

At Limerick he captured Dr. Cadame, a notable priest long resident there, but at Carrick-on-Suir two of the worst priests in Ireland just eluded him. William Sarsfield, mayor of Cork, had been fined 100l. for disobedience to the mandates in the summer of 1606. The general answer given by him and others in the same position was ‘that their forefathers had continued as they were in the Popish religion, and that their consciences tied them to the same,’ not one of them, according to Brouncker’s return, ‘being able to define what conscience was.’ Before the year was out, the President was able to report that Sarsfield, in spite of his Spanish education and his first stubbornness, had ‘by a little correction been brought to church, and so in love with the word preached, and so well satisfied in conscience, that he offered to communicate with him.’ This sounds rather like a profane joke by a man who had been brought up among the countrymen of Suarez and Escobar, and in any case conformity so obtained was of little value. Bishop Lyon, however, had done his duty in providing preachers in his diocese, and perhaps some real progress might have been made if all bishops had been like him. At all events there was a congregation of 600 at Youghal, and some tendency to conformity was apparent even to Chichester’s eyes. Both President and Bishop received the thanks of the English Council, and Salisbury encouraged Brouncker to persevere, but when he died[Pg 25] in the following spring James found that ‘his zeal was more than was required in a governor, however allowable in a private man.’ It was not easy to serve a sovereign who insisted on proclaiming the duty of persecution while shrinking from the unpopularity which his own words naturally produced. The fines imposed at Kinsale were altogether remitted in regard to the poverty of the town, elsewhere they were much reduced. The total, however, was considerable, while individuals were ‘reasonably well contented’ at escaping so easily.[23]

In Connaught Clanricarde had been made Lord President for his services at Kinsale, and no doubt his influence had been increased by his marriage to Essex’s widow. He was in England at the end of 1605, and Sir Robert Remington, the Vice-President, made some show of proceeding like Brouncker. Mandates were issued and a few fines imposed upon citizens of Galway, but these were not fully paid, and there is no evidence that anything was done outside that single town.[24]

A petition against interference ‘with the private use of their religion and conscience’ was presented to the Lord Deputy, and signed by two hundred and nineteen gentlemen of the Pale, of whom five were peers. The principal framer of this document was probably Henry Burnell, the lawyer, who was now very old, but who was still the same man who had opposed Sidney thirty years before, and Richard Netterville, who had then been his colleague. The chief promoter was Sir Patrick Barnewall, who was Tyrone’s brother-in-law, and from whose house of Turvey the northern chief had eloped[Pg 26] with Mabel Bagenal in 1591. According to Carew, he was ‘the first gentleman’s son of quality that was ever put out of Ireland to be brought up in learning beyond the seas.’ The petition was presented to Chichester by Sir James Dillon and others during the last days of November, and an answer was soon pressed for. The movement being evidently concerted, and Catesby’s plot being very recent, Burnell and Netterville were restrained in their own houses on account of their infirmity, while Barnewall, Lord Gormanston, Dillon, and others were imprisoned in the Castle. Gormanston and three other peers forwarded a copy of the petition to Salisbury, and complained bitterly of the severe measures which had been taken against the aldermen for no offence but absence from the Protestant service. With something of prophetic instinct Barnewall expressed a fear that the Irish Government were laying the foundation of a rebellion, ‘to which, though twenty years be gone, the memory of those extremities may give pretence.’ Most of the prisoners were soon released on giving bonds to appear when called upon, but Barnewall had to go to England.[25]

What we mean by toleration was nowhere understood in the early part of the seventeenth century. Even Bacon, who admired the edict of Nantes, which had not wiped out the memory of St. Bartholomew, had no idea of abrogating the Elizabethan penal code. Henry IV.’s famous edict was an exception; it was one of the kind that proves the rule, for he saw no way of securing the French Protestants but by giving them a kind of local autonomy which could not last. Rochelle was an impossibility in a modern state, and when that frail bulwark was destroyed persecution gradually resumed its sway. Of Spain, the birthplace and fixed home of the Inquisition, it is unnecessary to speak. In Germany neither party practised any real toleration. In Italy Spanish interests were dominant, and Elizabeth died an excommunicated[Pg 27] Queen. Clement VIII. abstained from treating her successor in the same way, but he had hopes by mildness to obtain better terms for the faithful in England. Both in England and Ireland any intention of forcing men’s consciences was always disclaimed, while outward conformity was insisted on. And in the case of the Roman Catholics, who took their orders from a foreign and hostile power, it was really very difficult to say exactly how much belonged to Cæsar. Bacon was more liberal than anyone else, but his ideas fell very far short of what is now generally accepted. In Ireland, he advised Cecil, after the Spaniards had been foiled at Kinsale, ‘a toleration of religion (for a time not definite), except it be in some principal towns and precincts, after the manner of some French edicts, seemeth to me to be a matter warrantable by religion, and in policy of absolute necessity. And the hesitation in this point I think hath been a great casting back of the affairs there. Neither if any English Papist or recusant shall for liberty of his conscience transfer his person, family, and fortunes thither do I hold it a matter of danger, but expedient to draw on undertaking and to further population. Neither if Rome will cozen itself, by conceiving it may be some degree to the like toleration in England, do I hold it a matter of any moment, but rather a good mean to take off the fierceness and eagerness of the humour of Rome, and to stay further excommunications or interdictions for Ireland.’ Bacon saw the difficulty clearly, and perhaps he saw the working solution, but to persevere steadily in such a course was not in James’s nature, though Chichester might conceivably have done so if he had had a free hand.[26]

Sir Patrick Barnewall was committed prisoner to the Castle on December 2, 1605. ‘Well,’ said he, ‘we must endure as we have endured many other things, and especially the miseries of the late war.’ ‘No, sir,’ answered Chichester, ‘we have endured the misery of the war, we have lost our blood and our friends, and have indeed endured extreme miseries to suppress the late rebellion, whereof your priests, for whom you make petition, and your wicked religion, was[Pg 28] the principal cause.’ In writing to Salisbury afterwards Sir Patrick attributed the invention of the mandates to Chief Justice Ley, but it is much more likely that Davies was their author. After an imprisonment of three months, Barnewall was again brought before the Irish Council, and argued soundly in maintaining that recusancy was only an offence in so far as it was made one by statute, and that therefore all prosecution of it except that prescribed by Act of Parliament was illegal. At a further examination when the Chancellor, who was a bishop and ought to have known better, spoke of the King’s religion, Barnewall saw his advantage and exclaimed ‘That is a profane speech.’ He was not sent to England till near the end of April, and at the end of May the English Government had not yet found time to attend to him. At first he was allowed to live under restraint at his own lodgings in the Strand, but was afterwards sent to the Tower, probably with the idea of making an impression upon the public mind in Ireland. It was found impossible to answer his arguments, and the Privy Council asked the Irish Government for information as to the ‘law or precedent for the course taken in issuing precepts under the Great Seal to compel men to come to church.’ They admitted that such authority was ‘as yet unknown to them,’ but rather sarcastically supposed that the Lord Deputy and Council were better informed. The Irish Government were acting entirely by prerogative; but several of the judges in England pronounced the mandates not contrary to precedent or authority. Barnewall was induced to make some sort of submission more than a year after his original arrest. Being called upon to make one in more regular form he refused, and was then sent to the Fleet prison for a month. Having signed a bond to appear within five days of his arrival, he was returned to Ireland at the beginning of March, 1607, and Chichester at once saw that no progress had been made.

Barnewall refused to make any submission in Dublin, and in the end it was found necessary to drop all proceedings against him. His detention in London was really a triumph, for the Irish recusants regarded him as their agent, and sub[Pg 29]scribed largely for his support. Waterford contributed 32l. and the collection was general all over Ireland. He gained in fact a complete victory, and such progress as Brouncker had made in procuring outward conformity was at once arrested. The mandates were never again resorted to.[27]

[17] Irish Statutes, 2 Eliz. chaps. i. and ii. James I.’s Apology for the Oath of Allegiance against the two breves of Pope Paulus Quintus, &c., in his Works, 1616 (the oath is at p. 250).

[18] Enclosure in letter of John Byrd to Devonshire, September 8, 1603. Archbishop of Dublin and Bishop of Meath to the Privy Council, March 5, 1604. Davies to Cecil, April 19 and December 8. Bishop of Ossory to the Deputy and Council, June 8, 1604. Chief Justice Saxey to Cranbourne, 1604, No. 397. Hogan’s Life of H. Fitzsimon, pp. 58 sqq.

[19] Proclamation of July 4, 1605; Davies to Salisbury, No. 603 in Cal. Lords of the Council to Chichester, January 24, 1606; Chichester to Salisbury and to Chichester, February 26; Roger Wilbraham’s Diary, in vol. x. of the Camden Miscellany.

[20] Davies to Cecil, December 8, 1604, January 6, 1605; Saxey to Cecil, 1604, No. 397; the King to Chichester, June 27, 1605; his proclamation against toleration, July 4; Cornwallis to the Privy Council, April 19, 1608, in Winwood.

[21] The Case of Præmunire in Sir John Davies’s Reports, London, 1628. Lalor was arrested in March 1605-6, and finally convicted early in the following year.

[22] Lord Deputy and Council to the Privy Council, December 5, 1605; Chichester to Salisbury, December 7.

[23] Brouncker to Cecil, August 23 and October 17, 1604; Salisbury to Brouncker, March 3, 1606; Brouncker’s letter of September 12; Return of fines imposed 4 James I. printed in Irish Cal. ii. 41; Brouncker to the Privy Council, November 18; Chichester to Salisbury, December 1, 1606, and February 10, 1607; The King to Chichester, July 16, 1607; Privy Council to Chichester, January 17, 1608-9; Davies to Salisbury, June 10, 1609.

[24] Brouncker to Cecil, August 23, 1604; observation by Sir John Davies, May 4, 1606; Lord Deputy and Council to the Privy Council, September 12, 1606; Brouncker to the Privy Council, February 10, 1606-7. For Connaught see preface to State Papers, Ireland, 1606-1608, p. 46.

[25] Chichester to Salisbury, December 7 and 9, 1605; petition by the nobility and gentry of the English Pale, No. 593; Lords Gormanston, Trimleston, Killeen, and Howth to Salisbury, December 8; Davies to Salisbury, No. 603; Barnewall to Salisbury, December 16. Carew’s Brief Relation of passages in the Parliament of 1613 in Carew.

[26] Letter to Cecil, 1602, Spedding, iii. 49.

[27] Calendar of State Papers, Ireland, from December 1605 to September 1607.