This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

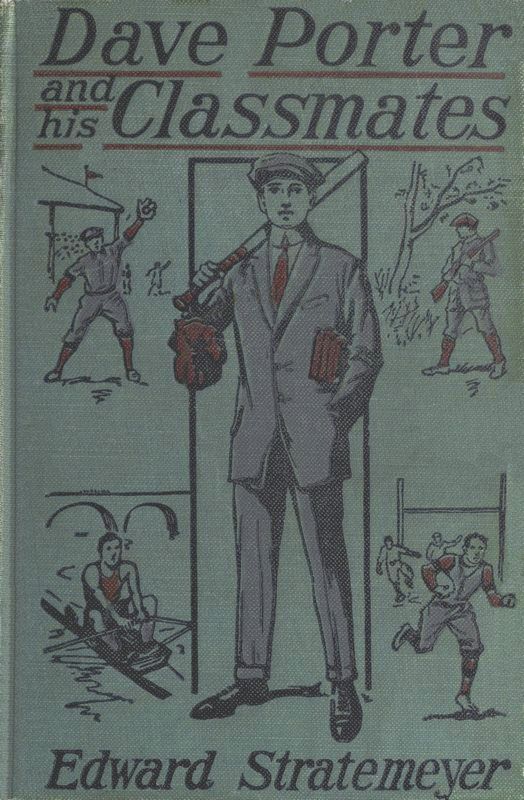

Title: Dave Porter and His Classmates

For the Honor of Oak Hall

Author: Edward Stratemeyer

Release Date: October 30, 2016 [eBook #53414]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DAVE PORTER AND HIS CLASSMATES***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/daveporterhiscla00straiala |

EDWARD STRATEMEYER'S BOOKS

Old Glory Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Net $1.75 per volume.

| UNDER DEWEY AT MANILA. | UNDER OTIS IN THE PHILIPPINES. | |

| A YOUNG VOLUNTEER IN CUBA. | THE CAMPAIGN OF THE JUNGLE. | |

| FIGHTING IN CUBAN WATERS. | UNDER MacARTHUR IN LUZON. |

Soldiers of Fortune Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Net $1.75 per volume.

| ON TO PEKIN. | AT THE FALL OF PORT ARTHUR. | |

| UNDER THE MIKADO'S FLAG. | WITH TOGO FOR JAPAN. |

Colonial Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Net $1.75 per volume.

| WITH WASHINGTON IN THE WEST. | ON THE TRAIL OF PONTIAC. | |

| MARCHING ON NIAGARA. | THE FORT IN THE WILDERNESS. | |

| AT THE FALL OF MONTREAL. | TRAIL AND TRADING POST. |

Mexican War Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Price Per volume $1.00.

| FOR THE LIBERTY OF TEXAS. | WITH TAYLOR ON THE RIO GRANDE. |

Pan-American Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.00.

| LOST ON THE ORINOCO. | YOUNG EXPLORERS OF THE AMAZON. | |

| THE YOUNG VOLCANO EXPLORERS. | TREASURE SEEKERS OF THE ANDES. | |

| YOUNG EXPLORERS OF THE ISTHMUS. | CHASED ACROSS THE PAMPAS. |

Dave Porter Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Net $1.75 per volume.

| DAVE PORTER AT OAK HALL. | DAVE PORTER ON CAVE ISLAND. | |

| DAVE PORTER IN THE SOUTH SEAS. | DAVE PORTER AND THE RUNAWAYS. | |

| DAVE PORTER'S RETURN TO SCHOOL. | DAVE PORTER IN THE GOLD FIELDS. | |

| DAVE PORTER IN THE FAR NORTH. | DAVE PORTER AT BEAR CAMP. | |

| DAVE PORTER AND HIS CLASSMATES. | DAVE PORTER AND HIS DOUBLE. | |

| DAVE PORTER AT STAR RANCH. | DAVE PORTER'S GREAT SEARCH. | |

| DAVE PORTER AND HIS RIVALS. | DAVE PORTER UNDER FIRE. |

Lakeport Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Net $1.75 per volume.

| THE GUN CLUB BOYS OF LAKEPORT. | THE FOOTBALL BOYS OF LAKEPORT. | |

| THE BASEBALL BOYS OF LAKEPORT. | THE AUTOMOBILE BOYS OF LAKEPORT. | |

| THE BOAT CLUB BOYS OF LAKEPORT. | THE AIRCRAFT BOYS OF LAKEPORT. |

American Boys' Biographical Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Net $1.75 per volume.

AMERICAN BOYS' LIFE OF WILLIAM McKINLEY.

AMERICAN BOYS' LIFE OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT.

DEFENDING HIS FLAG. Price $1.75.

DAVE PORTER AND HIS CLASSMATES

OR

FOR THE HONOR OF OAK HALL

BY

EDWARD STRATEMEYER

Author of "Dave Porter at Oak Hall," "The Old Glory Series,"

"Colonial Series," "Pan-American Series,"

"Soldiers of Fortune Series," etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY CHARLES NUTTALL

BOSTON

LOTHROP, LEE & SHEPARD CO.

Published, March, 1909

Copyright, 1909, by Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co.

All rights reserved

Dave Porter and His Classmates

Norwood Press

Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass.

U. S. A.

"Dave Porter and His Classmates" is a complete story in itself, but forms the fifth volume in a line issued under the general title of "Dave Porter Series."

The first book of this series, "Dave Porter at Oak Hall," introduced to the reader a typical American youth of to-day, full of vim and vigor, and with a true sense of manliness, and related the particulars of some doings at a modern boarding school. At this institution of learning Dave, by pluck and perseverance, fought his way to the front, and was admired accordingly.

There was a cloud on the youth's parentage, and in order to clear this away he took a long and eventful sea voyage, as related in the second volume of the series, called "Dave Porter in the South Seas." Thousands of miles from home he found an uncle and learned something of his father and sister, who were then traveling in Europe.

As was but natural, the lad was anxious to meet all his relatives, but the address of his father and sister could not be obtained, and while waiting for this he returned to Oak Hall, as related in the [Pg iv] next volume, entitled "Dave Porter's Return to School." At school Dave lived a truly strenuous life, becoming innocently involved in some robberies, aiding to win some great football games, and helping to bring the bully of the academy to a realization of his better self.

In the midst of his school life Dave learned that his father had been heard from. More anxious than ever to meet his parent he, in company with an old chum, set sail for England, and then went to Norway, as related in "Dave Porter in the Far North." Here, amid the ice and snow of the Land of the Midnight Sun, Dave found his father, and learned much of his sister, which filled him with great satisfaction.

It was now time for the youth to return to school, and in the present volume I have related some of the things that took place at Oak Hall after Dave got back,—how he worked hard, played hard, overcame his enemies, and what he did for the honor of the academy.

Once more I thank the young people for the interest they have shown in my books. I trust that the reading of the present volume will do them much good.

Edward Stratemeyer.

February 1, 1909

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Dave and His Past | 1 |

| II. | What Laura Had To Tell | 11 |

| III. | On the Way To School | 21 |

| IV. | The Fun of a Night | 31 |

| V. | What Happened to Nat Poole | 41 |

| VI. | What a Big Snowball Did | 51 |

| VII. | Prisoners in the School | 61 |

| VIII. | A Move in the Dark | 71 |

| IX. | Vera Rockwell | 81 |

| X. | Dave Speaks His Mind | 91 |

| XI. | At the Old Granary | 101 |

| XII. | Gus Plum's Story | 111 |

| XIII. | The Gee Eyes' Initiation | 121 |

| XIV. | In Which Job Haskers Gets Left in the Cold | 131 |

| XV. | What Mike Marcy Had to Tell | 141 |

| XVI. | Something about Lessons | 151 |

| XVII. | Shadow Hamilton's Peril | 161 |

| XVIII. | The Boxing Bout | 171 |

| XIX. | At the Express Office | 181 |

| XX. | A Misunderstanding | 191 |

| XXI. | In Which the Boys Give an Entertainment | 201 |

| XXII. | Forming the Baseball Club | 211 |

| XXIII. | A Great Victory | 221 |

| XXIV. | On Bush Island | 231 |

| XXV. | What an Automobile Did | 241[Pg vi] |

| XXVI. | A Defeat for Oak Hall | 250 |

| XXVII. | Stuck on a Sandbar | 260 |

| XXVIII. | Link Merwell Has His Say | 270 |

| XXIX. | Dave Makes up His Mind | 280 |

| XXX. | Dave Takes the Law in His Own Hands | 289 |

| XXXI. | More Victories—Conclusion | 298 |

| PAGE | |

| The big touring car shot past the carryall (page 249) | Frontispiece |

| The big snowball hit the craft and bowled it over, (missing) | 52 |

| "It's a shame to make you eat without a fork, Phil" | 74 |

| "Now to Jackson's Gully with him!" | 124 |

| Dave pointed out the form of the sleep-walker, (missing) | 164 |

| Down went the back part, letting him fall most unexpectedly | 208 |

| "Well, you can row if you want to," sneered Poole | 232 |

| Raising his oar, he hit the bully a blow on the shoulder | 274 |

"I suppose you feel very happy to-day, Dave."

"Yes, Roger, happy and anxious," answered Dave Porter. "And who wouldn't feel so if he was in my place? Just think of it! I am to see my sister at last—somebody I've never seen before in my life! Why, sometimes I have to pinch myself to make certain I am really awake."

"More than likely Laura is just as anxious as you are," went on Roger Morr. "She'll surely want to know how her long-missing brother looks. Remember, she hasn't had a photograph of you, while you have seen several of her."

"That is so," answered Dave. His usually smiling face took on a serious look. "I trust she isn't disappointed in me or my looks."

"Oh, she won't be, don't worry about that. You're a good-looking fellow, even if I do have to [Pg 2] say it for you, Dave. If you don't believe it, just ask Jessie Wadsworth." And Roger Morr began to grin. "I know Jessie will say at once that you are the dearest, sweetest——"

"Come now, Roger, let up!" interrupted Dave, growing red in the face. "Supposing Jessie should hear you?" And he looked anxiously toward the sitting-room door, which was partly open.

"There is no harm in telling the truth," returned Roger, with a calmness that made Dave blush still more. "But joking aside, Dave, I really hope this day proves to be the happiest of your life, and Laura turns out to be the jolliest of sisters."

"Hello, in there!" came a pleasant, boyish voice from the doorway, and a youth showed himself, with a pair of bright, nickel-plated skates on his arm. "Thought you were going skating, Roger?"

"So I am, Phil. I just stopped to speak to Dave for a moment. He is going off now to meet his sister."

"Oh!" Phil Lawrence came into the room and faced his chum. "Well, I can't say any more than what I've said before, Dave—I wish you the best of luck. I am sure you'll find it awfully nice to have a sister—especially after what you've had to put up with in the past."

"Don't you fellows really want to go with me?" asked Dave.

"Of course we do, but—— Well, Roger and I talked it over and we—that is—well, we thought it would be nice to let you go with your father and uncle—kind of family gathering, you know. We'll be on hand by the time you get back to the house."

At that moment the merry jingle of sleighbells sounded from outside the mansion and a comfortable two-seated sleigh came up to the door, driven by one of the men from the barn.

"There is your turnout ready for you!" cried Roger. "What time does that Western train get in?"

"Ten-twenty, if it's on time," replied Dave promptly, for he had the time-table well in mind. "But the snowstorm may have delayed it."

"Well, I hope for your sake the train is on time," said Phil Lawrence. "If it isn't, I suppose every minute's delay will seem like an hour to you."

"More like two," answered Dave, and then, as he heard his father calling to him, he hurried out into the hall. There stood Mr. David Porter and his brother Dunston, both ready for the long drive to the depot. Behind the pair were a lady and gentleman of middle age, Mr. and Mrs. Wadsworth, and their daughter Jessie, while in the library [Pg 4] door, holding a ponderous volume on botany in his hands, was an elderly man with white hair, Caspar Potts.

All of the party looked at Dave, for they knew what was in the youth's mind and what was on his heart. He had waited a long, long time for this day to come, and now he was a little timid about the result; why, he could not exactly tell. Perhaps because he had pictured his sister Laura to be one kind of a person and he was afraid she might prove something different.

"We mustn't be late," said Mr. Porter, breaking a momentary silence. He, too, was anxious over the coming meeting of son and daughter. It made his heart bound with pleasure to think that his little family were to be united at last.

"Remember, dinner will be waiting for you, no matter if the train is late," said Mrs. Wadsworth.

"And I'm to sit on one side of Laura and Dave on the other," put in Jessie, flinging back her curls that insisted at times on falling about her face. "Oh, won't it be glorious, Dave! I know I am going to love Laura, and I know she is going to love me—at least, I hope so."

Dave looked at her and smiled—he thought a great deal of Jessie, he simply couldn't help it. Then he turned and followed his father and Uncle Dunston down to the sleigh. The three got in and Mr. Porter took up the reins. A word to the [Pg 5] stylish team and off they sped, through the spacious grounds of the Wadsworth mansion and down the road leading to the railroad station.

Dave wanted to talk to his father and uncle, but somehow his heart was too full and the words would not come. His whole mind was centered upon meeting his sister, whom, so far as he could remember, he had never seen. He did not dream of the unexpected news Laura would bring him.

To those who have read the former volumes of this "Dave Porter Series," the characters already mentioned will need no special introduction. For the benefit of others let me state that Dave Porter was a youth who had had a varied experience in life. When a small boy he had been found wandering along the railroad tracks just outside of the village of Crumville. Nobody knew who he was or where he came from, and as a consequence he was put in the local poorhouse, where he remained until about nine years old. Then an old college professor, Caspar Potts, who on account of broken health had taken up farming, took the boy to live with him.

Caspar Potts meant well, but he got in the grasp of a money-lender, Aaron Poole, as related in detail in my first story, called "Dave Porter at Oak Hall." Times looked exceedingly black for the old man and for Dave when there came a happening which turned the whole aspect of affairs.

In an elegant mansion of the outskirts of the town lived Mr. Oliver Wadsworth, a rich manufacturer, with his wife and daughter Jessie, the latter a beautiful miss some years younger than Dave. One day Dave called at the mansion on business. Jessie was waiting for an automobile ride, and through an accident to the gasoline tank of the car the girl's clothing took fire, and she might have been burned to death had not Dave rushed to her assistance and put out the flames.

Of course the Wadsworths were exceedingly grateful, and when the gentleman of the place learned that Caspar Potts was one of his old college professors he at once interested himself in the old man's behalf.

"You must come and live with me," he said. "You can do some work around the place and in arranging my library—and you must bring the boy with you." He had had a son who had died, and Dave reminded him strongly of that offspring.

At the Wadsworth home Dave made himself a great favorite, and he and Jessie became the closest of friends. The rich manufacturer wanted the lad to have a good education, and so he was sent off to Oak Hall, a fine institution of learning. With Dave went Ben Basswood, a youth of Crumville who had been the poorhouse lad's chum for some years.

At Oak Hall, Dave proved himself a leader in many sports, and as a consequence he gained a host of friends, including Roger Morr, the son of a United States senator, and Phil Lawrence, the offspring of a wealthy shipowner. He also made several enemies, not the least of whom was Nat Poole, the son of the money-lender who had caused Caspar Potts so much worry.

One day Dave's enemies raised the cry of "poorhouse nobody" against him. This cut the high-spirited lad to the quick. A fight ensued, in which Dave was victorious, and then the boy resolved, at any cost, to solve the mystery of his parentage.

How this was accomplished has been related in detail in "Dave Porter in the South Seas." With information obtained from an old sailor the youth journeyed almost half around the world, and there fell in with his uncle, Dunston Porter, who gave him much information concerning his father, David Breslow Porter, and also about his sister Laura, one year younger than himself, and told how the family had become separated.

Happy in the knowledge that he was no longer a "poorhouse nobody," but a well-to-do lad with a large sum of money coming to him when he should be of age, Dave returned to the United States. His father and sister were in Europe, and while waiting to hear from them he went back to Oak Hall, as told in "Dave Porter's Return to [Pg 8] School." Here he made many more friends. His enemies could no longer twit him about his parentage, yet some of them, notably a fellow named Jasniff and Nat Poole, and a bully named Gus Plum, did what they could to torment him. Plum, when Dave did him a great service, tried to reform, but Jasniff, who was a hot-tempered fellow, attempted to strike Dave down with a heavy Indian club. This was a dastardly attack, roundly condemned by those who saw it, and fearful of what might follow, Nick Jasniff ran away from school and set sail for England.

Dave had waited long to hear from his father and sister, and at last when he learned that Jasniff had met them in London, he resolved to go in quest of them, although he did not yet have their address. In company with Roger Morr he crossed the Atlantic, only to find that his parent had joined an expedition for the upper part of Norway. How he and his chum journeyed to the land of the Midnight Sun has been told in all its particulars in "Dave Porter in the Far North." Here Dave at last met his father face to face,—a joyous reunion no words can express. Then the boy learned that his sister Laura had gone to the United States some time before, in company with some friends named Endicott, who owned a ranch in the Far West.

"We must telegraph at once for Laura," said [Pg 9] Mr. Porter, and several telegrams were sent without delay, and, as a consequence, word came back that Laura would come as fast as the overland express could bring her.

When Dave's friends heard the good news that he had found his father some of them came to the Wadsworth home to congratulate him. Among the number was Phil Lawrence, and he and Roger were invited to remain with Dave until the latter returned to Oak Hall.

"You can all go back together—after Dave has seen his sister," said Mr. Porter. "I will fix it up with Doctor Clay, so you won't have any trouble over staying out of school a week longer." And so it was arranged.

Just before leaving school for his trip to Europe Dave had had a bitter quarrel with Nat Poole and a new student at Oak Hall named Link Merwell. Merwell was an aggressive fellow, tall and powerful, the son of a cattle-owner of the West. His taunting remarks to Dave had led to a fight in which the cattle-owner's son had gotten the worse of it.

"I'll get square for this," Link Merwell had said to his crony. "I'll make Dave Porter eat humble pie before I am done with him." Then had come another quarrel between the Western boy and Mr. Dale, the head assistant teacher, and Merwell had come close to being expelled. He [Pg 10] had gone home for a vacation, stating that he believed Phil Lawrence had gotten him into "the mess," as he expressed it, and he had added that he would not forgive either Dave or Phil as long as he lived.

"Well, what did you do?" questioned Dave, when he and the shipowner's son talked this affair over.

"I didn't do anything," answered Phil. "Merwell wanted me to say that he hadn't gone out one night when I knew he did go out. I refused, and then he was found out. Oh, but wasn't he mad when he left on his vacation! He pounded his fist on a desk and vowed he'd fix me as soon as he got back,—and then he added that he'd fix you, too, as soon as you got back."

"Mighty interesting," said Dave. "We'll have to watch him and see what comes of it." And there the subject was dropped. But it was to come up very soon again, and in a manner not anticipated.

The train was nearly an hour late, and during that time Dave walked impatiently up and down the railroad platform. Occasionally he thought of school matters, and his friends and enemies, but most of the time his mind was on his sister. His father and his uncle talked together and did not interrupt his meditations.

At last a far-away whistle proclaimed the coming of the Western express, and Dave's face took on a more eager look than ever. His father gazed into his clear eyes and caught him by the arm.

"I trust with all my heart you find Laura all you desire," he said in a low tone, and Dave nodded, for his throat was so choked up that he could not speak.

The long train rolled in and the passengers for Crumville began to alight. "There she is!" cried Dunston Porter and ran forward, with his brother and Dave at his heels. A mist seemed to come over the boy's eyes and his heart thumped furiously. [Pg 12] Then he saw a tall girl standing before him, her eyes looking deeply into his own.

"Laura, this is Dave," he heard his father say. Then the girl came closer, reached out her arms, and in a moment more brother and sister were locked in the closest of embraces. It was such a moment Dave had longed for—prayed for—and all on the instant he knew that Laura was what he had hoped she would be and that they should love each other with the sweetest of sisterly and brotherly love as long as they lived.

Laura was handsome rather than pretty. She had an aristocratic air which had come down to her from her mother and grandmother. She was stately in her movements and her voice charmed Dave the moment he heard it.

"Just to think, you are really and truly my brother!" she exclaimed. "Isn't it wonderful!"

"It's wonderful for me to find a sister—and a father," answered Dave. "Sometimes I am afraid I'll wake up and find it all a dream."

"When I got papa's telegram I thought it was a dream. One of the cowboys on the ranch brought it over from the railroad station. At first I thought there must be some mistake, but Mr. Endicott said there couldn't be, and so I arranged to come east at once. A gentleman and his wife, who had been stopping at the ranch, came with me as far as Buffalo. Oh, I really couldn't get here [Pg 13] fast enough! Did you get the telegram I sent from Chicago?"

"Yes," answered her father. "And the one from the ranch, too."

"I want to hear the whole of the wonderful story just as soon as possible," continued Laura. "I promised Belle Endicott I'd send her the particulars, for she is dying to know. Belle is my friend, you know. Her father is a railroad president, but he owns that ranch, too, and they go out there whenever they feel like it, winter or summer. Belle said she'd rather read my next letter than a story book." And Laura smiled brightly.

"And I shall want to hear all about you and your travels," answered Dave. "Oh, I guess we'll have enough to talk about to last a week."

The party of four were soon in the sleigh, with Laura and Dave on the front seat. The youth showed how he could handle the team, and in a short while drove up to the stepping-stone of the Wadsworth mansion. At once there was a rush from within, and the girl was introduced to those who had in the past done so much for her brother, and those who were Dave's chums. Jessie was a trifle shy at first, but this presently wore away, and when Laura heard what the Wadsworths had done for her brother she speedily took mother and daughter to her heart, and Jessie and she became the best of friends.

It was assuredly a grand gathering around the bountiful table which the Wadsworths had supplied, and all lingered long, listening to what the various members of the Porter family had to tell: of Dave's doings on the Potts farm, at school, and in quest of his relatives; of Dunston Porter's treasure hunt in the South Seas; of Mr. David Porter's trip to Europe with Laura; and of the girl's adventures on the ranch and elsewhere.

"Strange as it may seem, I have met two boys who knew Dave," said Laura, during the course of the conversation. "One was that scamp, Nick Jasniff, who tried to make himself agreeable in London."

"Yes, I know about him," answered Dave. "But who was the other?"

"The other is the son of the man who owns the cattle ranch next to Mr. Endicott's, Mr. Felix Merwell."

"Merwell!" cried Dave, Roger, and Phil in a breath.

"Yes. Why do you look so astonished?"

"Do you mean Link Merwell's father?" asked her brother.

"Yes. Link came out there just a few days before I started for the East. He seemed to be a nice sort, and he is one of the best horseback riders I ever saw."

"Did you—er—go out with him?" stammered Dave.

"Yes, twice, but not alone—Belle was along." Laura looked at her brother, whose face was a study. "What makes you look so queer? You know Mr. Merwell, don't you?"

"Oh, yes, we know him," answered Phil, before Dave could speak.

"We'd like to know less of him," added Roger.

"Oh!" And now Laura's face showed her wonder.

"You see, it's this way," continued the senator's son, thinking it might be difficult for Dave to explain. "Link Merwell tried to lord it over a lot of us fellows at Oak Hall. He's a domineering chap, and some of us wouldn't stand for it. I gave him a piece of my mind once, and so did Phil, and Dave did more—gave him a sound thrashing."

"Oh, Dave, did you really!" Laura's face showed her distress. "Why, I—I thought he was nice enough. Maybe it was only a boyish quarrel," she added, hopefully. "I know boys do fight sometimes with hardly a reason for it."

"Dave had a good reason for hitting Merwell," said Phil. "The best reason in the world." He looked at Jessie and Mrs. Wadsworth and the others. "I'll not spoil this gathering by saying what it was. But it was something very mean, and Merwell deserved the drubbing he got."

"Oh, I am so sorry! That is, I don't mean I am sorry Dave thrashed him—if he deserved it—but I am sorry that I—I went out with him, and that I—I started a correspondence with him. I thought he was nice, by his general looks."

"Oh, he can make himself look well, when he dresses up," said Roger. "And he can act the gentleman on the outside. But if you get to know him thoroughly you'll find him a different sort."

"I don't wish to know him if he's that kind," answered Laura, quickly. "But I thought he was all right, especially as he was the son of the owner of the next ranch. I am sorry now I ever spoke to him."

"And you have been writing to him?" asked Dave. "I thought you said you had met him only a few days before you came away?"

"So I did. But he wanted me to buy something for him in Chicago—a lens for his camera, and asked me to write from there, and I did. And, just for fun, I sent him two letters I wrote on the train—along with some letters to Belle and some other folks I know. I did it to pass the time,—so I wouldn't know how long it was taking me to get here. It was foolish to do so, and it will teach me a lesson to be careful about writing in the future."

"I'm sorry you wrote to him," answered Dave, soberly. But how sorry he was to be, and how [Pg 17] distressed his sister was to become, he was still to learn.

Not further to mar the joy of the occasion Link Merwell's name was dropped, and Roger and Phil told of some funny initiations into the secret society at Oak Hall, which set everybody to laughing, and then Dunston Porter related the particulars of a hunt after bears he had once made in the Rockies. Thus the afternoon and evening wore away swiftly and all too soon it was time to retire. Laura was given a room next to that occupied by Dave, and long after the rest of the house was quiet brother and sister sat by a window, looking out at the moonlight on the snow and discussing the past.

"You look very much like father," said Laura, "and much like Uncle Dunston, too. No wonder that old sailor, Billy Dill, thought he had seen you when he only saw Uncle Dunston."

"And father tells me you look like mother," answered Dave, softly. "I do not remember her, but if she looked like you she must have been very handsome," and Dave smiled and brushed a stray lock back from his sister's brow.

"It is too bad she cannot see us now, Dave—how happy it would make her! I have missed her so much—it is no easy thing to get along without a mother's care, is it?—or a father's care, either. Perhaps if mamma were alive I'd be different in [Pg 18] some things. I shouldn't be so careless in what I do—in making friends with that Link Merwell, for instance, and sending him letters." Laura looked genuinely distressed as she uttered the last words.

"Well, you didn't know him, so you are not to blame. But I shouldn't send him any more letters."

"You can depend upon it I won't."

"He is the kind who would laugh at you for doing it, and make fun of you to all his friends."

"He'll not get another line from me, and if he writes I'll return the letters," answered Laura, firmly.

"Did he say when he was going back to Oak Hall?"

"Inside of two weeks. He said he had had a little trouble with a teacher, and the master of the school had advised him to take a short vacation and give the matter a chance to blow over."

Laura had arrived at Crumville on Thursday, and it was decided that Dave, Roger, and Phil should not return to Oak Hall until the following Monday. On Friday and Saturday the young folks went sleighing and skating, Jessie being one of the party, and on Sunday the entire household attended church. It was a service into which Dave entered with all his heart, and he thanked God from the bottom of his soul that at last his sister, [Pg 19] as well as his father and his uncle, had been restored to him.

"After I go back to boarding school where are you and Laura and Uncle Dunston going to stay?" questioned Dave of his father.

Mr. Porter smiled faintly. "I have a little secret about that, Dave," he answered. "I'll tell you later—after everything is ripe."

"I know the Wadsworths would hate to have me leave them—and Professor Potts won't want me to go either."

"Well, you wait, Dave,—and see what comes," answered his father; and with this the lad had to be content.

Bright and early Monday morning the three boys had breakfast and started for the depot, to take the train for Oakdale, the nearest town to Oak Hall. Laura, Jessie, and Mr. David Porter went along to see them off.

"Now, Dave, I want to see you make the most of this term at school," said Mr. Porter. "Now you have Laura and me, you won't have so much to worry about."

"I'll do my level best, father," he answered. "We want you to come out at the top of the class," said Laura.

"And Dave can do it too—I know he can," remarked Jessie, and gave him a sunny smile of encouragement.

"How about us poor chaps?" asked Roger. "Can't we come in somewhere?"

"Yes, you must come in right after Dave," answered Laura, and this made everybody laugh.

"The higher we get in school the harder the work becomes," came from Phil. "But I am going to peg away at it—provided the other fellows will let me."

"Phil always was very studious," said Dave, with an old-time grin spreading over his face. "He'd rather study a problem in geometry or translate Latin than read a story book or play baseball; wouldn't you, Phil?"

"Not much! and you know it. But if a fellow has got to grind, why——"

"He can grind—and play baseball, too," added Mr. Porter. "My parting advice is: when you study, study for all you are worth, and when you play, play for all you are worth."

"Here comes the train!" cried Laura, and turning, she kissed her brother. "Good-bye, Roger; good-bye, Phil!"

"Good-bye!" came from the others, and a general handshaking followed. Then the three chums ran for the train, got aboard, and were off for school once more.

"There is one thing I've forgotten to mention to you," said Phil, as the train rolled on its way and Crumville was left far behind. "That is that this term Doctor Clay has offered a special set of prizes to the students standing highest in various subjects. There is a prize for history, another for Latin, and a third for English literature and theme-writing. In addition there is to be a special prize for the student who can write the best paper on 'The Past and Future of our Country.' This last contest is open only to those who stand above the eighty per cent. level in their classes."

"That's interesting," answered Dave. "How many reach that level, do you think, Phil?"

"Not more than thirty all told, and of those I don't believe more than twenty will send in papers."

"Dave, you ought to try," said Roger. "You were always good at composition."

"So are you, Roger."

"I'm not as good as you, and I know it. I like [Pg 22] history more than anything else, and I guess I'll try for that prize."

"Well, what is the past of our country but history?" continued Dave, with a smile.

"That part might be easy; but what of the future? I'm no good at prophesying."

"Oh, couldn't you speak of the recent inventions and of what is coming—marvelous submarine boats, airships, wireless telegraphy, wonderful cures by means of up-to-date surgery, and then of the big cities of the West, of the new railroads stretching out everywhere, and of the fast ocean liners, and the Panama Canal, and the irrigation of the Western dry lands, and——"

"Hold on, Dave!" cried Phil. "You are giving Roger all your ammunition. Put that in your own paper."

"Oh, there's a whole lot more," was the smiling answer. "The thirty-and forty-storied buildings in our big cities, the underground railways, the tubes under the rivers, the tremendous suspension bridges, the automobile carriages and business trucks,—not to mention the railroad trains that are to run on one rail at a speed of a hundred miles an hour. Oh, there are lots of things—if one only stops to think of them."

"The prize is yours, Dave!" exclaimed the senator's son. "You've mentioned more in three [Pg 23] minutes than I would have thought of in three weeks. I'll stick to history."

"And I'll stick to English literature—I'm pretty well up on that, thank goodness!" said the shipowner's son.

After that the talk drifted to other things—of the doings of the students at Oak Hall, and of how Job Haskers, one of the assistant teachers, had caught some of the lads playing a trick on Pop Swingly, the janitor, and punished them severely for it.

"The trick didn't amount to much," said Phil, "and I rather believe Swingly enjoyed it. But old Haskers was in a bilious mood and made the fellows stay in after school for three days."

"Were you in it?" asked Dave.

"Yes; and all of us have vowed to get square on Haskers."

"It's a wonder Doctor Clay doesn't get rid of Haskers—he is so unpopular," was Roger's comment.

"Haskers is a fine teacher, that's why he is kept. But I like Mr. Dale much better," said Dave.

"Oh, everybody does!"

"All but Link Merwell," said Phil. "Isn't it strange, he seems to get along very well with Haskers."

"Two of a kind maybe," returned the senator's son.

After a long run the Junction was reached, where the boys had to change cars for Oakdale. They got off and found they had twenty-five minutes to wait.

"Remember the time we were here and had the trouble with Isaac Pludding?" asked Roger.

"I'll never forget it," answered Dave, with a grin. "By the way, as we have time to spare let us go around to Denman's restaurant and have a cup of chocolate and a piece of pie. That car was so cold it chilled me."

Growing boys are always hungry, so, despite the generous breakfast they had had, they walked over to the restaurant named. The man who kept it remembered them well and smiled broadly as they took seats at a table.

"On your way to school, I suppose," he said, as he served them. "Ain't following up Ike Pludding this trip, are you?"

"Hardly," answered Dave. "What do you know of him?"

"I know he is about down and out," answered Amos Denman. "And served him right too."

The boys were about to leave the restaurant when Dave chanced to glance in one of the windows. There, on a big platter, was an inviting heap of chicken salad, above which was a sign announcing it was for sale at thirty cents a pint.

"Let me try that salad, will you?" Dave asked.

"Certainly. Want to take some along?" And Amos Denman passed over a forkful.

"What are you going to do with chicken salad?" questioned Roger.

"Oh, I thought we might want to celebrate our return by a little feast, Roger."

"Hurrah! just the thing!" ejaculated the senator's son. "Is it good? It is? All right, I'll take a quart."

"I'll take a quart, too," said Dave. "I guess you can put it all together."

"Are those mince pies fresh?" asked Phil, pointing to some in a case.

"Just out of the oven. Feel of them."

"Then I'll take two."

In the end the three youths purchased quite a number of things from the restaurant keeper, who tied up the articles in pasteboard boxes wrapped in brown paper. Then the lads had to run for the train and were the last on board.

It had begun to snow again and the white flakes were coming down thickly when the train rolled into the neat little station at Oakdale. The boys were the only ones to alight and they looked around eagerly to see if the school carryall was waiting for them.

"Hello, fellows!" cried a voice from the end of the platform, and Joseph Beggs, usually called [Pg 26] Buster because of his fatness, waddled up. "Thought you'd be on this train."

"How are you, Buster?" answered Dave, shaking hands. "My, but aren't you getting thin!" And he looked the fat boy over with a grin.

"It's worry that's doing it," answered Buster, calmly. "Haven't slept a night since you went away, Dave. So you really found your dad and your sister! Sounds like a regular six-act-and-fourteen-scene drama. We'll have to write it up and get Horsehair to star in it. First Act: Found on the Railroad Tracks; Second Act: The Faithful Farm Boy; Third Act: The King of the School; Fourth Act——"

"Waiting for the Stage," interrupted Dave. "Keep it, Buster, until we're on the way to Oak Hall. Did you come down alone?"

"Not much he didn't come down alone!" cried a voice at Dave's elbow, and Maurice Hamilton, always called Shadow, appeared. Maurice was as tall and thin as Buster was stout. "Let me feel your hand and know you are really here, Dave," he went on. "Why, your story is—is—what shall I say?"

"Great," suggested Roger.

"Marvelous," added Phil.

"Out of sight," put in Buster Beggs.

"All good—and that puts me in mind of a story. One time there was a——"

"Shadow—so early in the day!" cried the senator's son, reproachfully.

"Oh, you can't shut him off," exploded Buster. "He's been telling chestnuts ever since we left the Hall."

"This isn't a chestnut, it's a——"

"Hickory nut," finished Phil; "hard to crack—as the darky said of the china egg he wanted to fry."

"It isn't a chestnut or a hickory nut either," expostulated the story-teller of the school. "It's a brand-new one. One time there was a county——"

"If it's new you ought to have it copyrighted, Shadow," said Roger.

"Perhaps a trade-mark might do," added Dave. "You can get one for——"

"Say, don't you want to hear this story?" demanded Shadow.

"Yes, yes, go on!" was the chorus.

"Now we've had the first installment we'll have to have the finish or die," continued Phil, tragically.

"Well, one time there was a county fair, with a number of side shows, snakes, acrobats, and such things. One tent had a big sign over it, 'The Greatest and Most Marvelous Wonder of the Age—A man who plays the piano better with his feet than most skilled musicians can play with their [Pg 28] hands. Admission 10 cents.' That sign attracted a big crowd and brought in a lot of money. When the folks got inside a man came out, sat down in front of a piano that played with paper rolls, and pumped the thing for all he was worth with his feet!"

"Oh, what a sell!" roared Phil. "Shadow, that's the worst you ever told."

"Quite a feat," said Dave.

"But painful to the understanding," added Roger. He looked around. "Hello, here's Horsehair at last."

He referred to Jackson Lemond, the driver for the school, who was always called Horsehair because of the hairs which invariably clung to his clothing. The driver was coming down the main street of the town with a package of harness dressing in his hand.

"Had to git this," he explained. "How de do, young gents? All ready to go to the Hall?"

"Horsehair, we're going to write a play about Dave's discoveries," said Buster. "We want you to star in it. We know you can make a hit."

"No starrin' fer me," answered the driver, who had once played minor parts in a barn-storming theatrical company. "I'll stick to the hosses."

"But think of it, Horsehair," went on Buster. "We'll have you eaten up by cannibals of the [Pg 29] South Seas, frozen to death in Norway snowstorms, shooting bears as big as elephants, and——"

"Oh, Buster, do let up!" cried Dave. "None of those things are true, and you know it. Come ahead, I am anxious to see the rest of the fellows," and Dave ran for the carryall, with his dress-suit case in one hand and one of the packages from the restaurant in the other.

Soon the crowd had piled into the turnout, Phil on the front seat beside the driver, and away they went. The carryall had been put on runners and ran as easily as a cutter, having two powerful horses to pull it.

All of the boys were in high spirits and as they sped over the snow they sang and cracked jokes to their hearts' content. They did not forget the old school song, sung to the tune of "Auld Lang Syne," and sang this with a vigor that tested their lungs to the uttermost:

"By the way, how is Gus Plum getting along these days?" asked Dave of Shadow Hamilton, during a pause in the fun. He referred, as my old [Pg 30] readers know, to a youth who in days gone by had been a great bully at the Hall.

"Gus Plum needs watching," was the low answer, so that none of the other boys might hear. "He is better in some ways, Dave, and much worse in others."

"How do you mean, Shadow?"

"I can't explain here—but I'll do it in private some day," answered Shadow; and then the carryall swept up to the school steps and a number of students ran forth from the building to greet the new arrivals.

As my old readers know, Oak Hall was a large structure of brick and stone, built in the shape of a broad cross, with wide hallways running from north to south and east to west. All of the classrooms were on the ground floor, as were also the dining hall and kitchen, and the head master's private office. On the second floor were the majority of the dormitories, furnished to hold four, six, and eight pupils each. The school was surrounded by a wide campus, running down to the Leming River, where was located a good-sized boathouse. Some distance away from the river was a neat gymnasium, and, to the rear of the school, were commodious stables and sheds. At the four corners of the campus grew great clumps of giant oaks, and two oaks stood like sentinels on either side of the gateway—thus giving the Hall its name.

As Dave leaped to the piazza of the school he was met by Sam Day, another of his old chums, who gave his hand a squeeze that made him wince. [Pg 32] Close by was Chip Macklin, once the toady of Gus Plum, but now "quite a decent sort," as most of the lads would say. Further in the rear was Gus Plum, looking pale and troubled. Evidently something was wrong with him, as Shadow had intimated.

"Sorry I couldn't get down to the depot," said Sam. "But I had some examples in algebra to do and they kept me until after the carryall had left."

There was more handshaking, and Dave did not forget Macklin or Gus Plum. When he took the hand of the former bully he found it icy cold and he noticed that it trembled considerably.

"How are you, Gus?" he said, pleasantly.

"Oh, I'm fair," was the hesitating answer. "I—I am glad to see you back, and doubly glad to know you found your father."

"And sister, Gus; don't forget that."

"Yes, and your sister." And then Gus Plum let Dave's hand fall and stepped back into the crowd and vanished. Dave saw that he had something on his mind, and he wondered more than ever what Shadow might have to tell him.

Soon Doctor Clay appeared, a man well along in years, with gray, penetrating eyes and a face that could be either kindly or stern as the occasion demanded.

"As the boys say, it is all very wonderful, and I am rejoiced for your sake, Porter," he said. [Pg 33] "Your trip to Norway certainly turned out well, and you need not begrudge the time lost from school. Now, with your mind free, you can go at your studies with vigor, and such a bright pupil as you ought to be able to make up all the ground lost."

"I intend to try my best, sir," answered Dave.

The only lad at Oak Hall who did not seem to enjoy Dave's reappearance was Nat Poole. The dudish youth from Crumville, whose father had, in times past, caused old Caspar Potts so much trouble, kept himself aloof, and when he met Dave in a hallway he turned his head the other way and pretended not to notice.

"Nat Poole certainly feels sore," said Dave to Ben Basswood, his old friend from home, when Ben came to meet him, having been kept in a classroom by Job Haskers.

"Yes, he is sore on everybody," answered Ben. "Well, he is having a hard time of it, seems to me. First Chip Macklin cut him, and then Gus Plum. Then he got mixed up with Nick Jasniff, and Jasniff had to run away. Then he and Link Merwell became chums, and you know what happened to both. Now Merwell is away and Nat is about left to himself. He is a bigger dude than ever, and spends a lot of money that the doctor doesn't know anything about, and yet he can't make himself popular."

"Well, I'm glad money doesn't count at Oak Hall, Ben."

"I know you feel that way, Dave, and it does you credit. I guess now you are about as rich as anybody, and if money did the trick——"

"I want to stand on my merits, not on my pocketbook. Perhaps Nat would make friends if he wasn't forever showing off and telling how wealthy his father is."

"I believe you there."

"By the way, Ben, do you know anything about Gus Plum? There seems to be a big change in him."

"There is a change, but I can't tell you what it is. Shadow Hamilton knows. He and Plum came home late one night, both having been to Oakdale, and Shadow was greatly excited and greatly worried. Some of us fellows wanted to know what it was about, but Shadow refused to say a word, excepting that he was going to let you know some time, because you appeared to have some influence over Gus."

Ben's words surprised Dave, coming so shortly after what Shadow himself had said. He was on the point of asking Ben some more questions, but reconsidered the matter and said nothing. He could wait until such a time as Shadow felt in the humor to unburden his mind.

Dave and his chums roomed in dormitories Nos. [Pg 35] 11 and 12, two large and well-lighted apartments, with a connecting door between. Not far away was dormitory No. 13, which was now occupied by Nat Poole and some others, including Link Merwell when that individual was at Oak Hall. One bed was vacant, that which Nick Jasniff had left so hurriedly.

In a quiet way the news was spread that Dave and his chums had provided some good things for a feast, and that night about twenty boys gathered in No. 11 and No. 12 to celebrate "the return of our leader," as Luke Watson expressed it. Luke was on hand with his banjo and his guitar, to add a little music if wanted.

"Say, boys, we couldn't have chosen a better time for this sort of thing than to-night," announced Sam Day. "Haskers has gone to town and Mr. Dale is paying a visit to a neighbor; I heard the doctor tell Mr. Dale he was tired and was going to bed early, and best of all Jim Murphy says he won't hear a thing, provided we set out a big piece of mince pie for him." Murphy was monitor of the halls.

"Good for Jim!" cried Dave. "I'll cut that piece of pie myself," and he did, and placed it where he felt certain that the monitor would find it.

The boys were allowed to do as they pleased until half-past nine, and they sang songs and [Pg 36] cracked jokes innumerable. But then the monitor stuck his head in at the door.

"Got to be a little quiet from now on," he said, in a hoarse whisper and with a broad grin on his face. "I'm awfully deaf to-night, but the doctor will wake up if there's too much racket."

"Did you get the pie?" questioned Dave.

"Not yet, and I'll take it now, if you don't mind."

"Jim, do you mean to say you didn't get that pie?" demanded Dave.

"Oh, he's fooling," interrupted Phil. "He wants a second piece."

"That's it," came from Shadow. "Puts me in mind of a story about a boy who——"

"Never mind the story now, Shadow," interrupted Dave. "Tell me honestly, Jim, whether you got the pie or not? Of course you can have another piece, or some chicken salad——"

"I didn't get any pie,—or anything else," answered the monitor.

"I put it on the bottom of the stand in the upper hallway."

"Nothing there when I went to look."

"Then somebody took it on the sly," said Roger. "For I was with Dave when he put it there. Anybody in these rooms guilty?" And he gazed around sternly.

All of the boys shook their heads. Then of a [Pg 37] sudden a delicate youth who looked like a girl arose in astonishment and held up his hands.

"Well, I declare!" he lisped.

"What now, Polly?" asked Phil.

"I wonder if it is really possible," went on Bertram Vane.

"What possible?" questioned Dave.

"Why, when I was coming through the hall a while ago I almost ran into Nat Poole. He had something in one hand, under his handkerchief, and as I passed him I really thought I smelt mince pie!"

"Nat Poole!" cried several.

"Oh, the sneak!" burst out Roger. "He must have been watching Dave. Maybe he heard us promise Murphy the pie."

"Bad luck to him if he stole what was coming to me," muttered the monitor. "I hope the pie choked him."

"If Nat Poole took the pie we'll fix him for it," said Dave. "Just you leave it to me." Then he got another portion of the dainty and handed it to the monitor, who disappeared immediately.

"What will you do?" questioned Roger.

"Since Nat has had some pie I think I'll treat him to some chicken salad," was the reply. "Nothing like being generous, you know."

"Why, Dave, you don't mean you are going [Pg 38] to let Nat Poole have any of this nice salad!" cried Phil. "I'd see him in Guinea first!"

"He shall have some—after it has been properly doctored."

"Eh? Oh, I see," and the shipowner's son began to grin. "All right then. But doctor it good."

"I shall make no mistake about that," returned Dave.

While Shadow was telling a story of a little boy who had fallen down a well and wanted somebody to "put the staircase down" so he could climb up, Dave went to a small medicine closet which he had purchased during his previous term at Oak Hall. From this he got various bottles and powders and began to "doctor" a nice portion of the chicken salad.

"Say, Dave, that won't hurt anybody, will it?" asked Ben, who saw the movement.

"It may hurt Nat Poole, Ben."

"Oh, you don't want to injure him."

"This won't do any harm. I am going to give him what Professor Potts called green peppers. Once, when he was particularly talkative, he related how he had played the joke on a fellow-student at college. It won't injure Nat Poole, but if he eats this salad there will surely be fun, I can promise you that."

"How are you going to get it to him?"

"Take it to him myself."

"You! He'll be suspicious at once and won't touch it."

"Perhaps not—we'll wait and see."

When the feast was practically at an end, Dave put the doctored salad in a dessert dish, topping it with some that was sweet and good. On all he laid some fancy crackers which one of the boys had contributed.

"Now, here is where I try the trick," he said, and put on a sweater, leaving the upper portion partly over his face. Then, leaving his dormitory, he tiptoed his way to No. 13 and pushed open the door softly.

As he had surmised, Nat Poole had gone to bed and had just fallen asleep. Going noiselessly to his side, Dave bent over him and whispered into his ear:

"Here, Nat, is something I stole for you from that crowd that was having the feast. Eat it up and don't tell the other fellows."

"Eh, what? The feast?" stammered Nat, and took the plate in his hand. "Who are you?"

"Hush!" whispered Dave, warningly. "Don't wake the others. I stole it for you. Eat it up. I'll tell you how I did it in the morning. It's a joke on Dave Porter!" And then Dave glided away from the bed and out of the room like a ghost, shutting the door noiselessly after him.

Half asleep, Nat Poole was completely bewildered by what he heard. In the semi-darkness he could not imagine who had brought the dish full of stuff. But he remembered the words, "eat it up" and "don't tell the other fellows" and "a joke on Dave Porter." That was enough for Nat. He sat up, looked at the fancy crackers and the salad, and smacked his lips.

"Must have been one of our old crowd," he mused. "Maybe Shingle or Remney. Well, it's a joke on Dave Porter right enough, and better than taking that pie he left for Murphy." And then he began to munch the crackers and eat the salad, using a tiny fork Dave had thoughtfully provided. He liked chicken salad very much, and this seemed particularly good, although at times it had a bitter flavor for which he could not account.

Peering through the keyhole of the door, Dave saw his intended victim make way with the salad. Then he ran back to his dormitory.

"It's all right," he said. "Now all of you undress and go to bed,—and watch for what comes!"

The students of dormitories No. 11 and No. 12 scarcely had time to get to bed when they heard a noise in the apartment Nat Poole and some others occupied. First came a subdued groan, followed by another, and then they heard Nat Poole get up.

"What's the matter?" they heard a student named Belcher ask.

"Why—er—I'm burning up!" gasped Nat Poole. "Let me get a drink of water!" And he leaped from his bedside to where there was a stand with a pitcher of ice-water and a glass.

He was so eager to get the water that, in the semi-darkness, he hit the stand with his arm. Over it went, and the pitcher and glass fell to the floor with a crash. The noise aroused everybody in the dormitory.

"What's the matter?"

"Are burglars breaking in?"

"Confound the luck!" muttered Nat Poole. "Oh, I must get some water! I am burning up alive!"

"What's done it?" questioned Belcher.

"I—er—never mind now. I am burning up and must have some water!" roared the dudish pupil, and dashed out of the dormitory in the direction of a water tank located at the end of the hall.

Here he was a little more careful and got the drink he desired. But scarcely had he taken a mouthful when he ejected it with great force.

"Wow! how bitter that tastes!" he gasped. Then of a sudden he commenced to shiver. "Wonder if that salad poisoned me? Who gave it to me, anyhow?"

He tried the water again, but it was just as bitter as before. Then he ran to a bathroom, to try the water there. By this time his mouth and throat felt like fire, and, thoroughly scared, he ran back to his sleeping apartment and began to yell for help.

His cries aroused a good portion of the inmates of Oak Hall, and students came from all directions to see what was the matter. They found poor Nat sitting on a chair, the picture of misery.

"I—I guess I'm poisoned and I'm going to die!" he wailed. "Somebody better get a doctor."

"What did you eat?" demanded half a dozen boys.

"I—er—I ate some salad a fellow brought to me in the dark. I don't know who he was. Oh, my [Pg 43] throat! It feels as if a red-hot poker was in it! And I can't drink water either! Oh, I know I am going to die!"

"Try oil—that's good for a burn," suggested one student, and he brought forth some cod liver oil. Nat hated cod liver oil almost as much as poison, but he was scared and took the dose without a murmur. It helped a little, but his throat felt far from comfortable and soon it commenced to burn as much as ever.

By this time Doctor Clay had been aroused and he came to the dormitory in a dressing gown and slippers.

"Nat Poole has been poisoned!" cried several.

"Poisoned!" ejaculated the master of the Hall. "How is this, Poole?" and he strode to the suffering pupil's side.

"I—I don't know," groaned Nat. "I—er—ate some mince pie and some salad——"

"Perhaps it is only indigestion," was the doctor's comment. "You may get over it in a little while."

"But my throat——" And then the dudish boy stopped short. The fire in his mouth and throat had suddenly gone down—like a tooth stopping its aching.

"What were you going to say?" asked Doctor Clay.

"Why, I—that is—my throat isn't so bad now." [Pg 44] And Nat's face took on a sudden sheepish look. In some way he realized he had been more scared than hurt.

"Let me have a look at your throat," went on the master of the Hall and took his pupil to a strong light. "It is a little red, but that is all. Is your stomach all right?"

"It seems to be—and the pain in my throat and mouth is all gone now," added Nat.

The doctor handed him a glass of water a boy had brought and Nat tried it. The liquid tasted natural, much to his surprise, and the drink made him feel quite like himself once more.

"I—I guess I am all right now," he said after an awkward pause. "I—er—am sorry I woke you up."

"After this be careful of how much you eat," said the doctor, stiffly. "If a boy stuffs himself on mince pie and salad he is bound to suffer for it." Then he directed all the students to go to bed at once, and retired to his own apartment.

If ever a lad was puzzled that lad was Nat Poole. For the life of him he could not determine whether he had suffered naturally or whether a trick had been played on him. He wanted very much to know who had brought him the salad, but could not find out. For days after the boys would yell "mince pie" and "salad" at him, much to his annoyance.

"That certainly was a good one," was Phil's comment. "I reckon Nat will learn to keep his hands off of things after this." And he and the others had a good laugh over the trick Dave had played. It proved to be perfectly harmless, for the next day Poole felt as well as ever.

As Dave had said, he was determined to make up the lessons lost during his trip to England and Norway, and he consequently applied himself with vigor to all his studies. At this, Mr. Dale, who was head teacher, was particularly pleased, and he did all he could to aid the youth.

As during previous terms, Dave had much trouble with Job Haskers. A brilliant teacher, Haskers was as arbitrary and dictatorial as could be imagined, and he occasionally said things which were so sarcastic they cut to the quick. Very few of the boys liked him, and some positively hated him.

"I always feel like fighting when I run up against old Haskers," was the way Roger expressed himself. "I'd give ten dollars if he'd pack his trunk and leave."

"And then come back the next day," put in Phil, with a grin.

"Not much! When he leaves I want him to stay away!"

"That puts me in mind of a story," said Shadow, who was present.

"What, another!" cried Dave, with a mock groan. "Oh, but this is dreadful!"

"Not so bad—as you'll soon see. A boy had a little dog, who could howl morning, noon, and night, to beat the band. Next door to the boy lived a very nervous man. Said he to the boy one day: 'Will you sell me that dog for a dollar?' 'Make it two dollars and the dog is yours,' answered the boy. So the man, to get rid of that howling dog, paid the boy the two dollars and shipped the dog to the pound. Then he asked the boy: 'What are you going to do with the two dollars?' 'Buy two more dogs,' said the boy. Then the man went away and wept."

"That's all right!" cried Sam Day, and everybody laughed. Then he added: "What can disturb a fellow more than a howling dog at night?"

"I know," answered Dave, quietly.

"What?"

"Two dogs," and then Dave ducked to avoid a book that Sam threw at him.

"Speaking of dogs reminds me of something," said Buster Beggs. "You all remember Mike Marcy, the miserly old farmer whose mule we returned some time ago."

"I am not likely to forget him," answered Dave, who had had more than one encounter with the fellow, as my old readers are aware.

"Well, he has got a very savage dog and has posted signs all over his place, 'Beware of the Dog!' Two or three of the fellows, who were crossing his corner lot one day, came near being bitten."

"Were you one of them?" asked Roger.

"Yes, and we weren't doing anything either—only crossing the vacant lot to take a short-cut to the school, to avoid being late."

"I was in the crowd," said Luke Watson, "and I had a good mind to kill the dog."

"We'll have to go over some day and see Marcy," said Phil. "I haven't forgotten how he accused me of stealing his apples."

"He once accused me of stealing a chicken," put in a boy named Messmer. "I'd like to take him down a peg or two for that."

"Let us go over to his place next week some time and tease him," suggested another boy named Henshaw, and some of the others said they would bear his words in mind.

Messmer and Henshaw were the owners of an ice-boat named the Snowbird. They had built the craft themselves, and, while it was not very handsome, it had good going qualities, and that was all the boys wanted.

"Come on out in the Snowbird," said Henshaw, to Dave and several of the others, on the following Saturday afternoon, when there was no school. [Pg 48] "The ice on the river is very good, and the wind is just right for a spin."

"Thanks, I'll go with pleasure," answered Dave; and soon the party was off. The river, frozen over from end to end, was alive with skaters and ice-boats, and presented a scene of light-heartedness and pleasure.

"There goes an ice-boat from the Rockville military academy," said Messmer, presently. "I guess they don't want to race. They haven't forgotten how we beat them." And he was right; the Rockville ice-boat soon tacked to the other side of the river, the cadets on board paying no attention to the Oak Hall students.

The boys on the ice-boat did not go to their favorite spot, Robber Island, but allowed the Snowbird to sweep up an arm of the river, between several large hills. The hills were covered with hemlocks and cedars, between which the snow lay to a depth of one or two feet.

"Do you know what I'd like to do some day?" remarked Roger. "Come up here after rabbits." He had a shotgun, of which he was quite proud.

"I believe you'd find plenty," answered Dave. "I'd like to go myself. I used to hunt, when I was on the farm."

"Let us walk up the hills and take a look around—now we are here," continued the senator's son. [Pg 49] "If we see any rabbits' tracks we'll know they are on hand."

Dave agreed, and he, Roger, and Phil left the ice-boat, stating they would be back in half an hour.

"All right!" sang out Messmer. "We'll cruise around in the meantime. When we get back we'll whistle for you."

The tramp through the deep snow was not easy, yet the three chums enjoyed it, for it made them feel good to be out in the clear, cold atmosphere, every breath of which was invigorating. They went on silently, so as not to disturb any game that might be near.

"Here are rabbit tracks!" said Dave, in a low tone, after the top of the first hill was gained, and he pointed to the prints, running around the trees and bushes. "Shooting ought certainly to be good in this neighborhood."

From one hill they tramped to another, the base of which came down to the river at a point where there was a deep spot known as Lagger's Hole. Here the ice was usually full of air-holes and unsafe, and skaters and ice-boats avoided the locality.

From the top of the hill the boys commenced to throw snowballs down on the ice, seeing who could throw the farthest. Then Phil suggested they make a big snowball and roll it down.

"I'll bet, if it reaches the ice, it will go clear across the river," said the shipowner's son.

"All right, let's try it," answered Dave and Roger, and the three set to work to make a round, hard ball. They rolled it around the top of the hill until it was all of three feet in diameter and then pushed it to the edge.

"Now then, send her down!" cried Phil, and the three boys gave a push that took the big snowball over the edge of the hill. Slowly at first and then faster and faster, it rolled down the hill, increasing in size as it progressed.

"It's getting there!" sang out Roger. "See how it is shooting along!"

"Look!" yelled Dave, pointing up the river. "An ice-boat is coming!"

All looked and saw that he was right. It was a craft from the Rockville academy, and it was headed straight for the spot where the big snowball was about to cross.

"If the snowball hits them, there will be a smash-up!" cried Roger.

"And that is just what is going to happen, I fear," answered Dave.

As the ice-boat came closer the boys on the hill saw that it contained four persons, two cadets and two young ladies. The latter were evidently guests, for they sat in the stern and took no part in handling the craft.

Dave set up a loud cry of warning and his chums joined in. But if those on the ice-boat heard, they paid no heed. On and on they came, heading for the very spot for which the great snowball, now all of six feet in diameter, was shooting.

"The ice is full of holes, maybe the snowball will drop into one of them," said Phil. But this was not to be. The snowball kept straight on, until it and the ice-boat were less than a hundred feet apart.

It was then that one of the cadets on the craft saw the peril and uttered a cry of alarm. He tried to bring the ice-boat around, and his fellow-student aided him. But it was too late, and in a few seconds more the big snowball hit the craft, bowled [Pg 52] it over, and sent it spinning along the ice toward some of the largest of the air-holes.

"They are going into the water!" gasped Roger.

"Come on—let us see if we can help them!" returned Dave, and plunged down the hill. He took the course the big snowball had taken, and his chums came after him. More than once they fell, but picked themselves up quickly and kept on until the ice was gained. At the edge they came to a halt, for the air-holes told them plainly of the danger ahead.

"There they go—into the water!" cried Dave, and waiting no longer, he ran out on the ice, picking his way between the air-holes as best he could. Several times the ice cracked beneath his weight, but he did not turn back. He felt that the occupants of the ice-boat were in peril of their lives and that in a measure he was responsible for this crisis.

The river at this point was all of a hundred yards wide and the accident had occurred close to the farther side. The ice-boat had been sent to where two air-holes were close together, and the weight of the craft and its occupants had caused it to crack the ice, and it now rested half in and half out of the water. One of the cadets and one of the young ladies had been flung off to a safe place, but the other pair were clinging desperately to the framework.

"Oh, we shall be drowned! We shall be drowned!" cried the maiden in distress.

"Can't you jump off?" asked the cadet who was safe on the ice.

"I—I am afraid!" wailed the girl. "Oh, the ice is sinking!" she added, as an ominous sound reached her ears.

To the credit of the cadet on the ice-boat, he remained the cooler of the two, and he called to his fellow-student to run for a fence-rail which might be used to rescue the girl and himself. But the nearest fence was a long way off, and time, just then, was precious.

"Cut a couple of ropes!" sang out Dave, as he dashed up. "Cut one and throw it over here!"

The cadet left on the overturned craft understood the suggestion, and taking out his pocketknife, he cut two of the ropes. He tied one fast to the other and sent an end spinning out toward Dave and the cadet on the ice. The other end of the united ropes remained fast to the ice-boat.

By this time Phil and Roger had come up, and all the lads on the firm ice took hold of the rope and pulled with all their might. Dave directed the operation, and slowly the ice-boat came up from the hole into which it had partly sunk and slid over toward the shore.

"Hurrah! we've got her!" cried Phil.

"Vera, are you hurt?" asked the girl on the ice, anxiously.

"Not at all, Mary; only one foot is wet," answered the girl who had been rescued.

"Oh, I'm so glad!" And then the two girls embraced in the joy of their escape.

"I'd like to know where that big snowball came from," growled the cadet who had been flung off the ice-boat when the shock came. He looked at Dave and his companions. "Did you start that thing?"

"We did," answered Dave, "but we didn't know you were coming."

"It was a mighty careless thing to do," put in the cadet who had been rescued. "We might have been drowned!"

"I believe they did it on purpose," said the other cadet. He looked at the letters on a sweater Roger wore. "You're from Oak Hall, aren't you?"

"Yes."

"Thought you'd have some sport, eh?" This was said with a sneer. "Say, Cabot, we ought to give 'em something for this," he added, turning to his fellow-cadet.

"So we should," growled Cabot, who chanced to be the owner of the craft that had been damaged. "They have got to pay for breaking the ice-boat, anyway."

"Oh, Mr. Anderson, please don't get into a quarrel!" pleaded one of the girls.

"Well, those rowdies deserve a thrashing," answered Anderson. He was a big fellow, with rather a hard look on his face.

"Thank you, but we are not rowdies," retorted Roger. "We were having a little fun and did not dream of striking you with the snowball."

"If you know anything about the river, you know ice-boats and skaters rarely if ever come this way," added Phil. "The ice around here is always full of air-holes and consequently dangerous."

"Oh, you haven't got to teach me where to go," growled Anderson.

"I'm only stating a fact."

"The ice is certainly not very nice around here," said one of the girls. "Perhaps we might have gotten into a hole even if the big snowball hadn't struck us."

At this remark Dave and his chums gave the girl a grateful look. The cadets were annoyed, and one whispered something to the other.

"You fellows get to work and fix the ice-boat," said Cabot.

"And do it quick, too," added Anderson.

"I—I think I'll walk the rest of the way home," said one of the girls. "Will you come along, Vera?"

"Yes," answered the other. She stepped up to Dave's side. "Thank you for telling Mr. Cabot what to do, and for pulling us out of the hole," she went on, and gave the boys a warm smile.

"Going to leave us?" growled Anderson.

"Yes."

"That ain't fair. You promised——"

"To take a ride on the ice-boat," finished the girl named Vera. "We did it, and now I am going home."

"And so am I," added the other girl. "Good-bye."

"But see here——" went on Anderson, and caught the girl named Vera by the arm.

"Please let go, Mr. Anderson."

"I want——"

"Let the young lady go if she wishes to," said Dave, stepping up.

"This isn't your affair," blustered Anderson.

"No gentleman would detain a lady against her will."

"Good-bye," said the girl, and stepped back several paces when released by the cadet.

"All right, Vera Rockwell, I'll not take you out again," growled Anderson, seeing she was bound to go.

"You'll not have the chance, thank you!" flung back the girl, and then she joined her companion, [Pg 57] and both hurried away from the shore and to a road running near by.

After the girls had gone there was an awkward silence. Both Cabot and Anderson felt sore to be treated in this fashion, and especially in the presence of those from Oak Hall, a rival institution to that where they belonged.

"Well, what are you going to do about the damage done?" grumbled Anderson.

"I don't think the ice-boat is damaged much," answered Dave. "Let us look her over and see."

"If she is, you'll pay the bill," came from Cabot.

"Well, we can do that easily enough," answered Roger lightly.

The craft was righted and inspected. The damage proved to be trifling and the ice-boat was speedily made fit for use.

"If I find she isn't all right, I'll make some of you foot the bill," said Cabot.

"I am willing to pay for all damage done," answered Dave. "My name is Dave Porter."

"Oh! I've heard of you," said Anderson. "You're on the Oak Hall football team."

"Yes, and I've had the pleasure of helping to beat Rockville," answered Dave, and could not help grinning.

"Humph! Wait till next season! We'll show you a thing or two," growled Anderson, and then [Pg 58] he and Cabot boarded the ice-boat, trimmed the sail, and stood off down the river.

"Well, they are what I call a couple of pills," was Phil's comment. "I don't see how two nice girls could go out with them."

"They certainly were two nice girls," answered Roger. "That Vera Rockwell had beautiful eyes and hair. And did you see the smile she gave Dave! Dave, you're the lucky one!"

"That other girl is named Mary Feversham," answered Phil. "Her father is connected with the express company. I met her once, but she doesn't seem to remember me. I think she is better-looking than Miss Rockwell."

"Gracious, Phil must be smitten!" cried Dave.

"When is it to come off, Phil?" asked the senator's son. "We want time to buy presents, you know."

"Oh, you can poke fun if you want to," grumbled the shipowner's son. "She's a nice girl and I'd like to have the chance to meet her. Somebody said she was a good skater."

"Well, if you go skating with her, ask Miss Rockwell to come, too, and I'll be at the corner waiting for you," said the senator's son. "That is, if Dave don't try to cut me out."

"No danger—Jessie wouldn't allow it," replied Phil.

"You leave Jessie out of it," answered Dave, flushing a trifle. "Just the same, I agree with both of you, those girls looked to be very nice."

The three boys walked along the river bank for nearly half a mile before they came in sight of the Snowbird. Then Messmer and Henshaw wanted to know what had kept them so long.

"I'd not go in there with my boat," said Messmer, after he had heard their story. "Those air-holes are too dangerous."

When the lads got back to Oak Hall they found a free-for-all snowball fight in progress. One crowd was on the campus and the other in the road beyond.

"This suits me!" cried Roger. "Come on, Dave," and he joined the force on the road. His chums did the same, and sent the snowballs flying at a brisk rate.

The fight was a furious one for over an hour. The force on the campus outnumbered those in the road and the latter were driven to where the highway made a turn and where there were several clumps of trees and bushes. Here, Dave called on those around him to make a stand, and the other crowd was halted in its onward rush.

"Here comes Horsehair in a cutter!" cried one of the students, presently. "Let us give him a salute."

"All right!" called back Dave. "Some snow [Pg 60] will make him strong, and brush off some of the hair he carries around with him."

The boys made a number of snowballs and, led by Dave, waited for the appearance of the cutter. Soon it turned the bend, the horse on a trot and the sleighbells jingling merrily.

"Now then, all together!" shouted Dave, and prepared to hurl a snowball at the man who was driving.

"Hold on!" yelled Roger, suddenly.

But the warning cry came too late for Dave and Phil, who were in the lead. They let fly their snowballs, and the man in the cutter was struck in the chin and the ear. He fell backward, but speedily recovered and stopped his horse.

"You young rascals!" he spluttered hoarsely. "What do you mean by snowballing me in this fashion!"

"Job Haskers!" murmured Dave, in consternation.

"What a mistake!" groaned Phil. "We are in for it now!"

Dave and Phil had indeed made a serious mistake, and they knew at once that they were in for a severe lecture, and worse. Job Haskers was naturally an irascible man, and for the past few days he had been in a particularly bad humor.

"Excuse me, Mr. Haskers," said Dave, respectfully. "I didn't know you were in the cutter."

"You did it on purpose—don't deny it, Porter!" fumed the teacher. "It is outrageous, infamous, that a pupil of Oak Hall should act so!"

"Really, Mr. Haskers, it was a mistake," spoke up Phil. "We thought it was Horsehair—I mean Lemond, who was driving."

"Bah! Do I look like Lemond? And, anyway, what right would you have to snowball the driver for this school? It is scandalous! I shall make an example of you. Report to me at the office in five minutes, both of you!"

The boys' hearts sank at this order, and they felt worse when they suddenly remembered that both Doctor Clay and Mr. Dale were away and [Pg 62] that, consequently, Job Haskers was, for the time being, in authority. The teacher went back to the cutter, took up the reins, and drove out of sight around the campus entrance.

"Too bad!" was Roger's comment. "I yelled to you not to throw."

"I know you did, but I had already done so," answered Dave.

"And so had I," added Phil.

"Say, that puts me in mind of a story," exclaimed Shadow, who was in the crowd. "A man once had a mule——"

"Who wants to listen to a story at this time?" broke in Ben Basswood.

"Never mind, let's have the yarn," said Dave. "Perhaps it will serve to brighten our gloom," and he smiled feebly.