Plate V.

Plate V.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Floor of the Ocean | 9 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Aquarium | 19 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Vegetation of the Marine Aquarium | 39 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Zoöphytes | 51 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Molluscs, &c. | 64 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Ascidians, Barnacles, Sea-Cucumbers, Naked Molluscs, Sea-Worms, &c. | 86 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Fish and Crustaceans of the Aquarium | 95 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Conclusion | 106 |

| PLATE I. | ||

| SEA-WEEDS. | ||

| No. | PAGE | |

| 1. Delesseria sanguinea | The Crimson Delesseria | 45 |

| 2. Punctaria latifolia | The Broad-leaved Punctaria | 45 |

| 3. Chordaria flagelliformis | The Whip-like Chordaria | 45 |

| 4. Vaucheria submarina | The Submarine Vaucheria | 45 |

| 5. Hildenbrandtia rubra | The Red Hildenbrandtia | 45 |

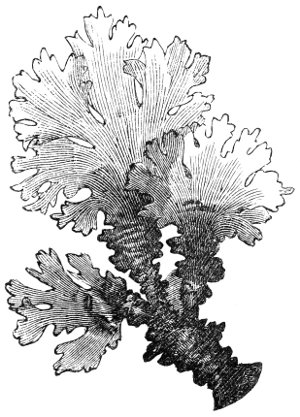

| PLATE II. | ||

| SEA-WEEDS. | ||

| 1. Bangia fusco-purpurea | The Dark-purple Bangia | 46 |

| 2. Codium tomentosum | The Closely-haired Codium | 46 |

| 3. Bryopsis plumosa | The Feathery Bryopsis | 41, 46 |

| 4. Callithamnion arbuscula | The Tree-like Callithamnion | 46 |

| 5. Leathesia Berkleyi | Berkley’s Leathesia | 46 |

| 6. Laminaria phyllitis | The Leafy Laminaria | 46 |

| PLATE III. | ||

| 1. Porphyra vulgaris | The Common Porphyra | 46 |

| 2. Dumantia filiformis | The Slender Dumantia | 46 |

| 3. Asperococcus Turneri | Turner’s Asperococcus | 47 |

| 4. Rytiphlæa pinastris | The Pine-like Rytiphlæa | 47 |

| 5. Chrysymenia rosea | The Rose-coloured Chrysymenia | 47 |

| 6. Peyssonetia Dubyi | Duby’s Peyssonetia | 47 |

| 7. Chordaria divaricata | The Minutely-branching Chordaria | 47 |

| 8. Ectocarpus siliculosus | The Podded Ectocarpus | 46 |

| 9. Nemaleon multifida | The Many-cleft Nemaleon | 46 |

| 10. Nytophyllum punctatum | The Spotted Nytophyllum | 46 |

| PLATE IV. | ||

| SEA-WEEDS. | ||

| 1. Chondrus crispus | The Curly Chondrus | 41, 47 |

| 2. Gigartina acicularis | The Needle-shaped or Pointed Gigartina | 47 |

| 3. Ceramium strictum | The Pink Ceramium | 47 |

| 4. Zonaria atomaria | The Speckled Zonaria | 47 |

| 5. Plocamium coccineum | The Scarlet Plocamium | 47 |

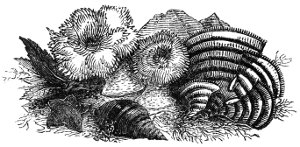

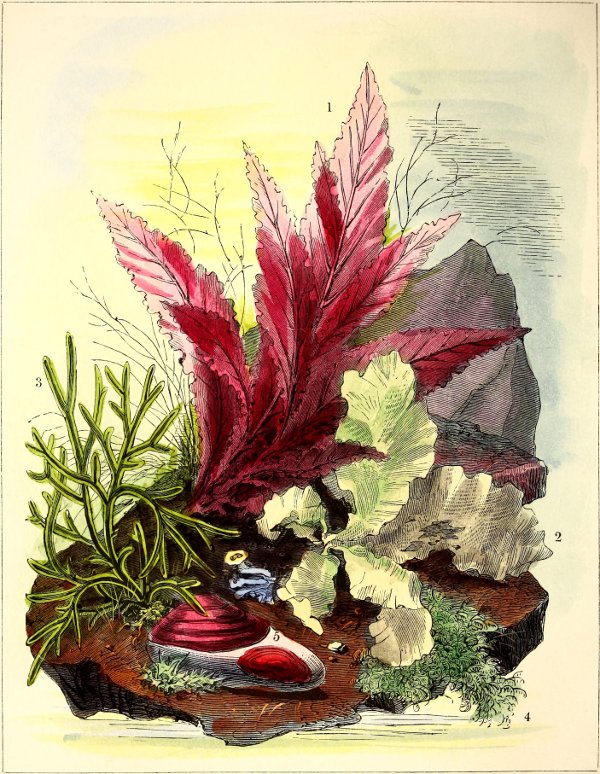

| PLATE V. | ||

| SEA-WEEDS. | ||

| 1. Laurencia pinnatifolia | The Pinnate-leaved Laurencia | 42, 48 |

| 2. Polysphonia parasitica | The Parasitic Polysphonia | 48 |

| 3. Ulva latissima | The Broad-leaved Ulva | 48 |

| 4. Rhodymenia lacinata | The Lace-edged Rhodymenia | 42, 48 |

| 5. Gracilaria confervoides | The Sponge-like Gracilaria | 49 |

| 6. Codium bursa | The Purse-like Codium | 49 |

| 7. Iridæa edulis | The Eatable Iridea | 48 |

| 8. Zonaria parvula | The Lesser Zonaria | 48 |

| 9. Ectocarpus tomentosus | The Hairy Ectocarpus | 49 |

| 10. Corallina officinalis | The Common Corallina | 49 |

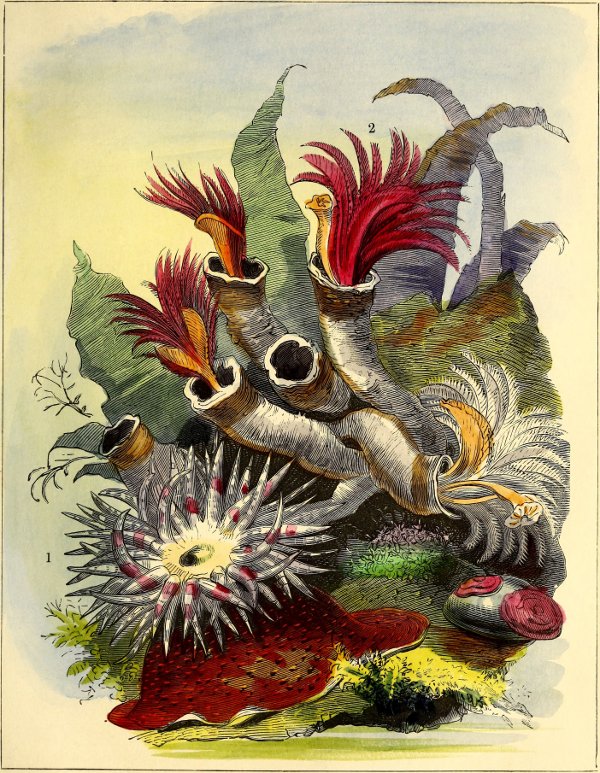

| PLATE VI. | ||

| SEA-ANEMONES, STAR-FISH, ETC. | ||

| 1. Geniaster equestres | The Small Scarlet Star-fish | 101 |

| 2. Asterina gibbosa | The Gibbous Star-fish | 101 |

| 3. Palmipes membranaceus | The Bird’s-foot Star | 101 |

| 4. Cribella oculata | The Eyed Star-fish | 101 |

| 5. Palæmon serratus | The Common Prawn | 98 |

| 6. Edwardsia vestita | The Clothed Sea-Anemone | 54 |

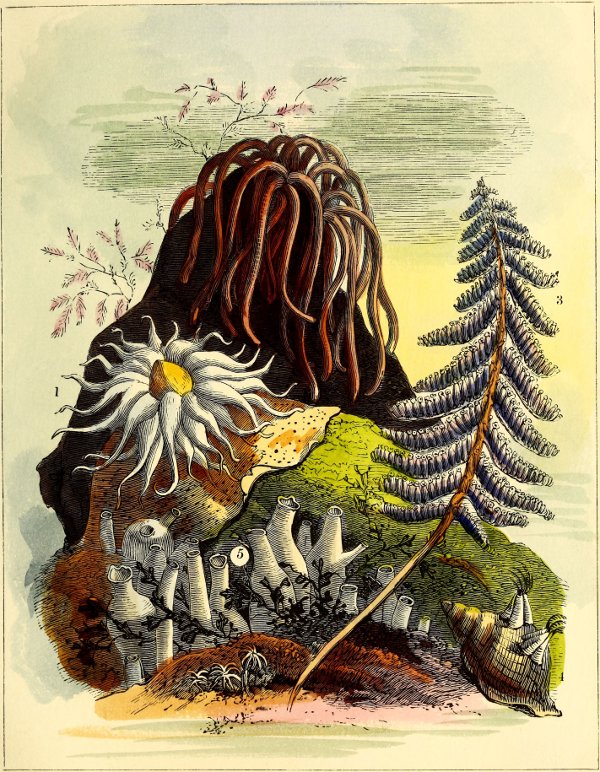

| PLATE VII. | ||

| 1. Actinia clavata | The Nailed Sea-Anemone | 55 |

| 2. Pennatula phosphorea | The Phosphoric Sea-pen | 61 |

| 3. A Group of Ascidians | 86 | |

| 4. A Shell of the Common Whelk, on which are two specimens of Balanus | The Acorn-shell | 88 |

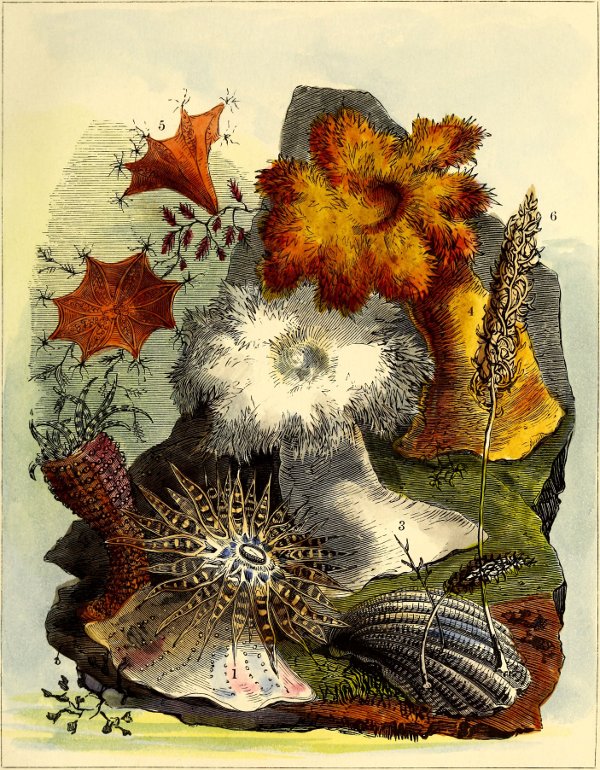

| PLATE VIII. | ||

| 1 & 2. Actinia mesembrianthemum | The Carnation-like Sea-Anemone of different colours | 57 |

| 3. Actinia gemmacea | The Gemmed Sea-Anemone | 55 |

| 4. Lucernaria auricula | The Auricula-like Lucernaria | 59 |

| 5. Virgularia mirabilis | The Rod-like Sea-Pen | 62 |

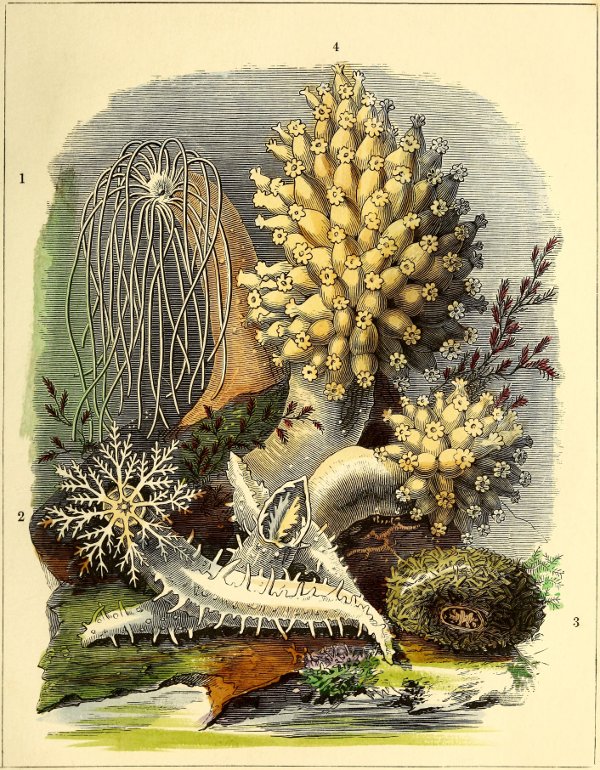

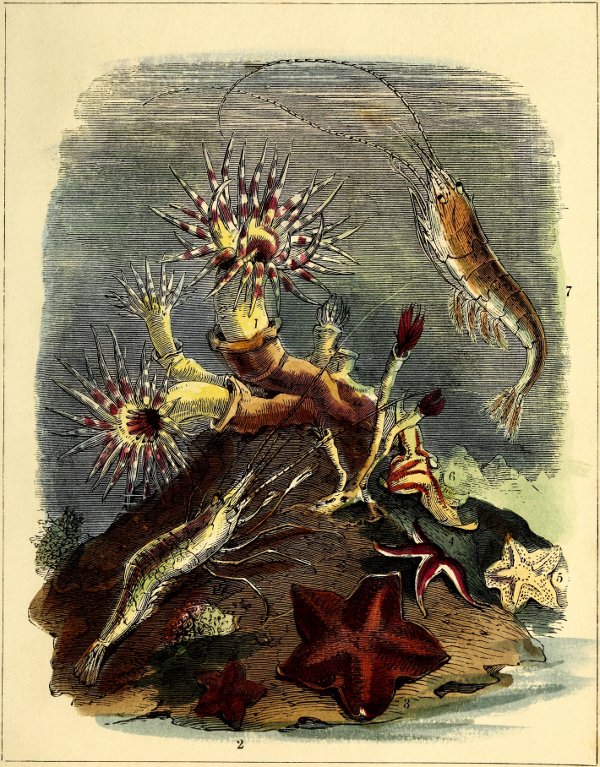

| PLATE IX. | ||

| 1. Actinia anguicoma | The Serpent-haired Sea-Anemone | 57 |

| 2. Alyconium digitatum | The Many-fingered Alyconium | 61 |

| 3. Echinus sphæra | The Common Sea-Egg | 103 |

| 4. Cucumis hyalinus | The Glassy Sea-Cucumber | 89 |

| PLATE X. | ||

| 1. A group of Serpula contortuplicata | The Twisted Serpula | 87 |

| 2. Actinia crassicornis | The Thick-horned Sea-Anemone | 57 |

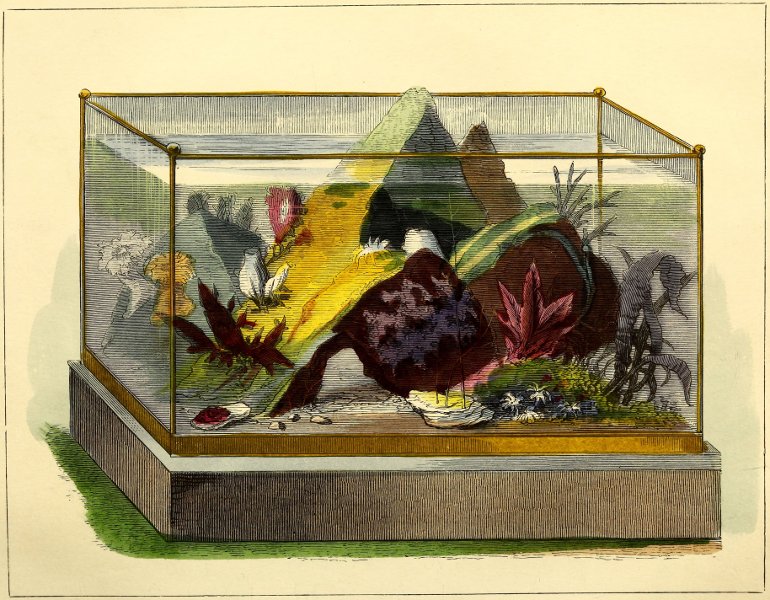

| PLATE XI. | ||

| A Design for a Plainly-mounted Aquarium | 34 | |

| PLATE XII. | ||

| A Design for an Aquarium mounted in handsome Rustic-work | 34 | |

What the vast majority of our migratory flocks of summer and autumnal idlers generally do and think at the sea-side, cannot be better exemplified than by reference to the clever sketches which are found occupying entire pages of our illustrated periodicals and newspapers, during the season of marine migration. But the habits and customs of the annual shoal of visitors to our watering-places, may be still more intimately comprehended through the medium of the sprightly essays which generally accompany those truly artistic delineations.

And is there really nothing better to do—no 2better regime to go through, than the daily repetition of the monotonous programme of entertainment thus playfully described and ridiculed?

Surely the visitor at the sea-side is in reach of something more pleasant and profitable than such a routine!

Do not the sublime aspects of the ocean—the sound of its deep, ceaseless voice—the eternal on-coming of its waves, now in calm undulations, and now in hurtling wildness against the base of those cliffs whose white brows are wreathed with perennial flowers—suggest other matters both for reflection and amusement? Surely the very whispering of the breeze that has travelled so far over that vast moving surface of the fathomless deep, and which seems muttering of its mysteries, while laden with its sweet saline odour—“ce parfum acre de la mer,” as Dumas has termed it—might lead us towards other and higher trains of thought. Surely those voices in the wind, mingling with the strange murmur of the waves as they break in cadenced regularity upon the shore, rouse, in the feelings of those who hear them for the first time, or after a long absence, strange sensations of admiration, and curiosity, and wonder. But no; to most of the idle crowd those sights and sounds are invisible and 3unheard. Their ears have not been tutored to understand the word-music of Nature’s language, nor to read the brightly-written signs on its mighty page.

To appreciate Nature, as well as Art, the mind requires a special education, without which the eye and the ear perceive but little of the miracles passing before them. To the eye of the common observer, the farthest field in the landscape is as green as the nearest, in the scene outspread before him; while to the practised glance of the accomplished artist, every yard of distance lends its new tone of colour to the tints of the herbage, till, through a thousand delicate gradations, the brightest verdure at last mingles with the atmospheric hue, and is eventually lost in the pervading azure. If, then, the ordinary aspects of Nature may not be fully interpreted by the untutored eye, how should her more hidden mysteries be felt or understood, or even guessed at? And, in fact, they are not, or the visitor to the sea-side, looking over that wide tremulous expanse of water that covers so many mysteries, would feel, like the child taken for the first time within the walls of a theatre, an intense anxiety to raise the dark-green curtain which conceals the scene of fairy wonders he is greedily longing to 4behold and enjoy. But the lounger at the sea-side does not guess at the wonders concealed by the dark-green curtain of the ocean, and, consequently, never dreams of wishing to peep beneath its waving folds, to gratify a curiosity which, in fact, does not exist.

When, however, the language of Nature is learnt, and her voice is no longer a confused murmur to the ear, but becomes a brilliant series of eloquent words, full of deep and exquisite meaning, then the student will see as well as hear; but till then, in his intercourse with Nature, he is both deaf and blind. “Speak,” said Socrates to a youth; “say something, that I may see you.” Socrates saw not a silent man; and those who do not hear and understand Nature’s language, cannot see her wondrous beauty.

The mill-like repetition of worldly affairs brings on a torpor of mind, in regard to all without the narrow circle of selfish interests and easily purchased pleasures, which it is very difficult to wake up from. But I would warn the suffering victims of that baneful, though secret, presence; for when the consciousness of its existence is aroused, the first step will have been taken towards its eradication.

5I would remind all those suffering from inactivity of mind, of the wholesome dread of that kind of mental torpor entertained by the Gymnosophists; who, as Apuleus tells us, when they met at meals, required that each should be able to narrate the particulars of some discovery, or original thought, or good action, or it was deemed that he did not exhibit a sufficient reason for being allowed to consume a share of the viands, and he was consequently excluded from the repast. Were each of our most idle sea-side loungers to impose upon himself the necessity of a discovery, or an original thought, before he considered himself entitled to dine, that torpor, so deadening to the natural capacities of his mind, would soon give way to a state of mental activity, which, were it only from the brightness of the contrast, would be found highly agreeable, to say nothing of its advantages, or of the elevating and refining trains of thought to which it would necessarily give rise.

I know of nothing more likely to stimulate the mind to healthy exertion, and take it out of the immediate track of common interests and pleasures, the monotony of which is so oppressive, than the study of natural history in some of its least explored fields, especially its extraordinary development in 6connection with the waters of the ocean. And yet, how few there are who seek that charming mode of dissipating the dreary monotony of social life, such as it is made by the routine of fashion or habit! A popular love of natural history, even in its best known divisions, is, in fact, of quite recent growth. Indeed, the very existence of such a science has been, till recently, altogether ignored by our great national seats of learning. The earnest investigators, who have done so much to lay bare its wonders, were either openly ridiculed, or treated with but small respect—as useless dreamers upon very small and insignificant matters. The very names of such true labourers in the mine of science as our glorious old naturalist Ray, or his follower Pulteney, or the indefatigable Ellis, the first detector of the true nature of Zoöphytes, who measured pens with the giant Linnæus, received no academic honour; and those of their undiscouraged successors have been rarely heard, either in our universities or among our general public, till the vast discoveries of geology and other allied branches of science, in our own times, have at last aroused attention to their importance.

Any popular knowledge of that branch of natural history which especially concerns our seas and 7shores, is indeed of still more recent date. The subject, in fact, is but even now beginning to develop itself beneath the pens of an enterprising band of marine naturalists, with such leaders as Johnston, Harvey, John Edward Gray, the indefatigable Gosse, and the revered shade of the lamented Forbes at their head.

A truly popular knowledge even of those more accessible regions of our woods and fields, is but little more ancient; for, till Gilbert White had made the story of such knowledge as attractive as romance, in his “Natural History of Selborne,” few guessed what an arena of ever new interests and discoveries it presented.

Through the fascinating interpretation of the good Gilbert, many now understand the attraction of those branches of natural history which he so curiously investigated; but few are willing to admit that it is as easy to make the natural features of some obscure fishing-village, with no herbage on its bare rocks, and no bush, no blade of grass, no bird to be seen or heard, equally interesting; yet I can assure them, that by lifting even the mere border of that green curtain of the ocean, or by awaiting its unveilings, as the retiring tide bears back its folds, a host of wonders will be revealed, sufficient to rouse the 8most torpid mind of the most inactive idler to their earnest and deeply-inquiring contemplation, and arouse him to their devout admiration, as among the most exquisite miracles of that creative and sustaining Power which is the source of their existence.

The wonders of the ocean floor do not reveal themselves to vulgar eyes. As the oracle was inaudible to sacrilegious listeners, and as none but poetic ears heard the cadenced beating of the feet that danced to unearthly music, near the fountain haunted by the Muses of classic fable—so, none but the initiated can see the myriad miracles that each receding tide reveals on the ocean floor. The initiation, however, is not mysterious; there are no dark rites to observe—no Herculean labours to accomplish, before entering upon the noviciate, which at once opens a large area of unexpected pleasures, and an ample field for admiration and investigation. A few elementary works carefully studied, or even this present little book attentively perused, would supply the first helps towards seeing, at all events, a portion of the “wonders of the shore,” as the brilliant author of “Glaucus” has eloquently termed those revelations of the retiring deep.

It is the seeing that is everything. But let none 10despair of acquiring that power. “The name of the Devonshire squire, Colonel George Montague” (thus wrote the late Professor Edward Forbes), “might have become one of the greatest in the whole range of British science, had his whole career been devoted to marine physiology;” and that mainly because, from a sincere devotion to a favourite pursuit of his leisure, he acquired the art of seeing—an art sought by so few, though open to all who will earnestly seek it.

Each department of science requires a separate and distinct kind of sight. The astute merchant deciphers at a glance the precise state of the most intricate accounts, in the midst of thousands of seemingly conflicting figures; but of the thousand interesting and wonderful things concerning the little beetle that crosses his path in his country walk, he is incapable of seeing any single particle; while the despised entomologist, whom he has contemptuously observed turning over the stones at the road-side, and peering curiously beneath them, could tell him a tale of wonder, could preach him a sermon upon that tiny type, such as would surely wake up many latent and unsuspected powers in his mind, that would enable him to see wonders where all had previously been blank, and teach him that 11there are things well worthy of investigation beyond the region of money-making, and the attractive but narrow circle distinguished by the fascinating characters, £ s. d.

Those who cannot see Nature, who cannot see more than an unclean thing in the little creeping beetle, are like one gazing at a carved Egyptian record, who perceives, in the hieroglyphic scarabæus, simply the sculptured figure of a beetle, and no more—they are in a state of “Egyptian darkness” as regards one of the highest and most enchanting fields of human research. But to those who have acquired this rare though easy art, and learned to see Nature, even to a moderate extent (for in that art are an infinite number of degrees and gradations), the aspect of the ocean floor must present an appearance as beautiful and strange, and seemingly as supernatural, as the wildest imagination could depicture.

When poets would travel, in their inventive flights, to other floating and revolving worlds than ours, they describe rosy skies, instead of azure, and trees like branching crystals, with jewel-like fruits glittering on every stem. They present us with pictures, in short, in which all the ordinary aspects of our planet are reversed, or metamorphosed, in the region of their invention; but in their most fanciful 12pictures they do not surpass in strangeness the wonders of the world beneath the sea.

On the land, we have, as the ordinary aspect of Nature, the green herbaceous mantle of the earth below the eye, and the azure sky above; while a spectator, standing beneath the water on the ocean floor, would see these features more than reversed: he would see above him a liquid atmosphere of green, and below, an herbage of red or of purple hue, exhibiting strange yet exquisite forms, such as no terrestrial vegetation displays. Roseate shrubs of jointed stone, and arborets of filmy glass, and creatures full of active, energetic life, whose forms are stranger still, both in structure and in appearance; mere worms, whose colours are gorgeous as the tints of the butterfly’s wing, or the peacock’s tail, or the humming-bird’s breast.

What scenery is formed by that translucent and miniature forest of Delesseria sanguinea, how lovely in its tones of soft rich crimson; and those fan-like shrubs, in crisply graceful tufts, the bright and singular Padina pavonia; and the tree-like masses of Callithamnion arbuscula, and the delicate Ptilota plumosa, and the purple-tinted Corallines, forming those

And then the high waving fronds of the grandly 13graceful Porphyra vulgaris, the deep carmine of the Iridæa edulis, the nacreous tinges of the Chondrus crispus, and the blood-red of the splendid Rhodymenia lacinata, with its embroidered and lace-like edges; these, with the gorgeous tufts of the rich purple Bangia, and other objects which form the elements of still life in a submarine landscape, surely cannot be surpassed, either for magnificence of colour or variety of structure.

But to these features must be added others more extraordinary—forms that the elder naturalists imagined to be links between the animal and vegetable creation, but which are now known to have no affinity whatever with plants, though they exhibit the appearance of expanded flowers of various hues, displaying the forms of the Carnation, the Anemone, the Mesembryanthemum, and other beautiful flowers whose names they bear. These curiously beautiful Zoöphytes, the wonderful Actiniæ, exhibit every tone of colour, from purple and scarlet, to green and white, and might be taken in their picturesquely-placed groups for rare exotic flowers, planted among the rosy-tinted shrubs expressly to add the last touch of richness and effect to the scenery of an ocean flower-show.

Yet they are not flowers, but animals—sea 14monsters, whose seeming delicate petals are but their thousand Briarean arms, disguised as the petals of a flower, and expanded to seize the unconscious victim as he passes near the beautiful form—fatal to him as the crater of a volcano; in which he is soon engulphed by the closing tentacles of his unsuspected enemy. And if he pass not near enough for that deadly floral embrace, those pretty crimson tubercles that dot so gracefully the seeming stalk, beneath the seeming flower, can shoot forth a thread, armed, like the fisher’s line, with a barbed hook, which strikes and secures the distant prey; and so the unwary Annelid or Infusory is captured and devoured. In this capacity the creature has been compared to Pope’s spider, who

But then the living thread of the Actinia (or of the Cirriped, which has a similar power) is a fact, while the sensitive gossamer of the poet is a fiction.

But notwithstanding these ogre-like attributes, the lovely Actinia long deceived our naturalists as to its true nature—and of course the poets—from whom his flower-like disc and petaloid tentacles completely concealed his grosser nature. Then, as the tide recedes, he so meekly closes his beautiful 15oubliette, with so much grace, and looking so much like those shrinking flowers that close at eve, as though they dared not to look on the black darkness of the night, that it is no wonder poets were beguiled, and that the romantic Southey sings of the Actinia as of some lily of the deep that, on the retiring of the ocean,

To add to the wonders of this strange landscape come the creeping Nudibranchs and Tectibranchs, gliding over the gracefully-waving Algæ; their elegant forms decorated with their external breathing apparatus, like the pale skeleton of some delicate flower, so fine are its milk-white filaments, arranged nearly always in a symmetrical and star-like form. And then there are the singular and shadowy Medusæ floating past, in the form of parachutes, with low suspended cars, just as though the science of ballooning had been carried to perfection under the sea; and that they were made of elastic glass, instead of silk, though richly flushed with iridescent and varying tinges, sometimes metallic azure, and anon emerald green; hues that seem added by some delicate process which the glass-blowers above the water have not yet discovered. Some of these creatures are fragile as a 16soap-bubble, to which their transparency and prismatic flashes of colour give them a curious resemblance; and their ephemeral existence, dependent upon the will of even an angry ripple of the element in which they live, is doubtless as brief.

The deep has even its butterflies, as well as the land. The fluttering of the fins of some small and brightly-coloured fish has been compared to the action of the wings of moths—as also the members, likewise used for locomotive purposes, of some of the animals of the univalve shells. Then there are minute phosphorescent animals, which represent the fire-flies of the south, pouring a living flood of light as they glide along—some emitting silvery, and others golden flashes, like floating lamps that seem hurrying to light up the darkness of the far ocean depths.

Even the worms are gorgeous and wonderful in this subaqueous world. The Serpulæ, with their radiating coronets of crimson branchiæ; the Pectinaria, with its golden comb, glittering in burnished brightness; and the Nereis, with white and crimson stripes—are all wonderful as well as beautiful objects. But the Halithea, or sea-goddess, as Lamark has named it, from the extraordinary beauty and the gorgeous colours that radiate from the silky hairs with which it is clothed, surpasses them all.

17These, and other wonders of still greater beauty, will reward the persevering student who learns to see them; but then he must learn. Even the intellectual giant, Shakspeare, could not see clearly many of the minuter things of Nature. In his line upon the slow-worm, for instance, vulgarly called the blind-worm, which he describes as

are concentrated two mistakes; in the first place, the minute eyes of this little creature are brilliant in the extreme, and not very difficult to discover, to the naturalist who has learnt to see nature; and, in the second place, it has no venom, its tiny bite being perfectly harmless. In another place he speaks of

But it is useless to multiply examples of the physiological errors of great men who had not learned to see Nature; or, Milton’s errors in regard to the leaf of the Banyan-tree, and many others, might be readily cited.

There are many glorious things to be seen in the sea, but we have to learn to see them; and those who find they cannot see with their own eyes, must do so through the more gifted sense of others. To many—how many, unguided by an able Cicerone—the fields 18round Selborne would appear common and uninteresting enough; but guided by a Gilbert White, whose searching eye knew even the hidden forms of plants, whose ear at once distinguished and classified the song of birds, and even the buzz of insects—guided by him, things assume a far different aspect; like another Prospero, he waves his wand, and every object begins to brighten, and a thousand new and beautiful features develop themselves under the magic of his descriptions; crowds of marvels springing up around, as from enchanted ground. In like manner, guided by the fascinating science of a Johnston or a Harvey, or the persuasive industry of a Gosse, or the eloquently glowing descriptions of a Kingsley, students, who have not the energy or leisure to work for themselves, will find the dark ocean glow with an unexpected light; and the delighted explorer will long for the power to renew the impressions of his sea-side rambles after his return to his inland home, perhaps in the heart of a densely-populated city. Even this he may now do through the medium of the marine Aquarium, within the narrow boundaries of which he may, with a little care and experience, establish in healthy existence some of the most beautiful of the animal and vegetable forms that people the caves and depths of the ocean, and make its watery world a region of wonders.

The successful treatment of aquatic plants and animals, in the confined space of a glass Aquarium, depends entirely upon the discovery that there exists in Nature a self-adjusting balance between the supply of oxygen created in water, with the quantity consumed by aquatic animals. And it became equally necessary to know the means by which that supply was continually generated. Without the knowledge of these facts, and the principles by which they are regulated, it would have been impossible to establish such a marine Aquarium as that we may now any day examine in the Regent’s Park; where, in a few glass tanks of very moderate size, we may see examples of some of the most curious forms of animal and vegetable life peculiar to the depths of the ocean—forms so singular, that their first exhibition created a sense of wonder little less intense than that which must have been caused, long years ago, by the first public display of the mountain form of the elephant to the 20people of cold northern countries; and much more so than the recent introduction of the giraffe or hippopotamus, although they have never been seen in Europe since the days of the Romans.

Those principles, the knowledge of which was requisite to enable us thus to view the wonders of the ocean in their living state in an Aquarium, were not mastered at once, or by one man, or in one generation. The nature of certain relations between animal and vegetable life, upon which they are founded, was first advanced by Priestley, towards the close of the last century, who proved that plants give forth the oxygen necessary to animal life. The learned Ingenhauss, a native of Breda, but who principally resided in England, defined this principle still more clearly, in a work the title of which pretty fully explains the entire nature of his discovery. It was published in French, at Leyden, in 1778, and in London, in English, in 1779. The French edition is before me, the title of which I translate, “Experiments upon Plants, which prove their important influence in the purification of the atmospheric air when they are exposed to the rays of the sun, and the contrary results which ensue when they are placed in the shade, or during the night.” The action of the sun’s rays in disengaging 21the oxygen generated in plants is thus clearly announced, and the knowledge of this principle is one of those which have mainly conduced, as I have said, to the successful establishment of Aquaria.

In the course of his essay Ingenhauss states, still more directly, that plants “immersed in water,” when exposed to the action of light, emit an air which he announces as oxygen gas; and this idea is the key-stone of the Aquarium.

But, although the discovery of Ingenhauss at once rendered the thing practicable, Aquaria did not then come into fashion. The science of natural history was not at that time sufficiently advanced; for the specimens, even in public museums, were merely heterogeneous collections, assembled without the slightest regard to classification, or any other useful purpose. A stuffed cat with nine legs, stood, perhaps, next to a bottled snake, followed by the skin of a crocodile, to be succeeded in turn by a very moth-eaten specimen of a King Charles spaniel, “supposed, upon good authority, to have belonged to Nell Gwynne.” A few scores of such objects, with the addition of an ostrich egg and a few sea-shells, without any attempt at name or description, formed a very respectable museum in those times; and we may, therefore, easily conceive 22that (in so far as experiments illustrative of natural science were concerned) the suggestions of Ingenhauss remained tolerably dormant.

It was not till the year 1833, that Professor Daubeny communicated, to the British Association at Cambridge, a paper concerning some new researches prosecuted in the same direction; and not till 1837, that Mr. Ward became the first to apply the principle to any purpose analogous to that of the Aquarium. In that year he made a report to the British Association, on the hermetically closed glass cases in which he had succeeded in growing many classes of plants, and keeping them in a healthy state without any fresh supply of air. He stated, at the same time, his belief that certain classes of animals would live and thrive under similar circumstances. This was the first direct hint towards the formation of a closed Vivarium, whether atmospheric or aquatic.

In 1842, Dr. Johnston satisfactorily proved the true vegetable nature of Corallines by observing their growth in a vessel containing sea-water; and thus was established the first true Aquarium. With the experimental tuft of Coralline was a small frond of a green Ulva, and numerous Rissoæ, &c., and several Annelids afterwards appeared, having been, 23no doubt, attached to the branches of the Coralline, or the fronds of the Ulva. At the end of four weeks the water was still pure, the Molluscs and other animals alive, and the Confervæ grown; the Coralline having thrown out several additional articulations. After eight weeks, the water still remained sweet. But had any animal, of even the lowest order, been so confined, without the accompanying presence of vegetables giving off oxygen, all of that vital gas contained in so small a quantity of water would have been quickly exhausted, and the water would have become corrupt, ammoniacal, and poisonous to the life of any living thing. But the author of this experiment had not in view the testing of the possibility of preserving the forms of ocean life in a healthy state in confinement; his business had been to settle an important point connected with the classification of the Corallines; and having successfully decided that question, the embryo Aquarium was abandoned.

On the 4th of June, 1850, Mr. R. Warrington communicated to the Chemical Society a series of observations on the adjustment of certain relations between the animal and vegetable kingdoms, very important to our present purpose. Two small gold-fish were placed in a glass receiver, a small plant of 24Valisneria spiralis being planted at the same time in some earth, beneath a layer of sand in the same vessel. All went on well by this arrangement, without any necessity for changing the water; the oxygen given off by the plant proving itself sufficient for the supply of its animal co-tenants, and the water therefore remaining clean and pure, until some decaying leaves of the Valisneria caused turbidity, and confervoid growth began to accumulate on the sides of the vessel. To remedy this evil, Mr. Warrington brought to bear the results of previous observations on water in natural ponds under analogous circumstances; and, guided by these observations and their results, he placed a few common pond-snails in the vessel containing his gold-fish and plant of Valisneria.

The new inmates, immediately upon their introduction, began to feed greedily upon the decaying vegetable matter, and all was quickly restored to a healthy state. They proved, indeed, of still further advantage, for the masses of eggs which they deposited evidently presented a kind of food natural to the fishes, which was eagerly devoured by them, so that the snails became not only the scavengers, but also the feeders of the little colony. And so this first of true Aquaria prospered; the animals and 25plants proving of mutual value and support to each other. The snails disposed of the decaying leaves, which would have tainted the water and rendered it unfit for the healthy existence of the plant, and the plant in turn gave forth, under the rays of sunlight, the supply of oxygen necessary to both fish and snails.

In January, 1852, Mr. Warrington, commenced a series of similar experiments with sea-water; which were, at first, not so satisfactory, but in the end proved as entirely successful. In the course of his experiments, he found the red and brown Algæ, or sea-weed, less proper for the formation of oxygen than the green. Of the latter class he procured specimens of Enteromorpha and Ulva latissima, which he chiselled from the rocks about Broadstairs, along with the pieces of chalk or flint to which they were attached; and, when he placed them in his own marine Aquarium, he put in along with them, to represent the pond-snails in the fresh-water tank, some of the common sea-snail, better known as the Periwinkle (Littorina littorea). But these proved, it appears, insufficient for the destruction of the mucous and gelatinous matter that arose from the decay of the red sea-weeds, which, however, I have no doubt may yet be cultivated with 26equal success with the green, as I shall state when describing them. Under the existing difficulty, Mr. Warrington found it necessary to aerate the water by other means, many processes being equally available; such as injecting fresh-water from a syringe, or establishing a drip, of some height, from a vessel containing a supply of entirely fresh-water. Mr. Warrington also discovered, in the course of these experiments, the necessity that the light should pass directly through the surface of the water to the plants, as in natural ponds and seas—a very important step in the successful management of Aquaria; and he therefore had a slab of slate adjusted to the side of his tank which stood next to the light.

These successful experiments, both in fresh-water and marine Aquaria, assign to Mr. Warrington, beyond dispute, the credit of being the originator, or inventor, if the term may be so used, of these charming additions to our conservatories, corridors, and even living-rooms, to which they are certainly a much more attractive and instructive addition than the old globe of blank water, with its pair of gold-fish swimming round and round in ceaseless gyrations, tiresome to behold, in the vain hope of escaping from their glaring and inconvenient prison; 27in which they would inevitably have perished very shortly but for the daily change of water, which, previous to our knowledge of air-emitting plants and their use, was absolutely necessary.

But another experimentalist was now in the field. Mr. Gosse, whose charming works upon Aquaria and other subjects connected with natural science, have, perhaps, made his name more widely known than that of his predecessor, Mr. Warrington, commenced a series of experiments on the subject of the marine Aquarium, about the same time as the last-named gentleman, in the beginning of January, 1852. His experiments were crowned with such complete success that he was induced to put himself in communication with Mr. David Mitchell, the enterprising Secretary of the Zoological Society, the result of which was the removal of the collection of Annelids and Zoöphytes which Mr. Gosse had formed, to the gardens of the Society in the Regent’s Park; where it formed the nucleus from which has grown the magnificent series of Aquaria in the building constructed specially for their reception. These marine Aquaria at once became a subject of public as well as private interest, and the Aquarium house was so crowded daily with its curious visitors, that it was difficult to get a glimpse of the 28wonders of the “ocean floor,” and its zoöphytic denizens, which were so successfully exhibited there; principally through the skilful aid and untiring industry of Mr. Gosse, through whose hands above five thousand specimens passed at the time, collected at the request of the Zoological Society.

In his interesting record of his early essays, Mr. Gosse gives us many valuable particulars concerning his successive experiments, and the various disappointments to which he was at first subjected; many of them from causes now too well understood to require repetition. His principal difficulty arose from over-crowding, although his tank did not appear, as he states, too much filled. Another disappointment was caused by putting in animals before the smell of the putty, with which the glass sides were fixed, had sufficiently gone off.

Mr. Gosse’s tank was made with a slate bottom, and birch pillars, in which were grooves to receive the glass; and its dimensions were, two feet long by one foot six wide, the depth not being mentioned.

Taking these dimensions into consideration, it will be easy to conceive, when the following list of specimens which Mr. Gosse introduced into his Aquarium is examined, that his population was too dense for the extent of his province, although the 29space might not have appeared too much filled for picturesque effect. Of vegetable specimens, he introduced at once the following:—

In a few days the water, poured carefully to these specimens, became clear as pale green crystal, the green tinge being too slight to obscure the colour of any object seen through its medium.

From these weeds alone, before any supply of Zoöphytes or Molluscs were intentionally added, a whole host of minute animal life swarmed forth; some, doubtless, issuing from eggs newly hatched; others from the shelter of the matted ramifications of some of the sea-weeds, in which they had been taken, as in a net. Among these swarming creatures were Annelids of the genus Syllis, Rissoæ, and other minute shell-fish, but principally Isopodous and Entomostracous Crustacea, many of them being so minute as not to be perceived without the use of a powerful lens.

30Of the animals next placed in this tank, of only two feet by one foot six inches, the following is the list given:—

| FISH. | |

| 1. Fifteen, Spined Stickleback | Gasterosteus spinachia. |

| 2. Seven, Gray Mullet (young) | Mugil capito. |

| 3. One, Black Goby | Gobious niger. |

| 4. One, Corkwing | Crenilabrus cornubicus. |

| 5. One, Five-bearded Rockling | Motella 5-cirrata. |

| 6. One, Great Pipe-fish (young) | Syngnathus acus. |

| 7. One, Worm Pipe | Syngnathus lumbriformis. |

| SHELLS, MOLLUSCS, ETC. | |

| 1. Two, Ashy Top | Trochus cinerarius. |

| 2. One, Navel Top | Trochus umbilicatus. |

| 3. Three, Common Periwinkle | Littorina littorea. |

| 4. Three, Yellow Periwinkle | Littorina littoralis. |

| 5. One, Purple | Purpura lapillus. |

| 6. One, Scrobicularia. | |

| 7. One, Anomia. | |

| 8. Two, Common Cockle | Cardium edule. |

| 9. Two, Ascidia. | |

| CRUSTACEA, ETC. | |

| 1. Two, Hermit Crab | Pagurus Bernhardus. |

| 2. One, ditto | Pagurus Prideauxii. |

| 3. Four, Sand Shrimp | Cragnon vulgaris. |

| 4. One, Prawn | Palæmon serratus. |

| 5. Three, Crown Worm | Serpula triquetra. |

| 6. Three, White-line Worm | Nereis bilineata. |

| ZOÖPHYTES. | |

| 1. Two, Thick-horned Anemone | Actinia crassicornis. |

| 312. Three, Weymouth Anemone | Actinia clavata. |

| 3. Two, Parasitic Anemone | Actinia parasitica. |

| 4. Six, Plumose Anemone | Actinia dianthus. |

| 5. Five, Daisy Anemone | Actinia bellis. |

There were thus above seventy specimens, animal and vegetable, already in the tank, without counting the swarms of smaller creatures, some the young of large species, daily increasing in size; yet, our bold experimentalist, anxious to conquer his “Russia” at one grand invasion, still poured in fresh specimens. These consisted of:—

| FISH. | |

| 1. One, Æquorial Pipe-fish | Syngnathus æquoreus. |

| MOLLUSCS, CRUSTACEANS, ETC. | |

| 1. One, Rough Doris | Doris pilosa. |

| 2. Two, Magus Top | Trochus magus. |

| 3. One, Nerit | Natica Alderi. |

| 4. One, Squin | Pecten opercularis. |

| 5. One, Pholas | Pholas parvæ. |

| 6. One, Pisa | Pisa tetraodon. |

| 7. One, Cleanser Crab | Portunus depurator. |

| 8. One, Ebalia | Ebalia Pennantii. |

| 9. One, Hermit (small) | Pagurus . . . . . . |

| 10. Three, Lobster Prawn | Athanas nilescens. |

| STAR-FISH, ETC. | |

| 1. One, Brittle Star | Ophiocoma rosula. |

| 2. One, Eyed Cribella | Cribella oculata. |

| 3. Two, Scarlet Sun-Star | Solaster papposa. |

| 324. One Bird’s-foot Star | Palmipes membranaceus. |

| 5. Three, Gibbons Starlet | Asterina gibbosa. |

| 6. One, Purple-tipped Urchin | Echinus miliaris. |

| 7. Seven, Scarlet Madrepore | Balanophillia regia. |

| 8. Three, Cloak Anemone | Adamsia palliata. |

These additions brought the collection up to above a hundred specimens, and no doubt the tank made a glorious show; but Mr. Gosse, though the Napoleon of his specialty, was forced to acknowledge that there was an “impossible.” Although his collection was superb, and his interesting tank did not look over-crowded, yet he soon discovered that a forbidden limit had been passed, and that the creatures of the ocean that have yards—fathoms—of their native element to their own separate share, cannot accommodate themselves to the allotment system, in the proportion of a square inch to each individual.

To remedy this state of things, the evil effects of which soon became apparent, artificial aeration was resorted to, by means of another vessel, which kept up a continuous supply of dripping fresh water. But even this assistance did not enable the crowded colony to exist more than ten days. In the first place, there were many predatory species, which destroyed their associates; these kinds must, therefore, be excluded from an Aquarium, or kept in a 33separate tank. But, after all, the impossibility of providing a sufficient supply of oxygen was evidently the great and principal cause of failure. The Univalves and smaller Crustacea disappeared first, a disagreeable smell giving intimation that decay was going on, the creatures that had perished having, many of them, died in concealment, under the stones, weeds, &c., at the bottom of the Aquarium. The first signs of unpleasant effluvia rising from the tank must, therefore, be carefully attended to; and, in such cases, the Aquarium ought to be immediately searched for the cause; which, when discovered, should be immediately removed.

Plate XI.

A DESIGN FOR A PLAINLY-MOUNTED AQUARIUM.

Mr. Gosse having taken out the whole of the specimens, dead and alive, and carefully cleansed the tank, a much smaller number was put in, which, being well selected, and having sufficient space, throve abundantly well; and the ingenious experimentalist was at last amply rewarded for all his persevering exertions. This result benefited others as well as himself, for a general taste suddenly arose for this kind of pursuit, among all who read the various works which soon appeared on the subject; and, to gratify the new taste, a host of dealers 34in Aquaria have sprung up, who are driving a brisk and profitable trade.

The first experiments of Mr. Gosse sufficiently point out the kind of cautions to be observed in the formation of a marine Aquarium. The vessel itself may be either quite plain in its frame-work, as shown in Plate XI., or made more or less ornamental, to assimilate, if necessary, with surrounding objects or furniture. The rustic style of frame, designed in Plate XII., has been found to accord well with the general character of the Aquarium itself, and it produces an agreeable contrast with the usual forms of the furniture of our ordinary sitting-rooms.

Plate XII.

A DESIGN FOR AN AQUARIUM MOUNTED IN HANDSOME RUSTIC-WORK.

Those made by the dealers are generally formed with slate floors and backs, and zinc columns and mountings; the smallest and most simple, about fifteen inches long by ten inches broad, costing from a guinea to twenty-five shillings, and those of the proportion of two feet by one foot six costing from two pounds ten to three pounds. A small syphon will be useful, in order to remove a portion of the water, if required, without disturbance; and also a syringe, in order to aerate the water when necessary, if a second reservoir of fresh-water, in 35a suitable position, should not be convenient. A miniature landing-net is also useful for the removal of decaying matter, or occasionally the living specimens when any change may be required.

A layer of sand and pebbles, about three inches deep, placed upon the slate flooring, is the first step towards arranging the interior of the tank. Upon this beginning, removing the sand and stones in places to procure a firm basis, the rock-work may be built; which should be picturesque and fanciful in character, as partially suggested in the two Plates, leaving miniature archways and caves for the shelter of such creatures as shun the light, either constantly or occasionally. Such a disposition of the rock imparts, at the same time, many pleasing effects to the pictorial composition. These matters are not, however, much attended to by dealers, whose arrangements of the Aquaria they offer for sale are generally tasteless enough. But that is perhaps all the better, as it entails upon the amateur the necessity of providing his own taste, which is at all times both a useful and pleasant effort of mind, and which, moreover, leaves, after each period of exertion, a permanent trace of an increased refinement which influences the whole character.

36In the distribution of the rocks, I would always allow at least one point to project above the water, in order to afford the opportunity to those animals whose instincts lead them to seek occasional exposure to the air, the means of gratifying it by that contrivance. I have thought, indeed, of constructing a kind of double Aquarium, and perfecting a contrivance by means of which a large portion of water should flow gradually from one tank to the other at fixed periods, in imitation of the ebb and flow of the tide. Many interesting phenomena would be exhibited in this manner, such as the closing of the Actiniæ as the water receded, and their expansion as it covered them on its return. This alternation, too, might be found highly advantageous to the health and development of the animals whose natural habitat lies between high and low water-mark, and whose constitution is therefore framed to require entire or partial exposure to the air at certain intervals of time. I also prefer, as preserving a similar set of analogies, a sloping bottom, similar to that of the coast. For instance, if the slate back of the Aquarium be placed next the light, which is its proper position, as the light ought to penetrate the water entirely through its upper or horizontal surface, then I 37would fill the side next the slate back nearly to the top with pieces of rock, gradually reducing their height, till, at the other side, they should hardly rise above the floor of sand and pebbles, leaving, at last, a flat portion of the pebbly or sandy bottom quite level.

When this form of rock-work is decided upon, the Aquarium should be of rather wider proportions than usual, in order to allow of the slope being pretty gradual. Supposing the tank to fill entirely the recess of a spare window, which is a position in which it looks exceedingly well, a solid slate back may be found to darken the vessel or the room too much; in such a case, a glass back must be preferred, which can be shaded from the direct influence of the light by a blue or green shade of calico neatly fitted to the frame; and it must be borne in mind, as essential, that the Aquarium must be so placed as to receive the direct rays of light during some part of the day, being screened by a white blind when the sun may be too powerful; as should the water become tepid, it would be fatal to many of the inhabitants of the miniature sea.

With due observance of these precautions, the amateur may hope to frame and establish an 38Aquarium in a suitable form, and in a suitable position for the reception of its inmates; an account of which, and of the manner of their introduction, will form the subject of the ensuing chapters.

As the forest must be planted before its denizens can luxuriate in its shades, so the submarine shrubbery of the Aquarium must be perfected before the aquatic animals can be introduced. For it has been shown, in tracing the history of the experiments which resulted in the establishment of the principles that regulate the formation of Aquaria, that it is by plants only that a supply of oxygen can be kept up, sufficient for the health and existence of all forms of animal life beneath the water.[1] It is necessary, also, that the rays of sunlight should fall upon the foliage directly through the surface of the water; and when an Aquarium, with its plants, is placed in a position to receive the light in this manner, their fronds may be observed giving forth the gas in small silvery bubbles and corruscations, which have a brilliant and gem-like appearance.

1. Analogous principles are at work in our fields and forests, but we have now only to do with the submarine production of oxygen.

40Some marine plants appear to succeed much better than others, but I believe that happens only from their treatment being imperfectly understood; and I believe, not only that all the exquisitely beautiful marine Algæ of our own shores may be successfully grown, but also that the more splendid varieties of the tropical seas may be made to thrive in properly-heated Aquaria, and thus form one of the most attractive features of our hot-houses—one that has not yet been dreamed of.

In ordinary Aquaria, such as I am now treating of, I shall name first those species of sea-weed recommended by Mr. Gosse and others as most easily cultivated, but I shall also point out many other species, which I feel convinced may be successfully grown under proper management; and they certainly deserve every effort that can be made to establish them in Aquaria, as they are among the most beautiful of their tribe.

If not purchased of dealers, the plants must be very carefully collected by the amateur himself, taking care to detach a portion of the substance to which they are growing, and packing them in damp refuse sea-weed, keeping them out of their native element as short a time as possible.

The plants in most flourishing condition in the 41marine tanks of the Zoological Gardens, were at first those of the Chlorospermatous order, but others have since succeeded nearly as well. Plants of Ulva and Conferva have done very well, but the most successful growth has been that of a plant of the genus Bryopsis, which, entirely enveloping a large stone in its mossy and almost feather-like foliage, produces a very beautiful appearance. Those unlearned in scientific names will be glad, perhaps, to learn that these beautiful Algæ derive their title from two Greek words, Bryon (βρυον), a moss, and opsis (οψιϛ), a resemblance, from their likeness to some of the most delicate and feather-like mosses of our woods. The delineation of Bryopsis plumosa in Plate II., on the extreme left near the lower part of the Plate, will convey some idea of these elegant sea-weeds.

Chondrus crispus is a beautiful plant, and well suited to the Aquarium. It will often be found under ledges of rock, completely concealed by a pendant veil of Fucus, commonly known as the olive-weed; and, on lifting the tangled mass of its rank growth, many beautiful and unexpected plants are frequently found, but none strike the explorer more than the Chondrus. Its nacreous tints, like those of a pearl shell, varying wonderfully 42according to situation, being very remarkable. It is the Carrageen Moss of the herb market. This plant forms the principal object in the lower part of Plate IV., to the right.

Laurencia pinnatifolia is a pretty branching plant, also varying in hue according to the aspect in which it grows. In the shade it is purple, but when receiving the full influence of the sun’s rays, it assumes a light-yellow tone; just as the Lycopodium, known as Fortune’s Moss, is purple when grown in the darkest part of a room, but becomes of an ordinary green tone when placed for some time near the light. The Laurencia is shown at the upper part of Plate V., coloured pale-violet.

The splendid plant Rhodymenia palmata, with its finely-coloured, semi-transparent fronds, is also recommended. It is the Dulse, or Dellis, eaten by the inhabitants of our northern coasts as a delicacy. Another species of R. lacinata is represented to the left of Plate V., the transparent light-crimson fronds of which are excessively beautiful. Mr. Gosse tells us that the Rhodymenia palmata is not suited to an Aquarium, because it appears to require the motion of the sea, and soon begins to decay in still water. If that be the case, let us provide a remedy, for the plant is one of the most beautiful among all its 43lovely congeners. When a plant of the gigantic lily of the Amazon river was first introduced, it refused to flower in the tank provided for its northern home, at the Duke of Devonshire’s residence at Chatsworth. But Sir Joseph Paxton, who then directed the floricultural operations of that magnificent abode, was not discouraged; and, seeking to impart to the still water of the tank something of the motion of a deep and majestic river, he contrived that a small but continuous stream should enter at one end of the tank, and, as it entered, turn a small paddle-wheel, the action of which imparted a gentle, undulating motion to the water of the whole tank. The device was triumphant, and the glorious Victoria regia formed and expanded its giant flowers in the house which its curator had constructed for it, the plan of which eventually suggested the creation of the “Crystal Palace.” Let us not despair, therefore, of cultivating successfully the beautiful Rhodymenia palmata in our Aquaria. The construction of a suitable apparatus for imparting motion to the too still waters, will form a pleasant passetemps for some of our fair admirers of the pursuits of the Aquarium; and their success would be a signal triumph. But at present the beautiful red weeds, in general, are difficult of cultivation, 44and when they begin to exhibit spots of orange—a vegetable plague-spot not to be mistaken—it is a symptom of decay which should at once cause their removal from the Aquarium, before their decomposition leads to further mischief.

The common Coralline, Corallina officinalis, of which a small spray is represented in the extreme lower part of Plate V., near the centre, is the “arboret of jointed stone” alluded to by the poet, and is well suited to Aquaria, thriving with little trouble. The smaller and slenderer kind is also suitable; but care must be taken, in collecting, not to choose the detached white fragments, which are washed up with every tide, for they are only the skeletons of the plant. It is the rosy-tinted specimens, verging to violet and purple, and still attached to pieces of rock, that are alone fit to remove to the Aquarium.

Plate I.

The Cladophoræ are also stated to be very suitable, C. rupestris being a very useful plant for the purpose. It is of a bluish-green, that harmonizes well with the tone of the sea-water, and fills up little chasms in the artificial rocks with very good effect, especially in contrast with the reddish-purple tufts of Polysiphonia arceolata, which do well in an Aquarium, and are a great aid to the foliage of the 45little marine landscape. The elegant, fan-formed, and brightly-radiated Padina pavonia is likewise mentioned, and should at all events be tried, as the tufts of that graceful marine plant form very singular as well as beautiful objects in the tank.[2]

2. A list of the plants with which Mr. Gosse furnished his first Aquarium is given in Chapter III.

I would also recommend the trial of all the plants delineated in the five Plates devoted to the sea-weeds in this little book.

In Plate I., the first, occupying the upper part, with leaf-like fronds of transparent crimson, is the beautiful and not uncommon sea-weed, Delesseria sanguinea. The delicate pale plant below, to the right, is Punctaria latifolia, thin as tissue-paper, and speckled over its pale-buff surface with bright but minute grains of black. To the left is a branch of Chordaria flagelliformis, the rich olive of which contrasts well with the red kinds of Algæ. In the front, growing on a detached pebble, is the Lichen-like Hildenbrandtia rubra, the rich carmine of which might be made to form an exquisite touch of colour, if tastefully placed in the Aquarium; and to the extreme right is a small tuft of Vaucheria submarina.

In Plate II., the principal object, near the top of 46the Plate, is a bush of Callithamnion arbuscula, which receives its name from the tree-like aspect which it assumes more distinctly than any other of the marine Algæ. Behind it, to the right, are the tall and graceful forms, with their crimped edges, of the slender Laminaria phyllitis. And below, still to the right, is a branch of Codium tomentosum, distinguished by its light, vivid green, and the edging of delicate ciliæ, which have the appearance of a border of paler green, to every branchlet. Still to the right, in the extreme foreground, is a broken piece of rock on which plants of the curious Leathesia Berkleyi have grown, like convex kernels of bronze. To the left are the red-violet tufts of the Bangia fusco-purpurea, and behind them, a branch of Bryopsis plumosa.

Plate II.

In Plate III. the bright-green feathery plant in the extreme background is Ectocarpus siliculosus; and behind it, the violet, antler-like fronds of Nemaleon multifida. The large, gracefully-bending frond of rich purple, with narrower and younger fronds springing from the same root, is Porphyra vulgaris, one of the commonest, but most splendid of our marine Algæ, with which, in combination with other plants of suitable contrast, the vegetation of the Aquarium may be rendered truly splendid, if 47it once be successfully cultivated; of which I have no doubt, when its natural wants are sufficiently studied and ingeniously supplied. The splendidly-marked plant to the right, with its black maculations and richly-frilled edge, is Nitophyllum punctatum, one of our most splendid species; and the curious pale-buff, tubular plant in front of it, is Asperococcus Turneri. Near the foot of the Nitophyllum is a little tuft of the delicate Dumontia filiformis; and, to the extreme left, a branch of the brown-fronded Rytiphæa pinastris, which receives its specific name from the somewhat Pine-like growth it frequently assumes. Immediately beneath it, on the extreme right, is a little cluster of Chordaria divaricata; and below, in the left foreground, are a few pink fronds of the curious Alga, Chrysemenia rosea; while, in the foreground, to the right, on a detached pebble, is a small mass of the pale-crimson Peyssonetia Dubyi.

In Plate IV. the principal object is a fasciculus of Taonia atomaria, rising behind the point of rock at the top of the Plate, behind which are two long fronds of the spotted Asperococcus; to the left is the horn-like Gigartina acicularis; and in the front, to the left, the crimson tufts of a pretty weed 48(Ceramium strictum), which our artist has made too like the Bangia fusco-purpurea.

In Plate V. the violet-toned Laurencia pinnatifolia is grouped behind the solid, deep-crimson fronds of Iridæa edulis, which are often perfectly Pear-shaped, like pieces of crimson leather neatly cut in that form; but the action of tides in rough weather often tears the edges, and wears holes through the texture of the plant, as shown in the principal frond. To the left is the bright-crimson Rhodymenia lacinata—one of our most exquisitely beautiful marine Algæ. The fronds are as thin as the finest conceivable tissue, and beautifully transparent, which is shown wherever the lacinations of the edge overlap each other, in which places the double thickness of the texture doubles, at the same time, the intensity of the colour, as indicated in the representation. On the same level, to the right, is a small group of the delicate green Ulva latissima—a plant which has proved useful beyond all others in Aquaria, as throwing off, under the action of the light, a much greater profusion of silvery globules of oxygen than any other species yet known. At the same level still, on the extreme right, is a sprig of the delicately-branched parasite, Polysphonia 49parasitica, growing on a small mass of pale sulphur-coloured Melobesia lichenoides, the Lichen-like Melobesia. To the extreme left, under the beautiful Rhodymenia, is a small branch of the bright, olive-tinted Ectocarpus tomentosus, looking much like a spray of wild Broom, and immediately below it, a few purple branchlets of Gracilaria confervoides; while in the left foreground lies a pebble, partly covered by a small plant of Zonaria parvula, from beneath which straggles a little branch of the common but pretty Coralline, the Corallina officinalis; and, to the right, a globe of the curious Codium bursa, of the French coast, which might easily be added to our native species in the Aquarium.

Plate III.

Such are a few of our beautiful coast Algæ, all of which I would advise the admirers of the beauties of the marine Aquarium to try; and if some refuse, in the present state of our knowledge of their habits and requirements, to make themselves happy in their pretty “crystal palace,” choosing rather to consider it a “prison of glass,” still a good number of them, I am persuaded, may be coaxed into displaying their beauties very genially within its transparent walls, which admit the bright sun rays as freely as the pale-green liquid glass which forms their native element.

50The best time for making collections at the sea-side is a day or two after the full moon, when the tide recedes to its greatest extent, and parts of the shore become exposed, where some of the finest species grow, which cannot be conveniently approached at any other time. It must be borne in mind, also, that few of the floating pieces will grow, however fresh and seemingly washed off with their root. Certain success is only to be secured by chiselling off a portion of the substance on which the weed is growing—thus transplanting it with its own soil, as it were, about its roots, into the ocean garden of the Aquarium.

Plate IV.

The Aquarium having been furnished with its vegetation, and rendered as picturesque as possible by the well-arranged juxtaposition of felicitously-contrasting forms and colours, the water must be allowed to settle for some days, until it is as clear as pale-green crystal, before the animals are introduced to their new home. When the Alpine scenery of the submarine landscape appears perfectly settled, and all its colours and forms are seen with beautiful distinctness through the clarified waters, then the still life is ready to be associated with the more active organizations of animated creatures. Before speaking of Molluscs, or Crustacea, or of Fish, suitable to the Aquarium, let us first devote all our attention to our Zoöphytes, those singular creatures whose strange instincts and anomalous forms have been mainly instrumental in attracting the attention of many classes of the public to that curious interest in Aquaria, which is fast spreading into a mania, threatening to absorb all others in its 52vortex, like Infusoriæ drawn within the fatal tentacles of the Actinia.

First, of the Actiniæ, or Sea-Anemonies. These flower-formed animals were once thought to form a curious and astonishing link between the animal and vegetable world; and many curious speculations, based upon that idea, were put forth, among which the links between man and the inferior animals, and between quadrupeds and fishes, were asserted in further illustration of the theory. But the deceptiveness of superficial knowledge, based upon imperfect observations, was never more strikingly exemplified than in the present instance. It was thought that, because these creatures were found attached to rocks, they necessarily drew their nourishment principally through the medium of roots, as all true plants do; more accurate observation, however, has shown that they are not permanently fixed to the rocks, and that they have the power of moving from one place to another, and attaching themselves anew, whenever a sufficiently disturbing cause renders such removal desirable. Again, oysters and mussels remain fixed to rocks without being considered allied to plants on that account; and even some fish have the power of attaching themselves to such and other substances by means of curiously-formed 53ventral fins, peculiarly fitted for the purpose. The pretty little two-spotted sucker, Lepidogaster bimaculatus, possesses this faculty.

But the flower-like form into which the arms, or food-seizers, of the Actiniæ are spread, radiating from a centre like the petals of a flower, was the main reason for supposing a close analogy between these strange creatures and plants—a fancy now utterly abandoned, as it is quite evident that they are furnished with a mouth and stomach, like all true animals, and with a set of arms called tentacles for seizing their prey; and, perhaps, at the same time, through the medium of delicate ciliæ with which the tentacles are connected, with a breathing apparatus, through which a current of water is taken in, and discharged after its oxygen has been abstracted.

The discovery of the true nature of these singular creatures has not, however, changed their flower-like appearance, which to a superficial observer is as deceptive as ever; and few (not professed naturalists), observing these singular Zoöphytes for the first time, would hesitate to pronounce them a kind of sea-plant.

Let us turn, for example, to Plate VIII., and note the appearance of the two varieties of Actinia 54dianthus—the carnation-like Actinia, as its name imports—and we shall easily excuse our early naturalists their pretty but erroneous fancies concerning them. This species is more subject than many others to vary in colour, even like the flower after which it is named, being found of every tone between snow-white, orange, pale scarlet, and blood red—while some specimens take duskier tints, from a dull brown to a kind of orange green. But we will describe our illustrations of this genus in regular succession, noting what is most peculiar in the subjects of each Plate.

Plate VI. contains a representation of one of the last-discovered species of Actiniæ—one which displays a habit that distinguishes it from all its congeners hitherto described by naturalists, and which has entitled it to be classed as a separate genus, and named Edwardsia vestita. The generic name is from that of a well-known naturalist, and the specific name, vestita, from its habit of forming for itself a shell, or clothing, into which it has the faculty of retiring at pleasure; or, if an inhabitant of the shallow water, when the tide recedes, and leaves it inconveniently exposed to the air. This species, unless it have the power of quitting its shell, like some Molluscs, is of necessity permanently fixed and 55confined to the position in which the egg from which it was hatched was placed by the instinct of the parent, or the caprice of the waves. The other objects in Plate VI. will be described in another place.

Plate VII.

In Plate VII. we have two remarkable species; the one with drooping tentacles of dull brick-red, being a very curious variety. The species below is Actinia clavata, one of the most delicately-beautiful species, which, from its brilliant whiteness, at once attracts the attention.

In Plate VIII. are two varieties, previously described, of Actinia dianthus, the plumose or feather-like Anemone. In front, below them, is the representation of one of the most splendid of all the species, having received the specific name Gemmacea, from the gem-like appearance produced by the touches of colour—blue, buff, and brown—about the orifice of the mouth or stomach, and about its sharply-pointed tentacles. The stem or body is also variegated with rows of brightly tinted tubercles, and its whole surface is clouded with pale iridescent, or rather nacreous, tones of pink and azure, varied with occasional flashes of orange. All the species are furnished with tubercles of a similar description about the stem or body, but in many they are not so conspicuous, and in others almost imperceptible; 56yet they no doubt exist in all, as they are not merely ornamental, but essential organs, peculiar to this class of creatures; being reservoirs from which they can shoot forth a thread, furnished with a barbed and poisoned dart, by means of which they are able to attain an enemy, or victim, far beyond the reach of their tentacles. Mr. Gosse very graphically describes the death of a small fish struck by one of these thread-borne poisoned arrows, at some distance from the offended Actinia, who launched his dart, as it seemed, for no greater provocation than a slight disturbance of the water rather nearer to his retreat than was agreeable.

Plate VIII.

The Actinia gemmacea, it would appear, is a more voracious creature than most of his congeners, for Dr. Johnston, in his splendid work on the British Zoöphytes, describes one of this species that had managed to swallow a shell of Pecten maximus as large as a common saucer, its own natural diameter not exceeding two inches. It managed, however, to distend its elastic form sufficiently to receive the enormous prey; but the shell divided the stomach into two completely separate departments, the lower one being thus perfectly shut off from its usual supplies. To meet this difficulty, the organic economy of the creature adapted itself 57in a most extraordinary manner; a new mouth was opened below the division, furnished with two rows of new tentacles, and thus the lower portion regained a means of taking in nourishment, the whole creature forming a singular double monster, that, not contented with its one giant mouth, surrounded with its hundred arms to supply its voracious appetite, had actually succeeded in supplying itself with a second, equally furnished with its formidable feeding apparatus.

In Plate IX. a very beautifully distinct form of this singular race of animals is very carefully delineated—Actinia anguicoma—which seems to be shaking loose a mass of serpent-like hair, like another Medusa; from which appearance, its specific name anguicoma, signifying snake-haired, has doubtless been given.

The tentacles of the Actinia mesembrianthemum are generally of a beautiful rosy-pink, and the body of a rich warm brown. But of all the species, A. crassicornis—represented in the lower part of Plate X.—is perhaps the handsomest, the orifice or mouth being of a delicate straw tone, the tentacles white, variegated with bands of delicate pink, and the body, or stem, a rich orange-brown, thickly sprinkled with tubercles of bright yellow. This fine 58species sometimes measures five inches across, when the tentacles are fully expanded.

When the Actiniæ are in a state of repose or sleep, the tentacles are entirely drawn in, and the stem or body closes over the orifice, leaving only a slight indent to mark its existence. In this state they might be mistaken for short-stemmed fungi, the pale-bodied species being very much like a half-grown mushroom, if one can imagine it placed close to the ground, without any visible stem.

Most of the species can be easily detached from the rocks to which they are found adhering, but in some cases it is found necessary to cut out the portion to which they cling, by means of a hammer and chisel. But when this is done, and they are placed in the Aquarium, they often willingly leave the stone to which they are attached, which they would not do by gentle persuasion, or any moderate amount of force; and they then take up their station on some suitable portion of the artificial rock-work, just as those do that have been originally detached from their native rocks. Above twenty species of Actiniæ are known to British naturalists.

Plate IX.

The Lucernariæ are another class of Zoöphytes, or plant-like creatures, as the term Zoöphyte implies, 59being formed of the Greek word, Zoön (ξωον), signifying a thing possessed of animal life, and phyton (φυτον) a plant. This general term is applied to all the creatures—some of very distinct character—that belong to this class, which forms a separate division of natural science, known as Zoöphytology.

The species of Lucernaria, which has received the specific denomination of auricula, from its slight resemblance in form to the flower of that name, is delineated in Plate VIII., attached to a slender branch of sea-weed, just above the two large Sea-Anemonies. This species of Lucernaria is generally of a light pinkish colour, and is, in general form, perhaps more like a Convolvulus than an Auricula. Two species have been most beautifully delineated in all their details by Mrs. Johnston, in her husband’s magnificent work on British Zoöphytes. These drawings are, in fact, so charmingly and, at the same time, accurately executed, that it would seem that the pencil ought to be guided by delicate female fingers when portraying these minutely-intricate and unusual forms of animal life. The exquisite drawings by Mrs. J. E. Gray, in her work on the curious molluscous animals, whose habitations alone, the beautiful sea-shells of our cabinets, were, till recently, all that was known of them, afford further 60evidence, if it were needed, of the aptitude of the more finely-strung female capacity for this department of scientific portraiture. The name of Mrs. Griffiths is also honourably associated with the study of natural science, especially that connected with our marine Algæ—a beautiful division of sea-weeds—having received its name Griffithsia, in honour of the esteemed services of that accomplished lady.

The Lucernaria campanulata, which is of a somewhat more bell-shaped form than the preceding, is of an uniform liver colour; and in the hollow of the flower-like cup the “mouth” projects, in a square form in the centre. There are three known species of British Lucernariæ, which would all form highly curious objects in the Aquarium; but they are excessively delicate and fragile creatures, hanging suspended from the object to which they are attached, when taken out of the water, like a mere lump of jelly, and would doubtless be very difficult of transport, and probably not capable of retaining life in a state of confinement, except for a short time.

The “compound Zoöphytes,” or, more properly, Polyps, as being, as it were, many creatures in one, are still more curious than the two classes just 61described. A common example of this class is the Alyconium digitatum, looking like a mass of short fingers, when the final florets are closed, as its specific name imports, being sometimes called, by the fishermen of our northern coasts, Dead-men’s-toes. Each finger-like cell contains a separate creature, whose tentacles, when expanded, form the floret, after the manner of those of the Sea-Anemonies, but yet each separate creature is vitally attached to a central polypidom, or spine, which binds the whole group into one existence.

Of this class are the curious Pennatulidæ, one of which is commonly known as the Sea-Pen. The three species of this class of Polyps known to inhabit the British seas, are so distinct from each other that they form at the same time three distinct genera. The most beautiful of the three is the Pennatula phosphorea, the Sea-Pen, which is not uncommon on some parts of our northern coasts. It is represented in Plate VII. The purple branches, or pinnæ, of the upper portion, form the feathered part of the quill pen to which it is likened; the bare portion of the polypidom below having certainly some resemblance to the quill. This curious zoöphytic form is often seen in an erect position, planted, as it were, in the mud like 62a miniature purple Pine, though it is capable of motion through the water from place to place, by some action of its organs which has not been accurately detected. It is one of the handsomest of our British Zoöphytes. The polypidom, or trunk, is three or four inches long, fleshy, and of a purplish red. It is naked at the lower end, and feathered above with long, closely-set pinnæ, along the margins of which the polyp-cells are placed. The pinnæ are curved backward, and capable of either separate or united motion. They are supposed by some to be capable of the action of regular oars; but this is very doubtful, though their bearing on the polypidom, which is strengthened by an internal column of calcareous or bony matter, would give them considerable power for that purpose. The creature’s specific name, phosphorea, must not lead to the supposition that it always emits a phosphorescent light, for it is only when irritated that this is produced. If plunged into fresh-water, it scatters a shower of phosphoric sparks in all directions, which forms a magnificent and curious spectacle, far more brilliant, no doubt, than the fabled hues of the dying dolphin.

The Virgularia mirabilis is another of this class of creatures, almost as elegant as the Sea-Pen, but 63more slender, and in the form of a branching rod, as its name imports. (See Plate VIII.)

The Sponges form a curious class of Zoöphytes, which have perhaps a much closer affinity to plants than any other. They are occasionally very sportive, and curious in their forms; and Dr. Johnston enumerates fifty-six species belonging to our coasts; they are, however, unsuited to the Aquarium in the present state of our knowledge; and when portions of rock are collected on the shore, for the tank, care should be taken to clear off any Sponge formations that are perceived, as their certain and rapid decay would be liable to injure the condition of the whole colony of the Aquarium.