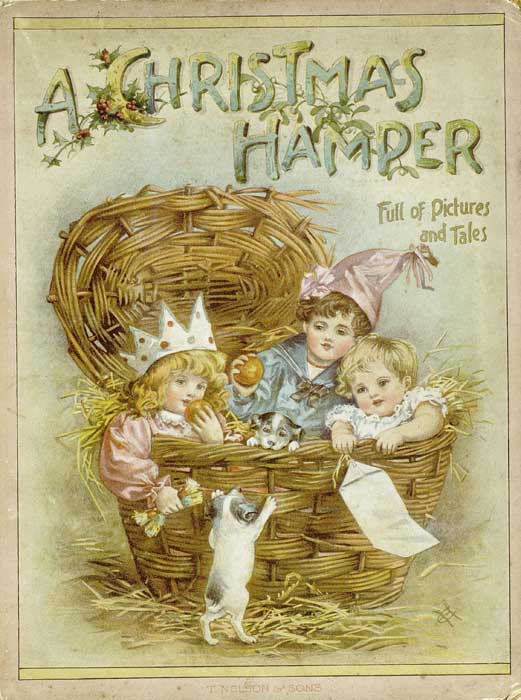

A Volume of Pictures and Stories

for Little Folks

T. Nelson & Sons

London, Edinburgh &

New York

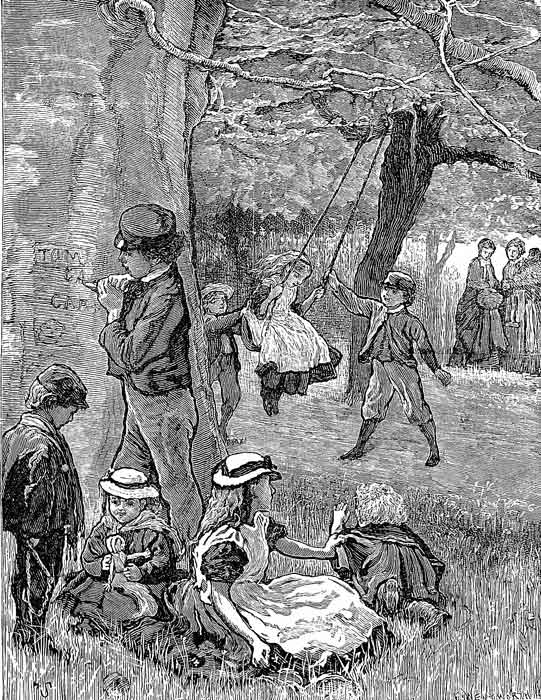

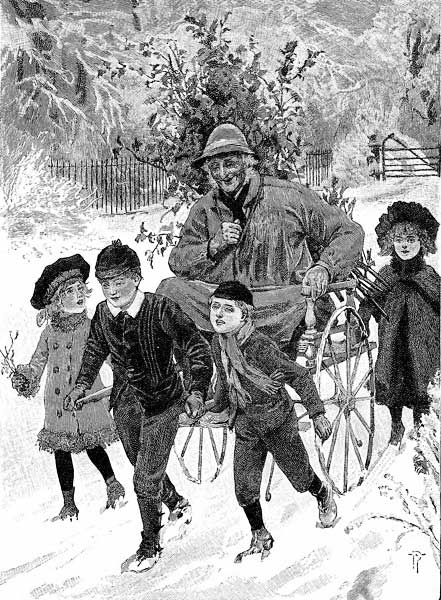

He seemed a funny old gentleman, the children thought, but still rather nice, especially when he brought those sweets out of his pocket and let them dip into the bag and take what they liked. They had seen him walking through the wood, and then when they left off playing, he had come to sit down beside them, and asked them their names.

“Mine’s Hugh, like father,” said the eldest; “and this is Lily, and this is Tom.”

The old gentleman looked a little quickly at Tom.

“Who is he named after?” he said.

The children’s faces grew grave.

“He is named after poor Uncle Tom,” said Lily in a low voice, “who went to sea and was drowned.”

There was silence for a minute. Then the old gentleman spoke again,—

“So poor Uncle Tom was drowned, was he?”

“Yes,” said Hugh. “His ship was lost, and everybody was drowned, ’cept two or three that got in the boat, and Uncle Tom wasn’t among them. Father waited and waited, but it wasn’t any good. So then he put up a monument in the church just where we can see it from our pew.”

“And we always sings about the saints of God on his burfday,” said Lily, “and father cries a little.”

“No, he don’t!” said Hugh indignantly. “Father’s a man, and men don’t cry!”

“But he does,” said Lily. “I saw a weeny little tear on his cheek this morning, for to-day is Uncle Tom’s burfday, and his voice goes all shaky like, ’cause he was so fond of poor Uncle Tom, and says he was so good.”

The old gentleman sat silent, staring hard at the ground.

“Is it long since Uncle Tom went away?” he said at last.

“It is ten years,” replied Hugh. “It was the year I was born.”

“Ten years—so it is,” murmured the old gentleman—“only ten years, and it has seemed like a hundred.”

The children looked at one another surprised.

“Did you ever know Uncle Tom?” asked Hugh curiously.

“Yes, I knew him well. I was on his ship.”

“But you aren’t drowned!” cried Lily.

The old gentleman smiled.

“No,” he said, “I wasn’t drowned; I got off safe. Uncle Tom used to talk to me, though, about his old home, and one day he said that he had carved his name on a tree in the park, and I was to go and see it if I ever got home.”

“Oh, I’ll show you,” said little Tom. “It is on a beech tree close by here. I’ll show you. There it is.”

He pointed to a tree on which some initials and a date were cut deep into the bark.

“It has kept very fresh,” said the old gentleman. “I thought it would have been grown over by now.”

“Father always comes and tidies it up on uncle’s birthday,” said the boy. “See, he is coming now! I’ll go and tell him you are here.—Father!” he shouted, running off—“father, here’s a gentleman who knew Uncle Tom!”

But when father came near and saw the old gentleman, he stared at him for a moment as if he had seen a ghost, and then he gave a great cry.

“Tom, Tom, it is you yourself!”

And it was Uncle Tom, who had not been drowned after all, but when the ship was wrecked had managed to get ashore to an island, and there had lived on the fish he caught, and birds’ eggs, and cocoa-nuts, watching for a sail, like Robinson Crusoe. At last the sail came after ten long years. And when he reached England he did not write, but came down to his old home to see who was there, for of course he had heard no tidings all the time.

Nobody recognized him at the village, for the tropical sun had burned his skin brown, and the long waiting and the sorrow and the hardships had turned his hair white. Only his brother knew him by his eyes, for they two had loved each other very much.

“But what will father do with your tombstone?” said Lily gravely, as she sat on her uncle’s knee that night. “It is such a pretty one, with a beautiful angel on it!”

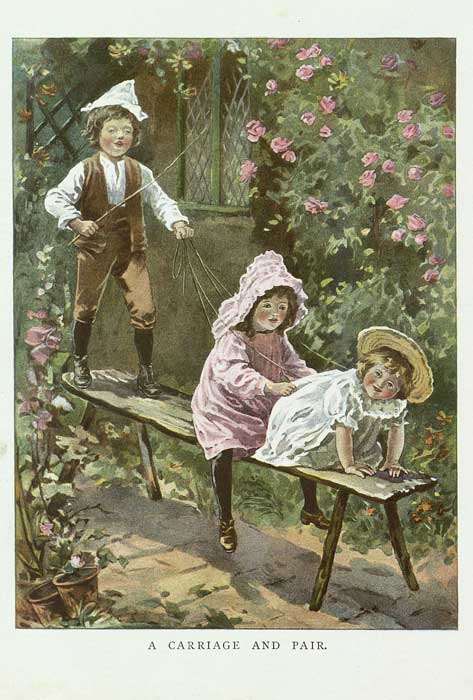

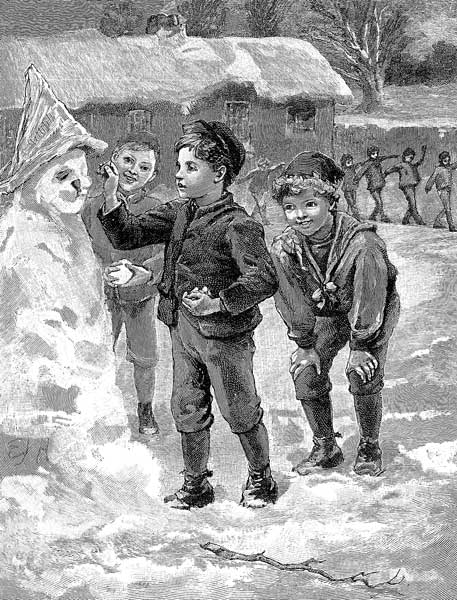

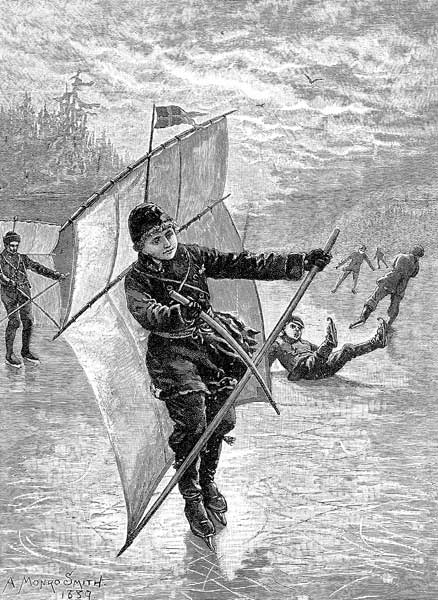

“ISN’T it fun, Dolly?” asked Eric, as he and his little sister ran along the sea front as fast as their sturdy legs could carry them.

Eric was the jolliest little boy imaginable, but, unfortunately, a little bit too fond of mischief, and Dolly was generally only too eager to join in her brother’s pranks.

Just now they were running away from nurse, who was down on the sands with baby. They waited until her head was turned away, then off they ran.

“We’ll go out to the rocks and play at being shipwrecked sailors,” Eric went on. “I’ve got some biscuits in my pocket, and I’ll dole them out, piece by piece, and pretend we shan’t have any more food unless a boat takes us off.”

Poor Eric! his play very soon became earnest, for he and Dolly waded out to a big rock in a very lonely part of the coast, and so interested were they in their game that they never noticed the tide coming in until it had surrounded them, and there was no getting back.

They waited on and on, hoping some one would come for them, and fearing every moment that the sea would cover the rock, and that they would be drowned.

It was long past dinner-time, and they were wet through and hungry and wretched when at last a fisherman, who had been sent out to search for them, spied the two forlorn little figures, and rescued them.

They went home hand in hand, very solemn and silent, expecting to get a good scolding; but instead of that, mother burst into tears of relief, and both Eric and Dolly felt so thoroughly ashamed of themselves for having frightened their darling mother so terribly that it was a very long, long time before they got into mischief again.

THE sunniest of days, the clearest and loveliest of blue seas, and I, a little lobster, young, proud, and as lively as a cricket—that is what people say; but I can’t help thinking “as lively as a shrimp” would sound better.

I always wear a lovely suit of armour, like those old warriors you read about. It is strong and firm and well jointed, so that I can move ever so fast—of course not so fast as that silly little fish.

He has armour too, he says, but wears it inside. That seems queer to me; I can’t quite believe it.

But I want to tell you what a queer thing happened to mine not long ago. It grew small and shabby, like your last year’s dress; that is why I have called this story “Old Clothes.”

Listen. I lived a very happy life out at sea for some time, till one day I fell into a strange basket-box thing.

There were several other lobsters and one or two crabs sitting there, looking anxious and disturbed. And I soon found out that they had need to feel so, for there was no exit. That means “way out” in plain words.

Our basket was joined to a strong rope, and that was attached to a cork floating on the top of the water.

Not long after I had fallen into this basket, which I now know was a lobster-trap, a boat rowed out from the shore, stopped just above us, and then we were lifted up, up, right out of the water, and placed in the boat.

The next thing was a good deal of pushing and knocking about, and then some one tossed me carelessly out on the beach, saying roughly, “Too small for any use.”

But some one else thought differently. Another hand touched me, and another voice said, “Just the thing for my aquarium.”

What that meant I could not even guess; but it turned out to be the tiniest sea in the world. Steady old limpets, red anemones, hermit crabs, and shrimps were all there.

It was a very nice home, with plenty of good food, the only drawback being want of space.

And now the event happened that I promised to tell you about.

My armour took to hurting me. You will hardly believe me. We all know that new clothes hurt sometimes, but old ones!

It grew tighter and tighter. I wriggled about, feeling miserable. Oh, if only I could get out of this!

At last I grew desperate. This choked, tight feeling was too much. I gave a tremendous struggle, and shook myself; crickle, crackle went my old armour, off it came, and out I stepped.

But, oh, so tender, and so nervous! The shrimps pranced round and knocked up against me, pricking and tormenting till I could have screamed.

I crept behind a stone and looked at my old armour half sadly. It looked just like old me, only so still, and rather as if I had been out in the rain all night and had shrunk.

Then I glanced at the new me. Well, I was a pretty fellow—not blue-black any longer, but a reddish pink of lovely hue.

Some one else took pride in my appearance, for I heard again a voice say, “Look at my lobster; he has cast his shell.”

I hadn’t, you know—it was the shell that had cast me; but these men can’t know everything.

The man touched me, but he hurt me almost as much as the shrimps, and I shrank farther still behind the stone out of his way. There I quietly lay for some days, till one morning, feeling braver and ever so much bigger, I stepped out for an early saunter.

That moment came a voice, “Oh, here is my lobster! How he has grown, more than half as big again!” Down came the hand as before; and just to show him I was also half as strong again, I gave him a nip.

He keeps his hands above water now, and me at arm’s length.

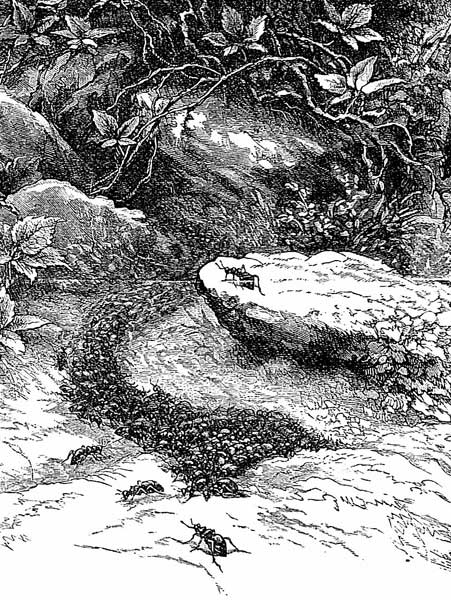

OUT in the garden Mary sat hemming a pocket-handkerchief, and there came a little insect running—oh, in such a hurry!—across the small stone table by her side.

The sewing was not done, for Mary liked doing nothing best, and she thought it would be fun to drop her thimble over the little ant. “Now he is in the dark,” said she. “Can he mind? He is only such a little tiny thing.”

Mary ran away, for her mother called her, and she forgot all about the ant under the thimble.

There he was, running round and round and round the dark prison, with little horns on his head quivering, little perfect legs bending as beautifully as those of a race-horse, and he was in quite as big a fright as if he were an elephant.

“Oh,” you would have heard him say, if you had been clever enough, “I can’t get out, I can’t get out! I shall lie down and die.” ” Mary went to bed, and in the night the rain poured. The handkerchief was soaked as if somebody had been crying very much, when she went out to fetch it as soon as the sun shone. She remembered who was under the thimble. “I wonder what he is doing,” said Mary. But when she lifted up the thimble the little tiny thing lay stiff and still.

“Oh, did he die of being under the thimble?” she said aloud. “I am afraid he did mind.”

“Why did you do that, Mary?” said her father, who was close by, and who had guessed the truth. “See! he moves one of his legs. Run to the house and fetch a wee taste of honey from the breakfast-table for the little thing you starved.”

“I didn’t mean to,” said Mary.

She touched the honey in the spoon with a blade of grass, and tenderly put a drop of it before the little ant. He put out a fairy tongue to lick up the sweet stuff. He grew well, and stood upon his pretty little jointed feet. He tried to run.

“Where is he in such a hurry to go, do you think?” said father.

“I don’t know,” said Mary softly. She felt ashamed.

“He wants to run home,” said father. “I know where he lives. In a little round world of ants, under the apple tree.”

“Oh! Has such a little tiny thing a real home of his own? I should have thought he lived just anywhere about.”

“Why, he would not like that at all. At home he has a fine palace, with passages and rooms more than you could count; he and the others dug them out, that they might all live together like little people in a little town.”

“And has he got a wife and children—a lot of little ants at home?”

“The baby ants are born as eggs; they are little helpless things, and must be carried about by their big relations. There are father ants and mother ants, and lots of other ants who are nurses to the little ones. Nobody knows his own children, but all the grown-up ones are kind to all the babies. This is a little nurse ant. See how she hurries off! Her babies at home must have their faces washed.”

“O father!” cried Mary; “now that is a fairy story.”

“Not a bit of it,” said father. “Ants really do clean their young ones by licking them. On sunny days they carry their babies out, and let them lie in the sun. On cold days they take them downstairs, away from the cold wind and the rain. The worker ants are the nurses. Though the little ones are not theirs, they love them and care for them as dearly as if they were.”

“Why, that’s just like Aunt Jenny who lives with us, and mends our things, and puts baby to bed, and goes out for walks with us.”

“Just the same,” said father, laughing.

“Is that the reason we say Ant Jenny?”

“You little dunce! Who taught you to spell? But it is not a bad idea, all the same. It would be a good thing if there were as many ‘ant’ Jennys in this big round world of ours as there are in the ants’ little round world—folk who care for all, no matter whose children they are.”

While they were talking, the little ant crept to the edge of the table, and down the side, and was soon lost among the blades of grass.

“He will never find his way,” said Mary.

“Let him alone for that,” said father. “The ants have paths leading from their hill. They never lose their way. But they meet with sad accidents sometimes. What do you think I saw the other day? One of these small chaps—it may have been this very one—was carrying home a scrap of something in his jaws for the youngsters at home. As he ran along, a bird dropped an ivy berry on him. Poor mite of a thing! This was worse than if a cannon ball were to fall from the sky on one of us. He lay under it, not able to move. By-and-by one of his brother ants, who was taking a stroll, caught sight of him under the berry.

“What did he do?” said Mary.

“First he tried to push the berry off his friend’s body, but it was too heavy. Next he caught hold of one of his friend’s legs with his jaws, and tugged till I thought it would come off. Then he rushed about in a frantic state, as if he were saying to himself, ‘What shall I do? what shall I do?’ And then he ran off up the path. In another minute he came hurrying back with three other ants.”

“Is it quite true, father?”

“Quite. The four ants talked together by gentle touches of their horns. They looked as if they were telling one another what a dreadful accident it was, and how nobody knew whose turn would come next. After this they set to work with a will. Two of them pushed the berry as hard as they could, while the other two pulled their friend out by the hind legs. When at last he was free, they crowded round as if petting and kissing him. You see these little ant folk have found out that ‘’Tis love, love, love, that makes the world go round.’ I shouldn’t wonder if that ant you teased so thoughtlessly is gone off to tell the news at home that there is a drop of honey to be had here.”

“Oh, he couldn’t, father!”

“Wait and see,” said father.

In a little while back came the ant with a troop of friends.

“He has been home and told them the good news about the honey,” said father. “Do you think that all children are as kind as that?”

Mary said, “No, they’re not. I don’t run to call all the others when I find a good place for blackberries.”

“Then,” said father, “don’t be unkind to the ant, who is kinder than you, though he is only a little tiny thing.”

THERE was once a dear little, queer little cat,

The sweetest kit e’er seen,

Who made up her mind to journey

To town to see the queen.

|

|

| Mr. Puggy, a teacher of manners and dancing,

Gave her a lesson or two.

“Observe my instructions, Miss Tabby,

And be sure to do as I do.”

|

But Tabby espied her saucer of milk,

And made a dart at that,

While Pug distressfully murmured,

“What a very ill-bred cat!”

|

|

“DON’T do it, Dick!” pleaded Dolly.

“Girls always spoil sport!” growled Mark, as he saw Dick ready to give in.

“We shan’t hurt the boat! Don’t be silly, Dolly. Even if the sails do get wet, Tom can get fresh ones. And it will be better for him to know whether it will sail or not.” And the twins departed for the seashore with the boat in their hands.

How they wished they had taken Dolly’s advice, when they saw the ship, which had sailed so gallantly at first in the little cove, break from its moorings and drift out to sea!

Tom had worked very hard for the prize of £2 offered in a weekly paper for the best-made boat, not only for the sake of the money, but because the toys were to go to the Home for Orphans. And now all his work was gone.

“Oh! well, it can’t be helped,” he said good-naturedly, when his first feeling of anger had passed; “but I wish you chaps would leave my things alone.”

“But it can be helped,” said Dolly, rushing in. “See! a fisherman brought it to shore, and it isn’t a bit broken.”

So the orphans got the boat after all, and had great fun sailing it in the river near the Home; and what was perhaps more wonderful, Tom won the prize.

“MOTHER dear,” said a little mouse one day, “I think the people in our house must be very kind; don’t you? They leave such nice things for us in the larder.”

There was a twinkle in the mother’s eye as she replied,—

“Well, my child, no doubt they are very well in their way, but I don’t think they are quite as fond of us as you seem to think. Now remember, Greywhiskers, I have absolutely forbidden you to put your nose above the ground unless I am with you, for kind as the people are, I shouldn’t be at all surprised if they tried to catch you.”

Greywhiskers twitched his tail with scorn; he was quite sure he knew how to take care of himself, and he didn’t mean to trot meekly after his mother’s tail all his life. So as soon as she had curled herself up for an afternoon nap he stole away, and scampered across the pantry shelves.

Ah! here was something particularly good to-day. A large iced cake stood far back upon the shelf, and Greywhiskers licked his lips as he sniffed it. Across the top of the cake there were words written in pink sugar; but as Greywhiskers could not read, he did not know that he was nibbling at little Miss Ethel’s birthday cake. But he did feel a little guilty when he heard his mother calling. Off he ran, and was back in the nest again by the time his mother had finished rubbing her eyes after her nap.

She took Greywhiskers up to the pantry then, and when she saw the hole in the cake she seemed a little annoyed.

“Some mouse has evidently been here before us,” she said, but of course she never guessed that it was her own little son.

The next day the naughty little mouse again popped up to the pantry when his mother was asleep; but at first he could find nothing at all to eat, though there was a most delicious smell of toasted cheese.

Presently he found a dear little wooden house, and there hung the cheese, just inside it.

In ran Greywhiskers, but, oh! “click” went the little wooden house, and mousie was caught fast in a trap.

When the morning came, the cook, who had set the trap, lifted it from the shelf, and then called a pretty little girl to come and see the thief who had eaten her cake.

“What are you going to do with him?” asked Ethel.

“Why, drown him, my dear, to be sure.”

The tears came into the little girl’s pretty blue eyes.

“You didn’t know it was stealing, did you, mousie dear?” she said.

“No,” squeaked Greywhiskers sadly; “indeed I didn’t.”

Cook’s back was turned for a moment, and in that moment tender-hearted little Ethel lifted the lid of the trap, and out popped mousie.

Oh! how quickly he ran home to his mother, and how she comforted and petted him until he began to forget his fright; and then she made him promise never to disobey her again, and you may be sure he never did.

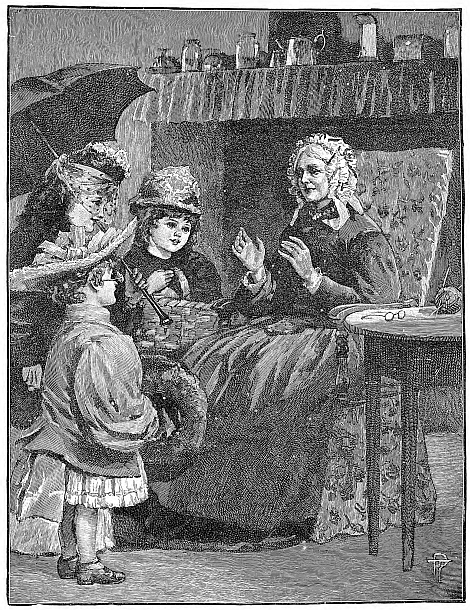

“DID you ever see a fairy, grannie?” said Trots.

“No,” she said, “but my great-grandmother did.”

“Oh, do tell me!” cried Trots.

“Well, once upon a time, as she was carrying her butter to market, she picked up a crooked sixpence. And with it, and what she sold her butter for, she bought a little black pig. Now, coming home, she had to cross the brook; so she picked piggy up in her arms and carried her over the brook. And, lo, instead of a pig, there was a little fairy in her arms!”

“Oh!” cried Trots, “what was it like?”

“Well, it had a red cap on its head, and a green frock, and it had gauzy wings, and it wanted to fly away, but great-grandmother held it tight.

“‘Please let me go,’ said the fairy.

“‘What will you give me?’ said great-grandmother.

“‘I will give you one wish,’” answered the fairy.

So great-grandmother thought and thought what was the best thing to wish for, and at last she said,—

“‘Give to me and to my daughters to the eleventh generation the lucky finger and the loving heart.’

“‘You have wished a big wish,’ said the fairy, ‘but you shall have it.’” So she kissed great-grandmother’s eyes and mouth, and then she flew away.

“And did the wish come true?” asked Trots.

“Always—always,” answered grannie. “We have been since then the best spinners and knitters in all the countryside, and the best wives and daughters.”

“But,” said Trots, “what will the eleventh generation do when the wish stops and the good-luck?”

“I don’t know,” said grannie, shaking her head. “I suppose they’ll have to catch a fairy of their own.”

Table of Contents was created for this HTML version.

Not Such Fun as it Seemed:

... and Dolly was generally only too eager to join in her brothers pranks. Brothers corrected to brother’s. ... and Dolly was generally only too eager to join in her brother’s pranks.

The Little Tiny Thing:

... said father. Do you think that all children are as kind as that?” Missing opening quotation mark before the word Do. Opening quotation mark inserted. ... said father. “Do you think that all children are as kind as that?”

Great-Granmother’s Wish:

“‘I will give you one wish,’ answered the fairy. Missing ending closing double quotation mark. Inserted “‘I will give you one wish,’” answered the fairy.