The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pilgrim Story, by William Franklin Atgood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Pilgrim Story

Being largely a compilation from the documents of Governor

Bradford and Governor Winslow, severally and in

collaboration; together with a list of Mayflower passengers.

Author: William Franklin Atgood

Illustrator: Leo Schreiber

Release Date: October 13, 2016 [EBook #53270]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PILGRIM STORY ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, xteejx and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BEING LARGELY A COMPILATION FROM THE DOCUMENTS OF GOVERNOR BRADFORD AND GOVERNOR WINSLOW, SEVERALLY AND IN COLLABORATION; TOGETHER WITH A LIST OF MAYFLOWER PASSENGERS.

Compiled and written by

WILLIAM FRANKLIN ATWOOD

ILLUSTRATED BY LEO SCHREIBER

Published by MPG Communications, Plymouth, Mass.

Copyright 1940

By

PAUL W. BITTINGER

Plymouth, Mass.

Second Edition

October, 1947

Third Edition

June, 1950

Fourth Edition

June, 1952

Fifth Edition

April, 1955

Sixth Edition (revised)

April, 1958

Seventh Edition

January, 1963

Eighth Edition

January, 1966

Ninth Edition

April, 1968

Tenth Edition

May, 1971

Eleventh Edition

May, 1975

Twelfth Edition

April, 1980

Thirteenth Edition

April, 1984

Fourteenth Edition

July, 1987

Linotyped, Printed and Bound

by MPG Communications, Plymouth, Mass.

Distributed by Plimoth Plantation, Plymouth, MA 02360

NOTE—Many well-known pictures of the Pilgrims have grossly misinterpreted their true spirit. A “Signing of the Compact” or a “Departure from Delfthaven,” for example, that employs the sentimental piety, the eyes and arms raised to heaven, of Italian Baroque art, (that Jesuitical, most Catholic art), fails to reflect the real spirit of the Protestant Pilgrims. The use of the gracefully reclining and swooning figures of Italianate renaissance art is likewise inappropriate.

Reacting sharply from this, the illustrations in the book portray in the modern spirit both the activities of the Pilgrims and their settings with strict realism.

Unsparing effort in consulting authorities, old documents, prints, and actual scenes was expended to secure convincing authenticity.

No phase of early American history presents a finer example of faith, fortitude and determination of purpose than the story of that little band of devout souls who landed at Plymouth in the winter of 1620 and to whom we refer as the Pilgrims.

In the following limited pages the writer attempts to present something of the conditions obtaining in England prior to the Departure, also something of the struggles, privations, courage and forbearance during the first years of the settlement at Plymouth.

In so doing dependence is placed particularly upon the contemporaneous writings of Bradford and Winslow, both members of the Mayflower party.

With the vast bibliography relating to the Pilgrim history, together with the requirements of brevity, it is indeed fortunate that we are able to look to those who played such an important part in this historic episode and who were thoughtful enough to leave a record for posterity.

It is difficult to epitomize a story so broad and sweeping in its ramifications, its religious and material aspects and its touch of romanticism. Consequently it is intended to include only such events as may prove of interest and value to the reader as adduced from the recognized authorities.

These authorities as before indicated are:

Note:—With regard to the original manuscript of Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation, it may be stated that it was first obtained by Thomas Prince, the historian, from Judge Sewall, to whom it was “lent but only lent” by Major John Bradford of Kingston, son of Major William Bradford, formerly Deputy Governor of the Plymouth Colony, and grandson of Governor William Bradford.

This precious document which seems to have passed through several hands, finally found refuge, together with Prince’s library, in the tower of the Old South Church in Boston, whence it later disappeared.

In 1856 it was found in the library of the Lord Bishop of London, at Fulham Palace. A transcript was made and it was printed in Boston the same year, under the auspices of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

In 1897 the original manuscript was brought to this country by the Hon. Thomas F. Bayard, our Ambassador to England at the time, to whom it had been delivered by the Rt. Rev. Mandell Creighton, Lord Bishop of London. Much credit is due to the late Senator George F. Hoar of Massachusetts, to the former Bishop of London, Dr. Temple, who later became the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the aforementioned Ambassador Bayard, who were all in accord as to the right and justice of the transfer.

This historic document now reposes in the state library in the State House in Boston, priceless in both historic and sentimental value.

W. F. A.

The early settlements on Cape Cod all came about under the aegis of the parent colony in Plymouth. Several times in Pilgrim chronicles we read how Captain Myles Standish was sent to Sandwich, Barnstable and Yarmouth on tours of inspection and to supervise the division of lands purchased for little or nothing by the newcomers from the remnants of an Indian population decimated years before by disease.

Direct Pilgrim influence on the religious life, the administration and the courts of the Cape settlements continued from the earliest beginnings at Sandwich in 1637, with steadily diminishing strength, until the election of Thomas Prence of Eastham as Governor of Plymouth Colony in 1657. Meanwhile the parent settlement itself was coming under the domination of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and its Puritan hierarchs. The Plymouth connection finally lapsed, for all practical purposes, in 1685, when Plymouth Colony was divided up into Plymouth, Barnstable and Bristol Counties.

First Cape settlement was in 1637, when a band of Puritan families from Saugus and Lynn on the North Shore got permission from the Pilgrim Fathers to migrate to the precincts of the Plymouth Colony, of which the Cape was a part. Some Pilgrim families from Duxbury and Plymouth came along with these first settlers to carve out homesteads in the Sandwich area.

Next towns to be settled were Yarmouth and Barnstable, in 1639, an earlier attempt to populate the Mattacheesett section of what is now Barnstable having failed.

Yarmouth was a direct offshoot of Pilgrim Plymouth, and prominent among its settlers was Giles Hopkins, son 8 of Stephen Hopkins, who came over with his father on the Mayflower.

Barnstable, at its inception, was dominated by the personality of the Rev. John Lothrop, a very strongminded man of dissident Pilgrim persuasion who, together with fifty of his parishioners, had once served two years in jail in England for religious schism. For a time the spirit of controversy continued in the new Cape Colony, fanned by the radical views of Marmaduke Matthews, a firebrand Welshman. But by the time Captain Myles Standish and two companions came down from Plymouth in 1643 to divide up the salt hay marshes, cleared farmlands and woods of Barnstable into legally recorded homesteads, the colony had settled down and become absorbed with more workaday matters.

Last of the very early Cape Cod towns to be settled was Eastham in 1644, by a party led by the Rev. John Mayo, bearer of another of the names later to become famous on the Cape in its great mercantilist period.

Falmouth, in 1686, fissioned off quite directly from Plymouth, and was incorporated in 1686, originally under the name of Succonesset. Harwich officially came into being in 1694, as an offshoot from Barnstable, and very much later, in 1803, gave rise to Brewster. Dennis, meanwhile, had fissioned from Yarmouth in 1794. But by this time Pilgrim origins and influence were but the dimmest of memories.

Also influential on the early Cape, after the middle 1650’s, were the Quakers, at first persecuted, but eventually accepted as a manifestly superior kind of people. They, too, quickly merged during the following century into the Cape Cod way of life, and became indistinguishable from families of Pilgrim or Puritan origin.

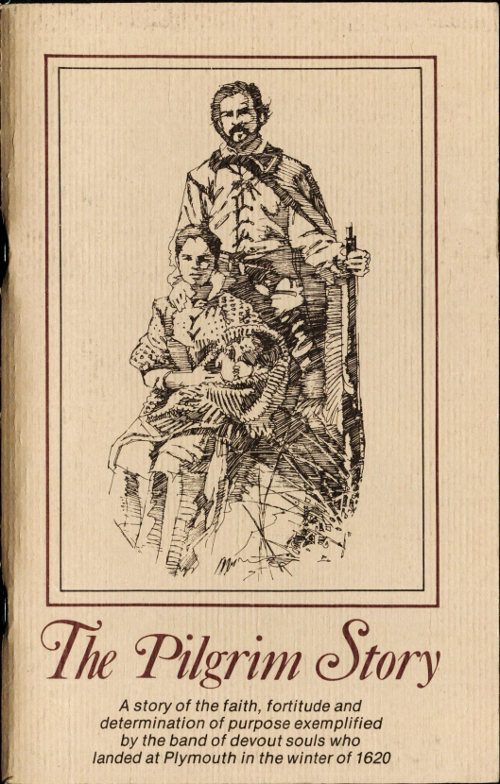

Stock Scene, showing church attended by Brewster and approximate location of the stocks in Scrooby

The Pilgrim story may well begin from the period of the Reformation or the ascendency of the Protestant Church in England. Previous to 1600 much friction had existed between the Crown and the Papacy in matters ecclesiastical and civil. The process of reform however had been crystalizing during the reign of Queen Elizabeth. This came to culmination in the establishment of the English Church (known as the Church of England) as the official or state church of which the King was to be the temporal head with the Archbishop of Canterbury, the spiritual head or primate.

But still there was friction. It was like a house divided against itself. There were those who could not conscientiously subscribe to the laws and rituals laid down by the established church. They were dissenters or non-conformists and are best described by Bradford as follows: “The one side labored to have the right worship of God and discipline of Christ established in the Church, according to the simplicity of the gospel, without the mixture of men’s inventions, and to have and be ruled by the laws of God’s 10 word, dispensed in those offices and by those officers of Pastors, Teachers and Elders, etc., according to the Scriptures.”

“The other party endeavored to have episcopal dignity (after the popish manner) with their large power and jurisdiction still retained.”

Note: In the subject matter in quotations, the spelling of some words has been changed to the modern form without otherwise affecting the text.

This strained and anomalous situation led to the founding of the Separatist Church in 1602 in the Old Hall in Gainsborough, with John Smyth as pastor.

Smyth was highly esteemed by the non-conformist group. He was a graduate of Cambridge, “an eminent man in his time,” and his pastorate at Gainsborough extended from 1602 until 1606 when he was forced to retire.

The Scrooby fraternity, an off-shoot from Gainsborough, was presided over by Richard Clyfton as first pastor. Prominent among the non-conformists at Scrooby were William Brewster, born in Scrooby in 1560, William Bradford, born in Austerfield, a village three miles distant, in 1588, and John Robinson, born in Lincolnshire about 1576. Robinson received orders from the Church of England, was suspended for non-conformity and later joined the Congregation at Scrooby where he was made pastor.

This triumvirate became the ruling spirits of the Scrooby community, Brewster became the Elder of the Church and later the religious leader of the Plymouth settlement, of which Bradford became Governor. Robinson, to whom both looked for inspiration and guidance, was destined by circumstances to remain in Holland where he had later been forced to take refuge.

These independent thinkers who firmly asserted their right to worship according to their belief, were brought into constant conflict with the constituted authorities of the Church of England. As Bradford says: “This contention was so great, as neither the honour of God, the common persecution, nor the mediation of Mr. Calvin and other worthies of the Lord in those places, could prevail with those thus episcopally minded, but they proceeded by all means to disturb the peace of this poor persecuted church, even so far as to charge (very unjustly and ungodly, yet prelate like) some of their chief opposers, with rebellion and high treason....” And then regarding their treatment he says: “They could not long continue in any peaceable condition but were hunted and persecuted on every side.”

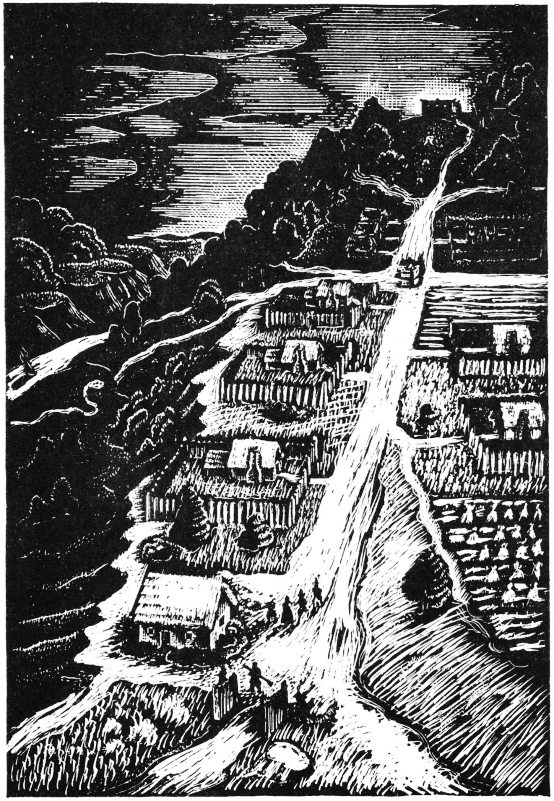

Birdseye view of Brewster Manor in Scrooby

From 1603 when King James I succeeded Elizabeth who had reigned as Queen during the preceding forty-five years, conditions grew increasingly worse until as Bradford continues:

“Seeing themselves thus molested and that there was no hope of their continuance there, they resolved to go into the Low Countries, where they heard was freedom of religion for all men; as also how sundry from London, and other parts of the land had been exiled and persecuted for the same cause, and were gone thither and lived at Amsterdam and in other places of the land. So after they had continued together about a year, and kept their meetings every sabbath, in one place or other, exercising the worship of God amongst themselves, notwithstanding all the diligence and malice of their adversaries, they seeing they could no longer continue in that condition, they resolved to get over into Holland as they could which was in the year 1607-1608.”

Church at Scrooby

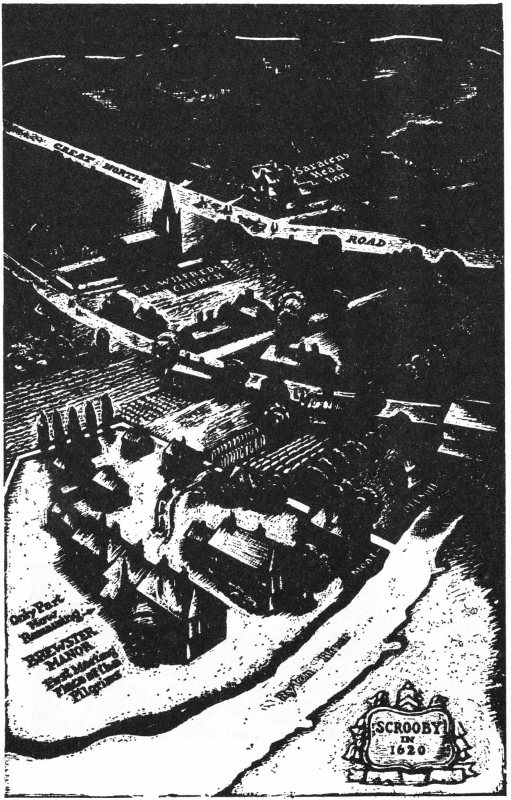

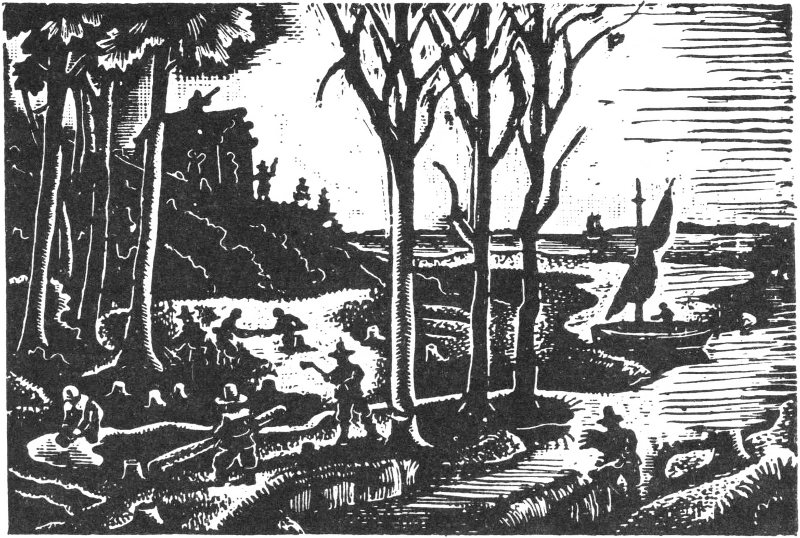

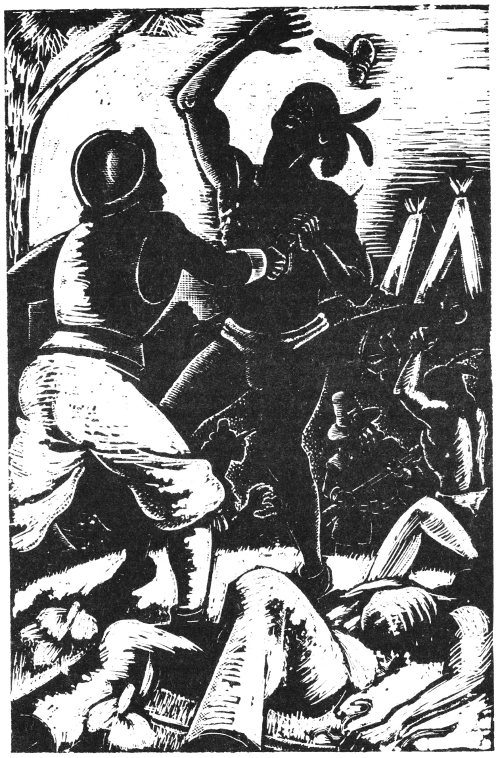

Capture of escaping Pilgrims by an English mob

The Migration to Holland was not accomplished without its set-backs and misgivings. In the first place it was unlawful under an old statute which made emigrating without authority a penal crime. They were several times intercepted in their attempt to depart from English soil. But they were determined in purpose and brave in heart.

“Being thus constrained to leave their native country, their lands and livings, and all their friends and familiar acquaintance, it was much, and thought marvellous by many. But to go into a country they knew not, but by hearsay, where they must learn a new language, and get their livings they knew not how, it being a dear place, and subject to the miseries of war,[1] it was by many thought an adventure almost desperate, a case intolerable, and a misery worse than death; especially seeing they were not acquainted with trades nor traffic, (by which the country doth subsist) but had only been used to a plain country life and the innocent trade of husbandry. But these things 14 did not dismay them, (although they did sometimes trouble them,) for their desires were set on the ways of God, and to enjoy his ordinances. But they rested on his providence, and knew whom they had believed. Yet this was not all. For although they could not stay, yet were they not suffered to go; but the ports and havens were shut against them, so as they were fain to seek secret means of conveyance, and to fee the mariners, and give extraordinary rates for their passages. And yet were they oftentimes betrayed, many of them, and both they and their goods intercepted and surprised, and thereby put to great trouble and charge; of which I will give an instance or two, and omit the rest.”

“There was a great company of them purposed to get passage at Boston, in Lincolnshire; and for that end had hired a ship wholly to themselves, and made agreement with the master to be ready at a certain day, and take them and their goods in, at a convenient place, where they accordingly would all attend in readiness. So after long waiting and large expenses, though he kept not the day with them, yet he came at length, and took them in, in the night. And when he had them and their goods aboard, he betrayed them, having beforehand complotted with the searchers and other officers so to do; who took them and put them into open boats, and there rifled and ransacked them, searching them to their shirts for money, yae, even the women, further than became modesty; and then carried them back into the town, and made them a spectacle and wonderment to the multitude, which came flocking on all sides to behold them. Being thus by the catchpole officers riffled and stripped of their money, books and much other goods, they were presented to the magistrates, and messengers sent to inform the Lords of the Council of them; and so they were committed to ward. Indeed the magistrates used them courteously, and showed them what favor they could; but could not deliver them until order came from the Council table. But the issue was, that after a month’s imprisonment the greatest part were dismissed, and sent to the places from whence they came; but seven of the principal men were still kept in prison and bound over to the assizes.”

In the spring of 1608 another attempt was made to embark and another Dutch shipmaster engaged. This second party assembled at a point between Grimsby and Hull not far from the mouth of the Humber. The women and children arrived in a small bark which became grounded at low water and while some of the men on shore were taken off in the ship’s boat they were again apprehended. And to quote again:

“But after the first boat-full was got aboard, and she was ready to go for more, the master espied a great company, both horse and foot, with bills and guns and other weapons: for the country was raised to take them.”

“But the poor men which were got on board were in great distress for their wives and children, which they saw thus to be taken, and were left distitute of their helps, and themselves also not having a cloth to shift them with, more than they had on their backs, and some scarce a penny about them, all they had being on the bark. It drew tears from their eyes, and anything they had they would have given to have been on shore again. But all in vain; there was no remedy; they must thus sadly part; and afterwards endured a fearful storm at sea, being fourteen days or more before they arrived at their port; in seven whereof they neither saw sun, moon, nor stars, and were driven to the coast of Norway; the mariners themselves often despairing of life, and once with shrieks and cries gave over all, as if the ship had been foundered in the sea, and they sinking without recovery. But when man’s hope and help wholly failed, the Lord’s power and mercy appeared for their recovery; for the ship rose again, and gave the mariners courage again to manager her; and if modesty would suffer me, I might declare with what fervent prayers they cried unto the Lord in this great distress, (especially some of them,) even without any great distraction.”[2]

Those left ashore were in a pitiable state, women were left without their husbands and children without their fathers, their property had been sold in anticipation of a 16 safe departure and the situation was, for a time at least, desperate. But a kind Providence intervened and while their purpose was thus hindered, they finally were united at Amsterdam. As Bradford states: “Notwithstanding all these storms of opposition, they all got over at length, some at one time and some at another, and yet met together again, according to their desires, with no small rejoicing.”

Let us pause here a moment and reflect. In our contemplation of the present and concern for the future, we must not be unmindful of the past. It was not easy to make final decision in such matter as permanently breaking away from homes, relatives and friends, not to mention the material factors involved. Fortunately however for them and for us, this devout band was imbued with enduring faith. Faith fortified by grim determination.

Thus they planned and executed. They left the land of their nativity. They braved the perils of an unknown ocean and a still more unknown future that they might find a refuge free from religious bondage and where they might worship God according to their conscience. This they accomplished in the face of almost insurmountable hardships.

They made concord with the Indians, they builded homes, they framed laws and agreements in accordance with the time and the necessity. They established a governmental process sufficient for their needs, an outgrowth of the government of their religious life in which decisions were made by the will of the majority. They paved the way for future generations. They suffered much. They attained much. They left a heritage that must not be sacrificed.

We of today are faced with ominous problems. A re-dedication to the faith, vision and determination of our fathers, will be America’s salvation.

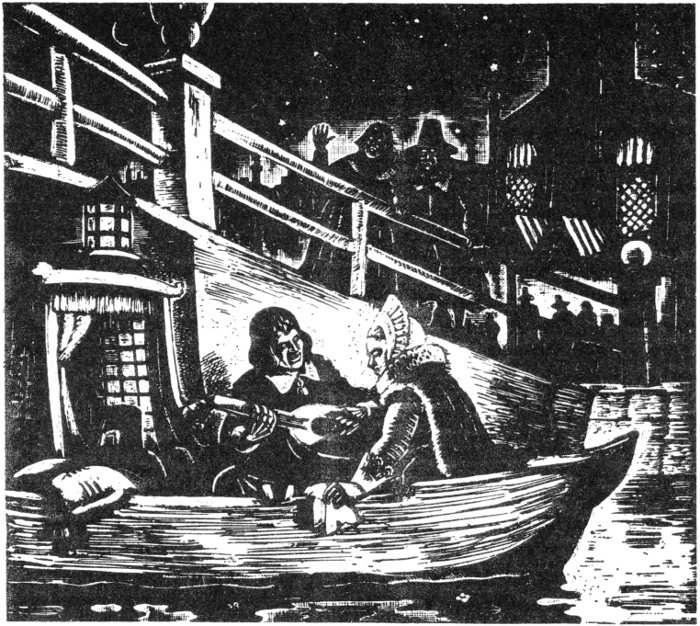

Love Scene, showing actual bridge and the Cloth Hall in Leyden, headquarters of the guild of woolen workers, of whom the Pilgrims were a part

They remained in Amsterdam about a year when for both material and spiritual reasons they decided to move to Leyden 22 miles distant. They had come into some contention with the church that had established itself before them which seemed difficult to settle to their satisfaction and their means of livelihood had become so restricted that they were threatened with poverty. “For these and some other reasons they removed to Leyden, a fair and beautiful city. But being now here pinched, they fell to such trades and employments as they best could, valuing peace and their spiritual comfort above any other riches whatsoever; and at length they came to raise a competent and comfortable living, but with hard and continual labor.”

Some eleven or twelve years were spent in Leyden where they enjoyed “much sweet and delightful society and spiritual comfort together, in the ways of God, under the able ministry and prudent government of Mr. John Robinson and Mr. William Brewster, who was an assistant unto him in the place of an Elder, unto which he was now called and chosen by the church; so as they grew in knowledge and other gifts and graces of the spirit of God; and lived together in peace, and love, and holiness.”

Yet while they seemed to have more spiritual freedom and to have enjoyed the society of their Dutch neighbors and had established a good credit among them, they were confronted with the fear of final absorption in an alien country. They preferred to maintain their language and traditions as English men and women. Moreover, King James was beginning to exercise an unwarrantable influence in the Low Countries. This went to the extreme of confiscating their types[3] and presses and the suppression of the religious matter printed and issued by William Brewster, the Elder of the Leyden congregation. A compelling force seemed to drive them on to seek some place of permanent settlement. And to quote from Bradford:

“Although the people generally bore all their difficulties very cheerfully and with a resolute courage, being in the best of their strength, yet old age began to come on some of them; and their great and continual labors, with other crosses and sorrows, hastened it before the time; so as it was not only probably thought, but apparently seen, that within a few years more they were in danger to scatter by necessity pressing them, or sink under their burdens, or both; and therefore, according to the divine proverb, that ‘a wise man seeth the plague when it cometh, and hideth himself,’ so they, like skilful and beaten soldiers, were fearful either to be entrapped or surrounded by their enemies, so as they should neither be able to fight nor 19 fly; and therefore thought it better to dislodge betimes to some place of better advantage and less danger, if any could be found.”

“Lastly (and which was not the least,) a great hope and inward zeal they had of laying some good foundation, or at least to make way thereunto, for the propagating and advancing the Gospel of the kingdom of Christ in these remote parts of the world; yea, though they should be but as stepping-stones unto others for performing of so great a work.”

“The place they had thoughts on were some of those unpeopled countries of America, which are fruitful and fit for habitation, being devoid of all civil inhabitants, where there are only savage and bruitish people, which range up and down little otherwise than the wild beasts. This proposition being made public, and coming to the scanning of all, it raised many variable opinions amongst men, and caused many fears and doubts amongst themselves. Some from their reasons and hopes conceived, labored to stir up and encourage the rest to undertake and prosecute the same; others again, out of their fears, objected against it, and sought to divert from it, alleging many things, and those neither unreasonable nor unprobable: as that it was a great design, and subject to many inconceivable perils and dangers; as, besides the casualties of the seas, (which none can be freed from,) the length of the voyage was such as the weak bodies of women and other persons worn out with age and travail, (as many of them were,) could never be able to endure; and yet if they should, the miseries of the land which they should be exposed unto would be too hard to be borne, and likely, some or all of them, to consume and utterly to ruinate them. For there they should be liable to famine, and nakedness, and the want, in the manner, of all things.”

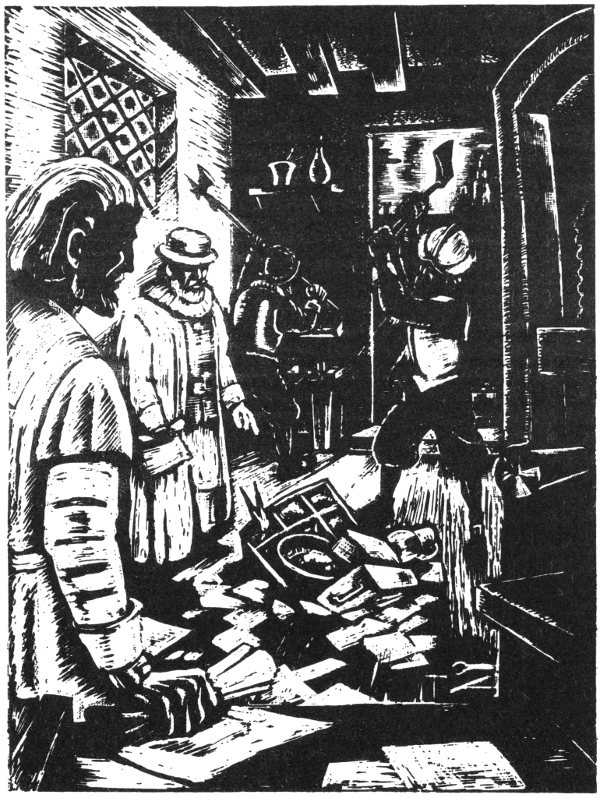

Destruction of Brewster’s printing shop

“It was answered, that all great and honorable actions were accomplished with great difficulties, and must be both enterprised and overcome with answerable courages. It was granted the dangers were great, but not desperate, and the difficulties were many, but not invincible; for although there were many of them likely, yet they were not certain. It might be that some of the things feared might never befall them; others, by providence, care and use good of means, might in a great measure be prevented; and all of them through the help of God, by fortitude and patience, might either be borne or overcome. True it was that such attempts were not to be made and undertaken but upon good ground and reason, not rashly or lightly, as many have done for curiosity or hope of gain, etc. But their condition was not ordinary. Their ends were good and honorable, their calling lawful and urgent, and therefore they might expect a blessing of God in their proceeding; yea, although they should lose their lives in this action, yet they might have comfort in the same; and their endeavours would be honorable.”[4]

“They lived here but as men in exile and in a poor condition; and as great miseries might possibly befall them in this place; for the twelve years of truce were now out,[5] and there was nothing but beating of drums and preparing for war, the events whereof are always uncertain. The Spaniard might prove as cruel as the savages of America, and the famine and pestilence are sore here and there, and their liberty less to look out for remedy.”

“After many other particular things answered and alleged on both sides, it was fully concluded by the major part to put this design in execution, and to prosecute it by the best means they could.”

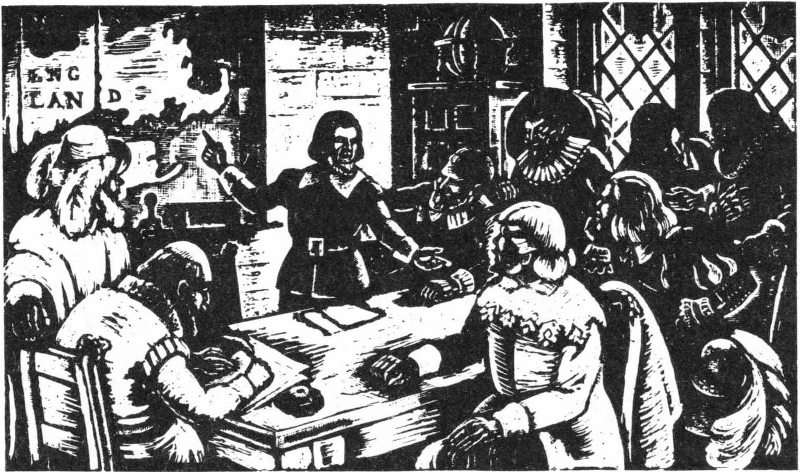

Cushman before the Merchant Adventurers

The coast of North America was not entirely unknown. There had been several attempts at settlement and exploration. One by Sir Walter Raleigh in 1584. He had taken possession under a patent confirmed by act of Parliament, of the territory from the Carolinas north to Virginia, the name Virginia being given the new country in honor of the Virgin Queen.

In 1606 another party under command of Capt. John Smith sailed in three small vessels under authority of a charter granted by James I. They landed at a point in Chesapeake Bay, thirty-two miles from the mouth of the James river in Virginia and established a settlement called Jamestown.

In 1614 Smith made a voyage to the North Virginia coast at which time he made a comprehensive map calling this section New England. Upon his return to England he showed this map to Charles I, then a prince, who in applying the names of English towns to points along the coast gave the place which was to become the Pilgrim settlement the name of Plymouth, which it has since retained.

There were many matters of moment to be settled 23 before the Pilgrims could depart their native shores. The liquidation of what property they had acquired was to be augmented by further financing. It was necessary to obtain a patent to any land they might acquire for settlement and the matter of how many and who should go first had to be determined.

“Those that stayed, being the greater number, required the pastor to stay with them; and indeed for other reasons he could not then well go, and so it was the more easily yielded unto. It was also agreed on by mutual consent and covenant that those who went should be an absolute church of themselves, as well as those that stayed, seeing in such a dangerous voyage, and a removal to such a distance, it might come to pass that they should (for the body of them) never meet again in this world. Yet with this proviso, that if any of the rest came over to them, or of the other returned upon occasion, they should be reputed as members without further admission or testimonial. It was also promised to those that went first, by the body of the rest, that if the Lord gave them life and means, and opportunity, they should come to them as soon as they could.”

The next step was to secure a patent. Already letters-patent had been granted two companies of Englishmen to territory 100 miles in width on the Atlantic coast of North America from the 34th to the 45th degrees north latitude. These were designated as the South and North Virginia companies. Through emissaries sent to England a patent was obtained bearing date of Feb. 12th, 1620. This patent was issued to John Pierce and Associates and covered territory in the vicinity of the Virginia Capes. As it happened the Pilgrims settled outside the limits defined therein and another patent was granted covering the territory around Cape Cod Bay. This patent bears the date of June 1st, 1621, and was issued by the Council of New England which had been created by royal authority to succeed the North Virginia Company after the departure of the Pilgrims from England.

It shows the signatures of the Duke of Lenox, the Marquis of Hamilton, the Earl of Warwick, Lord Sheffield and Sir Ferdinand Gorges. Several parts of this ancient 24 document have broken away, including the seal of Hamilton and the seal and signature of John Pierce, the party of the second part thereto. This valuable document, the oldest state document in New England, was brought over in the Fortune in 1621 and now reposes in Pilgrim Hall.

Arrangements were concluded with a group of London business men who styled themselves the Merchant Adventurers who were in sympathy with the movement and who had agreed to finance the expedition. Perhaps they are best described by Capt. John Smith who wrote in 1624:

“The adventurers which raised the stock to begin and supply this plantation, were about seventy, some gentlemen, some merchants, some handicraftsmen, some adventuring great sums, some small, as their estates and their affection served. These dwelt most about London. They are not a corporation, but knit together by a voluntary combination in a society without constraint or penalty, aiming to do good and to plant religion.”

The Articles of Agreement entered into with the Merchant Adventurers were as follows:—

“1. The adventurers and planters do agree, that every persons that goeth, being aged sixteen years and upward, be rated at ten pounds, and ten pounds to be accounted a single share.

2. That he that goeth in person, and furnisheth himself out with ten pounds, either in money or other provisions, be accounted as having twenty pounds in stock, and in the division shall receive a double share.

3. The persons transported and the adventurers shall continue their joint stock and partnership together the space of seven years, (except some unexpected impediments do cause the whole company to agree otherwise,) during which time all profits and benefits that are got, by trade, traffic, trucking, working, fishing, or any other means, of any person or persons, shall remain in the common stock until the division.

4. That at their coming there they choose out such a number of fit persons as may furnish their ships and boats 25 for fishing upon the sea; employing the rest in their several faculties upon the land, as building houses, tilling and planting the ground, and making such commodities as shall be most useful for the colony.

5. That at the end of the seven years, the capital and profits, viz., the houses, lands, goods and chattels, be equally divided among the adventurers and planters; which done, every man shall be free from other of them of any debt or detriment concerning the adventure.

6. Whosoever cometh to the colony hereafter, or putteth any into the stock, shall at the end of the seven years be allowed proportionally to the time of his so doing.

7. He that shall carry his wife and children or servants, shall be allowed for every person now aged 16 years and upward, a single share in the division; or if he provide them necessaries, a double share, or if they be between 10 years old and 16 then two of them to be reckoned for a person, both in transportation and division.

8. That such children as now go and are under the age of 10 years, have no other share in the division, but 50 acres of unmanured land.

9. That such persons as die before the seven years be expired, their executors to have their part or share at the division, proportionally to the time of their life in the colony.

10. That all such persons as are of this colony are to have their meat, drink, apparel and all provisions out of the common stock and goods of the said colony.”

It has been declared by some commentators that this agreement savored of communism. This interpretation is however unfair. As a matter of record it was not entirely satisfactory to the colonists but was imposed upon them by the Merchant Adventurers who, looking to the final liquidation of their advancements, preferred to hold the community as a whole to meet the obligation. Several letters written by Robert Cushman to his associates in Leyden tend to substantiate this view and emphasize that he had made the best possible terms under the circumstances.

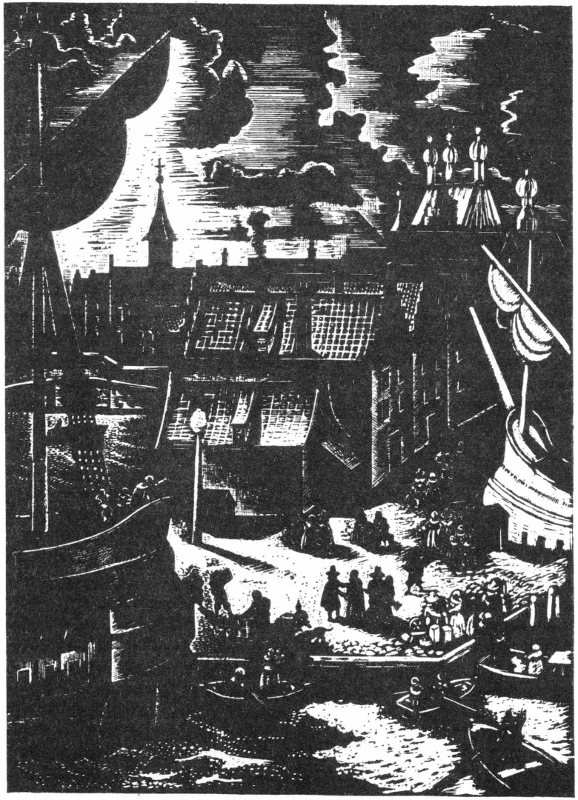

Embarkation, showing buildings and actual wharf from which the Pilgrims departed

Pertinent to the foregoing it is interesting to quote from Young’s Chronicles, page 84, as follows:—“There is no foundation for this charge. The Plymouth people were not ‘misguided by their religious theories,’ nor influenced by an ‘imitation of the primitive Christians,’ in forming their joint stock company. They entered into this hard and disadvantageous engagement with the Merchant Adventurers not voluntarily, but of necessity, in order to obtain shipping for transporting themselves to America; and they put their own little property into a common fund in order to purchase provisions for the voyage. It was a partnership that was instituted, not a community of goods, as that phrase is commonly understood.”

A small vessel of about sixty tons called the Speedwell and commanded by Captain Reynolds was secured in Holland and another, somewhat larger, the Mayflower, of London, commanded by Captain Jones. The Speedwell left Delft-Haven in July, 1620, with a company of thirty, including William Bradford, William Brewster, John Carver, Edward Winslow, Isaac Allerton, Samuel Fuller and John Howland. Captain Myles Standish was also a member of the company although not of the congregation. He was a soldier whose value to the Colony proved outstanding. They left with the blessing of John Robinson who intended to follow but whose dreams were never to be realized.

Note: Dates following accord with the modern calendar except those marked O.S. indicating Old Style.

The first party reached Southampton where the Mayflower awaited them with ninety passengers. On the fifteenth of August both vessels set sail but had gone but a short distance when the Speedwell began to leak. They put back to Dartmouth where eight days were spent in repairs when the ships again put to sea. They had covered scarcely three hundred miles when the Speedwell again began leaking. Both vessels turned back, putting into Plymouth harbor where the leaking craft was abandoned. Here eighteen of her passengers decided not to continue.

Sighting of Provincetown, showing deck construction of Mayflower type of boat

The Mayflower with its added burden, now numbering one hundred and two souls, left Plymouth September 16th, 1620, and began its historic journey westward. For a goodly part of the voyage of over two months duration the ship was buffeted by equinoctial winds and high seas and, as they neared the coast, a death is recorded, that of William Butten, a youth, servant of Samuel Fuller. The records also disclose the birth of a son, Oceanus, to Stephen and Elizabeth Hopkins. “After long beating at sea they fell with that land which is called Cape Cod; the which being made and certainly known to be it, they were not a little joyful. After some deliberation had amongst themselves and with the master of the ship, they tacked about and resolved to stand for the southward (the wind and weather being fair) to find some place about Hudson River for their habitation.

“But after they had sailed the course about half the day, they fell amongst dangerous shols and roaring breakers, and they were so far entangled therewith as they conceived themselves in great danger; and the wind shrinking upon them withall; they resolved to bear up again for the Cape, and thought themselves happy to get out of those 29 dangers before night overtook them, as by God’s providence they did. And the next day they got into the Cape Harbor where they rode in safety.”

It was the 21st of November (present calendar) when the Mayflower dropped anchor in the sheltered and quiet waters of Provincetown Harbor and one may well imagine the happiness and gratitude of these weary voyagers when they sighted this haven of refuge and were once more able to place their feet upon dry land. As Bradford records: “Being thus arrived in a good harbor and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees and blessed the God of heaven who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean, and delivered them from all the perils and miseries thereof, again to set their feet on the firm and stable earth, their proper element.”

On Monday the 23rd a landing was made, the men to make repairs to the shallop and the women to wash, thus establishing Monday as the generally accepted “Washday.”

The Mayflower Compact was drawn up and signed in all probability before Mayflower dropped anchor in Provincetown Harbor. This document was partly the result of friction that had arisen during the voyage and the intimation that some among them might exercise their individual liberty without restraint and against the peace and welfare of the community as a whole. The text follows with Bradford’s explanatory note:

“I shall a little return back and begin with a combination made by them before they came ashore, being the first foundation of their government in this place; occasioned partly by the discontented and mutinous speeches that some of the strangers amongst them had let fall from them in the ship—That when they came ashore they would use their own liberty; for none had power to command them, the patent they had being for Virginia, and not for New England, which belonged to another Government, with which the Virginia Company had nothing to do. And partly that such an act by them done (this their condition considered) might be as firm as any patent, and in some respects more sure.”

“In the name of God, Amen. We whose names are underwritten, the loyal subjects of our dread sovereign Lord, King James, by the grace of God, of Great Britain, France and Ireland King, defender of the faith, etc., having undertaken, for the Glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith, and honor of our King and country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the northern parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions and offices from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof, we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape Cod, the 11th of November, in the year of the reign of our sovereign lord, King James of England, France, and Ireland the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth. Anno Domino. 1620.”

The earliest known list of the signers of the Compact is that contained in Morton’s “New-Englands Memoriall,” published in 1669. The names follow:

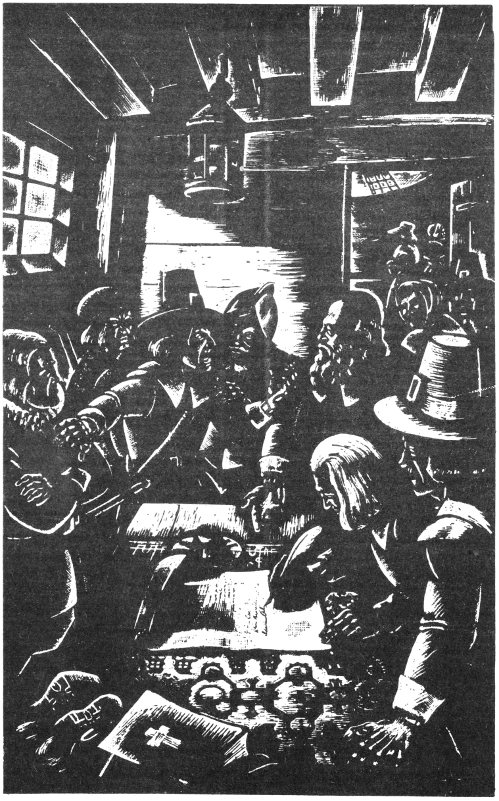

Signing the Compact

“After this they chose, or rather confirmed, Mr. John Carver (a man godly and well approved amongst them) their Governor for that year.”

This meeting, held in the cabin of the Mayflower, is generally accepted as the first New England town meeting, although on the 27th of February following, a meeting, later referred to, was held in the common house for the purpose of establishing a military guard at which Myles Standish was chosen captain.

On April 2nd another meeting was held on “common business” and at which laws “convenient for the common state” were passed.

From these first meetings evolved our present form of town meeting, held, and elections made, according to the will of the majority.

On November 25th, a party of sixteen men under the leadership of Captain Standish set out on foot looking for a place for permanent settlement “having such instructions as was thought meet.” They had proceeded but a short distance when they met a small party of Indians who fled upon approach. They were followed for some miles, when, darkness coming on, they made camp for the night.

The following day further exploration was made. Some Indian corn was discovered, also fresh water from which they drank being sorely in need thereof “this being the first New England water drunk of.”

Returning from the vicinity of Truro and the Pamet River to which their exploration had taken them, they saw deer and “great flocks of wild geese and ducks, but they were fearful of us.”[6] Also signs of Indian habitation and “heaps of sand newly padled with their hands, which they, digging up, found in them divers fair Indian baskets filled with corn, and some in ears, fair and good, of divers colors, which seemed to them a goodly sight (having never seen any such before). So their time limited to them being expired, they returned to the ship, lest they should be in fear of their safety; and took with them part of the corn ... of which on their return they were marvellously glad....”

The days immediately following were occupied in completing repairs to the shallop, in cutting wood and getting tools in readiness, in anticipation of a permanent landing.

With this in view a party of thirty set forth on Dec. 7, “for the better discovery of this place.” They found signs of Indian habitation also “more of their corn and of their beans of various colors. The corn and beans they brought away proposing to give them good satisfaction when they should meet with any of them (as about 6 months afterward they did, to their good content).” “And here it is to be noted a special Providence of God, and a great mercy to this poor people that here they got seed to plant them corn the next year or else they might have starved, for they had none, nor any likelihood to get any until the season had been past (as the sequel did manifest).”

Not finding the desired harborage or place for permanent settlement this party returned to the Mayflower.

During their absence and while the Mayflower lay in the Harbor of Provincetown, a son was born to Susanna White, wife of William White. He was named Peregrine.

On the sixteenth of December another party set out in the shallop “upon further discovery intending to circulate that deep bay of Cape Cod.” This party consisted of Myles Standish, John Carver, William Bradford, Edward Winslow, John Tilley, Edward Tilley, John Howland, Richard Warren, Stephen Hopkins, Edward Dotey, John Allerton, Thomas English, the ship’s mates, Mr. Clark and Mr. Coppin, and the master gunner and three sailors.

“The weather was very cold and it froze so hard as the spray of the sea lighting on their coats, they were as if they had been glazed.”

Proceeding as far as Wellfleet they discovered a party of “ten or twelve Indians very busy about a black thing,—what it was we could not tell,—until afterwards they saw us, and ran to and fro, as if they had been carrying something away. We landed a league or two from them where we made us a barricade and got firewood and set out sentinels and betook us to our lodging, such as it was.” This landing was at Eastham ten miles distant.

When morning came the company was divided, eight cruising along shore in the shallop while the remainder explored the land bordering thereon. They came to the spot “where they saw the Indians the night before and found they had been cutting up a great fish like a grampus.” (small whale or blackfish).

Nothing of importance having been discovered this day, they returned to the shallop which had come ashore at their calling. “So being weary and faint,—for we had eaten 35 nothing all day,—we fell to make our rendezvous and get firewood and we fed upon such victuals as we had, and betook us to our rest, and we had set out our watch.”

In the early morning of the 18th, they had their first encounter with the Indians “some thirty or forty of them, though some thought that they were many more.” Many arrows were shot but “none of them either hit or hurt us, though many came close by us and on every side of us and some coats which hung up in our barricade were shot through and through.” But after several shots were fired at them, they all left with apparently no casualties. This was the first actual encounter with the Indians.

During the day the reunited party skirted the coast, the wind increasing during the afternoon to gale force. The boat’s rudder was broken and the mast split and they were dependent upon their oars for steering. In this condition they were driven across the bay toward Saquish where the high seas prevented landing. By skillful maneuvering however they managed to round Saquish head and “although it was very dark and rained sore, yet in the end they got under the lee of a small island,[7] and remained there all the night in safety.”

“Yet, God gave them a morning of comfort and refreshment for the next day was a fair and sunshiny day and they found themselves to be on an island secure from the Indians, where they might dry their stuff, fix their pieces and rest themselves. And this being the last day of the week, they prepared there to keep the Sabbath.”

This Sabbath was spent on Clark’s Island where they rested and held service. “On Monday they sounded the harbor and found it fit for shipping, and marched into the land,[8] and found divers cornfields, and little running brooks, a fit place 36 for situation; at least it was the best they could find, and the season, and their present necessity, made them glad to accept it. So they returned to their ship again with this news to the rest of their people, which did much comfort their hearts.”

The romance surrounding the Rock that has become famous in history is not easily discredited. The fact is, that Elder Thomas Faunce, who was born in Plymouth in 1647 and died in 1746 at the age of ninety-nine years, made a statement a few years prior to his death, at a time when removal or covering of the rock was under contemplation, protesting vigorously at what he considered the desecration of an object of deep veneration. He stated in the presence of many hearers that his father, John Faunce, who came over in the ship Anne, had told him that it was on that rock that the Pilgrims landed as stated by them to him. It is further probable that they may have imparted this information to him directly as a number of the Mayflower passengers lived for many years subsequent to his birth.

This information has passed from generation to generation. “Plymouth Rock has now become a symbol of the Pilgrim venture into the unknown of their day and has inspired present-day Americans with a new Faith in democracy and in the American way of living.”

It was during their absence on December 17th, that Dorothy Bradford, wife of William Bradford, was drowned in Provincetown harbor.

On the 25th, they set out in the Mayflower for Plymouth, but the wind being unfavorable, they failed to make the harbor and put back to Provincetown. “But it pleased God, the next day being Saturday, the wind came fair, and we put to sea again and came safely into a safe harbor.” This was the first arrival of the Mayflower at Plymouth. Sunday was spent on the ship.

It is evident that they were favorably impressed both with the security of the harbor and the general surroundings, although there was some division of opinion as to the best location for a permanent settlement as the following discloses: “This bay is a hopeful place, innumerable store of fowl, skate, cod, turbot and herring we have tasted of; abundance of muscles, the greatest and best that ever we saw; crabs and lobsters, in their time infinite.”

“Monday we went aland manned with the master of the ship and three or four of the sailors. We marched along the coast in the woods seven or eight miles, but saw not an Indian nor an Indian house; only we found where formerly had been some inhabitants, and where they had planted their corn.”

“We found not any navigable river but four or five small running brooks of very sweet fresh water, that all ran into the sea.”

They speak of the trees, the herbs and the soil, some sandy and some rich and fertile. They also speak of the streams that are beginning to fill with fish. That night they returned to the ship, “many being weary with marching.”

The next day being Tuesday, Dec. 29, the party divided, some going on foot and some in the shallop. They came to a creek and “went up three English miles, a very pleasant river[9] at full sea. This place we had a great liking to plant in, but that it was so far from our fishing, our principal profit, and so encompassed with woods that we should be in much danger of the savages. Some of us, having a good mind for safety, to plant in the greater isle,[10] we crossed the bay, which is there five or six miles over. We judged it cold for our corn and some part very rocky; yet divers thought of it as a place defensible, and of great security.”

That night they returned again to the Mayflower determined to settle the next day on a permanent location.

The final selection of a place for settlement is described as follows: “After our landing and viewing of the places, so well as we could, we came to a conclusion, by most voices, to set on the main land, on the first place, on a high ground, where there is a great deal of land cleared, and hath been planted with corn three or four years ago; and there is a very sweet brook, runs under the hillside, and many delicate springs of as good water as can be drunk, and where we may harbor our shallops and boats exceeding well; and in this brook much good fish in their seasons; on the further side of the river also much corn-ground cleared. In one field is a great hill, on which we point to make a platform, and plant our ordinance, which will command all round about.”

“So there we made our rendezvous, and a place for some of our people, about twenty, resolving in the morning to come all ashore and to build houses.”

The first building, showing position in relation to Town Brook and Pilgrim Spring

From the foregoing the reader will readily recognize Coles Hill and Burial Hill and the site of the first fort, marked now by an appropriate tablet. Also Town Brook and the adjacent spring which has quenched the thirst of many a modern day pilgrim as well as residents of this historic town.

During Dec. 31, and Jan. 1, a violent storm prevailed and it was Saturday, Jan. 2, before work on shore could be started. In the several days following trees were felled, timbers shaped, and work begun on the Common House and the “platform” or fort on the hill.

Allotments of land were made, first by taking notice of “how many families there were, willing all single men that had not wives, to join with some family as they thought fit, that so we might build fewer houses; which was done and we reduced them to nineteen families.” 40 Friday and Saturday being stormy and Jan. 10 being the Sabbath, work was resumed on Monday, Jan. 11. During this period the greater number were living on the Mayflower which presumably anchored in the lower harbor, necessitated going to and fro and in bad weather seriously interfered with work on shore. It was on Monday, the 18th, that Francis Billington made a visit to the “great sea” as he thought and which he had seen from a tree the week previous. This fine pond of sparkling water “full of fish and fowl” thus derived its name Billington Sea.

After some interruptions occasioned by bad weather, work was again resumed on the 19th. “We agreed that every man should build his own house, thinking by that course men would make more haste than working in common.”

With this end in view work was resumed and “we went to labor that day in the building of our town, in two rows of houses for more safety. We divided by lot the plot of ground whereon to build our town, after the proportion formerly allotted. The common house in which for the first we made our rendezvous, being near finished, wanted only covering, it being only about twenty foot square. Some should make mortar, and some gather thatch; so that in four days half of it was thatched.”

During this period William Bradford was seriously ill which caused much concern. Two of the colony became lost in the nearby woods and after a night’s exposure to cold, found their way back in an exhausted condition. Indians were seen upon several occasions. The roof of the Common House was set on fire by a spark but fortunately only the thatch burned. John Goodman was attacked by “two great wolves” but succeeded in fighting them off. A shed was built for common storage. On Sunday, Jan. 31st, they held their first meeting on land. A heavy wind on Sunday, Feb. 14th, did some damage to their houses and on Friday, Feb. 19th, the roof of the little house they had built for their sick caught fire but no serious damage resulted. “That evening the master going ashore, killed five geese, which he friendly distributed among the sick people.”

The First Street, in its true topographical setting

On Friday, Feb. 26th, a party of twelve Indians were seen near the plantation and on the same day the tools of Captain Myles Standish and Francis Cooke, who had been at work in the woods, were stolen during their absence.

On the morning of the next day, Saturday, Feb. 27th, a meeting was called, Myles Standish was chosen Captain and given authority to command in military affairs. Two Indians were seen on this day “upon the top of a hill” (Watson’s Hill) but upon the approach of Captain Standish and Stephen Hopkins, they ran away.

These frequent visitations caused much alarm among the colonists and “caused us to plant our great ordinances in most convenient places.”

On Saturday, Mar. 13th, they experienced their first thunderstorm. This occurred in the afternoon following a day of sunshine and warmth while “birds sang in the woods most pleasantly.”

On Wednesday, Mar. 17th, though the weather was cold, it was fair and they planted their garden seed.

Nothing has been said thus far about the crushing losses the first winter this little colony sustained through exposure and disease. Their sufferings must have been well nigh indescribable, yet history records very little complaint. William Bradford bore his sufferings with the rest and it seems fitting to quote here his vivid description:

“But that which was most sad and lamentable was, that in two or three months time half of their company died, especially in January and February, being the depth of winter, and wanting houses and other comforts, being infected with the scurvy and other diseases, which this long voyage and their inaccommodate condition had brought 43 upon them; so as there died sometimes two or three a day, in the aforesaid time; that of 100 and odd persons, scarce 50 remained. And of these in the time of most distress, there was but 6 or 7 sound persons, who, to their great commendations be it spoken, spared no pains, night nor day, but with abundance of toil and hazard of their own health, fetched them wood, made them fires, dressed them meat, made their beds, washed their loathsome clothes, clothed and unclothed them; in a word did all the homely and necessary offices for them which dainty and queasy stomachs cannot endure to hear named; and all this willingly and cheerfully, without any grudging in the least, showing herein their true love unto their friends and brethren. A rare example and worthy to be remembered. Two of these seven were Mr. William Brewster, their reverend elder, and Myles Standish, their Captain and military commander, unto whom myself and many others, were much beholden in our low sick condition. And yet the Lord so upheld these persons, as in this general calamity they were not at all infected either with sickness or lameness. And what I have said of these, I may say of many others who died in this general visitation, and others yet living, that while they had health, yea, or any strength continuing, they were not wanting to any that had need of them. And I doubt not but their recompence is with the Lord.”

They who died the first winter were buried on Coles Hill. A fitting memorial now marks the spot.

Samoset’s Visit

On Friday, Mar. 26, an Indian walked boldly into the settlement. He saluted them in English and bade them “Welcome.” He explained that his home was in Maine where he had learned some English from the captains of fishing vessels that frequented the coast in the vicinity of Monhegan Island, lying half way between the Penobscot and Kennebec Rivers and about twelve miles off the coast. From him they gathered much information. “He discoursed of the whole country and of every province and of their sagamores and their number of men and strength.”

“He told us that the place where we now live is called ‘Patuxet’ and that about four years ago all the inhabitants died of an extraordinary plague and there is neither man, woman nor child remaining, as indeed we have found none; so there is none to hinder our possession, or lay claim unto it.”

The night Samoset stayed at the house of Stephen Hopkins where they “watched him,” being suspicious of the scattering bands previously seen. He had told them of 45 another Indian whose name was Squanto, a native of the place who had been in England and could speak better English than himself and whom he would later bring with him.

The following day he returned to the Wampanoags whence he had come. This tribe, with the Nausets, occupied the territory lying between Narragansett Bay and Cape Cod. He also spoke particularly of the Nausets to the southeast who were one hundred strong while the former numbered approximately sixty. Massasoit was the Sachem or overlord of the Indians in the territory stated. It appeared that the Nausets were much provoked against the English, having been deceived by a Captain Hunt who “got them under cover of trucking with them, twenty out of this very place and seven men from the Nausets, and carried them away and sold them for slaves.”

It seems that the Indian Squanto who was one of the number had fortunately made his escape and had been returned through the good offices of certain Englishmen who were friendly to the colonists.

On Sunday, March 28, Samoset again appeared, bringing with him five others. They brought with them a few skins but, it being the Sabbath, no trading was done. However, they accepted the hospitality of the settlement and “did eat liberally of our English victuals.” They also returned the tools which had been taken from the woods during the absence of the settlers. That night they departed with a promise to come again. Samoset, who was reluctant to go, remained until Wednesday, May 31.

On April 1, he returned with Squanto. They reported that Massasoit, their great sagamore, with his brother Quadequina was near with all their men. “They could not express well in English what they would, but after an hour the King came to the top of a hill (Watson’s Hill) over against us and had in his train sixty men, that we could well behold them, and they us. We were not willing to send our governor to them and they were unwilling to come to us.”

Squanto was accordingly sent to confer with them and 46 returned with word that they should send one to “parley with him.” Edward Winslow was selected to go that they might “know his mind and signify the mind and will of our governor which was to have trading and peace with him.”

Hostages were exchanged and Captain Standish with a half dozen armed men met them at the brook (Town Brook) whence they were “conducted to a house then in building where we placed a green rug and three or four cushions.” Here they were met by the governor and others and after due felicitations and assurances of friendship were exchanged, a treaty which may well have marked the first diplomatic agreement in New England history. It was faithfully observed by both parties during the reign of Massasoit and was in force thereafter until the breaking out of the King Philip War in 1675.

It seems of interest to state here that this outbreak was instigated by Metacom or Philip as he was called by the English. He was the youngest son of Massasoit and had succeeded his brother Wamsutta or Alexander as head of the Wampanoags. But the recital of that devastating struggle is not within the sphere of this booklet. Suffice it to say that it resulted in the practical extermination of Indians including the Narragansetts, who were hostile to the white settlers and who for some years had been a perpetual and growing menace.

“1. That neither he nor any of his, should injure or do hurt to any of their people.

2. That if any of his did any hurt to any of theirs, he should send the offender that they might punish him.

3. That if anything were taken away from any of theirs, he should cause it to be restored; and they should do the like to his.

4. That if any did unjustly war against him, they would aid him; if any did war against them, he should aid them.

5. That he should send to his Neighbor-Confederates to certify them of this that they might not wrong them, but might be likewise comprised of these Conditions of Peace.

6. That when his men came to them upon any occasion, they should leave their bows and arrows behind them as we should do our pieces when we came to them.

Lastly, that doing thus, King James, their Sovereign Lord, would esteem him his friend and ally.”

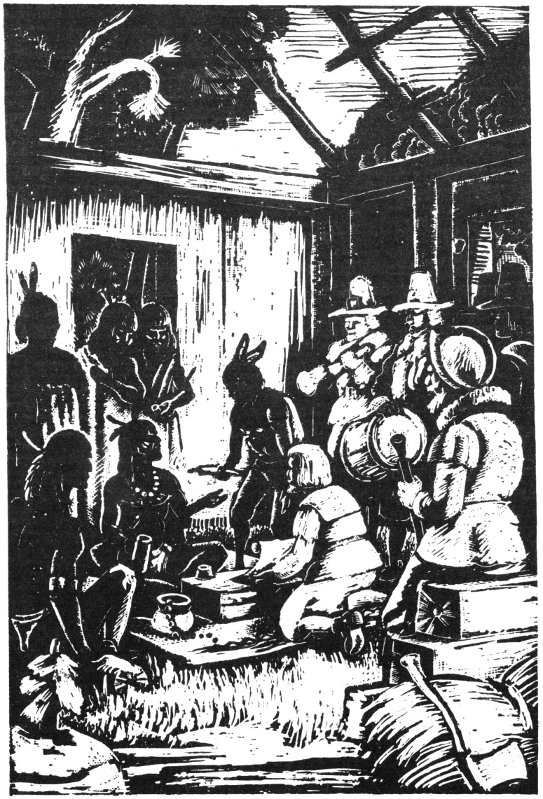

The Treaty with Massasoit, in its actual setting, “an unfinished building”

Early in April John Carver was re-elected governor and laws and regulations were made for the conduct of the colony. During this month Governor Carver died. He had come “out of the field very sick, it being a hot day; he complained greatly of his head and lay down, and within a few hours his senses failed, so as he never spoke more until he died. Whose death was much lamented, and caused great heaviness amongst them as there was cause. He was buried in the best manner they could, with some volleys of shot by all that bore arms; and his wife, being a weak woman, died within 5 or 6 weeks after him.”

William Bradford was chosen governor in his stead, and not having fully recovered from his recent severe illness, wherein he had been near the point of death, Isaac Allerton was chosen to be an assistant “unto him who, by renewed election every year, continued sundry years together.”

It may be stated that Bradford was re-elected to the same office no less than 30 times, for a total term of 33 years—every year from 1622.[11] He was Governor of Plimoth Colony continuously from 1627-1656 inclusive excepting for five years when he “by importunity gat off.”

On April 15th, the Mayflower left on her return voyage to England. During this month the first offence is recorded, that of John Billington who had defied the authority of Captain Standish. It seems however that the offence was more a matter of words or “opprobrious speeches” than of deeds.

The first marriage in the colony took place on the 22nd of May, that of Edward Winslow to Susanna White, widow of William White. This marriage was performed “according to the laudable custom of the Low Countries in which they had lived, was thought most requisite to be performed by the magistrate, as being a civil thing, upon which many questions about inheritances do depend, with other things most proper to their cognizance and most consonant to the scriptures (Ruth 4) and nowhere found in the gospel to be laid on the ministers as a part of their office.”

What is recorded as the first duel fought in New England was between Edward Dotey and Edward Leister, servants of Mr. Hopkins. They fought with sword and dagger and both were wounded, one in hand and the other in the thigh. This was the second offence for which punishment was invoked by the entire company. It was ordered that their heads and feet be tied together and to so lie for twenty-four hours. Their sufferings being great however they were released by the governor “upon their promise of better carriage.”

The months of July and August were featured by several events of interest. On July 12, Edward Winslow and Stephen Hopkins paid a visit to Massasoit taking with them clothing and other small gifts which the chieftain gladly accepted. They learned that the Wampanoags had been greatly reduced by the plague that had visited them prior to the coming of the colonists, “wherein thousands of them died, they not being able to bury one another; their skulls and bones were found in many places, lying still above aground, where their houses and dwellings had been, a very sad spectacle to behold.”

It was learned also that the Narragansetts “lived but on the other side of that great bay and were a strong people 50 and many in number, living compact together and had not been at all touched by this wasting plague.”

During the last of July John Billington, Jr., became lost in the woods lying to the south of the settlement and was forced to subsist for several days on berries and whatever nature afforded. He came in contact with an Indian plantation below Manomet whence he was conducted to the Nausets on the Cape. Word reached Massasoit who, in turn, informed the Plymouth company as to his whereabouts. A party of ten men was despatched in the shallop by the Governor and he was located and returned to the colony apparently none the worse for the experience.

It was about this time that Hobamack, another Indian, came to live at the settlement. He was a friend of Squanto and “faithful to the English until he died.” During a visit to Nemasket (Middleboro) they came into conflict with a sachem named Corbitant who was a minor sachem under Massasoit and who was held to be deceitful both to his superior and the whites. Hobamack was seized and held against his will by Corbitant but being of great strength he broke away making his escape to Plymouth. Fearing that Squanto might have been killed “it was resolved to send the Captain and 14 men well armed” to investigate and to seek retribution if harm had befallen him. They entered the house of Corbitant who at the moment was away while others in attempting to leave against the Captain’s orders, were injured and were later taken to Plymouth where their injuries were treated to their apparent satisfaction. Squanto was uninjured and made his way back to the settlement. Corbitant later explained that his actions were only in the nature of threats and that he intended no harm. He also sought the mediation of Massasoit to regain the friendship of the whites.

On September 28th a party of ten men with Squanto for guide and interpreter, set out in the shallop to explore in and around Massachusetts Bay. They made friendly contact with the Indians of the neighborhood and returned with “A good quantity of beaver.”

On November 19th the Fortune, a vessel of small tonnage, arrived bringing Robert Cushman and thirty-five others. They brought practically no provisions except some clothing but being mostly able-bodied young men the colony was thus augmented in man power of which it had been much depleted, there remaining but fifty of the original colony at this time. They came to settle permanently and were made welcome.

Let us now step ahead a few months. As the patent to the lands they now occupied arrived on the Fortune, it is not irrelevant to mention here the abortive attempt of John Pierce to get control of the Plymouth colony. On April 20, 1622, Pierce obtained another patent, superseding the first, broader in scope and running to himself, his heirs, associates and assigns forever.

As an evidence of his intention let us quote from a letter from one of the English company to Governor Bradford—“in regard he, whom you and we so confidently trusted, but only to use his name for the company, should aspire to be lord over us all, and so make you and us tenants at his will and pleasure, our assurance or patent being quite void and disannuled by his means.” etc. The adventurers protested in vain and it is further stated that he demanded “500 pounds which cost him but 50 pounds” for the surrender of the patent.

Whether or not this or any sum was paid there seems to be no record. However the same letter states that “with great trouble and loss we have got Mr. John Pierce to assign over the grand patent to the company, which he had taken in his own name and made quite void our former grant.”

Furthermore the records of the Council for New England which appear in Palfrey’s History of New England furnish the following: “Whereas there were several 52 differences between John Pierce citizen and clothmaker of London and the Treasurer and other the associates of him the said John Pierce that were undertaken with him for the settling and advancement of the plantation at Plymouth, in the parts of New England, said differences, after the full hearing and debating thereof before us were finally concluded upon by the offer of the said John Pierce, and mutual adoption of the said Treasurer and Company then present, in behalf of themselves and the rest of said Company, that the said associates with their undertakers and servants now settled or to be settled in Plymouth aforesaid should remain and continue tenants unto the Council established for the managing of the aforesaid affairs of New England, notwithstanding a grant, bearing date the 20th of April, 1622, by said Pierce obtained without the consent of the said associates, from the said Council, contrary to a former grant to the said Pierce made in behalf of himself and his said associates dated the 1st of June, 1621.”

Thus the new patent was cancelled and the patent dated June 1st, 1621, remained in force. —Ancient Landmarks of Plymouth. Wm. T. Davis, 1883. p. 45.

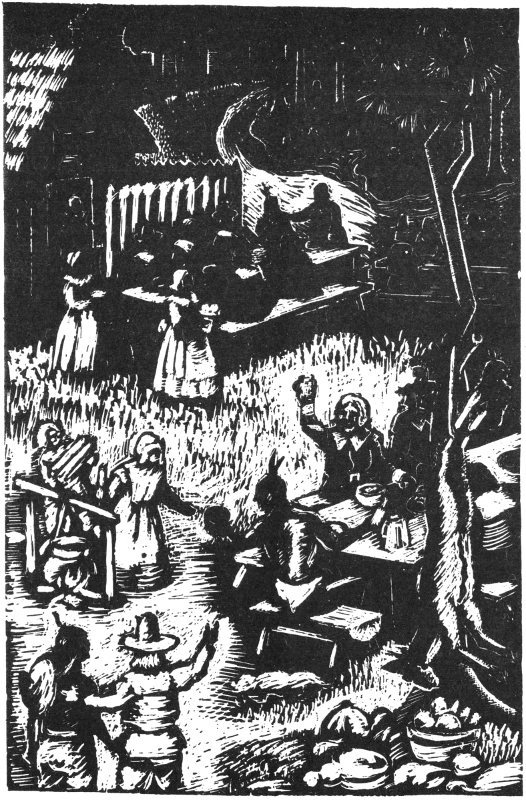

A Good Harvest

The harvest season drawing near, attention was given to gathering their crops and to putting their houses in readiness for the approaching winter. While some were thus engaged others were employed in fishing and their store of cod, bass and other fish seems to have been plentiful, for “‘every family had their portion.’” Of water-fowl, wild turkeys and venison, there seems, at this time, to have been an abundance. They had a peck of meal a week to a person, also Indian corn in like proportion of which they had planted some twenty acres with six acres of barley and peas.

“Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner, rejoice together after we had gathered the fruits of our labors. These four, in one day, killed as much fowl as, with a little help besides, served the company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our 54 arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted;[12] and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain and others.”

The quotations in the few preceding paragraphs are from Bradford’s history, and, more especially from Winslow’s letter to a friend in England. This letter was sent when the Fortune made its return voyage. It further stated that since their arrival in the new country in spite of their reduced numbers, they had succeeded in building seven dwelling-houses and four for the use of the Plantation; that they had made friends with the Indians in the immediate vicinity and that they “walked as peacefully and safely in the woods as in the highways in England.”

It is presumable that this letter was inspired, at least in part by the letter from Mr. Weston which had arrived with the Fortune. Weston was one of the Adventurers who had helped to finance the Plymouth colony. His letter which follows is cold and unsympathetic and according to both Bradford and Winslow he seems to have been a man of questionable sincerity as his unsuccessful attempt to establish a rival colony at Weymouth might indicate.

Weston’s letter said in part:—“That you sent no lading in the ship is wonderful, and worthily distasted. I know your weakness was the cause of it, and I believe more weakness of judgment than weakness of hands. A quarter of the time you have spent in discoursing, arguing and consulting, would have done much more. If you mean, bona fide, to perform the conditions agreed upon, do us the favor to copy them out fair, and subscribe them with the principal of your names. And likewise give us account as particularly as you can how our moneys were laid out. And consider that the life of the business depends on the lading of this ship.” etc.

If Weston had been acquainted with the condition of 55 the Plymouth colony, their great depletion and hardships the first winter (and it is reasonable to suppose that he was, upon the return of the Mayflower) his letter seems unnecessarily harsh and unjust. It was addressed to Mr. Carver, the news of whose death had not yet reached England.

Governor Bradford’s letter in reply to which he added an itemized accounting, follows in part. His dignified reproof, his presentation of conditions obtaining in the colony, the extenuating circumstances, I think the reader will agree cannot reasonably be omitted from this brief chronicle.

“Sir: Your large letter written to Mr. Carver, and dated the 6 of July, 1621, I have received the 10 of November, wherein (after the apology made for yourself) you lay many imputations upon him and us all. Touching him, he is departed this life, and now is at rest in the Lord from all those troubles and incumbencies with which we are yet to strive. He needs not my apology; for his care and pains were so great for the common good, both ours and yours, as that therewith (it is thought) he oppressed himself and shortened his days; of whose loss we cannot sufficiently complain. At great charges in this adventure, I confess you have been, and many losses may sustain; but the loss of his and many other honest and industrious men’s lives, cannot be valued at any price. Of the one, there may be hope of recovery, but the other no recompence can make good. But I will not insist in generals but come more particularly to the things themselves. You greatly blame us for keeping the ship so long in the country, and then to send her away empty. She lay 5 weeks at Cape Cod, whilst with many a weary step (after a long journey) and the endurance of many a hard brunt, we sought out in the hard winter a place of habitation. Then we went in so tedious a time to make provision to shelter us and our goods, about which labor, many of our arms and legs can tell us to this day we were not negligent. But it pleased God to visit us then, with death daily, and with so general a disease, that the living were scarce able to bury the dead; and the well not in any measure sufficient to tend the sick. And now to be so greatly blamed, for not freighting the ship, doth indeed go near us, and much discourage us. But you say you know we will pretend weakness; and do you think we had not cause? Yes, you tell us you believe it, but it was more weakness of judgement than of hands. Our weakness herein is great we confess, therefore we will bear this check patiently amongst the rest, till God send us wiser men. But they which told you we spent so much time in discoursing and consulting, etc., their hearts can tell their tongues they lie. They cared not, so they might salve their own sores, how they wounded others. Indeed, it is our calamity that we are (beyond expectation) yoked with some ill-conditioned people, who will never do good, but corrupt and abuse others, etc.”

Thanksgiving Feast

Unfortunately the Fortune on her return was overhauled by French pirates and all her cargo of value taken. Robert Cushman, who was aboard on his return to England, later wrote “By God’s providence we got well home the 17th[13] of February. Being robbed by the Frenchmen by the way, and carried by them into France, and were kept there 15 days and lost all that we had that was worth taking; but thanks be to God, we escaped with our lives and ship.”

The Snakeskin Warning

After the departure of the Fortune the Plymouth colony faced a serious situation. Their provisions were not sufficient to meet the demands of their suddenly increased numbers and the threat of attack hovered over their little community.