UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Stewart L. Udall, Secretary

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Conrad L. Wirth, Director

HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER TWENTY-FIVE

This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents.

by James R. Sullivan

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 25

Washington, D. C., 1956

(Reprint 1961)

The National Park System, of which Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and inspiration of its people.

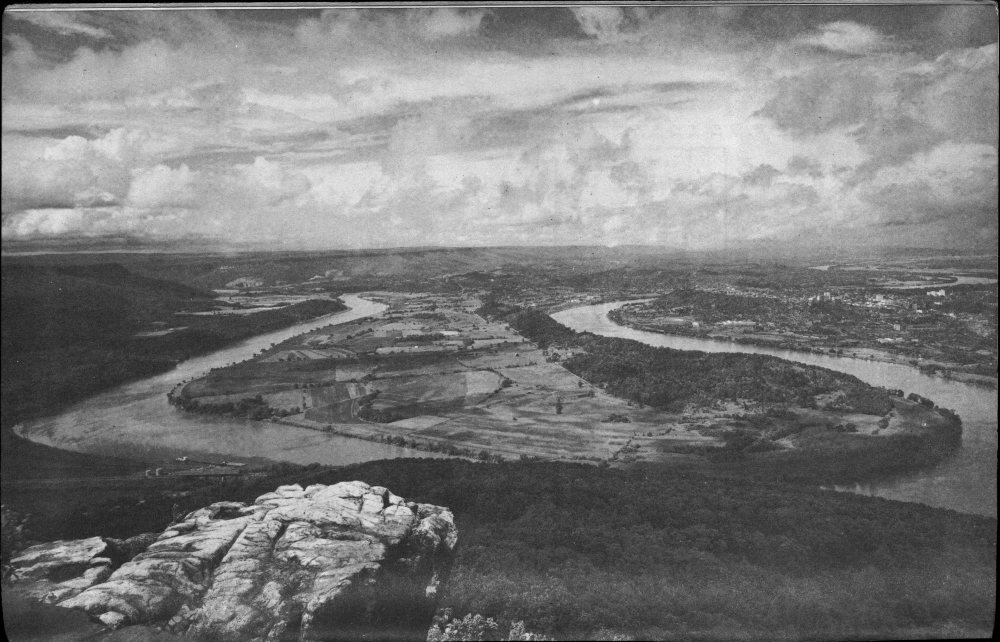

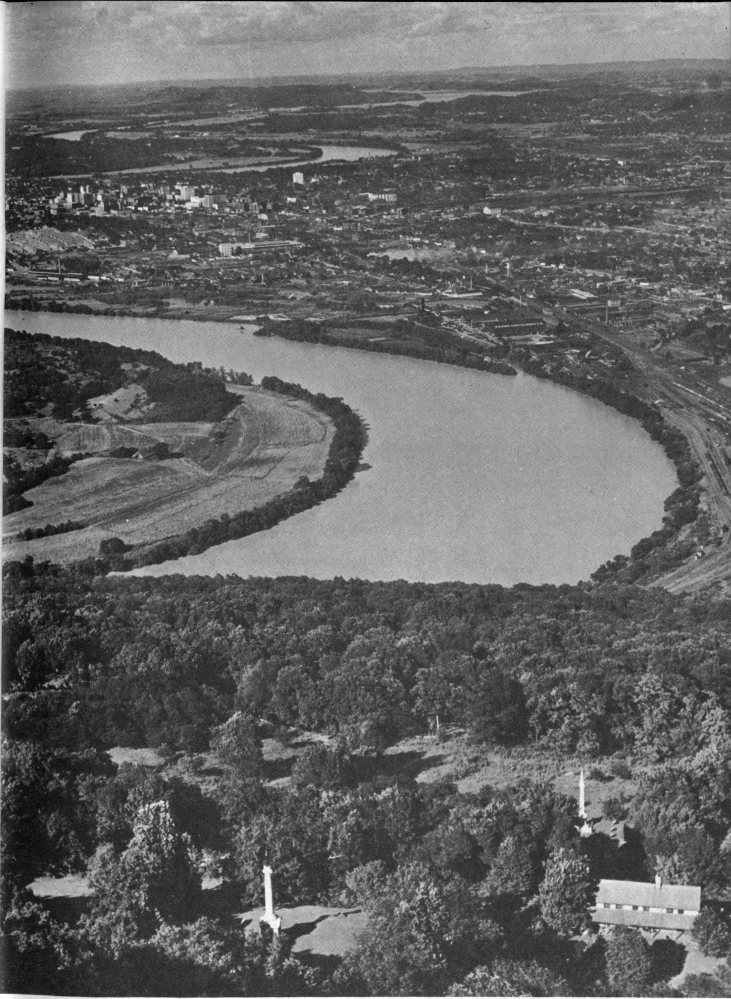

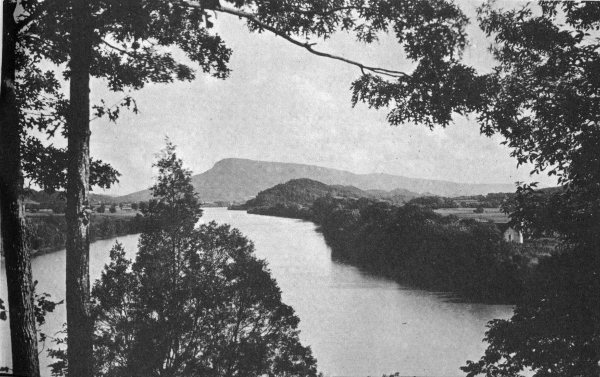

Moccasin Bend of the Tennessee River from Point Park on Lookout Mountain.

In and around strategically important Chattanooga, Tenn., in the autumn of 1863, there occurred some of the most complex maneuvers and hard fighting of the Civil War. The Confederate victory at Chickamauga (September 19-20) gave new hope to the South after the defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in July of that year. At Chattanooga (November 23-25) Union forces under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant blasted this hope and prepared the way for the capture of Atlanta and Sherman’s “March to the Sea.” Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, oldest and largest of the national military parks, commemorates the heroic soldiers of both North and South in the battles for the control of Chattanooga.

The year 1863 proved to be one of victory for the Union forces. Three great campaigns took place which shaped the destiny of the war. The first, a decisive blow at Gettysburg, forced a Confederate army under Gen. Robert E. Lee to abandon its attempt to invade Northern soil. Lee began an orderly retreat to Virginia on July 4.

On the same day, but far removed from the fields of Gettysburg, Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton surrendered his army and the City of Vicksburg, Miss., to General Grant. The fall of Vicksburg, simultaneous with the victory at Gettysburg, gave heart and strength to the North, while Confederate morale dropped.

The third campaign, Murfreesboro to Chattanooga, slow and uncertain in its first phases, and including later the great Confederate victory at Chickamauga, culminated nearly 5 months after the other two in ultimate victory for the North in the Battle of Chattanooga.

Chattanooga had only 2,545 inhabitants in 1860, but its importance was out of all proportion to its size. Situated where the Tennessee River passes through the Cumberland Mountains, forming gaps, it was called the “Key to East Tennessee” and “Gateway to the deep South.” The possession of Chattanooga was vital to the Confederacy, and a coveted goal of the Northern armies.

Chattanooga’s principal importance during the Civil War was its position as a railroad center. Four lines radiated in the four principal directions—to the North and Middle West via Nashville, to the western States via Memphis, to the South and southern seaboard via Atlanta, and to Richmond and the North Atlantic States via Knoxville.

By 1863 both sides were aware of the great advantages of strategic railroad lines. Lt. Gen. Braxton Bragg had made skillful use of the railroads in 1862, when he suddenly shifted his army from Mississippi to Chattanooga to begin his drive across Tennessee and into Kentucky. President Lincoln had long recognized the importance of railroads in this area. In the same year Lincoln said, “To take and hold the railroad at or east of Cleveland, in East Tennessee, I think fully as important as the taking and holding of Richmond.” And in 1863 Lincoln wrote Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, “If we can hold Chattanooga and East Tennessee, I think the rebellion must dwindle and die. I think you and [General] Burnside can do this, and hence doing so is your main object.”

The armies that traversed this region found it a fertile farming area. East Tennessee’s rich grain fields supplied not only wheat, corn, and hay, but beef, pork, bacon, horses, and mules. It was a vital region for the armies of the Confederacy. It not only supported the troops that occupied that region, but large quantities of provisions were shipped to other armies.

In addition to the military and economic reasons, a political factor had to be considered in the struggle for control of East Tennessee. The people there, living in a mountainous area unlike the rest of the State, wished to adhere to the Union. The people maintained their allegiance to the Old Whig party, and there was an attitude of suspicion and distrust toward the Democrats. They were mostly small farmers with little cash income, who had a dislike for the wealthy plantation- and slave-owning class.

After fighting broke out at Fort Sumter, neighbors began to take sides. An uneasy truce prevailed until November 1861 when small groups of Union men struck blows at widely dispersed railroad bridges. The cancellation of a projected northern campaign into East Tennessee left the Unionists there without support, and the Confederates took retaliatory measures. Many of the Unionists in East Tennessee fled to Kentucky to enlist in the Union Army; others hid in the mountains. While relief to this section of Tennessee by the Union Army was not to come until 1863, it was not forgotten by President Lincoln.

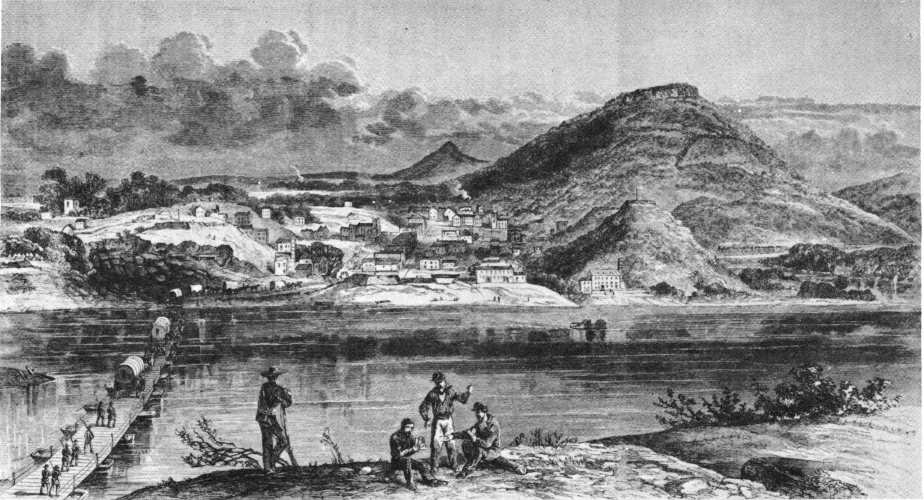

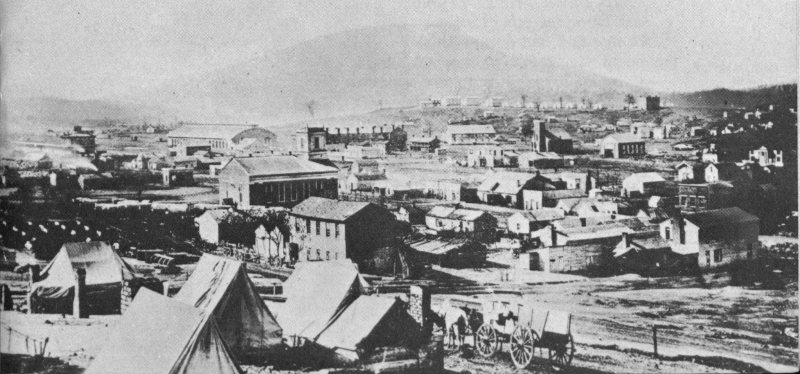

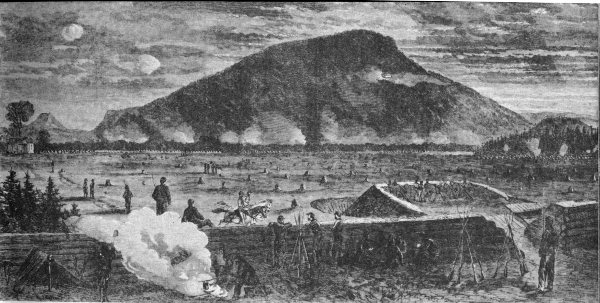

Wartime view of Chattanooga from north bank of the Tennessee River. From Harper’s Pictorial History of the Great Rebellion.

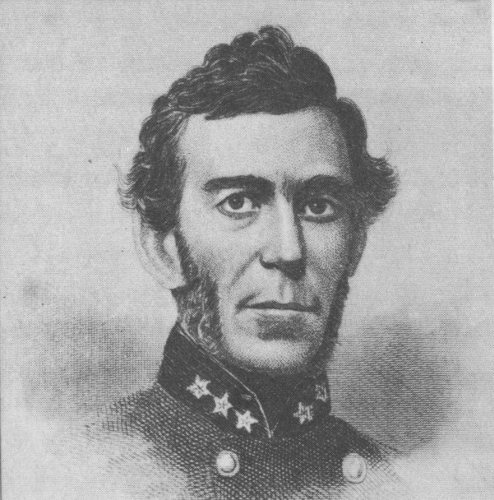

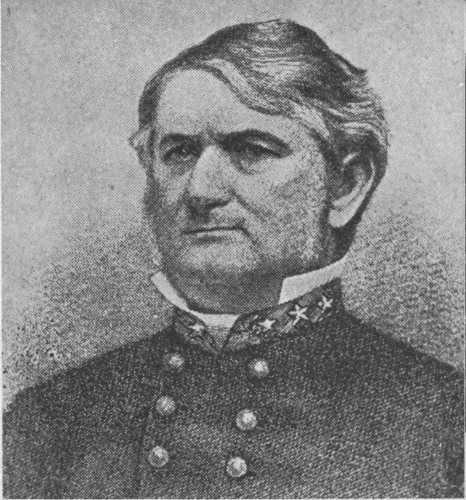

Gen. Braxton Bragg, Commander Army of Tennessee. Courtesy National Archives.

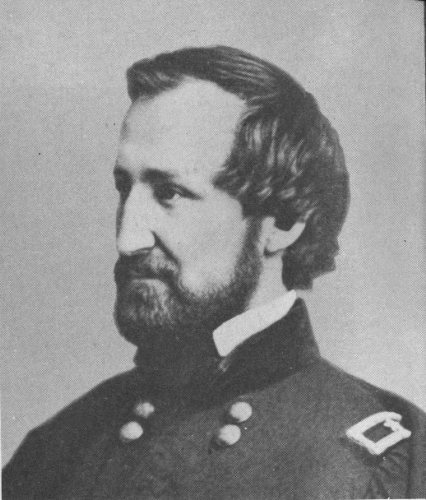

Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, Commander Army of the Cumberland. Courtesy National Archives.

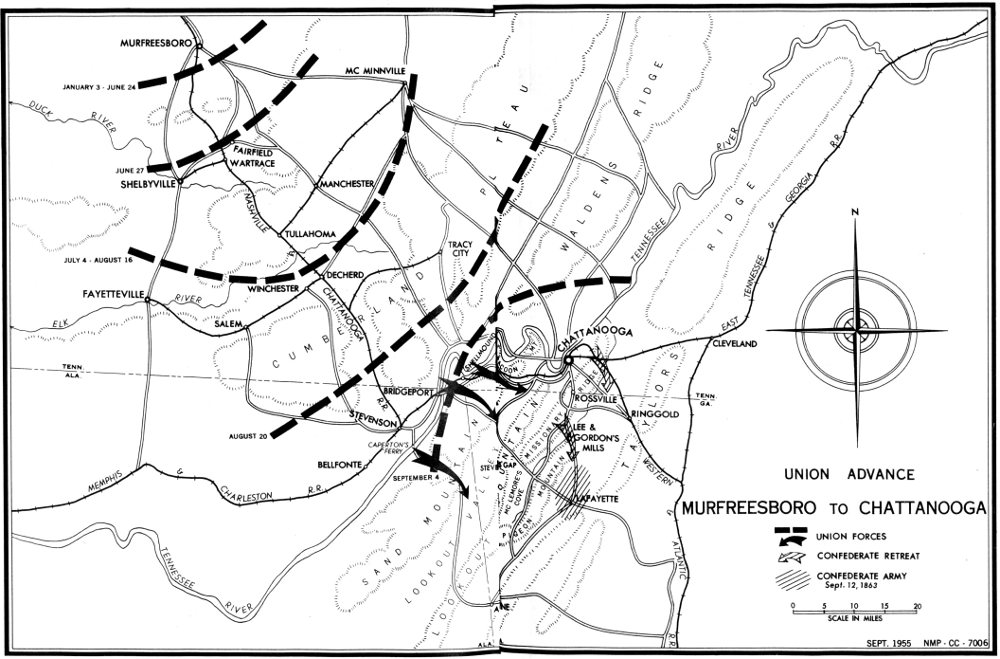

After the battle of Stones River, or Murfreesboro, Tenn., December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863, the Union Army of the Cumberland, under Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, and the Confederate Army of Tennessee, commanded by Gen. Braxton Bragg, remained relatively inactive for several months. During this time the Union forces entrenched themselves at Murfreesboro. General Bragg withdrew his forces southward and established his headquarters at Tullahoma. He placed his army in a defensive position to cover the routes, both rail and road, to Chattanooga.

Impatient at the inaction, the War Department in Washington urged Rosecrans to move against Bragg’s army. Grant, conducting his Vicksburg campaign, wanted pressure applied against Bragg’s army to prevent all or part of it from reinforcing the Confederates in Mississippi. At the same time Andrew Johnson, Military Governor of Tennessee, reminded the authorities in Washington of the plight of the East Tennesseans. During this period, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside gathered a Union force and made plans to invade East Tennessee.

Rosecrans hesitated to move. His lack of cavalry was a disadvantage in gathering intelligence and prevented him from countering the Confederate cavalry which harassed him constantly. In June, Maj. Gen. 5 Henry W. Halleck, general in chief, U. S. Army, wired Rosecrans asking him, “Is it your intention to make an immediate movement forward? A definite answer, yes or no, is required.” Rosecrans telegraphed: “In reply to your inquiry, if immediate means tonight or tomorrow, no. If it means as soon as all things are ready, say five days, yes.” On June 24, General Rosecrans put his army of some 60,000 men in motion.

The Army of the Cumberland—the Union force—had undergone a reorganization since the Battle of Stones River. It now comprised three corps: The Fourteenth, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas in command; the Twentieth, Maj. Gen. Alexander McD. McCook in command; and the Twenty-first, Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden in command. Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley commanded the Cavalry Corps. Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger commanded the Reserve Corps.

The left wing of General Bragg’s defense line was at Shelbyville under Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk and its right wing at Wartrace and Fairfield under Lt. Gen. William Hardee—a line nearly 13 miles long. Two Confederate cavalry corps occupied positions on either flank—that on the right at McMinnville under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, the other on the left at Columbia under Brig. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest. The total strength of the Army of Tennessee was approximately 43,000 men at this time.

The Confederate position was good. The terrain favored a defensive fight. To traverse the Cumberland Plateau the Union Army would have to move along roads that pierced the mountains by way of Hoover’s, Liberty, and Guy’s Gaps. The railroad to Chattanooga and another road passed through Bellbuckle Gap. This latter route and the road by way of Shelbyville were well fortified. Rosecrans resolved to make a feint toward Shelbyville with Granger’s Reserve Corps and most of the cavalry while the rest of his army moved toward the Confederate right. After stubborn fights at Hoover’s and Liberty Gaps the Confederates withdrew toward Tullahoma. So successful was Rosecrans’ flanking movement that Col. John T. Wilder’s mounted infantry brigade reached Decherd, on the main line of the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, and destroyed the depot and a few hundred yards of track. Although Wilder withdrew when superior Confederate forces appeared, his raid against the railroad was of great importance in forcing Bragg to evacuate Tullahoma.

UNION ADVANCE

MURFREESBORO TO CHATTANOOGA

Rough terrain and bad weather were the worst enemies of the Union Army. Brig. Gen. John Beatty records in his diary that “The road was exceedingly rough, and the rebels had made it impassable, for artillery, by rolling great rocks into it and felling trees across it.” He frequently mentions the rain which fell incessantly during the campaign. His entry of July 5 states that “Since we left Murfreesboro (June 24) rain has been falling almost constantly; today it has been coming down in torrents, and the low grounds around us are overflowed.” Yet, in spite of mountains and rain and the Confederate Army, Rosecrans, by this series of brilliant flanking maneuvers, forced Bragg to evacuate Tullahoma on July 1 and withdraw toward Chattanooga.

After the Tullahoma campaign, the two armies adopted their previous policy of remaining stationary. Each began to gather forces and equipment for a future struggle. The Union Army occupied a line from Winchester to McMinnville—the same territory the Confederates had occupied previously—while the Confederate General Bragg established his headquarters at Chattanooga. There the Army of Tennessee strengthened its defensive position and prepared to close the “gate” to further advances of the Army of the Cumberland.

During July and August, Halleck again urged Rosecrans to move against Bragg’s forces, but Rosecrans failed to budge. In the latter’s judgment, three things were needed to insure a successful campaign. The first was ripe corn which would not be ready until August; the second was the repair of the railroad to the Tennessee River; and the third was support for his flanks. In spite of the constant flow of dispatches from Halleck to Rosecrans, it was not until August 16 that he began his movement southward to cross the river.

As Rosecrans moved toward the Tennessee River and Chattanooga, another Union army under command of General Burnside entered east Tennessee to threaten Knoxville. General Bragg, supposing that the two armies would join forces to attack him, made urgent appeals for help. Though the shortage of manpower at this time was a major problem of the Confederacy, troops were sent hurrying to Bragg from several directions.

Rosecrans’ strategy, after viewing several possibilities, was to cross the river below Chattanooga, turn the Confederate left and interrupt his opponent’s communications and supply line from Atlanta. This movement if successful would effectively cut all railroad lines to Chattanooga, and Bragg would find himself shut in between Burnside on the north and east and Rosecrans on the west and south. To deceive Bragg as to the point of crossing the Tennessee River, Rosecrans sent Hazen’s and Wagner’s infantry brigades, Wilder’s mounted infantry, and Minty’s cavalry, all under the command of Brig. Gen. William B. Hazen, to make a feint at the river north of the town and to annoy the enemy as much as possible.

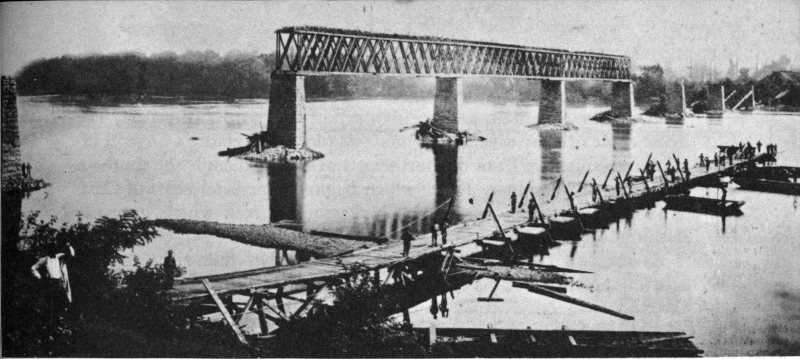

Union troops constructing a pontoon bridge across the Tennessee River at Bridgeport, Ala. Ruins of Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad bridge shown. Courtesy Library of Congress.

The ruse was successful, and so thoroughly was Bragg deceived into thinking the attack would come from upstream on the north side of the Tennessee, he left the crossings below Chattanooga practically unguarded. Rosecrans with the bulk of his army then crossed the river in the vicinity of Bridgeport and Caperton’s Ferry, Ala., and Shellmound, Tenn. By September 4, the Army of the Cumberland, thus meeting little opposition, was safely across a great barrier and was threatening Bragg from new positions.

When Bragg learned that the Union Army had crossed the Tennessee below Chattanooga and was threatening his supply lines, he decided after much deliberation to abandon his position and retreat southward.

Once the Union Army had crossed the river, Thomas’ corps marched toward Trenton, Ga.; McCook’s took the road to Alpine, Ga.; and Crittenden moved toward Chattanooga. On the 9th of September, Rosecrans, believing the Confederates to be in full retreat, ordered McCook to press forward toward Alpine, covered by the cavalry, and make attempts to cut Bragg off; Crittenden to garrison Chattanooga with one brigade and pursue Bragg by way of the Ringgold Road with the rest of his force; and Thomas to continue toward Trenton.

In order to understand the importance of the movements of both commanding generals, the geography of the country must be considered. When the Union commanders climbed to the top of the Lookout Mountain range and viewed the country, they began to have misgivings about their divided army. Thomas and McCook, 20 and 40 miles southwest of Chattanooga, respectively, found themselves on a mountain ribbed by ridges and hills, more than 1,000 feet above the valley floor. The few roads which ran over the mountain were narrow, rough, stony, and unusually steep.

Thomas, looking to the east, saw Pigeon Mountain, a spur that juts off Lookout Mountain and veers in a northeastwardly direction. The acute angle of these diverging mountains forms McLemore’s Cove. Running into this cove from the northeast and ending there is the southern extremity of Missionary Ridge which begins immediately east of Chattanooga. Here, also, originates Chickamauga Creek which gave the ensuing battle its name.

As the two Union corps moved eastward they found the country sparsely populated. There were a few farms, but most of the land was covered with cedar thickets and tangled undergrowth. The roads connecting farm and village were dry and dusty.

The Union Army was now split into three distinct columns with its flanks more than 40 miles apart. In mountainous terrain, this made it impossible for them to support one another. In the period September 10-12, corps commanders began to receive reports that a large Confederate force was at LaFayette, Ga. It was Bragg’s army. He had not retreated as far south as Rosecrans had thought—he had stopped at LaFayette behind Pigeon Mountain. There he concentrated his army and awaited reinforcements.

Wooden railroad trestle at Cumberland Ravine, Ga., erected by Union Army to replace bridge destroyed by Confederates. Courtesy National Archives.

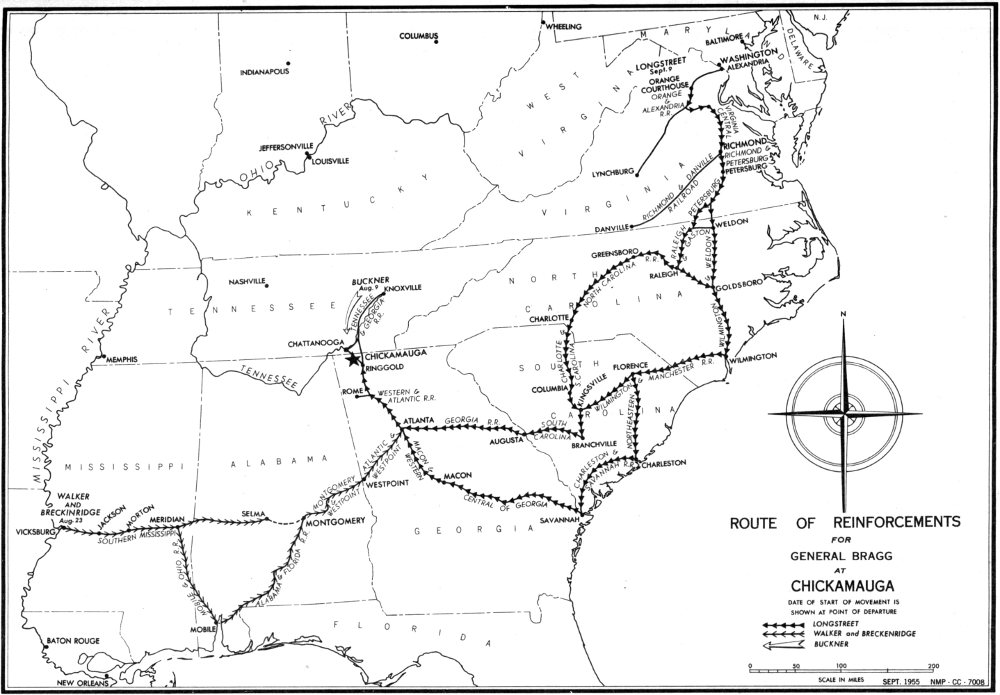

General Bragg had purposely given the impression that his army was disorganized and in full flight before Rosecrans. Actually, however, he was not running away but was quietly preparing for battle and gathering strength as reinforcements began to reach him. Realizing that Maj. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner’s Corps could not defend Knoxville from Burnside, and having no troops to spare for reinforcements, Bragg ordered Buckner to rejoin the Army of Tennessee. Buckner’s Corps of 8,000 men joined Bragg about the time the latter evacuated Chattanooga. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston from his army in Mississippi sent two divisions (about 9,000 men), under command of Major Generals John C. Breckinridge and W. H. T. Walker. A little later at Bragg’s insistence Johnston sent two brigades, under command of Brigadier Generals John Gregg and Evander McNair. These brigades added 2,500 more troops to Bragg’s Army.

ROUTE OF REINFORCEMENTS FOR GENERAL BRAGG AT CHICKAMAUGA

About this same time preparations were under way to reinforce General Bragg further with Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s corps from the Army of Northern Virginia.

The movement of Longstreet’s troops from Virginia to reinforce General Bragg in Georgia was an outstanding logistical achievement for the Confederacy. Even though by this time railroads had become an important factor in the strategy of war, no major troop movement involving so many lines over such a long distance had yet been attempted. It also shows the great concern the Southern War Department felt for the approaching battle.

From the Army of Northern Virginia to General Bragg’s forces in Georgia was a distance of some 900 miles by railroad lines through Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. It was necessary for the troops to take this longer and roundabout route of reaching General Bragg because General Burnside had cut the railroad line by way of Knoxville.

By the summer of 1863 the railroads in the Confederacy were in very poor condition, for it had been extremely difficult to replace rails and rolling stock as the war continued. For the most part, the lines were comparatively short; were not connected at many points; lacked bridges across some of the major rivers; and like railroads everywhere, had different gauges. Sixteen different railroad lines were involved in the transfer as all parallel routes and all types of rolling stock were pressed into service.

In spite of all these difficulties, however, the movement was attended with dispatch and secrecy. Leaving the vicinity of Orange Courthouse, Va., on or about September 9, the advance brigades of Longstreet’s Corps were joining General Bragg 9 days later. Mrs. Mary B. Chestnut recorded in her diary what she saw of this troop movement:

At Kingsville (S. C.) on my way to Camden, I caught a glimpse of Longstreet’s Corps going past.... It was a strange sight. What seemed miles of platform cars, and soldiers rolled in their blankets lying in rows with their heads all covered, fast asleep. In their grey blankets packed in regular order, they looked like swathed mummies. One man nearby was writing on his knee. He used his cap for a desk, and he was seated on a rail.

Information on the details of the movement, of the delays, the hazards encountered, as well as the number of men, animals, and artillery 13 transported is difficult to find. A fair estimate of the number of troops is 15,000.

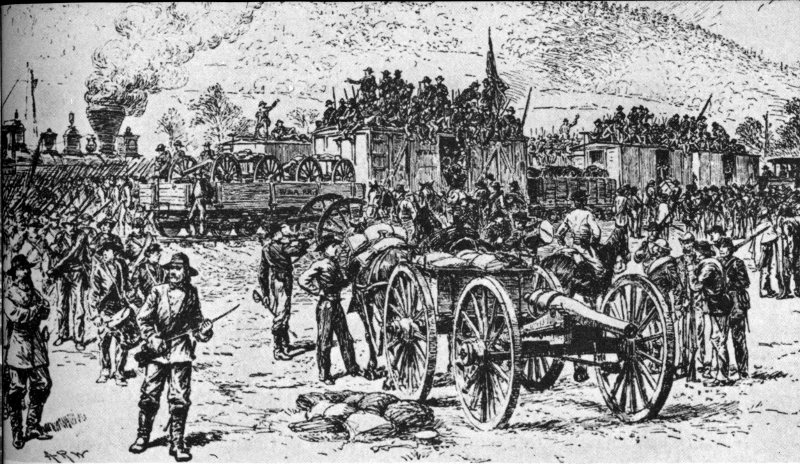

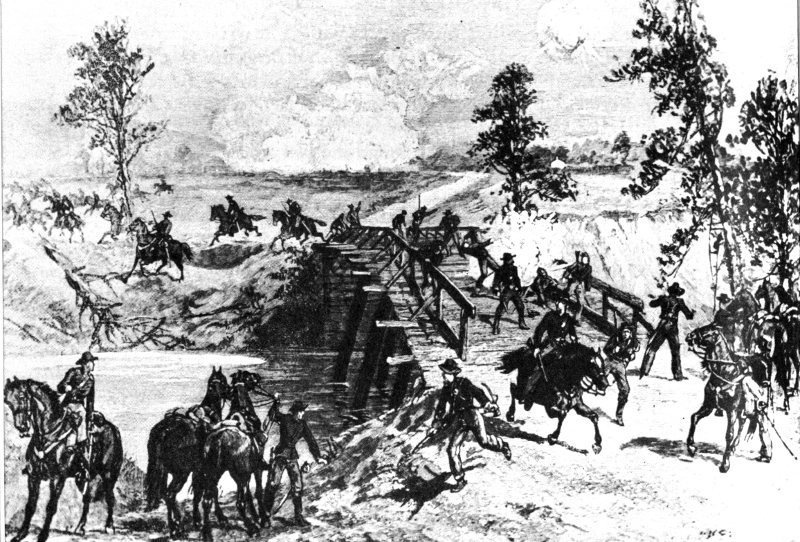

Longstreet’s soldiers detraining below Ringgold, Ga., September 18, 1863. From there they marched into battle at Chickamauga. A. R. Waud wartime sketch. From Battlefields in Dixie Land and Chickamauga National Military Park.

Only part of the infantry troops, and none of the artillery, arrived in time to participate in the Battle of Chickamauga; Longstreet himself was not present for the first day’s fighting but three of his brigades were. The five brigades (about 9,000 men) which took part in the second day of battle became heroes along with their commander when they broke through the Union line.

Bragg was aware of the isolated positions of the Union Army, and he saw an opportunity to strike his opponent in detail, one corps at a time, while they were not in supporting distance of each other. He issued orders to Maj. Gen. T. C. Hindman and Lt. Gen. D. H. Hill to strike Maj. Gen. James S. Negley’s division of Thomas’ corps, which was in an advanced position at McLemore’s Cove, but Hill failed to carry out his order. Bragg ordered Buckner to join Hindman which he did on September 10. Instead of attacking Negley, the two Confederate commanders decided that a different plan was needed for the situation and sent their recommendation to Bragg. While this correspondence passed back and forth, Negley withdrew and rejoined the rest of Thomas’ 14 corps. The Confederates had now lost their opportunity to strike and possibly destroy this division.

Two days later a similar situation arose with the same result—loss of the opportunity to strike another corps in detail. This time Bragg ordered Polk to move his and Walker’s corps to Lee and Gordon’s Mills to strike Union General Crittenden’s divided force. Two of Crittenden’s divisions had marched toward Ringgold; one had moved to Lee and Gordon’s Mills. Polk, instead of attacking, went on the defensive and asked for reinforcements. For the second time in 3 days, subordinate Confederate commanders allowed a Union corps to regroup.

Rosecrans now realized Bragg had concentrated and reinforced his army, and that his own force was in danger of annihilation in its divided condition. Accordingly he ordered General Granger, commanding the Reserve Corps in the vicinity of Bridgeport, Ala., to Chattanooga; General Crittenden to position at Lee and Gordon’s Mills on Chickamauga Creek, some 12 miles south of Chattanooga; and General Thomas to move northward toward Crittenden as soon as he was joined by General McCook’s Corps, which had been commanded to make haste in joining the other corps.

In the hurried concentration of the Army of the Cumberland, McCook withdrew from Alpine and chose to retrace his way by crossing over Lookout Mountain, thence up Lookout Valley where he had to recross the mountain to join General Thomas. It took McCook approximately 5 days (September 13 to 17) to complete this movement, greatly to the consternation of Rosecrans who had expected McCook to follow the shorter route on top of Lookout Mountain or roads through McLemore’s Cove. Some of the troops, however, such as the Second Division, did forced marches in some instances of 25 miles in a day.

Bragg made no effort to prevent this concentration of the Union forces, and during the night of September 17 the three corps were within supporting distance of each other. The Union left was at Lee and Gordon’s Mills, and from there the line extended west and south through McLemore’s Cove to Stevens Gap through Lookout Mountain.

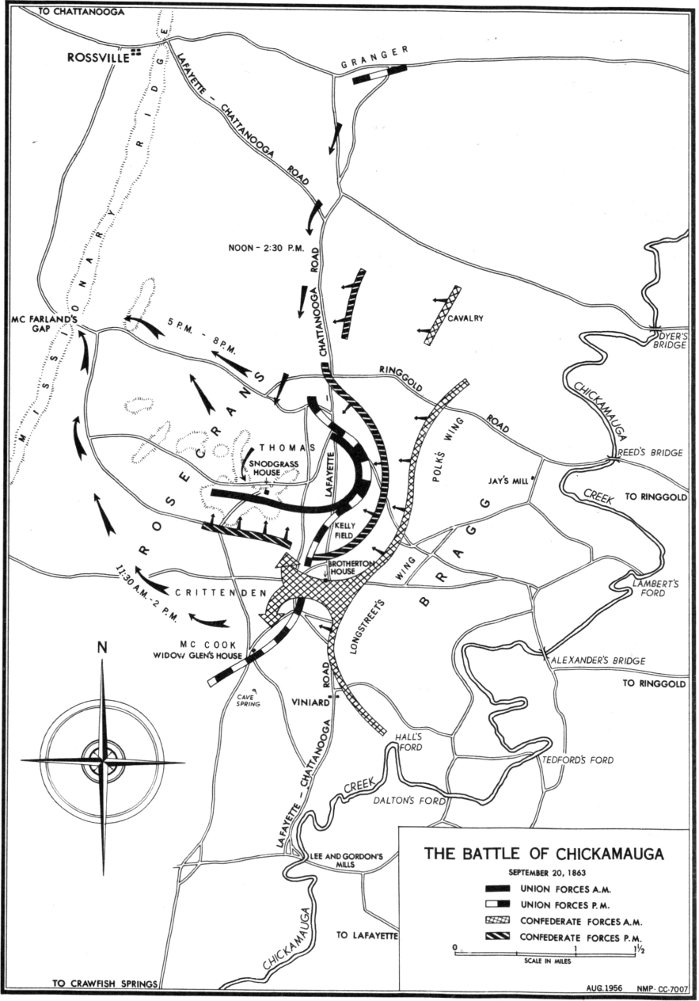

Chafing over the failure of his subordinate commanders to strike the divided units of Rosecrans’ army and wishing to seize the initiative, General Bragg had his troops do an “about face.” Turning northward, he planned an all-out attack on General Crittenden who had been following in his rear since the evacuation of Chattanooga and was now at Lee and Gordon’s Mills. General Bragg moved his troops northward on the east side of the Chickamauga Creek. His plan was to cross the Chickamauga north of Lee and Gordon’s Mills, seize the roads leading 15 to Chattanooga, bear down on Crittenden, and crush this corps or drive it back into the Union center in McLemore’s Cove. By turning the Union left in this manner, he hoped to force Rosecrans back into the mountains and to reoccupy Chattanooga.

Maj. Gen. John B. Hood (Longstreet’s Corps) and Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s troops were to cross at Reeds Bridge and turn left; Walker’s Corps to cross at Alexander’s Bridge; Buckner to cross at Tedford’s Ford; Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk’s Corps to cross at Lee and Gordon’s Mills; and Hill’s Corps to cover the Confederate left.

Bragg did not seem to suspect that Rosecrans had guessed his intentions, and was hurriedly moving to support Crittenden and deploying his troops so as to protect the roads to Chattanooga.

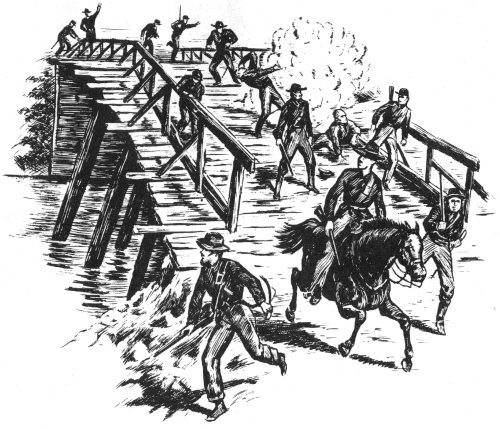

On the morning of the 18th the three advanced brigades of Longstreet’s Corps from Virginia arrived at Ringgold. One brigade immediately joined Bushrod Johnson’s division as it prepared to cross Chickamauga Creek at Reed’s Bridge. Union cavalry under Col. Robert H. G. Minty and mounted infantry under command of Col. John T. Wilder, guarding the bridges, offered stout resistance and delayed the crossing of the southern troops for several hours. During the skirmishing, Minty’s men dismantled Alexander’s Bridge and forced Walker to proceed to Lambert’s Ford, a half-mile downstream. The Confederates used other fords and crossings throughout the late afternoon and night as all of Bragg’s forces, except three divisions, crossed to the west side of Chickamauga Creek.

The Union forces were not idle, and during the night Rosecrans moved Thomas’ corps northeastward above and back of Crittenden, so that Bragg would not outflank the Federal line. Negley’s Division remained near Crawfish Springs (now Chickamauga), Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds’ Division near Widow Glenn’s, and Brigadier Generals Absalom Baird’s and John M. Brannan’s Divisions covered the roads leading to Reed’s and Alexander’s Bridges. General McCook’s Corps moved to position in McLemore’s Cove.

The situation at dawn on the 19th found the two armies facing each other over a stretch of several miles along the banks of the Chickamauga. Rosecrans had been able in a short time to maneuver the Army of the Cumberland into position so that it interposed between Bragg and Chattanooga. His Reserve Corps under General Granger was at McAfee’s Church, near Rossville. Thomas’ Fourteenth Army Corps composed the Union’s left a few miles south of Granger, and formed a southwesterly line to Crawfish Spring where it joined McCook, forming the right in McLemore’s Cove. Crittenden’s Twenty-First Army Corps remained concentrated at Lee and Gordon’s Mills, somewhat in front of the other two corps, to protect the Union 16 center.

Table 1.—Union Army at Chickamauga

Army of the Cumberland—Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans

“The First Gun at Chickamauga.” Confederates open fire on Union cavalry at Reed’s Bridge. A. R. Waud wartime sketch. From Brown, The Mountain Campaign in Georgia.

Table 2.—Confederate Army at Chickamauga

Army of Tennessee—Gen. Braxton Bragg[1]

Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, except three divisions, was concentrated on the west side of the Chickamauga from Reeds Bridge almost to Dalton’s Ford, near Lee and Gordon’s Mills. The divisions had been shuffled around during the night, and remained so for the first day’s battle. Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry held the right flank at Reeds Bridge; then, in succession toward the left (south), were Walker’s Corps; Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham’s Division (Polk’s Corps); Longstreet’s Corps (under Maj. Gen. John B. Hood); and Buckner’s Corps. On the east side of the stream and forming the 18 right were Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne’s Division (Hill’s Corps), preparing to cross at Tedford’s Ford; Maj. Gen. T. C. Hindman’s Division (Polk’s Corps) opposite Lee and Gordon’s Mills; and Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s Division (Hill’s Corps) forming the extreme left opposite Glass’ Mill. Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry, stationed at the upper fords of the Chickamauga, held the left flank.

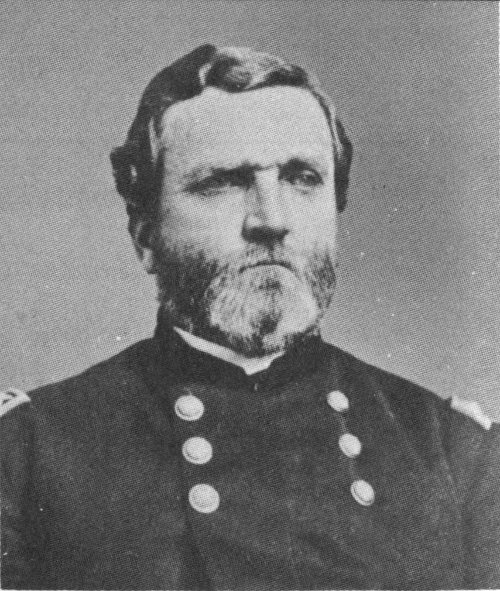

Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, “The Rock of Chickamauga.” Courtesy National Archives.

Neither army knew the exact position of the other as they maneuvered for position during the night. The densely wooded area, covered with tangled undergrowth, brambles and cedar thickets, prevented easy movement or good observation, and many of the officers had difficulty keeping in touch with their own commands.

The armies were so close to each other, in some instances only a few hundred yards apart, that it was inevitable a clash would soon take place, but at what point no one could say.

Early in the morning of September 19, Thomas ordered Brannan forward to reconnoiter the Confederate forces which had crossed the Chickamauga. In this manner, Col. John T. Croxton’s brigade of infantry accidentally ran into some of Forrest’s cavalry, which were dismounted and serving as infantry, at Jay’s Mill near Reed’s Bridge. And so the battle began.

Croxton drove Forrest back, but reinforcements hurried to the latter forced Croxton to give ground. Suddenly the commanding generals realized that a major conflict was upon them, and they hurriedly sent troops into the fight as first one side and then the other gained the upper hand. Rosecrans, by rapid and forced marches, brought up his troops from Crawfish Springs. Bragg ordered his left wing divisions to cross to the west side of the Chickamauga. By mid-afternoon major fighting had spread along a jagged line some 3 miles in length. All the Union divisions, with the exception of Granger’s reserve force, became involved. The Confederate troops were also largely engaged, 19 except Hindman and Breckinridge who crossed over during the late afternoon and night.

When the battle ended for the day, little progress could be shown by either side. The fighting had been furious and without much plan. Bragg’s troops had reached the LaFayette-Chattanooga Road but were not able to hold the position. Neither side could claim a victory. Bragg had failed to crush the Union left, and Rosecrans remained in possession of the roads to Chattanooga. The losses on both sides were heavy.

As night fell and darkness settled over the battlefield the fighting stopped, but there was little rest for the weary soldiers. Rosecrans brought the Army of the Cumberland into a more compact defensive line; Thomas’ Corps, heavily reinforced, formed the left in a bulge east of the LaFayette Road at Kelly’s Field.

Throughout the night the Confederates heard the ring of axes as the Union troops cut trees and logs to form breastworks. McCook’s Corps in the center faced LaFayette Road; Crittenden’s Corps on the right was a little withdrawn west of the road.

During the night, Longstreet arrived with two more brigades ready for action. Bragg then decided to form the Army of Tennessee into two wings for offensive action the next day. He placed General Polk in command of the right wing and General Longstreet the left. The Confederate Army, facing west between Chickamauga Creek and the LaFayette Road formed a line more or less parallel with the road.

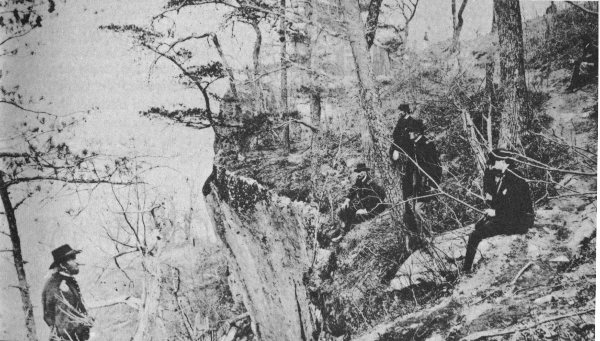

Confederate line of battle in woods at Chickamauga. From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

General Bragg issued orders to his subordinates to resume the battle at daybreak. On the Confederate right Breckinridge’s Division was to begin the attack which would be taken up by successive divisions to the left. Sunday morning came. Daylight began to creep over the battlefield. The sun rose, but no attack came. Bragg waited impatiently. Finally, the orders reached Hill at 7:30 a.m. Further delay followed as the troops moved into position. About 9:30 a.m. Breckinridge advanced to attack, followed by Cleburne. The extreme left of the Union line fell back, but the fire from the Union breastworks halted further Confederate advance. Reinforcements hurried to Thomas. In further fighting at this part of the line neither side made any considerable gain, as Rosecrans sought to hold his left against Polk’s furious attacks. Almost equally matched, neither Thomas nor Polk could show any appreciable gains throughout the morning. About 11 o’clock a lull occurred as Longstreet’s wing prepared to move against the center in Bragg’s plan of attack.

THE BATTLE OF CHICKAMAUGA

SEPTEMBER 20, 1863

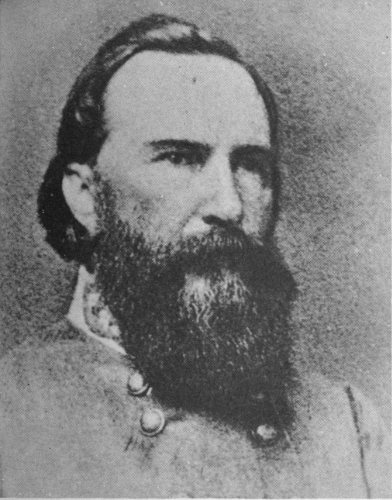

Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. Courtesy National Archives.

Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk. Courtesy National Archives.

The Union center at which Longstreet pointed his attack was held by Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood’s Division which had replaced Negley’s Division in the line when the latter had reinforced Thomas early in the morning. To the immediate left of Wood were the troops of Brannan’s Division, and on Brannan’s left, Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds’ Division.

An hour before noon as the Confederate right wing poised to strike, an irreparable blunder occurred on the Union side. A staff officer riding from Thomas’ headquarters near Kelly Field reported to Rosecrans that he had noticed Brannan’s Division was out of line and believed “General Reynolds’ right was exposed.” Rosecrans, without further investigation, immediately ordered Wood to “close up on Reynolds as fast as possible and support him.” In order to do this, Wood had to pull his division out of line and march behind Brannan’s Division toward Reynolds. Wood’s division had left its place in the line, creating a true gap where none had actually existed before, and had started to march northward behind Brannan when Longstreet’s column of five divisions accidentally struck into the gap.

Longstreet’s attack hit Wood’s and Brannan’s Divisions on their exposed flank and drove them from the immediate field of battle. On the other side of the gap the Confederates struck Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis’ Division, which was marching up to take Wood’s place in the line, and Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s Division in flank. In a 22 very short time the entire Union right flank was in disorder and driven from the field. Wilder’s brigade on the extreme right made a valiant stand for a while, employing to good effect the heavy fire power of the Spencer repeating carbine with which it was armed. Nothing, however, seemed to daunt the onrush of the Confederates, and Wilder withdrew for fear of being cut off from escape.

The routed divisions from the Union right withdrew northwestward through McFarland’s Gap to Rossville. Generals Rosecrans, Crittenden, and McCook were caught in the breakthrough and fled the field. General Thomas was now in command of the Union forces left there.

The altered conditions of the battlefield now dictated a change in Confederate strategy. The original plan of enveloping the Union left changed to a sweep from the Union right to the left. A pause in the fighting enabled Thomas to form a new line quickly to his rear on Snodgrass Hill, almost at a right angle with the Union left. From this vantage point he met the onslaught of Longstreet’s troops with such stubborn and determined resistance on that Sunday afternoon that he earned the name “Rock of Chickamauga.”

The Union line on Snodgrass Hill was composed of Brannan’s Division with fragments of Wood’s, Negley’s, and Van Cleve’s Divisions. Longstreet vigorously assaulted the line again and again and nearly succeeded in enveloping Brannan’s right. Confederate success seemed assured as Thomas’ troops were hard hit and were short of ammunition, but at this moment unexpected reinforcements reached General Thomas.

The Battle of Chickamauga. Scene from diorama in the Museum, Park Headquarters Building.

General Granger, without orders and following the sound of battle, had hastened to the aid of Thomas. He arrived at Snodgrass Hill at a very opportune moment and just in time to stop the Confederates 23 from enveloping Brannan’s right. A fierce engagement took place as Brig. Gen. James B. Steedman’s Division of Granger’s Corps forced the southern troops from the crest of the hill.

Midafternoon found Longstreet once again attempting to wrest the hill from Thomas’ troops, using McLaw’s, Hindman’s, and Bushrod Johnson’s Divisions, and again he was repulsed. Later in the afternoon, Longstreet asked Bragg for reinforcements but was told none were available and that the right wing “had been beaten back so badly that they could be of no service” to him. Longstreet determined to make one more effort. He formed a column of such troops as were available and again assaulted the hill. The fight was desperate and lasted until nightfall. The Union troops repulsed some of the Confederate charges with the bayonet as their ammunition was nearly exhausted. Finally, Longstreet pushed Steedman back to the next ridge and occupied the ground to the right of Brannan.

The left of the Union line around Kelly Field spent a relatively quiet afternoon compared to their comrades on Snodgrass Hill. However, about 4 p.m., the divisions of Hill’s corps and part of Walker’s again assaulted the Union positions there. By 6 p.m., Cheatham’s Division had joined the attack. This attack succeeded in enveloping the Union left, and the road to Rossville, through Rossville Gap, was cut off for the moment.

Headquarters, Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger, Reserve Corps, Army of the Cumberland, at Rossville Gap. The house was built by John Ross, Cherokee Indian Chief, who lived in it until 1832. Ross gave his name to the village in the gap. From Elson, The Civil War Through the Camera.

In the meantime, Thomas received orders from Rosecrans to “Assume command of all the forces, and with Crittenden and McCook take a strong position and assume a threatening attitude at Rossville.” Although Thomas received these orders with little delay, it was late 24 afternoon before he sent instructions to Reynolds to begin the withdrawal and move into position to cover the retirement of the other troops on the left. In executing this movement, Reynolds was forced to drive off the Confederate troops who had begun to envelop the Union left. The Union army withdrew in relatively good order. The troops holding Kelly Field moved out first, followed by those who had stubbornly resisted Longstreet’s attacks upon Snodgrass Hill.

While the retreat from the battlelines may have been in “good order,” General Beatty’s description of the march to Rossville amply describes the scene: “The march to Rossville was a melancholy one. All along the road, for miles, wounded men were lying. They had crawled or hobbled slowly away from the fury of the battle, become exhausted, and lain down by the roadside to die.” Beatty reached Rossville between “ten and eleven” and reported, “At this hour of the night (eleven to twelve o’clock) the army is simply a mob. There appears to be neither organization nor discipline. The various commands are mixed up in what seems to be inextricable confusion.”

Nevertheless, Thomas placed his forces at Rossville Gap and along Missionary Ridge in preparation against further attacks. The morning of the 21st found the Union Army of the Cumberland more or less reorganized. With the exception of some skirmishing, the Union forces were not molested.

The losses on both sides were appalling and the percentages surprisingly equal. The following tabulation of casualties at the Battle of Chickamauga is based on Thomas L. Livermore’s Numbers and Losses in the Civil War in America, 1861-65:

| Army | Total Strength | Total Casualties | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Percent Casualties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Union | 58,222 | 16,170 | 1,657 | 9,756 | 4,757 | 28 |

| Confederate | 66,326 | 18,454 | 2,312 | 14,674 | 1,468 | 28 |

Thomas remained in position at Rossville throughout the 21st, but it was evident that the Confederates could turn his right flank and cut him off from Chattanooga. He suggested to Rosecrans that the Union Army concentrate at Chattanooga. In anticipation of receiving an order to withdraw to the town, Thomas instructed his officers to prepare their commands for the movement. Rosecrans adopted the suggestion and that evening Thomas withdrew the Union forces to Chattanooga. All wagons, ambulances, and surplus artillery had already departed for Chattanooga during the day. By morning of September 22, all Union troops were in position in the town.

Wartime view. Lee and Gordon’s Mills, Chickamauga Battlefield. Courtesy National Archives.

The situation in which the men in blue found themselves in Chattanooga was not pleasant. The Tennessee River walled them in on the north, although a pontoon bridge and two ferries offered escape possibilities. Lookout Mountain blocked the way on the west, and Missionary Ridge to the east and south, now held by the Confederates, completed the circle.

Wartime view of Chattanooga in 1863—Lookout Mountain in distance. Courtesy National Archives.

Bragg issued orders for the pursuit of the Army of the Cumberland, then countermanded them. Instead, the Confederate troops began to take up siege positions around Chattanooga. In these positions the Confederates dominated the Union lines. Bragg’s men controlled all the railroads leading into the town; Confederate batteries and sharpshooters commanded the Tennessee River, and river traffic ceased; they controlled the roads on the south side of the river and kept under fire the one road north of the river leading to Bridgeport, the nearest Union supply base. Only the road over Walden’s Ridge and down through the Sequatchie Valley to Bridgeport was open to General Rosecrans.

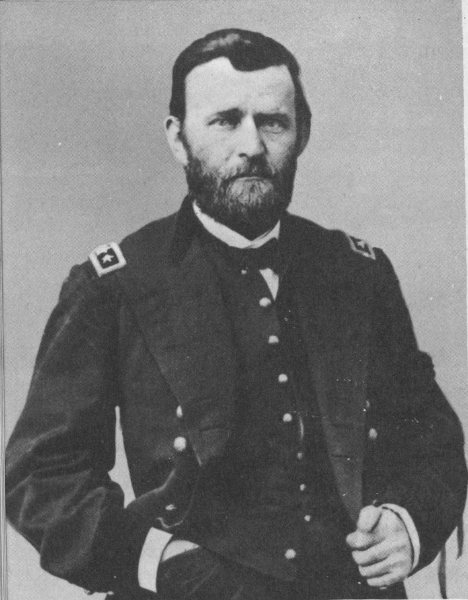

Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Courtesy National Archives.

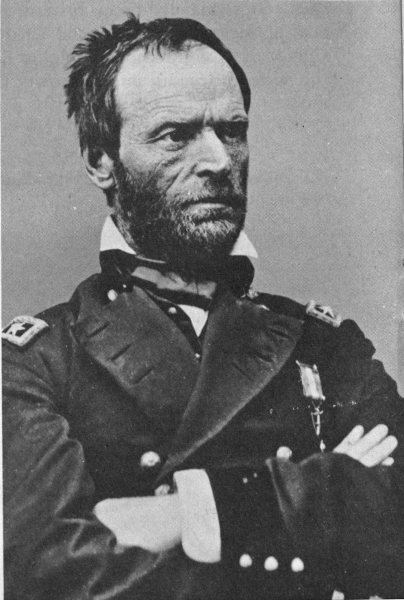

Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. Courtesy National Archives.

As early as September 13, General in Chief Halleck ordered reinforcements sent to Rosecrans. His dispatches on September 13, 14, and 15 to Major Generals Hurlbut at Memphis and Grant and Sherman at Vicksburg directed the troop movements. These dispatches, however, were delayed for several days en route from Cairo to Memphis and, in the meantime, the Battle of Chickamauga was fought. Grant received the orders on the 22nd and immediately instructed four divisions under Sherman to march to Chattanooga.

One division of the Seventeenth Corps, already in transit from Vicksburg to Helena, Ark., was ordered to proceed on to Memphis. General Sherman quickly brought three divisions of his Fifteenth Army Corps from the vicinity of the Big Black River into Vicksburg, where they embarked as fast as water transportation could be provided. By October 3, all of the movement of 17,000 men was under way.

The route of travel was by boat to Memphis, then by railroad and overland marches to Chattanooga. From Memphis the troops followed closely the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, which Sherman was ordered to repair as he advanced. By November 15, the troops were at Bridgeport, Ala., having traveled a distance of 675 miles.

When the War Department in Washington received word that the Army of the Cumberland was besieged in Chattanooga, it considered the situation so critical that President Lincoln was called out of bed late at night to attend a council meeting. This meeting occurred on the night of September 23, and is described by Nicolay and Hay:

Immediately on receipt of Rosecrans’ dispatch, Mr. Stanton sent one of the President’s secretaries who was standing by to the Soldier’s Home, where the President was sleeping. A little startled by the unwonted summons,—for this was “the first time” he said, Stanton had ever sent for him,—the President mounted his horse and rode in through the moonlight to the War Department to preside over an improvised council to consider the subject of reinforcing Rosecrans.

There were present General Halleck, Stanton, Seward and Chase of the Cabinet; P. H. Watson and James A. Hardie of the War Department, and General D. C. McCallum, Superintendent of Military Transportation. After a brief debate, it was resolved to detach the Eleventh and Twelfth Corps from the Army of the Potomac, General Hooker to be placed in command of both....

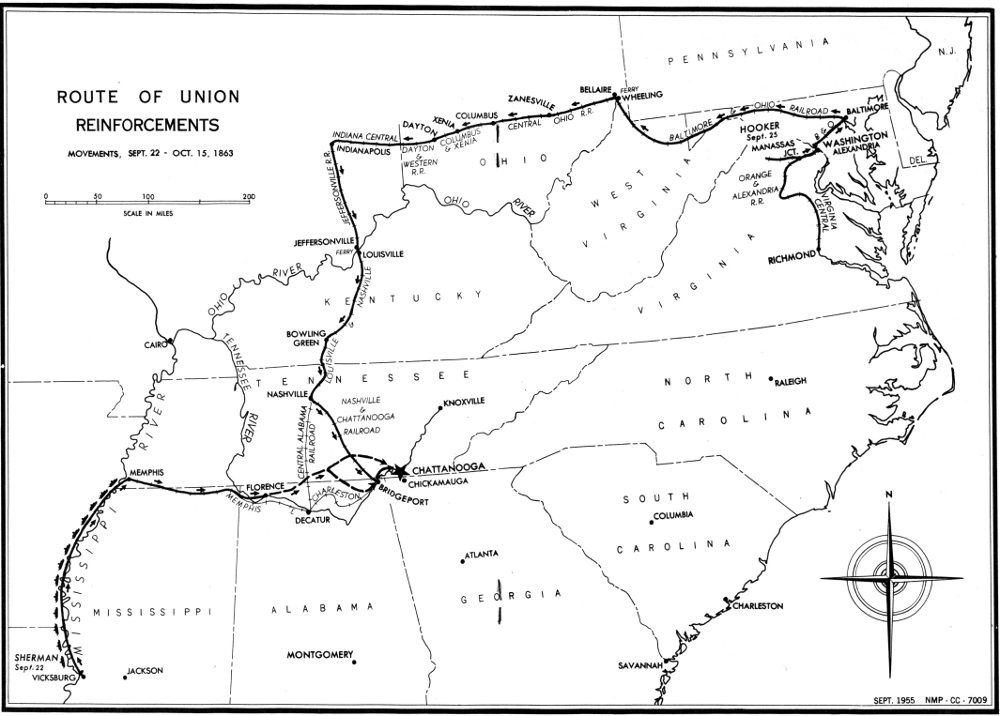

ROUTE OF UNION REINFORCEMENTS

MOVEMENTS, SEPT. 22-OCT. 15, 1863

Chattanooga headquarters of General Rosecrans during the siege. Courtesy National Archives.

The movement of the Eleventh and Twelfth Army Corps from the Army of the Potomac to Tennessee eclipsed all other such troop movements by rail up to that time. It represented a high degree of cooperation between the railroads and the government and was a singular triumph of skill and planning. It also shows the great importance the War Department attached to the Chattanooga campaign.

The troops began to entrain at Manassas Junction and Bealton Station, Va., on September 25, and 5 days later on September 30 the first trains arrived at Bridgeport, Ala. The route traveled was by way of Washington, D. C.; Baltimore, Md.; Bellaire and Columbus, Ohio; Indianapolis, Ind.; Louisville, Ky.; Nashville, Tenn.; and Bridgeport, Ala. Several major railroad lines, including the Baltimore and Ohio, Central Ohio, Louisville and Nashville, and Nashville and Chattanooga were involved.

Not all of the troops, however, made such good time as the first trains, and for the majority of the infantry the trip consumed about 9 days. The movement of the artillery, horses, mules, baggage, and impedimenta was somewhat slower, but by the middle of October, all were in the vicinity of Bridgeport ready to help break the siege.

These two corps under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, comprising 20,000 troops and more than 3,000 horses and mules, traveled 1,157 miles. Differences in the railroad gauges hampered the movement, but most of the changes in gauge occurred at river crossings which had no bridges and the troops had to detrain at these points anyway.

Confederate cavalry raids, bent on destroying the railroad bridges and otherwise interfering with the reinforcing effort, imposed a more serious difficulty, but, except for delaying the latter part of the movement a few days, the raids were ineffective.

At the beginning of the siege, the Union Army had large supply trains in good condition and transporting supplies seemed feasible. But 31 early in October rain began to fall and the roads became almost impassable. To make the situation more critical Bragg sent Wheeler to harass and destroy the Union supply trains as they moved over Walden’s Ridge on their trips to and from Bridgeport. Wheeler destroyed hundreds of wagons and animals and it was not long before the Union soldier received less and less food. Wagon horses and mules and artillery horses were on a starvation diet and many died each day.

Command of the two hostile armies had undergone a considerable change during the siege period. Grant received orders to meet “an officer of the War Department” at Louisville, Ky. He proceeded by rail to Indianapolis, Ind., and just as his train left the depot there, en route to Louisville, it was stopped. A message informed Grant that Secretary of War Stanton was coming into the station and wished to see him. This was the “officer” from the War Department who gave Grant command of the newly organized Military Division of the Mississippi. Thomas replaced Rosecrans. McCook and Crittenden had previously been relieved of their commands and their corps consolidated into the Fourth Corps under command of Granger. Stanton accompanied Grant to Louisville and there the two spent a day reviewing the situation.

In Bragg’s camp, Polk was relieved of his command, and Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee rejoined the army. Bragg’s army was reorganized into three corps commanded by Longstreet, Hardee, and Breckinridge.

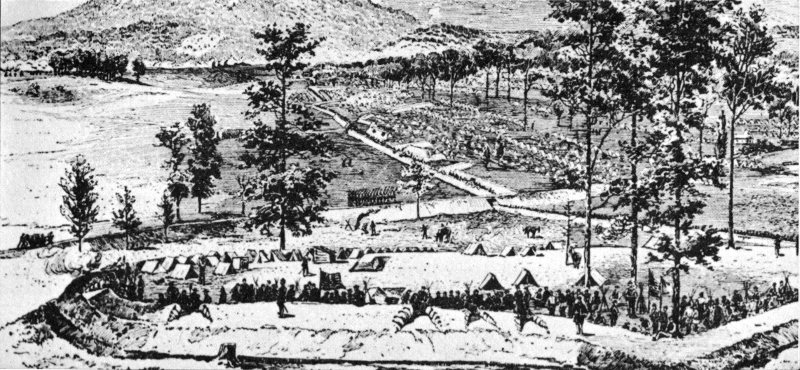

Entrenchments of Thomas’ Corps, Army of the Cumberland in front of Chattanooga. Lookout Mountain in distance. From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

When Grant reached Chattanooga on October 23 he found a plan already drawn up to open a new supply line for the besieged army. This plan of necessity was conditioned upon the terrain and the configuration of the river between Bridgeport, the railhead and base of supplies for the Union Army, and Chattanooga. (After the Tennessee River passes the city it flows southward for some 2 miles until it strikes Lookout Mountain where, after a short westerly course, it 32 curves northward. This elongated loop of the river is called Moccasin Bend.)

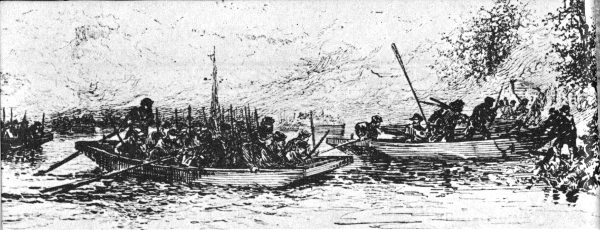

The plan called for 1,500 men on pontoons to float down the river from Chattanooga during the night of October 26-27 while another force marched across Moccasin Point to support the landings of the river-borne troops. Grant ordered the plan executed. The pontoon-borne troops quickly disembarked upon striking the west bank at Brown’s Ferry, drove off the Confederate pickets, and threw up breastworks. The troops marching across the neck of land came up to the east side of the ferry, joined this group, and constructed a pontoon bridge.

Hooker’s advance from Bridgeport coincided with this action. He marched by the road along Raccoon Mountain into Lookout Valley. There he met the advance post of a Confederate brigade and drove it back. Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard’s Eleventh Corps moved to within 2 miles of Brown’s Ferry, while Brig. Gen. John W. Geary of the Twelfth Corps remained at Wauhatchie to guard the road to Kelley’s Ferry.

The Confederates made a night attack against Geary which the latter repulsed, but both sides lost heavily. After this action, the short line of communication with Bridgeport by way of Brown’s and Kelley’s Ferries was held by Hooker without further trouble.

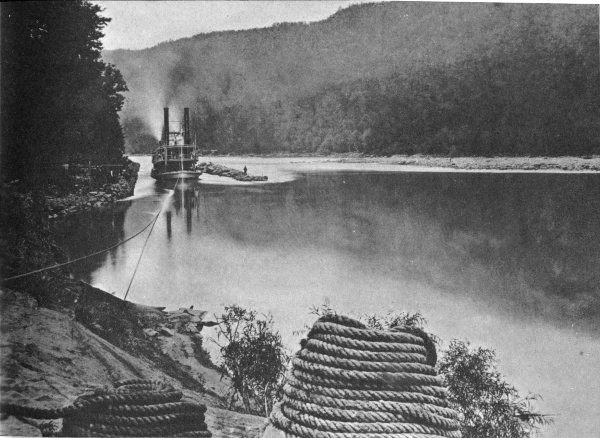

With the successful seizure of Brown’s Ferry and construction of a pontoon bridge across the Tennessee River there, and Hooker’s equally successful advance from Bridgeport and seizure of the south side of the river at Raccoon Mountain and in Lookout Valley, the way was finally clear for the Union Army to reopen a short line of supply and communication between Chattanooga and Bridgeport, the rail end of its supply line. This “Cracker Line” ran by boat up the Tennessee River from Bridgeport to Kelley’s Ferry. Above Kelley’s Ferry, the swift current made the stream unnavigable at certain points to boats then available. Accordingly, at Kelley’s Ferry, the “Cracker Line” left the river and crossed Raccoon Mountain by road to Brown’s Ferry. There it crossed the river on the pontoon bridge, thence across Moccasin Point, and finally across the river once more into Chattanooga.

Early in November, Bragg ordered Longstreet to march against Burnside in East Tennessee with Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaw’s and Maj. Gen. John B. Hood’s Divisions of infantry, Col. E. Porter Alexander’s and Maj. A. Leyden’s battalions of artillery, and five brigades of cavalry under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler—about 15,000 men in all. This movement caused great anxiety in Washington and the authorities urged Grant to act promptly to assist Burnside. Grant felt that the quickest way to aid him was to attack Bragg and force the latter to recall Longstreet. On November 7, Thomas received Grant’s order to attack Bragg’s right. Thomas replied that he was 33 unable to move a single piece of artillery because of the poor condition of the horses and mules. They were not strong enough to pull artillery pieces. In these circumstances, Grant could only answer Washington dispatches, urge Sherman forward, and encourage Burnside to hold on.

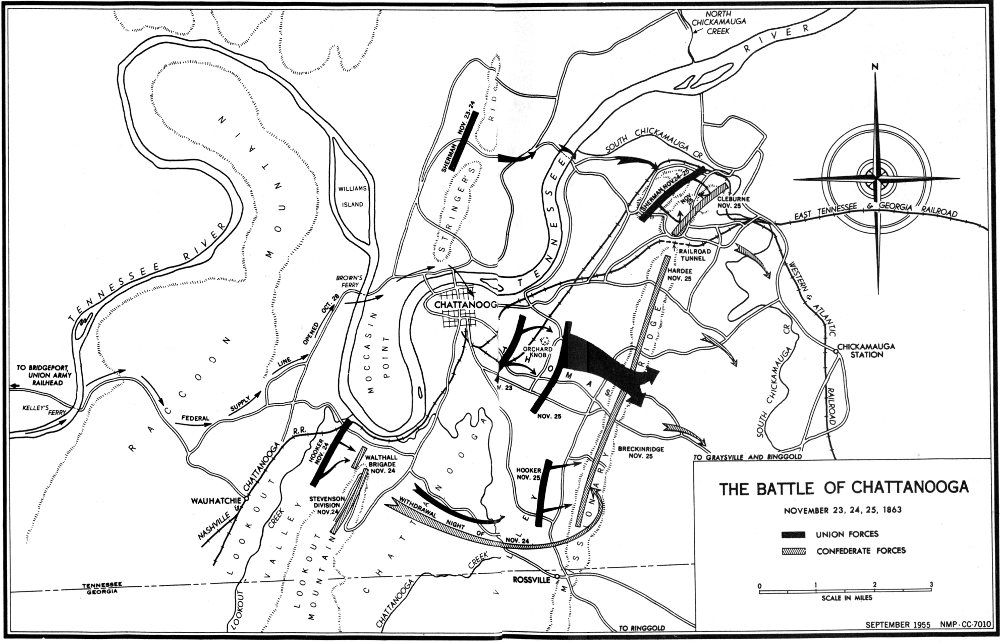

(See map on pages 36-37.)

With the Confederate Army in front of Chattanooga divided into two corps, Hardee on the right and Breckinridge on the left on Missionary Ridge, and General Stevenson with a small force occupying Lookout Mountain, Bragg waited.

Grant’s plan of battle was for Sherman with his four divisions to cross the Tennessee River at Brown’s Ferry and march behind Stringer’s Ridge, concealed from the eyes of the Confederates, and take a position near the North Chickamauga Creek. He was to recross the river by pontoon bridge at the mouth of the South Chickamauga Creek, strike the north end of Missionary Ridge and capture it as far as the railroad tunnel. Thomas was to move his Army of the Cumberland to the left, and connect with Sherman. This united force was to sweep the Confederates southward off Missionary Ridge and away from their base of supplies at Chickamauga Station. Howard’s Corps was to act as a general reserve for this force. Hooker, with the Twelfth Corps and Brig. Gen. Charles Cruft’s Division (Fourth Corps), was to hold Lookout Valley. Col. Eli Long’s Cavalry was to cover Sherman’s left and when no longer needed for this task was to strike Bragg’s communications. This original plan, however, was changed several times to fit the situation.

The rains that hampered movement of Union supplies also delayed Sherman’s movement across the Tennessee. High water broke the bridge at Brown’s Ferry and Osterhaus’ Division could not cross the river. Subsequently it received orders to join Hooker in Lookout Valley.

On November 22, Grant received word that Bragg was withdrawing his army; actually the movement reported was Buckner leaving to reinforce Longstreet. To “test the truth” of the report, Grant changed his plans and ordered Thomas to make a demonstration to his front on the 23rd. This began the battles of Chattanooga.

The Union Army of the Cumberland had made its positions very strong during the time it was besieged by Bragg’s army. One of its strong points was Fort Wood on an elevated point east of the town. Thomas, according to instructions, sent Maj. Gen. Philip H. 34 Sheridan’s and Brig. Gen. T. J. Wood’s divisions to level ground at Fort Wood and there formed them in line—Wood on the left, Sheridan on the right, with Brig. Gen. Absalom Baird supporting Sheridan. Brig. Gen. R. W. Johnson’s troops held the trenches, and Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard’s Corps, which had crossed from the north bank of the river, acted as the reserve.

Table 3.—Union Army at Chattanooga

Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

At 2 p. m. on November 23, the lines of blue moved forward, driving the Confederate outposts and their supports back to the base of Missionary Ridge, and captured Orchard Knob, a low hill a little more than a mile in front of the ridge. The Union forces occupied the 35 captured entrenchments and erected a battery on Orchard Knob. Except for occasional artillery firing, the fighting ended for the day.

Table 4.—Confederate Army at Chattanooga

Gen. Braxton Bragg

During the night of November 23-24, Sherman began to carry out his role in the drama. He selected Brig. Gen. Giles A. Smith’s brigade to man the pontoon boats, concealed in North Chickamauga Creek, to cross the Tennessee River and secure a bridgehead near the mouth of the South Chickamauga Creek. During the hours of darkness the brigade landed at its designated place. A few soldiers stopped at the mouth of the creek, surprising and capturing the pickets there. The remaining troops landed and prepared to build bridges across the Tennessee River and South Chickamauga Creek. By early afternoon they had finished the bridge across the river, and Sherman’s forces were across and ready to attack. Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis’ Division (Fourteenth Corps), which had guarded the pontoons, also crossed and became part of Sherman’s force.

Sherman attacked and seized the north end of Missionary Ridge at 4 p.m. against only Confederate outpost opposition. To his surprise, Sherman found a deep and wide ravine separating the north end of the ridge from Tunnel Hill immediately southward, his real objective. Cleburne’s Division of Confederate troops had hurried to Tunnel Hill only an hour or two before Sherman seized the north end of Missionary Ridge, and they were busily engaged entrenching there when Sherman arrived across the ravine from them. Sherman did not attack Tunnel Hill that afternoon, but entrenched where he was.

While operations were in progress, east of Chattanooga, Hooker moved into action west of the town. The failure of Osterhaus’ Division to join Sherman resulted in another change of orders. A new plan for Hooker to take Lookout Mountain and descend into Chattanooga Valley replaced the original one of having him merely hold Lookout Valley and the route to Bridgeport. Hooker had three divisions in his force commanded by Brigadier Generals Peter J. Osterhaus, John W. Geary, and Charles Cruft, each from a different army corps. Geary was on the right at Wauhatchie, Cruft in the center, and Osterhaus near Brown’s Ferry. It was a unique team. One who was present wrote, “We were all strangers, no one division ever having seen either of the others.”

THE BATTLE OF CHATTANOOGA

NOVEMBER 23, 24, 25, 1863

The terrain that confronted Hooker’s command was rugged, steep, heavily timbered, and topped by a rocky cliff. At the northern end, at the cliff base and halfway up the mountain, was a bench of nearly level land. On it stood the Cravens Farm. At 8 a. m. on November 24 Hooker sent 38 Geary’s Division, supported by a brigade from Cruft’s Division, to effect a crossing of Lookout Creek. The troops accomplished this with little opposition and Geary climbed the mountain until the head of his column reached the cliff. The division then moved to the left and proceeded northward toward the point of the mountain.

Hazen’s men landing from pontoon boats at Brown’s Ferry, Tennessee River. Theodore R. Davis wartime sketch. From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

While Geary climbed the mountain, Cruft, with his force, moved farther down the valley toward the Tennessee River and seized a bridge over the creek. Osterhaus’ Division then crossed the stream at that point in the face of sharp skirmishing with Confederate defenders before the latter retreated up the mountain. The three Union divisions soon joined on a common line and, supported by Union batteries on Moccasin Point, steadily drove Walthall’s Confederate brigade around the point of Lookout Mountain to the Cravens farmhouse. By noon, Hooker’s forces were in possession of the farm but the Confederates made a stand beyond the Cravens house within prepared defense works, and were joined there by two brigades from the top of the mountain. Fog which covered the mountainside most of the morning became so heavy that by 2 p. m. it was almost impossible to see. This factor, plus a shortage of ammunition, caused Hooker to halt and consolidate his position. Later in the afternoon, Carlin’s brigade arrived with a resupply of ammunition.

During the night, General Stevenson withdrew the Confederate forces from Lookout Mountain and marched them to Missionary Ridge where they joined their comrades holding that sector of the line.

“The Battle Above the Clouds” was fought on the bench of land surrounding the Cravens house. There was no fighting on top the mountain. The romantic name given in later years to this action on the Union right was the result of the fog and mist which shrouded the mountain that day from observers below. It was not until the next morning that the 8th Kentucky Volunteers planted the Stars and Stripes on top of the bluff.

Lookout Mountain from Union works in Chattanooga. From Harper’s Pictorial History of the Great Rebellion.

The decisive blow of the battle was at hand. Grant’s orders for the morning of November 25 were as follows: “Sherman was directed to attack at daylight. Hooker was ordered to move at the same hour, and endeavor to intercept the enemy’s retreat, if he still remained; if he had gone, then to move directly to Rossville and operate against the left and rear of the force on Missionary Ridge. Thomas was not to move until Hooker had reached Missionary Ridge.”

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant on Lookout Mountain, 1863. Grant is in the lower left corner. Courtesy National Archives.

Missionary Ridge from a Union trench. From Elson, The Civil War Through the Camera.

Sherman began his attack, as directed, just after sunrise. His troops attacked Cleburne’s Division frontally, but without success. All night the Confederates had worked at strengthening their position on Tunnel Hill which now formed the Confederate right. These field works gave good protection to Cleburne’s men from enemy fire. The stubbornly fighting Confederates held their positions against repeated attacks by superior numbers. This fight continued until 3 p. m., and is a notable example of the value to a greatly outnumbered defending force of field works on a good position. Some Union troops did make a lodgment on the slopes of Tunnel Hill in the afternoon, but a Confederate charge drove them off. Cleburne’s soldiers held the hill.

In the meantime, Hooker was in trouble—not with the enemy, but with Chattanooga Creek. He started for Rossville bright and early to get into position to strike Bragg’s left. Stevenson’s men, who had evacuated Lookout Mountain during the night, had burned the bridge across Chattanooga Creek and had done all they could to obstruct the roads that Hooker needed to march to Rossville. Hooker lost 3 hours building a bridge across the creek and it was late afternoon before his men took their places on Missionary Ridge.

From his post on Orchard Knob, Grant realized that Sherman’s attacks had failed to gain their objective and that Hooker had been delayed in reaching his assigned position. To relieve some of the pressure on Sherman, Grant ordered Thomas to move out against the Confederate center on Missionary Ridge.

The ridge that lay before the Union troops was rough and steep. It rose from 200 to 400 feet higher than the level ground at its base. Its steep slopes were broken by ravines, strewn with boulders, and dotted with stumps, the latter reminders of recently felled timber. The first line of Confederate breastworks was at the foot of the ridge. Some unfinished works had been built half-way up the slope. Finally, a third line of works was built on the natural, instead of the military, crest of the hill. Thus, Confederate fire from the crest could not cover some of the ravine approaches.

Four Union divisions—Baird, Wood, Sheridan, and R. W. Johnson, from left to right—started toward the ridge. The hard charging Union soldiers soon overwhelmed the gray defenders in the rifle pits at the base of the ridge. Scarcely halting, and generally without orders to continue, the men in blue charged up the ridge. They followed the retreating Confederates so closely from the rifle pits that the Confederates on the crest in many places hesitated to fire for fear of hitting their own men. It was not long before units of the Army of the Cumberland pierced the Confederate line in several places and sent Bragg’s veterans reeling in retreat down the east slope of the ridge toward Chickamauga Creek. Sheridan pushed forward in pursuit of the retreating army, capturing men, artillery, and equipment. Even though the Confederate center had disintegrated, Hardee held his position on the Confederate right until darkness, and then began his withdrawal with Cleburne’s Division covering the retreat. Bragg’s army crossed Chickamauga Creek during the night, carrying out a surprisingly successful retreat.

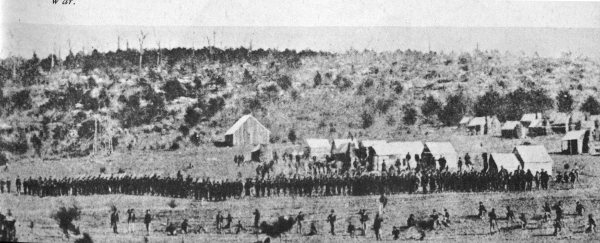

A skirmish line and regimental line behind it—Union troops drilling at Chattanooga, circa January 1864. This gives a conception of how the soldiers of the Civil War ordinarily fought. A skirmish line moved ahead of the main regimental line, which charged upon order. The Union attack on Missionary Ridge must have looked something like this to watching Confederate soldiers. From Miller, Photographic History of the Civil War.

During the evening of the 25th, Grant issued orders to Thomas and Sherman to pursue Bragg. The next morning, Sherman advanced by way of Chickamauga Station, and Thomas’ troops marched on the Rossville Road toward Graysville and Ringgold. In the vicinity of 42 Ringgold, Cleburne’s Confederates held a strong position on Taylor’s Ridge covering Bragg’s retreat. Cleburne’s men repulsed a Union attack, inflicting heavy casualties, until Bragg’s army had successfully withdrawn southward, and then they followed. Union troops then occupied Taylor’s Ridge. There the pursuit stopped.

This decisive Union victory raised the siege of Chattanooga.

The following tabulation of strength and casualties at the Battle of Chattanooga is based on Livermore’s studies:

| Army | Total Strength | Total Casualties | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Percent Casualties |

| Union | 56,360 | 5,824 | 753 | 4,722 | 349 | 10 |

| Confederate | 46,165 | 6,667 | 361 | 2,160 | 4,146 | 14 |

Meanwhile, in East Tennessee, Burnside attempted to hold Longstreet in check by abandoning territory and skirmishing when necessary, but avoiding any serious fight. This took Longstreet farther away from Chattanooga and lessened his opportunity to assist Bragg. Burnside gained precious time by using these tactics. Grant’s plan was to “whip” Bragg and then help Burnside.

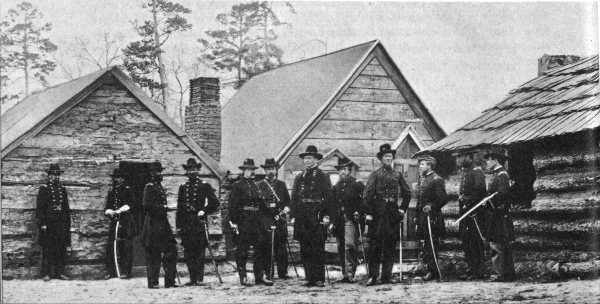

Gen. Joseph Hooker and his staff. Hooker is sixth from the right. Courtesy National Archives.

After Missionary Ridge, with Bragg in full retreat, Thomas prepared to send Granger’s Corps and detachments from other commands, about 20,000 men altogether, toward Knoxville. In addition, Sherman was to march along the Hiwassee River to protect Granger’s flank. Grant reports that upon “Returning from the front on the 28th, I found that Granger had not yet got off.... I therefore determined ... to send 43 him [Sherman] with his command, and orders ... were sent him at Calhoun to assume command of the troops with Granger, in addition to those with him, and proceed, with all possible dispatch, to the relief of Burnside.”

Steamboat with supplies for Union Army being warped up narrows of Tennessee River between Bridgeport, Ala. and Chattanooga. Courtesy National Archives.

Skirmishing was more or less continuous around Knoxville. Burnside followed the original plan of buying time by giving up ground and fell back toward Knoxville, withdrawing into the city during the night of November 16-17. Longstreet drew up before the city the next day, and on the 29th made his initial attack against the Union position at Fort Sanders. The assault was repulsed and before it could be renewed Longstreet received word of Bragg’s defeat on Missionary Ridge. The Confederate commander deemed it necessary to maintain a threatening position before Knoxville until the approaching Union relief columns were but a day’s march distant. On December 4, Longstreet began his retreat toward Virginia. Sherman arrived on the 6th, and preparations for the pursuit of Longstreet were soon under way. Burnside’s command moved out in pursuit of Longstreet’s force; Granger’s Corps became the garrison of Knoxville; and Sherman’s command returned to Chattanooga.

The battles around Chattanooga must be considered as ending in one of the most complete victories of the war. Bragg’s army was defeated, men and material captured, and the Confederates driven south. The mountainous defense line which the Confederacy hoped to hold had been pierced and large sections of it were in Union control. Chattanooga, the railroad center, was now in Union hands and the interior line of communication from this section of the Confederacy to Richmond, by way of Knoxville, was destined to remain in Union control for the remainder of the war. Not only Chattanooga, but Knoxville and the rich, food-producing East Tennessee section was lost to the Confederacy. With this came relief for the Union sympathizers in East Tennessee. Virtually all of Tennessee was now under Northern control.

The fortunes of war brought changes to both commanders. Bragg asked to be relieved from his command and went to Richmond to become military advisor to Jefferson Davis. President Lincoln promoted Grant, in March 1864, to command of all Union armies in the field. Grant then left Chattanooga for the East, to lead the attack against General Lee in Virginia.

In the spring of 1864, the Union armies began to move into the heart of the Confederacy. Grant attached himself to the Army of the Potomac (General Meade) and began operations against Lee; Sherman moved against Gen. Joseph E. Johnston in Georgia.

The Army of the Potomac launched a campaign against Richmond. In the bitter battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House, in May 1864, Grant reduced Lee’s offensive power. After being repulsed at Cold Harbor, Grant moved against Petersburg and a 10-month siege finally forced Lee to evacuate the city. Lee moved westward to Appomattox Court House where on April 9, 1865, Grant forced him to surrender.

While Lee and Grant fought it out in Virginia, Sherman, using Chattanooga for his base of supplies, conducted a strenuous campaign against the Army of Tennessee, first under Johnston and then Hood, finally entering Atlanta on September 2. In November, Sherman began his famous “march to the sea,” reaching Savannah in late December. From there he struck northward through the Carolinas and forced the surrender of Joseph E. Johnston’s army on April 26. By June all isolated Confederate forces had laid down their arms.

Chattanooga from Point Park, Lookout Mountain. The Cravens House and portion of “Battle above the Clouds” battlefield around it lies in the foreground.

CHICKAMAUGA BATTLEFIELD

Park Administration and Museum Building.

A self-guided tour of the battlefield may be made by automobile. This 8-mile tour begins at park headquarters and follows the yellow line on the tour road. On the gravel roads a yellow arrow points the way. Red markers indicate Confederate forces and blue markers show Union forces. As you read the markers or sight along the barrel of a field gun, you face the direction the troops moved at the time of the battle. There are several monuments of spherical, iron shells along the tour. Of these, the low square monuments mark the sites of various army and corps headquarters; the taller, triangular shaped monuments designate the sites where eight brigade commanders were killed during the battle.

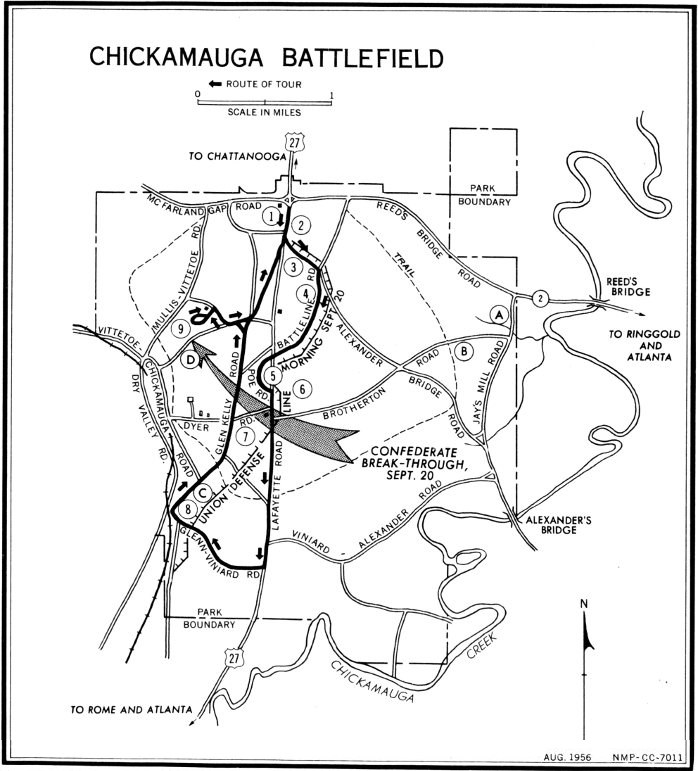

The numbered sections in the following guide correspond to location numbers on the map on page 46.

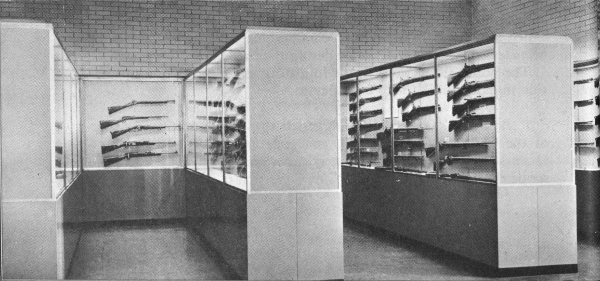

1. Park Headquarters. It is suggested that before making the tour of the Chickamauga Battlefield, you stop first at park headquarters located on U. S. 27, where an attendant is on duty. Exhibits there describe the battle, and the Fuller Gun Collection is displayed.

The Claud E. and Zenada O. Fuller Collection of American Military Arms contains almost every type of shoulder arms used by the military forces of America. There are several rare or unique items in the collection. The Harpers Ferry Blunderbuss, manufactured in 1808, and the Texas Rifle (1844) are the only ones known to exist. The Jenks Rifle, the pattern for the model 1840 Musket, the pattern for the model 1817 Rifle, and the Sharps, with coffeemill in the stock, are extremely rare. The Confederate section, while not complete, contains some outstanding weapons.

2. Florida Monument. Immediately after leaving park headquarters, you will see the Florida Monument to your left on U. S. 27.

3. Kentucky Monument. Bear to the left at this monument.

4. Battleline Road. Make a right turn to enter Battleline Road. The positions of the Confederate right wing are on the left in the wooded area some 75 to 250 yards east of the road. Union troops occupied the line along the road during the second day of the battle.

5. Poe Road. Cross U. S. 27 and follow Poe Road. This route is a continuation of the Union defense line that you have followed along Battleline Road. You will note in this area that several Confederate batteries are so situated that it would appear they must have fired into their own infantry. This situation resulted from Longstreet’s breakthrough. The Confederate troops in this sector turned right after crossing the highway and struck the right center of the Union line. A careful examination of the metal markers at each battery will give the movements of each unit and the time element involved.

A metal marker designates the site of the Poe House.

Part of Fuller Gun Collection, Park Headquarters and Museum Building, Chickamauga Battlefield.

Brotherton House, scene of Confederate breakthrough. Chickamauga Battlefield. Courtesy Chattanoogans, Inc.

Union monuments along Battleline Road, Chickamauga Battlefield.

Georgia Monument, Chickamauga Battlefield.

Wilder Monument, Chickamauga Battlefield.

6. Georgia Monument. This imposing shaft is directly in front of you as you leave Poe Road to enter the main highway. Upon entering the main highway turn right.

7. Brotherton House. (Please face the house). This reconstructed house marks the site of the old Brotherton home, famous for the Confederate breakthrough. Here Longstreet found the gap in the Union lines (to the rear of the house at the wooded area) and sent his troops forward. The Confederate troops emerged from the wooded area back of you, crossed the LaFayette Road, and drove westward and northward. This action was the turning point in the Battle of Chickamauga.

The monument of shell across the highway in back of you marks Maj. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner’s headquarters site.

After leaving the Brotherton House, you continue for 1.1 miles and make a right turn. The triangular shell monument on the right along the highway commemorates Col. Hans C. Heg (Union).

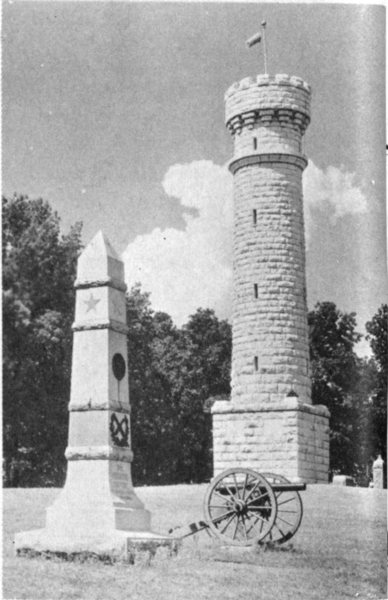

8. Wilder Monument. This imposing monument was authorized in 1892 and completed in 1902, to honor Col. John T. Wilder and his troops. It is built of Chickamauga limestone and rises to a height of 86 feet. A spiral staircase leads to a platform at the top where you can obtain an excellent view of the battlefield and surrounding area.

Wilder’s troops occupied the ground in this vicinity when Longstreet sent the left wing of the Confederate Army forward. This brigade 51 of mounted infantry was armed with the Spencer repeating carbine, a seven-shot weapon. These troops, numbering more than 2,000 men, poured a deadly fire into Longstreet’s veterans, but were unable to stop the Confederate advance. They remained on the field until the last minute and had to fight to get to their horses.

The monument stands upon the ground where General Rosecrans had his headquarters on the 19th and early morning of the 20th of September 1863.

9. Snodgrass Hill. The log cabin on Snodgrass Hill marks the home of the Snodgrass family.

The troops from the center of the Union line began to fall back toward this hill when Longstreet’s men rushed through the gap in the Union line. Brannan’s Division and fragments of Negley’s, Wood’s, and Van Cleve’s Divisions held the positions on the hill. About 2 p. m. Steedman’s Division arrived to reinforce the line on the extreme right. The Union troops held the hill during the afternoon and at dusk began the withdrawal that led them through McFarland’s Gap and into Rossville.

Union monuments at Viniard field, Chickamauga Battlefield.

Snodgrass House, Chickamauga Battlefield. Courtesy Walter H. Miller.

The tour ends on Snodgrass Hill. To return to park headquarters and U. S. 27, please follow park headquarters signs and the yellow lines.

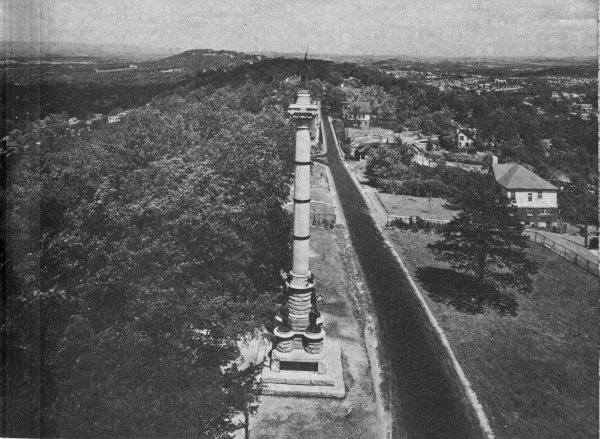

To reach Missionary Ridge, after leaving Chickamauga Battlefield, you should drive north 3 miles toward Chattanooga on U. S. 27 to Crest Road. A right turn on Crest Road will start you on your tour of the ridge. Crest Road runs the entire length of the line occupied by the Confederates during the Battle of Missionary Ridge. Small reservations, markers, monuments, tablets, and gun positions along the road provide information, and excellent views of Chattanooga are obtained along this drive. Moving northward the more important units of the park are: Bragg Reservation, where the Confederate commander had his headquarters; Ohio Reservation, an area set aside to commemorate the participation of Ohio troops in the battle; DeLong Reservation, site of one of the Union penetrations in the Confederate line; and Sherman Reservation, where Sherman’s forces unsuccessfully attacked the north end of the Confederate line.

Sherman Reservation marks the end of Crest Road and the park on Missionary Ridge.

Looking north along Missionary Ridge with Chattanooga and Tennessee Rivers to the left, and the Illinois Monument at Bragg’s Headquarters site in center foreground. This point is about one-third distance from Rossville to north end of the ridge.

Looking south along Missionary Ridge from DeLong Reservation.

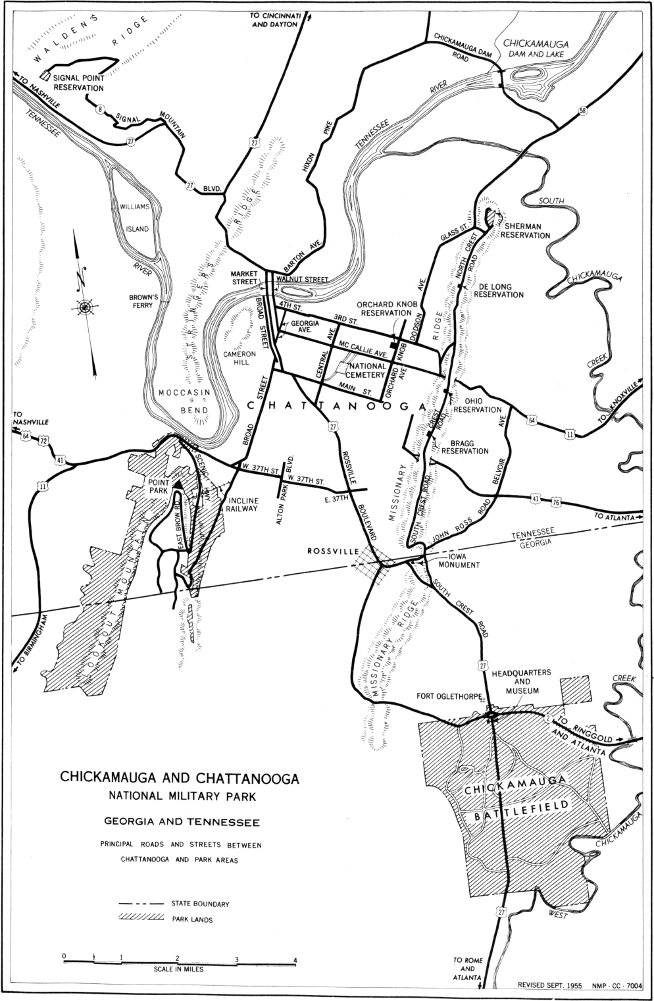

CHICKAMAUGA AND CHATTANOOGA

NATIONAL MILITARY PARK

GEORGIA AND TENNESSEE

PRINCIPAL ROADS AND STREETS BETWEEN CHATTANOOGA AND PARK AREAS

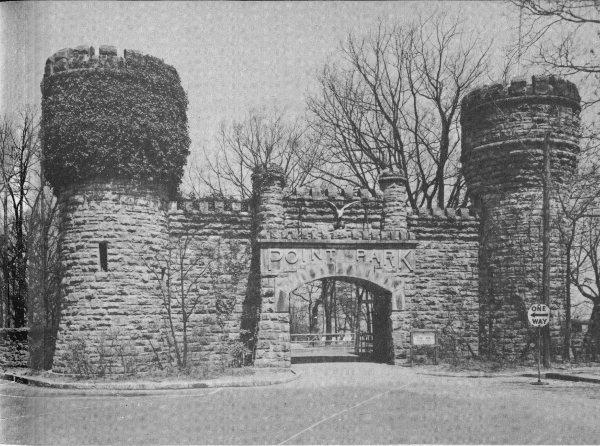

Entrance to Point Park, Lookout Mountain, built to resemble Army Corps of Engineers insignia.

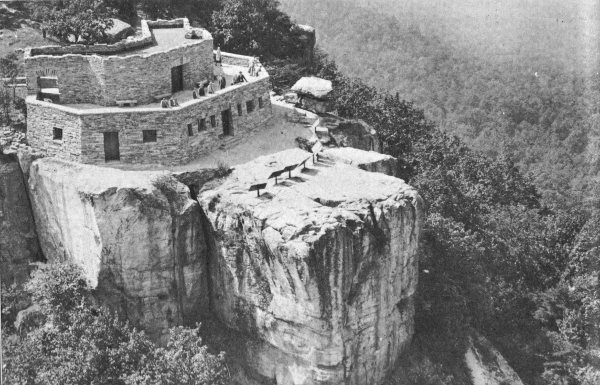

Visitors to the Chattanooga Battlefields are urged to go first to Point Park. There, from the terrace of the Adolph S. Ochs Observatory and Museum, high above the winding Tennessee River, you will have a wide view of the battlefields. This point is acclaimed one of the finest overlooks in the South. Markers throughout the area identify important landmarks and troop positions. A National Park Service attendant is there to assist you. The observatory and museum bears the name of one of the park’s major benefactors, the late Adolph S. Ochs, Publisher of the Chattanooga Times and the New York Times.

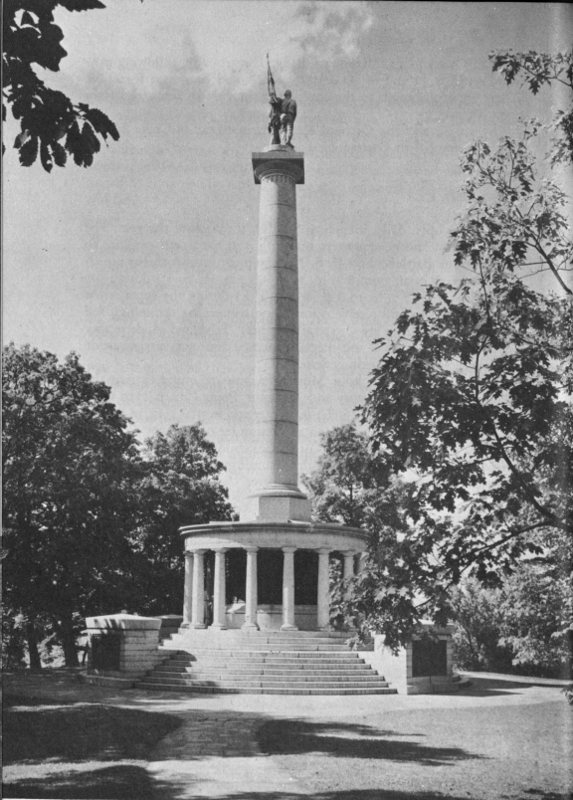

The New York Monument, completed in 1907, is in the center of the area.

The Cravens House, where part of the “Battle Above the Clouds” was fought, can be seen from the museum terrace. Near the house, stand three large monuments—New York, Iowa, and Ohio—honoring troops who were in this battle.

From Lookout Point several foot trails provide interesting walks. These reveal unusual rock formations and provide ever changing and beautiful vistas of the countryside below.

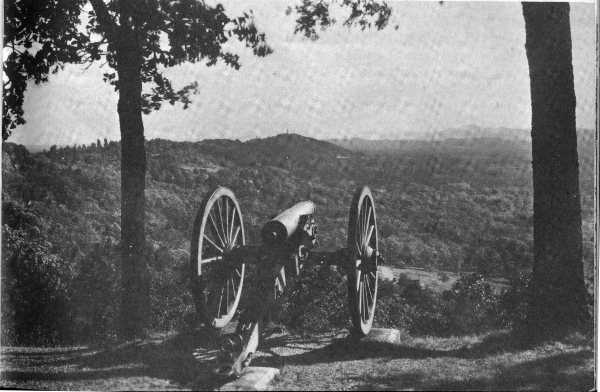

Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park is composed of several separate areas, the more important of which are: Chickamauga Battlefield in Georgia; Point Park and the Battlefield of Lookout Mountain, in Tennessee; Orchard Knob in Chattanooga; a chain of small reservations located on Missionary Ridge; and Signal Point on Signal Mountain. The park contains approximately 8,190 acres of Federal land.

Chickamauga Battlefield is 9 miles south of Chattanooga on U. S. 27. This section of the park is also reached by Georgia Route 2 connecting with U. S. 41 at Ringgold, Ga. Buses from Chattanooga run on a schedule to the battlefield throughout the week.

Point Park is reached from Chattanooga by U. S. 11, 41, 64, and 72 which combine as they leave the city and skirt the base of Lookout Mountain. The Scenic Highway turns off from these highways at the base of Lookout Mountain and winds up the slope to the park entrance. You may also visit the park by means of the St. Elmo buses from Chattanooga which connect with the Lookout Mountain Incline Railway at the foot of the mountain. The top of the incline is within short walking distance of the Point Park entrance.

The Ochs Memorial in Point Park, Lookout Mountain.

From Chattanooga, Missionary Ridge is reached by following eastward on U. S. 11 and 64; 41 and 76; or 27; and Tennessee Route 58. There are access roads to the top of the ridge and Crest Road from these highways.

Orchard Knob is on Orchard Knob Avenue near McCallie Avenue (U. S. 11 and 64) in Chattanooga.