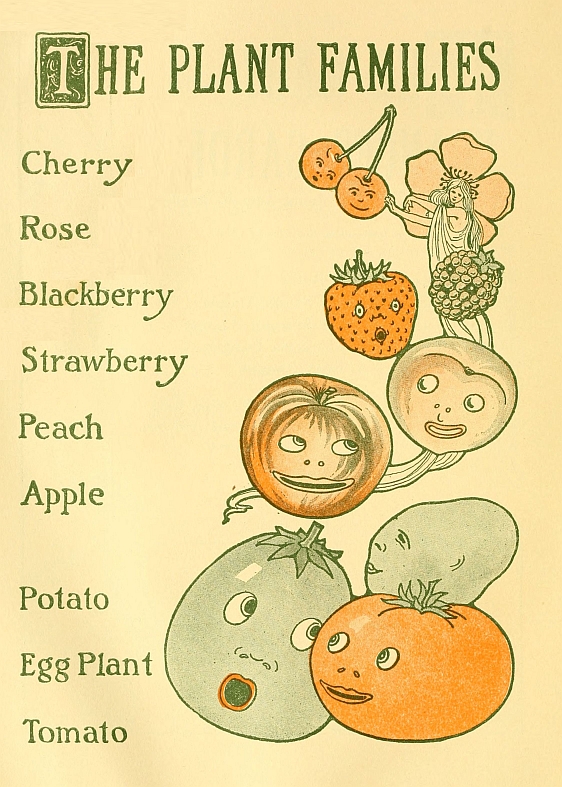

Project Gutenberg's The Mary Frances Garden Book, by Jane Eayre Fryer

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

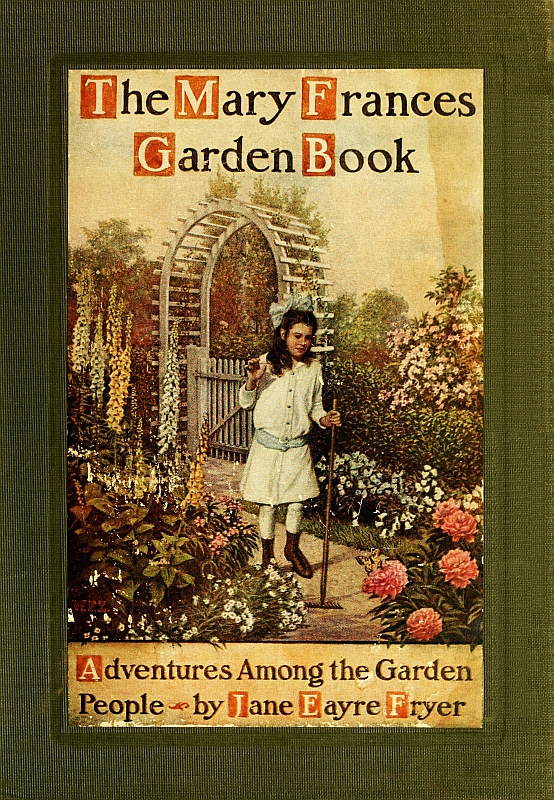

Title: The Mary Frances Garden Book

or Adventures Among the Garden People

Author: Jane Eayre Fryer

Illustrator: William F. Zwirner

Release Date: September 20, 2016 [EBook #53098]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MARY FRANCES GARDEN BOOK ***

Produced by Emmy, MWS and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The entire contents of this book are protected by the stringent new copyright law, and all persons are warned not to attempt to reproduce the text, in whole or in part, or any of the illustrations.

The Mary Frances Cook Book is the exceptionally clever and fascinating story of a little girl who wanted to learn to help her mother. Only it is much more than a story. It tells in story form how Mary Frances learned to cook. She wants to know what all the kitchen pots and pans are for, so she asks them. And they tell her—the pots and pans talk. The book gives recipes in the simplest, plainest words. It describes every operation clearly—just what Mary Frances did, and how she learned to avoid mistakes. The book stimulates the imagination and creates a desire to follow Mary Frances’ example. 8vo. Cloth, 170 pages. Over 200 colored illustrations by Margaret G. Hayes and Jane Allen Boyer.

It tells, in as quaint and delightful a story as ever appealed to a child’s imagination, how the fairy Thimble People teach Mary Frances to sew. It teaches the reader how to sew—how to make every variety of garment—how to make the various stitches—how to use patterns—how to fold and cut the material—how to piece it together. The book includes a complete set of patterns for doll-clothes—undergarments—street clothes—coats—hats—even a wedding dress. Illustrated with 300 colored drawings that for interest and instruction are absolutely inimitable. 320 pages. 8vo. Cloth bound, with colored inlay on front. Colored illustrations by Jane Allen Boyer on every page.

A glimpse into this book is enough to make a girl’s heart leap. Here she finds not only the story of the Paper Doll Family of Sandpile Village, and how they acquired a home, but also the paper dolls themselves—thirty-six large sheets of dolls and of the new, patented kind of cut-out furniture. The practical explanations of household duties and management are woven in so skilfully that as the story tells how Mary Frances learned to dust, or sweep, or make beds, the little reader takes it all in eagerly as part of the story. 250 pages. 7¼ x 9½ inches. Illustrations on every page. Cloth, with colored inlay on front.

Dear Boys and Girls:

Mary Frances and Billy have been growing up, and with their growing, they have learned to love the great out-of-doors.

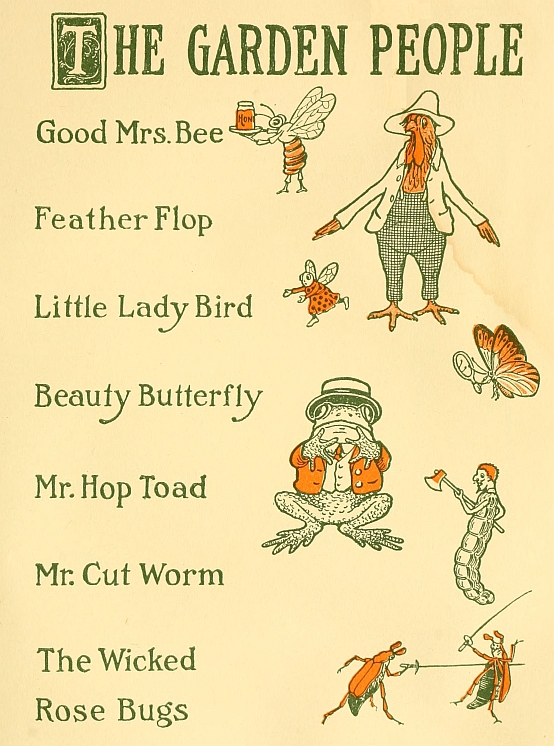

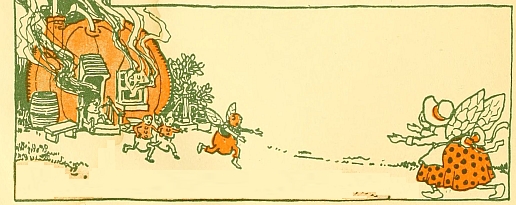

No, they haven’t outgrown fairy folk, at least Mary Frances hasn’t, for that is a part of this story—how Feather Flop, the rooster, and Jack-in-the-Pulpit and Bouncing Bet, the fairies of the wood, helped teach her to garden.

But in their study and work, Mary Frances and Billy learned more than that—they learned to appreciate what a wonderful amount of energy is expended by Mother Nature in growing one little plant from a seed; how careful she is that nothing be wasted; and what pleasure there is in tilling the soil, and helping things grow!

Everything else in the Mary Frances stories had[vi] to do with indoors: in cooking, feeding the body; in sewing, clothing the body; in housekeeping, sheltering the body. In gardening, which took them out-of-doors, the children had so much fun and had so much to learn, that the whole story cannot be put down here—you must finish it out for yourselves in your own gardens.

That you, too, may learn to help things grow, and share the pleasure which Mary Frances and Billy, and their friends, Eleanor and Bob, had in making a garden, is the wish of

Merchantville, N. J.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Feather Flop, the Garden Boss | 17 |

| II. | Feather Flop Oversleeps | 22 |

| III. | Billy Plans the Garden | 26 |

| IV. | Feather Flop’s Argument | 31 |

| V. | Gardens for Little Folks | 34 |

| VI. | Gardens for Big Boys and Girls | 46 |

| VII. | Early Spring Garden | 51 |

| VIII. | Early Summer Garden | 54 |

| IX. | Mid-Summer Garden | 56 |

| X. | Autumn Garden | 61 |

| XI. | Some Favorite Annuals | 63 |

| XII. | Window Boxes | 69 |

| XIII. | Billy Tests the Soil | 74 |

| XIV. | How to Plant | 79 |

| XV. | The Outdoor Seed-Bed | 84 |

| XVI. | Seed Babies and Their Nurses | 89 |

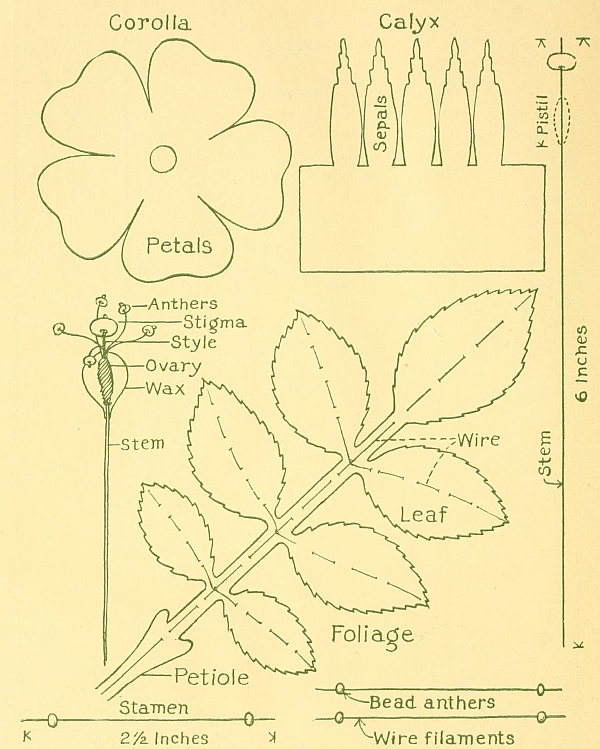

| [viii]XVII. | Names of Parts of Flowers | 96 |

| XVIII. | Good Mrs. Bee | 102 |

| XIX. | The Story of Fertilization | 106 |

| XX. | The Story of the Honey Bee | 113 |

| XXI. | How the Bees Work | 119 |

| XXII. | The Children’s Money-making Plans | 126 |

| XXIII. | Mr. Hop Toad Hops In | 131 |

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| XXIV. | Mr. Cutworm, the Villain | 142 |

| XXV. | Birds as Plants’ Friends | 145 |

| XXVI. | Little Ladybird | 153 |

| XXVII. | Curly Dock | 157 |

| XXVIII. | The Stupid Honey Drops | 161 |

| XXIX. | Some Sprays for Garden Pests | 165 |

| XXX. | Early Vegetables | 170 |

| XXXI. | Feather Flop’s Temptation | 175 |

| XXXII. | Feather Flop Gets Angry | 178 |

| XXXIII. | Father and Mother’s Surprise | 183 |

| XXXIV. | Feather Flop Makes Up | 188 |

| XXXV. | Roses | 192 |

| [ix]XXXVI. | The Best Roses to Plant | 199 |

| XXXVII. | The Wicked Rose Bugs | 211 |

| XXXVIII. | The Fairy Wood Nymphs | 217 |

| XXXIX. | Good and Bad Weeds | 225 |

| XL. | Bouncing Bet and Her Friends | 233 |

| XLI. | Buttercup and Daisy Families | 242 |

| XLII. | Water Babies | 249 |

| XLIII. | How Plants Grow | 257 |

| XLIV. | A Wicked Innkeeper | 262 |

| XLV. | Uninvited Guests | 267 |

| XLVI. | How Seed Babies Travel | 270 |

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| XLVII. | Have a Seat on a Toad Stool | 274 |

| XLVIII. | Some Ways to Rid of Weeds | 280 |

| XLIX. | Queen’s Lace Trims Well | 287 |

| L. | The Wild Flower Garden | 292 |

| LI. | Growing Perennials from Seed | 298 |

| LII. | The Money the Children Made | 303 |

| LIII. | Mary Frances’ Garden Party | 310 |

| LIV. | Feather Flop’s Conceit | 323 |

| LV. | Bob and Billy’s Vacation | 328 |

| [x]LVI. | Daffodil and Other Bulbs | 334 |

| LVII. | Billy Builds a Hotbed | 344 |

| LVIII. | Some Hints on Growing Vegetables | 348 |

| LIX. | The City Garden | 360 |

| LX. | Garden Color-Pictures | 364 |

| LXI. | Patterns for Paper Flowers | 367 |

| LXII. | The Mary Frances Garden Cut-Outs | 371 |

| LXIII. | Little Gardeners’ Calendar | 373 |

| LXIV. | Budding and Grafting | 376 |

| LXV. | Prizes at the County Fair | 377 |

| INSERTS | |

| 1. Mary Frances’ Play House | I, II |

| 2. Mary Frances’ Early Spring Garden | III |

| 3. Mary Frances’ Early Summer Garden | IV |

| 4. Mary Frances’ Mid-Summer Garden | V |

| 5. Mary Frances’ Autumn Garden | VI |

These cut-outs will familiarize the child with the plants shown, and their season of bloom, and inspire a love for practical out-of-door gardening.

| CHAPTER | ||

| 1. | To Prepare the Soil | XIII, XIV |

| 2. | How to Plant Seeds | XIV, XV |

| 3. | Names of Parts of Flowers | XVII, LXI |

| 4. | Fertilization or Reproduction | XIX-XXI |

| 5. | Insect Enemies and Remedies | XXIX |

| 6. | How to Plant Bulbs | LVI |

| 7. | Concerning Vegetables | LVIII |

| 8. | Roses: How to Plant and Tend | XXXV-XXXVII |

| 9. | The Best Roses to Grow | XXXVI |

| 10. | Annuals: When and How to Plant | XI |

| 11. | Perennials: When and How to Plant | LI |

| 12. | How to Tell the Common Wild Flowers | XXXIX-XLVIII |

| 13. | How Plants Grow | XLIII |

| 14. | How to Make a Hotbed | LVII[xiv] |

| 15. | Best List for Children’s Flower Gardens | V |

| 16. | Best List for Children’s Vegetable Gardens | V |

| 17. | Outline of Each Month’s Work for a Year | LXIII |

“OH, dear, I can’t understand a word this book says,” sighed Mary Frances, who was sitting on the garden bench, looking over a seed catalogue. “I can’t understand it!”

“Of course you can’t,” said a strange voice. “Not without help.”

Mary Frances was startled; she looked about, but saw no one.

“Why, who can it be?” she exclaimed.

“You can’t without help, I said.”

Feather Flop, the big Rhode Island Red rooster, came strutting around the corner of the bench.

“Why, is it you?” cried Mary Frances. “What do you know about gardening?”

“I ought to know a lot about gardening. I’ve lived in a garden most of the time ever since I was hatched,” shrilled Feather Flop.

“Yes, you have,” laughed Mary Frances, “and you’ve eaten up what you oughtn’t to, too.”

“That was when I was bad. I’m going to be good now.”

“Oh, well, that is different,” replied Mary Frances. “What’s the first thing to do?”

“Let me see,” said Feather Flop, scratching his head with one foot. “Let me see—why, the first thing—the first thing is to get the ground ready!”

“What do you do to get it ready?” asked Mary Frances.

“Why, dig, of course,” answered Feather Flop. “I can dig.”

“Well, well,” replied Mary Frances, “I see you really want to help me, so we’ll plan out what we’re going to do. I want all kinds of flowers and vegetables.”

“Did you start the seeds in the house in March so that some would be ready to set out now?” asked Feather Flop anxiously.

“Oh, no,” said Mary Frances, “but Billy did. He has a lot of little seedlings growing.”

“Can’t you steal some?” asked Feather Flop.

“Oh, I wouldn’t do that, Feather Flop,” said Mary[19] Frances. “Would you? I’d rather ask Billy for them.”

“Don’t say anything about me when you do,” begged the rooster.

“Why?” queried Mary Frances.

“I’m afraid of him. He’s chased me out of the——”

“Vegetable garden several times this Spring, already,” laughed Mary Frances. “Maybe if he knew how much you wanted to help with this surprise garden of mine, he would be kinder to you.”

“He’s kind enough,” said Feather Flop, “but I’m not anxious to know him much better yet a while. So I’ll ask you not to mention me.”

“All right,” agreed Mary Frances, “I think I understand. But Billy wouldn’t hurt you.”

“Do you really wish me to help you, Miss Mary Frances?” asked the rooster.

“I certainly do, Feather Flop,” said the little girl; “if you will be so kind.”

She could scarcely keep from laughing at how pleased and proud he looked.

“Then, let us take a look at the garden plot,” he[20] said, leading the way to the front of Mary Frances’ play house.

“I’ll set right to work,” said Feather Flop, beginning to scratch, “right to work, and dig the whole afternoon, and early to-morrow morning, too.”

“Don’t work too hard,” said the little girl. “I think I ought to help you.”

“Oh, no, little Miss,” answered Feather Flop. “Why, see what’s done already.”

Mary Frances put her hand over her mouth to keep from laughing aloud as she looked at the little round hole the rooster had made.

“You do splendidly,” she said, “and to-morrow morning I’ll be here bright and early.”

“Just one question,” called Feather Flop. “Is the garden a secret?”

Mary Frances turned back. “In a way,” she explained. “You see, Father gave Billy a part of our big garden for his camp and garden——”

“I know,” said Feather Flop, nodding. “I was down there one day—and I don’t care to go again.”

“I wanted to ask Father for a garden plot of my own,” went on Mary Frances, “but Billy said, ‘Why[21] don’t you have a flower garden in front of your play house, and a vegetable garden back of it and surprise all the folks?’ You can’t imagine, Feather Flop, how delighted I was with that idea.”

“Fine idea!” agreed Feather Flop, scratching again. “Won’t it be splendid when the things grow!”

“And won’t it be a perfectly lovely surprise!” cried Mary Frances.

“I won’t tell anybody,” volunteered Feather Flop. “It will be grand to have a real secret with someone.”

“Oh, thank you, good old Feather Flop,” answered Mary Frances. “Are you certain you don’t want me to help spade up the garden?”

“Claws were made before spades,” said Feather Flop, scratching away. “I’d like to do this myself, please. Come bright and early in the morning when you hear me crow.”

VERY early in the morning Mary Frances awoke and listened a long time for Feather Flop’s signal, but not a sound was to be heard except the faint crowing of a distant rooster at the far end of the village.

“I expect he crowed before I was awake,” concluded Mary Frances, as she quickly dressed and went down-stairs on tiptoe.

The sun was just getting up as she ran out into the garden.

“Hello, Feather Flop,” she called softly as she hurried along, but there was not a sight or sound of Mr. Rooster.

“Mercy,” she thought, “I hope nothing’s happened to him. Where can he be? Oh, see, he’s dug—let me count,” (counting them off) “eighteen holes! My, it must have tired him out.”

“But where can he be?” she went on, and called again and again as loudly as she dared:

“Feather Flop!”

“Feather Flop!”

“FEATHER FLOP!”

“Oh, maybe he’s in my play house!” she suddenly thought and ran to look. And there he was—where do you think? Fast asleep in one of the doll’s beds with the covers tucked close up under his bill!

“Well, you’re a funny kind of a gardener,” laughed Mary Frances as soon as she recovered from her astonishment. “Here it is long past crowing time.”

Feather Flop turned over. Then he began to mutter sleepily:

“Oh, Feather Flop!” cried Mary Frances. “Oh, Feather Flop! How you disappoint me! Why, I’ve gotten up early because you promised to help in my garden! Come, get up!” going toward the bed.

“Excuse me!” exclaimed Feather Flop, hopping out of bed. “Excuse my bad manners, dear Miss,”[24] and away he ran out the door and into the garden before Mary Frances could catch up.

“My, but you can dress quickly, Feather Flop,” she called.

“Oh, nothing like having your clothes grow on you,” answered Feather Flop, lifting his wings, “especially if they are pretty.”

Mary Frances laughed. “Come, come, no conceited remarks, please,” she chided; “and now to work.”

“It takes longer than you’d think,” said Feather Flop, beginning to scratch, “especially with an empty stomach.”

“How dreadful of me not to think of your breakfast, Feather Flop,” she said, and ran to get some corn.

“Thanks, thanks,” said Feather Flop, hungrily eating. “If they only didn’t keep the food locked up, I could help myself, and not have to trouble anybody.”

“Well, this is not gardening,” he went on; “and besides, I want my dessert. I had splendid luck yesterday—four hundred and fifty-one grubs I ate, and several score of nice long worms. Besides, I let Robin Redbreast have a hundred or so.”

“Oh, my,” shuddered Mary Frances.

“What’s the matter?” asked Feather Flop, looking up. “You didn’t want any, did you? I’d have been delighted to have saved some for you.”

“Oh, my, no!” cried Mary Frances. “Oh, no, thank you! No!”

“You’re sure?” inquired Feather Flop. “Well, you must certainly be glad they are not left here in the garden to eat up your plants, I know.”

“Indeed! I’m much obliged, Feather Flop,” said Mary Frances. “While you dig, I’m going into the house to get some seeds, and to plan out my garden.”

“All right!” said Feather Flop. “Don’t mention me, please, to——you know.”

“MARY FRANCES,” called Billy, as she came into the house, “I say, let’s start work in your garden to-day. The first thing to do is to dig and spade it.”

“Oh, Billy, it looks as though it had been done,” answered Mary Frances. “I guess I can plant it right away.”

“Ha! Ha!” laughed Billy. “Why, it has to be dug deep; the earth has to be turned under, and compost mixed with it and all pulverized before little seeds or plants can take hold with their roots.”

“How deep?” asked Mary Frances.

“Oh, about a foot, I guess,” said Billy; “but don’t let’s talk too loud if you want to keep this garden a secret. Let’s go out and have a look at it.”

“You needn’t mind—” began Mary Frances, but Billy was well on the way.

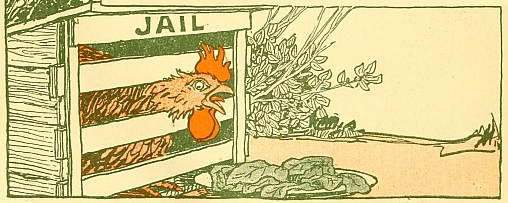

“That old Rhode Island Red! See what he’s done!” exclaimed Billy, throwing a stone at the rooster.

“Oh, Billy,” begged Mary Frances. “Poor old Feather Flop! Don’t scare him! Maybe he thought he was helping!”

“Helping?” laughed Billy. “Helping! If he tries to help that way when things come up, I’ll wring his neck!”

“Oh, you wouldn’t do that, Billy,” cried Mary Frances. “He’ll be good, I know.”

“Well,” said Billy, “you’re responsible for his behavior then—he’s your rooster. I’d like to clip his wings and cut his tail off right up next his ears—maybe.”

“He will be good, Billy, I feel sure,” answered Mary Frances. “But you are very kind to dig my garden up.”

“Well,” answered Billy with a very grown-up air, “I know what sort of an undertaking this is. How’re you going to lay the garden out?”

“Oh, I don’t know yet,” answered Mary Frances. “Won’t you help me plan it?”

“Yes, but it’s best to begin with pencil and paper; that’s the first thing Miss Gardener told us in our ‘Home Garden Course.’”

“Well, here they are,” laughed Mary Frances, throwing open the play house door.

“Fine,” said Billy, seating himself at Mary Frances’ little desk and helping himself to the articles needed.

“But wait,” he continued. “If I show you how to plan this surprise garden you must carry out my directions. I don’t get caught with any promise to do all the work.”

“Oh, no! No—indeedy! Of course not; I’m just crazy to start and I promise not to trouble you a bit.”

“Well then,” said Billy, “here goes for the—

First: How much ground have you to work in?

Let us say 15 x 25 ft. in front of the play house for the Flower Garden, and 15 x 15 ft. in the rear for the Vegetable Garden.”

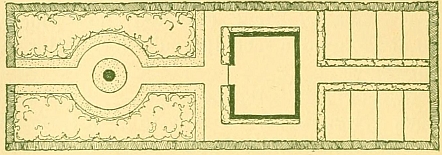

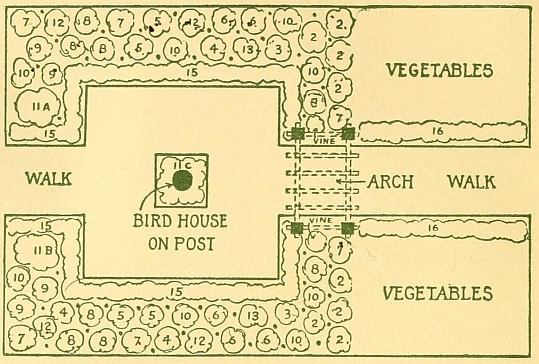

He rapidly drew an outline of the two gardens with a pretty sketch of the play house between.

“Now,” he went on, “you will wish to leave a walk down the center with a border of flowers on each side,” sketching them in.

“You see, the beauty of a garden depends so much on the way it is laid out that garden planning has become a profession, and the man who studies it is known as a landscape gardener.”

“My,” laughed Mary Frances, “how much you learned at the garden school; you’re lots better than a seed catalogue.”

“Much obliged,” replied Billy, “that’ll do for bouquets. Now listen: the way to grow early Spring flowers is to plant bulbs in the Autumn—about the first of November. Then, early in March, sometimes even in February, tiny snowdrops will pop up and, a little later, beautiful crocuses.”

“Won’t that be grand!” cried Mary Frances.

“Yes, in the next lesson perhaps, I’ll give you a list of bulbs and plants which you can set out at the proper time.

“The best scheme for the vegetable garden is to work it out into small rectangular beds between well-kept walks,” said Billy, finishing the—

“How perfect!” exclaimed Mary Frances examining the sheet of paper which Billy handed her. “I can just imagine how beautiful my gardens will look. Isn’t it a lovely idea to have that circle in the walk!”

“It would look fine if it had a sun-dial built in the center,” said Billy, much pleased with his sister’s praise.

“Oh, Billy, Billy,” laughed Mary Frances, “I believe, I do believe you are going to surprise me!”

“What are you talking about?” cried Billy. “I must be going—another lesson to-morrow, if you say so, because you didn’t interrupt more than twice while I was talking.”

“It pays to be good,” he teased as he went off.

NEITHER of the children had noticed the head of the big rooster as he peered curiously through the curtained window of the play house while they were talking.

As Mary Frances came out of the door, Feather Flop walked around the corner of the house. The little girl was so absorbed in looking at the plan that she did not see the rooster.

“Caw-caw!” Feather Flop cleared his throat. “Caw-caw!”

“Why, Feather Flop,” cried Mary Frances, “How you surprised me! I was so busy studying out Billy’s plan for the garden——”

“Is he anywhere about?” inquired Feather Flop, looking around anxiously. “I thought I saw him go.”

“Yes, he’s gone, Feather Flop,” laughed Mary Frances. “But let me show you—he has been planning such a delightful garden for me.”

“Delightful!” shrilled Feather Flop. “Delightful! I don’t think so.”

“Why, what makes you say that? How do you know what he planned?” inquired Mary Frances.

“I heard every word, every word,” said the rooster. “Of course you didn’t see me—I was peeping in the window.”

“Oh, Feather Flop!” cried Mary Frances. “Were you eaves-dropping?”

“I was listening,” acknowledged Feather Flop, “and I don’t approve of the plan at all.”

“Why, what’s wrong with it?” asked Mary Frances. “I think it’s beautiful.”

“It’s not sensible!” said Feather Flop. “It’s not useful!”

“But it seems perfect to me. How would you change it, Feather Flop?”

“Nobody can eat flowers!” exclaimed Feather Flop. “See here,” he looked over Mary Frances’ shoulder as she sat down on the bench, and pointed with his claw, “that plan fills the entire front yard with bloomin’ plants and gives only the little back yard for such things as taste good!”

“Dearie me! Dearie me!” laughed Mary Frances. “Is that it, Feather Flop? Why, don’t you love to see beautiful flowers?”

“Not half as much as I do to eat beautiful lettuce and beet tops and other beautiful vegetables,” declared Feather Flop, shaking his head sadly.

“It’s too bad, Feather Flop,” said Mary Frances, smoothing his fine feathers, “but I’ll see that you get plenty of such green things as you like.”

“Oh, thank you, little Miss,” said the rooster. “If you will do that, I’m ready to help with your silly—I mean your brother’s, plan.”

“Thank you, Feather Flop, for all your help,” said the little girl, “and good-bye for now. I must go or maybe mother will send Billy to look for me.”

“Good-bye! good-bye!” cried Feather Flop, jumping off the bench and running away as fast as possible.

“HOW would you like another lesson on gardening to-day, Mary Frances?” asked Billy the next morning as he appeared at the door of the play house.

“Oh, Billy, you know I’d just love to have one!” said Mary Frances, getting the desk ready.

“This time we are to make a list of what to plant, if I remember correctly,” said Billy, taking a seat.

“Let me see: we will try to plant the garden so that we will have flowers in bloom from early Spring till late Fall.

In order to have flowering plants continuously in the garden, we must use the class of flowers called Per-en-ni-als,[A] the roots of which live from year to year.

If we depend on An-nu-als,[B] the seeds of which must[35] be planted every Spring, we will not have blooms until Summer or early Fall.

So you see, in order to plan wisely, our next lesson is very important, and it is our—

Now, Mary Frances, I have really planned a delightful landscape flower garden for you to plant in front of your play house, and a wonderfully useful vegetable garden for the back of the play house; but before I give you that outline, I am going to pretend that you are a very little girl, and I will give you a list, just as our teacher handed it to us. I have it here:

1. Plan out the garden; that is, make a list of what you wish to plant.

2. Draw a picture map of your garden, marking the space where each different kind of flower or vegetable is to be planted.

3. Remember that low-growing plants should be placed in the foreground (front part) of the garden, and tall-growing plants in the background.

4. Order the plants or seeds.

5. Get the ground ready. (See Chapter XIV.)

6. Now begin to plant, following instructions in Chapter XV.[36]

If space for your garden is about 10 x 15 ft. it would be delightful to plant it as shown by the picture-map drawn here.

Plant Daffodils and Tulips between Hardy Perennials as indicated on plan with dots.

Now, for an—

These bulbs should be planted in late October or early November. They bloom in the early Spring and then die down, to come up the next Spring.

| No. on Map. | No. of Flowers to Plant. |

How Deep to Plant. |

Color. | Average Price. |

| (.) | 6 Emperor Daffodils. | 4 inches. | Yellow. | 25c for ½ doz. |

| (.) | 6 Cottage Garden Tulips, called also May-flowering Tulips. |

4 inches. | All colors. | 15c for ½ doz. |

| (.) | 6 Darwin Tulips. Bloom later than “Cottage Garden” Tulips; grow taller. |

4 inches. | All colors. | 15c for ½ doz. |

| (2) | 6 German Iris roots, called also “Blue Flags.” |

4 inches. | Blue, purple, and yellow. |

50c for ½ doz. |

The plants whose roots live on from season to season, or “winter over,” and come up every Spring, are called Hardy Perennials.

The plants whose roots die in the Fall, and do not “winter over,” are called Annuals.

When a boy or a girl undertakes to start a flower garden, how much more desirable it seems to plant, for the most part, Hardy Perennials, which will “come up” the next Summer and the next, and so on for years; instead of Annuals, the seeds of which must be sowed every Spring.

Of course, the seeds of Hardy Perennials may be sowed in the Spring, but Hardy Perennial plants raised from seeds, seldom bloom until the next year after the seeds are planted.

![]() Therefore, it is best for the beginner, in most cases, to

buy plants of Hardy Perennials.

Therefore, it is best for the beginner, in most cases, to

buy plants of Hardy Perennials.

If you wish to start seeds, however, see Chapter LI on “Perennials.”

Following is the list of—

| No. on Map. | Name and Number of Plants. | Remarks. | Average Price. |

| (3) | 2 Bleeding Hearts. | Pink heart-shaped flowers on graceful stems.

Buy the plants in clumps in the Fall. |

15c a plant. |

| (4) | Hardy Py-re-thrums. | Red, pink, white daisy-like flowers.

When ordering, use the name: “Pyrethrum Hybridum.”

It is best to plant seeds in early Spring or August, to get plants which will “winter over” and bloom the next Summer.

Plants may be purchased if you wish blooms the first year. |

20c a plant. 10c a package. |

| (5) | Sweet-Williams (London Tufts). |

“Biennials,” which means the plants “come up” the second year, but do not do well after that.

Plant every other year; preferably in August.

Order mixed seed.

Sweet-Williams often sow their own seed. |

10c a package. |

| (6) | 3 Hardy Phlox. | 1 Salmon Pink: order “Elizabeth Campbell,” or “Rheinlander.”

1 White: order “Mrs. Jenkins.”

1 Lavender: order “La Vague,” or “La Mahdi.”

[40]Buy the plants of Hardy Phlox. The seeds are not generally satisfactory, because they should be sowed within a short time after ripening. |

20c a plant. |

| (7) | Blue Thoroughwort (“Eu-pa-to-ri-um”). |

Order “Eupatorium Celestium.”

Blue misty flowers, sometimes called “Blue Mist,” pretty in mixed bouquet. Bloom late in season.

Buy the plant. |

15c a plant. |

| (8) | 1 Co-re-op-sis. | Order “Coreopsis Lanceolata Grandiflora.” Yellow daisy-like flowers. A large, bushy plant.

Keep the flowers well picked, to get continuous bloom.

Easily raised from seed if planted early. |

15c a plant. |

| (9) | 1 Blanket Flower (Hardy “Gail-lard-i-a”). |

Large reddish-brown flowers with yellow edges, etc.

It loves to bloom.

If sowed very early, it often blooms the first season.

Order mixed seed. |

10c a package. |

| (10) | 3 Chrys-an-the-mums. | Order “Hardy Pompon” (1 yellow, 1 red, 1 bronze).

Bloom very late in the Fall.

Buy the plants.

|

3 for 45 cts. |

| [41](11) | Roses (See Chapter XXXV). | Dwarf “Baby Ramblers”:

(a) 1 Fairy Rose—“Cecile Brunner.”Little double flowers of soft rosy pink on a creamy white ground.

(b) 1 Baby Tausendschön—“Louise Walter.” Larger flowers of a tender shade of pink.

Chinese Rose: “Hermosa”—pink. |

50c a plant. |

| (12) | 3 Hardy Asters (“Mich-ael-mas Dai-sies”). | Lavender, pink, white and purple little daisy-like flowers, growing in clusters on large tall bushes.

Buy the plants. |

15c a plant. |

| (13) | Iceland Poppies. | All colors.

Sow mixed seed in August to grow plants which will bloom the next Summer.

Cover with leaves in the Fall.

Order mixed seeds of “Papaver Nudicaule.” |

10c a package. |

Sow the seeds of Annuals early in the Spring. The roots of Annuals do not live over Winter, and seeds must be sowed every Spring.

| No. on Map. | Name and Number of Plants. | Remarks. | Average Price. |

| (14) | Cos´-mos. | Easily grown in poor soil. Grow over 4 feet tall. Flowers: pink,white, garnet, with yellow centers.

Buy mixed seed, “Summer or Early Flowering” Cosmos which will bloom early and continue until frost. |

10c a package. |

| (15) | Sweet A-lys´-sum. | A charming edging plant. Order “Little Gem,” which grows 4 inches tall, and blooms like a snow carpet. |

5c a package. |

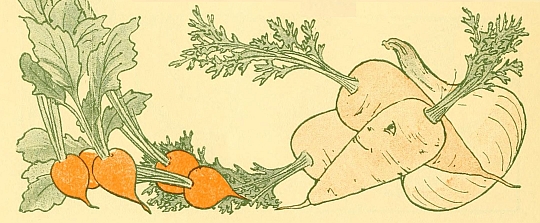

| Name. | Remarks. | Average Price per Package Seed. |

| Nasturtiums. Buy “Tom Thumb” or Dwarf. |

In the early Spring, sow seeds of dwarf nasturtiums for narrow border along the walk of the vegetable garden. |

5c. |

| Lettuce. Buy “Early All-heart;” Early Cos; Late Lettuce. |

Plant a small quantity of Early Lettuce seeds in the early Spring; when plants are two inches high, plant more seeds; thin plants out,

that the ones left standing may grow

large. Plant a few seeds every week

until weather grows very warm.

[43]Lettuce does not grow well in very

warm weather.

Plant late variety in early Fall.

Cos or Romaine lettuce is easily

grown, and stands the heat better

than the other varieties. It has a

very crisp fleshy rib in the leaf,

but the leaf part is not so delicate

as of the other varieties.

All lettuce needs very rich soil. |

5c. |

| Parsley. Buy “Dwarf Curly.” |

Plant in early Spring.

Soak seed overnight in warm water,

mix sand in the water, and fling

sand and seed over the prepared

ground. Sometimes it takes six weeks

for parsley seed to “come up.”

Except far north, it lives over

winter if well covered with leaves.

Plant some parsley every year, as

what has “wintered over” goes to

seed very easily. |

5c. |

| Onions. Buy yellow “Onion sets.” |

“Onion sets” are tiny little onions

which are set out in early Spring,

about 2 inches apart in rows.

Usually when they are partially

grown, they are pulled, and green

tops and bulbs are used for salads

and in soup. |

10c a pint. |

| [44]Thyme. | A very pretty low-growing herb, used

to flavor soup, and “stuffing” for

meat. Grows easily from seed if

sowed early. Lives over winter

—except far north—if covered with

leaves. Is, therefore, a

“perennial.”

Plant in the Spring in the northern

states.

Plant in the Fall in the southern

states. |

5c. |

| Radishes. Buy Little Red Globe-shaped. |

Sow a few radish seeds every week

for four weeks, to have new young

tender radishes ready for pulling

each week.

Radishes do not do well in very hot

weather.

The late or “winter” radish is

planted in the early Fall. |

5c. |

| Tomatoes. Buy 2 plants early and 2 of of late varieties. |

Tomato seeds may be sowed in a

box placed in a sunny window or

under glass in the hot bed in very

early Spring, but unless a large

number of plants is needed, it is

better to buy the young plants.

A very interesting variety is

“cherry tomatoes,” which grow in

little clusters of red fruit

resembling cherries in appearance.

Buy 1 plant. |

2 for 5c. |

The approximate cost of this garden for little folks is three dollars.

Seeds of all these vegetables may be started in the house. See Chapter XIV, page 81, “To Plant Seeds in Boxes.” The young plants may be put out in the garden when they are of some size, about which you will read later.

“OH, Billy,” cried Mary Frances, as her brother laid down the paper, “that doesn’t sound a bit babyish to me! If I could just have a garden like that——”

“That’s an all-right garden,” interrupted Billy, “but, Mary Frances, it isn’t much compared with my plan for your wonderful play house garden, as you’ll soon see when I give you the—

The following-named flowers, which are pictured in the Mary Frances Garden Cut-Outs, are described in the outlines that follow the lists.

Do not attempt to plant all the flowers named, but read the lists, and study the descriptions carefully. Then select the plants you prefer for your garden, and make your own list ready for ordering.

You will notice that certain names are repeated in several instances. This is only to show the period of bloom, whether early Spring, Summer, or Autumn, or throughout the season.

Dear Girl or Boy:

No doubt you will wish, just as Mary Frances did, to be able to cut flowers every few days from your garden for your mother to use as a “centerpiece” on the dining table, or for your father’s desk, or for your grandmother’s dresser, or to give to some dear friend.

Now, anyone can have a few plants which will bloom at some time or other, but the garden you and Mary Frances have in mind is one which will have flowers blooming from March, through April, May, June, July, August, September, October, and on into November, until killed by frost.

Flowers nearly nine months of the year! Yes, that is quite possible in almost every part of our country—if you study carefully the outlines given on pages 51-62, inclusive.

The first outline gives a list of plants which bloom in the Early Spring. (See Garden Cut-Out No. 1.)

The second names the plants which bloom in the Early Summer. (See Garden Cut-Out No. 2.)

The third, the plants which bloom in Mid-Summer. (See Garden Cut-Out No. 3.)

The fourth, those blooming in Late Summer or Early Autumn. (See Garden Cut-Out No. 4.)

For instructions for making the Garden Cut-Outs, see Chapter LXII, page 373.

| Aster (Wild) | ||

| Alkanet (Anchusa) | ||

| Baby’s Breath | ||

| Bellflower | ||

| Bergamot | ||

| Blanket Flower | ||

| Bleeding Heart | ||

| Campanula | ||

| Candytuft | ||

| Centaurea | ||

| Chrysanthemum | ||

| Columbine | ||

| Coreopsis | ||

| English Daisy | ||

| Forget-me-not | ||

| Foxglove | ||

| Hollyhock | ||

| Larkspur | ||

| Lupine | ||

| Marguerite | ||

| Monkshood | ||

| Pæony | ||

| Pinks— | Moss Hardy | |

| Poppy— | Iceland Oriental | |

| Phlox (Hardy) | ||

| Pyrethrum | ||

| Poker Plant | ||

| Rock Cress | ||

| Roses | ||

| Sneezewort | ||

| Speedwell | ||

| Sweet Alyssum (yellow) | ||

| Sweet-William | ||

| Thoroughwort | ||

| Violet and Viola | ||

| Wall Flower | ||

| Windflower | ||

Dear Boy or Girl:

No doubt you will wish, just as Mary Frances did, to be able to cut flowers every few days from your garden, for your mother to use as a “center piece” on the dining table, or for your father’s desk, or for your grandmother’s dresser, or as a gift for a friend.

Now, anyone can have a few plants which will bloom at some time or other, but the garden you and Mary Frances have in mind is one which will have flowers in bloom from March, through April, May, June, July, August, September, October, and into November until ruined by frost.

Flowers over eight months of the year! Yes, that is possible in nearly every part of our country—if you study carefully the outlines following this page.

The first outline gives a list of plants which bloom in the Early Spring.

The second names the plants which bloom in Early Summer.

The third, the plants which bloom in Mid-Summer.

The fourth, those blooming in Autumn.

These lists are nearly like the ones given Billy by his teacher, which he and Mary Frances used in planting a garden in front of the Play House. As you read these lists, turn to the pictures of the Mary Frances Garden Cut-Outs, and try to recognize the flower named.

All that Mary Frances wished, she and Billy made “come true,” and every day through the flowering season she gathered flowers[49] from, her garden—but that is part of the story, so now begin to read

In using the following lists, if the garden space is small, select only the names marked with a star.

The height of each plant is given because it is always desirable to plant low-growing flowers in the foreground; and tall ones in the background.

The following-named Perennials (the roots of which live from year to year) may be grown from seeds, but cannot be depended upon to bloom the first year.

Instead of beginners starting seeds of Perennials, it is well to buy the young plants from a reliable dealer to start the permanent garden, and to experiment with seeds after acquaintance with those plants already established.

Do not buy many plants of any kind, as a few, well cared for, will increase in number the next year.

Annuals (the roots of which die in the Fall) will bloom the same season as planted. Start seeds early, either in a box in a sunny window, or in a warm sunny corner out of doors early in May.

The first step in garden-making is the planning of the garden.

(See Chapter LXII on “The Mary Frances Garden Cut-Outs.”)

The second step is selection of the seed, and the ordering of the same from one of the best seed firms.

Never try inferior or untested seeds. It is no economy.

In regard to “color scheme,” see Chapter LX.

For artistic effect, it is usually best to plant the same kind of flowers close together to obtain “masses” of bloom.

Plant the following named bulbs in the Fall. See Chapter LVI.

| Names. | Remarks. |

| Snowdrops. | Pure white small bells, blooming late in February or

early in March, whenever the snow leaves the ground. Leave bulbs in the ground over Winter, covered with

leaves.

Plant 4 inches deep. |

| Nar-cis-sus or Daff-o-dils.* | Daffodil bulbs are very hardy, and increase in

number from year to year. They should be covered

with leaves over Winter.

The best varieties are “Emperor”* and “Empress.”

Plant 4 inches deep.

Barii Conspicuus, a Star Narcissus, is beautiful for

cutting.

Poet’s Narcissus have beautiful white petals, with

golden and red center. |

| [52]Cottage Garden* (May-flowering) Tulips. | Beautiful large flowers of all colors, making the Spring garden bright and gay.

Plant bulbs 4 inches deep.

Plants grow 18 to 24 inches high. |

| Darwin Tulips. | These beautiful, stately tulips grow two feet high

and more. Large globe-shaped brilliant blooms.

They come in all colors except yellow.

Plant 4 inches deep. |

| Hy-a-cinths. | Plant only a few hyacinth bulbs, because they do not

“winter over” well; new bulbs should be added

every year, as the old ones deteriorate.

Colors: pink, purple, white. |

| Common Name. | Botanical Name. | Remarks. | Height. |

| Rock-cress. | Ar-a-bis Al-pi-na. |

Little white flowers

blooming in early Spring.

|

6-8 inches. |

| English Daisies. | Bel-lis Per-en-nis. |

Little white and pink flowers, blooming in

April and May.

Pretty among Poet’s

Narcissus, or mixed in an

edging. |

3-6 inches. |

| [53]Bleeding Hearts.* | Di-el-y-tra. |

Pink heart-shaped drops

on graceful stem.

Raised from plants only.

Buy clumps in the Fall. |

24 inches. |

| Moss Pinks. | Phlox Sub-u-la-ta. |

White, rose, lilac, little flowers blooming

in April and May.

Blooms make a carpet of

flowers.

Buy only a few plants as

they soon spread. |

4-6 inches. |

| Violets. | There are native and double Russian varieties.

Buy plants of

sweet-scented double

Russian variety. |

4 inches. | |

| Yellow Alyssum “Basket of Gold.” | A-lys-sum Sax-a-tile. |

Little yellow clustered heads of flowers.

Pretty for edging flower

beds.

Sow seed in August. |

12 inches. |

| Wallflower. | Not perfectly hardy in

all places.

Fragrant brown and yellow

flowers.

Plant seeds in August, in

a protected southern

corner, where they may

“winter over” if the

weather is not very

severe. Plant needs sun. |

15 inches. | |

| In order to obtain good Spring blooms, plant these flowers in August of the Summer before, or earlier. | |||

| Common Name. | Botanical Name. | Remarks. | Height. |

| Yellow Alyssum.* | A-lys-sum Sax-a-tile. | See List No. 1 for description. |

12 inches. |

| Columbine. | A-qui-le-gi-a. | Airy, graceful plants,

with spurred flowers, in

red, blue, violet, white,

yellow. Buy the seed of

“Long Spurred Hybrids.” |

18-24 inches. |

German Iris (“Blue Flags”). |

I-ris Ger-man-i-ca. |

Lavender, purple, yellow, white.

“Corm” roots which

“winter over” and take

care of themselves,

“coming” up every Spring

in increased numbers. |

24-30 inches. |

| Lily of the Valley. | Con-val-la-ria. | Sweet-scented tiny white bells.

Buy clumps and roots in

Spring or Fall. |

6 inches. |

| [55]Alkanet or Bugloss. | An-chu-sa I-tal-i-ca. | Buy “Dropmore” variety.

Blue flowers.

Buy the plants. |

36 inches. |

| Lupines. | Lu-pi-nus. | Varieties in blue, white, pink. |

24-28 inches. |

| Tufted Pansies.* | Vi-o-la Cor-nu-ti. | Sow seed early.

Resemble pansies, not so

large; but bloom all

Summer. |

5-8 inches. |

| Bleeding Hearts. | Di-el-y-tra. | See List No. 1 for description. |

|

| Hardy Candytuft.* | I-be-ris. | Buy “Iberis Sempervirens”: white.

Pretty for edging. |

8-10 inches. |

| Forget-me-Not. | My-o-so-tis. | Buy “Myosotis Palustris

Semperflorens.” Sky-blue little flower. |

8-10 inches. |

Hardheads or Knap Weeds.

Perennial Cornflower. |

Cen-tau-re-a. | “Centaurea Montana” is

known as the Perennial

Bears large

violet-blue flowers from

July to September. |

2 feet. |

| Rambler roses also bloom in early Summer. | |||

| Common Name. | Botanical Name. | Remarks. | Height. |

Hardy Lark-spur.* |

Del-phin-i-um. |

Order plants of varieties

named, “Belladonna” and

“Formosum,” which are

turquoise blue and dark

blue.

Buy the plants, or seeds. |

24 inches. |

Pæony. |

Bloom but once in the season.

Beautiful showy large

rose-like flowers.

Foliage of plant dies

down in Winter, coming up

in young new “shoots” in

the Spring.

Colors: red, pink and

white.

There is also a “tree”

variety.

Most pæonies bloom in

early Summer.

|

3 feet. | |

Alkanet or Bugloss. |

An-chu-sa. |

See List No. 2 for description. |

|

[57]Bellflower.* |

Cam-pa-nu-la. |

Perennial Varieties:

(a) Campanula Carpatica

(Carpathian Hare-Bell).

Bloom from June to

October. Blue. |

8 inches. |

(b) Campanula

Persicafolia (Peach

Bells). One of the best.

Large blue, and white

varieties. |

2-3 feet. | ||

(c) Campanula

Pyramidalis (The Chimney

Bellflower). Stately

pyramid form plant, with

many blue flowers. There

is also a white variety.

It is best to buy plants

of the above.

Note.—There are also

biennial varieties of

Campanula; namely,

Campanula Medium or

Canterbury Bells, and

Campanula Calycanthema

(Cup and Saucer).

Biennial means of two

season’s duration.

|

4-5 feet. | ||

Madonna Lily.* |

Li-li-um Can-di-dum. |

Pure white lilies,

resembling Easter Lilies,

growing on strong stems.

Plant in the Fall (or

possibly in the early

Spring), 6 inches deep,

preferably in the shade

of some other perennial.

Lay bulbs on the side

when planting. |

2-3 feet. |

Oriental Poppy. |

Pa-pa-ver O-ri-en-tal-is. |

Very large showy poppies

in various colors.

Buy plants in clumps in

August. |

36 inches. |

[58]Foxglove. |

Dig-i-tal-is. |

See tall flowers pictured

on cover of this book.

Various colors. |

36 inches. |

Sweet William.* |

Di-an-thus Bar-ba-tus. |

Red, white and various colors.

|

18 inches. |

Hardy Garden Pinks.* |

Di-an-thus Sem-per-flo-rens. |

Buy plants.

Various colors.

Old-fashioned favorites,

with spicy odor.

Excellent for cutting.

Also: “Dianthus

Latifolius Atcroccineus.”

Hybrid Sweet-William,

with brilliant crimson

double flowers, blooming

all Summer. |

6-12 inches. |

Iceland Poppy.* |

Pa-pa-ver. |

Buy “Papaver Nudicaule” mixed seed.

See description in Garden

for Little Folks. |

9-15 inches. |

Marguerite.* |

An-the-mis Tinc-to-ri-a. |

Buy “Anthemis Tinctoria.”

Color: yellow.

Buy plant. |

15 inches. |

Coreopsis.* |

Co-re-op-sis Lan-ce-o-la-ta. |

See Garden for Little

Folks for description.

Buy plant. |

24 inches. |

Blanket Flower. |

Gail-lard-i-a. |

Buy Gaillardia

Grandiflora. Crimson and

yellow.

Sow seed early. |

24 inches. |

[59]Hardy Phlox.* |

Phlox Suffruticosa are

the Early-flowering Hardy

Phlox.

Phlox Decussata are the

later Hardy Phlox, and

are the variety most

used.

All colors: Crimson,

white, salmon pink, etc.

|

||

Hardy Pyrethrums.* |

Py-re-thrum Hy-brid-um. |

Red, rose, white flowers.

|

18-24 inches. |

Tufted Pansies.* |

Vi-o-la Cor-nu-ti. |

See List No. 2 for description. |

3-6 inches. |

Baby’s Breath. |

Gyp-so-phi-la Pa-nic-u-la-ta. |

Tiny white misty flowers,

beautiful to use in

bouquets, making a

“cobwebby” filmy spray

over the flowers. |

20-30 inches. |

Hardy Candytuft. |

I-be-ris Sem-per-vi-rens. |

White low-growing

flowers. |

8-10 inches. |

Hollyhocks.* |

A grandmother’s

favorite—picturesque in

a garden background. Red,

white, yellow, rose,

pink.

Cut down the stalks when

the seeds are dry.

Plant seeds; they will

bloom the next season. |

5-8 feet. | |

Speedwell. |

Ve-ron-i-ca. |

Blue, rose, white.

Plant seeds in August. |

12-24 inches. |

[60]Hybrid Tea Roses. |

See Chapter XXXV on Roses. |

||

Japanese Bellflower.

Balloon Flower. |

Plat-y-co-don. |

Blue, and white flowers;

deep-cupped and star

shaped. Buds resemble

tiny balloons. Easily

grown. Buy plants. |

|

Yellow Day Lily. |

Hem-e-ro-cal-lis. |

Yellow and orange tall lilies.

These are not pictured in

the Cut-outs, but are

very similar to the

madonna lily in form.

They will grow in the

shade. |

18-36 inches. |

Summer Violet. |

Vi-o-la Cor-nu-ti Pur-pu-re-a. |

Resembles single violets,

and very desirable, for

flowers appear when

blooming season of

violets is passed. |

4 inches. |

Turn to Chapter LX on “Garden Color-Pictures,” to read about combinations of color for the garden.

| Common Name. | Botanical Name. | Remarks. | Height. |

Hardy Larkspur. |

Del-phin-i-um. |

See List No. 3 for

description. |

|

Monks Hood. |

Ac-o-ni-tum. |

Curiously shaped blue and

white flowers. Will grow

in shade.

Buy the plants. |

3-5 feet. |

Hardy Phlox.* |

|||

Sneezewort. |

He-len-i-um. |

Yellow, old-gold,

changing to terra-cotta,

daisy-like flowers.

Buy “Riverton Gem,”

“Riverton Beauty.”

Plant seed in August, or

buy the plants. |

36 inches. |

Hardy Asters* (“Starwort”). |

Mich-ael-mas Dai-sies. |

See Garden for Little

Folks for description. |

36 inches. |

[62]Hardy Chrysanthemums.* |

All colors except blue and purple. |

15-24 inches. |

|

Wind Flower. |

A-nem-o-ne Ja-pon-i-ca. |

Rose, pink, white

flowers. If grown from

seed, protect with

shade-cover until

started.

Cover well in the Fall

with straw or leaves.

Will not grow in all

soils. |

2-4 feet. |

Blanket Flower. |

Gail-lard-i-a. |

See Garden for Little

Folks for description. |

|

Coreopsis.* |

See Garden for Little

Folks for description. |

||

| Red Hot Poker. Flame Flower. Torch Lily. |

Tri-to-ma. |

Yellow-orange-scarlet

showy flowers hanging

downward in long clusters

on “spike” heads.

Buy plants. Not shown in

the Cut-Out. |

36 inches. |

Tufted Pansies. |

Vi-o-la Cor-nu-ta. |

See List No. 3 for

description. |

|

Hybrid Tea Roses. |

See Chapter XXXV on

Roses. |

||

Thoroughwort.* |

Eu-pa-to-ri-um. |

See Garden for Little

Folks for description. |

|

Note.—Most seed houses furnish collections of seeds of Wild Flowers. They may be had in tall-growing and dwarf varieties for a very reasonable price. |

|||

A few Annuals may well be added to these lists. Even though Annuals must be planted every Spring, there are many worth the trouble; in fact, a garden would look lonesome without some of the old favorites.

A very convenient arrangement is to give one bed in the vegetable garden to the starting of Annuals.

The plants may be moved, when some size, to the hardy garden, near the place of some of the Perennials which die down; for instance, hyacinths, tulips, and other bulbs. Indeed, those having short roots may be placed directly over the bulbs after their leaves have withered and dried.

A border of low-growing Annuals along the vegetable beds makes the vegetable garden a place of beauty.

If you live where there is snow in Winter, in order to have early Summer blooms, the seeds must be started early, under glass protection, in a sunny window, or in a hotbed. A box with a glass cover is a good substitute for a hotbed. If the seeds of Annuals are planted out of doors, they rarely bloom before Mid-Summer, while many Perennials, which have been out all Winter, bloom in early Spring. Select from the following lists the flowers which from the description are most pleasing to you.

| Common Name. | Botanical Name. | Remarks. | Height. |

Cockscomb.* |

Cin-e-ra-ri-a. |

Crimson, showy flowers

easily grown. Resemble

the comb of a rooster.

Bloom in the Fall. |

24 inches. |

Princess Feather.

Feathered Coxcomb. |

Ce-lo-si-a Plu-mo-sa. |

Yellow and crimson,

feathering spikes of bloom.

Easily raised.

Large-flowering Dwarf are

the best seeds to plant. |

About 2½ feet. |

Youth-and-Old-Age.* |

Zin-ni-as. |

All brilliant colors.

Bloom late in Fall. |

2 feet. |

Mad Wort.* |

Sweet A-lys-sum. |

Charming edging plant.

Tiny white thick flower

heads.

Buy “Little Gem.” |

4 inches. |

Wild Cucumber Vine. |

A rapid Annual Climber. |

||

Floss Flower. |

A-ger-a-tum. |

Blooms from early Summer

to late Fall.

Buy “Blue Perfection;”

small blue flossy flowers

which grow in thick

clusters. Excellent for

blue among cut flowers. |

12-15 inches. |

[65]Snapdragon* (“Biennial” plants). |

An-tir-rhi-num. |

Resemble sweet peas,

but are easily cared for;

need no trellis or

support. Excellent for

cutting, having stout

stems. Sow in February or

March in seed-boxes.

Bloom from July to

November. Best variety;

large Flowering Half

Dwarf.

Colors: garnet, red,

rose, pink, copper,

orange, yellow, white.

Plants sometimes sow

their own seed for next

season. |

18 inches. |

Scarlet Sage. |

Sal-vi-a Splen-dens. |

Brilliant red bloom from

Summer through Fall. Too

harsh a shade for a

border plant. Use only in

a mass in the garden. |

24 in. |

Cornflowers.* |

Cen-tau-re-a Cy-an-us. |

Sometimes called:

“Bachelor’s Buttons,”

“Blue Bottle,” “Ragged

Robin.”

Buy “Double Blue”

variety. |

15 inches. |

Nasturtiums. |

Orange, yellow, salmon

color.

Buy “Dwarf” variety.

Excellent for edging.

There is a tall growing

variety which clings to a

support, or “climbs.” |

10 inches. |

|

Cosmos. |

See Garden for Little

Folks for description. |

||

[66]Verbenas. |

Buy sweet-scented

verbenas which come in

red, rose, pink, purple,

lavender, white. |

18-24 inches. |

|

Four-o’Clocks. |

Mi-rab-i-lis Jal-ap-a. |

Do well everywhere.

Mixed colors. Give each

plant twelve inches of

room. Interesting because

often visited by humming

birds. |

2 feet. |

Mourning Bride.

Pincushion Flower. |

Sca-bi-o-sa. |

Our grandmothers loved also lady slippers, heliotrope, mignonette; but the perennial flowers have taken the place of many old-fashioned Annuals because they require less care.

Among the most interesting Annuals are—

which may be dried and will keep their color for years. They make charming winter decorations for the table. There are several varieties.

Do not try all of the varieties named, but select from the descriptions the one or two which would be most pleasing to you.

| Common Name. | Different Varieties. | Height. |

Everlasting Flowers or “Imortelles” (pronounced

im-mor-tél). |

A-cro-lin-i-um. Pretty white and rosy-pink while in the bud state. |

15 inches. |

Hel-i-chry-sum (Strawflower). One of the 30 inches.

best “Everlasting” flowers. Plant 12 inches

apart. Mixed colors.

Xer-an-the-um. One of the prettiest of

“Everlastings.” Purple, white, rose. |

30 inches. | |

Globe Am-a-ranth (Bachelor’s Buttons).

Resemble clover heads in white and purple. | 12 inches. |

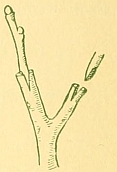

In drying “Everlasting” Flowers, make a paper flower holder in the following manner:

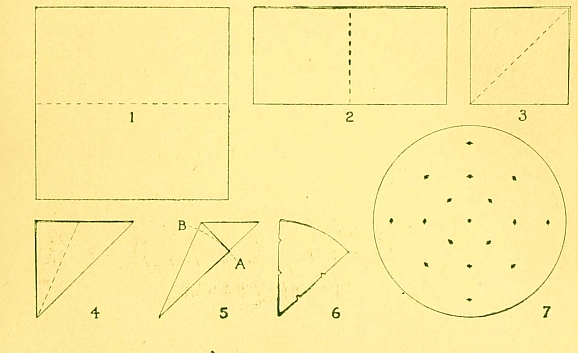

1. Cut a large square from a heavy piece of paper. Eight inches is a good size.

2. Fold the paper across four times, as shown by the dotted lines in figures 1, 2, 3, 4.

3. Cut along dotted line A-B, figure 5.

4. Open to form figure 6. Clip a tiny piece off the point, and clip along the edges as shown.

5. Spread the paper open. Set it over the mouth of deep vase or jar, and let the stems of the “Everlastings” hang full length through the little openings cut in the holder until dried. This method of dried Everlasting flowers gives long straight stems.

“Some list, that,” said Billy at length, “and we haven’t yet thought of what we will plant in the

“WHY, Billy, the very thought of a garden like this almost frightens me,” cried Mary Frances. “I don’t believe I ever, ever can remember one-quarter of the names!”

“Pshaw!” exclaimed Billy, “that’s just like a girl! I wouldn’t let a few names scare me! Besides, there aren’t so many names; some are repeated in each list. That’s not a very difficult garden, if managed just as Miss Gardiner explained.”

“Oh, I’m not scared—exactly,” said Mary Frances, “not when I have such a wonderful teacher, ahem! Professor Billy, when does my next lesson come?”

“Can’t promise,” said Billy not knowing whether to be pleased or vexed, “next lesson begins work. Hello! I see by my note book, I’ve left out a part of this lesson. I suppose it is because we’ve never had window boxes that I overlooked this list.”

“Window gardens are almost like a doll’s garden, it seems to me,” said Mary Frances, as Billy started to read:

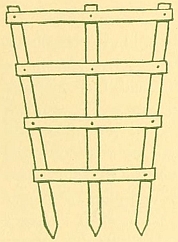

1. Have the boxes made with small holes, or outlets, so that there may be good drainage; for although plants love to drink water, they do not enjoy having “soaking wet feet” all the time.

2. In the bottom of the box place some pebbles or broken stone; this, also, to make the drainage good.

3. Fill box with sifted sand and humus (or manure) very much as for seed boxes. See Chapter XIV.

Following is a list of—

| Petunias. | Many beautiful colors. Sow the seeds indoors; the

plants may be placed out as soon as danger of

frost is passed. If seeds are saved, they should

be taken from the weakest plants, as they will

give better results than from stronger plants.

Bloom until killed by frost. Buy double large

flowering.

|

Zinnias (”Youth-and-Old-Age“). |

All colors except blue and purple. Buy “Dwarf

Double” varieties. Bloom late into the Fall. |

Phlox Drummondi (Annual Phlox). |

Very many beautiful mixed colors.

Easily grown. |

Sweet Alyssum. |

Buy the tall variety, of trailing habit: “Alyssum

Maritimum.” Plant near edges of box. |

Cuphea (Cigar Plant). |

Interesting little plant, growing one foot high.

Little scarlet flowers, shape of hollow cigars,

with black and white tip, resembling ashes. |

[71]Ageratum (Floss Flower). |

Buy Dwarf Variety. See List of Annuals for

description. |

Verbenas. |

Sweet-scented Verbenas.

Colors: Rose, pink, white, purple, lavender, etc. |

Vinca Major Varigata (“Variegated Periwinkle”). |

Excellent for trailing over the edges of window

boxes. Leaves glossy green with light green edges.

Flowers, blue. |

Geraniums. |

Too well known to need description. Easily grown

from “cuttings.” See Chapter XXXV.

Do not expect geraniums to bloom the year round.

Give them rest in Winter or Summer by pinching off

the buds. |

One of the prettiest shallow window boxes is planted with Violas in mixed colors, with “Tom Thumb” Alyssum for edging.

“Oh, Billy, will you build me a window box soon for my play house?” asked Mary Frances with enthusiasm.

“Will I? Indeed, Mary Frances, what do you think! I don’t believe you’ll find another fellow——”

“Oh, Billy, I didn’t think! I didn’t! You’re so good to give me these lessons! I’ll wait until later for the window box.”

“You’d better,” said Billy; “you interrupted my notes. There is just one more flower mentioned in these lists. It is—

Lemon Verbena (not hardy). |

An old-fashioned favorite, because of the sweet-scented

foliage. It is better grown in the garden than in window

boxes. The flowers are insignificant, but the

lemon-scented leaves are a delight.

|

“Some ‘Lemon verbena’ I shall have!” exclaimed Mary Frances. “I remember it well in Grandma’s garden, don’t you?”

“I remember it, but I remember another sweet-scented leaf better:

Ber-ga-mot. |

Hardy, easily grown.

Flowers: Brilliant red; pretty, but not beautiful. Leaves

very fragrant. Humming birds often gather nectar from the

flowers. |

“Oh, Billy, I remember that, too. Wasn’t it lovely! I know Grandma will give me some roots. Now, let’s begin the next lesson. I am so anxious to get to the place where I really begin to do something!”

“Well, you could do something right away,” said Billy. “You could start in this box which I filled with earth yesterday, and hung outside your play house window——”

“Oh, Billy!” breathed Mary Frances, “I didn’t see it! My, how pleased I am!”

“Humm!” Billy acknowledged her gratitude and continued: “You could start—

| Parsley. | See List of Vegetables for Little Folks’ Garden. |

| Sage. | A savory herb. Buy the plant. It grows about 15 inches tall. |

| Mint. | Used for “mint sauce.” Easily grown. Buy the plant. |

| Chives. | Somewhat like small delicate green onion tops. Bear a pretty

blue flower. Buy clump of roots. |

| Thyme. | Edge the box with thyme.

See List of Vegetables for Little Folks’ Garden. |

“I’ll start it immediately,” declared Mary Frances, who was very fond of cooking, “I’ll get my purse and go to the florist’s right now to buy the plants.”

“Good-bye, then!” called Billy, “I’ve done my part. My next help is in eating the soup—or sauce!”

“DO you suppose, Professor—I mean Billy—do you imagine we can keep the garden a secret?”

The early Spring day was so lovely that the children were sitting in the summer house.

“I guess the folks will suspect something,” answered Billy, “when they see us digging and spading, but they won’t for a moment think of all we’re planning to do.”

“They can’t help seeing things grow,” Billy went on, “but how little they’ll expect you to come in some day with radishes and lettuce from your own garden.”

“You’re just like Feather Flop!” exclaimed Mary Frances.

“Well, I like that!”

“I mean,” Mary Frances caught her breath, “I mean you think only of the vegetables, and forget that I will bring in a beautiful bouquet of flowers for the table.”

“Oh, to be sure,” nodded Billy, “but you won’t have either unless we begin the next lesson. The first thing after making out the list, so our professor told us, is to understand about the soil. He said that after knowing what to plant, we must learn how to plant. So let us go have a look at the soil near the play house.”

In front of the play house, Billy caught up a handful of earth.

“Listen, Mary Frances,” he said, earnestly, “let us examine this closely. To test the soil is the most important point in gardening, as you will readily see after you have heard—

There are very few places where the soil is “just right” for plants.

In order to find out what kind of soil is in your garden, you may make a little test by squeezing some tight in your hand.

Almost any soil, if very damp, will “hold together;” that is, if a handful is squeezed, it will stay in the shape of the hand, so do not make the test until two or three days after a rain, when it will be quite dry.

If, in a couple of days after a rain, the soil is sticky, something like putty, and a squeezed handful holds together, and shows the marks of your fingers, it is clayey soil.

Now, if the soil in your garden is clayey, it will never, never do for plant babies. No indeed!

You see, it holds so close together that the little roots cannot push it apart, and cannot grow. So to clayey soil you must add something which will lighten it up; like sand, or even coal ashes, or stable manure which contains a large quantity of straw.

Deep digging and forking help a lot, too, in breaking up the tight hold which clay grains have upon each other. Sometimes that in itself will make the clay sufficiently light.

Little plant babies are so delicate that a very sandy bed would not do for them either, for a rain might wash away the soil from their roots.

All plants are very particular, and grow best if their bed is “just right.”

So, if in a couple of days after a rain, a squeezed handful of your garden soil will not hold together at all, and sifts through your fingers, heavier material must be added.

A little clay worked into the sand and run over with a roller helps; but there is something even better—it is stable manure.

Stable manure[C] not only helps hold sandy soil together and lightens clayey soils, but it contains a very great deal of plant food in the form of humus, and without humus all the other plant food in the soil is of very little value to the plant.

I know you are going to ask me what humus is; but first I want to ask you to think what the soil is. Yes, dirt, that is right; but dirt came from where?

For the most part from broken and crumbled-up rock, for this earth was once nearly all of rock.

But dirt or soil is not only rotten and broken and crumbled-up rock, as you will see in one minute.

Do you remember how the leaves fell off the tree last Autumn, and how the grass died down? What became of the leaves and grass?

They died, yes, and turned into leaf mold, which is one form of humus.

You have guessed right, Mary Frances. Humus is decayed vegetable matter.

Humus mixed with water makes humus soup, which is the very best kind of plant food, and the plant babies love it. They drink it through their roots, you know.

Not only does humus help with the matter of food, but it holds moisture in the soil, and in some almost magic way makes other plant food into a form which the plant can use.

Of course, you wish to give your plants the best kind of food, and of course you will want humus.

But suppose you cannot readily get stable manure, or leaf mold from the woods, why then, you can make humus. Every day the very things you need to make humus may be going to waste.

Save all the vegetable tops, leaves, grass, etc. Pile them up and let them decay. When decayed, they are humus.

Another way to make a compost heap is to dig grass sods about eight inches square, and make them into a pile about two feet high, with layers of earth and manure between, and let stand in the weather to decay. Turn over when decayed. When wanted for use, cut some down, knock apart and spread.

You have heard of sowing rye or oats, and “ploughing the crop under” to enrich the soil; this makes humus out of the green rye or oats and their roots.

The plant baby and big plants, too, need many different kinds of food, but the most important is humus.

“OH, yes,” continued Billy “I’m going to tell you how the plants eat, and why they are so fond of plant-food soup, and why they like bones (of course, for soup! that is right); but I think you would prefer that story later on, and would rather talk now about—

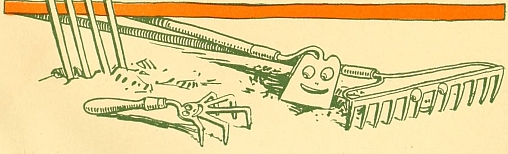

The best small garden tools are a “Ladies’ Set,” for they are strong and yet small and pleasant to handle.

A fork for digging; a rake and a hoe and a “cultivator” are necessary.

1. Drive the fork down into the ground, with your left foot on top of the prongs, and lift the clod of earth high enough to turn over.

2. After dropping it, “spank” it apart into little lumps and dust.

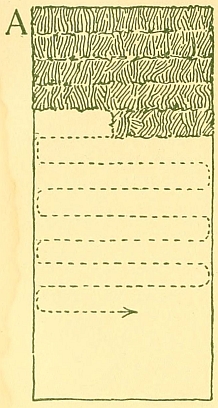

Commence this work at the back of the garden, and step[80] backward over the untouched earth, until you have covered the entire plot. Begin at the left-hand corner “A” and across to the right.

In this way, you will not step on the loosened soil, nor pack it down.

Of course, in large fields, this work is done with a plow.

1. Spread humus or manure, or both, all over the surface and dig it in, in the same manner in which you first dug up the garden, if you wish to be entirely certain of having success.

But even then, the soil is not fine enough. No. I see you shake your head. But, Mary Frances, if you want a lovely garden, you must get the garden table ready for the plant roots in the most enticing way.

2. Next, take your rake and “comb” the earth to and fro until it is all light and feathery.

Of course, in large fields, this work of raking is done with a harrow.

3. After planting the seeds, pat the soil down firmly so that[81] it will be firm enough for the little rootlets to “get a hold,” yet will be movable so that they may grow.

Little seeds are not always started, or planted, out of doors.

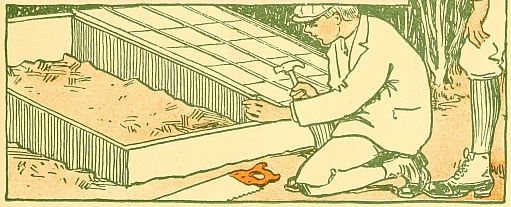

Instead, early in the Spring, seeds are often started in boxes in a sunny window, or in hotbeds. (See Chapter LVII.)

We’ll make a hotbed of our own one of these days, Mary Frances, but at present we’ll have to be satisfied with seed boxes.

1. For starting seeds indoors, use shallow boxes, placed in a sunny window.

Cigar boxes are of a convenient size for children to use. The soil should be fine and rich in humus.

2. Sift some soil from the compost heap, or some leaf loam (soil from the woods), or some well rotted stable manure,[D] through a large mesh sieve (ash sifter) and mix with the same amount of fine sand.

3. Fill the boxes with this mixture; water it well with a fine sprinkler.

1. Sow the seeds thinly, sprinkle them like pepper from a shaker on the surface, and over them spread a very, very little sand.

2. If possible, cover the box with glass to prevent the soil from drying, but let the air into the box by tilting the glass on one side, using a cork on the edge.

1. Do not water often, but when necessary to do so, use the finest sprinkler possible.

2. Water seed boxes in the morning. For if watered at night, the tiny plants may “damp off,” or mildew.

“Oh,” exclaimed Mary Frances, “how careful a gardener has to be! What lovely beds must be made for little seeds!”

“Exactly so,” agreed Billy. “I see you get the point of the lesson. It is really about how to make the beds for the seed babies.”

“The dear little things,” said Mary Frances. “Billy, I had no idea how easily I would learn to love the thought of them.”

“Well, then you’ll enjoy the next lesson,” said[83] Billy, turning over the leaves of his note book. “Our professor told us next a good deal about the seed babies.”

“Can’t we go right on now with that lesson?” asked Mary Frances, in delight at the willingness of Billy to teach her.

“I guess so,” replied Billy, looking at his watch. “The ball team doesn’t meet until two-thirty.”

“LET me see,” said Billy. “What lesson is this?”

“It’s the fourth lesson,” Mary Frances counted on her fingers. “I remember perfectly.”

“Right you are,” replied Billy, rising and bowing; “and I shall begin this lecture by reciting a little piece of poetry, called—

Billy made a deep bow, and Mary Frances clapped her hands; then Billy opened his note book, cleared his throat, and began:

Having found how to get the outdoors seed-bed ready, we will next learn how to plant the seed.

Of course, you have made your list of the seeds needed, and have received them from the dealer.

If possible, it is best to run the planting of the rows or drills north and south so that the sun will shine upon the rows of plants all day, from the east in the mornings; from the west in the afternoons.

You will need a garden line to make a straight first row.

1. Cut two sticks about as large around as a broom handle, each eighteen inches long.

2. Point the ends so that they may be easily stuck into the ground.

3. Tie one end of a strong twenty-five foot cord to each stick. Roll the cord on the stick.

1. Decide where you wish the first row of plants to grow.

2. Push the stick, not having the roll of cord, down into the ground at the end of this imaginary row.

3. With the other stick in hand walk back, unrolling the cord until you reach the other end of the imaginary row of little plants. Try to make this row very straight, as all the other rows will be measured from it.

By the way, this row should be quite near the edge of the bed, so that you will not have to step on the loose “feathery” soil.

4. Drive the other stick down into the earth, drawing the cord tight.

1. Prepare the rake to mark the little rows, or drills, for the seed. Have ready three good-sized corks. Stick the middle tooth of the rake half way through one cork.

2. Do the same to the two end teeth.

3. Run one end tooth of the rake along the stretched garden line keeping all the teeth parallel with the line. Continue to use the rake across the entire bed. This is a convenient method of getting straight rows. Make the drills (hollows) about a half inch deep.

Seed are often not sowed in “drills,” but are “broadcast;” where plants are to be thinned out when they come up, and not to be transplanted, the drills are better.

Broadcasting is throwing the seeds lightly over the surface of the ground, so that each will fall a little way apart from the other, like sprinkling with pepper from a pepper shaker.

After the seeds are sown, draw the earth lightly over them either with your hands or with the back of the rake. It is best to sow seeds just before a rain, except when the seeds are very small; then, just after a rain. If there is no rain, sprinkle lightly, but thoroughly dampen the earth.

Pat the earth down gently with the palms of your hands or with a board.

A board is much the better if seed has been broadcast.

The reason? Oh, yes, the reason is that the soil will be too light and airy unless firmed.

The little seed rootlets need close-packed light earth, with[88] no lumps. Just imagine how tiny they are, and how near to them must be the tiny grains of sand for them to take hold on.

After the seeds are planted, drive down at the ends of the first and last rows little stakes, marked with the names of the kind of seed planted in the section.

“Perhaps you think you will remember what kinds of seed you’ve planted; but one is never certain. Once I thought I had planted carrots and when the plants grew, I had beets. It is not safe to try to remember.

“So much, then, for how to put seed babies into their beds.

“By and by, they are going to wake up, and we must understand how to take care of them. The best way to learn how to take care of them is to find out what they are, and what they need.”

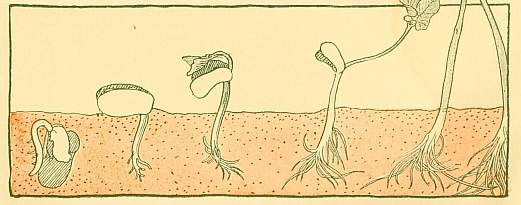

“FIRST of all, we must understand that the seed has a coat which holds the living, sleeping baby. You see, the baby itself is so tiny and delicate that it would not be safe for it to be out without its seed coat. The wind and the sun would soon dry it up and kill it; then, too, it would die of hunger, for it is too little to find its own food. So its mother wraps the baby up in its strong seed coat, and puts its food in beside it, in the same coat. And there the seed baby lies sound asleep until—until everything is just right for it to wake up. The time it likes best to awaken is in Spring, when the weather is getting warm.

You will put your seed babies, coats and all, into the warm ground early in the Spring, when they will feel like growing. Then you will dampen them, for without moisture and food, the seed baby will not wake up. The moisture swells the seed coat, and wakens the baby, and gets the food ready for the baby to eat.

The baby begins to eat the food its mother put inside the seed coat; it stretches itself, and pretty soon sends down into the earth a “teeny-weeny” rootlet. This rootlet takes a little food from the earth up to the baby. Oh, yes, plant soup, that is the kind of food it takes. Plant soup is mixed earth and water.

How good it is for the plant child, depends on how sweet the soil is, and how much humus or compost or manure food is in the soup. Humus soup tastes wonderfully good to the baby plant.

Well, not only does the baby plant send down this tiny rootlet, but its tiny stem grows upward, and bursts through the seed coats and show two tiny leaves.

The two tiny leaves which appear on top of this stem, while down in the soil grew larger, threw open the seed coat, and came up to the surface for the air and sunshine.

These leaves are called the seed-leaves, or cŏt-ŷ-lē´-dŏns. They are not the true leaves of the plant baby, but are nurse-leaves which go ahead of the leaves of the baby plant, and really hold the true leaf of the baby between them.

These nurse-leaves take care of and feed the tiny plant baby until it can send out its own tiny leaves to gather air and digest food for itself.

If you pull up a Lima Bean Seed Baby after it has started to grow you will see the nurse-leaves.

No plant should be moved or transplanted until at least two true leaves, or leaves of its own, not nurse-leaves (cotyledons), have appeared.

Of course, when the little plants first come up there will be so many that each will choke the other, and so we must learn about—

When the little plants are about two inches high, pull up all the weak plants, leaving the stronger ones from one to six inches apart, according to the kind of plants.