Project Gutenberg's The Tales and Novels, Complete, by Jean de La Fontaine This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Tales and Novels, Complete Author: Jean de La Fontaine Illustrators: Eisen, Lenart, Boudler, Pater and Others Release Date: September 21, 2004 [EBook #5300] Last Updated: July 25, 2014 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TALES AND NOVELS, COMPLETE *** Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

The Cudgelled and Contented Cuckold

The Peasant and His Angry Lord

The Avaricious Wife and Tricking Gallant

The Princess Betrothed to the King of Garba

PREFACE (To The Second Book)

The Countryman Who Sought His Calf

The Convent Gardener of Lamporechio

King Candaules and the Doctor of Laws

The Ear-maker, and the Mould-mender

The Confidant Without Knowing It, or the Stratagem

The Quid Pro Quo, or the Mistakes

To Promise is One Thing, to Keep It, Another

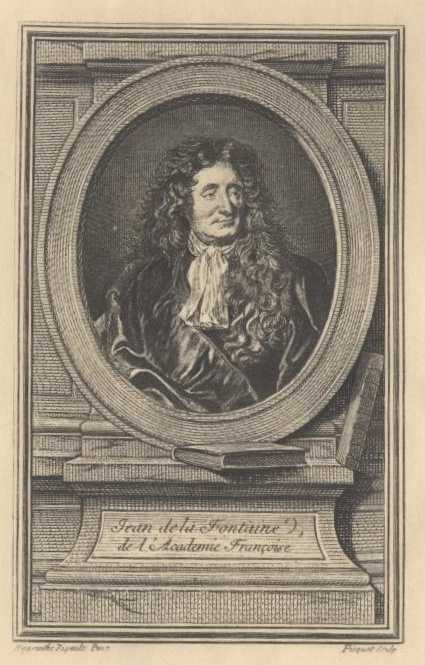

Jean de La Fontaine was born on the 8th of July, 1621, at Chateau-Thierry, and his family held a respectable position there.

His education was neglected, but he had received that genius which makes amends for all. While still young the tedium of society led him into retirement, from which a taste for independence afterwards withdrew him.

He had reached the age of twenty-two, when a few sounds from the lyre of Malherbe, heard by accident, awoke in him the muse which slept.

He soon became acquainted with the best models: Pheedrus, Virgil, Horace and Terence amongst the Latins; Plutarch, Homer and Plato, amongst the Greeks; Rabelais, Marot and d'Urfe, amongst the French; Tasso, Ariosto and Boccaccio, amongst the Italians.

He married, in compliance with the wishes of his family, a beautiful, witty and chaste woman, who drove him to despair.

He was sought after and cherished by all distinguished men of letters. But it was two Ladies who kept him from experiencing the pangs of poverty.

La Fontaine, if there remain anything of thee, and if it be permitted to thee for a moment to soar above all time; see the names of La Sabliere and of Hervard pass with thine to the ages to come!

The life of La Fontaine was, so to speak, only one of continual distraction. In the midst of society, he was absent from it. Regarded almost as an imbecile by the crowd, this clever author, this amiable man, only permitted himself to be seen at intervals and by friends.

He had few books and few friends.

Amongst a large number of works that he has left, everyone knows his fables and his tales, and the circumstances of his life are written in a hundred places.

He died on the 16th of March, 1695.

Let us keep silence about his last moments, for fear of irritating those who never forgive.

His fellow-citizens honour him in his posterity to this day.

Long after his death, foreigners went to visit the room which he had occupied.

Once a year, I shall go to visit his tomb.

On that day, I shall tear up a fable of La Mothe, a tale of Vergier, or several of the best pages of Grecourt.

He was buried in the cemetery of Saint-Joseph, by the side of Moliere.

That spot will always be held sacred by poets and people of taste.

I had resolved not to consent to the printing of these Tales, until after

I had joined to them those of Boccaccio, which are those most to my taste;

but several persons have advised me to produce at once what I have

remaining of these trifles, in order to prevent from cooling the curiosity

to see them, which is still in its first ardour. I gave way to this advice

without much difficulty, and I have thought well to profit by the

occasion. Not only is that permitted me, but it would be vanity on my part

to despise such an advantage. It has sufficed me to wish that no one

should be imposed upon in my favour, and to follow a road contrary to that

of certain persons, who only make friends in order to gain voices in their

favour by their means; creatures of the Cabal, very different from that

Spaniard who prided himself on being the son of his own works. Although I

may still be as much in want of these artifices as any other person, I

cannot bring myself to resolve to employ them; however I shall accommodate

myself if possible to the taste of the times, instructed as I am by my own

experience, that there is nothing which is more necessary. Indeed one

cannot say that all seasons are suitable for all classes of books. We have

seen the Roundelays, the Metamorphoses, the Crambos, reign one after

another. At present, these gallantries are out of date and nobody cares

about them: so certain is it that what pleases at one time may not please

at another! It only belongs to works of truly solid merit and sovereign

beauty, to be well received by all minds and in all ages, without

possessing any other passport than the sole merit with which they are

filled. As mine are so far distant from such a high degree of perfection,

prudence advises that I should keep them in my cabinet unless I choose

well my own time for producing them. This is what I have done, or what I

have tried to do in this edition, in which I have only added new Tales,

because it seemed to me that people were prepared to take pleasure in

them. There are some which I have extended, and others which I have

abridged, only for the sake of diversifying them and making them less

tedious. But I am occupying myself over matters about which perhaps people

will take no notice, whilst I have reason to apprehend much more important

objections. There are only two principal ones which can be made against

me; the one that this book is licentious; the other that it does not

sufficiently spare the fair sex. With regard to the first, I say boldly

that the nature of what is understood as a tale decided that it should be

so, it being an indispensable law according to Horace, or rather according

to reason and common sense, that one must conform one's self to the nature

of the things about which one writes. Now, that I should be permitted to

write about these as so many others have done and with success I do not

believe it can be doubted; and people cannot condemn me for so doing,

without also condemning Ariosto before me and the Ancients before Ariosto.

It may be said that I should have done better to have suppressed certain

details, or at least to have disguised them. Nothing was more easy, but it

would have weakened the tale and taken away some of its charm: So much

circumspection is only necessary in works which promise great discretion

from the beginning, either by their subject or by the manner in which they

are treated. I confess that it is necessary to keep within certain limits,

and that the narrowest are the best; also it must be allowed me that to be

too scrupulous would spoil all. He who would wish to reduce Boccaccio to

the same modesty as Virgil, would assuredly produce nothing worth having,

and would sin against the laws of propriety by setting himself the task to

observe them. For in order that one may not make a mistake in matters of

verse and prose, extreme modesty and propriety are two very different

things. Cicero makes the latter consist in saying what is appropriate one

should say, considering the place, the time, and the persons to whom one

is speaking. This principle once admitted, it is not a fault of judgment

to entertain the people of to-day with Tales which are a little broad.

Neither do I sin in that against morality. If there is anything in our

writings which is capable of making an impression on the mind, it is by no

means the gaiety of these Tales; it passes off lightly; I should rather

fear a tranquil melancholy, into which the most chaste and modest novels

are very capable of plunging us, and which is a great preparation for

love. As to the second objection, by which people reproach me that this

book does wrong to womankind, they would be right if I were speaking

seriously: but who does not see that this is all in jest, and consequently

cannot injure? We must not be afraid on that account that marriages in the

future will be less frequent, and husbands more on their guard. It may

still be objected that these Tales are unfounded or that they have

everywhere a foundation easy to destroy; in short that they are

absurdities and have not the least tinge of probability. I reply in a few

words that I have my authorities: and besides it is neither truth nor

probability which makes the beauty and the charm of these Tales: it is

only the manner of telling them. These are the principal points on which I

have thought it necessary to defend myself. I abandon the rest to the

censors; the more so as it would be an infinite undertaking to pretend to

reply to all. Criticism never stops short nor ever wants for subjects on

which to exercise itself: even if those I am able to foresee were taken

from it, it would soon have discovered others.

IN Lombardy's fair land, in days of yore,

Once dwelt a prince, of youthful charms, a store;

Each FAIR, with anxious look, his favours sought,

And ev'ry heart within his net was caught.

Quite proud of beauteous form and smart address,

In which the world was led to acquiesce,

He cried one day, while ALL attention paid,

I'll bet a million, Nature never made

Beneath the sun, another man like me,

Whose symmetry with mine can well agree.

If such exist, and here will come, I swear

I'll show him ev'ry lib'ral princely care.

A noble Roman, who the challenge heard,

This answer gave the king his soul preferr'd

—Great prince, if you would see a handsome man,

To have my brother here should be your plan;

A frame more perfect Nature never gave;

But this to prove, your courtly dames I crave;

May judge the fact, when I'm convinc'd they'll find:

Like you, the youth will please all womankind;

And since so many sweets at once may cloy,

'Twere well to have a partner in your joy.

THE king, surpris'd, expressed a wish to view

This brother, form'd by lines so very true;

We'll see, said he, if here his charms divine

Attract the heart of ev'ry nymph, like mine;

And should success attend our am'rous lord,

To you, my friend, full credit we'll accord.

AWAY the Roman flew, Joconde to get,

(So nam'd was he in whom these features met;)

'Midst woods and lawns, retir'd from city strife,

And lately wedded to a beauteous wife;

If bless'd, I know not; but with such a fair,

On him must rest the folly to despair.

THE Roman courtier came, his business told

The brilliant offers from the monarch bold;

His mission had success, but still the youth

Distraction felt, which 'gan to shake his truth;

A pow'rful monarch's favour there he view'd;

A partner here, with melting tears bedew'd;

And while he wavered on the painful choice,

She thus address'd her spouse with plaintive voice:

CAN you, Joconde, so truly cruel prove,

To quit my fervent love in courts to move?

The promises of kings are airy dreams,

And scarcely last beyond the day's extremes

By watchful, anxious care alone retain'd,

And lost, through mere caprice, as soon as gain'd.

If weary of my charms, alas! you feel,

Still think, my love, what joys these woods conceal;

Here dwell around tranquillity and ease;

The streams' soft murmurs, and the balmy breeze,

Invite to sleep; these vales where breathe the doves,

All, all, my dear Joconde, renew our loves;

You laugh!—Ah! cruel, go, expose thy charms,

Grim death will quickly spare me these alarms!

JOCONDE'S reply our records ne'er relate,

Nor what he did, nor how he left his mate;

And since contemp'raries decline the task;

'Twere folly, such details of me to ask.

We're told, howe'er, when ready to depart,

With flowing tears she press'd him to her heart;

And on his arm a brilliant bracelet plac'd,

With hair around her picture nicely trac'd;

This guard in full remembrance of my love,

She cried;—then clasped her hands to pow'rs above.

TO see such dire distress, and poignant grief,

Might lead to think, soon death would bring relief;

But I, who know full well the female mind,

At best oft doubt affliction of the kind.

JOCONDE set out at length; but that same morn;

As on he mov'd, his soul with anguish torn,

He found the picture he had quite forgot,

Then turn'd his steed, and back began to trot.

While musing what excuse to make his mate,

At home he soon arriv'd, and op'd the gate;

Alighted unobserv'd, ran up the stairs;

And ent'ring to the lady unawares,

He found this darling rib, so full of charms;

Intwin'd within a valet's brawny arms!

'MIDST first emotions of the husband's ire;

To stab them while asleep he felt desire;

Howe'er, he nothing did; the courteous wight;

In this dilemma, clearly acted right;

The less of such misfortunes said is best;

'Twere well the soul of feeling to divest;

Their lives, through pity, or prudential care;

With much reluctance, he was led to spare;

Asleep he left the pair, for if awake,

In honour, he a diff'rent step would take.—

Had any smart gallant supplied my place,

Said he, I might put up with this disgrace;

But naught consoles the thought of such a beast;

Dan Cupid wantons, or is blind at least;

A bet, or some such whim, induc'd the god,

To give his sanction to amours so odd.

THIS perfidy Joconde so much dismay'd;

His spirits droop'd, his lilies 'gan to fade;

No more he look'd the charmer he had been;

And when the court's gay dames his face had seen;

They cried, Is this the beauty, we were told,

Would captivate each heart, or young or old?

Why, he's the jaundice; ev'ry view displays

The mien of one,—just fasted forty days!

WITH secret pleasure, this, Astolphus learn'd;

The Roman, for his brother, risks discern'd,

Whose secret griefs were carefully conceal'd,

(And these Joconde could never wish reveal'd;)

Yet, spite of gloomy looks and hollow eyes,

His graceful features pierc'd the wan disguise,

Which fail'd to please, alone through want of life,

Destroy'd by thinking on a guilty wife.

THE god of love, in pity to our swain,

At last revok'd BLACK CARE'S corroding reign;

For, doubtless, in his views he oft was cross'd,

While such a lover to the world was lost.

THE hero of our tale, at length, we find

Was well rewarded: LOVE again proved kind;

For, musing as he walk'd alone one day,

And pass'd a gall'ry, (held a secret way,)

A voice in plaintive accents caught his ear,

And from the neighb'ring closet came, 'twas clear:

My dear Curtade, my only hope below,

In vain I love;—you colder, colder grow;

While round no fair can boast so fine a face,

And numbers wish they might supply thy place,

Whilst thou with some gay page prefer'st a bet,

Or game of dice with some low, vulgar set,

To meeting me alone; and when just now

To thee I sent, with rage thou knit'st thy brow,

And Dorimene, with ev'ry curse abus'd

Then played again, since better that amus'd,

And left me here, as if not worth a thought,

Or thou didst scorn what I so fondly sought.

ASTONISHMENT, at once, our Roman seiz'd;

But who's the fair that thus her bosom eas'd?

Or, who's the gay Adonis, form'd to bless?

You'd try a day, and not the secret guess,

The queen's the belle:—and, doubtless you will stare,

The king's own dwarf the idol of her care!

THE Roman saw a crevice in the wood,

Through which he took a peep from where he stood;

To Dorimene our lovers left the key,

Which she had dropt when lately forc'd to flee,

And this Joconde pick'd up, a lucky hit,

Since he could use it when he best thought fit.

It seems, said he, I'm not alone in name,

And since a prince so handsome is the same,

Although a valet has supplied my place,

Yet see, the queen prefers a dwarf's embrace.

THIS thought consol'd so well,—his youthful rays

Returned, and e'en excelled his former days;

And those who lately ridicul'd his charms,

Now anxious seem'd to revel in his arms

'Twas who could have him,—even prudes grew kind;—

By many belles Astolphus was resign'd;

Though still the king retain'd enough, 'twas seen;—

But now let us resume the dwarf and queen.

OUR Roman, having satisfied his eyes,

At length withdrew, confounded by surprise.

Who follows courts, must oft with care conceal,

And scarcely know what sight and ears reveal.

YET, by Joconde the king was lov'd so well,

What now he'd seen he greatly wish'd to tell;

But, since to princes full respect is due,

And what concerns them, howsoever true,

If thought displeasing, should not be dispos'd

In terms direct, but obviously dispos'd,

To catch the mind, Joconde at ease detail'd,

From days of yore to those he now bewail'd,

The names of emp'rors and of kings, whose brows,

By wily wives, were crown'd with leafless boughs!

And who, without repining, view'd their lot,

Nor bad made worse, but thought things best forgot.

E'en I, who now your majesty address,

Continued he, am sorry to confess,

The very day I left my native earth,

To wait upon a prince of royal birth,

Was forced t'acknowledge cuckoldom among

The gods who rule the matrimonial throng,

And sacrifice thereto with aching heart

Cornuted heads dire torments oft impart:

THE tale he then detail'd, that rais'd his spleen;

And what within the closet he had seen;

The king replied, I will not be so rude,

To question what so clearly you have view'd;

Yet, since 'twere better full belief to gain,

A glimpse of such a fact I should obtain,

Pray bring me thither; instantly our wight;

Astolphus led, where both his ears and sight

Full proof receiv'd, which struck the prince with awe;

Who stood amaz'd at what he heard and saw.

But soon reflection's all-convincing pow'r

Induced the king vexation to devour;

True courtier-like, who dire misfortunes braves,

Feels sprouting horns, yet smiles at fools and knaves:

Our wives, said he, a pretty trick have play'd,

And shamefully the marriage bed betray'd;

Let us the compliment return, my friend,

And round the country our amours extend;

But, in our plan the better to succeed,

Our names we'll change; no servants we shall need;—

For your relation I desire to pass,

So you'll true freedom use; then with a lass

We more at ease shall feel, more pleasure gain;

Than if attended by my usual train.

JOCONDE with joy the king's proposal heard;

On which the latter with his friend conferr'd;

Said he, 'twere surely right to have a book,

In which to place the names of those we hook,

The whole arrang'd according to their rank,

And I'll engage no page remains a blank,

But ere we leave the range of our design,

E'en scrup'lous dames shall to our wish incline,

Our persons handsome, with engaging air,

And sprightly, brilliant wit no trifling share,—

'Twere strange, possessing such engaging charms,

They should not tumble freely in our arms.

THE baggage ready, and the paper-book,

our smart gallants the road together took,

But 'twould be vain to number their amours;

With beauties, Cupid favoured them by scores;

Blessed, if only seen by either swain,

And doubly bless'd who could attention gain:

Nor wife of alderman, nor wife of mayor,

Of justice, nor of governor was there,

Who did not anxiously desire her name

Might straight be entered in the book of fame!

Hearts, which before were thought as cold as ice,

Now warm'd at once and melted in a trice.

SOME infidel, I fancy, in my ear

Would whisper-probabilities, I fear,

Are rather wanting to support the fact;

However perfectly gallants may act,

To gain a heart requires full many a day

If more be requisite I cannot say;

'Tis not my plan to dupe or young or old,

But such to me, howe'er the tale is told,

And Ariosto never truth forsakes;

Yet, if at ev'ry step a writer takes,

He's closely question'd as to time and place,

He ne'er can end his work with easy grace.

To those, from whom just credence I receive,

Their tales I promise fully to believe.

AT length, when our advent'rers round had play'd,

And danc'd with ev'ry widow, wife, and maid,

The full blown lily and the tender rose,

Astolphus said, though clearly I suppose,

We can as many hearts securely link,

As e'er we like, yet better now, I think,

To stop a while in some delightful spot,

And that before satiety we've got;

For true it is, with love as with our meat;

If we, variety of dishes eat,

The doctors tell us inj'ry will ensue,

And too much raking none can well pursue.

Let us some pleasing fair-one then engage,

To serve us both:—enough she'll prove I'll wage.

JOCONDE at once replied, with all my heart,

And I a lady know who'll take the part;

She's beautiful; possesses store of wit;

And is the wife of one above a cit.

WITH such to meddle would be indiscreet,

Replied the king, more charms we often meet,

Beneath a chambermaid or laundress' dress,

Than any rich coquette can well possess.

Besides, with those, less form is oft requir'd,

While dames of quality must be admir'd;

Their whims complied with, though suspicions rise;

And ev'ry hour produces fresh surprise,

But this sweet charmer of inferior birth

A treasure proves; a source of bliss on earth.

No trouble she to carry here nor there;

No balls she visits, and requires no care;

The conquest easy, we may talk or not;

The only difficulty we have got,

Is how to find one, we may faithful view;

So let us choose a girl, to love quite new.

SINCE these, replied the YOUTH, your thoughts appear,

What think you of our landlord's daughter here?

That she's a perfect virgin I've no doubt,

Nor can we find a chaster round about;

Her very doll more innocent won't prove,

Than this sweet nymph design'd with us to move.

THE scheme our prince's approbation met;

The very girl, said he, I wish'd to get;

This night be our attack; and if her heart

Surrenders when our wishes we impart,

But one perplexity will then remain;

'Tis who her virgin favours shall obtain?

The honour 's all a whim, and I, as king,

At once assuredly should claim this thing:

The rest 'tis very easy to arrange;

As matters suit we presently can change.

IF ceremony 'twere, Joconde replied,

All cavil then we quickly could decide;

Precedence would no doubt with you remain:

But this is quite another case 'tis plain;

And equity demands that we agree,

By lot to settle which the man shall be.

THE noble youths no arguments would spare,

And each contended for the spoiler's care;

Howe'er Joconde obtained the lucky hit,

And first embrac'd this fancied dainty bit.

THE girl who was the noble rival's aim,

That ev'ning to the room for something came;

Our heroes gave her instantly a chair,

And lavished praises on her face and hair;

A diamond ring soon sparkled in her eyes;

Its pleasing pow'rs at sight obtain'd the prize.

THE bargain made, she, in the dead of night,

When silence reign'd and all was void of light,

With careful steps their anxious wish obey'd,

And 'tween them both, she presently was laid;

'Twas Paradise they thought, where all is nice,

And our young spark believ'd he broke the ice.

THE folly I forgive him;—'tis in vain

On this to reason—idle to complain;

The WISE have oft been dup'd it is confest,

And Solomon it seems among the rest.

But gay Joconde felt nothing of the kind,

A secret pleasure glow'd within his mind;

He thought Astolphus wond'rous bliss had missed,

And that himself alone the fair had kiss'd;

A clod howe'er, who liv'd within the place,

Had, prior to the Roman, her embrace.

THE soft amour extended through the night,

The girl was pleas'd, and all proceeded right;

The foll'wing night, the next, 'twas still the same;

Young Clod at length her coldness 'gan to blame;

And as he felt suspicious of the act,

He watch'd her steps and verified the fact:

A quarrel instantly between them rose;

Howe'er the fair, his anger to compose,

And favour not to lose, on honour vow'd,

That when the sparks were gone, and time allow'd,

She would oblige his craving, fierce desire;—

To which the village lad replied with ire:—

Pray what care I for any tavern guest,

Of either sex; to you I now protest,

If I be not indulg'd this very night,

I'll publish your amours in mere despite.

HOW can we manage it, replied the belle,

I'm quite distressed—indeed the truth to tell,

I've promis'd them this night to come again,

And if I fail, no doubt can then remain,

But I shall lose the ring, their pledg'd reward,

Which would, you know for me, be very hard.

TO you I wish the ring, replied young Clod,

But do they sleep in bed, or only nod?

Tell me, pray; oh, said she, they sleep most sound;

But then between them plac'd shall I be found,

And while the one amidst Love's frolicks sports,

The other quiet lies, or Morpheus courts.

On hearing this the rustick lad proposed,

To visit her when others' eyes were closed.

Oh! never risk it, quickly she replied;

'Twere folly to attempt it by their side.

He answer'd, never fear, but only leave

The door ajar, and me they'll not perceive.

THE door she left exactly as he said;

The spark arriv'd, and then approach'd the bed,

('Twas near the foot,) then 'tween the sheets he slid,

But God knows how he lay, or what he did.

Astolphus and Joconde ne'er smelt a rat,

Nor ever dreamt of what their girl was at,

At length when each had turn'd and op'd his eyes,

Continual movement fill'd him with surprise.

The monarch softly said:—why how is this?

My friend has eaten something, for in bliss,

He revels on, and truly much I fear,

His health will show, it may be bought too dear.

THIS very sentiment Joconde bethought;

But Clod a breathing moment having caught,

Resum'd his fun, and that so oft would seek:

He gratified his wishes for a week;

Then watching carefully, he found once more;

Our noble heroes had begun to snore,

On which he slyly took himself away,

The road he came, and ere 'twas break of day;

The girl soon follow'd, since she justly fear'd,

Still more fatigues:—so off she quickly steer'd,

AT length when both the nobles were awake;

Astolphus said, my friend you rest should take,

'Twere better till to-morrow keep in bed,

Since sleep, with such fatigues, of course has fled:

You talk at random, cried the Roman youth;

More rest I fancy you require in truth;

You've led a pretty life throughout the night;

I? said the king; why I was weary quite,

So long I waited; you no respite gave,

But wholly seem'd our little nymph t' enslave;

At length to try if I from rage could keep,

I turn'd my back once more, and went to sleep.

If you had willingly the belle resign'd,

I was, my friend, to take a turn inclin'd;

That had sufficed for me, since I, like you,

Perpetual motion never can pursue.

YOUR raillery, the Roman youth replied,

Quite disconcerted, pray now lay aside,

And talk of something else; you've fully shown,

That I'm your vassal, and since you are grown

So fond that you to keep the girl desire,

E'en wholly to yourself, why I'll retire;

Do with her what you please, and we shall see,

How long this furor will with you agree.

IT may, replied the king, for ever last,

If ev'ry night like this, I'm doom'd to fast.

SIRE, said Joconde, no longer let us thus,

In terms of playful raillery discuss;

Since such your pleasure, send me from your view;

On this the youthful monarch angry grew,

And many words between the friends arose;

The presence of the nymph Astolphus chose;

To her they said, between us judge, sweet fair,

And every thing was stated then with care.

THE girl with blushing cheeks before them kneel'd,

And the mysterious tale at once reveal'd.

Our heroes laugh'd; the treach'ry vile excus'd;

And gave the ring, which much delight diffus'd;

Together with a handsome sum of gold,

Which soon a husband in her train enroll'd,

Who, for a maid, the pretty fair-one took;

And then our heroes wand'ring pranks forsook,

With laurels cover'd, which in future times,

Will make them famous through the Western climes;

More glorious since, they only cost, we find,

Those sweet ATTENTIONS pleasing to the MIND.

So many conquests proud of having made,

And over full the BOOK of—those who'd play'd;

Said gay Astolphus we will now, my friend,

Return the shortest road and poaching end;

If false our mates, yet we'll console ourselves,

That many others have inconstant elves.

Perhaps, in things a change will be one day,

And only tender flames LOVE'S torch display;

But now it seems some evil star presides,

And Hymen's flock the devil surely rides.

Besides, vile fiends the universe pervade,

Whose constant aim is mortals to degrade,

And cheat us to our noses if they can,

(Hell's imps in human shape, disgrace to man!)

Perhaps these wretches have bewitch'd our wives,

And made us fancy errors in their lives.

Then let us like good citizens, our days

In future pass amidst domestick ways;

Our absence may indeed restore their hearts,

For jealousy oft virtuous truths imparts.

IN this Astolphus certainly believ'd;

The friends return'd, and kindly were receiv'd;

A little scolding first assail'd the ear;

But blissful kisses banish'd ev'ry fear.

To balls and banquets ALL themselves resigned;

Of dwarf or valet nothing more we find;

Each with his wife contentedly remained:—

'Tis thus alone true happiness is gained.

SOME time ago from Rome, in smart array,

A younger brother homeward bent his way,

Not much improved, as frequently the case

With those who travel to that famous place.

Upon the road oft finding, where he stayed,

Delightful wines, and handsome belle or maid,

With careless ease he loitered up and down.—

One day there passed him in a country town,

Attended by a page, a lady fair,

Whose charming form and all-engaging air,

At once his bosom fired with fond desire;

And nearer still, her beauties to admire.

He most gallantly saw her safely home;

Attentions charm the sex where'er we roam.

OUR thoughtless rambler pleasures always sought:

From Rome this spark had num'rous pardons brought;

But,—as to virtues (this too oft we find),

He'd left them,—with his HOLINESS behind!

THE lady was, by ev'ry one, confessed,

Of beauty, youth, and elegance possessed;

She wanted naught to form her bliss below,

But one whose love would ever fondly flow.

INDEED so fickle proved this giddy youth,

That nothing long would please his heart or tooth;

Howe'er he earnestly inquired her name,

And ev'ry other circumstance the same.

She's lady, they replied, to great 'squire Good,

Who's almost bald from age 'tis understood;

But as he's rich, and high in rank appears,

Why that's a recompense you know for years.

THESE facts our young gallant no sooner gained,

But ardent hopes at once he entertained;

To wily plots his mind he quickly bent,

And to a neighb'ring town his servants sent;

Then, at the house where dwelled our noble 'squire,

His humble services proposed for hire.

PRETENDING ev'ry sort of work he knew,

He soon a fav'rite with old Square-toes grew,

Who (first advising with his charming mate),

Chief falc'ner made him o'er his fine estate.

THE new domestick much the lady pleased;

He watched and eagerly the moment seized,

His ardent passion boldly to declare,

In which he showed a novice had no share.

'TWAS managed well, for nothing but the chase,

Could Square-toes tempt to quit her fond embrace,

And then our falc'ner must his steps attend:—

The very time he wished at home to spend.

The lady similar emotions showed;

For opportunity their bosoms glowed;

And who will feel in argument so bold,

When this I say, the contrary to hold?

At length with pity Cupid saw the case,

And kindly lent his aid to their embrace.

ONE night the lady said, with eager eyes,

My dear, among our servants, which d'ye prize,

For moral conduct most and upright heart?

To this her spouse replied, the faithful part

Is with the falc'ner found, I must decide:

To him my life I'd readily confide.

THEN you are wrong, said she,—most truly so,

For he's a good-for-nothing wretch I know;

You'll scarcely credit it, but t'other day,

He had the barefaced impudence to say,

He loved me much, and then his passion pressed:

I'd nearly fallen, I was so distressed.

To tear his eyes out, I designed at first,

And e'en to choke this wretch, of knaves the worst;

By prudence solely was I then restrained,

For fear the world should think his point was gained.

THE better then to prove his dark intent,

I feigned an inclination to consent,

And in the garden, promised as to-night,

I'd near the pear-tree meet this roguish wight.

Said I, my husband never moves from hence;

No jealous fancy, but to show the sense

He entertains of my pure, virtuous life,

And fond affection for a loving wife.

Thus circumstanced, your wishes see are vain,

Unless when he's asleep a march I gain,

And softly stealing from his torpid side,

With trembling steps I, to my lover, glide.

So things remain, my dear; an odd affair:—

On this Square-toes 'gan to curse and swear;

But his fond rib most earnestly besought,

His rage to stifle, as she clearly thought,

He might in person, if he'd take the pain,

Secure the rascal and redress obtain

You know, said she, the tree is near the door,

Upon the left and bears of fruit great store;

But if I may my sentiments express,

In cap and petticoats you'd best to dress;

His insolence is great, and you'll be right,

To give your strokes with double force to night;

Well work his back; flat lay him on the ground:—

A rascal! honourable ladies round,

No doubt he many times has served the same;

'Tis such impostors characters defame.

To rouse his wrath the story quite sufficed;

The spouse resolved to do as she advised.

Howe'er to dupe him was an easy lot;

The hour arrived, his dress he soon had got,

Away he ran with anxious fond delight.

In hopes the wily spark to trap that night.

But no one there our easy fool could see,

And while he waited near the fav'rite tree,

Half dead with cold, the falc'ner slyly stole,

To her who had so well contrived the whole;

Time, place, and disposition, all combined

The loving pair to mutual joys resigned.

When our expert gallant had with the dame,

An hour or more indulged his ardent flame,

Though forced at length to quit the loving lass,

'Twas not without the favourite parting glass;

He then the garden sought, where long the 'squire,

Upon the knave had wished to vent his ire.

NO sooner he the silly husband spied,

But feigning 'twas the wily wife he eyed,

At once he cried,—ah, vilest of the sex!

Are these thy tricks, so good a man to vex?

Oh shame upon thee! thus to treat his love,

As pure as snow, descending from above.

I could not think thou hadst so base a heart,

But clear it is, thou need'st a friendly part,

And that I'll act: I asked this rendezvous

With full intent to see if thou wert true;

And, God be praised, without a loose design,

To plunge in luxuries pronounced divine.

Protect me Heav'n! poor sinner that I'm here!

To guard thy honour I will persevere.

My worthy master could I thus disgrace?

Thou wanton baggage with unblushing face,

Thee on the spot I'll instantly chastise,

And then thy husband of the fact advise.

THE fierce harangue o'er Square-toes pleasure spread,

Who, mutt'ring 'tween his teeth, with fervour said:

O gracious Lord! to thee my thanks are due—

To have a wife so chaste—a man so true!

But presently he felt upon his back

The falc'ner's cudgel vigorously thwack,

Who soundly basted him as on he ran,

To gain the house, with terror, pale and wan.

THE squire had wished his trusty man, no doubt,

Had not, at cudgelling, been quite so stout;

But since he showed himself so true a friend,

And with his actions could such prudence blend,

The master fully pardoned what he knew,

And quickly to his wife in bed he flew,

When he related every thing that passed

Were we, cried he, a hundred years to last,

My lovely dear, we ne'er on earth could find

A man so faithful, and so well inclined.

I'd have him take within our town a wife,

And you and I'll regard him during life.

In that, replied the lady, we agree,

And heartily thereto I pledged will be.

WHEN Francis (named the first) o'er Frenchmen reign'd,

In Italy young Arthur laurels gained,

And oft such daring valour showed in fight,

With ev'ry honour he was made a knight;

The monarch placed the spur upon his heel,

That all around his proper worth might feel.

Then household deities at home he sought,

Where—not at prayers his beauteous dame he caught:

He'd left her, truly, quite dissolv'd in tears;

But now the belle had bid adieu to fears;

And oft was dancing joyously around,

With all the company that could be found.

GALLANTS in crowds Sir Arthur soon perceived;

At sight of these the knight was sorely grieved;

And, turning in his mind how best to act;

Cried he, Can this be truly held a fact,

That I've been worthy while I'd fame in view,

Of cuckoldom at home, and knighthood too?

It ought to be but half:—the truth let's know;

From constancy the purest blessings flow.

Then like a father-confessor he dressed,

And took his seat where priests their flock confessed.

His lady absolution sought that day,

And on her knees before him 'gan to pray;

The minor sins were told with downcast eyes,

And then for hearing those of larger size,

The husband-confessor prepared his ears:—

Said she, Good father, ('mid a flood of tears),

My bed receives, (the fault I fear's not slight,)

A gentleman, a parson, and a knight.

Still more had followed, but, by rage o'ercome,

Sir Arthur cut the thread, and she was mum;

Though, doubtless, had the fair been let proceed,

Quite long her Litany had been decreed.

THe husband, in a rage, exclaimed, thou jade,

A parson, say'st thou? t'whom dost think thou'st made

This curst confession?—To my spouse, cried she,

I saw you enter here, and came with glee,

Supposing you'd a trick to raise surprise;

Howe'er 'tis strange that one so very wise,

The riddle should not fully comprehend:—

A KNIGHT, the king created you, my friend;

A GENTLEMAN, your rank was long ago;

A PARSON, you have made yourself you know.

Goon heav'ns! exclaimed the knight, 'tis very clear,

And I a blockhead surely must appear.

WE'RE told, that once a cobbler, BLASE by name;

A wife had got, whose charms so high in fame;

But as it happened, that their cash was spent,

The honest couple to a neighbour went,

A corn-factor by trade, not overwise

To whom they stated facts without disguise;

And begged, with falt'ring voice denoting care,

That he, of wheat, would half a measure spare,

Upon their note, which readily he gave,

And all advantages desired to wave.

THE time for payment came; the money used;

The cash our factor would not be refused;

Of writs he talked, attorneys, and distress;

The reason:—heav'n can tell, and you may guess;

In short, 'twas clear our gay gallant desired,

To cheer the wife, whose beauty all admired.

SAID he, what anxiously I wish to get,

You've plenty stored, and never wanted yet;

You surely know my meaning?—Yes, she cried;

I'll turn it in my mind, and we'll decide

How best to act. Away she quickly flew,

And Blase informed, what Ninny had in view.

Zounds! said the cobbler, we must see, my dear,

To hook this little sum:—the way is clear;

No risk I'm confident; for prithee run

And tell him I've a journey just begun;

That he may hither come and have his will;

But 'ere he touch thy lips, demand the bill;

He'll not refuse the boon I'm very sure;

Meantime, myself I'll hide and all secure.

The note obtained, cough loudly, strong, and clear;

Twice let it be, that I may plainly hear;

Then forth I'll sally from my lurking place,

And, spite of folly's frowns, prevent disgrace.

THE plot succeeded as the pair desired;

The cobbler laughed, and ALL his scheme admired:

A purse-proud cit thereon observed and swore;

'Twere better to have coughed when all was o'er;

Then you, all three, would have enjoyed your wish,

And been in future all as mute as fish.

OH! sir, replied the cobbler's wife at ease,

Do you suppose that use can hope to please,

And like your ladies full of sense appear?

(For two were seated with his wedded dear;)

Perhaps my lady 'd act as you describe,

But ev'ry one such prudence don't imbibe.

ONCE on a time, as hist'ry's page relates,

A lord, possessed of many large estates,

Was angry with a poor and humble clod,

Who tilled his grounds and feared his very nod.

Th' offence (as often happens) was but small,

But on him, vowed the peer, his rage should fall—

Said he, a halter, rascal, you deserve;

You'll never from the gallows-turnpike swerve:

Or, soon or late you swinging will be found

Who, born for hanging, ever yet was drowned?

Howe'er you'll smile to hear my lenient voice;

Observe, three punishments await your choice;

Take which you will.—The first is, you shall eat,

Of strongest garlick, thirty heads complete;

No drink you'll have between, nor sleep, nor rest;

You know a breach of promise I detest.

Or, on your shoulders further I propose,

To give you, with a cudgel, thirty blows.

Or, if more pleasing, that you truly pay,

The sum of thirty pounds without delay.

THE peasant 'gan to turn things in his mind:—

Said he, to take the heads I'm not inclined;

No drink, you say, between; that makes it worse;

To eat the garlick thus, would prove a curse.

Nor can I suffer on my tender back,

That, with a cudgel, thirty blows you thwack.

Still harder thirty pounds to pay appeared;

Uncertain how to act, he hanging feared.

The noble peer he begged, upon his knees,

His penitence to hear, and sentence ease.

But mercy dwelled not with the angry lord

Is this, cried he, the answer?—bring a cord.

The peasant, trembling lest his life was sought;

The garlick chose, which presently was brought.

UPON a dish my lord the number told;

Clod no way liked the garlick to behold.

With piteous mien the garlick head he took,

Then on it num'rous ways was led to look,

And grumbling much, began to spit and eat,

just like a cat with mustard on her meat,

To touch it with his tongue he durst not do;

He knew not how to act or what pursue.

The peer, delighted at the man's distress,

The garlick made him bite, and chew, and press,

Then gulp it down as if delicious fare;

The first he passed; the second made him swear;

The third he found was every whit as sad,

He wished the devil had it, 'twas so bad.

In short, when at the twelfth our wight arrived,

He thought his mouth and throat of skin deprived.

Said he, some drink I earnestly intreat;

What, Greg'ry, cried my lord, dost feel a heat;

In thy repasts dost love to wet thy jaws?

Well! well! I won't object; thou know'st my laws;

Much good may't do thee; here, some wine, some wine!

Yet recollect, to drink, since you design,

That afterward, my friend, you'll have to choose

The thirty blows, or thirty pounds to lose.

But, cried the peasant, I sincerely pray,

Your lordship's goodness, that the garlick may

Be taken in the account, for as to pelf,

Where can an humble lab'rer, like myself,

Expect the sum of thirty pounds to seize?

Then, said the peer, be cudgelled if you please;

Take thirty thwacks; for naught the garlick goes.

To moisten well his throat, and ease his woes,

The peasant drank a copious draught of wine,

And then to bear the cudgel would resign.

A SINGLE blow he patiently endured;

The second, howsoe'er, his patience cured;

The third was more severe, and each was worse;

The punishment he now began to curse;

Two lusty wights, with cudgels thrashed his back

And regularly gave him thwack and thwack;

He cried, he roared, for grace he begged his lord,

Who marked each blow, and would no ease accord;

But carefully observed, from time to time,

That lenity he always thought sublime;

His gravity preserved; considered too

The blows received and what continued due.

AT length, when Greg'ry twenty strokes had got,

He piteously exclaimed:—if more's my lot

I never shall survive! Oh! pray forgive,

If you desire, my lord, that I should live.

Then down with thirty pounds, replied the peer,

Since you the blows so much pretend to fear;

I'm sorry for you; but if all the gold

Be not prepared, your godfather, I'm told,

Can lend a part; yet, since so far you've been,

To flinch the rest you surely won't be seen.

THE wretched peasant to his lordship flew,

And trembling cried—'tis up! the number view!

A scrutiny was made, which nothing gained;

No choice but pay the money now remained;

This grieved him much, and o'er the fellow's face;

The dewy drops were seen to flow apace.

All useless proved:—the full demand he sent,

With which the peer expressed himself content.

Unlucky he whoe'er his lord offends!

To golden ore, howe'er, the proud man bends:

'TWAS vain that Gregory a pardon prayed;

For trivial faults the peasant dearly paid;

His throat enflamed—his tender back well beat—

His money gone—and all to make complete,

Without the least deduction for the pain,

The blows and garlick gave the trembling swain.

THE Lombard princes oft pervade my mind;

The present tale Boccace relates you'll find;

Agiluf was the noble monarch's name;

Teudelingua he married, beauteous dame,

The last king's widow, who had left no heir,

And whose dominions proved our prince's share.

No Beauty round compare could with the queen;

And ev'ry blessing on the throne was seen,

When Cupid, in a playful moment, came,

And o'er Agiluf's stable placed his flame;

There left it carelessly to burn at will,

Which soon began a muleteer to fill,

With LOVE'S all-powerful, all-consuming fire,

That naught controls, and youthful breasts desire.

THE muleteer was pleasing to the sight:

Gallant, good-humoured, airy, and polite,

And ev'ry way his humble birth belied;

A handsome person, nor was sense denied;

He showed it well, for when the youth beheld,

With eyes of love, the queen, who all excelled,

And ev'ry effort anxiously had made,

To stop the flames that would his heart invade;

When vain it proved, he took a prudent part:—

WHO can, like Cupid, manage wily art?

Whate'er stupidity we may discern,

His pupils more within a day can learn,

Than MASTERS knowledge in the schools can gain,

Though they in study should ten years remain;

The lowest clown he presently inspires,

With ev'ry tendency that love requires;

Of this our present tale's a proof direct,

And none that feel—its truths will e'er suspect:

THE am'rous muleteer his thoughts employed;

Consid'ring how his wish might be enjoyed.

Without success to certainty were brought,

Life seemed to him not worth a slender thought;

To hazard ev'ry thing; to live or die!

Possession have!—or in the grave to lie!

THE Lombard custom was, that when the king,

Who slept not with his queen, (a common thing

In other countries too), desired to greet

His royal consort, and in bed to meet,

A night-gown solely o'er his back he threw,

And then proceeded to the interview,

Knocked softly at the door, on which a fair,

Who waited on the queen with anxious care,

Allowed the prince to enter; took his light,

(Which only glimmered in the midst of night,)

Then put it out, and quickly left the room:—

A little lantern to dispel the gloom,

With waxen taper that emitted rays—

In diff'rent countries various are their ways!

OUR wily, prying, crafty muleteer,

Knew well these forms were current through the year:

He, like the king, at night himself equipped,

And to the queen's superb apartment slipped.

His face concealed the fellow tried to keep;

The waiting dame was more than half asleep;

The lover got access:—soon all was clear;

The prince's coming he had but to fear,

And, as the latter had, throughout the day,

The chase attended an extensive way,

'Twas more than probable he'd not be led,

(Since such fatigue he'd had,) to quit his bed.

PERFUMED, quite neat, and lively as a bird,

Our spark (safe entered) uttered not a word.

'Twas often customary with the king,

When state affairs, or other weighty thing,

Displeasure gave, to take of love his fill,

Yet let his tongue the while continue still.

A singularity we needs must own,

With this the wife was long familiar grown.

OUR am'rous wight more joys than one received,

If our narrator of the tale's believed;

(In bed a muleteer is worth three kings,

And value oft is found in humble things.)

The queen began to think her husband's rage

Had proved a stimulus such wars to wage,

And made him wond'rous stout in pleasure's sport,

Though all the while his thoughts were-'bout the court.

WITH perfect justice Heav'n its gifts bestows;

But equal talents all should not compose.

The prince's virtues doubtless were designed,

To take command, and govern o'er mankind.

The lawyer, points of difficulty views,

Decides with judgment, and the truth pursues.

In Cupid's scenes the muleteer succeeds:—

Each has his part:—none universal meeds.

WITH pleasures feasted, our gallant retired,

Before the morn fresh blushes had acquired.

But scarcely had he left the tender scene,

'Ere king Agiluf came to see his queen,

Who much surprise expressed, and to him said:

My dear, I know your love, but from this bed,

You'll recollect how recently you went,

And having wonders done, should be content.

For heav'n's sake, consider more your health;

'Tis dearer far to me than Croesus' wealth.

WITHIN the royal breast suspicions rose,

But nothing then the monarch would disclose.

He instantly withdrew without a word;

His sentiments to speak had been absurd,

And to the stable flew, since he believed

The circumstances, which his bosom grieved,

Whate'er mysterious doubts might then appear,

Proceeded from some am'rous muleteer.

WHEN round the dorture he began to creep,

The troop appeared as if dissolved in sleep,

And so they truly were, save our gallant,

Whose terrors made him tremble, sigh, and pant:

No light the king had got; it still was dark;

Agiluf groped about to find the spark,

Persuaded that the culprit might be known,

By rapid beating of the pulse alone.

The thought was good; to feel the prince began,

And at the second venture, found his man,

Who, whether from the pleasures he'd enjoyed,

Or fear, or dread discov'ry to avoid,

Experienced (spite of ev'ry wily art,)

At once quick beating of the pulse and heart.

In doubt how this adventure yet might end,

He thought to seem asleep would him befriend.

MEANWHILE the king, though not without much pains,

Obtained the scissors used for horses' manes.

With these, he said, I'll mark the fond gallant,

That I may know again the one I want.

THE monarch from the muleteer with care,

In front, snipt off a bulky lock of hair.

This having done, he suddenly withdrew;

But carelessly away the trophy threw;

Of which the sly gallant advantage took,

And thus the prince's subtle project shook;

For instantly began our artful spark,

His fellow servants like himself to mark.

WHEN day arrived the monarch was surprised,

To see each muleteer alike disguised;

No hair in front of either now was seen;

Why, how is this? said he: What can it mean?

Fifteen or more, if I believe my sight,

My wife has satisfied this very night.

Well! well! he'll now escape if mum he prove;

But there again I trust he ne'er shall move.

BOCCACE alone is not my only source;

T'another shop I now shall have recourse;

Though, certainly, this famed Italian wit

Has many stories for my purpose fit.

But since of diff'rent dishes we should taste;

Upon an ancient work my hands I've placed;

Where full a hundred narratives are told,

And various characters we may behold;

From life, Navarre's fair queen the fact relates;

My story int'rest in her page creates;

Beyond dispute from her we always find,

Simplicity with striking art combin'd.

Yet, whether 'tis the queen who writes, or not;

I shall, as usual, here and there allot

Whate'er additions requisite appear;

Without such license I'd not persevere,

But quit, at once, narrations of the sort;

Some may be long, though others are too short.

LET us proceed, howe'er (our plan explained:)

A pretty servant-girl a man retain'd.

She pleas'd his eye, and presently he thought,

With ease she might to am'rous sports be brought;

He prov'd not wrong; the wench was blithe and gay,

A buxom lass, most able ev'ry way.

AT dawn, one summer's morn, the spark was led

To rise, and leave his wife asleep in bed;

He sought at once the garden, where he found

The servant-girl collecting flow'rs around,

To make a nosegay for his better half,

Whose birth-day 'twas:—he soon began to laugh,

And while the ranging of the flow'rs he prais'd,

The servant's neckerchief he slyly rais'd.

Who, suddenly, on feeling of the hand,

Resistance feign'd, and seem'd to make a stand;

But since these liberties were nothing new,

They other fun and frolicks would pursue;

The nosegay at the fond gallant was thrown;

The flow'rs he kiss'd, and now more ardent grown

They romp'd and rattl'd, play'd and skipt around;

At length the fair one fell upon the ground;

Our am'rous spark advantage took of this,

And nothing with the couple seem'd amiss.

UNLUCKILY, a neighbour's prying eyes

Beheld their playful pranks with great surprise,

She, from her window, could the scene o'erlook;

When this the fond gallant observ'd, he shook;

Said he, by heav'ns! our frolicking is seen,

By that old haggard, envious, prying quean;

But do not heed it; instantly he chose

To run and wake his wife, who quickly rose;—

So much the dame he fondl'd and caress'd,

The garden walk she took at his request,

To have a nosegay, where he play'd anew

Pranks just the same as those of recent view,

Which highly gratified our lady fair,

Who felt dispos'd, and would at eve repair,

To her good neighbour, whom she bursting found,

With what she'd seen that morn upon the ground.

THE usual greetings o'er, our envious dame,

With scowling brow exclaim'd,—my dear, your fame,

I love too much not fully to detail,

What I have witnessed, and with truth bewail;

Will you continue, in your house to keep

A girl, whose conduct almost makes me weep?

Anon I'd kick her from your house, I say;

The strumpet should not stay another day.

The wife replied, you surely are deceiv'd;

An honest, virtuous creature she's believ'd.

Well, I can easily, my friend, suppose,

Rejoin'd the neighbour, whence this favour flows;

But look about, and be convinc'd, this morn

From my own window (true as you are born,)

Within the garden I your husband spi'd

And presently the servant girl I ey'd;

At one another various flow'rs they threw,

And then the minx a little graver grew.

I understand you, cried the list'ning fair;

You are deceiv'd:—myself alone was there.

NEIGHBOUR

But patience, if you please: attend I pray

You've no conception what I meant to say:

The playful fair was actively employ'd,

In plucking am'rous flow'rs—they kiss'd and toy'd.

WIFE

'Twas clearly I, howe'er, for her you took.

NEIGHBOUR

The flow'rs for bosoms quickly they forsook;

Large handfuls frequently they seem'd to grasp,

And ev'ry beauty in its turn to clasp.

WIFE

But still, why think you, friend, it was not I?

Has not your spouse with you a right to try

What freaks he likes?

NEIGHBOUR

But then, upon the ground

This girl was thrown, and never cried nor frown'd;

You laugh.—

WIFE

Indeed I do, 'twas myself.

NEIGHBOUR

A flannel petticoat display'd the elf.

WIFE

'Twas mine:

NEIGHBOUR

Be patient:—and inform me, pray,

If this were worn by you or her to-day?

There lies the point, for, if you'll me believe,

Your husband did—the most you can conceive.

WIFE

How hard of credence!—'twas myself I vow.

NEIGHBOUR

Oh! that's conclusive; I'll be silent now;

Though truly I am led to think, my eyes

Are pretty sharp, and much I feel surprise

At what you say; in fact, I would have sworn,

I saw them thus at romps this very morn;

Excuse the hint, and do not turn her off.

WIFE

Why, turn her off?—the very thought I scoff;

She serves me well.

NEIGHBOUR

And so it seems is taught;

By all means keep her then, since thus she's thought.

AS o'er their wine one day, three gossips sat,

Discoursing various pranks in pleasant chat,

Each had a loving friend, and two of these

Most clearly managed matters at their ease.

SAID one, a princely husband I have got.

A better in the world there's surely not;

With him I can adjust as humour fits,

No need to rise at early dawn, like cits,

To prove to him that two and three make four,

Or ask his leave to ope or shut the door.

UPON my word, replied another fair,

If he were mine, I openly declare,

To judge from what so pleasantly you say,

I'd make a present of him new-year's day.

For pleasure never gives me full delight,

Unless a little pain the bliss invite.

No doubt your husband moves as he is led;

Thank heav'n a different mortal claims my bed;

To take him in, great nicety we need;

But howsoe'er, at times I can succeed;

The satisfaction doubly then is felt:—

In fond emotion bosoms freely melt.

With neither of you, husband or gallant,

Would I exchange, though these so much you vaunt.

ON this, the third with candour interfer'd;

She thought that oft the god of love appear'd,

Good husbands playfully to fret and vex,

Sometimes to rally couples: then perplex;

But warmer as the conversation grew,

She, anxious that each disputant might view

Herself victorious, (or believe it so,)

Exclaim'd, if either of you wish to show

Who's in the right, with argument have done,

And let us practise some new scheme of fun,

To dupe our husbands; she who don't succeed

Shall pay a forfeit; all replied, "Agreed."

But then, continued she, we ought to take

An oath, that we will full discov'ry make,

To one another of the various facts,

Without disguising even trifling acts.

And then, good upright Macae shall decide;

Thus things arrang'd, the ladies homeward plied.

SHE, 'mong the three, who felt the most constraint

Ador'd a youth, contemporaries paint,

Well made and handsome, but with beardless chin,

Which led the pair a project to begin;

For yet no opportunity they'd found,

T' enjoy their wishes, save by stealth around;

Most ardently she sought to be at ease,

And 'twas agreed the lucky thought to seize

That like a chambermaid he should be dress'd,

And then proceed to execute the jest,

Attend upon the wily, wedded pair,

And offer services with modest air

And downcast eyes; the husband on her leer'd,

And in her favour prepossess'd appear'd,

In hopes one day, to find those pleasing charms

Resign'd in secret to his longing arms.

Such pretty cheeks and sparkling eyes he thought,

Had ne'er till then his roving fancy caught;

The girl was hir'd, but seemingly with pain,

Since PRUDENCE ultimately might complain,

That (maid and master both so very young)

'Twould not be wonderful if things went wrong.

AT first the husband inattention show'd,

And scarcely on the maid a look bestow'd;

But presently he chang'd his conduct quite,

And presents gave, with promises not slight;

At length the servant feign'd to lend an ear,

And anxious seem'd obliging to appear.

THE trap our cunning lovers having laid,

One eve this message brought the smiling maid;

My lady, sir, is ill, and rest requires,

To sleep alone to-night she much desires.

To grant the master's wish the girl was led,

And they together hurried off to bed.

THE husband 'tween the sheets himself had plac'd;

The nymph was in her petticoat, unlac'd;

When suddenly appear'd the wily wife,

And promis'd harmony was turn'd to strife.

Are these your freaks, cried she with mark'd surprise;

Your usual dish it seems then don't suffice;

You want, indeed, to have some nicer fare?

A little sooner, by the saints I swear,

You'd me a pretty trick, 'tis clear, have shown,

And doubtless, then, tit bits to keep been prone.

This, howsoe'er, to get you're not design'd,

So elsewhere you may try what you can find.

And as to you, miss Prettyface, you jade,

Good heav'ns! to think a paltry servant maid

Should rival me? I'll beat you black and blue!

The bread I eat, indeed, must be for you?

But I know better, and indeed am clear,

Not one around will fancy I appear

So void of charms, so faded, wither'd, lost,

That I should out of doors at once be tost;

But I will manage matters:—I design

This girl no other bed shall have than mine;

Then who so bold to touch her there will dare?

Come, Miss, let's to my room at once repair;

Away—your things to-morrow you can seek;

If scandal 'twould spread around, I'd wreak

My vengeance instantly, and turn you out;

But I am lenient, and desire no rout;

Perhaps your ruin may be sav'd by care;

So night and day your company I'll share;

No more my bosom then will feel dismay,

For I shall see that you no frolicks play.

ON this the trembling girl, o'ercome with fears;

Held down her head and seem'd to hide her tears;

Pick'd up her clothes and quickly stole away,

As if afraid her mistress more might say;

And hop'd to act the maid while Sol gave light,

But play at ease the fond gallant at night;

At once she fill'd two places in the house,

And thought in both the husband she should chouse,

Who bless'd his stars that he'd escap'd so well,

And sneak'd alone to rest within his cell,

While our gay, am'rous pair advantage took,

To play at will, and ev'ry solace hook,

Convinc'd most thoroughly, once lovers kiss'd,

That OPPORTUNITY should n'er be miss'd.

Here ends the trick our wily gossip play'd;

But now let's see the plot another laid.

THE second dame, whose husband was so meek,

That only from her lips the truth he'd seek,

When seated with him 'neath a pear tree's shade,

Contriv'd at ease and her arrangement made.

The story I shall presently relate;

The butler, strong, well dress'd, and full of prate:

Who often made the other servants trot,

Stood near when madam hit upon her plot,

To whom she said, I wish the fruit to taste;

On which the man prepar'd with ev'ry haste,

To climb the tree, and off the produce shook;

But while above, the fellow gave a look

Upon the ground below, and feign'd he saw

The spouse and wife—do more than kiss and paw:

The servant rubb'd his eyes, as if in doubt,

And cried: why truly, sir, if you're so stout,

That you must revel 'mid your lady's charms,

Pray elsewhere take her to your longing arms,

Where you at ease may frolick hours or days,

Without my witnessing your loving ways;

Indeed, I'm quite surprised at what I spy

In publick, 'neath a tree such pranks to try!

And, if you don't a servant's presence heed,

With decency howe'er you should proceed.

What, still go on? for shame, I say, for shame!

Pray wait till by and by; you're much to blame;

Besides, the nights are long enough you'll find;

Heav'n genial joys for privacy design'd;

And why this place, when you've nice chambers got?

What, cried the lady, says this noisy sot?

He surely dreams; Where can he learn these tales?

Come down; let's see what 'tis the fellow ails.

Down William came. How? said the master, how?

Are we at play?

WILLIAM

Not now, sir, no, not now.

HUSBAND

Why, when then, friend?

WILLIAM

While I was in the tree,

Alive, sir, flay me, if I did not see

You on the verdant lawn my lady lay,

And kiss, and toy, and other frolicks play.

WIFE

'Twere surely better if thou held'st thy tongue,

Or thou'lt a beating get before 'tis long.

HUSBAND

No, no, my dear, he's mad, and I design

The fellow in a madhouse to confine.

WILLIAM

Is't folly, pray, to see what we behold?

WIFE

What hast thou seen?

WILLIAM

What I've already told:—

My master and yourself at Cupid's game,

Or else the tree 's enchanted I proclaim.

WIFE

ENCHANTED! nonsense; such a sight to see!

HUSBAND

To know the truth myself, I'll climb the tree,

Then you the fact will quickly from me learn;

We may believe what we ourselves discern.

SOON as the master they above descried,

And that below our pair he sharply eyed,

The butler took the lady in his arms,

And grew at once familiar with her charms;

At sight of this the husband gave a yell:

Made haste to reach the ground, and nearly fell;

Such liberties he wish'd at once to stop,

Since what he'd seen had nearly made him drop.

How! how!—cried he:—what, e'en before my sight?

What can you mean? said she without affright.

HUSBAND

DAR'ST thou to ask again?

WIFE

AND why not, pray?

HUSBAND

FINE, pretty doings!—Presently you'll say;

That what I've seen 'tis folly to believe.

WIFE

Too much is this:—such accusations grieve.

HUSBAND

Thou did'st most clearly suffer his embrace.

WIFE

I? WHY, you dream!

HUSBAND

This seems a curious case.

MY reason's flown'! or have I lost my eyes?

WIFE

CAN you suppose my character I prize

So very little, that these pranks I'd play

Before your face, when I might ev'ry day

Find minutes to divert myself at will,

And (if lik'd such frolicks) take my fill?

HUSBAND

I KNOW not what to think nor what to do;

P'rhaps this same tree can tricks at will pursue;

Let's see again; aloft he went once more,

And William acted as he'd done before;

But now the husband saw the playful squeeze;

Without emotion, and returned at ease.

To find the cause, said he, no longer try,

The tree's enchanted, we may well rely.

SINCE, that's the fact, replied the cunning jade;

To burn it, quickly William seek fort aid;

The tree accurst no longer shall remain;

Her will the servant wish'd not to restrain,

But soon some workmen brought, who felled the tree;

And wondered what the fault our fair could see.

Down hew it, cried the lady, that's your task;

More concerns you not; folly 'tis to ask.

OUR second gossip thus obtained success;

But now the third: we'll see if she had less:

To female friends she often visits paid,

And various pastimes there had daily play'd;

A leering lover who was weary grown,

Desired ONE night she'd meet him quite alone.

TWO, if you will, replied the smiling fair;

A trifle 'tis you ask, and I'll repair

Where'er you wish, and we'll recline at ease;

My husband I can manage, if I please,

While thus engag'd.—The parties soon agreed;

But still the lady for her wits had need,

Since her dear man from home but rarely went,

No pardons sought at Rome, but was content

With what he nearer got, while his sweet wife

More fondness mark'd for gratifying life,

And ever anxious, warmest zeal to show,

Was always wishing distant scenes to know;

As pilgrim oft she'd trod a foreign road,

But now desir'd those ancient ways t'explode;

A plan more rare and difficult she sought,

And round her toe our wily dame bethought,

To tie a pack-thread, fasten'd to the door,

Which open'd to the street: then feign'd to snore

Beside her husband, Harry Berlinguier,

(So, usually, they nam'd her wedded dear.)

HOWE'ER, so cunningly with him she dealt,

That Harry turn'd, and soon the pack-thread felt,

Which rais'd distrust, and led him to suspect

Some bad design the thread was meant t'effect.

A LITTLE time, as if asleep, he lay

Considering how to act, or what to say;

Then rose, (his spouse believing not awake,)

And softly treading, lest the room should shake;

The pack-thread follow'd to the outer door,

And thence concluded (what he might deplore,)

That his dear partner from her faith would stray,

And some gallant that night design'd to play

The lover's part and draw the secret clue,

When she would rise, and with him freaks pursue,

While he (good husband!) quietly in bed

Might sleep, not dreaming that his wife had fled.

FOR otherwise, what use such pains to take?

A visit cuckoldom, perhaps, might make;

An honour that he'd willingly decline;

On which he studied how to countermine;

And like a sentinel mov'd to and fro',

To watch if any one would thither go

To pull the string, that he could see with ease,

And then he'd instantly the culprit seize.

THE reader will perceive, we may suppose,

Besides the entrance which the husband chose,

On t'other side a door, where our gallant

Could enter readily, as he might want,

And there the spark a chambermaid let in:—

Oft servants prone are found a bribe to win.

WHILE Berlinguier thus watch'd around and round;

The friends with one another pleasures found;

But heav'n alone knows how nor what they were:—

No fact transpir'd save all was free from care;

So well the servant kept the careful watch,

That not a chance was given the pair to catch:

THE spark at dawn the lady left alone,

And ere the husband came the bird was flown;

Then Harry, weary, took his place again,

Complaining, that he'd felt such racking pain,

And dreading, lest alarms her breast should seize,

Within another room he'd sought for ease.

Two days had pass'd, when madam thought once more,

To set the thread, as she had done before;

He left the bed, pretending he was sick,

Resumed his post; again the lover came,

And, with my lady, play'd the former game.

THE scheme so well succeeded, that the pair

Thrice wish'd to try the wily pack-thread snare;

The husband with the cholic mov'd away,

His place the bold gallant resum'd till day.

AT length their ardour 'gan, it seems, to cool,

And Harry, they no longer tried to fool;

'Twas time to seek the myst'ry of the plot,

Since, to three acts, the comedy was got.

AT midnight, when the spark had left the bed;

A servant, by his orders, drew the thread;

On whom the husband, without fear, laid hold,

And with him enter'd like a soldier bold,

Not then supposing he'd a valet seiz'd;

Well tim'd it prov'd, howe'er;—the lady pleas'd

Her voice to raise, on hearing what was said,

And through the house confusion quickly spread.

THE valet now before them bent the knee,

And openly declar'd, he came to see

The chambermaid, whom he was wont to greet,

And by the thread to rouse when time to meet:

ARE these your knavish tricks, replied the dame,

With eyes upon her maid that darted flame;

When I by chance observ'd about your toe,

A thread one night, I then resolv'd to know

Your scheme in full, and round my own I tied

A clue, on which I thoroughly relied,

To catch this gay gallant, that you pretend

Your husband will become, I apprehend.

Be that as 'twill, to-night from hence you go.

My dear, said Berlinguier, I'd fain say no;

Let things remain until to-morrow, pray

And then my lady presently gave way.

A fortune Harry on the girl bestow'd;

The like our valet to his master ow'd;

To church the happy couple smiling went:—

They'd known each other long, and were content.

THUS ended then, the third and last amour;

The trio hasten'd Macae to implore,

To say which gain'd the bet, who soon replied:—

I find it, friends, not easy to decide.

THE case hangs up, and there will long remain;

'Tis often thus when justice we'd obtain:

OFT have I seen in wedlock with surprise,

That most forgot from which true bliss would rise

When marriage for a daughter is designed,

The parents solely riches seem to mind;

All other boons are left to heav'n above,

And sweet SIXTEEN must SIXTY learn to love!

Yet still in other things they nicer seem,

Their chariot-horses and their oxen-team

Are truly matched;—in height exact are these,

While those each shade alike must have to please;

Without the choice 'twere wonderful to find,

Or coach or wagon travel to their mind.

The marriage journey full of cares appears,

When couples match in neither souls nor years!

An instance of the kind I'll now detail:

The feeling bosom will such lots bewail!

QUINZICA, (Richard), as the story goes,