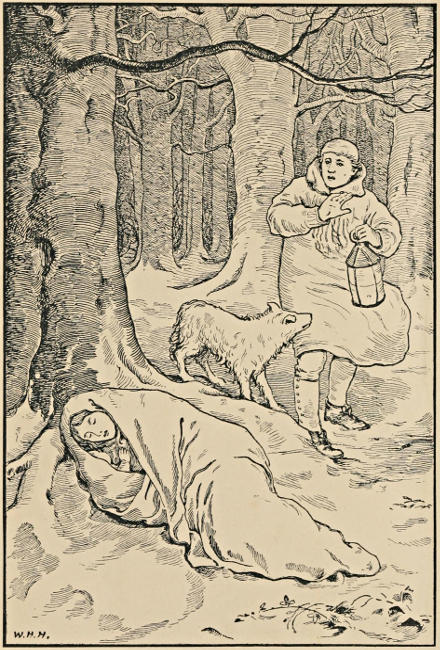

“What have we here? S. Joseph help us!”

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Last Abbot of Glastonbury

A Tale of the Dissolution of the Monasteries

Author: A. D. (Augustine David) Crake

Release Date: September 8, 2016 [eBook #53010]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LAST ABBOT OF GLASTONBURY***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/lastabbotofglast00crakrich |

The

Last Abbot of Glastonbury.

A Tale of the Dissolution of the

Monasteries.

By the

REV. A. D. CRAKE, B.A.,

Fellow of the Royal Historical Society; Vicar of

Havenstreet, I.W.;

Author of

Fairleigh Hall, The Chronicles of Æscendune, The Camp on the

Severn, etc., etc.

Oxford and London:

A. R. MOWBRAY & CO.

The Author humbly ventures to offer the ninth of his series of original tales, illustrating Church History, to the public; encouraged by the favourable reception the previous volumes have found.

In the tales, “Æmilius,” “Evanus,” and “The Camp on the Severn,” he has endeavoured to describe the epoch of the Pagan persecutions, under the Roman Empire; in the “Three Chronicles of Æscendune,” successive epochs of Early English history; in the “Andredsweald,” the Norman Conquest; in “Fairleigh Hall,” the Great Rebellion; and in the present volume, one of the earliest of the series of events ordinarily grouped under the general phrase “The Reformation,” the destruction of the Monasteries.

It is many years since the writer was first attracted and yet saddened by the tragical story of the fate of the last Abbot of Glastonbury, and amongst the tales by which he was wont to enliven the Sunday evenings in a large School, this narrative found a foremost place, and excited very general interest.

A generation ago, few English Churchmen cared to say a good word for the unhappy monks, who suffered so cruel a persecution at the hands of Henry the Eighth and his vicar-general, Thomas Cromwell. Many, indeed, confessed a sentimental regret when they visited the ruins of such glorious fanes as Tintern, Reading, or Furness, and reflected that but for the vandalism of the period, such buildings might yet vie with the cathedrals, with which they were coeval, and if not retained for their original uses, might yet be devoted to the service of religion and humanity, in[ii] various ways; but the fear of being supposed to betray a leaning to the doctrines once taught within these ruined walls, has prevented many a writer from doing justice to the sufferers under atrocious tyranny.

Yet did an act of parliament now pass the legislature giving the various episcopal palaces, deaneries, rectories, and vicarages in England, with all their furniture, to the Crown, and were the present occupants ruthlessly ejected, and hung, drawn, and quartered in case of resistance, active or passive, the injustice would not be greater, the outrage on the rights of property more flagrant, than in the case of the monasteries.

The late Rev. W. Gresley, in his tale, “The Forest of Arden,” was (so far as the writer remembers) the first writer of historical fiction, amongst modern Churchmen, who attempted to render justice to our forefathers, who, born and bred under the papal supremacy, could not disguise their convictions, or transfer their allegiance to a lustful tyrant.

But even he spake with “bated breath” when compared with Dean Hook, who, later on, thus writes in his lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury:—

“To an Englishman, taught to regard his house as his castle, these acts of invasion on property appear to be monstrous; our blood boils within us when we learn that by blending the Acts of Supremacy with the Treason Acts the Protestant enthusiasts under Cromwell condemned to death not fewer than 59 persons, who, however mistaken they were in their opinions, were as honest as Latimer, and more firm than Cranmer.

“Of the murders of Bishop Fisher and Sir Thomas Moore, the former the greatest patron of learning, the latter ranking with the most learned men the age produced, both of them men of undoubted piety, the reader must not expect in these pages a justification or even an attempt at palliation; we should be as ready to accord the crown of martyrdom to the Abbots of Reading and Glastonbury and to the Prior of[iii] S. John’s, Colchester, when rather than betray their trust they died, as we are to place it on the heads of Cranmer, Ridley, and Latimer. Although the latter had the better cause, yet we must all admit that atrocious as were the proceedings under Mary and Bonner, the persecutions under Henry and Cromwell fill the mind with greater horror.”

But it may be asked, were not the atrocious crimes laid to the charge of the monks in the celebrated “Black Book,” the “Compendium compertorum,” a sufficient justification? Did not the very parliament at the recital cry “Down with them.”

The opinion of such parliaments as those which passed the absurd and bloody treason acts dictated by Henry, or which condemned so many innocent victims by Acts of Attainder, or passed those most atrocious acts, “the Vagrant Acts,” by which a cruel form of slavery was established in England, only England would not put it in practice,—the professed opinion of such parliaments will weigh little with modern Englishmen.

But it appears that the very accusers themselves, or at least the Government who employed them, could not have believed in the accusations; for no less than eleven of the Abbots were made Bishops to save the Government their pensions, and some of them men against whom the worst charges had been made; others became deans, and others were put into positions of trust, as parochial priests, under Cranmer himself.

And who were the witnesses? Their leader, Dr. London, was put to penance for the most grievous incontinency, and afterwards thrown into prison for perjury, where he died miserably. Another, Layton, who figures in the tale, becoming dean of York, pawned the cathedral plate. Upon the testimony of such witnesses one would not hang a dog.

But this is not the place for an investigation of the subject, nor is it one to be commended to the pure-minded reader,[iv] such garbage did these venal and foul-mouthed spies invent to justify the rapacity of their employers. Not that we would maintain the absolute purity of the monasteries, or that there was no foundation whatsoever upon which such a superstructure was reared: many of the brotherhoods had fallen far below the high ideal of their profession, or even the spiritual attainments of their brethren in earlier and better days; but there is absolute proof that in many instances the reports of the visitors were pure inventions. No just Lots were they, “vexed with the filthy conversation of the wicked,” but men of evil imaginations, who were paid to invent scandal if they could not find it.[1]

I have not, therefore, hesitated to make the sufferings of the last Abbot of Glastonbury the theme of a story, but while I have adhered to the main facts of the tragedy, I have availed myself somewhat of the usual license accorded to all writers of historical fiction, justified by the example of the great and revered founder of the school, Sir Walter Scott.

In particular, the words put into the mouth of the Abbot, both in his last sermon at Glastonbury and in the trial at Wells, were actually used by his fellow-sufferer, the Prior of the Charterhouse, John Houghton, under precisely similar circumstances: the reader will find the whole of the touching story in the second volume of Froude’s “History of England;” it is well worth perusal.

It may be objected that one so young as the hero of the latter portion of the story, “Cuthbert the foundling,” could scarcely have been exposed to the operation of the Treason Acts, or required to take the oath of supremacy, in his[v] twenty-first year; but there are examples of sufferers under this régime at a more tender age: a month or two, more or less, made small difference in the Tudor period, especially when the interests of the Crown were concerned, or the will of the despot expressed. The concealment of the Abbey treasure, and the sympathy of the Abbot with the Pilgrimage of Grace (how could he be otherwise disposed) are matters of history.

An attempt has been made, within our memory, by a modern historian, to whitewash the memory of the royal “Blue Beard,” under whom such fearful atrocities were committed; we are asked to believe that the Carthusians, dying dismembered and mutilated in so horrible a manner, or in the filth of the fetid dungeons in which they were thrown, that the aged Countess of Salisbury flying about the scaffold with her gray hairs dabbled in blood, that the Protestants who were burnt, and Catholics who were drawn and quartered, sometimes on the same day and at the same place, that such victims as Fisher, More, and Surrey, were all unwilling sacrifices to a high sense of duty on the part of the king who slew them, who also was a right honourable husband, plagued by unworthy wives, and hence deserving of the pity of married men.

But to the writer, the following paragraph from a deservedly popular history, appears more nearly to represent the truth:—

“The temper of such a legislator as Henry the Eighth, and the thorough subservience, the otherwise incredible cowardice and baseness of his parliaments, can only be fully exhibited by an enumeration of their penal laws, which for number, variety, severity, and inconsistency are perhaps unequalled in the annals of jurisprudence.

“Instead of the calmness, the foresight, and the wisdom which are looked for in a legislator, we find the wild fantasies and ever-changing, though ever selfish caprices of a spoiled child, joined to the blind fierce malignant passions[vi] of a brutal and cruel savage. It would seem as if the disembodied demon of a Caligula or a Nero, the evil spirit that once bore their human form, had again become incarnate upon earth, let loose for some wise (though to dull mortal eyes, dimly discerned) end, to repeat in a distant age, and another clime that same strange, wild, extravagant medley of buffoonery and horror, which is fitted to move at once the laughter and execration of mankind.” (Knight’s Pictorial History).

This is strong language, but when one rises from a perusal of the deeds committed during this reign of terror, it seems justified.

The destruction also of the monastic libraries, and the decay of solid learning (Latimer being witness), must ever be regretted by the scholar. Fuller tells us that “the English monks were bookish of themselves, and much inclined to hoard up monuments of learning.” But all these treasures were ruthlessly destroyed or scattered, including books and valuable MS., which would now be worth their weight in gold. John Ball, by no means a laudator temporis acti, wrote to Edward VI.:—

“A number of them which purchased these superstitious mansions (the monasteries) reserved of their library books, some to serve their jakes, some to scour their candlesticks, and some to rub their boots, some they sold to the grocers and soap sellers; and some they sent over sea to the bookbinders—not in small number, but at times whole ships full. ... I know a merchant man, which shall at this time be nameless, that bought the contents of two noble libraries for forty shillings a piece. A shame it is to be spoken. This stuff hath he occupied instead of grey paper by the space of more than these ten years, and yet he hath store enough for as many years to come.”

It is true the monks were accused of leading idle lives; but to the unlearned, especially those who get their bread by physical labour, the student poring over his books is always “a drone.”

It may be most true that the monastic system, so serviceable[vii] in the middle ages, the only shelter for peaceful men in the midst of bloodshed and strife, the only refuge for learning amongst the densely ignorant, had had its day; that the hospitals, the almshouses, the workhouses, the schools and colleges, do all the work they once did, and do it better, that in the ages, then to come, they could have filled no useful purpose had they survived.

Well! supposing this granted, does it in any way justify the cruelty of the suppression? The judicious Hallam well observes, that “it is impossible to feel too much indignation at the spirit in which these proceedings were conducted.” Had vested and life interests been respected, had the admission of further novices been prohibited, and the buildings themselves, when no longer needed, utilized as hospitals and colleges, and the like; whatever men might think of the change, they would at least admit the moderation of the government; but what consideration can justify the intolerable barbarity of the persecutions.

Two questions may be asked, first, what became of the monks, nearly a hundred thousand, in a population of some three millions, who were thus, with the most meagre of pensions, cruelly turned out of house and home.

It must be replied that a large number, in fact all who could by any contrivance be brought under the scope of either of the numerous laws involving capital punishment, perished by the hand of the executioner. For example, begging in the first instance was punished by whipping, in the second by mutilation, and in the third the beggar was doomed “to suffer pains and execution of death as a felon, and enemy of the commonwealth.”[2] This cruel law, which was probably drawn up by Henry himself, was doubtless aimed especially at the unfortunate monks, who unfitted[viii] for labour by their sedentary lives, and unable to obtain work, would often be forced to the dreadful alternative of starvation or hanging. How many starving monks must have fallen into this dreadful trap, for their pensions even if regularly paid were miserably insufficient, and preferred to hang than to starve; doubtless they formed a large proportion of the eighty thousand criminals, who are said to have perished, by the hands of the executioner, in this dreadful reign.

Secondly: what became of the monastic property amounting, it has been said, to a sum equivalent to fifty millions sterling of our present money, which was to have almost superseded taxation, and accomplished other wonderful ends? It disappeared under Henry’s incomprehensible extravagance, and at the hands of his greedy courtiers; and not only was he forced in his latter days to debase the currency, but moreover in the last November of his life, his venal parliament conferred upon him the absolute disposal of all colleges, charities, and hospitals in the kingdom, with all their manors, lands, and hereditaments, receiving only in return his gracious promise that they should all be applied for the public good. Had God not summoned the tyrant to give an account of his stewardship, within two months of the act, we might not have had a college, school, almshouse, or hospital left in England, any more than a monastery; “had he survived a little while longer,” says the impartial writer I have before quoted, “he would not have left an hospital for the care of the sick, or a school for the instruction of youth.”

But I have already taxed the patience of my readers; I have promised them a tale and instead I am writing an essay.

A. D. C.

December, 1883.

[1] The reader will find this subject fully and fairly treated in the sixth chapter of the Rev. J. H. Blunt’s “History of the Reformation” and the first introductory chapter of the first volume of the new series of Dean Hook’s “Lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury,” from which I have already quoted.

[2] 22 Henry VIII. Cap. 12, and 27 Henry VIII. Cap. 25.

| CHAP. | PAGE. | |

| PART I.—The Last Abbot. | ||

| Prologue | 1 | |

| 1.— | All Hallow Even | 7 |

| 2.— | Retrospect | 16 |

| 3.— | The Secret Chamber | 27 |

| 4.— | The Arrest | 33 |

| 5.— | The Road-Side Inn | 44 |

| 6.— | The Trial | 55 |

| 7.— | Glastonbury Tor | 65 |

| 8.— | On the Track | 74 |

| 9.— | In the Ruins of the Abbey | 91 |

| PART II.—Cuthbert the Foundling. | ||

| 1.— | The Old Manor House | 101 |

| 2.— | An Eventful Ramble | 111 |

| 3.— | An Act of Gratitude | 122 |

| 4.— | Exeter Gaol | 135 |

| 5.— | Put to the Question | 145 |

| 6.— | An Unexpected Disclosure | 154 |

| 7.— | Castle Redfyrne | 164 |

| 8.— | Led Forth to Die | 177 |

| 9.— | Breathing Time | 187 |

| 10.— | The Shadows Darken | 198 |

| 11.— | An Ancient Inn | 210 |

| 12.— | The Hand of God | 221 |

| 13.— | The Trust Fulfilled | 232 |

| 14.— | Suum Cuique Tribuitur | 243 |

| Epilogue | 252 | |

| Notes | 257 | |

Page 169, line 5, Read appetens for appietens.

The Last Abbot.

It is a cold wintry night in the year 1524, the fifteenth of the high and mighty Lord, Henry, Eighth of that name, “by the grace of God King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland,” as the heralds vainly style him.

All day long the clouds have been hanging over the forest of Avalon, heavy and dull as lead, and now towards eventide they descend in snow, an east wind arises, which blows the flakes before it, with such frantic violence, that their direction seems almost parallel to the earth, penetrating every nook of the forest, filling each hollow.

Darkness descends upon the earth, as the storm increases; it is dark everywhere, but darkest in[2] the depths of the sombre wood, amidst the tangled copse, beneath the bare branches of the huge oaks, which wave wildly as if in torture, and anon fall with a crash which startles the boldest beasts of the forest.

A road leads through the heart of this mighty wood, leads towards the famous Abbey-town of Glastonbury, where as folks say Joseph of Arimathæa arrived long ago, and planting his staff, which grew like Aaron’s rod, and put forth buds, determined the site of the future Benedictine Monastery. Do they not yet show the strange foreign thorn tree which grew from that holy staff?[3]

But we are in the wood, and happy were it for us, if we could but rest before the huge fire which imagination pictures in that far off great chamber of the Abbey.

Through the darkness comes a step softly falling on the snow; it draws nearer, and dim outlines become distinct. It is a woman and she carries an infant.

A woman and her child out to-night! the Saints preserve them, especially S. Joseph of Glastonbury; with what a timid glance too she looks behind her from time to time. Does she fear pursuit?

See how she clasps the child to her breast, how she wraps her robe around it, regardless of the exposure of her own person: poor mother, what has brought her out in this wild night? Alas, her strength seems failing: see she stumbles, almost falls, the wind blows so fiercely that she can hardly stand against it,—she stumbles again.

We, as invisible spectators, stand beneath the shade, or what would be in summer the shade of a spreading beech; around its base there is a mossy bank, gently rising, or rather would be were it not covered with snow.

She approaches the tree and falls on the slope as one who can do no more, who gives up the struggle.

Still she shelters the poor babe.

An hour passes away, she lies as if dead, only there is a ceaseless cry from the child, and from time to time a faint moan from the mother.

Look, there is a light in the wood; it is moving, and now a heavy step, crushing the frozen snow; it is a countryman, and he carries a horn lantern.

A dog, a shepherd’s dog, runs by his side.

Will the man pass the tree?—yes he may but the dog will not; see he is “pointing,” and now he runs to his master, and takes hold of the skirts of his smock.

“What have we here? S. Joseph help us! a[4] woman! Why mistress what doest thou here? Get up, or thou wilt be frozen stiff and stark before morning.”

Only a moan in answer: he stoops down and gently, for a rustic, looks at her face; he does not know her, but he sees by the dress and by something indescribable in the face, that she is one of “gentle blood.”

“Canst thou not move?”

Another moan.

He strives to raise her, and the dog looks wistfully on, as if in full sympathy. Thy canine heart, poor Tray, is softer than that of the men who drove her forth to-night.

Ah, that is right; she takes courage, strives to rise,—no, she is down again.

“I cannot,” she says, “my limbs are frozen; take the child, save my Cuthbert.”

“I would fain save you both,” says the man, but he strives in vain to do so, it is beyond his power to carry them, and she can move no further; she but rises to sink again on the bank, her limbs have lost their power.

“Take my child,” she says once more, “and leave me to die; heaven is kinder than man, and the good angels are very near.”

The yeoman, for such he is, hesitates, “No one shall say that Giles Hodge forsook thee in thy strait, yet, there is the keeper’s cottage within a[5] mile, if I run and take the babe, I may come back and save thee.”

“Go, go, for heaven’s sake, my boy must live, his precious life must be saved, then come back for me; he is the heir of”—

Here her voice failed her.

“She speaks the words of wisdom,” says Giles, and he takes the babe, leaving the shawl wrapped round the mother.

“Nay, the shawl, take the shawl for the babe.”

“I can carry it ’neath my smock, and ’twill come to no harm, thou wouldst die without it.”

She starts up, imprints one fervent kiss upon the babe ere it leaves her; alas, it is the last feeble outcome of strength.

Giles runs along the road, as fast as the ground, heavy with snow, and the wind, will permit him; he reaches the house of Stephen Ringwood, the deputy keeper; it is now Curfew time, and the honest woodman is just putting out his fire to go to bed.

“Stephen, Stephen,” shouts Giles, as he knocks at the door.

A loud and heavy barking from the throats of deep-chested dogs.

“Who is there?”

“Thy old crony, Giles Hodge; open to me at once.”

The door opens. “What Saint has sent thee here! and a babe too?”

“Oh, Stephen, come directly, and help me bring the mother in; she is out in the snow, spent with toil, and if we arrive not soon she will be dead.”

“I have some warm milk on the fire; here, Susan, give some to the babe and give me the rest,” and putting it into a horn, the two started back, leaving the infant with the keeper’s wife.

They reach the tree again.

How still she is.

Giles trembles, bless his tender heart. It is no discredit to thy manhood, Giles.

“Yes, she is dead, she has given her last kiss to the babe.”

They put together some short poles and cord they have brought, which make a sort of litter.

“Carry her gently, Stephen,” says Giles as he wipes his eyes with the sleeves of his smock, “carry her gently, she said the good angels were near her, and I believe they are watching us now, if they are not on the road to paradise with her soul.”

[3] See Note A., Antiquities of Glastonbury.

It was the All-Hallow Even of the year 1538, and the first Evensong of the festival of All Saints had been sung, in the noble Abbey Church of Glastonbury, with all those solemn accessories, which gave such dignity, yet such mystery, to the services of the mediæval Church of England.

The air was yet redolent with the breath of incense, the solemn notes of the Gregorian psalmody yet seemed to echo through the lofty aisles, as the long procession of the Benedictine brethren left the choir, and passed in procession down the church, the Abbot in his gorgeous robes closing the procession.

A noble looking old man was he, that Richard Whiting,—last and not least of the hundred mitred Abbots who had filled that seat of honour and dignity since the first conversion of England. A face full of sweet benignity—one which inspired reverence while it commanded love. His life had been distinguished throughout by the virtues[8] which had ever found congenial home at Glastonbury—piety towards God, and love towards man.

And now the lay congregation who filled the noble nave and aisles, beyond the transept, were leaving the church; the lights were slowly extinguished, and the gloom of the wintry evening was filling the church, save where the one solitary light burnt all night before the high altar.

In the porch, after the doors were closed, stood the sacristan and a young acolyte—one of the choristers, for since a large school was attached to the monastery, they had the assistance of a youthful choir. It was a bright happy face, that of the boy, upon which the moon shone brightly, as he bade “good night” to the sacristan—saying that he had leave to spend the evening at home, and should not return till morning—then passed with light footsteps through the Abbey precincts, and then across a green, to some distant cottages which skirted the common land. Let us describe him more fully. He was somewhat sunburnt in complexion, with brown hair, and had those blue eyes, beneath long dark eye-brows, which give a sort of dreamy expression to the face, but the features were redeemed from the charge of effeminacy by the bold open brow, the firm thin lips, and by the nose which was slightly aquiline.

His dress was studiously simple, yet very[9] unlike that of modern days, but if my youthful readers have ever met a “blue coat boy” they will have no difficulty in picturing the attire of the period. To sum up, he was a lad whose appearance inspired interest, as we hope his fortunes, to be herein depicted, will do, for they were passing strange.

It was a picturesque house before which he stopped—a cottage overgrown with ivy, not unlike those cottages, now alas fast vanishing, which may be met in many an Oxfordshire village—and which strolling artists delight to paint, lovely to look at, but not so comfortable, it may be, as the new style of brick and slate tenements, which painters would disdain to transfer to canvas.

The fire within shone brightly through the windows, and the flickering light made the heart of Cuthbert, for such was his name, leap with the anticipation of the joys of the ingle-nook,—the endearments of home.

He lifted the latch without knocking, and entered; an aged man and woman sat by the fire, a comely old couple, who were eager, in spite of their infirmities, to greet the darling of their old age.

And was not there a meal spread on the table near the fire? It was not “tea,” that beverage was yet unknown, but there was plenty to tempt a[10] boy’s appetite, and the frosty air had sharpened Cuthbert’s.

And when it was over, and the old man sat in his high-backed arm-chair, the grandmother went out and the lad went into the “chimney corner” to his favourite seat.

“Chimney corner!” what a nook of delight on the winter’s evening, when the snow-flakes steal gently down the chimney and hiss as they meet the blazing logs! Well does the writer remember filling such a seat many winters ago.

“Grandfather, do you remember that this night is Hallow-e’en, when all the ghosts are abroad? I want you to tell me something about them—the old tales which used to make my flesh creep when I was younger.”

“Why, boy, it is thought to be a night when the dead can’t rest quiet in their graves, though why they should not rest on a holy night like this I can hardly tell.”

“Did you ever see a ghost? Oh, here is grandmother with nuts, apples, and ale! Why do we always eat nuts and apples on Hallow-e’en?”

“They always have been eaten to-night, that is all I know; sometimes they tie up an apple with a string to the beam, and when they have tied the hands, set the young ones to eat it with the help of their teeth only—catch who catch can.”

“And about the nuts?”

“Oh, lads and maidens who are in love with each other will take two nuts, and call them lad and lass: if they burn quietly together they conclude that they will have a happy wedded life, but if lad or lass bounce out of the fire, that there will be strife and quarrels between them, in which case, dear boy, I think they had better not go together to the altar; better live apart than have nought but strife and quarrels.”[4]

“But I wanted to ask you about something more wonderful than this; the boys were saying, when we were talking about Hallow-e’en in the cloisters, that if you went into the church porch at midnight, you would see the fetches[5] of all the folk who are to die this year come and choose the place for their graves.”

“I have heard the tale, and don’t believe it; it is all nonsense, my boy.”

“Anyhow I promised that I would go and see to-night.”

“Nay, my child, you must be in bed and asleep at midnight, and I do not think you would dare to try.”

“That is what they said, the other boys I mean, and they dared me to go.”

“I don’t think you would catch a ghost, but I[12] think you would catch your death of cold, it is freezing sharply to-night.”

Cuthbert thought it best to drop the subject, lest he should be forbidden to make the adventure, upon which he had set his heart, not without some trepidation, but still with the longing to be the hero of the occasion, who should test the truth of the legend—for he had bound himself to his schoolfellows to make the experiment, and there was much speculation as to the probable results.

After a very pleasant evening the hour of bed-time approached. Our ancestors thought Curfew (8 p.m.) the proper time for retiring, and nine was looked upon as a very late hour.

So, soon after Curfew had rung from the tower of the Abbey, the embers of the fire were “raked out,” and the old couple retired to their rooms, after seeing Cuthbert safe in his little chamber, which opened upon the roof.

The rudeness of the furniture in those days has been somewhat exaggerated by modern writers; indeed we are apt to conclude, because in this nineteenth century such progress has been made in the arts of civilization as puts us quite upon a different footing from our grandfathers, that a similar difference existed between those grandfathers themselves and their ancestors. But it was not so, there was scant difference between the[13] sixteenth and eighteenth centuries in this respect.

So in Cuthbert’s room there was a comfortable bed, on a carved wooden bedstead, a chair, a table, a chest for clothes, and the like, much as in the present day.[6]

The lad did not undress, but, after he had said his prayers, lay down on the bed in his clothes, and did what he could to keep himself awake, till the time came for his adventure.

He counted the hours as the Abbey clock struck, until eleven boomed forth, when he rose, put on his doublet, opened the door, and went very softly down stairs.

He listened at his grandfather’s room as he went by—they were fast asleep, he heard their breathing. He descended to the “living” room, opened the outer door carefully, and stole forth.

Once on the green, the freshness of the air and the bright moonlight revived him; he felt his spirits rise in spite of the involuntary chill which now and then crept over him.

He reached the grave-yard of the parish church, for this had been selected as the scene of the experiment, since the monks would be singing the night office in the Abbey.

And as he went through the church-yard to the[14] porch, he could not help looking timorously from side to side, it seemed so strange to be alone with the dead, when the living were asleep; he was glad to get inside, the shadows of the yew trees looked so ghastly on the cold graves, and the chill moon looked upon the last low resting places with such a ghostly light.

He tried the door of the church; it was locked, as usual at that hour.

There was a broad bench on each side the porch; he sat and waited.

And I think he fell asleep and dreamt, but this was the story he told.

When the clock tolled the hour of midnight the last sound of the bell was prolonged, as if the organ in its softest tones had taken up the note; the music grew louder, until the introit of the Mass for the dead pealed out distinctly.

“Requiem æternam dona eis Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis.”

Then as he started up in amazement, the door swung open, and the “fetches or doubles” of those who were to die that year, that is, their ghostly likenesses, came out to seek their graves.

And there were many whom the boy knew, but last of all came out from the church the form of his benefactor, Richard Whiting, Lord Abbot of Glastonbury.

And around his neck there hung a ghastly cord,[15] and close by his side followed Prior and Sub-Prior, and cords were about their necks too.

Then the boy grew faint, and knew no more till he awoke, or recovered from his faint, whichever it was, and returning home, undressed, shivering as he did so, and went to bed.

When he afterwards told this tale, there were many who refused to believe that he had ever left his bed, and always insisted that he had dreamt the scene in the porch.

But if it was a dream, it was not without inspiration.

Coming events cast their shadows before.

[6] An ancient inventory of the furniture of such a house lies before the writer as he pens these lines.

Three centuries and more have rolled away since the dissolution of the monasteries, which once rose in architectural beauty in each district of mediæval England, gladdening the eye of the wayfarer with the assurance of hospitality, and of the poor with that of help and protection.

Their pious founders built in marble—

Alas! for such hopes; the tyrant Tudor, taking advantage of the palpable declension of the inmates from their first love, levelled them with the ground, and left the country shorn of such glorious fanes as arose over the conquerors at Battle, or the tombs of the mighty dead at Glastonbury. Yet still they had welcomed the wayfarer and the stranger, tended the sick, taught[17] the young, found labour for the poor, were good masters to their tenants, built bridges, made roads, and were the centres of civilization in their several districts.

Two rebellions ruthlessly extinguished in blood—the pilgrimage of grace, and the later rising in Devon and Cornwall—testified to the popular sense of loss when the servile courtier, ever the tyrant at home, had succeeded to the gentle old monks.

For all that is now done for the poor, and too often in a wooden kind of way by workhouses, hospitals, and the like, was then done by the monasteries, and their suppression was a cruel wrong to the poor.

Reformed, they needed to be, or they had never fallen, but that the treasures given by their founders in trust for God and His poor should pass into the hands of Henry’s fawning courtiers was too monstrous an iniquity.

The legendary history of Glastonbury has been told by the author before,[7] its supposed foundation by S. Joseph of Arimathæa, devoutly believed in in that credulous age, and the holy thorn-tree which blossomed from the staff which he there struck into the ground; there King Arthur was buried, and his body found after the lapse of[18] ages; there, like a city set on a hill, the lamp of faith had been kept burning for forty generations, if alas, tarnished (which we sadly own) by superstition and credulity.

Amongst other good works, they educated the young of Christ’s flock, for at Glastonbury there was a school of two or three hundred boys, who were taught by the learned Benedictines of the Abbey; for the Benedictines were the scholars of the day.

The discipline was somewhat severe, and the life hard, as modern boys would think it.

The hour of rising, summer or winter, was four; they breakfasted at five, after the service of Lauds in the chapel, upon beef and beer on ordinary days, and on a dish of sprats or herrings instead of meat on fast days.

Then to their lessons, and we shall grieve our younger readers when we tell that Solomon was held in much respect, and therefore the rod was freely used in case of idleness or insubordination; but of the latter there was very little under monastic discipline.

There was a short space for recreation before the chapter Mass at nine o’clock, which all attended, after which work was resumed until Sext, which was followed by a simple but hearty dinner.

There was again another period of work in the[19] afternoon, after Nones, but as it was necessary that the boys should not be behind the world in physical prowess, ample leisure was afforded for exercise and rough sports.

Modern schoolboys complain of compulsory football; their remote ancestors had little choice in such matters, whether schoolboys or rustic lads on the village green. By Act of Parliament, tutors in the one case, or magistrates in the other, were bound to see that the lads under their jurisdiction, omitting idle sports, did exercise themselves in archery, the broad-sword exercise, the tilt yard, and such-like martial pastimes.

Fighting, or mock-fighting—and the imitation was not altogether unlike the reality—was alike the amusement and the chief accomplishment of life, especially in England, which had then, not without cause, the reputation of being the “fiercest nation in Europe.” “English wild beasts,” an Italian writer calls them, yet who would not prefer the manly and honest Englishman to the Italian of the day, with his poisoners and bravoes?

And our readers must imagine how the Glastonbury boys were excited by such stories as that of the four hundred London apprentices, who went out as volunteers to the garrison of Calais, and kept all the neighbouring districts of France in terror, until they were overwhelmed by[20] six times their number, and died fighting with careless desperation to the last.

So, even in the calm atmosphere of a monastery school, the world intruded.

As for their book-lore, they learned Latin practically, for they were forced to use it during a great part of the day in conversation, while they read daily in the Fathers and classical authors. Fabyan’s Chronicles and other old English historians supplied their history, and they were fairly instructed in the rudiments of mathematics. Altogether it was a sound education which the monastic school supplied.

We will now proceed with our story, after a digression which may be easily omitted by those who dislike to understand what they read.

The reader has, we doubt not, already identified the hero of the midnight adventure in the church porch, with the babe of our prologue.

Honest old Giles Hodge had told the whole story to the Abbot, within whose jurisdiction the babe was found, and with whom he sought an early interview. Strict search had been made after the surviving parent, if perchance there was one upon whom that epithet could be bestowed.

But no trace was found; only the delicate apparel of the lady, and the fine linen in which[21] the child was wrapped, led to the conclusion that they were members of some “gentle house.” Upon the linen there were marks: a crest which had been picked out, and two initials yet remaining, “C. R.”

“The poor little foundling shall be our care,” said the good Abbot, “but here alack, we have no nursery, and your good wife, who has so recently lost her own babe, must be his foster mother if she be willing. I will provide for his maintenance hereafter, whether in the cloister or the world, unless his friends claim him.”

“And what name shall we give him, your reverence?”

“Let me see, C must be his Christian name; let us call him Cuthbert, better patron than S. Cuthbert he could not have; the R must yet be a mystery—he will not need two names yet.”

So the years rolled by; Cuthbert grew up strong and hearty, but no one ever came to claim him. And he was still known only by one name, a peculiarity little commented upon where his story was so well known.

He grew up a general favourite, especially, it was supposed, with the Abbot; and yet the self-restrained austere old man showed little traces of such weakness, save to very observant eyes.

He loved the young, one and all, and often visited the school. He knew every face there,[22] and it was a great delight to him to watch them at their sports, perhaps recalling his own younger days, when Henry the Seventh was King.

In time little Cuthbert was chosen to be a chorister, and soon afterwards, by the Abbot’s desire, he was made an “acolyte,”—one who served at the altar,—and there his reverent and unassuming demeanour won him yet further regard.

But my readers must not think him the least bit of a milksop; they know, I trust, that the bravest lad is he who fears God, and fears nought besides. Cuthbert was not one of those lads who talked much about religion, if there were such then, nor again one who courted notice by obtrusive acts of devotion—his religion was of a manlier type.

And meanwhile, as we shall show, he gained the respect of his companions by his proficiency in manly sports and exercises; he was one of the best archers, one of the best at fencing and sword play; in the tilt yard he was always up to the mark. In the same way some of the best boys I remember at a certain school were conspicuous at football and cricket, the modern equivalents.

It was a fine evening in May, and all the lads of Glastonbury School were in the archery ground. A silver arrow had to be contended for as a prize—the prize of the year—and there were many competitors.

All Glastonbury looked on at the sport; many were there who had been great archers themselves in their youth, and who, like Nestor of old, were never tired of talking of the great things that had been done when they were young.

For full two hundred years had gunpowder been in common use, yet all that time the bow held its own; an arrow would fly much farther than the bullets of that day, nay of much later days, for it was actually ordered by Act of Parliament, in the directions to the villages, for the maintenance of “buttes,” that no person of full age should shoot with the light-flight arrow at a less distance than two hundred and twenty yards, that is a whole furlong: under that distance the heavy war arrow had to be used in all trials of skill.[8]

And now four lads of fourteen stand forth to contend for the prize; the target is a furlong off, the arrows, light ones, in regard to the age of the competitors.

We will introduce them to our readers in proper order.

There stands Gregory Bell, son of the squire of a neighbouring village, tall and slim, but tough in muscle, and very sound in wind and limb; his round face and laughing black eyes will be remembered[24] many a day. His long-bow is long indeed,—three fingers thick, and six feet long, well got up, polished, and without knots; few English boys could bend it now, it came of practice.

He draws the bow—the light arrow cleaves the air—he has struck the first circle of blue, not the bull’s-eye itself—a cheer from his schoolfellows.

“Well done, Gregory, well done, old fellow.”

“The lad will do well enough,” said an old bowman, “yet not like his father; but where be the bowmen of Crecy now? At the last bout we had with them, the French turned their backs upon us at long range, and bid us shoot, whereas had we been the men our sires were, they would have paid dearly for their fool-hardy challenge.”

Then stood up Adam Banister, a round thick-set youth, with brown hair and rosy face.

“Good luck to thee, Banister,” was the cry.

How easily he drew his ponderous bow: the arrow whizzed—alas, only the second circle was attained.

And now the third champion.

It is Nicholas Grabber. Let our readers mark him, he will often figure in these pages.

A lad of average height, with a head of very bright red hair, which seems positively to shine; his face is deeply freckled, but his appearance not altogether unprepossessing, save for a certain expression of slyness which would indicate a mixture[25] of the fox in his character; those who believed in the transmigration of souls might recognize the retriever in Gregory, the bull in Banister, the fox in Grabber, and—well we will leave them to designate the fourth after reading his history, for it was Cuthbert.

One after the other they discharge their arrows; the first shaft strikes the bull’s-eye, but amid shouts of admiration, the second, that of Cuthbert, pierces as near the centre.

“Hurrah!” “Grabber!” “Cuthbert!” and the names were repeated again and again by the crowd.

“Move the target fifty yards further, and let them shoot yet again.”

They were rivals, these two boys, and not such good friends as they should have been. Grabber envied Cuthbert his place in the Abbot’s favour, which he had utterly failed to attain; for had he not run away, and had not his father sent him back to school, coupled between two foxhounds, under the charge of the huntsman, a story never forgotten by his schoolfellows.[9] However, he was a good shot, a ringleader in boyish mischief, and not without his friends.

Again the arrows flew, but at this distance Grabber failed the bull’s-eye, just alighting on the rim.

A few moments of breathless anticipation, and Cuthbert’s shaft, soaring through the air, attains the very centre, amidst shouts of wonder and admiration.[10]

Grabber turned away disgusted, as Cuthbert advanced to receive the silver arrow from the chief forester, who superintended the “buttes.”

Then rang out the Abbey bell for Compline, and the field was deserted to the townsfolk, who kept up the pastimes of archery, cudgel playing, bowls, and the like, till darkness set in.

[7] See “Edwy the Fair,” and “Alfgar the Dane,” by the same author.

[8] Froude, vol. I, p. 67. He well observes that he could hardly believe the figures from his experience of modern archery, but such was the Act 33, Henry VIII., cap. 9.

[10] A far more remarkable instance of English archery is given in Scott’s “Anne of Geirstein.”

The Compline service was over, and the lads, many of whom slept in the abbey, while others lodged in the town, were retiring to their beds, when a lay brother arrested Cuthbert’s progress, and said in a low voice, “The Abbot requires thy presence.”

Somewhat startled,—for the summons was an unusual one at that hour, although he often acted in turn with other lads as a page-in-waiting on the Abbot, an office none would then despise,—Cuthbert followed the laic.

Threading various passages, they reached the Abbot’s lodgings, and there the messenger knocked and retired, leaving Cuthbert to obey the summons, “Enter.”

Richard Whiting, the last of that long line of mitred Abbots, sat near the window of his study, which was a plainly furnished room, simple as the personal tastes of the Abbot.

He was now but a weak and infirm old man,[28] yet of many good brethren the best;—“small in stature, in figure venerable, in countenance dignified, in manner most modest, in eloquence most sweet, in chastity without stain; not without that austerity of expression which we often notice in the portraits of these great mediæval ecclesiastics.”

“My son,” he said, “I have somewhat to say to thee ere perchance I be taken from thee.”

“Taken from me, Father?”

“Yes, the clouds are gathering thick around our devoted house, and the shelter thou hast long received may fail thee and all others here, ere long.”

Cuthbert looked amazed.

“Tidings have reached me, my child, that I must be taken to London, there to answer to certain treasons of which they falsely accuse me; the bolt may fall at any moment, and I have to discharge two duties, the first towards thee.”

The Abbot took up a little chest from the sideboard.

“Thou hast long been my son, and hast not needed thy natural parents, but dost thou not oftentimes wonder who they were?”

“They come to me in dreams.”

“And as yet only in dreams, my child; perchance thou art an orphan, but in that chest are the few relics of thy poor mother, which we[29] possess; these are the little clothes which swathed thee when thou wast found in Avalon forest—there a ring which encircled thy mother’s finger, and a full description of the circumstances of thy arrival here.”

“But what use would they be to me didst thou leave me alone in the world, Father?”

“Thou wilt never be alone, God will be ever with thee, He is the Father of the fatherless; should aught happen to drive thee hence, thee and others, take refuge with thy foster-parents until one seek thee, bearing this ring which thou seest on my finger, to him thou mayest safely commit thyself, and the secrets I am about to entrust thee for him.”

Here the tapestry moved in the wind, and a knock was heard at the door, which stood ajar; a fact the Abbot had not noticed.

To Cuthbert’s surprise there stood Nicholas Grabber.

“Quid vis fili?” was the Abbot’s interrogation.

“The lay brother Francis said that thou wantedst me.”

“It was an error, I sent for Cuthbert, and he is here. Pax tecum, go to rest.”

“My son,” said the Abbot, when Grabber was gone, “I am about to reveal to thee a mystery which thou alone mayest share, until the friend I have mentioned seeks thee, and presents thee[30] with this ring, which thou now seest on my finger; it will not be till I am gone.”

Cuthbert felt his spirits sink within him at the sad words of his protector, but he restrained himself, and listened reverently as to the words of a saint.

“Shut the door carefully, and draw the bolt.”

Cuthbert did so.

“Now touch the rose which thou seest in the carving of the cornice there, the fourth rose in order from the door, and the third from the floor.”

The wainscotting of the room was divided into small squares; in each one a rose—S. Joseph’s rose—formed the centre.

“The third and the fourth, canst thou remember?”

“Third from the floor, fourth from the door.”

“Now press the centre of the bud sharply with thy thumb.”

Cuthbert did so, and a bookcase, which seemed a fixture in the wall, and which none could have suspected to have been aught but a fixture, flew open in the manner of a door, and revealed a flight of circular steps, such steps as we see in old towers to this day.

“Follow me,” said the Abbot, as he took a lamp and descended the steps.

Thirty steps down, and as the Abbot’s room was on the ground-floor, they must have been[31] below the foundations of the Abbey when they came upon a solid iron door; the Abbot touched a spring, bidding Cuthbert observe the manner in which it worked, and entered.

“Fasten the door carefully back by this stay,” said the Abbot, “for should it sway to, we are dead men; the lock is a spring lock, and opens only from the outside, nor is there other exit save into the vaults of the dead. Dost thou see this chest? Here is the key, open it.”

Cuthbert turned the lock, raised the ponderous lid, and let it rest against the wall behind, then gazed upon the contents.

There were the most precious jewels of the Abbey, gemmed reliquaries, golden and jewelled pixes, chalices of solid gold, coined money, and the like, but beyond all this enormous wealth were rolls of parchment, and bundles of letters.

“My son, I have marked in thee from childhood a nature free from guile, and incapable of treachery, therefore do I place this confidence in thee. Those golden and jewelled treasures are not the most important things in the chest, but the parchments, the letters. They contain secrets, which, if made known, might cost many lives—lives of some of the truest patriots and most faithful sons of Holy Church.[11] I need not detail their nature to thee, nor why I may not destroy[32] them now. The secret thou hast learned is not for thee, thou wilt keep it until the arrival of the hour and the man.”

“His name?”

“I will but tell thee this much, he will be known to thee as the Father Ambrose.”

“Have I never yet met him?”

“Never, he has lived abroad; and now, my child, I will tell thee why I have chosen thee for the repository of this secret. He, who will be thy guardian and guide, when I am no more, who has undertaken the care of thy future, will also share alone with thee this knowledge. Ordinarily it has been confined to the Abbot, Prior, and Sub-Prior of this Abbey, and by them handed down to their successors. They share my danger, and may not survive me; otherwise they may be taken when inquisition is made for these papers, and put to torture to make them declare the hiding-place, and the like danger would hang over all high in office, but not, I trust, over one so young as thou art. Therefore thou must live quietly at thy stepfather’s home, until the day come when thy future guardian shall arrive, and may He, Who is the Father of the orphan, ever guard thee, my Cuthbert. But let us hasten to leave these vaults; I am old, and the damp air affects my aged breath.”

No event of importance followed immediately upon the disclosure of the secret chamber;—the summer passed swiftly and pleasantly away, the orchards were already laden with the golden riches of autumn, ere the bolt, so long foreseen, fell.

We can hardly, ourselves, enter into the difficulties and trials which beset the Abbot of Glastonbury. We are accustomed to the spectacle of a Church, divided, at least externally, but to men who had grown up with the belief, that outward unity was essential to the preservation of Christianity, the absolute command to abjure the Papal Supremacy, to break off all relations with Rome, and acknowledge the King as the “Head of the Church of England,” was a matter of life or death.

So Sir Thomas More and Bishop Fisher, not to mention hosts of others, died sooner than comply, while the more timid, shocked at the scandal, for[34] such it was to them, gave outward obedience, and in their hearts prayed fervently that “this tyranny might be over past.”

Let it not, however, be inferred that therefore they were right in contending for the supremacy of Rome, only in the right, inasmuch as it is far nobler to die, than to deny one’s belief, or to swear falsely to what one does not believe in one’s heart.

And so while we reject their teaching on this point, we can feel the deepest sympathy with the sufferings of these noble, yet mistaken souls.

On the first visitation of his monastery, three years previously, the Abbot had taken the Oath of Supremacy, feeling that it was not a cause for which a man was bound to die, but he had never been a happy man since, he was too old to change his convictions. Therefore he absented himself from the place in Parliament, which was his as a mitred Abbot, who was ranked as the equal of a Bishop, and strove to hide his sorrows in obscurity. No fault was then alleged against him, the earlier visitors reported that his house was, and had long been, “full honourable.”

But the eye of the “Malleus Monachorum,” the arch enemy of the monks, Thomas Cromwell, was upon him, and at last this vigilant enemy, equally cruel and unscrupulous, found the pretext he desired, for sending the Abbot of Glastonbury,[35] as also the Abbots of Reading and Colchester to the gibbet and the quartering block. Most of the Abbots had been led to save themselves by a voluntary surrender of their house and estates; those who did not thus bend to the storm, had to be destroyed on one pretence or another.

It was the sixteenth Sunday after Trinity, in the year of grace 1539.

The day was a bright day of early autumn, one of those sweet balmy days, when summer seems to put out all her parting beauties ere she yields her dominion to winter,—the air was laden with fragrance, and there was a dreamy haze upon the scenery around, which seemed typical of heavenly peace.

But there was a sad despondent feeling, which weighed like lead, upon the hearts of all the elders present at the High Mass on that day, in the great Abbey Church, whose majestic ruins yet strike the beholder with awe.

After the Creed, the Abbot ascended the pulpit and gazed round upon the congregation, as upon those to whom he was about to preach for the last time; he took for his text the parting words of S. Paul at Miletus,—“And now behold, I[36] know that ye all, among whom I have gone preaching the kingdom of God, shall see my face no more.”

As he uttered the words there was an audible expression of feeling on the part of the monks in the choir, the boys in the transepts, and the citizens in the spacious nave: was the text prophetical? One or two sobs might be heard.

Danger was at hand, and he knew it, and after a brief exordium he told it out plainly: the Royal Commissioners, with charge to bring him before the Council, were already on their way.

“Very sorry am I,” said he, “for you, my brethren, and especially my younger friends, of whom I see so many around. They will destroy this House of God, as they have so many others, they will spare you in the flesh, but if you are taken hence, and sent into a cold-hearted and wicked world, for which you are unfitted, having begun in the spirit, ye may be consumed in the flesh, and what shall I say, or what shall I do, if I cannot save those whom God has entrusted to my charge?”

Here a common utterance broke forth from the brethren which could not be suppressed.

“Let us die together in our integrity, and heaven and earth shall witness for us how unjustly we be cut off.”

“Would that it might be even so,” continued[37] the preacher, “that so dying we might pass in a body to our Father’s home above, but they will not do us so great a kindness. Me and the elder brethren they may indeed kill, but you who are younger will be sent back into the world ye have once forsaken, where divers temptations assail you. Alas, who is sufficient for these things?”

Here he paused, and then continued, “This may be the last time we meet within these sacred walls: the last time that they re-echo the tone of thanksgiving, which has arisen for nigh fifteen centuries on this spot.[12] But it is meet that we prepare for the stroke, and that we may do so the better, let us ask pardon for all the faults we may have committed against each other, and let each forgive, that so we may say the divine prayer, ‘Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us.’”

A solemn pause followed, during which there came a strange interruption, a sweet soft sound as of angels’ voices singing in harmony: not from the organ came that strange music, nor from any visible orchestra, but all felt it as it thrilled into their hearts. The venerable preacher was so moved that he sank down in tears, and for a long time could not resume his discourse, while all in[38] the choir sat as if astonished, yet rejoicing in the token, as they believed it was, of God’s presence amongst them.

And the burden of the song seemed, “O rest in the Lord, wait patiently on Him.”

That sermon ended in broken words of faith, love, and hope—words of deep emotion never forgotten by any present—and then the Celebration proceeded, with its stores of rich comfort and celestial joy.[13]

The following day the Abbot left early in the morning for a small country house belonging to the Abbey about a mile-and-a-half away. This he did that the scandal of an open arrest, and a probable conflict, might be averted, for he felt that his people might not peacefully bear the spectacle of their venerated Father led away like a criminal.

But he made no concealment of his retreat, so when the Commissioners arrived, later in the morning, they had no difficulty in learning the place, and they followed him to the country house.

In an old oak-panelled apartment sat the once powerful Abbot, writing calmly a few parting directions, chiefly concerning the disposal of such[39] personal property as might serve as mementoes to those who loved him, when they should see his face no more.

He was calm and resigned, although once, as he wrote, tears issued from fountains which had been long dry, and rolled down his aged and worn cheek,—he was but human.

In the window seat, his eyes fixed upon the road which led from the Abbey, sat Cuthbert.

Suddenly he rose hastily.

“Father,” he said, “they are coming; a number of mounted men are in sight, wilt thou not fly? We may yet hide thee, they will be ten minutes ere they arrive; fly for our sakes, for my sake—thy adopted child.”

“My son, I cannot; life has little yet to tempt me, and far better for me that I should bear witness to my faith with my blood, and receive the martyr’s palm which God hath already granted to many of my brethren, than live a few more miserable years, and see the wild boar rooting up the vineyard of the Lord, and the beasts of the field devouring it.”

After a pause he continued,—

“Dost thou see them plainly? Who is their guide?”

“Shame upon him, it is Nicholas Grabber; rather should they have cut my feet off than have forced me to do the like.”

“Nay, my child, I left word where I was, and strict directions that no concealment should be attempted.”

“Yet some other guide were more fitting than one of thine own children, shame upon him. Oh, my more than father, do fly; they will drag thee to a shameful death, like thy brethren of Reading and Abingdon. Is it not written, ‘When they persecute you in one city flee ye into another?’”

“Too late, my son, they are at the gate.”

“We will hide thee; there must be some place to hide in here, some secret chamber.”

“They are on the stairs, my son; do not let them see thee weep, be manly.”

Cuthbert strove to repress his emotion and to maintain outward composure, when the door opened and three men entered, rude of aspect.

“My name is Layton,” said the foremost, “and these two worthy men be Masters Pollard and Moyle; we be pursuivants of the King, and in his name, and by virtue of his warrant, we have charge to arrest thee, unless thou clear thyself by thy answers to certain questions.”

“What are they?” said the Abbot, calmly.

“Hast thou taken the Oath of Supremacy?”

“I have, to my great sorrow.”

“To his great sorrow, mark that, Master Pollard; and why to thy great sorrow?”

“Because it was a treason to the Church.”

“Then thou wilt not renew it?”

“Never.”

“That is enough to hang thee, proud Abbot, but thy talk interests me, and I would fain hear a little more from thee; what dost thou think of the King’s divorce?”

“I am not fain to answer thee on that matter.”

“But the law enables us to compel an answer from every man, and construes silence as treason; loyal men need not conceal their thoughts, and there is no room in England for disloyalty.”[14]

“Construe my silence as treason if thou wilt, I have naught to say on the matter.”

“There is something more for me to say. Dost thou love life, Master Abbot? For if so, in spite of thy treasons just uttered, thou mayst save it; we know full well that the names of the men who supplied money and arms for the late most unnatural and parricidal rebellion in the north,[42] which men call the Pilgrimage of Grace, are known to thee, only reveal the secret, and thou art safe.”

“Get thee behind me, Satan; dost thou think I would save my life at the expense of others, and take reward to slay the innocent?”

The Abbot’s manner was so firm and decided, the answer so bravely given, that the villain started. “I will patter with thee no more, thou hoary sinner,” he said at last; “thou hast the papers concerning this rebellion concealed somewhere, and we know it; we will pull thy Abbey down, stone by stone, if we find them not: thy answers are cankered and traitorous, and to the Tower thou shalt go, the Tower of London. Ah, who is that boy?”

“Thou mayst take me too,” said Cuthbert, as he stood before them, emerging from the curtained recess of the window with flashing eyes and burning cheeks, “for all that the Lord Abbot hath said, I say also.”

“Ah, thou young cockatrice, we see well what a dam hath hatched thee—another treason to the account of the wily priest here.”

“Cuthbert,” said the Abbot, “thou art running into needless danger—God calls thee not to suffer.”

“What is good for thee, Father, must be good for me also.”

“We may as well take him up to town too,” said Master Pollard.

“Nay, it is not our business,” said Layton; “if we arrested every young fool this traitor hath taught, we should go up to town with three hundred boys behind us, and should need their nurses to take care of them; the ground-ash were fitter for this young master’s back, but we have no time to waste on his folly, let us be moving, we have to search the chambers at the Abbey, perchance we may come across these papers.”

Need we say they searched in vain.

[12] The Abbot’s history is wrong, but he is under the belief that Joseph of Arimathæa founded Glastonbury Abbey, or at least first preached the Gospel on that spot.

[14] This was actually the case. Henry would not allow his subjects the privilege of concealing their thoughts. It is scarcely possible now, to believe the fact that the treason statute touched the life and enacted the fearful penalties of high treason against all who would not admit and assent in words to the royal supremacy; it made it treason not only to speak against the king’s prerogatives, but even to “imagine” anything against them. “Malicious silence,” which was assumed to imply such evil imaginations, was to be interpreted as treason and punished by death. See Perry’s History of English Church, p. 112-3.

The evening of Tuesday, the twelfth of November, in the year of grace fifteen hundred and thirty-nine, was closing in.

The day had been very fine, such a day as we sometimes enjoy, even in November; the golden sunbeams had brightened the foliage which yet hung upon many of the trees of the forest, and turned the russet plumage into gold. Now and then, in the calm atmosphere, a leaf would flutter down, and break the oppressive silence of the forest of Avalon.

It is broken more seriously; hark, that is the tread of many feet, and those voices are the voices of lads out for a day in the woods. See here they come into this lonely haunt, where no road or path exists, startling yon raven from his perch; see how sulkily he flies away, as if to say, “What right have these intruders here?”

A large chestnut-tree has dropped its fruit on the ground, and amidst the dead leaves the lads[45] are searching, and loading their pockets with the spoil; there are about twenty of them, evidently a band of the Glastonbury boys, and amidst them we recognise two old acquaintances, Cuthbert and Nicholas Grabber.

“It is time to be moving,” says Cuthbert; “we promised the Prior to be home in time to sing vespers.”

“Sing vespers! how pious we are!” said Nicholas, and the irreverent fellow clasped his hands together affectedly, and began to chant in a ridiculous voice the Psalm “Dixit Dominus.”

“Stop that,” said several voices at once, and Nicholas obeyed, finding the general feeling was against such mockery, as it ought to be with sensible and manly boys.

“Well, thank God, there will not be many more services in the Abbey; I am for freedom, for shaking off the yoke of bondage under which the old monks have kept us: those visitors who have been taking an inventory of the goods and chattels at the place, are only a token that the end is near; and it can’t come too soon for me.”[15]

“More shame for you to say so, after you have been educated at the cost of the Abbey,[46] and eaten and drunk its fare for many years,” said Cuthbert.

“And poor fare I have found it: I daresay the Abbot’s favourites get better,” replied Nicholas.

“‘Abbot’s favourites,’ what do you mean?” said Cuthbert, colouring.

“Let those who find the cap fit, put it on.”

“He means it for you, Cuthbert,” said two or three voices at once.

“I suppose one can’t help being liked,” said Gregory Bell.

“Nay, but one should not curry favour at the expense of others.”

“That isn’t fair,” cried Adam Banister; “no one can say Cuthbert is a sneak.”

“Sneak! who guided the commissioners to find the Abbot? that was the part of a sneak,” said Cuthbert; “but I know one way in which I could avoid favour; by running away from school and being brought back tied between two foxhounds, on all fours.”

A general burst of laughter, and then Nicholas lost all self-control, and struck Cuthbert in the face.

“A blow!” “A fair blow!” “A fight!” “A fight!”

Yes, a fight was inevitable under the circumstances; according to the moral (or immoral)[47] code of the fifteenth century, no one could receive a blow from an equal without returning it, unless he wished to be exiled from the society, whether of boys or men. Nothing was clearer to their eyes than that the duty of all good Christians was to fight each other.

So the blow was returned, straight between the eyes. But a fight was too good a thing to be lost in that irregular manner: a ring was formed, two seconds selected, Gregory Bell for Cuthbert, and a cousin, like-minded with himself, for Grabber.

Now we are not going to enter into the details of the fight—those who like a scene of the kind will find one well described in “Tom Brown’s School Days,”—suffice it to say in this instance, that the contest was long and desperate, not to say bloody, and that in spite of Grabber’s greater physical strength and weight, the skill and endurance of Cuthbert gave him the advantage, as indeed I think he deserved to have it.

So intent were the twenty lads upon the scene, that they did not notice how the sun went down amidst rising clouds, how the wind began to sigh through the forest; darkness was gathering over the spectators and combatants, who had now fought many rounds, lasting nearly an hour, when at last, to the great joy of many present, Grabber, at the conclusion of a round, in which[48] he had exhausted all his strength, got a knock-down blow, and was unable to “come up to time,” so amidst deafening cheers, Cuthbert was hailed as the victor.

He advanced to Grabber who was supported on the knee of his second.

“Give me your hand, Nicholas, and let us forgive and forget. I hope you are not much hurt.”

Grabber sullenly refused.

“That shows a bad heart; a fellow should never bear malice for a fair thrashing, one can only do his best after all,” said Gregory.

And the majority shared his opinion.

“We must make haste out of the woods, or we shall lose our way and be here all night.”

Three or four boys remained with Grabber, for he was not without his sympathizers,—we are sorry to say there are black sheep even in the best schools,—and these would not leave the spot with the rest, but said they could find their own way home.

The others struck boldly towards the west, which was easily distinguished, owing to the reddened and angry clouds, which showed where the monarch of the day had gone down.

But soon these also disappeared, and the road was not yet attained; darkness fell upon the scene, and the lads who were with Cuthbert wandered[49] about lost, utterly lost, until a distant light gladdened their eager sight, and with a joyous cry they bent their course towards it.

In a few minutes they emerged from the woods on the high-road from London, where a well-known inn, “The Cross Keys,” hung out a lamp as a guide to travellers.

They all knew their way now, and would fain have started home at once, only Cuthbert was faint after his late exertions, and a cup of “Malmsey” seemed the right thing.

“You had better let him have a good wash; cold water will revive him, and remove the blood from his face too,” said the landlord, who saw the lad had been fighting, and a fight was too common a thing, we are sorry to say, to excite any further comment or enquiries, on his part.

So they adjourned to the pump, where, with the help of a rough towel, Cuthbert soon made himself presentable, although he still bore very evident traces of the conflict.

This necessary task accomplished, the boys entered the inn, ordinarily a forbidden place to them, and the landlord brought a cup of wine for Cuthbert.

But while they were there a body of armed men entered the house.

They wore the uniform of the King’s guard: there was no regular army in those days, every[50] man was a soldier in time of need, but there was a small body of men kept about the King’s person, who were sent from time to time on special services, and were called the King’s “beef-eaters.”

And these were some of them.

“Landlord, bring us some mulled sack,” said one who appeared to be their leader, “and tell us, have you seen that fox the Abbot of Glastonbury pass this way to-day on his road home?”

“He has not yet returned from London?”

“Nay, but he is on his way,—we have no listening ears have we?” The boys were separated by a partition. “Are you for Abbot or King?”

“I am a friend to the King.”

“Well said, so should every good Englishman be; and we have charge to arrest this wily Abbot on his return, as a foe to King Harry, and take him to Wells to be tried for his life.”

“Has he not been tried and acquitted?”

“He has been solemnly condemned in a Court where Thomas Cromwell sat as prosecutor, jury and judge: but that is not quite the law, so he has been dismissed home, and we have been sent by an after thought to take him to Wells for a regular trial.”[16]

“On what charge?”

“Robbing the Abbey Church.”

“Good heavens!”

“Why, I thought thee a friend of the King.”

“So I am, but what can all this mean?”

“That he hid the Abbey plate, so that the King’s visitors could not find it, when they wanted to make an inventory, and confiscate patens and chalices for the King’s use.”

“But it was his own.”

“Only in trust, you see.”

“Still he might hide it in trust for the Abbey, that would not be robbery.”

“Friend, I should advise thee to consider it robbery in these days; it is better for all men who do not want their necks stretched to think as the King and his minister, Thomas Cromwell, think; don’t fear but we shall find men to bring him in guilty.”

The poor inn-keeper was silent; perhaps he remembered that one of his predecessors had been hanged for saying he would make his son heir to the “Crown,” meaning the “Crown Inn.”

The boys stole out unobserved.

“What shall we do?”

“Go and meet the Abbot and warn him, he will pass Headly Cross.”

“But then we may but share his fate,” said several.

“I shall go if I go alone,” said Cuthbert.

“And so shall I,” said Gregory Bell.

“Well, two are as good as the lot of us, and better; more likely to pass unobserved,” said Adam Banister; “the rest of us had better get home, and tell the monks all we have heard and seen.”

It was a wild place, Headly Cross, where two woodland roads crossed each other. Report said that a cruel murder had been committed there years agone, and that the place was haunted; every one believed in haunted places then.

But as there was a choice of routes, and the Abbot might come either way, it was the right thing to await him where the roads converged.

And there Cuthbert and Gregory waited all alone, as the dark hours rolled away, until they heard the “Angelus” ring from a distant tower, and knew it was nine o’clock, when decent people, in those days, went to bed.

The chime had hardly died away, when they heard the tread of horses, and soon three riders came in view in the dim light of the stars; and the boys recognised the Abbot, with two attendants, one his faithful serving man, the other a stranger.

Cuthbert dashed forward. “My Lord Abbot,”[53] he said, “one moment, it is I, Cuthbert, and here is Gregory Bell.”

“Cuthbert and Gregory Bell; why are you here, boys?”

“We have heard a plot against you: men are waiting at the ‘Cross Keys’ to arrest you, and take you for trial at Wells; they say it will cost your life.”

“On what charge?”

“Concealing the Abbey plate.”

The Abbot smiled sadly.

“My children,” he said, “this can hardly be true, yet if it be as you say, I will not fly a jury of my countrymen.”

“Neither could he,” said the stranger on his left hand, “if he would; my duty is to see him safe to Glastonbury, unless relieved beforehand by royal authority.”

“You see, my Cuthbert and Gregory, that your devotion is all in vain; neither would I avail myself of it if I could. Mount on the pillion behind me, Cuthbert; my good Ballard here will take Gregory behind him, and you may return with us to Glastonbury, if such return be permitted.”

“It never will be, never will be,” said Cuthbert, with sinking heart.

And how that young heart beat, as they approached the “Cross Keys,” and as a line of men, forming across the road, stopped the cavalcade.

“My Lord Abbot, we arrest you in the King’s name.”

“On what charge?”

“Robbery of the Abbey Church.”

“This is a base pretence, to deprive me of the credit of martyrdom for my convictions: but there was One who suffered more for me.”

And the Abbot yielded himself peacefully to those who sought his life.

[15] Advantage was taken of the Abbot’s compulsory absence to take the necessary steps for the dissolution of the monastery. (Froude.)

[16] In some private memoranda of Thomas Cromwell, which still exist in his own hand-writing, occur the words,—“Item. The Abbot of Glaston to be tried at Glaston, and also to be executed there with his accomplices.” The trial, however, took place at Wells, the execution (a foregone conclusion) at Glastonbury, as related in the story.

The period of English history of which we are now writing has been aptly called “The Reign of Terror.” England under Thomas Cromwell, and France under Robespierre, were alike examples of the utter prostration which may befall a mighty nation beneath the sway of one ruthless intellect.