This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Grave-mounds and Their Contents

A Manual of Archæology, as Exemplified in the Burials of the Celtic, the Romano-British, and the Anglo-Saxon Periods

Author: Llewellynn Frederick William Jewitt

Release Date: August 29, 2016 [eBook #52906]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GRAVE-MOUNDS AND THEIR CONTENTS***

| Note: |

Images of the original pages are available through

Internet Archive. See

https://archive.org/details/gravemoundstheir00jewiuoft Some characters might not display in this html version. If so, the reader should consult the UTF-8 text file 52906-0.txt (http://www.gutenberg.org/files/52906/52906-0.txt) or the original page images referred to above. |

i

ii

iii

iv

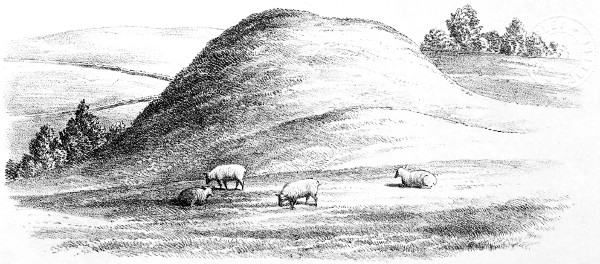

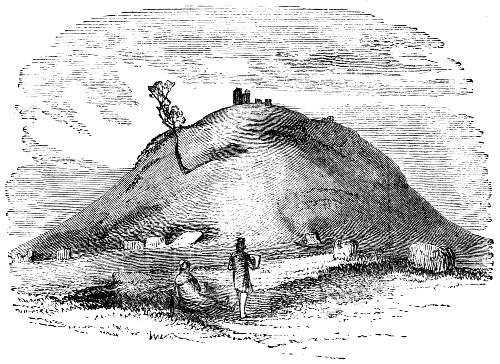

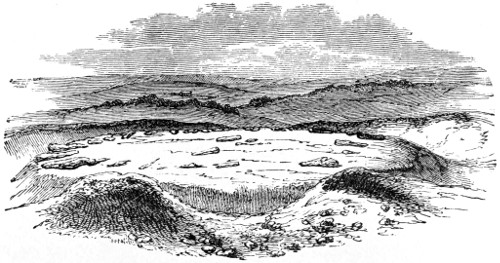

CIB HILL TUMULUS, NEAR ARBOR-LOW, DERBYSHIRE.

v

Grave-mounds and their Contents:

A MANUAL OF ARCHÆOLOGY,

AS EXEMPLIFIED IN THE

BURIALS OF THE CELTIC, THE ROMANO-BRITISH, AND

THE ANGLO-SAXON PERIODS.

BY

LLEWELLYNN JEWITT, F.S.A.,

ETC., ETC.

With nearly Five Hundred Illustrations.

LONDON:

GROOMBRIDGE AND SONS,

5, PATERNOSTER ROW.

1870.

vi

TO

MY OLD AND MUCH-ESTEEMED FRIEND,

JOSEPH MAYER, Esq.,

FELLOW OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF LONDON;

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF NORTHERN ANTIQUARIES

OF COPENHAGEN;

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY;

MEMBER OF THE SOCIETIES OF ANTIQUARIES OF

FRANCE, NORMANDY, THE MORINI,

ETC., ETC., ETC.;

ONE OF THE MOST ARDENT AND ZEALOUS OF ARCHÆOLOGISTS,

AND MOST KINDLY OF MEN;

THE PRINCELY DONOR TO THE PUBLIC

OF THE FINEST AND MOST EXTENSIVE

MUSEUM OF ANTIQUITIES

EVER COLLECTED TOGETHER BY A SINGLE INDIVIDUAL;

I, WITH TRUE PLEASURE,

Dedicate this Volume.

LLEWELLYNN JEWITT.

vii

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

| Page | |

| Grave-mounds in general—Their Historical Importance—General Situation—Known as Barrows, Houes, Tumps, and Lows—List of Names—Division into Periods | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Ancient British or Celtic Period—General characteristics of the Barrows—Modes of construction—Interments by inhumation and by cremation—Positions of the Body—Hitter Hill Barrow—Elliptical Barrow at Swinscoe—Burial in contracted position—In sitting and kneeling positions—Double Interments | 6 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Ancient British or Celtic Period—Interment by cremation—Discovery of lead—Burial in Urns—Positions of Urns—Heaps of burnt Bones—Burnt Bones enclosed in cloth and skins—Stone Cists—Long-Low—Liff’s-Low, etc.—Pit Interments—Tree-coffins | 31 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Ancient British or Celtic Period—Sepulchral Chambers of Stone—Cromlechs—Chambered Tumuli—New Grange and Dowth—The Channel Islands—Wieland Smith’s Cave, and others—Stone Circles—For what purpose formed—Formation of Grave-mounds—Varieties of Stone Circles—Examples of different kinds—Arbor-Low, etc. | 50 viii |

| CHAPTER V. | |

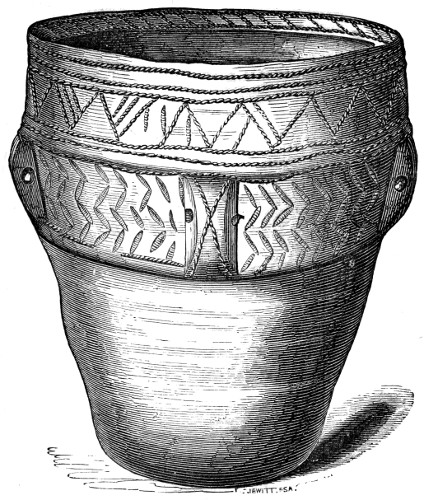

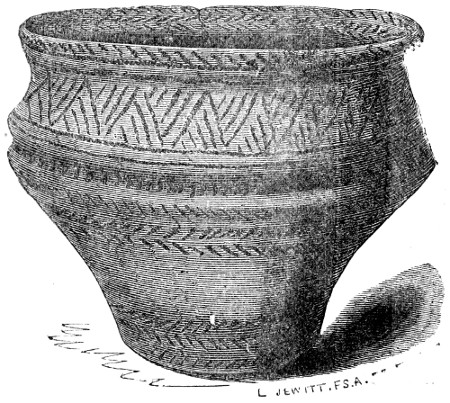

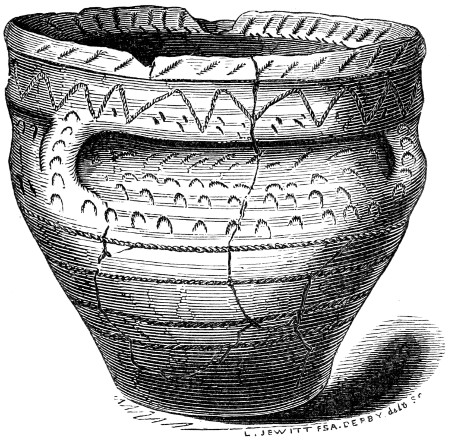

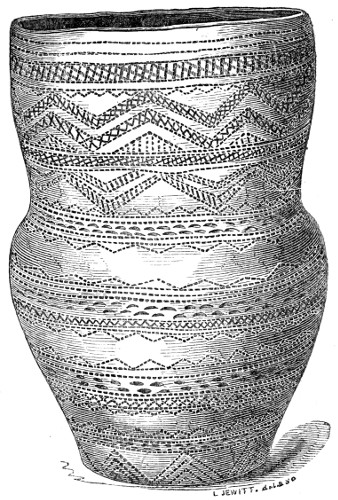

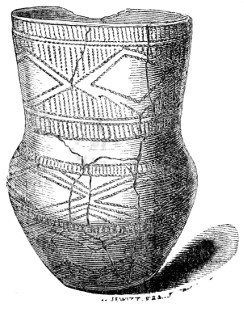

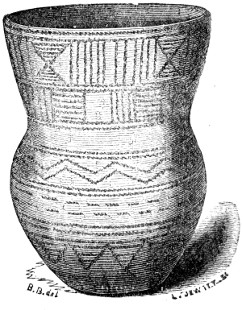

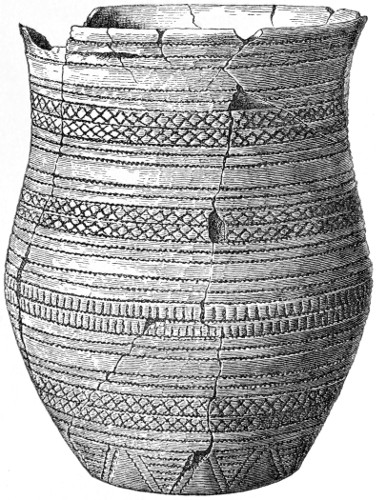

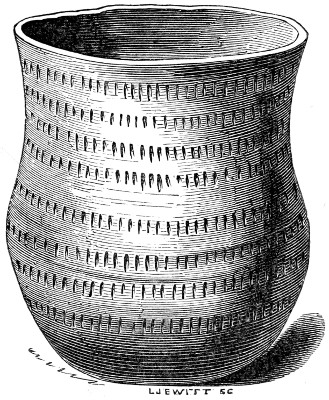

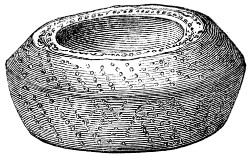

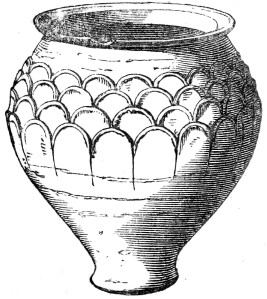

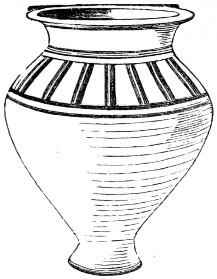

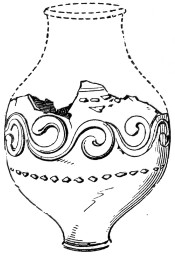

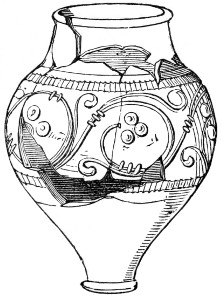

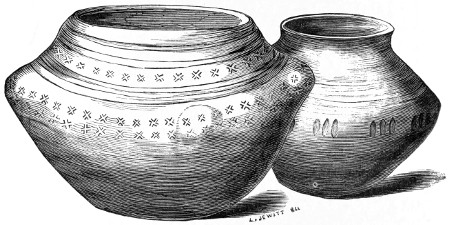

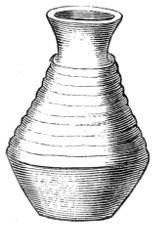

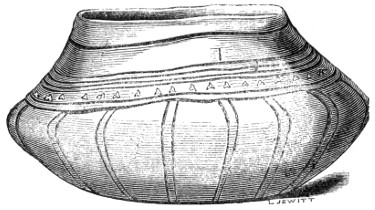

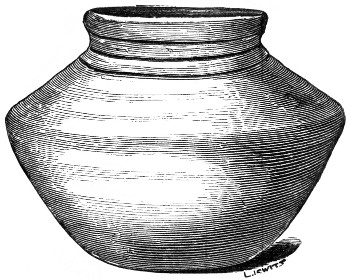

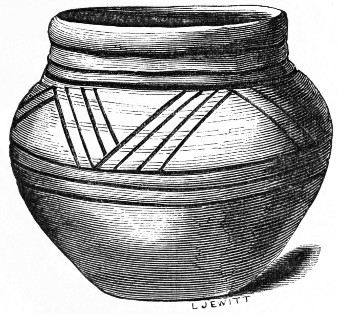

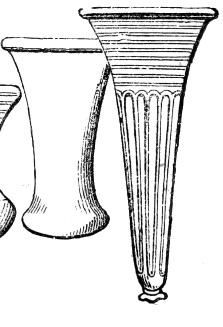

| Ancient British or Celtic Period—Pottery—Mode of manufacture—Arrangement in classes—Cinerary or Sepulchral Urns—Food Vessels—Drinking-cups—Incense Cups—Probably Sepulchral Urns for Infants—Other examples of Pottery | 83 |

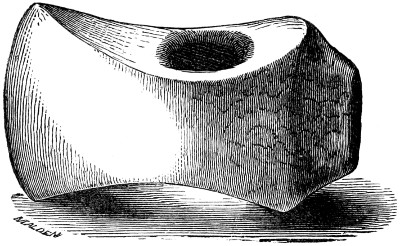

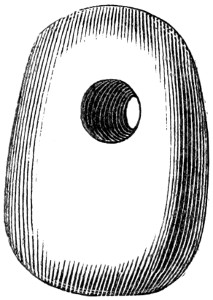

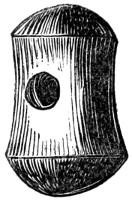

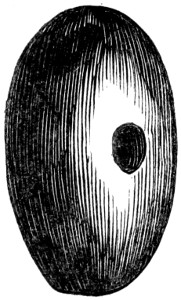

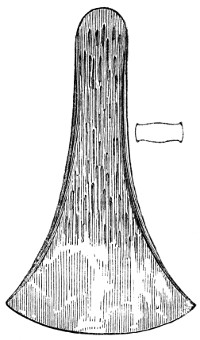

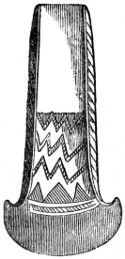

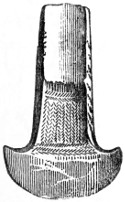

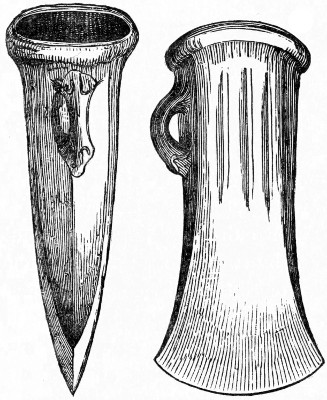

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Ancient British or Celtic Period—Implements of Stone—Celts—Stone Hammers—Stone Hatchets, Mauls, etc.—Triturating Stones—Flint Implements—Classification of Flints—Jet articles—Necklaces, Studs, etc.—Bone Instruments—Bronze Celts, Daggers, etc.—Gold articles | 109 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

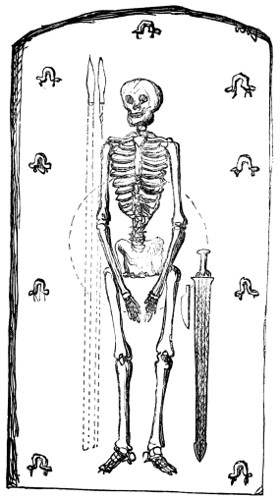

| Romano-British Period—General Characteristics—Modes of Burial—Customs attendant on Burial—Interments by cremation and by inhumation—Barrows—Tombs of Stone—Lead Coffins—Clay and Tile Coffins—Sepulchral Inscriptions, etc. | 134 |

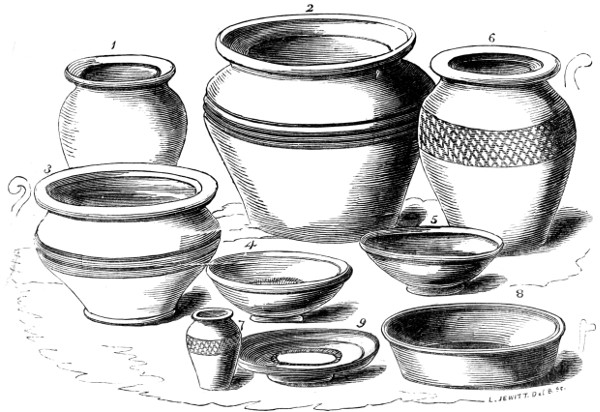

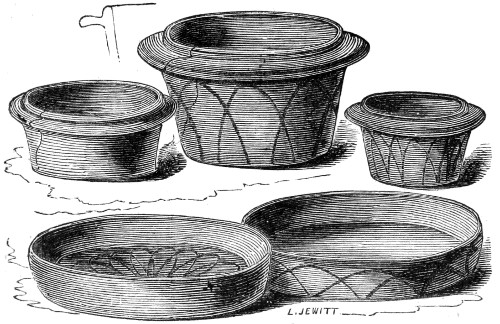

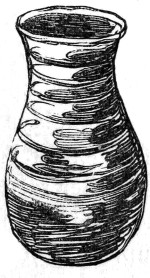

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

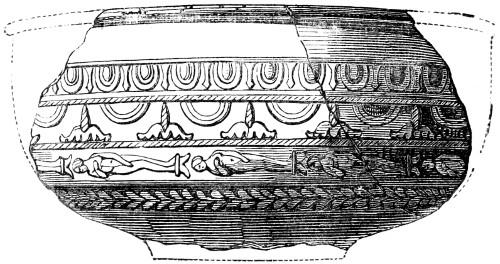

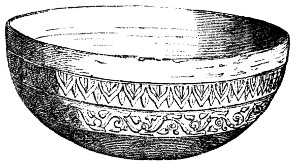

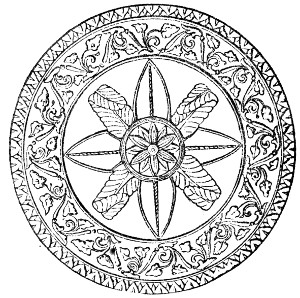

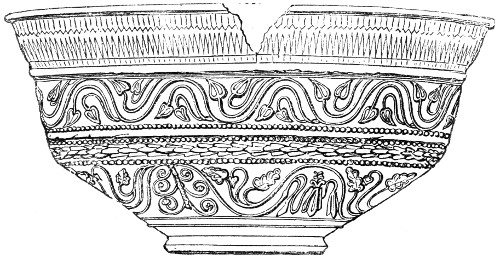

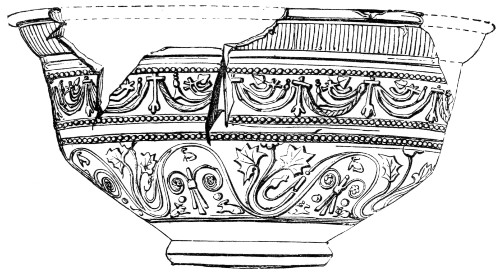

| Romano-British Period—Pottery—Durobrivian Ware—Upchurch Ware—Salopian Ware—Pottery found at Uriconium—Potteries of the New Forest, of Yorkshire, and of other places—Sepulchral Urns—Domestic and other vessels | 151 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

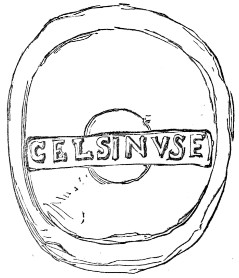

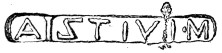

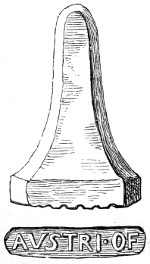

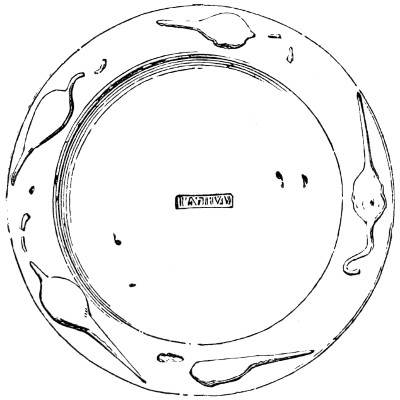

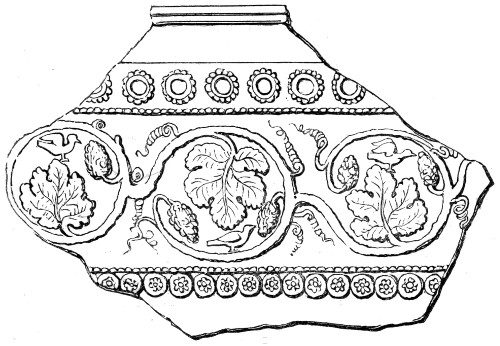

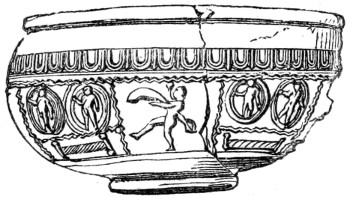

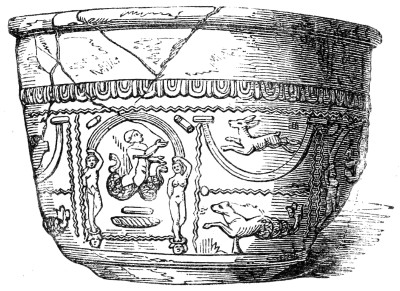

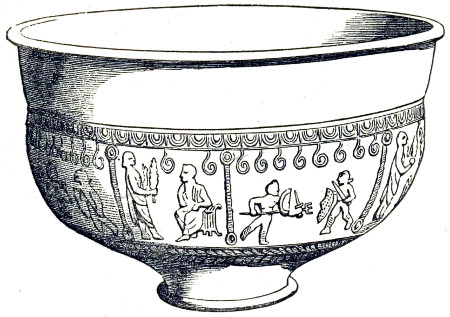

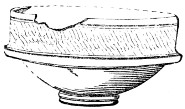

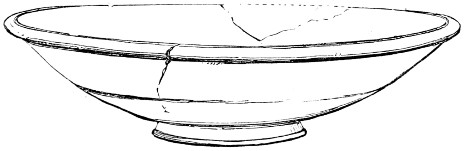

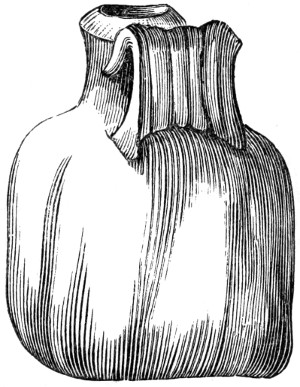

| Romano-British Period—Pottery—Samian Ware—Potters’ Stamps—Varieties of Ornamentation—Glass Vessels—Sepulchral Vases, etc.—Lachrymatories—Bowls—Beads—Coins found with Interments | 175 |

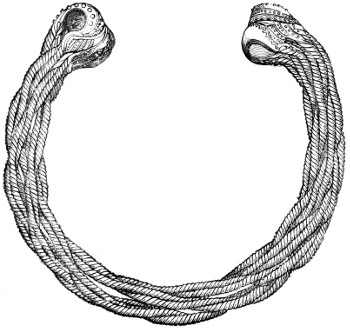

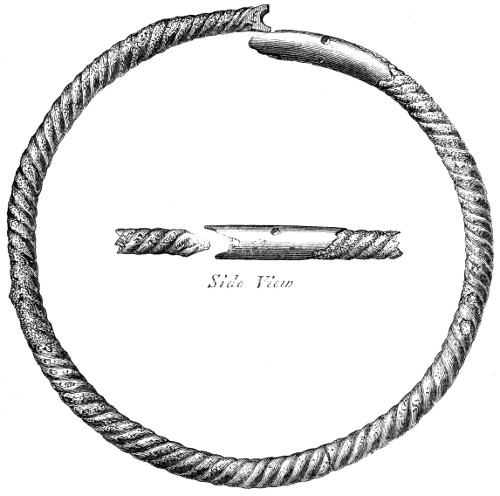

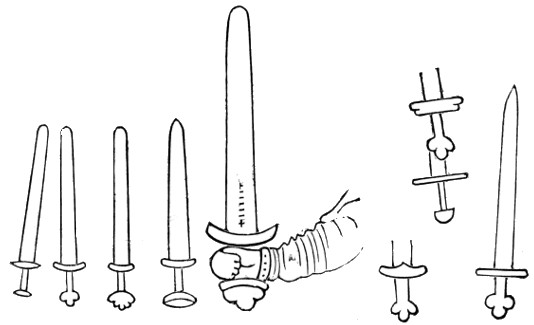

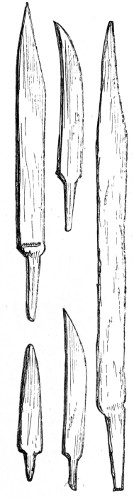

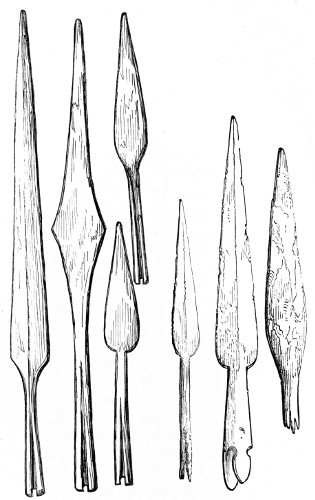

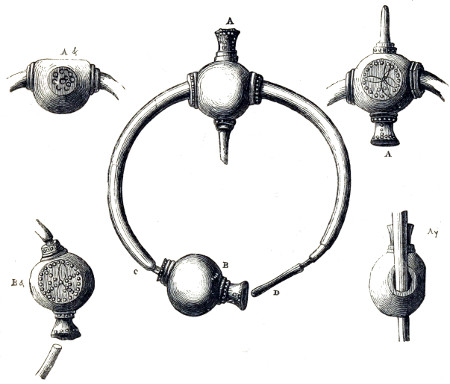

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Romano-British Period—Arms—Swords—Spears, etc.—Knives—Fibulæ—Armillæ—Torques of Gold, etc.—Other Personal Ornaments | 190 ix |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Anglo-Saxon Period—Distribution of Anglo-Saxon Population over England—General characteristics of Grave-mounds—Modes of Burial—Poem of Beowulf—Interments by cremation and by inhumation—Articles deposited with the Dead—Positions of the Body—Double and other Interments—Burial in Urns—Cemeteries and Barrows | 202 |

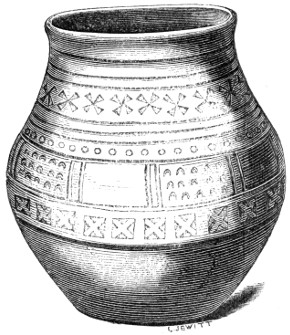

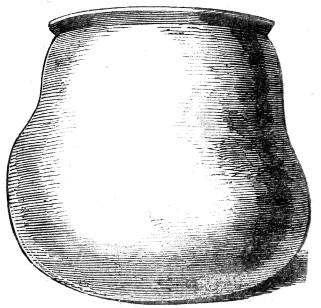

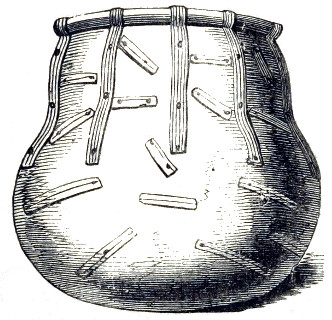

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Anglo-Saxon Period—Pottery, general characteristics of—Cinerary Urns—Saxon Urn with Roman Inscription—Frankish and other Urns—Cemeteries at Kings Newton, etc.—Mode of manufacture—Impressed Ornaments | 214 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

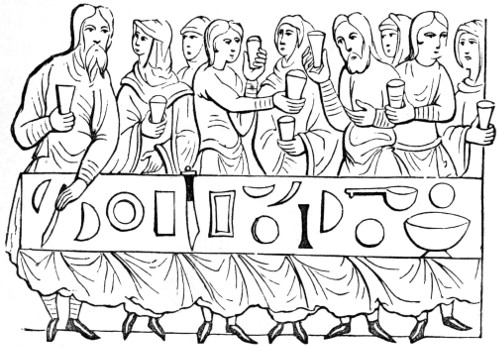

| Anglo-Saxon Period—Glass Vessels—Drinking-glasses—Tumblers—Ale-glasses—Beads—Necklaces—Ear-rings—Coins, etc. | 228 |

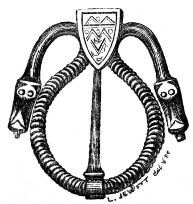

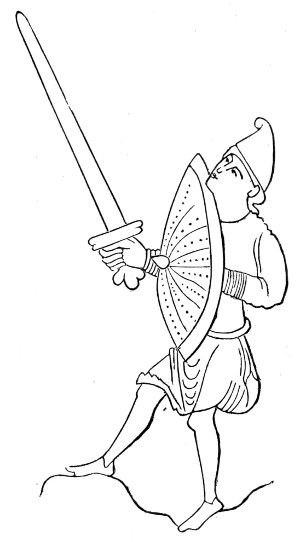

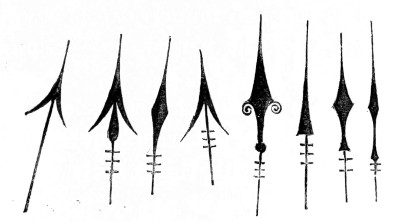

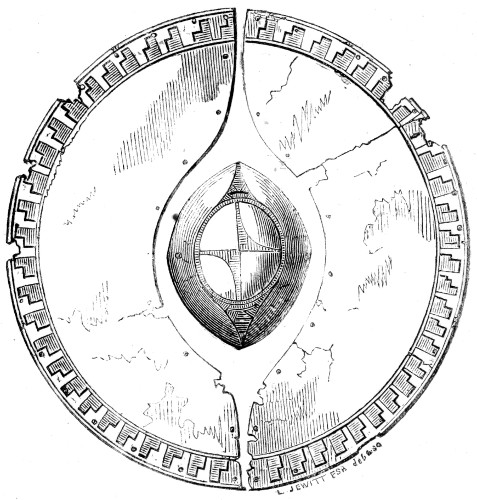

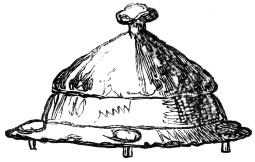

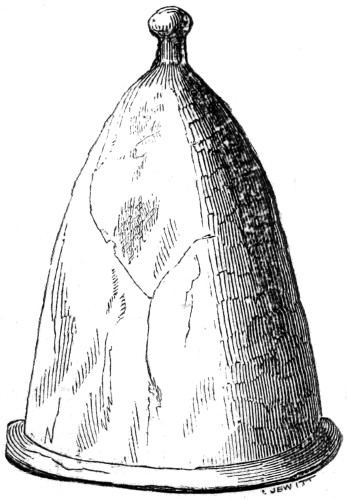

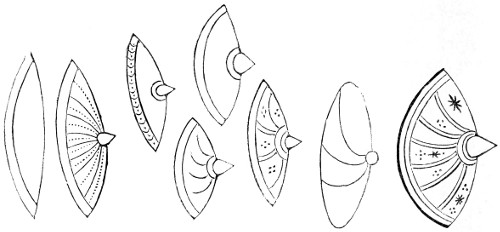

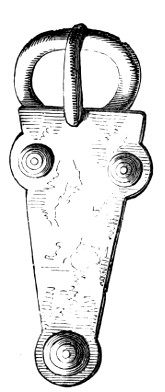

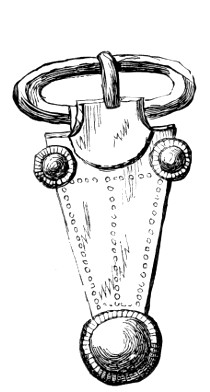

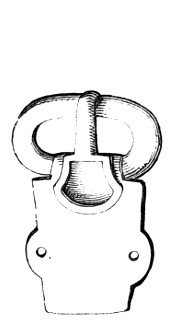

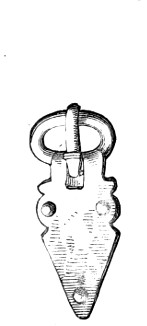

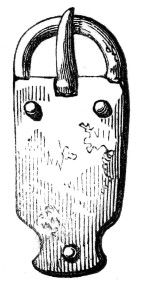

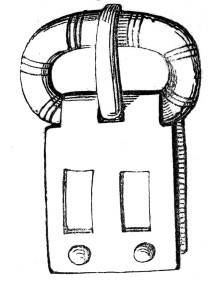

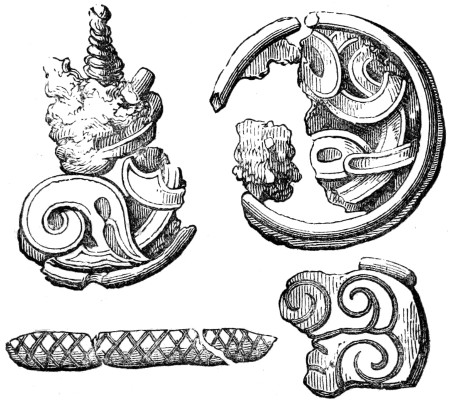

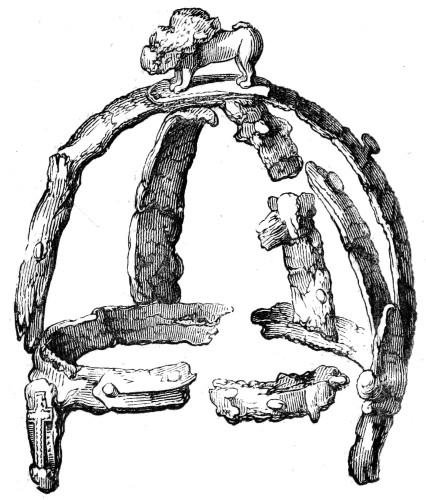

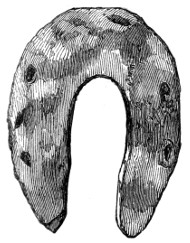

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Anglo-Saxon Period—Arms—Swords—Knives—Spears—Shields—Umbones of Shields—Buckles—Helmets—Benty-Grange Tumulus—The Sacred Boar—Grave at Barlaston—Enamelled Discs and pendant Ornaments, etc.—Horse-shoes | 236 |

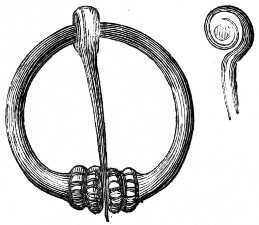

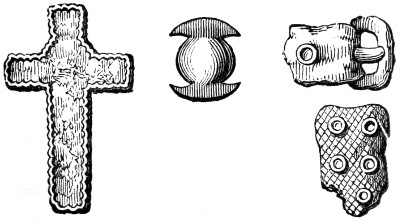

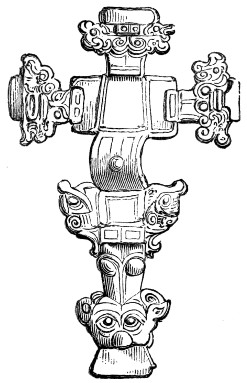

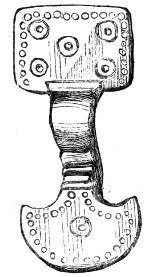

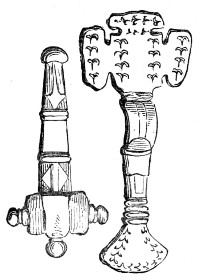

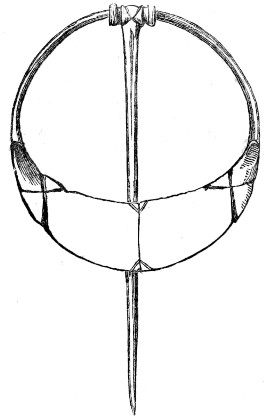

| CHAPTER XV. | |

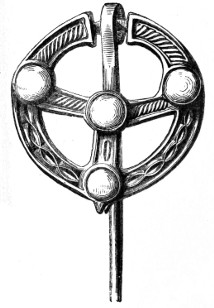

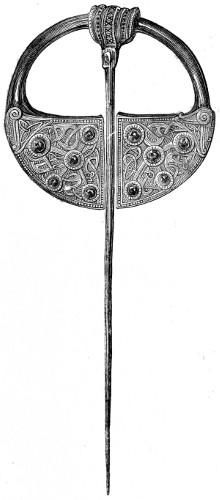

| Anglo-Saxon Period—Fibulæ—Enamelled circular Fibulæ—Gold Fibulæ—Pendant Cross—Cruciform Fibulæ—Penannular Fibulæ—Irish and English examples—Pendant Ornaments, etc. | 266 |

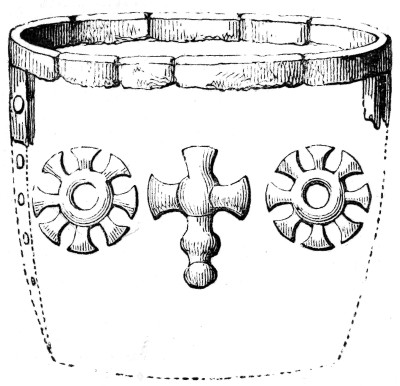

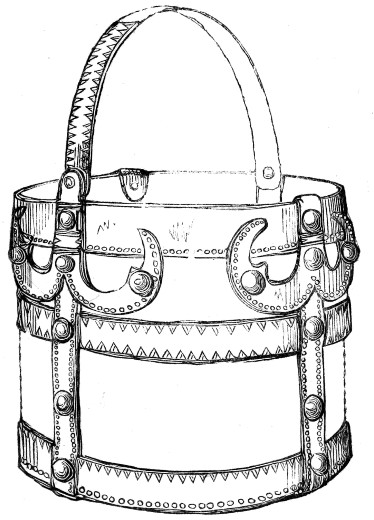

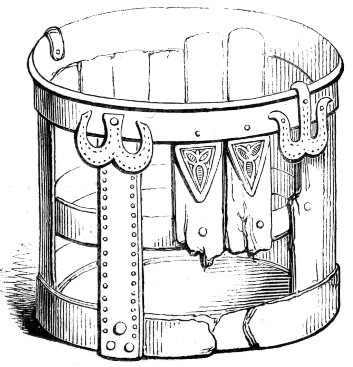

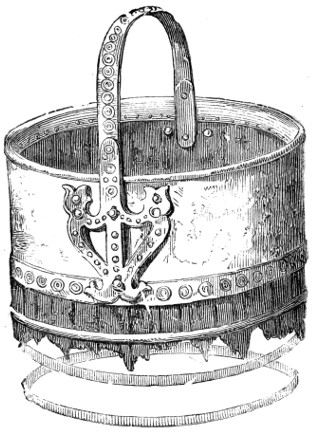

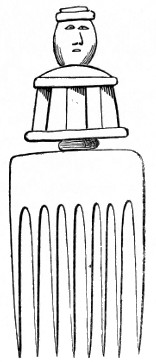

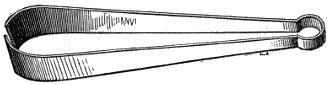

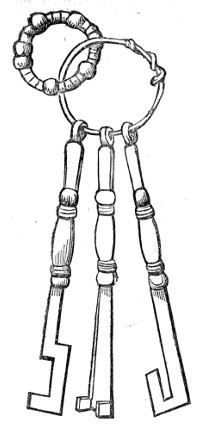

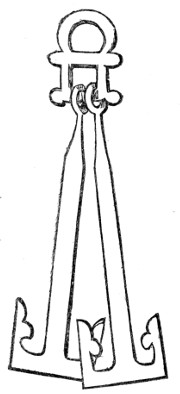

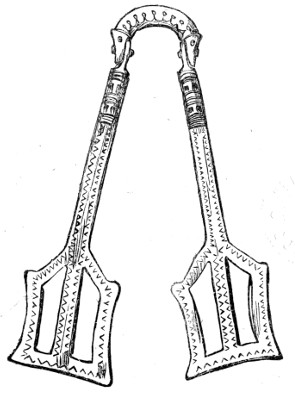

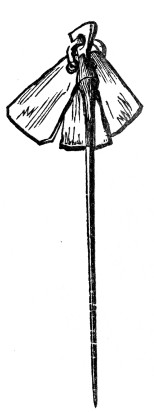

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

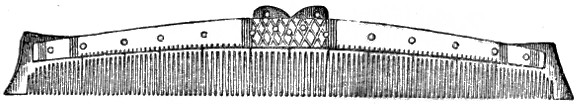

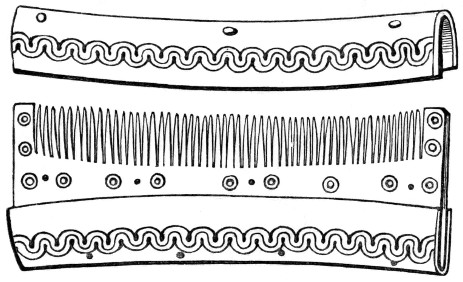

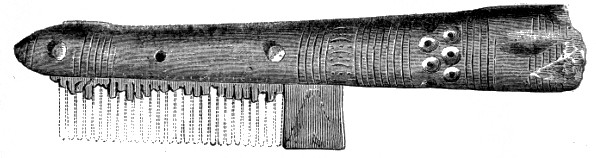

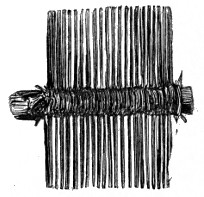

| Anglo-Saxon Period—Buckets—Drinking-cups of wood—Bronze Bowls—Bronze Boxes—Combs—Tweezers—Châtelaines—Girdle Ornaments—Keys—Hair-pins—Counters, or Draughtmen, and Dice—Querns—Triturating Stones, etc.—Conclusion | 280 |

x

xi

xxii

xxiii

The object of the following work is, I apprehend, so obvious as to render an introduction scarcely needful. It may be well, however, to remark, that it is the only work of its kind which has ever been issued, and that therefore, taking a stand of its own, and following no other either in plan or treatment of its subject, it is hoped that it will command the attention of antiquaries and of all who are interested in the history and the manners and habits of our early forefathers.

It has long appeared to me that a general résumé of the almost endless store of knowledge presented by the very varied relics of the grave-mounds of the three great divisions of our history—the Celtic, the Romano-British, and the Anglo-Saxon—kept distinct from the histories of those peoples, and from extraneous matters, and treating them more in a general than in an ethnological manner, could not fail to be a useful addition to our archæological literature, and would prove of great value and convenience to the general reader, as well as to the antiquary and the historian. Thus it is that I have been induced to prepare the present volume. xxiv

I have treated my subject in a popular manner, divesting it of technicalities, of theories, and of discursive matter, and have endeavoured, as far as space would permit, to give, simply and clearly, as correct an insight as possible into the modes of burial adopted in early times in our own country, and into the various remains of different races which an examination of their grave-mounds discloses.

Having great faith in the usefulness of engravings, and believing that, if judiciously introduced, a work of the kind cannot be too profusely illustrated, I have brought together in my present volume a larger number of engravings than could well have been expected; and these, I trust, will add much to its usefulness and value. To all my kind friends who have aided me in this matter I give my hearty thanks.

The work may have some, perhaps many, defects. If such exist, I shall be thankful to have them pointed out, and to remedy them in a future edition.

Winster Hall,

Derbyshire.

1

Grave-mounds and their Contents.

Grave-mounds in General—Their Historical Importance—General Situation—Known as Barrows, Houes, Tumps, and Lows—List of Names—Division into Periods.

To the grave-mounds of the early inhabitants of our island, more than to any other source, we are indebted for our knowledge of their arts, their habits, and their occupations. Indeed, to these mounds and their contents, we owe almost all the knowledge we possess as to the history of the races and peoples who have preceded us, and are enabled to determine, approximately, their chronological succession as masters of the soil.

From the very earliest ages men of every race have bestowed peculiar care over the graves of the dead, and have marked to later ages, in an unmistakable manner, these places of sepulture, which have, in many instances, been preserved with religious care to modern times. Thus the relics which they contain have come down to us intact, and even now tell their wondrous tale, in a language of their own, of ages and of races of beings long since passed away. A single implement of stone or of flint; a weapon or an ornament of bronze, of iron, or of bone; a bead of jet or of glass; an urn, or even a fragment of pottery; or any one 2 of the infinity of other relics which are exhumed, no matter to what period they belong, or from what locality they may have come; one and all tell their own tale, and supply new links to our ever-extending chain of knowledge.

To the graves, then, of our earliest ancestors, must we mainly turn for a knowledge of their history and of their modes of life; and a careful examination and comparison of their contents will enable us to arrive at certain data on which, not only to found theories, but to build up undying and faultless historical structures.

As, wherever the country was populated, interments of the dead must, as a necessity, have taken place, these all-important store-houses of after-knowledge exist, or have existed, to more or less extent in almost every district throughout the land, and give evidence, whenever opened by experienced hands, of their historical value and importance. The earliest grave-mounds are mostly found in the mountainous districts of the land—among the hills and fastnesses; the latter overspreading hill and valley and plain alike. Thus, in Cornwall and Yorkshire, in Derbyshire and in Dorsetshire, in Wiltshire and in many other districts, the earliest interments are, or have been, abundant; while the later ones, besides being mixed up with them in the districts named, are spread over every other county. In the counties just named Celtic remains abound more than those of any other period. In Dorsetshire, for instance, that county, as the venerable Stukeley declares, “for sight of barrows not to be equalled in the world,” the early mounds abound on the downs and on the lofty Ridgeway, an immense range of hills of some forty miles in extent, while those of a later period lie in other parts of the county. In Yorkshire, again, they abound chiefly in the wolds; and in Cornwall, on the high lands. The same, again, of Derbyshire, where they lie for the most part scattered over the wild, mountainous, and beautiful district known as the High Peak—a district occupying nearly 3 one half of the county, and containing within its limits many towns, villages, and other places of extreme interest. In this it resembles Dorsetshire; for in the district comprised in the Ridgeway and the downs are very many highly interesting and important places, around which the tumuli are most plentiful.

It is true that here and there in Derbyshire, as in other counties, an early grave-mound exists in the southern or lowland portion of the county; but, as a rule, they may be almost said to be peculiar, and confined, to the northern, or hilly district, where in some parts they are very abundant. Indeed, there are districts where there is scarcely a hill, even in that land, where

where a barrow does not exist or is not known to have existed. In passing along the old high-road, for instance, over Middleton Moor by way of Arbor Low,1 Parcelly Hay, High Needham, Earl Sterndale, and Brier Low, to Buxton, or along the high-roads by way of Winster, Hartington, or Newhaven, the practised eye has no difficulty in resting on the forms of grave-mounds on the summits of the different hills or mountains, whose outlines stand out clear and distinct against the sky.

The situations chosen by the early inhabitants for the burial of their dead were, in many instances, grand in the extreme. Formed on the tops of the highest hills, or on lower but equally imposing positions, the grave-mounds commanded a glorious prospect of hill and dale, wood and water, rock and meadow, of many miles in extent, and on every side stretching out as far as the eye could reach, while they themselves could be seen from afar off in every direction by the tribes who had raised them, while engaged either 4 in hunting or in their other pursuits. They became, indeed, land-marks for the tribes, and were, there can be but little doubt, used by them as places of assembling.

Sepulchral tumuli are known as barrows, lows, houes, tumps, etc. Barrow is of pretty general use; low is almost universal in Derbyshire, Staffordshire, and other districts; tump is in use in Gloucestershire, etc.; and houe in Yorkshire.

In Derbyshire and Staffordshire, the term “Low” is so very usual that, wherever met with, it may be taken as a sure indication of a barrow now existing or having once existed at the spot. As a proof of this, it will only be necessary to say that at about two hundred places in Derbyshire alone, and at about half that number on the neighbouring borders of Staffordshire, which bear the affix of Low, barrows are known to exist or have already been opened. For my present purpose, it will be sufficient to give the few following names:—Arbor-Low, Kens-Low, Ringham-Low, Blake-Low, Fox-Low, Gib-Low, Green-Low, Great-Low, Grind-Low, Cal-Low, Chelmorton-Low, Casking-Low, Larks-Low, Thirkel-Low, Ribden-Low, Har-Low, Bas-Low, High-Low, Foo-Low, Lean-Low, Huck-Low, Borther-Low, Dow-Low, Totman’s-Low, Staden-Low, Stan-Low, Blind-Low, Boar-Low, Bottles-Low, Brown-Low, Caldon-Low, Calver-Low, Cock-Low, Cop-Low, Cow-Low, Cronkstone-Low, Dars-Low, Drake-Low, Elk-Low, End-Low, Far-Low, Pike-Low, Fowse-Low, Galley-Low, Gris-Low, Grub-Low, Herns-Low, Hawks-Low, Horning-Low, Hard-Low, Knock-Low, Knot-Low, Laidmans-Low, Lady-Low, Liffs-Low, Lomber-Low, Lousy-Low, Mick-Low, Moot-Low, Money-Low, Musden-Low, May-Low, Needham-Low, Nether-Low, Ox-Low, Off-Low, Pars-Low, Painstor-Low, Peg-Low, Pigtor-Low, Pike-Low, Pinch-Low, Queen-Low, Ravens-Low, Rains-Low, Rick-Low, Rocky-Low, Rolley-Low, Round-Low, Rusden-Low, Saint-Low, Sitting-Low, Sliper-Low, Thoo-Low Three-Lows, 5 Ward-Low, Warry-Low, White-Low, Whithery-Low, Wool-Low, and Yarns-Low. To some of these I shall again have occasion to make reference. In Yorkshire, the names of William Houe, Three Houes, and Three Tremblers Houes, will be sufficient indication of the local use of the term “Houe.”

Grave-mounds may, naturally, be divided into the three great periods; the Celtic, the Romano-British, and the Anglo-Saxon. This division will be adopted in the present volume, and it will be its aim, while speaking of the characteristics of each, to classify and describe their contents, and to point out, briefly, such circumstances of interment, and such evidences of customs, as they may present, and which may appear to be of sufficient interest and importance to its plan.

Of the forms of barrows, and their characteristics and modes of construction, occasion will be taken to speak in a later chapter. 6

Ancient British, or Celtic, Period—General characteristics of the Barrows—Modes of construction—Interments by inhumation and by cremation—Positions of the body—Hitter Hill Barrow—Elliptical Barrow at Swinscoe—Burial in contracted position—In sitting and kneeling positions—Double interments.

The barrows of the Celtic, or ancient British, period vary in their form and size as much as they do in their modes of construction, and in their contents. Sometimes they are simply mounds of earth raised over the interment; sometimes heaps of stones piled up over the body; and sometimes again a combination of cist and earth and stone. Generally speaking the mounds are circular, rising gradually and gently from the level of the ground towards the centre, but in some instances the rise is somewhat acute. Now and then they are oval in form. Where elliptical barrows occur (generally known as “long barrows”), they are, I have reason to believe, not matters of original design, but of accident, through additional interments; and I much doubt the propriety of archæologists at the present day continuing the very questionable nomenclature adopted by Sir R. C. Hoare and others. In some cases, however, as in the instances of chambered or walled tumuli, the elliptical form of the barrow can be easily understood. An examination of a very large number of barrows leads me to the opinion that the original form of all was circular, and that no deviation from that form, and no difference in section, can be taken as indicative of period or of race. 7

The other appellation occasionally used, of “twin barrows,” is further evidence of this—two interments having been made within a short distance of each other, and the mounds raised over them running into and joining each other. It may, however, for purposes of description, and for this alone, be well to retain the names, while discarding much of the theory and of the system which has been attempted to be established regarding them.

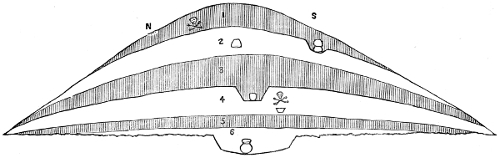

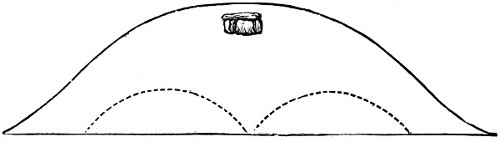

The mounds of earth alluded to, present occasionally highly interesting and curious features, and show that, like those of a different construction, they have frequently been used for successive interments. The section of one of these is shown on the next page. It is one of a group of six barrows on Lord’s Down, in the parish of Dewlish, in Dorsetshire. It was eighty-two feet in diameter, and fourteen feet in height in the centre. The primary interment, an urn, was placed in a cist cut in the chalk sub-soil. Over the urn was raised a small cairn of flints, and the cist was then filled in, and raised a little above the surface with chalk rubble. Over this was a layer of earth, upon which an interment had taken place, and in its turn covered with a thick layer of chalk rubble, in the centre of which, in a cist, another interment had again been made. Above this rose another layer of earth, another of chalk, and then a final one of earth, on each of which interments had at different periods been made. Thus the tumulus, which was formed of alternate layers of chalk and earth, exhibited no less than six successive sepulchral deposits.2 The interments were both by inhumation and cremation.

Fig.2.

1. Earth to the depth of three feet.

2. Chalk, two feet in depth.

3. Earth to the depth of three feet.

4. Loose rubble chalk, three feet in depth.

5. Earth, one foot in depth.

6. Chalk rubble, six inches in depth.

Cist, filled with chalk rubble and flints, two feet in depth.

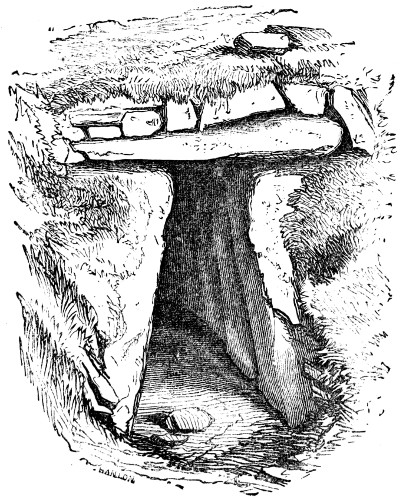

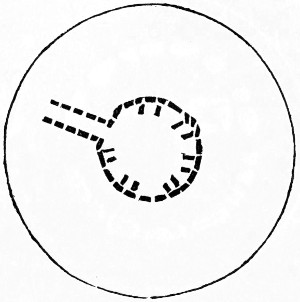

Another example of a barrow of this period is shown in section on the fig. 3. There had originally been four 8 9 small mounds, or barrows, formed in a group, on the natural surface of the ground (see the two dotted lines in the engraving). They were composed of tempered earth, approaching in tenacity almost to clay, and on these the general mound was raised to a height of about eighteen feet, and was composed of earth, intermixed with loose rubbly limestones. Nearly at the top, in the centre, a stone cist, enclosing an interment, was discovered. It was in form a perfect, though miniature, example of what are commonly called cromlechs.

Fig. 3.

It is not an unfrequent occurrence in barrows to find that interments have been made at different periods and by different races, as will be hereafter shown.

The two examples of mounds of earth already given will show the successive layers which have occurred in their formation. The simpler, and intact, mounds of earth, which are very common, require no illustration. They are simply immense circular heaps of earth raised over the interment, whether in cist or not.

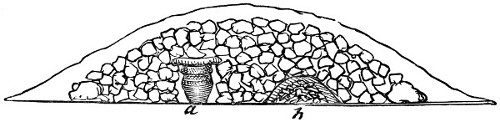

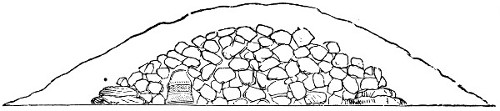

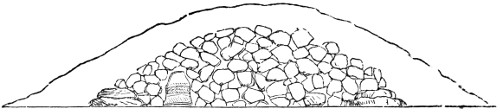

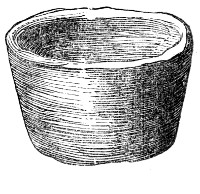

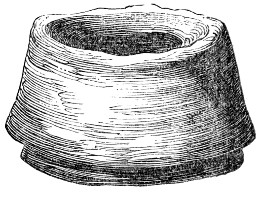

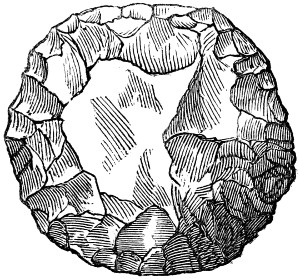

Barrows, or mounds, of stone are of frequent occurrence. They are of very simple construction. The interment, whether by cremation or otherwise, having been made in a natural or artificial cist, or simply laid upon the natural surface of the ground, rough stones were placed in a large circle around it, and an immense quantity of stones were then piled up to a height of several feet. Some of these 10 cairns are of very great size, and cover a large area of ground. Sections of two tumuli of this description are given in figs. 4 and 5. The cairn of stone was, as will be seen, covered to some depth with earth; perhaps in some instances this might be a part of the original design, but in most cases the soil which now covers these stone barrows may be traced to the ordinary process of decay of vegetation in successive ages.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

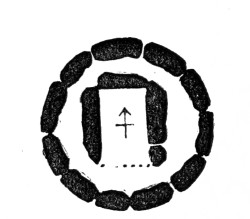

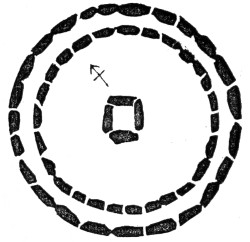

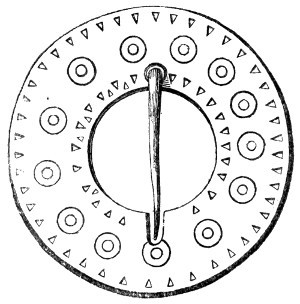

Barrows were not unfrequently surrounded by a circle of stones, set upright in the ground. These circles, in many instances, remain to the present day in different parts of the kingdom, and, the barrow itself having disappeared, are commonly called by the general appellation of “Druidical circles.” But of these, later on. The construction of the stone circles varied considerably. In some instances the upright stones were pretty close together; in others, wide apart; and in others, again, the spaces between the uprights were filled in with a rude loose rubble masonry, which thus formed a continuous wall.

Some tumuli contained stone chambers and passages, formed of massive upright slabs, and covered with immense 11 blocks of stone. Over these chambers, etc., the mounds of earth, or of stone, or of both combined, were raised, as will be hereafter shown.

Interments in the Celtic grave-mounds were both by inhumation and cremation, and the modes of interment, in both these divisions, was very varied.

Where inhumation obtained, the body was sometimes laid on its side, in a contracted position; at others, extended full length on its back or side; and in other instances, again, was placed in an upright sitting or kneeling posture. Occasionally, too, where more than one body has been buried at the same time, they have been laid face to face, with their arms encircling each other; at other times an infant has been placed in its mother’s arms.

When cremation has been practised, the remains have either been gathered together in a small heap on the surface of the ground—sometimes enclosed in a small cist, at others left uncovered, and at others covered with a small slab of stone—or wrapped in a cloth or skin (the bone or bronze pin which has fastened the napkin being occasionally found), or enclosed in cinerary urns, inverted or otherwise. In some instances, even when placed in urns, they were first enclosed in a cloth.

These are the general characteristics of the interments of the Celtic period, and they will be best understood by the following examples.

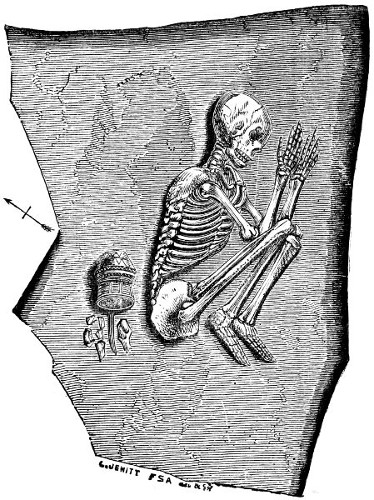

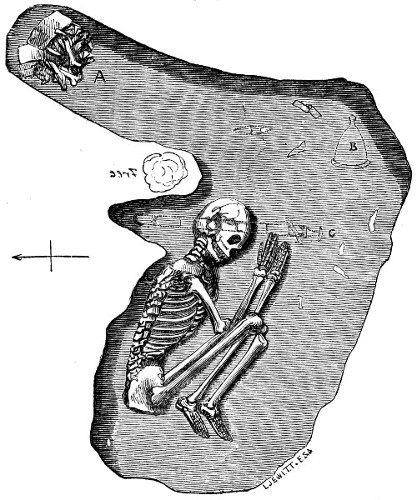

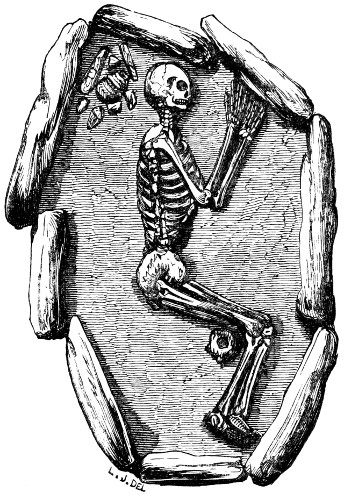

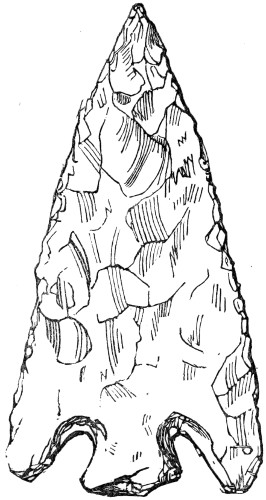

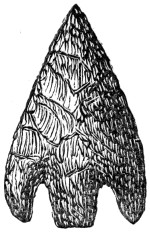

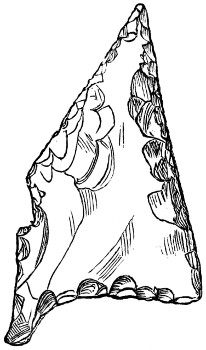

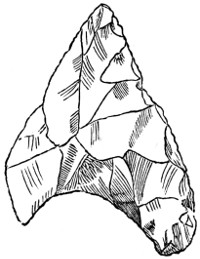

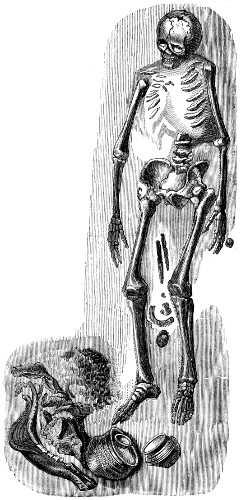

When the body has been buried in a contracted position, it is found lying on its side; the left side being the most usual. The head generally inclines a little forward; the knees are drawn up near to the chest, and the heels to the thighs; the elbows are brought near to the knees,—frequently, indeed, one of them will be found beneath, and the other on, the knees, which have thus been held between them; and the hands are frequently brought up to the front of the face. This position, which is after all, perhaps, 12 the most easy and natural one to choose, will be best understood by the following engraving (fig. 6), which shows an interment found in a barrow on Smerril Moor, opened by my much lamented friend the late Mr. Thomas Bateman. In this case the body had been laid on its left side in an irregularly formed cavity on the surface of the natural rock, on a bed of clay, over which, as usual, the mound was formed of loose stones and mould. Behind the skeleton, as will be seen in the engraving, was found a remarkably fine “drinking cup,” along with a bone meshing rule or modelling tool, twelve inches long, made from the rib of a horse or cow; a flint dagger; an arrow-head; and some other implements, also of flint, all of which had 13 been burned. The femur of this skeleton measured nineteen and a half inches, and the tibia sixteen inches.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 7.

The next example (fig. 7), from Tissington, will be seen to have been laid in very much the same position. It lies on its left side, the knees drawn up, and the feet, elbows, and hands in the position I have already described. This barrow possessed considerable interest, from the fact that a later interment—of the Anglo-Saxon period—had been made immediately above the figure here subjoined. To this I shall refer under the head of Anglo-Saxon. In the same barrow, shown at A on the engraving, was a deposit of burnt bones. Fig. 8, again, shows an interment 14 in the contracted position, the head, in this instance, resting upon the left hand. The skeleton lay in an oblong oval cist, five feet long by two and a half feet wide, smoothly hollowed out of the chalk, and over this the mound was raised. 15 16 Along with it were found a bronze dagger, a barbed arrow-head of flint, a beautiful drinking cup and other objects. This example is from Roundway Hill, in North Wiltshire.3 Another excellent example, from Hitter Hill, Derbyshire, is given in the next engraving (fig. 9), which shows successive interments, each being on the left side, in the usual contracted position.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 9.

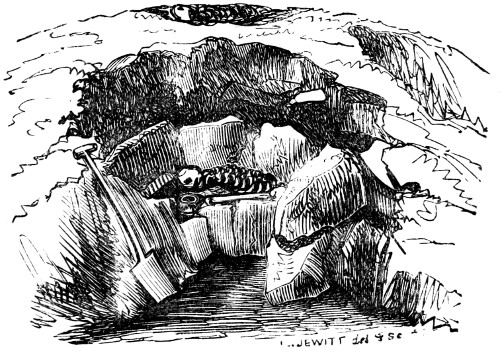

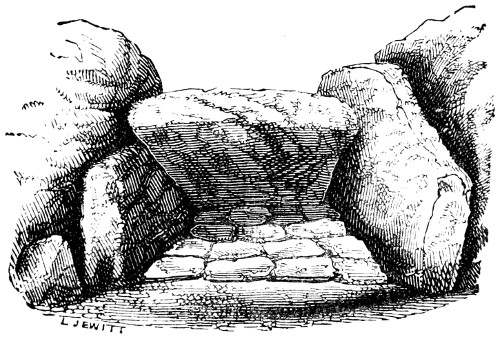

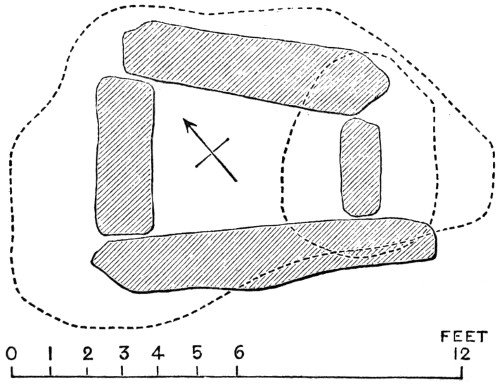

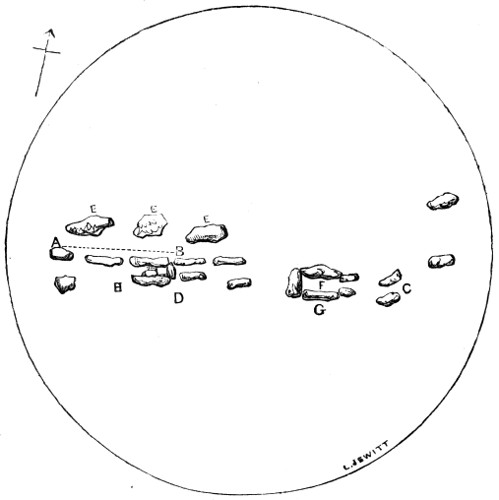

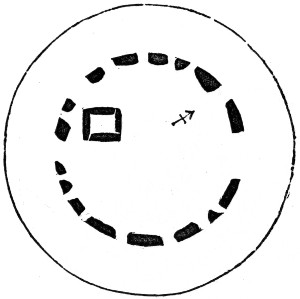

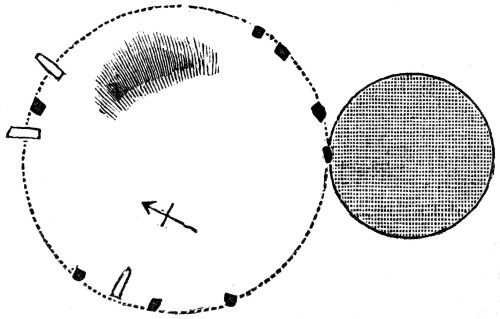

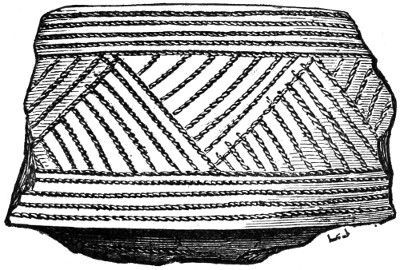

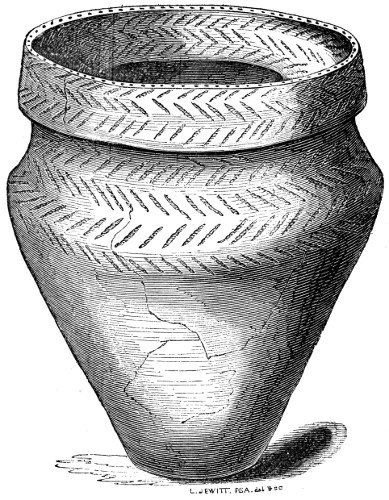

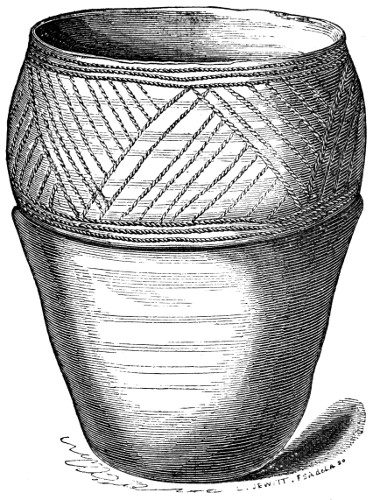

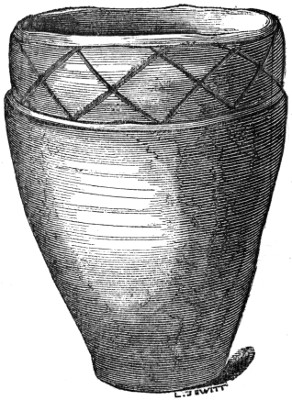

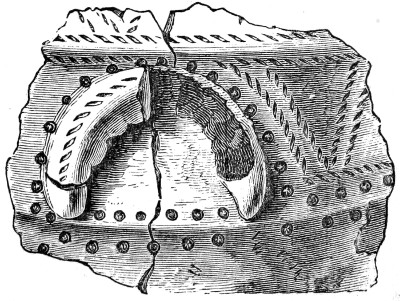

Of this barrow, the opening of which presented peculiarly interesting features, a tolerably detailed account will be advisable. It was opened by myself and Mr. Lucas in 1862. The mound, which was about twenty-two feet in diameter, was composed of rough stone and earth intermixed. It was only about three feet in height, its centre being somewhat sunk. The first opening was made at the part marked A on the accompanying ground-plan (fig. 10), where, from the outside, we cut a trench, four feet in width, in a north-easterly direction, towards the centre of the barrow, and soon came upon an interment of burnt and unburnt human bones. Along with these were an immense quantity of rats’ bones4 and snail-shells. After proceeding to a distance 17 of seven feet, we came upon the side, or what may almost be called the entrance, of a cist formed partly of the natural rock, and partly of stones set up edgewise. The dimensions of this cist were about forty inches by twenty-six 18 inches, and it was two feet in depth, the floor being three feet six inches below the surface. The cist was formed between two portions of natural rock, and protected at its entrance by a large flat stone set up edgwise, and other stones filled up the interstices at the sides. It was also covered with a large flat stone. On clearing away the surrounding earth, after removing the covering stone, we were rewarded by finding that the cist contained the fragmentary remains of a young person, which had lain on its right side, in the usual position, with the knees drawn up. The accompanying engraving (fig. 11) will show the opened cist, with the stone across its entrance, and the interment in situ. In front of the skeleton, and close to its hands, was a remarkably good and perfect food vessel, which was richly ornamented with the diagonal and herring-bone lines, formed by twisted thongs impressed into the soft clay.

Fig. 10.

Fig. 11.

19

The next morning we dug a trench four feet wide, on the west side towards the centre, as shown at B on the plan (fig. 10), and the day’s labours had an equally satisfactory result. At about the same distance as on the previous day we came to the side of a cist, immediately in front of which, at F on the plan, lay a heap of burnt bones, and a few flakes of burnt flint. Having cleared away the surrounding stones and earth, and removed the large flat covering stones, which showed above the surface of the mound, we found the cist to be composed on one side by the natural rock, and on the other by flat stones set up on edge. Its dimensions were about one foot ten inches by four feet, and it contained a large quantity of rats’ bones and snails’ shells. In this cist was an interment of an adult, much crushed by one of the large covering stones having fallen upon it. Thanks to this circumstance, however, a food vessel, which we discovered, owed its preservation. The body lay in the usual contracted position, on its right side, as shown on the ground-plan at B, and in front and close to the hands was the food vessel, which, like the other, was taken out entire. It is five and a quarter inches in height, and six and a quarter inches in diameter at the top, and is richly ornamented.

Continuing the excavations to the south, we found that another cist C adjoined the one just described, and was, like it, formed of flat stones set up edgewise; in fact, it was like one long cist divided across the middle. In this second cist, besides the usual accompaniment of rats’ bones, was the remains of an interment, sufficiently in situ to show that the skeleton had, like the others, been deposited in a contracted position. A small fragment of pottery was also found, but owing to the cist being so near the surface the stones had been partially crushed in, and thus both the deposit and the urn had become destroyed. A portion of a stone hammer was also found.

The two cists are here shown (fig. 12), which also shows 20 the central interment at a higher level, to be hereafter described.

On the following Monday we resumed our operations by making an opening on the north-west side, as shown at D on the plan. Here, again, at a few feet from the outer edge, we came upon an interment H, without a cist, accompanied by an unusual quantity of rats’ bones. Continuing the excavation, we were again rewarded by the discovery of a fine cist, but at a greater depth than those before described. Above this cist we found some large bones of the ox, and on the covering stone was a deposit of burnt bones and ashes, with innumerable quantities of rats’ bones.

Fig. 12.

Fig. 13.

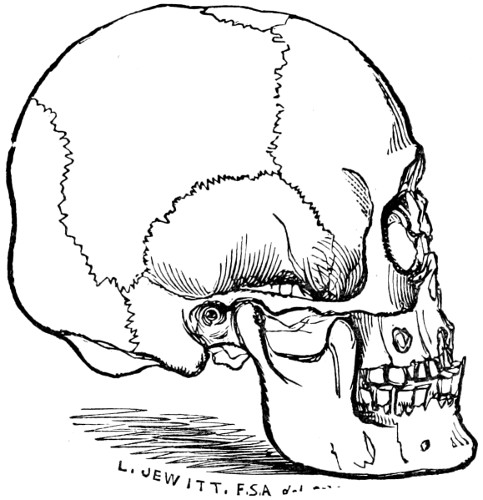

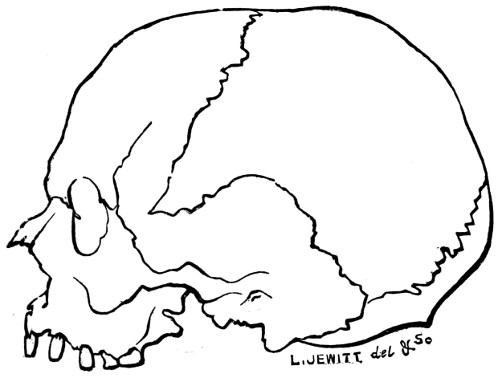

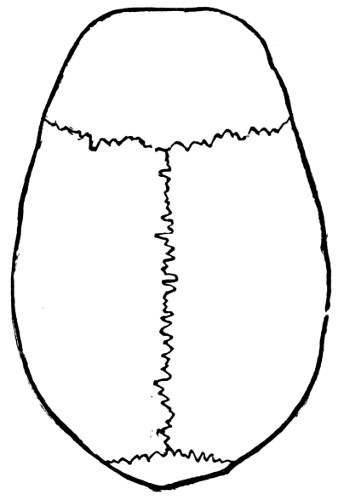

The cist, which was covered with one extremely large flat stone, we found to be formed partly of the natural rock, and partly—like the others—of flat stones set up edgewise; and it was, without exception, the most compact and neatly formed of any which have come under our observation. Its form will be seen on the plan at D, and its appearance, when the interior soil was removed, is shown on fig. 9. The dimensions of the cist were as follows:—Width at the foot, twenty-four inches; extreme length, forty inches; general 21 depth, twenty inches. The floor was composed of the natural surface of the rock, with some small flat stones laid to make it level, and at the narrow end a raised edge of stone, rudely hollowed in the centre, formed a pillow on which the head rested. The sides of the cist were square on the one side to the length of twenty-eight, and on the other of twenty-one, inches, and it then gradually became narrower until at the head its width was only ten inches. When the cist was cleared of its accumulation of soil and rats’ bones—of which scores of jaw-bones were present, thus showing the large number of these ravaging animals which had taken up their abode there—it presented one of the most beautiful and interesting examples of primeval architecture ever exhumed. It contained the skeleton of an adult, laid on his left side, in the usual contracted position, but without any pottery or flint. The skull, of which an outline engraving is given on fig. 13, is a most interesting and characteristic example of the cranium of an ancient Coritanian Briton. It is brachy-cephalic, and is the subject of deformity from nursing on the cradle-board in 22 infancy.5 It is the skull of a middle-aged man, and is remarkably well formed. The bones, with the exception of some of the small ones, were all remaining, and formed a skeleton of considerable ethnological interest. The small bones were gnawed away by the rats, and it is curious to see to what distances, in some interments, these active little animals have dragged even large bones from their original resting-places. It may not be without interest to note, that within the skull of this skeleton the bones of a rat, head and all, were found imbedded in the soil, along with some small stones, which he doubtless had dragged in with him on his last excursion. We continued our excavations in a north-easterly direction, as shown at G on the plan, and found another interment, but without a cist or any other notable remains; and next day we commenced opening that portion of the centre of the barrow between the cists already described, and soon came upon an interment of an adult person, as shown on the plan at E. The bones were very much disturbed, but sufficient remained to show that the deceased had been placed on his left side, in the same contracted position as the others in this mound. The body was not more than twelve inches below the surface, and was much disturbed, but it is more than probable the top of the barrow had at some distant time been taken off, most likely for the sake of the stone. The position of this interment will be seen on reference to the plan, and it is also shown on figs. 9, 11, and 12.

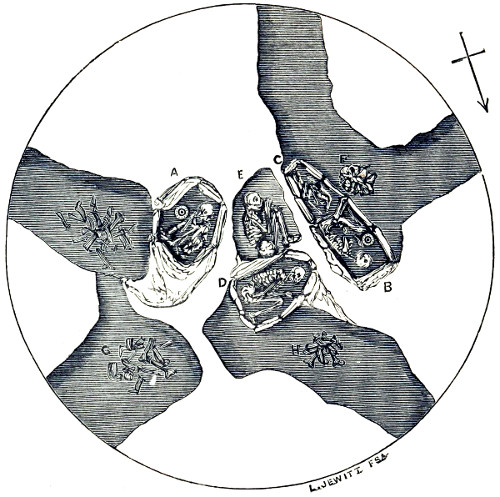

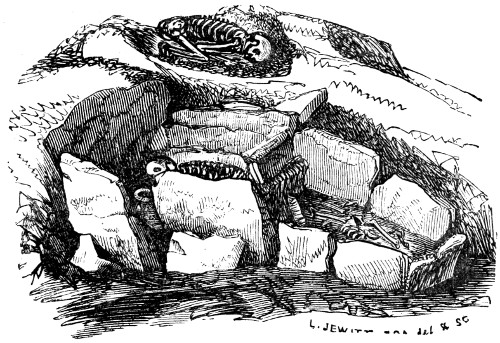

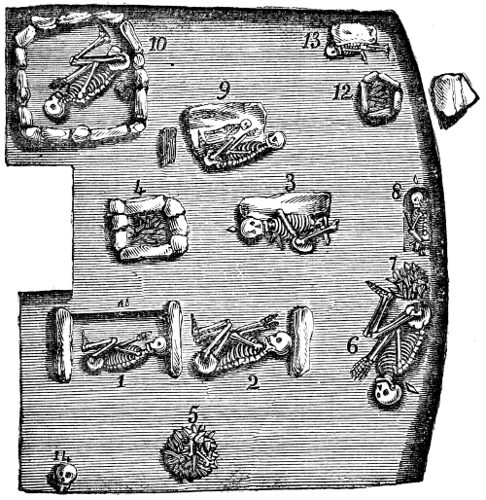

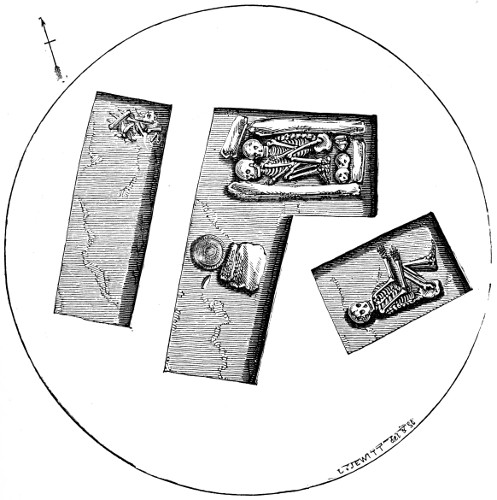

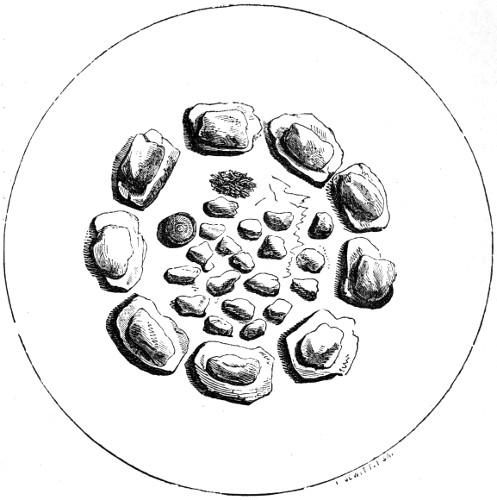

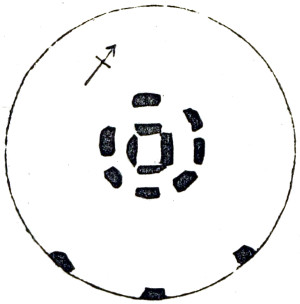

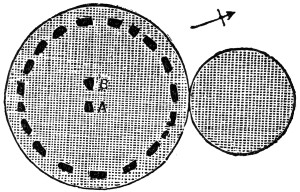

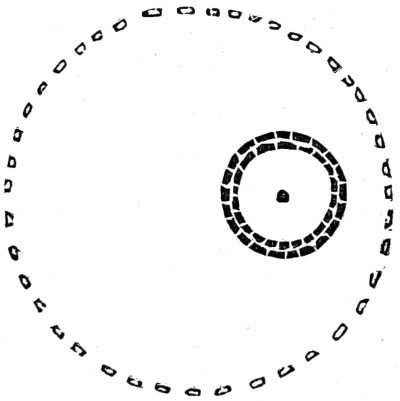

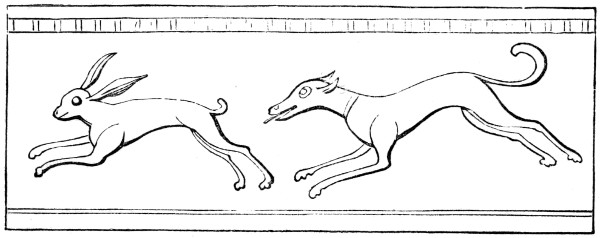

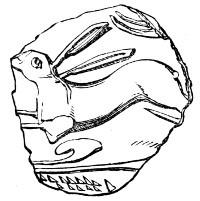

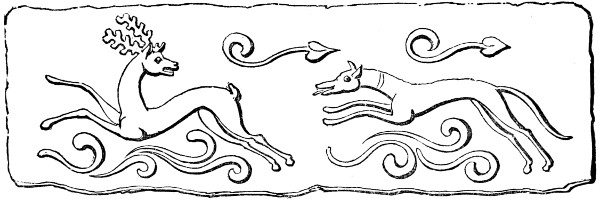

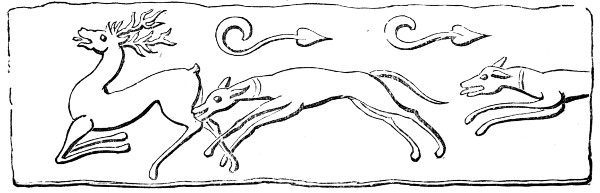

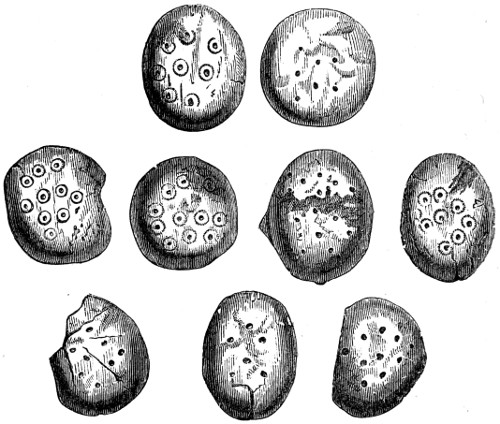

In addition to these illustrations, it will be sufficient to give the annexed engraving (fig. 14), which shows the position of a number of interments uncovered by Mr. Bateman in the centre of an elliptical barrow6 at Swinscoe. The 23 interments were as follows:—1. A young adult, lying in a contracted position, on its right side, in a shallow grave cut about six inches deep in the chert rock, with a stone placed on edge at the head, and another at the feet. 2. A young adult, lying on its right side, an upright stone at its head. 3. A middle-aged person, lying with the face upwards, and guarded by a large stone at its side. 4. The bones of a young hog, enclosed in a stone cist. 5. Remains of a cinerary urn and burnt bones. 6. Skeleton of an aged man, lying in a contracted position, on its left side, upon a thin layer of charred wood. 7. A deposit of burnt bones. 8. Skeleton, very fragmentary. 9. A double interment, consisting of two skeletons, with a flat stone on edge by their side. These were an adult, and a child of a few months old only. 10. Skeleton of 24 an aged man, lying in the usual position, on his left side, enclosed in a circle of stones. Behind him lay a handsome drinking-cup. 12. Portions of a skeleton in a pentagonal cist. 13. Skeleton of a young person, placed close up to an upright flat stone. 14. Skull and portions of a skeleton. Several flints and other remains were found with these various interments.

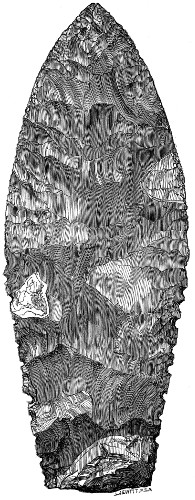

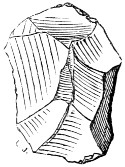

Fig. 14.

Interments where the body has lain extended are of much rarer occurrence, in this period, than those just described. Some few instances have been brought to light in Derbyshire, and in other counties, but they are indeed “few and far between,” and are the very rare exceptions to a general rule. One of the most interesting of these instances is the one called “Shuttlestone Low,” opened a few years ago by Mr. Bateman, and thus described by him: “It consisted of a compact mass of tempered earth down to the natural surface of the land, below which point, in the centre of the barrow, there appeared a large collection of immense limestones, the two uppermost being placed on edge, and all below being laid flat, though without any other order or design than was sufficient to prevent the lowest course resting upon the floor of the grave inside which they were piled up, and which was cut out to the depth of at least eight feet below the natural surface; thus rendering the total depth, from the top of the mound to the floor of the grave, not less than twelve feet. Underneath the large stones lay the skeleton of a man, in the prime of life, and of fine proportions, apparently the sole occupant of the mound; who had been interred while enveloped in a skin of dark-red colour, the hairy surface of which had left many traces both upon the surrounding earth and upon the verdigris, or patina, coating; a bronze axe-shaped celt and dagger deposited with the skeleton. On the former weapon there are also beautifully distinct impressions of fern leaves, handfuls of which, in a compressed and half-decayed state, surrounded the bones from head to 25 foot. From these leaves being discernible on one side of the celt only, whilst the other side presents traces of leather alone, it is certain that the leaves were placed first as a couch for the reception of the corpse, with its accompaniments, and after these had been deposited, were then further added in quantity sufficient to protect the body from the earth. The position of the weapons with respect to the body is well ascertained, and is further evidenced by the bronze having imparted a vivid tinge of green to the bones where in contact with them. Close to the head were one small black bead of jet and a circular flint; in contact with the left upper arm lay a bronze dagger with a very sharp edge, having two rivets for the attachment of the handle, which was of horn, the impression of the grain of that substance being quite distinct around the studs. About the middle of the left thigh-bone was placed the bronze celt which is of the plainest axe-shaped type. The cutting edge was turned towards the upper part of the person, and the instrument itself has been inserted vertically into a wooden handle, by being driven in for about two inches at the narrow end—at least the grain of the wood runs in the same direction as the longest dimension of the celt,—a fact not unworthy of the notice of any inclined to explain the precise manner of mounting these curious implements. The skull—which is decayed on the left side, from the body having lain with that side down—is of the platy-cephalic form, with prominent parietal tubers—the femur measures 18½ inches.”

Another good instance is from Yorkshire, where two skeletons were found side by side, extended, with their heads respectively east and west, lying in a bed of charcoal.

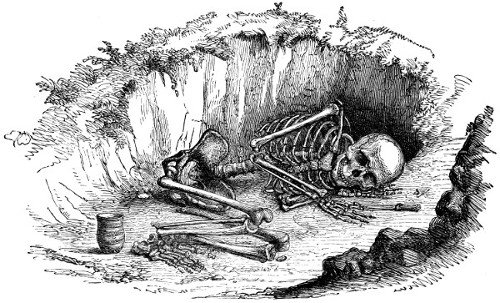

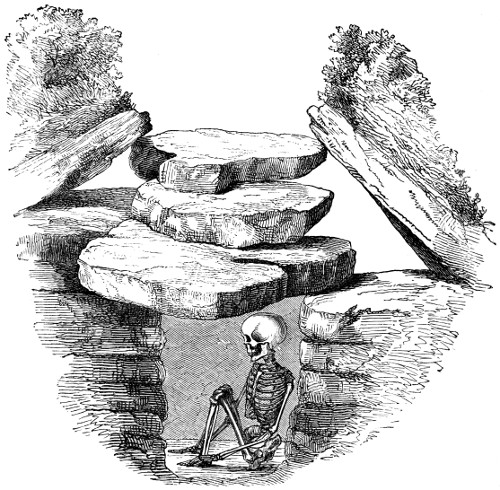

Occasionally, as has been stated on a previous page, interments have been made in an upright sitting position. Instances of this kind are rare and very curious. Our engraving (fig. 15) shows an interment of this kind, which occurred in a barrow at Parcelly Hay. The body had been 26 placed in a sitting posture, leaning back against the side of the cist, which was only three feet in height, and not more than that in its greatest width. The cist was roughly covered in with large slabs of limestone. The skull, which was a remarkably fine one, has been engraved in “Crania Britannica.”7 On the covering-stones lay another skeleton, among the loose stones of which the barrow itself was composed. This secondary interment was accompanied by a fine axe-head of stone and a bronze dagger. Of course the seated skeleton must have been of an earlier date still. 27

Fig. 15.

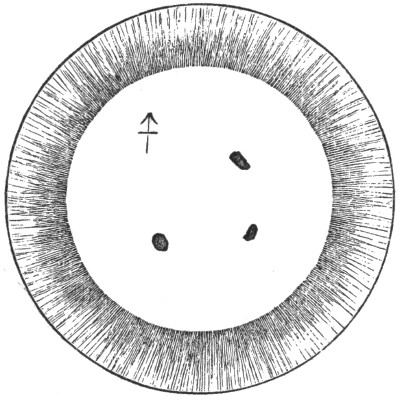

Another remarkable instance of this kind of interment—but this time in a kneeling position—was discovered in the Cromlech De Tus, or De Hus, in Guernsey, by Mr. F. C. Lukis.8 This interesting relic is situated near Paradis, in the parish of Vale, and is a chambered tumulus of simple but excellent construction. The mound is surrounded by a circle of stones, about twenty yards in diameter. In the centre is the principal chamber, covered with large flat stones, and from it to the extremity of the mound, on the east, was a passage formed by upright stones, and covered here and there with cap-stones dividing it into chambers. On the north side of this passage was a chamber formed by upright stones, on which rested the large flat covering stone; and close to this was another similar but smaller chamber. In the first were discovered “vases, bone instruments, celts, and human remains.” In the latter, on removing the soil at the top, “the upper part of two human skulls were exposed to view. One was facing the north, and the other the south, but both disposed in a line from east to west,”—in other words, side by side, and shoulder to shoulder, but facing opposite ways. They were skeletons of adult males, and, on clearing away the soil, they were found to have been buried at the same time. “The perfect regular position of a person kneeling on the floor, in an upright posture, with the arms following the direction of the column, pelvis, and thigh-bones, and gradually surrounded by the earth, in like manner as may be conceived would be done were the persons buried alive, will give an exact representation of this singular discovery.”

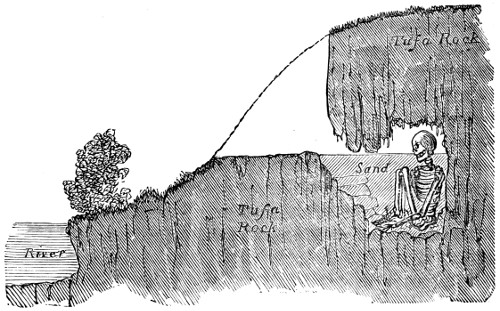

Another excellent example of this very unusual mode of interment—this time in a sitting posture—was discovered by some tufa-getters, and examined by Mr. Bateman, in 28 Monsal Dale, and is shown on the accompanying engraving, fig. 16, which exhibits a section of the rock, etc.; and shows the position of the skeleton, and the manner in which the cavity containing the body had been filled up with the river sand. The body in this case, as in the last, had been placed in the cavity, in a sitting position, and must have been so placed from an opening in front. The cavity was ten or twelve feet above the bed of the river Wye, and above it were some five feet in thickness of solid tufa rock, while, from the face of the rock, the cavity was about twelve feet. The body may therefore be said to have been entombed in the middle of the solid rock. The roof of the cavity when found was beautifully covered with stalactites. The skeleton was that of a young person, and near it were found a flint and some other matters. The cavity was filled to part way up the skull with sand.

Fig. 16.

Another example of interment in a sitting posture was discovered some years ago, at Kells in Ireland. These will be sufficient to show the curious character of this mode of interment. 29

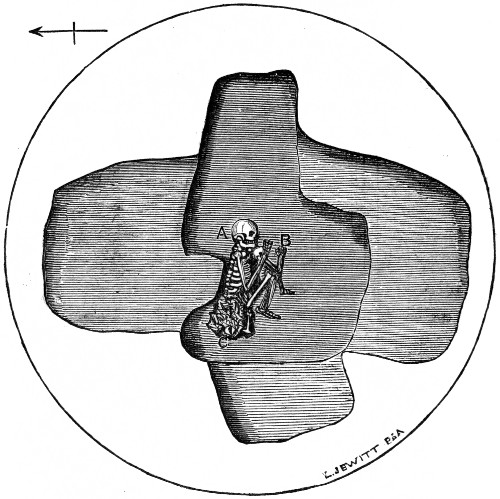

Fig. 17.

Several examples of double interments, besides those described above, have been discovered in different localities. One of the most curious is the one in the largest cist, in fig. 17. In this cist, which is composed of four upright slabs of stone,9 were the skeletons of a man and woman, and the remains of two children; the family having probably been immolated at the death of its head, and all buried together. A small urn was found in the same cist; 30 and in the same barrow, in other portions which were excavated, as shown in the plan, were other interments, both by cremation and by inhumation.

Fig. 18.

In No. 9, on fig. 14, an interment of a mother and her child together is shown. Another instance is shown on the next engraving, fig. 18. In this instance the woman was laid in the usual contracted position, on her left side, with her head to the east. Close in front of the breast, lying in the arms in the same contracted position, lay the infant. Some flints and a fragment of pottery were found along with this touching interment. 31

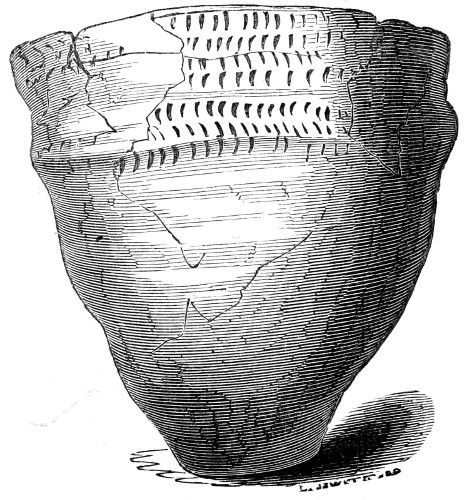

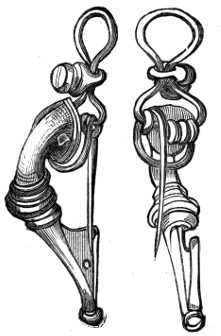

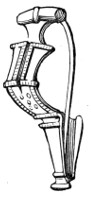

Ancient British or Celtic Period—Interment by cremation—Discovery of lead—Burial in urns—Positions of urns—Heaps of burnt bones—Burnt bones enclosed in cloth and skins—Stone cists—Long-Low—Liff’s-Low, etc.—Pit interments—Tree-coffins.

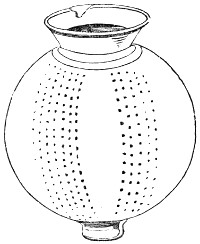

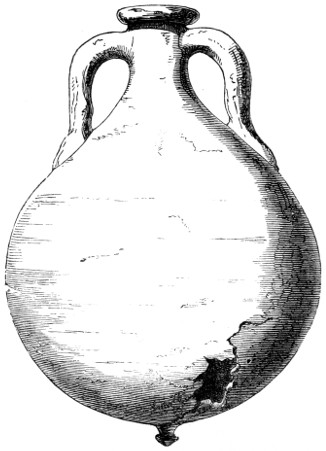

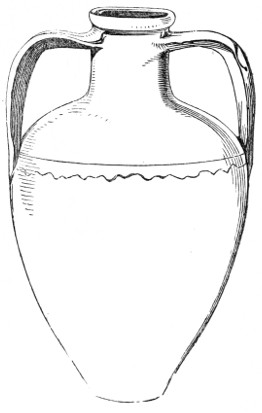

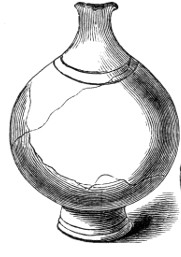

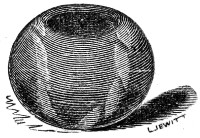

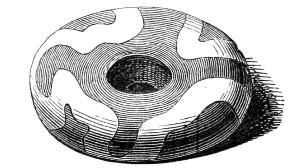

When the interment has been by CREMATION, the remains of the burnt bones, etc., have been collected together and placed either in a small heap, or enclosed in a skin or cloth, or placed in a cinerary urn, which is sometimes found in an upright position, its mouth covered with a flat stone, and at others inverted over a flat stone or on the natural surface of the earth. This position, with the mouth downwards, is, perhaps, the most usual of the two. In some instances the bones were clearly enclosed, or wrapped, in a cloth before being placed in the urn. The place where the burning of the body has taken place is generally tolerably close to the spot on which the urn rests, or on which the heap of burnt bones has been piled up. Wherever the burning has taken place there is evidence of an immense amount of heat being used; the soil, for some distance below the surface, being in many places burned to a redness almost like brick. Remains of charcoal, the refuse of the funeral pyre, are very abundant, and in some instances I have found the lead ore, which occurs in veins in the limestone formation of Derbyshire, so completely smelted with the heat that it has run into the crevices among the soil and loose stones, and looks, when dug out, precisely like straggling roots of trees.

Is it too much to suppose that the discovery of lead may 32 be traced to the funeral pyre of our early forefathers? I think it not improbable that, the fact of seeing the liquid metal run from the fire as the ore which lay about became accidentally smelted, would give the people their first insight into the art of making lead—an art which we know was practised at a very early period in Derbyshire and other districts of this kingdom.10 Pigs of lead of the Romano-British period, inscribed with the names of emperors and of legions, have occasionally been found; but much earlier than these are some cakes (if the term can be allowed) of lead which have evidently been cast in the saucer-shaped hollows of stones. Of these, which are purely British, some examples have fortunately been preserved.

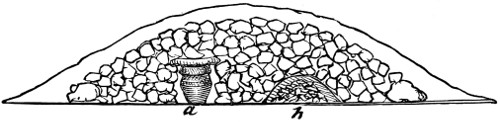

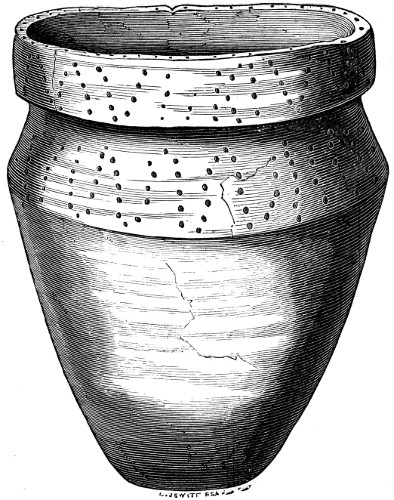

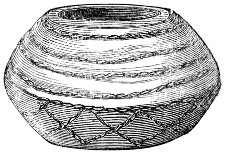

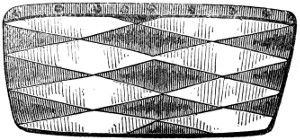

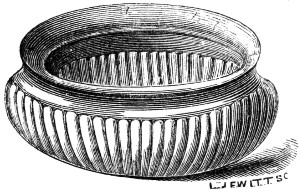

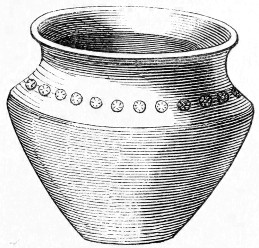

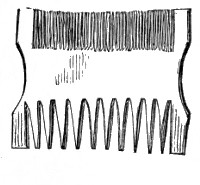

But to resume. The positions I have spoken of in which the cinerary urns and heaps of burnt bones have been usually found, will be best understood by the accompanying engravings. The first (fig. 19) represents a section of a barrow in which, at a, is shown a sepulchral urn in an upright position, capped with a flat stone; and at b a heap of burnt bones piled up in the usual fashion, and first covered with earth and then with the loose stones of which the whole barrow was composed.

Fig. 19.

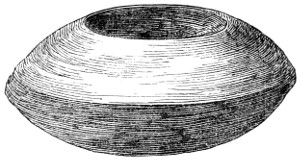

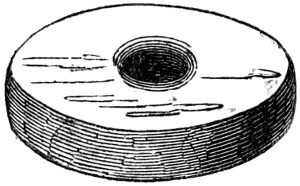

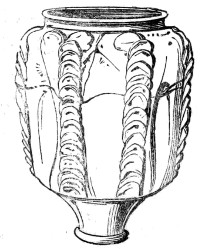

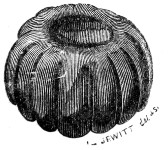

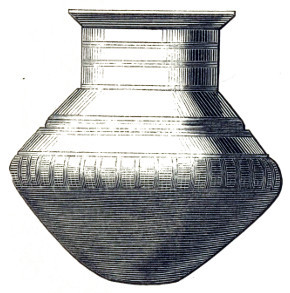

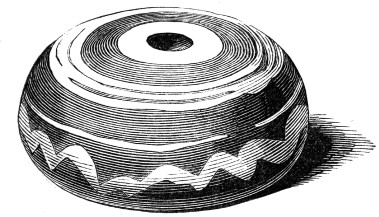

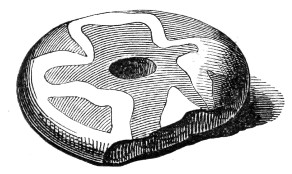

The next engraving (fig. 20) again shows, within a cist, 33 in a barrow on Baslow Moor called “Hob Hurst’s House,”11 two heaps of bones, the one simply collected together in a small heap, and the other guarded by a row of small sandstone “boulders” all of which had been subjected to fire. The next illustration (fig. 21) gives a section of the Flax Dale barrow at Middleton by Youlgreave, which shows the inverted position of the sepulchral urn. This barrow was formed on a plan commonly adopted by the ancient Britons, and will therefore serve as an example of mode of construction as well as of the inverted position of the 34 urn. A circle of large rough stones was laid on the surface of the ground, marking the extent of the proposed mound. Within this the interments, whether in an urn or not, were placed, and the mound was then raised of stones to the required height, and afterwards covered to some thickness with earth, and thus the outer circle of the barrow was considerably extended, as will be seen by the engraving.

Fig. 20.

Fig. 21.

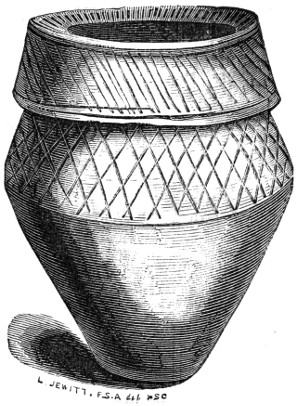

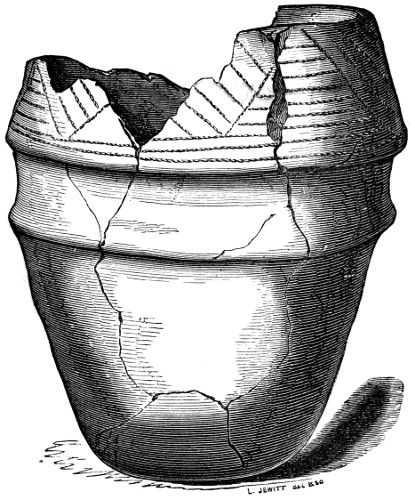

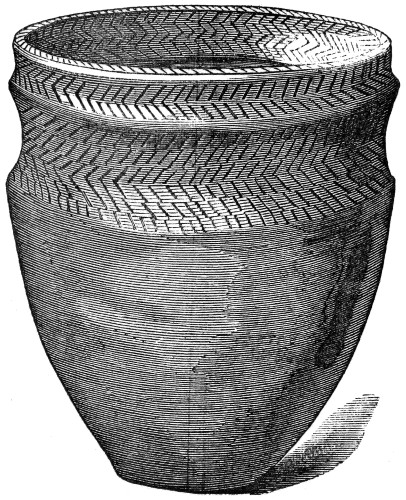

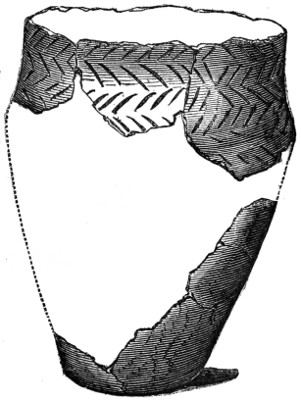

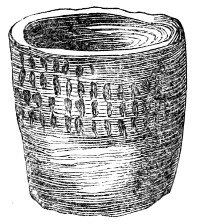

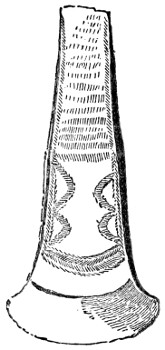

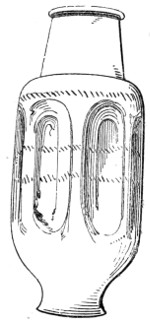

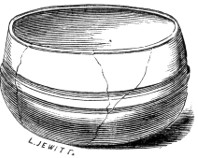

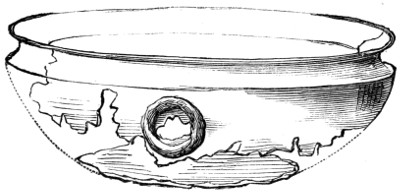

Another excellent example of the inverted position of the sepulchral urns is here given (fig. 22) from one of the cists in Rolly-Low, near Wardlow. I have chosen it because, when found by Mr. Bateman, it had received a considerable fracture on one side, and thus showed the burnt bones which it contained, through the aperture. The urn was about sixteen inches in height and twelve inches in diameter, and was ornamented in the usual manner with indentations produced by a twisted thong. It was inverted over a deposit of calcined human bones, among which was a large red deer’s horn, also calcined. The urn was so fragile as to be broken to pieces on removal.

Fig. 22.

35

In some urns discovered in Cambridgeshire, at Muttilow Hill, the Hon. R. C. Neville found that the calcined bones had been collected and wrapped in cloth before being placed in the urns. The contents of one of the urns he describes as “burnt human bones enveloped in a cloth, which, on looking into the vessel, gave them the appearance of being viewed through a yellow gauze veil, but which upon being touched dissolved into fine powder.”12 The urns were all inverted.

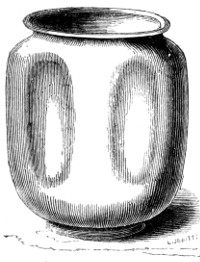

A somewhat peculiar feature of urn burial was discovered at Broughton, in Lincolnshire, where the urn containing the burnt bones was placed upright on the surface of the ground, and another urn, made to fit the mouth, inverted into it to form a cover.

In instances where the ashes of the dead have been collected from the funeral pyre, and laid in a skin or cloth before interment, the bone or bronze pins with which the “bundle” was fastened still remain, although, of course, the cloth itself has long since perished.

In other instances small stones have been placed around, and upon, the heap of burnt bones before raising the mound over the remains.

It is frequently found in barrows, where the interment has been by cremation, that there will be one or more deposits in cinerary urns, while in different parts of the mound, sometimes close by the urn, there will be small heaps of burnt bones without any urn. The probable solution of this is, that the simple heaps of bones were those of people who had been sacrificed at the death of the head of the family, and burned around him. 36

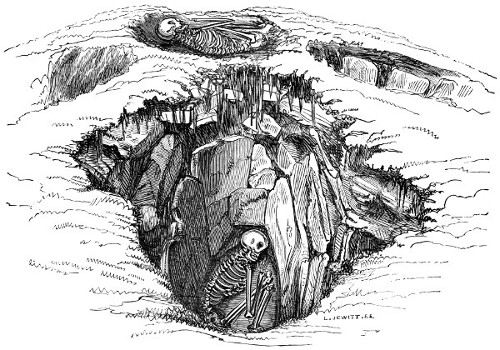

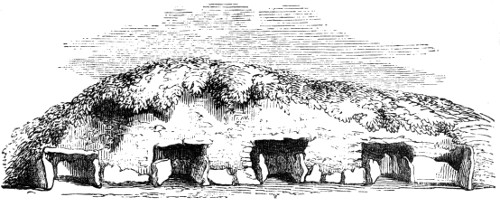

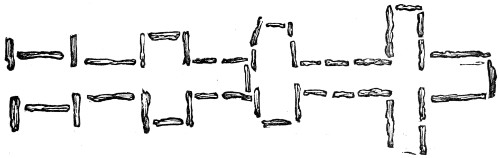

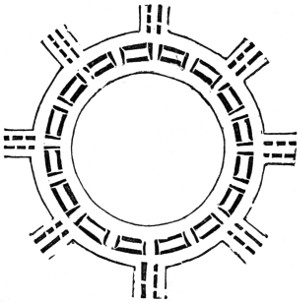

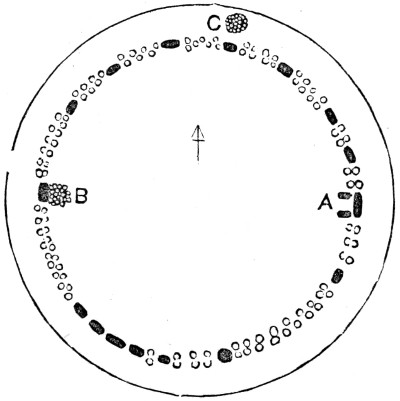

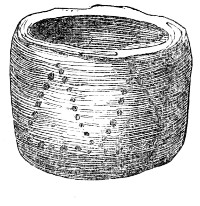

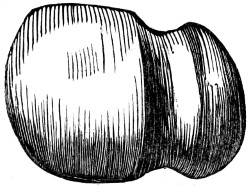

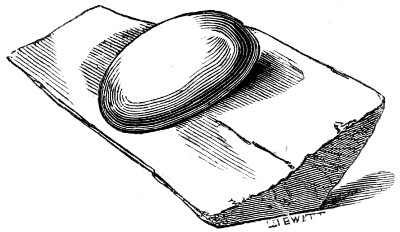

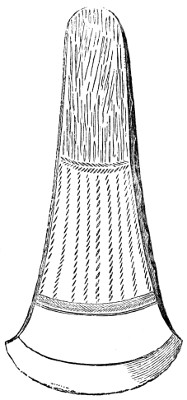

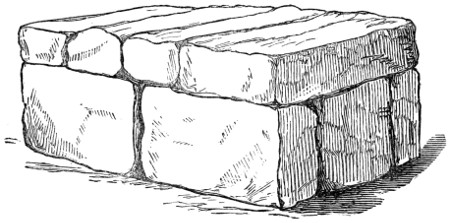

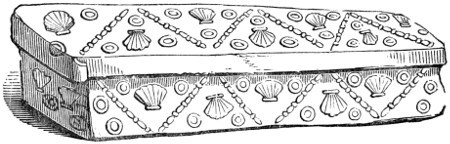

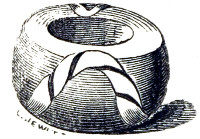

It is a very frequent occurrence in barrows for the interments to be made in stone cists, and these, of course, vary both in size and in form, according to the nature of the spot chosen, and to the requirements of each particular case. The cists are usually formed of rough slabs of limestone, grit-stone, granite, or other material which the district offers, set up edgeways on the surface of the ground, so as to form a sort of irregular-square, rhomboidal, or other shaped compartment. In this the interment, whether of the body itself or of the urn containing the calcined bones, or of the calcined bones without an urn, has been made, and then the cist has been covered with one or more flat stones, over which the cairn of stones, or earth, or both, has been raised. Some barrows contain several such cists, in each of which a single, or in some instances a double, interment has been made. Excellent examples of these are afforded by the accompanying engravings, and by figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 17, 20, 28, and 29. Occasionally, when the natural surface of the ground was not sufficiently even or solid for the interment to be as conveniently made as might be wished, a flooring of rough slabs of stone was laid for the body to rest upon. This was the case in a barrow called “Long-Low,” near Wetton, in the moorlands of Staffordshire (shown on fig. 24), which was opened by Mr. Carrington.

Fig. 23.

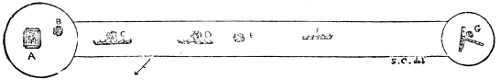

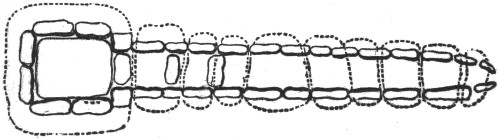

As there are some singular features connected with this barrow, a detailed account of the mode of its construction becomes necessary. This very peculiar barrow had been thought, time out of mind, to be a “mine rake,” and attempts have from time to time been made by lead miners to 37 find a shaft, by removing certain portions of the mound—a shaft had, in fact, been sunk very nearly in the centre of the barrow. This rendered the operations of opening both difficult and laborious. Long-Low is what is usually denominated a “twin barrow,” consisting of two circular mounds, connected by a bank, which altogether are 220 yards long. A plan of this barrow, drawn to scale, is shown on the accompanying engraving (fig. 23). The circular mound at the north-east end is thirty yards across and seven feet high in the centre, that at the south-west end not so large; the connecting bank at its base is fifteen yards wide, and where entire about six feet in height, with regular sloping sides where not mutilated. “The barrow runs in a straight line along the highest part of the land, a strong wall, separating the fields, is built over it lengthways, the stone for which, like other field walls in the vicinity, appears to have been procured from the bank of the tumulus, which, with the exception of some parts of the surface, is formed of large flat stones, which have evidently been procured in the immediate neighbourhood, where the surface of the land is lowered to a considerable extent. This is the only instance (as far as my experience goes) of a barrow being formed of stones got by quarrying, they being generally composed of such stones as are found on the surface of uncultivated land, which, owing to exposure to the atmosphere, have their angular points rounded. The strata in the neighbourhood of this barrow are but slightly consolidated, and are separated from each other by a thin seam of earthy matter, and abound with vertical cracks, so that it would not be a difficult task to dig out stones with sharpened stakes—the principal instruments, I presume, for such purposes in primitive times.”

The internal construction of this cairn is singular. By making holes in various places along the bank, was found a low wall in the centre, built with large stones, which appears 38 to be carried the whole length of the bank. Against this, large flat stones, with their tops reclining against the wall, are placed, thus leaving many vacancies, and showing an economical way of raising the mound at less expenditure both of labour and materials. The portions of this which have been laid bare are, with remains of interments, shown on the plan (fig. 23) at C, D, E, and F.

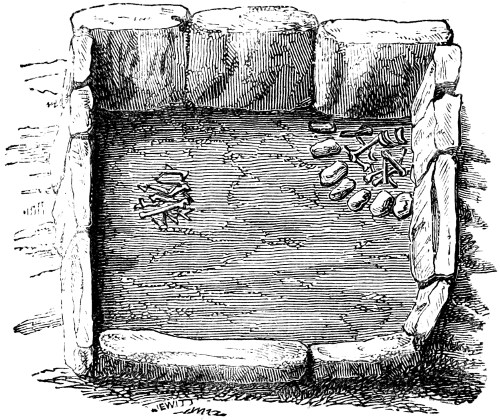

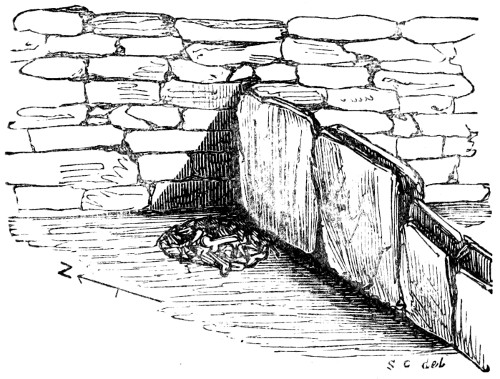

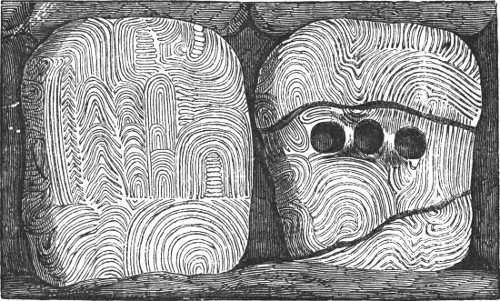

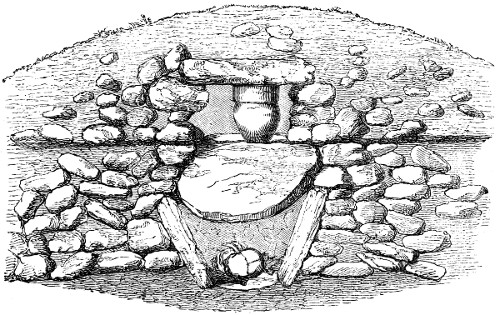

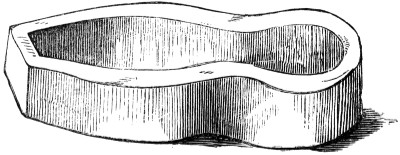

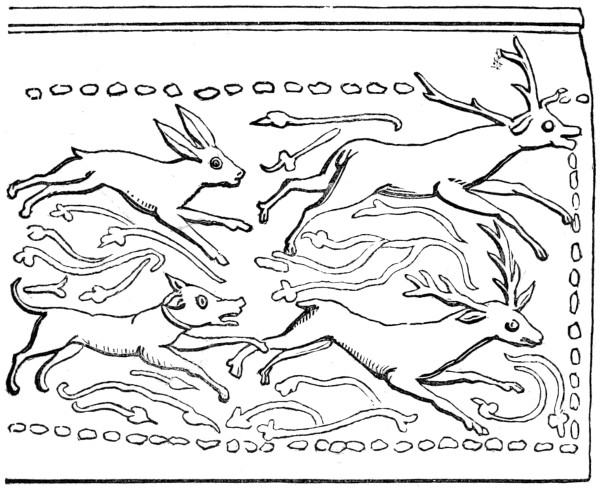

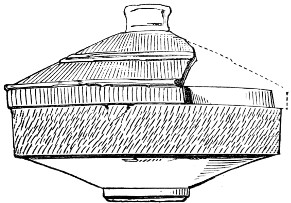

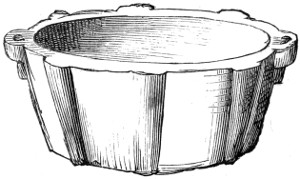

A large cist, or chamber, was discovered near the centre of the large mound. It was formed by four immense stones, inclosing an area six feet long, five feet wide, and about four feet deep. In all probability the capstone had been removed, as none was found. On the cist being cleared, was discovered a regular paved floor of limestone, entirely covered over with human bones, presenting a confused mass of the relics of humanity. The skeletons lying in the primitive position, crossed each other in all directions. They proved to be the remains of thirteen individuals, both males and females, varying from infancy to old age. The interior of this cist is shown on the accompanying engraving, and its position in the mound will be seen at A on the plan.

Fig. 24.

On the floor were found three arrow-heads of flint, wrought into beautiful thin leaf-shaped instruments, and many other calcined flakes of the same material; also 39 bones of the ox, hog, deer, and dog. Not far from the cist, and near the surface, was found a skeleton minus the head, imbedded in gravel, rats’ bones, and charcoal. On the floor some animal bones were found that had been burned, also neatly wrought arrow-heads and pieces of flint, and fragments of two human skulls. The point of a bone spear and a bone pin were found during our labours in this mound. “Another skeleton was found in the bank, crushed into small fragments; and where another grave had been made in the bank, for a secondary interment, the sides and bottom were found to have been burned to lime, which now resembled old mortar, to an extent that could not have been effected by an ordinary fire. It is not unusual to find small stones burnt to lime on the floors of barrows; in the present instance it had acquired a hardness almost equal to the stones, effected during a very long period by imbibing carbonic acid gas from the atmosphere, to which it had free access; pieces several inches thick were broken up intermixed with charcoal.”

Fig. 25.

Fig. 26.

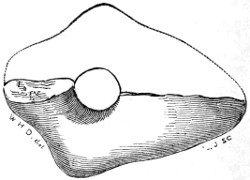

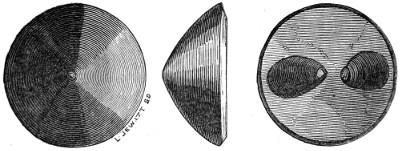

On one side of the cist two skulls lay close together, and mixed up with a skeleton, the bones of which, in some 40 instances, crossed each other; in the centre lay the fine skull shown in figs. 25 and 26.13 Two other remarkable skulls, one of a woman of about fifty years of age, and the other of a girl not more than seven years old, were also found.

Fig. 27.

When the mound at the other extremity of the “bank” was opened, calcined bones and animal remains only were found, but the singular construction of this portion of the barrow made ample compensation for the paucity of relics. It appeared that the longitudinal wall, noticed before, terminated in the centre of this mound; and at its termination another and well-built wall was carried crossways at right angles with it (fig. 27), which was laid bare to the length of more than 41 half the diameter of the mound—it was three feet in height—the whole extent was not proved. From the centre of this wall, and forming a straight line with the longitudinal one, there was a row of thin moderately large stones, set on edge, by the ends being set in the soil that formed the floor of the mound; these were placed with their edges close together, and occasionally in two or three ranks, as if for better support in an upright position. They were from 1½ to 2 feet in height, and were extended from the wall to the length of five yards. The burnt bones were found in the west angle formed by the cross wall and the upright stones, as shown in the engraving. It appeared as though the bones had originally been deposited near the surface, as they were now found in the interstices betwixt the stones, from near the top to the bottom. This mound was formed of large stones, like the other parts, reared against each other all around, with their tops inclining towards the centre.

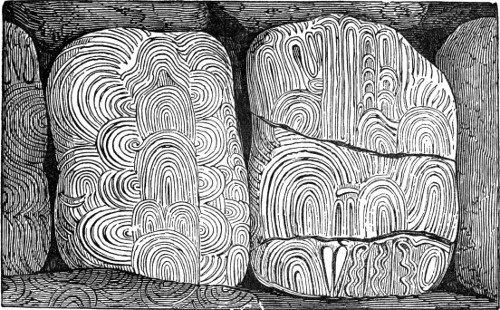

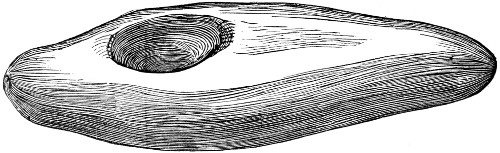

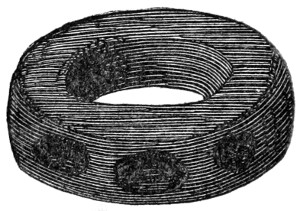

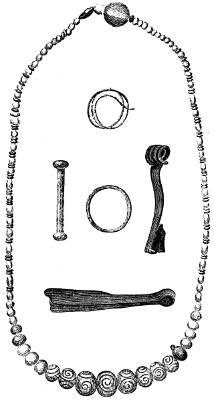

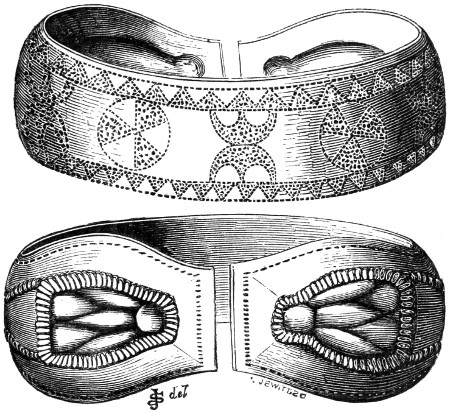

A tolerably good cist, formed of rough masses of stone surrounding the body, is the one engraved on fig. 28, from Middleton. This cist contained the skeleton of a woman, lying on her left side, in a partially contracted position. Above her lay the remains of an infant, and about her neck were the beads of a remarkably fine necklace of jet.

Fig. 28.

Fig. 29.

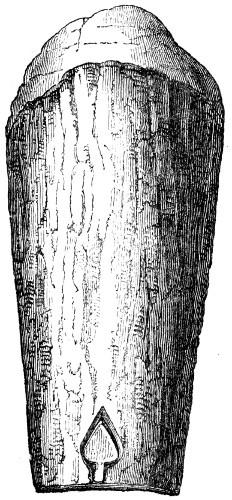

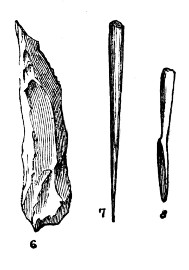

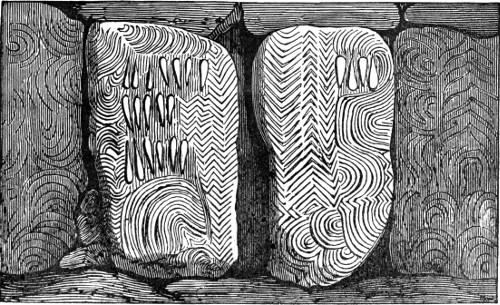

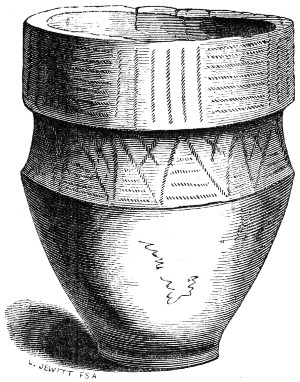

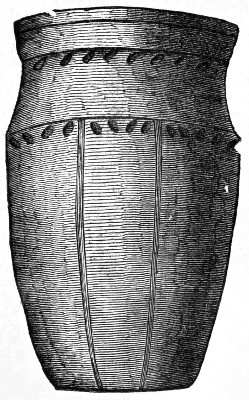

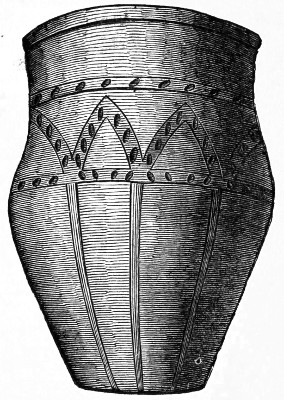

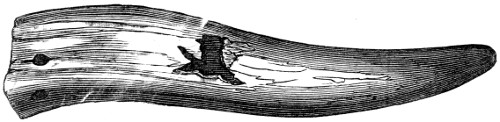

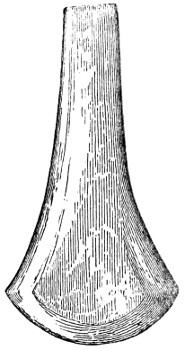

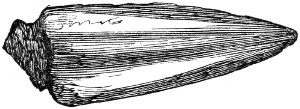

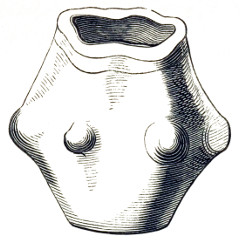

Another good example of a stone cist is the next (fig. 42 29), from Liff’s-Low. The cist was formed of eight large slabs of rough limestone, set edgewise; and formed a chamber of very compact and almost octagonal form. It contained the skeleton of a man, lying in a partly contracted posture on his left side, the face looking to the west. Behind the knees was placed a hammer-head, formed of the lower part of the horn of the red deer. One end is rounded and polished, and the other knotched across, somewhat, (to use a homely comparison) like what is usually called a “wafer-seal.” Behind the head were a number of miscellaneous but highly interesting articles, showing, as they did after the lapse of so many centuries, that “the savage Briton, reposing in this cairn, had cultivated the art of making war amongst the inhabitants of the forest in preference 43 to molesting his fellow savages; as almost the first observed articles were a pair of enormous tusks of the wild boar, trophies of some, perhaps his last, sylvan triumph. Next came two arrow-heads of flint, delicately chipped, and of unusual form; two spear-heads of the same material; two flint knives, polished on the edge, one of them serrated on the back in order to serve as a saw; and numerous pieces of flint of indescribable form and use, which, together with all the flint instruments enumerated above, seem to have undergone a partial calcination, being gray, tinted with various shades of blue and pink. With these articles were found three pieces of red ochre, the rouge of these unsophisticated huntsmen, which, even now, on being wetted, impart a bright red colour to the skin, which is by no means easy to discharge.” With these articles lay a small urn of unique form.

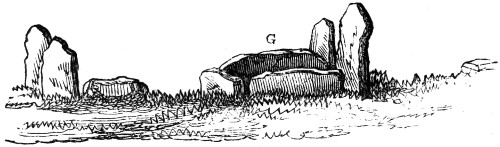

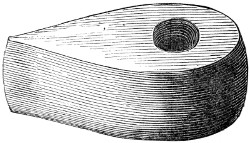

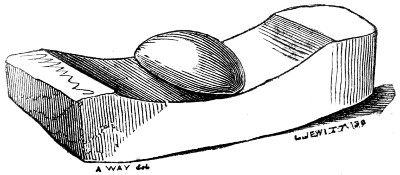

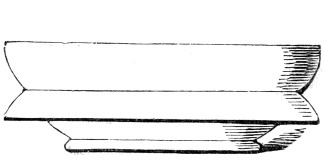

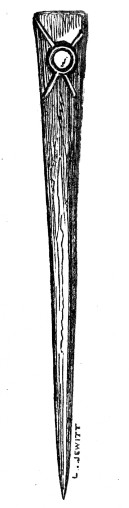

On fig. 30 is shown a remarkably pretty cist, formed of four upright stones, supporting a capstone. It contained a vase of good form.

Fig. 30.

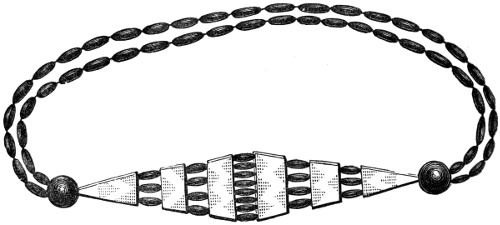

Pit interments are occasionally met with, but are very rare. One instance will suffice: it is that at Craike Hill, 44 near Fimber, Yorkshire, and was opened by Mr. Mortimer.14 In it no less than four interments were made, one above another, in a pit or grave covered over by a mound. The two lower and the upper were skeletons in the usual contracted positions; the other a heap of calcined bones, with a fine food vessel. Near the upper skeleton was another heap of burnt bones and another food vessel. With one of the skeletons, that of a female, was found a splendid necklace of jet, and a drinking cup of elaborate design. These are all engraved in the present volume.

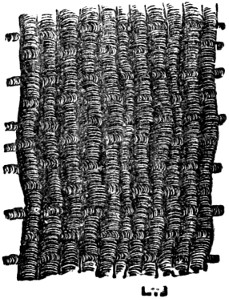

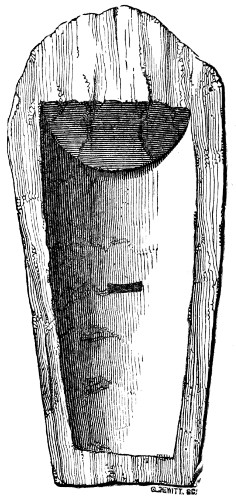

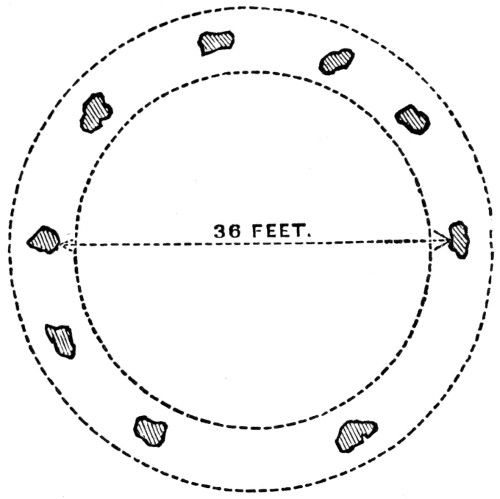

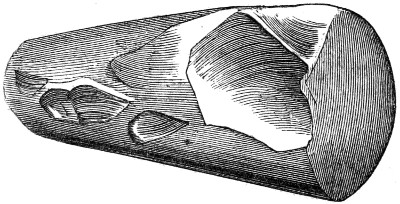

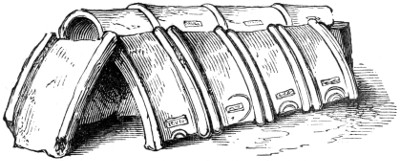

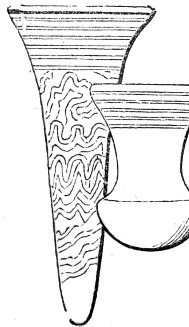

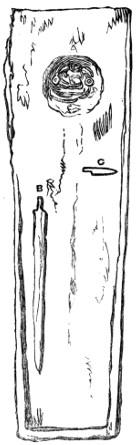

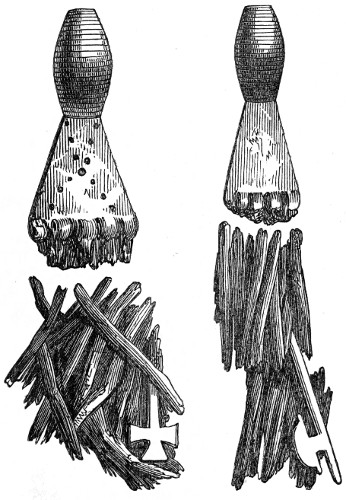

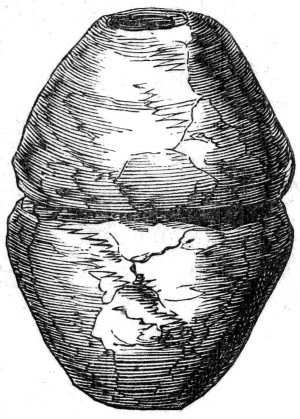

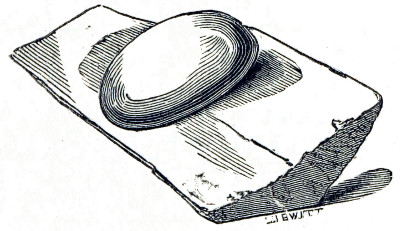

Burials in tree-coffins, of various periods, have been occasionally met with in grave-mounds, and a few words concerning them may here be introduced. One of the most interesting was found recently by that indefatigable antiquary, the Rev. Canon Greenwell, at Scale House, in Yorkshire.15 The barrow was about thirty feet in diameter, and five feet in height, and was surrounded by a circle of soil at the base. It was entirely composed of soil, interspersed here and there with fragments of charcoal, firmly compacted. On the top, for a space of about six or seven feet in diameter, a covering of flattish stones was laid just below the surface. On digging down at this spot it was found that a hollow had been made in the natural surface, that had been filled up with soil, upon which had been placed a few stones and then a coffin, constructed of the trunk of a small oak tree. This primitive coffin was laid north and south, the thicker end, which no doubt contained the head of the corpse, towards the south; which was also the case in the Gristhorpe barrow. The oaken trunk, or tree-coffin, was seven feet three inches in length, and one foot eleven inches in diameter, at the spot in which it was measured. The Gristhorpe coffin “is seven feet and a 45 half long, and three feet three inches broad.” Above the coffin the soil was finer, and upon this finer stratum was situated a layer of dark matter a good deal burned, and containing pieces of charcoal. Over the whole was a covering of the ordinary compacted soil of which the barrow was composed. The body inhumed in this tree-coffin, and not burned, had gone totally to decay, leaving only a whitish unctuous matter behind. This substance was no doubt adipocire, the production of which is to be accounted for by the extreme wetness of the barrow. Before interment the corpse had been clothed, or wrapped, from head to foot in a woollen fabric,16 a specimen of which is represented in the following figure:—

Fig. 31.

There were no flint chippings discovered in the soil of which the barrow was composed, or other object, and nothing else was contained in the tree-coffin, save the body in its wrappings. Some pieces of a bright black substance 46 like pitch, which appeared to have been placed on the inside of the coffin, on examination are found to be composed of carbon and oxide of iron.

It is most unfortunate that this curious and interesting barrow had been previously opened at the top. By this proceeding the tree-coffin had been broken through, and its contents disturbed about the middle. And it is also much to be regretted that the barrow was saturated with moisture, which had percolated into the coffin, carrying the soil with it. By this means all the contents of the barrow, save the adipocire of the body itself, including both the tree-coffin and the woollen garment, had acquired a rottenness which precluded the recovery of anything more than mere fragments. Those of the woollen dress were so filled with particles of soil, and at the same time so tender, as to admit of being reclaimed only in a very imperfect manner. The woollen cloth, which went from head to foot, there is no doubt had been loosely wrapped round the body, in the manner of a shroud, not swathed like an Egyptian mummy, so that “the fabric filled the whole of the inside of the coffin from end to end.” Hence, as is confirmed by the barrows opened in Jutland, there is every reason to infer that it was the ordinary woollen dress of the individual interred in the tumulus, who must have held such a position in society as to ensure these great attentions to his remains.

“In many ancient British barrows marks of the garments of the deceased have been discovered, in which the body appears to have been wrapped before interment. Indications of skin dresses are seen early, and after these, in the bronze and iron periods, where the rust of weapons has retained impressions of such grave-clothes, tissues of linen and woollen appear. Mr. Bateman met with signs of such textures, and in the case of the Tosson cists, in Northumberland, from one of which the skull of plate 54 of the 47 Crania Britannica was derived, an iron spear-head was found in one of them, and there were signs of two fabrics of cloth impressed upon the oxidized surface of this relic.

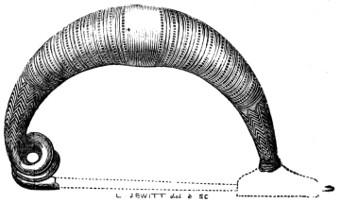

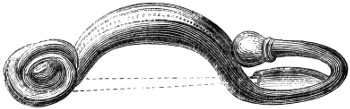

“Again, British barrows have been opened containing tree-coffins, in which the remains have been inhearsed. The celebrated Gristhorpe barrow, the skeleton from which is preserved in the Scarborough Museum, and of the skull of which there is a fine engraving, plate 52, and a careful description by Dr. Thurnam, in the work just named, offers an instance of a tree-coffin formed of a split oak of small girth. In this case, the body had been wrapped in the skin of some animal having soft hair. The interment had belonged to the ancient British late stone or the bronze period. The coffin contained three flakes, or rude implements of flint, as well as objects made of bronze and bone. In the course of the description alluded to, there are references to many other examples of coffins hollowed out of solid trunks, oaken and tree-coffins. These appear to belong to very different periods, extending from the ancient British to early Saxon, and perhaps Christian times. That called the “King Barrow,” at Stowborough, in Dorsetshire, contained an oaken tree-coffin with the body in an envelope of deer-skins. It is said, that more recently a barrow opened in the wolds of Yorkshire offered fragments of an oaken coffin, together with the remains of a British urn. Also, at Wath, in the North Riding of Yorkshire, in an oaken coffin an urn was found of the later British type, the whole being enclosed in a barrow.”

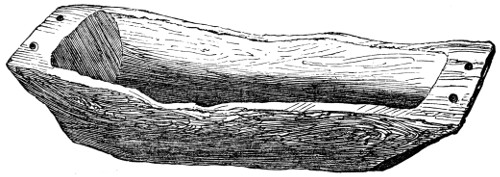

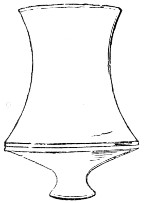

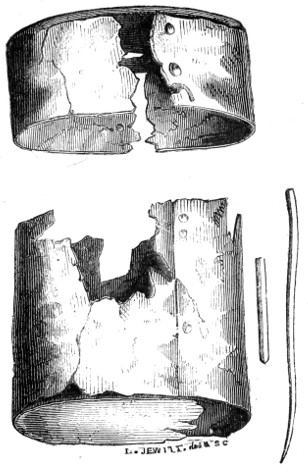

Fig. 32.

Fig. 33.

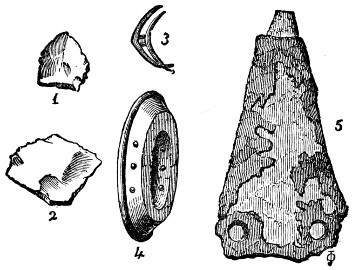

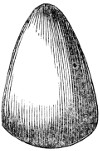

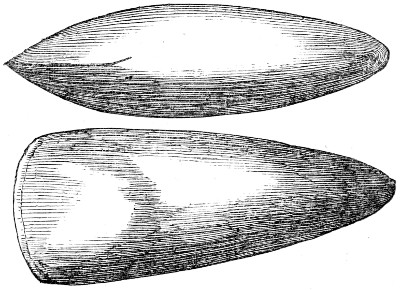

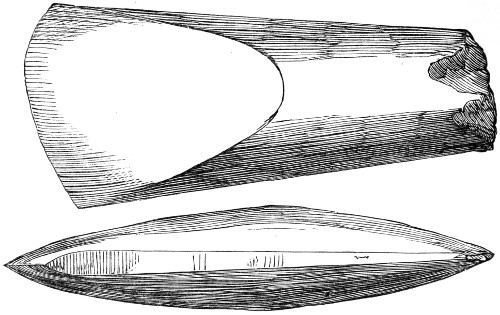

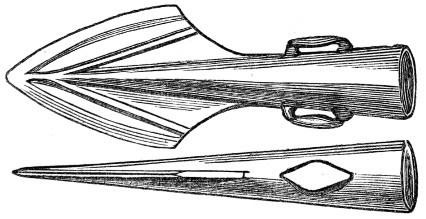

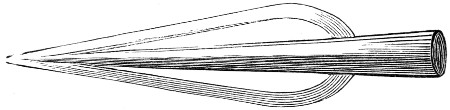

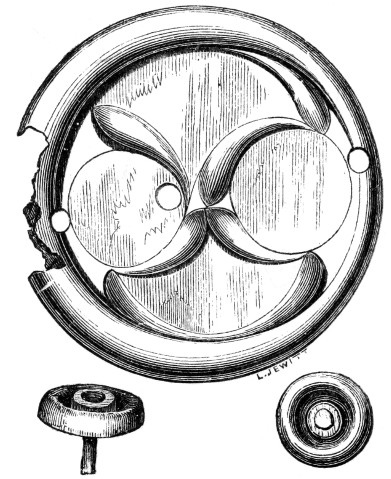

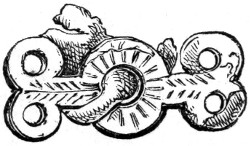

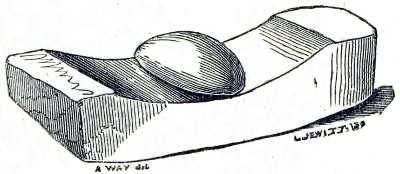

The Gristhorpe coffin, shown on figs. 32 and 33, consisted of the trunk of a large oak, roughly hewn, and split into two portions. The markings seemed to indicate that it had been hollowed with chisels of flint; but that the tree had been cut down with a much larger tool, the marks being such as would be made by a stone hatchet. It is seven and a half feet long and three feet three inches broad. In the 48 bottom is a hole three inches in length. The lid was kept in place by the uneven fracture of the wood. The back was in good preservation, with its coatings of lichens distinct. At the narrow end of the lid, cut in the bark, was a sort of leaf-shaped knob, perhaps intended for a handle. The objects found in the coffin alluded to above are shown on figs. 34 and 35. In these engravings, Nos. 1, 2, and 6 are flakes of flint. The first has been slightly chipped at the edge, but the others are simply split off from the native flint. No. 5 is a bronze dagger, three and a half inches long, but much corroded—the two rivets showing that the handle was not of much thickness. No. 4, no doubt the top of such handle, is a disc of bone, polished, and of oval shape with perforations on either side for the pins by which it was fastened. No. 8 is a small implement of wood, with 49 a rounded head, and flattened on one side to about half its length. No. 3 is the fragment of a ring of horn—a fastening, perhaps, of the dress. On the lower part of the breast was an ornament of very brittle material, in the form of a rosette, with two loose ends. By the side was a shallow basket, about six inches in diameter, formed of bark, curiously stitched with the sinews of animals; at the bottom were decomposed remains, perhaps of food. There was also a quantity of vegetable substance, mixed with lanceolate foliage supposed to be that of the mistletoe.

Fig. 34.

Fig. 35.

Fig. 36.

Another form—which may be called the “boat shape”—of tree-coffin is here shown for the purpose of comparison. 50

Ancient British or Celtic Period—Sepulchral Chambers of stone—Cromlechs—Chambered Tumuli—New Grange and Dowth—The Channel Islands—Wieland Smith’s Cave, and others—Stone Circles—For what purpose formed—Formation of Grave-mounds—Varieties of Stone Circles—Examples of different kinds—Arbor Low, etc.

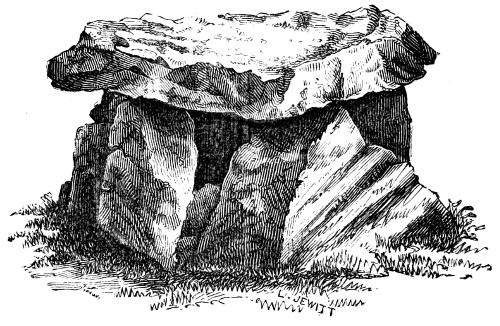

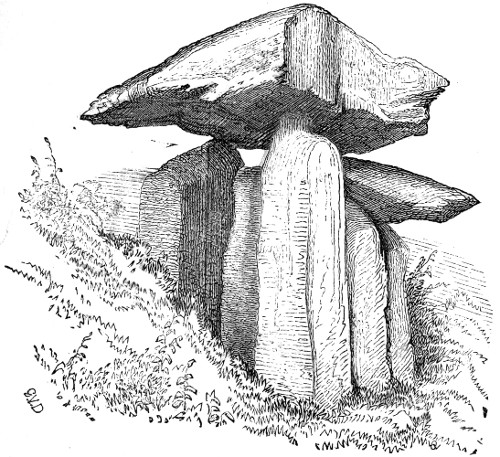

One of the most important classes of barrows is that which contains sepulchral chambers of stone; not the simple cists which have been spoken of in the preceding chapter, but of a larger, more complicated, or colossal character. Mounds of this description exist, to more or less extent, in different districts. In most instances the mound itself, i.e., the earth or loose stones of which the superincumbent mound was composed, has been removed, and the gigantic sepulchral chamber alone left standing. In many instances the mounds have been removed for the sake of the soil of which they were formed, or for the purpose of levelling the ground in the destructive march of agricultural progress. In many cases, however, they have doubtless been removed in the hope of finding treasure beneath; it being a common belief that immense stores of gold—in one instance the popular belief was that a “coach of gold” was buried beneath—were there for digging for. Where the mounds have been removed, and the colossal megalithic structures allowed to remain, they have an imposing and solemn appearance, and seem almost to excuse the play of imagination indulged in by our early antiquaries in naming them Cromlechs, and in giving to them a false interest by making them out to be “Druids’ altars”—altars on which the Druids made their sacrifices. These 51 same authorities have, indeed, gone so far in their inventions as to affirm, that when the capstone was lower on one side than another, as must necessarily frequently be the case, it was so constructed that the blood of the victims might run off in that direction, and be caught by the priests; that some of the naturally formed hollows in the stones were scooped out by hand to receive the heart and hold its blood for the highest purposes; and that when the cromlech was a double one, the larger was used for the sacrifice, and the smaller for the Arch-Druid himself whilst sacrificing.

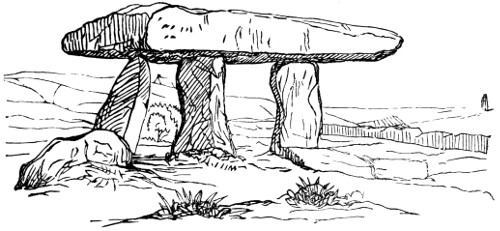

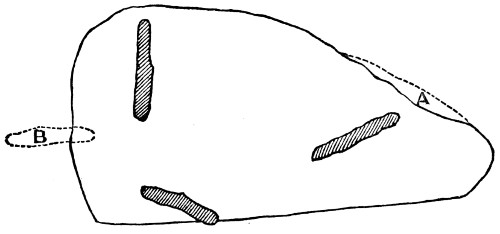

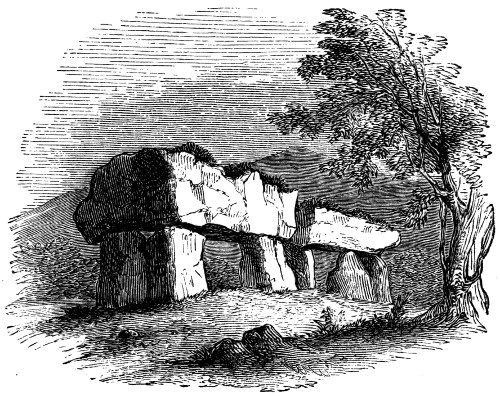

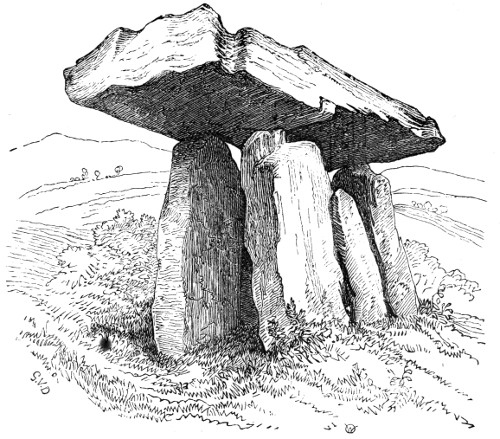

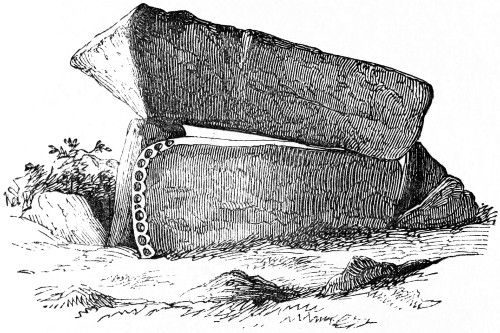

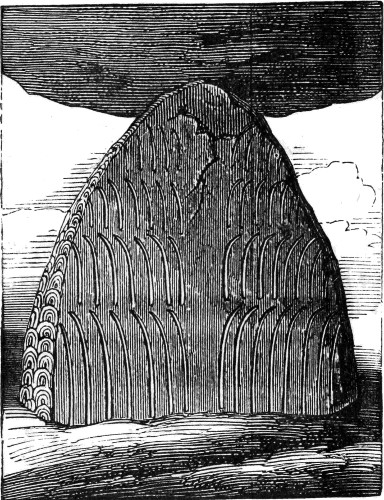

Researches which have been made in recent times show the absurdity of all this, and prove beyond doubt that the cromlechs are neither more nor less than sepulchral chambers denuded of their mounds. In several instances they have been found intact, and, these mounds being excavated, have been brought to light in a perfect state. These instances have occurred in Cornwall, in Derbyshire, and in other districts of England, as well as in the Channel Islands and elsewhere. One instance is that of the Lanyon cromlech in Cornwall. It seems that some seventy years ago “the farmer” to whom the ground belonged cast a longing eye on what appeared to be an immense heap of rich mould, and he resolved to cart it away and spread it over his fields. Accordingly he commenced operations, his men day after day digging away at the mound, and carting the soil off to the fields. By the time some hundred cart loads or so had been removed the men came to a large stone, which defied their efforts at removal, and, not knowing what it might be, or what it might lead to, they went on removing the surrounding earth, and gradually cleared, on all its sides, the majestic cromlech which is now one of the prides of Cornwall. This highly interesting chamber contained a heap of broken urns and human bones. This “Lanyon cromlech,” a view of which is given on fig. 37, consists 52 now of three immense upright stones, on which rests an enormous capstone, measuring about eighteen and a half feet in length and about nine feet in width, and is computed to weigh above fifteen tons. How such stones were raised and placed on the rough upright stone supports which had been prepared for them is almost beyond comprehension, when it is recollected that they were raised by a people who were devoid of machinery.

Fig. 37.

Fig. 38.

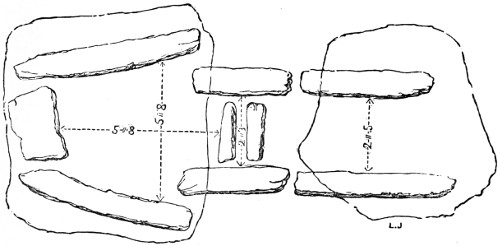

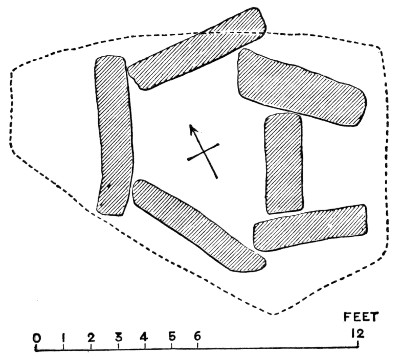

This cromlech when first uncovered consisted of four upright stones, on which rested the capstone. In 1815, during a tremendous storm, the capstone and one of the 53 supports were thrown down. In 1824 the capstone was replaced, under the superintendence of Lieut. Goldsmith, R.N., and at this time a piece was broken off at A. The fourth upright stone was not replaced, having been broken when thrown down. Fig. 37 shows the cromlech as replaced. Fig. 38 is a plan of it, showing the uprights and the capstone. The large outline is the capstone, the part marked A being the part broken off; the shaded parts are the present three uprights; and B the fourth upright, broken.

Fig. 39.

Fig. 40.

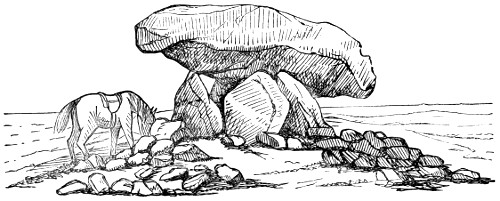

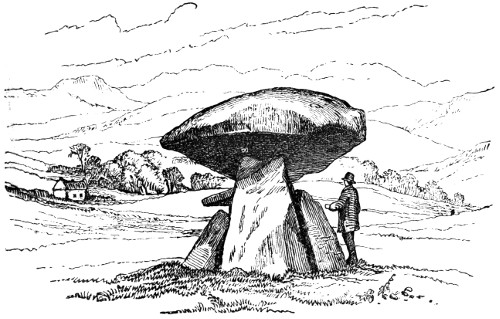

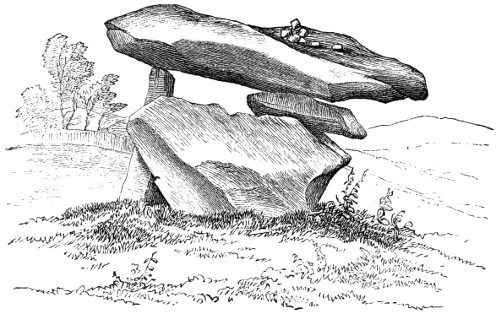

Kits Cotty House, in Kent; the Chun cromlech, in Cornwall (figs. 39 and 40)—the covering stone of which is calculated 54 to weigh twenty tons; the Molfra cromlech, in the same county, which consists of a compact cist closed on three sides and open on the fourth; the Zenor cromlech; the Plas Newydd cromlech, and many others which it is not necessary to enumerate, are all of the same class. The Plas Newydd (fig. 41) is a double cromlech, the two chambers being close together, end to end. The capstone of the largest, which is about twelve feet in length by ten feet in breadth, originally rested on seven stones, two of which have disappeared. The two erections undoubtedly were originally covered with a single mound.

Fig. 41.

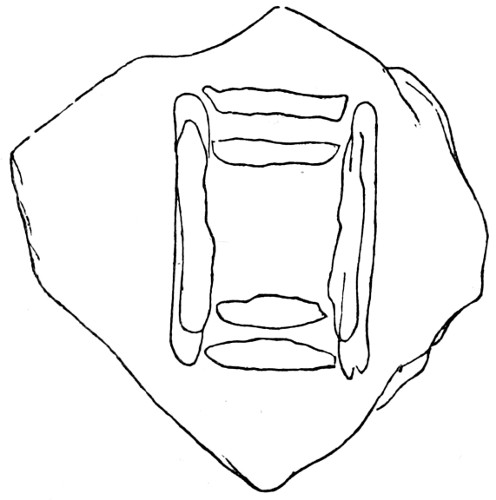

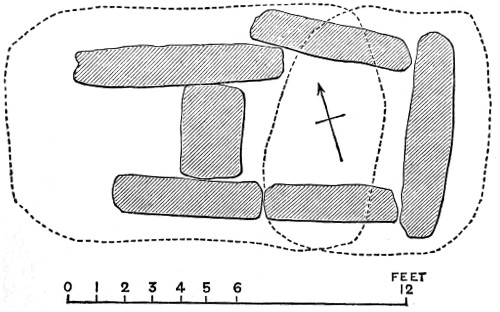

At Minninglow, in Derbyshire, erections of this kind occur, but, not being denuded of their mounds, are still partially buried. The mound is of large size. Under the centre and in four places in the area of the circle are large cists, which if cleared from the earth would be fine cromlechs of precisely the same form as those just described. They are formed of large slabs of the limestone of the district, placed upright on the ground, and are covered with immense capstones of the same material. All these 55 chambers had contained interments. The accompanying plan (fig. 42) of some of these cists gives the situation of the stones forming the sides of the large chamber; of the passage leading to it; of the slabs which closed its entrance; and of the covers or capstones. The chamber is rather more than five feet in height, and the largest capstone about seven feet square, and of great thickness. A kind of wall similar to those which have been found to encircle some of the Etruscan tumuli, forms the circle of this mound, which rises to a height of more than fifteen feet from the surface of the ground.17

Fig. 42.

The general arrangement of this example will be seen to bear an analogy to the Plas Newydd and others spoken of, and shows by what an easy transition the building of galleries, or a series of chambers for family tombs, in these large mounds, would be arrived at. Of this kind some very large examples exist in Ireland, and in the Channel Islands, as well as in various parts of England. 56

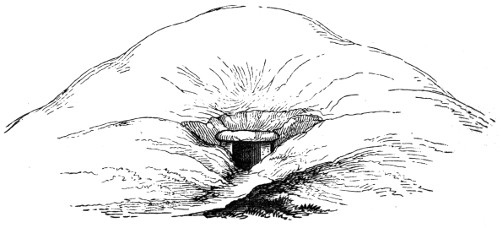

Fig. 43.

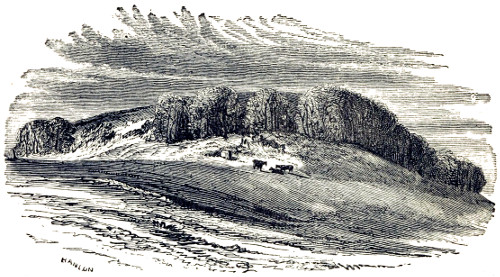

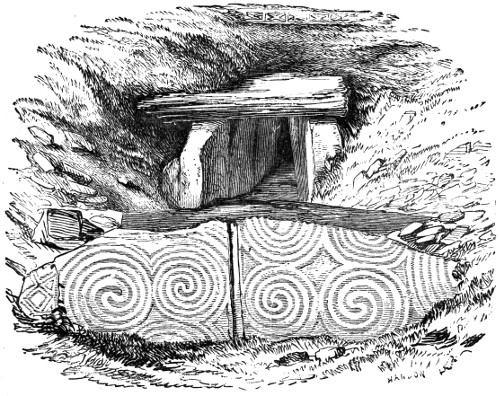

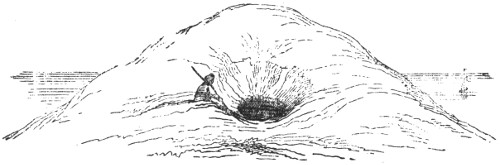

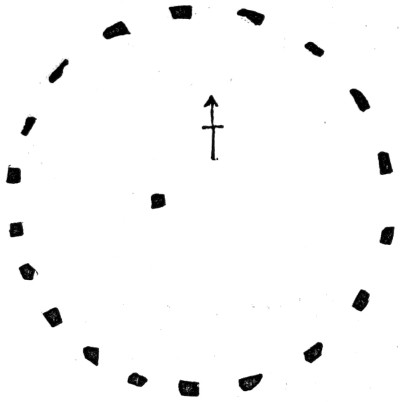

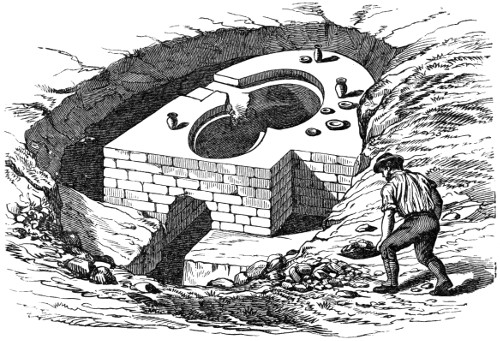

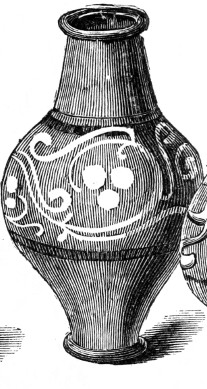

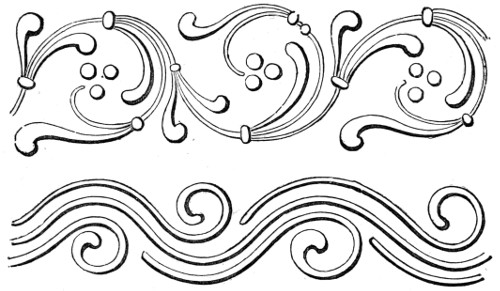

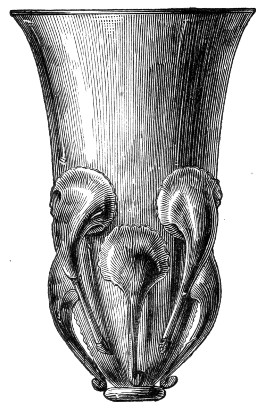

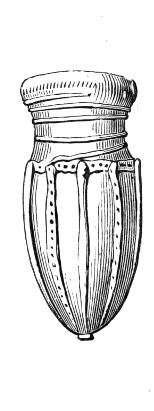

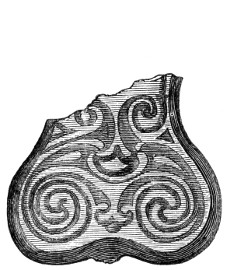

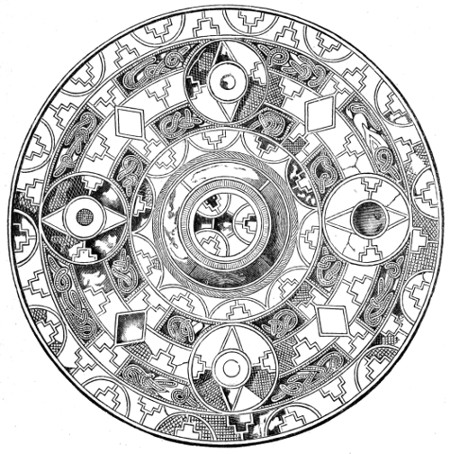

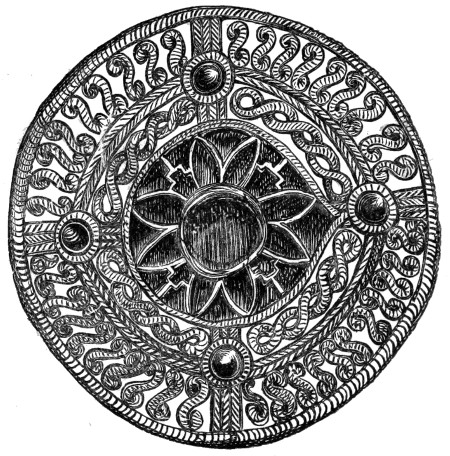

One of the most important in size, as well as in general interest; is the one at New Grange, county Meath. “The cairn, which even in its present ruinous condition measures about seventy feet in height, and is nearly three hundred feet in diameter, from a little distance presents the appearance of a grassy hill, partly wooded; but upon examination the coating of earth is found to be altogether superficial, and in several places the stones, of which the hill is entirely composed, are laid bare. A circle of enormous stones, of which eleven remain above ground,18 originally encircled its base. The opening (of which an engraving is shown on fig. 44) was accidentally discovered about the year 1699, by labouring men employed in the removal of stones for the repair of a road. The gallery, of which it is the external entrance, extends in a direction nearly north and south, and communicates with a chamber, or cave, nearly in the 57 centre of the mound. This gallery, which measures in length about fifty feet, is at its entrance from the exterior about four feet in height, in breadth at the top three feet two inches, and at the base three feet five inches. These dimensions it retains, except in one or two places, where the stones appear to have been forced from their original position, for a distance of twenty-one feet from the external entrance. Thence towards the interior its sides gradually increase, and its height where it forms the chamber is eighteen feet. Enormous blocks of stone, apparently water-worn, and supposed to have been brought from the mouth of the Boyne, form the sides of the passage; and it is roofed with similar stones. The ground plan of the chamber is cruciform; the head and arms of the cross being formed by three recesses, one placed directly fronting the entrance, 58 the others east and west, and each containing a basin of granite. The sides of these recesses are composed of immense blocks of stone, several of which bear a great 59 variety of carvings.19 In front of the entrance (fig. 44) will be seen one of these carved stones.”

Fig. 44.

Fig. 45.

Fig. 46.

Fig. 47.

Fig. 48.

Fig. 49.

Fig. 50.

At Dowth and Nowth (Dubhath and Cnobh), very similar 60 chambered tumuli exist, the former of which is also remarkable 61 for its sculptural stones, which bear a strong resemblance to those at New Grange. The Cairn of Dowth here engraved (fig. 45), is of immense size, and contains a cruciform chamber similar to that at New Grange, with a passage twenty-seven feet in length, composed—as was the chamber—of enormous stones. On some of the stones were carvings and Oghams. The mouth of the passage leading to the cruciform chamber is shown on fig. 46.

Fig. 51.

Fig. 52.

Fig. 53.

Other excellent examples of Irish cromlechs and chambers are those at Monasterboise (“Calliagh Dirras House”); Drumloghan (full of Oghams); Kells; Knockeen (figs. 47 and 48); where the right supporting stones are six in number, and arranged rectangularly, so as to form a distinct chamber 62 at the S.E. end, the large covering stone being 12 feet by 8 feet, and weighing about four tons, and the smaller one about half that size; Gaulstown (figs. 49 and 50), the inner chamber of which measures 7 feet by 6 feet 4 inches, and is seven feet in height; Ballynageerah (figs. 51, 52, and 53), the capstone of which is cleverly and 63 curiously poised on two only of the upright stones, as will be seen by the engravings;20 Howth, Shandanagh, Brennanstown, Glencullen, Kilternan, Mount Brown, Rathkenny, Mount Venus, and Knock Mary, Phœnix Park, as well as at many other places.