Project Gutenberg's Cricket, by Allan Gibson Steel and Robert Henry Lyttelton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Cricket

Author: Allan Gibson Steel

Robert Henry Lyttelton

Illustrator: Lucien Davis

Release Date: July 31, 2016 [EBook #52684]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CRICKET ***

Produced by MWS, Fay Dunn and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Full page figures have been moved near to the text they illustrate. Figures in the text have been moved to the start or end of the paragraph.

Footnotes have been moved to the end of chapters.

Variant spelling and inconsistent hyphenation are retained, in a few cases, missing punctuation has been added for consistency, e.g. to match quotation marks. A few palpable printing errors have been corrected.

Other changes that have been made are listed at the end of the book.

The Badminton Library

OF

SPORTS AND PASTIMES

EDITED BY

HIS GRACE THE DUKE OF BEAUFORT, K.G.

ASSISTED BY ALFRED E. T. WATSON

CRICKET

28 Volumes. Crown 8vo. 10s. 6d. each volume.

LONGMANS, GREEN, & CO. 39 Paternoster Row, London and Bombay.

CRICKET

BY

A. G. STEEL

AND THE

HON. R. H. LYTTELTON

WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY

A. LANG, W. G. GRACE, R. A. H. MITCHELL, AND F. GALE

WITH NUMEROUS ENGRAVINGS AFTER LUCIEN DAVIS

AND FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

Sixth Edition, thoroughly revised

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

AND BOMBAY

1898

All rights reserved

First Edition, June 1888; Reprinted August 1888, January 1889, September 1890. New Edition, thoroughly revised and with additions, December 1893. New Edition, thoroughly revised and with additions, July 1898.

Badminton: June, 1888.

Having received permission to dedicate these volumes, the Badminton Library of Sports and Pastimes, to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, I do so feeling that I am dedicating them to one of the best and keenest sportsmen of our time. I can say, from personal observation, that there is no man who can extricate himself from a bustling and pushing crowd of horsemen, when a fox breaks covert, more dexterously and quickly than His Royal Highness; and that when hounds run hard over a big country, no man can take a line of his own and live with them better. Also, when the wind has been blowing hard, often have I seen His Royal Highness knocking over driven grouse and partridges and high-rocketing pheasants in first-rate[vi] workmanlike style. He is held to be a good yachtsman, and as Commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron is looked up to by those who love that pleasant and exhilarating pastime. His encouragement of racing is well known, and his attendance at the University, Public School, and other important Matches testifies to his being, like most English gentlemen, fond of all manly sports. I consider it a great privilege to be allowed to dedicate these volumes to so eminent a sportsman as His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, and I do so with sincere feelings of respect and esteem and loyal devotion.

BEAUFORT.

PREFACE.

A few lines only are necessary to explain the object with which these volumes are put forth. There is no modern encyclopædia to which the inexperienced man, who seeks guidance in the practice of the various British Sports and Pastimes, can turn for information. Some books there are on Hunting, some on Racing, some on Lawn Tennis, some on Fishing, and so on; but one Library, or succession of volumes, which treats of the Sports and Pastimes indulged in by Englishmen—and women—is wanting. The Badminton Library is offered to supply the want. Of the imperfections which must be found in the execution of such a design we are[viii] conscious. Experts often differ. But this we may say, that those who are seeking for knowledge on any of the subjects dealt with will find the results of many years’ experience written by men who are in every case adepts at the Sport or Pastime of which they write. It is to point the way to success to those who are ignorant of the sciences they aspire to master, and who have no friend to help or coach them, that these volumes are written.

To those who have worked hard to place simply and clearly before the reader that which he will find within, the best thanks of the Editor are due. That it has been no slight labour to supervise all that has been written he must acknowledge; but it has been a labour of love, and very much lightened by the courtesy of the Publisher, by the unflinching, indefatigable assistance of the Sub-Editor, and by the intelligent and able arrangement of each subject by the various writers, who are so thoroughly masters of the subjects of which they treat. The reward we all hope to reap is that our work may prove useful to this and future generations.

THE EDITOR.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The History of Cricket |

1 |

| II. | Batting |

34 |

| III. | Bowling |

94 |

| IV. | Captaincy |

187 |

| V. | Umpires |

217 |

| VI. | Fielding |

245 |

| VII. | Country Cricket |

280 |

| VIII. | Border Cricket |

292 |

| IX. | How to Score |

299 |

| X. | The Australians |

313 |

| XI. | The University Cricket Match |

328[x] |

| XII. | Gentlemen and Players |

356 |

| XIII. | The Art of Training young Cricketers |

375 |

| XIV. | Single Wicket |

386 |

| INDEX | 395 |

ILLUSTRATIONS.

(Engraved by J. D. Cooper and R. B. Lodge, after Drawings by Lucien Davis, and Photographs by G. Mitchell, Martin & Tyler, and Medrington & Co.)

| ARTIST | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Caught and Bowled | Lucien Davis | Frontispiece | |

| A Young Cricketer | From a picture ascribed to Gainsborough, belonging to the M.C.C. | To face p. | 1 |

| Cricket | After Hayman’s picture, belonging to M.C.C. | ″ | 12 |

| Royal Academy Club in Marylebone Fields | ″ ″ | ″ | 28 |

| Caught at the Wicket | Lucien Davis | ″ | 68 |

| Run Out | ″ | ″ | 198 |

| A. E. Stoddart | From a photograph | ″ | 212 |

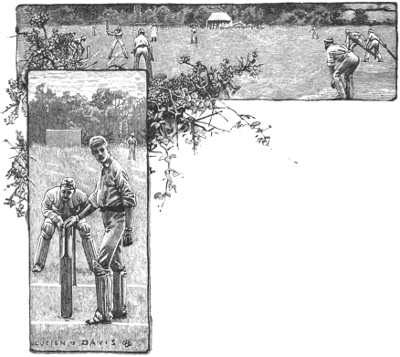

| Country Cricket (Mitcham) | Lucien Davis | ″ | 280 |

| M.C.C. and Ground v. Australians, Lord’s, May 22, 1884 | ″ | ″ | 308 |

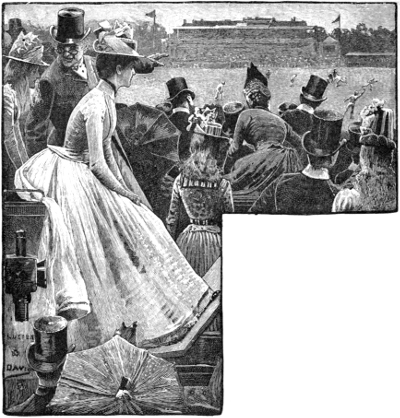

| The Critics | ″ | ″ | 324 |

| The Interval | ″ | ″ | 348 |

| Kennington Oval, 1854 | ″ | 366 | |

| Our National Game | Lucien Davis | ″ | 376 |

CRICKET.

CHAPTER I.

THE HISTORY OF CRICKET.

(By Andrew Lang.)

Archæology of the Game.

Hundreds of pages have been written on the origin and early history of Cricket. The Egyptian monuments and Holy Scriptures, the illuminated books of the Middle Ages, and the terra-cottas and vases of Greece have been studied, to no practical purpose, by historians of the game. Outside of England,[1] and before the fortieth year of the reign of Elizabeth, there are no documents for the existence of cricket. Doubtless in rudimentary and embryonic forms, it may have existed. Of those forms we still possess a few, as ‘rounders’ and ‘stool-ball,’ and we can also study degraded shapes of cricket, which naturally revert to the early germs of the pastime as degenerate human types throw back to the monkey. There is a sport known at some schools as ‘stump-cricket,’ ‘snob-cricket,’ or (mysteriously and locally) as ‘Dex,’[2] which is a degenerate shape of the game, and which is probably very like the rudimentary shapes. These degradations are reversals or returns to primitive forms.

A ball, more or less light and soft, is bowled or tossed at any fixed object, which, in turn, is defended by a player armed with a stick, stump, hair-brush, or other instrument. The player counts as many points as he can run backwards and forwards, after hitting the ball, between the object he defends and some more or less distant goal, before the ball is returned. He loses his position when the object he defends is struck by the ball, or when the ball is caught, after he has hit it, before touching the ground. Such is the degraded form of cricket, and such, apparently, was its earliest shape. Ancient surviving forms in which a similar principle exists are ‘rounders’ and ‘stool-ball.’ The former has been developed in America into the scientific game of ‘base-ball,’ the name being Old English, while the scientific perfection is American. It is impossible to trace cricket farther back than games in which points are scored in proportion to the amount of ground that the hitter can cover before the return of the struck ball. Now other forms of ball-play, as tennis, in different guises, can be found even among the ancient Aztecs,[3] while the Red Indians practised the form which is hockey among us, and the French and Walloons have sports very closely corresponding to golf; but games with the slightest analogy to cricket are very rare. Stool-ball is the most important foreshadowing of cricket. As early as 1614, Chapman, in his translation of the sixth book of the ‘Odyssey,’ makes Nausicaa and her girls play stool-ball. Chapman gives certain technical terms, which, of course, have nothing corresponding to them in Homer, but which are valuable illustrations of the English game.

Nausicaa seems to have received a trial ball—

Again,

thereby, doubtless, scoring a lost ball. He describes this as ‘a stool-ball chance.’ Chapman does not say whether the ball was bowled to Nausicaa. Everything shows that Dr. Johnson was writing at random when he described stool-ball as a game ‘in which a ball is driven from stool to stool.’ Chapman conceives Nausicaa as making a ‘boundary hit.’ There would be no need of such hitting if balls were only ‘driven from stool to stool.’

Strutt’s remarks on stool-ball merely show that he did not appreciate the importance of the game as an early form of cricket. ‘I have been informed,’ he says, ‘that a pastime called stool-ball is practised to this day in the northern parts of England, which consists simply in setting a stool upon the ground, and one of the players takes his place before it, while his antagonist, standing at a distance, tosses a ball with the intention of striking the stool, and this it is the business of the former to prevent by beating it away with his hand, reckoning one to the game for every stroke of the ball,’ apparently without running. ‘If, on the contrary, it should be missed by the hand and strike the stool, the players change places.’ Strutt adds, in a note, that he believes the player may be caught out. He describes another game in which stools are set as ‘bases’ in a kind of base-ball. He makes the usual quotations from Durfey about ‘a match for kisses at stool-ball to play.’[4]

Brand’s notes on stool-ball do no more than show that men and women played for small wagers, as in Herrick,

It is plain enough that stool-ball was a game for girls, or for boys and girls, and Herrick and Lucia. As at present played stool-ball is a woman’s game; but no stool is used: what[4] answers to the wicket is a square board at a certain height on a pole, much as if one bowled at the telegraph instead of the stumps. Consequently, as at base-ball, only full pitches can be tossed. However, in stool-ball we recognise the unconscious beginnings of better things. As much may be said for ‘cat-and-dog.’ This may be regarded either as a degraded attempt at early cricket, played by economists who could not afford a ball, or as a natural volks-kriket, dating from a period of culture in which balls had not yet been invented. The archæologist will prefer the latter explanation, but we would not pedantically insist on either alternative. In Jamieson’s ‘Scotch Dictionary,’[6] cat-and-dog is described as a game for three.[7] Two holes are cut at a distance of thirteen yards. At each hole stands a player with a club, called a ‘dog.’ A piece of wood,[8] four inches long by one in circumference, is tossed, in place of a ball, to one of the dogsmen. His object is to keep the cat out of the hole. ‘If the cat be struck, he who strikes it changes places with the person who holds the other club, and as often as the positions are changed one is counted as won in the game by the two who hold the clubs.’ Jamieson says this is an ‘ancient sport in Angus and Lauder.’ A man was bowled when the cat got into the hole he defended. We hear nothing of ‘caught and bowled.’[9]

Cat-and-dog, or, more briefly, cat, was a favourite game with John Bunyan. He was playing when a voice from heaven (as he imagined) suddenly darted into his soul, with some warning remarks, as he was ‘about to strike the cat from the hole.’ The cat, here, seems to have been quiescent. ‘Leaving my cat on the ground, I looked up to Heaven,’ and beheld a vision. Let it be remembered that Bunyan was playing on Sunday. The game of cat, as known to him, was,[5] apparently, rather a rude variety of knurr and spell than of cricket. This form is mentioned by Strutt.[10] Both stool-ball and cat-and-dog have closer affinities with cricket than club-ball as represented in Strutt’s authorities.[11] Perhaps we may say that wherever stool-ball was played, or cat-and-dog, there cricket was potentially present. As to the derivation of the word ‘cricket,’ philologists differ as much as usual. Certainly ‘cricket’ is an old word for a stool, though in this sense it does not occur in Skeat.[12] In Todd’s ‘Johnson,’ we find, ‘Cricket: a low seat or stool, from German kriechen, to creep.’ In Scotland we talk of a ‘creepy-stool.’

says Allan Ramsay, meaning the stool of repentance. If, then, stool-ball be the origin of cricket, and if a cricket be a stool, ‘cricket’ may be merely a synonym for stool-ball. Todd’s ‘Johnson,’ with ignominious ignorance, styles cricket ‘a sport in which the contenders drive a ball with sticks or bats in opposition to each other.’ Johnson must have known better. In the ‘Rambler,’ No. 30, he writes, ‘Sometimes an unlucky boy will drive his cricket-ball full in my face.’ Observe, he says ‘drive,’ not ‘cut,’ nor ‘hit to leg.’

Professor Skeat says nothing of this derivation of ‘cricket’ from cricket, a stool. He thinks ‘et’ may be a diminutive, added to the Anglo-Saxon cricc, a staff. If that be so, cricket will mean club-play rather than stool-ball. In any case, Professor Skeat has a valuable quotation of ‘cricket’ from the French and English Dictionary compiled in 1611, by Mr. Randle[6] Cotgrave. He translates the French crosse, ‘a crosier, or bishop’s staffe, also a cricket staffe, or the crooked staffe wherewith boies play at cricket.’ Now the name of the club used in French Flanders at the local kind of golf is la crosse. It is a heavy, barbaric kind of golf-club.[13]

Thanks to Cotgrave, then, we know that in 1611 cricket was a boy’s game, played with a crooked staff. The club, bat, or staff continued to be crooked or curved at the blade till the middle of the eighteenth century or later; and till nearly 1720 cricket was mainly a game for boys. We may now examine the authorities for the earliest mentions of cricket.

People have often regarded Florio’s expression in his Italian Dictionary (1598) cricket-a-wicket as the first mention of the noble game. It were strange indeed if this great word first dropped from the pen of an Italian! The quotation is ‘sgrittare, to make a noise as a cricket; to play cricket-a-wicket, and be merry.’ I have no doubt myself that this is a mere coincidence of sound. The cricket (on the hearth) is a merry little beast, or has that reputation. The term ‘cricket-a-wicket’ is a mere rhyming reduplication of sounds like ‘hob-nob’ or ‘tooral-ooral,’ or the older ‘Torelore,’ the name of a mythical country in a French romance of the twelfth century. It is an odd coincidence, no doubt, that the rhyming reduplication should associate wicket with cricket. But, for all that, ‘cricket-a-wicket’ must pair off with ‘helter-skelter,’ ‘higgledy-piggledy,’ and Tarabara to which Florio gives cricket-a-wicket as an equivalent.[14]

Yet cricket was played in England, by boys at least, in Florio’s time. The proof of this exists, or existed, in the ‘Constitution Book of Guildford,’ a manuscript collection of records once in the possession of that town. In the ‘History of Guildford,’ an anonymous compilation, published by Russell in the[7] Surrey town, and by Longmans in London (1801), there are extracts from the ‘Constitution Book.’ They begin with a grant anno li. Ed. III. For our purpose the only important passages are pp. 201, 202. In the thirty-fifth year of Elizabeth one William Wyntersmoll withheld a piece of common land, to the extent of one acre, from the town. Forty years before, John Parvishe had obtained leave to make a temporary enclosure there, and the enclosure had never been removed. In the fortieth year of[8] Elizabeth this acre was still in dispute, when John Derrick, gent, aged fifty-nine, one of the Queen’s Coroners for the county, gave evidence that he ‘knew it fifty years ago or more. It lay waste and was used and occupyed by the inhabitants of Guildeford to saw timber in and for saw-pitts.... When he was a scholler in the free school of Guildeford he and several of his fellowes did run and play there at crickett and other plaies.’

This is the oldest certain authority for cricket with which I am acquainted. Clearly it was a boy’s game in the early years of Elizabeth. Nor was it a very scientific game if it could be played on a wicket agreeably diversified by ‘saw-pitts.’ William Page may have played cricket at Eton and learned to bat as well as ‘to hick and hack, which they will do fast enough of themselves, and to cry horum.’ It has already been shown that, in 1611, ‘boyes played at crickett,’ with a crooked bat or ‘cricket-staffe.’

In 1676 we get a view of a summer day at Aleppo, and of British sailors busy at the national game.

Henry Teonge, Chaplain on board H.M.S. ships ‘Assistance,’ ‘Bristol,’ and ‘Royal Oak,’ Anno 1675 to 1679, writes:—

[At Aleppo].

6.—This morning early (as it is the custom all summer longe) at the least 40 of the English, with his worship the Consull, rod out of the cytty about 4 miles to the Greene Platt, a fine vally by a river syde, to recreate them selves. Where a princely tent was pitched; and wee had severall pastimes and sports, as duck-hunting, fishing, shooting, handball, krickett, scrofilo; and then a noble dinner brought thither, with greate plenty of all sorts of wine, punch, and lemonads; and at 6 wee returne all home in good order, but soundly tyred and weary.[15]

When once the eighteenth century is reached cricket begins to find mention in literature. Clearly the game was rising in the world and was being taken up, like the poets of the period, by patrons. Lord Chesterfield, whom Dr. Johnson found a[9] patron so insufficient, talked about cricket in a very proper spirit in 1740.[16] ‘If you have a right ambition you will desire to excell all boys of your age at cricket ... as well as in learning.’ That is the right style of fatherly counsel; but Philip Stanhope never came to ‘European reputation as mid-wicket-on,’ like a hero of Mr. James Payn’s. Lord Chesterfield also alludes to ‘your various occupations of Greek and cricket, Latin and pitch-farthing,’ very justly coupling the nobler language with the nobler game. Already in the fourth book of the ‘Dunciad,’ line 592, Mr. Alexander Pope had sneered at cricket.[17] At what did Mr. Pope not sneer? The fair, the wise, the manly,—Mrs. Arabella Fermor, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Mr. Colley Cibber, and a delightful pastime,—he turns up his nose at them and at everyone and everything!

See, he cries to Dulness, see—

Cricket was played at Eton early. Gray, writing to West, says, ‘There is my Lords Sandwich and Halifax—they are statesmen—do you not remember them dirty boys playing at cricket?’[18] In 1736 Walpole writes, ‘I can’t say I am sorry I was never quite a school-boy: an expedition against bargemen, or a match at cricket may be very pretty things to recollect; but, thank my stars, I can remember things very near as pretty.’[19] The bargee might have found an interview with Miss[10] Horace pretty to recollect, but when Horace pretends that he might have been in the Eleven if he liked, the absurdity becomes too glaring. We are reminded of Charles Lamb’s ‘Here is Wordsworth saying he might have written “Hamlet” if he had had the “mind.”’ Cowper pretends (in 1781) that ‘as a boy I excelled at cricket and football,’ but he adds, with perfect truth, ‘the fame I acquired by achievements that way is long since forgotten.’ The author of the ‘Task,’ and of a good many hymns, was no Mynn nor Grace. We shall find but few of the English poets distinguished as cricketers, or fond of tuning the lyre to sing Pindaric strains of batters and bowlers. Byron tells a friend how they ‘together joined in cricket’s manly toil’ (1807). Another noble exception is George Huddesford,[20] author of ‘Salmagundi’ (1791, p. 66)—

This passage gives us the costume—white drawers and red slippers. The contemporary works of art, whereof see a little gallery on the walls of the pavilion at Lord’s, show that men when they played also wore a kind of jockey cap. In a sketch of the Arms of Shrewsbury School, little boys are playing; the bat is a kind of hockey-stick as in the preceding century. There are only two stumps, nor more in Hayman’s well-known picture engraved 1755. The fields are well set for the bowling, and are represented with their hands ready for a catch. There[11] are umpires in their usual places; the scores are kept by men who cut notches in tally-sticks. Such ‘notches’ were ‘got’ by ‘Miss Wicket’ a sportive young lady in a somewhat later caricature (p. 7). The ball (1770) has heavy cross-seams. But a silver ball, about a hundred years old, used as a snuff-box by the Vine Club at Sevenoaks, is marked with seams like those of to-day. Miss Wicket, also, carries a curved bat, but it has developed beyond the rustic crooked stick, and more nearly resembles some of the old curved bats at Lord’s, with which a strong man must have hit prodigious skyers. We may doubt if bats were ever such ‘three-man beetles’ as the players in an undated but contemporary picture at Lord’s do fillip withal. The fields, in this curious piece, are all in a line at square-leg, and disappear in a distance unconscious of perspective.

Cricket had even before this date reached that height of prosperity which provokes the attention of moralists. ‘Here is a fine morning: let us go and put down some form of enjoyment,’ says the moralist. In 1743 a writer in the ‘Gentleman’s Magazine’ was moved to allege that ‘the exercise may be strained too far.... Cricket is certainly a very good and wholesome exercise, yet it may be abused if either great or little people make it their business.’ The chief complaint is that great and little people play together—butchers and baronets. Cricket ‘propagates a spirit of idleness at the very time when, with the utmost industry, our debts, taxes, and decay of trade will scarcely allow us to get bread.’ The Lydians, according to Herodotus, invented games to make them forget the scarcity of bread. But the gentleman in the magazine is much more austere than Herodotus. ‘The advertisements most impudently recite that great sums are laid’; and it was, indeed, customary to announce a match for 500l. or 1,000l. Whether these sums were not drawn on Fancy’s exchequer, at least in many cases, we may reasonably doubt. In his ‘English Game of Cricket’ (p. 138) the learned Mr. Box quotes a tale of betting in 1711, from a document which he does not describe. It appears that in 1711 the county of Kent played All England,[12] and money was lost and won, and there was a law-suit to recover. The court said, ‘Cricket is, to be sure, a manly game and not bad in itself, but it is the ill-use that is made of it by betting above 10l. on it that is bad.’ To a humble fiver on the University match this court would have had no kind of objection to make. The history of betting at cricket is given by Mr. Pycroft in the ‘Cricket Field’ (chap. vi.). A most interesting chapter it is.

The earliest laws of the game, or at least the earliest which have reached us, are of the year 1774. A committee of noblemen and gentlemen (including Sir Horace Mann, the Duke of Dorset, and Lord Tankerville) drew them up at the ‘Star and Garter’ in Pall Mall. ‘The pitching of the first wicket is to be determined by the toss of a piece of money.’ Does this mean that the sides tossed for which was to pitch the wicket? As Nyren shows, much turned on the pitching of the wicket. Lumpy (Stevens) ‘would invariably choose the ground where his balls would shoot.’[21] In the rules of 1774, the distance between the stumps is the same as at present. The crease is cut, not painted.[22] The stumps are twenty-two inches in height; there is only one bail, of six inches in length. ‘No ball,’ as far as crossing the crease goes, is just like ‘no ball’ to-day. Indeed, the game was essentially the game of to-day, except that if a ball were hit ‘the other player may place his body anywhere within the swing of his bat, so as to hinder the bowler from catching her, but he must neither strike at her nor touch her with his hands.’

At this moment of legislation, when the dim heroic age of cricket begins to broaden into the boundless day of history, Mr. James Love, comedian, appeared as the epic poet of the sport.[23] His quarto is dedicated to the Richmond Club, and is[15] inspired ‘by a recollection of many Particulars at a time when the Game was cultivated with the utmost Assiduity, and patronised by the personal Appearance[24] and Management of some of the most capital People in the Kingdom.’ Mr. Love, in his enthusiasm, publishes an exhortation to Britain, to leave all meaner sports, and cultivate cricket only.

sings Love, as he warms to his work. He denounces ‘puny Billiards,’ played by ‘Beaus, dressed in the quintessence of the fashion. The robust Cricketer plays in his shirt, the Rev. Mr. W——d, particularly, appears almost naked.’

One line of Mr. Love’s,

appears to him so excellent that he thinks it must be plagiarised, and, in a note, invites the learned reader to find out where he stole it from. To this a critic, Britannicus Severus, answers that ‘Gentlemen who have Cricket in their heads cannot afford to pore over a parcel of musty Authors.’ Indeed, your cricketer is rarely a bookworm.

and play up,’ cries this English bard.

In the second book, the poet comes to business—Kent v. All England. The poet, after the custom of his age, gives dashes after an initial, in place of names. In notes he interprets his dashes, and introduces us to Newland, of Slendon, in Sussex, a farmer, and a famous batsman; Bryan, of London, bricklayer; Rumney, gardener to the Duke of Dorset; Smith,[16] keeper of the artillery ground; Hodswell, the bowling tanner of Dartford; Mills, of Bromley; Robin, commonly called Long Robin; Mills, Sawyer, Cutbush, Bartrum, Kips, and Danes; Cuddy, the tailor; Derigate, of Reigate; Weymark, the miller, with Newland, Green, two Harrises, and Smith made up the teams. The match is summed up in the Argument of the Third Book.

The Game.—Five on the side of the Counties are out for three Notches. The Odds run high on the side of Kent. Bryan and Newland go in; they help the Game greatly. Bryan is unfortunately put out by Kips. Kent, the First Innings, is Thirteen ahead. The Counties go in again, and get Fifty-seven ahead. Kent, in the Second Innings, is very near losing, the two last Men being in. Weymark unhappily misses a Catch, and by that means Kent is victorious.

It was a splendid close match—but let us pity Weymark, immortal butter-fingers. In the first innings the wicket-keeping of Kips to the fast bowling of Hodswell was reckoned fine.

If Love was the Homer of cricket, the minstrel who won from forgetfulness the glories of the dim Heroic Age, Nyren, was the delightful Herodotus of the early Historic Period. John Nyren dedicated his ‘Cricketer’s Guide and Recollections of the Cricketers of my Time,’ to the great Mr. William Ward, in 1833. He speaks of cricket as ‘an elegant relaxation,’ and congratulates Mr. Ward on ‘having gained the longest hands of any player upon record.’ This famed score was made on July 24, 25, 1820, on the M.C.C. ground. The number was 278, ‘108 more than any player ever gained;’ Aylward’s 167 had previously been the longest score I know. Mr. Ward’s feat, moreover, was ‘after the increase of the stumps in 1817.’ Old Nyren was charmed in his declining hours by a deed like this, yet grieved by the modern bowlers, and their habit ‘of throwing the ball.’ The history of that innovation will presently be sketched.

Nyren was born at Hambledon, in Hampshire, on December 15, 1764, and was therefore a small boy when Love sang. He died at Bromley, June 28, 1837. Like most very great men, he[17] was possibly of Scottish blood. He was a Catholic and believed that the true spelling of the family name was Nairne, and that they came south after being ‘out in the ’15 or ’45.’ Mr. Charles Cowden Clarke describes him as a thoroughly good and amiable man, and as much may be guessed from his writings.

Mr. Clarke agreed with him in his dislike of round-hand bowling, save when Lillywhite was pitted against Fuller Pilch—a beautiful thing to see, as the Bishop of St. Andrews testifies, ‘speaking,’ like Dares Phrygius of the heroes at Troy, ‘as he that saw them.’ In Nyren’s youth—say 1780—Hambledon was the centre of cricket. The boy had a cricketing education. He learned a little Latin of a worthy old Jesuit, but was a better hand at the fiddle. In that musical old England, where John Small, the noted bat, once charmed an infuriated bull by his minstrelsy, Nyren performed a moral miracle. He played to the gipsies, and so won their hearts that they always passed by his hen-roost when they robbed the neighbours. Music and cricket were the Hambledon man’s delight. His father, Richard Nyren, was, with Thomas Brett, one of the chief bowlers. Brett was ‘the fastest as well as straightest bowler that was ever known’; no jerker, but with a very high delivery. The height of the delivery was not à la Spofforth, but was got by sending the ball out from under the armpit. How this manœuvre could be combined with pace is a great mystery. Richard Nyren had this art, ‘always to the length.’ Brett’s bowling is described as ‘tremendous,’ yet Tom Sueter could stump off it—Tom of the honourable heart, and the voice so sweet, pure and powerful. Yet on those wickets Tom needed a long-stop to Brett—George Lear. The Bishop has seen three long-stops on to Brown; ‘but he was a jerker.’ At that date the long-stop commonly dropped on one knee as he received the ball. An old Eton boy, G. B., who was at school between 1805 and 1814, says, in a letter to the Standard (dated September 21, 1886), that ‘a pocket-handkerchief was allowed round the dropping knee of long-stop.’ A bowler with a low delivery was Lambert, ‘the little farmer.’ [18]‘His ball would twist from the off stump into the leg. He was the first I remember who introduced this deceitful and teasing way of delivering the ball.’ Cricket was indeed rudimentary when a break from the off was a new thing. ‘The Kent and Surrey men could not tell what to make of that cursed twist of his.’ Lambert acquired the art as Daphnis learned his minstrelsy, while he tended his father’s sheep. He would set up hurdles instead of a net and bowl for hours. But it needed old Nyren to teach him to bowl outside the off stump, so little alert was the mind of this innovator. Among outsiders, Lumpy, the Surrey man, was the most accurate ‘to a length,’ and he was much faster than Lord Frederick Beauclerk. In these days the home bowlers pitched the wickets to suit themselves. Thus they had all the advantage of rough wickets on a slope; yet, even so, a yokel with pluck and ‘an arm as long as a hop-pole,’ has been known to slash Lumpy all over the field. But this could only have been done at single wicket. A curious bowler of this age was Noah Mann, the fleetest runner of his time, and a skilled horseman. He was a left-handed bowler, and, as will be seen, he anticipated the magical ‘pitching’ of experts at base-ball. How he did this without throwing or jerking is hard to be understood. ‘His merit consisted in giving a curve to the ball the whole way. In itself it was not the first-rate style of bowling, but so very deceptive that the chief end was frequently attained. They who remember the dexterous manner with which the Indian jugglers communicated the curve to the balls they spun round their heads by a twist of the wrist or hand will at once comprehend Noah’s curious feat in bowling.’ He once made a hit for ten at Windmill-down, to which the club moved from the bleakness of Broadhalfpenny.

We have followed Nyren’s comments on bowlers for the purpose of elucidating the evolution of their ingenious art. All the bowlers, so far, have been under-hand, but now we hear of ‘these anointed clod-stumpers’ the Walkers. They were not of Broadhalfpenny, but joined the club at Windmill-down, when the move there was made on the suggestion of the Duke of[19] Dorset. ‘About a couple of years after Walker had been with us’ (probably about 1790), ‘he began the system of throwing instead of bowling, now so much the fashion.’ He was no-balled, after a council of the Hambledon Club, called for the purpose. This disposes of the priority of Mr. Willes (1807), and incidentally casts doubt on the myth that a lady invented round-hand bowling. Nyren says, ‘The first I recollect seeing revive the custom was Wills, a Sussex man.’

From the heresiarch, Tom Walker, we come to the classic model of a bowler in the under-hand school—that excellent man, christian and cricketer, David Harris.

It would be difficult, perhaps impossible, to convey in writing an accurate idea of the grand effect of Harris’s bowling; they only who have played against him can fully appreciate it. His attitude, when preparing for his run previously to delivering the ball, would have made a beautiful study for the sculptor. Phidias would certainly have taken him for a model. First of all, he stood erect like a soldier at drill; then, with a graceful curve of the arm, he raised the ball to his forehead, and drawing back his right foot, started off with his left. The calm look and general air of the man were uncommonly striking, and from this series of preparations he never deviated. I am sure that from this simple account of his manner, all my countrymen who were acquainted with his play will recall him to their minds. His mode of delivering the ball was very singular. He would bring it from under the arm by a twist, and nearly as high as his arm-pit, and with this action push it, as it were, from him. How it was that the balls acquired the velocity they did by this mode of delivery, I never could comprehend.

When first he joined the Hambledon Club, he was quite a raw countryman at cricket, and had very little to recommend him but his noble delivery. He was also very apt to give tosses. I have seen old Nyren scratch his head, and say,—‘Harris would make the best bowler in England if he did not toss.’ By continual practice, however, and following the advice of the old Hambledon players, he became as steady as could be wished; and in the prime of his playing very rarely indeed gave a toss, although his balls were pitched the full length. In bowling, he never stooped in the least in his delivery, but kept himself upright all the time.[20] His balls were very little beholden to the ground when pitched; it was but a touch, and up again; and woe be to the man who did not get in to block them, for they had such a peculiar curl that they would grind his fingers against the bat; many a time have I seen the blood drawn in this way from a batter who was not up to the trick: old Tom Walker was the only exception—I have before classed him among the bloodless animals.

Harris’s bowling was the finest of all tests for a hitter, and hence the great beauty, as I observed before, of seeing Beldham in, with this man against him; for unless a batter were of the very first class, and accustomed to the first style of stopping, he could do little or nothing with Harris. If the thing had been possible, I should have liked to have seen such a player as Budd (fine hitter as he was) standing against him. My own opinion is, that he could not have stopped his balls, and this will be a criterion, by which those who have seen some of that gentleman’s brilliant hits, may judge of the extraordinary merit of this man’s bowling. He was considerably faster than Lambert, and so superior in style and finish, that I can draw no comparison between them. Lord Frederic Beauclerc has been heard to say that Harris’s bowling was one of the grandest things of the kind he had ever seen; but his lordship could not have known him in his prime; he never saw him play till after he had had many fits of the gout, and had become slow and feeble.

To Harris’s fine bowling I attribute the great improvement that was made in hitting, and above all in stopping; for it was utterly impossible to remain at the crease, when the ball was tossed to a fine length; you were obliged to get in, or it would be about your hands, or the handle of your bat; and every player knows where its next place would be.

This long extract is not too long, for it contains a dignified study of the bowler.

Harris was admired for ‘the sweetness of his disposition and his manly contempt of every action that bore the character of meanness,’ and he chiefly bowled for catches, as did Lord Frederick Beauclerk. Nyren is no great hand at orthography, and he soon comes to speak of a Sussex bowler named Wells.[21] This is apparently the Wills, or Willes, who has more credit than perhaps he deserves for bringing in round-hand. ‘He was the first I had seen of the new school, after the Walkers had attempted to introduce the system in the Hambledon Club.’ Willes had a twist from leg, and Nyren thinks Freemantle showed astonishing knowledge of the game because he went in front of his wicket and hit Willes, and ‘although before the wicket, he would not have been out, because the ball had been pitched at the outside of the stump.’ A man might play hours on that system ‘by Shrewsbury clock,’ but I doubt if David Harris would have approved of Freemantle’s behaviour.

The student of the evolution of round-hand and over-hand bowling now turns to the early exploits of William Lillywhite (b. June 13, 1792). Whatever Mr. Willes may have done, whatever Tom Walker may have dreamed, William Lillywhite and Jem Broadbridge are practically the parents of modern bowling. When Lillywhite came out, the law was that in bowling the hand must be below the elbow. Following the example of Mr. G. Knight, of the M.C.C., or rather going beyond it, Lillywhite raised the hand above the shoulder, though scarcely perceptible. Lillywhite’s performances in 1827 caused much discussion among cricketers and in the ‘Sporting Magazine.’ Letters on this subject are reprinted by Mr. W. Denison, in ‘Sketches of the Players,’ London, 1846.[25]

The last great match of 1827 was between Sussex and Kent, with Saunders and Searle given. Mr. Denison, reviewing the match at the time, predicted that if round-hand were allowed, there would be no driving and no cutting to point or slip. This of course is part of Unfulfilled Prophecy. ‘Broadbridge and others will shew that they cannot be faced on hard ground without the most imminent peril.’ As a compromise, Mr. Denison was for allowing straight-armed bowling, [22]‘so that the back of the hand be kept under when the ball is delivered.’ Mr. Steel’s chapter on bowling shows what the effect of that rule must have been.

In February, 1828, Mr. Knight published his letters in defence of round-hand bowling. There had been, in the origin of cricket, no law to restrain the bowlers. About 1804, the batting acquired such mastery, and forward play with running-in (as Nyren knew) became so vigorous, that Willes and Tom Walker tried round-hand. This round-hand was ‘straight armed, and for a time (1818–28) did very well, till bowlers took to raising the hand, even above the head.’ M.C.C. then proclaimed an edict against all round-hand bowling. Mr. Knight proposed to admit straight-armed bowling, which could not be called ‘throwing.’ To define a throw was as hard then as now—a man knows it when he sees it; it is like the trot in horses. Mr. Knight’s proposed law ran, ‘The ball shall be bowled; if it be thrown or jerked, or if any part of the hand or arm be above the shoulder at the time of delivery, the umpire shall call No Ball.’

In one of the trial matches (Sept. 1827) it is said that Mr. Knight, Broadbridge, and Lillywhite, all bowled high over the shoulder. There are no wides in the score. When a man was caught, the bowler’s name was not given. Lillywhite has thus no wicket to his name.

Mr. Knight’s law was discussed at Lord’s (May 19, 1828), and the word elbow substituted for shoulder. But Lillywhite and Broadbridge bowled as before, and found many followers, till the M.C.C. passed the law proposed by Mr. Knight. But the hand was soon raised, and the extraordinary pace of Mr. Mynn (born 1807) was striven for by men who had not his weight and strength. These excesses caused a re-enactment of the over-the-shoulder law in 1845.

Lillywhite was now recognised as the reviver of cricket. His analysis in 1844 and 1845 gives about 6⅞ runs for each wicket. Round-hand, with a practical license for over-hand, was now established; but, as late as 1860, a high delivery was a[23] rarity. The troublesome case of Willsher ended in permitting any height of delivery, and the greatest of all bowlers, Mr. Spofforth, sends in the ball from the utmost altitude.

This is a brief account of the evolution of round and over-hand bowling. As to slow and fast bowling, Lord Frederick Beauclerk and one of the Walkers were very slow bowlers in old days. William Clarke (b. Dec. 24, 1798) was the classical slow bowler. Clarke was not a regular lob bowler, but, like Lambert, delivered ‘about midway between the height of the elbow and the strict under-hand, accompanied by a singular peculiarity of action with the hand and wrist just as the ball is about to be discharged.[26]’ He had a tremendous twist, and great spin and ingenuity. Perhaps his success was partly due to the rarity of slow bowling in his time. Men imitated Mr. Mynn, who was as big a man as Mr. W. G. Grace, and a very fast bowler. In old underhand times, Brett had a ‘steam-engine pace,’ and later, Browne of Brighton was prodigiously fast. The Bishop of St. Andrews remembers seeing a ball of Browne’s strike the stumps with such force and at such a point that both bails flew back as far as the bowler’s wicket. That was at Brighton. He also remembers how at Lord’s, when Browne bowled, all the field were placed behind the wicket, or nearly so, that is at slip, leg, and long-stop, till Ward went in, who, playing with an upright bat, contrived to poke the ball to the off, and Browne himself (a tall, heavy man) had to go after it. But this having happened more than once, a single field was placed in front. Yet Beldham, as Mr. Pycroft tells, quite mastered Browne, and made 76 off him in a match. Beldham was then fifty-four. Browne’s pace was reckoned superior to that of Mr. Osbaldeston. It is not easy to decide who has been the fastest of fast bowlers. In our own day, I think that Mr. Cecil Boyle, when he bowled for Oxford (1873), was the swiftest I have seen, except a bowler unknown south of the Tweed, Mr. Barclay, now a clergyman in Canada. Mr. Barclay was faster with under-hand than with round-hand. Beldham and his comrades played Browne without[24] pads; I have seen this tried against Mr. Barclay—the results were damaging. Famous names of fast bowlers are Mynn, Marcon, Fellowes, Tarrant, Jackson, Freeman, Hope Grant, Powys, and Robert Lang.

The history of bowling precedes that of batting, because the batsman must necessarily adapt his style to the bowling, not vice versâ. He must also adapt it to the state of the wickets. There are times when a purely rural style of play, a succession of ‘agrarian outrages,’ is the best policy. Given an untrustworthy wicket, good bowling, fielding ground in heavy grass, a stone wall on one side, and another wall, with a nice flooded burn beyond, on another side, and a batsman will be well advised if he lifts the ball over the boundaries and into the brook. Perhaps Mr. Steel will recognise the conditions described, and remember Dalbeattie. In the origin of cricket, when the stumps were low, and the bat a crooked club, hitting hard, high, and often must have been the rule. A strong man with good sight must have been the pride of the village. When David Harris, Tom Walker, Lumpy, Brett, and other heroes brought in accuracy, spin, twist, and pace, with taller wickets to defend, this batting was elaborated by Beldham and Sueter and others into an art. Tom Sueter, first, fathered the heresy of leaving the crease, and going in to the pitch or half-volley.[27] Sir Horace Mann’s bailiff, Aylward, was the Shrewsbury of an elder age. ‘He once stayed in two whole days, and got the highest number of runs that had ever been gained by any member—one hundred and sixty-seven.’ Tom Walker was a great stick. Lord Frederick was bowling to him at Lord’s. Every ball he dropped down just before his bat. Off went his lordship’s white, broad-brimmed hat, dash upon the ground (his constant action when disappointed), calling him at the same time ‘a confounded old beast.’ ‘I doan’t care what ee zays,’ said Tom, whose conduct showed a good deal more of courtesy and self-control than Lord Frederick’s. Perhaps the master-bat of old times was William Beldham from Farnham. He comes into[25] Bentley’s ‘Cricket Scores’ as early as 1787. The players called him ‘Silver Billy.’ He was coached by Harry Hall, the gingerbread baker of Farnham. Hall’s great maxim was ‘the left elbow well up.’

From Nyren I extract a description of Beldham’s batting:—

Beldham was quite a young man when he joined the Hambledon Club; and even in that stage of his playing, I hardly ever saw a man with a finer command of his bat; but, with the instruction and advice of the old heads superadded, he rapidly attained to the extraordinary accomplishment of being the finest player that has appeared within the latitude of more than half a century. There can be no exception against his batting, or the severity of his hitting. He would get in at the balls, and hit them away in a gallant style; yet, in this single feat, I think I have known him excelled; but when he could cut them at the point of the bat, he was in his glory; and upon my life, their speed was as the speed of thought. One of the most beautiful sights that can be imagined, and which would have delighted an artist, was to see him make himself up to hit a ball. It was the beau idéal of grace, animation, and concentrated energy. In this peculiar exhibition of elegance with vigour, the nearest approach to him I think was Lord Frederick Beauclerc. Upon one occasion at Mary-le-bone, I remember these two admirable batters being in together, and though Beldham was then verging towards his climacteric, yet both were excited to a competition, and the display of talent that was exhibited between them that day was the most interesting sight of its kind I ever witnessed. I should not forget, among his other excellencies, to mention that Beldham was one of the best judges of a short run I ever knew; add to which, that he possessed a generally good knowledge of the game.

In 1838 Beldham used to gossip with Mr. Pycroft. That learned writer gives Fennex great credit for introducing the modern style of forward play about 1800; this on the evidence of Fennex himself (1760–1839). But probably accurate bowling, with a fast rise, on fairly good wickets, must have taught forward play naturally to Fennex, Lambert, Fuller Pilch, and others. It is not my purpose to compile a minute chronicle of cricket, to mark each match and catch, nor to chant[26] the illustrious deeds of all famous men. The great name of Mr. Ward has been already mentioned. The Bishop of St. Andrews, when a Harrow boy, played against Mr. Ward, and lowered his illustrious wicket for three runs.[28] Thus, with Mr. Ward, we come within the memory of living cricketers. Much more is this the case with Mr. Budd, Fuller Pilch, Alfred Mynn, Hayward and Carpenter, Humphrey and Jupp. Mr. Mynn was the son of a gentleman farmer at Bearstead, near Maidstone. His extraordinary pace actually took wickets by storm; men were bowled before they knew where they were. The assiduous diligence of Mr. Ward was a match for him. When about to meet Mynn, he would practise with the fastest of the ground bowlers at Lord’s, at eighteen or nineteen yards’ rise, so to speak. Mr. Ward’s great reach also stood him in good stead. Mr. Mynn’s pace, and the excesses committed by his imitators, for some time demoralised batting. Few balls were straight (among the imitatores, servum pecus), and men went in to hit what they could reach. The joy of getting hold of a leg-ball from a very fast bowler, or of driving him, overpowered caution, and these violent delights might have had violent ends if accuracy had not returned to bowling. In 1843 Mr. Mynn’s analysis gave 5⅖ a wicket. His average was but 17 an innings. Scores were shorter fifty years ago.[29]

My attempt has been to trace the streams of tendency in cricket rather than to produce a chronicle—a work which would require a volume to itself. Nothing has been said about fielding; because, however the ball is bowled, and however hit, the tasks of catching it, stopping it, and returning it with speed have always been the same. True, different styles of batting[27] and bowling require alterations in the position of the fielders.[30] But the principles of their conduct and the nature of their duty remain unaltered. One change may be noted. In ‘Juvenile Sports,’ by Master Michel Angelo,[31] the author speaks of byes and overthrows as ‘a new mode,’ ‘an innovation with which I am by no means pleased. It is indeed true that this places the seekers out continually on their guard, and obliges them to be more mindful of their play; but then it diminishes the credit of the player, in whose hands the bat is, as a game may be won by a very bad batsman owing to the inability of the wicket-man, or the inattention of the seekers-out.’

The fallacy of this argument does not need to be exposed.

No sketch of the history of cricket would be complete without a note on the fortunes of the Marylebone Club. This is the Parliament of cricket, and includes almost all the amateurs of merit. There is nothing very formal in its construction; and any clubs which please may doubtless arrange among themselves to play not according to M.C.C. rules. But nobody so pleases; and Marylebone legislates practically for countries that were not even known to exist when wickets were pitched at Guildford in the reign of Henry VIII. Marylebone is the Omphalos, the Delos of cricket.

The club may be said to have sprung from the ashes of the White Conduit Club, dissolved in 1787. One Thomas Lord, by the aid of some members of the older association, made a ground in the space which is now Dorset Square. This was the first ‘Lord’s.’ As to Lord, he is dubiously said (like the ancestors of Nyren) to have been a Scot and a Jacobite, or mixed up, at least, in some way with the ’45. Lord was obliged to move to North Bank, and finally, in 1814, to the[28] present ground. The famous Mr. Ward had played at Lord’s before this migration; his first match here was in 1810, and he played, more or less, till 1847, being then sixty years of age. His bats are said to have weighed four pounds. Mr. Ward bought the lease of the ground from Lord in 1825, ‘at a most exorbitant rate;’ and, in 1830, Dark bought the remainder of the lease from him. The first match on our present Lord’s, or the first recorded, was M.C.C. v. Hertfordshire, June 22, 1814. In 1825 the pavilion was burned, after a Winchester and Harrow match. The burning of the Alexandrian Library may be compared to the wholesale destruction of cricket records on this melancholy occasion. In 1816 the Club reviewed the Laws: the result will be found in Lillywhite’s ‘Scores,’ i. 385. ‘No more than two balls to be allowed at practice when a fresh bowler takes the ball before he proceeds.’ A great deal too much time is now wasted over these practice balls. ‘The ball must be delivered underhanded, not thrown or jerked, with the hand below the elbow at the time of delivering the ball.’ The umpire is to call ‘no ball,’ ‘if the back of the hand be uppermost.’ As to l.b.w., the batter is out ‘if with his foot or leg he stop the ball which the bowler, in the opinion of the umpire, shall have pitched in a straight line to the wicket, and would have hit it.’

The names of the Presidents are only on record after the fire. Ponsonby, Grimston, Darnley, Coventry are among the most notable. The renowned Mr. Aislabie was secretary till his death in 1842; in the pavilion his bust commemorates him. Mr. Kynaston and Mr. Fitzgerald, of ‘Jerks In from Short Leg,’ are other celebrated secretaries. In 1868 the Club purchased a lease of 99 years, at the cost of 11,000l. There have been recent additions to the area, and to that celebrated monument, the pavilion.

Lord’s is, as all the world knows, the scene, not only of Club and of Middlesex matches, but of Eton and Harrow, Oxford and Cambridge, and Gentlemen and Players, which is also contested at the Oval. Winchester used moreover to play[31] Eton here, but the head-masters have long preferred a home and home affair. In other chapters these great matches will be chronicled and criticised.

The various epochs in the history of the game may now be briefly enumerated by way of summary. First we have the prehistoric age, when cricket was dimly struggling to evolve itself out of the rudimentary forms of cat-and-dog, and stool-ball. This preceded 154-, when we find an authentic mention of the name of Cricket. Just about the end of the seventeenth century it was mainly a boys’ game. With the Augustan age it began to be taken up by statesmen, and satirised by that ideal whippersnapper, the ingenious but in all respects unsportsmanlike, Mr. Pope. By 1750 the game was matter of heavy bets, and scores began to be recorded. The old Hambledon Club gave it dignity, and the veterans endured till quite modern times dawn with Mr. Ward. Then came the prosperous heresy of round-hand bowling, which battled for existence till about 1845, when it became a recognised institution. The wandering clubs, chiefly I. Z. and the Free Foresters at first, carried good examples into the remoter gardens of our country. The migratory professional teams, the United and All England Elevens at least, showed the yokels what style meant, and taught them that Jackson and Tinley were their masters. But the lesson lasted too long. Nothing was less exhilarating than the spectacle of twenty provincial players, with Hodgson and Slinn, making many duck’s eggs, and fielding in a mob. ‘The first ‘ad me on the knee, the next on the wrist, the next blacked my eye, and the fourth bowled me,’ says the Pride of the Village, in ‘Punch,’ after enjoying ‘a hover from Jackson.’ Such violent delights had violent ends. The old travelling elevens are extinct, but railways have ‘turned large England to a little’ field, so to speak, and clubs may now meet which of old scarcely knew each other by name. The Australian elevens have in recent days given a great impulse to patriotic exertions.

Scotch cricket is a thing of this century. Football and golf are the native pastimes of my countrymen, as hurling is of Ireland. The Old Grange Club is the M.C.C. of the North. The West of Scotland and Drumpellier are other clubs of standing. That ever-flourishing veteran, Major Dickens, still upholds the honour of Kelso. The Moncrieffs have been the Wards and Budds of Edinburgh, nor will a touching patriotism allow me here to omit the name of George Charles Hamilton Dunlop. For some reasons Scotland has not been productive of bowlers. Professionals are seldom reared there, nor have amateurs devoted themselves to the more scientific and less popular part of the game. Mr. Barclay has already been commemorated for his speed; a few only will remember Mr. Sinclair and Mr. Glassford, who died young, and very much regretted. Few men have done more for Scotch cricket than Mr. H. H. Almond, head-master of Loretto School, which has contributed several players to the Oxford eleven. An old ‘pewter’ may here congratulate Mr. Almond on the energy with which he kept his boys to the mark, and on the undaunted example which he set by always going in first. The names of Arthur Cheyne, Jack Mackenzie, Edward Henderson, Chalmers, Hay Brown, Leslie Balfour, and Tom Marshall are only a few that crowd on the memory of the elderly Caledonian cricketer. In the Border district, of which more hereafter, the houses of Buccleuch and Roxburgh have been great friends of the game, and that was a proud day for ‘the Rough Clan’ when Lord George Scott scored over 160 in the University match of 1887. Abbotsford, too, has been well to the front, thanks to the Hon. J. Maxwell Scott, and, for some reason, Scotland has been occasionally represented by Mr. A. G. Steel, and the Hon. Ivo Bligh, known to the local press as ‘the Titled Batsman.’ But these are alien glories et non sua poma.

Three things are prejudicial to Scotch cricket. First, there is the climate, about which more words were superfluous. Next, boys leave school earlier than in England, for professions or for college. Lastly, the University ‘session’ is in the winter[33] months, and the University clubs are therefore at a great disadvantage. I shall never forget the miraculous wickets we tried to pitch on the old College Green at Glasgow, and the courage displayed by divinity students in standing up to Mr. Barclay there. As for St. Andrews, golf is too much with us on that friendly shore, and will brook no rival.

*** The author of the historical introduction is much indebted to the Bishop of St. Andrews, a veteran of the first University Match, for his kindness in revising proofs, and adding notes. He has also to thank the Viscountess Wolseley for the loan of her picture of ‘Miss Wicket’; and Mr. Charles Mills, M.P., for a sight of the silver ball of the Vine Club. It was filled with snuff, and tossed from hand to hand after dinner; he who dropped it being fined in claret, or some other liquor.

Fig. 1.—The champion.

Fig. 1.—The champion.

The great and supreme art of batting constitutes to the large majority of cricketers the most enjoyable part of the game. There are three especially delightful moments in life connected with games, and only those who have experienced all three can realise what these moments are. They are (1) the cut stroke at tennis, when the striker wins chase one and two on the floor; (2) the successful drive at golf, when the globe is despatched on a journey of 180 yards; (3) a crack to square-leg off a half-volley just outside the legs. When once the sensation has been realised by any happy mortal, he is almost entitled to chant in a minor key a ‘Nunc Dimittis,’ to feel that the supreme moment has come, and that he has not lived in vain.

After[35] what has been said in the foregoing chapter we shall here only touch upon the cricket of the past in so far as seems necessary to make this dissertation on batting tolerably complete, and shall then proceed to discuss the principles and science of the art as it now exists.

The shape of the bat in the year 1746—which may be taken as a beginning, for it was in that year that the first score of a match was printed and handed down to posterity, at any rate in Lillywhite’s ‘Scores and Biographies’—resembled a thick crooked stick more than a modern bat.

From the shape of the bat, obviously adapted to meet the ball when moving along the ground, one may infer that the bowlers habitually delivered a style of ball we now call a ‘sneak.’ How long this system of bowling remained in vogue cannot exactly be told. The famous William Beldham, who was born in 1766, and lived for nearly one hundred years, is reported by Nyren to have said that when he was a boy nearly all bowling was fast and along the ground. As long as this was the case it is probable that the bat was nothing but a club, for if the ball never left the ground the operative part of the bat would naturally be at the very bottom, as is usual in clubs. The renowned Tom Walker was the earliest lob bowler; he probably took to the style late in life, or about the year 1800, and several bowlers, notably the great E. H. Budd, raised the arm slightly; but it is believed that the first genuine round-arm bowlers were William Lillywhite and James Broadbridge, both of Sussex, who first bowled the new style in 1827. That year was from this cause a year of revolution in cricket, and the shape of the modern bat dates from that period. As a rule, up[36] to the year 1800 the style of batting was back. William Fennex is supposed to have been the inventor of forward play, and Beldham reports a saying of one Squire Paulett, who was watching Fennex play: ‘You do frighten me there, jumping out of your ground.’ The great batsmen of the early era of cricket were Lord Frederick Beauclerk, Mr. Budd, Beldham, Bentley, Osbaldeston, William Ward, Beagley, William Lambert, Jem Broadbridge, W. Hooker, Saunders, and Searle. The great skill of these players, when opposed to under-hand bowling, was what determined the Sussex players to alter the style of bowling, and, indeed, it is generally the fact that too great abundance of runs raises questions as to the desirability of altering rules.

After the year 1827 the shape of the bat became very like what it is now, but it was much heavier in the blade and thinner in the handle, which seems to indicate that the play was mostly of the forward driving style, and the great exponent of this method of play was the renowned Fuller Pilch. Anyone who has the opportunity of handling a bat of this period will find that its weight renders it inconvenient for cutting, but suitable for forward play. The change from under-hand bowling to round-arm having been effected by slow developments makes it probable that the style of play was generally forward until the under-hand bowling was altogether superseded by round-arm. Some bowlers followed the new order of things by changing from under to round-arm. Round-arm bowling was at first less accurate than under-hand, and consequently all-round hitting greatly developed; and we find Felix, the father of cutting, who began play in 1828, chiefly renowned for this hit. Scoring greatly diminished when round-arm bowling was thoroughly established, and increased again as grounds got better.

Judging from the scores of that day, the best bat in England from 1827 to 1850 was Fuller Pilch, and his scoring would compare favourably with that of nearly all modern players till 1874, with the exception of W. G. Grace. He was a tall man, and used to smother the ball by playing right out forward.

The principle on which his whole play was founded was evidently to get at the pitch and take care of the ball before breaks, bumps, and shooters had time to work their devilries. In order to carry out this method, he used frequently to leave his ground, and consequently the famous Wm. Clarke always found Pilch a harder nut to crack than any of his other contemporaries.

Clarke’s slow balls tolerably well up were met by Pilch, who left his ground and drove him forward with a straight bat. His master appears to have been the great Sam Redgate, who was fast and ripping, and who on one occasion got him out for a pair of spectacles, while, on the other hand, twice in his life he got over 100 runs against Wm. Lillywhite’s bowling, considered in those days to be an extraordinary feat. After Pilch, Joseph Guy, of Nottingham, and E. G. Wenman, of Kent, were considered the best; but several—C. G. Taylor, Mynn, Felix, and Marsden, for example—scored largely, and they all passed through a golden age of bowling, namely, about 1839, when Lillywhite, Redgate, Mynn, Cobbett, and Hillyer all flourished, to say nothing of Sir F. Bathurst, Tom Barker, and others.

From the year 1855, when Fuller Pilch left off play, to the year 1868, when W. G. Grace burst on the world with a lustre that no previous batsman had ever approached, there was, nevertheless, a grand array of batsmen—among professionals, Hayward, Carpenter, Parr, Daft, Caffyn, Mortlock, and Julius Cæsar; and among amateurs, Hankey, F. H. Norman, C. G. Lane, C. G. Lyttelton, Mitchell, Lubbock, Buller, V. E. Walker, and Maitland. These are a few of the great names. They are, however, surrounded by several almost as renowned, such as Stephenson, T. Humphrey, Hearne, Cooper, Burbidge, Griffith, and others; all these, we think, made this era of the game productive of more exciting cricket than has been known since. It may seem odd, but the overpowering genius of W. G. Grace after this time somewhat spoilt the excitement of the game. His side was never beaten. Crowds thronged to see him play, all bowling was alike to him, and the record of Gloucestershire[38] cricket, champion county for some time through his efforts, is the only instance of one man practically making an eleven for several years. The other Gloucestershire players will be the first to acknowledge the truth of this. Gloucestershire rose with a bound into the highest rank among counties when W. G. Grace attained his position amongst batsmen, a head and shoulders above any other cricketer. In his prime Gloucestershire challenged and on one occasion defeated England; when he declined, Gloucestershire declined; in his old age she shows signs of renewing her youth, for which all credit is due to young Townsend, Jessop, Champain, and Board. To return to the period between 1855 and 1868: the greater equality of players made the matches more exciting and established a keener because more evenly balanced rivalry. The grounds were not so true as those of to-day, and the matches were not so numerous; consequently cricketers were not so frequently worn out by the wear and tear of long fielding and days and nights of travel as they are now. The long individual scores having been less in number and at longer intervals, the few great innings were more vividly stamped on the memory, and it is doubtful if even the modern 200 runs per innings will survive as historical facts longer than Hankey’s famous innings of 70 against the Players on Lord’s, Daft’s 118 in North v South on the same ground, and Hayward’s 112 against Gentlemen, also on Lord’s.

The bowling during this period was generally fast or medium, varied by lobs, but of genuine slow round, like that of Peate, Buchanan, Alfred Shaw, and Tyler, there was hardly any in first-class matches. To fast bowling runs come quicker than they do to slow; consequently the game was of more interest to the ordinary spectator, and there was none of that painful slowness, in consequence of the extraordinary accuracy of modern slower bowling, that is so common now, and helps to produce so many drawn matches. Though now, in the year 1897, the average bowling pace is slower than it was in the sixties, it is nevertheless faster than it[39] was in the seventies. The professionals had literally only one genuine slow round-arm bowler in those days—George Bennett, of Kent—and of course this fact accounted largely for the batting style of the period. Wickets being often rough, the most paying length for fast bowling was naturally that length which gave the ground most chance, and prevented the smothering style of play—a little shorter than the blind spot, compelling back play over the crease, instead of forward play. The best batsmen were great masters of this style of play, with which the name of Carpenter is strongly identified. To modern players the sight of Carpenter or Daft dropping down on a dead shooter from a bowler of the pace of George Freeman or Jackson was a wonderful one; but it is rapidly becoming a memory only, for in these days a shooter may be said not to exist. Now, in 1897, a wonderful feature of our great fast bowlers—pre-eminently Richardson—is not that they bowl straighter than Freeman or Jackson, but that they never bowl a ball on the legs or outside the legs. The result is that orthodox leg hitting, and in particular the smite to long-leg with a horizontal bat, and much nearer the ground than a square-leg hit, is never seen. During the entire progress of a match nowadays, between Notts and Lancashire, or Yorkshire and Notts, the unhappy batsman will not get a single ball outside his legs to hit. So great is the accuracy of the bowling, that over after over will go by, and not even a ball on his legs will soothe his careworn and anxious brain. This accurate bowling has caused another change in the way of batting. As no ball is bowled on the leg side at all, so it consequently follows there is no fieldsman on the on side except a forward short-leg and a deep field. The batsman therefore waits till the bowler slightly overtosses a ball—whether pitched outside the off stump or on the wicket he cares not; he sweeps it round to square leg, where no fieldsman stands, and he makes four runs by the hit. In other words, he deliberately ‘pulls’ it. Twenty years ago, on seeing such a hit, the famous Bob Grimston would have shown his emphatic disapproval in a[40] characteristic manner. But the match must be won by runs; to attain this object the ball must be hit where there is no field, and it is useless to waste energy by hitting the ball to every fieldsman on the off side.

W. W. Read, Stoddart, and F. S. Jackson are all masters of this stroke, which revives the drooping attention of the crowd and relieves the monotony of the scorers. To all fast bowling the cut is a hit largely in vogue, and the perfection to which some players arrive with regard to this stroke is a joy to themselves and to the spectators. It is, of course, as will be explained later on, much easier to cut fast bowling than slow, and the heroes of the cut whenever fast bowling is on are, and were, always numerous.

The champion cutter of old times, by universal testimony, was C. G. Lyttelton, whose hits in the direction of point are remembered by spectators to this day. Tom Humphrey, of Surrey, was another great cutter; and there was a player, not of the first rank, who was famous for this hit—namely, E. P. Ash, of the Cambridge University Eleven, 1865 and 1866.

The five champion bats of this era—1855 to 1868—were, in the opinion of the writer, Hayward, Carpenter, Parr, Daft, and R. A. H. Mitchell. The scoring of Hayward and Carpenter between 1860 and 1864 was very large; both excelled on rough wickets, and it is on these wickets that genius exhibits itself.

In all times of cricket, until the appearance of W. G. Grace, there has been a large predominance of skill amongst the professionals as compared with the amateurs. We are talking now of batting; in bowling the difference has been still more to the advantage of the professionals. The Gentlemen won a match now and then, but their inferiority was very great. W. G. Grace altered all this; and from 1868 to 1880 the Gentlemen had a run of success which will probably never be seen again. It was entirely owing to him, though the Players were astonishingly weak in batting from 1870 to 1876; but[41] nothing could stop the crack, and his scoring in the two annual contests was simply miraculous.

We will now attempt to lay before our readers a more detailed exposition of the principles which ought to govern sound batting, and a careful observance of which is found in the method of every sound player. The first consideration is the choice of a bat, and as to this each individual must determine for himself what is the most suitable. It is probable that a strong man will prefer a heavier bat than a batsman of less muscular calibre. In any case the style of play is an important consideration, but the secret of all batting, and especially hitting, is correct timing; this is a quality which cannot be taught, but this is what makes a weak man hit harder than a strong man—the one knows exactly the fraction of a second when all that is muscular, all that he has got in wrist and shoulders, must be applied, the other does not.

At the beginning of this century, when the bowling was fast under-hand, the bat used was of a style suitable for meeting such balls—namely, a heavy blade with great weight at the bottom; for, as already mentioned, the bowling being straight and frequently on the ground, driving was the common stroke, and for this a heavy blade is best adapted. So now, if a player finds that he does not possess a wrist style of play, but a forward driving game, he will probably choose a heavier bat than the wrist-player; for a forward drive is more of a body stroke—that is, the whole muscular strength of the shoulders and back is brought into use, and the ball, being fully met, gives more resistance to the bat than a ball which is cut. This, perhaps, needs a little explanation. Just consider for a moment, and realise the fact that a tolerably fast ball, well up and quite straight, has been delivered. Such a ball is just the ball that ought to be driven. The batsman lunges forward and meets it with very nearly the centre of his bat, just after the ball has landed on the ground, at the time, therefore, when, if there is any spin on it, it is going at its fastest pace. Obviously, therefore, when the pace and weight of the ball are taken into consideration, there is great resistance[42] given to the lunge forward of the bat. The heavier the blade of the bat the better is it able to withstand and resist the contrary motion of the ball. As a rule, players are not equally good both at the forward driving and the wrist-playing games. Some few excel in both, but usually batsmen have preferences. Now let us examine the cut—of course we are now discussing a ball on the off side of the wicket. A wrist-player will cut a ball that the exponent of the driving style would drive, and therefore meet with the full, or nearly full, bat. The cutter does not meet the ball, for the ball has gone past him before he hits it. Take a common long-hop on the off side. The driver meets it with a more or less horizontal bat, and hits it forward between cover-point and mid-off, or cover-point and point, thereby resisting the ball and sending it almost in an opposite direction to its natural course. He hits the ball some time before it arrives on a level with his body, while the cutter, on the other hand, does not hit the ball so soon; in fact, he hits it when it is about a foot in front of the line of the wicket, sometimes almost on a level with the wicket. He then, with his wrist, hits it in the direction of third man. He does not meet the ball at all, but he takes advantage of the natural pace of the ball and, as it were, steers it from the normal course towards long-stop, in the direction of third man. The whole essence of the distinction lies in this fact, that in driving the ball is met directly by the bat; in cutting this is not so; but the ball is, as it were, helped on, only in a different direction. The faster the bowling, the harder, therefore, will be the cut. The reader will at once see from this that the wrist-player will probably prefer a lighter bat than the driving batsman, and a bat that comes up well, as it is called, or is more evenly balanced.

We will now suppose a batsman properly equipped in pads and, at any rate, one glove on the right hand, and with a bat to his taste; our next inquiry must be as to his position at the wicket. He must remember that, after having chosen one position—the most natural and convenient to him—he ought to adopt that position invariably; not alter it from[43] day to day. You never see any material alteration in the position of any great player, and if anyone takes the very necessary trouble to find out the easiest position, he will be a foolish man who varies it, as any change must be for the worse. There is an old engraving, often seen, of a match between Surrey and Kent about the year 1840. Old William Lillywhite is about to bowl, and Fuller Pilch is about to play. The attitude and position of Pilch were taken by the author of ‘The Cricket Field’ as a model; and there is no objection to be raised to the position: it is a fair assumption that it was the natural and most convenient position for Fuller Pilch himself. The author, however, goes on to say that this is substantially the attitude of every good batsman. To this we can only rejoin, that out of the thousands of batsmen who have played cricket, it would be difficult to find two who stand exactly alike. To begin with, some stand with their feet close together, others have them apart; some indeed so far apart that it almost seems as if they were trying to solve the problem of how much length of ground can be covered between the two feet. Some stand with the right foot just on the leg side of a straight line drawn between the leg-stump of the batsman’s wicket and the off stump of the opposite wicket; others stand with the right foot twelve inches or thereabouts from the leg-stump in the direction of short-leg. Players who adopt this position run a risk of being bowled off their legs, one would think; but they ought to know best; we should not, however, advise a beginner to adopt this attitude. W. G. Grace faces the ball, and there is no intervening space between his hands whilst holding the bat and his legs. If you look at the position of Pilch, you will see a considerable interval of distance from the back of his left hand and the right leg. There were three notable batsmen—namely, A. N. Hornby, W. Yardley, and F. E. R. Fryer—who used to throw their left leg right across the wicket so as almost to hide it from the view of the bowler.