The Project Gutenberg EBook of Stage, Study & Studio, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Stage, Study & Studio

The Fun Library

Author: Various

Editor: J. A. Hammerton

Illustrator: Fred Barnard

W. S. Brunton

George du Maurier

and others

Release Date: July 21, 2016 [EBook #52614]

[Last updated: August 8, 2016]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STAGE, STUDY & STUDIO ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Harry Lamé and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text. The texts inside some of the illustrations may be read by clicking on the caption.

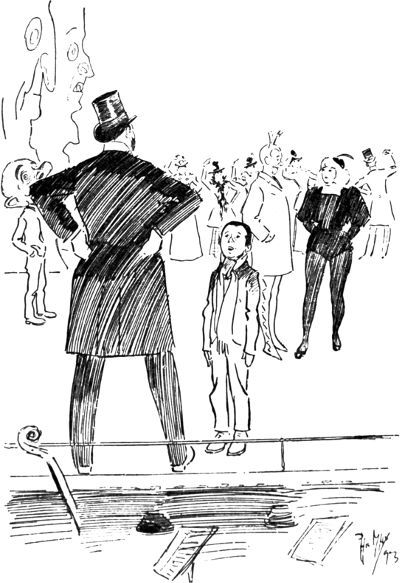

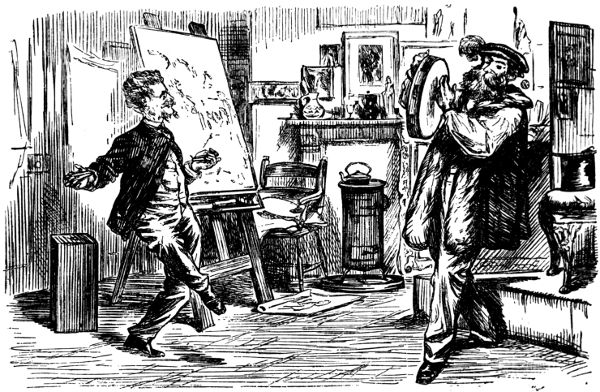

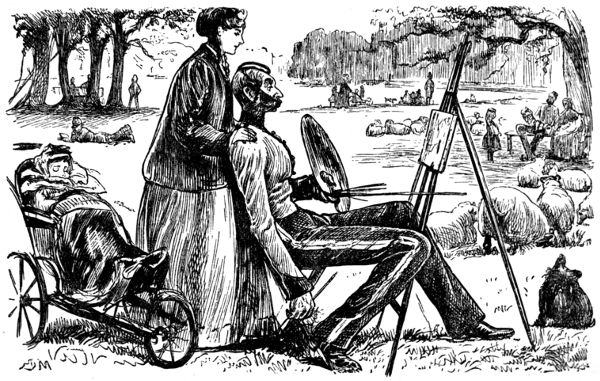

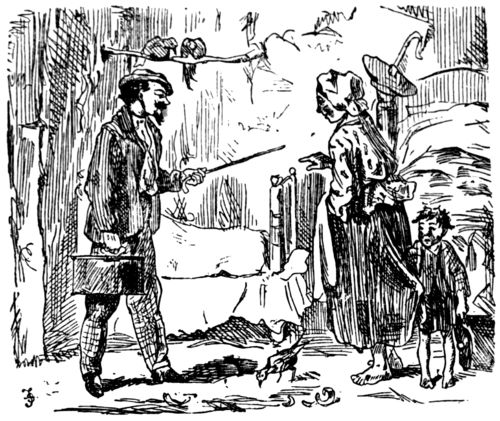

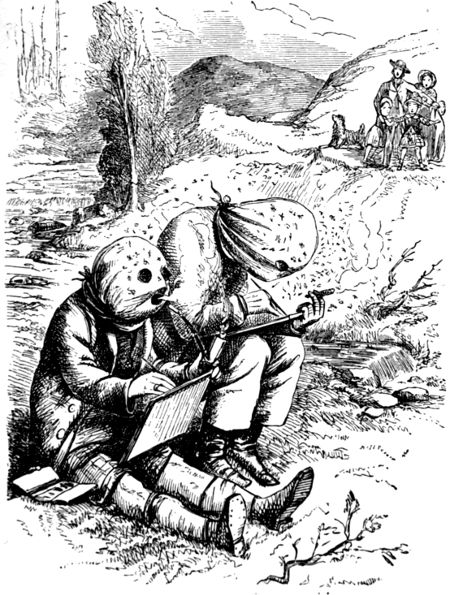

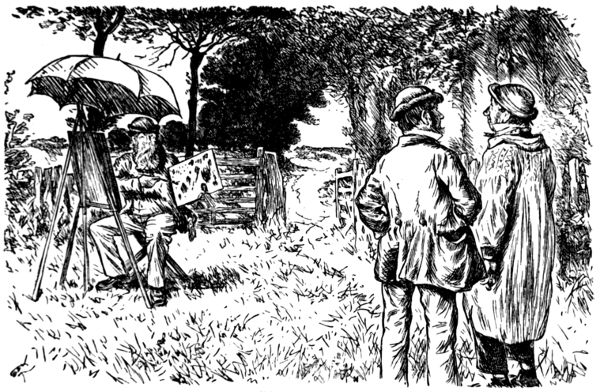

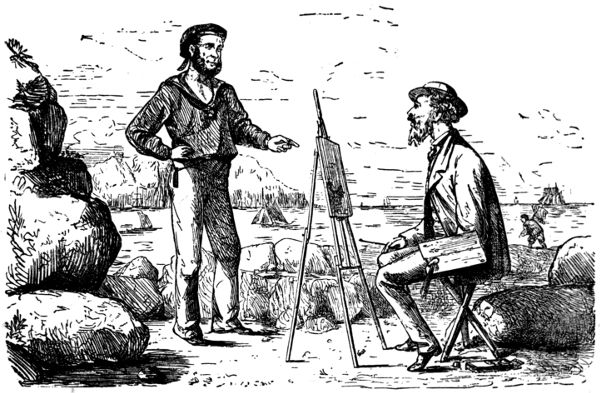

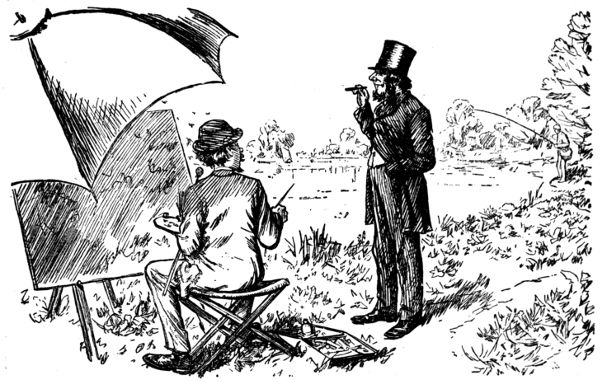

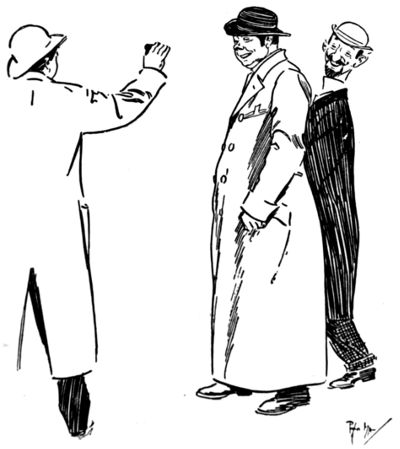

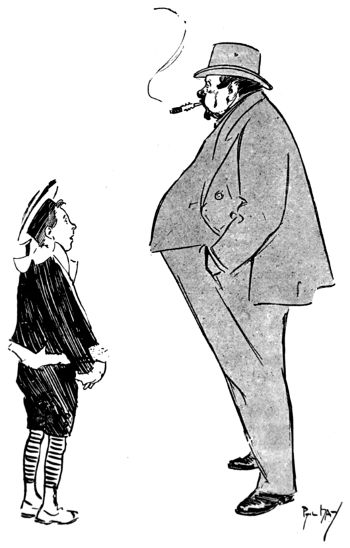

The Artist.—It’s no good making that noise, my good fellow. As I told you just now, being a landscape-painter, I don’t want models.

(From a drawing by Philip Baynes.)

The Fun Library

Edited by

J.A. Hammerton

Editor of the

Punch Library

of Humour

As pictured by Fred Barnard, W. S. Brunton, George du Maurier, Ernest Griset, Charles Keene, John Leech, Phil May, Gordon Thomson, H. M. Bateman, J. L. C. Booth, W. K. Haselden, Philip Baynes, Thomas Maybank, Charles Pears, and many other humorists of the pencil.

LONDON: EDUCATIONAL BOOK CO Ltd

[i]

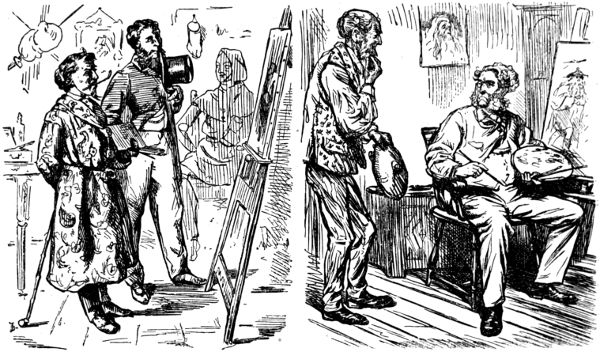

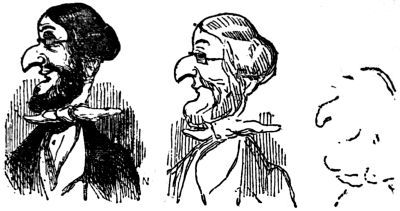

The life of what still passes in London for “Bohemia”—in and about the theatres, the studios and the literary clubs—figures conspicuously in the pictorial humour of our time. It is but natural that the artist in search of inspiration should occasionally turn his attention to his own immediate surroundings, and find subjects for his art in the comic representation of his fellows of the brush and pencil, his friends the authors and the actors, and not infrequently, himself! Some of the most pointed jokes of Keene, Du Maurier and Phil May introduced “the artist,” and in the case of the last mentioned he usually depicted his own form and features, as Cruikshank was fond of doing more than half a century before him.

This tradition has been well maintained among the artists of a later day. We shall find that a very considerable proportion of the humorous art of the moment concerns itself with the sayings and doings of our Bohemians—a term, by the way, that indicates a very mild and inoffensive variety of an almost extinct type of character.

The Bohemian of the twentieth century is a much more wholesome person than his prototype of the middle of the nineteenth. He may be still as irresponsible, as unconventional in his manners, but he is at least clean and less apt to degenerate into the “sponger.” He of the older generation provided picturesque material for the humorist of[ii] the pencil; but the stage, the study, and the studio still furnish much matter for mirth, as the admirable work of Mr. W. K. Haselden, Mr. Bert Thomas, Mr. H. M. Bateman, Mr. J. L. C. Booth, Mr. Charles Pears, and other living artists of note, represented in the present collection, bear ample witness.

It is obvious from the Index that this volume contains a most representative survey of its subject, and is probably second-to-none in The Fun Library for the high spirits and good humour which it reflects. The collection ranges from the day of Cruikshank onward, and presents many examples of such talented artists of the past as Fred Barnard, Du Maurier, Keene, Leech, Phil May, Doyle, and many others, as well as examples of Mr. Gordon Thomson, the veteran survivor of the merry men who made Fun and Judy serious rivals of Punch fifty years ago.

The sources from which the illustrations have been drawn are much the same as those that have provided the other volumes of The Fun Library. In the present volume there is a particularly fine selection from the work of Mr. Haselden, reprinted here by special permission of the editor of The Daily Mirror, and it also contains an important series by the late Phil May, reprinted by arrangement with The Sketch, while we are indebted to Mr. Gilbert Dalziel for permission to use a considerable number of excellent items from Fun and Judy, with which journals he was so long and honourably associated. To Mr. Punch’s collections of the “’sixties” we owe the numerous examples of Leech, Keene and Du Maurier at their best.

In brief, it may be claimed for “Stage, Study and Studio” that the collection is fully up to the high standard we have sought to maintain in all the volumes of The Fun Library.

J. A. H.

[iii]

TO THE ILLUSTRATIONS

| PANTOMIMICS | |

| PAGE | |

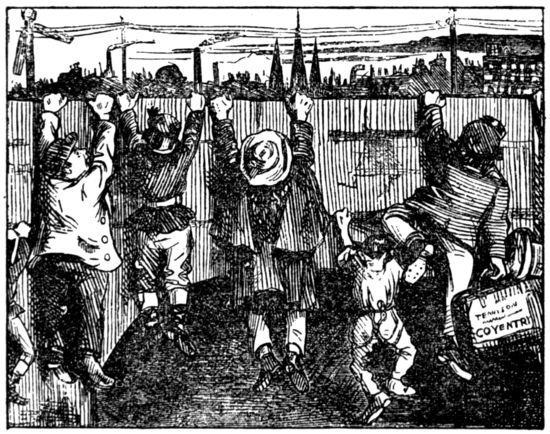

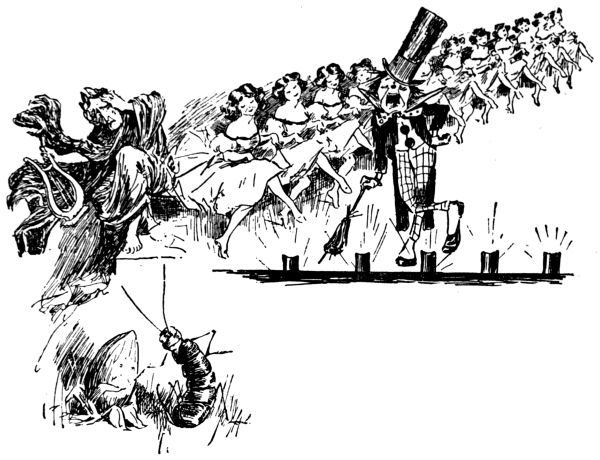

| Rehearsing the “fish” ballet | 1 |

| Billy and Bunny | 3 |

| Winning the gloves | 4 |

| Modern languages taught in one lesson | 5 |

| Theatre Royal—Nursery | 6 |

| An ex(bus)horse-tive argument | 7 |

| A pict-ure | 8 |

| A swallow out of season | 9 |

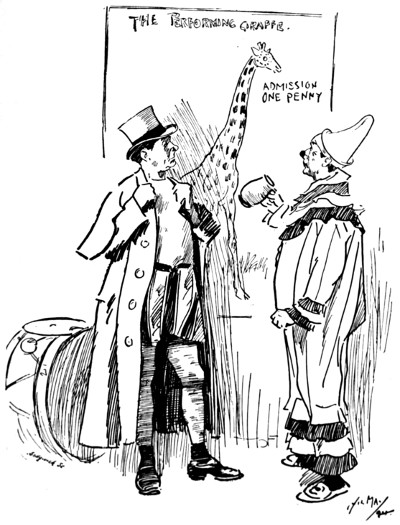

| “With a neck like that” | 11 |

| Experienced young fellow | 12 |

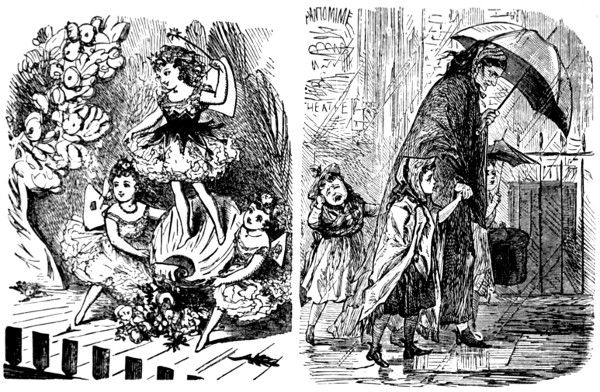

| Two transformation scenes | 13 |

| Not the correct way of pudding it | 15 |

| Humanizing influence of pantomime | 16 |

| ON THE STAGE AND OFF | |

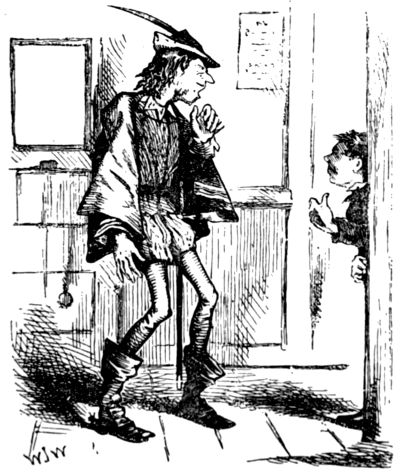

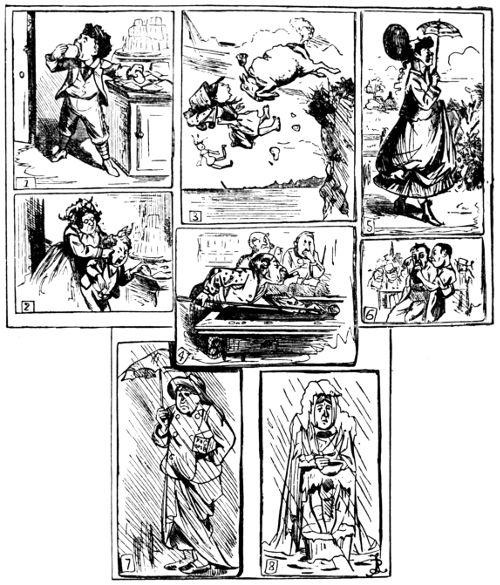

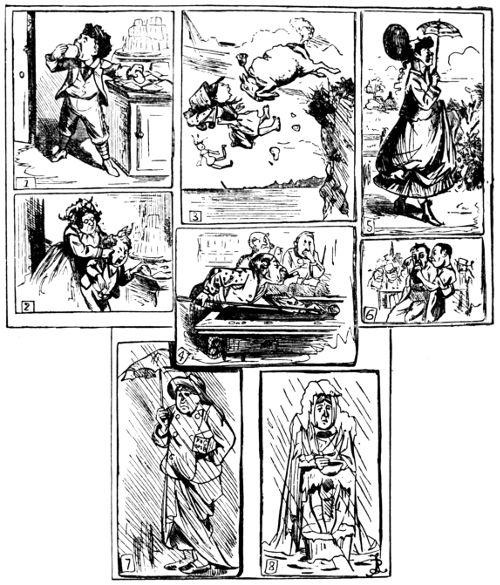

| Prompt but not prepared | 17 |

| A wordless story | 18 |

| English as she is spoke | 23 |

| Cassius | 24 |

| Acting under difficulties | 25 |

| Ever-popular criminal on the stage | 27 |

| On the stage—and off | 28-9 |

| When actors are Members of Parliament | 31 |

| When actors become modest | 32 |

| “Still running” | 33 |

| The part of Hamlet | 34 |

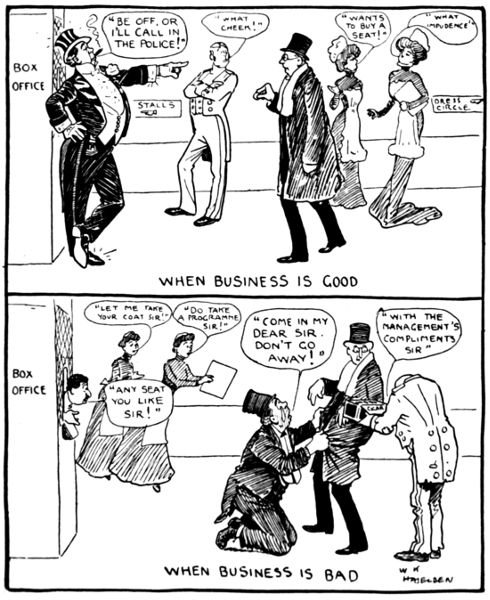

| Good and bad business at the theatre | 35 |

| “A little padding” | 37 |

| The actor’s one topic—himself | 39 |

| A side-box talk | 40 |

| The bald baron | 41-4 |

| FUN AT THE PLAY | |

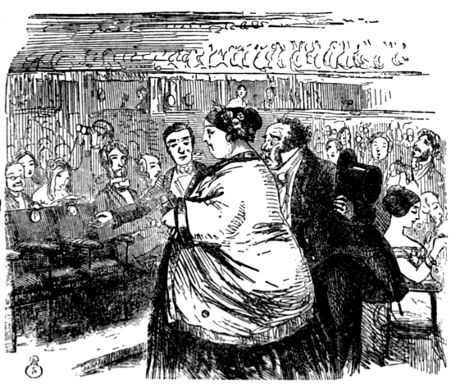

| “Are you sitting on my hat?” | 45 |

| Delights of theatre-going | 46-7 |

| “Not so long as four solos” | 49 |

| A little ruse | 50 |

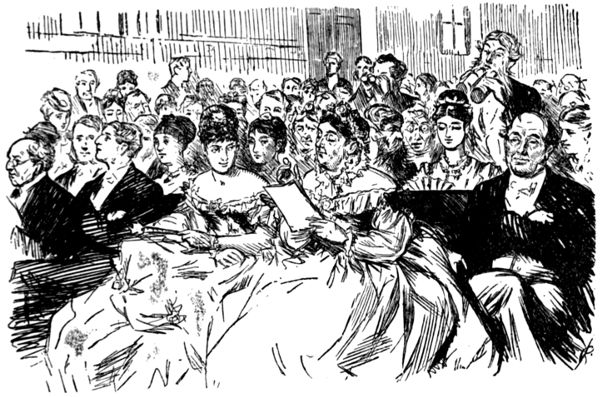

| A morning concert | 52 |

| Pit, boxes, and gallery | 54 |

| Playgoers and their eccentricities | 56 |

| Credit where credit is due | 57 |

| A “civil” retort | 58 |

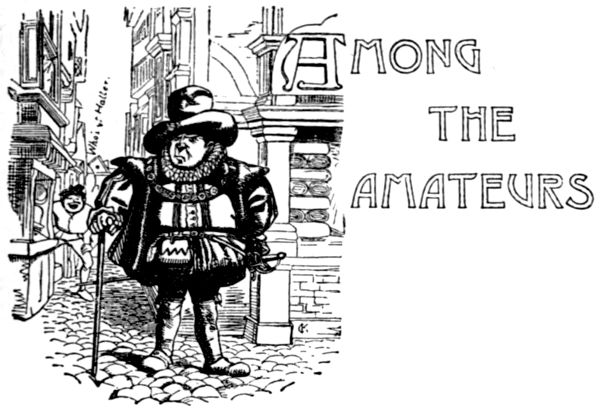

| AMONG THE AMATEURS[iv] | |

| At a fancy ball | 61 |

| Private theatricals | 63 |

| Private theatricals at the Titwillows’ | 65 |

| THE POETS’ CORNER | |

| Portrait of a gentleman | 67 |

| The poets illustrated | 69 |

| No! Don’t | 70 |

| The poets illustrated | 74 |

| “Mariar Martin, or the Red Baarn” | 75 |

| An illustrated edition of the poets | 77-9 |

| Poets and their patrons | 80 |

| MAINLY ABOUT AUTHORS | |

| Would-be novelist | 85 |

| Lady Audley’s secret | 86 |

| Perfect sincerity, or, thinkings aloud | 88 |

| The ancient Britons | 88 |

| A rural study | 89 |

| “The great cypher work” | 90 |

| Author’s miseries | 92-7 |

| Harris-ing reflections | 99 |

| “Hemily Fitz-Hosborn” | 100 |

| THE EDITOR IN HIS DEN | |

| The editor at home | 101 |

| Romance of advertising | 103 |

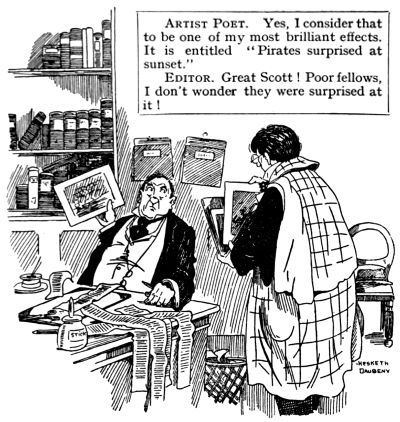

| “Pirates surprised at sunset” | 104 |

| Fancy portrait—Oliver Twist | 105 |

| A fact! | 106 |

| A new reading | 111 |

| STUDIES FROM THE STUDY | |

| “He’s sent the books” | 113 |

| Returned—with thanks | 114 |

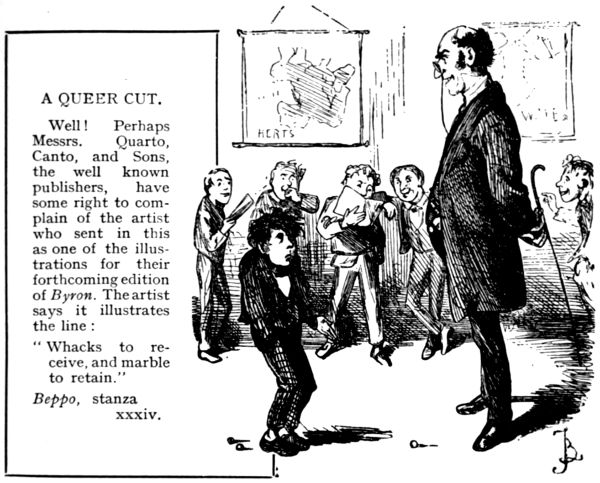

| A queer cut | 115 |

| The pursuit of letters | 116 |

| Grand march of Intellect | 116 |

| Catalogue of the letter P. | 117 |

| The age of intellect | 118 |

| Subject for a picture | 119 |

| An awful apparition | 121 |

| The musical neighbour | 123 |

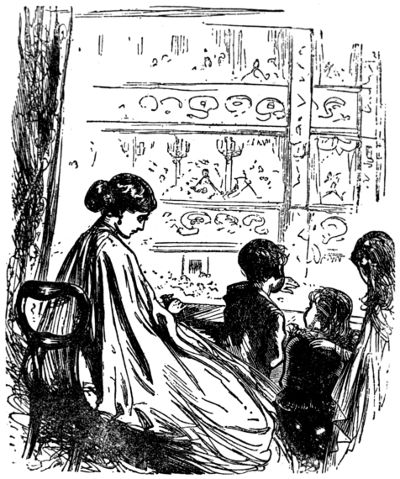

| British Museum catalogue | 124 |

| Analytical papers | 125 |

| “Couldn’t read Miss Frump’s new book” | 127 |

| The philosopher’s revenge | 129-136 |

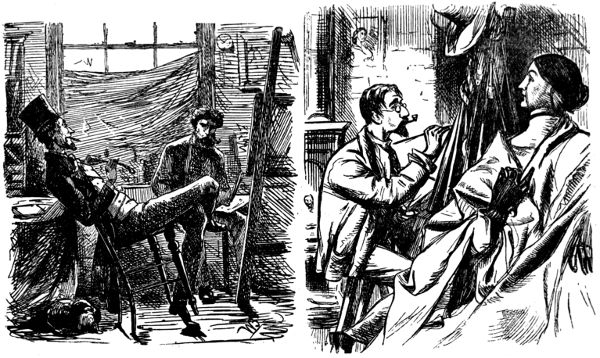

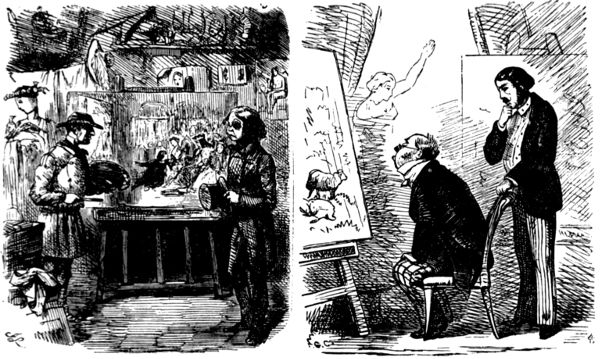

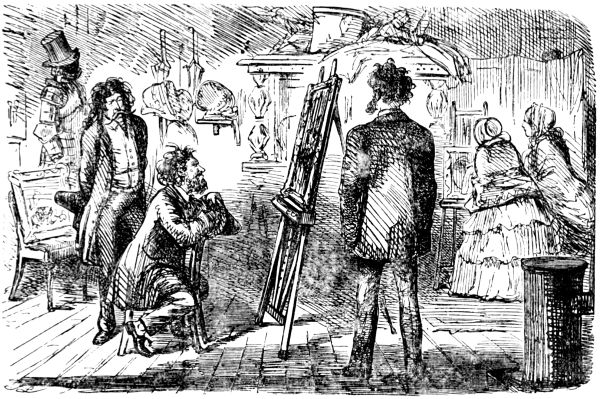

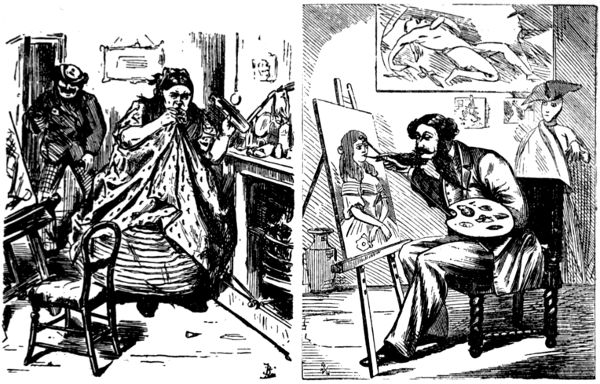

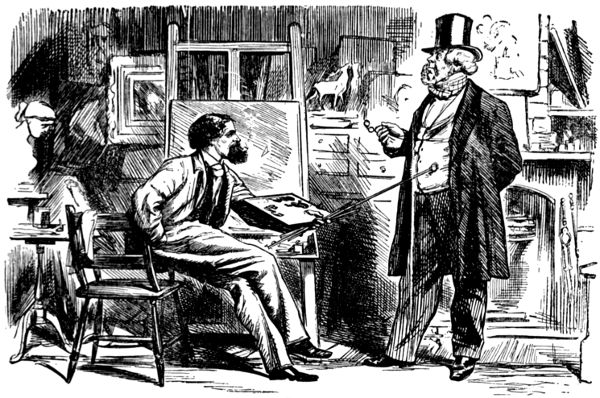

| FUN IN THE STUDIO | |

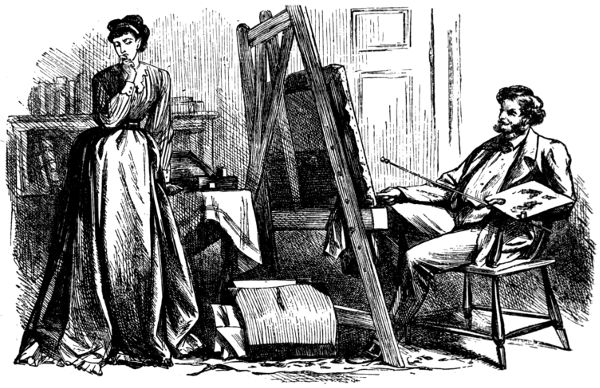

| “Present company always excepted!” | 137 |

| “Very tiring” | 138 |

| Wholesale | 139 |

| “Qualifications” | 140 |

| Behind the scenes | 141 |

| “Asking for it” | 142 |

| The commercial side | 143 |

| Gaddy’s academy picture on view | 144 |

| “Flattering” | 145 |

| Profession and practice | 146 |

| A rapid genius | 147 |

| “English langweege” | 148 |

| “Only their mothers” | 149 |

| For exhibition? | 150 |

| Pretty innocent | 151 |

| “Aye, there’s the rub!” | 152 |

| “Work hard and get your own living” | 153 |

| March of science | 154 |

| The real | 154 |

| Pleasures of the studio | 155 |

| A happy medium | 155 |

| The ideal | 156 |

| Two principal figures | 157 |

| Answers for our artist | 158 |

| The mother of invention | 159 |

| Kindly meant | 160 |

| “Where’s your beard?” | 160 |

| How some old painters must have worked[v] | 161 |

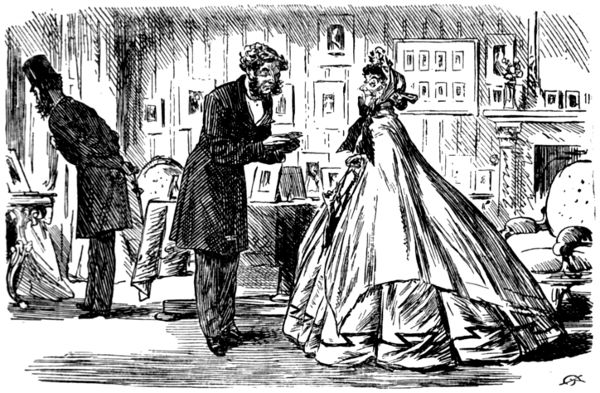

| Studio persuasion | 162 |

| “A portrait painter” | 163 |

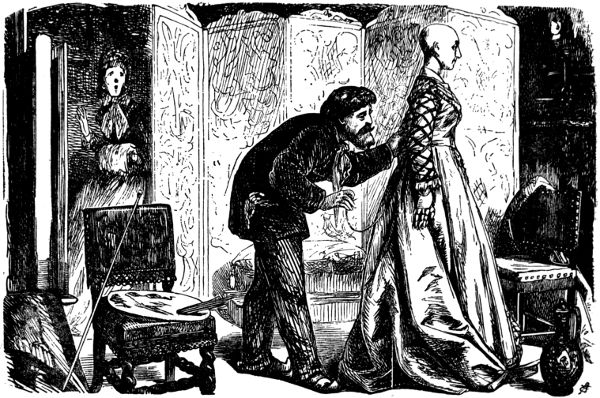

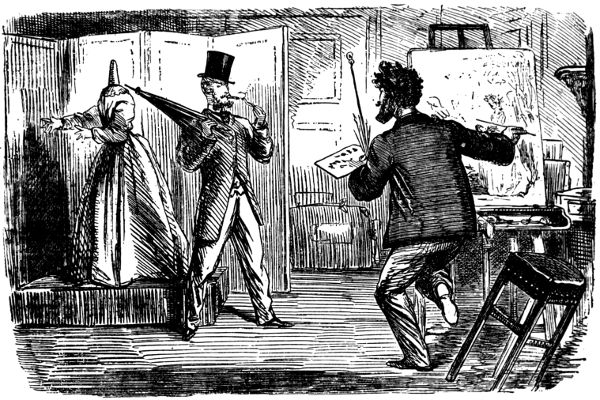

| Model husband and a lay figure | 164 |

| Marvellous! | 165 |

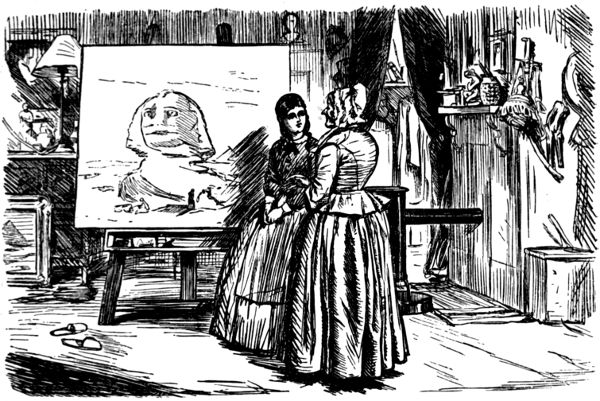

| A visit to the studio | 166 |

| Scene in a studio | 167 |

| Ballet of action | 168 |

| Turps v. Turpitude | 169 |

| One use for “Dundrearys” | 169 |

| Accommodating! | 170 |

| “Lucky fellow!!” | 171 |

| “Noblesse oblige!” | 172 |

| Our art-school conversazione | 173 |

| “Only one spur a-piece” | 174 |

| “Sharp’s the word” | 175 |

| The sympathies of art | 176 |

| Under a great master | 176 |

| “Sent it to the wash!” | 177 |

| “Ugly and as ridiculous as possible” | 178 |

| Perfect sincerity; or, thinkings aloud | 179 |

| Easily satisfied | 180 |

| Compliments of the season | 181 |

| “Skyed” | 182 |

| ROUND THE GALLERIES | |

| Caution | 183 |

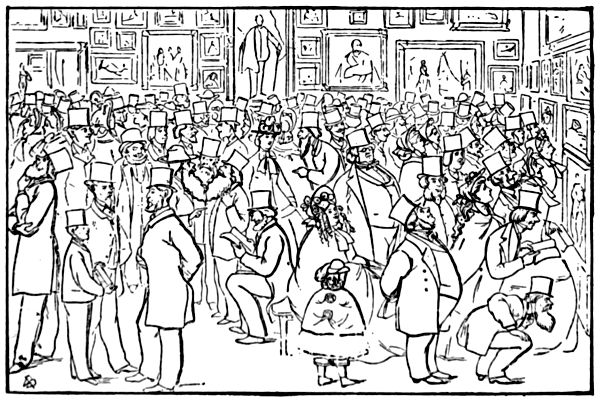

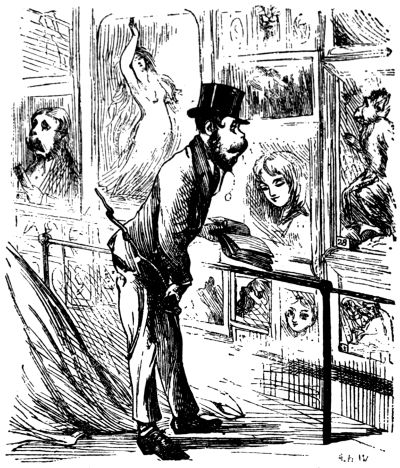

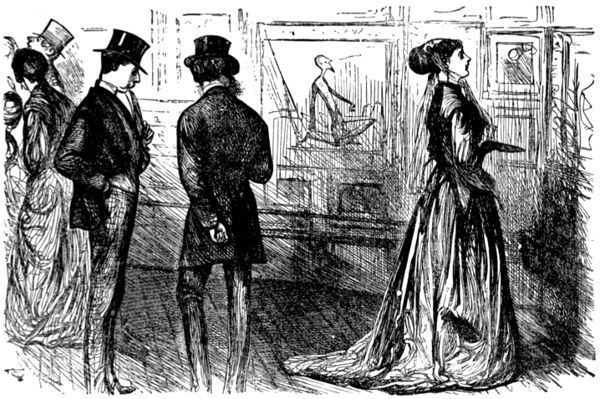

| Painters and gazers | 185 |

| An artist’s dream | 186 |

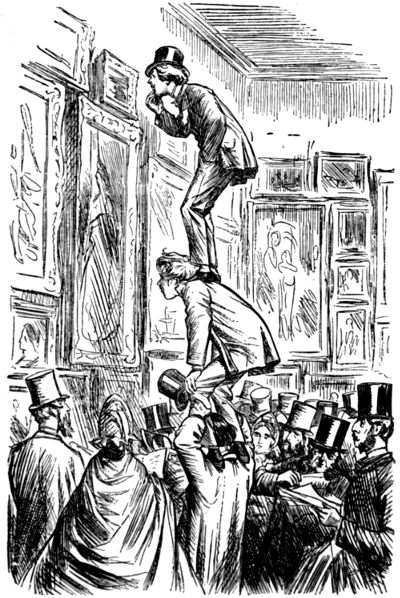

| “Athletic exercises” | 187 |

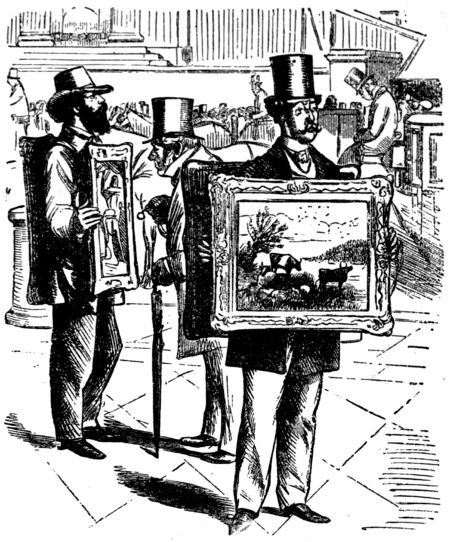

| Let them exhibit their pictures outside | 188 |

| Pleasures of the Royal Academy | 189 |

| Art in the National Gallery | 190 |

| Outside the Royal Academy | 191 |

| Charming fashion of long skirts | 192 |

| “Unto this last” | 193 |

| “Very like—very like” | 194 |

| The umbrella question | 195 |

| Pictures of the English, painted by the French | 196 |

| A-musing | 197 |

| Perhaps | 198 |

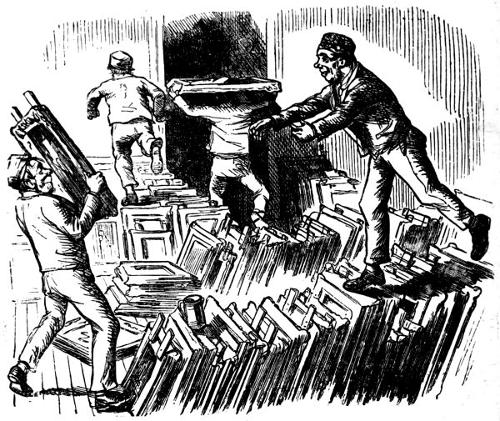

| Reception of pictures at Royal Academy | 199 |

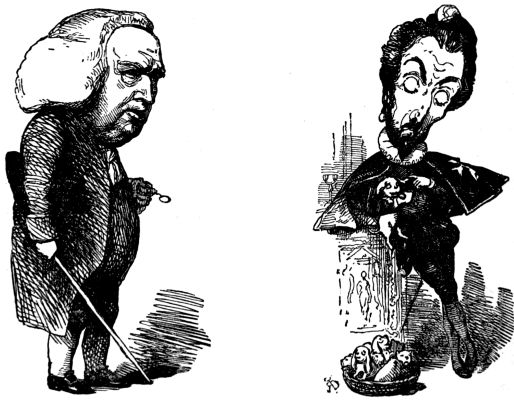

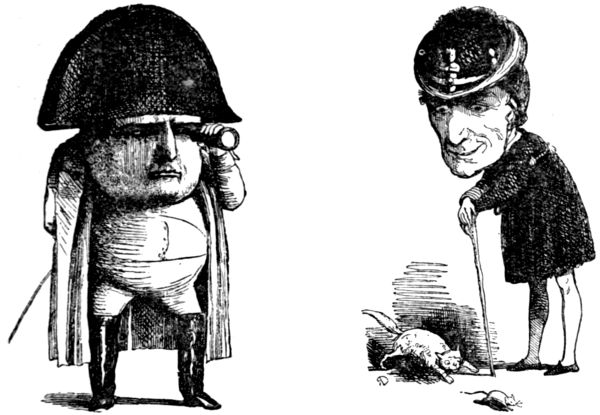

| Our historical portrait gallery | 200-1 |

| A study | 202 |

| Overheard at the Academy | 203 |

| Suggestions for the Royal Academy catalogue | 206 |

| THE ARTIST OUT OF DOORS | |

| “It’s an ill wind,” etc. | 207 |

| The old cottage | 208 |

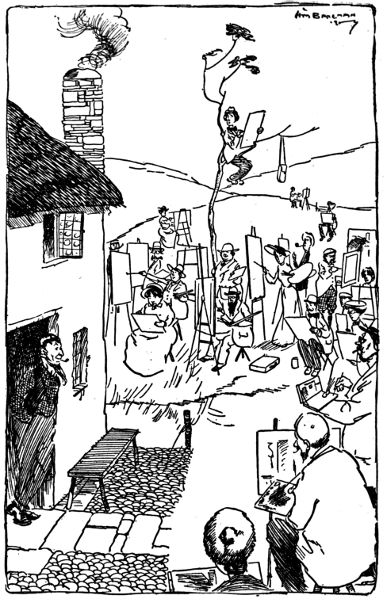

| The elysium of artists | 209 |

| “A pretty prospect” | 210 |

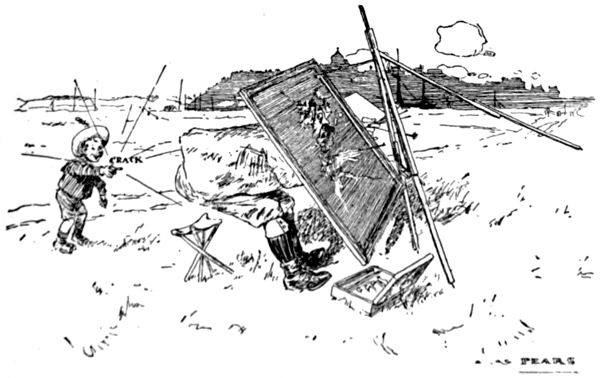

| Possibilities of a penny pistol and a box of caps | 211 |

| Technical and practical | 212 |

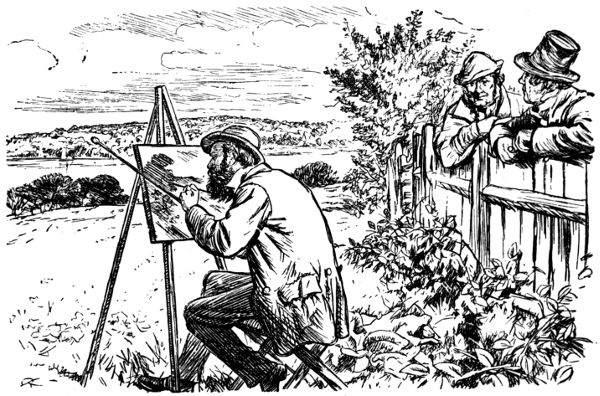

| “Impertinent curiosity of the vulgar” | 213 |

| “That pre-Raphaelite fellow” | 214 |

| Where ignorance is bliss | 215 |

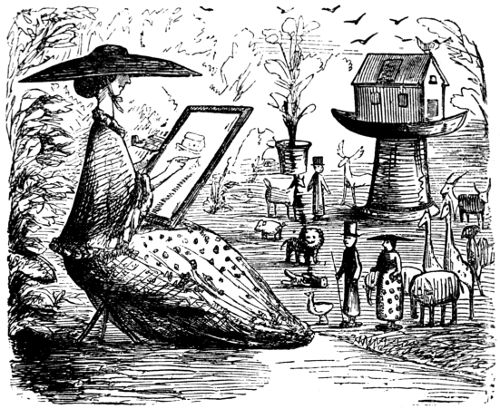

| Design for an album | 216 |

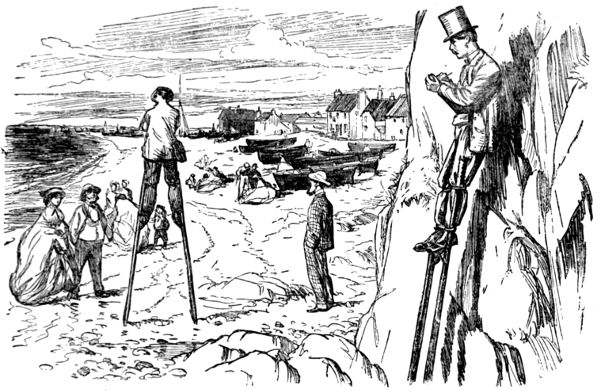

| Studying skies | 217 |

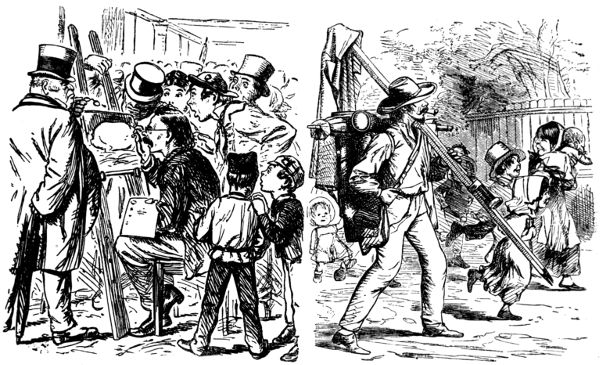

| Culture for the million | 218 |

| An artist scamp in the Highlands | 220 |

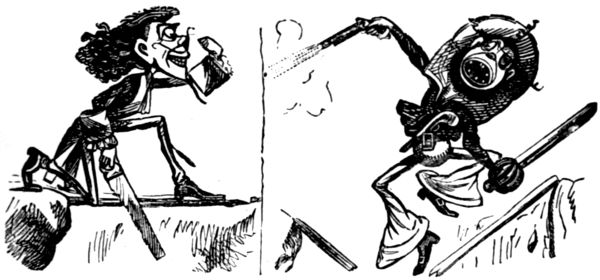

| Ingenious protection against midges | 221 |

| Sketching from Nature | 222 |

| “Very nearly a pound” | 223 |

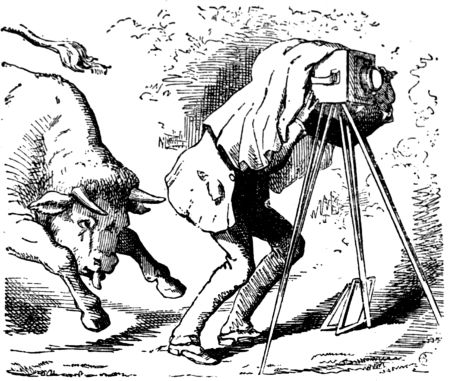

| Art at a cattle show | 224 |

| What an artist has to put up with | 224 |

| Enjoying himself in the Highlands | 225 |

| “Compliments of the (sketching) season” | 226 |

| “Fine Art” | 227 |

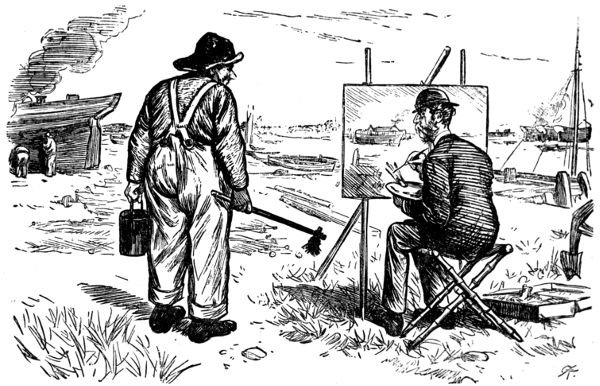

| “Brother Brush” | 228 |

| Making the best of it | 229 |

| One reason, certainly! | 230 |

| Æsthetics[vi] | 230 |

| A broad hint | 231 |

| Pleasant for Jack Daubs | 231 |

| Flattering! | 232 |

| Our adventurous artist | 233 |

| Art and science | 234 |

| An eye for colour | 235 |

| Ignorance was bliss | 235 |

| Our artist | 236 |

| SCULPTURE AND COMEDY | |

| “Well broke!” | 237 |

| Venus of Milo | 238 |

| “Ingenuas didicisse” | 241 |

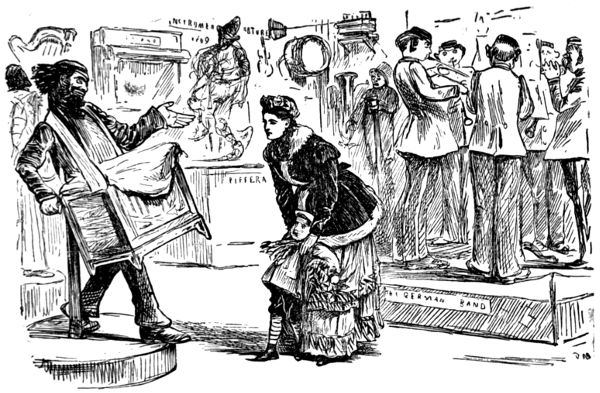

| At the great exhibition of 1861 | 243 |

| Popular history | 244 |

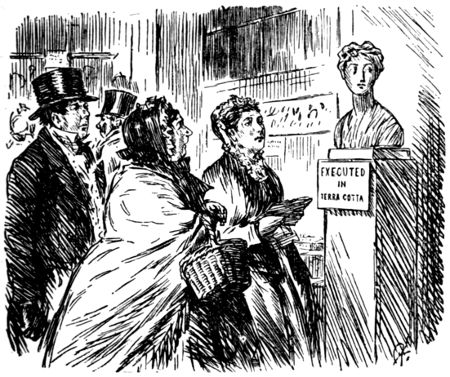

| Capital punishment | 245 |

| A flagrant attempt | 246 |

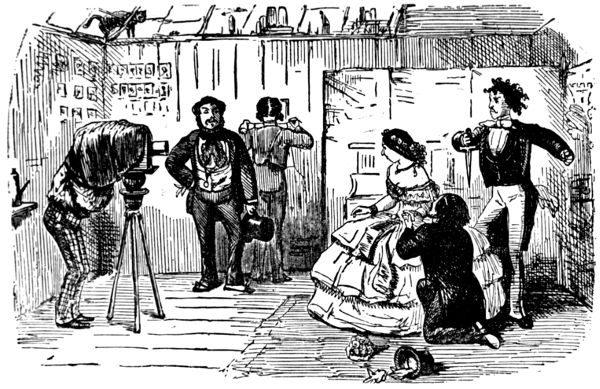

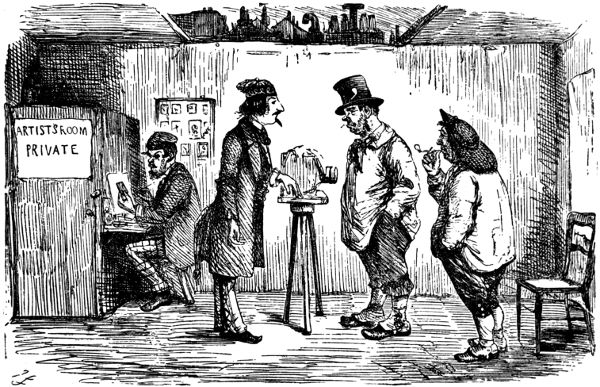

| FUNNY FILMS: HUMOURS OF PHOTOGRAPHY | |

| “Many a true word spoke in jest” | 247 |

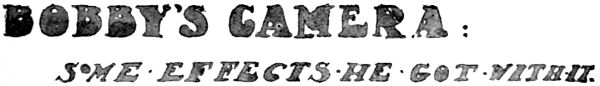

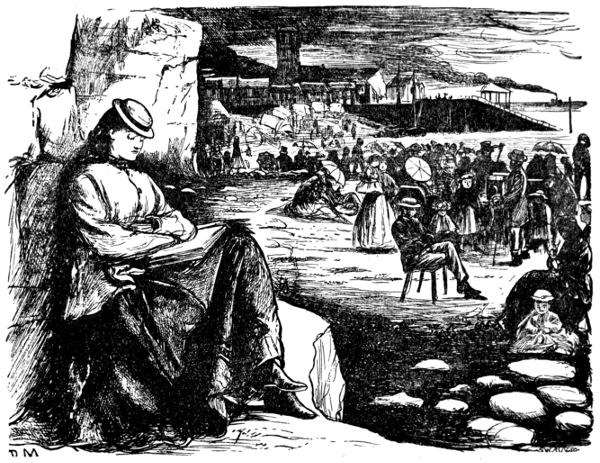

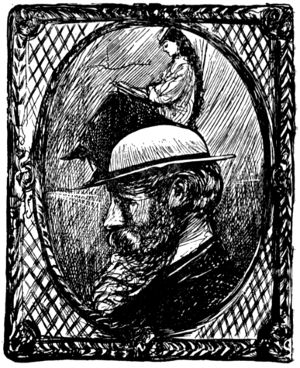

| Bobby’s camera | 249 |

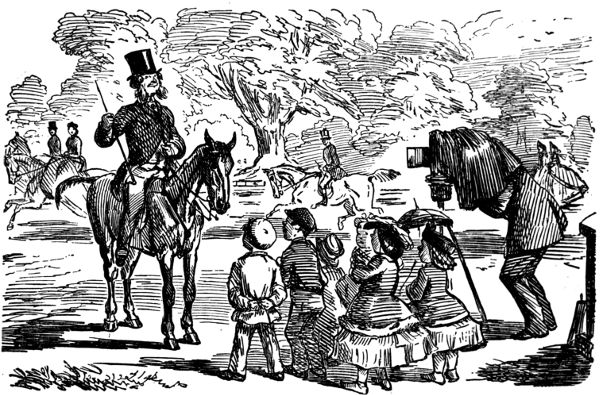

| Interesting group posed for a photograph | 250-251 |

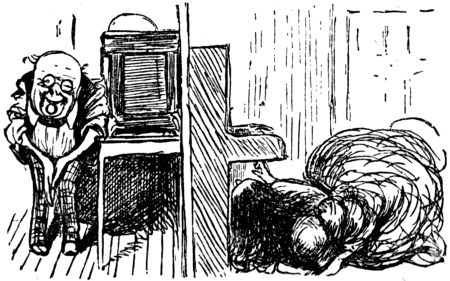

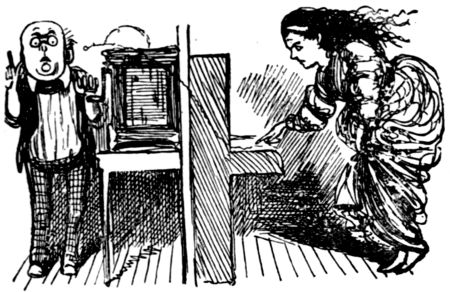

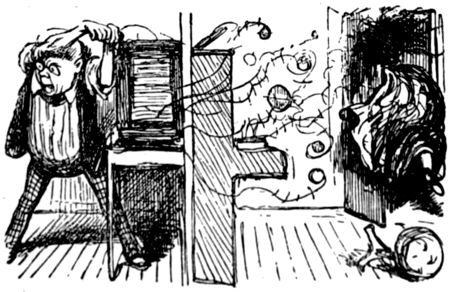

| Happy thought | 252-253 |

| Pleasant for Simpkins | 254 |

| Unanswerable | 255 |

| Can the camera lie? | 256 |

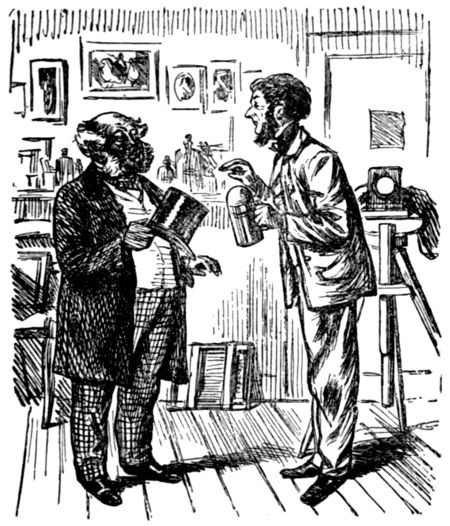

| The artistic(!) studio | 257 |

| “What for?” | 259 |

| Portrait of a distinguished photographer | 260 |

| A photographic picture | 261 |

| Encouragement of art | 263 |

| “A florid complexion” | 265 |

| Artful! | 266 |

| Subject for a picture | 267 |

| Photographic beauties | 268 |

| WANDERING MINSTRELS | |

| Christmas waits | 269 |

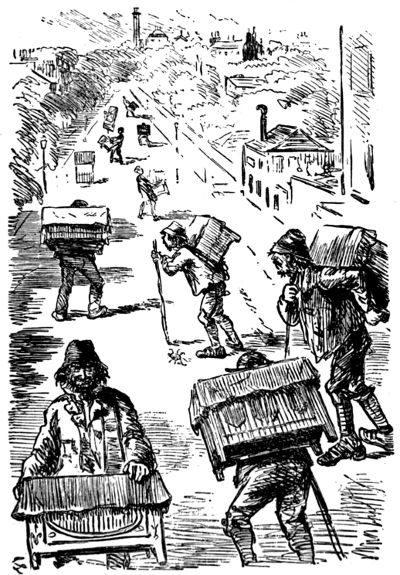

| Division of labour | 271 |

| Culture for the million | 273 |

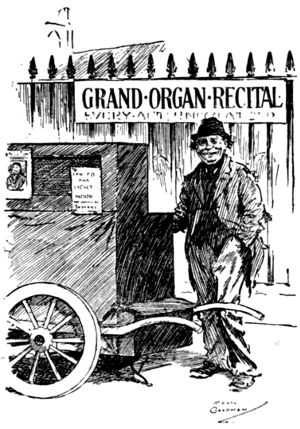

| Nothing like advertising yourself | 275 |

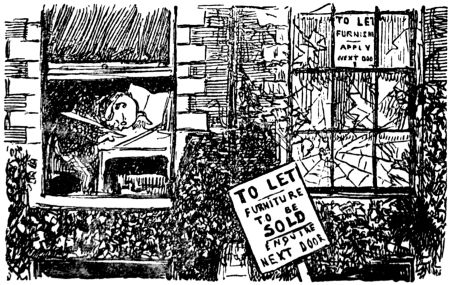

| Sketch from a study window | 277 |

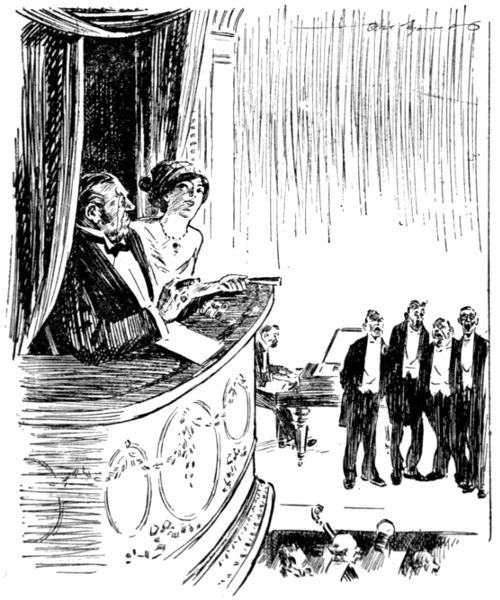

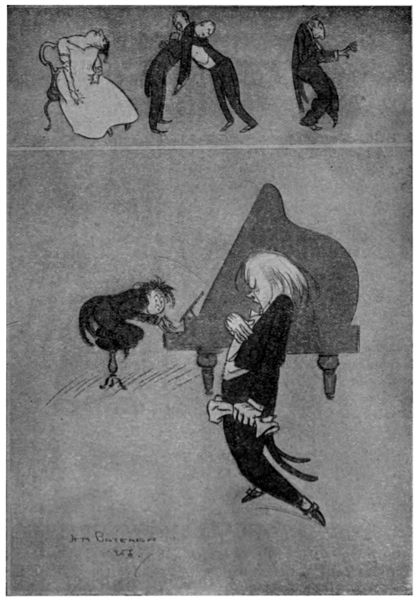

| THROUGH THE OPERA GLASSES | |

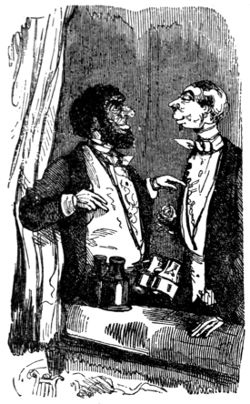

| The opera | 281 |

| What indeed? | 284 |

| “French without a master” | 285 |

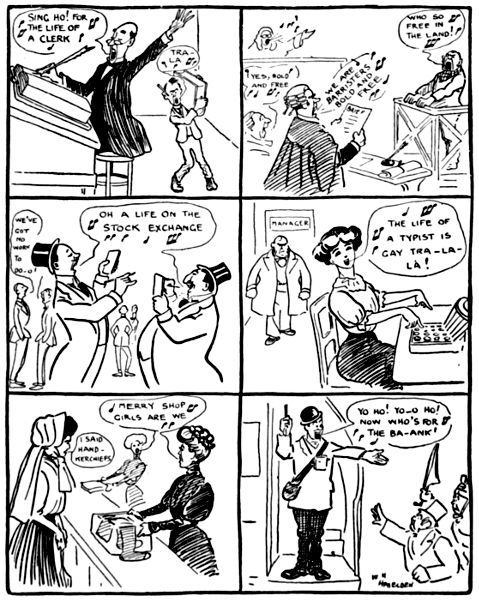

| We don’t sing enough | 287 |

| The high note | 288 |

| The low note | 289 |

| “Only twenty-two” | 291 |

| Culture for the million | 292 |

| Gentle rebuke | 293 |

[vii]

[viii]

| PAGE | |

| PLAYERS’ PRANKS | 2 |

| EMMA AND ULPHO | 19 |

| HUMOURS OF THE PLAYHOUSE | 22 |

| SCENERY AND COSTUME OF THE STAGE | 48 |

| ASS YOU LIKE IT | 55 |

| HAMLET’S LAST SOLILOQUY | 58 |

| AT THE MASQUERADE | 60 |

| AMATEUR FLUTE-PLAYER | 62 |

| ONLY SEVEN | 64 |

| LYCEUM LYRICS | 66 |

| THE POETS AT PLAY | 68 |

| MOTLEY’S KINGDOM | 76 |

| MY MANUSCRIPTS | 81 |

| A MAN I HATE | 84 |

| MARK TWAIN AND THE KEY | 87 |

| HUMOURS OF THE PRINTING HOUSE | 91 |

| HARRIS-ING REFLECTIONS | 98 |

| HUMOURS OF ADVERTISING | 102 |

| APPROVED BY THE EDITOR | 109 |

| RULES FOR NEWSPAPER CORRESPONDENTS | 110 |

| LITERARY FLUNKEYISM | 112 |

| HUMOURS OF OUR LANGUAGE | 114 |

| MORE HUMOURS OF ADVERTISING | 120 |

| HE NEVER CALLED AGAIN | 126 |

| A DANGEROUS WRITER | 128 |

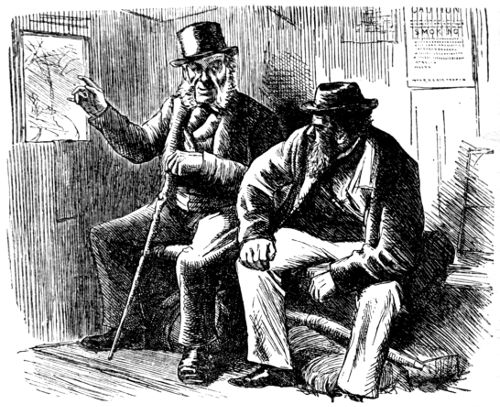

| PAINTERS AND GAZERS | 184 |

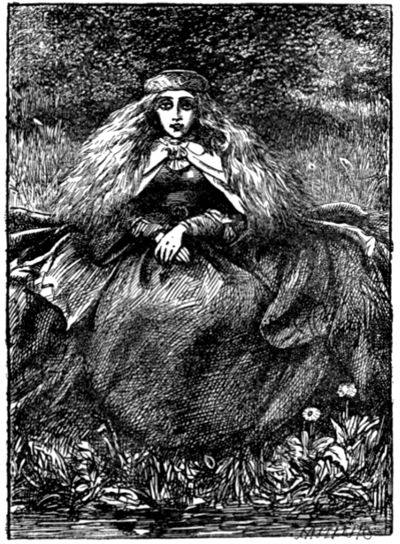

| A DREAM OF UNFAIR WOMEN | 204 |

| IMAGINARY CONVERSATIONS | 209 |

| PYRAMUS AND THISBE | 239 |

| PHOTOGRAPHIC FAILURES | 248 |

| THE PHOTOGRAPHS | 258 |

| MRS BROWN AND THE GERMAN BAND | 270 |

| STREET MUSICIANS | 280 |

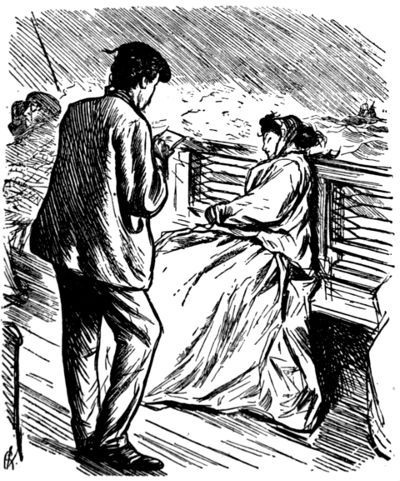

| THE BOHEMIAN GIRL | 282 |

| RECOLLECTIONS OF THE OPERA | 286 |

| A WOMAN’S THOUGHTS ABOUT WOMEN | 290 |

| THE ONION GIRL | 294 |

[1]

PANTOMIMICS

REHEARSING THE “FISH” BALLET (A FACT).

Stage Manager. What are you, boy? Boy. Please, sir, I’m a whelk.

[2]

PLAYERS’ PRANKS

Practical joking might correctly be described as a remnant of the barbaric ages, when strength and muscle received the respect we now award to mind and brain. Indeed, it still passes current among modern barbarians for humour, while in civilized States, where humour is something that appeals to the intellect, joking in the practical sort is generally regarded as buffoonery. Having admitted thus much, it may be said that even practical joking is not all bad, and is sometimes “a source of innocent merriment.”

Joking of the practical kind is very often a pronounced characteristic of the actor, as the countless stories of players and their pranks abundantly prove. The reason for this is most likely to be found in the fact that it requires something of the actor’s talent successfully to carry out a practical joke, and actors, knowing they possess the ability, are often tempted to exercise it. The name of the genial J. L. Toole, of happy memory, will naturally occur to every one in this connexion, and the fact of that good-hearted soul having had a strong weakness for this diversion is ample proof that practical joking is quite compatible with geniality of character. The stories that are told of Toole and those which he told of himself would easily fill a couple of volumes. For the purpose of the present chapter a typical one will suffice.

[3]

BILLY AND BUNNY.

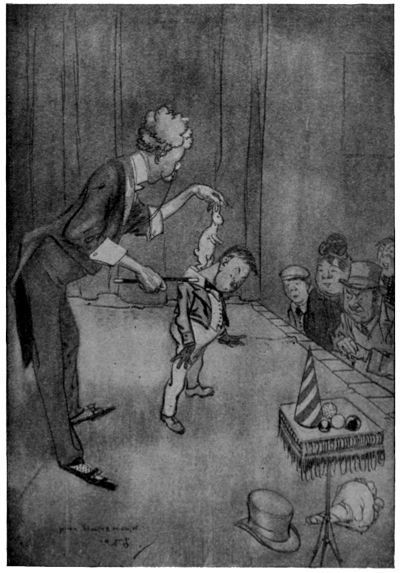

Irate Parent (in front row) of Small Boy assisting Conjuror. Disobedient young monkey! Why, it was only last week I forbade him to keep rabbits.

[4]

A FANCY SCENE—WINNING THE GLOVES.

From the grand pugilistic ballet of the fight for the championship, which might, could, should, and ought to be

played at one of the operas.

[5]

THE MODERN LANGUAGES TAUGHT IN ONE LESSON!

German Professor (on “la Perche”) to Italian ditto below. Be steadier, Bill, will yer, or I’m blowed if I don’t come down!

The comedian once entered a dairy, and solemnly remarked to the shopman—“I will take a boy,” with a glance at his shelves. “A boy, sir?” asked the puzzled shopman. “Yes, or a girl,” replied the comedian. The man never doubted but his visitor was a lunatic, and said, mildly—“Pardon me, this is a milkshop.” “Come outside,” said Toole, and taking the dairyman by the arm he led him out of the shop and pointed to the sign. “I’ll take a boy or a girl,” he solemnly repeated. “Read what your notice states—‘Families supplied in any quantity.’”

E. A. Sothern, the famous “Lord Dundreary,” had an insatiable propensity for practical joking, and many are the stories of his pranks. One of the most amusing, though, perhaps, a little cruel, tells of his treatment of his guests on the occasion of a dinner party to a number of congenial souls. They were all assembled but one, who was rather late. After waiting a few minutes, the host suddenly exclaimed—“Here he comes—let’s all get under the table—make haste.” Anticipating a joke, they all scrambled under, except Sothern himself. Enter guest—“Hallo! where are all the other fellows?” “Oh, they all got under the table[6] when they heard you coming. I’m sure, I don’t know why.” The ignominous crawling forth one by one that ensued can safely be left to the imagination of the reader.

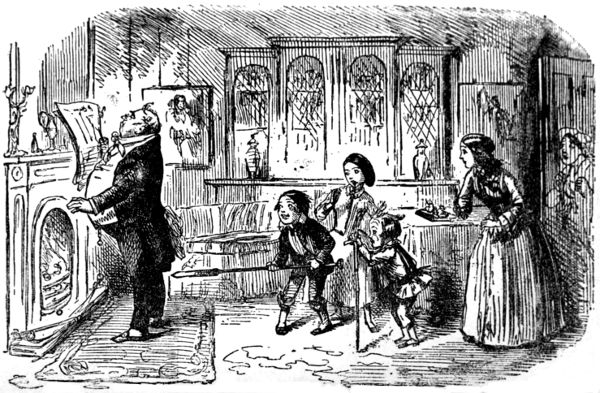

THEATRE ROYAL—NURSERY.

Master Reginald’s tender years having prevented his attendance at the Pantomime, Messrs. Tom, Charlie and Co. kindly give him a résumé of the evening’s performance.

It is always a good thing when we find the subject of a practical joke joining good-naturedly in the mirth, and this we have in a story told by the late Mr. G. A. Sala of a joke played upon him by Lord Dundreary. “I remember going down to the Derby,” writes the famous journalist, “in a highly festive fashion, with poor Edward Sothern, the never-to-be forgotten Lord Dundreary. On this particular day Sothern, the kindest, but still the most provoking of practical jokers, was as full of mischievous pranks as an egg is full of meat. He offered to bet me a guinea before we reached Clapham that I would lose my temper, and lose it badly, before 2 p.m. ‘But why, my dear Sothern,’ I asked, ‘should I lose it? The weather is beautiful, I did my work by getting up at six this morning, I am in the best of all good company, and I haven’t got a penny on the race.’ ‘Never mind,’ persisted Lord Dundreary, ‘I will bet you one guinea that you will blaze up like a vesuvian thrown into the fire before 2 p.m.’

[7]

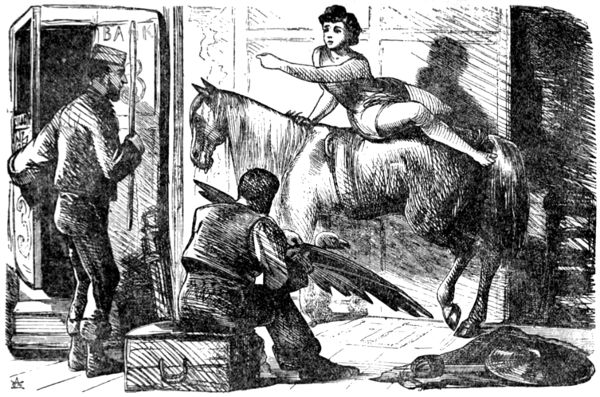

AN EX(BUS)HORSE-TIVE ARGUMENT.

Mazeppa.

Now, just you bang that ’bus door smarter to-night, or the old hoss’ll never get a good start.

Carpenter. All right, miss. Cue’s “wild career.”

[N.B.—The noble steed is an old “Favourite.”

[8]

A PICT-URE.

Show-ing what Mas-ter Tom did af-ter see-ing a pan-to-mime—but

you would not do so—oh dear no!—be-cause

you are a good boy.

[9]

A SWALLOW OUT OF SEASON.

Scene—Boxing-night.

Gentleman

in Front (bawling). ’Ar-reee!!!

’Arry, at Back. ’Ullo!!

G. in F. (as before). Where’s Bill-leee!!

’Arry. Why,

the young beggar’s been an’ swallered his sixpence in the

crowd, and they won’t let ’im in!

[10]

“It was half-past one when we reached the course, and one of the officious red-jackets who haunt the Hill stepped forward and gave me the customary brush down. I strolled a few paces onward, when another red-jacket pounced down on me, and, notwithstanding my expostulations, brushed me down again, hissing meanwhile as though he were grooming a horse. I essayed to light a cigar, when a third brush-fiend was upon me; but when a fourth made his appearance, brandishing his implement of torture, the dams of my long pent-up temper broke down, and a torrent of adjectives, the reverse of complimentary, flowed over the fourth brush-demon. My wrath was at its height when I found myself quickly tapped on the shoulder, and beheld the maliciously chuckling countenance of Sothern. ‘I will trouble you for one guinea,’ he said, and proceeded to explode with laughter. Of course he had followed me about, and feed the brush-fiends to harry me to desperation.”

W. J. Florence, a well-known American comedian in his day, was very much on a par with Sothern in the matter of practical joking, and the story of a good-natured trick he played on the latter, as related by himself in one of his posthumous papers, is very entertaining. “Meeting Sothern on Broadway one fine morning,” so the story goes, “I told him that there was an oat for him at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, taking care to pronounce my words in such a careless, inarticulate way that the genial comedian thought I said there was a note for him at the hostelry I had named. He accordingly started off post-haste up town—we had met near the battery, whither we both had strolled for a morning constitutional—to get his oat. When he reached the Fifth Avenue Hotel and the clerk, in response to his inquiry, handed him out the grain of oats which I had left for him, he saw the joke immediately, and laughed at it most heartily, devoting the remainder of the day to telling everybody he met what a capital joke Florence had played on him.”

[11]

“With a neck like that, what a fine thing it must be to be thirsty!”

[12]

Experienced Young Fellow. Ah, Clara, you should have seen the Pantomimes that I’ve seen; these modern affairs ain’t half so good.

The late Fred Leslie was another popular comic actor who, like Sothern and Toole and so many of “the profession” past and present, was never so happy as when planning some harmless practical joke, which was always sure to amuse every one concerned. One of his most successful efforts in this direction was made during his tour in America with the Gaiety Company, and is related by the late Clement Scott in his recollections of this celebrated comedian.

[13]

TWO TRANSFORMATION SCENES.

Scene No. 1.—“The Rosy Realms of Boundless Bliss.”

Scene No. 2.—En route from Rosy Realms to Rag-and-Bottle Alley, St. Giles’s.

[14]

One night (says Mr. Scott) several of his confrères had been invited to a supper, and the number included the musical director of the theatre they were then playing at. His absence from the orchestra nearly the entire evening in question was generally commented on, and it subsequently leaked out that he had been busily employed composing the music of a song which he intended to submit to them for approval before the party broke up. The night being a fine one, it was agreed to walk from the theatre to the house of their host. The composer, when he sallied from the stage door, was seen to have a huge roll of music, carefully tied up, peeping from one of his overcoat pockets. This was just as carefully abstracted, and some one was deputed to stroll leisurely onward and engage the victim in apparently earnest conversation, while the rest remained behind and committed the music to memory, after which the manuscript was skilfully returned without arousing the slightest suspicion.

At the termination of the meal, and before the musician could reach the piano, Leslie began to whistle a few bars of the melody, which, it is scarcely necessary to add, attracted universal attention. When pressed to continue, Leslie gave the air from beginning to end, and when, at the conclusion, he remarked that it was an old English ballad, cold beads of perspiration gathered on the forehead of the unhappy composer. His solemn asseveration that he had that evening written an original melody to the same air, note for note, was received on every hand with apparent unbelief; and in order to verify Leslie’s statement, most of those present followed his lead and sang or whistled the composition through. The musician, we are told, was allowed to play it over, and the resemblance, of course, was so striking that he himself began to doubt his own sanity. But when he came to know of the trick by which he had been bamboozled, he enjoyed the joke as much as those who carried it out.

[15]

NOT THE CORRECT WAY OF PUDDING IT.

Master Gussy. Oh, boohoo! What a shame to go throwing plum-pudding about like that!

[16]

THE HUMANIZING INFLUENCE OF PANTOMIME.

Depraved Child. Oh, mamma, do look, the clown’s been and run a red-hot poker right through that policeman—isn’t it fun?

[17]

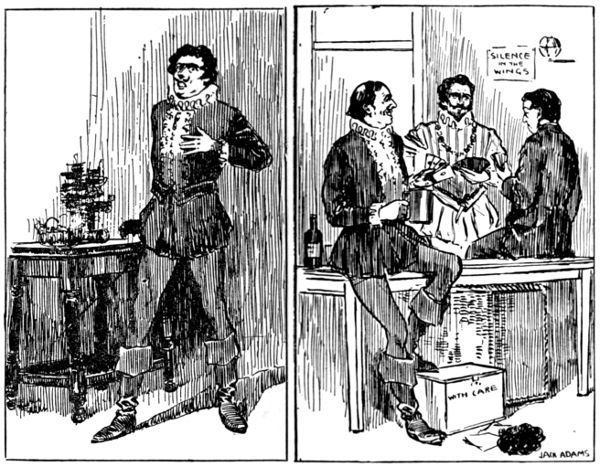

ON THE STAGE AND OFF

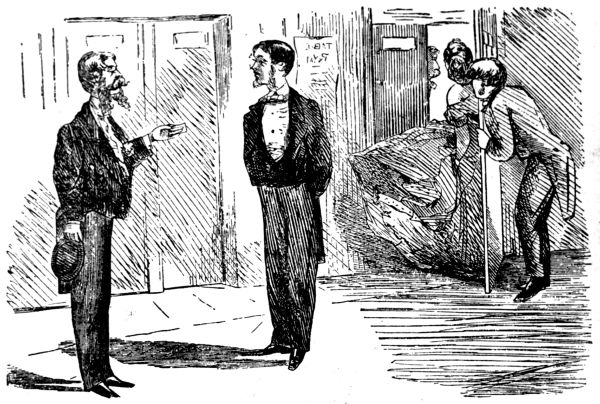

PROMPT BUT NOT PREPARED.

[The call-boy has just called that distinguished amateur Muddle, who is

doing Iago for the first time.]

Muddle. Very odd! Knew every word of it this morning, too, but I’ll be hanged if I can remember how it begins!

[18]

A WORDLESS STORY.

[19]

(A dark night. The curtain rises, and discovers nobody on the stage.)

(Ulpho speaks.) How dark it is.

(He is answered by a hollow voice which is inaudible.)

Ulpho. I do not feel comfortable, nor as I once did. (Sighs.)

(The stage gradually fills till Ulpho is forced forward to the footlights, which go out. The crowd parts asunder suddenly, and a figure comes slowly forward.)

Figure. (Says nothing.)

Ulpho. I feel chilly.

(Figure smiles contemptuously and puts his hands in his breeches’ pockets. He then addresses Ulpho silently, and, after hesitating more than once, breaks down at last altogether.)

(Still darker night. Graves spring their rattles and watchmen open. Fate is seen sitting in the background in the shape of a policeman. A glow-worm roars, and the side-scenes shake perceptibly. The moon, which has been slowly rising, falls suddenly down.)

Ulpho. Unfortunate moon!

Emma. Will you never cease to despond?

Ulpho. Nothing on earth shall ever induce me.

(He takes his cap from his head, and hangs it carefully on a hat-stand. In a fit of desperation he begins to tear his hair from his head. Emma sinks into a swoon, and leaving Ulpho in the centre of the stage, she goes off at both wings.)

[20]

(The morning breaks, and is already in many pieces. The first rays of the sun are reflected in several hundred dewdrops which are rocking themselves in the gently waving brush-wood. Two masks drop from the trees and rush on each other’s swords.)

1st Mask. Are you dead?

2nd Mask. Only parts of me.

Enter Emma.

1st Mask. Lady, may I ask if you have any present intention of giving up the ghost, if so, perhaps I could——?

Emma. I am much obliged to you, but I have already made my own arrangements——

(A pair of jack-boots are carried across the stage.)

Emma. Are those, perhaps, the mortal remains of my Ulpho?

(Ulpho enters in carpet slippers.)

Ulpho. I am still alive, but I wear boots no more.

(The river rises, and a Dragoon Regiment, which has been stationed on the opposite bank, are carried away, one by one, by the flood. Ulpho fetches an umbrella from the side scenes.)

Emma. Would we could share it together!

(Ulpho is about to give it to her, when a thunderbolt descends, and the umbrella falls between them.)

Ulpho. Fate has decided otherwise.

(They embrace, and the curtain falls in an agitated manner.)

(Enter an old man with a very broad-brimmed hat.)

Old Man. Woe! Woe!

[21]

Ulpho. What brought you here?

Old Man (wildly). Can I never preserve my incognito?

[He stabs himself.

Emma (regarding the body).

[She stabs herself.

Ulpho. Ah! now I feel lighter, better.

[He starves himself to death.

Enter the Duke: A lay figure is also brought on to the stage.

Lay Figure. Behold the victims of thy revenge.

[Grand scena—Furies enter and tear the Duke slowly to pieces. The end of the drama now approaches rapidly, and whilst everything is trembling in every direction, the Prompter rushes on to the small piece of stage still remaining, and stabs himself with a pair of snuffers, and

THE CURTAIN AND THE THEATRE FALL TOGETHER.

Punch, 1844.

[22]

The function of the stage is a much discussed question. We shall assume that it is first and foremost a place of entertainment. Many are the comedies, from Shakespeare’s to Shaw’s, that have tickled the ribs of the “groundlings,” but there is also about stage performances a frequent element of diversion supplied by effects entirely unrehearsed. In most cases these “unrehearsed effects” assume the form of amusing blunders, in others they may be witty impromptus on the part of an actor or an auditor, “gags,” “wheezes,” what not! A laughable mistake has often afforded relief to a dull play; while, on the other hand, it may have been the means of spoiling an otherwise effective scene.

A curious thing about stage blunders is that, when one of the characters makes a mistake it is almost a certainty that some other member or members of the cast will follow suit. It is related of Charles Matthews, the famous comedian, that if he made one mistake in the course of a performance he was sure to commit several blunders before the conclusion of the play; this, no doubt, arising from over-anxiety to guard against slips. On one occasion he informed an astonished audience that he saw “a candle going along a gallery with a man in its hand,” and later in the play he stated that he had “locked the key and put the door in his pocket.”

John Kemble, according to an anecdote told of him in Tom Moore’s Diary, once made a very ludicrous mistake. He was performing one of his most famous parts at some country theatre, and, as is common in some provincial temples of the Drama, a child had been making its presence very pronounced by emitting the shrill noises peculiar to the average infant. At last Kemble could bear the infantine interruptions no longer, and advancing to the front of the stage he assumed his most tragic air and said—“Ladies and gentlemen, unless the play is stopped, the child cannot possibly go on.” Kemble’s audience on that occasion was not like the one in San Francisco in its early days. An opera company was performing in the rowdy city of the “Pacific Slope,” when a child in the auditorium created a great disturbance. The burly gold-seekers, who mainly composed the audience, ordered the players to stop till the child was finished with its entertainment, as an infant’s voice was such a rarity in the Wild West at that time that it awakened pleasant memories of the old home and tugged at the heart-strings of the rough-and-ready miners. This is a genuine instance of the play being stopped and “the child going on.”

[23]

ENGLISH AS SHE IS SPOKE.

Touchstone (to Stage Manager). ’Ow do you expect me to speak my lines correct with all that ’owling and ’ooting and ’issing going on in front?

[24]

[25]

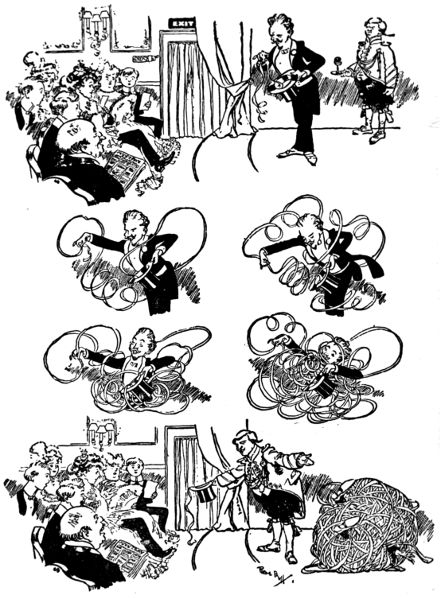

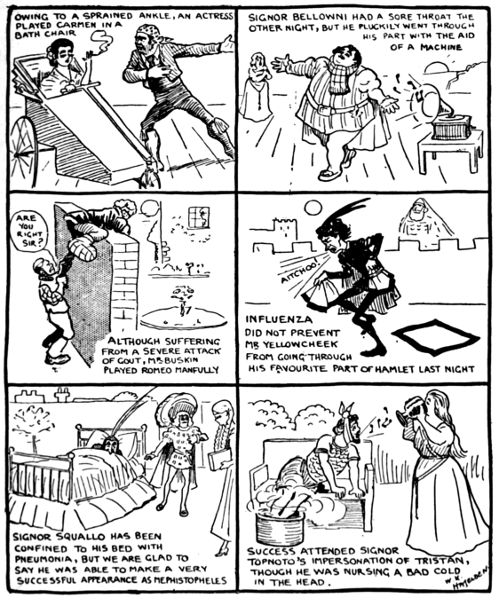

The public insist on seeing their stage favourites, even when they are not quite fit. A well-known actress sang “Carmen” from a bath-chair recently. What next?

[26]

A very amusing mistake is laid to the credit of Quin. On one occasion, while he was acting “Judge Balance” in The Recruiting Officer, he addressed Mrs. Peg Woffington in these terms—

“Sylvia, what age were you when your dear mother married?”

Peg made no reply to the embarrassing query, so Quin proceeded—

“I ask you what age you were when your mother was born?”

Thus going from bad to worse. The actress fortunately did not lose her presence of mind, and replied—

“I regret I cannot answer your question; but I can tell you how old I was when my mother died.”

Amusement is frequently afforded by some member of the audience losing himself in the play, and fancying that the scene before him is a page from real life. When such incidents occur, they form excellent testimonials to the dramatic abilities of the actors. A striking instance of this kind is related in connexion with the late Fanny Kemble. It occurred while she was appearing in Philadelphia as “Juliet.” She had just repeated the lines—

when a tall, lanky, medical student in a stage box, who had evidently been deeply absorbed in the scene, thrust his hat on his head in great excitement, crying out in a voice that could be heard all over the theatre—“Keep him up, Juliet; I’ll run and fetch the stomach pump.”

An incident of a similar nature occurred many years ago at the London Princess Theatre. A well-known conveyancer, noted for absence of mind, during a performance of Macbeth, one of the witches replying to the Thane, that they were “doing a deed without a name,” started up exclaiming, to the bewilderment of the audience—“A ’deed without a name’! Why, it’s void. It’s not worth sixpence!” The last time Kean played Louis XI at the Edinburgh Theatre Royal, a young Irishman who had been sitting spellbound in the stalls, after the attendants had proclaimed, “The King is dead!” exclaimed, “And may the Lord have mercy on his guilty soul.”

[27]

THE EVER-POPULAR CRIMINAL ON THE STAGE.

Criminals (on the stage) are extraordinarily popular. In real life, we do not like being stolen from. On the stage, we love to see a fine, dashing criminal stealing from other people. The worse he is, the louder we applaud him.

[28]

ON THE STAGE— —AND OFF.

Sometimes a voice from the “gods” may be the means of swamping a play. This was the case with the only dramatic piece ever written by Miss Braddon, the famous novelist. In one of the acts a child was kidnapped from its mother, and at the end, when all the characters in the play were being made happy, the restoration of the child was taken for granted. This was a dramatic mistake, and while suited for a novel, was not to be accepted in the theatre. The omission passed unnoticed for half a minute after the fall of the curtain; then one of the “gods” leaned over the gallery and coolly inquired—“What about the kid?” The piece was doomed in the uncontrollable peals of laughter that followed.

[29]

Instances where members of a cast, through ignorance or forgetfulness, take some scene or dialogue literally, are most mirth-moving, if somewhat rare. A highly entertaining instance of this kind occurred once when John Kemble was playing Hamlet in a country town. An actor, who was sustaining the part of “Guilderstein,” was, or imagined himself to be, a capable musician. “Hamlet,” in the usual course of the play, asked him—

“Will you play upon this pipe?”

“My Lord, I cannot.”

“I do beseech you.”

“Well, if your lordship insists upon it, I will do as well as I can.”

And to the great consternation of “Hamlet” and the amazement of the audience, he proceeded to play “God Save the King.”

A delightful piece of literalism is told about a property man who on one occasion was deputizing at a rehearsal of Macbeth in which a well-known actor was filling the title rôle. Here is a scrap of the dialogue—

[30]

Property Man. As I looked towards Birnam, anon, methought the wood began to move.

Macbeth: Liar and slave!

P.M.: S’help me bob, sir, the blokes told me to say so.

To ludicrous instances there is no end; but perhaps one of the most comical occurred in a wretched little French theatre during the time of the first Revolution. Madame de Larme, who was playing “Juliet” on the occasion, was lying in the death scene on a tombstone. Outside, it was raining in torrents. A drop came through the roof and fell on “Juliet’s” nose. She made a face. Another drop found its way to her eyelid. She winked. Finally, she took to watching the drops and dodging them. The situation was at once appreciated by the audience, and it sympathized with the actress.

“Look out, Mrs. Juliet,” said one fellow, “there’s a big one coming. I see it.”

“Mind your eye,” said another.

“Madame,” said a third, rising, “will you accept my umbrella?”

But “Juliet” bore up bravely to the end, and finished the scene amid the applause of a sympathetic audience.

In a Glasgow theatre some forty years ago, the playgoers were treated to a very diverting scene that was not in the programme. The play was After Dark, and in one of the acts there is a very exciting railway scene in which a train crosses the stage just as one of the characters who has been tied to the rails is released. The manner in which the train is manipulated is very simple. A number of men, concealed behind it, run across the stage. On this occasion the man who was working the engine tripped and fell, carrying the engine with him, when about halfway across the stage. The man in charge of the tender, not having time to clear out of the way, fell over the engine-keeper, and the third fell over him, the curtain being run down on the most exciting railway disaster that ever occurred in Stageland, the audience laughing heartily the while.

[31]

[32]

[33]

Comedian. Is your play still running?

Tragedian. No—but the manager is!

At a theatre in Glasgow the writer witnessed a very amusing incident in the course of a representation of Theodora by Miss Grace Hawthorne’s Company. There is a tremendously “bluggy” scene in this drama, which closes with the heroine standing in the middle, while a collection of corpses strew the stage. On the night in question the drop curtain refused to perform its office, and after[34] coming half-way down complacently stuck there. The dead bodies lay in dreadful suspense for some time, and then in despair got up and walked off!

Bill. See that cove, ’Arry? He takes the part of Hamlet.

’Arry. Well, good luck to him if the bloke’s in the right.

While this immensely delighted a nineteenth-century audience as an absurdity, it appears to have been quite the custom on the Restoration Stage, when players “died” in front of the curtain and were either carried off or walked away afterwards! This is seen from the famous epilogue spoken by Nell Gwynne in Dryden’s Tyrannick Love. She played a serious part on this occasion, and in the last act stabs herself twice, and dies. She lies dead on the stage; then, when the bearer comes to carry her off, she starts to her feet, exclaiming—

“Hold! Are you mad? You damned confounded dog! I am to rise and speak the epilogue.”

[35]

GOOD AND BAD BUSINESS AT THE THEATRE.

When a play is a success the theatre-goer is treated with less consideration than when it is a failure. In the latter case he is overwhelmed with attention and kind words.

[36]

Stage “waves” have often afforded no little amusement to the audience. The troubled ocean is simulated on the stage by a number of men lying on their backs under a painted canvas, kicking their legs and throwing their arms about with a certain amount of regularity, the men being blindfolded to prevent the dust getting into their eyes. During a performance of the Black Flag, at Dundee, a scene in which the waves were required was introduced and went with its usual success till one evening the curtain got entangled with the sea-cloth, and on the former being raised it carried the latter with it, exposing to the view of the audience the group of wave-makers lying on their backs vainly kicking the air. The audience, of course, screamed with laughter, which set the wave men wondering, and, thinking something was amiss, they unfastened the bandages over their eyes and discovered their undignified positions, quitting the stage with the greatest rapidity. The audience were not in a mood for settling down to watch the surging sea after this, and the remainder of the scene was omitted from that performance.

In this connexion the experience of a well-known comedian who started his career as a humble “wave,” will afford the reader some merriment. He writes:—“At last the shipwreck came on, and I was hustled under the sea-cloth along with a dozen other ‘supes.’ Our business was to make the sea rise in its might and wreck the gallant ship. We had been repeatedly cautioned at rehearsal not to use our hands, but to go down on all fours and produce the foaming billows by ‘humping’ our backs up and down. This was a very trying exercise; it was much easier to use our hands, though it gave to the rolling billows a jagged and unnatural appearance, and when the dry white paint sifted freely through the cloth, covering us up, choking and blinding us as the climax approached, I commenced in a fit of desperation to use my hands, so as to dodge the foam as much as possible, and keep it from totally blinding me. But I was soon perceived by the stage carpenter, who instantly dived under the cloth, labouring under wild excitement, and commenced cursing me in dumb show for not ‘humping’ my back as I had been told to do. He was so fierce that I quickly edged away from him. This made him worse. He signalled me to come back. I edged away a little further, and a moment later stood up through a hole in the cloth, as big as a barn door, in the midst of the angry breakers, and covered from head to foot with the white powder. There was not a sound in the house until I gave a terrible ‘chahoo!’ and suddenly dived back under the waves. Then you could not have heard the report of an eighty-ton gun a hundred yards away.”

[37]

Distinguished

Amateur (who has been cast for the part of Sir Toby Belch). I

suppose I shall want a little padding?

Costumier. Certainly. (Shouting) Ernest, bring down a full-size stomach!

[38]

A very droll interruption occurred one evening in a St. Helens theatre when the late Signor Foli was singing. The celebrated bass had just finished the first verse of his favourite song, “The Raft,” when a baby started squalling, and still continued as he began the second verse, commencing—

but he got no further, being seized with uncontrollable laughter, which for the moment puzzled the audience, but presently it dawned upon them that the next line was—

and they joined the Signor in his mirth. He left the stage for a moment, and returned and sang in his exquisite style “Out on the Deep.”

[39]

THE ACTOR’S ONE TOPIC—HIMSELF.

Actors are charming people, but unfortunately they are so keen about their work, that their thoughts constantly recur to it, and they cannot keep their own latest achievements out of the talk. A lunch at an actors’ club is apt, in consequence, to be a trifle monotonous.

[40]

A SIDE-BOX TALK.

Roguy and Poguy.

Roguy. See that girl looking at me,

Poguy?

Poguy. Don’t I? I declare she can’t

keep her eyes off you.

Roguy. What women care for, Poguy,

my boy, is not features, but expression.

[He pokes Poguy in the waistcoat.

Many good stories are told of the facetiousness of Dublin audiences. Here is one that Macready used to relate:—One night while performing “Pierre” in Venice Preserved, the Jaffier, an actor ponderous in person as well as in style, was drowsing out his dying speech, when a voice from the gallery exclaimed, “Ah, now, die at once!” to which another from the opposite side of the house responded, “Hould your tongue, you blackguard!” then, in a patronising tone to the Jaffier, “Take your time now!”

There was humour, and what is often much akin to that, pathos, in the appeal wrung from the unlucky representative of crook-backed Richard, who, finding it impossible to make head against the disapprobation evoked by his histrionic efforts, dropped blank verse, and in very plain prose told his audience—“Mr. Kean is playing this part in London at a salary of thirty pounds a night; I receive but fifteen shillings a week; and if it isn’t good enough for the money, may Heaven give you more humanity!”

At a crowded country theatre in France a woman fell from the gallery into the pit, and was picked up by one of the spectators, who, hearing her groaning, asked her if she was much injured. “Much injured!” exclaimed the woman; “I should think I am. I have lost the best seat in the very middle of the front row.”

[41]

Bald Baron. Alas, noble stranger, my heir was taken off eighty years ago!

Noble Stranger. Yer’s a-go—old man, be-hold thy long-lost chyield.

(They embrace.)

[Curtain.

[42]

Agnes. Oh, agonies! sixty years have I waited for my Willie. Oh, will he never come.

(Enter) False Heir. Beauteous Screecher, fly with me—(Agnes faints)—ha, ha, she’s mine. Away!

(Enter Will.) Where there’s a will there’s a way.

[Curtain.

[43]

Scene, the private pass and the seedy glen.

Will. Treachery; I’ve got a drop too much.

False Heir. One down, who’ll make two?

Agnes (suddenly entering). Vill-ian—you!

[Curtain.

[44]

Terrific combat of many hours’ duration.

False Heir (mortally wounded). My time has come—Here are the papers—You are the Baron de la Bluebags.

[Grand display of blue-fire, and fall of Curtain.

[45]

FUN AT THE PLAY

He. Excuse me, madam, but you are sitting on my hat.

She. Oh, I’m so sorry; I thought it was my husband’s.

[46]

THE DELIGHTS OF THEATRE-GOING.

The pleasures of the cloak-room. No less than one attendant to each million hats and coats. Charge only sixpence (exclusive of tip), and every customer is allowed to fish out his own wearing apparel from the pile, if he can find it. Each attendant guaranteed to be innocent of all knowledge of figures, so that every client gets the wrong things. This adds a gambling interest to the general scuffle.

[47]

THE DELIGHTS OF THEATRE-GOING.

The unmannerly rush for drinks and smokes between the acts. As the space between the rows of seats is so narrow, the drinking brigade have to tread on those they leave behind, tearing frocks, smashing corns, and elbowing inoffensive ladies and gentlemen in the face.

[48]

We must assume there is something very peculiar in the rural landscapes and the town residences inhabited by the dramatic population, if the haunts of their rustics and the dwelling-places of their citizens are to be judged by the representations of these places which we see upon the British stage. The dramatic idea of the country consists usually of a series of set pieces, backed by a six-inch deal bridge, surmounting a two-foot waterfall, and leading to a profile cottage of such diminutive dimensions that when the feet of any one entering it are on the basement, his head soars into the second story, and he cannot, without doubling himself completely up, go either in or out of the door. In some cases the cottages have no pretension to habitable qualities, but are simply “made out” of a single piece of canvas, on which a clearly “impracticable” window is painted, and which the business of the scene does not require to be opened, the cottage being only needed as the cue for some song or sentiment, such as “Ah! that humble cot—how its aspect makes me sigh for Home, Sweet Home!” or, “The sight of that lowly roof makes me feel no envy for pampered pride in its palace, or venal villany in its villa; for I am convinced more and more of the beautiful truth, that it is in the cottage alone contentment can be found.”

[49]

Daughter. What do you think of the quartette?

Grumpy Father. Humph, won’t take as long as four solos!

[50]

“My dear Lady Thompson, I had no idea you’d broken your arm.”

“Don’t be alarmed, dear. These horrid people would never have let Fido in, so I had recourse to a little ruse!”

[51]

Sometimes there is, by way of background, a castle, frightfully foreshortened, with its battlements half a yard high, and its towers towering among the sky-borders, while its foundations rest on a rock no higher than the top of the low comedian’s hat; but the structure is sufficient to admit of its being apostrophized by some young gentleman in hessians and a chocolate surtout as “Deserted halls of my ancestors, whose pavements have rung to the clang of the usurper’s hoof, and whose donjon-keep has echoed to the noisy revels of a stranger band.” When the occasion is an operatic one, the distant castle forms an admirable subject for something like the following—

RECITATIVE.

Every playgoer is familiar with the “mossy bank” of dramatic rural scenery, with one end slightly elevated for the head of the weary wayfarer or benighted traveller, and a bit of an old bolster craftily crammed underneath the canvas to complete the mossiness of the contrivance.

The town scenery of the stage is not less peculiar than its landscapes, and the exteriors are particularly adapted for teaching “what to avoid” to the youthful architect. If young Dashington calls upon Lord Toplofty, the latter lounges lazily out of the first-floor French window, in which his head and shoulders are a pretty tight fit, while the former bears about the same proportion to the house that the peasant bears to the cottage we have already been speaking of. It is a singular fact that the inside of any one room is no sooner represented to us, than we find it to be much larger than the whole house when judged by its external appearance; and though the mansion itself may be only ten feet high from the basement to the tip of the topmost chimney-pot, the smallest apartment is found to be as wide as the wings are apart, and as lofty as the proscenium.

[52]

A MORNING CONCERT.

Wife. George! George! You are not in church!

[53]

In costume, the stage presents some really astounding phenomena; and we have often been struck by the similarity of the dresses worn by the retainers of every country, every age, and indeed of almost every family. One would think that the word retainer referred to the fact of the same habiliments being always retained under all circumstances, whether the wearer happens to be a creature of the house of Hapsburg, a vassal of a Norman noble, or a member of a bellowing band of Swiss patriots, shouting such choruses as the following:—

Punch.

[54]

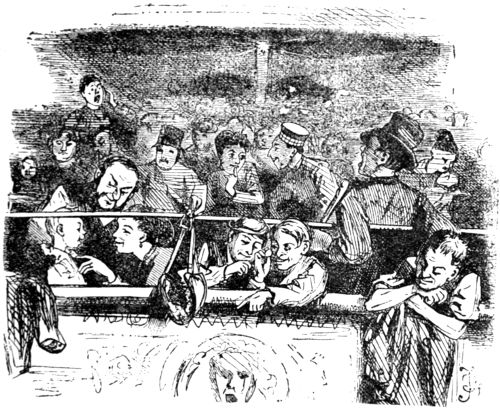

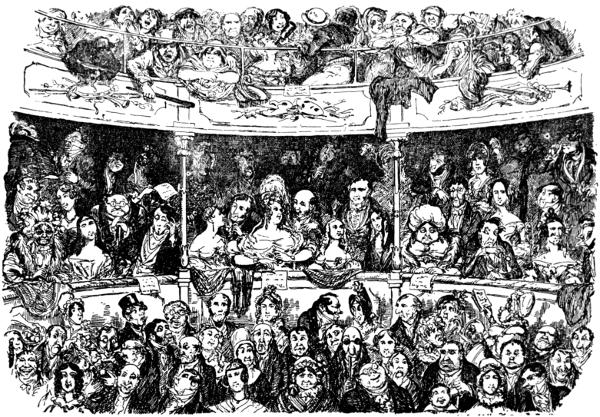

PIT, BOXES AND GALLERY.

[55]

The forthcoming show of donkeys promises to be a great success. The only difficulty that seems to us likely to embarrass the manager is the selection of a locality large enough for the exhibition. If but a tenth part of the asses in the metropolis make an exhibition of themselves on this, as they are apt to do on ordinary occasions, nothing smaller than the grounds of the Crystal Palace or the Alexandra Park could possibly accommodate them.

The following, we believe, are already entered:—

An egregious ass, that believes in the speedy subjugation of the Confederates by the Federals in America.

An awful donkey, who prefers Tupper to Tennyson.

An old ass, who, by means of false teeth, tight waist, a wig, and rouge, imagines himself a lady-killer.

A young ass, who, by smoking strong cigars until he is sick, imagines himself manly.

Several thundering donkeys, who are always sending money anonymously to the Chancellor of the Exchequer for unpaid income-tax.

A still larger number of even more hopeless asses, who patronize quack-doctors, cheap, puffing tailors, delineators of character by handwriting, and other advertising swindles.

An irreclaimable ass (supposed to be the only one living), who does not see any merit in Fun. The greatest ass alive.

There are several others we could mention, but the astounding asinine qualities of the last-named donkey have quite taken away our breath. In the forthcoming “competitive examination, of donkeys,” let him by all means bear away the prize! Fun, 1863.

[56]

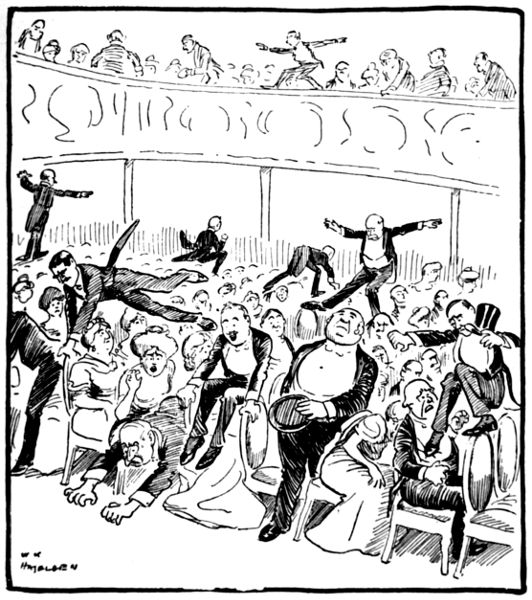

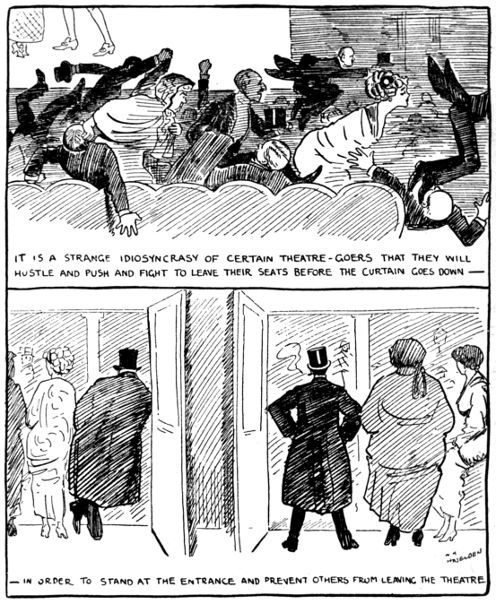

PLAYGOERS AND THEIR ECCENTRICITIES.

Chief eccentricity is the amazing mania for rushing out of the theatre before anybody else, in order that you may stand firmly at the door, preventing everybody from getting away.

[57]

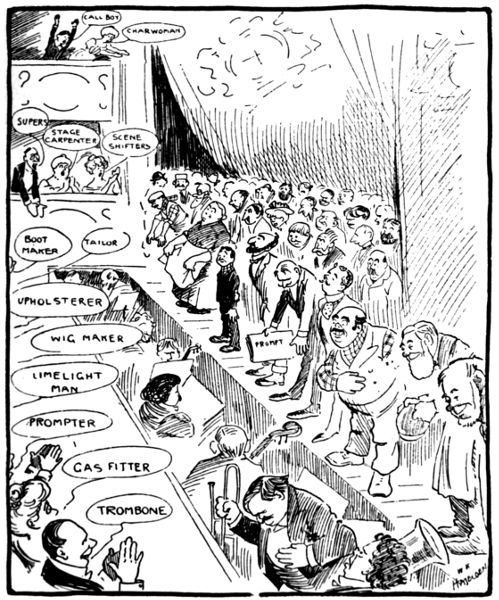

At a theatrical first night there were loud cries on the part of the audience for the scene painter, whose splendid work had contributed largely to the success of the piece. Now certain other functionaries in theatres think they should be called out also.

[58]

A “CIVIL” RETORT.

Captain de Plunger. I say! aw—you tha-ar—are you, aw—the

boxkeepar?

Civilian Fellow. No, my boy; I’m not. Are you?

(From Fun, 1863.)

[Rushes out at the rate of £40 a week.

[59]

[60]

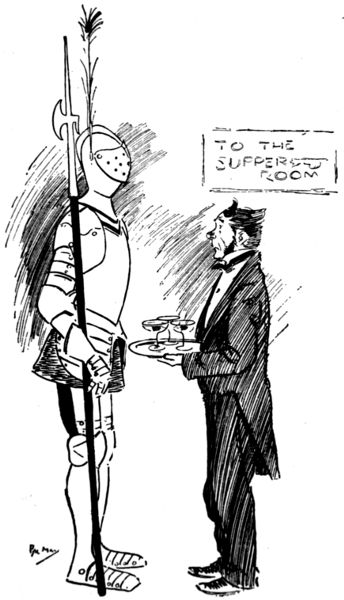

AT A FANCY BALL. Voice Within (to waiter). I’m starving! For goodness sake, get a can opener. I can’t get this beastly visor up.

PRIVATE THEATRICALS—THE MOUSTACHES.

Lady

B. (a wicked Marquis). But have you made me fierce enough, Charles?

Charles. Fierce!—ferocious!

[64]

A Pastoral Story, after Wordsworth.

Postscript.

Fun, 1865.

[65]

PRIVATE THEATRICALS AT THE TITWILLOWS’.

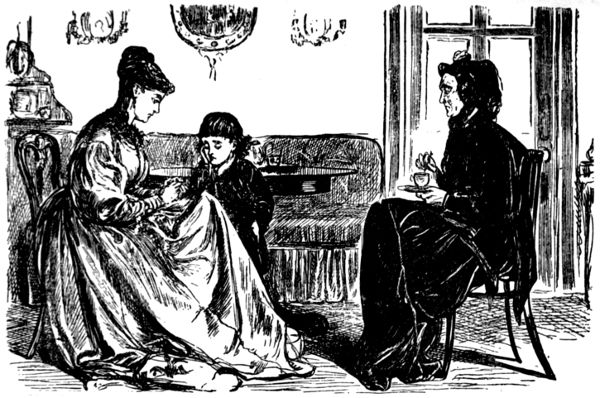

Mr. Titwillow, having undertaken a comic part, is about to render his appearance more effective by reddening the tip of his dear little nose. His wife, mother, and sister, in a passionate appeal to his nobler feelings, implore him not to desecrate his dignity by such an act. [His bosom friend cynically contemplates the touching family scene.

[66]

—Fun, 1863.

[67]

THE POETS’ CORNER

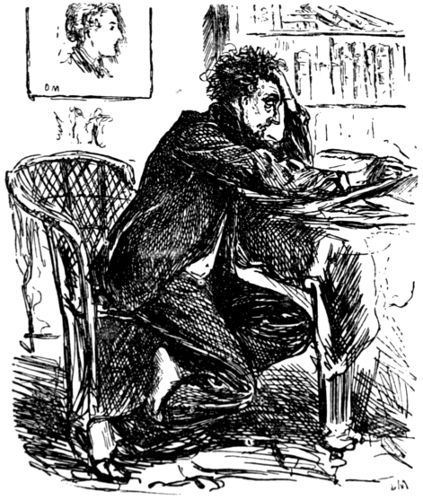

PORTRAIT OF A GENTLEMAN

In the act of writing a funny poem, that will make you die of laughing

when you read it.

[The enlarged photograph on the wall represents the same party when not engaged in comic composition.

[68]

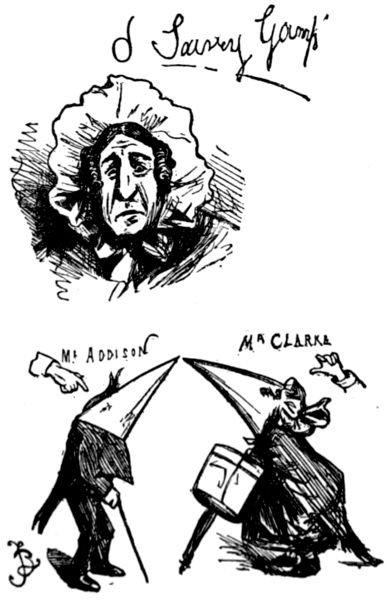

Addison in his Papers on Wit makes vigorous onslaught against “false wit.” “The first species of false wit which I have met with is venerable for its antiquity, and has produced several pieces which have lived very near as long as the Iliad itself; I mean those short poems printed among the minor Greek poets, which resemble the figure of an egg, a pair of wings, an axe, a shepherd’s pipe, and an altar.”

Further on, he says, referring to these conceits, “the poetry was to contract or dilate itself according to the mould in which it was cast. In a word, the verses were to be cramped or extended to the dimensions of the frame that was prepared for them, and to undergo the fate of those persons whom the tyrant Procustes used to lodge in his iron bed; if they were too short he stretched them on a rack; and if they were too long he chopped off a part of their legs, till they fitted the couch which he had prepared for them.”

Most people accept this dictum of Addison as a final pronouncement on the distinction between true and false wit; but on further consideration it may be found that “much can be said on the other side.” Addison asserts that the matter must suffer if it has to be squeezed into a certain shape. This may be so, but it need not be much more so in the forming of a pair of wings in verse, than in the construction of a sonnet. Every sonnet, no matter how inspired, must follow an artificial measure, every poem, be it never so soulful, must have a definite number of feet in each of its lines and a preconceived arrangement; yet, no one advances the opinion that Scott was wasting his sense of poetry by casting it in the form of octo-syllabic verse, or that Shakespeare had a difficulty in fitting his thoughts to the measure of his sonnets or the blank verse of his plays.

[69]

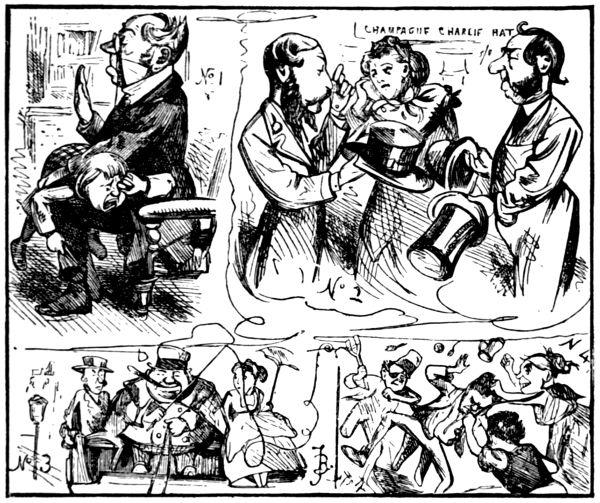

THE POETS ILLUSTRATED.

1.—“For, indeed, my father did something smack—.”—Merchant of Venice.

2.—“Take any shape but that!”—Macbeth.

3.—“Light only on the box.”—Bryant and May.

4.—“—sigh to think that he had found

4.—“His warmest welcome at an inn.”—Shenstone.

The most that can be advanced against those poetic conceits of the kind condemned by Addison is that they appeal in a greater degree to the eye than to the ear, and while we may be conscious of their artificial nature we should also be catholic enough to admit their ingenuity, and when they are sufficiently amusing to provoke laughter, or excite a smile, they should not be denied the attributes of wit; for, after all, when we free ourselves from the suspicion of affectation, do we not agree that the chief end of wit is to amuse?

[70]

NO! DON’T. (Period 1854.)

“So they are sending out books to amuse the poor fellows at Scutari—and very proper. I will send five-and-twenty copies of my last five-act tragedy of ‘The Roman Grandmother.’”

These remarks have been suggested to the writer by his discovering in one of his old scrap-books a little collection of curiosities of verse culled in Bookland byways “oompty” years ago. These do not consist of specimens of the minor Greek poets’ eccentricities, but in every case they are examples of what Addison would have unhesitatingly catalogued as “false wit”; and yet, not only are some of them genuinely amusing and others highly ingenious, but several display a painstaking which almost amounts to genius—if genius be “the capacity for taking pains.”

We can, for example, appreciate the immense industry of the author who set himself to compose a series, of verses in which the letter “e” should be entirely omitted, and the painstaking of the author will be yet further acknowledged when it is known that “e” is the most used letter in the English alphabet, the relative proportion of its use being 120 times to j 4, k 8, g 17, and i 40.

There are two such pieces among the writer’s literary curiosities and he regards them as, perhaps, the most unique. The first one is as follows—

The first word in the second line of the third stanza is evidently a misprint. “Night’s” is most likely the word used by the author, meaning that the coming of the morn extinguished the stars—

Here is the other specimen, which is even more ingenious than that just quoted, each stanza containing every member of the alphabet except the letter “e”—

[72]

A happy thought is well worked out in the following quaint little jeu d’esprit which the writer came across in an old magazine many years ago. If you read it line after line you will find the author cheerfully contemplating the prospect of matrimony; but if you only read each alternate line you will discover him to be a confirmed old bachelor—

A somewhat common form of poetic conceit is the arranging into one intelligent poem of lines from a number of well-known poets and thus forming what may be called a mosaic of verses. I here print one of the best examples of this kind that I have come across; the author, like those of the “e”-less verses, is unknown to fame—

The composite poem thus formed may not be praised for beauty of thought, for absolute sequence of expression; but it is certainly a most ingenious composition and a monument of literary research.

The remarkable sibilance of the English language is cleverly exaggerated in the following lines, which are commended to the attention of those who lisp—

Needless to say these diverting lines were written and published originally beyond the westering wave.

[74]

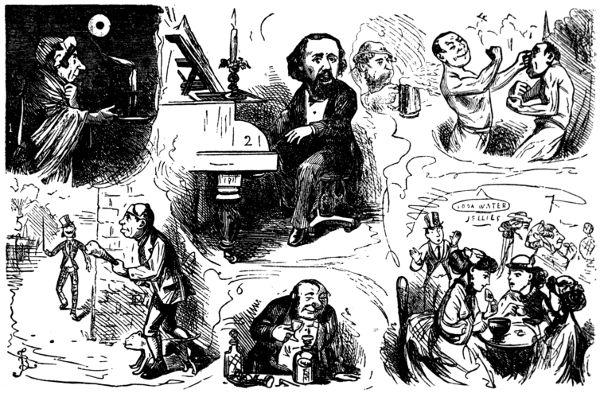

THE POETS ILLUSTRATED.

1.—“Dip forward under starry light.”—Tennyson.

2.—“It sounds to him like her mother’s Weiss Singing——”—Longfellow.

3.—“Off with his head.”—Cibber.

4.—“A pouncet box which ever an I anon

4.—“He gave his nose, and took’t away again,

4.—“... and still he smiled.”—Shakespeare.

5.—“Tis sweet to know there is an eye will mark

5.—“Our coming, and grow brighter when we come.”—Byron.

6.—“Lightly they’ll speak of the spirit that’s gone.”—Wolfe.

7.—“That we may call these delicate creatures ours—

7.—“But not their appetites.”—Shakespeare.

[75]

Country Critic (who the previous evening patronised “Muggins’ Travelling Theatre”). They poets just are clever chaps, and noa mistake! I see a thing last night as I never wishes to see not noa better. Darned if I doant thin’k that Mariar Martin, or the Red Baarn arn’t the best play as ever Muster Shakespeare wroat!—(Period 1865.)

[76]

By Brobert Rowning.

Fun, 1866.

[77]

“What’s ’A-cuba to him, or he to ’A-cuba?”

—Shakespeare.

“Mark’d you her eye?”

—Sheridan.

“Alarms! Excursions! Parties fighting.”

—Shakespeare.

[78]

“Methinks I scent the morning hair!”

—Shakespeare.

“Parting is such sweet sorrow.”

—Shakespeare.

—Tennyson.

[79]

“My custom always of an afternoon.”

—Shakespeare.

“Say what can Chloe want? She wants a heart.”

—Pope.

—Byron.

[80]

Vast is the difference between the Poets’ Patron of the past and of the present period. Formerly the noble was the encourager of the lofty strains of inspiration, but nowadays Moses is the Mæcenas of the Muses. In times gone by the bard was accustomed to write lays to laud the lazy lordling, but now he sings pæans to the paletot, and invests the vest with the graceful trimmings of fancy.

The poet has turned puffer instead of parasite. Should another Pope arise, he would sing the praises of another Chesterfield; but instead of being the Earl of that name, it would be the wrapper he would take for the subject of his lucubrations. The following is a fair specimen of the style of thing to which a new Pope would most probably devote his poetical talents:—

[81]

I.

I.

II.

III.

[82]

IV.

V.

IV.

V.

[83]

VI.

VII.

[84]

Fun, 1866.

[85]

MAINLY ABOUT AUTHORS

Would-be Novelist (writes). Even as he read the letter, De Brooke’s face blanched. The dreaded blow had fallen! The estate would never be his—and he must be content with a mere existence on a paltry nine hundred a year.

[86]

LADY AUDLEY’S SECRET

On the way to the office of his publishers one crisp autumn morning, Mr. James Whitcomb Riley, the celebrated “Hoosier” poet of America, who is almost as well known in England, met an unusually large number of acquaintances who commented conventionally upon the fine weather. This unremitting applause amused him. When greeted at the office with “Nice day, Mr. Riley,” he smiled broadly.

“Yes,” he agreed. “Yes, I’ve heard it very highly spoken of.”

[87]

“Once when I was going out to visit some friends,” Mark Twain is alleged to have said, in relating this one of the innumerable “yarns” fathered on him, “I told George, my negro servant, to lock the house and put the key under a certain stone near the steps. He agreed to do so.

“It was late at night when I returned. I went to the stone under which the key was supposed to have been hidden. It was gone. I hunted around the premises for about fifteen minutes, but still no key.

“Finally I went to George’s house—he lived outside—and rapped, vigorously upon the door. A black head, which I had no difficulty in recognizing as George’s, popped out of an upstairs window.

“‘Where did you put that key, you black rascal?’ I roared.

“‘Oh, massa,’ answered George, ‘I found a better place for it.’”

DESCEND, YE NINE.

[88]

PERFECT SINCERITY, OR, THINKINGS ALOUD.

Genius. By the way, did you glance over that article of mine on “The Intellect of Woman, and her Social Position?” I don’t care twopence about your opinion; only, if you can say something favourable, of course I shall be pleased.

Common Sense. Why, I tried to get through it, but upon my life, I found it such contemptible rubbish, that I couldn’t get on; and, to tell you the truth, I think that a snug little thing in the cheese-mongering line would be more in your way than literature.

Genius. Ah, you must be a fool!

HISTORY—THE ANCIENT BRITONS.

Emily (reads). In the summer they were naked, and instead of clothes they put paint upon their bodies. They were fond of a fine blue colour, which they made of a plant called woad, which they found in their woods. They squeezed out the juice of the woad, and then stained themselves all over with it, so that in summer they looked as if they were dressed in tight blue clothes.

Arthur. And did they walk in the park and go to church so?

[89]

A RURAL STUDY.

BURLESQUE-WRITER FORCING PUNS.

[90]

Genius. Ha! I may be unrecognized, my dear, but I’ll have my revenge on posterity. When the great cypher work is dug out of the Thames it will show that everything Meredith, Hardy, Kipling and Marie Corelli ever wrote was mine—mine!

[91]

The printing-house is notoriously the place for fun. Every shop has its selection of funny men who are ever ready to co-operate with the “devils” in manufacturing mirth. And there are always the “fossils,” who afford many an opportunity for a hearty laugh at them, if not with them. Often have I been amused with, the idiosyncrasies of these typographical gray beards; their chief charm being their colossal assurance as to their invariably being right, and everybody else, who presumes to differ from them, wrong. I recollect one of these ancient typesetters (an old Scotsman) who used to be the butt of countless jokes in the shop where he toiled so patiently. On one occasion he set up an article from my pen, beginning, “Long before the introduction of Pears’ Soap”; and I am bothered if he didn’t turn the last two words into “Pea Soup!” But the real fun of the matter was, that on his mistake being pointed out, he blandly suggested our letting the words appear as he had set them—“it wid dae jist as weel!”

The printer does not seem to be deeply concerned about his future, indeed, he has many a gay dig at that grave subject; as, for instance—

[92]

AUTHOR’S MISERIES.

Having corresponded with Miss Rudge, the gifted poetess (authoress of “Floranthe,” “The Lovelock of Montrose,” “Moans of the Heartstrings,” etc.), and exchanged portraits and your own poems with her, you meet at last.

You are disappointed in her appearance and find her about forty years older than her picture; perhaps you, too, have grown rather fat and seedy since yours was taken twenty years ago.

The printer’s “devil,” by the way, is a queer fish, and there is a story about a certain metropolitan imp that fits any of the little sinners to a T. This particular youngster had just received his week’s wages, eleven shillings, when he was heard to soliloquize in these terms—“Let me see. I’ll go the Coliseum to-night, that’s a shilling; supper with bottled beer, that’s eighteenpence; ’baccy for the week, a shilling; beer ditto, two shillings; theatre one night next week, that’s one-and-six, and supper, one-and-six; and I’ll buy that swell walking stick, and that’ll just leave sixpence to take home to mother towards my week’s board.” He must have been a regular bad ’un, that.

Another favourite medium of printing-house fun is found in adapting Gilbert’s famous line and mourning that a “printer’s lot is not a happy one,” or magnifying the annoyances from authors and editors with which printers have to put up. In this connexion we find one printer relieving his troubled soul thus—

Working for forty editors and scores of authors, every one of whom is as sensitive[93] as a sore thumb, and as lively and interesting as a hornet, no wonder that printers die young, and only pachydermatus, grizzly, mulish specimens get their share of life. The writer wishes he could offer himself as an awful example of the perils which environ a man who meddles with cold type. A thoroughly trained printer should have had a stepmother, and then a stepfather, and then have been bound out to a tanner, and then have married a scolding wife, and lived in a smoky house, and have had a family of babies who were afflicted with colic. He should have added to all this discipline a thorough knowledge of science, art, law, language, theology, history and biography. If, in addition, he has a vicious looking countenance and an amiable disposition, he may stand some chance with these authors and editors ; but the probabilities are, after all, that they will worry him to death.

AUTHORS’ MISERIES.

As you are labouring on your great work (in a style, let us add, equal to the subject), Lady Anna Maria Tomnoddy’s compliments arrive, and she requests you will cast your eye over the accompanying manuscript in six volumes, “The Mysteries of Mayfair,” correct the errors, if any, and find a publisher for the same.

N.B.—You have in your bookcase Captain Bangle’s “Buffaloes and Banyan Trees,” in MS.; the Rev. Mr. Growl’s “Sermons to a Congregation at Swansea,” ditto ditto; Miss Piminy’s “Wildflower Coronal, a Wreath of Village Poesy”; and Mr. Clapperton’s six manuscript tragedies; of all of which you are requested to give your opinion.

Then there is a certain freedom about printers’ humour which we don’t find elsewhere, save among editors: but printers, like editors, have ever been privileged individuals, and we are told that when the recording angel observes a printer hold a bit of bent brass rule between his fingers, while he misses it with a hammer, the trustworthy scribe drops into a brown study, and pretends not to hear anything. Nor is it logical to assume that a printer is a saint because he sets up a hymn-book.[94] You might as well regard an editor as a fool because you didn’t exactly agree with what was in his paper.

AUTHORS’ MISERIES.

Perhaps you flatter yourself that you have made an impression on Miss Flannigan (at Worthing), and you find her asleep over your favourite book.

Illustrative of this there is an excellent anecdote told by the late Max O’Rell in his book, A Frenchman in America.

A former proprietor of the New York Times and Post was wont every morning to select a text from the Bible to be printed above the leader. One morning, by some mischance, the text got lost, and Max tells us that the comps might have been heard asking in pretty loud stage whispers, “If anybody knew where that d—— text was?”

Perhaps the wit of the compositor is most amusing when it appeals to the eye. That is, when he gives rein to his fancy, and uses his types for suggesting witty ideas. Here is a very happy illustration of this kind of fun—

“TThhee ccoommppoossiittoorr wwhhoo sseett tthhiiss ppaarr. hhaass hhaadd eexxaaccttllyy aa ggllaassss aanndd aa hhaallff ttoooo mmuucchh aanndd tthhiiss iiss pprreecciisseellyy wwhhaatt hhee ffeeeellss lliikkee.”

Yes, that compositor may only have had “a glass and a-half too much,” but the typo who is supposed to have set up the appended advertisement has manifestly indulged to even a greater extent—

£ DOGSH LOSHT!

Reward Five Shtrayed or Shtolen,

Bandy Coloured Liver Legged Dog

Had on Collar Marked “Rover,”

Answers to name of C.B., Esq.

Whoever bringsh 5£ receive dogsh reward. No

furtherdogsh will be offered.

[95]

AUTHORS’ MISERIES.

As you are conducting Lady Gotobed to her carriage from Lady Highjink’s “noble party,” and fancying yourself a man of fashion, you hear the servants in the hall saying one to another, “that’s him—that’s Poonch!”

American printers are much given to these diverting devices, and in the following instance we have a number of papers vieing with one another in extracting fun from the technical terms for the various signs and punctuations—

“If brevity is the soul of wit, how is this for a funny ¶?—‘Wheeling Journal.’

It is without a ‖.—‘New York Enterprise.’ Did you expect anybody to “ ” that?—‘Philadelphia

Sunday Mirror.’ Those are the worst jokes of the .—‘Washington

Critic.’ My * * *, you’re pointed as a †, aren’t you?—‘Burlington Enterprise.’

We ![]() the opportunity to say these

are ,cal ? ? ? you fellows pro£.—‘Gold.’

Well, they afford a $ous sort of amusement

at best and —— our spirits

greatly.—‘New York “L.” R. Journal.’”

the opportunity to say these

are ,cal ? ? ? you fellows pro£.—‘Gold.’

Well, they afford a $ous sort of amusement

at best and —— our spirits

greatly.—‘New York “L.” R. Journal.’”

Here is another of the same, as they say about the Psalms of David—

“A company of printers from Constantinople

have joined the Turkish

army. They ought to be good at a

— at the enemy in the :ized region

of Bulgaria. It is surprising that they

should be so foolish * their lives where

shot and shell may put an untimely .

to their existence. Let them ![]() the

first opportunity 2 , way from that §

where the murderous work of †† is

un‖ed, and may the ☞ of Providence

guide them to a latitude where

they may live with a greater ° of

safety.”

the

first opportunity 2 , way from that §

where the murderous work of †† is

un‖ed, and may the ☞ of Providence

guide them to a latitude where

they may live with a greater ° of

safety.”

The man who likes a joke.

The man who doesn’t.

The printer can also make fun with a few brackets and other typographical oddments, as shown above.

[96]

AUTHORS’ MISERIES.

Old Gentleman. Miss Wiggets. Two Authors.

Old Gentleman. I am sorry to see you occupied, my dear Miss Wiggets, with that trivial paper Punch. A railway is not a place, in my opinion, for jokes. I never joke—never.

Miss W. So I should think, sir.

Old Gentleman. And besides, are you aware who are the conductors of that paper, and that they are Chartists, Deists, Atheists, Anarchists, and Socialists, to a man? I have it from the best authority, that they meet together once a week in a tavern in Saint Giles’s, where they concoct their infamous print. The chief part of their income is derived from threatening letters which they send to the nobility and gentry. The principal writer is a returned convict. Two have been tried at the Old Bailey; and their artist—as for their artist....

Guard. Swin-dun! Sta-tion! [Exeunt two Authors.

In taking leave of this very entertaining subject one cannot do better than quote a printer’s “little joke,” which is at once mirth-provoking, and eminently suited as a “tail-piece” for this paper—

☟ ☟ ☟ ☟ ☟ ☟

[97]

AUTHORS’ MISERIES.

The printer’s boy is sitting in the hall; the editor has written to say that your last contributions are not up to the mark, and that you must be more funny, if you please. Mr. Snip, the tailor, has called again that morning; you have a splitting headache, from a transaction over-night, and as you are writing an exceedingly light and humorous article, your dear Anna-Maria wishes to know how you dare dine at Greenwich, and with whom you dined?

I suppose she found the bill in your coat-pocket. How changed Anna-Maria is from what she was when you married her! and how uncommonly ill-tempered she has grown!

Mr. Tims and a Good-natured Friend.

G.-N. F. Have you read the Macadamiser, Tims?

T. Hem! no. Do people read the Macadamiser?

G.-N. F. He, he! I say, Tims, there’s a most unjustifiable attack upon you in it. Look here. (He kindly takes out the “Macadamiser.”)

T. (reads). “This person is before us again. He is ignorant, vulgar, and a Cockney. He is one of that most contemptible race of men, a professional buffoon. He is,” etc., etc. (Tims reads ad libitum.) Thank you, my dear fellow; it was uncommonly good-natured of you to bring the critique.

[98]

Written after a Visit to the Olympic.

Fun, 1868.

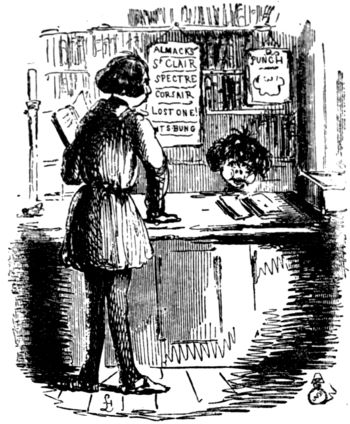

“Is this a libery?”

“Yes.”

“Then let me have the last number of Hemily Fitz-Hosborn.”

[101]

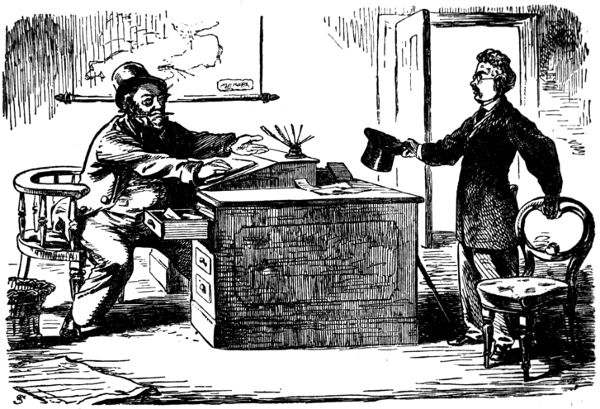

THE EDITOR IN HIS DEN

THE EDITOR AT HOME.

Mary. Please, sir, I’ve been looking everywhere for the third volume of that book you was reading.

Lodger. Oh, I took it back to the library this morning. I——

Mary. Oh! then will you tell me, sir, if as how the “Markis” found out as she’d pisoned ’er two fust ’usbands?

[102]

America is the fatherland of Modern Advertising, and Cousin Jonathan’s inherent taste for fun and unconventionality has led him to adopt striking and often humorous methods of appeal. Thus the Washington hotel-keeper who issued a glowing announcement of the attractions of his establishment would certainly lose nothing when he humorously added to his advertisement in a Chicago paper: “Clergymen find this the best place for rest, as book agents cannot climb the hill.”

An enterprising Yankee who runs a hotel at Minnetonka, rejoicing in the somewhat ominous name of Mosquitos Rest, sends forth an announcement remarkable for the manner in which it mixes the sublime with the commonplace. Here is a literal extract—

Delightful scenery. Clam bakes and ox tail soup every morning for breakfast. No cyclones allowed to register. Dogs, children, and other pets not allowed on the grass. Rates range from 3 dols. per day to 21 dols. per week. Excursions to Pike’s Peak every afternoon. Newspaper publishers can all pay their board by promising to give us a write-up when they get home. All kinds of baths on draft.

Perhaps the most amusing descent from the sublime is to be found in the advertisement of the proprietor of a building site in Wisconsin, who offered his land for sale in these terms—

The town of Poggis and surrounding country is the most beautiful which nature ever made. The scenery is celestial—divine; also two waggons to sell, and a yoke of steers.

[103]

A Pennsylvania clergyman who was evidently a bit of a humorist, and was anxious to earn an honest penny outside of his own slender salary, once advertised thus—

Cupid and Hymen. The little brown cottage at Cambridge, Pa., is the place to call and have the marriage knot promptly and strongly tied. Inquire of Rev. S. S. Whitcomb.

What benedict could resist an invitation so gracefully given?

ROMANCE OF ADVERTISING.

“I wish, mister, you’d be so good as to stop the Press and put this in a good place (reads): ‘Hemily. Don’t delay, but return to yer broken-arted Adolphus, or there’s no knowing what may be the consequence!!!’”