The Project Gutenberg EBook of Wide World Magazine, Vol. 22, No. 132, March 1909, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Wide World Magazine, Vol. 22, No. 132, March 1909 Author: Various Release Date: June 25, 2016 [EBook #52408] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WIDE WORLD MAGAZINE, MARCH 1909 *** Produced by Victorian/Edwardian Pictorial Magazines, Jonathan Ingram, Lesley Halamek, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

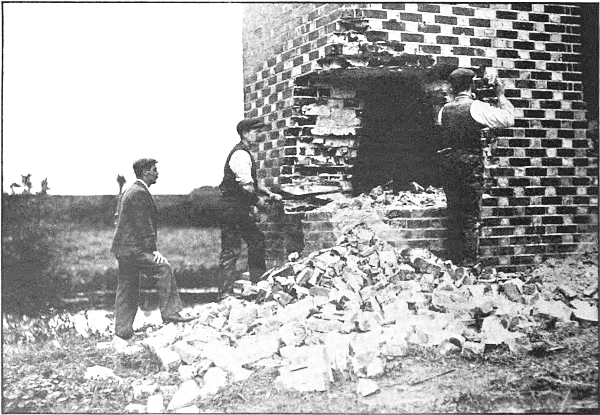

A further instalment of a budget of breezy little narratives—exciting, humorous, and curious—hailing from all parts of the world. This month's collection deals with a thrilling fight between a jaguar and a boa-constrictor, the tragic fate of a Canadian cowboy, and a night adventure in Japan.

IN the month of November, 1907, I arrived at the Isthmus of Panama to do some zoological work, and incidentally to get a better knowledge of the geography of the infant republic. I landed at Colon, a dirty, dingy town of about eight thousand inhabitants, built on a low, swampy island separated from the mainland by a narrow but deep lagoon. Here I secured the services of two Spaniards to act as carriers, and, going by boat some ten miles up the coast, disembarked in a drenching rain near the mouth of the Santa Rita River.

I carried a small supply of tinned and tabloid foods, and these we packed through the jungle to the highest point of the Santa Rita mountains, a distance of ten miles. We made a very comfortable camp, and after a hearty meal turned in for the night.

I slept very little, tired though I was, being kept awake by the howlings of jaguars, cougars, and bobcats. However, after a hasty breakfast in the early morning, I started out alone with my Winchester strapped on my back and carrying a single-barrelled sixteen-gauge shot-gun in my hand. I also carried a short but sharp and heavy machete, without which it is impossible to travel in this impenetrable jungle of mahogany, cedar, yellow-wood, and palms of various kinds, all supporting vines of every size and character. Some of these vines hang from a height of seventy-five feet, touching the ground and sending out tendrils which climb to unknown heights on other trees, thus forming a most intricate network, through which it is impossible to see more than a few feet ahead.

THE AUTHOR, DR. T. A. STODDARD, WHO WAS AN EYE-WITNESS OF A TERRIFIC FIGHT BETWEEN A JAGUAR AND A BOA-CONSTRICTOR,

OF WHICH HE HERE GIVES A GRAPHIC ACCOUNT, AND ALSO OF HIS OWN ENCOUNTER WITH A SECOND HUGE SNAKE.

From a Photograph.

I had been travelling for about an hour, trying to locate the source of the Santa Rita, and winning every inch of ground by hacking and slashing with the machete, when I was startled by a most fearful scream, which seemed to come from somewhere immediately behind me. To say that my blood "froze in my veins," even in this tropical climate, would be but a poor and inadequate figure of speech to describe my feelings. I had heard of the treachery of the San Blas Indians who inhabit the country to the eastward, and my first thought was of them. Turning round and looking back anxiously over the trail I had just made, I saw a great commotion taking place among the vines, dead leaves, and decaying branches which carpeted the ground, and the blood-curdling screams I had heard rang out again and again. For what seemed hours to me, but were really only seconds, I could not comprehend what was transpiring so close to me, and what kind of creature was giving utterance to such agonizing cries. At length, however, venturing a little nearer, I discovered it to be a "tiger," or, properly speaking, a jaguar or American leopard, and [pg 524] it was writhing in the coils of an enormous boa-constrictor. The great snake appeared to have the side of the jaguar's head in its mouth, and a coil or two of its body around the neck of the beast, which was making frantic efforts to regain its liberty. The snake had its tail coiled round a small ebony tree about a foot in diameter, and whenever the hapless jaguar relaxed its efforts the serpent would swiftly release itself from the tree and make an attempt to get another coil around the body of its opponent.

I stood there fascinated with horror, and yet forgetting my fear in the interest I was taking in this terrible fight between beast and reptile. Presently the snake, with an incomprehensibly quick movement—in fact, almost too quick for the eye to follow—succeeded in getting two more coils around the body of the jaguar, but not without receiving several severe lacerations from the formidable claws of its victim. Then letting go the jaguar's head, where it seemed to have a firm hold, the boa-constrictor raised its head, seemingly in triumph, and, with its tail still wrapped round the tree, lifted the body of the jaguar up in the air. I heard the bones crack under the fearful strain, and with one awful, despairing scream the jaguar fell back—dead!

During all this time I stood rooted to the spot, too spellbound to stir. Now, however, I realized that I stood in considerable danger, for other constrictors might be near, who would treat me in the same manner as this one had treated the unfortunate jaguar. Taking a hasty look around I saw nothing but trees and hanging vines in all directions. I then decided that I wanted the jaguar as much as the snake did, and, moreover, that I wanted to kill the snake. I had a charge of small shot in the gun which I carried in my hand, and, withdrawing this, I replaced it with a cartridge containing B.B. shot. By this time the serpent had uncoiled himself from his dead victim and also from the tree, and seemed to be dressing his wounds, for he was rubbing his nose, if a snake can be said to have such an organ, over the lacerations caused by the claws of the jaguar. Raising my gun and taking deliberate aim, I was about to shoot the reptile through the head, when I detected a slight rustling from the direction in which I had been travelling. Turning round suddenly, I peered through the hanging vines and leaves of the jungle, but could see nothing. Then, wiping the perspiration from my forehead and out of my eyes, I looked again carefully, but could not see anything animate.

I was about to wheel again to secure my snake when I noticed that one of the vines was swinging as if disturbed by the wind. Looking up, I saw that not a leaf was stirring on the trees; there was no breeze whatever. I thought this somewhat strange, and decided to investigate more closely. So, taking my machete out [pg 525] of the sheath, I leaned the gun against a tree and started cutting my way towards the swinging vine. I had taken but a few steps when the vine swung rapidly towards me. Then, to my intense horror, I discovered it to be another boa-constrictor, hanging from the bough of a mahogany tree, its mouth wide open.

Instinctively I screamed, ducked, and slashed savagely at it with my machete. I drew some blood from its neck, but almost before I could recover myself the creature swung viciously towards me again. I repeated my first performance, not forgetting the yell, for I was far too frightened to run. This time, however, I succeeded much better with the machete, for I inflicted a severe wound over the reptile's eye.

Again it retreated and again swung towards me, and thus we fought, I succeeding at each swing in doing my adversary some damage. Once it struck me on the left shoulder with the point of its lower jaw, sending me reeling to the ground. Wildly I sprang to my feet and dashed with renewed vigour into the struggle, cutting, slashing, and screaming continually, without presence of mind enough to run or think of my gun. Finally, in maddened desperation, I made a frantic slash as the horrible thing was swinging towards me, and by the merest good fortune caught it fairly behind the head with the sharpest and broadest part of the machete, almost severing its head from its body. Its tail uncoiled from the limb above and its sinuous body fell with a crash to the ground. A second later there was another fall—myself. I lay there trembling with weakness, fully conscious, but dripping with perspiration and too much exhausted to stand.

After some time I remembered the jaguar and the live snake which lay but a few yards away, and at once sprang to my feet, caught up my gun, and turned to investigate. I speedily discovered the reason for the snake's quiescence. The jaguar was rapidly disappearing down the capacious throat of his successful enemy. Again I took careful aim, and put the whole load of large shot fairly through the body of the snake about two feet from its head and about two inches from the nose of the jaguar, which was being swallowed whole. Having killed the snake, I secured the skin of the jaguar, which measured from tip of tail to nose nine feet four inches; it was a male, and beautifully marked. The constrictor that killed the jaguar measured twenty-nine feet two inches in length and twenty-eight inches round at the largest part. The one with which I had the encounter was twenty-five feet long and twenty-two inches round.

I reached camp about noon, covered with blood, but proudly carrying my jaguar-skin, and just for fun I informed the Spaniards that I had killed the animal with my ·22. They examined the skin for the bullet-hole, but failed to find it. Thereupon I calmly told them that I always shot animals like that in the eye, so as not to spoil the skin! They now think the "Gringo" a mighty hunter indeed.

In 1907 I was employed as a cowboy on the Wally Ranch, situated a little to the north of Fort Saskatchewan, in Alberta, Canada. It was there that an incident occurred which I shall never forget as long as I live. Such a thing has never happened before in Canada, so far as I am aware, and I hope it will never happen again.

During the particular week I have in mind we had a pretty rough time of it and were all more or less tired out, but we had to keep going. There had been some heavy storms and the cattle were unusually restive, needing a lot of attention. One Thursday, about two in the morning, we were seated round the camp fire getting something to eat. There were five of us there, amongst us a comparative new-comer named Harry Munroe. He was a splendid young fellow, and took to the work from the first. He was a capital rider and a first-class shot. I had always liked him, and used to take him with me to outlying posts on every possible occasion. On this particular night we had a mob of about two thousand five hundred head of cattle to look after. The weather outlook had been very threatening for a long time. Great clouds rolled one after the other across the face of the moon, and presently the latter disappeared behind them altogether. The next moment, without warning, the storm burst upon us. In an instant we were on our horses, everyone ready for action, for each man of us knew that at the first flash of lightning the cattle would stampede. Only those who have experienced the spectacle of a thunderstorm on the American prairies can have any idea of its grandeur. It is a magnificent display of Nature's powers for a human being who can understand and appreciate it, but a terrifying thing indeed for a herd of helpless beasts.

I thought it best to take young Munroe along with me, as he was not experienced enough in following a stampede to go alone. The three [pg 526] others were old hands and needed no directions. Very often the cattle will suddenly turn right about without any warning, and it needs an experienced and cool-headed man to keep his saddle and save his life when such a thing occurs.

We had not long to wait—only a few seconds—and then our work began. A flash of baleful light zigzagged across the skies, and the terror-stricken beasts rushed off headlong into the night. It was an appalling sight to see the fear-maddened brutes racing over the prairie. Heads upraised, mouths open, and tails lashing the air, they neither knew nor cared where they were going. Sometimes one would stumble and fall, only to be immediately trodden under foot by his comrades, and the thudding of their feet could be heard as a dull rumble in the lulls of the storm.

On and on they went in their mad career, horses and men close behind them. We could do nothing but follow them and, when the storm abated, collect them and drive them back to the station. The rain came down in torrents and the lightning almost blinded one, so vivid and terrific were the flashes, while the claps of thunder which followed seemed to shake the earth. We had been going at a tremendous pace for perhaps ten minutes, when a small range of hills loomed up in front. I knew what would happen when the cattle reached this, and was of course prepared. I yelled out to Munroe to keep close to me, so as to follow my instructions.

"The beasts will stop at these hills and either wheel round or else turn off to the right or left," I shouted.

Suddenly the whole herd stopped and, sniffing the air for a moment, seemed undetermined what course to take. At that critical moment an awful flash of lightning rent the air, completely blinding me for a moment, and simultaneously I heard a terrific report immediately behind me. These two occurrences decided the cattle, and they turned and went pell-mell along the foot of the hills to the right. For the moment I scarcely knew what had happened, but as the last of the herd disappeared I turned round and called to young Munroe. "Are you there, Harry?" I cried, but I got no answer. Again and again I shouted, riding a little distance after every shout, but no answering hail reached me. I knew Munroe would not follow the herd without me, and at length I came to the conclusion that something must be amiss with him. Perhaps his horse had stumbled and thrown him, or he had been caught and overwhelmed by the passing herd. There was nothing to be done, however, but to wait for the daylight; I dare not move in the pitch blackness for fear of trampling upon him.

Already drenched to the skin, and with the rain still pouring down in torrents, the lightning and the deafening peals of thunder combined to make that night the most miserable of my existence. I had to keep on the look-out, too, for any signs of the cattle, as they might easily, from some cause or another, return along the base of the hills.

They did not appear, however, and so I kept my watch through that awful night alone. I do not know how long the storm lasted, but it must have been two or three hours at least.

LIONEL BEAKBANE, THE COWBOY WHO HERE TELLS THE STORY OF THE TERRIBLE

FATE THAT BEFELL HIS COMPANION ON THE PRAIRIE DURING AN APPALLING THUNDERSTORM.

From a Photograph.

At last, to my infinite relief, the dawn arrived, and I looked round anxiously for some signs of Harry Munroe. I had not gone far when, at a short distance, I discerned the figures of poor Harry and his horse, lying motionless on the ground. Leaving my own horse I ran towards them. It was apparent, [pg 527] long before I reached them, that both man and horse were dead.

"Good heavens!" I involuntarily exclaimed, as I came nearer. "What has happened?" Then, suddenly, I realized the awful thing that had occurred. The lightning had struck Munroe's cartridge-belt, exploding the whole of the cartridges simultaneously, and killing man and horse on the spot. Poor Munroe! It was a terrible end; the only consolation was that it must have been instantaneous.

Shocked and saddened by this awful calamity I stayed by my dead friend, for I knew the boys would soon be coming to seek us. Then, a very quiet procession, we bore our poor comrade's body off to the ranch for burial.

By P. V. Alpiser, of the Bureau of Posts, Manila, Philippine Islands.

The traveller who has visited Japan has, as a general rule, nothing but good to say of the land and its very polite people; and as a rule, also, it may be said that such praise is well merited, for the Japanese certainly try exceedingly hard to please all visitors, and, if they do not always succeed, the fault in all probability lies with the visitors and not with the people. Unpleasant experiences rarely occur to the foreigner in the domains of the Mikado. The Japanese cities and the country are perfectly policed, and robberies are seldom heard of. However, I can testify from personal experience that one can meet with unpleasant incidents in this well-regulated kingdom.

In the early spring of 1903 I was journeying to the Philippines, and arrived in Yokohama during the latter part of April—in the midst of the cherry-blossom season, a most delightful time to visit Japan. The air was full of the agreeable aroma of the cherry blossoms, and all Yokohama was in festival attire, making a scene of great animation and gorgeousness.

On the evening of my last day, after dinner, I strolled through the main streets of the city, down gay Theatre Street, with its rows of flaunting, unreadable banners, and far out along a broad avenue across a number of oddly-constructed wooden bridges, not noticing and not caring whither I went.

My walk took me much farther than I had supposed, and when I started to return I discovered that a strong wind was blowing and a storm threatening. When about half-way back to the steamship pier I found, to my annoyance, that I had lost one of my gloves, and decided that I had left it in the small restaurant where I had had dinner—a very nice place kept by a Japanese family who had lived in Boston, Massachusetts, for a number of years, and which the doctor of our ship had highly recommended. It seemed to me that I could not be very far from this place, and I decided to call in for my glove. The restaurant was located in a side street in the curio district of the city, branching off from the main thoroughfare I was on.

When I turned down this side-street it was entirely deserted. Not a living thing was in sight and the road was absolutely and totally dark, neither the city nor the residents, apparently, providing any lights to illuminate the street. I had gone some little way down this gloomy lane when a door on the opposite side of the street suddenly burst open and two men jumped out and came running towards me. I stopped and asked them the whereabouts of the restaurant. One of them answered gruffly, and in bad English, that he did not know. I turned to go on, noting out of the tail of my eye that the men, after speaking together for a moment, followed me.

As I walked slowly away one of the pair gave a peculiar call.

It was instantly responded to by two more men, who stepped into the street from a house just behind me, and as the light from within the doorway shone upon them for a brief moment I plainly saw the glint of steel from a long knife one held in his hand.

Late that afternoon, as it happened, I had bought a heavy, curiously-carved cane as a souvenir, and, fortunately, I had this cane with me. Now, realizing that I was in a tight corner, I increased my pace somewhat, swinging the cane with the small end in my hand, and watching narrowly to prevent any one of the four from getting in front of me, or stealing upon me unawares from behind.

In another moment I saw they were preparing for a rush, and I knew that, although I might down one or two of them with my stick, the others would easily overpower me. Vainly I looked up the street; no one was to be seen! The houses on both sides were as black as pitch; there was not a light anywhere! Not even a star twinkled above, for heavy clouds obscured the sky.

For some reason it did not occur to me to call for help. In fact, I have always been a rather silent man, doing my work in the quietest manner possible, and taking my diversions in the same manner. I do not think I should have uttered a sound if these ruffians had ended my career then and there. Perhaps a cry would have brought me ready assistance from a score of adjacent houses, but it never occurred to me to give it.

I had proceeded but a short distance, always with an eye on my followers, when I saw, or felt, perhaps, that the rush was coming. I heard no sound, for the rascals were absolutely noiseless in their movements.

Hastily I jumped to the nearest house and, with my back to it, prepared to lay about with my stout stick. The four villains were right at my heels, he with the knife a little in advance of the others. A picture of the group at that moment would have made a most interesting souvenir of Japan.

I was just beginning to regret that I had not suffered the loss of my glove without protest, when the foremost scoundrel made a lunge towards me. Simultaneously, a loud ringing, clanging sound smote my ears, and the quartet disappeared from my view like magic. I am not sure now that I did not rub my eyes vigorously to see if I was awake.

The noise that had saved me proceeded from the next side-street parallel to the one I was on, and I was at a loss to account for it. It was repeated time after time, gradually growing fainter, and finally ceasing altogether.

Needless to say, I took instant advantage of the respite thus afforded me, and hurried along at my best pace. I felt sure that my late assailants would not give up their attempt so easily, and before I had gone thirty steps my fears were realized.

Glancing back nervously every few yards, I presently saw several dark shadows gliding along behind me, and I unconsciously drew over towards the opposite side of the street. As I passed very near the door of a house that protruded into the street some little way beyond the other buildings a side door burst open ahead of me and a young Jap stood in the doorway just long enough for the lamplight to strike squarely on his face and to reveal, to my surprise, the features of my rickshaw man of that very afternoon!

A low whistle sounded from behind me and the man jumped out of the door and stepped in front of me. It was quite plain to me that this rickshaw man, having seen that I carried considerable money that day, had organized this attempt to rob me, and that he was determined to succeed at any cost.

I was surrounded, but, so far as I knew, only one of the precious lot had a weapon—the man with the knife. I felt the rush again, the one in front and the two or three behind, and I jumped towards the house, but was compelled to turn before reaching it and defend myself.

My rickshaw man was the first upon me, and I had the sweet satisfaction of laying him flat on his back with a tremendous crack over the head. At the same instant, before I could turn, I felt the sharp swish of something flying past my head and heard the ripping of cloth at my side.

The man with the knife had slashed at me and had cut my clothes open from my right shoulder to my hip, but, luckily, so far as I could feel, without even scratching the skin. I swung about quickly, and as he raised his arm for another and perhaps more effective stroke brought my cane down fiercely on his arm; the knife fell to the ground with a clatter. Another of the rascals stooped to pick it up, while the rickshaw man began to sit up. It was a critical moment, but the age of miracles is not yet past!

Again that harsh, ringing clang broke through the blackness of the night, and this time from almost at my side, and a moment later into the street, a few doors away, there stepped a black figure, and brought a long steel rod down on the hard ground with a noise that sent all four of my assailants scuttling away into complete obscurity for once and all.

My rescuer was clad in a long black cloak with a sort of helmet on his head, also black, and carried a steel rod, perhaps eight feet long, to which were attached several iron rings and a long chain. He was, it appeared, a night-watchman, and as he proceeded on his rounds he struck the ground with the rod, thus announcing to all, evil-doers and righteous as well, that an arm of the law was at hand. This quaint old watchman—for he was quite old and grizzled—in his queer costume, seemed a relic of the Middle Ages; he was quite different from the regular Japanese policemen in their smart and jaunty uniform.

I stepped forward and, kicking something with my foot, stooped to see what it was, and found the knife which the would-be robbers had failed to carry off with them. The watchman silently surveyed me for a time, and then to my surprise spoke slowly in English. "You no good here!" he said; "go hotel soon!"

I lost no time in taking his advice, and in about an hour's time reached the hotel near the pier. To my intense astonishment, however, I found the doors locked. I tried for a few minutes to rouse someone, but failed entirely.

I then went to three other hotels, without better result. This consumed some time, of course, and finally, giving up in disgust, I walked back to the pier, entered the Customs House, and saw it was but a little past eleven o'clock. [pg 530] Think of it! Hotels closed, locked, and barred at 11 p.m.! This was another new experience for me; I had evidently not yet learned everything about Japan.

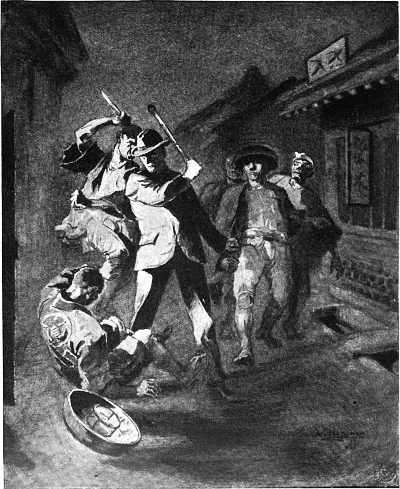

"I HAD THE SWEET SATISFACTION OF LAYING HIM FLAT ON HIS BACK WITH A TREMENDOUS CRACK OVER THE HEAD."

I then tried to get a boatman to take me out to my ship, but none would do so, all saying that a typhoon was blowing. "No can do; too much typhoon; turn boat down up!" There was nothing to be done, therefore, but to wait in a corner of the Customs House for daylight. When it came I hailed a sampan and went to the steamer, taking with me my cane and the knife—interesting souvenirs of my night's adventure.

The story of an exciting day's sport on the Athi River, British East Africa. The lions came not singly, but in troops, and no fewer than ten fell to the rifles of the party of three! The last lion, however, nearly bagged a member of the party before being killed by a plucky native.

WE were visiting British East Africa in quest of big game, and on our arrival at Mombasa at once proceeded by the railway to Stony Athi Station, taking with us a Swahili headman named Abdullah, a cook, four gun-bearers, three tent boys, and over fifty porters, who had been engaged in advance for us by one of the leading trading houses.

Soon after leaving Mombasa one gets into a very desolate thorn-bush country, which continues without intermission till one reaches Voi. After Voi one catches occasional glimpses of antelope in the thin thorn-bush, but it is not until the Capiti plains are reached that they are seen in numbers.

The vibration of the train unfortunately made the use of field-glasses impossible, but for all that we saw numbers of zebras and Grant's and Thomson's gazelle; and once we descried a rhino walking ponderously along about half a mile off. The country from here onward is similar in character, being perfectly open plain with short grass, occasionally broken by a dry watercourse, whilst on either side hills, or rather rows of kopjes, rose up in clumps. From the dak bungalow at Kia we could see Kilimanjaro, rising majestically from the flat plain and looking about four miles off instead of the seventy odd which we knew it to be. It was cold at this point, as we arrived quite early in the morning, and we were very thankful for our excellent breakfast.

We all felt rather forlorn, being dumped down on to the station platform with no one but a Babu station-master to give us advice, for we were all new at the game except Captain H——, who had done a little shikar in India. He had brought with him his sister, Miss Sybil H——, who, being a born sportswoman, was anxious to try her hand at big game.

The station-master soon fired our imaginations by telling us that five lions came to drink at a spot close by at which, as it was too late that day to go farther, we should have to camp. We got our loads carried there, and soon had the tents up. We also built roaring fires all about the camp, for, though we were very anxious to meet a lion, we did not want our first encounter to take place in the middle of the night. However, none turned up, so next day we made a march of about eight miles to Lucania, a kopje of considerable height, round which lions were said to be numerous.

Daybreak showed us a herd of hartebeeste within half a mile of us, whilst farther off were two small herds of zebra and several lots of Grant's gazelle and "Tommies," as Thomson's gazelle is usually called. They were all somewhat shy, but we each managed to bag something, Miss H—— getting two wildebeeste and Captain H——an impala.

These uncanny-looking beasts were scarce where we were at that particular time; we were told they migrated to Kilimanjaro and returned later. This certainly seemed to be correct, as later on we saw them blackening the plain quite close to Nairobi. I was with the young lady when she bagged them, and it occurred in rather a lucky way. We were sitting under a thorn-bush in a little depression, when we saw the two wildebeeste coming towards us at a trot. As they got near their movements became most threatening. After standing for a few moments surveying us they threw up their heels and, with heads down and tails waving, charged savagely straight at us. They made several stoppages in order to inspect us better, but the demonstrations grew more and more savage, and they had got within sixty yards when Miss H—— took a steady aim at the biggest and fired. He turned and rushed off at a terrific pace, the other following suit. Number one, however, had not covered more than fifty yards when he fell dead, and his comrade, pulling up to see what was happening, was killed by a second shot from Miss H——'s Mauser.

We were much elated at her success, as wildebeeste are most imposing-looking. We afterwards learnt that the apparently savage charge was nothing more than sheer curiosity concerning an object which they could not distinctly identify. Hassan, Miss H——'s gun-bearer, being a devout Mohammedan, rushed up to "chinja" the animals, their religion prescribing that unless the throat has been cut from ear to ear, and the blood allowed to flow, the meat is unclean. The Swahilis were very particular about this so long as it in no way interfered with their convenience.

The following morning we had just started breakfast when one of the porters came running in to say that whilst he was gathering firewood he had seen seven lions, including three fine maned ones. We started at once, accompanied by our gun-bearers and two Masai boys who were recommended to us to carry second guns. We were all armed alike, having Rigby's ·275 Mausers loaded with double ·450 cordite.

The plain hereabouts was broken up by watercourses, in some of which water still remained, and owing to the moisture there were some large trees and more bush marking the course than in other parts; indeed, we could tell exactly where the watercourses were by the lines of vegetation. Large beds of high reeds covered some of these depressions.

On our way to the place where the lions had been seen we had to cross a perfectly open grassy plain, intersected every now and then by small, dry watercourses. Any one of these might hold a lion, as he is an animal who likes to slink along unseen. Every donga we came to, therefore, we searched, expecting to find lions. We passed a lot of game on the way, but were afraid to fire for fear of disturbing the lions. Miss H—— was radiant at the prospect, and it required all our firmness to prevent her rushing on ahead, such was her eagerness. Personally I was also very keen to get a lion, but I had a lurking consciousness of my inexperience, which was not improved by the fearful lion stories, true and otherwise, with which we had been regaled by every man we met. Captain H—— showed no emotion of any sort. He was an old hand at meeting danger, but I could not help admiring his unmoved expression, which showed that he knew what danger was and was prepared to meet it. Miss H——, on the other hand, had forgotten all about danger, and her only thought was to get to close quarters with the utmost speed.

We were not far from the trees when we saw a lion slinking along a depression in the ground towards a clump of dry reeds, which he entered. After a council of war, it was decided that one of the men should go round and set fire to the reeds, whilst we posted ourselves as for a pheasant drive. Miss H—— was in the middle, facing the reeds, whilst Captain H—— was on her left and I was on her right. Soon the reeds were blazing high, with a noise like a waterfall. A crashing, as of a big beast coming in our direction, made our hearts beat faster, and soon out came, not a lion, but a poor little female reedbuck, followed soon after by her lord. We let them go with a shock of disappointment, not unmixed with relief.

An instant later, however, straight in front of Captain H——, a large lioness bounded across a gap in the reeds, followed by several other forms not easily distinguishable. She had evidently seen us, for immediately after the rushing sound stopped and growls succeeded, increasing in volume as the flames came nearer.

Suddenly, without the slightest warning, out rushed no fewer than seven lions, no doubt the ones the porter had previously seen. They passed between Miss H—— and myself, and appeared to be in full flight, when two lionesses, apparently attracted by the movement the young lady made in putting up her gun, turned and made straight for her. They were exactly in a line between me and her, so that I was unable to shoot. Miss H—— had not descended from a long line of soldiers for nothing. Standing up boldly, she put in three shots as they advanced. The first lioness went over like a rabbit, with a bullet in its left eye which penetrated the brain; the two other shots merely checked the second. Unable to do anything to help her, in another instant I expected to see Miss H—— hurled to the ground and worried to death by the enraged beast. But at this critical juncture her gun-bearer, Hassan, thinking matters were getting somewhat too exciting, took to his heels.

The lioness, attracted by the sight of the fleeing man, or else afraid of the fearless figure in front, who was not to be intimidated by her charge, swerved off suddenly and made after the fugitive. The man had not more than twenty yards start, and the great brute rapidly overtook him. Miss H—— fired again, and we men both fired as well, but we were not near enough to make a good running shot. The wretched man, with a courage born of desperation, turned at the last moment and hit at the lioness with his rifle. The blow fell a bit short, and the enraged brute, snapping at what came nearest, caught the weapon in her mouth at the muzzle. The pace at which she was travelling was so great that Hassan was hurled backwards, and in falling his finger caught the triggers, letting [pg 534-5] off both barrels. By the most extraordinary piece of luck the rifle was pointing straight down the beast's throat at the moment, and down she went, with her head nearly shot away, right on top of him. When we had at length hauled him out he was a deplorable-looking object, simply smothered in blood, chiefly the lioness's, for his only wounds were claw-marks on his thigh, caused by the contraction of the animal's muscles after death. These were slight, however, and as soon as Hassan realized he had, albeit accidentally, shot the lioness himself, he began to strut about in a ludicrous fashion, bragging to the other men as to what a great lion-killer he was.

Miss H——, who, in spite of the narrow escape she had had, seemed to have forgotten it already in her pride at having killed her first lioness, insisted on following up the others, who had now gone into some long grass on the open plain. We therefore advanced in line, about eighty yards apart. We had gone about a mile when my gun-bearer pointed out the top of a lion's head and ears, just visible above the grass in a hollow. We passed the word along and at once made for the place. There was a dry watercourse here, and just in front of Miss H—— along the edge of it were some big rocks. She was within fifty yards when, in the gap between the stones, she saw a head. She fired, and it disappeared. A moment later up it came again. Another shot, and again it disappeared, only to reappear a third time. Once more she pulled trigger, and then there was a veritable stampede, for a lion and five lionesses broke out of the grass, galloping in huge bounds across the plain. They passed right across my front, and my second bullet knocked over the lion as dead as a door-nail and my fourth a lioness, which I got with a lucky shot at the back of its head.

Captain H——, who had seen them coming, had kept down out of sight, for fear they should pass out of range, and they went straight towards him. On seeing him they stopped, giving him an easy shot at about forty yards. He killed one lioness, and then, taking his ·450 from his gun-bearer, took the neatest right and left I ever expect to see at the other two, who, having separated, were rushing past him at about sixty yards' distance. This made seven lions that we had seen dead, or as good as dead, and we expected to find the eighth, which Miss H—— had had three shots at. What was our amazement and delight when, after a very cautious approach to the rocks, we found not one, but three fine maned lions lying dead in a heap, a Mauser bullet through the brain of each! Two had [pg 536] light-coloured manes, whilst the other had a black one.

They must have been a different lot entirely to the other troop, and, as each one fell, the next one, excited by curiosity, must have stepped on to a slab of rock which enabled him to see through the gap in the rocks. Hence, what appeared to be the same lion was in reality a different one each time. It was an extraordinary piece of luck, as they evidently could not quite understand what Miss H—— was, as she and her gun-bearer were sitting down, and, the distance being short, she was able to make a dead shot at each.

Captain H—— had just left us to look at my two lions, when we heard a terrific growl and my apparently dead lion rose up as if unhurt and jumped at Captain H——. He did not [pg 537] spring; he simply pushed him over. The Captain had no time to do anything, and went down like a log, the impetus of the lion's movement sending him yards away. Miss H—— and I, after an instant of absolute stupefaction, rushed for our guns, which we had put down. Before we had time to shoot, however, it was all over. The Masai boy, who was following close beside Captain H——, with the splendid pluck of his race, drew his simé (a sort of sword, with all its weight at the business end) and hit the lion across the spine. The beast simply stiffened spasmodically, and before it had time to fall over the plucky Masai had sheathed his weapon in the beast's shoulder three or four times. Then we rushed up to Captain H——, who looked in a terrible plight; he was covered with blood from head to foot, and unconscious.

We had, during the chase, got nearer the railway line, and we could see a train in the distance puffing slowly up the incline towards Athi River Station. The Masai are very fine runners, so we dispatched one of them to stop the train, and proceeded to contrive some sort of a litter to carry Captain H—— in. Miss H——, with a woman's wit, at once proposed to skin a lion and use its hide. We accordingly started to rip off the skin of the very beast which had mauled him, having first propped up our coats over Captain H—— to give him a little shade. What was our joy, in the middle of our work, to hear his voice and see him sitting up, smiling as well as he could from a face that was all blood except what was dirt. He said he felt perfectly well, and could easily walk back to camp.

It appeared that he had simply been stunned by the terrific fall he had had, and that he remembered nothing more till he woke and found himself under a canopy made of our coats. On examining him, expecting to find a shattered arm, we were astounded to find he had only received some very nasty-looking gashes. The explanation of this we soon saw. My shot, which appeared to have killed the lion, had hit the beast at the base of the jaw, smashing the bone to pieces and stunning him. When he dashed at Captain H—— his lower jaw was absolutely useless, so that the upper teeth only acted as a rake instead of nut-crackers.

However, the wounds looked serious enough, for we knew that very few men recover from lion-bites, most of them dying of blood-poisoning. Captain H——, however, was able with assistance to walk very comfortably the mile which separated us from the line, and before we got to it we were met by an engineer on the railway, who had his travelling carriage attached to a goods train. He at once placed the carriage and train at our disposal, and, best of all, produced a bottle of carbolic crystals. He insisted that the carbolic should be put in undiluted, as the action of the pure acid is so rapid that it kills the tissues which it touches so quickly that no pain is felt.

Certainly this seemed to hold good, for Captain H—— took it quite calmly, and assured us he was in no great pain. We all took the train for a few miles to the point nearest our camp, when I left them. It was arranged that I was to pack up the camp and follow into Nairobi, Miss H—— and the engineer attending the patient to the hospital, where, it appeared, he would have to stay for a period, as a high temperature was by this time apparent, coupled with a feeling of extreme exhaustion, caused by reaction after his narrow escape. I had also to superintend the skinning of the lions, which Captain H——, in spite of his condition, was most anxious about. I was much relieved to hear the next day that he was going on splendidly, though still prostrated by the shock and likely to be detained in hospital for the next few weeks to get his arm healed.

The Masai boy we sent away rejoicing with a present of a cow, as well as some smaller gifts in money and kind. Cattle are the one and only form of riches amongst the Masai—except, perhaps, wives—so he was proportionately pleased, and promised to join us again as soon as we were ready to start. But we hardly expect to bag ten lions in a day again.

Twice—and twice only—the famous explorer met "Dalton," the gentleman wanderer, and he here relates the story of the two encounters and the tragic episode which finally revealed to him the man's real character.

"

GOOD-BYE, De Windt; I don't envy you the trip," were the last words that rang in my ears as the lights of Vancouver faded away in the wintry darkness.

My friends were right. Business of vital importance called me, or I should certainly not have left Vancouver at a season when the journey to Montreal is generally attended with discomfort, not to say danger. In the summertime it is pleasant enough, for the scenery outrivals that of Switzerland, and the Canadian Pacific Railway is justly noted for the perfection of its cars and cuisine. But now the passes were blocked by snow, and a train had recently been "held up" in the wild, mountainous district between Banff and Calgary. It was Christmas Eve, so that I had the cars pretty much to myself. Indeed, east of Lytton, where a party of Victorians left us to spend the New Year, the train was practically empty. We numbered, after leaving Lytton, a dozen passengers in all; none too many to dig a way through the drifts which, to judge from the steadily-falling snow, were grimly looming ahead.

The prospect of a week or more of weary travel was not inviting, and I dined the first evening unable to appreciate a dinner worthy of the Paris boulevards. The cheerless meal over, I smoked a solitary cigar in a dimly-lit and silent "smoker," and towards bedtime summoned the conductor, in sheer desperation, to share a hot grog. Afterwards I sought my couch. But the frequent stoppages due to the tempest and driving snow kept me awake—a revolver handy in case of a "hold-up"—until a cold grey dawn was peering through the window-blinds. For notes to the amount of thirty thousand dollars reposed in a note-case under my pillow, and the fact that a friend in Montreal was awaiting them did not tend to lessen my anxiety.

But fortune and the Arctic weather favoured us, for a starving wolf would scarcely have faced that blinding blizzard, let alone a train-robber. We were detained for a time by a fallen snow-shed, but we forged steadily ahead through minor difficulties, and, on the morning of the third day, steamed safely into Calgary. Here I put away my pistol with an easy mind, for open country now lay before us. The robbers who lurked in the mountains, where trackless forests on either side of the line afford an easy means of escape, were not likely to trouble us on the plains.

Dark days were now followed by a blue sky and brilliant sunshine as we rattled over the prairie, clad in a mantle of dazzling snow. The monotony of this journey can only be realized by those who, day after day, have watched the same dreary landscape unfold, as void of life and colour as the moon itself. A desert, in summer, of withered grass; in winter the scene of snow-clad desolation so wearies the eye that the sight of a ruined log-hut or a solitary crow comes as a positive relief. It was therefore some consolation when, at the little log-town of Regina, a solitary passenger entered the train.

I surveyed the new-comer with an interest engendered by three days of solitary boredom. He was middle-aged, with the clean-shaven, clear-cut face and keen grey eyes common in America, but which, upon this occasion, were clearly imported. For, although the man's appearance betrayed rough experiences, his tattered tweeds retained a certain symmetry more suggestive of Bond Street than Broadway. A "Zingari" ribbon round his shabby grey hat also hinted at the wearer's nationality, which was further proclaimed when he called in pure English for a whisky and soda. The speaker was a gentleman, as shown by his manner and certain subtle signs that denote the species all over the world. At first I put him down as a wealthy sportsman, but the usual arsenal and piles of personal baggage were missing. The traveller, whoever he was, was uncommunicative, for he drained his whisky at a draught with a sigh of relief, lay full length upon the cushions, and slept like a baby until dinner-time.

I generally mistrust the chance acquaintance on Canadian railway cars, but there was nothing of the "sport" or "bunco-steerer" about this man. At dinner we got into conversation, and the discovery of mutual acquaintances in England banished any lingering suspicions on my part; my companion was apparently glad, [pg 539] after many months of solitude, to exchange ideas with a fellow-countryman. The stranger had not seen England for seven years, during which period he had apparently tried his luck at most things—from gold at Coolgardie to rubies in Rangoon, in the lazy, desultory fashion of one to whom money is no object. His name, "Edgar Dalton," told me nothing, but the magic words, "Turf Club," in a corner of his card augured much. I expressed surprise at this lengthened and voluntary exile, but Dalton's sudden change of manner warned me that I was skating on thin ice. Domestic trouble, perhaps, or a woman, had sent him aimlessly roving over the world, and, anyhow, it was no business of mine. My eccentric friend had lately turned his attention to fur trading, he told me, and was now returning to Chicago from York Factory on Hudson Bay. The winter journey is a perilous one, but Dalton spoke of a thousand miles in a dog-sled as though it were a summer picnic. "I like roughing it," he said, frankly; "civilization bores me, and I loathe the very sight of a frock-coat!" I did not quite believe him, for the most ardent globe-trotter occasionally yearns for a sight of Piccadilly; but, anyhow, as I have said, it was no business of mine.

The evening passed pleasantly, for Dalton was excellent company, and we sat long and late over our cigars, chatting over his reminiscences, which would have filled an entire issue of The Wide World Magazine. It was only towards bedtime that a subject was broached destined to bring about strange consequences. "You say you know Milford well," said Dalton, naming a small town in Yorkshire; "did you ever meet a Mrs. W—— there?" The words were spoken with a hesitation that made me glance sharply at the speaker. Could this be the secret of his life—a hopeless passion for the beautiful woman whose sufferings had excited universal sympathy and whose love so many had sought in vain? To know Milford was to know or, at any rate, to have heard of Mary W——, who, a few years since, had figured as the innocent heroine of a notorious forgery case. The affair never reached a criminal court, for James W—— had successfully absconded with a large sum of money, and had never since been seen or heard of. Rumours were rife; some said he had gone to Australia, others that he was in the Argentine, others that suicide had wiped him out of existence as completely as a pebble dropped into the sea. And he would have been no great loss, for, according to all accounts, a more heartless scoundrel never breathed. But Mary W—— was still leading a quiet and lonely life, although she might legally have chosen a second husband from among the many men who had sought her hand. W—— I had never known, but his portrait had been freely circulated at the time of the crime, and a momentary suspicion that Dalton might himself be the man was quickly dispelled when I recalled the portly frame and bearded countenance of the forger. Not only did I know Mrs. W——, but I had, only the preceding winter, saved her life in an ice accident—a fact which raised me considerably in my fellow-traveller's estimation.

"I only asked you if you knew her," he said, "because I happened to know him. Poor beggar! He was shot last year in a gambling hell in Coolgardie."

Here the subject might have dropped, but that fleeting hours and the frequent reappearance of the conductor with refreshments revived it. There had clearly been something between Dalton and the forger's beautiful wife, either before or after her marriage. "I may tell you in confidence," were his last words that night, "that Mary W—— is and always has been very dear to me." A cloud passed over Dalton's face as he continued: "If things were different I should have been a better and a happier man. There, I won't bore you with my troubles, but here's my hand, Mr. de Windt, for saving that brave, unselfish woman's life. And remember, if ever you need a friend you'll find one in Edgar Dalton."

I was right, then, after all. This was but another victim who had worshipped vainly at the shrine of pretty Mary W——, and I wondered vaguely, as I dropped off to sleep, whether the "good angel of Milford," as she was called, had yet heard of her merciful release. For here, possibly, was a man who might bring some sunshine into her lonely life.

The next morning found Dalton seated at breakfast with a mysterious individual who had joined the train during the night. The stranger was a stout, florid man of about fifty, with shifty blue eyes, grey whiskers, and a perpetual smile. He wore a serge suit and a yachting cap, also a profusion of tawdry jewellery, and might have been anything from a prosperous drover to the skipper of a tramp steamer. The new-comer addressed Dalton as "Cap," and until the mystery was explained I marvelled at his apparent familiarity with the quiet, refined Englishman. But Mr. Hiram Knaggs, it appeared, had acted as agent in Chicago for Dalton during his northern trip, and had now met him by appointment to settle about the disposal of a consignment of valuable furs. Knaggs was a cheery, amusing fellow, notwithstanding his vulgarity and a painful habit of parading his [pg 540] wealth. At dinner that night he displayed a bulky pocket-book with which he pleasantly averred he could buy up the train and everyone in it. Encouraged, perhaps, by champagne and good fellowship, I then carelessly alluded to the comparatively modest sum that had caused me such anxiety, but a significant look from Dalton closed my lips. "Knaggs, of course, is all right," he explained afterwards, "but in a public car you can never be too careful." The incident struck me as being curious, for at the time there was no one within earshot of our table.

Dalton and his agent were leaving us at Winnipeg, and we had reached that town—then far from being the bustling city it has now become—when I awoke on the following morning. The berths lately occupied by my friends were empty, and I was surprised that Dalton, at any rate, should have left without a word of farewell. There was yet half an hour before departure, and I dressed hastily, intending to alight for a breath of fresh air. But a terrible shock was in store for me. My heart stood still and a cold sweat bedewed my temples, for when I placed my hand under the pillow it encountered only a worthless silver watch. My pocket-book and the thirty thousand dollars had gone!

I was about to call loudly for help, when a touch on the shoulder arrested me. It was Dalton, with a smile upon his face and the missing note-case in his hand.

"I was the thief," he said, quietly. "Here are your notes, but take my advice. Never talk about your money before strangers." Intense relief overcame a feeling of resentment at the trick played upon me, and, after all, was it not in my own interest? So I put my pride—and my notes—in my pocket and thanked my friend for the service he had rendered me, which I never duly appreciated until long afterwards.

On the platform we found Knaggs in a very surly frame of mind, which Dalton laughingly ascribed to overnight indulgence in "tanglefoot." [pg 541] But the joke was apparently ill-timed, for the American turned and left us with an oath, to his friend's amusement.

"Good-bye, De Windt," said the latter. "We may meet again, and if ever I can do you a turn, for Mary W——'s sake, count upon me."

Three or four months elapsed, during which period I heard nothing more of my fellow-travellers, but I received a letter from Mrs. W——, who had been informed of her husband's death by an anonymous correspondent—Dalton, no doubt. This was in the spring of 1897, however, and my mind was too much engrossed with personal affairs to give the matter much attention. A bad attack of the gold-fever then raging on the Pacific Coast had resulted in my resolve to leave Vancouver and seek a fortune in the Klondike. I need not describe the now familiar perils and privations of that ghastly voyage: the grim passes, stormy lakes, and treacherous rapids; the cold and starvation that littered the dark and dangerous road to the "Arctic El Dorado" with dead and dying victims. Suffice it to say that I eventually reached my destination, and in less than a year had "struck it rich" enough to acquire several good claims. Early in March, 1898, I returned from my claim up the Koyukuk to Dawson City, and took up my quarters at an hotel, intending to return by the first steamer to St. Michael, and thence, by the sea route, home.

The River View Hotel was not a cheerful residence, although its numerous guests were very festively inclined. The restaurant at dinner-time resembled a bear-garden, and between meals dapper New York barmen ministered to the wants of a rowdy mixture of nationalities from all ends of the earth. Time hung heavily on my hands, although there was plenty of gaiety of the disreputable kind to be found in most mining camps. Dawson swarmed with gambling and drinking saloons, but crime was rare, for the North-West Police keep a sharp eye on evildoers, especially the harpies of both sexes who fleece lucky miners. You did not need, in those days, to go to the creeks for gold, for the dust was flung about so recklessly that modest incomes were made by sweeping out the dancing halls. One night of debauchery often left wealthy men as poor as when they first started out from home without a penny. And there was some excuse for the poor prospector, coming straight from months of cold, hunger, and hard work on some lonely gulch into a crowded, brightly-lit saloon, with champagne, music, and friends galore, to say nothing of a gambling table in the background. Even I, who should have known better, was occasionally drawn into some dazzling pandemonium which, by daylight, would have sickened me to contemplate.

Thus it came to pass that I found myself one night at the Imperial Casino in company with a friend who, like myself, was heartily sick of his gloomy bedroom at the River View Hotel. The Imperial, like most of its kind, consisted of a dancing-hall leading into a smaller compartment screened with green baize, which occasionally parted to disclose a roulette table. The noise and stifling air of the first room were, as usual, unbearable, and we struggled through a rowdy crowd of men and women to the inner sanctum, where a number of players were assembled. For a time we watched the game with interest, for the high stakes would have attracted a crowd at Monte Carlo, but these ragged, mud stained gamblers lost or won their money gracefully and without the push or wrangle that often occurs on the Riviera. I have seen more fuss made over a five-franc piece at Monte Carlo than over a thousand dollars in Klondike.

To this day I don't know what induced me to fling a stake upon the table. My friend, sick of the fetid atmosphere, had left me, and I was following him, when the solitary number I had backed turned up. I then carelessly heaped my winnings on the zero and became the unwilling object of all eyes when the ivory ball jumped into the space numbered by that wicked little circle. From that moment I won without cessation, chiefly, I suppose, because of my absolute indifference to loss. In an hour I was the gainer of an enormous sum, which, consisting largely of nuggets and gold-dust, was difficult to handle. A carpet-bag was borrowed from the proprietor, by whose friendly advice I made my exit through a back door, and hastened along the snowy, silent street to my hotel. As I neared my hotel a figure stood out from the doorway of the River View, and I recognised Barlow, of the North-West Mounted Police, who a few hours previously had been my guest at dinner.

"Don't shoot, old man," said my friend, as a revolver gleamed in the moonlight; "it's only me. We have got a big job on. The safe in the office here was rifled last night, and the thief is supposed to be living in the hotel. J——, of Scotland Yard, and ten of my men are inside; so if the joker tries any games on to-night it will be all up with him. By the way, you look a bit suspicious with that bag. Gold from Gluckstein's, is it? Whew! Oh, pass in; you're a match for any hotel sneak." And with a cheery "Good night" I left my friend vainly endeavouring to keep warm in a temperature that would have tried the patience of a Polar bear.

The barrack-like building was in darkness, and by the aid of a wax match I groped my way to my bedroom, a garret for which I paid, daily, the sum of twenty dollars. The door was fitted with a cheap lock which a missing key rendered useless, but I secured my winnings, which I carefully locked up, and then retired to rest with a mind at ease, thanks to a revolver under my pillow. I must have dropped off to sleep suddenly, for when I awoke the fag-end of my candle was sputtering in the socket. The next moment it had gone out, leaving me with no matches and an unpleasant suspicion that, while I slept, someone had entered the room. Conviction followed when I heard a moving body and loudly challenged the intruder. But there was no reply.

"If you don't answer, I shoot!" I cried [pg 543] through the darkness. There is short shrift for thieves in mining camps, and the next moment I had fired at random in the direction of the sound. Simultaneously the door was thrown open with a crash and the room flooded with the light of many lanterns. J——, the Scotland Yard man, and half-a-dozen policemen were soon surrounding a prostrate figure, clad in a grey sleeping-suit, which lay with a dark crimson mark over the heart, showing where my bullet had reached its mark. Great heavens! Had I killed him?

The bare idea filled me with horror, as I pushed my way through a ring of excited men and, kneeling by the side of the wounded man, gently raised his head. The features were already twitching in the death agony, the eyes were dull and glazed, but a faint smile flickered over the face as I realized, with the appalling terror of a nightmare, that I was looking upon the features of Edgar Dalton.

"Forgive me," he gasped, faintly, as I bent closer to catch his whispered words. "I never knew it was you. Knaggs will tell you. Give her——" The hand was raised, with a last effort, towards a thin gold chain around the neck, but death arrested it half-way. Edgar Dalton, killed by my hand, had expired in my arms!

"Come, sir, we can do no good," said J——, presently, as I continued to gaze vacantly upon the ashy face of the corpse. It was borne away by six stalwart troopers through the now crowded passages and stairway. "You've no need for remorse," added the detective, "for you've rid the world of as clever and cruel a scoundrel as it's ever been my lot to come across—and I have seen a few. Why, he has murders enough on his hands in Australia alone to hang him ten times over."

"Mr. Edgar Dalton?" I asked, almost speechless with amazement.

"Is that the name you knew him by?" said the Scotland Yard man, with ill-disguised pity for my ignorance. "Edgar Dalton, indeed! Why, the Australian Government has offered a reward of one thousand pounds for this man, dead or alive, for the past three years. I have been after him for seven years as James W——, the forger, and I think I am fairly entitled to the reward," he added. "For, you see, I have netted both birds this time. There's the other"—and he pointed to a man standing handcuffed between two troopers by the open doorway. His dejected appearance contrasted oddly with a gay suit of pink pyjamas, but although the smiling lips were now screened by a bristly moustache, and a carefully-curled auburn wig concealed the scanty grey locks, I had little trouble in recognising my old friend and fellow-traveller, Mr. Hiram Knaggs.

I was permitted to visit him the next day, and found him shivering, heavily ironed, in a cold, miserable shanty known as the town jail. Knaggs made light of his discomfort and the long term of imprisonment before him, but was inconsolable at the death of his leader. "A whiter man never breathed, Mr. de Windt," said the man, with tears in his eyes; and although I knew Knaggs for a consummate villain, I could scarcely restrain a feeling of pity for the abject figure before me. Nor, indeed, could I think of the dead man without compunction, for I could not forget the feeling of gratitude that had prompted him to save my notes from the greedy grasp of his confederate.

"He always spoke well of you," said the man, "and if he'd only known last night that the swag was yours he'd have been alive now. But I suppose the game was up, anyhow, with that J—— on our tracks."

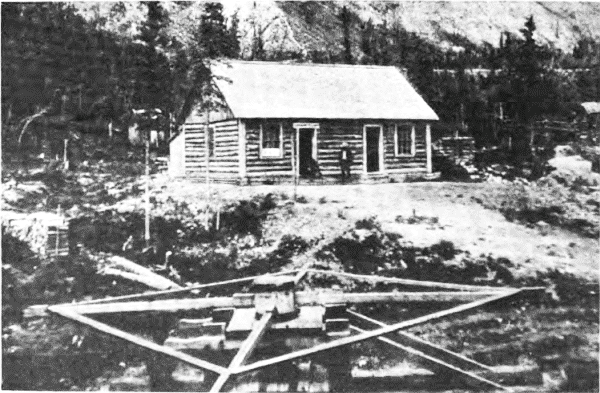

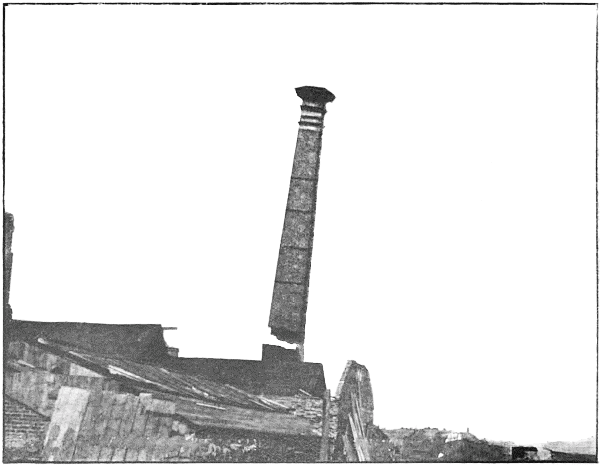

A FORM OF PUNISHMENT FOR CRIMINALS USED IN THE KLONDIKE AND KNOWN AS THE "WOOD-PILE."

From a Photograph.

And Hiram ground his teeth in silent rage as I left him—to be eventually sentenced to ten years "on the wood-pile," a local form of punishment which, owing to the Arctic climate, is seldom endured for long.

I was permitted to retain the gold chain and medallion, which contained a faded portrait of W——'s wife. Mary W—— still wears the little locket in memory of the worthless scamp who wrecked her life, but who, nevertheless, had loved her in his own wild way.

After six weeks of conventional sight-seeing in Japan the authoress and her friend decided that they had not yet seen the real thing, and so they decided to spend a week off the tourist track, living as far as possible the life of the natives. This amusing little article shows how they fared during their pilgrimage.

GLADYS and I had been six weeks in Japan; we had worked hard at sight-seeing, and done all that was expected of us during that time, and yet we were not satisfied. Why? Well, we had luxuriated all the while in the most charming European hotels; we had slept in cosy beds with soft, springy mattresses; we had lounged in easy-chairs, eaten with knives and forks, and had been waited on hand and foot by noiseless Japanese "boys," who anticipated our every want. Within a week of our departure for Australia the full extent of our slackness was borne in upon us, and we at once decided to make up for lost time and to sacrifice personal comfort in a final effort to "see" Japan—the real Japan.

A trip down the Inland Sea was arranged, as affording a suitable opportunity to carry out our resolves, and one bright spring morning we set off from Kobe, armed with a basket of provisions and eating utensils—to be used only in case of dire necessity!

We travelled all day in an up-to-date, conventional train, and arrived at Onomichi towards evening. The proprietor of the principal inn had been informed of our intended arrival, so he came in person to meet us at the station, and we set off on foot for our new abode with an escort of some twenty to thirty of the inhabitants.

The "hotel" was a two-storeyed, wooden house, like most of its fellows. On reaching the threshold we discarded our shoes, took a surreptitious peep at our stockings, in order to assure ourselves that no holes were visible, and boldly entered.

A hearty—but unintelligible—welcome was extended to us by "madame" and her surrounding bevy of profusely-bowing attendants, and we were ushered into a room on the first floor which had been set aside for our use.

Our apartment was divided from the adjoining one by sliding panels which made no pretence at reaching the ceiling; it was entirely destitute of furniture, but at one side was a tiny alcove where a single vase reposed upon a raised dais, while hanging on the wall at the back was an elaborate "kakimono." The floor was covered with fine matting, and the inner walls were made of opaque white paper divided into diminutive squares. Round the outside of the house ran a tiny veranda, which was closed in at night with wooden panels.

Previously to starting Gladys and I had thoroughly primed ourselves as to the correct behaviour in Japanese circles, and as we knew that we should be expected to take a hot bath immediately on arrival we inquired at once for the bathroom. Another reason for not wishing to delay the important function of bathing sprang from our vague fear that every member of the household would perform his ablutions in the same water, and we were naturally anxious to have the first "look in."

After inspecting the bathroom our determination wavered,—but we pulled ourselves together and descended to the lower regions armed with towels and wrappers. Our first difficulty was with the entrance-panel, which, in addition to having no locks or bolts, absolutely refused to close properly. After several vain attempts the gap was eventually stuffed up, and we entered the dressing-room. I have yet to discover the intended use of the latter apartment, as for all the privacy it provided one might just as well have undressed in the public passage. About three yards square, and communicating with the bathroom, it was furnished with two large windows looking on to the hall, and there was not even so much as a pane of glass to obstruct the view of the passers-by. Gladys and I spent a considerable time in carefully filling these openings, and then, having satisfied ourselves that we were beyond the public gaze at last, we began, very diffidently, to undress, and afterwards entered the bathroom together, as we simply dared not venture in alone.

The bath itself—which looked like a large box—was a wooden structure built into a corner, and all round the inside ran a convenient ledge, for sitting on. The water being little short of boiling, our movements were decidedly cautious, and, curling ourselves up on the ledge, we tried to grow accustomed to the temperature by degrees before plunging right in. When, thinking to remove the traces of our journey by a vigorous application of soap, we began to scrub ourselves, it suddenly occurred to us that such a proceeding was not "etiquette," out of consideration [pg 546] to the other bathers. So we stepped out, soaped ourselves well, and rinsed our bodies with the wooden ladles supplied for the purpose, before getting back into the water again.

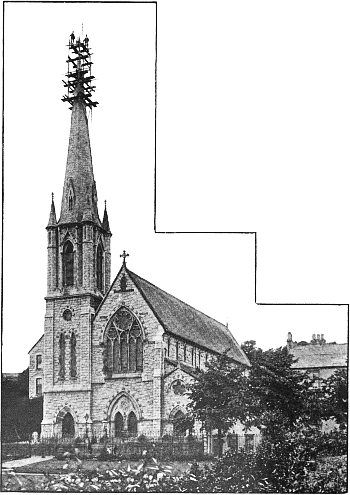

A GLIMPSE OF THE SITTING-ROOM, WITH ITS SPOTLESSLY-CLEAN FLOOR, SLIDING DOORWAYS, AND PAPER WALLS.

From a Photograph.

We were sitting on the ledge, chatting peacefully, when a sudden premonition of danger made me look up, and the spectacle which greeted my eyes caused me to utter one agonized gasp and then sink rapidly out of sight. The pains we had taken to block up the gap at the entrance had all been in vain, for the various garments which we had used for the purpose lay scattered on the floor, and the opening was occupied by a line of little heads, one above the other, whilst ten gleaming eyes were interestedly fixed upon us! Having followed the direction of my horrified gaze, Gladys gave a shriek of dismay and joined me at the bottom of the bath with surprising celerity; and there we remained in agony, feeling as though we were being boiled alive, and gazing ruefully at our garments, which all lay well out of reach. Help came at length in the shape of the proprietor, who, lighting upon the little group of spectators, immediately sent them off about their business. Feeble and helpless, we eventually emerged from our retreat and retired behind our towels to dry; but our trials were not yet over, for Gladys, leaning too heavily against the flimsy framework which constituted the partition wall, suddenly disappeared from sight, and the whole wall with her! Fortunately, the only occupant of the passage at that moment was a little maid-servant, who speedily rushed to her assistance, and the damage was soon repaired. Feeling much shattered in mind, we at length departed from the scene of our disasters and returned to our own apartment. With the help of two merry little "nésans," who thoroughly enjoyed the proceedings, we succeeded in donning kimonos and obis more or less after the correct manner, and then, determined to carry out the programme quite properly, we sat down on our heels to partake of our evening meal before a table three inches high. We drank fish soup out of lacquer bowls, we dissected unfamiliar concoctions with chopsticks (no easy matter) and tried manfully to do our duty by them, but when a large bowl of rice made its appearance we flung etiquette—and chopsticks—to the winds and fell back upon spoons, as being the only way of ensuring ourselves anything to eat. Also, when we were certain of being unobserved (as certain as it is possible to be in a land of paper walls and sliding panels), we hastily demolished huge chunks of bread from our [pg 547] private provision store, as, though we did not wish to hurt the feelings of the "chef," we felt that our inward cravings must have something substantial to satisfy them.

After dinner we ventured on a stroll through the town; but the fact that we were repeatedly obliged to retrace our steps in order to pick up our sandals—which showed an extraordinary facility for parting company with our feet—considerably hindered our progress, and the close companionship of many of the inhabitants, who were vastly interested in us, prevented us from gaining a very good view of the streets.

When we returned to our abode the little maids made us up beds on the floor out of "futans" (thick quilts) which were pulled forth from wonderfully hidden cupboards, and we retired to rest, thoroughly wearied out by our first day of Japanese life.

The next morning we were awakened early by the arrival of green tea in baby cups with no handles, and big, luscious peppermint creams. After tasting both, and appreciating the latter, we rose to dress. Our landlord had entertained European visitors before and considered that he was thoroughly acquainted with their habits, as well as knowing how to provide for their comfort; consequently, the pride of his heart was a wash-stand—which was an object of wonderment to the whole household—and that useful article of furniture was placed on the outer veranda, in full view of the main street! It went to our hearts to hurt the feelings of "mine host," but in this case we felt it to be unavoidable, and the household treasure was removed to a more secluded spot before we performed our ablutions.

Later in the morning we took steamer to Myajima, and sailed all day down the beautiful Inland Sea. There were no seats on board, so we made ourselves comfortable on a big coil of rope, and as there was also no buffet we were obliged to picnic for our meals. We reached Myajima at dusk and halted in mid-stream. A sampan came out to take us on shore, and we were hauled down the side of the steamer by a piece of rope, swaying feebly about in mid-air before being unceremoniously seized by the feet and deposited in safety.

As we crashed on to the pebble beach a number of girls came round from the hotel to meet us, each one carrying a paper lantern, which waved fantastically to and fro from the end of a long pole. We were escorted by them round the narrow, winding path to our quarters, which consisted this time of a little summer-house away from the main building of the hotel and in the midst of a delightful wood. We were too tired to examine our surroundings that night, and tumbled as soon as possible on to our lowly couches, where we slept "the sleep of the just."

On opening our eyes next morning our first thought was that we had wandered into fairy-land; the smiling-faced "nésan" had arrived during our slumbers and pulled back the outer wooden shutters, and as one of the inner panels was ajar we could look straight out on to the [pg 548] woods. The sun was shining brightly through the green of the trees, a spring of clear water trickled musically down by the side of our hut, and but a few hundred yards away lay the Inland Sea itself, looking like a huge lake amidst the surrounding chain of misty, blue-grey mountains.

Our tiny habitation, which consisted of two compartments and a small veranda only, was scrupulously clean, and we could have eaten off the floor, as well as sit on it, without the least misgiving.

Every morning we interviewed the landlord on the subject of our day's menu, as, after the first evening, we decided that a strictly Japanese diet would not be conducive to either strength or comfort. There was not much variety in the food which we managed to obtain, but it was both healthy and harmless, consisting chiefly of fried fish, omelettes, and wild strawberries.

Myajima is a sacred island, and no means of conveyance are allowed to profane its shores. The temple is built out into the sea, a unique specimen of its kind, and a great, dark torü rises from the water some yards in front; all along the main coast, and built at irregular intervals, are the sacred stone lanterns, five hundred in number.

For three days we spent our time in wandering about the island, swimming, lounging on our tiny veranda, and darning, European stockings being scarcely equal to Japanese "tabi" in the matter of endurance. The third evening being beautifully fine and calm, we arranged—by paying a very modest sum—to have all the five hundred lanterns lit up for our benefit, and rowed out in a sampan to see the effect from the water. Nature seemed to be at her devotions, and such a wonderful hush spread over all around that the scene was impressive as well as beautiful.

On the fourth day it began to rain. A Japanese inn does not exactly lend itself to either comfort or amusement in wet weather, our stock of literature was limited, and by midday we were at our wits' end. And still it rained.

Finally, in desperation, we invested in brilliantly-coloured oil-paper Japanese umbrellas, and wandered about holding these huge structures over our heads, so that only our feet—mounted on high, wet-weather "geta"—were visible. Still it rained, and rained unceasingly. On the evening of the fifth day—the deluge showing no signs of abatement—we packed up our baggage and sorrowfully departed, taking our seats in the evening express for Kobe, after a damp passage across to the mainland in a sampan.

The train was crowded with Japanese, and as each person was accompanied by at least four mysterious and peculiar-shaped bundles there was not much room to spare, and before long I had a pile of "luggage" two yards high in front of me. When some of the little ladies in the carriage with us grew tired of sitting up in European fashion they slipped off their sandals and climbed right on to the seat, where they sat comfortably on their heels and were happy at last.

When night came the long seat was divided up into portions, the upper berths were pulled down, and we all huddled into our respective bunks, men and women mixed up together. It was distinctly trying to be obliged to hoist oneself up into a high upper berth before a mixed assembly, and more trying still to descend in the morning with the very incomplete toilet which one was enabled to make in a reclining position, but the blissful ignorance of our Japanese neighbour that there was anything unusual in such a proceeding considerably relieved our embarrassment. His attitude and calm matter-of-factness was very reassuring, and the wonderfully cheerful conductor who brushed our clothes and fastened our blouses seemed to consider himself specially suited for the post of lady's-maid.

We arrived back at our hotel in Kobe feeling that for the first time in our existence we had really seen life in a different aspect, and a few days later we left Japan with a clear conscience, satisfied that we had fully accomplished our duty, as well as considerably added to our experiences.

By John Mackie.

The story of an eventful journey in the Australian bush, with hostile blacks on the track. Mr. Mackie got through, but the passage of the last creek was a distinctly touch-and-go affair.