CHEYNE

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Historians' History of the World in

Twenty-Five Volumes, Volume 2, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Historians' History of the World in Twenty-Five Volumes, Volume 2

Israel, India, Persia, Phoenicia, Minor Nations of Western Asia

Author: Various

Editor: Henry Smith Williams

Release Date: May 28, 2016 [EBook #52177]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTOIANS' HISTORY ***

Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: As a result of editorial shortcomings in the original, some reference letters in the text don’t have matching entries in the reference-lists, and vice versa.

CHEYNE

THE HISTORIANS’

HISTORY

OF THE WORLD

A comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations

as recorded by over two thousand of the great writers of

all ages: edited, with the assistance of a distinguished

board of advisers and contributors,

by

HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS, LL.D.

IN TWENTY-FIVE VOLUMES

VOLUME II—ISRAEL, INDIA, PERSIA, PHOENICIA,

MINOR NATIONS OF WESTERN ASIA

The Outlook Company

New York

The History Association

London

1905

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

THE TROW PRESS

201-213 E. 12TH ST.

NEW YORK

U. S. A.

| VOLUME II | |

| PART IV. ISRAEL | |

| PAGE | |

| Introductory Essay. Israel as a World Influence. By Bernhard Stade | 1 |

| A Critical Survey of the Scope and Sources of Israelitic History to the Destruction of Jerusalem | 4 |

| Hebrew History in Outline (1180 B.C.-70 A.D.) | 30 |

| CHAPTER I | |

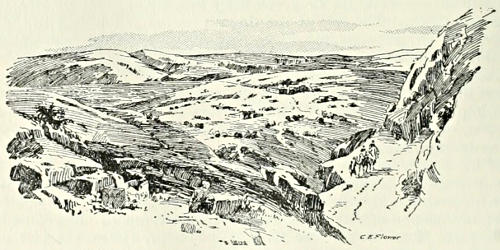

| Land and People | 45 |

| The land, 46. The people, 48. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Origin and Early History (2300-1200 B.C.) | 56 |

| The age of the patriarchs, 57. Early movements of the Israelites, 57. The Egyptian sojourn, 58. Biblical account of Moses and the Exodus, 61. Israel’s early neighbours, 63. The conquest of Canaan, 66. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Judges (1200-1020 B.C.) | 72 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Samuel and Saul (1020 B.C.-1002 B.C.) | 77 |

| Samuel and Saul, 78. The rise of David, 79. David in revolt against Saul, 80. The death of Saul and the struggle for the succession, 83. David secures the crown, 85. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| David’s Reign (1002-970 B.C.) | 86 |

| David’s greatness in time of peace, 89. Further wars break out, 91. David and [viii]Absalom, 93. Renan’s estimate of David, 98. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Solomon in his Glory (970-930 B.C.) | 99 |

| The early years of Solomon’s reign, 100. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Decay and Captivity (930-586 B.C.) | 106 |

| The schism of the Ten Tribes, 106. The Moabite stone, 109. Destruction of the two kingdoms, 113. The Babylonian Captivity, 118. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Return from Captivity (586-415 B.C.) | 122 |

| The prophecy of the return, 122. The condition of the exiles, 125. The coming of Cyrus, 126. The return to Jerusalem, 127. The walls upraised again, 130. | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| From Nehemiah to Antiochus (415-166 B.C.) | 133 |

| Under Persian rule, 133. Persian influences on Jewish religion, 134. Alexander the Great, 134. Under the Seleucids, 135. The Syrian dominion; Antiochus the Great, 138. Antiochus Epiphanes, 139. Jason and Antiochus torment the people, 140. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The Maccabæan War (166-142 B.C.) | 147 |

| Independence, 156. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| From the Maccabees to the Romans (135-4 B.C.) | 159 |

| The warring sects, 160. Antipater, 163. Herod, 164. | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| The Rise of Christianity (4 B.C.-62 A.D.) | 168 |

| A critical view of Christ and other messiahs, 168. The development of the messianic idea, 169. | |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

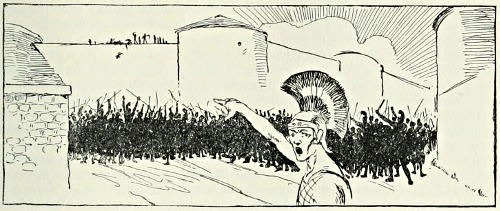

| The Revolt against Rome (62-68 A.D.) | 177 |

| [ix]The defence of Jotapata described by Josephus, 180. | |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| The Fall of Jerusalem (68-73 A.D.) | 190 |

| Josephus’ account of the famine, 193. The close of Jewish history, 199. | |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Hebrew Civilisation | 203 |

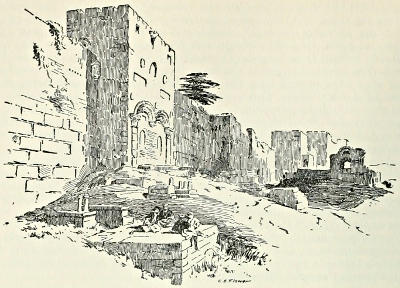

| The life and customs of the Israelites, 205. Hebrew art, architecture: the temple tombs, etc., 209. | |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| The Prophets and the History of Semitic Style. By Dr. D. H. Müller | 213 |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 227 |

| A General Bibliography of the History of Israel | 229 |

| PART V. PHŒNICIA | |

| Introductory Essay. Individuality of Phœnician History, and Origin of the Name. By Richard Pietschmann | 243 |

| Phœnician History in Outline (3800 B.C.-1516 A.D.) | 246 |

| Carthaginian History in Outline (813 B.C.-697 A.D.) | 251 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Land and People | 255 |

| Origin of the Phœnicians, 259. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Early History and Influences | 263 |

| Beginnings of the history and civilisation of Phœnicia, 263. The colonies, 270. Voyages and trading-stations, 274. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Phœnician Time of Power (980-532 B.C.) | 279 |

| The reign of Hiram I, 279. The successors of Hiram, 283. | |

| [x]CHAPTER IV | |

| Phœnicia under the Persians (525-323 B.C.) | 289 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Phœnicia under the Greeks, the Romans, and the Saracens (301 B.C.-1516 A.D.) | 301 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Story of Carthage (813 B.C.-697 A.D.) | 308 |

| The site and early history of Carthage, 310. Mommsen’s account of Carthage, 312. War in Sicily between Rome and Carthage, 319. Rome and Carthage, 321. Last days of Carthage, 325. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Phœnician Commerce | 329 |

| Sea trade, 330. Manufactures and land trade of the Phœnicians, 334. Silver and gold in antiquity as money, 339. The slave trade of Phœnicia, 342. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Phœnician Civilisation | 346 |

| The Phœnicians and the alphabet, 347. Manners and customs; religion, 348. Culture; art, 352. The Phœnician influence on history, 353. | |

| APPENDIX A | |

| Classical Traditions | 356 |

| “The voyage of Hanno, beyond the pillars of Hercules, which he deposited in the temple of Saturn,” 356. Himilco’s voyage of discovery, 358. Pomponius Mela on the Phœnicians, 359. Appianus Alexandrinus on the founding of Carthage by Dido, 360. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 361 |

| A General Bibliography of Phœnician History | 363 |

| PART VI. WESTERN ASIA | |

| Introductory Essay. The Position of Asia Minor in History. By William J. Hamilton | 373 |

| History in Outline of the Minor Kingdoms of Western Asia (1528-546 B.C.) | 380 |

| CHAPTER I | |

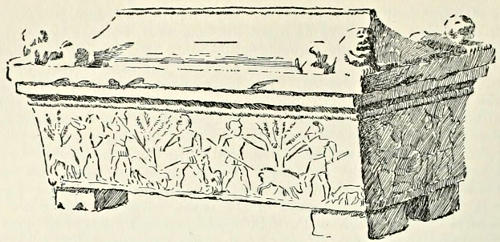

| The Hittites | 391 |

| Recent Hittite research, 393. The Hittites and the Egyptians, 394. The Hittites [xi]and the Hebrews, 395. Hittite art, 396. Hittite monuments in Asia Minor, 397. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Scythians and Cimmerians | 400 |

| The Scythians, 400. Scythian influences in Asia Minor, 400. Scythian movements, 401. Herodotus on the customs of the Scythians, 404. The Cimmerians, 410. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Some Peoples of Syria, Asia Minor, and Armenia | 413 |

| The Aramæans, 413. Phrygia, 413. The Cappadocians, 415. The Cilicians, 416. Pamphylia and Pisidia, 416. The Carians, 417. The Lycians, 417. The Mysians, 419. The Bithynians and the Paphlagonians, 419. Armenia, 420. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Lydians | 421 |

| The land, 422. The people, 423. Sardis and the name of Asia, 424. Early history of Lydia, 426. Ardys, 427. Early dynasties, 429. Gyges, 430. The triumph of Persia, 431. Lydian civilisation, 433. A picture of life in Lydia, 434. | |

| APPENDIX A | |

| Classical Traditions | 438 |

| Justin’s account of the Scythians and the Amazons, 438. Pomponius Mela on the Scythians and other tribes, 441. Diodorus on the Amazons and the Hyperboreans, 444. Herodotus on the legendary Gyges, 446. The story of Crœsus as told by Herodotus, 448. Crœsus and Solon, 449. The vision of Crœsus, 451. Crœsus loses his son, 453. Crœsus consults the oracles, 454. The reply of the oracles, 455. Crœsus makes an alliance with Sparta, 456. Crœsus invades Cappadocia, 457. Crœsus in conflict with Cyrus, 458. The siege of Sardis, 460. The fate of Crœsus, 460. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 464 |

| A General Bibliography of the History of the Minor Nations of Western Asia | 465 |

| PART VII. ANCIENT INDIA | |

| Indian History in Outline (2000 B.C.-1556 A.D.) | 475 |

| Græco-Bactrian dominion in the Indus region, 480. | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Land and People | 482 |

| [xii]The land, 484. The early peoples of India, 488. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Indian History—Legend and Reality | 493 |

| Chronology and ancient history of the Hindus, 493. The authority of the Vedas, 496. Monumental records, 496. Legends of the early heroes, 498. An inscription of Asoka, 499. Traditional kings, 500. Brahmanic learning, 501. The epochs of Indian history, 502. Vedic period, 503. The Buddhist period, 503. Chandra Gupta, 504. Twelve centuries of obscurity, 505. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Manners and Customs of the Ancient Hindus | 508 |

| Division and employment of classes, 508. The property of the Brahman, 510. The despised Sudra, 511. Mixture of classes, 513. The administration of justice, 515. Criminal law, 516. Civil law, 517. Hindu commerce, 519. Precious metals, 520. Coinage; precious stones; weaving, 520. Intoxicants; spices; perfumery, 521. Commercial routes, 523. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Brahmanism and Buddhism | 525 |

| The origin and development of Brahmanism, 525. The Vedas, 529. Soul transmigration, 533. Buddhism, 535. Disappearance of Buddhism in India, 538. New light on Buddhism, 542. The actual piety of the Hindus and the Hindu separation of religion from fine morals, 545. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 549 |

| A General Bibliography of Indian History | 550 |

| PART VIII. ANCIENT PERSIA | |

| Persian History in Outline (700-330 B.C.) | 559 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Land and People | 565 |

| Racial and dynastic origins, 567. The land, 568. The people, 569. Character of the empire of the Achæmenides, 570. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Median or Scythian Empire (700-550 B.C.) | 573 |

| The rise and fall of the Median Empire according to Herodotus, 573. The [xiii]Median Empire: a modern interpretation, 580. New light on the Medes, 583. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

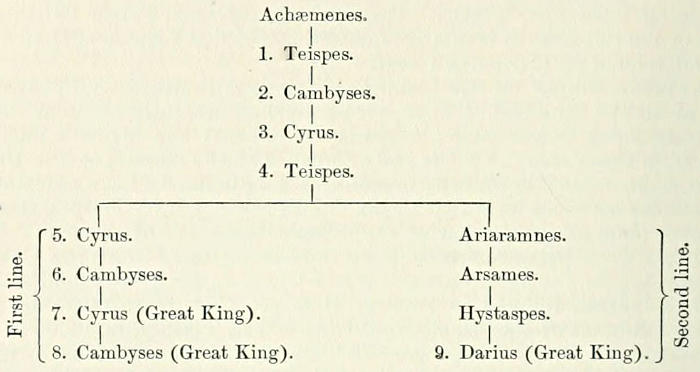

| The Early Achæmenians and the Elamites, Cyrus and Cambyses (836-522 B.C.) | 587 |

| The death of Cyrus, 593. Character and influence of Cyrus, 596. Xenophon’s estimate of Cyrus, 596. A modern estimate of the character and importance of Cyrus, 597. Cambyses, 600. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

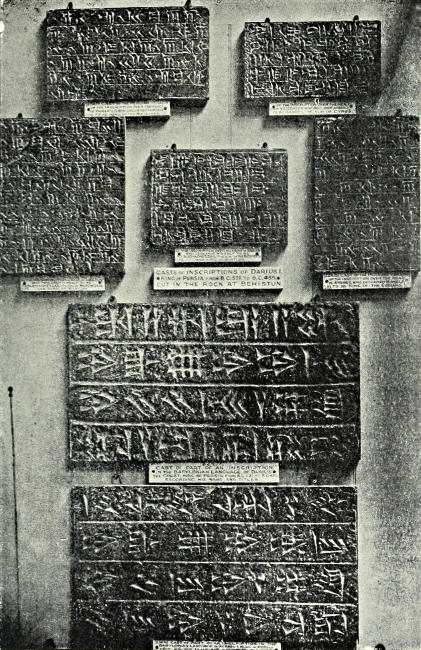

| The Persian Dynasty: Darius I to Darius III (521-330 B.C.) | 605 |

| Darius I, 605. Organisation of Darius’ empire, 607. Later conquests of Darius, 609. Affairs in Egypt since the Persian conquest, 611. Xerxes I, 614. The successors of Xerxes, 615. Darius II, 618. Artaxerxes II, 619. Artaxerxes III, 626. The fall of the empire, 630. The old Orient at the end of the Persian Empire, 631. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

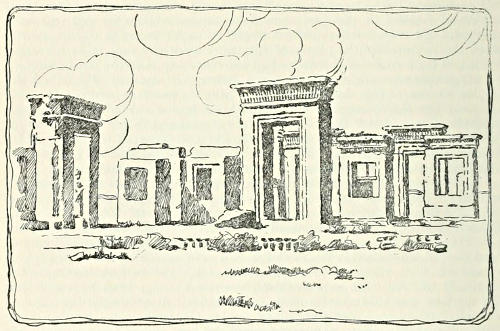

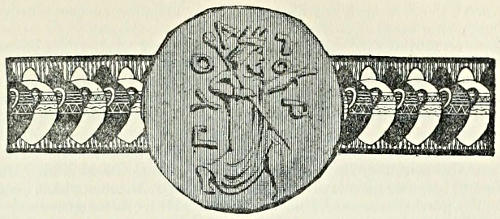

| Persian Civilisation | 634 |

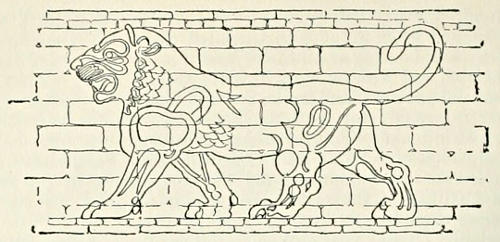

| Religion and social orders, 635. Organisation of the Persian court, 641. Administration of the provinces; financial system; satraps, 645. Military methods, 652. The fine arts, 657. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 662 |

| A General Bibliography of Persian History | 663 |

PART IV

THE HISTORY OF ISRAEL

BASED CHIEFLY UPON THE FOLLOWING AUTHORITIES

ERNEST BABELON, THE HOLY BIBLE, T. K. CHEYNE, MAX DUNCKER,

G. H. A. EWALD, EDWARD GIBBON, F. HITZIG, J. JAHN,

FLAVIUS JOSEPHUS, RUDOLF KITTEL, E. LEDRAIN,

MAX LÖHR, L. MÉNARD, H. H. MILMAN, D. H.

MÜLLER, SALOMON MUNK, F. W. NEWMAN,

E. RENAN, A. H. SAYCE, GEORGE

SMITH, BERNHARD STADE

TOGETHER WITH AN INTRODUCTORY ESSAY ON

ISRAEL AS A WORLD INFLUENCE

BY

BERNHARD STADE

A CRITICAL SURVEY OF THE SCOPE AND SOURCES OF

ISRAELITIC HISTORY

BY

THOMAS KELLY CHEYNE

AND A STUDY OF

THE PROPHETS AND THE HISTORY OF SEMITIC STYLE

BY

DAVID HEINRICH MÜLLER

AND WITH ADDITIONAL CITATIONS FROM

THE APOCRYPHA, DAVID CASSEL, DION CASSIUS, J. G. EICHHORN, G. W. F.

HEGEL, JUSTIN, F. R. LAMENNAIS, GASTON C. C. MASPERO, FELIX

PERLES, T. G. PINCHES, POLYBIUS, EDUARD REUSS, CLEMENS

ROMANUS, ASARJA DE ROSSI, BARUCH SPINOZA,

STRABO, SUETONIUS, CORNELIUS TACITUS,

COMTE DE VOLNEY, GEORG WEBER,

R. T. M. WEHOFER,

J. ZENNER

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

By BERNHARD STADE

Translated for the present work from Geschichte des Volks Israel.

Many a nation has walked God’s earth, has long enjoyed its good things, has come into being and passed away, without our knowing anything of its history, or even whether it had a history at all. For no nation has a history except one that makes history, that is to say, that influences the course of human development. It is with races as with individuals; none is kept in mind by posterity save those who have distinguished themselves by ideas that have modified the life of mankind, or (which comes to the same thing) have been pioneers in fresh fields of action. The greater the spiritual gain a nation has brought to the rest of the world, the longer and more steadily its life has flowed in the channels it was the first to make, the longer is its history told among them. The nations of history are those which have put forward, in one fashion or another, their claim to the dominion of the world.

Thus we may fitly ask what claim it is that is made upon our interest by the history of the Jewish nation. And the answer will be, that nothing which excites our attention, or stirs us to admiration or imitation in the history of other nations, is here present in any large measure. Israel was always a small, nay, a petty nation, settled in a narrow space, never of any considerable importance in the political history of the East; it never brought forth a Ramses II, a Sargon, an Esarhaddon, an Asshurbanapal, a Nebuchadrezzar, or a Cyrus to bear its banner into distant lands. Yet, for all this, the history of Israel has, for us, an interest quite different from that of those other nations of antiquity.

And if, as we see, Israel is far surpassed in martial glory by the peoples of the great empires, and by the Romans in their influence on the development of law, there are yet other points in which it must yield unquestioned precedence to other nations of antiquity. We do not find in Israel the same feeling for beauty as among the Greeks, who, like no nation before them or after, showed forth the laws of beauty in every sphere of intellectual life, and to this day, in such matters, stand forth in a perfection which has never again been attained, far less excelled. Among the Hebrews there is nothing analogous, nothing comparable to what we admire in the Hellenic people. It has no epic, nothing that can be compared with the Iliad and the Odyssey, against which the Germans set the Nibelungen Lied, and the Finns the Kalewala; it has not the slightest rudiments of a drama—the Song of Songs and Job are not dramas. There is a school of lyrical poetry unsurpassed for all time, and the music that corresponds to it. But the bent towards science, which actuates the Greeks, is wholly lacking—wholly lacking the bent towards[2] philosophy. Nor was it ever eminent in ancient days, in the walks of commerce, enterprise and invention, by which, also, a nation may conquer the world; its intellectual life is absolutely one-sided, a one-sidedness that produces on us the effect of extreme singularity.

But the attraction it has for us does not lie in this singularity. It is due, rather, to the circumstance that this small nation has exerted a far greater influence over the course of the history of the whole human race than the Greeks or Romans, that to us it has become typical in many more respects than they. Our present modes of thought and feeling, our lives and actions, are far more profoundly influenced by the world of thought and feeling which Israel brought to the birth, than by that of Greece or Rome. Our whole civilisation to-day is saturated with tendencies and impulses which have their origin in Israel.

The reason for this is that in Israel one side of human nature had developed to a very high perfection, a side which is of far greater consequence to mankind in general than art or science, law or philosophy. While in Hellas, philosophy first, and then, indirectly, science, developed out of mythology, in Israel the age of mythology was succeeded by that of religion. And we may say that the religion of Israel is still the active religion of mankind in a far higher degree than the philosophy of the Greeks is still its active philosophy. What Israel did in the sphere of religion is without a doubt far more epoch-making, unique, and effective than what the Romans did in the sphere of politics, or the Greeks in that of art or science. As Israel assumed the leadership of the human race in religion, so Rome did in matters of government, and Greece in questions of philosophy; but while the civilised nations which adopted Roman law strove with increasing energy to free themselves from the band of Roman legal conceptions; while the relics of Greek art and science only roused the enthusiasm of a chosen few, and the philosophy which the Greeks had created was confined within ever-narrowing limits by religion on the one hand, and the ever-widening field of science on the other; religion embraces all classes of the people, from the king to the beggar, and strives more and more to embrace all the nations upon earth. Moreover, however men may shut their eyes to the fact, among ourselves to-day religion is a subject of far more universal interest than art, science, or any political institution whatsoever. Disputed questions of religion shake kingdoms and kindle the most sanguinary wars. By this means it changes the character of nations and brings forth new national types. The spiritual features of mankind at the present time, under Mohammedan and European civilisation alike, are substantially the product of the monotheistic religion that arose in Israel.

We cannot find a more striking example of the effect of Israelitish ideas on mankind nowadays than by recalling the importance of the religious figures of ancient Israel in the eyes of our own people. For the bulk of the nation, Biblical history stands for all the history there is. The populace knows more about Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, about Saul, David, and Solomon, about Samuel and Elijah, than about the heroes of its own history, and feels them (in marked contrast with its sentiments towards their posterity, which it beholds with the eyes of the body and not with the eyes of the spirit) to be flesh of its flesh and bone of its bone. In this respect our own nation is thoroughly Hebraised, or, if you prefer it, Semiticised.

And this is even more strikingly the case with nations which have adopted the creed of Islam. In the eyes of Mohammedans, Abraham was a Mohammedan; through Ishmael, his first-born and rightful heir, he is the[3] progenitor of the People of the Revelation; in their eyes all the religious figures of Israel of old are Mohammedan saints.

Thus the importance of Israel in the history of mankind, and, consequently, our interest in its own history, is due to the leading part it took in the sphere of religion. In Israel, indeed, religion—or, as most people prefer to express it, monotheism—first came into being. Let not the reader misunderstand the latter word. The monotheism of Israel is not the acknowledgment that there is but one Supreme Being. That is not a religious but a philosophical idea. The God of the Israel of old is not to be defined as the sole, supreme, and absolutely perfect being, but as the Not-World, or, better still, as the sum of all forces present and active in the world conceived of apart from the substratum through which they are manifest in phenomena. Hence the God of Israel of old is simply the Mighty One. But in the eyes of the Israelite of old the world was no wider than the land that nourished him. For this reason the God of ancient Israel is the God of the Land of Israel, and the actual existence of the gods of other nations is not denied. They exercise in the lands of other nations the same sway as Israel’s God in the world of Israel.

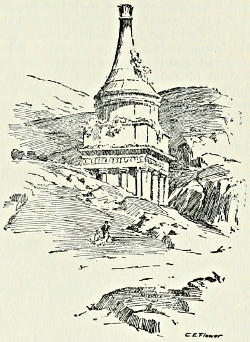

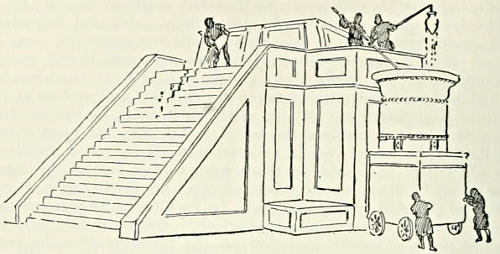

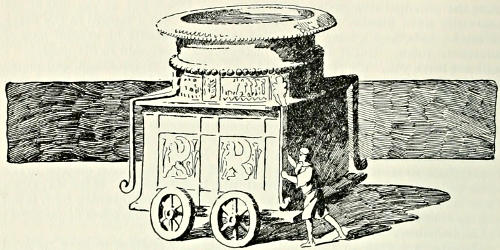

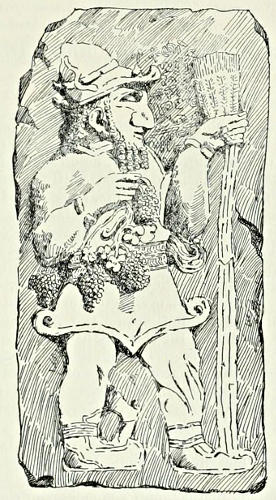

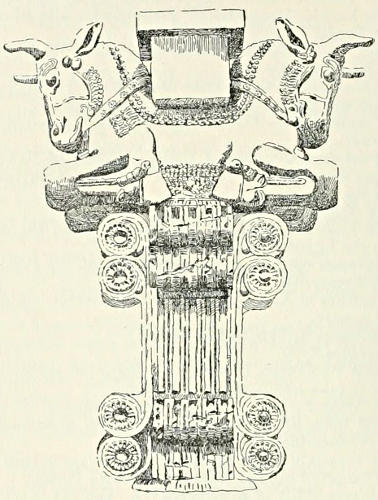

Brazen Fountain used for supplying Water to the Temple, Ancient Judea

Written Specially for the Present Work

By Rev. THOMAS KELLY CHEYNE, D. Litt., D. D.

Oriel Professor of the Interpretation of Scripture, Oxford; Joint Editor of the Encyclopædia Biblica

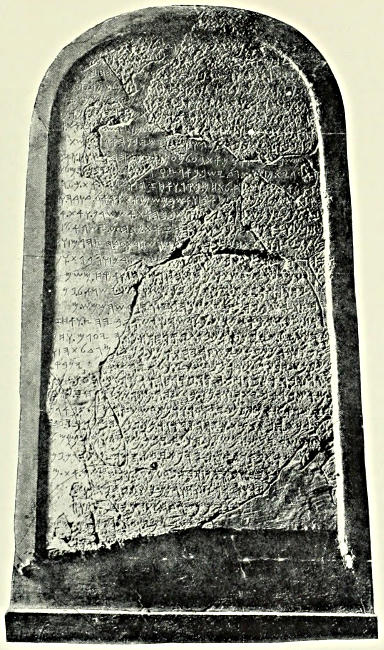

The difficulty of sketching the outlines of the history of Israel in pre-Maccabean times is unusually great. Historical curiosity was denied to this people, and the Captivities were literary as well as political disasters. The record of events which may have been kept, partly in the royal archives, partly perhaps in the temples, had disappeared; nor have any royal inscriptions as yet been discovered. It is only the land of Moab which has yielded up an historical inscription, to which we shall refer in due course as an illustration of contemporary Israelitish history. It is probable that the disciples of the prophets kept some record of interesting events in the lives of their masters—and the greater prophets were personages of political as well as religious importance—but the inveterate tendency of such history to become hagiology, compels us to read the fragments of prophetic narrative literature which have survived, even more critically than the passages of narrative which may, perhaps, have been derived from royal annals.

There were also, however, collections of popular traditions which, though suffused with imagination, were doubtless more precious to the early Israelites than the dry facts of contemporary or nearly contemporary history. They were the imaginative vesture of vague and distorted recollections of long-past events. In the form in which they have reached us, they must have lost much of the original spirit and of the primitive phraseology; on the other hand, the narrators, some of whom were gifted writers as well as religiously progressive men, have contributed original elements which, for many of us, must outweigh the most interesting folklore, because we find in them the germs of Jewish monotheism. The historian, however, must constantly remember the consciously or unconsciously didactic object of these narrators, or rather schools of narrators. Five of them are specially well known, and of these it is only the so-called Elohist who is comparatively free from preoccupation with definite ethical and religious principles. The[5] Yahvist is very distinctly on the side of the greater prophets; the Deuteronomist, the Priestly Narrator, and the Chronicler have for their chief object the direct or indirect enforcement of the religious principles of the earlier or the later law, to which in the Chronicler’s case we may add the glorification of the temple at Jerusalem, its various classes of ministers, and its ritual.

The composition of these works ranges over a long period, extending at any rate from the eighth to the third century B.C.; the upper limit is not certain. It is the task of the critic to extract the passages belonging to the first four of these narrators (or rather sometimes schools of narrators) from the composite works in which they are found, and also to investigate the sources from which they may have been drawn. On the first part of this task much skill has been lavished by a long succession of critics, but the second part is still very far behindhand. And it must regretfully be said that owing to the backward condition of the criticism of the text of the Old Testament, there is some uncertainty in the basis of all constructive treatment of the political and religious history. The scantiness of outside material, which is peculiarly needed as a check on the subjective Hebrew writers, is also no slight hindrance to the formation of thoroughly trustworthy conclusions.

Tradition tells that the founder of the Israelitish nation first saw the light in Egypt, where a number of Hebrew tribes were sojourning. A change in the sentiments of the court towards the Hebrews had brought about a cruel oppression. According to the Elohist (one of the narrators mentioned above, fragments of whose work are preserved in the Pentateuch), Moses, the child of a Hebrew man and woman of a tribe called Levi, was hidden in an “ark of bulrushes” by the Nile, on account of a royal edict that all male children of the Hebrews should be put to death. Pharaoh’s daughter saw the child, had compassion on him, and finally adopted him as her son. This, however, is by no means a contemporary account, and the details would never have been thought of, but for the existence in popular Hebrew tradition of a mythic tale of the setting adrift of a divine or at least heroic infant on water.

The earliest traditions respecting Moses knew nothing of this. They place the cradle of the national existence of the Israelites, and must consequently have placed the cradle of the deliverer Moses, not in Mizraim or Egypt, but in a region of northern Arabia called Mizrim, the border of which on one side adjoined Egypt.

The whole story of the Exodus from Egypt appears to be due to a confusion between Mizraim and Mizrim—a confusion which is presupposed by what remains of the Yahvist’s and the Elohist’s narratives in their present form, but which was probably not made by these narratives in their original form, and cannot be shown indisputably to have been made by the earliest prophets (Amos ii. 10; iii. 1; v. 25; ix. 7; Hosea ii. 15; viii. 13; ix. 3; xi. 1, 5; xii. 9, 13; xiii. 4).

The residence of Moses in Egypt constitutes, in fact, a considerable difficulty. Had Moses been reared as an Egyptian prince, he would have received an Egyptian name, an Egyptian office and an Egyptian wife. We are told, however, that he married one of the seven daughters of Hobab, the[6] priest of a tribe of Midianites (or Kenites) which dwelt not far from Yahveh’s sacred mountain, Horeb. Her name is Zipporah, and, in accordance with the undoubtedly true theory that the relations of tribes were expressed by the Hebrews under the form of genealogies, we may assume that the seven daughters of Hobab were the tribes occupying seven districts in Arabia, in the neighbourhood of Horeb. Where Horeb or Sinai was, is disputed; it is even doubted whether the Old Testament is entirely consistent with itself on this point. The traditional view, however, which comes down to us from Christian antiquity, that the mountain of the giving of the Law was on the western side of the Sinaitic peninsula, is sufficiently refuted by this one historical fact, that in the days when the Exodus from Egypt (if Egypt was really the temporary abode of the primitive Israelites) may be conceived to have taken place, a portion of the peninsula was occupied by Egyptian officials and miners, and garrisoned by Egyptian troops. The student may well be perplexed by the divergent views as to the situation of Horeb (which in the original tradition was probably a synonym for Sinai), nor can we digress to relieve his perplexity. All that we can say is that, if he accepts our guidance, he will have provisionally to adopt the view (strongly opposed to the later tradition) that Horeb or Sinai was near the sacred town of Kadesh, better known as Kadesh-Barnea, on the northern Arabian border, and also to assume that Zipporah (the name of the traditional wife of Moses) is connected with Zarephath (the vowels of this name are uncertain), a place which Moses (i.e., the Moses-clan) may be supposed to have acquired, either by cession or by conquest.

To couple this with the traditional belief that there was once a person called Moses, would be to misconceive the possible range of oral tradition, and to forget the universal tendency to imagine the ancestors or founders of tribes and races. That there was a clan bearing a name like Mosheh or Moses; that, owing to a close connection with a Yahveh-worshipping tribe of Kenites, this clan became ardently devoted to the service of Yahveh; and that its chief centre was at Zarephath [Sarepta] (whence, be it noted, another prophetic hero of tradition, Elijah, probably sprung), may, however, be admitted as probable. Other kindred clans must have gathered round that which bore the name of Moses, and we find that when the northward migration of those whom we know as Israelites took place, the number of the emigrants was increased by the adhesion of other North Arabians. All who were thus brought together must have had the link of a common worship—the worship of the god called Yahveh, a name which must originally have expressed a physical relation or phenomenon, but which in course of time came to be explained by some as meaning the truly existent or the self-manifesting One.

This God was believed to be specially present on Mount Sinai, whence it is natural that the Yahveh-worshipping tribes of Israel conceived themselves to have derived laws and institutions which were really of late origin. The Israelites in Arabia were nomads, but the three great annual festivals referred to in the Pentateuch are those of an agricultural people, and must have been adopted by the Israelites after they had passed into a settled mode of life. One portion of the first of these feasts, however—the so-called Passover—is really a monument of the nomadic life of the Israelites; it corresponds to a[7] similar spring-festival which we know to have been observed by the ancient Arabians. The festival of the New Moon, which was entirely unconnected with agriculture, and that of sheep-shearing, may have been retained by the Israelites from their nomadic period.

The city of Zarephath seems to have been regarded as on the border-line between the country known as Mizrim or Muzri, and the pastoral country called in Hebrew the Negeb, though there are some Old Testament passages which indicate that in later times a more southerly limit was fixed, viz., at Kadesh. It is possible that among the pre-Israelitish inhabitants of the Negeb were the “sons of Anak” or Anakites, and that these Anakites (whose terribleness was magnified by legend) were identical with, or closely related to, the “Rephaim” or Rephaites, whose king, called Og, is commonly, by a very early error of the text, transferred to the country on the east of the Jordan, and who were really Amalekites, i.e., Jerahmeelites (the leading race of northern Arabia in primitive times, including Edomites). In fact, Og and Agag (the latter a traditional Amalekite name) are names which could only, for some strong philological or historical reason, be separated.

It is too true that the Hebrew texts are often sadly corrupt, but among other things we can still see, underneath the corruption, that the first migration of the Israelites from Kadesh (near Horeb or Sinai) was neither to the western nor to the eastern part of Canaan, but to the country on the south of Palestine (the Negeb) where the inhabitants had passed (as probably those of Mizrim had also passed) into a settled mode of life and were flourishing agriculturists; their vineyards were especially renowned in ancient legend. This region, in consequence, became the scene of a large number of Hebrew legends, and the sacred spots in it continued to draw reverent pilgrims as late as the fall of the kingdom of Judah. (This follows from a critical examination of Jeremiah xli.) Among these legends are those of the patriarchs in their earlier form, and perhaps even those of the so-called Judges. The period when the Israelitish centre was still in the Negeb was one in which very little unity of action was possible, and the first attempts to introduce personal sovereignty appear to have had full success only within the sphere of single tribes (see especially the stories of Jephthah and Gideon). It need hardly be added that regal government presupposes the possession of cities, towns, and villages.

The most trustworthy record that we possess of the transitional pre-regal period is the so-called Song of Deborah (Judges v.) which celebrates the successful war of a number of Hebrew clans, confederated for the present occasion, against the common enemy, who, according to the corrupt text of Judges iv. (compare also v. 19, also corrupt), was king of Canaan; but according to a more trustworthy reading, derived by methodical criticism from the corrupt text, was king of Kenaz (a widely spread tribe related to Edom). The Song appears to represent tradition at a point when it may still be called historical. It shows that in times of great need it was possible for the clans to unite, and a parallel case, which we could easily believe to be historical, is mentioned in Judges iii. 8-11: the oppression of the Israelites by a Jerahmeelite king called Cushan (properly a race name), which was closed by the intervention of a friendly clan of Kenizzite origin called Othniel (Ethan?). This Othniel-clan must have had a leader of more[8] than common heroism, who induced the other clans to follow him. Such occurrences, renewed, perhaps, at frequent intervals, must have prepared the way for regal government.

The adversaries of Israel evidently derived their power not merely from their superior armour and experience in warfare, but from their union. It was possible for nomads, by the fierceness and suddenness of their attacks, to effect conquests in settled and civilised territories; it was not so easy to maintain these conquests against the assaults of determined, united and well-equipped foes. To what extent the Israelite clans had settled themselves in Canaan, as distinct from the Negeb, we can hardly be said to know, but we find a territory known as Benjamin in the hands of Israelite clans at the close of the transitional period, and we cannot doubt that between Benjamin and the Negeb there must have been settlements of Israelite clans interspersed with the older populations; and we may venture to assert that one of the most important of these clans was called Judah and another Caleb. That the Israelites were also established in the centre and to some extent in the north of Palestine is, of course, not to be questioned. But then, no very certain Hebrew traditions on this point have been preserved, and the supposition that the tribe of Asher was so called because its seats were in the once important land of Asaru (mentioned in Egyptian inscriptions) in what became western Galilee, and may, indeed, at one time have possessed all Galilee, is less probable than the theory that the name is a modification of Ashkhur, derived from a time when this tribe dwelt in the neighbourhood of a Tekoa in Calebite territory far away to the south (1 Chronicles ii. 24, iv. 5). We cannot, therefore, say anything about the Israelitish occupation of central and northern Palestine, nor can we venture to assume that the Israelites of this region were in any sense, however limited, subjects of King Saul.

As to the chronology of the events of the pre-regal period, great uncertainty prevails. We are not, indeed, without some light from external sources, but this light leads us in an unexpected and undesired direction. In 1896 Professor Flinders Petrie discovered an inscription of the Pharaoh Meneptah in which that king speaks of having conquered not only Askalon, Gezer, and Yenuam, but Israel. Kharu (a land) is also mentioned, the exact position of which is uncertain. The situation of Askalon and Gezer is well known. The former is a Philistine city, the site of the latter is on the right of the railway from Joppa to Jerusalem, south of Lydda. The position of Yenuam is less certain. A city called Janoah is mentioned in 2 Kings xv. 29 between Abel-beth-maacah and Kadesh, in connection with Gilead, Galilee, and Naphtali, but the correctness of the received geographical view of the reference of these old names cannot be implicitly relied upon. Naville thinks that we may identify Yenuam with Jabneel or Jamnia, but the names can hardly be connected philologically. We do know, however, that Naamah is a clan name of southern Palestine and northern Arabia, and there being in 2 Kings xv. 29 probably a confusion between Asshur (Assyria) and Ashkhur (a northern Arabian kingdom, perhaps Melukhkha, often mentioned in Assyrian inscriptions), it appears most critical to assume that Meneptah’s Yenuam was in the south of Palestine. It thus becomes a plausible view that clans of Israelites existed in the south of Palestine about 1273 B.C.[9]

Let us go a step further. From the treaty of peace between Ramses II (father of Meneptah) and the king of the Kheta or Hittites (about 1300 B.C.) we seem to gather that the south of Palestine was at that time garrisoned by Egyptian troops. Only the south was Egyptian; the north continued to be under the control of the Hittites. Even Seti I (father of Ramses II), who had a course of unbroken success in northern Arabia and southern Palestine, could occupy permanently no fortress in Canaan to the north of Megiddo. From these facts we may conclude that one section of Israelites may perhaps have penetrated from Kadesh into southern Palestine before the reign of the Pharaoh Seti I, during the period of the decline of the Egyptian authority in Asia. And it so happens that we have in the famous Tel-el-Amarna correspondence unimpeachable statements of the trouble caused in southern Palestine in the century preceding Ramses II by certain people called Khabiri, whom some have identified with the Israelites; and it is Abd-khiba, king or at least governor of Urusalim or Jerusalem, who complains to his liege lord the king of Egypt that the king’s dominion is being lost to the Khabiri.

These Khabiri were apparently plundering nomad tribes, which were on the way to adopt a settled mode of life. It is not improbable that the name is equivalent to Ibrim (Hebrews); only if we adopt this equation, we must not confine the application of the term “Hebrews” to the Israelites, but extend it to “all the sons of Eber” (Genesis x. 24), a Biblical phrase which shows that the Israelites themselves were by no means narrow in the use of the term. Sooner than identify the Khabiri with the Israelites, who probably became to a large extent agriculturists in the Negeb, one would suppose the chieftain of Jerusalem to refer to those whom we know as the Amalekites. Still one cannot deny the bare possibility that the people in southern Canaan called “Israel” by the Pharaoh Meneptah may have been partly derived from some of the plundering clans called Khabiri.

The facts of importance for the history of Israel to be gained from the Tel-el-Amarna letters are these:

1. The continuance of the Babylonian language and the cuneiform characters—a proof of the intensity of the early Babylonian influence over Syria and Palestine.

2. The semi-independence of the cities—a consequence of the disintegration of the Egyptian empire in Asia.

3. The existence of names (Milkili, Abd-Milki) pointing to a Jerahmeelite element in the settled population of Palestine.

4. The name Urusalim (Jerusalem), and the importance of the city so-called.

5. The name Khabiri, possibly connected with Ibrim, “Hebrews.”

6. The importance of the Hittites in northern Palestine (including the later kingdom of Israel).

7. The restless activity of warlike nomads, some of whom entered the service of kings and chiefs.

8. The favour shown to natives of Palestine at the Egyptian court, reminding us of the story of Joseph.

We cannot pause to comment on each of these facts, but may point out that the story of Joseph, as it now stands, certainly has a more historical appearance than any other of the early Hebrew legends. The Egyptian functionary who superintends the magazines of grain in the land of Yarimuta, according to the Amarna tablets, reminds us of Joseph in a similar office; and the question arises whether at the root of the story of Joseph there may[10] not be a tradition of some gifted member of one of the clans of Jacob or Israel who found favour and employment at the court of Amenhotep IV (one of the Pharaohs of the Amarna tablets).

Still, the story of Joseph may, like the other ancient Hebrew legends, have had an earlier form, in which the scene of the events was in the wide region to the south of Palestine, and the king spoken of was a North Arabian. And though there may have been an “Israel” in South Palestine in the thirteenth century B.C., yet the same authority which appears to state this as a fact also says that the victorious Egyptian king laid Israel waste, leaving no fruits of the field, and the context suggests that the male population had been carried captive, or slain.

We return to Saul, whom the legend represents as the first king of Israel, but who, if his story be critically regarded, was no more than the dictator of the South Israelitish tribes in a time of continually renewed warfare. His foes, according to our present texts, were the Ammonites, the Philistines, and the Amalekites, but in the original legends, only one great foe was referred to—those whom the Amarna tablets called the Khabiri, i.e., North Arabian tribes, sometimes called Jerahmeelites (whence the name “Amalekites”), sometimes Zarephathites (whence probably “Pelethites” and “Pelishtim” or Philistines). The notice in 1 Samuel xiv. 47, 48, that Saul had wars with other foreign foes besides these here mentioned, viz., the northern Aramæans, is not to be relied upon; it is evident that there has been both interpolation and confusion of names. It is only the latter part that concerns the historian, for it gives the achievement of the reign of Saul in a nutshell, “He smote Amalek, and delivered Israel out of the hand of his spoiler.” Another pithy and truthful saying is, “There was sore war against the Philistines (Zarephathites) all the days of Saul” (1 Samuel xiv. 52).

It is probable, however, that Saul had another foe. This is not expressly indicated in our texts, but the language of 1 Samuel xvi. 28; xviii. 8 acquires a new force when regarded as an echo of this deliberately suppressed fact. That foe was the man who became Saul’s successor—David. It is important to know where this opponent of Saul came from. He was a native of one of several places called (originally) Beth-jerahmeel: a later editor made a geographical mistake and supposed that it was a Beth-jerahmeel better known as “Beth-lehem of Judah,” whereas really it was a Beth-jerahmeel in the “Negeb” or steppe-country. It is a significant fact that David’s sister Abigail married a man of Jezreel (near Carmel in Judah, whence came David’s favourite wife Abigail), and that David himself took his first wife from that place. All this points to a place nearer than Beth-lehem to northern Arabia; probably it was not far from Maon and Carmel. Nominally this district of the Negeb was a part of Saul’s dominion. This we infer from 2 Samuel ii. 9, which states (rightly interpreted) that Saul’s son (and consequently Saul, himself, before him) was king over (the southern Gilead) Asshur, Jezreel and Ephraim, as well as over Benjamin. Judah is not mentioned, because, according to the legend, David had lately been made king over the “house of Judah” in Hebron. But to hold so many semi-independent clans in check was beyond Saul’s power, and David, a member of one of them, conceived the idea of carving out a principality for himself in the[11] south till such time as the ripe fruit of a larger kingdom should drop into his mouth. His political rôle began when he gathered round him a band of freebooters, consisting partly of his own kinsmen, partly of desperate outlaws. Among his haunts are especially mentioned Adullam, Keilah, Carmel and Ziklag—all places in the “Negeb.” The last-named place is represented to us as belonging to Achish, king of Gath. But a Philistine suzerain of an Israelite free-lance is inconceivable, and again and again in the Hebrew narratives we find that the name Gath has sprung by corruption out of a mutilated fragment of “Rehoboth.” A little to the northeast of the site of Rehoboth (Ruhaibeh), in the direction of Beersheba, stand the ruins of Halasa, the Elusa of the early Christian age, famous in that period for its peculiar heathen cult. This is not improbably David’s Ziklag. While David was prince of Ziklag, the fatal contest between Saul and the Zarephathites (Philistines) took place, the scene of which was not Mount Gilboa in the north (as textual criticism shows), but Mount Jerahmeel in the south. Whether the traditional narrative is right in asserting David’s abstention from the battle, no one can tell.

That David all this time had acted with consummate craft, we need not doubt. At the time of the death of Saul, he was not only lord of Ziklag, but had become by marriage chief of a powerful clan settled in the neighbourhood of the southern Carmel, i.e., probably near his own home. His object must have been to detach the clans of the Negeb from Saul, and to prepare them to receive himself as their lord, or, where Saul had not even won the nominal allegiance of a clan, to bring the clans into personal relation to himself by doing them some service. At last David was strong enough to have himself proclaimed king. This implies that a number of clans dwelling near together (compare 1 Samuel xxx. 27-31) trusted or feared him enough to promise him obedience. What was the centre of his dominion? and was he really independent, or was he the vassal of a more powerful king?

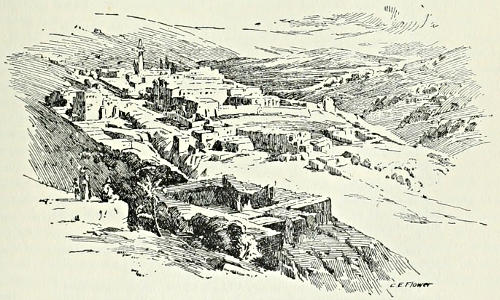

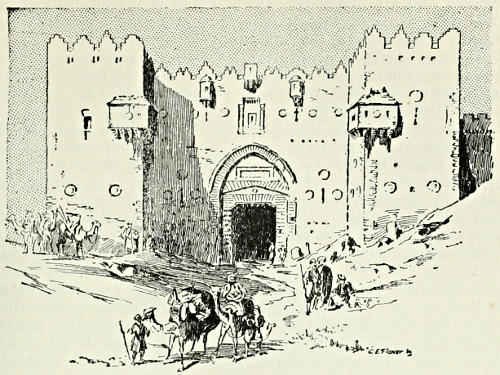

The capital of David’s earlier realm was Hebron, that is, he had succeeded in winning allegiance where Saul had failed. The clan of Judah (not as yet a “tribe”), and with it other clans which had common interests with Judah, joined together, and recognised David as their king. After this David carried out another great stroke of policy. He was scheming for a larger kingdom than that of Judah, and at once selected and fought for his capital. This capital was a Jebusite (Ishmaelite, i.e., Jerahmeelite) city, which had succeeded thus far in preserving its independence—Jerusalem. Its geographical position and natural strength, and the circumstance that it was unconnected with any Israelite clan or tribe, made it admirably suited for the capital of an extensive Palestinian kingdom. But before he could proceed further he had to cope with foes. The Rehobothites and Zarephathites, who had been not unfriendly to David, regarding him as the foe of Saul, now saw that he had stepped into the position of Saul, and would carry on that king’s patriotic work. In the neighbourhood of “Gob” or “Gath” or rather Rehoboth (of which both names are a corruption), and also in the valley of Rephaim, David and his warriors fought with and conquered the Zarephathites, and it is a reasonable conjecture that the “Cherethites and Pelethites,” who, according to the present text, became David’s bodyguard, were men of Rehoboth and Zarephath, who, seeing that it was hopeless to[12] fight against David, chose the next best part—that of fighting with him. It must have been this victory which enabled David to bring back the sacred ark of Yahveh from its place of captivity among the Jerahmeelites.

David’s next task was to put down Saul’s successor, Eshbaal or Ishbosheth, and to conquer what remained to this weakling of Saul’s realm. That more blood was shed than our texts allow, may be assumed. The legend-makers idealised David, but the historian is bound to go behind the legend. The epithets hurled at David by Shimei, according to 2 Samuel xvi. 7, must have something more for their justification than the concession professedly made by David to the vengeance of the Gibeonites (2 Samuel xxi. 1-14); and the strange legend of the destruction of Benjamin in Judges xx., xxi., is probably a disguise of an historical fact which took place later than the period assumed in the legend. Both Benjamin and parts of the Negeb had to be won by force, and from the nature of the case, as well as from the fact that Saul’s general and relative, Abner, took the side of Eshbaal, we may assume that this war lasted for some time. What took place in the large part of Palestine, which did not, so far as we can be said to know, enter into the dominion of Saul, we would gladly be able to tell, but the traditions have faded away. That David had statecraft as well as great ability in war, may be accepted from the tradition, and the advantages of unity may have been patent to tribes which had a fertile territory, and were liable to be swept by Midianite and Aramæan invasions. Still, fear of David, as well as a regard for self-interest, may have contributed to the annexation, as we may fairly call it, of central and northern Israel to the empire of the adventurer from the Negeb. Probably, however, this event did not take place as soon as the present form of our texts suggests; probably, too, the union of north and south was never as close as that which came to exist between Judah, and part, at least, of Benjamin. Further investigation may throw some rays of light on this subject.

Two revolts are recorded as having occurred in the latter part of David’s reign. In both cases the narratives have to be closely and critically examined. At the present stage of the inquiry it appears that the rebellion of Sheba is wrongly connected with the revolt of Absalom, and occurred at an earlier part of David’s reign. David had probably not as yet succeeded in crushing the independent spirit of the Benjamites, and Sheba, who was sheikh of the important clan (it was Saul’s clan) of the Bicrites, raised the standard of revolt supported not only by the Bicrites, but to some extent by the Israelitish inhabitants of Maacah in the Negeb (2 Samuel xx. 14). What he aimed at was probably a revival of the kingdom of Saul, and a definite renunciation of the ambitious scheme of a Palestinian empire. His attempt, however, failed. The revolt of Absalom was similar, but its chief supporters were not in Benjamin (which, indeed, had most probably by this time been subjugated), but in Judah. This tribe was, no doubt, the creation of David, but the elements which had been combined with the old clan of Judah, being Calebite or Jerahmeelite, still felt the keenest interest in the country to the south of Palestine called the Negeb, and when Absalom, the child of a northern[13] Arabian mother, adopted their aspirations as his own, the whole Israelitish population of the Negeb flocked to his standard. This well-conceived plan, however, which probably presupposes further successful warfare of David against the southern Aram (i.e., the Jerahmeelites in and near the Negeb), was also doomed to failure.

David’s successor, Solomon, reached the throne by a coup d’état. His success was largely due to the energy of the Jerusalem priest, Zadok, who was devoted to the service of David’s new sanctuary on Mount Zion. The friendship of the priestly party had important results both for Solomon (whom the priests of Jerusalem naturally idealised in legend) and for the state, which now possessed a sanctuary officially recognised as supreme. The erection of a temple required a large supply both of timber and of stone, and our texts represent that the timber and the stone came from Lebanon by the friendly offices of the king of Tyre, to whose territory Lebanon is supposed to have belonged. Underneath the present texts, however, we can discern a different and much more probable form of text, in which the king whose help is requested is the king of Mizzur (the North Arabian land of Muzri), and it is also presumably the same king (called in this case the king of Muzri) whose daughter became Solomon’s wife.

Afterwards, however, the relations between the two kings, Solomon and Hiram, appear to have changed for the worse. Twenty cities are recorded to have been ceded by Solomon to Hiram, and (in the original text) a large sum of money to have been paid. We can hardly doubt that this was the price of peace; hostilities must have broken out between the two kings, whose territories adjoined each other. It is possible that the war was occasioned, not only by the memories of wrongs done to Mizrim by David, but also by the desire on Hiram’s part for commercial advantages. Solomon was bent on enriching himself by commercial voyages, and Hiram would not be behind him. Ezion-geber, at the head of the Gulf of Akabah, formed part of Solomon’s dominion. Hiram can have had no mariners of his own, but was resolved not to allow all the profits of the voyages which started from Ezion-geber to go to his rival. So he sent his own “servants,” i.e., probably commissioners and merchants, to carry on traffic for him at the different ports touched at, the chief of which was doubtless Ophir, the port of the great Arabian or East African gold-land. Nor was the King of Mizrim the only North Arabian prince who made Solomon’s position a difficult one. For a time the region adjoining the Negeb, called Cusham, had received Israelite garrisons, but an adventurer named Rezon expelled the Israelites, and founded a new line of kings of Cusham, which was destined to cause infinite trouble to future Israelite kings.

Another bitter opponent of Solomon was the once fugitive Edomite or rather Aramite prince, Hadad, who returned to his own country (the southern Aram or Jerahmeel) and distressed Israel. And a third was Jeroboam,[14] son of Nebat, an Ephrathite of mixed parentage (his mother was a Mizrite). That he belonged to the northern tribe of Ephraim, cannot be safely argued; Ephrath was the name of a district in the Negeb, and it was the district to which Jeroboam belonged. His home was at Zeredah, otherwise called Tirzah, and seeing that he was “industrious” and specially interested in the Negeb, Solomon “put him in charge over all the burden of the house of Ishmael,” i.e., over the compulsory work (the corvée) of the northern Arabian subject population. This position of trust Jeroboam used for his own ambitious ends. Naturally, he incurred Solomon’s resentment, and had to flee for his life to his mother’s country, Mizrim.

The suppression of Jeroboam’s revolt left behind it angry feelings towards the Davidic family. When, therefore, the fugitive returned after Solomon’s death, the Israelites in the Negeb were prepared to espouse his claims to sovereignty. What line was taken by the Israelites of Ephraim and the other northern tribes, was not expressly stated in the original narrative. We may be sure, however, that they took no interest in Solomon’s temple, but the greatest possible interest in the sanctuaries of the Negeb. They had to support Jeroboam because they loved the land in which the patriarchs had dwelt. Its sanctuaries were to them the holiest spots upon earth; Canaan without the Negeb would have been like a temple without its altar. Consequently, whether the northern tribes sent representatives, or not, on the death of Solomon, to the national assembly at the venerable city of Cusham-Jerahmeel (later scribes, and hardly by mere accident, wrote “Shechem”), the voice of the nation was adequately expressed, and the doom pronounced on the house of David, in the name of the northern Israelites and the kindred clans in the Negeb, was final.

Most probably, however, the story of the national assembly is a legend, and Jeroboam and his party at once appealed to the arbitrament of war. There may have been fighting on the northern border, but the field of battle was no doubt chiefly in the Negeb, which, henceforth, according to several indications in our texts, was partly Israelite, partly Judahite, at least when Aramite or Jerahmeelite invaders did not take advantage of some temporary relaxation of vigilance on the part of Israel and Judah. So Jeroboam, not unaided perhaps by his Mizrite friends, became the king of the northern, and Rehoboam, the son of Solomon, of the southern part of Israel.

All the Israelite tribes from Asher to Ephraim adhered to Jeroboam; Judah and Benjamin to Rehoboam. The Holy Land of the Negeb appears to have been claimed by both, but especially by northern Israel. Jeroboam, we are assured, occupied Beth-el, and if we may venture to hold that this means the southern Bethel (in the Negeb), a new light is thrown on many Old Testament passages of great importance for the history of religion. In the Bethel sanctuary Jeroboam is said to have placed an image of a bull overlaid with gold. This bull must have represented the Jerahmeelite Baal, whom Jeroboam identified with the Yahveh, whose worship the ancient Israelites adopted from the Kenites of Kadesh (on the border of the Jerahmeelite Negeb), who conducted them in their migration. To this cultus Jeroboam was naturally devoted. We cannot, indeed, suppose that there was no such image of Baal at Bethel till he placed one there, but at least by making Bethel the “king’s sanctuary” (Amos vi. 13) he gave fresh prestige to the cultus.

We cannot, therefore, be surprised if in northern Israel the Jerahmeelite Baal more and more threw Yahveh into the shade, so that men swore, not by Yahveh, but by the Baal of Beth-el, and shut themselves entirely off from the forces, so active in Judah, which made for religious progress. Meantime the outward condition both of Israel and of Judah was so prosperous, that even a king of Egypt (Shashanq) thought it worth while to raid both territories. Sculptures on the south wall of the great temple at Karnak (Egyptian Thebes) appear to record this.

The new dynasty did not long maintain itself. Jeroboam’s son, Nadab, was slain by Baasha, of the tribe of Issachar, while he was besieging (so our text says) Gibbethon in Philistia. It was a military revolution such as became frequent in northern Israel. Baasha energetically resumed the war with Judah, whose king Asa, however, paralysed Baasha by invoking the help of Ben-Hadad (probably Bir-dadda), king of Cusham in northern Arabia, who sent an army against the cities of Israel (in the Negeb). It is remarkable to see the two kings, who jointly represent Israel, contending with one another for the favour and protection of a northern Arabian power. Presumably, Asa offered a larger payment than Baasha. Elah, Baasha’s son, quickly suffered the fate of Nadab, before the Philistine fortress of Gibbethon. Whether the singularly exact correspondence between the circumstances of the first two northern Israelite dynasties is historical, has not unnaturally been questioned.

Zimri, “who slew his master,” did not live many days in the enjoyment of royalty. The majority of the warriors were not on his side, but favoured the commander-in-chief Omri. The late king had been murdered in Tirzah. From Gibbethon, therefore, Omri and the army moved to Tirzah, and besieged the city. Zimri met his death in his burning palace.

But Omri had yet to fight for his crown. Another party of the people favoured the claims of Tibni; after a civil war, the party of Omri finally prevailed. The result was for the good of northern Israel. Omri, though not always fortunate in war (1 Kings xx. 34), was a highly capable ruler. This appears from three particulars which have come down to us; (1) the subjugation of Moab by northern Israel in his reign, (2) his foundation of the city of Shomeron, or, rather, Shimron, better known as Samaria, and we may perhaps add, (3) the respect given to his name by the Assyrians, who after his death designated the kingdom of northern Israel mat Khumri or Bit Khumri, “land” or “house of Omri.”

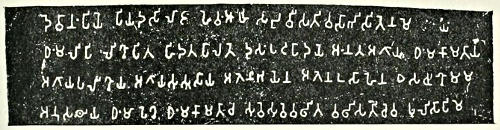

The first of these facts is recorded in the famous “Moabite Stone,” which tells how Omri afflicted Moab and took possession of the land of Medeba, and how Israel dwelt therein, during his days, and half his son’s days—forty years. The second, if correctly reported, is equally interesting; for Omri’s predecessors, and Omri himself for the first six years of his reign, held their court at Tirzah, which appears to have been a strong city in the Negeb. If Omri really built the northern Shimron, he not improbably named it after a city called Shimron in the Negeb, not far from Beth-el.[16] The resolution to place his capital in central Palestine, if it be a fact, was a most judicious one, considering the increasing danger from Assyria and from the northern Aram. Perhaps, some day, the spade of the excavator may remove the slight doubt which seems to exist on this point.

The misfortune is that the fragments of Hebrew historical tradition, critically regarded, tell us very little that can be trusted respecting the contact of the northern Israelites with these two powers at this period. Shalmaneser II tells us in an inscription that (in 854 B.C.) he was victorious at Qarqar, near Hamath, over a league of kings, the first of whom was Dad-idri, or Bir-idri, of Damascus, the second Irkhulina of Hamath, and the third Akhabbu of Israel (?). Of this important fact not a hint is given in 1 Kings; indeed, the Hebrew account of the last campaign of Ahab is not strictly reconcilable with the Assyrian inscription. The same Assyrian king records that (in 842) Yaua, son of Khumri, together with the Tyrians and Sidonians, paid him tribute. Not a word of this in 1 Kings. Similar records of the northern Aramæans are, unhappily, not extant. The final editor of the narratives in 1 Kings must have believed that the Israelites had serious conflicts with northern Aram, but underneath the traditional Hebrew text, lie narratives, which can still be approximately restored, in which the contending powers were not Israel and Aram-Damascus, but Israel and Aram-Cusham. The Shimron and the Jezreel spoken of in these narratives are not Samaria and the northern Jezreel, but places bearing those names in the “Negeb.”

The name Ben-Hadad, given in 1 Kings to the king of Aram, corresponds not to Bir-idri (the name of a contemporary king of Damascus), but to Bir-dadda, the possibility of which, as the name of a North Arabian king, is shown by its occurrence in the inscriptions. Hazael, too, is equally possible on similar grounds, as the name of a king of the northern Arabian land of Cusham. Elijah and Elisha, too, in the original Hebrew narratives, were certainly represented (according to recent criticism) as prophets of the Negeb. The appearances and disappearances of Elijah now cease to be meteoric; he has not so very far to go either to Shimron to meet the king, or to Horeb to revive his spiritual energies by communion with the God who specially dwelt on the summit of that mountain.

The whole religious history of northern Israel now becomes a good deal more intelligible. It is the Jerahmeelite Baal whom the Israelites worship, identifying him with the God of the Exodus; and the unprogressive character of his cultus, which addressed itself largely to the senses, was the reason why the prophets of Judah used such vehement language in denouncing its votaries. Elijah, we may be sure, that is, the school of prophets whom he represents (i.e., Amos), never entered a Jerahmeelite temple. But the sanctity of Horeb, in so far as it was not impaired by a corrupt cultus and its buildings, was not denied by these successors of Moses.

It is commonly held that Ahab was the husband of a Tyrian wife and the promoter of a newly imported Tyrian variety of Baal-worship. The[17] analogous history of Solomon, however, warns us to caution, and a critical view of the text shows that Ahab’s wife was a northern Arabian princess from Mizrim, and his offence, from the point of view of Elijah, was in giving a fresh official sanction to what we may call Jerahmeelitism. Jeroboam had given his royal favour to the sanctuary of Bethel; Ahab conferred a similar distinction on the new sanctuary at Shimron. It was this southern city of Shimron, and not its northern namesake, that Ben-Hadad (Bir-dadda?) of Cusham besieged. The ultimate result of the siege, of which we have probably two accounts (1 Kings xxi. 22 and 2 Kings vi. 24-vii.), was fortunate for Ahab. On the other hand, Ramoth (or Ramath), in the southern Gilead, still had to be fought for by Ahab, and the brave king met his death by a chance shot from an Aramite bow. It was also before Ramoth in Gilead that Jehoram, son of Ahab, who succeeded his elder brother Ahaziah, received those wounds of which we hear in the story of the rebellion of Jehu.

Turning to the southern kingdom, we notice that it was some time before the Davidic king made an effort to obtain foreign protection. In Jeroboam’s time, indeed, it would have been useless. In Rehoboam’s fifth year the king of Mizrim proved his regard for Jeroboam and for his own selfish advantage by invading the Jewish dominion. Resistance was hopeless; Jerusalem itself was taken, and the departure of Cushi (the name is corrupted in our own texts into Shishak) was only purchased at a great price. It was the third king, Asa, who, finding himself in danger of becoming the vassal of Baasha, became virtually the vassal of the king of Cusham; the story of his having defeated an army of Cushite invaders (at Zephath, or Zarephath?) must surely be apocryphal. Asa and his son Jehoshaphat are both praised for their fidelity to Yahveh. The latter king, however, managed to exchange a Cushite for an Israelite suzerain, and according to the (late) Chronicler gained a victory over the (southern) Aramites or Jerahmeelites in the Negeb (the text of 2 Chronicles xx. has suffered, as regards the geographical setting).

In the war against Moab, Jehoshaphat did a vassal’s service to Ahab, and we may suppose that there was a Judahite contingent in the force of ten thousand men sent by Ahab to the battle of Qarqar. We are also told that he sought to open once more direct communication by sea with the gold-country Ophir. His son Jehoram continued loyal to the northern Israelitish king. Asa had found it impossible to oppose a marriage between the crown-prince and Athaliah, the daughter of Jezebel. So, officially at any rate, there was religious as well as political union between northern and southern Israel; Jehoram, we are told, “walked in the way (i.e., practised the cultus) of the house of Ahab.”

The revolt of the Edomites, who had hitherto recognised the supremacy of Judah, marks the reign of Jehoram. His son Ahaziah continued his policy, and just after he had performed a vassal’s duty before Ramoth in the southern Gilead (still fought for by the Aramites), he fell a victim with his uncle and suzerain, Jehoram of Israel, to the machinations of the ambitious general, Jehu. The name of Jehu (as it seems, an Israelite of the Negeb) is attached to a revolution which had different results from those which had been contemplated. We have only the account of it which was given by the prophetic school of narrators. According to this, the revolution was planned by a[18] prophet named Elisha, and received the sanction of the sheikh of a subdivision of the Kenites, called Rechabites. Certainly it is probable enough that the prophets of the Negeb interfered with politics, and that that portion of the Kenites which had not adopted a settled mode of life was greatly agitated by the continuance of that sensuous form of cultus which was favoured by the house of Omri.

Jehu, too, may have been widely known as an energetic and unscrupulous man whose ambition could be used in the interests of religious reformation. At any rate the Baal-worship of the court, which, as we are assured, had become aggressive, was violently put down by Jehu, and this bold adventurer now began to scheme for a united kingdom of Israel, like David’s of old. With this object, he massacred not only Jehoram of Israel, but Ahaziah of Judah, though, as the event proved, he reckoned without his host, for Athaliah, the queen-mother in Judah, on her side, massacred all the children of the other wives of Jehoram of Judah, and, in intention, also the son of Ahaziah (he escaped, however), and usurped the throne. The consequence was that north and south Israel, for the present, went each its own way.

In 842 B.C. Jehu found it expedient to send rich presents to Shalmaneser II, which this king denominated “tribute.” Here we are painfully conscious of the meagreness of our information. What was the policy of the queen of Judah during the six years of her reign? Did she intrigue with Cusham against northern Israel? We know that Hazael, the Cushamite king, renewed the war in the Negeb with double fury. Next, what was the policy of the other Hazael—the king of Damascus—towards northern Israel? The editor of Kings seems to have thought that this Hazael was an opponent of Jehu. This might account for the “present” sent by Jehu to Shalmaneser, who waged war with Hazael. On the other hand, Jehu does not appear to have sent any gifts in 839 B.C., when Shalmaneser had his second encounter with Hazael, and Tyre, Sidon, and Gebal again sent tribute. Had Jehu in the interval been obliged to become a vassal of the king of Damascus, who was still able to withstand the repeated attacks of the Assyrians?

The furious onslaught of Hazael of Cusham continued after Jehu’s death. So large a part of the Negeb was taken either by Hazael or by his successor Ben-Hadad, i.e., Bir-dadda, and so many of its Israelite inhabitants had been either slain in battle or carried away into slavery, that the most valued jewel in the crown of Israel’s kings seemed to have been lost. A turn for the better in Israel’s fortunes took place under Joash. Probably this was mainly due to the victories of the Assyrian king, Adad-nirari III, who claims to have received tribute from Tyre, Sidon, Khumri (Israel), Edom, and Philistia, and who humbled, though he did not destroy, Mari, the brave king of Damascus. If, as one may plausibly suppose, the latter king punished Jehoahaz for his father’s Assyrian proclivities, we can understand that when Damascus ceased to be dangerous, the son of Jehoahaz, stimulated by prophets like Elisha, might make a supreme, successful effort against invaders of the Negeb.

The work of liberation, however, had still to be completed; this was the achievement of Jeroboam II. It was he who reconquered the venerable city of Cusham-jerahmeel, and recovered the region of Maacath (or[19] Jerahmeel) for Israel. This period, as criticism is able to show, receives vivid illustration from the work of Amos, the account of whose conflict with Amaziah, the priest of the southern Bethel, refers to Jeroboam by name. The war was still going on, however, when this prophet of evil tidings wrote. It is probable that for some part of the reigns of Joash and Jeroboam the king of Judah was once more in vassalage to the king of Israel.

The death of Jeroboam was the beginning of the end for the northern realm. Murders and revolutions succeeded each other with fearful rapidity. Of Zechariah and Shallum there is nothing to be said. Menahem’s reign, however, marks an epoch. Tiglathpileser III states in his Annals that he received tribute from Kushtashpi of Kummukh, Rasunnu of Damascus and Minihimi of Samirina. It is plausible to identify the third king with Menahem of Samaria. The identification, however, is not certain; some other city may perhaps have been meant. Moreover, the Hebrew record speaks of an invasion of the northern kingdom, and calls the invader Pul (a Greek reading is Paloch) king of Asshur. Now there is good evidence in the Book of Hosea that the Israelites at this period were suing for the favour of the North Arabian kings of Mizrim and of Asshur. Mizrim we know to be the land otherwise called Muzri; Asshur (Ashkhur) we may suspect to be the land called by the Assyrians Melukhkha. Probably, therefore, it is the king of Melukhkha, the greatest of the North Arabian kings, who invaded Menahem’s realm, and exacted tribute from Menahem. In this case it was not central Palestine which he invaded, but the Negeb. In the next reign but one—that of Pekah—the same king of Asshur (called this time, not Pul, but by the equally inaccurate name Tiglath pileser or Tilgath pilneser) returned to the Negeb, a part of which he conquered, deporting its Israelite inhabitants into northern Arabia.

Probably he was displeased because the impoverished kingdom of Israel could not pay its tribute. The North Arabian king, however, must have had some additional reason for his activity. The true Assyrian Tiglathpileser tells us of the queen of Aribi and of the minor Arabian sheikhs who paid him tribute, and we may well suppose that, knowing the ambitious projects and the intrigues of Assyria, the greatest North Arabian potentate sought to strengthen the North Arabian border by introducing colonists on whom he could depend. Shortly afterwards he treated Cusham in a similar manner, deporting its inhabitants to Kir. Again we must regret the paucity of external information illustrating this period. The Hebrew text as it stands speaks of Pekah of Israel as joining the king of the northern Aram in an invasion of Judah. This, as we shall see, is highly doubtful. There is also much besides in the traditional history of this period which is liable to revision. The confusion between the two Shimrons and the two Asshurs is as troublesome as the confusion between the two Arams and the two Muzurs. But, have the Assyrian inscriptions no facts to communicate? On the contrary, they mention both Pekah and Hoshea. The former they present to us as a member of the anti-Assyrian party which existed in Samaria,[20] as elsewhere, and we gather from the Annals that, as a punishment for this, the inhabitants of a large part of Bit-Khumri (Samaria) were deported by the Assyrians, and that when Pekah had been assassinated, Tiglathpileser ratified the appointment of Hoshea as king of the scanty remnant of North Israel (733 B.C.).

From the same source we learn that early in Sargon’s reign (722 B.C.?) that king besieged and captured Samirina (Samaria), carried away 27,290 of its inhabitants, reserved fifty of their chariots, placed a governor over the remnant of the people, and imposed upon them the tribute of the former king. This is all that we know about the doings of the Assyrians; for those of the Asshurites we must turn to the prophet Hosea and to the second Book of Kings. The former, writing probably when the doom of the southern Shimron was already sealed, prophesies not only that it will be taken, but that the king of Israel will meet his death through Asshur. He also probably gives the name of the Asshurite king who succeeded Pul or Paloch as Shalman (Hosea xi. 14), referring to some typical barbarities of which this king had been guilty.

Shalman appears incorrectly in 2 Kings as Shalmaneser. We learn that for some years Hoshea paid tribute to Shalman (eser), but that after this, relying upon the help of the king of Mizrim, he withheld it; the Asshurite king therefore cast him into prison. If the letter of 2 Kings xvii. 4, 5, is correct, this preceded an Asshurite invasion of the land (i.e., the Negeb), which ended with a siege of Shimron. The siege lasted three years, at the end of which the king of Asshur took Shimron, and deported a large part of the remaining Israelite population of the Negeb into his own land, filling their place in the Negeb with North Arabian colonists. These new Shimronites are the people who caused the Jews so much trouble in the days of Nehemiah.

Thus the two sections of that large part of Israel which had rejected the Davidic Dynasty were all but annihilated, for history can take no further account of the remnants which survived both in northern Israel and in the Negeb, remnants which, though they retained the divine name Yahveh, in their cultus, were in no essential respect different from the non-Israelites with whom they mingled. We do, indeed, gather from 2 Kings xvii. 25-33 that the North Arabian colonists in the Negeb combined the ritual worship of Yahveh with that of their own gods, and we may assume that they learned the “manner” or ceremonial prescriptions of Yahveh, not from a single priest—the sole representative of Israel in the wide land of the Negeb—but from a scanty remnant of Israelites left by the conqueror (compare 2 Kings xxiii. 20). But of what value or significance for the history of Israel or of Israel’s history, is this poor and uninteresting fact? Henceforth the world-historical mission of Israel was confined to that portion of the people which was loyal to the Davidic Dynasty, and in which, thanks to prophets largely drawn from the Negeb (a land of opposites in religion), the elements of progress were still active in spite of great hindrances.