HORSLEY, 1857-1916

DEJERINE, 1849-1917

VAN GEHUCHTEN, 1861-1914

IN MEMORIAM

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/shellshockother00sout |

THE

CASE HISTORY SERIES

CASE HISTORIES IN MEDICINE

BY

Richard C. Cabot, M.D.

Third edition, revised and enlarged

DISEASES OF CHILDREN

BY

John Lovett Morse, M.D.

Third edition, revised and enlarged

Presented in two hundred Case Histories

ONE HUNDRED SURGICAL PROBLEMS

BY

James G. Mumford, M.D.

Second Printing

CASE HISTORIES IN NEUROLOGY

BY

E. W. Taylor, M.D.

Second Printing

CASE HISTORIES IN OBSTETRICS

BY

Robert L. DeNormandie, M.D.

Second Edition

DISEASES OF WOMEN

BY

Charles M. Green, M.D.

Second Edition

Presented in one hundred and seventy-three Case Histories

NEUROSYPHILIS

MODERN SYSTEMATIC DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Presented in one hundred and thirty-seven Case Histories

BY

E. E. Southard, M.D., Sc.D.

AND

H. C. Solomon, M.D.

Being Monograph Number Two of the Psychopathic Department of the Boston State Hospital, Massachusetts. (Monograph Number One was A Point Scale for Measuring Mental Ability by Robert M. Yerkes, James W. Bridges and Rose S. Hardwick. Published by Warwick and York. Baltimore 1915.)

SHELL SHOCK and other NEUROPSYCHIATRIC PROBLEMS

Printed in five hundred and eighty-nine Case Histories

BY

E. E. Southard, M.D., Sc.D.

Being Monograph Number Three of the Psychopathic Department of the Boston State Hospital, Massachusetts

HORSLEY, 1857-1916

DEJERINE, 1849-1917

VAN GEHUCHTEN, 1861-1914

IN MEMORIAM

PRESENTED IN FIVE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY-NINE

CASE HISTORIES

FROM THE

WAR LITERATURE, 1914-1918

BY

E. E. SOUTHARD, M.D., Sc.D.

Director (1917-1918), U. S. Army Neuropsychiatric Training School (Boston Unit); Late

Major, Chemical Warfare Service, U. S. Army; Bullard Professor of Neuropathology,

Harvard Medical School; Director, Massachusetts State Psychiatric

Institute (of the Massachusetts Commission on Mental Diseases);

Late President, American Medico-Psychological Association

WITH A BIBLIOGRAPHY BY

NORMAN FENTON, S.B., A.M.

Sergeant Medical Corps, U. S. Army (Assistant in Psychology to the Medical Director,

Base Hospital 117 A. E. F.); late interne in Psychology, Psychopathic Department,

Boston State Hospital; Assistant in Reconstruction, National Committee for

Mental Hygiene

AND AN INTRODUCTION BY

CHARLES K. MILLS, M.D., L.L.D.

Emeritus Professor of Neurology, University of Pennsylvania

BY VOTE OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON STATE HOSPITAL

MONOGRAPH NUMBER THREE

OF THE

PSYCHOPATHIC DEPARTMENT

BOSTON

W. M. LEONARD, Publisher

1919

COPYRIGHT, 1919, BY

W. M. LEONARD

To

THE NATIONAL COMMITTEE FOR

MENTAL HYGIENE

AND

ITS WORK IN

WAR AND PEACE

This compilation was begun in the preparedness atmosphere of the U. S. Army Neuropsychiatric Training School at Boston, 1917-18. This particular school had to adapt itself to the clinical material of the Psychopathic Hospital. Although war cases early began to drift into the wards (even including some overseas material), it was thought well to supplement the ordinary “acute, curable, and incipient” mental cases of the hospital wards and out-patient service with representative cases from the literature.

As time wore on, this “preparedness” ideal gave place to the ideal of a collection of cases to serve as a source-book for reconstructionists dealing with neuroses and psychoses. Shortage of medical staff and delays incidental to the influenza epidemic held the book back still further, and, as meantime Brown and Williams had served the immediate need with their Neuropsychiatry and the War, it was determined to make the compilation the beginning of a case-history book on the neuropsychiatry of the war, following in part the traditions of various case-books in law and medicine.

With the conclusion of the armistice, there is by no means an end of these problems. Peace-practice in neuropsychiatry is bound to undergo great changes and improvements, if only from the influx into the peace-community of many more trained neuropsychiatrists than were ever before available. This is particularly true in the American community by reason of the many good men specially trained in camp and hospital neuropsychiatry, both at home and in the A. E. F., through the enlightened policy of our army in establishing special divisions of the Surgeon-General’s Office dealing separately with those problems.

Though a book primarily for physicians, some of its material has interest for line-officers, who may see how much “criming” is matter for medical experts, by running through the boxed headings (especially of Sections A and B) and[ii] reading the simulation cases. As Chavigny remarks, “shooting madmen neither restrains crime nor sets a good example.”

But parts of the book look ahead to Reconstruction. Surely occupation-workers, vocationalists, war risk insurance experts, and in fact all reconstructionists, medical and lay, must find much to their advantage in the data of Section D (Treatment and Results). Had time permitted, the whole old story of “Railway Spine”—Shell-shock’s congener—might have been covered in a series of cases from last century’s literature, together with others illustrating the effects of suggestion and psychotherapy; but this must be a post-bellum task.

The compiler, who has personally dictated (and as a rule redictated and twice condensed) all the cases from the originals (or in a few instances, e.g., Russian, from translations), hopes he has not added anything new to the accounts. The cases are drawn from the literature of the belligerents, 1914-1917, English, French, Italian, Russian, and—so far as available here—German and Austrian.

I would call the collection not so much a posey of other men’s flowers as a handful of their seeds. For I have constantly not so much transcribed men’s general conclusions as borrowed their specific fine-print and footnotes. The lure of the 100 per cent has been very strong in many authors; but the test of fine-print, viz., of the actual case-protocols, saves us from premature conclusions, and the plan of the book allows us to confront actualities with actualities. One gets the impression of a dignified debate from the way in which case-histories automatically confront each other, say in Section C (Diagnosis).

Obligations to the books of Babinski and Froment, Eder, Hurst, Mott (Lettsomian Lectures), Roussy and Lhermitte, Elliot Smith and Pear, and others are obvious. Yealland’s book came too late for sampling its miracles, though cases of his in the periodical literature had already been incorporated in my selection.

Some of the cases in Section A, I, had already been abstracted in Neurosyphilis: Modern Systematic Diagnosis and Treatment (Southard and Solomon, 1917).[iii]

What we actually have made is a case-history book in the newly combined fields now collectively termed neuropsychiatry. The more general the good general practitioner of medicine, the more of a neuropsychiatrist! And this is no pious wish or counsel of perfection. Neuropsychiatry, mental hygiene, psychotherapy and somatotherapy—all these will flourish intra-bellum and post-bellum, in days of destruction and in days of reconstruction. And who amongst us, medical or lay, will not have to deal in reconstruction days with cases like some here compiled? A minor blessing of the war will be the incorporation of mental hygiene in general medical practice and in auxiliary fields of applied sociology, e.g., medico-social work.

Subsidies aiding publication are due to the National Committee for Mental Hygiene; the Permanent Charity Foundation (Boston Safe Deposit and Trust Company); Mrs. Zoe D. Underhill of New York; Mr. H. T. White of New York; and Dr. W. N. Bullard of Boston—to all of these the various military recipients of the book will be under obligations, as well as others who would otherwise have had to pay the great majoration de prix due to war times.

Of those great dead contributors to neurology laid (in the Epicrisis) at the feet of the neo-Attila, perhaps only Sir Victor was in a narrow sense the Kaiser’s victim: still, but for the war, they might all remain to us.

By the way, just as I found John Milton had said things that fitted neurosyphilis, so also Dante is observed in the chosen mottoes to have had inklings even of Shell-shock. To the Inferno it was natural to turn for fitting mottoes (Carlyle’s renderings mainly used). The pages might have been strewn with them. A glint of too great optimism might seem to shine—in the pre-Epicrisis motto—from the lance of Achilles with its “sad yet healing gift;” but out of Shell-shock Man may get to know his own mind a little better, how under stress and strain the mind lags, blocks, twists, shrinks, and even splits, but on the whole is afterwards made good again.

E. E. Southard.

Washington,

November, 1918.

The duties of an introducer, whether of a platform speaker to an audience, or of a writer to his anticipated readers, are not always clearly defined. It has been sometimes said that the critic or reviewer may meet with better success if he has not acquainted himself too thoroughly with the contents of the book about which he writes, as in that case he will have a larger opportunity to indulge his imagination, but a critique thus produced may have the disadvantage of possible shortcoming or unfairness. In the case of this volume, however, I have felt it worth while to acquaint myself with its contents, no light task when one is confronted with a thousand pages.

The great war just closing has done much to enlighten us as to the causes, nature, outcome, and treatment of injuries and diseases to which its victims have been subjected. The object of this book is to present both the data and the principles involved in certain neuropsychiatry problems of the war. These are presented in a wealth of detail through an extraordinary series of case records (589 in all) drawn from current medical literature, during the first three years of the conflict. Case reporting is here seen at its best, and the experiences recorded are largely allowed to speak for themselves, although comments are not wanting and are often illuminating.

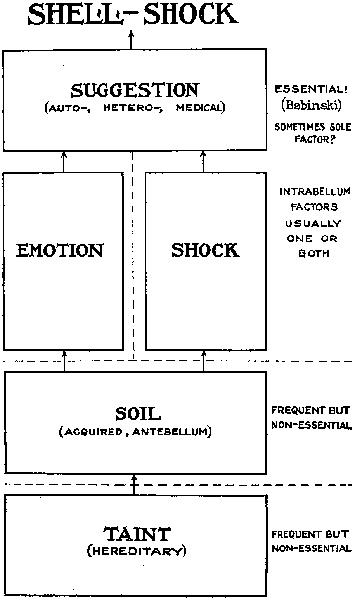

Many criticisms have been heard on the use of the term Shell-shock as applied to some of the most important psychiatric and neurological problems of the recent war; but that the designation has meaning will be evident if Dr. Southard’s book is not simply skimmed over by the reader, but is studied in its entirety. The symptoms of a very large number, if not the majority, of the cases recorded, had for their initiating influence the psychic[vi] and physical horrors of life among exploding shells. As the author and those from whom he has received his clinical supply not infrequently point out, in many cases it would appear that purely psychic influences have played the chief rôle, but in others physical injuries have not been lacking. Much more than this is true: in many instances the soil was prepared by previous defect, disease, or injury, or to use one of Dr. Southard’s favorite expressions, “weak spots” were present before martial causes became operative.

While the contributions to the medical and surgical history of the war have been somewhat numerous in current medical journals and in monographs, few comprehensive volumes have appeared. The reasons for this are not far to seek. The conflict has been of such magnitude, and the demands on the bodily and mental activity of the medical profession have been so intense and continuous, that time and opportunity for the careful and complete recording of experiences have not been often available; but works are beginning to appear in the languages of all the belligerent countries and these will increase in number and value during the next lustrum and decade, although it may be that some of the most important contributions will come after a decade or more is past. The great work before me is one that will leave its lasting impress, not only upon military but on civil medicine, for the lessons to be drawn from its pages are in large part as applicable to the one as to the other.

Looking backward to our Civil War, one is strongly impressed with the fact that the present volume, one of the earliest works of its kind to appear in book form, deals largely with psychiatry and functional nervous diseases, whereas during and after the American conflict the most important contributions to neurology related to organic disease, especially as illustrated by the work of Weir Mitchell and his collaborators on injuries of nerves. This is the more interesting when it is remembered that Mitchell not very long after the close of the Civil War became the most prominent exponent of functional neurology, from the diagnostic[vii] and therapeutic sides. To him the profession the world over has been indebted for the development of new views as to the nature of neurasthenia and hysteria and new methods for combating these disorders. In this fact is to be found matter for thought. Those who handled best the neuropsychiatric problems of the present war were in large part qualified not merely by a knowledge of psychology and psychiatry, but far more by a thorough training in organic neurology. The problems of psychiatry can be grasped fully only by those who have a fundamental knowledge of the anatomy, physiology, and diseases of the nervous system.

Dr. Southard, preëminently a neuropathologist, is well grounded in organic neurology, and shows at every turn his capabilities for considering the neuroses, psychoses, and insanities from the standpoint of the neurologist. Moreover, he clearly shows training and insight into the problems of non-neurological internal medicine.

The ideal method of training a student for neuropsychiatric work—if one had the opportunity of directing his course from the time of his entry into medicine—would be to see to it, after a good grounding in the fundamental sciences like anatomy, physiology, and chemistry, that medicine and surgery in their broadest phases first received school and hospital attention; that the fields of neurology, pure and applied, were then fully explored; and that psychology and psychiatry received late but thorough consideration. When after America’s entrance into the world war the writer assisted in preparing medical reserve officers for neuropsychiatric service, those men did best both during their postgraduate work and in base hospitals and in the field, who had built from the bottom after the manner indicated.

At the outset of Dr. Southard’s book, for more than two hundred and fifty pages, the author considers under ten subdivisions the acquired diseases and constitutional defects which may predispose the soldier to functional and reflex nervous disease.[viii] Neurosyphilis, on which Dr. Southard and Dr. Solomon have already given us a valuable treatise, the pharmacopsychoses, especially alcoholism, and the somatopsychoses covering fevers like typhoid and paratyphoid, are considered in numerous carefully chosen case reports. The reader needs only to look closely into the case records of the first quarter of the volume to get a knowledge of the affections chiefly predisposing the soldier or civilian to functional and reflex nervous diseases. To those familiar with the medical history of the war it is well known that one of the reasons for the efficiency of the American Expeditionary Force resided in the fact that the preliminary examinations of the recruits received the fullest attention not only from the points of view of acquired and inherited disease, but also from those of special psychiatric and even psychological deficiencies. Our country, however, had for its guidance the experience of nations which were fighting for three years before we entered the arena and in addition had a large surplus of material from which to cull out the weaklings.

Among the predispositional affections considered—besides syphilis, alcohol, and other drug habits, and the somatopsychoses—are the feeble-mindednesses or hypophrenoses, the epilepsies, the psychoses due to focal brain lesions, the presenile and senile disorders, the schizophrenoses including dementia præcox and allied affections, the cyclothymoses like manic depressive insanity, the psychoneuroses, and the psychopathoses. The last two subjects indicated, considered in special chapters, seem to some extent to be receptacles for affections which cannot well be otherwise placed,—hallucinoses, hysteria, neurasthenia, and psychasthenia,—and under the psychopathoses, pathological lying, Bolshevism, delinquencies of various sorts, homosexuality, suicide and self-mutilation, nosophobia, and even claustrophobia with its exemplar who preferred exposure to shell-fire to remaining in a tunnel.

Under the encephalopsychoses are found interesting illustrations of focal lesions and the general effects of infection and[ix] toxemia. Cases of brain abscess, of spinal focal lesions, and meningeal hemorrhage are in evidence, aphasias, monoplegias, Jacksonian spasm, and thalamic disease receiving consideration.

All neurologists know the difficulties in diagnosticating epilepsy in the absence of opportunities to see attacks and to receive the carefully analyzed statement of the observers of the patient. All this and much more is well brought out in the chapter on the epileptoses. Many epileptics found their way into the armies either through the carelessness of examiners or by suppression of the facts on the part of those who desired to serve.

The fact that an imbecile can shoot straight and face fire comes out in one or two places, but this does not seem to prove that a good rifleman is necessarily an all-round good soldier.

A book like Dr. Southard’s could be made of much use in teaching students, especially postgraduates, by having them, when a particular subject like epilepsy or schizophrenia, for instance, is under discussion, use as collateral reading the case reports of this work.

Dr. Southard’s book will prove useful to many workers—to the medical officer whose duty it is to examine recruits for the service or to pass upon and treat them while in service; almost equally to the medical officer in time of peace; to authors of textbooks and treatises and to contributors to neurological and psychiatric journals; to lecturers and clinical demonstrators; to the examiner for the juvenile courts; and to members of the psychopathic, psychiatric, and neurological staffs of our hospitals.

One is not called upon in an introduction to review at length the contents of the volume, but it may prove of value to the reader to dip here and there into the pages of the work to which his attention is being invited.

It will be remembered that fifty years ago and much later, down to the time of Babinski’s active propaganda in favor of the theories of suggestion, counter-suggestion, and persuasion in hysteria, various affections of a vasomotor and thermic type[x] were included in the list of hysterical phenomena. These and some other phenomena sometimes classed as hysterical, Babinski and those who accord with him now find it necessary to sweep entirely from the domain of hysteria, which being produced by suggestion and cured by counter-suggestion or persuasion cannot include symptoms which are beyond the control of the will and intellect of the patient.

According to the new or rather revived pronouncement, these must be due either to definite organic lesion, or to a disorder of reflex origin, connoting the occurrence of changes in the nervous centers as long ago taught by Vulpian and Charcot. In the records of cases and in the discussions thereon this differentiation receives much consideration.

It is held that the paralysis in the reflex cases is more limited, more persistent, and assumes special forms not observable in hysteria. The attitudes in hysterical palsies conform more to the natural positions of the limbs than do those observed in reflex paralysis. Probably the presence of marked amyotrophies in the reflex nervous disorders is the most convincing factor in separating these from pithiatic affections. These atrophies correspond to the arthritic muscular atrophies of Vulpian, Charcot, Gowers, and others, and cannot for a moment be regarded as caused by suggestion or as removable by counter-suggestion or persuasion. They are influenced, discounting the effect of time and natural recuperation, only by methods of treatment designed to improve the peripheral and central nutrition of the patient. Pithiatic atrophies are slight and probably always to be accounted for by disuse or the association of some peripheral neural disorder with the hysteria. Affections of the sudatory and pilatory systems are more definitely pronounced in reflex cases than in those of a strictly hysterical character.

Some of the facts brought forward by Babinski and Froment to demonstrate the differentiation of reflex paralyses from pithiatic disorders of motion are challenged in the records of this volume by others, as for instance, by Dejerine, Roussy, Marie,[xi] and Guillain. Babinski tells us that in pithiatism, properly so designated, the tendon reflexes are not affected. He believes that even in pronounced anesthesia of the lower extremities the plantar reflexes can always be elicited and are not abnormal in exhibition. Dejerine, however, produces cases to illustrate the fact that in marked hysterical anesthesia of the feet plantar responses cannot be produced. I have personally studied cases which lend some strength to either contention. In some of these I was not able to conclude that either the use of the will or the presence of contractions in extension was sufficient to exclude the normal responses.

Differences in muscle tonicity, in mechanical irritability of the muscles, and the presence or absence of fibrotendinous contractions are indications of a separation between the reflex and purely functional cases, as apparently demonstrated in some of the case records. True trophic disorders of the skin, hair, and bones observed in the reflex cases are also said to have no place in the illustrations of pithiatism.

The delver into the case histories of this volume will find numerous instructive combinations of hystero-reflex and organo-hysterical associations which are not to be enumerated in an introduction. The great importance of what all recognize as pathognomonic signs of organic disease—Babinski extensor toe response, persistent foot clonus, reactions of degeneration, marked atrophy, lost tendon jerks, etc.—is, of course, continuously in evidence. Extraordinary associations of hysterical, organic, and reflex disorders with other affections due to direct involvement of bone, muscle, and vessels and with the secondary effects of cicatrization and immobilization are brought out on many pages. In quitting this branch of our subject it might be remarked that considerable changes must be made in our textbook descriptions of nervous diseases in the light of the contributions to the neurology of the present war.

One is reminded in the details of some of the cases of the discussions some decades since on the subject of spinal traumatisms;[xii] of the work of Erichsen which resulted in giving his name and that of “railway spine” to many of the cases now commonly spoken of as traumatic hysteria and traumatic neurasthenia; of the rejoinders of Page and his views regarding spinal traumatisms; and of Oppenheim’s development of the symptom complex of what he prefers to term the traumatic neurosis. One who has taken part in much court work cannot but read these case records with interest, for the neurology of the war as presented in this volume and in numerous monographs which are now appearing, throws much light upon many often mooted medicolegal problems. I recall how many able and honest neurological observers have changed their points of view since the early days of Erichsen’s “railway spine,” a pathological suggestion which is said to have cost the corporations of England an almost fabulous sum during a score of years. I recall also that a certain Court of Appeals in one of our states even felt itself called upon to promulgate an opinion intended to exorcise entirely the plea for damages for alleged injuries if it could be shown that these were due to fright. The data of this book do not put weapons entirely into the hands of the attorney and the expert for either the plaintiff or the defendant.

Some of the French writers on the neurology of the war, as illustrated in the records collected by Dr. Southard, have brought to our attention distinctions which they draw between états commotionnels and états émotionnels—happy terms, and yet not sufficient in their invention or in the explanations which accompany them, fully to satisfy the requirements of the facts presented. These writers seem to think of the commotional states as denoting some real disease or condition of the brain, and yet one which is really curable and reversible. They explicitly tell us, however, that these commotions fall short of being lésionnel. After all, is this not somewhat obscure? Is it not something of a return to the period of “railway spine” when one of the comparisons sometimes made was that the injury suffered by the nervous tissues produced in them a state[xiii] comparable to that of a magnet which had been subjected to a severe blow? At any rate, in commotion thus discussed the nervous structures are supposed to sustain some real injury of a physiochemical character, whereas in the emotional states the neurones are, as Southard puts it, affected somewhat after the manner of normal emotional functioning, except perhaps that they are called upon to deliver an excessive stream of impulses. The latter would be classed among the psychopathic, the former among the physiopathic affections, and yet the distinction between the two is not always quite clear.

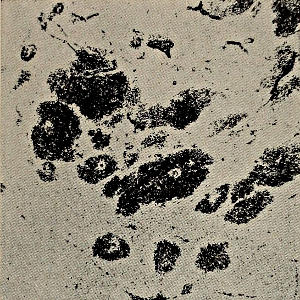

In not a few instances of Shell-shock—although these are not numerous, so far as records have been obtained—actual structural lesions have been recorded even in cases in which no direct external injury of a material kind was experienced as a result of the explosion of shells. In others the evidences of external injury were relatively unimportant. Various lesions, in some cases recognizable even by the naked eye, were present. Mott, for example, found not only minute hemorrhages, but in one instance a bulbar extravasation of moderate massiveness, the patient not showing external signs of injury. Cases are also recorded of hematomyelia; others with edematous or necrotic areas in the cord; and still others with lesions of the ependyma or even with splitting of the spinal canal, reminding one of the classical experiments of Duret on cerebral and cerebrospinal traumatisms.

It has been argued that too much stress should not be laid on a few cases of this sort—but are they as few as they seem to be? The fact is that necropsical opportunities are not often afforded. May not such scattered lesions often be present without resulting in death or even in long continued disturbance? There is no essential reason why minute hemorrhages into the brain and spinal cord, and especially into their membranes, may not undergo rapid absorption or even remain unchanged for some time without dire results.

One of the reported cases in which lung splitting occurred from[xiv] severe concussion without external injury is not without interest in this connection, reminding one, as the commentator says, of those cases of severe concussion in which the interior of a building is injured while the exterior escapes. In the same connection also the cited experiments of Mairet and Durante on rabbits are not without instructiveness. As a result of explosives set off close to these animals, pulmonary apoplexy, spinal cord and root hemorrhages, and extravasations, perivascular and ependymal, and into the cortical and bulbar gray were found. Russca obtained direct and contrecoup brain lesions, etc., in a similar way.

Here and there throughout the book will be found references to symptoms and syndromes which will have a particular interest for the reader—soldier’s heart, trench foot, congealed hand, tics, tremors, convulsions, sensory areas variously mapped, and forms of local tetanus, the last being distinctly to be differentiated from pithiatic contractures and those due to organic lesions of the nervous system. Cases of an affection described by Souques as camptocormia, from Greek words meaning to bend the trunk, were shown to the Neurological Society of Paris in 1914 and later, the main features of this affection being pronounced incurvation forward of the trunk from the dorsolumbar region, with extreme abduction and outward rotation of the lower limbs, pain in the back, and difficult and tremulous walking. In some of these cases, organic lesions of the trunkal tissues were present, but in addition psychic elements played a not unimportant part, and the cases were restored to health by a combination of physical measures with psychotherapy, enforced by electrical applications.

The part of this book given over to the discussion of treatment will doubtless to some prove the most interesting section. The presentation of the subject of therapeutics is in some degree a discussion also of diagnosis and prognosis; and so it happens in various parts of the volume that the particular subject under consideration is more or less a reaffirmation or anticipation of remarks under other headings.

Similar results are brought about by various therapeutic procedures. Nonne, Myers, and a few others bring hypnosis into the foreground, although non-hypnotic suggestion plays a larger rôle by far.

Miracle cures are wrought through many pages. Mutism, deafness and blindness, palsies, contractures, and tics disappear at times as if by magic under various forms of suggestion. Ether or chloroform narcosis drives out the malady at the moment when it reveals its true nature. Verbal suggestion has many adjuvants and collaborators—electricity, sometimes severely administered, lumbar puncture, injections of stovaine into the cerebrospinal fluid, injections of saline solution, colored lights, vibrations, active mechanotherapy, hydrotherapy, hot air baths and blasts, massage, etc. Painful and punitive measures have their place—one is inclined to think a less valuable place than is given them by some of the recorders. In some instances the element of suggestion, while doubtless present, is overshadowed by the material methods employed. Persuasion and actual physical improvement are in these cases highly important. Reëducation is not infrequently in evidence. The patient in one way or another is taught how to do things which he had lost the way of doing.

It is interesting to American neurologists to note how frequently in the reports, especially of French observers, the “Weir Mitchell treatment” was the method employed, including isolation, the faradic current, massage, and Swedish movements, hydrotherapy, dietetic measures, reëducative processes, and powerful suggestion variously exhibited, especially through the mastery of the physician over the patient. It is rather striking that few records of Freudian psychoanalytic therapy are presented.

When all is said, however, counter-suggestion and persuasion, in whatever guise made use of, were not always sufficient and this not only in the clearly organic cases, but in those which are ranked under the head of reflex nervous disorders. In these the long-continued use of physical agencies was found necessary to[xvi] supplement the purely psychic procedures, these facts sometimes giving rise in the Paris Society of Neurology and elsewhere to animated discussion as to the real nature of the cases. The pithiatic features of the case at times disappear, but leave behind much to be explained and more to be accomplished. The cures wrought are not always permanent and in some cases post-bellum experiences may be required to prove the real value of the measures advocated. The reader must study well the detailed records in order to arrive at just conclusions; nevertheless, the tremendous efficacy of suggestion and persuasion stands out in many of the recitals.

Perhaps the author may permit the introducer a little liberty of comment. His non-English interpellations, especially Latin and French, may be regarded by some as overdone or perhaps pedantic, but are rather piquant, giving zest to the text. Diagnosis per exclusionem in ordine is sonorous and has a scholarly flavor, but does not prevent the reader who lives beyond the faubourgs of Boston from understanding that the author is speaking of an ancient and well-tried method of differential diagnosis. Passim may be more impressive or thought-fixing than its English translation, but this to the reader will simply prove a matter of individual opinion. Psychopathia martialis is not only mouth-filling like Senegambia or Mesopotamia, but really has a claim to appreciation through its evident applicability. It is agreeable to note that the book seems nowhere to indicate that psychopathia sexualis and psychopathia martialis are convertible terms.

The bibliography of the volume challenges admiration because of its magnitude and thoroughness and is largely to be credited, as the author indicates, to the energy and efficiency of Sergeant Norman Fenton, who did the work in connection with the Neuropsychiatric Training School at Boston, resorting first-hand to the Boston Medical Library and the Library of the New York Academy of Medicine. After Sergeant Fenton joined the American Expeditionary Force, Dr. Southard greatly increased the value of the bibliography by his personal efforts.

This bibliography covers not only the 589 case histories of the book, but it goes beyond this, especially in the presentation of references for 1917, 1918, and even 1919. Owing to the time when our country entered the war, American references are, in the main, of later date than the case histories. They will be found none the less of value to the student of neuropsychiatric problems.

The references in the bibliography number in all more than two thousand, distributed so far as nationalities are concerned about as given below, although some mistakes may have crept into this enumeration for various reasons, like the publication of the same articles in the journals of different countries. The list of references includes French, 895; British (English and Colonial), 396; Italian, 77; Russian, 100; American, 253; Spanish, 5; Dutch, 5; Scandinavian, 5; and Austrian and German, 476. It will be seen, therefore, that the bibliography covers in number nearly four times the collected case studies, most of these records being from reports made during the first three years of the war. The author has wisely made an effort to bring the bibliographic work up to and partially including 1919.

The manner in which the French neurologists and alienists continued their work during the strenuous days of the terrible conflict is worthy of all praise. The labors of the Society of Neurology of Paris never flagged, its contributions in current medical journals having become familiar to neurologists who have followed closely the trend of medical events during the war. Cases and subjects were also frequently presented and discussed at the neurological centers connected with the French and allied armies in France.

It may be almost invidious to specify names, the work done by many was of so much interest and value. Dejerine in the early days of the war, before his untimely sickness and death, contributed his part. Marie from the beginning to the end of the conflict continued to make the neurological world his debtor. The name of Babinski stands out in striking relief. Other[xviii] names frequently appearing among the French contributors are those of Froment, Clovis Vincent, Roussy and Lhermitte, Léri, Guillain, Souques, Laignel-Lavastine, Courbon, Grasset, Claude, Barre, Benisty, Foix, Chavigny, Charpentier, Meige, Thomas, and Sollier.

For a work of this character not only as complete a bibliography as possible, but a thorough index is absolutely necessary, and this has been supplied. The author has not made the index too full, but with enough cross-references to enable those in all lines of medical work interested to cull out the cases and comments which most concern them.

My prologue finished, I step aside for the play and the player, with the recommendation to the reader that he give close heed to the performance—to the recital of the cases, the comments thereon, and the general discussion of subjects—knowing that such attention will be fully rewarded, for in this wonderful collection of Dr. Southard is to be seen an epitome of war neurology not elsewhere to be found.

Charles K. Mills.

Philadelphia, May, 1919.

| SECTION A. PSYCHOSES INCIDENTAL IN THE WAR | |||

| I. The Syphilitic Group (Syphilopsychoses) | |||

| Case | Page | ||

| 1. | Desertion of an officer | Briand, 1915 | 8 |

| 2. | Visions of a naval officer | Carlill, Fildes, Baker, 1917 | 9 |

| 3. | Aggravation of neurosyphilis by war | Weygandt, 1915 | 10 |

| 4. | Same | Hurst, 1917 | 10 |

| 5. | Same | Beaton, 1915 | 10 |

| 6. | Same | Boucherot, 1915 | 11 |

| 7. | Same | Todd, 1917 | 12 |

| 8. | Same | Farrar, 1917 | 13 |

| 9. | Same | Marie, Chatelin, Patrikios, 1917 | 14 |

| 10. | Root-sciatica | Long, 1916 | 15 |

| 11. | Disciplinary | Kastan, 1916 | 17 |

| 12. | Same | Kastan, 1916 | 18 |

| 13. | Same? | Kastan, 1916 | 19 |

| 14. | Hysterical chorea versus neurosyphilis | de Massary, du Sonich, 1917 | 20 |

| 15. | Traumatic general paresis | Hurst, 1917 | 22 |

| 16. | Head trauma; shell-shock; mania; W. R. positive | Babonneix, David, 1917 | 23 |

| 17. | Head trauma in a syphilitic | Babonneix, David, 1917 | 24 |

| 18. | Shell wound: general paresis | Boucherot, 1915 | 25 |

| 19. | “Shell-shock” ocular palsy: syphilitic | Schuster, 1915 | 26 |

| 20. | Shell-shock: general paresis | Donath, 1915 | 27 |

| 21. | Shell-shock: tabes | Logre, 1917 | 28 |

| 22. | Same | Duco, Blum, 1917 | 28 |

| 23. | Pseudotabes (Shell-shock) | Pitres, Marchand, 1916 | 29 |

| 24. | Shell-shock neurosyphilis | Hurst, 1917 | 30 |

| 25. | Shell-shock neurosyphilis | Hurst, 1917 | 31 |

| 26. | Pseudoparesis (Shell-shock) | Pitres, Marchand, 1916 | 32 |

| 27. | War strain and Shell-shock in a syphilitic | Karplus, 1915 | 34 |

| 28. | Shell-shock recurrence of syphilitic hemiplegia | Mairet, Piéron, 1915 | 36 |

| 29. | Shell-shock (functional!) amaurosis in a neurosyphilitic | Laignel-Lavastine, Courbon, 1916 | 37 |

| 30. | Shell-shock (functional) phenomena in a neurosyphilitic | Babonneix, David, 1917 | 39 |

| [xx]31. | Vestibular symptoms in a neurosyphilitic | Guillain, Barré, 1916 | 40 |

| 32. | Syphilophobic suicidal attempts | Colin, Lautier, 1917 | 41 |

| 33. | Simulated chancre | Pick, 1916 | 42 |

| 34. | Exaggeration | Buscaino, Coppola, 1916 | 43 |

| II. The Feeble-minded Group (Hypophrenoses) | |||

| 35. | A feeble-minded person fit for service | Pruvost, 1915 | 44 |

| 36. | An imbecile superbrave | Pruvost, 1915 | 45 |

| 37. | An imbecile fit for barracks work | Pruvost, 1915 | 45 |

| 38. | A feeble-minded inventor | Laignel-Lavastine, Ballet, 1917 | 47 |

| 39. | A feeble-minded simulator | Pruvost, 1915 | 49 |

| 40. | Enlistment for amelioration of character | Briand, 1915 | 49 |

| 41. | An imbecile fit for service at the front | Pruvost, 1915 | 50 |

| 42. | An imbecile with sudden initiative | Lautier, 1915 | 51 |

| 43. | Emotional fugue in subnormal subject | Briand, 1915 | 52 |

| 44. | Regimental surgeon versus alienist re feeble-mindedness | Kastan, 1916 | 53 |

| 45. | An imbecile rifleman | Kastan, 1916 | 55 |

| 46. | An imbecile hypomaniacal | Haury, 1915 | 57 |

| 47. | Feeble-minded desire to remain at the front | Kastan, 1916 | 58 |

| 48. | An imbecile sent back by Germans | Lautier, 1915 | 60 |

| 49. | Unfit for service: feeble-mindedness? | Kastan, 1916 | 61 |

| 50. | Oniric delirium in a feeble-minded subject | Soukhanoff, 1915 | 62 |

| 51. | Shell-shock and burial: situation not rationalized | Duprat, 1917 | 63 |

| 52. | Shell-shock in weak-minded subject; fear, fugues | Pactet, Bonhomme, 1917 | 64 |

| III. The Epileptic Group (Epileptoses) | |||

| 53. | Epilepsy: neurosyphilis | Hewat, 1917 | 65 |

| 54. | Epilepsy brought out by syphilis | Bonhoeffer, 1915 | 66 |

| 55. | Syphilis in a psychopathic subject | Bonhoeffer, 1915 | 67 |

| 56. | Epileptic imbecile court-martialed | Lautier, 1916 | 68 |

| 57. | Psychogenic seizures in feeble-minded subject | Bonhoeffer, 1915 | 69 |

| 58. | Drunken epileptic: responsibility? | Juquelier, 1917 | 71 |

| 59. | Epilepsy: disciplinary case | Pellacani, 1917 | 74 |

| 60. | Same | Pellacani, 1917 | 76 |

| 61. | Desertion: epileptic fugue | Verger, 1916 | 78 |

| 62. | Specialist in escapes | Logre, 1917 | 80 |

| 63. | Epilepsy and other factors: disciplinary case | Consiglio, 1917 | 82 |

| 64. | Strange conduct and amnesia in epileptic | Hurst, 1917 | 83 |

| 65. | Epilepsy after antityphoid inoculation | Bonhoeffer, 1915 | 84 |

| 66. | Shell-shock: Jacksonian seizures—decompression | Leriche, 1915 | 86 |

| 67. | Blow on head: hysterical convulsions—cure by neglect | Clarke, 1916 | 87 |

| 68. | Epilepsy with superposed hysteria | Bonhoeffer, 1915 | 88 |

| 69. | Musculocutaneous neuritis: Brown-Séquard’s epilepsy | Mairet, Piéron, 1916 | 89 |

| [xxi]70. | Bullet wound: reactive epilepsy? | Bonhoeffer, 1915 | 92 |

| 71. | Epilepsia tarda | Bonhoeffer, 1915 | 93 |

| 72. | Convulsions by auto-suggestion | Hurst, 1916 | 95 |

| 73. | Epilepsy, emotional | Westphal, Hübner, 1915 | 97 |

| 74. | Hysterical convulsions | Laignel-Lavastine, Fay, 1917 | 98 |

| 75. | Desertion: fugue, probably not epileptic | Barat, 1914 | 100 |

| 76. | Epileptic episode | Bonhoeffer, 1915 | 102 |

| 77. | Narcoleptic seizures | Friedmann, 1915 | 103 |

| 78. | Sham fits | Hurst, 1917 | 106 |

| 79. | Epileptoid attacks controllable by will | Russel, 1917 | 106 |

| 80. | Epileptic taint brought out at last by shell-shock | Hurst, 1917 | 107 |

| 81. | Shell-shock epilepsia larvata | Juquelier, Quellien, 1917 | 108 |

| 82. | To illustrate a theory of Shell-shock as epileptic | Ballard, 1915 | 110 |

| 83. | Same | Ballard, 1917 | 110 |

| 84. | Same | Ballard, 1917 | 111 |

| 85. | Epileptic equivalents | Mott, 1916 | 112 |

| IV. The Alcohol-Drug-Poison Group (Pharmacopsychoses) | |||

| 86. | Pathological intoxication | Boucherot, 1915 | 113 |

| 87. | Same | Loewy, 1915 | 116 |

| 88. | Desertion in alcoholism: fugue | Logre, 1916 | 117 |

| 89. | Alcoholic amnesia experimentally reproduced | Kastan, 1915 | 118 |

| 90. | Desertion and drunkenness | Kastan, 1915 | 119 |

| 91. | Desertion by alcoholic dement | Kastan, 1915 | 121 |

| 92. | Desertion by alcoholic with other factors | Kastan, 1915 | 124 |

| 93. | Alcoholism: disciplinary case | Kastan, 1915 | 126 |

| 94. | Atrocity, alcoholism | Kastan, 1915 | 127 |

| 95. | Atrocity, alcoholic | Kastan, 1915 | 128 |

| 96. | Alcoholism and amnesia: disciplinary case | Kastan, 1915 | 129 |

| 97. | Post-traumatic intolerance of alcohol | Kastan, 1915 | 130 |

| 98. | Adventure with Parisian stranger | Briand, Haury, 1915 | 131 |

| 99. | Morphinism: tetanus | Briand, 1914 | 131 |

| 100. | Morphinism: medicolegal question | Briand, 1914 | 132 |

| 101. | Two morphinists | Briand, 1914 | 132 |

| 102. | |||

| V. The Focal Brain Lesion Group (Encephalopsychoses) | |||

| 103. | Aphasia and left hemiplegia: local and contrecoup lesions | L’Hermitte, 1916 | 133 |

| 104. | Gunshot head wound and alcohol: amnesia | Kastan, 1916 | 135 |

| 105. | Bullet in brain: cortical blindness and hallucinations | Lereboullet, Mouzon, 1917 | 136 |

| 106. | Content of existent psychosis changed by head trauma | Laignel-Lavastine, Courbon, 1917 | 139 |

| [xxii]107. | Meningococcus meningitis; apparent recovery: dementing psychosis | Maixandeau, 1915 | 141 |

| 108. | Meningococcus meningitis | Eschbach and Lacaze, 1915 | 143 |

| 109. | Shell-shock: meningitic syndrome | Pitres and Marchand, 1916 | 145 |

| 110. | Brain abscess in a syphilitic: matutinal loss of knee-jerks | Dumolard, Rebierre, Quellien, 1915 | 147 |

| 111. | Spinal cord lesion: early recovery | Mendelssohn, 1916 | 149 |

| 112. | Shell explosion and meningeal hemorrhage: pneumococcus meningitis | Guillain, Barré, 1917 | 150 |

| 113. | Ante bellum cortex lesion: shrapnel wound determines athetosis | Batten, 1916 | 151 |

| 114. | Hysterical versus thalamic hemianesthesia | Léri, 1916 | 152 |

| 115. | Shell-shock: multiple sclerosis syndrome | Pitres, Marchand, 1916 | 154 |

| 116. | Mine explosion: hysterical and organic symptoms | Smyly, 1917 | 156 |

| 117. | Same | Smyly, 1917 | 156 |

| VI. The Symptomatic Group (Somatopsychoses) | |||

| 118. | Rabies: neuropsychiatric phenomena | Grenier de Cardenal, Legrand, Benoit, 1917 | 162 |

| 119. | Tetanus, psychotic | Lumière, Astier, 1917 | 164 |

| 120. | Tetanus fruste versus hysteria | Claude, L’Hermitte, 1915 | 165 |

| 121. | British officer’s letter concerning local tetanus | Turrell, 1917 | 166 |

| 122. | Dysentery: psychosis | Loewy, 1915 | 168 |

| 123. | Typhoid fever: hysteria | Sterz, 1914 | 169 |

| 124. | Dementia praecox versus posttyphoid encephalitis | Nordmann, 1916 | 170 |

| 125. | Paratyphoid fever: psychosis outlasting fever | Merklen, 1915 | 171 |

| 126. | Paratyphoid fever: psychopathic taint brought out | Merklen, 1915 | 172 |

| 127. | Diphtheria: post diphtheritic symptoms | Marchand, 1916 | 173 |

| 128. | Diphtheria: hysterical paraparesis | Marchand, 1915 | 174 |

| 129. | Malaria: amnesia | De Brun, 1917 | 175 |

| 130. | Malaria: Korsakow’s syndrome | Carlill, 1917 | 176 |

| 131. | Malaria: ventral horn symptoms | Blin, 1916 | 178 |

| 132. | Trench foot; acroparesthesia | Cottet, 1917 | 180 |

| 133. | Bullet injury of spine; bronchopneumonia: état criblé of spinal cord | Roussy, 1916 | 181 |

| 134. | Shell-shock (shell not seen); sensory and motor symptoms: decubitus; recovery | Heitz, 1915 | 183 |

| 135. | Shell-shock; later typhoid fever: neuritis (ante bellum hysteria) | Roussy, 1915 | 185 |

| 136. | Bullet wound of pleura: hemiplegia and ulnar syndrome | Phocas, Gutmann, 1915 | 186 |

| 137. | Tachypnoea, hysterical | Gaillard, 1915 | 188 |

| 138. | Soldiers’ heart | Parkinson, 1916 | 190 |

| 139. | Soldiers’ heart? | Parkinson, 1916 | 191 |

| 140. | War strain and shell wound: diabetes mellitus | Karplus, 1915 | 192 |

| 141. | Dercum’s disease | Hollande, Marchand, 1917 | 193 |

| [xxiii]142. | Hyperthyroidism | Tombleson, 1917 | 195 |

| 143. | Hyperthyroidism?, neurasthenia | Dejerine, Gascuel, 1914 | 196 |

| 144. | Hyperthyroidism | Rothacker, 1916 | 197 |

| 145. | Graves’ disease, forme fruste | Babonneix, Célos, 1917 | 198 |

| 146. | Shell-shock hysteria: surgical complications | Oppenheim, 1915 | 199 |

| VII. The Presenile and Senile Group (Geriopsychoses)—No cases. | |||

| VIII. The Dementia Praecox Group (Schizophrenoses) | |||

| 147. | Hatred of Prussia: diagnosis, dementia praecox | Bonhoeffer, 1916 | 200 |

| 148. | Dementia praecox: arrest as spy | Kastan, 1915 | 201 |

| 149. | Fugue, catatonic | Boucherot, 1915 | 203 |

| 150. | Desertion: schizophrenic? | Consiglio, 1916 | 204 |

| 151. | Schizophrenia; alcoholism: disciplinary case | Kastan, 1915 | 206 |

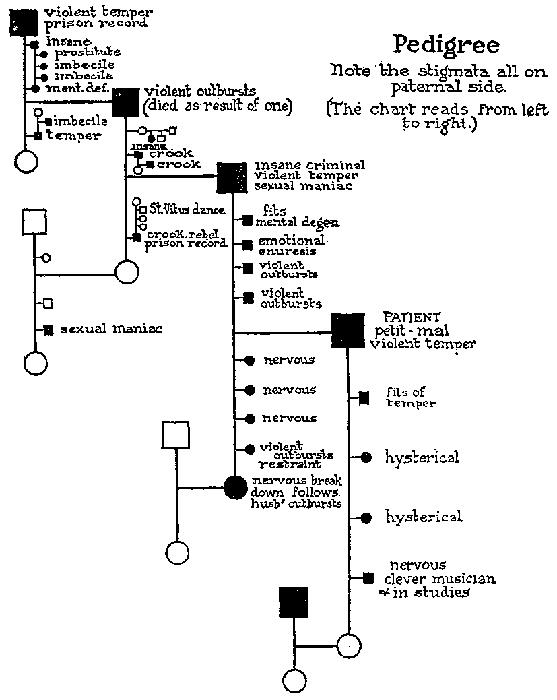

| 152. | Schizophrenia aggravated by service | de la Motte, 1915 | 208 |

| 153. | Shot himself in hand: delusions | Rouge, 1915 | 209 |

| 154. | Dementia praecox volunteer | Haury, 1915 | 210 |

| 155. | Hysteria versus catatonia | Bonhoeffer, 1916 | 211 |

| 156. | “Hysteria” actually dementia praecox | Hoven, 1915 | 213 |

| 157. | Hallucinatory and delusional contents influenced by war experiences | Gerver, 1915 | 214 |

| 158. | Iron cross winner, hebephrenic | Bonhoeffer, 1915 | 215 |

| 159. | Occipital trauma; visual hallucinations | Claude, L’Hermitte, 1915 | 217 |

| 160. | Shell-shock: Dementia praecox | Weygandt, 1915 | 219 |

| 161. | Same | Dupuoy, 1915 | 220 |

| 162. | Shell-shock; fatigue; fugue; delusions | Rouge, 1915 | 221 |

| IX. The Manic-Depressive Group (Cyclothymoses) | |||

| 163. | A maniacal volunteer | Boucherot, 1915 | 222 |

| 164. | Fugue, melancholic | Logre, 1917 | 223 |

| 165. | Apples in No-man’s-land | Weygandt, 1914 | 224 |

| 166. | Trench life: depression; hallucinations; arteriosclerosis; age, 38 | Gerver, 1915 | 225 |

| 167. | War stress: manic depressive psychosis | Dumesnil, 1915 | 226 |

| 168. | Predisposition; war stress: melancholia | Dumesnil, 1915 | 227 |

| 169. | Depression; low blood pressure; pituitrin | Green, 1916 | 228 |

| X. The Psychoneurotic Group (Psychoneuroses) | |||

| 170. | Three phases in a psychopath | Laignel-Lavastine, Courbon, 1917 | 229 |

| 171. | Fugue, probably hysterical | Milian, 1915 | 232 |

| 172. | Hysterical Adventist | de la Motte, 1915 | 234 |

| 173. | Fugue, psychoneurotic | Logre, —— | 235 |

| 174. | Shell-shy; war bride pregnant: fugue with amnesia and mutism | Myers, 1916 | 236 |

| [xxiv]175. | A neurasthenic volunteer | E. Smith, 1916 | 237 |

| 176. | War stress: neurasthenia in subject without heredity or soil | Jolly, 1916 | 238 |

| 177. | Arterial hypotension in psychasthenia | Crouzon, 1915 | 239 |

| 178. | War stress: psychasthenia | Eder, 1916 | 240 |

| 179. | Ante bellum attacks: neurasthenia | Binswanger, 1915 | 241 |

| 180. | Antityphoid inoculation: neurasthenia | Consiglio, 1917 | 244 |

| 181. | Neurasthenia (one symptom: sympathy with the enemy) | Steiner, 1915 | 245 |

| XI. The Psychopathic Group (Psychopathoses) | |||

| 182. | Claustrophobia: shells preferred to tunnel | Steiner, 1915 | 246 |

| 183. | Pathological liar | Henderson, 1917 | 247 |

| 184. | Psychopath almost Bolshevik | Hoven, 1917 | 249 |

| 185. | Hysterical mutism: persistent delusional psychosis | Dumesnil, 1915 | 250 |

| 186. | Psychopathic inferiority brought out by the war | Bennati, 1916 | 251 |

| 187. | Psychopathic episodes | Pellacani, 1917 | 252 |

| 188. | Maniacal and hysterical delinquent | Buscaino, Coppola, 1916 | 253 |

| 189. | Psychopathic delinquent | Buscaino, Coppola, 1916 | 254 |

| 190. | Psychopathic excitement | Buscaino, Coppola, 1916 | 255 |

| 191. | Desertion: dromomania | Consiglio, 1917 | 256 |

| 192. | Suppressed homosexuality | R. P. Smith, 1916 | 257 |

| 193. | Psychopathic: at first suicidal, then self-mutilative | MacCurdy, 1917 | 258 |

| 194. | Bombardment: psychasthenia | Laignel-Lavastine, Courbon, 1917 | 259 |

| 195. | Nosophobia | Colin, Lautier, 1917 | 261 |

| 196. | Psychopath: Attacks of disgust and terror | Lattes, Goria, 1915 | 262 |

| SECTION B. SHELL-SHOCK: NATURE AND CAUSES | |||

| 197. | Shell explosion: Autopsy—hemorrhages; vagoaccessorius chromatolysis | Mott, 1917 | 265 |

| 198. | Mine explosion: Autopsy—hemorrhages | Chavigny, 1916 | 270 |

| 199. | Mine explosion: Autopsy—hemorrhages | Roussy, Boisseau, 1916 | 271 |

| 200. | Shell fragment in back: Autopsy—softenings in spinal cord | Claude, L’Hermitte, 1915 | 272 |

| 201. | Shell explosion: Autopsy—lungs burst! | Sencert, 1915 | 274 |

| 202. | Shell explosion: Hemorrhage in spinal canal and bladder | Ravaut, 1915 | 276 |

| 203. | Shell explosion: Hemorrhage and pleocytosis of spinal fluid | Froment, 1915 | 277 |

| 204. | Shell explosion: Pleocytosis of spinal fluid | Guillain, 1915 | 279 |

| 205. | Shell explosion: Pleocytosis of spinal fluid as late as a month after explosion | Souques, Donnet, 1915 | 280 |

| 206. | Burial: Thecal hemorrhage | Leriche, 1915 | 282 |

| 207. | Shell explosion: Hypertensive spinal fluid | Leriche, 1915 | 283 |

| 208. | Bullet wound: Hematomyelia; partial recovery | Mendelssohn, 1916 | 284 |

| 209. | Shell explosion, subject prone: Hematomyelia | Babinski, 1915 | 286 |

| [xxv]210. | Struck by missile: Hysterical paraplegia? Herpes; segmentary symptoms | Elliot, 1914 | 288 |

| 211. | Mine explosion: Head bruises, labyrinth lesions, canities unilateral | Lebar, 1915 | 291 |

| 212. | Shrapnel wounds: Focal canities; hysterical symptoms | Arinstein, 1915 | 292 |

| 213. | Burial: Organic (?) hemiplegia | Marie, Lévy, 1917 | 293 |

| 214. | Shell explosion; no wound: Organic and functional symptoms | Claude, L’Hermitte, 1915 | 294 |

| 215. | Gassing: Organic symptoms | Neiding, 1917 | 296 |

| 216. | Gassing: Mutism, battle dreams | Wiltshire, 1916 | 297 |

| 217. | Shell explosion: Organic deafness; hysterical speech disorder | Binswanger, 1915 | 298 |

| 218. | Distant shell explosion not seen or heard: Tympanic rupture, cerebellar symptoms | Pitres, Marchand, 1916 | 300 |

| 219. | Mine explosion: Organic and functional symptoms | Smyly, 1917 | 302 |

| 220. | Shrapnel skull wound: Differential recovery from functional symptoms | Binswanger, 1917 | 303 |

| 221. | Shell explosion shrapnel wound: Battle memories, scar hyperesthetic | Bennati, 1916 | 305 |

| 222. | Shrapnel wounds, operation: Hysterical facial spasm | Batten, 1917 | 306 |

| 223. | Shell explosion: Tremors and emotional crises | Myers, 1916 | 307 |

| 224. | Shell explosion, comrades killed: Tremors, crises | Meige, 1916 | 308 |

| 225. | Under fire: Tremophobia: French artist’s description | Meige, 1916 | 310 |

| 226. | Shell explosion: German soldier’s account of Shell-shock symptoms | Gaupp, 1915 | 312 |

| 227. | A British soldier’s account of shell-shock | Batten, 1916 | 315 |

| 228. | Blown up by shell: Crural monoplegia; hysterical four days later | Léri, 1915 | 317 |

| 229. | Shell explosion nearby: Description of treatment to demonstrate hysterical nature of characteristic symptoms | Binswanger, 1915 | 318 |

| 230. | Leg wound: Pseudocoxalgic monoplegia and anesthesia | Roussy, L’Hermitte, 1917 | 323 |

| 231. | Leg contusion: Crural monoplegia, hysterical; later crutch paralysis, organic | Babinski, 1917 | 324 |

| 232. | War strain: Arthritis; crural monoplegia and anesthesia; hysterical “conversion hysteria” | MacCurdy, 1917 | 325 |

| 233. | Lance thrust in back; Crural monoplegia | Binswanger, 1915 | 326 |

| 234. | Shell explosion: After six days, crural monoplegia (“metatraumatic” suggesting persisting hypersensitive phase after shell-shock) | Schuster, 1916 | 329 |

| 235. | Wound of foot: Acrocontracture, seven months’ duration; psycho-electric cure at one sitting | Roussy, L’Hermitte, 1917 | 330 |

| 236. | Shell explosion: Trauma; emotion; hysterical paraplegia | Abrahams, 1915 | 332 |

| 237. | Shell explosion: Burial; paraplegia | Elliot, 1914 | 334 |

| 238. | Shell explosion: Paraplegia and sensory symptoms, organic? | Hurst, 1915 | 335 |

| [xxvi]239. | War strain and rheumatism; no emotional factors: Paraplegia, later brachial tremor | Binswanger, 1915 | 336 |

| 240. | Emotion in fever patient from watching barrage creep up: Paraplegia | Mann, 1915 | 338 |

| 241. | Incentives, domestic and medical, to paraplegia | Russel, 1917 | 338 |

| 242. | Bullet in back: Hysterical bent back; “camptocormia” | Souques, 1915 | 339 |

| 243. | Shell explosion: Camptocormia | Roussy, L’Hermitte, 1917 | 340 |

| 244. | Shell explosion; burial: camptocormia | Roussy, L’Hermitte, 1917 | 342 |

| 245. | Shell explosion; burial; Paraplegia, later camptocormia | Joltrain, 1917 | 344 |

| 246. | Bullet in thigh: Astasia-abasia. Wound of neck: Again astasia-abasia | Roussy, L’Hermitte, 1917 | 346 |

| 247. | Shell explosion: Wound of thorax; astasia-abasia | Roussy, L’Hermitte, 1917 | 346 |

| 248. | War strain and fall in trench without trauma: Dysbasia | Nonne, 1915 | 347 |

| 249. | Shell explosion: Partial burial; hysterical symptoms in parts buried | Arinstein, 1916 | 349 |

| 250. | Wound of hand: Acroparalysis | Roussy, L’Hermitte, 1917 | 350 |

| 251. | Wound of arm: Hysterical paralysis | Chartier, 1915 | 351 |

| 252. | Wound in brachial plexus region: Supinator longus contracture | Léri, Roger, 1915 | 353 |

| 253. | Contusion of muscle with “stupefactive” paralysis of biceps (supinator longus still functioning) | Tinel, 1917 | 355 |

| 254. | Wound of arm: Blockage of impulses to hand movements | Tubby, 1915 | 356 |

| 255. | Shell explosion: Bilateral symmetrical phenomena | Gerver, 1915 | 357 |

| 256. | Shell explosion: Paralytic symptoms on side exposed: Contralateral irritative symptoms | Oppenheim, 1915 | 359 |

| 257. | Shell explosion: Bilateral asymmetrical symptoms | Gerver, 1915 | 360 |

| 258. | Shell explosion: Sensory disorder on side exposed | Gerver, 1915 | 362 |

| 259. | Shell explosion: Hysterical deafness and other symptoms; relapse | Gaupp, 1915 | 363 |

| 260. | Shell explosion: Deafness | Marriage, 1917 | 365 |

| 261. | Mine explosion: Deafmutism; recovery on epistaxis and fever | Liébault, 1916 | 366 |

| 262. | Shell explosion: Deafmutism | Mott, 1916 | 367 |

| 263. | Shell explosion: Deafmutism and convulsions | Myers, 1916 | 368 |

| 264. | Gunfire: Aphonia | Blässig, 1915 | 370 |

| 265. | Shell-shock mutism: (a), observed, (b) dreamed of, (c), developed by victim of shell explosion | Mann, 1915 | 370 |

| 266. | Mortar explosion: Deafness | Lattes, Goria, 1917 | 371 |

| 267. | Shell-explosion: onomatopœic noises | Ballet, 1914 | 371 |

| 268. | Shell explosion: Gravel in eyes; eye and face symptoms | Ginestous, 1916 | 372 |

| 269. | Shell explosion; burial; blow on occiput; Blindness | Greenlees, 1916 | 373 |

| 270. | Shell-shock amblyopia: Composite data | Parsons, 1915 | 374 |

| 271. | Factors in shell-shock amblyopia: Excitement, blinding flashes, fear, disgust, fatigue | Pemberton, 1915 | 375 |

| [xxvii]272. | Shell explosion amblyopia | Myers, 1915 | 376 |

| 273. | Shell windage without explosion: Cranial nerve disorder | Pachantoni, 1917 | 378 |

| 274. | Initial case in Babinski’s series to show chloroform elective exaggeration of reflexes | Babinski, Froment, 1917 | 380 |

| 275. | Wound of ankle: Contracture, chloroform effect | Babinski, Froment, 1917 | 383 |

| 276. | “Reflex” disorder of right leg: Chloroform effect | Babinski, Froment, 1917 | 384 |

| 277. | Bullet in calf: Hysterical lameness cured—reflex disorder associated therewith not cured | Vincent, 1916 | 385 |

| 278. | Trauma of foot: Hysterical dysbasia and reflex disorders; differential disappearance of hysterical symptoms | Vincent, 1917 | 386 |

| 279. | Shell-shock and paraplegia: Vasomotor and secretory disorder twenty months later | Roussy, 1917 | 387 |

| 280. | Tetanus clinically cured: Phenomena reproduced under chloroform anesthesia | Monier-Vinard, 1917 | 388 |

| 281. | Example of a “reflex” disorder after shell explosion at great distance | Ferrand, 1917 | 390 |

| 282. | Shell fire: Shell-shock symptoms delayed | McWalter, 1916 | 391 |

| 283. | Shell-shock symptoms early and late | Smyly, 1917 | 392 |

| 284. | Wounds: Gassing; burial; collapse on home leave | Elliot Smith, 1916 | 393 |

| 285. | Late sympathetic nerve effect after bullet wound of neck | Tubby, 1915 | 394 |

| 286. | Hysterical crural monoplegia after fall from horse under fire (reminiscence of similar ante bellum accident) | Forsyth, 1915 | 395 |

| 287. | Shell explosion, cave-in: Right leg symptoms (ante bellum experiences) | Myers, 1916 | 396 |

| 288. | Shell explosion, wound of back: Paraparesis (subject always weak in legs) | Dejerine, 1915 | 397 |

| 289. | Wound near heart: Fear; paraparesis (subject always weak in legs) | Dejerine, 1915 | 399 |

| 290. | Wounds: Tic on walking and recovery except frontalis tic (emphasis of ante bellum habit) | Westphal, Hübner, 1915 | 401 |

| 291. | Fatigue and emotion: Hysterical hemiplegia (similar hemiplegia ante bellum) | Roussy, L’Hermitte, 1917 | 402 |

| 292. | War strain: Hemiplegia (similar hemiplegia ante bellum, subject’s father hemiplegic) | Duprés, Rist, 1914 | 403 |

| 293. | Shell explosion and burial: Deafmutism (speech difficulty ante bellum) | MacCurdy, 1917 | 405 |

| 294. | War strain: Shell-shock and psychotic symptoms determined to parts ante bellum | Zanger, 1915 | 406 |

| 295. | Mine explosion: Emotion; delirium (previous head trauma without unconsciousness) | Lattes, Goria, 1917 | 407 |

| 296. | Sniper stricken blind in shooting eye | Eder, 1916 | 408 |

| [xxviii]297. | Anticipation of warfare: Fall while mounting sentry; hysterical blindness | Forsyth, 1915 | 408 |

| 298. | Spasmodic neurosis from bareback riding (similar episode ante bellum) | Schuster, 1914 | 409 |

| 299. | Ante bellum spasm of hands | Hewat, 1917 | 409 |

| 300. | Quarrel: Hysterical chorea, reminiscent of former attack and itself reminiscent of organic chorea in subject’s mother | Dupuoy, 1915 | 411 |

| 301. | Hallucinations and delusions of ante bellum origin: Treatment by explanation | Rows, 1916 | 412 |

| 302. | Tremors and convulsive crises in a poor risk | Rogues de Fursac, 1915 | 413 |

| 303. | Emotionality and tachycardia in a martial misfit | Bennati, 1916 | 415 |

| 304. | Hereditary instability | Wolfsohn, 1918 | 416 |

| 305. | Genealogical tree of a shoemaker | Wolfsohn, 1918 | 417 |

| 306. | Traumatic hysteria without hereditary or acquired psychopathic tendency | Donath, 1915 | 418 |

| 307. | Mine explosion, burial: Neurosis in perfectly normal soldier | MacCurdy, 1917 | 419 |

| 308. | Shell explosion: Tremophobia | Meige, 1916 | 421 |

| 309. | Frozen in bog: Glossolabial hemispasm | Binswanger, 1915 | 424 |

| 310. | Bruise by horse: Invincible pain—subject cured by performing heroic feat | Loewy, 1915 | 426 |

| 311. | Kick by horse: Hysterical symptoms including monocular diplopia | Oppenheim, 1915 | 427 |

| 312. | Windage from non-exploding shell: Emotion; homonymous hemianopsia | Steiner, 1915 | 428 |

| 313. | Shell-shock psoriasis | Gaucher, Klein, 1916 | 429 |

| 314. | Croix de guerre and Shell-shock got simultaneously: Hallucinatory bell-ringing reminiscent of civilian work | Laignel-Lavastine, Courbon, 1916 | 430 |

| 315. | Waked by shell explosion: Nystagmiform tremor (occupational reminiscence in cinema worker) and tachycardia | Tinel, 1915 | 432 |

| 316. | Synesthesialgia: Foot pain on rubbing dry hands | Lortat-Jacob, Sézary, 1915 | 433 |

| 317. | Shell-shock and burial: Clonic spasms, later stupor | Gaupp, 1915 | 435 |

| 318. | War stress (liquid fire) and shell-shock: Puerilism | Charon, Halberstadt, 1916 | 437 |

| 319. | Bombed from aeroplane: Battle dreams; dizziness; fugue | Lattes, Goria, 1917 | 439 |

| 320. | Hyperthyroidism after box drops from aeroplane | Bennati, 1916 | 440 |

| 321. | Shell dropped without bursting: Stupor and delirium | Lattes, Goria, 1917 | 441 |

| 322. | Subject carrying explosives is jostled: Unconsciousness, deafmutism, later camptocormia | Lattes, Goria, 1917 | 443 |

| 323. | Grazed by sliding cannon: Stupor and amnesia | Lattes, Goria, 1917 | 444 |

| 324. | Shell explosions nearby: Emotion and insomnia | Wiltshire, 1916 | 445 |

| [xxix]325. | Shell explosion: symptoms after hearing artillery twelve days later | Wiltshire, 1916 | 446 |

| 326. | Exhaustion (heat?): Hyperthyroidism, hemiplegia | Oppenheim, 1915 | 447 |

| 327. | War strain and rheumatism: tremors | Binswanger, 1915 | 448 |

| 328. | Shell explosion; emotion: Fear and dreams | Mott, 1916 | 451 |

| 329. | Under fire; barbed wire work: tremors and sensory symptoms | Myers, 1916 | 452 |

| 330. | Shell explosion: Emotional crises; twice recurrent mutism | Mairet, Piéron, Bouzansky, 1915 | 453 |

| 331. | Shell explosion: Emotional crises (fright at a frog) | Claude, Dide, Lejonne, 1916 | 455 |

| 332. | War strain; wound; burials; shell-shock: neurosis with anxiety and dreams: Relapse | MacCurdy, 1917 | 457 |

| 333. | Bombed by airplane: Suicidal thoughts; oniric delirium; “moving picture in the head” | Hoven, 1917 | 460 |

| 334. | Shell explosion; emotion at death of best friend: Stupor and amnesia | Gaupp, 1915 | 462 |

| 335. | Emotional shock from shooting comrade: Horror, sweat, stammer, nightmare | Rows, 1916 | 463 |

| 336. | Emotion at death of comrade: Phobias | Bennati, 1916 | 464 |

| 337. | Shell explosion: Fright; delayed loss of consciousness | Wiltshire, 1916 | 465 |

| 338. | Shell explosion; burial work: amnesia; unpleasant ideas reflexly conditioned by shell whistling | Wiltshire, 1916 | 467 |

| 339. | Comrade’s death witnessed: Suicidal depression | Steiner, 1915 | 468 |

| 340. | Marching and battles: Neurasthenia? | Bonhoeffer, 1915 | 469 |

| 341. | English schoolmaster’s account of dreams | Mott, 1918 | 470 |

| 342. | War dreams shifting to sex dreams | Rows, 1916 | 472 |

| 343. | Shock at death of comrade: War and peace dreams | Rows, 1916 | 474 |

| 344. | War dreams including hunger and thirst | Mott, 1918 | 475 |

| 345. | Burial work: Olfactory dreams and vomiting | Wiltshire, 1916 | 476 |

| 346. | War dreams: Phobia conditioned on postoniric suggestion | Duprat, 1917 | 477 |

| 347. | Service in rear: War dreams not based on actual experiences | Gerver, 1915 | 478 |

| 348. | Hysterical astasia-abasia: Heterosuggestive “big belly” | Roussy, Boisseau, Cornil, 1917 | 479 |

| 349. | Collapse going over the top: Neurasthenia | Jolly, 1916 | 481 |

| 350. | Battles: Mania and confusion | Gerver, 1915 | 483 |

| 351. | Machine-gun battle: Mania and hallucinations | Gerver, 1915 | 484 |

| 352. | Attacks and counter-attacks: Incoherence and quick development of scenic war hallucinations | Gerver, 1915 | 485 |

| 353. | Hysterical stupor under shell fire after 2 days in the trenches | Gaupp, 1915 | 486 |

| 354. | Monosymptomatic amnesia | Mallet, 1917 | 488 |

| 355. | Aviator shot down: Mental symptoms, organic | MacCurdy, 1917 | 489 |

| 356. | Shell fire and corpse work: Daze with relapse; mutism | Mann, 1915 | 491 |

| [xxx]357. | Mine explosion: Confusion | Wiltshire, 1916 | 492 |

| 358. | Shell explosion: Alternation of personality | Gaupp, 1915 | 493 |

| 359. | “A Horse in the Unconscious” | Eder, 1916 | 497 |

| 360. | Shell explosion, gassing, fatigue: Anesthesia | Myers, 1916 | 498 |

| 361. | Shell explosion and burial: Somnambulism; dissolution of amnesia under hypnosis | Myers, 1915 | 499 |

| 362. | Shell explosion with injuries: Somnambulism | Donath, 1915 | 502 |

| 363. | Shock: Stupor as if dead | Régis, 1915 | 503 |

| 364. | Emotions over battle scenes: Twenty-four days’ somnambulism | Milian, 1915 | 504 |

| 365. | Putative loss of brother in battle: Somnambulism and mutism twenty-seven days | Milian, 1915 | 506 |

| 366. | Shell explosion: Trauma, windage: Somnambulism four days | Milian, 1915 | 508 |

| 367. | Burial, head trauma; gassing: Tremors, convulsions, confusion, fugue | Consiglio, 1916 | 509 |

| 368. | Shell explosion: Hysterical symptoms and tendency to fugue | Binswanger, 1915 | 510 |

| 369. | Burial: Dissociation of personality | Feiling, 1915 | 512 |

| 370. | Ear Complications and hysteria | Buscaino, Coppola, 1916 | 516 |

| SECTION C. SHELL-SHOCK DIAGNOSIS | |||

| 371. | Value of lumbar puncture | Souques, Donnet, 1915 | 524 |

| 372. | Meningeal and intraspinal hemorrhage: Lumbar puncture | Guillain, 1915 | 525 |

| 373. | Burial: Slight hyperalbuminosis | Ravaut, 1915 | 526 |

| 374. | Paraplegia, organic: Lumbar puncture | Joubert, 1915 | 527 |

| 375. | Gunshot of spine: Spinal concussion, quadriplegia, cerebellospasmodic disorder | Claude, L’Hermitte, 1917 | 528 |

| 376. | Trauma of spine: Anesthesia and contracture, homolateral, with trauma | Oppenheim, 1915 | 529 |

| 377. | Mine explosion combining hysterical and lesional effects | Dupouy, 1915 | 530 |

| 378. | Shell explosion: Hysterical and organic symptoms | Hurst, 1917 | 532 |

| 379. | Gunshot: Cauda equina symptoms, combined with functional paraplegia | Oppenheim, 1915 | 533 |

| 380. | Intraspinal lesion: Persistent anesthesia | Buzzard, 1916 | 534 |

| 381. | Functional shell-shock: Erroneous diagnosis | Buzzard, 1916 | 534 |

| 382. | Retention of urine after shell-shock | Guillain, Barré, 1917 | 535 |

| 383. | Same | Guillain, Barré, 1917 | 536 |

| 384. | Incontinence of urine after shell-shock and burial | Guillain, Barré, 1917 | 536 |

| 385. | Struck by missile: Crural monoplegia; plantar reflex absent | Paulian, 1915 | 537 |

| 386. | Shell explosion: Crural monoplegia; sciatica (neuritis?) | Souques, 1915 | 538 |

| 387. | Functional paraplegia and internal popliteal neuritis | Roussy, 1915 | 540 |

| [xxxi]388. | Bullet in hip: Local “stupor” of leg | Sebileau, 1914 | 542 |

| 389. | Localized catalepsy: Hysterotraumatic | Sollier, 1917 | 544 |

| 390. | Contracture: Hysterotraumatic | Sollier, 1917 | 545 |

| 391. | Crural monoplegia, tetanic: Recovery | Routier, 1915 | 546 |

| 392. | Spasms, contracture, crises—tetanic | Mériel, 1916 | 548 |

| 393. | Shell explosion, windage, flaccid paraplegia, not “spinal contusion” | Léri, 1915 | 550 |

| 394. | Scalp wound: Quadriparesis; paraplegia, cataleptic rigidity of anesthetic legs | Clarke, 1916 | 551 |

| 395. | Shell explosion: Spasmodic contractions of sartorii, persistent in sleep | Myers, 1916 | 553 |

| 396. | Shell explosion: Brown-Séquard’s syndrome, hematomyelic? | Ballet, 1915 | 555 |

| 397. | Question of structural injury of spinal cord | Smyly, 1917 | 557 |

| 398. | Dysbasia, psychogenic round an organic nucleus (cerebellar?) | Cassirer, 1916 | 557 |

| 399. | Shell explosion: Dysbasia, in part hysterical, in part organic? | Hurst, 1915 | 558 |

| 400. | Peculiar walking tic | Chavigny, 1917 | 559 |

| 401. | Mine explosion: Camptocormia. Hospital rounder twenty months—cure by electrotherapy, 1 hour | Marie, Meige, Béhagne, Souques, Megevand, 1917 | 561 |

| 402. | Astasia-abasia | Guillain, Barré, 1916 | 563 |

| 403. | Shell wounds: Abdominothoracic contracture, tetanic, four months after injury | Marie, 1916 | 564 |

| 404. | Shoulder dislocation: Hysterical paralysis of arm | Walther, 1914 | 566 |

| 405. | Gunshot: Paralysis of arm increasing in degree | Oppenheim, 1915 | 567 |

| 406. | Wound of wrist: Differential glove anesthesias | Römner, 1915 | 568 |

| 407. | Hysterical contracture combined with edema and vasomotor disorder | Ballet, 1915 | 569 |

| 408. | Hemiparesis with syringomyelic dissociation of sensations: Hematomyelia? | Ravaut, 1915 | 570 |

| 409. | Brachial monoplegia: Tetanic | Routier, 1915 | 571 |

| 410. | Paralysis of right leg: Hysterical? Organic? “Microörganic”? | Von Sarbo, 1915 | 572 |

| 411. | Shell explosion: Burial: Paralysis on third day | Léri, Froment, Mahar, 1915 | 573 |

| 412. | Shell explosion: Hemiplegia. Plantar areflexia | Dejerine, 1915 | 575 |

| 413. | Shell explosion: Tic versus spasm | Meige, 1916 | 577 |

| 414. | Shell explosion: Tremors, anæsthesias | Mott, 1916 | 580 |

| 415. | Hysteria, appendix to trauma | MacCurdy, 1917 | 582 |

| 416. | Peripheral nerve injury: Neurasthenic hyperalgesia | Weygandt, 1915 | 583 |

| 417. | Soldier lead worker: Peripheral neuritis | Shufflebotham, 1915 | 584 |

| 418. | “Peripheral neuritis” cured by faradism | Cargill, 1916 | 585 |

| 419. | Late tetanus | Bouquet, 1916 | 586 |

| [xxxii]420. | Spasmodic neurosis and neurasthenia | Oppenheim, 1915 | 588 |

| 421. | Hysterical and reflex (“physiopathic”) disorders | Babinski, 1916 | 590 |

| 422. | Bullet wound: Paralysis non-“organic,” non-hysterical, i.e. reflex | Babinski, Froment, 1917 | 592 |

| 423. | Asymmetry of reflexes under chloroform | Babinski, Froment, 1917 | 594 |

| 424. | Reflexes under chloroform | Babinski, Froment, 1915 | 595 |

| 425. | Same | Babinski, Froment, 1915 | 596 |

| 426. | Shrapnel wound: Monoplegia, hysterical and organic | Babinski, Froment, 1917 | 597 |

| 427. | Gunshot, later Erb’s palsy: “reflex”? | Oppenheim, 1915 | 598 |

| 428. | Paralysis hysterical? Organic? | Gougerot, Charpentier, 1916 | 600 |

| 429. | Same | Gougerot, Charpentier, 1916 | 602 |

| 430. | Same | Gougerot, Charpentier, 1916 | 604 |

| 431. | Reflex “paralysis” | Delherm, 1916 | 606 |

| 432. | |||

| 433. | Shell explosion: Functional blindness, monosymptomatic | Crouzon, 1915 | 609 |

| 434. | Retrobulbar neuritis (nitrophenol) | Sollier, Jousset, 1917 | 611 |

| 435. | Eye symptoms, hysterical | Westphal, 1915 | 613 |

| 436. | Sandbag on head: Eye symptoms: Lenses | Harwood, 1916 | 615 |

| 437. | Hemianopsia, organic or functional? | Steiner, 1915 | 616 |

| 438. | Hysterical pseudoptosis | Laignel-Lavastine, Ballet, 1916 | 617 |

| 439. | Shell explosion: Rombergism | Beck, 1915 | 620 |

| 440. | Case for otologists and neurologists | Roussy, Boisseau, 1917 | 622 |

| 441. | Jacksonian syndrome: Hysterical | Jeanselme, Huet, 1915 | 625 |

| 442. | Leg tic: Phobia against crabs | Duprat, 1917 | 627 |

| 443. | Convulsions reminiscent of fright | Duprat, 1917 | 628 |

| 444. | Fatigue, delusions, fugue | Mallet, 1917 | 629 |

| 445. | Obsessions and fugue | Mallet, 1917 | 631 |

| 446. | Aprosexia and birdlike movements | Chavigny, 1915 | 632 |

| 447. | Shell explosion: Unconsciousness (45 days): Mutism | Liébault, 1916 | 633 |

| 448. | Shell explosion: Recurrent amnesia | Mairet, Piéron, 1917 | 634 |

| 449. | Shell explosion: Comrade killed: Amnesia | Gaupp, 1915 | 635 |

| 450. | Shell explosion: Recurrent amnesia | Mairet, Piéron, 1915 | 636 |

| 451. | Soldiers’ heart, neurotic and organic | MacCurdy, 1917 | 639 |

| 452. | Soldiers’ heart, neurotic | MacCurdy, 1917 | 640 |

| 453. | Shell explosion: Hysteria: Malingering (?) | Myers, 1916 | 642 |

| 454. | Officer who could not kick | Mills, 1917 | 644 |

| 455. | “Simulation”: Diagnosis incorrect | Voss, 1916 | 645 |

| 456. | Wound: Hysterical edema? | Lebar, 1915 | 646 |

| 457. | Head trauma: simulation? Hysteria? Surgical? | Voss, 1916 | 648 |

| 458. | Disease and disorder to avoid service | Collie, 1916 | 649 |

| 459. | Yes-No test in anesthesia | Mills, 1917 | 651 |

| 460. | Guardhouse test | Roussy, 1915 | 651 |

| 461. | Light in a dark room | Briand, Kalt, 1917 | 652 |

| [xxxiii]462. | Mutism simulated | Sicard, 1915 | 654 |

| 463. | Deafmutism simulated | Myers, 1916 | 655 |

| 464. | Same: Explained by patient | Myers, 1916 | 657 |

| 465. | Deafmutism: Appearance of malingering | Gradenigo, 1917 | 658 |

| 466. | A lame rascal | Gilles, 1917 | 659 |

| 467. | Picric acid jaundice | Briand, Haury, 1916 | 660 |

| 468. | Swelling of hand and arm, 7 months | Léri, Roger, 1915 | 663 |

| 469. | Shell-shy German | Gaupp, 1915 | 664 |

| 470. | Germany sends back a simulator | Marie, 1915 | 664 |

| 471. | Simulation of Quincke’s disease | Lewitus, 1915 | 665 |

| 472. | “Pensionitis” | Collie, 1915 | 666 |

| SECTION D. SHELL-SHOCK TREATMENT AND RESULTS | |||

| 473. | Deafmutism: Spontaneous cure | Mott, 1916 | 672 |

| 474. | Two returns to the front | Gilles, 1916 | 675 |

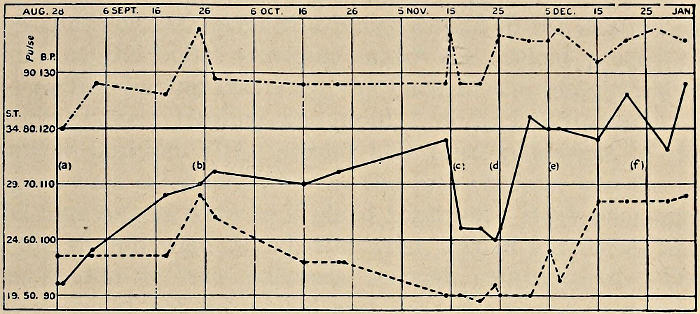

| 475. | Vicissitudes in 15 months | Purser, 1917 | 676 |

| 476. | Deafmutism: Spontaneous cure | Jones, 1915 | 678 |

| 477. | Course of an oniric delirium | Buscaino, Coppola, 1916 | 679 |

| 478. | Same | Buscaino, Coppola, 1916 | 681 |

| 479. | Paraplegia: Cure by Iron Cross | Nonne, 1915 | 682 |

| 480. | Mutism cured by getting drunk | Proctor, 1915 | 682 |

| 481. | Mutism cured by working in vineyard | Anon, 1916 | 683 |

| 482. | Deafmutism: Spontaneous recovery of speech. Recovery of hearing by isolation | Zanger, 1915 | 684 |

| 483. | Excess of sympathy on furlough | Binswanger, 1915 | 685 |

| 484. | Hysterical seizures treated by hydrotherapy | Hirschfeld, 1915 | 688 |

| 485. | Low blood pressure treated by pituitrin | Green, 1917 | 690 |

| 486. | Manual contracture: Various treatments | Duvernay, 1915 | 691 |

| 487. | Massage and mechanotherapy | Sollier, 1916 | 692 |

| 488. | Mine explosion; headache: Lumbar puncture | Ravaut, 1915 | 693 |

| 489. | Hysterical clenched fist: Treatment by fatigue of flexors | Reeve, 1917 | 694 |

| 490. | Hysterical adduction of arm: Treatment by induced fatigue | Reeve, 1917 | 695 |

| 491. | Hysterical cross-legs: Treatment by induced fatigue | Reeve, 1917 | 696 |

| 492. | Hysterical torticollis: Treatment by induced fatigue | Reeve, 1917 | 697 |

| 493. | Claw foot (2 years): Cure by induced fatigue | Reeve, 1917 | 698 |

| 494. | Traumatic and post-traumatic effects: Surgical treatment | Binswanger, 1917 | 699 |

| 495. | Vomiting: Cure by restoration of self-confidence | McDowell, 1917 | 701 |