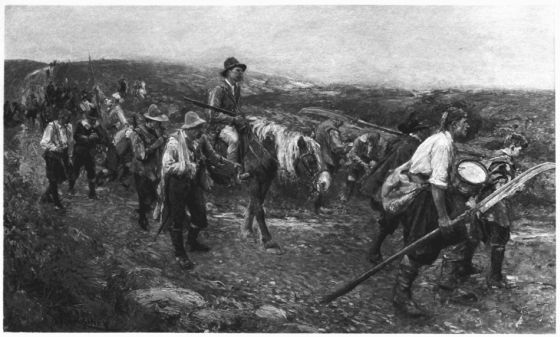

By permission of Messrs. S. Hildesheimer & Co., Ld.

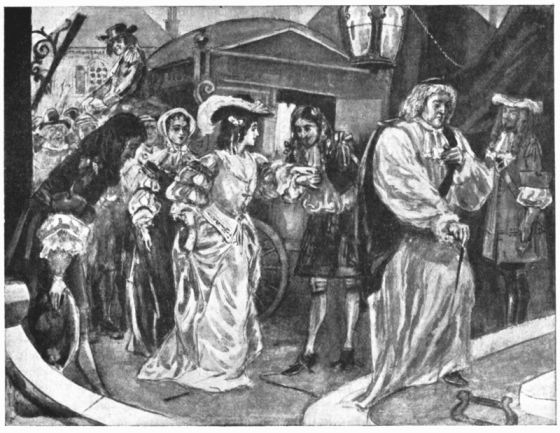

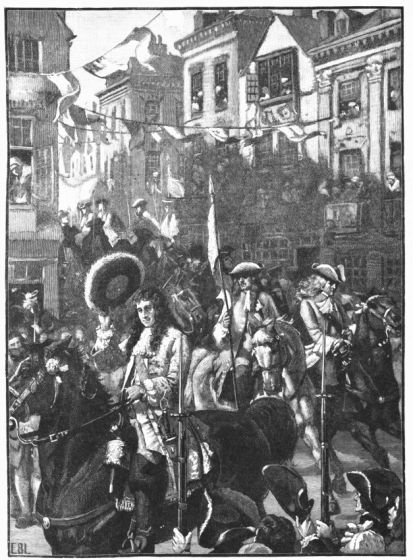

CHARLES I. ON HIS WAY TO EXECUTION, 1649.

From the Picture by ERNEST CROFTS, R.A.

Project Gutenberg's Cassell's History of England. Vol III, by Cassell

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Cassell's History of England. Vol III

From the Great Rebellion to the Fall of Marlborough.

Author: Cassell

Release Date: May 11, 2016 [EBook #52045]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CASSELL'S HISTORY OF ENGLAND, VOL III ***

Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

FROM THE GREAT REBELLION TO

THE FALL OF MARLBOROUGH

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS,

INCLUDING COLOURED

AND REMBRANDT PLATES

VOL. III

THE KING'S EDITION

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LIMITED

LONDON, NEW YORK, TORONTO AND MELBOURNE

MCMIX

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

THE GREAT REBELLION. PAGE

Condition of Ireland—Roger Moore's Pilgrimage—Negotiations of the Anglo-Irish with Charles—Hugh M'Mahon betrays the Plot—Rising of the Native Irish—Massacre of Protestants—Measures taken by the English Parliament—Return of Charles to London—The Grand Remonstrance—The King's Answer—His Lieutenant of the Tower—Riots in London—Blunder of the Bishops—Attempted Arrest of the Five Members—Charles leaves London—The Queen goes to Holland—Charles at York—His Repulse from Hull—Preparations for War—The Royal Standard Raised—Prince Rupert's Headstrong Folly—Battle of Edge Hill—Charles marches on London—He returns to Oxford—Cromwell in the East—The Queen in Yorkshire—Death of Hampden—Parliamentary Disasters—Battle of Newbury—Death of Lord Falkland—Negotiations with the Scots and Irish—Death of Pym—Royal Parliament at Oxford—Battle of Marston Moor—Disastrous Failure of Essex in Cornwall—Second Battle of Newbury—The Self-denying Ordinance—The New-modelled Army 1

THE GREAT REBELLION (concluded).

The Assembly at Westminster—Trial and Death of Laud—Negotiations at Uxbridge—Meeting of the Commissioners—Impossibility of a Settlement—Prospect of Help to the King from the Continent—Charles agrees to the demands of the Irish Catholics—Discipline and Spirit of the Parliamentary Army—Campaign of the New-modelled Army—Hunting the King—Battle of Naseby—Fairfax in the West—Exploits of Montrose—Efforts of Charles to join Him—Battle of Kilsyth—Fall of Bristol—Battle of Philiphaugh—Last Efforts of the Royalists—Charles Offers to Treat—Discovery of his Correspondence with Glamorgan—Charles Intrigues with the Scots—Flight from Oxford—Surrender to the Scots at Newark—Consequent Negotiations—Proposals for Peace—Surrender of Charles to Parliament 34

END OF THE REIGN OF CHARLES I.

Differences between the Presbyterians and Independents—The King at Holmby—Attempt to Disband the Army—Consequent Petitions to Parliament—The Adjutators—Meeting at Newmarket—Seizure of the King—Advance of the Army on London—Stubbornness of the Presbyterians—The Army Marches through London—Its Proposals to Charles—Their Rejection—The King throws away his best Chances—The Levellers—Cromwell's Efforts on behalf of Charles—Renewed Intrigues of Charles—Flight to Carisbrooke—Attempts to Rescue the King—Charles Treats with the Scots—Consequent Reaction in his Favour—Battle of Preston and Suppression of the Insurrection—Cromwell at Edinburgh—The Prince of Wales in Command of the Fleet—Negotiations at Newport—Growing Impatience of the Army—Petitions for the King's Trial—Charles's Blindness and Duplicity—He is Removed to Hurst Castle—Pride's Purge—Supremacy of the Independents—The Whiggamores—Hugh Peters' Sermon in St. Margaret's, Westminster—Ordinance for the King's Trial—Trial and Execution of Charles I. 59

THE COMMONWEALTH.

Proclamation of the Prince of Wales Forbidden—Decline of the Peerage—Ultimus Regum—Establishment of a Republican Government—Abolition of the House of Lords and the Monarchy—Council of State—The Oath Difficulty—The Engagement—Religious Toleration—Trials of Royalists—Discontent among the People—The Levellers—Activity of John Lilburne—Quelling the Mutiny in Whalley's Regiment—Lockyer's Funeral—Arrest of Lilburne—Spread of the Disaffection to other Regiments—Suppression of the Insurrection—Cromwell appointed Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland—Royalist Movement in Scotland—Charles's Son proclaimed King—The Scottish Deputation at the Hague—Charles's[vi] Court—Assassination of Dr. Dorislaus—Affairs in Ireland—Cromwell's Campaign—Defeat and Death of Montrose—Cromwell in Scotland—Battle of Dunbar—Movements of Charles—His March into England—Battle of Worcester—Charles Escapes to France—Vigorous Government—Foreign Difficulties—Navigation Act—War with Holland—Contest between Parliament and the Army—Expulsion of the Rump—The Little Parliament—Cromwell made Protector 90

THE COMMONWEALTH (concluded).

Naval Victory over the Dutch—Death of Van Tromp—Quasi-Royal State of the Lord-Protector—Disaffection against Cromwell—His Vigorous Rule—Charles II. offers a Reward for his Assassination—Rebellions in Scotland—Cromwell's Dealings with the Portuguese Ambassador—Reform of the Court of Chancery—Commission for Purgation of the Church—The Reformed Parliament—Exclusion of the Ultras—Dissolution of Parliament—Danger from Plots—Accident to the Protector—Death of Cromwell's Mother—Royalist Outbreaks—Cromwell's Major-Generals—Foreign Policy—War with Spain—Massacre of the Piedmontese—Capture of Jamaica—The Jews Appeal for Toleration—Cromwell's Third Parliament—Plots against his Life—The Petition and Advice—Cromwell refuses the Royal Title—Blake's Brilliant Victory at Santa Cruz—Death of Blake—Successes against Spain—Failure of the Reconstructed Parliament—Punishment of Conspirators—Victory in the Netherlands—Absolutism of Cromwell—His Anxieties, Illness, and Death—Proclamation of Richard Cromwell—He calls a Parliament—It is Dissolved—Reappearance of the Rump—Richard Retires—Royalist Risings—Quarrels of the Army and the Rump—General Monk—He Marches upon London—Demands a Free Parliament—Royalist Reaction—Declaration of Breda—Joyful Reception of Charles 123

THE PROGRESS OF THE NATION UNDER JAMES I., CHARLES I., AND THE COMMONWEALTH.

Manufactures and Commerce—Trade under the Stuarts—English Commerce and Dutch Competition—The East India Company—Vicissitudes of its Early History—Rival Companies—The American Colonies and West Indies—Growth of London—National Revenue—Extravagance of the Stuarts—Invention of the Title of Baronet—Illegal Monopolies—Cost of Government—Money and Coinage—Agriculture and Gardening—Dramatists of the Period—Shakespeare and his Contemporaries—Poets of the Occult School—Herbert, Herrick, Quarles—A Wealth of Poetry—Prose-Writers—Bacon's "Novum Organum"—Milton's Prose Works—Hales, Chillingworth, Jeremy Taylor, Fuller, and other Theological Writers—Harrington's "Oceana"—Sir Thomas Browne—Historians and Chroniclers—First Newspapers—Harvey's Discovery of the Circulation of the Blood—Napier's Invention of Logarithms—Music—Painting, Engraving, and Sculpture—Architecture—Manners and Customs—Sports and Pastimes—Furniture and Domestic Embellishment—Costumes—Arms and Armour—Condition of the People 165

CHARLES II.

Character of Charles II.—The King's First Privy Council—The Convention Parliament—Submission of the Presbyterian Leaders—The Plight of those who took Part in the late King's Trial—Complaisance of the Commoners—Charles's Income—The Bill of Sales—The Ministers Bill—Settlement of the Church—Trial of the Regicides—Their Execution—Marriage of the Duke of York—Mutilation of the Remains of Cromwell—The Presbyterians Duped—The Revenue—Fifth-Monarchy Riot—Settlements of Ireland and Scotland—Execution of Argyll—Re-establishment of Episcopacy—The new Parliament violently Royalist—The King's Marriage—His Brutal Behaviour to the Queen—State of the Court—Trial of Vane and Lambert—Execution of Vane—Assassination of Regicides—Sale of Dunkirk—The Uniformity Act—Religious Persecution—Strange Case of the Marquis of Bristol—Repeal of the Triennial Act—The Conventicle and Five Mile Acts—War with Holland—Appearance of the Plague—Gross Licentiousness of the Court—Demoralisation of the Navy—Monk's Fight with the Dutch—The Great Fire 193

REIGN OF CHARLES II. (continued).

Demands of Parliament—A Bogus Commission—Crushing the Covenanters in Scotland—The Dutch in the Thames—Panic in London and at Court—Humiliation of England—Peace is Signed—Fall of Clarendon—The Cabal—Sir [vii]William Temple at the Hague—The Triple Alliance—Scandals at Court—Profligacy of the King and the Duke of Buckingham—Attempt to Deprive the Duke of York of the Succession—Persecution of Nonconformists—Trial of Penn and Mead—The Rights of Juries—Secret Treaty with France—Suspicious Death of Charles's Sister—"Madam Carwell"—Attack on Sir John Coventry—National Bankruptcy—War with Holland—Battle of Southwold Bay—Declaration of Indulgence—Fall of the Cabal—Affairs in Scotland and Ireland—Progress of the Continental War—Mary Marries William of Orange—Louis Intrigues with the Opposition—Peace of Nimeguen—The Popish Plot—Impeachment of Danby—Temple's Scheme of Government—The Exclusion Bill—Murder of Archbishop Sharp—Bothwell Bridge—Anti-Catholic Fury—Charges against James—Execution of Lord Stafford 221

REIGN OF CHARLES II. (concluded).

Charles's Embarrassments—Exclusion Intrigues—Parliament Dissolved—The King again Pensioned by Louis—New Parliament at Oxford—Violence of the Whigs—Charles Dissolves the Oxford Parliament—Execution of Archbishop Plunket—Arrest of Shaftesbury—Dismay of the Gang of Perjurers—Oates turned out of Whitehall—Shaftesbury's Lists—Visit of William of Orange—James in Scotland—Defeat of the Cameronians—Cargill's Manifesto—The Duke of York's Tyranny—Flight of Argyll—The Torture in Edinburgh—Arrogance of Monmouth—Contest between the Court and the City—Death of Shaftesbury—Rye House Plot—Suicide of the Earl of Essex—Trial of Lord William Russell—Extraordinary Declaration of the University of Oxford—Trial of Algernon Sidney—The Duke of Monmouth Pardoned—Base Conduct of Monmouth—Trial of Hampden—Trials in Scotland—Absolutism of Charles—Forfeiture of Charters by the Corporations—Influence of the Duke of York—Opposition of Halifax—Sickness and Death of the King 267

REIGN OF JAMES II.

James's Speech to the Council—Rochester supersedes Halifax—Other Changes in the Ministry—James Collects the Customs without Parliament—French Pension continued—Scottish Parliament—Oates and Dangerfield—Meeting of Parliament—It grants Revenue for Life—Monmouth and Argyll—Argyll's Expedition—His Capture and Execution—Monmouth's Expedition—He enters Taunton—Failure of his Hopes—Battle of Sedgemoor—Execution of Monmouth—Cruelties of Kirke and Jeffreys—The Bloody Assize—The Case of Lady Alice Lisle—Decline of James's Power—He Breaks the Test Act—Revocation of the Edict of Nantes—Prorogation of Parliament—Acquittal of Delamere—Alienation of the Church—Parties at Court—The Dispensing Power Asserted—Livings granted to Catholics—Court of High Commission Revived—Army on Hounslow Heath—Trial of "Julian" Johnson—James's Lawlessness in Scotland and Ireland—Declaration of Indulgence—The Party of the Prince of Orange and the Princess Mary—Expulsion of the Fellows of Magdalen College—New Declaration of Indulgence—Protest of the Seven Bishops—Birth of the Prince of Wales—Trial and Acquittal of the Bishops—Invitation to William of Orange—Folly of James—William's Preparations—Blindness of James, and Treachery of his Ministers—William's Declaration—James convinced, makes Concessions—William lands at Torbay—His Advance to Exeter—Churchill's Treason—Flight of the Princess Anne and her Husband—James sends Commissioners to Treat with William—Flight of James—Riots in London—Return of James—His Final Flight to France—The Convention—The Succession Question—Declaration of Rights—William and Mary joint Sovereigns 289

PROGRESS OF THE NATION FROM THE CIVIL WAR TO THE GREAT REVOLUTION.

Religion: Nonconformist Sects—Imprisonment of Bunyan—Fox and the Society of Friends—The Punishment of James Naylor—Expulsion of Roger Williams—Other Religious Sects—Literature: Milton—His Works—Cowley—Butler—Dryden—Minor Poets—Dramatists of the Restoration—Prose Writers: Milton and Dryden—Hobbes—Clarendon—Baxter—Bunyan—Waiton—Evelyn and Pepys—Founding of the Royal Society—Physical Science—Discoveries of Napier, Newton and Flamsteed—Mathematicians and Chemists—Harvey and Worcester—Painting, Sculpture, and Engraving—Coinage—Music—Furniture—Costume—Manners and Customs—State of London—Sports and Amusements—Country Life—Travelling—The Clergy—Yeomen—Village Sports—Growth of the Revenue and Commerce—Growing prosperity of the North of England—The Navigation Act—Norwich and Bristol—Postal Arrangements—Advantages Derived from the Industries of the Foreign Refugees—The East India Company—Condition of the People: Wages—The Poor Law—Efforts of Philanthropists 352

REIGN OF WILLIAM AND MARY.

Accession of William and Mary—Discontent of the Church and the Army—William's First Ministry—His Dutch Followers—The Convention becomes a Parliament—Oath of Allegiance—Settlement of the Revenue—Suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act—The Mutiny Bill—Settlement of Religion—The Coronation—Declaration of War with France—Violence of the Revolution in Scotland—Parties in the Scottish Parliament—Letter from James—Secession of Dundee—Edinburgh in Arms—Settlement of the Government—Dundee in the Highlands—Battle of Killiecrankie—Mackay Concludes the War—Revolution in Ireland—Panic among the Englishry—Londonderry and Enniskillen Garrisoned—Negotiations of Tyrconnel—His Temporary Success—Landing of James—He Enters Dublin—His Journey into Ulster—The Siege of Londonderry—It is Saved—Legislation of the Irish Parliament—Arrival of Schomberg—Factiousness of the English Whigs—State of the English Army in Ireland—Renewed Violence of the Whigs—The Corporation Act Thrown Out—William Threatens to Leave England—Dissolution of Parliament—Tory Reaction—Venality of the New Parliament—Settlement of the Revenue—Whig Propositions—The Act of Grace—Preparations for War—A Jacobite Plot—William goes to Ireland—Progress of the War under Schomberg—Gradual Improvement of his Position and Ruin of the Jacobite Army—The Battle of the Boyne—Flight of James—William Enters the Irish Capital—News from England—Siege of Limerick—Battle of Beachy Head—Landing of the French in Torbay—Courage of the English People—Settlement of Scotland—Marlborough's Successes in Ireland—Parliament Grants Liberal Supplies—Preston's Plot Thwarted—William Sets Out for Holland—Vigour of Louis—Fall of Mons—Trial of Jacobite Conspirators—Treason in High Places—Punishment of the Non-Jurors—The Continental Campaign—Condition of Ireland—Arrival of St. Ruth—Siege of Athlone—Battle of Aghrim—Second Siege and Capitulation of Limerick 396

REIGN OF WILLIAM AND MARY.

Proceedings in Parliament—Complaints against Admiral Russell—Treason in the Navy—Legislation against the Roman Catholics—The East India Company—Treasons Bill—The Poll Tax—Changes in the Ministry—Marlborough is deprived of his Offices—His Treachery—The Queen's Quarrel with the Princess Anne—William goes Abroad—Fall of Namur—Battle of Steinkirk—Results of the Campaign—The Massacre of Glencoe—Proposed Invasion of England—James's Declaration—Russell's Hesitation overcome by the Queen—Battle of La Hogue—Gallant Conduct of Rooke—Young's Sham Plot—Founding of Greenwich Hospital—Ill Success of the Fleet—Discontent of the People—Complaints in the Lords and Commons—The Land Tax—Origin of the National Debt—Liberty of the Press—The Continental Campaign—Battle of Landen—Loss of the Smyrna Fleet—Attack on the Navy—New Legislation—Banking Schemes of Chamberlayne and Paterson—The Bank of England Established—Ministerial Changes—Negotiations for Peace—Marlborough's Treason and the Death of Talmash—Illness and Death of Queen Mary 448

Reign of WILLIAM III. (continued).

Rising Hopes of the Jacobites—Expulsion of Trevor for Venality—Examination of the Books of the East India Company—Impeachment of Leeds—The Glencoe Inquiry—The Darien Scheme—Marlborough's Reconciliation with William—Campaign of 1695—Surrender of Namur—William's Triumphant Return—General Election and Victory of the Whigs—New Parliament—Re-establishment of the Currency—Treasons Bill passed—A Double Jacobite Plot—Barclay's Preparations—Failure of Berwick's Insurrection Scheme—William Avoids the Snare—Warnings and Arrests—Sensation in the House of Commons—Trial and Execution of the Conspirators—The Association Bill becomes Law—Land Bank Established—Commercial Crisis—Failure of the Land Bank—The Bank of England supplies William with Money—Arrest of Sir John Fenwick—His Confession—William ignores it—Good Temper of the Commons—They take up Fenwick's Confession—His Silence—A Bill of Attainder passes both Houses—Execution of Fenwick—Ministerial Changes—Louis desires Peace—Opposition of the Allies—French Successes—Terms of Peace—Treaty of Ryswick—Enthusiasm in England 476

REIGN OF WILLIAM III. (concluded).

William Meets his Parliament—Reduction of the Standing Army—Visit of Peter the Great—Schemes of Louis—The East India Company—Spanish Partition Scheme—Its Inception and Progress—Somers's Hesitation—The Treaty is [ix]Signed—New Parliament—Tory Reaction—Dismissal of the Dutch Guards—William forms an Intention of Quitting England—Attack on the late Ministry—Jobbery in the Admiralty—Paterson's Darien Scheme—Douglas's Reasons against It—Enthusiasm of the Scots—Departure of the First Expedition and its Miserable Failure—The Untimely End of the Second Expedition—Second Partition Scheme—Double-dealing of the French—New Parliament—Attack on Somers—Report on the Irish Grants—Resumption Bill passed—William's Unpopularity—Death of the Duke of Gloucester—Conclusion of the New Partition Treaty and its Results—Charles makes over his Dominions to the French Candidate—His Death—Disgust of William at Louis's Duplicity—Tory Temper of the House—The Succession Question—Debates on Foreign Policy—The Succession Act passed—New Negotiations with France—Attack on the Whig Ministers—Acknowledgment of the Spanish King—Impeachment of the Whigs—The Kentish Petition—Its Reception by the House—The Legion Memorial—Panic in the House—Violent Struggle between the two Houses—The Impeachments dropped—William goes Abroad—The Grand Alliance and its Objects—Beginning of the War—Death of James II.—Louis acknowledges the Pretender—Reaction in England—New Parliament and Ministry—The King's Speech—British Patriotism is Roused—Voting of Supplies—The Bills of Attainder and Abjuration—Illness and Death of William—His Character 502

THE REIGN OF QUEEN ANNE.

Accession of the Queen—Meeting of the Houses of Parliament—Scotland and Ireland—Power of Marlborough—The Revenue—Tory Colour of the Ministry—The Coronation—Declaration of War—Marlborough goes to the Seat of War—General Aspect of Affairs—Marlborough's Difficulties—His Campaign—Operations by Sea—Meeting of Parliament—Supply—Marlborough's Dukedom—The Occasional Conformity Bill—Dismissal of Rochester—Opening of the Campaign of 1703—Fall of Bonn—Failure to take Antwerp—Savoy and Portugal join the Allies—Visit of the Archduke Charles to England—The Storm—Jacobite Conspiracy—Ashby versus White—Queen Anne's Bounty—Marlborough's Great Plans—The States-General hoodwinked—His March—Dismay of the French—Junction with Eugene—Advance on the Danube—Assault of the Schellenberg—The Prince of Baden's Conceit—Approach of Tallard—The Eve of Blenheim—The Battle—Conclusion of the Campaign—Marlborough's Diplomacy—Capture of Gibraltar—Battle of Malaga—Proceedings in Parliament—The Campaign of 1705—Attempt to recover Gibraltar—Peterborough's Exploits in Spain—Proposal to Invite the Electress Sophia to England—Consequent Legislation—Battle of Ramillies—Eugene relieves Turin—Disasters in Spain—Meeting of the Commissioners for the Union—Condition of the Treaty—Opposition in Scotland—Riots in Edinburgh—Conduct of the Opposition—The Measure carried by Bribery—Its Discussion in the English Parliament—The Royal Assent given 535

THE REIGN OF QUEEN ANNE (continued).

Negotiations for Peace—The Ministry becomes Whig—Harley—Marlborough and Charles of Sweden—The Allies in Spain—Battle of Almanza—The French Triumphant in Spain—Attack on Toulon—Destruction of Shovel's Fleet—Jacobitism in Scotland—First Parliament of Great Britain—Abigail Hill—The Gregg Affair—Retirement of Harley and St. John from the Ministry—Attempted Invasion of Scotland—Campaign of 1708—Battle of Oudenarde—Capture of Lille—Leake takes Sardinia and Minorca—Death of Prince George of Denmark—The Junto—Terrible Plight of France—Marlborough's Plans for 1709—Louis Negotiates with Holland—Torcy's Terms—Ultimatum of the Allies—Rejection of the Terms—Patriotism of the French Nation—Fall of Tournay—Battle of Malplaquet—Meeting of Parliament—Dr. Sacheverell's Sermons—His Impeachment resolved upon—Attitude of the Court—The Trial and Sacheverell's Defence—The Riots—Dispersal of the Rabble—The Sentence—Bias of the Queen—The Tories in Power—Renewed Overtures for Peace—Their Failure—The Campaigns in the Netherlands and in Spain—Brihuega and its Consequence—Marlborough's Reign at an End—Unpopularity of Marlborough—Dismissal of the Duchess—Triumph of the Tories—Guiscard's Attack on Harley—Popularity of Harley—Marlborough's Last Campaign—Failure of the Attack on Quebec—The Ministry determine to make Peace—Overtures to the Pretender—He refuses to Change his Religion—Gualtier's Mission to Versailles—Indignation of the Dutch—The Basis of Negotiations—Signing of the Preliminaries—Excitement Abroad and at Home—Prorogation of Parliament—Strengthening of the Ministry—Debates in the two Houses—The Whigs adopt the Occasional Conformity Bill—Creation of Peers—Dismissal of Marlborough from his Employments—Walpole expelled the House 574

| PAGE | |

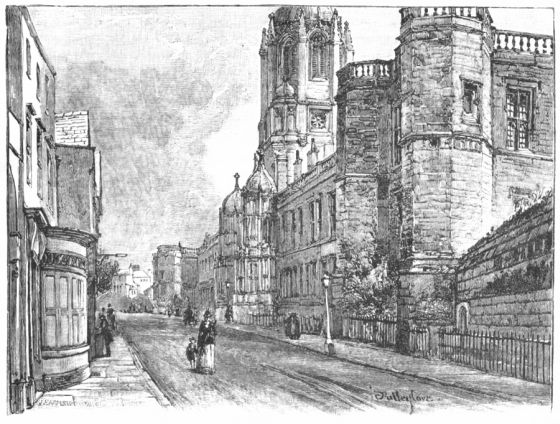

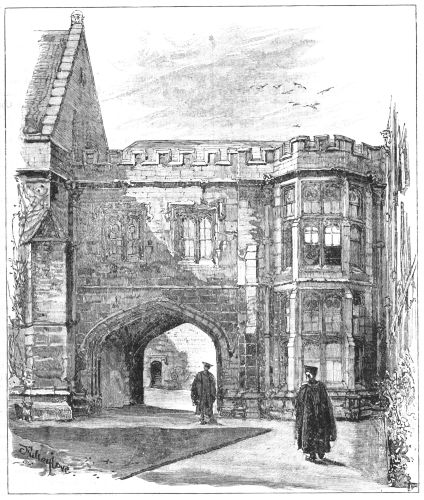

| Christ Church, Oxford, from St. Aldate's (looking West) | 1 |

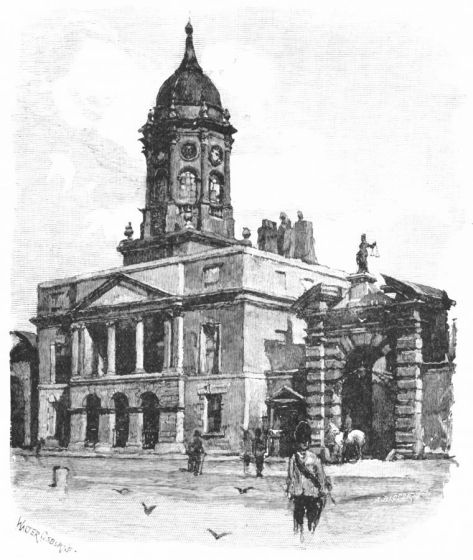

| The Clock Tower, Dublin Castle | 5 |

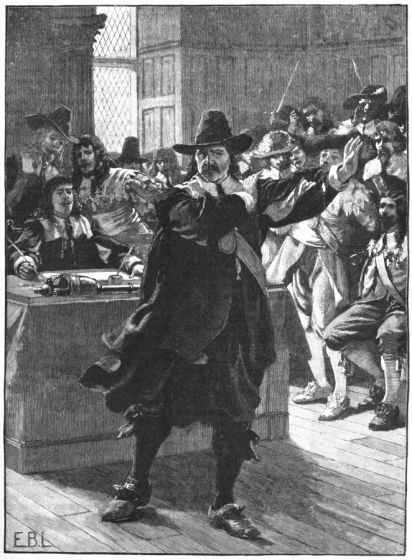

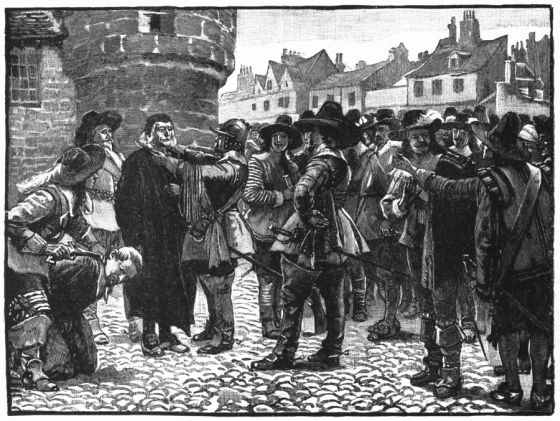

| Charles demanding the Surrender of the Five Members | 9 |

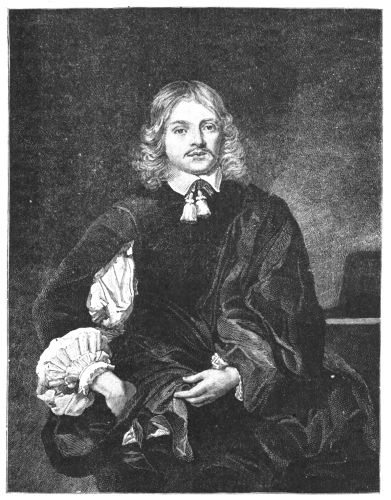

| Lord Falkland | 13 |

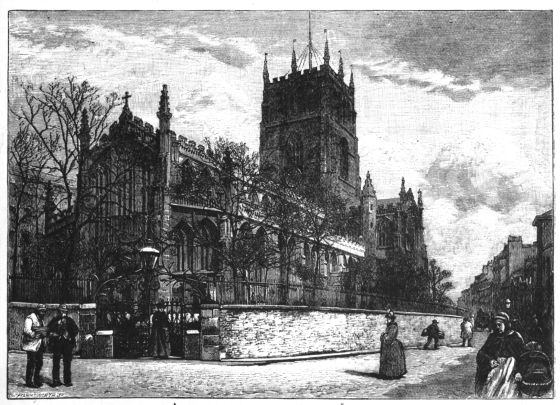

| St. Mary's Church, Nottingham | 17 |

| Hampden mortally Wounded at Chalgrove | 21 |

| Archbishop Laud's Library, East Quadrangle, John's College, | |

| Oxford | 25 |

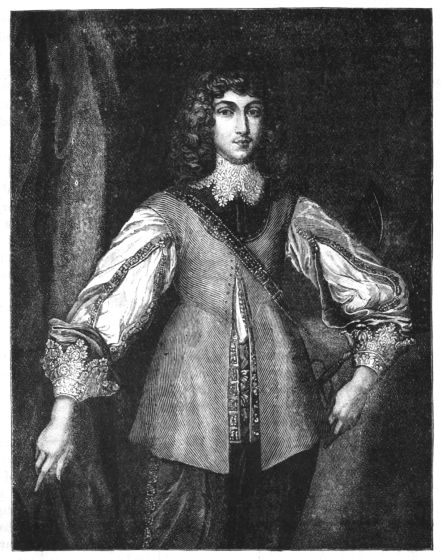

| Prince Rupert | 28 |

| Siege-piece of Charles I.—Newark (Half-crown) | 29 |

| Siege-piece of Charles I.—Pontefract (Shilling) | 29 |

| Siege-piece of Charles I.—Beeston (Two Shillings) | 29 |

| Siege-piece of Charles I.—Colchester (Ten Shillings, Gold) | 29 |

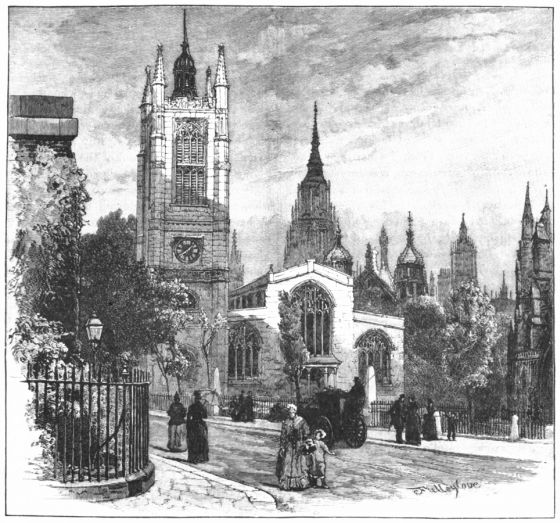

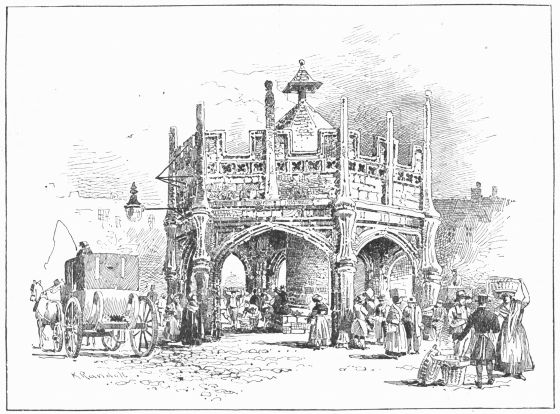

| St. Margaret's, Westminster | 33 |

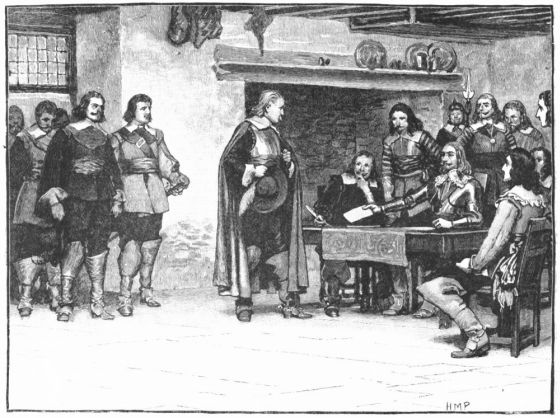

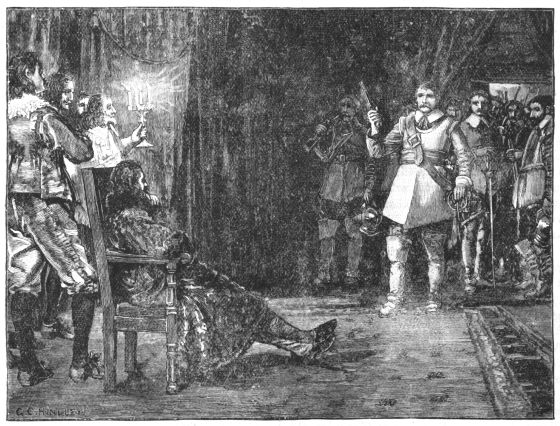

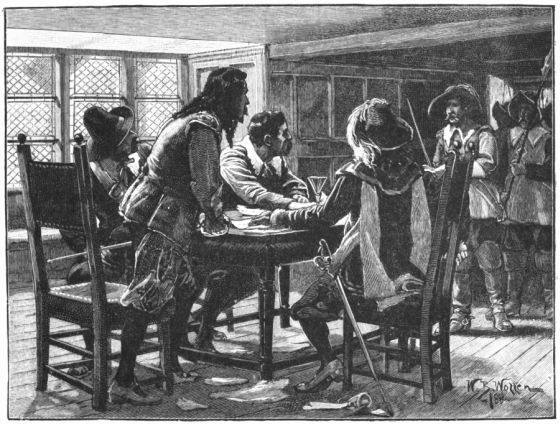

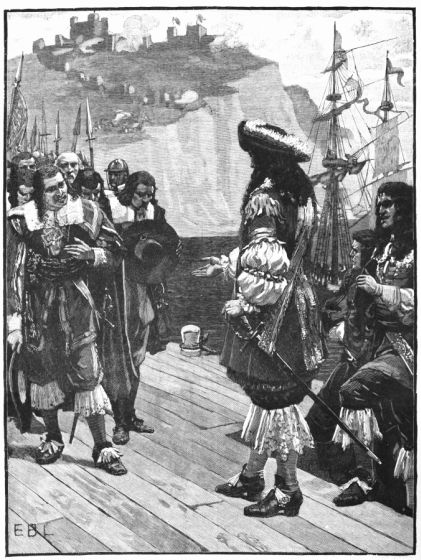

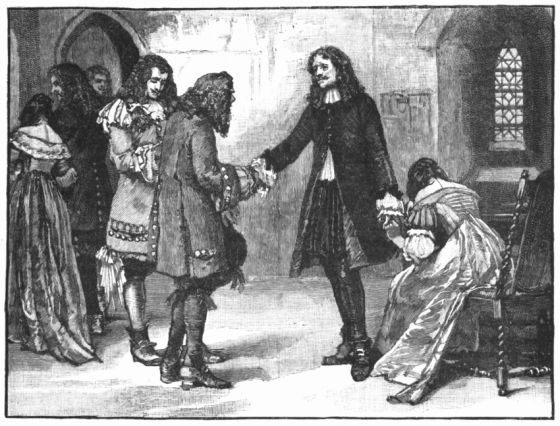

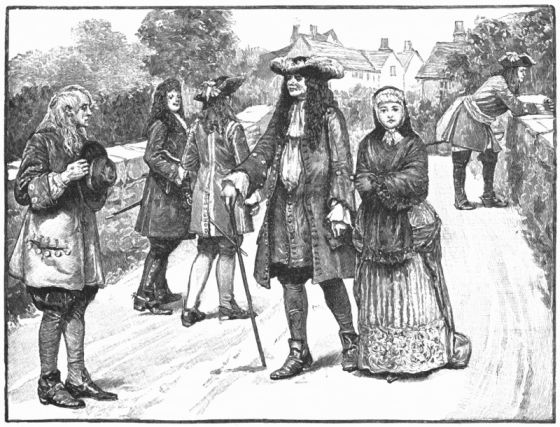

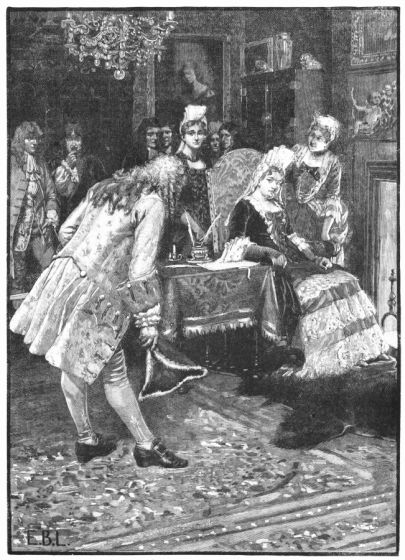

| Interview between Charles and the Earl of Denbigh | 36 |

| Roundhead Soldiers | 37 |

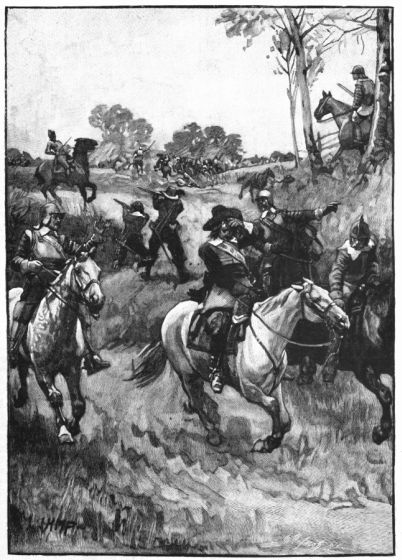

| Charles at the Battle of Naseby | 41 |

| Cavalier Soldiers | 45 |

| Raglan Castle | 49 |

| Flight of Charles from Oxford | 53 |

| Queen Henrietta's Drawing-room and Bedroom, Merton | |

| College, Oxford | 57 |

| Lord Fairfax | 61 |

| Cornet Joyce's Interview with Charles | 64 |

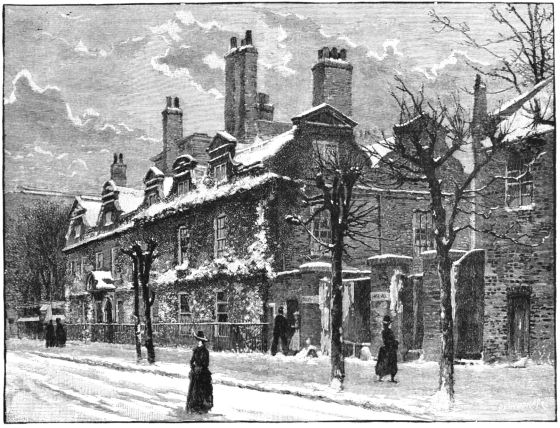

| Fairfax House, Putney | 65 |

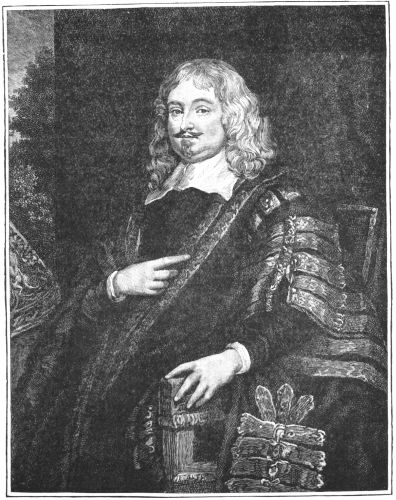

| Lord Clarendon | 69 |

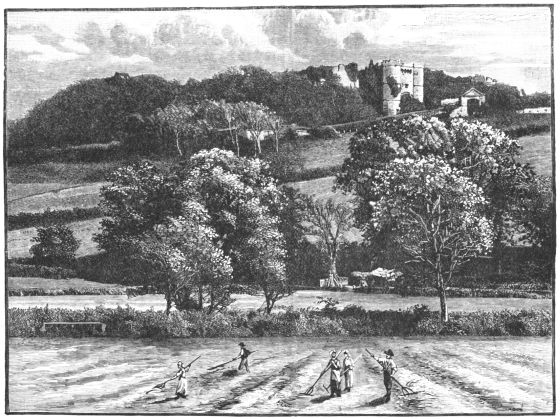

| Carisbrooke Castle, Isle of Wight | 73 |

| Rising of the London Apprentices on behalf of Charles | 76 |

| Execution of Sir Charles Lucas and Sir George Lisle | 77 |

| Arrival of Charles under Guard at Hurst Castle | 81 |

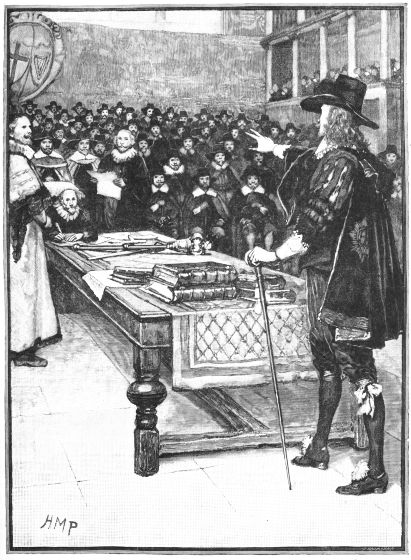

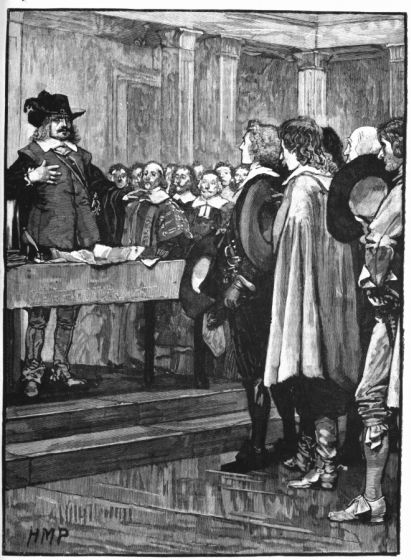

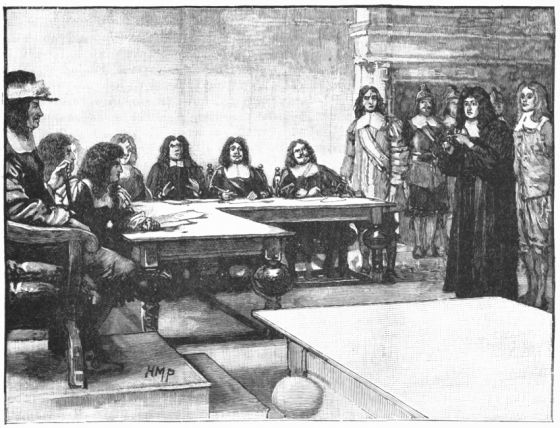

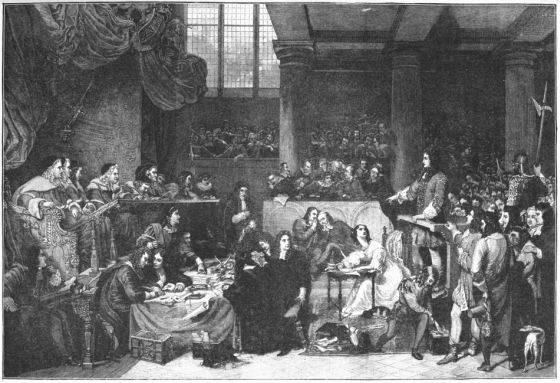

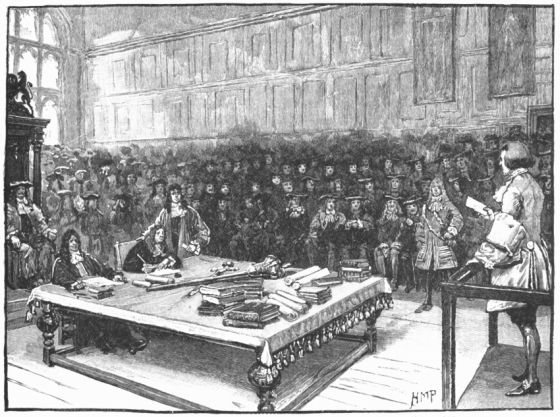

| Trial of Charles | 85 |

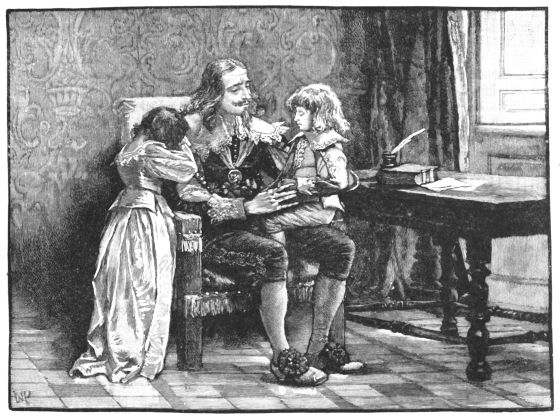

| Charles's Farewell Interview with the Duke of Gloucester | |

| and the Princess Elizabeth | 89 |

| Oliver Cromwell | 93 |

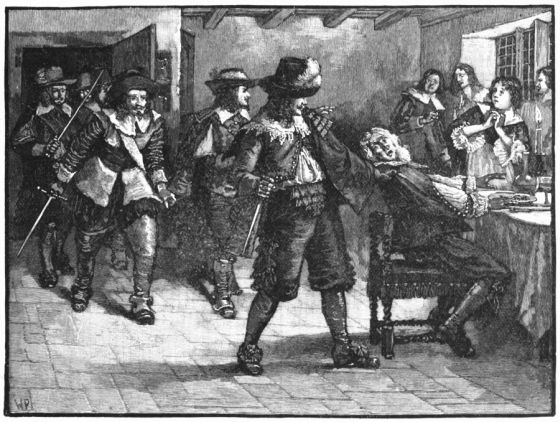

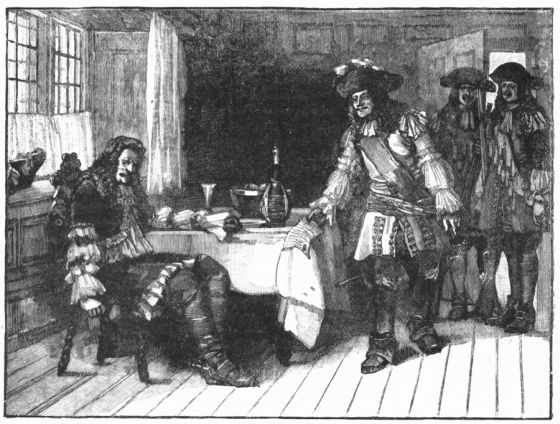

| Assassination of Dr. Dorislaus | 97 |

| Great Seal of the Commonwealth | 101 |

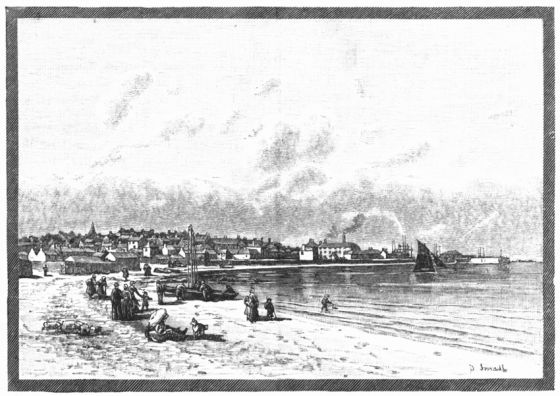

| Dunbar | 105 |

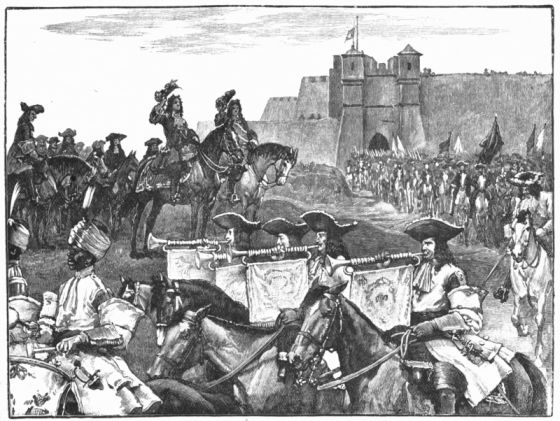

| Cromwell on his way to London after the Battle of Worcester | 108 |

| Henry Ireton | 109 |

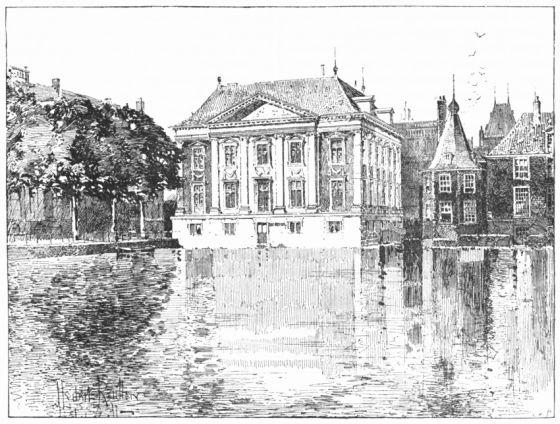

| Royal Museum and Picture Gallery, The Hague | 113 |

| Cromwell addressing the Long Parliament for the Last Time | 117 |

| Token of the Commonwealth (Copper) | 121 |

| Broad of the Commonwealth (Gold) | 121 |

| Crown of the Commonwealth (Silver) | 121 |

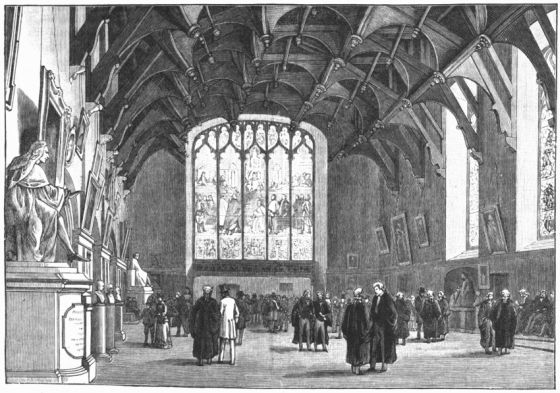

| The Great Hall, Hampton Court Palace | 125 |

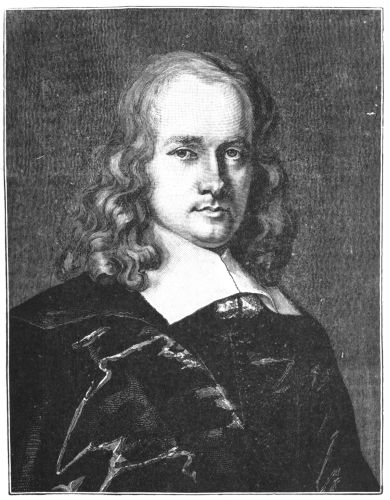

| John Milton | 129 |

| The Royalist Plotters at Salisbury insulting the Sheriff | 132 |

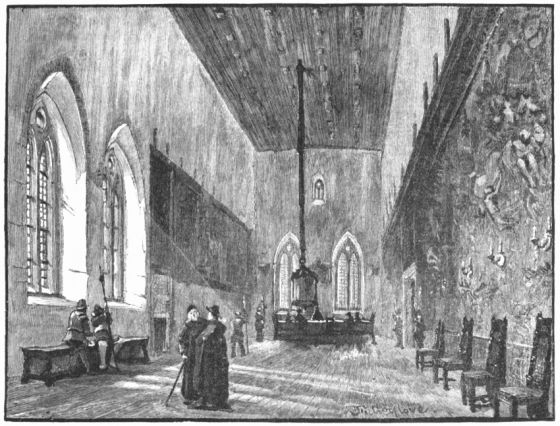

| The Painted Chamber, Westminster | 133 |

| Admiral Blake | 137 |

| Cromwell refusing the Crown | 141 |

| Arrest of Conspirators at the "Mermaid" | 145 |

| John Thurloe | 149 |

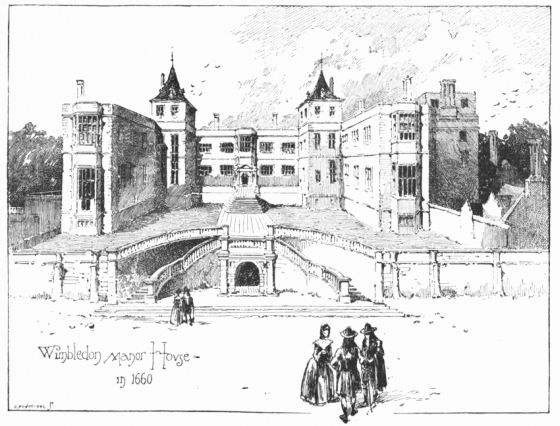

| The Manor House, Wimbledon (1660) | 153 |

| Richard Cromwell | 156 |

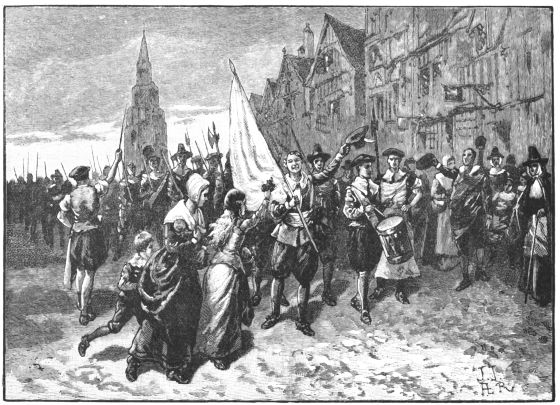

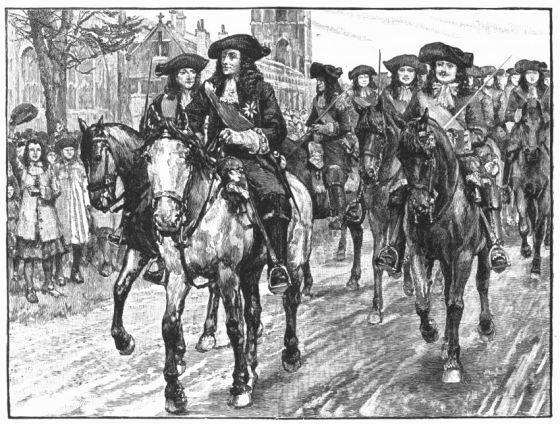

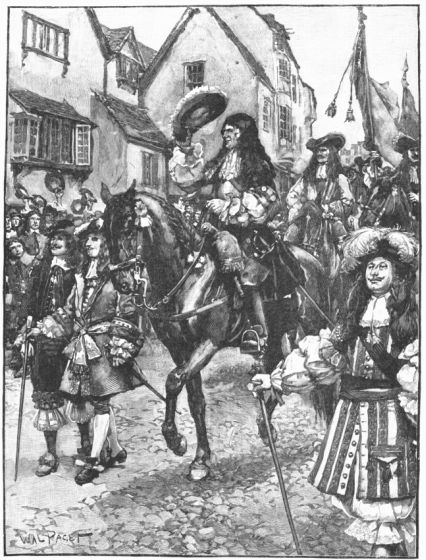

| Reception of Monk in the City of London | 157 |

| Interior of the Painted Chamber, Westminster (looking East) | 161 |

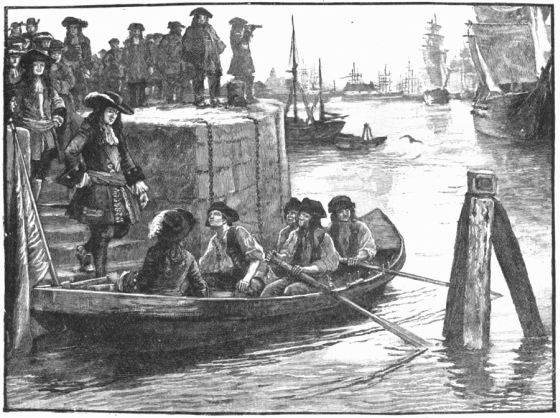

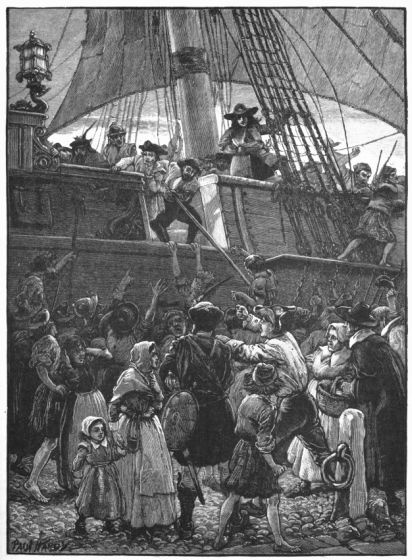

| Landing of Charles II. at Dover | 164 |

| Cecil, Second Lord Baltimore | 169 |

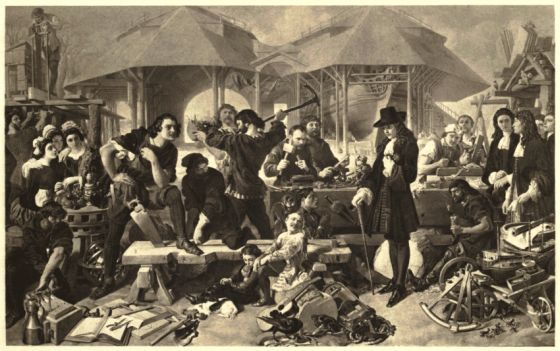

| Cheapside and the Cross in 1660 | 172 |

| The "Globe" Theatre, Southwark (with the "Rose" | |

| Theatre in the Distance), in 1613 | 173 |

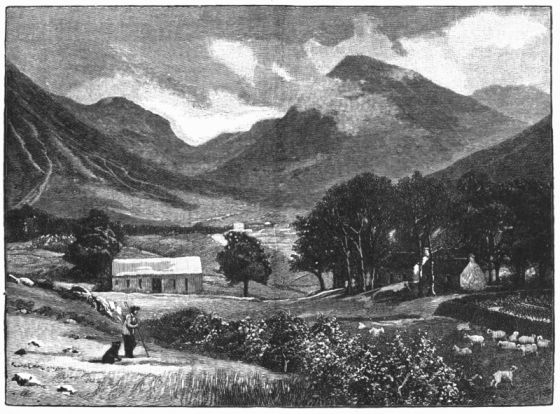

| Hawthornden in 1773 | 177 |

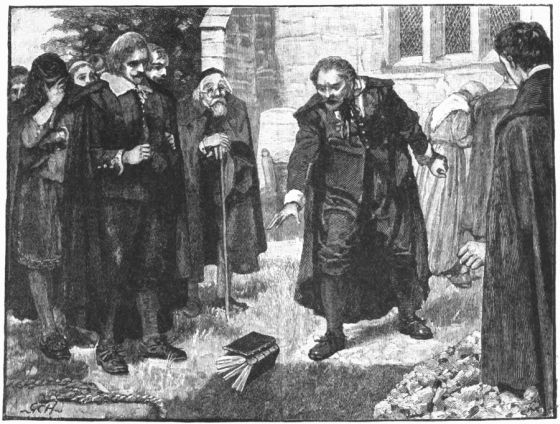

| Scene at the Funeral of Chillingworth | 181 |

| William Harvey | 184 |

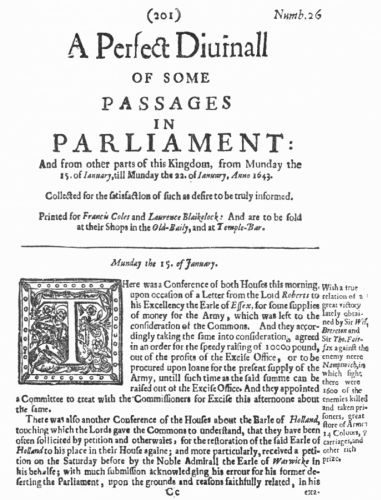

| Reduced Facsimile of Front Page of No. 26 of "A Perfect Diurnall" | 185 |

| Shopkeeper and Apprentice in the Time of Charles I. | 189 |

| Great Seal of Charles II. | 193 |

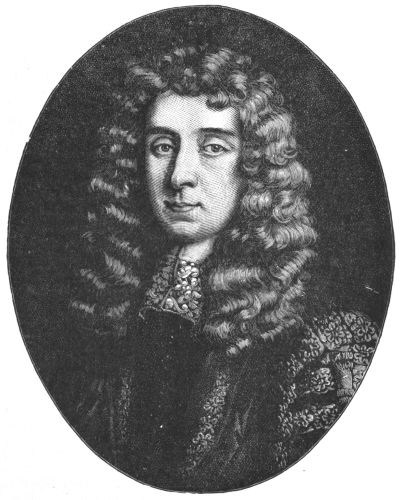

| Charles II. | 197 |

| Arrest of Argyll | 200 |

| Shilling of Charles II. | 205 |

| Halfpenny (with Figure of Britannia) of Charles II. | 205 |

| Crown of Charles II. | 205 |

| Five-Guinea Piece of Charles II. | 205 |

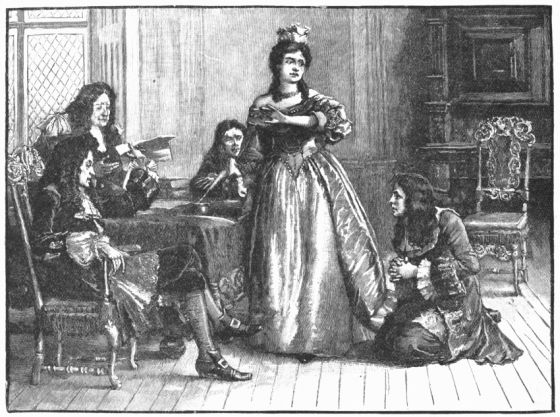

| Sir Harry Vane taking Leave of his Wife and Friends | 209 |

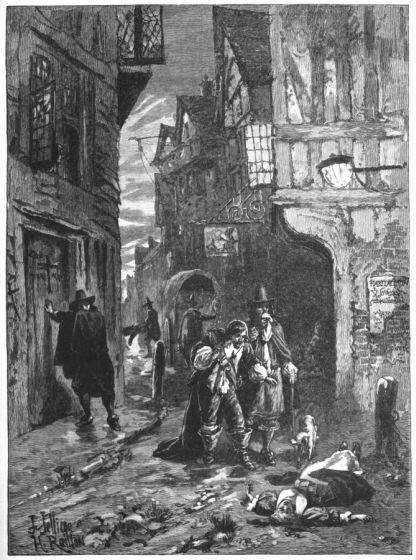

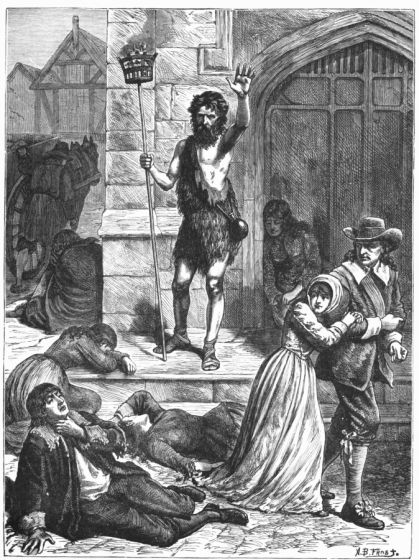

| The Great Plague: Scene in the Streets of London | 213 |

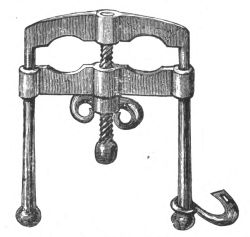

| Thumbscrew | 214 |

| The Great Plague: The Maniac pronouncing the Doom of London | 217 |

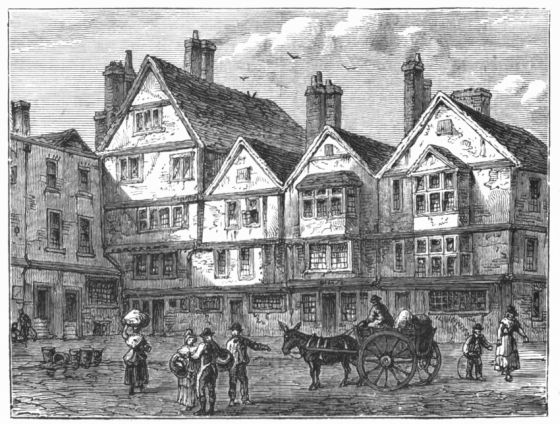

| Pie Corner, Smithfield, where the Great Fire reached its Limits | 220 |

| George Monk, Duke of Albemarle | 221 |

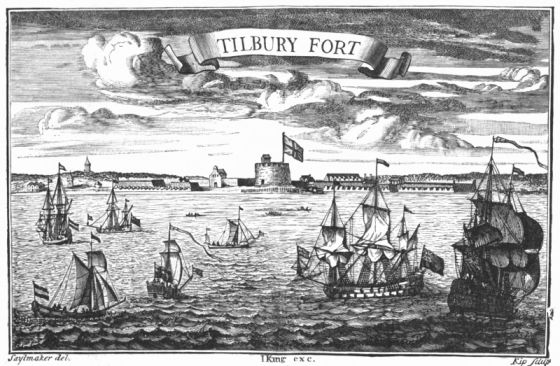

| Tilbury Fort | 225 |

| Samuel Pepys | 229 |

| The Assault on Sir John Coventry | 232 |

| Anthony Ashley Cooper, First Earl of Shaftesbury | 237 |

| View in the Hague: The Gevangenpoort in which Cornelius | |

| and John De Witt were imprisoned (1672) | 241 |

| Sir William Temple | 245 |

| Titus Oates before the Privy Council | 249 |

| Thomas Osborne, first Duke of Leeds | 253 |

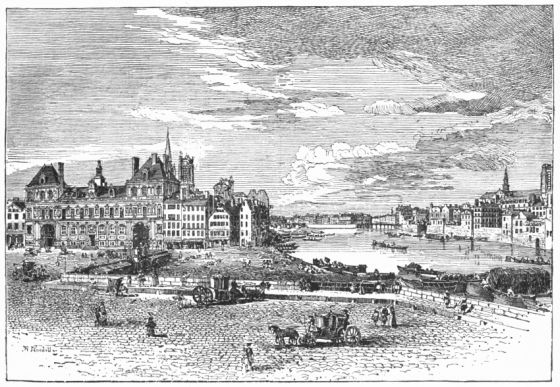

| Hôtel de Ville, Paris, in the Eighteenth Century | 257 |

| Assassination of Archbishop Sharp | 260 |

| The Duke of Monmouth | 265 |

| Arrival of Charles at Oxford | 268 |

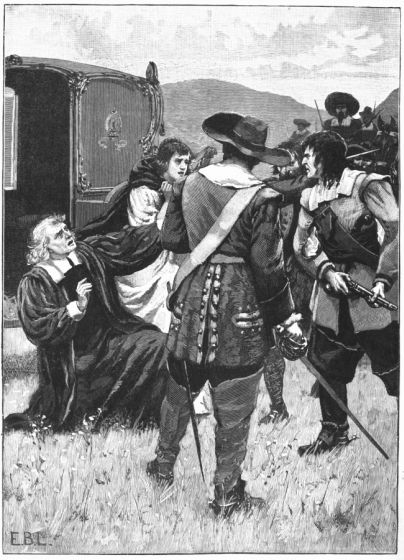

| Escape of Argyll | 273 |

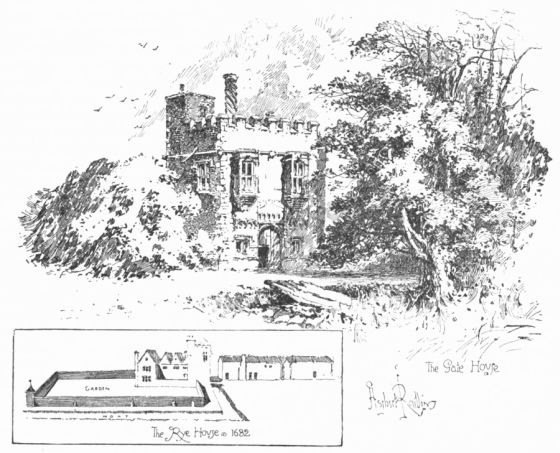

| The Rye House | 277 |

| Trial of Lord William Russell | 281 |

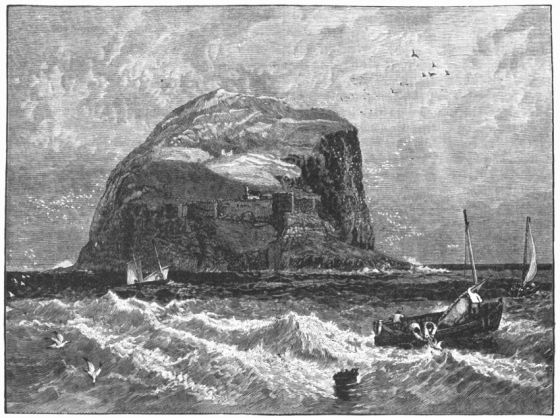

| The Bass Rock | 284 |

| Great Seal of James II. | 289 |

| James II. | 293 |

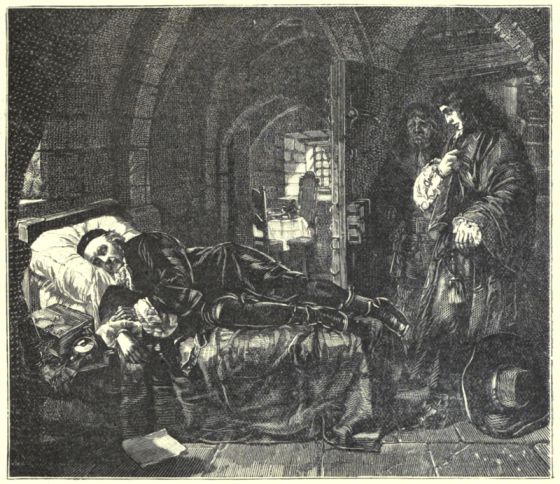

| The Last Sleep of Argyll | 297 |

| The Cross, Bridgewater, where Monmouth was proclaimed King | 300 |

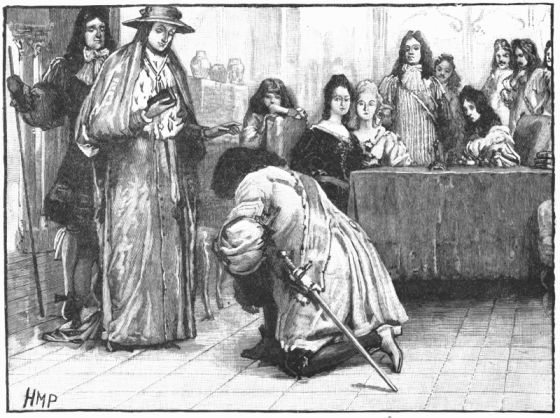

| Monmouth's Interview with the King | 304 |

| Judge Jeffreys | 309 |

| Fourpenny Piece of James II. | 311 |

| Five-Guinea Piece of James II. | 311 |

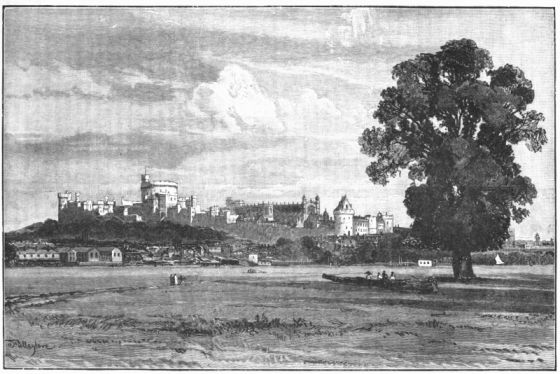

| Windsor Castle, from the Brocas | 313 |

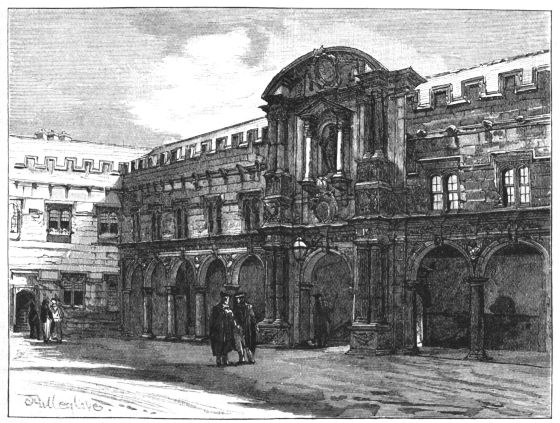

| Parliament Hall, Edinburgh | 317 |

| John Dryden | 321 |

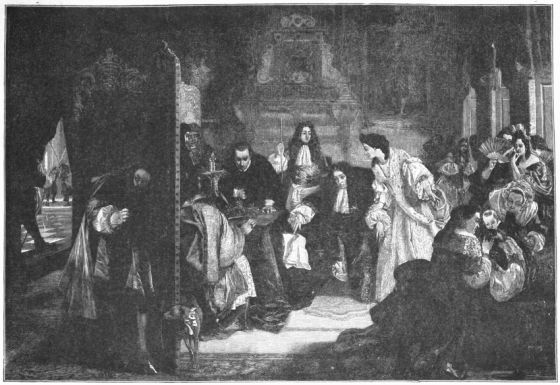

| James doing Homage to the Papal Nuncio | 324 |

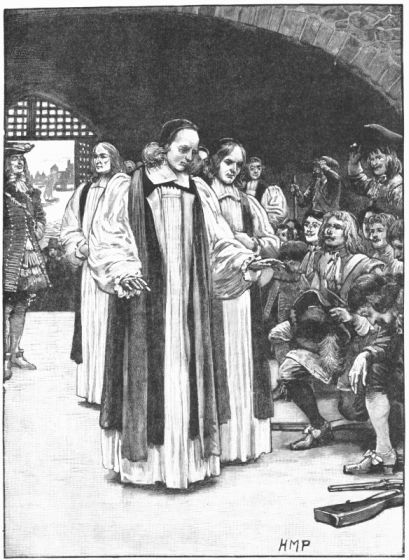

| The Seven Bishops entering the Tower | 329 |

| View in the Hague: The Hall of the Knights in the Binnenhof | 333 |

| [xi] | |

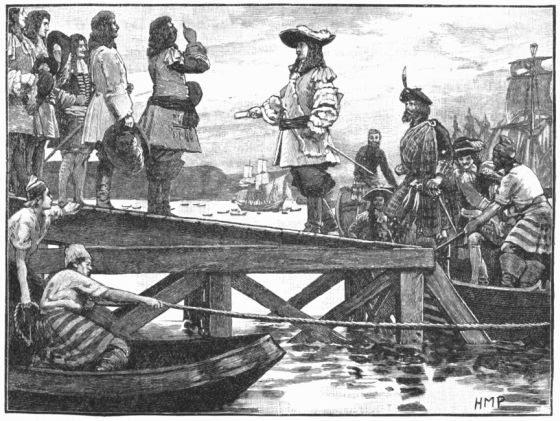

| William of Orange embarking to join the "Brill" | 337 |

| William of Orange entering Exeter | 341 |

| James hearing of the Landing of William of Orange | 345 |

| Roger Williams leaving his Home in Massachusetts | 353 |

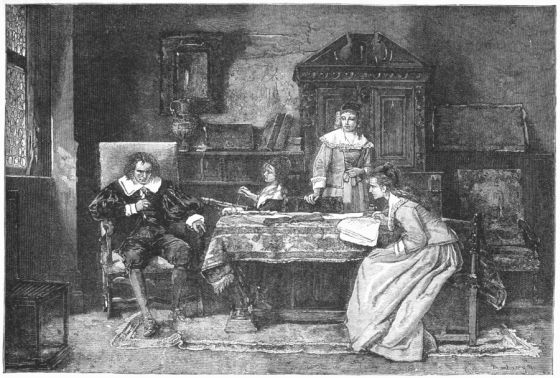

| Milton dictating "Paradise Lost" to his Daughters | 357 |

| Samuel Butler | 361 |

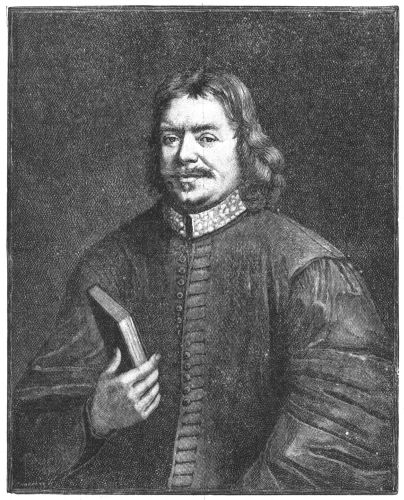

| John Bunyan | 364 |

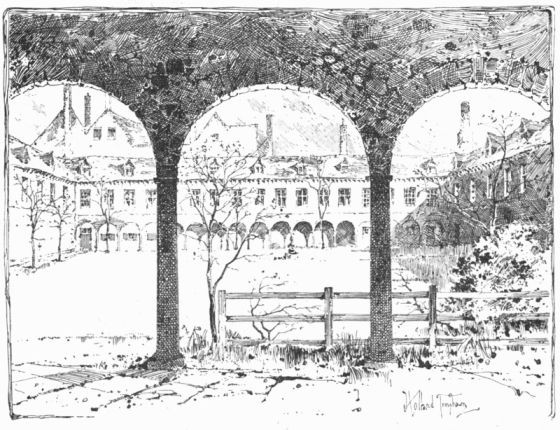

| Gresham College, where the Royal Society was first Housed | 365 |

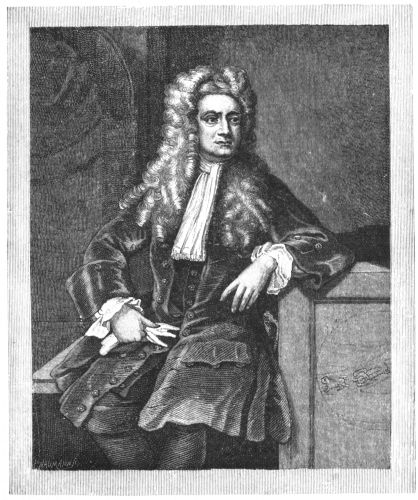

| Sir Isaac Newton | 369 |

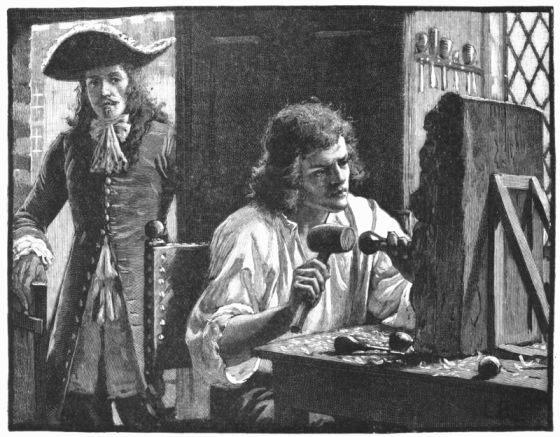

| Evelyn "Discovering" Grinling Gibbons | 372 |

| Costumes of the Time of Charles II. | 377 |

| Chelsea Hospital | 380 |

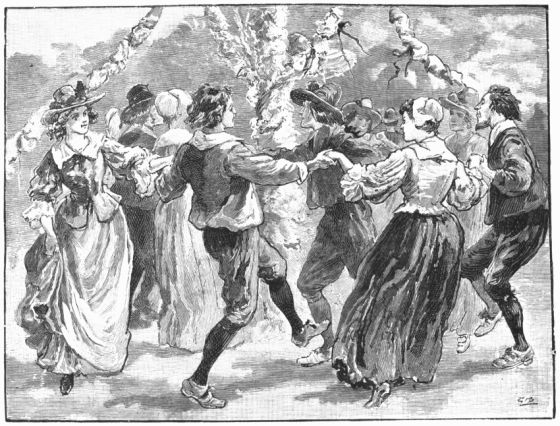

| May-Day Revels in the Time of Charles II. | 384 |

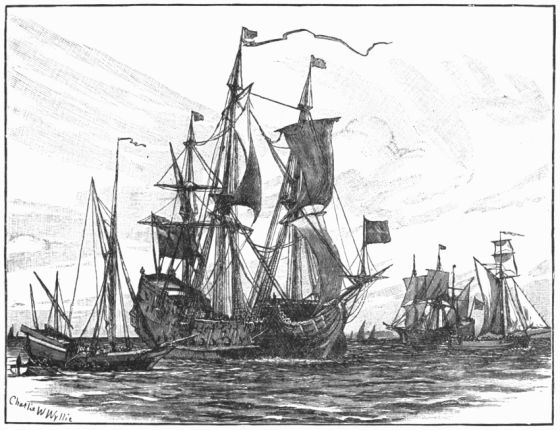

| Ships of the Time of Charles II. | 385 |

| The Old East India House in 1630 | 389 |

| Great Seal of William and Mary | 396 |

| Kensington Palace | 397 |

| William III. | 400 |

| Mary II. | 401 |

| Covenanters evicting an Episcopalian Clergyman | 405 |

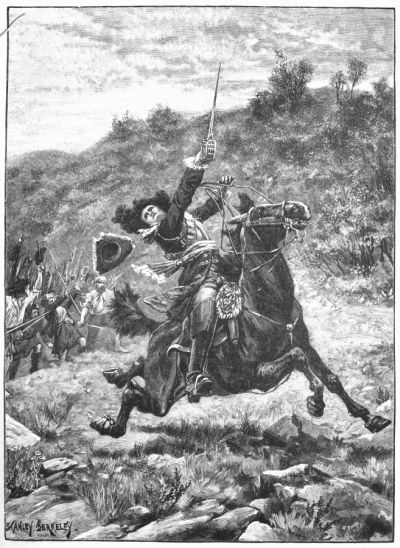

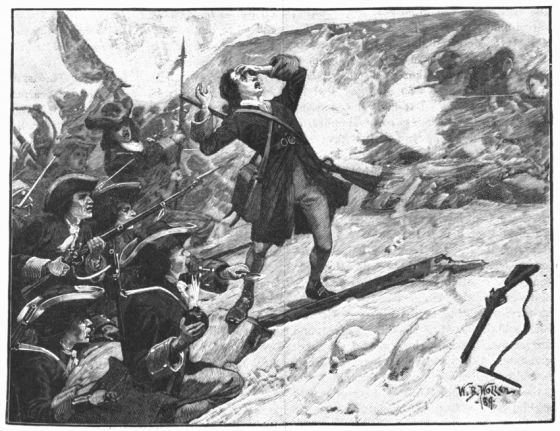

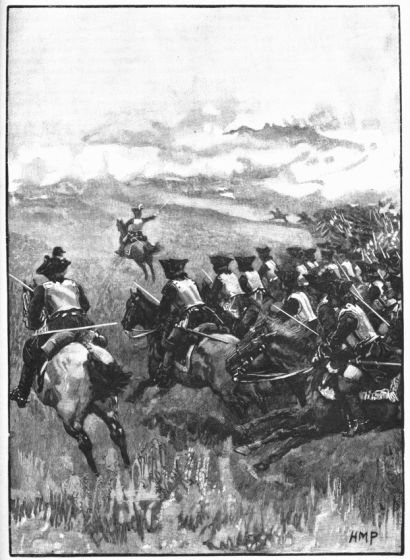

| Battle of Killiecrankie: The Last Charge of Dundee | 409 |

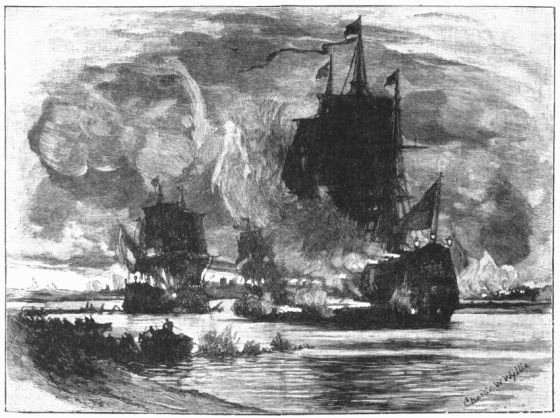

| The Mountjoy and Phœnix breaking the Boom at Londonderry | 416 |

| Landing of Marshal Schomberg at Carrickfergus | 417 |

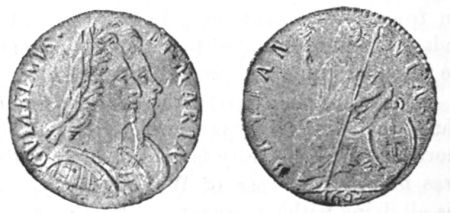

| Five-Guinea Piece of William and Mary | 420 |

| Crown of William and Mary | 420 |

| Fourpenny Piece of William and Mary | 420 |

| Halfpenny of William and Mary | 420 |

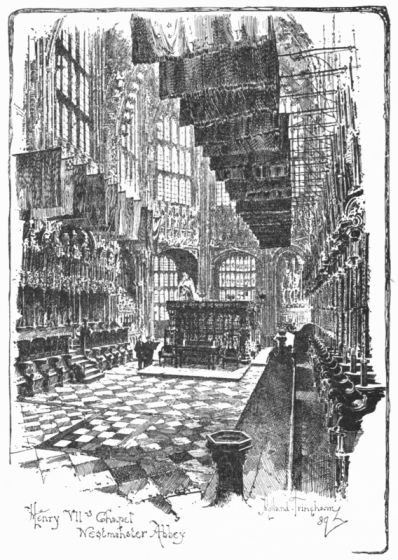

| Henry VII.'s Chapel, Westminster Abbey | 424 |

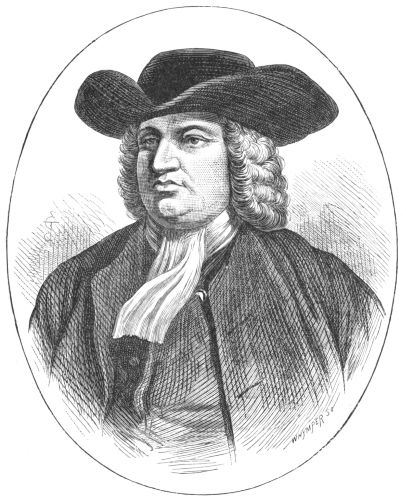

| William Penn | 425 |

| James entering Dublin after the Battle of the Boyne | 429 |

| The French retreating from Torbay | 433 |

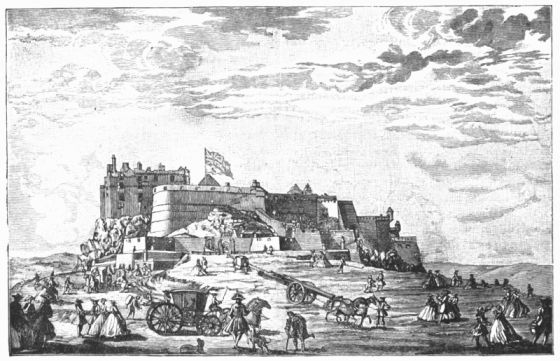

| Edinburgh Castle in 1725 | 436 |

| The Duke of Marlborough | 441 |

| The Assault of Athlone | 444 |

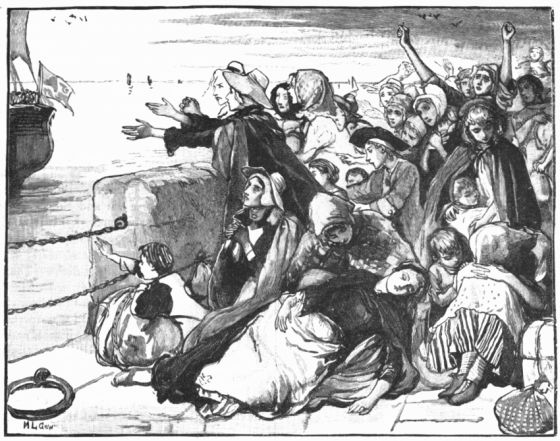

| Scene at the Removal of the Irish Soldiers from Limerick | 445 |

| George Saville, Marquis of Halifax | 449 |

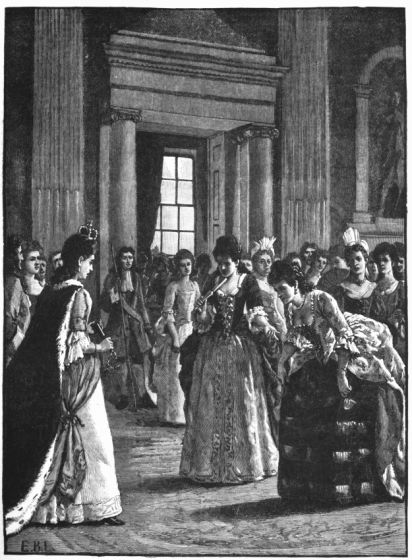

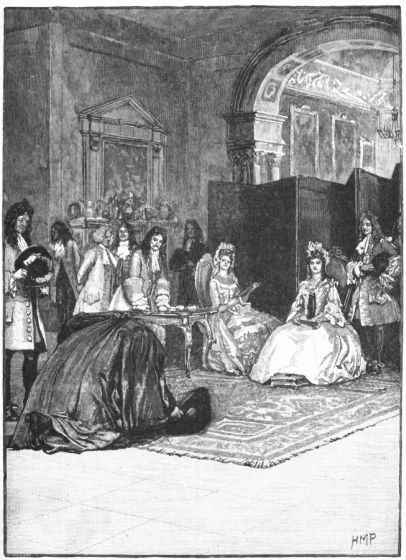

| Lady Marlborough and the Princess Anne at the Queen's | |

| Drawing-Room | 453 |

| Glencoe: Scene of the Massacre | 457 |

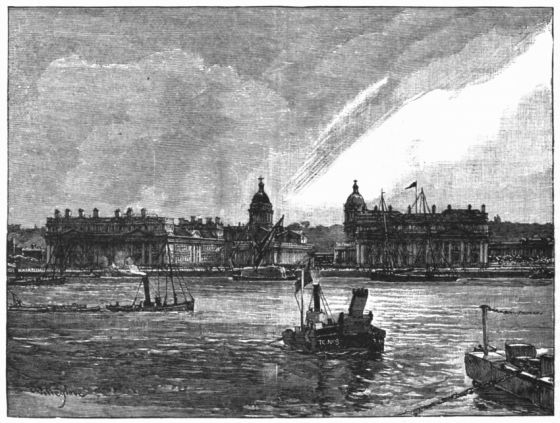

| Greenwich Hospital | 464 |

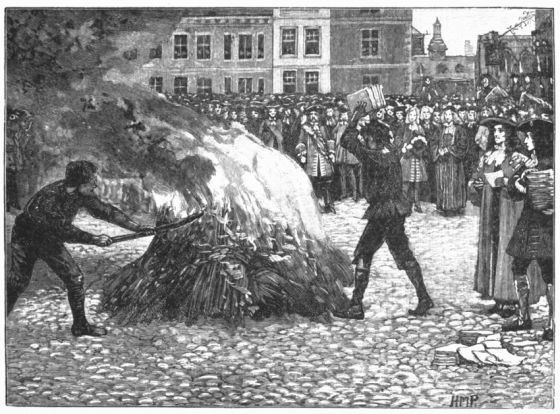

| Burning of Blount's Pamphlet by the Common Hangman | 465 |

| Louis XIV. | 469 |

| Costumes of the Time of William and Mary | 473 |

| William Paterson | 477 |

| Five-Guinea Piece of William | 480 |

| Half-Crown of William | 480 |

| Surrender of Boufflers | 481 |

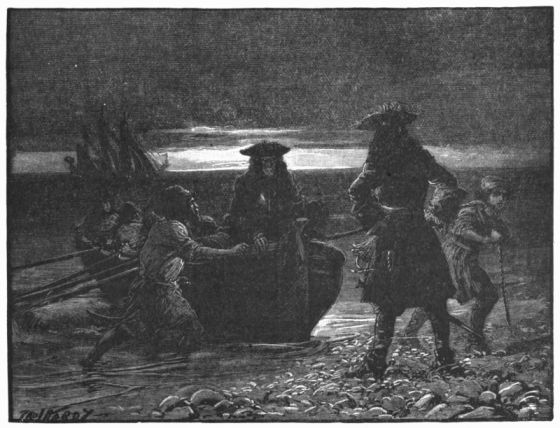

| Conspirators landing at Romney Marsh | 485 |

| Bishop Burnet | 489 |

| Old Mercers' Hall, where the Bank of England was first | |

| Established | 492 |

| Lady Fenwick interceding for her Husband | 493 |

| Lord Somers | 497 |

| William's triumphant Procession to Whitehall | 500 |

| View in the Hague: Old Gate in the Binnenhof, with the | |

| Arms of the County of Holland | 505 |

| Charles Montague, Earl of Halifax | 509 |

| Scene at the Departure from Leith of the Darien Expedition | 513 |

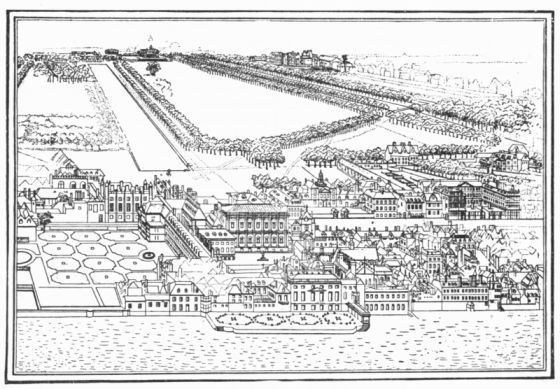

| The Royal Palace of Whitehall, from the Thames, in the beginning | |

| of the 17th Century | 520 |

| Captain Kidd before the Bar of the House of Commons | 525 |

| The Pretender proclaimed King of England by Order of | |

| Louis XIV. | 529 |

| View in the Hague: Chamber of the States-General in | |

| the Binnenhof | 533 |

| Bishop Burnet announcing her Accession to Anne | 537 |

| Lord Godolphin | 541 |

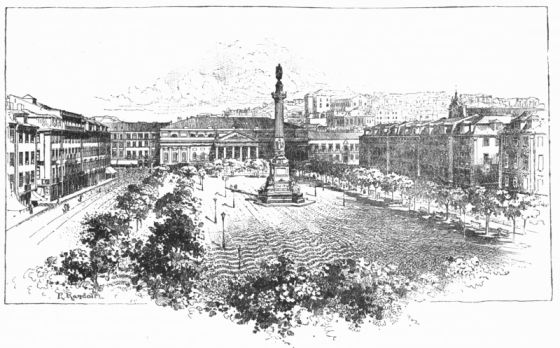

| View in Lisbon: The Práça de Dom Pedro | 545 |

| The King of Spain at Windsor: His Gallantry to the | |

| Duchess of Marlborough | 549 |

| Prince Eugene of Savoy | 553 |

| The Battle of Blenheim | 557 |

| Queen Anne | 561 |

| Great Seal of Queen Anne | 568 |

| The People of Edinburgh Escorting the Duke of Hamilton | |

| to Holyrood Palace | 569 |

| Costumes of the Reign of Queen Anne | 572 |

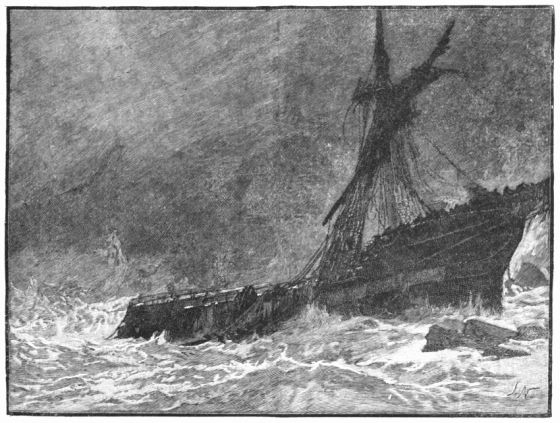

| Wreck of Sir Cloudesley Shovel's Fleet | 577 |

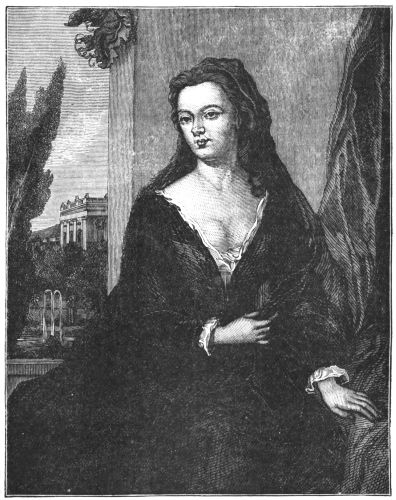

| Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough | 581 |

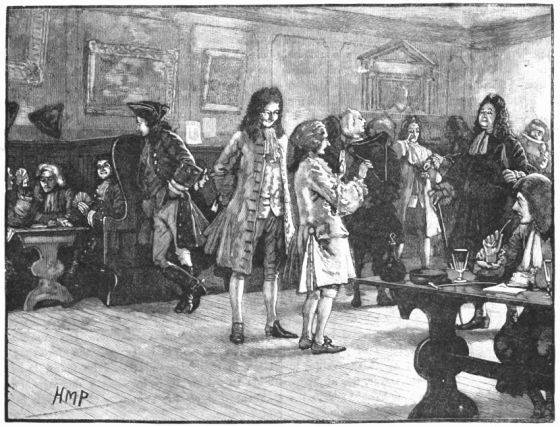

| London Coffee House in the Reign of Queen Anne | 585 |

| Five-Guinea Piece of Queen Anne | 588 |

| Farthing of Queen Anne | 588 |

| Two-Guinea Piece of Queen Anne | 588 |

| Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford | 589 |

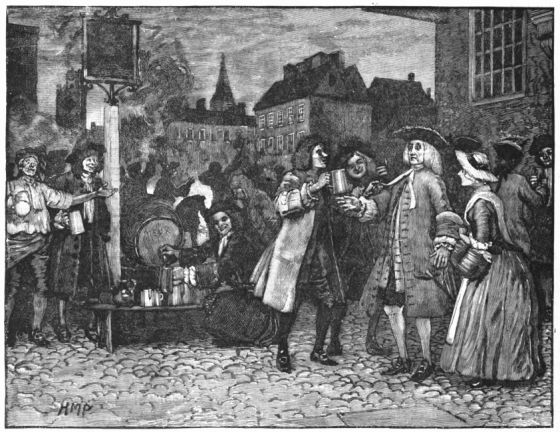

| Drinking to the Health of Dr. Sacheverell | 592 |

| Making Friends with Mrs. Masham | 593 |

| The Duke of Marlborough's Interview with Queen Anne | 597 |

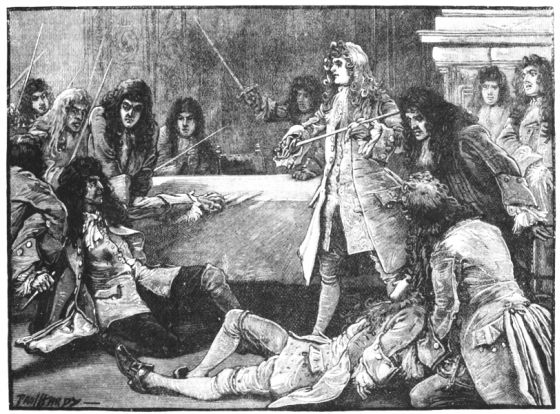

| The Fracas in the Privy Council | 601 |

| Marlborough House in the Time of Queen Anne | 604 |

| Henry St. John (afterwards Viscount Bolingbroke) | 605 |

Charles I. on his Way to Execution, 1649. (By Ernest Crofts, R.A.) Frontispiece

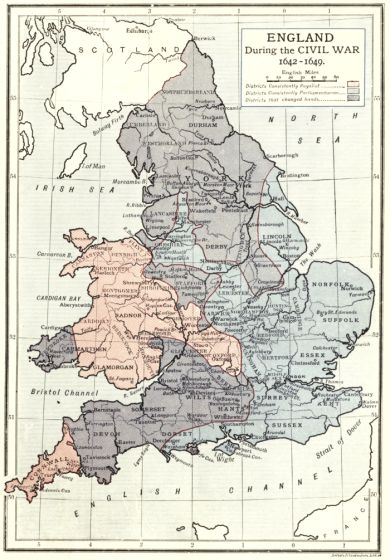

Map of England during the Civil War, 1642-1649. To face p. 50

The Children of Charles I. (By Miss Margaret I. Dicksee) " 71

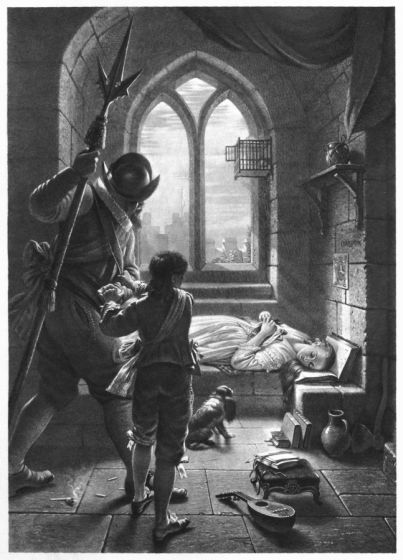

Death of the Princess Elizabeth, Carisbrooke Castle, Sept. 8th, 1650. (By C. W. Cope, R.A.) " 102

Cromwell Refusing the Crown. (By J. Schex) " 145

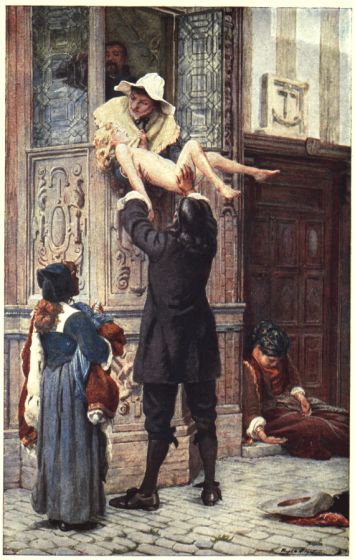

Rescued from the Plague, London, 1665. (By F. W. W. Topham, R.I.) " 209

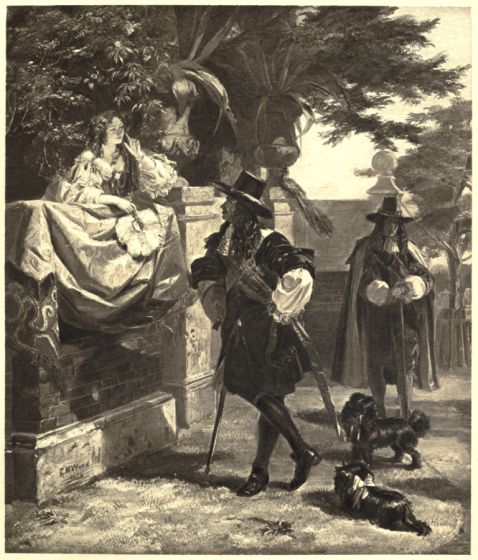

Charles II. and Nell Gwynn. (By E. M. Ward, R.A.) " 210

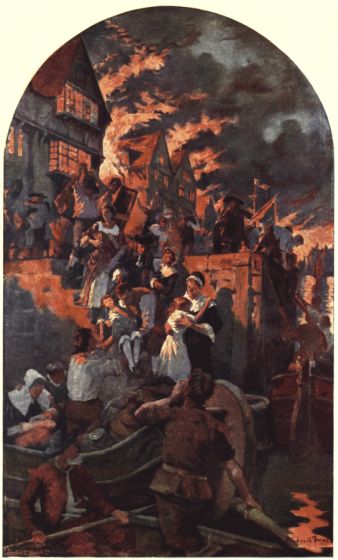

The Great Fire of London, 1666. (By Stanhope A. Forbes, A.R.A.) " 225

The Disgrace of Lord Clarendon after his Last Interview with the King in Whitehall Palace, 1667. (By E. M. Ward, R.A.) " 233

The Ante-Chamber of Whitehall during the Last Moments of Charles II., 1685. (By E. M. Ward, R.A.) " 289

"After Sedgemoor." (By W. Rainey, R.I.) " 302

Covenanters Preaching. (By Sir George Harvey, R.S.A.) " 402

William III. at the Battle of the Boyne. (By Jan Wyck) " 430

A Lost Cause: Flight of James II. after the Battle of the Boyne, 1690. (By Andrew C. Gow, R.A.) " 433

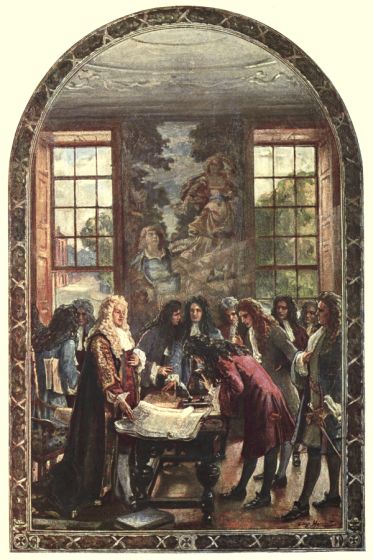

The Founding of the Bank of England, 1694. (By George Harcourt) " 471

Peter the Great at Deptford Dockyard. (By Daniel Maclise, R.A.) " 503

H.R.H. Princess Anne of Denmark, afterwards Queen of England. (By W. Wissing and J. Vandervaart) " 545

By permission of Messrs. S. Hildesheimer & Co., Ld.

CHARLES I. ON HIS WAY TO EXECUTION, 1649.

From the Picture by ERNEST CROFTS, R.A.

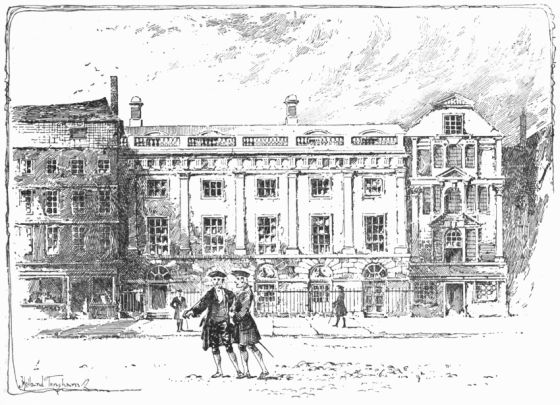

CHRIST CHURCH, OXFORD, FROM ST. ALDATE'S (LOOKING WEST.)

THE GREAT REBELLION.

Condition of Ireland—Roger Moore's Pilgrimage—Negotiations of the Anglo-Irish with Charles—Hugh M'Mahon betrays the Plot—Rising of the Native Irish—Massacre of Protestants—Measures taken by the English Parliament—Return of Charles to London—The Grand Remonstrance—The King's Answer—His Lieutenant of the Tower—Riots in London—Blunder of the Bishops—Attempted Arrest of the Five Members—Charles leaves London—The Queen goes to Holland—Charles at York—His Repulse from Hull—Preparations for War—The Royal Standard Raised—Prince Rupert's Headstrong Folly—Battle of Edge Hill—Charles marches on London—He returns to Oxford—Cromwell in the East—The Queen in Yorkshire—Death of Hampden—Parliamentary Disasters—Battle of Newbury—Death of Lord Falkland—Negotiations with the Scots and Irish—Death of Pym—Royal Parliament at Oxford—Battle of Marston Moor—Disastrous Failure of Essex in Cornwall—Second Battle of Newbury—The Self-denying Ordinance—The New-modelled Army.

The causes which drove the Irish to rebellion were for the most part of long standing. Their religion had been ruthlessly persecuted; their property had been confiscated by whole provinces at a time; their ancient chiefs had been driven from their lands, and many of them exterminated. Elizabeth, James, and Charles, had proffered them new titles on condition of making large sacrifices, but had never kept their word, and at this moment, the graces promised[2] by Charles to tolerate their religion and confirm the titles of their estates, were unfulfilled. The example of the Scots had aroused them to the hope of achieving a like triumph. Their great enemy the Earl of Strafford had fallen, but, on the other hand, they were menaced by Parliament with a still more fierce persecution, and even an avowed extermination of their religion. They believed that the Scottish Presbyterians would join with avidity in the attempt to subdue them, and come in for a share of the plunder of their estates; and they now seized on the idea of rising and reclaiming their ancient power and property. True, they were not one united people like the Scots: there were the ancient Irish, and the Anglo-Irish of the pale, that is, English settled in Ireland holding the estates of the expelled native chiefs, but keeping themselves aloof from the Irish. Yet many of the pale were Catholics, and the Catholic religion was the unanimous object of attachment on the part of the natives. The Parliament and the Scottish settlers in the north were banded against this religion, and this produced a counter-bond between the Catholic natives and the Catholics of the pale. From the British Parliament neither of these parties had anything to hope for on the score of religion; but the king was in need of aid against this Parliament, and it occurred to them that they might make common cause with him.

Roger Moore, a gentleman of Kildare, entered into this scheme with all the impetuosity of his nation. He saw the lands of his ancestors for the most part in the hands of English and Scottish settlers, and he made a pilgrimage into almost every quarter of Ireland to incite his countrymen to grasp this opportunity, when the king and Parliament of England were engrossed by their disputes, to recover their rights. Everywhere he was listened to with enthusiasm, and the natives held themselves ready to rise, and take a terrible vengeance on the usurpers of their lands at the first signal. The great chiefs of Ulster, Cornelius Maguire, Baron of Enniskillen, and Sir Phelim O'Neil, who had become the chieftain of the sept of Tyrone after the death of the son of the late persecuted Tyrone, fell into his views with all their followers. The Catholic members of the pale were more disposed to negotiate with Charles than to rush into insurrection against his authority. They knew that it was greatly to his interest at this moment to conciliate his Irish subjects, and they despatched to him a deputation previous to his journey to Scotland, demanding the ratification of those graces for which he had received the purchase money thirteen years before, and offering in return their warmest support to his authority in Ireland. Charles received them very graciously, promised them the full satisfaction of all their demands, and by Lord Gormanstown, who headed the deputation, and on whom he lavished the most marked attentions, he sent word to the Earls of Ormond and Antrim to secure in his interest the eight thousand troops which had been raised by Strafford, to keep them in efficient discipline, to augment rather than decrease their number, and to surprise the castle of Dublin, where they would find twelve thousand stand of arms.

But the English Parliament were by no means unaware of the danger from the army in Ireland, which consisted almost entirely of Catholics. They insisted on its being disbanded, as promised by the king on the Scottish pacification. He was not able to prevent this, and signed the order; but at the same time sent secret instructions by Gormanstown to Ormond and Antrim, to frustrate this by enlisting the whole body as volunteers to serve the King of Spain in Flanders.

At this juncture Sir William Parsons and Sir John Borlase were at the head of the English Government in Ireland; they were in the interest of the Parliament, and were detested by almost all classes of Irish. Sir John Clotworthy, in the House of Commons, had openly declared that "the conversion of the Papists in Ireland was only to be effected by the Bible in one hand, and the sword in the other." Pym was reported to have said that they would not leave a priest in Ireland; and at a public entertainment Parsons had echoed those sentiments by declaring that "in a twelvemonth not a Catholic would be left in that country." The Irish were, therefore, delighted with their success with the king, and Gormanstown and his associates hastened home again, with two Bills signed by the king, granting the possession of lands which had been held sixty years, and setting aside all the sequestrations made by Strafford. But Parsons and Borlase, aware that the passing of these Bills would attach Ireland to the interests of the king, defeated the object by proroguing Parliament a few days before the arrival of the deputies.

It was now resolved by Ormond and Antrim to defer any movement till the reassembling of the Irish Parliament in November, when they could at the same moment secure Dublin castle and the persons of Parsons and Borlase, and issue[3] in the name of the two Houses his Majesty's concession to the people of Ireland. But the native Irish, stimulated by the addresses of Moore, could not wait so long. They determined to rise, without waiting for the combined force, on the 23rd of October. Two hundred and twenty men were to surprise the castle, but at the time appointed only eighty appeared. They concluded to wait till the next day for the arrival of the rest, but that night one Hugh M'Mahon, in a drunken fit, betrayed the secret to Owen O'Connelly, a servant of Sir John Clotworthy, and a Protestant. He instantly carried the news to Sir William Parsons; the city gates were closed, and a quick search was made for the conspirators. All but M'Mahon and Lord Maguire escaped, but the castle was saved.

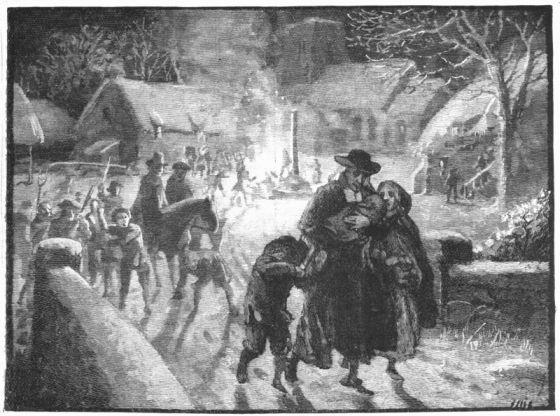

Ignorant of the failure of the plot, the people of Ulster rose on the appointed day. Charlemont and Dungannon were surprised by Sir Phelim O'Neil, Mountjoy by O'Quin, Tanderagee by O'Hanlan, and Newry by Macginnis. In little more than a week all the open country in Tyrone, Monaghan, Longford, Leitrim, Fermanagh, Cavan, Donegal, Derry, and part of Down, were in their hands. The other colonies in which there were English or Scottish plantations followed their example, and the greater part of Ireland was in a dreadful state of anarchy and terror. The Protestant people on the plantations fell beneath the butchering revenge of the insurgents, or fled wildly into the fortified towns. The horrors of the Irish massacre of 1641 have assumed a fearful place in history; the cruelties, expulsions, and oppressions of long years were repaid by the most infuriated cruelty. Men, women, and children, fell indiscriminately in the onslaught, and they who escaped, says Clarendon, "were robbed of all they had, to their very shirts, and so turned naked to endure the sharpness of the season, and by that means, and for want of relief, many thousands of them perished by hunger and cold."

Great care has been taken by Catholic writers to contradict these accounts, and to represent the atrocities committed as of no extraordinary extent. They remind us that no accounts of these barbarous slaughters were transmitted in the reports to the English Parliament, which would have been only too glad to spread, and even exaggerate bloody deeds of the Catholics. They reduce the number of people slain during the whole insurrection to about ten thousand, instead of the grossly exaggerated statements of Milton in his "Iconoclastes," that there were one hundred and fifty-four thousand in Ulster alone, or of Sir John Temple, that three hundred thousand were slain or expelled altogether. But nothing less than a most frightful massacre could have left the awful impression which still lives in tradition, and the calculations of moderate historians do not make the number massacred less than from fifteen thousand to twenty thousand. The Earl of Castlehaven, a Catholic, says that all the water in the sea could not wash from the Irish the taint of that rebellion. Whilst remembering the vengeance, however, we must never forget the long and maddening incentives to it. Much blame was attached to the Deputy-Governors, Borlase and Parsons, who, shut up in security in Dublin, took no measures for suppressing the insurgents. They were charged with purposely allowing the rebellion to spread, in order that there might be more confiscations, in which they would find their own benefit; but it must not be forgotten that they had few soldiers on whom they could rely, for these were nearly all Catholics; nor did the insurgents escape without severe chastisement in many places, for wherever there was a trusty garrison, the soldiers easily repelled the disorderly mob of plunderers; and Sir Phelim O'Neil suffered during the month of November severe losses.

Before Charles reached England, O'Connelly, the discoverer of the plot, arrived in London, with letters from the lords justices, and was called before the House of Lords to relate all that he knew. They immediately invited the House of Commons to a conference on the state of Ireland, and on the better providing for the security of England. They presented O'Connelly with five hundred pounds in money, and settled on him an annuity of two hundred pounds a year. It was resolved to look well after the Catholics in England, and to put the ports into a state of defence. The Commons voted that two hundred thousand pounds should be set apart for the requirements of Ireland; that six thousand foot and two thousand horse should be raised for service there; and that the fleet should carefully guard its coast. The Earl of Leicester, the Lord-Lieutenant, was desired to furnish a list of the most suitable officers for the service, and arms and ammunition were prepared in haste, to be despatched to Dublin. A pardon was offered to all rebels who laid down their arms by a certain day, at the same time that a reward was set on the heads of the leaders. But the Commons did not stop there; they passed a resolution never to tolerate the Catholic worship either in Ireland or in any part of his Majesty's dominions. Commissioners were[4] appointed to disarm the recusants in every part of the kingdom; pursuivants were sent out in every direction to seize priests and Jesuits; orders were given for the trial of all such persons; and the king was advised not to pardon or reprieve them. The queen's chapel was closed, her priests were dismissed, her confessor was sent to the Tower, and no less than seventy Catholic lords and gentlemen were denounced by the Commons to the Lords, as persons who ought to be secured to prevent them from doing injury to the State.

Such was the condition of things when Charles arrived in London. He was well received by the Lord Mayor and aldermen of the city, and in return gave them an entertainment at Hampton Court; but he was greatly chagrined at the proceedings of the Commons, telling them that they were converting the war in Ireland, which was a civil war, into a war of religion. He took umbrage also at Parliament sitting with a guard round their House. The Earl of Essex, on the king's arrival, surrendered his command of the forces south of the Trent to the king, and announced to the Lords that having resigned his commission, he could no longer furnish the guard. A message was sent from the Houses, requesting the king to restore them the guard, but he refused, saying he saw no occasion for it; but the Commons let him know that many dangerous persons, Irish and others, were lurking about, and that the "Incident" in Scotland, and the late attempt to surprise the castle in Dublin, warned them of their danger; and that not only must they have a guard, but they must nominate the commander of it themselves.

Whilst Charles was pondering on the answer which he should return to this unwelcome message, Sir Ralph Hopton appeared at Hampton Court with another address from the Commons yet more ominous. This bore the alarming title of a "Remonstrance on the state of the kingdom." It had been drawn up and passed by the Commons before the king came back from Scotland, that is, on the 22nd of November; and it was resolved to present it to him on his return. It was the act of the Commons alone, and had not been carried even there without a violent debate, which lasted till two o'clock in the morning, the House having sat that day eighteen hours. The heat to which the proposal gave rise was such, that Sir Philip Warwick says, "We had sheathed our swords in each others' bowels, had not the sagacity and calmness of Mr. Hampden, by a soft speech, prevented it." Cromwell is reported by Clarendon to have said to Lord Falkland as they came out, that had it not been carried, he would have sold all and gone to America. "So near," adds the Royalist historian, "was the poor kingdom at that time to its deliverance."

And yet this famous Remonstrance was only carried by a majority of nine, according to Clarendon; according to others, by eleven. It was, as Clarendon describes it, "a very bitter representation of all the illegal things that had been done from the first hour of the king's coming to the crown, to that minute." It consisted of two hundred and six clauses, and dealt among other matters with the war against the French Protestants; the innovations in the Church; the illegal imposition of ship-money; forced loans; the cruelties of the Star Chamber and High Commission; the forcing of episcopacy on Scotland; the forcing of it on the Irish by Strafford, and all the other illegal proceedings there; the opposition of the king and his ministers to necessary reforms; and the plotting of the queen with the Papists at home and abroad. It went on to remind the king of what they had done in pulling down his evil counsellors, and informed him that other good things were in preparation.

THE CLOCK TOWER, DUBLIN CASTLE.

The king the next day delivered his answer in the House of Lords, protesting, as usual, his good intentions, telling the Commons, before he removed evil counsellors, they must point out who they were and bring real facts against them; at the same time he significantly reminded them that he had left Scotland in perfect amity with him, so that they might infer that they were not to look for support against him there, and calling on them to stir themselves in aiding him to put down the rebellion in Ireland. Matters continued getting worse every day between the king and Parliament. From the 8th to the 20th of December there was a sullen humour between them. So far from granting the Parliament the usual guard, Charles had posted a guard of his own near the Commons. They summoned the commander of the guard before them, pronounced its being placed there a breach of their privileges, and demanded that it should be removed. On the 14th of December Charles objected to their ordering the impressment of soldiers from Ireland, that being his prerogative, but that he would permit it for the time on the understanding that his right was not thereby affected. The next day the Commons passed an order for the printing and publishing of their Remonstrance, which measure they had failed to carry at the same time as the Remonstrance itself. This had a[5] great effect with the public, and the king, in a restless, angry humour, prevailing in nothing against the House, sought to strengthen himself by getting into the Tower a lieutenant of his own party. But in this movement he was equally injudicious and equally unfortunate. Charles dismissed Sir William Balfour, who had honestly resisted his warrant and refused a bribe of Strafford to permit his escape; but to have deprived the Commons of any plea for interfering in what was unquestionably his own prerogative, he should have replaced him by a man of character. Instead of that, he gave the post to Colonel Lunsford, a man of desperate fortunes and the most unprincipled reputation; outlawed for his violent attacks on different individuals, and known to be capable of executing the most lawless designs. The City immediately petitioned the Commons against the Tower being in the hands of such a man; the Commons called for a conference with the Lords on the subject, but the Lords refused to meddle in what so clearly was the royal prerogative. The Commons then called on them to enter the protest they had made on their books; but the Lords took time to consider it. On Thursday, December 23rd, a petition was addressed to the Commons, purporting to be from the apprentices of London, against Papists and prelates, who, they contended, caused the destruction of trade by their plots, and the fears which thence unsettled men of capital; whereby they, the apprentices, "were nipped in the bud," on[6] entering the world. The Corporation waited on his Majesty on Sunday, the 26th, to assure him that the apprentices were contemplating a rising, and meant to carry the Tower by storm, unless Lunsford were removed; and that the merchants had already taken away their bullion from the Mint for fear of him, and the owners of ships coming in with new would not carry it there. That evening Charles took the keys from his new lieutenant, and appointed Sir John Byron in his place.

And now, notwithstanding their reluctance, the Lords were compelled to entertain this question, for they found Lord Newport, the Constable of the Tower, also brought into controversy by the king. It appeared that during Charles's absence in Scotland, at a meeting of a number of the peers and members of the Commons at Kensington, regarding some rumour of plots against Parliament, Lord Newport was reported to have said, "Never mind, we have his wife and children." Newport stated in the House that he had waited on the queen at the time, and assured her that no such words had been spoken; yet on Friday last the king had reminded him of it, and intimated his belief of it. It was now the turn of the Lords to call for a conference with the Commons. This was granted on Monday, and whilst it was sitting, the House of Parliament was surrounded by tumultuous mobs, crying, "Beware of plots! No bishops! no bishops!"

Poor Williams, made Archbishop of York on the 4th of this month, was surrounded by this mob and much frightened; but he got away unhurt, any further than in his feelings, from the execrations heaped on the bishops. One David Hide, however, a ruffian officer, who had been in the army in the north, and was now appointed to the service in Ireland, drew his sword, and swore that "he would cut the throats of those roundheaded dogs that bawled against bishops," and by that expression, says Clarendon, gave the first utterance to the name "roundheads," which was at once universally applied to the Parliamentary party; the term "cavaliers" soon being introduced to designate the Royalists. The same day Lunsford had the insolence to go through Westminster Hall with thirty or forty of his partisans at his back. The mob fell on them, and they drew their swords and cut right and left among the crowd. Presently there came pouring down to Westminster hundreds of fresh apprentices, with swords, cudgels, and other weapons, crying, "Slash us now! Slash us now!" And this was renewed by thousands the next day, December 28th, with the same "Slash us now, whilst we wait on the honourable House to request an answer to our petition." Some of the youths were shut into the abbey and brought before Williams, whilst those without cried that if they were not released, they would break in and pull down the organs. This, however, they were prevented from doing, by numbers of the bishop's men coming out on the abbey leads, and flinging down stones upon them, by which many were injured; and Sir Richard Wiseman, who happened to be passing, was so much hurt that he died of his injuries.

Williams, the archbishop, was so incensed at the cry against the bishops, that he forgot his usual cunning, and got eleven other bishops to join him in an address to the king, declaring that the bishops could not get to their places for the riotous crowds, and from fear of their lives from them; and therefore, as bishops had at all times formed part and parcel of the Upper House, that House, so long as they were detained from it, was no longer a competent House, and that all its acts, of whatever kind, would be utterly invalid. This was supposed to be a manœuvre of the king's to get rid of the authority of Parliament for the present, and thus of his unfortunate surrender of the powers of adjournment; but the Lords, taking no notice of the protest of the bishops, desired a conference with the Commons, and then denounced the protest of the bishops as subversive of the fundamental rights of Parliament. The Commons, on their part, instead of contenting themselves with passing a resolution condemnatory of the folly of the bishops, at once declared them guilty of high treason, and called on the Lords to apprehend them, which was at once done, and ten of the bishops were committed to the Tower, and two, on account of their age, to the custody of the Usher of the Black Rod.

On the last day of this eventful year, Denzil Holles waited on his Majesty, by order of the Commons, to represent to him, that whilst his faithful Parliament was ready to shed the last drop of its blood in defence of his Majesty, it was itself daily exposed to the danger of plots and ruffians who had dared to shed the blood of the people coming to petition at the very doors of the House. They demanded, therefore, a guard. Charles had taken care to surround his own palace day and night since the commotions. Such a guard was reluctantly granted three days after.

But if 1641 had been an astonishing year, 1642 was destined to cast even it into the shade, and[7] its very opening was with nothing short of the first trumpet note of civil war. On the 3rd of January Charles sent his answer to the Commons respecting the guard, acceding to the request, but immediately followed it up by a demand that electrified the Houses, and was soon to electrify the nation. Whilst the Commons were debating on the royal message, the king's new Attorney-General, Herbert, appeared at the bar of the House of Lords, and presented articles of high treason against six leading Members of Parliament, one peer and five commoners. These members were, Lord Kimbolton in the Peers, and Holles, Hazelrig, Pym, Hampden, and Strode, in the Commons. There were seven articles exhibited against them of high treason and other misdemeanour. These were stated in the following words:—"1st. That they have traitorously endeavoured to subvert the fundamental laws and government of the kingdom of England, to deprive the king of his royal power, and to place in subjects an arbitrary and tyrannical power over the lives, liberties, and estates of his Majesty's liege people. 2nd. That they have traitorously endeavoured, by many foul aspersions upon his Majesty and his Government, to alienate the affections of his people, and to make his Majesty odious unto them. 3rd. That they have endeavoured to draw his Majesty's late army to disobedience to his Majesty's commands, and to side with them in their traitorous designs. 4th. That they have traitorously invited and encouraged a foreign power to invade his Majesty's kingdom of England. 5th. That they have traitorously endeavoured to subvert the rights and the very being of Parliaments. 6th. That for the completing of their traitorous designs, they have endeavoured, so far as in them lay, by force and terror, to compel the Parliament to join with them in their traitorous designs, and to that end have actually raised and countenanced tumults against the king and Parliament. 7th. And that they have traitorously conspired to levy, and actually have levied war against the king."

"The House of Peers," says Clarendon, "was somewhat startled by this alarm, but took time to consider it till the next day, that they might see how their masters, the Commons, would behave themselves." Lord Kimbolton declared his readiness to meet the charge: the Lords sent a message upon the matter to the Commons; and at the same time came the news that officers of the Crown were sealing up the doors, trunks, and papers of Pym, Hampden and the other impeached members. The House immediately ordered the seals put upon the doors and papers of their Members to be broken, and they who had presumed to do such an act to be seized and brought before them. At this moment the serjeant-at-arms arrived at the door of the House; they ordered him to be admitted, but without his mace, and having heard his demand for the delivery of the five Members, they bade him withdraw, and sent Lord Falkland and three other Members to inform the king that they held the Members ready to answer any legal charge against them. But the next day the Commons were informed by Captain Languish, that the king, at the head of his gentlemen pensioners, and followed by some hundreds of courtiers and officers, armed with swords and pistols, was advancing towards the House. The House was well supplied with halberds, which they had previously ordered into it when the king withdrew their guard; but they saw the advantage of preventing an armed collision, and ordered the accused Members to withdraw.

Charles entered the House, his attendants remaining at Westminster Hall, and at the door of the Commons. As he advanced towards the Speaker's chair, he glanced towards the place where Pym usually sat, and then approaching the chair, said, "By your leave, Mr. Speaker, I must borrow your chair a little." The House, at his entrance, arose and stood uncovered; Lenthall, the Speaker, dropped upon his knees, and Charles, much excited, said, "Gentlemen, I am sorry for this occasion of coming unto you. Yesterday I sent a serjeant-at-arms to apprehend some that at my command were accused of high treason, wherewith I did expect obedience, and not a message; and I must declare unto you here, that albeit no king that ever was in England shall be more careful of your privileges, to maintain them to the utmost of his power, than I shall be; yet you must know that in cases of treason no person hath a privilege, and therefore I am come to know if any of those persons that I have accused, for no slight crime, but for treason, are here. I cannot expect that this House can be in the right way that I do heartily wish it, therefore I am come to tell you that I must have them, wheresoever I find them." He looked earnestly round the House, but seeing none of them, demanded of the Speaker where they were. Lenthall, still on his knees, declared that he had neither eyes to see, nor tongue to speak, but as the House directed. "Well," said the king, "since I see all the birds are[8] flown, I do expect that as soon as they return hither, you do send them to me." And with mingled assurances that he meant no force, yet not without a threat, he withdrew. As he walked out, there were raised loud cries of "Privilege! Privilege!" and the House instantly adjourned.

The Commons, to testify that they no longer felt themselves safe in their own House, betook themselves to the City where, establishing a permanent committee to sit at the Grocers' Hall, they adjourned till the 11th of January. The next day Charles, taking his usual attendants, went into the City, and at Guildhall demanded of the Lord Mayor and aldermen that they should hunt out and deliver to him the accused Members who had taken refuge amongst them. His demand was coldly received, and after dining with one of the sheriffs he returned. His passage through the city was attended by continued cries of "Privilege! Privilege of Parliament!" And one Henry Walker, an ironmonger and political pamphleteer, threw into his Majesty's carriage a paper bearing the words, "To your tents, O Israel!" Scarcely had Charles reached Whitehall, when a deputation from the Corporation waited on him, complaining of the Tower being put into unsafe hands, of the fortifying of Whitehall, the wounding of citizens on their way to petition Parliament, of the dangerous example of the king entering the House of Commons attended by armed men, and praying him to cease from the prosecution of the five Members of Parliament, and to remove from Whitehall and the Tower all suspicious personages.

As Charles still persisted by proclamation in endeavouring to get possession of the five Members, and as a hundred stand of arms, with gunpowder and shot, had been removed from the Tower to Whitehall, a thousand marines and boatmen signed a memorial to the committee of the Commons sitting at Guildhall, offering to guard them on the appointed day to their House in Westminster. The committee accepted the offer, which was immediately followed by one from the apprentices. Seeing that the City, the seamen, and everybody were of one mind in condemning his violent invasion of the national sanctuary of the House of Commons, Charles on the 10th of January, the day previous to the meeting again of Parliament, quietly withdrew with his family to Hampton Court, and the next day removed thence to Windsor. Little did he imagine, deplorable as was his retreat, that he would never enter his capital again till he came as a prisoner in the hands of this insulted Parliament. Yet his feelings at this moment must have been melancholy in the extreme. "In this sad condition," says Clarendon, "was the king at Windsor; fallen in ten days from a height and greatness that his enemies feared, to a lowness, that his own servants durst hardly avow the waiting on him."

Charles had now decided on war. But money was necessary, and to obtain it he determined to send the queen abroad. A pretext was easily found. The Princess Mary, who had been some time betrothed to the Prince of Orange, though she was yet a mere child, only about ten years of age, was to be delivered to the Dutch Court, and nothing was more natural than that her mother should accompany her. Even the stern reformers, who had forbidden her twice before leaving the kingdom, could find no excuse for forbidding this maternal office. On the 9th of February Charles and the Court returned from Windsor to Hampton Court, and the next day the royal party set out for Dover, where, on the 23rd, the queen and her daughter embarked for Holland. The Prince of Orange received her majesty with all kindness, which he indeed owed her, for she had always taken the part of him and his country against Richelieu; but the civic authorities were not so glad to see her, fearing that she might embroil them with the all-powerful Parliament of England. They entered her presence with their hats on, seated themselves in her presence, and took their leave without a bow or a word. But Henrietta restrained her disgust better than her husband would have done, for she had great interests at stake, and succeeded by her flattering courtesies in so melting the Dutch phlegm, that she eventually succeeded in borrowing of the authorities of Amsterdam eight hundred and forty-five thousand guilders, at Rotterdam sixty-five thousand, of the merchants at the Hague one hundred and sixty-six thousand, besides pawning her pearls for two hundred and thirteen thousand, and six rubies for forty thousand, thus raising for her husband two million pounds sterling.

CHARLES DEMANDING THE SURRENDER OF THE FIVE MEMBERS. (See p. 7.)

Whilst the king was at Canterbury waiting for the queen's departure, the Commons urged him to sign the two Bills for the removal of the bishops from Parliament, and of them and the clergy from all temporal offices, and for power to press soldiers for the service of Ireland. He passed them, the second Bill to be in force only till the 1st of November. The Commons expressed their satisfaction, but still urged the removal of all Privy Councillors and officers of State, except such as held posts hereditarily, and the appointment[10] of others having the confidence of Parliament. They then returned to the subject of the Militia Bill, which would put the whole force of the army into the hands of Parliament; but there Charles made a stand. He sent orders that the Prince of Wales should meet him at Greenwich. The Parliament—which watched his every movement and no doubt was informed of his intentions—sent a message to the king, praying him to allow the prince to remain at Hampton Court; but Charles, complaining of these suspicions, ordered the prince's governor, the Marquis of Hertford, to bring him to Greenwich. On Sunday, the 27th of February, some of the Lords went to Greenwich, to endeavour to bring the prince back; but Charles would not suffer it, declaring that the prince should accompany him wherever he went. He removed to Theobalds, and there again a deputation followed him, urging him to grant the matter of the militia, or that the Parliament would feel compelled to assume it for the safety of the kingdom. They also renewed their request for the return of the prince. Charles expressed much surprise at these importunities, and refused them both.

On receiving this answer, the two Houses issued an order to fit out the fleet, and put it into the command of the Earl of Northumberland, as Lord High Admiral. The Lords, who had hesitated to join the Commons in the demand of the control of the militia, now passed the ordinance for it with very few dissentients. Fifty-five Lords and Commons were named as lord-lieutenants of counties, many of them Royalists, but still not such as the Commons feared joining the king in an open rupture. The Commons then proceeded to issue a declaration, expressing their apprehensions of the favour shown to the Irish rebels by the Court; of the intention of evil advisers of the king to break the neck of Parliament, and of the rumours of aid from abroad for these objects from the Pope, and the Kings of France and Spain. The Lords, with only sixteen dissentient voices, joined in this declaration, and the Earls of Pembroke and Holland waited on the king with it at Royston. On hearing this outspoken paper read, Charles testified much indignation, pronouncing some assertions in it, in plain terms, lies; and when the earls entreated him to consent to the granting of the militia for a time, he exclaimed:—"No, by God, not for an hour. You have asked that of me which was never asked of any king, and with which I should not trust my wife and children." This was true, but he had formerly said he would sooner lose his life than consent to the Bill against the bishops, and yet he gave them up. That he would on the first opportunity break his word, was certain; that at this very moment his wife was moving heaven and earth abroad, and pawning her jewels for money to put down Parliament and people, was equally well known. In vain, therefore, were the solemn asseverations which he made, that he desired nothing so much as to satisfy his subjects.

At this moment he was stealing away towards the north. He got away to Newmarket, thence to Huntingdon, next to Stamford, and from that place wrote to the two Houses, informing them that he proposed to take up his residence for a time in York. The deputies had strongly importuned him to return to the neighbourhood of his Parliament; this was his answer, accompanied by a positive refusal to put the militia into their hands. The Houses were at once roused to action. War was inevitable; the king was intending to take them by surprise. They therefore voted that the king's absence was most detrimental to the affairs of Ireland; that the king was easily advised, and that it was necessary for Parliament that the power of commanding the militia must be exercised by the sole authority of Parliament, and orders for that purpose were issued to the lieutenants and deputy-lieutenants of the counties.

Charles had meanwhile proceeded by Doncaster to York, where he arrived on the 19th of March. On the 26th the Lords Willoughby and Dungarvan, with Sir Anthony Ereby, arrived from Parliament with a justification of their proceedings. They admitted that he had passed many satisfactory Bills at their instance, but that always at the same time some attempts had been set on foot to render them abortive. They informed him that they had certain information of preparations making abroad, and of a design to enter Hull with foreign forces. Charles denied the truth of these allegations, and assured them that he would return and reside near his Parliament as soon as he was sure of the safety of his person. He did not forget, however, the words dropped about Hull. It was of immense consequence to obtain possession of that place; but it was in the keeping of the stout Sir John Hotham and his son, who had declared in Parliament "fall back, fall edge, he would carry out the wishes of Parliament." As Charles could not hope to obtain it by force, he conceived the idea of winning it by stratagem.[11] He sent the Earl of Newcastle to request that the town and arsenals might be put into his hands. Newcastle assumed the name of Sir John Savage to obtain admission to the town, but was discovered, and this clumsy trick only increased the suspicions of the people. Parliament then sent an order for the removal of the arms and ammunition to the Tower of London; but Charles told them that he claimed them as purchased with money borrowed on his own account, and begged they would leave him to look after his own property. He also sent them word that it was his intention to pass over to Ireland, to suppress the rebellion; that he should require all the arms and ammunition for that purpose, and that they would be necessary for the use of his guard of two thousand foot and two hundred horse, which he meant to embark there for Ireland.

On the 22nd of April he sent the Duke of York, the Prince Palatine, his nephew, the Lords Newport, Willoughby, and some other persons of distinction, but without any armed force, to see the town of Hull. Sir John Hotham and the mayor received them with all honour, and entertained them as became their rank. They were shown the place, and were to dine with the governor on the morrow, being St. George's Day. Just before dinner-time, however, Hotham was startled by the sudden appearance of Sir Lewis Dives, brother-in-law of the outlawed Lord Digby, who informed him that his Majesty intended to do him the honour to dine with him, and was already within a mile of the town, accompanied by three hundred horse. Sir John, who saw the trick, instantly ordered the drawbridges to be raised, and shut the gates in the king's face, for by this time he had arrived at the Beverley gate.

Charles commanded Sir John to open the gate and admit him and his guard, but Sir John replied that, though a loyal subject of his Majesty, he could not do so without consent of Parliament, which had put the town into his keeping. If his Majesty would be pleased to enter with the prince and twelve attendants he should be welcome; but Charles refused to enter without the whole of his guard. He staid before the gate from one o'clock till four, continuing the parley, trusting to the people being affected by the sight of their sovereign, and compelling the governor to admit him. But he was disappointed, and at four, going away for an hour, he gave Hotham that time to consider of it. On his return at five Hotham still refused entrance to more than before, when Charles proclaimed him a traitor, and rode off with the prince and his guard to Beverley. The next day he sent a herald to offer Hotham pardon and promotion on surrender of the town, but in vain; and he then returned to York.

Each party now hastened to raise forces and prepare for the struggle. On the 5th of May the Parliament issued a declaration that as the king refused his consent to the Militia Bill, they called on all men to obey their own ordinance for the raising of forces and the defence of the king. In this ordinance they nominated the lieutenants of counties, who nominated their deputy-lieutenants, subject to the approbation of Parliament. Amongst these deputies appeared Hampden, Whitelock, St. John, Selden, Maynard, Grimstone, and other leaders of Parliament, who now became equally zealous enrollers and drillers of soldiers. The king, on his side, denounced the order as traitorous and illegal, forbade all men obeying it, and summoned a county meeting at York for promoting the levy of troops for his service. At that meeting we find Sir Thomas Fairfax stepping forward as a Parliamentary leader, and laying on the pommel of the king's saddle a strong remonstrance from the freeholders and farmers of Yorkshire, who advised the king to come to an agreement with his Parliament.

The country was now come to that crisis when every man must make up his mind, and show to which side of the dispute he leaned. It was a day of wonderful searching of characters and interests, and many strange revolutions took place. Towns, villages, families, now appeared in convulsion and strife, and some fell one way, some another, not without much heart-ache and many tears, old friends and kindred parting asunder, to meet again only to shed each others' blood. Then was there a strange proclaiming and contradiction of proclamations, one party denouncing and denying the proceedings of the other. The king raised only a troop of horse and a regiment of foot; the Parliament soon found themselves at the head of eight thousand men, consisting of six regiments, commanded by zealous officers, and the month of May saw the fields of Finsbury white with tents, and Major-General Skippon manœuvring his train-bands.

The next shift was for the fleet. The Earl of Northumberland being ill, or more probably indisposed, the Commons ordered him to surrender his command to the Earl of Warwick for the time. The Lords hesitated, on account of the king's sanction being wanted for such an appointment; but the Commons settled it alone.[12] Clarendon says that the king remained passive, confiding in the attachment of the sailors, whose pay he had advanced; but we hear from other sources that Charles had contrived to alienate the mariners as much as the rest of his subjects, by calling them "water-rats." His popularity with them was soon tested, for he ordered the removal of Warwick, and that Pennington should take his place; but the sailors would not receive him. Without ammunition or arms, Charles's forces were of little use, and the Commons proclaimed that any one who should bring in such material without consent of Parliament, or should bring in money raised on the Crown jewels, would be considered an enemy to the country.