CHARACTERS

Gordon Johns, a Young Business Man

Laura, Mrs. Gordon Johns

Mrs. Sheffield, Lauras Mother

Mrs. Johns, Gordons Mother

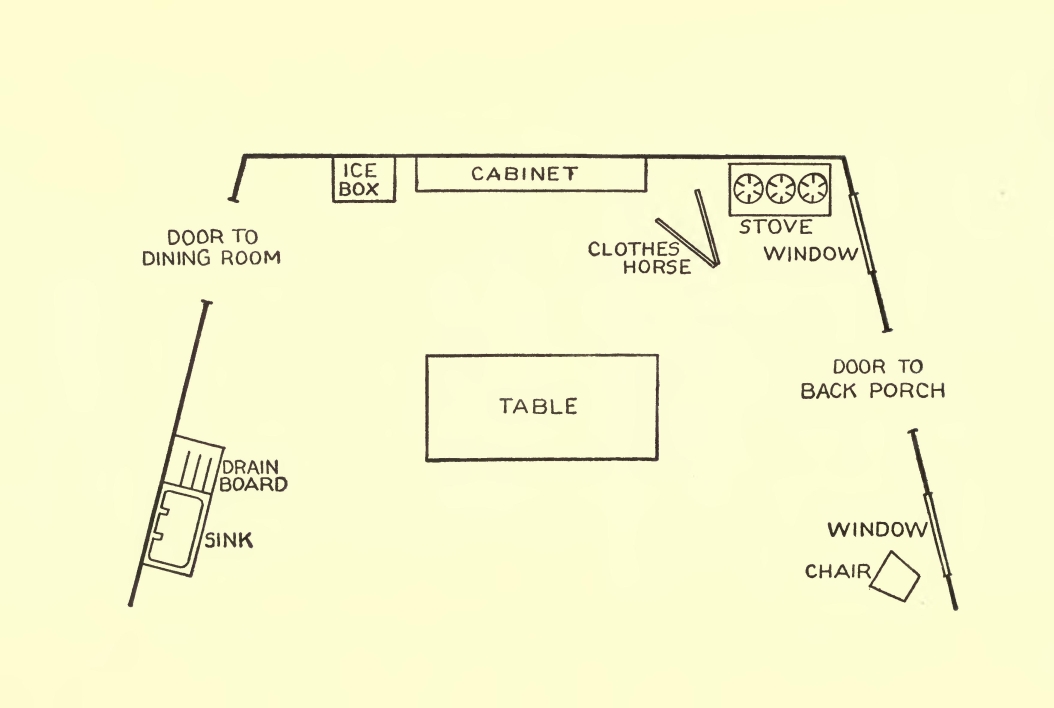

A small suburban kitchen in the modest home of Mr. and Mrs. Gordon Johns. A meal has recently been cooked, as is shown by a general confusion of pots and pans and dish-cloths. At the rear, an icebox standing in the corner. Rear, center, two shelved cabinets, one containing groceries and household sundries, the other dishes and glassware. Rear, L, an oil range. Some baby linen and very small shirts (such as would be suitable for a child of about ten months') are hanging on a clothes-horse near the stove. Boor R leads out to back porch; there are two windows in R wall, one each side of door. Door L to diningroom. At the corner in the rear, L, door opening on back stairs, which ascend to upper parts of the house. Down stage, L, against side wall, a sink and oil-cloth covered drain-board or shelf beside it. In the center of stage a small table covered with oil-cloth. A kitchen chair in corner, down R.

When the scene opens, GORDON and LAURA are carrying in soiled dishes through door, L. They come in and out several times, making methodical arrangements for cleaning up. They pile the dishes on the shelf by the sink. Gordon takes dishpan from a hook under the sink, and fills it with hot water from the kettle on the stove. LAURA, who is an attractive little person, aged about twenty-three, is in that slightly tense condition of a young hostess who has had a long and trying day with house and baby, and has also cooked and served a dinner for four.

All right, Creature, just wait till I light my pipe and we'll polish this up. (Lights pipe and rolls up shirtsleeves.)

(taking an apron from chair in corner)

Put this on first. That's the only decent pair of trousers you've got.

(Enter Mrs. Sheffield, carrying dishes.)

Now you children run along and take it easy. I'll do all this.

No, no, mother. You go and talk to Mrs. Johns. (Pointedly.) Don't let her come in here. mrs. sheff (ultramaternally)

Poor baby, she's tired. You've been on your feet all day, now let Mother wash up for you. That was a big dinner to cook.

No tireder than you are, Mother darling. You cooked lunch.

Both of you clear out; I can get this done in no time.

(patting Laura's cheek)

Busy with the baby all afternoon, and then cooking such a delicious dinner—Dearie, won't you let Mother do this for you?

There isn't room in this kitchen for everybody— (Enter Mrs. Johns, carrying dishes.)

Gordon, you and Laura go and rest. Let the two grandmothers—

Now listen, little people, this is my job. I always wash up on Thursday evenings—

You go and read your newspaper. I can see you're all fagged out after that long day in the office—

(to Laura)

Please go and lie down, Baby. You're so tired.

(with waning patience)

You two go and amuse yourselves; Gordon and I'll attend to this. (They gently eject the two mothers-in-law.)

Come on, now, the good old system! (He takes the small table from center of stage, and puts it carefully midway between sink and dish cabinet. Takes chair from corner, down R, and sets it beside table. Laura sits down on chair and wipes silverware and dishes as he hands them to her after washing.)

The silver first, while the water's clean.

Right. We make a pretty good team at this, don't we?

(holds up a small silver jug)

That darling old cream jug. Mother used that when she was a little girl.

I love our little Thursday evening suppers. I think they're more fun than any other night.

I'm glad, Gordie.

We get better grub on Thursdays, when Ethel goes out, than we ever do when she's in.

I tried to have everything specially nice tonight. Some visitors are very critical.

It was lovely. I'm afraid it was hard for you, Creature, to have Mother come just now. (A short pause,) Especially when your Mother was here.

Didn't she know Mother was here?

No. I hadn't told her. You see your Mother is here so much more often. I didn't know your mother would still be here. I was afraid Mother might be a little hurt—

Mother helps me a great deal. I think it's a queer thing if a wife can't have her mother stay with her once in a while—

(aware of danger, changes the subject)

Ye Gods, Ethel has cracked the Copenhagen platter. (Laura is silent.) That's one of the set Mother gave us when we were married.

It's a stock pattern. You can get another at any department store.

I'll bet that coon didn't empty the icebox pan before she went. I never saw a cook yet who could remember to do that—

If you had to go out and hunt for them you wouldn't be so particular. She's better than no one.

(goes to icebox and removes a large, brimming pan from under it)

What did I tell you! (The water slops over from pan as he carries it gingerly to sink and empties it. He replaces the pan under icebox.)

You'd better heat some more water. You've poured that ice-water into the dishpan.

(getting a little peevish; refills kettle and puts it on stove)

It's perfectly absurd not having any pantry to keep the icebox in. In here, the heat of the stove melts the ice right away. (Goes back to icebox and slams its doors shut.) Of course, she never keeps the doors properly closed. (He returns to sink and resumes dishwashing.) It's a funny thing.

What is?

Why, that a presumably intelligent coon can't understand the doors of an icebox are meant to be kept tight shut, to save ice. What does she suppose those little clamps are for? (Laura is silent. There is a pause, while Gordon scrapes portions of food off the soiled plates. He examines some of these plates rather carefully, and picks out several large pieces of meat, lettuce, butter, etc. which he puts on one plate at one side. Then he seems to resume his good humor and relights his pipe.) Well, it's jolly to have both the grandmothers here together, isn't it?

Gordon, dear, put the silver away in the sideboard before it gets wet again. (He gathers up silver from the table in front of her and exit L. Laura steps outside door R, and returns, bringing garbage can, which she puts down by the sink. She begins to wash dishes, and sees the plate of odds and ends which Gordon has carefully put to one side. She scrapes its contents into the garbage pail. While she is washings Gordon enter, L.)

Now, Creature, let me do that. You don't want to spoil those pretty hands. (Takes them, with an attempt to be affectionate.)

I guess it isn't any worse for them than washing the baby's things.

Come on, old man, let me. (Gently removes her from sink, and pushes her to the chair by the table. She sits down and wipes dishes as he hands them to her.) It doesn't take long when there are two of us.

Gordie, these dishes aren't properly clean. You can't get that grease off without hot water.

I guess that kettle's hot by now. (To stove, feels water in kettle.) Give it a minute longer. (Stands by stove and puffs at his pipe. In a moment of false security, he foolishly reopens a dangerous topic.) You know, I'm a little worried about Mother.

(putting away dishes)

Why?

I don't think she's as well as usual. She hardly ate any of her salad.

(turns as though about to say somethings but checks herself and pauses a moment. This time it is she who tries honorably to avert the gathering storm)

Oh, Gordie, I forgot to tell you! Junior drank out of a cup to-day—the first time!

He did! The little rascal!

Look, here's the cup. (Shows a small silver cup.)

(affectionately, putting his arm around her)

Well, well. (Looks at cup.) What cup is that? I don't seem to remember it—

Why—Mother brought it with her. She used it when she was a baby.

Where's that nice old Christening mug of mine? I think Junior would like to use that once in a while, too.

I put it away, dear. I was afraid Ethel might dent it.

(takes kettle from stove, goes back to sink)

I hope Mother isn't feeling poorly. I noticed at supper—

When hot meat is served, refined people usually call it dinner—

(looks at her cautiously, and suddenly seems to realize that they are on the edge of an abyss)

Now, honey, you're tired. You go and rest, I'll finish up here.

No, thank you. I like to see that everything gets cleaned up properly. Someone might come snooping out here, and then there'd be hints about my housekeeping. Of course, I'll admit I wasn't brought up to be a cook—

(seeks inspiration by relighting his pipe, and takes up a handsome silver coffee pot)

One thing I never can make out is, how to prevent coffee grounds from going down the sink. (He talks desperately, trying to tide over the mutually realized danger point.) Perhaps if I could invent some kind of a little coffee-ground strainer I'd make our fortune. That coffee was delicious, Creature.

Take care of that urn, it's one of the few handsome things we have.

It is a beauty.

Jack Davis gave it to me—

(puts it down with distaste)

I guess I'd better attend to the garbage.

(nervously)

It's all fixed.

I always like Thursdays because that's the one evening Ethel doesn't get a chance to throw away about five dollars' worth of good food.

I fixed the garbage. You can put the pail outside.

(hunting among plates on the shelf beside sink)

Where's that plate I put here? There was a lot of perfectly good stuff I saved—

(blows up at last)

Well, if you think I'm going to keep a lot of halfeaten salad your Mother picked over—

(seizes garbage pail, lifts it up to the sink and begins to explore its contents. His fuse also is rapidly shortening.)

My Lord, it's no wonder we never have any money to spend if we chuck half of it away in waste. (Picking out various selections.) Waste! Look at that piece of cheese, and those potatoes. You could take those things, and some of this meat, and make a nice economical hash for lunch—

It's a wonder you wouldn't get a job as a scavenger. I never heard of a husband like you, rummaging through the garbage pail.

(blows up)

Do you know what the one unforgivable sin is? The sin against the Holy Ghost? It's Waste! It makes me wild to think of working and working like a dog, and half of what I earn just thrown away by an ignorant coon. Look at this, just look at it! (Displays a grisly object.) There's enough meat on that bone to make soup. And ye gods, here's that jar of anchovy paste! (Holds it up.) I thought you got that for me as a little treat. I wondered where it had gone to. Why, I hadn't eaten more than just the top of it.

Well, you left it, and left it, and it got mildewed.

Scrape it off. A little mildew won't hurt anybody. There'll be mildew on my bank account if this kind of thing goes on. (Still examining garbage pail.) Look here, about half a dozen slices of bread. What's the matter with them, I'd like to know.

I think it's the most disgusting thing I ever heard of. To go picking over the garbage pail like that. You attend to your affairs and I'll attend to mine.

I guess throwing away good, hard-earned money is my affair, isn't it?

You're always quick enough to find fault. I know Ethel's careless, but she's the best I can get out here in this godforsaken suburb. Maybe you'll be good enough to find me a better servant. A well-trained girl wouldn't work in this old dump, where there isn't even gas. You don't seem to know when you're lucky. You come back at night and find your home well cared for and me slaving over a hot dinner, and do you ever say a word of thanks? No, all you can think of is finding fault. I can't imagine how you were brought up. Your Mother—

Just leave my mother out of it. I guess she didn't spoil me the way yours did you. Of course, I wasn't an only daughter—

I wish you had been. Then I wouldn't have married you.

I suppose you think that if you'd married Jack Davis or some other of those profiteers you'd never have had to see the inside of a kitchen—

If Junior grows up with your disposition, all I can say is, I hope he'll never get married.

If he gets married, I hope it'll be to some girl who understands something about economy—

If he gets married, I hope he'll be man enough not to be always finding fault—

Well, he won't get married! I'll put him wise to what marriage means, fussing like this all the time—

Yes, he will get married. He shall get married!

Oh, this is too absurd—

He shall get married, just to be a humiliating example to his father. I'll bring him up the way a husband ought to be.

In handcuffs, I suppose—

And his wife won't have to sit and listen to perpetual criticism from his mother—

If you're so down on mothers-in-law, it's queer you're anxious to be one yourself. The expectant mother-in-law!

All right, be vulgar. I dare say you can't help it.

Great Scott, what did you think marriage was like, anyway? Did you expect to go through life having everything done for you, without a little hard work to make it interesting?

Is it necessary to shout?

Now let me tell you something. Let's see if you can ratify it from your extensive observation of life. Is there anything in the world so cruel as bringing up a girl in absolute ignorance of housework, believing that all her days she's going to be waited on hand and foot, and that marriage is one long swoon of endearments—

There's not much swooning while you're around.

Why, I believe you actually think your life is wrecked if you aren't being petted and praised every minute. You pretend to think marriage is so sacred and yet you're buffaloed by a few greasy dishes. I like my kind of sacredness better than yours, and that's the sacredness of common sense. Marriage ought not to be performed before an altar, but before a kitchen sink.

(furiously)

I ought to have known that oil and water won't mix. I ought to have known that a vulgar, selfish, conceited man couldn't make a girl happy who was brought up in a refined family.

I was a Sheffield, and why I ever became a Johns is more than I can imagine, Johns—I suppose that's camouflage for Jones. You're too common, too ordinary, to know when you're lucky. You get a charming aristocratic wife and expect her to grub along like a washerwoman. You try to crush all the life and spirit out of her. You ought to have married an icebox—that's the only thing in this house you're really attentive to.

Now listen—

(will not be checked)

Talk about being spoiled—why, your Mother babies you so, you think you're the only man on earth. (Sarcastically.) Her poor, overworked boy, who tries so hard and gets all fagged out in the office and struggles so nobly to support his family! I wonder how you'd like to run this house and bear a child and take care of it and shuffle along with an ignorant coon for a maid and then cook a big dinner and be sneered at and never a word of praise. All you can think of is picking over the garbage pail and finding fault—

(like a fool)

I didn't find fault. I found some good food being wasted.

All right, if you love the garbage pail better than you do your wife, you can live with it. (Flings her dishtowel on the floor and exit, L.)

(Gordon stands irresolutely at the sink, and makes a few gloomy motions among the unfinished dishes. He glares at the garbage can. Then he carefully gathers those portions of food that he had chosen as being still usable, contemplates them grimly, then puts them on a plate and, after some hesitation, puts the plate in the icebox. He takes the garbage can and puts it outside door, R. He returns into the kitchen, but then a sudden fit of anger seizes him.)

It's always the way! (Tears off apron, throws it on the floor, and exit R, slamming door.)

(After a brief pause, the door at the rear opening onto the back stairs, is cautiously opened, and Mrs. Sheffield enters quietly. She takes one swift look around the disordered kitchen, picks up dishtowel and apron from the floor, and sets to work rapidly to clean up. Then the back stairs door is again opened in the same stealthy way, and Mrs. Johns enters. The two ladies seem to take each other's measure with instinctive shrewdness, and fall into a silent, businesslike team-play in putting things to rights. Mrs. Johns takes charge at the sink, and the remaining dishes spin under her capable hands. Mrs. Sheffield takes them from her, rapidly polishes them, and puts them away on the shelves. There is unconscious comedy in the trained precision and labor-saving method of their actions, which are synchronized so that every time Mrs. Johns holds out a washed dish, Mrs. Sheffield is moving back from the cabinet, ready to receive it. They work like automatons, for perhaps two minutes not a word is said, and the two seem, by searching side-glances, to be probing each other's mood.)

If it wasn't so tragic I'd laugh. (A pause, during which they work busily.)

If it wasn't so comic I'd cry. (Another pause.) I guess it's my fault. Poor Laura, I'm afraid I have spoiled her.

My fault, I think. Two mothers-in-law at once is too much for any young couple. I didn't know you were here, or I wouldn't have come.

Laura is so dreadfully sensitive, poor child—

Gordon works so hard at the office. You know he's trying to get promoted to the sales department, and I suppose it tells on his nerves—

If Laura could afford to have a nurse to help her with the baby she wouldn't get so exhausted—

Gordon says he wants to take out some more insurance, that's why he worries so about economy. It isn't for himself, he's really very unselfish—

(a little tartly)

Still, I do think that sometimes—(They pause and look at each other quickly.) My gracious, we'll be at it ourselves if we don't look out!

(She goes to the clothes-horse and rearranges the garments on it. She holds up a lilliputian shirt, and they both smile.)

That darling baby! I hope he won't have poor Gordon's quick temper. It runs in the Johns family, I'm afraid. I was an Armstrong before I married Gordon's father—I didn't know what temper was until I married—either my own or his.

I was a Thomson—Thomson without the P, you know, from Rhode Island. All families are hot tempered. All husbands' families, anyway.

Gordon's father used to say that Adam and Eve didn't know when they were well off. He said that was why they called it the Garden of Eden.

Why?

Because there was no mother-in-law there.

Poor children, they have such a lot to learn! I really feel ashamed, Mrs. Johns, because Laura is an undisciplined little thing, and I'm afraid I've always petted her too much. She had such a lot of attention before she met Gordon, and was made so much of, it gave her wrong ideas.

I wish Gordon was a little younger, I'd like to turn him up and spank him. He's dreadfully stubborn and tactless—

But I'm afraid I did make a mistake. Laura was having such a good time as a girl, I was always afraid she'd have a hard awakening when she married. But Mr. Sheffield had a good deal of money at that time, and he used to say, 'She's only young once, let her enjoy herself.'

My husband was shortsighted, too. He had had to skimp so, that he brought up Gordon to have a terror of wasting a nickel.

Very sensible. I wish Mr. Sheffield had had a little more of that terror. I shall have to tell him what his policy has resulted in. But really, you know, when I heard them at it, I could hardly help admiring them. (With a sigh.) It brings back old times!

So it does! (A pause.) But we can't let them go on like this. A little vigorous quarreling is good for everybody. It's a kind of spiritual laxative. But they carry it too far.

They're awfully ingenious. They were even bickering about Junior's future mother-in-law. I suppose she's still in school, whoever she may be!

Being a mother-in-law is almost as painful as being a mother.

I think every marriage ought to be preceded by a treaty of peace between the two mothers. If they understand each other, everything will work out all right.

You're right. When each one takes sides with her own child, it's fatal.

(lowering her voice)

Look here, I think I know how we can make them ashamed of themselves. Where are they now?

(goes cautiously to door L and peeps through)

Laura is lying on the couch in the living-room. I think she's crying—her face is buried in the cushions.

Splendid. That means she's listening with all her ears—(Tiptoes to window, R.) I can't see Gordon, but I think he's walking round the garden—

(quietly)

If we were to talk a little louder he'd sit on the back steps to hear it—

Exactly. Now listen! (They put their heads together and whisper; the audience does not hear what is said.)

Fine! Oh, that's fine! (Mrs. Sheffield whispers again, inaudible to the spectators.) But wait a moment. Don't you think it would be better if I praise Laura and you praise Gordon? They won't expect that, and it might shame them—

No, no! Don't you see—(Whispers again, inaudibly.)

You're right. Cunning as serpents and harmless as doves—(They carefully set both doors, L and R ajar.)

I only hope we won't wake the baby—(They return to the task of cleaning up, and talk very loudly in pretended quarrel.)

Where do these dessert plates go?

On this shelf.

You're here so much more often than I, naturally you know Laura's arrangements better.

It's a lucky thing I am here. I don't know what poor Laura would do without me at such a dreadful time—

Poor Laura! I should say she's very fortunate, such a good husband—

I think it's rather sad for a girl who has had as much as she has, to come down to this—

It's perfectly wonderful how Gordon has got on in business—

He ought to, with such a lovely home, run like a clock—

Yes. An alarm clock.

Well, I'm not going to see my daughter's happiness ruined—

I always knew he'd make some girl a fine husband—

Perhaps. But he seems to have picked the wrong girl. Laura has too much spirit to be bullied—

Well, perhaps it was all a mistake. Poor Gordon, he works so hard. I believe his hair is going white over his ears already.

Stuff! That's lather from where he shaved this morning. He's too slovenly to wash it off.

It isn't right that a young man should have to slave the way he does—

(apparently in a passion)

Do you think that business slavery can compare to household slavery? I think it's heartrending to see an attractive girl like Laura shut up in a poky little house doing drudgery and tending a baby. Think of it, having to take care of her own baby! Why, it's an outrage. If Gordon was half a man, he'd get her a trained baby nurse so she wouldn't have to look at the poor little thing—

(scathing)

Yes, how sad that Gordon should have to entrust his son to amateur care when it needs scientific attention.

Poor darling Laura—she never ought to have had a baby.

Gordon is too intellectual to be bothered with these domestic details. He ought to be able to concentrate on his work.

(coming close to Mrs. Johns, feigning great rage, but grimacing to show it is merely acting)

Well, if you don't think my daughter is good enough for your son, I can always take her home with me. I guess I can find room for her, and we can put the child in an institution. (Both nearly laughs but recover themselves.)

Don't worry. I'll take the child. He's a Johns anyway, not a Sheffield. And you just watch Gordon, when he's relieved of all this family worry and quarreling. He'll make his mark in the world. He's too fine to be tied down by a wife that doesn't understand him.

Oh, how happy Laura will be to hear this. My sweet, clever, attractive, economical, sensible little girl, free at last. Her married life has been a nightmare. That great, hulking, selfish man has tried to trample all the joy out of her. He shan't do it.

I never heard of a young husband as self-sacrificing as Gordon. I don't believe he ever goes out for an evening with other men, and he never spends anything on himself—

I think the way Laura runs her little home is just wonderful. See how she struggles to keep her kitchen in order—this miserable, inconvenient little kitchen, no gas, no pantry, no decent help. I think it's terrible she has had to put up with so much—(They pause, and listen at the door, L. The kitchen is now spick and span. Mrs. Johns makes a gesture to indicate that Laura is taking it all in, offstage.)

Well, then, it's all settled.

Yes. As Laura's mother, I can't let her go on like this. A husband, a home, and a baby—it's enough to ruin any woman.

It's only fair to both sides to end it all. I never heard of such brutal hardships. Gordon can't fight against these things any longer. Throwing away a soupbone and three slices of bread! I wonder he doesn't go mad.

We've saved them just in time. (They look at each other knowingly, with the air of those who have done a sound bit of work, Then they stealthily open the door at the rear, and exeunt up the back stairs,)

(There is a brief pause; then the door L opens like an explosion, and Laura bursts in, She stands for a moment, wild-eyed, stamps her foot in a passion, Then she seizes one of the baby shirts from the rack, and drops into the chair by the table, crying. She buries her head in her arms, concealing the shirt, Enter Gordon, R, He stands uncertainly, evidently feeling like a fool.)

I'm sorry, I—I left my pipe in here. (Finds it by the sink,)

(her face still hidden)

Oh, Gordie, was it all a mistake?

(troubled, pats her shoulder tentatively)

Now listen, Creature, don't. You'll make yourself sick.

I never thought I'd hear such things—from my own mother.

I never heard such rot. They must be mad, both of them.

Then you were listening, too—

Yes. Why, they're deliberately trying to set us against each other.

They wouldn't have dared speak like that if they had known we could hear. Gordon, I don't think it's legal—

I'm afraid the law doesn't give one much protection against one's mothers.

(miserably)

I guess she's right. I am spoiled, and I am silly, and I am extravagant—

Don't be silly, darling. That's crazy stuff. I'm not overworked, and even if I were I'd love it, for you—

I don't want a nurse for Junior. I wouldn't have one in the house. (Sits up, dishevelled, and displays the small shirt she has been clutching.) Gordon, I'm not an amateur! I love that baby and I am scientific. I keep a chart of his weight every week.

Yes, I know, ducky, Gordon understands. Soon we'll be able to buy that scales you want, and we won't have to weigh him on the meat balance.

Nobody can take away my darling baby—

It was my fault, dear. I am obstinate and disagreeable—

I'll speak to Ethel about the garbage—

Ethel's all right. We're lucky to have her.

Gordon, you mustn't work too hard. You know you're all I have—(A sob.) since Mother's gone back on me.

(patting her)

I think it's frightful, the things they said. What are they trying to do, break up a happy home?

We are happy, aren't we?

Well, I should say so. Did you ever hear me complain? (Takes her in his arms.)

No, Gordie. It was cruel of them to try to make trouble between us—but, perhaps, some of the things they said—

Were true?—

Well, not exactly true, dear, but—interesting! —your mother is right, you do have a hard time, and I'll try—

(stops her)

No, your mother is right. I've been a brute—

I'm lucky to have such a husband—(They are silent a moment.)

I suppose you'll think it an awful anticlimax—

What, dear?

Suppose we have something to eat?

(happily)

Good idea. Quarreling always makes me hungry. (They go to the icebox.) I didn't really get any supper to speak of, I was worrying about everything so—

(opening icebox)

You mean dinner, honey—among refined people!

Don't be a tease. Come on, we'll have a snack— (She discovers Gordon s plate of left-overs.)

Throw out that junk—I was idiotic to save it.

No, Gordie, you were quite right. We must save everything we can. Four or five heads of lettuce would make a new shirt for Junior.

(bewildered)

Lettuce?

I mean, if we saved that much, it would make enough money to buy him a new little vest. He's getting so enormous—(She puts plate of left-overs on the table, with some other cold food.)

There, now, this is better. (They sit down at table.)

(thoughtfully)

You know, Gordie, we mustn't let them know we heard them.

No, I suppose not. But it's hard to forgive that sort of talk.

Even if they did say atrocious things, I think they really love us—

We'll be a bit cold and stand-offish until things blow over.

(complacently)

If I'm ever a mother-in-law, I shall try to be very understanding—

Yes, Creature. Do you remember why I call you Creature?

Do I not?

There was an adjective omitted, you remember.

Oh, Gordie, that's one of the troubles of married life. So many of the nice adjectives seem to get omitted.

Motto for married men: Don't run short of adjectives!—You remember what the adjective was?

Tell me.

Adorable, It was an abbreviation for Adorable Creature—(Holds her, They are both perfectly happy.) I love our little Thursday evenings. laura (partly breaks from his embrace)

Sssh! (Listens,) Was that the baby?