The Project Gutenberg EBook of Sandburrs and Others, by Alfred Henry Lewis This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Sandburrs and Others Author: Alfred Henry Lewis Illustrator: Horace Taylor and George B. Luks Release Date: May 3, 2016 [EBook #51981] Last Updated: March 12, 2018 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SANDBURRS *** Produced by David Widger from page images generously provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

A SANDBURR is a foolish, small vegetable, irritating and grievously useless. Therefore this volume of sketches is named Sandburrs. Some folk there be who apologize for the birth of a book. There's scant propriety of it. A book is but a legless, dormant creature. The public has but to let it alone to be safe. And a book, withal! is its own punishment. Is it a bad book? the author loses. Is it very bad? the publisher loses. In any case the public is preserved. For all of which there will be no apology for SAND-BURRS. Nor will I tell what I think of it. No; this volume may make its own running, without the handicap of my apology, or the hamstringing of my criticism. There should be more than one to do the latter with the least of luck. The Bowery dialect—if it be a dialect—employed in sundry of these sketches is not an exalted literature. The stories told are true, however; so much may they have defence.

New York, Nov. 15, 1899.

Martin is the barkeeper of an East Side hotel—not a good hotel at all—and flourishes as a sporting person of much emphasis. Martin, in passing, is at the head of the dog-fighting brotherhood. I often talk with Martin and love him very much.

Last week I visited Martin's bar. There was “nothin' doin',” to quote from Martin. We talked of fighting men, a subject near to Martin, he having fought three prize-fights himself. Martin boasted himself as still being “an even break wit' any rough-and-tumble scrapper in d' bunch.”

“Come here,” said Martin, in course of converse; “come here; I'll show you a bute.”

Martin opened a door to the room back of the bar. As we entered a pink-white bull terrier, with black spots about the eyes, raced across to fawn on Martin. The terrier's black toe-nails, bright and hard as agate, made a vast clatter on the ash floor.

“This is Spot,” said Martin. “Weighs thirty-three pounds, and he's a hully terror! I'm goin' to fight him to-night for five hundred dollars.”

I stooped to express with a pat on his smooth white head my approbation of Spot.

“Pick him up, and heft him,” said Martin. “He won't nip you,” 'he continued, as I hesitated; “bulls is; d' most manful dogs there bees. Bulls won't bite nobody.”

Thereupon I picked up Spot “to heft him.” Spot smiled widely, wagged his stumpy tail, tried to lick my face, and felt like a bundle of live steel.

“Spot's goin' to fight McDermott's Pincher,” said Martin. “And,” addressing this to Spot, “you want to watch out, old boy! Pincher is as hard as a hod of brick. And you want to look out for your Trilbys; Pincher'll fight for your feet and legs. He's d' limit, Spot, Pincher is! and you must tend to business when you're in d' pit wit' Pincher, or he'll do you. Then McDermott would win me money, an' you an' me, Spot, would look like a couple of suckers.”

Spot listened with a pleased air, as if drinking in every word, and wagged his stump reassuringly. He would remember Pincher's genius for crunching feet and legs, and see to it fully in a general way that Pincher did not “do” him.

“Spot knows he's goin' to fight to-night as well as you and me,” said Martin, as we returned to the bar. “Be d' way! don't you want to go?”

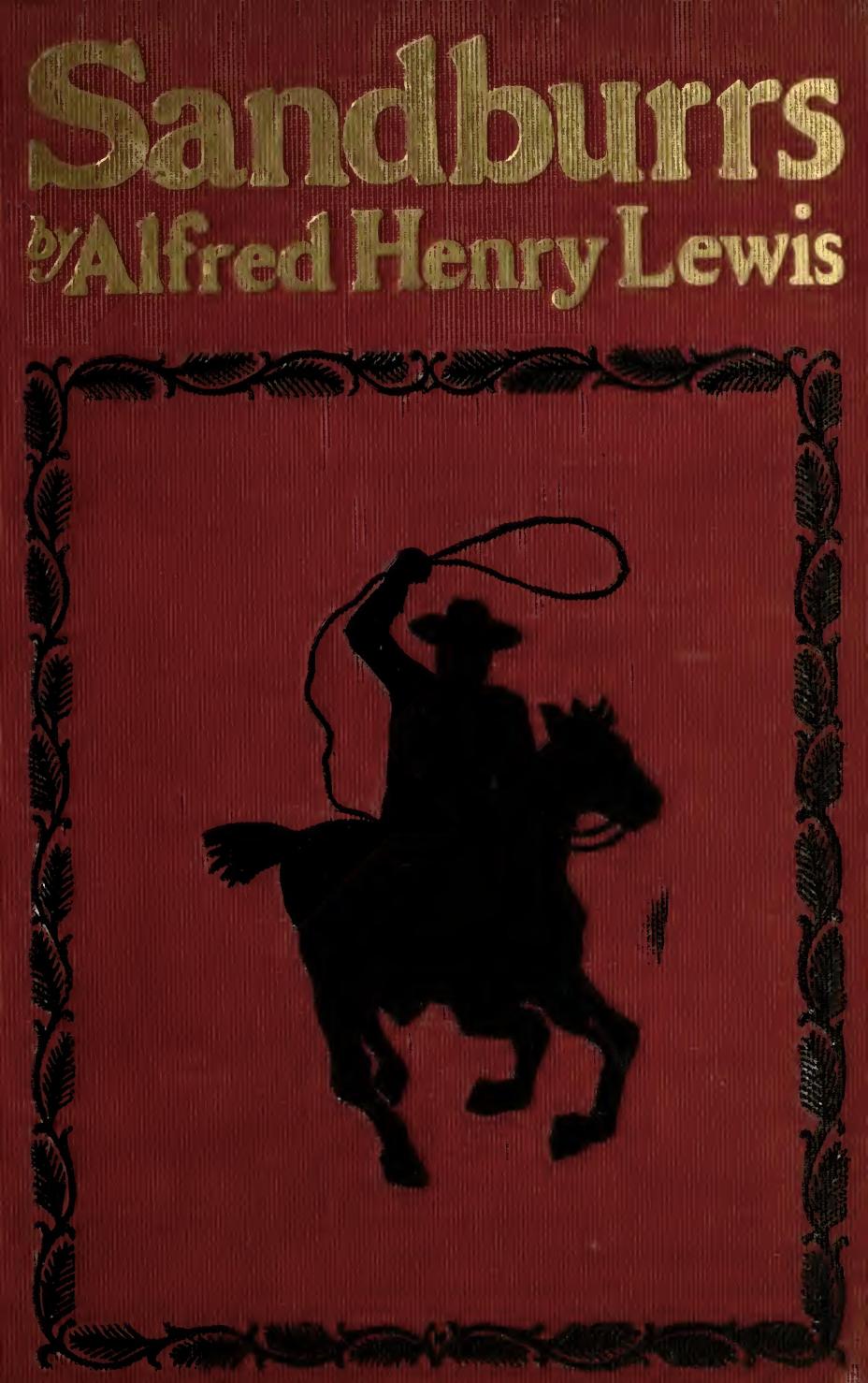

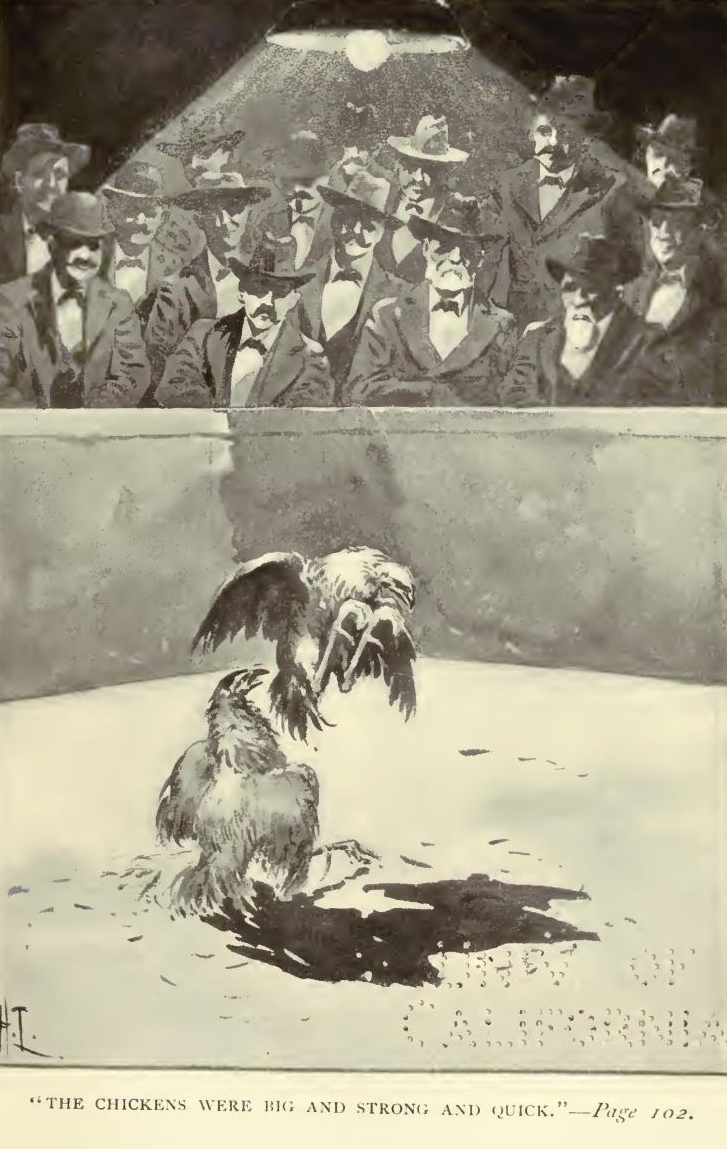

It was nine o'clock that evening. The pit, sixteen feet square, with board walls three feet high, was built in the centre of an empty loft on Bleecker street. Directly over the pit was a bunch of electric lights. All about, raised six inches one above the other, were a dozen rows of board seats like a circus. These were crowded with perhaps two hundred sports. They sat close, and in the vague, smoky atmosphere, their faces, row on row, tier above tier, put me in mind of potatoes in a bin.

Fincher was a bull terrier, the counterpart of Spot, save for the markings about the face which gave Spot his name. Pincher seemed very sanguine and full of eager hope; and as he and Spot, held in the arms of their handlers, lolled at each other across the pit, it was plain they languished to begin. Neither, however, made yelp or cry or bark. Bull terriers of true worth on the battle-field were, I learned, a tacit, wordless brood, making no sound.

Martin “handled” Spot and McDermott did kindly office for Pincher in the same behalf. Martin and McDermott “tasted” Spot and Pincher respectively; smelled and mouthed them for snuffs and poisons. Spot and Pincher submitted to these examinations in a gentlemanly way, but were glad when they ended.

At the word of the referee, Spot and Pincher were loosed, each in his corner. They went straight at each other's throats. They met in the exact centre of the pit like two milk-white thunderbolts, and the battle began.

Spot and Pincher moiled and toiled bloodily for forty-five minutes without halt or pause or space to breathe. Their handlers, who were confined to their corners by quarter circles drawn in chalk so as to hem them in, leaned forward toward the fray and breathed encouragement.

What struck me as wonderful, withal, was a lack of angry ferocity on the parts of Spot and Pincher. There was naught of growl, naught of rage-born cry or comment. They simply blazed with a zeal for blood; burned with a blind death-ardour.

When Spot and Pincher began, all was so flash-like in their motions, I could hardly tell what went on. They were in and out, down and up, over and under, writhing like two serpents. Now and then a pair of jaws clicked like castanets as they came together with a trap-like snap, missing their hold. Now and then one or the other would get a half-grip that would tear out. Then the blood flowed, painting both Spot and Pincher crimson.

As time went on my eyes began to follow better, and I noted some amazing matters. It was plain, for one thing, that both Spot and Pincher were as wise and expert as two boxers. They fought intelligently, and each had a system. As Martin had said, Pincher fought “under,” in never-ending efforts to seize Spot's feet and legs. Spot was perfectly aware of this, and never failed to keep his fore legs well back and beneath him, out of Pinchers reach.

Spot, on his part, set his whole effort to the enterprise of getting Pincher by the throat. A dog without breath means a dead dog, and Spot knew this. Pincher appeared clear on the point, too; and would hold his chin close to his breast, and shrug his head and shoulders well together whenever Spot tried to work for a throat hold.

Now and then Spot and Pincher stood up to each other like wrestlers, and fenced with their muzzles for “holds” as might two Frenchmen with foils. In the wrestling Spot proved himself a perfect Whistler, and never failed to throw Pincher heavily. And, as I stated, from the beginning, the two warriors battled on without cry. Silent, sedulous, indomitable; both were the sublimation of courage and fell purpose. They were fighting to the death; they knew it, joyed in it, and gave themselves to their destiny without reserve. Each was eager only to kill, willing only to die. It was a lesson to men. And, as I looked, I realised that both were two of the happiest of created things. In the very heat of the encounter, with throbbing hearts and heaving sides, and rending fangs and flowing blood, they found a great content.

All at once Spot and Pincher stood motionless. Their eyes were like coals, and their respective stump tails stood stiffly, as indicating no abatement of heart or courage. What was it that brought the halt? Spot had set his long fangs through the side of Pinchers head in such fashion that Pincher couldn't reach him nor retaliate with his teeth. Pincher, discovering this, ceased to try, and stood there unconquered, resting and awaiting developments. Spot, after the manner of his breed, kept his grip like Death. They stood silent, motionless, while the blood dripped from their gashes; a grim picture! They had fought, as I learned later, to what is known in the great sport of dog fighting as “a turn.”

“It's a turn!” decided the referee.

At this Martin and McDermot seized each his dog and parted them scientifically. Spot and Pincher were carried to their corners and refreshed and sponged with cold water. At the end of one minute the referee called:

“Time!”

At this point I further added to my learning touching the kingly pastime of dog-fighting. When two dogs have “fought to a turn,” that is, locked themselves in a grip, not deadly to either if persisted in, and which still prevents further fighting,—as in the case of Spot and Pincher,—a responsibility rests with the call of “Time” on the dog that “turns.” In this instance, Pincher. At the call of “Time” Spot would be held by his handler, standing in plain view of Pincher, but in his corner. It was incumbent on Pincher—as a proof of good faith—to cross the pit to get at him. If Pincher failed when released on call of “Time” to come straight across to Spot, and come at once; if he looked to right or left or hesitated even for the splinter of a second, he was a beaten dog. The battle was against him.

“Time!” called the referee.

Just prior to the call I heard Martin whisper huskily over his shoulder to a rough customer who sat just back of and above him, at Spot's corner of the pit:

“Stand by wit' that glim now!” Martin muttered without turning his head.

At the call “Time!” McDermot released Pincher across in his corner. Pincher's eyes were riveted on Spot, just over the way, and there's no doubt of Pincher's full purpose to close with him at once. There was no more of hesitation in his stout heart than in Spot's, who stood mouth open and fire-eyed, waiting.

But a strange interference occurred. At the word “Time!” the rough customer chronicled slipped the slide of a dark lantern and threw the small glare of it squarely in Pincher's eyes. It dazed Pincher; he lost sight of Spot; forgot for a moment his great purpose. There stood poor Pincher, irresolute, not knowing where to find his enemy; thrall to the glare of the dark lantern.

“Spot win!” declared the referee.

At that moment the dark-lantern rough-customer closed the slide and disappeared.

Few saw the trick or its effects. Certainly the referee was guiltless. But McDermot, who had had the same view of the dark lantern Pincher had, and on whom for a moment it had similar effect, raised a great clamour. But it was too late; Martin had claimed the thousand dollars from the stake-holder, and with it in his pocket was already in a carriage driving away, with Spot wrapped up in a lap robe occupying the front seat.

“Let McDermot holler!” said Martin, with much heat, when I mentioned the subject the next day. “Am I goin' to lose a fight and five hundred dollars, just because some bloke brings a dark lantern to d' pit and takes to monkeyin' wit' it? Not on your life!”

Chucky d' Turk” was the nom de guerre of my friend. Under this title he fought the battles of life. If he had another name he never made me his confidant concerning it. We had many talks, Chucky and I; generally in a dingy little bar on Baxter Street, where, when I wearied of uptown sights and smells, I was wont to meet with Chucky. Never did Chucky call on me nor seek me. From first to last he failed not to conduct himself towards me with an air of tolerant patronage. When together I did the buying and the listening, and Chucky did the drinking and the talking. It was on such occasion when Chucky told me the story of Mulberry Mary.

“Mary was born in Kelly's Alley,” remarked Chucky, examining in a thoughtful way his mug of mixed ale; “Mary was born in Kelly's Alley, an' say! she wasn't no squealer, I don't t'ink.

“When Mary grows up an' can chase about an' chin, she toins out a dead good kid an' goes to d' Sisters' School. At this time I don't spot Mary in p'ticler; she's nothin' but a sawed-off kid, an' I'm busy wit' me graft.

“D' foist I really knows of Mary is when she gets married. She hooks up wit' Billy, d' moll-buzzard; an' say! he's bad.

“He gets his lamps on Mary at Connorses spiel, Billy does; an' he's stuck on her in a hully secont. It's no wonder; Mary's a peach. She's d' belle of d' Bend, make no doubt.

“Billy's graft is hangin' round d' Bowery bars, layin' for suckers. An' he used to get in his hooks deep an' clever now an' then, an' most times Billy could, if it's a case of crowd, flash quite a bit of dough.

“So when Billy sees Mary at Connorses spiel, like I says, she's such a bute he loses his nut. You needn't give it d' laugh! Say! I sees d' map of a skirt—a goil, I means—on a drop curtain at a swell t'eatre onct, an' it says under it she's Cleopatra. D' mark nex' me says, when I taps for a tip, this Cleopatra's from Egypt, an' makes a hit in d' coochee coochee line, wit' d' high push of d' old times, see! An' says this gezeybo for a finish: 'This Cleopatra was a wonder for looks. She was d' high-roller tart of her time, an' d' beauti-fulest.'

“Now, all I got to say is,” continued Chucky, regarding me with a challenging air of decision the while; “all I has to utter is, Mary could make this Cleopatra look like seven cents!

“Well,” resumed Chucky, as I made no comment, “Billy chases up to Mary an' goes in to give her d' jolly of her life. An', say! she's pleased all right, all right; I can see it be her mug.

“An' Billy goes d' limit. He orders d' beers; an' when he pays, Billy springs his wad on Mary an' counts d' bills off slow, Linkin' it'll razzle-dazzle her. Then Billy tells Mary he's out to be her steady.

“'I've got money to boin,' says Billy, 'an' what you wants you gets, see!' An' Billy pulls d' long green ag'in to show Mary he's dead strong, an 'd' money aint no dream.

“But Mary says 'Nit! couple of times nit!' She says she's on d' level, an' no steady goes wit' her. It's either march or marry wit' Mary. An' so she lays it down.

“That's how it stands, when d' nex' news we hears Billy an' she don't do a t'ing but chase off to a w'ite-choker; followin' which dey grabs off a garret in d' Astorbilt tenement, an' goes to keepin' house.

“But Mary breaks in on Billy's graft. She says he's got to go to woik; he'll get lagged if he don't; an' she won't stand for no husband who spends half d' time wit' her an 'd' rest on d' Island. So he cuts loose from d' fly mob an' leaves d' suckers alone, an' hires out for a tinsmith, see!

“An' here's d' luck Billy has. It's d' secont day an' he's fittin' in d' tin flashin' round a chimbley on a five-story roof; an' mebby it's because he aint used to woik, or mebby he gets funny in his cupolo, bein' up so high; anyhow he dives down to d' pavement, an' when he lands, you bet your life! Billy's d' deadest t'ing that ever happened.

“Mary goes wild an' wrong after that. In half of no time Mary takes to chasin' up to Mott Street an' hittin' d' pipe. There's a Chink up there who can cook d' hop out o' sight, an' it aint long before Mary is hangin' 'round his joint for good. It's then dey quits callin' her Mulberry Mary, an' she goes be d' name of Mollie d' Dope.

“Mary don't last in d' Chink swim more'n a year before there's bats in her belfry for fair; any old stiff wit' lamps could see it; an' so folks gets leary of Mary.

“It runs on mebby two years after Billy does that stunt from d' roof, see! when there's a fire an' all d' kids run an' screeched, an' all d' folks hollered, an' all d' engines comes an' lams loose to put it out. D' fire's in a tenement, an 'd' folks who was in it has skipped, so it's just d' joint itself is boinin'.

“All at onct a kid looks out d' fort' story window wit 'd' fire shinin' behint him. You can see be d' little mark's mug he's got an awful scare t'run into him, t'inkin' he's out to boin in d' buildin*.

“'It's McManuses' Chamsey!' says one old Tommy, lettin' her hair down her back an' givin' a yell, 'Somebody save McManuses' Chamsey!'

“'Let me save him!' says Mary, at d' same time laughin' wild. 'Let me save him; I want to save him! I'm only Mollie d' Dope—Mollie d' hop fiend—an' if I gets it in d' neck it don't count, see!'

“Mary goes up in d' smoke an 'd' fire, no one knows how, wit' d' water pourin' from d' hose, an 'd' boards an' glass a-fallin' an' a-crashin', an' she brings out McManuses' Chamsey, Saves him; on d' dead! she does; an' boins all d' hair off her cocoa doin' it.

“Well, of course d' fire push stan's in an' gives Mary all sorts of guff an' praise. Mary only laughs an' says, while d' amb'lance guy is doin' up her head, that folks ain't onto her racket; that she d' soonest frail that ever walks in d' Bend.”

At this juncture Chucky desired another mixed ale. He got it, and after a long, damp pause he resumed his thread.

“Now what do youse t'ink of this for a finish? It's weeks ago d' fire is. Mary meets up wit' McManuses' Chamsey to-day—she's been followin' him a good deal since she saves him—an' as Chamsey is only six years old, he don't know nothin', an' falls to Mary's lead. It's an easy case of bunk, an' Chamsey only six years old like that!

“Mary gives Chamsey d' gay face an' wins him right off. She buys him posies of one Dago an' sugar candy of another; an' then she passes Chamsey a strong tip, he's missin' d' sights be not goin' down to d' East River.

“Here's what Mary does—she takes Chamsey down be d' docks—a longshoreman loafin' hears what she says. Mary tells Chamsey to look at all d' chimbleys an 'd' smoke comin' out!

“'An' in every one there's fire makin 'd' smoke,' says Mary. 'T'ink of all d' fires there must be, Chamsey! I'll bet Hell ain't got any more fires in it than d' woild! Do youse remember, Chamsey, how d' fire was goin' to boin you? Now, I'll tell you what we'll do, so d' fire never will boin us; we'll jump in,—you an' me!'

“An' wit' that, so d' longshoreman says, Mary nails Chamsey be d' neck wit' her left hook an' hops into d' drink. Yes, dey was drowned—d' brace of 'em. Dey's over to d' dead house now on a slab—Mary an' McManuses' Chamsey.

“What makes me so wet? I gets to d' dock a minute too late to save 'em, but I'm right in time to dive up d' stiffs. So I dives 'em up. It's easy money. That's what makes me cuffs look like ruffles an' me collar like a corset string.” And here Chucky called for a third mixed ale, as a sign that his talk was done.

It was evening in Jordan Hollow, and Singletree Jennings stood leaning on his street gate. Singletree Jennings was a coloured man, and, to win his bread, played many parts in life. He was a whitewasher; he sold fish; he made gardens; and during the social season he was frequently the “old family butler,” in white cotton gloves, at the receptions of divers families.

“I'm a pore man, honey!” Singletree Jennings was wont to say; “but dar was a time when me an' my ole Delia was wuf $1,800. Kase why? Kase we brought it at auction, when Marse Roundtree died—didn't we, Delia?”

This was one of Singletree Jennings's jokes.

“But pore man or no!” Singletree Jennings would conclude, “as de Lamb looks down an' sees me, I never wronged a man outen so much as a blue-laiged chicken in my life.”

This evening Singletree Jennings was a prey to dejection. Nor could he account for his gloom. His son opened the gate and went whistling up the street.

“Clambake Jennings, whar yo' gwine?” asked Singletree Jennings.

“Gwine ter shoot craps.”

“Have yo' got yer rabbit's foot?

“Yassir.”

“An' de snake's head outen de clock?”

“Yassir.”

Singletree Jennings relapsed into moody silence, and Clambake passed on and away.

The shouts and cries of some storm-rocked multitude was heard up the street. The Columbia College boys were taking home their new eight-oared boat. The shouts settled into something like the barking of a dog. It was the crew emitting the college cry.

“What's dat?” demanded Delia Jennings, coming to the door.

“De Lawd save us ef I knows!” said Singletree Jennings; “onless it's one of dem yar bond issues dey's so 'fraid'll happen.”

The tones of Singletree Jennings showed that he was ill at ease.

“What's de matter, Daddy Singletree?” demanded the observant Delia.

“I've got a present'ment, I reckon!” said Singletree Jennings. “I'm pow'ful feard dar'll somethin' bust loose wrong about dat Andrew Jackson goat.”

Singletree Jennings was the owner and business manager of a goat named Andrew Jackson. In the winter Singletree Jennings never came home without an armful of straw for Andrew Jackson. In the summer there was no need of straw. Andrew Jackson then ate the shirts off the neighbour's clothes-lines. Andrew Jackson had been known to eat the raiment off a screaming child, and then lower his frontlet at the rescue party. Andrew Jackson was a large, impressive goat; yet he never joked nor gave way to mirth. Ordinarily, Andrew Jackson was a calm, placid goat; aroused, he was an engine of destruction.

All of these peculiarities were explained by Singletree Jennings when Sam Hardtack and Backfence Randolph, a committee acting on behalf of the Othello Dramatic Club, desired the loan of Andrew Jackson. The church to which Singletree Jennings belonged was programming a social this very night, and divers and sundry tableaux, under the direction of the Othello Dramatic Club, were on the card. It was esteemed necessary by those in control to present as a tableau Abraham slaying Isaac. There was a paucity of sheep about, and Andrew Jackson, in this dearth of the real thing, was cast to play the character of the Ram in the Bush.

“An' Andrew Jackson is boun' to fetch loose,” reflected Singletree Jennings, with a shake of his head; “an' when he does, he'll jes' go knockin' 'round among de congregashun like a blind dog in a meat shop!”

Singletree Jennings's worst fears were realised. It was nine o'clock now, and he and Delia had come down to the social. Andrew Jackson had been restrained of his liberty for the previous four hours and held captive in a drygoods' box. He was now in a state of frenzy. When the curtain went up on Abraham and Isaac, Andrew Jackson burst his bonds at the rear of the stage and bore down on the Hebrew father and son like the breath of destiny. Andrew Jackson came, dragging his bush with him. The bush was, of course, a welcome addition. Abraham saw him coming, and fled into the lap of a fiddler. Isaac, however, wasn't faced that way. Andrew Jackson smote Isaac upon the starboard quarter. It was a follow shot, rather than a carom, and Andrew Jackson and his prey landed in the middle of the audience together. For two minutes Andrew Jackson mingled freely with the people present, and then retired by the back door.

“I knowed destrucshun was a-comin'!” murmured Singletree Jennings. “I ain't felt dat pestered, Delia, since de day I concealed my 'dentity in Marse Roundtree's smokehouse, an' dey cotched me at it.”

“Singletree Jennings!” observed the Reverend Handout F. Johnson, in a tone of solemn anger, while his pistol pocket still throbbed from the visitation of Andrew Jackson, “Elder Shakedown Bixby is in pursuit of dat goat of your'n with a razor. He has orders to immolate when cotched. At de nex' conference dar'll be charges ag'in you for substitutin' a deboshed goat for de Ram of Holy Writ. I keers nothin' for my pussonel sufferin's, but de purity of de Word mus' be protected. De congregashun will now join in singin' de pestilential Psalms, after which de social will disperse.”

It was sunset at the Cross-K ranch. Four or five cowboys were gloomily about outside the adobe ranch house, awaiting supper. The Mexican cook had just begun his fragrant task, so a half hour would elapse before these Arabs were fed. Their ponies were “turned” into the wire pasture, their big Colorado saddles reposed astride the low pole fence which surrounded the house, and it was evident their riding was over for the day.

Why were they gloomy? Not a boy of them could tell. They had been partners and campaneros, and “worked” the Cross-K cattle together for months, and nothing had come in misunderstanding or cloud. The ranch house was their home, and theirs had been the unity of brothers.

The week before, a pretty girl—the daughter she was of a statesman of national repute—had come to the ranch from the East. Her name was Jess.

Jess, the pretty girl, was protected in this venture by an old and gnarled aunt, watchful as a ferret, sour as a lime. Not that Jess, the pretty girl, needed watching; she was, indeed! propriety's climax.

No soft nor dulcet reason wooed Jess, the pretty girl, to the West; she came on no love errand. The visitor was elegantly tired of the East, that was all; and longed for western air and western panorama.

Jess, the pretty girl, had been at the Cross-K ranch a week, and the boys had met her, everyone. The meeting or meetings were marked by awkwardness as to the boys, indifference as to Jess, the pretty girl. She encountered them as she did the ponies, cows, horned-toads and other animals, domestic and fero naturo, indigenous to eastern Arizona. While every cowboy was blushingly conscious of Jess, the pretty girl, she was serenely guiltless of giving him a thought.

Before Jess, the pretty girl, arrived, the cowboys were friends and the tenor of their calm relations was rippleless as a mirror. Jess was not there a day, before each drew himself insensibly from the others, while a vague hostility shone dimly in his eyes. It was the instinct of the fighting male animal aroused by the presence of Jess, the pretty girl. Jess, however, proceeded on her dainty way, sweetly ignorant of the sentiments she awakened.

Men are mere animals. Women are, too, for that matter. But the latter are different animals from men. The effort the race makes to be other, better or different than the mere animal fails under pressure. It always failed; it will always fail. Civilisation is the veriest veneer and famously thin. A year on the plains cracks this veneer—this shell—and the animal issues visibly forth. This shell-cracking comes by the expanding growth of all that is animalish in man—attributes of the physical being, fed and pampered by a plains' existence.

To recur to the boys of the Cross-K. The dark, vague, impalpable differences which cut off each of these creatures from his fellows, and inspired him with an unreasoning hate, had flourished with the brief week of their existence. A philosopher would have looked for near trouble on the Cross-K.

“Whatever did you take my saddle for, Bill?” said Jack Cook to one Bill Watkins.

“Which I allows I'll ride it some,” replied Watkins; “thought it might like to pack a sure-'nough long-horn jest once for luck!”

“Well, don't maverick it no more,” retorted Cook, moodily, and ignoring the gay insolence of the other. “Leastwise, don't come a-takin' of it, an' sayin' nothin'. You can palaver Americano, can't you? When you aims to ride my saddle ag'in, ask for it; if you can't talk, make signs, an' if you can't make signs, shake a bush; but don't go romancin' off in silence with no saddle of mine no more.”

“Whatever do you reckon is liable to happen if I pulls it ag'in to-morry?” inquired Bill in high scorn.

Watkins was of a more vivacious temper than the gloomy Cook.

“Which if you takes it ag'in, I'll shorely come among you a whole lot. An' some prompt!” replied Cook, in a tone of obstinate injury.

These boys were brothers before Jess, the pretty girl, appeared. Either would have gone afoot all day for the other. Going afoot, too, is the last thing a cowboy will consent to.

“Don't you-all fail to come among me none,” said Bill with cheerful ferocity, “on account of it's bein' me. I crosses the trail of a hold-up like you over in the Panhandle once, an' makes him dance, an' has a chuck-waggon full of fun with him.”

“Stop your millin' now, right yere!” said Tom Rawlins, the Cross-K range boss, who was sitting close at hand. “You-alls spring trouble 'round yere, an' you can gamble I'll be in it! Whatever's the matter with you-alls anyway? Looks like you've been as locoed as a passel of sore-head dogs for more'n a week now. Which you're shorely too many for me, an' I plumb gives you up!” And Rawlins shook his sage head foggily.

The boys started some grumbling reply, but the cook called them to supper just then, and, one animalism becoming overshadowed by another, they forgot their rancour in thoughts of supplying their hunger. Towards the last of the repast, Rawlins arose, and going to another room, began overlooking some entries in the ranch books.

Jess, the pretty girl, did not sit at the ranch table. She had small banquets in her own room. Just then she was heard singing some tender little song that seemed born of a sigh and a tear. The boys' resentment of each other began again to burn in their eyes. None of these savages was in the least degree in love with Jess, the pretty girl.

The singing went on in a cooing, soft way that did not bring you the words; only the music.

“What I says about my saddle a while back, goes as it lays!” said Jack Cook.

The song had ceased.

As Cook spoke he turned a dark look on Watkins.

“See yere!” replied Watkins in an exasperated tone—he was as vicious as Cook—“if you're p'intin' out for a war-jig with me, don't go stampin' 'round none for reasons. Let her roll! Come a-runnin' an' don't pester none with ceremony.”

“Which a gent don't have to have no reason for crawlin' you!” said Cook. “Anyone's licenced to chase you 'round jest for exercise!”

“You can gamble,” said Watkins, confidently, “any party as chases me 'round much, will regyard it as a thrillin' pastime. Which it won't grow on him none as a habit.”

“As you-all seem to feel that a-way,” said the darkly wrathful Cook, “I'll sorter step out an' shoot with you right now!”

“An' I'll shorely go you!” said Watkins.

They arose and walked to the door. It was gathering dark, but it was light enough to shoot by. The other cowboys followed in a kind of savage silence. Not one word was said in comment or objection. They were grave, but passive like Indians. It is not good form to interfere with other people's affairs in Arizona.

Jess, the pretty girl, began singing again. The strains fell softly on the ears of the cowboys. Each, as he listened, whether onlooker or principal, felt a licking, pleased anticipation of the blood to be soon set flowing.

Nothing was said of distance. Cook and Watkins separated to twenty paces and turned to face each other. Each wore his six-shooter, the loose pistol belt letting it rest low on his hip. Each threw down his big hat and stood at apparent ease, with his thumbs caught in his belt.

“Shall you give the word, or me?” asked Cook.

“You says when!” retorted Watkins. “It'll be a funny passage in American history if you-all gets your gun to the front any sooner than I do.”

“Be you ready?” asked Cook.

“Which I'm shorely ready!”

“Then, go!”

“Bang! Bang!! Bang!!!” went both pistols together.

The reports came with a rapidity not to be counted. Cook got a crease in the face—a mere wound of the flesh. Watkins blundered forward with a bullet in his side.

Rawlins ran out. His experience taught him all at a look. Hastily examining Cook, he discovered that his hurt was nothing serious. The others carried Watkins into the house.

“Take my pony saddled at the fence, Jack,” said Rawlins, “an' pull your freight. This yere Watkins is goin' to die. You've planted him.”

“Which I shorely hopes I has!” said Cook, with bitter cheerfulness. “I ain't got no use for cattle of his brand; none whatever!”

Cook took Rawlins's pony. When he paused, the pony hung his head while his flanks steamed and quivered. And no marvel! That pony was one hundred miles from the last corn, as he cooled his nervous muzzle in the Rio San Simon.

“Some deviltry about their saddles, Miss; that's all!” reported Rawlins to Jess, the pretty girl.

“Isn't it horrible!” shuddered Jess, the pretty girl.

The next morning Jess and the gnarled aunt paid the injured Watkins a visit. This civility affected the other three cowboys invidiously. They at once departed to a line of Cross-K camps in the Northwest. This on a pretence of working cattle over on the Cochise Mesa. They looked black enough as they galloped away.

“Which it's shore a sin Jack Cook ain't no better pistol shot!” observed one, as the acrid picture of Jess, the pretty girl, sympathising above the wounded Watkins, arose before him.

“That's whatever!” assented the others.

Then, in moods of grim hatefulness, they bled their tired ponies with the spur by way of emphasis.

NIT; I'm in a hurry to chase meself to-night,” quoth Chucky, having first, however, taken his drink. “I'd like to stay an' chin wit' youse, but I can't. D' fact is I've got company over be me joint; he's a dead good fr'end of mine, see! Leastwise he has been; an' more'n onct, when I'm in d' hole, he's reached me his mit an' pulled me out. Now he's down on his luck I'm goin' to make good, an' for an even break on past favours, see if I can't straighten up his game.”

“Who is your friend?” I asked. “Does he live here?”

“Naw,” retorted Chucky; “he's a crook, an' don't live nowhere. His name's Mollie Matches, an 'd' day was when Mollie's d' flyest fine-woiker on Byrnes's books. An' say! that ain't no fake neither.”

“What did he do?” I inquired.

“Leathers, supers an' rocks,” replied Chucky. “Of course, d' supers has to be yellow; d' w'ite kind don't pay; an' d' rocks has to be d' real t'ing. In d' old day, Mollie was d' king of d' dips, for fair! Of all d' crooks he was d' nob, an' many's d' time I've seen him come into d' Gran' Central wit' his t'ree stalls an' a Sheeny kid to carry d' swag, an' all as swell a mob as ever does time.

“But he's fell be d' wayside now, an' don't youse forget it! Not only is he broke for dough, but his healt' is busted, too.”

“That's one of the strange things to me, Chucky,” I said, for I was disposed to detain him if I could, and hear a bit more of his devious friend; “one of the very strange things! Here's your friend Mollie, who has done nothing, so you say, but steal watches, diamonds and pocket-books all his life, and yet to-day he is without a dollar.”

“Oh! as for that,” returned Chucky wisely, “a crook don't make so much. In d' foist place, if he's nippin' leathers, nine out of ten of 'em's bound to be readers—no long green in 'em at all; nothin' but poi-pers, see! An' if he's pinchin' tickers an' sparks, a fence won't pay more'n a fort' what dey's wort'—an' there you be, see! Then ag'in, it costs a hundred plunks a day to keep a mob on d' road; an' what wit' puttin' up to d' p'lice for protection, an' what wit' squarin' a con or brakey if youse are graftin' on a train, there ain't, after his stalls has their bits, much left for Mollie. Takin' it over all, Mollie's dead lucky to get a hundred out of a t'ousand plunks; an' yet he's d' mug who has to put his hooks on d' stuff every time; do d' woik an' take d' chances, see!

“But I'll tip it off to youse,” continued Chucky, at the same time lowering his tone confidentially; “I'll put you on to what knocks Mollie's eye out just now. He's only a week ago toined out of one of de western pens, an' I reckon he was bad wit' 'em at d' finish—givin' 'em a racket. Anyhow, dey confers on Mollie d' Hummin' Boid, an dey overplays. Mollie's gettin' old, and can't stand for what he could onct; an', as I says, these prison marks gives him too much of 'd Hummin' Boid and it breaks his noive.

“Sure! Mollie's now what youse call hyster'cal; got bats in his steeple half d' time. If it wasn't for d' hop I shoots into him wit' a dandy little hypodermic gun me Rag's got, he'd be in d' booby house. An' all for too much Hummin' Boid! Say! on d' level! there ought to be a law ag'inst it.”

“What in heaven's name is the Humming Bird?” I queried.

“It's d' prison punishment,” replied Chucky. “Youse see, every pen has its punishment. In some, it's d' paddles, an' some ag'in don't do a t'ing but hang a guy up be a pair of handcuffs to his cell door so his toes just scrapes d' floor. In others dey starves you; an' in others still, dey slams you in d' dark hole.

“Say! if youse are out to make some poor mark nutty for fair, just give him d' dark hole for a week. There he is wit' nothin' in d' cell but himself, see! an* all as black as ink. Mebby if d' guards is out to keep him movin', dey toins d' hose in an' wets down d' floor before dey leaves him. But honest to God! youse put a poor sucker in d' dark hole, an' be d' end of ten hours it's apples to ashes he ain't onto it whether he's been in a day or a week. Keep him there a week, an' away goes his cupolo—he ain't onto nothin'. On d' square! at d' end of a week in d' dark, a mut don't know lie's livin'.

“D' cat-o'nine-tails, which dey has at Jeff City, ain't a marker to d' dark hole! D' cat'll crack d' skin all right, all right, but d' dark hole cracks a sucker's nut, see! His cocoa never is on straight ag'in, after he's done a stunt or two in d' dark hole.”

“But the Humming Bird?” I persisted. “What is it like?”

“Why! as I relates,” retorted Chucky, “d' Hummin Boid is what dey does to a guy in d' pen where Mollie was to teach him not to be too gay. It's like this: Here's a gezebo doin' time, see! Well, he gets funny. Mebby he soaks some other pris'ner; or mebby he toins loose and gives it to some guard in d' neck; or mebby ag'in he kicks on d' lock-step. I've seen a heap of mugs who does d' last.

“Anyhow, whatever he does, it gets to be a case of Hummin' Boid, an' dey brings me gay scrapper or kicker, whichever he is, out for punishment. An' this is what he gets ag'inst:

“Dey sets him in a high trough, same as dey waters a horse wit', see! Foist dey shucks d' mark—peels off his make-up down to d' buff. An' then dey sets him in d' trough, like I says, wit' mebby its eight inches of water in it.

“Then he's strapped be d' ankles, an' d' fins, and about his waist, so he can't do nothin' but stay where he is. A sawbones gets him be d' pulse, an' one of them 'lectrical stiffs t'rows a wire, which is one end of d' battery, in d' water. D' wire, which is d' other end, finishes in a wet sponge. An' say! hully hell! when dey touches a poor mark wit' d' sponge end on d' shoulder, or mebby d' elbow, it completes d' circuit, see! an' it'll fetch such a glory hallelujah yelp out of him as would bring a deef an' dumb asylum into d' front yard to find out what d' row's about.

“It's d' same t'ing as d' chair at Sing Sing, only not so warm. It's enough, though, to make d' toughest mug t'row a fit. No one stands for a secont trip; one touch of d' Hummin' Boid! an' a duck'll welch on anyt'ing you says—do anyt'ing, be anyt'ing; only so youse let up and don't give him no more. D' mere name of Hummin' Boid's good enough to t'run a scare into d' hardest an' d' woist of 'em, onct dey's had a piece.

“As I says about Mollie: it seems them Indians gives him d' Hummin' Boid; an' dey gives him d' gaff too deep. But I've got to chase meself now, and pump some dope into him. I ought to land Mollie right side up in a week. An' then I'll bring him over to this boozin' ken of ours, an' cap youse a knock-down to him. Ta! ta!”

WESTERN humour is being severely spoken of by the close personal friends of Peter Dean. Less than a year ago, Peter Dean left the paternal roof on Madison Avenue and plunged into the glowing West. On the day of his departure he was twenty-three; not a ripe age. He had studied mining and engineering, and knew in those matters all that science could tell. His purpose in going West was to acquire the practical part of his chosen profession. Peter Dean believed in knowing it all; knowing it with the hands as well as with the head.

Thus it befell that young Peter Dean, on a day to be remembered, tossed a careless kiss to his companions and fled away into the heart of the continent. Then his hair was raven black. Months later, when he returned, it was silver white. Western humour had worked the change; therefore the criticism chronicled. Peter Dean tells the following story of the bleaching:

“At Creede I met a person named Thompson; 'Gassy' Thompson he was called by those about him, in testimony to his powers as a conversationist. A barkeeper, who seemed the best-informed and most gentlemanly soul in town, told me that Gassy Thompson was a miner full of practical skill, and that he was then engaged in sinking a shaft. I might arrange with Gassy and learn the business. At the barkeeper's hint, I proposed as much to Gassy Thompson.

“'All right!' said Gassy; 'come out to the shaft to-morrow.'

“The next day I was at the place appointed. The shaft was already fifty feet deep. Besides myself and this person, Gassy, who was to tutor me, there was a creature named Jim. This made three of us.

“At the suggestion of Gassy, he and I descended into the shaft; Jim was left on the surface. We went down by means of a bucket, Jim unwinding us from a rickety old windlass.

“Once down, Gassy and I, with sledge and drill, perpetrated a hole in the bottom of the shaft. I held the drill, Gassy wielding the sledge. When the hole met the worshipful taste of my tutor, he put in a dynamite cartridge, connected a long, five-minute fuse therewith, and carefully thumbed it about and packed it in with wet clay.

“At Gassy's word, I was then hauled up from the shaft by Jim. I added my strength to the windlass, Gassy climbed into the bucket, lighted the fuse, and was then swiftly wound to the surface by Jim and myself. We then dragged the windlass aside, covered the mouth of the shaft, and quickly scampered to a distance, to be out of harm's reach.

“At the end of five minutes from the time that Gassy lighted the fuse, and perhaps three minutes after we had cleared away, the shot exploded with a deafening report. Tons of rock were shot up from the mouth of the shaft, full fifty feet in the air. It was all very impressive, and gave me a lesson in the tremendous power of dynamite. I was much pleased, and felt as if I were learning.

“Following the explosion Gassy and I again repaired to the bottom of the shaft. After clearing away the débris and sending it up and out by the bucket, we resumed the sledge and drill. We completed another hole and were ready for a second shot. This was about noon.

“It was at this point that the miscreant, Gassy, began to put into action a plot he had formed against me, and to carry out which the murderer, Jim, lent ready aid. You must remember that I had perfect confidence in these two villains.

“'I never seed no tenderfoot go along like you do at this business,' said Gassy Thompson to me.

“This was flattery. The miscreant was fattening me for the sacrifice.

“'Looks like you was born to be a miner,' he went on. 'Now, I'm goin' to let you fire the next shot. Usual, I wouldn't feel jestified in allowin' a tenderfoot to fire a shot for plumb three months. But you has a genius for minin'; it comes as easy to you as robbin' a bird's nest. I'd be doin' wrong to hold you back.'

“Of course, I naturally felt pleased. To be allowed to fire a dynamite shot on my first day in the shaft I felt and knew to be an honour. I determined to write home to my friends of this triumph.

“Gassy said he'd put in the shot, and he selected one of giant size. I saw the herculean explosive placed in the hole; then he attached the fuse and thumbed the clay about it as before. He gave me a few last words.

“'After I gets up,' he said, 'an' me an' Jim's all ready, you climb into the bucket an' light the fuse. Then raise the long yell to me an' Jim, an' we'll yank ye out. But be shore an' light the fuse. There's nothin' more discouragin' than for to wait half an* hour outside an' no cartridge goin' off. Especial when it goes off after you comes back to see what's the matter with her. So be shore an' light the fuse, an' then Jim an' me'll run you up the second follerin'. This oughter be a great day for you, young man! firin' a shot this away, the first six hours you're a miner!'

“Jim and Gassy were at the windlass and yelled:

“'All ready below?'

“I was in the bucket and at the word scratched a match and lit the fuse. It sputtered with alarming ardour, and threw off a shower of sparks.

“'Hoist away!' I called.

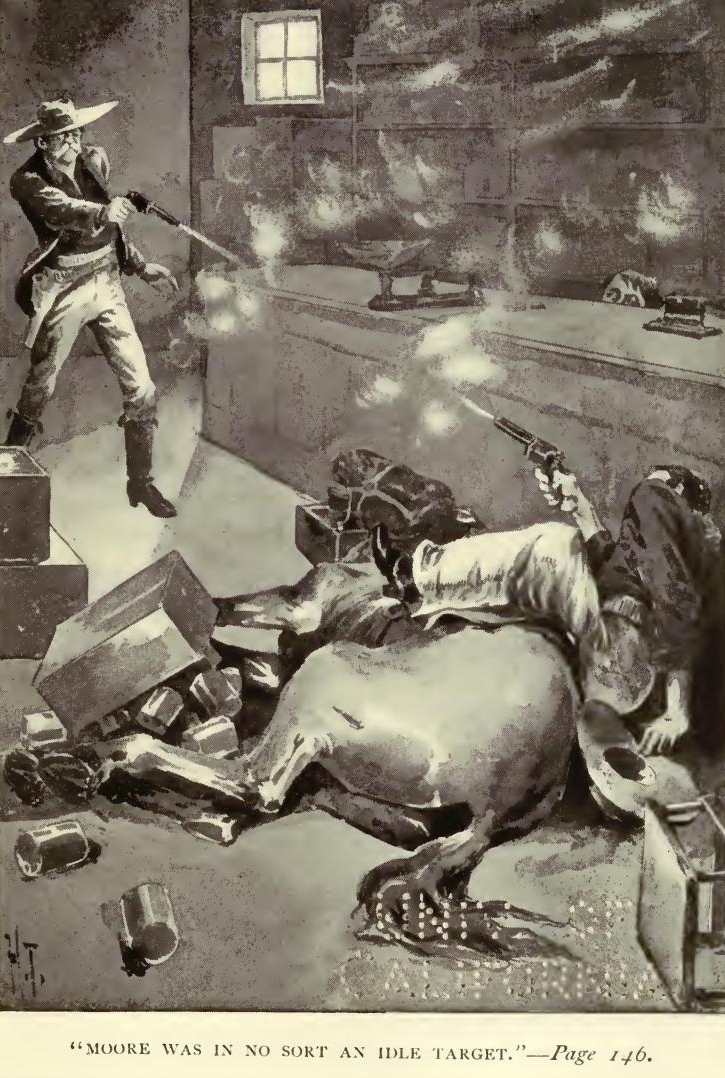

“The villains ran me up about twenty-five feet, and came to a dead halt. At this they seemed to get into an altercation. They both abandoned the windlass, and I could hear them cursing, threatening, and shooting; presumably at each other.

“'I'll blow your heart out!' I heard Gassy say.

“My alarm was without a limit. I'd seen one dynamite cartridge go off. Here I was, swinging some twenty-five feet over a still heavier charge, and about to be blown into eternity! Meanwhile the caitiffs, on whom my life depended, were sacrificing me to settle some accursed feud of their own.

“I cannot tell you of my agony. The fuse was spitting fire like forty fiends; the narrow shaft was choked with smoke. I swung helpless, awaiting death, while the two monsters, Gassy and Jim, were trying to murder each other above. Either from the smoke or the excitement, I fainted.

“When I came to myself I was outside the shaft, safe and sound, while Gassy and his disreputable assistant were laughing at their joke. There had been no shot placed in the drill-hole; the heartless Gassy had palmed it and carried it with him to the surface.

“At my very natural inquiry, made in a weak voice—for I was still sick and broken—as to what it all meant, they said it was merely a Colorado jest, and intended for the initiation of a tenderfoot.

“'It gives 'em nerve!' said Gassy; 'it puts heart into 'em an' does 'em good!'

“As soon as I could walk I severed my relations with Gassy Thompson and his outlaw adherent, Jim. The next morning my hair had turned the milky sort you see. The Creede people with whom I discussed the crime, laughed and said the drinks were on me. That was all the sympathy, all the redress, I got.

“After that I came East without delay. When I leave the city of New York again it will not be for Creede. Nor will my next mining connection be formed with such abandoned barbarians as Gassy Thompson and Jim.”

Pard! would you like to shoot at that lion?”

Bob usually gave me no title at all. But when in any stress of our companionship he was driven to it, I was hailed as “pard!” Once or twice on some lighter occasion he had addressed me by the Spanish “Amigo.” In business hours, however, my rank was “pard!”

Sundown in the hills. The scene was a southeast spur of the Rockies; call the region the Upper Red River or the Vermejo, whichever you will for a name. Forty miles due west from the Spanish Peaks would stand one on the very spot.

I had been out all day, ransacking the canyons, taking a Winter's look at the cattle to note how they were meeting the rigours of a season not yet half over. I had witnessed nothing alarming; my horned folk of the hills still made a smooth display as to ribs, and wore the air of cattle who had prudently stored up tallow enough the autumn before to carry them into the April grass.

“Many a day have I dwelt in a wet saddle, only to crawl into a wetter blanket at night; and all for cows!” It was Bob Ellis who fathered this rather irrelevant observation. I had cut his trail an hour before, and we were making company for each other back to camp. I put forth no retort. Bob and I abode in the same small log hut, and I saw much of him, and didn't feel obliged to reply to those random utterances which fluttered from him like birds from a bush.

It had been snowing for three days. This afternoon, however, had shaken off the storm. It is worth while to see the snow come down in the hills; flakes soft and clinging and silently cold; big as a baby's hand. Out in the flat valleys free of the trees the snow was deep enough to jade and distress our ponies. Therefore Bob and I were creeping home among the thick sown pines which bristled on the Divide like spines on a pig's back. There was very little snow under the trees. What would have made an easy depth of two feet had it been evenly spread on the ground over which our broncos picked their tired way, was above our heads in the pines. That was the reason why the trees were so still and silent. Your pine is a most garrulous vegetable in a sighing fashion, and its complaining notes sing for ever in your ears; sometimes like a roar, sometimes like a wail. But the three-days' snow in their green mouths gagged them; and never a tree of them all drew so much as a breath as we pushed on through their ranks.

“Like the Winchester you're packin?” asked Bob.

I confessed a weakness for the gun.

“Had one of them magazine guns once myse'f,” Bob remarked. “Model of '78. Never liked it, though; always shootin' over. As you pump the loads outen 'em and empty the magazine, the weight shifts till toward the last the muzzle's as light as a feather. Thar you be! shootin' over and still over, every pull.”

Having no interest in magazine guns beyond the act of firing them, I paid no heed to Bob's assault on their merits.

“Now a single-shot gun,” continued Bob, as he rode an oak shrub underfoot to come abreast of me, “is the weepon for me. Never mind about thar bein' jest one shot in her! Show me somethin' to shoot, an' I'll sling the cartridges into her frequent enough for the most impatient gent on earth. This rifle I'm packin' is all right—all except the hind sight. That's too coarse; you could drag a dog through it.”

Bob's dissertation on rifles was entertaining enough. My mood was indifferent, and his wisdom ran through my wits like water through a funnel, keeping them employed without filling them up. Bob had just begun again—all about a day far away when muzzle loaders were many in the hills—when my pony made sudden shy at something in the bushes. The muzzle of my gun instantly pointed to it, as if by an instinct of its own. Even as it did I became aware of the harmless cause of my pony's devout breathings—one of those million tragedies of nature which makes the wilderness a daily slaughter pen. It was the carcass of a blacktail deer. Its torn throat and shoulders, as well as the tracks of the giant cat in the snow, told how it died. The panther had leaped from the big bough of that yellow pine.

“Mountain lion!” observed Bob, sagely, as he con templated the torn deer. “The deer come sa'nterin' down the slope yere, an' the lion jest naturally jumps his game from that tree. This deer was a bigger fool than most. You wouldn't ketch many of 'em as could come walkin' down the wind where the brush and bushes is rank, and gives the cats a chance to lay for 'em and bushwhack 'em!”

It was becoming shadowy in among the pines by this time, and, having enough of Bob's defence of the dead buck and apology for its errors, I pushed on through the bushes for the camp. As we crossed a burnt strip where the fires had made a meal of the trees, the sun was reluctantly blinking his last before going to bed in the Sangre de Christo Range, which rolled upward like some tremendous billow in an ocean of milk full five scores of miles to the west.

Bob and I were smoking our pipes in our log home that evening. Perhaps it was nine o'clock. A pitch-pine fire—billets set up endwise in the fireplace—roared in one corner. Our chimney was a vast success. Out back of our log habitat the surveyors had peeled the base of a pine and made a red-paint statement to the effect that even in the bottom of our little valley we were over 8,000 feet above the sea. This rather derogated from the pride of our chimney's performance; because, as Bob with justice urged, “a chimney not to 'draw' at an altitude of 8,000 feet would have to be flat on the ground.”

I was sprawled on a blanket, softly taking in the smoke of a meerschaum. My eyes, fascinated by the glaring, pitch-pine blaze, were boring away at the fire as if it guarded a treasure. But neither the tobacco smoke nor the flames were in my thoughts; the latter were idly going back to the torn deer.

As if in deference to a fashion of telepathy, Bob would have been thinking of the deer, also. It's possible, however, he had the cat in his meditations.

Suddenly he broke into my quiet with the remark which opens this yarn. Then he proceeded.

“Because,” Bob continued, as I turned an eye on him through my tobacco smoke, “you might get it easy. He's shorely due to go back to-night an' eat up some of that black-tail, unless he's got an engagement. It's even money he's right thar now.”

I stepped to the door and looked out. The roundest of moons in the clearest of skies shone down. Then there was the snow; altogether, one might have read agate print by the light. I picked up my rifle and sent my eye through the sights.

“But how about it when we push in among the pines; it'll be darker in there?”

“Thar'll be plenty of light,” declared Bob. “You don't have to make a tack-head shot. It ain't goin' to be like splittin' a bullet on a bowie. This mountain lion will be as big as you or me. Thar'll be light enough to hit a mark the size of him.”

Our ponies were heartily scandalised at being resaddled so soon; but they were powerless to enforce their views, and away we went, Indian file, with souls bent to slay the lion.

“Which I shorely undertakes the view that we'll get him,” observed Bob as we rode along.

“Did you ever hear the Eastern proverb which says, 'The man who sold the lion's hide while yet upon the beast was killed in hunting him'?” I asked banteringly.

“Who says so?” demanded Bob, defiantly.

“It is an Eastern proverb.”

“Well, it may do for the East,” responded Bob, “but you can gamble it ain't had no run west of the Mississippi. Why! I wouldn't be afraid to bet that one of these panthers never killed a human in the world. They do it in stories, but never in the hills. Why, shore! if you went right up an' got one by his two y'ears an' wrastled him, he'd have to fight. You could get a row out of a house cat, an' play that system. But you can write alongside of the Eastern proverb, that 'Bob Ellis says that the lion them parties complain of as killin' their friend, must have been plumb locoed, an' it oughtn't to count.'”

At the edge of the trees we left the ponies standing. They pointed their ears forward as if wondering what all this mysterious night's work meant. It was entirely beside their experience. We left them to unravel the puzzle and passed as quietly among the trees as needles into cloth.

Both Bob and I had served our apprenticeship at being noiseless, and brought the noble trade of silence to a science. It wasn't distant now to the field of the deer's death. Soon Bob pointed out the yellow pine. Bob was a better woodsman than I. Even in the daylight I would have owned trouble in picking out the tree at that distance among such a piney throng.

What little wind we had was breathing in our faces. Bob hadn't made the black-tail's blunder of giving the lion the better of the breeze. Bob took the lead after he pointed out the yellow pine. Perhaps it was 150 yards away when he identified it. We didn't cover five yards in a minute. Bob was resolutely deliberate. Still, I had no thought of complaint. I would have managed the case the same way had I been in the lead.

Every ten feet Bob would pause and listen. There was now and then the sound of a clot of snow falling in the tops of the pines, as some bough surrendered its burden to the influence of the slight breeze. That was all my ears could detect of voices in the woods.

We were within forty yards of the yellow pine, when Bob, after lingering a moment, turned his face toward me and made a motion of caution. I bent my ear to a profound effort. At last I heard it; the unctuous sound of feeding jaws!

The oak bushes grew thick in among the pine trees. It did not seem possible to make out our game on account of this shrub-screen. At this point, instead of going any nearer the yellow pine, Bob bore off to the left. This flank movement not only held our title to the wind, but brought the moon behind us. After each fresh step Bob turned for a further survey of that region at the base of the yellow pine, where our lion, or some one of his relatives, was busy at his new repast.

Then the climax of search arrived. To give myself due credit, I saw the panther as soon as did Bob. A fallen pine tree opened a lane in the bushes. Along this aisle I could dimly make out the body of the beast. His head and shoulders were protected by the trunk of the yellow pine, from the limb of which he had ambuscaded the black-tail. A cat's mouth serves vilely as a knife; the teeth are not arranged to cut well. His inability to sever a morsel left nothing for our lion to do, but gnaw at the carcass much as a dog might at a bone. This managed to keep his head out of harm's way behind the tree.

Nothing better was likely to offer, and I concluded to try what a bullet would bring, on that part of the panther we could see. I found as I raised my Winchester that there was to be a strong element of faith in the shot. It was dim and shadowy in the woods, conditions which appeared to increase the moment you tried to point a gun. The aid my aim received from the gun-sights was of the vaguest. Indeed, for that one occasion they might as well have been left off the rifle. But as I was as familiar with the weapon as with the words I write, and could tell to the breadth of a hair where to lay it against my face to make it point directly at an object, there was nothing to gain by any elaboration of aim. As if to speed my impulse in the matter, a far-off crashing occurred in the bushes to the rear. A word suffices to read the riddle of the interruption. Our ponies, tired of being left to themselves, were coming sapiently forward to join us.

With the first blundering rush of the ponies I unhooked my Winchester. The panther had no chance to take stock of the ponies' careless approach. If they had started five minutes earlier he might have owed them something.

With the crack of the Winchester, the panther gave such a scream as, added to the jar of the gun—I was burning 120 grains of powder—served to make my ears sing. There were fear, amazement and pain all braided together in that yell. The flash of the discharge and the night shadows so blinded me that I did not make a second shot. I pumped in the cartridge with the instinct of precedent, but it was of no use. On the heels of it, our ponies, as if taking the shot to be an urgent invitation to make haste, came up on a canter, tearing through the bushes in a way to lose a stirrup if persisted in.

Bob had run forward. There was blood on the snow to a praiseworthy extent. As we gazed along the wounded animal's line of flight there was more of it.

“He's too hard hit to go far,” said Bob. “We'll find him in the next canyon, or that blood's a joke.” Bob walked along, looking at the blood-stained snow as if it were a lesson. Suddenly he halted, where the moonlight fell across it through the trees.

“You uncoupled him,” he said. “Broke his back plumb in two. See where he dragged his hind legs!”

“He can't run far on those terms,” I suggested.

“I don't know,” said Bob, doubtfully. “A mountain lion don't die easy. Mountain lions is what an insurance sharp would call a good resk. But I'll tell you how to carry on this campaign: I'll take the horses and scout over to the left until I get into the canyon yonder. Then I'll bear off up the canyon. If he crosses it—an' goin' on two legs that away, I don't look for it—I'll signal with a yell. If he don't, I'll circle him till I find the trail. Meanwhile you go straight ahead on his track afoot. Take it slow an' easy, for he's likely to be layin' somewhere.”

The trail carried me a quarter of a mile. As nearly as I might infer from the story the panther's passage had written in the snow, his speed held out. This last didn't look much like weakness. Still, the course was a splash of blood in red contradiction. The direction he took was slightly uphill.

The trail ended sharp at the edge of a wide canyon. There was a shelf of scaly rock about twelve feet down the side. This had been protected from the storm by the overhanging brink of the canyon, and there was no snow on the shelf. That and the twelve feet of canyon side above it were the yellow colour of the earth.

Below the shelf the snow again was deep, as the sides took an easier slope toward the bottom of the canyon. The panther had evidently scrambled down to the shelf. It took me less than a second to follow his wounded example. Once down I looked over the edge at the snow a few feet below to catch the trail again. The unmarred snow voiced no report of the game I hunted. I stepped to the left a few paces, still looking over for signs in the snow. There were none. As the shelf came to an end in this direction, I returned along the ledge, still keeping a hawk's eye on the snow below for the trail. I heard Bob riding in the canyon.

“Have you struck his trail?” I shouted.

“Thar's been nothin' down yere!” shouted Bob in reply. “The snow's as unbroken as the cream-cap on a pan of milk.”

Where was my panther? I had begun to regard him as a chattel. As my eye journeyed along the ledge the mystery cleared up. There lay my yellow friend close in against the wall. I had walked within a yard of him, looking the other way while earnestly reading the snow.

The panther was sprawled flat like a rug, staring at me with green eyes. I had broken his back, as Bob said. As I brought the Winchester to my face, his gaze gave way. He turned his head as if to hide it between his shoulder and the wall. I was too near to talk of missing, even in the dim light, and the next instant he was hiccoughing with a bullet in his brain. Six and one-half feet from nose to tip was the measurement; whereof the tail, which these creatures grow foolishly long, furnished almost one-half.

It was clear and cold and dry—excellent weather, indeed, for a snowless Christmas. Everywhere one witnessed evidences of the season. One met more gay clothes than usual, with less of anxiety and an increase of smiling peace in the faces. Each window had its wreath of glistening green, whereof the red ribbon bow, that set off the garland, seemed than common a deeper and more ardent red. Or was the elevation in the faces, and the greenness of the wreaths, and the vivid sort of the ribbon, due to impressions, impalpable yet positive, of Christmas everywhere?

All about was Christmas. Even our Baxter Street doggery had attempted something in the nature of a bowl of dark, suspicious drink, to which the barkeeper—he was a careless man of his nomenclature, this barkeeper—gave the name of “apple toddy.” Apple toddy it might have been.

When Chucky came in, an uncertain shuffle which was company to his rather solid tread showed he was not alone. I looked up. Our acquaintance, Mollie Matches, expert pickpocket,—now helpless and broken, all his one time jauntiness of successful crime gone,—was with him.

“It was lonesome over be me joint,” vouchsafed Chucky, “wit' me Bundle chased over to do her reg'lar anyooal confession to d' priest, see! an' so I fought youse wouldn't mind an' I bring Mollie along. Me old pal is still a bit shaky as to his hooks,” remarked Chucky, as he surveyed his tremulous companion, “an' a sip of d' booze wouldn't do him no harm. It ain't age; Mollie's only come sixty spaces; it's that Hum-min' Boid about which I tells youse, that's knocked his noive.”

Drinks were ordered; whiskey strong and straight for Matches. No; I've no apology for buying these folk drink. “Drink,” observed Johnson to the worthy Boswell, “drink, for one thing, makes a man pleased with himself, which is no small matter.” Heaven knows! my shady companions, for the reason announced by the sagacious doctor, needed something of the sort. Besides, I never molest my fellows in their drinking. I've slight personal use for breweries, distilleries, or wine presses; and gin mills in any form or phase woo me not; yet I would have nothing of interference with the cups of other men. In such behalf, I feel not unlike that fat, well-living bishop of Westminster who refused to sign a memorial to Parliament craving strict laws in behalf of total abstinence. “No,” said that sound priest, stoutly, “I will sign no such petition to Parliament. I want no such law. I would rather see Englishmen free than sober.”

It took five deep draughts of liquor, ardently raw, to put Matches in half control of his hands. What with the chill of the day, and what with the torn condition of his nerves, they shook like the oft-named aspen.

“Them don't remind a guy,” said Matches, as he held up his quivering fingers, “of a day, twenty-five years ago, when I was d' pick of d' swell mob, an 'd' steadiest grafter that ever ringed a watch or weeded a leather! It would be safe for d' Chief to take me mug out of d' gallery now, an' rub d' name of Mollie Matches off d' books. Me day is done, an' I'll graft no more.”

There was plaintiveness in the man's tones as if he were mourning some virtue, departed with his age and weakness. Clearly Matches, off his guard and normal, found no peculiar fault with his past.

“How came you to be a thief?” I asked Matches bluntly. I had counted the sixth drink down his throat, which meant that he wouldn't be sensitive.

“It's too far off to say,” retorted Matches. “I can't t'row back to d' time when I wasn't a crook. Do youse want to know d' foist trick I loined? Well, it wasn't t'ree blocks from here, over be d' Bowery. I couldn't be more'n five. There was a fakir, sellin' soap. There was spec'ments of d' long green all over his stand, wit' cakes of soap on 'em, to draw d' suckers. Standin' be me side was a kid; Danny d' Face dey called him. He was bigger than me, an' so I falls to his tips, see!”

“'When you see him toin round,' said Danny d' Face, 'swipe a bill, an' chase yourself up d' alley wit' it.'

“Danny goes behint, an' does a sneak on d' fakir's leg wit' a pin. Of course, he toins an' cuts loose a bluff at Danny, who's ducked out of reach. As he toins, up goes me small mit, an' d' nex' secont I'm sprintin' up d' alley wit 'd' swag.

“Nit; d' mug wit' d' soap don't chase. He never even makes a holler; I don't t'ink he caught on. But Danny cuts in after me, an 'd' minute he sees we ain't bein' followed, or piped, he gives me d' foot, t'rows me in a heap, an' grabs off d' bill. I don't get a smell of it. An 'd' toad skin's a fiver at that!

“D' foist real graft I recalls,” continued Matches, as he took a meditative sip of the grog, “I'm goin' along wit' an old fat skirt, called Mother Worden, to Barnum's Museum down be Ann Street an' Broadway. Mebbe I'm seven or eight then. Mother Worden used to make up for d' respectable, see! an' our togs was out of sight. There was no flies on us when me an' Mother Worden went fort' to graft. What was d' racket? Pickin' women's pockets. Mother Worden would go to d' museum, or wherever there was a crush, an' lead me about be me mit. She'd steer me up to some loidy, an' let on she's lookin' at whatever d' other party has her lamps on. Meanwhile, I'm shoved in between d' brace of 'em, an' that's me cue to dip in wit' me free hook an' toin out d' loidy's pocket, see! An' say! it was a peach of a play; an' a winner. We used to take in funerals, an' theaytres, an' wherever there was a gang. Me an' Mother Worden was d' whole t'ing; there was nobody's bit to split out; just us. We was d' complete woiks.

“Now an' then there was a squeal. Once in a while I'd bungle me stunt, an' d' loidy I was friskin' would tumble an' raise d' yell. But Mother Worden always 'pologised, an' acted like she's shocked, an' cuffed me an' t'umped me, see! an' so she'd woik us free. I stood for d' t'umpin', an' never knocked. Mother Worden always told me that if we was lagged, d' p'lice guys would croak me. An' as d' wallopin's she gives me was d' real t'ing,—bein' she was hot under d' collar for me failin' down wit' me graft,—d' folks used to believe her, an' look on me fin in their pocket, that way, as d' caper of a kid. Oh, d' old woman Worden was dead flossy in her day, an' stood d' acid all right, all right, every time.

“But like it always toins out, she finds her finish. One day she makes a side-play on her own account, somethin' in d' shopliftin' line, I t'ink; an' she's pinched, an' takes six mont's on d' Island. I never sees her ag'in; at which I don't break no record for weeps. She's a boid, was Mother Worden; an' dead tough at that. She don't give me none d' best of it when I'm wit' her, an' I'm glad, in a kid fashion, when she gets put away.

“That's d' start I gets. Some other time I'll unfold to youse how I takes me name of Mollie Matches. Youse can hock your socks! I've seen d' hot end of many an alley! I never chases be Trinity buryin' ground, but I t'inks of a day when I pitched coppers on one of d' tombstones, heads or tails, for a saw-buck, wit' a party grown, before I was old enough an' fly enough to count d' dough we was tossin' for. But we'll pass all that up to-night. It's gettin' late an' I'll just put me frame outside another hooker an' then I'll hunt me bunk. I can't set up, an' booze an' gab like I onct could; I ain't neither d' owl nor d' tank I was.”

François St. Cyr is a Frenchman. He is absent two years from La Belle France. He and his little wife, Bebe, live not far from Washington Square. They love each other like birds. Yet François St. Cyr is gay, and little Bebe is jealous. Once a year the Ball of France is held at the Garden. Bebe turns up a nose and will not so belittle herself. So François St. Cyr attends the Ball of France alone. However, he does not repine. François St. Cyr is permitted to be more de gage; the ladies more abandon. At least that is the way François St. Cyr explains it.

It is the night of the Ball of France. François St. Cyr is there. The Garden lights shine on fair women and brave men. It is a masque. The costumes are fancy, some of them feverishly so. A railroad person present says there isn't enough costume on some of the participants to flag a hand-car. No one has any purpose, however, to flag a hand-car; the deficiency passes unnoticed. Had the railroader spoken of flagging a beer waggon—mon Dieu! that would have been another thing!

A prize, a casket of jewels, is to be given to the best dressed lady. A bacchante in white satin trimmed with swans' down and diamonds the size and lustre of salt-cellars is appointed the beneficiary by popular acclaim. François St. Cyr, as one of the directors of the ball, presents the jewels in a fiery speech. The music crashes, the mad whirl proceeds. A supple young woman, whose trousseau would have looked lonely in a collar-box, kicks off the hat of François St. Cyr. Sapriste! how she charms him! He drinks wine from her little shoe!

The morning papers told of the beauty in swans' down; the casket of jewels, and the presentation rhetoric of François St. Cyr, flowing like a river of oral fire. Bebe read it with the first light of dawn. Peste! Later, when François St. Cyr came home, Bebe hurled the clock at him from an upper window. Bebe followed it with other implements of light housekeeping. François St. Cyr fled wildly. Then he wept and drank beer and talked of his honour.

The supple person who kicked the hat of François St. Cyr was a chorus girl. The troop in whose outrages she assisted was billed to infuriate Newark that evening. François St. Cyr would seek surcease in Newark. He would bind a new love on the heart bruised and broken by the jealous Bebe. Mon Dieu! yes!

The curtain went up. François St. Cyr inhabited a box. He was very still; no mouse was more so. No one noticed François St. Cyr. At last the chorus folk appeared.

“Brava! mam'selle, brava!” shouted François St. Cyr, springing to his feet, and performing with his hands as with cymbals.

What merited this outburst? The chorus folk had done nothing; hadn't slain a note, nor murdered a melody. The audience stared at the shouting François St. Cyr. What ailed the man? At last the audience admonished François St. Cyr.

“Sit down! Shut up!”

Those were the directions the public gave François St. Cyr.

“I weel not sit down! I weel not close up!” shouted François St. Cyr, bending over the box-rail and gesticulating like a monkey whose reason was suffering a strain. Then again to the chorus girl:

“Brava! mam'selle, brava!”

The other chorus girls looked disdainfully at the chorus girl whom François St. Cyr honoured, so as to identify her to the contempt of the public.

Francois St. Cyr suddenly discharged a bouquet at the stage. It was the size of a butter tub. It mowed a swath through the chorus like a chain shot.

“Put him out!” commanded the public.

“Poot heem out!” repeated François St. Cyr with a shriek of sneering contempt. “Canaille! I def-fy you! I am a Frenchman; I do not fee-ar to die!”

Wafted to his duty on the breath of general opinion, a gend'arme of Newark acquired François St. Cyr, and bore him vociferating from the scene of his triumph.

As he was carried through the foyer, he raised his voice heroically:

“Vive le Boulanger!”

The next public appearance of François St. Cyr was in the Newark Police Court. He was pale and limp, and had thoughts of suicide. He was still clothed in his dress suit, which clung to him as if it, too, felt “des-pond.”

François St. Cyr was fined $20.

Bebe, the jealous, the faithful little Bebe, was there to pay the money. Mon Dieu! how he loved her! He would be her bird and sing to her all her life! Never would he leave his Bebe more! As for the false one of the chorus: François St. Cyr “des-spised” her.

Also Bebe had brought the week-day suit of François St. Cyr. Could an angel have had more forethought? François St. Cyr changed his clothes in a jury room, and Bebe and he came home cooing like turtle doves.

By virtue of the every-day suit, the St. Cyrs were home by 4 o'clock in the afternoon. Otherwise, under the rules, being habited in a dress suit, François St. Cyr could not have returned until 6,

And they were happy!

Albert Edward Murphy is a high officer in one of the departments of the city. He holds his position with credit to the administration, and to his own celebration and renown. He has a wife and a family of children; and sets up his Lares and Penates in a home of his own in Greenwich Village.

Among other possessions of a household sort, Albert Edward Murphy, until lately, numbered one pug dog. It was a dog of vast spirit and but little wit. Yet the children loved it, and its puggish imbecility only seemed to draw it closer to their baby hearts.

The pug's main delusion went to the effect that he could fight. Good judges say that there wasn't a dog on earth the pug could whip. But he didn't know this and held other views. As a result, he assailed every dog he met, and got thrashed. The pug had taken a whirl at all the canines in the neighbourhood, and been wickedly trounced in every instance. This only made him dearer, and the children loved him for the enemies he made.

The pug's name was John.

One day, John, the pug, fell heir to a frightful beating at the paws and jaws of the dog next door. All that saved the life of John, the pug, on this awful occasion, was the lucky fact that he could get between the pickets of the line fence, and the neighbour's dog could not. The neighbour's dog was many times the size and weight of John, the pug; but, as has been suggested, what John didn't know about other dogs would fill a book; and he had gone upon the neighbour's premises and pulled off a fight.

Now these divers sporting events in which John, the pug, took disastrous part worried Albert Edward Murphy. They worried him because the children took them to heart, and wept over the wounds of John, the pug, as they bound them with tar and other medicaments. At last Albert Edward Murphy resolved upon a campaign in favour of John, the pug. His future should have a protector; his past should be avenged.

There was a forty-pound bulldog resident of Philadelphia. He whipped every dog to whom he was introduced. His name was Alexander McBride. He was referred to as “McBride's Dandy” in his set, whenever his identification became a conversational necessity. Of the many dogs he had met and conquered, Alexander McBride had killed twenty-three.

Albert Edward Murphy resolved to import Alexander McBride. He knew the latter's owner. A letter adjusted the details. The proprietor of Alexander McBride was willing his pet should come to the metropolis on a visit. Alexander McBride had fought Philadelphia to a standstill, and his owner's idea was that, if Alexander McBride were to go on a visit and remain away for a few months, Philadelphia would forget him, and on his return he might ring Alexander in on the town as a stranger, and kill another dog with him. *****

Alexander McBride got off the cars in a chicken crate. The expressmen were afraid of him. Albert Edward Murphy was notified. He hired a coloured person, who looked on life as a failure, to convey Alexander McBride to his new home. They tied him to a bureau when they got him there.