CONTENTS

Dorothy frowns slightly, but slightingly, at the title; but when challenged to put her frown into words she has nothing worse to say about it than that it has a certain catchpenny click—the world is talking about The Peace and she has an impression that to introduce the word even without the very definite article is an attempt to derive profit from a topic of the hour—something like backing a horse with a trusty friend for a race which you have secret information it has won five minutes earlier—a method of amassing wealth resorted to every day, I am told by some one who has tried it more than once, but always just five minutes too late.

I don't like Dorothy's rooted objection to my literary schemes, because I know it to be so confoundedly well rooted; so I argue with her, assuring her that literary men of the highest rank have never shown any marked reluctance to catch the pennies that are thrown to them by the public when they hit upon a title that jingles with the jingle of the hour. To descend to an abject pleasantry I tell her that a taking title is not always the same as a take-in title; but, for my part, even if it were——

And then I recall how the late R. D. Blackmore (whose works, by the way, 1 saw in a bookseller's at Twickenham with a notice over them—“by a local author”) accounted for the popularity of Lorna Doone: people bought it believing that it had something to do with the extremely popular engagement—“a Real German Defeat,” Tenniel called it in his Punch cartoon—of the Marquis of Lorne and the Princess Louise. And yet so far from feeling any remorse at arriving at the Temple of Fame by the tradesman's entrance, he tried to get upon the same track again a little later, calling his new novel Alice Lorraine: people were talking a lot about Alsace-Lorraine at the time, as they have been doing ever since, though never quite so loudly as at the present moment (I trust that the publishers of the novel are hurrying on with that new edition).

But Dorothy's reply comes pat: If Mr. Blackmore did that, all she can say is that she doesn't think any the better of him for it; just what the Sabbatarian Scotswoman said when the act of Christ in plucking the ears of corn on the Sabbath Day was brought under her ken.

“My dear,” I cry, “you shouldn't say that about Mr. Blackmore: you seem to forget that his second name was Doddridge, and I think he was fully justified in refusing to change the attractive name of his heroine of the South Downs because it happened to catch the ears (and the pence) of people interested in the French provinces which were pinched by the Germans, who added insult to injury by transforming Alsace-Lorraine to Elsass-Lothringen. And so far as my own conscience is concerned——”

“Your own what?” cried Dorothy.

“My own conscience—literary conscience, of course.”

“Oh, that one? Well?”

“I say, that so far as—as—as I am concerned, I would not have shrunk from calling a book A Garden in Tipperary if I had written it a few years ago when all England and a third of France were ringing with the name Tipperary.

“Only then it would have been a Garden of War, but now it suits you—your fancy, to make it a Garden of Peace.”

“It's not too late yet; if you go on like this, I think I could manage to introduce a note of warfare into it and to make people see the appropriateness of it as well; so don't provoke me.”

“I will not,” said Dorothy, with one of her perplexing smiles.

And then she became interesting; for she was ready to affirm that every garden is a battlefield, even when it is not run by a husband and his wife—a dual system which led to the most notorious horticultural fiasco on record. War, according to Milton, originated in heaven, but it has been carried on with great energy ever since on earth, and the first garden of which there is a literary record maintained the heavenly tradition. So does the last, which has brought forth fruit and flowers in abundance through the slaughter of slugs, the crushing of snails, the immolation of leather-jackets, the annihilation of 'earwigs, and is now to be alluded to as a Garden of Peace, if you please.

Dorothy con be very provoking when she pleases and is wearing the right sort of dress; and when she has done proving that the most ancient tradition of a garden points to a dispute not yet settled, between the man and his wife who were running it, she begins to talk about the awful scenes that have taken place in gardens. We have been together in a number of gardens in various parts of the world: from those of the Borgias, where, in the cool of the evening, Lucrezia and her relations communed on the strides that the science and art of toxicology was making, on to the little Trianon where the diamond necklace sparkled in the moonlight on the eve of the rising of the people against such folk as Queens and Cardinals—on to the gardens of the Temple, where the roses were plucked before the worst of the Civil Wars of England devastated the country—on to Cherry' Orchard, near Kingston in the island of Jamaica, where the half-breed Gordon concocted his patriotic treason which would have meant the letting loose of a jungle of savages upon a community of civilisation, and was only stamped out by the firm foot of the white man on whose shoulders the white man's burden was laid, and who snatched his fellow-countrymen from massacre at the sacrifice of his own career; for party government, which has been the curse of England, was not to be defrauded of its prey because Governor Eyre had saved a colony from annihilation. These are only a few of the gardens in which we have stood together, and Dorothy's memory for their associations is really disconcerting. I am disconcerted; but I wait, for the wisdom of the serpent of the Garden comes to me at times—I wait, and when I have the chance of that edgeways word which sometimes I can't get in, I say,—

“Oh, yes, those were pleasant days in Italy among the cypresses and myrtles, and in Jamaica with its palms. I think we must soon have another ramble together.”

“If it weren't for those children—but where should we go?” she cried.

“I'm not sure,” I said, as if revolving many memories, “but I think some part of the Pacific Slope——”

“Gracious, why the Pacific Slope, my man?”

“Because a Pacific Garden must surely be a Garden of Peace; and that's where we are going now with the title-page of a book that is to catch the pennies of the public, and resemble as nearly as I can make it—consistent with my natural propensity to quarrel with things that do not matter in the least—one of the shadiest of the slopes of the Island Valley of Avilion—

Where falls not hall, or rain, or any snow,

Nor ever wind blows loudly, for it lies

Deep-meadow'd, happy, fair with orchard-lawns

And bowery hollows, crown'd with summer sea.”

Luckily I recollected the quotation, for I had not been letter-perfect I should have had a poor chance of a bright future with Dorothy.

As it was, however, she only felt if the big tomato was as ripe as it seemed, and said,—

“'Orchard-lawns.' H'm, I wonder if Tennyson, with all his 'careful-robin' observation of the little things of Nature was aware that you should never let grass grow in an apple orchard.”

“I wonder, indeed,” I said, with what I considered a graceful acquiescence. “But at the same time I think I should tell you that there are no little things in Nature.”

“I suppose there are not,” said she. “Anyhow, you will have the biggest tomato in Nature in your salad with the cold lamb. Is that the bell?”

“It is the ghost-tinkle of the bell of the bell-wedder who was the father of the lamb,” said I poetically.

“So long as you do not mention the mother of the lamb when you come to the underdone stratum, I shall be satisfied,” said she.

PS.—(1.30)—And I didn't.

PFS.—(1.35)—But I might have.

This town of ours is none other than Yardley Parva. Every one is supposed to know that the name means “The Little Sheltered Garden,” and that it was given this name by a mixed commission of Normans and Romans. The Normans, who spoke a sort of French, gave it the first syllable, which is the root of what became jardin, and which still survives in the “backyard” of American literature; meaning not the backyard of an English home, where broken china and glass and other incidental rubbish are thrown to work their way into the bowels of the earth, but a place of flowers and beans and pumpkins. The surname, Parva, represents the influence of the Romans, who spoke a sort of Latin. Philologists are not wholehearted about the “ley,” but the general impression is that it had a narrow escape from being “leigh,” an open meadow; ley, however, is simply “lee,” or a sheltered quarter, the opposite to “windward.” Whatever foundation there may be for this philology—whether it is derived from post hoc evidence or not—every one who knows the place intimately will admit that if it is not literally exact, it should be made so by the Town Council; for it is a town of sheltered little gardens. It has its High Street: and this name, a really industrious philologist will tell you, is derived, not from its occupying any elevated position, but from the fact that the people living on either side were accustomed to converse across the street, and any one wishing to chat with an opposite neighbour, tried to attract his attention with the usual hail of “hie there!”; and as there was much crossquestioning and answering, there was a constant chorus of “hie, hie!” so that it was really the gibe of strangers that gave it its name, only some fool of a purist seven or eight hundred years ago acquired the absurd notion that the word was “High” instead of “Hie!” So it was that Minnesingers' Lane drifted into Mincing Lane, I have been told. It had really nothing to do with the Min Sing district of China, where the tea sold in that street of tea-brokers came from. Philology is a wonderful study; and no one who has made any progress in its by-paths should ever be taken aback or forced to look silly.

The houses on each side of the High Street are many of them just as they were four or five hundred years ago. Some of them are shops with bow fronts that were once the windows of parlours in the days when honest householders drank small ale for breakfast and the industrious apprentices took down the shutters from their masters' shops and began their day's work somewhere about five o'clock in midsummer, graduating to seven in midwinter. There are now some noble plate-glass fronts to the shops, but there are no apprentices, and certainly no masters. Scores of old, red-tiled roofs remain, but they are no more red than the red man of America is red. The roofs and the red man are of the same hue. Sixty years ago, when slate roofs became popular, they found their way to Yardley Parva, and were reckoned a guarantee of a certain social standing. If you saw a slate roof and a cemented brick front you might be sure that there was a gig in the stable at the back. You can now tell what houses had once been tiled by the pitch of the roofs. This was not altered on the introduction of the slates.

But with the innovations of plate-glass shop-fronts and slate roofs there has happily been no change in the gardens at the back of the two rows of the houses of the High Street. Almost every house has still its garden, and they remain gay with what were called in my young days “old-fashioned flowers,” through the summer, and the pear-trees that sprawl across the high dividing walls in Laocoon writhings—the quinces that point derisive, gnarled fingers at the old crabs that give way to soundless snarls against the trained branches of the Orange Pippins—the mulberries that are isolated on a patch of grass—all are to-day what they were meant to be when they were planted in the chalk which may have supplied Roman children with marbles when they had civilized themselves beyond the knuckle-bones of their ancestors' games.

I cannot imagine that much about these gardens has changed during the changes of a thousand years, except perhaps their shape. When the Anglo-Saxon epidemic of church-building was running its course, the three-quarters-of-a-mile of the High Street did not escape. There was a church every hundred yards or so, and some of them were spacious enough to hold a congregation of fifty or sixty; and every church had its church-yard—that is, as we have seen—its garden, equal to the emergencies of a death-rate of perhaps two every five years; but when the churches became dwelling-houses, as several did, the church-yard became the back-yard in the American sense: fruit-trees were planted, and beneath their boughs the burgesses discussed the merits of ale and the passing away of the mead bowl, and shook their heads when some simpleton suggested that the arrow that killed Rufus a few months before was an accidental one. There are those gardens to-day, and the burgesses smoke their pipes over the six-thirty edition of the evening paper that left London at five-fifteen, and listen to stories of Dick, who lost a foot at the ford of the Somme, or of Tom, who got the M.C. after Mons, and went through the four years without a scratch, or of Bob, who had his own opinion about the taking of Jerusalem, outside which two fingers of his left hand are still lying, unless a thieving Arab appropriated them.

There the chat goes on from century to century on the self-same subject—War, war, war. It is certain that men left Yardley Parva for the First Crusade; one of the streets that ran from the Roman road to the Abbey which was founded by a Crusading Norman Earl, returns the name that was given to it to commemorate the capture of Antioch when the news reached England a year or so after the event; and it is equally certain that Yardley men were at Bosworth Field, and Yardley men at Tournai in 1709 as well as in 1918—at the Nile in 1798 as well as in 1915; and it is equally certain that such of them as came back talked of what they had seen and of what their comrades had done. The tears that the mothers proudly shed when they talked of those who had not come home in 1918 were shed where the mothers of the Crusaders of 1099 had knelt to pray for the repose of the souls of their dear ones whose bones were picked by the jackals of the Lebanon. On the site of one of the churches of the market-place there is now built a hall of moving pictures—Moving Pictures—that is the whole sum of the bustle of the thousand years—Moving Pictures. The same old story. Life has not even got the instinct of the film-maker: it does not take the trouble to change the scenes of the exploits of a thousand—ten thousand—years ago, and those of to-day. Egypt, the Nile, Gaza, Jerusalem, Damascus, Mesopotamia. Moving pictures—walking shadows—walking about for a while but all having the one goal—the Garden of Peace; those gardens that surrounded the churches, where now the apple-trees bloom and fruit and shed their leaves.

These little irregular back-gardens are places of enchantment to me and I think I like those behind the smallest of the shops, which are not more than thirty feet square, rather than those higher up the town, of a full acre or two. These bigger ones do not suggest a history beyond the memory of the gardeners who trim the hedges and cut the grass with a machine. The small and irregular ones suggest a good deal more than a maiden lady wearing gloves, with a basket on her arm and a pair of snipping shears opening its jaws to bite the head off every bloom that has a touch of brown on its edge. But with me it is not a matter of liking and not liking; it is a matter of liking and liking better—it is the artisan's opinion of rival beers (pre-war): all good but some better than others. The little gardens behind the shops are lyrics; the big ones behind the villas are excellent prose, and excellent prose is frequently quite as prosy as excellent verse. They are alive but they are not full of the joy of living. The flowers that they bring forth suggest nice girls whose education is being carefully attended to by gentlemen who are preparing for Ordination. Those flowers do not sing, and I know perfectly well that if they were made to sing it would be to the accompaniment of a harmonium, and they would always sing in tune and in time: but they would need a conductor, they would never try anything on their own—not even when it was dark and no one would know anything about it. Somehow these borders make me think of the children of Blundell's Charity—-a local Fund which provides for the education on religious principles of fifteen children born in wedlock of respectable parents. They occupy a special bench in the aisle of one of the churches, and wear a distinctive dress with white collars and cuffs. They attend to the variations of the Sacred Service, and are always as tidy and uninteresting as the borders in the wide gardens behind the houses that are a quarter of a mile beyond the gardens of the High Street shops.

But it is in these wide gardens that the earliest strawberries are grown, and to them the reporter of the local newspaper goes in search of the gigantic gooseberry or the potato weighing four pounds and three ounces; and that is what the good ladies with the abhorred shears and the baskets—the Atropussiies, in whose hands lie the fates of the fruits as well as of the flowers—consider the sum of high gardening: the growth of the abnormal is their aim and they are as proud of their achievement as the townsman who took to poultry was of his when he exhibited a bantam weighing six pounds.

Now I hold that gardens are like nurseries—nurseries of children, I mean—and that all make an appeal to one's better nature, that none can be visited without a sense of pleasure even though it may be no more than is due to the anticipation of getting away from them; therefore, I would not say a word against the types which I venture to describe; as I have found them. The worst that I can say of them is that they are easily described, and the garden or the girl that can be described will never be near my heart. Those gardens are not the sort that I should think of marrying, though I can live on the friendliest of terms with them, particularly in the strawberry season. They do not appeal to the imagination as do the small and irregular ones at the rear of the grocer's, the stationer's, the fishmonger's, the bootmaker's, or the chymist's—in this connection I must spell the name of the shop with a y: the man who sits in such a garden is a chymist, not a chemist. I could not imagine a mere chemist sniffing the rosemary and the tansy and the rue au naturel: the mere chemist puts his hand into a drawer and weighs you out an ounce of the desiccated herbs.

In one of Mr. Thomas Hardy's earlier novels—I think it is The Mayor of Casterbridge—he describes a town, which is very nearly as delightfully drowsy as our Yardley Parva, as one through which the bees pass in summer from the gardens at one side to those at the other. In our town I feel sure that the bees that enter among the small gardens of sweet scents and savours at one end of the High Street, never reach the gardens of the gigantic gooseberry at the other; unless they make a bee-line for them at the moment of entering; for they must find their time fully occupied among the snapdragons of the old walls, the flowers of the veronica bushes, and the buttons of the tall hollyhocks growing where they please.

When I made, some years ago, a tour of Wessex, I went to Casterbridge on a July day, and the first person I met in the street was an immense bee, and I watched him hum away into the distance just as Mr. Hardy had described him. He seemed to be boasting that he was Mr. Hardy's bee, just as a Presbyterian Minister, who had paid a visit to the Holy Land to verify his quotations, boasted of the reference made to himself in another Book.

“My dear friends,” said he, “I read in the Sacred Book the prophecy that the land should be in heaps; I looked up from the page, and there, before my very eyes, lay the heaps. I read that the bittern should cry there; I looked up, and lo! close at hand stood the bittern. I read that the Minister of the Lord should mourn there: I was that Minister.”

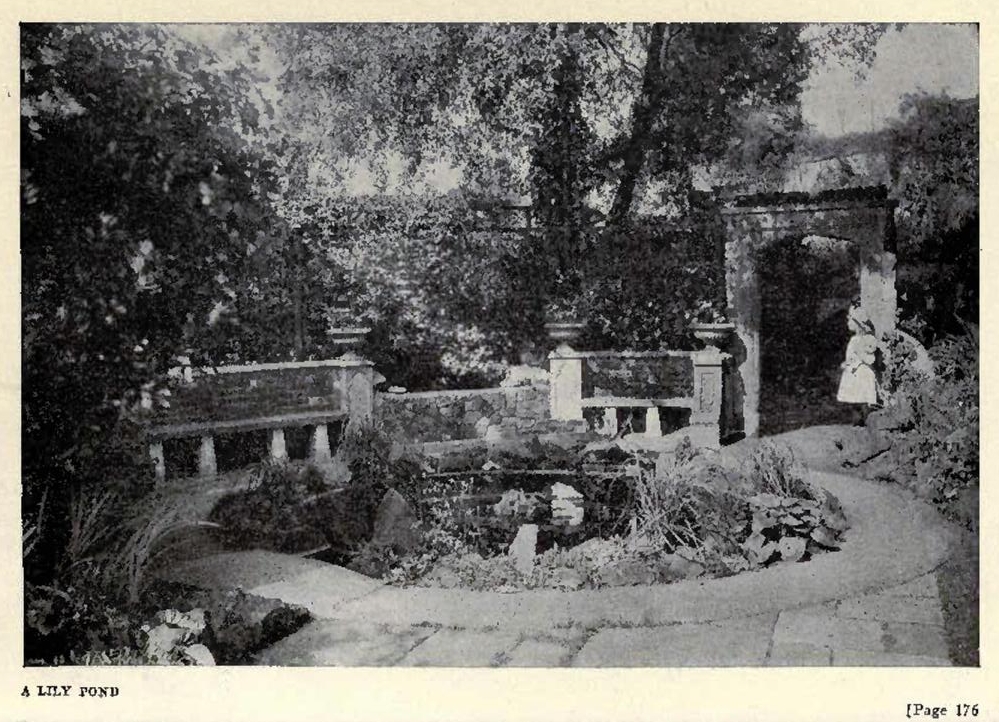

But there are two or three gardens—now that I come to think of it there are not so many as three—governed by the houses of the “better-class people” (so they were described to me when I first came to Yardley Parva), which are everything that a garden should he. Their trees have not been cut down as they used to be forty years ago, to allow the flowers to have undisputed possession. In each there are groups of sycamore, elm, and silver birch, and their position makes one feel that one is on the border of a woodland through which one might wander for hours. There are tulip-trees, and a fine arbutus on an irregular, slightly-sloping lawn, and a couple of enormous drooping ashes—twenty people can sit in the green shade of either. In graceful groups there are laburnums and lilacs. Farther down the slope is a well-conceived arrangement of flower-beds cut out of the grass. Nearly everything in the second of these gardens is herbaceous; but its roses are invariably superb, and its lawn with a small lily pond beside it, is ideal. The specimen shrubs on a lower lawn are perfect as regards both form and flower, and while one is aware of the repose that is due to a thoughtful scheme of colour, one is conscious only of the effect, never being compelled to make use of the word artistic. As soon as people begin to talk of a garden being artistic you know that it has failed in its purpose, just as a portrait-painter has failed if you are impressed with the artistic side of what he has done. The garden is not to illustrate the gardener's art any more than the portrait is to make manifest the painter's. The garden should be full of art, but so artfully introduced that you do not know that it is there. I have heard a man say as if he had just made a unique discovery,—

“How extraordinary it is that the arrangements of colour in Nature are always harmonious!”

Extraordinary!

Equally extraordinary it is that

“Treason doth never prosper; what's the reason?

For if it prospers none dare call it treason.”

All our impressions of harmony in colour are derived from Nature's arrangements of colour, and when there is no longer harmony there is no longer Nature. Is it marvellous that Nature should be harmonious when all our ideas of harmony are acquired from Nature? A book might be written on this text—I am not sure that several books have not been written on it. It is the foundation of the analysis of what may be called without cant, “artistic impression.” It is because it is so trite that I touch upon it in my survey of a Garden of Peace. We love the green of the woodland because it still conveys to us the picture of our happy home of some hundreds of thousands of years ago. We find beauty in an oval outline because our ancestors of the woodland spent some happy hours bird-nesting. Hogarth's line of beauty is beautiful because it is the line of human life—the line that Nature has ever before her eyes—the line of human love. The colours of countless fruits are a delight to us because we have associated those colours for tens of thousands of years with the delight of eating those fruits, and taking pleasure in the tints of the fruits; we take pleasure in the tints of flowers because they suggest the joys of the fruits. The impression of awe and fear that one of Salvator Rosa's “Rocky Landscapes” engenders is due to our very distant ancestors' experience of the frequent earthquakes that caused these mighty rocks to be flung about when the surface of our old mother Earth was not so cool as it is to-day, as well as to the recollection of the very, fearsome moments of a much less remote ancestor spent in evading his carnivorous enemies who had their dens among these awful rocks. From a comparatively recent pastoral parent we have inherited our love for the lawn. There were the sheep feeding in quiet on the grass of the oasis in the days when man had made the discovery that he could tame certain animals and keep them to eat at his leisure instead of having to spend hours hunting them down.

But so deep an impression have the thousands of years of hunting made upon the race, that even among the most highly civilised people hunting is the most popular of all enjoyments, and the hunter is a hero while the shepherd is looked on as a poor sort.

Yes, there are harmonies in Nature, though all makers of gardens do not appreciate them; the discordant notes that occasionally assail a lover of Nature in a garden that has been made by a nurseryman are due to the untiring exertions of the hybridiser. It is quite possible to produce “freaks” and “sports” both as regards form and colour—“Prodigious mixtures and confusion strange.” I believe that some professional men spend all their time over experiments in this direction, and I have no doubt that some of them, having perpetrated a “novelty,” make money out of it. Equally sure I am that the more conscientious, when they bit upon a novelty that they feel to be offensive, destroy the product without exhibiting it. They have not all the hideous unscrupulousness of Dr. Moreau—the nearest approach to a devil trying to copy the Creator who made man in His own image. Dr. Moreau made things after his own likeness. He was a great hybridiser. (Mr. H. G. Wells, after painting that Devil for us, has recently been showing his skill in depicting the God.)

Now, every one knows that the garden of to-day owes most of its glory to the judicious hybridiser, but I implore of him to be merciful as he is strong. I have seen some heartrending results of his experiments which have not been suppressed, as they should have been. I am told that a great deal in the way of developing the natural colours of a certain group of flowers can be done by the introduction of chemicals into their drinking water. It is like poisoning a well! By such means I believe an unscrupulous gardener could turn a whole border into something resembling a gigantic advertisement card of aniline dyes.

But I must be careful in my condemnations of such possibilities. There is a young woman named Rosamund, who is Dorothy's first-born, and she is ready at all seasonable times to give me the benefit of her fourteen years' experiences of the world and its ways, and she has her own views of Nature as the mother of the Arts. After listening to my old-fashioned railings against such chromatic innovations as I have abused, she maintained a thoughtful silence that suggested an absence of conviction.

“Don't you see the awfulness of re-dying a flower—the unnaturalness of such an operation?” I cried.

“Why, you old thing, can't you see that if it's done by aniline dyes it's all right—true to Nature and all that?”

“Good heavens! that a child of mine—Dorothy, did you hear her? How can you sit there and smile as if nothing had happened? Have you brought her up as an atheist or what?”

“Every one who doesn't agree with all you say isn't a confirmed atheist,” replied Dorothy calmly. “As for Rosamund, what I'm afraid of is that, so far from being an atheist, she is rather too much in the other direction—like 'Lo, the poor Indian.' She'll explain what's in her mind if you give her a chance What do you mean, my dear, by laying the emphasis on aniline dyes? Don't you know that most of them are awful?”

“Of course I do, darling,” said Rosamund. “But I've been reading about them, and so—well, you see, they come from coal tar, and coal is a bit of a tree that grew up and fell down thousands of years ago, and its burning is nothing more than its giving back the sunshine that it—what is the word that the book used?—oh, I remember—the sunshine that it hoarded when it was part of the forest. Now, I think that if it's natural for flowers to be coloured by the sunshine it doesn't matter whether it's the sunshine of to-day or the sunshine of fifty thousand years ago; it comes from the sun all the same, and as aniline dyes are the sunshine of long ago it's no harm to have them to colour flowers now.”

“Daddy was only complaining of the horrid ones, my dear,” said the Mother, without looking at me. “Isn't that what you meant?” she added, and now she looked at me, and though I was suspicious that she was smiling under her skin, I could not detect the slightest symptom of a smile in her voice.

“Of course I meant the hideous ones—magenta and that other sort of purple thing. I usually make my meaning plain,” said I, with a modified bluster.

“Oh,” remarked Rosamund, in a tone that suggested a polite negation of acquiescence.

There was another little silence before I said,—“Anyhow, it was those German brutes who developed those aniline things.”

“Oh, yes; they could do anything they pleased with coal tar,” said Dorothy. “But the other sort could do anything he pleased with the Germans—and he did.”

“The other sort?” said I inquiringly.

“Yes, the other sort—the true British product—the Jack Tar,” said Dorothy; and Rosamund, who has a friend who is a midshipman in the Royal Navy, clapped her hands and laughed.

It is at such moments as this that I feel I am not master in my own house. Time was when I believed that my supremacy was as unassailable as that of the Lord High Admiral; but since those girls have been growing up I have come to realise that I have been as completely abolished as the Lord High Admiral—once absolute, but now obsolete—and that the duties of office are discharged by a commission. The Board of Admiralty is officially the Lords Commissioners for discharging the office of Lord High Admiral.

I hope that this ménage will be maintained. The man who tries to impose his opinions upon a household because he is allowed to pay all the expenses, is—anyhow, he is not me.

I believe I interrupted myself in the midst of a visit to one of the gardens of the “better-class people” who live in the purely residential end of the High Street. These are the people whose fathers and grandfathers lived in the same houses and took a prominent part in preparing the beacons which were to spread far and wide the news that Bonaparte had succeeded in landing on their coast with that marvellous flotilla of his. And from these very gardens more than two hundred and fifty years earlier the still greater grandfathers had seen the blazing beacons that sent the news flying northward that the Invincible Armada of Spain was plunging and rolling up the Channel, which can be faintly seen by the eye of faith from the tower of the Church of St. Mary sub-Castro, at the highest part of the High Street. The Invincible Armada! If I should ever organise an aggressive enterprise, I certainly would not call it “Invincible.” It is a name of ill omen. I cannot for the life of me remember where I read the story of the monarch who was reviewing the troops that he had equipped very splendidly to go against the Romans. When his thousand horsemen went glittering by with polished steel cuirasses and plumed helmets—they must have been the Household Cavalry of the period—his heart was lifted up in pride, and he called out tauntingly to his Grand Vizier, who was a bit of a cynic,—

“Ha, my friend, don't you think that these will be enough for the Romans?”

“Sure,” was the reply. “Oh, yes, they will be enough, avariciuus though the Romans undoubtedly are.”

This was the first of the Invincible enterprises. The next time I saw the word in history was in association with the Spanish Armada, and to-day, over a door in my house, I have hung the carved ebony ornament that belonged to a bedstead of one of the ships that went ashore at Spanish Point on the Irish coast. Later still, there was a gang of murderers who called themselves “Invincibles,” and I saw the lot of them crowded into a police-court dock whence they filed out to their doom. And what about the last of these ruffians that challenged Fate with that arrogant word? What of Hindenburg's Invincible Line that we heard so much about a few months ago? “Invincible!” cried the massacre-monger, and the word was repeated by the arch-liar of the mailed fist in half a dozen speeches. Within a few months the beaten mongrels were whimpering, not like hounds, but like hyenas out of whose teeth their prey is plucked. I dare say that Achilles, who made brag a speciality, talked through his helmet about that operation on the banks of the Styx, and actually believed himself to be invincible because invulnerable; but his mother, who had given him the bath that turned his head, would not have recognised him when Paris had done with him.

The funny part of the Hindenburg cult—I suppose it should be written “Kult”—was that there was no one to tell the Germans that they were doing the work of necromancy in hammering those nails into his wooden head. Everybody knows that the only really effective way of finishing off an enemy is to make a wooden effigy of him and hammer nails into it (every sensible person knows that as the nails are hammered home the original comes to grief). The feminine equivalent of this robust operation is equally effective, though the necromancers only recommended it for the use of schools. The effigy is made of wax, and you place it before a cheerful fire and stick pins into it. It has the advantage of being handy and economical, for there are few households that cannot produce an old doll of wax which would otherwise be thrown away and wasted.

But the Germans pride themselves on having got rid of their superstition, and when people have got rid of their superstition they have got rid of their sense of humour. If they had not been so hasty in naming their invincible lines after Wagner's, operas they would surely have remembered that with the Siegfried, the Parsifal, and the rest there was bound to be included Der Fliegende Hollander, the pet name of the German Cavalry: they were the first to fly when the operatic line was broken; and then—Gôtterdàmmerung Hellroter!

And why were the Bolsheviks so foolish as to forget that the Czar was “Nicky” to their paymaster, William, and that that name is the Greek for “Victory”?

Having destroyed Nicky, how could they look for anything but disaster?

The connection of these jottings with our gardens may not be apparent to every one who reads them. But though the sense of liberty is so great in our Garden of Peace that I do not hold myself bound down to any of the convenances of composition, and though I cultivate rather than uproot even the most flagrant forms of digression in this garden, yet it so happens that when I begin to write of the most distinguished of the gardens of Yardley Parva, I cannot avoid recalling that lovely Saturday when we were seated among its glorious roses, eating peaches that had just been plucked from the wall. We were a large and chatty company, and among the party that were playing clock golf on a part of a lovely lawn of the purest emerald, there did not seem to be one who had read the menace of the morning papers. Our host was a soldier, and his charming wife was the daughter of a distinguished Admiral. At the other side of the table where the dish of peaches stood there was another naval officer, and while we were swapping stories of the Cape, the butler was pointing us out to a telegraph messenger who had come through the French window. The boy made his way to us, taking the envelope from his belt. He looked from one of us to the other, saying the name of my vis-a-vis—“Commander A————?”

“I'm Commander A————” said he, taking the despatch envelope and tearing it open. He gave a whistle, reading his message, and rose.

“No reply,” he told the messenger, and then turned to me.

“Great King Jehoshaphat!” he said in a low tone. “There is to be no demobilisation of the Fleet, and all leave is stopped. I'm ordered to report. And you said just now that nothing was going to happen. Good-bye, old chap! I've got to catch the 6.20 for Devonport!”

We had been talking over the morning's news, and I had said that the Emperor was a master of bluff, not business.

“I'm off,” he said. “You needn't say anything that I've told you. After all, it may only be a precautionary measure.”

He went off; and I never saw him again.

The precautionary measure that saved England from the swoop that Germany hoped to bring off as successfully as Japan did hers at Port Arthur in 1904, was taken not by the First Lord of the Admiralty, but by Prince Louis of Battenberg, who was hounded out of the Service by the clamorous gossip of a few women who could find no other way of proving their power.

And the First Lord of the Admiralty let him go; while he himself returned to his “gambling”—he so designated the most important—the most disastrous—incident of his Administration—“a legitimate gamble.” A legitimate gamble that cost his country over fifty thousand lives!

Within a month of the holding of that garden party our host had marched away with his men, and within another month our dear hostess was a widow.

That garden, I think, has a note of distinction about it that is not shared by any other within the circle taken by the walls of the little town, several interesting fragments of which still remain. The house by which it was once surrounded before the desire for “short cuts” caused a road to be made through it, is by far the finest type of a minor Elizabethan mansion to be found in our neighbourhood. It is the sort of house that the house-agents might, with more accuracy than is displayed in many of their advertisements, describe as “a perfect gem.” It has been kept in good repair both as regards its stone walls and its roof of stone slabs during the three hundred—or most likely four hundred years of its existence, and it has not suffered from that form of destruction known as restoration. It had some narrow escapes in its time, however. An old builder who had been concerned in some of the repairs shook his head sadly when he assured me that a more pigheaded gentleman than the owner of the house at that time he had never known.

“He would have it done with the old material,” he explained sadly. “That's how it comes to be like what it is to-day.” And he nodded in the direction of the exquisitely-weathered old Caen blocks with the great bosses of house-leek covering the coping. “It was no use my telling him that I could run up a nine-inch brick wall with proper coping tiles that would have a new look for years if no creepers were allowed on it, for far less money; he would have the old stone, and those squared flints that you see there.”

“Some people are very obstinate, thank God!” said I.

“I could have made as good a job of it as I did of St. Anthony's Church—you know the new aisle in St. Anthony's, sir,” said he.

I certainly did know the new aisle in St. Anthony's; but I did not say that I did in the tone of voice in which I write. It is the most notorious example of what enormities could be perpetrated in the devastating fifties and sixties, when a parson and his churchwardens could do anything they pleased to their churches.

In a very different spirit was the Barbican of the old Castle of Yardley repaired under the care of a reverential, but not Reverend, director. Every stone was numbered and put back into its place when the walls were made secure.

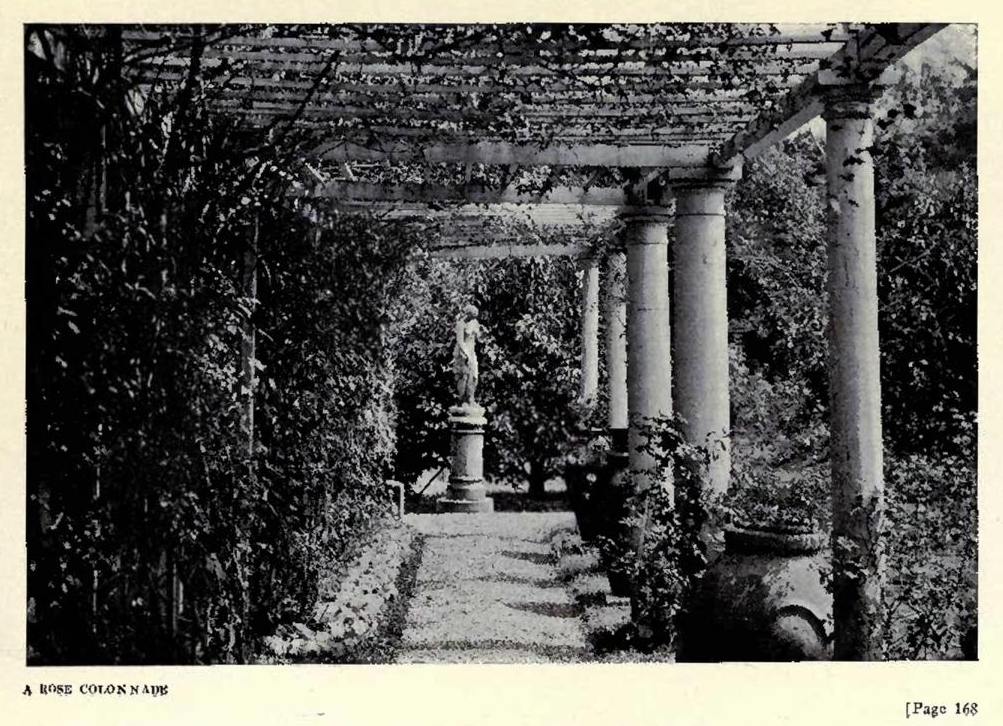

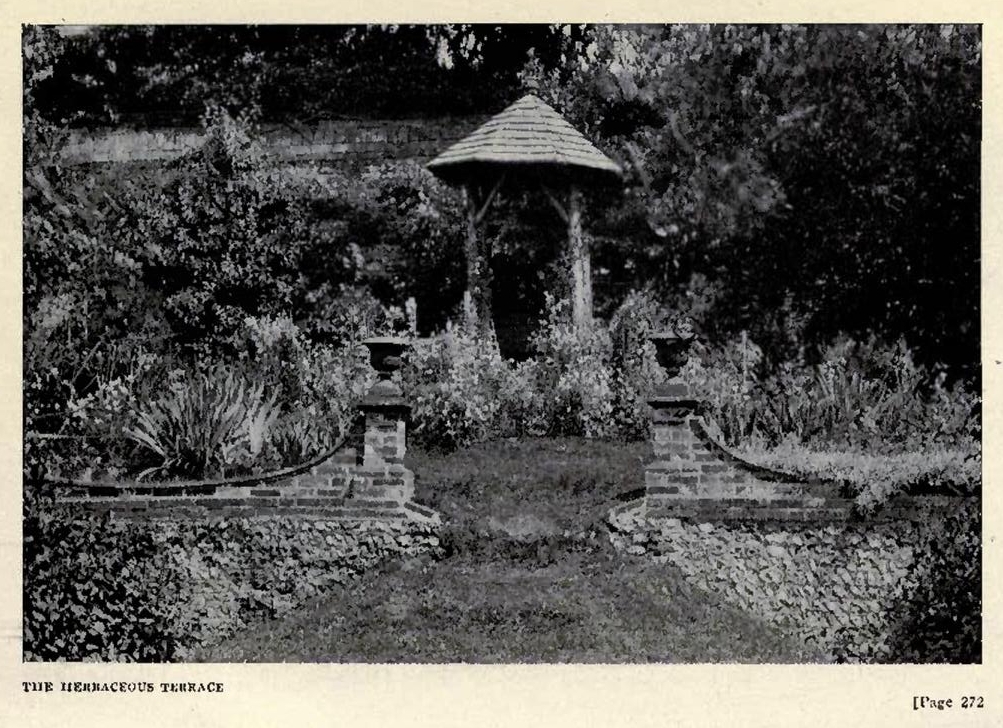

The gardens and orchards and lawns behind the walls which were reconstructed by the owner whose obstinacy the builder was lamenting, must extend over three or four acres. Such a space allows for a deep enough fringe of noble trees, giving more than a suggestion of a park-land which had once had several vistas after the most approved eighteenth century type, but which have not been maintained by some nineteenth century owners who were fearful of being accused of tolerating anything so artificial as design in their gardens. But the “shrubberies” have been allowed to remain pretty much as they were planted, with magnificent masses of pink may and innumerable lilacs. The rose-gardens and the mixed borders are chromatic records of the varying tastes of generations.

What made the strongest appeal to me when I was wandering through the grounds a year or two before that fatal August afternoon was the beauty of the anchusas. I thought that I had never seen finer specimens or a more profuse variety of their blues. One might have been looking down into the indigo of the water under the cliffs of Capri in one place, and into the delicate ultramarine spaces of the early morning among the islands of the Ægean in another.

I congratulated one of the gardeners upon his anchusas, and he smiled in an eminently questionable way.

“Maybe I'm wrong in talking to you about them,”

I said, looking for an explanation of his smile. “Perhaps it is not you who are responsible for this bit.”

“It's not that, sir,” he said, still smiling. “I'm ready to take all the responsibility. You see, sir, I was brought up among anchusas: I was one of the gardeners at Dropmore.”

I laughed.

“If I want to know anything about growing anchusas I'll know where to come for information,” I said.

The great charm about these gardens, as well as those of the Crusaders' planting now enjoyed by the people of the High Street, is that among the mystery of their shady places one would not be surprised or alarmed to come suddenly upon a nymph or a satyr, or even old Pan himself. It does not require one to be

“A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn,”

to have such an impression conveyed to one, any more than it is necessary for one to be given over exclusively to a diet of nuts and eggs to enjoy, as I hope we all do, a swing on a bough, or, as we grow old, alas! on one of those patent swings made in Paris, U.S.A., where one gets all the exuberance of the oscillation without the exertion. Good old Pan is not dead yet, however insistently the poet may announce his decease. He will be the last of all the gods to go. We have no particular use for Jove, except as the mildest form of a swear word, nor for Neptune, unless we are designing a fountain or need to borrow an emblem of the Freedom of the Seas—we can even carry on a placid existence though Mercury has fallen so low as to be opposite “rain and stormy” on the barometric scale, but we cannot do without our Pan—the jolly, wicked old fellow whom we were obliged to incorporate in our new theological system under the name of Diabolus. It was he, and not the much-vaunted Terpsichore, who taught the infant world to dance, to gambol, and to riot in the woodland. He is the patron of the forest lovers still, as he was when he first appeared in the shape of an antelope skipping from rock to rock while our arboreal ancestors applauded from their boughs and were tempted to give over their ridiculous swinging by their hands and tails and emulate him on our common mother Earth.

Is there any one of us to-day, I wonder, who has not felt as Wordsworth did, that the world of men and cities is too much with us, and that the shady arbours hold something that we need and that we cannot find otherwhere? The claims of the mysterious brotherhood assert themselves daily when we return to our haunts of a hundred thousand years ago: we can still enjoy a dance on a woodland clearing, and a plunge into the sparkling lake by which we dwelt for many thousand years before some wretch found that the earth could be built up into caves instead of dug into for domestic shelter.

Let any one glance over the illustrated advertisements in Country Life and see how frequently the “old world gardens” are set forth as an irresistible attraction of “a desirable residence.” The artful advertisers know that the appeal of the old world is still all-powerful, especially with those who have been born in a city and have lived in a city for years. Around Yardley there has sprung up quite recently a colony of red-brick and, happily, red-roofed villas. Nearly all have been admirably constructed, and with an appreciation of the modern requirements in which comfort and economy are combined. They have all gardens, and no two are alike in every particular; but all are trim and easily looked after. They produce an abundance of flowers, and they are embowered in flowering shrubs, every one of which seems to me to be a specimen. More cheerful living-places could not be imagined; but it is not in these gardens that you need look for the cloven vestiges of a faun or the down brushed from the butterfly wings of a fairy. Nobody wants them there, and there is no chance of any of these wary folk coming where they are not wanted. If old Pan were to climb over one of these walls and his footprints were discovered in the calceolaria bed, the master of the house would put the matter in the hands of the local police, or write a letter signed “Ratepayer” to the local Chronicle, inquiring how long were highly-taxed residents to be subjected to such incursions, and blaming the “authorities” for their laxity.

But there is, I repeat, no chance of the slumbers of any of the ratepayers being disturbed by a blurred vision of Proteus rising from the galvanised cistern, or by the blast of Triton's wreathed horn. They will not be made to feel less forlorn by a glimpse of the former, and they would assuredly mistake the latter for the hooter of Simpson's saw-mill.

“The authorities” look too well after the villas, and the very suggestion of “authorities” would send Proteus and Triton down to the deepest depths they had ever sounded. They only come where they are wanted and waited for. It takes at least four generations of a garden's growth to allow of the twisted boughs of the oak or the chestnut turning into the horns of a satyr, or of the gnarled roots becoming his dancing shanks.

It was one of the most intelligent of the ratepayers of these bright and well-kept “residences” who took me to task for a very foolish statement he had found in a novel of mine (6d. edition) which he said he had glanced at for a few minutes while he was waiting for a train. I had been thoughtless enough to make one of the personages, an enterprising stockbroker, advocate the promotion of a company for the salvage of the diamonds which he had been told Queen Guinevere flung into the river before the appearance of the barge with the lily maid of Astolat drifting to the landing-place below the terrace.

“But you know they were not real diamonds—only the diamonds of the poet's imagination,” he said.

“I do believe you are right,” said I, when I saw that he was in earnest. And then the mongoose story came to my mind. “They were not real diamonds,” I said. “But then the man wasn't a real company promoter.”

Two hundred years is not a long time to look back upon in the history of Yardley Parva: but it must have been about two hundred years ago that there were in the High Street some houses of distinction. They belonged to noblemen who had also mansions in the county, but who were too sociable and not sufficiently fond of books to be resigned to such isolation from their order as a mansion residence made compulsory. In the little town they were in touch with society of a sort: they could have their whist or piquet or faro with their own set every afternoon, and compare their thirsts at dinner later in the day.

One of these modest residences of a ducal family faces the street to-day, after suffering many vicissitudes, but with the character of its façade unimpaired. The spacious ground-floor has been turned into shops—it would be more correct to say that the shops had been turned into the ground-floor, for structurally there has been no drastic removal of walls or beams, it has not been subjected to any violent evisceration, only to a minor gastric operation—say for appendicitis. On the upper floors the beautiful proportions of the rooms remain uninjured, and the mantelpieces and the cornices have also been preserved.

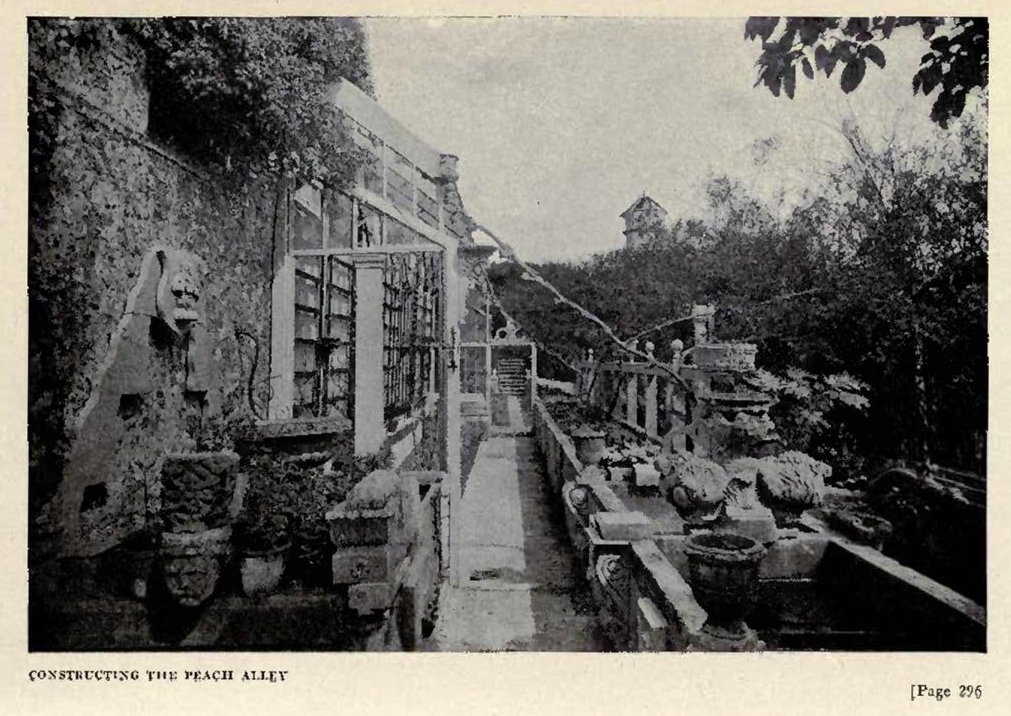

The back of this house gives on to a part of the dry moat from which the screen-wall of our Castle rises, for Yardley had once a Castle of its own, and picturesque remnants of the Keep, the great gateway, and the walls remain with us. Forty feet from the bed of the moat on this side the walls rise, and the moat must have been the site of the gardens of the ducal house, curving to right and left for a couple of hundred yards, and his lordship saw his chance for indulging in one of the most transfiguring fads of his day by making two high and broad terraces against the walls, thereby creating an imposing range of those hanging gardens that we hear so much of in old gardening books. The Oriental tradition of hanging gardens may have been brought to Europe with one of those wares of Orientalism that were the result of the later crusades; for assuredly at one time the reported splendours of Babylon, Nineveh, and Eckbatana in this direction were emulated by the great in many places of the West, where the need for the protection of the great Norman castles was beginning to wane, and the high, bare walls springing from the fosses, dry and flooded, looked gaunt and grim just where people wanted a more genial outlook.

Powis Castle is the best example I can think of in this connection. No one who has seen the hanging gardens of these old walls can fail to appreciate how splendidly effective must have been the appearance of the terraces of Yardley when viewed from the moat below. But in the course of time, as the roads improved, making locomotion easier, the ducal mansion was abandoned in favour of another some miles nearer the coast, and the note of exclusiveness being gone from the shadow of the Castle walls, the terraces ceased to be cultivated; the moat being on a level with the High Street, it became attractive as a site of everyday houses, until in the course of time there sprang up a row, and then a public-house or two, and corporate offices and law-courts that only required a hanging garden at assize times, when smugglers and highwaymen were found guilty of crimes that made such a place desirable—all these backed themselves into the moat until it had to be recognised as a public lane though a cul-de-sac as it is to-day. At the foot of the once beautiful terraces outhouses and stables were built as they were needed, with the happiest irregularity, but joined by a flint wall over which the straggling survivors of the trees and fruits of the days gone by hang skeleton branches. One doorway between two of the stables opens upon a fine stairway made of solid blocks of Portland stone, leading into a gap in the screen-wall of the Castle, the terrace being to right and left, and giving access to the grounds beyond, the appreciative possessor of which writes these lines. Sic transit gloria. Another stone stairway serves the same purpose at a different place; but all the other ascents are of brick and probably only date back to the eighteenth century. They lead to some elevated but depressing chicken-runs.

I called the attention of our chief local antiquarian to the succession of broad terraces and suggested their decorative origin. He shook his head and assured me that they were ages older than the ducal residence in the High Street. They belonged to the Norman period and were coeval with the Castle walls. When I told him that I was at a loss to know why the Norman builder should first raise a screen-wall forty feet up from a moat, to make it difficult for an enemy to scale, and then go to an amazing amount of trouble to make it easily accessible to quite a large attacking force by a long range of terraces, he smiled the smile of the local antiquarian—a kindly toleration of the absurdities of the tyro—saying,—

“My dear sir, they would not mind such an attack. They could always repel it by throwing stones down from the top—it's ten feet thick there—yes, heavy stones, and melted lead, and boiling water.”

I did not want to throw cold water upon his researches as to the defence of a mediæval stronghold, so I thanked him for his information. He disclaimed all pretensions to exclusive knowledge, and said that he would be happy to tell me anything else that I wanted to learn about such things.

I could not resist expressing my fear to him, as we were parting, that the Water Company would not sanction the domestic supply from the kitchen boiler being used outside the house for defensive purposes; but he stilled my doubts by an assurance that in those days there was no Water Company. This was well enough so far as it went, but when I asked where the Castle folk got their water if there was no Company to supply it, he was slightly staggered, I could see; but, recovering himself, he said there would certainly have been a Sussex dew-pond within the precincts, and, as every one knew, this was never known to dry up.

I did not say that in this respect they had something in common with local antiquarians; but asked him if it was true that swallows spent the winter in the mud at the bottom of these ponds. He told me gravely that he doubted if this could be; for there was not enough mud in even the largest dew-pond to accommodate all the swallows. So I saw that he was as sound a naturalist as he was an antiquarian.

By the way, I wonder how White of Selborne got that idea about the swallows hibernating in the mud at the bottom of ponds. When so keen a naturalist as White could believe that, one feels tempted to ask what is truth, and if it really is to be found, as the swallows are not, at the bottom of a well. One could understand Dr. Johnson's crediting the swallow theory, and discrediting the story of the great earthquake at Lisbon, for he had his own lines of credence and incredulity, and he was what somebody called “a harbitrary gent”; but for White to have accepted and promulgated such an absurdity is indeed an amazing thing.

But, for that matter, who, until trustworthy evidence was forthcoming a few months ago, ever fancied that English swallows went as far south as the Cape of Good Hope? This is now, however, an established fact; but I doubt if White of Selborne would have accepted it, no matter what evidence was claimed for its accuracy. Several times when aboard ship off the Cape I have made pets of swallows that came to us and remained in the chief saloon so long as there was a fly to be found; and once in the month of October, on the island of St. Helena, I watched the sudden appearance of a number of the same birds; but it was never suggested that they had come from England. I think I have seen them at Madeira in the month of January, but I am not quite certain about my dates in regard to this island; but I know that when riding through Baines' Kloof in South Africa, quite early in January, swallows were flying about me in scores.

What a pity it seems that people with a reputation for wisdom were for so long content to think of the swallows only as the messengers of a love poem: the “swallow sister—oh, fleet, sweet swallow,” or the “swallow, swallow, flying, flying south”—instead of piling up data respecting the wonder of their ways! The same may be said of the nightingale, and may the Lord have mercy on the souls of those who say it!

Are we to be told to be ready to exchange Itylus for a celluloid tab with a date on It? or Keats's Ode for a corrected notation of the nightingale's trills? At the same time might not a poet now and again take to heart the final lines—the summing up of the next most beautiful Ode in the language—

“Beauty is Truth, Truth beauty?

Every fact in Nature seems to me to lead in the direction of poetry, and to increase the wonder of that of which man is but an insignificant part. We are only beginning to know a little about the part we were designed to play in Nature, but the more we know the more surprised, and, indeed, alarmed, we must be when by a revelation its exact position is made known to us. We have not yet learned to live. We have been fools enough to cultivate the forgetting of how to do things that we were able to do thousands of years ago. The half of our senses have been atrophied. It is many years since we first began to take leave of our senses and we have been at it ever since. It is about time that we started recognising that an acquaintance with the facts of Nature is the beginning of wisdom. We crystallised our ignorance in phrases that have been passed on from father to son, and quoted at every opportunity. We refer to people being “blind as a bat,” and to others being—as “bold as a lion,” or “harmless as a dove.” Did it never strike the inventor of any of these similes that it would be well before scattering them abroad to find out if they were founded on fact? The eyesight of the bat is a miracle. How such a creature can get a living for the whole year during the summer months is amazing. The lion is a cowardly brute that runs away yelling at the sight of a rhinoceros and submits without complaint to the insults of the elephant. A troop of doves will do more harm to a wheat-field in an hour than does a thunderstorm.

And the curious thing is that in those quarters where one would expect to find wisdom respecting such incidents of Nature one finds foolishness. Ten centuries of gamekeepers advertise their ignorance in documentary evidence nailed to the barn doors; they have been slaughtering their best friends all these years and they continue doing so.

After formulating this indictment I opened my Country Life, and found in its pages a confirmation of my evidence by my friend F. C. G., who is proving himself in his maturity as accomplished a Naturalist as, in his adolescence, he was a caricaturist in the Westminster Gazette. These are his lines:—

Two stoats, a weasel, and a jay,

In varied stages of decay,

Are hanging on the gibbet-tree

For all the woodland folk to see,

And tattered rags swing to and fro

Remains of what was once a crow.

What were their crimes that when they died

The Earth was not allowed to hide

Their mangled corpses out of sight,

Instead of dangling in the light?

They didn't sin against the Law

Of “Naturered in tooth and claw,”

But 'gainst the edicts of the keeper

Who plays the part of Death the Reaper,

And doth with deadly gun determine

What creatures shall be classed as vermin.

Whether we gibbets find, or grace,

Depends on accident of place,

For what is vice in Turkestan

May be a virtue in Japan.

And what about gardeners? Why, quite recently I was solemnly assured by one of the profession that I should “kill without mercy”—those were his words—every frog or toad I found in a greenhouse!

But for that matter, don't we remember the harsh decrees of our pastors and masters when as children we yielded to an instinct that had not yet been atrophied, and slaughtered all the flies that approached us. I remember that, after a perceptor's reasoning with me through the medium of a superannuated razor-strop, I was told that to kill a bluebottle was a sin. Now science has come to the rescue of the new generation from the consequences of the ignorance of the old, and the boy who kills most flies in the course of a season is handsomely rewarded. What is pronounced a sin in one generation is looked on as a virtue in the next.

I recollect seeing it stated in a Zoology for the Use of Schools, compiled by an F.R.S., with long quotations from Milton at the head of every chapter, that the reason why some fishes of the Tropics were so gorgeously coloured was to enable them to be more easily seen by the voracious enemy that was pursuing them. That was why God had endowed the glowworm with his glow—to give him a better chance of attracting the attention of the nightingale or any other bird that did not go to roost before dark! And God had also given the firefly its spark that it might display its hospitality to the same birds that had been entertained by the glow-worm! My Informant had not mastered the alphabet of Nature.

Long after I had tried to see things through Darwin's eyes I was perplexed by watching a cat trying to get the better of a sparrow in the garden. I noticed that every time it had crouched to make its pounce the cat waved its tail. Why on earth it should try to make itself conspicuous in this way when it was flattening itself into the earth that was nearest to it in colour, and writhing towards its prey, seemed to me remarkable. Once, however, I was able to watch the cat approach when I was seated beyond where the sparrow was digging up worms, and the cat had slipped among the lower boughs of an ash covered with trembling leaves.

There among the trembling leaves I saw another trembling leaf—the soothing, swaying end of my cat's tail; but if I had not known that it was there I should not have noticed it apart from the moving leaves. The bird with all its vigilance was deceived, and it was in the cat's jaws in another moment.

And I had been calling that cat—and, incidentally, Darwin—a fool for several years! I do not know what my Zoologist “for the Use of Schools” would have made of the transaction. Would he have said that a cat abhorred the sin of lying, and scorned to take advantage of the bird, but gave that graceful swing to its tail to make the bird aware of its menacing proximity?

I lived for eleven years in a house in Kensington with quite a spacious garden behind it, and was blest for several years by the company of a pair of blackbirds that made their nest among the converging twigs of a high lilac. No cat could climb that tree in spring, as I perceived when I had watched the frustrated attempts of the splendid blue Persian who was my constant companion. Of course I lived in that garden for hours every day during the months of April, May, June, and July, and we guarded the nest very closely, even going so far as to disturb the balance of Nature by sending the cat away on a visit when the young birds were being fledged. But one month of May arrived, and though I noticed the parent blackbirds occasionally among the trees and shrubs, I never once saw them approaching the old nest, which, as in previous seasons, was smothered out of sight in the foliage about it, for a poplar towered above the lilac, and was well furnished.

I remarked to my man that I was afraid our blackbirds had deserted us this year, and he agreed with me. But one day early in June I saw the cat look wistfully up the lilac.

“He hasn't forgotten the nest that was there,” I said. “But I'm sure he'll find out in which of the neighbouring gardens the new one has been built.”

But every day he came out and gazed up as if into the depths of the foliage above our heads.

“Ornithology is his hobby,” said I, “but he's not so smart as I fancied, or he would be hustling around the other gardens where he should know murder can be done with impunity.”

The next day my man brought out a pair of steps, and placing them firmly under the lilac, ascended to the level of where the nest had been in former years.

At once there came the warning chuckle of the blackbirds from the boughs of the poplar.

“Why, bless my soul! There are four young ones in the nest, and they're nearly ready to fly,” sang out the investigator from above, and the parents corroborated every word from the poplar.

I was amazed. It seemed impossible that I could have sat writing under that tree day after day for two months, watching for signs that the birds were there, and yet fail to notice them at their work either of hatching or feeding. It was not carelessness or indifference they had eluded; it was vigilance. I had looked daily for their coming, and there was no fine day in which I was not in the garden for four hours, practically immovable, and the nest was not more than ten feet from the ground, yet I had remained in ignorance of all that was going on above my head!

With such an experience I do not think that it becomes me to sneer too definitely at the stupidity of gamekeepers or farmers. It is when I read as I do from week to week in Country Life of the laborious tactics of those photographers who have brought us into closer touch with the secret life of birds than all the preceding generations of naturalists succeeded in doing, that I feel more charitably disposed toward the men who mistake friends for foes in the air.

Every year I give prizes to the younger members of our household to induce them to keep their eyes and their ears open to their fellow-creatures who may be seen and heard at times. The hearing of the earliest cuckoo meets with its reward, quite apart from the gratifying of an aesthetic sense by the quoting of Wordsworth. The sighting of the first swallows is quoted somewhat lower on the chocolate exchange, but the market recovers almost to a point of buoyancy on hearing the nightingale. The cuckoo is an uncertain customer and requires some looking after; but the swallows are marvellously punctual. We have never seen them in our neighbourhood before April the nineteenth. For five years the Twenty-first is recorded as their day. The nightingale does not visit our garden, which is practically in the middle of the town; but half a mile away one is heard almost every year. Upon one happy occasion it was seen as well as heard, which constituted a standard of recognition not entertained before.

I asked for an opinion of the bird from the two girls who had had this stroke of luck.

Each took a different standpoint in regard to its attainments.

“I never heard anything so lovely in all my life,” said Rosamund, aged ten. “It made you long to—to—I don't know what. It was lovely.”

“And what was your opinion, Olive?” I asked of the second little girl.

My Olive branch looked puzzled for a few minutes, but she had the sense to perceive that comparative criticism is safe, when a departure from the beaten track is contemplated. Her departure was parabolic.

“I didn't think it half as pretty a bird as Miss Midleton's parrot,” she said with conviction.

Miss Midleton's parrot is a gorgeous conglomeration of crimson and blue, like the 'at of 'arriet, that should be looked at through smoked glasses and heard not at all.

I think that I shall have Olive educated to take her place in a poultry run; while Rosamund looks after the rose garden.

My antiquary came to me early on the day after I had asked him for information about the hanging gardens.

“I've been talking to my friend Thompson on the subject of those hanging gardens of the Duke's,” said he; “and I thought that you would like to hear what he says. He agrees with me—I fancied he would. The Duke had no power to hang any one in his gardens, Thompson says; and even if he had the power, the pear-trees that we see there now weren't big enough to hang a man on.”

“A man—a man! My dear sir, I wasn't thinking of his hanging men there: it was clothes—clothes—linen—pants—shirts—pajamas, and the like.”

“Oh, that's quite another matter,” said he.

I agreed with him.

In a foregoing page I brought those who are ready to submit to my guidance up to the boundary wall of my Garden of Peace by the stone staircases sloping between the terraces of the old hanging gardens of the Castle moat. With apologies for such a furtive approach I hasten to admit them through the entrance that is in keeping with their rank and station. I bow them through the Barbican Entrance, which is of itself a stately tower, albeit on the threshold of modernity, having been built in the reign of Edward II., really not more than six hundred years ago. I feel inclined to apologise for mentioning this structure of yesterday when I bring my friends on a few yards to the real thing—the true Castle gateway, gloriously gaunt and grim, with the grooves for the portcullis and the hinges on which the iron-barbed gate once swung. There is no suggestion in its architecture of that effeminacy of the Perpendicular Period, which may be seen in the projecting parapet of the Barbican, pierced to allow of the molten lead of my antiquary being ladled out over the enemy who has not been baffled by the raising of the drawbridge. Molten lead is well enough in its way, and no doubt, when brought up nice and warm from the kitchen, and allowed to drop through the apertures, it was more or less irritating as it ran off the edge of the helmets below and began to trickle down the backs of an attacking party. The body-armour was never skintight, and molten lead has had at all times an annoying way of finding out the joinings in a week-day coat of mail; we know how annoying the drip of a neighbour's umbrella can be when it gets through the defence of one's mackintosh collar and meanders down one's back.—No, not a word should be said against molten lead as a sedative; but even its greatest admirers must allow that as a medium of discouragement to an enemy of ordinary sensitiveness it lacked the robustness of the falling Rock.

The Decorative note of the Perpendicular period may have been in harmony with such trifling as is incidental to molten lead, but the stern and uncompromising Early Norman gate would defend itself only with the Rock. That was its character; and when a few hundredweight of solid unsculptured stone were dropped from its machicolated parapet upon the armed men who were fiddling with the lock of the gate below, the people in the High Street could hardly have heard themselves chatting across that thoroughfare on account of the noise, and tourists must have fancied that there was a boiler or two being repaired by a conscientious staff anxious to break the riveting record.

Everything remains of the Castle gateway except the Gate. The structure is some forty feet high and twelve feet thick. The screen-wall was joined to it on both sides, and when you pass under the arch and through a more humble doorway in the wall you are at the entrance to my Garden of Peace.

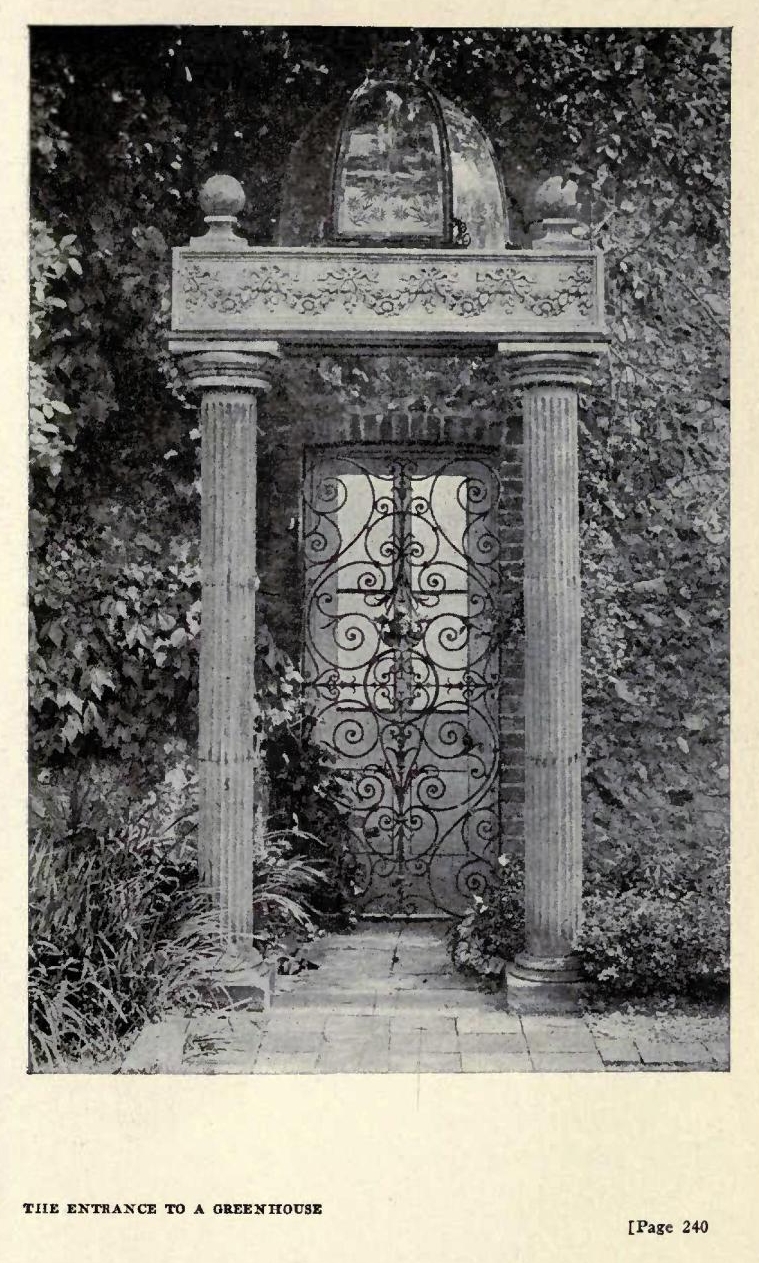

This oaken door has a little history of its own. For several years after I came to Yardley Parva I used to stand opposite to it in one of the many narrow lanes leading to the ramparts of the town. I knew that the building to which it belonged, and where some humble industry was carried on, embodied the ancient church of Ste. Ursula-in-Foro. The stone doorway is illus-=trated in an old record of the town, and I saw where the stone had been worn away by the Crusaders sharpening the barbs of their arrows on it for luck. I had three carefully thought-out plans for acquiring this door and doorway; but on consideration I came to the conclusion that they were impracticable, unless another Samson were to come among us with all the experience of his Gaza feat.

I had ceased to pass through that ancient lane; it had become too much for me; when suddenly I noticed building operations going on at the place; a Cinema palace was actually being constructed on the consecrated site of the ancient church! Happily the door and the doorway were not treated as material for the housebreaker; they were removed into the cellar of the owner of the property, and from him they were bought by me for a small sum—much less than I should have had to pay for the shaped stones alone. The oak door I set in the wall of my house, and the doorway I brought down my garden where it now features as an arch spanning one of the paths.

But my good fortune did not end here; for a few years later a fine keystone with a sculptured head of Ste. Ursula was dug up in the little garden behind the site of the tiny church, and was presented to me with the most important fragments of two deeply-carved capitals such as one now and again sees at the entrance to a Saxon Church; and so at last these precious relics of mediaeval piety are joined together after a disjunctive interval of perhaps five or six hundred years, and, moreover, on a spot not more than a few hundred feet from where they had originally been placed.

Sir Martin Conway told some years ago of his remarkable discovery in the grounds of an English country house, of one of the missing capitals of Theodocius, with its carved acanthus leaves blown by the wind and the monogram of Theodocius himself. A more astounding discovery than this can hardly be imagined. No one connected with it was able to say how it found its way to the place where it caught the eye of a trustworthy antiquarian; and this fact suggested to me the advisability of attaching an engraved label to such treasure trove, giving their history as far as is known to the possessors. The interest attaching to them would be thereby immensely increased, and it would save much useless conjecture on the part of members of Antiquarian Societies. Some people seem to think that paying a subscription to an Antiquarian Society makes one a fully qualified antiquarian, just as some people fancy that being a Royal Academician makes one a good painter.

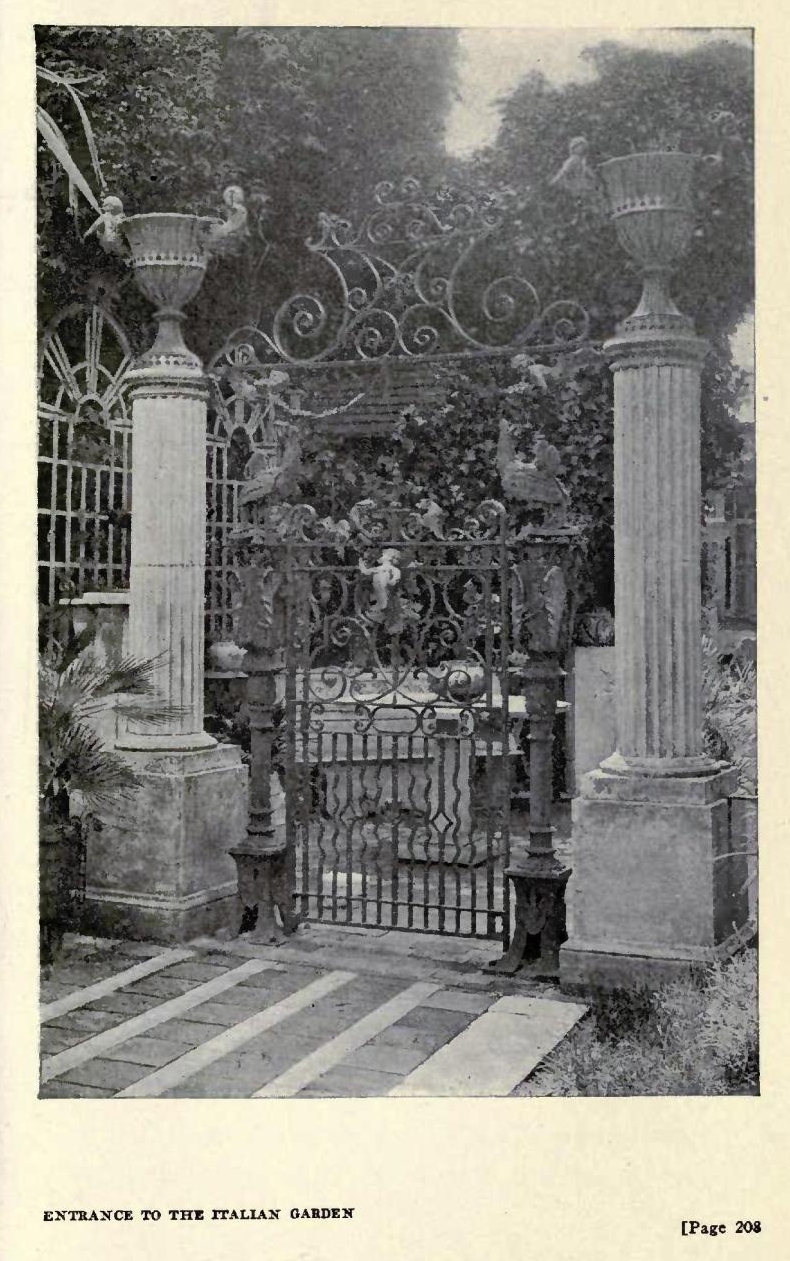

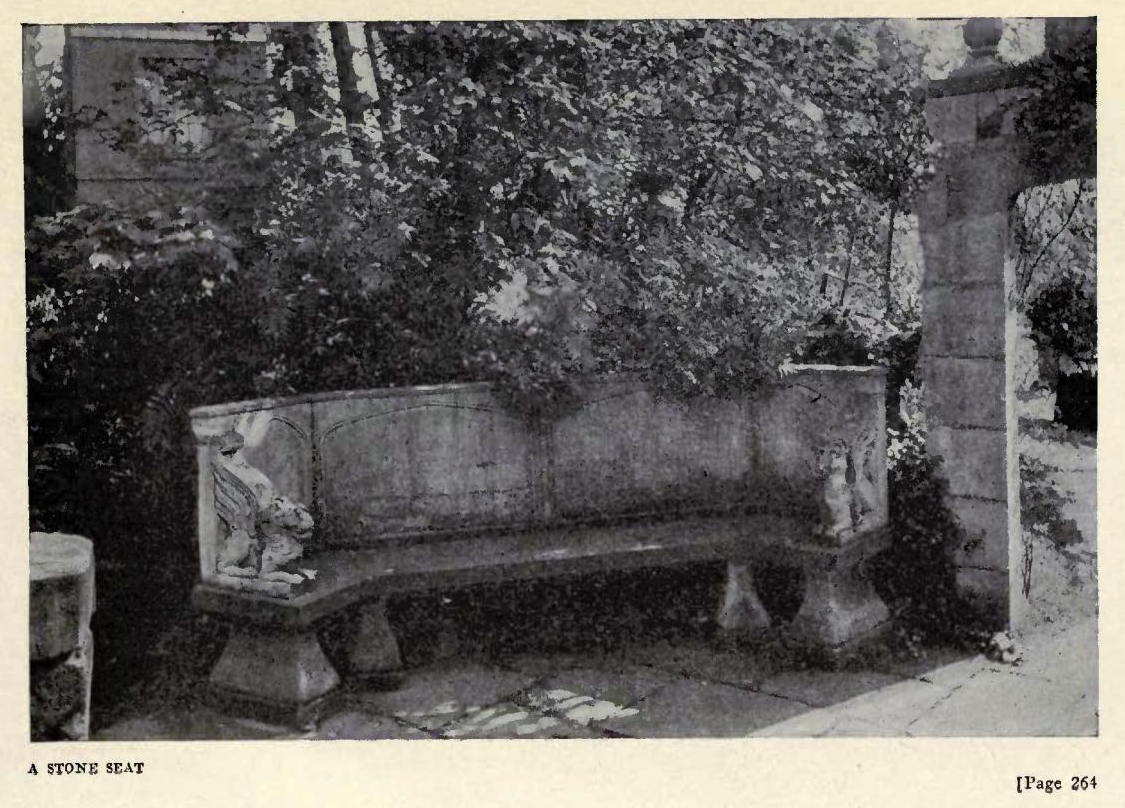

The great revival in this country in the taste for the Formal Garden and the Dutch Garden has brought about the introduction of an immense number of sculptured pieces of decoration; and one feels that in the course of lime our gardens will be as well furnished in this way as those of Italy. The well-heads of various marbles, with all the old ironwork that one sees nowadays in the yards of the importers, are as amazing as the number of exquisite columns for pergolas, garden seats of the most imposing character, vases of bronze as well as stone or marble, and wall fountains. And I have no doubt that the importers would make any purchaser acquainted with the place of origin of most of these. Of course we knew pretty well by now where so many of the treasures of the Villa Borghese are to be found; but there are hundreds of other pieces of sixteenth and seventeenth century Italian work that arrive in England, and quite as many that go to the United States, without any historical record attached to them. I do hope that the buyers of these lovely things will see how greatly their value and the interest attaching to them would be increased by such memoranda of their origin.

The best symbol of Peace is a ploughshare that was once a sword; and surely a garden that has been made in the Tiltyard of a Norman Castle may be looked on as an emblem of the same Beatitude. That is how it comes that every one who enters our garden cries,—

“How wonderfully peaceful!”

I have analysed their impression that forces them to say that. The mild bustle of the High Street of a country town somehow imposes itself upon one, for the simple reason that you can hear it and observe it. The hustle of London is something quite different. One is not aware of it. You cannot see the wood for the trees. It is all a wild roar. But when our High Street is at its loudest you can easily distinguish one sound from another.

Then the constant menace of motor-cars rushing through the High Street leaves an impression that does not vanish the moment one turns into the passage of the barbican; and upon it comes the sight of the defensive masonry, which is quite terrific for the moment; then comes the looming threat of the Norman gateway which gives promise of no compromise! It is not necessary that one should have a particularly vivid imagination to hear the clash and clang of armoured men riding forth with lances and battleaxes; and when one steps aside out of their way, the rest is silence and the silence is rest.

“How wonderfully peaceful!” every one cries.

And so't is.

You can hear the humming of a bee—the flick of a swallow's wing, the tinkle of the fountain—a delightful sound like the counting out of the threepenny pieces in the Church Vestry after a Special Collection—and the splash of a blackbird in its own particular bath. These are the sounds that cause the silence to startle you. “Darkness visible,” is Milton's phrase. But to make an adaptation of it is not enough to express what one feels on entering a walled garden from a street even of a country town. There is an outbreak of silence the moment the door is closed, and it is in a hushed tone that one says, when one is able to speak,—

“How wonderfully peaceful!”

I think that a garden is not a garden unless it is walled. Perhaps a high hedge of yew or box conveys the same impression as a built-up wall; but I am not quite certain on this point. The impression has remained with us since the days when an Englishman's home was his castle and an Englishman's castle his home. What every one sought was security, and a consciousness of security only came when one was within walls. In going through a country of wild animals one has a kindred feeling when the fire is lighted at nightfall. Another transmitted instinct is that which forces one to look backward on a road when the sound of steps tells one that one is being followed. The earliest English gardens of which any record remains were walled. In the illustrations to the Romaunt of the Rose, we see this; and possibly the maze became a feature of the garden in order to increase the sense of security from the knife of an enemy whose slaughter had been overlooked by the mediaeval horticultural enthusiast, who sought for peace and quiet on Prussian principles.

I think it was the appearance of the walls that forced me to buy my estate of a superficial acre. Certainly until I saw them I had no idea of such a purchase. If any one had told me on that morning when I strolled up the High Street of Yardley Parra while the battery of my car was being re-charged after the manner of those pre-magneto times, that I should take such a step I would have laughed. But it was a day of August sunshine and there was an auction of furniture going on in the house. This fact gave me entree to the “old-world garden” of the agent's advertisement, and when I saw the range of walls ablaze with many-coloured snapdragons above the double row of hollyhocks in the border at their foot, I “found peace,” as the old Revivalists used to phrase the sentiment, only their assurance was of a title to a mansion in the skies, while I was less ambitious. I sought peace and ensued it, purchasing the freehold, and I have been ensuing it ever since.

The mighty walls of the old Castle compass us about as they did the various dwellers within their shelter eight hundred years ago. On one side they vary from twelve feet to thirty in height, but on the outer side they rise from the moat and loom from forty to fifty feet above the lowest of the terraces. At one part, where a Saxon earthwork makes a long curved hillock at the farther end of the grounds, the wall is only ten feet above the grassy walk, but forty feet down on the other side. The Norman Conqueror simply built his wall resting against the mound of the original and more elementary fortification. Here the line of the screen breaks off abruptly; but we can see that at one time it was carried on to an artificial hill on the summit of which the curious feature of a second keep was built—the well-preserved main keep forms an imposing incident of the landscape in the opposite direction.