Historic Nacogdoches

By R. B. BLAKE

Illustrations by Roy Henderson, Charlotte Baker Montgomery, and Dr. George L. Crocket.

1This booklet is an enlarged and revised reprint of two earlier booklets, one prepared by Mr. Blake and the Reverend George L. Crocket in 1936 as a part of the Celebration of the Texas Centennial. The second booklet was published in 1939 by the Nacogdoches Historical Society and dedicated to the memory of Dr. Crocket, who, among the other labors of a singularly useful and beneficient life, was an untiring student of the history and traditions of East Texas. Since he was one of the earliest workers in the field, much material which would otherwise have been lost was preserved by Dr. Crocket’s industry and enthusiasm. The demand for information concerning Historic Nacogdoches has been so great that the supply has been exhausted. Many copies have been furnished historians, school children, historical societies and people generally interested in the rich, historical background of this area. This third edition was financed by the Nacogdoches Chamber of Commerce and will be supplied free upon request.

Published By

NACOGDOCHES HISTORICAL SOCIETY

and the

NACOGDOCHES CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

BY KARLE WILSON BAKER

(By permission of the Southwest Press)

I was The Gateway. Here they came, and passed,

The homespun centaurs with their arms of steel

And taut heart-strings: wild wills, who thought to deal

Bare-handed with jade Fortune, tracked at last

Out of her silken lairs into the vast

Of a man’s world. They passed, but still I feel

The dint of hoof, the print of booted heel,

Like prick of spurs—the shadows that they cast.

I do not vaunt their valors, or their crimes:

I tell my secrets only to some lover,

Some taster of spilled wine and scattered musk.

But I have not forgotten; and, sometimes,

The things that I remember arise, and hover,

A sharper perfume in some April dusk.

For the beginnings of Nacogdoches we must go back to the shadowy times when heroic figures march with majestic tread across the stage of tradition, obscured by the mists of centuries. Having no written language with which to record the glories of their race, the Tejas Indians recounted the tales of their beginnings around their home fires, thus passing them down from father to son through the long centuries before the coming of the Europeans.

Thus it is recounted that in the days of long ago an old Caddo chief lived on the bank of the Sabine, the river of the cypress trees. To him twin sons were born: Natchitoches, swarthy of features with straight black hair and flashing black eyes; and Nacogdoches, fair of complexion with blue eyes and yellow hair. As the old man neared the end of his days, before being ushered into the happy hunting-grounds, he called his two sons into his presence to receive his final blessings. He commanded that immediately following his death, Natchitoches should gather his wife and children together, turn his face towards the rising sun, and after three days’ march should build his home and rear his tribe; while Nacogdoches was instructed to travel a like distance toward the setting sun, where he should rear his children and children’s children. Thus the twin tribes of Nacogdoches and Natchitoches were founded 100 miles apart, and thus Nacogdoches was the father of the Tejas, the white Indians of Eastern Texas.

The two tribes were a sufficient distance apart to prevent friction over their hunting-grounds, and thus through the succeeding centuries they were ever on friendly terms, the one with the other. This friendly communication and barter between the tribes was such that they beat out a broad highway between them and through their confines, which became El Camino Real, extending from Natchez, on the Father of Waters, to the Trinity river on the west, through Natchitoches, Louisiana, and Nacogdoches, Texas.

During the succeeding centuries the Tejas lived on the Redlands, building comfortable homes around the ceremonial mounds which they had erected, where they left their wives and children while they pursued the bison, the deer and the black bear. Then another figure of heroic mold emerges from the mists of the past, when Red Feather rules his people.

The story of Red Feather is delightfully recounted by Miss Adina de Zavala, of San Antonio, Texas, in her “Origin of the Red Bird.” Red Feather taught his people the gentle arts of husbandry—the cultivation of Indian corn, beans, peas, melons and pumpkins; taught the women to make preserves of the fruit of the persimmon tree, and to store the fruits of the soil and the chase in their homes for winter. Great was the mourning when Chief Red Feather died; while his subjects reverently laid his body to rest on the chief mound in Nacogdoches, his spirit soared upward on the crimson wings of the first red bird, and hovered in the majestic trees above the mounds, as if guarding his people from danger.

Less than fifty years after Columbus sighted America, Hernando De Soto, in the winter of 1541-42, penetrated as far west as Nacogdoches, where he spent the winter, sending out scouting parties further west in search for the seven cities of the Cibolo. He remained in Nacogdoches because he found here a well-settled, hospitable Indian town, with an agricultural population, having well-built homes, provided with comfortable furnishings.

Nearly eighty years after De Soto’s visit, on the borderline between tradition and history, came the ministration of Mother Maria de Jesus de Agreda, “the angel in blue,” teaching the Tejas tribes the Christian religion, in 1620. So great was the influence of this saintly woman that in 1690 the chief of the Tejas told Massanet that they wished to do as she had done, and even wanted to be buried in blue garments.

The first definite description of Nacogdoches and its aboriginal population is in the account of LaSalle’s visit here in 1685. On this visit Robert Sieur de LaSalle became desperately ill and remained in Nacogdoches for a month, recuperating from disease. Here the Frenchman received such hospitable treatment at the hands of the natives that four of his men deserted and remained here when LaSalle started back to Fort St. Louis.

LaSalle found numerous evidences of prior contact with both French and Spanish here. Perhaps the Indian traditions pointed to the presence here of DeSoto and Coronado, and the traditional appearances of Mother Maria de Agreda, already referred to.

DeLeon and his followers, in 1691-1692, made the first serious attempts to educate the Tejas Indians in European ways by taking several of the young members of the tribes back to the College of Zacatecas in Mexico. Among these were two children of the chief of the Hainai Indians, living near what is now known as the Goodman Crossing on the Angelina river, about eighteen miles southwest of Nacogdoches. The young man, who afterwards became head chief of the Hasinai Confederation, the Spaniards named Bernadino, which name was also given to his father, the chief; the young woman they named Angelina, and the river was named for her. She 5 also acted as interpreter between the Indians and the Spanish explorers, including the followers of Captain Ramon in 1716, and those of the Marquis de Aguayo in 1721.

The first permanent European settlement in the town of Nacogdoches was made in June, 1716, when Fray Antonio Margil de Jesus founded the Mission Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe de Nacogdoches on what is now North street, overlooking the valley of the Banito, “little bath.” The Spaniards named the town Nuestra Senora del Pilar de Nacogdoches.

In the struggle between the French and Spanish for mastery of Eastern Texas (called the Province of the New Philippines), the Mission Guadalupe had an eventful history. Deserted at times but never permanently abandoned, it finally decayed and its very site was utterly forgotten, though the information concerning its location has been preserved in the ancient Spanish parchments of our Nacogdoches archives.

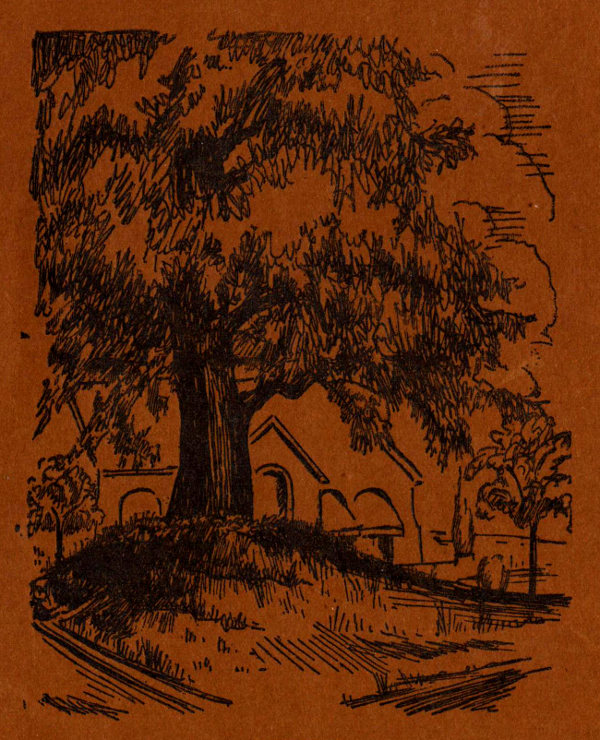

When the Spanish settlers began making their homes in the old Indian town, they found several mounds within the limits of the town, relics of the centuries of Indian occupation before the coming of the white man. Three of the larger of these mounds were located on what became the Nacogdoches University campus, now the high school campus. The importance of these mounds was not recognized by those who founded the university, and they were razed in an effort to level the ground of the campus. Only one now remains, on Mound street, so named because of these monuments to the antiquity of the town. A large oak tree, whose age has been estimated at about two hundred years, grows from the summit of this remaining mound.

With the French cession of Louisiana to Spain in 1764, the necessity for the Spanish garrison in Nacogdoches ceased; and the town was abandoned as a military post in 1773, to be refounded by Captain Antonio Gil Ybarbo and his compatriots in 1779.

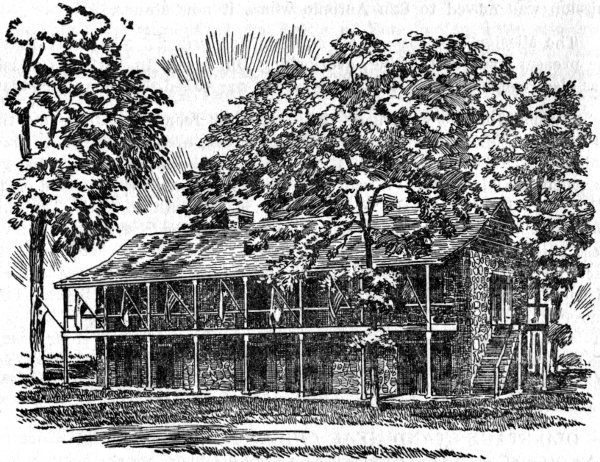

The Red House

Built in 1827 for accommodation of Mexican officials. See page 23.

The city of Nacogdoches, as a civic corporation, dates from that year, in which that sturdy old Spaniard, Ybarbo, conducted his harassed and bewildered followers from their experimental settlement of Bucareli on 6 the Trinity river, to the old Mission of Guadalupe. The eastern boundary of Texas was at that time a shadowy, uncertain quantity, somewhere between the Sabine and Red rivers. Louisiana belonged to Spain, and the government was but little concerned to mark out definitely the exact limitation between its provinces.

Gil Ybarbo recognized the necessity of a commissary for the storing of military and commercial supplies, and after applying to the authorities in Mexico for such a building, and growing weary of the endless delays and red tape, that industrious old Spaniard erected on his own account what he and his followers called “The Stone House,” now generally referred to as “The Old Stone Fort.” It was not erected primarily as a fort, but as a house of commerce; and that has been its main use throughout its varied history. But the construction of its walls—almost a yard in thickness—made it practically impregnable to the ordinary means of offense; so that it naturally became a place of refuge and haven of safety in the successive perils that visited the old border-town.

Gil Ybarbo, ruling his people as a benevolent despot, was officially known as Lieutenant Governor of the Eastern Province of the New Philippines and Military Comandante of the Post of Our Mother of the Pilar of Nacogdoches. He promulgated the first Book of Ordinances for the government of the city in 1780, the original of which is now in the Nacogdoches Archives in the Capitol at Austin.

The new city grew apace, and by the beginning of the Nineteenth Century embraced a population of several hundred souls. In 1792 General Don Ramon de Castro sent Don Juan Antonio Cortez, captain of cavalry at LaBahia, to Nacogdoches for the purpose of conducting an investigation of the irregularities of verbal land grants made by Ybarbo, as well as of his illegal traffic with the French and Indians. The result of the investigation was the removal of Ybarbo from his office; he was sent to Bexar while the investigation proceeded. Don Carlos de Zepeda succeeded Ybarbo as Lieutenant Governor, and in turn was followed by a succession of officials who had charge of the public business of the town, and superintended legal and commercial affairs, in addition to leading what military expeditions were needed in their infrequent exigencies. Nacogdoches was at that time the second largest town in Texas.

In 1800 Nacogdoches was a loyal Spanish town, as was shown by the part it took in the suppression of Philip Nolan’s expedition. Nolan had been reared by General James Wilkinson, commander of the United States forces at Natchez, Mississippi. In furtherance of the schemes of Wilkinson and Aaron Burr (then Vice President of the United States), Nolan invaded Texas with a small band of adventurers, on the pretext of horse-trading. The population of the town were largely behind Lieutenant M. Musquiz and his Garrison, when they were ordered to pursue and arrest the little band. Musquiz and his men were accompanied by William Barr, of the trading firm of Barr and Davenport, who acted as interpreter between the Spanish and Americans. Lieutenant Bernardo D’Ortolan, a Frenchman by birth, was left in charge of the garrison here while Musquiz 7 was on his expedition; during this time he conveyed titles to land to such settlers as applied for them.

Nolan was overtaken on the banks of the Blanco river, at the block house he had built, and in the ensuing engagement he was killed and the remainder of the expedition were captured and brought back to Nacogdoches. They were placed in the Old Stone Fort, from whence they were taken prisoners to Mexico; the sole survivor of the band, so far as history records, was Peter Ellis Bean, one of the most colorful and resourceful men Texas has seen.

Correspondence found in the possession of Nolan enabled Musquiz to discover various ramifications of the plot of Nolan, Burr and Wilkinson among the inhabitants in Nacogdoches. One of the local leaders was a Spanish woman, Gertrudis Leal, and her husband, Antonio Leal, who were tried for treason by Musquiz. The priest in charge of Mission Guadalupe, Padre Bernadino Vallejo, was also one of the conspirators, but the robes of St. Francis saved him from punishment for his part in the plot. Samuel Davenport was also found to be in some manner connected with the affair, but he was shrewd enough to escape being tried, as was also a man by the name of Cook, who then lived at Nacogdoches.

In the beginning of the new century the purchase of Louisiana by the United States from the French, in consequence of the Napoleonic upheaval in Europe, brought about a great change in the political and military affairs of Nacogdoches. There was great jealousy between the two countries, and a territorial dispute to be settled before the old status of somnolent peace could prevail. The Americans built Fort Jesup, west of Red River, near Natchitoches, and in 1806, Governor Cordero, with 1500 Spanish troops, advanced to Nacogdoches to meet the American threat across the Sabine. As a result of the negotiations of Governor Cordero and General Wilkinson, there was formed The Neutral Ground, a strip of territory lying between the Sabine and the Rio Hondo, over which neither government exercised dominion, and which consequently became the rendezvous of the lawless, until the settlement of the present boundary between Texas and Louisiana.

The next band of adventurers found Nacogdoches in a very different temper. In 1810 the Mexicans rebelled against the government of Spain, and Nacogdoches lost no time in assisting in the formation of the Magee-Gutierrez expedition, under the leadership of Lieut. Augustus Magee, who resigned his position in the United States garrison at Fort Jesup to take command of the American and Mexican forces in their effort to throw off the yoke of Spain.

It is said that every able-bodied man east of the Trinity river joined in this expedition. For a time it prospered, and by 1813 had successfully driven the Spanish military forces from Eastern Texas and pursued them to San Antonio, where Governor Manuel Salcedo and most of the high Spanish officials there were butchered.

One of the interesting incidents of this expedition, to the whole province as well as to Nacogdoches, was the publication of two newspapers here, the first ventures of their kind in Texas; the first of these, “The 8 Gazette,” appeared in May, 1813, while the second, “El Mejicano,” was published the following month.

Vengeance of Spain was swift, and the Spanish army sent into Texas swept the inhabitants of Nacogdoches beyond the Sabine and into American territory, where they remained until 1818-20. Erasmo Seguin was sent by the new government of Mexico in 1821 to Nacogdoches to invite the old settlers back to their former homes, as well as to welcome Stephen F. Austin to Texas.

The settlement of the boundary dispute between the United States and Texas on February 22, 1819, by fixing the Sabine river as the boundary, met with strong opposition in Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi, as well as Eastern Texas. The American settlers had contended for the Neches river as the true boundary, and Dr. James Long, who had married the daughter of a wealthy planter at Natchez, Mississippi, lost no time in exploiting his scheme of forming the Republic of Texas. Leaving Natchez June 17, 1819, with 75 men, he reached Nacogdoches with approximately 300, including Samuel Davenport, Bernado Guitierrez de Lara, and many others who had fled in 1813.

Upon reaching Nacogdoches, Long’s forces occupied the Old Stone Fort, organized a provisional government, and issued a proclamation declaring Texas a free and independent republic, and another newspaper—the third in Nacogdoches as well as in Texas—was published by Horatio Bigelow. It was called “The Mexican Advocate.”

It is very probable that Dr. Long’s expedition would have been completely successful if it had been organized a year later, after the revolutionary movement had begun in Spain but in 1819 the royalists were in control in Mexico; and that fact, together with Long’s division of his forces after leaving Nacogdoches for the West, so weakened his fighting units as to cause them to fall an easy prey to the successive onslaughts of the Spanish Army sent against him under Colonel Perez.

With the capture of his block houses and forts on the Brazos, Trinity and Red rivers, Mrs. Jane Long, who had been left at Nacogdoches, fled across the Sabine, and her husband soon followed, thus ending his first attempt at freeing Texas, in October, 1819.

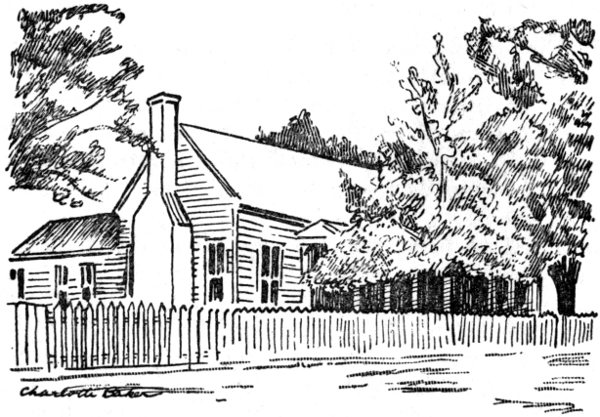

Frost Thorne Home—Hart Hotel

Residence of Texas’ first millionaire. Built 1825. See page 12.

Under the leadership of Alcalde James Dill Nacogdoches soon regained its former prestige as the largest town in East Texas, and settlers from the United States began coming in increasing numbers under the beneficient colonization laws of the new government in Mexico; but things were much changed. In 1825 Haden and Benjamin Edwards secured their ill-fated contract as empresarios. When Edwards began to plant his colonists, sometimes on land which had once belonged to the Mexican inhabitants and had been abandoned temporarily in the flight of 1813, the friction between the Americans and Mexicans increased. On the northwest of them also had settled a tribe of Cherokee Indians, who claimed the right to occupy a vast territory which had formerly been the habitation of the friendly Tejas Indians.

This triangular situation bred distrust and antagonism that at last broke out into open warfare, and threw the country into the wildest disorder, in what is known as the Fredonian War in 1826. The coup of Edwards was at first successful, and he and his followers were able to seize the “Stone House” and fortify it; but the citizenship of Nacogdoches and the surrounding country was not behind the movement, and it was doomed to failure from its inception.

The Fredonian rebellion resulted in many of the prominent citizens of the town being expelled in 1827—among whom were John S. Roberts, Haden and Benjamin Edwards, Adolphus Sterne and Martin Parmer. The Mexican general, Ahumada, who occupied Nacogdoches upon this occasion, was a genuine diplomat, and with the assistance and advice of Stephen F. Austin, who came to Nacogdoches with Ahumada, soon had the old town peaceful again. However, the man whom Ahumada selected as comandante here proved to be an unfortunate choice, and Colonel Jose de las Piedras soon aroused the hostility of the American settlers with his high-handed, arbitrary methods, as was the case with Col. Bradburn at Anahuac.

Adolphus Sterne Home

Where Sam Houston was baptized. Standing at corner Lanana and Pilar street. See page 22.

For the real cause of the Battle of Nacogdoches, we must go back to 10 Bustamente’s Law of April 6, 1830, forbidding further immigration from the United States, while permitting Europeans to come in unimpeded. Juan Antonio Padilla had been appointed as commissioner general for granting land titles in East Texas, assuming his duties on January 1, 1830. Upon the passage of the law of April 6th, Padilla was unwilling to enforce its provisions, and in the latter part of April he was ordered by Don Ramon Musquiz, political chief in Bexar, to be imprisoned and suspended on a trumped-up-charge of murder.

An outbreak was prevented in Nacogdoches only by prompt action on the part of Col. Piedras, while the people of Ayish Bayou and the Palo Gacho met and passed resolutions of an inflammatory nature. Stephen F. Austin refused to cooperate in this opposition and thus for a time the trouble was delayed.

The military force in Nacogdoches was doubled during 1830, and passports of all immigrants going through Nacogdoches for Austin’s colony, which was exempted by Bustamente’s Decree, were required to be signed by Austin in person.

Under the dictatorship of Bustamente the military comandantes continually encroached upon the power of the civil authorities, and finally, in June, 1832, the settlers at Anahuac rebelled and ousted Bradburn, Piedras arriving too late with troops from Nacogdoches and Fort Teran. Becoming alarmed at the rising tide of opposition, Col. Piedras, upon his return, ordered the people of Nacogdoches to surrender all their arms. This order was followed immediately by an appeal from the ayuntamiento in Nacogdoches, issued July 28, 1832, to the neighboring communities to present an united front against this action; copies of this resolution were sent to Ayish Bayou, the Palo Gacho, Tenaha and San Felipe de Austin and met immediate response from all except San Felipe. Two companies came from the Ayish Bayou settlement, commanded by Capts. Samuel Davis and Bailey Anderson, one from Sabine and one from Shelby and Capt. James Bradshaw’s company from the Neches settlement; while the people of Nacogdoches were led by Alcalde Encarnacion Chirino. On the morning of August 2, 1832, these forces met in the eastern outskirts of Nacogdoches and elected Colonel James W. Bullock as commander-in-chief of approximately 500 men.

Colonel Piedras commanded approximately the same number of Mexican soldiers, and proceeded to fortify the Stone House, the old Catholic church and the Red House. An Ultimatum from the settlers for Piedras to declare in favor of Santa Anna and the Constitution of 1824, or surrender at discretion to an officer to be selected by Colonel Bullock, brought forth the answer that none of the demands would be complied with, and that he was prepared to fight.

Colonel Piedras advanced to meet the Americans and the fighting commenced in the eastern part of town about eleven o’clock. By noon the Mexicans had retreated to the business part of town, around the Stone House. Alexander Horton, a member of the American forces, says: “We were armed with shotguns and various other guns such as citizens used for hunting purposes, while the Mexicans were armed with splendid English muskets; so we turned north and marched down North street. As we began 11 our march we heard a French horn. When we had gotten about opposite the Stone House the Mexican cavalry made a furious charge upon us, pouring upon us a heavy fire of small arms; they advanced to within a few steps of our lines, but were forced back with considerable loss.” This cavalry charge met the American force near the Catholic church, which had been used by Piedras as quarters for his soldiers.

The Mexicans about mid-afternoon were driven out of the Stone House, and the main body of their army was concentrated in the cuartel or Old Red House, the older part of which was built of adobe, and almost as strong as stone; it also had the advantage of several dormer windows on the second floor, from which sharpshooters could better defend the building. The fighting continued with unabated fury until night separated the combatants. Colonel Piedras evacuated Nacogdoches during the night of the 2nd, under the protecting cloak of a heavy fog, retreating westward toward the Angelina river.

The next morning James Carter, with seventeen volunteers, set out in pursuit of the Mexican army, overtaking them at Durst lake, and after a skirmish at that point, Carter and his men went further south, crossing the Angelina at the Goodman Crossing, and marched northward to the West side of Durst’s Ferry to oppose the crossing of the Mexican troops. Here Piedras lost many of his men in an unsuccessful attempt to cross the river. It was from this event that the name Buckshot Crossing was given to this place.

During the following morning Colonel Piedras surrendered the command to Captain Francisco Medina, who in turn declared for Santa Anna and surrendered to James Carter the entire Mexican force of some four hundred men.

Col. James Bowie, who reached Nacogdoches a few days after the battle, agreed to convey the Mexican troops to San Antonio, and in his report stated that there were 33 Mexicans killed and 17 or 18 wounded; the Americans losing three men killed and seven wounded.

The Battle of Nacogdoches was the opening gun in the Texas Revolution, and resulted in the expulsion of all Mexican troops from the territory east of San Antonio, giving the Texans an opportunity to hold their Convention without military interference of the enemy.

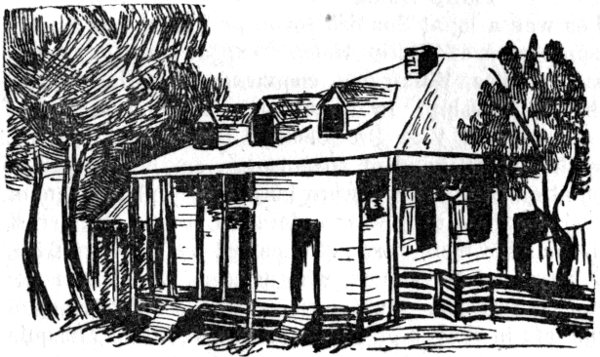

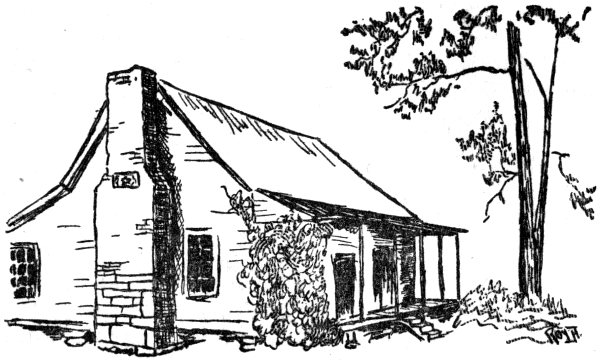

Peter Ellis Bean Home

Built 1829. Standing 4½ miles east of Nacogdoches near Old King’s Highway. See page 21.

Nacogdoches now became more and more American in its character. In 12 1834 the neighboring municipality of San Augustine was organized, and the two sister towns grew in numbers and influence. Nacogdoches was the capital of the department of the same name, and held jurisdiction over all the region east of Trinity River. The alcaldes who presided over the civil affairs of the municipality from the first reorganization in 1820 had usually been chosen from among the Mexican people living there, but after the expulsion of the Mexican troops in 1832 Americans were selected to fill that office, and the town gradually assumed a character more American than Mexican. American customs prevailed over those of former times, and the business fell into the hands of enterprising merchants and tradesmen from the States. The Indians to the northeast were impressed by the power and vigor of the new people and left them unmolested, although they also had increased until they greatly outnumbered the whites.

Business was thriving, the population was increasing, and new settlers were coming into the town, or taking up land in the country. Commerce was greatly aided by the communication with the other colonies in the interior, and an era of prosperity seemed to have dawned. But in the midst of all came more political troubles in the republic of Mexico. Santa Anna, by a rapid series of measures, overturned the constitution of 1824, under which the settlement of the province by Americans had begun. The guarantees of liberty seemed to be disappearing. In Austin’s colony there arose a “war party,” which advocated resistance to these measures by force of arms. Trouble began to arise at Galveston and at Anahuac. Still Nacogdoches remained peaceful, hoping even against hope that all would yet be well.

At length, however, the ambition of the Mexican dictator began to unfold itself, and his designs against the lovers of freedom in Texas became manifest. Even yet the mind of the people refused to move towards complete independence. Delegates from the war party at San Felipe visited the town, and by their persuasion at length convinced the people that it was in vain to lie still any longer. Then East Texas was ready to act, and from Nacogdoches and San Augustine armed soldiers set forth on the long march across the State to the threatened region around San Antonio.

With the coming of Sam Houston to Nacogdoches in 1833, followed by such men as General Thomas J. Rusk in 1835; with the backing of Colonel Frost Thorne, Haden Edwards, Adolphus Sterne, Charles S. Taylor, John S. Roberts, William G. Logan, Henry Raguet, Dr. James H. Starr, John Forbes, Kelsey H. Douglass, Wm. B. Ochiltree and a host of others, Nacogdoches practically financed the Texas Revolution, feeding and arming the men pouring in from the United States to the defence of the new Republic.

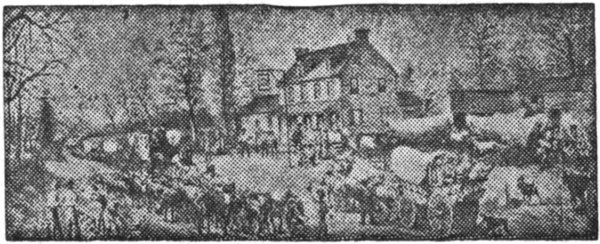

The tide of war never really rolled near to East Texas. For a time General Sam Houston was accused of intending to flee through Nacogdoches to the Sabine, where an American army was supposed to be expecting him, but he had other designs, which were consummated on the field of San Jacinto, and the danger was dispelled. East Texas, however, did suffer the throes of a paroxysm of panic. It was known that Mexican agents were 13 dispersed among the Cherokee and other Indians north of the settlements. Reports, highly colored no doubt, were disseminated that these Indians were about to move in an overwhelming body on the unprotected settlements, whose men were in the field against the Mexican army, and wipe out town and countryside alike. Fugitives from the devastated West, passing through, helped to spread the terror, and so it happened that the “Run-Away Scrape” came to include both Nacogdoches and San Augustine in the frantic flight to safety beyond the Sabine.

The news of victory soon restored the minds of the people to sanity, and they entered with alacrity into the work of establishing the new government of the Republic. After the disorganization of the West and South, which were devastated by the advance of the enemy. East Texas remained in a position of leadership, and furnished perhaps more than its share of the prominent officials of the Republic. The towns, including Nacogdoches, were alive with the discussions of governmental problems, and the advocacy of the names of the foremost citizens for high offices. After the repression of Mexican domination, politics arose to unprecedented heights, and everybody was affected by political fervor. Among the first officials of the new-formed Republic, Nacogdoches furnished Sam Houston for President, General Thomas J. Rusk as Secretary of War; Colonel John Forbes as Commissary General of the Army.

Following the formation of the new government, the business men of Nacogdoches entered upon a period of expansion, resulting in the laying out of numerous new towns in the then Nacogdoches county, extending almost to the Gulf of Mexico on the south and including Dallas on the north. Among the towns thus formed following the Revolution may be mentioned Pattonia south of Nacogdoches on the Angelina river, and a little further south the town of Travis on the same river, Mount Sterling at the home of John Durst on the Angelina river west of Nacogdoches, and a few miles further up the river where the present highway crosses, the town of Angelina where James Durst and his father, Joe Durst, lived. The original town of Rusk was south of Nacogdoches where the road to Fort Teran crossed the Angelina river on the Pierre Roblo grant. Thornville, near the present village of Mahl; Liberty, a few miles northwest of Douglass; Jackson, built on an island on the Attoyac not far from where Chireno was later founded. Haden Edwards founded two towns north of Nacogdoches on the Sabine river, near the present town of Longview, one of which was named Fredonia, in memory of his ill-fated revolution, and the other he called Cotton-Plant. In addition to these ghost towns of long ago, we may mention such towns as Attoyac, Melrose, Chireno and Douglass, each of which was regularly laid out in lots and blocks, in anticipation of the boom to come.

But the war was not over yet. The Mexican army had been defeated and expelled, but there were enemies at home. The town of Nacogdoches was aroused to feverish excitement when the preacher and congregation of a country meeting came in one night with the news that the Mexican population of the country had risen in arms under the leadership of a former 14 alcalde, Vicente Cordova, and were on the warpath against the American citizens. General Rusk at once called for volunteers, and scouts were sent everywhere to discover the whereabouts of the insurgents. All the next day their efforts were in vain, but at length John Durst and a party of scouts under him, came in with the report that they were encamped across the Angelina river in what is now Cherokee county, where they were doubtless waiting to join those Indians to make war against the American settlers. Rusk appealed to the people of San Augustine and Sabine counties, and within forty-eight hours they began to arrive, armed and equipped for a campaign. After some delay, caused by contradictory orders from President Houston, Rusk marched into the Indian country, where he found that the rebels had gone to other tribes, and were beyond his reach. He marched to the Cherokee and Shawnee villages and so impressed them with the readiness with which he had assembled so considerable a body of soldiers that they readily premised peace and disavowed any connection with the Mexican insurgents.

In the meantime the town began to grow. It was the home of many of the prominent leaders of Texas during the time of the republic, whose influence was felt in the public affairs of the country. General Thomas J. Rusk was a citizen of Nacogdoches until his death. Sam Houston frequently was a resident until his removal to Huntsville. Charles S. Taylor was very prominent in public affairs. William B. Ochiltree lived here for a time. Thomas J. Jennings, the elder, lived here until his removal to Marshall, as did Dr. James H. Starr. James Reily, who was minister to the United States, had his home here. These are some of the men more prominent in public life; among private citizens there were also many whose names were well known throughout the land. Adolphus Sterne, Archibald Hotchkiss, Henry Raguet and others might be mentioned. Of the county officers Oscar L. Holmes, Richard Parmalee, Murray Orton, William Hart and others were prominent. Colonel Haden Edwards, who returned to Nacogdoches after the bitterness of the Fredonian rebellion had subsided, was here until his death, and his family continued to live here for many years afterwards.

S. M. Orton Home

Built in 1840.

Has “Strong Room” built for temporary detention of prisoners by Sheriff Orton.

The invaluable services of Nacogdoches and its people in opening up the great northern regions of Texas, after the expulsion of the Indians, had the result, unfortunate for it but inevitable, of diminishing the population and importance of the town. New centers of agriculture and trade sprang up and became towns which attracted more and more people to themselves, and new opportunities presented themselves for business enterprise. It was easier to fence in the prairies than to clear the forest lands of East Texas. Many of the citizens of Nacogdoches, including some of the more prominent persons, removed to other places.

After the annexation of Texas to the United States, Nacogdoches gradually settled down to the station of one of the many flourishing towns of the State, and lost the preeminence in political and social matters which had been its lots from the beginning of its history. With San Augustine it still continued to be the center of this section of the State, and the two towns cooperated harmoniously in the development of the surrounding regions.

Nacogdoches has always been an important social center. Even under Spanish rule it was noted for the culture of its inhabitants, and during the residence of the Governor of the State at this place in the unsettled period after the Louisiana purchase, there was a social life here that was not unworthy of a larger city. During the third and fourth decade of the Nineteenth Century social amenities prevailed even through the confusion of changing political scenes of that time. The Mexican officers at that time were, as a rule, gentlemen, and the American immigrants included many persons of high culture and attainments. After the revolution the social standing of the place grew even stronger. It was not merely in entertainments and enjoyments that Nacogdoches and San Augustine set the pace in East Texas; they became centers of learning as well. Schools flourished, and a refined taste in literary and scholastic affairs exhibited higher ideals of mental achievements. The University of Nacogdoches was established in 1845, and attracted many persons who were desirous of scholastic training.

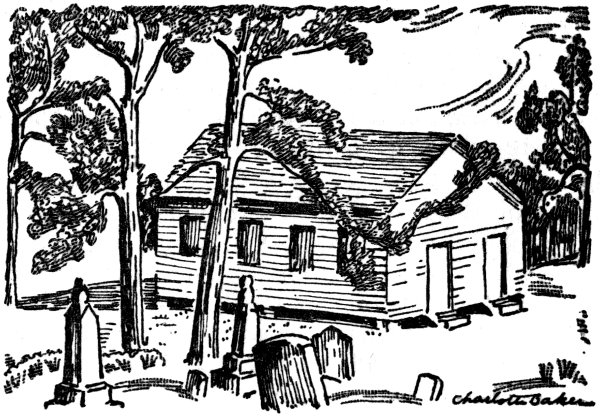

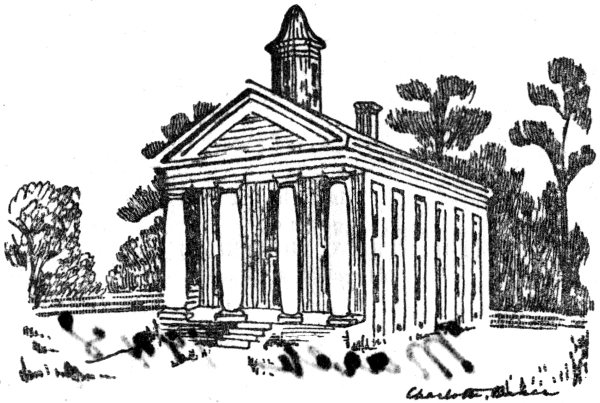

Old North Church

Founded 1838.

Standing four miles north Nacogdoches. See page 22.

When the shadow of war fell over the country in 1861, Nacogdoches at 16 once took her place among those who were ready to offer their belongings and their lives upon the altar of their country. Her soldiers went to the front and did gallant service for the cause of the Confederacy. At home, the women and other non-combatants worked and prayed for the success and safety of their loved ones far away on the battlefield. But war brought ruin to the town; the schools were overwhelmed in the general desolation. Business enterprise was at an end, and the great stores gave place to little shops, which barely supplied the necessities of life. The soldiers came home and went back to their farms, but the old plantations had disappeared and the fields barely produced a living for their owners and workers. The town itself was reduced to the proportions of an insignificant village. The people bravely kept up the traditions of a more affluent existence, but it was a mournful struggle against untoward conditions.

These conditions prevailed for twenty years, but at length a harbinger of better times appeared in the shape of a railroad, the Houston East and West Texas, connecting Houston and Shreveport. It was a narrow-gauge road, burning wood for fuel and creeping along at an extremely low rate of speed, but it was the first road to pass through East Texas, where formerly the wagon and the two-horse hack formed the sole means of transportation. It brought new business, new people and new ambitions to the place which soon began to be built up in brick in place of the old wooden houses of the earlier years. Soon cotton wagons assembled, bearing bales of wealth, and in the autumn season the streets were filled with people from surrounding counties selling their crops and buying supplies.

There was no boom. The town grew gradually and slowly. Greater business enterprises were undertaken and accomplished and various kinds of improvements were effected in the way of conveniences of living. For many years the village spirit remained among the people. Everybody knew everybody else, and each was interested in the welfare of all. New churches were erected and a new court house and also, sad to relate, a new jail. A large lumber mill was erected on the east side of town which added to the prosperity of the place.

Finally, after the World War, when a number of new teachers colleges were authorized by the Legislature, the enterprising spirit of the citizens secured the location of that one named for Stephen F. Austin in Nacogdoches, and the promise of cultured prosperity evinced in the days of the Republic, but sadly interrupted by war, was at length realized. Nacogdoches had now become one of the fairest of the little cities of Texas and bids a hearty welcome to all comers within her borders.

And so we close the story of Nacogdoches under nine flags: The Lilies of France with LaSalle in 1685; the Flag of Castile and Aragon of Spain in 1716; the green flag of the Magee-Guitierrez Expedition in 1813; Long’s flag of the First Republic of Texas in 1819; the white and red flag of the Republic of Fredonia in 1826; the flag of the Mexican Republic—1821-1836; the Lone Star Flag of the Republic of Texas; the Stars and Bars of the Southern Confederacy—1861-1865; and finally the Stars and Stripes forever.

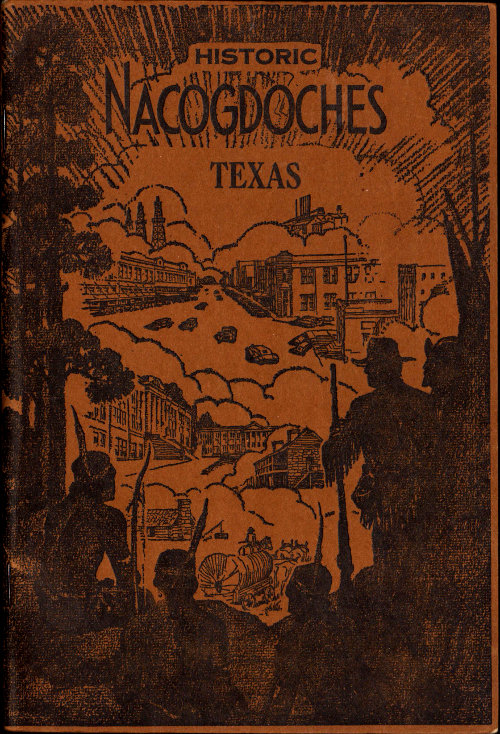

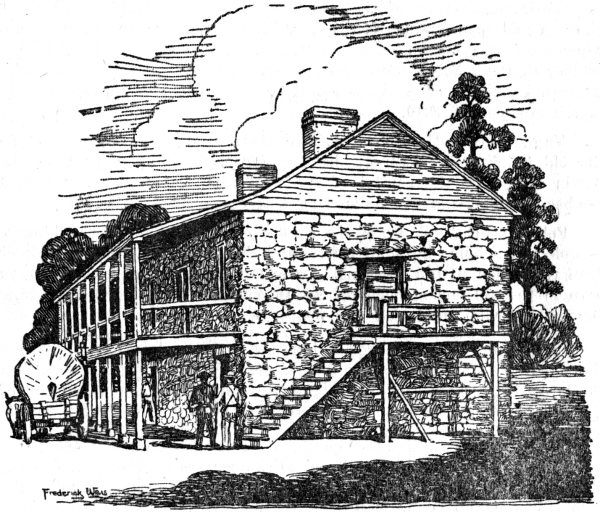

THE OLD STONE FORT

The above drawing was made from the earliest photograph of the Old Stone Fort. The

original picture has been re-photographed and the reproduction forms a treasured scene in

many homes of the city.

For one hundred fifty years tradition has thrown a veil of romance around the old building that formerly stood at the corner of Main and Fredonia streets, facing the northeast corner of the Plaza Principal in Nacogdoches, where the two main branches of El Camino Real merged.

Even as early as Revolutionary days it was regarded by many as being one of the old mission buildings, and later years this belief was strengthened when a wandering sign painter, with the permission of John S. Roberts, painted a sign for the front of his saloon in the old structure: “The Old Stone Fort, erected in 1719”.

The Stone House, as it was called in the early records, has a history more intriguing, more romantic, than any other building in the state of Texas, not even excluding the Alamo. Over its walls all but one of the nine flags of Nacogdoches have flown.

Built as a private enterprise by Antonio Gil Ybarbo in 1779, as a trading post, it soon became the most important building in the New Philippines. In 1801 Lieut. Musquiz brought Peter Ellis Bean and the remainder 18 of Philip Nolan’s expedition and placed them in the Old Stone Fort, where they remained for thirty days.

Cordero, governor of the Province of Texas, together with General Herrera and 1300 Spanish troops, had his headquarters in the stone house when the treaty creating the “Neutral Ground” was agreed upon on November 6, 1806. For three months it was the seat of government of the Eastern Provinces of Spain, when Governor Manuel de Salcedo was here in the summer of 1810.

Magee and Gutierrez proclaimed their republican government from the old building in 1813; as did Dr. James Long on August 14, 1819. Again it became the capitol of the Fredonian Government, and on December 23, 1826, the Fredonian flag was raised over its walls.

Following the collapse of the Fredonian republic, the old building was occupied as a home by John Durst, and the happy laughter of little children resounded within its walls. Louis O. and Miss Benigna Durst were born in the old house, inherited by Durst from his foster-father Samuel Davenport, who purchased the property in 1806.

In 1831 John Durst moved to his new home on the Angelina river and the Old Stone Fort was sold to Juan Mora, the district judge, and Vicente Cordova, district attorney under the Mexican regime, in 1834. The official records were again placed in the old building, where they remained until a courthouse was built in 1840.

Within its walls the oath of allegiance was administered by the Mexican authorities to such celebrities as James Bowie, Thomas J. Rusk, Sam Houston and David Crockett. Around its walls the forces of Bustamente and Santa Anna vied for supremacy on August 2, 1832, at the Battle of Nacogdoches. Then in the spring of 1836, the stone walls of the old building seemed a bulwark of safety to the few brave souls who refused to flee from threatened Indian massacre in the Runaway Scrape.

On March 17, 1837, the first regular term of district court under the republic assembled in the Old Stone Fort, followed by a special term in August of the same year, presided over by “Three-legged” Willie, with a pistol as his gavel, at which time General Thomas J. Rusk delivered one of his famous orations, which has been preserved to us in our court records.

Even the transfer of title to the old house from Vicente Cordova brings an element of tragedy and in some respects even comedy. Cordova was the leader in the so-called Cordova Rebellion in 1838, in which Zechariah Fenley was murdered and one of his slaves taken away. Following this, in 1840, Rebecca Fenley filed suit for damages against Cordova, not for the death of her husband, but for the loss of her slave. Cordova was a fugitive and a judgment against him for $1500 resulted in a sale of his half-interest in the Old Stone Fort under execution, being purchased by Rebecca Fenley, who was a daughter of Mrs. John S. Roberts.

The Old Stone Fort remained in the Roberts family until it was purchased by Perkins Brothers in 1901; after which it was torn down, the material given to the Cum Concilio Club of Nacogdoches, who used the stones in the erection of the Stone Fort Memorial in 1907 at the northwest corner of Washington Square, where it remained as a museum until 1936, when the State of Texas again used the material from the Old Stone Fort in the erection of the present Replica of the Old Stone Fort on the beautiful campus of Stephen F. Austin State Teachers College at the intersection of Griffith and Clark Boulevards.

REPLICA OF THE OLD STONE FORT

Replica of the Old Stone Fort, erected by the State of Texas as a part of its Centennial

program, 1936. It stands on the campus of the Stephen F. Austin State Teachers College and

is maintained by the State as a museum.

THE MISSIONS AND PRESIDIO.—During the summer of 1716, under the direction of Captain Don Domingo Ramon, three missions and a presidio were erected in the present Nacogdoches county. The Presidio Nuestra Senora de los Dolores, built in 1716, was repaired and enlarged by the Marquis de Aguayo in 1721, and abandoned about 1730. Built by the Spanish government as a fort and headquarters for soldiers guarding the East Texas Missions and the borders of the New Philippines, it overlooked Los Terreros or Mill creek, near the intersection of the Lower Douglass road with the road from Douglass to Wells.

The Mission Nuestra Senora de la Purissima Concepcion was built 1.25 miles northeast of Goodman crossing of the Angelina river, near “two bubbling springs” in the heart of the Hainai Indian village. In 1731 this mission was moved to San Antonio where it now stands.

The Mission San Jose de los Nazonis was built 2.6 miles northeast of the present town of Cushing, overlooking Dill creek. In 1731 this mission was also removed to San Antonio, where it was called San Juan Capistrano.

Mission Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe was founded at the same time on the west side of North street in Nacogdoches, overlooking Banito creek, which was called “the creek of the mission.” This mission was never permanently abandoned until it was replaced by the church which stood on the little plaza in front of the present court house, built in 1802. The third Catholic church was formerly the home of Nathaniel Norris at the northwest corner of Hospital and North streets. The fourth church was the Sacred Heart church on Pecan street, built in 1847 under the influence of Bishop J. N. Odin; which was in turn replaced by the present Sacred Heart church, built in 1937 on a portion of the homestead of Judge Charles S. Taylor on North street, the house of the old Sacred Heart church being rebuilt about eight miles south of Nacogdoches as the Fern Lake church. The sites of the presidio and missions have been appropriately marked by the State of Texas.

OLD STAGE STAND NEAR CHIRENO.—On Highway 21 about two miles west of the town of Chireno is a very old house on the north side of the road. It was built in the early forties of last century by Mr. James B. Johnson, who was the first mayor of San Augustine. It was used as a halfway station between San Augustine and Nacogdoches for the old Concord coaches used at that time for mail and passenger service. Here the horses were changed and passengers had meals. Another station on the same coach line stands in the town of Douglass, fourteen miles west of Nacogdoches.

EYES OF FATHER MARGIL.—The old Spanish legend relates that in the first year after the Mission Guadalupe was built there was a great drouth and water was scarce. Father Margil went out in faith and smote the rock on the bank of LaNana creek, which had completely dried up, and two unfailing springs gushed out. They were called “Los Ojos de Padre Margil,” The Eyes of Father Margil, and are located in what was formerly known as Mims Park, now a pasture in the rear of the J. R. Gray residence.

RESIDENCE OF PETER ELLIS BEAN.—One of the members of Nolan’s expedition; was captured by Lieut. Musquiz and held prisoner many years in Mexico. During the Revolution under Morelos he made his escape and joined the revolutionary forces. Settled in East Texas and had several homes there. One of these was on the Carrizo creek, on the upper Melrose road, four and one-fourth miles east of Nacogdoches. Marked by the State of Texas.

OAK GROVE CEMETERY.—The State of Texas has placed granite markers at the graves of the four signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence who are buried in this cemetery: Thomas J. Rusk, Charles S. Taylor and John S. Roberts, who represented the Municipality of Nacogdoches, and William Clark, who represented Sabine District. The graves of the following veterans of the Battle of San Jacinto have also been marked: E. E. Hamilton, Capt. Hayden Arnold. Markers have been placed at the graves of Haden Edwards, empresario and leader of the Fredonians, and his wife, Susan Beal Edwards; General Kelsey Harris Douglass, commander-in-chief of the forces that drove the Indians out of East Texas in 1839; Dr. Robert Anderson Irion, Secretary of State in the Cabinet of Sam Houston, first president of the Republic of Texas, and Thos. Y. Buford.

GRAVE OF WILLIAM GOYENS.—Goyens family cemetery, four miles southwest of Nacogdoches, near Aylitos creek. Only negro to be honored by the State of Texas with a Centennial marker. Participated in Battle of New Orleans. Came to Texas in 1821. Indian Agent under Mexican government, lawyer in Alcalde court. Participated in the Texas Revolution in 1836; noted for his private charities. Although the Constitution of Republic and State both forbade the holding of land by negroes, Goyens amassed a considerable fortune with his land deals and was owner of thousands of acres of land at his death in 1856. His white wife, whom he married in 1828, is buried by his side.

GRIFFITH PARK.—The park fronting North street and extending from Caroline street on the south to the southern border of the campus of Stephen F. Austin State Teachers College on the north. Given to the city of Nacogdoches by the Griffith heirs in memory of Dr. L. E. Griffith and his wife, Sarah Jane Clark Griffith, and Dr. Griffith’s brother, Alfred. Dr. L. E. Griffith came to Nacogdoches from San Augustine about 1850 and was one of the builders of modern Nacogdoches. The park was dedicated to Dr. Griffith and the early pioneers of Nacogdoches.

INDIAN MOUNDS.—On the corner of the school campus at Mound and Arnold streets, was a large Indian Mound 150×75 feet and about fifteen feet high. On the corner opposite was a circular Mound about 75 feet in diameter. These Mounds were leveled to make room on the campus. One small mound still remains on the front lawn of the T. M. Reavley home. An oak tree of considerable size grows from the summit of it. (See back cover).

OLD NORTH CHURCH.—About four miles north near Highway 35, North Church was built in 1838, but the congregation had met for some time before the house was built, under an oak tree, the lower part of the trunk of which still stands. It was first known as Union church, being intended for two bodies of Baptists as well as other denominations. It has since become the property of the Missionary Baptists, who hold regular services there. The old cemetery contains the graves of many of the early settlers of Nacogdoches county. Marked by the State of Texas.

ADOLPHUS STERNE’S HOME.—The old home of Adolphus Sterne is situated on LaNana street, formerly called Sterne street. Built about 1830, in this house General Sam Houston was baptized into the Roman Catholic church in May, 1833. Now known as the Hoya home. Marked by the State of Texas.

NACOGDOCHES UNIVERSITY.—The Nacogdoches University was established in 1845, and at first occupied the “Old Red House” on Pilar street. Later the Sons of Temperance Hall was acquired, and in 1856 the present high school campus was donated to the University and given the name of Washington Square. Two buildings were erected—a frame building for the Female Department of the University, and a brick house for the Male Department. The brick structure still stands in the center of the group of buildings. Marked by the State of Texas.

EPISCOPAL CHURCH.—The first Episcopal Church stood on Church street.

OLD SPANISH CEMETERY.—Where the courthouse now stands, was used from 1800 to 1825. The burial place of many of the earliest settlers of Nacogdoches, among whom was Antonio Gil Ybarbo, founder of Modern Nacogdoches. Marked by the State of Texas.

THE PROTESTANT ELM.—The noted Elm Tree stood immediately east of the Southern Pacific freight depot and just south of a brick warehouse now there. Henry Stephenson preached under this tree in 1819.

HOSPITAL STREET.—The old Spanish hospital, from which the street derives its name, was situated on the corner of Pecan and Hospital, in front of the Methodist church. Across Pecan street was the old Cabildo or jail, built in 1835. Adjoining it on the west was the Hall of the Sons of Temperance during the period of the Republic of Texas. On the block where the First Presbyterian church now stands was the old Bull Ring, where bull fights were held during the Spanish and Mexican regime.

THE OLD SOLEDAD.—Famous throughout East Texas prior to 1800 as the headquarters of William Barr and Samuel Davenport, Indian traders; was located on the block on which the Texan Theatre now stands. Marked by the State of Texas.

THE RED HOUSE.—About 1827 Colonel Piedras, comandante of the Mexican garrison in Nacogdoches, built a house—part adobe and part frame—on Pilar street in the block west of the Square, for the accommodation of his officers and as headquarters for his forces. After the Texas Revolution this house was sold under execution on a judgment against Colonel Jose de las Piedras and became the property of Gen. Thomas J. Rusk. General Rusk made his home there when he first came to Nacogdoches in 1835, and remained there for eight or nine years. In 1845 the University of Nacogdoches used it for class rooms. Later it was used by various parties as an inn.

THOMAS F. McKINNEY.—Site of mercantile establishment of Thomas F. McKinney—1823-1830. As senior member of the firm of McKinney and Williams, built first wharf at Galveston. Financial adviser of the Republic and creator of the Texas Navy. Site marked by the State of Texas.

HOMES IN NACOGDOCHES.—Sites of the following residences of early settlers of Nacogdoches have been marked by the State of Texas:

James Dill, southeast corner of North and Hospital streets. Pioneer Indian trader; recognized by King of Spain. First alcalde of Nacogdoches, 1821. Home built in 1804.

William Clark, Jr., northwest corner Main and North streets, signer of Texas Declaration of Independence, member Second Congress of the Republic of Texas. Home originally built by John J. Simpson in 1835, acquired by Clark in 1840.

Charles S. Taylor, southeast corner North street and Mims avenue. Born in London, 1808; died in Nacogdoches, November 1, 1865, Signer Texas Declaration of Independence. Land Commissioner 1833, Chief Justice Nacogdoches county 1837, Rio Grande Land Commissioner 1854. Home built before the Texas Revolution.

Don Juan Antonio Padilla, site now occupied by Westminster Presbyterian church on North street. Born in Nacogdoches on Rancho Santo Domingo; died in Houston 1839, while there on business. Served as an officer in the Spanish army; Secretary of State of Coahuila and Texas; Land Commissioner for Eastern Texas; delegate from Victoria county to the convention which declared Texas independent; member of deputation that demanded the surrender of Goliad, and volunteer to the Army of the Republic before San Antonio. Home built in 1830 on land granted to his grandfather.

Thomas J. Rusk, opposite campus of Stephen F. Austin State Teachers college, west side of North street; born 1803, died 1857. Hero of San Jacinto, Commander-in-Chief of the army 1836. Chief Justice of the Supreme Court 1839. President of the Constitutional Convention 1845. United States Senator 1846. Nacogdoches was his home from 1835 to 1857. Home built about 1844.

Antonio Gil Ybarbo, Main street, site now occupied by Cason-Monk Hardware store; born 1729, died 1809. Founder of modern Nacogdoches in 1770; builder of Old Stone Fort. This Spanish frontiersman matched wits with Spanish governors in the interest of the early settlers of this region.

Sam Houston, site now occupied by the Liberty Hotel. First home owned by Sam Houston in Texas. Erected by John Forbes, Commissary General of the Army of San Jacinto, in 1836. Purchased by Sam Houston in 1839.

John S. Roberts, on block facing south side of Plaza Principal; born 1796, died 1871. Came to Texas December, 1826. Participated in Fredonian Rebellion, a leader in the Battle of Nacogdoches 1832; delegate to Consultation, November 3, 1835; signer of Texas Declaration of Independence. Home originally built and occupied as a residence by Samuel Davenport during early years of the Nineteenth Century.

MOUNT STERLING.—Site of town of Mount Sterling; surveyed off for John Durst in 1837. One of important river ports for Nacogdoches for many years, at present known as Goodman crossing on the Angelina River. John Durst residence overlooked the boat landing and used as a refuge for his and his neighbors’ families during the Indian and Mexican troubles. Site marked by the State of Texas.

NORTH STREET.—Oldest street north of Mexico. Originally a street in the Nacogdoches Indian village leading to the road from Nacogdoches to the Nassonite village near Cushing. On this street the Mission Guadalupe was built in 1716. Travelled by Spanish missionaries, soldiers and settlers, French traders and American filibusterers before Anglo-American colonists came to make Texas their home. Marked by the State of Texas.

NACOGDOCHES COUNTY.—Marker placed by the State of Texas three miles north of Nacogdoches on east side of Highway 35.

The old King’s Highway, known to the Spaniards as “El Camino Real,” which runs through Nacogdoches, San Augustine and Sabine counties, was followed by La Salle and his men in 1685, at which time they spoke of this road as being “as well beaten a road as that from Paris to Orleans.” This road was followed by St. Dennis in 1714, as he was making his way from Natchitoches on Red River to San Juan Bautista on the Rio Grande. It was doubtless an Indian trail to the western borders of the Tejas Indians, probably about the Trinity river, and from there to San Antonio the best route was determined by use. After the Mexican Revolution and the coming of the American settlers it was straightened into a cart-road or Camino Carretera, and was known as the Old San Antonio Road. State Highway 21 now follows approximately the track of the old road.

Highway 21 leads east to San Augustine, the sister town to Nacogdoches from the earliest days, where are the sites of the old Mission of Dolores, the home of General James Pinckney Henderson, Governor O. M. Roberts, and many of the prominent men of the Republic of Texas. The home of Stephen W. Blount, signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence, many of whose descendants live in Nacogdoches and San Augustine, was built on the north side of the King’s Highway, and is in an excellent state of preservation.

Seven miles west of San Augustine on this highway was the home of Thomas S. McFarland, who laid out the town of San Augustine in 1834. The house was built about 1830 and was provided with port-holes for shooting Indians in case of attack.

Pendleton Ferry was the original ferry on the King’s Highway across the Sabine river; now spanned by a splendid interstate bridge. Not far from the road is McMahan’s Chapel, the first Methodist Church in Texas, and the site of old Sabine-town.

MASONIC LODGE.—Some time in the Spring of 1837, immediately following the organization of a permanent government in Nacogdoches county, a movement for the organization of a Masonic lodge began which culminated in a dispensation from the Grand Lodge of Louisiana for the Milam Lodge No. 40, which was dated July 29, 1837.

One of the leaders in the Masonic circles of Nacogdoches was Adolphus Sterne, who was a past master of a lodge in New Orleans, and also a 32nd degree Scottish Rite Mason, the first Scottish Rite Mason to come to Texas. Haden Edwards was also a past master of another lodge. The other charter members of Milam Lodge No. 40 were: Isaac W. Burton, John H. Hyde, George A. Nixon, John S. Roberts, Charles H. Sims, Frost Thorn, Simon Weiss, as Master Masons, and Kelsey H. Douglass and John W. Lowe as Estered Apprentice and Fellow Craft respectively.

The first meeting of the Lodge under dispensation was held in the Old Stone Fort on August 16, 1837, with the following present: Haden Edwards, Master; John H. Hyde, Senior Warden; J. S. Roberts, Junior Warden; Chas. H. Sims, Treasurer pro tem; Adolphus Sterne, Secretary pro tem; with George A. Nixon, Simon Weiss and J. W. Lowe, members. The Charter from the Grand Lodge of Louisiana was granted September 22, 1837, and was received in the Lodge on its meeting November 20, 1837.

Upon suggestions from Holland Lodge No. 36, Houston, Texas, a committee consisting of Adolphus Sterne, I. W. Burton, Thomas J. Rusk, Charles S. Taylor and Kelsey Douglass, was appointed to attend a meeting in Houston to consider the formation of the Grand Lodge of Texas. Their mission was accomplished in the city of Houston on February, 1838, with the organization of the Grand Lodge of Texas, and this lodge became Milam Lodge No. 2.

After the first meeting, the Lodge began using the upper floor of Simon Weiss’ store for its meeting-place, and during its long history, it held its meetings in several houses in Nacogdoches, but never succeeded in building its own permanent home until the completion of its present Temple in May, 1931, on North Fredonia street.

During the administration of Haden Edwards as Worshipful Master of Milam Lodge No. 40, one dozen chairs were made for the use of the Lodge, which were of hickory, turned on an old-fashioned lathe, with seats of rawhide. These chairs served the Lodge long and faithfully, and have witnessed the degrees conferred on every Mason made in Milam Lodge for 110 years. In 1914 a resolution was passed, instructing the worshipful 27 master to present to the old past masters then living and to the sons of those old pioneers that had passed away, one of these chairs, that they might be kept as relics and mementos of the long ago. One of them was retained by the Lodge and now occupies a prominent place in the East, there to remain for all time to come, never to be used again except it be by the President of the United States, the governor of Texas, or the Grand Master of the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge of Texas.

Many of the men prominent in the affairs of Texas have been members of Milam Lodge No. 2, and the minutes show Sam Houston a visitor on more than one occasion.

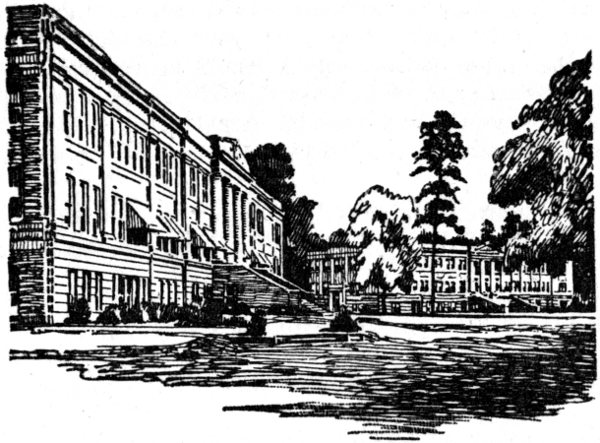

STEPHEN F. AUSTIN STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE

Nacogdoches, Texas

A glimpse of Stephen F. Austin State Teachers College, the Thomas J. Rusk building on the right. General Rusk made his home in Nacogdoches from his arrival in Texas in 1834 until his death in 1857. He is buried in Oak Grove cemetery. The college buildings are located on the Thomas J. Rusk homestead.

BY VIRGIE SANDERS

The project of rebuilding the exterior of the historic Nacogdoches University, as recently proposed by the Nacogdoches school board, is now partially completed.

The sum allocated by the board has been used discreetly and the replacement of brick on outside walls, new window frames and panes with new lumber added supporting the antiquated structure, guarantees safety to the public school children who play on the hallowed ground of the Old Nacogdoches University built by subscription with some state aid during the days of the Texas Republic.

We feel that now is the time to emulate the spirit of the pioneers. Let us be awakened to this opportunity to complete the noble edifice, making it available to be used by the citizens as a club center and a museum.

Printed in the

office of

THE HERALD PUBLISHING CO.

Nacogdoches, Texas

PRICE TEN CENTS

PER COPY

INDIAN MOUND

Located on Mound Street Opposite High School Building