Ten feet of furred lightning landed squarely on the cage

A BIFF BREWSTER

MYSTERY ADVENTURE

By ANDY ADAMS

GROSSET & DUNLAP PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK

© BY GROSSET & DUNLAP, INC. 1962

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

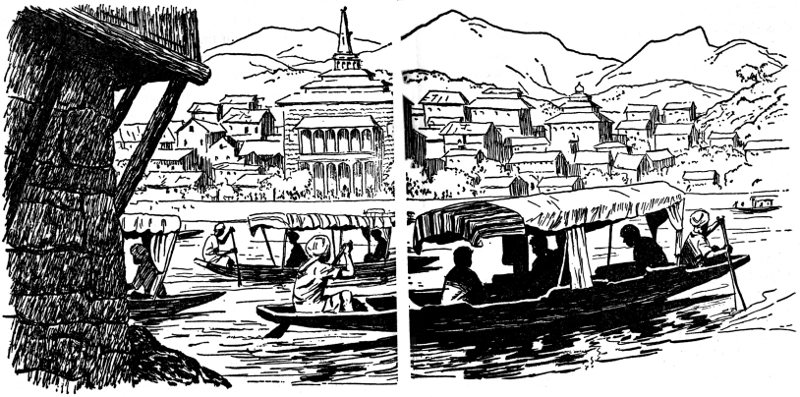

It was sunset along the Calcutta waterfront. The reflection of the vivid tropical sky turned the murky water of the Hooghly River into a rippling rainbow. The river was alive with a variety of craft, including native sailboats, side-wheel steamers that plied up and down the Hooghly between Calcutta and the Bay of Bengal, eighty miles south, as well as sturdy tugs, launches, and lighters that served the ocean-going ships moored in midstream along the strand.

Biff Brewster was standing at the bow of a big freighter, the 10,000-ton Northern Star, which only that afternoon had cast anchor in the Port of Calcutta. Biff was a blond-haired youth of sixteen, with broad, square shoulders and blue-gray eyes that were as keen and expressive as his strong, well-formed features. With Biff were two other boys, his companions in previous adventures.

One was Kamuka, a Brazilian boy of Biff’s own size and age. They had met at the headwaters of the Amazon, where Biff had accompanied his father, Thomas Brewster, in an adventurous search for a fabulous gold mine. Kamuka, who had spent most of his life on jungle rivers, was keenly interested in the scenes he now was viewing along the Hooghly.

The other boy was slightly younger and smaller of build, but quite as wiry and athletic as his two companions. He was Likake Mahenili, a Hawaiian youth known as “Li” to his friends. Li, a skilled diver, had helped Biff crack the riddle of a vanished sloop when they had teamed in a thrilling sea hunt off the Hawaiian shores.

Now, all three were newly arrived in India, the land of mystery. But there was no mystery as to why and how they happened to be together. That was due to a simple turn of events.

Months ago, Biff’s father had gone to India to open long-neglected gold mines in some of the former princely states that had been absorbed by the Indian Republic. It had taken much longer than Mr. Brewster expected—as many of his jobs did—so he had arranged for the family to come by air to India and join him there.

Meanwhile, Biff had invited Kamuka to come from Brazil and spend his vacation in the United States. By a quick switch of plans, Biff and Kamuka had flown to San Francisco just in time to take last-minute passage on the Northern Star, which cost less for both than Biff’s trip would have by air.

The freighter had been scheduled to call at Honolulu, so Biff had written ahead to Li, who had not only met the ship there, but had decided to come along on his own. They had broken the monotony of the long voyage with brief stops at ports on the way, but so far, it had been more of a sightseeing tour than an adventure. They still had one more night to spend on shipboard as the Northern Star had reached Calcutta a day ahead of schedule.

“Tomorrow,” Biff declared, “Dad will be here to meet us. By now, my mother and the twins should have reached Darjeeling, so he may be bringing them along to visit the gold fields.”

“I hope that Mr. Brewster shows us the Kolar Mines at Mysore,” declared Li enthusiastically. “They have shafts that go down two miles, the deepest in the world.”

“Except for those in South America,” put in Kamuka stoutly. “They are the world’s deepest. I learned that at technical school in Brasilia.”

“And I suppose they taught you that South America has the biggest mountains, too,” returned Li. “Just wait until we see Mt. Everest. Those Himalayas will make your Andes look like a lot of ant hills.”

“I shall wait until I see them before I judge,” said Kamuka complacently. “But since you speak of ant hills, the ones we have in Brazil are bigger than anywhere else.”

“You can’t win, Li,” laughed Biff. “Kamuka has an answer for everything.”

“You’re telling me?” returned Li, with a grin. “He even answers questions before I ask them.”

This good-natured banter had been going on all across the Pacific. In the friendly disputes between Kamuka and Li, Biff had been called upon to act as judge. So now he gestured toward the river, with the comment:

“Let’s keep our minds on what we’re watching for—the tidal bore coming up the river. I’d say it’s due any moment now, the way those boats are getting ready for it.”

Tugs and side-wheelers were bracing to buck the incoming tide, while the native boats were hoisting colorful sails and poising in midstream, ready to take off up the river. Biff had his movie camera with him and he began taking color pictures of the scene, including activity along the shore, where tiny craft were hastily shoving off.

“They’ll have to clear those piers,” Biff commented, “or they may be smashed like eggshells when the bore hits.”

The other boys nodded as they scanned the deepening purple of the river. But even their keen eyes failed to detect a motion on the darkened steps of an old pier. There, a slim, furtive figure was crouched close to the water, looking out toward mid-channel.

Carefully, the huddled watcher fingered a watertight packet attached to a thin chain around his neck; then, satisfied that it was safe, he slid his sleek, brown form into the river and began swimming smoothly, swiftly toward the Northern Star. He might have been mistaken for a snout-nosed crocodile from the delta of the Hooghly, or a floating log swirling in the eddies of the changing tide. But no one noticed him, least of all the boys high on the big freighter’s bow, for their attention now was fully gripped by what was happening downstream.

Distant whistles blared; their deep-throated signal was relayed by other ships closer by. Tugs added shrill blasts as a great crest of water came rushing upstream, churning the muddy Hooghly into a whitish foam. Tiny boats were tossed like match boxes by the six-foot wave that swept from shore to shore. Launches rocked, tugs jounced, and the sailing craft caught the stiff wind that accompanied the tidal bore, letting its billows carry them along.

While Biff and his companions were watching the wave surge toward them, the sleek, brown swimmer reached the bow of the Northern Star. If the arriving wall of water didn’t overwhelm him, it seemed sure to crush him against the side of the big ship. But as it was almost upon him, his quick hands came up and grabbed the freighter’s anchor chain. An instant later, he was out of the water and while scrambling upward like a monkey the white foam churned just beneath him.

Clinging there, he waited while the freighter strained at its moorings, because of the sudden lift. Then, satisfied that the chain would not swing him against the ship, he continued his climb, his dripping figure scarcely visible.

On the deck above, the boys had gone to the starboard side, where Biff was taking pictures of the boats that were riding upstream. None of them noticed the head and shoulders that appeared over the port rail. A sleek figure followed, slid behind a row of crates, and worked along to a companionway. There it darted swiftly up the steps to the cabin deck above.

Biff had been following the bore with his camera, until it faded, tiny sailing ships and all, beneath the towering bulk of the Howrah Bridge, which spanned the quarter-mile width of the Hooghly River.

“Well, what did you think of it?” Biff asked.

“We have bigger bores on the Amazon,” replied Kamuka nonchalantly. “This was only six feet. Ours are as high as sixteen.”

“And the way those sailboats took off was nothing,” put in Li. “Not compared with the way we ride the rollers with our surfboards at Waikiki.”

“It’s nice to hear you fellows agree on something,” laughed Biff. As he spoke, a gong sounded from amidships. “And there is something else you both like, the first call to dinner. Wait while I put my camera in the cabin; then I’ll join you.”

Biff had left the door of his cabin unlocked. When he opened the door, he was conscious of a slight stir within. Biff looked toward the porthole that served as a window. Momentarily, it blacked out, then showed plainly against the dimming sunset, as though a figure had squirmed through. Biff stepped out, closing the door, and called down to Li and Kamuka:

“Take a look over the port side and see if someone is hanging on outside my cabin!”

A figure had been hanging on, but no longer. Pushing off from the side of the ship, it straightened in mid-air and plummeted down the side of the freighter, punching the water with scarcely a splash. By the time Li and Kamuka looked over the rail and Biff was gazing from the porthole of the cabin, the lithe brown swimmer was heading shoreward, unseen on the now darkened surface of the river.

The cabin itself was empty. Of that, Biff felt sure as he turned on the light, until a familiar voice spoke almost at his elbow.

“Listen carefully, Biff,” the voice announced. “I have something important to tell you—”

The effect was electric on Biff. “It’s Dad’s voice!” he exclaimed. By then, the door of the cabin had opened again, and Li and Kamuka were staring in, both bewildered as the voice continued:

“I cannot meet you as I planned, so follow these instructions exactly. Tomorrow morning, at ten o’clock, be at the New India Bazaar in Calcutta—”

At this, Li exclaimed excitedly, “It’s Mr. Brewster’s voice!” and Kamuka added, “But where is he? I don’t see him?” Then, Biff was pointing, showing them the answer. The voice was coming from a tape recorder that was on a table in the corner, and was connected with a lamp socket in the cabin wall.

“And there you will receive another message,” Mr. Brewster’s voice declared. “Follow it exactly, and you will meet a man we both can trust. He will have more to tell you, so obey his orders to the letter, as if they came from me.”

The tape ran on silently from that point. Biff stopped the recorder as Li asked, in a puzzled tone, “Is this a joke, Biff?” Kamuka, his eyes wide, was silently asking the same question, but Biff shook his head.

“Far from it,” said Biff. “I never heard this tape before, but it’s Dad’s voice, as you both know. He has a recorder just like mine; in fact, I brought this one along because Dad told me that if he had a special message, he would put it on tape for me—just as he has!”

With that, Biff strode to the porthole and looked out over the black river, toward the thousands of lights that were now gleaming from the vastness of Calcutta, largest city in India, and the second greatest metropolis of what had once been the British Empire.

“But who brought the message?” queried Li.

“And why?” added Kamuka.

“Those questions,” returned Biff, “will be answered tomorrow, at the New India Bazaar!”

The last call for dinner interrupted any further comments on the mysterious message. Tonight was a big event, for the chief steward of the Northern Star had gone the limit to please the three youthful passengers on the freighter. The meal consisted of specialties in Brazilian, Hawaiian, and American dishes, with little speeches in between.

But the boys found it difficult to share the spirit of the other passengers and ship’s officers, who were doing their best to entertain them on this last evening together. Biff was sure that morning would bring some confirmation of his father’s message, while Li and Kamuka were wondering whether or not he had sufficient reason to be that confident.

Early the next morning, the three boys were up and on deck when a mail boat came to the Northern Star. A uniformed Hindu handed a telegram to Captain Peterson, the skipper of the freighter, who passed it on to Biff with the comment:

“This is for you rather than for me.”

Li and Kamuka were peering over Biff’s shoulders as he read the message aloud:

“NOTIFY BIFF BREWSTER HIS FATHER CANNOT MEET HIM IN CALCUTTA. HE AND FRIENDS ARE TO PICK UP PLANE RESERVATIONS FOR DARJEELING AND JOIN HIS FAMILY THERE.”

The message was signed by the New Delhi representative of the Ajax Mining Company, for which Biff’s father worked. Captain Peterson told the boys to let him know if they had any trouble finding their plane reservations at the Grand Hotel, where the bus left for the Calcutta Airport at Dum Dum. Biff and his two companions said good-by and packed themselves ashore.

They took a taxicab past the Maidan, the huge park where hundreds of Hindus were asleep on the grassy expanse. Still more were sprawled along the sidewalk of Chowringhi Road, which brought them to the Grand Hotel. There, they found that plane reservations had been made for Darjeeling, but instead of picking them up immediately, Biff inquired the way to the New India Bazaar and found that it was a short rickshaw ride from the hotel.

Soon the boys were riding swiftly through the native quarter of Calcutta, in a two-wheeled, man-hauled carriage that followed narrow streets flanked by rows of old tenement houses and other crude structures filled with the city’s teeming population.

At the New India Bazaar, they found rows of small shops surrounding a busy square where shoppers in Hindu attire carefully side-stepped a sacred cow that was sprawled complacently on the sidewalk. Barkers were babbling in Hindustani, trying to attract trade and one youth, attired in shorts and loose white jacket, was drumming up business by beating the ends of a wooden keg, tom-tom style, drawing a crowd along with him.

The Indian boy looked tall because he was thin, even to his smiling face. He eyed Biff and the other boys closely as he passed them, giving the drum a few quick, extra beats as an invitation to come along. Biff turned to his companions and ran his hand through his shock of blond hair.

“Dad must have given his friend a good description of me,” Biff told the others, “so I am sure to be spotted soon. The more we circulate, the easier it will be to find me, so we may as well see where this drummer boy is leading us.”

They wound up at an open corner where some buildings had been demolished to make way for one of the wide new streets that were being cut through the city’s congested areas. Temporarily, at least, it had been turned into an outdoor theater, for a man in baggy white clothes and a huge turban was beckoning the crowd his way as he announced:

“I, Jinnah Jad, greatest jadoo wallah in Bengal. I make jadoo with duck. You see.”

By “jadoo” Jinnah Jad meant “magic,” and the term “wallah” signified that he performed it. The jadoo wallah filled a small tub with water from a big jar, then placed a miniature imitation duck in the tiny pond thus formed. As Jinnah Jad made mystic passes over the toy duck, it dived into the water, only to come popping up again at his command.

As the boys moved closer with the interested crowd, Jinnah Jad gestured them into a semicircle and announced:

“I show you magic with mango. First I make tent where it can grow—”

As he spoke, he set three sticks in the ground so they formed a tripod about four feet high. He took a cloth from a big heap and wrapped it around the sticks, making a little tepee. He held up a mango seed, about the size of a large pear, then pushed it in through the opening of the tent, as though planting it.

Soon Jinnah Jad pulled away the cloth and showed a little sprout instead of just a seed. He formed the tent again, using a larger cloth. He piped a tune on a hollow gourd that he used as a flute and pulled away the cloth. There, spreading out from the tent, was a small mango tree, with fruit on its branches!

As the crowd buzzed its admiration, Jinnah Jad turned to the slender boy with the drum and said, “Chandra, you bring me rupees, so I make more jadoo.” The boy promptly picked up a wooden bowl and started through the crowd, taking up a collection, nudging people with the bowl and gesturing to their pockets whenever they hesitated at contributing a few coins.

Biff, meanwhile, was speaking in a low voice to his companions. “Let’s spread out, so you two can watch to see if anyone is watching me,” he suggested. “Then no one will know that we are together.” To that, Li and Kamuka agreed. As they moved away, they each passed Chandra and added coins to the collection at the Hindu boy’s urging. Then Chandra reached Biff and asked politely, “You have rupees, maybe, sahib?”

Biff pulled two rupee notes from his pocket and dropped them in the bowl. Chandra bowed and brushed past, taking the bowl to Jinnah Jad, who picked out the rupee notes and glowered his dissatisfaction at the rest. Two men were passing by, carrying a heavy basket that dangled by its handles from a long pole. Jinnah Jad told them to set down their burden and remove the bundles that it contained. Then:

“This boy is good for nothing,” declared Jinnah Jad, indicating Chandra. “So I make him go for good. You watch.”

Before Chandra could dart away, Jinnah Jad grabbed him and thrust him into the basket, which was roundish and bulging at the sides. Jinnah Jad threw a cloth over the boy’s head and shoulders and suddenly, Chandra’s form collapsed beneath it. Triumphantly, Jinnah Jad jumped into the basket and trampled the cloth there.

Chandra had vanished from the basket, and to prove it, Jinnah Jad not only stamped his feet all around, he squatted down in the basket, filling it with his fat form, while he clucked like a happy hen seated on a nest. Then, emerging from the basket, Jinnah Jad snatched up a long sword, shouting, “I show you boy is really gone!” With that, he stabbed the sword through one side of the basket and out the other side.

While the crowd gasped, Jinnah Jad repeated the thrust again and again, one direction, then another. The jadoo wallah had worked himself into a frenzy when the men who owned the basket stopped him and babbled in a native dialect.

“They know the boy is gone,” translated Jinnah Jad, for the benefit of the crowd. “They do not want me to spoil their basket.” He waved to the basket and told the two bearers, “All right, take it.”

Eagerly, the two natives piled their bundles into the basket, thrust the pole through its handles and hoisted it on their shoulders. By then, Jinnah Jad was in the midst of another miracle. He was pouring rice from a bowl into a square teakwood box that had a glass front, while he stated:

“One time, in India, there was great famine, with people everywhere needing rice. So a great yogi in the Himalayas fill a box with rice like this—”

The throng was hushed, for Calcutta itself had suffered from great famines, even in comparatively recent years.

“So by magic, he sent rice everywhere, to everybody!” Jinnah Jad gave the box a flip. Instantly, the rice was gone from behind the glass and he was opening the box wide, showing it to be totally empty. “Yes, to everybody! To you—to you—to you.” Jinnah Jad was jabbing his finger from person to person. “So look in your pockets and find it! You, sahib—you, babu—find rice!”

People were bringing fistfuls of rice from their pockets. Biff smiled, thinking these were friends of the jadoo wallah, until he saw total astonishment on faces close by. Those included Li’s, for a dozen feet away, the Hawaiian youth was bringing out two handfuls of the tiny grains from each coat pocket. Still skeptical, Biff thrust his hands into his own pockets and brought them out—containing rice!

The deeper he dug, the more he found. Biff was almost ready to accept the jadoo of Jinnah Jad as real indeed, when he brought out something else, a crinkly wad of paper, with more rice inside it. Puzzled, Biff pulled it open and found it to be a penciled note that stated:

Follow men who go with basket. Go alone. Tell no one where you go. Important.

None of the other spectators had found a note like that, for they were simply staring at the rice, while Jinnah Jad moved through the crowd, taking up a new collection in person. Biff looked for the basket bearers and saw them starting slowly away, as if they had waited just long enough for Biff to find the note.

So Biff started after them, working his way through the crowd so that he went past Li. Quickly, Biff muttered:

“Don’t look now. Just find Kamuka and wait for me here. I’ll be back—soon.”

By the time the basket carriers had turned a few corners, Biff was not so sure that he would rejoin his companions as soon as he expected. The lazily moving pair suddenly stepped up their pace and the narrow, poorly paved streets looked so much alike that Biff had no idea where they were leading him.

The streets were flanked by chawls or native houses that were scarcely more than hovels. From the suspicious glances that Biff received, and from the way the buildings encroached upon the narrow alleys, he felt as though a whole sea of humanity was closing in upon him. He realized that he would need a compass to find his way back. There was no telling by the sun, which was out of sight even over the low roofs, although the day was becoming so hot that Biff wished he were back in a rickshaw instead of footing it through these dismal, dirty streets.

Then they reached a better section, where the buildings were higher, with occasional shop fronts. There, the basket bearers slackened pace and turned into a passage beneath an archway that bore the sign:

D. CHAND & BROS.

Import—Export

Warehouse

Biff followed cautiously and saw the two men cross a little courtyard and continue through another archway well beyond. There they disappeared from view but only long enough to set down the basket, because one of them returned to the inner arch and closed a big metal gate behind him. He then went to rejoin his companion.

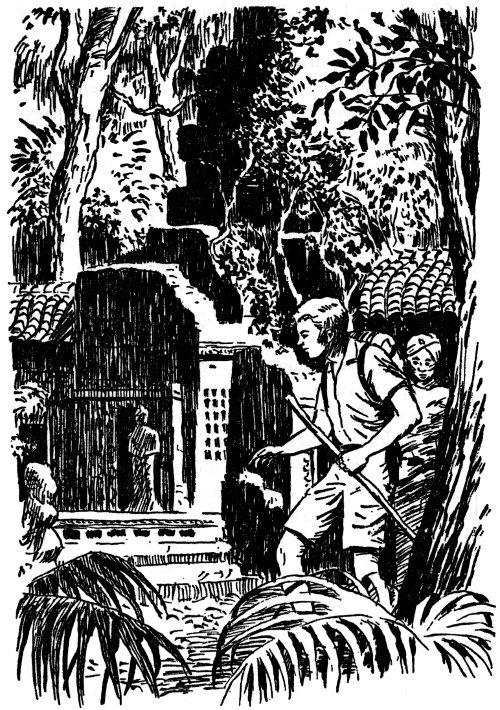

By then, Biff was moving into the courtyard himself. He edged over to one side and gained a look through the inner arch. Beyond the closed gate he saw what appeared to be a large storeroom, for there were many crates, boxes, and other bulky objects stacked there. From his angle, Biff could see nothing of the two men, so he moved cautiously toward the inner arch, hoping to get a closer and more direct view.

At that moment, a clang sounded behind him, and Biff turned to see that another gate had closed in the outer arch. A tall man in baggy white clothes had stepped in from the street and was now locking the gate behind him. Biff was trapped in the open space between the archways. He looked quickly for an outlet, and saw one on the other side of the courtyard, in the form of an open doorway.

Biff hurried in that direction, only to stop short as a man appeared in the doorway to meet him with a polite, welcoming bow. The man was dressed in European clothes, but his broad, bland face, with fixed smile and bushy eyebrows above his large-rimmed glasses, was definitely Asiatic. So was his cool, even-toned pronouncement:

“I am Diwan Chand. I have been expecting you. Come in.”

Then, as Biff hesitated, glancing back at the white-garbed Hindu, who was coming from the outer gate, Diwan Chand added a further introduction:

“This is Nathu, my special watchman. I thought it best to have him lock the gate, so we cannot be disturbed. He will wait here until we return.”

Chand said nothing about the pair who had gone through the inner archway with the basket. Biff followed the bland merchant through a room equipped with a long row of vacant desks, like an old-fashioned counting house.

“Our clerks work here,” explained Chand, “but they have all gone out to lunch, so no one will know of your visit.”

Whether that was good or bad, Biff wasn’t sure. He felt a nervous tingling that seemed an instinctive warning of some close danger; yet it might be that all these precautions were for his benefit.

This seemed doubly so when they reached Chand’s quiet private office at the rear of the long counting room. There, the merchant closed the door, gestured Biff to a chair, and opened a small safe that was cunningly concealed in the elaborately carved woodwork of the wall.

“You received your father’s message,” commented Mr. Chand, “and now I have something for you to take to him. This.”

Biff gasped at the object Mr. Chand placed on the table before him. There, in a small case lined with white velvet, gleamed the largest and most magnificent gem that Biff had ever seen. It was a blood-red ruby, with a touch of purple that gave it a glow like living fire, even in the subdued light of the office. In his study of mineralogy, Biff had viewed many fine stones, but never one that even approached this ruby.

“A padmaraga,” Mr. Chand said. “A true Brahmin ruby, not to be confused with those of lesser caste. Whoever carries such a gem as this one can live in perfect safety in the midst of many enemies, totally without fear.”

At first, Biff thought that Mr. Chand was simply repeating some Hindu legend concerning rubies, but he soon saw that the merchant’s steady smile had become very serious.

“For this I can vouch,” Mr. Chand continued. “The Light of the Lama, as this ruby is known, brought good fortune to the descendants of the rajah who originally owned it. While I have been its custodian, I, too, have prospered. There has been no trouble here, despite riots and disturbances in other parts of Calcutta, in fact, throughout India.”

Mr. Chand picked up the squarish jewel case and started to place it in a chamois bag, as he added:

“And now good fortune goes with you. They say that even the power of invisibility is granted to those who hold this gem. Perhaps that is why danger has passed me by.”

“But in that case,” Biff asked frankly, “why are you giving it to me? Shouldn’t you keep it for yourself?”

“It is my duty to pass it along,” replied Mr. Chand solemnly, “and besides, I have noticed that the Light is losing some of its fire, which is a bad sign. See for yourself!”

He moved the ruby closer to Biff, who saw now that the gem was in a simple golden setting; but more important, just as Mr. Chand said, its sparkle had dwindled. Then, as Biff himself held the jewel, its wine-red depth kindled with new flame, so suddenly that Biff caught his breath.

“A good sign!” exclaimed Mr. Chand, closing the little case and thrusting it into the bag. “That proves it is in the hands where it belongs!” He pressed it into Biff’s hands as he spoke. “So guard it well”—he paused and his fixed smile became whimsical for once—“or I should say, it will guard you well. We have just seen proof of that.”

Evidently, Mr. Chand referred to the ruby’s sudden glow, which was quite puzzling to Biff. But something else puzzled him still more.

“Why must I take this ruby to my father?”

“He will tell you when you see him,” replied Mr. Chand. “The less I say, the better, now that I no longer have the ruby to protect me.”

“And where will I find my father now?”

“In New Delhi. Go there, but do not contact his company except to ask for him by telephone. If he is not there, go to the United States Embassy, but be careful even then, as spies are watching everywhere. Trust only your father’s voice as you did when you received the taped message that I sent you.”

Biff nodded, recognizing the wisdom of all that. Then, thoughtfully, he remarked:

“In that message, my father said I would meet a man that he and I could both trust. I am sure he meant you, Mr. Chand.”

If the merchant had beamed at the compliment, Biff might have been suspicious, for he still felt the odd sensation of some impending danger. But Mr. Chand was modest.

“You can trust me,” he said simply, “but your father meant another man, Barma Shah. He was the contact who brought us together. I had hoped that he would be here to meet you and go with you now, but he is probably being watched.”

“By the same spies you mentioned, Mr. Chand?” Biff inquired.

“Yes. Barma Shah told me he would stay away if danger threatened here. That was a month ago and shortly afterward, new riots broke out in Calcutta. Some were rather close by, the nearest that they have been. Naturally, Barma Shah did not come that day. He has stayed away since—and wisely—so I sent word to you myself, as was arranged for such a situation.”

Above Mr. Chand’s quiet voice, Biff thought he heard a rising murmur, much like the approach of the tidal bore along the Hooghly. Whether or not it was his imagination, he felt more closed in than ever.

“The day of the riots,” Mr. Chand went on, “I looked at the Light of the Lama and saw it had clouded. I was afraid, not for myself, but for Barma Shah. I was glad when he did not come here—”

The murmur was louder now, no longer like wave beats, but more a human babble, with occasional muffled shouts. Mr. Chand heard them, too, for he raised his hand and exclaimed: “Listen!” Timed to the action came a sudden pounding at the office door and the excited voice of Nathu, the watchman:

“Master! There is danger! Another riot has started, outside our very gate!”

As Chand unlocked the office door and opened it, the babble rose to a bedlam of howls, shrieks, and the clang of metal as the mob battered at the big gate. At Chand’s mention of the ruby, Biff had thrust his hand into his pocket to see if he still had the chamois bag that he had placed there. It was safe, and as Biff clenched it tensely, his palm seemed to burn as though the gem were actually glowing through its wrappings.

There was a huge crash as the metal gate collapsed and now, through the barred windows of the counting room, Biff could see the milling figures of the native rioters as they flooded the courtyard, swinging clubs, slashing with knives, and hurling rocks at one another. Some of those missiles smashed the glass in the barred windows, adding to the crowd’s glee, for they were eager to destroy property along with lives.

Mr. Chand showed surprising speed as he whisked Biff back into the little office and through a door in the opposite wall, at the same time saying excitedly, “Go through the godown! It is your only way!”

Biff thought “godown” meant some steps, but instead, Mr. Chand was referring to the storeroom. As Biff started off among the crates, there was another clang from the courtyard, where the rioters were smashing at the inner gate leading into the storage room itself.

“Not that way!” called Mr. Chand. “At the back, you will find another darwaza—another gate! Turn left on the back street until you reach the chowk—the market place! You will be safe there.”

Mr. Chand turned back into his office to help Nathu try to stem the attack, and Biff shoved his way among the crates, clambering over boxes, until he reached the rear exit that Mr. Chand had mentioned, but too late. Already, the back street teemed with rioters. Leering faces turned Biff’s way, and eager fingers pointed at him through the bars of the rear gate.

Then hands were bashing the gate itself as others threw stones through the grillwork. Biff dodged back among the crates, realizing hopelessly that he was caught between two fires. A great crash told that the gate from the courtyard had given way; and an echoing clang from the other direction signified that the rear gate had met the same fate.

What Biff’s own fate would be, the next few moments would tell. Grimly, he found himself gripping the chamois bag in his pocket, wondering if the Light of the Lama could save him now. As if in answer, something plucked his shoulder and Biff turned quickly, bringing both fists up to fight off the first of a hundred enemies.

Instead, he found himself looking into the face of Chandra, the Indian boy who had vanished from the basket back at the New India Bazaar. Above the babble of the rioters came Chandra’s words:

“Quick! Come with me—this way!”

Escape from the frenzied mob seemed impossible, but at least Chandra was making a try as he pushed Biff toward a deep corner of the big storeroom, the only direction in which the invaders had not yet spread. But there was no door, no outlet, nothing except a solid stone wall beyond the last lot of crates.

Those offered no good hiding place, because the rioters already were overturning or yanking open chests and boxes which blocked them, while they kept up an excited shout, “Farangi! Farangi!”

That was one word that Biff knew. It meant “European”—which in his case could be translated as “American”—and it signified that they were definitely after Biff, though probably they would attack any Farangi that they encountered. And now, Biff and Chandra were practically in the corner, with no way to turn, except one, which looked like the worst trap of all.

Just ahead stood a tall, rather bulky cabinet shaped in the form of a pagoda, with half a dozen sides and a pair of front doors that were partly open. Quickly, Chandra thrust Biff inside and pushed him to the back, saying, “In there—keep quiet—do not move!” Then he pressed an inner door shut, and Biff found himself alone in pitch darkness, clamped in a space so tight that Chandra’s admonition not to move was quite unnecessary.

Chandra was gone by then, dodging off among the crates, perhaps to save his own sleek hide at the expense of Biff’s. For Biff, realizing now that he was really boxed, was beginning to regret that he had trusted the Indian youth so completely. Chandra, a native himself, probably had friends among the mob. Maybe he had even told them that he would lure Biff here.

Until now, Biff had had a chance either for fight or flight. Those were both gone, and if he didn’t suffocate in this bandbox, he would probably be yanked out and torn apart before he could even make a move. He was so tightly jammed, he couldn’t even reach into his pocket and find the ruby, which he felt was the real cause of his misfortune, despite the soft talk Diwan Chand had given him.

Even now, Biff heard voices: “Farangi—we find him—look there....” And he could hear crates being turned over close by. Next, the shouters were clambering in and out of the cabinet itself, for Biff could feel it shake and the hoarse, snarly voices were almost at his elbow. They were even pulling the pagoda out from the wall, for its platform was set on wheels; and they were literally spinning it about, with Biff still inside it, yet for some reason, they passed by him in the blackness.

More shouts, louder crashes were suddenly punctuated by pistol shots, leading to a last round of tumult that soon died. Biff heard receding footsteps; then came a deadly silence, which was even worse. Biff felt totally helpless and abandoned, unable to move, afraid even to call for help. He was drenched in perspiration, and why he hadn’t suffocated or been found he couldn’t understand, until a sharp click interrupted his numbed thoughts.

Biff lurched forward, found the front doors and stepped shakily from the pagoda cabinet to find one person in the dim light of the warehouse waiting, grinning, to receive him. That was Chandra.

Briefly, the Indian boy explained things.

“They took a good look for you, all right,” he said. “Some of them did, anyway, while the rest kept fighting each other. They looked a lot, but they didn’t find you—or me.”

“But where did you go, Chandra?”

“Back in basket that brought me here,” replied Chandra, widening his grin. He reached past a crate, pulled out the basket, squatted in it and suddenly squirmed from sight, as if the basket were bottomless. Biff looked in and was amazed to see nothing except a heap of old cloth.

Then, the heap stirred, and Chandra twisted into view from the basket’s bulging sides where he had artfully coiled his thin, agile body.

“So that’s how you vanished!” exclaimed Biff. “Why, you were still in the basket when the two men took it away!”

“How else could I get here so quick?” retorted Chandra. “They are friends of Jinnah Jad, who show up with basket at the right time. This godown is where Jinnah Jad keeps all his tricks, like the new pagoda he built to make people vanish. So I put you there.”

“And I was thinking—”

Biff cut himself short, but Chandra picked him up.

“You think maybe the big ruby made you invisible,” declared Chandra, “as it is supposed to do. But no, it was the pagoda trick. It hid you, the basket hid me.”

Biff was cooler now, and he felt an actual shudder as he looked around at the wreckage and saw some silent human figures lying near the gate to the courtyard. Otherwise, the warehouse was deserted, except for Biff and Chandra.

“But where did they all go, Chandra?” Biff asked.

“You heard shooting?” returned Chandra. “That was the police. They came to help Diwan Chand. Lucky they didn’t use tear gas, which they do a lot. We would have gotten it, too.”

Chandra was looking around at the broken boxes. He saw one that interested him and beckoned Biff that way.

“We must get out before police come back and ask us to be witnesses,” declared Chandra. “But the people who are after the ruby will be watching for you. So you must wear other clothes—like these.”

Chandra was picking some native garments from those that had been dumped from an overturned chest. Studying Biff, Chandra noted the deep tan that Biff had acquired during his long voyage on the Northern Star.

“Your face is dark enough,” decided Chandra, “but your light hair will have to be hidden. So we will make you into a Sikh. A Sikh always wears a turban. That will fool everyone.”

Soon, Biff was attired in a costume that made him feel top-heavy. It consisted of shorts, shirt, and jacket, and a huge turban, which completely covered Biff’s ears as well as his head, after Chandra helped him wrap it. They bundled up Biff’s clothes along with some other garments and went out by the rear gate.

It was fortunate that both were in native garb, because Biff could sense that eyes were watching them as they followed the street to the market place. Chandra knew it too, for he said, “Don’t look around. They will suspect us if you do.”

There were natives in the market place, gathered in little clusters, discussing the recent riot. They glanced at the boys as they passed, but that was all. Chandra gave a pleased chuckle, then added cautiously, “It looks good now, but still we play it safe. We go the long way, past the thana.”

By thana, Chandra meant police headquarters, a place that suspicious characters would avoid. After passing it, the boys were satisfied that they were not being followed, so they doubled back to the New India Bazaar, where they saw Li and Kamuka studying the passersby from the doorway of a sporting goods shop.

It was Biff’s move now. He eased up to Li, tapped him on the shoulder, and said, “Salaam, Sahib.” Li turned and blinked puzzled at the face beneath the turban until Biff could no longer restrain a grin.

“Biff!” exclaimed Li. “But where—and why—”

“We can’t talk here,” interposed Biff. “Meet me around the corner and bring Kamuka.”

Chandra was with Biff when the other boys arrived. After introducing the Indian youth, Biff said:

“I must go to New Delhi. If Chandra can go with me, it is up to him to decide who can accompany us.”

“I can go,” Chandra assured him, “and Kamuka, too. But not Li.” He turned to the Hawaiian youth. “Too many people saw you with Biff while you were watching Jinnah Jad make jadoo. You might be recognized, one because of the other.”

Before Li could even show the disappointment that he felt, Biff softened the situation.

“Somebody will have to go up to Darjeeling,” he reminded his friend, “to tell the family where I’ve gone. Canceling those extra plane reservations and handling our luggage is a tough job, too. It looks like you’re elected, Li.”

Li not only was elected; he did his job well. He went to the Grand Hotel and returned by taxi, rejoining the group at a restaurant that Chandra had specified. Li had canceled the air reservations without difficulty; he had brought hiking packs for Biff and Kamuka, and he had arranged for shipment of the excess baggage.

After a substantial meal, Li returned to the hotel by cab, to catch the Darjeeling plane. The other boys boarded a big bus for Howrah, across the river. Biff and Kamuka looked down from the tremendous cantilever span and viewed the muddy Hooghly, hoping to spot the Northern Star moored in the dim distance. They were talking about it—in English, unfortunately—when Chandra hissed for silence.

They realized then that they were an odd group as it was—too odd to be using English as a common language. Biff, whose features didn’t properly match his Sikh’s costume; Kamuka, who might have come from an upcountry tribe, but was wearing European clothes; Chandra, who with his dhoti and jacket, looked like a jadoo wallah’s boy, which was exactly what he was, and therefore the most outlandish of the trio.

In short, they were attracting too much attention. Biff and Kamuka promptly subsided. Biff, particularly, felt that he should show some dignity, so he did, by looking squarely at the other passengers, until he caught the eye of a distinguished-looking man across the aisle.

The man had a large beard and a huge turban, which marked him as a Sikh, and a genuine one. He was studying Biff with sharp eyes that continued their piercing probe until the bus reached Howrah Station. Then, as they were stepping from the bus, the bearded Sikh suddenly spoke to Biff in what was their own common language, except that Biff couldn’t understand a word of it.

All that saved Biff was a surge of the crowd, with people pushing one way, then another, cutting him off from the bearded Sikh. Next, Biff was on the outskirts of the milling throng, and Chandra was yanking him away, along with Kamuka.

“Thanks, Chandra!” Biff gasped. “If you hadn’t dragged me out of that jam, the Sikh would have known I was a fake—”

“That wasn’t why!” returned Chandra. “That wouldn’t have bothered us. Maybe you’re a fake, but he’s a bigger one. I saw his beard close enough to know.”

Biff looked back and saw that Chandra was right. Caught in the crowd, the man with the big turban wasn’t trying to follow the three boys; in fact, he couldn’t even see them. The reason was that his false beard had been pulled up over his eyes, and he was madly trying to straighten it.

Hand in his pocket, Biff was gripping the packet that he had transferred from his own clothes, wondering if the Light of the Lama again had saved him from an enemy!

Right then, Biff’s one hope was that he and his two companions could lose themselves in another and bigger crowd and thus dodge the disguised stranger who was so intent upon following them.

They couldn’t have chosen a better place than the Howrah Station. It seemed five times bigger than any other railway station Biff had ever seen, and it contained ten times as many people. The afternoon had reached its peak of stifling heat, so they had come in here and sprawled over the acres of cool marble floors in preference to the Calcutta sidewalks.

The boys had to step around prostrate bodies or clamber over them, as did hundreds of other travelers who were thronging the great depot. Practically all of those travelers were natives, and many of them were carrying huge bundles that contained most of their worldly possessions.

Chandra explained that many of Calcutta’s three million citizens were constantly on the move, due to lack of food or jobs; but that as fast as they left town, others poured in to replace them. He added that the population was still shifting between India and Pakistan, which accounted for more travel, particularly since the East Pakistan border was so near Calcutta. He also mentioned that many were pilgrims bound for Benares and other places holy to Hindu cults.

While the boys picked their way through the immense station, Chandra pointed out examples of each group. He also called attention to occasional Europeans and well-dressed Indians, including Hindus of high caste.

“Those few,” declared Chandra, “go first- or second-class. Always, some talk English and ask too much about everybody’s business. I know, because I have gone second-class with Jinnah Jad. So we will go third-class and talk just to each other.”

That satisfied Biff and Kamuka. It wasn’t a matter of saving money, for they had pooled their cash and had more than enough to travel in luxury, with Chandra included. But getting to New Delhi unnoticed was essential, and the train trip, which required more than twenty-four hours, was the sort that promised complications, so the more they avoided, the better.

Chandra had a bright idea on that score, too. Biff gave him enough money to buy three third-class tickets, but when Chandra rejoined the other boys, he returned half the cash.

“I only buy tickets halfway,” he stated, “so nobody will know we are going to New Delhi. They will think maybe we are going to Benares or Allahabad, but instead we will go on to a little village where my uncle lives and start again from there.”

“You’re the boss of this expedition, Chandra,” Biff assured him. “Anything that will cover our trail is a good idea.”

Breaking the trip also seemed a good idea when Biff saw the accommodations that the third-class carriages offered. Biff had been afraid that he might be noticed on the station platform, the way he had been on the bus, but that worry soon was over. The platform was thicker with milling humanity than the station itself. People would have been pushed onto the track, if the train hadn’t been there to receive them.

Many were crowding into first- and second-class compartments, only to be pushed out and ordered back to where they belonged, in third class. Amid the commotion, Chandra found one third-class compartment that looked full, but wasn’t, because the occupants had simply spread their luggage in a haphazard way. Chandra began piling them together like so many bundles of wash, until he had made room for all three boys, including their own luggage.

The seats in the compartment were little better than benches, but Biff gladly drew himself into the deepest and most uncomfortable corner, rather than be observed too closely when members of the train crew closed the doors, for some of them were genuine Sikhs who might have seen through his thin disguise.

The platforms were still crowded when the train pulled out—as many people had come to the station simply to see the others off. Then the train was rolling into the open country, what little Biff could see of it. The rattle of wheels mixed with swirls of dust and blended with the smell of garlic and spices, for everyone was bringing out native food, bowls of rice, bananas, and other fruit. Biff’s appetite was suddenly roused.

“Think of all that rice Jinnah Jad wasted,” Biff said to Kamuka, “when he did that trick! I could eat some of it now.”

“He didn’t waste it,” reminded Kamuka. “He put it in our pockets, remember? We should have kept it.”

“Say, that was a neat trick.” Biff turned to Chandra. “How did Jinnah Jad work that part of it? Or don’t you know?”

Chandra grinned broadly.

“That is one trick I do know,” he declared. “Remember when I went through the crowd, tapping people’s pockets, asking for rupees, like this?” He tapped Biff’s pocket, then Kamuka’s, and they both nodded. “While I do that,” Chandra went on, “I use my other hand to put rice in other pockets. So later, the people find it there.”

“So that was it!” Almost instinctively, Biff thrust his hand in his other pocket, then brought it out in amazement, with a pair of candy bars. Kamuka, reaching into his own pocket, found himself staring at a handful of loose peanuts.

“You must have bought these when you went for the tickets,” said Biff to Chandra, “and then you slipped them into our pockets while you were telling us how you did it! Candy for me—peanuts for Kamuka—”

“And now you have peanuts, too,” put in Chandra, “in the pocket where you keep the big ruby.”

Again Chandra was right, and Biff’s amazement at the Indian boy’s skill was complete. They ate their chocolate bars and peanuts along with some fruit that Chandra had also brought them. Then, when the other passengers were no longer noticing them, Chandra remarked:

“Remember how the big man with the fake beard got tangled in the crowd, when we were leaving the bus?”

Biff and Kamuka nodded.

“I do that too,” declared Chandra proudly. “I push one person like this”—he nudged Biff forward—“and another like that”—he gave Kamuka a backward push—“and pretty soon all are in each other’s way.”

Biff smiled at that, too; then he turned solemn.

“We’ve been watched,” he declared, “and that’s for sure. So let’s be still more careful from now on.”

At various stops, the train disgorged many passengers who filled up water jars that they had brought along and returned to the train before it started. Biff and Kamuka let Chandra handle that job for their party, rather than show themselves on station platforms.

Occasionally, though, Kamuka waved from the compartment window to fruit sellers who also supplied milk and soft drinks. At such stops, first- and second-class passengers went ahead to the dining car or had attendants bring choice dishes to their compartments; but third-class travelers didn’t rate such service.

It was turning dark when the train reached the great coal fields in western Bengal. That part of the trip interested Biff most, because of the mining activity. But there was little to be seen, and soon, despite the rattle and jouncing of the train and the discomfort of the stuffy corner, Biff began dozing off.

Once, Chandra nudged him and whispered, “Watch your turban! Keep it on straight!” and Biff woke sufficiently to realize that he had one ear out of the cumbersome headgear. He worked it into place, saw Chandra nod approval, and then went back to sleep.

Again, Chandra woke both Biff and Kamuka, who was sleeping, too, telling them, “Watch out, now! New passengers coming on board. Don’t let them look at you too close.”

So Biff and Kamuka kept their heads together and engaged in low conversation until the new passengers gave up looking at them and fell asleep themselves. That gave Biff and Kamuka the right to do the same. This time, Biff’s sleep was sound, undisturbed by the joltings of the train or the blare of the locomotive whistle as it rushed on through the thick night.

It was a dream that wakened Biff. He imagined that he was clutching the big ruby, while hands were trying to snatch it from him. He was confronted by bearded Sikhs and as he clawed wildly at their faces, their beards came away, until he saw only one smooth face and opened his eyes to find that the dream, in a sense, was real.

Biff was clutching the bag that contained the ruby, but his hand was deep in his jacket pocket. The hands that were clutching him were Chandra’s, shaking him awake; and the smooth face, too, was Chandra’s. Quickly, the Indian boy put his finger to his lips for silence.

The train was standing still. All was silent in the compartment except for the snores of other passengers. The lights looked dimmer than before, because it was no longer pitch dark outside. Faint streaks of dawn were reddening the sky beyond low-lying hills. The compartment at last seemed slightly cool.

Biff risked a whisper. “Where are we?”

“At an engine-changing station,” Chandra whispered back. “Our own is farther on, but we cannot wait until then.”

He gestured toward Kamuka, who was still asleep. Between them, Biff and Chandra shook Kamuka and roused him instantly. Like a team, the three boys gathered their packs and stepped carefully past the knees and over the legs of sleeping passengers. Moments later, they were on a weather-beaten platform alongside the long, silent train. A few dozen human figures were stretched on the station platform, with white sheets of cloth drawn completely over their motionless forms, like shrouds.

“Railroad workers, mostly,” whispered Chandra, “waiting for the next shift. No one else gets on or off here, at least, not often.”

“But why are they covered over?” asked Biff, impressed by the weird appearance of the figures.

“Because the night was cool for them,” replied Chandra, “but not too cool for the insects. Soon, now, the covering over their heads will keep the sun from waking them.”

The boys stole across the platform past a square-shaped station where more such figures lay asleep. Kamuka, looking back at the train, put the next query:

“But why did we get off here?”

“Too many passengers changed places in the night,” replied Chandra. “I saw new faces; then later, I recognized some of the old again. If we had gotten off at a crowded station, we could easily have been followed. Here, no one else can leave the train without our seeing them.”

Chandra was right. The boys had reached a road that led at an angle from the tracks. Looking back, they could see the full length of the brightly colored train, as they continued on their way. In the gathering daylight, their keen eyes would surely note any motion on the steps of any of the cars. Ahead, the road led through a grove of trees. Once there, the boys themselves would be out of sight.

There was just one spot the boys’ roving eyes did not cover; that was the portion of the platform obscured by the squatty station. There, three white-shrouded shapes were rising like ghosts in the gray dawn. They dropped away their sleeping sacks, revealing limber figures clad in dark clothes that blended with the background of the station wall, as well as the trees beyond.

One man gave an order in a native dialect and like human bloodhounds, the stealthy trio stalked off along the very road that the three boys had taken!

When the dawn had broadened into full daylight, the change was not too noticeable, for by now the boys were trudging along a narrow, winding road that was flanked by vivid tropical foliage and thick, overhanging tree boughs that cut off much of the sunlight.

To Kamuka, this was intriguing indeed, for it carried him back to his own jungle life in Brazil, especially when he caught the chatter of the monkeys from the higher branches. But to Chandra, who was familiar with it all, such sounds were an annoyance as he tried to explain his plans to Biff.

“This road will take us to the Grand Trunk Road,” stated Chandra, “which we will follow until nightfall to reach the village of Supari, where my uncle is patwari—”

“Patwari?” interposed Biff. “What is that?”

“The same as karnam or kulkarni or talati—I have heard it called by all those names—but it means in English, the man who keeps the village accounts.”

“That would be the town clerk in America.” Biff nodded. “So your uncle is an important man. Go on.”

“On the Grand Trunk Road,” continued Chandra, “we will look like everybody else, because all India is there. You will see hathi, oont, ekka—”

“Wait now, Chandra,” put in Biff. “Hathis are elephants, that I know. And oonts are camels. But I never heard of ekkas. What are they?”

“Pony carts,” returned Chandra seriously, “and you will also see bicycles and jeeps.”

“It sounds good,” decided Biff. “But what if we were being watched on the train. Do you think they will catch up with us?”

“They cannot catch up,” returned Chandra, “because they have gone ahead. If they talked to ticket agent or to the man who took our tickets, they know where we should get off and will look for us there.”

“When does the train reach our station?” Kamuka asked.

“Not for about an hour,” calculated Chandra, “counting change of engines. Before they come back to look for us, we will be on the Grand Trunk Road.”

Despite his assurance, Chandra was moving rather cautiously, but for another reason. He was looking from side to side, for they were in the jungle now and there was no telling what night creatures might still be on the prowl. Chandra knew this from occasional experience in such a setting, as any Indian boy would who had lived in a native village like Supari. But Kamuka, the boy from Brazil, recognized it instinctively, for he was jungle born and bred, though in the opposite hemisphere.

“Remember, Biff?” queried Kamuka. “The time the big jaguar jumped at you?”

“I remember,” replied Biff, “because it was you who stopped it, Kamuka.”

“I just helped,” said Kamuka. “But this jungle reminds me of jaguars. Do they have them here?”

“They have cheetahs, leopards, and tigers. Those should be enough—and more.”

“And big sucuria, too?”

“Yes, they have those.” Biff turned to Chandra. “He means a boa constrictor. We ran into a big one up the Amazon, a snake the size of your python.”

“What about Macu?” demanded Kamuka.

“Head hunters,” translated Biff to Chandra. “He wants to know if you have them, too.”

“We have something much worse,” declared Chandra solemnly. “We have thugs, or stranglers, who ride on trains with us. They are after your ruby, Biff, if you still have it.”

Anxiously, Biff brought the bag from his pocket, opened it and held the Light of the Lama in his palm, where it caught the glint of the sunlight and reflected it with a vivid crimson sparkle that seemed to dye Biff’s entire hand. The great ruby was larger than the biggest walnut, and as Biff turned it in the light, its flattened surfaces, or facets, rivaled one another with their fiery glow.

Chandra, who had been around the gem markets of Calcutta and other Indian cities, and Kamuka, who had seen the finest of South American stones during his studies in Brazil—both were swept with awe.

“Never have I seen such fire!” exclaimed Chandra. “The red ruby, like the blue sapphire, is often beautiful in color, yet very dull.”

“This one loses its sparkle sometimes,” Biff declared. “And according to Mr. Chand, it’s a bad sign when it does.”

“It gives us a good sign now,” observed Kamuka. “In South America, we have the finest of all gems, the green emerald from Colombia. They say it glows brighter than any red ruby, but now I am not so sure.”

Biff smiled, as he recalled Kamuka’s debates with Li while they were on the freighter voyage. For Kamuka to admit that a product of South America could be matched by those of any other continent, was a concession indeed.

“That ruby,” calculated Chandra, “must be worth ten lakhs at least, ten times a hundred thousand rupees. But that is not why your father wants it. He needs it for some special purpose; that was why he went to New Delhi. That much I have heard Mr. Chand tell Jinnah Jad.”

“So it was through Jinnah Jad,” inquired Biff, “that my father’s message reached me?”

“It was more through me,” returned Chandra proudly. “I swam out to the ship, carrying the tape in this.” He produced a watertight bag on a neck chain. “I looked for the cabin with the tape recorder. I put on the tape, the way Mr. Chand showed me. Then I heard you coming, so I went out through porthole quick, and dropped straight down.”

“A neat trick,” complimented Biff. “I’d like to see you do it some time. Tell me, Chandra, did you ever meet my father?”

“Yes, I see Sahib Brewster twice, when I was there at Chand and Brothers, with Jinnah Jad.”

“And did you meet his friend, Barma Shah?”

“No, never. He came only to see Mr. Chand in secret. He is what you call undercover. He stayed away on purpose, when others began to find out that the ruby was there. Like thugs I speak about.”

They were trudging along the road again, and now Biff recalled that it was Chandra’s mention of thugs, or stranglers, that had caused him to stop and make sure that he still had the priceless ruby safely tucked away.

“These thugs,” questioned Biff, “do they want the ruby because of its value?”

“They want it because of the goddess Kali,” replied Chandra. “That is why they started riot outside of Chand and Brothers. They would have strangled Mr. Chand, but they found the ruby gone—”

“So they were looking for me because I had it, and they would have killed me for it!” Biff explained.

“That is right. But thugs will strangle almost anybody if they find suitable time and place, because they believe in Kali.”

Biff was putting the ruby back into its bag. Chandra paused to hand him the chain with the waterproof bag, suggesting that he put the packet in that, which Biff decided was a good idea. As they started on again, Biff urged:

“Tell us more about this Kali business, Chandra.”

“People say Kali was a great goddess who killed a huge monster that wanted to destroy the world,” Chandra related. “But each drop of monster blood sprang up into a new monster. So Kali taught men to strangle monsters with a special cloth called rumal, about this long”—Chandra spread his hands approximately a yard apart—“and after monsters were all gone, men began to strangle men in the same way, never shedding any blood. And so they do today.”

“But all that was stopped a hundred years ago—”

“You mean the time when British Raj said there should be no more thugee? Look there”—Chandra stopped abruptly and pointed to an anthill at the side of the road—“and you see white ants. They are dangerous, like thugs, so I stamp them out.” Roughly, Chandra trampled the anthill and the insects teeming around it. “But are they all stamped out? No, some have gone under—how do you say it?”

“Underground,” returned Biff.

“That is it,” nodded Chandra. “That is the way the thugs went. Underground. Now they have come up again.”

“But why do they want the ruby for Kali?”

“Because they think that rubies are drops of demon blood that will become new demons unless Kali stops them. Your ruby would make biggest demon of all, so they want it most. So Jinnah Jad tells me.”

“How many thugs do you think were on the train with us, Chandra?” Biff asked.

“There always must be three,” declared Chandra. “Two to use the rumal while the third holds the person they strangle. Always, they pick some quiet place. Often they work in many secret bands, so they have a special call, which Jinnah Jad has heard and warned me against. It goes like this—”

Stopping short, Chandra tilted his head back and gave a long, weird howl, “Hyyyyaaaaahhhh!” that sent shivers up Biff’s spine, despite the increasing warmth of the morning. Biff pulled off his big turban and mopped his forehead.

Kamuka, too, was impressed. Never in the jungle of his own native Amazon had the Brazilian boy heard a cry as strange as that. It was a curious cross between a human shriek for help and an animal’s anguished wail. In jungle or village, it would strike a familiar, yet fearful note.

But as Biff and Kamuka stared in silence, Chandra’s own face turned suddenly tense. From beyond the bend in the narrow road behind them came a distant, echoing answer:

“Hyyyyaaaaahhhh!”

It was Biff who broke the grim hush.

“Try it again, Chandra. Let’s see how close they are.”

Chandra repeated the call in a louder wail that must have carried farther, for now the answer came, not from behind them, but from the jungle reaches up ahead. To the startled boys, their plight was all too grimly plain.

On a forgotten road, walled on both sides by solid jungle, they were trapped between two murderous bands of approaching thugs!

As the boys stood rooted, the strange cries came again; first from one direction, then the other. But now there was a change in their weird tones. They trailed longer, as though the thugs were telling each other something, perhaps that they had helpless victims caught between.

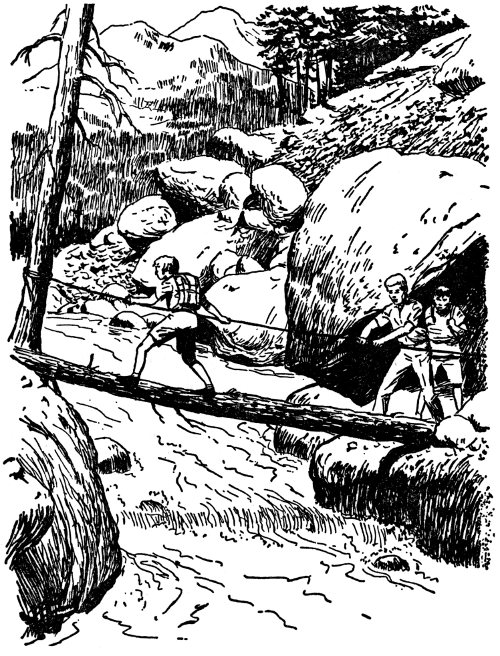

Both Kamuka and Chandra sensed it. Kamuka was for taking to the jungle, a setting that he knew so well, even though it meant facing creatures different from those in Brazil. Chandra was willing to go along with that, but Biff overruled them with a single vote.

“They’d start beating the brush for us,” he argued, “and that would only drive us deeper. It’s not going into the jungle that I mind; it’s our chance of ever coming out.”

He was beckoning the other boys along the road as he added: “We must keep ahead of that bunch behind us, because they are really hot on our trail. Those up front are farther away, even though they are coming toward us. We may still have time to find a clearing where we can hide, or better still, some jungle path.”

Tensely, the boys quickened their pace. The road here was winding more sharply, for it was veering in among the low-lying hills. As they passed a turn in the road, Biff pointed ahead to a gap in the thick jungle, exclaiming, “That may be it!”

Again, long trailing cries came from both directions as though taunting Biff’s hopes. The call from in back was still as far behind, but the one ahead was much closer. Gritting his teeth, Biff muttered for his own benefit, “This will have to be a path—or else!”

It was a path, but a rocky one, leading up a steep slope that flanked the road. But the boys took to it eagerly, climbing rapidly despite their packs, so as to reach the first spot where the path itself made a sharp turn amid the thick foliage.

Once there, they were out of sight from the road below, so they paused for a breather while they dipped water from a little stream that tumbled down among the rocks beside the zigzag path.

Biff asked Chandra, “Any idea where this path may take us?”

“Maybe nowhere,” responded Chandra glumly. “It may just be an old stream gone dry.”

“I don’t think so.” Kamuka studied the course of the stream with a practiced eye. “Look at the smooth rocks here in the stream, yet all those on the path are rough. If water came up there a lot, they would be smooth, too.”

Chandra still was doubtful until Kamuka pointed far up the path.

“See where the path takes a short cut over the little hump of ground?” he said. “The stream would go around that, even in the wet season. This is a path, all right.”

“And we’d better be using it,” Biff put in, “before those thugs get the same idea.”

Low calls of “Hyyaahh” from both directions down on the road below indicated that the pursuing groups were close together, probably closing what they thought were the jaws of a trap. Now that they had regained their wind, the boys lost no time in resuming their climb, this time at a steady, even speed that they were sure would keep them well ahead.

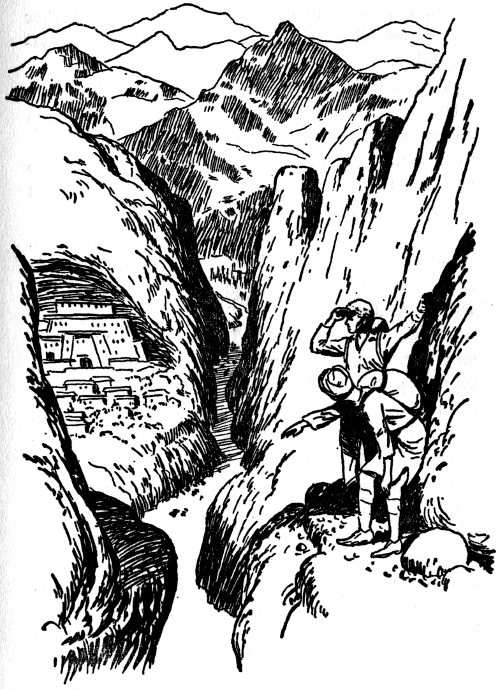

Kamuka was correct about the path. It was a real one, for soon it veered away from the stream entirely and brought the boys to a jutting promontory that gave them a good view over the green wave of the jungle slope below. There they rested again, while Biff traced the course of the road that they had left.

“If we could only cut across and strike the road a few miles up the line,” he said, “we would really shake off those thugs. But no such luck, I guess. We’d never hack our way through all that growth. Let’s stick to the path.”

Sticking to the path meant further climbing, but it proved short, as the top of the hill was only a little way above. As they reached the final hump and emerged from the thick foliage, the boys stopped in surprise. Perched on the summit was a ruined temple, its white marble steps showing through the tangled underbrush, which was climbing up the battered pillars and weather-worn walls.

Perched on the summit was a ruined temple

A corner of the tiled roof had fallen in and a tree projected there instead of a small dome, one of a group surrounding a larger central dome, which was also in a battered state. As the boys reached the steps, there was a sudden chatter from within the ruined temple, and troupes of monkeys scampered out through the holes in the roof and the long window slits in the walls.

“A good hiding place,” decided Chandra, “if the monkeys have been using it as their home.”

“Then we can lie low here,” Biff said, “until after the thugs have gone.”

They were entering through a fancifully tiled archway as Biff spoke. Chandra extended a restraining hand as Biff turned toward an inner corner, where a battered stone railing marked a stairway leading to a floor below.

“Be careful where you lie low,” warned Chandra. “These old places are alive with deadly cobras.”

“But how can the monkeys live with the snakes?”

“They don’t. Monkeys stay up there”—Chandra pointed to a balcony where tiny faces and quick little eyes were peering through what was left of a once ornamental railing—“and the cobras live in the pits below.”

Biff saw that the stairway was blocked by broken chunks from the floor, but he eased away on the chance that a poisonous snake might be lurking in the rubble. Kamuka, meanwhile, had crossed the floor to a small domed platform that was reached by steps leading up from three sides. Kamuka called:

“Biff,” he called. “Come look! See who is here!”

Biff joined Kamuka and stared up at the most hideous idol he had ever seen. It was carved from a dark wood and had white, glaring eyes formed of tiny pearls with a jet-black stone in the center. Larger pearls formed the teeth of an open mouth, from which a carved, red-painted tongue extended.

The ferocious image had four arms extended from its body. One hand held an actual knife with jeweled handle and long curved blade, as though ready for a downward stroke. Another hand was raised in a warning gesture. The third dangled a carved human head. The fourth hand was thrust slightly forward and was cupped, but empty.

From the idol’s neck hung a chain of human skulls, forming a huge, grotesque necklace. Biff had already guessed the identity of the carved horror, when Chandra arrived and gasped the name: “Kali!”

Biff stared at Chandra, wondering why he was so shaken. In a frightened tone, Chandra exclaimed:

“This temple is old and broken, but the idol is a new one! We can’t hide here! This is where the thugs themselves meet to worship Kali. They have driven us up into their trap, and they will come here to hunt us down. See that hand, Biff, the one like a cup? It is supposed to hold blood, so it is waiting for the big ruby that you carry!”

An odd fascination had gripped Biff as he studied the hideous figure of Kali. He snapped out of it now.

“What are we waiting for?” he demanded. “Let’s get out of here!”

They couldn’t go out the way they had come in. Already, a long-drawn cry was sounding from the path leading up to the temple. It was answered almost from the doorway, and the boys realized now that other members of the Kali cult must have been lurking in the fringes of the jungle, watching their arrival.

Kamuka, quick as ever, pointed out a corner stairway leading up to a stone balcony in the rear wall, just above the Kali statue. Sunlight shone through a slitted window that was located there. Grabbing their belongings, the boys raced up the steps, then along the balcony, where they jumped its broken gaps. They reached the window slit and squeezed themselves through to a narrow outer ledge, where they pressed their backs against the wall and stared downward hopelessly.

They were high up in the temple now, the equivalent of about three floors in an ordinary building. There, a full thirty feet below, was a stone court at the rear of the temple wall. The paving was cracked, but as hard as ever—anything but a happy landing.

Close to the wall was the circular rim of a stone well, but it was built up only a few feet from the courtyard. Not a slit, not an opening showed in the wall itself, as the boys studied it cautiously, except for a few irregular cracks that would afford no hold whatever.

If they had arrived here sooner, they could have planned some way to lower themselves to the courtyard, but that was too late for Biff and his companions now.

Already, high-pitched cries of glee were sounding from within the very walls of the crumbling temple that the thugs had turned into a trap baited with their idol, Kali.

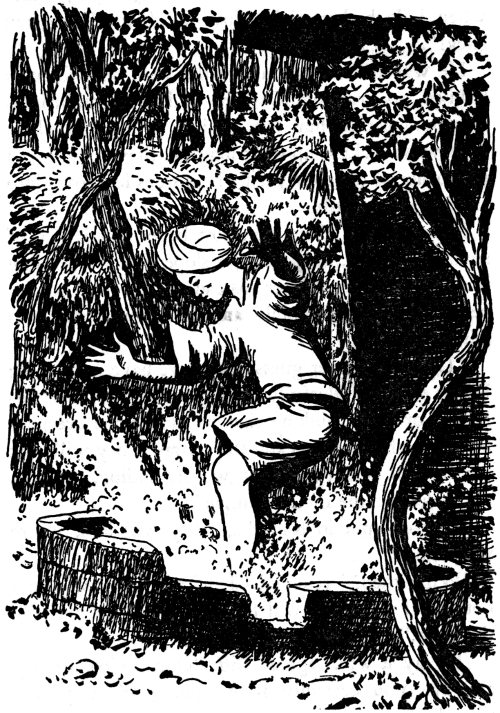

Chandra, crouched on the ledge, was holding a chunk of stone in his extended hand as he pressed Biff slightly to one side. Chandra dropped the stone, and Biff watched it plummet downward into the courtyard well, where it struck with a splash that sent ripples spreading like a bull’s eye.

“Now watch me,” said Chandra. He tossed his pack down into the courtyard and stood straight up at the exact spot where he had crouched. “My feet are here, by this mark. I step off to there”—he extended his arm again—“and bring hands at sides, feet together....”

Chandra finished by doing just that. He stepped out into space, hands at sides, brought his other foot forward and arrowed straight downward! Biff and Kamuka watched amazed, expecting a crash landing. Instead, Chandra followed the exact path of the stone that he had dropped. The circular well seemed to spread its opening wide to receive him as he hit the water with a sharp plunk and vanished.

Then, after what seemed interminable seconds, Chandra popped up from the surface, reached his arms wide and pulled himself out of the well, which Biff was pleased to see was larger in diameter than it looked. That, Biff realized, was the real mental hazard.

“Either look straight ahead, Kamuka,” he told his friend, tossing his pack-kit and his Sikh turban down into the court, “or just shut your eyes the way I am going to do. Anyway, stand right on Chandra’s mark”—Biff took that position as he spoke—“step off, bring your feet together—”

With that, Biff, too, dropped. Never before had he known a split second to divide itself into as many moments as those. All the way down, he was wondering if his step had been too long or too short, or whether he had let his body waver. Thirty feet seemed like thirty years, until Biff punched the water squarely and went deep, deep, deep, then came upward faster, faster, and hauled himself out the way Chandra had.

Before Chandra could extend congratulations to Biff, another pack-kit hit the paving beside them. Kamuka was ready to take off, and for the first time, Chandra expressed the worry that he really felt.

“Climb up quick, Biff!” he said, from his side of the well. “If Kamuka misses—if he wiggles—we must keep him from hitting stones too hard!”

Biff came up on the opposite side, ready to help break Kamuka’s fall, but it proved unnecessary. A lithe brown form streaked feet first between the ready hands that Biff and Chandra extended and was gone as the water sprayed up from the well.

Chandra popped up from the surface and reached his arms wide

“Gone!” exclaimed Chandra. “Like Jinnah Jad says when I do basket trick. Now watch me bring him back!”

He waved his hands above the well, and Kamuka bobbed up grinning. Chandra and Biff grabbed his arms and hauled him out, anxious to get started on their way. Picking up their luggage, they cut off to a far corner of the courtyard where steps led down into another jungle path.

Minutes later, they were lost beneath a lattice of spreading green, descending a slope that was leading them away from danger instead of into it. Chandra began to chuckle happily and finally exploded into mirth.

“They will never guess where we have gone,” the Indian boy said gleefully. “They will wait, those followers of Kali, thinking that we will come creeping back like the monkeys and the cobras. They will look for us and will think that we are hiding, waiting, somewhere in the ancient temple.”

“Maybe,” put in Kamuka, “they will look where we jumped.”

“What then?” rejoined Chandra. “They will find nothing. Everything will be dry around the well by that time.”

“I’ll say it will,” agreed Biff. “Our clothes are dry already. You certainly found the quick way out, Chandra.”

“Like I did from the porthole in your cabin,” reminded Chandra. “You said it was a good trick, so I showed you.”

“But where did you learn it?”

“From my great-great-great-grandfather, up near Delhi. He still dropped into an eighty-foot well when he was eighty years old.”

Biff had heard of the famous well jumpers, who for centuries had performed their amazing feat of dropping straight down an eighty-foot shaft that was only eight feet wide. That dated back to when the Great Moguls had ruled India and the skill had been handed down from father to son for generations until the British government had forbidden it as too dangerous.

“But I thought they stopped well jumping—”

Biff caught himself, afraid that he would offend Chandra, but the Indian boy took it in good humor.

“You mean like they stop thugee?” laughed Chandra. “They tried, but thugs go underground so we still go under water. The big difference”—Chandra turned serious now—“was that thugs hurt other people and should be stopped, but well jumpers hurt nobody but themselves and even then, not very often.”

“I guess not,” agreed Biff, “or your great-great-grandfather wouldn’t have been in the game at eighty.”

“My great-great-great-grandfather.”

“My mistake,” said Biff. “So your people still kept on jumping down wells?”

“No, we obey the law,” returned Chandra. “We stop. But we practice in open pools, just like other people dive. Sometimes at night, we take full moon as target. We drop a stone from a high riverbank, where the moon shows in the water. Then we step off like we three just did.”

“It’s lucky you showed us how, Chandra,” Biff said. “We never would have tried it on our own. Would we, Kamuka?”

Kamuka shook his head emphatically. “I should say not!” he responded.

Fortunately, Biff, who was a good diver, had often stepped off springboards or diving platforms as a stunt. Kamuka, too, had used the same technique from the edge of high piers on the Amazon, when boats were moored too close to allow a normal dive. So they had been ready and able to copy Chandra’s well jump without hesitation, when the time had called for instant action.

A few hours of steady plodding along the gradually descending path brought the boys to a level clearing studded with the remains of a long-abandoned town. Piles of ancient bricks represented the walls of houses, though enough were still standing to mark the lines of streets and market squares. A slightly higher clearing showed a row of sculptured stone pillars, remains of an ancient temple. From another such space loomed the ruins of what must have been a maharajah’s palace, for its walls gleamed like alabaster in the sunlight.

“I have heard of this place,” nodded Chandra. “They have been making excavations here. Down a road we will come to a waterfall, then we will go past big quarries, then finally we will reach the Grand Trunk Road.”