BY JIM HARMON

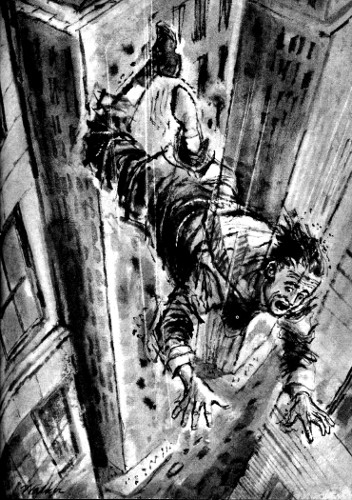

Illustrated by WALKER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine August 1961.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Let the dead past bury its dead?

Not while I am alive, it won't!

It surely was all right for me to let myself do it now. I couldn't have been more safe. In the window of the radio store a color television set was enjoying a quiz by itself and creased in my pocket was the newspaper account of the failure of a monumental human adventure in the blooming extinction of a huge rocket. The boys on the corner seemed hardly human, scowling anthropoids in walrus-skin coats. It was my own time. Anybody could see I was safe, and I could risk doing what I ached to do.

I turned the corner.

The breaks were against me from the start. It didn't come as any surprise. I could never get away with it. I knew that all along.

There was a Packard parked just beyond the fire plug.

The metal and glass fronts of the buildings didn't show back here, only seasoned brick glued with powdering chalk. The line of the block seemed to stretch back, ever further away from the glossy fronts into the crumbling stone.

A man brushed past me, wearing an Ivy League suit and snap-brim hat, carrying a briefcase. And, reassuringly, he was in a hurry.

I decided to chance it. I certainly wanted to do it in the worst way.

My footsteps carried me on down the block.

A little car spurted on past me. One of those foreign jobs, I decided. Only it wasn't. I fixed the silhouette in my mind's eye and identified it. A Henry J.

Still, I wasn't worried. It was actually too early in the day. It wasn't as if it were evening or anything like that.

The little store was right where I left it, rotting quietly to itself. The Back Number Store, the faded circus poster proclaimed in red and gold, or now, pink and lemon. In the window, in cellophane envelopes, were the first issue of Life, a recent issue of Modern Man with a modern woman fronting it, a Big Big Book of Buck Rogers and the Silver Cities of Venus, and a brand-new, sun-bleached copy of Doctor Zhivago.

There was a little car at the curb. This time I recognized that it wasn't an import, just a Crosley.

I went in, the brass handle making me conscious of the sweat on my palm.

The old man sat behind a fortress of magazines and books, treacherously reading the funnies in a newspaper. His bald head swiveled on the hunched shoulders of his sweater which was azuring toward white. He grinned, toothless.

"Came back for more of the stuff, did you?"

He laid down the newspaper. (That subheadline couldn't really be making so nasty a suggestion to a noted general, could it?)

"Yes," I laughed, not very true.

"I know what a craving can be. I shouldn't smoke, but I do. I've tried to stop but I lie there thinking about cigarettes half the night. Long ones, short ones, smoked ones, ones unlit. I feel like I could smoke one in each hand. It like that with you?"

"Not that bad. To me it's just—"

"Don't tell me reading isn't a craving with some of you fellows. I've seen guys come in here, hardly two threads stuck together on them, and grab up them horror magazines and read and read, until sweat starts rolling off the end of their nose. I've hardly got the heart to throw 'em out."

Horror magazines. Ones with lovely girls about to have their flesh shredded by toothy vampires. Yes, they were a part of it. Not a big part, but a part.

"That's not what I want to see. I want—"

The old man snickered. "I know what you want. Indeed I do. This way."

I followed his spidering hand and sure enough, there they were. Stacks upon stacks of air-war pulp magazines.

"Fifteen cents for ones in good condition," the old man pronounced the ritual, "a dime for ones with incomplete covers, three for a quarter, check 'em at the desk when you go."

I ran my hand down a stack. Wings, Daredevil Aces, G-8 and his Battle Aces, The Lone Eagle, all of them.

The old man was watching me. He skittered back across the floor and snatched up a magazine. It was a copy of Sky Fighters with a girl in a painted-on flying suit hanging from the struts of a Tiger Moth.

"This one, this one," he said. "This must be a good one. I bet she gets shoved right into that propeller there. I bet she gets chopped to pieces. Pieces."

"I'll take it."

Reluctantly he handed over the magazine, waited a moment, then left me.

I stared at the stacks of flying story magazines and I felt the slow run of the drop of sweat down my nose.

My sickness was terrible. It is as bad to be nostalgic for things you have never known as for an orphan who has never had a home to be homesick.

Living in the past, that was always me. I never watched anything on TV made later than 1935. I was in love with Garbo, Ginger Rogers, Dolores del Rio. My favorite stars were Richard Dix, Chester Morris and Richard Arlen.

The music I listened to was Gershwin and Arlen and Chicago jazz.

And my reading was the pulp literature harking back to the First World War. This was the biggest part of it all, I think.

You identify with the hero of any story if it's well enough written. But the identification I felt with the pilots in air-war stories was plainly ridiculous.

I was there.

I was in the saddle of the cockpit, feeling on my face the bite of the slipstream—no, that was a later term—the prop-wash?—no, that was still later—the backlash from the screw, that was it. I was lifting to meet the Fokker triplanes in the dawn sky. Then in a moment my Vickers was chattering in answer to Spandaus, firing through the screw outfitted with iron edges to deflect bullets that did not pass to the left and right. And back through the aerial maps in the cockpit pocket at my knee.

Here he comes, the Spandaus firing right through the screw in perfect synchronization. Look at that chivalrous wave. You can almost see the dueling scar on his cheek from old Krautenberg. He can afford to be chivalrous in that Fokker. I'd like to trade this skiddoo for it. That may be just what I do too if I don't watch it.

You ain't any Boelcke, mister, but this is from the Fifth for Squadron 70.

Missed!

Hard on that rudder! God, look at the snake in that fabric. At least it was a lie about them using incendiaries.

One of your own tricks for you, Heinie. Up on the stick, up under your tail, into the blind spot. Where am I? Where am I? Right here.

Look at that tail go. Tony can't be giving you as good stuff as he claims.

So long. I'm waving, see.

He's pulling her up. No tail and he's pulling her up. He's a good man. Come on. A little more. A little more and you can deadstick her. Come on, buddy. You're doing it. You're pulling her up—

But not enough.

God, what a mess.

I'm sick.

That damned castor oil in the carburetor. I'll be in the W. C. until oh-six-hundred....

No, the air wasn't one of castor oil but the pleasant smell of aged paper and printer's ink.

I'd been daydreaming again. I shouldn't forget things were getting different lately. It was becoming dangerous.

I gathered up an armload of air-war magazines at random.

Leaning across the table, I noticed the curtain in back for the first time. It was a beaded curtain of many different colors. Theda Bara might have worn it for a skirt. Behind the curtain was a television set. It was a comforting anti-anachronism here.

The six- or eight-inch picture was on a very flat tube, a more pronounced Predicta. The size and the flatness didn't seem to go together. Then I saw that the top part of the set was a mirror reflecting an image from the roof of the cabinet where the actual picture tube lay flat.

There was an old movie on the channel. An old, old movie. Lon Chaney, Sr., in a western as a badman. He was protecting a doll-faced blonde from the rest of the gang, standing them off from a grove of rocks. The flickering action caught my unblinking eyes.

Tom Santschi is sneaking across the top of the rocks, a knife in his dirty half-breed hand. Raymond Hatton makes a try for his old boss, but Chaney stops his clock for him. Now William Farnum is riding up with the posse. Tom makes a try with the knife, the girl screams, and Chaney turns the blade back on him. It goes through his neck, all the way through.

The blonde is running toward Farnum as he polishes off the rest of the gang and dismounts, her blouse shredded, revealing one breast—is that the dawn of Bessie Love? Chaney stands up in the rocks. Farnum aims his six-shooter. No, no, say the girl's lips. "No!" "No!" says the subtitle. Farnum fires. Swimming in blood, Chaney smiles sadly and falls.

I had seen movies like that before.

When I was a kid, I had seen Flicker Flashbacks between chapters of Flash Gordon and Johnny Mack Brown westerns. I looked at old movies and heard the oily voice making fun of them. But hadn't I also seen these pictures with the sound of piano playing and low conversation?

I had seen these pictures before the war.

The war had made a lot of difference in my life.

Comic books were cut down to half their size, from 64 to 32 pages, and prices had gone up to where you had to pay $17 for a pair of shoes, so high that people said Wilson should do something about it.

Tom Mix had gone off the air and he and his Cowboy Commandos beat the Japs in comic books. Only, hadn't he sold Liberty Bonds with Helen Morgan?

And at school I had bought Defense—War—Savings—Security—Liberty—Freedom—I had bought stamps at school. I never did get enough to trade in for a bond, but Mama had taken my book and traded parts of it in for coffee. She could never get enough coffee....

"Nobody would look at my magazines," the old man chuckled, "if I put it out front. My boy got me that. He runs a radio and Victrola store. A good boy. His name's in the fishbowl."

I pressed some money on him and walked myself out of the store. Shutting the door, I saw that the copy of Doctor Zhivago had been replaced by Gone With the Wind.

The street was full of wooden-paneled station wagons, blunt little roadsters with canvas tops, swept-back, tailless sedans. Only one dark, tailed, over-thyroided car moved through the traffic. It had a light on the roof.

I dodged in front of a horse-drawn garbage wagon and behind an electric postal truck and ran for that light, leaving a trail of gaudy air battles checkering the street behind me.

I grabbed the handle on the door, opened it and threw myself into the back seat.

"Madison Avenue," I said from my diaphragm, without any breath behind it.

Something was wrong. Two men were in the front seat. The driver showed me his hard, expressionless face. "What do you think you are doing?"

"This isn't a taxicab?" I asked blankly.

"Park Police."

I sat there while we drove on for a few minutes.

"D. & D.," the second man said to the driver.

"Right into our laps."

The second officer leaned forward and clicked something. "I'll get the City boys."

"No, kill it, Carl. Think of all that damned paper work."

Carl shrugged. "What will we do with him?"

I was beginning to attach myself to my surroundings. The street was full of traffic. My kind of traffic. Cars that were too big or too small.

"Look, officers, I'm not drunk or disorderly. I thought this was a cab. I just wanted to get away from back then—I mean back there."

The two policemen exchanged glances.

"What were you running from?" the driver asked.

How could I tell him that?

Before I even got a chance to try, he said: "What did you do?"

"I didn't do anything!"

The car was turning, turning into shadows, stopping. We were in an alley. Soggy newspapers, dead fish, prowling cats, a broken die, half a dice, looking big in the frame of my thick, probably bullet-proof window.

The men opened their doors and then mine.

"Out."

I climbed out and stood by the car, blinking.

"You were causing some kind of trouble in that neighborhood back there," the driver announced.

"Really, officers—"

"What's your name?"

"Hilliard Turner. There—"

"We don't want you going back there again, Turner, causing trouble. Understand?"

"Officer, I only bought some books—I mean magazines."

"These?" the second man, Carl, asked. He had retrieved them from the back seat. "Look here, Sarge. They look pretty dirty."

Sarge took up the Sky Fighters with the girl in the elastic flying suit. "Filth," he said.

"You know about the laws governing pornography, Turner."

"Those aren't pornography and they are my property!"

I reached for them and Carl pulled them back, grinning. "You don't want to read these. They aren't good for you. We're confiscating them."

"Look here, I'm a citizen! You can't—"

Carl shoved me back a little. "Can't we?"

Sarge stepped in front of me, his face in deadly earnest. "How about it, Turner? You a narcotics user?"

He grabbed my wrist and started rolling up my sleeve to look for needle marks. I twisted away from him.

"Resisting an officer," Sarge said almost sadly.

At that, Carl loped up beside him.

The two of them started to beat me.

They hit clean, in the belly and guts, but not in the groin. They gave me clean white flashes of pain, instead of angry, red-streaked ones. I didn't fight back, not against the two of them. I knew that much. I didn't even try to block their blows. I stood with my arms at my sides, leaning back against the car, and hearing myself grunt at each blow.

They stood away from me and let me fold helplessly to the greasy brick.

"Stay away from that neighborhood and stay out of trouble," Sarge's voice said above me.

I looked up a little bit and saw an ugly, battered hand thumbing across a stack of half a dozen magazines like a giant deck of cards.

"Why don't you take up detective stories?" he asked me.

I never heard the squad car drive away.

Home. I lighted the living room from the door, looked around for intruders for the first time I could remember, and went inside.

I threw myself on the couch and rubbed my stomach. I wasn't hurt badly. My middle was going to be sorer in the morning than it was now.

Lighting up a cigarette, I watched the shapes of smoke and tried to think.

I looked at it objectively, forward and back.

The solution was obvious.

First of all, I positively could not have been an aviator in World War One. I was in my mid-twenties; anybody could tell that by looking at me. The time was the late 'Fifties; anybody could tell that from the blank-faced Motorola in the corner, the new Edsels on the street. Memories of air combat in Spads and Nieuports stirred in me by old magazines, Quentin Reynolds, and re-runs of Dawn Patrol on television were mere hallucinations.

Neither could I remember drinking bootleg hooch in speak-easies, hearing Floyd Gibbons announce the Dempsey-Tunney fight, or paying $3.80 to get into the first run of Gone with the Wind.

Only ... I probably had seen GWTW. Hadn't I gone with my mother to a matinee? Didn't she pay 90¢ for me? So how could I remember taking a girl, brunette, red sweater, Cathy, and paying $3.80 each? I couldn't. Different runs. That was it. The thing had been around half a dozen times. But would it have been $3.80 no more than ten years ago?

I struck up a new cigarette.

The thing I must remember, I told myself, was that my recollections were false and unreliable. It would do me no good to keep following these false memories in a closed curve.

I touched my navel area and flinched. The beating, I was confident, had been real. But it had been a nightmare. Those cops couldn't have been true. They were a small boy's bad dream about symbolized authority. They were keeping me from re-entering the past where I belonged, punishing me to make me stay in my trap of the present.

Oh, God.

I rolled over on my face and pushed it into the upholstery.

That was the worst part of it. False memories, feelings of persecution, that was one thing. Believing that you are actively caught up in a mixture of the past with the present, a Daliesque viscosity of reality, was something else.

I needed help.

Or if there was no help for me, it was my duty to have myself placed where I couldn't harm other consumers.

If there was one thing that working for an advertising agency had taught me, it was social responsibility.

I took up the phone book and located several psychiatrists. I selected one at random, for no particular reason.

Dr. Ernest G. Rickenbacker.

I memorized the address and heaved myself to my feet.

The doctor's office was as green as the inside of a mentholated cigarette commercial.

The cool, lovely receptionist told me to wait and I did, tasting mint inside my mouth.

After several long, peaceful minutes the inner door opened.

"Mr. Turner, I can't seem to find any record of an appointment for you in Dr. Rickenbacker's files," the man said.

I got to my feet. "Then I'll come back."

He took my arm. "No, no, I can fit you in."

"I didn't have an appointment. I just came."

"I understand."

"Maybe I had better go."

"I won't hear of it."

I could have pulled loose from him, but somehow I felt that if I did try to pull away, the grip would tighten and I would never get away.

I looked up into that long, hard, blank face that seemed so recently familiar.

"I'm Dr. Sergeant," he said. "I'm taking care of Dr. Rickenbacker's practice for him while he is on vacation."

I nodded. What I was thinking could only be another symptom of my illness.

He led me inside and closed the door.

The door made a strange sound in closing. It didn't go snick-bonk; it made a noise like click-clack-clunk.

"Now," he said, "would you like to lie down on the couch and tell me about it? Some people have preconceived ideas that I don't want to fight with at the beginning. Or, if you prefer, you can sit there in front of my desk and tell me all about it. Remember, I'm a psychiatrist, a doctor, not just a psychoanalyst."

I took possession of the chair and Sergeant faced me across his desk.

"I feel," I said, "that I am caught up in some kind of time travel."

"I see. Have you read much science fiction, Mr. Turner?"

"Some. I read a lot. All kinds of books. Tolstoi, Twain, Hemingway, Luke Short, John D. MacDonald, Huxley."

"You should read them instead of live them. Catharsis. Sublimate, Mr. Turner. For instance, to a certain type of person, I often recommend the mysteries of Mickey Spillane."

I seemed to be losing control of the conversation. "But this time travel...."

"Mr. Turner, do you really believe in 'time travel'?"

"No."

"Then how can there be any such thing? It can't be real."

"I know that! I want to be cured of imagining it."

"The first step is to utterly renounce the idea. Stop thinking about the past. Think of the future."

"How did you know I keep slipping back into the past?" I asked.

Sergeant's hands were more expressive than his face. "You mentioned time travel...."

"But not to the past or to the future," I said.

"But you did, Mr. Turner. You told me all about thinking you could go into the past by visiting a book store where they sold old magazines. You told me how the intrusion of the past got worse with every visit."

I blinked. "I did? I did?"

"Of course."

I stood up. "I did not!"

"Please try to keep from getting violent, Mr. Turner. People like you actually have more control over themselves than you realize. If you will yourself to be calm...."

"I know I didn't tell you a thing about the Back Number Store. I'm starting to think I'm not crazy at all. You—you're trying to do something to me. You're all in it together."

Sergeant shook his head sadly.

I realized how it all sounded.

"Good—GOD!" I moaned.

I put my hands to my face and I felt the vein over my left eye swelling, pulsing.

Through the bars of my fingers I saw Sergeant motion me down with one eloquent hand. I took my hands away—I didn't like looking through bars—and sat down.

"Now," Sergeant said, steepling his fingers, "I know of a completely nice place in the country. Of course, if you respond properly...."

Those hands of his.

There was something about them that wasn't so. They might have been the hands of a corpse, or a doll....

I lurched across the desk and grabbed his wrist.

"Please, Mr. Turner! violence will—"

My fingers clawed at the backs of his hands and my nails dragged off ugly strips of some theatrical stuff—collodion, I think—that had covered the scrapes and bruises he had taken hammering away at me and my belt buckle.

Sergeant.

Sarge.

I let go of him and stood away.

For the first time, Sergeant smiled.

I backed to the door and turned the knob behind my back. It wouldn't open.

I turned around and rattled it, pulled on it, braced my foot against the wall and tugged.

"Locked," Sergeant supplied.

He was coming toward me, I could tell. I wheeled and faced him. He had a hypodermic needle. It was the smallest one I had ever seen and it had an iridescence or luminosity about it, a gleaming silver dart.

I closed with him.

By the way he moved, I knew he was used to physical combat, but you can't win them all, and I had been in a lot of scraps when I had been younger. (Hadn't I?)

I stepped in while he was trying to decide whether to use the hypo on me or drop it to have his hands free. I stiff-handed him in the solar plexus and crossed my fist into the hollow of the apex arch of his jawbone. He dropped.

I gave him a kick at the base of his spine. He grunted and lay still.

There was a rapping on the door. "Doctor? Doctor?"

I searched through his pockets. He didn't have any keys. He didn't have any money or identification or a gun. He had a handkerchief and a ballpoint pen.

The receptionist had moved away from the door and was talking to somebody, in person or on the phone or intercom.

There wasn't any back door.

I went to the window. The city stretched out in an impressive panorama. On the street below, traffic crawled. There was a ledge. Quite a wide, old-fashioned ornamental ledge.

The ledge ran beneath the windows of all the offices on this floor. The fourteenth, I remembered.

I had seen it done in movies all my life. Harold Lloyd, Douglas Fairbanks, Buster Keaton were always doing it for some reason or other. I had a good reason.

I unlatched the window and climbed out into the dry, crisp breeze.

The movies didn't know much about convection. The updraft nearly lifted me off the ledge, but the cornice was so wide I could keep out of the wind if I kept myself flat against the side of the building.

The next window was about twenty feet away. I had covered half that distance, moving my feet with a sideways crab motion, when Carl, indisputably the second policeman, put his head out of the window where I was heading and pointed a .38 revolver at me, saying in a let's-have-no-foolishness tone: "Get in here."

I went the other way.

The cool, lovely receptionist was in Sergeant's window with the tiny silver needle in readiness.

I kept shuffling toward the girl. I had decided I would rather wrestle with her over the needle than fight Carl over the rod. Idiotically, I smiled at that idea.

I slipped.

I was falling down the fourteen stories without even a moment of windmilling for balance. I was just gone.

Lines were converging, and I was converging on the lines.

You aren't going to be able to Immelmann out of this dive, Turner. Good-by, Turner.

Death.

A sleep, a reawakening, a lie. It's nothing like that. It's nothing.

The end of everything you ever were or ever could be.

I hit.

My kneecap hurt like hell. I had scraped it badly.

Reality was all over me in patches. I showed through as a line drawing, crudely done, a cartoon.

Some kind of projection. High-test Cinerama, that was all reality meant.

I was kneeling on a hard surface no more than six feet from the window from which I had fallen. It was still fourteen flights up, more or less, but Down was broken and splattered over me.

I stood up, moving forward a step.

It brought me halfway through the screen, halfway through the wall at the base of the building. The other side of the screen. The solid side, I found, stepping through, bracing a hand on the image.

Looking up fourteen floors, I saw an unbroken line of peacefully closed panes.

I remembered riding up in the elevator, the moments inside, the faint feeling of vertigo. Of course, who was to say the elevator really moved? Maybe they had only switched scenery on me while I was caught inside, listening to the phony hum, seeing the flashing lights. Either cut down or increase the oxygen supply inside the cubicle suddenly and that would contribute a sensation of change, of movement. They had it all worked out.

My fingers rubbed my head briskly, both hands working, trying to get some circulation in my brain.

I guessed I had to run. There didn't seem much else to do.

I ran.

Get help?

Not this old lady and her daughter. Not this Neanderthal sailor on his way to a bar and a blonde. Not the bookkeeper. Maybe the car salesman, ex-Army, Lions Club member, beefy, respectable, well-intentioned, not a complete fool. The guy on the corner reading a newspaper by the bus stop.

"I need help," I panted to him. "Somebody's trying to kidnap me."

"Really makes you sick to hear about something like that, doesn't it?" he said. "I'm in favor of the Lindbergh Law myself."

"I'm not sure whether—"

"This heat is murder, isn't it? Especially here in these concrete canyons. Sometimes I wish I was back in Springfield. Cool, shaded streets...."

"Listen to me! These people, they're conspiring against me, trying to drive me insane! Two men, a girl—"

"For my money, Marilyn Monroe is the doll of the world. I just don't understand these guys who say she hasn't got class. She gets class by satirizing girls without any...."

He was like anybody you might talk to on the street. I knew what he would say if I cued him with "baseball" or "Russia" instead of the key words I had used.

I should have known better, but I wanted to touch him in some way, make him know I was alive. I grabbed him and shook him by the shoulders, and there was a whoosh and as I might have expected he collapsed like the insubstantiality he was.

There was a stick figure of a man left before me, an economical skeleton supporting the shell of a human being and two-thirds of a two-trouser suit.

Hide.

I went into the first shop I came to—Milady's Personals.

Appropriately, it was a false front.

A neutral-colored gray surface, too smooth for concrete, stretched away into some shadows. The area was littered with trash.

Cartons, bottles, what looked like the skin of a dehydrated human being—obviously, on second thought, only the discarded skin of one of the things like the one I had deflated.

And a moldering pile of letters and papers.

Something caught my eye and I kicked through them. Yes, the letter I had written to my brother in Sioux Falls, unopened. And which he had answered.

My work.

The work I had done at the agency, important, creative work. There was my layout, the rough of the people with short, slim glasses, the parents, children, grandparents, the caption: Vodka is a Part of the American Tradition.

All of it lying here to rot.

Something made me look away from that terrible trash.

Sergeant stood in the entrance of Milady's, something bright in his hand.

Something happened.

I had been wrong.

The shining instrument had not been a hypodermic needle.

"You're tough," Sergeant said as I eased back into focus.

"You aren't, not without help," I told him in disgust.

"Spunky, aren't you? I meant mental toughness. That's the one thing we can never judge. I think you could have taken the shock right from the start. Of course, you would still have needed the conditioning to integrate properly."

"Conditioning? Conditioning?" It came out of me, vortexing up, outside of my piloting. "What have you done to my mind?"

"We've been trying to get it to grow back up," Sergeant said reasonably. "Think of this. Fountain of Youth. Immortality. Rejuvenation. This is it. Never mind how it works. Most minds can't stand being young and knowing they will have to go through the same damned thing all over again. We use synapse-shift to switch your upper conscious memories to your id and super-ego, leaving room for new memories. You remember only those things out of the past you have to, to retain your identity."

"Identity," I repeated. "I have no identity. My identity is a dream. I have two identities—one of them years beyond the other."

Sergeant tilted his head and his eyes at me and slapped me across the face. "Don't go back on me now. We gave you the best we could. The Rejuvenation Service couldn't help it if you were too old for a beta. You shouldn't have waited until you were so old, so very old. We used the very oldest sets and mock-ups we had for betas, but you, you had to keep wandering onto alpha territory, while they were striking sets, even. Beta or not, we gave you good service. Don't slip now."

I heard the voice and I heard another voice, and it said "What could you expect of a beta?" and they were only some of the voices I was hearing, and I wondered what you could expect from a beta, and I didn't know, or think that I would ever know.