By GEORGE O. SMITH

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

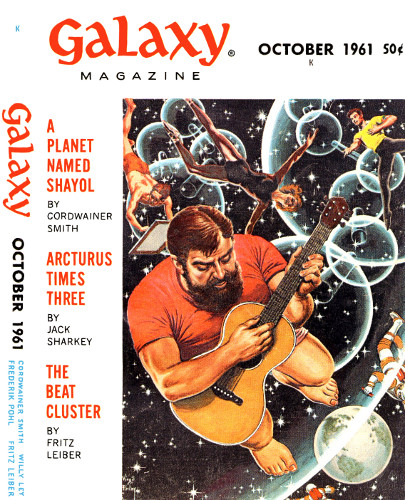

Galaxy Magazine October 1961.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The creature from Venus didn't know right from

left—and life and death hung in the balance!

Paul Wallach came into my office. He looked distraught. By some trick of selection, Paul Wallach, the director of Project Tunnel, was one of the two men in the place who did not have a string of doctor's and scholar's degrees to tack behind their names. The other was I.

"Trouble, Paul?" I asked.

He nodded, saying, "The tunnel car is working."

"It should. It's been tested enough."

"Holly Carter drew the short straw."

"Er—" I started and then stopped short as the implication became clear. "She's—she's—not—?"

"Holly made it to Venus all right," he said. "Trouble is we can't get her back."

"Can't get her back?"

He nodded again. "You know, we've never really known very much about the atmosphere of Venus."

"Yes."

"Well, from what little came through just before Holly blacked out, it seems that there must be one of the cyanogens in the atmosphere in a concentration high enough to effect nervous paralysis."

"Meaning?"

"Meaning," said Paul Wallach in a flat tone, "that Holly Carter stopped breathing shortly after she cracked the airlock. And her heart stopped beating a minute or so later."

"Holly—dead?"

"Not yet, Tom," he said. "If we can get her back in the next fifteen or twenty minutes, modern medicine can bring her back."

"But there'll be brain damage!"

"Oh, there may be some temporary impairment. Nothing that retraining can't restore. The big problem is to bring her back."

"We should have built two tunnel cars."

"We should have done all sorts of things. But when the terminal rocket landed on Venus, everybody in the place was too anxious to try it out. Lord knows, I tried to proceed at a less headlong pace. But issuing orders to you people is a waste of time and paper."

I looked at him. "Doc," I asked, giving him the honorary title out of habit, "Venus is umpty-million miles from here. We haven't another tunnel car, and no rocket could make it in time to do any good. So how can we hope to rescue Holly?"

"That's the point," said Wallach. "Venus, it appears, is inhabited."

"Oh?"

"That's what got Holly caught in the first place. She landed, then saw this creature approaching. Believing that no life could exist in an atmosphere dangerous to life, she opened the airlock and discovered otherwise."

"So?"

"So now all we have to do is to devise some way of explaining to a Venusian the difference between left and right. I thought you might help."

"But I'm just a computer programmer."

"That's the point. We all figured that you have developed a form of communication to that machine of yours. The rest of the crew, as you know, have a bit of difficulty in communicating among themselves in their own jargon, let alone getting through to normal civilians. When it comes to a Venusian, they're licked."

I said, "I'll try."

Project Tunnel is the hardware phase of a program started a number of years ago when somebody took a joke seriously.

In a discussion of how the tunnel diode works, one of the scientists pointed out that if an electron could be brought to absolute rest, its position according to Heisenberg Uncertainty would be completely ambiguous. Hence it had as high a possibility of being found on Venus as it had of being found on Earth or anywhere else. Now, the tunnel diode makes use of this effect by a voltage bias across the diode junction. Between narrow limits, the voltage bias is correct to upset the ambiguity of Mr. Heisenberg, making the electron nominally found on one side of the junction more likely to be found on the other.

Nobody could deny the operability of the tunnel diode. Project Tunnel was a serious attempt to employ the tunnel effect in gross matter.

The terminal rocket mentioned by Paul Wallach carried the equipment needed to establish the voltage bias between Venus and the Earth. Once established, Project Tunnel was in a state that caused it to maroon the most wonderful girl in the world.

Since the latter statement is my own personal opinion, my pace from the office to the laboratory was almost a dead run.

The laboratory was a madhouse. People stood in little knots, arguing. Those who weren't talking were shaking their heads in violent negation.

The only one who appeared un-upset was Teresa Dwight, our psi-girl. And here I must confess an error. When I said that Paul Wallach and I were the only ones without a string of professorial degrees, I missed Teresa Dwight. I must be forgiven. Teresa had a completely bland personality, zero drive, and a completely unstartling appearance. Teresa was only fourteen. But she'd discovered that her psi-power could get her anything she really wanted. Being human, therefore, she did not want much. So forgive me for passing her by.

But now I had to notice her. As I came in, she looked up and said, "Harla wants to know why can't he just try."

Wallach went white. "Tell that Venusian thing 'NO!' as loud as you can."

Teresa concentrated, then asked, "But why?"

"Does this Harla understand the Heisenberg Effect?"

She said after a moment, "Harla says he has heard of it as a theory. But he is not quite prepared to believe that it does indeed exist as anything but an abstract physical concept."

"Tell Harla that Doctor Carter's awkward position is a direct result of our ability to reduce the tunnel effect to operate on gross matter."

"He realizes that. But now he wants to know why you didn't fire one of the lower animals as a test."

"Tell him that using animals for laboratory experiments is only possible in a police state where the anti-vivisection league can be exiled to Siberia. Mink coats and all. And let his Venusian mind make what it can of that. Now, Teresa—"

"Yes?"

"Tell Harla, very carefully, that pressing the left-hand button will flash the tunnel car back here as soon as he closes the airlock. But tell him that pushing the right-hand button will create another bias voltage—whereupon another mass of matter will cross the junction. In effect, it will rip a hole out of this laboratory near the terminal, over there, and try to make it occupy the same space as the tunnel car on Venus. None of us can predict what might happen when two masses attempt to occupy the same space. But the chances are that some of the holocaust will backfire across the gap and be as violent at this end, too."

"Harla says that he will touch nothing until he has been assured that it is safe."

"Good. Now, Tom," he said, addressing me, "how can we tell right from left?"

"Didn't you label 'em?"

"They're colored red on the right and green on the left."

"Is Harla color-blind?"

"No, but from what I gather Harla sees with a different spectrum than we do. So far as he is concerned both buttons look alike."

"You could have engraved 'em 'COME' and 'GO'."

Frank Crandall snorted. "Maybe you can deliver an 'English, Self-Taught' course through Teresa to the Venusian?"

I looked at Crandall. I didn't much care for him. It seemed that every time Holly Carter came down out of her fog of theoretical physics long enough to notice a simpleton who had to have a machine to perform routine calculations, we were joined by Frank Crandall who carted her off and away from me. If this be rank jealousy, make the most of it. I'm human.

"Crandall," I said, "even to a Hottentot I could point out that the engraved legend 'GO' contains two squiggly symbols, whereas the legend 'RETURN' contains 'many'."

Wallach stepped into the tension by saying, "So we didn't anticipate alien life. But now we've got the problem of communicating with it."

Crandall didn't appear to notice my stiff reply. He said, "Confound it, what's missing?"

"What's missing," I told him, "is some common point of reference."

"Meaning?"

"Meaning that I could define left from right to any semi-intelligent human being who was aware of the environment in which we live."

"For example?"

I groped for an example and said, lamely, "Well, there's the weather rule, valid for the northern hemisphere. When the wind is blowing on your back, the left hand points to the low pressure center."

"Okay. But how about Venus? Astronomical information, I mean."

I shook my head.

"Why not?" he demanded. "If we face north, the sun rises on our right, doesn't it?"

"Yes. Even in the southern hemisphere."

"Well, then. So it doesn't make any difference which hemisphere they're in."

"You're correct. But you're also making the assumptions that Venus rotates on its axis, that the axis is aligned parallel to the Earth's and that the direction of rotation is the same."

"We know that Venus rotates!"

"We have every reason to believe so," I agreed. "But only because thermocouples measure a temperature on the darkside that is too high to support the theory that the diurnal period of Venus is equal to the year. I think the latest figures say something between a couple of weeks and a few months. Next, the axis needn't be parallel to anything. Shucks, Crandall, you know darned well that the solar system is a finely made clock with no two shafts aligned, and elliptical gears that change speed as they turn."

"Practically everything in the solar system rotates in the same direction."

I looked at him. "Would you like to take a chance that Venus agrees with that statement? You've got a fifty percent chance that you'll be right. Guess wrong and we have a metric ton of hardware trying to occupy the same space as another metric ton of matter."

"But—"

"And furthermore," I went on, "we're just lucky that Polaris happens to be a pole star right now. The poles of Mars point to nothing that bright. Even then, we can hardly expect the Venusian to have divided the circumpolar sky into the same zoo full of mythical animals as our forebears—and if we use the commonplace expression, maybe the Venusian never paused to take a long-handled dipper of water from a well. Call them stewpots and the term is still insular. Sure, there's lots of pointers, but they have to be identified. My mother always insisted that the Pleiades were—er—was the Little Dipper."

Teresa Dwight spoke up, possibly for the second or third time in her life without being spoken to first. She said, "Harla has been listening to you through me. Of astronomy he has but a rudimentary idea. He is gratified to learn from you that there is a 'sun' that provides the heat and light. This has been a theory based upon common sense; something had to do it. But the light comes and goes so slowly that it is difficult to determine which direction the sun rises from. The existence of other celestial bodies than Venus is also based on logic. If, they claim, they exist, and their planet exists, then there probably are other planets with people who cannot see them, either."

"Quoth Pliny the Elder," mumbled Paul Wallach.

I looked at him.

"Pliny was lecturing about Pythagoras' theory that the Earth is round. A heckler asked him why the people on the other side didn't fall off. Pliny replied that on the other side there were undoubtedly fools who were asking their wise men why we didn't fall off."

"It's hardly germane," I said.

"I'm sorry. Yes. And time is running out."

The laboratory door opened to admit a newcomer, Lou Graham, head of the electronics crew.

He said, "I've got it!"

The chattering noise level died out about three decibels at a time. Lou said, "When a steel magnet is etched in acid, the north pole shows selective etching!"

I shook my head. "Lou," I said, "we don't know whether Venus has a magnetic field, whether it is aligned to agree with the Earth's—nor even whether the Venusians have discovered the magnetic compass."

"Oh, that isn't the reference point," said Lou Graham. "I'm quite aware of the ambiguity. The magnetic field does have a vector, but the arrow that goes on the end is strictly from human agreement."

"So how do you tell which is the north pole?"

"By making an electromagnet! Then using Ampere's Right Hand Rule. You grasp the electromagnet in the right hand so that the fingers point along the winding in the direction of the current flow. The thumb then points to the north pole."

"Oh, fine! Isn't that just the same confounded problem? Now we've got to find out whether Harla is equipped with a right hand complete with fingers and thumbs—so that we can tell him which his right hand is!"

"No, no," he said. "You don't understand, Tom. We don't need the right hand. Let's wind our electromagnet like this: We place the steel bar horizontally in front of us. The wire from 'Start' leaves us, passes over the top of the bar, drops below the bar on the far side, comes toward us on the under side, rises above the bar on the side toward us, and so on around and around until we've got our electromagnet wound. Now if the 'start' is positive and the 'end' is negative, the north pole will be at the left. It will show the selective etching in acid."

I looked at him. "Lou," I said slowly, "if you can define positive and negative in un-ambiguous terms as well as you wound that electromagnet, we can get Holly home. Can you?"

Lou turned to Teresa Dwight. "Has this Harla fellow followed me so far?"

She nodded.

"Can you speak for him?"

"You talk, I hear, he reads me. I read him and I can speak."

"Okay, then," said Lou Graham. "Now we build a Le Clanche cell. Ask Harla does he recognize carbon. A black or light-absorbing element. Carbon is extremely common, it is the basis of life chemistry. It is element number six in the periodic chart. Does Harla know carbon?"

"Harla knows carbon."

"Now we add zinc. Zinc is a light metal easily extracted from the ore. It is fairly abundant, and it is used by early civilizations for making brass or bronze long before the culture has advanced enough to recognize zinc as an element. Does Harla know zinc?"

"He may," said Teresa very haltingly. "What happens if Harla gets the wrong metal?"

"Not very much," said Lou. "Any of the light, fairly plentiful metals that are easily extracted from the ore will suffice. Say tin, magnesium, sodium, cadmium, so on."

"Harla says go on."

"Now we make an electrolyte. Preferably an alkaline salt."

"Be careful," I said. "Or you'll be asking Harla to identify stuff from a litmus paper."

"No," said Lou. He faced Teresa and said, "An alkaline substance burns the flesh badly."

"So do acids," I objected.

"Alkaline substances are found in nature," he reminded me. "Acids aren't often natural. The point is that an acid will work. Even salt water will work. But an alkaline salt works better. At any rate, tell Harla that the stuff, like zinc, was known to civilized peoples many centuries before chemistry became a science. Acids, on the other hand, are fairly recent."

"Harla understands."

"Now," said Lou Graham triumphantly, "we make our battery by immersing the carbon and the zinc in the electrolyte. The carbon is the positive electrode and should be connected to the start of our electromagnet, whereas the end of the winding must go to the zinc. This will place the north pole to the left hand."

"Harla understands," said Teresa. "So far, Harla can perform this experiment in his mind. But now we must identify which end of the steel bar is north-pole magnetic."

"If we make the bar magnetic and then immerse it in acid, the north magnetic pole will be selectively etched."

"Harla says that this he does not know about. He has never heard of it, although he is quite familiar with electromagnets, batteries, and the like."

I looked at Lou Graham. "Did you cook this out of your head, or did you use a handbook?"

He looked downcast. "I did use a handbook," he admitted. "But—"

"Lou," I said unhappily, "I've never said that we couldn't establish a common frame of reference. What we lack is one that can be established in minutes. Something physical—" I stopped short as a shadowy thought began to form.

Paul Wallach looked at me as though he'd like to speak but didn't want to interrupt my train of thoughts. When he could contain himself no longer, he said, "Out with it, Tom."

"Maybe," I muttered. "Surely there must be something physical."

"How so?"

"The tunnel car must be full of it," I said. "Screws?"

I turned to Saul Graben. Saul is our mechanical genius; give him a sketch made on used Kleenex with a blunt lipstick and he will bring you back a gleaming mechanism that runs like a hundred-dollar wrist watch.

But not this time. Saul shook his head.

"What's permanent is welded and what's temporary is snapped in with plug buttons," he said.

"Good Lord," I said. "There simply must be something!"

"There probably is," said Saul. "But this Harla chap would have to use an acetylene torch to get at it."

I turned to Teresa. "Can this psi-man Harla penetrate metal?"

"Can anyone?" she replied quietly.

Wallach touched my arm. "You're making the standard, erroneous assumption that a sense of perception will give its owner a blueprint-clear grasp of the mechanical details of some machinery. It doesn't. Perception, as I understand it, is not even similar to eyesight."

"But—" I fumbled on—"surely there must be some common reference there, even granting that perception isn't eyesight. So how does perception work?"

"Tom, if you were blind from birth, I could tell you that I have eyesight that permits me to see the details of things that you can determine only by feeling them. This you might understand basically. But you could never be made to understand the true definition of the word 'picture' nor grasp the mental impression that is generated by eyesight."

"Well," I persisted, "can he penetrate flesh?"

"Flesh?"

"Holly's heart has stopped," I said. "But it hasn't been removed. If Harla can perceive through human flesh, he might be able to perceive the large, single organ in the chest cavity near the spine."

Teresa said, "Harla's perception gives him a blurry, incomplete impression." She looked at me. "It is something like a badly out-of-focus, grossly under-exposed x-ray solid."

"X-ray solid?" I asked.

"It's the closest thing that you might be able to understand," she said lamely.

I dropped it right there. Teresa had probably been groping in the dark for some simile that would convey the nearest possible impression. I felt that this was going to be the nearest that I would ever get to understanding the sense of perception.

"Can't he get a clear view?"

"He has not the right."

"Right!" I exploded. "Why—"

Wallach held up his hand to stop me. "Don't make Teresa fumble for words, Tom. Harla has not the right to invade the person of Holly Carter. Therefore he can not get a clearer perception of her insides."

"Hell!" I roared. "Give Harla the right."

"No one has authority."

"Authority be dammed!" I bellowed angrily. "That girl's life is at stake!"

Wallach nodded unhappily. "Were this a medical emergency, a surgeon might close his eyes to the laws that require authorization to operate. But even if he saved the patient's life, he is laying himself open to a lawsuit. But this is different, Tom. As you may know, the ability of any psi-person is measured by their welcome to the information. Thus Teresa and Harla, both willing to communicate, are able."

"But can't Harla understand that the entire bunch of us are willing that he should take a peek?"

"Confound it, Tom, it isn't a matter of our permission! It's a matter of fact. It would ease things if Holly were married to one of us, but even so it wouldn't be entirely clear. It has to do with the invasion of privacy."

"Privacy? In this case the very idea is ridiculous."

"Maybe so," said Paul Wallach. "But I don't make the rules. They're natural laws. As immutable as the laws of gravity or the refraction of light. And Tom, even if I were making the laws I might not change things. Not even to save Holly Carter's life. Because, Tom, if telepathy and perception were as free and unbounded as some of their early proponents claimed, life would be a sheer, naked hell on earth."

"But what has privacy to do with it? This Harla isn't at all humanoid. A cat can look at a king—"

"Sure, Tom. But how long would the cat be permitted to read the king's mind?"

I grunted. "Has this Harla any mental block about examining the outside?"

He looked at me thoughtfully. "You're thinking about a scar or some sort of blemish?"

"Yes. Birthmark, maybe. No one is perfect."

"You know of any?"

I thought.

It was not hard for me to conjure up a picture of Holly Carter. Unfortunately, I looked at Holly Carter through the eyes of love, which rendered her perfect. If she had bridgework, I hadn't found it out. Her features were regular and her hair fell loose without a part. Her complexion was flawless ... at least the complexion that could be examined whilst Holly sunned herself on a deck chair beside the swimming pool.

I shook my head. Then I faced an unhappy fact. It hurt, because I wanted my goddess to be perfect, and if she were made of weak, mortal flesh, I did not want to find it out by asking the man who knew her better than I did.

Still, I wanted her alive. So I turned to Frank Crandall.

"Do you?" I asked.

"Do I what?"

"Know of any scars or birthmarks?"

"Such as?"

"Oh, hell," I snapped. "Such as an appendix scar that might be used to tell left from right."

"Look, Tom, I'm not her physician, you know. I can only give you the old answer: 'Not until they wear briefer swim suits.'"

My heart bounced lightly. That Holly was still in mortal danger was not enough to stop my elation at hearing Frank Crandall admit that he was not Holly's lover, nor even on much better terms than I. It might have been better to face the knowledge that Holly was all woman and all human even though the information had to come from someone who knew her well enough to get her home.

Then I came back to earth. I had my perfect goddess—in deadly peril—instead of a human woman who really did not belong to any man.

I hadn't seen Saul Graben leave, but he must have been gone because now he opened the door and came back. He was carrying a heavy rim gyroscope that was spinning in a set of frictionless gymbals. He looked most confused.

He said, "I've spent what seems like an hour. You can't tell me that this gizmo is inseparable from the selfish, insular intellect of terrestrial so-called homo sapiens."

He turned the base and we all watched the gymbal rings rotate to keep the gyro wheel in the same plane. "It should be cosmic," he said. "But every time I start, I find myself biting myself on the back of the neck. Look. If you make the axle horizontal in front of you and rotate the gyro with the top edge going away from you, you can define a common reference. But motion beyond that cannot be explained. If the axle is depressed on the right side, the gyro will turn so the far edge looks to the right. But that's defining A in terms of A. So I'm licked."

Frank Crandall shook his head. "There's probably an absolute to that thing somewhere, but I'm sure none of us know it. We haven't time to find it. In fact, I think the cause is lost. Maybe we'd better spend our time figuring out a plausible explanation."

"Explanation?" blurted Wallach.

"Let's face it," said Crandall. "Holly Carter's life is slipping away. No one has yet come close to finding a common reference to describe right from left to this Harla creature."

"So what's your point?"

"Death is for the dying," Crandall said in a monotone. "Let them have their hour in peace and dignity. Life is for the living, and for the living there is no peace. We who remain must make the best of it. So now in about five minutes Holly will be at peace. The rest of us have got to answer for her."

"How do you mean?"

"How do you propose to explain this unfortunate incident?" asked Crandall. "Someone will want to know what happened to the remains of Holly Carter. I can see hell breaking loose. And I can see the whole lot of us getting laughed right off the Earth because we couldn't tell right from left. And I can see us all clobbered for letting the affair take place."

"You seem to be more worried about your professional reputation than about Holly Carter's life!"

"I have a future," he said. "Holly doesn't seem to. Hell," he groaned, "we can't even gamble on it."

"Gamble?"

"How successful do you think you'd be in getting this Venusian to risk his life by closing his eyes and making a fifty-fifty stab in the dark at one of those buttons?"

"Well—" started Wallach—"we'd be gambling too, you know. But—"

"Wait a moment," I said. "I've got a sort of half-cracked theory. May I try?"

"Of course."

"Not 'of course.' I'll have to have quiet, with just Teresa to communicate through."

"If you have any ideas, try them," said Wallach.

"Do you really know what you're doing?" demanded Frank Crandall.

"I think so," I replied. "If it works, it'll be because I happen to feel close to Holly."

"Could be," he said with a shrug. I almost flipped. Duels have been fought over less. But instead of taking offense, Crandall topped it off by adding, "You could have been a lot closer if you'd tried. She always said you had the alert, pixie-type mind that was pure relaxation instead of a dead let-down after a period of deep concentration. But you were always scuttling off somewhere. Well, go ahead and try, Tom. And good luck!"

I took a deep breath.

"Teresa?" I asked.

"Yes, Mr. Lincoln?"

"Tell Harla to concentrate on the buttons."

"He is."

"There is a subtle difference between them."

"This he knows, but he does not know what it is."

"There is a delicate difference in warmth. One button will be faintly warmer than the other."

"Harla has felt them."

I dropped the third-person address and spoke to Teresa as if she were but one end of a telephone line. "Harla," I said, "only part of the difference lies in the warmth to physical touch. There should be another kind of warmth. Are you not affected by a feeling that one is better than the other?"

Harla's reply came direct through Teresa: "Why yes, I am indeed drawn to the warmer of the two. Were this a game I would wager on it. But that is emotion and hardly suitable as a guide."

"Ah, but it is!" I replied quickly. "This is our frame of reference. Press the warmer of the but—"

I was violently interrupted. Wallach shook me violently and hurled me away from Teresa. Frank Crandall was facing the girl, shouting, "No! No! The warm one will be the red one! You must press the green—"

And then he, too, was interrupted.

Displaced air made a near-explosive woosh! and the tunnel car was there on its pad. In it was a nightmare horror holding a limp Holly Carter across its snakelike tentacles. A free tentacle opened the door.

"Take her while I hold my breath," said Harla, still talking through Teresa. "I'll return the tunnel car empty. I can, now that I know that warmth is where the hearth is."

Harla dropped the unconscious girl in my arms and snapped back into the car. It disappeared, then returned empty just as the doctor was bending over Holly.

So now I have my Holly, but every now and then I lie awake beside her in a cold sweat. Harla could have guessed wrong. Just as Wallach and Crandall had been wrong in assuming the red button would be warmer than the green. Their reaction was as emotional as Harla's.

I hope Harla either forgives me or never finds out that I had to sound sure of myself, and that I had to play on his emotions simply to get him to take the fifty-fifty chance on his—hers—our lives.

And I get to sleep only after I've convinced myself that it was more than chance ... that somehow our feelings and emotions guided Harla where logic and definition fail.

For right and left do not exist until terrestrial man defines them.