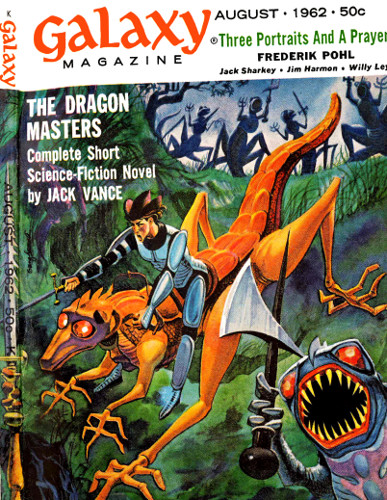

By JIM HARMON

Illustrated by RITTER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine August 1962.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

You too can be a Qurono. All you need do is

geoplanct. All you need know is when to stop!

Barnhart sauntered right into the middle of them. He covertly watched the crew close in around him and he never twitched an eyelash. Officers must never panic, he reminded himself, and manipulated the morning sighting on the nearest sun through the Fitzgerald lens. It was exactly 900:25:30, Galactic Time.

He jotted the reading in, satisfied. The warm breath tickling the back of his neck was unnerving. If he showed fear and grabbed a blaster from the locker he could probably control them, but he was devastingly aware that a captain must never show fear.

"Captain Barnhart," Simmons, the mate, drawled politely, "do you still plan on making the jump at 900 thirty?"

The captain removed his eyeglasses and polished the lenses.

"Simmons," he said in comforting, confiding tones, "you are well aware that regulations clearly state that a spaceship that phases in on a star in major trans-spot activity is required to re-phase within twenty-four hours to avoid being caught in turbulence."

"Yes, sir," Simmons said. "But, as I have stated before, it is my belief that regulation means that a ship should phase to avoid the possibility of being caught in an energy storm. We landed right in the middle of one. As you are aware, sir, if we phase now there is an excellent chance we will warp right into the sun!"

Barnhart shook his lean, bronze head wearily. "Simmons, the Admiralty has gone through this thousands of times. Obviously they know our danger is greater by staying where we are. Why, Ignatz 6Y out there may nova! We'll have to take our chances."

"No, sir." Simmons thrust his pale, blue-veined jaw at him, his light eyes Nordicly cold below a blond cropping. "The storm spots are dying down. We aren't phasing yet."

Barnhart drew himself up and looked down at the mate. Behind Simmons, York moved closer. The captain was suddenly aware of York's low forehead and muscular, free-swinging arms. It was probably sheer bias, but he had frequently entertained the idea that Englishmen were closer to our apelike ancestor than most people ... the way they ran around painted blue when everybody was civilly wearing clothes and all. Obviously York was incapable of thinking for himself and was willing to do anything Simmons commanded him to do.

It became transparent to Barnhart that they were going to mutiny to avoid following their duty as clearly outlined in regulations. Judging from York's twitching knuckles, they were going to resist by strangling him.

Barnhart wondered if this was the time to show fear and unlock a weapon to defend himself.

York clamped onto him before he could decide on the proper interpretation of the regulations and just as his mind settled on the irresolvable question: If a captain must never show fear, why was he given the key to a hand weapons locker to use when in fear of his life?

Barnhart gazed around the purple clearing with clouded eyes. He trembled in near traumatic shock. It was almost too much to bear.

Regulations clearly stated that no officer was to be marooned on a .9 Earth-type planet at fourteen-forty Galactic Time, early evening local.

Or (he brushed at his forehead) he was damned certain they at least strongly implied it.

But fear was such a foreign element to his daily routine he discarded it.

The scene took him back to his boyhood.

He sorted out the survival supplies, lifting even the portable nuclear generator effortlessly under the .67 gravity, and remembered how he used to go camping regularly every month when he was a Boy Scout. He had been a bookish child, too obsessed with reading, they told him. So he had put himself on a regular schedule for play. Still, it never seemed to make people like him much better. After he established his routine he didn't try to change it—he probably couldn't make things better and he certainly couldn't stand them any worse.

Barnhart paused in his labors and stripped off his soaked uniform shirt, deciding to break out his fatigues. As the wet sleeve turned wrong side out he noticed his wristwatch showed fifteen hundred hours.

As usual he fetched his toothbrush from the personals kit and started to scrub his teeth.

This was when he saw his first qurono in the act of geoplancting.

It was a deeply disturbing experience.

Barnhart and the lank, slick-bodied alien ignored each other every morning while the marooned captain had his coffee and the native chronoped; each afternoon while Barnhart laid down for a nap and the other xenogutted; and of course before retiring while Barnhart brushed his teeth and the alien did his regular stint of geoplancting.

The captain sat about arranging living quarters on the planet. The crew of the Quincey had provided him with every necessity except communications gear. Still he was confident he would find a way back and see that Simmons and the rest got the punishment clearly called for in Regulation C-79, Clause II.

This driving need to have the regulation obeyed was as close as he could get to anger.

His lot was a rough and primitive one, but he sat down to doing the best with things that he could. Using the nuclear reactor, he synthesized a crude seven-room cottage. He employed an unorthodox three-story architecture. This gave him a kind of observation tower from which he could watch to see if the natives started to get restless. Traditionally, this would be a bad sign.

Humming to himself, he was idly adding some rococo work around the front door when thirteen-hundred-thirty came up and he stopped for his nap. At the edge of the now somewhat larger clearing the alien was xenogutting in the indigo shadows of a drooping bush-tree. Since he hadn't furnished the house yet, Barnhart stretched out on the grass. Suddenly he sat upright and shot a glance at the alien. Could this sort of thing be regarded as restless activity?

He was safe so long as the aliens maintained their regular routine but if they started to deviate from it he was in trouble.

He tossed around on the velvet blades for some minutes.

He got to his feet.

The nap would have to be by-passed. As much as he resented the intrusion on his regular routine he would have to find some other natives. He had to know if all the aliens on the planet xenogutted each afternoon as he was having his nap.

The thought crossed his mind that he might not wake up some afternoon if his presence was causing the aliens to deviate dangerously from their norm.

The most unnerving thing about the village was that there were exactly ten houses and precisely one hundred inhabitants. Each house was 33.3 feet on a side. The surfaces were hand-hewn planking or flat-sided logs. There were four openings: each opposing two were alternately one foot and an alarming ten feet high. Barnhart couldn't see the roof. The buildings appeared square, so he supposed the houses were 33.3 feet tall.

At the end of the single packed, violet-earthed street facing up the road was a large sign of some unidentifiable metal bearing the legend in standard Galactic:

THIS IS A VILLAGE OF QURONOS

Barnhart received the information unenthusiastically. He had never before encountered the term. The sign might as well have told him the place was a town of jabberwockies.

The single scarlet sun with its corona of spectrum frost was drawing low on the forest-covered horizon. Barnhart, dry of mouth and sore of foot, had not encountered yet a single one of the hundred inhabitants. He had missed his nap and his dinner, and now (he ran his tongue over his thick-feeling teeth) he was about to miss his nightly brushing of his teeth. He had taken only a minimum survival kit with him—which did not include a smaller personals kit.

His wristwatch, still on good, reliable ship's time, recorded nearly fifteen hundred hours straight up. His body chemistry was still operating on the Captain's Shift, whereby he spent part of the time with both the day and night shifts. It was nearly time for him to go to bed. Fortunately it was almost night on the planet.

He was searching out his portable force field projector from some loose coins and keys when the one hundred quronos came out of their houses and began geoplancting.

Fifth Day Marooned

The Journal of

Captain T. P. Barnhart,

Late of the U.G.S. Quincey

It becomes apparent that I may never leave alive this planet whose name and co-ordinates have been kept from me. By reason, justice and regulations, the men who put me here must pay (see formal attached warrant against First Mate O. D. Simmons and the remainder of my crew). For this reason and in the interest of science I am beginning this journal, to which I hope to continue contributing from time to time, barring sudden death.

At this writing I am in a village of ten houses identified as a settlement of quronos. These tall, hairless humanoids have performed an intricate series of indescribable actions since I first encountered them. My problem, as is apparent, is to decide whether these actions constitute their normal daily routine or whether I have instigated this series of actions.

If the latter is the case: where will it all end?

1700: Fifth day

Barnhart was not used to being ignored.

It was certainly not a part of his normal routine. Often in his life he had been scorned and ridiculed. Later, when he earned a captaincy in the exploration service, the men around him had to at least make a show of respect and paying attention to him. Being ignored was a new experience for him. While it was a strange thing to say of an explorer, Barnhart didn't particularly like new experiences ... or rather he only liked the same kind of new experiences.

He kicked the wine-colored soil in red-faced impotence the first few dozen times quronos went silently past him on the way to gather fruit from the forest, or hew logs to keep the buildings in repairs (which seemed to be a constant occupation.)

However, when the twenty-fifth alien shouldered past him the morning after he first discovered the village, Barnhart caught him by the shoulder, swung him half around and slugged him off his feet with a stabbing right cross.

The alien shook his head foggily a few times and slowly climbed to his feet.

Barnhart bit at his under lip. That hadn't been a wise thing to do at all. He should know that unorthodox moves like that led only to certain disaster. He fumbled for his force-field projector, and with a flush of adrenalin discovered he had lost it.

Now, he thought, the alien will signal the rest of them. And they, all one hundred of them (now does that include the one I first saw in the clearing or not?) they will converge on me and—

The qurono marched off into the forest.

Everyone was still ignoring Barnhart.

Barnhart munched on a steak sandwich listlessly and watched the aliens through the faint haze of the force field.

He had found the projector half stamped into the earth and he was testing it. But even a test was foolish. None of them was close enough to him to harm him with so much as a communicable disease. He might as well quit roughing it and get back to the cottage.

In the last few days he had had time to think. He took up his journal.

Eighth Day

I can only suppose that these actions of the aliens represent some kind of religious ritual. Again I am presented with the problem of whether these rituals are a part of their normal, daily life, or are they a special series instigated by my presence?

Yesterday I observed two of the quronos repairing one of the village houses. The native lumber seems to be ill-suited to construction purposes. Several times I have noticed logs tearing themselves free and crawling back into the virgin forest. Due to the instability of their building materials the aliens are constantly having to repair their houses.

In watching the two quronos at work I observed something highly significant.

The humanoids worked smoothly as a team, splitting and planing down the reluctant logs with double-bladed axes. Then, putting the lumber in place, they fastened it down with triangular wooden pegs. They pounded these pegs home awkwardly with the flat side of the axes.

The axes are crude and obviously indigenous to the culture.

I view this with considerable alarm.

Obviously any culture that can produce an axe is capable of inventing the hammer.

The quronos are not using their hammers in front of me. I am producing a change in their routine.

Where will it end?

What are they saving their hammers for?

800: Eighth Day

Barnhart had written that just before dawn, but as usual the aliens had continued to ignore him. For all he knew the ritual might go on for years—before they used their hammers. Or whatever they were planning.

It was drawing near time for his nap, but he felt completely wide awake even inside the safety of the force field. His throat hurt and the backs of his legs ached with the waiting, the waiting for the natives to come out and begin xenogutting.

He wiped his hands together and forced a smile. Why should he worry what the natives did? He was completely safe. He could live out his life in immutable security.

But this wasn't his world. No part of it was his ... or at least only the part he had brought with him. Sanity lay in holding to what was left of his own world. But sanity didn't always mean survival.

What if he could make the quronos' world his own?

Barnhart wiped at the tiny stings against his face and his fingertips came away moist with beads of perspiration.

The aliens began marching out of the houses, in twos from the ten-foot doors, singly from the foot-square openings of every other facing wall.

It wasn't his world of fire-works-streaked Ohio summers and bold green hills, this planet cowled with nun-like secrecy, looking acrid, tasting violet and transmitting a beauty and confusion only a trio of physical scientists could solve.

But there was only one thing to do.

Barnhart let down his force field and went out.

The human body wasn't well-adapted for it but Barnhart did his best to join the quronos in xenogutting.

Instantly the cry welled up.

"Master."

Barnhart stood up and faced the aliens, deeply disturbed.

He was even more disturbed when, later, he wrote again in his journal:

Ninth day

"Qurono," I have learned from the Leader, is a term referring to a particular type of sub-human android. The synthetic process used in manufacturing these men does not allow them to develop beyond a certain point—a built-in safety factor of their creators, I can only suppose. Thus they were given the concept of the axe and have retained it, but they were able only to devise the idea of using the axe to hammer things with and are not capable of thinking of a special hammering tool.

With almost complete lack of creative ability they are bound to the same routine, to which they adhere with an almost religious fanaticism.

Since last night I have been treated as virtually a god. I have been given one of their buildings entirely for my own use.

I find this turn of events absolutely surprising. I intend to discuss this with the Leader today. (Note to any ethnologist who may see these papers: Since all quronos are built to the same standards none is superior to another. But, recognizing the need for one director, each of the one hundred has an alternate term as Leader.)

900: Ninth day

Despite the upsetting turn of events Barnhart decided he was more comfortable in his familiar role of command.

He glanced at his wristwatch and was surprised to note that he had overslept. The time for both breakfast and chronopting was past. He made himself ready and left the building.

The alien was waiting just outside the door. He looked as if he hadn't moved all night. Yet, Barnhart thought, he seemed a trifle shorter.

"Are you the Leader?" Barnhart asked.

"I am the Leader. But you are the Master."

As an officer of a close-confines spaceship that sounded a little stuffy even to Barnhart. The fellow still looked shorter. Maybe they had changed Leaders the way he had been told the night before. Or maybe quronos shrank when left out in the night air.

"Let's go someplace where we can sit down. And, incidentally, just call me 'sir' or 'captain.'"

"Yes, sir."

Barnhart nodded. He had been expecting: Yes, Master, I will call you 'captain.'

But the alien didn't move. He finally decided that the Leader thought they could sit on the ground where they were standing.

Barnhart squatted.

The Leader squatted.

Before they could speak a muffled explosion vibrated the ground and Barnhart caught a fleeting glimpse of an unstable chemical rocket tearing jerkily into the maroon sky.

"Celebration for my arrival?" Barnhart asked.

"Perhaps so. We are putting the un-needed ones in status."

He decided to let that ride for the moment.

"Tell me, why didn't you recognize me before I joined you in your—ritual, Leader?"

The alien tilted his head. "What was there to recognize? We thought you were some new variety of animal. Before you xenogutted how were we to know you were rational life?"

Barnhart nodded. "But how did you so cleverly deduce that I was your Master?"

"There are one hundred of us. You were the one hundred and first. You had to be the Master returned."

The Master had been some friendly lifeform in the Federation, obviously. Otherwise the qurono androids wouldn't speak Galactic. Barnhart nibbled on his under lip.

"I want to find out how much you still know after the Master has been away so long," the captain said. "Tell me, how do you communicate with the Master?"

"What for?" The Leader began to look at Barnhart oddly.

"For anything. Where's the sub-space radio?"

The direct approach produced a rather ironic expression on the qurono's narrow face but no answer. But if there was a radio on the planet Barnhart meant to find it. Spacemen forced to abandon their craft were required to report to the nearest Federation base as quickly as possible. Besides, he meant to see that Simmons and his Anglo stooge and all the others paid for their mutiny. But, he decided, perhaps he had better not press the matter at the moment.

Another rocket punctuated the moment of silence.

"Take me to your launching area," Barnhart said.

The android stood up and walked. But he walked at Barnhart's side, forcing the captain to catch his stride a half-step to let the alien lead him. He wasn't sure if it was a mark of respect not to get ahead of the Master or an attempt to see if he knew where the launching site was located. The quronos were limited, but just how limited Barnhart was beginning to wonder.

They rounded the clump of drooping lavender trees and Barnhart saw the eight men laying on the ground in the transparent casings. Not men, but quronos, he corrected himself; in a molded clear membrane of some sort.

"They are in status," the Leader explained, answering the captain's unasked question.

"This is how you keep your population at one hundred," Barnhart thought aloud, removing his glasses to rest his eyes and to get a better look at the bodies. Despite regulations he could still see better without his spectacles.

"It is how you arranged it, Master. But as you know we are now ninety and one."

The captain put his glasses back on. "I'll test you. Why are you now ninety and one?"

"Naturally," the Leader said emotionlessly, "you required a whole shelter unit to yourself. We had to dispose of the ten who previously had the unit."

Barnhart swallowed. "Couldn't you think of anything less drastic? Next time just build a new unit."

"But master," the alien protested, "it takes a great deal of work to construct our units. Our lumber escapes so badly no matter how often we beat it into submission. Our work capacity is limited, as you are aware. Is it really desirable to overwork us so much?"

The captain was a little shocked. Was this humorless, methodical android really protesting a command from his Master? "How do you suppose the ten you are putting in status feel about it?" he managed.

"They would doubtlessly prefer not to be overworked. Our fatigue channels can only stand so much."

But it wasn't the work, Barnhart suddenly knew. It was the idea that there could be eleven houses, instead of ten. The concept of only ninety quronos and a master must be only slightly less hideous to them. They couldn't really be so overjoyed to see him.

A third rocket jarred off, rising unsteadily but surely in the low gravity. It was a fairly primitive device—evidently all they retained from the original model supplied them by the Master.

Barnhart looked at the figures on the ground. Only seven.

"The ones in status go into the rockets!" Barnhart gasped.

"And circle in the proper orbits," the Leader agreed.

This time he saw the quronos lifting a stiff form and taking it to the crude rocket. It looked entirely too much like a human body. Barnhart looked away.

But at the edge of his peripheral vision he saw the quronos halt and stand up their fellow in status. He glanced at his wrist. Fifteen hundred hours. The aliens began geoplancting.

Barnhart ran his tongue over his teeth, noting that they needed brushing. He came to himself with a start.

Of course. He had almost forgot.

Barnhart faced the others and joined them in geoplancting.

A hideous cry built from one plateau of fury to another.

"He's no better than us!" the Leader screamed.

Ninth day

I have made a serious mistake.

While it was necessary for me to conform to the quronos' ritual to get myself recognized, I should not have continued to adhere to it. Apparently by these creatures' warped reasoning I established myself as a reasoning creature by first joining them in their routine; but when I continued to act in accord with them I proved myself no better than they are. As Master I am supposed to be superior and above their mundane routine.

At the moment they are milling belligerently outside my force-field screen. As I look into their stupid, imaginationless faces I can only think that somewhere in the past they were invented by some unorthodox Terran scientist, probably of English descent. They—

Wait.

The force field. It's wavering. It must have been damaged when it got tramped underfoot. They are going to get in to me. It—

Barnhart watched them prepare the rocket that would blast him into an orbit circling the planet. He could see and even hear the sound that vibrated through the thin membrane in which he was encased, but he could not move a nerve-end. Fortunately his eyes were focused on infinity, so he could see everything at least blurrily.

The Leader, who seemed to have grown a few inches, wasted no time. He gave the orders and the quronos lifted him into the rocket. The hatch closed down on the indigo day and he was alone.

The blast of takeoff almost deafened him but he didn't feel the jar—only because, he realized, he could feel nothing.

A few weeks later the centrifugal force of the spinning rocket finally nudged the latch and the hatch swung open. Barnhart was exposed to naked fire-bright blackness itself.

After a day or two he stopped worrying about that, as he had stopped fretting about breathing.

He grew accustomed to the regular turn around the planet every fourteen hours. For two out of every three seconds he faced out into space and that was always changing. Yet, all poetry aside, the change was always the same.

He didn't have to worry about keeping on a schedule. He kept on one automatically.

And he didn't like it.

So he kept retreating further and further from it....

"We couldn't leave him there!"

What? Who? Barnhart thought along with at least seven other double-yous. He returned to himself and found that he was standing in the airlock of a spaceship, faced by his first mate Simmons and his stooge York.

"We couldn't leave him there," Simmons repeated with feeling. "That would be the nastiest kind of murder. We might maroon him. But none of us are killers."

"It's not the punishment we will get for the mutiny," York complained. "It's having to go back to his old routine. That time-schedule mind of his was derailing mine. He was driving the whole crew cockeyed. Even if he wasn't going to kill us all by the rule book, I think we would have had to maroon him just to get rid of him."

Simmons fingered a thin-bladed tool knife. "I wonder how he got up there in that rocket and in this transparent shroud? I'm sure he's alive, but this is the most unorthodox Susp-An I've ever seen. Almost makes you believe in destiny, the way we lost our coordinate settings and had to back-track—and then found him out there. ("I'll bet he jimmied the calculator," York grouched.) You know, York, it's almost as if the world down there marooned him right back at us."

The first mate inserted the knife blade. The membrane withered and Barnhart lived.

"Now the arrest," York murmured.

"What are you muttering about, York?" Captain Barnhart demanded. "What are we standing around here for? You can't expect me to waste a whole afternoon on inspection. We have to get back on schedule." He looked to his wrist. "Fifteen hundred hours."

"He doesn't remember," York said behind him.

"He remembers the same old routine," Simmons said. "Here we go again."

Barnhart didn't say anything. In the close confines of a spaceship there was bound to be a certain degree of informality.

He stepped inside his cabin at the end of the corridor and did what he always did at fifteen hundred hours.

York and the first mate were deeply disturbed.

Barnhart looked out at them sharply. "Well, spacemen, I run a taut ship here. I expect everyone to hit the mark. Adhere to the line. Follow my example. Snap to it!"

Simmons looked at York and his shoulders sagged. They couldn't go through the whole thing again, the marooning, the rescue, then this. That routine would drive them crazy.

Even this was preferable.

They joined Barnhart in geoplancting.