Fig. 1.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of ASCE 1190 The Valuation of Public Service

Corporation Property, by Henry Earle Riggs

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: ASCE 1190 The Valuation of Public Service Corporation Property

Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers,

vol. LXXII, June, 1911

Author: Henry Earle Riggs

Release Date: February 24, 2016 [EBook #51298]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK VALUATION--PUBLIC SERVICE CORP. PROPERTY ***

Produced by Richard Tonsing, Juliet Sutherland and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

With Discussion by Messrs. F. Lavis, Charles H. Higgins, S. D. Newton, William V. Polleys, C. P. Howard, J. E. Willoughby, Henry C. Adams, Carl C. Witt, R. A. Thompson, Charles H. Ledlie, William G. Raymond, W. H. Williams, P. E. Green, E. Kuichling, Richard T. Dana, George T. Hammond, Leonard Metcalf, Charles Hansel, J. Martin Schreiber, Clinton S. Burns, Halbert P. Gillette, Arthur L. Adams, C. D. Purdon, A. Mordecai, W. B. Ruggles, and Henry Earle Riggs.

The industrial and economic development of the past two decades has opened many new lines of special work in the Profession of Engineering, none of which is more difficult and complicated or of greater ultimate value to the public at large than that of the appraisal or valuation of the property owned and operated by public service corporations; and none of the fields of engineering specialization requires greater care or calls for more skill, experience, integrity, or sound judgment.

The individual engineer, or commission of engineers, entering upon an appraisal of large magnitude, particularly one including properties of more than one company, will find conditions varying in every one, and each property presenting new, complex, and confusing elements of value to pass upon and determine.

Prior to 1900 there had been few calls on engineers for large appraisals, and the literature descriptive of engineering effort along 2this line was practically nothing. Since 1900 many extensive appraisals have been undertaken by States, by railroad and banking corporations, and by cities; certain well-defined lines of practice have been developed; many differing opinions as to certain methods and principles have been brought out; and enough has been added to the printed literature to enable one to compare methods of work and to fix with reasonable certainty upon some as correct, and to discard others as improper.

There are so many complex factors entering into the problem of valuation, so many widely different plans have been presented, and there are so many thinking men who have opposed and do honestly and sincerely oppose any form of valuation, that a most thorough study of the subject should be made. It should be examined from all angles, and every possibility of danger from legislation regarding it should be weighed with utmost care.

The question of railroad valuation, involving as it does the largest industry of the nation, naturally takes first place in such a discussion, but so many of the general principles of railroad valuation are applicable to the appraisement of corporate property, so many arguments have been advanced by engineers and others, and so many judgments of the Courts have been rendered in connection with water-works and gas-works valuations, that it is not desirable to limit this discussion wholly to the problem of railroad valuations.

The reasons for requiring that valuations be made may be broadly divided into two general classes:

First.—As a Matter of Public Interest.—The public, and particularly the investing public, requires valuations in order to guard against unworthy and dishonest corporation securities, to be assured that corporations are bearing their legitimate and proper share of the burden of taxation, and to furnish a proper basis for fixing equitable and just rates for the services rendered by the corporation.

Under this class would come all appraisals made for information to be used as a basis for legislation relative to:

(a) Taxation of Corporations.—Such were the valuations in Michigan and Wisconsin.

(b) Rate Regulation.—This was the reason which prompted the work in Minnesota and Nebraska.

(c) Limitation of Capitalization.—The regulation of issue of stocks and bonds was the purpose of the Texas valuation.

3(d) Fixing a Price for Sale.—Many of the water-works and electric light valuations were made in order to determine a fair price to be paid for the property at the expiration of the franchise.

(e) The General Information of the Public.—To be used in connection with the fixing of terms for franchise renewals, etc., etc.

Second.—As a Matter of Corporation Necessity or Expediency.—Valuations are made in order to guide large investors, to secure a safe and up-to-date basis on which to negotiate a sale, a purchase, or a reorganization of the property, or a consolidation with other like properties, and to secure justice to honestly administered corporations.

The great majority of appraisals under this head have been in accordance with some other methods than those adopted in the State valuations. It is not intended in this paper to engage in any argument as to the various purposes of appraisals, or even to urge the necessity or desirability of a general appraisal of properties. An absolutely accurate and correct statement of the cost of reproduction of all the physical properties of the railroads of the country, a correct statement of the actual capital needed to reproduce these properties as they exist, and, along with this, a statement of the actual physical depreciation, would be a document of vital interest.

This paper is confined to a discussion of the methods which should be used in arriving at a correct figure of cost of reproduction and depreciation—it does not take up questions involving the propriety of those figures when reached. The propriety or legality of using such figures as a basis for an assessed valuation, as a basis for rate-making (rate-making being an art in itself involving complications as great as those encountered in valuation), or any arguments as to the justice or injustice of legislation restricting issues of stocks or bonds, will be conceded no place in this paper. It is assumed that all these questions would have been taken up and a satisfactory answer reached before a valuation could have been ordered.

The different elements of value in property, the relations of this property to the public, the method of determining the worth of these elements of value which have been adopted in the past by men engaged on valuation work, a comparison of these methods, a discussion of the objections that have been made to them, and a presentation, not only 4of the writer's views as to proper methods, but those in which he disagrees with usages adopted by others—these define the scope of this paper.

No matter what particular end is to be served by a valuation, the commission engaged upon it will be asked to furnish a fair value, perhaps with reasonable limitations in the instructions, perhaps with a general and indefinite instruction to find the value. They will encounter, among other difficulties:

First.—The fact that human machines are not exact duplicates, and that allowance must be made for a large measure of error, on account of the personal equation of the men engaged on the work, as individual errors of judgment are frequent on any work of magnitude. This personal element must be corrected by uniformity of method, by constant checking, and, as far as possible, by subordination of personality to system.

Second.—The fact that human selfishness is a dominant quality—the railroad manager who opposes methods which he believes will increase values in an appraisal for taxation, or who, on the other hand, uses every possible argument to increase values if the work be as a basis for rate-making or for restriction of bond issues, or the State official who is desirous of using original cost on a valuation to be used for rate-making in order to keep the valuation down to a minimum, and the politician who depends on an unenlightened public opinion to create sufficient outcry to influence the work to his advantage—are all actuated by a perfectly human wish to attain ends which seem to them desirable, and are but typical of men who will endeavor to influence every appraisal.

In view of these considerations, it is a question whether results are not frequently affected by the knowledge of their intended use, and whether a system which will entirely remove such causes of error can be applied to the work.

If an engineer, or a commission of engineers, is directed to examine a certain property and report the true cost of reproduction, depreciation, or present value, taking into account all facts connected therewith, the final figures should not differ, whether the report is to be used as a basis for reorganization, sale to another corporation, or is to be used by a State legislature as a basis for formulating a rate bill, or as a basis for a value for taxation. The result secured is a 5necessary preliminary on which depends the accuracy, fairness, and justice of the other work which is to follow. This is an engineering work, a statement of certain physical property, the estimated cost of reproducing it new, less the estimated depreciation, and, beyond the differences due to personal judgment, these figures may not vary.

The word "value" is in common use, and yet, in the minds of many people, its exact meaning is vague. It is true that the "value" of a property is an unstable figure, subject to fluctuations due to natural or artificial causes, and that a material change in value may occur suddenly, but the "value" of any given property on any given date is, or should be, from an engineering standpoint, a definite sum which may not be varied or changed to suit the whim or will of the people for whom the work is done.

In all the subsequent discussion of values and methods of obtaining values, it is assumed that, unless specifically limited to a determination of cost of reproduction and depreciation, a valuation commission should be governed by the following rules:

1.—No account may be taken of the purpose for which the resultant figure of value is to be used; and the result should not vary, no matter what that purpose may be.

2.—The resultant figure should be the honest judgment of the men composing the commission, as to the actual cost of reproduction, present physical value, or "fair value," and should be ascertained by a systematic and scientific method which takes into account all the facts concerning the property, its physical value, its strategic location, its operating revenues and expenses, and its franchises, rights, competition, opposition, and all other tangible or intangible elements which would affect values. The method of valuation should be such as to minimize or entirely eliminate all differences due to errors of personal judgment.

3.—All properties being appraised are considered as operating properties. One which is dead, inert, and not in use, cannot be considered as coming under such a discussion as this, and such properties are not treated in this paper. The term "going concern" is not used in connection with the physical property, any element of value implied by the term, over and above the "overhead charges," being treated as an intangible or non-physical element of value.

6In stating this position, the writer is aware that it is a difficult matter indeed to get away from the fact that some specific purpose—taxation, for example—is the definite end in view in every valuation, and that, instinctively, men engaged on the appraisal will find themselves modifying their figures to meet some real or fancied condition which they conceive might arise, or to prevent some injustice which they believe might be done. Every subordinate employee needs to be watched, every man in charge must watch himself, or he will find himself unwittingly, almost instinctively, coloring his results by some old prejudice of his early years of employment, or some loyalty to his own ideas of governmental or economic policy. The writer has noted this in every appraisal on which he has been engaged, and calls particular attention to it as the first difficulty which must be overcome in the organization of the force for a large appraisal.

In the following pages all complications which might arise from the purpose of the appraisement are considered as eliminated, and the possibility of erroneous conclusions being reached by reason of the personal factor (while recognized as being ever present) will not be specially emphasized.

1. Presented at the meeting of January 4th, 1911.

In reference to questions of value, the engineering commission must hear, consider, and reconcile arguments advanced by adverse and often hostile interests. On the one side stand the corporations, with large financial interests involved, often with an excessive amount of stock and bonds issued on the property, the existence of which issues the corporation wishes to justify, and, whether properly capitalized or not, the management being imbued with the perfectly human desire to defend corporate interests from attack of any kind; on the other side is public opinion, often unreasonable, often misinformed, and frequently prejudiced.

It appears necessary, therefore, to consider briefly the relation which these interests bear to one another, to study the causes which have led to mutual misunderstandings, and to note the proper relations which should, if possible, be established and maintained between the people and those corporations organized to perform certain of the functions of the State.

7A public service or quasi-public corporation is a corporation which is operating under the terms of rights, grants, or franchises given by the public, either to this particular corporation direct or granted by statute to a class of corporations.

The property of the corporation is used to render certain services to the public, with the expectation of financial gain.

It is not material whether the grant be a franchise permitting a water-works company to use the streets and alleys of a city for its mains, and the service be the pumping of water for domestic service and fire protection, or whether the grant be the statutory rights of corporate existence and eminent domain, and the service rendered be the transportation of freight and passengers; the general principle is the same; the company has secured from the people certain rights which enable it to do business, and the people are directly benefited by the services rendered by the company. The increased comfort of living makes for the growth of the city; the increased transportation facilities build and develop the country traversed by the railroad; and this growth and development, not only operate to the advantage of the people, but also to that of the company in the way of increased business and increased revenues.

The capital required to build and develop these properties was furnished in the hope of, and with the expectation of, a proper financial reward. It has frequently happened that such properties have been built years in advance of sufficient development to support the enterprise, built, in fact, without expectation of immediate returns, and long periods of time have often elapsed before any profit has been secured.

It has also frequently happened that corporations have been aided to a very large extent by public funds, by the voting of aid bonds, by the donation of large tracts of land, by payment for certain service at such rates as would largely relieve the company from loss in operation, by the remission of taxes, or by the direct donation of funds.

The company is clearly entitled to earn a reasonable profit on the actual capital invested, in addition to the legitimate cost of operation, payment of taxes, and sinking funds to cover depreciation and obsolescence.

The public is clearly entitled to good service at the lowest rates that will permit the company to earn its reasonable profit and expenses. Increases in tonnage, population, and consequent net earnings 8of the corporation should entitle the public to a benefit in reduced charges for service, when the increased earning is of a permanent character.

The general tendency of the Courts has been to treat a franchise as a contract, and to be governed closely by the language and evident intent of the makers, but to safeguard the rights of the public to the fullest extent consistent with justice.

A franchise requires specific performance of specific acts. Nothing will be assumed or implied. The Courts recognize that the investors are entitled to reasonable returns, and that the public is entitled to fair rates.

In the case of Los Angeles Water Company vs. City of Los Angeles (103 U. S., 711), the United States Courts held that at the expiration of a 30-year franchise, which provided that the city was to pay for the value of all improvements, when the city failed to agree upon, tender, or pay such value, so long as the company complied with the terms of the contract, and until the city terminated it by making or tendering payment, the passage of an ordinance by the city fixing rates was void.

In the case of Weatherly vs. Capital City Water Company (Ala. 22 So., 140), the Alabama Courts held that the acceptance of a franchise involved a grave responsibility, and that the company could not stop furnishing water and fire protection, even if the work was done at a loss.

In the case of Myer vs. Brown (65 Cal., 589), the Court said:

"It is well occasionally to recall the fact that there is no more reason to permit a municipal government to repudiate its obligations entered into for value, than to permit an individual to do so. Good faith and fair dealing should be exacted of one equally with the other."

Judge Brewer, in the Kansas City Water-Works case (62 Fed. Rep., 853), said:

"All contracts involving property rights and obligations, between municipalities and individuals, must be presumed to be based upon and to recognize the ordinary laws of business transactions."

In 1903 the Maine Supreme Court issued a set of instructions to appraisers appointed to fix values of certain properties. The Court set forth its views as follows:

"Summarized, these elemental principles are, the right of the company to derive a fair income based upon the fair value of the property 9at the time it is being used for the public, taking into account the cost of maintenance and depreciation and the current operating expenses, and the right of the public to demand that the rates shall be no higher than the services are worth to them, not in the aggregate, but as individuals."

The Supreme Court of the United States has again and again given its views, which may be summarized as follows:

"It cannot be said that a corporation is entitled, as of right, without reference to the interests of the public, to realize a given per cent. upon its capital stock. When a question arises whether the legislature has exceeded its constitutional powers in prescribing rates to be charged by a corporation controlling a public highway, stockholders are not the only persons whose rights and interests are to be considered. The rights of the public are not to be ignored.

"The public cannot properly be subjected to unreasonable rates in order simply that stockholders may earn dividends. The legislature has the authority in every case, where its power has not been restrained by contract, to proceed upon the ground that the public may not rightfully be required to submit to unreasonable exactions for the use of a public highway established and maintained under legislative authority." (164 U. S., 578.)

"It is not to be inferred that the power of limitation or regulation is itself without limit. This power to regulate is not a power to destroy, and limitation is not the equivalent of confiscation. Under pretense of regulating fares and freights the State cannot require a railroad corporation to carry persons or property without reward, neither can it do that which in law amounts to the taking of private property for public use without just compensation. * * *" (116 U. S., 307.)

In the case of Smyth vs. Ames (169 U. S., 466), the Court said:

"If a railroad corporation has bonded its property for an amount that exceeds its fair value, or if its capitalization is largely fictitious, it may not impose upon the public the burden of such increased rates as may be required for the purpose of realizing profits upon such excessive valuation or fictitious capitalizations; and the apparent value of the property and franchises used by the corporations, as represented by its stocks, bonds and obligations, is not alone to be considered when determining the rates that may reasonably be charged. * * *

"We hold, however, that the basis of all calculations as to the reasonableness of rates to be charged by a corporation maintaining a highway under legislative sanction must be the fair value of the property being used by it for the convenience of the public.

10"What the company is entitled to ask is a fair return upon the value of that which it employs for the public convenience. On the other hand, what the public is entitled to demand is that no more be exacted from it for the use of a public highway than the services rendered by it are reasonably worth."

The relations between the corporations and the public that they serve have been clearly defined by the Courts, as the foregoing quotations show.

That the mutual relations existing between the management of the corporations and the public are far from what they should be, there can be no doubt. On the one hand, the great mass of the voting public is uninformed as to actual revenues, disbursements, and operations of the corporations, as to whether their income is unreasonably large, or whether they are struggling to exist. The sums of money involved in the dealings of the corporations are so stupendous in comparison with the amounts used in an ordinary private business—even in one of considerable magnitude—that the majority of the public cannot comprehend them. The published statistics are in such form that only the careful student of affairs can understand or analyze them, and but few of the public officials who receive them are able to read the reports of the properties and comprehend them. As a consequence, the corporation, as a political issue, has been the subject of jest, gibe, and cartoon; there has not been an intelligent public discussion of available reports and statistics, and it may be said that, generally, the mass of the public has come to class all corporations as grasping, overbearing, and unjust, and to consider them all as exceedingly prosperous. This has been taken advantage of by politicians for their own selfish ends, and has led to sundry legislation, some of which has been unreasonable and unjust to the corporations, and much of which is aimed at real abuses that never ought to have existed.

The reasonableness of a rate depends, not alone on the amount of capital invested, but on the volume of traffic, the density of population, the actual cost of service, and many other elements. Rate legislation has been attempted without full investigation. Acts have been passed compelling the establishment of stations and terminals, the improvement of roadway and structures, the purchase of new equipment, the installation of safety appliances and block signals, and many other requirements have been made, some (but by no means all) of 11which are unreasonable and burdensome. Nearly one-half the States of the Union have by law required a 2-cent, or 2½-cent, passenger fare, regardless of density of population, amount of traffic, or other considerations which might render such rates unreasonable. The regulation of the carriers, by legislature, by railroad commissions, by State officials, and by Courts, the addition of burdens of expense, and the cutting off of revenue, all give considerable ground for the opposition of the carriers to anything that looks like hostile legislation, and compels the student of affairs to admit that there is justice in the claim of the managements, that there is grave danger, not only of seriously crippling many roads, but of so impairing the credit of the railroads as a class that it will be increasingly difficult to secure capital to provide for the necessary extensions and development of the transportation facilities of the country.

On the other hand, perfect frankness compels the admission that the state of public opinion which compelled the passage of these laws has been caused largely by the corporation officials themselves. There is probably no more loyal body of men in America to-day than the officials and employees of railroads. Their loyalty, however, is all to "our company." They enter its service as boys or young men; they grow up to the full strength of manhood working for its good; they take little or no part in public affairs; they have no time for the study of public questions. Their friends are almost exclusively among their own associates in the service of the road, and their development is along the lines of their own special work in the service. As a body of honest, honorable, and worthy men, absolutely loyal to their employers, they have few equals; but it is doubtful if any equal number of men, of equal intelligence, have as limited a knowledge of the fundamental truths of government, or knowledge so colored by bias. It is also doubtful whether any equal number of men have in their ranks so few who bear an active part in the duties and activities of citizenship, or who exercise large influence on their neighbors.

While the foregoing statement is believed to be absolutely true, it will not do to pass over the notable exceptions. Such men as James J. Hill, F. Am. Soc. C. E., M. E. Ingalls, and others of the higher officials, who have taken an active part in public affairs, have had commanding influence. Theirs has been the sound policy, as the property in their hands has not suffered. The short-sighted 12policy which, in December, 1909, induced the management of one road to compel all its employees holding municipal offices to resign, is bound to react and create hostile feeling on the part of the public.

The entire trend of a training in railway service is to fill a man with prejudice against all things that undertake to regulate or control the corporations, and often goes so far as to enable him to do, willingly and as a matter of right, things which with a broader view of the interest of the whole community he would not agree with at all. The result of this intensive training is that the railway service has in it thousands of men who become impatient with any effort to regulate or control; who permit their irritation to show; and who, by their own attitude, create unnecessary hostility. F. A. Delano, M. Am. Soc. C. E., President of the Wabash, in an address[2] at Hannibal, Mo., on March 25th, 1909, said:

"In ordinary manufacturing or commercial undertakings, every man has his own notions about the conduct of his business, and does not want to be interfered with, or dictated to by people who know less about his business than he does himself. Now, while it may be argued in the case of public service corporations that the people who have put their money into these enterprises, have done it with their eyes open and with full knowledge that they were subject to governmental regulation and control, there is nothing in that argument which makes public interference any more palatable to the man or group of men who are interfered with."

This address well expresses the spirit of the railway managers and employees toward all forms of investigation, and the complete lack of understanding, on the part of these managers, of the legal and moral relations which they bear to the communities which they serve. It is extremely unfortunate that railway and corporation people have not taken the public fully into their confidence, and fully and freely given out correct information as to the operation and depreciation of their properties; also, it is unfortunate that, when a corporation official does feel a grievance, he permits himself to make a partisan speech, or write an unwise article for publication. Much hostility is traceable to foolish, undiplomatic sayings or writings of corporation managers (which are often but half quoted), or to equally foolish speeches or newspaper editorials in opposition to the corporations, which are taken seriously by the managers. Whatever may be the cause, there 13is a regrettable hostility, and, on the part of the corporation officials, there is an apparent unwillingness to admit right motives to anyone advancing theories regarding corporate regulation and control, due largely to the training and atmosphere surrounding the corporate service.

The public has a large bill of particulars, one of which is the promotion of wildcat companies, such, for instance, as the "New York and Chicago Air Line" project which, only a year or so ago, drew from $2,000,000 to $3,000,000 from the people in a limited territory. These people were "investing" in railway stocks. A Federal control of the issue of stocks and bonds would have prevented this and hundreds of like swindles. Any move to secure such a law has always been opposed by the management of large and legitimately operated corporations, under the impression that they are about to be persecuted, and, naturally, the victim classes these corporations with the alleged one that secured his money.

The issue of stocks and bonds far in excess of any possible cost or value of railroad, street railroad, and other properties, and the making of large personal fortunes by the promoters, are matters of such frequent occurrence that it is difficult, indeed, to dismiss them with a mere denial. There is hardly a community of any size which has not had its example of "consolidation," "combine," or "merger," which has resulted in the issue of excessive securities; and there is hardly a citizen of any intelligence who has not either seen or had experience with some form of corporation promotion carried on strictly within the law, but which, nevertheless, in plain language, was a swindle. These, to say nothing of some gigantic deals involving millions, will sooner or later compel some form of regulation of the issues of stocks and bonds. In the last analysis, it is the money of the people, the hundreds of thousands of small investors, depositors in banks, and owners of life insurance, whose money goes into corporation securities, and, until the officers of the great railroads co-operate in securing such forms of control of stock and bond issues as will make impossible the purely speculative "wildcat" corporations, and thus safeguard minor corporations, as to furnish at least reasonable security to those whose money is invested, all forms of corporation security must be under suspicion with the public, and the agitation for control must continue.

14It is not, as Mr. Delano says, a case of put your money in with your eyes wide open; it is an effort on the part of the people to safeguard this form of corporate security in such a way that it can be treated as any other form of sound investment. It should not be necessary to require that all investors in corporate securities be financial experts. It is the writer's opinion, based on his observation and professional practice, that the railroads are not generally open to charges of over-capitalization. While there are flagrant instances, the chief culprits are among other classes of corporations. If such be the fact, it would seem that the interests of the great railway corporations would be in no wise jeopardized by sane and reasonable control.

The theory of taxation is that every one shall bear his proportionate burden of the cost of maintaining the government.

Regardless of any opinions that may be held as to the propriety of the methods adopted in the Interstate Commerce Commission's commercial valuation of railroad properties, it will be conceded that the results gave a set of figures for all the States of the Union, secured by a uniform method of computation and distribution. Table 1, which is a compilation from Tables 1 to 11 of Bulletin 21, shows clearly why, in certain States, corporate taxation is a live issue, and if (as suggested by Mr. Williams in his article, elsewhere referred to) amendment of the Constitutions of some of the States is necessary, it is safe to assume that the condition of inequality shown by this table is such as to compel these changes.

It is needless to cite further instances; enough has been said to indicate:

First.—That the corporations and the public have such intimate business relations that a blow at either must necessarily injure the other seriously;

Second.—That the Courts have defined quite clearly the legal relation existing between the two interests;

Third.—That there is lacking a proper spirit of mutual confidence, and the two interests at the present time are generally hostile;

Fourth.—That there have been errors and abuses on the part of both corporations and public; and

Fifth.—That capital invested in corporations is, and should be, the money of the people, and should be safeguarded so as to prevent its loss by manipulation, and insure a fair return.

| State or territory. | Miles of single track. | Commercial value: June 30th, 1904. | VALUATION FOR ASSESSMENT. | Ratio of assessed to commercial valuation: Percentage. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year. | Amount. | ||||

| Alabama | 4,669.35 | $150,211,000 | 1905 | $53,926,026 | 35.9 |

| Arkansas | 4,126.44 | 124,626,000 | 1904 | 34,709,623 | 27.8 |

| California | 6,262.54 | 350,694,000 | 1904 | 92,378,550 | 26.3 |

| Colorado | 4,976.24 | 198,261,000 | 1903 | 49,492,135 | 25.0 |

| Connecticut | 1,017.72 | 105,369,000 | 1904 | 120,493,648 | 114.4 |

| Florida | 3,555.84 | 80,467,000 | 1904 | 21,817,478 | 27.1 |

| Georgia | 6,304.72 | 156,603,000 | 1903 | 63,105,810 | 40.3 |

| Idaho | 1,461.53 | 91,877,000 | 1904 | 10,115,378 | 11.0 |

| Illinois | 11,622.74 | 805,057,000 | 1904 | 425,709,055 | 63.8 |

| Indiana | 6,917.85 | 375,541,000 | 1904 | 165,863,367 | 44.2 |

| Iowa | 9,859.23 | 344,847,000 | 1904 | 57,535,160 | 16.7 |

| Kansas | 8,811.43 | 356,356,000 | 1904 | 60,093,534 | 16.9 |

| Kentucky | 3,253.00 | 155,772,000 | 1904 | 77,658,040 | 49.9 |

| Louisiana | 3,898.74 | 123,401,000 | 1904 | 29,044,195 | 28.9 |

| Michigan | 8,660.29 | 277,597,000 | 1904 | 196,795,000 | 70.9 |

| Minnesota | 7,811.04 | 466,734,000 | |||

| Mississippi | 3,480.25 | 107,884,000 | 1902 | 29,847,640 | 27.7 |

| Missouri | 7,711.05 | 309,768,000 | 1903 | 97,916,869 | 31.6 |

| Montana | 3,267.10 | 196,209,000 | 1904 | 36,759,827 | 18.7 |

| Nebraska | 5,820.88 | 263,170,000 | 1904 | 46,082,853 | 18.5 |

| Nevada | 986.56 | 43,745,000 | 1904 | 13,778,049 | 31.5 |

| New Hampshire | 1,275.97 | 79,786,000 | 1904 | 22,625,000 | 28.3 |

| New Jersey | 2,277.85 | 333,568,000 | 1904 | 231,655,525 | 69.5 |

| New York | 8,297.29 | 898,222,000 | 1903 | 229,582,064 | 25.6 |

| North Carolina | 4,075.00 | 113,146,000 | 1904 | 69,480,974 | 61.4 |

| North Dakota | 3,190.77 | 689,797,000 | 1904 | 133,858,945 | 19.4 |

| Oklahoma | 2,611.03 | 78,668,000 | 1905 | 11,936,317 | 15.2 |

| Pennsylvania | 11,023.24 | 1,420,680,000 | |||

| Rhode Island | 211.89 | 25,719,000 | 1904 | 15,832,003 | 61.6 |

| South Carolina | 3,175.28 | 75,500,000 | 1903 | 29,467,716 | 39.0 |

| South Dakota | 3,047.14 | 49,646,000 | 1904 | 14,354,930 | 28.9 |

| Tennessee | 3,480.83 | 131,166,000 | 1903 | 58,536,566 | 46.6 |

| Texas | 11,848.03 | 237,718,000 | 1904 | 95,209,785 | 40.0 |

| Utah | 1,779.69 | 90,325,000 | 1904 | 20,682,461 | 22.9 |

| Vermont | 1,063.25 | 37,311,000 | 1902 | 27,344,020 | 73.3 |

| Virginia | 3,932.33 | 211,315,000 | 1904 | 63,269,623 | 37.7 |

| West Virginia | 2,836.83 | 201,799,000 | 1904 | 28,771,358 | 14.2 |

| Washington | 3,355.83 | 182,837,000 | 1904 | 26,066,949 | 14.3 |

| Wisconsin | 7,048.76 | 284,510,000 | 1904 | 218,024,900 | 76.6 |

| Wyoming | 1,247.70 | 100,307,000 | 1904 | 7,498,232 | 7.5 |

| Arizona | 1,751.35 | 68,356,000 | 1904 | 6,667,349 | 9.7 |

| District of Columbia | 32.00 | 5,578,000 | 1904 | 2,486,024 | 44.6 |

| New Mexico | 2,504.66 | 8,640,000 | 1904 | 8,511,538 | 9.9 |

| Total, U.S.A. | 213,932.13 | 11,244,852,000 | |||

In concluding this subject, it may not be amiss to quote the language of the Supreme Court in the Knoxville Water Case (212 U. S., 1), as follows:

"Regulation of public service corporations, which perform their duties under conditions of necessary monopoly, will occur with greater and greater frequency as time goes on. It is a delicate and dangerous function, and ought to be exercised with a keen sense of justice on the part of the regulating body, met by a frank disclosure on the part of the company to be regulated. The Courts ought not to bear the 16whole burden of saving property from confiscation, though they will not be found wanting when the proof is clear.

"The legislatures and subordinate bodies to whom the legislative power has been delegated ought to do their part. Our social system rests largely upon the sanctity of private property, and that State or community which seeks to invade it will soon discover the error, in the disaster that follows. The slight gain to the consumer, which he would obtain from a reduction in the rates charged by Public Service Corporations, is as nothing compared with his share in the ruin which would be brought about by denying to private property its just reward, thus unsettling values and destroying confidence. On the other hand, the companies to be regulated will find it to their lasting interest to furnish freely the information upon which a just regulation can be based."

2. Railroad Age Gazette, April 16th, 1909, p. 857.

In order that there may be no doubt as to the exact meaning of the terms used throughout this paper, a few definitions or explanations are submitted:

Appraisal, or Valuation.—These words are used interchangeably, and refer to the engineering work of determining the present worth of both physical and intangible properties of corporations.

Cost of Reproduction.—This expression refers to the estimate of cost of reproducing the physical properties as they exist on the date of the appraisal, all elements entering into the cost being considered as new and not affected by the elements of depreciation or obsolescence.

Cost, or Original Cost.—These terms refer to the actual amount of money paid for the property, either when it was originally constructed, or in its condition at the time of appraisal, the latter case being the original cost plus the cost of additions and betterments, less abandoned, replaced, or worn-out property. This figure ought to be represented by the "book cost," but it is not often that "book cost" and "actual cost" are the same.

Present Value, or Present Physical Value.[3]—These terms are used in describing the physical property as reproduced after it is affected by all elements of depreciation or appreciation. The use of the word "value" in this expression is unfortunate, as it may lead to some confusion. It must be kept clearly in mind that, where this term is used, it refers only to physical property as depreciated, and is in no case intended to refer to the final or "fair value" of the property.

17Non-physical, or Intangible, Value.—These terms are used to represent those elements, entering into the final worth of the property as a business concern, which arise out of the operation of the property and are not attachable to the physical property.

All the foregoing terms have to do with the determination of the elements which enter into the final value.

What is "value"? In defining the exact meaning of this term, as applied to the property of a public service corporation, many elements must be taken into account. Standard authorities give many definitions of "value," none of which appears to meet fully the requirements of the term as used herein. Before considering the elements which enter into the value of corporation property, or attempting to determine the methods to be used in fixing proper figures of worth for each of these elements, it is proper and necessary to obtain a clear definition of "value," the thing sought to be ascertained by the inquiry.

The term, "commercial value," has been considered in place of "value," but is not used because it is held to be more properly applicable to the selling or exchanging value of fractional interests in the property, and the methods of computing the commercial value of securities which are in common use cannot be adopted in an engineering valuation. The Standard Dictionary definition of "commercial value" is:

"The source of commercial value, according to different schools of economists, is (1) the degree of want felt for a commodity as shown in the relation of supply and demand, (2) the amount of labor embodied in it, or (3) the cost of reproduction. Practically, commercial value is that for which a thing can be sold or exchanged at a given time and place."

The definition given by Professor Adams is:

"The estimate placed upon the worth of a property, regarded as a business proposition."

Both these definitions are in a measure involved, and the writer considers that the term, "Commercial Value," is too narrow and restricted to be properly used.

As a definition of that estimate of worth which an engineering commission should report as the result of a complete appraisal, the writer submits the following:

The value of a property is its estimated worth at a given time, measured in money, taking into account all the elements which add 18to its usefulness or desirability as a business or profit-earning proposition.

There are two classes of elements entering into the final value:

(1) The "Physical Property" Element of Value.—This consists of those things which are visible and tangible, capable of being inventoried, their cost of reproduction determined, their depreciation measured, and without which the property would be unable to produce the commodity on the sale of which income depends. This physical property is considered as an operating entity, and not as collateral of inert and partly worn-out equipment, and, being so considered, carries, as part of the physical value, those costs and charges which are an inseparable part of the cost of construction but do not appear in the inventory of the completed property.

(2) The "Non-Physical" or "Intangible" Elements of Value.—These are those things which, added to or taken from the worth of the physical property, make up the value, and include whatever accrues to the property by reason of its operation, or by reason of grants, contract rights, competition, or location, which at the time of appraisal affect favorably or unfavorably the worth of the property.

The worth of the physical property is primarily that on which the value of the whole property rests.

While it is clear that the worth of the physical property, being the cost of reproduction less depreciation, is not necessarily the value of the property, it is equally clear that the physical worth must bear some very definite relation to value, and the writer is strongly of the conviction that this relation is such that "value" cannot be ascertained without a determination of physical worth. The physical property element represents the investment on which a fair return is to be earned, and in most cases an appraisal is necessary for the determination of the amount of money actually invested. As illustration of the fact that "physical value" and "value" are not the same, the case of two railroads actually existing and in operation between two cities in Michigan may be cited.

Road "A" occupies a narrow valley through high and abrupt hills. Its alignment is fair for hilly country; its maximum grade is 1 per cent. It has a number of bridges, all short and low. Its cost of reproduction might reasonably be placed at $28,000 per mile. A mining town at one end ships a heavy tonnage down grade to a lake port at the other.

19Road "B" was constructed several years later, and, being barred from the only valley, built a line across the hills, involving heavy grading, very long and high steel trestles, a longer line, maximum grades of 2%, and a heavy climb from the mining town to the summit before starting to drop to the lake. The cost of construction was more than double that of Line "A," and the tonnage which can be hauled in either direction is but a small fraction of that which can be hauled with the same power by Road "A." A reasonable figure for cost of reproduction may be given as $60,000 per mile.[4]

Here is clearly a case where the older, less expensively built road has a value as an earning proposition far in excess of that of the new road. The rate on commodities does not affect the relative difference. A higher rate, while permitting Road "B" to live, greatly adds to the value of Road "A," while the latter can operate at a profit on rates which would not permit Road "B" to pay expenses.

This example indicates the existence of non-physical values, not only positive in the case of Road "A," but also negative as to Road "B."

Many properties have been built in the United States, representing large investments of capital, which are not, and some of which can never be, profitable business investments. In all such the physical valuation will exceed the final value where the property is considered as an operating concern, and a negative factor to cover improper location, uneconomical design, ill-advised investment, or whatever the trouble may be, should be applied.

The physical property is that which enables the corporation to do business. Without physical property it could not produce the commodity which it sells. The amount of money actually invested in acquiring that physical property represents the measure of capital on which it is morally entitled to earn interest and profit; and, in the stage of promoting and financing the enterprise, all hope of earnings is based on the amount of money required to construct the property. These considerations lead the writer to contend that the true method of valuing a corporate property is first to determine the cost of reproduction of the property and its depreciation, and modify this figure by any applicable positive or negative non-physical elements of value.

3. 20The term "present value," as used in this paper, should not be confounded with its use by bankers or accountants, or with the present worth of a sum of money due at some future time.

4. In this case, traffic as to Line "B" is limited, and as it is feasible to double-track Line "A" at less cost than Line "B," no advantage can be assigned to Line "B" on account of development of future business.

The State Legislature of Michigan, at the session of 1899, passed an act creating a Board of State Tax Commissioners and outlining and prescribing their duties. This act authorized the board to "inquire into and ascertain the value of the property of corporations paying specific taxes under any of the laws of this State."

The object of this valuation was to determine the rate at which the corporations were paying taxes, to the end that necessary laws should be passed so that all taxable properties in the State might be taxed uniformly.

On September 1st, 1900, the Board of Tax Commissioners appointed Professor Mortimer E. Cooley Appraiser of Properties. Immediately thereafter the general organization was mapped out along the following lines of division of labor and responsibility:

1.—Administration.—All matters of general policy in regard to the conduct of the work, all matters relating to negotiations and conferences with officials of corporations, all transactions with the State Tax Commission, the Governor, or the Board of State Auditors, and the entire direction of all relations with the public through newspapers and other channels, were retained by the appraiser, who was the final arbiter on all matters referred to him regarding the details of the work.

2.—Civil Engineering.—The appraisal of all property which in the course of construction would fall under the supervision of the civil engineering department of a road, including land, roadway, bridges, and structures, was in charge of the writer.

3.—Mechanical Engineering.—The appraisal of all motive power, rolling stock, and property which in the course of construction would fall under the supervision of the mechanical engineer, including power and electric plants, shop tools and machinery, water stations, etc., was in charge of Mr. Theodore H. Hinchman, Jr., of Detroit, Mich.

In the matter of the final assembling of figures, computation of percentage values, and compilation of final results, Mr. Hinchman and the writer worked together with joint general supervision.

4.—Telegraphs.—The inspection and appraisal of all telegraph properties was under charge of Mr. William S. Conant, of Detroit, Mich.

215.—Telephones.—The appraisal of all telephone properties was directed by Mr. William J. Rice, of New York.

6.—Vessel Properties.—All vessels belonging to companies whose property was involved by the appraisal were inspected and appraised by Herbert C. Sadler, Professor of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering at the University of Michigan.

In the following narrative, no special mention is made of the work executed under the direction of Messrs. Conant, Rice, and Sadler, because they really had charge of independent appraisals which were conducted on lines similar to those adopted in the railroad appraisal, and their methods were not different from those of the latter; hence any description of their work would be in a large measure repetition. This omission is in no wise to be construed as any reflection on the importance or high character of their work.

The organization as just outlined, while necessarily touching and overlapping at points, was generally defined so clearly that there was no duplication of work. Each head of department was responsible for the work of his special division, and directed the laying out and execution of the work done by his men.

The first task, after deciding on the general organization, was to determine the general methods to be adopted and the manner of getting the necessary detailed information. The magnitude of the work was appalling. There were seventy-eight different incorporated companies, owning some 10,000 miles of railroad, scattered over 54,000 sq. miles of territory. In addition, there were a number of small unincorporated railroads, telegraph, telephone, plank road, and other corporations, many of which had no records, no complete inventory, and no department organized so that the information could be readily secured. It was determined:

(1) To make or secure a complete detailed inventory of every piece or parcel of property belonging to each company;

(2) To examine each separate thing, place on it an estimate of cost of reproduction and depreciation;

(3) To prepare, as a basis for the final figure of value, an estimate of the present value, being the cost of reproduction less the depreciation.

Having determined on a detailed physical inventory and appraisal, the next step was to outline the work so as to secure absolute uniformity. 22The difficulties which confronted the appraiser at this period were many, chief among which were:

(a) Lack of Complete Understanding on the Part of the State Officials.—The Governor and Board of Tax Commissioners rendered every possible assistance, but the Board of State Auditors was not at first fully committed to the work, and the uncertainty as to whether or not bills would be paid, delayed seriously the employment of men and the full commencement of work for 3 or 4 weeks after the first organization was made.

(b) The Attitude of the Railroad Corporation Managers.—While this was not actively hostile, it was a serious cause of delay, as they could not foresee what effect the work might have on the interests in their charge, and, while not refusing access to their records, they delayed and held back information; in fact, a long time elapsed before all the companies opened their records to the appraiser and his staff.

(c) The Confused Condition of the Records. Many small corporations had absolutely nothing in the way of records of buildings, bridges, land, or other properties. Others had very complete records in certain departments and very imperfect ones in others; still others had records which had every appearance of being complete, but they were not up-to-date.

Facing an appraisal of this magnitude, with a time limit of only 4 months for the entire work, with delays at the outset which seriously hampered the organization for 2 or 3 weeks, the appraiser was compelled to occupy this time in preparing the blank forms to be used on the work, and in conducting correspondence with the men who were to make up the working force, investigating their references, etc.

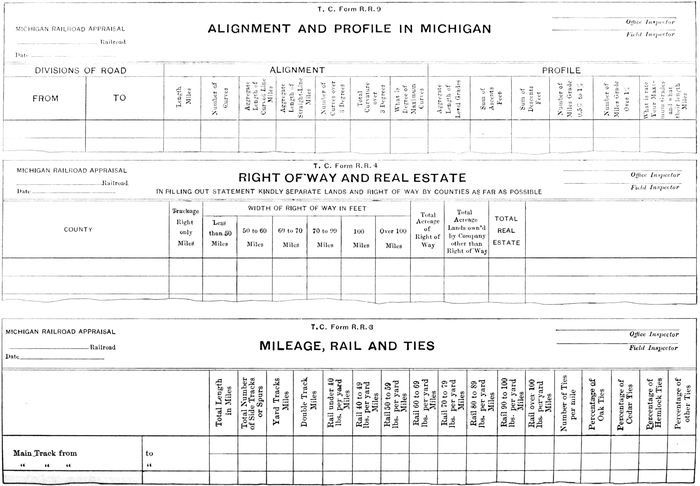

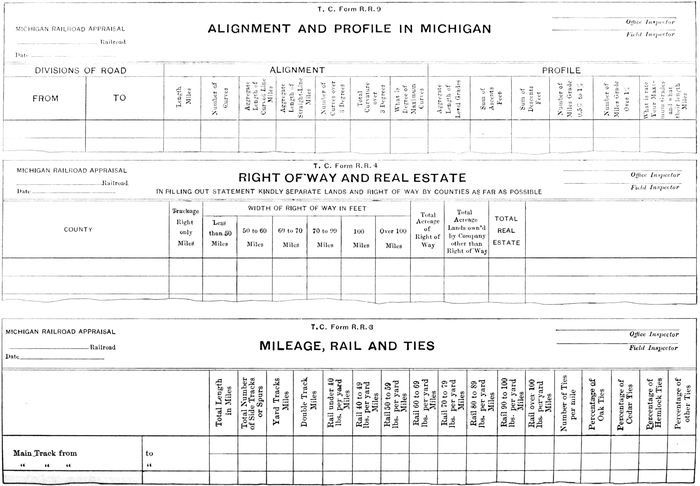

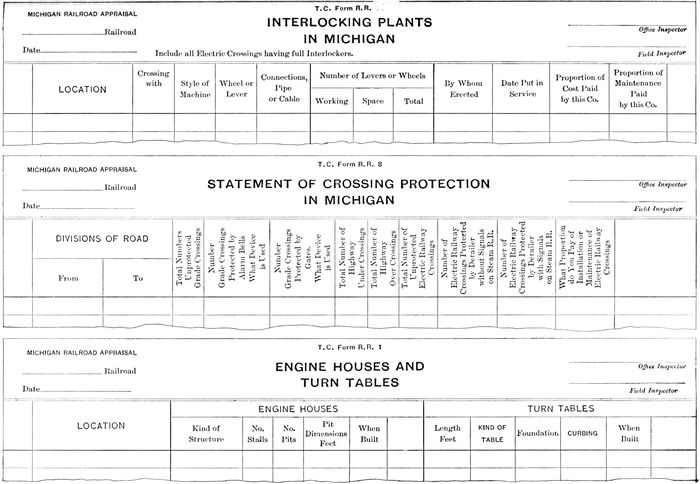

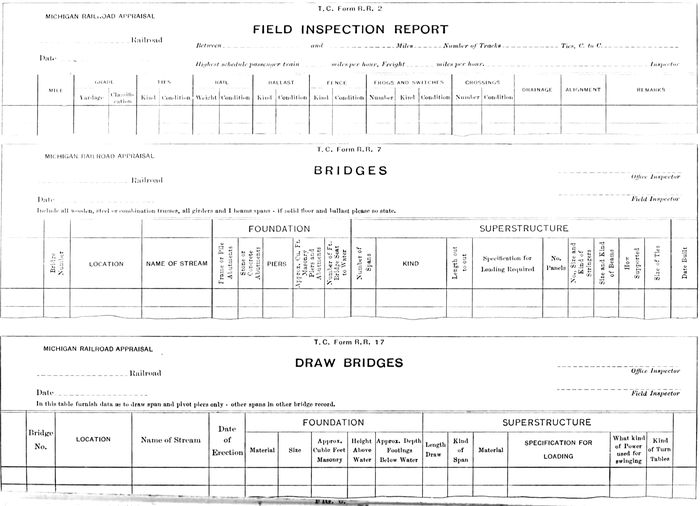

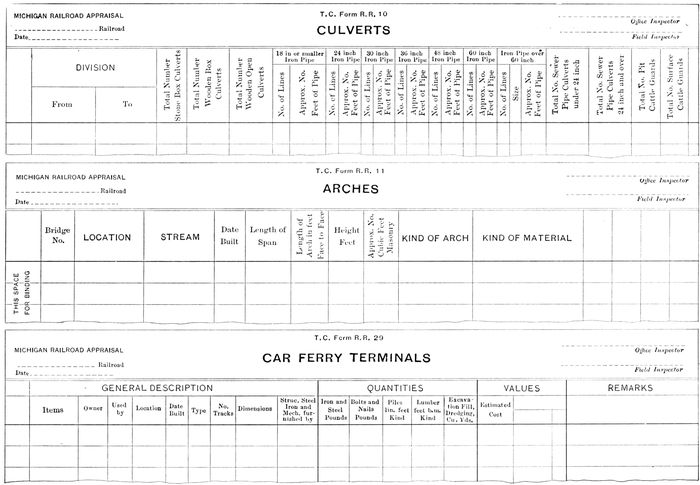

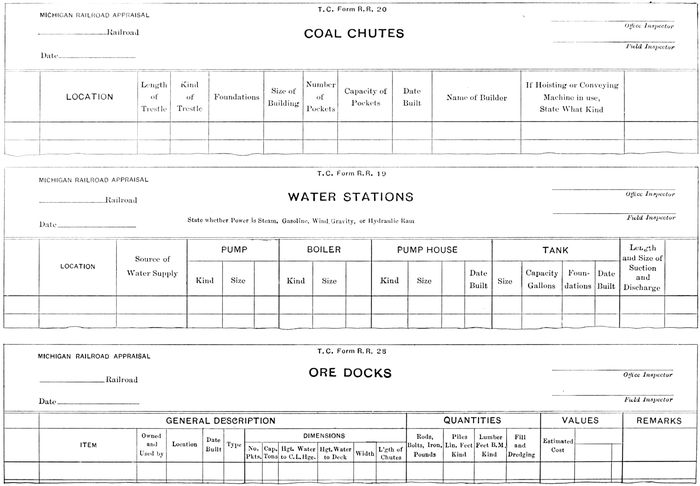

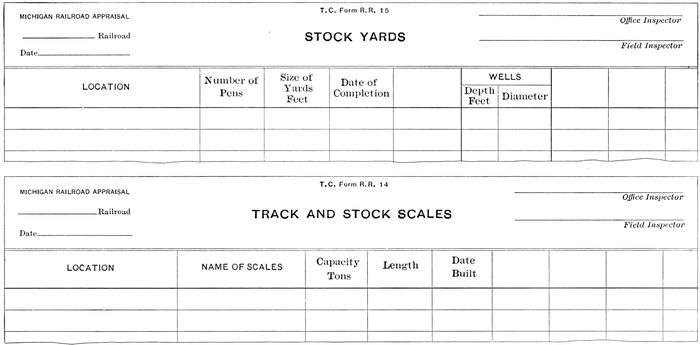

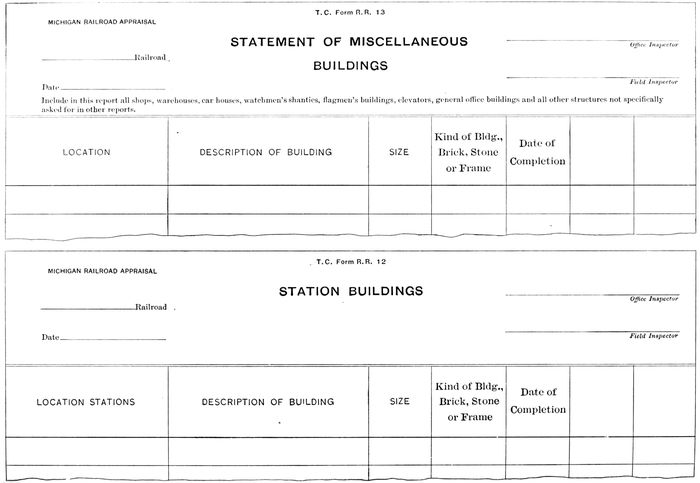

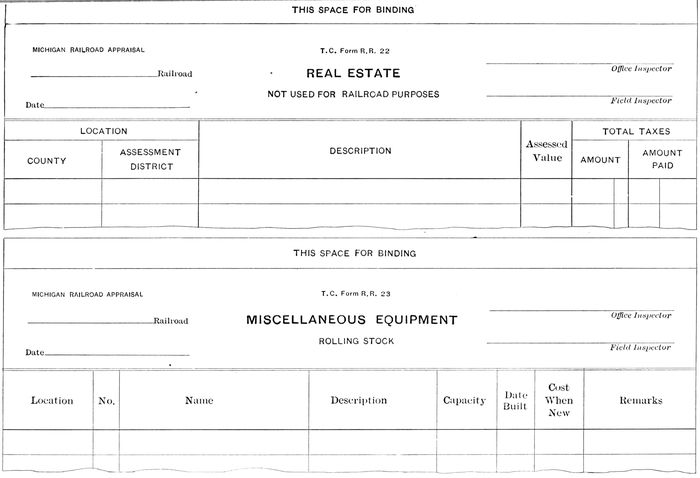

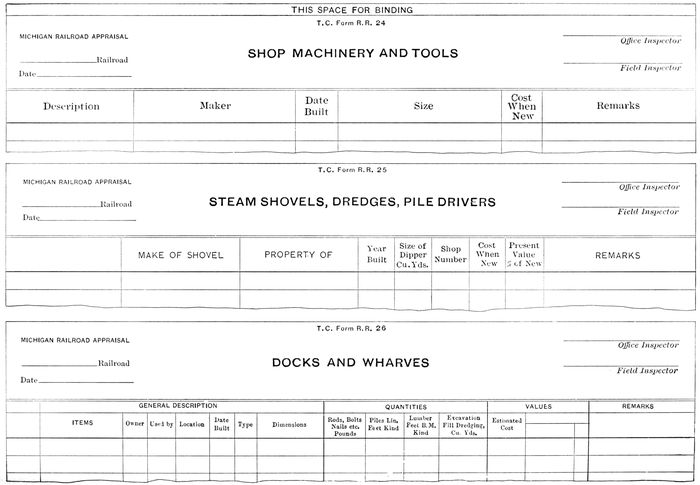

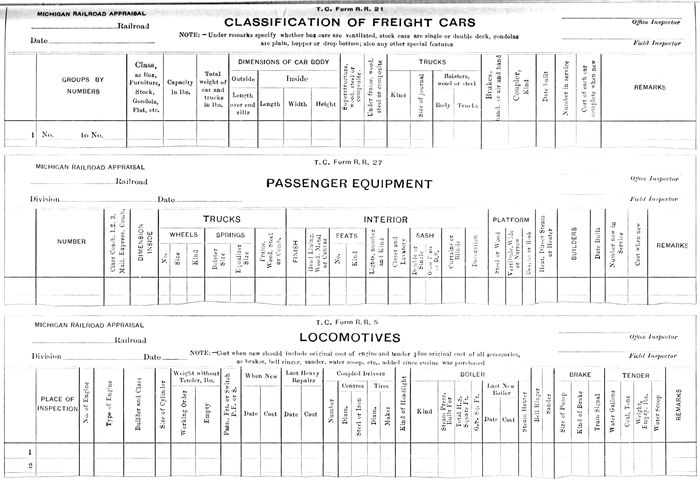

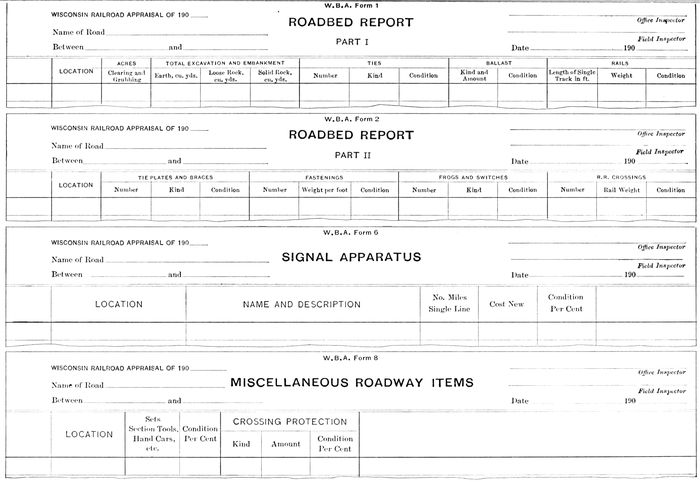

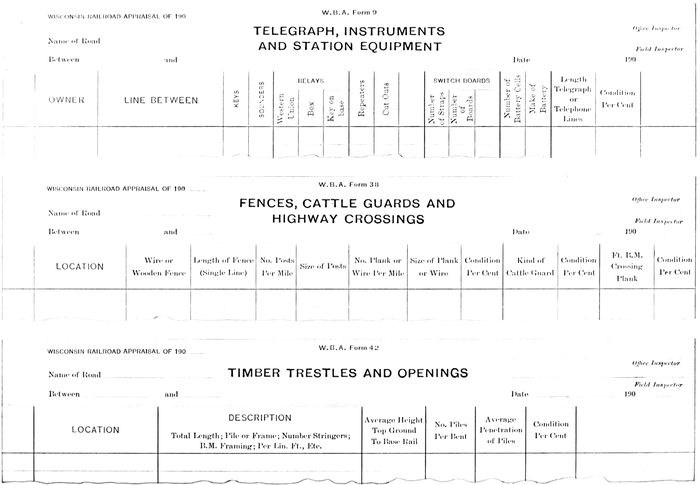

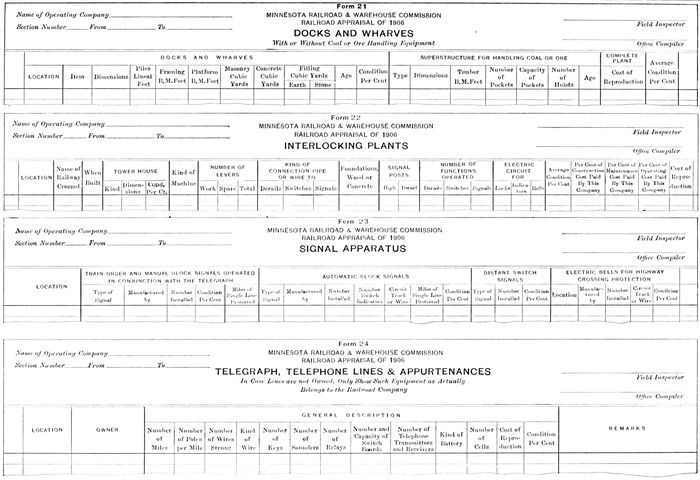

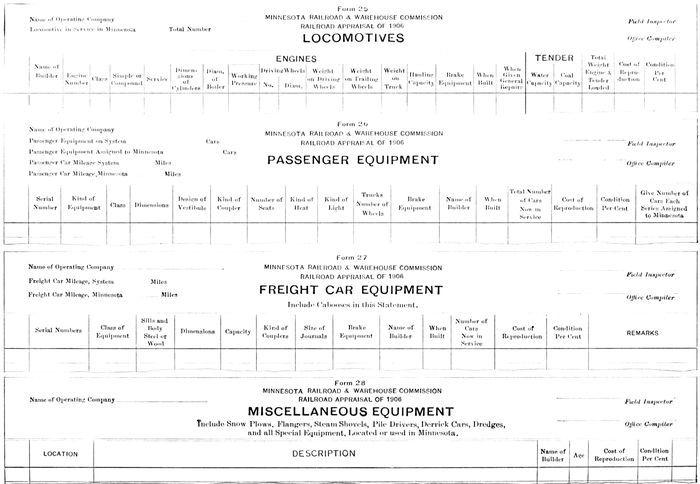

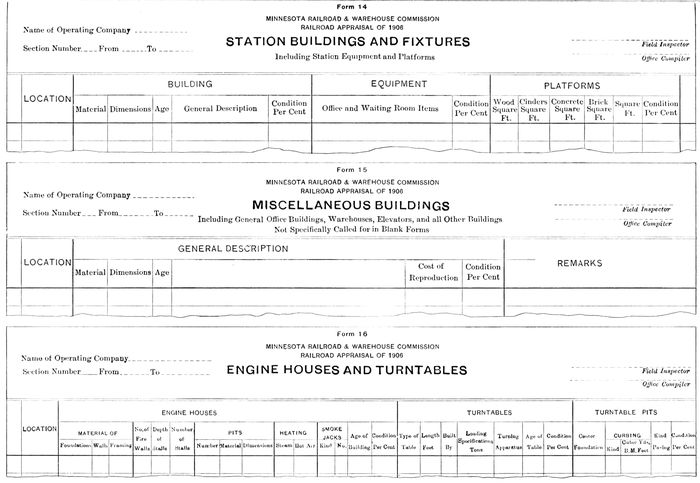

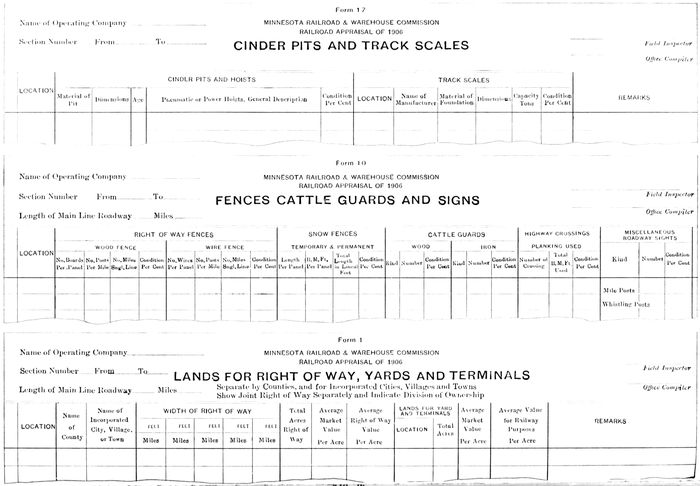

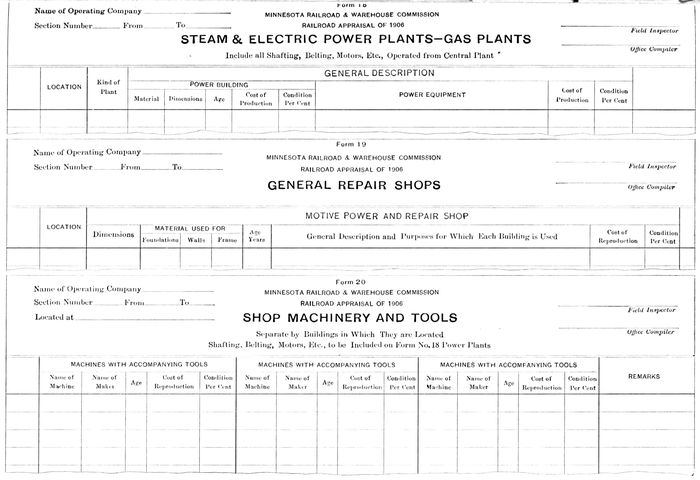

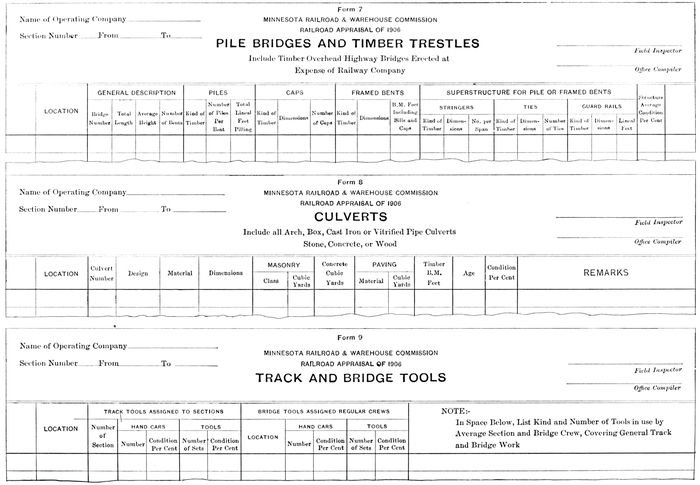

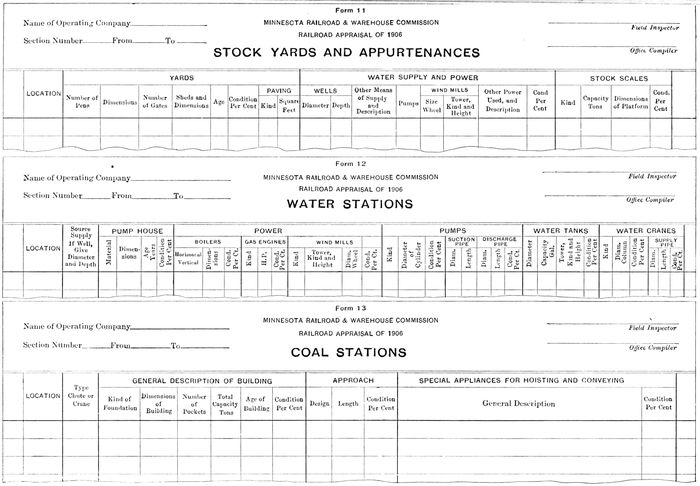

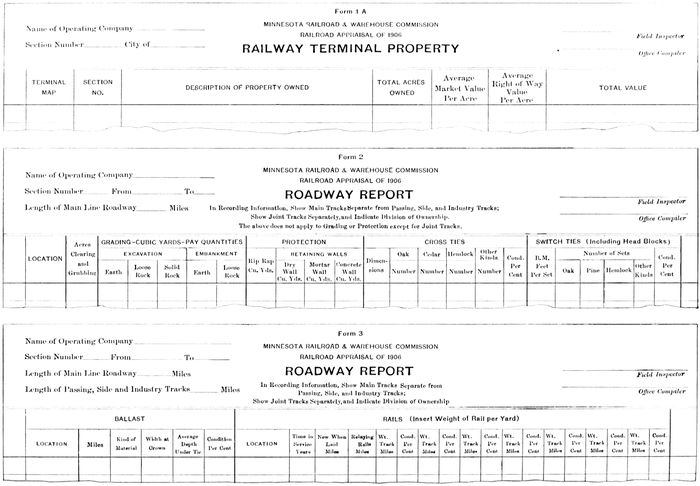

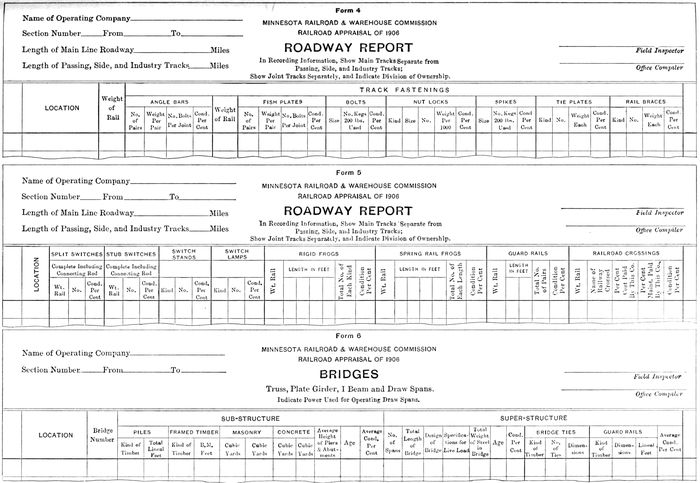

The blank forms, Figs. 1 to 10, were the result of a series of conferences between the members of the staff. By this time it was quite evident that no great amount of help could be hoped for from the corporations. Had it been possible to secure access to the records of such railroad companies as the Michigan Central or the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern before the final drafts of the forms were prepared, the writer believes that several might have been simplified and many improvements could have been made. However, this was not possible, and the forms were prepared and printed before access to any railroad office had been granted.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 10.

33That a few changes were made in 1904 was to have been expected; that these forms were almost in their entirety made a basis for the similar work of the Wisconsin appraiser, some three years later, was in the nature of a high compliment and goes far toward answering the criticisms of this part of the work, generally to the effect that the forms call for much more information than could possibly be used, and that they show lack of care in arrangement.

It may be said here, properly, that the uncertainty as to the final attitude of the companies made it essential that the appraiser prepare, if need be, to make his inventory by personal inspection in the field. Indeed, this was done in the case of several roads, and, while most of the companies finally accorded every courtesy, either giving the appraiser access to their records, or furnishing the information desired, it is not probable that the shortness of the time limit would have enabled the appraiser to secure any sort of result had a modified plan been adopted.

The law provided no requirement that the companies should furnish any information. In order to secure the data, it would have been necessary to employ a large number of men, and this would have been such a serious expense to the companies that refusal to comply would probably have followed such a request. Many of the companies had no men in their service able to prepare the required data; and, finally, eight or ten men after having worked in the files of companies owning reasonably full records, were much better able to take off the desired data intelligently from the records of other companies than men unfamiliar with the needs of the appraiser and with no prior experience. Then, too, the work secured was that of one body of technical men, all experienced in different phases of railway work, and thus was uniform and consistent. Had seventy-five or eighty different men or sets of men prepared these inventories, there would certainly have been a great variation in their worth and reliability.

It must be kept clearly in mind that lack of time was the main feature which kept the appraiser from considering any such plan of co-operation with the railroads as was adopted later in Wisconsin and Minnesota, and that no distrust of the railroads, or lack of desire to co-operate, had anything to do with the appraiser's decision to use the method which was adopted.

Shortly after the preparation of the blanks, access was granted to 34the records of the Ann Arbor Railroad, and almost immediately thereafter several other companies opened their files to the appraiser; the State Board of Auditors determined to pay the bills, as approved by the appraiser; and the initial difficulties were so far removed that it was possible to carry out, without any further delays, the plan of organization which had been perfected.

The personnel of the staff was considered to be of the greatest importance, and, in the selection of men, the requirements desired were: experience in the construction and operation of railroads, thorough technical training, high standing in the Profession, as shown by membership in the American Societies of Civil or Mechanical Engineers, or of other Societies of high standing, and high moral character. Politics, residence in the State, or local influence, had absolutely no weight in the selection of any of the men. In a number of cases men were secured who had for some years occupied the position of Chief Engineer of important lines. In a very large number of cases men who were engaged on this work have since its completion held the position of Chief or Principal Assistant Engineer of important railroads, and practically all of them returned to railway service. Dozens of these men are well known, and their work deserves that full credit should be given to each, but it is impossible to do so within the limits of this paper.

The minor positions, such as assistants in the field and in the computing and compiling rooms, were assigned to younger men, generally with some railroad experience, and in many cases they were graduates of technical schools, Cornell, Yale, Rensselaer, Michigan, Ohio State, and other schools having representatives.

The writer believes that no more harmonious or loyal organization was ever gathered together before, or has been since. Men who had held Chief Engineer-ships trudged miles in the wilds of Michigan on foot, inspecting and inventorying property, and came into the office and worked long hours at the computing tables with the utmost cheerfulness and camaraderie. There was complete harmony, absolute loyalty, and as perfect a spirit of unselfish devotion to the work as the writer has ever seen in any organization.

The fact that such a staff of engineers, of wide experience in railroad construction and maintenance, had been assembled, made it feasible to carry out a plan of the appraiser which proved to be of 35great value. At frequent intervals, during the progress of the work, conferences were held which were attended by all the heads of departments and by many of the older and more experienced engineers. Matters of policy, details, general principles, and rules and methods for conducting the appraisal, were fully discussed, and stenographic records were made of the discussion and conclusions. These conferences covered practically every question that arose; they were of such a nature as to draw out the opinions of the men fully and freely; and their effect was to eliminate the error due to individual judgment, and harmonize and unify the methods and results of the appraisal.

Special emphasis has been laid on the organization of the staff, because the criticism has been made that this work was lacking in care, was hurriedly done, and was unreliable. The work must be judged by its results, but the criticism that it did not receive proper care is absolutely unjustified in fact. The men engaged were of the highest type of experienced, technically educated, and highly qualified engineers; they entered the work unreservedly, and gave the best there was in them. The Michigan appraisal was not a one-man job; it was the work of many men, and all are entitled to credit.

That some men in an organization such as this, gathered from all over the United States, should prove to be lacking, and should fail to hold their place with their fellows, was to have been expected. That the number of such men should not exceed half a dozen was remarkable. In fact, almost every such case was found when the first notes were returned to the office, and in only two or three instances was it necessary to send a second man to do work which had been once covered. In several cases men were sent over certain sections which had been inspected by some one else, with a view of getting an idea of the personal judgment of the different men, but in such cases the results were astonishingly close, and created the greatest confidence in the figures of depreciation which were being received.

Looking back on this work, after the lapse of 10 years, after having fully reviewed it twice, and examined all records, after having heard the men engaged on it testify in court, and knowing the record of these men since the completion of the work, the writer believes himself fully justified in stating that, no matter what opinion may be held as to the accuracy, reliability, or value of the result, no charge of carelessness, 36neglect, undue haste, or lack of consideration can be sustained as against the staff.

To strengthen the work further, to eliminate the element of personal error, to guard against the danger of dulled perceptions due to constant application to the work, and to forestall, if possible, every point of objection to methods, a Board of Review was chosen by Appraiser Cooley to whom were referred:

(a) The methods of inventory and valuation, as determined by the staff;

(b) All points on which special discussion or difference of opinion were noted in the working conferences;

(c) Questions as to elements of value in the physical property which were in themselves not tangible or capable of inventory; and finally,

(d) The results of the whole work.

The members of this board were chosen on account of pre-eminent standing in the Profession, and on account of experience and prominence in railway engineering. The board was composed of four men, as follows:

Chairman, Octave Chanute, Past-President, Am. Soc. C. E., former Consulting Engineer, Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway, but at the time not engaged in active railway work.

George W. Vaughn, M. Am. Soc. C. E., Engineer in charge of Track Elevation in Chicago.

Charles E. Greene, M. Am. Soc. C. E., Dean of the School of Engineering, University of Michigan.

Charles Hansel, M. Am. Soc. C. E., former Engineer, Wabash Railroad, former Chief Engineer, Illinois Railway and Warehouse Commission, and at that time General Manager of the National Switch and Signal Company.

These gentlemen were not engaged in any detailed work on the appraisal; they came to the work for one week each month with minds entirely clear of all confusion raised by issues of detail, and were thus enabled to pass as a court upon all matters laid before them. Their association was of inestimable value in giving confidence to the members of the staff. The many years of railway service of Messrs. Chanute and Vaughn, and their unquestioned ability in that 37special field of engineering, gave the stamp of finality to points decided by them. The special knowledge of Mr. Hansel in the field of signal engineering, and his known ability as an expert in organization and administration, were of the greatest value. The service of Professor Greene was that of the analyst and logician; his clear and judicial mind enabled him to formulate the final arguments in many cases under consideration.

The writer wishes to make it perfectly clear that he has not attempted to minimize the work of Professor Cooley by stating the exact relation of the many engineers on the staff to this work, but to bring out and emphasize the fact that no one man, or no two or three men, were responsible for any single part, but that the whole represents the best efforts of sixty or seventy experienced men working to secure a fair, honest, unprejudiced, engineering estimate along such lines as would eliminate, as far as possible, all errors of individual judgment.

It has never been claimed for the work that it was perfect, or that it was entirely free from errors. It has been and is claimed for it that it probably represents as close and conservative an estimate of cost of reproduction and depreciation as it would be possible for any set of men to make under the conditions then existing.

Professor Cooley was in constant touch with the work, knew its every detail, passed upon and approved every rule and order, presided at every conference, and nothing more than his activity, optimism, and constant watchful care and tireless energy kept the force at work day and night and brought about the prompt completion of the details. His recognized high standing, his remarkable ability as an executive and organizer, and his powers of diplomacy, more than anything else, brought about the final acquiescence of the railroad managers and kept up the confidence of the State authorities; his personality pervades the entire work. After giving all due credit to the staff, and they were entitled to much credit, the real honor must go to Professor Cooley. It was his conception, his plan, and the brunt of the battle was his.

The preliminaries of the organization having been completed, and the forms prepared, a portion of the working force was brought on 38the ground, and the work was actively commenced. It was subdivided into four parts:

(1) Office inspection, or inventory;

(2) Field inspection;

(3) Computation;

(4) Compilation for the permanent record.

The men chosen as field inspectors were old and experienced railroad engineers. As far as possible, they were assigned for a short period to office inspection, then they were sent into the field, after which they worked at the computation of values; so that each man was engaged on many different phases of the work, and handled the notes of many of his fellows, and no one man made up one complete appraisal, except as specially noted.

Making the Inventories.—Office inspection, or the preparation of inventories, was assigned to parties usually of one or two experienced men with from two to four younger engineers as assistants in the computing-room. These men went to the general offices of the railroad companies and made a complete examination of maps, profiles, bridge and building records, records of motive power, rolling stock, etc. In short, they prepared, as far as it was possible to do so, a complete inventory of every building, structure, or piece of property owned by the road; they took off complete abstracts of real estate and right-of-way records; they noted principal yards and terminals, and secured maps of such as were most complex, or furnished lists of such maps and records as were most essential for the field men, and they made as complete a report as possible of the corporate history of the road and the general condition of its engineering records. No effort whatever was made to examine or audit the financial books of any company, or to secure from such books any data as to cost of property; the work was entirely limited to the listing of physical property.

Most of the railroad companies co-operated, and gave access to their records; one or two filled in the forms; a number had practically no records, and only one or two companies withheld information. Requests for blue prints of large yards and terminals, and of plans of standard structures were generally granted cheerfully, and, although there was no such spirit of co-operation as was shown later by the Wisconsin roads, much labor was saved by the data furnished.

39The result of the office inspection was the filing of inventories, which were generally quite complete, the securing of maps and plans, the gathering of data as to prevailing prices of labor and material, and the securing of some very valuable cost data as to special structures and classes of structures. All inventories were made up for roads, or for divisions of roads, with each class of property listed separately, for example, station buildings, interlocking plants, bridges, etc., so that, if necessary, any special class of inspection might be assigned to one man, while to others could be assigned the remainder of the work on that particular road or division.

Office Inspection as a Check on Field Work.—The office inspection furnished many valuable data for checking the judgment of the field men. For example, the number of cubic yards of excavation and embankment on probably the greater part of the mileage had to be secured by the field inspectors, either because the records had not been kept or the changes of line and grade had been so extensive as to destroy their reliability. Every field inspector, therefore, made his own estimate of the yardage of pay earth. The office inspection reports, however, gave reliable data (from profiles or original contract estimate files) of the actual yardage on possibly 2000 or 3000 miles of line, so widely scattered that it constituted a check on the work of a majority of the field men.

This work of office inspection disclosed the following points, which will be practically common to all large valuation jobs:

(a) There was no uniformity of method in the keeping of records of permanent way and structures;

(b) There was a vast amount of carelessness in keeping records up to date, even on the larger roads;

(c) The smaller roads, not only had little or nothing in the way of records, but had in many cases no department with employees qualified to make or keep such records;

(d) The purchase of new equipment, the construction of new buildings and bridges, and the destruction, sale, or removal of old property, create a condition of continuous change which is seldom recorded by either operating or accounting officials, and makes book inventories derived from the roads of very doubtful value for use in an appraisal.

40Field Inspection.—The decision had been reached, after careful discussion, not to permit the field inspectors to place a money value on any structure, but to examine it, make a full description of it in all particulars, and assign to it a percentage which should represent the present value, or the depreciation from a similar new structure rated at 100 per cent.

The field inspectors were furnished with the records of the office inspection covering the district assigned. They were given notebooks, tape lines, and various blanks for reporting progress and recording original estimates in the field. Provision was made for inspection by the field men, either by the use of hand-cars, gasoline inspection cars, or velocipede cars, although, with one or two of the roads, no satisfactory arrangement could be made, and the men were compelled to go on foot. A careful inspection of every structure was made. If any correction to the office inspection record was necessary, it was made; if the structure was new, it was carefully measured and described, and everything noted which would be of service in estimating its value. Side-tracks were measured, and the weight and type of rail noted. All culverts and bridges were examined, described, and their condition noted. Estimates were made of excavation and embankment, clearing and grubbing, etc. (based on the standing timber at the time of the examination), and careful estimates were made of classifications of material. The records of the field inspector generally contained only the description and the percentage, but, occasionally, when apparently valuable information as to cost of any particular structure was available it was noted, as was special information of local matters affecting the value of any part of the work.

It was the plan (carried out with but few exceptions) to complete the record with the field inspector so that from his notes a full and accurate descriptive inventory might be made. There were a few exceptions to the general method of field inspection work as outlined, which were:

Special Work on the Chicago and Northwestern Railway.—The Chicago and Northwestern Railway had no records of any sort, all construction papers having been destroyed by fire. This company organized and placed in the field four complete engineering parties, each under one of its own engineers, and with each party was sent one field inspector. The line was carefully surveyed and cross-sectioned, 41and complete records of every building and structure were made, side-tracks were measured, and data taken for rail and ballast charts, etc. All work was done in the presence of the field inspector, and he was given copies of all notes. He placed his own percentage of depreciation on everything. The estimates, made up independently by the Chicago and Northwestern engineers and the appraisal staff, using in the latter case the same unit prices as applied elsewhere in the Upper Peninsula, varied less than 2 per cent.

Special Valuations.—Certain special structures, such as ore docks and ore and coal handling machinery, were of such a character as to require expert appraisal. These were examined in the field, appraised, and valued by G. H. Hutchinson, M. Am. Soc. C. E., whose special training and experience in such work had qualified him perhaps better than any other man. Interlocking and signaling plants were specially appraised by the late Elliot F. Moore, who for 10 years had been Engineer of the Michigan Railroad Commission, and whose intimate personal knowledge of almost every plant in the State specially qualified him for this work.

Some of the bridges were of such a character as to require expert knowledge, and this inspection was assigned to William Dunbar Jenkins, M. Am. Soc. C. E., a man of ripe experience and sound judgment. The larger and more elaborate station buildings were examined and appraised, and values finally placed by Mr. F. G. Susemihl, Chief Architect of the Michigan Central System, whose special work in railway buildings made him thoroughly familiar with these values.

Work equipment and special equipment were appraised by Mr. G. L. Lewis, who had been connected with the Marion Steam Shovel Company for many years.

Except for these special assignments, all the field inspection was handled in accordance with the appraiser's plan.

As stated previously, in only two or three cases was it necessary to re-inspect, and, while several sections were intentionally gone over a second time, without letting the field inspector know who had done the work previously, or what his percentages had been, the result of all these checks was to justify the figures in the earlier inspection and to strengthen confidence in the work.

42The field inspection of the Mechanical Department involved examining and placing a percentage value on each locomotive, passenger car, and piece of special equipment, and on all shop machinery. Inasmuch as several points of special interest are involved in this inspection, it will be discussed at more length in the section of the paper relating to the methods of work of the Mechanical Department.

Computation.—After the completion of the field inspection, all notes were placed in the hands of the computing force. This organization consisted of two classes of men, engineers brought in from field inspection, and younger engineers. All computations were made independently by two men, and all work was checked carefully.

Every man in the computing room was furnished a large bound blank-book, in which he was required to make all his notes and computations, no figures of any sort being made on loose paper. The name of each man was placed on his notebook, and each set of field and office inspection notes worked upon by him was signed with his initials. It was easy to trace the work of every man, and in the subsequent trial of the Tax Cases, every man in the service returned, and, not only testified as to his office and field inspection, but was able to turn to and identify all the computations made by him, and produce his original figures and memoranda.

Very soon it became evident that such a volume of reports, notebooks, memoranda, maps, plans, pamphlets, and other data was being accumulated that, unless a special system was developed for filing and handling in the office, the confusion would be serious and costly.

Filing in Office.—The system of filing and record keeping had the merit of being simple and inexpensive. There was borne in mind, in devising this plan, the necessity of keeping all papers connected with one division of any road together, the need for reducing to a minimum the labor of filing and indexing, the constant use of papers, and their frequent withdrawal from the files, making it necessary that they could be at once located when they were not in the files.

The vault in the appraisers' office was arranged so that large manilla envelopes, each of sufficient size to hold all the reports, notes, maps, etc., of each road or division, could be filed vertically. Each road was given a number; if there were several divisions, each division was given a letter, as "15-A," "15-B," etc., and each division was filed separately.

43Every report, book, map, or other paper was stamped with its road or division number and letter, and given a sheet number. In this manner every paper was identified, and could be at once placed. A record was kept in a book, describing every paper filed in each envelope.

In issuing papers for work, the entire file was taken and kept together at all times.