The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Venoms, by A. Calmette

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Venoms

Venomous Animals and Antivenomous Serum-therapeutics

Author: A. Calmette

Translator: Ernest E. Austen

Release Date: January 30, 2016 [EBook #51078]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK VENOMS ***

Produced by deaurider, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

i

ii

iii

Mr. E. E. Austen, of the British Museum, has been good enough to undertake the translation of my book on “Venoms.” For the presentation of my work to the scientific public in an English dress I could not have hoped to find a more faithful interpreter. To him I express my liveliest gratitude for the trouble that he has so kindly taken, and I thank Messrs. John Bale, Sons and Danielsson for the care they have bestowed upon the preparation of this edition.

Institut Pasteur de Lille, A. Calmette, M.D. June 17, 1908. iv

v

In the month of October, 1891, during the rains, a village in the vicinity of Bac-Lieu, in Lower Cochin-China, was invaded by a swarm of poisonous snakes belonging to the species known as Naja tripudians, or Cobra-di-Capello. These creatures, which were forced by the deluge to enter the native huts, bit four persons, who succumbed in a few hours. An Annamese, a professional snake-charmer in the district, succeeded in catching nineteen of these cobras and shutting them up alive in a barrel. M. Séville, the administrator of the district, thereupon conceived the idea of forwarding the snakes to the newly established Pasteur Institute at Saigon, to which I had been appointed as director.

At this period our knowledge of the physiological action of venoms was extremely limited. A few of their properties alone had been brought to light by the works of Weir Mitchell and Reichard in America, of Wall and Armstrong in India and England, of A. Gautier and Kaufmann in France, and especially by Sir Joseph Fayrer’s splendidly illustrated volume (“The Thanatophidia of India”), published in London in 1872.

An excellent opportunity was thus afforded to me of vi taking up a study which appeared to possess considerable interest on the morrow of the discoveries of E. Roux and Behring, with reference to the toxins of diphtheria and tetanus, and I could not allow the chance to escape. For the last fifteen years I have been occupied continuously with this subject, and I have published, or caused to be published by my students, in French, English, or German scientific journals, a fairly large number of memoirs either on venoms and the divers venomous animals, or on antivenomous serum-therapeutics. The collation of these papers is now becoming a matter of some difficulty, and it appeared to me that the time had arrived for the production of a monograph, which may, I hope, be of some service to all who are engaged in biological research.

Antivenomous serum-therapy, which my studies, supplemented by those of Phisalix and Bertrand, Fraser, George Lamb, F. Tidswell, McFarland, and Vital Brazil, have enabled me to establish upon scientific bases, has now entered into current medical practice. In each of the countries in which venomous bites represent an important cause of mortality in the case of human beings and domestic animals, special laboratories have been officially organised for the preparation of antivenomous serum. All that remains to be done is to teach its use to those who are ignorant of it, especially to the indigenous inhabitants of tropical countries, where snakes are more especially formidable and deadly. This book will not reach such people as these, but the medical men, naturalists, travellers, and explorers to whom it is addressed will know how to popularise and apply the information that it will give them. vii

I firmly believe also that physiologists will read the book with profit. Its perusal will perhaps suggest to them the task of investigating a host of questions, which are still obscure, relating to toxins, their mode of action upon the different organisms, and their relations to the antitoxins. There is no doubt that in the study of venoms a multitude of workers will, for a long time to come, find material for the exercise of their powers of research.

At the moment of completing this work I would like to be allowed to cast a backward glance upon the stage that it marks in my scientific career, and to express my heartfelt gratitude to my very dear master and friend, Dr. Émile Roux, to whom I owe the extreme gratification of having been able to dedicate my life to the study of experimental science, and of having caused to germinate, grow, and ripen a few of the ever fertile seeds that he sows broadcast around him.

I am especially grateful to those of my pupils, C. Guérin, A. Deléarde, F. Noc, L. Massol, Bernard, and A. Briot, who have helped me in my work, while showering upon me the marks of their confidence, esteem, and attachment; to my former chiefs, colleagues, and friends of the Colonial Medical Staff, Drs. G. Treille, Kermorgant, Paul Gouzien, Pineau, Camail, Angier, Lépinay, Lecorre, Gries, Lhomme, and Mirville; and to my numerous foreign or French correspondents, George Lamb, Semple, C. J. Martin, Vital Brazil, Arnold, de Castro, Simon Flexner, Noguchi, P. Kyes, Morgenroth, J. Claine, Piotbey, and R. P. Travers, several of whom have come to work in my laboratory, or have obligingly procured for me venoms and venomous animals. viii

I have experienced at the hands of a large number of our ministers, consuls, or consular agents abroad the most cordial reception on repeatedly addressing myself to them in order to obtain the papers or information of which I was in need. It is only right for me to thank them for it, and to acknowledge the trouble that M. Masson has most kindly taken in publishing this book.

Institut Pasteur de Lille, A. Calmette. March 10, 1907. ix

| PAGE | ||

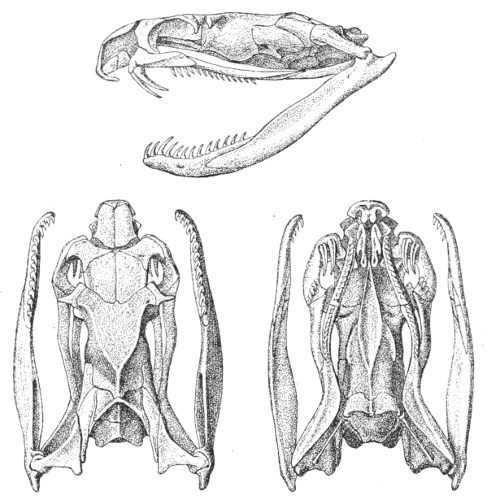

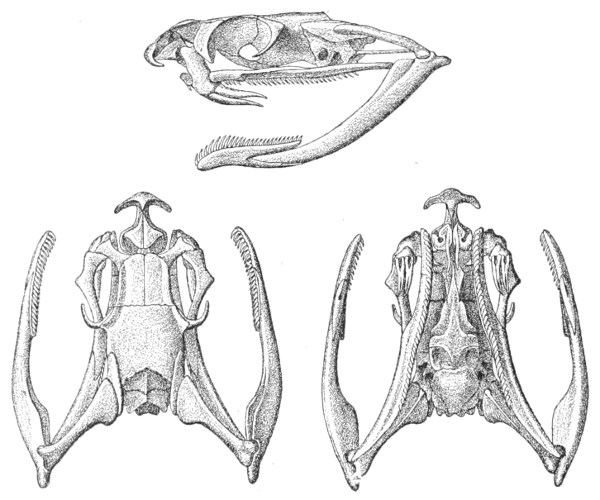

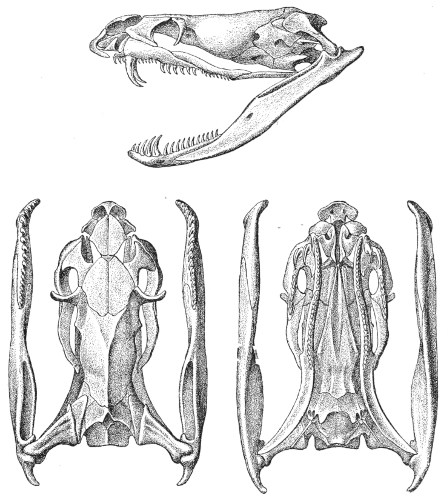

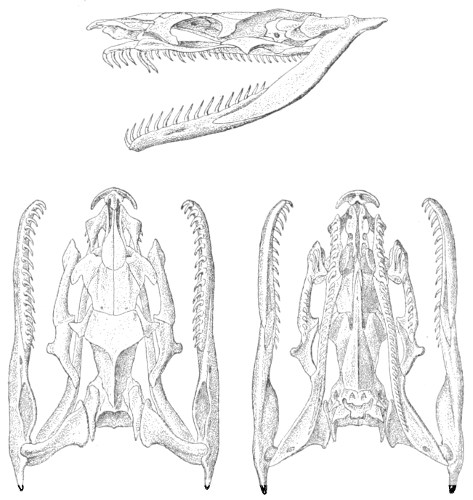

| Fig. 1.— | A. Skull of one of the non-poisonous Colubridæ (Ptyas mucosus) | 7 |

| B. Skull of one of the poisonous Colubridæ (Naja tripudians) | 7 | |

| C. Skull of one of the poisonous Colubridæ (Bungarus fasciatus) | 7 | |

| D. Skull of one of the Viperidæ (Vipera russellii) | 7 | |

| E. Skull of one of the Viperidæ Crotalinæ (Crotalus durissus) | 7 | |

| F. Skull of one of the Colubridæ Hydrophiinæ (Hydrophis pelamis) | 7 | |

| Fig. 2.— | A. Maxillary bone and fangs of one of the Viperidæ (Vipera russellii) | 8 |

| B. Maxillary bone and fangs of one of the Colubridæ (Naja tripudians) | 8 | |

| C. Maxillary bone and fangs of one of the Colubridæ (Bungarus fasciatus) | 8 | |

| D. Maxillary bone and teeth of one of the non-poisonous Colubridæ (Ptyas mucosus) | 8 | |

| Fig. 3.— | A. Fang of one of the Viperidæ (Vipera russellii) | 8 |

| D. Transverse section of the fang | 8 | |

| Fig. 4.— | B. Fang of one of the Colubridæ (Naja tripudians) | 9 |

| E. Transverse section | 9 | |

| Fig. 5.— | C. Fang of one of the Hydrophiinæ (Hydrophis pelamis) | 9 |

| F. Transverse section | 9 | |

| Fig. 6— | Three transverse sections of a poison-fang of one of the Colubridæ | 9 |

| Fig. 7— | Marks produced on the skin by the bites of different species of snakes | 10 |

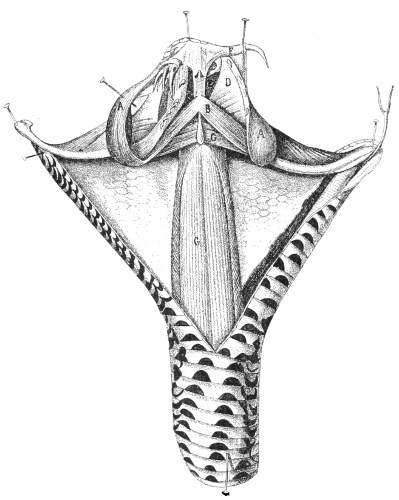

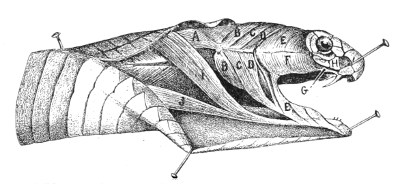

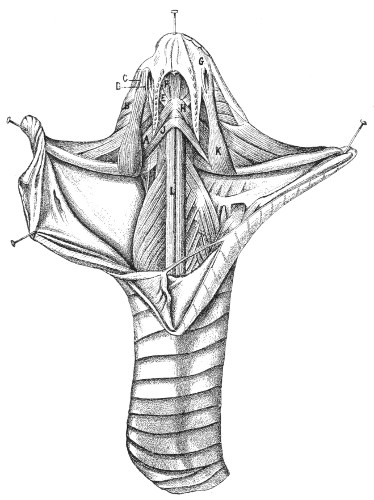

| Fig. 8— | Poison-gland and fangs of a venomous snake (Naja tripudians) | 11 |

| Fig. 9— | Muscular apparatus and poison-gland of Vipera russellii | 12 |

| Fig. 10— | Muscular apparatus and poison-gland of Vipera russellii | 12 |

| Fig. 11— | Muscular apparatus and poison-gland of Naja tripudians | 13 |

| Fig. 12— | Muscular apparatus and poison-gland of Naja tripudians | 13 |

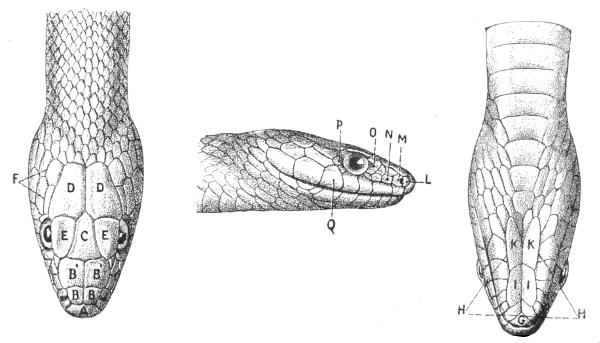

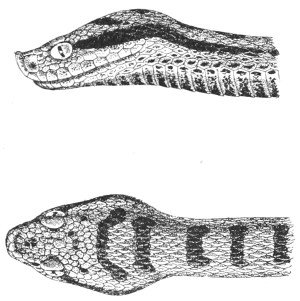

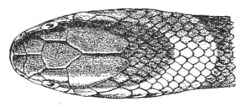

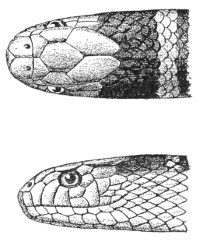

| Fig. 13— | Arrangement of the scales of the head in one of the non-poisonous Colubridæ (Ptyas mucosus) | 14 |

| Fig. 14— | Arrangement of the scales of the head in one of the poisonous Colubridæ (Naja tripudians) | 15 |

| Fig. 15— | Feeding a poisonous snake (first stage) | 18 |

| Fig. 16— | Feeding a poisonous snake (second stage) | 18 xiv |

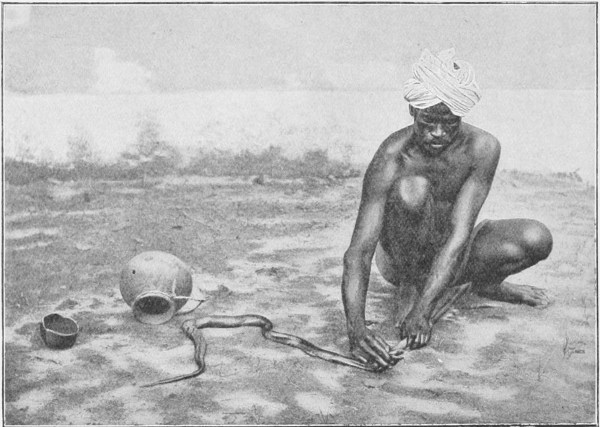

| Fig. 17— | Capture of a Naja tripudians (first stage) | 19 |

| Fig. 18— | Capture of a Naja tripudians (second stage) | 20 |

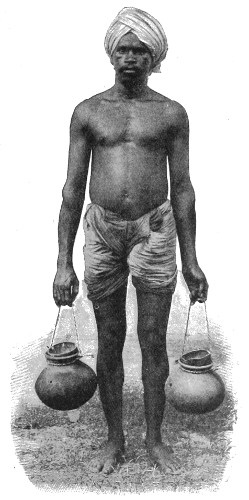

| Fig. 19— | Hindu carrying two captured Cobras in “chatties” | 21 |

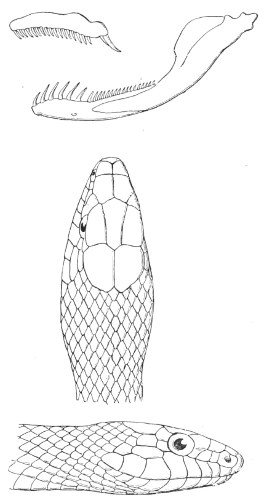

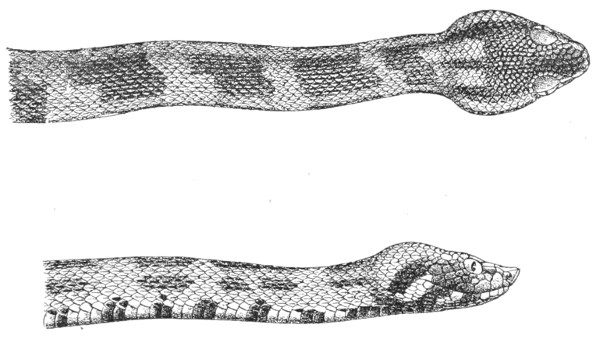

| Fig. 20— | Maxillary bone, mandible, and head of Cœlopeltis monspessulana | 23 |

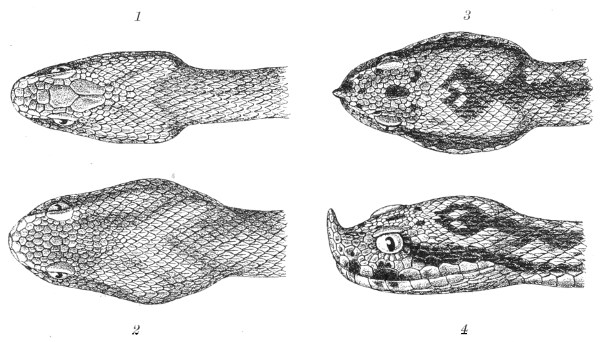

| Fig. 21— | (1) Vipera berus; (2) Vipera aspis; (3) Vipera ammodytes; (4) Vipera ammodytes | 25 |

| Fig. 22— | Vipera aspis, from the Forest of Fontainebleau | 28 |

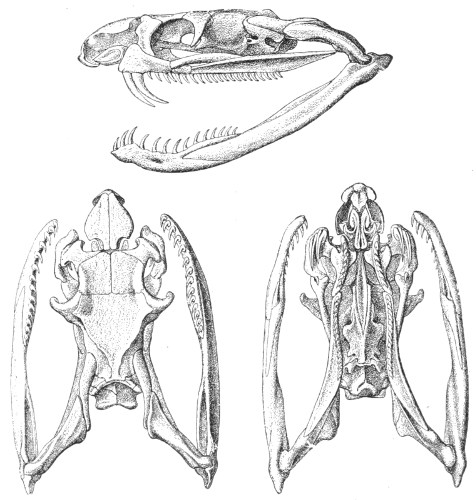

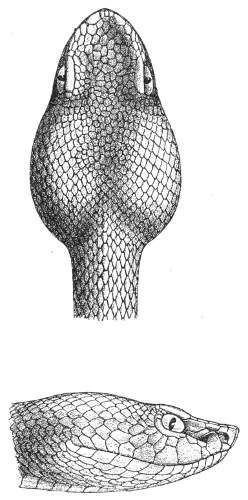

| Fig. 23— | Skull of Bungarus | 31 |

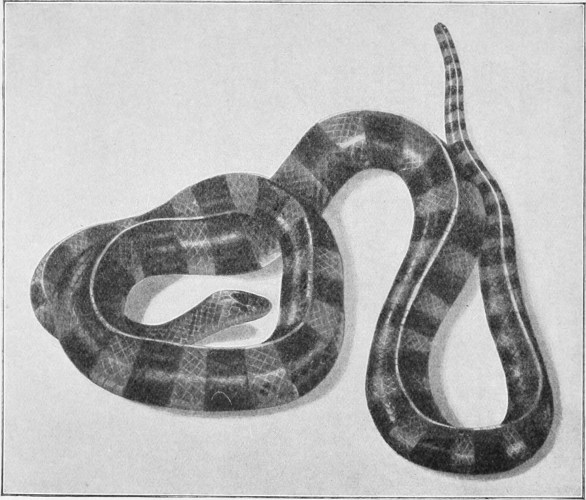

| Fig. 24— | Bungarus fasciatus (India) | 32 |

| Fig. 25— | Skull of Naja tripudians | 34 |

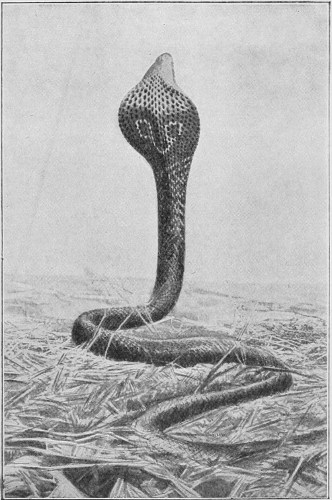

| Fig. 26— | Naja tripudians (Cobra-di-Capello) on the defensive, preparing to strike | 35 |

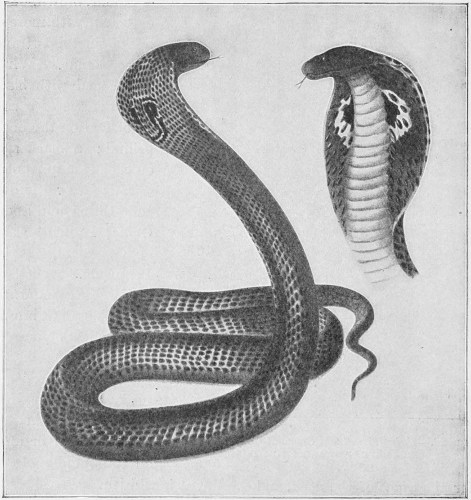

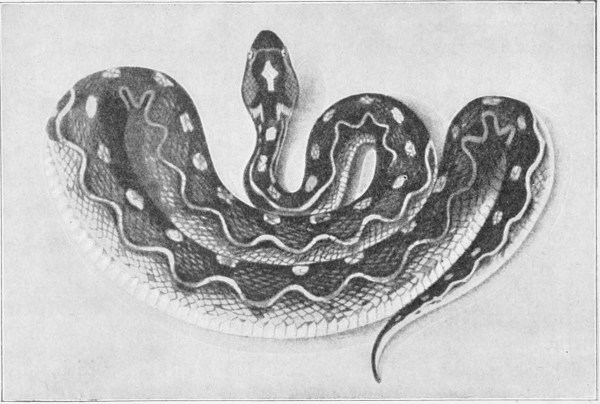

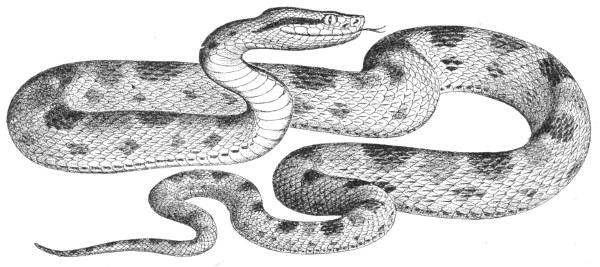

| Fig. 27— | Naja tripudians (Cobra-di-Capello) | 36 |

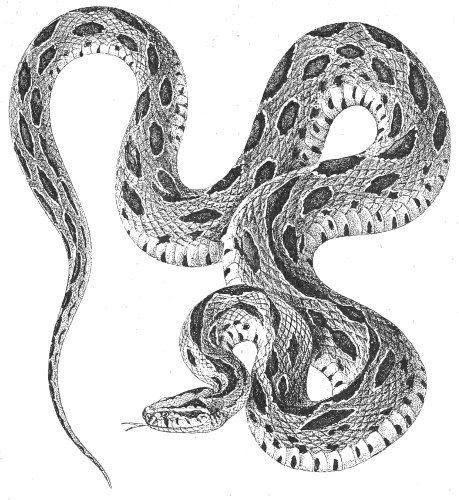

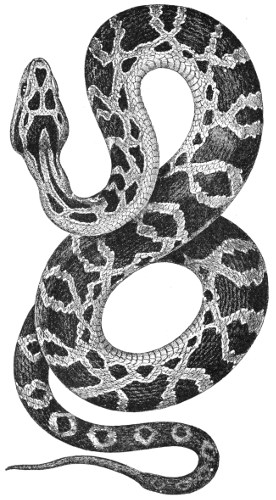

| Fig. 28— | Vipera russellii (Daboia) | 45 |

| Fig. 29— | Pseudocerastes persicus | 47 |

| Fig. 30— | Echis carinatus (India) | 48 |

| Fig. 31— | Ancistrodon hypnale (Carawalla, of Ceylon) | 50 |

| Fig. 32— | Lachesis okinavensis | 52 |

| Fig. 33— | Lachesis flavomaculatus | 55 |

| Fig. 34— | Skull of Dendraspis viridis | 65 |

| Fig. 35— | Skull of Causus rhombeatus | 68 |

| Fig. 36— | Skull of Bitis arietans (Puff Adder) | 70 |

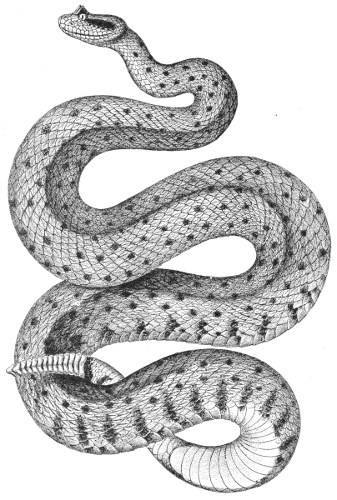

| Fig. 37— | Bitis arietans (Puff Adder) | 71 |

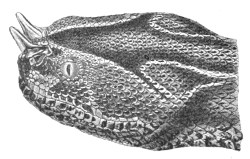

| Fig. 38— | Bitis cornuta | 73 |

| Fig. 39— | Bitis rasicornis | 74 |

| Fig. 40— | Cerastes cornutus | 75 |

| Fig. 41— | Echis coloratus | 77 |

| Fig. 42— | Skull of Atractaspis aterrima | 79 |

| Fig. 43— | Skull of Glyphodon tristis (Australian Colubrine) | 83 |

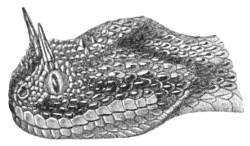

| Fig. 44— | Pseudelaps krefftii | 85 |

| Fig. 45— | Pseudelaps harriettæ | 85 |

| Fig. 46— | Pseudelaps diadema | 85 |

| Fig. 47— | Diemenia psammophis | 86 |

| Fig. 48— | Diemenia olivacea | 86 |

| Fig. 49— | Diemenia textilis | 86 |

| Fig. 50— | Diemenia nuchalis | 87 |

| Fig. 51— | Pseudechis porphyriacus (Black Snake) | 87 |

| Fig. 52— | Denisonia superba (Copperhead) | 89 |

| Fig. 53— | Denisonia coronoides | 89 |

| Fig. 54— | Denisonia ramsayi | 90 |

| Fig. 55— | Denisonia signata | 90 |

| Fig. 56— | Denisonia maculata | 91 |

| Fig. 57— | Denisonia gouldii | 91 |

| Fig. 58— | Hoplocephalus bitorquatus | 94 |

| Fig. 59— | Notechis scutatus (Tiger Snake) | 95 |

| Fig. 60— | Skull of Acanthophis antarcticus (Death Adder) | 96xv |

| Fig. 61— | Acanthophis antarcticus | 97 |

| Fig. 62— | Rhynchelaps australis | 98 |

| Fig. 63— | Skull of Furina occipitalis | 99 |

| Fig. 64— | Furina occipitalis | 99 |

| Fig. 65— | Skull of Elaps marcgravii | 101 |

| Fig. 66— | Elaps fulvius (Harlequin Snake) | 105 |

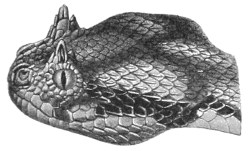

| Fig. 67— | Head and Skull of Crotalus horridus (Horrid Rattle-snake) | 109 |

| Fig. 68— | Ancistrodon piscivorus (Water Viper) | 110 |

| Fig. 69— | Lachesis lanceolatus (Fer-de-Lance) | 112 |

| Fig. 70— | Lachesis neuwiedii (Urutù) | 116 |

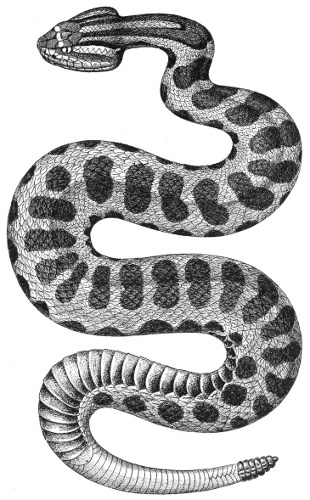

| Fig. 71— | Sistrurus catenatus (Prairie Rattle-snake) | 121 |

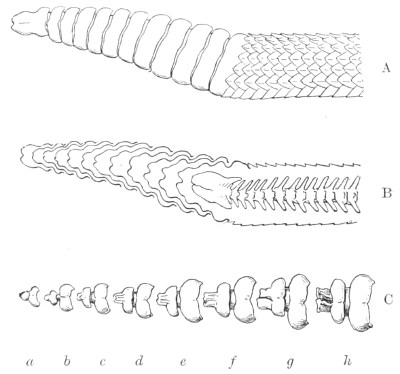

| Fig. 72— | A. Horny appendage (rattle) of a Crotalus horridus | 122 |

| B. Horny appendage, longitudinal section | 122 | |

| C. Separated segments of the appendage | 122 | |

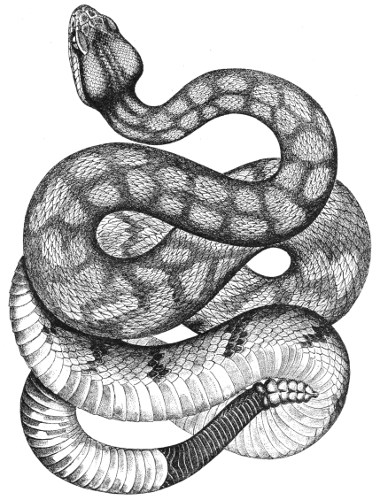

| Fig. 73— | Crotalus terrificus (Dog-faced Rattle-snake) | 123 |

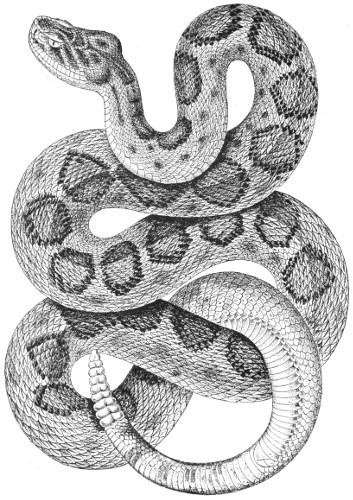

| Fig. 74— | Crotalus scutulatus (Texas Rattle-snake) | 126 |

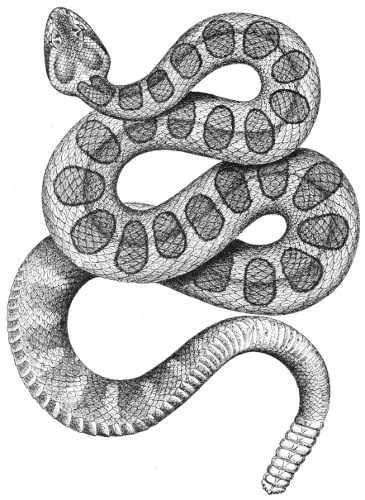

| Fig. 75— | Crotalus confluentus (Pacific Rattle-snake) | 128 |

| Fig. 76— | Crotalus cerastes (Horned Rattle-snake) | 130 |

| Fig. 77— | Skull of Hydrus platurus | 132 |

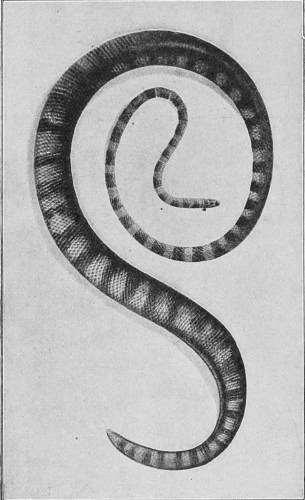

| Fig. 78— | Hydrus platurus | 133 |

| Fig. 79— | Hydrophis coronatus | 134 |

| Fig. 80— | Hydrophis elegans | 135 |

| Fig. 81— | Skull of Distira | 137 |

| Fig. 82— | Enhydrina valakadien (E. bengalensis) | 138 |

| Fig. 83— | Skull of Platurus colubrinus | 139 |

| Fig. 84— | Platurus laticaudatus (P. fischeri) | 140 |

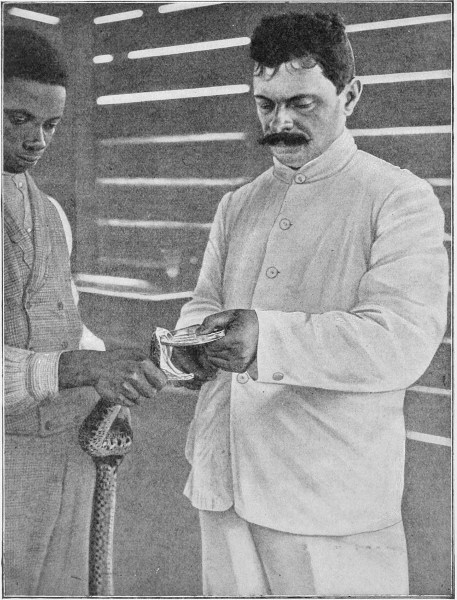

| Fig. 85— | Collecting venom from a Lachesis at the Serotherapeutic Institute of São Paulo (Brazil) | 154 |

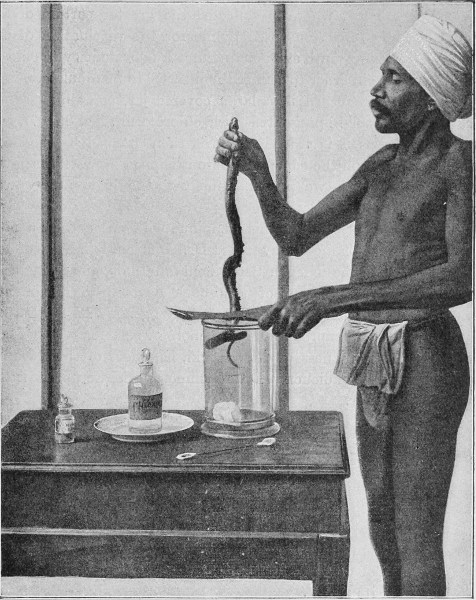

| Fig. 86— | Chloroforming a Cobra in order to collect venom at Pondicherry (first stage) | 155 |

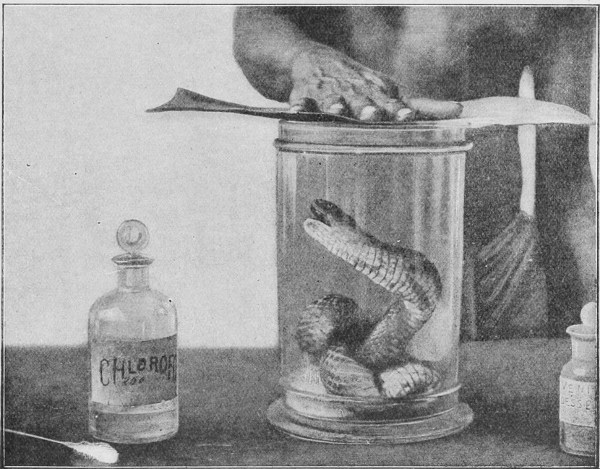

| Fig. 87— | Chloroforming a Cobra in order to collect venom at Pondicherry (second stage) | 157 |

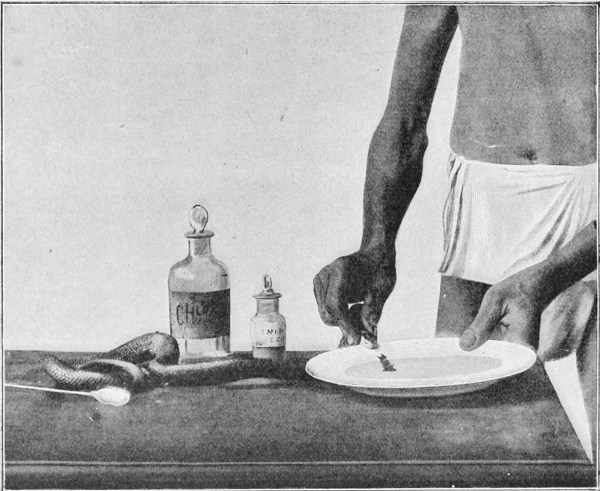

| Fig. 88— | Collecting Cobra-venom at Pondicherry (third stage) | 158 |

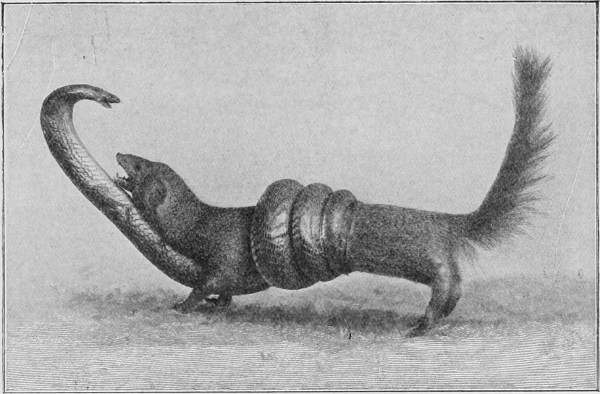

| Fig. 89— | Mongoose seized by a Cobra | 225 |

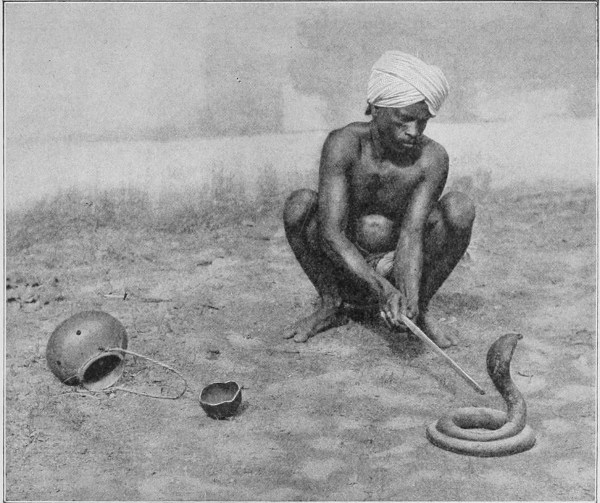

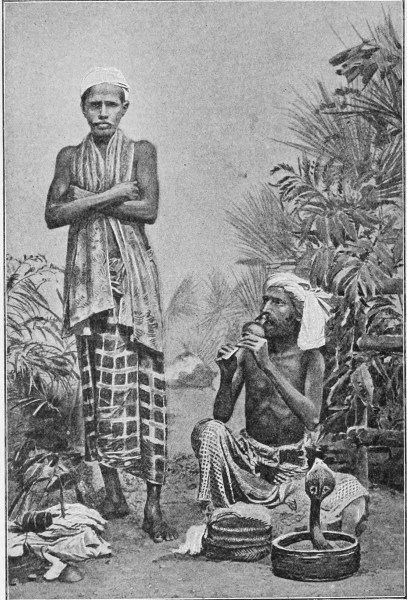

| Fig. 90— | Indian Snake-charmer at Colombo (Ceylon) | 230 |

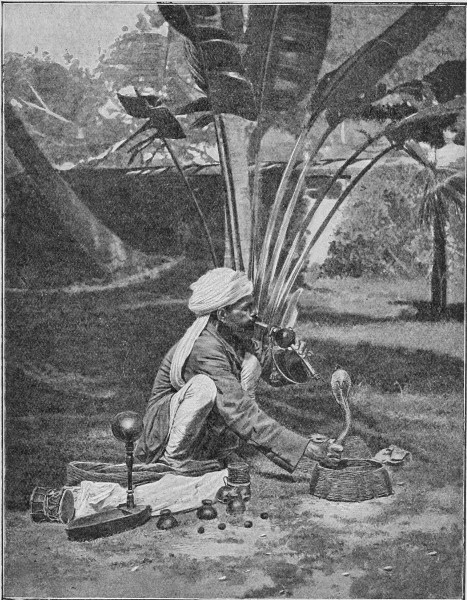

| Fig. 91— | Indian Snake-charmer at Colombo (Ceylon) | 231 |

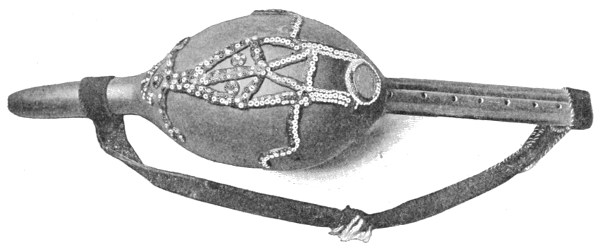

| Fig. 92— | Musical instrument used by Indian snake-charmers to charm Cobras | 232 |

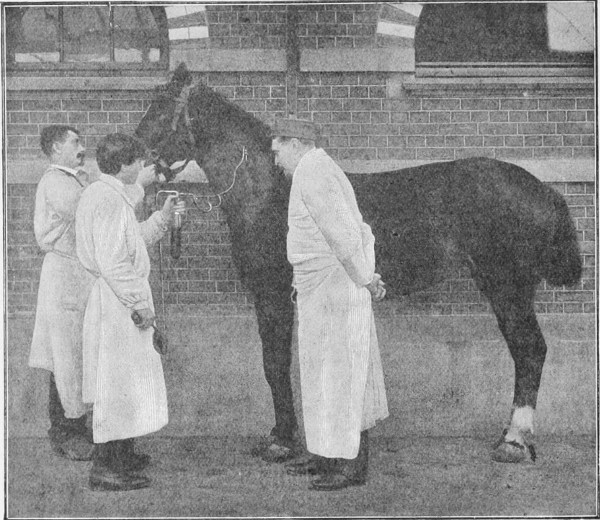

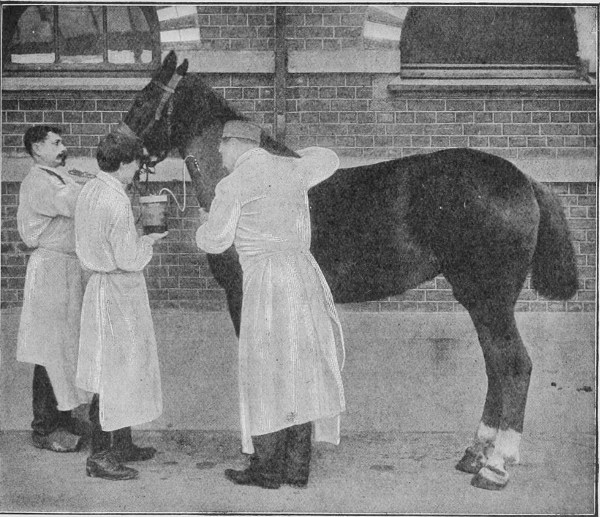

| Fig. 93— | Vaccinating a horse against venom at the Pasteur Institute, Lille | 244 |

| Fig. 94— | Aseptically bleeding a horse, vaccinated against venom, in order to obtain antivenomous serum, at the Pasteur Institute, Lille | 245 |

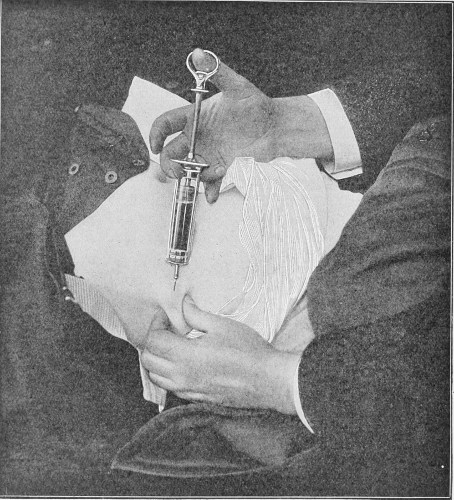

| Fig. 95— | Technique of injecting antivenomous serum beneath the skin of the abdomen | 264 |

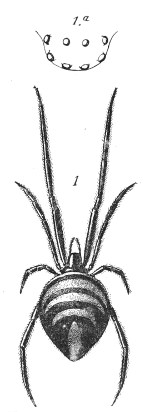

| Fig. 96— | Lactrodectus mactans | 275 |

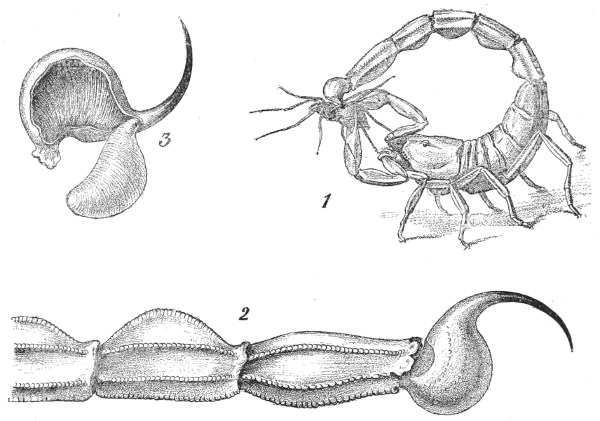

| Fig. 97— | Scorpio occitanus | 277 |

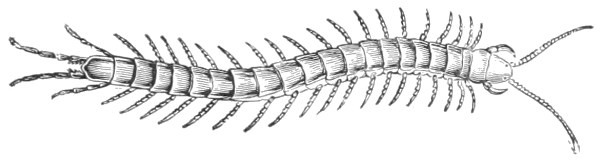

| Fig. 98— | Scolopendra morsitans | 280xvi |

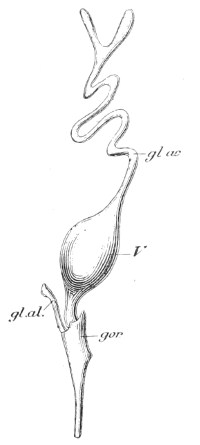

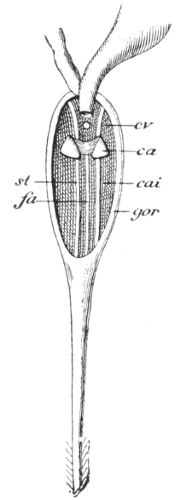

| Fig. 99— | Poison-apparatus of the bee | 281 |

| Fig. 100— | Interior of the gorget of the Bee | 282 |

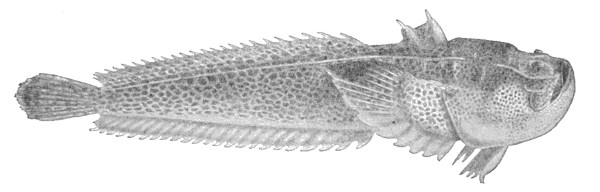

| Fig. 101— | Synanceia brachio var. Verrucosa | 291 |

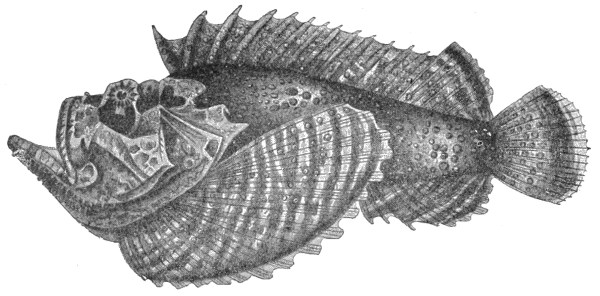

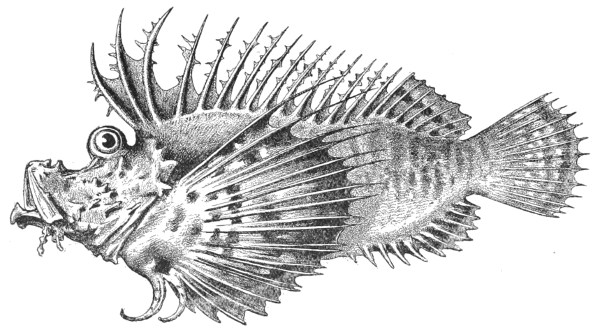

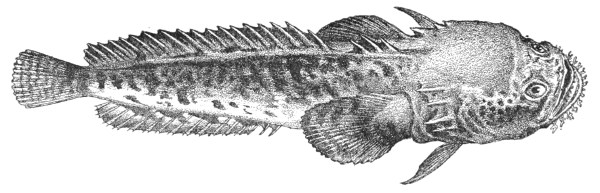

| Fig. 102— | Cottus scorpius (Sea Scorpion, or Father Lasher) | 292 |

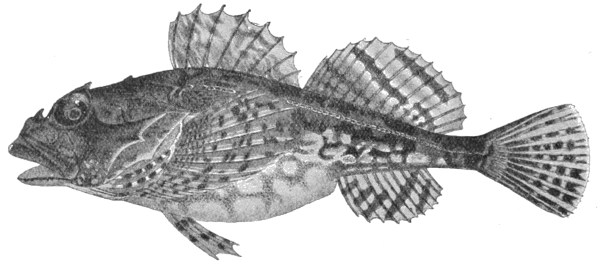

| Fig. 103— | Scorpæna grandicornis | 293 |

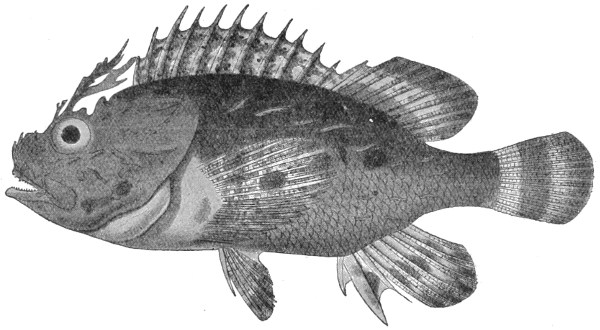

| Fig. 104— | Scorpæna diabolus | 294 |

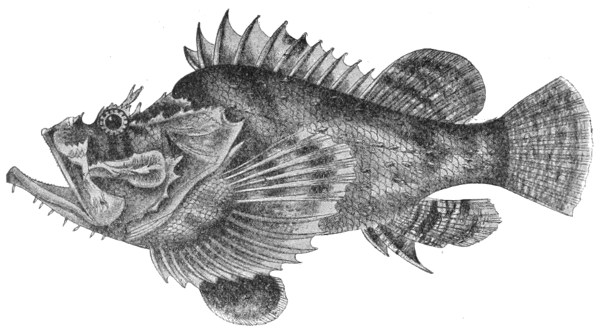

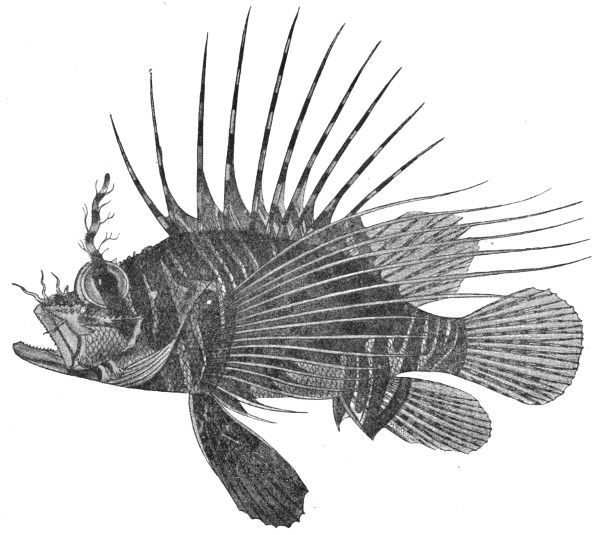

| Fig. 105— | Pterois artemata | 295 |

| Fig. 106— | Pelor filamentosum | 296 |

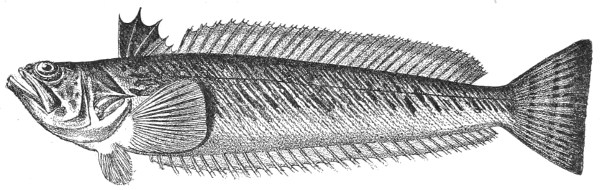

| Fig. 107— | Trachinus vipera (Lesser Weever) | 297 |

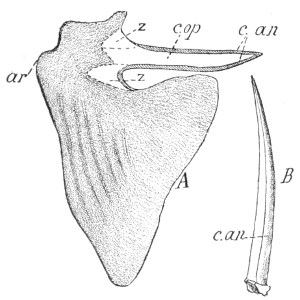

| Fig. 108— | Operculum and opercular spine of the Lesser Weever | 298 |

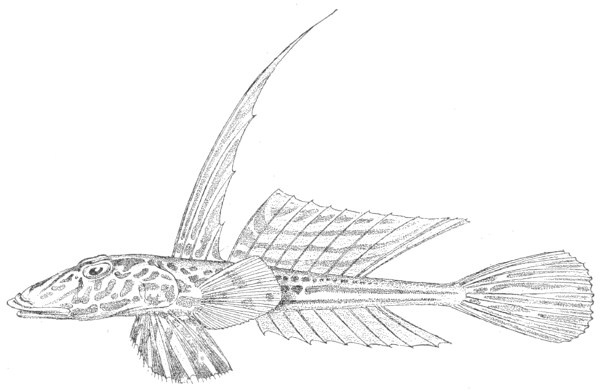

| Fig. 109— | Callionymus lyra (Dragonet) | 300 |

| Fig. 110— | Batrachus grunniens | 302 |

| Fig. 111— | Thalassophryne reticulata | 302 |

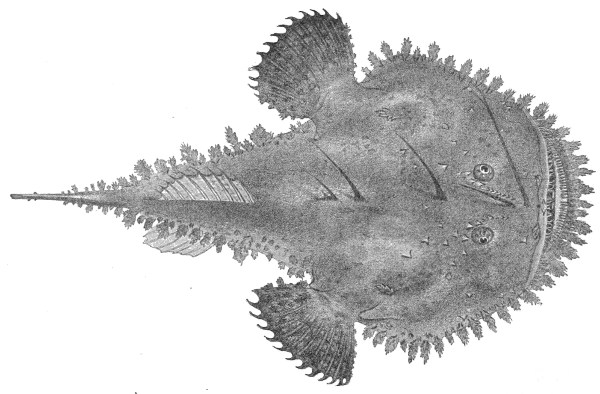

| Fig. 112— | Lophius setigerus | 303 |

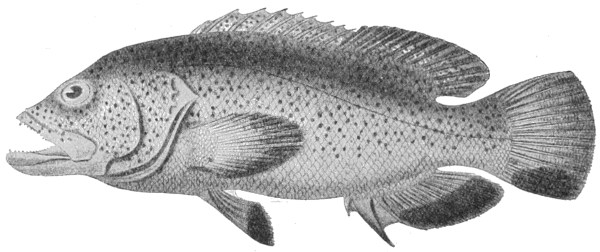

| Fig. 113— | Serranus ouatabili | 304 |

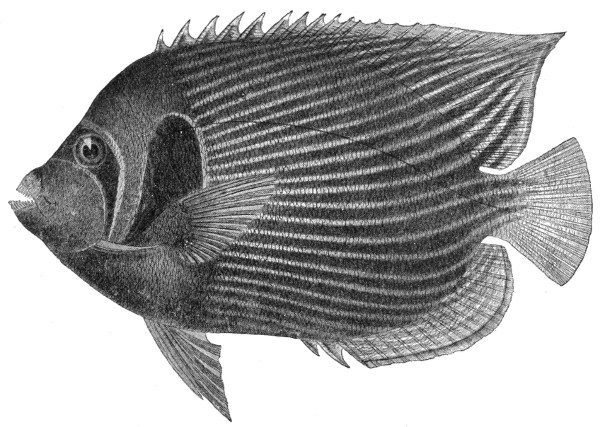

| Fig. 114— | Holacanthus imperator | 305 |

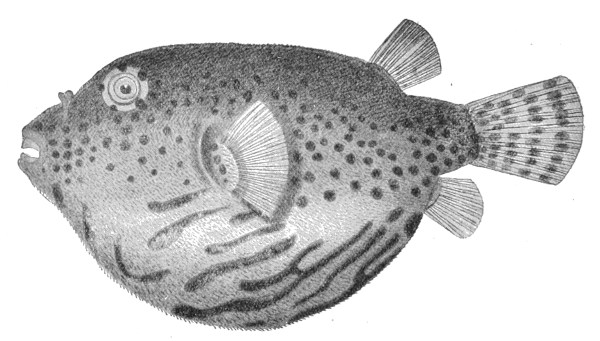

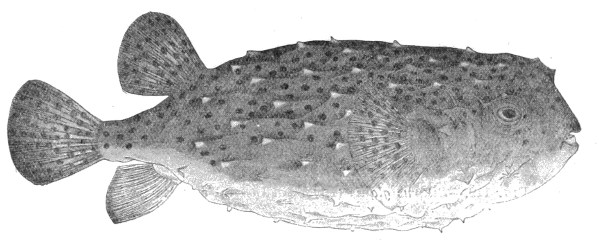

| Fig. 115— | Tetrodon stellatus | 306 |

| Fig. 116— | Tetrodon rubripes | 306 |

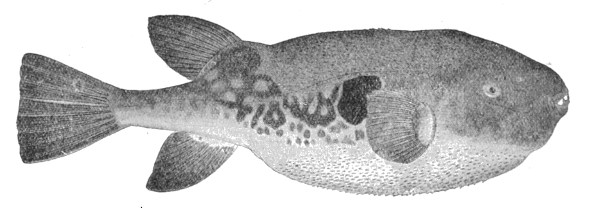

| Fig. 117— | Chilomycterus orbicularis | 307 |

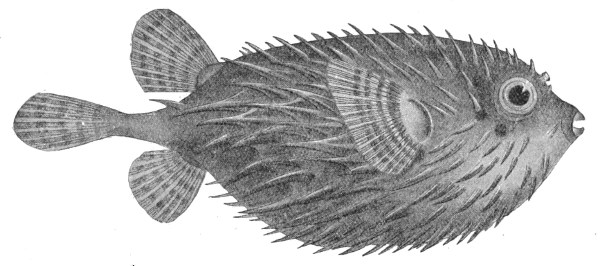

| Fig. 118— | Chilomycterus tigrinus | 307 |

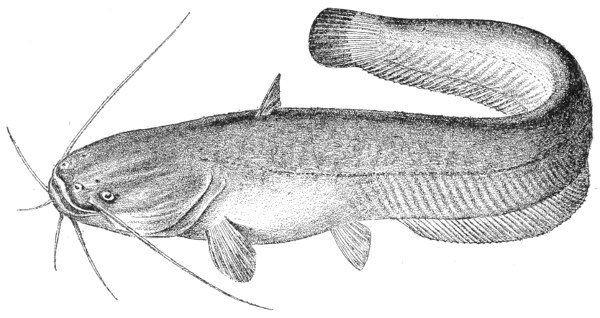

| Fig. 119— | Silurus glanis | 308 |

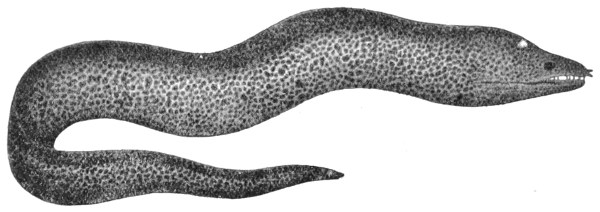

| Fig. 120— | Muræna moringa | 310 |

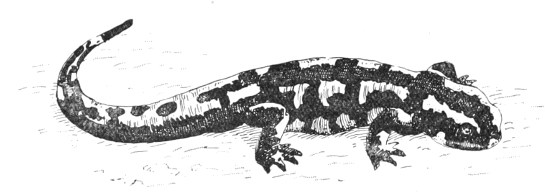

| Fig. 121— | Salamandra maculosa (Spotted Salamander) | 314 |

| Fig. 122— | Triton marmoratus (Marbled Newt) | 314 |

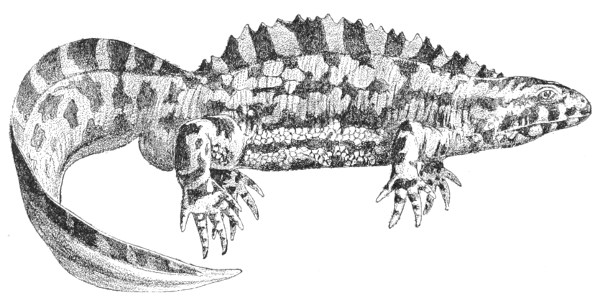

| Fig. 123— | Cryptobranchus japonicus (Great Japanese Salamander) | 315 |

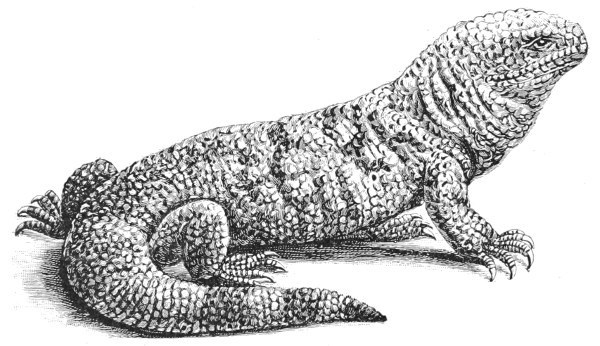

| Fig. 124— | Heloderma horridum | 322 |

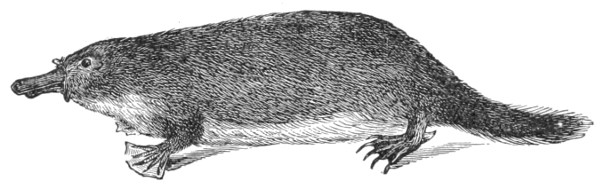

| Fig. 125— | Ornithorhynchus paradoxus (Duck-billed Platypus) | 324 |

1

VENOMS.

A large number of animals possess special glandular organs capable of secreting toxic substances called venoms.

Sometimes these substances are simply discharged into the surrounding medium, and serve to keep off enemies (toad, salamander); sometimes they mingle with the fluids and digestive juices, and then play an important part in the nourishment of the animal that produces them (snakes); in other cases, again, they are capable of being inoculated by means of stings or teeth specially adapted for this purpose, and then they serve at once as a means of attack or defence, and as a digestive ferment (snakes, spiders, scorpions, bees).

An animal is said to be venomous when it possesses the power of inoculating its venom.

Venomous species are met with in almost all the lower zoological groups, in the Protozoa, Cœlenterates, Arthropods, Molluscs, and in a large number of Vertebrates (fishes, amphibians, and reptiles).

The reptiles are best endowed in this respect, and it is in this class of creatures that we meet with the species most dangerous 2 to man and to mammals in general. The study of their venom, too, is of considerable interest, since it should lead to the quest of means of protection sufficiently efficacious to preserve us from their attacks.

Venomous reptiles are not always easy to distinguish from those devoid of any inoculatory apparatus. For this reason both classes alike have at all times inspired mankind with a lively dread, which is displayed among the various races in legends and religious beliefs.

In ancient days the cult of the snake occupied a prominent place. In Genesis the serpent is the incarnation of the Evil One, tempting and deceitful. In Greece it was the symbol of wisdom and prudence. In Egypt it was associated with the Sacred Scarabæus and the flowers of the lotus to represent Immortality!

At Rome epidemics ceased when the snake sacred to Æsculapius was brought from Epidaurus.

According to Kraff, the Gallas of Central Africa consider the snake as the ancestor of the human race, and hold it in great respect.

In India the cult of the Seven-headed Naja, or serpent-god, was formerly almost as flourishing as that of Buddha. It is still regarded as a crime to kill a Cobra when it enters a hut; prayers are addressed and food is offered to it. Its presence is an omen of happiness and prosperity; it is believed that its death would bring down the most terrible calamities on whomsoever should have brought it about, and on his family.

Nevertheless, in the Indian Peninsula alone, the Cobra, the Krait, and a few other extremely poisonous species of snakes cause every year an average of 25,000 deaths. The number of fatalities from the same cause is likewise considerable in Burma, Indo-China, the Dutch Indies, Australia, Africa, the West Indies and Tropical America generally.

The temperate regions of the globe are less severely affected; 3 but in North America the Rattle-snake and the Moccasin are especially deadly.

In France the Common Viper abounds in Jura, Isère, Ardèche, Auvergne, Vendée, and the Forest of Fontainebleau. Three hundred thousand have been killed in twenty-seven years in the Department of Haute-Saône alone. Every year this snake causes the death of some sixty persons. Cow-herds, shepherds, and sportsmen fear it greatly, since it is very dangerous to cattle, sheep, and dogs.

Poisonous snakes are divided by naturalists into two great Families, the Colubridæ and Viperidæ, distinguished from each other by certain anatomical characters, and especially by the dentition.

The Colubridæ resemble harmless snakes, which renders them all the more dangerous.

They are divided into two groups: Opisthoglypha (ὄπισθεν, behind; γλυφὴ, a groove) and Proteroglypha (πρότερον, before; γλυφὴ, a groove).

The Opisthoglypha have the upper jaws furnished in front with smooth or non-grooved teeth, but behind with one or several rows of long, canaliculate teeth.

This group includes three Sub-families:—

A. The Homalopsinæ, having valved nostrils, placed above the snout.

B. The Dipsadomorphinæ, in which the nostrils are lateral in position, and the dentition is highly developed.

C. The Elachistodontinæ, which have but rudimentary teeth only on the posterior portion of the maxillary, on the palatine and on the pterygoid bones.

Almost all the snakes belonging to these three sub-families are 4 poisonous, but only slightly so. They are not dangerous to man. Their venom merely serves to paralyse their prey before deglutition takes place; it does not afford them an effective means of defence or attack.

All the Homalopsinæ are aquatic; they bring forth their young in the water, and are met with commonly in the Indian Ocean, starting from Bombay, and especially in the Bay of Bengal, on the shores of Indo-China and Southern China, from Singapore to Formosa, in the Dutch Indies, in Borneo, the Philippines, New Guinea and the Papuan Archipelago, and as far as the north of Australia.

The Dipsadomorphinæ comprise a large number of highly cosmopolitan genera and species, found in all the regions of the earth except the northerly portions of the Northern Hemisphere. None of these reptiles is capable of causing serious casualties among human beings, owing to the peculiarly defective arrangement of their poison-apparatus. I therefore do not think it worth while to linger here over their description.

The Elachistodontinæ are of even less importance; at the present time only two species are known, both of small size and confined to Bengal.

The Proteroglypha group of the Colubridæ is of much greater interest to us, since all the snakes belonging to it are armed with powerful fangs, in front of the upper maxillaries. These fangs, which are provided with a channel in the shape of a deep groove, communicate at the base with the efferent duct of poison glands, which are often of very large size.

The group is composed of two Sub-families:—

A. The Hydrophiinæ (sea-snakes), provided with a flattened oar-shaped tail. The body is more or less laterally compressed; the eyes are usually small, with circular pupils; the scales of the nose have two notches on the upper labial border.

The normal habitat of all the members of this sub-family is the 5 sea, near the shore, with the exception of the genus Distira, which is met with in the fresh water of a lake in the Island of Luzon, in the Philippines. They are frequently found in very large numbers in the Indian seas and throughout the tropical zone of the Pacific Ocean, from the Persian Gulf to the west coast of the American Continent, but they are entirely absent from the West Coast of Africa.

B. The Elapinæ (land-snakes), with a cylindrical tail, and covered with smooth or carinate scales. These serpents are frequently adorned with brilliant colours. Some of them (belonging to the genus Naja) have the faculty of expanding the neck in the shape of a parachute, by spreading out the first pairs of ribs when they are alarmed or excited: the breadth of the neck then greatly exceeds that of the head. They are distributed throughout Africa, Asia, and North and South America, and are also found in Australia, where almost all the snakes that are known belong to this sub-family.

The Family Viperidæ is characterised by a triangular head, which is widened posteriorly, and by the general aspect of the body, which is usually thick-set and terminated by a short tail. The bones of the face are movable. The præfrontal bone is not in contact with the nasal; the maxillary is greatly shortened and may be articulated perpendicularly to the ectopterygoid; it bears a pair of large poison-fangs, one on each side, and these are always accompanied by several teeth to replace them, folded back in the gum; these latter teeth come in succession to take the place of the principal tooth, when this is broken or falls out of itself when the snake sheds its skin.

The poison-fangs are not grooved, as in the Proteroglyphous Colubridæ; they are pierced by a perfectly formed canal, the upper end of which inosculates with the efferent duct of the corresponding poison-gland, while its lower extremity opens to the exterior a little above and in front of the tip. The latter is always very sharp. 6

The palate and lower jaw are furnished with small hooked teeth, which are solid and non-venomous.

With the exception of the species of Atractaspis, these snakes are all ovoviviparous. The majority are terrestrial; a few lead a semi-aquatic existence, while others are arboreal.

Their distribution includes Europe, Asia, Africa (with the exception of Madagascar), and North and South America. They do not exist in Australia.

They are divided into two Sub-families:—

A. The Viperinæ, in which the head, which is very broad and covered with little plates and scales, has no pit between the nose and the eyes;

B. The Crotalinæ (κρὁταλον, a rattle), in which the head is incompletely covered with scales, and exhibits a deep pit on each side, between the eye and the nostril.

Among snakes, the characters that serve as a basis for the determination of genera and species are the general shape of the body, especially that of the head, the arrangement of the cephalic scales, the cranial skeleton, and the dentition.

Cranial Skeleton.—The cranium is composed of a certain number of bones, the homologues of which are found in the mammalian skeleton; but the bones are complex, and subject to modifications according to the structure and habitat of each species.

The special arrangement of the bones of the face is above all characteristic of the poisonous snakes. Those forming the upper jaw, the palate and the mandibles or “inter-maxillaries” are movable upon each other and on the cranium. The upper and lower maxillaries are united by an extensile ligament and articulated with the tympanic bone, which permits the mouth to be opened very widely when the animal swallows its prey.

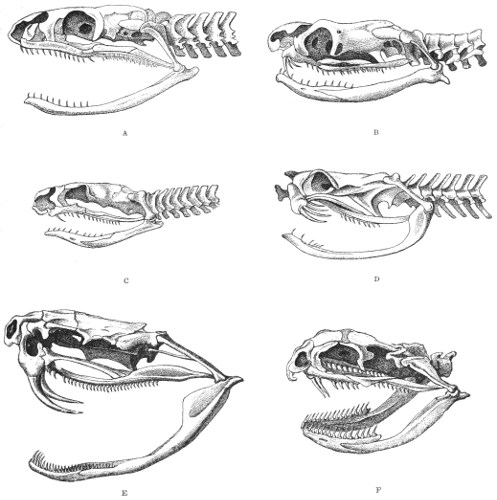

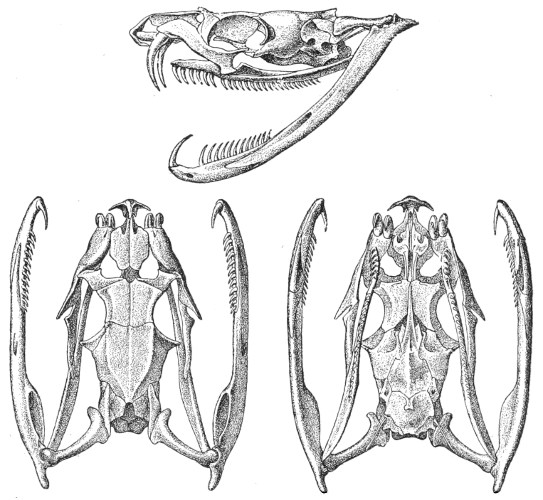

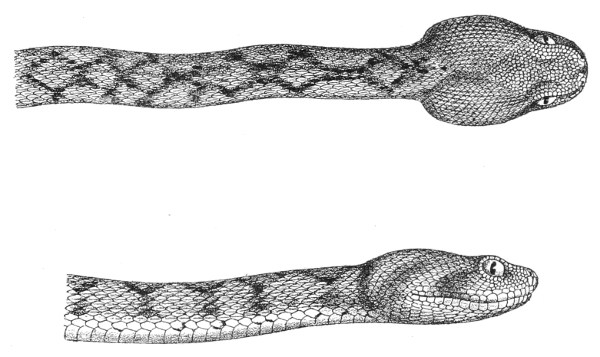

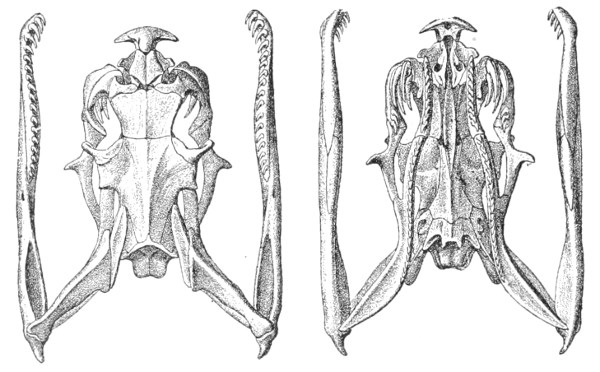

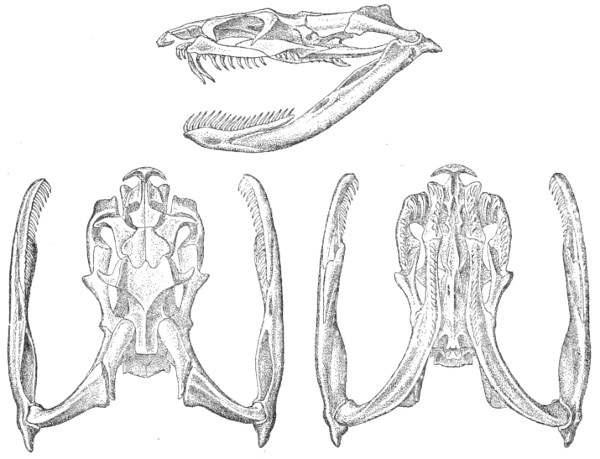

Dentition.—The non-poisonous snakes have two rows of teeth in the upper jaw—one external, the maxillary, usually composed of 7 8 from 35-40 small, backwardly curved teeth; the other internal, the palatine, which only numbers from 20-22 teeth, having the same curvature (fig. 1, A).

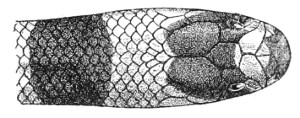

Fig. 1.—A, Cranial skeleton of one of the non-poisonous Colubridæ (Ptyas mucosus); B, cranial skeleton of one of the poisonous Colubridæ (Naja tripudians); C, cranial skeleton of one of the poisonous Colubridæ (Bungarus fasciatus); D, cranial skeleton of one of the Viperidæ (Vipera russellii); E, cranial skeleton of one of the Viperidæ Crotalinæ (Crotalus durissus); F, cranial skeleton of one of the Colubridæ Hydrophiinæ (Hydrophis pelamis).

In the poisonous snakes the maxillary bones are shorter, and the outer row is represented by a single long and tubular or grooved tooth (the fang), fused with the maxillary bone, which is itself movable (fig. 1, B, C, D, E, F).

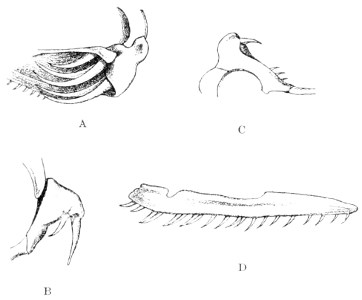

Fig. 2.—A, Maxillary bone and fangs of one of the Viperidæ (Vipera russellii); B, maxillary bone and fangs of one of the Colubridæ (Naja tripudians); C, maxillary bone and fangs of one of the Colubridæ (Bungarus fasciatus); D, maxillary bone and teeth of one of the non-poisonous Colubridæ (Ptyas mucosus). (After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

Certain species (Dipsas) have maxillary teeth which increase in size from front to rear; the longest teeth are grooved and serve for the better retention of prey, and also to impregnate it with saliva; but they are not in communication with the poison-glands.

The poison-fangs are normally covered with a fold or capsule of mucous membrane, in which they are sheathed. This fold conceals a whole series of reserve teeth in different degrees of development, which eventually become attached to the extremity of the maxillary when the principal tooth falls out or is broken (fig. 2).

Fig. 3.—A, Fang of one of the Viperidæ (Vipera russellii); D, transverse section of the fang.

Poison Apparatus.—The grooved or furrowed teeth in the Proteroglypha and the canaliculate teeth in the Solenoglypha are arranged, not for the purpose of seizing 9 prey, but in order to deal it a mortal blow by injecting the venom into its flesh.

In the normal position they lie almost horizontally, and exhibit no mobility of their own. But, when the animal prepares to bite, their erection is effected by the snake throwing its jaw back; and this movement, which is always very sudden, enables it at the same time to compress its poison-glands, by the aid of special constrictor muscles.

On examining the various species of poisonous snakes, we observe very sharply marked differences in the arrangement and dimensions of the teeth. Thus, in the Viperidæ they are long, extraordinarily sharp, and capable of producing deep wounds (fig. 2, A, and fig. 3). They are traversed by an almost completely closed canal, from the base, which communicates with the poison-duct, to the neighbourhood of the point, where it opens very obliquely on the convex surface (fig. 3, A and D).

Fig. 4.—B, Fang of one of the Colubridæ (Naja tripudians); E, transverse section.

Fig. 5.—C, Fang of one of the Hydrophiinæ (Hydrophis pelamis); F, transverse section.

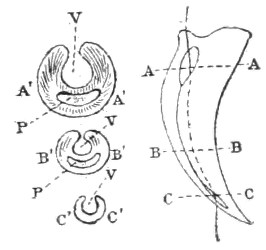

Fig. 6.—Three transverse sections of a poison-fang of one of the Colubridæ, through A A, B B, C C; P P, pulp cavity; V V V, poison-canal (groove). (After C. J. Martin.)

In the Elapinæ sub-family of the Colubridæ, and especially in the Hydrophiinæ, the teeth are much shorter and simply grooved or canaliculate; that is to say, the canal communicates with the exterior throughout its extent by a narrow slit, which traverses the entire convex surface of the tooth (figs. 4, 5, and 6).

It does not follow from this that the bites of these reptiles are less dangerous; 10 the contrary, indeed, is the case, for their venom is infinitely more active.

These differences, as well as the particular mode of arrangement of the other little non-poisonous teeth in both jaws, enable us in many cases to recognise, by the mere appearance of the bite, the species of snake by which the bite has been inflicted.

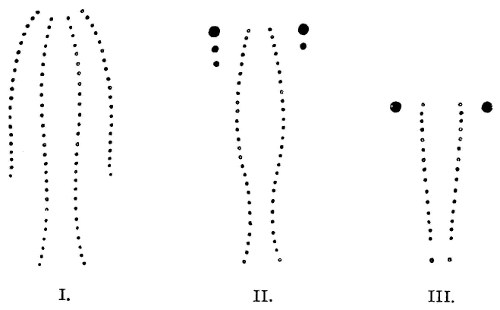

Fig. 7.—Marks produced on the Skin by the Bites of different Species of Snakes.

I. Non-venomous Colubrine.—The bite is marked only by the imprint of from 35-40 small palatine or pterygoid teeth, and 20-22 upper maxillary teeth (on the outside of the foregoing) on each side.

II. Venomous Colubrine (Naja tripudians, Proteroglypha).—The bite exhibits 25 or 26 punctures from the pterygoid or palatine teeth, and, on each side, one or two, rarely three, circular wounds produced by the principal poison-fangs and by the reserve teeth.

III. Viperidæ (Solenoglypha).—The sole indication of the bite consists of 8 or 10 punctures from the palatine or pterygoid teeth, and one little round wound, on each side, produced by the poison-fangs.

(After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

Fig. 7, above, shows how it is possible to distinguish the marks left by a non-venomous reptile, and by one of the Proteroglypha or Solenoglypha respectively.

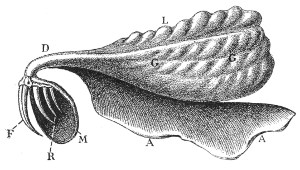

Poison-glands.—The poison-glands occupy an extensive inter-muscular space behind the eyes, on each side of the upper jaw. 11 They are oval in shape, and may, in Naja tripudians for example, attain the size of a large almond (fig. 8).

Their structure is the same as that of the salivary glands of the larger animals. The poison that they secrete accumulates in their acini and in the efferent duct that opens at the base of the corresponding fang.

Each gland is surrounded by a capsule, to which are partly attached the fibres of the masseter muscle, which violently compresses it and drives the poison, just as the piston of a syringe would do, into the canaliculi or groove of the fang.

Fig. 8.—Poison-gland and Fangs of a Venomous Snake (Naja tripudians, Colubridæ). (Natural size.)

L, Lobe of the gland; D, poison-duct; F, fang attached to the maxillary bone; G G, gland; M, capsule of mucous membrane surrounding the fangs; R, reserve fangs; A A, muscular fascia covering the gland.

(After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

In a few venomous snakes the gland is developed to such an extent that it extends as far as the first ribs.

The species, on the contrary, that have the poison-teeth placed in the hinder part of the mouth (Opisthoglypha) have glands but little developed.

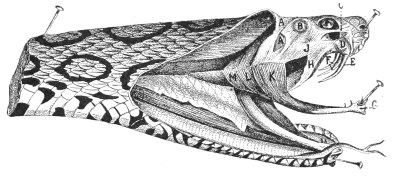

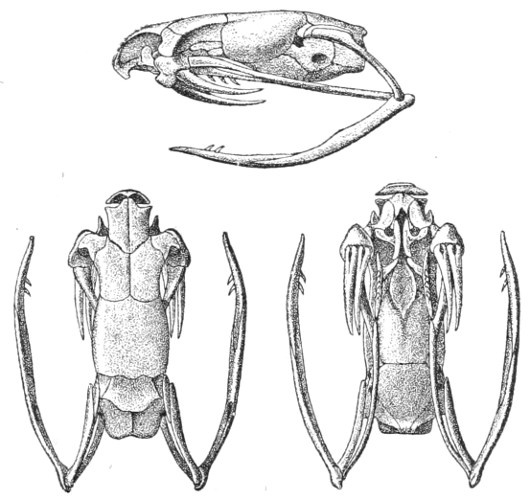

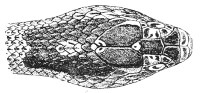

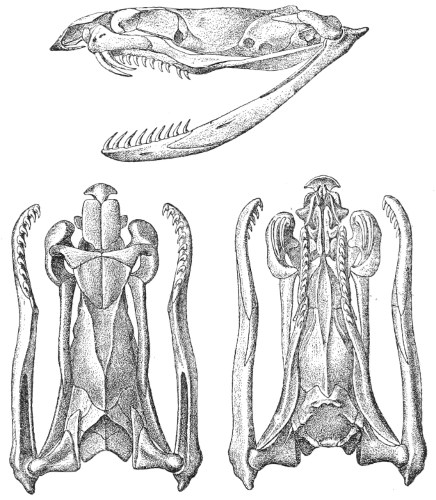

Muscular Apparatus of the Head.—Figs. 9 and 10, 11 and 12 show the arrangement of the principal muscles that work the jaws and glandular organs in Vipera russellii and Naja tripudians, which respectively represent the most formidable types of Viperidæ and venomous Colubridæ.

It is not necessary to give a detailed description of each of these muscles. Let it suffice to point out that all contribute in giving the greatest elasticity to the jaws, and at the same time strength 12 13 14 sufficient to retain the prey and to cause it to pass from front to rear towards the œsophagus, by a series of alternate antero-posterior movements and analogous lateral ones. By means of these movements, which are participated in by the upper and lower maxillary bones, the palatines, mandibles or inter-maxillaries, and the pterygoids, the animal in a manner draws itself over its prey like a glove, since the arrangement of its dentition does not admit of mastication.

A A, Fascia covering the anterior and posterior temporal muscles; B, small gland; C, tendinous insertion of the fascia; D, poison-duct; E, poison-fang; F, reserve fangs; G, mandible; H, ectopterygoid muscle; J, poison-gland covered by the masseter; K, masseter inserted in the mandible; L, insertion of the temporal muscle; M, digastric muscle.

A A, Ectopterygoid muscle; B, præ-spheno-pterygoid muscle; C, intermandibular muscle; D, præ-spheno-palatine muscle; E præ-spheno-vomerine muscle; F, capsule of mucous membrane surrounding the fangs; G, long muscle of the neck.

Figs. 9 and 10.—Muscular Apparatus and Poison-gland of Vipera russellii

(Viperidæ). (After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

A, Tracheo·mastoid muscle; B B, digastric muscle; C C, posterior temporal muscle; D D, anterior temporal muscle; E E, masseter; F, poison-gland, covered by the masseter and fascia; G, poison-duct; H, maxillary bone; I, neuro-mandibular muscle; J, costo-mandibular muscle.

A, Entopterygoid muscle; B, poison-gland; C, poison-duct; D, poison-fangs; E, præ-spheno-palatine muscle; F, præ-spheno-vomerine muscle; G, capsule of mucous membrane surrounding the fangs; H, præ-spheno-pterygoid muscle (which erects the fangs); J, inter-mandibular muscle; K, ectopterygoid muscle; L, long muscle of the neck (longus colli).

Figs. 11 and 12.—Muscular Apparatus and Poison-gland of Naja tripudians

(Colubridæ). (After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

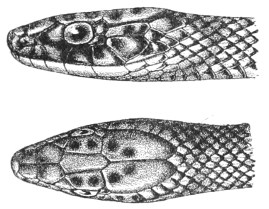

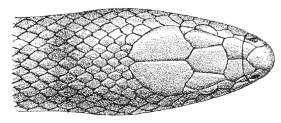

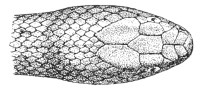

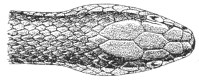

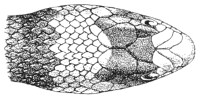

Fig. 13.—Arrangement of the Scales of the Head in one of the Non-poisonous Colubridæ (Ptyas mucosus). (After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

A, Rostral scale; B, anterior frontals; B1, posterior frontals; C, vertical; D, occipitals; E, supra-ciliaries; F, temporals; L, M, nasals; N, loreals, or frenals; O, anterior oculars, or præ-orbitals; P, posterior oculars, or post-orbitals; Q, supralabials; G, median infralabial; H H, lateral infralabials; I K, mentals.

The enormous extensile power of the mouth and œsophagus thus enables snakes to swallow animals, the size of which is several times in excess of their own diameter.

Deglutition is slow and painful, but the gastric and intestinal juices are so speedy in action, that the digestion of the most 15 resistant substances rapidly takes place. The very bones are dissolved, and the fæces, which are voided some days later, contain only a few osseous remains and a felt-like material composed of hair or feathers.

Scales.—The skin of snakes, which is very elastic and extensile, is covered with scales, small on the back, and in great transverse plates on the entire ventral surface.

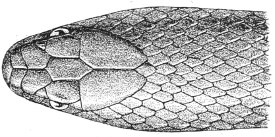

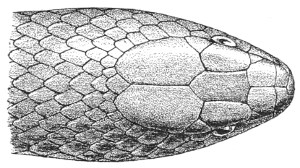

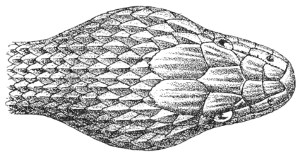

Fig. 14.—Arrangement of the Scales of the Head in one of the Poisonous Colubridæ (Naja tripudians, OR Cobra-di-Capello). (After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

The shape and dimensions of the scales of the head are highly characteristic in each species. It is therefore necessary to know their names and the arrangement that they exhibit: these details are shown with sufficient clearness in figs. 13 and 14.

Coloration.—The colouring exhibited by the scales of snakes is governed generally by the biological laws of mimicry. It is therefore not a character of specific value, and may be modified several times in the course of the existence of the same reptile, according to the surroundings in which it is obliged to live. 16

“Nature,” write Dumeril and Bibron, “seems to have caused the tints and colours of snakes to vary in accordance with their habits and modes of life. Generally speaking, the colours are greyish or dull in species that are wont to live among sand, or which bury themselves in loose earth, as also in those that lie in wait on the trunks or large boughs of trees; while these hues are of a bluish-green, resembling the tint of the leaves and young shoots of plants, in snakes that climb among bushes or balance themselves at the end of branches. It would be difficult to describe all the modifications revealed by a general study of the colours of their skins. Let us imagine all the effects of the decomposition of light, commencing with white and the purest black, and passing on to blue, yellow, and red; associating and mixing them together, and toning them down so as to produce all shades, such as those of green, of violet, with dull or brilliant tints more or less pronounced, and of iridescent or metallic reflections modified by spots, streaks, and straight, oblique, undulating, or transverse lines. Such is the range of colours to be found in the skin of snakes.”

This skin is covered by a thick epidermis, which is periodically detached in its entirety, most frequently in a single piece. Before effecting its moult, the reptile remains in a state of complete repose for several weeks, as if asleep, and does not eat. Its scales grow darker and its skin becomes wrinkled. Then one day its epidermis tears at the angle of the lips. The animal thereupon wakes up, rubs itself among stones or branches, divests itself entirely of its covering as though it were emerging from a sheath, and proceeds forthwith in quest of food.

The moult is repeated in this way three or four times every year. 17

All poisonous snakes are carnivorous. They feed on small mammals (rats, mice), birds, batrachians, other reptiles or fish, which they kill by poisoning them by means of their fangs.

They almost always wait until their prey is dead before swallowing it.

Some of them are very fond of eggs, which they well know how to find in the nests of birds, and swallow whole.

When a poisonous snake wishes to seize its prey, or strike an enemy, it raises its head, and depresses the lower and elevates the upper jaw in such a way that the fangs are directed straight forward. Then, with the quickness of a spring when it is released, the reptile makes a sudden dart and strikes its victim. After inflicting the wound it draws back, doubles up its neck and head, and remains prepared to strike again.

So rapid is the action of the venom, that the wounded animal falls to the ground almost immediately; it is forthwith stricken with paralysis, and dies in a few moments. In most cases the snake holds it in its mouth until death ensues; the reptile then sets to work to swallow its victim, an operation which is always slow and painful.

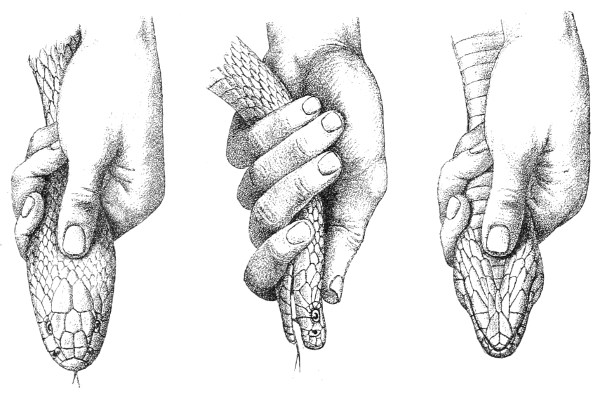

In captivity poisonous snakes almost always refuse to take any food whatever. If it be desired to keep them for a long time, it is often necessary to resort to artificial feeding. For this purpose the snake is seized by the head by means of a strong pair of long forceps; it is then grasped by the neck with the left hand without 18 19 squeezing too hard (fig. 15), taking care at the same time not to give the body a chance of coiling itself round anything. Next, one or more lumps of beef or horse-flesh are introduced into the jaws, and gently forced down deep into the œsophagus by means of a glass rod, which is polished in order not to injure the mucous membrane. The œsophagus is then gently massaged in a downward direction, in order to cause the bolus of food to descend into the stomach (fig. 16). This operation is repeated every fortnight.

Fig. 15.—Feeding a Poisonous Snake, First Stage.

Fig. 16.—Feeding a Poisonous Snake, Second Stage.

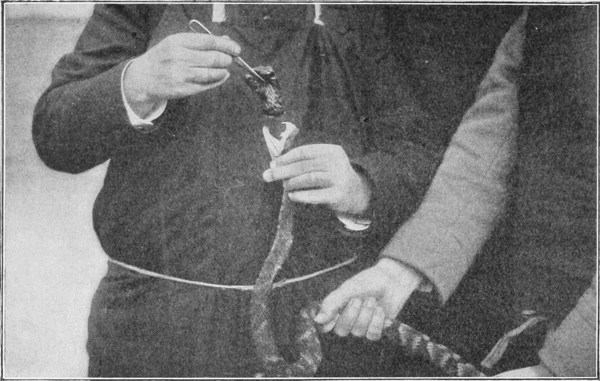

Fig. 17.—Catching a Cobra-di-Capello (Naja tripudians), First Stage. (At the French Settlement of Pondicherry, in India.)

In this way, at my laboratory, I have been able to preserve, in perfect condition for more than two years, Indian Cobras and 20 Fers-de-lance from Martinique, taking care to keep them in a hothouse, at a temperature of about 82° to 86° F.

It is also very important to place inside the cases a vessel full of water, which should be frequently changed, for almost all snakes drink often and like to bathe for whole days at a time.

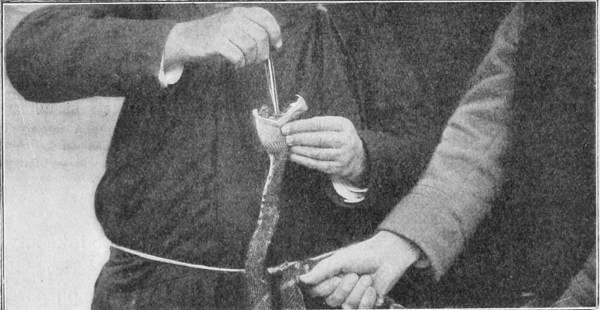

Fig. 18.—Catching a Cobra-di-Capello (Naja tripudians), Second Stage. (At the French Settlement of Pondicherry, in India.)

Within their reach should be placed in addition branches and rockwork, against which they rub at the moulting times, in order periodically to rid themselves of their scarf-skin.

While moulting, snakes must neither be touched nor fed, since to force them to take food at such a time would be fatal.

Snake-catching.—The capture of poisonous snakes, in order to keep them alive, can only be performed without danger by skilful persons, who are possessed of much coolness. 21

The best way of securing them is suddenly to pin the neck to the ground by means of a stick held horizontally, or a small two-pronged fork of wood or metal (fig. 17).

The stick is rolled along until close to the occiput (fig. 18). The animal can then be seized with the hand immediately behind the head, in such a way that it is impossible for it to turn and bite. It is then put into a wire cage, provided with a small movable trapdoor, with the fastening on the outside.

In this way poisonous snakes can be sent to a distance, and left without food for one or even two months, provided that they be kept in a place which is somewhat moist and sufficiently warm.

Fig. 19 shows how captured cobras are carried in India, in the environs of Pondicherry. They are enclosed in earthern chatties, or in baskets of plaited bamboo, which are provided with covers, and are very convenient for carrying snakes short distances.

Fig. 19.—Hindu carrying Two Captured Cobras in “Chatties.” 22

Poisonous snakes are especially common in the tropical zones of the Old and New Worlds. The species found in Europe are but of small size and not very formidable. In hot countries, on the other hand, they attain large dimensions, their venom is much more active, and, although they hardly ever attack man, and in most cases avoid him, they cause a considerable number of fatal accidents.

It is sometimes a rather difficult matter to recognise from the mere appearance of a snake whether it is poisonous or not. Naturalists themselves are occasionally deceived. It is therefore useful to learn to distinguish the most dangerous species by their external characters, and to know in what countries there is a risk of their being encountered.

Of the continents of the Old World, the poorest in poisonous snakes is Europe. The only species found there are a Cœlopeltis (belonging to the Sub-family Dipsadomorphinæ of the Opisthoglypha), and certain Viperinæ, which rarely exceed 75 centimetres in length.

Cœlopeltis, the cranial skeleton and head of which are represented in fig. 20, is characterised by a narrow, concave frontal shield, 23 projecting supraciliaries, short snout, large eyes, with round pupils, two poison-fangs at the back of the upper maxillaries, and a cylindrical body. The scales of the back are finely grooved, and in the adult slightly concave.

Fig. 20.—Maxillary, Mandible, and Head of Cœlopeltis monspessulana.

The coloration, olivaceous-brown, or deep red on the back, becomes on the ventral surface pale yellow with brown streaks, and from five to seven longitudinal series of small spots, which are blackish and edged with yellow on the sides.

The mean total length is 1,800 millimetres. The tail is somewhat tapering, and about 350 millimetres long.

The only European species is Cœlopeltis monspessulana, which is met with pretty commonly in France, in the neighbourhood of Montpellier, and Nice, near Valencia in Spain, and in Dalmatia. It is likewise found throughout North Africa, and in Asia Minor.

A second species, Cœlopeltis moilensis, occurs in Southern Tunis, Egypt, and Arabia.

The European Viperinæ belong exclusively to the Genus Vipera, the principal zoological characters of which are as follows:—

Head distinct from the neck, covered with small scales, with or without frontal and parietal shields; eyes small, with vertically 24 elongate pupils, separated from the labials by scales; nostrils lateral. Body cylindrical. Scales keel-shaped, with an apical pit, in from 19-31 rows; ventral scales rounded. Tail short; subcaudal scales in two rows.

The Genus Vipera is represented in Europe by several species, which are likewise found in Western Asia and North Africa.

These species are:—

V. ursinii, V. berus, V. aspis, V. latastii, and V. ammodytes. 1

Snout obtuse, soft on its upper surface, with the frontal and parietal shields distinct, the former about one and a half times as long as broad, and almost always longer than the parietals. A single series of scales between the eyes and the free margin of the lips.

Temporal shields smooth. Body scales in from 19 to 21 rows, strongly keeled on the back, less strongly on the sides.

Colour yellowish or pale brown above, grey or dark brown on the sides, sometimes uniform brown; spots more or less regular on the vertebral column, oval, elliptic or rhomboidal, dark brown or flecked with white, sometimes forming an undulous or zigzag band; two or three longitudinal series of dark brown or black spots on the sides; small dark dots running obliquely from the eye to the angle of the mouth; nose and lips white, and one or two dark angular streaks on the head; chin and throat yellowish; belly black, with transverse series of white or grey dots. No sexual differences in coloration.

Total length from 420-500 millimetres; tail 50-55. 25

Habitat: South-east France (Basses-Alpes); Italy (Abruzzi); Istria; Mountains of Bosnia; Plains of Lower Austria; Hungary (environs of Buda-Pesth).

Snout rounded, short and truncate; pupil vertically elongate; vertical diameter of the eyes equal to or greater than the distance separating them from the mouth; frontal and parietal shields distinct, the former as long as broad, usually shorter than the space separating it from the rostral shield; 6-13 scales round the eyes; one or rarely two series of scales between the eyes and the lips; nasal shield single, separated from the rostral by a naso-rostral shield; temporal scales smooth. Body scales in 21 rows (exceptionally 19 or 23), strongly keeled; 132-150 ventral shields; 38-36 subcaudals.

Fig. 21.—(1) Vipera berus; (2) Vipera aspis; (3, 4) Vipera ammodytes.

(Natural size.)

Colour very variable, grey, yellowish, olive, brown, or red above, 26 generally with an undulating or zigzag band along the vertebral column, and a series of lateral spots. A black spot shaped like a V, an X, or a circumflex accent, on the head. The tip of the tail is yellow or reddish. Some specimens are entirely black.

Total length from 350 to 700 millimetres; tail 75 to 90.

Habitat: Northern Europe, and especially the mountains of Central Europe; irregularly distributed in Southern Europe; Northern Spain and Portugal, Northern Italy, Bosnia, Caucasus.

This viper, which is very common in France, ranges as far as the Scandinavian Peninsula to about the 65th parallel of North Latitude. It is sometimes met with among the mountains at an altitude of about 6,500 feet (2,000 metres). It is found on heaths, in grass-lands, vineyards, and forests. Certain parts of the sandy moors of North Germany are literally infested with it. It abounds in the Jura, Isère, Ardèche, Auvergne, Brittany, Vendée, and the Forest of Fontainebleau.

It seeks its prey by night, and feeds on voles, small birds, frogs, lizards, and small fish. During the summer it shows a preference for moist places, often even remaining in the water, in which it swims with ease.

Light and fire attract it. It does not climb trees, but is frequently found coiled up on boughs of dead wood scattered on the ground.

When on the defensive, and preparing to bite, it throws its head back, and makes a sudden dart of from a foot to sixteen inches. If irritated it makes a sort of hissing noise.

To pass the winter it retires into the crevices of rocks or into old tree-trunks, where it entwines itself closely with a number of its congeners. In this way ten or fifteen vipers are frequently found together in the same hole.

In April, the whole company awakes, and copulation then takes place. The eggs are laid in August and September, and the young immediately crawl out of the shell, already prepared to bite, and 27 capable of finding their own food. Their length at birth amounts to 230 millimetres.

The two glands of an adult adder contain about 10 centigrammes of poison. This small quantity is sometimes sufficient to cause death; out of 610 persons bitten, Rollinger returns 59 deaths, or about 10 per cent.

In the departments of Vendée and Loire-Inférieure alone, Viaud Grand Marais has noted during a period of six years 321 cases of bites from adders, 62 of which were followed by death. In Auvergne, Dr. Fredet2 (of Royat) returns 14 cases, which caused 6 deaths.

Snout slightly turned up, soft and squarely truncate; vertical diameter of the eyes equal to the space separating them from the mouth; upper surface of the head usually covered with small, imbricate, smooth or feebly keeled scales, in 4-7 series, between the supraocular shields, which are prominent. The frontal and parietal shields are usually wanting; sometimes they are distinct, but small and irregular; the former are separated from the supraoculars by two series of scales; 8-13 scales round the eyes; two (rarely three) series of scales between the eyes and the labials; nasal shield single, separated from the rostral by a naso-rostral shield. Body scales in 21-23 rows, strongly keeled; 134-158 ventrals; 32-49 subcaudals.

Coloration very variable, grey, yellowish, brown, or red above, with a zigzag band as in V. berus. Usually a black U-shaped mark on the hinder part of the head, with a longitudinal black streak behind the eyes; upper lip white, or yellowish. Ventral surface yellow, white, grey, or black, with lighter or darker markings.

Total length, 620-675 millimetres; tail 75-95. 28

Habitat: France (especially Vendée, the Forest of Fontainebleau, and the South), Pyrenees, Alsace-Lorraine, the Black Forest, Switzerland, Italy and Sicily, and the Tyrol.

This viper especially frequents dry, rocky, and arid hillsides, which are exposed to the sun. Like the adder, it hibernates in tree-trunks and old walls. It lays from 6 to 15 eggs, from which the living young immediately issue, provided with poison. It feeds upon small rodents, worms, insects, and young birds. Raptorial birds, storks, and hedgehogs pursue it and devour it in large numbers.

Fig. 22.—Vipera aspis. (Natural size.) (From the Forest of Fontainebleau.)

Intermediate between V. aspis and V. ammodytes. Snout less turned up into a corneous appendage than in the latter. Head covered with small, smooth, or feebly keeled, subimbricate scales, among which an enlarged frontal shield may sometimes be distinguished; 5-7 longitudinal series of scales between the supraocular shields; 9-13 scales round the eyes; 2 or 3 series between the eyes and the labials; nasal shield entire, separated from the rostral by a naso-rostral. Body scales in 21 rows, strongly keeled; 125-147 ventrals; 32-43 subcaudals.

Coloration grey or brown above, with a longitudinal zigzag band, usually spotted with white; head with or without spots on 29 the vertex; black streak behind the eyes; ventral surface grey, spotted with black and white; tip of the tail usually yellow or with yellow spots.

Total length, 550-610 millimetres; tail 80-85.

Habitat: Spain and Portugal.

Snout terminated in front by a horny appendage covered with 10-20 small scales; vertical diameter of the eyes less than the distance separating them from the mouth; upper surface of the head covered with small, smooth, or feebly keeled scales, among which an enlarged frontal and a pair of parietal shields are sometimes distinguishable; 5-7 longitudinal series of scales between the supraoculars; 10-13 scales round the eyes; two series between the eyes and the labials; nasal shield entire, separated from the rostral by a naso-rostral. Body scales in 21-23 rows, strongly keeled; 133-162 ventrals; 24-38 subcaudals.

Coloration grey, brown, or reddish above, with a zigzag dorsal band, usually spotted with white; black streak behind the eyes; belly grey or violaceous; end of the tail yellow, orange, or coral-red.

Total length, 550-640 millimetres; tail 70-80.

Habitat: Southern Tyrol, Carinthia, Styria, Hungary, Danubian principalities and kingdoms, Turkey. Does not pass beyond the 48th parallel of North Latitude.

This viper loves very sunny places, and hillsides planted with vines. It rarely hibernates.

In districts in which it is plentiful, it is only necessary to light a fire at night in order to attract this species in swarms; this is the best method of taking it.

Its food consists of small rodents, lizards, and birds. 30

The species of snakes most dangerous to man are found in the warmer regions of Asia. India especially is infested by the famous Cobra-di-Capello (Naja tripudians), which possesses the highly remarkable faculty of dilating its neck in the form of a hood when irritated, and whose sculptured image appears on almost all the Hindu monuments.

We shall describe in a separate section (see below, F.) the Hydrophiinæ, or Sea-snakes, a large number of species of which frequent the shores of the Indian Ocean, the Strait of Malacca, the China Sea, the Moluccas, Celebes, and North Australia. In the case of certain species the area of distribution includes the whole of the tropical and sub-tropical zones of the Pacific Ocean, as far as the West Coast of America. It is therefore preferable to group them together for the purpose of comprehensive study.

Besides the above, the continent of Asia harbours a multitude of poisonous snakes belonging to the two Families Colubridæ and Viperidæ.

The genera and species belonging to these are so diverse, that we must confine ourselves to mentioning the essential characters of those that present most interest.

| I.—Family Colubridæ. | |

|---|---|

| Subfamily Elapinæ: Genera | |

| { (a) Bungarus. | |

| { (b) Naja. | |

| { (c) Hemibungarus. | |

| { (d) Callophis. | |

| { (e) Doliophis. | |

(a) Bungarus.

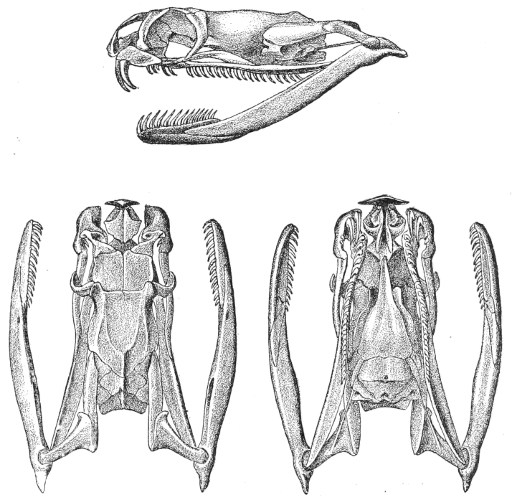

Head hardly distinct from the neck; eyes small, with round or vertically elliptic pupils; nostril between two nasal shields. Two large poison-fangs followed by one or two small, slightly grooved 31 teeth (fig. 23). Scales smooth, oblique, in 13-17 rows, enlarged and hexagonal in shape on the vertebral column; ventral scales round. Tail relatively short; subcaudal scales in one or two rows.

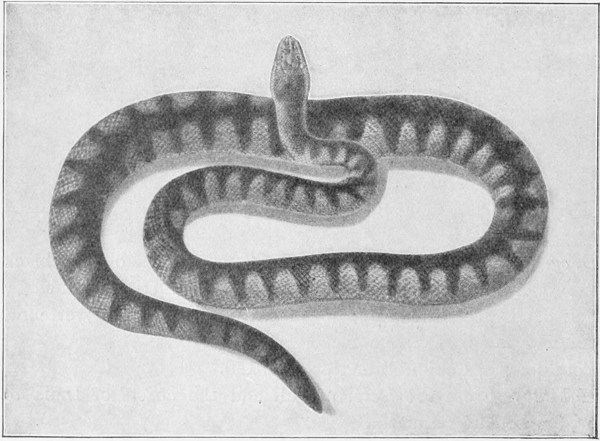

Two very dangerous snakes found in India and Indo-China belong to this genus, B. fasciatus and B. candidus (var. cæruleus). Both are fairly common. In Ceylon B. ceylonicus is met with, and in South China B. candidus (var. multicinctus). The length of these snakes is from 1,000-1,500 millimetres. The back is compressed in the shape of a keel. The neck is not dilatable.

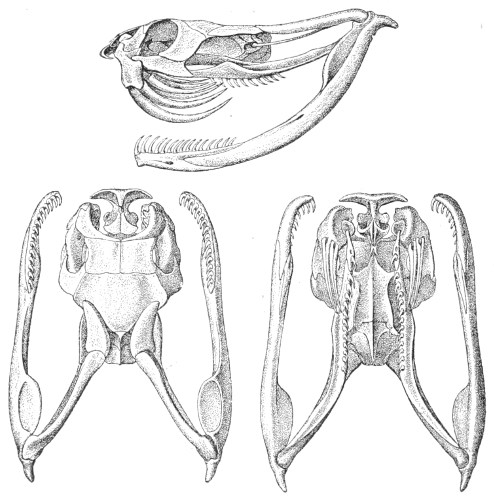

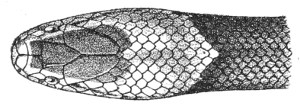

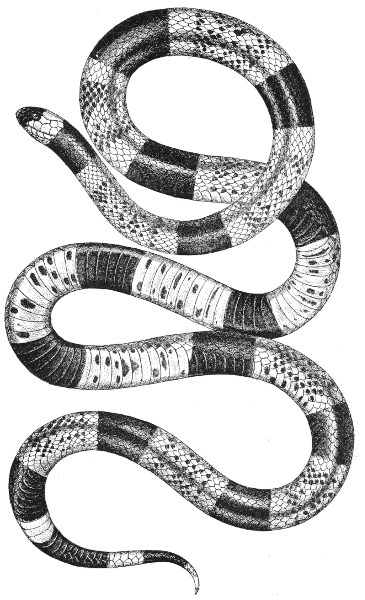

Fig. 23.—Skull of Bungarus. (After G. A. Boulenger, op. cit.)

Colour bright yellow, ringed with black, with a black band commencing between the eyes, and broadening behind upon the nape and neck (fig. 24). 32

Especially abundant on the Coromandel Coast, in Bengal, and in Burma. In the North-west Provinces of India it is known as the Koclia-Krait. Its bite is very serious, but does not cause nearly so many fatalities as that of the Cobra, since its fangs are smaller.

Dogs bitten by B. fasciatus die in from four to five hours.

Fig. 24.—Bungarus fasciatus (India). (After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

Blackish-brown or bluish, with narrow transverse white streaks, or small white spots, or alternate rings of yellow and dark brown; belly white. Smaller than the foregoing, scarcely exceeding 1,000 millimetres in length. It is known as the “Krait” in India, where, 33 after the Cobra, the variety cæruleus causes most deaths among human beings. It is found in jungles and rice-fields, and commonly secretes itself in old trees and old walls. It frequently penetrates into houses, verandahs, bathrooms, and even beds. Sir Joseph Fayrer relates the story of a lady, who, when travelling in a palanquin, found on arriving at her destination a “Krait” coiled up in her luggage, the snake having thus made the journey with her throughout a whole night.

The Krait may easily be confused with Lycodon aulicus, a harmless snake which closely resembles it, though it can at once be distinguished by examining its mouth.

Head scarcely distinct from the neck; eyes with round pupils; nostril between two nasal shields and an internasal. A pair of solid grooved poison-fangs. Body elongate, cylindrical, terminated by a conical and pointed tail. Scales smooth, disposed obliquely, in 15-25 rows. Ventral scales round.

Head small, covered with large shields, a frontal as long as broad, a supraocular, a præocular, 3 postoculars, 2 + 3 or 3 + 3 temporals, 7 upper labials, 4 lower labials. Neck dilatable by the separation of the first cervical ribs; 21-35 scales round the neck, 17-25 round the middle of the body; 163-205 ventrals; 42-75 subcaudals.

Total length, 1,500-1,900 millimetres; tail 230.

Coloration very variable, usually cinereous grey or almost black with a bluish sheen; belly lighter, sometimes tinted with red. The head is frequently tinged with golden-yellow; it is spotted with yellowish-white above, and is pure white underneath. 34

This species is distributed throughout the whole of Southern Asia, from the south of the Caspian Sea to South China and the Malay Archipelago.

Fig. 25.—Skull of Naja tripudians. (After G. A. Boulenger, op. cit.)

Several varieties occur, and of these the principal are:—

(1) Var. Typica (fig. 27), with a black-and-white spectacle-shaped mark on the middle of the dorsal surface of the most dilatable portion of the neck, and one or more dark transverse bands on the ventral surface, behind the head.

Habitat: India, Ceylon. 35

(2) Var. Cæca.—Colour, pale brown or uniform dark grey, without mark on the neck, and with one or more dark transverse bands on the anterior part of the belly.

Habitat: Transcaspian region, India, Java.

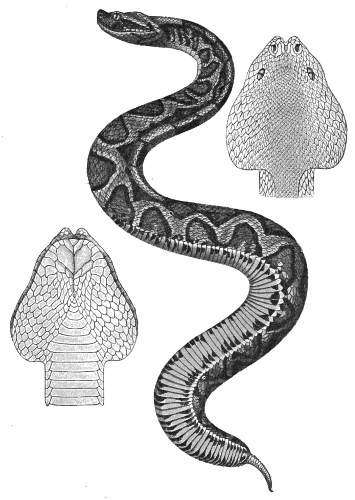

Fig. 26.—Naja tripudians (Cobra-di-Capello) on the Defensive, preparing to Strike.

(3) Var. Fasciata.—Colour, brown, olive, or black, with more or less distinct light transverse bands. White spot edged with black in the shape of a ring or of a U on the neck, behind; a black spot on each side in front.

Habitat: India, Indo-China and South China, Hainan, Cambodia, Siam, Malay Peninsula.

(4) Var. Sputatrix.—Black or dark brown, with yellow or orange-coloured spots on the sides of the head and neck. The young have a pale spot in the shape of a U or an O on the middle of the dorsal surface of the neck, and the throat is whitish.

Habitat: Chusan Islands and South China, Burma, Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java.

(5) Var. Leucodira.—Brown or black, without mark on the neck. Throat yellowish-white, followed by a black transverse band.

Habitat: Sumatra, Malay Peninsula. 36

(6) Var. Miolepis.—Brown or black; sides of the head and throat yellowish, no mark on the neck. Young with white rings completely encircling the body and tail.

Habitat: Sarawak, Labuan, Borneo.

Fig. 27.—Naja tripudians (Cobra-di-Capello). (After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

Internasal shields shorter than the præfrontals, and in contact with the præoculars; 1-3 large occipital shields behind the 37 parietals; 1 præocular and 3 postoculars; 2 + 2 or 2 + 3 temporals; 7 supralabials, 4 infralabials; 21-23 scales across the neck, 17-19 across the middle of the body; 159-175 ventrals; 45-50 subcaudals.

Coloration black or sometimes yellowish above; pale brown or yellowish on the belly; neck black.

Total length, 1,000 millimetres; tail 160.

Habitat: Philippine Islands.

A pair of large occipital shields; 1 præocular; 3 postoculars; 2 + 2 temporals; 7 supralabials, 4 infralabials; 19-21 scales across the neck, 15 across the middle of the body; 215-262 ventral scales, 80-117 subcaudals. Neck dilatable.

Coloration very variable, yellowish, brown, olive, or black, with or without dark transverse bands.

Total length, 3,900 millimetres; tail 630.

Habitat: India, Burma, Indo-China, Siam, Southern China, Malay Peninsula and Archipelago.

The species of Naja are oviparous, and usually lay some twenty eggs, elliptical in shape and as large as those of a pigeon, with a soft shell.

These snakes do not fear the proximity of man, and feed upon rats, mice, and birds; they seek their prey chiefly in the evening, after sunset.

They swim extremely well, and frequent the neighbourhood of water-courses.

Indian legends relate that Brahma, having descended on earth and fallen asleep one day at high noon, a Naja placed itself in front of him and, dilating its broad neck, procured for him kindly shade. In order to repay it for the service rendered, Brahma gave 38 Naja the marks that it bears on its neck, intended to frighten the kites and other birds of prey, which are implacable enemies of this snake.

When a native of the Malabar Coast finds a Naja in his dwelling, he begs it in a friendly way to depart; if the request be without avail, he offers it food in order to attract it outside; if the snake still does not move, the Hindu goes in search of the pious servitors of one of his divinities, who, procuring an offering, address the most touching supplications to it (Brehm).

The mortality due to the bite of this snake, which is by far the most common in India, is considerable. In the course of a period of eight years, from 1880 to 1887, it amounted on the average to 19,880 human beings and 2,100 head of cattle every year.

In 1889, 22,480 persons and 3,793 head of cattle perished from snake-bite. Since then, the annual tale of fatalities always fluctuates between 16,000 and 22,000, in spite of the rewards for the destruction of snakes which the Indian Government has been obliged to institute, which represent an expenditure of about £10,000 per annum.

For every 100 persons bitten, it is estimated that on an average from 25 to 30 die, and in most cases death supervenes in from two to twelve hours after the bite.

Naja bungarus, or the Hamadryad, is the largest and most formidable of poisonous snakes. It is very vigorous and very aggressive, but is more rarely met with than Naja tripudians. It loves the vicinity of rivers and streams, lives in forests and jungles, and climbs trees with facility. It feeds upon other snakes (whence its name Ophiophagus), and also on birds, fish, and small mammals.

Hindu snake-charmers assert that it is very difficult to capture, and dangerous owing to its strength; they handle it only after having extracted its poison-fangs.

A very intelligent Hindu told Torrens how he had seen the way in which the Hamadryad procures the snakes that form its favourite 39 food. The Hindu in question happened to be on the flat roof of his house, when a young Hamadryad appeared quite close to him. The snake raised its head, expanded its neck, and emitted a shrill hissing noise. Thereupon a dozen snakes came crawling up from all directions and assembled round the Hamadryad, when the latter made a dart at one of them and hastened to devour it (Fayrer).

The Hamadryad is dreaded with good reason, for not only is it aggressive, and hurls itself boldly upon its adversary, but it also pursues him, a trait exhibited by no other poisonous snake.

Cantor relates that in Assam an officer met with several young Hamadryads which were being watched over by their mother. The latter turned towards its enemy, who took to his heels with all speed, pursued by the terrible reptile. The course taken led to a river, which the fugitive did not hesitate to swim in order to gain the opposite bank, hoping thus to make good his escape; all, however, to no purpose. The snake still pursued him, and the officer saved himself only by a stratagem. He dashed his turban on the ground; the snake threw itself upon it and savagely bit it several times, thus giving the officer time to reach a place of safety.

Cantor’s experiments show that the venom of the Hamadryad is extremely rapid in its action. A dog usually dies a quarter of an hour after being bitten, and Nicholson states that he has seen an elephant bitten by a snake of this species die in three hours.

This genus includes several species of snakes of somewhat small size, rarely exceeding 700 millimetres in length, with an elongate, cylindrical body; the head is scarcely distinct from the neck, the pupil round, and the tail short, while the nostril is situate between two nasal shields. The temporal shields are arranged in a single row. The poison-glands sometimes extend into the abdominal 40 cavity. Scales in 13 or 15 rows; 190-260 ventrals, 12-44 subcaudals in 2 rows.

Four species belonging to this genus are known:—

(1) H. calligaster.—2 + 3 temporal scales, 6 supralabials.

Colour purple, with black transverse bands separated by narrow white bars; belly and end of tail red; snout yellow, with a black band on the upper lip below the eyes.

Total length, 520 millimetres; tail 30.

Habitat: Philippine Islands.

(2) H. collaris.—No anterior temporal scales.

Colour black on the back, with black and red bands on the belly; a yellow collar on the occiput.

Total length, 430 millimetres; tail 15.

Habitat: Philippine Islands.

(3) H. nigrescens.—Scales in 13 rows. A single temporal scale; 218-251 ventrals; 33-44 subcaudals.

Belly uniformly red; upper lip yellow in front of and behind the eyes.

Total length, 1,100 millimetres; tail 115.

Habitat: Hills of Western India, from Bombay to Travancore.

(4) H. japonicus.—Scales in 13 rows; 190-216 ventrals; 28-29 subcaudals; temporals 1 + 1.

Colour red on the back, with 1-5 black bands crossed by other black bands edged with yellow. Snout and sides of head black. Belly yellow, with large black spots alternating with black transverse bands.

Total length, 520 millimetres; tail 40.

Habitat: Loo Choo Islands.

This genus is characterised by the maxillary bones extending forwards beyond the palatines, with a pair of large poison-fangs, but without other teeth. Head and eyes small, pupils round; 41 nostril between two nasal shields. Body cylindrical, greatly elongate. Scales smooth, in 13 rows; ventrals rounded; subcaudals in 2 rows.

Five species are known:—

(1) C. gracilis.—Red or pale brown, with three longitudinal black lines passing through brown, or black spots; the lateral spots alternating with the vertebræ. Black and yellow bands under the tail and on the belly.

Total length, 740 millimetres; tail 35.

Habitat: Malay Peninsula, Sumatra.

(2) C. trimaculatus.—Head and nape black, with a yellow spot on each side of the occiput; belly uniform red; tail with two black rings.

Total length, 335 millimetres; tail 21.

Habitat: India and Burma.

(3) C. maculiceps.—Head and nape black, with one or two yellow bands on each side. Belly red, two black rings on the tail. Diameter of the eyes equal to two-thirds of the space separating them from the mouth.

Total length, 485 millimetres; tail 30.

Habitat: Burma, Indo-China, Malay Peninsula.

(4) C. macclellandii.—Head and neck black, with a yellow transverse band behind the eyes. The space separating the eyes equal to that separating them from the mouth. Colour reddish-brown on the back, with regular and equi-distant black streaks; belly yellow, with black bands or quadrangular spots. The head exhibits two black transverse bands separated by a yellow band.

Total length, 620 millimetres; tail 55.

Habitat: Nepal, Sikkim, Assam, Burma, Southern China.

(5) C. bibronii.—Met with by Beddome in the forests of Malabar, at an altitude of 3,280 feet. Back purplish-brown, with a pearly lustre, and about forty irregular black transverse bands, extending to the tip of the tail. Head black in front, cherry-red on the occiput. 42

Total length, 640 millimetres; tail 50.

Habitat: Malabar.

All the snakes belonging to the genus Callophis are remarkable for their bright and varied colours, whence the generic name, which signifies “beautiful snakes.”

They feed exclusively on other snakes belonging to the Family Calamaridæ; consequently they are not found in regions where Calamaridæ do not occur, as, for instance, in Ceylon.

They are essentially terrestrial, and live in old tree-trunks, or clefts in rocks. They are sluggish, slow-moving, and chiefly nocturnal.

As a rule they do not seek either to defend themselves or to bite; consequently fatal accidents caused by them are scarcely known in the case of human beings. Their venom, however, is very toxic to animals.

This genus exhibits the same characters as Callophis, except that the poison-glands, instead of being confined to the temporal region, extend a very long way on each side of the body, to about one-third of its length, gradually growing thicker and terminating at the base of the heart.

It includes four species:—

(1) D. bivirgatus.—Colour reddish-purple or black on the back, red on the head, tail, and belly.

Total length, 1,610 millimetres; tail 190.

Habitat: Burma, Indo-China, Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo.

(2) D. intestinalis.—Brown or black on the back, with darker or lighter longitudinal streaks; tail red beneath; belly red, crossed with black streaks.

Total length, 580 millimetres; tail 45. 43

Habitat: Burma, Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Celebes.

(3) D. bilineatus.—Black on the back, with two white streaks along the whole length of the body. Snout white; belly striped with black and white bands. Tail orange, with two or three black rings or spots.

Total length, 710 millimetres; tail 45.

Habitat: Philippine Islands.

(4) D. philippinus.—Back with dark brown cross-bands, merging into black transverse ventral streaks, which are separated by yellow or red interspaces. Head brown, with small yellow spots.

Total length, 430 millimetres; tail 35.

Habitat: Philippine Islands.

The Family Viperidæ is represented in Asia by a considerable number of snakes belonging to the two Subfamilies Viperinæ and Crotalinæ.

The Asiatic Viperinæ belong to the genera:—

(a) Vipera. (b) Pseudocerastes. (c) Cerastes. (d) Echis.

The Crotalinæ consist of only two genera:—

(e) Ancistrodon. (f) Lachesis.

We shall not recapitulate here the characters of the Genus Vipera, which we described in dealing with the vipers of Europe. The genus is represented by several species, the geographical range of which is chiefly confined to Eastern and Central Asia. 44

(1) Vipera renardi.—Resembles V. berus, but the snout is pointed and soft, with a turned-up tip; a single series of scales between the eyes and the lips; nostril pierced in the lower half of a single nasal shield; 8-9 supralabial shields; 4 infralabials. Body scales in 21 rows; 130-150 ventrals; 24-37 subcaudals.

Coloration the same as in the European V. ursinii, but the snout and lips are spotted with black or brown.

Total length, 395-620 millimetres; tail 40-75.

Habitat: Central Asia, Turkestan.

(2) V. raddii.—Snout rounded; supraocular shields erectile; eyes surrounded by a complete circle of 14-17 scales; 9-10 supralabials; body scales in 23 rows; 150-180 ventrals; 23-32 subcaudals.

Coloration pale brown or grey on the back, with a dorsal series of small reddish spots arranged in alternating pairs. A black mark like a circumflex accent on the occiput, and a black band behind the eyes. Belly yellow, speckled with black and white.

Total length, 740 millimetres; tail 50.

Habitat: Armenia.

(3) V. lebetina.—Snout rounded and obtuse, with a well-marked prominence; 7-12 longitudinal series of scales between the eyes; supraocular shields well developed or narrow, or broken up into several small portions; 12-18 scales round the eyes; 9-12 supralabials; 4-5 infralabials; body scales in 23-27 rows; 147-180 ventrals; 29-51 subcaudals.

Coloration variable, grey or pale brown on the back, with a series of large dark spots. Large brown mark like a circumflex accent on the crown of the head and another on the occiput. Belly whitish, speckled with grey-brown; end of tail yellow.

Total length, 960 millimetres; tail 120. The female may attain the length of 1,350 millimetres.

Habitat: Cyprus, Galilee, Syria, Asia Minor, Transcaspia, Persia, Mesopotamia, Afghanistan, Baluchistan, Cashmir. 45

(4) V. russellii (Daboia, or Russell’s Viper). (fig. 28.)—This viper, which may attain a length of as much as 2,000 millimetres, is magnificently coloured. Its dorsal surface is brownish-yellow, marked with large oval spots of blackish-brown, edged with yellow or white. The belly is covered with transverse bands, with beautiful triangular black spots, bordered with white. The head, which is long, ends in front in a thick, rounded snout; it is covered above 46 with small keeled scales. The nostril, which is large and laterally placed, is surrounded by three shields and soft smooth skin.

Fig. 28.—Vipera russellii (Syn. Vipera elegans. Daboia, or Russell’s Viper). India.

(After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

The species is found throughout India, from Bombay to Bengal, in Ceylon, Burma, and Siam. It is particularly common in Burma, around Rangoon. For walking in the jungle and rice-fields, the natives of this region encase their feet and legs in a special kind of jack-boots made of coarse jute-cloth, in order to protect themselves from the bites of this snake, which cause a large number of fatal accidents.

The Daboia ascends the Himalayas to an altitude of 5,250 feet. It lives in thickets, under stones, and in the clefts of rocks. When disturbed it makes a terrible hissing, but bites only when attacked or irritated.

It feeds upon small vertebrates, such as mice, rats, birds, and frogs, and often enters houses in pursuit of rats.

“Schrott had the opportunity of observing a Daboia on the defensive. A lady carrying a child on her arm was returning home towards evening; she had almost reached her house when a bulldog accompanying her began to bark furiously. Although the lady saw nothing, she was, nevertheless, frightened and called for help. Schrott, who was not far away, ran to the spot, and saw a Daboia lying across the path by which the lady had to proceed. The reptile had its neck thrown back and its head in a horizontal position; its bright eyes followed all the movements of the dog, to whose barks it replied by shrill hisses. It was only waiting for an opportunity to strike. Schrott called off the dog, and the snake at once disappeared among the high grass close by. Next day it was killed at the same spot” (Brehm).

The venom of this viper is terribly potent. According to Russell, a large dog exhibited symptoms of poisoning five minutes after being bitten. At the end of a quarter of an hour it lay down, uttering heartrending cries, began to breathe with difficulty and noisily, was seized with spasms of the jaws and cramps, and died in frightful agony less than half an hour after the wound was inflicted. Fowls 47 in most cases die in less than two minutes. A horse succumbed in half an hour, and another in eleven hours.

It appears that in India many cattle are killed by Daboias while grazing (Fayrer).

This genus is represented by a single species (Pseudocerastes persicus), which appears to be exclusively confined to Persia.

The head is very distinct from the neck, and covered with small imbricate scales; the eyes, which are small, have vertical pupils; they are separated from the lips by small scales. The nostrils are directed upwards and outwards. The snout is very short and rounded. The cylindrical body has 23-25 rows of scales; 151-156 ventrals; 43-49 subcaudals.

Fig. 29.—Pseudocerastes persicus.

(After Duméril and Bibron.)

The coloration is gray or brown, with four series of large black spots, and the head exhibits two longitudinal black streaks behind the eyes. The belly is whitish, dotted with black.

Total length, 890 millimetres; tail 110.

The vipers belonging to this genus are much more common in North Africa, and we shall therefore study them in conjunction with the African snakes. Cerastes cornutus alone, the special habitat of which is Egypt, is sometimes met with in Arabia and on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal. 48

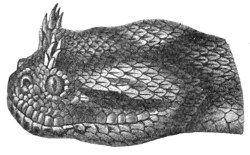

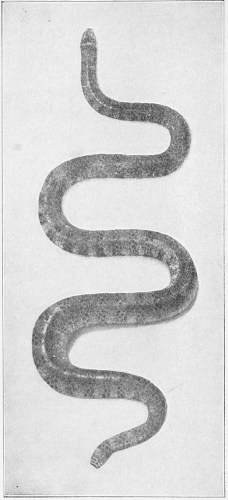

Echis carinatus (the Phoorsa). (Fig. 30).—This viper is characterised by the subcaudal shields being arranged in a single row. It is savage and very aggressive, being always ready to attack. Its length does not exceed 600 millimetres at the most. The colour of the body is grey, more or less dark and adorned with streaks, spots, and dots of blackish-brown. The back displays yellowish-white wavy lines, forming X-shaped markings. The upper side of the head exhibits a yellow spot surrounded by brown, and other small black spots, the whole arrangement forming a fairly good representation of a cross.

Fig. 30.—Echis carinatus. India. (After Sir Joseph Fayrer.)

This species is found in India, Persia, Baluchistan, Arabia, and Palestine; while, as we shall see, it also occurs in Africa. It is fairly common in the environs of Aden. 49

In moving over the ground a peculiar sound is produced by the friction of its scales. It is capable of springing with great agility a fairly long distance on to its prey. When it believes itself in danger it coils up, doubling its body twice in the shape of a crescent, in the middle of which it places its head, ready to strike. Its venom is very rapid in taking effect.