This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Japan-Russia War

An Illustrated History of the War in the Far East

Author: Sydney Tyler

Release Date: January 28, 2016 [eBook #51066]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE JAPAN-RUSSIA WAR***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See https://archive.org/details/japanrussiawaril00tyle |

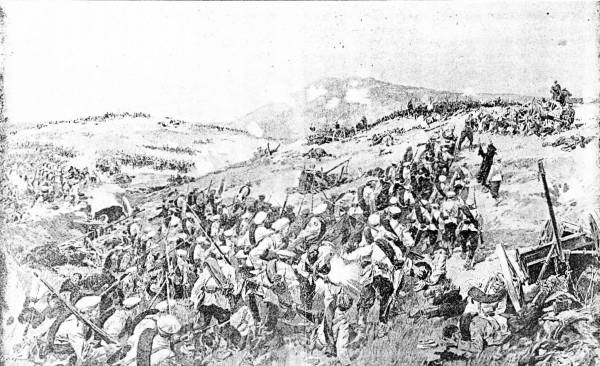

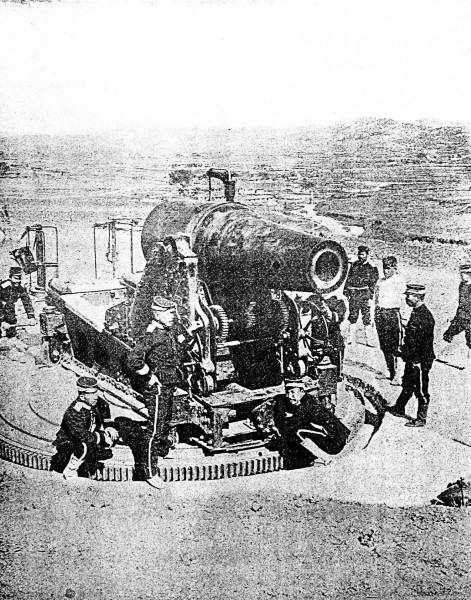

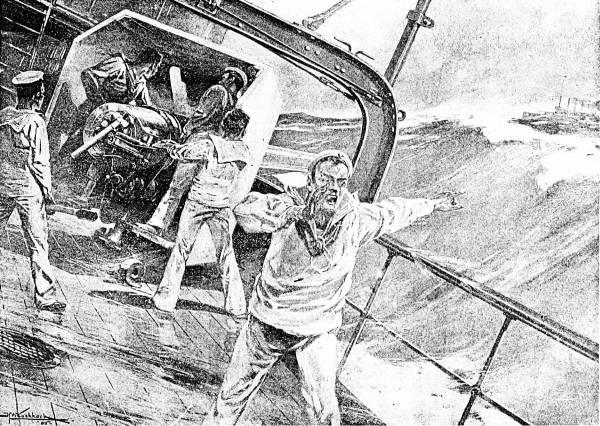

A SILENCED GUN IN PORT ARTHUR.

The Japan-Russia War goes into history as the greatest military struggle the world has known. Its story, therefore, rivals in interest those of the great wars of the past which have been an unceasing inspiration in every field of art and literature. The political machinations of great and little kings, of famed prime ministers, of peoples and states have attracted attention in more or less limited circles, but the world's wars have appealed to every class and rank. The world's vast army of readers have never wearied of the classic stories of feats of arms by men and armies told of the dawning days of world history; the tales of later map-making struggles of Asia, of Europe, of America, have never grown old or dull. So in the Orient of to-day. The great political battles which have centred about China and Japan for the last half century have interested the few. But to-day the attention of the world is centred on the lands bordering the Pacific, because a war has waged; because the whole human family loves the stories of valorous deeds, of military achievement, of the history-making that is done with the sword.

The purpose of this volume is to bring American readers face to face with the events of the struggle of such stupendous magnitude, now drawn to a close. From battlefield to battlefield the author carries his thrilling narrative, bringing the scenes before the mind's eye as only one could do who stood within sound of the roaring guns, within sight of the onrush of resistless battalions, elbow to elbow with Japan's brilliant history makers. From the opening of the struggle to its close there was never a moment when stupendous events were not either in the process of making or so imminent that the civilized world held its breath. A single year's campaign in Manchuria and around famed Port Arthur furnish three land battles, greater in the number engaged in the awful cost of life, in the period of duration, than is presented by all of the pages of history. The siege of Port Arthur has no duplicate among all recorded military achievements. The opening of the second year of the war added a battle, that at Mukden, so vast, so brilliant from the standpoint of the victors, so disastrous from the standpoint of the defeated, that it has been accorded by masters of strategy a niche by itself in the chronicles of war. The author saw this wonderful panorama of events unfolded. His story bristles with dramatic touches, flashes of enlightening description that bring the scene home to the reader with a vividness that thrills.

American readers have a more immediate interest in the struggle than the universal love of the stories of battle. With Japan victor over Russia, with the great Muscovite Empire deprived of a foothold on the Pacific, Japan and America remain the only Powers there to divide the rich spoils of Oriental commerce. Our possessions, the Philippines, are Japan's nearest neighbors, and their proximity to Japan, their bearing upon the Asiatic problem open the way for events of more than ordinary importance, if not of seriousness. Already the statement has been made that Japan covets these Islands. Will the United States, one day be called upon to go to war in their behalf? The question is one which no American can ignore. The nation must educate itself to decide one day, the issue, for or against a struggle with this wonderful little Empire, the Great Britain of Asia. The volume, therefore, in addition to its value and interest as a chronicle of a marvelous series of bloody battles is educational, the pioneer, blazing the way to an appreciation of events, of possibilities for our own country which lie in the story of Japan's overwhelming success. Will the Mikado come to believe that having humbled and crushed what was Europe's mightiest Power, he can as readily drive from the Pacific the American Republic?

The author in this volume has even more completely demonstrated his genius as a chronicler of war than in any of his earlier efforts. Step by step he followed the British in Africa and at the conclusion of that struggle contributed to British literature a history which was generally conceded to have been more accurate, more graphic, less warped by prejudices than any other. Step by step he followed the unfolding of our own Spanish war and the story of that struggle as told by Mr. Tyler became at once the standard not only in Great Britain, but in the several Continental countries in which it appeared. With the priceless experience of these two wars to ably equip him, Mr. Tyler has contributed one more narrative of a great war to military literature and the assertion is unhesitatingly made that it will not be equalled by any of the hosts of volumes destined to be written of this memorable war.

Along with the author went his camera. To that fact the reader is indebted to a series of illustrations never before attempted in the portrayal of military campaigns. What little the author has left to the imagination is supplied by these graphic pictures that bridge nine thousand miles and bring the sights and almost the sounds of battle to the reader.

In brief, this volume as a description of the succeeding struggles of the Japan-Russia War, for accuracy, graphic qualities, detail and literary finish; for its educational value and significance, for the hitherto unattempted excellence of its illustration is presented to the American public with confidence that an appreciative reception will not possibly be denied.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Causes of the War | 13 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The First Blow | 39 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Korean Campaign | 69 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Naval Operations | 101 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Sinking of the "Petropavlovsk" | 133 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Battle of the Yalu | 167 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Cutting off Port Arthur | 197 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Assault that Failed | 225 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Battle of Liaoyang | 257 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Naval Battle off Port Arthur | 289 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Battle of the Sha-ho | 317 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The North Sea Outrage | 347 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Surrender of Port Arthur | 379 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The First Year of the War | 409 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| After Port Arthur | 430 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| In Winter Quarters | 453 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Battle of Mukden | 467 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Retreat towards Harbin | 497 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The Battle of the Japan Sea | 523 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The Treaty of Peace | 557 |

| Page | |

| A Silenced Gun at Port Arthur | Frontispiece |

| Japanese Infantry Attacking a Chinese Position | 21 |

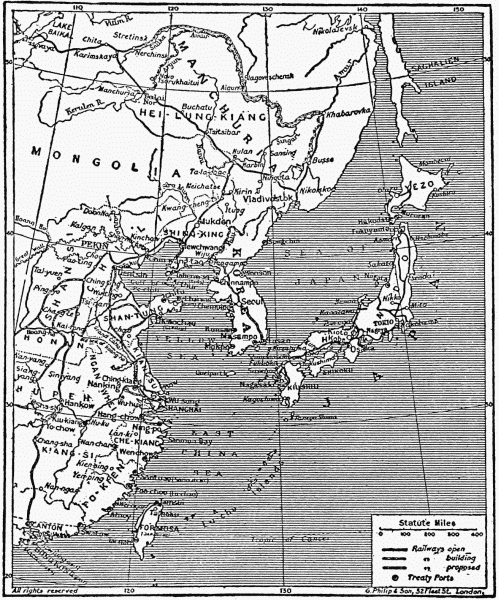

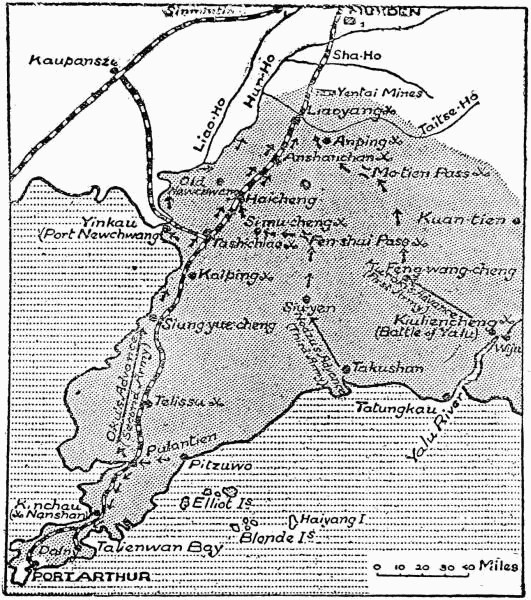

| Map Showing the Area Affected by the Dispute | 25 |

| The Japanese at Port Arthur | 27 |

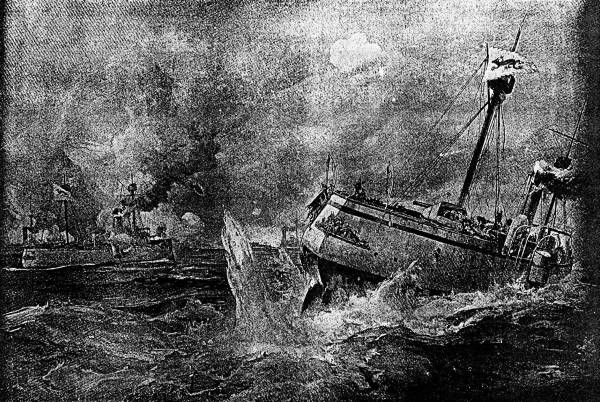

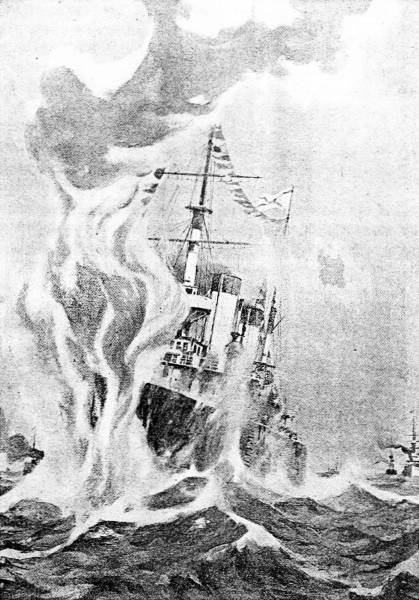

| Battle of the Yalu—Sinking of the Chih-yuen | 38 |

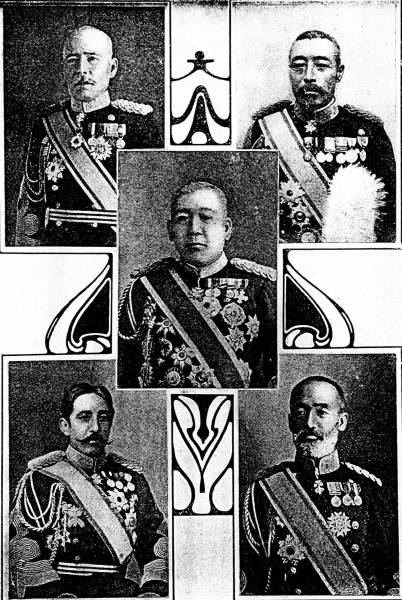

| Japanese and Russian Admirals | 48 |

| Japanese Generals | 57 |

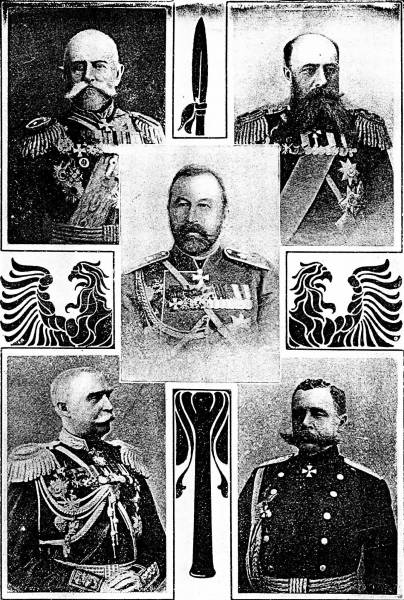

| Russian Generals | 68 |

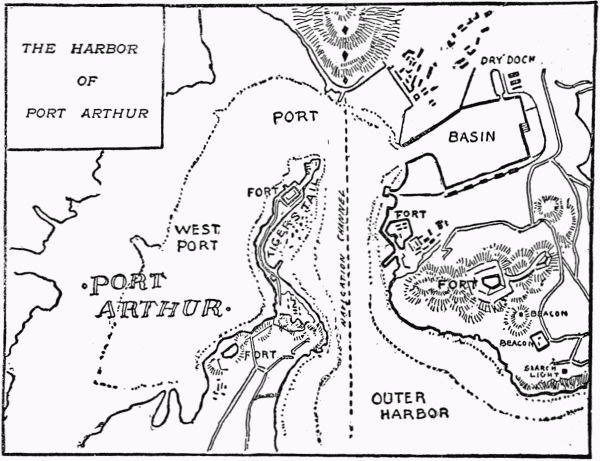

| The Harbor of Port Arthur | 71 |

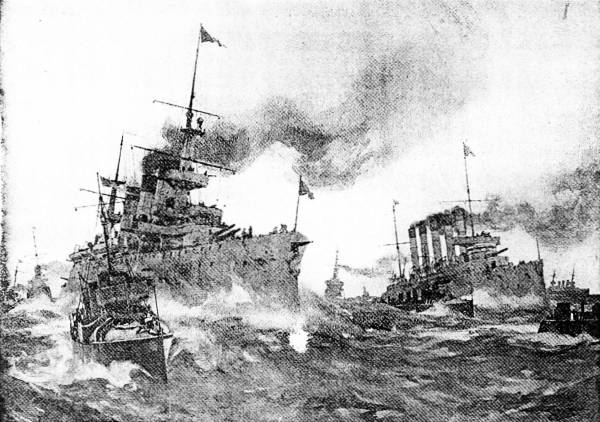

| Russian Fleet Trying to Leave Port Arthur | 77 |

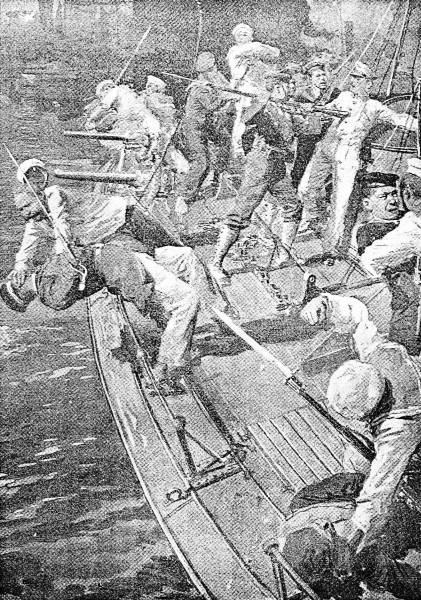

| Russian and Japanese Destroyers at Close Quarters | 88 |

| The Czar | 97 |

| The Mikado | 97 |

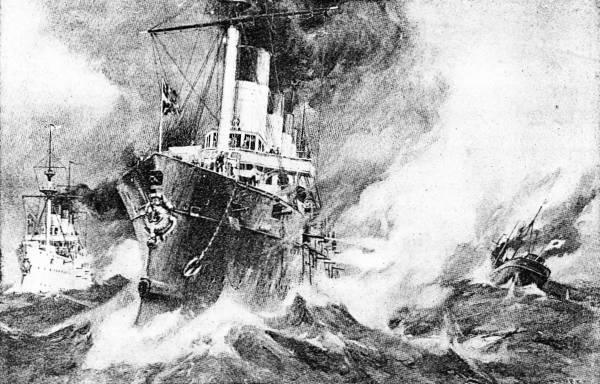

| Raid by the Vladivostock Fleet | 107 |

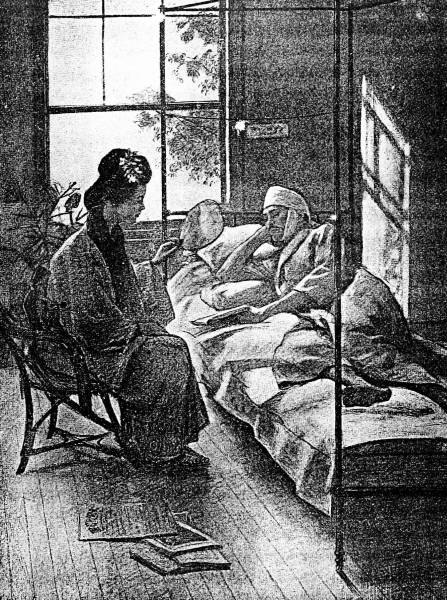

| The Tokio Military Hospital—Officers Quarters | 118 |

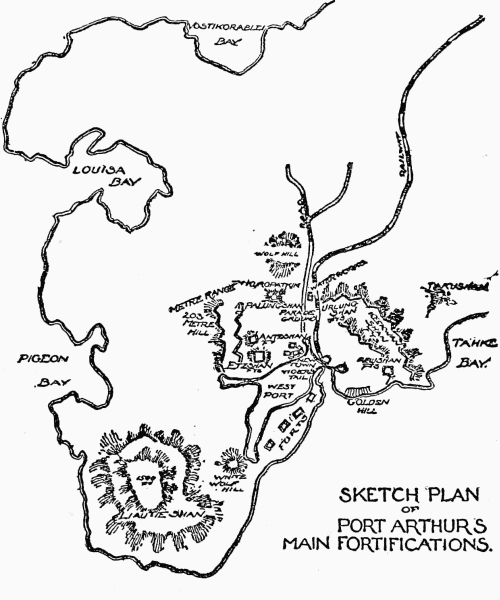

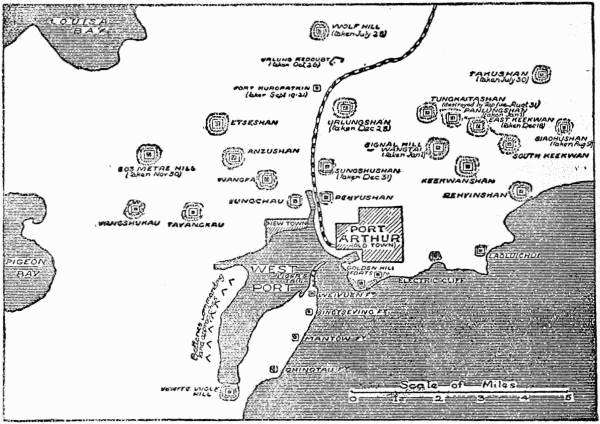

| Sketch Plan of Port Arthur's Main Fortifications | 121 |

| Funeral Procession of a Japanese Officer in Yokohama | 125 |

| A Skirmish Between Japanese and Russian Cavalry | 129 |

| Desolation in Manchuria | 140 |

| Blowing up of the Petropavlovsk | 145 |

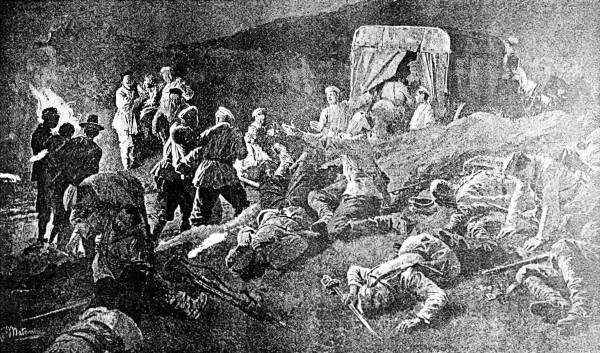

| Arrival of a Dispatch for General Kuropatkin | 152 |

| Russian Concentration on the Yalu | 161 |

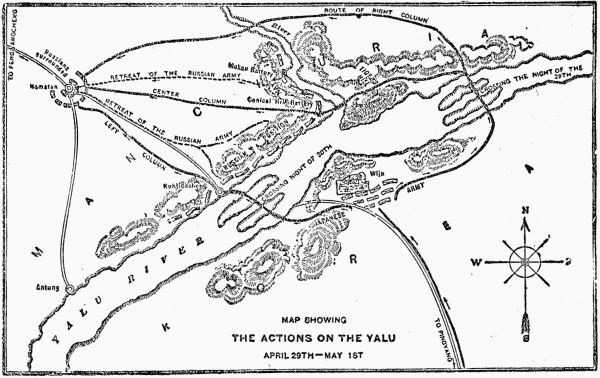

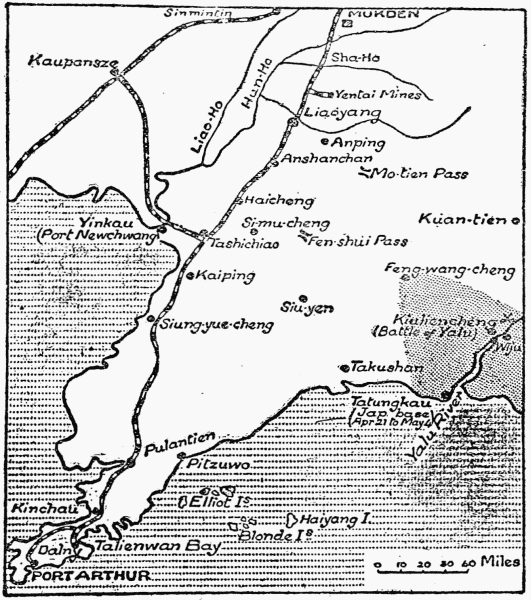

| Map Showing the Actions on the Yalu, April 29th-May 1st | 169 |

| Hauling a Japanese Howitzer into Position under Fire | 171 |

| Russians Collecting Wounded on the Night after the Battle | 182 |

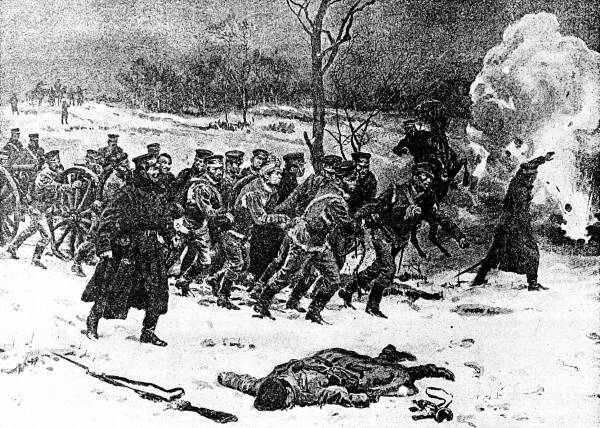

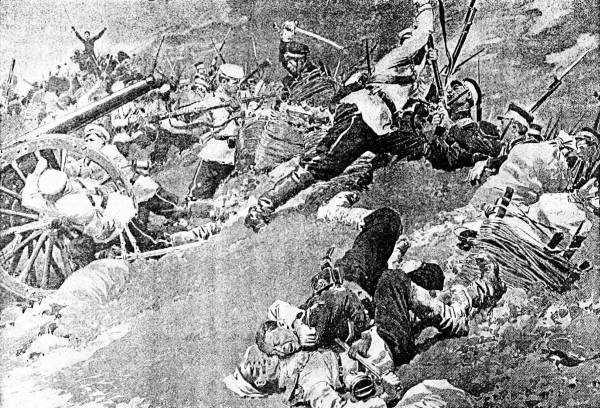

| A Last Gallant Stand of Russian Gunners | 191 |

| After Three Months | 199 |

| In the Russian Trenches | 202 |

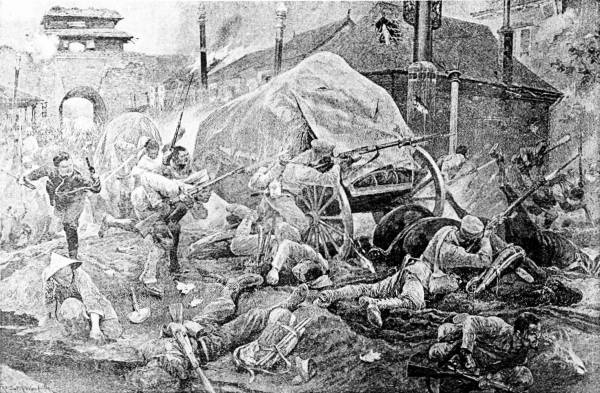

| A Desperate Encounter at Port Arthur | 211 |

| General Stoessel Exhorting his Troops in the Defence of Port Arthur | 222 |

| Outside Port Arthur | 227 |

| A Skirmish on the Manchurian Railway | 234 |

| Russians Charging Japanese Trenches at Port Arthur | 243 |

| After Four Months | 247 |

| Russian Priest in the Trenches with General Stackelberg's Army | 250 |

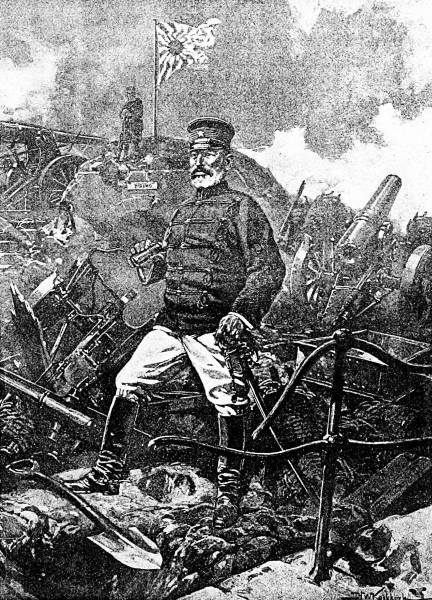

| General Nogi before Port Arthur | 257 |

| After Five Months | 261 |

| Food for the Japanese Army | 265 |

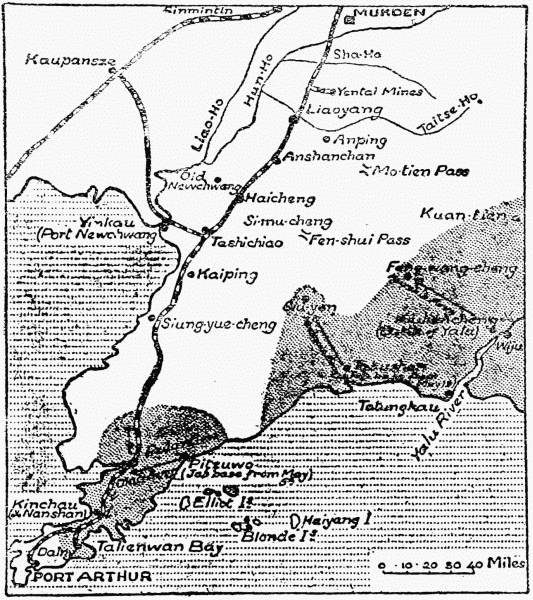

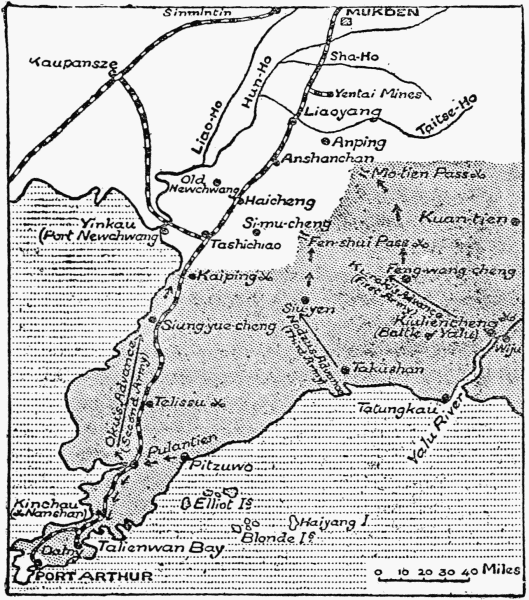

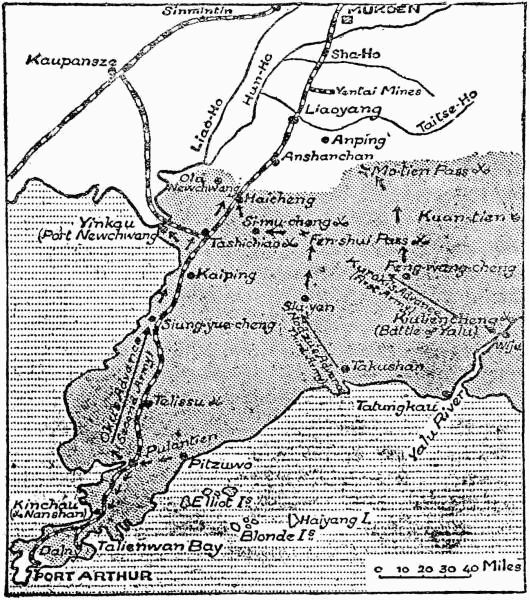

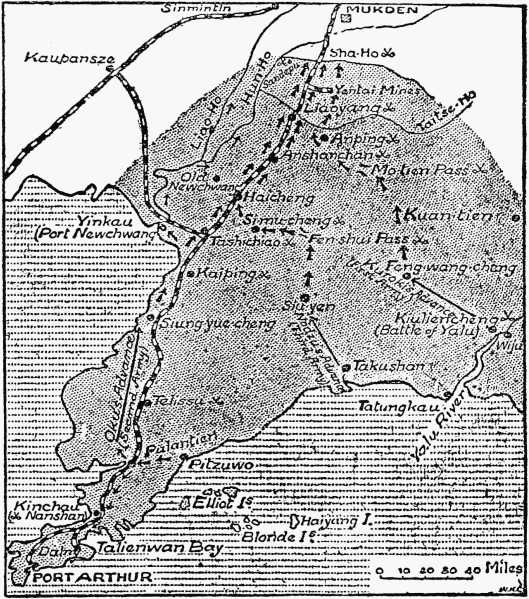

| Map Showing Territory Adjacent to Liaoyang | 269 |

| After Six Months | 273 |

| Death of Count Keller at Yang-Ze-Ling Pass | 275 |

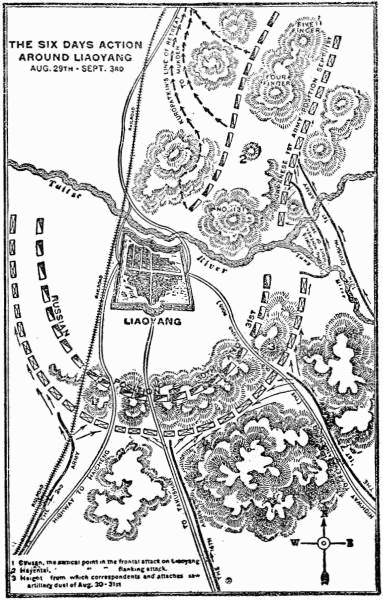

| The Six Days' Action Around Liaoyang, Aug. 29-Sept. 3d | 281 |

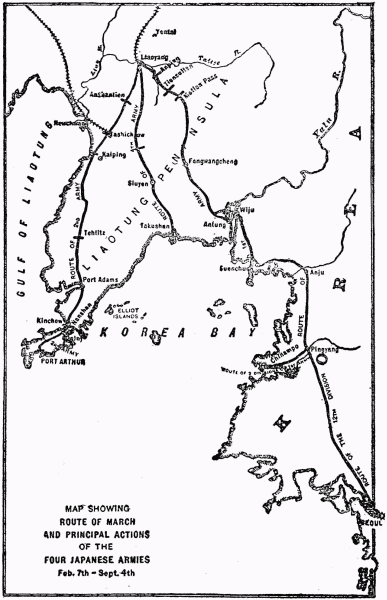

| Map Showing Route of March and Principal Actions of the Four Japanese Armies, Feb. 7th-Sept. 4th | 283 |

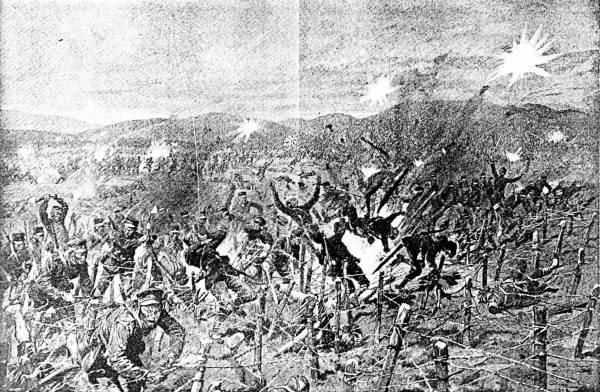

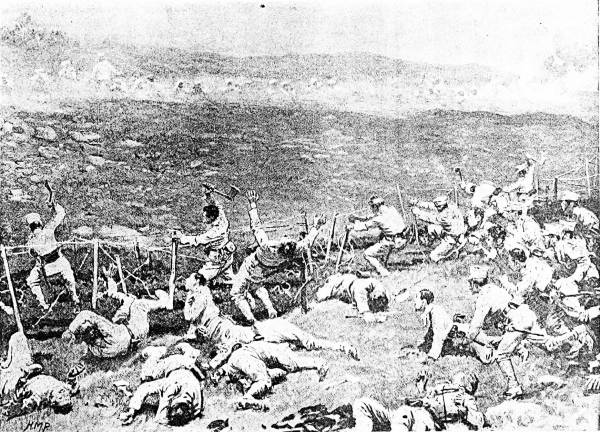

| Japanese Assault on a Russian Position at Liaoyang | 286 |

| Russians Recapturing their Lost Guns at Liaoyang | 295 |

| On the Deck of the "Rurik" | 307 |

| After Seven Months | 313 |

| Capture of the "Reshitelni" at Chifu | 316 |

| Japanese Outpost Relieving Guard near the Sha-ho | 325 |

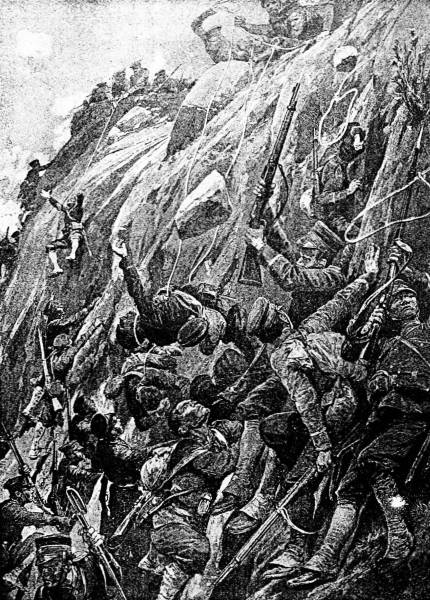

| Japanese Scaling Fort at Port Arthur | 335 |

| The Remnant of a Regiment After the Battle of the Sha-ho | 347 |

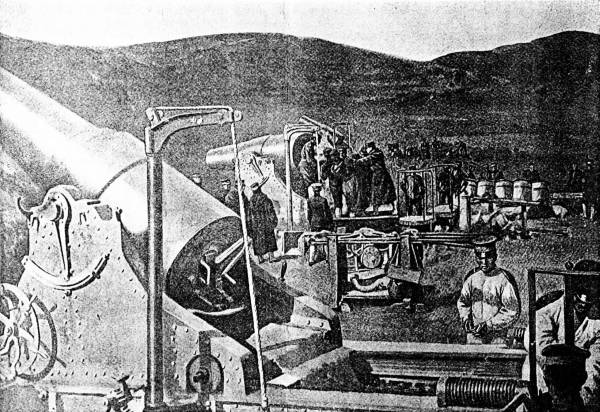

| Huge Siege Guns before Port Arthur | 355 |

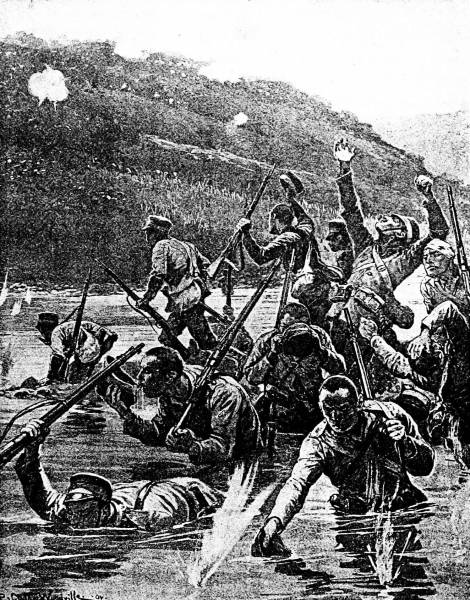

| Thirsty Japanese Troops Crossing the Sha-ho | 366 |

| Fight in Street of Lin-Shin-Pu, Battle of Sha-ke River | 375 |

| Port Arthur and the Surrounding Forts | 381 |

| Hauling Guns Up a Captured Hill at Port Arthur | 386 |

| Japanese Eleven-Inch Mortar before Port Arthur | 396 |

| The Evacuation of Port Arthur | 405 |

| After Twelve Months | 408 |

| Cossacks in Retreat After a Reconnaissance Near Liaoyang | 415 |

| The Garrison of Port Arthur—Leaving the Fortress | 426 |

| The Bamboo Gun at Port Arthur | 435 |

| On the Slopes of Ojikeishan before Port Arthur | 446 |

| A Night Attack on a Russian Position | 455 |

| Japanese Troops Caught in Barbed Wire Entanglement | 466 |

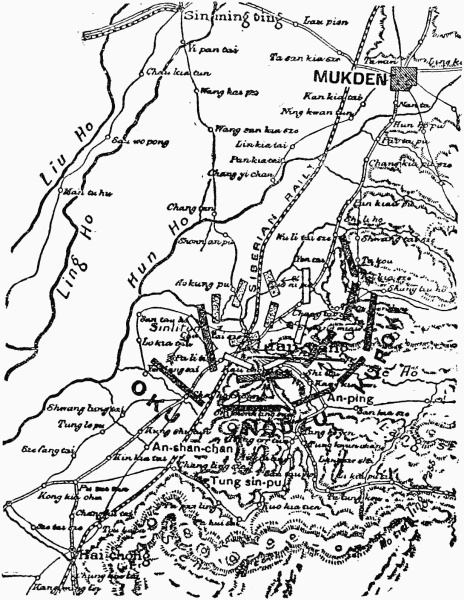

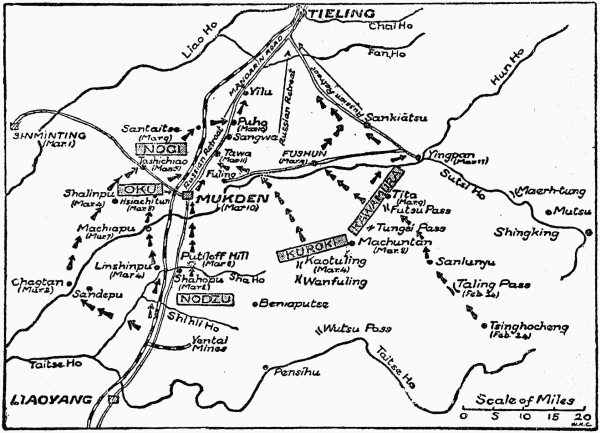

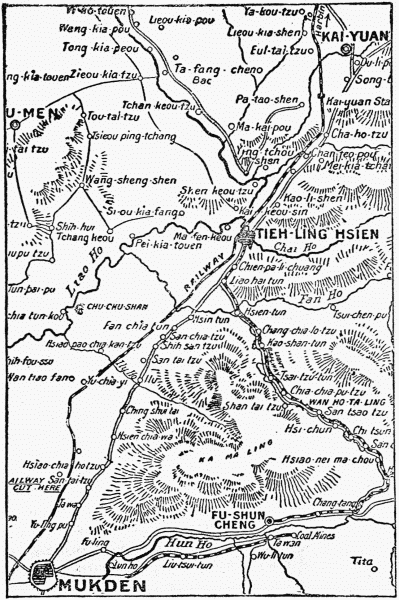

| Map of the Battle of Mukden | 469 |

| Russian Retreat in Manchuria | 475 |

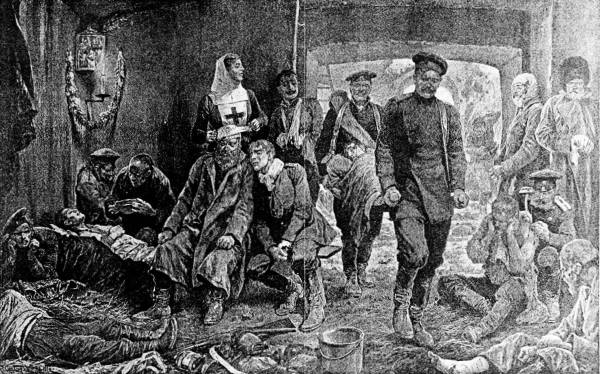

| Russian Suffering after the Battle of Mukden | 486 |

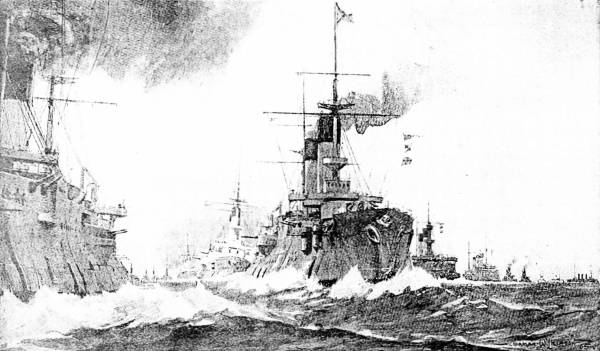

| On Board a Japanese Battle ship during the Battle of the Japan Sea | 496 |

| The Russian Fleet in the Battle of the Japan Sea | 505 |

| The Retreat from Mukden | 519 |

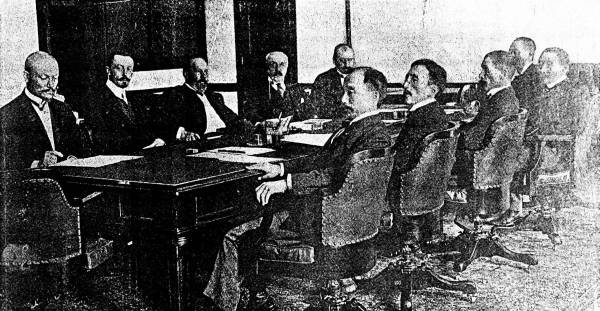

| Peace Envoys in Session at Portsmouth | 556 |

Two Irreconcilable Destinies—Progress v. Stagnation—Europe's Danger—Insatiable Russia—A Warm Water Port—Japan's Warlike Progress—The Chino-Japanese War—Russia's "Honor"—M. Pavloff—Russia in China—The Russo-Chinese Bank—The Mailed Fist—Russian "Leases"—Benevolent Professions—Wei-Hai-Wei—Niuchwang Railway—Pavloff in Korea—Russia and Manchuria—Russo-Chinese Treaty—Anglo-Japanese Alliance—Russians in Korea—Japanese Protests—Russia's Discourtesy.

Never since the great Napoleonic wars which convulsed Europe a century ago has the world witnessed an appeal to arms so momentous in its issues and so tremendous in its possibilities as that which has just been tried between Russia and Japan in the Far East. The great internecine struggle in the United States in the middle of the last century, the disastrous duel between France and Germany which followed, and England's recently-concluded campaign in South Africa, have each, indeed, left a deep mark upon history. But while their import was at most Continental, if not local, the conflict between Japan and Russia is fraught with consequences which must inevitably be world-wide in scope. There is no civilized Power in either hemisphere whose interests are not more or less directly concerned in the question—Who shall be the dominant Power in the China Seas? For the whole course of the world's development in that quarter must depend on whether the mastery remains to the obstructive and oppressive Colossus of the North or to the progressive and enlightened island-Empire which, like Pallas in Pagan myth, has sprung fully armed from an ancient civilization into the very van of modern progress. It was no mere dynastic jealousy or racial animosity that brought about this fateful collision. It was the inevitable antagonism of two irreconcilable destinies. "Two stars keep not their motion in one sphere"; and the ambitions of Russia and the aspirations of Japan cannot find room for fulfilment together. One or the other must be crushed.

For Japan, the question is one of national existence. With Russia established in Manchuria and dominating the Yellow Sea, the absorption of Korea becomes a mere matter of time; and then the very independence of Japan would be subject to a perpetual and intolerable menace; while the new life which has dawned for its wonderfully gifted people would be crushed at the outset. But if Japan is fighting for her life, Russia is fighting for something almost as precious—the consummation of an ambition which has been the dream and the fixed goal of her statesmen for more than a generation. The expansion of the Russian Empire has been steadily eastwards; and the further conquest and dominion have spread, the more has the necessity been felt for an outlet to the navigable seas. Unless all the labor and sacrifices of years are to be in vain, and the great Siberian Empire is to remain a mere gigantic cul-de-sac, Russia must establish herself permanently in the Gulf of Pechili, and find in its ice-free ports that natural outlet for her trans-continental railway which will enable the life-blood of commerce to circulate through her torpid bulk. The struggle, therefore, was one between two irreconcilable destinies.

But if the issue was immediately of such paramount significance to the two combatants, it was only less charged with import for all Asia, Europe and America. The victory of Japan would incontestably give her the predominance in the Far East, commercially as well as politically. Not only would she be a formidable trade rival to the European nations whose methods she has so successfully adopted, but she would be able to influence the conditions under which that trade was carried on. The immensely valuable and as yet imperfectly developed market of China would be practically within her control; and European Powers would no longer be able with impunity to seize naval bases and proclaim exclusive spheres of influence in Chinese territory. On the other hand, if Russia were to emerge victorious from the war, the whole of China would become a mere vassal state, if indeed its integrity could be preserved. Trade would be discouraged and finally extinguished by the exclusive methods of Russian policy, and except on sufferance no other Power could obtain a footing in the Far East. The whole future of this vast region, therefore, hung in the balance, for the battle was between freedom, progress and enlightenment, as represented by Japan, and obscurantism, oppression and stagnation, as represented by Russia.

But the anxious concern of the world in this Far Eastern war was based not only upon a calculation of material interests. Every civilized Government had before its eyes the imminent danger of other countries being dragged into the conflict. The situation was such that at any moment some untoward incident might set Europe in a blaze. The specific obligations of France to Russia under the terms of the Dual Alliance, and of Great Britain to Japan under the Treaty of Alliance concluded in 1901, made the limitation of the struggle to the original combatants not only difficult, but even precarious. A breach of neutrality by any third Power would at once have compelled France to join forces with her Russian ally, or Great Britain to come to the assistance of Japan. Such a breach might have been merely trivial or technical, and yet sufficient to give a hard-pressed belligerent ground for calling her ally to her assistance. It might even have been deliberately provoked, in the hope of retrieving disaster by extending the area of conflict; and if the two Western Powers were once dragged into war, no statesman would be bold enough to put a limit to the consequences. Both Germany and the United States are profoundly interested in the Far East and in the issue of this great struggle for predominance; and one or both of them might at any moment have been ranged on one side or the other. From such an Armageddon the factors which determine the balance of power throughout the world, and therefore the development of national destinies, could hardly have emerged without profound modification; and the ultimate establishment of peace would have found many more international rivalries and antagonisms resolved than those which are immediately connected with the Far East. Lord Beaconsfield once said that there were only two events in history—the Siege of Troy and the French Revolution. It seems more than possible that the Russo-Japanese war will have to be reckoned as a third supreme factor in the progress of the world.

The outbreak of the present war became practically inevitable as long ago as 1895, when, on the conclusion of peace between China and Japan the three European Powers—Russia, France and Germany—stepped in and robbed the Mikado and his people of the fruits of their hard-earned victory. From that time up to the present Russia has steadily, and without ceasing, tightened her grip upon the Northern province of the hapless Chinese Empire, and has ended by threatening the independence of Korea, the legitimate sphere of influence of Japan, and the indispensable buffer between herself and the insatiable and ever-advancing Northern Power.

It must be borne in mind that the determining consideration which led Russia to cast longing eyes upon Manchuria—apart from that eternal hunger for territory which is one of her strongest characteristics—was the necessity of acquiring a warm water port as a naval base and commercial harbor. The port of Vladivostock—which, by the way, she acquired from China as early as 1860 by a truly Russian piece of bluff—has proved of little use in this respect, owing to the fact that during the winter months it is almost entirely icebound. A striking illustration of the embarrassment such a state of things must cause was afforded in the course of the present war by the plight into which the Russian Cruiser Squadron stationed there fell. There can be no doubt that the ambitions of the Czar's advisers had for years been directed towards the acquisition of the fortress and harbor of Port Arthur (known to the Chinese as Lu-shun-kau), which situated as it is upon the narrow neck of land at the extreme southernmost point of the Liao-tung Peninsula, should, if properly served by a strong and efficient naval force, dominate the Gulf of Pechili, and prove the most powerful strategic post in Northern China.

It is not known, of course, what path the development of Russian plans in this respect would have followed if they had been allowed to proceed without interruption; but, as it turned out, they were suddenly threatened with a dangerous obstacle in the complete and unexpected success of Japan over China and her capture of the whole of the Liao-tung Peninsula. This short but sanguinary conflict between China and Japan is memorable for having first revealed to the world the amazing progress which Japan had made in her efforts to engraft and assimilate the characteristics of Western civilization. It proved that in less than twenty years Japan had earned for herself an established position in the community of progressive nations. The war also made it possible for the first time to estimate the influence and effect in warlike operations of the tremendous engines of destruction with which modern science has equipped the fleets and armies of to-day. The navy of Japan had been organized on the latest model, and her officers had been trained in British schools; and though China's equipment was not to be compared with that of her antagonist, she possessed several powerful armorclads of the latest type, officered and engineered by experienced Europeans.

The salient features of the war were, at sea, the battles of the Yalu River and of Wei-hai-Wei; and on land, the rout of the Chinese at Ping-Yang, the passage of the Yalu and storming of Port Arthur. The first of these in order of time was the battle of Ping-Yang, a town situated near the north-west coast of Korea. Here the Chinese troops under General Tso attempted to prevent the advance of the Japanese towards the Yalu. By a series of skilful movements carried out on September 15th and 16th, 1894, the Japanese Commander-in-Chief, Marshal Yamagata, completely surrounded the Chinese and defeated them with great slaughter, their General himself falling dead upon the field. On the next day the Chinese fleet stationed at the mouth of the Yalu, which had proved entirely ineffective in preventing the landing of the enemy's forces upon Korea, gave battle to the Japanese. The ships of the latter Power were mainly cruisers, but the extraordinary skill with which they were manœuvred and the rapidity of their fire completely outweighed the advantage possessed by the Chinese Admiral in battleships. He sustained a crushing defeat, and eight of his best vessels were destroyed. In the meanwhile Marshal Yamagata continued his march to the North, and after a bloody but indecisive conflict near Wiju on October 22nd he succeeded in crossing the Yalu River and driving his antagonists in rout before him. The Japanese now proceeded to overrun Manchuria and the Liao-tung Peninsula, capturing all the principal positions one after the other with unvarying success. A great army under Marshal Oyama invested Port Arthur in November, and on the 20th and 21st he took that powerful fortress by storm, the defenders being massacred to a man. The final and decisive act of the war was the bombardment of Wei-hai-Wei and the island fortress of Leu-Kung-tan by the combined naval and military forces of Admiral Ito and Marshal Oyama. The operations lasted from January 30th, 1895, till February 12th, when, unable to hold out any longer against the terrific assault, Admiral Ting, the Chinese Commander, surrendered his fleet and the forts under honors of war. A closing touch of tragedy was the suicide of Ting and his principal officers, unable to bear the shame of their defeat. On March 19th negotiations for peace were opened at Shimonoseki, and the final treaty was signed on April 17th. The Treaty of Shimonoseki gave Japan unqualified possession of that Peninsula and also, of course, of Port Arthur—a very moderate territorial prize, considering the absolute character of her victory over China, and the sacrifices she had made to obtain it. But Russian susceptibilities were alarmed, and the Government of St. Petersburg decided upon a drastic step to avert the calamity which threatened to render its ambitions futile. Gaining the support of both Germany and France, it compelled Japan, by threats of force which that Power could not resist, to retire from Port Arthur and the Liao-tung Peninsula, and to restore the territory to China. The reason alleged for this high-handed action was the specious plea that the presence of the Japanese on the Asiatic mainland would endanger the independence of China and Korea, and would be a constant menace to the peace of the Far East. Naturally enough the indignation of Japan was intense, but defiance of three such powerful antagonists was impossible for her at that moment, isolated as she was and exhausted by the exertions of a great war. Great Britain was asked by the other three Powers to act jointly with them in this matter, but she refused to assist in depriving the gallant Island people of their rightful spoils of victory. The attitude of Lord Rosebery's Government on this occasion, although it gave no positive aid to Japan, undoubtedly led to a better understanding between the two countries, and paved the way ultimately to the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Alliance, which, by rescuing Japan from her position of isolation, enabled her to enter effectively into the momentous and complicated game which the European diplomatists were playing, with varying fortunes, at Peking.

Meanwhile, however, Japanese aspirations received a check from which they were to take several years to recover. The statesmen of the Mikado were even unable to obtain a pledge from China that the territories yielded back to her by Japan would never be alienated to a third Power. Russia's delicate sense of honor, it appeared, revolted against the imputation implied, and therefore China must give no pledge. On the other hand, Russia would be so generous as to give an assurance on her own account that she had no designs upon Manchuria. Forced to content herself with the cold comfort of this empty and meaningless declaration, and baffled upon all essential points, Japan sullenly withdrew her troops from the mainland and settled down to nurse her just wrath, and prepare for the inevitable day of reckoning.

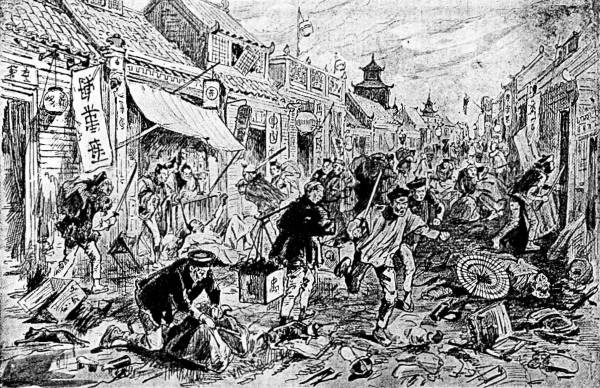

JAPANESE INFANTRY ATTACKING A CHINESE POSITION.

The centre of interest was now shifted to Peking, where began that amazing scramble among the European Powers for commercial, and especially for railway, concessions in China, which, by unmasking the ambitions of some countries, and revealing the community of interests of others, has led ultimately to important modifications of international policy, and to a re-arrangement of alliances. The complexity of the game, the swiftness of the moves, and the ignorance of the average man, not only of the issues involved, but even of the main geographical and economic features of the immense country which was the object of the struggle—all contrived to puzzle the mind and to darken the understanding; but a vague feeling, only too clearly justified by the events, arose in this country that England and America were not getting the best of the conflict, and that Russia and Germany were making all the running. In truth, there is no doubt that the skill, or perhaps, to speak more correctly, the duplicity, of the Russian diplomatists both in Peking and in St. Petersburg left their competitors completely behind. Foremost among them there emerges at this time the sinister figure of M. Pavloff, the Minister of the Czar at the Chinese Court. The tortuous diplomacy of the Muscovite has produced no more characteristic tool. M. Pavloff has been the stormy petrel of the Far East. Intrepid, resourceful to a degree, unscrupulous beyond the average, he is ever in the forefront of the diplomatic battle line. His appearance in any part of the field is the signal for new combinations, fresh aggressions, the stirring up of bad blood between nations, and the unsettlement of apparently settled questions. A man whose god is the Czar; a man with whom the expansion of the Empire of the Little White Father is an ideal cherished with almost religious fervor; a man who indeed in all probability honestly regards the extension of the Russian autocracy over the world as essential to the due progress of higher civilization—he is thoroughly typical of the class of agents whose devoted services Russia has always managed to secure for the spread of her Empire and the gradual but steady absorption of fresh territory all over Asia, whether in China, Persia, Turkestan or Tibet.

Such was the instrument possessed by the Government of the Czar at the Court of Peking, and he was not likely to neglect the unique opportunity which lay ready to his hand. By her action in restoring Port Arthur to the nerveless grasp of China, Russia naturally assumed the character of a powerful friend whose smile was to be courted and whose frown was to be proportionately dreaded. What more natural, in the circumstances, than that the Emperor should grant to the subjects of his brother and ally, the Czar, peculiar commercial privileges in the country which had been so generously rescued from the grip of Japan and restored to the Empire of the King of Heaven?

MAP OF THE AREA AFFECTED BY THE WAR.

The first result of M. Pavloff's policy of disinterested friendship became manifest in 1896, when the Chinese Government concluded an agreement with the Russo-Chinese Bank, providing for the formation of a company to be styled the Eastern Chinese Railway Company, the ownership of which was to be vested solely in Russian and Chinese subjects and which was to construct and work a railway within the confines of China, from one of the points on the western borders of the province of Heh-Lung-Kiang to one of the points on the eastern borders of the province of Kirin; and to the connection of this railway with those branches which the Imperial Russian Government would construct to the Chinese frontier from Trans-Baikalia and the Southern Ussuri lines. The institution, which went by the plain, solid, commercial name of the Russo-Chinese Bank, was, of course, merely a sort of Far Eastern annex of the Finance Bureau of M. de Witte, and the line thus modestly announced was the nucleus of the great railway which has since played such a large part in consolidating the Russian dominion over Manchuria. At the outset it was pretended that the line was to be merely a short cut to Vladivostock, but the true ambitions at the bottom of the scheme became apparent when Russian engineers began to pour into the country followed by squadrons of Cossacks, nominally for the protection of the new railway, but really in pursuance of Russia's invariable policy of impressing the natives with a due sense of her enormous military strength.

The construction of the line, however, had not proceeded very far when, in 1897, an event occurred which gave the Czar's Government the chance for which they had long been anxiously looking. The massacre of some German missionaries led to swift and stern reprisals on the part of the Kaiser. The port of Kiao-Chau, in the province of Shantung, was seized until reparation was made for the outrage committed upon the majesty of the German Empire, and to placate the offended "mailed fist," the feeble Government of China were compelled to hand over this important position to Germany as a permanent possession, although, by a characteristic euphemism of diplomacy, the transaction was conveniently styled a "lease." Russia's opportunity was now too good to be neglected. Emboldened by the example of Germany, she demanded—for that is what her so-called "request" amounted to in reality—permission from the Chinese Government to winter her fleet at Port Arthur. Perhaps it may be imputed to her for righteousness that, unscrupulous as she is, she has never found it necessary to employ the missionaries of Christ as instruments of aggression; at all events on this occasion she had no such excuse at hand. The helpless Chinese assented, of course, to her request; but now Great Britain, awake at last to the dangers which threatened her Treaty rights, endeavored to intervene. Strong representations were made by the English Minister to the Tsung-lai-yamen as to the necessity for turning the port of Ta-lien-wan—which lies immediately adjacent to Port Arthur—into a Treaty port; that is to say, throwing it open to the trade of the world on the same terms as obtain at Shanghai, Canton, Hankau, and other ports of China at which the policy of the Open Door prevails.

THE JAPANESE AT PORT ARTHUR.

English statesmen, however, were no match for the wily Russians, who had the ear of the Chinese mandarins. The Government of the Czar successfully opposed the suggestion, and backed up its representations at Peking by significant display of force, for a considerable fleet of men-of-war arrived at Port Arthur and Ta-lien-wan in the spring of 1898 and practically took possession. Then, by a mingled process of terrorism and corruption, the Chinese Government were induced to grant the Czar a "lease" of the two harbors on the same terms as those on which Germany had been granted possession of Kiao-Chau, and, equally important, to permit the extension of the line of the Eastern Chinese Railway Company to Port Arthur. Thus came into being the Manchurian Railway, the construction of which was pushed on with feverish activity.

The first step towards the complete acquisition and control of Manchuria had now been successfully accomplished, and English diplomacy sought in vain to wrest from Russia the advantage she had thus skilfully acquired. Of course Russia was prolific of "assurances" as she always has been in similar circumstances. The Government of the Czar solemnly declared, for the satisfaction of any confiding person who was willing to believe it, that it had "no intention of infringing the rights and privileges guaranteed by existing treaties between China and foreign countries," and that the last thing it contemplated was interference with Chinese sovereignty over the province of Manchuria. The sincerity of these benevolent professions was to be judged by the fact that, having once secured a grip of Port Arthur, Russia hastened to convert it into a fortified post of great strength and magnitude, and closed it absolutely against the commerce of the world; and that, while on the one hand she so far met the anxious representations of the British Government as to constitute Ta-lien-wan a free port in name, on the other hand she deprived the concession of all real meaning by an irritating system of passports and administrative restrictions upon trade.

Great Britain attempted to neutralize the advantage her rival had gained in the Gulf of Pechili by securing a port on her own account, and, with the support of Japan, she induced the Chinese Government to enter into an agreement for the acquisition "on lease" of Wei-hai-Wei, a harbor situated on the southern shore of the Gulf and opposite to Port Arthur. It was imagined at the time that the port could be turned into a powerful naval base, but the naval and military surveys afterwards taken showed that it was of little use for strategic purposes, and it has consequently sunk into the position of a health station for the English China Squadron.

In the meantime Russia steadily increased her hold upon Manchuria, and large bodies of troops continued to be poured into the country. Her position had now become so strong in the counsels of the Chinese Court that in July, 1898, she openly opposed the concession, which British capitalists were seeking, of an extension of the Northern Railways of China to the Treaty Port of Niuchwang, which lies to the north of Port Arthur, at the extremity of the Gulf. The importance of this extension to British and American commerce was immense. Niuchwang is the main outlet of the trade of Manchuria, and was at that time a busy thriving town of about 60,000 inhabitants. Its value from the commercial point of view may be estimated from the fact that its total trade rose from £1,850,000 in 1881 to £7,253,650 in 1899, the year before it fell absolutely into Russian hands. Russia's attempt to deprive her commercial rivals of practical access by land to this valuable port were, however, on this occasion only partially successful; the construction of the Shan-hai-Kwan-Niuchwang Railway was finally permitted; but the agreement was greatly modified to suit Russian views.

Concurrently with these events, significant developments had been taking place in Korea, which brought Japan once more upon the stage. For some time after the Japanese had been driven from Port Arthur, Russia left Korea alone. She even entered into formal engagements with Japan, recognizing that Power's peculiar commercial rights and interests in Korea. But now M. Pavloff arrived upon the scene at Seoul. In March, 1900, he gave the Japanese the first taste of his quality by endeavoring to obtain a lease of the important strategic port of Masampo, situated in the southeast of Korea, facing the Japanese coast and dominating the straits between. At the same time he stipulated that the Korean Government should not alienate to any other Power the island of Kojedo, which lies just opposite to Masampo. Japan successfully resisted this bold stroke of policy; and matters were in this position when the Boxer rising gave Russia a supreme opportunity. Her troops in Manchuria were attacked by the rebels, and she at once hurried in reinforcements and seized the whole country. Resistance to her arms was put down with relentless vigor—with a vigor, indeed, far transcending the necessities of the case, and the Blagovestchensk massacres, in which thousands of unarmed Chinamen were offered up as a sacrifice to the offended majesty of Russia, will long be a stain upon the escutcheon of the Imperial Prophet of Peace. In the drastic process of absorption which was now adopted, the treaty port of Niuchwang was naturally included, and the interests of other Powers there became of very small account indeed.

It was evident that the Manchurian question had now assumed a more serious form. Of course the Czar's Government was profuse in its explanations. No permanent territorial advantage was being sought, we were told; as soon as lasting order had been established in Manchuria, and indispensable measures taken for the protection of the railway Russia would not fail to recall her troops from the province; above all "the interests of foreign Powers and of international companies at the port of Niuchwang must remain inviolate." The restoration of lasting order, however, appeared to be a very tedious process. More and more troops were drafted into the province and on the naval side also preparations were made for an imposing demonstration.

Admiral Alexeieff, commanding the Russian fleet, though not yet advanced to the dignity of Viceroy of the East, now took charge of the Czar's interests, one of his first acts being to invite China to resume the government of Manchuria "under the protection of Russia." On November 11th, 1900, an agreement was signed at Port Arthur between the Russian and Chinese representatives. The terms of this remarkable document, which were promptly disclosed by the able and well-informed correspondent of the London Times at Peking, were a startling revelation. They provided virtually for a Russian military protectorate over Manchuria. Mukden, the ancient capital of Manchuria and the burial-place of the Manchu dynasty, was to be the centre of control, and a Russian political resident was to be stationed there. This city, which now possesses a population of about 250,000, has in modern times become a great place of trade. It is situated 110 miles to the northeast of Niuchwang, and its position in the centre of the Manchurian railway system renders it a place of much strategical importance. Not only were these vast concessions made to Russia, but the Treaty rights of other Powers at Niuchwang itself were disregarded. Great Britain and the United States necessarily entered an urgent protest against this singular method of preserving their interests inviolate. But Count Lamsdorff, the Russian Minister for Foreign Affairs, declared to our Ambassador that the Russo-Chinese Agreement was merely a temporary arrangement.

The value of the solemn assurance of the Foreign Minister was exposed to the world almost immediately afterwards by the invaluable correspondent of the London Times, who sent to his paper the terms of a new and more far-reaching Agreement which the Russian diplomatists were trying to force upon the Chinese Court.

The position of affairs was now profoundly altered by the conclusion of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. This important Treaty gave Japan the strength and the encouragement ultimately to intervene on her own account and endeavor to curb the restless ambitions of Russia. Russia gave a definite pledge that her troops would be withdrawn from Manchuria by instalments on the expiration of a certain period. That period expired on October 8th, 1903, but the pledge was never redeemed. A show of evacuation was made in 1902, but the troops returned, and at the end of October of 1903 Mukden was re-occupied in force. Never during the whole period did Russia lose her grip upon Niuchwang.

Notwithstanding the conclusion of the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Alliance in the beginning of 1902, Japan waited for eighteen months before entering into the diplomatic lists alone against Russia. But at last, in August of 1903, this course was rendered imperative upon her, not only by the failure of the Czar's Government to carry out their engagements in regard to Manchuria, but by their aggressive policy in Korea. M. Pavloff, rebuffed at Masampo in 1900, had turned his energies in another direction. He secured for his countrymen valuable mining rights in Northern Korea, and Russians then began to cross the Yalu River and ultimately occupied Yongampo, a town of some importance on the southern bank. Not content with railway enterprises, they even started to construct fortifications. The Japanese, of course, interposed energetically and succeeded in modifying the Russian activity; but it now became apparent that, unless some binding arrangement could be arrived at, Korea was destined to share the fate of Manchuria.

Representations were therefore made at St. Petersburg calling for a revision of the Treaties of 1896 and 1898, and a friendly settlement of the respective rights of the two Powers. The story of the negotiations which ensued is a simple one. It is a story of courteous and moderate representation on the one side, and of studied delay and contemptuous refusals on the other. The negotiations on behalf of Russia were in the hands of Admiral Alexeieff, now elevated to the position of Viceroy of the East, and it is said to be mainly due to his influence that his Government adopted such an unbending attitude. Japan asked for a repetition by Russia of the pledges she had given that she would recognize the integrity and independence of China and Korea; and, further, that she should recognize the preponderance of Japanese political and commercial interests in Korea. Russia haughtily refused to give Japan any pledge as to the integrity of China, and contended that her position in Manchuria was regulated by treaties with China in which Japan had no right to interfere. As to Korea, she proposed the establishment of a neutral zone in the north of the province, leaving the south of the country to become a sphere of commercial influence for Japan, but she expressly stipulated that the latter Power should make no use of any portion of Korean territory for strategic purposes. The proposal was so absurdly one-sided that Japan returned to the charge with the suggestion that a neutral zone should be established both on the Manchurian and the Korean sides of the frontier. She also reiterated her request for an agreement as to the maintenance of the territorial integrity of Manchuria and China.

Russia contemptuously delayed reply to these representations in spite of the courteous requests of the Japanese Government. In the meanwhile she kept augmenting her forces in the Far East till the situation became impossible of continuance.

Every day that passed threatened to transfer the balance of naval power in favor of the European Power, for a powerful fleet was being hurried out to the Far East, and the badly-finished warships in Port Arthur were being patched up by an army of mechanicians. Mr. Kurino, who conducted the negotiations at St. Petersburg, pressed for an answer, but was put off with promises no less than six times. Such discourtesy could only have one result. The dignity of Japan could brook no further insolence, and the Czar and his Ministers were politely informed that under such circumstances negotiations were useless. It was in vain that hurried telegrams were dispatched to Admiral Alexeieff to present a reply to the justly incensed Cabinet at Tokio. The die had been cast, and the big bully of the North, who had for so long baited the plucky little Japanese, realized at last that threats and bluff no longer were of any avail, and that the matter was now referred to the God of Battles.

On February 7th, 1904, Japan formally broke off the negotiations and withdrew her Minister from St. Petersburg. The war cloud had burst.

BATTLE OF THE YALU—SINKING OF THE CHIH-YUEN.

Russia Bluffing—Japan's Navy—"Nisshin" and "Kasaga"—New and Efficient—Japan's Dockyards—Opposing Figures—Russian Navy—Belated Help—Japan's Superiority—Russian Harbor—Japan on Land—Russia's Army—East of Baikal—Weak Communications—Port Arthur—Korea as Base—Command of the Sea—The First Blow—World-Wide Interest—A Graphic Account—Russian Losses—The Fight of February 9th—Russian Bravery—Japanese Modesty—Damage Understated—Only One Repairing Dock—Alexeieff's Reason for Casualties—The Fight at Chemulpo—The First Shot—Japanese Disembarkation—A Brave Russian Captain—A Target for Japanese Gunners—The Plucky "Korietz"—Wounding and Burning—Japan's Handicap.

The growing menace of the situation in the Far East had been for months attracting the anxious attention of the whole world, and at the beginning of 1904 it became evident that war was inevitable, unless one or other of the disputants was prepared to make a complete surrender of its essential claims. The unlikelihood of this remote possibility being fulfilled was confirmed by the steady and, on the Russian side at least, the feverish preparations for hostilities which were carried on as an accompaniment to the repeated protestations of pacific intentions by the Czar's Government and its diplomatic agents abroad. Those who still believed in peace were sustained by the conviction that one of the parties to the dispute was bluffing. Sympathizers with Russia pointed to the tremendous power and inexhaustible resources of the Northern Empire, and asked whether it were possible that a young and small country like Japan should dare to try conclusions with so gigantic an antagonist. On the other hand, the friends of Japan emphasized the weakness of the Russian position in the Far East and the well-known financial embarrassments beneath which her Exchequer was laboring. It is, therefore, apropos to survey at this point the military and strategic position in the Far East which revealed itself immediately before the final rupture of diplomatic negotiations and the beginning of active hostilities.

In any conflict between Russia and Japan it was obvious that the first struggle must be for the mastery of the sea, and it is, therefore, interesting to consider primarily the relative naval strength of the two Powers in Far Eastern waters. The navy of Japan has been built, not only on English models, but for the most part in English yards; and since the Chino-Japanese War it has been increased by a number of vessels of the latest and most powerful type. The result is that the most formidable feature of Japan's naval strength is its complete homogeneity. The tabular statement on page 41, gives the names and principal characteristics of what may be called Japan's first fighting line at sea.

Towards the close of 1903 the Japanese Government, with great enterprise, managed to secure a powerful accession to this fleet by purchasing from Argentina two freshly constructed cruisers of the most modern and efficient type. These two vessels, which have been re-christened the Nisshin and Kasaga, were hastily equipped for sea at Genoa, and, commanded for the time being by retired English officers and manned by English crews, started in January for the long voyage to the Far East. Although war had not yet been declared, it was clearly imminent, and the Russian squadron in the Mediterranean received orders to watch the new cruisers closely, with the object, of course, of capturing them in case hostilities broke out before the vessels had reached Japan. The taste of their quality, however, which the Nisshin and Kasaga were able to give to the Russians proved how valuable an addition they were to the Japanese navy, for they easily outdistanced their slow-footed pursuers, and what promised at one time to be an exciting race degenerated practically into a walk over. The new cruisers arrived safely at Yokohama on February 16th, and were at once sent into dock to refit and prepare for active service. These splendid fighting machines must, therefore, be added to the list.

| BATTLESHIPS. | |||||

| Nominal | Gun | Weight of | |||

| Name | Displacement | I.H.P. | Speed | Protection | Broadside Fire |

| Hatsuse | 15,000 | 15,000 | 18.0 | 14—6 | 4,240 |

| Asahi | 15,000 | 15,000 | 18.0 | 14—6 | 4,240 |

| Shikishima | 15,000 | 15,000 | 18.0 | 14—6 | 4,240 |

| Mikasa | 15,200 | 16,000 | 18.0 | 14—6 | 4,225 |

| Yashima | 12,300 | 13,000 | 18.0 | 14—6 | 4,000 |

| Fuji | 12,300 | 13,000 | 18.0 | 14—6 | 4,000 |

| ARMORED CRUISERS. | |||||

| Tokiwa | 9,750 | 18,000 | 21.5 | 6—6 | 3,568 |

| Asama | 9,750 | 18,000 | 21.5 | 6—6 | 3,568 |

| Yakuma | 9,850 | 16,000 | 20.0 | 6—6 | 3,368 |

| Adzuma | 9,436 | 17,000 | 21.0 | 6—6 | 3,368 |

| Idzumo | 9,800 | 15,000 | 24.7 | 6—6 | 3,568 |

| Iwate | 9,800 | 15,000 | 24.7 | 6—6 | 3,568 |

| PROTECTED CRUISERS. | |||||

| Takasago | 4,300 | 15,500 | 24.0 | 4-1/2—2 | 800 |

| Kasagi | 4,784 | 15,500 | 22.5 | 4-1/2 | 800 |

| Chitose | 4,784 | 15,500 | 22.5 | 4-1/2 | 800 |

| Itsukushima | 4,277 | 5,400 | 16.7 | 11—4 | 1,260 |

| Hashidate | 4,277 | 5,400 | 16.7 | 11—4 | 1,260 |

| Matsushima | 4,277 | 5,400 | 16.7 | 11—4 | 1,260 |

| Yoshino | 4,180 | 15,750 | 23.0 | — | 780 |

| Naniwa | 3,727 | 7,120 | 17.8 | — | 1,196 |

| Takachiho | 3,727 | 7,120 | 17.8 | — | 1,196 |

| Akitsushima | 3,150 | 8,400 | 19.0 | — | 780 |

| Niitaka | 3,420 | 9,500 | 20.0 | — | 920 |

| Tsushima | 3,420 | 9,500 | 20.0 | — | 920 |

| Suma | 3,700 | 8,500 | 20.0 | — | 335 |

| Akashi | 2,700 | 8,500 | 20.0 | — | 335 |

The table, it will be observed, does not include a number of coast defence vessels, nor—more important for offensive purposes—the torpedo flotilla, which is of great strength and of remarkable efficiency, and includes over a score of 30-knot destroyers of the most modern type. The first four battleships in the list were completed less than two years before the war, while the armored cruisers were built between 1899 and 1901. The protected cruisers include several of the vessels that defeated the Chinese fleet at the battle of the Yalu.

For the accommodation of her fleet Japan possesses four well-equipped dockyards, capable not only of repairing damaged vessels of any class, but of constructing new ones; and this is, perhaps, the greatest advantage which the island kingdom has over Russia in the present struggle.

The naval strength of Russia in the Far East at the outbreak of hostilities is shown in the tabular statement appearing on page 44, which, again, does not include vessels of the smallest class nor the torpedo-boat flotilla.

It will be remarked that the Russian battleships offered a great variety in design and fighting power—a serious disadvantage, for in manœuvring the efficiency of the whole squadron sinks to the level of that of the least effective vessel it contains. The Czarevitch and the Retvisan, which were the latest vessels to arrive at Port Arthur, were also the most powerful members of the fleet. The former vessel was built in France after the latest French model, and the latter in Philadelphia. This fleet was divided, at the outbreak of war, between Port Arthur and Vladivostock, the four powerful cruisers, Gromoboi, Bogatyr, Rossia, and Rurik being stationed at the latter port.

While negotiations were still proceeding, though at a critical point, Russia prepared to send out very formidable reinforcements to the Far East from her Mediterranean Fleet. These reinforcements included the Osliabia, a battleship of over 12,000 tons displacement, with a speed of 19 knots; the Dmitri Donskoi, an armored cruiser of 6,000 tons displacement and a speed of 15 knots; the Aurora, a swift protected cruiser of the largest class; several cruisers of the volunteer fleet, with troops, naval drafts, and supplies; and a number of torpedo craft. This squadron had begun to assemble at Port Said before the outbreak of war, and the vessels at once began to pass through the Canal. But before they were ready to sail for the China seas, war broke out, and the departure was delayed. The initial Russian reverses at sea made it practically impossible for this reinforcing fleet to proceed to the seat of war, as it would have been liable to interception by the Japanese fleet in overwhelming strength. Accordingly, after cruising aimlessly about in the Red Sea for some weeks, the ships were ordered to return to the Baltic; and in the beginning of March they passed through the Suez Canal again on their way north.

| BATTLESHIPS. | |||||

| Nominal | Gun | Weight of | |||

| Name | Displacement | I.H.P. | Speed | Protection | Broadside Fire |

| Tons | Knots. | In. | Lbs. | ||

| Poltava | 10,950 | 11,200 | 17.0 | 10—5 | 3,367 |

| Petropavlovsk | 10,950 | 11,200 | 17.0 | 10—5 | 3,367 |

| Sevastopol | 10,950 | 11,200 | 17.0 | 10—5 | 3,367 |

| Peresviet | 12,674 | 14,500 | 19.0 | 10—5 | 2,672 |

| Pobieda | 12,674 | 14,500 | 19.0 | 10—5 | 2,672 |

| Retvisan | 12,700 | 16,000 | 18.0 | 10—5 | 3,434 |

| Czarevitch | 13,100 | 16,300 | 18.0 | 11—6-3/4 | 3,516 |

| ARMORED CRUISERS. | |||||

| Nominal | Gun | Weight of | |||

| Name | Displacement | I.H.P. | Speed | Protection | Broadside Fire |

| Tons | Knots. | In. | Lbs. | ||

| Bogatyr | 6,750 | 19,500 | 23.0 | 5—4 | 872 |

| Askold | 6,500 | 9,500 | 23.0 | — | 772 |

| Varyag | 6,500 | 20,000 | 23.0 | 5 | 510 |

| Diana | 6,630 | 11,600 | 20.0 | 4-1/2 | 632 |

| Pallada | 6,630 | 11,600 | 20.0 | 4-1/2 | 632 |

| Boyarin | 3,200 | 11,500 | 22.0 | — | 180 |

| Novik | 3,000 | 18,000 | 25.0 | — | 180 |

| ARMORED CRUISERS. | |||||

| Nominal | Gun | Weight of | |||

| Name | Displacement | I.H.P. | Speed | Protection | Broadside Fire |

| Tons | Knots. | In. | Lbs. | ||

| Gromoboi | 12,336 | 18,000 | 20.0 | 6—3/4 | 1,197 |

| Bayan | 7,800 | 17,000 | 22.0 | 7—3 | 952 |

| Rossia | 12,200 | 18,000 | 20.0 | 2 | 1,348 |

| Rurik | 10,940 | 3,500 | 18.0 | 3 | 1,345 |

Though nominally the fleets of the two Powers were fairly equal, Japan possessed several very considerable advantages which, in the opinion of experts, changed that paper equality to marked superiority on her side. In the first place, the Chino-Japanese war only ten years ago had given her naval officers and men an invaluable experience of fighting on the grand scale under modern conditions; in the next place, their fleet was much more of a pattern; and in the third place it was operating from a base fully capable of providing all the needs and reinforcements entailed by losses in war, including a ready coal supply.

Russia, on the other hand, had for its only bases Port Arthur and Vladivostock, the one inadequate to the multifarious needs of her fleet, and the other ice-bound in winter, and so situated geographically as to be completely isolated from what promised to be the main scene of operations. Although Port Arthur had been rendered almost impregnable as a fortress, the Russians had not had time to complete it as a naval dockyard, and at the outbreak of war it possessed only one dry dock, and that not capable of accommodating vessels of the largest size. At Vladivostock the channel out of the harbor could only be kept free by ice-breakers. In the event of naval disasters, Russia, therefore, had no possibility of repairing her lame ducks, while the radius of her fleet's activity was limited by the fact that her only supplies of coal were to be obtained at Port Arthur. In the situation, therefore, which presented itself at the outbreak of war, this powerful naval force was practically deprived of mobility. It could not leave Port Arthur for more than a short cruise; and while it remained there it must be specially vulnerable to attack, lying in an open roadstead and huddled together in order to enjoy the protection of the guns of the fortress.

With regard to the land forces of the two belligerent Powers, it was only possible to reckon with certainty those of Japan; for it remained doubtful, until the progress of active operations revealed the facts, how much of Russia's enormous military strength had been concentrated in the Far East. Broadly speaking, Japan could put into the field in the last resort an army of between 400,000 and 450,000 men. The standing army amounts to almost 200,000 men, and it was immediately available for mobilization. To this number another 35,000 men was added by the reserve, while the militia of all arms could be reckoned at 200,000 men. The Japanese infantry soldier is armed with the Midji magazine rifle, and the artillery with the Arisaka quick-firing gun; but the adoption of this latter weapon has been so recent that the whole of the artillery is not yet supplied with it, and in this one respect at least the Russian gunners are believed to possess a very great advantage. The Japanese army has been organized largely on German models. It proved its efficiency as a fighting machine in the Chino-Japanese War; while the Japanese troops that took part in the relief of the Peking Legations earned the unstinted praise of all the military experts who watched their behavior. Until the present war, however, the Japanese army had never undergone the supreme ordeal of facing a European adversary.

Of the Russian military organization, the strength and weakness have long been known to the world, and the great question for strategists in contemplating the present hostilities was the number of troops which the Northern Power could bring into the field to confront her foe. Various estimates had been given, from the overwhelming army of 400,000 men confidently claimed by Russia's partisans, to a force of little more than a quarter of that strength. But though the actual figures were in doubt, it was possible by collating the information from various sources to arrive at an approximate estimate of the truth. At the time of the Boxer outbreak in 1900 Russia had 35,000 men in the Far East, and that force was, within little more than a year, trebled. Since the possibility of trouble with Japan had loomed on the horizon, reinforcements had been steadily dribbling over the Trans-Siberian Railway and over seas in the volunteer transports, until the army under the command of the Viceroy of the Far East could not number much less than 150,000 men of all arms, with 286 guns. Of this force, at least a half must have been absorbed in the defence of the long line of railway communications and in garrisoning fortresses; but the troops available for active operations consisted largely of Russia's most formidable fighting material—namely, the Cossacks, who possess an endurance and mobility which must be of the utmost value in such a country as that in which the present war was to be fought out.

| ADMIRAL TOGO. | ADMIRAL KAMIMURA. | |

| ADMIRAL MAKAROFF. | ||

| ADMIRAL SKRYDLOFF. | ADMIRAL ROZHDESTVENSKY. |

JAPANESE AND RUSSIAN ADMIRALS.

In the latter part of January the well-informed correspondent of the London Times at Peking telegraphed an estimate of the Russian forces east of Lake Baikal, which, in its circumstantiality and exhaustiveness, bore the evidence of truth. According to this authority, Russia had available at that time a total of 3,115 officers, 147,479 men, and 266 guns; and these numbers included the railway guards over the whole of the Manchurian railways and the garrisons of the principal fortresses. The infantry of this force numbered 108,000 officers and men, and the cavalry 22,000 officers and men, of whom nearly the whole were Cossacks. The garrisons of Port Arthur and Vladivostock alone absorbed 45,000 men, and remembering that the railway line to be guarded, east of Lake Baikal, was over 1,500 miles in length, and traverses a country of which the inhabitants were more or less hostile, it is evident that the troops available to take the field at the end of January could not have exceeded, on this estimate, more than 50,000 men. Lake Baikal is 400 miles in length, and though a railway round its southern extremity was in course of construction, it was far from completion at the outbreak of hostilities. The lake is frozen over during the winter months, when transit has to be effected by sledges. But in the emergency the Russians laid railway lines across the lake, and thus by the end of February had established a through service of sorts. But even then the number of reinforcements and the quantity of supplies that could be moved up to the theatre of war were strictly limited by the delays inseparable from the working of a single track railway, and it is doubtful whether more than 25,000 men at the outside had been added to the field force by the beginning of March.

The strategical problem which presented itself at the outbreak of hostilities was a comparatively simple one—for Japan at any rate. The power of Russia in the Far East depended on the maintenance of two great arteries of communication with the heart of the Russian Empire. One of these was the over-sea passage from the Black Sea or the Baltic through the Suez Canal and the East Indian Archipelago—a voyage occupying six weeks at least, and however feasible in time of peace, rendered particularly difficult and even precarious under war conditions owing to the possibility of interception and the absence of any intermediate coaling stations. The other connecting link between Port Arthur and St. Petersburg was the Trans-Siberian Railway, that gigantic enterprise which, completed in 1899, brought the capital of Russia within 15 days' journey of its furthermost outpost in the Yellow Sea. From Moscow to Port Arthur is a distance of some 4,000 miles, but at two-thirds of its length the railway is interrupted by the great inland sea known as Lake Baikal. At this point transshipment across the lake had to take place, a circumstance that offered an insurmountable hindrance to rapid transit. In the building of the railway, too, soundness had been sacrificed to rapidity of construction; the line was only a single track one, with stations and sidings at intervals of about 25 miles; and even when the whole service was monopolized for military purposes the number of trains that could be passed over the railway in one day was a fixed and very limited quantity. Even with this line open, therefore, the rate at which Russia could reinforce her troops in the Far East had to be determined by other circumstances than military urgency, and the number of her reinforcements also had to be governed by the capacity of the line to bring up not only men, but supplies; for Manchuria itself does not provide the means of support for a large army. The experience of the American Army in Cuba and of the British Army in South Africa proved what tremendous difficulties may be encountered in carrying supplies to a large force at a distance much less remote from its base than Russia's was. For years past Russia has sent out her troops and supplies to the Far East mainly by sea. For twelve months before the war broke out a constant stream of transports, colliers and supply ships had passed from the Black Sea to the Gulf of Pechili, and this stream was only interrupted on the outbreak of war—a significant admission of the incompleteness of the Russian preparations, as well as of the inadequacy of the Trans-Siberian Railway to supply her needs.

It was evident, therefore, that Japan's first object was to shut off Port Arthur from the sea, and her next to cut the railway communication to the North. This done, the Russian fortress, however impregnable to assault, must ultimately fall to investment. From Port Arthur, which, as a glance at the map will show, lies at the very tip of Liao-tung Peninsula, the railway runs due north for six hundred miles through Niuchwang and Mukden to Harbin, where it joins the branch line to Vladivostock. Though Russia has for several years been in occupation of this territory, her hold upon it is by no means secure. The population is distinctly unfriendly, and for the mere defence of the line thousands of troops are necessary. Indeed, it was this necessity that Russia urged as an excuse for her military occupation of Manchuria.

Within the triangle of which Harbin is the apex, of which the lines to Port Arthur and Vladivostock are sides, and of which the course of the Yalu River is the base, the sphere of immediate military operations practically had to be confined, as the ice-bound condition of the coast to the west of Port Arthur made a landing in force there impossible till the spring. The necessity of maintaining communications tied the Russian forces very largely to the railway lines. But for either belligerent the helpless kingdom of Korea, which lies south of a line drawn between Port Arthur and Vladivostock, for aggressive operations, afforded the most convenient line of advance. Through Korea Russia could menace Japan, and through Korea Japan could most easily march against Port Arthur. Naturally, therefore, Russia's first care was to mass her available troops on the line of the Yalu, and concentrate reinforcements at Harbin ready to be moved to whatever point might prove the objective of the Japanese attack.

But the command of the sea was the essential condition to attack by land by either combatant. With the Russian fleet masked or destroyed, Japan could choose as a landing-place for her armies any of the numerous ports on the western coast of Korea, and so approach in force the Yalu River, which divides Korea from Manchuria and the Liao-tung Peninsula. With imperfect command of the sea, Japan would have a second resource. She could land her troops at Masampo, separated only by a hundred miles of sea from her own ports, or she could, at a push, land her forces on the east coast of Korea, at Yuen San or Gensan. But the former plan of operations would have entailed a long overland march before the objective was reached, and the latter the maintenance of communications over difficult and mountainous country. Evidently, then, immeasurable importance attached to the result of the first naval engagements, and to their influence in giving the command of the sea to the one or the other of the two belligerent Powers.

On February 5th M. Kurino, the Japanese Minister at the Court of St. Petersburg, announced to the Government of the Czar that Japan could wait no longer for the long-delayed Russian reply, and that further negotiations were broken off. This startling news reached Europe and America on the evening of Sunday, February 7th; and while its significance was still being anxiously discussed in every capital, and while statesmen and jurists were still trying to convince one another that the rupture of diplomatic negotiations did not necessarily imply the beginning of war, there burst like a thunder-clap the further news that the first grim and irretrievable blow had been struck. Having decided that the arbitrament of war was inevitable, Japan acted on her decision with swift and terrible effect. On the night of Monday, February 8th, a daring attack by torpedo-boats was made on the Russian fleet lying at anchor in the Port Arthur roadstead, and at one fell swoop the boasted might of Russia at sea was hopelessly broken. This astounding intelligence was first conveyed to the world in an official telegram from Admiral Alexeieff to the Czar, couched in the following terms:—

"I most devotedly inform your Majesty that about midnight between the 26th and 27th of January (February 8th and 9th) Japanese torpedo-boats delivered a sudden mine attack on the squadron lying in the Chinese roads at Port Arthur, the battleships Retvisan and Czarevitch and the cruiser Pallada being holed. The degree of seriousness of the holes has to be ascertained. Particulars will be forwarded to your Imperial Majesty."

The stunning effect of this news was only enhanced when fuller details of the incident so baldly and laconically announced came to hand. No news of the movements of the Japanese fleet had been allowed to leak out, and its presence before Port Arthur was wholly unexpected by others as well as the Russians. On the 3rd of February the Russian fleet had put to sea, and for twenty-four hours the world was agog with the news of so momentous a movement. But the speculation died suddenly when it appeared that the fleet had returned immediately to its anchorage. The Japanese, with characteristic alertness, realized the splendid opportunity which the necessarily exposed position of the Russian ships afforded to an enterprising enemy.

While everything was still tranquil at Port Arthur, and the Russian authorities were confidently announcing that the foe could not be expected for three or four days, the blow fell. According to the graphic account of an eye-witness, every one at Port Arthur had settled down for the night, when suddenly across the bay reverberated the shock of three violent and successive explosions. In a moment all was bustle and confusion on the Russian warships. Searchlights flashed bewilderingly and without purpose across the waters, and quick-firing guns from vessel after vessel began a panic fusillade, which Admiral Alexeieff, in his official report, euphemistically described as "a well concentrated fire at the right time."

It was midnight, and in the darkness and confusion it was impossible for any one to know exactly what was happening; but when the morning light broke over Port Arthur the two proudest possessions of the Russian fleet, the powerful battleships Retvisan and Czarevitch, were seen passing slowly towards the harbor entrance, across which they presently lay in evidently a badly damaged condition. The cruiser Pallada followed, listing heavily to port, and she also was grounded outside the entrance to the harbor.

It was at ten o'clock the next day, the 9th of February, that the Russians obtained their first glimpse of the enemy. In the distance three Japanese cruisers were described hanging observant upon the Russian fleet, and immediately what remained of that once powerful squadron put to sea in pursuit of the audacious enemy. But, as before, this bold movement had no result, and the Russian ships returned to anchor. Scarcely had they done so when the Japanese squadron of sixteen vessels, including six battleships and four first-class cruisers, steamed into view in fighting formation. As the leading vessels at a distance of some three miles came into line with the harbor entrance the flash of their great guns broke through the mist, and for nearly an hour the Japanese shells continued to burst over the forts, along the beach and among the Russian ships, who replied vigorously, and whose fire was assisted by that of the powerful land batteries. Again the Russian squadron steamed out to meet the enemy.

Some of the cruisers advanced towards the Japanese fleet with great gallantry, the Novik, the Diana, and the Askold particularly distinguishing themselves, with the result that they were all rather seriously hit by the Japanese fire and were compelled to retire upon the main squadron. Several other of the Russian ships were damaged before the Japanese fleet drew off.

The official dispatch of Admiral Togo to his Government upon the momentous achievements of his fleet during these two days was a model of modesty and self-restraint. Dated "February 10th, at Sea," it ran:—

"After the combined fleet left Sasebo, on the 6th, everything went off as planned. At midnight on the 8th the advance squadron attacked the enemy's advance squadron, the latter being mostly outside the bay. The Poltava, Askold and others were apparently struck by torpedoes.

"At noon on the 9th the fleet advanced to the offing of Port Arthur Bay and attacked the enemy for forty minutes, I believe doing considerable damage. I believe the enemy were greatly demoralized. They stopped fighting at one o'clock, and appeared to retreat to the harbor.

| GENERAL KUROKI. | GENERAL OKU. | |

| MARSHAL OYAMA. | ||

| GENERAL NODZU. | GENERAL NOGI. |

JAPANESE GENERALS.

"The Japanese fleet suffered but very slight damage, and its fighting strength is not decreased. Our casualties were 4 killed and 54 wounded. The Imperial Princes on board suffered no harm.

"The conduct of the officers was cool, and not unlike their conduct at manœuvres.

"This morning, owing to heavy south wind, detailed reports from the vessels have not been received, so I merely report the above fact."

This dispatch, as we know both from the Russian official accounts and from independent witnesses, really understated the extent of the blow which the Japanese Admiral had dealt to the Russian fleet; the vessels torpedoed were not cruisers only, but the two crack battleships upon which Admiral Alexeieff necessarily placed peculiar dependence, and the "considerable damage" which Admiral Togo believed had been done by the subsequent bombardment had put out of action, for the time being, the battleship Poltava and the cruisers Diana, Askold and Novik. Of these the Poltava and the Novik were badly hit on the water line—damage the seriousness of which needs no comment.

The most significant confession, indeed, of the crushing character of the blow which at the very commencement of the war the Japanese had succeeded in dealing to their powerful adversary was contained in a subsequent dispatch from the Viceroy to the Czar. Telegraphing on February 11th, Admiral Alexeieff reported "the Czarevitch and the Pallada were brought on the 9th inst. into the inner harbor. The leak in the Retvisan is being temporarily stopped. The repairing of an ironclad is a complicated business, the period for the completion of which it is hard to indicate." This guarded language must be read in the light of the fact that the Russians had only one repairing dock capable of holding a large ship at Port Arthur, and the terrible character of the disaster which within forty-eight hours had befallen the naval power of the haughty Muscovite in the Far East will be realized. The losses in men were not very serious, amounting in all to 10 men killed and 2 officers and 41 men wounded, but the injury to the fleet was practically irreparable. Seven out of Russia's best vessels had been placed hors de combat, her battleships' strength being reduced to 4, namely, the Petropavlovsk, Peresviet, Pobieda and Sevastopol (the last two being themselves under repair when the war broke out), and her already small cruiser force being reduced to two, namely, the Bayan and the Boyarin. The following is the list of the damaged ships:—

It should be added that the repairs to the Askold were quickly executed, and that she was able to take part in the subsequent operations a few days later.

Admiral Alexeieff's dispatch to the Czar stated that the majority of the wounded belonged to the Pallada. The reason for this was that they were "poisoned by gases produced by the explosion of the torpedo charged with melinite."

The Japanese fleet, naturally, did not emerge from such an action unscathed. Its losses in men were officially reported as 4 killed and 54 wounded; and although the fighting efficiency of the fleet was not seriously impaired, two armored cruisers, the Iwote and the Yakumo, were injured, and, as the casualties show, several other vessels were struck. But the most remarkable circumstance was that the torpedo-boats by which the night attack had been delivered escaped scot-free.

While the Russian capital was still reeling under the shock of this unexpected disaster, there came the news of a fresh blow struck by the Japanese arms in another quarter of the theatre of war. This was the naval engagement at Chemulpo—a port on the northwest coast of Korea—in which two of the Czar's warships and one transport steamer were destroyed. It is true that only one of these vessels had any fighting capacity, and that the conflict in itself was of much less consequence than the battle at Port Arthur, but the incident gave a further and mortifying revelation of the disorganization of the naval forces of Russia in the Far East, and of the total absence of anything like a bold and definite plan of operations from the minds of her commanders. In spite of the critical position in which the negotiations between the two Powers had been standing for weeks, the Russian fleet in the Yellow Sea was unconcentrated and generally unprepared for war. The outbreak of hostilities found two vessels, the Varyag, a protected cruiser of 6,500 tons, and the Korietz, a gunboat, old, indeed, but not without some use for coast defence, quietly stationed at Chemulpo, a ready prey for a Japanese squadron.

On the 8th instant a Russian steamer called the Sungari, which was employed for the transport of stores, entered the harbor with the news that a large fleet, which her captain believed to be Japanese, was fast approaching. The Korietz was sent out to reconnoitre. The columns of smoke on the horizon did indeed come from the funnels of the enemy's ships. The advancing squadron consisted of a first-class battleship flying the flag of Admiral Uriu, and the cruisers Akashi, Takachiho, Naniwa and Chiyoda, as well as seven torpedo-boats, the whole convoying transports with 2,500 Japanese troops on board. The Korietz cleared her decks for action and fired—one account says that the shot was accidental—upon the rapidly approaching foe. The latter replied by discharging two torpedoes at the daring gunboat, which then retreated back into harbor. It is interesting to note that, whether the gunner of the Korietz acted under orders or not, he fired the first shot in the war, for the incident occurred several hours before the torpedo attack upon Port Arthur.