Transcriber's notes

GERMANY’S FIGHTING MACHINE

Her Army, Her Navy, Her Air-ships, and

Why She Arrayed Them Against the

Allied Powers of Europe

By

Short History of Germany

History of Germany in the Middle Ages

Blücher, Etc., Etc.

WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS

INDIANAPOLIS

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

COPYRIGHT 1914

THE

BOBBS-MERRILL

COMPANY

CHARLES FRANCIS PRESS, NEW YORK

GERMANY’S FIGHTING MACHINE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Part I | The War |

| Part II | The Army |

| Part III | The Navy |

| Appendix | List of Illustrations |

[Pg 1]

GERMANY’S

FIGHTING MACHINE

THE WAR

But a few weeks ago the author of this little book was in Germany studying the land and its institutions and full of admiration for its achievements in every field. Two days after he had taken ship for America Germany was practically at war with France and Russia. England soon joined in the conflict, and the splendid Hamburg liner on which the author was a passenger was a hunted thing on the ocean, owing her safety at last to a friendly fog. The great shipping company, with its nearly two hundred vessels, was out of the running as a commercial enterprise, a symbol of the paralyzed industries of the whole country.

To the ordinary observer the conflict came like a bolt from the blue, but to the historian and to the man who reads the foreign newspapers it was not unexpected. The historians recognized that it was the appointed time [Pg 2] for a war between the great nations. The Franco-Prussian War took place forty-three years ago. When, since the days of the grandsons of Charlemagne, have the chief powers kept out of war for so long a time? In the ninth and tenth centuries the question of Lorraine was as troublesome as it has been in the nineteenth and twentieth; in the eleventh and twelfth an expedition against Italy was in the day’s work of almost every German emperor; and England and Sicily were conquered by the Normans; in 1215 took place the first general international battle; in 1250 the final expeditions against the Emperor Frederick II; in 1272 the Sicilian wars of the house of Anjou. The Guelphs and Ghibellines carry us on to the Hundred Years’ War; the Hapsburg struggles against Italy and the Turks bring us down to the invasion of Italy by Charles VIII of France, to the campaigns of Maximilian, to the Field of the Cloth of Gold, to the religious wars of Charles V. Close on the heels of the latter struggles came not only the French religious wars but the invasion of England by Philip II’s great armada. The Thirty Years’ War, Louis XIV’s war of conquest, the Spanish Succession, the Silesian and the Seven Years’ Wars fill the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; the Napoleonic, Crimean and Franco-Prussian Wars the nineteenth. Yes, it was time for a new struggle.

[Pg 3]When a great and extraordinary event takes place it is easy, somewhere in the world, to point to omens and prophecies that have heralded it. But in the case of the present war we can see in the German newspapers how, from month to month of the present year, the struggle was felt to be more and more imminent and how Russia, the power that eventually precipitated the catastrophe, was felt to be the center of real danger. “In well-informed diplomatic circles,” writes the Magdeburger Zeitung in January, 1914, “the impression can not be concealed that in Russia at present there prevails a thoroughly hostile attitude to Germany and Austria-Hungary, and that the agitation in the czar’s realm is greater even than during the last Balkan crisis. … It looks as though Russia were preparing to make an extraordinarily great show of strength against a specific, not far distant date.” And the Deutsche Tageszeitung: “What is Russia’s purpose in building a mighty fleet of dreadnaughts for the Baltic? Surely not merely to coerce Sweden.” Again the Madgeburg paper: “The Russian government, which already owes French capitalists twelve billions, has received a new loan of two billions five hundred millions, of which five million are yearly to be issued in Paris. This whole gigantic sum is exclusively to be spent for building strategic railways along the German-Russian boundary. … France compelled Russia [Pg 4] to do this. The French general staff thinks that Russia, because of her clumsiness in mobilizing, but especially for lack of tracks leading to the German frontier, will not be able, in a new war with Germany, to bring help to France in time. Russia has now fulfilled France’s wishes in this regard. Thus does the Franco-Russian alliance, which of late seemed to be falling into oblivion, celebrate its resurrection.”

In February the Hallesche Zeitung writes: “To keep friendship with Russia is one of the chief aims of our foreign policy, but it is sometimes made very hard for us indeed. … They keep the peace because it is to the advantage of the czar’s empire to do so; but they are to be had for every combination directed against Germany.” And the Dresdener Nachrichten: “The Russian-German relations leave very much to be desired at the moment. The Russian government fails to show the least approachableness in foreign questions and Russian society and the press are in an extremely anti-German mood. Evidences of the same thing are to be seen in their attitude to Austria. … The Russian policy lets itself be taken more and more in tow by the French desires, and has nothing but polite speeches left for Germany.” The Weser Zeitung finds the explanation of the hostility in Germany’s efforts to help the Turks reorganize their army, and declares, “Here we have [Pg 5] touched one of the weakest spots in Russia’s world-policy, her endeavor to get to the Mediterranean.” The Fränkische Kurier thinks that Russia intends to form a protectorate over the Balkan states as a military weapon against Austria and her allies: “The soul of this endeavor is the Russian diplomacy and the Servian minister-president, Pasitsch.” The Dresdener Anzeiger observes that the influence of the Pan-Slavist party over the Russian government is steadily growing and that the extraordinary activity in military matters ill suits the constant peace assurances: “The measures are pointed against Austria-Hungary.”

On March second an article in the Kölnische Zeitung aroused great excitement all over Germany. It declared that Russia was not yet in a position to supplement political threats by military action, however much France might “rattle with the Russian saber.” But in three years all the enormous preparations would be completed, and already “it is openly said even in official military periodicals, that Russia is arming for war against Germany.” There is no immediate danger, the article continued, but the legend of the historical German-Russian friendship had better be thrown to the dogs.

The papers took different attitudes toward this article, but there were not wanting those who considered the warnings of the Kölnische Zeitung justified. General [Pg 6] Keim, in the Tag, declares that the German-Russian boundary is one huge camp, that the underlying thought of the whole armament is an offensive war against Germany, that France had proceeded in the same way just before 1870 and that the recent visit to St. Petersburg of President Poincaré and his chief of staff Joffre had not been merely a pleasure jaunt. Had not a French general, only last summer, declared in a treatise published anonymously that the tension between Russia and Austria was ground for a European war “perhaps in the near future”? And had not this French officer even gone so far as to spread the legend that in case of war Germany would disregard the neutrality of Belgium and Luxemburg in order to be able to envelop the French left wing?

Several of the March newspapers bring the Russian hostility into connection with the commercial treaty that has only about two years more to run. Russia, by making a bold front, can gain from Germany better terms than she has had in the past. “Russia, with her military preparations,” writes the Pester Lloyd, “wishes to put Austria and Germany under military pressure in order to achieve diplomatic successes and harm her neighbors economically.” The idea that France is behind it all crops out repeatedly. The Neue Preussische Zeitung speaks of the pressure “ever stronger, that the French [Pg 7] need for revenge is exercising on the Russian ally and debtor.” The Hannöverische Courier accuses the French press of having first caused the agitation of public opinion in Russia, on which it afterward comments as so remarkable. As far back as March 10th, 1913, the Kölnische Zeitung had written: “Never was our relation to our western neighbor so strained as to-day, never has the idea of vengeance shown itself so openly and never has it been made so evident that in France the Russian alliance, the English friendship, are claimed only for the purpose of reconquering Alsace-Lorraine. In whatever corner of the world the flame starts up it is quite certain that we shall have to cross swords with France. When that will be, no one can tell.”

The Russian military preparations cause the German papers much concern in the month of April also. The Vossische Zeitung considers them a gigantic bluff, and declares that they have been worth millions to the Russian government. “For only because France thinks that in Russia she possesses an ally ready for war has she heaped billions and billions on her in the form of loans. … That the latest French loans to Russia were accompanied by instructions seriously to take up the anti-Austrian and anti-German preparations no one doubts. Just as little is it doubted that Pan-Slavism is not pleased with the latest changes in the Balkans or that [Pg 8] the freedom of the Dardanelles and the seizure of Constantinople still present themselves as the goal of Russian policy. Hatred of the Germans is increasing. … One thing is certain: Russia is arming to a gigantic extent. She wishes to throw a heavy weight into the scale of the national quarrels. Germany and Austria have every reason to be on their guard.” The Allgemeine Zeitung, of Chemnitz, writes that “The goals of French and Russian policy are unattainable without world-shattering callings-to-account,” and the Weser Zeitung, after speaking of Pan-Slavism as threatening the existence of the Austrian-Hungarian monarchy, finally exclaims, “It neither can nor should be concealed that if—which God forbid!—this direction gain the upper hand in Russian politics it would mean the very war-danger against which we sought and found refuge in the Triple Alliance.”

The newspapers of May have a somewhat calmer tone than those of March and April. “There is, to be sure,” writes the Tag, “danger for peace in the possibility that the anti-German tendency in Russia may prove so strong that the government will not be able to check it. Another danger lies in the relations of Russia and Austria. … Although there is much talk to the effect that we shall once more be compelled to fight for our national existence, it is not absolutely necessary that [Pg 9] such a war shall come.” On the other hand, Admiral Breusing, in the Tägliche Rundschau of May the seventh, writes: “The striving of the Slavic and Mongolian races to extend their power and possessions will surely lead to an encounter with the German race.” The Rheinisch-Westphälische Zeitung declares of France that “public sentiment in military and political circles has long gone over from the defensive to the offensive. Apparently the aim is to create a situation where Germany will have to choose between receding or attacking.” The Dresdener Anzeiger, too, thinks that the “relations between Germany and France give the key to the grouping of the European powers,” and the Berliner Tageblatt says, “The future and salvation of Europe and its culture lies solely in a German-French-English rapprochement; that alone will guarantee the world-peace.” Toward the end of the month the Dresdener Anzeiger writes: “The German-Russian relations have latterly taken a remarkable change for the worse. Certainly the nationalistic elements in Russia are once more conspicuously active. … Should the whole mass of the Russian people once become conscious of its nationality the world will see the most mighty movement both as regards extent and elemental intensity. … For Russia, Pan-Slavism is the idea of the Russian leadership over all Slavs.”

[Pg 10]Already in May, more than two months before there is a sign that the conflict is at hand, doubts begin to be expressed whether Italy’s alliance would be of any value in case of war. The Berlin Neueste Nachrichten has to acknowledge that as far as Austria is concerned the alliance is “more a matter of the intellect than of the heart;” while the Rheinisch-Westphälische Zeitung reports on May twelve that “in more than ten years such a senseless agitation against Austria has not been seen in Italy. … The Italian government is by no means master of the difficult situation in which it is placed by the demonstrations of protest against Austria-Hungary. … Were war to break out to-day the easily excited Italian people would compel any government of theirs, however friendly to the Triple Alliance, to declare against Austria-Hungary.”

The nearer we approach to the crisis the more serious is the situation regarded by the better newspapers. The Neue Preussische Zeitung in June tells of the surprising spirit of sacrifice there is in France and of the quiet efforts that are being made to strengthen the army: “If the revenge cries have almost ceased that does not in the least mean that the idea has been given up; on the contrary, they already reckon on the war as on a sure thing.” Of the Russian military preparations, the Vienna Neue Freie Presse writes on June twelve: “About two months [Pg 11] ago it became known that Russia had set aside two hundred sixteen million kronen (a krone is about a franc) for military exercises and especially for a ‘mobilization.’ The great amount of this sum will be realized when one remembers that Austria spends about ten millions for all of its military exercises put together. Under the harmless title of ‘trial-mobilization’ and the still more harmless one of ‘exercises for the reserves’ Russia, then, for a period of six weeks, is placing its giant army practically on a war-footing. Think of 1,800,000 men holding military exercises at a time when Austria has 200,000, Germany from 300,000 to 400,000 trained men at her immediate disposal! Whether it be intentional or not this implies so imminent a threat that the neighbors will need the greatest ‘cold-bloodedness’ to allow these ‘military exercises’ to pass without friction. These exercises signify the most colossal endangering of the peace that was ever attempted under the form of a periodically recurring measure of organization, and it would not be surprising if all those who long for a peaceful turn of political affairs were to be completely embittered…. To add to this dark aspect comes the relatively enormous credit demanded by the Servian military administration—123,000,000. It is as much in proportion as though Austria were to demand a billion and a half. Since 1908 Servia has been arming uninterruptedly, [Pg 12] and now again spends this sum on military purposes the tendency of which practically amounts to a direct threatening of her neighbors.” The Hallesche Zeitung on the twenty-third of June discusses the various alliances: “Originally the Russian-French alliance was a military convention, in the last few months there has been added a naval agreement. It is desired to enter with united forces into the great decisive struggle for the division of the world. Russia wants elbow-room as far as the North Atlantic Ocean and the Southern Baltic, besides free entry into the Mediterranean.”

I have quoted all these newspaper extracts because they seem to me absolutely indicative of the sentiment that prevailed in Germany just before the war broke out, whether that sentiment be based on correct impressions or not. We have the Russian side of it in an article written by Professor Maxim Kowaleski, for the Frankfurter Zeitung: “In Russia people believe that Germany and Austria are arming against Russia, in Germany and Austria they take for granted that the opposite is the case.”

To the unprejudiced observer it looks very much as though Servia, thinking her hour had come and feeling sure of Russia’s support, had instigated the murder of the heir to the Austrian throne with the deliberate intention of starting a great conflagration. The preliminary [Pg 13] inquiry into the matter, which was carried on very deliberately by Austria, with no sensational charges or accusations, revealed a great plot reaching to the very steps of the Servian throne. Around that throne, as the world well knows, were the men who had deliberately murdered their own previous king and queen and who had been rewarded with high positions for their share in that dark transaction. It was proved to Austria’s satisfaction—and she had so much to lose by a war of aggression that no ulterior motive could have influenced her—that the royal Servian arsenal had provided the weapons of death and that a high official in the army had been directly concerned. Servia’s attitude during the preliminary investigation had been provocative. Then Austria hurled her ultimatum.

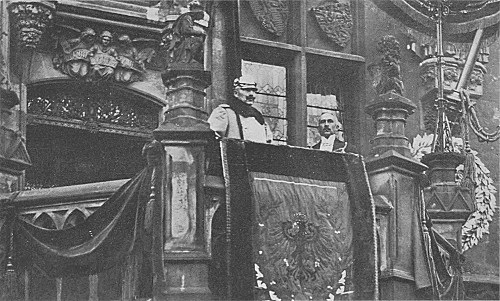

It was an unheard-of ultimatum—that much an Austrian friend acknowledged to me at the time. But, he added, the whole situation was equally unheard of. In Germany, except in the ranks of the social democrats, who glory in having no national sentiments, Austria’s act met with the most complete approval. Truth to tell, no one had expected such firmness and decision. The seriousness of the matter was not for a moment overlooked. In my own immediate neighborhood and, I imagine, from end to end of Germany, the first impulse on hearing the news was to sing national hymns. One [Pg 14] heard them throughout that whole night—especially the solemn “Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser” and “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles.” There was a resigned feeling, too, a feeling that Servia had been such a menace since 1908 that the time had come when something must be done. My Austrian friend believed that the powers would sympathize with his country’s desire to chastise a band of assassins; that the Russian czar especially would never take sides with regicides; that England would see fair play.

To blame the German emperor for what followed is the attitude of the uninformed. Germany has foreseen the struggle, as our extracts from the newspapers show, but her one idea has been self-defense. The worst that can be said of her is that her wonderful prosperity has made her a little boastful and that she has talked too much about her share in world politics and her own “place in the sun.” That indeed was an unfortunate remark of his imperial majesty. In general, however, he has honestly tried to keep the peace, and that Germany, with her blooming trade, her model educational system and her splendid fleet and army should have a larger voice in the affairs of nations was not an unreasonable aim. Those who accuse her of greed for territory should look at the history of their own country and see if they are entitled to throw stones. Nor should they [Pg 15] attribute her recent army-increase to a mere spirit of aggression. So hemmed in is Germany, so exposed are her frontiers in every direction, that she can not help taking alarm at the movements of her neighbors. Actually touching her borders are nations with a total population more than doubling her own, not to speak of England with her enormous fleet.

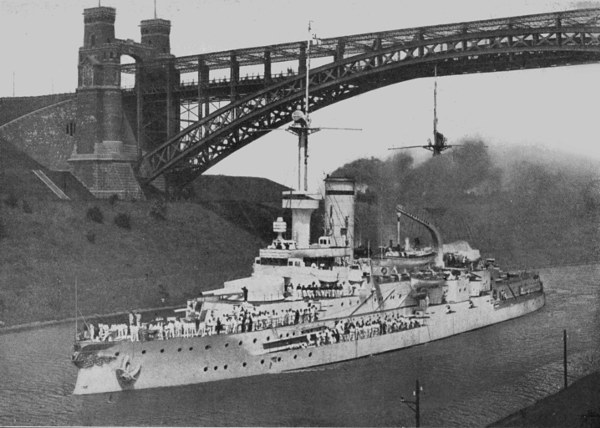

England of late has stood for the restriction of armaments provided her own naval superiority be preserved in the present proportions. Germans believe, probably falsely, that before making such a proposition England hastily ordered the laying of the keels of three new battle-ships which in the ordinary course of events would not have been begun until later. At any rate England leads in the matter of supplying other countries with deadly instruments of war and her attitude is not unlike that of her own rich beer-brewing families to the temperance question. They preach against the use of alcohol, but go on deriving their income from it. The largest factory of Whitehead torpedoes is at Fiume, in Austria; Armstrong and Vickers have branches in Italy and supply that government with naval guns; while the British Engineers’ Association, with a capital of $350,000,000, is endeavoring to corner the trade of the world in firearms. England introduced dreadnaughts and not only builds them for herself but also furnishes them on [Pg 16] demand to Japan and South America. With a cannon factory on the Volga and an arsenal equipped by Armstrong and Vickers on the Golden Horn, England has fairly fattened of late on war. By building the first dreadnaught, indeed, she did herself a poor service. Previously Germany was out of the running as regards the number of ships; now, where only dreadnaughts count, she is becoming a good second. Was there not something more than naïvete in Sir Edward Grey’s serious proposal that Germany and England should restrict the number of their battle-ships but always preserve the proportion of ten to six in England’s favor? We have here, I think, the whole gist of the differences between the two countries. England has steadily preserved her attitude of superiority everywhere its basis was disappearing. She has been jealous of Germany’s commerce, of her colonial progress. These Germans are to England upstarts who need to be kept in their place and are not to be allowed to have a word in the larger world-policies. Almost every Englishman feels that a German is his social inferior. Such assumptions provoke bumptiousness and self-assertion, which, I do not deny, have at times been evidenced. Just before this war broke out, indeed, the feeling of mutual antagonism seemed to be lessening. The English fleet was welcomed [Pg 17] at Kiel, the English trade delegation in Berlin. The press of both countries had softened and sweetened.

As for England’s present alliance with Russia against Germany, it is the most monumental act of folly in modern history. Has Britannia been attacked by sclerosis? At home a maudlin sentiment keeps her from enforcing obedience to her laws and abroad she allows her real enemies to pull her about by the nose. It is as though in the middle ages a Henry or an Edward had joined hands with a Genghis Khan or a Timour the Tartar. Can England gain anything whatever by humiliating Germany and furthering Pan-Slavism? A little commercial advantage, possibly, though America will be correspondingly strengthened and the final result will be no better. Britannia, wake up! It is less far from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic than it is from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Gibraltar will soon be as irksome to Pan-Slavism as are now the forts on the Dardanelles. Your own race is made up mainly of Angles and Saxons—all your ideals, all your real interests are far closer to those of the Germans than they are to those of the Russians. The time may come, and very soon, when you are only too glad to throw yourself around Germany’s neck and beg her aid in opposing the hordes from the East. In Russia’s wake are your allies, [Pg 18] the Japanese, who now for the first time have taken a hand in European affairs. Japan has been likened by a bright American girl to a man who has never been invited to dinner in certain circles but who at last has invited himself and simply can not be turned out of the house.

Germany, though drawn into the matter merely by the plain terms of her alliance with Austria, stands virtually alone, for Italy is faithless and Austria, as usual, is only half prepared. We may see a recurrence of those exciting days when for seven years Frederick the Great of Prussia—of a Prussia less than half the size that it is now—held his own not only against the great powers of Europe but against the rest of Germany as well. The help that he had from England was not greater than may be expected from Austria to-day, and even the English deserted him at last. Again and again Frederick risked, even as our contemporary Hohenzollern is likely to do, le tout pour le tout. And like Frederick, I think that William, because of better equipment, better discipline and better strategy, is likely to prevail even over the many millions arrayed against him.

England to-day throws the whole blame for the terrible war on Germany, who was lukewarm, so England declares, in counseling Austria not to let her strained relations with Servia develop into war; and in the [Pg 19] English press at least there are no words too scathing for the violation by Germany of Belgium neutrality. The average Englishman, I am sure, considers that the reason for England joining in the struggle. Yet what are we to think of Sir Edward Grey’s own words in the “Correspondence respecting the European Crisis” laid before the Houses of Parliament and received here from London August twenty-fifth.

July 31.—The German ambassador asked me to urge the Russian government to show good-will in the discussions and to suspend their military preparations. … I informed the German ambassador that, as regards military preparations, I did not see how Russia could be urged to suspend them unless some limit were put by Austria to the advance of her troops into Servia.

August 1.—I told the German ambassador to-day … if there were a violation of the neutrality of Belgium by one combatant while the other respected it it would be extremely difficult to restrain public feeling in this country. … He asked me whether, if Germany gave a promise not to violate Belgium neutrality, we would engage to remain neutral. I replied that I could not say that. … The ambassador pressed me as to whether I could not formulate conditions on which we would remain neutral. He even suggested that the integrity of France and her colonies might be guaranteed. I said that I felt obliged to refuse definitely any promise to remain neutral on similar terms, and I could only say that we must keep our hands free.

So England, directly from the first, took sides with Servia in a matter that concerned only Servia and Austria. She “could not see how Russia could be urged to [Pg 20] suspend preparations” and would not, even for the sake of Belgium, state the terms on which she would agree to remain neutral in the new German-Russian mobilization dispute. Why Germany finally did violate Belgian neutrality is explained by a telegram from the German foreign office to the German ambassador in London, Prince Lichnowsky, on August four. … “Please impress upon Sir E. Grey that German army could not be exposed to French attack across Belgium, which was planned according to absolutely unimpeachable information. Germany had consequently to disregard Belgian neutrality, it being for her a question of life or death to prevent French advance.”

All eyes then are likely for the next few months to be fixed on the German army and it has seemed worth while to me hastily to collect and publish all the items concerning the land, naval and aerial forces that will be of general interest in America. No one will look, I hope, for much originality in a work of this kind. My information is taken from Major von Schreibershofen’s excellent book Das deutsche Heer, from Colonel von Bremen’s Das deutsche Heer nach der Neuordnung von 1913; from Lieutenant Neumann’s Luftschiffe and his Flugzeuge; from Count Reventlow’s interesting Deutschland zur See; Troetsch’s Deutschland’s Flotte im Entscheidungskampf and Toeche-Mittler: Die deutsche Kriegsflotte. The three last mentioned works, [Pg 21] and also Von Bremen’s, are absolutely new, having been published in 1914; Schreibershofen’s dates from 1913. The two others have no date but one can see that they have appeared very recently. The large new works Das Jahr 1913, Deutschland unter Kaiser Wilhelm II, and the Handbuch der Politik have also been of use to me. For the last six months I have followed very carefully in the Zeitungs-Archiv all the newspaper extracts bearing on our subject. The war has doubtless interrupted the publication of the Archiv, so that I shall remain “up to date” for some little time to come.

[Pg 22]

THE ARMY

The great military authority, Bernhardi, in an article in Das Jahr 1913, points out various ways in which military science has developed since the Franco-Prussian War and shows how completely we have had to abandon many of the conceptions gained by a study of earlier campaigns. Responsible in the main for the changes are the increased size of the armies and the new technical inventions of our age.

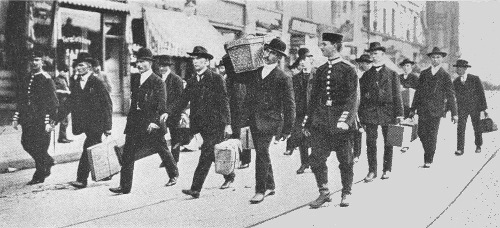

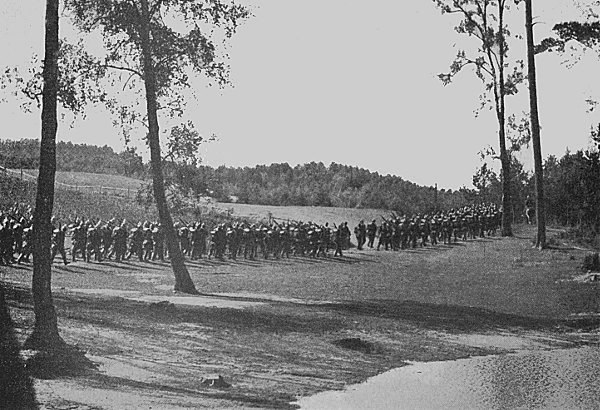

Almost all the states of continental Europe have gone over to the principle of universal military service, with the result that the armies are greater now in time of peace than ever before in time of war, and that when mobilization is called for and the reserves are summoned, the number of men in the field amounts to millions. The first result has been that far other means of transporting and concentrating such masses have to be employed than used to be the case and that networks of railroads have had to be built for purely strategic purposes. In the maneuvers that were to have taken place this coming autumn at Münster in Germany it had been intended to make a record in the matter of quick transportation and to dispose of 120,000 men in the course of a single morning [Pg 23] without interrupting the regular passenger traffic. The old method of victualing armies, too, has had to be changed, for it is impossible for such hordes to nourish themselves by what they chance to find in the enemy’s country. Problems of another kind have arisen. Modern armies are composed of regulars and reservists alike: the reservists are not so hardened as the regulars and often not so efficient, so that it has become a custom to distribute them in such a way as to achieve the best results. As a rule, the regulars must be spared for decisive actions and reservists must occasionally be sacrificed, apparently needlessly. There may be cases, for instance, where the reserves must expose themselves to a murderous fire while the regulars are engaged in the more difficult but less dangerous task of cutting off the enemy’s line of retreat.

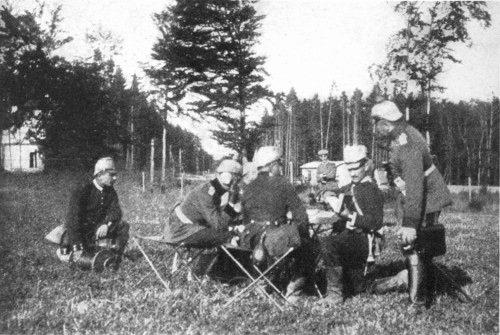

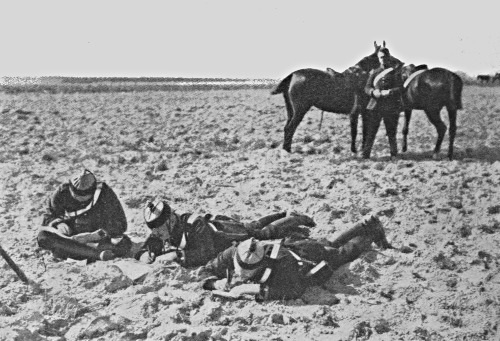

Technical improvements, such as the longer range and quicker fire of the guns, swifter means of communication and of signaling and the like, not to speak of other considerations due to experience, have so changed the old tactics that a line of battle is now more than ten times as long as it was only a few years ago. At Sadowa, with 215,000 men, the Austrians had a front of only 10 kilometers; at Mukden the attacking line of the Japanese, who had only 170,000 men, extended for 110 kilometers. “The broken line,” writes Bernhardi, “is to-day the only [Pg 24] battle formation of the infantry.” To-day, officers and men fight in trenches and take every advantage of the inequalities of the ground; in 1870 it was considered disgraceful to take such advantages and the officers stood erect in the most deadly fire. In consequence of the length of the lines a check in one quarter is no longer so serious a matter as it used to be; a modern battle is a succession of single engagements of which the victor only needs to win a good majority. The commander no longer takes up a position, as Napoleon did at Leipzig, where he can oversee the whole field of operations; the best place for him is some railroad junction or central telephone station, with wireless and ordinary telegraph equipment, where messages can constantly be sent and received, and to and from which he can despatch troops, automobiles, motor-wagons or aeroplanes. One of the chief modern problems is supplying sufficient ammunition for quick-firing guns—the baggage trains must not be so long as to hinder the advance of the troops, yet where there are many guns and each shoots off hundreds of shots a minute, great quantities of ammunition are needed.

I have spoken of military service being almost universally compulsory in Europe. This means that every man of a certain age and with the requisite health and strength is obliged to report for duty. It has not hitherto [Pg 25] meant that every eligible recruit was obliged to serve. In Germany a large contingent, even of the capable, was formerly excused. In 1910, for instance, nearly 235,000 were declared more or less unfit for service, although in France they would probably nearly all have been accepted. By the German army bills of 1911, 1912 and 1913 indeed the numbers of those required for active service were steadily increased: 9,482 in the first named year, some 29,000 in the second, and then the great increase of 63,000 in the third. But there were still, up to the present mobilization, some thirty thousand able-bodied recruits who could not be placed.

In the Prussian military-service law of 1814, and again in the constitution of the North German Confederation of 1867, the principle was laid down that the army should consist of one per cent. of the population. This had long been disregarded as the population increased, and the proportion had sunk as low as eight-tenths of one per cent. It has now been raised to a little over the original figure. The population as given officially in 1913 was 64,925,993, while the number of common soldiers (I quote the figures given by Stavenhagen in the Handbuch der Politik) was 647,811.[*]

[Pg 26]The cost of the German army has been enormous—more than twenty-five billion marks between 1872 and 1910, and in 1913 alone, 1,608,653,300 marks. The extraordinary defense contribution for 1913, 1914 and 1915, a tax, not on income but on capital direct, is estimated to bring nearly 1,300,000,000 marks. Strange to say, the tax was very popular—every party in the Reichstag voted for it, even the social democrats, whose delight in a measure that fell most heavily on the rich (small properties were exempted) made them swallow the fact that the money was for national and military purposes. The yearly sums that the sudden increase in the army entails are to be paid by a curious tax on the increase of property value to be estimated every three years.

The estimates as to how much the army numbers when on a war footing varies between two and three-fourths millions and four millions. Austria’s army, on paper at least, numbers 380,000 men in time of peace, which number gradually was to have risen to 410,000 in the next few years. In war-time it is estimated at 1,300,000 men. Curiously enough Italy, with a peace army of only 300,000, estimates her war army officially at 3,400,000, or about as much as either Germany or France.

For the armies of the Triple Entente we have an estimate published by the Deutsche Tageszeitung in January, [Pg 27] 1914, which is worth quoting at some length, as it is from a well-known military writer, Lieutenant Colonel von Bremen:

The basis of France’s military increase in 1913 is the reintroduction of the three years’ term of service. By retaining these third-year men the peace-showing is increased by almost a third. This year 185,000 men are to be called in. The peace strength of the French army will, from the autumn of 1916 on, amount to 33,000 officers and officials and some 833,000 men, while up to that period we can reckon with 780,000 men. One must add to this, 28,000 gendarmes, customs and forest officials, who likewise belong to the territorial army (like the Landwehr). In Germany we have for 1913 and 1914, counting officers, non-commissioned officers and men, 802,000, to which, in 1915, will be added 13,000 men. Deducting from the present strength of both armies the mere laborers who have to do with supplies, etc., Germany’s peace force is momentarily the higher, but not if we reckon France’s gendarmerie, etc. Counting in this, France, with 40,000,000 inhabitants, has a larger army in time of peace than Germany, with 65,000,000. The French army has further advantages in the longer training and in the increased readiness for war. The troops covering the eastern frontiers have two hundred men to a company (four-fifths of the war strength) and even at the time when the recruits are being mustered in, one hundred forty trained men; while our companies at the same time can dispose of only half so strong a number. And what it means in case of war to have at hand two fully trained years’ contingents (especially in the cavalry) during the period of training the recruits is self-evident. Further advantages in the French army lie in the longer training of the inactive officers and in the good provision for officers and non-commissioned officers. In the house of deputies negotiations are pending regarding advancement regulations tending to lower the age limit of the whole body of officers. And, above all, it has been [Pg 28] made possible to create a new, twenty-first army corps. So we see that France, in 1913, has made a very great step forward.

The Russian armaments of 1913 are also significant. The most important event was the appearance in October of the draft of a law to prolong the term of active service by three months and that in the decisive time from January first (fourteenth) to April first (fourteenth). As in Russia, the recruits are called in at latest by November fifteenth. Russia will, until spring, still have under arms, besides the recruits, the trained contingents of three years in the infantry—four, indeed, in the cavalry. That considerably increases her readiness for war. And in addition to lengthening the term of service the number of recruits is still further increased by twenty thousand men. The momentary military strength of the Russian empire is about one and one-half millions, of which about 1,200,000 concern Europe (thirty army corps and twenty-four cavalry divisions). But already for 1914 we can reckon on the formation of from two to three new army corps and on a considerable increase of the artillery by at least forty batteries, for which purpose three hundred twenty million marks have been called for. To make mobilization speedier and to facilitate the march to the west boundary railroads are to be built. The estimates for this are about two hundred sixty million marks. The following stretches are under consideration: 1. Nowogeorgiewsk to Plozk on the Vistula. 2. Cholm—Tomoschow—Belzek. 3. Schepetowka—Proskurow—Larga. In addition a number of lines are planned of which one is to encircle our province of East Prussia. Along the German frontier, too, the erection of wireless stations has energetically been taken in hand. Likewise they have begun to modernize their fort and field artillery. Side by side with these endeavors go intended improvements in military education and training and organized changes in the situation of the officers’ corps and general staff in the way of raising salaries and of quicker advancement. Thus for the Russian army, too, and its capacity for service the year 1913 is to be looked upon as important.

Furthest in arrears of the armies of the Triple Entente is the [Pg 29] English, which made no progress worth speaking of in 1913. England in her war plans against us long reckoned with landing an army of invasion on our coast. The idea has been given up because it was declared that probably the weak, active army would be more needed elsewhere, especially as its maximum of about 130,000 men could not play a decisive part against the millions-of-men armies of Germany. Nor has the “territorial army,” destined for protection at home, shown any progress; of its required strength there were still lacking in October, 1913, seventy thousand men and all efforts to bring it to the intended height of 314,000 men have failed. The thought of tunnel connection with France, however, in spite of the dislike of the Britisher, so proud of the isolation the sea offers him, has found more adherents than was formerly the case.

If now we draw our conclusions from our military review of the year 1913 the armaments of Austria and Italy on the one hand and Russia and England on the other are insignificant as compared with those of Germany and France. The two latter remain well in the foreground, and indeed in a European war, too, it is they who first and foremost would have to try conclusions with each other.

These observations, made by an expert at the beginning of 1914, are exceedingly interesting in view of what is now going on. Since Von Bremen wrote, however, there have been several interesting developments. In February it became known that of the French soldiers no less than 265,000 had died, were on the sick-list, or had been discharged during the previous month. The explanation is, that in order to raise the figures even the poorest kind of material had been accepted, that old unhealthy barracks were overcrowded and that new ones had been occupied while the plaster was still wet on the [Pg 30] walls; that the army was short of physicians to the extent of many hundreds. An official note in a Paris paper declares that two-thirds of the recruits arrive in a tuberculous condition. Together with these revelations comes a book, by a French military aeronaut, complaining of the utter neglect of the air fleet, and declaring that at the moment France has not one serviceable hydroplane. The whole appropriation for air-ships in connection with the navy was but 400,000 francs in 1913, as compared with millions appropriated by the rival powers. At the same time come revelations regarding the regular navy itself. Although there are nine dreadnaughts building, but two are ready, and no cruisers.

In March appeared the “general annual report of the British army,” published by the War Office, which showed that Von Bremen’s statement as to the shortage of men was not only not exaggerated but greatly underestimated. The regular army is 9,211 men short, the territorial army 66,969, the special reserve 29,370. The explanation lies in the greater attractiveness of the navy and in the high emigration figures (178,468 males in 1913).

In April we hear of great appropriations in Austria both for the army and the navy. Official estimates place the strength of the army at 390,250 men, but a German critic points out that of these 60,000 are Landwehr, or [Pg 31] reserves, and ought not to be counted. There is to be a yearly increase of 31,300 recruits, but the measure is not to take full effect until 1918. For the navy, 427,000,000 kronen are appropriated, of which 4,000,000 are to go for military air-ships; but the expenditures are to be extended over a period of five years. It has been Austria’s fate throughout the centuries always to be several years behind.

In June, finally, we learn that Russia has set aside for military expenditures in 1914 alone the monstrous sum of 2,500,000,000 marks, and by 1916 will have added 400,000 men—more than Austria’s whole force—to her standing army, which will amount, in the winter months at least, to 2,200,000 men. “Characteristic,” writes the Tägliche Rundschau in commenting on it, “is the strengthening of the western boundary-strip and the improvement of the strategic network of railroads in order to hasten the forwarding of troops.” On the other hand, attention is drawn in the Danziger Zeitung to the fact that Russia has at the moment in the Baltic but four battle-ships, all old-fashioned, although by 1915 it is hoped to have ready four dreadnaughts.

We shall hear much in the next few months of infantry and cavalry, of field artillery and foot artillery, of pioneers, of Verkehrstruppen or communication [Pg 32] troops, and of the Train or transport division. I therefore preface this section with the definition of these terms given by a staff officer in the newest book of instructions for the one-year volunteers.

The infantry represent the main troops of the army. Their value lies in their endurance when marching, in their correct shooting and in their brave dashing against the enemy. The infantry is armed with the ninety-eight gun and bayonet; the sword-knot non-commissioned officers (Portepeeunteroffiziere), battalion-drummers and ambulance-men carry revolvers.

To the infantry belong the sharpshooter battalions (Jägerbataillone), the guard sharpshooter battalion (Gardejägerbataillon) and the guard rifle-battalion (Gardeschützenbataillon). The infantrymen are known as grenadiers, musketeers and fusileers.

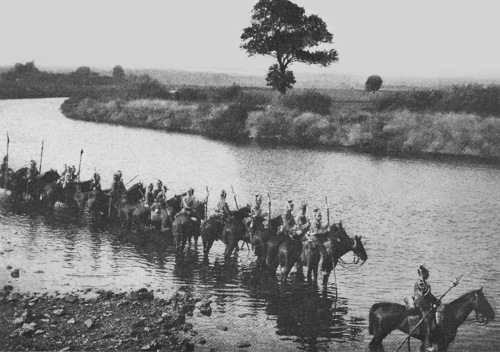

The cavalry is armed with lance, saber and carbine. Its chief value is for scouting and for precautionary service, but it is also used for riding down the enemy and piercing him with the lance. The cavalry may also dismount and fight on foot like the infantry. For shooting it uses the carbine.

The cavalry consists of cuirassiers, uhlans, hussars, dragoons and mounted riflemen. (In Saxony guard-riders (Gardereiter) and carbineers; in Bavaria heavy riders and light horse (Chevaulegers).)

The field artillery is effective through the swiftness with which it rides up and through the certainty of aim of its quick-firing guns. The field artillery carries batteries of cannon for firing against visible goals and light howitzer batteries, for shooting at objects behind cover and for demolishing light field fortifications. The drivers carry a sword and revolver, the cannoneers a dagger and revolver. Every man of the horse-drawn division is mounted and carries sword and revolver.

The foot artillery has to serve the fort and siege artillery as well as the heavy artillery guns of the field army; in attacking a fortress it must silence the enemy’s heavy fort guns and make breaches in the [Pg 33] fortifications; when defending it must overcome the enemy’s heavy siege guns. The men are called cannoneers; they carry the carbine and the ninety-eight bayonet.

The pioneers see to the throwing up of entrenchments, the building and destroying of bridges, obstructions, etc.; they are armed like the infantrymen.

The communication troops consist of the railroad regiments, which in time of war have to see to the building and running of railroads; of the telegraph battalions, which put up telegraph lines; of the fortress telephone companies, which attend to all telephone matters in the fortress; of the air-ship and aeroplane battalions, who are entrusted with spying out the land and the enemy’s positions by means of balloons, air-ships and aeroplanes.

The communication troops are armed like the infantry.

The transport service (Train) supplies every kind of column of the army with bridge materials, food, ammunition, etc. Its weapons are swords, carbines and revolvers.

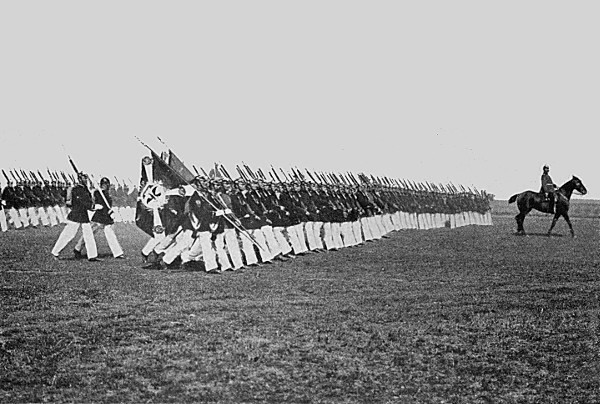

It is not worth while here to enter into the question of uniforms. In time of peace the blue coats and red collars of the infantry, the varied colored attilas and fur caps of the hussars, the helms with the flying eagles of the guards, the tresses, the gleaming epaulettes, the scarves, the waving plumes, are all interesting enough, especially to the other sex; but in war that is all laid aside. In order to be as invisible as possible to the enemy all categories of troops wear the same ashen gray—a comparatively recent adaptation of the principle of protective coloring.

In the German army the cavalry is merely an adjunct of the infantry. It is the infantry which decides battles—not [Pg 34] the cavalry, not even the artillery. However, the infantry of to-day is something very different from the infantry of the eighteenth and even from that of a great part of the nineteenth century. German military writers acknowledge that the world learned new tactics from the sharpshooters and riflemen of the American war of the rebellion. The whole modern battle formation rests on the idea of giving more play to the individual. In spite of the technical progress that has made of armies great machines, more weight than ever before is laid on quick judgment, on good shooting, on physical bravery and endurance. I know that an idea quite contrary to this prevails, that many consider war reduced to the art of setting off the greatest quantities of explosives within a given time. But this is very far from the truth. The battles of the past were of much shorter duration than are those of the present. Wagram was won in two hours, Mukden took three days.

One learns to adapt one’s self even to quick-firing guns and incredible rifle-ranges. It has been mathematically demonstrated that, with the rifles now in the hands of the German infantry, a bullet fired from a distance of three hundred yards will pass right through five men standing closely one behind the other and lodge in the body of the sixth. But men in battle line no longer stand closely one behind the other, nor even closely side [Pg 35] by side. Even in what is considered a thick firing line they stand about three feet apart.

I have said that the modern idea is to give more play to the individual. Within certain limits the men choose their own position, find the proper rests for their rifles, get each the range for himself, determine the speed of their own fire and use their own judgment in the economizing of ammunition. They are expected to advance according as they see their opportunity.

A glance at the methods of training the infantry will give some idea of the care and thoroughness with which the Germans have made their preparations for war. The old drill has not been entirely abandoned—indeed, some military critics think that there is still too much of the goose-step marching and of the parade tricks. But these have lost their old importance and the tendency of late years is toward the most realistic representation of the circumstances and problems of actual combat. The parade-ground has given place to the maneuvering field, acres and miles in extent. For the first time in Germany, this autumn, whole army corps were to have engaged in mock combat with one another.

In the ordinary rifle practise the men are taught first to shoot well individually, then in groups and detachments, next in whole troops and companies and finally in conjunction with cavalry and artillery. They are [Pg 36] made to adapt themselves to the most unfamiliar and unusual surroundings. Even the targets are of the most varied description: targets that fall to the ground when hit, targets that burst, targets surrounded by smoking objects or colored fires so that there will be some of the semblance of battle, fixed targets and targets that move or that float in the air, targets that have been lying flat on the ground but that suddenly appear here and there like an enemy issuing from the bushes. The rifleman must learn never to be surprised at anything, but to keep his eyes open in all directions.

The German army rifle is of a type first introduced in 1888, and so much improved in 1898 that it is now known as the ninety-eight gun. All the infantry carry the same, for there is no longer any essential distinction between musketeers, fusileers and grenadiers. It is a quick-loading rifle which renders it possible to take aim and shoot as many as twenty-five times a minute. The caliber is seven and nine-tenths millimeters, a fact which may not at first seem to the American reader of great importance, but which becomes more interesting when it is realized that this is the smallest caliber which will inflict sufficient injury on an enemy to make its use profitable. In other words, if it does not kill him at once it will put him out of the fight and keep him out for a reasonable time. It was found [Pg 37] in the Russian-Japanese War that a smaller bullet could, and in a number of cases did, pass through a foeman’s body without rendering him hors de combat, and that no less than forty per cent. of all wounded were back with their troops in three months.

There are Maxim rifles which can fire as many as a hundred shots a minute and which have other advantages too; but the German government is well satisfied with its own gun, considers it superior to that of any of its neighbors’ and has never seriously considered the question of changing. It has a smokeless powder, the process of manufacture of which is a carefully guarded secret.

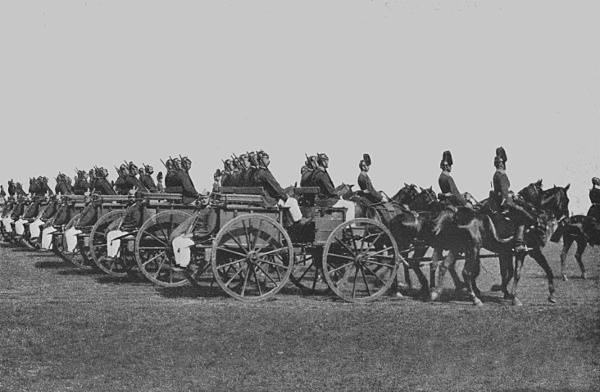

A recent innovation is the supplying of the infantry—for that matter of the cavalry also—with so-called machine guns. They are the Gatling guns of our own country, and every German infantry regiment now—since the army reform of 1913—has a machine-gun company. It consists of ninety men and forty horses, with six guns and three ammunition wagons. As the newest guns can fire at the rate of six hundred shots a minute, and as there are more than two hundred infantry regiments, not to speak of the cavalry and artillery, which also have their companies of “Gatlings,” one can gain some impression of the deadliness of modern campaigning. Many of the quick-firing guns now are supplied with stands on pivots so that they can be pointed in the [Pg 38] air against balloons and aeroplanes. But their chief use will be in guarding bridges and narrow passes. Their bullets carry for two miles, but they can be silenced by heavy artillery far beyond this range, nor can they carry enough ammunition for long-continued use. Altogether, however, a comparison of their fire with the simple flames of the traditional hell makes the latter place seem a mere pleasure-resort.

The training of a soldier has of late years become more and more humane and rational, and is no longer confined to manning guns, shooting rifles and performing long marches. Those Germans with whom I have spoken on the subject look back to their term of service with pleasure, and my general conviction is that the army in time of peace is the most perfect educational institution in existence. With school learning every boy when he comes to “serve” is more or less equipped. What he learns is esprit de corps, manly bearing, endurance and the feeling that his tasks must be quickly and faultlessly performed—in other words, regularity and discipline. The mere change of surroundings and interests is a benefit, and the outlook on the world is immeasurably broadened. The old argument against compulsory military training—that, namely, young men in their best years are withdrawn from productive work, does not amount to much in an age [Pg 39] where the general complaint is of overcrowdedness in almost every calling and profession. The German boy does his work all the better for his military training and the nation has thoroughly adjusted itself to the falling out of these two years. There are dispensations for cases where the boy’s presence at home is a vital matter for the support of others, and, as a rule, a place that he filled before is kept open for him against his return.

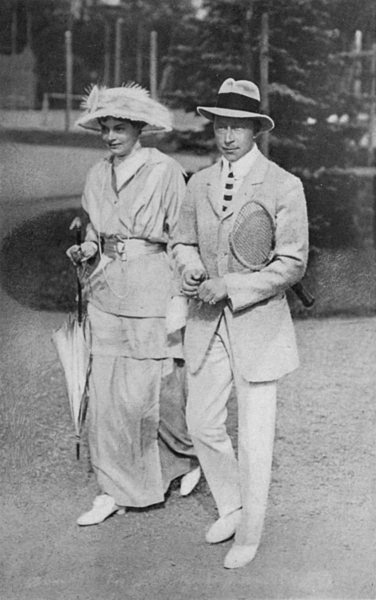

One of the pleasantest recent developments has been the enthusiasm for sport that had taken hold of the army. The authorities encouraged it in every way, for it was in keeping with the new tactics of training the individual to be efficient and independent. The author had the pleasure of attending the first great military athletic meet that has ever taken place. It was held in June, 1914, in the great stadium that has been erected near Berlin for the Olympic games of 1916, and that army which is now fighting so strenuously for the very existence of its country was represented in all its pomp and glory. On an elevated terrace was the emperor with his court. Next came the logen or boxes which were blue with the uniforms of the officers. A large majority of the spectators were soldiers, for whom whole sections had been reserved; they marched in in seemingly unending lines, looking very neat in their summer undress uniforms. The exercises began with gymnastics or [Pg 40] turnen, to which, all over Germany, the greatest importance is attached. There was the usual running, jumping and throwing of weights—with us it is a shot, with them it is a discus. There was a cross-country run of four miles which started and ended in the stadium, and in which some fifty or sixty officers took part. It was won by a splendid young prince of the royal house, Prince Frederick Leopold. The best comment that I heard on him was that he looked like a first-class American.

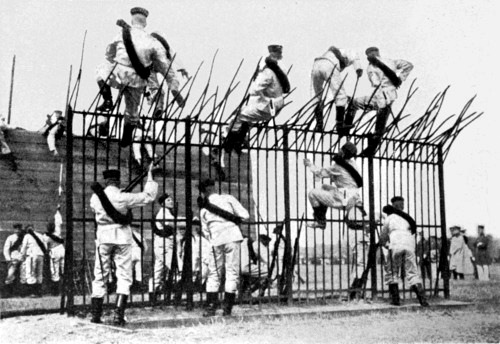

But most interesting of all was the obstacle race for the common soldiers. A part of their regular training consists in climbing walls and trees; and on their parade grounds you will find special tracks with ditches, walls and palisades; while occasionally the obstacles are of the most serious kind—iron railings with twisted spikes through which they must make their way. In the stadium games the soldiers lined up on the farther side of a great swimming-pool that runs along one end of the field below the spectators. At a given signal they plunged into the water, swam for dear life to the other side, climbed the low protecting wall and were off helter-skelter for the hurdles and other obstacles. Behind one of the hurdles, concealed by green boughs, was a slimy watery hole, but it detained them but for a moment. Across the track a high straight impromptu wall was [Pg 41] held in place by soldiers and up it all the contestants had to clamber. One almost stuck at the top; you watched him breathlessly to see if he could achieve it, but there was no jeering, as I fear there would have been at home. The whole race, in which were some fifty or more participants, was run with a wonderful freshness, joyousness and what the Germans call schneidigkeit, which corresponds to our American slang expression “toniness.”

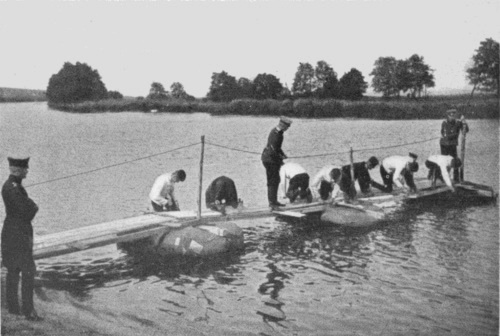

Even in the ordinary practise on the parade-ground an adjutant keeps a record of the time that the soldiers need to overcome the different obstacles. Whole companies have to pass the required tests. The whole thing is already reduced to such a system that in war an officer will know to the smallest detail what he can expect of his men. Great importance is attached to swimming, for occasions are sure to arise in a campaign when streams are to be forded or where the pontoon divisions have to be assisted.

On the whole the rise of sport has had a great leveling influence in the army. Soldiers and officers do not, indeed, compete with each other as a rule; but they take part in the same meets, and I have observed that the soldier seems to rise in importance while the tendency of the officer is to forget himself in the excitement of the moment. I have a vision of non-participants flying [Pg 42] across the field with the tails of their long coats flapping behind them to carry tidings or encouragement to some tired runner—which denotes a very great change from the unswervingly dignified bearing of other days. Soldiers and officers now are encouraged to join athletic associations, which makes for less exclusiveness.

If the infantry is the mainstay of the German army, the cavalry is indispensable for reconnoitering, for making raids and for pursuit. Each cavalryman, as has been said, carries a lance, a sword and a carbine. Much time is spent in training the men to the use of the lance, which is of hollow steel. Men of straw, for instance, are placed on the ground and the lancer, riding by, has to inflict a wound in exactly the place designated. Or a straw head is placed on a stake and must be knocked off in passing. The carbines, which are stuck in the saddle, are of a perfected modern type and are but little inferior to the muskets of the infantry.

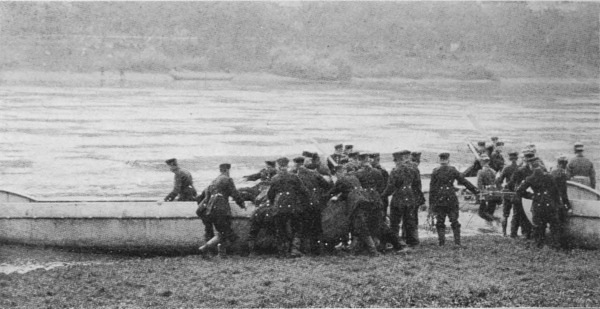

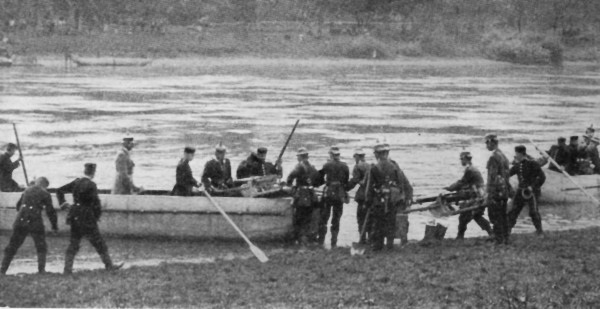

Cavalry regiments, with which speed of progress is the first consideration, carry their own bridge-wagons, so that they can either repair bridges that have been destroyed, or construct entirely new ones. It has been found that rafts made of fodder-bags stuffed with straw and held together by lances, boards, logs, etc., can carry comparatively heavy weights. Six such bags as I have described can, at a pinch, carry six men. Barrels and chests are still more useful if they happen to be at hand. [Pg 43] Needless to say, the cavalry bridge-wagons also carry explosives for destroying the enemy’s bridges and other defenses.

It has been thought in some quarters that aeroplanes and other contrivances for scouting and communication would supersede cavalry, but the German army administration evidently does not think so, as it has more than 150,000 horses in use even in time of peace. In time of war all private horses are subject to requisition, as are also automobiles, motor-trucks, motor-wheels and aeroplanes. The better riders in a regiment train the horses for the rest, and there is a constant mustering out of the inferior ones in favor of others that are stronger or younger or more docile. There are military riding schools at Hanover, Dresden and Munich, where officers are taught not only to ride well and to instruct others but also to break in young horses.

Prussia has her own stud-farms in which the royal family, since the days of Frederick William I, has taken the greatest interest. There is a regular Prussian type, small and tough. The theory has lately been advanced that Asiatic horses are more free from disease and that they proved more enduring in the recent Turkish-Bulgarian War, while the Prussian horse, through faults in the manner of raising, has degenerated during the long period of unbroken peace. This, however, is simply an [Pg 44] academic question and nothing short of war itself can demonstrate that under all conditions another type of horse will be preferable.

The Russian-Japanese War brought the old cavalry raid, such as we associate with the names of Sheridan and Wilson, once more to honor, and an expedition of Mischtschenko’s in February, 1905, though not wholly successful, aroused much interest in cavalry circles in Europe. It is considered not unlikely that such “raids” will play a great part in the present war. The Germans use the American word for the maneuver.

If cavalry is merely an adjunct of infantry, this is still more true of artillery. Its function, according to the latest German writers, is to facilitate the advance of the infantry, or, in other words, to break and open the path by which the infantry shall storm. It has sometimes been thought of the battle of the future that it would consist of two parts: the great artillery duel and the infantry struggle; and that the infantry would have to stand aside until the artillery duel was over. The contrary is the case. The two, in this coming war, will fight side by side: the artillery opening the breach, the infantry coming in.

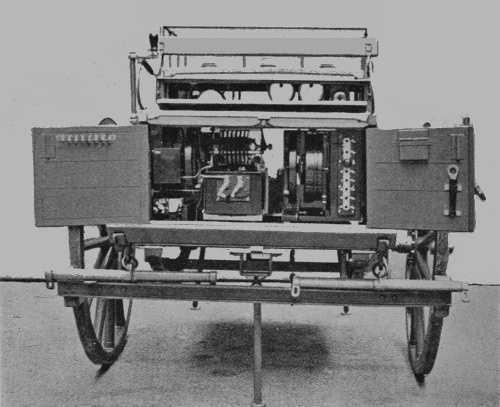

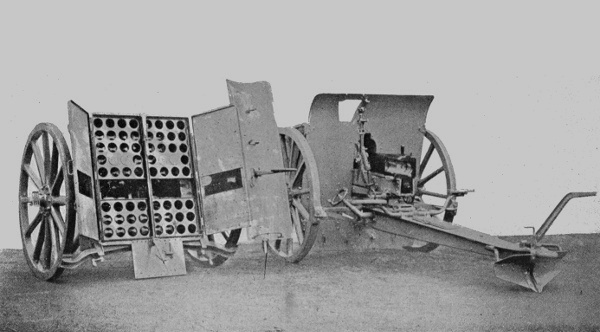

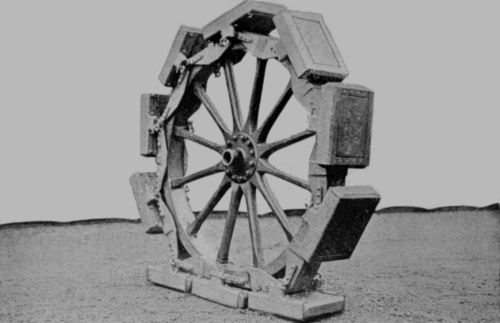

German batteries consist of six guns, while those of the French have only four. Good authorities, even in [Pg 45] Germany, prefer the French system, but the change would mean more expense than was considered warrantable. A novelty is that the guns now have great steel shields that protect the gunners. Another most useful innovation is the so-called wheel belt. A number of flat blocks or shoes, wider than the tire and hinged so as to form a great chain, protect the wheels of the gun-carriage and prevent them from sinking into the mud. Formerly a supply of beams, jackscrews and the like had to be carried along for use in extricating the cannon when they stuck fast. Now every large gun in the army has its belt, which can be removed and put on again at will, the operation lasting but six minutes.

The largest guns accompanying the infantry have a bore of twenty-one centimeters, which is much less, of course, than the fixed guns in fortresses or those used for coast defense. The size of these is ever increasing, and there is already talk of forty centimeter guns. The field guns fire shells and shrapnel and there is a so-called “unit charge” which is a combination of the two. A shrapnel is a thin metal ball filled with explosive bullets and can be discharged either by ignition or percussion. It is considered preferable to have it burst in the air, just above the point aimed at, as the shock is downward. Krupp has patented a shell that explodes by clock-work.

One further fact concerning artillery may interest [Pg 46] those who follow the present campaigns. In all the older famous battles the greatest efforts were made to drag the artillery up the hills and have it crown the heights. According to recent strategy it chooses rather low-lying protected spots. Howitzers can shoot right over a hill and have the shell curve and descend on the other side. The calculations as to just where it will strike are made with astounding accuracy, even though the goal itself may be invisible. The guns are being constantly improved, but the greatest secrecy is observed with regard to them. They are shrouded as they pass through the streets and no one can inspect them without a written order.

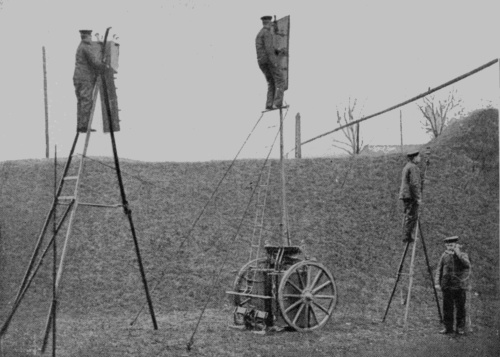

The low situation has its great advantages as well as its disadvantages, but the latter can be counteracted. In order to be able to overlook the field, each battery now has an observation ladder or column, of which the parts can be telescoped into short space and carried between two wheels. When desired it is projected into the air. One advantage of this new invention is that the wheeled observation ladder can be sent off to quite a distance carrying a portable telephone by means of which it is possible at all times to communicate with the gunners.

Many cannon now have telescopes attached to them to assist the gunner in taking aim. When we reflect [Pg 47] that some of the guns can shoot five and six miles, the necessity of this will be apparent.

For storming fortifications there are special heavy siege guns. A modern fortress is something very different from a medieval or even from an early nineteenth century one. The old city walls, however solidly built, are now regarded as mere pleasant bits of antiquity, and in dozens of German towns have been razed to the ground and converted into rings or boulevards. So in the city of Cologne, in Ulm. In their place we now have groups of sunken guns, of protected batteries and of underground bomb-proof rooms with walls of reinforced concrete twelve and fifteen feet thick. Here and there armored turrets project a few feet above the ground. Some of the rooms are large enough for a whole company of infantry. The sunken guns can rise from their resting-places, fire their charges and sink back into their beds. Germany has twenty-eight land forts in all, of which nine are modern in every regard, and eight coast fortifications. Should the Russians enter Prussia we may hear much of the great forts at Königsberg, Graudenz and Thorn, at Danzig, Kulm and Marienburg, or of the Silesian forts Glogau, Neisse and Glatz, which played a part already in the wars of Frederick the Great. In the west, Metz and Strasburg have been immeasurably strengthened since they passed [Pg 48] into German hands, and Mainz, Coblenz, Cologne, Germersheim and Wesel are all formidable. To the south are Ulm and Ingolstadt, while in the north are Kustrin and Spandau, the latter but a few miles from Berlin. In Saxony is the Königstein, which, by reason of its natural position, is considered as impregnable as any fortress can be.

Whether the Germans will ever be forced back into these strong positions remains to be seen. Their policy is to keep to the offensive and spare their own land as much as possible. However, what strength of arms may fail to accomplish may be reserved for famine. With her commerce entirely cut off, the food supply for the nation at large will be but scanty, and of all the criticisms I have read on the German army during the last six months those on the commissariat department have been the most severe. A change in the whole administration was ordered a few months before the war broke out, but it has scarcely as yet had time to go into full effect.

Probably the greatest difference between ancient and modern warfare lies in the systematic use that is now made of balloons, air-ships, aeroplanes and kites, also of telegraphy, both fixed and wireless, and of the telephone. [Pg 49] I should add to these, automobiles, motor-trucks, motorcycles and simple bicycles.

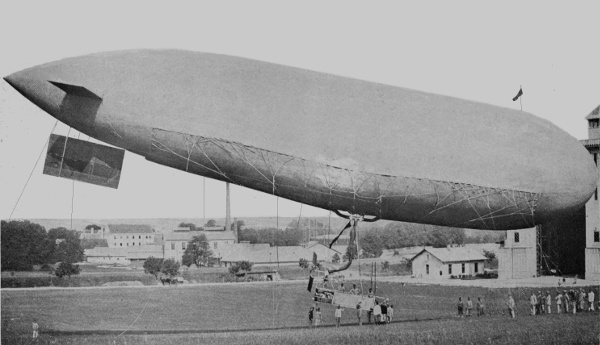

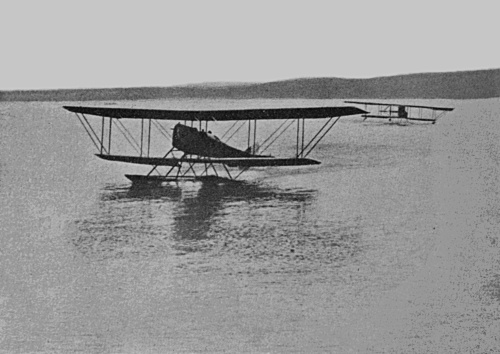

It may not be generally known that as far back as 1870 Germany attempted to make regular use of military balloons, and that two balloons and equipment were purchased from an English aeronaut. Several ascents were successfully made with a member of the general staff as passengers. Before Paris, however, it proved impossible to obtain the gas for inflation, and the whole balloon detachment was dissolved. Fourteen years later, in 1884, regular experiments regarding the taking of observations and the exchanging of signals were begun. Fifty thousand marks a year were set aside for the purpose, and so satisfactory were the results that in 1887 a regular balloon corps was organized with a major, a captain, three lieutenants and fifty non-commissioned officers and men. The discovery that the gas could be transported in steel cases in a greatly condensed form placed military ballooning on a much securer basis and the corps, greatly increased, has taken part in the yearly maneuvers since 1893. The captive balloon is still used as a sort of training-ship for recruits, but the free balloon has been practically superseded.

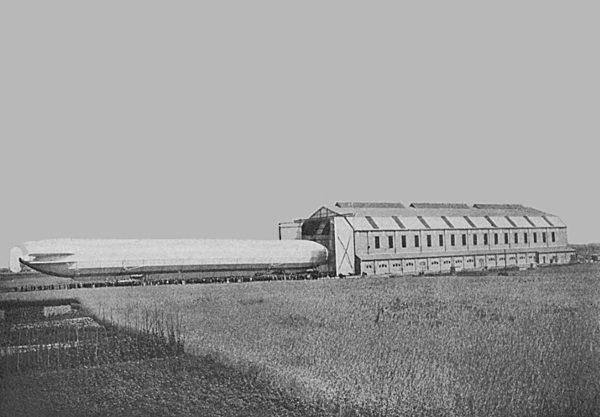

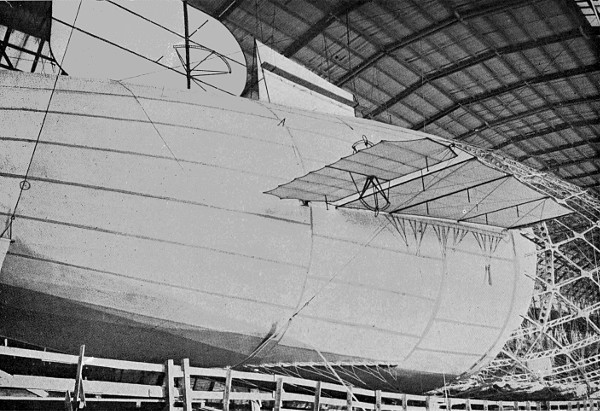

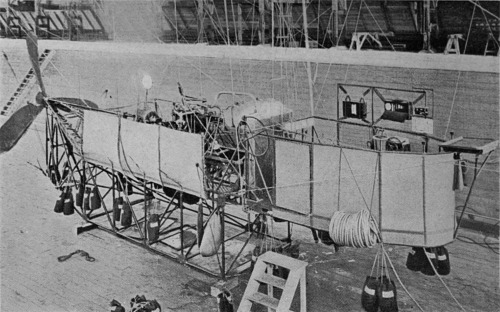

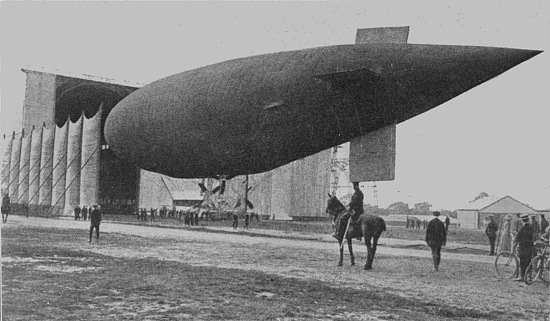

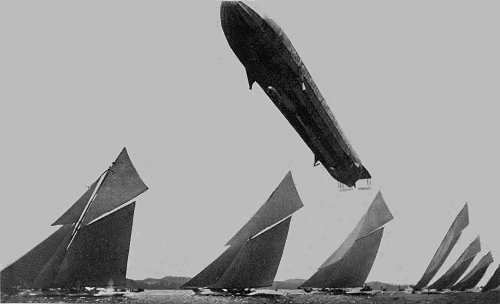

The first Zeppelin and the first Parseval air-ships were acquired in 1907 and, in spite of frequent accidents, have become as much a part of the armed forces as have batteries or battle-ships. There are now no less than five [Pg 50] air-ship battalions under the “general board of inspection of military, air and power transport matters.” The combined appropriations of Prussia, Bavaria and Württemberg for their air fleets in 1913 amounted to 70,000,000 marks. The recent ships, which are not necessarily confined to the Zeppelin type, though built along the same lines, are almost as large as ocean steamships. Last year the “L II” carried twenty-eight passengers on its trial trip. It exploded in mid-air and twenty-seven were killed, among them almost all of Germany’s chief military aeronautic experts. “L III,” which is nearly completed, will have a displacement of 32,000 cubic meters. The largest and newest ship at present, the Schütte-Lanz II, has a displacement of between 23,000 and 24,000 cubic meters, is run by four Maybach motors, each of one hundred seventy horse-power, and beats the previous Zeppelin record for speed (seventy-nine kilometers or forty-nine and three-eighths miles an hour) by six kilometers. No other country has any air-ship that can in any way compare with this. Under construction is the twenty-fifth Zeppelin, which will have a length of some four hundred fifty feet. All modern air-ships are equipped with wireless telegraphy having a range of about four hundred kilometers, and can carry light Gatling guns. They can lift a weight of some 16,000 [Pg 51] pounds and their cost is from 700,000 marks upward. The Germans have practised very industriously with their air-ships—only the other day a pilot completed his seven hundredth trip.

Whether in war the Zeppelins will come up to the expectations that have been formed of them remains of course to be seen. One can conceive of a single ship, under favorable conditions, throwing down enough explosives on an army to put it completely to rout. But the Zeppelin is a very big target and its motors make enough noise to warn a whole city of its approach. Russia and Germany herself now have many vertical guns for shooting air-ships. On the other hand, a Zeppelin can fly very high and can take refuge behind a cloud. Its chief objects of attack will doubtless be arsenals, dockyards, bridges and tunnel-mouths, though no fleet near the shore and no camp can feel quite safe from it in future. It would be so tempting to drop a shell in the midst of an enemy’s general staff and thus bring confusion into the whole guidance of the army!

The Zeppelin has dangerous enemies in the ordinary aeroplanes. A Frenchman has just vowed to run the nose of his “plane” into the first air-ship that appears over Paris. It is possible for the airman to shoot, too, at close range, or to fly above the monster and let down ropes with hooks that shall tear its sides. The new [Pg 52] ships, however, as I have said, can carry Gatling guns, and it is only a question of how they can best trail them on the enemy. The latest idea is a shaft that shall extend right through the body of the Zeppelin and come out on the upper surface. This arrangement has been tried on the newest Schütte-Lanz.

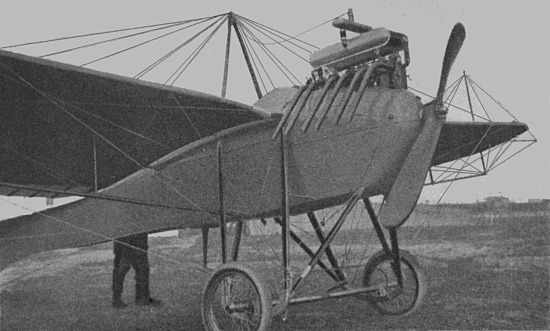

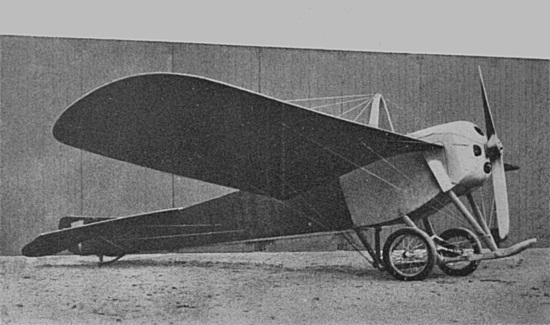

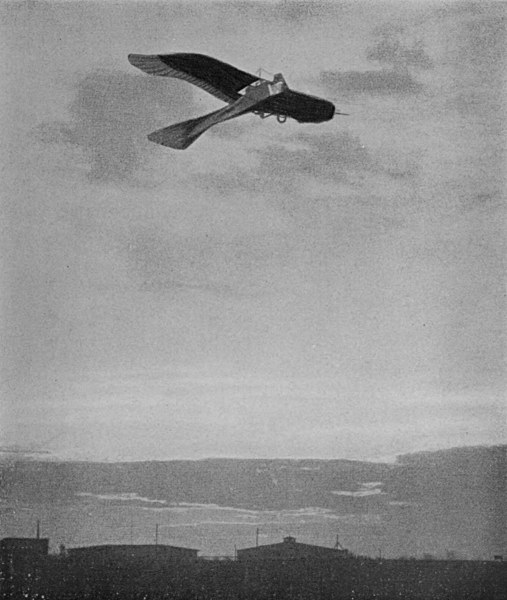

To the value of aeroplanes as instruments of war Germany awakened late. Not until after an exhibition of the American, Orville Wright, on the Templehof field near Berlin in 1910 was the matter taken very seriously. Now there are four flying battalions in the army with nearly fifteen hundred men, and it is believed that the machines are more solid and stable than those of the French. All records were broken by German machines during the past year, and the great Prince Henry races in May, though fatal accidents occurred, demonstrated very well about what may be expected from a troop of airmen in time of war. The conditions were extremely severe and the weather was not favorable, yet twelve out of twenty-nine starters achieved the final goal within the time limit.

The favorite machine in the German army is the Albatross-Taube, which looks quite warlike with its metal armor covering motor and all. Both monoplanes and biplanes are used. In case of war all aeroplanes, even the stock in trade of the manufacturer, are commandeered. These aeroplanes are easily transportable [Pg 53] by rail so that a number of them can be concentrated close to the scene of action. They will be used for scouting, carrying despatches and dropping bombs, and undoubtedly will have a great effect upon warfare. It is likely that more maneuvering will be done under the cover of night than formerly in order to escape the spying eyes of the birdmen, that false marches and maneuvers will be undertaken, that bivouac fires will be lighted in unoccupied places merely for the purpose of deceiving. It will be easy to conceal cannon by covering them with green boughs.

The German soldiers are already being trained for these new night operations which the aeroplane and air-ship will necessitate. They are taught to make their way by the moon and stars, to place their ears to the ground and catch and interpret sounds. It is possible for a finely trained ear to tell in the case of a passing horse whether it is running free or whether it is carrying a load, also to estimate the approximate number of a passing troop. Silent marching is practised, too, the greatest care being taken that the objects carried shall not clash or rattle. The enemy carries powerful electric search-lights against aeroplanes; a single apparatus requires several vehicles, each drawn by four horses. There must be a motor, a dynamo, a great mirror, a water wagon [Pg 54] and a portable tower thirty feet high. The infantry carries lighter apparatus, too, that can now be loaded on an automobile, the motor of which can be used for running the dynamo. Aeroplanes, too, now carry search-lights.

An enormous number of automobiles are used in the army. The German government has a special arrangement with motor-truck owners (the same is done with steamship companies) by which it pays a subsidy for new trucks on the understanding that they shall be at its disposal in time of need. It has been estimated that nine motor-wagons can replace one hundred thirty-nine horses and will need thirty instead of one hundred two men. Such a wagon will carry easily four tons of baggage.

With all the technical aids and inventions, however, the decisive factor in a war remains the men and more especially the officers.

I recently overheard a well-known Boston woman teacher holding forth with the positiveness of complete conviction on the subject of the German officer and commiserating him on the life of idleness circumstances forced him to lead “except, of course, during the three or four hours a day when he is obliged to exercise.” The remark was addressed to a distinguished Harvard [Pg 55] professor—anti-military, however, to the core—who had no contradiction to offer. I should have marked both of these great people zero for flat ignorance of the subject had I had them in a class. The German officer, I grant, may occasionally seem as idle and as frivolous as the son of a new American millionaire: the only difference would be that the American conceals his idleness under a show of industriousness, sending telegrams when he has nothing else to do, while the German conceals the fact that he has been up since four in the morning training a mass of raw recruits, that he has spent several hours at the Kriegsakademie studying languages, geography, political economy and the like and that he has as a permanent job some important problem in tactics to work out. Those who know the methods of the Prussian government could never accuse it of giving its employees too little work. A list is kept of all officers in which their industry, their interest in their work and their general good conduct is noted. The ideal that is kept before them may not be exactly our ideal, but it is a wonderful one of knightly virtue all the same. The man may never forget that he is a leader of men; he must grip his standard of honor, such as it is, like grim death and be willing unhesitatingly to lay down his life for it. If he flinch or falter in physical encounter or in any way is “guilty of conduct unbecoming an officer” he has to [Pg 56] resign his position. He has to conform not only to the rule of his superiors but also to the code of his fellow officers. There are things in that code that one would like not to see there and one misses much that might well be included, but to down the profession as a sinecure “except, of course, during the three or four hours a day” is the purest folly.

And peace-time is the mere waiting-period, the period of training for the real work. In war-time the fate of the whole country hangs on the officer. An Italian, Mangiarotti, recently inquired of some two thousand soldiers who had just taken part in the African campaign regarding their sensations when facing the enemy. “The great ideals of God, king and fatherland,” he writes, “incorporate themselves in one single personality, the officer.” The lieutenant who does his duty in the firing line is an absolute hero to his men. But only real superiority of mind and body can keep him at this height.

There are more than thirty thousand officers in the regular standing army, the great majority of them belonging to the nobility, who feel that they have a hereditary right to these positions. I am inclined to think that this feeling of caste will not be disadvantageous in war. The military career from youth up has been the one serious object and occupation in life. The memory [Pg 57] of Jena has been preventative of pride and an incentive to hard work. The habit of commanding gained as lord of the manor—as Herr Graf or as Herr Baron—will not be useless in the field.