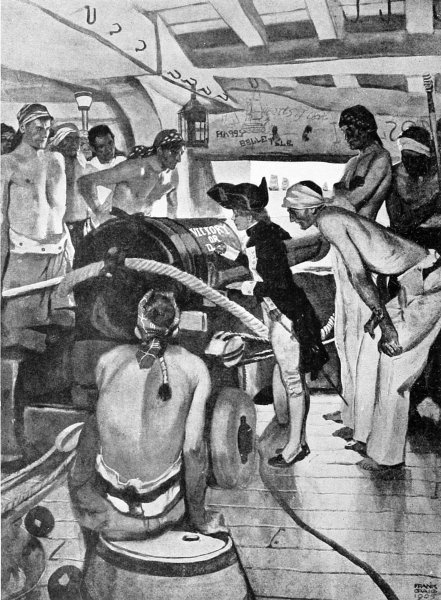

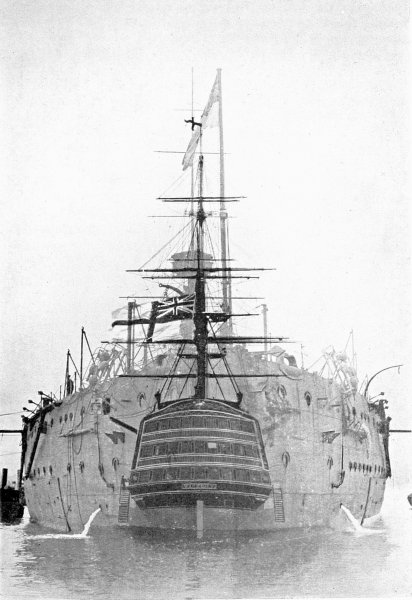

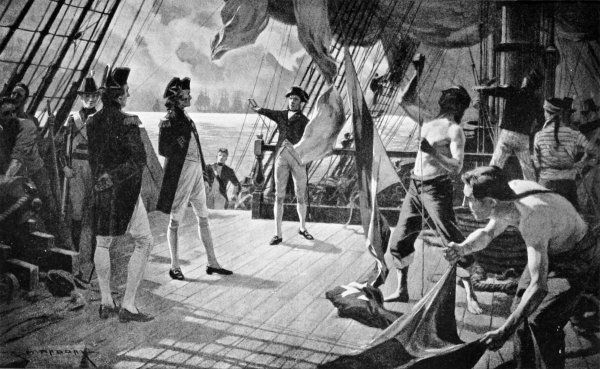

The “Belleisle” went into action at Trafalgar with the words “Victory or Death” chalked on her guns

Frank Craig, from a sketch by C. W. Cole

Fr.

Uniform with this Volume

THE STORY OF NAPOLEON

By Harold F. B. Wheeler, F.R.Hist.S. With 16 full-page Illustrations.

FAMOUS VOYAGES OF THE

GREAT DISCOVERERS

By Eric Wood. With 16 full-page Illustrations.

THE STORY OF THE CRUSADES

By E. M. Wilmot-Buxton, F.R.Hist.S. With 16 full-page Illustrations by M. Meredith Williams.

STORIES OF THE

SCOTTISH BORDER

By Mr and Mrs William Platt. With 16 full-page Illustrations by M. Meredith Williams.

The “Belleisle” went into action at Trafalgar with the words “Victory or Death” chalked on her guns

Frank Craig, from a sketch by C. W. Cole

Fr.

BY

Harold F. B. Wheeler F.R.Hist.S.

MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

JOINT-AUTHOR OF

‘NAPOLEON AND THE INVASION OF ENGLAND’ AND

‘THE WAR IN WEXFORD 1798’

AUTHOR OF

‘THE MIND OF NAPOLEON’ ‘THE BOYS’ NAPOLEON’ AND

‘THE MAXIMS OF NAPOLEON’

‘He is the only man who has ever lived

who, by universal consent, is without a peer’

ADMIRAL SIR CYPRIAN BRIDGE G.C.B.

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Printed by Turnbull & Spears, Edinburgh

DEDICATED TO

MY FATHER AND MOTHER

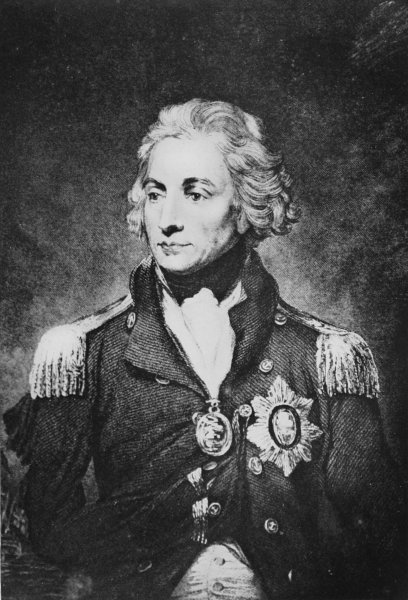

The career of the little one-eyed, one-armed man who frustrated Napoleon’s ambitious maritime plans for the subjugation of England, who is to sailors what Napoleon is to soldiers, who represented in his person all that sea power meant when the very existence of our forefathers was threatened in the latter days of the eighteenth century and the first half-decade of its successor, must ever appeal to those for whom Great Britain means something more than a splash of red on a coloured map.

I do not wish to suggest that his fame is insular. On the contrary, it is universal. Other lands and other peoples share in our admiration of him. We must not forget that it was an American naval officer, Admiral Mahan, who first gave us a really great book about this truly great man. In his “Life of Nelson,” we have the hero’s career reviewed by an expert whose knowledge of tactics has not blinded him to the more romantic aspects of Nelson’s forty-seven years of life. Before its appearance readers were dependent upon the facts and fancies of the biography by Clarke and McArthur, the “Memoirs” of Pettigrew, or the stirring but often inaccurate pictures of Southey. The seven substantial tomes of “Nelson’s Letters and Despatches,” edited with indefatigable industry by Sir Harris Nicolas, were not compiled for the general public, although they have furnished much material for later historians and must necessarily be the foundation of every modern book on Nelson.

On our own side of the Atlantic there is no more8 eminent authority than Sir J. Knox Laughton, Litt.D., Professor of Modern History at King’s College, London. He has not only epitomised Nicolas’s work, but added to our knowledge by his excellent “Nelson” (English Men of Action Series), “Nelson and his Companions in Arms,” and “From Howard to Nelson.” His numerous miscellaneous contributions to the subject are also of great interest to the serious student.

Although there is no Nelson cult like that which is associated with the memory of Napoleon, England’s great sailor has inspired a considerable literature, as even the shelves of my own library bear witness. There are works on his career as a whole, the campaigns associated with his name, his relations with Lady Hamilton, and so on. The only excuse I can offer for adding to the list is, I hope, a valid one. It seems to me that Nelson’s life, told in his own words as much as possible, would specially appeal to the young, and there is, so far as I am aware, no book which does this in the simple manner which I deem to be necessary. For help in carrying out my plan of writing a volume of the kind indicated I am particularly indebted to Nicolas’s “Letters” and Prof. Sir J. Knox Laughton’s edition of them.

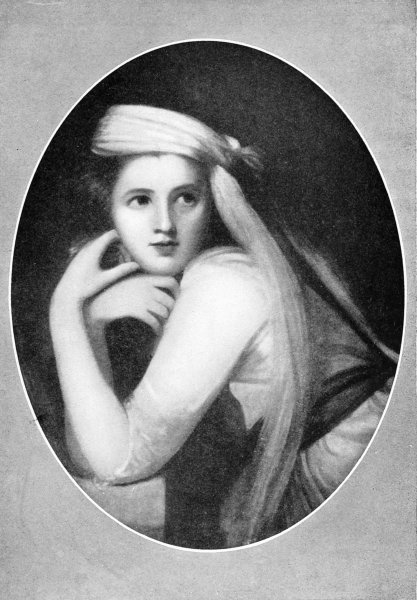

For good or evil the name of Emma, Lady Hamilton, is inextricably associated with that of Nelson. Many and varied have been the attempts to whitewash the character of her whom he regarded as “one of the very best women in the world.” While it is difficult to associate the possessor of the beauty which appealed with such irresistible force to such painters as Romney, Reynolds, Lawrence, and Madame Vigée Le Brun, with “a most inherent baseness,” it is an indisputable fact that she exercised an adverse influence on Nelson’s career. Her humble origin, her loveliness, her poses, her attempts at statecraft, above all, her connection with the great sailor, have made her the subject of almost innumerable volumes. For those who wish to9 read an impartial study I would recommend Mr Walter Sichel’s “Emma, Lady Hamilton.”

Nelson’s written communications are not studied literary efforts, but spontaneous expressions of his inmost thoughts. For these reasons they are of inestimable value in an attempt to sum up his life and aims. The kindest of men, he sometimes chose to mix vitriol with his ink. He wrote what he meant, and it was always very much to the point. Less eminent folk have sometimes disguised what they thought and written what they imagined would please. Such was never Nelson’s way.

“This high man with a great thing to pursue,”1 was never a trifler. He recognised the importance of a supreme navy and the supreme importance of its personnel. He watched the health of his men as a loving mother watches that of her children. Proof of this is furnished in a Report of the Physician to the Fleet, dated the 14th August 1805.2 In it Dr Leonard Gillespie says that “the high state of health” was “unexampled perhaps in any fleet or squadron heretofore employed on a foreign station.” He attributes this to such causes as the attention paid to the victualling and purveying for the ships; a sane system of heating and ventilation; lack of idleness and intemperance, due to “the constant activity and motion in which the fleet was preserved”; the promotion of cheerfulness by means of music, dancing, and theatrical amusements; comfortable accommodation of the sick; and by the serving of Peruvian bark, mixed in wines or spirits, to men “employed on the service of wooding and watering,” which obviated any ill effects.

Nelson was quite able to “stand on his dignity,” to use a colloquial and comprehensive phrase, and several instances will be discovered by the reader as he10 peruses the following pages, but it is quite wrong to think that he was in the least a martinet. For instance, during the trying period when he was hungering for the French fleet to leave Toulon, he wrote to an officer: “We must all in our several stations exert ourselves to the utmost, and not be nonsensical in saying, ‘I have an order for this, that, or the other,’ if the king’s service clearly marks what ought to be done.” Everyone has heard how Nelson referred to his captains and himself as “a band of brothers.” You have only to turn to the memoirs of these gallant officers to learn the truthfulness of this remark. They loved him: that is the only term that exactly meets the case.

What of the humbler men who worked the ships? Read the following, which was sent home by a rough but large-hearted sailor of the Royal Sovereign, Collingwood’s flagship at Trafalgar, when he heard that the Master Mariner lay cold in the gloomy cockpit of the Victory: “Our dear Admiral is killed, so we have paid pretty sharply for licking ’em. I never set eyes on him, for which I am both sorry and glad; for to be sure I should like to have seen him—but then, all the men in our ship who have seen him are such soft toads, they have done nothing but blast their eyes and cry ever since he was killed. God bless you! Chaps that fought like the Devil sit down and cry like a wench.”

This spontaneous and perhaps unconscious tribute is worth more than the encomiums of all modern historians and biographers put together.

In studying the life of one who has played a leading rôle on the stage of history there are always a number of subsidiary authorities which will repay perusal. The memoirs of the men who were associated with him, of those of his contemporaries who occupied official or high social positions, even of much humbler folk who have transferred their opinions to paper or had it done for them, are oftentimes extremely important. To print a bibliography of the works of this kind which I have consulted would be inadvisable in such a volume11 as this, necessarily limited as it is to a certain number of pages. I need only say that the nooks and crannies have been explored besides the main thoroughfare.

In the Foreword to my companion volume upon Napoleon, I endeavoured to show that periods of history are merely make-believe divisions for purposes of clearness and reference. I wish to still further emphasise this extremely important point, because I find that one of our most cherished delusions is that history is largely a matter of dates. Nothing of the kind! Those who think thus are confusing history with chronology—in other words, mistaking one of the eyes for the whole body. Dates are merely useful devices similar to the numerals on the dial of a clock, which enable us to know the hour of the day without abstruse calculations. The figures 1805 help us to memorise a certain concrete event, such as the battle of Trafalgar, but they do not tell us anything of the origin of that event any more than a clock defines the meaning of time.

The age in which Nelson lived was not conspicuous for its morals. This is a factor which must be taken into consideration when we attempt to sum up his character. The standards of 1911 are scarcely the standards of over a century ago. The code of virtue varies, although the law does not. The grave of Nelson’s moral reputation was dug in Sicily, where he had every provocation, but he certainly never attempted to extricate himself from the pit into which he had fallen. “De mortuis nil nisi bonum” is a good maxim for the Gospel of Things as they Ought to Be, but cannot apply to the Testament of Things as they Were. The vanity of both Nelson and Lady Hamilton contributed to their downfall, the sordid story of which is necessarily referred to in later pages of this work. I am of opinion that the lack of sympathy shown to the Admiral, particularly during Pitt’s administrations, was largely due to Court influence. George III. was a man of frigid austerity, and Nelson’s private life was too well12 known for the King to countenance it by showing him favours. He recognised the value of the man’s services, but preferred to take as little notice as possible of the man himself. In this he was unjust.

Although Nelson hated the French so vehemently, I cannot help thinking, after a prolonged study of his career, that he had many of their characteristics. His vivacity, his imagination, his moods tend to confirm me in this. A less typical specimen of John Bull would be difficult to find.

A word or two concerning Nelson’s crowning victory and then I must bring my lengthy introduction to a conclusion. It has a literature all its own. A wordy warfare, which was indulged in the correspondence columns of the Times from July to October 1905, made one almost believe that it is easier to fight a battle than to describe it accurately. To use Prof. Sir J. Knox Laughton’s terse phrase, “the difficulty is that the traditional account of the battle differs, in an important detail, from the prearranged plan.” The late Admiral Colomb held a brief for the theory that the two columns of the British fleet moved in line abreast, or in line of bearing, as against the old supposition of two columns, line ahead. In this contention, he is supported by Admiral Sir Cyprian Bridge, G.C.B., whose ideas are set forth in a pamphlet issued by the Navy Records Society, an institution which is doing excellent work in rescuing historical documents relating to the service from ill-deserved oblivion. To add further to the discussion would probably serve no useful purpose. The second volume of “Logs of the Great Sea-fights (1794–1805),” and “Fighting Instructions, 1530–1816,” both published by the Society already mentioned, will be found extremely useful to those who would pursue the subject in detail.

Tennyson’s “Mighty Seaman” has been apotheosised in poetry as well as in prose,

13 to quote Meredith’s superb lines. Wordsworth, Scott, Rossetti, Henley, Swinburne, Newbolt and others have said noble things of the Man of Duty, while Nelson looms large in Thomas Hardy’s magnificent epic, “The Dynasts.” No one who has read it is likely to forget:

| PAGE | ||

| Foreword | 7 | |

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | Boyhood and First Years at Sea | 19 |

| II. | A Hero in the Making | 29 |

| III. | Pleasure in France and Work in the West Indies | 42 |

| IV. | The Beginning of the Great War | 52 |

| V. | “I Wish to be an Admiral” | 66 |

| VI. | Nelson’s First Great Fight: The Battle of Cape St Vincent | 74 |

| VII. | From Triumph to Failure: The Attempt on Santa Cruz | 87 |

| VIII. | In Chase of the French Fleet | 96 |

| IX. | The Battle of the Nile | 102 |

| X. | The Neapolitan Court and Lady Hamilton | 112 |

| XI. | The Neapolitan Rebels and their French Allies | 125 |

| XII. | Nelson in Temporary Command | 139 |

| XIII. | Disobedience to Orders | 148 |

| XIV. | The Campaign of the Baltic | 162 |

| XV. | The Battle of Copenhagen | 171 |

| XVI. | The Threatened Invasion of England | 182 |

| XVII. | The Vigil off Toulon | 19516 |

| XVIII. | Twelve weary Months in the Mediterranean | 207 |

| XIX. | The Crisis | 215 |

| XX. | Nelson’s Last Command | 225 |

| XXI. | The Rout in Trafalgar Bay | 232 |

| PAGE | |||

| The “Belleisle” at Trafalgar | (Frank Craig) | Frontispiece | |

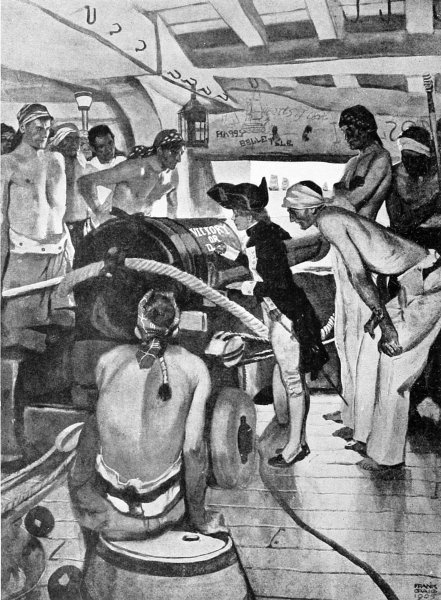

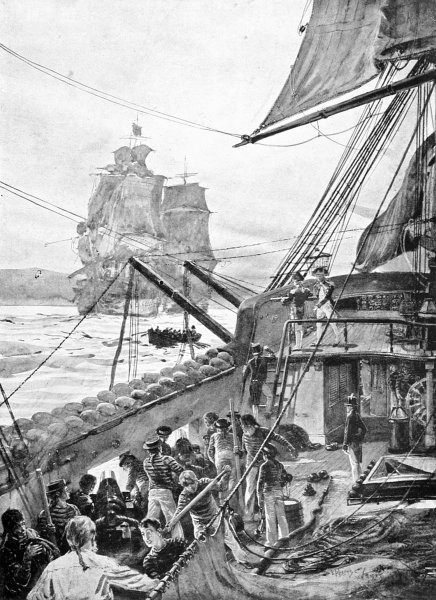

| Nelson and the Bear | (Stephen Reid) | 26 | |

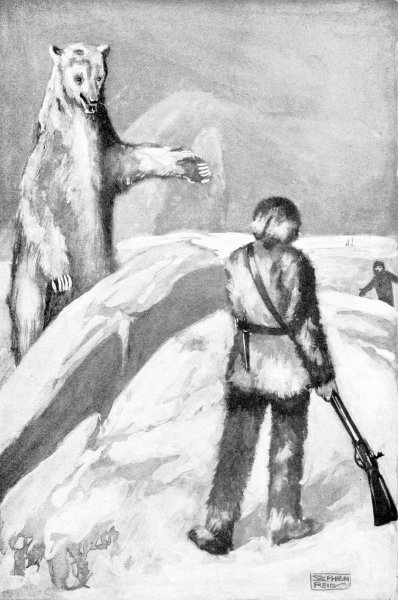

| “He had the ill-luck to fall upon hard stones” | (Stephen Reid) | 44 | |

| Comparison of the “Victory” with the “Hercules” | 64 | ||

| “I’ll not lose Hardy!” | (H. C. Seppings Wright) | 76 | |

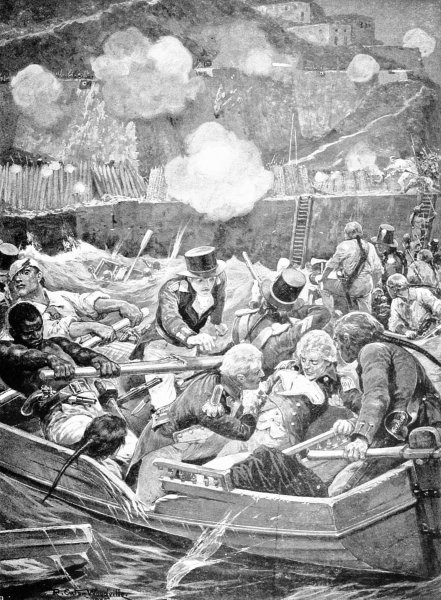

| Nelson Wounded at Santa Cruz | (R. Caton Woodville) | 90 | |

| “The Flame that lit the Battle’s Wreck” | (Chas. Dixon, R.I.) | 106 | |

| The Execution of Caracciolo | (Stephen Reid) | 136 | |

| Lady Hamilton | (Romney) | 156 | |

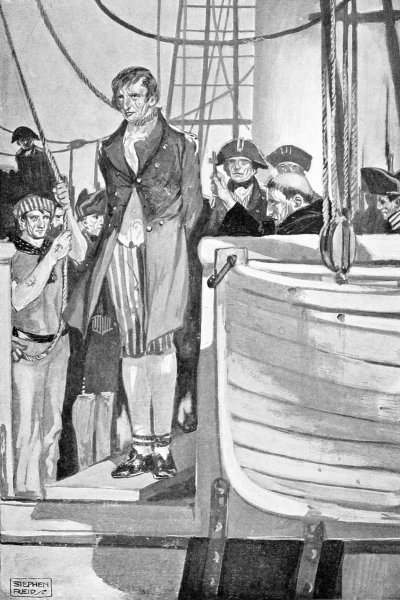

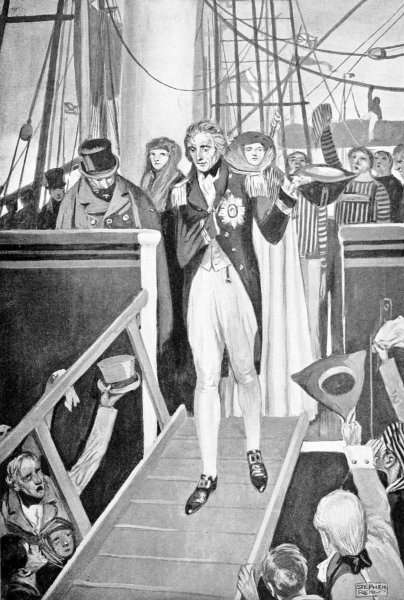

| Nelson Landing at Yarmouth | (Stephen Reid) | 160 | |

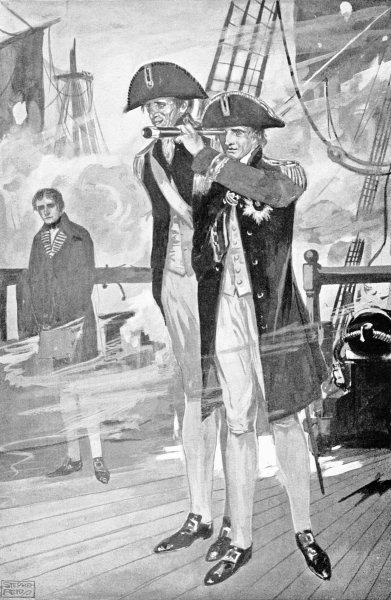

| “I really do not see the Signal” | (Stephen Reid) | 172 | |

| Lord Nelson | 192 | ||

| Hoisting the Famous Signal | (C. M. Padday) | 234 | |

| Nelson and Collingwood Cutting the Enemy’s Lines | (H. C. Seppings Wright) | 238 | |

| The Battle of Trafalgar | (W. L. Wyllie, A.R.A.) | 242 | |

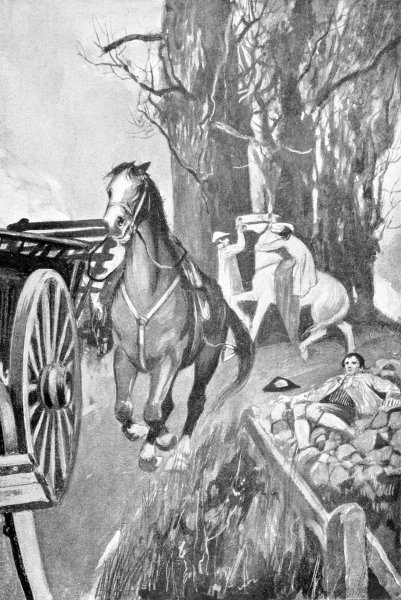

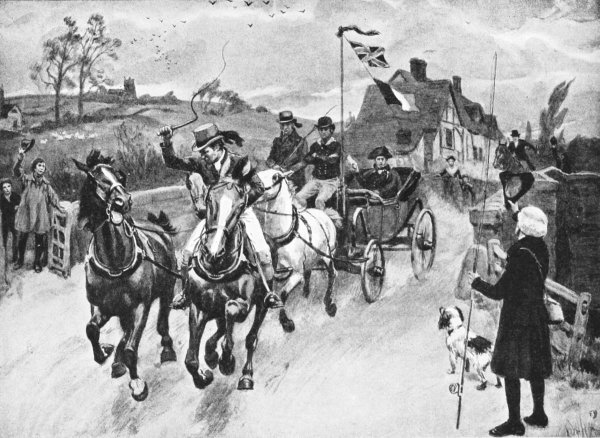

| How the News of Trafalgar was Carried to London | (Frank Dadd, R.I.) | 246 | |

The headpiece, a sketch by Mr W. L. Wyllie, R.A., is printed by permission of the Art Union of London, 112 Strand.

Thus3 runs one of the verses of a song dear to the British sailor for many a long year. Nelson, dead over a century, is still revered in the King’s Navy. To the landsman there is no more popular hero. The Victory, riding at anchor in the placid waters of the Solent and in view of the cobble-covered sally port through which the Hero walked to his barge, still flies an admiral’s flag. One of the most modern battleships in the service bears his name, the most famous of London’s many columns is crowned by his effigy. Canvas sails have given place to steam turbines, the days of oak and hemp are gone, but the memory of “the greatest sea captain of all time” is at once an incentive and an inspiration to every true patriot. His ashes lie in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral; his spirit lives in the nation for whom he sacrificed his life. Perhaps we should not be far wrong in venturing the apparent paradox that the further we recede from20 his life and times the more clearly we understand his consummate genius and appreciate the value of his achievements. There is no sunset, only an added glory with the passing of the years.

Horatio Nelson was born in the quaint old parsonage house of Burnham Thorpe, a Norfolk Sleepy Hollow, on the 29th September 1758. His father, the Rev. Edmund Nelson, M.A., was rector of the parish, and as a clergyman was following the profession of his immediate ancestor. His mother, Catherine Nelson, was the daughter of the Rev. Dr Maurice Suckling, Rector of Wooton, Norfolk, Prebendary of Westminster, and grandnephew of Sir John Suckling, whose name is known to all students of English literature and of history. Galfridus Walpole, another of Mrs Nelson’s relatives, had displayed considerable bravery in an engagement with the French in Vado Bay in 1711. It was through Captain Maurice Suckling, Nelson’s uncle, that the young son of the parsonage eventually entered the Navy. In addition, his mother was a grandniece of Sir Robert Walpole, the famous Whig statesman, and could therefore boast a distinguished lineage.

Horatio was the sixth child of a constantly growing family, and early caused anxiety owing to his delicate constitution. In later years his letters and despatches teem with reference to his ill-health, which was accentuated, of course, by injuries which he received in the performance of his duty. However, he breathed deeply of the North Sea air which wafted through his native village, was tenderly cared for by loving parents, and became sufficiently robust to be sent to the High School at Norwich. The venerable building, endowed by Edward VI., stands within the cathedral precincts. It is now fronted by a statue of its illustrious scholar. Later he attended a school at North Walsham, now one of the yachting centres of the Norfolk Broads, where the curious will find a brick on which the letters H. N. are scratched.

21 It is somewhat remarkable that so few boys who become great men ever attract sufficient notice during their early scholastic career for their comrades to remember anecdotes about them likely to be of assistance to the biographer. Few anecdotes of Nelson in his younger days have been handed down to posterity, but the following have probably some basis of fact.

When quite a small boy he stayed for a time with his grandmother. On one occasion he did not return at the accustomed dinner-hour, thereby causing the good dame considerable anxiety, especially as gipsies were in the neighbourhood and kidnapping was by no means unknown. He was eventually found seated on the banks of a brook examining with considerable interest a number of birds’ eggs he had secured in company with a chum. “I wonder, child, that fear did not drive you home!” the old lady said when the missing Horatio was restored to her. “Fear, grandmamma!” he replied in a tone of disgust, “I never saw fear—what is it?”

There you have the secret of Nelson’s life summed up in a single pregnant sentence. His total lack of fear carried him through many a trying ordeal, enabled him at times to defy the command of a senior officer when he was convinced that his own plan of operations was better, and helped him to bear the heat and burden of the day when his physical energy was almost exhausted.

On another occasion he was “dared” by some companions to visit the graveyard unattended at night. As a token of good faith he was to bring a twig from a certain yew tree at the south-west corner of All Saints’ Church. The uncanny task was successfully accomplished. From thenceforth he was a hero, as he deserved to be.

A further instance of Nelson’s early lack of fear is afforded us. His master at North Walsham was particularly proud of a certain pear-tree, and his scholars were equally covetous of the delicious fruit which it22 bore. Each preferred the other in the task of picking any of the pears because of the speedy retribution which they knew would follow. One night Horatio volunteered the task. His friends tied several sheets together and lowered him from the dormitory to the garden. He swarmed up the tree, secured the forbidden and therefore much prized fruit, and was hauled up again. On distributing the booty, he justified his action in his own mind by assuring the recipients that he had only taken the pears “because every other boy was afraid.” Few hours passed before the schoolmaster found that his tree had been plundered. It redounds to the credit of the boys that they refused to “split” on their comrade, although it is said that a tempting reward was offered for the discovery of the culprit.

One winter morning Horatio and his brother William set out for school on their ponies. They had not gone very far before they found the snow so deep as to be almost impassable. They returned to the Parsonage and told their father of the great drifts. He persuaded them to try again, adding that he left it to their honour not to turn back unless it was absolutely necessary.

The snow was falling in heavy flakes when they made their second attempt. William’s heart soon failed him. He suggested that they had sufficient reason to return. Horatio was as adamant. “Father left it to our honour. We must go forward,” he replied, and in due course they arrived at the school.

William, who was the elder by seventeen months, had the greatest affection and esteem for his brother. In later years he was his constant correspondent, and after Horatio’s death he was created Earl Nelson of Trafalgar. Like his father and grandfather, William became a clergyman, in which profession he rose to the dignity of Prebendary and Vice Dean of Canterbury.

23 It was during the Christmas vacation of 1770 that Nelson casually picked up a newspaper and read of Captain Maurice Suckling’s appointment to the Raisonnable, a ship of sixty-four guns. The announcement seems to have had an instant effect upon Horatio. “Oh, William,” he exclaimed to his brother, who was standing near, “do, do write to father, and tell him that I want to go to sea with uncle!”

The Rev. Edmund Nelson was staying at Bath owing to ill-health. When he received his son’s letter he was inclined to dismiss the proposition as a mere boyish whim. On thinking it over a little more carefully he decided that perhaps the youngster really desired what he asked, and he accordingly consulted his brother-in-law on the matter. The officer replied in the easy-going manner of sailors, “Well, let him come and have his head knocked off by the first cannon-ball—that will provide for him.” He was afraid Horatio would never be able to stand the rough-and-ready life, but he had the good sense to know that there is nothing like putting a theory to a practical test.

The Navy was not then the skilfully-organised machine it has since become. It was one of the privileges of a captain that he might take two or three lads to sea with him as midshipmen or to serve in some subordinate position. Captain Suckling accordingly sent for Horatio, and we find his name on the ship’s books under date of the 1st January 1771. The Raisonnable was then anchored in the Medway.

The lad’s father accompanied his twelve-year-old son as far as London, put him into the Chatham stagecoach, and then left him to his own resources. It was neither a pleasant journey in the rambling old carriage, nor were the streets of Chatham particularly inviting when he set foot in them. Nobody met the adventurer, and for some time he wandered about until he met an officer who directed him to the ship which was to be his temporary home. When he was safely24 on board it was to find that his uncle had not arrived.4

The Raisonnable was one of the vessels commissioned when hostilities between Great Britain and Spain appeared imminent owing to trouble respecting the Falkland Islands, a group in the South Atlantic. In 1770 Spain had insulted the British colonists there by compelling the garrison at Fort Egmont to lower their flag. The matter was settled amicably, for the all-sufficient reason that Spain did not feel strong enough to come to blows with Great Britain unless she was assisted by France, and as the support of that Power was not forthcoming, she climbed down. Consequently Nelson was not introduced to the horrors of naval warfare at this early stage, and the cannon-ball which his uncle prophesied would knock off the lad’s head did not leave the cannon’s mouth.

When the Raisonnable was paid off Captain Suckling was given command of the guard-ship Triumph (74), stationed in the Medway, and recognising that no good could come to his nephew by staying on such a vessel, he secured a position for him shortly afterwards in a merchant ship bound for the West Indies. This was not a difficult matter, because the Master was John Rathbone, who had served with Suckling on the Dreadnought during part of the Seven Years’ War, that great struggle in which Louis XV. of France had been forced to cede Canada to Great Britain.

Nelson seems to have enjoyed the experience. In a sketch of his life, which he wrote several years later for the Naval Chronicle, he says:

“From this voyage I returned to the Triumph at Chatham in July 1772; and, if I did not improve in my education, I returned a practical seaman, with a horror of the Royal Navy, and with a saying, then25 constant with the seamen, ‘Aft the most honour, forward the better man!’ It was many weeks before I got in the least reconciled to a man-of-war, so deep was the prejudice rooted; and what pains were taken to instil this erroneous principle in a young mind! However, as my ambition was to be a seaman, it was always held out as a reward, that if I attended well to my navigation, I should go in the cutter and decked longboat, which was attached to the commanding officer’s ship at Chatham. Thus by degrees I became a good pilot, for vessels of that description, from Chatham to the Tower of London, down the Swin, and to the North Foreland; and confident of myself amongst rocks and sands, which has many times since been of the very greatest comfort to me. In this way I was trained, till the expedition towards the North Pole was fitted out; when, although no boys were allowed to go in the ships (as of no use), yet nothing could prevent my using every interest to go with Captain Lutwidge in the Carcass; and, as I fancied I was to fill a man’s place, I begged I might be his coxswain: which, finding my ardent desire for going with him, Captain Lutwidge complied with, and has continued the strictest friendship to this moment. Lord Mulgrave, who I then first knew, continued his kindest friendship and regard to the last moment of his life. When the boats were fitted out to quit the two ships blocked up in the ice, I exerted myself to have the command of a four-oared cutter raised upon, which was given me, with twelve men; and I prided myself in fancying I could navigate her better than any other boat in the ship.”

In this cold, matter-of-fact way, Nelson dismisses a phase of his life fraught with peril and adventure. When the majority, if not all, of his former school-fellows were reading of the doings of gallant seamen and brave soldiers he was undergoing actual experiences. The expedition in question had been suggested by the Royal Society, and was commanded by Captain26 Constantine John Phipps, eldest son of Lord Mulgrave. The Racehorse and Carcass, heavy ships known as bombs because they mounted one or more mortars for use in bombardments when on ordinary service, sailed from the Nore on the 4th June 1773. All went well until the 31st July, when the ice closed upon the vessels, and further progress became impossible.

Nelson and the Bear

Stephen Reid

“The following day,” says Colonel J. M. Tucker in his “Life and Naval Memoirs of Lord Nelson,” “there was not the smallest opening, the ships were within less than two lengths of each other. The ice, which the day before had been flat, and almost level with the water’s edge, was now in many places forced higher than the mainyard by the pieces squeezing together. A day of thick fog followed; it was succeeded by clear weather; but the passage by which the ships had entered from the westward was closed, and no open water was in sight, either in that or any other quarter. By the pilot’s advice, the men were set to cut a passage and warp5 through the small openings to the westward. They sawed through pieces of ice twelve feet thick; and this labour continued the whole day, during which their utmost efforts did not move the ships above three hundred yards, while they were driven together, with the ice, far to the north-east and east by the current. Sometimes a field of several acres square would be lifted up between two larger islands, and incorporated with them; and thus these larger pieces continued to grow by cohesive aggregation. Another day passed, and there seemed no probability of getting the ships out, without a strong east or north-east wind.

“The season was far advanced, and every hour lessened the chance of extricating themselves. Young as he was, Nelson was appointed to command one of the boats which were sent out to explore a passage into the open water. It was the means of saving a boat belonging to the Racehorse from a singular but imminent danger. Some of the officers had fired at, and wounded,27 a walrus.... The wounded animal dived immediately, and brought up a number of its companions; and they all joined in an attack upon the boat. They wrested an oar from one of the men; and it was with the utmost difficulty that the crew could prevent them from staving or upsetting her, till the Carcass’s boat, under Nelson, came up. The walrusses, finding their enemies thus reinforced, dispersed.

“A short time after this occurrence, young Nelson exposed himself in a more daring manner. One night, during the mid-watch, he stole from the ship with one of his comrades, taking advantage of a rising fog, and set out over the ice in pursuit of a bear. Nelson, in high spirits, led the way over the frightful chasms in the ice, armed with a rusty musket, as was his companion. It was not, however, long before the adventurers were missed by those on board; and, as the fog had much increased, the anxiety of Captain Lutwidge and his officers for them was very great. Between three and four in the morning, the mist having nearly dispersed, the hunters were discovered at a considerable distance, attacking a large bear. The signal for their return was instantly made; but it was in vain that Nelson’s companion urged him to obey it. He was at this time divided by a rent in the ice from his shaggy antagonist, which probably saved his life; for the musket had flashed in the pan, and their ammunition was expended. ‘Never mind,’ exclaimed Horatio, ‘do but let me get a blow at this devil with the butt end of my musket, and we shall have him.’ His companion, finding that entreaty was in vain, left him, and regained the ship. The Captain, seeing the young adventurer’s danger, ordered a gun to be fired to terrify the enraged animal; this had the desired effect; but Nelson was obliged to return without his bear. Captain Lutwidge, though he could not but admire so daring a disposition, reprimanded him rather sternly for such rashness, and for conduct so unworthy of the situation he occupied; and desired to know what motive he28 could have for hunting a bear. ‘Sir,’ he replied, pouting his lip, as he was wont to do when agitated, ‘I wished to kill a bear, that I might carry its skin to my father.’”

Towards the middle of August the two ships were able to forge their way through the ice, although not without considerable difficulty, and duly sailed for home waters.

“True honour, I hope, predominates in my mind far above riches”

—Nelson.

We are fortunate in having an account of Nelson’s early career at sea penned by himself, otherwise the material at our disposal would be extremely scanty. The story of the next few years is therefore told in his own words. What it lacks in picturesqueness is made up for in authenticity:

“On our arrival in England,” he says, “and paid off, 15 October [1773], I found that a squadron was fitting out for the East Indies; and nothing less than such a distant voyage could in the least satisfy my desire of maritime knowledge: and I was placed in the Seahorse of 20 guns, with Captain Farmer, and watched in the foretop; from whence in time I was placed on the quarter-deck: having, in the time I was in this ship, visited almost every part of the East Indies, from Bengal to Bussorah. Ill-health induced Sir Edward Hughes, who had always shown me the greatest kindness, to send me to England in the Dolphin of 20 guns, with Captain James Pigot, whose kindness at that time saved my life. This ship was paid off at Woolwich on 24 September, 1776. On the 26th I received an order from Sir James Douglas, who commanded at Portsmouth, to act as lieutenant of the Worcester, 64, Captain Mark Robinson, who was ordered30 to Gibraltar with a convoy.6 In this ship I was at sea with convoys till 2 April, 1777, and in very bad weather. But although my age might have been a sufficient cause for not entrusting me with the charge of a watch, yet Captain Robinson used to say, ‘he felt as easy when I was upon deck, as any officer in the ship.’

“On [the 9th] April, 1777, I passed my examination as a lieutenant; and received my commission the next day, as second lieutenant of the Lowestoffe frigate of 32 guns, Captain (now Lieutenant-Governor of Greenwich Hospital) William Locker. In this ship I went to Jamaica; but even a frigate was not sufficiently active for my mind, and I got into a schooner, tender to the Lowestoffe. In this vessel I made myself a complete pilot for all the passages through the (Keys) Islands situated on the north side [of] Hispaniola. Whilst in this frigate, an event happened which presaged my character; and, as it conveys no dishonour to the officer alluded to, I shall relate it.

“Blowing a gale of wind, and very heavy sea, the frigate captured an American letter of marque.7 The first lieutenant was ordered to board her, which he did not, owing to the very high sea. On his return on board, the captain said, ‘Have I no officer in the ship who can board the prize?’ On which the master ran to the gangway, to get into the boat; when I stopped him, saying, ‘It is my turn now; and if I come back, it is yours.’ This little incident has often occurred to my mind; and I know it is my disposition, that difficulties and dangers do but increase my desire of attempting them.

“Sir Peter Parker, soon after his arrival at Jamaica, 1778, took me into his own flag-ship, the Bristol, as third lieutenant; from which I rose by succession to be first. Nothing particular happened whilst I was31 in this ship, which was actively employed off Cape François, being the commencement of the French war.”

A few words with reference to the hostilities mentioned are needed as explanation. The war between Great Britain and her colonists in North America, which culminated in the birth of a new World-Power, now known as the United States, had broken out in 1775, although the seeds of dissension had been sown much earlier. This unfortunate and disastrous quarrel had also embroiled “the mother of nations” in a strife with France and Spain, whose help the New Englanders secured in 1778 and 1779 respectively. In 1780 Holland became involved. The foolishness of not having sufficiently watched the doings of a potential enemy now became apparent. For several years “resolute Choiseul, the abrupt proud man” of Carlyle, had bent his energies on increasing the French navy, and when the Brest fleet of thirty-two sail-of-the-line, under Count D’Orvilliers, met the British fleet of thirty sail, under Vice-Admiral the Hon. A. Keppel, off Ushant on the 27th July 1778, the action was indecisive. In American waters Lord Howe hove in sight of the fleet under D’Estaing, the French commander having better ships and heavier metal, but while Howe was manœuvring to attack the enemy a storm parted the would-be contestants. Both suffered considerable damage by wind and not by shot as had been anticipated. Shortly afterwards Admiral Byron took over Howe’s command and endeavoured to come up with D’Estaing’s ships. Unfortunately the Frenchman had sailed to the West Indies, which “in this protracted contest,” to use the words of Admiral Mahan, was to be “the chief scene of naval hostilities....” “The West Indies is the Station for honour,” said Nelson sometime later. Froude, the historian, predicted that “If ever the naval exploits of this country are done into an epic poem—and since the Iliad there has been no subject better fitted for such treatment or better deserving it—the West Indies will be the scene of the most brilliant32 cantos.” We shall have occasion to refer to this great strategic point many times in these pages, especially in the great game of hide-and-seek between Napoleon’s captains and Nelson immediately preceding the Trafalgar campaign.8 The year 1778 was not a brilliant one in British naval annals, although it closed by Hotham and Barrington attacking D’Estaing off St Lucia and preventing him from landing more than half the troops intended for the subjugation of that island. As a consequence the force under Chevalier de Michaud surrendered, and St Lucia was won.

“On 8 December, 1778,” Nelson continues, “I was appointed commander of the Badger brig; and was first sent to protect the Mosquito shore, and the Bay of Honduras, from the depredations of the American privateers. Whilst on this service, I gained so much the affections of the settlers, that they unanimously voted me their thanks, and expressed their regret on my leaving them; entrusting to me to describe to Sir Peter Parker and Sir John Dalling their situation, should a war with Spain break out. Whilst I commanded this brig, H.M.S. Glasgow, Captain Thomas Lloyd, came into Montego Bay, Jamaica, where the Badger was laying: in two hours afterwards she took fire by a cask of rum; and Captain Lloyd will tell you, that it was owing to my exertions, joined to his, that her whole crew were rescued from the flames.”

This stirring incident merits a more detailed description than the bare facts which Nelson chose to set forth. The crew was in a panic when he and his men set foot on the deck of the doomed vessel, and by almost superhuman exertions managed to throw all the gunpowder in the magazine overboard before the flames reached it. He also ordered that the loaded cannon should be directed upward, so that when they exploded, owing to the intense heat, no damage would result. Thus early in his career did Nelson show that he was not at a loss when the unusual and unexpected33 happened. In a letter to Captain Locker, who was ill, the young officer describes the fate of the Glasgow as “a most shocking sight; and had it happened half an hour later, in all probability a great many people would have been lost.” He also notes that the company of the derelict were falling ill very fast owing to the constant tropical rains to which the men were exposed, there being no room for them on the Badger.

“On 11 June, 1779,” Nelson continues, “I was made post into the Hinchinbrook. When, being at sea, and Count d’Estaing arriving at Hispaniola (Haïti) with a very large fleet and army from Martinique, an attack on Jamaica was expected. In this critical state, I was by both admiral and general entrusted with the command of the batteries at Port Royal; and I need not say, as the defence of this place was the key to the port of the whole naval force, the town of Kingston, and Spanish Town, it was the most important post in the whole island.”

D’Estaing’s fleet consisted of twenty-two sail-of-the-line, excluding transports and privateers which had attached themselves to him, and it was commonly reported that he had no fewer than 20,000 troops on board. Nelson, as noted above, was now Post-Captain, and although he had no occasion to prove his ability as a commander of land batteries, he seems to have taken kindly to the situation. In a letter to his friend Captain Parker, dated the 12th August 1779, he states that “Jamaica is turned upside down since you left it,” and furnishes particulars of the measures made for the defence of the island. “You must not be surprised to hear of my learning to speak French,” he remarks as a humorous aside.

To help to achieve the downfall of the wily d’Estaing was not to fall to Nelson’s lot. That worthy hastened to Savannah, which was attacked by troops under General Lincoln and himself. They were routed by the British lines, whereupon d’Estaing sailed away.

Great Britain was now at war with Spain, which had34 thrown in her lot with France, and was soon to feel the effects of the Armed Neutrality, consisting of Russia, Sweden, Denmark, Holland, and Prussia. They resented England’s right to search neutral ships, with the result that the latter Power could not retain her supremacy at sea, a cause of Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown and the consequent loss of the American Colonies. In January 1780 it was resolved to make an attempt to take the important post of Fort San Juan, on the river of that name. This would materially aid the British to secure the city of Granada, on Lake Nicaragua, and to sever the communications of the enemy between their northern and southern dominions. The idea originated with Dalling, Governor of Jamaica, to whom history has scarcely done justice. The naval force was entrusted to Nelson, the command of the troops to Captain John Polson.

The soldiers at the disposal of the intrepid adventurers were a mere handful, scarcely 500 in all, but perhaps that fact added the necessary spice of danger. Nelson left his ship, and “carried troops in boats one hundred miles up a river, which none but Spaniards since the time of the buccaneers had ever ascended,” to use his own words. He “boarded” an outpost of the enemy, situated on an island in the river; “made batteries, and afterwards fought them, and was a principal cause of our success.” When the miniature expedition arrived at Fort San Juan the rainy season had commenced, bringing malaria in its train. Nelson was all for making an immediate attack, but Polson ruled the slower, and perhaps surer, method of erecting batteries and so forth, in which Nelson lent a willing hand. “I want words to express the obligations I owe to Captain Nelson,” Polson told Governor Dalling. “He was the first on every service, whether by day or night. There was not a gun fired but was pointed by him, or by Captain Despard, Chief Engineer.” Fever played havoc with the men; of the 200 sailors of the Hinchinbrook, no fewer than “eighty-seven took to35 their beds in one night; and of the two hundred, one hundred and forty-five were buried in mine and Captain Collingwood’s9 time: and I believe very few, not more than ten, survived of that ship’s crew; a proof how necessary expedition is in those climates.” Nelson’s own health was undermined by dysentery. A few hours before the Spanish flag gave place to the Union Jack he left the region of the fort in order to join the Janus (44 guns), of which he had been given command. The ship being stationed at Jamaica, he was taken to Port Royal in a sloop. Here he met with a good and tender-hearted friend in Lady Parker, the wife of Sir Peter Parker, Commander-in-Chief at Jamaica, but he gained so little in strength that he was compelled to ask leave of absence and leave the West Indies for England. Had he stayed it is improbable that he could have rendered useful service while in such a low condition. The expedition eventually ended in failure. He sailed on the 4th September 1780 in the Lion, commanded by Captain the Hon. William Cornwallis, a younger son of Earl Cornwallis, who acted the part of nurse to the patient’s entire satisfaction, and cemented a friendship which lasted until Nelson’s death.

Having to resign the Janus probably caused Nelson more torture than his physical suffering, for he was intensely ambitious. It is stated that when he arrived in England he would not proceed to Bath to drink the waters until he had been conveyed to the Admiralty to beg for another vessel. “This they readily promised me,” he observed in a humorous way, “thinking it not possible for me to live.” At Bath he stayed with Mr Spry, an apothecary, who resided at 2 Pierrepont Street; his medical adviser was Dr Woodward.

On the 23rd January 1781 Nelson was able to inform Captain Locker that he was “now upon the mending hand,” although he had been “obliged to be carried to and from bed, with the most excruciating tortures.” Some three weeks later further progress was reported;36 “My health, thank God, is very near perfectly restored; and I have the perfect use of all my limbs, except my left arm, which I can hardly tell what is the matter with it. From the shoulder to my fingers’ ends are as if half dead; but the surgeon and doctors give me hopes it will all go off. I most sincerely wish to be employed, and hope it will not be long.”

Again the flicker of ambition is evident, always a good sign in a patient. “I never was so well in health that I can remember,” he writes on the 5th March. On Monday of the following week he began his return journey to London. Unfortunately his progress was intermittent. He had “good” days and “bad” days. Two months later we find Nelson telling his beloved brother William that he has entirely lost the use of his left arm and nearly of his left leg and thigh. However, the surgeon who was attending him gave him hopes of recovery, “when I will certainly come into Norfolk, and spend my time there till I am employed.”

At this period Nelson did not have to eat out his heart in chagrin and disappointment owing to neglect as some of our modern naval officers have had to do. In August 1781, when his health had improved, he was given command of the Albemarle, a frigate of 28 guns, and on the 23rd of that month he hoisted his pennant at Woolwich. The appearance of the little vessel pleased him considerably, his officers and men even more so, as his letters abundantly testify. “My quarter-deck is filled, much to my satisfaction, with very genteel young men and seamen”; “I have an exceeding good ship’s company. Not a man or officer in her I would wish to change”; “I am perfectly satisfied with both officers and ship’s company. All my marines are likewise old standers,” are some of his remarks to correspondents. We must not imagine that Nelson necessarily had a pattern-ship and a pattern-crew because of the kind things he said of them. His recent recovery from serious illness has doubtless to37 be taken into consideration. We all see the world and its inhabitants through rose-coloured glasses after an enforced absence from the ordinary duties and modes of life. A natural sweetness of disposition may also partly account for his optimism. In later years Samuel Rogers, the Banker-poet, recorded in his entertaining “Table Talk” that “Lord Nelson was a remarkably kind-hearted man. I have seen him spin a teetotum with his one hand, a whole evening, for the amusement of some children.”

The young captain’s first voyage in the Albemarle was not unattended by adventures. His reference to his experiences in the Autobiography is slightly tinged with a semi-humorous cynicism one can readily forgive, although it contrasts oddly with the remarks just quoted. “In August, 1781,” he writes, “I was commissioned for the Albemarle; and, it would almost be supposed, to try my constitution, was kept the whole winter in the North Sea.” He cruised to Elsinore, where he found a number of vessels waiting for convoy to Portsmouth and Plymouth. “We have not had any success;” he complains, “indeed, there is nothing you can meet, but what is in force: the Dutch have not a single merchantman at sea. One privateer was in our fleet, but it was not possible to lay hold of him. I chased him an hour, and came fast up with him, but was obliged to return to the fleet. I find since, it was the noted Fall, the pirate.... What fools the Dutch must have been not to have taken us into the Texel. Two hundred and sixty sail the convoy consisted of.”

On another occasion the British ships in the Downs mistook Nelson and his motley collection for a Dutch fleet. Many of the sail-of-the-line prepared for action and would have chased their friends had not Nelson sent a cutter to inform the officers of their ludicrous error. In the early days of 1782 the Albemarle was ordered to Portsmouth to take in eight months’ provisions, “and I have no doubt was meant to go to the38 East Indies with Sir Richard Bickerton,10 which I should have liked exceedingly, but alas, how short-sighted are the best of us.” The young captain then goes on to tell his brother William of the fate which overtook him. During a fierce gale an East India store ship collided with the Albermarle. “We have lost our foremast, and bowsprit, mainyard, larboard cathead, and quarter gallery, the ship’s [figure] head, and stove in two places on the larboard side—all done in five minutes. What a change! but yet we ought to be thankful we did not founder. We have been employed since in getting jury-masts, yards, and bowsprit, and stopping the holes in our sides. What is to become of us now, I know not. She must go into dock, and I fear must be paid off, she has received so much damage.”

A letter to the same correspondent, dated the 8th February 1782, reveals something of Nelson’s philosophy of life. “We all rise by deaths,” he asserts. “I got my rank by a shot killing a post-captain, and I most sincerely hope I shall, when I go, go out of [the] world the same way; then we go all in the line of our profession—a parson praying, a captain fighting.” He had his wish gratified, as we all know. There was something more than a suspicion of the Stoic in Nelson, for while it cannot be said that he was unaffected by passion, he certainly displayed praiseworthy indifference to creature comforts when at sea. That he grumbled to the authorities proves nothing to the contrary. It was usually with reference to half-unseaworthy ships, which added to the trials and troubles of his men and oftentimes precluded him from doing himself justice where the enemy was concerned. His letters prove conclusively that he had the utmost faith in God, whom he regarded as a powerful Ally.

Shortly afterwards Nelson sailed with a convoy to39 Newfoundland and Quebec. The experience was anything but pleasant, and when he returned to the latter place in the middle of September he was “knocked up with scurvy,” the old-time sailor’s curse, owing to a diet of salt beef for eight weeks. “In the end,” he says, “our cruise has been an unsuccessful one; we have taken, seen, and destroyed more enemies than is seldom done in the same space of time, but not one arrived in port. But, however, I do not repine at our loss: we have in other things been very fortunate, for on 14 August we fell in with, in Boston Bay, four sail-of-the-line,11 and the Iris, French man-of-war, part of M. Vaudreuil’s squadron, who gave us a pretty dance for between nine or ten hours; but we beat all except the frigate, and though we brought to for her, after we were out of sight of the line-of-battle ships, she tacked and stood from us. Our escape I think wonderful: they were, upon the clearing up of a fog, within shot of us, and chased us the whole time about one point from the wind....” Nelson managed to avoid the enemy by “running them amongst the shoals of St George’s Bank,” a manœuvre which caused the larger ships to stop pursuit. When he prepared for action the commander of the frigate, deeming discretion the better part of valour, wisely decided to rejoin his comrades.

After taking another convoy from Quebec to New York, Nelson sailed under the command of Lord Hood for the West Indies, “the grand theatre of actions.” Here he captured a French vessel attached to Vaudreuil’s fleet, thereby getting some compensation for the loss of the frigate. Her cargo consisted of naval material, and as some of the British ships were urgently in want of topmasts the prize was more than usually valuable.

He also attempted to recapture Turk’s Island, which had been taken by the French. The proceeding was audacious in the extreme, as he had very few ships at his disposal. An officer was sent on shore, under cover40 of a flag of truce, to demand surrender. This proving abortive, a little band of 167 seamen and marines, under Captain Charles Dixon, was landed. The Admiral Barrington then came up, and together with the Drake, was about to bombard the town, when a concealed battery opened upon them. A steady fire was maintained for an hour before Captain Dixon, who had hoped to reach the enemy’s works while the ships were engaging some of the French defenders, decided that the experiment was too dangerous. The enemy’s guns were fought by seamen, the troops had several field-pieces at their disposal, and two pieces of cannon were mounted on a hill, consequently continued persistence would have been foolhardy. “With such a force,” says the instigator of this expedition, “and their strong position, I did not think anything further could be attempted.”

Nelson succeeded in making himself thoroughly acquainted with Lord Hood, who in his turn introduced him to Prince William, then a midshipman and afterwards William IV., “our Sailor King.” There was mutual admiration. “He will be, I am certain, an ornament to our Service,” Nelson tells Locker. “He is a seaman, which you could hardly suppose. Every other qualification you may expect from him. But he will be a disciplinarian, and a strong one: he says he is determined every person shall serve his time before they shall be provided for, as he is obliged to serve his.” Such is Nelson’s comment. That of the future monarch was not made at the time, but when Nelson went on board the Barfleur the incident made such an impression on the Prince that he was able to paint a graphic word-picture of the event many years after. Nelson “appeared to be the merest boy of a captain I ever beheld.... He had on a full-laced uniform; his lank, unpowdered hair was tied in a stiff Hessian tail, of an extraordinary length; the old-fashioned flaps of his waistcoat added to the general quaintness of his figure, and produced an appearance which particularly41 attracted my notice; for I had never seen anything like it before, nor could I imagine who he was, nor what he came about. My doubts were, however, removed when Lord Hood introduced me to him. There was something irresistibly pleasing in his address and conversation; and an enthusiasm when speaking on professional subjects that showed he was no common being.... Throughout the whole of the American War the height of Nelson’s ambition was to command a line-of-battle ship; as for prize-money, it never entered his thoughts: he had always in view the character of his maternal uncle.”

On the 25th June 1783 Nelson was again at Portsmouth. After seeing to the well-being of his sailors he travelled on the leisurely stage-coach to London, where he was presented to the King by Lord Hood. In the following September hostilities were concluded between Great Britain, America, France, Spain, and Holland by the signature of the Treaty of Versailles. The officer, therefore, found no difficulty in obtaining six months’ leave to visit France. There he realised that perhaps there might be some truth in the old adage to the effect that Jack has a sweetheart in every port.

Nelson took the greatest possible interest in everything he saw in France: “Sterne’s ‘Sentimental Journey’ is the best description I can give of our tour.” He travelled in a chaise without springs, slept on a straw bed—“O what a transition from happy England!”—but had less fault to find with the scenery about Montreuil, which he describes as “the finest corn country that my eyes ever beheld, diversified with fine woods, sometimes for two miles together through noble forests. The roads mostly were planted with trees, which made as fine an avenue as to any gentleman’s country seat.” At St Omer he lodged with “a pleasant French family,” and incidentally made the acquaintance of “two very agreeable young ladies, daughters, who honour us with their company pretty often.... Therefore I must learn French if ’tis only for the pleasure of talking to them, for they do not speak a word of English.” Soon all thoughts of study and of the “very agreeable” maidens were banished from his impressionable mind by his43 introduction to a Miss Andrews, the daughter of an English clergyman. The affair rapidly ripened into something more than friendship.

Nelson’s letters go far to prove the truth of Pope’s couplet. Miss Andrews was, according to him, “the most accomplished woman my eyes ever beheld.” Unfortunately marriage is necessarily based on that mundane and concrete thing, money. When the ardent young officer came to look into the financial aspect of the matter he found that his income did not exceed £130 a year. His lady-love’s dowry was “1,000l. I understand.” He therefore appealed to his uncle, William Suckling, to allow him £100 per annum until he could earn that sum for himself. Failing this source of supply, would his relative “exert” himself “to get me a guard-ship, or some employment in a public office where the attendance of the principal is not necessary...? In the India Service I understand (if it remains under the Directors) their marine force is to be under the command of a captain in the Royal Navy: that is a station I should like.” He prays that his uncle and his family “may never know the pangs which at this instant tear my heart.”

Cupid’s shaft neither proved deadly nor barbed. On his return to England Nelson dismissed his love affair, and was soon “running at the ring of pleasure” in London. He visited Lord Howe, First Lord of the Admiralty, “who asked me if I wished to be employed, which I told him I did”; dined with Lord Hood, who made him feel quite at home, and told him “that the oftener I came the happier it would make him.” In January 1784 he was at Bath, and wrote to his brother that he thought of paying a second visit to the Continent till autumn and then spending the winter with him at Burnham Thorpe. “I return to many charming women, but no charming woman will return44 with me,” is the plaint. “I want to be a proficient in the language, which is my only reason for returning. I hate their country and their manners,” which hatred, it may be said, increased with the passing of the years. This pessimistic strain is doubtless due to Nelson’s undesirable position as a half-pay officer, but in the middle of March his somewhat mercurial temperament underwent a change to “set fair” on his appointment to the Boreas, a frigate of 28 guns, under orders for the Leeward Islands. The passengers included Lady Hughes, wife of Rear-Admiral Sir Richard Hughes, Bart., the Commander-in-Chief, and her daughter, whom he very ungallantly described as “lumber.” His brother, the Rev. William Nelson, accompanied him as chaplain of the Boreas, but returned on the last day of September 1784 owing to ill-health.

Before leaving Spithead Nelson had an alarming adventure. He was riding what he describes as a “blackguard horse” in company with a lady, when both animals bolted. In order to save his legs from being crushed in a narrow road blocked by a waggon the young gallant was obliged to throw himself, and he had the ill-luck to fall upon hard stones, which injured his back and one of his limbs. His fair companion was only saved from death by the presence of mind of a passer-by who pluckily seized the bridle of the terrified animal to which she was frantically clinging.

“He had the ill-luck to fall upon hard stones”

Stephen Reid

The voyage to Antigua was devoid of incident. It was monotonous, and Nelson hated nothing so much as monotony. Lady Hughes bored him, although it is only just to add that he does not appear to have let her know it. The lady herself was certainly impressed with the kindly way Nelson treated “the young gentlemen who had the happiness of being on his Quarter-Deck,” to quote a letter written by her in 1806. “It may reasonably be supposed,” she goes on, “that among the number of thirty, there must be timid as well as bold: the timid he never rebuked, but always45 wished to show them he desired nothing of them that he would not instantly do himself: and I have known him say—‘Well, sir, I am going a race to the masthead, and I beg I may meet you there.’ No denial could be given to such a wish, and the poor fellow instantly began his march. His Lordship never took the least notice with what alacrity it was done, but when he met in the top, instantly began talking in the most cheerful manner, and saying how much a person was to be pitied that could fancy there was any danger, or even anything disagreeable, in the attempt.... In like manner he every day went to the schoolroom and saw them do their nautical business, and at twelve o’clock he was first upon the deck with his quadrant. No one there could be behindhand in his business when their Captain set them so good an example. One other circumstance I must mention which will close the subject, which was the day we landed at Barbadoes. We were to dine at the Governor’s. Our dear Captain said, ‘You must permit me, Lady Hughes, to carry one of my aides-de-camp with me,’ and when he presented him to the Governor, he said, ‘Your Excellency must excuse me for bringing one of my midshipmen, as I make it a rule to introduce them to all the good company I can, they have few to look up to besides myself during the time they are at sea.’ This kindness and attention made the young people adore him; and even his wishes, could they have been known, would have been instantly complied with.”

When Nelson made the acquaintance of Sir Richard Hughes he disliked him as much as he did her ladyship. Probably the officer’s methods rather than the man aroused this feeling of antagonism. “The Admiral and all about him are great ninnies,” he writes, and he soon showed in no vague way that he refused to support the Commander-in-chief’s happy-go-lucky policy. Truth to tell, Nelson had no love of authority. He preferred to be a kind of attached free-lance, although he was a strict disciplinarian in all relations between46 his junior officers and himself. “I begin to be very strict in my Ship,” is an expression he used while in the Boreas. In particular he fell foul of Hughes in the matter of putting the Navigation Act into force. This law had been passed by the Rump Parliament in 1651, when the Dutch held the proud position of the world’s maritime carriers. It was enacted that only English ships, commanded by an Englishman and manned by a crew three-fourths of whom were also of the same nationality, should be allowed to carry the products of Asia, Africa, and America to home ports. In a similar manner, European manufactures had to be brought in English vessels or those of the countries which produced the goods. In the latter case the duties were heavier. It was Protection pure and simple.

The Government of Charles II. and the Scottish Parliament passed similar Acts in later years, thereby fostering the trading companies which helped to lay the foundations of our colonial empire. Such measures were a constant “thorn in the flesh” to foreign statesmen. Several of the statutes were repealed in 1823, but the Navigation Act was not entirely abandoned by Great Britain until 1848, after an existence of nearly two hundred years.

Owing to their separation from the Motherland, the former British colonists of America were, technically, “foreigners,” and should have been subject to restrictions in their commercial intercourse with the West Indies. “I, for one,” Nelson confides to Locker, “am determined not to suffer the Yankees to come where my Ship is; for I am sure, if once the Americans are admitted to any kind of intercourse with these Islands, the views of the Loyalists in settling Nova Scotia are entirely done away. They will first become the Carriers, and next have possession of our Islands, are we ever again embroiled in a French war. The residents of these Islands are Americans by connexion and by interest, and are inimical to Great Britain.47 They are as great rebels as ever were in America, had they the power to show it.... I am determined to suppress the admission of Foreigners all in my power.”

“The Americans,” Nelson tells us in his Autobiography, “when colonists, possessed almost all the trade from America to our West India Islands; and on the return of peace, they forgot, on this occasion, that they became foreigners, and of course had no right to trade in the British Colonies.

“Our governors and custom-house officers pretended that by the Navigation Act they had a right to trade; and all the West Indians wished what was so much for their interest. Having given governors, custom-house officers, and Americans, notice of what I would do, I seized many of their vessels, which brought all parties upon me; and I was persecuted from one island to another, so that I could not leave my ship.” In this matter it may be said that Nelson found it necessary to keep himself “a close prisoner” to avoid being served with writs which had been issued against him by the owners of certain vessels which he had taken, and who assessed their damages at several thousands of pounds. “But conscious rectitude,” he adds, “bore me through it; and I was supported, when the business came to be understood, from home; and I proved (and an Act of Parliament has since established it) that a captain of a man-of-war is in duty bound to support all the maritime laws, by his Admiralty commission alone, without becoming a custom-house officer.”

The ardent captain also fell foul of Hughes in another matter. The commissioner of the dockyard at Antigua was Captain Moutray, a half-pay officer whom Hughes, going beyond his powers, made commodore. Nelson refused to recognise him as such. The case was investigated by the Admiralty at the instigation of both parties, with the result that Nelson was reprimanded for taking the law into his own hands. Professor Sir J. Knox Laughton, while admitting that “In both cases Nelson was right in his contention,” is forced48 to add that “The first duty of an officer is to obey orders, to submit his doubts to the Commander-in-chief, and in a becoming manner to remonstrate against any order he conceives to be improper; but for an officer to settle a moot-point himself, and to act in contravention of an order given under presumably adequate knowledge of the circumstances, is subversive of the very first principles of discipline. And these were not, it will be noticed, questions arising out of any sudden and unforeseen emergency, in providing for which Nelson was forced to depart from his instructions. Such emergencies do arise in the course of service, and the decision of the officer may be a fair test of his personal worth; but neither at St Kitts nor at Antigua was there anything calling for instant decision, or any question which might not have waited, pending a reference to the Commander-in-chief or to the Admiralty. And this was the meaning of the Admiralty minute on Nelson’s conduct at Antigua, a most gentle admonition for what might have been punished as a grave offence.”

It must not be inferred that there was any personal bitterness on Nelson’s part regarding the Moutray affair. He conceived it to be a question of principle, of doing right and shunning wrong: “The character of an Officer is his greatest treasure: to lower that, is to wound him irreparably.” He was certainly on excellent terms with the Commissioner’s wife, for whom he cherished the most friendly feelings. Indeed, in one of his letters he calls her his “dear, sweet friend.... Her equal I never saw in any country, or in any situation.” Let it be frankly admitted, however, that Nelson sometimes wore his heart on his sleeve, and readily betrayed a state of feeling approaching deep affection for any member of the gentler sex who showed by her ready sympathy that she possessed a kindly disposition. In the communication in which the above passage occurs he notes that several of his comrades had similar amorous tendencies. One officer has proposed and been refused, another is forestalled in49 proposing to the lady of his choice by a more venturesome lover, a third is “attached to a lady at Nevis,” the said lady being a relation of the future Mrs Nelson. He concludes with a reference to a niece of Governor Parry, who “goes to Nevis in the Boreas; they trust any young lady with me, being an old-fashioned fellow.”

On the 12th May 1785 Nelson confides to his brother William that he has made the acquaintance of “a young Widow,” and towards the end of the following month he tells the same correspondent, “between ourselves,” that he is likely to become a “Benedict.... Do not tell.” The lady of his choice was Mrs Nisbet, then twenty-seven years of age and the mother of a boy. We are fortunate in having copies of many of his letters to her, for there is a wealth of affection—scarcely love—and much sage philosophy in them. “My greatest wish is to be united to you;” he writes on the 11th September 1785, “and the foundation of all conjugal happiness, real love and esteem, is, I trust, what you believe I possess in the strongest degree towards you.... We know that riches do not always insure happiness; and the world is convinced that I am superior to pecuniary considerations in my public and private life; as in both instances I might have been rich.” “You are too good and indulgent;” he avers on another occasion, “I both know and feel it: but my whole life shall ever be devoted to make you completely happy, whatever whims may sometimes take me. We are none of us perfect, and myself probably much less so than you deserve.” “Fortune, that is, money, is the only thing I regret the want of, and that only for the sake of my affectionate Fanny. But the Almighty, who brings us together, will, I doubt not, take ample care of us, and prosper all our undertakings. No dangers shall deter me from pursuing every honourable means of providing handsomely for you and yours....”

The messages lack the passionate fire of Napoleon’s notes to Josephine, and on occasion are apt to be rather50 too business-like for love letters. The romance did not end like the fairy stories, they did not live “happily ever after,” but there is no reason to doubt that Nelson cherished a fond affection for the young widow. “Her sense,” he informs his brother, “polite manners, and to you I may say, beauty, you will much admire: and although at present we may not be a rich couple, yet I have not the least doubt but we shall be a happy pair:—the fault must be mine if we are not.” Subsequent events proved the truth of the latter remark.

In due course Sir Richard Hughes was succeeded in the command of the Leeward Islands by Sir Richard Bickerton. Nelson complains towards the end of 1786 that “A total stop is put to our carrying on the Navigation Laws,” thereby showing that the old problem had by no means been solved so far as he was concerned.

On the 12th March 1787 Nelson and Mrs Nisbet were married at Nevis. Prince William Henry, then captain of the Pegasus and under Nelson’s command, gave away the bride. Three months later the newly-wedded captain was at Spithead, the almost unseaworthy condition of the Boreas making it impossible for her to stand another hurricane season in the West Indies.

Nelson was placed on half-pay, a state which he by no means liked. In May 1788 he had reason to believe that he would be employed again. “I have invariably laid down,” he tells a friend, “and followed close, a plan of what ought to be uppermost in the breast of an Officer: that it is much better to serve an ungrateful Country, than to give up his own fame. Posterity will do him justice: a uniform conduct of honour and integrity seldom fails of bringing a man to the goal of Fame at last.”

Nelson visited Plymouth, Bath, and London, and finally settled down at Burnham Thorpe. His letters reveal the keenness with which he desired to obtain employment. He applied to both Viscount Howe, First Lord of the Admiralty, and to Lord Hood, but all51 his overtures came to nought. In September 1789 he tells his old friend Locker that “I am now commencing Farmer, not a very large one, you will conceive, but enough for amusement. Shoot I cannot, therefore I have not taken out a license; but notwithstanding the neglect I have met with, I am happy, and now I see the propriety of not having built my hopes on such sandy foundations as the friendships of the Great.”

Not until January 1793 were his dearest wishes granted. “After clouds comes sunshine,” he writes to his wife from London. “The Admiralty so smile upon me, that really I am as much surprised as when they frowned. Lord Chatham yesterday made many apologies for not having given me a Ship before this time, and said, that if I chose to take a Sixty-four to begin with, I should be appointed to one as soon as she was ready; and whenever it was in his power, I should be removed into a Seventy-four. Everything indicates War....”

“Duty is the great business of a sea officer”

Nelson.

So far back as 1753 Lord Chesterfield prophesied a revolution in France. “All the symptoms,” he said, “which I have ever met with in history, previous to great changes and revolutions in government, now exist and daily increase in France.” Warning rumbles heralded the storm, disregarded and thought of no account by some, full of grave portent to others. It burst in 1789.

At first William Pitt, First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer, steadily refused to believe that England was menaced by the Power which Fox had termed “the natural enemy of Great Britain.” In January 1792 he assured Parliament that “unquestionably there never was a time in the history of this country when, from the situation of Europe, we might more reasonably expect fifteen years of peace than we may at the present moment.” Either he was over anxious to persuade himself that things were as he would like them to be, or he was sadly mistaken. Pitt had by no means the pugnacious disposition of his father, the famous first Earl of Chatham. He thought that the fire would burn itself out, that it would be of short duration, whereas it steadily gained strength and eventually involved practically every country in Europe. Not until he was convinced that war was53 inevitable did the youngest Premier who ever handled the reins of a British government accept the French Revolution as of more than local consequence. Hitherto domestic and financial questions had occupied his attention and absorbed his energies. If France ignored the nation which he represented, if she refrained from poaching on British preserves or those of her allies, he was quite content to return the compliment. Then came the decree that the navigation of the river Scheldt should be thrown open. It had previously been guaranteed to the Dutch by Great Britain as well as by other Powers, including France. The execution of Louis XVI. followed, which led to Chauvelin, the French Ambassador, being given his passports. If Pitt had been slumbering he had wooed somnolence with one eye open since the annexation of Savoy. He was now fully awake, calm and self-reliant, for he recognised the inevitable. It came in a declaration of war by the French Convention against Holland and Great Britain on the 1st February 1793. Macaulay, writing from an essentially Whig point of view, states that Pitt’s military administration “was that of a driveller,” but to the impartial historian nothing is further from the truth. He abandoned his schemes of social reform to plunge whole-heartedly into the titanic struggle which was to cost him his life. That he made mistakes is obvious—what statesman has not?—but he fell in his country’s cause as nobly as Nelson at Trafalgar and Moore at Coruña.

When Nelson joined the Agamemnon he was immensely pleased with her. He describes the vessel as “without exception, the finest 64 in the service, and has the character of sailing most remarkably well.” She was a unit of the fleet under Lord Hood, her destination the Mediterranean. The captain was accompanied by his step-son, Josiah, whose first experience of life at sea cannot have been pleasant. Off the Nore the Agamemnon encountered a gale, with the result that Josiah was “a little sea-sick.” However,54 “he is a real good boy, and most affectionately loves me,” as his mother was informed. Off Cadiz Nelson is able to report, “My Ship is remarkably healthy; myself and Josiah never better.”

While part of the fleet was watering at Cadiz, Nelson dined on board the Concepcion (112), a huge Spanish sail-of-the-line. The experience afforded him food for thought as well as for physical sustenance. He relates the incident to his wife, criticises the four Spanish first-rates in commission at the port as “very fine Ships, but shockingly manned,” and adds that if the crews of the six barges attached to the British vessels had boarded one of these great vessels they could have taken her: “The Dons may make fine Ships,—they cannot, however, make men.” This summing-up of the morale of the Spanish Navy is particularly valuable. A dozen years later, when Napoleon was planning his wonderful combinations to elude the prowess of Nelson, the lack of skill displayed by the Spaniards was a constant source of annoyance both to the Emperor and his naval officers. Their bravery in action during the Trafalgar Campaign is not questioned; their happy-go-lucky code of discipline is on record in documentary evidence. A bull fight which Nelson saw sickened and disgusted him. “We had what is called a fine feast, for five horses were killed, and two men very much hurt: had they been killed, it would have been quite complete.”