THE COLLISION ON LAKE CHAMPLAIN. Page 15.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Snug Harbor, by Oliver Optic

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Snug Harbor

or The Champlain Mechanics

Author: Oliver Optic

Release Date: December 12, 2015 [EBook #50678]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SNUG HARBOR ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Carol Brown, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The Boat-Builder Series.

I.

ALL ADRIFT;

OR,

THE GOLD WING CLUB.

II.

SNUG HARBOR;

OR,

THE CHAMPLAIN MECHANICS.

III.

SQUARE AND COMPASS;

OR,

BUILDING THE HOUSE.

IV.

STEM TO STERN;

OR,

BUILDING THE BOAT.

V.

ALL TAUT;

OR,

RIGGING THE BOAT.

VI.

READY ABOUT;

OR,

SAILING THE BOAT.

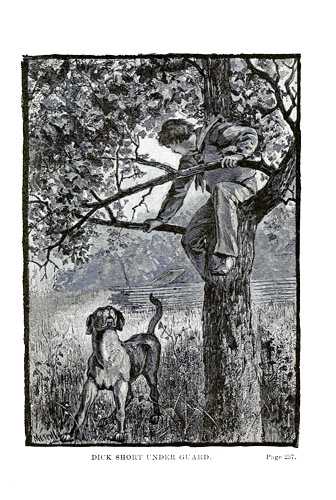

THE COLLISION ON LAKE CHAMPLAIN. Page 15.

OLIVER OPTIC’S

BOAT-BUILDER

SERIES

SNUG HARBOR

BOSTON,

LEE AND SHEPARD

PUBLISHERS.

The Boat-Builder Series

OR

THE CHAMPLAIN MECHANICS

BY

AUTHOR OF “YOUNG AMERICA ABROAD,” “THE GREAT WESTERN SERIES,”

“THE ARMY AND NAVY SERIES,” “THE WOODVILLE SERIES,” “THE

STARRY-FLAG SERIES,” “THE BOAT-CLUB STORIES,” “THE

ONWARD AND UPWARD SERIES,” “THE YACHT-CLUB

SERIES,” “THE LAKE-SHORE SERIES,” “THE

RIVERDALE STORIES,” “ALL ADRIFT,”

ETC., ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON

LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK

CHARLES T. DILLINGHAM

1884

Copyright, 1883,

By WILLIAM T. ADAMS.

All rights reserved.

TO MY YOUNG FRIEND

HARRY CLINTON WHITE

This Book

IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED.

“Snug-Harbor” is the second volume of “The Boat-Builder Series.” Though it contains its fair proportion of story and adventure, there is less of these elements than in its predecessor; though the writer believes there is enough to keep up the interest of his young readers. Dory Dornwood, the hero of the initial volume of the series, is again presented, and about a quarter of a hundred others; though all of them cannot be heroes. Like the former volume, the scene is laid on Lake Champlain and its shores.

In accordance with the hint thrown out in the preface of the first volume, the Beech-Hill Industrial School makes a beginning in this book; and its pupils are gathered together in the schoolroom and the workshop. The boys are instructed only in those branches of learning which will be of the greatest practical utility to them as mechanics. They are taken into the shop, and set to work as carpenters and machinists; and some idea is given of their operations at the bench. But in a work of this kind the author finds it hardly practicable to describe in detail the work done by the Champlain mechanics; though he has done so to some extent, as a suggestion rather than as a system of instruction for boy-workmen. Without a vast number of drawings, the tools and machinery used by the carpenter and machinist cannot be described and explained so as to be of any great practical service. The book is rather to create an interest in these trades than to furnish a guide to young mechanics.

The author regrets that there is no American work of the kind mentioned. Our English cousins have sent us over some excellent works on the subject, which are very useful, though not fully adapted to the needs of American boys. A new friend suggests that such a book be prepared, and with his aid it may yet be done.

Captain Gildrock, the founder and patron of the Beech-Hill Industrial School, has some radical ideas on the subject of education; and probably many of the older readers of this book will disagree with him: but the question he argues is worthy of attention and discussion, however it may be finally settled.

Though the author is not a mechanic by trade, he has worked in his own shop for many years. With the carpenter’s bench, the turning-lathe, and the various implements for working in wood and metals, he finds not only his needed exercise, but a degree of pleasure which makes it all the more healthy and exhilarating; and he commends the work to his young friends, both for their amusement and instruction.

Dorchester, Mass., Aug. 20, 1883.

| CONTENTS. | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| The Sloop that went to the Bottom | 13 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Young Man with a Long Name | 23 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Mr. Bolingbroke Millweed tells his Story | 34 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Goldwing anchors for the Night | 44 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| A Quarrel on Board of the Juniper | 54 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Impulsive Assault of the Engineer | 65 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Bolingbroke Millweed out of a Place | 76 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Pupils for the Beech-Hill Industrial School | 87 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Volunteer Helmsman and his Movements | 97 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Battle near Garden Island | 107 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The Master-Carpenter disposes of his Prisoner | 117 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Captain Gildrock’s First Lesson in Navigation | 128 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Handling a Steamer in a Fog | 138 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Strong-Room at the Beech-Hill Industrial School | 148 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Something about the Affairs of the Millweed Family | 159 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Organization of the Ship’s Company | 170 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Officers and Crew of the Sylph | 180 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Another Battle at Plattsburg | 190 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Something that happened on Shore | 201 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The New Head of the Millweed Family | 212 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Captain Gildrock argues against High-Schools | 223 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| The Champlain Mechanics in the Shop | 234 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Something about Tools and Work | 244 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Work for the Head and the Hands | 255 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| The Second Class at the Carpenter’s Bench | 266 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| The End of the First School-Day at Beech Hill | 277 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Oscar Chester takes a Lesson in Boating | 288 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| The Upsetting of the Monkey and its Lesson | 299 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| An Afternoon in the Machine-Shop | 310 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| What the Students found at Thompson’s Point | 320 |

SNUG-HARBOR;

OR,

THE CHAMPLAIN MECHANICS.

“Starboard your helm! hard a-starboard!” shouted Dory Dornwood, as he put the helm of the Goldwing to port in order to avoid a collision with a steam-launch which lay dead ahead of the schooner.

“Keep off! you will sink me!” cried a young man in a sloop-boat, which lay exactly in the course of the steam-launch.

“That’s just what I mean to do, if you don’t come about!” yelled the man at the wheel of the steamer. “Why didn’t you stop when I called to you?”

“Keep off, or you will be into me!” screamed the skipper of the sloop, whose tones and manner indicated that he was very much terrified at the situation.

And he had reason enough to be alarmed. It was plain, from his management of his boat, that he was but an indifferent boatman; and probably he did not know what to do in the emergency. Dory had noticed the sloop coming up the lake with the steam-launch astern of her. The latter had run ahead of the sloop, and had come about, it now appeared, for the purpose of intercepting her.

When the skipper of the sloop realized the intention of the helmsman of the steamer, he put his helm to port; but he was too late. The sharp bow of the launch struck the frail craft amidships, and cut through her as though she had been made of card-board.

The sloop filled instantly; and, a moment later, the young man in her was struggling on the surface of the water. The boat was heavily ballasted, and she went down like a lump of lead. It was soon clear to Dory that the skipper could not swim, for he screamed as though the end of all things had come.

Very likely it would have been the end of all things to him, if Dory had not come about with the Goldwing, and stood over to the place where the young man was vainly beating the water with his feet and hands. With no great difficulty the skipper of the Goldwing, who was an aquatic bird of the first water, pulled in the victim of the catastrophe, in spite of the apparent efforts of the sufferer to prevent him from doing so.

It was a very warm day towards the end of August, and a bath in the cool waters of Lake Champlain was not the worst thing in the world to take. The victim of the collision was more scared than hurt; and he lay in the bottom of the yacht, puffing and blowing like a black bass just stolen from his native element. He did not seem to be able to speak, and Dory thought he was making a great fuss about a very small affair.

The Goldwing had been headed across the lake when her skipper picked up the victim; and, when he was safely on board, she continued on her course. Dory had come out to cool off and take a sail, and it made no difference to him where he went. The Beech-hill Industrial School had not yet commenced operations, and he had nothing on earth to do the greater part of the time.

His father had died a few weeks before; but he had found a snug harbor at Beech Hill, where he resided with his mother and sister in the elegant mansion of his uncle, Captain Royal Gildrock. The captain had acquired an immense fortune by his operations in various parts of the world; but as his wife was dead, and he had no children, it had bothered him a good deal to determine what to do with all his money.

For many years there had been a feud between the head of the Dornwood family and the owner of Beech Hill. Mr. Dornwood was an intemperate man, and never more than half supported his family; though he had good wages as a pilot on the lake. He had married the captain’s only sister in spite of the opposition of all her friends, and especially of her brother.

When the captain attempted to assist his sister in taking care of her two children, her husband ordered him out of his house; for a great many sharp words had passed between them. The wife was afraid of her inebriate husband, and the attempts of the wealthy brother to help the family had ended in the complete estrangement of the brother and sister.

But as soon as Mrs. Dornwood was a widow, the captain hastened to her assistance. Though Dory had made an earnest effort to support the family, he had finally consented to reside with his mother at Beech Hill. The pilot’s wife and children had always lived in the humblest tenements, worn the meanest garments, and lived upon the plainest and cheapest food.

Their lot at the new home was in tremendous contrast with their former condition. Captain Gildrock was a plain man himself, and inclined to regard the elegancies and luxuries of life with contempt. Though his house was large, it was plainly furnished. If his table was not garnished by the skill of a French cook, it was loaded with the best that could be procured. To the Dornwoods every thing about the house was luxurious.

Captain Gildrock was a thinking man, and he had ideas as well as money. The two go well together, for ideas are often barren things when one has not the means to carry them out. The worthy shipmaster had studied society and human nature in many lands and climes. After he retired from the sea and business generally, he had given his attention wholly to the affairs in his own country. After he had done so for a year or two, he was disposed to exclaim with the inspired writer, “Vanity of vanities! All is vanity!”

Perhaps the standard of the captain was too high for this world, but he felt that the American people were slipping away from first principles. The nation had prospered by toil,—by inducing and compelling the earth to yield her increase. Life had been something more than a pleasure-excursion.

“When I was young,” he used to say, “the boys worked on the farm, learned a trade, or went to sea. Now all the young men go into stores, become counter-jumpers and man-milliners. Men get rich now by making corners, betting on futures, and in speculation of all sorts. A big thief is a gentleman: a little one is a criminal, after he is caught. The boys and girls have been educated too much: they get above their station in life, and then half starve themselves in order to be genteel.”

The captain did not believe that the young people were educated too much; only that they were trained in useless accomplishments, as he regarded them. He did not think that the Genverres high-school, though a very successful institution in the opinion of the school-board and the citizens generally, was really a blessing to the town. He was confident that he had discovered the philosopher’s stone in education, though he found himself almost alone in his opinions.

“That school only spoils good farmers and mechanics, good seamen and engineers. It gives them altogether too high notions of themselves. It turns its pupils out on the world fit only to be genteel. The education which the fathers of New England meant, when they planted the schoolhouse alongside the church, was simply a common-school education, without any high-school bosh on the tail-end of it. It’s all well enough for rich people: it is a luxury they can afford, and one they ought to pay for.”

Very likely the captain was too ultra in his views, but the question he argued is one which must be settled before the lapse of many years.

The shipmaster was a practical man, and he did not talk without acting. He believed in industrial education, not in the grammar-school, but in place of the high-school. He had talked his views in town-meeting, and printed them in the papers; but the people were not inclined to adopt them.

A year before, he had taken a number of young men, and instructed them in seamanship and the construction and management of the marine engine. It was only a partial experiment, but he regarded it as an eminently successful one. Most of his pupils had obtained situations as engineers, and they were competent to fill them.

Captain Gildrock hoped to convince the people that his views were correct, and he was ready to spend his money in demonstrating the truth of what he preached. His class of the preceding year had been rather too old when he took them in hand. He wanted boys from the grammar-school, twelve or fourteen years old, before they had “bowed down to the vanity of this world,” before they had learned to be genteel, before they oiled their hair, and spent half an hour a day in adjusting their neckties.

After the death of his brother-in-law, the pilot, he had captured his nephew, after a hard struggle, and found he was the leading spirit of the Goldwing Club, which had taken its name from Dory’s boat. These boys were rather wild, but not bad. The captain succeeded in gathering them all into the Beech-hill Industrial School, as he decided to call the new institution. But the boys in Genverres were shy of the new school, or their parents were shy for them. Not a few of the latter regarded the retired shipmaster as a sort of harmless lunatic, liberal with his money, but, like all reformers, an unsafe leader to follow.

Several boys from the high-school had made excellent records out in the world, and each fond parent expected his own son would join the galaxy of bright stars from its graduates. The captain could find only three boys in the whole town who would join the new school, while thirty went to the high-school. Possibly the requirement that the pupils should reside at Beech Hill had some influence with the parents.

It looked as though the school was to begin with eight pupils,—hardly enough to man the Sylph, the captain’s elegant steam-yacht, the largest and finest craft of the kind on the lake. All the boys in the high-school would have liked to flirt about the lake in the magnificent steamer; but to do it as seamen, firemen, engineers, waiters, and cooks, was not wholly to the taste of the parents, if it suited that of the boys.

Dory Dornwood was waiting for the school to begin. Great boxes of tools, machinery, and other material for the workshops, had arrived at Beech Hill; but the captain would not allow them to be opened until the boys came. Besides, he was very busy in looking up pupils for the new institution. He wanted twenty-four to begin with, and he was searching for them in some of the interior towns where he was acquainted.

Dory was very impatient for the school to begin, though he was very happy in the midst of his new surroundings. He was a natural mechanic, and tools of any kind suited him better than books. He was fond of adventure, and wondered if he should ever have another time as lively as that on the lake before he was captured by his uncle.

The young man he had picked up on the lake was about sixteen years old, and was a stranger to him. His wet garments, though poor enough, betrayed an effort at some style. After a while he recovered his breath, and seemed to be in condition to give an account of himself.

“You had a narrow squeak that time,” said Dory Dornwood, as soon as he thought the victim of the disaster was in condition to do a little talking. “It is lucky you didn’t get tangled up in the rigging of your boat. She went to the bottom like a pound of carpet-tacks; and she would have carried you down in a hurry if you hadn’t let go in short metre.”

“I think I am remarkably fortunate in being among the living at this moment,” replied the stranger, looking out over the stern of the Goldwing. “That was the most atrocious thing a fellow ever did.”

“What was?” inquired Dory, who was not quite sure what the victim meant by the remark, or whether he alluded to him or to the man in the steam-launch.

“Why, running into me like that,” protested the passenger with no little indignation in his tones.

“Let me see, ‘atrocious’ means something bad or wicked, don’t it?” continued Dory.

“Something very bad and very wicked,” replied the stranger, with a sickly smile, as he bestowed a patronizing glance upon his deliverer.

“I thought it was something of that sort. I suppose you don’t use such big words as that before breakfast, do you?”

“Why not before breakfast as well as after? It is a common word, in use every day in the week.”

“I didn’t know but it might put your jaws out of joint, and spoil your appetite,” added Dory, as he glanced behind him to see what had become of the steam-launch.

“My appetite is not so easily spoiled.”

“I suppose you came up from Burlington?” said Dory suggestively, as though he considered an explanation on the part of the stranger to be in order at the present time.

“I have just come from Burlington,” answered the victim, who appeared to be disposed to say nothing more. “Do you suppose I can get that boat again?”

“I should say that the chance of getting her again was not first-rate. She went down where the water is about two hundred and fifty feet deep; and it won’t be an easy thing to get hold of her,” replied Dory. “If you had let him run into you between Diamond Island and Porter’s Bay, where the water is not more than fifty or sixty feet deep, you could have raised her without much difficulty. I don’t believe you will ever see her again.”

“That’s bad,” mused the stranger. “She did not belong to me.”

“Then you are so much in. Perhaps, if she had belonged to you, you would not have let the steam-launch run into you,” added Dory, who did not quite like the way the victim was taking things; for he did not seem to remember that he had been pulled out of the water by the skipper of the Goldwing when he was in great danger of drowning.

“I did not let the steam-launch run into me. The man in her did it on purpose. It was not an accident,” answered the stranger.

“I heard the fellow say that he meant to sink you; and, after he said that, I thought you were a little out of your head to let him do it.”

“I didn’t let him do it.”

“I thought you did. If I had been at the tiller of that sloop, he wouldn’t have done it.”

“Probably you are a better boatman than I am: I don’t pretend to know much about the management of a yacht,” replied the victim meekly, as he finished wiping the water from his face.

“Then you ought not to be sailing a boat in a fresh breeze, such as we are having to-day. Why didn’t you put your helm down when you saw that he was going to run into you?”

“Down where?” asked the victim with a vacant stare.

“Down cellar!” exclaimed Dory, disgusted at the ignorance of the skipper of the sunken sloop. “No fellow ought to sail a boat if he don’t know how to put the helm down.”

“A fellow can’t know every thing in the world.”

“Then, I suppose you know every thing else: but how to put the helm down was the one thing you ought to have known, when that fellow was kind enough to tell you beforehand that he meant to sink you.”

“Don’t be too rough on me, Mr.— I don’t know your name. I am under very great obligations to you for the signal service you have rendered me, and I shall be glad to know you better.”

“My name is Theodore Dornwood,—Dory for short. What is yours?”

“Dory Dornwood!” exclaimed the victim, bestowing a look of astonishment upon the modest skipper. “I have heard of you before, and I am particularly glad to meet you.”

“I should think you might be, since I picked you up in deep water. But you did not give me your name.”

“My name is Bolingbroke Millweed.”

“Is that all the name you have?” asked Dory, as he opened his eyes till they were as big as a pair of saucers—very small saucers. “I didn’t quite make it out, for it fairly snarled up my intellect.”

“Bolingbroke Millweed,” repeated the stranger with a slight frown upon his brow. “It’s all the name I have.”

“It’s name enough, I should say.”

“It is hardly worth while to make fun of my name: I am not responsible for it, and it is the best I have.”

“I beg your pardon, Mr.— I don’t know what your name is now, for really I did not take it in,” pleaded Dory, who was sometimes very brusk in his manner, though he did not mean to hurt anybody’s feelings. “Honestly, I did not understand you.”

“You cannot have read English history very much, or you would have recognized the first name.”

“I never did read English history much: in fact, I never did much reading of any kind.”

“My first name is Bolingbroke, and my surname is Millweed. The whole of it is Bolingbroke Millweed,” added the victim, mollified as he pitied the ignorance of his deliverer.

“All right, Mr. Millweed: I won’t tackle the first name until I get a little better acquainted with it.”

“Viscount Henry St. John Bolingbroke, after whom I was named, was a prime minister of England, and a fine scholar; though he was charged with treason. But I did not pick out the name myself: it was my mother’s choice, but I can’t say that I approve it. I suppose I shall be called ‘Bolly’ as long as I live.”

“Of course your friends can’t handle such a jaw-breaker as Bolingbroke every time they want to ask you which way the wind is. But never mind the name, Mr. Millweed. I picked you up in deep water, and that’s how you happen to be on board of the Goldwing.”

“The famous Goldwing! I am extremely happy to be on board of her; though I wish our meeting had been under more favorable circumstances,” added Mr. Bolingbroke Millweed, as he poured the water out of one of his shoes.

“I only said that you were on board of the Goldwing; and the question now is, what shall I do with you, for I see the steam-launch is headed this way. I should judge from his actions that the man at the wheel of her wants to see you.”

“He does want to see me! I am the victim of a conspiracy!” exclaimed Mr. Millweed in tragic tones, as he sprang to his feet.

“The victim of a conspiracy? Is that what you call the sinking of a sloop?”

“I feel that the brave and noble Dory Dornwood will be my friend, and"—

“Clap a stopper on your jaw-tackle!” interposed the skipper of the Goldwing, borrowing an expression his uncle had quoted in his presence. “If you mean to blarney me, I shall be your enemy; and I will put you ashore on Diamond Island, without benefit of clergy.”

“Excuse me: I did not mean to offend you, Mr. Dornwood,”—

“Avast heaving! Don’t ‘mister’ me. Call me Dory; but don’t call me too late for dinner,” laughed the skipper.

“Since I know who you are, I shall tell you my story, and explain how I happened to be sailing the sloop, and”—

“I know how you were sailing her, and you sailed her to the bottom. Tell me the rest of it.”

“I will tell you why that man ran into me, and why he was chasing me up the lake.”

“That’s the point; but make the yarn a short one, or the steam-launch will be upon us before you get through with it. You have the floor, Mr. Millweed,” replied Dory, as he glanced at the approaching steamer.

“But I don’t want to be caught by that man! It might be fatal to me. He is a conspirator; and he is seeking to destroy my good name,” pleaded Mr. Millweed earnestly.

“I don’t understand the matter. Is the man an officer?”

“Not at all: he is chief clerk in a store in Burlington, and the steam-launch belongs to his employer. But he is rapidly overtaking us,” said the passenger.

“Why should he be after you? What have you been doing that is wrong?” asked Dory, who had no idea of enlisting on the wrong side in anybody’s cause.

“I have done nothing wrong. I will tell you all about the matter, only don’t let that man get hold of me. Upon my sacred honor, I am guilty of no crime,” continued Bolingbroke Millweed.

Dory was greatly tempted. He had a reputation on Lake Champlain, won but a short time before he made his snug harbor at Beech Hill. On two occasions he had successfully kept out of the way of a steamer. He had been pursued all one day by the swiftest steam-yacht on the lake, but by his “tactics” he had kept out of her reach.

If the young man had been guilty of a crime, he would do nothing for him. His passenger spoke fairly; but, if he had been doing wrong, he would not scruple to lie about it. Dory decided to keep out of the way of the steam-launch long enough to hear Bolingbroke’s story. It was an exciting game to dodge a steamer, and he desired to play it. The water in the lake had been very low all summer, and no heavy rains had yet raised it. The low-water soundings on the chart needed no corrections.

The Goldwing was a schooner, and Dory had been sailing under jib and mainsail only. This was about all the sail she could comfortably carry. The skipper looked over the situation very carefully. The yacht was on the wind, headed across the lake. After the sinking of the sloop, the two men in the steamer had a long talk before they started her screw again; and she was all of half a mile astern of the Goldwing.

Coming up into the wind, Dory set the mainsail; and then it was a staggering wind for the Goldwing. By a little manœuvring the skipper brought Diamond Island between his own craft and the steam-launch.

The pursuer had gained on him while he was setting the foresail. Starting his sheets, he stood off to the south-west until the steamer was abreast of the island. She could not head him off; and then he came about again, steering her due south.

The skipper was ready for the explanation, and the passenger proceeded to relate it.

The wind was blowing very fresh; and the Goldwing staggered wildly, as she went ahead nearly before it. Mr. Bolingbroke Millweed appeared to be a little nervous, for the schooner carried twice as much sail in proportion to her size as the sloop in which he had come from Burlington.

“She acts just as though she was going to tip over,” said he, clinging to the wash-board.

“Tip over! She don’t do that sort of thing. She has got over all her bad habits,” replied the skipper. “But I should like to have you spin your yarn before we get up to Field’s Bay, so that I may know what to do with you.”

“I have been looking for a place in a store for a year, for I was graduated at the high-school last summer,” Mr. Millweed began. “I know a young man by the name of Hackett Tungwood, who is in a store in Burlington. He wanted a vacation of a week, and he engaged me to take his place while he was absent.”

“Did his boss agree to it?” asked Dory.

“His employer did agree to it, and treated me very kindly when I went to the store at seven o’clock this morning. About nine o’clock Mr. Lingerwell, who is Hack’s brother-in-law, and the head man in the store, sent me to the safe for the cash-book.”

“I got the book, and gave it to him. Just then Mr. Longbrook, the proprietor, came in, and asked Mr. Lingerwell for the four hundred and fifty dollars which had been put in the safe the night before. I saw the head man go to the safe, and then both he and his employer seemed to be in great consternation.”

“Short words, or you never will finish,” interposed Dory.

“I did not know what the matter was, but Mr. Lingerwell used a great many exclamations.”

“What did he do with them?”

“He uttered them, of course: what else could he do with them? If you continue to interrupt with irrelevant questions, it will take me a long time to tell the story,” replied Mr. Millweed impatiently. “I was putting up goods near the desk, or I should not have noticed what was going on. In a little while I heard enough to satisfy me that the four hundred and fifty dollars was missing.

“Mr. Longbrook called me to the desk, and asked if I had been to the safe. I told him I had taken the cash-book from the safe, as I had been told to do. He looked me sharply in the eye. Mr. Lingerwell said no one else had been to the safe since he opened it in the morning.

“I was sent back to my work, and the two men kept on talking about the money. It was clear enough to me that I was suspected of taking it, and I felt as though I was already in the State prison. I heard Mr. Lingerwell say he was sure I had taken the money, for it was all right when he opened the safe. I never was so terrified before in my life. Hack Tungwell had told me he did not expect to keep his place much longer: he might not return at all. If I pleased his employer, I might get the situation.

“What I heard seemed to be the knell of all my hopes. I had done my best to get a place, for my father sadly needs what little I could earn. Then the two men talked in low tones for a while. Presently Mr. Longbrook went out of the store. I was sure he had gone for an officer to arrest me.

“The idea of being arrested and marched through the streets by a constable was about as bad to me as being shot through the head. When Mr. Lingerwell went to the back part of the store, I rushed out at the front door.”

“You left!” exclaimed Dory with something like indignation in his tones.

“I did: I was wholly unwilling to be dragged through the streets by an officer.”

“That was worse than sinking the sloop in two hundred and fifty feet of water. Do I understand you to say that you did not take the money from the safe?” demanded Dory.

“Do I look like a thief?” asked Mr. Millweed, rising from his seat in the standing-room in deep disgust; though he was immediately thrown back again by the motion of the yacht.

“Never mind how you look: you acted just like a thief,” retorted Dory warmly. “You don’t say yet that you didn’t take the money when you went to the safe for the book.”

“I do say now, most emphatically, that I did not take the money when I went to the safe for the cash-book, or at any other time. I didn’t even know there was any money in the safe,” protested Mr. Millweed very earnestly.

“That’s coming to the point; but you have done the best you could to convince your employer and his head man that you did take it. I advise you to go straight back to Burlington, and then straight to the store, and face the music. If anybody says I stole any money, I want to see the man that says so.”

“That would all be very well under ordinary circumstances,” pleaded Mr. Millweed.

“It’s all very well under any circumstances.”

“I had a theory of my own.”

“I don’t care any thing about your theory: I say the way is to face the music. If you had let them search you before you went out of the store, you would have been all right. They would not have found the money upon you, and you had had no chance to get rid of it. Now they will say you buried it somewhere on the shore of the lake.”

“But I tell you I have a theory. I believe Tim Lingerwell took the money himself. How easy it would have been for him to slip the wallet, or the package, whatever it was, into my pocket when I was not looking.”

“That thing has been done in a hundred and fifty novels and stories, but it isn’t done every day in Burlington. If Tim Lingerwell wanted the money bad enough to steal it, he wouldn’t put it into your pocket.”

“He isn’t any too good to do such a thing. He and Hack belong in Genverres; and people here wouldn’t trust either of them with a pewter quarter,” argued Mr. Millweed.

“Perhaps you are right: I don’t know. You have given yourself away, and made it look bad for you. If Tim Lingerwell took the money, what did he do with it?”

“That’s more than I know. He has the care of the safe, and he and I were the only persons who had been near it when Mr. Longbrook came in for the money. I know I did not take it; and if I didn’t, he did. That’s the whole of it.”

Dory believed his passenger had been a fool to run away; but, without knowing why, he could not help believing that he was telling the truth.

“Where did you get the sloop in which you came up the lake?” he asked. “You said she did not belong to you.”

“She belongs to Sim Green, a friend of mine, who lives next door to me. He was going down to Burlington to stay a few days with his uncle. Money is a scarce article in our family, and I had none to pay my fare by railroad. I was going to walk; but, at Sim’s invitation, I went down in his sloop. When I left the store, I went down to the boat, and got into it. Then I thought I would go home, and tell my father and mother what had happened.”

“Then you took the boat without leave?”

“I knew Sim would not care, and he won’t come home before Saturday. I meant to send it back before that time,” Mr. Millweed explained.

“That may be all right; but Sim won’t thank you for taking it, when he learns that she has gone down in two hundred and fifty feet of water. Now, what is to be done?” asked Dory. “Will you go back to Burlington, and face the music?”

“I don’t know what to do,” replied Mr. Millweed, evidently overwhelmed with perplexity.

“I have told you what I would do if I were in your place,” added Dory.

“Then I will go back; but I don’t want to be dragged into Burlington by Tim Lingerwell,” replied Mr. Millweed, as he glanced at the steam-launch.

“All right, if you will only go back. What makes you think Tim Lingerwell took the money?” asked Dory.

“The more I think of it, the more certain I feel that he took the money. Why should he call me from my work to get the cash-book out of the safe for him, when he was within six feet of it? Why should he send me to the safe at all, and leave it unlocked, when he knew there was so much money in it? Why didn’t he search me before Mr. Longbrook went out? He managed it all to suit himself,” replied the passenger with energy.

Dory thought his passenger was right. If the head man in the store believed the substitute clerk had taken the money from the safe, he could not see why he had been permitted to leave the store.

“Did they chase you in the street after you left the store?” asked Dory, who was rather inclined to do a little detective business on his own account, as he had had a taste of it during the summer.

“No one chased me. I did not see any one from the store. I was off Split Rock when I first saw the launch, but I didn’t know Tim was in her till just before he ran into the sloop. The moment I heard his voice, I understood it all; but I did not know enough about a boat to get out of the way.”

“I don’t believe you did, or you would not have sunk that sloop. The wonder is, that you got as far as you did without capsizing her.”

“I hoisted the sail, and let her go. The wind was fair, and all I had to do was to keep her away from the shore. She frightened me out of my wits two or three times when the waves were high.”

“With this breeze we can run away from that steam-launch. If you like, I will take you back to Burlington, after I have told my mother where I am going.”

“I should like that very much,” replied Mr. Millweed.

“But we can’t run away from the steamer beating down the lake, and we must dodge her in some way,” suggested Dory.

“I will do just as you say, Dory; and I begin to see what an idiot I was to run away, though I still think Tim Lingerwell had some plan to trip me up,” added the passenger.

Dory had already decided upon his plan of operations. The steamer was on the wrong side of him: he wished he was below instead of above her; for he wanted to run into Beaver River, which he could not do on the open lake without encountering his pursuer.

His southerly course had by this time brought him near the east shore of the lake. The steam-launch was all of half a mile distant. From the mouth of the river a shoal extends a mile out into the lake, and over a mile to the southward. Dory struck this shallow water at its southern extremity.

The deepest water is near the shore, and the skipper followed it. The launch continued on her former course for a while, and then stopped her screw. Tim Lingerwell at the wheel was perplexed; but Dory found his way across the shoal, and entered the river. Then the launch went around the shoal, and continued the chase.

As soon as the Goldwing was fairly in the river, Dory found the wind was light compared with what it had been on the open lake. But the skipper had made up his mind that his passenger should not be taken out of the boat: his plan for another movement was ready.

“She is catching us, and I might as well make up my mind to go back to Burlington in the Juniper;” for that was the name of the steam-launch. “I believe Tim Lingerwell has that money in his pocket at this minute; for he probably has had no chance to get rid of it,” said Mr. Millweed in utter despondency.

“You can make up your mind any way you please; but, if you don’t want to go with him, you needn’t. If you will do as I say, I will land you in Burlington to-night,” replied Dory, as the yacht passed the narrow neck of land between the river and Porter’s Bay.

“I will do just as you tell me, Dory; for I know you are capable of doing big things.”

“It won’t be a very big thing, but we can dodge the Juniper a great deal easier than you can go to bed without your supper. I shall make a landing at the cross-cut. You will go on shore, and follow the path until you get to the other side of the woods. Then take the other path to the river, and strike it half a mile above the landing.”

“What is all that for?” asked Mr. Millweed, perplexed by the instructions.

“You do just as I tell you, and ask no questions. I will be responsible for the result.”

“All right: I will do so. But I might as well go home, for I shall be half-way there when I get to the other side of the woods.”

“If you go home, Tim Lingerwell will find you there. He will think you have gone home; and that is just what I want him to think,” said Dory, as he made the landing at the cross-cut, which was a short way to reach the northern outskirts of the town.

“I will do just what you say, Dory.”

“Very well; but don’t be in a hurry. Wait till the Juniper gets a little nearer, so that Tim can see you. Then start off as though you meant business.”

They had not long to wait, for the steam-launch had been gaining rapidly on the yacht since they entered the river. When she was near enough to enable those on board of her to see just what was done, Mr. Millweed leaped ashore, and ran with all his might.

“Stop him! Don’t let him go!” shouted the helmsman of the Juniper. “He is a thief! He has been stealing a large sum of money!”

“I am not a constable,” answered Dory quietly. “I pulled him out of deep water, and brought him ashore. If you want him, you can take him.”

Tim Lingerwell rang his bell, and the engine stopped. He ran her up to the shore, carrying her bow line to a post, as he leaped upon the bank.

“What did you let him go for?” demanded Tim, turning to Dory, who had also landed.

“It’s none of my business where he goes,” replied Dory. “This is a free country.”

“But I told you he had been stealing. Come, Greeze, we must catch him. He lives up this way; and we shall find him at home, if we don’t catch him before he gets there.”

The engineer abandoned his machine, and the two men started off on a run in the direction taken by the fugitive. But Mr. Millweed had a good start, and the wood concealed him from his pursuers.

As soon as they were out of sight, Dory took a survey of the Juniper. He had often seen her before, though he had never been on board of her; and he improved the present opportunity to do so. He made a more careful examination of her than a mere inspection seemed to require. Like Mr. Millweed, he had a theory. He looked into all the lockers, and even examined the space under the ceiling as far as he could get at it.

Just as he was beginning to think his theory was entirely at fault, he drew out a large pocket-book, which seemed to be well filled with something. He opened it, and found that it contained a large pile of bank-bills. Mr. Millweed’s theory was correct: Tim Lingerwell had had no opportunity to dispose of the money, and he had put it where he supposed no mortal could possibly find it.

Mr. Bolingbroke Millweed’s honesty was demonstrated. Dory had been right in trusting him. It was a great satisfaction to him to find that he had judged his passenger correctly. But Tim Lingerwell was quite as big a fool as Mr. Millweed; and the same might be truly said of any person who commits a robbery.

Dory took the money from the pocket-book, and put it into his hip-pocket. He put a portion of a newspaper into the place from which he had taken the bills, so as to make the pocket-book look as it had before its valuable contents had been removed. Then he placed it under the ceiling precisely as he had found it. His business on board of the Juniper was finished, and he hastened to get the Goldwing under way again.

Mr. Millweed had faithfully followed his instructions, and was on the bank of the river above the woods. The passenger leaped on board when the bow touched the shore.

“Did you see them, Dory?” asked Mr. Millweed, greatly excited.

“Of course I saw them. They landed where you did, and started off at a dead run after you. Lingerwell said you had gone home; and they expect to find you there,” replied Dory, as he headed the yacht on her course up the river again.

“They won’t find me there,” added the passenger, chuckling at the success of Dory’s plan. “But won’t they find us at Beech Hill if you go there?”

“It will be two hours before they get back to the Juniper again, and then they won’t know where to look for you. We are all right.”

Dory did not go into Beech-Hill Creek, which led to the lake in the rear of the mansion of Captain Gildrock, but continued on his course till he came to the river-road, on which the estate was located. At this point he made a landing; and, leaving his charge in the boat, he hastened to the house.

Dory found his mother and sister in the garden. As briefly as he could, he told the story of his passenger, and announced his intention of going to Burlington at once. As he did so, they walked to the house, where Mrs. Dornwood put up a heavy lunch for her son. The skipper showed the money he had taken from the Juniper, to prove his statement; but this was a secret she was not to reveal to any person at present.

Mrs. Dornwood volunteered to call upon the Millweeds, and inform them of the true state of the case; for the visit of Tim Lingerwell was likely to give them much trouble and anxiety before the whole truth came out.

With the large lunch-basket and his overcoat, Dory hastened back to the place where he had left the Goldwing. He found his passenger in a very nervous and troubled frame of mind, fearful that Tim Lingerwell might pounce upon him while he was waiting for the skipper. He re-assured him by his confident words, and they embarked without losing a moment.

“It is a little more than an hour since we left the steamer; and Lingerwell may see us as we go down the river, though I don’t think he has got back yet,” said Dory, when the yacht was under way.

“Why not wait here until after the Juniper has started?” suggested Mr. Millweed.

“We should have to wait all night, I think; for I don’t believe Lingerwell will go back without you,” replied Dory.

“But you have to sail back to Burlington with the wind against you: the Juniper will be sure to catch us,” added Mr. Millweed anxiously.

“I am willing to take the chances; and, whatever happens to us, I will promise that you shall be all right when you have faced the music,” answered Dory, keeping a sharp lookout ahead for the steam-launch.

“All right: you have carried me through so far, and I will trust you to the end. You saved my life; and I shall never cease to be grateful to you, even if you do nothing more for me,” said the passenger with more feeling than he had before exhibited.

As the yacht approached the place where the fugitive had landed, Dory saw that the Juniper was still there. As the skipper was obliged to beat a portion of the distance down the river, he made a tack within twenty feet of her.

“Hold on, there!” shouted a voice from her; but it was not that of Lingerwell.

At the same moment a man rose from the bottom of the launch. He proved to be Greeze, the engineer. The pilot had evidently sent him back to attend to the boat.

“We will see you in Burlington,” replied Dory, with abundant good nature, when he was satisfied that Lingerwell was not on board of her.

“We want that thief!” yelled Greeze.

“You will take him down to Burlington with you when you go.”

Doubtless this answer perplexed the engineer; but the yacht passed out of hailing-distance, and no explanation was practicable. After going around the bend of the river, the Goldwing could lay her course for the lake, close-hauled.

“The engineer has left the boat again,” said Mr. Millweed, just before the yacht reached the bend. “Where do you suppose he is going now?”

“He is going to find Lingerwell, and tell him that you have gone down the river. But he may not find him for two hours. Of course he is moving about looking for you. Very likely he will go to my uncle’s house to inquire for me, though he will not be any the wiser for his visit. But I feel as though it was about supper-time,” continued Dory, as he consulted the watch his uncle had given him on his last birthday. “It is quarter-past six.”

“I have the same sort of a feeling; for I had no dinner to-day, and took my breakfast at six this morning,” added Mr. Millweed.

“Why didn’t you say so before? You might have been working your jaws from the time we left the shore-road,” said Dory, as he handed the lunch-basket to his passenger. “Help yourself, and I will feed as the helm gives me time.”

Mr. Millweed showed that he had an appetite by the time the Goldwing reached the lake. As the sun went down, the wind died out, though not till the schooner had passed Split Rock.

“I am afraid we shall not get to Burlington to-night; for we can’t go without wind,” said Dory, when the breeze had nearly deserted them.

“Then I am sure to be caught,” added the passenger.

“Not at all: don’t give it up.”

Dory kept the boat moving a mile farther; and then came to anchor inside of Cedar Island, where the masts of the Goldwing could not be seen from the lake. At the skipper’s suggestion, the passenger turned in, and went to sleep.

Dory had put on his overcoat, and gone to sleep on the cushions of the standing-room. The jib had been lowered, but the fore and main sails were still set. The skipper had passed the main-sheet around his arm, so that any motion of the sail would wake him. This signal disturbed him about eleven by jerking him off the seat upon the floor of the standing-room.

The wind had begun to come in fresh between Garden Island and Thompson’s Point, indicating that its direction was from the south-west. It was fair for Burlington; but, before he got up the anchor, he listened attentively for any sounds that might come from the open lake, for he had a suspicion that he heard something.

A moment later he was confident that he heard the puff of steam from the escape-pipe of a steamer. It was cloudy, and the night was dark. He looked out between the islands and the mainland, but he could see nothing. The sounds came nearer for a time: then they ceased for a few minutes, and were followed by a splash in the water. He was satisfied that a steamer had anchored at no great distance from Cedar Island.

The skipper’s nap had refreshed him, and he was not inclined to sleep while there was wind enough to move the schooner. Very likely the steamer which had anchored was the Juniper. Probably Tim Lingerwell realized that the Goldwing could not sail without wind; and he was afraid he might pass her if he continued on his course. Doubtless he suspected that she had put in behind some island.

Dory got up the anchor, hoisted the jib, and, with the wind on the beam, stood off to the north-west. He had no doubt the steamer he had heard was the Juniper. The noise of her screw, and the puff of her escape-pipe, indicated that she was a very small craft. He concluded that Tim Lingerwell would keep a sharp lookout for him, and he expected to be chased as soon as he passed the island.

When he could see between the two islands, he discovered a light, which marked the position of the Juniper. The Goldwing passed within a quarter of a mile of her; but the wind was coming quite fresh from the south-west, and Dory thought that he could take care of himself and his sleeping passenger.

Though it was very dark, the skipper had not deemed it prudent to light one of his lanterns; for it would be sure to betray his presence. As the yacht continued silently on her course, Dory heard the sound of voices in the direction of Garden Island, behind which he could see the Juniper’s light.

It was evident that the pursuers were not asleep. Dory listened with all his might, for he was deeply interested in what was taking place on board of the steam-launch. It seemed to him that the captain and engineer were talking a great deal louder than the occasion required. As they were in the same craft, it was hardly necessary for them to yell at each other. After he had listened a while, Dory thought the tones of the speakers were angry and even violent.

The skipper brought the Goldwing up into the wind, for a short distance farther would carry the yacht out of sight of the Juniper. He listened again; and the tones of the crew of the steam-launch were more violent than before. What was the matter? There was clearly a quarrel in progress between the captain and the engineer. As the voices became louder and more forcible, the disputants were plainly approaching a crisis in the quarrel.

“Help! Help! Murder!” yelled one of the angry men; and Dory was confident it was the voice of the engineer.

The skipper of the Goldwing did not wait to hear any more, or to speculate upon the cause of the difficulty on board of the Juniper. Hauling in his sheets, he filled away on the starboard tack. The schooner could just lay her course for the steamer’s light. It looked a little like a stormy time ahead, and Dory decided to call his passenger.

Leaving the helm for a moment, he went to the cabin forward; and a sharp word roused Mr. Millweed from his slumbers. Hastening back to the helm, he seized the tiller before the schooner had time to broach-to. At that moment the cry from the steamer was repeated, though it was fainter than before.

“What’s the matter, Dory?” asked Mr. Millweed, as he rushed into the standing-room. “Didn’t I hear a yell just now?”

“If you are not deaf, you did,” replied Dory, still gazing at the steamer’s light. “There is a row on board of the Juniper. The engineer is shouting for help.”

“What does it all mean?” inquired the passenger anxiously.

“I don’t know what it means, but I am going up there to find out.”

“Do you think it is safe to go near them?” inquired Mr. Millweed.

“I don’t know whether it is safe or not; but men don’t yell murder in the middle of the night without some good reason.”

“What can be the meaning of it?” asked the fugitive, evidently believing that the skipper ought to be able to tell him all about it.

“You can guess as well as I can, Bolly,” answered Dory. “Tim and the engineer are the only persons on board of the Juniper, and the quarrel must be between them. That’s all I know about it. But, if we are going to take a hand in this fight, we had better have some sort of weapons.”

“You don’t mean to take a hand in any fight, do you, Dory?” asked Bolingbroke, not a little alarmed at the announcement.

“Not if I can help it; but I don’t mean to let Lingerwell kill his companion, without putting a finger in the pie. Go to the cabin, and bring out the long tiller. You will find it under the berth you slept in.”

“But I don’t like the idea of getting into a fight with such a fellow as Tim Lingerwell,” protested Bolingbroke, without heeding the request.

“I don’t care whether you like it or not. It is plain enough that we ought to do something when a man is trying to kill another. Bring out the tiller!”

Mr. Millweed obeyed the order this time. Dory took the tiller, and placed it at his side, where it would be ready for use if the occasion should require.

“There is a round stick by the centre-board casing. You had better have that in your hand, for you may want to defend yourself before we get through with this business. I don’t know what the quarrel is about; but we are likely to find out very soon,” added Dory.

“Help! Help! Murder!”

“There it is again!” exclaimed the skipper, not a little excited by this time.

“It’s awful, isn’t it, Dory?” added Bolingbroke, his teeth chattering with terror at the terrible sounds that were borne over the dark waters.

“Juniper, ahoy!” screamed Dory, forming a speaking-trumpet with his two hands. “What’s the matter?”

No reply came back in answer to the question. Just then Dory began to wonder whether or not these cries were not a trick to call the Goldwing out from her hiding-place. The wind had just breezed up; and Tim Lingerwell might fear that the fugitive would escape him, after all his labor and pains to capture him.

He thought enough of the idea to mention it to his passenger. Bolingbroke was ready to adopt the opinion that it was a trick: he was ready to adopt any thing rather than go near the Juniper, whether there was a fight or not on board of her.

“Of course it is a ruse to get you out of your hiding-place,” said he with energy. “I thought of that myself.”

“If the wind hadn’t just breezed up, I should not have thought of such a thing,” added Dory, still musing upon the point; for he did not like the idea of having his passenger taken from the Goldwing by a trick.

On the other hand, it was possible, perhaps probable, that the two men had fallen out, and come to blows. Dory knew that Lingerwell was a bad man, and it is always easy for such men to make trouble. Strange as it may seem, the skipper did not connect the large sum of money in his hip-pocket with the quarrel on board of the Juniper. He did not even think of the bills he had taken from the steam-launch in the absence of her crew.

“I wouldn’t go near her, Dory,” argued Bolingbroke. “I hope you won’t step into the trap Tim has set for you to fall into.”

“I am not afraid of Tim Lingerwell, and I am going over there to see if any thing is the matter. We will be a little cautious about approaching the steamer.”

“But you can’t run away from her if you find it is only a trick,” reasoned Bolingbroke.

“We must take our chances,” replied Dory.

By this time the Goldwing was entering the passage between Cedar and Garden Islands. The Juniper was close to the shore, and the islands were about the eighth of a mile apart. The wind was freshening every minute; and Dory decided to run by the steamer, going as near as it was prudent to go.

He could still hear the voices of the two men, though their tone had greatly changed. The skipper saw that the steamer was still at anchor, for she had swung around with her head to the wind. He was satisfied, by this fact, that the call for help was not a trick: if it had been, the Juniper would have been under way by this time.

“Juniper, ahoy!” called Dory, as the Goldwing came up with the launch. “What is the matter on board?”

“Nothing is the matter. Greeze has had the nightmare, and shouted murder in his sleep,” replied Lingerwell, trying to laugh it off, though the effort was a very sickly one.

“Help! help!” shouted the engineer from the other end of the boat.

“He don’t seem to have got over his nightmare yet,” added Dory.—“What is the matter there? What ails you?” demanded the skipper.

“Lingerwell has nearly killed me: he says I stole his money while he was after the Millweed fellow,” replied Greeze.

“Shut up, you stupid blockhead! Silence! Don’t say another word about it, and we will fix up the matter,” said Lingerwell in a wheedling tone, as though he would have given something handsome to have sealed the lips of the engineer.

“I won’t shut up! I have been insulted and abused; and I will have satisfaction if it costs me my life. I didn’t take your money. I didn’t know you had any,” growled Greeze, moving aft.

This explanation on the part of the engineer enabled Dory to understand the nature of the quarrel between the two men. When the Juniper had anchored, Lingerwell had evidently taken the pocket-book from its hiding-place, and found that worthless paper had been put in the place of the four hundred and fifty dollars. As he was not aware that Dory, or any other person, had been on board, he naturally concluded that the engineer must have robbed him of his ill-gotten money.

Dory had come up into the wind under the lee of the Juniper. The lantern hung on a stanchion in the after part of the steamer, so that the skipper of the Goldwing and his passenger could see what took place on board of her. The engineer had no sooner reached the place where Lingerwell stood, than he leaped upon him with the fury of a tiger.

The engineer was evidently suffering under the humiliation of his former defeat; and now he was seeking to satisfy his revengeful feelings rather than gain any point, for Lingerwell had offered to “fix up the matter.” His onslaught was so sudden and unexpected that Lingerwell was borne down beneath him.

Dory was wise enough to see, on the instant, that the impulsive attack of the engineer was a great mistake; but it was too late to correct it. In this case his sympathies were not “with the bottom dog;” for the engineer had the right on his side, in spite of his blunder.

The skipper of the Goldwing felt called upon to take a hand in the conflict; and, when Lingerwell was about to shake off his opponent, he went to the assistance of the latter. The engineer had thrown his man upon his face, and he was in the act of turning over when Dory put his knees on the back of the fallen one.

“Put your foot on his back, and grab one of his hands!” exclaimed Dory, as he grasped an arm.

“I can hold him! He tried to kill me, and I will get even with him!” gasped Greeze.

“I will pay him off for what he did to me!” cried the engineer.

“If you strike him, or kick him, I will leave at once!” added Dory decidedly. “We can hold him, and keep him from harming you again.”

“He abused me, and I will get even with him,” replied Greeze, a little mollified by the threat of Dory; for he saw that he could not manage the steamer alone.

“Don’t harm him: the law will punish him,” continued Dory. “Bolly.”

The passenger in the Goldwing had been looking on with no little surprise and terror, and had not ventured upon the deck of the Juniper. Possibly he was too much alarmed to realize that the tables had been turned.

“What is it, Dory?” he responded to the call.

“Bring me the rope that lies under the tiller.”

Bolingbroke found the line, and carried it to the skipper; but he was careful not to go too near the fallen tiger, for such he had proved to be to him. Dory took the line, and succeeded in making it fast to the arm of Lingerwell.

“What are you about, you young villain? Do you mean to tie my hands?” demanded the fallen man.

“That’s the idea exactly,” replied Dory, as he attempted to pass the line around the arm held by the engineer.

Lingerwell had been quiet for a minute after Dory took hold of him, but the idea of being captured and tied up like a felon was too much for him. With a series of heavy oaths, he made a desperate effort to shake off his assailants. The engineer meant business, though the direction of the assault had been taken out of his hands by the new-comer. He lay down upon his victim, and jammed his knees into the small of his back, so that escape was impossible. Dory passed the line around the other wrist of the conspirator, and the two were securely bound together behind him.

“He is all right now, and cannot harm anybody,” said Dory. “Get another line, and we will secure his feet.” Bolingbroke brought the rope, for by this time he could see that his great enemy was powerless.

Dory fastened the feet of Lingerwell together, and then turned him on his side, so that he could be more comfortable. Again the victim struggled to loose himself; but Dory had done his work well, and he could produce no impression upon the rope.

“This is an outrage!” yelled he, furious with passion.

“I suppose it isn’t an outrage to try to kill a man,” replied Dory, as he took the lantern and examined the fastenings he had put on the prisoner.

“I didn’t try to kill him! That is all nonsense!” replied Lingerwell, suspending his struggles.

“We won’t argue the matter now,” replied Dory, walking to the forward part of the boat.

He was followed by the engineer, who seemed to be desirous to explain the affair. Doubtless he was grateful for the service the boy had rendered to him, and looked upon the skipper of the Goldwing as his friend.

“You are a plucky boy, Dory,” said Greeze, when they reached the wheel, near the bow of the boat. “But I think I could have handled that fellow alone.”

“It is very strange that you should get into a quarrel out here in the middle of the night,” added Dory.

“It wasn’t a quarrel of my making; and, if he hadn’t taken me when I was not thinking of such a thing, the boot would have been on the other leg. He’s bigger than I am, but I can handle him if I have fair play.”

“How did you happen to get into such a row?”

“I stopped the boat when we reached this place, and then let go the anchor, at Lingerwell’s order. When I went forward, I found him on the floor, feeling about under the ceiling. I didn’t know what he was doing; and he didn’t care to have me know, for he told me to go aft and bank the fire in the furnace. I did so, and when I got through I went forward again. Lingerwell was at the lantern, looking over what was in a big pocket-book he had in his hands.”

“Had he said any thing about a pocket-book before?” asked Dory.

“Not a word. When I got to him, he looked as though he was very nervous and excited. He poked the pocket-book over, and then fished his pockets all through. I asked him what the matter was. He said he had dropped his pocket-book on the floor, some time during the day; he didn’t know when. He had just found it; but the money had all been taken out, and a piece of newspaper put in its place to swell it out.”

“Did he say how much money was in it?” inquired Dory.

“He said there was a good deal in it, but he didn’t tell me how much.”

“Did he say there was a hundred dollars or more?”

“He didn’t say a word about it. He kept getting more excited, and at last he said I must have taken the money from the pocket-book. I answered, that I didn’t do it: I hadn’t seen his pocket-book, and didn’t know he had any money with him. On that he got mad, and I was as mad as he was.

“We had a long jaw about it, and then he pitched into me. He got me by the throat before I knew what he was about. He put me down, and then tried to fish my pockets. I yelled for help, for I thought he would kill me. I hardly knew what I did; but I shook him off, and we had another savage jaw about it. Then he pitched into me again. He had a club in his hand; and I think he would have used it on me, if he hadn’t heard you yell just at this time.”

“I hoped my hail would let him know there was some one at hand, though it was only a boy,” added Dory.

“That was what made him let up on me. Then he tried to smooth it over; but I never was treated like that before, and I meant to have it out with him.”

“Well, here we are; and what is to be done next?” asked Dory.

“We were waiting down here to catch that Millweed fellow that stole the money from the safe,” replied Greeze.

“He says he didn’t take the money from the safe, and he is going back to Burlington to face the music.”

“We might as well go along then: we haven’t any more business up here. You can steer the Juniper, and we will tow the Goldwing,” suggested the engineer. “I don’t know how this thing is coming out, but I am ready to go to Burlington. I suppose Lingerwell will have me discharged after this, but I don’t care for that. You have tied him hand and foot, and I don’t know what you mean by that. I meant to take what I owed him out of his hide.”

“I tied him to keep him from pitching into you again. I want to see Mr. Longbrook as soon as we get to Burlington; and he can do what he likes with him,” replied Dory. “We will start for Burlington as soon as you are ready.”

When the excitement was over, Bolingbroke Millweed had returned to the Goldwing, and to his berth in the cabin, where he was now fast asleep. The engineer replenished his fire, and in half an hour the Juniper was under way. At four o’clock in the morning she was at her wharf in Burlington. The Goldwing was made fast alongside of her. It was nearly daylight, and it would be quite by the time Dory could reach the residence of Mr. Longbrook.

Bolingbroke was roused from his slumbers in the cabin, but he objected to calling upon the storekeeper at so early an hour in the morning. Dory did not care for his opinion, and insisted upon going without any delay. Greeze was to keep watch over Lingerwell until he heard from Dory, and Mr. Longbrook was to decide what was to be done with the prisoner.

The house of the storekeeper was easily found. It was about five by this time, and the early visitors saw that the people were up. To Dory’s inquiry for the head of the family, the servant said he had gone to the store. He had staid there till midnight the night before, and had left the house as soon as it was light.

Dory was not a little astonished at this severe devotion to business; but he hastened to the store, and found Mr. Longbrook was busy over his books. He had locked himself in, but he opened the door in answer to the skipper’s vigorous knocks.

“I am too busy to see any one now,” said the storekeeper impatiently. “Come at nine o’clock, and I will see you.”

“This young man wants to see you at once,” added Dory, pulling Bolingbroke into the doorway.

“What, Millweed! So you have come back, young man,” added Mr. Longbrook, as he recognized his late assistant.

“I have come back to tell you, sir, that I did not take the money from your safe,” stammered Bolingbroke.

“What did you run away for, then?” demanded the merchant severely.

“Because I was a fool and was frightened. I found that Mr. Lingerwell was determined to convict me, guilty or innocent; and I had not the courage to stay and see it out,” replied Bolingbroke honestly.

“You lost four hundred and fifty dollars from your safe, Mr. Longbrook,” interposed Dory.

“That was just the amount taken, and this young fellow took it. It looks as though he came to work here at this time for the purpose of getting it, and he left as soon as he had the money,” said the merchant angrily. “What have you done with the money, you young rascal?”

“I have not had it, I have not seen it,” protested Bolingbroke.

“Don’t tell me that! No one else could have taken it. You and Lingerwell were the only two persons who went to the safe.”

“Possibly Mr. Lingerwell took it himself,” suggested Dory.

Mr. Longbrook knit his brows into a frown, and turned away as though he was thinking of something. Doubtless he was considering whether or not it was possible that his trusted head man could have done such a deed.

“At any rate here is the money,” added Dory, pulling the roll of bills from his pocket.

The merchant opened his eyes very wide, and so did Mr. Bolingbroke Millweed.

Mr. Longbrook took the bills, and a smile of satisfaction overspread his troubled face. He looked at Dory with astonishment, and then glanced from him to Bolingbroke. The latter was quite as much surprised as the owner of the four hundred and fifty dollars.

Dory had not given a hint to his companion or to the engineer that he had the money. He had concealed the fact from prudential motives. He had told his mother all about it, but he was not inclined to lead either of his associates in the boat into temptation.

“I see,” said Mr. Longbrook, nodding his head at Dory. “Your friend has concluded to give up the money, and expects me to say nothing more about it.”

“I never saw the money before; and I didn’t know till this minute that Dory had it,” protested Bolingbroke earnestly.

“He tells the exact truth,” added Dory. “Neither he nor any one but my mother, who is at Genverres, knew that I had the money. I think you had better hear the whole story, and then you can judge for yourself.”

Mr. Longbrook was quite willing to hear the story, for he was deeply interested by this time. He asked Dory and his companion into the store, and locked the door again. Bolingbroke gave his part of the narrative first, and Dory finished it out.

“I believed Bolingbroke told me the truth; and I accepted Mr. Lingerwell’s statement that one of the two must have stolen the money,” said Dory. “When the skipper and engineer left the Juniper to catch my passenger, I looked the steamer over, and found the pocket-book. I put the piece of newspaper into the place where I took out the bills, hoping that Mr. Lingerwell would suppose he had the bills until he got to Burlington.”

Then followed the skipper’s account of the quarrel on board of the Juniper, which confirmed Dory’s statement. It was as clear to the merchant as it was to Dory, that the head man had stolen the money.

“Where is Lingerwell now?” asked Mr. Longbrook.

“He is on board of the Juniper, tied hand and foot; and the engineer is keeping guard over him. He did not know I had been on board of the Juniper in his absence; and he was sure that Greeze must have taken the money from the pocket-book, and put the newspaper in its place. You can do what you like with him.”

“I knew that man was a villain!” exclaimed Bolingbroke when Dory had finished his explanation. “I saw why I was sent to the safe for the cash-book, when it was almost within reach of his hands; and that was one of my reasons for running away. I was a fool, but I was frightened.”

“I wish I had known that Lingerwell was a rascal a little sooner. Since he went after this young man yesterday, I have been examining my books. I am satisfied that he has robbed me of hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars. I can see just how he has done it. Now we will go down and see him, and we will have a warrant for his arrest.”

By this time it was seven o’clock, and the merchant departed for the warrant and the officer to serve it. Dory and Bolingbroke went with him. As they passed the Van Ness House, Dory was not a little surprised to see his uncle standing at the entrance of the hotel with quite a little crowd of boys. The skipper counted ten of them, and he wondered if they were to be pupils in the Beech-Hill Industrial School.

“You are here in good time, Theodore,” demanded Captain Gildrock, as he recognized his nephew.

“I came up on a little business, uncle,” replied Dory.

“Very important business it was to me, Captain Gildrock,” added Mr. Longbrook. “I am under very great obligations to him.”

The breakfast-bell rang, and the boys were sent in to obtain the morning meal. The merchant gave an outline of the loss and recovery of his money. The captain asked a great many questions, which were all answered to his satisfaction. Then he insisted that the party should breakfast with him.

Mr. Longbrook accepted the invitation, and they entered the hotel. In the vestibule the merchant met the justice to whom he intended to apply for the warrant. He stated his case to him, and the gentleman promised to have the warrant ready by the time he had finished his breakfast. The party seated themselves at the table.

“A telegram for you, Captain Gildrock,” said one of the clerks, bringing the message to him.

“‘Dory away; no pilot; cannot go up the lake.—Jepson,’” read the captain from the despatch in his hand. “Then you did not come down in the Sylph, Theodore. Of course you did not. I have heard the story of your movements during the night. I telegraphed to you last night from here to come down in the steamer, and take the new scholars to Beech Hill.”

“I have the Goldwing here, and I can take them home in her,” replied Dory.

“But I have ten boys with me: there they are at the other table. They are about as wild and harum-scarum a set of youngsters as I ever saw in my life. But we will take all that out of them in a few days, when I get them to Beech Hill,” replied the captain confidently.

“I can take the crowd up in the Goldwing.”

“We will see about that when we have done breakfast, and you have disposed of your prisoner.”

“The Juniper is at your service, Captain Gildrock.”

“Thank you: perhaps we may want to use her.”

Mr. Longbrook inquired in regard to the sloop that had been sunk. It was not likely that Lingerwell would be able to pay for the mischief he had done; and the merchant said he had a sloop, not a very fine one, which he was willing to give as a substitute for the one lost. Bolingbroke was delighted with this offer, and promptly accepted it.

After breakfast the party proceeded to the wharf where the Juniper lay, the recruits for the Industrial School being required to report at the hotel at ten o’clock. Mr. Longbrook found things on board of his steam-launch precisely as represented to him by Dory. Lingerwell still lay on the floor in the after part of the steamer. Greeze sat near him, and apparently had not taken his eye off him since the departure of Dory early in the morning.

The officer with the warrant had not yet put in an appearance. The merchant, before he showed himself to his delinquent head man, called the engineer up the wharf, and questioned him in regard to the events of the night. His statement did not vary from that of Dory and Bolingbroke, though Greeze as yet had no suspicion that the money he had been charged with stealing had been taken from the safe of his employer.

“I think there are enough of us to handle this man,” said Mr. Longbrook, as he returned to the steam-launch. “You may untie his hands, Greeze.”

“With fair play I can handle him alone,” replied the engineer, as he proceeded to release the wrists of the culprit on the floor. Greeze helped him to get upon his feet, and then gave him a seat opposite the merchant.

“Well, Lingerwell, I find you did not capture the thief,” said the storekeeper.

“I did not: he found an accomplice in Dory Dornwood, who helped him to escape,” replied the prisoner doggedly; and, as he had no knowledge of what had transpired at the store, he was not prepared to admit any thing.

“But how does it happen that I find you a prisoner, bound hand and foot?” asked the merchant.

“I am the victim of an outrage. I had some difficulty with the engineer in the night, and he joined forces with Dory against me. By taking me unawares, they succeeded in making me a prisoner. I had some money with me, and dropped my pocket-book on the floor near the wheel. When I found it, the money was taken out, and its place filled with a piece of newspaper.” This statement also confirmed that of Dory.

“How much money did you happen to have with you?” inquired his employer.

“About a hundred dollars. Of course I knew that the engineer had done this, for no one but Greeze and myself had been on board of the steamer.”

“Are you sure of that?”

“As sure as I can be of any thing in this world,” persisted Lingerwell.

“Are you correct about the amount of money in your pocket-book?”