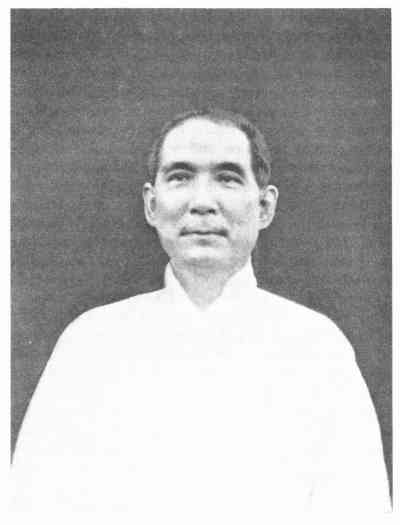

Generalissimo Chiang K'ai-shek

Generalissimo Chiang K'ai-shek

Generalissimo Chiang K'ai-shek

Generalissimo Chiang K'ai-shek

BY

PAUL M. A. LINEBARGER

Duke University

GREENWOOD PRESS, PUBLISHERS

WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT

The Library of Congress has catalogued this publication as follows:

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Linebarger, Paul Myron Anthony, 1913-1966.

The China of Chiang K'ai-shek; a political study.Reprint of the 1943 ed. published by World Peace Foundation, Boston.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. China—Politics and government—1912-1949.

2. Chiang, Kai-shek, 1886-.I. Title.

DS774.L48 1973320.9'51'04273-725

ISBN 0-8371-6779-5

Copyright 1942 by World Peace Foundation

Originally published in 1943

by World Peace Foundation, Boston

Reprinted with the permission

of World Peace Foundation

First Greenwood Reprinting 1973

Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 73-725

ISBN 0-8371-6779-5

Printed in the United States of America

TO MY MOTHER

With Love

Acknowledgments, for a work of this type, are always insufficient and often ungracious. Today, political and military conditions forbid mention of some of the persons to whom I am most indebted. Furthermore, it is unfeasible to thank those teachers and friends who have prepared me in years past for the present work. Nevertheless, courtesy and candor demand that I indicate the extent of my obligation, and tender these inadequate thanks.

For interviews, hospitality and other kindnesses shown me in Western China I wish to thank Generalissimo and Mme. Chiang K'ai-shek; Their Excellencies, Sun K'ê, Yü Yu-jen, H. H. Kung, Wang Ch'ung-hui, Chang Chia-ngau, T. F. Tsiang, Yeh Ch'u-tsang, Kan Nai-kuang, Ch'ên Kuo-fu, Wang Shih-chieh, Ch'u Chia-hua, Hollington Tong, and Ma Chao-chun; Major Generals J. L. Huang and Ch'u Shih-ming; Bishop Paul Yu-pin; and Messrs. Foo Ping-shêng, Chên Ming-shu, Lo Chia-lun, Edward Bing-shuey Lee, Han Lih-wu, P. C. Kuo, Ch'ên Chih-mai, Kinn-wei Shaw, James Y. C. Yen, Wang Shen-tsu, Shuming T. Liu, Jen Shieh, Li Ch'in-shui, and Ma P'in-ho. Among the foreign community, I wish to thank the American Ambassador, Mr. Nelson Johnson, and Mr. E. F. Drumwright for their kind reception; and to thank Mr. Tillman Durdin, Mr. Theodore White, Mr. George Fitch, Dr. J. B. Tayler, Professor Frank Price, and Professor and Mrs. J. B. Slocum.

I feel myself peculiarly fortunate in having three such good, loyal friends as Drs. Chu Djang, Miao Chung-yi, and Yin Pao-yü, whose kindnesses to me have continued ever since our student days together at the Johns Hopkins.

Dean Shen Ch'un-lu, Mr. Tso T'ao-fên and their associates in the National Salvation movement; Colonel Ch'in Po-k'u of the Communist Party; Mr. Chang Peh-chuen of the Third Party; Dr. Carson Chang of the National Socialist Party, and other spokesmen for minority and unofficial groups were most generous with their time and information.

Messrs. You Shoo-tseng, Yang Chun, Wu Hsüeh-ping, Hawthorne Chen and others translated Chinese materials for or with me. Save for their help, so liberally and painstakingly rendered, this book would have been delayed for months if not years. These gentlemen are not to be held responsible for the selection of materials, nor for the translations in their present form, since I have sought to check and revise this work as far as time and my imperfect command of written Chinese have permitted.

The International Peace Campaign (China Branch), The People's Foreign Relations Association, The Chinese-American Institute for Cultural Relations, and other institutions in Free China were generous with their hospitality and facilities. I owe particular thanks to the Central Bank of China for the high courtesy shown me through the Chief Secretary and the following gentlemen: Mr. T. T. Wang, Chief of the Engineering Division; Mr. Ch'ên Yin-sung, Manager, Kiating Branch; and Mr. Yang Hsia-tz'ŭ, Manager, Chengtu Branch. The officers of the Bank went to enormous pains to ensure my timely, safe return to Chungking when I was ill, hurried, tardy, and in danger of missing my prearranged bookings back to America. Special acknowledgment must also be offered to Mr. C. C. Chi, for his unfailing kindness in providing interviews and trips, and to the China National Aviation Corporation for their unusual courtesies.

In Hong Kong, I was assisted by Dr. Eugene Chen, Dr. Wên Yüan-ning, Dr. Ch'en Han-seng, and Mr. Liu Yu-wan.

In Shanghai, Mr. T. Nakada of the Japanese consulate-general was most helpful.

In Nanking, Messrs. Wên Chung-yao, Kiang Kang-hu, Tsu Min-yi, Lin Pai-shêng, Li Shêng-wu, Hsü Liang, George Wên, P. C. Huang, T'ang Leang-li, K. S. James Woo and L. K. Kentwell were most hospitable. Mr. M. Kimura, of the Japanese Embassy in Nanking, was kind and courteous. I wish to thank these gentlemen for their friendliness to an alien scholar who had just come from the other side of the war.

In Tokyo, Messrs. Yokachiro Suma, Yoji Hirota, Kaneo Tsuchida, and Nobuo Fujimura of the Foreign Office were hospitable and informative.

Mr. Robert Kempton, Mr. George Giffen, and Dr. Louis Wilkinson showed me great kindness on my journey.

In the United States, I am indebted for introductions and advice to Dr. Hu Shih, the Chinese Ambassador; Professor George Taylor, of the University of Washington; and Mr. Frederick V. Field, of the American Council of the Institute of Pacific Relations.

My colleagues and friends at Duke University have been very helpful. Professors Homer Dubs and Paul H. Clyde, my colleagues in the Far Eastern field, read the manuscript and made invaluable suggestions; Professor Dubs' command of Chinese has saved me from many predicaments. Professor Robert R. Wilson has been unfailing in his encouragement, sympathetic interest, and facilitation of my plans.

The Duke University Research Council has assisted me with annual grants for the collections of documentary materials on Chinese politics. Save for this, I have received no financial aid or subsidy from any institution, person, or government whatever.

Mr. J. C. Yang, Mr. and Mrs. R. E. Hosack, Mrs. Freda Townsend, and Mrs. Margaret Linebarger have assisted me with manuscripts and proof.

I wish to thank the Director, Dr. S. Shepard Jones, and the staff of the World Peace Foundation for their patience, and helpfulness during the preparation of this work for the press. Miss Marie J. Carroll has been especially helpful.

All opinions and statements herein expressed are my own, unless clearly indicated as quotation. These acknowledgments are a record of thanks. I assume sole and complete responsibility for the contents of this book.

P. M. A. L.

Durham, North Carolina

March 31, 1941

|

WORLD PEACE FOUNDATION 40 Mt. Vernon Street, Boston, Massachusetts Founded in 1910 |

| Board of Trustees George H. Blakeslee, President Frank Aydelotte James Phinney Baxter, 3d Harvey H. Bundy Leonard W. Cronkhite Stephen Duggan Harry A. Garfield Christian A. Herter Bruce C. Hopper Manley O. Hudson A. Lawrence Lowell J. Grafton Rogers Charles Seymour John H. Williams Henry M. Wriston General Staff S. Shepard Jones, Director Denys P. Myers, Research Marie J. Carroll, Reference Mary J. MacDonald, Treasurer |

The World Peace Foundation is a non-profit organization which was founded in 1910 by Edwin Ginn, the educational publisher, for the purpose of promoting peace, justice and good-will among nations. For many years the Foundation has sought to increase public understanding of international problems by an objective presentation of the facts of international relations. This purpose is accomplished principally through its publications and by the maintenance of a Reference Service which furnishes on request information on current international problems. Recently increased attention has been focused on American foreign relations by study groups organized for the consideration of actual problems of policy. |

| Frontispiece—Generalissimo Chiang K'ai-shek | |||

| PAGE | |||

| Introduction | 1 | ||

| The Chinese Political Inheritance: Some Continuing Aspects | 1 | ||

| China at the Outbreak of War | 6 | ||

| The Beginning of Active Hostilities | 11 | ||

| The Hankow Period | 15 | ||

| The Chungking Period | 19 | ||

| I. | The Constitution | 21 | |

| The Yüeh-fa of 1931 | 22 | ||

| The Draft Permanent or Double Five Constitution | 25 | ||

| The Issue of Constitutional Change | 31 | ||

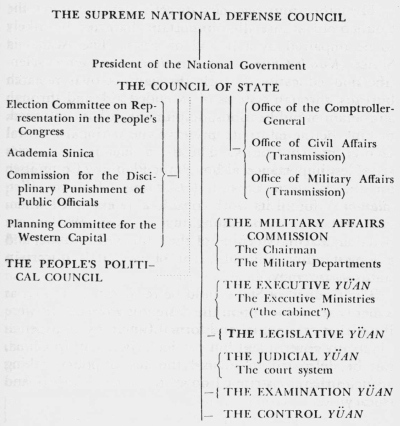

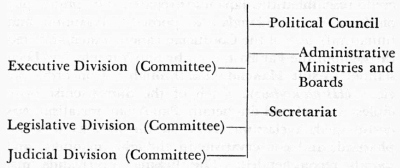

| II. | The Political Organs of the National Government | 41 | |

| The Five-Power Constitution | 42 | ||

| The Supreme National Defense Council | 46 | ||

| The President of the National Government | 52 | ||

| The Council of State | 53 | ||

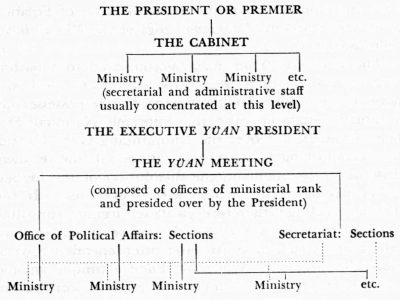

| The Executive Yüan | 56 | ||

| The Military Affairs Commission | 60 | ||

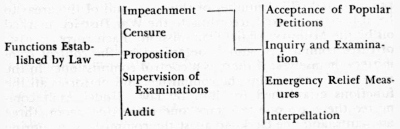

| The Judicial, Legislative, Examination and Control Yüan | 65 | ||

| III. | Consultative and Administrative Organs | 69 | |

| The People's Political Council | 69 | ||

| The Administrative Pattern | 79 | ||

| The Political Ministries | 81 | ||

| Social and Cultural Agencies | 83 | ||

| The Economic Ministries | 85 | ||

| IV. | Provincial, Local, and Special-Area Government | 98 | |

| Chart on Provincial and Urban Government | facing 98 | ||

| The Provinces | 99 | ||

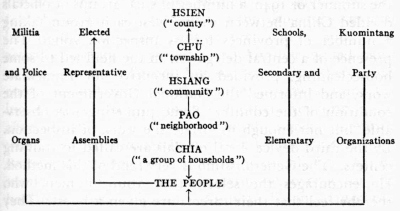

| Local Government | 103 | ||

| The Communist Zone | 111 | ||

| Guerrilla Governments | 116 | ||

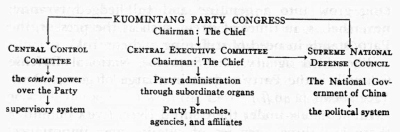

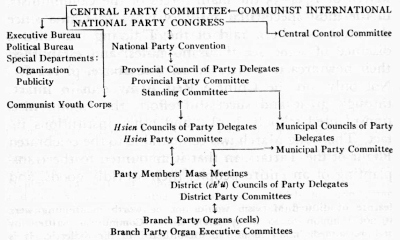

| V. | The Kuomintang | 124 | |

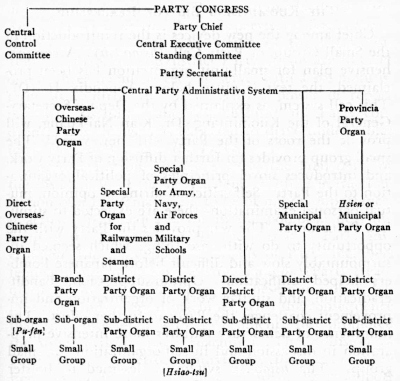

| The Party Constitutional System | 125 | ||

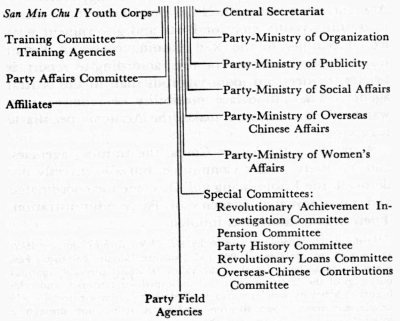

| Party Organization | 129 | ||

| The Kuomintang Bid for Leadership | 140 | ||

| Intra-Kuomintang Politics | 142 | ||

| The New Life Movement and Other Affiliates | 149 | ||

| VI. | The Communist and Minor Parties | 159 | |

| The Chinese Communists: Party and Leaders | 160 | ||

| Communism: Patriotism or Betrayal? | 171 | ||

| The National Salvation Movement | 175 | ||

| The Third Party | 178 | ||

| The Chinese National Socialist Party | 179 | ||

| Social Democrats and La Jeunesse | 181 | ||

| VII. | Governing Institutions of the Japanese and Pro-Japanese | 183 | |

| The Japanese Army as a Chinese Government | 185 | ||

| The Problem of Puppet States | 188 | ||

| The Provisional and Reformed Governments | 192 | ||

| The Reorganized National Government of Wang Ch'ing-wei | 197 | ||

| VIII. | Extra-Political Forces | 211 | |

| The Foundations of Chinese Government | 212 | ||

| Mass Education | 214 | ||

| Rural Reconstruction | 218 | ||

| The Chinese Industrial Cooperatives | 223 | ||

| Unorganized Pressure | 234 | ||

| IX. | Sun Yat-sen and Chiang K'ai-shek | 239 | |

| Sun Yat-sen | 240 | ||

| The San Min Chu I | 250 | ||

| Chiang K'ai-shek | 254 | ||

| Chinese Appraisals of Chiang | 266 | ||

| The Ideology of Chiang | 269 | ||

| Conclusion | 273 | ||

| The Chief Alternatives in China | 274 | ||

| The United States in Chinese Politics | 277 | ||

| APPENDICES | |||

| PAGE | |||

| Appendix I: Government Documents | 283 | ||

| A. | The Government Draft of the Proposed Constitution | 283 | |

| B. | The System of Organization of the National Congress | 300 | |

| C. | Act of the Legislative Yüan, April 31, XXVI (1937) Governing the Election of Representatives to the National Congress | 302 | |

| D. | The Program of Resistance and Reconstruction | 309 | |

| E. | An Outline of War-time Controlment | 313 | |

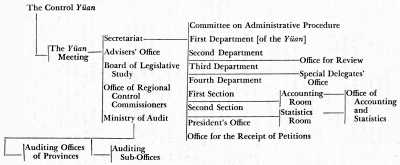

| F. | A Chart of the Control Yüan from July 1937 to June 1940 | 318 | |

| G. | Regulations Concerning the Organization of the Various Classifications of Hsien | 324 | |

| H. | A Chart of Government Organization | facing 330 | |

| Appendix II: Documents on Party Politics | 331 | ||

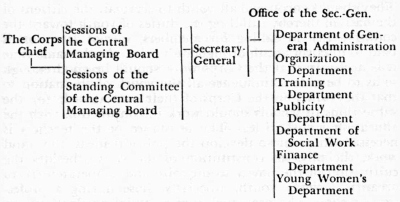

| A. | A Chart on Kuomintang Organization | facing 331 | |

| B. | Constitution of the San Min Chu I Youth Corps, Year XXVII (1938) | 331 | |

| C. | The Duties and General Activities of the San Min Chu I Youth Corps (Ch'ên Ch'êng) | 340 | |

| D. | The Hsiao-tsu (Small Group) Training Program | 354 | |

| E. | Party Constitution of the Chinese Communist Party | 359 | |

| Appendix III: Materials on Policy | 371 | ||

| A. | Reply to Questions (Chiang K'ai-shek) | 371 | |

| B. | What I Mean by Action, or A Philosophy of Action (Chiang K'ai-shek) | 373 | |

| C. | Definition of the Problems Concerning the Organization of the Various Classifications of Hsien (Chiang K'ai-shek) | 388 | |

| Chart on Hsien Classifications | facing 388 | ||

| D. | A Discussion of Mao Tsê-tung's Comments on the Present State of International Relations (Ch'ên Kuo-hsin) | 403 | |

| E. | China's Long-range Diplomatic Orientation (Wang Ch'ung-hui) | 418 | |

| Glossary | 423 | ||

| Index | 435 | ||

The National Government of the Republic of China, located at the auxiliary capital of Chungking, is one of the most important governments in contemporary world affairs. It has provided fairly effective unification for the largest nation on earth, and has fought a great power to a standstill.

The present work is an analysis of this government. Not a biography of Chiang K'ai-shek, it is instead a delineation of the institutions, the parties and movements, and the armies which today determine the Chinese destiny. Free China, mutilated as it is, is still far more populous and complex than the Soviet Union or Germany. Its political institutions cannot be reduced to the terms of one man's caprice, and the personality of Chiang—while brilliantly conspicuous—is not the entire picture of China. Generalissimo Chiang works, perhaps because he wishes to, certainly because he must, within the framework of a triune organization: the National Government, the central armies and the Kuomintang. These institutions have developed to their present efficacy only by means of thirty years of war, preceded by almost thirty years more of conspiracy. They have become the norm of contemporary China and, whatever their particular future, significant determinants of China's eventual development.

Because of cultural and historical differences between China and the West, the application of identical terms to both is probably either wrong or meaningless.[Pg 2] Nevertheless, Westerners can live in China, deal with the Chinese, scrutinize their affairs, and transpose these to such Western descriptions as may suit the purpose. In reading of China, however, one should keep in mind the fact that the words are English, freighted with special meanings, and are used not by scientific choice but for lack of others. Part of this difference can be bridged if one recalls the salient peculiarities of China as against the Western world.

No other society comparable in size, duration and extent has ever existed; the Chinese Empire, from the beginning of the Ch'in (221 B.C.) to the end of the Manchus (A.D. 1911), remains the greatest social edifice mankind has yet brought forth. As such, its modern successor is everywhere stamped with archaic catholic traits which are today both obsolescent and futuristic. To these must be added the characteristics of China as a special area—a cultural zone seeking national form; fragmented economies working their way out of backwardness in technology and helplessness in world economics; a people in quest of government which will give them power without enslaving them. This modern "Chinese Republic," a Western-form state only by diplomatic courtesy in the years succeeding 1912, has been the widest zone of anarchy in the modern world; the Japanese attack on its emergent institutions has helped immeasurably to re-identify the Chinese-speaking people and the officers who presume to govern them.

To understand Chinese government in war time, one might first check the outstanding points of old Chinese development and their modern derivatives.

Pre-eminently, China has been pro forma Confucian ever since the tenth century after Christ. This has meant an ordering of classes in society based on the ideal of scholarship and public administration, rather than on ideals of valor, piety or acquisitiveness. By[Pg 3] setting the requirements of the examinations, and through concealed but sharp discouragement of heterodoxy or wilful originality, the governing mechanism made of itself a vast machine of scholars which—because its authority rested in tradition, in language, in social usages—was able to ride out domestic revolution and foreign invasion, and was in a position to ensure its own perpetuation despite political or military interruption.

The traditions of scholastic bureaucracy working in a pluralistic society have left the Chinese people largely independent of the routine functioning of government. The Western state becomes the articulation of society. The government of old China was pseudomorphic as a state, having only some of the functions of the Western state, and its governing power was the residual capacity of an organization devoted to the ends of ceremony, exemplarization, education and the cultivation of personality. Administration was confined chiefly to revenue collection, flood control and defense. In the West, the most important purposes of society are framed in law after discussion, and are executed as policy; in China these purposes, defined by the Confucian ideology, were known throughout the society, with scholar-officials as their expositors. Fulfillment was by no means a prerogative of government alone. By contrast with the Confucian standards, the Western states, whether democracies or not, are capricious, despotic and nonmoral; by Western standards, Chinese society was unresponsive, sanctimonious and amorphous.

This political excellence and stability was accompanied by economic phenomena which are, by modern standards, less desirable. Overcrowding and a slow rate of progress have been fairly constant features of Chinese society since the Han. Owen Lattimore has recently appraised the economics behind the dynastic cycle in[Pg 4] China.[1] Each community in old China was cell-like, largely autonomous and autarkic. Hence, the increase of wealth was sought within the cell, and not within a larger framework of economic advance—such as commerce or invention would provide—and the economically predominant class (the landowners) possessed a vested interest in overpopulation (which cheapened agricultural labor and maintained a high, even urgent, demand for food products). Equilibrium was reached, and a cycle of diminishing returns initiated, when population began to outrun the land's subsistence maximum. This drop in returns, in the face of continued population rise, led to peasant rebellion, distributism and a reinauguration of the same type of state—made necessary by the monopoly of managerial expertness (essential to water conservancy, land wealth and the familiar intensive cultivation) in the ideographically literate class. Control of the richest water-conservancy region meant the hegemony of China.

The impact of Western imperialism has struck China in the past century, during the critical or revolutionary phase of this immemorial cycle. Chinese politics took the color of a back-country struggle. The centers of modern power were beyond Chinese administrative reach. The emergent Chinese state, deprived of its foci of power in the metropolises, was promised control thereof only when it had become an effective and complete state—a condition largely unobtainable without control of Shanghai, Tientsin, Hankow, and the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong.

In theory, the Chinese Republic was established January 1, 1912. In practice, the name Republic has masked a mêlée of governments and power-organizations, ranging from bandit gangs with pretentious political color to[Pg 5] authentic regional governments administering large areas. This culminated in the National Government which, beginning as a conspiracy, becoming the leading regional government, is now in the position of de facto government for virtually all Free China, the Chinese dominions, and much of the occupied area. None of these governments has ever held an election based on wide suffrage; none has systematically subordinated policy to law; none has possessed a treasury, fleet or air force worthy of a second-class power, until the present war. Out of these unpromising materials the counter-attacking Chinese state has arisen; only by legal formula is it the same Republic as its predecessors; only by courtesy is this the Year XXX (1941) of the Republic.[2]

The governmental developments of the Republican era fall conveniently into four periods: the period of establishment, 1911-1916; the period of tuchünism, 1917-1926; the rule of the National Government, 1927-1936; the period of invasion, 1937 to the present. The turning points between these periods are, respectively, the fall of the Manchu Empire of China (1911), the death of the dictator-President Yüan Shih-k'ai (1916), the Great Revolution under Kuomintang-Communist leadership (culminating, 1927), and the Sian affair (December 1936) followed by full-scale invasion (July 1937).

The present governments of China are accordingly the successors of a wide variety of decaying imperial administration, experimental modernism and outright confusion. Any change in China had to be made at the[Pg 6] expense of the haves—the Western powers and Japan. Japan, in seeking the control of China, is fighting China and the Western powers; China, in fighting back, must fight Japan, and behind Japan the whole structure of imperialism. Most Chinese have abandoned hope of surviving as a people without eventually triumphing as a state. In the past, they absorbed conquerors whose bases were transferred to China; today, they cannot accommodate invaders who come as transients from an overseas base. The Chinese war of resistance is a revolution. It is a continuation of the Nationalist revolution, begun against the Manchus, continued against the imperialist powers, and now directed against the Japanese and their Chinese associates. At the same time, this revolution struggles to incorporate in its dynamics the drive of an endemic peasant rebellion, Communist in its extreme phase. Nationalist in supreme emphasis, the revolution finds its highest expression in the articulation of an effective state—something not known in China for twenty-two centuries.

Sun Yat-sen's legacy of doctrine included a program of revolution by three stages:

(1) the military conquest of power by the Kuomintang;

(2) the tutelary dictatorship of the Kuomintang while democracy was being instilled and adopted from the bottom up; and

(3) constitutionalism, requiring abdication of the Kuomintang in favor of a popularly elected government.[3]

Upon coming to power in Nanking, the National Government had begun promising a short period of tutelage and had made various gestures in favor of experimental popular government. A Provisional Constitution was adopted by a Kuo-min Hui-i (commonly termed, National People's Convention) in 1931, operating under complete government supervision; a transition instrument, self-acknowledged as such, it anticipated a Permanent Constitution upon the accomplishment of constitutional government in a majority of provinces (Articles 86, 87).[4] Although the Kuomintang has ruled parts of China for more than fifteen years, and is by profession the party of democracy, it has not yet relinquished power. The period of tutelage is still legally in force.

In the years immediately preceding the outbreak of war, this monopoly of governmental power by the Kuomintang was not only an important political irritant but also an obstacle to effective Chinese unity. Discontent was aggravated by inelasticity of the Party. Overweighted with petty bureaucracy, it offered too few up-channel opportunities for potential leaders. Since Nationalists were the Ins, Kuomintang membership carried privileges rather than obligations. Many distinguished and active citizens either refused to join, or let their purely nominal membership ride along. The Party was saved from complete decline because it included most of the government personnel, and new recruits to government service gave it some freshness, vigor and inward criticism.

The leading difficulty of both state-building and democratization had been overcome by the creation of a government which was well-designed, functioning de facto and able to meet most of the specialized problems of modern administration. The regime was far from being a crude hierarchy of soldiers and taxgatherers,[Pg 8] but had accrued about its policy-making core the essential staff and line services of modern rule. Inadequacies lay not in absolute lack of species of personnel or structure, but in the relative weakness of many key functions. During the third decade of the Republic the then Nanking Government, under Chiang's leadership, gave China its first modern national government.

Despite this beginning, which—without the invasion—stood a very good chance of evolving into a paternalistic oligarchy in democratic form, such as Brazil, there were enormous difficulties still facing genuine China-wide government. First among these difficulties was the question of regional autonomy—lingering vestiges of tuchünism, reinforced by a vigorous provincialism. Whole regions of China were under the merely nominal control of the National Government.

The second difficulty was that of personal politics. Modern China has had ample politics of principle. It is a rare ideological cult, of any kind, anywhere, which does not have its Chinese affiliates. No other nation has known such a wide choice of doctrines, each represented by armed forces and by definite political leadership. At the same time, this ideological struggle was and is paralleled by the politics of individuals and cliques. This made the National Government function as an oligarchy based on three patterns of control:

(1) ideological eminence, orthodoxy, appeal and timeliness;

(2) military or economic control of power in the form of soldiers or cash, the two being for the most part interchangeable; and

(3) governmental incumbency.

A man like Hu Han-min could owe his importance almost altogether to his past associations with the Party and with Dr. Sun, to his authority as an exponent of the San Min Chu I, and to his appeal to the sense of prestige, dignity and stability on the part of other people[Pg 9] who did not possess such power, which was exercised in the name of the Kuomintang and its ideology. T. V. Soong, in money matters, or Chang Hsüeh-liang, in military matters, were important because they had under their immediate influence so much cash or so many troops, the availability and mobility of which from day to day determined their actual share of power. Lastly, these same men possessed political authority by narrowly lawful means, i.e., by the governmental offices which they held.

Thirdly, the government was deeply out of harmony with an overwhelming majority of college students, much of the professional and intellectual classes, and a broad section of the articulate farmer and labor groups. In the pre-war years of strain, unofficial persons could follow world fashions in ideas associated with Leftism. Although the full Western pattern of Right, Center, and Left was not imposed upon Chinese politics, many of the most active publicists wrote in these terms. There was, accordingly, a traditional China and a Leftist China; the latter faithfully imported European concepts and did much to change the language of Chinese political struggle. The government—itself Left from the point of view of the pre-existent order, yet committed to modes of thought and policy formally little more radical than the American New Deal—was constantly recalled to the most cold-blooded of realpolitische considerations.

Fourthly, the student movement—in some phases a part of the general Leftist drive—proved a constant source of difficulty and trouble. Chinese students (both collegiate and secondary) are self-conscious, frequently arrogant inheritors of the Chinese tradition of rule by literati. Their influence over the masses is impressive; their patriotism, however unreflective, is ardent; and their interest in international affairs is violent.[5]

Fifthly, Chinese society, accustomed to acting independently of government, urged varied foreign policies and sought wars. Almost every kind of organization, from archaic guilds and secret societies to business groups, sought to wage its own attack on Japan. Uncanalized, counter-attacked, dammed up, these efforts might have undone the government. Toward the end, the government raced frenziedly with time, losing power through unpopularity, and increasing power through rearmament and technical preparation. The vigorous extra-governmental pressure of a populace accustomed to spontaneous mass action is a factor which qualifies and will probably continue to qualify Chinese foreign policy. It is often left out of account in Western comment on China.

Sixthly, in the winter and spring of 1936-37, the National Government was under pressure from its own subjects to begin the negotiation of national unity, starting with a Communist armistice and continuing with the incorporation of as many regions as possible into the sphere of the government; but despite such increasing pressure, the government took no effective step in this direction until after the kidnapping of Chiang at Sian.[6] [Pg 11] As a result of this melodramatic affair, however, the National Government revised policies which had become traditions ten years old and agreed to an armistice with the Communists. The Kuomintang—bearing full responsibility for an actual emergent state—found intra-Chinese diplomacy as perplexing as foreign.

Thus, at the outbreak of war, the National Government had reached a higher level of actual political and administrative power than its predecessors, but was faced with grave problems. In any other country the government would presumably have been on the verge of ruin. Controlling only major sections of its internationally recognized territory; faced by autonomous provinces, half-legal military satrapies and outright warlord despotism, all backed by vehement provincialism, great distances, linguistic difficulties and mutual geographical isolation; unpopular with its own student, intellectual and professional elites; ridden by personal politics; just emerging from a ten years' civil war—with these handicaps, a second-rate power undertook to challenge the greatest power of Asia to an irreversibly fateful war. The Chinese went further: they sought in the war not only victory, but unity, democracy and prosperity as well! This background of purpose makes China's internal politics richly meaningful in relation to the world scene.

After nearly six years of military and political conflict, a full quasi-war[7] broke out with the episode at Loukouchiao[Pg 12] on the night of July 7-8, 1937. It was the evident intention of the Japanese to end an unsatisfactory state of affairs (i.e., Chinese control) in that area once and for all, although they were perfectly willing to express temporary amity and ad interim non-aggression toward what was left of China. The National Government, after a few days of uncertainty, began real preparations for war. Since the government's appeasement policy had accustomed many to think of resistance in terms of the Left, there was an enormous inflation of Leftist sentiment, not deflated for about eighteen months.

While new mass organizations were formed, the Chinese military command framed a plan for a three-stage war:

(1) a period of resistance by heavy regular forces fighting positionally;

(2) a period of stalemate wherein enemy forces, immobilized by opposing regular armies, found lines of communication, supplies and business harassed by guerrillas and saboteurs;

(3) a period of counter-attack in which the Chinese, having prepared themselves technologically during the stalemate and having weakened the enemy by a test of endurance, should drive the Japanese back into the sea.

The strategy of this type of war was based upon the plan of retreating in space in order to advance in time—that is, to yield area slowly and purposefully, without too great cost to oneself, in order to outlast the enemy and reach victory. In thus purchasing time by the mile, the Chinese could not afford to yield intact cities, factories, communications, mines, docks, warehouses and the other goods of business; such cessions would only profit Japan: hence the scorched earth policy. The strategy was obviously suited to a country rich in territory and population, but poor in matériel. It not only made both regulars and guerrillas effective against Japan but made each truly reliant upon the other. Without[Pg 13] the Nationalist regular armies, who in attempting to suppress the Communists had done almost everything which the Japanese now had to do—guarding railroads, pacifying disaffected and hostile rural areas, promoting industries and watching agitation—the Japanese forces might disperse enough to enable Japan to patrol and pacify enough of China to pay for the occupation. Chiang had to hold the Japanese together, immobilize large bodies of their troops, keep their war expenses up, and wait for the time to counter-attack. Meanwhile the guerrillas, together with the Communist veterans, were to prevent the Japanese from settling down, to worry them with agitation, to sabotage their economic efforts and to wear them out for Chiang's révanche.

One of the first governmental changes in wartime was the re-institution of an effective propaganda service under the Political Department of the Military Affairs Commission. In this Department, many of China's most active controversialists, censored or exiled for years, found officially sanctioned scope for their energies. Formal unity came slowly. Although Shanghai was attacked on August 13, 1937, it was not until September 10 following that a fairly definitive arrangement was reached in regard to the Communist-occupied zone in the Northwest.

The settlement transformed a pre-existing armistice into an intranational alliance; technically it amounted to submission by the Communists and their incorporation into the national government and armies. The area of the Chinese Soviet Republic assumed the name Special Regional Government of the Chinese Republic (Chunghua Min-kuo T'ê-ch'ü Chêng-fu), which it had been using informally for months; the Chinese Red Army became the Eighth Route Army (Pa-lu-chün); and the Chinese Communist Party accepted the San Min Chu I as the constitutional state ideology of China, abandoning immediate measures of class war and[Pg 14] expropriation. The settlement was in the form of a Communist reply to Kuomintang terms offered in February 1937 and the reply of the Generalissimo as Chief of the Kuomintang to the Communist declaration.[8]

For the first few months the war kept its quasi-European pattern. The greater part of the fighting was done in the Shanghai area, while Japanese forces proceeded down from North China. The Japanese still had some expectation of localizing the North China and the Shanghai conflicts. At most, they expected the war to be a short one, not extending beyond the capture of Nanking. Occupation of the capital was counted on for the ruin of the central government, the end of Chiang and the reversion of China to a condition of malleable anarchy.

December 1937 was the blackest month of the war for the Chinese. The Japanese advanced toward Nanking, with Chinese resistance crumbling; part of the armies withdrew in good order, but on occasion there were hopeless, panicky routs. To this month the Japanese looked for victory, and were so confident that they formed the pro-Japanese Provisional Government of the Republic of China, in Peking on December 11.[9] Four days later the Japanese forces entered Nanking, and the ensuing fortnight set the record for atrocity in the modern world. The Japanese forces were preoccupied with their own disorder. The National Government[Pg 15] escaped up-river to Hankow, where it promptly began to function under the three-headquarters plan: some offices at Hankow, some at Changsha and some at Chungking. The presence of the foreign affairs, propaganda, and military agencies at Hankow made this the practical capital of China, although Nanking was and is the constitutional capital.

The greatest part of the year XXVII (1938) was spent in continuation of slow retreat and heavy frontal resistance. Until October communications with the outside world were wide open through the railroad to Canton. Heavy supplies could arrive by the shipload. Hundreds of Japanese air attacks on the railroad disrupted schedules but never led to serious suspension of service. Leftist influence became overwhelming in Hankow. That city had been the capital of the ill-fated Wu-han Kuomintang-Communist government, which fell with the secession of Chiang to Nanking eleven years before; its connotations still lingered. Even conservative Kuomintang leaders, who had gone to lengths of appeasement at which Neville Chamberlain would have blanched, tried to talk like Negrin or Alvarez del Vayo.

In January 1938, two organizations were formed which, along with the Communist zone in the Northwest, were to be among the most active agencies of guerrilla leadership. The first of these was the New Fourth Army (Hsin-ssŭ-chün), which emerged in the area just south of the Japanese forces at the Yangtze mouth. It was composed of peasant and student militia, of regular army fragments, and of some Kuomintang volunteers, under the leadership of Communist remnants which had hidden away, banditti-fashion, when the Red Army trekked Northwest. Its emergence was recognized by legal order of the National Military Affairs[Pg 16] Commission.[10] The other organization was the Provisional Executive Committee of the Shansi-Chahar-Hopei Border Region (Chin-ch'a-chi Pien-ch'ü Lin-shih Hsing-chêng Wei-yüan-hui), established by a conference at Fup'ing, January 8-15, and authorized by central government mandate. This agency also sprang from Leftist organizations—in this case, a bold, determined, student-peasant guerrilla army—which had first developed despite government opposition. It was designed to provide an emergency guerrilla government for those portions of the three provinces which were under occupation by the Japanese. Unoccupied portions of the provinces retained their existing administrations.

In the next month, February 1938, there was established an agency of supreme importance, the Supreme National Defense Council.[11] This replaced the Central Political Council,[12] which had exercised routine functions of the Party's sovereign control over the government; like its predecessor, the Supreme National Defense Council tended to act as the supreme governmental organ, although it was technically a Party organ. The Council provided and provides a unified civilian-military control for the duration of the war; but the Kuomintang shares its power with other groups only in the consultative organs of state, not in the executive.

March 1938 followed with another political step forward—the Emergency Session of the Kuomintang[Pg 17] Party Congress. The Party Congress had the functions of a special constituent assembly in part, and in part those of a restricted parliament; in this session two further actions were taken. The first was the adoption of the momentous Program of National Resistance and Reconstruction (K'ang-chan Chien-kuo Kang-ling),[13] which provides a plan for the war and commits the Kuomintang and the National Government to a policy of victory, of industrialization, and of economic reform as a means to war.

The second step taken by this important Congress was the provision for a People's Political Council (Kuo-min Ts'an-chêng Hui, also translatable as People's Advisory Political Council). This was the first breach in the Kuomintang monopoly of government since the establishment of the Party dictatorship.[14] The government, through the constitutional fiction of appointing members as representative individuals, provided a rough, approximate, but fair representation of the active political forces in China.

While the Emergency Session of the Party Congress took these steps for further national defense, the Japanese were collecting a coterie of ex-politicians, friends of Japan, and old men to serve as the Reformed Government of the Republic of China at Nanking. They disregarded the anomaly of having two "Chinese" national governments—the Provisional Government in Peiping being undisturbed by these measures—and continued to seek the division of China, even on the level of the pro-Japanese States. The Reformed Government was established on March 27, 1938.

The autumn of 1938 brought another phase of discouragement. Relying on the prestige of British power[Pg 18] and the nearness of Hong Kong, the Chinese were not watchful in the Canton area. The Japanese landed almost unopposed. Chinese negligence, corruption, and a little treachery worked in their favor. The landing forces performed almost superhuman feats of endurance in forced marches overland; on several occasions Japanese advance troops ran so far ahead of schedule that Japanese warplanes, thinking them disguised Chinese, strafed them![15] Canton fell without a major battle. Hankow, the great radical capital, scene of the 1926-27 Leftist upsurge and of the anti-Fascist enthusiasm of 1938, was entered by the Imperial Japanese army, and the entire Wu-han area was lost to China.

Not only was the Hankow period ended. By breaking the last rail connection of the Chinese government and the outside world, and by driving the Chinese leadership into the remote interior, Japan shut off the ready play of international influence on domestic Chinese politics. Foreign visitors became more rare. The government, moving to the mountain fastnesses of Szechuan, found a home on the great Gibraltar-like promontory of Chungking city, tiered along cliffs above the Yangtze and Kialing rivers. The last withdrawal was a final test of strength. Hankow, six hundred miles up-river, was commercially, architecturally, and politically a coastal city. It was still an outpost of world imperialism and of modern technology. With the next remove the Chinese government found itself beyond tangible Western influence; for the first time since 1860 the capital was out of the military reach of Western[Pg 19] powers, and in a city which had only slight traces of Western influence.

The Chungking period began with the transfer of further government offices to the West, to join President Lin Shên, and marks a distinct phase in the process of government-building in China. As the Chungking regime, the National Government took new forms of temper and character. Government, Kuomintang, Communists—all were in the position of an inner-Asiatic state, without convenient access to the sea, seeking to fight an oceanic nation whose trade reached every port in the world. Foreign imperialism could no longer be blamed for the demoralizations of the hour; foreign aid was too tenuous and remote to qualify the inner play of Chinese political growth. Politically, the Chinese had to stand on their own feet.

The second phase of the war had begun. Chinese armies stood front-to-front against the Japanese, and kept hundreds of thousands of invading troops immobilized. The guerrillas got to work. Most of all, the machinery of modernization began functioning; all the programs had been completed, and the task was clear. The international developments of the time—the first American loan, $25,000,000 in 1938; the brief Manchoukuo-Outer Mongol war of 1939, wherein Japan and Russia fought each other through their respective dependencies; even the outbreak of the European war—were remote from this far inland scene. Military events had some effect, but nothing comparable to the Japanese victories at Shanghai, Nanking, Canton, and Hankow recurred. The Japanese invaded Kwangsi in the fall of 1939; they left a year later, when their drive into French Indo-China made it unnecessary to cut those colonies off from China. In South Hunan the Japanese suffered catastrophically when they advanced boldly and[Pg 20] contemptuously into non-modern areas and were encircled by the Chinese. Even the flight and treason of Wang Ch'ing-wei at the year's end of 1938, and his open cooperation with Japan in March 1940, did not change the general picture. The emphasis was no longer on sudden changes, on personality, on dramatic shifts of power. It was on construction—on the development of a modern, democratic, technically equipped Chinese state out of the vast resources of China's hinterland. The China which was to win had to be created before it could counter-attack.[16]

[1] Lattimore, Owen, Inner Asian Frontiers of China, New York, 1940, p. 45 and passim. The author, a noted geographer, presents significant new analyses of the interconnections of Chinese economics and culture.

[2] Detailed descriptions of the political history of the period are to be found, inter alia, in Holcombe, Arthur N., The Chinese Revolution, Cambridge, 1930; MacNair, Harley F., China in Revolution, Chicago, 1931; and, most popularly, Escarra, Jean, China Then and Now, Peiping, 1940. Descriptions of the government are Wu Chih-fang, Chinese Government and Politics, Shanghai, 1934; Lum Kalfred Dip, Chinese Government, Shanghai, 1934; and Linebarger, Paul M. A., Government in Republican China, New York and London, 1938.

[3] This is given in the Chien Kuo Ta Kang (Outline of National Reconstruction), of April 12, XIII (1924), particularly points 3, 5, 6, 7, and 23. Translations are to be found in Hsü, Leonard Shihlien, Sun Yat-sen: His Political and Social Ideals, Los Angeles, 1933, and Wu Chih-fang, work cited, p. 430 ff.

[4] For the text of this constitution, see Wu Chih-fang, cited, p. 430 ff.

[5] In particular, see Freyn, Hubert, Prelude to War: The Chinese Student Rebellion of 1935-1936, Shanghai, 1939. Reference to contemporary Left-liberal and Left publications in Europe and America will disclose numerous sympathetic eyewitness accounts of the troubles and the fortitude of the students. Some of these accounts now possess a wry, inadvertent humor in their characterization of Chiang as a willing accomplice of Japan.

[6] For the Generalissimo's own diary of the kidnapping, together with a narrative by his wife, see Chiang, Mme. Mayling Soong, Sian: A Coup d'Etat, bound with Chiang K'ai-shek, A Fortnight in Sian: Extracts from a Diary, Shanghai, 1938. The Chinese edition of this appeared as Chiang Wei-yüan-chang [Chairman Chiang], Hsi-an Pan Yüeh-chi [A Fortnight's Diary from Sian], Shanghai, XXVI (1937). A first-hand Western account is Bertram, James M., First Act in China, New York, 1938. Edgar Snow, in Red Star over China, New York, 1938, p. 395 ff., gives an account sympathetic to the Left; Harold Isaacs, in The Tragedy of the Chinese Revolution, London, 1938, p. 445 ff., presents a penetrating Trotskyist critique. An excellent factual summary of this crucial year, written by a well-known writer who visited the scene at first hand, is to be found in Bisson, T. A., Japan in China, New York, 1938.

[7] "War" used to mean the reciprocal application of violence by public, armed bodies; private and informal homicide was termed "murder" or was otherwise clearly designated. Today these distinctions are less clear. The author must enter a caveat lector: no term is employed in other than a general (i.e., literary) meaning, except upon special notice. The Sino-Japanese hostilities differ greatly from war in several interesting but technical respects; they are a very special Japanese invention. Yet it would be cumbersome to refer to Chinese changes in Conflict-time, or to speak meticulously of armies engaged in an Incident.

[8] See Council of International Affairs, The Chinese Year Book, 1938-39 [Hong Kong], 1939; article by Chu Chia-hua, "Consolidation of Democracy in China," Chapter IV; "Reconciliation with the Communists," p. 339-40. This Council is an informal and extra-legal offshoot of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs; accordingly the annual, rich in official materials, provides insufficient data on Communist, guerrilla, and unofficial activities. See also, Epstein, I., The People's War [Shanghai], 1939, p. 88 ff., for an excellent, clear account of this period.

[9] See below, p. 193. See also Taylor, George E., The Struggle for North China, New York, 1940, in the Inquiry Series of the Institute of Pacific Relations.

[10] See Epstein, I., work cited, p. 235 ff. and The Chinese Year Book 1938-39, cited, article by the late P. C. Nyi, "Plans for Political and Economic Hegemony in China"; this includes a full administrative description of the Border Region, p. 254 ff. The North China zone is arbitrarily translated "Border Region," to distinguish it from the quondam Chinese Soviet Republic in the Northwest, translated as "Frontier Area."

[12] See chart on p. 47. Descriptions of the pre-war Central Political Council are to be found in the texts cited on p. 5, n. 2, and in the first two issues of The Chinese Year Book, 1935-36 and 1936-37, Shanghai, passim.

[14] See below, p. 69. This is to be distinguished from the various constitutional conventions, the proposed national congress (kuo-min ta-hui) which exists only in contemplation of the constitutional drafters, and the Kuomintang Party Congress.

[15] An engrossing first-hand account of this is to be found in Hino, Ashihei, Sea and Soldiers, Tokyo, 1940. This, with its three companion volumes, Mud and Soldiers, Flower and Soldiers, and Barley and Soldiers, Tokyo, 1939 and 1940, forms an eloquent, humane, sensitive narrative of a young Japanese writer serving with the Imperial forces in China. The series ranks with the great narratives of the European war of 1914-18, and expresses the Japanolatrist devoutness, the naïveté, and bewildering courage of much of the Japanese infantry, but does so through the medium of a literary craftsmanship rare in any army.

[16] The literature of the war and of the struggles of Free China has already reached an enormous extent. The present work makes no attempt to present a step-by-step account of the interplay of personal politics, the progress of the armies, or to provide a first-hand personal account. Observers other than the author have presented these topics exceedingly well. A few of the outstanding works may be mentioned, however; a Shanghai press line usually signifies that the book was reprinted there from a British or North American edition. Epstein, I., The People's War, London, 1939, is a spirited, detailed account of development down to the spring of 1939, particularly useful for the New Fourth Army and the Border Region. Among accounts of the war are Bertram, J. M., Unconquered, New York, 1939; Oliver, Frank, Special Undeclared War, London, 1939, containing interesting accounts, in particular, of Japanese military and political behavior in China. Andersson, J. G., China Fights for the World [Shanghai], 1939; Utley, Freda, China at War [Shanghai], 1939, a significant personal account with special interest for the Hankow period; Mowrer, Edgar, Mowrer in China, Harmondsworth (England), 1938, published in America as The Dragon Wakes, New York, 1939; Booker, Edna Lee, News Is My Job [Shanghai], 1940, a reminiscent anecdotage; Lady Hosie, Brave New China, [Shanghai], n.d., a far more informed work than most of the autobiographical accounts, by the daughter and widow of two British Orientalists, herself a distinguished literary writer on China. On the North China situation, four popular works stand out: Snow, Edgar, Red Star Over China, New York, 1938, the great "scoop" on the Communists; and three other books based on first-hand reconnaissance: Bisson, T. A., work cited above; Hanson, Haldore, "Humane Endeavour" [Shanghai], n.d.; and Carlson, Evans Fordyce, Twin Stars of China, New York, 1940, the work of the U. S. Marine Corps Observer in the guerrilla area, unique in its value as professional military interpretation. Gunther, John, Inside Asia, New York, 1939, contains much of great interest. Very special viewpoints are represented in the account of a National-Socialist German observer, Urach, Fürst A., Ostasien, Kampf um das Kommende Grossreich, Berlin, 1940; the commentary of two British poets, Auden, W. H., and Isherwood, Christopher, Journey to a War, New York, 1939; and the reportage of a distinguished Soviet fellow-traveller, Strong, Anna Louise, One-Fifth of Mankind, New York, 1938.

The constitutional system, basic in most Western states, plays a peculiar, subordinate role in China. Consideration of the issue of constitutionalism high-lights the most practical aspects of the issues of full democracy. Although the purely legal aspects of constitutional development are still unimportant in the internal power politics of China, further constitutional development involves a very real shift in the domestic balance of power. The fullness of national unity, and therefore the effectiveness of resistance against Japan, depend in part on the successful solution or compromise of the problems of constitutionalism.

Ever since the beginnings of political modernization in China, demands for constitutional government have included a written constitution as an imperative prerequisite. The formidable Empress Dowager was troubled in her last days by the Imperial constitution, a rather unimaginative plagiarism of the Japanese Constitution of 1889. Since the Republic began in 1912, China has continued constitutional drafting, amendment, replacement, and suppression; many of these constitutions have gone into legal effect. Law being what it was, practical politics flowed on untroubled.[1] [Pg 22] Only with the establishment of the National Government at Nanking did constitutional structure and actual government develop similarities.

In 1931, after three years' operation under an Organic Law, the National Government adopted the Yüeh Fa (Provisional Constitution),[2] designed to cover the period between the first stage of the revolution, military conquest, and the final one of constitutional government. This intermediate period was formally labelled the stage of political tutelage, although in fact the military unification of the country continued. The Provisional Constitution, designed for five years' use, has continued in force to the present (March 1941). It possesses the merit of attempting to make actual practice and constitutional form correspond. Grandiloquent, unenforceable provisions concerning elections are omitted, and full exercise of the powers of sovereignty are frankly entrusted to the tutelary Party, the Kuomintang. Such a constitution, formally making the Kuomintang different from and higher than any other party in China—and, for all that, in the world, since the Fascist, National Socialist, and Communist parties are not formally the constitutional superiors of their respective governments—and giving the Party unrestricted authority, has provided China with government realistic if not libertarian.

The constitutional basis of the present Party-dictatorship in China is well summarized by the distinguished constitutional commentator, Dr. Wang Shih-chieh:

According to Sun Chung-shan's[3] Chien-kuo Ta-kang [Outlines of National Reconstruction], China should pass through a period of political tutelage under the Chinese Kuomintang,[4] before the stage of constitutional government be reached. The National Government is merely an organization through which a true republic may be formed. Hence, in order to demonstrate the structure of the National Government clearly, we must first understand the meaning of tang chih [party government].

"Party government," so-called, signifies that the whole system of government is under the control or dictatorship of one political party only. The only difference between party government and dictatorship is that the former is under the dictatorship of an entire political party, while the latter is under that of a single person. Party government is of course different from democracy, inasmuch as with democracy, all policies are to be decided by the entire body of citizens, while with party government, policies are to be decided by all the members of the particular party only. In other words, the entire party as one man can exercise political dictatorship, without taking into consideration the opinions of those who are not the members of the party. Any resolution passed by that party is considered a law not only in fact, but sometimes even in name; moreover, the party may cancel or change a law by a resolution passed in a meeting.

The above-mentioned points are phenomena common to countries under party governments.

After the Chinese Kuomintang has come into power, the system of party government is not only a fact, but even prescribed in laws. The Laws Governing the System of Organization of the National Government of the Republic [Pg 24]of China promulgated for the first time on July 1, Year XIV (1925) were originally formulated by the Political Council of the Chinese Kuomintang. Article I in this code of laws provided: "The National Government discharges all the political affairs of the entire country, under the direction and superintendency of the Chinese Kuomintang." The said code has been constantly amended since its first promulgation, but this article has always remained unchanged. By the summer of Year XVII (1928), when the successful Northern Expedition undertaken by the National Revolutionary Army unified China under one government, the period of political tutelage of the Chinese Kuomintang began with the formulation and promulgation of the Outlines of Political Tutelage on October 3, Year XVII (1928). Article I of the said "Outlines" provided: "During the period of political tutelage of the Republic of China, the National Party Congress of the Chinese Kuomintang will take the place of the National Convention to lead the people and enforce all policies." By the beginning of June, in Year XX (1931), when the Provisional Constitution for the period of political tutelage was promulgated, the Outlines of Political Tutelage were again formed into a part of the Provisional Constitution, thereby giving party government a constitutional recognition. Besides the Outlines of Political Tutelage, Article 72 ("The National Government [Council of State] has a President and a certain number of state councillors, appointed by the Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang."), and Article 58 ("The Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang is vested with the power of interpreting this Provisional Constitution.") of the Provisional Constitution, and Article 10 ("The National Government has a President, twenty-four to thirty-six state councillors, a President and a Vice-President of every Yüan, appointed by the Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang."), and Article 15 ("Before the promulgation of the Constitution, the Executive, Legislative, Judicial, Examination and Control Yüan will each be responsible to the Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang.") of the Laws Governing the System of Organization of the National Government (December 30, Year XX [1931]) now being enforced, form the legal basis for party government.[5]

Under Kuomintang trusteeship, demands have been heard within and without the Party, for the promised abdication of the Party and for the initiation of popular government. Since the Kuomintang, unlike European one-party groups, established itself only for the formal purpose of democratic training, and was pledged to tolerate multi-party government as soon as possible, the continued monopoly of power was a frustration of the Party ideology and programs. The frustration was serious; involving much loss of popular sympathy for the government, this and appeasement rather demoralized the Party in the years preceding the invasion.

The Legislative Yüan brought forth on May 5, 1936 (in Chinese chronology, 5/5/XXV, or double-five twenty-five), the celebrated Hsien-fa Ts'ao-an (Draft Permanent Constitution), which was promptly dubbed the Double Five Constitution. Ever since its first promulgation, this document has formed the center of all Chinese constitutional debate, and—with very minor modifications—still stands as the official proposal for a permanent constitution, awaiting ratification by the Kuo-min Ta-hui (National [Constituent] Congress), when and if that long-postponed body ever convenes.[6] The Draft Constitution is the joint work of many outstanding legal scholars. A product of collective research[Pg 26] and study, it thereby resembles collective private codification of municipal and international law in the West more than it does the creation of a deliberative assembly. The celebrated Chinese jurist, Dr. John C. H. Wu, prepared the first informal draft,[7] and the 5/5/XXV version represents the fourth draft of the Legislative Yüan. The preparation of the various drafts has not, from the scholastic point of view, been secretive or private; but broad popular participation has neither been offered nor solicited.

The Constitution consists of eight Chapters, comprising one hundred and forty-seven articles. Chapter I defines the Chinese state as "a San Min Chu I Republic" (Art. 1), declares sovereignty to be "vested in the whole body of its citizens" (Art. 2), defines the territories of the republic, specifies racial equality for the "races of the Republic of China," designates the national flag, and declares Nanking to be the capital. Chapter II covers, in nineteen very specific articles, the entire field of private rights and of the civic privileges of individuals. Most specifications carry the qualification, "in accordance with law" or "except in accordance with law." Since law is defined further in the Constitution as "that which has been passed by the Legislative Yüan and promulgated by the President," the qualification[Pg 27] impresses many persons as sinister rather than encouraging. Except for this point, the specific constitutional guarantees exceed in number and specificity those of almost any other modern constitution.

The Kuo-min Ta-hui (either "National Congress" or "People's Congress") is the subject of Chapter III. This body has a function unlike that of any Western agency; the nearest equivalent is the National Assembly of the Third French Republic. This Congress is an electoral and constituent body with fundamental legislative powers. It is not intended to usurp the functions of the Legislative Yüan by fulfilling the role of a United States Congress, French Deputies and Senate, or a British Parliament. Meeting once every three years for a one-month session, it will be manifestly unable to act as a routine Western-type legislature.

The Central Government is the topic of the fourth Chapter. The first section of the Chapter describes the Presidency; the remaining five, the five Yüan. This applies the five-fold separation of powers. Sun Yat-sen held that a three-fold separation of powers, as known in the West and applied to American government, was efficacious; he also considered that the Imperial Chinese separation of powers (an implicit one only) was also desirable. The West had executive, legislative, judicial; old China combined these three into the governing power, and joined thereto the examinative power and the chien-ch'a[8] power. (The chien-ch'a power involved the functions of the traditional Chinese censorate; overt and active expressions are found in auditing and in the lodgment of impeachment charges. The term is fundamentally untranslatable, but if the tribunician connotations of Censor or the emergency meaning of Control be recalled, either of these terms will serve.) Sun Yat-sen[Pg 28] combined the Western and the old-Chinese separations, developing a theory of the five powers. The Draft Constitution, like its two working predecessors, is a five-power constitution, with five great Yüan (Boards, Presidencies, or Courts), each headed by a Yüan-chang (Yüan President). The fourth Chapter, by including the President and all five Yüan, almost covers the full reach of Chinese government.

This Chapter contemplates the creation of a strong President. In the Organic Law of 1928, the five Presidents of the Yüan were relatively less strong, and the Chairman of the Kuo-min Chêng-fu Wei-yüan-hui (National Government Council; or, Council of State) was the key figure in the government. Most of this time, Chiang himself was Chairman. In the 1931 Provisional Constitution, now in force, the Chairman of the National Government—termed President by courtesy—is an officer comparable to the President of the Third French Republic; the President of the Executive Yüan is a more active officer: Chiang K'ai-shek is President of the Executive Yüan. The new President, under the Draft Constitution, is one of the world's most powerful officers. Holding office for six years, eligible for re-election, commander of all armed forces, declarer of war, negotiator of peace, treaty-maker, chief appointing and removing officer of the state, holder of an emergency power greater than that conveyed by Article 48 of the German Weimar Constitution, and superior to the executive, legislative, judicial, examinative and control branches of the government—such a President is fully responsible to the triennial People's Congress, and to that only! Since the proposed President may be recalled at any time by the People's Congress, he is in that respect similar to parliamentary chiefs of state.[9]

The President of the Executive Yüan, together with his subordinates, is to be appointed and removed by the President of the Republic. The Yüan includes Cabinet Ministers—appointed to their posts from among a special group of Executive Members of the Yüan, thereby providing a simple, rational equivalent of Cabinet and Privy Council, as in Japan or (less similarly) in Great Britain.

The Legislative Yüan is an interesting semi-cameral legislative body, which seeks to embody the better features of legislative research organs and of representative bodies. The Judicial Yüan rationalizes the structure and administration of courts and of judicial process.

The Control [or Censor] Yüan is, like the Legislative Yüan, a quasi-cameral body, with indirect election of members by the People's Congress from territorial electorates. Its functions are audit, inquiry, and impeachment, with such ancillary powers as practice to date has already indicated.[10]

Chapter V of the Draft Permanent Constitution deals with local government. The institutions of provincial government are wittingly minimized, because of recent trouble with provincial satrapies and the dangerously centrifugal effect of provincial autonomism. In contrast to this, government at the district (hsien) level is designed in strict accordance with the realities of twenty-odd centuries' experience. It is probable that no other constitution in the world provides for such careful guarantee of district, county, canton, or Kreis autonomy. The old Imperial Chinese system was a loose pseudo-centralized federation of two thousand near-autarkic and near-autonomous commonwealths; the Draft Constitution attempts to reinstitute (at the political level) this vigorous cooperative independence of the hsien. The hsien meeting, extrapolitical, unsystematic, and occasional in the past, is made the foundation for the new[Pg 30] legal structure. (These proposed reforms are now being anticipated under the Provisional Constitution and current statutory changes.[11])

Chapter VI provides that the economic system shall rest on Sun Yat-sen's principle of min shêng (q.v., below). Willing to apply whatever worked best, Sun himself had no theoretical objections to capitalism, communism, state socialism, or any other economic doctrine. Hence, proletarian ownership of the means of production is not guaranteed; yet state ownership is not restricted, and is specifically required in the case of "all public utilities and enterprises of a monopolistic nature" (Art. 123). Henry George's influence on Sun is shown by mandatory taxation of unearned increment (Art. 119). Room for free future adaptation from corporative economic techniques successful in the outside world is assured (Art. 125): "Labor and capital shall, in accordance with the principles of mutual help and cooperation, develop together productive enterprises." It is likely that any imaginable economic system would be constitutional on this basis, provided that it was initiated by due legal procedure and without hardships irresponsibly imposed.

Chapter VII, on Education, opens: "The educational aim of the Republic of China shall be to develop a national spirit, to cultivate a national morality, to train the people for self-government and to increase their ability to earn a livelihood, and thereby to build up a sound and healthy body of citizens" (Art. 131), and continues, "Every citizen of the Republic of China shall have an equal opportunity to receive education" (Art. 132). State, secular control of educational policy is assured. Articles 134 and 135 provide for tuition-free elementary education for children and free elementary education for previously non-privileged adults. (The constitutional guarantee concerning tuition is indicative[Pg 31] of the scholastic traditions of the Chinese, of the modern educational revolution, and is reminiscent of Art. 12 of the 1931 Constitution of the Chinese Soviet Republic: "The Soviet Government in China shall guarantee to all workers, peasants, and the toiling masses the right to education. The Soviet Government will, as far as possible, begin at once to introduce free universal education.")[12]

Chapter VIII deals with the interpretation and enforcement of the Constitution. It was a labor of love by shrewd legal theorists, and defines terms with great clarity. Interpretive power is vested in the Judicial Yüan.

Nowhere in China is there outright denial of a need for constitutional change. The need exists; the Double Five Draft is the government's answer. Yet there are few patent demerits in the existing constitutional system; the present political structure is more realistic, more broadly national, more expressive of effective opinion than any other in modern China. The question arises from commitments (dating back to the Empire) promising to create actual constitutional government. The National Government was established on the basis of this pledge. The democratic ideology, whatever sects it may include, has a clean sweep of the field of doctrine in China. No one seriously advocates monarchy, separatism, or permanent dictatorship. The only question is: how and when?

At the close of the third session of the advisory People's Political Council, Chiang K'ai-shek replied to demands for immediate broadening of popular control[Pg 32] over the government by reaffirmation of his adherence to the democratic dogma of Sun Yat-sen, together with the following warnings:

The democracy which Tsung-Li [The Leader, i.e., Sun Yat-sen] wished to establish was of the purest kind without the slightest vestige of make-believe or artificiality. Unfortunately, the Chinese people, having inherited all the evil practices handed down throughout the numerous dynasties of autocratic rule, were then at a low ebb both in intelligence and in vitality. The people were used to disorganization and selfishness....

We have to wait until our lost territories have been recovered and domestic disorders liquidated before we can have political tutelage and prepare ourselves for constitutionalism....

People at that time [the inauguration of the Republic in 1912] made the mistake of neglecting the necessary procedures and instead they rivalled each other in talking about democracy.... As a result, democracy has remained an ideal....

We must make it clear to our people that democracy is not a synonym for lack of law and order, or for anarchy.

The public opinion on which democracy is based must be sound, collective, and representative of the majority of the people's wills. The freedom which democracy endows on people should not conflict with public welfare, nor should it go beyond the sphere as marked by laws of the State. With our nation facing the worst invasion in history, we must teach the people to respect the absolute authority of laws of the State.[13]

The clamor for a constitution continued. The difficulties of introducing mass suffrage to Western China were apparent to everyone, but many leaders felt that the advantages of constitutionalism would outweigh the inescapable loss of efficiency, and would mobilize public opinion behind the war and further democratic progress. The Generalissimo found this view hard to reconcile with his military, direct notions of doing first things[Pg 33] first, as he saw them, but he yielded in the fourth session of the People's Political Council and accepted the demand. He stated:

In China ... [democratization] is a tremendously heavy task which cannot be completed within a few days. I think that the Constitution and laws may as well be promulgated at an earlier date. But, gentlemen, please do not forget the Tsung-li's painful consideration ... [of the necessity of an intermediate stage of real democratic training]. Political tutelage does not end with the training of the citizens by the government. It requires training of the citizens by themselves.

Today we should understand our object: to start the building of a constitutional government. This means laying a permanently sound basis for the nation. We are not concerned with the time of starting constitutional government. Whether to start it early or later does not matter much. What we are really concerned with is, do we have a real intention of forming a constitutional government? If we are truly so minded, we might as well promulgate the Constitution before the labor of political tutelage is completed.[14]

Chiang thus reconciled the beginning of constitutionalism and the continuance of political tutelage, although implying acquiescence, not recommendation. A theorist holding all men to be driven by "a perpetuall and restlesse desire of Power after power, that ceaseth only in Death,"[15] might consistently suppose that Chiang merely dissimulated an inward lust for authority; more plausible is the postulation that a man who has for years lived with and for a doctrine, giving his life and future reputation to the fulfilment of a program, would incline to prudence and realism in climaxing that doctrine and program. In Chiang's case this is Sun Yat-sen's San Min Chu I. Chiang's reluctance to apply democracy then and there is understandable whatever the inmost motive; so, too, is his yielding to a widespread demand.

The convening of a special Kuo-min Ta-hui as a national constituent assembly was set for November 12, 1940; this day was chosen because it was traditionally the seventy-fourth birthday of Sun Yat-sen. Administrative machinery for preparation of a hall, secretariat, publications, and other necessities was established and set in motion. Following the severe fires of August 19-20, and the subsequent large-scale demolition of above-ground downtown Chungking by raids, indefinite postponement of the Congress was announced on September 25—on the grounds that military hazard prevented adequate assembly of delegates, and no reasonably safe place for such a meeting could be found.

Meanwhile, recent years have seen an uproar of constitutional debate. This may be summarized briefly, with the case against the Constitution stated first:

Constitutionalization would lead to the legalization of other parties, instead of a mere condition of non-prosecution; this would disrupt the orderliness required[Pg 35] of a people at war. Why add discord in war time? Reply: legitimization of other parties is not a struggle for power but an act of union. It would widen the periphery of cooperation.[16]

Sun Yat-sen required three stages of the revolution: conquest, tutelage, constitution. China is not ready for mass suffrage. The majority of the people are not yet literate. Public opinion is just developing. The nation is, in fact, still in the period of military recapture of national territories. Reply: Sun Yat-sen must not be interpreted mechanically. If this is done, tutelage will never end, and Sun's cherished democracy will remain forever in the future. Furthermore, the guerrillas, the Border Region, and other instances have shown that the Chinese masses can and will practice democracy right now. Again, the issue has already been decided; the government has been committed to the immediate inauguration of the Constitution. First it was to be 1939; the elections were held in part, until the war finally stopped them on August 13, 1937. It is too late to raise the issue: is China ready? Everyone—government, Kuomintang, independent groups—has decided that China is.

Why change constitutions? The present one is satisfactory. If a war-time amplification of the Yüeh Fa is needed, it can be found in the Program of Resistance and Reconstruction.[17] If a convocation of the talents is needed, the People's Political Council is already there. What is the use of a constitutional change in war time? Reply: the constitutionalist movement is no new development. The Program was a democratic advance. "Besides, formation of the People's Political Council was a step toward democracy. The constitutional[Pg 36] movement was not forced on the government, but was an outgrowth of the war; it has not appeared overnight, but has a clear historical background. As soon as the Sino-Japanese hostilities broke out, it was evident that more democratic rule was necessary. As the war became prolonged, the preliminary steps proved inadequate. A more perfect constitution, whereby the whole people can be mobilized, is imminent. This fact was duly recognized by the people and is the motive power of the present constitutional movement." (This is the comment of an independent writer.)[18]

A pointed question is raised and answered by Tso Tao-fen, one of the Seven Gentlemen (Ch'i Chüntzu) who led the National Salvationists: