The Project Gutenberg EBook of Herman Melville, by Raymond M. Weaver

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Herman Melville

Mariner and Mystic

Author: Raymond M. Weaver

Release Date: November 15, 2015 [EBook #50461]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HERMAN MELVILLE ***

Produced by Henry Flower and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

RAYMOND M. WEAVER

HERMAN MELVILLE

MARINER AND MYSTIC

BY

RAYMOND M. WEAVER

COPYRIGHT, 1921,

BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO

PROFESSOR FRANKLIN T. BAKER

“—il maestro cortese”

To Professor Carl Van Doren, to Miss Cora Paget, and to Mrs. Eleanor Melville Metcalf, I am, in the writing of this book, very especially indebted. By Professor Van Doren’s enthusiasm and scholarship I was instigated to a study of Melville. It has been my privilege to enjoy Miss Paget’s very valuable criticism and assistance throughout the preparation of this volume. Mrs. Metcalf gave me access to all the surviving records of her grandfather: Melville manuscripts, letters, journals, annotated books, photographs, and a variety of other material. But she did far more. My indebtedness to Mrs. Metcalf’s vivid interest, her shrewd insight, her keen sympathy can be stated only in superlatives. To Mrs. and Mr. Metcalf I owe one of the richest and most pleasant associations of my life.

Raymond M. Weaver.

October 1, 1921.

Most of the letters of Melville to Hawthorne included in this volume are quoted from Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Wife, by Julian Hawthorne. These letters, and other citations from Mr. Hawthorne’s memoir, are included through the courtesy of Messrs. Houghton Mifflin Company.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Devil’s Advocate | 15 |

| II | Ghosts | 33 |

| III | Parents and Early Years | 53 |

| IV | A Substitute for Pistol and Ball | 77 |

| V | Discoveries on Two Continents | 98 |

| VI | Pedagogy, Pugilism and Letters | 113 |

| VII | Blubber and Mysticism | 128 |

| VIII | Leviathan | 153 |

| IX | The Pacific | 170 |

| X | Man-Eating Epicures—The Marquesas | 194 |

| XI | Mutiny and Missionaries—Tahiti | 215 |

| XII | On Board a Man-of-War | 233 |

| XIII | Into the Racing Tide | 250 |

| XIV | Across the Atlantic Again | 283 |

| XV | A Neighbour of Hawthorne’s | 305 |

| XVI | The Great Refusal | 334 |

| XVII | The Long Quietus | 349 |

| Bibliography | 385 | |

| Index of Names | 391 |

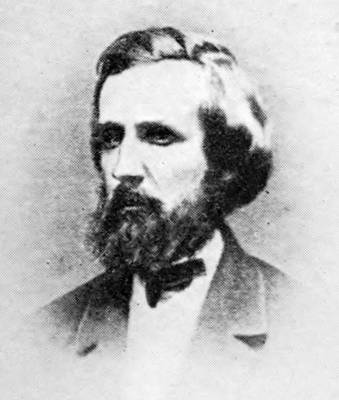

| Herman Melville | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

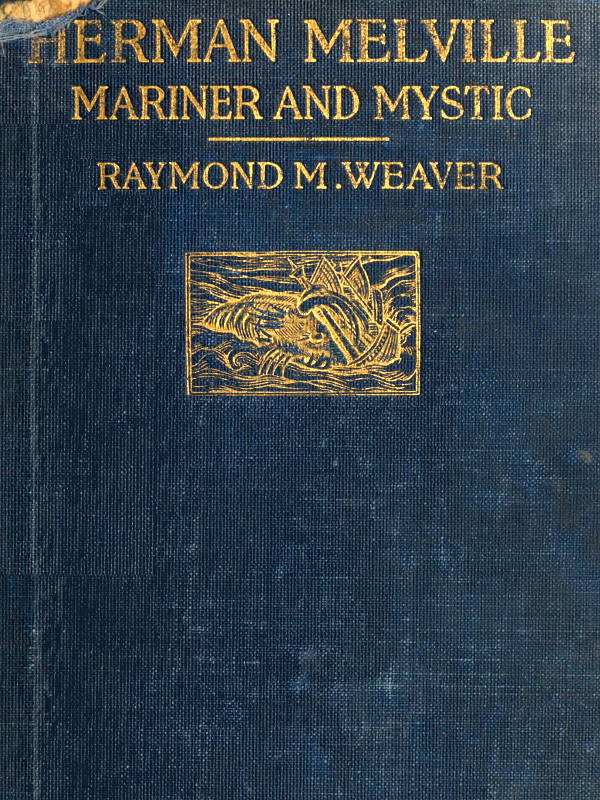

| Melville’s Grandfathers | 40 |

| General Peter Gansevoort | |

| Major Thomas Melville | |

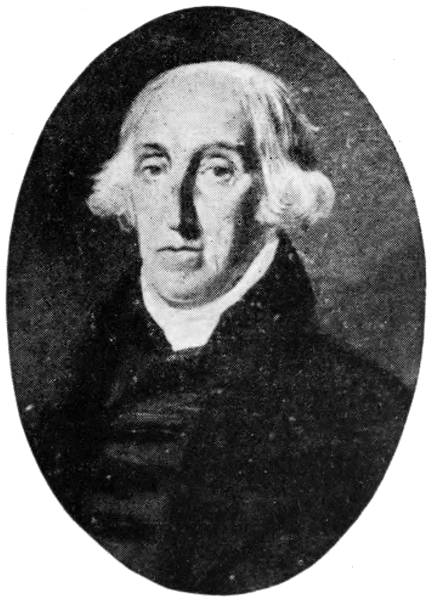

| Allan Melville | 56 |

| Maria Gansevoort Melville | 64 |

| In 1820 | |

| In 1865 | |

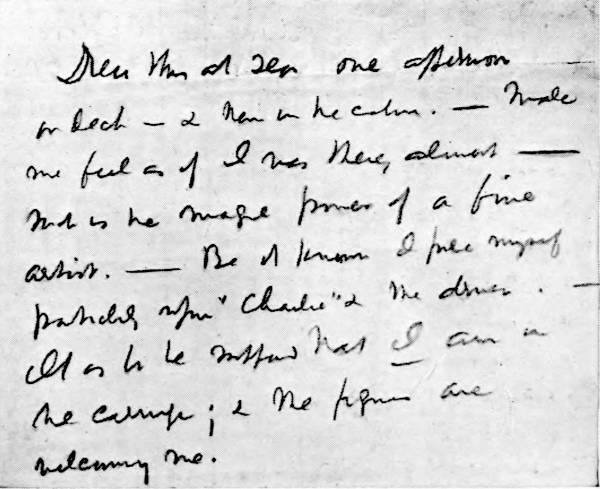

| A Page from One of Melville’s Journals | 104 |

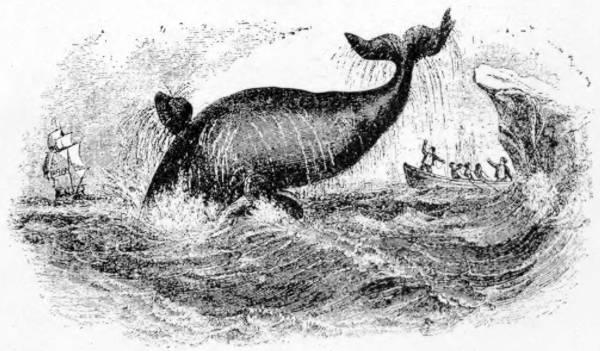

| Throwing the Harpoon | 136 |

| Sounding | 136 |

| Sperm Whaling. The Capture | 160 |

| One of Six Whaling Prints | 160 |

| “Toby.” Richard Tobias Greene | 164 |

| In 1846 | |

| In 1865 | |

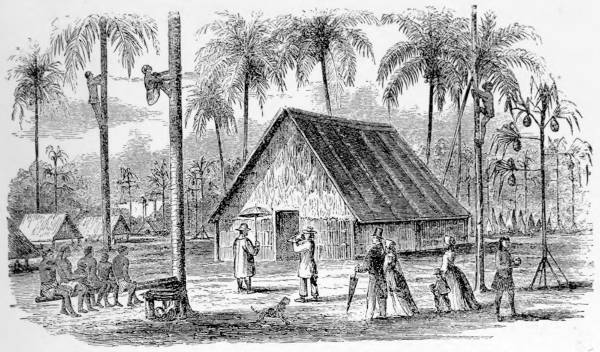

| Evangelising Polynesia | 184 |

| Richard Tobias Greene. In 1885 | 200 |

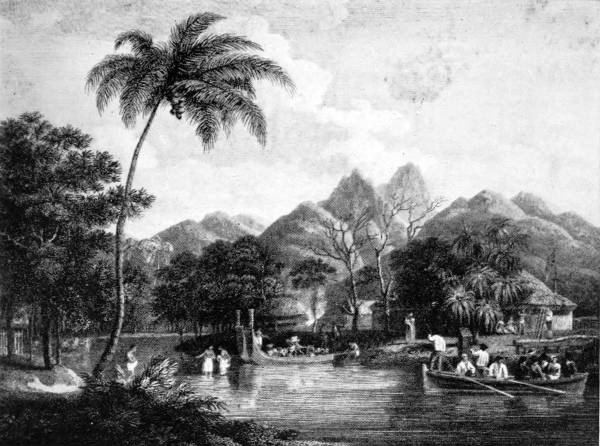

| First Home of the Protestant Missionaries in Tahiti | 224 |

| The Fleet of Tahiti | 224 |

| Elizabeth Shaw Melville | 272 |

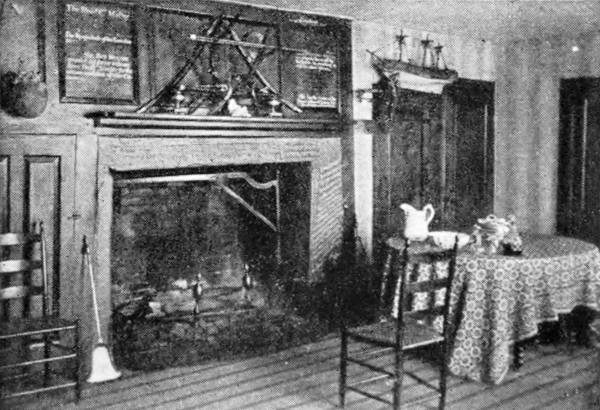

| Arrowhead | 312 |

| The Fireplace. Arrowhead | 312 |

| Herman Melville. In 1868 | 352 |

| Melville As Artist | 368 |

| Melville’s Children | 376 |

HERMAN MELVILLE

Mariner and Mystic

“If ever, my dear Hawthorne,” wrote Melville in the summer of 1851, “we shall sit down in Paradise in some little shady corner by ourselves; and if we shall by any means be able to smuggle a basket of champagne there (I won’t believe in a Temperance Heaven); and if we shall then cross our celestial legs in the celestial grass that is forever tropical, and strike our glasses and our heads together till both ring musically in concert: then, O my dear fellow mortal, how shall we pleasantly discourse of all the things manifold which now so much distress us.” This serene and laughing desolation—a mood which in Melville alternated with a deepening and less tranquil despair—is a spectacle to inspire with sardonic optimism those who gloat over the vanity of human wishes. For though at that time Melville was only thirty-two years old, he had crowded into that brief space of life a scope of experience to rival Ulysses’, and a literary achievement of a magnitude and variety to merit all but the highest fame. Still did he luxuriate in tribulation. Well-born, and nurtured in good manners and a cosmopolitan tradition, he was, like George Borrow, and Sir Richard Burton, a gentleman adventurer in the barbarous outposts of human experience. Nor was his a kid-gloved and expensively staged dip into studio savagery. “For my part, I abominate all honourable respectable toils, trials, and tribulations of every kind whatsoever,” he declared. And as proof of this abomination he went forth penniless as a common sailor to view the watery world. He spent his youth and early man[16]hood in the forecastles of a merchantman, several whalers, and a man-of-war. He diversified whale-hunting by a sojourn of four months among practising cannibals, and a mutiny off Tahiti. He returned home to New England to marry the daughter of Chief Justice Shaw of Massachusetts, and to win wide distinction as a novelist on both sides of the Atlantic. Though these crowded years had brought with them bitter hardship and keen suffering, he had sown in tears that he might reap in triumph. But when he wrote to Hawthorne he felt that triumph had not been achieved. Yet he needed but one conclusive gesture to provoke the world to cry this as a lie in his throat: one last sure sign to convince all posterity that he was, indeed, one whom the gods loved. But the gods fatally withheld their sign for forty years. Melville did not die until 1891.

None of Melville’s critics seem ever to have been able to forgive him his length of days. “Some men die too soon,” said Nietzsche, “others too late; there is an art in dying at the right time.” Melville’s longevity has done deep harm to his reputation as an artist in dying, and has obscured the phenomenal brilliancy of his early literary accomplishment. The last forty years of his history are a record of a stoical—and sometimes frenzied—distaste for life, a perverse and sedulous contempt for recognition, an interest in solitude, in etchings and in metaphysics. In his writings after 1851 he employed a world of pains to scorn the world: a compliment returned in kind. During the closing years of his life he violated the self-esteem of the world still more by rating it as too inconsequential for condemnation. He earned his living between 1866 and 1886 as inspector of Customs in New York city. His deepest interest came to be in metaphysics: which is but misery dissolved in thought. It may be, to the all-seeing eye of truth, that Melville’s closing years were the most glorious of his life. But to the mere critic of literature, his strange career is like a star that drops a line of streaming fire down the vault of the sky—and then the dark and blasted shape that sinks into the earth.

There are few more interesting problems in biography than[17] this offered by Melville’s paradoxical career: its brilliant early achievement, its long and dark eclipse. Yet in its popular statement, this problem is perverted from the facts by an insufficient knowledge of Melville’s life and works. The current opinion was thus expressed by an uncircumspect critic at the time of Melville’s centenary in 1919: “Owing to some odd psychological experience, that has never been definitely explained, his style of writing, his view of life underwent a complete change. From being a writer of stirring, vivid fiction, he became a dreamer, wrapping himself up in a vague kind of mysticism, that rendered his last few books such as Pierre: or The Ambiguities and The Confidence Man: His Masquerade quite incomprehensible, and certainly most uninteresting for the average reader.”

Unhampered by diffidence—because innocent of the essential facts—critics of Melville have been fluent in hypothesis to account for this “complete change.” A German critic patriotically lays the blame on Kant. English-speaking critics, with insular pride, have found a sufficiency of disruptive agencies nearer at home. Some impute Melville’s decline to Sir Thomas Browne; others to Melville’s intimacy with Hawthorne; others to the dispraise heaped upon Pierre. Though there is a semblance of truth in each, such attempts at explanation are, of course, too shallow and neat to merit reprobation. But there is another group of critics, too considerable in size and substance to be so cavalierly dismissed. This company accounts for Melville’s swift obscuration in a summary and comprehensive manner, by intimating that Melville went insane.

Such an intimation is doubtless highly efficacious to mediocrity in bolstering its own self-esteem. But otherwise it is without precise intellectual content. For insanity is not a definite entity like leprosy, measles, and the bubonic plague, but even in its most precise use, denotes a conglomerate group of phenomena which have but little in common. Science, it is true, speaking through Nordau and Lombroso, has attempted to show an intimate correlation between genius and degeneracy; and if the creative imagination of some of the disciples of Freud is to be trusted, the choir invisible is little more than a[18] glorified bedlam. Plato would have accepted this verdict with approval. “From insanity,” said Plato, “Greece has derived its greatest benefits.” But the dull and decent Philistine, untouched by Platonic heresies, justifies his sterility in a boast of sanity. The America in which Melville was born and died was exuberantly and unquestionably “sane.” Its “sanity” drove Irving abroad and made a recluse of Hawthorne. Cooper alone throve upon it. And of Melville, more ponderous in gifts and more volcanic in energy than any other American writer, it made an Ishmael upon the face of the earth. With its outstanding symptoms of materialism and conformity it drove Emerson to pray for an epidemic of madness: “O Celestial Bacchus! drive them mad.—This multitude of vagabonds, hungry for eloquence, hungry for poetry, starving for symbols, perishing for want of electricity to vitalise this too much pasture, and in the long delay indemnifying themselves with the false wine of alcohol, of politics, of money.”

From this it would appear that a taste for insanity has been widespread among poets, prophets and saints: men venerated more by posterity than by their neighbours. It is well for Socrates that Xantippe did not write his memoirs: but there was sufficient libel in hemlock. In ancient and mediæval times, of course, madness, when not abhorred as a demoniac possession, was revered as a holy and mysterious visitation. To-day, witch-burning and canonisation have given place to more refined devices. The herd must always be intolerant of all who violate its sacred and painfully reared traditions. With an easy conscience it has always exterminated in the flesh those who sin in the flesh. In times less timid than the present it dealt with sins of the spirit with similar crude vindictiveness. We boast it as a sign of our progress that we have outgrown the days of jubilant public crucifixions and bumpers of hemlock: and there is ironic justice in the boast. Openly to harbour convictions repugnant to the herd is still the unforgivable sin against that most holy of ghosts—fashionable opinion; and carelessly to let live may be more cruel than officiously to cause to die.

Melville sinned blackly against the orthodoxy of his time.[19] In his earlier works, he confined his sins to an attack upon Missionaries and the starchings of civilisation: sins that won him a succes de scandal. The London Missionary Society charged into the resulting festivities with its flag at half mast. Cased in the armour of the Lord, it with flagrant injustice attacked his morals, because it smarted under his ideas. But when Melville began flooding the very foundations of life with torrents of corrosive pessimism, the world at large found itself more vulnerable in its encasement. It could not, without absurdity obvious even to itself, accuse Melville of any of the cruder crimes against Jehovah or the Public. Judged by the bungling provisions of the thirty-nine articles and the penal code, he was not a bad man: more subtle was his iniquity. As by a divine visitation, the Harper fire of 1853 effectually reduced Pierre—his most frankly poisonous book—to a safely limited edition. And the public, taking the hint, ceased buying his books. In reply, Melville earned his bread as Inspector of Customs. The public, defeated in its righteous attempts at starvation, hit upon a more exquisite revenge. It gathered in elegiacal synods and whispered mysteriously: “He went insane.”

To view Melville’s life as a venturesome romantic idyll frozen in mid-career by the deus ex machina of some steadily descending Gorgon is possible only by a wanton misreading of patent facts. Throughout Melville’s long life his warring and untamed desires were in violent conflict with his physical and spiritual environment. His whole history is the record of an attempt to escape from an inexorable and intolerable world of reality: a quenchless and essentially tragic Odyssey away from home, out in search of “the unpeopled world behind the sun.” In the blood and bone of his youth he sailed away in brave quest of such a harbour, to face inevitable defeat. For this rebuff he sought both solace and revenge in literature. But by literature he also sought his livelihood. In the first burst of literary success he married. Held closer to reality by financial worry and the hostages of wife and children, the conflict within him was heightened. By a vicious circle, with brooding disappointment came ill health. “Ah, muskets the gods have made[20] to carry infinite combustion,” he wrote in Pierre, “and yet made them of clay.” The royalties from his books proved inadequate for the support of his family, so for twenty years he earned a frugal living in the customs houses in New York. During his leisure hours he continued to write, but never for publication. Two volumes of poetry he privately printed. His last novel, surviving in manuscript, he finished a few months before his death. Though it is for the second half that his critics have felt bound to regret, it seems that in serenity and mental equipoise, the last state of this man was better than the first.

In his early manhood he wrote in Mardi: “Though essaying but a sportive sail, I was driven from my course by a blast resistless; and ill-provided, young, and bowed by the brunt of things before my prime, still fly before the gale.... If after all these fearful fainting trances, the verdict be, the golden haven was not gained;—yet in bold quest thereof, better to sink in boundless deeps than float on vulgar shoals; and give me, ye gods, an utter wreck, if wreck I do.” To the world at large, it has been generally believed that the Gods ironically fulfilled his worst hopes.

One William Cranston Lawton, in an Introduction to the Study of American Literature—a handy relic of the parrot judgment passed upon Melville during the closing years of his life—so enlightens young America: “He holds his own beside Cooper and Marryat, and boy readers, at least, will need no introduction to him. Nor will their enjoyment ever be alloyed by a Puritan moral or a mystic double meaning.” And Barrett Wendell, in A Literary History of America—a volume that modestly limits American literature of much value not only to New England, but even tucks it neatly into the confines of Harvard College—notes with jaunty patronage: “Herman Melville with his books about the South Seas, which Robert Louis Stevenson is said to have declared the best ever written, and his novels of maritime adventure, began a career of literary promise, which never came to fruition.”

These typical pronouncements, unperverted by the remotest touch of independent judgment, transcend Melville’s worst[21] fears. “Think of it!” he once wrote to Hawthorne. “To go down to posterity is bad enough, any way; but to go down as a ‘man who lived among the cannibals!’ When I think of posterity in reference to myself, I mean only the babes who will probably be born in the moment immediately ensuing upon my giving up the ghost. I shall go down to them, in all likelihood. Typee will be given to them, perhaps, with their gingerbread.” In that mythical anomaly known as the “popular mind,” Melville has, indeed, survived as an obscure adventurer in strange seas and among amiable barbarians. Typee and Omoo have lived on as minor classics. Though there have been staccato and sporadic attacks upon the ludicrous inadequacy of the popular judgment upon Melville, not until recently, and then chiefly in England has there been any popular and concerted attempt to take Melville’s truer and more heroic dimensions. An editorial in the London Nation for January 22, 1921, thus bespeaks the changing temper of the times:

“It is clear that the wind of the spirit, when it once begins to blow through the English literary mind, possesses a surprising power of penetration. A few weeks ago it was pleased to aim a simultaneous blast in the direction of a book known to some generations of men as Moby-Dick. A member of the staff of The Nation was thereupon moved in the ancient Hebrew fashion to buy and to read it. He then expressed himself on the subject, incoherently indeed, but with signs of emotion as intense and as pleasingly uncouth as Man Friday betrayed at the sight of his long-lost father. While struggling with his article, and wondering what the deuce it could mean, I received a letter from a famous literary man, marked on the outside ‘Urgent,’ and on the inner scroll of the manuscript itself ‘A Rhapsody.’ It was about Moby-Dick. Having observed a third article on the same subject, of an equally febrile kind, I began to read Moby-Dick myself. Having done so I hereby declare, being of sane intellect, that since letters began there never was such a book, and that the mind of man is not constructed so as to produce such another; that I put its author with Rabelais, Swift, Shakespeare, and other minor and disputable worthies; and that I advise any adventurer of the soul[22] to go at once to the morose and prolonged retreat necessary for its deglutition.”

Having earlier been hailed in France as an “American Rabelais;” prized in England by the author of The City of Dreadful Night; greeted by Stevenson with slangy enthusiasm as a “howling cheese;” rated by Mr. Masefield as unique among writers of the sea; the professed inspirer of Captain Hook of Sir James Barrie’s Peter Pan, Melville is beginning to appear as being vastly more than merely a “man who lived among the cannibals” and who returned home to write lively sea stories for boys.

The wholesale neglect of Melville at the hands of his countrymen—though explained in some part as a consummation of Melville’s best efforts—has not been merely unintelligent, but thoroughly discreditable. For Melville, from any point of view, is one of the most distinguished of our writers, and there is something ludicrous in being before all the world—as, assuredly, we sometimes are—in recognising our own merit where it is contestable, and in neglecting it where it is not.

It has been our tradition to cherish our literature for its embodiment of Queen Victoria’s fireside qualities. The repudiation of this tradition—as a part of our repudiation of all tradition—has made fashionable a wholesale contempt for our native product. “I can’t read Longfellow” is frequently remarked; “he’s so subtle!” Our critical estimates have laboured under the incubus of New England provincialism: a provincialism preserved in miniature in the first pages of Lowell’s essay on Thoreau. At present we need to have the eminence of the section recalled to us; but during the period of Melville’s productivity, it was at its apex, and in its bosom Melville wrote. This man, whose closest literary affinities were Rabelais, Zola, Sir Thomas Browne, Rousseau, Meredith, and Dr. John Donne,—a combination to make the uninitiated blink with incredulity—was indebted to Nathaniel Hawthorne for the best makeshift for companionship he was ever to know: one of the most subtly ironical associations the imps of comedy ever brought about. Nor was the comedy lessened by Mrs. Hawthorne’s presence upon the scene. Shrewd was her in[23]stinctive resentment of her husband’s friend. Viewed by his neighbours “as little better than a cannibal and a ‘beach comber’”—such was the report of the late Titus Munson Coan in a letter to his mother written immediately after a pilgrimage to Melville in the Berkshires—Melville turned to Hawthorne for understanding. Frank Preston Stearns, in his Life and Genius of Nathaniel Hawthorne (1906) says that for Hawthorne “the summer of 1851 in Lenox was by no means brilliant.... Hawthorne’s chief entertainment seems to have been the congratulatory letters he received from distinguished people.... For older company he had Herman Melville and G. P. R. James, whose society he may have found as interesting as that of more distinguished writers.” But Mrs. Hawthorne had studied Melville with a closer scrutiny and was not so easily convinced of Melville’s insignificance. Melville had visited the Hawthornes in the tiny reception room of the Red House, where Mrs. Hawthorne “sewed at her stand and read to the children about Christ;” in the drawing room, where she disposed “the embroidered furniture,” and where, in the farther corner, stood “Apollo with his head tied on;” in Hawthorne’s study, which to Mrs. Hawthorne’s wifely adoration was consecrated by “his presence in the morning.” Mrs. Hawthorne looked from the “wonderful, wonderful eyes” of her husband—each eye “like a violet with a soul in it,”—to Melville’s eyes, and confessed to her mother her grave and jealous suspicion of Melville: “I am not quite sure that I do not think him a very great man.... A man with a true, warm heart, and a soul and an intellect,—with life to his finger-tips; earnest, sincere and reverent; very tender and modest.... He has very keen perceptive power; but what astonishes me is, that his eyes are not large and deep. He seems to see everything very accurately; and how he can do so with his small eyes, I cannot tell. They are not keen eyes, either, but quite undistinguished in any way. His nose is straight and rather handsome, his mouth expressive of sensibility and emotion. He is tall, and erect, with an air free, brave and manly. When conversing, he is full of gesture and force, and loses himself in his subject. There is no grace nor polish. Once in a[24] while, his animation gives place to a singularly quiet expression, out of these eyes to which I have objected; an indrawn, dim look, but which at the same time makes you feel that he is at that moment taking deepest note of what is before him. It is a strange, lazy glance, but with a power in it quite unique. It does not seem to penetrate through you, but to take you into itself. I saw him look at Una so, yesterday, several times.”

Mrs. Hawthorne must ever enjoy a lofty eminence as one of Melville’s most penetrating critics. Her husband dwelt apart, and less because he found the atmosphere of New England wholly uncongenial than because he shared his wife’s conviction that he was like a star. And shrewdly his wife resented the presence of a second luminary—treacherously veiled and of heaven knows what magnitude!—in her serene New England sky. Time may yet harp her worst fears aright.

For despite his comparative obscurity, Melville is—as cannot be too frequently iterated—one of the chief and most unusual figures in our native literature. And his claim to such high distinction must rest upon three prime counts.

First—because most obvious—Melville was the literary discoverer of the South Seas. And though his ample and rapidly multiplying progeny includes such names as Robert Louis Stevenson, Charles Warren Stoddard, John La Farge, Jack London, Louis Becke, A. Safroni-Middleton, Somerset Maugham, and Frederick O’Brien, he is still unsurpassed in the manner he originated. On this point, all competent critics are agreed.

Melville’s second achievement is most adequately stated by the well-known English sea-writer, W. Clark Russell, in A Claim of American Literature (reprinted from The North American Review in The Critic for March 26, 1892). “When Richard Henry Dana, and Herman Melville wrote,” says Russell, “the commercial sailor of Great Britain and the United States was without representation in literature.... Dana and Melville were Americans. They were the first to lift the hatch and show the world what passes in a ship’s forecastle; how men live down in that gloomy cave, how and what they[25] eat, and where they sleep; what pleasures they take, what their sorrows and wrongs are; how they are used when they quit their black sea-parlours in response to the boatswain’s silver summons to work on deck by day and by night. These secrets of the deep Dana and Melville disclosed.... Dana and Melville created a new world, not by the discovery, but by the interpretation of it. They gave us a full view of the life led by tens of thousands of men whose very existence, till these wizards arose, had been as vague to the general land intelligence as the shadows of clouds moving under the brightness of the stars.” And to Melville and Dana, so Russell contends, we owe “the first, the best and most enduring revelation of these secrets.” On this score, Conrad, Kipling, and Masefield must own Melville as master.

Melville’s third and supreme claim to distinction rests upon a single volume, which, after the order of Melchizedek, is without issue and without descent: “a work which is not only unique in its kind, and a great achievement” to quote a recent judgment from England, “but is the expression of an imagination that rises to the highest, and so is amongst the world’s great works of art.” This book is, of course, Moby-Dick, Melville’s undoubted masterpiece. “In that wild, beautiful romance”—the words are Mr. Masefield’s—“Melville seems to have spoken the very secret of the sea, and to have drawn into his tale all the magic, all the sadness, all the wild joy of many waters. It stands quite alone; quite unlike any other book known to me. It strikes a note which no other sea writer has ever struck.”

The organising theme of this unparalleled volume is the hunt by the mad Captain Ahab after the great white whale which had dismembered him of his leg; of Captain Ahab’s unwearied pursuit by rumour of its whereabouts; of the final destruction of himself and his ship by its savage onslaught. On the white hump of the ancient and vindictive monster Captain Ahab piles the sum of all the rage and hate of mankind from the days of Eden down.

Melville expresses an ironical fear lest his book be scouted “as a monstrous fable, or still worse and more detestable, a[26] hideous and intolerable allegory.” Yet fabulous allegory it is: an allegory of the demonism at the cankered heart of nature, teaching that “though in many of its visible aspects the world seems formed in love, the invisible spheres were formed in fright.” Thou shalt know the truth, and the truth shall make you mad. To the eye of truth, so Melville would convince us, “the palsied universe lies before us as a leper;” “all deified Nature absolutely paints like a harlot, whose allurements cover nothing but the charnal house within.” To embody this devastating insight, Melville chooses as a symbol, an albino whale. “Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?”

An artist who goes out to find sermons in stones does so at the peril of converting his stone pile into his mausoleum. His danger is excessive, if, having his sermons all ready, he makes it his task to find the stones to fit them. Allegory justifies itself only when the fiction is the fact and the moral the induction; only when its representation is as imaginatively real as its meaning; only when the stones are interesting boulders in a rich and diversified landscape. So broadly and vividly is Moby-Dick based on solid foundation that even the most literal-minded, innocent of Melville’s dark intent, have found this book of the soul’s daring and the soul’s dread a very worthy volume. One spokesman for this congregation, while admitting that “a certain absorption of interest lies in the nightmare intensity and melodramatic climax of the tale,” finds his interest captured and held far more by “the exposition of fact with which the story is loaded to the very gunwale. No living thing on earth or in the waters under the earth is so interesting as the whale. How it is pursued, from the Arctic to the Antarctic; how it is harpooned, to the peril of boat and crew; how, when brought to the side, ‘cutting in’ is accomplished; how the whale’s anatomy is laid bare; how his fat is redeemed—to be told this in the form of a narrative, with all manner of dramatic but perfectly plausible incidents interspersed, is enough to make the book completely engrossing without the white whale and Captain Ahab’s fatal monomania.”

So diverse are the samples out of which Moby-Dick is compounded, yet so masterful is each of its samples, that there is[27] still far from universal agreement as to the ground colour of this rich and towering fabric. Yet by this very disagreement is its miraculous artistry affirmed.

In Moby-Dick, all the powers and tastes of Melville’s complex genius are blended. Moby-Dick is at once indisputably the greatest whaling novel, and “a hideous and intolerable allegory.” As Mr. Frank Jewett Mather, Jr. has said, “Out of the mere episodes and minor instances of Moby-Dick, a literary reputation might be made. The retired Nantucket captains Bildad and Peleg might have stepped out of Smollett. Father Mapple’s sermon on the book of Jonah is in itself a masterpiece, and I know few sea tales that can hold their own with the blood feud of Mate Rodney and sailor Steelkilt.” Captain Hook of Peter Pan is but Captain Boomer of Moby-Dick with another name: and this an identity founded not on surmise, but on Sir James Barrie’s professed indebtedness to Melville. There are, in Moby-Dick, long digressions, natural, historical and philosophical, on the person, habits, manners and ideas of whales; there are long dialogues and soliloquies such as were never spoken by mortal man in his waking senses, conversations that for sweetness, strength and courage remind one of passages from Dekker, Webster, Massinger, Fletcher and the other old dramatists loved both by Melville and by Charles Lamb; in the discursive tradition of Fielding, Sir Thomas Browne and the anatomist of melancholy, Melville indulges freely in independent moralisings, half essay, half rhapsody; withal, scenes like Ishmael’s experience at the “Spouter-Inn” with a practising cannibal for bed-fellow, are, for finished humour, among the most competent in the language. When Melville sat down to write, always at his knee stood that chosen emissary of Satan, the comic spirit: a demoniac familiar never long absent from his pages.

There are those, of course, who would hold against Dante his moralising, and against Rabelais his broad humour. In like manner, peculiarity of temperament has necessarily coloured critical judgment of Moby-Dick. But though critics may mouth it as they like about digressions, improbability, moralising reflections, swollen talk, or the fetish of art now[28] venerated with such articulate inveteracy, all wonderfully agree upon the elementary force of Moby-Dick, its vitality, its thrilling power. That it achieves the effect of illusion, and to a degree peculiar to the highest feats of the creative imagination, is incontestable. No writer has more. On this point it is simply impossible to praise Melville too highly. What defects Moby-Dick has are formal rather than substantial. As Thackeray once impatiently said of Macaulay: “What critic can’t point them out?” It was the contention of James Thomson that an overweening concern for formal impeccability is a fatal sign of weakened vitality. Intensity of imagination—and Melville exhibited it prodigally in Moby-Dick—is an infinitely rarer and more precious gift than technical sophistication. Shakespeare has survived, despite his “monstrous irregularities.” But since Shakespeare, as Francis Thompson has observed, there has been a gradual decline from imperfection. Milton, at his most typical, was far too perfect; Pope was ruined by his quest for the quality. No thoughtful person can contemplate without alarm the idolatry bestowed upon this quality by the contemporary mind: an idolatry that threatens to reduce all art to the extinction of unendurable excellence. How insipid would be the mere adventures of a Don Quixote recounted by a Stevenson.

The astonishing variety of contradictory qualities synthesised in Moby-Dick exists nowhere else in literature, perhaps, in such paradoxical harmony. These qualities, in differences of combination and emphasis, are discoverable, however, in all of Melville’s writings. And he published, besides anonymous contributions to periodicals, ten novels and five volumes of poetry (including the two volumes privately printed at the very close of his life). There survives, too, a bulk of manuscript material: a novel, short stories, and a body of verse. And branded on everything that Melville wrote is there the mark of the extraordinary personality that created Moby-Dick.

Though some of Melville’s writing is distinctly disquieting in devastating insight, and much of it is very uneven in inspiration, none of it is undistinguished. Yet only four of his books have ever been reprinted. The rest of his work, long[29] since out of print, is excessively rare, some of it being practically unavailable. The scarcity of a book, however, is not invariably a sign of its insignificance. It is one of the least accessible of Melville’s books that Mr. Masefield singles out for especial distinction. “The book I love best of his,” says Mr. Masefield, “is one very difficult to come by. I think it is his first romance, and I believe it has never been reprinted here. It is the romance of his own boyhood. I mean Redburn. Any number of good pens will praise the known books, Typee and Omoo and Moby-Dick and White-Jacket, and will tell their qualities of beauty and romance. Perhaps Redburn will have fewer praises, so here goes for Redburn; a boy’s book about running away to sea.” Even more difficult of access is Pierre—a book at the antipodes from Redburn. Far from being a boy’s book, Pierre was prophetic of the pessimism of Hardy and the subtlety of Meredith. From Redburn to Pierre; from Typee, a spirited travel-book on Polynesia, to Clarel, an intricate philosophical poem in two volumes: these mark the antithetical extremes of the art that mated poetry and blubber, whaling and metaphysics. The very complexity and versatility of Melville’s achievement has been an obstacle in the way of his just appreciation. Had Mandeville turned from his Travels, to write The City of Dreadful Night, the incompatibility would have been no less extraordinary or bewildering.

Indeed, Melville’s complete works, in their final analysis, are a long effort towards the creation of one of the most complex, and massive, and original characters in literature: the character known in life as Herman Melville. “I am like one of those seeds taken out of the Egyptian Pyramids,” he wrote to Hawthorne while he was in the middle of Moby-Dick, “which, after being three thousand years a seed and nothing but a seed, being planted in English soil, it developed itself, grew to greenness, and then fell to mould. So I. Until I was twenty-five, I had no development at all. From my twenty-fifth year I date my life. But I feel that I am now come to the inmost leaf of the bulb, and that shortly the flower must fall to the mould. It seems to me now that Solomon was the truest man who[30] ever spoke, and yet that he managed the truth with a view to popular conservatism.”

Blighted by disillusionment, and paralysed by doubt, Melville came to treat as an irrelevancy, the making of books. “He informed me that he had ‘pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated,’” wrote Hawthorne in his Note-book, after Melville visited him in Southport, England, in 1856; “but still he does not seem to rest in that anticipation. It is strange how he persists—as he has persisted ever since I knew him, and probably long before—in wandering to and fro over these deserts, as dismal and monotonous as the sandhills amidst which we were sitting. He can neither believe nor be comfortable in his unbelief; and he is too honest and courageous not to try to do one or the other.” If, in contempt for the orthodox interpolations by which pious scribes attempted to sweeten Solomon’s bitter message, Melville ever managed truth as he saw it, it was more to violate popular conservatism than to propitiate it. “We incline to think that God cannot explain His own secrets,” he editorially wrote Hawthorne in 1851, “and that He would like a little information upon certain points Himself. We mortals astonish Him as much as He us.” And as Melville grew in disillusionment, he grew in astonishment. In his relentless pessimism he boasted himself “in the happy condition of judicious, unencumbered travellers in Europe; they cross the frontiers into Eternity with nothing but a carpet bag,—that is to say, the Ego.” It was his ripest conviction that the exclamation point and the triumphant perpendicular pronoun were interchangeable signs. But to the end, he bristled with minor revelations.

Though he boasted that he crossed the frontier into Eternity with nothing but a carpet bag, he had, in fact, sent more bulky consignments on ahead. And at the final crack of doom, this dead and disappointed mariner may yet rise to an unexpected rejoicing. For at that time of ultimate reckoning, according to the eschatology of Mr. Masefield, “then the great white whale, old Moby-Dick, the king of all the whales, will rise up from his quiet in the sea, and go bellowing to his mates. And all the whales in the world—the sperm-whales, the razor-back,[31] the black-fish, the rorque, the right, the forty-barrel Jonah, the narwhal, the hump-back, the grampus and the thrasher—will come to him, ‘fin-out,’ blowing their spray to the heavens. Then Moby-Dick will call the roll of them, and from all the parts of the sea, from the north, from the south, from Callao to Rio, not one whale will be missing. Then Moby-Dick will trumpet, like a man blowing a horn, and all that company of whales will ‘sound’ (that is, dive), for it is they that have the job of raising the wrecks from down below.

“Then when they come up the sun will just be setting in the sea, far away to the west, like a ball of red fire. And just as the curve of it goes below the sea, it will stop sinking and lie there like a door. And the stars and the earth and the wind will stop. And there will be nothing but the sea, and this red arch of the sun, and the whales with the wrecks, and a stream of light upon the water. Each whale will have raised a wreck from among the coral, and the sea will be thick with them—row-ships and sail-ships, and great big seventy-fours, and big White Star boats, and battleships, all of them green with the ooze, but all of them manned by singing sailors. And ahead of them will go Moby-Dick, towing the ship our Lord was in, with all the sweet apostles aboard of her. And Moby-Dick will give a great bellow, like a fog-horn blowing, and stretch ‘fin-out’ for the sun away in the west. And all the whales will bellow out an answer. And all the drowned sailors will sing their chanties, and beat the bells into a music. And the whole fleet of them will start towing at full speed towards the sun, at the edge of the sky and water. I tell you they will make white water, those ships and fishes.

“When they have got to where the sun is, the red ball will swing open like a door, and Moby-Dick, and all the whales, and all the ships will rush through it into an anchorage in Kingdom Come. It will be a great calm piece of water, with land close aboard, where all the ships of the world will lie at anchor, tier upon tier, with the hands gathered forward, singing. They’ll have no watches to stand, no ropes to coil, no mates to knock their heads in. Nothing will be to do except singing and beating on the bell. And all the poor sailors who[32] went in patched rags, my son, they’ll be all fine in white and gold. And ashore, among the palm-trees, there’ll be fine inns for the seamen.” And there, among a numerous company, will be Fayaway, and Captain Ahab, and Jack Chase, and Jarl, and Toby, and Pierre, and Father Mapple, and Jackson, and Doctor Long Ghost, and Kory-Kory, and Bildad, and Peleg, and Fedallah, and Tashetego, and Marnoo, and Queequeg. But it seems hardly likely that Melville will there find Hawthorne to tempt by a basket of champagne into some little shady corner, there to cross their legs in the celestial grass that is forever tropical, and to discourse pleasantly of all the things manifold which once so much distressed them. In my Father’s house are many mansions.

“We are full of ghosts and spirits; we are as grave-yards full of buried dead, that start to life before us. And all our dead sires, verily, are in us; that is their immortality. From sire to son, we go on multiplying corpses in ourselves; for all of which, are resurrections. Every thought’s a soul of some past poet, hero, sage. We are fuller than a city.” —Herman Melville: Mardi.

The High Gods, in a playful and prodigal mood, gave to Melville, to Julia Ward Howe, to Lowell, to Kingsley, to Ruskin, to Whitman, and to Queen Victoria, the same birth year. On August 1, 1819, Herman Melville was born at No. 6 Pearl Street, New York City.

Melville’s vagabondage as a common sailor on a merchantman, on whaling vessels, and in the United States Navy, together with his Bohemian associations with cannibals, mutineers, and some of the choicest dregs of our Christian civilisation, must have wrenched a chorus of groans from a large congregation of shocked ancestral ghosts. For Melville was descended from a long and prolific line of the best American stock. Through his mother, Maria Gansevoort, he traced back to the earliest Dutch emigrants to New York; through his father, Allan Melville, to pre-revolutionary Scotch-Irish emigrants to New England. Both of his grandfathers distinguished themselves in the Revolutionary War. His ancestors, on both sides, came to this country in the days when some of the best blood of Europe was being transferred to America.

Though Melville was too ironic a genius ever to have been guilty of the ill-breeding that makes an ostentation of ancestry, still he looked back upon his descent with self-conscious pride: a pride drawn by childhood absorption from his parents who, by resting on the achievements of their forebears, added several cubits to their stature. Lacking the prophetic vision to[34] glory in being ancestors, they chose the more comfortable rôle of parading as descendants. Melville’s father, Allan, was sufficiently absorbed in his genealogy to compile, in 1818, an elaborately branching family tree that sent its master root back to one Sir Richard de Melvill, del Compte de Fife, a worthy of the thirteenth century. And at the proud conclusion of his labours he inscribed the Melville motto, Denique Coelum—“Heaven at last.” Melville’s mother, Maria Gansevoort, though too absorbed in domesticity to compete with Allan in drawing up a parallel document, still sat opposite her spouse with a stiff spine, conscious that she could counter his ancestry, grandfather for grandfather. It is true, she had no thirteenth century count to fall back upon; and though her line lost itself in a cluster of breweries, they were very substantial breweries, and owned by a race of stalwart and affluent and uncompromising burghers. Her ancestor, Harmen Harmense Van Gansevoort, was brewing in Beverwyck as early as 1660, and with sufficient success to acquire such extended investments in land that he bequeathed to his heirs a baronial inheritance. During the centuries following his death his name crossed itself with that of the Van Rensselaers, the Ten Broeks, the Douws, the Van Schaicks,—with the proudest names that descended from the earlier Colonial Dutch families. Melville’s mother, Maria, is remembered as a cold, proud woman, arrogant in the sense of her name, her blood, and the affluence of her forebears.

She was the only daughter and oldest child in a family of six, of General Peter Gansevoort and Catharine Van Schaick. Her father, born in Albany, New York, July 17, 1749, was among the outstanding patriots of the American Revolution. He was among the troops which accompanied Schuyler, in 1775, in his advance towards Canada. In December of the same year he was with Montgomery, as Major, in the unfortunate assault upon Quebec. In the summer of 1777, when Burgoyne’s semi-barbarous invading army was slowly advancing down Lake Champlain and the Hudson, he was Colonel in command of Fort Stanwix. By his obstinate and gallant defence of Fort Stanwix in August, 1777, he prevented the junc[35]ture of St. Leger with Burgoyne, and so changed the course of the whole subsequent campaign. Washington keenly and warmly recognised this, and Congress passed a vote of thanks to Colonel Gansevoort. Peter Gansevoort did other brilliant service in the Revolutionary War, and in 1809, when the War of 1812 was approaching, he was made brigadier general in the United States army. He was sheriff of Albany County from 1790 to 1792, and regent of the University of New York from 1808 until his death in 1812.

Of his sons, Hon. Peter Gansevoort, who was born in Albany in 1789, was long one of the most prominent and honoured citizens of Albany. The elder son, General Herman Gansevoort, from whom Melville received his name, lived at Gansevoort, a village in the township of Northumberland, Saratoga County, New York. In 1832-33, the brothers built on the site of the birthplace of their father what is now the Stanwix Hotel. As a boy, Melville spent most of his summers as guest of the Gansevoorts, and in his novel Pierre, the childhood recollections of his hero are transparent autobiographical references to his own early memories. “On the meadows which sloped away from the shaded rear of the manorial mansion, far to the winding river, an Indian battle had been fought, in the earlier days of the colony, and in that battle the great-grandfather of Pierre, mortally wounded, had sat unhorsed on his saddle in the grass, with his dying voice still cheering his men in the fray.... Far beyond these plains, a day’s walk for Pierre, rose the storied heights, where in the Revolutionary War his grandfather had for several months defended a rude but all-important stockaded fort, against the repeated combined assaults of Indians, Tories and Regulars. From behind that fort, the gentlemanly but murderous half-breed, Brandt, had fled, but survived to dine with General (Gansevoort) in the amiable times that followed that vindictive war. All the associations of Saddle-Meadows were full of pride to Pierre. The (Gansevoort) deeds by which their estate had been so long held, bore the cyphers of three Indian kings, the aboriginal and only conveyancers of those noble woods and plains. Thus loftily, in the days of his circum[36]scribed youth, did Pierre glance along the background of his race.... Or how think you it would be with this youthful Pierre if every day, descending to breakfast, he caught sight of an old tattered British banner or two, hanging over an arched window in the hall: and those banners captured by his grandfather, the general, in fair fight?”

On February 22, 1832, so it is recorded in Joel Munsell, The Annals of Albany (Vol. IX, Albany, 1859) “the military celebrated the centennial anniversary of the birthday of Washington. Col. Peter Gansevoort, on this occasion, presented to the artillery a large brass Drum, a trophy of the revolution, taken from the British on the 22nd August, 1777, at Fort Stanwix, by his father, General Peter Gansevoort.” The sound of this drum was tapping in Melville’s memory, when he goes on to ask: “Or how think you it would be if every time he heard the band of the military company of the village, he should distinctly recognise the peculiar tap of a British kettle-drum also captured by his grandfather in fair fight, and afterwards suitably inscribed on the brass and bestowed upon the Saddle-Meadows Artillery Corps? Or how think you it would be, if sometimes of a mild meditative Fourth of July morning in the country, he carried out with him into the garden by way of ceremonial cane, a long, majestic, silver-tipped staff, a Major-General’s baton, once wielded on the plume-nodding and musket-flashing review by the same grandfather several times here-in-before mentioned?”

Not content to leave this a rhetorical query, Melville answers his own catechism in unambiguous terms: “I should say that considering Pierre was quite young and very unsophisticated as yet, and withal rather high-blooded; and sometimes read the History of the Revolutionary War, and possessed a mother who very frequently made remote social allusions to the epaulettes of the Major-General his grandfather;—I should say that upon all these occasions, the way it must have been with him was a very proud, elated sort of way.”

Melville did not preserve throughout his long life this early and proud elation in his descent, and in later years he thought it necessary to apologise for the short-sighted and provincial[37] self-satisfaction that he absorbed from his parents in his early youth. “And if this seem but too fond and foolish in Pierre,” he pleads in a mood both of apology and of prophecy; “and if you tell me that this sort of thing in him showed him no sterling Democrat, and that a truly noble man should never brag of any arm but his own; then I beg you to consider again that this Pierre was but a youngster as yet. And believe me, you will pronounce Pierre a thorough-going Democrat in time; perhaps a little too Radical altogether to your fancy.”

Radical he came to be, indeed: it was the necessary penalty of being cursed with an intelligence above that of the smug and shallow optimism of his country and his period. Democratic he may have been, but only in the most unpopular meaning of that once noble term. He was a democrat in the same relentless sense that Dante or Milton were democrats. Lucifer rebelled, let it be remembered, to make Heaven “safe for Democracy:” the first experiment in popular government. “Hell,” says Melville, “is a democracy of devils.” In Mardi, Melville indulges lengthy reflections on a certain “chanticleer people” who boast boisterously of themselves: “Saw ye ever such a land as this? Is it not a great and extensive republic? Pray, observe how tall we are; just feel of our thighs; are we not a glorious people? We are all Kings here; royalty breathes in the common air.” Before the spectacle of this lusty republicanism, Melville exhibits unorthodox doubts. “There’s not so much freedom here as these freemen think,” he makes a strolling deity observe; “I laugh and admire.... Freedom is more social than political. And its real felicity is not to be shared. That is of a man’s own individual getting and holding. Little longer, may it please you, can republics subsist now, than in days gone by. Though all men approached sages in wisdom, some would yet be more wise than others; and so, the old degrees would be preserved. And no exemption would an equality of knowledge furnish, from the inbred servility of mortal to mortal; from all the organic causes, which inevitably divide mankind into brigades and battalions, with captains at their heads. Civilisation has not ever been the brother of equality.”

As Melville grew away from boyhood, he came to distinguish between the accidentals and the essentials that distinguish man from man. At his mother’s breast he had absorbed with her milk a vivid and exaggerated belief that the accidents concomitant upon birth that range men into artificial classes, were ingrain in the very woof of the universe. When he later discovered that his parents tinted life with a very perishable dye, he also found, set below their cheap calico patterns, an unchangeable texture of sharper and deeper and more variegated colours. And he discovered, too, that his uncritical boyhood pride in his blood was, withal, not entirely a mere savage delight in calico prints.

He was, as he boasts in the sub-title of Redburn, “the son-of-a-gentleman,” reared in an environment rich with the mellowing influences of splendid family traditions. And these associations left an indelible stamp upon him. In Mardi, in speaking of the impossibility of belying one’s true nature while at sea and in the fellowship of sailors, he offers himself as an example to point. “Aboard of all ships in which I have sailed,” he says, “I have invariably been known by a sort of drawing-room title. Not,—let me hurry to say,—that I put hand in tar bucket with a squeamish air, or ascended the rigging with a Chesterfieldian mince. No, no, I was never better than my vocation. I showed as brown a chest, and as hard a hand, as the tarriest tar of them all. And never did shipmate of mine upbraid me with a genteel disinclination to duty, though it carried me to truck of main-mast, or jib-boom-end, in the most wolfish blast that ever howled. Whence, then, this annoying appellation? for annoying it most assuredly was. It was because of something in me that could not be hidden; stealing out in an occasional polysyllable; an otherwise incomprehensible deliberation in dining; remote, unguarded allusions to belle-lettres affairs; and other trifles superfluous to mention.”

Though his grandfather, General Peter Gansevoort, had been dead seven years when Melville was born, so vital were the relics of him that surrounded Melville’s boyhood, so reverently was his memory tended by his first child and only[39] daughter, that the image of Peter Gansevoort was one of the most potent influences during Melville’s most impressionable years. The heroic presence that dominated Melville’s imagination, “measured six feet four inches in height; during a fire in the old manorial mansion, with one dash of the foot, he had smitten down an oaken door, to admit the buckets of his negro slaves; Pierre had often tried on his military vest, which still remained an heirloom at Saddle-Meadows, and found the pockets below his knees, and plenty additional room for a fair-sized quarter-cask within its buttoned girth; in a night scuffle in the wilderness before the Revolutionary War, he had annihilated two Indian savages by making reciprocal bludgeons of their heads. And all this was done by the mildest hearted, the most blue-eyed gentleman in the world, who, according to the patriarchal fashion of those days, was a gentle, white-haired worshipper of all the household gods; the gentlest husband and the gentlest father; the kindest master to his slaves; of the most wonderful unruffledness of temper; a serene smoker of his after dinner pipe; a forgiver of many injuries; a sweet-hearted, charitable Christian; in fine, a pure, cheerful, childlike, blue-eyed, divine old man; in whose meek, majestic soul the lion and the lamb embraced—fit image of his God.” His portrait was to Melville “a glorious gospel framed and hung upon the wall, and declaring to all people, as from the Mount, that man is a noble, god-like being, full of choicest juices; made up of strength and beauty.” Most of the images of God that Melville met in actual secular embodiment, suffered tragically by comparison with this image of mortal perfection which Melville nursed in his heart. Most men that Melville met, in falling short of the mythical excellence of Peter Gansevoort, whom he never knew in the flesh, seemed to Melville, to be libels upon their Divine Original. According to Melville’s account, he could never look upon his grandfather’s military portrait without an infinite and mournful longing to meet his living aspect in actual life. Yet such was the temper of Melville’s mind, his life such a tragic career of dreaming of elusive perfection, dreams invariably to be dashed and bruised and shattered by an incompatible reality, that it is safe to sur[40]mise—with no impiety to the memory of Peter Gansevoort—that had Melville known his maternal grandfather, the old General’s six feet four of blood and bone would have shrunk, with his extravagance of all human excellence, to more truly historical dimensions.

MAJOR THOMAS MELVILLE

Melville’s paternal grandfather, Major Thomas Melville, who died in 1832, when Melville was thirteen years old, inspired his grandson to no such glowing tributes. Born in Boston, in 1751, an only child, he was left an orphan at the age of ten. It appears by the probate records on the appointment of his guardian in 1761, that he inherited a considerable fortune from his father. He was reared by his maternal grandmother, Mrs. Mary Cargill. Mrs. Mary Cargill’s brother was the celebrated and eccentric dissenter and polemic writer, John Abernethy of Dublin, who in his Tracts (collected in 1751) measured swords with Swift himself triumphantly; her son, David, was both a celebrated warrior against the Indians, and the father of twenty-three children, fifteen of whom were sons. Whatever the immediate male relatives of Mrs. Mary Cargill did, it would appear, they did vigorously, and on an enterprising scale. She was herself an old lady of very independent ideas about the universe, and her grandson, Thomas Melville—Melville’s grandfather,—perpetuated much of her independence. Indifferent to the caprices of fashion, Thomas Melville persisted until his death in 1832, in wearing the old-fashioned cocked hat and knee breeches. Oliver Holmes said of him: “His aspect among the crowds of a later generation reminded me of a withered leaf which has held to its stem through the storms of autumn and winter, and finds itself still clinging to its bough while the new growths of spring are bursting their buds and spreading their foliage all around it.”

And so the Autocrat wrote:

In his boyhood, Thomas Melville was sent by his grandmother (who lived on till her grandson was thirty years old, clinging as tenaciously to life as to every other good thing she set hands upon) to the College of New Jersey, now Princeton. He was graduated in 1769. From both Princeton and Harvard he later received an M.A. Between 1771 and 1773 he visited his relatives in Scotland. During this visit he was presented with the freedom of the city of St. Andrews and of Renfrew. He returned to Boston to become a merchant and to enter with spirit into the patriotic ferment then so actively brewing. He was a member of the Long Room Club, in sympathy with the Sons of Liberty, and with Paul Revere, one of the “Indians” to take part in the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773. There still survive a few unbrewed leaves from this cargo of tea: the carefully preserved shakings from Major Melville’s shoes, resurrected when he relaxed into slippers immediately upon his return home from the excitements of revolutionary defiance. Though Major Melville was, throughout his life, an extreme conservative, it was his very conservatism that fired him to revolution. He believed that what needed to be conserved was the constitutional—British constitutional—rights of his country, not the innovation of Hanoverian tyranny. He commanded a detachment sent to Nantucket, the centre of whaling, to watch the movement of the British fleet; in the expedition into Rhode Island, in 1778, he took the rank of Major in Croft’s regiment of Massachusetts artillery. His resignation, dated Boston, Oct. 21, 1778, states “that he had been almost three years in said service and would willingly continue to serve, but owing to inadequate pay and subsequent inability to support his family he felt compelled to resign his commission.” In 1789 he was commissioned by Washington as naval officer of the port of Boston: a commission renewed by all succeeding presidents down to Andrew Jackson’s time in 1824. Major Melville was the nearest surviving male relative of the picturesque General Robert Melville, who was the first and only Captain General and Governor-in-Chief of the islands ceded to England by France in 1763, and at the time of his death in[43] 1809, with one exception, the oldest General in the British Army.

In 1779, Major Melville was elected fire ward of Boston, and when he resigned in 1825, he was offered a vote of thanks “for the zeal, intrepidity and judgment with which he has on all occasions discharged his duties as fire ward for forty-six years in succession, and for twenty-six as chairman of the board.” In those days, volunteer fire companies were fashionable sporting clubs, and such was the distinction attached to membership that a premium was often paid for the privilege of belonging to such an exclusive and diverting fraternity. Melville’s father-in-law, Lemuel Shaw, Chief Justice of Massachusetts, was Fire Warden between 1818 and 1821. Melville’s grandfather and future father-in-law may have met at many a fire and, for all we know to the contrary, the intimacy between the Shaws and the Melvilles that culminated in Herman’s marriage, may have been first kindled by a burning house.

The tradition survives of Major Melville that the excitement of running to fire grew upon him like gambling upon more sedentary mortals, and that his death was caused by over-fatigue and exposure at a fire near his house he attended at the age of eighty-one.

Of Melville’s two grandmothers, Catharine Van Schaick and Priscilla Scollay, there is no mention in any of his writings. It is a peculiarity of Melville’s writings indeed, completely to disregard all of his female relatives,—with the notable exceptions of his mother, his mother-in-law, and his wife.

Major Thomas Melville, by his marriage with Priscilla Scollay, is said to have aggravated an already ample fortune, though the terms of his resignation from the Revolutionary army argue a dwindling of income during unsettled times. The Scollays, one of the oldest of Boston families, were related to Melville not only by direct blood descent, but Melville’s great-great-uncle, John Melville (who died in London in 1798) married Deborah Scollay, Melville’s great-aunt. Deborah Scollay, Priscilla’s sister, was the first of thirteen children; Priscilla the tenth. The Scollays, in brave competition[44] with the Melvilles and the Gansevoorts, seem to have devoutly accepted the Mosaic edict to increase and multiply: they were, as Carlyle says of Dr. Thomas Arnold, of “unhastening, unresting diligence.” Major Thomas Melville had eleven children by his wife Priscilla, Melville’s father Allan being the fourth child and second son. Of the influence of Allan’s numerous brothers and sisters upon Melville there are scant records to show. His aunt Priscilla, however, mentioned him in her will.

Allan’s oldest sister, Mary (1778-1859) married Captain John DeWolf II. of Bristol, Rhode Island. In Moby-Dick, in offering instances of ships being charged upon by whales, Melville quotes from the Voyages of Captain Langsdorff, a member of Admiral Krusenstern’s famous Discovery Expedition in the beginning of the last century. In the passage quoted by Melville is mentioned a Captain D’Wolf. “Now, the Captain D’Wolf here alluded to as commanding the ship in question,” says Melville, “is a New Englander, who, after a long life of unusual adventures as a sea captain, this day resides in the village of Dorchester, near Boston. I have the honour of being a nephew of his. I have particularly questioned him concerning this passage in Langsdorff. He substantiates every word.” In Redburn, Melville speaks of “an uncle of mine, an old sea-captain, with white hair, who used to sail to a place called Archangel in Russia, and who used to tell me that he was with Captain Langsdorff, when Captain Langsdorff crossed over by land from the sea of Okotsk in Asia to St. Petersburg, drawn by large dogs in a sled.... He was the very first sea captain I had ever seen, and his white hair and fine handsome florid face made so strong an impression upon me that I have never forgotten him, though I only saw him during this one visit of his to New York, for he was lost in the White Sea some years after.” Just what, if anything besides two contradictory statements—Melville owed to this uncle it would be worthless to surmise.

Another of Melville’s uncles, however, Thomas—Allan’s older brother—played an important rôle in Melville’s development. After an eventful residence of twenty-one years in[45] France, Thomas returned to America with his wife Françoise Raymonde Eulogie Marie des Douleurs Lamé Fleury, shortly before the War of 1812. Enlisted in the army, he was sent to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, with the rank of Major. After the war he continued in Pittsfield, and with his family set up at what is now Broadhall.

Broadhall, built by Henry Van Schaek in 1781, bought by Elkanah Watson in 1807, was, in 1816, acquired by Major Thomas Melville of the cocked hat. His son, Major Thomas Melville of the French wife, lived in Broadhall until 1837, when he moved to Galena, Illinois, where he died on August 1—Melville’s birthday—1845. By a parallel irony of fate, just as the Stanwix House of the Gansevoorts is now a hotel, Broadhall of the Melvilles is now a country club.

It was a strange transplanting, that of Major Thomas Melville and his wife, Marie des Douleurs, from Paris to the rustic crudities of the farming outskirts of civilisation. Marie des Douleurs rapidly pined and wilted in the harsh brusque air. A bundle of her letters survive, written in a delicate drooping hand: letters that might have been written by a wasted and homesick nun. In 1814, within the space of a single month, Mrs. Thomas Melville and two of her children died of consumption. Thomas, of more vigorous stock, survived to marry again—this time to Mary Anna Augusta Hobard, and to take actively to farming. He achieved a local reputation for his successful devotion to the soil; presiding at meetings of the Berkshire Agricultural Association, and winning a first prize at a ploughing match at the Berkshire Fair. As a boy, Melville was sent to alternate his visits to the Gansevoorts by trips to his uncle at Pittsfield. The single record of his life at Broadhall is preserved in The History of Pittsfield (1876) “compiled and written, under the general direction of a committee, by J. E. A. Smith.” Melville says:

“In 1836 circumstances made me the greater portion of a year an inmate of my uncle’s family, and an active assistant upon the farm. He was then grey haired, but not wrinkled; of a pleasing complexion, but little, if any, bowed in figure; and preserving evident traces of the prepossessing good looks[46] of his youth. His manners were mild and kindly, with a faded brocade of old French breeding, which—contrasted with his surroundings at the time—impressed me as not a little interesting, not wholly without a touch of pathos.

“He never used the scythe, but I frequently raked with him in the hay field. At the end of the swath he would at times pause in the sun and, taking out his smooth worn box of satinwood, gracefully help himself to a pinch of snuff, while leaning on his rake; quite naturally: and yet with a look, which—as I recall it—presents him in the shadowy aspect of a courtier of Louis XVI, reduced as a refugee to humble employment in a region far from gilded Versailles.

“By the late October fire, in the great hearth of the capacious kitchen of the old farm mansion, I remember to have seen him frequently sitting just before early bed time, gazing into the embers, while his face plainly expressed to a sympathetic observer that his heart, thawed to the core under the influence of the general flame—carried him far away over the ocean to the gay boulevards.

“Suddenly, under the accumulation of reminiscences, his eye would glisten and become humid. With a start he would check himself in his reverie, and give an ultimate sigh; as much as to say ‘ah, well!’ and end with an aromatic pinch of snuff. It was the French graft upon the New England stock, which produced this autumnal apple: perhaps the mellower for the frost.”

It was immediately following upon the heels of this sojourn in Pittsfield in 1836, that Melville went down to the sea and shipped before the mast. Of Melville’s companionship with his Pittsfield cousins during this visit, nothing seems to be known. Melville’s uncle, Thomas, had two children living at the time: Anna Marie Priscilla, who died in Pittsfield in 1858, and Pierre François Henry Thomas Wilson, thirteen years Melville’s senior, who in 1842 died in the Sandwich Islands. That Pierre’s adventures to the far corners of the earth may have had some influence upon Melville’s taking to a ship is a tempting surmise; but a surmise whose only cogency is its possibility.

Whatever the influence of Pittsfield in sending Melville to[47] sea, it was to Pittsfield he finally returned, when, after wide wanderings, he faced homeward. The old Major, his uncle, was dead, and Broadhall, descended to one of his sons, was rented as a hotel. During the summer of 1850, Melville and his wife boarded at Broadhall. In October of the same year, they settled in Pittsfield, not at Broadhall, as has been repeatedly stated, but at a neighbouring farm, christened Arrowhead by Melville. Arrowhead was Melville’s home for the following thirteen years.

Melville’s great-grandfather, Allan—father of The Last Leaf—came to America in 1748, and settled in Boston as a merchant. This Allan was the son of Thomas Melville, a clergyman of the Scotch Kirk. This Thomas Melville was from 1718 to 1764 minister of Scoonie Parish, Levin, Fifeshire. In 1769 he “ended his days in a state of most cheerful tranquillity.”

Thomas Melville of Scoonie was second in lineal descent from Sir John Melville of Carnbee: a worthy knighted by James VI. According to Sir Robert Douglas’ The Baronage of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1798), this Sir John Melville of Carnbee was thirteenth in direct blood descent from one Sir Richard Melvill, a man of distinction in the reign of Alexander III, and who in 1296 was compelled to swear allegiance to Edward I of England when he overran Scotland.

If this remote tracing of Melville’s descent were a discovery of facts unknown to Melville, it would be an ostentatious irrelevancy to flaunt it in his biography. But Melville was ironically conscious of his lineage, and when his earlier novels had won him reputation at home and in England as an entertaining literary vagabond, in France (see the typically patronising Études sur la Littérature et les Mœurs des Anglo-Américains du XIXe Siècle—Paris, 1851—by M. Philarete Chasles) as a representative product of a crude and traditionless civilisation, he took satirical unction to his soul at the illustrious associations that clung around his ancient name. In his own person he felt that he contradicted the conceit of the European world “that in demagogical America the sacred Past hath no fixed statues erected to it, but (that) all things irreverently[48] seethe and boil in the vulgar caldron of an everlasting, uncrystallising Present.” Founding his defence upon the knowledge of his own ancestry, he maintained in Pierre that if America so chose to glorify herself, she could make out a good general case with England in the little matter of long pedigrees—pedigrees, that is, without a flaw. In monarchical Europe, Melville takes pains to contend, the proudest families are but grafted families that successively live and die on the eternal soil of a name. In the pride of unbroken lineal blood descent from a thirteenth century count, he matched his blood and patronym with the most honoured in England. “If Richmond, and St. Albans, and Grafton, and Portland, and Buccleugh, be names almost as old as England herself, the present Dukes of those names stop in their own genuine pedigrees at Charles II., and there find no very fine fountain; since what we would deem the least glorious parentage under the sun, is precisely the parentage of a Buccleugh, for example; whose ancestress could not well avoid being a mother, it is true, but had incidentally omitted the preliminary rites. Yet a King was the sire.... All honour to the names, and all courtesy to the men; but if St. Albans tell me he is all-honourable and all-eternal, I must politely refer him to Nell Gwynne.” Melville bitterly resented the fashionable foreign imputation that his was a rootless and upstart people. Through its grilling of bars sinister, he viewed the superior pretensions of monarchical aristocracy with his finger at his nose. “If in America,” he boasted, “the vast mass of families be as the blades of grass, yet some few there are that stand as the oak; which, instead of decaying, annually puts forth new branches; whereby Time, instead of subtracting, is made to capitulate into a multiple virtue.”

If Melville took over-elaborate pains to point to himself as swinging at the dizzy crest of such a patriarchal tree, it was not to derive personal glory from mere altitude. By exhibiting the humorous incompatibility between his destiny and his descent, he strove to show, at one and the same time, both the absurdity of all pride in blood, and the ironic poignancy of his own apparent defeat.

Melville’s parents, however, qualified their ancestral pride[49] with no such ironic considerations. With whole-hearted gratitude they thanked God for their descent; nor did they, in their thanksgiving, fail to acknowledge, with becoming humility, a Heavenly Father who, in power and glory, transcended even terrestrial counts and brewers.

Allan was always a man of devout protestations; and although he always signed his own name with an underscoring of tangled flourishes, he wrote the name of God—and his correspondence is liberally scattered with Deity—with three conspicuous capitals of his most ornate penmanship. Melville was patently modelling the father of Pierre after his own male parent, when he recorded Pierre’s father’s platitudinous insistence “that all gentlemanhood was vain, all claims to it preposterous and absurd, unless the primeval gentleness and golden humanities of religion had been so thoroughly wrought into the complete texture of the character, that he who pronounced himself gentleman, could also rightly assume the meek but knightly style of Christian.”

Allan, proud in the sense of this humility, in untangling his descent back to Sir John Melville of Carnbee, seems to have rested serenely in the pious faith that he had established his kinship to all the titled and illustrious Melvilles in history. So he carried his head high—as he felt a republican should—and with a generous and comprehensive fraternity claimed as his more than kith—as indeed they were—an impressive congregation of courtiers, scholars and divines.

So prolific has been the Melville family, so extended its history, that its intricate branchings from the veritable Aaron’s rod in which it had its source, have never been completely untangled by even the most arduous genealogical historians. With what directness and potency the different Melville strains were active in Melville’s blood it would be utterly absurd to pretend to determine. But if not forces in Melville’s blood, Allan made them vital presences in his son’s boyhood imagination.

The most illustrious of this shadowy company of adopted ancestors was the old Viking, Andrew Melville (1545-1622), the dauntless “Episcopomastrix” or “Scourge of Bishops,”[50] second in fame among Scotch reformers only to John Knox. In October, 1577, at an interview between Andrew and the Regent Morton, the latter, irritated at the intrepidity of the assembly, exclaimed: “There will never be quiet in this country till half a dozen of you be hanged!” Whereupon Andrew, in language Morton dared not resent, exclaimed: “Hark! Sir; threaten your courtiers after that manner. It is the same to me whether I rot in the air or in the ground. The earth is the Lord’s. Patria est ubicunque est bene.” Another Andrew (1624-1706) among these ghostly presences was a soldier of fortune who in the preface of his Memoires de M. de Chevalier de Melville (Amsterdam, 1704) was eulogised for his valour and his protestantism.