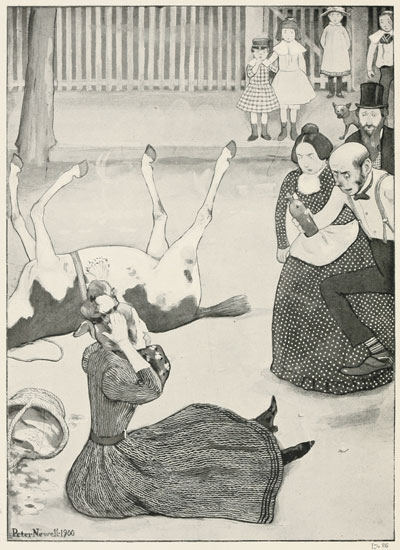

"'WILL YOU TELL ME IF IT'S STRAIGHT?'"

Project Gutenberg's Mother Goose for Grown-ups, by Guy Wetmore Carryl

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Mother Goose for Grown-ups

Author: Guy Wetmore Carryl

Illustrator: Peter Newell

Gustave Verbeek

Release Date: October 25, 2015 [EBook #50310]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MOTHER GOOSE FOR GROWN-UPS ***

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Melissa McDaniel, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

MOTHER GOOSE

FOR GROWN-UPS

By GUY WETMORE CARRYL

With Illustrations by Peter

Newell and Gustave Verbeek

NEW YORK AND LONDON

HARPER & BROTHERS

1900

Copyright, 1900, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved

In memory of other days,

Dear critic, when your whispered praise

Cheered on the limping pen.

How short, how sweet those younger hours,

How bright our suns, how few our showers,

Alas, we knew not then!

If but, long leagues across the seas,

The trivial charm of rhymes like these

Shall serve to link us twain

An instant in the olden spell

That once we knew and loved so well,

I have not worked in vain!

I have pleasure in acknowledging the courteous permission of the editors to reprint in this form such of the following verses as were originally published in Harper's Magazine, the Saturday Evening Post, and the London Sketch.

G. W. C.

| PAGE | |

| The Admirable Assertiveness of Jilted Jack | 3 |

| The Blatant Brutality of Little Bow Peep | 9 |

| The Commendable Castigation of Old Mother Hubbard | 15 |

| The Discouraging Discovery of Little Jack Horner | 21 |

| The Embarrassing Episode of Little Miss Muffet | 27 |

| The Fearful Finale of the Irascible Mouse | 33 |

| The Gastronomic Guile of Simple Simon | 39 |

| The Harmonious Heedlessness of Little Boy Blue | 47 |

| The Inexcusable Improbity of Tom, the Piper's Son | 53 |

| The Judicious Judgment of Quite Contrary Mary | 59 |

| The Linguistic Languor of Charles Augustus Sprague | 65 |

| The Mysterious Misapprehension Concerning a Man in Our Town | 71 |

| The Opportune Overthrow of Humpty Dumpty | 77 |

| The Preposterous Performance of an Old Lady of Banbury | 83 |

| The Quixotic Quest of Three Blind Mice | 89 |

| The Remarkable Regimen of the Sprat Family | 95 |

| The Singular Sangfroid of Baby Bunting | 101 |

| The Touching Tenderness of King Karl the First | 107 |

| The Unusual Ubiquity of the Inquisitive Gander | 113 |

| PAGE | ||

| "'WILL YOU TELL ME IF IT'S STRAIGHT?'" | Frontispiece | |

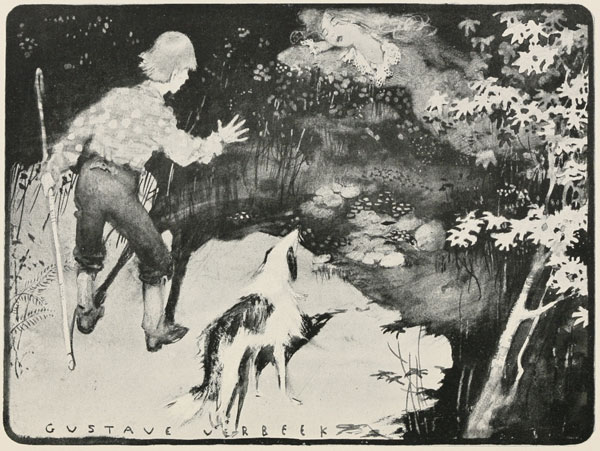

| "SHE WAS SO CHARMINGLY WATTEAU-LIKE" | Facing p. 10 | |

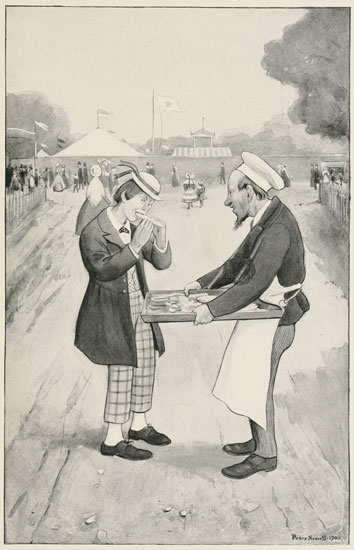

| "NOW SIMON'S TASTES WERE MOST PROFUSE" | Facing p. 40 | |

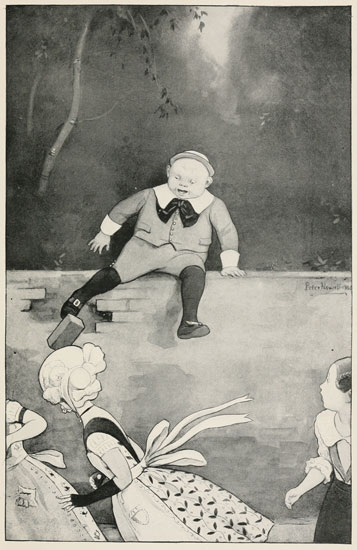

| "WHILE BY KICKS HE LOOSENED BRICKS" | Facing p. 78 | |

| "SHE PLUCKED HIM WITH RELENTLESS FROWN" | Facing p. 114 |

A noble and a generous mind

Was Jack's;

Folks knew he would not talk behind

Their backs:

But when some maiden fresh and young,

At Jack a bit of banter flung,

She soon discovered that his tongue

Was sharp as any ax.

A flirt of most engaging wiles

Was Jill;

On Jack she lavished all her smiles,

Until

Her slave (and he was not the first)

Of lovesick swains became the worst,

His glance a strong box might have burst,

His sighs were fit to kill.

One April morning, clear and fair,

When both

Of staying home and idling there

In sloth

Were weary, Jack remarked to Jill:

"Oh, what's the sense in sitting still?

Let's mount the slope of yonder hill."

And she was nothing loth.

But as she answered: "What's the use?"

The gruff

Young swain replied: "Oh, there's excuse

Enough.

Your doting parents water lack;

We'll fill a pail and bring it back."

(The reader will perceive that Jack

Was putting up a bluff.)

Thus hand in hand the tempting hill

They scaled,

And Jack proposed a kiss to Jill,

And failed!

One backward start, one step too bold,

And down the hill the couple rolled,

Resembling, if the truth were told,

A luggage train derailed.

With eyes ablaze with anger, she

Exclaimed:

"Well, who'd have thought! You'd ought to be

Ashamed!

You quite forget yourself, it's plain,

So I'll forget you, too. Insane

Young man, I'll say oafweederzane."

(Her German might be blamed.)

But Jack, whose linguist's pride was pricked,

To shine,

Asked: "Meine Königin will nicht

Be mine?"

And when she answered: "Nein" in spleen,

He cried: "Then in the soup tureen

You'll stay. You're not the only queen

Discarded for a nein!"

The moral's made for maidens young

And small:

If you would in a foreign tongue

Enthrall,

Lead off undaunted in a Swede

Or Spanish speech, and you'll succeed,

But they who in a German lead

No favor win at all.

Though she was only a shepherdess,

Tending the meekest of sheep,

Never was African leopardess

Crosser than Little Bow Peep:

Quite apathetic, impassible

People described her as: "That

Wayward, contentious, irascible,

Testy, cantankerous brat!"

Yet, as she dozed in a grotto-like

Sort of a kind of a nook,

She was so charmingly Watteau-like,

What with her sheep and her crook;

"She is a dryad or nymph," any

Casual passer would think.

Poets pronounced her a symphony,

All in the palest of pink.

Thus it was not enigmatical,

That the young shepherd who first

Found her asleep, in ecstatical

Sighs of felicity burst:

Such was his sudden beatitude

That, as he gazed at her so,

Daphnis gave vent to this platitude:

"My! Ain't she elegant though!"

Roused from some dream of Arcadia,

Little Bow Peep with a start

Answered him: "I ain't afraid o' yer!

P'raps you imagine you're smart!"

Daphnis protested impulsively,

Blushing as red as a rose;

All was in vain. She convulsively

Punched the young man in the nose!

All of it's true, every word of it!

I was not present to peep,

But if you ask how I heard of it,

Please to remember the sheep.

There is no need of excuse. You will

See how such scandals occur:

If you recall Mother Goose, you will

Know what tail-bearers they were!

Moral: This pair irreclaimable

Might have made Seraphim weep,

But who can pick the most blamable?

Both saw a little beau peep!

"SHE WAS SO CHARMINGLY WATTEAU-LIKE"

She was one of those creatures

Whose features

Are hard beyond any reclaim;

And she loved in a hovel

To grovel,

And she hadn't a cent to her name.

She owned neither gallants

Nor talents;

She borrowed extensively, too,

From all of her dozens

Of cousins,

And never refunded a sou:

Yet all they said in abuse of her

Was: "She is prouder than Lucifer!"

(That, I must say, without meaning to blame,

Is always the way with that kind of a dame!)

There never was jolli-

Er colley

Than Old Mother Hubbard had found,

Though cheaply she bought him,

She'd taught him

To follow her meekly around:

But though she would lick him

And kick him,

It never had any effect;

He always was howling

And growling,

But goodness! What could you expect?

Colleys were never to flourish meant

'Less they had plenty of nourishment,

All that he had were the feathers she'd pluck

Off an occasional chicken or duck.

The colley was barred in

The garden,

He howled and he wailed and he whined.

The neighbors indignant,

Malignant

Petitions unanimous signed.

"The nuisance grows nightly,"

Politely

They wrote. "It's an odious hound,

And either you'll fill him,

Or kill him,

Or else he must go to the pound.

For if this howling infernally

Is to continue nocturnally—

Pardon us, ma'am, if we seem to be curt—

Somebody's apt to get horribly hurt!"

Mother Hubbard cried loudly

And proudly:

"Lands sakes! but you give yourselves airs!

I'll take the law to you

And sue you."

The neighbors responded: "Who cares?

We none of us care if

The sheriff

Lock every man jack of us up;

We won't be repining

At fining

So long as we're rid of the pup!"

They then proceeded to mount a sign,

Bearing this ominous countersign:

"Freemen! The moment has come to protest

And Old Mother Hubbard delendum est!"

They marched to her gateway,

And straightway

They trampled all over her lawn;

Most rudely they harried

And carried

Her round on a rail until dawn.

They marred her, and jarred her,

And tarred her

And feathered her, just as they should,

Of speech they bereft her,

And left her

With: "Now do you think you'll be good!"

The moral's a charmingly pleasing one.

While we would deprecate teasing one,

Still, when a dame has politeness rebuffed,

She certainly ought to be collared and cuffed.

A knack almost incredible for dealing with an edible

Jack Horner's elder sister was acknowledged to display;

She labored hard and zealously, but always guarded jealously

The secrets of the dishes she invented every day.

She'd take some indigestible, unpopular comestible,

And to its better nature would so tenderly appeal

That Jack invoked a benison upon a haunch of venison,

When really she was serving him a little leg of veal!

Jack said she was a miracle. The word was not satirical,

For daily climbing upward, she excelled herself at last:

The acme of facility, the zenith of ability

Was what she gave her brother for his Christmas Day repast.

He dined that evening eagerly and anything but meagerly,

And when he'd had his salad and his quart of Extra Dry,

With sisterly benignity, and just a touch of dignity,

She placed upon the table an unutterable pie!

Unflagging pertinacity, and technical sagacity,

Long nights of sleepless vigil, and long days of constant care

Had been involved in making it, improving it, and baking it,

Until of other pies it was the wonder and despair:

So princely and so prominent, so solemn, so predominant

It looked upon the table, that, with fascinated eye,

The youth, with sudden wonder struck, electrified, and thunder struck,

Could only stammer stupidly: "Oh Golly! What a pie!"

In view of his satiety, it almost seemed impiety

To carve this crowning triumph of a culinary life,

But, braced by his avidity, with sudden intrepidity

He broke its dome imposing with a common kitchen knife.

Ah, hideous fatality! for when with eager palate he

Commenced to eat, he happened on an accident uncouth,

And cried with stifled moan: "Of it one plum I tried. The stone of it

Had never been extracted, and I've broke a wisdom tooth!"

Jack's sister wept effusively, but loudly and abusively

His unreserved opinion of her talents he proclaimed;

He called her names like "driveller" and "simpleton" and "sniveller,"

And others, which to mention I am really too ashamed.

The moral: It is saddening, embarrassing, and maddening

A stone to strike in what you thought was paste. One thing alone

Than this mischance is crueller, and that is for a jeweller

To strike but paste in what he fondly thought to be a stone.

Little Miss Muffet discovered a tuffet,

(Which never occurred to the rest of us)

And, as 'twas a June day, and just about noonday,

She wanted to eat—like the best of us:

Her diet was whey, and I hasten to say

It is wholesome and people grow fat on it.

The spot being lonely, the lady not only

Discovered the tuffet, but sat on it.

A rivulet gabbled beside her and babbled,

As rivulets always are thought to do,

And dragon-flies sported around and cavorted,

As poets say dragon-flies ought to do;

When, glancing aside for a moment, she spied

A horrible sight that brought fear to her,

A hideous spider was sitting beside her

And most unavoidably near to her!

Albeit unsightly, this creature politely

Said: "Madam, I earnestly vow to you,

I'm penitent that I did not bring my hat. I

Should otherwise certainly bow to you."

Though anxious to please, he was so ill at ease

That he lost all his sense of propriety,

And grew so inept that he clumsily stept

In her plate—which is barred in Society.

This curious error completed her terror;

She shuddered, and growing much paler, not

Only left tuffet, but dealt him a buffet

Which doubled him up in a sailor-knot.

It should be explained that at this he was pained:

He cried: "I have vexed you, no doubt of it!

Your fist's like a truncheon." "You're still in my luncheon,"

Was all that she answered. "Get out of it!"

And The moral is this: Be it madam or miss

To whom you have something to say,

You are only absurd when you get in the curd

But you're rude when you get in the whey.

Upon a stairway built of brick

A pleasant-featured clock

From time to time would murmur "Tick"

And vary it with "Tock":

Although no great intelligence

There lay in either word,

They were not meant to give offence

To anyone who heard.

Within the pantry of the house,

Among some piles of cheese,

There dwelt an irritable mouse,

Extremely hard to please:

His appetite was most immense.

Each day he ate a wedge

Of Stilton cheese. In consequence

His nerves were all on edge.

With ill-concealed impatience he,

Upon his morning walk,

Had heard the clock unceasingly,

Monotonously talk,

Until his rage burst every bound.

He gave a fretful shout:

"Well, sakes alive! It's time I found

What all this talk's about."

With all the admirable skill

That marks the rodent race

The mouse ran up the clock, until

He'd crept behind the face,

And then, with words that no one ought

To use, and scornful squeals,

He cried aloud: "Just what I thought!

Great oaf, you're full of wheels!"

The timepiece sternly said: "Have done!"

And through the silent house

It struck emphatically one.

(But that one was the mouse!)

To earth the prowling rodent fell,

In terror for his life,

And turned to flee, but, sad to tell,

There stood the farmer's wife.

She did not faint, she did not quail,

She did not cry out: "Scat!"

She simply took him by the tail

And gave him to the cat,

And, with a stern, triumphant look,

She watched him clawed and cleft,

And with some blotting paper took

Up all that there was left.

The moral: In a farmer's home

Run down his herds, his flocks,

Run down his crops, run down his loam,

But when it comes to clocks,

Pray leave them ticking every one

In peace upon their shelves:

When running down is to be done

The clocks run down themselves.

Conveniently near to where

Young Simple Simon dwelt

There was to be a county fair,

And Simple Simon felt

That to the fair he ought to go

In all his Sunday clothes, and so,

Determined to behold the show,

He put them on and went.

(One-half his clothes was borrowed and the other half was lent.)

He heard afar the cheerful sound

Of horns that people blew,

Saw wooden horses swing around

A circle, two and two,

Beheld balloons arise, and if

He scented with a gentle sniff

The smells of pies, what is the dif-

Ference to me or you?

(You cannot say my verse is false, because I know it's true.)

As Simple Simon nearer came

To these attractive smells,

Avoiding every little game

Men played with walnut shells,

He felt a sudden longing rise.

The sparkle in his eager eyes

Betrayed the fact he yearned for pies:

The eye the secret tells.

('Tis known the pie of county fairs all other pies excels.)

So when he saw upon the road,

Some fifty feet away,

A pieman, Simple Simon strode

Toward him, shouting: "Hey!

What kinds?" as lordly as a prince.

The pieman said: "I've pumpkin, quince,

Blueberry, lemon, peach, and mince:"

And, showing his array,

He added: "Won't you try one, sir? They're very nice to-day."

Now Simon's taste was most profuse,

And so, by way of start,

He ate two cakes, a Charlotte Russe,

Six buns, the better part

Of one big gingerbread, a pair

Of lady-fingers, an eclair,

And ten assorted pies, and there,

His hand upon his heart,

He paused to choose between an apple dumpling and a tart.

Observing that upon his tray

His goods were growing few,

The pieman cried: "I beg to say

That patrons such as you

One does not meet in many a moon.

Pray, won't you try this macaroon?"

But soon suspicious, changed his tune,

Continuing: "What is due

I beg respectfully to add's a dollar twenty-two."

Then Simple Simon put a curb

Upon his appetite,

And turning with an air superb

He suddenly took flight,

While o'er his shoulder this absurd

And really most offensive word

The trusting pieman shortly heard

To soothe his bitter plight:

"Perhaps I should have said before your wares are out of sight."

The moral is a simple one,

But still of consequence.

We've seen that Simon's sense of fun

Was almost too intense:

Though blaming his deceitful guise,

We with the pieman sympathize,

The latter we must criticize

Because he was so dense:

He might have known from what he ate that Simon had no cents.

"NOW SIMON'S TASTES WERE MOST PROFUSE"

Composing scales beside the rails

That flanked a field of corn,

A farmer's boy with vicious joy

Performed upon a horn:

The vagrant airs, the fragrant airs

Around that field that strayed,

Took flight before the flagrant airs

That noisome urchin played.

He played with care "The Maiden's Prayer;"

He played "God Save the Queen,"

"Die Wacht am Rhein," and "Auld Lang Syne,"

And "Wearing of the Green:"

With futile toots, and brutal toots,

And shrill chromatic scales,

And utterly inutile toots,

And agonizing wails.

The while he played, around him strayed,

And calmly chewed the cud,

Some thirty-nine assorted kine,

All ankle-deep in mud:

They stamped about and tramped about

That mud, till all the troupe

Made noises, as they ramped about,

Like school-boys eating soup.

Till, growing bored, with one accord

They broke the fence forlorn:

The field was doomed. The cows consumed

Two-thirds of all the corn,

And viciously, maliciously,

Went prancing o'er the loam.

That landscape expeditiously

Resembled harvest-home.

"Most idle ass of all your class,"

The farmer said with scorn:

"Just see my son, what you have done!

The cows are in the corn!"

"Oh drat," he said, "the brat!" he said.

The cowherd seemed to rouse.

"My friend, it's worse than that," he said.

"The corn is in the cows."

The moral lies before our eyes.

When tending kine and corn,

Don't spend your noons in tooting tunes

Upon a blatant horn:

Or scaling, and assailing, and

With energy immense,

Your cows will take a railing, and

The farmer take offense.

A Paris butcher kept a shop

Upon the river's bank

Where you could buy a mutton chop

Or two for half a franc.

The little shop was spruce and neat,

In view of all who trod the street

The decorated joints of meat

Were hung up in a rank.

This Gallic butcher led a life

Of highly moral tone;

He never raised his voice in strife,

He never drank alone:

He simply sat outside his door

And slept from eight o'clock till four;

The more he slept, so much the more

To slumber he was prone.

One day outside his shop he put

A pig he meant to stuff,

And carefully around each foot

He pinned a paper ruff,

But, while a watch he should have kept,

His habit conquered, and he slept,

And for a thief who was adept

That surely was enough.

A Scottish piper dwelt near by,

Whose one ungracious son

Beheld that pig and murmured: "Why,

No sooner said than done!

It seems to me that this I need."

And grasping it, with all his speed

Across the Pont des Invalides

He started on a run.

Then, turning sharply to the right,

Without a thought of risk,

He fled. 'Tis fair to call his flight

Inordinately brisk.

But now the town was all astir,

In vain his feet he strove to spur,

They caught him, shouting: "Au voleur!"

Beside the Obelisk.

The breathless butcher cried: "A mort!"

The crowd said: "Conspuez!"

And some: "A bas!" and half a score

Responded: "Vive l'armée!"

While grim gendarmes with piercing eye,

And stern remarks about: "Canaille!"

The pig abstracted on the sly.

Such is the Gallic way!

The piper's offspring, his defeat

Deep-rooted in his heart,

A revolutionary sheet

Proceeded then to start.

Thenceforward every evening he

In leaders scathed the Ministry,

And wished he could accomplish the

Return of Bonaparte.

The moral is that when the press

Begins to rave and shout

It's often difficult to guess

What it is all about.

The editor we strive to pin,

But we can never find him in.

What startling knowledge we should win

If we could find him out!

Though Mary had the kind of face

The rudest wind would softly blow on;

Though she was full of simple grace,

Sweet, amiable, and kind, and so on;

I would not have you understand

That she was meek. You'd be mistaken.

She worked out logarithms, and

Her favorite essayist was Bacon.

And, though not positive, I think

She'd heard about Savonarola,

Had studied Maurice Maeterlinck,

And read the works of Emile Zola,

And Emerson's and some of Kant's,

And all of mine and Shopenhauer's;

But still she cultivated plants,

And spent her life in tending flowers.

She had a little hedge of box,

Azalias, and a bed of tansy,

A double row of hollyhocks,

And every different kind of pansy:

And, though so innocent of look,

She'd lovers by the scores and dozens,

And learned, by talking with the cook,

To tell her friends they were her cousins.

The first was French, the second Greek,

The third was born upon the Mersey,

The fourth one came from Mozambique,

The fifth one from the Isle of Jersey.

I cannot tell about the rest,

But, judging from their dress and faces,

They came from north, east, south, and west,

But all of them from different places.

Now, such was Mary's sense of pride,

Despite their fervent protestations,

Before she vowed to be a bride

She set them all examinations:

She asked each one to tell the date

Of Washington and Cleopatra,

Name Dickens' novels, and locate

The site of Yonkers and Sumatra.

But so it chanced that, from a score

Of suitors resolute and haughty,

One gained a mark of sixty-four,

And all the rest were under forty.

One swain alone the rest outclassed;

Because of one audacious guess, he

This strict examination passed

When Mary asked the date of Crécy.

The moral shows that when a maid

Her life devotes unto a garden,

When horticultural skill's displayed

Her heart she does not dare to harden.

So crafty suitors, scorn the fates

And you may lay this flattering balm to

Your souls; if you but get your dates

The chances are you'll get the palm, too!

A child of nature curious

Was Charles Augustus Sprague;

He made his parents furious

Because he was so vague:

Although his age was nearly two

Eleven words were all he knew,

These sounded much as sounds the Dutch

That's spoken at The Hague.

A few of his errata

'Tis just I should avow,

He called his mother "Tata,"

And "moo" he dubbed a cow,

Nor was it altogether plain

Why "choo-choo" meant a railway train.

He called a cat "miouw," and that

No purist would allow.

Within his father's orchard

There stood, for all to see,

With branches bent and tortured,

An ancient apple tree:

That Charles Augustus Sprague might drowse

His mother on its swaying boughs

His cradle hung, and, while it swung,

She sang with energy.

A sudden blow arising

One day, the branches broke,

With suddenness surprising

The sleeping babe awoke,

And crashing down to earth he fell.

Ah me, that I should have to tell

The words that mild and genial child

On this occasion spoke!

His face convulsed and chequered

With passion and with tears,

He blotted out the record

Of both his speechless years:

His mother stupefied, aghast,

Heard Charles Augustus speak at last;

He opened wide his mouth and cried

These ill conditioned sneers.

"Sapristi! Accidente!

Perchance my speech is late,

But, be she two or twenty,

A nincompoop I hate!

What idiot said that woman's 'planned

To warn, to comfort, and command?'"

His words I quench. Excuse my French—

Je dis que tu m'embêtes!

The moral: Common clocks, we find,

In silence take a sudden wind,

But only heroes, as we know,

In silence take a sudden blow.

There was a man in our town,

Half beggar, half rapscallion,

Who, just because his eyes were brown,

Was thought to be Italian:

And, though with much insistence

He said that people erred,

And bitterly to Italy

He frequently referred,

The false report, as is the way

Of false reports, had come to stay!

So every one who'd been to Rome

By aid of Cook's or Gaze's,

Would call upon him at his home

To flaunt Italian phrases.

"Capite Questa lingua?"

The inquiry would be:

"Pochissimo? Benissimo!

Vi prego, ditemi,

Siete voi contento qua,

Lontano dall'Italia?"

The victim, plunged in deep disgust,

Grew nervous, could not slumber;

Said he, "I'm called Italian, just

Because my eyes are umber,

And if this persecution

Is ever to be stopped,

Some stern and stoic, hard, heroic

Course I must adopt!"

And so, to everyone's surprise,

He calmly scratched out both his eyes!

The neighbors said: "So strange a thing

Might seem to be an omen.

We thought his wits were wandering,

But now we know they're Roman!"

And so at him by legions,

By bevies, hosts, and herds,

Professors, purists, tramps, and tourists

Screamed Italian words.

Perceiving all he'd done was vain,

He scratched his eyesight in again.

The moral: If your neighbors say

You're one thing or another,

You'll find there isn't any way

Their prejudice to smother.

What matter if they think you

From Italy or Greece?

I beg you, treasure no displeasure:

Bow and hold your peace.

Like Omar, underneath the bow

You'll find there's paradise enow!

Upon a wall of medium height

Bombastically sat

A boastful boy, and he was quite

Unreasonably fat:

And what aroused a most intense

Disgust in passers-by

Was his abnormal impudence

In hailing them with "Hi!"

While by his kicks he loosened bricks

The girls to terrify.

When thus for half an hour or more

He'd played his idle tricks,

And wounded something like a score

Of people with the bricks,

A man who kept a fuel shop

Across from where he sat

Remarked: "Well, this has got to stop."

Then, snatching up his hat,

And sallying out, began to shout:

"Look here! Come down from that!"

The boastful boy to laugh began,

As laughs a vapid clown,

And cried: "It takes a bigger man

Than you to call me down!

This wall is smooth, this wall is high,

And safe from every one.

No acrobat could do what I

Had been and gone and done!"

Though this reviled, the other smiled,

And said: "Just wait, my son!"

Then to the interested throng

That watched across the way

He showed with smiling face a long

And slender Henry Clay,

Remarking: "In upon my shelves

All kinds of coal there are.

Step in, my friends, and help yourselves.

And he who first can jar

That wretched urchin off his perch

Will get this good cigar."

The throng this task did not disdain,

But threw with heart and soul,

Till round the youth there raged a rain

Of lumps of cannel-coal.

He dodged for all that he was worth,

Till one bombarder deft

Triumphant brought him down to earth,

Of vanity bereft.

"I see," said he, "that this is the

Coal day when I get left."

The moral is that fuel can

Become the tool of fate

When thrown upon a little man,

Instead of on a grate.

This story proves that when a brat

Imagines he's admired,

And acts in such a fashion that

He makes his neighbors tired,

That little fool, who's much too cool;

Gets warmed when coal is fired.

"WHILE BY KICKS HE LOOSENED BRICKS"

Within a little attic a retiring, but erratic

Old lady (six-and-eighty, to be frank),

Made sauces out of cranberry for all the town

of Banbury,

Depositing the proceeds in the bank.

Her tendency to thriftiness, her scorn of any

shiftiness

Built a bustling business, and in course

Of time her secret yearnings were revealed,

and all her earnings

She squandered in the purchase of a horse.

"I am not in a hurry for a waggonette or

surrey,"

She said. "In fact, I much prefer to ride."

And spite of all premonishment, to everyone's

astonishment,

The gay old lady did so—and astride!

Now this was most periculous, but, what was

more ridiculous,

The horse she bought had pulled a car,

and so,

The lazy steed to cheer up, she'd a bell upon

her stirrup,

And rang it twice to make the creature go!

I blush the truth to utter, but it seems a

pound of butter

And thirty eggs she had to sell. Of course,

In scorn of ways pedestrian, this fatuous

equestrian

To market gaily started on the horse.

Becoming too importunate to hasten, the un—

fortunate

Old lady plied her charger with a birch.

In view of all her cronies, this stupidest of

ponies

Fell flat before the Presbyterian church!

If it should chance that one set a red Italian

sunset

Beside a Beardsley poster, and a plaid

Like any canny Highlander's beside a Fiji

Islander's

Most variegated costume, and should add

A Turner composition, and with clever intuition,

To cap the climax, pile upon them all

The aurora borealis, then veracity, not malice,

Might claim a close resemblance to her fall.

At sight of her disaster, with arnica and plaster

The neighbors ran up eagerly to aid.

They cried: "Don't do that offen, ma'am, or

you will need a coffin, ma'am,

You've hurt your solar plexus, we're afraid.

We hope your martyrdom'll let you notice

what an omelette

You've made in half a jiffy. It is great!"

She only clutched her bonnet (she had fallen

flat upon it),

And answered: "Will you tell me if it's

straight?"

The moral's rather curious: for often the

penurious

Are apt to think old horses of account

If you would ride, then seek fine examples of

the equine,

And don't look on a molehill as a mount.

A maiden mouse of an arrogant mind

Had three little swains and all were blind.

The reason for this I do not know,

But I think it was love that made them so,

For without demur they bowed to her,

Though she treated them all with a high hauteur.

She ruled them, schooled them, frequently fooled them,

Snubbed, tormented, and ridiculed them:

Mice as a rule are much like men,

So they swallowed their pride and called again.

The maiden mouse of an arrogant mind

To morbid romance was much inclined.

The reason for this I have not learned,

But I think by novels her head was turned.

She said that the chap who dared to nap

One hour inside of the farmer's trap

Might gain her, reign her, wholly enchain her,

Woo her, win her, and thence retain her!

Hope ran high in each suitor's breast,

And all determined to stand the test.

The maiden mouse of an arrogant mind

Laughed when she saw them thus confined.

The reason for this I can't proclaim,

But I know some girls who'd have done the same!

As thus they kept to their word, and slept,

The farmer's wife to the pantry stept:

She sought them, caught them, carefully brought them

Out to the light, and there she taught them

How that chivalry often fails,

By calmly cutting off all their tails!

The maiden mouse of an arrogant mind

Treated her swains in a way unkind.

The reason for this is not complex:

That's always the way with the tender sex.

With impudent hails she cried: "What ails

You all, and where are your splendid tails?"

She jeered so, sneered so, flouted and fleered so,

Giggled, and altogether appeared so

Lacking in heart, that her slaves grew bored,

And threw up the sponge of their own accord.

The maiden mouse of an arrogant mind

Watched and waited, and peaked and pined.

The reason for this, I beg to state,

Is all summed up in the words Too Late!

The moral intwined is: Love is blind,

But he never leaves all his wits behind:

You may beat him, cheat him, often defeat him,

Though he be true with torture treat him:

One of these days you'll be bereft,

You think you're right, but you'll find you're left.

The Sprats were four in number,

Including twins in kilts:

All day Jack carted lumber,

All day his wife made quilts.

Thus heartlessly neglected

Twelve hours in twenty-four,

As might have been expected,

The twins sat on the floor:

And all the buttons, I should state,

They chanced to find, they promptly ate.

This was not meat, but still it's true

We did the same when we were two.

The wife (whose name was Julia)

Maintained an ample board,

But one thing was peculiar,

Lean meat she quite abhorred.

Here also should be stated

Another fact: 'tis that

Her spouse abominated

The very taste of fat.

This contrast curious of taste

Precluded any thought of waste,

For all they left of any meal

No self-respecting dog would steal.

No generous table d'hôte meal,

No dainties packed in tins,

But only bowls of oatmeal

They gave the wretched twins;

And yet like princes pampered

Had lived those babes accursed,

Could they have fed unhampered:—

I have not told the worst!

Since nothing from the dining-room

Was left to feed the cook and groom,

It seems that these domestics cruel

Were led to steal the children's gruel!

The twins, all hopes resigning,

And wounded to the core,

Confined themselves to dining

On buttons off the floor.

No passionate resentment

The docile babes displayed:

Each day in calm contentment

Three hearty meals they made.

And daily Jack and Mrs. Sprat

Ate all the lean and all the fat,

And every day the groom and cook

The children's meal contrived to hook.

But when the twins grew older,

As twins are apt to do,

And, shoulder touching shoulder,

Sat Sundays in their pew.

They saw no Christian glory

In parting with a dime,

And in the offertory

Dropped buttons every time.

Said they: "What's good enough for Sprats

Is good enough for heathen brats."

(I most sincerely wish I knew

What was the heathen's point of view.)

The moral: Anecdotes abound

Of buttons in collections found.

Thus on the wheels of progress go,

And heathens reap what Christians sew!

Bartholomew Benjamin Bunting

Had only three passions in life,

And one of the trio was hunting,

The others his babe and his wife:

And always, so rigid his habits,

He frolicked at home until two,

And then started hunting for rabbits,

And hunted till fall of the dew.

Belinda Bellonia Bunting,

Thus widowed for half of the day,

Her duty maternal confronting,

With baby would patiently play.

When thus was her energy wasted

A patented food she'd dispense.

(She had bought it the day that they pasted

The posters all over her fence.)

But Bonaparte Buckingham Bunting,

The infant thus blindly adored,

Replied to her worship by grunting,

Which showed he was brutally bored.

'Twas little he cared for the troubles

Of life. Like a crab on the sands,

From his sweet little mouth he blew bubbles,

And threatened the air with his hands.

Bartholomew Benjamin Bunting

One night, as his wife let him in,

Produced as the fruit of his hunting

A cottontail's velvety skin,

Which, seeing young Bonaparte wriggle,

He gave him without a demur,

And the babe with an aqueous giggle

He swallowed the whole of the fur!

Belinda Bellonia Bunting

Behaved like a consummate loon:

Her offspring in frenzy confronting

She screamed herself mottled maroon:

She felt of his vertebræ spinal,

Expecting he'd surely succumb,

And gave him one vigorous, final,

Hard prod in the pit of his tum.

But Bonaparte Buckingham Bunting,

At first but a trifle perplexed,

By a change in his manner of grunting

Soon showed he was terribly vexed.

He displayed not a sign of repentance

But spoke, in a dignified tone,

The only consecutive sentence

He uttered. 'Twas: "Lemme alone."

The Moral: The parent that uses

Precaution his folly regrets:

An infant gets all that he chooses,

An infant chews all that he gets.

And colics? He constantly has 'em

So long as his food is the best,

But he'll swallow with never a spasm

What ostriches couldn't digest!

For hunger and thirst King Karl the First

Had a stoical, stern disdain:

The food that he ordered consistently bordered

On what is described as plain.

Much trouble his cook ambitiously took

To tickle his frugal taste,

But all of his savoury science and slavery

Ended in naught but waste.

Said the steward: "The thing to tempt the King

And charm his indifferent eye

No doubt is a tasty, delectable pasty.

Make him a blackbird pie!"

The cook at these words baked twenty-four birds,

And set them before the King,

And the two dozen odious, bold, and melodious

Singers began to sing.

The King in surprise said: "Dozens of pies

In the course of our life we've tried,

But never before us was served up a chorus

Like this that we hear inside!"

With a thunderous look he ordered the cook

And the steward before him brought,

And with a beatified smile: "He is satisfied!"

Both of these innocents thought.

"Of sinners the worst," said Karl the First,

"Is the barbarous ruffian that

A song-bird would slaughter, unless for his daughter

Or wife he is trimming a hat.

We'll punish you so for the future you'll know

That from mercy you can't depart.

Observe that your lenient, kind, intervenient

King has a tender heart!"

He saw that the cook in a neighboring brook

Was drowned (as he quite deserved),

And he ordered the steward at once to be skewered.

(The steward was much unnerved.)

"It's a curious thing," said the merciful King,

"That monarchs so tender are,

So oft we're affected that we have suspected that

We are too kind by far."

The moral: The mercy of men and of Kings

Are apt to be wholly dissimilar things.

In spite of "The Merchant of Venice," we're pained

To note that the quality's sometimes strained.

"SHE PLUCKED HIM WITH RELENTLESS FROWN"

A gander dwelt upon a farm

And no one could resist him,

For had he died, such was his charm,

His neighbors would have missed him:

His scorn for any loud display,

His cheerful hissing day by day,

Would win your heart in such a way

You almost could have kissed him.

This bird was always nosing 'round.

Most patiently he waited

Until an open door he found,

And then investigated.

He loved to poke, he loved to peek,

In every knothole, so to speak,

He quickly thrust his prying beak,

For what was hid he hated.

The farm exhausted: "Now," said he:

"My policy's expansion.

When one's convinced how things should be

The proper course he can't shun.

His mind made up, he followed it,

Relying on his native wit,

And soon had wandered, bit by bit,

Through all his master's mansion.

"At least," he said: "It's not my fault

If everything's not seen to:

I've gone from garret down to vault,

And glanced into the lean-to.

In every room I've chanced to stop;

A supervising glance to drop,

I've looked below, I've looked on top,

Behind, and in between, too!"

One thing alone he found to blame,

As thus his time he squandered,

For, seeing not the farmer's dame,

Into her room he wandered,

And mounting nimbly on the bed:

"Why, bless my careful soul!" he said:

"These pillows are as hard as lead.

Now, how comes that?" he pondered.

The farmer's dame for half an hour

Had watched the bird meander,

And finding him within her power,

She leaped upon the gander.

"Why, how de do, my gander coy?"

She shouted: "What will be my joy

To dream to-night on you, my boy!"

(This was no baseless slander.)

For with a stoutish piece of string

Securely was this fool tied,

And by a leg and by a wing

Unto an oaken stool tied:

While, pinning towels around her gown,

She plucked him with relentless frown,

And stuffed the pillows with his down,

And roasted him for Yuletide.

The moral is: When you explore

Don't try to be superior:

Be cautious, and retire before

Your safety grows inferior.

'Tis best to stay upon the coast,

Or some day you will be like most

Of all that bold exploring host

That's gone to the interior.

THE END

End of Project Gutenberg's Mother Goose for Grown-ups, by Guy Wetmore Carryl

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MOTHER GOOSE FOR GROWN-UPS ***

***** This file should be named 50310-h.htm or 50310-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/5/0/3/1/50310/

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Melissa McDaniel, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

[email protected]

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.