Project Gutenberg's Pioneer Imprints From Fifty States, by Roger J. Trienens This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Pioneer Imprints From Fifty States Author: Roger J. Trienens Release Date: April 26, 2015 [EBook #48794] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PIONEER IMPRINTS FROM FIFTY STATES *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Diane Monico, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

by Roger J. Trienens

Descriptive Cataloging Division, Processing Department

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

WASHINGTON

1973

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Trienens, Roger J.

Pioneer imprints from fifty States.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Printing—History—United States. 2. United

States. Library of Congress. 3. Bibliography—Early

printed books. I. United States. Library

of Congress. II. Title.

Z208.T75 686.2'0973 72-10069

ISBN 0-84444-0038-6

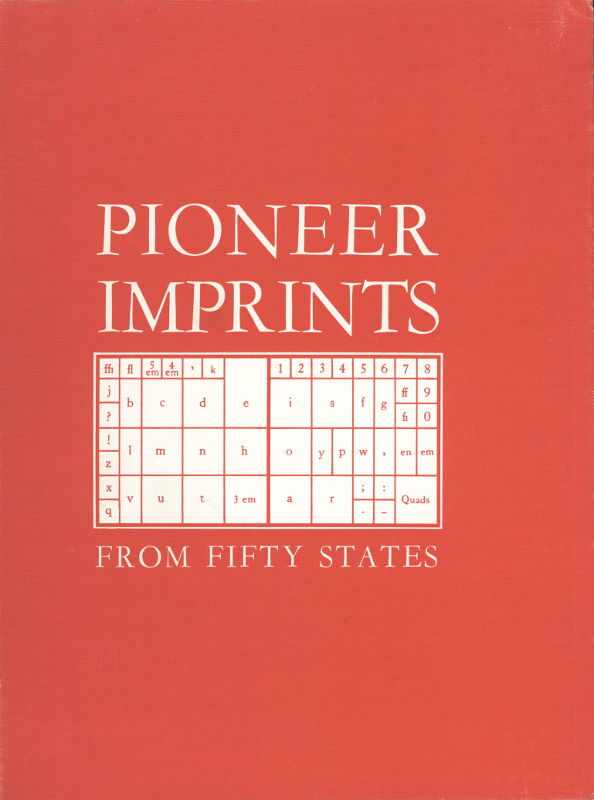

Cover: A standard tray (case) of type. Frequency of a letter's use determined the size and position of the letter compartment.

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Washington, D.C. 20402.—Price $4.25

Stock Number 3000-0059

Pioneer Imprints From Fifty States will enable readers to view the Library of Congress collections from an unaccustomed angle. It takes for its subject the Library's earliest examples of printing from within present-day boundaries of each State in the Union, providing for each in turn 1) a brief statement about the origin of printing; 2) identification of the Library's earliest examples—among them broadsides, newspapers, individual laws, almanacs, primers, and longer works; and 3) information, if available, about the provenance of these rarities.

Each of the 50 sections may be consulted independently. To those who read it through, however, Pioneer Imprints will give some idea of the movement of printers and presses across the Nation, as well as insight into the nature and history of the Library's holdings.

The author wishes to express his indebtedness to Frederick R. Goff, Chief of the Library of Congress Rare Book Division from 1945 to 1972, who has been constantly helpful and encouraging; to Thomas R. Adams, Librarian of the John Carter Brown Library, Providence, R.I., who read the first 13 sections before their publication under the title "The Library's Earliest Colonial Imprints" in the Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress for July 1967; and to Marcus A. McCorison, Director and Librarian of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass., who read the manuscript of the later sections. These scholars cannot, of course, be held responsible for any errors or faults in this bibliographical investigation. The author's indebtedness to printed sources is revealed to some extent by notes appearing at the end of each section. He is obliged for much of his information to the staffs of the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and the Smithsonian Institution, as well as to the following correspondents: Alfred L. Bush, Curator, Princeton Collections of Western Americana, Princeton University Library; G. Glenn Clift, Assistant Director, Kentucky Historical Society; James H. Dowdy, Archivist, St. Mary's Seminary, Baltimore; Caroline Dunn, Librarian, William Henry Smith Memorial Library, Indianapolis; Joyce Eakin, Librarian, U.S. Army Military History Research Collection, Carlisle Barracks, Pa.; Arthur Perrault, Librarian, Advocates' Library, Montreal; P. W. Filby, Librarian, Maryland Historical Society; Lilla M. Hawes, Director, Georgia Historical Society; Earl E. Olson, Assistant Church Historian, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Salt Lake City; and Frank S. Richards, Piedmont, Calif.

| 1 | Massachusetts |

| 3 | Virginia |

| 4 | Maryland |

| 5 | Pennsylvania |

| 6 | New York |

| 8 | Connecticut |

| 10 | New Jersey |

| 12 | Rhode Island |

| 14 | South Carolina |

| 16 | North Carolina |

| 18 | New Hampshire |

| 20 | Delaware |

| 21 | Georgia |

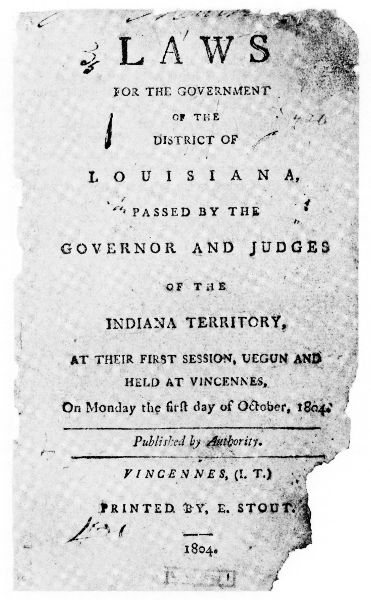

| 23 | Louisiana |

| 25 | Vermont |

| 27 | Florida |

| 29 | Maine |

| 30 | Kentucky |

| 32 | West Virginia |

| 34 | Tennessee |

| 36 | Ohio |

| 38 | Michigan |

| 39 | Mississippi |

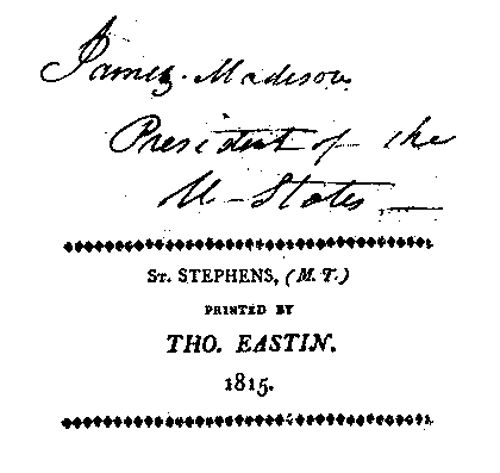

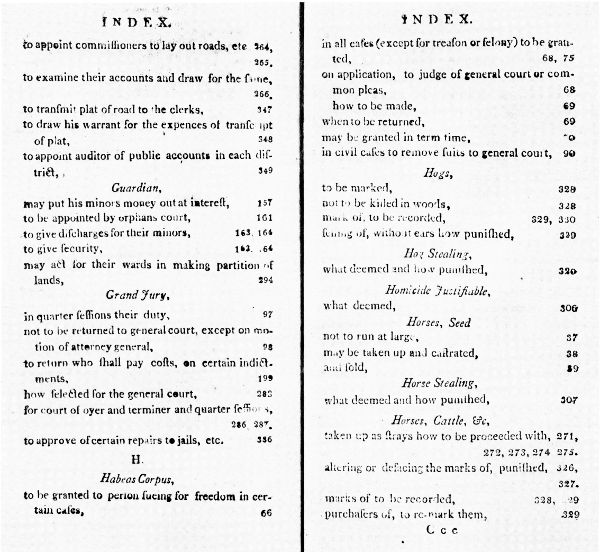

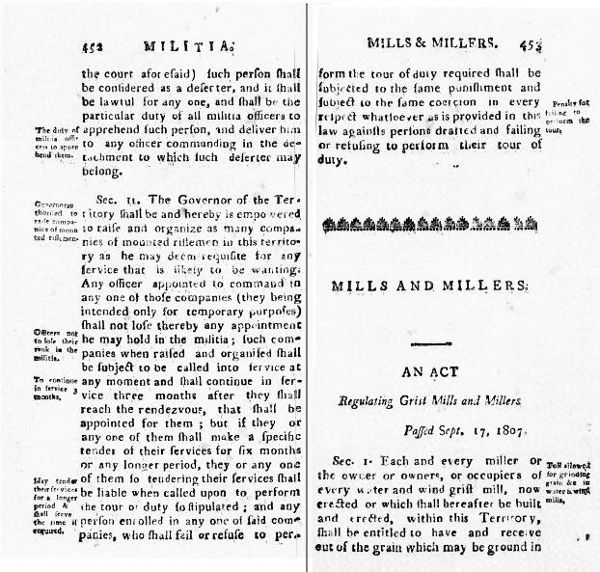

| 41 | Indiana |

| 43 | Alabama |

| 44 | Missouri |

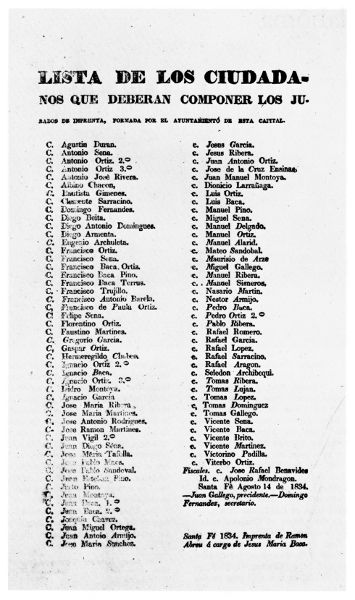

| 46 | Texas |

| 48 | Illinois |

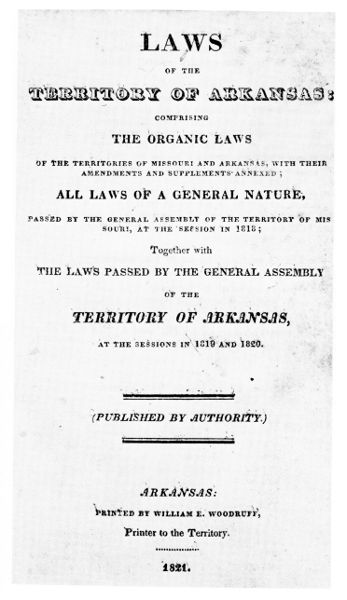

| 50 | Arkansas |

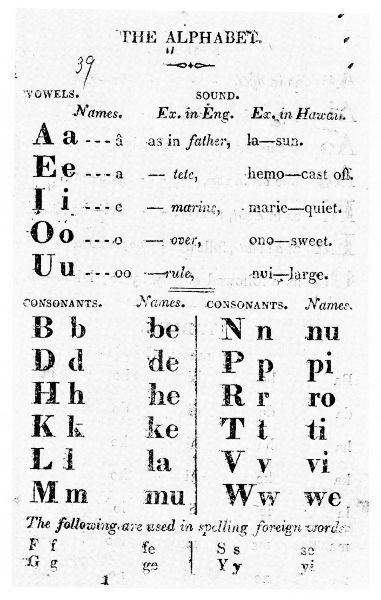

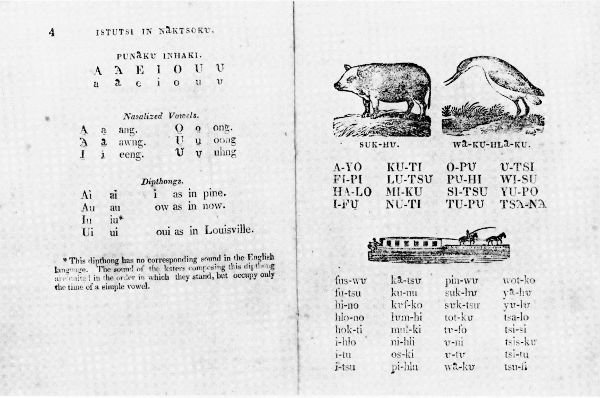

| 52 | Hawaii |

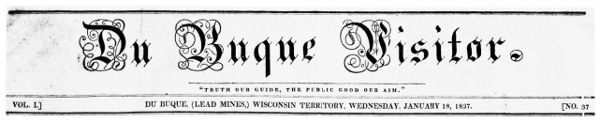

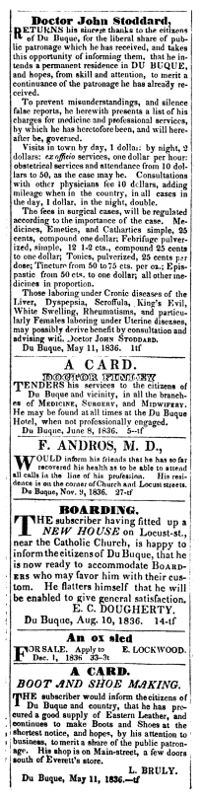

| 53 | Wisconsin |

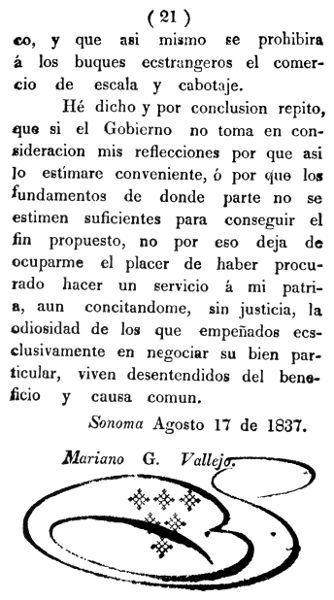

| 54 | California |

| 56 | Kansas |

| 58 | New Mexico |

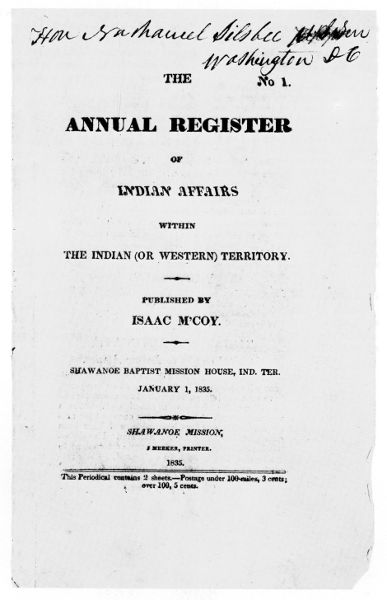

| 60 | Oklahoma |

| 61 | Iowa |

| 63 | Idaho |

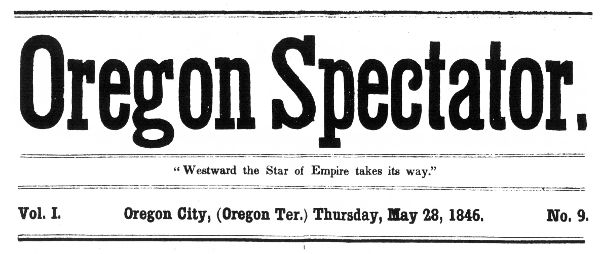

| 64 | Oregon |

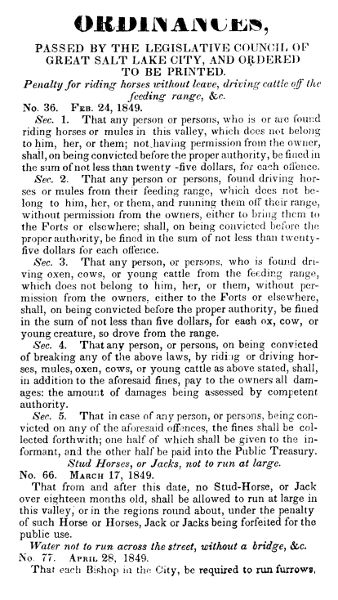

| 66 | Utah |

| 68 | Minnesota |

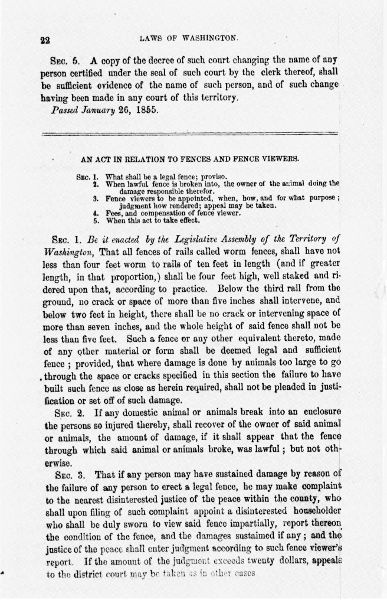

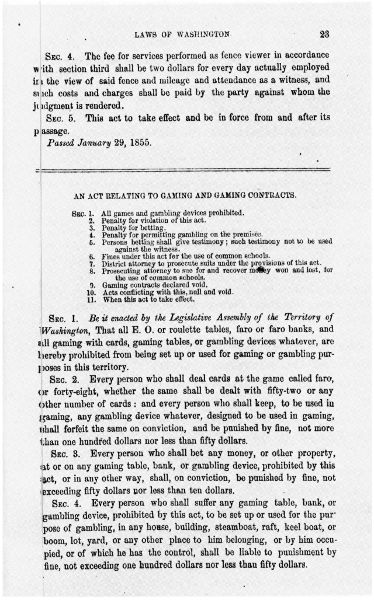

| 70 | Washington |

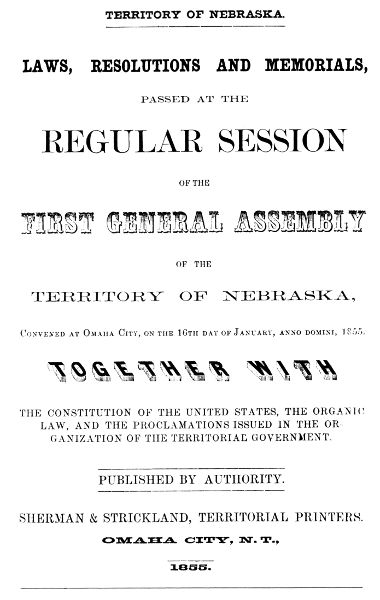

| 72 | Nebraska |

| 74 | South Dakota |

| 76 | Nevada |

| 78 | Arizona |

| 80 | Colorado |

| 82 | Wyoming |

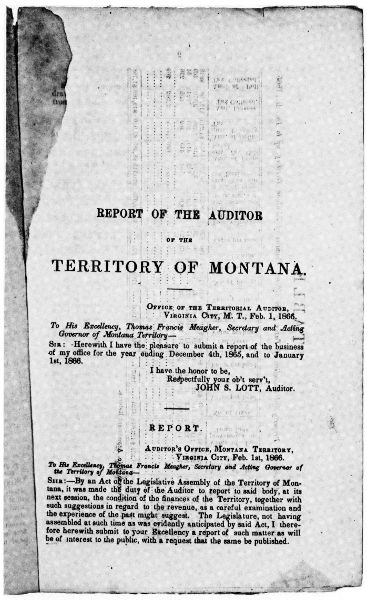

| 83 | Montana |

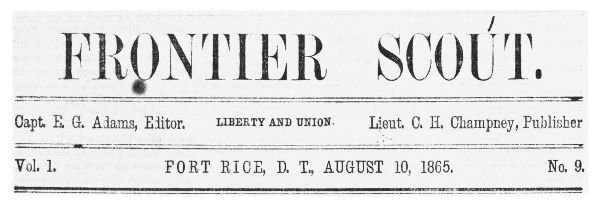

| 85 | North Dakota |

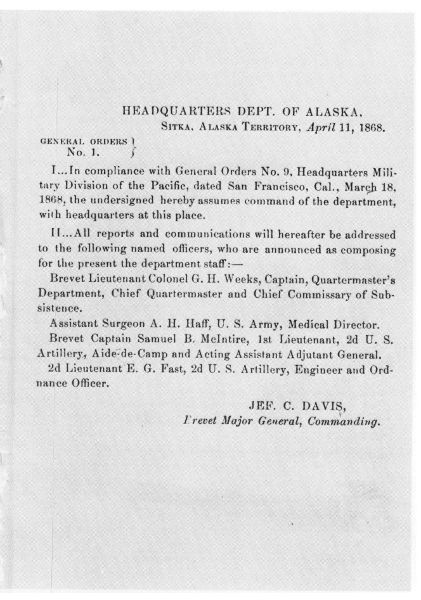

| 86 | Alaska |

PIONEER

IMPRINTS

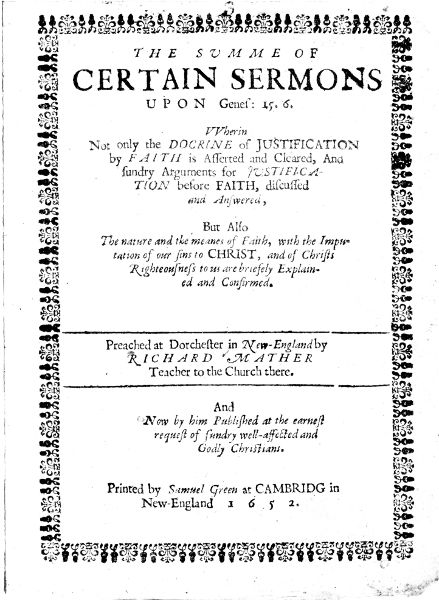

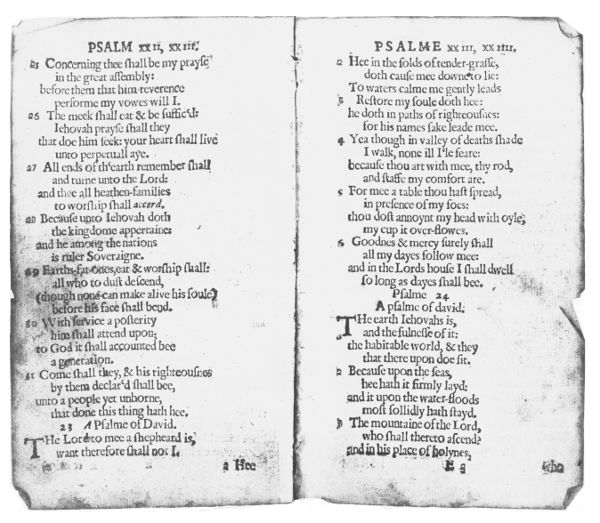

Stephen Daye, the first printer of English-speaking North America, established his press at Cambridge late in 1638 or early in 1639 and printed the famed Bay Psalm Book there in 1640. This volume of 295 pages is the first substantial book and the earliest extant example of printing from what is now the United States. Mrs. Adrian Van Sinderen of Washington, Conn., deposited an original copy of the Bay Psalm Book in the Library of Congress at a formal ceremony held in the Librarian's Office on May 2, 1966. Mrs. Van Sinderen retained ownership of the book during her lifetime; it became the Library's property upon her death, April 29, 1968.

The book is properly entitled The Whole Booke of Psalmes Faithfully Translated into English Metre. Of 11 extant copies this was the last in private hands, and it filled the most serious single gap in the Library's collection of early American printing. It is an imperfect copy, lacking its title page and 18 leaves. Bound in calfskin, it is one of the five copies in an original binding.

Zoltán Haraszti's authoritative study The Enigma of the Bay Psalm Book (Chicago, 1956) includes information about all the surviving copies. Mrs. Van Sinderen's copy was one of five that were collected by scholarly Thomas Prince of Boston (1687-1758), who bequeathed his extensive library to Old South Church. It was from the church that the Cambridge wool merchant and Bible collector George Livermore obtained it in 1849. By an exchange agreement between Livermore and the prominent bookseller Henry Stevens, 12 leaves were removed from the volume to complete another copy, which Stevens sold to James Lenox in 1855 and which now belongs to the New York Public Library. Livermore's collection, deposited at Harvard after his death, was auctioned in 1894 in Boston, his Bay Psalm Book realizing $425 and going to Mrs. Van Sinderen's father, Alfred Tredway White of Brooklyn.

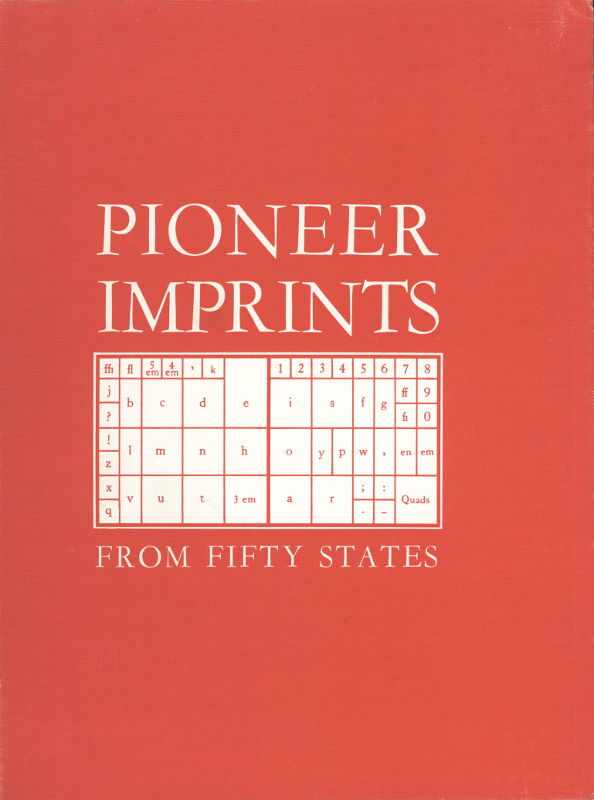

Before 1966 the earliest Massachusetts imprint, as well as the earliest imprint of the Nation, in the Library was Richard Mather's The Summe of Certain Sermons upon Genes: 15.6, printed at Cambridge in 1652. Its author was the progenitor of the powerful Mather family of New England divines, and he was among the translators contributing to the Bay Psalm Book. Its printer, Samuel Green, operated the first Massachusetts printing press after Stephen Daye's son Matthew died in 1649, Stephen having retired from the press[Pg 2] in 1647. Mather's book contains his revised notes for sermons preached at Dorchester.

The Library of Congress copy—one of four extant—is inscribed by an early hand, "James Blake his Booke." In the mid-19th century this copy apparently came into the possession of Henry Stevens, whereupon it was bound in full morocco by Francis Bedford at London; and it presumably belonged to the extensive collection of Mather family books that Stevens sold in 1866 to George Brinley, of Hartford, Conn.[1] The Library of Congress obtained the volume with a $90 bid at the first sale of Brinley's great library of Americana, held at New York in March 1879.

[1] See Wyman W. Parker, Henry Stevens of Vermont (Amsterdam, 1963), p. 267-268.

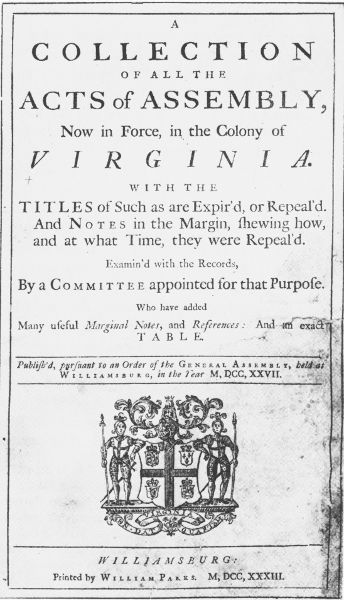

A press that William Nuthead started at Jamestown in 1682 was quickly suppressed, and nothing of its output has survived. It was William Parks who established at Williamsburg in 1730 Virginia's first permanent press. Here Parks issued the earliest Virginia imprint now represented in the Library of Congress: A Collection of All the Acts of Assembly Now in Force, in the Colony of Virginia (1733). Printing of this book may have begun as early as 1730. In a monograph on William Parks, Lawrence C. Wroth cites evidence "in the form of a passage from Markland's Typographia, which indicates that its printing was one of the first things undertaken after Parks had set up his Williamsburg press."[2]

Two Library of Congress copies of this imposing folio—one of them seriously defective—are housed in the Law Library; while yet another copy, which is especially prized, is kept with the Jefferson Collection in the Rare Book Division since it belonged to the library which Thomas Jefferson sold to the Congress in 1815.[3] The 1815 bookplate of the Library of Congress is preserved in this rebound copy, and Jefferson's secret mark of ownership can be seen—his addition of his other initial to printed signatures I and T. A previous owner wrote "Robert [?] Lewis law Book" on a flyleaf at the end, following later acts bound into the volume and extending through the year 1742. He may well have been the same Robert Lewis (1702-65) who served in the House of Burgesses from 1744 to 1746.[4]

The Library possesses the only known copy of another early Virginia imprint bearing the same date: Charles Leslie's A Short and Easy Method with the Deists. The Fifth Edition.... Printed and sold by William Parks, at his Printing-Offices, in Williamsburg and Annapolis, 1733. Inasmuch as an advertisement for this publication in the Maryland Gazette for May 17-24, 1734, is headed "Lately Publish'd," it was most likely printed early in 1734 but dated old style, and so it probably followed the publication of the Acts of Assembly. The Library purchased the unique copy for $8 at the second Brinley sale, held in March 1880.

[2] William Parks, Printer and Journalist of England and Colonial America (Richmond, 1926), p. 15.

[3] No. 1833 in U.S. Library of Congress, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, Compiled with Annotations by E. Millicent Sowerby (Washington, 1952-59).

[4] See Sarah Travers Lewis (Scott) Anderson's Lewises, Meriwethers and Their Kin (Richmond, 1938), p. 61-62.

After departing from Virginia, William Nuthead set up the first Maryland press at St. Mary's City sometime before August 31, 1685. This press continued in operation until a few years after Nuthead's widow removed it to Annapolis about 1695; yet nothing more survives from it than a single broadside and some printed blank forms.

In 1700 Thomas Reading began to operate a second press at Annapolis, and his output in that year included a collection of laws which is the earliest Maryland imprint now represented in the Library of Congress. Since the Library's is the only extant copy, it is particularly regrettable that its title page and considerable portions of the text are lacking. Catalogers have supplied it with the title: A Complete Body of the Laws of Maryland.[5]

The copy was formerly in the possession of the lawyer and diplomat John Bozman Kerr (1809-78). It might not have survived to this day were it not for his awareness of its importance, as shown in his flyleaf inscription:

? would this have been printed in Md at so early a period as 1700—in Md or elsewhere in the Colonies—It is dedicated to Mr Wm Bladen father, it is presumed, of Govr Thos Bladen, of whom Pope, the Poet, speaks so harshly—Having given much attention to Md History I know no book—calculated to throw more light upon manners & customs than this printed copy of the body of Md Law in 1700—The language of the early acts of assembly was much modified in 1715 & 1722—Here the Exact words are preserved as in the original acts—Unless in some old collection in England, five thousand dollars would not procure a like copy—Many years ago there was Extant, in MS, in Charles Co Court records, as I have been told, a similar collection—This printed copy is "the schedule annexed to 1699. c 46 & the act of 1700. c 8—

Sept 22d 1858

William Bladen, to whom the book is dedicated, was then clerk of the Upper House and had been instrumental in bringing Thomas Reading to Maryland. In fact, the records indicate that he assumed the role of publisher. If John Bozman Kerr had had access to the proceedings of the Lower House for the year 1700, he would have been most interested to find there Bladen's written proposal:

That if the house are desirous the body of Laws should be printed soe that every person might easily have them in their houses without being troubled to goe to the County Court house to have recourse thereto.

That the house made [sic] an Order for printeing thereof and that every County be Oblidged to take one faire Coppy endorsed and Titled to be bound up handsomely and that for the encouragement of the undertaker each County pay him therefore 2000lbs of Tobo upon delivery the said booke of Laws....

This was approved on May 9.[6] The printing was not wholly satisfactory, for on May 17 of the next year an errata list was ordered printed.[7]

[5] It is no. 7 in Lawrence C. Wroth's A History of Printing in Colonial Maryland (Baltimore, 1922). Besides listing it in his bibliography, Wroth discusses the book at length on p. 22-26.

[6] Archives of Maryland, vol. 24 (1904), p. 83-84.

[7] Ibid., p. 198.

Like William Nuthead, William Bradford introduced printing in more than one Colony, and he began his American career by establishing the first Pennsylvania press at Philadelphia in 1685. Here that same year he printed Good Order Established in Pennsilvania & New-Jersey in America, the earliest Pennsylvania imprint in the Library of Congress and the second known example of Bradford's press. The author, Thomas Budd, was a successful Quaker immigrant, who settled first at Burlington, N.J., and later at Philadelphia. He intended his description of the two Colonies to stimulate further immigration, and he printed this statement on the title page verso:

It is to be noted, that the Government of these Countries is so settled by Concessions, and such care taken by the establishment of certain fundamental Laws, by which every Man's Liberty and Property, both as Men and Christians, are preserved; so that none shall be hurt in his Person, Estate or Liberty for his Religious Perswasion or Practice in Worship towards God.

Because neither place nor printer is named in the book, it was long thought to have been printed at London, but typographical comparisons made during the latter part of the 19th century demonstrated conclusively that it issued from William Bradford's press.

The Library of Congress copy was bound at London by William Pratt for the bookseller Henry Stevens. F. J. Shepard traces this much of its later provenance in his introduction to a reprint issued in Cleveland in 1902:

A copy in full levant morocco, by Pratt, belonging to John A. Rice of Chicago, was sold in March, 1870, to Sabin & Sons for $155. The same copy fetched $150 at the sale of the library of William Menzies of New York (1875),[8] when it was described in Sabin's catalogue as "one of the rarest of books relating to Pennsylvania." It was again, presumably, the same copy which at the sale in New York of S. L. M. Barlow's books in 1889 brought $400, although it was still incorrectly described as printed in London. After passing through the hands of two dealers and one collector, it reached Dodd, Mead & Co., who advertised it in their November, 1900, catalogue for $700, and sold it at that price to a private collector whose name is not given.

The copy was among several Americana from the library of C. H. Chubbock, a Boston collector,[9] which were sold at auction by C. F. Libbie & Co. on February 23 and 24, 1904, the Library of Congress obtaining it for $600.

[8] Sabin's catalog is dated 1875, but the sale did not occur until November 1876.

[9] See American Book-Prices Current, vol. 10 (1904), p. vii.

William Bradford moved from Pennsylvania to New York in the spring of 1693, but what was the first product of his New York press has not been established.[10] The Library of Congress owns two Bradford imprints from this period, neither containing any indication of the place of publication. Nevertheless, both are listed in Wilberforce Eames' bibliography of early New York imprints.[11] One of them, entitled New-England's Spirit of Persecution Transmitted to Pennsilvania, and the Pretended Quaker Found Persecuting the True Christian-Quaker, in the Tryal of Peter Boss, George Keith, Thomas Budd, and William Bradford, at the Sessions Held at Philadelphia the Nineth, Tenth and Twelfth Days of December, 1692. Giving an Account of the Most Arbitrary Procedure of That Court, has been conjectured to be the first New York imprint (Eames 1). Eames states that the work "seems to be the joint production of George Keith and Thomas Budd, including Bradford's own account of the trial. As it mentions the next Court Session of March, 1693, it could hardly have been printed before May...." He confesses that Bradford may have printed it at Philadelphia. The Library of Congress purchased its copy—one of six recorded in the National Union Catalog—for $50 at the November 1876 auction of the library of Americana formed by a New York collector, William Menzies.

The other Bradford imprint conjecturally assigned to New York is Governor Benjamin Fletcher's proclamation of April 29, 1693, prohibiting "the Breaking of the LORDS DAY, all Prophane Swearing, Cursing, Drunkenness, Idleness and unlawful Gaming, and all manner of Prophaneness whatsoever" (Eames 9). Eames gives no reason why this broadside should be listed as a later imprint. An eminent New Yorker, Stuyvesant Fish, presented the unique copy to the Library of Congress in 1915 and in an accompanying letter to the Librarian told how it had come into his possession:

The broadside now sent you was given me by Mrs. Fish's mother, the late Mrs. William Henry Anthon, with the statement that she had found it among the papers left by her brother-in-law, Professor Charles Edward Anthon (b. Dec. 6, 1823; d. June 7, 1885). The latter was much given to collecting coins, manuscripts, &c., but no effort of mine has enabled me to learn where, when or how he became possessed of the paper.

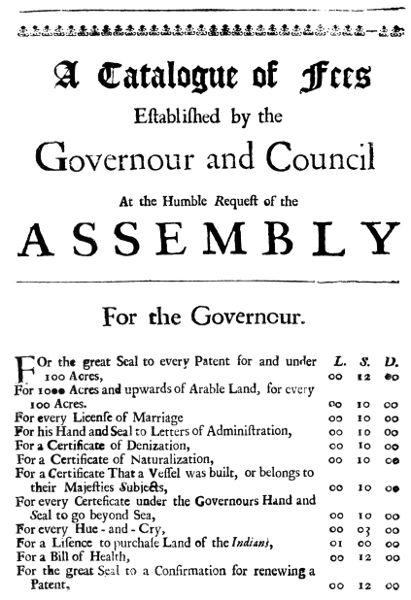

In view of the uncertain assignment of these two imprints to New York, the Library's earliest imprints naming New York as the place of publication should also be mentioned. A Catalogue of Fees Established by the Governour and Council at the Humble Request of the Assembly (New-York, William Bradford, 1693) is an 11-page work printed sometime after September 20, 1693. The Library's copy, like others, is appended to Bradford's printing of The Laws & Acts of the General Assembly (New-York, 1694), which in Eames' opinion was itself probably begun in 1693, perhaps as early as July or August. Among the owners of the volume containing these early imprints was the bibliographer Charles R. Hildeburn, who gave the following history in a note prefixed to an 1894 facsimile edition of The Laws & Acts:

This [copy], lacking a title-page, was formerly part of a volume of laws and other folio tracts printed by Bradford between 1694 and 1710, which was bought at a sale at Bangs's, in New-York, about ten years ago, by the late Dr. George H. Moore, for $26. In 1890 Dr. Moore sold the volume as he bought it for $1750 to the writer, who, having supplied the title-page in facsimile, sold so much of "the Laws of 1694 as issued" as it contained to the late Mr. Tower for $600. The volume then passed by the gift of Mr. Towers's widow, with the Tower collection, to the Historical society of Pennsylvania, and, having been replaced by a perfect copy ..., was sold to Dodd, Meade & Company, of New-York for $400. From the firm last mentioned it was purchased by Mr. [Abram C.] Bernheim.[12]

Now in a full morocco binding by Bradstreet's, the volume contains the bookplates of Abram C. Bernheim, who lectured on New York history at Columbia College, Henry C. Bernheim, and Russell Benedict. At the New York auction[Pg 7] of Judge Benedict's library in 1922 Halstead H. Frost, Jr., purchased it for $3,000; yet in 1926 at an auction by the same house of "Rare Americana including the collection of the late A. R. Turner, Jr. and selections from the collection of the late Charles A. Munn," the same copy drew only $1,800. In 1931 the Library of Congress obtained it from the firm of Lathrop C. Harper for $2,929.55, and it was duly noted in the subsequent annual report as "the most precious acquisition of the year by the law library."

[10] Alexander J. Wall, Jr., "William Bradford, Colonial Printer," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1963, vol. 73, p. 368.

[11] The First Year of Printing in New-York (New York, 1928).

[12] P. clvii. The facsimile was made from the Bernheim copy, which apart from its missing title page was considered to be the best preserved.

Thomas Short, who learned his trade at Boston, became Connecticut's first printer when he went to New London to do the official printing for the Colony in 1709.

The Library of Congress owns two Thomas Short imprints dated 1710, and one of them is believed to be the first book printed in Connecticut: The Necessity of Judgment, and Righteousness in a Land. A Sermon, Preached at the General Court of Election, at Hartford in the Colony of Connecticut, on May 11th. 1710. By Eliphalet Adams, Pastor of the Church in New-London. Eliphalet Adams was an influential clergyman whose 43 years of service at New London had just begun in 1709. The work is an election sermon, of a type delivered annually at the opening of certain New England legislatures. Although not especially worthy of remembrance, it manages to suggest the ceremony of the occasion. Adams closes his sermon by addressing the Governor, Deputy Governor, and magistrates, next turning to the assembled clergy, and finally concluding:

Shall I now turn my self to the General Assembly of the Colony at present met together. And even here I may promise my self an easie Reception, while I plead for Judgment & Righteousness. The welfare of the Country is in a great measure Intrusted in your hands and it is indeed a matter Worthy of your best Thoughts and chiefest cares. It should be Ingraven, if not upon the Walls of your House, yet upon each of your Hearts, Ne quid Detrimenti Respublica Capiat, Let the Common-wealth receive no damage. It is in your power partly to frame Laws for the Direction & Government of the people of the Land. Now too much care cannot be taken, that they may be strictly agreable to the standing Rules of Justice & Equity, that they may not prove a grievance in stead of an advantage to the Subject; If the Rule be crooked, how shall our manners be Regular?...[13]

The Library of Congress copy, in a 19th-century morocco binding, contains no evidence of provenance, but it was undoubtedly in the Library's possession by 1878, for the title is listed in the Library catalog published that year. Another copy sold at auction in 1920 for $1,775, which was the largest amount ever paid for a Connecticut imprint.[14]

The Library's other Connecticut imprint with a date of 1710 is entitled A Confession of Faith Owned and Consented to by the Elders and Messengers of the Churches in the Colony of Connecticut in New-England, Assembled by Delegation at Saybrook September 9th. 1708.... Herein is the historic Saybrook Platform, whereby individual congregations of the Colony submitted to the firmer control of synods. There exists documentary evidence that the printing of this book did not begin until late in 1710, and apparently it was not completed until 1711.[15] Elizabeth Short, the printer's widow, was paid £50 in 1714 for binding all 2,000 copies in calfskin and birchwood covers.[16] The Library's copy retains the original binding. Of further interest is the evidence supplied by the Library's bookplate that the volume formerly belonged to Peter Force, the American historian and archivist, whose notable collection was obtained through a special Congressional appropriation in 1867.

[13] P. 30-31.

[14] See Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, vol. 27 (1934), p. 4.

[15] W. DeLoss Love, Thomas Short the First Printer of Connecticut ([Hartford] 1901), p. 35-38; Thomas W. Streeter, Americana—Beginnings (Morristown, N.J., 1952), p. 25-26.

[16] Love, p. 37-38.

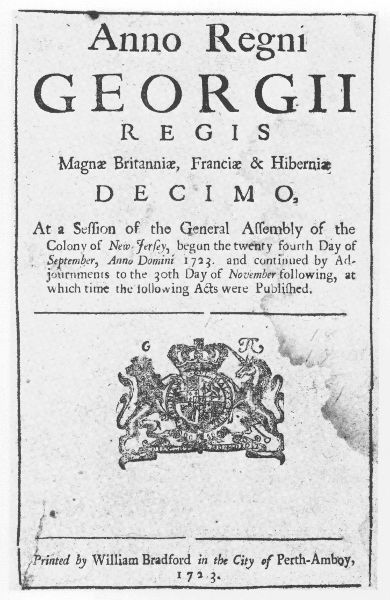

In 1723 William Bradford is thought by some to have transported a press from New York to Perth Amboy, then the capital of New Jersey, to print paper currency for the Colony.[17] If this is true he was the first New Jersey printer, although printing was not established there on a permanent basis until three decades later. In any event, in 1723 Bradford produced the first book with a New Jersey imprint: Anno Regni Georgii Regis Magnae Britanniae, Franciae & Hiberniae decimo, at a Session of the General Assembly of the Colony of New Jersey, begun the twenty fourth Day of September, Anno Domini 1723. and continued by Adjournments to the 30th Day of November following....

Douglas C. McMurtrie distinguishes three variant issues of the edition in A Further Note on the New Jersey Acts of 1723 (Somerville, N.J., 1935); but the Library of Congress copy, containing 30 numbered and four unnumbered pages, represents a fourth variant. It is one of two issues (the other bearing a New York imprint) in which the type for the later pages was reset.

In the section on paper money, which has a prominent place in the New Jersey laws, is an interesting sidelight on printing history: the text of an oath to be administered to the printer upon his delivery of the bills to those authorized to sign them, requiring him to declare

That from the time the Letters were set, and fit to be put in the Press for Printing the Bills of Credit now by me delivered to you, until the same Bills were printed, and the Letters unset and put in the Boxes again, I went at no time out of the Room in which the said Letters were, without Locking them up, so as they could not be come at, without Violence, a false Key, or other Art then unknown to me; and therefore to the best of my Knowledge no Copies were printed off but in my Presence; and that all the Blotters and other Papers whatever, Printed by the said Letters, which set for printing the said Bills, to the best of my Knowledge are here Delivered to you together with the Stamps for the Indents, and Arms.

The Library of Congress copy is bound in the midst of a folio volume of early New Jersey laws and ordinances that C. S. Hook of Atlantic City, a dealer in old law books, sold to the Library in 1925 for $2,337.50. Though dilapidated, the volume retains its original calf binding, and the names of two early owners are inscribed on its front flyleaf: "Mr Bard" and "John Wright Esq:r" The former may well be the same Peter Bard, a Huguenot immigrant, who served as member[Pg 11] of the Council from 1720 to 1734 and who was one of those authorized to sign the above-mentioned bills.

Some authorities doubt that Bradford would have moved a press to New Jersey for only a short time and think it more likely that he actually printed the acts of 1723 in New York.[18] In that case the earliest New Jersey imprint in the Library of Congress would be an 18-page pamphlet containing an act passed on June 3, 1757, which James Parker printed at Woodbridge on the first permanent press in the Colony: ... A Supplementary Act to the Act, Entitled, An Act for Better Settling and Regulating the Militia of this Colony of New-Jersey; for the Repelling Invasions, and Suppressing Insurrections and Rebellions; As [sic] also, for Continuing Such Parts and Clauses of the Said Laws, as are not Altered or Amended by This Act. The Library's copy, inscribed "Capt. Monrow" on its title page, probably belonged originally to John Monrow, a resident of Burlington County.[19] The Central Book Company of New York sold it to the Library for $150 in 1939.

[17] See Lawrence C. Wroth, The Colonial Printer (Portland, Maine, 1938), p. 34-36.

[18] See Streeter, Americana—Beginnings, no. 21, where this view is attributed to R. W. G. Vail.

[19] See Archives of the State of New Jersey, 1st series, vol. 10 (1886), p. 15 and 17; H. Stanley Craig, Burlington County, New Jersey, Marriages, Merchantville, N.J. (1937), p. 159.

After a stay in prison resulting from his publishing activities in Boston, James Franklin, elder brother of Benjamin, chose to settle at Newport, where he established the first Rhode Island press in 1727.

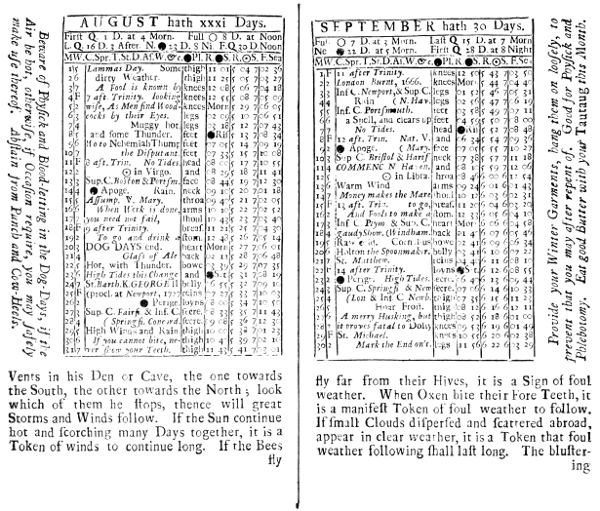

When the Library of Congress acquired its unique copy of Franklin's Rhode-Island Almanack for the Year 1728 in 1879, it was thought to be the earliest book printed in Rhode Island. Not until 1953, when copies of two religious tracts by John Hammett came to light, was it relegated to third place. Those two tracts were printed before July 25, 1727, while Franklin's pseudonymous preface to his almanac is dated August 30 of that year.[20]

Although it may no longer be regarded as the first Rhode Island book, this small almanac nevertheless is of exceptional interest. Four years before Benjamin Franklin inaugurated Poor Richard's Almanack his elder brother presented himself in this wise:

Tho' I have not given you my proper Name, yet I assure you I have had one the greatest part of half an hundred Years; and I know of no Necessity for parting with it at this Time, since I presume my Almanack will answer all the Ends design'd without that Expence. So, wishing you a happy new Year; bid you adieu.

James Franklin strove to make his almanac entertaining, and he did not refrain from injecting anticlerical gibes or a bit of ribaldry. He obviously relished such pithy sayings as "More religion than honesty" and "If you cannot bite, never show your Teeth."

The Library of Congress purchased its unique copy for $35 at the Brinley sale of 1879. It then had seven leaves and seemed to lack an eighth leaf at the end. Much later, George Winship, librarian of the John Carter Brown Library, reported a curious happening in an article that he contributed to The Providence Sunday Journal, November 19, 1911:

A few weeks ago some one noticed that a leaf which was bound at the end of a book in the Boston Public Library had nothing whatever to do with that book. It was apparently a leaf of an old almanac, and after some research Alfred B. Page of the Massachusetts Historical Society Library was successful in identifying it, not only as the last leaf of the almanac for 1728, which was printed in Newport toward the end of the preceding year, but as the identical leaf which originally formed a part of the copy now belonging to the Library of Congress.

The officials in Washington sent their book to Boston to make certain of the identification, and in return they have been presented with the missing member, so long separated from its proper body. On its way back to Washington, this precious little waif is making a visit to the State of its origin, and will be for a few days on exhibition at the John Carter Brown Library, in company with various of its contemporary rivals, predecessors and followers.

A reprint of the almanac with an introduction by Mr. Winship, signing himself as Philohistoricus, was published at this time. And while at Boston the copy was encased in a variegated morocco binding by the Hathaway Book Binding Company on Beacon Street.

[20] See Rhode Island History, vol. 12 (1953), p. 33-43, 105-109.

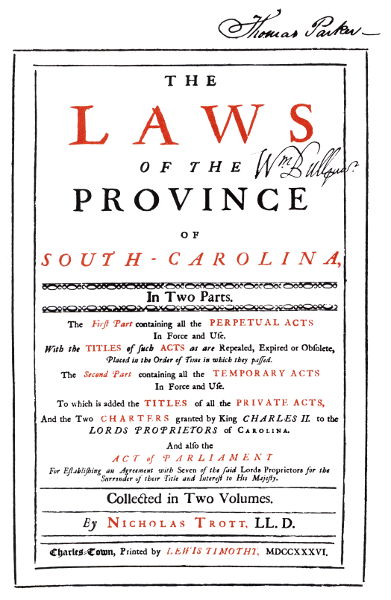

Printing commenced in South Carolina in 1731 when three competing printers migrated to Charleston: George Webb, Eleazer Phillips, Jr., and Thomas Whitmarsh. They were attracted by an offer of monetary aid that the government announced in order to secure a printer for the Colony.

The earliest Library of Congress copies of South Carolina imprints issued from the press of Lewis Timothy (otherwise Louis Timothée), a Frenchman trained in Holland and subsequently employed by Benjamin Franklin at Philadelphia. Through an arrangement with Franklin he took over the press of Thomas Whitmarsh after the latter's death in 1733, Webb having either died or departed from Charleston and Phillips having died in 1732. The Library has three Lewis Timothy imprints dated 1736: Josiah Smith's sermon, The Character and Duty of Minister and People; the session laws for November 15, 1733-May 29, 1736, entitled Acts Passed by the General Assembly of South-Carolina; and Nicholas Trott's compilation of The Laws of the Province of South-Carolina. The sermon, advertised in The South-Carolina Gazette for May 22, 1736, as just published, was completed first. Still earlier printing, however, is contained in the first volume of Trott's Laws, though the volume was not completed until September 1736. Timothy began to print the laws shortly after November 15, 1734, and the first sheets were ready in May 1735.[21]

This publication in two folio volumes is a landmark of Colonial printing; it was Timothy's most ambitious undertaking by far, one he carried out with remarkable taste and skill. The title page, printed in black and red, is particularly striking. Nicholas Trott, the editor, was a learned jurist who played a leading role in South Carolina's affairs, becoming chief justice in 1703. In the preface he sets forth his guiding purpose in compiling the Laws:

Thus I have endeavoured as much as in me lies, and have spared for no Pains, to make this Work not only useful, but plain and easy, even to the meanest Capacity, wherein if I have obtained my End, I shall not think my Labour ill bestowed: For as every Man is a Debtor to his Country, and we are not born only for our selves, so I tho't I could not do a more useful Service for the Province in which it has pleased God to cast my Lot for several years past, than to make such an Edition of the Laws, as might be of general Use to all the Inhabitants thereof; that so every one being acquainted with the Laws of the Place, may readily give Obedience to the same; in which (next to their religious Duties to GOD) not only their Duty, but also their Safety and happiness doth consist.

The Library of Congress owns three copies of this rare book, all lacking some pages. The copy most distinguished in its provenance bears on its title page the signature of William Bull, Jr., five times Acting Governor of South Carolina between 1760 and 1775. Also on this title page is the late 18th-century signature of one Thomas Parker. Another copy is inscribed "Thomas Farr junr. [another hand:] of St. Andrew's Parish 12th. May 1773"; and in the following century it was given "With Edward Logan's kind regards to James Parker Esq. 18 Feb 1868." Thomas Farr can be identified as a merchant,[22] but the later names have not been traced. The third Library copy retains no marks of previous ownership.

[21] Douglas C. McMurtrie, The First Decade of Printing in the Royal Province of South Carolina (London, 1933).

[22] A. S. Salley, ed., Marriage Notices in The South-Carolina Gazette and Its Successors (Baltimore, 1965), p. 21.

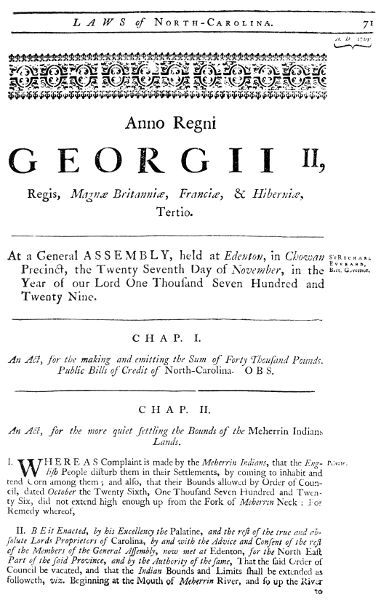

The first printer active in North Carolina was James Davis, a native of Virginia, who probably received his training from William Parks at Williamsburg.[23] Davis settled at New Bern in 1749, and in the same year he began printing The Journal of the House of Burgesses.

The earliest North Carolina imprint in the Library of Congress, printed by Davis in 1751, is carefully described in its title, A Collection of All the Public Acts of Assembly, of the Province of North-Carolina: Now in Force and Use. Together with the Titles of all such Laws as are Obsolete, Expired, or Repeal'd. And also, an exact Table of the Titles of the Acts in Force, Revised by Commissioners appointed by an Act of the General Assembly of the said Province, for that Purpose; and Examined with the Records, and Confirmed in full Assembly.

This collection is sometimes called "Swann's Revisal" after the commissioner William Swann, who did a major part of the editing and wrote the dedication to Governor Gabriel Johnston. One of the acts, passed on March 7, 1746, begins with the preamble, "Whereas for Want of the Laws of this Province being Revised and Printed, the Magistrates are often at a Loss how to discharge their Duty, and the People transgress many of them through Want of knowing the same...." These words reflect not only a shortage of copies, but also the need to rectify discrepancies in the manuscript copies by publishing a uniform text.

Davis did not complete the volume until about November 15, 1751, when he advertised it in his newspaper, The North-Carolina Gazette. Four distinct issues of the edition can be identified;[24] and of these, the Library of Congress owns both the third, in which the laws of 1751 and 1752 (not shown in the table) are added, and the fourth, which is like the third but with a title page dated 1752 and a new table.

The Library's copy of the third issue bears on the title page the signature of Michael Payne, a resident of Edenton, N.C., who served in the State legislature during the 1780's. The Library purchased it in 1936 from Richard Dillard Dixon of Edenton for $500. The copy of the fourth issue is signed "Will Cumming" in an early hand, and it is inscribed to Samuel F. Phillips, who was Solicitor General of the United States from 1872 to 1885 and who appears to have been the latest owner of the book before its addition to the Library in 1876.

[23] See W. S. Powell's introduction to The Journal of the House of Burgesses, of the Province of North-Carolina, 1749 (Raleigh, 1949), p. vii.

[24] Douglas C. McMurtrie, Eighteenth Century North Carolina Imprints (Chapel Hill, 1938), p. 50.

The Boston printer Daniel Fowle felt himself unjustly punished by the Massachusetts Assembly for supposedly printing an objectionable pamphlet in 1754. He consequently removed to Portsmouth in New Hampshire and started that Colony's first press in 1756.

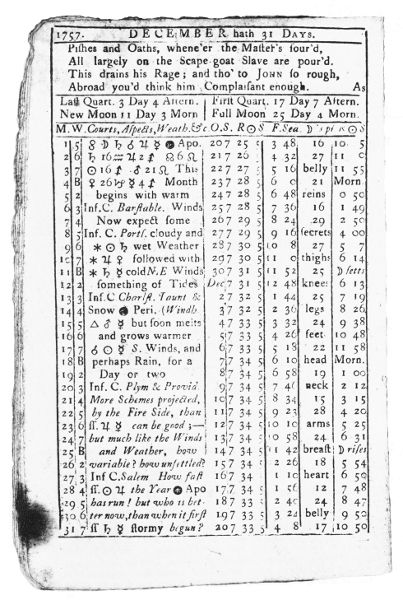

The first New Hampshire book, preceded only by issues of The New-Hampshire Gazette, was printed by Fowle in the same year. It is Nathaniel Ames' An Astronomical Diary: or, An Almanack for the Year of Our Lord Christ, 1757. The Library of Congress owns one of four known copies of a singularly interesting later issue or state of the edition, featuring on its next-to-last page a historical note printed within an ornamental border: "The first Printing Press set up in Portsmouth New Hampshire, was on August 1756; the Gazette publish'd the 7th of October; and this Almanack November following."

Almanacs written by Nathaniel Ames of Dedham, Mass., were bestsellers in mid-18th century America. This almanack for the year 1757, evidently reprinted from the Boston edition, is a somber one reflecting recent set-backs in England's conflict with France. A verse on the title page strikes the keynote:

The rebound Library of Congress copy, which bears no marks of previous ownership, is listed in the Library catalog of 1878 and presumably was obtained not long before then.

At about the same time the Library acquired and similarly rebound two other Daniel Fowle imprints of undetermined provenance, both of which are dated 1756 but were published later than the almanac. There is some question whether one of them, Jonathan Parsons' Good News from a Far Country, was begun at Boston or at Portsmouth. In any event, Fowle placed the following notice in the November 4, 1756, issue of his Gazette: "Good News from a far country: in seven discourses by Rev. Jonathan Parsons is soon to be published. Five of the sermons have already been set up and lack of paper prevents completion until a supply of paper arrives from London which is probable at an early date." Not until April 1757 did Fowle advertise the book for sale.[25] The other imprint dated 1756 is Samuel Langdon's The Excellency of the Word of God, in the Mouth of a Faithful Minister,[26] a sermon delivered on November 3 and also delayed in printing for lack of suitable paper. Both books were probably completed in the early months of 1757 but dated old style. There is a noticeable difference between the paper on which they are printed and the crude paper of the almanac, such as Fowle used for his newspaper.

[25] See Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1915, new series, vol. 25, p. 329.

[26] A Library of Congress stamp on this copy is dated 1876.

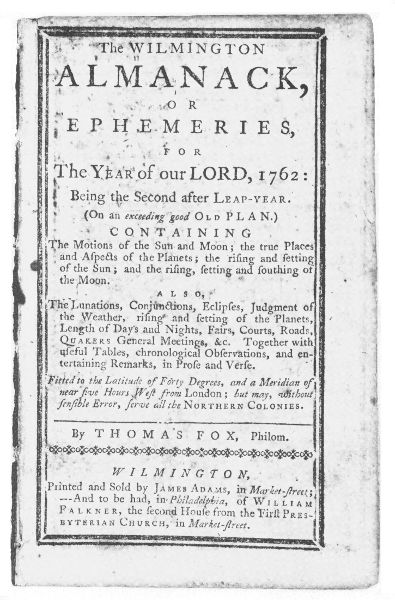

James Adams of Londonderry, Ireland, after working more than seven years with Franklin and Hall in Philadelphia, established Delaware's first press at Wilmington in 1761.

The Library of Congress possesses one of two extant imprints out of four that Adams is known to have issued at Wilmington in the latter part of that year: The Wilmington Almanack, or Ephemeries [sic], for the Year of Our Lord, 1762 ... By Thomas Fox, Philom.[27] Copies, according to the title page, were also "to be had, in Philadelphia, of William Falkner." The publication is the first in an annual series of "Wilmington Almanacs," all printed by Adams, that were prepared for the years 1762 to 1794.

The otherwise unknown author, Thomas Fox (possibly a pseudonym), brings himself to the reader's attention in this statement:

Kind Reader,

Having for some Years observed those Almanacks published in America; and having formerly, in Europe, learned the Use of Mr. Thomas Street's Tables, with some others, and being willing to crowd in among the rest, I have calculated an Almanack for the Year 1762....

More interesting than the colorless prose and verse selections accompanying the astronomical tables are the printer's advertisements, such as the following notice near the end of the book:

Bibles, Testaments, Psalters, Spelling-Books, Primers, Merchants blank Books, Writing-Paper, Ink, all Sorts of Blanks, viz., Bills of Lading, Kerry Bills, Penal Bills, Bills of Sale, Arbitration Bonds, Apprentices Indentures, Bonds with and without Judgment, to be sold at the Printing-Office in Wilmington.—Also, very good Lampblack.

* * * Ready money for clean Linen Rags, at the above Office.

The Library's copy of the almanac has been detached from a bound volume and bears no evidence of early ownership. It was acquired by exchange from Dodd, Mead & Company in 1908, at a valuation of $15.

[27] No. 3 in Evald Rink, Printing in Delaware 1761-1800 (Wilmington, 1969).

An act for the provision of printing, passed by the Georgia Legislature on March 4, 1762, stated that "James Johnston, lately arrived in this province from Great-Britain, recommended as a person regularly bred to and well skilled in the art and mystery of printing, hath offered to set up a printing press in the town of Savannah." Employed to print the Colony's statutes, Johnston had readied the first Georgia press by April 7, 1763, when he began to publish his newspaper, The Georgia Gazette.

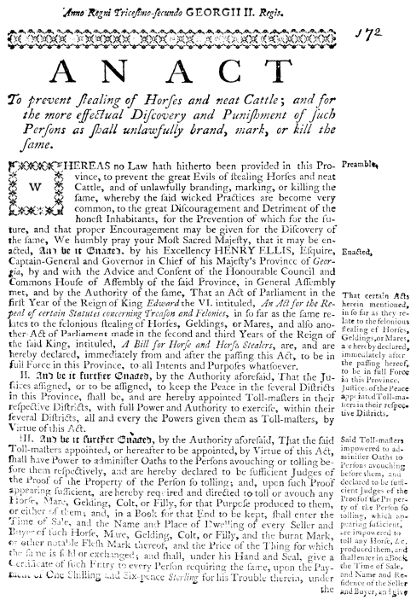

From the year 1763 the Library of Congress owns several official imprints bound up in a volume of Georgia laws enacted from 1755 to 1770 and one unofficial imprint, The South-Carolina and Georgia Almanack, for the Year of Our Lord, 1764 ... By John Tobler, Esq. This almanac, which the distinguished collector Wymberley Jones De Renne gave the Library in 1907, was published by December 8, 1763, and probably printed very shortly before. The earliest of Johnston's many official imprints, predating all his other work except The Georgia Gazette, are thought to be two acts advertised in that paper on June 2, 1763. They are entitled An Act to Prevent Stealing of Horses and Neat Cattle; and for the More Effectual Discovery and Punishment of Such Persons as Shall Unlawfully Brand, Mark, or Kill the Same and An Act for Ascertaining the Qualifications of Jurors, and for Establishing the Method of Balloting and Summoning of Jurors in the Province of Georgia. They had been passed on March 27, 1759, and April 24, 1760, and were printed in folio in four and six pages, respectively. Both acts are represented in the Library of Congress bound volume of early Georgia laws. Only two other copies of each are known to be extant.

Various owners inscribed their name in this book. Joseph Stiles, who operated the Vale Royal Plantation near Savannah from 1806 until his death in 1838, owned at least the latter part of it, where his signature and that of his son, the evangelist Joseph C. Stiles, may be seen. Another owner of the same part was John C. Nicholl (1793-1863), a prominent lawyer and jurist who served as mayor of Savannah in 1836 and 1837. A later owner of the entire volume was a certain S. H. McIntire, not known to have any Savannah connections, who inscribed it in June 1878. The Library of Congress purchased it in June 1909 from the Statute Law Book Company of Washington, D.C. for $2,500.

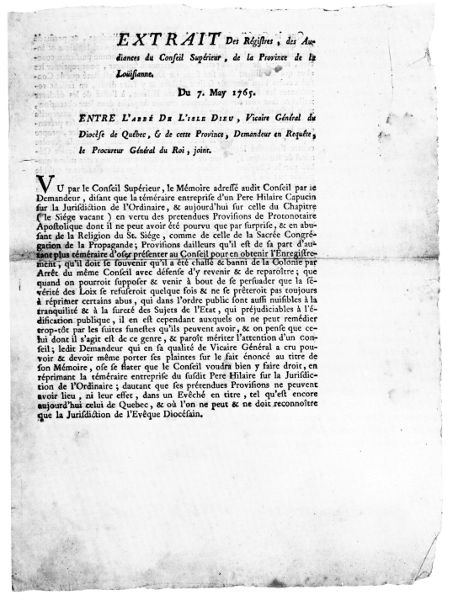

Only after printing penetrated the Thirteen Colonies did the French printer Denis Braud carry the art to Louisiana. His earliest known work, an official broadside concerning the transfer of Louisiana from French to Spanish ownership, was printed at New Orleans in 1764.

The earliest Louisiana imprint in the Library of Congress is the second extant example of Louisiana printing. The Library's unique copy is a four-page, folio-sized document signed by Garic, clerk of the Superior Council of Louisiana, and headed, "EXTRAIT De Régistres, des Audiances du Conseil Supérieur, de la Province de la Loüisiane. Du 7. May 1765. ENTRE L'ABBE DE L'ISLE DIEU, Vicaire Général du Diocèse de Québec, & de cette Province, Demandeur en Requête, le Procureur Général du Roi, joint." It is a decree restricting the activities of the Capuchin friar Hilaire Genoveaux and suppressing a catechism circulated by him which apparently had also been printed at New Orleans. The title of the catechism, as preserved in the text of the decree, is Catechisme pour la Province de la Loüisianne, &c. Rédigé par le R. P. Hilaire, Protonotaire du St. Siége & Supérieur Général de la Mission des Capucins en ladite Province, pour être seul enseigné dans sadite Mission. The contemporary importance of the surviving document lay in its connection with a far-reaching struggle between the Jesuit and Franciscan orders over ecclesiastical authority in Louisiana. Although it contains no imprint statement naming place of publication or printer, typographical features of the document serve to identify it as the work of Denis Braud.[28]

That this unique copy belonged to an official archive—presumably that of the Superior Council of Louisiana—the following manuscript additions make apparent. There is first a notation: "Joint a la lettre de M. Aubry, Command. a la Louisianne du 7. May 1765." (Aubry had succeeded d'Abbadie as commandant, or governor, after the latter's death in February 1765.) A second column in manuscript contains the same date as a filing guide and this descriptive title: "Arrest du Conseil Superieur de la Louisianne portant deffense au Pere Hilaire Capucin de simississer [i. e. s'immiscer] dans aucune Jurisdiction Ecclesiastique autre que celle qui lui est permise par son seul titre de superieur de la mission des RR. PP. Capucins de cette Colonie." At the end of the column is a cross reference: "Voyez les lettres de M. l'Abbe de LIsle Dieu Vicaire g[e]n[er]al de M. de Quebek en 1759 et 1760 et sa Correspond. a ce sujet."

The subsequent history of this document has not been traced before October 17, 1905, when C. F. Libbie & Co auctioned it off with the library of Israel T. Hunt, a Boston physician. The Library of Congress was able to obtain it on that date for $10.45.

[28] See Douglas C. McMurtrie, Early Printing in New Orleans (New Orleans, 1929), p. 25-26 and 88. McMurtrie mistakenly locates the original at the New York Public Library, which owns a photostat copy.

Formed as an independent republic in 1777, Vermont in the next year appointed the brothers Alden and Judah Padock Spooner of Connecticut to be her official printers. Publications under their imprint were issued at Dresden, before and later named Hanover, in 1778 and 1779; but in February 1779 this town, along with 15 others east of the Connecticut River, returned to the jurisdiction of New Hampshire. The earliest printing from within the present borders of Vermont came from the town of Westminster, where Judah Padock Spooner and Timothy Green, son of the State Printer of Connecticut, undertook the official printing late in 1780.

The Library of Congress possesses three Dresden imprints dated 1779. The first two listed here name Alden Spooner as printer, while the third names both brothers. They are Ira Allen's A Vindication of the Conduct of the General Assembly of the State of Vermont, Held at Windsor in October 1778, Against Allegations and Remarks of the Protesting Members, With Observations on Their Proceedings at a Convention Held at Cornish, on the 9th Day of December 1778; Ethan Allen's A Vindication of the Opposition of the Inhabitants of Vermont to the Government of New-York, and of Their Right to Form into an Independent State. Humbly Submitted to the Consideration of the Impartial World; and Acts and Laws of the State of Vermont, in America. The earliest of the three would appear to be Ira Allen's 48-page Vindication, known from a printer's bill of February 10, 1779, to have been produced by then in 450 copies.[29] The Library's rebound copy is inscribed "from ye author" beneath its imprint statement, and at the head of the title page is written, "Nathl Peabodys Book." Nathaniel Peabody (1741-1823), a New Hampshire legislator, served as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1779 and 1780. His book was ultimately listed in the Catalogue of Books Added to the Library of Congress During the Year 1871.

The Library holds the other two Dresden imprints in duplicate. A copy of the Acts and Laws was formerly in the Hazard Pamphlets, acquired with the collection of Peter Force (see p. 8, above). Ebenezer Hazard (1744-1817) was an early collector of Americana. The two copies of Ethan Allen's Vindication, both printed on blue paper, are in the Hazard Pamphlets, volume 47, number 3, and in Colonial Pamphlets, volume 19, number 6. The latter pamphlet volume originally formed part[Pg 26] of Thomas Jefferson's library, obtained by the Congress in 1815 (see p. 3, above).[30]

The earliest example of printing from present-day Vermont in the Library is a document printed by Judah Padock Spooner at Westminster in 1781[31]: Acts and Laws, Passed by the General Assembly of the Representatives of the State of Vermont, at their Session at Windsor, April 1781. In four pages, it contains only "An Act for the Purpose of emitting a Sum of Money, and directing the Redemption of the same." The Act provides for a land tax, stating in justification that "The Land is the great Object of the present War, and receives the most solid Protection of any Estate, a very large Part of which has hitherto paid no Part of the great Cost arisen in defending it, whilst the Blood and Treasure of the Inhabitants of the State has been spent to protect it, who many of them owned but a very small part thereof."

The Library of Congress copy bears the following inscription: "Secry's Office 10th August 1785. The preceding is a true Copy of an Act passed by the Legislature of the State of Vermont April 14th 1781—Attest Micah Townsend, Secry." Although a loyalist, Micah Townsend served as secretary of state in Vermont from October 1781 until 1789.[32] The Library's copy also bears the autograph of a private owner, Henry Stevens of Barnet, Vt., first president of the Vermont Historical Society. After his death in 1867, his son Henry Stevens, the bookseller, wrote that he left his home "full of books and historical manuscripts, the delight of his youth, the companions of his manhood, and the solace of his old age."[33] To judge from its present library binding, this thin volume has been in the Library of Congress collections since the 19th century.

[29] See no. 12 in Marcus A. McCorison's Vermont Imprints 1778-1820 (Worcester, 1963).

[30] No. 3146 in U.S. Library of Congress, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, Compiled with Annotations by E. Millicent Sowerby (Washington, 1952-59). See also no. 498.

[31] Imprint information supplied in McCorison, no. 47.

[32] See Chilton Williamson, Vermont in Quandary (Montpelier, 1949), p. 133. On Townsend's divulging secret intelligence to the British in April 1781, see J. B. Wilbur, Ira Allen (Boston and New York, 1928), p. 183-186.

[33] See W. W. Parker, Henry Stevens of Vermont (Amsterdam, 1963), p. 21.

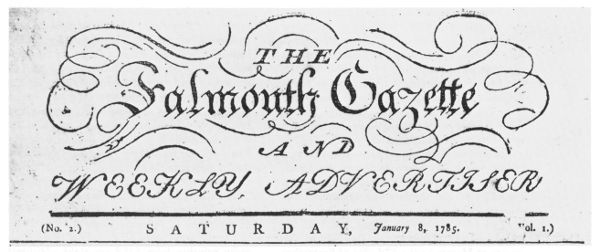

Dr. William Charles Wells, one of many American loyalists who took refuge in Florida, introduced printing at St. Augustine in 1783. There he published a loyalist paper, The East-Florida Gazette, under the imprint of his elder brother, the Charleston printer John Wells, and with the assistance of a pressman named Charles Wright. Apart from two books of 1784 bearing John Wells' imprint and a document printed at Amelia Island in 1817 during the Spanish rule, no other Florida publications survive from the years preceding United States acquisition of the territory.[34]

Richard W. Edes, grandson of the Boston printer Benjamin Edes, reestablished printing at St. Augustine, issuing the first number of his weekly paper, the Florida Gazette, on the day of the transfer of Florida's administration, July 14, 1821. The Library of Congress holds 10 issues, constituting the best surviving file of this paper. The earliest Florida printing in the Library is the third issue, published July 28 and the earliest issue extant. This happens to be a very curious example of printing. Of its four pages the second is half blank and the third is totally blank, the following explanation being given:

TO OUR PATRONS.

We are under the disagreeable necessity of issuing this number of the Gazette, in its present form, owing to a very lengthy advertisement, (occupying seven columns) being ordered out the moment the paper was ready for the Press. It being a personal controversy between Mr. William Robertson, and Messrs. Hernandez, Kingsley and Yonge, Esquires, and a reply to Mr. Hernandez's publication of last week, our readers would not have found it very interesting. Its publication was countermanded on account of an amicable arrangement being made by the parties about one o'clock this day.

We hope this will be a sufficient apology to our subscribers for the manner in which the Paper appears, as it is impossible for it to be issued this day in any other way, being short of hands. We pledge ourselves another instance of the kind shall never occur—and assure the public we feel much aggrieved at the imposition. The advertisement of Mr. Wm. Robertson, headed "Caution" and the reply by J. M. Hernandez, Esq. will be discontinued after this week, and no further altercation between the parties will be permitted thro' the medium of this Press.

The printed portions of this early issue include an installment of a "Historical Sketch of Florida," extracts from various newspapers, and among others the printer's own advertisements: "COMMERCIAL BLANKS, For Sale at this Office. Also, Blank Deeds, Mortgages, &c. &c." "Blank Bills of Lading, For Sale at the Gazette Office" and "BOOK AND JOB PRINTING, Of every description, executed at this Office." In this century the Library bound the 10 issues into a single volume. Those dated November 24 and December 1 are addressed in ink to the Department of State at Washington.

From the same year the Library of Congress holds 13 issues of The Floridian, published at Pensacola beginning August 18, some of which are also addressed to the Department of State. From this year, too, the Library possesses Ordinances, by Major-General Andrew Jackson, Governor of the Provinces of the Floridas, Exercising the Powers of the Captain-General, and of the Intendant of the Island of Cuba, Over the Said Provinces, and of the Governors of Said Provinces Respectively, printed at St.[Pg 28] Augustine by Edes. This pamphlet-sized volume was advertised as "just published" in the September 15 issue of the Florida Gazette; and the Library's copy, one of two extant,[35] was autographed twice by "John Rodman Esquire" at St. Augustine. Since he once added the designation "Collector" to his name, he is readily identified as the person who placed the following announcement in the November 24 issue of the Gazette: "JOHN RODMAN, Attorney & Counsellor at Law, May be consulted on professional business, at his Office in the Custom-House."

[34] See Douglas C. McMurtrie, "The Beginnings of Printing in Florida," in The Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 23 (1944-45), p. [63]-96.

[35] See no. 36 in Thomas W. Streeter's Americana—Beginnings (Morristown, N.J., 1952).

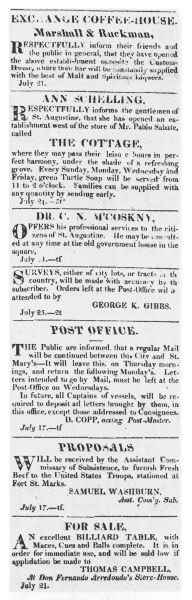

Benjamin Titcomb and Thomas B. Wait introduced printing in the District of Maine, then part of Massachusetts, with the first issue of The Falmouth Gazette and Weekly Advertiser, dated January 1, 1785. Titcomb was a native of Falmouth, now Portland, who had gained his experience at Newburyport, and Wait was formerly employed at Boston.[36]

The Library of Congress possesses nine issues of The Falmouth Gazette from this first year of printing in Maine. Of these the earliest is a partly mutilated copy of the second issue, dated January 8 and featuring a moralistic essay "On Entrance into Life, and the Conduct of early Manhood." This issue contains one piece of news, relayed from a Boston paper, that has importance for American printing history, namely, the arrival in this country from Ireland, "that land of gudgeons," of Mathew Carey, destined to become a leading printer and publisher at Philadelphia. Since the Library of Congress copy is inscribed "Messrs Adams & Nourse printers," it is interesting to note that one of the Falmouth news items was reprinted in their Boston paper, The Independent Chronicle, for January 20. Similarly, the Library's copy of the August 13 issue of the Gazette is addressed in manuscript to the famous printer Isaiah Thomas at Worcester, and it retains his editorial markings for the reprinting of two sections—a news item and a poem on atheism—that subsequently appeared in the September 1 and September 8 issues of Thomas's Massachusetts Spy; or, The Worcester Gazette. It was largely by means of just such borrowing amongst themselves that most early American newspapers were put together.

Four of the Library's nine issues, including the Isaiah Thomas copy, were purchased from Goodspeed's Book Shop for $13.50 in 1939. Four of the remaining five, including the very earliest, appear from their physical condition to have a common provenance. The five were listed initially in the 1936 edition of A Checklist of American Eighteenth-Century Newspapers in the Library of Congress.[37]

[36] See R. Webb Noyes, A Bibliography of Maine Imprints to 1820 (Stonington, Maine, 1930), p. 7.

[37] The preface to this edition is dated June 1, 1935. A sixth issue of the Gazette (March 5) listed here was later replaced by a better copy from the 1939 purchase.

The printing history of Kentucky begins with the August 11, 1787, issue of a Lexington newspaper, The Kentucke Gazette. John Bradford of Fauquier County, Va., established this paper in partnership with his younger brother, Fielding. They purchased their press at Philadelphia in the spring of 1787 and transported it to Lexington by way of Pittsburgh, where the first press to cross the Alleghenies had been active since the preceding summer.[38]

The earliest Kentucky imprint in the Library of Congress is The Kentucke Gazette for March 1, 1788. Like five other issues of the paper, available at the Library in facsimile, this original issue opens with "Extracts from the journals of a convention begun and held for the district of Kentucky at Danville in the county of Mercer on the 17th day of September 1787." The extracts are resolutions looking towards the separation of Kentucky from Virginia, and the following one accounts for their publication in this paper:

[Resolved][39] That full opportunity may be given to the good people of exercising their right of suffrage on an occasion so interesting to them, each of the officers so holding elections, shall continue the same from day to day, for five days including the first day, and shall cause these resolutions to be read immediately preceeding the opening of the election at the door of the courthouse, or other convenient place; and that Mr. Bradford be requested to publish the same in his Kentucky Gazette, six weeks successively, immediately preceeding the time of holding said elections.

At a time for important decisions The Kentucke Gazette served as a means of airing different opinions on statehood, independence, and constitutional questions. A long second portion of this March 1 issue is an essay on liberty and equality signed by "Republicus." Critical of certain sections of the proposed Federal Constitution, he opposes a bicameral legislature, fears undue influence of the Congress over State elections, and denounces any condoning of slavery. The remainder of the issue includes an announcement of the ice breaking up on the Ohio River, a report of an Indian raid, and an advertisement in this vein: "I have been told that a certain Jordan Harris asserted in a public and very positive manner, that I had acknowledged myself a liar and a scoundrel in a letter to maj. Crittenden." The writer, Humphrey Marshall, concludes that if said letter is published, "the public will then see who is the liar and the scoundrel." This early issue bears the name of the subscriber Richard Eastin, one of the first justices of the peace in Jefferson County.[40]

The Library's only other examples of Kentucky printing from 1788 are eight additional issues of the Gazette, for November 8 through December 27, which have been detached from a bound volume and are still joined together. These belonged to Walter Carr, who was serving as a magistrate in Fayette County by 1792 and who in 1799 attended the convention to form the second constitution of Kentucky.[41] Nothing more can be ascertained about the acquisition of these holdings than that the March 1 issue is first listed in the 1912 edition and that the later issues are first listed in the 1936 edition of A Checklist of American Eighteenth-Century Newspapers in the Library of Congress.

[38] See J. Winston Coleman, Jr., John Bradford, Esq. (Lexington, Ky., 1950).

[39] Brackets in text.

[40] J. Stoddard Johnston, Memorial History of Louisville (Chicago and New York [pref. 1896]), vol. 2, p. 3.

[41] C. R. Staples, The History of Pioneer Lexington (Lexington, 1939), p. 78 and 151.

Late in 1790 Nathaniel Willis, grandfather of the writer Nathaniel Parker Willis, established at Shepherdstown the first press within the present boundaries of West Virginia. For some years he had published The Independent Chronicle at Boston, and earlier in 1790 he had been printing at Winchester, Va. At Shepherdstown Willis published The Potowmac Guardian, and Berkeley Advertiser from November 1790 at least through December 1791.[42] By April 1792 he had moved to Martinsburg, where he continued publishing his newspaper under the same title.

The earliest example of West Virginia printing in the Library of Congress is a broadside printed at Martinsburg in 1792. Entitled Charter of the Town of Woodstock [Pa.], it consists of the printed text of a legal document in the name of one John Hopwood and dated November 8, 1791. The preamble of the document reveals its nature:

Whereas I John Hopwood, of Fayette-County, and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, have surveyed and laid out into convenient lots or parcels, for the purpose of erecting a Town thereon, the quantity of two hundred acres of land, being part of the tract of land on which I now live, situate in Union Township, and County aforesaid, on the great road leading from the Town of Union to Fort Cumberland, on the River Potowmack; and for the purpose of encouraging the settlement, growth, and prosperity of the said Town, as laid out agreeable to a plan and survey thereof, hereunto annexed and recorded, together with this instrument of writing, have determined to grant and confirm to all persons, who shall purchase or become proprietors of any lot or lots in the said Town, and to their heirs and assigns, certain privileges, benefits, and advantages herein after expressed and specified....

Access of the proposed town to the Potomac River is the clue to why this broadside relating to an otherwise remote location in Pennsylvania should have been printed in this part of West Virginia.

The Charter is the third recorded West Virginia imprint apart from newspaper issues, and the Library of Congress has the only known copy. Written on the verso is: Col. Morr[——] And other early hands have written there, "Hopwoods deeds" and "no body will have his Lotts."

At the Anderson Galleries sale of Americana held at New York on November 9, 1927, the presumed same copy of the Charter was sold from the library of Arthur DeLisle, M.D. (1851-1925), librarian of the Advocates' Library in Montreal.[43] It fetched $11. The Library of Congress obtained it in October 1935 from the Aldine Book Shop in Brooklyn for $35.

[42] The latest extant Shepherdstown issue of The Potowmac Guardian, for December 27, 1791, is reported in Clarence S. Brigham, Additions and Corrections to History and Bibliography of American Newspapers 1690-1820 (Worcester, Mass., 1961), p. 50.

[43] According to his obituary in the Montreal newspaper La Presse, December 22, 1925, Arthur DeLisle obtained a degree in medicine but never practiced that profession. "M. DeLisle s'intéressait vivement à toutes les choses de l'histoire et, par des recherches patientes et continues il fit de la bibliothèque du Barreau ce qu'elle est aujourd'hui, l'enrichissant sans cesse de livres et de documents précieux relatifs à l'histoire du droit, ainsi qu'à la biographie des juges et des avocats de Montréal depuis 1828."

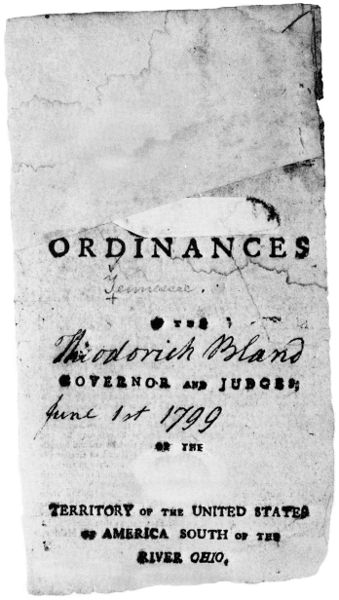

The printers George Roulstone and Robert Ferguson introduced the first Tennessee printing at Hawkins Court House, now Rogersville, with the November 5, 1791, issue of The Knoxville Gazette. Both men came to the Tennessee country, or Southwest Territory, by way of North Carolina. Their newspaper remained at Hawkins Court House until October 1792, while Knoxville, chosen as the seat of the Territorial government, was being constructed.

The earliest Tennessee imprint in the Library of Congress is probably the eight-page official publication entitled Acts and Ordinances of the Governor and Judges, of the Territory of the United States of America South of the River Ohio, which according to Douglas C. McMurtrie "was certainly printed by Roulstone at Knoxville in 1793, though it bears no imprint to this effect."[44] Its contents, relating principally to the definition of separate judicial districts within the Territory, are dated from June 11, 1792, to March 21, 1793, and the printing could have been accomplished soon after the latter date.

The Library of Congress copy is one of those afterwards prefixed to and issued with a much more extensive work printed by Roulstone in 1794: Acts Passed at the First Session of the General Assembly of the Territory of the United States of America, South of the River Ohio, Began and Held at Knoxville, on[Pg 35] Monday the Twenty-Fifth Day of August, M,DCC,XCIV. The Library's volume lost its 1794 title page at an early date, and it is the exposed second leaf, the title page of 1793, that bears the inscription, "Theodorick Bland June 1st 1799." Theodorick Bland (1777-1846) was to be chancellor of Maryland for many years. His correspondence preserved by the Maryland Historical Society reveals that he practiced law in Tennessee from 1798 to 1801. From such evidence as its Library of Congress bookplate, the volume would appear to have entered the Library around the late 1870's.

The earliest dated example of Tennessee printing in the Library is the Knoxville Gazette for June 1, 1793, issued a month after Ferguson retired from the paper. The issue begins with a lengthy selection by Benjamin Franklin, which is prefaced in this way:

Messrs. Printers,

I beg you to publish in your next number of the Knoxville Gazette, the following extracts, from a narrative of the massacres in Lancaster county, Pennsylvania; of a number of friendly Indians, by persons unknown; written by the late Dr. Benjamin Franklin, whose many benevolent acts, will immortalize his memory, and published in a British Magazine,[45] in April 1764.

The subscriber was undoubtedly William Blount, the Territorial Governor appointed by President Washington in 1790, who perhaps hoped that the sympathy towards Indians expressed by Franklin might temper public reaction against Indian raids figuring so large in the local news. Readers of the same June 1 issue learned of such crimes as the scalping of a child near Nashville, and they may have been moved by the following paragraph which the editor interjected in the news reports:

The Creek nation must be destroyed, or the south western frontiers, from the mouth of St. Mary's to the western extremities of Kentucky and Virginia, will be incessantly harassed by them; and now is the time. [Delenda est Carthago.][46]

Both this issue and the June 15 issue, the sole Library of Congress holdings of the Gazette for the year 1793, are inscribed "Claiborne Watkins, esqr." They probably belonged to the person of that name residing in Washington County, Va., who served as a presidential elector in 1792.[47]

[44] Early Printing in Tennessee (Chicago, 1933), p. 21.

[45] The Gentleman's Magazine. Franklin's A Narrative of the Late Massacres was published separately at Philadelphia in the same year.

[46] Brackets in text. Several issues carried this paragraph. See William Rule, ed. Standard History of Knoxville, Tennessee (Chicago, 1900), p. 74.

[47] See Calendar of Virginia State Papers, vol. 6 (1886), p. 140.

William Maxwell of New York, after failing to establish himself at Lexington, Ky., moved on to Cincinnati in the Northwest Territory and thereby became the first Ohio printer. His work at Cincinnati began with the November 9, 1793, issue of his newspaper, The Centinel of the North-Western Territory.[48]

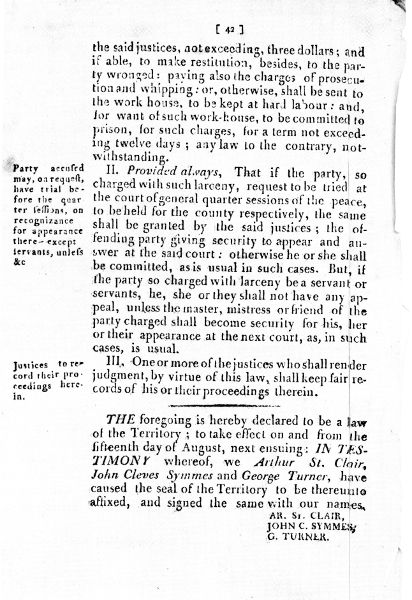

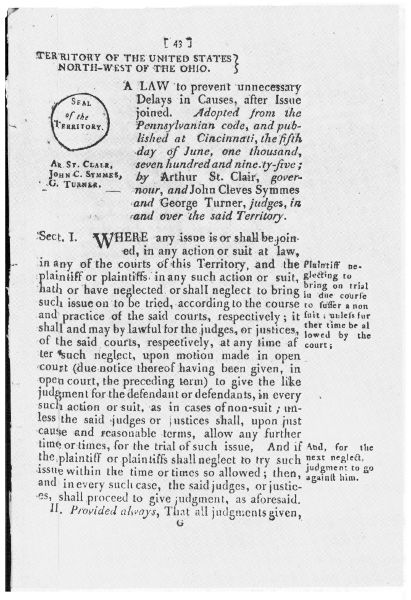

The earliest known Ohio book, also printed by Maxwell, is the earliest example of Ohio printing to be found at the Library of Congress: Laws of the Territory of the United States North-West of the Ohio: Adopted and Made by the Governour and Judges, in Their Legislative Capacity, at a Session Begun on Friday, the XXIX Day of May, One Thousand, Seven Hundred and Ninety-Five, and Ending on Tuesday the Twenty-Fifth Day of August Following.... Dated 1796, "Maxwell's Code," as this book is sometimes called, was not the first publication of Northwest Territory laws, others having been printed at Philadelphia in 1792 and 1794.

The printer set forth a "Proposal" concerning the forthcoming work in the Centinel of July 25, 1795:

W. Maxwell being appointed by the legislature to print for them 200 copies of their laws, he thinks it would be greatly conducive towards the instruction and common benefit of all the citizens to extend the impression to 1000 copies.... The price, in boards, to subscribers, will be at the rate of nineteen cents for every 50 pages, and to non-subscribers, thirty cents.[49]

He completed the volume in 225 pages, with numerous printed sidenotes that make it easy to consult. An incidental reference to printing occurs in a law for land partition (p. 185-197) which states that land proprietors "may subscribe a writing, and publish the same in one or more of the public News-papers printed in the Territory, in the State of Kentucky, and at the seat of government of the United States, for twelve successive weeks" in order to announce the appointment of commissioners to divide their property into lots. Subsequently,[Pg 37] advertisements were to be placed in the newspapers for six weeks to announce a balloting or drawing for the subdivided lots.

The Library of Congress owns two copies of this Cincinnati imprint. One, lacking the title page and final leaf, is bound in a volume of unknown provenance, possibly obtained about 1912, containing four early editions of Northwest Territory laws. The other is a separate copy, lacking the last three leaves. This more interesting copy has two inscriptions on its title page, the words written uppermost posing some difficulty: "Ex Biblioth[eca] Sem[inari]i [——] S[anc]ti Sulp[icii] Baltimoriensis"; but they make clear that this copy once belonged to the Sulpician seminary founded at Baltimore in 1791 and now named St. Mary's Seminary. A number of similarly inscribed books still retained by the seminary were once part of a special faculty library that merged with the regular seminary library about 1880. Many books from the faculty library bear signatures of individual priests who were their original owners. Thus the second inscription "Dilhet" refers to Jean Dilhet (1753-1811), a Sulpician who spent nine years in this country and was assigned to the pastorate of Raisin River (then in the Northwest Territory, in what is now Monroe County, Mich.) from 1798 to 1804. During 1804 and 1805 he worked in Detroit with Father Richard, who later established a press there (see next section).[50] Its absence from the Library's early catalogs implies that the present copy was acquired sometime after 1875. Two date stamps indicate that the Library had it rebound twice, in 1904 and 1947.

[48] See Douglas C. McMurtrie, Pioneer Printing in Ohio (Cincinnati, 1943).

[49] Quoted from Historical Records Survey, American Imprints Inventory, no. 17, A Check List of Ohio Imprints 1796-1820 (Columbus, 1941), p. 21.

[50] See the short biography of Dilhet in the preface to his Etat de l'église catholique ou Diocèse des Etats-Unis de l'Amérique septentrionale.... Translated and annotated by Rev. P. W. Browne (Washington, D.C., 1922).

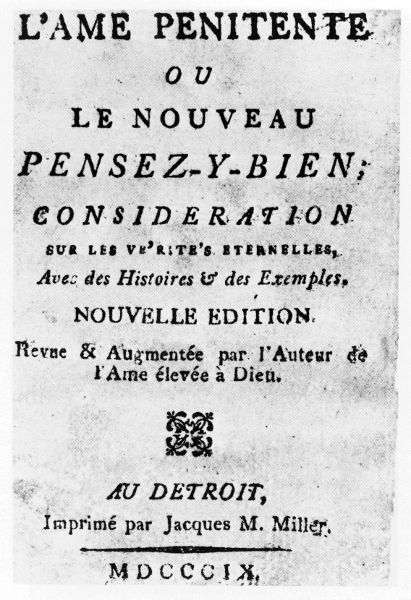

In 1796 John McCall, the earliest printer active in Michigan, issued at Detroit a 16-page Act of Congress relating to Indian affairs. Apart from blank forms printed on the same press before its removal to Canada in 1800, no other specimens of Michigan printing survive antedating the press that Father Gabriel Richard, the influential Sulpician priest, established at Detroit in 1809.

Entry number 2 in the Preliminary Check List of Michigan Imprints 1796-1850 (Detroit, 1942)[51] describes a 12-page publication said to exist in a unique copy at the Library of Congress: To the Honourable the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States. Memorial of the citizens of the United States, situated north of an east and west line, extending thro' the southward bend of Lake Michigan, and by the Act of Congress of 30th April 1802 attached to, and made part of the Indiana Territory ... ([Detroit? 1802?]). This entry is, in bibliographical parlance, a ghost. Actually, the Library of Congress possesses the work only as a negative photostat of a manuscript document which is preserved at the National Archives.[52]

The earliest bona fide Michigan imprint in the Library of Congress is L'Ame penitente ou Le nouveau pensez-y-bien; consideration sur les ve'rite's eternelles, avec des histoires & des exemples ... printed at Detroit in 1809. The printer, James M. Miller, of Utica, N. Y., was the first of three operators of Father Richard's press. This particular imprint is the fourth item in a standard bibliography of the press, which calls it "the first book of more than 24 pages printed in Detroit or Michigan."[53] As a matter of fact, it is a very substantial work of 220 pages, albeit in a small duodecimo format. It is a reprint of a devotional book first published in France in the 18th century and attributed to a prolific Jesuit author, Barthélemy Baudrand (1701-87). As head of the Catholic Church in the area, Father Richard wanted to make such religious literature available to the largely French-speaking inhabitants.

The Library of Congress copy of L'Ame penitente, in a speckled calf binding of uncertain date, was obtained through a 1954 exchange with Edward Eberstadt & Sons. It had been offered in one of the bookselling firm's catalogs earlier that year for $500.[54]

[51] Historical Records Survey, American Imprints Inventory, no. 52.

[52] The original is in Record Group 46 at the National Archives; the Library's photostat is in the Manuscript Division. The imaginary imprint recurs as no. 3168 in American Bibliography, a Preliminary Checklist for 1802, comp. by Ralph R. Shaw and Richard H. Shoemaker (New York, 1958).

[53] A. H. Greenly, A Bibliography of Father Richard's Press in Detroit (Ann Arbor, 1955).

[54] Catalogue 134, no. 392. Two years later the same firm offered another copy for $750, in its Catalogue 138, no. 428.

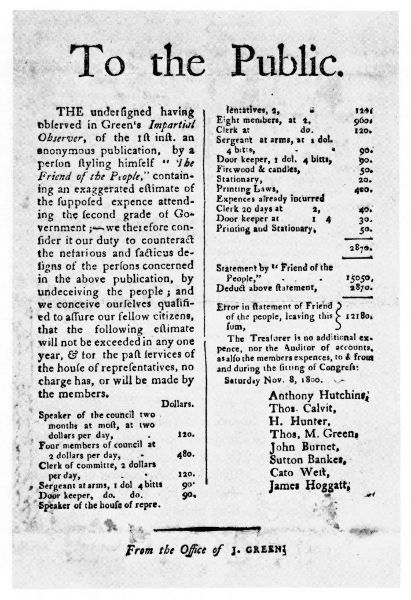

Mississippi's first printer was Andrew Marschalk of New York, an Army lieutenant stationed at Walnut Hills, close to the eventual site of Vicksburg.[55] There, probably in 1798, he attracted attention by printing a ballad on a small press he had acquired in London. At the request of Governor Winthrop Sargent, Marschalk undertook in 1799 to print the laws of Mississippi Territory, and for that purpose he built a larger press at Natchez. Late in 1799 a second printer, Ben M. Stokes, purchased this press from Marschalk and soon commenced a weekly paper, The Mississippi Gazette. On May 5, 1800, James Green, a printer from Baltimore, introduced a rival paper at Natchez, Green's Impartial Observer.